User login

CV deaths jumped in 2020, reflecting pandemic toll

Cardiovascular-related deaths increased dramatically in 2020, marking the largest single-year increase since 2015 and surpassing the previous record from 2003, according to the American Heart Association’s 2023 Statistical Update.

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the largest increases in cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths were seen among Asian, Black, and Hispanic people.

“We thought we had been improving as a country with respect to CVD deaths over the past few decades,” Connie Tsao, MD, chair of the AHA Statistical Update writing committee, told this news organization.

Since 2020, however, those trends have changed. Dr. Tsao, a staff cardiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, noted the firsthand experience that many clinicians had in seeing the shift.

“We observed this sharp rise in age-adjusted CVD deaths, which corresponds to the COVID-19 pandemic,” she said. “Those of us health care providers knew from the overfull hospitals and ICUs that clearly COVID took a toll, particularly in those with cardiovascular risk factors.”

The AHA Statistical Update was published online in the journal Circulation.

Data on deaths

Each year, the American Heart Association and National Institutes of Health report the latest statistics related to heart disease, stroke, and cardiovascular risk factors. The 2023 update includes additional information about pandemic-related data.

Overall, the number of people who died from cardiovascular disease increased during the first year of the pandemic, rising from 876,613 in 2019 to 928,741 in 2020. This topped the previous high of 910,000 in 2003.

In addition, the age-adjusted mortality rate increased for the first time in several years, Dr. Tsao said, by a “fairly substantial” 4.6%. The age-adjusted mortality rate incorporates the variability in the aging population from year to year, accounting for higher death rates among older people.

“Even though our total number of deaths has been slowly increasing over the past decade, we have seen a decline each year in our age-adjusted rates – until 2020,” she said. “I think that is very indicative of what has been going on within our country – and the world – in light of people of all ages being impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, especially before vaccines were available to slow the spread.”

The largest increases in CVD-related deaths occurred among Asian, Black, and Hispanic people, who were most heavily affected during the first year of the pandemic.

“People from communities of color were among those most highly impacted, especially early on, often due to a disproportionate burden of cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and obesity,” Michelle Albert, MD, MPH, president of AHA and a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a statement.

Dr. Albert, who is also the director of UCSF’s Center for the Study of Adversity and Cardiovascular Disease, does research on health equity and noted the disparities seen in the 2020 numbers. “Additionally, there are socioeconomic considerations, as well as the ongoing impact of structural racism on multiple factors, including limiting the ability to access quality health care,” she said.

Additional considerations

In a special commentary, the Statistical Update writing committee pointed to the need to track data for other underrepresented communities, including LGBTQ people and those living in rural or urban areas. The authors outlined several ways to better understand the effects of identity and social determinants of health, as well as strategies to reduce cardiovascular-related disparities.

“This year’s writing group made a concerted effort to gather information on specific social factors related to health risk and outcomes, including sexual orientation, gender identity, urbanization, and socioeconomic position,” Dr. Tsao said. “However, the data are lacking because these communities are grossly underrepresented in clinical and epidemiological research.”

For the next several years, the AHA Statistical Update will likely include more insights about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as ongoing disparities.

“For sure, we will be continuing to see the effects of the pandemic for years to come,” Dr. Tsao said. “Recognition of the disparities in outcomes among vulnerable groups should be a call to action among health care providers and researchers, administration, and policy leaders to investigate the reasons and make changes to reverse these trends.”

The statistical update was prepared by a volunteer writing group on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular-related deaths increased dramatically in 2020, marking the largest single-year increase since 2015 and surpassing the previous record from 2003, according to the American Heart Association’s 2023 Statistical Update.

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the largest increases in cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths were seen among Asian, Black, and Hispanic people.

“We thought we had been improving as a country with respect to CVD deaths over the past few decades,” Connie Tsao, MD, chair of the AHA Statistical Update writing committee, told this news organization.

Since 2020, however, those trends have changed. Dr. Tsao, a staff cardiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, noted the firsthand experience that many clinicians had in seeing the shift.

“We observed this sharp rise in age-adjusted CVD deaths, which corresponds to the COVID-19 pandemic,” she said. “Those of us health care providers knew from the overfull hospitals and ICUs that clearly COVID took a toll, particularly in those with cardiovascular risk factors.”

The AHA Statistical Update was published online in the journal Circulation.

Data on deaths

Each year, the American Heart Association and National Institutes of Health report the latest statistics related to heart disease, stroke, and cardiovascular risk factors. The 2023 update includes additional information about pandemic-related data.

Overall, the number of people who died from cardiovascular disease increased during the first year of the pandemic, rising from 876,613 in 2019 to 928,741 in 2020. This topped the previous high of 910,000 in 2003.

In addition, the age-adjusted mortality rate increased for the first time in several years, Dr. Tsao said, by a “fairly substantial” 4.6%. The age-adjusted mortality rate incorporates the variability in the aging population from year to year, accounting for higher death rates among older people.

“Even though our total number of deaths has been slowly increasing over the past decade, we have seen a decline each year in our age-adjusted rates – until 2020,” she said. “I think that is very indicative of what has been going on within our country – and the world – in light of people of all ages being impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, especially before vaccines were available to slow the spread.”

The largest increases in CVD-related deaths occurred among Asian, Black, and Hispanic people, who were most heavily affected during the first year of the pandemic.

“People from communities of color were among those most highly impacted, especially early on, often due to a disproportionate burden of cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and obesity,” Michelle Albert, MD, MPH, president of AHA and a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a statement.

Dr. Albert, who is also the director of UCSF’s Center for the Study of Adversity and Cardiovascular Disease, does research on health equity and noted the disparities seen in the 2020 numbers. “Additionally, there are socioeconomic considerations, as well as the ongoing impact of structural racism on multiple factors, including limiting the ability to access quality health care,” she said.

Additional considerations

In a special commentary, the Statistical Update writing committee pointed to the need to track data for other underrepresented communities, including LGBTQ people and those living in rural or urban areas. The authors outlined several ways to better understand the effects of identity and social determinants of health, as well as strategies to reduce cardiovascular-related disparities.

“This year’s writing group made a concerted effort to gather information on specific social factors related to health risk and outcomes, including sexual orientation, gender identity, urbanization, and socioeconomic position,” Dr. Tsao said. “However, the data are lacking because these communities are grossly underrepresented in clinical and epidemiological research.”

For the next several years, the AHA Statistical Update will likely include more insights about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as ongoing disparities.

“For sure, we will be continuing to see the effects of the pandemic for years to come,” Dr. Tsao said. “Recognition of the disparities in outcomes among vulnerable groups should be a call to action among health care providers and researchers, administration, and policy leaders to investigate the reasons and make changes to reverse these trends.”

The statistical update was prepared by a volunteer writing group on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular-related deaths increased dramatically in 2020, marking the largest single-year increase since 2015 and surpassing the previous record from 2003, according to the American Heart Association’s 2023 Statistical Update.

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the largest increases in cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths were seen among Asian, Black, and Hispanic people.

“We thought we had been improving as a country with respect to CVD deaths over the past few decades,” Connie Tsao, MD, chair of the AHA Statistical Update writing committee, told this news organization.

Since 2020, however, those trends have changed. Dr. Tsao, a staff cardiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, noted the firsthand experience that many clinicians had in seeing the shift.

“We observed this sharp rise in age-adjusted CVD deaths, which corresponds to the COVID-19 pandemic,” she said. “Those of us health care providers knew from the overfull hospitals and ICUs that clearly COVID took a toll, particularly in those with cardiovascular risk factors.”

The AHA Statistical Update was published online in the journal Circulation.

Data on deaths

Each year, the American Heart Association and National Institutes of Health report the latest statistics related to heart disease, stroke, and cardiovascular risk factors. The 2023 update includes additional information about pandemic-related data.

