User login

Index finger plaque

The characteristic finding of small, scattered vesicular lesions on the hands that sometimes coalesce, and often are itchy or irritated led to the diagnosis of vesicular hand dermatitis, a form of eczema. It also is referred to as dyshidrotic eczema or pompholyx. (Worth noting is the fact that common warts and flat warts usually present as raised papular—not vesicular—lesions on the hands.)

The exact etiology of vesicular hand dermatitis is unknown. It is more common in women than men and often occurs in patients 20 to 40 years of age who tend to have a positive family history of eczema. It usually develops acutely and often is triggered by topical irritants or frequent hand washing. Treatment during the acute phase includes topical steroids. Avoidance of topical irritants, use of mild cleansers instead of harsh soaps, reduction of hand washing frequency (if possible), and frequent application of emollients can reduce recurrence.

This patient’s eczema had been successfully treated with betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% in the past. Since she still had some at home, she was instructed to use it twice daily along with topical emmolients. She reported great improvement within 1 week.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Sobering G, Dika C. Vesicular hand dermatitis. Nurse Pract. 2018;43:33-37.

The characteristic finding of small, scattered vesicular lesions on the hands that sometimes coalesce, and often are itchy or irritated led to the diagnosis of vesicular hand dermatitis, a form of eczema. It also is referred to as dyshidrotic eczema or pompholyx. (Worth noting is the fact that common warts and flat warts usually present as raised papular—not vesicular—lesions on the hands.)

The exact etiology of vesicular hand dermatitis is unknown. It is more common in women than men and often occurs in patients 20 to 40 years of age who tend to have a positive family history of eczema. It usually develops acutely and often is triggered by topical irritants or frequent hand washing. Treatment during the acute phase includes topical steroids. Avoidance of topical irritants, use of mild cleansers instead of harsh soaps, reduction of hand washing frequency (if possible), and frequent application of emollients can reduce recurrence.

This patient’s eczema had been successfully treated with betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% in the past. Since she still had some at home, she was instructed to use it twice daily along with topical emmolients. She reported great improvement within 1 week.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The characteristic finding of small, scattered vesicular lesions on the hands that sometimes coalesce, and often are itchy or irritated led to the diagnosis of vesicular hand dermatitis, a form of eczema. It also is referred to as dyshidrotic eczema or pompholyx. (Worth noting is the fact that common warts and flat warts usually present as raised papular—not vesicular—lesions on the hands.)

The exact etiology of vesicular hand dermatitis is unknown. It is more common in women than men and often occurs in patients 20 to 40 years of age who tend to have a positive family history of eczema. It usually develops acutely and often is triggered by topical irritants or frequent hand washing. Treatment during the acute phase includes topical steroids. Avoidance of topical irritants, use of mild cleansers instead of harsh soaps, reduction of hand washing frequency (if possible), and frequent application of emollients can reduce recurrence.

This patient’s eczema had been successfully treated with betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% in the past. Since she still had some at home, she was instructed to use it twice daily along with topical emmolients. She reported great improvement within 1 week.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Sobering G, Dika C. Vesicular hand dermatitis. Nurse Pract. 2018;43:33-37.

Sobering G, Dika C. Vesicular hand dermatitis. Nurse Pract. 2018;43:33-37.

Does early introduction of peanuts to an infant’s diet reduce the risk for peanut allergy?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2016 systematic review identified 2 RCTs that examined whether early introduction of peanuts affects subsequent allergies.1 The first RCT recruited 1303 3-month-old infants from the general population in the United Kingdom.2 All patients had either a negative skin prick test (SPT) to peanuts or a negative oral peanut challenge (if an initial SPT was positive). The control group breastfed exclusively until age 6 months, at which time allergenic foods could be introduced at parental discretion.

Timing doesn’t affect peanut allergy in nonallergic patients

The intervention group received 6 common allergenic foods (peanuts, eggs, cow’s milk, wheat, sesame, and whitefish) twice weekly between ages 3 and 6 months. Researchers then performed double-blinded, placebo-controlled oral food challenges at ages 12 and 36 months.

More patients in the late-introduction group demonstrated peanut allergies by age 36 months than in the early-introduction group, but the difference wasn’t significant (2.5% vs 1.2%; P = 0.11).A key weakness of the study was combining peanuts with other common food allergens.2

Children with eczema, egg allergy benefit from earlier peanut introduction

The second RCT divided 640 infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both into 2 groups according to their response to an SPT to peanuts: patients with no wheal and patients with a positive wheal measuring 1 to 4 mm.3 Researchers then randomized patients to either early exposure (peanut products given from ages 4 to 11 months) or avoidance (no peanuts until age 60 months). The primary endpoint was a positive clinical response to oral peanut allergen at age 60 months.

In the negative SPT group (atopic children expected to have a lower risk for allergy), patients introduced to peanuts later had a higher rate of subsequent allergy than children exposed earlier (14% vs 2%; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 12%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3%-20%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 9).3

In the positive SPT group (atopic children expected to have a higher risk for allergy), later peanut introduction likewise increased risk compared to earlier introduction (35% vs 11%; ARR = 24%; 95% CI, 5%-43%; NNT = 5). Children in the early-exposure group, however, had more URIs, viral exanthems, gastroenteritis, urticaria, and conjunctivitis (4527 events in the early-exposure group vs 4287 in the avoidance group, P = 0.02; about 1 more event per patient over the course of the study).3

The authors of the systematic review performed a meta-analysis of the 2 RCTs (1793 patients). They concluded that early introduction of peanuts to an infant’s diet (between ages 3 and 11 months) decreased the risk for eventual peanut allergy (relative risk [RR] = 0.29; 95% CI, 0.11-0.74), compared with introduction at or after age 1 year.1 A key weakness, however, was the researchers’ choice to combine trials with very different inclusion criteria (infants with severe eczema and a general population).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2017 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases guideline recommends a 3-tiered approach to peanut introduction: 4

- For children with severe eczema or egg allergy who aren’t currently allergic to peanuts (per SPT or immunoglobulin E [IgE] test), the guideline advises adding peanuts to the diet between ages 4 and 6 months. (Patients with positive SPT or IgE should be referred to an allergy specialist.)

- Children with mild or moderate eczema can be introduced to peanuts around age 6 months “in accordance with family preferences and cultural practices.”

- Children with no evidence of allergy or eczema can be “freely introduced” to peanut-containing foods with no specific guidance on age.

Editor’s takeaway

Good-quality evidence supports family physicians encouraging introduction of foods containing peanuts at age 4 to 6 months for children at increased risk because of atopy, allergies, or eczema.

1. Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, et al. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1181-1192.

2. Perkin MR, Logan K, Tseng A, et al. Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1733-1743.

3. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-813.

4. Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:29-44.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2016 systematic review identified 2 RCTs that examined whether early introduction of peanuts affects subsequent allergies.1 The first RCT recruited 1303 3-month-old infants from the general population in the United Kingdom.2 All patients had either a negative skin prick test (SPT) to peanuts or a negative oral peanut challenge (if an initial SPT was positive). The control group breastfed exclusively until age 6 months, at which time allergenic foods could be introduced at parental discretion.

Timing doesn’t affect peanut allergy in nonallergic patients

The intervention group received 6 common allergenic foods (peanuts, eggs, cow’s milk, wheat, sesame, and whitefish) twice weekly between ages 3 and 6 months. Researchers then performed double-blinded, placebo-controlled oral food challenges at ages 12 and 36 months.

