User login

MitraClip effective for post-MI acute mitral regurgitation with cardiogenic shock

Percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip appears to be a safe, effective, and life-saving new treatment for severe acute mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to MI in surgical noncandidates, even when accompanied by cardiogenic shock, according to data from the international IREMMI registry.

“Cardiogenic shock, when adequately supported, does not seem to influence short- and mid-term outcomes, so the development of cardiogenic shock should not preclude percutaneous mitral valve repair in this scenario,” Rodrigo Estevez-Loureiro, MD, PhD, said in presenting the IREMMI (International Registry of MitraClip in Acute Myocardial Infarction) findings reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

Commentators hailed the prospective IREMMI data as potentially practice changing in light of the dire prognosis of such patients when surgery is deemed unacceptably high risk because medical management, the traditionally the only alternative, has a 30-day mortality of up to 50%.

Severe acute MR occurs in an estimated 3% of acute MIs, and in roughly 10% of patients who present with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS). The impact of intervening with the MitraClip in an effort to correct the acute MR arising from MI with CS has previously been addressed only in sparse case reports. The new IREMMI study is easily the largest dataset to date detailing clinical and echocardiographic outcomes, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro of Alvaro Cunqueiro Hospital in Vigo, Spain, said at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He reported on 93 consecutive patients who underwent MitraClip implantation for acute MR arising in the setting of MI, including 50 patients in CS at the time of the procedure. All 93 patients had been turned down by their surgical team because of extreme surgical risk. Three-quarters of the MIs showed ST-segment elevation. Only six patients had a papillary muscle rupture; in the rest, the mechanism of acute MR involved left ventricular global remodeling associated with mitral valve leaflet tethering. Percutaneous valve repair was performed at 18 expert valvular heart centers in the United States, Canada, Israel, and five European countries.

Procedural success

Time from MI to MitraClip implantation averaged 24 days in the CS patients and 33 days in the comparator arm without CS.

“These patients had been turned down for surgery, so the attending physicians generally followed a strategy of trying to cool them down with mechanical circulatory support and vasopressors. MitraClip wasn’t an option at the beginning, but after two or three failed weanings from all the possible therapies, then MitraClip becomes an option. This is one of the reasons why the time lapse between MI and the clip is so large,” the cardiologist explained.

Procedural success rates were similar in the two groups: 90% in those with CS and 93% in those without. However, average procedure time was significantly longer in the CS patients: 143 minutes versus 83 minutes in the patients without CS.

At baseline, 86% of the CS group had grade 4+ MR, similar to the 79% rate in the non-CS patients. Postprocedurally, 60% of the CS group were MR grade 0/1 and 34% were grade 2, comparable to the rates of 65% and 23% in the non-CS group.

At 3 months’ follow-up, 83.4% of the CS group had MR grade 2 or less, again not significantly different from the 90.5% rate in non-CS patients. Systolic pulmonary artery pressure was also similar: 39.6 mm Hg in the CS patients, 44 mm Hg in those without. While everyone was New York Heart Association functional class IV preprocedurally, 79.5% of the CS group were NYHA class I or II at 3 months, not significantly different from the 86.5% prevalence in the comparator arm.

Longer-term clinical outcomes

At a median follow-up of 7 months, the composite primary clinical outcome composed of all-cause mortality or heart failure rehospitalization did not differ between the two groups: a 28% rate in the CS group and 25.6% in non-CS patients. All-cause mortality occurred in 16% with CS and 9.3% without, again not a significant difference.

In a Cox regression analysis, neither surgical risk score, patient age, left ventricular geometry, nor CS was independently associated with the primary composite endpoint. Indeed, the only independent predictor of freedom from mortality or heart failure readmission at follow-up was procedural success, which is very much a function of the experience of the heart team, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro continued.

Michael A. Borger, MD, PhD, who comoderated the late-breaking clinical science session, was wowed by the IREMMI results.

“The mortality rates, I can tell you, compared to traditional surgical series of acute MR in the face of ACS [acute cardiogenic shock] are very, very respectable,” commented Dr. Borger, director of the cardiac surgery clinic at the Leipzig (Ger.) University Heart Center.

“Extremely impressive,” agreed discussant Vinayak N. Bapat, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon and valve scientist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. He posed a practical question: “Should we take from this presentation that patients should be stabilized with something like ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or Impella [left ventricular assist device], then transferred to an expert center for the procedure?”

“I think that the stabilization is essential in the patients with cardiogenic shock,” Dr. Estevez-Loureiro replied. “Unlike with surgery, it’s very difficult to establish a MitraClip procedure in a couple of hours in the middle of the night. You have to stabilize them and then treat for shock with ECMO, Impella, or both. I think they should be transferred to a center than can deliver the best treatment. In centers with less experience, patients can be put on mechanical support and transferred to an expert valve center, not only for MitraClip implantation, but for discussion of all the treatment possibilities, including surgery.”

At a press conference in which Dr. Estevez-Loureiro presented highlights of the IREMMI study, discussant Dee Dee Wang, MD, said the international coinvestigators “need to be applauded” for this study.

“Having these outcomes is incredible,” declared Dr. Wang, a structural heart disease specialist at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit.

While this is an observational study, it’s a high-quality dataset with excellent methodology. And conducting a randomized trial in patients with such high surgical risk scores – the CS group had an average EuroSCORE II of 21 – would be extremely difficult, according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Estevez-Loureiro reported receiving research grants from Abbott and serving as a consultant to that company as well as Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Estevez-Loureiro, R. TCT 2020, LBCS session IV.

Percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip appears to be a safe, effective, and life-saving new treatment for severe acute mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to MI in surgical noncandidates, even when accompanied by cardiogenic shock, according to data from the international IREMMI registry.

“Cardiogenic shock, when adequately supported, does not seem to influence short- and mid-term outcomes, so the development of cardiogenic shock should not preclude percutaneous mitral valve repair in this scenario,” Rodrigo Estevez-Loureiro, MD, PhD, said in presenting the IREMMI (International Registry of MitraClip in Acute Myocardial Infarction) findings reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

Commentators hailed the prospective IREMMI data as potentially practice changing in light of the dire prognosis of such patients when surgery is deemed unacceptably high risk because medical management, the traditionally the only alternative, has a 30-day mortality of up to 50%.

Severe acute MR occurs in an estimated 3% of acute MIs, and in roughly 10% of patients who present with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS). The impact of intervening with the MitraClip in an effort to correct the acute MR arising from MI with CS has previously been addressed only in sparse case reports. The new IREMMI study is easily the largest dataset to date detailing clinical and echocardiographic outcomes, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro of Alvaro Cunqueiro Hospital in Vigo, Spain, said at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He reported on 93 consecutive patients who underwent MitraClip implantation for acute MR arising in the setting of MI, including 50 patients in CS at the time of the procedure. All 93 patients had been turned down by their surgical team because of extreme surgical risk. Three-quarters of the MIs showed ST-segment elevation. Only six patients had a papillary muscle rupture; in the rest, the mechanism of acute MR involved left ventricular global remodeling associated with mitral valve leaflet tethering. Percutaneous valve repair was performed at 18 expert valvular heart centers in the United States, Canada, Israel, and five European countries.

Procedural success

Time from MI to MitraClip implantation averaged 24 days in the CS patients and 33 days in the comparator arm without CS.

“These patients had been turned down for surgery, so the attending physicians generally followed a strategy of trying to cool them down with mechanical circulatory support and vasopressors. MitraClip wasn’t an option at the beginning, but after two or three failed weanings from all the possible therapies, then MitraClip becomes an option. This is one of the reasons why the time lapse between MI and the clip is so large,” the cardiologist explained.

Procedural success rates were similar in the two groups: 90% in those with CS and 93% in those without. However, average procedure time was significantly longer in the CS patients: 143 minutes versus 83 minutes in the patients without CS.

At baseline, 86% of the CS group had grade 4+ MR, similar to the 79% rate in the non-CS patients. Postprocedurally, 60% of the CS group were MR grade 0/1 and 34% were grade 2, comparable to the rates of 65% and 23% in the non-CS group.

