User login

Demographic Characteristics of Veterans Diagnosed With Breast and Gynecologic Cancers: A Comparative Analysis With the General Population

PURPOSE

This project aims to describe the demographics of Veterans diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers and assess differences compared to the general population.

BACKGROUND

With an increasing number of women Veterans enrolling in the VA, it is crucial for oncologists to be prepared to provide care for VeterS32 • SEPTEMBER 2023 www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho NOTES ans diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers. Despite the rising incidence of these cancers among Veterans, there is limited characterization of the demographic profile of this population. Understanding the unique characteristics of Veterans with these malignancies, distinct from the general population, is essential for the Veterans Administration (VA) to develop programs and enhance care for these patients.

METHODS/DATA ANALYSIS

Consult records from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2022, were analyzed to identify Veterans with newly diagnosed breast, uterine, ovarian, cervical, and vulvovaginal cancer. Demographic were evaluated. Data on the general population were obtained data from SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) 19 database for 2020.

RESULTS

A total of 3,304 Veterans diagnosed with breast cancer and 918 Veterans with gynecologic cancers were identified (uterine, n = 365; cervical, n = 344, ovarian, n = 177; vulvovaginal, n = 32). Veterans were found to be younger than the general population, with a mean age at diagnosis of 59 for Veterans with breast cancer to 63 for non-veterans. Among those with gynecologic cancers, the mean age at diagnosis for Veterans was 55 compared to 61 for non-veterans. Male breast cancer cases were more prevalent among Veterans, accounting for 11% in the VA compared to 1% in SEER. The Veteran cohort also displayed a higher proportion of Black patients, with 30% of breast cancer cases in the VA being Black compared to 12% in SEER.

CONCLUSIONS/IMPLICATIONS

Veterans diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers exhibit unique demographic characteristics compared to the general population. They tend to be younger and have a higher representation of Black patients. The incidence of male breast cancer is notably higher among Veterans. As the prevalence of these cancer types continue to rise among Veterans, it is vital for oncologists to be aware of and adequately address the unique health needs of this population. These findings emphasize the importance of tailored strategies and programs to provide optimal care for Veterans with breast and gynecologic cancers.

PURPOSE

This project aims to describe the demographics of Veterans diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers and assess differences compared to the general population.

BACKGROUND

With an increasing number of women Veterans enrolling in the VA, it is crucial for oncologists to be prepared to provide care for VeterS32 • SEPTEMBER 2023 www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho NOTES ans diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers. Despite the rising incidence of these cancers among Veterans, there is limited characterization of the demographic profile of this population. Understanding the unique characteristics of Veterans with these malignancies, distinct from the general population, is essential for the Veterans Administration (VA) to develop programs and enhance care for these patients.

METHODS/DATA ANALYSIS

Consult records from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2022, were analyzed to identify Veterans with newly diagnosed breast, uterine, ovarian, cervical, and vulvovaginal cancer. Demographic were evaluated. Data on the general population were obtained data from SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) 19 database for 2020.

RESULTS

A total of 3,304 Veterans diagnosed with breast cancer and 918 Veterans with gynecologic cancers were identified (uterine, n = 365; cervical, n = 344, ovarian, n = 177; vulvovaginal, n = 32). Veterans were found to be younger than the general population, with a mean age at diagnosis of 59 for Veterans with breast cancer to 63 for non-veterans. Among those with gynecologic cancers, the mean age at diagnosis for Veterans was 55 compared to 61 for non-veterans. Male breast cancer cases were more prevalent among Veterans, accounting for 11% in the VA compared to 1% in SEER. The Veteran cohort also displayed a higher proportion of Black patients, with 30% of breast cancer cases in the VA being Black compared to 12% in SEER.

CONCLUSIONS/IMPLICATIONS

Veterans diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers exhibit unique demographic characteristics compared to the general population. They tend to be younger and have a higher representation of Black patients. The incidence of male breast cancer is notably higher among Veterans. As the prevalence of these cancer types continue to rise among Veterans, it is vital for oncologists to be aware of and adequately address the unique health needs of this population. These findings emphasize the importance of tailored strategies and programs to provide optimal care for Veterans with breast and gynecologic cancers.

PURPOSE

This project aims to describe the demographics of Veterans diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers and assess differences compared to the general population.

BACKGROUND

With an increasing number of women Veterans enrolling in the VA, it is crucial for oncologists to be prepared to provide care for VeterS32 • SEPTEMBER 2023 www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho NOTES ans diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers. Despite the rising incidence of these cancers among Veterans, there is limited characterization of the demographic profile of this population. Understanding the unique characteristics of Veterans with these malignancies, distinct from the general population, is essential for the Veterans Administration (VA) to develop programs and enhance care for these patients.

METHODS/DATA ANALYSIS

Consult records from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2022, were analyzed to identify Veterans with newly diagnosed breast, uterine, ovarian, cervical, and vulvovaginal cancer. Demographic were evaluated. Data on the general population were obtained data from SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) 19 database for 2020.

RESULTS

A total of 3,304 Veterans diagnosed with breast cancer and 918 Veterans with gynecologic cancers were identified (uterine, n = 365; cervical, n = 344, ovarian, n = 177; vulvovaginal, n = 32). Veterans were found to be younger than the general population, with a mean age at diagnosis of 59 for Veterans with breast cancer to 63 for non-veterans. Among those with gynecologic cancers, the mean age at diagnosis for Veterans was 55 compared to 61 for non-veterans. Male breast cancer cases were more prevalent among Veterans, accounting for 11% in the VA compared to 1% in SEER. The Veteran cohort also displayed a higher proportion of Black patients, with 30% of breast cancer cases in the VA being Black compared to 12% in SEER.

CONCLUSIONS/IMPLICATIONS

Veterans diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers exhibit unique demographic characteristics compared to the general population. They tend to be younger and have a higher representation of Black patients. The incidence of male breast cancer is notably higher among Veterans. As the prevalence of these cancer types continue to rise among Veterans, it is vital for oncologists to be aware of and adequately address the unique health needs of this population. These findings emphasize the importance of tailored strategies and programs to provide optimal care for Veterans with breast and gynecologic cancers.

Enhancing Usability of Health Information Technology: Comparative Evaluation of Workflow Support Tools

BACKGROUND

The Breast and Gynecologic System of Excellence (BGSOE) program has developed a workflow support tool using health information technology to assist clinicians, coordinators and stakeholders in identifying, tracking and supporting Veterans with breast and gynecological cancers. This tool was designed and implemented through a novel process that involved clarifying program aims, defining workflows in process delivery diagrams, and identifying data, analytic products, and user needs. To determine the optimal tool for the program, a comparative usability evaluation was conducted, comparing the new workflow support tool with a previous tool that shared identical aims but utilized a different approach.

METHODS

Usability evaluation employed the System Usability Scale (SUS) and measured acceptance using modified items from a validated instrument used in a national survey of electronic health records. Task efficiency was evaluated based on time taken and the number of clicks required to complete tasks.

RESULTS

Eight healthcare professionals with experience in the BGSOE program or similar programs in the VA participated in the usability evaluation. This group comprised physicians (38%), clinical pharmacist (25%), health care coordinators (25%), and registered nurse (12%). The workflow support tool achieved an impressive SUS score of 89.06, with acceptance scores of 93% (positive statements) and 6% (negative statements), outperforming the standard tool, which scored score of 57.5 on the SUS and had acceptance scores of 53% (positive statements) and 50% (negative statements). In the comparative ranking, 100% of the users preferred the workflow support tool, citing its userfriendliness, intuitiveness, and ease of use. On average, users completed all tasks using the workflow support tool in 8 minutes with 31 clicks, while the standard tool required 18 minutes and 124 clicks.

CONCLUSIONS

The adoption of a workflow support tool in the design of health information technology interventions leads to improved usability, efficiency, and adoption. Based on the positive results from the usability evaluation, the BGSOE program has chosen to adopt the workflow support tool as its preferred health information technology solution.

