User login

Psoriasis patients with mental illness report lower satisfaction with physicians

according to a retrospective analysis of survey data.

The findings highlight the importance of clinicians being supportive and adaptable in their communication style when interacting with psoriasis patients with mental illness.

“This study aims to evaluate whether an association exists between a patient’s psychological state and the perception of patient-clinician encounters,” wrote Charlotte Read, MBBS, of Imperial College London, and April W. Armstrong, MD, MPH, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in JAMA Dermatology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed longitudinal data from over 8.8 million U.S. adults (unweighted, 652) with psoriasis who participated in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 2004 to 2017. The nationally representative database includes various clinical information, such as data on patient demographics, health care use, and mental health comorbidities.

The primary outcome, patient satisfaction with their physician, was assessed using a patient-physician communication composite score. Mental health comorbidities were evaluated using standard questionnaires.

The mean age of study patients was 52.1 years (range, 0.7 years), and most were female (54%). In all, 73% of participants had no or mild psychological distress symptoms, and 27% had moderate or severe symptoms.

After analysis, the researchers found that patients with moderate psychological distress symptoms were 2.8 times more likely to report lower satisfaction with their physician than were those with no or mild symptoms (adjusted odds ratio, 2.8; P = .001). They also reported that patients with severe symptoms were more likely to report lower satisfaction (aOR, 2.3; P = .03).

“Patients with moderate or severe depression symptoms were less satisfied with their clinicians, compared with those with no or mild depression symptoms,” they further explained.

Based on the results, the coinvestigators emphasized the importance of bettering the patient experience for those with mental illness given the potential association with improved health outcomes.

“Because depressed patients can be more sensitive to negative communication, the clinician needs to be more conscious about using a positive and supportive communication style,” they recommended.

The authors acknowledged the inadequacy of evaluating clinician performance using patient satisfaction alone. As a result, the findings may not be generalizable to all clinical settings.

The study was funded by the National Psoriasis Foundation. Dr. Armstrong reported financial affiliations with several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Read C, Armstrong AW. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1054.

according to a retrospective analysis of survey data.

The findings highlight the importance of clinicians being supportive and adaptable in their communication style when interacting with psoriasis patients with mental illness.

“This study aims to evaluate whether an association exists between a patient’s psychological state and the perception of patient-clinician encounters,” wrote Charlotte Read, MBBS, of Imperial College London, and April W. Armstrong, MD, MPH, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in JAMA Dermatology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed longitudinal data from over 8.8 million U.S. adults (unweighted, 652) with psoriasis who participated in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 2004 to 2017. The nationally representative database includes various clinical information, such as data on patient demographics, health care use, and mental health comorbidities.

The primary outcome, patient satisfaction with their physician, was assessed using a patient-physician communication composite score. Mental health comorbidities were evaluated using standard questionnaires.

The mean age of study patients was 52.1 years (range, 0.7 years), and most were female (54%). In all, 73% of participants had no or mild psychological distress symptoms, and 27% had moderate or severe symptoms.

After analysis, the researchers found that patients with moderate psychological distress symptoms were 2.8 times more likely to report lower satisfaction with their physician than were those with no or mild symptoms (adjusted odds ratio, 2.8; P = .001). They also reported that patients with severe symptoms were more likely to report lower satisfaction (aOR, 2.3; P = .03).

“Patients with moderate or severe depression symptoms were less satisfied with their clinicians, compared with those with no or mild depression symptoms,” they further explained.

Based on the results, the coinvestigators emphasized the importance of bettering the patient experience for those with mental illness given the potential association with improved health outcomes.

“Because depressed patients can be more sensitive to negative communication, the clinician needs to be more conscious about using a positive and supportive communication style,” they recommended.

The authors acknowledged the inadequacy of evaluating clinician performance using patient satisfaction alone. As a result, the findings may not be generalizable to all clinical settings.

The study was funded by the National Psoriasis Foundation. Dr. Armstrong reported financial affiliations with several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Read C, Armstrong AW. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1054.

according to a retrospective analysis of survey data.

The findings highlight the importance of clinicians being supportive and adaptable in their communication style when interacting with psoriasis patients with mental illness.

“This study aims to evaluate whether an association exists between a patient’s psychological state and the perception of patient-clinician encounters,” wrote Charlotte Read, MBBS, of Imperial College London, and April W. Armstrong, MD, MPH, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in JAMA Dermatology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed longitudinal data from over 8.8 million U.S. adults (unweighted, 652) with psoriasis who participated in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 2004 to 2017. The nationally representative database includes various clinical information, such as data on patient demographics, health care use, and mental health comorbidities.

The primary outcome, patient satisfaction with their physician, was assessed using a patient-physician communication composite score. Mental health comorbidities were evaluated using standard questionnaires.

The mean age of study patients was 52.1 years (range, 0.7 years), and most were female (54%). In all, 73% of participants had no or mild psychological distress symptoms, and 27% had moderate or severe symptoms.

After analysis, the researchers found that patients with moderate psychological distress symptoms were 2.8 times more likely to report lower satisfaction with their physician than were those with no or mild symptoms (adjusted odds ratio, 2.8; P = .001). They also reported that patients with severe symptoms were more likely to report lower satisfaction (aOR, 2.3; P = .03).

“Patients with moderate or severe depression symptoms were less satisfied with their clinicians, compared with those with no or mild depression symptoms,” they further explained.

Based on the results, the coinvestigators emphasized the importance of bettering the patient experience for those with mental illness given the potential association with improved health outcomes.

“Because depressed patients can be more sensitive to negative communication, the clinician needs to be more conscious about using a positive and supportive communication style,” they recommended.

The authors acknowledged the inadequacy of evaluating clinician performance using patient satisfaction alone. As a result, the findings may not be generalizable to all clinical settings.

The study was funded by the National Psoriasis Foundation. Dr. Armstrong reported financial affiliations with several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Read C, Armstrong AW. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1054.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

What's your diagnosis?