At 3 months’ follow-up, 83.4% of the CS group had MR grade 2 or less, again not significantly different from the 90.5% rate in non-CS patients. Systolic pulmonary artery pressure was also similar: 39.6 mm Hg in the CS patients, 44 mm Hg in those without. While everyone was New York Heart Association functional class IV preprocedurally, 79.5% of the CS group were NYHA class I or II at 3 months, not significantly different from the 86.5% prevalence in the comparator arm.

Longer-term clinical outcomes

At a median follow-up of 7 months, the composite primary clinical outcome composed of all-cause mortality or heart failure rehospitalization did not differ between the two groups: a 28% rate in the CS group and 25.6% in non-CS patients. All-cause mortality occurred in 16% with CS and 9.3% without, again not a significant difference.

In a Cox regression analysis, neither surgical risk score, patient age, left ventricular geometry, nor CS was independently associated with the primary composite endpoint. Indeed, the only independent predictor of freedom from mortality or heart failure readmission at follow-up was procedural success, which is very much a function of the experience of the heart team, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro continued.

Michael A. Borger, MD, PhD, who comoderated the late-breaking clinical science session, was wowed by the IREMMI results.

“The mortality rates, I can tell you, compared to traditional surgical series of acute MR in the face of ACS [acute cardiogenic shock] are very, very respectable,” commented Dr. Borger, director of the cardiac surgery clinic at the Leipzig (Ger.) University Heart Center.

“Extremely impressive,” agreed discussant Vinayak N. Bapat, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon and valve scientist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. He posed a practical question: “Should we take from this presentation that patients should be stabilized with something like ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or Impella [left ventricular assist device], then transferred to an expert center for the procedure?”

“I think that the stabilization is essential in the patients with cardiogenic shock,” Dr. Estevez-Loureiro replied. “Unlike with surgery, it’s very difficult to establish a MitraClip procedure in a couple of hours in the middle of the night. You have to stabilize them and then treat for shock with ECMO, Impella, or both. I think they should be transferred to a center than can deliver the best treatment. In centers with less experience, patients can be put on mechanical support and transferred to an expert valve center, not only for MitraClip implantation, but for discussion of all the treatment possibilities, including surgery.”

At a press conference in which Dr. Estevez-Loureiro presented highlights of the IREMMI study, discussant Dee Dee Wang, MD, said the international coinvestigators “need to be applauded” for this study.

“Having these outcomes is incredible,” declared Dr. Wang, a structural heart disease specialist at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit.

While this is an observational study, it’s a high-quality dataset with excellent methodology. And conducting a randomized trial in patients with such high surgical risk scores – the CS group had an average EuroSCORE II of 21 – would be extremely difficult, according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Estevez-Loureiro reported receiving research grants from Abbott and serving as a consultant to that company as well as Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Estevez-Loureiro, R. TCT 2020, LBCS session IV.

Percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip appears to be a safe, effective, and life-saving new treatment for severe acute mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to MI in surgical noncandidates, even when accompanied by cardiogenic shock, according to data from the international IREMMI registry.

“Cardiogenic shock, when adequately supported, does not seem to influence short- and mid-term outcomes, so the development of cardiogenic shock should not preclude percutaneous mitral valve repair in this scenario,” Rodrigo Estevez-Loureiro, MD, PhD, said in presenting the IREMMI (International Registry of MitraClip in Acute Myocardial Infarction) findings reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

Commentators hailed the prospective IREMMI data as potentially practice changing in light of the dire prognosis of such patients when surgery is deemed unacceptably high risk because medical management, the traditionally the only alternative, has a 30-day mortality of up to 50%.

Severe acute MR occurs in an estimated 3% of acute MIs, and in roughly 10% of patients who present with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS). The impact of intervening with the MitraClip in an effort to correct the acute MR arising from MI with CS has previously been addressed only in sparse case reports. The new IREMMI study is easily the largest dataset to date detailing clinical and echocardiographic outcomes, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro of Alvaro Cunqueiro Hospital in Vigo, Spain, said at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He reported on 93 consecutive patients who underwent MitraClip implantation for acute MR arising in the setting of MI, including 50 patients in CS at the time of the procedure. All 93 patients had been turned down by their surgical team because of extreme surgical risk. Three-quarters of the MIs showed ST-segment elevation. Only six patients had a papillary muscle rupture; in the rest, the mechanism of acute MR involved left ventricular global remodeling associated with mitral valve leaflet tethering. Percutaneous valve repair was performed at 18 expert valvular heart centers in the United States, Canada, Israel, and five European countries.

Procedural success

Time from MI to MitraClip implantation averaged 24 days in the CS patients and 33 days in the comparator arm without CS.

“These patients had been turned down for surgery, so the attending physicians generally followed a strategy of trying to cool them down with mechanical circulatory support and vasopressors. MitraClip wasn’t an option at the beginning, but after two or three failed weanings from all the possible therapies, then MitraClip becomes an option. This is one of the reasons why the time lapse between MI and the clip is so large,” the cardiologist explained.

Procedural success rates were similar in the two groups: 90% in those with CS and 93% in those without. However, average procedure time was significantly longer in the CS patients: 143 minutes versus 83 minutes in the patients without CS.

At baseline, 86% of the CS group had grade 4+ MR, similar to the 79% rate in the non-CS patients. Postprocedurally, 60% of the CS group were MR grade 0/1 and 34% were grade 2, comparable to the rates of 65% and 23% in the non-CS group.

At 3 months’ follow-up, 83.4% of the CS group had MR grade 2 or less, again not significantly different from the 90.5% rate in non-CS patients. Systolic pulmonary artery pressure was also similar: 39.6 mm Hg in the CS patients, 44 mm Hg in those without. While everyone was New York Heart Association functional class IV preprocedurally, 79.5% of the CS group were NYHA class I or II at 3 months, not significantly different from the 86.5% prevalence in the comparator arm.

Longer-term clinical outcomes

At a median follow-up of 7 months, the composite primary clinical outcome composed of all-cause mortality or heart failure rehospitalization did not differ between the two groups: a 28% rate in the CS group and 25.6% in non-CS patients. All-cause mortality occurred in 16% with CS and 9.3% without, again not a significant difference.

In a Cox regression analysis, neither surgical risk score, patient age, left ventricular geometry, nor CS was independently associated with the primary composite endpoint. Indeed, the only independent predictor of freedom from mortality or heart failure readmission at follow-up was procedural success, which is very much a function of the experience of the heart team, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro continued.

Michael A. Borger, MD, PhD, who comoderated the late-breaking clinical science session, was wowed by the IREMMI results.

“The mortality rates, I can tell you, compared to traditional surgical series of acute MR in the face of ACS [acute cardiogenic shock] are very, very respectable,” commented Dr. Borger, director of the cardiac surgery clinic at the Leipzig (Ger.) University Heart Center.

“Extremely impressive,” agreed discussant Vinayak N. Bapat, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon and valve scientist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. He posed a practical question: “Should we take from this presentation that patients should be stabilized with something like ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or Impella [left ventricular assist device], then transferred to an expert center for the procedure?”

“I think that the stabilization is essential in the patients with cardiogenic shock,” Dr. Estevez-Loureiro replied. “Unlike with surgery, it’s very difficult to establish a MitraClip procedure in a couple of hours in the middle of the night. You have to stabilize them and then treat for shock with ECMO, Impella, or both. I think they should be transferred to a center than can deliver the best treatment. In centers with less experience, patients can be put on mechanical support and transferred to an expert valve center, not only for MitraClip implantation, but for discussion of all the treatment possibilities, including surgery.”

At a press conference in which Dr. Estevez-Loureiro presented highlights of the IREMMI study, discussant Dee Dee Wang, MD, said the international coinvestigators “need to be applauded” for this study.

“Having these outcomes is incredible,” declared Dr. Wang, a structural heart disease specialist at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit.

While this is an observational study, it’s a high-quality dataset with excellent methodology. And conducting a randomized trial in patients with such high surgical risk scores – the CS group had an average EuroSCORE II of 21 – would be extremely difficult, according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Estevez-Loureiro reported receiving research grants from Abbott and serving as a consultant to that company as well as Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Estevez-Loureiro, R. TCT 2020, LBCS session IV.