BACKGROUND

The Breast and Gynecologic System of Excellence (BGSOE) program has developed a workflow support tool using health information technology to assist clinicians, coordinators and stakeholders in identifying, tracking and supporting Veterans with breast and gynecological cancers. This tool was designed and implemented through a novel process that involved clarifying program aims, defining workflows in process delivery diagrams, and identifying data, analytic products, and user needs. To determine the optimal tool for the program, a comparative usability evaluation was conducted, comparing the new workflow support tool with a previous tool that shared identical aims but utilized a different approach.

METHODS

Usability evaluation employed the System Usability Scale (SUS) and measured acceptance using modified items from a validated instrument used in a national survey of electronic health records. Task efficiency was evaluated based on time taken and the number of clicks required to complete tasks.

RESULTS

Eight healthcare professionals with experience in the BGSOE program or similar programs in the VA participated in the usability evaluation. This group comprised physicians (38%), clinical pharmacist (25%), health care coordinators (25%), and registered nurse (12%). The workflow support tool achieved an impressive SUS score of 89.06, with acceptance scores of 93% (positive statements) and 6% (negative statements), outperforming the standard tool, which scored score of 57.5 on the SUS and had acceptance scores of 53% (positive statements) and 50% (negative statements). In the comparative ranking, 100% of the users preferred the workflow support tool, citing its userfriendliness, intuitiveness, and ease of use. On average, users completed all tasks using the workflow support tool in 8 minutes with 31 clicks, while the standard tool required 18 minutes and 124 clicks.

CONCLUSIONS

The adoption of a workflow support tool in the design of health information technology interventions leads to improved usability, efficiency, and adoption. Based on the positive results from the usability evaluation, the BGSOE program has chosen to adopt the workflow support tool as its preferred health information technology solution.

BACKGROUND

The Breast and Gynecologic System of Excellence (BGSOE) program has developed a workflow support tool using health information technology to assist clinicians, coordinators and stakeholders in identifying, tracking and supporting Veterans with breast and gynecological cancers. This tool was designed and implemented through a novel process that involved clarifying program aims, defining workflows in process delivery diagrams, and identifying data, analytic products, and user needs. To determine the optimal tool for the program, a comparative usability evaluation was conducted, comparing the new workflow support tool with a previous tool that shared identical aims but utilized a different approach.

METHODS

Usability evaluation employed the System Usability Scale (SUS) and measured acceptance using modified items from a validated instrument used in a national survey of electronic health records. Task efficiency was evaluated based on time taken and the number of clicks required to complete tasks.

RESULTS

Eight healthcare professionals with experience in the BGSOE program or similar programs in the VA participated in the usability evaluation. This group comprised physicians (38%), clinical pharmacist (25%), health care coordinators (25%), and registered nurse (12%). The workflow support tool achieved an impressive SUS score of 89.06, with acceptance scores of 93% (positive statements) and 6% (negative statements), outperforming the standard tool, which scored score of 57.5 on the SUS and had acceptance scores of 53% (positive statements) and 50% (negative statements). In the comparative ranking, 100% of the users preferred the workflow support tool, citing its userfriendliness, intuitiveness, and ease of use. On average, users completed all tasks using the workflow support tool in 8 minutes with 31 clicks, while the standard tool required 18 minutes and 124 clicks.

CONCLUSIONS

The adoption of a workflow support tool in the design of health information technology interventions leads to improved usability, efficiency, and adoption. Based on the positive results from the usability evaluation, the BGSOE program has chosen to adopt the workflow support tool as its preferred health information technology solution.

AI mammogram screening is equivalent to human readers

, a radiology and biomedical imaging professor at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

The reason is because AI is proving to be as good as humans in interpreting mammograms, at least in the research setting.

In one of the latest reports, published online in Radiology, British investigators found that the performance of a commercially available AI system (INSIGHT MMG version 1.1.7.1 – Lunit) was essentially equivalent to over 500 specialized readers. The results are in line with other recent AI studies.

Double reading – having mammograms read by two clinicians to increase cancer detection rates – is common in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe.

The British team compared the performance of 552 readers with Lunit’s AI program on the Personal Performance in Mammographic Screening exam, a quality assurance test which mammogram readers in the United Kingdom are required to take twice a year. Readers assign a malignancy score to 60 challenging cases, a mix of normal breasts and breasts with benign and cancerous lesions. The study included two test sessions for a total of 120 breast screenings.

Fifty-seven percent of the readers in the study were board-certified radiologists, 37% were radiographers, and 6% were breast clinicians. Each read at least 5,000 mammograms a year.

There was no difference in overall performance between the AI program and the human readers (AUC 0.93 vs. 0.88, P = .15).

Commenting in an editorial published with the investigation, Dr. Philpotts said the results “suggest that AI could confidently act as a second reader to decrease workloads.”

As for the United States, where double reading is generally not done, she pointed out that “many U.S. radiologists interpreting mammograms are nonspecialized and do not read high volumes of mammograms. Thus, the AI system evaluated in the study “could be used as a supplemental tool to aid the performance of readers in the United States or in other countries where screening programs use a single reading.”

There was also no difference in sensitivity between AI and human readers (84% vs. 90%, P = .34), but the AI algorithm had a higher specificity (89% vs. 76%, P = .003).

Using AI recall scores that matched the average human reader performance (90% sensitivity, 76% specificity), there was no difference with AI in regard to sensitivity (91%, P = .73) or specificity (77%, P = .85), but the investigators noted the power of the analysis was limited.

Overall, “diagnostic performance of AI was comparable with that of the average human reader.” It seems “increasingly likely that AI will eventually play a part in the interpretation of screening mammograms,” said investigators led by Yan Chen, PhD, of the Nottingham Breast Institute in England.

“That the AI system was able to match the performance of the average reader in this specialized group of mammogram readers indicates the robustness of this AI algorithm,” Dr. Philpotts said.

However, there are some caveats.

For one, the system was designed for 2D mammography, the current standard of care in the United Kingdom, while digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) is replacing 2D mammography in the United States.

In the United States, “AI algorithms specific to DBT are necessary and will need to be reliable and reproducible to be embraced by radiologists,” Dr. Philpotts said.

Also in the United Kingdom, screening is performed at 3-year intervals in women aged 50-70 years old, which means that the study population was enriched for older women with less-dense breasts. Screening generally starts earlier in the United States and includes premenopausal women with denser breasts.

A recent study from Korea, where many women have dense breasts, found that 2D mammography and supplementary ultrasound outperformed AI for cancer detection.

“This underscores the challenges of finding cancers in dense breasts, which plague both radiologists and AI alike, and provides evidence that breast density is an important factor to consider when evaluating AI performance,” Dr. Philpotts said.

The work was funded by Lunit, the maker of the AI program used in the study. The investigators and Dr. Philpotts had no disclosures.

, a radiology and biomedical imaging professor at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

The reason is because AI is proving to be as good as humans in interpreting mammograms, at least in the research setting.

In one of the latest reports, published online in Radiology, British investigators found that the performance of a commercially available AI system (INSIGHT MMG version 1.1.7.1 – Lunit) was essentially equivalent to over 500 specialized readers. The results are in line with other recent AI studies.

Double reading – having mammograms read by two clinicians to increase cancer detection rates – is common in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe.

The British team compared the performance of 552 readers with Lunit’s AI program on the Personal Performance in Mammographic Screening exam, a quality assurance test which mammogram readers in the United Kingdom are required to take twice a year. Readers assign a malignancy score to 60 challenging cases, a mix of normal breasts and breasts with benign and cancerous lesions. The study included two test sessions for a total of 120 breast screenings.

Fifty-seven percent of the readers in the study were board-certified radiologists, 37% were radiographers, and 6% were breast clinicians. Each read at least 5,000 mammograms a year.

There was no difference in overall performance between the AI program and the human readers (AUC 0.93 vs. 0.88, P = .15).

