User login

COVID cuts internists’ happiness in life outside work

Before the pandemic, a large majority of internists reported that they were generally happy with life outside of work, although by specialty, they were near the bottom in happiness.

But this year’s Medscape Internist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021 shows a sharp drop, with just 55% of respondents saying they are somewhat or very happy in life outside work, compared with 78% last year.

Internists were not alone among the more than 12,000 physicians who responded to the survey. The contrast from last year’s report was clear for physicians in general and reflects COVID-19’s substantial toll on clinicians.

Just 58% of physicians overall reported happy lives outside work, down from 82% last year.

Perhaps not surprising, given the particular demands on certain specialties, physicians in infectious disease were the least happy, at 45%, followed by pulmonologists (47%) and rheumatologists and intensivists, at 49%.

The highest happiness level was reported by those in diabetes and endocrinology, at 73% this year, but that proportion was also substantially lower than the 89% from last year.

Burnout has ‘strong impact on lives’

The percentage of internists who reported burnout or depression, however, has stayed fairly consistent.

More than half (52%) said that burnout had a strong or severe impact on their lives, and nearly 1 in 10 said it was severe enough that they are considering leaving medicine.

One percent of the internists who responded to the survey said they had attempted suicide, and 12% said they had thoughts of suicide but had not attempted it.

Most of those reporting burnout (82%) said it started before the COVID-19 pandemic, but 18% said it began with the pandemic.

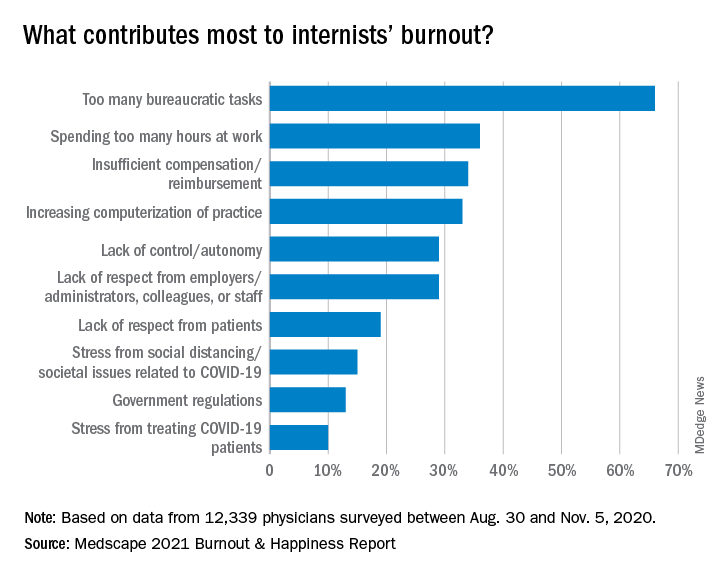

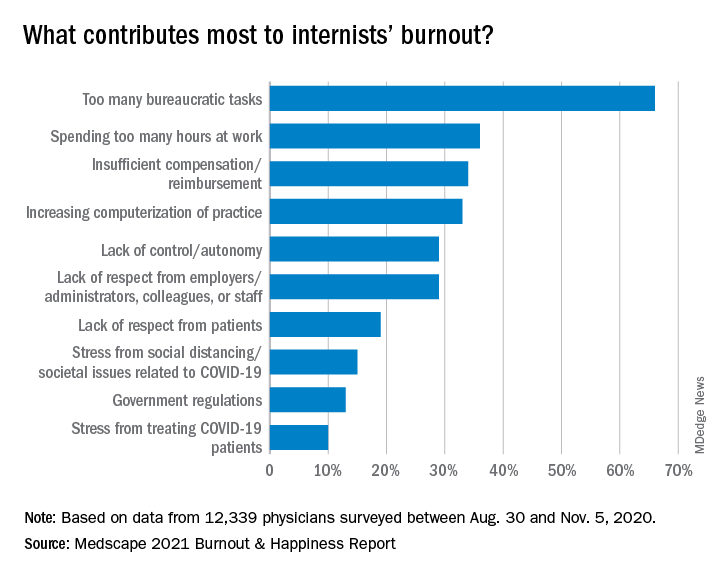

Notably, though, physicians ranked problems related to stress from COVID-19 near the bottom among burnout drivers. The top factor, by far, again, was “too many bureaucratic tasks.”

A large majority (78%) of internists work online for up to 10 hours a week, a number that could grow as telemedicine grows.

Exercise is top coping method

Responses gave a peek into how physicians are coping with burnout. Among internists, 49% put exercise at the top. Isolating themselves from others was the next most popular choice, at 45%. Eating junk food and drinking alcohol were further down the list, at 34% and 24%, respectively.

Few internists said they drink alcohol daily, a finding consistent with past years. In fact, 29% said they don’t drink at all, and 26% said they have fewer than one alcoholic drink per week. Only 7% said they had seven or more drinks per week.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism advises that men not have more than 14 alcoholic drinks per week and that women not have more than 7.

Work-life balance topped list of concerns

By far, internists said work-life balance was their top workplace concern. Nearly half (48%) chose that answer, more than twice the percentage who said compensation was the biggest concern (21%).

Asked whether they would take a salary cut for more work-life balance, a similar proportion (46%) said yes.

Forty-three percent of internists manage to take 3-4 weeks of vacation, and 10% take at least 5 weeks, similar to reported vacation time in last year’s survey.

The vast majority are in committed relationships, with 79% reporting that they are married, and 5% reporting that they are living with a partner. Of those who are married, 48% described the marriage as very good; 32%, good; 16%, fair; 2%, poor; and 1%, very poor; 1% preferred not to answer.

One in five internists said their spouse was a physician, and 24% said their spouse worked in the health care field but not as a physician.

Pandemic has increased burnout

Douglas S. Paauw, MD, and Eileen Barrett, MD, two members of the Internal Medicine News editorial advisory board, said they were not surprised by the survey findings.

“There is more burnout since the pandemic,” said Dr. Paauw, professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. “People may be working more hours, higher stress, but also, some may be working less hours, are socially isolated, taking on a new role of helping their kids in virtual education, andn living in cramped quarters with family that they may not be accustomed to spending so much time with.”

“Also, most physicians love travel, to detress, get back in balance, and that has by and large been taken away by the pandemic,” Dr. Paauw noted. “Unfortunately, bureaucracy did not go away during the pandemic!

Dr. Barrett, an internal medicine hospitalist, said, “It is most concerning to me today that 12% have had thoughts of suicide, and yet 39% are too busy to seek care for depression or burnout, and 17% aren’t seeking due to fear it will be disclosed,”

“Credentialing, medical license applications, and malpractice insurance applications can and must be changed posthaste to support physicians and stop stigmatizing mental health diagnoses and mental health care,” she said. “Removing application questions about physician mental health will be consistent with recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, medical professional societies, and the Americans with Disabilities Act, and is something actionable and achievable for every organization to do in 2021.” “From a public policy perspective, I am deeply concerned about the physician workforce and how patients will be able to receive care from exhausted, burned out physicians who may be reducing their clinical hours to restore their personal happiness – understandably so,” added Dr. Barrett, who is associate professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of internal medicine, at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

She pointed out that there are mental health resources available for physicians that don’t go through their employers or insurance such as www.emotionalppe.org/.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Katie Lennon contributed to this report.

Before the pandemic, a large majority of internists reported that they were generally happy with life outside of work, although by specialty, they were near the bottom in happiness.

But this year’s Medscape Internist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021 shows a sharp drop, with just 55% of respondents saying they are somewhat or very happy in life outside work, compared with 78% last year.

Internists were not alone among the more than 12,000 physicians who responded to the survey. The contrast from last year’s report was clear for physicians in general and reflects COVID-19’s substantial toll on clinicians.

Just 58% of physicians overall reported happy lives outside work, down from 82% last year.

Perhaps not surprising, given the particular demands on certain specialties, physicians in infectious disease were the least happy, at 45%, followed by pulmonologists (47%) and rheumatologists and intensivists, at 49%.

The highest happiness level was reported by those in diabetes and endocrinology, at 73% this year, but that proportion was also substantially lower than the 89% from last year.