FROM TCT 2020

Intravascular lithotripsy hailed as ‘game changer’ for coronary calcification

aimed at gaining U.S. regulatory approval.

The technology is basically the same as in extracorporeal lithotripsy, used for the treatment of kidney stones for more than 30 years: namely, transmission of pulsed acoustic pressure waves in order to fracture calcium. For interventional cardiology purposes, however, the transmitter is located within a balloon angioplasty catheter, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, explained in presenting the study results at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

In Disrupt CAD III, intravascular lithotripsy far exceeded the procedural success and 30-day freedom from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) performance targets set in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration. In so doing, the intravascular lithotripsy device developed by Shockwave Medical successfully addressed one of the banes of contemporary interventional cardiology: heavily calcified coronary lesions.

Currently available technologies targeting such lesions, including noncompliant high-pressure balloons, intravascular lasers, cutting balloons, and orbital and rotational atherectomy, often yield suboptimal results, noted Dr. Kereiakes, medical director of the Christ Hospital Heart and Cardiovascular Center in Cincinnati.

Severe vascular calcifications are becoming more common, due in part to an aging population and the growing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency. Severely calcified coronary lesions complicate percutaneous coronary intervention. They’re associated with increased risks of dissection, perforation, and periprocedural MI. Moreover, heavily calcified lesions impede stent delivery and expansion – and stent underexpansion is the leading predictor of restenosis and stent thrombosis, he observed at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Disrupt CAD III was a prospective single-arm study of 384 patients at 47 sites in the United States and several European countries. All participants had de novo coronary calcifications graded as severe by core laboratory assessment, with a mean calcified length of 47.9 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean calcium angle and thickness of 292.5 degrees and 0.96 mm by optical coherence tomography.

“It’s staggering, the level of calcification these patients had. It’s jaw dropping,” Dr. Kereiakes observed.

Intravascular lithotripsy was used to prepare these severely calcified lesions for stenting. The intervention entailed transmission of acoustic waves circumferentially and transmurally at 1 pulse per second through tissue at an effective pressure of about 50 atm. Patients received an average of 69 pulses.

This was not a randomized trial; there was no sham-treated control arm. Instead, the comparator group selected under regulatory guidance was comprised of patients who had received orbital atherectomy for severe coronary calcifications in the earlier, similarly designed ORBIT II trial, which led to FDA marketing approval of that technology.

Key outcomes

The procedural success rate, defined as successful stent delivery with less than a 50% residual stenosis and no in-hospital MACE, was 92.4% in Disrupt CAD III, compared to 83.4% for orbital atherectomy in ORBIT II. The primary safety endpoint of freedom from cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days was achieved in 92.2% of patients in the intravascular lithotripsy trial, versus 84.4% in ORBIT II.

The 30-day MACE rate of 7.8% in Disrupt CAD III was primarily driven by periprocedural MIs, which occurred in 6.8% of participants. Only one-third of the MIs were clinically relevant by the Society for Coronary Angiography and Intervention definition. There were two cardiac deaths and three cases of stent thrombosis, all of which were associated with known predictors of the complication. There was 1 case each of dissection, abrupt closure, and perforation, but no instances of slow flow or no reflow at the procedure’s end. Transient lithotripsy-induced left ventricular capture occurred in 41% of patients, but they were benign events with no lasting consequences.

The device was able to cross and deliver acoustic pressure wave therapy to 98.2% of lesions. The mean diameter stenosis preprocedure was 65.1%, dropping to 37.2% post lithotripsy, with a final in-stent residual stenosis diameter of 11.9%, with a 1.7-mm acute gain. The average stent expansion at the site of maximum calcification was 102%, with a minimum stent area of 6.5 mm2.

Optical coherence imaging revealed that 67% of treated lesions had circumferential and transmural fractures of both deep and superficial calcium post lithotripsy. Yet outcomes were the same regardless of whether fractures were evident on imaging.

At 30-day follow-up, 72.9% of patients had no angina, up from just 12.6% of participants pre-PCI. Follow-up will continue for 2 years.

Outcomes were similar for the first case done at each participating center and all cases thereafter.

“The ease of use was remarkable,” Dr. Kereiakes recalled. “The learning curve is virtually nonexistent.”

The reaction

At a press conference where Dr. Kereiakes presented the Disrupt CAD III results, discussant Allen Jeremias, MD, said he found the results compelling.

“The success rate is high, I think it’s relatively easy to use, as demonstrated, and I think the results are spectacular,” said Dr. Jeremias, director of interventional cardiology research and associate director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, N.Y.

Cardiologists “really don’t do a good job most of the time” with severely calcified coronary lesions, added Dr. Jeremias, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

“A lot of times these patients have inadequate stent outcomes when we do intravascular imaging. So to do something to try to basically crack the calcium and expand the stent is, I think, critically important in these patients, and this is an amazing technology that accomplishes that,” the cardiologist said.

Juan F. Granada, MD, of Columbia University, New York, who moderated the press conference, said, “Some of the debulking techniques used for calcified stenoses actually require a lot of training, knowledge, experience, and hospital infrastructure.

I really think having a technology that is easy to use and familiar to all interventional cardiologists, such as a balloon, could potentially be a disruptive change in our field.”

“It’s an absolute game changer,” agreed Dr. Jeremias.

Dr. Kereiakes reported serving as a consultant to a handful of medical device companies, including Shockwave Medical, which sponsored Disrupt CAD III.

SOURCE: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

aimed at gaining U.S. regulatory approval.

The technology is basically the same as in extracorporeal lithotripsy, used for the treatment of kidney stones for more than 30 years: namely, transmission of pulsed acoustic pressure waves in order to fracture calcium. For interventional cardiology purposes, however, the transmitter is located within a balloon angioplasty catheter, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, explained in presenting the study results at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

In Disrupt CAD III, intravascular lithotripsy far exceeded the procedural success and 30-day freedom from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) performance targets set in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration. In so doing, the intravascular lithotripsy device developed by Shockwave Medical successfully addressed one of the banes of contemporary interventional cardiology: heavily calcified coronary lesions.

Currently available technologies targeting such lesions, including noncompliant high-pressure balloons, intravascular lasers, cutting balloons, and orbital and rotational atherectomy, often yield suboptimal results, noted Dr. Kereiakes, medical director of the Christ Hospital Heart and Cardiovascular Center in Cincinnati.

Severe vascular calcifications are becoming more common, due in part to an aging population and the growing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency. Severely calcified coronary lesions complicate percutaneous coronary intervention. They’re associated with increased risks of dissection, perforation, and periprocedural MI. Moreover, heavily calcified lesions impede stent delivery and expansion – and stent underexpansion is the leading predictor of restenosis and stent thrombosis, he observed at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Disrupt CAD III was a prospective single-arm study of 384 patients at 47 sites in the United States and several European countries. All participants had de novo coronary calcifications graded as severe by core laboratory assessment, with a mean calcified length of 47.9 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean calcium angle and thickness of 292.5 degrees and 0.96 mm by optical coherence tomography.

“It’s staggering, the level of calcification these patients had. It’s jaw dropping,” Dr. Kereiakes observed.

Intravascular lithotripsy was used to prepare these severely calcified lesions for stenting. The intervention entailed transmission of acoustic waves circumferentially and transmurally at 1 pulse per second through tissue at an effective pressure of about 50 atm. Patients received an average of 69 pulses.

This was not a randomized trial; there was no sham-treated control arm. Instead, the comparator group selected under regulatory guidance was comprised of patients who had received orbital atherectomy for severe coronary calcifications in the earlier, similarly designed ORBIT II trial, which led to FDA marketing approval of that technology.

Key outcomes

The procedural success rate, defined as successful stent delivery with less than a 50% residual stenosis and no in-hospital MACE, was 92.4% in Disrupt CAD III, compared to 83.4% for orbital atherectomy in ORBIT II. The primary safety endpoint of freedom from cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days was achieved in 92.2% of patients in the intravascular lithotripsy trial, versus 84.4% in ORBIT II.