Overall, the number of people who died from cardiovascular disease increased during the first year of the pandemic, rising from 876,613 in 2019 to 928,741 in 2020. This topped the previous high of 910,000 in 2003.

In addition, the age-adjusted mortality rate increased for the first time in several years, Dr. Tsao said, by a “fairly substantial” 4.6%. The age-adjusted mortality rate incorporates the variability in the aging population from year to year, accounting for higher death rates among older people.

“Even though our total number of deaths has been slowly increasing over the past decade, we have seen a decline each year in our age-adjusted rates – until 2020,” she said. “I think that is very indicative of what has been going on within our country – and the world – in light of people of all ages being impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, especially before vaccines were available to slow the spread.”

The largest increases in CVD-related deaths occurred among Asian, Black, and Hispanic people, who were most heavily affected during the first year of the pandemic.

“People from communities of color were among those most highly impacted, especially early on, often due to a disproportionate burden of cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and obesity,” Michelle Albert, MD, MPH, president of AHA and a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a statement.

Dr. Albert, who is also the director of UCSF’s Center for the Study of Adversity and Cardiovascular Disease, does research on health equity and noted the disparities seen in the 2020 numbers. “Additionally, there are socioeconomic considerations, as well as the ongoing impact of structural racism on multiple factors, including limiting the ability to access quality health care,” she said.

Additional considerations

In a special commentary, the Statistical Update writing committee pointed to the need to track data for other underrepresented communities, including LGBTQ people and those living in rural or urban areas. The authors outlined several ways to better understand the effects of identity and social determinants of health, as well as strategies to reduce cardiovascular-related disparities.

“This year’s writing group made a concerted effort to gather information on specific social factors related to health risk and outcomes, including sexual orientation, gender identity, urbanization, and socioeconomic position,” Dr. Tsao said. “However, the data are lacking because these communities are grossly underrepresented in clinical and epidemiological research.”

For the next several years, the AHA Statistical Update will likely include more insights about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as ongoing disparities.

“For sure, we will be continuing to see the effects of the pandemic for years to come,” Dr. Tsao said. “Recognition of the disparities in outcomes among vulnerable groups should be a call to action among health care providers and researchers, administration, and policy leaders to investigate the reasons and make changes to reverse these trends.”

The statistical update was prepared by a volunteer writing group on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CIRCULATION

The long-range thrombolysis forecast calls for tiny ultrasonic tornadoes

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but clots will never hurt me

You’ve probably seen “Ghostbusters” or at least heard the theme song. Maybe you even know about the Discovery Channel’s “Mythbusters.” But now there’s a new buster in town, and it eats platitudes for breakfast: Meet Cliche-busters, LOTME’s new recurring feature.

This week, Cliche-busters takes on “Two wrongs don’t make a right.” Yum.

We start with blood clots, which are bad. Doctors go to a lot of trouble to get rid of the things because they are dangerous. A blood clot, then, is a bodily function gone wrong.

Tornadoes are also bad. Out there in the world, these violently rotating columns of air can destroy buildings, toss large objects long distances, and inspire mediocre action movies. They are examples of nature gone wrong.

Seemingly, these two wrongs – blood clots and tornadoes – are not about to make a right. Has Cliche-busters bitten off more than it can chew?

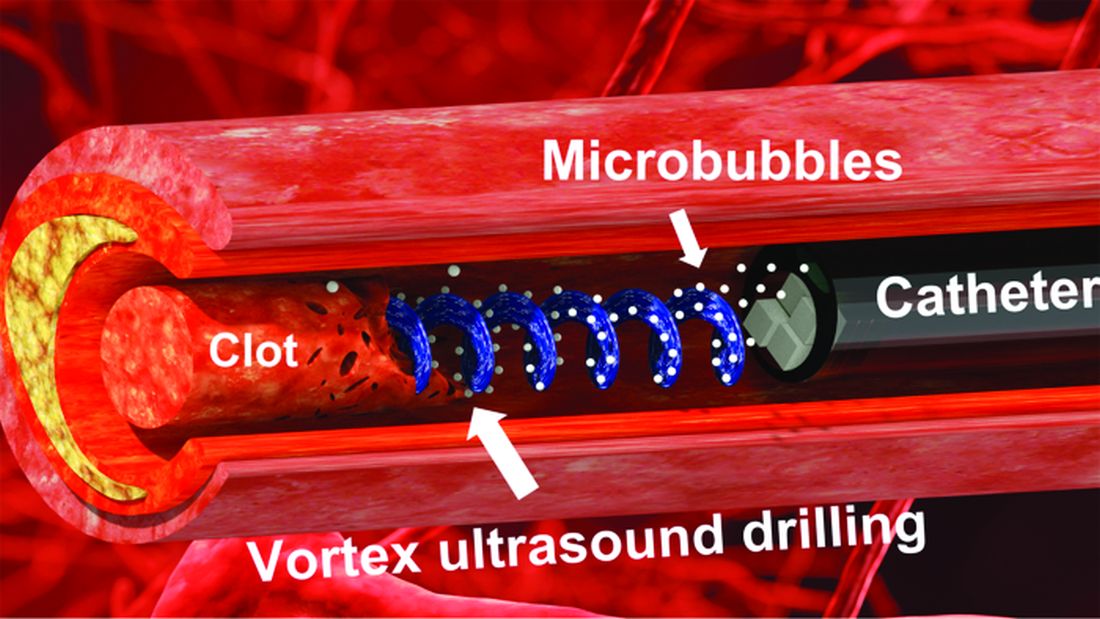

Not according to Xiaoning Jiang of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and his team of researchers. They’ve figured out a way to use a tiny ultrasonic tornado to break down clots in the brain. “Our new work uses vortex ultrasound, where the ultrasound waves have a helical wavefront. In other words, the ultrasound is swirling as it moves forward,” he said in a statement from the university.

Their new tool’s single transducer is small enough to fit in a catheter, and its “vortex ultrasound-induced shear force has the potential to break down clots safely and improve the efficacy of thrombolysis,” they explained in the open-access journal Research.

The investigators used cow blood in a 3D-printed model of the cerebral venous sinus for the proof-of-concept study and were able to dissolve an acute blood clot in less than 30 minutes, compared with the 15-30 hours needed with a pharmaceutical intervention, according to the written statement.

Can you hear the sound of two wrongs making a right? We can, and that closes the curtain on this cliche.

With age does not come wisdom

We’ve all met this person before. The sort of person who takes a 10-minute IQ test on a shifty-looking website and then proceeds to brag about a 180 IQ until the heat death of the universe. The one who worships at the altar of Mensa. Yeah, that guy. They’re never as smart as they think they are, but they’ll never, ever admit it.

It’s not exactly a secret that IQ as a measurement of intelligence is highly overrated. A lot of scientists doubt we should bother measuring it at all. That said, a higher IQ is associated with greater success in academic and financial endeavors, so it’s not absolutely worthless. And if we’re stuck with it, we may as well study it.

That brings us neatly to new research published in Brain and Behavior. Most studies into IQ and self-estimated intelligence have focused on younger adults, and the author of this study was curious if the stereotype of young men inflating their IQ, a stereotype backed up by research, persisted into older adulthood. So she conducted a survey of 159 younger adults and 152 older adults to find out.

The results in younger adults were not surprising: Younger men overestimated their actual IQ by 5-15 points, which tracks with previous research. We’re in for a bit of a surprise with the older adults, though, because the older men were more humble about their intelligence, with their estimation falling in line with their actual IQ. Older women, however, not so much. In fact, they overestimated their intelligence just as much as the younger men.

In addition, older women who perceived themselves as more attractive reported the highest self-estimated intelligence of all. That isn’t how intelligence works, but honestly, if Grandma’s out and about thinking she looks good and has the brains to go and win “Jeopardy!” do you really have the heart to tell her otherwise?