More patients in the late-introduction group demonstrated peanut allergies by age 36 months than in the early-introduction group, but the difference wasn’t significant (2.5% vs 1.2%; P = 0.11).A key weakness of the study was combining peanuts with other common food allergens.2

Children with eczema, egg allergy benefit from earlier peanut introduction

The second RCT divided 640 infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both into 2 groups according to their response to an SPT to peanuts: patients with no wheal and patients with a positive wheal measuring 1 to 4 mm.3 Researchers then randomized patients to either early exposure (peanut products given from ages 4 to 11 months) or avoidance (no peanuts until age 60 months). The primary endpoint was a positive clinical response to oral peanut allergen at age 60 months.

In the negative SPT group (atopic children expected to have a lower risk for allergy), patients introduced to peanuts later had a higher rate of subsequent allergy than children exposed earlier (14% vs 2%; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 12%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3%-20%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 9).3

In the positive SPT group (atopic children expected to have a higher risk for allergy), later peanut introduction likewise increased risk compared to earlier introduction (35% vs 11%; ARR = 24%; 95% CI, 5%-43%; NNT = 5). Children in the early-exposure group, however, had more URIs, viral exanthems, gastroenteritis, urticaria, and conjunctivitis (4527 events in the early-exposure group vs 4287 in the avoidance group, P = 0.02; about 1 more event per patient over the course of the study).3

The authors of the systematic review performed a meta-analysis of the 2 RCTs (1793 patients). They concluded that early introduction of peanuts to an infant’s diet (between ages 3 and 11 months) decreased the risk for eventual peanut allergy (relative risk [RR] = 0.29; 95% CI, 0.11-0.74), compared with introduction at or after age 1 year.1 A key weakness, however, was the researchers’ choice to combine trials with very different inclusion criteria (infants with severe eczema and a general population).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2017 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases guideline recommends a 3-tiered approach to peanut introduction: 4

- For children with severe eczema or egg allergy who aren’t currently allergic to peanuts (per SPT or immunoglobulin E [IgE] test), the guideline advises adding peanuts to the diet between ages 4 and 6 months. (Patients with positive SPT or IgE should be referred to an allergy specialist.)

- Children with mild or moderate eczema can be introduced to peanuts around age 6 months “in accordance with family preferences and cultural practices.”

- Children with no evidence of allergy or eczema can be “freely introduced” to peanut-containing foods with no specific guidance on age.

Editor’s takeaway

Good-quality evidence supports family physicians encouraging introduction of foods containing peanuts at age 4 to 6 months for children at increased risk because of atopy, allergies, or eczema.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2016 systematic review identified 2 RCTs that examined whether early introduction of peanuts affects subsequent allergies.1 The first RCT recruited 1303 3-month-old infants from the general population in the United Kingdom.2 All patients had either a negative skin prick test (SPT) to peanuts or a negative oral peanut challenge (if an initial SPT was positive). The control group breastfed exclusively until age 6 months, at which time allergenic foods could be introduced at parental discretion.

Timing doesn’t affect peanut allergy in nonallergic patients

The intervention group received 6 common allergenic foods (peanuts, eggs, cow’s milk, wheat, sesame, and whitefish) twice weekly between ages 3 and 6 months. Researchers then performed double-blinded, placebo-controlled oral food challenges at ages 12 and 36 months.

More patients in the late-introduction group demonstrated peanut allergies by age 36 months than in the early-introduction group, but the difference wasn’t significant (2.5% vs 1.2%; P = 0.11).A key weakness of the study was combining peanuts with other common food allergens.2

Children with eczema, egg allergy benefit from earlier peanut introduction

The second RCT divided 640 infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both into 2 groups according to their response to an SPT to peanuts: patients with no wheal and patients with a positive wheal measuring 1 to 4 mm.3 Researchers then randomized patients to either early exposure (peanut products given from ages 4 to 11 months) or avoidance (no peanuts until age 60 months). The primary endpoint was a positive clinical response to oral peanut allergen at age 60 months.

In the negative SPT group (atopic children expected to have a lower risk for allergy), patients introduced to peanuts later had a higher rate of subsequent allergy than children exposed earlier (14% vs 2%; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 12%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3%-20%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 9).3

In the positive SPT group (atopic children expected to have a higher risk for allergy), later peanut introduction likewise increased risk compared to earlier introduction (35% vs 11%; ARR = 24%; 95% CI, 5%-43%; NNT = 5). Children in the early-exposure group, however, had more URIs, viral exanthems, gastroenteritis, urticaria, and conjunctivitis (4527 events in the early-exposure group vs 4287 in the avoidance group, P = 0.02; about 1 more event per patient over the course of the study).3

The authors of the systematic review performed a meta-analysis of the 2 RCTs (1793 patients). They concluded that early introduction of peanuts to an infant’s diet (between ages 3 and 11 months) decreased the risk for eventual peanut allergy (relative risk [RR] = 0.29; 95% CI, 0.11-0.74), compared with introduction at or after age 1 year.1 A key weakness, however, was the researchers’ choice to combine trials with very different inclusion criteria (infants with severe eczema and a general population).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2017 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases guideline recommends a 3-tiered approach to peanut introduction: 4

- For children with severe eczema or egg allergy who aren’t currently allergic to peanuts (per SPT or immunoglobulin E [IgE] test), the guideline advises adding peanuts to the diet between ages 4 and 6 months. (Patients with positive SPT or IgE should be referred to an allergy specialist.)

- Children with mild or moderate eczema can be introduced to peanuts around age 6 months “in accordance with family preferences and cultural practices.”

- Children with no evidence of allergy or eczema can be “freely introduced” to peanut-containing foods with no specific guidance on age.

Editor’s takeaway

Good-quality evidence supports family physicians encouraging introduction of foods containing peanuts at age 4 to 6 months for children at increased risk because of atopy, allergies, or eczema.

1. Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, et al. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1181-1192.

2. Perkin MR, Logan K, Tseng A, et al. Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1733-1743.

3. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-813.

4. Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:29-44.

1. Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, et al. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1181-1192.

2. Perkin MR, Logan K, Tseng A, et al. Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1733-1743.

3. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-813.

4. Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:29-44.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Probably not, unless the child has severe eczema or egg allergy. In a general pediatric population, introducing peanuts early (at age 3 to 6 months) doesn’t appear to alter rates of subsequent peanut allergy compared with introduction after age 6 months (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized clinical trial [RCT] using multiple potential food allergens).

In children with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both, however, the risk for a peanut allergy is 12% to 24% lower when peanut-containing foods are introduced at age 4 to 11 months than after age 1 year. Early introduction of peanuts is associated with about 1 additional mild virus-associated syndrome (upper respiratory infection [URI], exanthem, conjunctivitis, or gastroenteritis) per patient (SOR: B, RCT).

Introducing peanuts before age 1 year is recommended for atopic children without evidence of pre-existing peanut allergy; an earlier start, at age 4 to 6 months, is advised for infants with severe eczema or egg allergy (SOR: C, expert opinion).

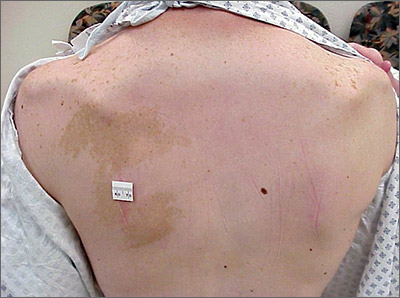

Hidradenitis Suppurativa in the Military

Case Report

A 19-year-old female marine with a 10-year history of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) presented with hyperpigmented nodules in the inguinal folds and a recurrent cyst in the right groin area of 2 to 3 weeks’ duration. She denied axillary or inframammary involvement. She underwent several incision and drainage procedures 1 year prior to her enlistment in the US Marine Corps at 18 years of age. She previously had been treated by dermatology with doxycycline 100-mg tablets twice daily, benzoyl peroxide wash 5% applied to affected areas and rinsed daily, and clindamycin solution 1% with minimal improvement. She denied smoking or alcohol intake and said she typically wore a loose-fitting uniform to work. As a marine, she was expected to participate in daily physical training and exercises with her military unit, during which she wore a standardized physical training uniform, including nylon shorts and a cotton T-shirt. She requested light duty—military duty status with physical limitations or restrictions—to avoid physical training that would cause further friction and irritation to the inguinal region.