The 30-day MACE rate of 7.8% in Disrupt CAD III was primarily driven by periprocedural MIs, which occurred in 6.8% of participants. Only one-third of the MIs were clinically relevant by the Society for Coronary Angiography and Intervention definition. There were two cardiac deaths and three cases of stent thrombosis, all of which were associated with known predictors of the complication. There was 1 case each of dissection, abrupt closure, and perforation, but no instances of slow flow or no reflow at the procedure’s end. Transient lithotripsy-induced left ventricular capture occurred in 41% of patients, but they were benign events with no lasting consequences.

The device was able to cross and deliver acoustic pressure wave therapy to 98.2% of lesions. The mean diameter stenosis preprocedure was 65.1%, dropping to 37.2% post lithotripsy, with a final in-stent residual stenosis diameter of 11.9%, with a 1.7-mm acute gain. The average stent expansion at the site of maximum calcification was 102%, with a minimum stent area of 6.5 mm2.

Optical coherence imaging revealed that 67% of treated lesions had circumferential and transmural fractures of both deep and superficial calcium post lithotripsy. Yet outcomes were the same regardless of whether fractures were evident on imaging.

At 30-day follow-up, 72.9% of patients had no angina, up from just 12.6% of participants pre-PCI. Follow-up will continue for 2 years.

Outcomes were similar for the first case done at each participating center and all cases thereafter.

“The ease of use was remarkable,” Dr. Kereiakes recalled. “The learning curve is virtually nonexistent.”

The reaction

At a press conference where Dr. Kereiakes presented the Disrupt CAD III results, discussant Allen Jeremias, MD, said he found the results compelling.

“The success rate is high, I think it’s relatively easy to use, as demonstrated, and I think the results are spectacular,” said Dr. Jeremias, director of interventional cardiology research and associate director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, N.Y.

Cardiologists “really don’t do a good job most of the time” with severely calcified coronary lesions, added Dr. Jeremias, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

“A lot of times these patients have inadequate stent outcomes when we do intravascular imaging. So to do something to try to basically crack the calcium and expand the stent is, I think, critically important in these patients, and this is an amazing technology that accomplishes that,” the cardiologist said.

Juan F. Granada, MD, of Columbia University, New York, who moderated the press conference, said, “Some of the debulking techniques used for calcified stenoses actually require a lot of training, knowledge, experience, and hospital infrastructure.

I really think having a technology that is easy to use and familiar to all interventional cardiologists, such as a balloon, could potentially be a disruptive change in our field.”

“It’s an absolute game changer,” agreed Dr. Jeremias.

Dr. Kereiakes reported serving as a consultant to a handful of medical device companies, including Shockwave Medical, which sponsored Disrupt CAD III.

SOURCE: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

aimed at gaining U.S. regulatory approval.

The technology is basically the same as in extracorporeal lithotripsy, used for the treatment of kidney stones for more than 30 years: namely, transmission of pulsed acoustic pressure waves in order to fracture calcium. For interventional cardiology purposes, however, the transmitter is located within a balloon angioplasty catheter, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, explained in presenting the study results at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

In Disrupt CAD III, intravascular lithotripsy far exceeded the procedural success and 30-day freedom from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) performance targets set in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration. In so doing, the intravascular lithotripsy device developed by Shockwave Medical successfully addressed one of the banes of contemporary interventional cardiology: heavily calcified coronary lesions.

Currently available technologies targeting such lesions, including noncompliant high-pressure balloons, intravascular lasers, cutting balloons, and orbital and rotational atherectomy, often yield suboptimal results, noted Dr. Kereiakes, medical director of the Christ Hospital Heart and Cardiovascular Center in Cincinnati.

Severe vascular calcifications are becoming more common, due in part to an aging population and the growing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency. Severely calcified coronary lesions complicate percutaneous coronary intervention. They’re associated with increased risks of dissection, perforation, and periprocedural MI. Moreover, heavily calcified lesions impede stent delivery and expansion – and stent underexpansion is the leading predictor of restenosis and stent thrombosis, he observed at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Disrupt CAD III was a prospective single-arm study of 384 patients at 47 sites in the United States and several European countries. All participants had de novo coronary calcifications graded as severe by core laboratory assessment, with a mean calcified length of 47.9 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean calcium angle and thickness of 292.5 degrees and 0.96 mm by optical coherence tomography.

“It’s staggering, the level of calcification these patients had. It’s jaw dropping,” Dr. Kereiakes observed.

Intravascular lithotripsy was used to prepare these severely calcified lesions for stenting. The intervention entailed transmission of acoustic waves circumferentially and transmurally at 1 pulse per second through tissue at an effective pressure of about 50 atm. Patients received an average of 69 pulses.

This was not a randomized trial; there was no sham-treated control arm. Instead, the comparator group selected under regulatory guidance was comprised of patients who had received orbital atherectomy for severe coronary calcifications in the earlier, similarly designed ORBIT II trial, which led to FDA marketing approval of that technology.

Key outcomes

The procedural success rate, defined as successful stent delivery with less than a 50% residual stenosis and no in-hospital MACE, was 92.4% in Disrupt CAD III, compared to 83.4% for orbital atherectomy in ORBIT II. The primary safety endpoint of freedom from cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days was achieved in 92.2% of patients in the intravascular lithotripsy trial, versus 84.4% in ORBIT II.

The 30-day MACE rate of 7.8% in Disrupt CAD III was primarily driven by periprocedural MIs, which occurred in 6.8% of participants. Only one-third of the MIs were clinically relevant by the Society for Coronary Angiography and Intervention definition. There were two cardiac deaths and three cases of stent thrombosis, all of which were associated with known predictors of the complication. There was 1 case each of dissection, abrupt closure, and perforation, but no instances of slow flow or no reflow at the procedure’s end. Transient lithotripsy-induced left ventricular capture occurred in 41% of patients, but they were benign events with no lasting consequences.

The device was able to cross and deliver acoustic pressure wave therapy to 98.2% of lesions. The mean diameter stenosis preprocedure was 65.1%, dropping to 37.2% post lithotripsy, with a final in-stent residual stenosis diameter of 11.9%, with a 1.7-mm acute gain. The average stent expansion at the site of maximum calcification was 102%, with a minimum stent area of 6.5 mm2.

Optical coherence imaging revealed that 67% of treated lesions had circumferential and transmural fractures of both deep and superficial calcium post lithotripsy. Yet outcomes were the same regardless of whether fractures were evident on imaging.

At 30-day follow-up, 72.9% of patients had no angina, up from just 12.6% of participants pre-PCI. Follow-up will continue for 2 years.

Outcomes were similar for the first case done at each participating center and all cases thereafter.

“The ease of use was remarkable,” Dr. Kereiakes recalled. “The learning curve is virtually nonexistent.”

The reaction

At a press conference where Dr. Kereiakes presented the Disrupt CAD III results, discussant Allen Jeremias, MD, said he found the results compelling.

“The success rate is high, I think it’s relatively easy to use, as demonstrated, and I think the results are spectacular,” said Dr. Jeremias, director of interventional cardiology research and associate director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, N.Y.

Cardiologists “really don’t do a good job most of the time” with severely calcified coronary lesions, added Dr. Jeremias, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

“A lot of times these patients have inadequate stent outcomes when we do intravascular imaging. So to do something to try to basically crack the calcium and expand the stent is, I think, critically important in these patients, and this is an amazing technology that accomplishes that,” the cardiologist said.

Juan F. Granada, MD, of Columbia University, New York, who moderated the press conference, said, “Some of the debulking techniques used for calcified stenoses actually require a lot of training, knowledge, experience, and hospital infrastructure.

I really think having a technology that is easy to use and familiar to all interventional cardiologists, such as a balloon, could potentially be a disruptive change in our field.”

“It’s an absolute game changer,” agreed Dr. Jeremias.

Dr. Kereiakes reported serving as a consultant to a handful of medical device companies, including Shockwave Medical, which sponsored Disrupt CAD III.

SOURCE: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

FROM TCT 2020

Key clinical point: Intravascular lithotripsy was safe and effective for treatment of severely calcified coronary stenoses in a pivotal trial.

Major finding: The 30-day rate of freedom from major adverse cardiovascular events was 92.2%, well above the prespecified performance goal of 84.4%.

Study details: Disrupt CAD III study is a multicenter, single-arm, prospective study of intravascular lithotripsy in 384 patients with severe coronary calcification.