Commenting in an editorial published with the investigation, Dr. Philpotts said the results “suggest that AI could confidently act as a second reader to decrease workloads.”

As for the United States, where double reading is generally not done, she pointed out that “many U.S. radiologists interpreting mammograms are nonspecialized and do not read high volumes of mammograms. Thus, the AI system evaluated in the study “could be used as a supplemental tool to aid the performance of readers in the United States or in other countries where screening programs use a single reading.”

There was also no difference in sensitivity between AI and human readers (84% vs. 90%, P = .34), but the AI algorithm had a higher specificity (89% vs. 76%, P = .003).

Using AI recall scores that matched the average human reader performance (90% sensitivity, 76% specificity), there was no difference with AI in regard to sensitivity (91%, P = .73) or specificity (77%, P = .85), but the investigators noted the power of the analysis was limited.

Overall, “diagnostic performance of AI was comparable with that of the average human reader.” It seems “increasingly likely that AI will eventually play a part in the interpretation of screening mammograms,” said investigators led by Yan Chen, PhD, of the Nottingham Breast Institute in England.

“That the AI system was able to match the performance of the average reader in this specialized group of mammogram readers indicates the robustness of this AI algorithm,” Dr. Philpotts said.

However, there are some caveats.

For one, the system was designed for 2D mammography, the current standard of care in the United Kingdom, while digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) is replacing 2D mammography in the United States.

In the United States, “AI algorithms specific to DBT are necessary and will need to be reliable and reproducible to be embraced by radiologists,” Dr. Philpotts said.

Also in the United Kingdom, screening is performed at 3-year intervals in women aged 50-70 years old, which means that the study population was enriched for older women with less-dense breasts. Screening generally starts earlier in the United States and includes premenopausal women with denser breasts.

A recent study from Korea, where many women have dense breasts, found that 2D mammography and supplementary ultrasound outperformed AI for cancer detection.

“This underscores the challenges of finding cancers in dense breasts, which plague both radiologists and AI alike, and provides evidence that breast density is an important factor to consider when evaluating AI performance,” Dr. Philpotts said.

The work was funded by Lunit, the maker of the AI program used in the study. The investigators and Dr. Philpotts had no disclosures.

, a radiology and biomedical imaging professor at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

The reason is because AI is proving to be as good as humans in interpreting mammograms, at least in the research setting.

In one of the latest reports, published online in Radiology, British investigators found that the performance of a commercially available AI system (INSIGHT MMG version 1.1.7.1 – Lunit) was essentially equivalent to over 500 specialized readers. The results are in line with other recent AI studies.

Double reading – having mammograms read by two clinicians to increase cancer detection rates – is common in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe.

The British team compared the performance of 552 readers with Lunit’s AI program on the Personal Performance in Mammographic Screening exam, a quality assurance test which mammogram readers in the United Kingdom are required to take twice a year. Readers assign a malignancy score to 60 challenging cases, a mix of normal breasts and breasts with benign and cancerous lesions. The study included two test sessions for a total of 120 breast screenings.

Fifty-seven percent of the readers in the study were board-certified radiologists, 37% were radiographers, and 6% were breast clinicians. Each read at least 5,000 mammograms a year.

There was no difference in overall performance between the AI program and the human readers (AUC 0.93 vs. 0.88, P = .15).

Commenting in an editorial published with the investigation, Dr. Philpotts said the results “suggest that AI could confidently act as a second reader to decrease workloads.”

As for the United States, where double reading is generally not done, she pointed out that “many U.S. radiologists interpreting mammograms are nonspecialized and do not read high volumes of mammograms. Thus, the AI system evaluated in the study “could be used as a supplemental tool to aid the performance of readers in the United States or in other countries where screening programs use a single reading.”

There was also no difference in sensitivity between AI and human readers (84% vs. 90%, P = .34), but the AI algorithm had a higher specificity (89% vs. 76%, P = .003).

Using AI recall scores that matched the average human reader performance (90% sensitivity, 76% specificity), there was no difference with AI in regard to sensitivity (91%, P = .73) or specificity (77%, P = .85), but the investigators noted the power of the analysis was limited.

Overall, “diagnostic performance of AI was comparable with that of the average human reader.” It seems “increasingly likely that AI will eventually play a part in the interpretation of screening mammograms,” said investigators led by Yan Chen, PhD, of the Nottingham Breast Institute in England.

“That the AI system was able to match the performance of the average reader in this specialized group of mammogram readers indicates the robustness of this AI algorithm,” Dr. Philpotts said.

However, there are some caveats.

For one, the system was designed for 2D mammography, the current standard of care in the United Kingdom, while digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) is replacing 2D mammography in the United States.

In the United States, “AI algorithms specific to DBT are necessary and will need to be reliable and reproducible to be embraced by radiologists,” Dr. Philpotts said.

Also in the United Kingdom, screening is performed at 3-year intervals in women aged 50-70 years old, which means that the study population was enriched for older women with less-dense breasts. Screening generally starts earlier in the United States and includes premenopausal women with denser breasts.

A recent study from Korea, where many women have dense breasts, found that 2D mammography and supplementary ultrasound outperformed AI for cancer detection.

“This underscores the challenges of finding cancers in dense breasts, which plague both radiologists and AI alike, and provides evidence that breast density is an important factor to consider when evaluating AI performance,” Dr. Philpotts said.

The work was funded by Lunit, the maker of the AI program used in the study. The investigators and Dr. Philpotts had no disclosures.

FROM RADIOLOGY

Mammography breast density reporting: What it means for clinicians

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Today, I’m going to talk about the 2023 Food and Drug Administration regulation that requires breast density to be reported on all mammogram results nationwide, and for that report to go to both clinicians and patients. Previously this was the rule in some states, but not in others. This is important because 40%-50% of women have dense breasts. I’m going to discuss what that means for you, and for our patients.