Fight temptation with empathy … and shoes

Relationships are tough. They all go through their respective ups and downs, but what happens when one person is feeling so down in the partnership that cheating comes to mind? Is there any way to stop it from happening?

Well, a recent study suggests that there is, and it’s as simple as putting yourself in the other person’s shoes. By observing 408 heterosexual, monogamous participants in a series of experiments, psychologists in Israel and New York found that practicing empathy and “perspective taking” doesn’t necessarily stop people from cheating but it does reduces the desire.

People cheat on their significant others for many different reasons – men for a lack of sexual needs being met and women for shortfalls regarding emotional needs – but prioritizing the other person’s perspective gives the idea of being unfaithful a different view and could make one act differently, the investigators said.

Perspective taking also promotes other positive attributes to the relationship, such as the promotion of compassion and the feeling of being understood, lead author Gurit Birnbaum of Reichman University in Herzliya, Israel, said in a written statement. These things ultimately help couples navigate the rough patches and strengthen bonds, making them even less likely to cheat.

The researchers noted that even people in satisfying relationships do cheat, but this approach does encourage people to stop and think before they act. It could ultimately prevent what might be a huge mistake.

Think before they act. Hmm, that’s kind of like look before they leap, right? Sounds like a job for the Cliche-busters.

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but clots will never hurt me

You’ve probably seen “Ghostbusters” or at least heard the theme song. Maybe you even know about the Discovery Channel’s “Mythbusters.” But now there’s a new buster in town, and it eats platitudes for breakfast: Meet Cliche-busters, LOTME’s new recurring feature.

This week, Cliche-busters takes on “Two wrongs don’t make a right.” Yum.

We start with blood clots, which are bad. Doctors go to a lot of trouble to get rid of the things because they are dangerous. A blood clot, then, is a bodily function gone wrong.

Tornadoes are also bad. Out there in the world, these violently rotating columns of air can destroy buildings, toss large objects long distances, and inspire mediocre action movies. They are examples of nature gone wrong.

Seemingly, these two wrongs – blood clots and tornadoes – are not about to make a right. Has Cliche-busters bitten off more than it can chew?

Not according to Xiaoning Jiang of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and his team of researchers. They’ve figured out a way to use a tiny ultrasonic tornado to break down clots in the brain. “Our new work uses vortex ultrasound, where the ultrasound waves have a helical wavefront. In other words, the ultrasound is swirling as it moves forward,” he said in a statement from the university.

Their new tool’s single transducer is small enough to fit in a catheter, and its “vortex ultrasound-induced shear force has the potential to break down clots safely and improve the efficacy of thrombolysis,” they explained in the open-access journal Research.

The investigators used cow blood in a 3D-printed model of the cerebral venous sinus for the proof-of-concept study and were able to dissolve an acute blood clot in less than 30 minutes, compared with the 15-30 hours needed with a pharmaceutical intervention, according to the written statement.

Can you hear the sound of two wrongs making a right? We can, and that closes the curtain on this cliche.

With age does not come wisdom

We’ve all met this person before. The sort of person who takes a 10-minute IQ test on a shifty-looking website and then proceeds to brag about a 180 IQ until the heat death of the universe. The one who worships at the altar of Mensa. Yeah, that guy. They’re never as smart as they think they are, but they’ll never, ever admit it.

It’s not exactly a secret that IQ as a measurement of intelligence is highly overrated. A lot of scientists doubt we should bother measuring it at all. That said, a higher IQ is associated with greater success in academic and financial endeavors, so it’s not absolutely worthless. And if we’re stuck with it, we may as well study it.

That brings us neatly to new research published in Brain and Behavior. Most studies into IQ and self-estimated intelligence have focused on younger adults, and the author of this study was curious if the stereotype of young men inflating their IQ, a stereotype backed up by research, persisted into older adulthood. So she conducted a survey of 159 younger adults and 152 older adults to find out.

The results in younger adults were not surprising: Younger men overestimated their actual IQ by 5-15 points, which tracks with previous research. We’re in for a bit of a surprise with the older adults, though, because the older men were more humble about their intelligence, with their estimation falling in line with their actual IQ. Older women, however, not so much. In fact, they overestimated their intelligence just as much as the younger men.

In addition, older women who perceived themselves as more attractive reported the highest self-estimated intelligence of all. That isn’t how intelligence works, but honestly, if Grandma’s out and about thinking she looks good and has the brains to go and win “Jeopardy!” do you really have the heart to tell her otherwise?

Fight temptation with empathy … and shoes

Relationships are tough. They all go through their respective ups and downs, but what happens when one person is feeling so down in the partnership that cheating comes to mind? Is there any way to stop it from happening?

Well, a recent study suggests that there is, and it’s as simple as putting yourself in the other person’s shoes. By observing 408 heterosexual, monogamous participants in a series of experiments, psychologists in Israel and New York found that practicing empathy and “perspective taking” doesn’t necessarily stop people from cheating but it does reduces the desire.

People cheat on their significant others for many different reasons – men for a lack of sexual needs being met and women for shortfalls regarding emotional needs – but prioritizing the other person’s perspective gives the idea of being unfaithful a different view and could make one act differently, the investigators said.

Perspective taking also promotes other positive attributes to the relationship, such as the promotion of compassion and the feeling of being understood, lead author Gurit Birnbaum of Reichman University in Herzliya, Israel, said in a written statement. These things ultimately help couples navigate the rough patches and strengthen bonds, making them even less likely to cheat.

The researchers noted that even people in satisfying relationships do cheat, but this approach does encourage people to stop and think before they act. It could ultimately prevent what might be a huge mistake.

Think before they act. Hmm, that’s kind of like look before they leap, right? Sounds like a job for the Cliche-busters.

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but clots will never hurt me

You’ve probably seen “Ghostbusters” or at least heard the theme song. Maybe you even know about the Discovery Channel’s “Mythbusters.” But now there’s a new buster in town, and it eats platitudes for breakfast: Meet Cliche-busters, LOTME’s new recurring feature.

This week, Cliche-busters takes on “Two wrongs don’t make a right.” Yum.

We start with blood clots, which are bad. Doctors go to a lot of trouble to get rid of the things because they are dangerous. A blood clot, then, is a bodily function gone wrong.

Tornadoes are also bad. Out there in the world, these violently rotating columns of air can destroy buildings, toss large objects long distances, and inspire mediocre action movies. They are examples of nature gone wrong.

Seemingly, these two wrongs – blood clots and tornadoes – are not about to make a right. Has Cliche-busters bitten off more than it can chew?

Not according to Xiaoning Jiang of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and his team of researchers. They’ve figured out a way to use a tiny ultrasonic tornado to break down clots in the brain. “Our new work uses vortex ultrasound, where the ultrasound waves have a helical wavefront. In other words, the ultrasound is swirling as it moves forward,” he said in a statement from the university.

Their new tool’s single transducer is small enough to fit in a catheter, and its “vortex ultrasound-induced shear force has the potential to break down clots safely and improve the efficacy of thrombolysis,” they explained in the open-access journal Research.

The investigators used cow blood in a 3D-printed model of the cerebral venous sinus for the proof-of-concept study and were able to dissolve an acute blood clot in less than 30 minutes, compared with the 15-30 hours needed with a pharmaceutical intervention, according to the written statement.

Can you hear the sound of two wrongs making a right? We can, and that closes the curtain on this cliche.

With age does not come wisdom

We’ve all met this person before. The sort of person who takes a 10-minute IQ test on a shifty-looking website and then proceeds to brag about a 180 IQ until the heat death of the universe. The one who worships at the altar of Mensa. Yeah, that guy. They’re never as smart as they think they are, but they’ll never, ever admit it.

It’s not exactly a secret that IQ as a measurement of intelligence is highly overrated. A lot of scientists doubt we should bother measuring it at all. That said, a higher IQ is associated with greater success in academic and financial endeavors, so it’s not absolutely worthless. And if we’re stuck with it, we may as well study it.