Disclosures: The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Shockwave Medical Inc., the study sponsor, as well as several other medical device companies.

Source: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

NACMI: Clear benefit with PCI in STEMI COVID-19 patients

Patients with COVID-19 who present with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) represent a unique, high-risk population with greater risks for in-hospital death and stroke, according to initial results from the North American COVID-19 ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Registry (NACMI).

Although COVID-19–confirmed patients were less likely to undergo angiography than patients under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19 or historical STEMI activation controls, 71% underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

“Primary PCI is preferable and feasible in COVID-19–positive patients, with door-to-balloon times similar to PUI or COVID-negative patients, and that supports the updated COVID-specific STEMI guidelines,” study cochair Timothy D. Henry, MD, said in a late-breaking clinical science session at TCT 2020, the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

The multisociety COVID-specific guidelines were initially issued in April, endorsing PCI as the standard of care and allowing for consideration of fibrinolysis-based therapy at non-PCI capable hospitals.

Five previous publications on a total of 174 COVID-19 patients with ST-elevation have shown there are more frequent in-hospital STEMI presentations, more cases without a clear culprit lesion, more thrombotic lesions and microthrombi, and higher mortality, ranging from 12% to 72%. Still, there has been considerable controversy over exactly what to do when COVID-19 patients with ST elevation reach the cath lab, he said at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

NACMI represents the largest experience with ST-elevation patients and is a unique collaboration between the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology, American College of Cardiology, and Midwest STEMI Consortium, noted Dr. Henry, who is medical director of the Lindner Center for Research and Education at the Christ Hospital, Cincinnati.

The registry enrolled any COVID-19–positive patient or person under investigation older than 18 years with ST-segment elevation or new-onset left bundle branch block on electrocardiogram with a clinical correlate of myocardial ischemia such as chest pain, dyspnea, cardiac arrest, shock, or mechanical ventilation. There were no exclusion criteria.

Data from 171 patients with confirmed COVID-19 and 423 PUI from 64 sites were then propensity-matched to a control population from the Midwest STEMI Consortium, a prospective, multicenter registry of consecutive STEMI patients.

The three groups were similar in sex and age but there was a striking difference in race, with 27% of African American and 24% of Hispanic patients COVID-confirmed, compared with 11% and 6% in the PUI group and 4% and 1% in the control group. Likewise, there was a significant increase in diabetes (44% vs. 33% vs. 20%), which has been reported previously with influenza.

COVID-19–positive patients, as compared with PUI and controls, were significantly more likely to present with cardiogenic shock before PCI (20% vs. 14% vs. 5%), but not cardiac arrest (12% vs. 17% vs. 11%), and to have lower left ventricular ejection fractions (45% vs. 45% vs. 50%).

They also presented with more atypical symptoms than PUI patients, particularly infiltrates on chest x-ray (49% vs. 17%) and dyspnea (58% vs. 38%). Data were not available for these outcomes among historic controls.

Importantly, 21% of the COVID-19 patients did not undergo angiography, compared with 5% of PUI patients and 0% of controls (P < .001), “which is much higher than we would expect or have suspected,” Dr. Henry said. Thrombolytic use was very uncommon in those undergoing angiography, likely as a result of the guidelines.

Very surprisingly, there were no differences in door-to-balloon times between the COVID-positive, PUI, and control groups despite the ongoing pandemic (80 min vs. 78 min vs. 86 min).

But there was clear worsening in in-hospital mortality in COVID-19–positive patients (32% vs. 12% and 6%; P < .001), as well as in-hospital stroke (3.4% vs. 2% vs. 0.6%) that reached statistical significance only when compared with historical controls (P = .039). Total length of stay was twice as long in COVID-confirmed patients as in both PUI and controls (6 days vs. 3 days; P < .001).

Following the formal presentation, invited discussant Philippe Gabriel Steg, MD, Imperial College London, said the researchers have provided a great service in reporting the data so quickly but noted that an ongoing French registry of events before, during, and after the first COVID-19 wave has not seen an increased death rate.

“Can you tease out whether the increased death rate is related to cardiovascular deaths or to COVID-related pneumonias, shocks, ARDSs [acute respiratory distress syndromes], and so on and so forth? Because our impression – and that’s what we’ve published in Lancet Public Health – is that the cardiovascular morality rate doesn’t seem that affected by COVID.”

Dr. Henry replied that these are early data but “I will tell you that patients who did get PCI had a mortality rate that was only around 12% or 13%, and the patients who did not undergo angiography or were treated with medical therapy had higher mortality. Now, of course, that’s selected and we need to do a much better matching and look at that, but that’s our goal and we will have that information,” he said.

During a press briefing on the study, discussant Renu Virmani, MD, president and founder of CVPath Institute, noted that, in their analysis of 40 autopsy cases from Bergamot, Italy, small intramyocardial microthrombi were seen in nine patients, whereas epicardial microthrombi were seen in only three or four.

“Some of the cases are being taken as being related to coronary disease but may be more thrombotic than anything else,” she said. “I think there’s a combination, and that’s why the outcomes are so poor. You didn’t show us TIMI flow but that’s something to think about: Was TIMI flow different in the patients who died because you have very high mortality? I think we need to get to the bottom of what is the underlying cause of that thrombosis.”

Future topics of interest include ethnic and regional/country differences; time-to-treatment including chest pain onset-to-arrival; transfer, in-hospital, and no-culprit patients; changes over time during the pandemic; and eventually 1-year outcomes, Dr. Henry said.

Press briefing moderator Ajay Kirtane, MD, director of the cardiac catheterization labs at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving, New York, remarked that “a lot of times people will pooh-pooh observational data, but this is exactly the type of data that we need to try to be able to gather information about what our practices are, how they fit. And I think many of us around the world will see these data, and it will echo their own experience.”

The study was funded by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology. Dr. Henry has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with COVID-19 who present with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) represent a unique, high-risk population with greater risks for in-hospital death and stroke, according to initial results from the North American COVID-19 ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Registry (NACMI).

Although COVID-19–confirmed patients were less likely to undergo angiography than patients under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19 or historical STEMI activation controls, 71% underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

“Primary PCI is preferable and feasible in COVID-19–positive patients, with door-to-balloon times similar to PUI or COVID-negative patients, and that supports the updated COVID-specific STEMI guidelines,” study cochair Timothy D. Henry, MD, said in a late-breaking clinical science session at TCT 2020, the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

The multisociety COVID-specific guidelines were initially issued in April, endorsing PCI as the standard of care and allowing for consideration of fibrinolysis-based therapy at non-PCI capable hospitals.

Five previous publications on a total of 174 COVID-19 patients with ST-elevation have shown there are more frequent in-hospital STEMI presentations, more cases without a clear culprit lesion, more thrombotic lesions and microthrombi, and higher mortality, ranging from 12% to 72%. Still, there has been considerable controversy over exactly what to do when COVID-19 patients with ST elevation reach the cath lab, he said at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

NACMI represents the largest experience with ST-elevation patients and is a unique collaboration between the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology, American College of Cardiology, and Midwest STEMI Consortium, noted Dr. Henry, who is medical director of the Lindner Center for Research and Education at the Christ Hospital, Cincinnati.

The registry enrolled any COVID-19–positive patient or person under investigation older than 18 years with ST-segment elevation or new-onset left bundle branch block on electrocardiogram with a clinical correlate of myocardial ischemia such as chest pain, dyspnea, cardiac arrest, shock, or mechanical ventilation. There were no exclusion criteria.

Data from 171 patients with confirmed COVID-19 and 423 PUI from 64 sites were then propensity-matched to a control population from the Midwest STEMI Consortium, a prospective, multicenter registry of consecutive STEMI patients.

The three groups were similar in sex and age but there was a striking difference in race, with 27% of African American and 24% of Hispanic patients COVID-confirmed, compared with 11% and 6% in the PUI group and 4% and 1% in the control group. Likewise, there was a significant increase in diabetes (44% vs. 33% vs. 20%), which has been reported previously with influenza.

COVID-19–positive patients, as compared with PUI and controls, were significantly more likely to present with cardiogenic shock before PCI (20% vs. 14% vs. 5%), but not cardiac arrest (12% vs. 17% vs. 11%), and to have lower left ventricular ejection fractions (45% vs. 45% vs. 50%).