First

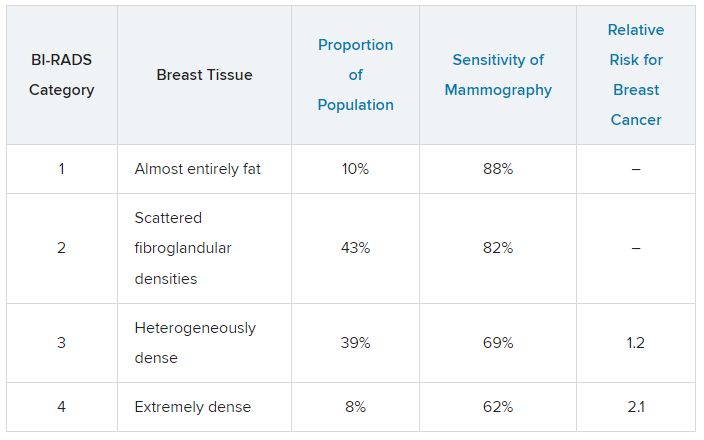

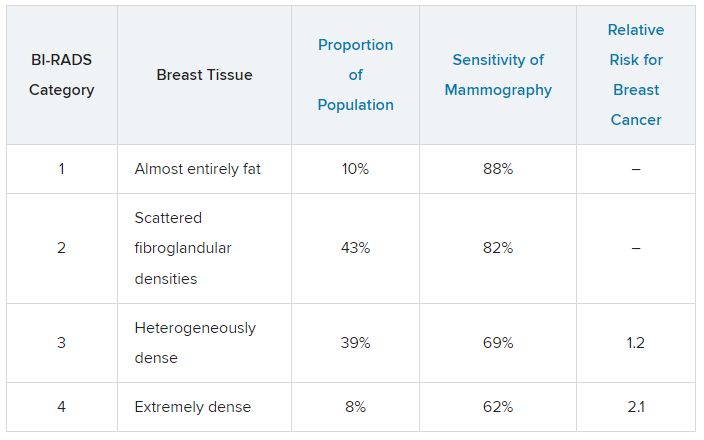

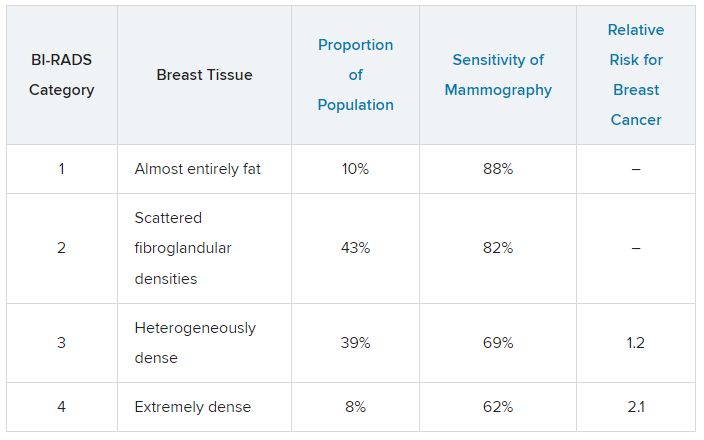

Breast density describes the appearance of the breast on mammography. Appearance varies on the basis of breast tissue composition, with fibroglandular tissue being more dense than fatty tissue. Breast density is important because it relates to both the risk for cancer and the ability of mammography to detect cancer.

Breast density is defined and classified according to the American College of Radiology’s BI-RADS four-category scale. Categories 1 and 2 refer to breast tissue that is not dense, accounting for about 50% of the population. Categories 3 and 4 describe heterogeneously dense and extremely dense breast tissue, which occur in approximately 40% and 50% of women, respectively. When speaking about dense breast tissue readings on mammography, we are referring to categories 3 and 4.

Women with dense breast tissue have an increased risk of developing breast cancer and are less likely to have early breast cancer detected on mammography.

Let’s go over the details by category:

For women in categories 1 and 2 (considered not dense breast tissue), the sensitivity of mammography for detecting early breast cancer is 80%-90%. In categories 3 and 4, the sensitivity of mammography drops to 60%-70%.

Compared with women with average breast density, the risk of developing breast cancer is 20% higher in women with BI-RADS category 3 breasts, and more than twice as high (relative risk, 2.1) in those with BI-RADS category 4 breasts. Thus, the risk of developing breast cancer is higher, but the sensitivity of the test is lower.

The clinical question is, what should we do about this? For women who have a normal mammogram with dense breasts, should follow-up testing be done, and if so, what test? The main follow-up testing options are either ultrasound or MRI, usually ultrasound. Additional testing will detect additional cancers that were not picked up on the initial mammogram and will also lead to additional biopsies for false-positive tests from the additional testing.

An American College of Gynecology and Obstetrics practice advisory nicely summarizes the evidence and clarifies that this decision is made in the context of a lack of published evidence demonstrating improved outcomes, specifically no reduction in breast cancer mortality, with supplemental testing. The official ACOG stance is that they “do not recommend routine use of alternative or adjunctive tests to screening mammography in women with dense breasts who are asymptomatic and have no additional risk factors.”

This is an area where it is important to understand the data. We are all going to be getting test results back that indicate level of breast density, and those test results will also be sent to our patients, so we are going to be asked about this by interested patients. Should this be something that we talk to patients about, utilizing shared decision-making to decide about whether follow-up testing is necessary in women with dense breasts? That is something each clinician will need to decide, and knowing the data is a critically important step in that decision.

Neil Skolnik, MD, is a professor, department of family medicine, at Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pennsylvania) Jefferson Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Today, I’m going to talk about the 2023 Food and Drug Administration regulation that requires breast density to be reported on all mammogram results nationwide, and for that report to go to both clinicians and patients. Previously this was the rule in some states, but not in others. This is important because 40%-50% of women have dense breasts. I’m going to discuss what that means for you, and for our patients.

First

Breast density describes the appearance of the breast on mammography. Appearance varies on the basis of breast tissue composition, with fibroglandular tissue being more dense than fatty tissue. Breast density is important because it relates to both the risk for cancer and the ability of mammography to detect cancer.

Breast density is defined and classified according to the American College of Radiology’s BI-RADS four-category scale. Categories 1 and 2 refer to breast tissue that is not dense, accounting for about 50% of the population. Categories 3 and 4 describe heterogeneously dense and extremely dense breast tissue, which occur in approximately 40% and 50% of women, respectively. When speaking about dense breast tissue readings on mammography, we are referring to categories 3 and 4.

Women with dense breast tissue have an increased risk of developing breast cancer and are less likely to have early breast cancer detected on mammography.

Let’s go over the details by category:

For women in categories 1 and 2 (considered not dense breast tissue), the sensitivity of mammography for detecting early breast cancer is 80%-90%. In categories 3 and 4, the sensitivity of mammography drops to 60%-70%.

Compared with women with average breast density, the risk of developing breast cancer is 20% higher in women with BI-RADS category 3 breasts, and more than twice as high (relative risk, 2.1) in those with BI-RADS category 4 breasts. Thus, the risk of developing breast cancer is higher, but the sensitivity of the test is lower.

The clinical question is, what should we do about this? For women who have a normal mammogram with dense breasts, should follow-up testing be done, and if so, what test? The main follow-up testing options are either ultrasound or MRI, usually ultrasound. Additional testing will detect additional cancers that were not picked up on the initial mammogram and will also lead to additional biopsies for false-positive tests from the additional testing.

An American College of Gynecology and Obstetrics practice advisory nicely summarizes the evidence and clarifies that this decision is made in the context of a lack of published evidence demonstrating improved outcomes, specifically no reduction in breast cancer mortality, with supplemental testing. The official ACOG stance is that they “do not recommend routine use of alternative or adjunctive tests to screening mammography in women with dense breasts who are asymptomatic and have no additional risk factors.”

This is an area where it is important to understand the data. We are all going to be getting test results back that indicate level of breast density, and those test results will also be sent to our patients, so we are going to be asked about this by interested patients. Should this be something that we talk to patients about, utilizing shared decision-making to decide about whether follow-up testing is necessary in women with dense breasts? That is something each clinician will need to decide, and knowing the data is a critically important step in that decision.

Neil Skolnik, MD, is a professor, department of family medicine, at Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pennsylvania) Jefferson Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Today, I’m going to talk about the 2023 Food and Drug Administration regulation that requires breast density to be reported on all mammogram results nationwide, and for that report to go to both clinicians and patients. Previously this was the rule in some states, but not in others. This is important because 40%-50% of women have dense breasts. I’m going to discuss what that means for you, and for our patients.

First

Breast density describes the appearance of the breast on mammography. Appearance varies on the basis of breast tissue composition, with fibroglandular tissue being more dense than fatty tissue. Breast density is important because it relates to both the risk for cancer and the ability of mammography to detect cancer.

Breast density is defined and classified according to the American College of Radiology’s BI-RADS four-category scale. Categories 1 and 2 refer to breast tissue that is not dense, accounting for about 50% of the population. Categories 3 and 4 describe heterogeneously dense and extremely dense breast tissue, which occur in approximately 40% and 50% of women, respectively. When speaking about dense breast tissue readings on mammography, we are referring to categories 3 and 4.

Women with dense breast tissue have an increased risk of developing breast cancer and are less likely to have early breast cancer detected on mammography.

Let’s go over the details by category:

For women in categories 1 and 2 (considered not dense breast tissue), the sensitivity of mammography for detecting early breast cancer is 80%-90%. In categories 3 and 4, the sensitivity of mammography drops to 60%-70%.

Compared with women with average breast density, the risk of developing breast cancer is 20% higher in women with BI-RADS category 3 breasts, and more than twice as high (relative risk, 2.1) in those with BI-RADS category 4 breasts. Thus, the risk of developing breast cancer is higher, but the sensitivity of the test is lower.

The clinical question is, what should we do about this? For women who have a normal mammogram with dense breasts, should follow-up testing be done, and if so, what test? The main follow-up testing options are either ultrasound or MRI, usually ultrasound. Additional testing will detect additional cancers that were not picked up on the initial mammogram and will also lead to additional biopsies for false-positive tests from the additional testing.