Physical examination demonstrated a woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and normal body mass index. There were hyperpigmented nodules and scarring in the inguinal folds, most consistent with Hurley stage 2. A single, 0.5-cm, draining lesion was visualized. No hyperhidrosis was noted. The patient was placed on light duty for 7 days, with physical training only at her own pace and discretion. Moreover, she was restricted from field training, rifle range training, and other situations where she may excessively sweat or not be able to adequately maintain personal hygiene. She was encouraged to continue clindamycin solution 1% to the affected area twice daily and was prescribed chlorhexidine solution 4% to use when washing affected areas in the shower. The patient also was referred to the dermatology department at the Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton (Oceanside, California), where she was treated with laser hair removal in the inguinal region, thus avoiding waxing and further aggravation of HS flares. Due to the combination of topical therapies along with laser hair removal and duty restrictions, the patient had a dramatic decrease in development of severe nodular lesions.

Comment

Presentation

Historically, the incidence of HS is estimated at 0.5% to 4% of the general population with female predominance.1 Predisposing factors include obesity, smoking, genetic predisposition to acne, apocrine duct obstruction, and secondary bacterial infection.2 During acute flares, patients generally present with tender subcutaneous nodules that drain malodorous purulent material.3,4 Acute flares are unpredictable, and patients deal with chronic, recurrent, draining wounds, leading to a poor quality of life with resulting physical, psychological, financial, social, and emotional distress.3-5 The negative impact of HS on a patient’s quality of life has been reported to be greater than other dermatologic conditions.6 Lesions can be particularly painful and can cause disfiguration to the surface of the skin.7 Lesion severity is described using the Hurley staging system. Patient quality of life is directly correlated with disease severity and Hurley stage. In stage 1, abscesses develop, but no sinus tracts or cicatrization is present. In stage 2, recurrent abscesses will form tracts and cicatrization. In stage 3, the abscesses become diffuse or near diffuse, with multiple interconnected tracts and abscesses across the entire area of the body.8,9

Severe or refractory HS within the physically active military population may require consideration of light or limited duty or even separation from service. Similarly, severe HS may pose challenges with other physically demanding occupations, such as the police force and firefighters.

Prevention Focus

Prevention of flares is key for patients with HS; secondary prevention aims to reduce impact of the disease or injury that has already occurred,10,11 which includes prevention of the infundibulofolliculitis from becoming a deep folliculitis, nodule, or fistula, as well as Hurley stage progression. Prompt diagnosis with appropriate treatment can decrease the severity of lesions, pain, and scarring. Globally, HS patients continue to experience considerable diagnostic delays of 8 to 12 years after onset of initial symptoms.11,12 Earlier accurate diagnosis and initiation of treatment from the primary care provider or general medical officer is imperative. Initial accurate management may help keep symptoms from progressing to more severe painful lesions. Similarly, patients should be educated on how to prevent HS flares. Patients should avoid known triggers, including smoking, obesity, sweating, mechanical irritation, stress, and poor hygiene.11

Shaving for hair reduction creates ingrown hair shafts, which may lead to folliculitis in mechanically stressed areas in skin folds, thus initiating the inflammatory cascade of HS.11,13 Therefore, shaving along with any other mechanical stress should be avoided in patients with HS. Laser hair removal has been shown to be quite helpful in both the prevention and treatment of HS. In one study, 22 patients with Hurley stage 2 to 3 disease were treated with an Nd:YAG laser once monthly. Results demonstrated a 65% decrease in disease severity after 3 monthly treatments.11 Similarly, other lasers have been used with success in several small case series; an 800-nm diode laser, intense pulsed light therapy, and a ruby laser have each demonstrated efficacy.14 Given these results, hair removal should be recommended to patients with HS. Military servicemembers (SMs) with certain conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and HS, are eligible for laser hair removal when available at local military treatment facilities. Primary care providers for military SMs must have a working understanding of the disease process of HS and awareness of what resources are available for treatment, which allows for more streamlined care and improved outcomes.

Treatment Options

Treatment options are diverse and depend on the severity of HS. Typically, treatment begins with medical therapy followed by escalation to surgical intervention. Medical therapies often include antibiotics, acne treatments, antiandrogen therapy, immunosuppressive agents, and biologic therapy.15,16 If first-line medical interventions fail to control HS, surgical interventions should be considered. Surgical intervention in conjunction with medical therapy decreases the chance for recurrence.3,15,16

Although HS is internationally recognized as an inflammatory disease and not an infectious process, topical antibiotics can help to prevent and improve formation of abscesses, nodules, and pustules.11 Agents such as clindamycin and chlorhexidine wash have proven effective in preventing flares.11,16 Other antibiotics used alone or in combination also are efficacious. Tetracyclines are recommended as monotherapy for mild stages of HS.17-19 Doxycycline is the most commonly used tetracycline in HS patients and has been demonstrated to penetrate Staphylococcus aureus biofilm in high enough concentrations to maintain its antibacterial activity.20 Moreover, doxycycline, as with other tetracyclines, has a multitude of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties21 and can reduce the production of IL-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-8; downregulate chemotaxis; and promote lipo-oxygenase, matrix metalloproteinase, and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling inhibition.17

Clindamycin is the only known agent that has been studied for topical treatment and utilization in milder cases of HS.17,22 Systemic combination of clindamycin and rifampicin is the most studied, with well-established efficacy in managing HS.17,23,24 Clindamycin has bacteriostatic activity toward both aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive bacteria by binding irreversibly to the 50S ribosomal subunit, thereby inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. Rifampicin binds to the beta subunit of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, inhibiting bacterial DNA-dependent RNA synthesis. Rifampicin has broad-spectrum activity, mostly against gram-positive as well as some gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, rifampicin has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, including evidence that it inhibits excessive helper T cell (TH17) responses by reducing inducible nitric oxide synthase transcription and NF-κB activity.25,26

Metronidazole, moxifloxacin, and rifampicin as triple combination therapy has been shown to be effective in reducing HS activity in moderate to severe cases that were refractory to other treatments.27 Research suggests that moxifloxacin has anti-inflammatory properties, mainly by reducing IL-1β, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor α; stabilizing IXb protein; suppressing NF-κB signaling; and reducing IL-17A.28,29

Ertapenem can be utilized as a single 6-week antibiotic course during surgical planning or rescue therapy.18 Moreover, ertapenem can be used to treat complicated skin and soft tissue infections and has been shown to substantially improve clinical aspects of severe HS.17,27

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are effective in the treatment of moderate to severe HS.17-19 In 2 phase 3 trials (PIONEER I and II), adalimumab was used as monotherapy or in conjunction with antibiotics in patients with moderate to severe HS compared to placebo.30 Results demonstrated a disease burden reduction of greater than 50%. Antibiotic dual therapy was not noted to significantly affect disease burden.30 Of note, use of immunosuppressants in the military affects an SM’s availability for worldwide deployment and duty station assignment.

