User login

Spike in Schizophrenia-Related ED Visits During COVID

TOPLINE:

, a new study showed. Researchers said the findings suggested a need for social policies that strengthen mental health prevention systems.

METHODOLOGY:

Investigators obtained data from the University of California (UC) Health Data Warehouse on ED visits at five large UC health systems.

They captured the ICD-10 codes relating to schizophrenia spectrum disorders for ED visits from January 2016 to December 2021 for patients aged 18 years and older.

TAKEAWAY:

Between January 2016 and December 2021, there were 377,800 psychiatric ED visits, 10% of which involved schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

The mean number of visits per month for schizophrenia spectrum disorders rose from 520 before the pandemic to 558 visits per month after March 2020.

Compared to prepandemic numbers and after controlling for visits for other psychiatric disorders, there were 70.5 additional visits (P = .02) for schizophrenia spectrum disorders at 1 month and 74.9 additional visits (P = .005) at 3 months following the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in California.

Investigators noted that prior studies indicated that COVID-19 infections may induce psychosis in some individuals, which could have been one underlying factor in the spike in cases.

IN PRACTICE:

“The COVID-19 pandemic draws attention to the vulnerability of patients with schizophrenia to macrosocial shocks, underscoring the importance of social policies related to income support, housing, and health insurance for future emergency preparedness and the need to strengthen mental healthcare systems,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Parvita Singh, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data used in the study excluded patients younger than 18 years. In addition, there was no analysis for trends by age or sex, which could have added valuable information to the study, the authors wrote. There was also no way to identify patients with newly diagnosed schizophrenia.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded through the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act and the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Study disclosures are noted in the original study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, a new study showed. Researchers said the findings suggested a need for social policies that strengthen mental health prevention systems.

METHODOLOGY:

Investigators obtained data from the University of California (UC) Health Data Warehouse on ED visits at five large UC health systems.

They captured the ICD-10 codes relating to schizophrenia spectrum disorders for ED visits from January 2016 to December 2021 for patients aged 18 years and older.

TAKEAWAY:

Between January 2016 and December 2021, there were 377,800 psychiatric ED visits, 10% of which involved schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

The mean number of visits per month for schizophrenia spectrum disorders rose from 520 before the pandemic to 558 visits per month after March 2020.

Compared to prepandemic numbers and after controlling for visits for other psychiatric disorders, there were 70.5 additional visits (P = .02) for schizophrenia spectrum disorders at 1 month and 74.9 additional visits (P = .005) at 3 months following the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in California.

Investigators noted that prior studies indicated that COVID-19 infections may induce psychosis in some individuals, which could have been one underlying factor in the spike in cases.

IN PRACTICE:

“The COVID-19 pandemic draws attention to the vulnerability of patients with schizophrenia to macrosocial shocks, underscoring the importance of social policies related to income support, housing, and health insurance for future emergency preparedness and the need to strengthen mental healthcare systems,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Parvita Singh, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data used in the study excluded patients younger than 18 years. In addition, there was no analysis for trends by age or sex, which could have added valuable information to the study, the authors wrote. There was also no way to identify patients with newly diagnosed schizophrenia.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded through the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act and the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Study disclosures are noted in the original study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, a new study showed. Researchers said the findings suggested a need for social policies that strengthen mental health prevention systems.

METHODOLOGY:

Investigators obtained data from the University of California (UC) Health Data Warehouse on ED visits at five large UC health systems.

They captured the ICD-10 codes relating to schizophrenia spectrum disorders for ED visits from January 2016 to December 2021 for patients aged 18 years and older.

TAKEAWAY:

Between January 2016 and December 2021, there were 377,800 psychiatric ED visits, 10% of which involved schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

The mean number of visits per month for schizophrenia spectrum disorders rose from 520 before the pandemic to 558 visits per month after March 2020.

Compared to prepandemic numbers and after controlling for visits for other psychiatric disorders, there were 70.5 additional visits (P = .02) for schizophrenia spectrum disorders at 1 month and 74.9 additional visits (P = .005) at 3 months following the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in California.

Investigators noted that prior studies indicated that COVID-19 infections may induce psychosis in some individuals, which could have been one underlying factor in the spike in cases.

IN PRACTICE:

“The COVID-19 pandemic draws attention to the vulnerability of patients with schizophrenia to macrosocial shocks, underscoring the importance of social policies related to income support, housing, and health insurance for future emergency preparedness and the need to strengthen mental healthcare systems,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Parvita Singh, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data used in the study excluded patients younger than 18 years. In addition, there was no analysis for trends by age or sex, which could have added valuable information to the study, the authors wrote. There was also no way to identify patients with newly diagnosed schizophrenia.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded through the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act and the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Study disclosures are noted in the original study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID Has Caused Thousands of US Deaths: New CDC Data

While COVID has now claimed more than 1 million lives in the United States alone, these aren’t the only fatalities caused at least in part by the virus. A small but growing number of Americans are surviving acute infections only to succumb months later to the lingering health problems caused by long COVID.

Much of the attention on long COVID has centered on the sometimes debilitating symptoms that strike people with the condition, with no formal diagnostic tests or standard treatments available, and the effect it has on quality of life. But new figures from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that long COVID can also be deadly.

More than 5000 Americans have died from long COVID since the start of the pandemic, according to new estimates from the CDC.

This total, based on death certificate data collected by the CDC, includes a preliminary tally of 1491 long COVID deaths in 2023 in addition to 3544 fatalities previously reported from January 2020 through June 2022.

Guidance issued in 2023 on how to formally report long COVID as a cause of death on death certificates should help get a more accurate count of these fatalities going forward, said Robert Anderson, PhD, chief mortality statistician for the CDC, Atlanta, Georgia.

“We hope that the guidance will help cause of death certifiers be more aware of the impact of long COVID and more likely to report long COVID as a cause of death when appropriate,” Dr. Anderson said. “That said, we do not expect that this guidance will have a dramatic impact on the trend.”

There’s no standard definition or diagnostic test for long COVID. It’s typically diagnosed when people have symptoms at least 3 months after an acute infection that weren’t present before they got sick. As of the end of last year, about 7% of American adults had experienced long COVID at some point, the CDC estimated in September 2023.

The new death tally indicates long COVID remains a significant public health threat and is likely to grow in the years ahead, even though the pandemic may no longer be considered a global health crisis, experts said.

For example, the death certificate figures indicate:

COVID-19 was the third leading cause of American deaths in 2020 and 2021, and the fourth leading cause of death in the United States in 2023.

Nearly 1% of the more than one million deaths related to COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic have been attributed to long COVID, according to data released by the CDC.

The proportion of COVID-related deaths from long COVID peaked in June 2021 at 1.2% and again in April 2022 at 3.8%, according to the CDC. Both of these peaks coincided with periods of declining fatalities from acute infections.

“I do expect that deaths associated with long COVID will make up an increasingly larger proportion of total deaths associated with COVID-19,” said Mark Czeisler, PhD, a researcher at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, who has studied long COVID fatalities.

Months and even years after an acute infection, long COVID can contribute to serious and potentially life-threatening conditions that impact nearly every major system in the body, according to the CDC guidelines for identifying the condition on death certificates.

This means long COVID may often be listed as an underlying cause of death when people with this condition die of issues related to their heart, lungs, brain or kidneys, the CDC guidelines noted.

The risk for long COVID fatalities remains elevated for at least 6 months for people with milder acute infections and for at least 2 years in severe cases that require hospitalization, some previous research suggested.

As happens with other acute infections, certain people are more at risk for fatal case of long COVID. Age, race, and ethnicity have all been cited as risk factors by researchers who have been tracking the condition since the start of the pandemic.

Half of long COVID fatalities from July 2021 to June 2022 occurred in people aged 65 years and older, and another 23% were recorded among people aged 50-64 years old, according a report from CDC.

Long COVID death rates also varied by race and ethnicity, from a high of 14.1 cases per million among America Indian and Alaskan natives to a low of 1.5 cases per million among Asian people, the CDC found. Death rates per million were 6.7 for White individuals, 6.4 for Black people, and 4.7 for Hispanic people.

The disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic people who developed and died from severe acute infections may have left fewer survivors to develop long COVID, limiting long COVID fatalities among these groups, the CDC report concluded.

It’s also possible that long COVID fatalities were undercounted in these populations because they faced challenges accessing healthcare or seeing providers who could recognize the hallmark symptoms of long COVID.

It’s also difficult to distinguish between how many deaths related to the virus ultimately occur as a result of long COVID rather than acute infections. That’s because it may depend on a variety of factors, including how consistently medical examiners follow the CDC guidelines, said Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research at the Veterans Affairs, St. Louis Health Care System and a senior clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Long COVID remains massively underdiagnosed, and death in people with long COVID is misattributed to other things,” Dr. Al-Aly said.

An accurate test for long COVID could help lead to a more accurate count of these fatalities, Dr. Czeisler said. Some preliminary research suggests that it might one day be possible to diagnose long COVID with a blood test.

“The timeline for such a test and the extent to which it would be widely applied is uncertain,” Dr. Czeisler noted, “though that would certainly be a gamechanger.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

While COVID has now claimed more than 1 million lives in the United States alone, these aren’t the only fatalities caused at least in part by the virus. A small but growing number of Americans are surviving acute infections only to succumb months later to the lingering health problems caused by long COVID.

Much of the attention on long COVID has centered on the sometimes debilitating symptoms that strike people with the condition, with no formal diagnostic tests or standard treatments available, and the effect it has on quality of life. But new figures from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that long COVID can also be deadly.

More than 5000 Americans have died from long COVID since the start of the pandemic, according to new estimates from the CDC.

This total, based on death certificate data collected by the CDC, includes a preliminary tally of 1491 long COVID deaths in 2023 in addition to 3544 fatalities previously reported from January 2020 through June 2022.

Guidance issued in 2023 on how to formally report long COVID as a cause of death on death certificates should help get a more accurate count of these fatalities going forward, said Robert Anderson, PhD, chief mortality statistician for the CDC, Atlanta, Georgia.

“We hope that the guidance will help cause of death certifiers be more aware of the impact of long COVID and more likely to report long COVID as a cause of death when appropriate,” Dr. Anderson said. “That said, we do not expect that this guidance will have a dramatic impact on the trend.”

There’s no standard definition or diagnostic test for long COVID. It’s typically diagnosed when people have symptoms at least 3 months after an acute infection that weren’t present before they got sick. As of the end of last year, about 7% of American adults had experienced long COVID at some point, the CDC estimated in September 2023.

The new death tally indicates long COVID remains a significant public health threat and is likely to grow in the years ahead, even though the pandemic may no longer be considered a global health crisis, experts said.