That brings us neatly to new research published in Brain and Behavior. Most studies into IQ and self-estimated intelligence have focused on younger adults, and the author of this study was curious if the stereotype of young men inflating their IQ, a stereotype backed up by research, persisted into older adulthood. So she conducted a survey of 159 younger adults and 152 older adults to find out.

The results in younger adults were not surprising: Younger men overestimated their actual IQ by 5-15 points, which tracks with previous research. We’re in for a bit of a surprise with the older adults, though, because the older men were more humble about their intelligence, with their estimation falling in line with their actual IQ. Older women, however, not so much. In fact, they overestimated their intelligence just as much as the younger men.

In addition, older women who perceived themselves as more attractive reported the highest self-estimated intelligence of all. That isn’t how intelligence works, but honestly, if Grandma’s out and about thinking she looks good and has the brains to go and win “Jeopardy!” do you really have the heart to tell her otherwise?

Fight temptation with empathy … and shoes

Relationships are tough. They all go through their respective ups and downs, but what happens when one person is feeling so down in the partnership that cheating comes to mind? Is there any way to stop it from happening?

Well, a recent study suggests that there is, and it’s as simple as putting yourself in the other person’s shoes. By observing 408 heterosexual, monogamous participants in a series of experiments, psychologists in Israel and New York found that practicing empathy and “perspective taking” doesn’t necessarily stop people from cheating but it does reduces the desire.

People cheat on their significant others for many different reasons – men for a lack of sexual needs being met and women for shortfalls regarding emotional needs – but prioritizing the other person’s perspective gives the idea of being unfaithful a different view and could make one act differently, the investigators said.

Perspective taking also promotes other positive attributes to the relationship, such as the promotion of compassion and the feeling of being understood, lead author Gurit Birnbaum of Reichman University in Herzliya, Israel, said in a written statement. These things ultimately help couples navigate the rough patches and strengthen bonds, making them even less likely to cheat.

The researchers noted that even people in satisfying relationships do cheat, but this approach does encourage people to stop and think before they act. It could ultimately prevent what might be a huge mistake.

Think before they act. Hmm, that’s kind of like look before they leap, right? Sounds like a job for the Cliche-busters.

Autism linked to problems with cardiovascular health

People with autism are more likely to face diabetes, high cholesterol, and heart disease than those without the neurologic condition, according to a study published in JAMA Pediatrics. Researchers also found that children with autism are especially likely to develop diabetes compared with their peers, and are at greater risk of hypertension, too.

While the link between autism and risk for obesity and gastrointestinal ailments is well-established, the new findings suggest that clinicians who care for these patients – particularly children – should focus on cardiometabolic health more broadly.

“Clinicians who are treating kids with autism need to pay more attention to this,” said Chanaka N. Kahathuduwa, MD, PhD, MPhil, of the department of neurology at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, in Lubbock, and a coauthor of the new study.

A pediatrician may prescribe an atypical antipsychotic medication such as risperidone to regulate the behavior of an autistic child, Dr. Kahathuduwa said, which may increase their cholesterol levels. Although this or similar drugs may be necessary in some cases, Dr. Kahathuduwa advised that clinicians explore other treatment options first.

Mining data from previously published studies

For the new analysis, Dr. Kahathuduwa and his colleagues pooled the results of 34 previously published studies, which included medical records of more than 276,000 people with autism and close to 8 million people without the condition.

Study participants were an average age of 31 years, and 47% were female. Some studies reported age ranges that enabled the researchers to differentiate between children and adults.

People with autism were 64% more likely to develop type 1 diabetes, 146% more likely to experience type 2 diabetes, and 46% more likely to have heart disease, overall, the study found. Children with autism were almost twice as likely as their peers to develop diabetes (184%) and high blood pressure (154%).

The study found associations, not causation, and does not include detailed data about medication prescribing patterns. While it would be ideal to understand why autism is linked to cardiometabolic risk, to address the link most effectively, Dr. Kahathuduwa said the causes likely are multifactorial. Medication history and genetics each play a role in a way that is hard to untangle. Even so, Dr. Kahathuduwa said he hoped the findings prompt clinicians to reevaluate how they treat their patients with autism.

“This may be an eye opener,” he said.

An editorial accompanying the study noted that people with autism may die up to 30 years earlier than people without autism, in part because of the physical health problems surfaced in the new research. They also are more likely than others to attempt suicide.

Elizabeth M. Weir, PhD, of the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge (England) and author of the editorial, argued that current health delivery models often fail autistic people by not taking their needs into account.

Dr. Weir told this news organization that making adjustments such as dimming the lights for a light-sensitive patient or allowing people with autism to bring an advocate to appointments could build rapport.

“I diagnose autism pretty much every day and I know families get so overwhelmed with all the recommendations that we give,” said Sonia Monteiro, MD, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston. Still, Dr. Monteiro said clinicians should help parents of children with autism address the potential long-term cardiovascular risks – but to do so by layering in the information rather than merely adding more bullet points to an already long presentation.

“We know this information now, but finding a way to share that with families without overwhelming them even more, I think is challenging,” Dr. Monteiro said. “But it’s not something we can ignore.”

Dr. Kahathuduwa, Dr. Weir, and Dr. Monteiro report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with autism are more likely to face diabetes, high cholesterol, and heart disease than those without the neurologic condition, according to a study published in JAMA Pediatrics. Researchers also found that children with autism are especially likely to develop diabetes compared with their peers, and are at greater risk of hypertension, too.

While the link between autism and risk for obesity and gastrointestinal ailments is well-established, the new findings suggest that clinicians who care for these patients – particularly children – should focus on cardiometabolic health more broadly.

“Clinicians who are treating kids with autism need to pay more attention to this,” said Chanaka N. Kahathuduwa, MD, PhD, MPhil, of the department of neurology at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, in Lubbock, and a coauthor of the new study.

A pediatrician may prescribe an atypical antipsychotic medication such as risperidone to regulate the behavior of an autistic child, Dr. Kahathuduwa said, which may increase their cholesterol levels. Although this or similar drugs may be necessary in some cases, Dr. Kahathuduwa advised that clinicians explore other treatment options first.

Mining data from previously published studies

For the new analysis, Dr. Kahathuduwa and his colleagues pooled the results of 34 previously published studies, which included medical records of more than 276,000 people with autism and close to 8 million people without the condition.

Study participants were an average age of 31 years, and 47% were female. Some studies reported age ranges that enabled the researchers to differentiate between children and adults.

People with autism were 64% more likely to develop type 1 diabetes, 146% more likely to experience type 2 diabetes, and 46% more likely to have heart disease, overall, the study found. Children with autism were almost twice as likely as their peers to develop diabetes (184%) and high blood pressure (154%).

The study found associations, not causation, and does not include detailed data about medication prescribing patterns. While it would be ideal to understand why autism is linked to cardiometabolic risk, to address the link most effectively, Dr. Kahathuduwa said the causes likely are multifactorial. Medication history and genetics each play a role in a way that is hard to untangle. Even so, Dr. Kahathuduwa said he hoped the findings prompt clinicians to reevaluate how they treat their patients with autism.

“This may be an eye opener,” he said.

An editorial accompanying the study noted that people with autism may die up to 30 years earlier than people without autism, in part because of the physical health problems surfaced in the new research. They also are more likely than others to attempt suicide.

Elizabeth M. Weir, PhD, of the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge (England) and author of the editorial, argued that current health delivery models often fail autistic people by not taking their needs into account.

Dr. Weir told this news organization that making adjustments such as dimming the lights for a light-sensitive patient or allowing people with autism to bring an advocate to appointments could build rapport.