Burnout has ‘strong impact on lives’

The percentage of internists who reported burnout or depression, however, has stayed fairly consistent.

More than half (52%) said that burnout had a strong or severe impact on their lives, and nearly 1 in 10 said it was severe enough that they are considering leaving medicine.

One percent of the internists who responded to the survey said they had attempted suicide, and 12% said they had thoughts of suicide but had not attempted it.

Most of those reporting burnout (82%) said it started before the COVID-19 pandemic, but 18% said it began with the pandemic.

Notably, though, physicians ranked problems related to stress from COVID-19 near the bottom among burnout drivers. The top factor, by far, again, was “too many bureaucratic tasks.”

A large majority (78%) of internists work online for up to 10 hours a week, a number that could grow as telemedicine grows.

Exercise is top coping method

Responses gave a peek into how physicians are coping with burnout. Among internists, 49% put exercise at the top. Isolating themselves from others was the next most popular choice, at 45%. Eating junk food and drinking alcohol were further down the list, at 34% and 24%, respectively.

Few internists said they drink alcohol daily, a finding consistent with past years. In fact, 29% said they don’t drink at all, and 26% said they have fewer than one alcoholic drink per week. Only 7% said they had seven or more drinks per week.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism advises that men not have more than 14 alcoholic drinks per week and that women not have more than 7.

Work-life balance topped list of concerns

By far, internists said work-life balance was their top workplace concern. Nearly half (48%) chose that answer, more than twice the percentage who said compensation was the biggest concern (21%).

Asked whether they would take a salary cut for more work-life balance, a similar proportion (46%) said yes.

Forty-three percent of internists manage to take 3-4 weeks of vacation, and 10% take at least 5 weeks, similar to reported vacation time in last year’s survey.

The vast majority are in committed relationships, with 79% reporting that they are married, and 5% reporting that they are living with a partner. Of those who are married, 48% described the marriage as very good; 32%, good; 16%, fair; 2%, poor; and 1%, very poor; 1% preferred not to answer.

One in five internists said their spouse was a physician, and 24% said their spouse worked in the health care field but not as a physician.

Pandemic has increased burnout

Douglas S. Paauw, MD, and Eileen Barrett, MD, two members of the Internal Medicine News editorial advisory board, said they were not surprised by the survey findings.

“There is more burnout since the pandemic,” said Dr. Paauw, professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. “People may be working more hours, higher stress, but also, some may be working less hours, are socially isolated, taking on a new role of helping their kids in virtual education, andn living in cramped quarters with family that they may not be accustomed to spending so much time with.”

“Also, most physicians love travel, to detress, get back in balance, and that has by and large been taken away by the pandemic,” Dr. Paauw noted. “Unfortunately, bureaucracy did not go away during the pandemic!

Dr. Barrett, an internal medicine hospitalist, said, “It is most concerning to me today that 12% have had thoughts of suicide, and yet 39% are too busy to seek care for depression or burnout, and 17% aren’t seeking due to fear it will be disclosed,”

“Credentialing, medical license applications, and malpractice insurance applications can and must be changed posthaste to support physicians and stop stigmatizing mental health diagnoses and mental health care,” she said. “Removing application questions about physician mental health will be consistent with recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, medical professional societies, and the Americans with Disabilities Act, and is something actionable and achievable for every organization to do in 2021.” “From a public policy perspective, I am deeply concerned about the physician workforce and how patients will be able to receive care from exhausted, burned out physicians who may be reducing their clinical hours to restore their personal happiness – understandably so,” added Dr. Barrett, who is associate professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of internal medicine, at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

She pointed out that there are mental health resources available for physicians that don’t go through their employers or insurance such as www.emotionalppe.org/.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Katie Lennon contributed to this report.

Before the pandemic, a large majority of internists reported that they were generally happy with life outside of work, although by specialty, they were near the bottom in happiness.

But this year’s Medscape Internist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021 shows a sharp drop, with just 55% of respondents saying they are somewhat or very happy in life outside work, compared with 78% last year.

Internists were not alone among the more than 12,000 physicians who responded to the survey. The contrast from last year’s report was clear for physicians in general and reflects COVID-19’s substantial toll on clinicians.

Just 58% of physicians overall reported happy lives outside work, down from 82% last year.

Perhaps not surprising, given the particular demands on certain specialties, physicians in infectious disease were the least happy, at 45%, followed by pulmonologists (47%) and rheumatologists and intensivists, at 49%.

The highest happiness level was reported by those in diabetes and endocrinology, at 73% this year, but that proportion was also substantially lower than the 89% from last year.

Burnout has ‘strong impact on lives’

The percentage of internists who reported burnout or depression, however, has stayed fairly consistent.

More than half (52%) said that burnout had a strong or severe impact on their lives, and nearly 1 in 10 said it was severe enough that they are considering leaving medicine.

One percent of the internists who responded to the survey said they had attempted suicide, and 12% said they had thoughts of suicide but had not attempted it.

Most of those reporting burnout (82%) said it started before the COVID-19 pandemic, but 18% said it began with the pandemic.

Notably, though, physicians ranked problems related to stress from COVID-19 near the bottom among burnout drivers. The top factor, by far, again, was “too many bureaucratic tasks.”

A large majority (78%) of internists work online for up to 10 hours a week, a number that could grow as telemedicine grows.

Exercise is top coping method

Responses gave a peek into how physicians are coping with burnout. Among internists, 49% put exercise at the top. Isolating themselves from others was the next most popular choice, at 45%. Eating junk food and drinking alcohol were further down the list, at 34% and 24%, respectively.

Few internists said they drink alcohol daily, a finding consistent with past years. In fact, 29% said they don’t drink at all, and 26% said they have fewer than one alcoholic drink per week. Only 7% said they had seven or more drinks per week.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism advises that men not have more than 14 alcoholic drinks per week and that women not have more than 7.

Work-life balance topped list of concerns

By far, internists said work-life balance was their top workplace concern. Nearly half (48%) chose that answer, more than twice the percentage who said compensation was the biggest concern (21%).

Asked whether they would take a salary cut for more work-life balance, a similar proportion (46%) said yes.

Forty-three percent of internists manage to take 3-4 weeks of vacation, and 10% take at least 5 weeks, similar to reported vacation time in last year’s survey.

The vast majority are in committed relationships, with 79% reporting that they are married, and 5% reporting that they are living with a partner. Of those who are married, 48% described the marriage as very good; 32%, good; 16%, fair; 2%, poor; and 1%, very poor; 1% preferred not to answer.

One in five internists said their spouse was a physician, and 24% said their spouse worked in the health care field but not as a physician.

Pandemic has increased burnout

Douglas S. Paauw, MD, and Eileen Barrett, MD, two members of the Internal Medicine News editorial advisory board, said they were not surprised by the survey findings.

“There is more burnout since the pandemic,” said Dr. Paauw, professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. “People may be working more hours, higher stress, but also, some may be working less hours, are socially isolated, taking on a new role of helping their kids in virtual education, andn living in cramped quarters with family that they may not be accustomed to spending so much time with.”

“Also, most physicians love travel, to detress, get back in balance, and that has by and large been taken away by the pandemic,” Dr. Paauw noted. “Unfortunately, bureaucracy did not go away during the pandemic!

Dr. Barrett, an internal medicine hospitalist, said, “It is most concerning to me today that 12% have had thoughts of suicide, and yet 39% are too busy to seek care for depression or burnout, and 17% aren’t seeking due to fear it will be disclosed,”

“Credentialing, medical license applications, and malpractice insurance applications can and must be changed posthaste to support physicians and stop stigmatizing mental health diagnoses and mental health care,” she said. “Removing application questions about physician mental health will be consistent with recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, medical professional societies, and the Americans with Disabilities Act, and is something actionable and achievable for every organization to do in 2021.” “From a public policy perspective, I am deeply concerned about the physician workforce and how patients will be able to receive care from exhausted, burned out physicians who may be reducing their clinical hours to restore their personal happiness – understandably so,” added Dr. Barrett, who is associate professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of internal medicine, at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

She pointed out that there are mental health resources available for physicians that don’t go through their employers or insurance such as www.emotionalppe.org/.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Katie Lennon contributed to this report.