Antiandrogen therapies have demonstrated some reduction in HS flares. Although recommendations for use in HS is based on limited evidence, one randomized controlled trial compared ethinyl estradiol–norgestrel to ethinyl estradiol and cyproterone acetate. Both therapies resulted in similar efficacy, with 12 of 24 (50%) patients reporting HS symptoms improving or completely resolved.31 In another retrospective study of women treated with antiandrogen therapies, including ethinyl estriol, cyproterone acetate, and spironolactone, 16 of 29 (55%) patients reported improvement.32 In another study, daily doses of 100 to 150 mg of spironolactone resulted in improvement in 17 of 20 (85%) patients, including complete remission in 11 of 20 (55%) patients. Of the 3 patients with severe HS, none had complete clearing of disease burden.33 Patients with polycystic ovary syndrome or HS flares that occur around menstruation are more likely to benefit from treatment with spironolactone.18,32,34

Retinoids frequently have been utilized in the management of HS. In some retrospective studies and other prospective studies with 5 or more patients, isotretinoin monotherapy was utilized for a 4- to 10-month period.18,35-38 In the Alikhan et al18 study, 85 of 207 patients demonstrated improvement of HS symptoms, with more remarkable improvements in milder cases. Isotretinoin for management of patients with HS who have concomitant nodulocystic acne would have two-fold benefits.18

Wound Care

Given the purulent nodular formation in HS, adequate wound care management is vital. There is an abundance of HS wound care management strategies utilized by clinicians and patients. When selecting the appropriate dressing, consideration for the type of HS wound, cost, ease of application, patient comfort, absorbency, and odor management is important.3 However, living arrangements for military SMs can create difficulties applying and maintaining HS dressings, especially if deployed or in a field setting. Active-duty SMs often find themselves in austere living conditions in the field, aboard ships, or in other scenarios where they may or may not have running water or showers. Maintaining adequate hygiene may be difficult, and additional education about how to keep wounds clean must be imparted. Ideal dressings for HS should be highly absorbent, comfortable when applied to the anatomic locations of the HS lesions, and easily self-applied. Ideally, dressings would have atraumatic adhesion and antimicrobial properties.3 Cost-effective dressing options that have good absorption capability include sanitary napkins, adult briefs, infant diapers, and gauze.3 These dressings help to wick moisture, thus protecting the wound from maceration, which is a common patient concern. Although gauze dressings are easier to obtain, they are not as absorbent. Abdominal pads can be utilized, but they are moderately absorbent, bulky, and more challenging to obtain over-the-counter. Hydrofiber and calcium alginate dressings with silver are not accessible to the common consumer and are more expensive than the aforementioned dressings, but they do have some antimicrobial activity. Silver-impregnated foam dressings are moldable to intertriginous areas, easy to self-apply, and have moderate-heavy absorption abilities.

Final Thoughts

Hidradenitis suppurativa poses cumbersome and uncomfortable symptoms for all patients and may pose additional hardships for military SMs or those with physically demanding occupations who work in austere environments. Severe HS can restrict a military SM from certain duty stations, positions, or deployments. Early identification of HS can help reduce HS flares, disfigurement, and placement on limited duty status, therefore rendering the SM more able to engage in his/her operational responsibilities. Hidradenitis suppurativa should be discussed with the patient, with the goal to prevent flares for SMs that will be in the field, placed in austere environments, or be deployed. Use of immunosuppressants in active-duty SMs may affect their deployability, duty assignment, and retention.

For a military SM with HS, all aspects of prevention and treatment need to be balanced with his/her ability to remain deployable and complete his/her daily duties. Military SMs are not guaranteed the ideal scenario for treatment and prevention of HS. Unsanitary environments and occlusive uniforms undoubtedly contribute to disease process and make treatment more challenging. If a military SM is in a field setting or deployed, frequent daily dressing changes should still be attempted.

- Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216-221.

- Beshara MA. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a clinician’s tool for early diagnosis and treatment. Nurse Pract. 2010;35:24-28.

- Kazemi A, Carnaggio K, Clark M, et al. Optimal wound care management in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;29:165-167.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Pazzaglia M, et al. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% under occlusion in the treatment of alopecia totalis/universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003:49:96-98.

- Blattner C, Polley DC, Ferrito F, et al. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013:4:50.

- Wolkenstein P, Loundou A, Barrau K, et al. Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:621-623.

- Smith HS, Chao JD, Teitelbaum J. Painful hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:435-444.

- Alavi A, Anooshirvani N, Kim WB, et al. Quality-of-life impairment in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a Canadian study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:61-65.

- Hurley HJ. Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa and familial benign pemphigus: surgical approach. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH Jr, eds. Dermatologic Surgery: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1996:623-645.

- Kligman AM. Welcome letter. 2nd International Conference on the Sebaceous Gland, Acne, Rosacea and Related Disorders; September 13-16, 2008; Rome Italy.

- Kurzen H, Kurzen M. Secondary prevention of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Reports. 2019;11:8243.

- Sabat R, Tsaousi A, Rossbacher J, et al. Acne inversa/hidradenitis suppurativa: an update [in German]. Hautarzt. 2017;68:999-1006.

- Boer J, Nazary M, Riis PT. The role of mechanical stress in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:37-43.

- Hamzavi IH, Griffith JL, Riyaz F, et al. Laser and light-based treatment options for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S78-S81.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Michel C, DiBianco JM, Sabarwal V, et al. The treatment of genitoperineal hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of the literature. Urology. 2019;124:1-5.

- Constantinou CA, Fragoulis GE, Nikiphorou E. Hidradenitis suppurativa: infection, autoimmunity, or both [published online December 30, 2019]? Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. doi:10.1177/1759720x19895488.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

- Zouboulis CC, Desai N, Emtestam, et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:619-644.

- Mandell JB, Orr S, Koch J, et al. Large variations in clinical antibiotic activity against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms of periprosthetic joint infection isolates. J Orthop Res. 2019;37:1604-1609.

- Sun J, Shigemi H, Tanaka Y, et al. Tetracyclines downregulate the production of LPS-induced cytokines and chemokines in THP-1 cells via ERK, p38, and nuclear factor-κB signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2015;4:397-404.

- Clemmensen OJ. Topical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with clindamycin. Int J Dermatol. 1983;22:325-328.

- Gener G, Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, et al. Combination therapy with clindamycin and rifampicin for hidradenitis suppurativa: a series of 116 consecutive patients. Dermatology. 2009;219:148-154.

- Griffiths CEM. Clindamycin and rifampicin combination therapy for hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:977-978.

- Ma K, Chen X, Chen J-C, et al. Rifampicin attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting pathogenic Th17 cells responses. J Neurochem. 2016;139:1151-1162.

- Yuhas Y, Berent E, Ovadiah H, et al. Rifampin augments cytokine-induced nitric oxide production in human alveolar epithelial cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:396-398.

- Join-Lambert O, Coignard H, Jais J-P, et al. Efficacy of rifampin-moxifloxacin-metronidazole combination therapy in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2011;222:49-58.

- Choi J-H, Song M-J, Kim S-H, et al. Effect of moxifloxacin on production of proinflammatory cytokines from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3704-3707.

- Weiss T, Shalit I, Blau H, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of moxifloxacin on activated human monocytic cells: inhibition of NF-kappaB and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and of synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines.” Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1974-1982.

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434.

- Mortimer PS, Dawber RP, Gales MA, et al. A double-blind controlled cross-over trial of cyproterone acetate in females with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:263-268.

- Kraft JN, Searles GE. Hidradenitis suppurativa in 64 female patients: retrospective study comparing oral antibiotics and antiandrogen therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11:125-131.

- Lee A, Fischer G. A case series of 20 women with hidradenitis suppurativa treated with spironolactone. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:192-196.