“I diagnose autism pretty much every day and I know families get so overwhelmed with all the recommendations that we give,” said Sonia Monteiro, MD, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston. Still, Dr. Monteiro said clinicians should help parents of children with autism address the potential long-term cardiovascular risks – but to do so by layering in the information rather than merely adding more bullet points to an already long presentation.

“We know this information now, but finding a way to share that with families without overwhelming them even more, I think is challenging,” Dr. Monteiro said. “But it’s not something we can ignore.”

Dr. Kahathuduwa, Dr. Weir, and Dr. Monteiro report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with autism are more likely to face diabetes, high cholesterol, and heart disease than those without the neurologic condition, according to a study published in JAMA Pediatrics. Researchers also found that children with autism are especially likely to develop diabetes compared with their peers, and are at greater risk of hypertension, too.

While the link between autism and risk for obesity and gastrointestinal ailments is well-established, the new findings suggest that clinicians who care for these patients – particularly children – should focus on cardiometabolic health more broadly.

“Clinicians who are treating kids with autism need to pay more attention to this,” said Chanaka N. Kahathuduwa, MD, PhD, MPhil, of the department of neurology at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, in Lubbock, and a coauthor of the new study.

A pediatrician may prescribe an atypical antipsychotic medication such as risperidone to regulate the behavior of an autistic child, Dr. Kahathuduwa said, which may increase their cholesterol levels. Although this or similar drugs may be necessary in some cases, Dr. Kahathuduwa advised that clinicians explore other treatment options first.

Mining data from previously published studies

For the new analysis, Dr. Kahathuduwa and his colleagues pooled the results of 34 previously published studies, which included medical records of more than 276,000 people with autism and close to 8 million people without the condition.

Study participants were an average age of 31 years, and 47% were female. Some studies reported age ranges that enabled the researchers to differentiate between children and adults.

People with autism were 64% more likely to develop type 1 diabetes, 146% more likely to experience type 2 diabetes, and 46% more likely to have heart disease, overall, the study found. Children with autism were almost twice as likely as their peers to develop diabetes (184%) and high blood pressure (154%).

The study found associations, not causation, and does not include detailed data about medication prescribing patterns. While it would be ideal to understand why autism is linked to cardiometabolic risk, to address the link most effectively, Dr. Kahathuduwa said the causes likely are multifactorial. Medication history and genetics each play a role in a way that is hard to untangle. Even so, Dr. Kahathuduwa said he hoped the findings prompt clinicians to reevaluate how they treat their patients with autism.

“This may be an eye opener,” he said.

An editorial accompanying the study noted that people with autism may die up to 30 years earlier than people without autism, in part because of the physical health problems surfaced in the new research. They also are more likely than others to attempt suicide.

Elizabeth M. Weir, PhD, of the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge (England) and author of the editorial, argued that current health delivery models often fail autistic people by not taking their needs into account.

Dr. Weir told this news organization that making adjustments such as dimming the lights for a light-sensitive patient or allowing people with autism to bring an advocate to appointments could build rapport.

“I diagnose autism pretty much every day and I know families get so overwhelmed with all the recommendations that we give,” said Sonia Monteiro, MD, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston. Still, Dr. Monteiro said clinicians should help parents of children with autism address the potential long-term cardiovascular risks – but to do so by layering in the information rather than merely adding more bullet points to an already long presentation.

“We know this information now, but finding a way to share that with families without overwhelming them even more, I think is challenging,” Dr. Monteiro said. “But it’s not something we can ignore.”

Dr. Kahathuduwa, Dr. Weir, and Dr. Monteiro report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long QT syndrome overdiagnosis persists

Five factors underlie the ongoing overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of long QT syndrome (LQTS), including temporary QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, a “pseudo”-positive genetic test result, family history of sudden cardiac death, transient QT prolongation, and misinterpretation of the QTc interval, a new study suggests.

Awareness of these characteristics, which led to a diagnostic reversal in 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients, could reduce the burden of overdiagnosis on the health care system and on patients and families, senior author Michael J. Ackerman, MD, PhD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conclude.

“The findings are a disturbing and disappointing sequel to the paper we published about LQTS overdiagnosis back in 2007, which showed that 2 out of every 5 patients who came to Mayo Clinic for a second opinion left without the diagnosis,” Dr. Ackerman told this news organization.

To date, Dr. Ackerman has reversed the diagnosis for 350 patients, he said.

The consequences of an LQTS diagnosis are “profound,” he noted, including years of unnecessary drug therapy, implantation of a cardioverter defibrillator, disqualification from competitive sports, and emotional stress to the individual and family.

By pointing out the five biggest mistakes his team has seen, he said, “we hope to equip the diagnostician with the means to challenge and assess the veracity of a LQTS diagnosis.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Time to do better

Dr. Ackerman and colleagues analyzed electronic medical records on 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients who presented with an outside diagnosis of LQTS but subsequently were dismissed as having normal findings. The mean age of these patients at their first Mayo Clinic evaluation was 22, 60% were female, and the mean QTc interval was 427 ±25 milliseconds.

Overall, 38% of misdiagnoses were the result of misinterpretation of clinical factors; 29%, to diagnostic test misinterpretations; 17%, to an apparently positive genetic test in the context of a weak or absent phenotype; and 16%, to a family history of false LQTS or of sudden cardiac or sudden unexplained death.

More specifically, the most common cause of an LQTS misdiagnosis was QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, which was misinterpreted as LQTS-attributed syncope.

The second most common cause was an apparently positive genetic test for an LQTS gene that turned out to be a benign or likely benign variant.

The third most common cause was an LQTS diagnosis based solely on a family history of sudden unexplained death (26 patients), QT prolongation (11 patients), or sudden cardiac arrest (9 patients).

The fourth most common cause was an isolated event of QT prolongation (44 patients). The transient QT prolongation was observed under myriad conditions unrelated to LQTS. Yet, 31 patients received a diagnosis based solely on the event.

The fifth most common cause was inclusion of the U-wave in the calculation of the QTc interval (40 patients), leading to an inaccurate interpretation of the electrocardiogram.

Dr. Ackerman noted that these LQTS diagnoses were given by heart-rhythm specialists, and most patients self-referred for a second opinion because a family member questioned the diagnosis after doing their own research.

“It’s time that we step up to the plate and do better,” Dr. Ackerman said. The team’s evaluation of the impact of the misdiagnosis on the patients’ lifestyle and quality of life showed that 45% had been restricted from competitive sports (and subsequently resumed sports activity with no adverse events); 80% had been started on beta-blockers (the drugs were discontinued in 84% as a result of the Mayo Clinic evaluation, whereas 16% opted to continue); and 10 of 22 patients (45%) who received an implanted cardioverter device underwent an extraction of the device without complications.

The authors conclude: “Although missing a patient who truly has LQTS can lead to a tragic outcome, the implications of overdiagnosed LQTS are not trivial and are potentially tragic as well.”

‘Tricky diagnosis’

LQTS specialist Peter Aziz, MD, director of pediatric electrophysiology at the Cleveland Clinic, agreed with these findings.

“Most of us ‘channelopathists’ who see LQTS for a living have a good grasp of the disease, but it can be elusive for others,” he said in an interview. “This is a tricky diagnosis. There are ends of the spectrum where people for sure don’t have it and people for sure do. Most clinicians are able to identify that.”

However, he added, “A lot of patients fall into that gray area where it may not be clear at first, even to an expert. But the expert knows how to do a comprehensive evaluation, examining episodes and symptoms and understanding whether they are relevant to LQTS or completely red herrings, and feeling confident about how they calculate the acute interval on an electrocardiogram.”

“All of these may seem mundane, but without the experience, clinicians are vulnerable to miscalculations,” he said. “That’s why our bias, as channelopathists, is that every patient who has a suspected diagnosis or is being treated for LQTS really should see an expert.”