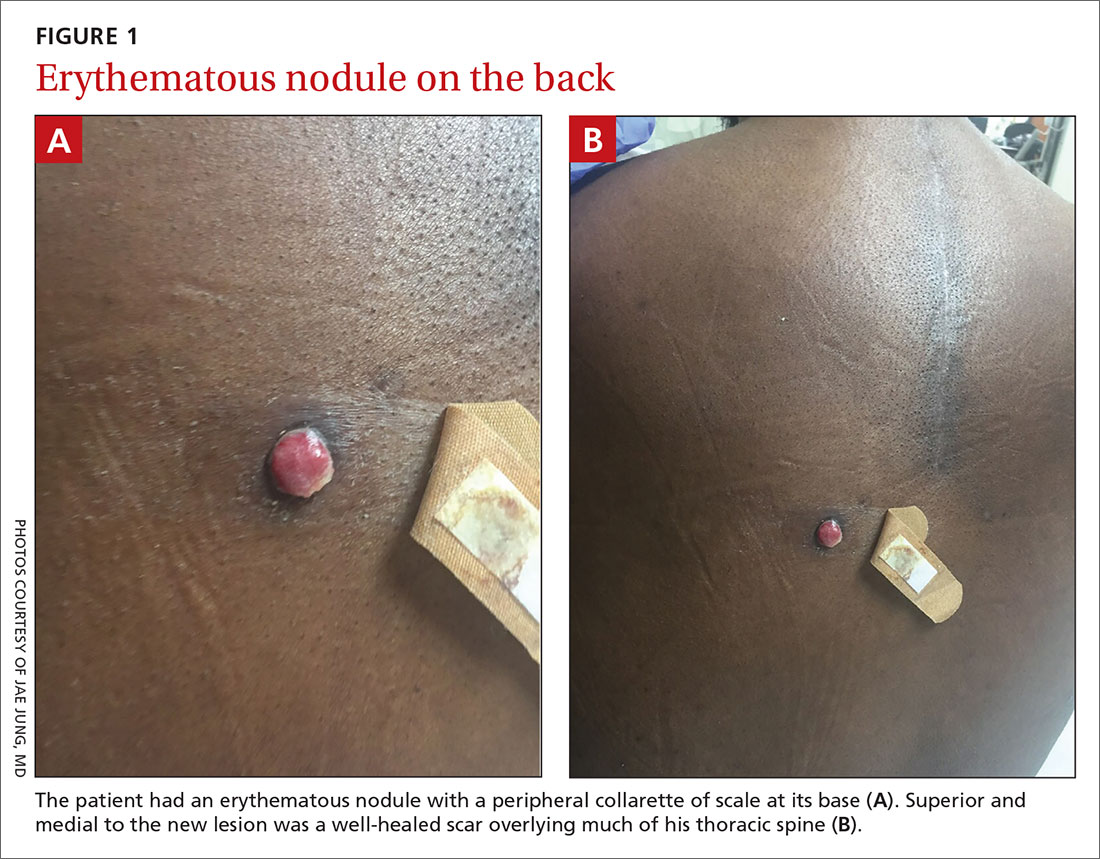

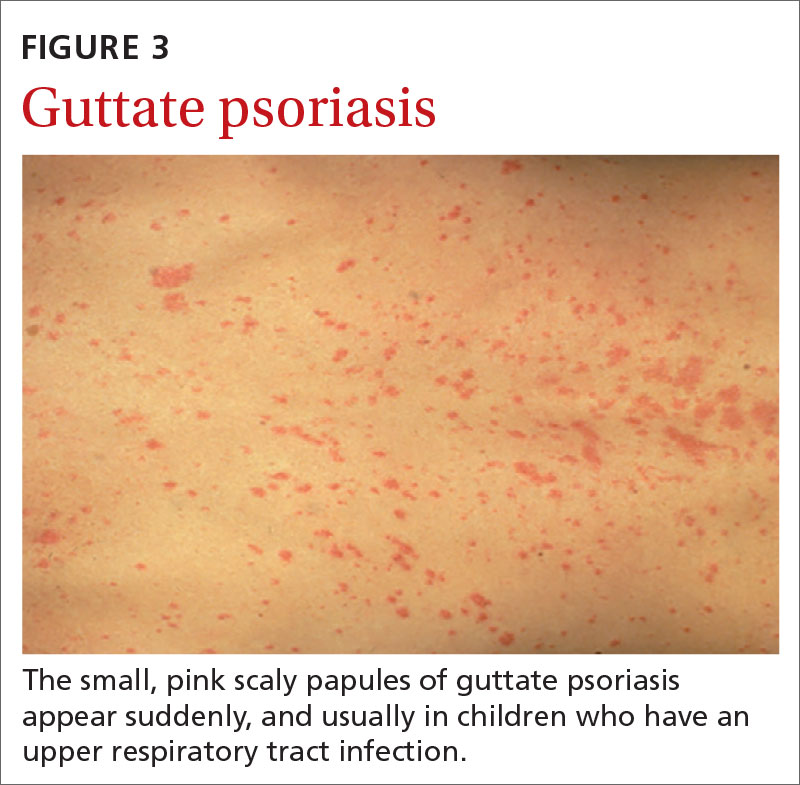

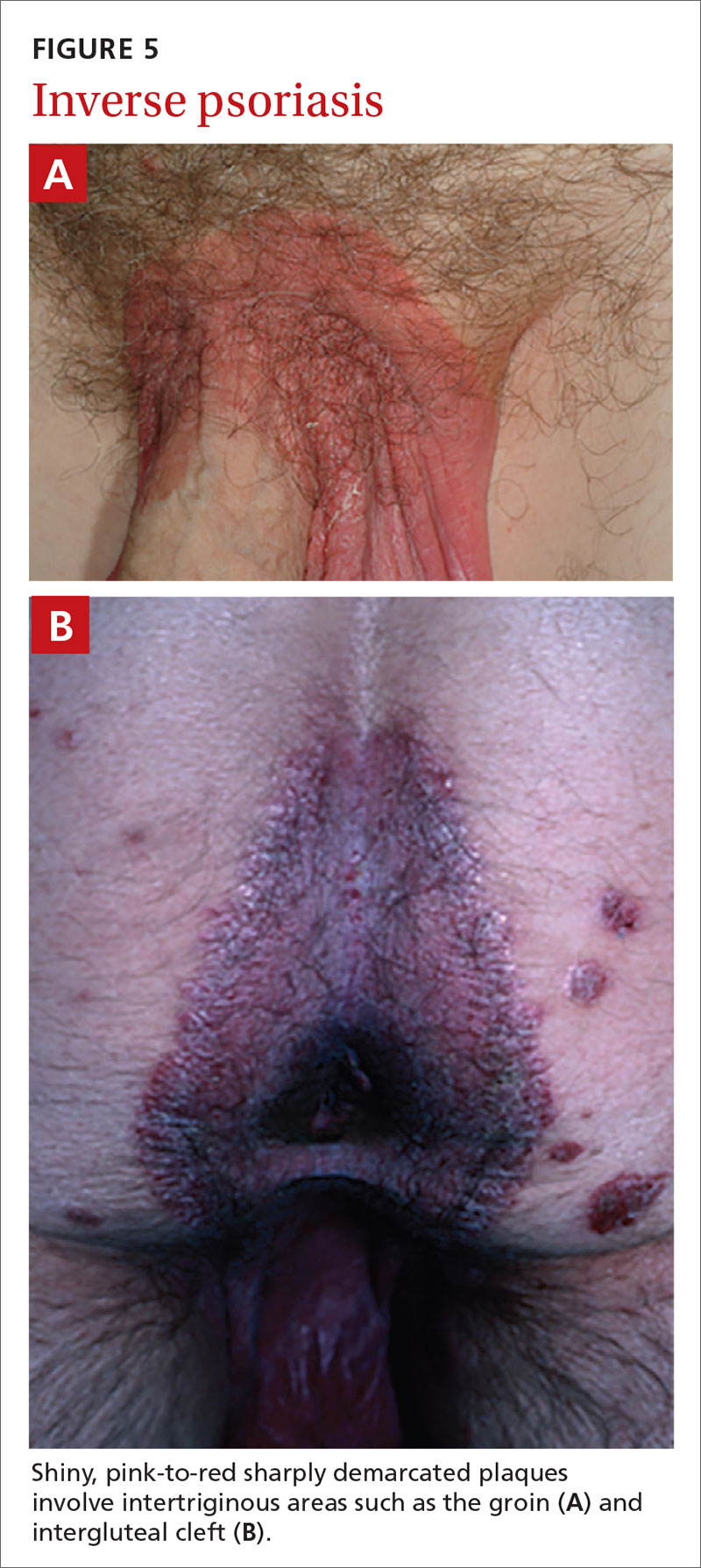

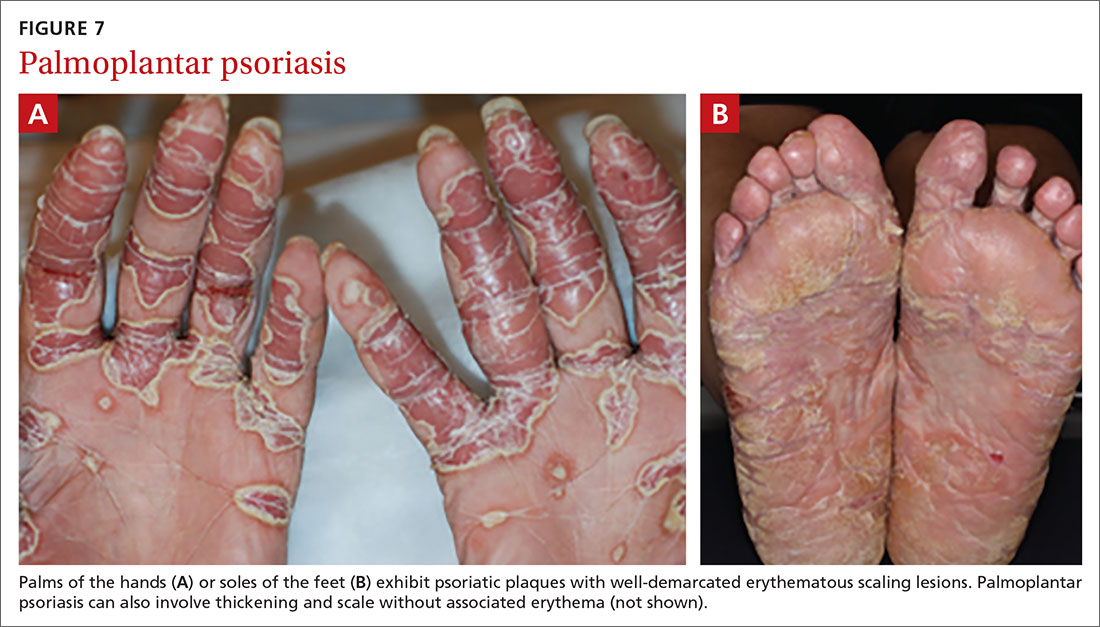

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is the name given to a heterogeneous group of rare inflammatory papulosquamous dermatoses. There are six sub-types that can present with various skin findings, however, the cardinal features across sub-types include well-defined, red-orange hued plaques with varying scale, palmoplantar keratoderma, and follicular keratosis. In the more generalized subtypes, there is a characteristic feature of intervening areas of unaffected skin often referred to as “islands of sparing.” The plaques may cover the entire body or just parts of the body such as the elbows and knees, palms and soles. Lesions are generally asymptomatic; occasionally patients complain of mild pruritus.

The etiology and pathophysiology of this group of disorders is not well understood. However, there are several hypotheses including dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism, autoimmune dysregulation, as well as environmental and immunologic triggers such as infection and ultraviolet exposure. Although most cases are sporadic, genetics do seem to play a role in the development of some cases. Caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 14 (CARD14) mutations are seen in familial PRP, and occasionally in patients with sporadic PRP, with gain of function mutations. Interestingly, CARD14 mutations are also associated with psoriasis in some individuals.1 The type-VI PRP variant has been associated with HIV, although this is incredibly rare in pediatrics.2

PRP shows significant clinical diversity, with six subtypes defined by age of onset, distribution, and appearance of lesions, and presence of HIV. This includes type I (classical adult onset), type II (atypical adult onset), type III (classical juvenile onset), type IV (circumscribed juvenile onset), type V (atypical juvenile onset), and type VI (HIV-associated). As mentioned earlier, shared features that appear across subtypes in variable degrees include red-orange papules and plaques, hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.

Of the six subtypes, type III, IV, and V occur in the pediatric population. Type III, classic juvenile PRP, typically occurs within the first 2 years of life or in adolescence. Only 10% of cases fall into this category. It shares similar features to type I PRP including red-orange plaques; islands of sparing, perifollicular hyperkeratotic papules; waxy palmoplantar keratoderma; and the distribution of affected skin is more diffuse overall. While some children clear within a few years, more recent studies stress a more prolonged course similar to the type IV variant.2

Type-IV PRP, also known as circumscribed juvenile PRP, is a focal variant, usually seen in prepubertal children and making up 25% of total cases. Clinically, these patients tend to have sharply demarcated grouped erythematous, follicular papules on the elbows, knees and over bony prominences.2

Type-V PRP is an atypical generalized juvenile variant which affects 5% of patients. It is a non-remitting hereditary condition with classic characteristics similar to type III with additional scleroderma-like changes involving the palms and soles.2

Diagnosis of PRP is based on clinical recognition and biopsy can be important to secure a diagnosis.

PRP, in many cases is self-limited and asymptomatic, and therefore does not necessarily require treatment. In other patients treatment can be challenging, and referral to a pediatric dermatology specialist is reasonable. Most practitioners recommend combination therapy with topical agents (emollients, topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and keratolytic agents such as urea, salicylic acid, or alpha-hydroxy acids) for symptomatic management and systemic therapies (methotrexate, isotretinoin) aimed at reducing inflammation. There is some data that CARD14-associated PRP can respond well to targeted biologic therapies.1

The subtypes of PRP can present in a myriad of ways and often the disease is misdiagnosed. Depending on the particular subtype and findings present, the differential can vary considerably. Commonly, physicians need to consider: psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, ichthyoses, and other conditions which can cause erythroderma.3 The characteristic red-orange color and variable associated edema helps to distinguish keratoderma of PRP from psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, ichthyosis, and hereditary palmoplantar keratoderma. Scalp involvement of PRP should be differentiated from the waxy scale of seborrheic dermatitis and the well demarcated silvery scale of psoriasis. History alone may assist in distinguishing PRP from other major causes of generalized erythroderma, although biopsy is warranted in these cases.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. They have no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Sep;79(3):487-94.

2. “Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris” (Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, July 20, 2019). 3. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jun 1;152(6):670-5.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is the name given to a heterogeneous group of rare inflammatory papulosquamous dermatoses. There are six sub-types that can present with various skin findings, however, the cardinal features across sub-types include well-defined, red-orange hued plaques with varying scale, palmoplantar keratoderma, and follicular keratosis. In the more generalized subtypes, there is a characteristic feature of intervening areas of unaffected skin often referred to as “islands of sparing.” The plaques may cover the entire body or just parts of the body such as the elbows and knees, palms and soles. Lesions are generally asymptomatic; occasionally patients complain of mild pruritus.