- Khandalavala BN, Do MV. Finasteride in hidradenitis suppurativa: a “male” therapy for a predominantly “female” disease. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:44-50.

- Dicken CH, Powell ST, Spear KL. Evaluation of isotretinoin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:500-502.

- Huang CM, Kirchof MG. A new perspective on isotretinoin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review of patient outcomes. Dermatology. 2017;233:120-125.

- Norris JF, Cunliffe WJ. Failure of treatment of familial widespread hidradenitis suppurativa with isotretinoin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1986;11:579-583.

- Soria A, Canoui-Poitrine F, Wolkenstein P, et al. Absence of efficacy of oral isotretinoin in hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study based on patients’ outcome assessment. Dermatology. 2009;218:134-135.

Case Report

A 19-year-old female marine with a 10-year history of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) presented with hyperpigmented nodules in the inguinal folds and a recurrent cyst in the right groin area of 2 to 3 weeks’ duration. She denied axillary or inframammary involvement. She underwent several incision and drainage procedures 1 year prior to her enlistment in the US Marine Corps at 18 years of age. She previously had been treated by dermatology with doxycycline 100-mg tablets twice daily, benzoyl peroxide wash 5% applied to affected areas and rinsed daily, and clindamycin solution 1% with minimal improvement. She denied smoking or alcohol intake and said she typically wore a loose-fitting uniform to work. As a marine, she was expected to participate in daily physical training and exercises with her military unit, during which she wore a standardized physical training uniform, including nylon shorts and a cotton T-shirt. She requested light duty—military duty status with physical limitations or restrictions—to avoid physical training that would cause further friction and irritation to the inguinal region.

Physical examination demonstrated a woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and normal body mass index. There were hyperpigmented nodules and scarring in the inguinal folds, most consistent with Hurley stage 2. A single, 0.5-cm, draining lesion was visualized. No hyperhidrosis was noted. The patient was placed on light duty for 7 days, with physical training only at her own pace and discretion. Moreover, she was restricted from field training, rifle range training, and other situations where she may excessively sweat or not be able to adequately maintain personal hygiene. She was encouraged to continue clindamycin solution 1% to the affected area twice daily and was prescribed chlorhexidine solution 4% to use when washing affected areas in the shower. The patient also was referred to the dermatology department at the Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton (Oceanside, California), where she was treated with laser hair removal in the inguinal region, thus avoiding waxing and further aggravation of HS flares. Due to the combination of topical therapies along with laser hair removal and duty restrictions, the patient had a dramatic decrease in development of severe nodular lesions.

Comment

Presentation

Historically, the incidence of HS is estimated at 0.5% to 4% of the general population with female predominance.1 Predisposing factors include obesity, smoking, genetic predisposition to acne, apocrine duct obstruction, and secondary bacterial infection.2 During acute flares, patients generally present with tender subcutaneous nodules that drain malodorous purulent material.3,4 Acute flares are unpredictable, and patients deal with chronic, recurrent, draining wounds, leading to a poor quality of life with resulting physical, psychological, financial, social, and emotional distress.3-5 The negative impact of HS on a patient’s quality of life has been reported to be greater than other dermatologic conditions.6 Lesions can be particularly painful and can cause disfiguration to the surface of the skin.7 Lesion severity is described using the Hurley staging system. Patient quality of life is directly correlated with disease severity and Hurley stage. In stage 1, abscesses develop, but no sinus tracts or cicatrization is present. In stage 2, recurrent abscesses will form tracts and cicatrization. In stage 3, the abscesses become diffuse or near diffuse, with multiple interconnected tracts and abscesses across the entire area of the body.8,9

Severe or refractory HS within the physically active military population may require consideration of light or limited duty or even separation from service. Similarly, severe HS may pose challenges with other physically demanding occupations, such as the police force and firefighters.

Prevention Focus

Prevention of flares is key for patients with HS; secondary prevention aims to reduce impact of the disease or injury that has already occurred,10,11 which includes prevention of the infundibulofolliculitis from becoming a deep folliculitis, nodule, or fistula, as well as Hurley stage progression. Prompt diagnosis with appropriate treatment can decrease the severity of lesions, pain, and scarring. Globally, HS patients continue to experience considerable diagnostic delays of 8 to 12 years after onset of initial symptoms.11,12 Earlier accurate diagnosis and initiation of treatment from the primary care provider or general medical officer is imperative. Initial accurate management may help keep symptoms from progressing to more severe painful lesions. Similarly, patients should be educated on how to prevent HS flares. Patients should avoid known triggers, including smoking, obesity, sweating, mechanical irritation, stress, and poor hygiene.11

Shaving for hair reduction creates ingrown hair shafts, which may lead to folliculitis in mechanically stressed areas in skin folds, thus initiating the inflammatory cascade of HS.11,13 Therefore, shaving along with any other mechanical stress should be avoided in patients with HS. Laser hair removal has been shown to be quite helpful in both the prevention and treatment of HS. In one study, 22 patients with Hurley stage 2 to 3 disease were treated with an Nd:YAG laser once monthly. Results demonstrated a 65% decrease in disease severity after 3 monthly treatments.11 Similarly, other lasers have been used with success in several small case series; an 800-nm diode laser, intense pulsed light therapy, and a ruby laser have each demonstrated efficacy.14 Given these results, hair removal should be recommended to patients with HS. Military servicemembers (SMs) with certain conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and HS, are eligible for laser hair removal when available at local military treatment facilities. Primary care providers for military SMs must have a working understanding of the disease process of HS and awareness of what resources are available for treatment, which allows for more streamlined care and improved outcomes.

Treatment Options

Treatment options are diverse and depend on the severity of HS. Typically, treatment begins with medical therapy followed by escalation to surgical intervention. Medical therapies often include antibiotics, acne treatments, antiandrogen therapy, immunosuppressive agents, and biologic therapy.15,16 If first-line medical interventions fail to control HS, surgical interventions should be considered. Surgical intervention in conjunction with medical therapy decreases the chance for recurrence.3,15,16

Although HS is internationally recognized as an inflammatory disease and not an infectious process, topical antibiotics can help to prevent and improve formation of abscesses, nodules, and pustules.11 Agents such as clindamycin and chlorhexidine wash have proven effective in preventing flares.11,16 Other antibiotics used alone or in combination also are efficacious. Tetracyclines are recommended as monotherapy for mild stages of HS.17-19 Doxycycline is the most commonly used tetracycline in HS patients and has been demonstrated to penetrate Staphylococcus aureus biofilm in high enough concentrations to maintain its antibacterial activity.20 Moreover, doxycycline, as with other tetracyclines, has a multitude of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties21 and can reduce the production of IL-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-8; downregulate chemotaxis; and promote lipo-oxygenase, matrix metalloproteinase, and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling inhibition.17

Clindamycin is the only known agent that has been studied for topical treatment and utilization in milder cases of HS.17,22 Systemic combination of clindamycin and rifampicin is the most studied, with well-established efficacy in managing HS.17,23,24 Clindamycin has bacteriostatic activity toward both aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive bacteria by binding irreversibly to the 50S ribosomal subunit, thereby inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. Rifampicin binds to the beta subunit of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, inhibiting bacterial DNA-dependent RNA synthesis. Rifampicin has broad-spectrum activity, mostly against gram-positive as well as some gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, rifampicin has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, including evidence that it inhibits excessive helper T cell (TH17) responses by reducing inducible nitric oxide synthase transcription and NF-κB activity.25,26

Metronidazole, moxifloxacin, and rifampicin as triple combination therapy has been shown to be effective in reducing HS activity in moderate to severe cases that were refractory to other treatments.27 Research suggests that moxifloxacin has anti-inflammatory properties, mainly by reducing IL-1β, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor α; stabilizing IXb protein; suppressing NF-κB signaling; and reducing IL-17A.28,29

Ertapenem can be utilized as a single 6-week antibiotic course during surgical planning or rescue therapy.18 Moreover, ertapenem can be used to treat complicated skin and soft tissue infections and has been shown to substantially improve clinical aspects of severe HS.17,27

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are effective in the treatment of moderate to severe HS.17-19 In 2 phase 3 trials (PIONEER I and II), adalimumab was used as monotherapy or in conjunction with antibiotics in patients with moderate to severe HS compared to placebo.30 Results demonstrated a disease burden reduction of greater than 50%. Antibiotic dual therapy was not noted to significantly affect disease burden.30 Of note, use of immunosuppressants in the military affects an SM’s availability for worldwide deployment and duty station assignment.