For example, the death certificate figures indicate:

COVID-19 was the third leading cause of American deaths in 2020 and 2021, and the fourth leading cause of death in the United States in 2023.

Nearly 1% of the more than one million deaths related to COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic have been attributed to long COVID, according to data released by the CDC.

The proportion of COVID-related deaths from long COVID peaked in June 2021 at 1.2% and again in April 2022 at 3.8%, according to the CDC. Both of these peaks coincided with periods of declining fatalities from acute infections.

“I do expect that deaths associated with long COVID will make up an increasingly larger proportion of total deaths associated with COVID-19,” said Mark Czeisler, PhD, a researcher at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, who has studied long COVID fatalities.

Months and even years after an acute infection, long COVID can contribute to serious and potentially life-threatening conditions that impact nearly every major system in the body, according to the CDC guidelines for identifying the condition on death certificates.

This means long COVID may often be listed as an underlying cause of death when people with this condition die of issues related to their heart, lungs, brain or kidneys, the CDC guidelines noted.

The risk for long COVID fatalities remains elevated for at least 6 months for people with milder acute infections and for at least 2 years in severe cases that require hospitalization, some previous research suggested.

As happens with other acute infections, certain people are more at risk for fatal case of long COVID. Age, race, and ethnicity have all been cited as risk factors by researchers who have been tracking the condition since the start of the pandemic.

Half of long COVID fatalities from July 2021 to June 2022 occurred in people aged 65 years and older, and another 23% were recorded among people aged 50-64 years old, according a report from CDC.

Long COVID death rates also varied by race and ethnicity, from a high of 14.1 cases per million among America Indian and Alaskan natives to a low of 1.5 cases per million among Asian people, the CDC found. Death rates per million were 6.7 for White individuals, 6.4 for Black people, and 4.7 for Hispanic people.

The disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic people who developed and died from severe acute infections may have left fewer survivors to develop long COVID, limiting long COVID fatalities among these groups, the CDC report concluded.

It’s also possible that long COVID fatalities were undercounted in these populations because they faced challenges accessing healthcare or seeing providers who could recognize the hallmark symptoms of long COVID.

It’s also difficult to distinguish between how many deaths related to the virus ultimately occur as a result of long COVID rather than acute infections. That’s because it may depend on a variety of factors, including how consistently medical examiners follow the CDC guidelines, said Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research at the Veterans Affairs, St. Louis Health Care System and a senior clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Long COVID remains massively underdiagnosed, and death in people with long COVID is misattributed to other things,” Dr. Al-Aly said.

An accurate test for long COVID could help lead to a more accurate count of these fatalities, Dr. Czeisler said. Some preliminary research suggests that it might one day be possible to diagnose long COVID with a blood test.

“The timeline for such a test and the extent to which it would be widely applied is uncertain,” Dr. Czeisler noted, “though that would certainly be a gamechanger.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

While COVID has now claimed more than 1 million lives in the United States alone, these aren’t the only fatalities caused at least in part by the virus. A small but growing number of Americans are surviving acute infections only to succumb months later to the lingering health problems caused by long COVID.

Much of the attention on long COVID has centered on the sometimes debilitating symptoms that strike people with the condition, with no formal diagnostic tests or standard treatments available, and the effect it has on quality of life. But new figures from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that long COVID can also be deadly.

More than 5000 Americans have died from long COVID since the start of the pandemic, according to new estimates from the CDC.

This total, based on death certificate data collected by the CDC, includes a preliminary tally of 1491 long COVID deaths in 2023 in addition to 3544 fatalities previously reported from January 2020 through June 2022.

Guidance issued in 2023 on how to formally report long COVID as a cause of death on death certificates should help get a more accurate count of these fatalities going forward, said Robert Anderson, PhD, chief mortality statistician for the CDC, Atlanta, Georgia.

“We hope that the guidance will help cause of death certifiers be more aware of the impact of long COVID and more likely to report long COVID as a cause of death when appropriate,” Dr. Anderson said. “That said, we do not expect that this guidance will have a dramatic impact on the trend.”

There’s no standard definition or diagnostic test for long COVID. It’s typically diagnosed when people have symptoms at least 3 months after an acute infection that weren’t present before they got sick. As of the end of last year, about 7% of American adults had experienced long COVID at some point, the CDC estimated in September 2023.

The new death tally indicates long COVID remains a significant public health threat and is likely to grow in the years ahead, even though the pandemic may no longer be considered a global health crisis, experts said.

For example, the death certificate figures indicate:

COVID-19 was the third leading cause of American deaths in 2020 and 2021, and the fourth leading cause of death in the United States in 2023.

Nearly 1% of the more than one million deaths related to COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic have been attributed to long COVID, according to data released by the CDC.

The proportion of COVID-related deaths from long COVID peaked in June 2021 at 1.2% and again in April 2022 at 3.8%, according to the CDC. Both of these peaks coincided with periods of declining fatalities from acute infections.

“I do expect that deaths associated with long COVID will make up an increasingly larger proportion of total deaths associated with COVID-19,” said Mark Czeisler, PhD, a researcher at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, who has studied long COVID fatalities.

Months and even years after an acute infection, long COVID can contribute to serious and potentially life-threatening conditions that impact nearly every major system in the body, according to the CDC guidelines for identifying the condition on death certificates.

This means long COVID may often be listed as an underlying cause of death when people with this condition die of issues related to their heart, lungs, brain or kidneys, the CDC guidelines noted.

The risk for long COVID fatalities remains elevated for at least 6 months for people with milder acute infections and for at least 2 years in severe cases that require hospitalization, some previous research suggested.

As happens with other acute infections, certain people are more at risk for fatal case of long COVID. Age, race, and ethnicity have all been cited as risk factors by researchers who have been tracking the condition since the start of the pandemic.

Half of long COVID fatalities from July 2021 to June 2022 occurred in people aged 65 years and older, and another 23% were recorded among people aged 50-64 years old, according a report from CDC.

Long COVID death rates also varied by race and ethnicity, from a high of 14.1 cases per million among America Indian and Alaskan natives to a low of 1.5 cases per million among Asian people, the CDC found. Death rates per million were 6.7 for White individuals, 6.4 for Black people, and 4.7 for Hispanic people.

The disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic people who developed and died from severe acute infections may have left fewer survivors to develop long COVID, limiting long COVID fatalities among these groups, the CDC report concluded.

It’s also possible that long COVID fatalities were undercounted in these populations because they faced challenges accessing healthcare or seeing providers who could recognize the hallmark symptoms of long COVID.

It’s also difficult to distinguish between how many deaths related to the virus ultimately occur as a result of long COVID rather than acute infections. That’s because it may depend on a variety of factors, including how consistently medical examiners follow the CDC guidelines, said Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research at the Veterans Affairs, St. Louis Health Care System and a senior clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Long COVID remains massively underdiagnosed, and death in people with long COVID is misattributed to other things,” Dr. Al-Aly said.

An accurate test for long COVID could help lead to a more accurate count of these fatalities, Dr. Czeisler said. Some preliminary research suggests that it might one day be possible to diagnose long COVID with a blood test.

“The timeline for such a test and the extent to which it would be widely applied is uncertain,” Dr. Czeisler noted, “though that would certainly be a gamechanger.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID Strain JN.1 Is Now a ‘Variant of Interest,’ WHO Says

the global health agency has announced.

JN.1 was previously grouped with its relative, BA.2.86, but has increased so much in the past 4 weeks that the WHO moved it to standalone status, according to a summary published by the agency. The prevalence of JN.1 worldwide jumped from 3% for the week ending November 5 to 27% for the week ending December 3. During that same period, JN.1 rose from 1% to 66% of cases in the Western Pacific, which stretches across 37 countries, from China and Mongolia to Australia and New Zealand.

In the United States, JN.1 has been increasing rapidly. The variant accounted for an estimated 21% of cases for the 2-week period ending December 9, up from 8% during the 2 weeks prior.

SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that causes COVID, and like other viruses, it evolves over time, sometimes changing how the virus affects people or how well existing treatments and vaccines work against it.

The WHO and CDC have said the current COVID vaccine appears to protect people against severe symptoms due to JN.1, and the WHO called the rising variant’s public health risk “low.”

“As we observe the rise of the JN.1 variant, it’s important to note that while it may be spreading more widely, there is currently no significant evidence suggesting it is more severe or that it poses a substantial public health risk,” John Brownstein, PhD, chief innovation officer at Boston Children’s Hospital, told ABC News.

In its recent risk analysis, the WHO did acknowledge that it’s not certain whether JN.1 has a higher risk of evading immunity or causing more severe symptoms than other strains. The WHO advised countries to further study how much JN.1 can evade existing antibodies and whether the variant results in more severe disease.

The latest CDC data show that 11% of COVID tests reported to the agency are positive, and 23,432 people were hospitalized with severe symptoms within a 7-day period. The CDC urgently asked people to get vaccinated against respiratory illnesses like the flu and COVID-19 ahead of the holidays as cases rise nationwide.

“Getting vaccinated now can help prevent hospitalizations and save lives,” the agency advised.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

the global health agency has announced.

JN.1 was previously grouped with its relative, BA.2.86, but has increased so much in the past 4 weeks that the WHO moved it to standalone status, according to a summary published by the agency. The prevalence of JN.1 worldwide jumped from 3% for the week ending November 5 to 27% for the week ending December 3. During that same period, JN.1 rose from 1% to 66% of cases in the Western Pacific, which stretches across 37 countries, from China and Mongolia to Australia and New Zealand.

In the United States, JN.1 has been increasing rapidly. The variant accounted for an estimated 21% of cases for the 2-week period ending December 9, up from 8% during the 2 weeks prior.

SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that causes COVID, and like other viruses, it evolves over time, sometimes changing how the virus affects people or how well existing treatments and vaccines work against it.

The WHO and CDC have said the current COVID vaccine appears to protect people against severe symptoms due to JN.1, and the WHO called the rising variant’s public health risk “low.”

“As we observe the rise of the JN.1 variant, it’s important to note that while it may be spreading more widely, there is currently no significant evidence suggesting it is more severe or that it poses a substantial public health risk,” John Brownstein, PhD, chief innovation officer at Boston Children’s Hospital, told ABC News.

In its recent risk analysis, the WHO did acknowledge that it’s not certain whether JN.1 has a higher risk of evading immunity or causing more severe symptoms than other strains. The WHO advised countries to further study how much JN.1 can evade existing antibodies and whether the variant results in more severe disease.

The latest CDC data show that 11% of COVID tests reported to the agency are positive, and 23,432 people were hospitalized with severe symptoms within a 7-day period. The CDC urgently asked people to get vaccinated against respiratory illnesses like the flu and COVID-19 ahead of the holidays as cases rise nationwide.

“Getting vaccinated now can help prevent hospitalizations and save lives,” the agency advised.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

the global health agency has announced.