One in 10 family docs with burnout consider quitting medicine

and 1 in 10 said it was serious enough to make them consider leaving medicine.

Yet, responses to the Medscape Family Medicine Physician Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021 also indicate that family physicians are in the middle of the pack again this year in rankings by specialty of physician happiness outside work. Overall, more than 12,000 physicians from more than 29 specialties responded to this year’s survey, conducted between Aug. 30 and Nov. 5, 2020.

Happiness levels sink for physicians

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, happiness levels took a sharp drop among physicians across the board. Last year, for instance, the happiness level was highest for physicians practicing in diabetes and endocrinology, at 89%. They remain the happiest this year, but the proportion saying they were happy dropped to 73%. Infectious disease physicians were the least happy outside work both last year and this year, with the proportion reporting they were happy dropping from 69% to 45%.

For family physicians, happiness levels outside work plunged from 79% last year to 57% this year.

Burnout and depression levels, however, remained steady. The portion saying they were either burned out or burned out and depressed was up only 1 percentage point, rising to 47%.

Fifteen percent of family physicians have had thoughts of suicide, and 1% said they had attempted it, according to the survey responses.

The most common strategy for coping with burnout, reported by 48% of family physicians, is talking with family members and close friends, followed closely by exercise, reported by 46%.

Sixty-eight percent of family physicians say they exercise at least twice a week, and 12% exercise every day.

However, not all coping strategies were as positive: Forty-five percent said they cope by isolating themselves from others; 40% turned to junk food; and 23%-24% said they drank alcohol or were binge-eating to cope. Respondents could choose more than one answer.

Among family physicians, 75% expressed anxiety about their futures, given the pandemic, which is similar to the proportion among physicians overall (77%) who had the same worries.

Work-life balance biggest worry

The survey also asked what workplace issues concern family physicians the most. The biggest concern, by far, was work-life balance, chosen by 51%. Next highest was compensation, at 19%, followed by combining parenthood and work (9%) and relationships with colleagues/staff (6%).

More than half (52%) of family doctors said they would take a cut in pay to have better work-life balance.

A little more than a third (36%) of family physicians – about the same percentage as physicians overall – said they always or most of the time spend enough time on their own health and wellness. One in five said they rarely or never do.

The amount of work required beyond the bedside continues to frustrate family physicians.

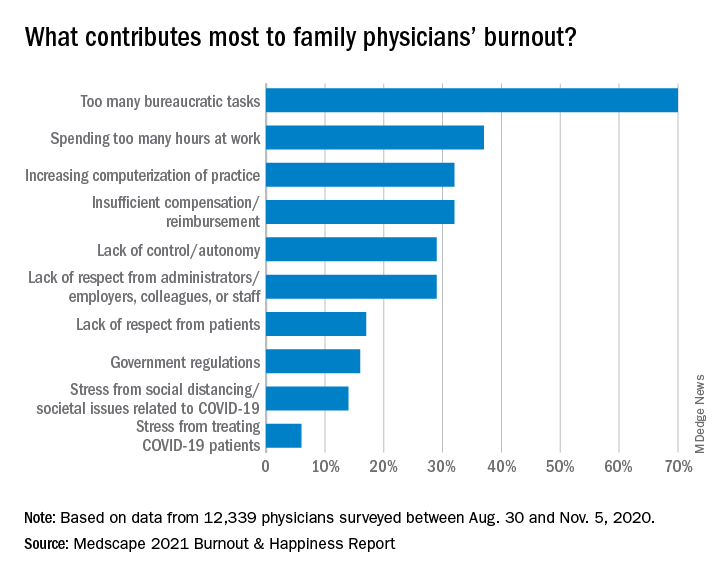

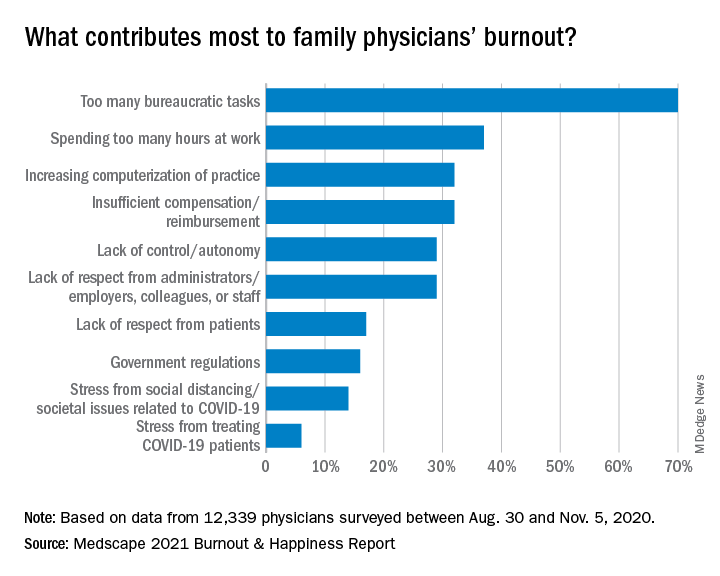

Again this year, the top cause of burnout, chosen by 70% of family physicians, was “too many bureaucratic tasks.” That was followed by “spending too many hours at work” (37%) and “increasing computerization of practice” (32%).

A large majority (82%) of family doctors report that they work online up to 10 hours a week, a number that could increase with the rise of telemedicine; 64% are personally online up to 10 hours a week. But even with combined personal and professional Internet time, family doctors don’t come close to the average time spent online among all Internet users, which Hootsuite and We Are Social report is an average of 7 hours per day.

Most in committed, satisfying relationships

Most family medicine physicians are juggling committed relationships with work life. In this survey, 78% said they were married, and another 5% said they were living with a partner.

A little more than half of married family doctors described their marriages as very good (51%). The rest were good (32%); fair (13%); poor (2%); and very poor (2%). Some (15%) had spouses who were also physicians, and 25% said their spouses worked in the health care field but were not physicians.

Almost all family physicians were able to take some vacation time during this reporting period – 43% took 3-4 weeks; 35% took 1-2 weeks; 10% took less than 1 week; 9% took 5-6 weeks; and 4% took more than 6 weeks.

If they drove to vacation destinations, they were likely to be in their favorite make of vehicle, which for family physicians were Toyotas (22%), Hondas (14%) and Fords (11%), according to the survey responses. Physicians overall favored Toyotas, Hondas, and BMWs.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and 1 in 10 said it was serious enough to make them consider leaving medicine.

Yet, responses to the Medscape Family Medicine Physician Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021 also indicate that family physicians are in the middle of the pack again this year in rankings by specialty of physician happiness outside work. Overall, more than 12,000 physicians from more than 29 specialties responded to this year’s survey, conducted between Aug. 30 and Nov. 5, 2020.

Happiness levels sink for physicians

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, happiness levels took a sharp drop among physicians across the board. Last year, for instance, the happiness level was highest for physicians practicing in diabetes and endocrinology, at 89%. They remain the happiest this year, but the proportion saying they were happy dropped to 73%. Infectious disease physicians were the least happy outside work both last year and this year, with the proportion reporting they were happy dropping from 69% to 45%.

For family physicians, happiness levels outside work plunged from 79% last year to 57% this year.

Burnout and depression levels, however, remained steady. The portion saying they were either burned out or burned out and depressed was up only 1 percentage point, rising to 47%.

Fifteen percent of family physicians have had thoughts of suicide, and 1% said they had attempted it, according to the survey responses.

The most common strategy for coping with burnout, reported by 48% of family physicians, is talking with family members and close friends, followed closely by exercise, reported by 46%.

Sixty-eight percent of family physicians say they exercise at least twice a week, and 12% exercise every day.

However, not all coping strategies were as positive: Forty-five percent said they cope by isolating themselves from others; 40% turned to junk food; and 23%-24% said they drank alcohol or were binge-eating to cope. Respondents could choose more than one answer.

Among family physicians, 75% expressed anxiety about their futures, given the pandemic, which is similar to the proportion among physicians overall (77%) who had the same worries.