The etiology and pathophysiology of this group of disorders is not well understood. However, there are several hypotheses including dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism, autoimmune dysregulation, as well as environmental and immunologic triggers such as infection and ultraviolet exposure. Although most cases are sporadic, genetics do seem to play a role in the development of some cases. Caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 14 (CARD14) mutations are seen in familial PRP, and occasionally in patients with sporadic PRP, with gain of function mutations. Interestingly, CARD14 mutations are also associated with psoriasis in some individuals.1 The type-VI PRP variant has been associated with HIV, although this is incredibly rare in pediatrics.2

PRP shows significant clinical diversity, with six subtypes defined by age of onset, distribution, and appearance of lesions, and presence of HIV. This includes type I (classical adult onset), type II (atypical adult onset), type III (classical juvenile onset), type IV (circumscribed juvenile onset), type V (atypical juvenile onset), and type VI (HIV-associated). As mentioned earlier, shared features that appear across subtypes in variable degrees include red-orange papules and plaques, hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.

Of the six subtypes, type III, IV, and V occur in the pediatric population. Type III, classic juvenile PRP, typically occurs within the first 2 years of life or in adolescence. Only 10% of cases fall into this category. It shares similar features to type I PRP including red-orange plaques; islands of sparing, perifollicular hyperkeratotic papules; waxy palmoplantar keratoderma; and the distribution of affected skin is more diffuse overall. While some children clear within a few years, more recent studies stress a more prolonged course similar to the type IV variant.2

Type-IV PRP, also known as circumscribed juvenile PRP, is a focal variant, usually seen in prepubertal children and making up 25% of total cases. Clinically, these patients tend to have sharply demarcated grouped erythematous, follicular papules on the elbows, knees and over bony prominences.2

Type-V PRP is an atypical generalized juvenile variant which affects 5% of patients. It is a non-remitting hereditary condition with classic characteristics similar to type III with additional scleroderma-like changes involving the palms and soles.2

Diagnosis of PRP is based on clinical recognition and biopsy can be important to secure a diagnosis.

PRP, in many cases is self-limited and asymptomatic, and therefore does not necessarily require treatment. In other patients treatment can be challenging, and referral to a pediatric dermatology specialist is reasonable. Most practitioners recommend combination therapy with topical agents (emollients, topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and keratolytic agents such as urea, salicylic acid, or alpha-hydroxy acids) for symptomatic management and systemic therapies (methotrexate, isotretinoin) aimed at reducing inflammation. There is some data that CARD14-associated PRP can respond well to targeted biologic therapies.1

The subtypes of PRP can present in a myriad of ways and often the disease is misdiagnosed. Depending on the particular subtype and findings present, the differential can vary considerably. Commonly, physicians need to consider: psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, ichthyoses, and other conditions which can cause erythroderma.3 The characteristic red-orange color and variable associated edema helps to distinguish keratoderma of PRP from psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, ichthyosis, and hereditary palmoplantar keratoderma. Scalp involvement of PRP should be differentiated from the waxy scale of seborrheic dermatitis and the well demarcated silvery scale of psoriasis. History alone may assist in distinguishing PRP from other major causes of generalized erythroderma, although biopsy is warranted in these cases.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. They have no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Sep;79(3):487-94.

2. “Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris” (Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, July 20, 2019). 3. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jun 1;152(6):670-5.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is the name given to a heterogeneous group of rare inflammatory papulosquamous dermatoses. There are six sub-types that can present with various skin findings, however, the cardinal features across sub-types include well-defined, red-orange hued plaques with varying scale, palmoplantar keratoderma, and follicular keratosis. In the more generalized subtypes, there is a characteristic feature of intervening areas of unaffected skin often referred to as “islands of sparing.” The plaques may cover the entire body or just parts of the body such as the elbows and knees, palms and soles. Lesions are generally asymptomatic; occasionally patients complain of mild pruritus.

The etiology and pathophysiology of this group of disorders is not well understood. However, there are several hypotheses including dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism, autoimmune dysregulation, as well as environmental and immunologic triggers such as infection and ultraviolet exposure. Although most cases are sporadic, genetics do seem to play a role in the development of some cases. Caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 14 (CARD14) mutations are seen in familial PRP, and occasionally in patients with sporadic PRP, with gain of function mutations. Interestingly, CARD14 mutations are also associated with psoriasis in some individuals.1 The type-VI PRP variant has been associated with HIV, although this is incredibly rare in pediatrics.2

PRP shows significant clinical diversity, with six subtypes defined by age of onset, distribution, and appearance of lesions, and presence of HIV. This includes type I (classical adult onset), type II (atypical adult onset), type III (classical juvenile onset), type IV (circumscribed juvenile onset), type V (atypical juvenile onset), and type VI (HIV-associated). As mentioned earlier, shared features that appear across subtypes in variable degrees include red-orange papules and plaques, hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.

Of the six subtypes, type III, IV, and V occur in the pediatric population. Type III, classic juvenile PRP, typically occurs within the first 2 years of life or in adolescence. Only 10% of cases fall into this category. It shares similar features to type I PRP including red-orange plaques; islands of sparing, perifollicular hyperkeratotic papules; waxy palmoplantar keratoderma; and the distribution of affected skin is more diffuse overall. While some children clear within a few years, more recent studies stress a more prolonged course similar to the type IV variant.2

Type-IV PRP, also known as circumscribed juvenile PRP, is a focal variant, usually seen in prepubertal children and making up 25% of total cases. Clinically, these patients tend to have sharply demarcated grouped erythematous, follicular papules on the elbows, knees and over bony prominences.2

Type-V PRP is an atypical generalized juvenile variant which affects 5% of patients. It is a non-remitting hereditary condition with classic characteristics similar to type III with additional scleroderma-like changes involving the palms and soles.2

Diagnosis of PRP is based on clinical recognition and biopsy can be important to secure a diagnosis.

PRP, in many cases is self-limited and asymptomatic, and therefore does not necessarily require treatment. In other patients treatment can be challenging, and referral to a pediatric dermatology specialist is reasonable. Most practitioners recommend combination therapy with topical agents (emollients, topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and keratolytic agents such as urea, salicylic acid, or alpha-hydroxy acids) for symptomatic management and systemic therapies (methotrexate, isotretinoin) aimed at reducing inflammation. There is some data that CARD14-associated PRP can respond well to targeted biologic therapies.1

The subtypes of PRP can present in a myriad of ways and often the disease is misdiagnosed. Depending on the particular subtype and findings present, the differential can vary considerably. Commonly, physicians need to consider: psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, ichthyoses, and other conditions which can cause erythroderma.3 The characteristic red-orange color and variable associated edema helps to distinguish keratoderma of PRP from psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, ichthyosis, and hereditary palmoplantar keratoderma. Scalp involvement of PRP should be differentiated from the waxy scale of seborrheic dermatitis and the well demarcated silvery scale of psoriasis. History alone may assist in distinguishing PRP from other major causes of generalized erythroderma, although biopsy is warranted in these cases.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. They have no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Sep;79(3):487-94.

2. “Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris” (Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, July 20, 2019). 3. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jun 1;152(6):670-5.

A 10-year-old, otherwise healthy female with no prior significant medical history is brought into clinic for evaluation of orange-red scaly papules and plaques that first started on the face, neck, and fingers and began spreading to the trunk, arms, and knees. The mother of the patient also had noticed thickening of the skin on her palms and soles. The rash has been present for 2 months. Patient does not appear to be itchy, and otherwise is in normal state without pain, fever, drainage from sites, or known exposures. She was initially treated with topical triamcinolone with minimal improvement.

On physical exam, she is noted to have reddish-orange hyperkeratotic scaling papules coalescing into large plaques with follicular prominence diffusely on the face, neck, trunk, and upper extremities with smaller islands of skin that are normal-appearing. There is diffuse fine scale throughout the scalp and thickening of the skin on the palms and soles with a yellowish waxy appearance.

A toddler with a fever and desquamating perineal rash

Kawasaki disease

Given (KD). An echocardiogram revealed diffuse dilation of the left anterior descending artery without evidence of an aneurysm. The patient was promptly started on 2 g/kg IVIG and high-dose aspirin. She was later transitioned to low-dose aspirin. Long-term follow-up thus far has revealed no cardiac sequelae.

KD, or mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, is a multisystem vasculitis with predilection for the coronary arteries that most commonly affects children between 6 months and 5 years of age.1 While the etiology remains unclear, the pathogenesis is thought to be the result of an immune response to an infection in the setting of genetic susceptibility.1 Approximately 90% of patients have mucocutaneous manifestations, highlighting the important role dermatologists play in the diagnosis and early intervention to prevent cardiovascular morbidity.

The diagnostic criteria include fever for at least 5 days accompanied by at least four of the following:

- Bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection without exudate that is classically limbal sparing.

- Oral mucosal changes with cracked fissured lips, “strawberry tongue,” or erythema of the lips and mucosa.

- Changes in the extremities: erythema, swelling, or periungual peeling.

- Polymorphous exanthem.

- Cervical lymphadenopathy, often unilateral (greater than 1.5 cm).

Although nonspecific for diagnosis, laboratory abnormalities are common, including anemia, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, elevated inflammatory markers, elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT), hypoalbuminemia, and sterile pyuria on urine analysis.1

Notably, a classic finding of KD is perineal dermatitis with desquamation occurring in the acute phase of disease in 80%-90% of patients.2-5 In a retrospective review, up to 67% of patients with KD developed a perineal rash in the first week, most often beginning in the diaper area.2 The perineal rash classically desquamates early during the acute phase of the disease.1

While most individuals with KD follow a benign disease course, it is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in the United States.1 Treatment is aimed at decreasing the risk of developing coronary abnormalities through the prompt administration of IVIG and high-dose aspirin initiated early in the acute phase.6 A second dose of IVIG may be given to patients who remain febrile within 24-48 hours after treatment.6 Infliximab has been used safely and effectively in patients with refractory KD.7 Long-term cardiac follow-up of KD patients is recommended.

Recently, there has been an emerging association between COVID-19 and pediatric multi-system inflammatory syndrome, which shares features with KD. Patients with pediatric multi-system inflammatory syndrome who meet clinical criteria for KD should be promptly treated with IVIG and aspirin to avoid long-term cardiac sequelae.