Similarly, Arthur A.M. Wilde, MD, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam, and Peter J. Schwartz, MD, of IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, write in a related editorial that it “has to be kept in mind that both diagnostic scores and risk scores are dynamic and can be modified by time and by appropriate therapy.

“Therefore, to make hasty diagnosis of a disease that requires life-long treatment is inappropriate, especially when this is done without the support of adequate, specific experience.”

No commercial funding or relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Five factors underlie the ongoing overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of long QT syndrome (LQTS), including temporary QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, a “pseudo”-positive genetic test result, family history of sudden cardiac death, transient QT prolongation, and misinterpretation of the QTc interval, a new study suggests.

Awareness of these characteristics, which led to a diagnostic reversal in 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients, could reduce the burden of overdiagnosis on the health care system and on patients and families, senior author Michael J. Ackerman, MD, PhD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conclude.

“The findings are a disturbing and disappointing sequel to the paper we published about LQTS overdiagnosis back in 2007, which showed that 2 out of every 5 patients who came to Mayo Clinic for a second opinion left without the diagnosis,” Dr. Ackerman told this news organization.

To date, Dr. Ackerman has reversed the diagnosis for 350 patients, he said.

The consequences of an LQTS diagnosis are “profound,” he noted, including years of unnecessary drug therapy, implantation of a cardioverter defibrillator, disqualification from competitive sports, and emotional stress to the individual and family.

By pointing out the five biggest mistakes his team has seen, he said, “we hope to equip the diagnostician with the means to challenge and assess the veracity of a LQTS diagnosis.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Time to do better

Dr. Ackerman and colleagues analyzed electronic medical records on 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients who presented with an outside diagnosis of LQTS but subsequently were dismissed as having normal findings. The mean age of these patients at their first Mayo Clinic evaluation was 22, 60% were female, and the mean QTc interval was 427 ±25 milliseconds.

Overall, 38% of misdiagnoses were the result of misinterpretation of clinical factors; 29%, to diagnostic test misinterpretations; 17%, to an apparently positive genetic test in the context of a weak or absent phenotype; and 16%, to a family history of false LQTS or of sudden cardiac or sudden unexplained death.

More specifically, the most common cause of an LQTS misdiagnosis was QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, which was misinterpreted as LQTS-attributed syncope.

The second most common cause was an apparently positive genetic test for an LQTS gene that turned out to be a benign or likely benign variant.

The third most common cause was an LQTS diagnosis based solely on a family history of sudden unexplained death (26 patients), QT prolongation (11 patients), or sudden cardiac arrest (9 patients).

The fourth most common cause was an isolated event of QT prolongation (44 patients). The transient QT prolongation was observed under myriad conditions unrelated to LQTS. Yet, 31 patients received a diagnosis based solely on the event.

The fifth most common cause was inclusion of the U-wave in the calculation of the QTc interval (40 patients), leading to an inaccurate interpretation of the electrocardiogram.

Dr. Ackerman noted that these LQTS diagnoses were given by heart-rhythm specialists, and most patients self-referred for a second opinion because a family member questioned the diagnosis after doing their own research.

“It’s time that we step up to the plate and do better,” Dr. Ackerman said. The team’s evaluation of the impact of the misdiagnosis on the patients’ lifestyle and quality of life showed that 45% had been restricted from competitive sports (and subsequently resumed sports activity with no adverse events); 80% had been started on beta-blockers (the drugs were discontinued in 84% as a result of the Mayo Clinic evaluation, whereas 16% opted to continue); and 10 of 22 patients (45%) who received an implanted cardioverter device underwent an extraction of the device without complications.

The authors conclude: “Although missing a patient who truly has LQTS can lead to a tragic outcome, the implications of overdiagnosed LQTS are not trivial and are potentially tragic as well.”

‘Tricky diagnosis’

LQTS specialist Peter Aziz, MD, director of pediatric electrophysiology at the Cleveland Clinic, agreed with these findings.

“Most of us ‘channelopathists’ who see LQTS for a living have a good grasp of the disease, but it can be elusive for others,” he said in an interview. “This is a tricky diagnosis. There are ends of the spectrum where people for sure don’t have it and people for sure do. Most clinicians are able to identify that.”

However, he added, “A lot of patients fall into that gray area where it may not be clear at first, even to an expert. But the expert knows how to do a comprehensive evaluation, examining episodes and symptoms and understanding whether they are relevant to LQTS or completely red herrings, and feeling confident about how they calculate the acute interval on an electrocardiogram.”

“All of these may seem mundane, but without the experience, clinicians are vulnerable to miscalculations,” he said. “That’s why our bias, as channelopathists, is that every patient who has a suspected diagnosis or is being treated for LQTS really should see an expert.”

Similarly, Arthur A.M. Wilde, MD, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam, and Peter J. Schwartz, MD, of IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, write in a related editorial that it “has to be kept in mind that both diagnostic scores and risk scores are dynamic and can be modified by time and by appropriate therapy.

“Therefore, to make hasty diagnosis of a disease that requires life-long treatment is inappropriate, especially when this is done without the support of adequate, specific experience.”

No commercial funding or relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Five factors underlie the ongoing overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of long QT syndrome (LQTS), including temporary QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, a “pseudo”-positive genetic test result, family history of sudden cardiac death, transient QT prolongation, and misinterpretation of the QTc interval, a new study suggests.

Awareness of these characteristics, which led to a diagnostic reversal in 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients, could reduce the burden of overdiagnosis on the health care system and on patients and families, senior author Michael J. Ackerman, MD, PhD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conclude.

“The findings are a disturbing and disappointing sequel to the paper we published about LQTS overdiagnosis back in 2007, which showed that 2 out of every 5 patients who came to Mayo Clinic for a second opinion left without the diagnosis,” Dr. Ackerman told this news organization.

To date, Dr. Ackerman has reversed the diagnosis for 350 patients, he said.

The consequences of an LQTS diagnosis are “profound,” he noted, including years of unnecessary drug therapy, implantation of a cardioverter defibrillator, disqualification from competitive sports, and emotional stress to the individual and family.

By pointing out the five biggest mistakes his team has seen, he said, “we hope to equip the diagnostician with the means to challenge and assess the veracity of a LQTS diagnosis.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Time to do better

Dr. Ackerman and colleagues analyzed electronic medical records on 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients who presented with an outside diagnosis of LQTS but subsequently were dismissed as having normal findings. The mean age of these patients at their first Mayo Clinic evaluation was 22, 60% were female, and the mean QTc interval was 427 ±25 milliseconds.

Overall, 38% of misdiagnoses were the result of misinterpretation of clinical factors; 29%, to diagnostic test misinterpretations; 17%, to an apparently positive genetic test in the context of a weak or absent phenotype; and 16%, to a family history of false LQTS or of sudden cardiac or sudden unexplained death.

More specifically, the most common cause of an LQTS misdiagnosis was QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, which was misinterpreted as LQTS-attributed syncope.

The second most common cause was an apparently positive genetic test for an LQTS gene that turned out to be a benign or likely benign variant.

The third most common cause was an LQTS diagnosis based solely on a family history of sudden unexplained death (26 patients), QT prolongation (11 patients), or sudden cardiac arrest (9 patients).

The fourth most common cause was an isolated event of QT prolongation (44 patients). The transient QT prolongation was observed under myriad conditions unrelated to LQTS. Yet, 31 patients received a diagnosis based solely on the event.

The fifth most common cause was inclusion of the U-wave in the calculation of the QTc interval (40 patients), leading to an inaccurate interpretation of the electrocardiogram.

Dr. Ackerman noted that these LQTS diagnoses were given by heart-rhythm specialists, and most patients self-referred for a second opinion because a family member questioned the diagnosis after doing their own research.