Work-life balance biggest worry

The survey also asked what workplace issues concern family physicians the most. The biggest concern, by far, was work-life balance, chosen by 51%. Next highest was compensation, at 19%, followed by combining parenthood and work (9%) and relationships with colleagues/staff (6%).

More than half (52%) of family doctors said they would take a cut in pay to have better work-life balance.

A little more than a third (36%) of family physicians – about the same percentage as physicians overall – said they always or most of the time spend enough time on their own health and wellness. One in five said they rarely or never do.

The amount of work required beyond the bedside continues to frustrate family physicians.

Again this year, the top cause of burnout, chosen by 70% of family physicians, was “too many bureaucratic tasks.” That was followed by “spending too many hours at work” (37%) and “increasing computerization of practice” (32%).

A large majority (82%) of family doctors report that they work online up to 10 hours a week, a number that could increase with the rise of telemedicine; 64% are personally online up to 10 hours a week. But even with combined personal and professional Internet time, family doctors don’t come close to the average time spent online among all Internet users, which Hootsuite and We Are Social report is an average of 7 hours per day.

Most in committed, satisfying relationships

Most family medicine physicians are juggling committed relationships with work life. In this survey, 78% said they were married, and another 5% said they were living with a partner.

A little more than half of married family doctors described their marriages as very good (51%). The rest were good (32%); fair (13%); poor (2%); and very poor (2%). Some (15%) had spouses who were also physicians, and 25% said their spouses worked in the health care field but were not physicians.

Almost all family physicians were able to take some vacation time during this reporting period – 43% took 3-4 weeks; 35% took 1-2 weeks; 10% took less than 1 week; 9% took 5-6 weeks; and 4% took more than 6 weeks.

If they drove to vacation destinations, they were likely to be in their favorite make of vehicle, which for family physicians were Toyotas (22%), Hondas (14%) and Fords (11%), according to the survey responses. Physicians overall favored Toyotas, Hondas, and BMWs.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and 1 in 10 said it was serious enough to make them consider leaving medicine.

Yet, responses to the Medscape Family Medicine Physician Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021 also indicate that family physicians are in the middle of the pack again this year in rankings by specialty of physician happiness outside work. Overall, more than 12,000 physicians from more than 29 specialties responded to this year’s survey, conducted between Aug. 30 and Nov. 5, 2020.

Happiness levels sink for physicians

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, happiness levels took a sharp drop among physicians across the board. Last year, for instance, the happiness level was highest for physicians practicing in diabetes and endocrinology, at 89%. They remain the happiest this year, but the proportion saying they were happy dropped to 73%. Infectious disease physicians were the least happy outside work both last year and this year, with the proportion reporting they were happy dropping from 69% to 45%.

For family physicians, happiness levels outside work plunged from 79% last year to 57% this year.

Burnout and depression levels, however, remained steady. The portion saying they were either burned out or burned out and depressed was up only 1 percentage point, rising to 47%.

Fifteen percent of family physicians have had thoughts of suicide, and 1% said they had attempted it, according to the survey responses.

The most common strategy for coping with burnout, reported by 48% of family physicians, is talking with family members and close friends, followed closely by exercise, reported by 46%.

Sixty-eight percent of family physicians say they exercise at least twice a week, and 12% exercise every day.

However, not all coping strategies were as positive: Forty-five percent said they cope by isolating themselves from others; 40% turned to junk food; and 23%-24% said they drank alcohol or were binge-eating to cope. Respondents could choose more than one answer.

Among family physicians, 75% expressed anxiety about their futures, given the pandemic, which is similar to the proportion among physicians overall (77%) who had the same worries.

Work-life balance biggest worry

The survey also asked what workplace issues concern family physicians the most. The biggest concern, by far, was work-life balance, chosen by 51%. Next highest was compensation, at 19%, followed by combining parenthood and work (9%) and relationships with colleagues/staff (6%).

More than half (52%) of family doctors said they would take a cut in pay to have better work-life balance.

A little more than a third (36%) of family physicians – about the same percentage as physicians overall – said they always or most of the time spend enough time on their own health and wellness. One in five said they rarely or never do.

The amount of work required beyond the bedside continues to frustrate family physicians.

Again this year, the top cause of burnout, chosen by 70% of family physicians, was “too many bureaucratic tasks.” That was followed by “spending too many hours at work” (37%) and “increasing computerization of practice” (32%).

A large majority (82%) of family doctors report that they work online up to 10 hours a week, a number that could increase with the rise of telemedicine; 64% are personally online up to 10 hours a week. But even with combined personal and professional Internet time, family doctors don’t come close to the average time spent online among all Internet users, which Hootsuite and We Are Social report is an average of 7 hours per day.

Most in committed, satisfying relationships

Most family medicine physicians are juggling committed relationships with work life. In this survey, 78% said they were married, and another 5% said they were living with a partner.

A little more than half of married family doctors described their marriages as very good (51%). The rest were good (32%); fair (13%); poor (2%); and very poor (2%). Some (15%) had spouses who were also physicians, and 25% said their spouses worked in the health care field but were not physicians.

Almost all family physicians were able to take some vacation time during this reporting period – 43% took 3-4 weeks; 35% took 1-2 weeks; 10% took less than 1 week; 9% took 5-6 weeks; and 4% took more than 6 weeks.

If they drove to vacation destinations, they were likely to be in their favorite make of vehicle, which for family physicians were Toyotas (22%), Hondas (14%) and Fords (11%), according to the survey responses. Physicians overall favored Toyotas, Hondas, and BMWs.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Roots of physician burnout: It’s the work load

Work load, not personal vulnerability, may be at the root of the current physician burnout crisis, a recent study has concluded.

The cutting-edge research utilized cognitive theory and work load analysis to get at the source of burnout among practitioners. The findings indicate that, although some institutions continue to emphasize personal responsibility of physicians to address the issue, it may be the amount and structure of the work itself that triggers burnout in doctors.

“We evaluated the cognitive load of a clinical workday in a national sample of U.S. physicians and its relationship with burnout and professional satisfaction,” wrote Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora and coauthors. The results were reported in the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

The researchers investigated whether task load correlated with burnout scores in a large national study of U.S. physicians from October 2017 to March 2018.

As the delivery of health care becomes more complex, physicians are charged with ever-increasing amount of administrative and cognitive tasks. Recent evidence indicates that this growing complexity of work is tied to a greater risk of burnout in physicians, compared with workers in other fields. Cognitive load theory, pioneered by psychologist Jonathan Sweller, identified limitations in working memory that humans depend on to carry out cognitive tasks. Cognitive load refers to the amount of working memory used, which can be reduced in the presence of external emotional or physiological stressors. While a potential link between cognitive load and burnout may seem self-evident, the correlation between the cognitive load of physicians and burnout has not been evaluated in a large-scale study until recently.

Physician task load (PTL) was measured using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), a validated questionnaire frequently used to evaluate the cognitive load of work environments, including health care environments. Four domains (perception of effort and mental, physical, and temporal demands) were used to calculate the total PTL score.

Burnout was evaluated using the Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization scales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a validated tool considered the gold standard for measurement.

The survey sample consisted of physicians of all specialties and was assembled using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, an almost complete record of all U.S. physicians independent of AMA membership. All responses were anonymous and participation was voluntary.

Results

Among 30,456 physicians who received the survey, 5,197 (17.1%) responded. In total, 5,276 physicians were included in the analysis.

The median age of respondents was 53 years, and 61.8% self-identified as male. Twenty-four specialties were identified: 23.8% were from a primary care discipline and internal medicine represented the largest respondent group (12.1%).

Almost half of respondents (49.7%) worked in private practice, and 44.8% had been in practice for 21 years or longer.

Overall, 44.0% had at least one symptom of burnout, 38.8% of participants scored in the high range for emotional exhaustion, and 27.4% scored in the high range for depersonalization. The mean score in task load dimension varied by specialty.

The mean PTL score was 260.9 (standard deviation, 71.4). The specialties with the highest PTL score were emergency medicine (369.8), urology (353.7), general surgery subspecialties (343.9), internal medicine subspecialties (342.2), and radiology (341.6).

Aside from specialty, PTL scores also varied by practice setting, gender, age, number of hours worked per week, number of nights on call per week, and years in practice.