JN.1 was previously grouped with its relative, BA.2.86, but has increased so much in the past 4 weeks that the WHO moved it to standalone status, according to a summary published by the agency. The prevalence of JN.1 worldwide jumped from 3% for the week ending November 5 to 27% for the week ending December 3. During that same period, JN.1 rose from 1% to 66% of cases in the Western Pacific, which stretches across 37 countries, from China and Mongolia to Australia and New Zealand.

In the United States, JN.1 has been increasing rapidly. The variant accounted for an estimated 21% of cases for the 2-week period ending December 9, up from 8% during the 2 weeks prior.

SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that causes COVID, and like other viruses, it evolves over time, sometimes changing how the virus affects people or how well existing treatments and vaccines work against it.

The WHO and CDC have said the current COVID vaccine appears to protect people against severe symptoms due to JN.1, and the WHO called the rising variant’s public health risk “low.”

“As we observe the rise of the JN.1 variant, it’s important to note that while it may be spreading more widely, there is currently no significant evidence suggesting it is more severe or that it poses a substantial public health risk,” John Brownstein, PhD, chief innovation officer at Boston Children’s Hospital, told ABC News.

In its recent risk analysis, the WHO did acknowledge that it’s not certain whether JN.1 has a higher risk of evading immunity or causing more severe symptoms than other strains. The WHO advised countries to further study how much JN.1 can evade existing antibodies and whether the variant results in more severe disease.

The latest CDC data show that 11% of COVID tests reported to the agency are positive, and 23,432 people were hospitalized with severe symptoms within a 7-day period. The CDC urgently asked people to get vaccinated against respiratory illnesses like the flu and COVID-19 ahead of the holidays as cases rise nationwide.

“Getting vaccinated now can help prevent hospitalizations and save lives,” the agency advised.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Reactive Angioendotheliomatosis Following Ad26.COV2.S Vaccination

To the Editor:

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE) is a rare self-limited cutaneous vascular proliferation of endothelial cells within blood vessels that manifests clinically as infiltrated red-blue patches and plaques with purpura that can progress to occlude vascular lumina. The etiology of RAE is mostly idiopathic; however, the disorder typically occurs in association with a range of systemic diseases, including infection, cryoglobulinemia, leukemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, peripheral vascular disease, and arteriovenous fistula. Histopathologic examination of these lesions shows marked proliferation of endothelial cells, including occlusion of the lumen of blood vessels over wide areas.

After ruling out malignancy, treatment of RAE focuses on targeting the underlying cause or disease, if any is present; 75% of reported cases occur in association with systemic disease.1 Onset can occur at any age without predilection for sex. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis commonly manifests on the extremities but may occur on the head and neck in rare instances.2

The rarity of the condition and its poorly defined clinical characteristics make it difficult to develop a treatment plan. There are no standardized treatment guidelines for the reactive form of angiomatosis. We report a case of RAE that developed 2 weeks after vaccination with the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine [formerly Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson]) that improved following 2 weeks of treatment with a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine.

A 58-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic with pruritus and occasional paresthesia associated with a rash over the left arm of 1 month’s duration. The patient suspected that the rash may have formed secondary to the bite of oak mites on the arms and chest while he was carrying milled wood. Further inquiry into the patient’s history revealed that he received the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. He denied mechanical trauma. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia and a mild COVID-19 infection 8 months prior to the appearance of the rash that did not require hospitalization. He denied fever or chills during the 2 weeks following vaccination. The pruritus was minimally relieved for short periods with over-the-counter calamine lotion. The patient’s medication regimen included daily pravastatin and loratadine at the time of the initial visit. He used acetaminophen as needed for knee pain.

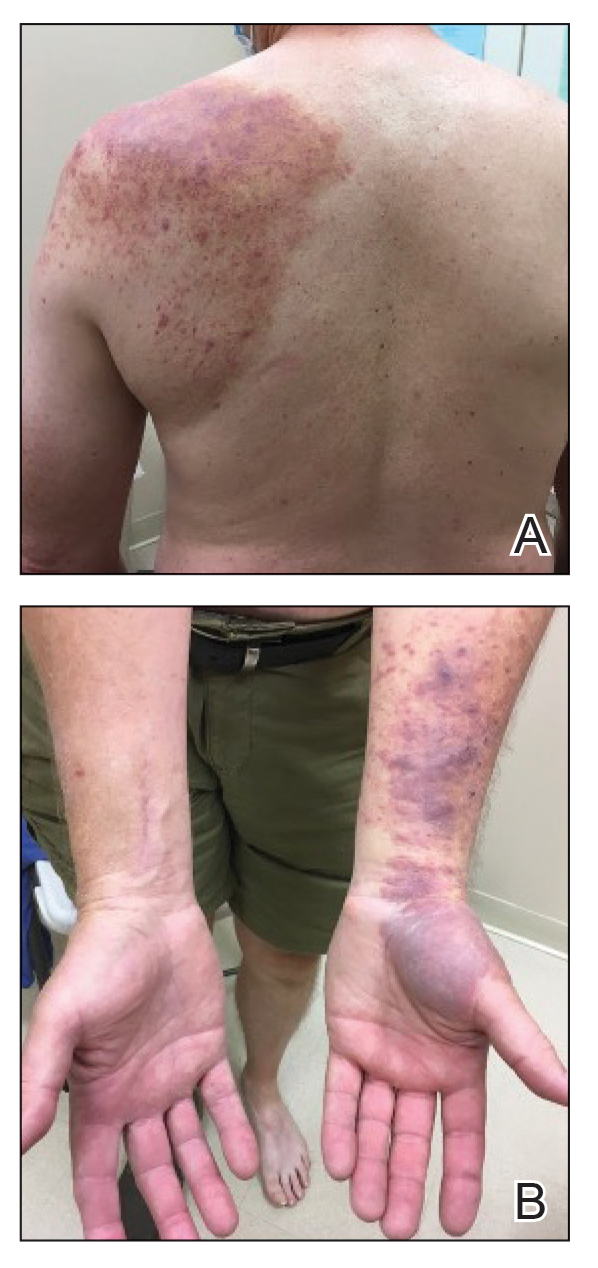

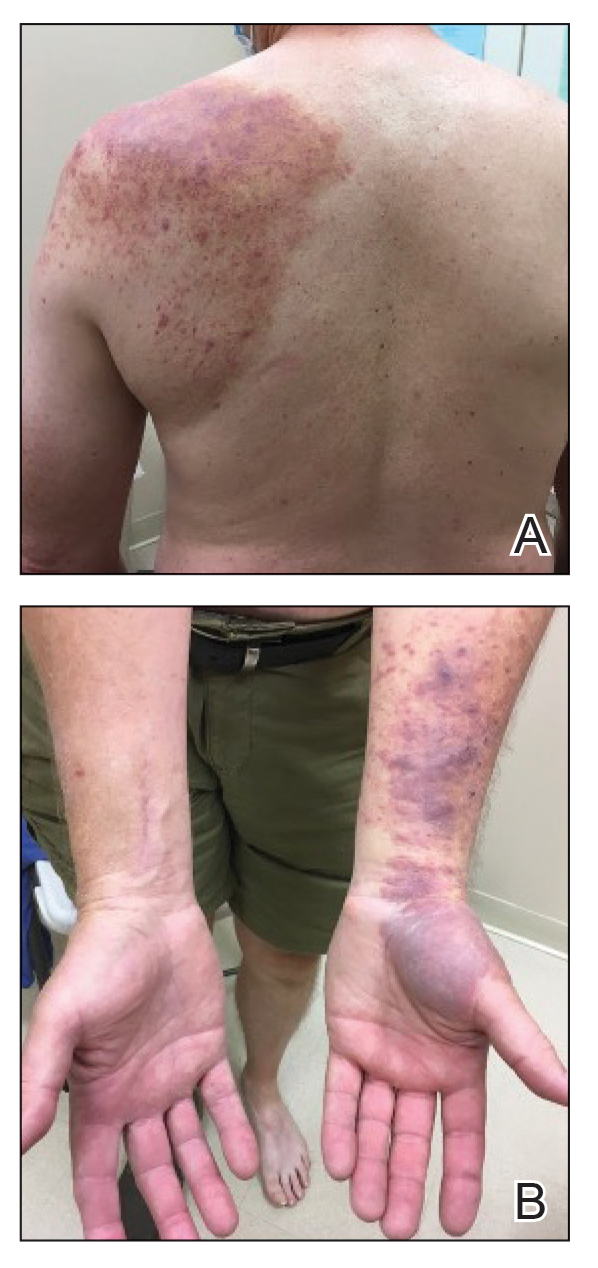

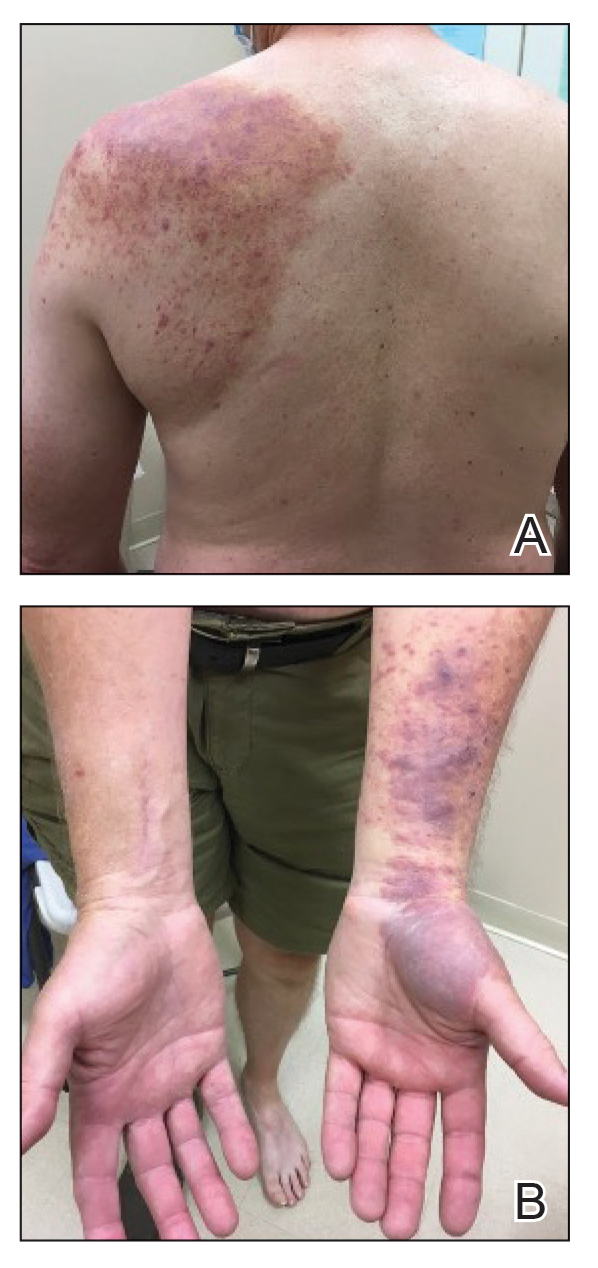

Physical examination revealed palpable purpura in a dermatomal distribution with nonpitting edema over the left scapula (Figure 1A), left anterolateral shoulder, left lateral volar forearm, and thenar eminence of the left hand (Figure 1B). Notably, the entire right arm, conjunctivae, tongue, lips, and bilateral fingernails were clear. Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed at the initial presentation: 1 perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence testing and 2 lesional biopsies for routine histologic evaluation. An extensive serologic workup failed to reveal abnormalities. An activated partial thromboplastin time, dilute Russell viper venom time, serum protein electrophoresis, and levels of rheumatoid factor and angiotensin-converting enzyme were within reference range. Anticardiolipin antibodies IgA, IgM, and IgG were negative. A cryoglobulin test was negative.