This case and the photos were submitted by Dr. Elizabeth H. Cusick and Dr. Molly E. Plovanich, both with the department of dermatology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.). Dr. Donna Bilu Martin edited the case.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Bayers S et al. (2013). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Oct;69(4):501.e1-11.

2. Friter BS and Lucky AW. Arch Dermatol. 1988 Dec;124(12):1805-10.

3. Urbach AH et al. Am J Dis Child. 1988 Nov;142(11):1174-6.

4. Fink CW. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1983 Mar-Apr; 2(2):140-1.

5. Aballi A J and Bisken LC. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984 Mar-Apr;3(2):187.

6. McCrindle BW et al. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):e927-e99.

7.Sauvaget E et al. J Pediatr. 2012 May; 160(5),875-6.

Kawasaki disease

Given (KD). An echocardiogram revealed diffuse dilation of the left anterior descending artery without evidence of an aneurysm. The patient was promptly started on 2 g/kg IVIG and high-dose aspirin. She was later transitioned to low-dose aspirin. Long-term follow-up thus far has revealed no cardiac sequelae.

KD, or mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, is a multisystem vasculitis with predilection for the coronary arteries that most commonly affects children between 6 months and 5 years of age.1 While the etiology remains unclear, the pathogenesis is thought to be the result of an immune response to an infection in the setting of genetic susceptibility.1 Approximately 90% of patients have mucocutaneous manifestations, highlighting the important role dermatologists play in the diagnosis and early intervention to prevent cardiovascular morbidity.

The diagnostic criteria include fever for at least 5 days accompanied by at least four of the following:

- Bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection without exudate that is classically limbal sparing.

- Oral mucosal changes with cracked fissured lips, “strawberry tongue,” or erythema of the lips and mucosa.

- Changes in the extremities: erythema, swelling, or periungual peeling.

- Polymorphous exanthem.

- Cervical lymphadenopathy, often unilateral (greater than 1.5 cm).

Although nonspecific for diagnosis, laboratory abnormalities are common, including anemia, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, elevated inflammatory markers, elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT), hypoalbuminemia, and sterile pyuria on urine analysis.1

Notably, a classic finding of KD is perineal dermatitis with desquamation occurring in the acute phase of disease in 80%-90% of patients.2-5 In a retrospective review, up to 67% of patients with KD developed a perineal rash in the first week, most often beginning in the diaper area.2 The perineal rash classically desquamates early during the acute phase of the disease.1

While most individuals with KD follow a benign disease course, it is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in the United States.1 Treatment is aimed at decreasing the risk of developing coronary abnormalities through the prompt administration of IVIG and high-dose aspirin initiated early in the acute phase.6 A second dose of IVIG may be given to patients who remain febrile within 24-48 hours after treatment.6 Infliximab has been used safely and effectively in patients with refractory KD.7 Long-term cardiac follow-up of KD patients is recommended.

Recently, there has been an emerging association between COVID-19 and pediatric multi-system inflammatory syndrome, which shares features with KD. Patients with pediatric multi-system inflammatory syndrome who meet clinical criteria for KD should be promptly treated with IVIG and aspirin to avoid long-term cardiac sequelae.

This case and the photos were submitted by Dr. Elizabeth H. Cusick and Dr. Molly E. Plovanich, both with the department of dermatology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.). Dr. Donna Bilu Martin edited the case.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Bayers S et al. (2013). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Oct;69(4):501.e1-11.

2. Friter BS and Lucky AW. Arch Dermatol. 1988 Dec;124(12):1805-10.

3. Urbach AH et al. Am J Dis Child. 1988 Nov;142(11):1174-6.

4. Fink CW. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1983 Mar-Apr; 2(2):140-1.

5. Aballi A J and Bisken LC. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984 Mar-Apr;3(2):187.

6. McCrindle BW et al. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):e927-e99.

7.Sauvaget E et al. J Pediatr. 2012 May; 160(5),875-6.

Kawasaki disease

Given (KD). An echocardiogram revealed diffuse dilation of the left anterior descending artery without evidence of an aneurysm. The patient was promptly started on 2 g/kg IVIG and high-dose aspirin. She was later transitioned to low-dose aspirin. Long-term follow-up thus far has revealed no cardiac sequelae.

KD, or mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, is a multisystem vasculitis with predilection for the coronary arteries that most commonly affects children between 6 months and 5 years of age.1 While the etiology remains unclear, the pathogenesis is thought to be the result of an immune response to an infection in the setting of genetic susceptibility.1 Approximately 90% of patients have mucocutaneous manifestations, highlighting the important role dermatologists play in the diagnosis and early intervention to prevent cardiovascular morbidity.

The diagnostic criteria include fever for at least 5 days accompanied by at least four of the following:

- Bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection without exudate that is classically limbal sparing.

- Oral mucosal changes with cracked fissured lips, “strawberry tongue,” or erythema of the lips and mucosa.

- Changes in the extremities: erythema, swelling, or periungual peeling.

- Polymorphous exanthem.

- Cervical lymphadenopathy, often unilateral (greater than 1.5 cm).

Although nonspecific for diagnosis, laboratory abnormalities are common, including anemia, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, elevated inflammatory markers, elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT), hypoalbuminemia, and sterile pyuria on urine analysis.1

Notably, a classic finding of KD is perineal dermatitis with desquamation occurring in the acute phase of disease in 80%-90% of patients.2-5 In a retrospective review, up to 67% of patients with KD developed a perineal rash in the first week, most often beginning in the diaper area.2 The perineal rash classically desquamates early during the acute phase of the disease.1

While most individuals with KD follow a benign disease course, it is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in the United States.1 Treatment is aimed at decreasing the risk of developing coronary abnormalities through the prompt administration of IVIG and high-dose aspirin initiated early in the acute phase.6 A second dose of IVIG may be given to patients who remain febrile within 24-48 hours after treatment.6 Infliximab has been used safely and effectively in patients with refractory KD.7 Long-term cardiac follow-up of KD patients is recommended.

Recently, there has been an emerging association between COVID-19 and pediatric multi-system inflammatory syndrome, which shares features with KD. Patients with pediatric multi-system inflammatory syndrome who meet clinical criteria for KD should be promptly treated with IVIG and aspirin to avoid long-term cardiac sequelae.

This case and the photos were submitted by Dr. Elizabeth H. Cusick and Dr. Molly E. Plovanich, both with the department of dermatology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.). Dr. Donna Bilu Martin edited the case.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Bayers S et al. (2013). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Oct;69(4):501.e1-11.

2. Friter BS and Lucky AW. Arch Dermatol. 1988 Dec;124(12):1805-10.

3. Urbach AH et al. Am J Dis Child. 1988 Nov;142(11):1174-6.

4. Fink CW. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1983 Mar-Apr; 2(2):140-1.

5. Aballi A J and Bisken LC. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984 Mar-Apr;3(2):187.

6. McCrindle BW et al. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):e927-e99.

7.Sauvaget E et al. J Pediatr. 2012 May; 160(5),875-6.

An otherwise healthy 18-month-old female presented to the emergency department with 5 days of fever, erythema, fissuring of the lips, conjunctival injection, and a desquamating perineal rash. In addition, she had nasal congestion and cough for which she was started on amoxicillin 2 days prior to presentation given concern for pneumonia.

On exam, she was also noted to have several palpable cervical lymph nodes and edematous hands with overlying erythema. Laboratory evaluation was notable for respiratory syncytial virus positivity by polymerase chain reaction assay, leukocytosis, and elevated inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein).