The researchers observed a dose response relationship between PTL and risk of burnout. For every 40-point (10%) reduction in PTL, there was 33% lower odds of experiencing burnout (odds ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.70; P < .0001). Multivariable analyses also indicated that PTL was a significant predictor of burnout, independent of practice setting, specialty, age, gender, and hours worked.

Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout

Coauthors of the study, Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University and Colin P. West, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., are both experts on physician well-being and are passionate about finding new ways to reduce physician distress and improving health care delivery.

“Authentic efforts to address this problem must move beyond personal resilience,” Dr. Shanafelt said in an interview. “Organizations that fail to get serious about this issue are going to be left behind and struggle in the war for talent.

“Much like our efforts to improve quality, advancing clinician well-being requires organizations to make it a priority and establish the structure, process, and leadership to promote the desired outcomes,” said Dr. Shanafelt.

One potential strategy for improvement is appointing a chief wellness officer, a dedicated individual within the health care system that leads the organizational effort, explained Dr. Shanafelt. “Over 30 vanguard institutions across the United States have already taken this step.”

Dr. West, a coauthor of the study, explained that conducting an analysis of PTL is fairly straightforward for hospitals and individual institutions. “The NASA-TLX tool is widely available, free to use, and not overly complex, and it could be used to provide insight into physician effort and mental, physical, and temporal demand levels,” he said in an interview.

“Deeper evaluations could follow to identify specific potential solutions, particularly system-level approaches to alleviate PTL,” Dr. West explained. “In the short term, such analyses and solutions would have costs, but helping physicians work more optimally and with less chronic strain from excessive task load would save far more than these costs overall.”

Dr. West also noted that physician burnout is very expensive to a health care system, and strategies to promote physician well-being would be a prudent financial decision long term for health care organizations.

Dr. Harry, lead author of the study, agreed with Dr. West, noting that “quality improvement literature has demonstrated that improvements in inefficiencies that lead to increased demand in the workplace often has the benefit of reduced cost.

“Many studies have demonstrated the risk of turnover due to burnout and the significant cost of physician turn over,” she said in an interview. “This cost avoidance is well worth the investment in improved operations to minimize unnecessary task load.”

Dr. Harry also recommended the NASA-TLX tool as a free resource for health systems and organizations. She noted that future studies will further validate the reliability of the tool.

“At the core, we need to focus on system redesign at both the micro and the macro level,” Dr. Harry said. “Each health system will need to assess inefficiencies in their work flow, while regulatory bodies need to consider the downstream task load of mandates and reporting requirements, all of which contribute to more cognitive load.”

The study was supported by funding from the Stanford Medicine WellMD Center, the American Medical Association, and the Mayo Clinic department of medicine program on physician well-being. Coauthors Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, and Dr. Shanafelt are coinventors of the Physician Well-being Index, Medical Student Well-Being Index, Nurse Well-Being, and Well-Being Index. Mayo Clinic holds the copyright to these instruments and has licensed them for external use. Dr. Dyrbye and Dr. Shanafelt receive a portion of any royalties paid to Mayo Clinic. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Work load, not personal vulnerability, may be at the root of the current physician burnout crisis, a recent study has concluded.

The cutting-edge research utilized cognitive theory and work load analysis to get at the source of burnout among practitioners. The findings indicate that, although some institutions continue to emphasize personal responsibility of physicians to address the issue, it may be the amount and structure of the work itself that triggers burnout in doctors.

“We evaluated the cognitive load of a clinical workday in a national sample of U.S. physicians and its relationship with burnout and professional satisfaction,” wrote Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora and coauthors. The results were reported in the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

The researchers investigated whether task load correlated with burnout scores in a large national study of U.S. physicians from October 2017 to March 2018.

As the delivery of health care becomes more complex, physicians are charged with ever-increasing amount of administrative and cognitive tasks. Recent evidence indicates that this growing complexity of work is tied to a greater risk of burnout in physicians, compared with workers in other fields. Cognitive load theory, pioneered by psychologist Jonathan Sweller, identified limitations in working memory that humans depend on to carry out cognitive tasks. Cognitive load refers to the amount of working memory used, which can be reduced in the presence of external emotional or physiological stressors. While a potential link between cognitive load and burnout may seem self-evident, the correlation between the cognitive load of physicians and burnout has not been evaluated in a large-scale study until recently.

Physician task load (PTL) was measured using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), a validated questionnaire frequently used to evaluate the cognitive load of work environments, including health care environments. Four domains (perception of effort and mental, physical, and temporal demands) were used to calculate the total PTL score.

Burnout was evaluated using the Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization scales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a validated tool considered the gold standard for measurement.

The survey sample consisted of physicians of all specialties and was assembled using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, an almost complete record of all U.S. physicians independent of AMA membership. All responses were anonymous and participation was voluntary.

Results

Among 30,456 physicians who received the survey, 5,197 (17.1%) responded. In total, 5,276 physicians were included in the analysis.

The median age of respondents was 53 years, and 61.8% self-identified as male. Twenty-four specialties were identified: 23.8% were from a primary care discipline and internal medicine represented the largest respondent group (12.1%).

Almost half of respondents (49.7%) worked in private practice, and 44.8% had been in practice for 21 years or longer.

Overall, 44.0% had at least one symptom of burnout, 38.8% of participants scored in the high range for emotional exhaustion, and 27.4% scored in the high range for depersonalization. The mean score in task load dimension varied by specialty.

The mean PTL score was 260.9 (standard deviation, 71.4). The specialties with the highest PTL score were emergency medicine (369.8), urology (353.7), general surgery subspecialties (343.9), internal medicine subspecialties (342.2), and radiology (341.6).

Aside from specialty, PTL scores also varied by practice setting, gender, age, number of hours worked per week, number of nights on call per week, and years in practice.

The researchers observed a dose response relationship between PTL and risk of burnout. For every 40-point (10%) reduction in PTL, there was 33% lower odds of experiencing burnout (odds ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.70; P < .0001). Multivariable analyses also indicated that PTL was a significant predictor of burnout, independent of practice setting, specialty, age, gender, and hours worked.

Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout

Coauthors of the study, Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University and Colin P. West, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., are both experts on physician well-being and are passionate about finding new ways to reduce physician distress and improving health care delivery.

“Authentic efforts to address this problem must move beyond personal resilience,” Dr. Shanafelt said in an interview. “Organizations that fail to get serious about this issue are going to be left behind and struggle in the war for talent.

“Much like our efforts to improve quality, advancing clinician well-being requires organizations to make it a priority and establish the structure, process, and leadership to promote the desired outcomes,” said Dr. Shanafelt.

One potential strategy for improvement is appointing a chief wellness officer, a dedicated individual within the health care system that leads the organizational effort, explained Dr. Shanafelt. “Over 30 vanguard institutions across the United States have already taken this step.”

Dr. West, a coauthor of the study, explained that conducting an analysis of PTL is fairly straightforward for hospitals and individual institutions. “The NASA-TLX tool is widely available, free to use, and not overly complex, and it could be used to provide insight into physician effort and mental, physical, and temporal demand levels,” he said in an interview.

“Deeper evaluations could follow to identify specific potential solutions, particularly system-level approaches to alleviate PTL,” Dr. West explained. “In the short term, such analyses and solutions would have costs, but helping physicians work more optimally and with less chronic strain from excessive task load would save far more than these costs overall.”

Dr. West also noted that physician burnout is very expensive to a health care system, and strategies to promote physician well-being would be a prudent financial decision long term for health care organizations.

Dr. Harry, lead author of the study, agreed with Dr. West, noting that “quality improvement literature has demonstrated that improvements in inefficiencies that lead to increased demand in the workplace often has the benefit of reduced cost.

“Many studies have demonstrated the risk of turnover due to burnout and the significant cost of physician turn over,” she said in an interview. “This cost avoidance is well worth the investment in improved operations to minimize unnecessary task load.”

Dr. Harry also recommended the NASA-TLX tool as a free resource for health systems and organizations. She noted that future studies will further validate the reliability of the tool.

“At the core, we need to focus on system redesign at both the micro and the macro level,” Dr. Harry said. “Each health system will need to assess inefficiencies in their work flow, while regulatory bodies need to consider the downstream task load of mandates and reporting requirements, all of which contribute to more cognitive load.”