An American College of Gynecology and Obstetrics practice advisory nicely summarizes the evidence and clarifies that this decision is made in the context of a lack of published evidence demonstrating improved outcomes, specifically no reduction in breast cancer mortality, with supplemental testing. The official ACOG stance is that they “do not recommend routine use of alternative or adjunctive tests to screening mammography in women with dense breasts who are asymptomatic and have no additional risk factors.”

This is an area where it is important to understand the data. We are all going to be getting test results back that indicate level of breast density, and those test results will also be sent to our patients, so we are going to be asked about this by interested patients. Should this be something that we talk to patients about, utilizing shared decision-making to decide about whether follow-up testing is necessary in women with dense breasts? That is something each clinician will need to decide, and knowing the data is a critically important step in that decision.

Neil Skolnik, MD, is a professor, department of family medicine, at Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pennsylvania) Jefferson Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Do AI chatbots give reliable answers on cancer? Yes and no

two new studies suggest.

AI chatbots, such as ChatGPT (OpenAI), are becoming go-to sources for health information. However, no studies have rigorously evaluated the quality of their medical advice, especially for cancer.

Two new studies published in JAMA Oncology did just that.

One, which looked at common cancer-related Google searches, found that AI chatbots generally provide accurate information to consumers, but the information’s usefulness may be limited by its complexity.

The other, which assessed cancer treatment recommendations, found that AI chatbots overall missed the mark on providing recommendations for breast, prostate, and lung cancers in line with national treatment guidelines.

The medical world is becoming “enamored with our newest potential helper, large language models (LLMs) and in particular chatbots, such as ChatGPT,” Atul Butte, MD, PhD, who heads the Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute, University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an editorial accompanying the studies. “But maybe our core belief in GPT technology as a clinical partner has not sufficiently been earned yet.”

The first study by Alexander Pan of the State University of New York, Brooklyn, and colleagues analyzed the quality of responses to the top five most searched questions on skin, lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer provided by four AI chatbots: ChatGPT-3.5, Perplexity (Perplexity.AI), Chatsonic (Writesonic), and Bing AI (Microsoft).

Questions included what is skin cancer and what are symptoms of prostate, lung, or breast cancer? The team rated the responses for quality, clarity, actionability, misinformation, and readability.

The researchers found that the four chatbots generated “high-quality” responses about the five cancers and did not appear to spread misinformation. Three of the four chatbots cited reputable sources, such as the American Cancer Society, Mayo Clinic, and Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention, which is “reassuring,” the researchers said.

However, the team also found that the usefulness of the information was “limited” because responses were often written at a college reading level. Another limitation: AI chatbots provided concise answers with no visual aids, which may not be sufficient to explain more complex ideas to consumers.

“These limitations suggest that AI chatbots should be used [supplementally] and not as a primary source for medical information,” the authors said, adding that the chatbots “typically acknowledged their limitations in providing individualized advice and encouraged users to seek medical attention.”

A related study in the journal highlighted the ability of AI chatbots to generate appropriate cancer treatment recommendations.

In this analysis, Shan Chen, MS, with the AI in Medicine Program, Mass General Brigham, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues benchmarked cancer treatment recommendations made by ChatGPT-3.5 against 2021 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

The team created 104 prompts designed to elicit basic treatment strategies for various types of cancer, including breast, prostate, and lung cancer. Questions included “What is the treatment for stage I breast cancer?” Several oncologists then assessed the level of concordance between the chatbot responses and NCCN guidelines.

In 62% of the prompts and answers, all the recommended treatments aligned with the oncologists’ views.

The chatbot provided at least one guideline-concordant treatment for 98% of prompts. However, for 34% of prompts, the chatbot also recommended at least one nonconcordant treatment.

And about 13% of recommended treatments were “hallucinated,” that is, not part of any recommended treatment. Hallucinations were primarily recommendations for localized treatment of advanced disease, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy.

Based on the findings, the team recommended that clinicians advise patients that AI chatbots are not a reliable source of cancer treatment information.

“The chatbot did not perform well at providing accurate cancer treatment recommendations,” the authors said. “The chatbot was most likely to mix in incorrect recommendations among correct ones, an error difficult even for experts to detect.”

In his editorial, Dr. Butte highlighted several caveats, including that the teams evaluated “off the shelf” chatbots, which likely had no specific medical training, and the prompts

designed in both studies were very basic, which may have limited their specificity or actionability. Newer LLMs with specific health care training are being released, he explained.

Despite the mixed study findings, Dr. Butte remains optimistic about the future of AI in medicine.

“Today, the reality is that the highest-quality care is concentrated within a few premier medical systems like the NCI Comprehensive Cancer Centers, accessible only to a small fraction of the global population,” Dr. Butte explained. “However, AI has the potential to change this.”

How can we make this happen?

AI algorithms would need to be trained with “data from the best medical systems globally” and “the latest guidelines from NCCN and elsewhere.” Digital health platforms powered by AI could then be designed to provide resources and advice to patients around the globe, Dr. Butte said.

Although “these algorithms will need to be carefully monitored as they are brought into health systems,” Dr. Butte said, it does not change their potential to “improve care for both the haves and have-nots of health care.”

The study by Mr. Pan and colleagues had no specific funding; one author, Stacy Loeb, MD, MSc, PhD, reported a disclosure; no other disclosures were reported. The study by Shan Chen and colleagues was supported by the Woods Foundation; several authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Butte disclosed relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

two new studies suggest.

AI chatbots, such as ChatGPT (OpenAI), are becoming go-to sources for health information. However, no studies have rigorously evaluated the quality of their medical advice, especially for cancer.

Two new studies published in JAMA Oncology did just that.

One, which looked at common cancer-related Google searches, found that AI chatbots generally provide accurate information to consumers, but the information’s usefulness may be limited by its complexity.

The other, which assessed cancer treatment recommendations, found that AI chatbots overall missed the mark on providing recommendations for breast, prostate, and lung cancers in line with national treatment guidelines.

The medical world is becoming “enamored with our newest potential helper, large language models (LLMs) and in particular chatbots, such as ChatGPT,” Atul Butte, MD, PhD, who heads the Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute, University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an editorial accompanying the studies. “But maybe our core belief in GPT technology as a clinical partner has not sufficiently been earned yet.”

The first study by Alexander Pan of the State University of New York, Brooklyn, and colleagues analyzed the quality of responses to the top five most searched questions on skin, lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer provided by four AI chatbots: ChatGPT-3.5, Perplexity (Perplexity.AI), Chatsonic (Writesonic), and Bing AI (Microsoft).

Questions included what is skin cancer and what are symptoms of prostate, lung, or breast cancer? The team rated the responses for quality, clarity, actionability, misinformation, and readability.

The researchers found that the four chatbots generated “high-quality” responses about the five cancers and did not appear to spread misinformation. Three of the four chatbots cited reputable sources, such as the American Cancer Society, Mayo Clinic, and Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention, which is “reassuring,” the researchers said.

However, the team also found that the usefulness of the information was “limited” because responses were often written at a college reading level. Another limitation: AI chatbots provided concise answers with no visual aids, which may not be sufficient to explain more complex ideas to consumers.

“These limitations suggest that AI chatbots should be used [supplementally] and not as a primary source for medical information,” the authors said, adding that the chatbots “typically acknowledged their limitations in providing individualized advice and encouraged users to seek medical attention.”

A related study in the journal highlighted the ability of AI chatbots to generate appropriate cancer treatment recommendations.

In this analysis, Shan Chen, MS, with the AI in Medicine Program, Mass General Brigham, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues benchmarked cancer treatment recommendations made by ChatGPT-3.5 against 2021 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

The team created 104 prompts designed to elicit basic treatment strategies for various types of cancer, including breast, prostate, and lung cancer. Questions included “What is the treatment for stage I breast cancer?” Several oncologists then assessed the level of concordance between the chatbot responses and NCCN guidelines.