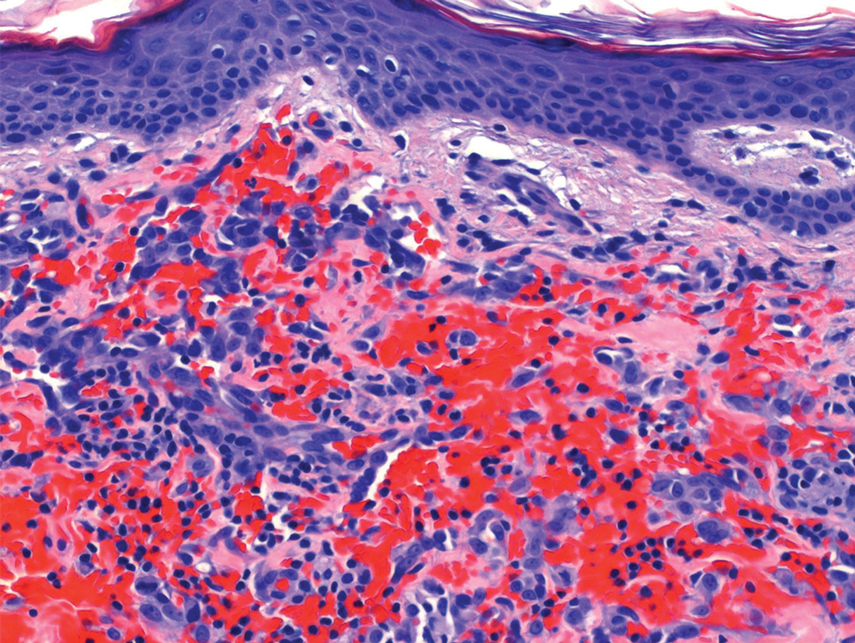

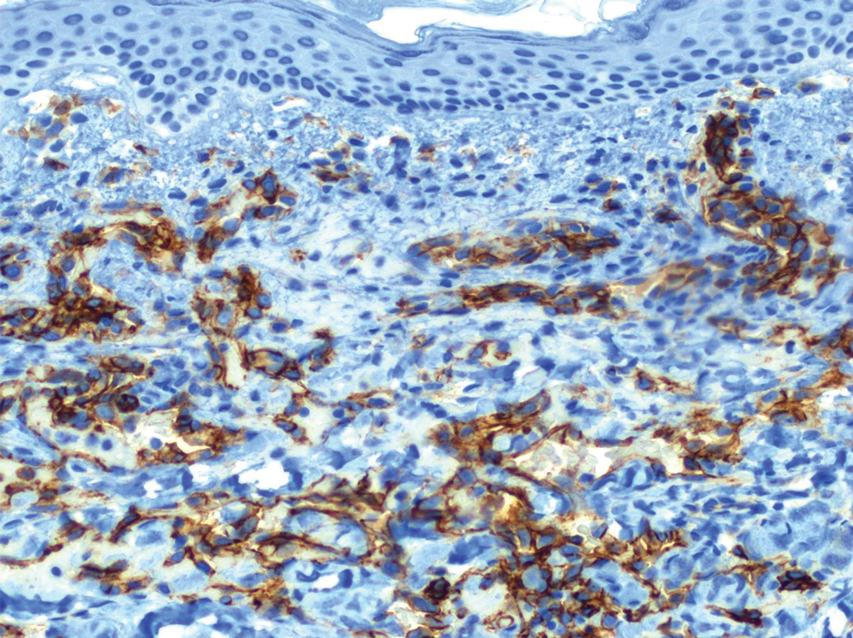

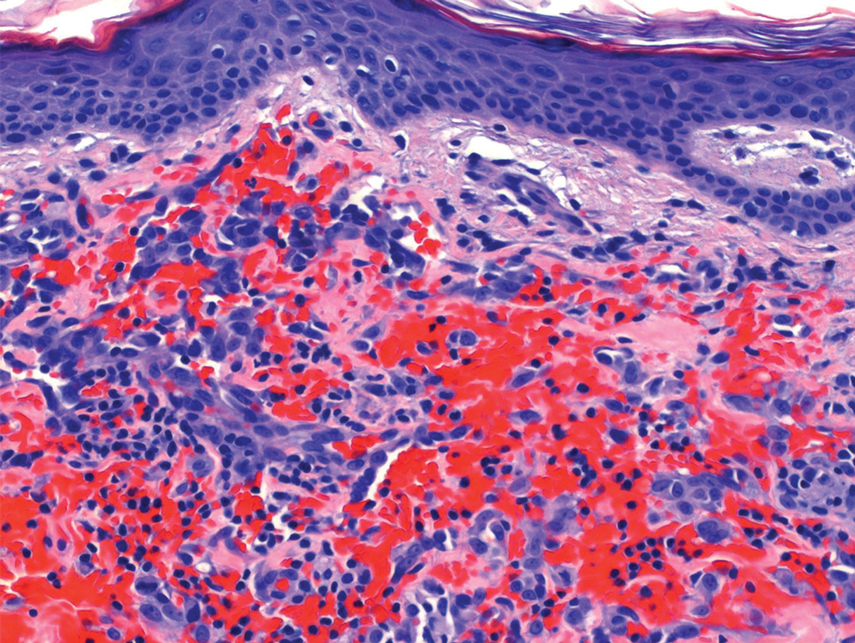

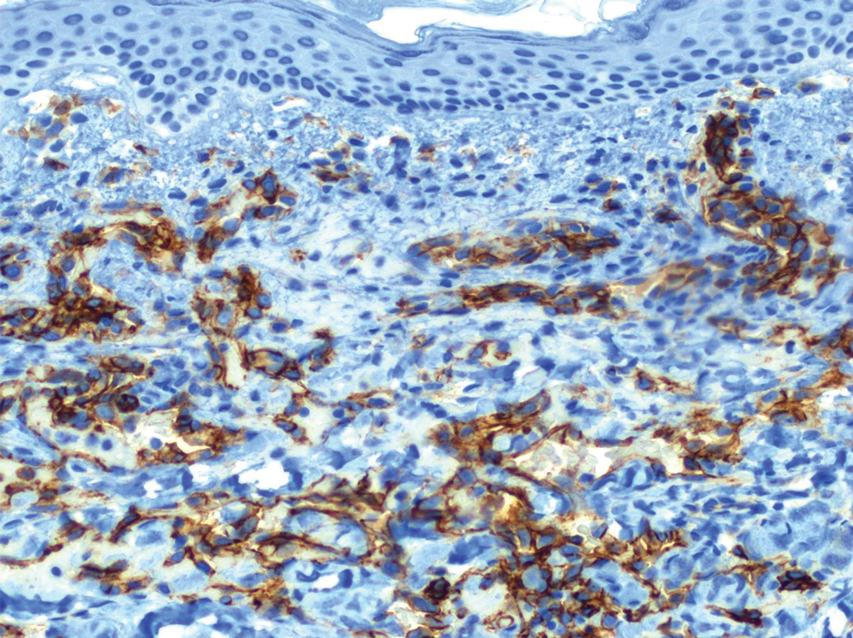

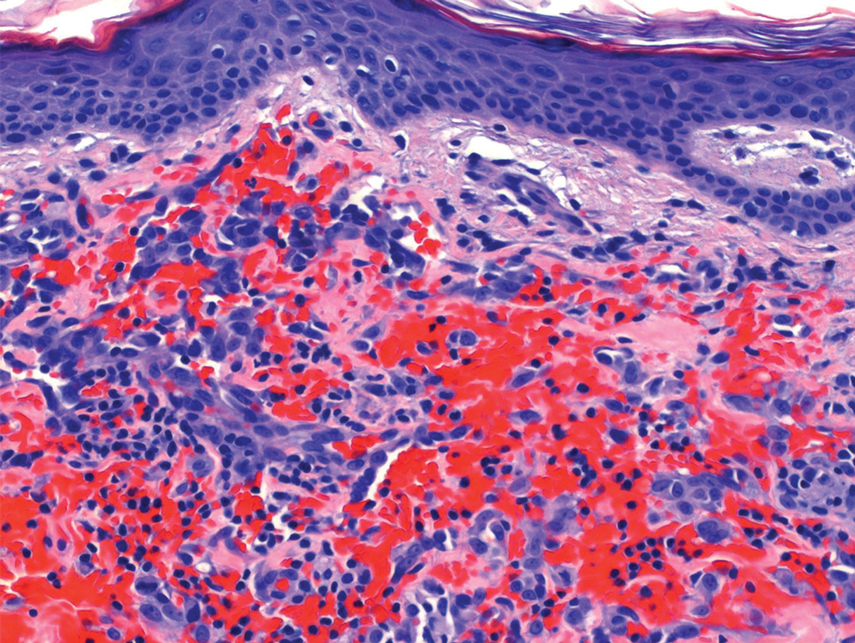

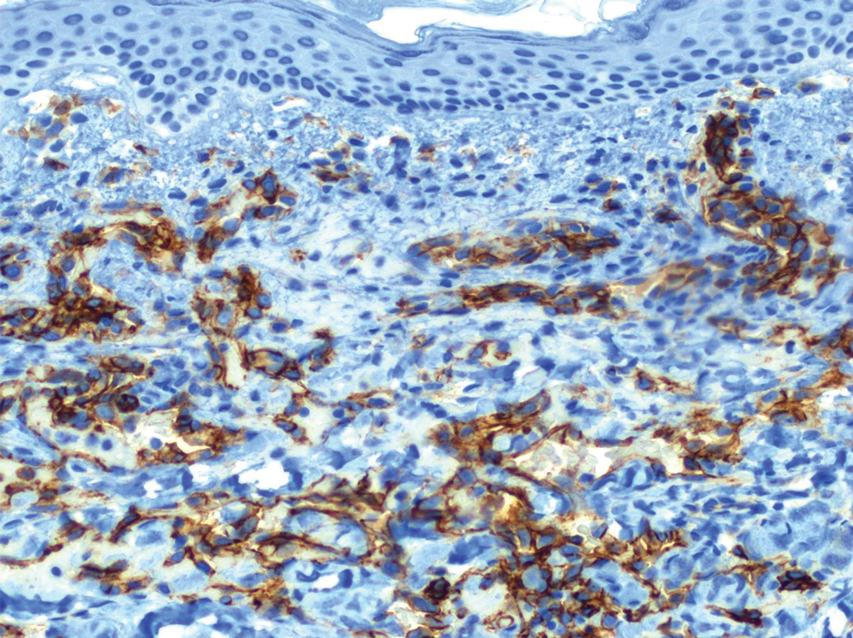

Histopathology revealed a proliferation of irregularly shaped vascular spaces with plump endothelium in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). Scattered leukocyte common antigen-positive lymphocytes were noted within lesions. The epidermis appeared normal, without evidence of spongiosis or alteration of the stratum corneum. Immunohistochemical studies of the perilesional skin biopsy revealed positivity for CD31 and D2-40 (Figure 3). Specimens were negative for CD20 and human herpesvirus 8. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional biopsy was negative.