The study was supported by funding from the Stanford Medicine WellMD Center, the American Medical Association, and the Mayo Clinic department of medicine program on physician well-being. Coauthors Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, and Dr. Shanafelt are coinventors of the Physician Well-being Index, Medical Student Well-Being Index, Nurse Well-Being, and Well-Being Index. Mayo Clinic holds the copyright to these instruments and has licensed them for external use. Dr. Dyrbye and Dr. Shanafelt receive a portion of any royalties paid to Mayo Clinic. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Work load, not personal vulnerability, may be at the root of the current physician burnout crisis, a recent study has concluded.

The cutting-edge research utilized cognitive theory and work load analysis to get at the source of burnout among practitioners. The findings indicate that, although some institutions continue to emphasize personal responsibility of physicians to address the issue, it may be the amount and structure of the work itself that triggers burnout in doctors.

“We evaluated the cognitive load of a clinical workday in a national sample of U.S. physicians and its relationship with burnout and professional satisfaction,” wrote Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora and coauthors. The results were reported in the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

The researchers investigated whether task load correlated with burnout scores in a large national study of U.S. physicians from October 2017 to March 2018.

As the delivery of health care becomes more complex, physicians are charged with ever-increasing amount of administrative and cognitive tasks. Recent evidence indicates that this growing complexity of work is tied to a greater risk of burnout in physicians, compared with workers in other fields. Cognitive load theory, pioneered by psychologist Jonathan Sweller, identified limitations in working memory that humans depend on to carry out cognitive tasks. Cognitive load refers to the amount of working memory used, which can be reduced in the presence of external emotional or physiological stressors. While a potential link between cognitive load and burnout may seem self-evident, the correlation between the cognitive load of physicians and burnout has not been evaluated in a large-scale study until recently.

Physician task load (PTL) was measured using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), a validated questionnaire frequently used to evaluate the cognitive load of work environments, including health care environments. Four domains (perception of effort and mental, physical, and temporal demands) were used to calculate the total PTL score.

Burnout was evaluated using the Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization scales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a validated tool considered the gold standard for measurement.

The survey sample consisted of physicians of all specialties and was assembled using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, an almost complete record of all U.S. physicians independent of AMA membership. All responses were anonymous and participation was voluntary.

Results

Among 30,456 physicians who received the survey, 5,197 (17.1%) responded. In total, 5,276 physicians were included in the analysis.

The median age of respondents was 53 years, and 61.8% self-identified as male. Twenty-four specialties were identified: 23.8% were from a primary care discipline and internal medicine represented the largest respondent group (12.1%).

Almost half of respondents (49.7%) worked in private practice, and 44.8% had been in practice for 21 years or longer.

Overall, 44.0% had at least one symptom of burnout, 38.8% of participants scored in the high range for emotional exhaustion, and 27.4% scored in the high range for depersonalization. The mean score in task load dimension varied by specialty.

The mean PTL score was 260.9 (standard deviation, 71.4). The specialties with the highest PTL score were emergency medicine (369.8), urology (353.7), general surgery subspecialties (343.9), internal medicine subspecialties (342.2), and radiology (341.6).

Aside from specialty, PTL scores also varied by practice setting, gender, age, number of hours worked per week, number of nights on call per week, and years in practice.

The researchers observed a dose response relationship between PTL and risk of burnout. For every 40-point (10%) reduction in PTL, there was 33% lower odds of experiencing burnout (odds ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.70; P < .0001). Multivariable analyses also indicated that PTL was a significant predictor of burnout, independent of practice setting, specialty, age, gender, and hours worked.

Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout

Coauthors of the study, Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University and Colin P. West, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., are both experts on physician well-being and are passionate about finding new ways to reduce physician distress and improving health care delivery.

“Authentic efforts to address this problem must move beyond personal resilience,” Dr. Shanafelt said in an interview. “Organizations that fail to get serious about this issue are going to be left behind and struggle in the war for talent.

“Much like our efforts to improve quality, advancing clinician well-being requires organizations to make it a priority and establish the structure, process, and leadership to promote the desired outcomes,” said Dr. Shanafelt.

One potential strategy for improvement is appointing a chief wellness officer, a dedicated individual within the health care system that leads the organizational effort, explained Dr. Shanafelt. “Over 30 vanguard institutions across the United States have already taken this step.”

Dr. West, a coauthor of the study, explained that conducting an analysis of PTL is fairly straightforward for hospitals and individual institutions. “The NASA-TLX tool is widely available, free to use, and not overly complex, and it could be used to provide insight into physician effort and mental, physical, and temporal demand levels,” he said in an interview.

“Deeper evaluations could follow to identify specific potential solutions, particularly system-level approaches to alleviate PTL,” Dr. West explained. “In the short term, such analyses and solutions would have costs, but helping physicians work more optimally and with less chronic strain from excessive task load would save far more than these costs overall.”

Dr. West also noted that physician burnout is very expensive to a health care system, and strategies to promote physician well-being would be a prudent financial decision long term for health care organizations.

Dr. Harry, lead author of the study, agreed with Dr. West, noting that “quality improvement literature has demonstrated that improvements in inefficiencies that lead to increased demand in the workplace often has the benefit of reduced cost.

“Many studies have demonstrated the risk of turnover due to burnout and the significant cost of physician turn over,” she said in an interview. “This cost avoidance is well worth the investment in improved operations to minimize unnecessary task load.”

Dr. Harry also recommended the NASA-TLX tool as a free resource for health systems and organizations. She noted that future studies will further validate the reliability of the tool.

“At the core, we need to focus on system redesign at both the micro and the macro level,” Dr. Harry said. “Each health system will need to assess inefficiencies in their work flow, while regulatory bodies need to consider the downstream task load of mandates and reporting requirements, all of which contribute to more cognitive load.”

The study was supported by funding from the Stanford Medicine WellMD Center, the American Medical Association, and the Mayo Clinic department of medicine program on physician well-being. Coauthors Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, and Dr. Shanafelt are coinventors of the Physician Well-being Index, Medical Student Well-Being Index, Nurse Well-Being, and Well-Being Index. Mayo Clinic holds the copyright to these instruments and has licensed them for external use. Dr. Dyrbye and Dr. Shanafelt receive a portion of any royalties paid to Mayo Clinic. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOINT COMMISSION JOURNAL ON QUALITY AND PATIENT SAFETY