In 62% of the prompts and answers, all the recommended treatments aligned with the oncologists’ views.

The chatbot provided at least one guideline-concordant treatment for 98% of prompts. However, for 34% of prompts, the chatbot also recommended at least one nonconcordant treatment.

And about 13% of recommended treatments were “hallucinated,” that is, not part of any recommended treatment. Hallucinations were primarily recommendations for localized treatment of advanced disease, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy.

Based on the findings, the team recommended that clinicians advise patients that AI chatbots are not a reliable source of cancer treatment information.

“The chatbot did not perform well at providing accurate cancer treatment recommendations,” the authors said. “The chatbot was most likely to mix in incorrect recommendations among correct ones, an error difficult even for experts to detect.”

In his editorial, Dr. Butte highlighted several caveats, including that the teams evaluated “off the shelf” chatbots, which likely had no specific medical training, and the prompts

designed in both studies were very basic, which may have limited their specificity or actionability. Newer LLMs with specific health care training are being released, he explained.

Despite the mixed study findings, Dr. Butte remains optimistic about the future of AI in medicine.

“Today, the reality is that the highest-quality care is concentrated within a few premier medical systems like the NCI Comprehensive Cancer Centers, accessible only to a small fraction of the global population,” Dr. Butte explained. “However, AI has the potential to change this.”

How can we make this happen?

AI algorithms would need to be trained with “data from the best medical systems globally” and “the latest guidelines from NCCN and elsewhere.” Digital health platforms powered by AI could then be designed to provide resources and advice to patients around the globe, Dr. Butte said.

Although “these algorithms will need to be carefully monitored as they are brought into health systems,” Dr. Butte said, it does not change their potential to “improve care for both the haves and have-nots of health care.”

The study by Mr. Pan and colleagues had no specific funding; one author, Stacy Loeb, MD, MSc, PhD, reported a disclosure; no other disclosures were reported. The study by Shan Chen and colleagues was supported by the Woods Foundation; several authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Butte disclosed relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

two new studies suggest.

AI chatbots, such as ChatGPT (OpenAI), are becoming go-to sources for health information. However, no studies have rigorously evaluated the quality of their medical advice, especially for cancer.

Two new studies published in JAMA Oncology did just that.

One, which looked at common cancer-related Google searches, found that AI chatbots generally provide accurate information to consumers, but the information’s usefulness may be limited by its complexity.

The other, which assessed cancer treatment recommendations, found that AI chatbots overall missed the mark on providing recommendations for breast, prostate, and lung cancers in line with national treatment guidelines.

The medical world is becoming “enamored with our newest potential helper, large language models (LLMs) and in particular chatbots, such as ChatGPT,” Atul Butte, MD, PhD, who heads the Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute, University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an editorial accompanying the studies. “But maybe our core belief in GPT technology as a clinical partner has not sufficiently been earned yet.”

The first study by Alexander Pan of the State University of New York, Brooklyn, and colleagues analyzed the quality of responses to the top five most searched questions on skin, lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer provided by four AI chatbots: ChatGPT-3.5, Perplexity (Perplexity.AI), Chatsonic (Writesonic), and Bing AI (Microsoft).

Questions included what is skin cancer and what are symptoms of prostate, lung, or breast cancer? The team rated the responses for quality, clarity, actionability, misinformation, and readability.

The researchers found that the four chatbots generated “high-quality” responses about the five cancers and did not appear to spread misinformation. Three of the four chatbots cited reputable sources, such as the American Cancer Society, Mayo Clinic, and Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention, which is “reassuring,” the researchers said.

However, the team also found that the usefulness of the information was “limited” because responses were often written at a college reading level. Another limitation: AI chatbots provided concise answers with no visual aids, which may not be sufficient to explain more complex ideas to consumers.

“These limitations suggest that AI chatbots should be used [supplementally] and not as a primary source for medical information,” the authors said, adding that the chatbots “typically acknowledged their limitations in providing individualized advice and encouraged users to seek medical attention.”

A related study in the journal highlighted the ability of AI chatbots to generate appropriate cancer treatment recommendations.

In this analysis, Shan Chen, MS, with the AI in Medicine Program, Mass General Brigham, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues benchmarked cancer treatment recommendations made by ChatGPT-3.5 against 2021 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

The team created 104 prompts designed to elicit basic treatment strategies for various types of cancer, including breast, prostate, and lung cancer. Questions included “What is the treatment for stage I breast cancer?” Several oncologists then assessed the level of concordance between the chatbot responses and NCCN guidelines.

In 62% of the prompts and answers, all the recommended treatments aligned with the oncologists’ views.

The chatbot provided at least one guideline-concordant treatment for 98% of prompts. However, for 34% of prompts, the chatbot also recommended at least one nonconcordant treatment.

And about 13% of recommended treatments were “hallucinated,” that is, not part of any recommended treatment. Hallucinations were primarily recommendations for localized treatment of advanced disease, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy.

Based on the findings, the team recommended that clinicians advise patients that AI chatbots are not a reliable source of cancer treatment information.

“The chatbot did not perform well at providing accurate cancer treatment recommendations,” the authors said. “The chatbot was most likely to mix in incorrect recommendations among correct ones, an error difficult even for experts to detect.”

In his editorial, Dr. Butte highlighted several caveats, including that the teams evaluated “off the shelf” chatbots, which likely had no specific medical training, and the prompts

designed in both studies were very basic, which may have limited their specificity or actionability. Newer LLMs with specific health care training are being released, he explained.

Despite the mixed study findings, Dr. Butte remains optimistic about the future of AI in medicine.

“Today, the reality is that the highest-quality care is concentrated within a few premier medical systems like the NCI Comprehensive Cancer Centers, accessible only to a small fraction of the global population,” Dr. Butte explained. “However, AI has the potential to change this.”

How can we make this happen?

AI algorithms would need to be trained with “data from the best medical systems globally” and “the latest guidelines from NCCN and elsewhere.” Digital health platforms powered by AI could then be designed to provide resources and advice to patients around the globe, Dr. Butte said.

Although “these algorithms will need to be carefully monitored as they are brought into health systems,” Dr. Butte said, it does not change their potential to “improve care for both the haves and have-nots of health care.”

The study by Mr. Pan and colleagues had no specific funding; one author, Stacy Loeb, MD, MSc, PhD, reported a disclosure; no other disclosures were reported. The study by Shan Chen and colleagues was supported by the Woods Foundation; several authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Butte disclosed relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Commentary: Alcohol, PPI use, BMI, and lymph node dissection in BC, September 2023

The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) can affect the bioavailability and effectiveness of concomitant medications, including cancer therapies. A retrospective study by Lee and colleagues aimed to identify the clinical outcomes of patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced or metastatic BC who were concomitantly using PPI and palbociclib. The study included 1310 patients, of which 344 received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib and 966 patients received palbociclib alone. Results showed that patients who received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib had significantly shorter progression-free survival (hazard ratio 1.76; 95% CI 1.46-2.13) and overall survival (hazard ratio 2.72; 95% CI 2.07-3.53) rates compared with those who received palbociclib alone. These results suggest that the concomitant use of PPI with palbociclib may alter the therapeutic efficacy of the drug. More research studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Pfeiler and colleagues examined the association of BMI with side effects, treatment discontinuation, and efficacy of palbociclib. This study looked at 5698 patients with early-stage HR+ BC who received palbociclib plus endocrine therapy as part of a preplanned analysis of the PALLAS trial. Results showed that in women who received adjuvant palbociclib, higher BMI was associated with a significantly lower rate of neutropenia (odds ratio for a 1-unit change in BMI 0.93; 95% CI 0.92-0.95) and a lower rate of treatment discontinuation (adjusted hazard ratio for a 10-unit change in BMI 0.75; 95% CI 0.67-0.83) compared with normal-weight patients. No effect of BMI on palbociclib efficacy was observed at 31 months of follow-up. Further studies are needed to validate these findings in different cohorts.