Antiandrogen therapies have demonstrated some reduction in HS flares. Although recommendations for use in HS is based on limited evidence, one randomized controlled trial compared ethinyl estradiol–norgestrel to ethinyl estradiol and cyproterone acetate. Both therapies resulted in similar efficacy, with 12 of 24 (50%) patients reporting HS symptoms improving or completely resolved.31 In another retrospective study of women treated with antiandrogen therapies, including ethinyl estriol, cyproterone acetate, and spironolactone, 16 of 29 (55%) patients reported improvement.32 In another study, daily doses of 100 to 150 mg of spironolactone resulted in improvement in 17 of 20 (85%) patients, including complete remission in 11 of 20 (55%) patients. Of the 3 patients with severe HS, none had complete clearing of disease burden.33 Patients with polycystic ovary syndrome or HS flares that occur around menstruation are more likely to benefit from treatment with spironolactone.18,32,34

Retinoids frequently have been utilized in the management of HS. In some retrospective studies and other prospective studies with 5 or more patients, isotretinoin monotherapy was utilized for a 4- to 10-month period.18,35-38 In the Alikhan et al18 study, 85 of 207 patients demonstrated improvement of HS symptoms, with more remarkable improvements in milder cases. Isotretinoin for management of patients with HS who have concomitant nodulocystic acne would have two-fold benefits.18

Wound Care

Given the purulent nodular formation in HS, adequate wound care management is vital. There is an abundance of HS wound care management strategies utilized by clinicians and patients. When selecting the appropriate dressing, consideration for the type of HS wound, cost, ease of application, patient comfort, absorbency, and odor management is important.3 However, living arrangements for military SMs can create difficulties applying and maintaining HS dressings, especially if deployed or in a field setting. Active-duty SMs often find themselves in austere living conditions in the field, aboard ships, or in other scenarios where they may or may not have running water or showers. Maintaining adequate hygiene may be difficult, and additional education about how to keep wounds clean must be imparted. Ideal dressings for HS should be highly absorbent, comfortable when applied to the anatomic locations of the HS lesions, and easily self-applied. Ideally, dressings would have atraumatic adhesion and antimicrobial properties.3 Cost-effective dressing options that have good absorption capability include sanitary napkins, adult briefs, infant diapers, and gauze.3 These dressings help to wick moisture, thus protecting the wound from maceration, which is a common patient concern. Although gauze dressings are easier to obtain, they are not as absorbent. Abdominal pads can be utilized, but they are moderately absorbent, bulky, and more challenging to obtain over-the-counter. Hydrofiber and calcium alginate dressings with silver are not accessible to the common consumer and are more expensive than the aforementioned dressings, but they do have some antimicrobial activity. Silver-impregnated foam dressings are moldable to intertriginous areas, easy to self-apply, and have moderate-heavy absorption abilities.

Final Thoughts

Hidradenitis suppurativa poses cumbersome and uncomfortable symptoms for all patients and may pose additional hardships for military SMs or those with physically demanding occupations who work in austere environments. Severe HS can restrict a military SM from certain duty stations, positions, or deployments. Early identification of HS can help reduce HS flares, disfigurement, and placement on limited duty status, therefore rendering the SM more able to engage in his/her operational responsibilities. Hidradenitis suppurativa should be discussed with the patient, with the goal to prevent flares for SMs that will be in the field, placed in austere environments, or be deployed. Use of immunosuppressants in active-duty SMs may affect their deployability, duty assignment, and retention.

For a military SM with HS, all aspects of prevention and treatment need to be balanced with his/her ability to remain deployable and complete his/her daily duties. Military SMs are not guaranteed the ideal scenario for treatment and prevention of HS. Unsanitary environments and occlusive uniforms undoubtedly contribute to disease process and make treatment more challenging. If a military SM is in a field setting or deployed, frequent daily dressing changes should still be attempted.

Case Report

A 19-year-old female marine with a 10-year history of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) presented with hyperpigmented nodules in the inguinal folds and a recurrent cyst in the right groin area of 2 to 3 weeks’ duration. She denied axillary or inframammary involvement. She underwent several incision and drainage procedures 1 year prior to her enlistment in the US Marine Corps at 18 years of age. She previously had been treated by dermatology with doxycycline 100-mg tablets twice daily, benzoyl peroxide wash 5% applied to affected areas and rinsed daily, and clindamycin solution 1% with minimal improvement. She denied smoking or alcohol intake and said she typically wore a loose-fitting uniform to work. As a marine, she was expected to participate in daily physical training and exercises with her military unit, during which she wore a standardized physical training uniform, including nylon shorts and a cotton T-shirt. She requested light duty—military duty status with physical limitations or restrictions—to avoid physical training that would cause further friction and irritation to the inguinal region.

Physical examination demonstrated a woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and normal body mass index. There were hyperpigmented nodules and scarring in the inguinal folds, most consistent with Hurley stage 2. A single, 0.5-cm, draining lesion was visualized. No hyperhidrosis was noted. The patient was placed on light duty for 7 days, with physical training only at her own pace and discretion. Moreover, she was restricted from field training, rifle range training, and other situations where she may excessively sweat or not be able to adequately maintain personal hygiene. She was encouraged to continue clindamycin solution 1% to the affected area twice daily and was prescribed chlorhexidine solution 4% to use when washing affected areas in the shower. The patient also was referred to the dermatology department at the Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton (Oceanside, California), where she was treated with laser hair removal in the inguinal region, thus avoiding waxing and further aggravation of HS flares. Due to the combination of topical therapies along with laser hair removal and duty restrictions, the patient had a dramatic decrease in development of severe nodular lesions.

Comment

Presentation

Historically, the incidence of HS is estimated at 0.5% to 4% of the general population with female predominance.1 Predisposing factors include obesity, smoking, genetic predisposition to acne, apocrine duct obstruction, and secondary bacterial infection.2 During acute flares, patients generally present with tender subcutaneous nodules that drain malodorous purulent material.3,4 Acute flares are unpredictable, and patients deal with chronic, recurrent, draining wounds, leading to a poor quality of life with resulting physical, psychological, financial, social, and emotional distress.3-5 The negative impact of HS on a patient’s quality of life has been reported to be greater than other dermatologic conditions.6 Lesions can be particularly painful and can cause disfiguration to the surface of the skin.7 Lesion severity is described using the Hurley staging system. Patient quality of life is directly correlated with disease severity and Hurley stage. In stage 1, abscesses develop, but no sinus tracts or cicatrization is present. In stage 2, recurrent abscesses will form tracts and cicatrization. In stage 3, the abscesses become diffuse or near diffuse, with multiple interconnected tracts and abscesses across the entire area of the body.8,9

Severe or refractory HS within the physically active military population may require consideration of light or limited duty or even separation from service. Similarly, severe HS may pose challenges with other physically demanding occupations, such as the police force and firefighters.