Family medicine has grown; its composition has evolved

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

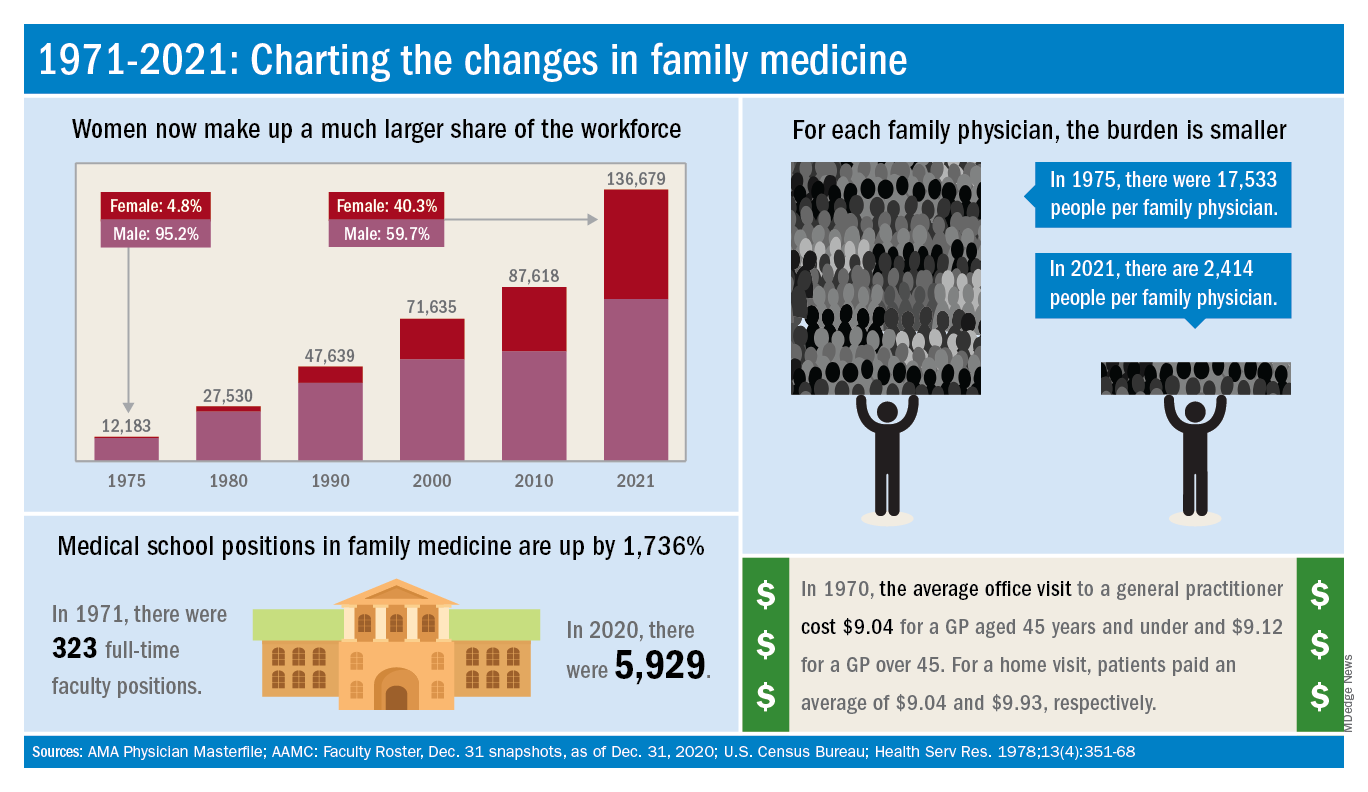

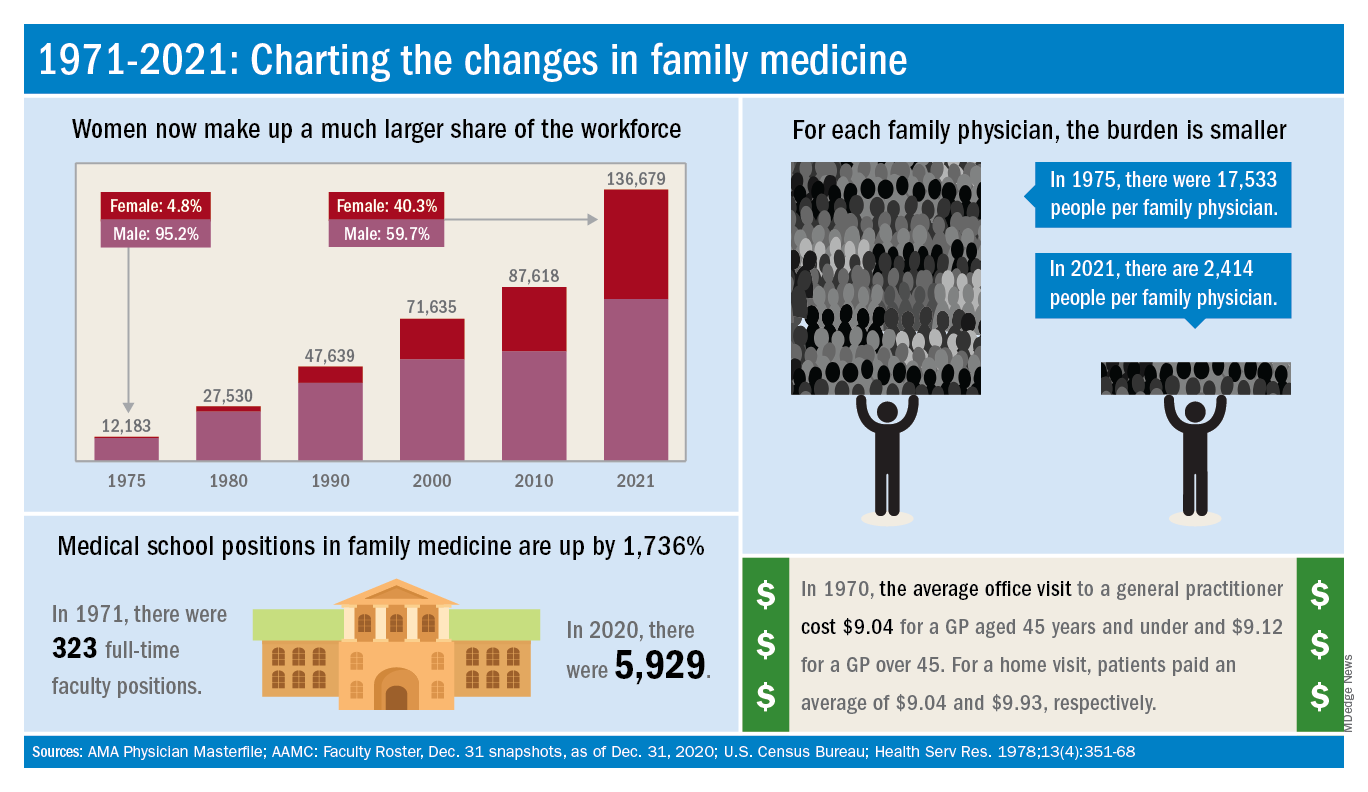

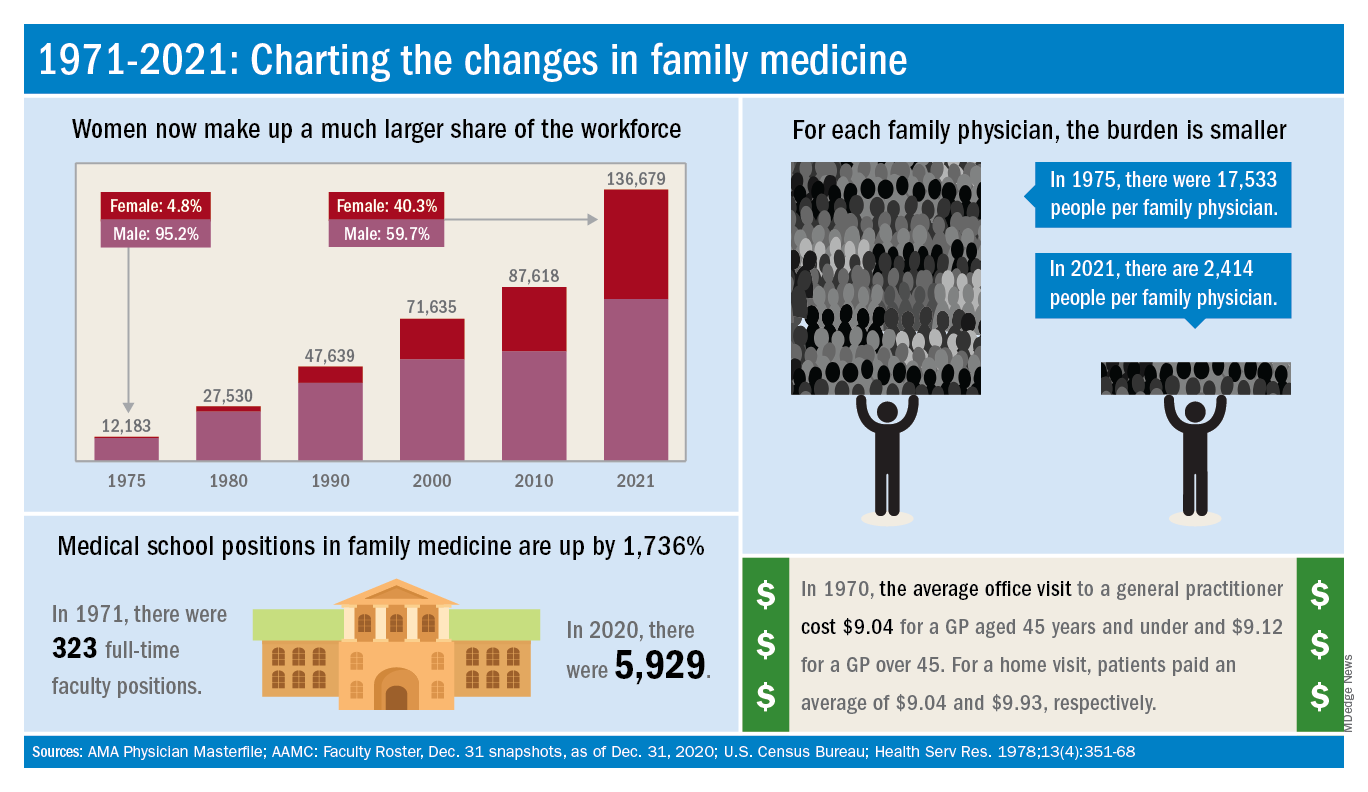

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

Medicaid and access to dermatologists

Recently, an interview titled “Dermatology a bellwether of health inequities during COVID-19,” was published by the AMA. In my opinion, the interview was largely accurate, but I took issue with the following statement in the article: “Dermatology is a lucrative specialty, and many dermatologists do not accept Medicaid.”