In cases of early-stage breast cancer (clinical T1, T2) where patients undergo upfront breast-conserving therapy and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), completion of axillary lymph node dissection (CLND) is often omitted if only one or two positive sentinel lymph nodes are detected. A study by Zaveri and colleagues looked at outcomes among 548 patients with cT1-2 N0 BC who were treated with upfront mastectomy and had one or two positive lymph nodes on SLNB. The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of overall locoregional recurrence was comparable between patients who underwent vs those who did not undergo CLND (1.8% vs 1.3%; P = .93); receipt of post-mastectomy radiation therapy did not affect the locoregional recurrence rate in both categories of patients who underwent SLNB alone and SLNB with CLND (P = .1638). These results suggest that CLND may not necessarily improve outcomes in this patient population. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) can affect the bioavailability and effectiveness of concomitant medications, including cancer therapies. A retrospective study by Lee and colleagues aimed to identify the clinical outcomes of patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced or metastatic BC who were concomitantly using PPI and palbociclib. The study included 1310 patients, of which 344 received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib and 966 patients received palbociclib alone. Results showed that patients who received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib had significantly shorter progression-free survival (hazard ratio 1.76; 95% CI 1.46-2.13) and overall survival (hazard ratio 2.72; 95% CI 2.07-3.53) rates compared with those who received palbociclib alone. These results suggest that the concomitant use of PPI with palbociclib may alter the therapeutic efficacy of the drug. More research studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Pfeiler and colleagues examined the association of BMI with side effects, treatment discontinuation, and efficacy of palbociclib. This study looked at 5698 patients with early-stage HR+ BC who received palbociclib plus endocrine therapy as part of a preplanned analysis of the PALLAS trial. Results showed that in women who received adjuvant palbociclib, higher BMI was associated with a significantly lower rate of neutropenia (odds ratio for a 1-unit change in BMI 0.93; 95% CI 0.92-0.95) and a lower rate of treatment discontinuation (adjusted hazard ratio for a 10-unit change in BMI 0.75; 95% CI 0.67-0.83) compared with normal-weight patients. No effect of BMI on palbociclib efficacy was observed at 31 months of follow-up. Further studies are needed to validate these findings in different cohorts.

In cases of early-stage breast cancer (clinical T1, T2) where patients undergo upfront breast-conserving therapy and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), completion of axillary lymph node dissection (CLND) is often omitted if only one or two positive sentinel lymph nodes are detected. A study by Zaveri and colleagues looked at outcomes among 548 patients with cT1-2 N0 BC who were treated with upfront mastectomy and had one or two positive lymph nodes on SLNB. The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of overall locoregional recurrence was comparable between patients who underwent vs those who did not undergo CLND (1.8% vs 1.3%; P = .93); receipt of post-mastectomy radiation therapy did not affect the locoregional recurrence rate in both categories of patients who underwent SLNB alone and SLNB with CLND (P = .1638). These results suggest that CLND may not necessarily improve outcomes in this patient population. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) can affect the bioavailability and effectiveness of concomitant medications, including cancer therapies. A retrospective study by Lee and colleagues aimed to identify the clinical outcomes of patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced or metastatic BC who were concomitantly using PPI and palbociclib. The study included 1310 patients, of which 344 received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib and 966 patients received palbociclib alone. Results showed that patients who received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib had significantly shorter progression-free survival (hazard ratio 1.76; 95% CI 1.46-2.13) and overall survival (hazard ratio 2.72; 95% CI 2.07-3.53) rates compared with those who received palbociclib alone. These results suggest that the concomitant use of PPI with palbociclib may alter the therapeutic efficacy of the drug. More research studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Pfeiler and colleagues examined the association of BMI with side effects, treatment discontinuation, and efficacy of palbociclib. This study looked at 5698 patients with early-stage HR+ BC who received palbociclib plus endocrine therapy as part of a preplanned analysis of the PALLAS trial. Results showed that in women who received adjuvant palbociclib, higher BMI was associated with a significantly lower rate of neutropenia (odds ratio for a 1-unit change in BMI 0.93; 95% CI 0.92-0.95) and a lower rate of treatment discontinuation (adjusted hazard ratio for a 10-unit change in BMI 0.75; 95% CI 0.67-0.83) compared with normal-weight patients. No effect of BMI on palbociclib efficacy was observed at 31 months of follow-up. Further studies are needed to validate these findings in different cohorts.

In cases of early-stage breast cancer (clinical T1, T2) where patients undergo upfront breast-conserving therapy and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), completion of axillary lymph node dissection (CLND) is often omitted if only one or two positive sentinel lymph nodes are detected. A study by Zaveri and colleagues looked at outcomes among 548 patients with cT1-2 N0 BC who were treated with upfront mastectomy and had one or two positive lymph nodes on SLNB. The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of overall locoregional recurrence was comparable between patients who underwent vs those who did not undergo CLND (1.8% vs 1.3%; P = .93); receipt of post-mastectomy radiation therapy did not affect the locoregional recurrence rate in both categories of patients who underwent SLNB alone and SLNB with CLND (P = .1638). These results suggest that CLND may not necessarily improve outcomes in this patient population. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

No link between most cancers and depression/anxiety: Study

from a large, individual participant data meta-analysis.

An exception was for lung and smoking-related cancers, but key covariates appeared to explain the relationship between depression, anxiety, and these cancer types, the investigators reported.

The findings challenge a common theory that depression and anxiety increase cancer risk and should “change current thinking,” they argue.

“Our results may come as a relief to many patients with cancer who believe their diagnosis is attributed to previous anxiety or depression,” first author Lonneke A. van Tuijl, PhD, of the University of Groningen and Utrecht University, the Netherlands, noted in a press release.

Analyses included data from up to nearly 320,000 individuals from the 18 prospective cohorts included in the international Psychosocial Factors and Cancer Incidence (PSY-CA) consortium. The cohorts are from studies conducted in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada, and included 25,803 patients with cancer. During follow-up of up to 26 years and more than 3.2 million person-years, depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses showed no association with overall breast, prostate, colorectal, and alcohol-related cancers (hazard ratios, 0.98-1.05).

For the specific cancer types, the investigators “found no evidence for an association between depression or anxiety and the incidence of colorectal cancer (HRs, 0.88-1.13), prostate cancer (HRs, 0.97-1.17), or alcohol-related cancers (HRs, 0.97-1.06).”

“For breast cancer, all pooled HRs were consistently negative but mean pooled HRs were close to 1 (HRs, 0.92-0.98) and the upper limit of the 95% confidence intervals all exceeded 1 (with the exception of anxiety symptoms),” they noted.

An increase in risk observed between depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses and lung cancer (HRs, 1.12-1.60) and smoking-related cancers (HRs, 1.06-1.60), in minimally adjusted models, was substantially attenuated after adjusting for known risk factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index (HRs, 1.04-1.08), the investigators reported.

The findings were published online in Cancer.

“Depression and anxiety have long been hypothesized to increase the risk for cancer. It is thought that the increased cancer risk can occur via several pathways, including health behaviors, or by influencing mutation, viral oncogenes, cell proliferation, or DNA repair,” the authors explained, noting that “[c]onclusions drawn in meta-analyses vary greatly, with some supporting an association between depression, anxiety, and cancer incidence and others finding no or a negligible association.”

The current findings “may help health professionals to alleviate feelings of guilt and self-blame in patients with cancer who attribute their diagnosis to previous depression or anxiety,” they said, noting that the findings “also underscore the importance of addressing tobacco smoking and other unhealthy behaviors – including those that may develop as a result of anxiety or depression.”

“However, further research is needed to understand exactly how depression, anxiety, health behaviors, and lung cancer are related,” said Dr. Tuijl.

Dr. Tuijl has received grants and travel support from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

from a large, individual participant data meta-analysis.