Itchy leg papules

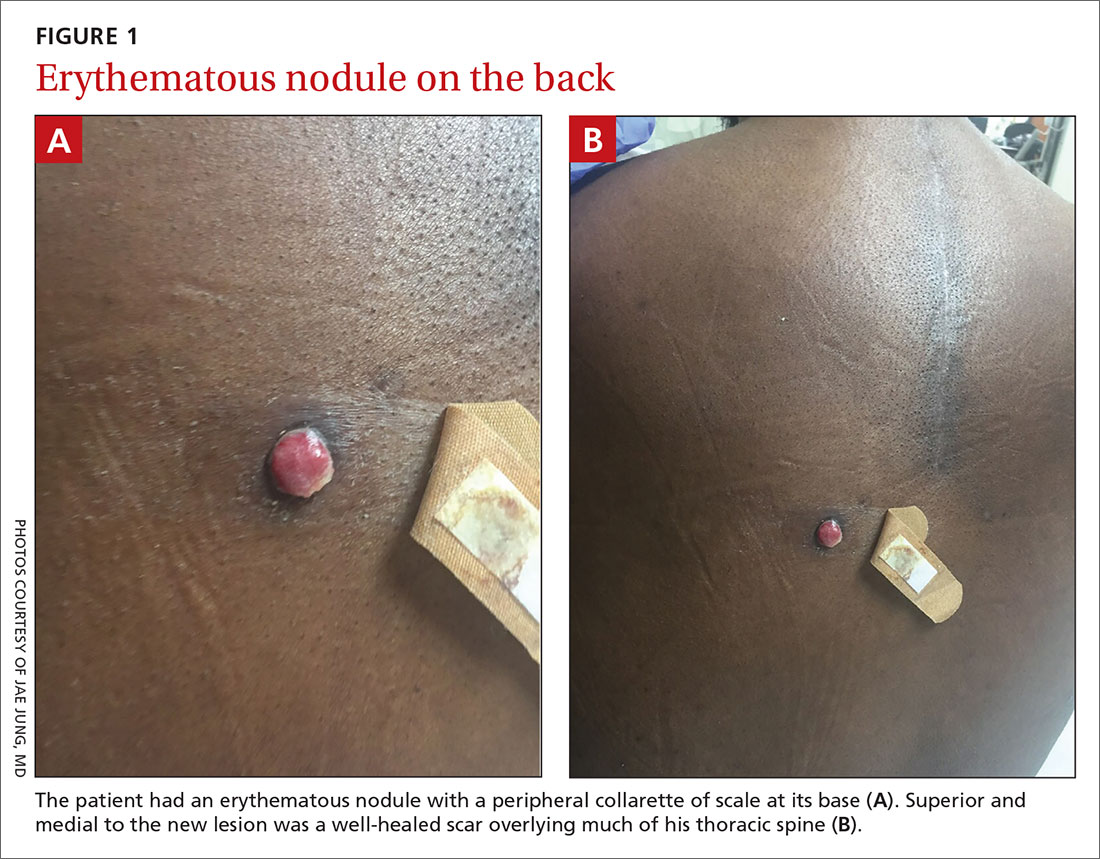

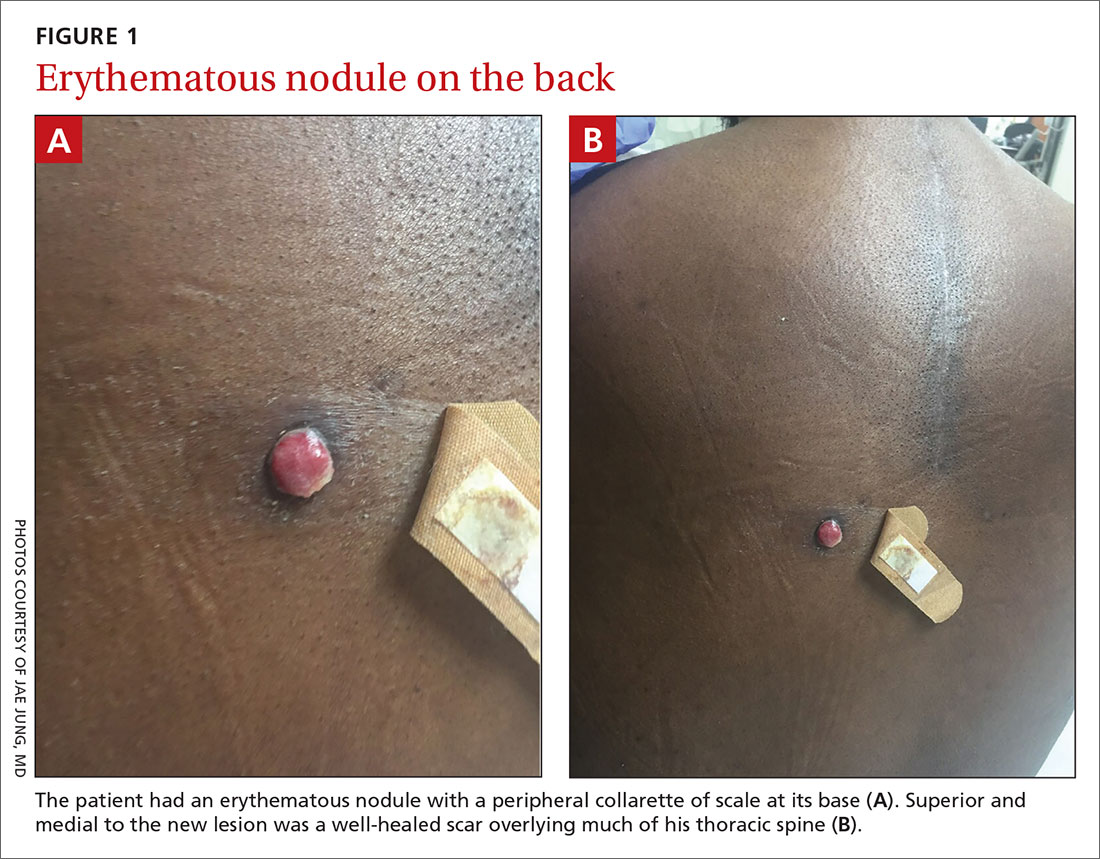

Punch biopsy revealed collagen extravasation consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, an uncommon acquired disease that is seen in patients with longstanding renal disease or diabetes mellitus. The patient’s history of end-stage renal disease, paired with the eruptive nature of the pink papules with central firm plugs, pointed to the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for lesions like these includes prurigo nodularis and eruptive keratoacanthomas. Prurigo nodules would itch but likely lack a central plug. Eruptive keratoacanthomas would have a central keratinaceous plug but would be less likely to itch. A biopsy can help distinguish these entities.

Reactive perforating collagenosis can affect up to 10% of hemodialysis patients. It also can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, liver disease, and sclerosing cholangitis. One theory of the etiology is that underlying disease causes skin itching and the subsequent trauma from scratching causes reactivity.

The work-up consists of a punch biopsy of the entire lesion or central plug. A biopsy limited to the edge of the lesion, or one that is shallow, may fail to connect altered dermal collagen with its follicular elimination and be misread as dermatitis.

Lesions often resolve spontaneously, but disease can be widespread. Topical steroids and antihistamines may reduce itching. Narrowband UVB, topical or systemic retinoids, tetracyclines, and cryotherapy all have had reported success. Narrowband UVB is especially helpful for uremic pruritus and, if available, may be the treatment of choice.

This patient was treated with topical steroids, oral cetirizine 10 mg/d, and cryotherapy to the most stubborn lesions. Over 3 months, the number of lesions and severity of symptoms improved. She continued hemodialysis and awaits a renal transplant.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660.

Punch biopsy revealed collagen extravasation consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, an uncommon acquired disease that is seen in patients with longstanding renal disease or diabetes mellitus. The patient’s history of end-stage renal disease, paired with the eruptive nature of the pink papules with central firm plugs, pointed to the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for lesions like these includes prurigo nodularis and eruptive keratoacanthomas. Prurigo nodules would itch but likely lack a central plug. Eruptive keratoacanthomas would have a central keratinaceous plug but would be less likely to itch. A biopsy can help distinguish these entities.

Reactive perforating collagenosis can affect up to 10% of hemodialysis patients. It also can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, liver disease, and sclerosing cholangitis. One theory of the etiology is that underlying disease causes skin itching and the subsequent trauma from scratching causes reactivity.

The work-up consists of a punch biopsy of the entire lesion or central plug. A biopsy limited to the edge of the lesion, or one that is shallow, may fail to connect altered dermal collagen with its follicular elimination and be misread as dermatitis.

Lesions often resolve spontaneously, but disease can be widespread. Topical steroids and antihistamines may reduce itching. Narrowband UVB, topical or systemic retinoids, tetracyclines, and cryotherapy all have had reported success. Narrowband UVB is especially helpful for uremic pruritus and, if available, may be the treatment of choice.

This patient was treated with topical steroids, oral cetirizine 10 mg/d, and cryotherapy to the most stubborn lesions. Over 3 months, the number of lesions and severity of symptoms improved. She continued hemodialysis and awaits a renal transplant.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Punch biopsy revealed collagen extravasation consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, an uncommon acquired disease that is seen in patients with longstanding renal disease or diabetes mellitus. The patient’s history of end-stage renal disease, paired with the eruptive nature of the pink papules with central firm plugs, pointed to the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for lesions like these includes prurigo nodularis and eruptive keratoacanthomas. Prurigo nodules would itch but likely lack a central plug. Eruptive keratoacanthomas would have a central keratinaceous plug but would be less likely to itch. A biopsy can help distinguish these entities.

Reactive perforating collagenosis can affect up to 10% of hemodialysis patients. It also can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, liver disease, and sclerosing cholangitis. One theory of the etiology is that underlying disease causes skin itching and the subsequent trauma from scratching causes reactivity.

The work-up consists of a punch biopsy of the entire lesion or central plug. A biopsy limited to the edge of the lesion, or one that is shallow, may fail to connect altered dermal collagen with its follicular elimination and be misread as dermatitis.

Lesions often resolve spontaneously, but disease can be widespread. Topical steroids and antihistamines may reduce itching. Narrowband UVB, topical or systemic retinoids, tetracyclines, and cryotherapy all have had reported success. Narrowband UVB is especially helpful for uremic pruritus and, if available, may be the treatment of choice.

This patient was treated with topical steroids, oral cetirizine 10 mg/d, and cryotherapy to the most stubborn lesions. Over 3 months, the number of lesions and severity of symptoms improved. She continued hemodialysis and awaits a renal transplant.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660.

Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660.