To me, this implies that physicians are to blame for poor health care access, which drives me insane. Dermatology is not a particularly lucrative specialty; it ranked 13th in a recent survey from the professional medical network Doximity. Furthermore, if payment for practice expense is removed, dermatology drops much further down, close to primary care.

There is a fundamental misunderstanding by the public and legislators about physician incomes. The reimbursements that are reported by Medicare for example, include the practice expense cost, which for dermatology is about 60% of the total remitted to the doctor, as I wrote in a 2015 column.

That is, the cost of providing the facility, supplies, staff, rent, and utilities are included in “reimbursement,” though this is money that goes out the door to pay the bills as quickly as it comes in. This is for overhead, nothing here for the practitioner’s time and work.

Even when dermatologists perform hospital consults, they usually bring their own supply kit from their office for skin biopsies, or other procedures since these are impossible to find in a hospital.

I also pointed out in my earlier column that most other specialties do not provide the majority of their procedures in the office, but instead, use the hospital, which provides supplies and staff for procedures. These other specialists are to be lauded for providing their services at charity rates, or for no pay at all, but at least they do not have to pay for the building, equipment, supplies, and staff out of pocket. Dermatologists do, since in a sense, they run their own “hospitals” as almost all of their procedures are based out of their offices.

The economics of a patient visit

I do not dispute that it is more difficult for a Medicaid patient to get an appointment with a dermatologist than it is for a patient with private insurance, but this is because Medicaid often pays less than the cost of supplies to see them. It is also easier to get an appointment for a cosmetic procedure than a rash because reimbursements in general are artificially suppressed, even for Medicare (which is also the benchmark for private insurers) by the federal government. Medicare reimbursements have not kept pace with inflation and are about 53% less than they were in 1992.

Let’s look at a skin biopsy. The supplies and equipment to perform a skin biopsy cost over $50. In Ohio, Medicare pays $96.19 for a skin biopsy. Medicaid pays $47.20. That’s correct: less than the cost of supplies and overhead. So, a private practitioner not only provides the service for free, but loses money on every visit that involves a skin biopsy. When I talk to legislators, I liken this to my standing in front of my office and handing out $5 bills. In Ohio, Medicare pays $105.04 for a level 3 office visit. Medicaid pays $57.76. Medicare overhead on a level 3 office visit is again about 50%, so the office visit is about a break-even proposition, if you donate your time.

Academic medical centers can charge additional facility fees, and some receive subsidies from the city and county to treat indigent patients, and are often obligated to see all. Most hospitals with high Medicaid and indigent patient loads pay their surgical specialists to take call at their emergency rooms and often subsidize their emergency room doctors as well.

I agree that dermatology is an important specialty to have access to in the COVID-19 pandemic. I agree that patients of color may be disproportionately impacted because they may be covered by Medicaid more often, or have no insurance at all. The finger of blame, however, should be squarely pointed at politicians who have woefully underfunded Medicaid reimbursement rates, as well as payments for physicians under the Affordable Care Act, while thumping their chests and boasting how they have provided health care to millions. I think this was eloquently demonstrated when as part of the “deal” Congress made with the AMA to get the ACA passed, Congress agreed to pay primary care physicians (but only primary care) Medicare rates for Medicaid patients for 2 years.

Some states have continued to pay enhanced Medicaid rates and have fewer Medicaid patient access issues.

Most convincing, perhaps, are the states that pay Medicare rates or better for their Medicaid enrollees, for example Alaska and Montana. In these states, you will not have access to care issues beyond the actual human shortage of physicians in remote areas.

So, in conclusion, I maintain that dermatology is not a particularly lucrative specialty, once the overhead expense payments are removed, and further argue, that even if it were, why does that obligate us to provide care to insurance plans at a loss? Medicaid access to dermatologists is a government economic issue, not a physician ethical one. Most Americans get to pick the charities they choose to donate to.

The federal government would love to force all physicians into a plan where you must see patients at their chosen rates or see no patients at all. Look no further than our Canadian neighbors, where long wait times to see specialists are legendary. It has been reported that there are only six to seven hundred dermatologists in all of Canada to serve 30 million people.

So, when the topic of poor patient access to care for the Medicaid enrollee or indigent comes up, stand tall and point your finger to your state capital. That is where the blame lies.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Recently, an interview titled “Dermatology a bellwether of health inequities during COVID-19,” was published by the AMA. In my opinion, the interview was largely accurate, but I took issue with the following statement in the article: “Dermatology is a lucrative specialty, and many dermatologists do not accept Medicaid.”

To me, this implies that physicians are to blame for poor health care access, which drives me insane. Dermatology is not a particularly lucrative specialty; it ranked 13th in a recent survey from the professional medical network Doximity. Furthermore, if payment for practice expense is removed, dermatology drops much further down, close to primary care.

There is a fundamental misunderstanding by the public and legislators about physician incomes. The reimbursements that are reported by Medicare for example, include the practice expense cost, which for dermatology is about 60% of the total remitted to the doctor, as I wrote in a 2015 column.

That is, the cost of providing the facility, supplies, staff, rent, and utilities are included in “reimbursement,” though this is money that goes out the door to pay the bills as quickly as it comes in. This is for overhead, nothing here for the practitioner’s time and work.

Even when dermatologists perform hospital consults, they usually bring their own supply kit from their office for skin biopsies, or other procedures since these are impossible to find in a hospital.

I also pointed out in my earlier column that most other specialties do not provide the majority of their procedures in the office, but instead, use the hospital, which provides supplies and staff for procedures. These other specialists are to be lauded for providing their services at charity rates, or for no pay at all, but at least they do not have to pay for the building, equipment, supplies, and staff out of pocket. Dermatologists do, since in a sense, they run their own “hospitals” as almost all of their procedures are based out of their offices.

The economics of a patient visit

I do not dispute that it is more difficult for a Medicaid patient to get an appointment with a dermatologist than it is for a patient with private insurance, but this is because Medicaid often pays less than the cost of supplies to see them. It is also easier to get an appointment for a cosmetic procedure than a rash because reimbursements in general are artificially suppressed, even for Medicare (which is also the benchmark for private insurers) by the federal government. Medicare reimbursements have not kept pace with inflation and are about 53% less than they were in 1992.

Let’s look at a skin biopsy. The supplies and equipment to perform a skin biopsy cost over $50. In Ohio, Medicare pays $96.19 for a skin biopsy. Medicaid pays $47.20. That’s correct: less than the cost of supplies and overhead. So, a private practitioner not only provides the service for free, but loses money on every visit that involves a skin biopsy. When I talk to legislators, I liken this to my standing in front of my office and handing out $5 bills. In Ohio, Medicare pays $105.04 for a level 3 office visit. Medicaid pays $57.76. Medicare overhead on a level 3 office visit is again about 50%, so the office visit is about a break-even proposition, if you donate your time.

Academic medical centers can charge additional facility fees, and some receive subsidies from the city and county to treat indigent patients, and are often obligated to see all. Most hospitals with high Medicaid and indigent patient loads pay their surgical specialists to take call at their emergency rooms and often subsidize their emergency room doctors as well.