An exception was for lung and smoking-related cancers, but key covariates appeared to explain the relationship between depression, anxiety, and these cancer types, the investigators reported.

The findings challenge a common theory that depression and anxiety increase cancer risk and should “change current thinking,” they argue.

“Our results may come as a relief to many patients with cancer who believe their diagnosis is attributed to previous anxiety or depression,” first author Lonneke A. van Tuijl, PhD, of the University of Groningen and Utrecht University, the Netherlands, noted in a press release.

Analyses included data from up to nearly 320,000 individuals from the 18 prospective cohorts included in the international Psychosocial Factors and Cancer Incidence (PSY-CA) consortium. The cohorts are from studies conducted in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada, and included 25,803 patients with cancer. During follow-up of up to 26 years and more than 3.2 million person-years, depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses showed no association with overall breast, prostate, colorectal, and alcohol-related cancers (hazard ratios, 0.98-1.05).

For the specific cancer types, the investigators “found no evidence for an association between depression or anxiety and the incidence of colorectal cancer (HRs, 0.88-1.13), prostate cancer (HRs, 0.97-1.17), or alcohol-related cancers (HRs, 0.97-1.06).”

“For breast cancer, all pooled HRs were consistently negative but mean pooled HRs were close to 1 (HRs, 0.92-0.98) and the upper limit of the 95% confidence intervals all exceeded 1 (with the exception of anxiety symptoms),” they noted.

An increase in risk observed between depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses and lung cancer (HRs, 1.12-1.60) and smoking-related cancers (HRs, 1.06-1.60), in minimally adjusted models, was substantially attenuated after adjusting for known risk factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index (HRs, 1.04-1.08), the investigators reported.

The findings were published online in Cancer.

“Depression and anxiety have long been hypothesized to increase the risk for cancer. It is thought that the increased cancer risk can occur via several pathways, including health behaviors, or by influencing mutation, viral oncogenes, cell proliferation, or DNA repair,” the authors explained, noting that “[c]onclusions drawn in meta-analyses vary greatly, with some supporting an association between depression, anxiety, and cancer incidence and others finding no or a negligible association.”

The current findings “may help health professionals to alleviate feelings of guilt and self-blame in patients with cancer who attribute their diagnosis to previous depression or anxiety,” they said, noting that the findings “also underscore the importance of addressing tobacco smoking and other unhealthy behaviors – including those that may develop as a result of anxiety or depression.”

“However, further research is needed to understand exactly how depression, anxiety, health behaviors, and lung cancer are related,” said Dr. Tuijl.

Dr. Tuijl has received grants and travel support from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

from a large, individual participant data meta-analysis.

An exception was for lung and smoking-related cancers, but key covariates appeared to explain the relationship between depression, anxiety, and these cancer types, the investigators reported.

The findings challenge a common theory that depression and anxiety increase cancer risk and should “change current thinking,” they argue.

“Our results may come as a relief to many patients with cancer who believe their diagnosis is attributed to previous anxiety or depression,” first author Lonneke A. van Tuijl, PhD, of the University of Groningen and Utrecht University, the Netherlands, noted in a press release.

Analyses included data from up to nearly 320,000 individuals from the 18 prospective cohorts included in the international Psychosocial Factors and Cancer Incidence (PSY-CA) consortium. The cohorts are from studies conducted in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada, and included 25,803 patients with cancer. During follow-up of up to 26 years and more than 3.2 million person-years, depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses showed no association with overall breast, prostate, colorectal, and alcohol-related cancers (hazard ratios, 0.98-1.05).

For the specific cancer types, the investigators “found no evidence for an association between depression or anxiety and the incidence of colorectal cancer (HRs, 0.88-1.13), prostate cancer (HRs, 0.97-1.17), or alcohol-related cancers (HRs, 0.97-1.06).”

“For breast cancer, all pooled HRs were consistently negative but mean pooled HRs were close to 1 (HRs, 0.92-0.98) and the upper limit of the 95% confidence intervals all exceeded 1 (with the exception of anxiety symptoms),” they noted.

An increase in risk observed between depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses and lung cancer (HRs, 1.12-1.60) and smoking-related cancers (HRs, 1.06-1.60), in minimally adjusted models, was substantially attenuated after adjusting for known risk factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index (HRs, 1.04-1.08), the investigators reported.

The findings were published online in Cancer.

“Depression and anxiety have long been hypothesized to increase the risk for cancer. It is thought that the increased cancer risk can occur via several pathways, including health behaviors, or by influencing mutation, viral oncogenes, cell proliferation, or DNA repair,” the authors explained, noting that “[c]onclusions drawn in meta-analyses vary greatly, with some supporting an association between depression, anxiety, and cancer incidence and others finding no or a negligible association.”

The current findings “may help health professionals to alleviate feelings of guilt and self-blame in patients with cancer who attribute their diagnosis to previous depression or anxiety,” they said, noting that the findings “also underscore the importance of addressing tobacco smoking and other unhealthy behaviors – including those that may develop as a result of anxiety or depression.”

“However, further research is needed to understand exactly how depression, anxiety, health behaviors, and lung cancer are related,” said Dr. Tuijl.

Dr. Tuijl has received grants and travel support from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

FROM CANCER

Breast cancer: Hope in sight for improved tamoxifen therapy?

A team at Lyon’s Cancer Research Center (CRCL) has revealed the role of an enzyme, PRMT5, in the response to tamoxifen, a drug used to prevent relapse in premenopausal women with breast cancer.

Muriel Le Romancer, MD, director of research at France’s Institute of Health and Medical Research, explained the issues involved in this discovery in an interview. She jointly led this research along with Olivier Trédan, MD, PhD, oncologist at Lyon’s Léon Bérard Clinic. The research concluded with the publication of a study in EMBO Molecular Medicine. The researchers both head up the CRCL’s hormone resistance, methylation, and breast cancer team.

Although the enzyme’s involvement in the mode of action of tamoxifen has been observed in close to 900 patients with breast cancer, these results need to be validated in other at-risk patient cohorts before the biomarker can be considered for routine use, said Dr. Le Romancer. She estimated that 2 more years of research are needed.

Can you tell us which cases involve the use of tamoxifen and what its mode of action is?

Dr. Le Romancer: Tamoxifen is a hormone therapy used to reduce the risk of breast cancer relapse. It is prescribed to premenopausal women with hormone-sensitive cancer, which equates to roughly 25% of women with breast cancer: 15,000 women each year. The drug, which is taken every day via oral administration, is an estrogen antagonist. By binding to these receptors, it blocks estrogen from mediating its biological effect in the breasts. Aromatase inhibitors are the preferred choice in postmenopausal women, as they have been shown to be more effective. These also have an antiestrogenic effect, but by inhibiting estrogen production.

Tamoxifen therapy is prescribed for a minimum period of 5 years. Despite this, 25% of women treated with tamoxifen relapse. Tamoxifen resistance is unique in that it occurs very late on, generally 10-15 years after starting treatment. This means that it’s really important for us to identify predictive markers of the response to hormone therapy to adapt treatment as best we can. For the moment, the only criteria used to prescribe tamoxifen are patient age and the presence of estrogen receptors within the tumor.

Exactly how would treatment be improved if a decisive predictive marker of response to tamoxifen could be identified?

Dr. Le Romancer: Currently, when a patient’s breast cancer relapses after several years of treatment with tamoxifen, we don’t know if the relapse is linked to tamoxifen resistance or not. This makes it difficult to choose the right treatment to manage such relapses, which remain complicated to treat. Lots of patients die because of metastases.

By predicting the response to tamoxifen using a marker, we will be able to either use another hormone therapy to prevent the relapse or prescribe tamoxifen alongside a molecule that stops resistance from developing. We hope that this will significantly reduce the rate of relapse.

You put forward PRMT5 as a potential predictive marker of response to tamoxifen. What makes you think it could be used in this way?