Acute bilateral hand edema and vesiculation

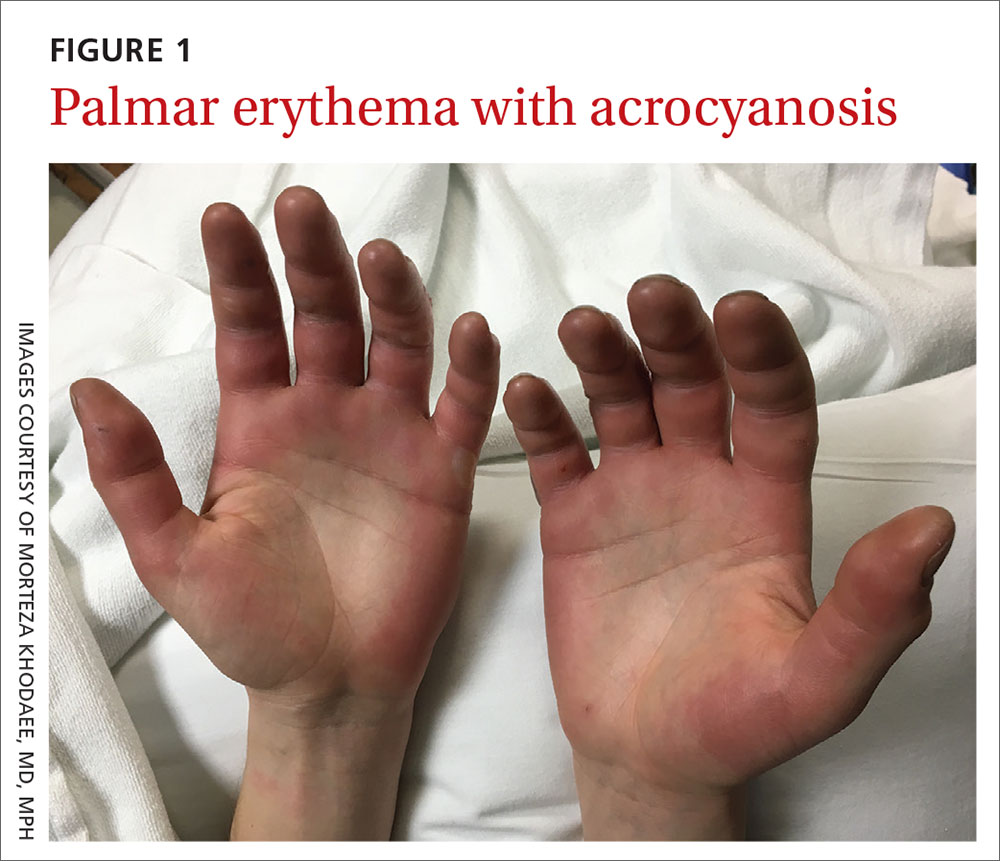

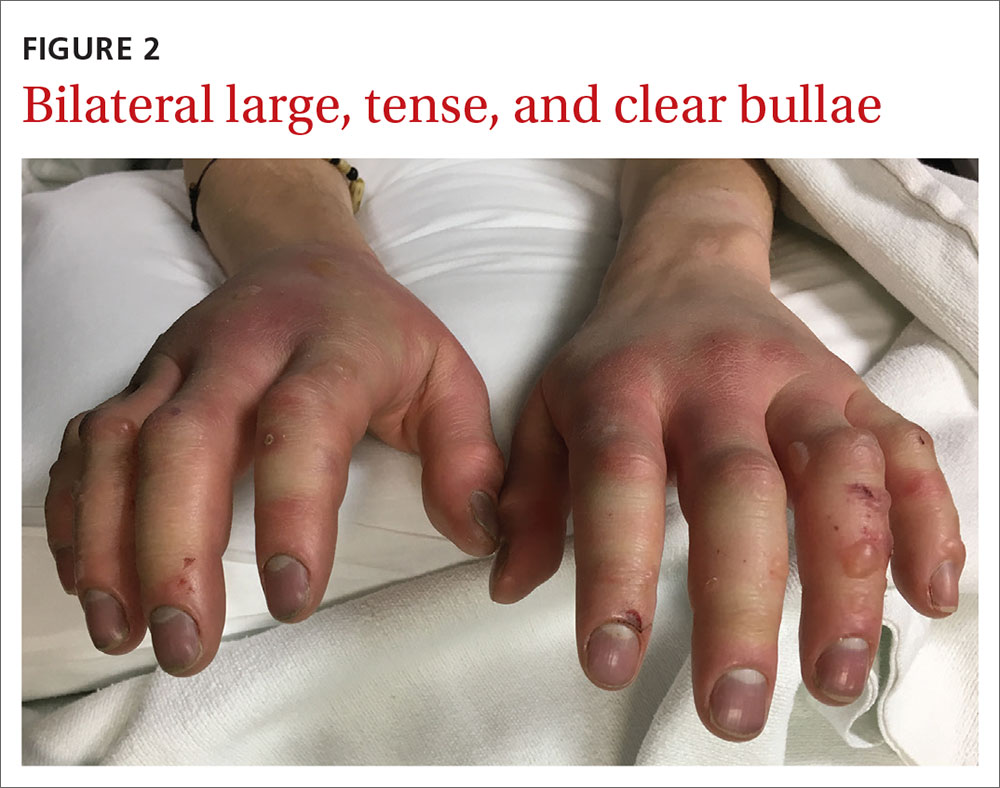

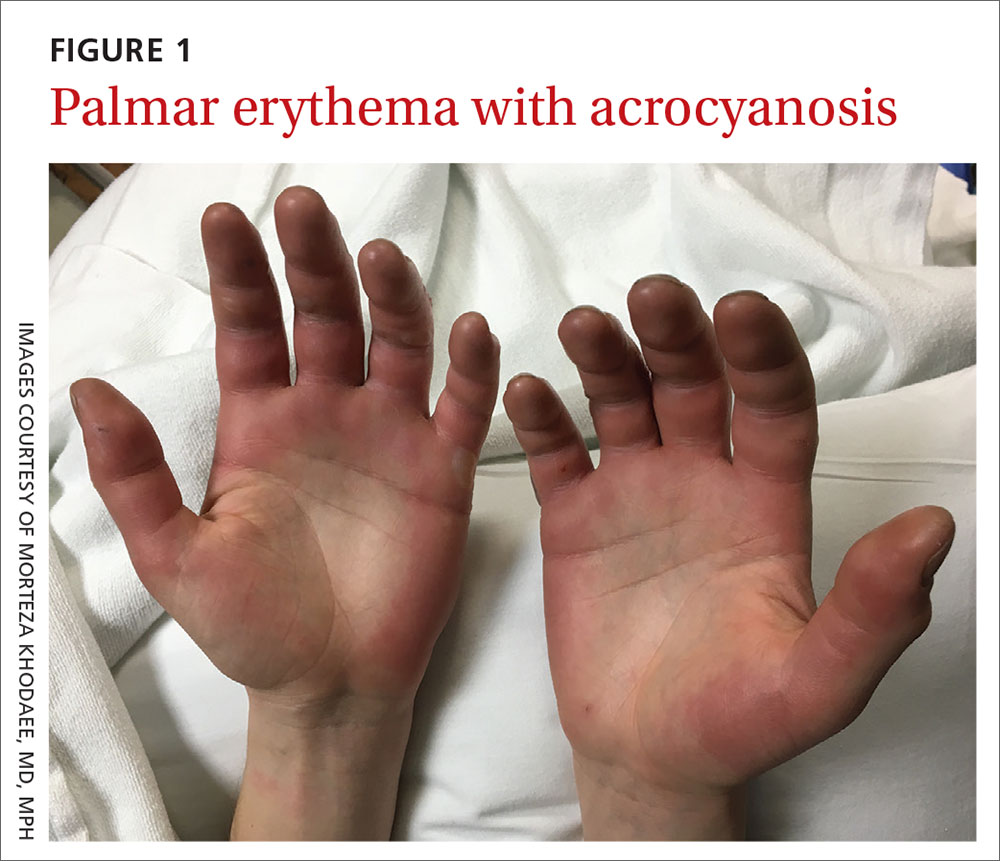

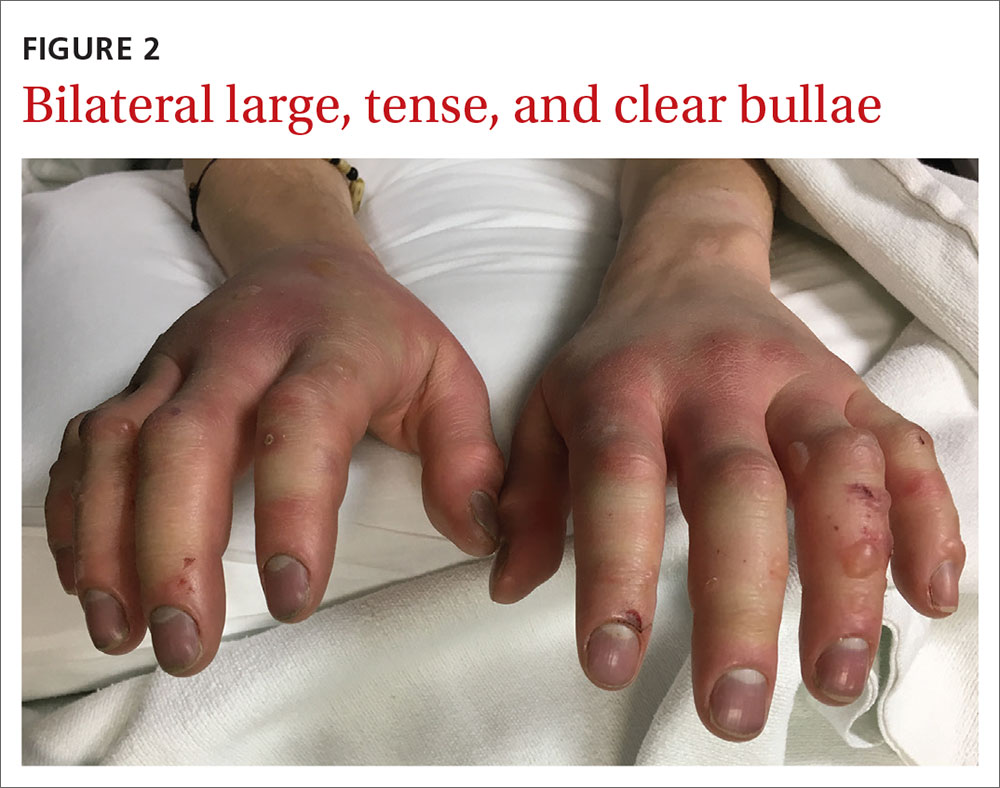

A 27-year-old man presented to the urgent care clinic with acute bilateral hand swelling, blisters, numbness, and pain. History taking revealed that these symptoms developed after he was locked outside of his apartment for 45 minutes in –22°C (–8°F) weather following a night of heavy drinking.

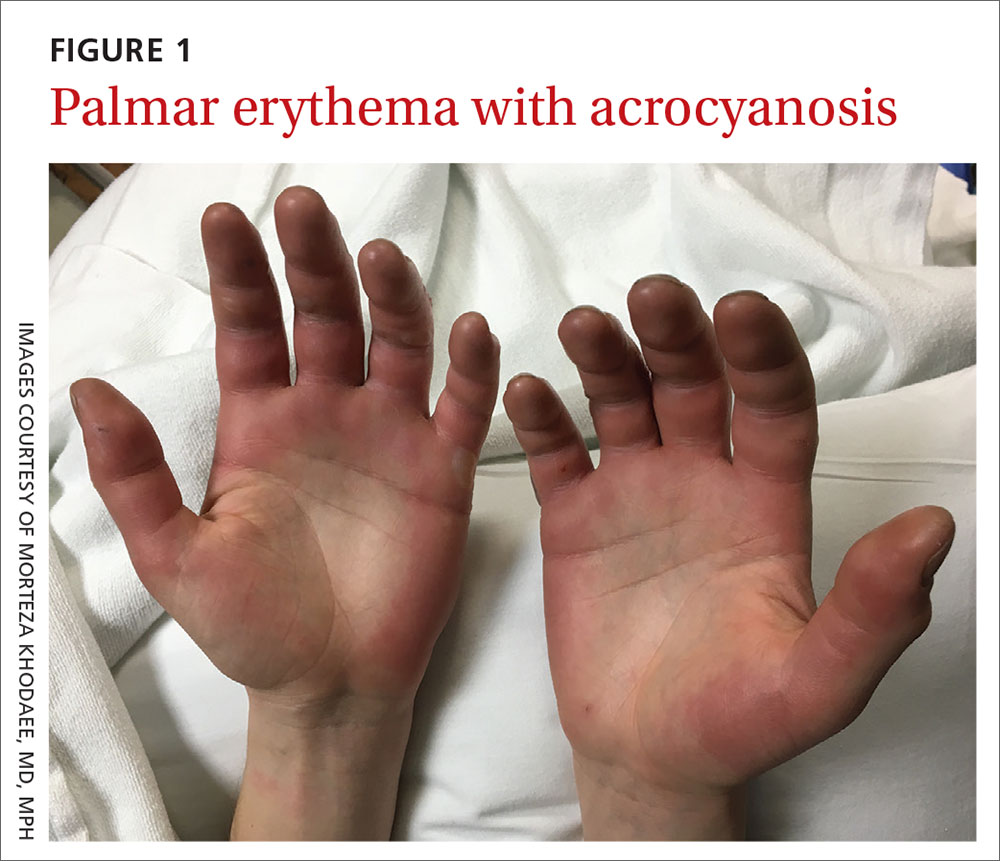

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 36.2°C (97.2°F) and a heart rate of 116 beats/min. He had