“It’s time that we step up to the plate and do better,” Dr. Ackerman said. The team’s evaluation of the impact of the misdiagnosis on the patients’ lifestyle and quality of life showed that 45% had been restricted from competitive sports (and subsequently resumed sports activity with no adverse events); 80% had been started on beta-blockers (the drugs were discontinued in 84% as a result of the Mayo Clinic evaluation, whereas 16% opted to continue); and 10 of 22 patients (45%) who received an implanted cardioverter device underwent an extraction of the device without complications.

The authors conclude: “Although missing a patient who truly has LQTS can lead to a tragic outcome, the implications of overdiagnosed LQTS are not trivial and are potentially tragic as well.”

‘Tricky diagnosis’

LQTS specialist Peter Aziz, MD, director of pediatric electrophysiology at the Cleveland Clinic, agreed with these findings.

“Most of us ‘channelopathists’ who see LQTS for a living have a good grasp of the disease, but it can be elusive for others,” he said in an interview. “This is a tricky diagnosis. There are ends of the spectrum where people for sure don’t have it and people for sure do. Most clinicians are able to identify that.”

However, he added, “A lot of patients fall into that gray area where it may not be clear at first, even to an expert. But the expert knows how to do a comprehensive evaluation, examining episodes and symptoms and understanding whether they are relevant to LQTS or completely red herrings, and feeling confident about how they calculate the acute interval on an electrocardiogram.”

“All of these may seem mundane, but without the experience, clinicians are vulnerable to miscalculations,” he said. “That’s why our bias, as channelopathists, is that every patient who has a suspected diagnosis or is being treated for LQTS really should see an expert.”

Similarly, Arthur A.M. Wilde, MD, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam, and Peter J. Schwartz, MD, of IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, write in a related editorial that it “has to be kept in mind that both diagnostic scores and risk scores are dynamic and can be modified by time and by appropriate therapy.

“Therefore, to make hasty diagnosis of a disease that requires life-long treatment is inappropriate, especially when this is done without the support of adequate, specific experience.”

No commercial funding or relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Elevated PCSK9 levels associated with psoriasis suggest new treatment target

A Mendelian randomization study employing data from nearly 300,000 individuals has linked elevated levels of the PCSK9 enzyme with an increased risk of psoriasis, suggesting it might be targetable as an intervention.

. Conversely, psoriasis risk did not appear to be affected when LDL-C was reduced by other pathways of lipid control.

This study “suggests that PCSK9 inhibition is causally associated with reduced risk of psoriasis,” reported a team of investigators led by Sizheng Steven Zhao, MD, PhD, of the division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences, University of Manchester (England). “Existing PCSK9 inhibitors hold potential as therapeutic targets for prevention, and possibly treatment, of psoriasis, although further clinical studies are needed,” they concluded.

In an interview, Dr. Zhao also noted that it will be interesting to look at psoriasis susceptibility in post hoc analyses of large randomized controlled trials of PCSK9 inhibitors for cardiovascular disease.

“Genetically proxied” inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase, which is targeted by statins, and NPC1L1 which is targeted by ezetimibe, “were not associated with psoriasis risk,” the investigators reported in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

Abnormal lipid metabolism is sufficiently common among people with psoriasis that screening in patients with moderate to severe disease is recommended in 2019 psoriasis guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation. However, the link between these diseases is unclear. This study was launched to explore genetically proxied relationships between psoriasis and LDL-C reductions as well as specific treatments for elevated LDL-C.

Mendelian randomizations were applied to deidentified data from two sources, a UK biobank and FinnGen, a Finnish-based project for identifying genotype-to-phenotype correlations. Genetic proxies for these variables were established on the basis of genomewide association studies on large population samples.

Ultimately, 34 genetic variants were selected to proxy for lipid lowering by PCSK9, 19 were selected to proxy for HMG-CoA reductase, and 9 for NPC1L1. In the Mendelian analyses performed on the two sources, genetically proxied PCSK9 inhibition was associated with about a 30% reduction in the odds ratio of psoriasis (OR, 0.69; P = .003). There were no robust associations with proxies for reductions in either HMG-CoA reductase or NPC1L1.

In sensitivity analyses, there was no evidence of bias from pleiotropy or genetic confounding, according to Dr. Zhao and his coauthors, who noted that the relationship between reductions in PCSK9 and reduced risk of psoriasis appeared to be independent of change in circulating LDL-C.

Given the prior evidence implicating the PCSK9 enzyme in psoriasis risk, “this is an exciting study that really highlights the importance of studying and targeting lipid metabolism in psoriasis for a few reasons,” according to Michael S. Garshick, MD, a researcher, cardiologist, and director of the cardio-rheumatology program, New York University Langone Health.

An investigator who has participated in several studies evaluating the relationship between cardiovascular risk and psoriasis, Dr. Garshick said there is increasing interest in PCSK9 as a biomarker or even a mediator of inflammation independent of blood lipid levels.

“In psoriasis regarding PCSK9, we and others have shown PCSK9 is elevated in psoriatic lesion skin, and studies are starting to investigate the unique lipidomic profile in psoriasis,” Dr. Garshick said in an interview. The study he led that showed elevated PCSK9 levels in psoriatic skin was published in 2021 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

While the Mendelian randomization provides only “an inference” that PCSK9 plays a role in mediating risk of psoriasis, Dr. Zhao and coauthors cited numerous studies linking elevated PCSK9 to psoriasis pathophysiology. This not only includes the elevated PCSK9 expression in psoriatic plaques as shown by Dr. Garshick and others but several sets of experimental evidence linking PCSK9 to inflammatory pathways, including upregulation of interleukin-17 and stimulation of macrophage activation.

While Dr. Zhao and coauthors suggested that clinical trials are now needed to test the potential of PCSK9 inhibitors to modify the risk of psoriasis, Dr. Garshick indicated that there are numerous variables to unravel in the relationship between elevated lipids, PCSK9, and psoriasis.

“In our own studies, we did see a statistical correlation between circulating PCSK9 and psoriasis severity,” Dr. Garshick said. But he added, “I think we are just beginning to understand the functions of circulating (extrahepatic) PCSK9 independent of lipid metabolism.”

While he is intrigued by the evidence that PCSK9 is linked to systemic inflammation, he pointed out that several medications used to treat dyslipidemias, such as statins, are associated with an anti-inflammatory effect.

This study “further emphasizes the need to conduct clinical trials treating dyslipidemia in psoriasis, including the targeting of PCSK9, whether it is with statins with lipid lowering and potential pleiotropic anti-inflammatory properties or PCSK9 inhibition,” he said. If positive, “both would be exciting.“

From a cardiologist’s point of view, there is an upside for including patients with psoriasis in lipid-lowering trials even if the effect on psoriasis is modest. Either way, “you still get the lipid-lowering benefit, which is important for reducing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Garshick said.

Dr. Zhao reported financial relationships with UCB, although UCB did not provide funding for this study. One author reported grants from Versus Arthritis and the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre during the study, grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Galapagos, and Pfizer, and personal fees from Chugai Roche outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. The study was supported by grants from Versus Arthritis and the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Garshick reported financial relationships with AbbVie and Horizon Therapeutics.

A Mendelian randomization study employing data from nearly 300,000 individuals has linked elevated levels of the PCSK9 enzyme with an increased risk of psoriasis, suggesting it might be targetable as an intervention.

. Conversely, psoriasis risk did not appear to be affected when LDL-C was reduced by other pathways of lipid control.

This study “suggests that PCSK9 inhibition is causally associated with reduced risk of psoriasis,” reported a team of investigators led by Sizheng Steven Zhao, MD, PhD, of the division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences, University of Manchester (England). “Existing PCSK9 inhibitors hold potential as therapeutic targets for prevention, and possibly treatment, of psoriasis, although further clinical studies are needed,” they concluded.

In an interview, Dr. Zhao also noted that it will be interesting to look at psoriasis susceptibility in post hoc analyses of large randomized controlled trials of PCSK9 inhibitors for cardiovascular disease.