They also presented with more atypical symptoms than PUI patients, particularly infiltrates on chest x-ray (49% vs. 17%) and dyspnea (58% vs. 38%). Data were not available for these outcomes among historic controls.

Importantly, 21% of the COVID-19 patients did not undergo angiography, compared with 5% of PUI patients and 0% of controls (P < .001), “which is much higher than we would expect or have suspected,” Dr. Henry said. Thrombolytic use was very uncommon in those undergoing angiography, likely as a result of the guidelines.

Very surprisingly, there were no differences in door-to-balloon times between the COVID-positive, PUI, and control groups despite the ongoing pandemic (80 min vs. 78 min vs. 86 min).

But there was clear worsening in in-hospital mortality in COVID-19–positive patients (32% vs. 12% and 6%; P < .001), as well as in-hospital stroke (3.4% vs. 2% vs. 0.6%) that reached statistical significance only when compared with historical controls (P = .039). Total length of stay was twice as long in COVID-confirmed patients as in both PUI and controls (6 days vs. 3 days; P < .001).

Following the formal presentation, invited discussant Philippe Gabriel Steg, MD, Imperial College London, said the researchers have provided a great service in reporting the data so quickly but noted that an ongoing French registry of events before, during, and after the first COVID-19 wave has not seen an increased death rate.

“Can you tease out whether the increased death rate is related to cardiovascular deaths or to COVID-related pneumonias, shocks, ARDSs [acute respiratory distress syndromes], and so on and so forth? Because our impression – and that’s what we’ve published in Lancet Public Health – is that the cardiovascular morality rate doesn’t seem that affected by COVID.”

Dr. Henry replied that these are early data but “I will tell you that patients who did get PCI had a mortality rate that was only around 12% or 13%, and the patients who did not undergo angiography or were treated with medical therapy had higher mortality. Now, of course, that’s selected and we need to do a much better matching and look at that, but that’s our goal and we will have that information,” he said.

During a press briefing on the study, discussant Renu Virmani, MD, president and founder of CVPath Institute, noted that, in their analysis of 40 autopsy cases from Bergamot, Italy, small intramyocardial microthrombi were seen in nine patients, whereas epicardial microthrombi were seen in only three or four.

“Some of the cases are being taken as being related to coronary disease but may be more thrombotic than anything else,” she said. “I think there’s a combination, and that’s why the outcomes are so poor. You didn’t show us TIMI flow but that’s something to think about: Was TIMI flow different in the patients who died because you have very high mortality? I think we need to get to the bottom of what is the underlying cause of that thrombosis.”

Future topics of interest include ethnic and regional/country differences; time-to-treatment including chest pain onset-to-arrival; transfer, in-hospital, and no-culprit patients; changes over time during the pandemic; and eventually 1-year outcomes, Dr. Henry said.

Press briefing moderator Ajay Kirtane, MD, director of the cardiac catheterization labs at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving, New York, remarked that “a lot of times people will pooh-pooh observational data, but this is exactly the type of data that we need to try to be able to gather information about what our practices are, how they fit. And I think many of us around the world will see these data, and it will echo their own experience.”

The study was funded by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology. Dr. Henry has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with COVID-19 who present with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) represent a unique, high-risk population with greater risks for in-hospital death and stroke, according to initial results from the North American COVID-19 ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Registry (NACMI).

Although COVID-19–confirmed patients were less likely to undergo angiography than patients under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19 or historical STEMI activation controls, 71% underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

“Primary PCI is preferable and feasible in COVID-19–positive patients, with door-to-balloon times similar to PUI or COVID-negative patients, and that supports the updated COVID-specific STEMI guidelines,” study cochair Timothy D. Henry, MD, said in a late-breaking clinical science session at TCT 2020, the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

The multisociety COVID-specific guidelines were initially issued in April, endorsing PCI as the standard of care and allowing for consideration of fibrinolysis-based therapy at non-PCI capable hospitals.

Five previous publications on a total of 174 COVID-19 patients with ST-elevation have shown there are more frequent in-hospital STEMI presentations, more cases without a clear culprit lesion, more thrombotic lesions and microthrombi, and higher mortality, ranging from 12% to 72%. Still, there has been considerable controversy over exactly what to do when COVID-19 patients with ST elevation reach the cath lab, he said at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

NACMI represents the largest experience with ST-elevation patients and is a unique collaboration between the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology, American College of Cardiology, and Midwest STEMI Consortium, noted Dr. Henry, who is medical director of the Lindner Center for Research and Education at the Christ Hospital, Cincinnati.

The registry enrolled any COVID-19–positive patient or person under investigation older than 18 years with ST-segment elevation or new-onset left bundle branch block on electrocardiogram with a clinical correlate of myocardial ischemia such as chest pain, dyspnea, cardiac arrest, shock, or mechanical ventilation. There were no exclusion criteria.

Data from 171 patients with confirmed COVID-19 and 423 PUI from 64 sites were then propensity-matched to a control population from the Midwest STEMI Consortium, a prospective, multicenter registry of consecutive STEMI patients.

The three groups were similar in sex and age but there was a striking difference in race, with 27% of African American and 24% of Hispanic patients COVID-confirmed, compared with 11% and 6% in the PUI group and 4% and 1% in the control group. Likewise, there was a significant increase in diabetes (44% vs. 33% vs. 20%), which has been reported previously with influenza.

COVID-19–positive patients, as compared with PUI and controls, were significantly more likely to present with cardiogenic shock before PCI (20% vs. 14% vs. 5%), but not cardiac arrest (12% vs. 17% vs. 11%), and to have lower left ventricular ejection fractions (45% vs. 45% vs. 50%).

They also presented with more atypical symptoms than PUI patients, particularly infiltrates on chest x-ray (49% vs. 17%) and dyspnea (58% vs. 38%). Data were not available for these outcomes among historic controls.

Importantly, 21% of the COVID-19 patients did not undergo angiography, compared with 5% of PUI patients and 0% of controls (P < .001), “which is much higher than we would expect or have suspected,” Dr. Henry said. Thrombolytic use was very uncommon in those undergoing angiography, likely as a result of the guidelines.

Very surprisingly, there were no differences in door-to-balloon times between the COVID-positive, PUI, and control groups despite the ongoing pandemic (80 min vs. 78 min vs. 86 min).

But there was clear worsening in in-hospital mortality in COVID-19–positive patients (32% vs. 12% and 6%; P < .001), as well as in-hospital stroke (3.4% vs. 2% vs. 0.6%) that reached statistical significance only when compared with historical controls (P = .039). Total length of stay was twice as long in COVID-confirmed patients as in both PUI and controls (6 days vs. 3 days; P < .001).

Following the formal presentation, invited discussant Philippe Gabriel Steg, MD, Imperial College London, said the researchers have provided a great service in reporting the data so quickly but noted that an ongoing French registry of events before, during, and after the first COVID-19 wave has not seen an increased death rate.

“Can you tease out whether the increased death rate is related to cardiovascular deaths or to COVID-related pneumonias, shocks, ARDSs [acute respiratory distress syndromes], and so on and so forth? Because our impression – and that’s what we’ve published in Lancet Public Health – is that the cardiovascular morality rate doesn’t seem that affected by COVID.”

Dr. Henry replied that these are early data but “I will tell you that patients who did get PCI had a mortality rate that was only around 12% or 13%, and the patients who did not undergo angiography or were treated with medical therapy had higher mortality. Now, of course, that’s selected and we need to do a much better matching and look at that, but that’s our goal and we will have that information,” he said.

During a press briefing on the study, discussant Renu Virmani, MD, president and founder of CVPath Institute, noted that, in their analysis of 40 autopsy cases from Bergamot, Italy, small intramyocardial microthrombi were seen in nine patients, whereas epicardial microthrombi were seen in only three or four.

“Some of the cases are being taken as being related to coronary disease but may be more thrombotic than anything else,” she said. “I think there’s a combination, and that’s why the outcomes are so poor. You didn’t show us TIMI flow but that’s something to think about: Was TIMI flow different in the patients who died because you have very high mortality? I think we need to get to the bottom of what is the underlying cause of that thrombosis.”