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Second-degree frostbite

Frostbite is the result of tissue freezing, which generally occurs after prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures (typically –4°C or below).1,2 The majority (~90%) of frostbite injuries occur in the hands and feet; however, frostbite has also been observed in the face, perineum, buttocks, and male genitalia.3

Frostbite is a clinical diagnosis based on a history of sustained exposure to freezing temperatures, paresthesia of affected areas, and typical skin changes. Evidence is lacking regarding the epidemiology of frostbite within the general population.2

Pathophysiology. Intra- and extracellular ice crystal formation causes fluid and electrolyte disturbances, cell dehydration, lipid denaturation, and subsequent cell death.1 After thawing, progressive tissue ischemia can occur as a result of endothelial damage and dysfunction, intravascular sludging, increased inflammatory markers, an influx of free radicals, and microvascular thrombosis.1

Classification. Traditionally, frostbite has been classified according to a 4-tiered system based on tissue appearance after rewarming.2 First-degree frostbite is characterized by white plaques with surrounding erythema; second degree by edema and clear or cloudy vesicles; third degree by hemorrhagic bullae; and fourth degree by cold and hard tissue that eventually progresses to gangrene.2

A simpler scheme designates frostbite as either superficial (corresponding to first- or second-degree frostbite) or deep (corresponding to third- or fourth-degree frostbite) with presumed muscle and bone involvement.2

Continue to: Risk factors

Risk factors. Frostbite is often associated with risk factors such as alcohol or drug intoxication, vehicular failure or trauma, immobilizing trauma, psychiatric illness, homelessness, Raynaud phenomenon, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, inadequate clothing, previous cold-weather injury, outdoor winter recreation, and the use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers).1-3 Apart from environmental exposure, frostbite can also occur by direct contact with freezing materials, such as ice packs or industrial refrigerants.3

Differential includes nonfreezing injuries

Frostnip, pernio, and trench foot are other cold-weather injuries distinguished by the absence of tissue freezing.4 Raynaud phenomenon is a condition that is triggered by either cold temperatures or emotional stress.5

Frostnip is characterized by pallor and paresthesia of exposed areas. It may precede frostbite, but it quickly resolves after rewarming.2

Pernio occurs when skin is exposed to damp, cold, nonfreezing environments.6 It results in edematous and inflammatory skin lesions that may be painful, pruritic, violaceous, or erythematous.6 These lesions are typically found over the fingers, toes, nose, ears, buttocks, or thighs.4,6 Pernio may be classified as either primary or secondary disease.5 Primary pernio is considered idiopathic.6 Secondary pernio is thought to be either drug induced or due to underlying autoimmune diseases, such as hepatitis or cryopathy.6

Trench foot develops under similar conditions to pernio but requires exposure to a wet environment for at least 10 to 14 hours.7 It is characterized by foot pain, paresthesia, pruritus, edema, erythema, cyanosis, blisters, and even gangrene if left untreated.7

Continue to: Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon results from transient, acral vasocontraction and manifests as well-demarcated pallor, cyanosis, and then erythema as the affected body part reperfuses.5 Similar to pernio, it can be categorized as either primary or secondary.5 Primary phenomenon is idiopathic. Secondary phenomenon is thought to be a result of autoimmune disease, use of certain medications, occupational vibratory exposure, obstructive vascular disease, or infection

In the absence of a history of exposure to subfreezing temperatures, frostbite can be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

Treatment entails rewarming

The aim of frostbite treatment is to save injured cells and minimize tissue loss.1 This is accomplished through rapid rewarming and—in severe cases—reperfusion techniques.

Tissue should be rewarmed in a 37°C to 39°C water bath with povidone iodine or chlorhexidine added for antiseptic effect.1 All efforts should be made to avoid refreezing or trauma, as this could worsen the initial injury.2 Oral or intravenous hydration may be offered to optimize fluid status.1 Supplemental oxygen may be administered to maintain saturations above 90%.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are helpful for analgesia and anti-inflammatory effect, and opioids can be used for breakthrough pain.1 It is recommended that blisters be drained in a sterile fashion and that all affected tissue be covered with topical aloe vera and a loose dressing.1,2,4

Treatment of severe frostbite. Angiography should be performed on all patients with third- or fourth-degree frostbite.3 If imaging shows evidence of vascular occlusion, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and heparin can be initiated within 24 hours to reduce the risk for amputation.8-10

Continue to: Iloprost is another...

Iloprost is another proposed treatment for severe frostbite. It is a prostacyclin analog that may lower the amputation rate in patients with at least third-degree frostbite.11 Unlike tPA, iloprost may be given to trauma patients, and it can be used more than 24 hours after injury.2

In cases of fourth-degree frostbite that is not successfully reperfused, amputation is delayed until dry gangrene develops. This often takes weeks to months.12

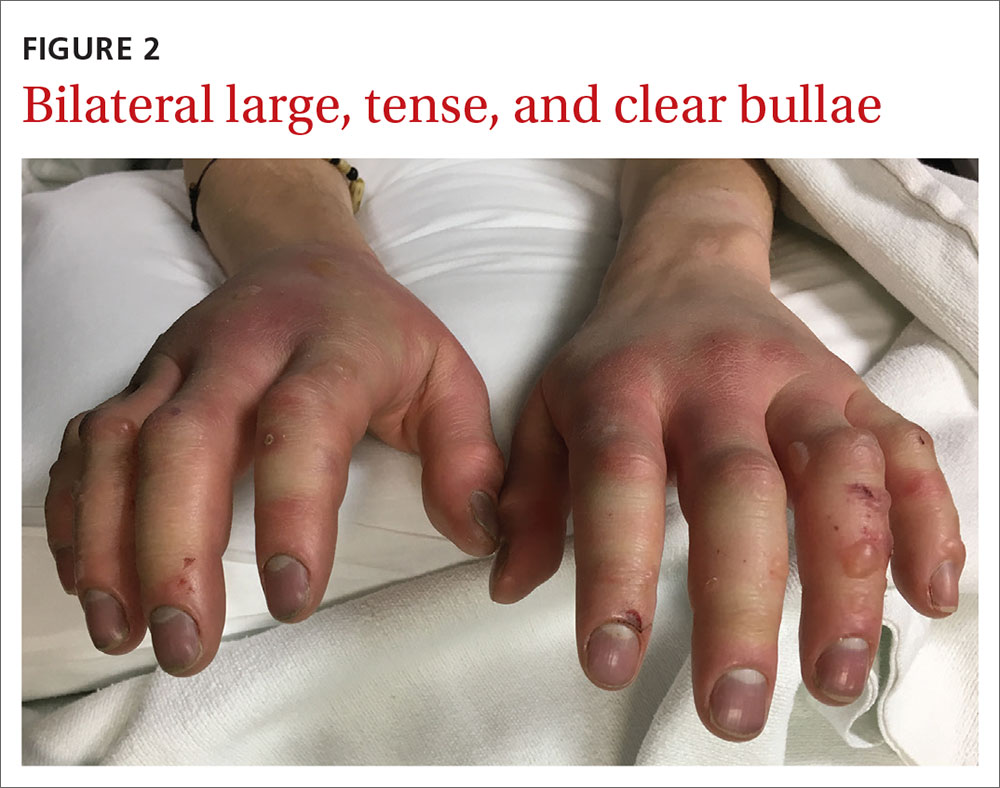

Our patient underwent rewarming and was orally rehydrated. He was discharged home with ibuprofen, oxycodone-acetaminophen, topical aloe vera, and loose dressings. His bullae enlarged the next day (FIGURE 3). One week later, his blisters were debrided and dressed with silver sulfadiazine at his plastic surgery follow-up. He experienced sensory deficits for a few months, but eventually made a full recovery after 6 months with no remaining sequelae.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Lisa Kim, MD, for her clinical care of this patient.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@ cuanschutz.edu

1. Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:281-299.

2. Heil K, Thomas R, Robertson G, et al. Freezing and non-freezing cold weather injuries: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2016;117:79-93.

3. Millet JD, Brown RK, Levi B, et al. Frostbite: spectrum of imaging findings and guidelines for management. Radiographics. 2016;36:2154-2169.

4. Long WB 3rd, Edlich RF, Winters KL, et al. Cold injuries. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2005;15:67-78.

5. Baker JS, Miranpuri S. Perniosis: a case report with literature review. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2016;106:138-140.

6. Bush JS, Watson S. Trench foot. Updated February 3, 2020. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482364/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

7. Musa R, Qurie A. Raynaud disease (Raynaud phenomenon, Raynaud syndrome). Updated February 14, 2019. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499833/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

8. Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546-551; discussion 551-553.

9. Gonzaga T, Jenabzadeh K, Anderson CP, et al. Use of intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy for acute treatment of frostbite in 62 patients with review of thrombolytic therapy in frostbite. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:e323-e334.

10. Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005;59:1350-1354; discussion 1354-1355.

11. Cauchy E, Cheguillaume B, Chetaille E. A controlled trial of a prostacyclin and rt-PA in the treatment of severe frostbite. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:189-190.

12. McIntosh SE, Opacic M, Freer L, et al; Wilderness Medical Society. Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of frostbite: 2014 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2014;25(4 suppl):S43-S54.

A 27-year-old man presented to the urgent care clinic with acute bilateral hand swelling, blisters, numbness, and pain. History taking revealed that these symptoms developed after he was locked outside of his apartment for 45 minutes in –22°C (–8°F) weather following a night of heavy drinking.