“Genetically proxied” inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase, which is targeted by statins, and NPC1L1 which is targeted by ezetimibe, “were not associated with psoriasis risk,” the investigators reported in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

Abnormal lipid metabolism is sufficiently common among people with psoriasis that screening in patients with moderate to severe disease is recommended in 2019 psoriasis guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation. However, the link between these diseases is unclear. This study was launched to explore genetically proxied relationships between psoriasis and LDL-C reductions as well as specific treatments for elevated LDL-C.

Mendelian randomizations were applied to deidentified data from two sources, a UK biobank and FinnGen, a Finnish-based project for identifying genotype-to-phenotype correlations. Genetic proxies for these variables were established on the basis of genomewide association studies on large population samples.

Ultimately, 34 genetic variants were selected to proxy for lipid lowering by PCSK9, 19 were selected to proxy for HMG-CoA reductase, and 9 for NPC1L1. In the Mendelian analyses performed on the two sources, genetically proxied PCSK9 inhibition was associated with about a 30% reduction in the odds ratio of psoriasis (OR, 0.69; P = .003). There were no robust associations with proxies for reductions in either HMG-CoA reductase or NPC1L1.

In sensitivity analyses, there was no evidence of bias from pleiotropy or genetic confounding, according to Dr. Zhao and his coauthors, who noted that the relationship between reductions in PCSK9 and reduced risk of psoriasis appeared to be independent of change in circulating LDL-C.

Given the prior evidence implicating the PCSK9 enzyme in psoriasis risk, “this is an exciting study that really highlights the importance of studying and targeting lipid metabolism in psoriasis for a few reasons,” according to Michael S. Garshick, MD, a researcher, cardiologist, and director of the cardio-rheumatology program, New York University Langone Health.

An investigator who has participated in several studies evaluating the relationship between cardiovascular risk and psoriasis, Dr. Garshick said there is increasing interest in PCSK9 as a biomarker or even a mediator of inflammation independent of blood lipid levels.

“In psoriasis regarding PCSK9, we and others have shown PCSK9 is elevated in psoriatic lesion skin, and studies are starting to investigate the unique lipidomic profile in psoriasis,” Dr. Garshick said in an interview. The study he led that showed elevated PCSK9 levels in psoriatic skin was published in 2021 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

While the Mendelian randomization provides only “an inference” that PCSK9 plays a role in mediating risk of psoriasis, Dr. Zhao and coauthors cited numerous studies linking elevated PCSK9 to psoriasis pathophysiology. This not only includes the elevated PCSK9 expression in psoriatic plaques as shown by Dr. Garshick and others but several sets of experimental evidence linking PCSK9 to inflammatory pathways, including upregulation of interleukin-17 and stimulation of macrophage activation.

While Dr. Zhao and coauthors suggested that clinical trials are now needed to test the potential of PCSK9 inhibitors to modify the risk of psoriasis, Dr. Garshick indicated that there are numerous variables to unravel in the relationship between elevated lipids, PCSK9, and psoriasis.

“In our own studies, we did see a statistical correlation between circulating PCSK9 and psoriasis severity,” Dr. Garshick said. But he added, “I think we are just beginning to understand the functions of circulating (extrahepatic) PCSK9 independent of lipid metabolism.”

While he is intrigued by the evidence that PCSK9 is linked to systemic inflammation, he pointed out that several medications used to treat dyslipidemias, such as statins, are associated with an anti-inflammatory effect.

This study “further emphasizes the need to conduct clinical trials treating dyslipidemia in psoriasis, including the targeting of PCSK9, whether it is with statins with lipid lowering and potential pleiotropic anti-inflammatory properties or PCSK9 inhibition,” he said. If positive, “both would be exciting.“

From a cardiologist’s point of view, there is an upside for including patients with psoriasis in lipid-lowering trials even if the effect on psoriasis is modest. Either way, “you still get the lipid-lowering benefit, which is important for reducing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Garshick said.

Dr. Zhao reported financial relationships with UCB, although UCB did not provide funding for this study. One author reported grants from Versus Arthritis and the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre during the study, grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Galapagos, and Pfizer, and personal fees from Chugai Roche outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. The study was supported by grants from Versus Arthritis and the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Garshick reported financial relationships with AbbVie and Horizon Therapeutics.

A Mendelian randomization study employing data from nearly 300,000 individuals has linked elevated levels of the PCSK9 enzyme with an increased risk of psoriasis, suggesting it might be targetable as an intervention.

. Conversely, psoriasis risk did not appear to be affected when LDL-C was reduced by other pathways of lipid control.

This study “suggests that PCSK9 inhibition is causally associated with reduced risk of psoriasis,” reported a team of investigators led by Sizheng Steven Zhao, MD, PhD, of the division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences, University of Manchester (England). “Existing PCSK9 inhibitors hold potential as therapeutic targets for prevention, and possibly treatment, of psoriasis, although further clinical studies are needed,” they concluded.

In an interview, Dr. Zhao also noted that it will be interesting to look at psoriasis susceptibility in post hoc analyses of large randomized controlled trials of PCSK9 inhibitors for cardiovascular disease.

“Genetically proxied” inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase, which is targeted by statins, and NPC1L1 which is targeted by ezetimibe, “were not associated with psoriasis risk,” the investigators reported in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

Abnormal lipid metabolism is sufficiently common among people with psoriasis that screening in patients with moderate to severe disease is recommended in 2019 psoriasis guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation. However, the link between these diseases is unclear. This study was launched to explore genetically proxied relationships between psoriasis and LDL-C reductions as well as specific treatments for elevated LDL-C.

Mendelian randomizations were applied to deidentified data from two sources, a UK biobank and FinnGen, a Finnish-based project for identifying genotype-to-phenotype correlations. Genetic proxies for these variables were established on the basis of genomewide association studies on large population samples.

Ultimately, 34 genetic variants were selected to proxy for lipid lowering by PCSK9, 19 were selected to proxy for HMG-CoA reductase, and 9 for NPC1L1. In the Mendelian analyses performed on the two sources, genetically proxied PCSK9 inhibition was associated with about a 30% reduction in the odds ratio of psoriasis (OR, 0.69; P = .003). There were no robust associations with proxies for reductions in either HMG-CoA reductase or NPC1L1.

In sensitivity analyses, there was no evidence of bias from pleiotropy or genetic confounding, according to Dr. Zhao and his coauthors, who noted that the relationship between reductions in PCSK9 and reduced risk of psoriasis appeared to be independent of change in circulating LDL-C.

Given the prior evidence implicating the PCSK9 enzyme in psoriasis risk, “this is an exciting study that really highlights the importance of studying and targeting lipid metabolism in psoriasis for a few reasons,” according to Michael S. Garshick, MD, a researcher, cardiologist, and director of the cardio-rheumatology program, New York University Langone Health.

An investigator who has participated in several studies evaluating the relationship between cardiovascular risk and psoriasis, Dr. Garshick said there is increasing interest in PCSK9 as a biomarker or even a mediator of inflammation independent of blood lipid levels.

“In psoriasis regarding PCSK9, we and others have shown PCSK9 is elevated in psoriatic lesion skin, and studies are starting to investigate the unique lipidomic profile in psoriasis,” Dr. Garshick said in an interview. The study he led that showed elevated PCSK9 levels in psoriatic skin was published in 2021 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

While the Mendelian randomization provides only “an inference” that PCSK9 plays a role in mediating risk of psoriasis, Dr. Zhao and coauthors cited numerous studies linking elevated PCSK9 to psoriasis pathophysiology. This not only includes the elevated PCSK9 expression in psoriatic plaques as shown by Dr. Garshick and others but several sets of experimental evidence linking PCSK9 to inflammatory pathways, including upregulation of interleukin-17 and stimulation of macrophage activation.