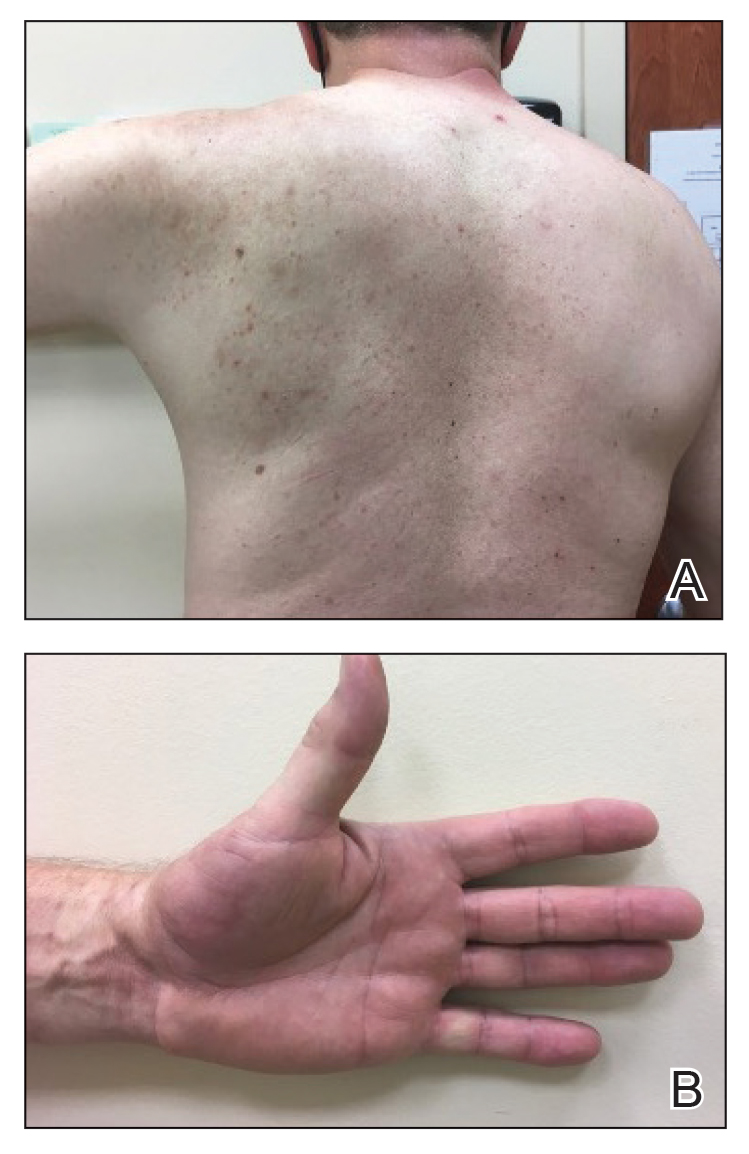

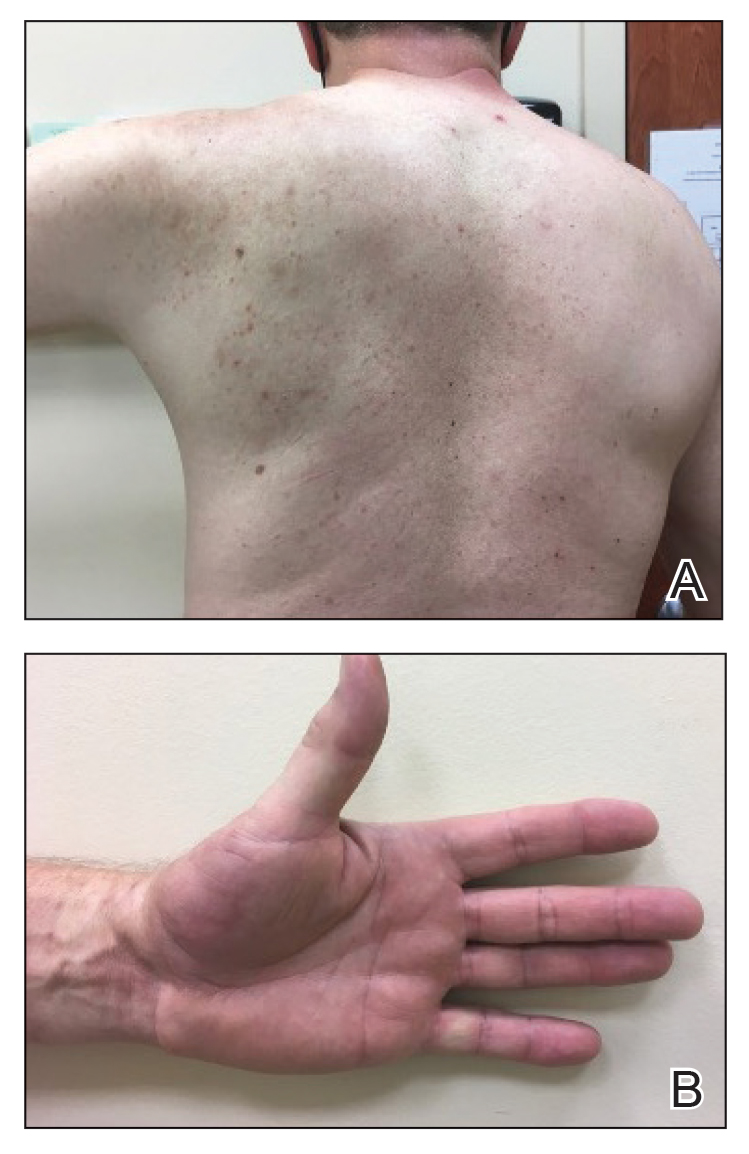

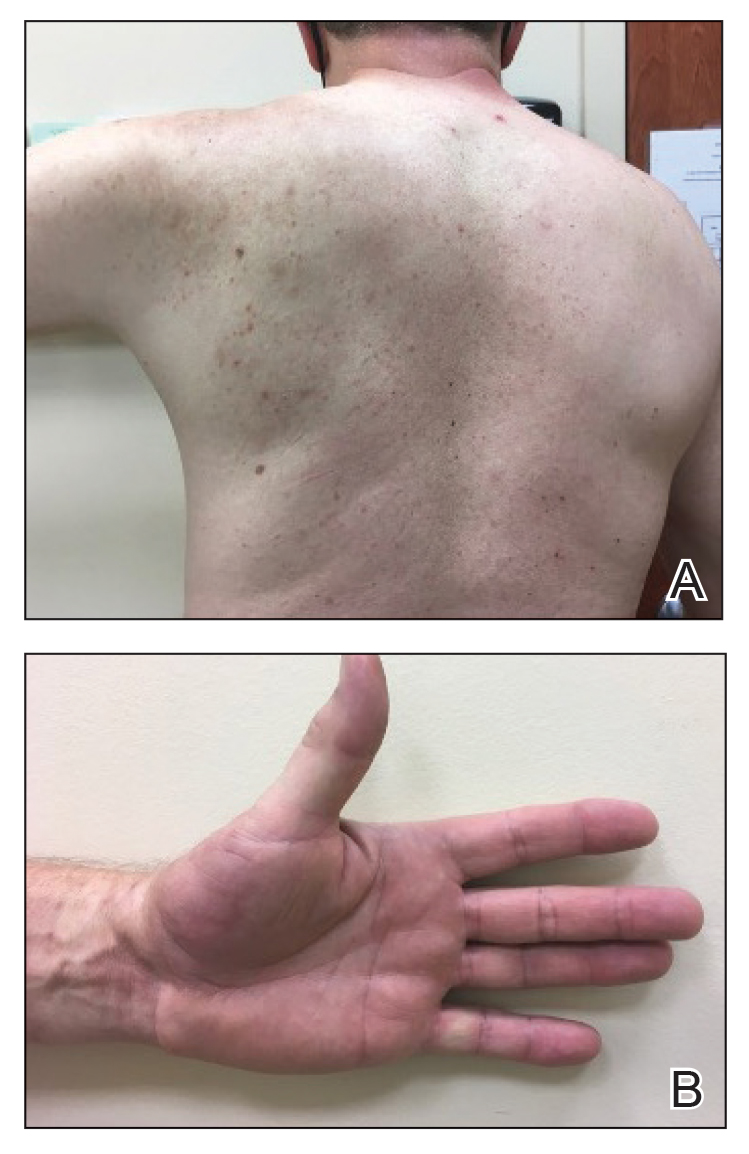

A diagnosis of RAE was made based on clinical and histologic findings. Treatment with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral cetirizine 10 mg twice daily was initiated. Re-evaluation 2 weeks later revealed notable improvement in the affected areas, including decreased edema, improvement of the purpura, and absence of pruritus. The patient noted no further spread or blister formation while the active areas were being treated with the topical steroid. The treatment regimen was modified to triamcinolone ointment 0.1% once daily, and cetirizine was discontinued. At 3-month follow-up, active areas had completely resolved (Figure 4) and triamcinolone was discontinued. To date, the patient has not had recurrence of symptoms and remains healthy.