Prevention Focus

Prevention of flares is key for patients with HS; secondary prevention aims to reduce impact of the disease or injury that has already occurred,10,11 which includes prevention of the infundibulofolliculitis from becoming a deep folliculitis, nodule, or fistula, as well as Hurley stage progression. Prompt diagnosis with appropriate treatment can decrease the severity of lesions, pain, and scarring. Globally, HS patients continue to experience considerable diagnostic delays of 8 to 12 years after onset of initial symptoms.11,12 Earlier accurate diagnosis and initiation of treatment from the primary care provider or general medical officer is imperative. Initial accurate management may help keep symptoms from progressing to more severe painful lesions. Similarly, patients should be educated on how to prevent HS flares. Patients should avoid known triggers, including smoking, obesity, sweating, mechanical irritation, stress, and poor hygiene.11

Shaving for hair reduction creates ingrown hair shafts, which may lead to folliculitis in mechanically stressed areas in skin folds, thus initiating the inflammatory cascade of HS.11,13 Therefore, shaving along with any other mechanical stress should be avoided in patients with HS. Laser hair removal has been shown to be quite helpful in both the prevention and treatment of HS. In one study, 22 patients with Hurley stage 2 to 3 disease were treated with an Nd:YAG laser once monthly. Results demonstrated a 65% decrease in disease severity after 3 monthly treatments.11 Similarly, other lasers have been used with success in several small case series; an 800-nm diode laser, intense pulsed light therapy, and a ruby laser have each demonstrated efficacy.14 Given these results, hair removal should be recommended to patients with HS. Military servicemembers (SMs) with certain conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and HS, are eligible for laser hair removal when available at local military treatment facilities. Primary care providers for military SMs must have a working understanding of the disease process of HS and awareness of what resources are available for treatment, which allows for more streamlined care and improved outcomes.

Treatment Options

Treatment options are diverse and depend on the severity of HS. Typically, treatment begins with medical therapy followed by escalation to surgical intervention. Medical therapies often include antibiotics, acne treatments, antiandrogen therapy, immunosuppressive agents, and biologic therapy.15,16 If first-line medical interventions fail to control HS, surgical interventions should be considered. Surgical intervention in conjunction with medical therapy decreases the chance for recurrence.3,15,16

Although HS is internationally recognized as an inflammatory disease and not an infectious process, topical antibiotics can help to prevent and improve formation of abscesses, nodules, and pustules.11 Agents such as clindamycin and chlorhexidine wash have proven effective in preventing flares.11,16 Other antibiotics used alone or in combination also are efficacious. Tetracyclines are recommended as monotherapy for mild stages of HS.17-19 Doxycycline is the most commonly used tetracycline in HS patients and has been demonstrated to penetrate Staphylococcus aureus biofilm in high enough concentrations to maintain its antibacterial activity.20 Moreover, doxycycline, as with other tetracyclines, has a multitude of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties21 and can reduce the production of IL-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-8; downregulate chemotaxis; and promote lipo-oxygenase, matrix metalloproteinase, and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling inhibition.17

Clindamycin is the only known agent that has been studied for topical treatment and utilization in milder cases of HS.17,22 Systemic combination of clindamycin and rifampicin is the most studied, with well-established efficacy in managing HS.17,23,24 Clindamycin has bacteriostatic activity toward both aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive bacteria by binding irreversibly to the 50S ribosomal subunit, thereby inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. Rifampicin binds to the beta subunit of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, inhibiting bacterial DNA-dependent RNA synthesis. Rifampicin has broad-spectrum activity, mostly against gram-positive as well as some gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, rifampicin has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, including evidence that it inhibits excessive helper T cell (TH17) responses by reducing inducible nitric oxide synthase transcription and NF-κB activity.25,26

Metronidazole, moxifloxacin, and rifampicin as triple combination therapy has been shown to be effective in reducing HS activity in moderate to severe cases that were refractory to other treatments.27 Research suggests that moxifloxacin has anti-inflammatory properties, mainly by reducing IL-1β, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor α; stabilizing IXb protein; suppressing NF-κB signaling; and reducing IL-17A.28,29

Ertapenem can be utilized as a single 6-week antibiotic course during surgical planning or rescue therapy.18 Moreover, ertapenem can be used to treat complicated skin and soft tissue infections and has been shown to substantially improve clinical aspects of severe HS.17,27

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are effective in the treatment of moderate to severe HS.17-19 In 2 phase 3 trials (PIONEER I and II), adalimumab was used as monotherapy or in conjunction with antibiotics in patients with moderate to severe HS compared to placebo.30 Results demonstrated a disease burden reduction of greater than 50%. Antibiotic dual therapy was not noted to significantly affect disease burden.30 Of note, use of immunosuppressants in the military affects an SM’s availability for worldwide deployment and duty station assignment.

Antiandrogen therapies have demonstrated some reduction in HS flares. Although recommendations for use in HS is based on limited evidence, one randomized controlled trial compared ethinyl estradiol–norgestrel to ethinyl estradiol and cyproterone acetate. Both therapies resulted in similar efficacy, with 12 of 24 (50%) patients reporting HS symptoms improving or completely resolved.31 In another retrospective study of women treated with antiandrogen therapies, including ethinyl estriol, cyproterone acetate, and spironolactone, 16 of 29 (55%) patients reported improvement.32 In another study, daily doses of 100 to 150 mg of spironolactone resulted in improvement in 17 of 20 (85%) patients, including complete remission in 11 of 20 (55%) patients. Of the 3 patients with severe HS, none had complete clearing of disease burden.33 Patients with polycystic ovary syndrome or HS flares that occur around menstruation are more likely to benefit from treatment with spironolactone.18,32,34

Retinoids frequently have been utilized in the management of HS. In some retrospective studies and other prospective studies with 5 or more patients, isotretinoin monotherapy was utilized for a 4- to 10-month period.18,35-38 In the Alikhan et al18 study, 85 of 207 patients demonstrated improvement of HS symptoms, with more remarkable improvements in milder cases. Isotretinoin for management of patients with HS who have concomitant nodulocystic acne would have two-fold benefits.18

Wound Care

Given the purulent nodular formation in HS, adequate wound care management is vital. There is an abundance of HS wound care management strategies utilized by clinicians and patients. When selecting the appropriate dressing, consideration for the type of HS wound, cost, ease of application, patient comfort, absorbency, and odor management is important.3 However, living arrangements for military SMs can create difficulties applying and maintaining HS dressings, especially if deployed or in a field setting. Active-duty SMs often find themselves in austere living conditions in the field, aboard ships, or in other scenarios where they may or may not have running water or showers. Maintaining adequate hygiene may be difficult, and additional education about how to keep wounds clean must be imparted. Ideal dressings for HS should be highly absorbent, comfortable when applied to the anatomic locations of the HS lesions, and easily self-applied. Ideally, dressings would have atraumatic adhesion and antimicrobial properties.3 Cost-effective dressing options that have good absorption capability include sanitary napkins, adult briefs, infant diapers, and gauze.3 These dressings help to wick moisture, thus protecting the wound from maceration, which is a common patient concern. Although gauze dressings are easier to obtain, they are not as absorbent. Abdominal pads can be utilized, but they are moderately absorbent, bulky, and more challenging to obtain over-the-counter. Hydrofiber and calcium alginate dressings with silver are not accessible to the common consumer and are more expensive than the aforementioned dressings, but they do have some antimicrobial activity. Silver-impregnated foam dressings are moldable to intertriginous areas, easy to self-apply, and have moderate-heavy absorption abilities.