Future topics of interest include ethnic and regional/country differences; time-to-treatment including chest pain onset-to-arrival; transfer, in-hospital, and no-culprit patients; changes over time during the pandemic; and eventually 1-year outcomes, Dr. Henry said.

Press briefing moderator Ajay Kirtane, MD, director of the cardiac catheterization labs at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving, New York, remarked that “a lot of times people will pooh-pooh observational data, but this is exactly the type of data that we need to try to be able to gather information about what our practices are, how they fit. And I think many of us around the world will see these data, and it will echo their own experience.”

The study was funded by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology. Dr. Henry has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

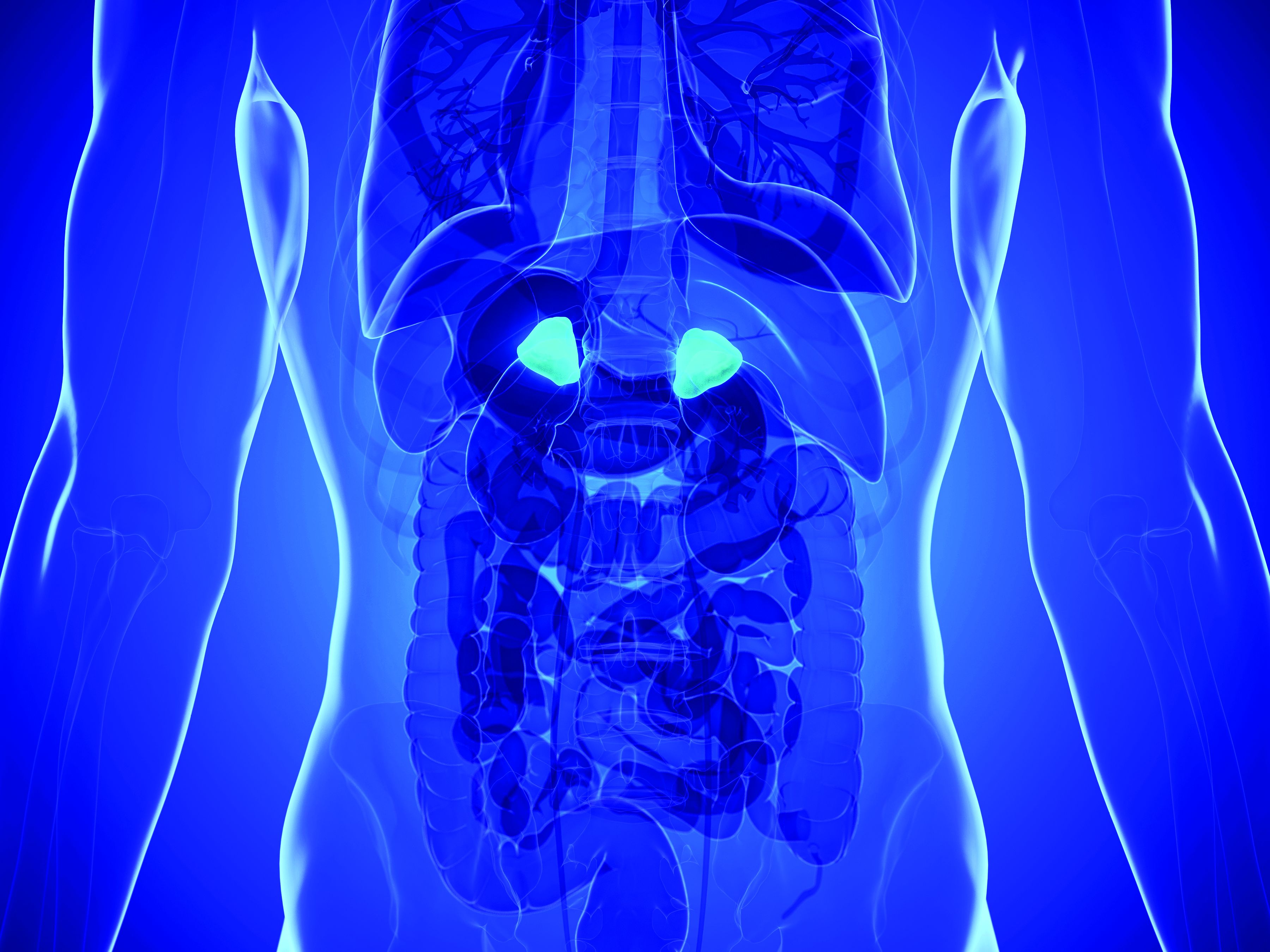

Entresto halves renal events in preserved EF heart failure patients

Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) who received sacubitril/valsartan in the PARAGON-HF trial had significant protection against progression of renal dysfunction in a prespecified secondary analysis.

The 2,419 patients with HFpEF who received sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) had half the rate of the primary adverse renal outcome, compared with the 2,403 patients randomized to valsartan alone in the comparator group, a significant difference, according to the results published online Sept. 29 in Circulation by Finnian R. McCausland, MBBCh, and colleagues.

In absolute terms, sacubitril/valsartan treatment, an angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), cut the incidence of the combined renal endpoint – renal death, end-stage renal disease, or at least a 50% drop in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) – from 2.7% in the control group to 1.4% in the sacubitril/valsartan group during a median follow-up of 35 months.

The absolute difference of 1.3% equated to a number needed to treat of 51 to prevent one of these events.

Also notable was that renal protection from sacubitril/valsartan was equally robust across the range of baseline kidney function.

‘An important therapeutic option’

The efficacy “across the spectrum of baseline renal function” indicates treatment with sacubitril/valsartan is “an important therapeutic option to slow renal-function decline in patients with heart failure,” wrote Dr. McCausland, a nephrologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and colleagues.

The authors’ conclusion is striking because currently no drug class has produced clear evidence for efficacy in HFpEF.

On the other hand, the PARAGON-HF trial that provided the data for this new analysis was statistically neutral for its primary endpoint – a reduction in the combined rate of cardiovascular death and hospitalizations for heart failure – with a P value of .06 and 95% confidence interval of 0.75-1.01.

“Because this difference [in the primary endpoint incidence between the two study group] did not meet the predetermined level of statistical significance, subsequent analyses were considered to be exploratory,” noted the authors of the primary analysis of PARAGON-HF, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Despite this limitation in interpreting secondary outcomes from the trial, the new report of a significant renal benefit “opens the potential to provide evidence-based treatment for patients with HFpEF,” commented Sheldon W. Tobe, MD, and Stephanie Poon, MD, in an editorial accompanying the latest analysis.

“At the very least, these results are certainly intriguing and suggest that there may be important patient subgroups with HFpEF who might benefit from using sacubitril/valsartan,” they emphasized.

First large trial to show renal improvement in HFpEF

The editorialists’ enthusiasm for the implications of the new findings relate in part to the fact that “PARAGON-HF is the first large trial to demonstrate improvement in renal parameters in HFpEF,” they noted.

“The finding that the composite renal outcome did not differ according to baseline eGFR is significant and suggests that the beneficial effect on renal function was indirect, possibly linked to improved cardiac function,” say Dr. Tobe, a nephrologist, and Dr. Poon, a cardiologist, both at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

PARAGON-HF enrolled 4,822 HFpEF patients at 848 centers in 43 countries, and the efficacy analysis included 4,796 patients.

The composite renal outcome was mainly driven by the incidence of a 50% or greater drop from baseline in eGFR, which occurred in 27 patients (1.1%) in the sacubitril/valsartan group and 60 patients (2.5%) who received valsartan alone.

The annual average drop in eGFR during the study was 2.0 mL/min per 1.73m2 in the sacubitril/valsartan group and 2.7 mL/min per 1.73m2 in the control group.

Although the heart failure community was disappointed that sacubitril/valsartan failed to show a significant benefit for the study’s primary outcome in HFpEF, the combination has become a mainstay of treatment for patients with HFpEF based on its performance in the PARADIGM-HF trial.

And despite the unqualified support sacubitril/valsartan now receives in guidelines and its label as a foundational treatment for HFpEF, the formulation has had a hard time gaining traction in U.S. practice, often because of barriers placed by third-party payers.