Gottron and Nikolowski3 reported the first case of RAE in an adult patient who presented with purpuric patches secondary to skin infarction. Current definitions use the umbrella term cutaneous reactive angiomatosis to cover 3 major subtypes: reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angioendotheliomatosis, and acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma [KS]). The manifestation of these subgroups is clinically similar, and they must be differentiated through histologic evaluation.4

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis has an unknown pathogenesis and is poorly defined clinically. The exact pathophysiology is unknown but likely is linked to vaso-occlusion and hypoxia.1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE, as well as a review of Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library, using the terms reactive angioendotheliomatosis, COVID, vaccine, Ad26.COV2.S, and RAE in any combination revealed no prior cases of RAE in association with Ad26.COV2.S vaccination.

By the late 1980s, systemic angioendotheliomatosis was segregated into 2 distinct entities: malignant and reactive.4 The differential diagnosis of malignant systemic angioendotheliomatosis includes KS and angiosarcoma; nonmalignant causes are the variants of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis. It is important to rule out KS because of its malignant and deceptive nature. It is unknown if KS originates in blood vessels or lymphatic endothelial cells; however, evidence is strongly in favor of blood vessel origin using CD31 and CD34 endothelial markers.5 CD34 positivity is more reliable than CD31 in diagnosing KS, but the absence of both markers does not offer enough evidence to rule out KS on its own.6

In our patient, histopathology revealed cells positive for CD31 and D2-40; the latter is a lymphatic endothelial cell marker that stains the endothelium of lymphatic channels but not blood vessels.7 Positive D2-40 can be indicative of KS and non-KS lesions, each with a distinct staining pattern. D2-40 staining on non-KS lesions is confined to lymphatic vessels, as it was in our patient; in contrast, spindle-shaped cells also will be stained in KS lesions.8

Another cell marker, CD20, is a B cell–specific protein that can be measured to help diagnose malignant diseases such as B-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Human herpesvirus 8 (also known as KS-associated herpesvirus) is the infectious cause of KS and traditionally has been detected using methods such as the polymerase chain reaction.9,10

Most cases of RAE are idiopathic and occur in association with systemic disease, which was not the case in our patient. We speculated that his reaction was most likely triggered by vascular transfection of endothelial cells secondary to Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. Alternatively, vaccination may have caused vascular occlusion, though the lack of cyanosis, nail changes, and route of inoculant make this less likely.

All approved COVID-19 vaccines are designed solely for intramuscular injection. In comparison to other types of tissue, muscles have superior vascularity, allowing for enhanced mobilization of compounds, which results in faster systemic circulation.11 Alternative methods of injection, including intravascular, subcutaneous, and intradermal, may lead to decreased efficacy or adverse events, or both.

Prior cases of RAE have been treated with laser therapy, topical or systemic corticosteroids, excisional removal, or topical β-blockers, such as timolol.12 β-Blocking agents act on β-adrenergic receptors on endothelial cells to inhibit angiogenesis by reducing release of blood vessel growth-signaling molecules and triggering apoptosis. In this patient, topical steroids and oral antihistamines were sufficient treatment.

Vaccine-related adverse events have been reported but remain rare. The benefits of Ad26.COV2.S vaccination for protection against COVID-19 outweigh the extremely low risk for adverse events.13 For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a booster for individuals who are eligible to maximize protection. Intramuscular injection of Ad26.COV2.S resulted in a lower incidence of moderate to severe COVID-19 cases in all age groups vs the placebo group. Hypersensitivity adverse events were reported in 0.4% of Ad26.COV2.S-vaccinated patients vs 0.4% of patients who received a placebo; the more common reactions were nonanaphylactic.13

There have been 12 reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, which sparked nationwide controversy over the safety of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine.14 After further investigation into those reports, the US Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that the benefits of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine outweigh the low risk for associated thrombosis.15

Although adverse reactions are rare, it is important that health care providers take proper safety measures before and while administering any COVID-19 vaccine. Patients should be screened for contraindications to the COVID-19 vaccine to mitigate adverse effects seen in the small percentage of patients who may need to take alternative precautions.

The broad tissue tropism and high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 are the main contributors to its infection having reached pandemic scale. The spike (S) protein on SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, the most thoroughly studied SARS-CoV-2 receptor, which is found in a range of tissues, including arterial endothelial cells, leading to its transfection. Several studies have proposed that expression of the S protein causes endothelial dysfunction through cytokine release, activation of complement, and ultimately microvascular occlusion.16

Recent developments in the use of viral-like particles, such as vesicular stomatitis virus, may mitigate future cases of RAE that are associated with endothelial cell transfection. Vesicular stomatitis virus is a popular model virus for research applications due to its glycoprotein and matrix protein contributing to its broad tropism. Recent efforts to alter these proteins have successfully limited the broad tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus.17

The SARS-CoV-2 virus must be handled in a Biosafety Level 3 laboratory. Conversely, pseudoviruses can be handled in lower containment facilities due to their safe and efficacious nature, offering an avenue to expedite vaccine development against many viral outbreaks, including SARS-CoV-2.18

An increasing number of cutaneous manifestations have been associated with COVID-19 infection and vaccination. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, a rare self-limiting exanthem, has been reported in association with COVID-19 vaccination.19 Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis manifests as erythematous blanchable papules that resemble angiomas, typically in a widespread distribution. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis has striking similarities to RAE histologically; both manifest as dilated dermal blood vessels with plump endothelial cells.

Our case is unique because of the vasculitic palpable nature of the lesions, which were localized to the left arm. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis formation after COVID-19 infection or SARS-CoV-2 vaccination may suggest alteration of ACE2 by binding of S protein.20 Such alteration of the ACE2 pathway would lead to inflammation of angiotensin II, causing proliferation of endothelial cells in the formation of angiomalike lesions. This hypothesis suggests a paraviral eruption secondary to an immunologic reaction, not a classical virtual eruption from direct contact of the virus on blood vessels. Although EPA and RAE are harmless and self-limiting, these reports will spread awareness of the increasing number of skin manifestations related to COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccination.

Acknowledgment—Thoughtful insights and comments on this manuscript were provided by Christine J. Ko, MD (New Haven, Connecticut); Christine L. Egan, MD (Glen Mills, Pennsylvania); Howard A. Bueller, MD (Delray Beach, Florida); and Juan Pablo Robles, PhD (Juriquilla, Mexico).

- McMenamin ME, Fletcher CDM. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: a study of 15 cases demonstrating a wide clinicopathologic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:686-697. doi:10.1097/00000478-200206000-00001

- Khan S, Pujani M, Jetley S, et al. Angiomatosis: a rare vascular proliferation of head and neck region. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:108-110. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.158448

- Gottron HA, Nikolowski W. Extrarenal Lohlein focal nephritis of the skin in endocarditis. Arch Klin Exp Dermatol. 1958;207:156-176.

- Cooper PH. Angioendotheliomatosis: two separate diseases. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:259. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1988.tb00556.x

- Cancian L, Hansen A, Boshoff C. Cellular origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-induced cell reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. Sep 2013;23:421-32. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2013.04.001

- Russell Jones R, Orchard G, Zelger B, et al. Immunostaining for CD31 and CD34 in Kaposi sarcoma. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1011-1016. doi:10.1136/jcp.48.11.1011

- Kahn HJ, Bailey D, Marks A. Monoclonal antibody D2-40, a new marker of lymphatic endothelium, reacts with Kaposi’s sarcoma and a subset of angiosarcomas. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:434-440. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3880543

- Genedy RM, Hamza AM, Abdel Latef AA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of D2-40 in differentiating Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. J Egyptian Womens Dermatolog Soc. 2021;18:67-74. doi:10.4103/jewd.jewd_61_20

- Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:707-719. doi:10.1038/nrc2888

- Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800061

- Zuckerman JN. The importance of injecting vaccines into muscle. Different patients need different needle sizes. BMJ. 2000;321:1237-1238. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1237

- Bhatia R, Hazarika N, Chandrasekaran D, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic reactive angioendotheliomatosis with topical timolol maleate. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1002-1004. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1770

- Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al; ENSEMBLE Study Group. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2187-2201. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2101544

- See I, Su JR, Lale A, et al. US case reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, March 2 to April 21, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325:2448-2456. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7517

- Berry CT, Eliliwi M, Gallagher S, et al. Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis following single-dose Janssen Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;15:11-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.07.002

- Flaumenhaft R, Enjyoji K, Schmaier AA. Vasculopathy in COVID-19. Blood. 2022;140:222-235. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012250

- Hastie E, Cataldi M, Marriott I, et al. Understanding and altering cell tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus. Virus Res. 2013;176:16-32. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2013.06.003

- Xiong H-L, Wu Y-T, Cao J-L, et al. Robust neutralization assay based on SARS-CoV-2 S-protein-bearing vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudovirus and ACE2-overexpressing BHK21 cells. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:2105-2113. doi:10.1080/22221751.2020.1815589

- Mohta A, Jain SK, Mehta RD, et al. Development of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis following COVID-19 immunization – apropos of 5 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e722-e725. doi:10.1111/jdv.17499

- Angeli F, Spanevello A, Reboldi G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: lights and shadows. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;88:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2021.04.019

To the Editor:

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE) is a rare self-limited cutaneous vascular proliferation of endothelial cells within blood vessels that manifests clinically as infiltrated red-blue patches and plaques with purpura that can progress to occlude vascular lumina. The etiology of RAE is mostly idiopathic; however, the disorder typically occurs in association with a range of systemic diseases, including infection, cryoglobulinemia, leukemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, peripheral vascular disease, and arteriovenous fistula. Histopathologic examination of these lesions shows marked proliferation of endothelial cells, including occlusion of the lumen of blood vessels over wide areas.

After ruling out malignancy, treatment of RAE focuses on targeting the underlying cause or disease, if any is present; 75% of reported cases occur in association with systemic disease.1 Onset can occur at any age without predilection for sex. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis commonly manifests on the extremities but may occur on the head and neck in rare instances.2

The rarity of the condition and its poorly defined clinical characteristics make it difficult to develop a treatment plan. There are no standardized treatment guidelines for the reactive form of angiomatosis. We report a case of RAE that developed 2 weeks after vaccination with the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine [formerly Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson]) that improved following 2 weeks of treatment with a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine.

A 58-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic with pruritus and occasional paresthesia associated with a rash over the left arm of 1 month’s duration. The patient suspected that the rash may have formed secondary to the bite of oak mites on the arms and chest while he was carrying milled wood. Further inquiry into the patient’s history revealed that he received the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. He denied mechanical trauma. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia and a mild COVID-19 infection 8 months prior to the appearance of the rash that did not require hospitalization. He denied fever or chills during the 2 weeks following vaccination. The pruritus was minimally relieved for short periods with over-the-counter calamine lotion. The patient’s medication regimen included daily pravastatin and loratadine at the time of the initial visit. He used acetaminophen as needed for knee pain.