Final Thoughts

Hidradenitis suppurativa poses cumbersome and uncomfortable symptoms for all patients and may pose additional hardships for military SMs or those with physically demanding occupations who work in austere environments. Severe HS can restrict a military SM from certain duty stations, positions, or deployments. Early identification of HS can help reduce HS flares, disfigurement, and placement on limited duty status, therefore rendering the SM more able to engage in his/her operational responsibilities. Hidradenitis suppurativa should be discussed with the patient, with the goal to prevent flares for SMs that will be in the field, placed in austere environments, or be deployed. Use of immunosuppressants in active-duty SMs may affect their deployability, duty assignment, and retention.

For a military SM with HS, all aspects of prevention and treatment need to be balanced with his/her ability to remain deployable and complete his/her daily duties. Military SMs are not guaranteed the ideal scenario for treatment and prevention of HS. Unsanitary environments and occlusive uniforms undoubtedly contribute to disease process and make treatment more challenging. If a military SM is in a field setting or deployed, frequent daily dressing changes should still be attempted.

- Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216-221.

- Beshara MA. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a clinician’s tool for early diagnosis and treatment. Nurse Pract. 2010;35:24-28.

- Kazemi A, Carnaggio K, Clark M, et al. Optimal wound care management in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;29:165-167.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Pazzaglia M, et al. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% under occlusion in the treatment of alopecia totalis/universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003:49:96-98.

- Blattner C, Polley DC, Ferrito F, et al. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013:4:50.

- Wolkenstein P, Loundou A, Barrau K, et al. Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:621-623.

- Smith HS, Chao JD, Teitelbaum J. Painful hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:435-444.

- Alavi A, Anooshirvani N, Kim WB, et al. Quality-of-life impairment in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a Canadian study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:61-65.

- Hurley HJ. Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa and familial benign pemphigus: surgical approach. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH Jr, eds. Dermatologic Surgery: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1996:623-645.

- Kligman AM. Welcome letter. 2nd International Conference on the Sebaceous Gland, Acne, Rosacea and Related Disorders; September 13-16, 2008; Rome Italy.

- Kurzen H, Kurzen M. Secondary prevention of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Reports. 2019;11:8243.

- Sabat R, Tsaousi A, Rossbacher J, et al. Acne inversa/hidradenitis suppurativa: an update [in German]. Hautarzt. 2017;68:999-1006.

- Boer J, Nazary M, Riis PT. The role of mechanical stress in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:37-43.

- Hamzavi IH, Griffith JL, Riyaz F, et al. Laser and light-based treatment options for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S78-S81.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Michel C, DiBianco JM, Sabarwal V, et al. The treatment of genitoperineal hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of the literature. Urology. 2019;124:1-5.

- Constantinou CA, Fragoulis GE, Nikiphorou E. Hidradenitis suppurativa: infection, autoimmunity, or both [published online December 30, 2019]? Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. doi:10.1177/1759720x19895488.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

- Zouboulis CC, Desai N, Emtestam, et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:619-644.

- Mandell JB, Orr S, Koch J, et al. Large variations in clinical antibiotic activity against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms of periprosthetic joint infection isolates. J Orthop Res. 2019;37:1604-1609.

- Sun J, Shigemi H, Tanaka Y, et al. Tetracyclines downregulate the production of LPS-induced cytokines and chemokines in THP-1 cells via ERK, p38, and nuclear factor-κB signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2015;4:397-404.

- Clemmensen OJ. Topical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with clindamycin. Int J Dermatol. 1983;22:325-328.

- Gener G, Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, et al. Combination therapy with clindamycin and rifampicin for hidradenitis suppurativa: a series of 116 consecutive patients. Dermatology. 2009;219:148-154.

- Griffiths CEM. Clindamycin and rifampicin combination therapy for hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:977-978.

- Ma K, Chen X, Chen J-C, et al. Rifampicin attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting pathogenic Th17 cells responses. J Neurochem. 2016;139:1151-1162.

- Yuhas Y, Berent E, Ovadiah H, et al. Rifampin augments cytokine-induced nitric oxide production in human alveolar epithelial cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:396-398.

- Join-Lambert O, Coignard H, Jais J-P, et al. Efficacy of rifampin-moxifloxacin-metronidazole combination therapy in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2011;222:49-58.

- Choi J-H, Song M-J, Kim S-H, et al. Effect of moxifloxacin on production of proinflammatory cytokines from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3704-3707.

- Weiss T, Shalit I, Blau H, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of moxifloxacin on activated human monocytic cells: inhibition of NF-kappaB and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and of synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines.” Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1974-1982.

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434.

- Mortimer PS, Dawber RP, Gales MA, et al. A double-blind controlled cross-over trial of cyproterone acetate in females with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:263-268.

- Kraft JN, Searles GE. Hidradenitis suppurativa in 64 female patients: retrospective study comparing oral antibiotics and antiandrogen therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11:125-131.

- Lee A, Fischer G. A case series of 20 women with hidradenitis suppurativa treated with spironolactone. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:192-196.

- Khandalavala BN, Do MV. Finasteride in hidradenitis suppurativa: a “male” therapy for a predominantly “female” disease. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:44-50.

- Dicken CH, Powell ST, Spear KL. Evaluation of isotretinoin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:500-502.

- Huang CM, Kirchof MG. A new perspective on isotretinoin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review of patient outcomes. Dermatology. 2017;233:120-125.

- Norris JF, Cunliffe WJ. Failure of treatment of familial widespread hidradenitis suppurativa with isotretinoin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1986;11:579-583.

- Soria A, Canoui-Poitrine F, Wolkenstein P, et al. Absence of efficacy of oral isotretinoin in hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study based on patients’ outcome assessment. Dermatology. 2009;218:134-135.

- Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216-221.

- Beshara MA. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a clinician’s tool for early diagnosis and treatment. Nurse Pract. 2010;35:24-28.

- Kazemi A, Carnaggio K, Clark M, et al. Optimal wound care management in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;29:165-167.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Pazzaglia M, et al. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% under occlusion in the treatment of alopecia totalis/universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003:49:96-98.

- Blattner C, Polley DC, Ferrito F, et al. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013:4:50.

- Wolkenstein P, Loundou A, Barrau K, et al. Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:621-623.

- Smith HS, Chao JD, Teitelbaum J. Painful hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:435-444.

- Alavi A, Anooshirvani N, Kim WB, et al. Quality-of-life impairment in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a Canadian study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:61-65.

- Hurley HJ. Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa and familial benign pemphigus: surgical approach. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH Jr, eds. Dermatologic Surgery: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1996:623-645.

- Kligman AM. Welcome letter. 2nd International Conference on the Sebaceous Gland, Acne, Rosacea and Related Disorders; September 13-16, 2008; Rome Italy.

- Kurzen H, Kurzen M. Secondary prevention of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Reports. 2019;11:8243.

- Sabat R, Tsaousi A, Rossbacher J, et al. Acne inversa/hidradenitis suppurativa: an update [in German]. Hautarzt. 2017;68:999-1006.

- Boer J, Nazary M, Riis PT. The role of mechanical stress in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:37-43.

- Hamzavi IH, Griffith JL, Riyaz F, et al. Laser and light-based treatment options for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S78-S81.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Michel C, DiBianco JM, Sabarwal V, et al. The treatment of genitoperineal hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of the literature. Urology. 2019;124:1-5.

- Constantinou CA, Fragoulis GE, Nikiphorou E. Hidradenitis suppurativa: infection, autoimmunity, or both [published online December 30, 2019]? Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. doi:10.1177/1759720x19895488.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.