PARAGON-HF was sponsored by Novartis, which markets sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto). Dr. McCausland has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tobe has reported participating on a steering committee for Bayer Fidelio/Figaro studies and being a speaker on behalf of Pfizer and Servier. Dr. Poon has reported being an adviser to Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Servier.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) who received sacubitril/valsartan in the PARAGON-HF trial had significant protection against progression of renal dysfunction in a prespecified secondary analysis.

The 2,419 patients with HFpEF who received sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) had half the rate of the primary adverse renal outcome, compared with the 2,403 patients randomized to valsartan alone in the comparator group, a significant difference, according to the results published online Sept. 29 in Circulation by Finnian R. McCausland, MBBCh, and colleagues.

In absolute terms, sacubitril/valsartan treatment, an angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), cut the incidence of the combined renal endpoint – renal death, end-stage renal disease, or at least a 50% drop in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) – from 2.7% in the control group to 1.4% in the sacubitril/valsartan group during a median follow-up of 35 months.

The absolute difference of 1.3% equated to a number needed to treat of 51 to prevent one of these events.

Also notable was that renal protection from sacubitril/valsartan was equally robust across the range of baseline kidney function.

‘An important therapeutic option’

The efficacy “across the spectrum of baseline renal function” indicates treatment with sacubitril/valsartan is “an important therapeutic option to slow renal-function decline in patients with heart failure,” wrote Dr. McCausland, a nephrologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and colleagues.

The authors’ conclusion is striking because currently no drug class has produced clear evidence for efficacy in HFpEF.

On the other hand, the PARAGON-HF trial that provided the data for this new analysis was statistically neutral for its primary endpoint – a reduction in the combined rate of cardiovascular death and hospitalizations for heart failure – with a P value of .06 and 95% confidence interval of 0.75-1.01.

“Because this difference [in the primary endpoint incidence between the two study group] did not meet the predetermined level of statistical significance, subsequent analyses were considered to be exploratory,” noted the authors of the primary analysis of PARAGON-HF, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Despite this limitation in interpreting secondary outcomes from the trial, the new report of a significant renal benefit “opens the potential to provide evidence-based treatment for patients with HFpEF,” commented Sheldon W. Tobe, MD, and Stephanie Poon, MD, in an editorial accompanying the latest analysis.

“At the very least, these results are certainly intriguing and suggest that there may be important patient subgroups with HFpEF who might benefit from using sacubitril/valsartan,” they emphasized.

First large trial to show renal improvement in HFpEF

The editorialists’ enthusiasm for the implications of the new findings relate in part to the fact that “PARAGON-HF is the first large trial to demonstrate improvement in renal parameters in HFpEF,” they noted.

“The finding that the composite renal outcome did not differ according to baseline eGFR is significant and suggests that the beneficial effect on renal function was indirect, possibly linked to improved cardiac function,” say Dr. Tobe, a nephrologist, and Dr. Poon, a cardiologist, both at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

PARAGON-HF enrolled 4,822 HFpEF patients at 848 centers in 43 countries, and the efficacy analysis included 4,796 patients.

The composite renal outcome was mainly driven by the incidence of a 50% or greater drop from baseline in eGFR, which occurred in 27 patients (1.1%) in the sacubitril/valsartan group and 60 patients (2.5%) who received valsartan alone.

The annual average drop in eGFR during the study was 2.0 mL/min per 1.73m2 in the sacubitril/valsartan group and 2.7 mL/min per 1.73m2 in the control group.

Although the heart failure community was disappointed that sacubitril/valsartan failed to show a significant benefit for the study’s primary outcome in HFpEF, the combination has become a mainstay of treatment for patients with HFpEF based on its performance in the PARADIGM-HF trial.

And despite the unqualified support sacubitril/valsartan now receives in guidelines and its label as a foundational treatment for HFpEF, the formulation has had a hard time gaining traction in U.S. practice, often because of barriers placed by third-party payers.

PARAGON-HF was sponsored by Novartis, which markets sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto). Dr. McCausland has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tobe has reported participating on a steering committee for Bayer Fidelio/Figaro studies and being a speaker on behalf of Pfizer and Servier. Dr. Poon has reported being an adviser to Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Servier.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) who received sacubitril/valsartan in the PARAGON-HF trial had significant protection against progression of renal dysfunction in a prespecified secondary analysis.

The 2,419 patients with HFpEF who received sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) had half the rate of the primary adverse renal outcome, compared with the 2,403 patients randomized to valsartan alone in the comparator group, a significant difference, according to the results published online Sept. 29 in Circulation by Finnian R. McCausland, MBBCh, and colleagues.

In absolute terms, sacubitril/valsartan treatment, an angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), cut the incidence of the combined renal endpoint – renal death, end-stage renal disease, or at least a 50% drop in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) – from 2.7% in the control group to 1.4% in the sacubitril/valsartan group during a median follow-up of 35 months.

The absolute difference of 1.3% equated to a number needed to treat of 51 to prevent one of these events.

Also notable was that renal protection from sacubitril/valsartan was equally robust across the range of baseline kidney function.

‘An important therapeutic option’

The efficacy “across the spectrum of baseline renal function” indicates treatment with sacubitril/valsartan is “an important therapeutic option to slow renal-function decline in patients with heart failure,” wrote Dr. McCausland, a nephrologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and colleagues.

The authors’ conclusion is striking because currently no drug class has produced clear evidence for efficacy in HFpEF.

On the other hand, the PARAGON-HF trial that provided the data for this new analysis was statistically neutral for its primary endpoint – a reduction in the combined rate of cardiovascular death and hospitalizations for heart failure – with a P value of .06 and 95% confidence interval of 0.75-1.01.

“Because this difference [in the primary endpoint incidence between the two study group] did not meet the predetermined level of statistical significance, subsequent analyses were considered to be exploratory,” noted the authors of the primary analysis of PARAGON-HF, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Despite this limitation in interpreting secondary outcomes from the trial, the new report of a significant renal benefit “opens the potential to provide evidence-based treatment for patients with HFpEF,” commented Sheldon W. Tobe, MD, and Stephanie Poon, MD, in an editorial accompanying the latest analysis.

“At the very least, these results are certainly intriguing and suggest that there may be important patient subgroups with HFpEF who might benefit from using sacubitril/valsartan,” they emphasized.

First large trial to show renal improvement in HFpEF

The editorialists’ enthusiasm for the implications of the new findings relate in part to the fact that “PARAGON-HF is the first large trial to demonstrate improvement in renal parameters in HFpEF,” they noted.

“The finding that the composite renal outcome did not differ according to baseline eGFR is significant and suggests that the beneficial effect on renal function was indirect, possibly linked to improved cardiac function,” say Dr. Tobe, a nephrologist, and Dr. Poon, a cardiologist, both at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

PARAGON-HF enrolled 4,822 HFpEF patients at 848 centers in 43 countries, and the efficacy analysis included 4,796 patients.

The composite renal outcome was mainly driven by the incidence of a 50% or greater drop from baseline in eGFR, which occurred in 27 patients (1.1%) in the sacubitril/valsartan group and 60 patients (2.5%) who received valsartan alone.

The annual average drop in eGFR during the study was 2.0 mL/min per 1.73m2 in the sacubitril/valsartan group and 2.7 mL/min per 1.73m2 in the control group.

Although the heart failure community was disappointed that sacubitril/valsartan failed to show a significant benefit for the study’s primary outcome in HFpEF, the combination has become a mainstay of treatment for patients with HFpEF based on its performance in the PARADIGM-HF trial.

And despite the unqualified support sacubitril/valsartan now receives in guidelines and its label as a foundational treatment for HFpEF, the formulation has had a hard time gaining traction in U.S. practice, often because of barriers placed by third-party payers.

PARAGON-HF was sponsored by Novartis, which markets sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto). Dr. McCausland has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tobe has reported participating on a steering committee for Bayer Fidelio/Figaro studies and being a speaker on behalf of Pfizer and Servier. Dr. Poon has reported being an adviser to Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Servier.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Ticagrelor monotherapy beats DAPT in STEMI

, a major randomized trial.

“This is the first report assessing the feasibility of ticagrelor monotherapy after short-term DAPT for STEMI patients with drug-eluting stents,” Byeong-Keuk Kim, MD, PhD, noted at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.