Physical examination revealed palpable purpura in a dermatomal distribution with nonpitting edema over the left scapula (Figure 1A), left anterolateral shoulder, left lateral volar forearm, and thenar eminence of the left hand (Figure 1B). Notably, the entire right arm, conjunctivae, tongue, lips, and bilateral fingernails were clear. Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed at the initial presentation: 1 perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence testing and 2 lesional biopsies for routine histologic evaluation. An extensive serologic workup failed to reveal abnormalities. An activated partial thromboplastin time, dilute Russell viper venom time, serum protein electrophoresis, and levels of rheumatoid factor and angiotensin-converting enzyme were within reference range. Anticardiolipin antibodies IgA, IgM, and IgG were negative. A cryoglobulin test was negative.

Histopathology revealed a proliferation of irregularly shaped vascular spaces with plump endothelium in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). Scattered leukocyte common antigen-positive lymphocytes were noted within lesions. The epidermis appeared normal, without evidence of spongiosis or alteration of the stratum corneum. Immunohistochemical studies of the perilesional skin biopsy revealed positivity for CD31 and D2-40 (Figure 3). Specimens were negative for CD20 and human herpesvirus 8. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional biopsy was negative.

A diagnosis of RAE was made based on clinical and histologic findings. Treatment with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral cetirizine 10 mg twice daily was initiated. Re-evaluation 2 weeks later revealed notable improvement in the affected areas, including decreased edema, improvement of the purpura, and absence of pruritus. The patient noted no further spread or blister formation while the active areas were being treated with the topical steroid. The treatment regimen was modified to triamcinolone ointment 0.1% once daily, and cetirizine was discontinued. At 3-month follow-up, active areas had completely resolved (Figure 4) and triamcinolone was discontinued. To date, the patient has not had recurrence of symptoms and remains healthy.

Gottron and Nikolowski3 reported the first case of RAE in an adult patient who presented with purpuric patches secondary to skin infarction. Current definitions use the umbrella term cutaneous reactive angiomatosis to cover 3 major subtypes: reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angioendotheliomatosis, and acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma [KS]). The manifestation of these subgroups is clinically similar, and they must be differentiated through histologic evaluation.4

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis has an unknown pathogenesis and is poorly defined clinically. The exact pathophysiology is unknown but likely is linked to vaso-occlusion and hypoxia.1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE, as well as a review of Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library, using the terms reactive angioendotheliomatosis, COVID, vaccine, Ad26.COV2.S, and RAE in any combination revealed no prior cases of RAE in association with Ad26.COV2.S vaccination.

By the late 1980s, systemic angioendotheliomatosis was segregated into 2 distinct entities: malignant and reactive.4 The differential diagnosis of malignant systemic angioendotheliomatosis includes KS and angiosarcoma; nonmalignant causes are the variants of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis. It is important to rule out KS because of its malignant and deceptive nature. It is unknown if KS originates in blood vessels or lymphatic endothelial cells; however, evidence is strongly in favor of blood vessel origin using CD31 and CD34 endothelial markers.5 CD34 positivity is more reliable than CD31 in diagnosing KS, but the absence of both markers does not offer enough evidence to rule out KS on its own.6

In our patient, histopathology revealed cells positive for CD31 and D2-40; the latter is a lymphatic endothelial cell marker that stains the endothelium of lymphatic channels but not blood vessels.7 Positive D2-40 can be indicative of KS and non-KS lesions, each with a distinct staining pattern. D2-40 staining on non-KS lesions is confined to lymphatic vessels, as it was in our patient; in contrast, spindle-shaped cells also will be stained in KS lesions.8

Another cell marker, CD20, is a B cell–specific protein that can be measured to help diagnose malignant diseases such as B-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Human herpesvirus 8 (also known as KS-associated herpesvirus) is the infectious cause of KS and traditionally has been detected using methods such as the polymerase chain reaction.9,10

Most cases of RAE are idiopathic and occur in association with systemic disease, which was not the case in our patient. We speculated that his reaction was most likely triggered by vascular transfection of endothelial cells secondary to Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. Alternatively, vaccination may have caused vascular occlusion, though the lack of cyanosis, nail changes, and route of inoculant make this less likely.

All approved COVID-19 vaccines are designed solely for intramuscular injection. In comparison to other types of tissue, muscles have superior vascularity, allowing for enhanced mobilization of compounds, which results in faster systemic circulation.11 Alternative methods of injection, including intravascular, subcutaneous, and intradermal, may lead to decreased efficacy or adverse events, or both.

Prior cases of RAE have been treated with laser therapy, topical or systemic corticosteroids, excisional removal, or topical β-blockers, such as timolol.12 β-Blocking agents act on β-adrenergic receptors on endothelial cells to inhibit angiogenesis by reducing release of blood vessel growth-signaling molecules and triggering apoptosis. In this patient, topical steroids and oral antihistamines were sufficient treatment.

Vaccine-related adverse events have been reported but remain rare. The benefits of Ad26.COV2.S vaccination for protection against COVID-19 outweigh the extremely low risk for adverse events.13 For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a booster for individuals who are eligible to maximize protection. Intramuscular injection of Ad26.COV2.S resulted in a lower incidence of moderate to severe COVID-19 cases in all age groups vs the placebo group. Hypersensitivity adverse events were reported in 0.4% of Ad26.COV2.S-vaccinated patients vs 0.4% of patients who received a placebo; the more common reactions were nonanaphylactic.13

There have been 12 reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, which sparked nationwide controversy over the safety of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine.14 After further investigation into those reports, the US Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that the benefits of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine outweigh the low risk for associated thrombosis.15

Although adverse reactions are rare, it is important that health care providers take proper safety measures before and while administering any COVID-19 vaccine. Patients should be screened for contraindications to the COVID-19 vaccine to mitigate adverse effects seen in the small percentage of patients who may need to take alternative precautions.

The broad tissue tropism and high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 are the main contributors to its infection having reached pandemic scale. The spike (S) protein on SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, the most thoroughly studied SARS-CoV-2 receptor, which is found in a range of tissues, including arterial endothelial cells, leading to its transfection. Several studies have proposed that expression of the S protein causes endothelial dysfunction through cytokine release, activation of complement, and ultimately microvascular occlusion.16

Recent developments in the use of viral-like particles, such as vesicular stomatitis virus, may mitigate future cases of RAE that are associated with endothelial cell transfection. Vesicular stomatitis virus is a popular model virus for research applications due to its glycoprotein and matrix protein contributing to its broad tropism. Recent efforts to alter these proteins have successfully limited the broad tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus.17

The SARS-CoV-2 virus must be handled in a Biosafety Level 3 laboratory. Conversely, pseudoviruses can be handled in lower containment facilities due to their safe and efficacious nature, offering an avenue to expedite vaccine development against many viral outbreaks, including SARS-CoV-2.18

An increasing number of cutaneous manifestations have been associated with COVID-19 infection and vaccination. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, a rare self-limiting exanthem, has been reported in association with COVID-19 vaccination.19 Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis manifests as erythematous blanchable papules that resemble angiomas, typically in a widespread distribution. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis has striking similarities to RAE histologically; both manifest as dilated dermal blood vessels with plump endothelial cells.

Our case is unique because of the vasculitic palpable nature of the lesions, which were localized to the left arm. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis formation after COVID-19 infection or SARS-CoV-2 vaccination may suggest alteration of ACE2 by binding of S protein.20 Such alteration of the ACE2 pathway would lead to inflammation of angiotensin II, causing proliferation of endothelial cells in the formation of angiomalike lesions. This hypothesis suggests a paraviral eruption secondary to an immunologic reaction, not a classical virtual eruption from direct contact of the virus on blood vessels. Although EPA and RAE are harmless and self-limiting, these reports will spread awareness of the increasing number of skin manifestations related to COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccination.

Acknowledgment—Thoughtful insights and comments on this manuscript were provided by Christine J. Ko, MD (New Haven, Connecticut); Christine L. Egan, MD (Glen Mills, Pennsylvania); Howard A. Bueller, MD (Delray Beach, Florida); and Juan Pablo Robles, PhD (Juriquilla, Mexico).

To the Editor:

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE) is a rare self-limited cutaneous vascular proliferation of endothelial cells within blood vessels that manifests clinically as infiltrated red-blue patches and plaques with purpura that can progress to occlude vascular lumina. The etiology of RAE is mostly idiopathic; however, the disorder typically occurs in association with a range of systemic diseases, including infection, cryoglobulinemia, leukemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, peripheral vascular disease, and arteriovenous fistula. Histopathologic examination of these lesions shows marked proliferation of endothelial cells, including occlusion of the lumen of blood vessels over wide areas.

After ruling out malignancy, treatment of RAE focuses on targeting the underlying cause or disease, if any is present; 75% of reported cases occur in association with systemic disease.1 Onset can occur at any age without predilection for sex. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis commonly manifests on the extremities but may occur on the head and neck in rare instances.2

The rarity of the condition and its poorly defined clinical characteristics make it difficult to develop a treatment plan. There are no standardized treatment guidelines for the reactive form of angiomatosis. We report a case of RAE that developed 2 weeks after vaccination with the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine [formerly Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson]) that improved following 2 weeks of treatment with a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine.

A 58-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic with pruritus and occasional paresthesia associated with a rash over the left arm of 1 month’s duration. The patient suspected that the rash may have formed secondary to the bite of oak mites on the arms and chest while he was carrying milled wood. Further inquiry into the patient’s history revealed that he received the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. He denied mechanical trauma. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia and a mild COVID-19 infection 8 months prior to the appearance of the rash that did not require hospitalization. He denied fever or chills during the 2 weeks following vaccination. The pruritus was minimally relieved for short periods with over-the-counter calamine lotion. The patient’s medication regimen included daily pravastatin and loratadine at the time of the initial visit. He used acetaminophen as needed for knee pain.

Physical examination revealed palpable purpura in a dermatomal distribution with nonpitting edema over the left scapula (Figure 1A), left anterolateral shoulder, left lateral volar forearm, and thenar eminence of the left hand (Figure 1B). Notably, the entire right arm, conjunctivae, tongue, lips, and bilateral fingernails were clear. Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed at the initial presentation: 1 perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence testing and 2 lesional biopsies for routine histologic evaluation. An extensive serologic workup failed to reveal abnormalities. An activated partial thromboplastin time, dilute Russell viper venom time, serum protein electrophoresis, and levels of rheumatoid factor and angiotensin-converting enzyme were within reference range. Anticardiolipin antibodies IgA, IgM, and IgG were negative. A cryoglobulin test was negative.

Histopathology revealed a proliferation of irregularly shaped vascular spaces with plump endothelium in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). Scattered leukocyte common antigen-positive lymphocytes were noted within lesions. The epidermis appeared normal, without evidence of spongiosis or alteration of the stratum corneum. Immunohistochemical studies of the perilesional skin biopsy revealed positivity for CD31 and D2-40 (Figure 3). Specimens were negative for CD20 and human herpesvirus 8. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional biopsy was negative.

A diagnosis of RAE was made based on clinical and histologic findings. Treatment with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral cetirizine 10 mg twice daily was initiated. Re-evaluation 2 weeks later revealed notable improvement in the affected areas, including decreased edema, improvement of the purpura, and absence of pruritus. The patient noted no further spread or blister formation while the active areas were being treated with the topical steroid. The treatment regimen was modified to triamcinolone ointment 0.1% once daily, and cetirizine was discontinued. At 3-month follow-up, active areas had completely resolved (Figure 4) and triamcinolone was discontinued. To date, the patient has not had recurrence of symptoms and remains healthy.

Gottron and Nikolowski3 reported the first case of RAE in an adult patient who presented with purpuric patches secondary to skin infarction. Current definitions use the umbrella term cutaneous reactive angiomatosis to cover 3 major subtypes: reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angioendotheliomatosis, and acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma [KS]). The manifestation of these subgroups is clinically similar, and they must be differentiated through histologic evaluation.4

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis has an unknown pathogenesis and is poorly defined clinically. The exact pathophysiology is unknown but likely is linked to vaso-occlusion and hypoxia.1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE, as well as a review of Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library, using the terms reactive angioendotheliomatosis, COVID, vaccine, Ad26.COV2.S, and RAE in any combination revealed no prior cases of RAE in association with Ad26.COV2.S vaccination.

By the late 1980s, systemic angioendotheliomatosis was segregated into 2 distinct entities: malignant and reactive.4 The differential diagnosis of malignant systemic angioendotheliomatosis includes KS and angiosarcoma; nonmalignant causes are the variants of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis. It is important to rule out KS because of its malignant and deceptive nature. It is unknown if KS originates in blood vessels or lymphatic endothelial cells; however, evidence is strongly in favor of blood vessel origin using CD31 and CD34 endothelial markers.5 CD34 positivity is more reliable than CD31 in diagnosing KS, but the absence of both markers does not offer enough evidence to rule out KS on its own.6

In our patient, histopathology revealed cells positive for CD31 and D2-40; the latter is a lymphatic endothelial cell marker that stains the endothelium of lymphatic channels but not blood vessels.7 Positive D2-40 can be indicative of KS and non-KS lesions, each with a distinct staining pattern. D2-40 staining on non-KS lesions is confined to lymphatic vessels, as it was in our patient; in contrast, spindle-shaped cells also will be stained in KS lesions.8

Another cell marker, CD20, is a B cell–specific protein that can be measured to help diagnose malignant diseases such as B-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Human herpesvirus 8 (also known as KS-associated herpesvirus) is the infectious cause of KS and traditionally has been detected using methods such as the polymerase chain reaction.9,10

Most cases of RAE are idiopathic and occur in association with systemic disease, which was not the case in our patient. We speculated that his reaction was most likely triggered by vascular transfection of endothelial cells secondary to Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. Alternatively, vaccination may have caused vascular occlusion, though the lack of cyanosis, nail changes, and route of inoculant make this less likely.

All approved COVID-19 vaccines are designed solely for intramuscular injection. In comparison to other types of tissue, muscles have superior vascularity, allowing for enhanced mobilization of compounds, which results in faster systemic circulation.11 Alternative methods of injection, including intravascular, subcutaneous, and intradermal, may lead to decreased efficacy or adverse events, or both.

Prior cases of RAE have been treated with laser therapy, topical or systemic corticosteroids, excisional removal, or topical β-blockers, such as timolol.12 β-Blocking agents act on β-adrenergic receptors on endothelial cells to inhibit angiogenesis by reducing release of blood vessel growth-signaling molecules and triggering apoptosis. In this patient, topical steroids and oral antihistamines were sufficient treatment.

Vaccine-related adverse events have been reported but remain rare. The benefits of Ad26.COV2.S vaccination for protection against COVID-19 outweigh the extremely low risk for adverse events.13 For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a booster for individuals who are eligible to maximize protection. Intramuscular injection of Ad26.COV2.S resulted in a lower incidence of moderate to severe COVID-19 cases in all age groups vs the placebo group. Hypersensitivity adverse events were reported in 0.4% of Ad26.COV2.S-vaccinated patients vs 0.4% of patients who received a placebo; the more common reactions were nonanaphylactic.13

There have been 12 reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, which sparked nationwide controversy over the safety of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine.14 After further investigation into those reports, the US Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that the benefits of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine outweigh the low risk for associated thrombosis.15

Although adverse reactions are rare, it is important that health care providers take proper safety measures before and while administering any COVID-19 vaccine. Patients should be screened for contraindications to the COVID-19 vaccine to mitigate adverse effects seen in the small percentage of patients who may need to take alternative precautions.

The broad tissue tropism and high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 are the main contributors to its infection having reached pandemic scale. The spike (S) protein on SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, the most thoroughly studied SARS-CoV-2 receptor, which is found in a range of tissues, including arterial endothelial cells, leading to its transfection. Several studies have proposed that expression of the S protein causes endothelial dysfunction through cytokine release, activation of complement, and ultimately microvascular occlusion.16

Recent developments in the use of viral-like particles, such as vesicular stomatitis virus, may mitigate future cases of RAE that are associated with endothelial cell transfection. Vesicular stomatitis virus is a popular model virus for research applications due to its glycoprotein and matrix protein contributing to its broad tropism. Recent efforts to alter these proteins have successfully limited the broad tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus.17

The SARS-CoV-2 virus must be handled in a Biosafety Level 3 laboratory. Conversely, pseudoviruses can be handled in lower containment facilities due to their safe and efficacious nature, offering an avenue to expedite vaccine development against many viral outbreaks, including SARS-CoV-2.18

An increasing number of cutaneous manifestations have been associated with COVID-19 infection and vaccination. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, a rare self-limiting exanthem, has been reported in association with COVID-19 vaccination.19 Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis manifests as erythematous blanchable papules that resemble angiomas, typically in a widespread distribution. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis has striking similarities to RAE histologically; both manifest as dilated dermal blood vessels with plump endothelial cells.

Our case is unique because of the vasculitic palpable nature of the lesions, which were localized to the left arm. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis formation after COVID-19 infection or SARS-CoV-2 vaccination may suggest alteration of ACE2 by binding of S protein.20 Such alteration of the ACE2 pathway would lead to inflammation of angiotensin II, causing proliferation of endothelial cells in the formation of angiomalike lesions. This hypothesis suggests a paraviral eruption secondary to an immunologic reaction, not a classical virtual eruption from direct contact of the virus on blood vessels. Although EPA and RAE are harmless and self-limiting, these reports will spread awareness of the increasing number of skin manifestations related to COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccination.

Acknowledgment—Thoughtful insights and comments on this manuscript were provided by Christine J. Ko, MD (New Haven, Connecticut); Christine L. Egan, MD (Glen Mills, Pennsylvania); Howard A. Bueller, MD (Delray Beach, Florida); and Juan Pablo Robles, PhD (Juriquilla, Mexico).

- McMenamin ME, Fletcher CDM. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: a study of 15 cases demonstrating a wide clinicopathologic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:686-697. doi:10.1097/00000478-200206000-00001

- Khan S, Pujani M, Jetley S, et al. Angiomatosis: a rare vascular proliferation of head and neck region. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:108-110. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.158448

- Gottron HA, Nikolowski W. Extrarenal Lohlein focal nephritis of the skin in endocarditis. Arch Klin Exp Dermatol. 1958;207:156-176.

- Cooper PH. Angioendotheliomatosis: two separate diseases. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:259. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1988.tb00556.x

- Cancian L, Hansen A, Boshoff C. Cellular origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-induced cell reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. Sep 2013;23:421-32. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2013.04.001

- Russell Jones R, Orchard G, Zelger B, et al. Immunostaining for CD31 and CD34 in Kaposi sarcoma. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1011-1016. doi:10.1136/jcp.48.11.1011

- Kahn HJ, Bailey D, Marks A. Monoclonal antibody D2-40, a new marker of lymphatic endothelium, reacts with Kaposi’s sarcoma and a subset of angiosarcomas. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:434-440. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3880543

- Genedy RM, Hamza AM, Abdel Latef AA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of D2-40 in differentiating Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. J Egyptian Womens Dermatolog Soc. 2021;18:67-74. doi:10.4103/jewd.jewd_61_20

- Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:707-719. doi:10.1038/nrc2888

- Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800061

- Zuckerman JN. The importance of injecting vaccines into muscle. Different patients need different needle sizes. BMJ. 2000;321:1237-1238. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1237

- Bhatia R, Hazarika N, Chandrasekaran D, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic reactive angioendotheliomatosis with topical timolol maleate. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1002-1004. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1770

- Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al; ENSEMBLE Study Group. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2187-2201. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2101544

- See I, Su JR, Lale A, et al. US case reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, March 2 to April 21, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325:2448-2456. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7517

- Berry CT, Eliliwi M, Gallagher S, et al. Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis following single-dose Janssen Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;15:11-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.07.002

- Flaumenhaft R, Enjyoji K, Schmaier AA. Vasculopathy in COVID-19. Blood. 2022;140:222-235. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012250

- Hastie E, Cataldi M, Marriott I, et al. Understanding and altering cell tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus. Virus Res. 2013;176:16-32. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2013.06.003

- Xiong H-L, Wu Y-T, Cao J-L, et al. Robust neutralization assay based on SARS-CoV-2 S-protein-bearing vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudovirus and ACE2-overexpressing BHK21 cells. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:2105-2113. doi:10.1080/22221751.2020.1815589

- Mohta A, Jain SK, Mehta RD, et al. Development of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis following COVID-19 immunization – apropos of 5 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e722-e725. doi:10.1111/jdv.17499

- Angeli F, Spanevello A, Reboldi G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: lights and shadows. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;88:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2021.04.019

- McMenamin ME, Fletcher CDM. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: a study of 15 cases demonstrating a wide clinicopathologic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:686-697. doi:10.1097/00000478-200206000-00001

- Khan S, Pujani M, Jetley S, et al. Angiomatosis: a rare vascular proliferation of head and neck region. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:108-110. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.158448

- Gottron HA, Nikolowski W. Extrarenal Lohlein focal nephritis of the skin in endocarditis. Arch Klin Exp Dermatol. 1958;207:156-176.

- Cooper PH. Angioendotheliomatosis: two separate diseases. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:259. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1988.tb00556.x

- Cancian L, Hansen A, Boshoff C. Cellular origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-induced cell reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. Sep 2013;23:421-32. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2013.04.001

- Russell Jones R, Orchard G, Zelger B, et al. Immunostaining for CD31 and CD34 in Kaposi sarcoma. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1011-1016. doi:10.1136/jcp.48.11.1011