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 36.2°C (97.2°F) and a heart rate of 116 beats/min. He had

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Second-degree frostbite

Frostbite is the result of tissue freezing, which generally occurs after prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures (typically –4°C or below).1,2 The majority (~90%) of frostbite injuries occur in the hands and feet; however, frostbite has also been observed in the face, perineum, buttocks, and male genitalia.3

Frostbite is a clinical diagnosis based on a history of sustained exposure to freezing temperatures, paresthesia of affected areas, and typical skin changes. Evidence is lacking regarding the epidemiology of frostbite within the general population.2

Pathophysiology. Intra- and extracellular ice crystal formation causes fluid and electrolyte disturbances, cell dehydration, lipid denaturation, and subsequent cell death.1 After thawing, progressive tissue ischemia can occur as a result of endothelial damage and dysfunction, intravascular sludging, increased inflammatory markers, an influx of free radicals, and microvascular thrombosis.1

Classification. Traditionally, frostbite has been classified according to a 4-tiered system based on tissue appearance after rewarming.2 First-degree frostbite is characterized by white plaques with surrounding erythema; second degree by edema and clear or cloudy vesicles; third degree by hemorrhagic bullae; and fourth degree by cold and hard tissue that eventually progresses to gangrene.2

A simpler scheme designates frostbite as either superficial (corresponding to first- or second-degree frostbite) or deep (corresponding to third- or fourth-degree frostbite) with presumed muscle and bone involvement.2

Continue to: Risk factors

Risk factors. Frostbite is often associated with risk factors such as alcohol or drug intoxication, vehicular failure or trauma, immobilizing trauma, psychiatric illness, homelessness, Raynaud phenomenon, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, inadequate clothing, previous cold-weather injury, outdoor winter recreation, and the use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers).1-3 Apart from environmental exposure, frostbite can also occur by direct contact with freezing materials, such as ice packs or industrial refrigerants.3

Differential includes nonfreezing injuries

Frostnip, pernio, and trench foot are other cold-weather injuries distinguished by the absence of tissue freezing.4 Raynaud phenomenon is a condition that is triggered by either cold temperatures or emotional stress.5

Frostnip is characterized by pallor and paresthesia of exposed areas. It may precede frostbite, but it quickly resolves after rewarming.2

Pernio occurs when skin is exposed to damp, cold, nonfreezing environments.6 It results in edematous and inflammatory skin lesions that may be painful, pruritic, violaceous, or erythematous.6 These lesions are typically found over the fingers, toes, nose, ears, buttocks, or thighs.4,6 Pernio may be classified as either primary or secondary disease.5 Primary pernio is considered idiopathic.6 Secondary pernio is thought to be either drug induced or due to underlying autoimmune diseases, such as hepatitis or cryopathy.6

Trench foot develops under similar conditions to pernio but requires exposure to a wet environment for at least 10 to 14 hours.7 It is characterized by foot pain, paresthesia, pruritus, edema, erythema, cyanosis, blisters, and even gangrene if left untreated.7

Continue to: Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon results from transient, acral vasocontraction and manifests as well-demarcated pallor, cyanosis, and then erythema as the affected body part reperfuses.5 Similar to pernio, it can be categorized as either primary or secondary.5 Primary phenomenon is idiopathic. Secondary phenomenon is thought to be a result of autoimmune disease, use of certain medications, occupational vibratory exposure, obstructive vascular disease, or infection

In the absence of a history of exposure to subfreezing temperatures, frostbite can be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

Treatment entails rewarming

The aim of frostbite treatment is to save injured cells and minimize tissue loss.1 This is accomplished through rapid rewarming and—in severe cases—reperfusion techniques.

Tissue should be rewarmed in a 37°C to 39°C water bath with povidone iodine or chlorhexidine added for antiseptic effect.1 All efforts should be made to avoid refreezing or trauma, as this could worsen the initial injury.2 Oral or intravenous hydration may be offered to optimize fluid status.1 Supplemental oxygen may be administered to maintain saturations above 90%.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are helpful for analgesia and anti-inflammatory effect, and opioids can be used for breakthrough pain.1 It is recommended that blisters be drained in a sterile fashion and that all affected tissue be covered with topical aloe vera and a loose dressing.1,2,4

Treatment of severe frostbite. Angiography should be performed on all patients with third- or fourth-degree frostbite.3 If imaging shows evidence of vascular occlusion, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and heparin can be initiated within 24 hours to reduce the risk for amputation.8-10

Continue to: Iloprost is another...

Iloprost is another proposed treatment for severe frostbite. It is a prostacyclin analog that may lower the amputation rate in patients with at least third-degree frostbite.11 Unlike tPA, iloprost may be given to trauma patients, and it can be used more than 24 hours after injury.2

In cases of fourth-degree frostbite that is not successfully reperfused, amputation is delayed until dry gangrene develops. This often takes weeks to months.12

Our patient underwent rewarming and was orally rehydrated. He was discharged home with ibuprofen, oxycodone-acetaminophen, topical aloe vera, and loose dressings. His bullae enlarged the next day (FIGURE 3). One week later, his blisters were debrided and dressed with silver sulfadiazine at his plastic surgery follow-up. He experienced sensory deficits for a few months, but eventually made a full recovery after 6 months with no remaining sequelae.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Lisa Kim, MD, for her clinical care of this patient.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@ cuanschutz.edu

A 27-year-old man presented to the urgent care clinic with acute bilateral hand swelling, blisters, numbness, and pain. History taking revealed that these symptoms developed after he was locked outside of his apartment for 45 minutes in –22°C (–8°F) weather following a night of heavy drinking.

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 36.2°C (97.2°F) and a heart rate of 116 beats/min. He had

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Second-degree frostbite

Frostbite is the result of tissue freezing, which generally occurs after prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures (typically –4°C or below).1,2 The majority (~90%) of frostbite injuries occur in the hands and feet; however, frostbite has also been observed in the face, perineum, buttocks, and male genitalia.3

Frostbite is a clinical diagnosis based on a history of sustained exposure to freezing temperatures, paresthesia of affected areas, and typical skin changes. Evidence is lacking regarding the epidemiology of frostbite within the general population.2

Pathophysiology. Intra- and extracellular ice crystal formation causes fluid and electrolyte disturbances, cell dehydration, lipid denaturation, and subsequent cell death.1 After thawing, progressive tissue ischemia can occur as a result of endothelial damage and dysfunction, intravascular sludging, increased inflammatory markers, an influx of free radicals, and microvascular thrombosis.1

Classification. Traditionally, frostbite has been classified according to a 4-tiered system based on tissue appearance after rewarming.2 First-degree frostbite is characterized by white plaques with surrounding erythema; second degree by edema and clear or cloudy vesicles; third degree by hemorrhagic bullae; and fourth degree by cold and hard tissue that eventually progresses to gangrene.2

A simpler scheme designates frostbite as either superficial (corresponding to first- or second-degree frostbite) or deep (corresponding to third- or fourth-degree frostbite) with presumed muscle and bone involvement.2

Continue to: Risk factors

Risk factors. Frostbite is often associated with risk factors such as alcohol or drug intoxication, vehicular failure or trauma, immobilizing trauma, psychiatric illness, homelessness, Raynaud phenomenon, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, inadequate clothing, previous cold-weather injury, outdoor winter recreation, and the use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers).1-3 Apart from environmental exposure, frostbite can also occur by direct contact with freezing materials, such as ice packs or industrial refrigerants.3

Differential includes nonfreezing injuries

Frostnip, pernio, and trench foot are other cold-weather injuries distinguished by the absence of tissue freezing.4 Raynaud phenomenon is a condition that is triggered by either cold temperatures or emotional stress.5

Frostnip is characterized by pallor and paresthesia of exposed areas. It may precede frostbite, but it quickly resolves after rewarming.2

Pernio occurs when skin is exposed to damp, cold, nonfreezing environments.6 It results in edematous and inflammatory skin lesions that may be painful, pruritic, violaceous, or erythematous.6 These lesions are typically found over the fingers, toes, nose, ears, buttocks, or thighs.4,6 Pernio may be classified as either primary or secondary disease.5 Primary pernio is considered idiopathic.6 Secondary pernio is thought to be either drug induced or due to underlying autoimmune diseases, such as hepatitis or cryopathy.6

Trench foot develops under similar conditions to pernio but requires exposure to a wet environment for at least 10 to 14 hours.7 It is characterized by foot pain, paresthesia, pruritus, edema, erythema, cyanosis, blisters, and even gangrene if left untreated.7

Continue to: Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon results from transient, acral vasocontraction and manifests as well-demarcated pallor, cyanosis, and then erythema as the affected body part reperfuses.5 Similar to pernio, it can be categorized as either primary or secondary.5 Primary phenomenon is idiopathic. Secondary phenomenon is thought to be a result of autoimmune disease, use of certain medications, occupational vibratory exposure, obstructive vascular disease, or infection

In the absence of a history of exposure to subfreezing temperatures, frostbite can be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

Treatment entails rewarming

The aim of frostbite treatment is to save injured cells and minimize tissue loss.1 This is accomplished through rapid rewarming and—in severe cases—reperfusion techniques.

Tissue should be rewarmed in a 37°C to 39°C water bath with povidone iodine or chlorhexidine added for antiseptic effect.1 All efforts should be made to avoid refreezing or trauma, as this could worsen the initial injury.2 Oral or intravenous hydration may be offered to optimize fluid status.1 Supplemental oxygen may be administered to maintain saturations above 90%.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are helpful for analgesia and anti-inflammatory effect, and opioids can be used for breakthrough pain.1 It is recommended that blisters be drained in a sterile fashion and that all affected tissue be covered with topical aloe vera and a loose dressing.1,2,4

Treatment of severe frostbite. Angiography should be performed on all patients with third- or fourth-degree frostbite.3 If imaging shows evidence of vascular occlusion, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and heparin can be initiated within 24 hours to reduce the risk for amputation.8-10

Continue to: Iloprost is another...

Iloprost is another proposed treatment for severe frostbite. It is a prostacyclin analog that may lower the amputation rate in patients with at least third-degree frostbite.11 Unlike tPA, iloprost may be given to trauma patients, and it can be used more than 24 hours after injury.2

In cases of fourth-degree frostbite that is not successfully reperfused, amputation is delayed until dry gangrene develops. This often takes weeks to months.12

Our patient underwent rewarming and was orally rehydrated. He was discharged home with ibuprofen, oxycodone-acetaminophen, topical aloe vera, and loose dressings. His bullae enlarged the next day (FIGURE 3). One week later, his blisters were debrided and dressed with silver sulfadiazine at his plastic surgery follow-up. He experienced sensory deficits for a few months, but eventually made a full recovery after 6 months with no remaining sequelae.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Lisa Kim, MD, for her clinical care of this patient.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@ cuanschutz.edu

1. Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:281-299.

2. Heil K, Thomas R, Robertson G, et al. Freezing and non-freezing cold weather injuries: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2016;117:79-93.

3. Millet JD, Brown RK, Levi B, et al. Frostbite: spectrum of imaging findings and guidelines for management. Radiographics. 2016;36:2154-2169.

4. Long WB 3rd, Edlich RF, Winters KL, et al. Cold injuries. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2005;15:67-78.

5. Baker JS, Miranpuri S. Perniosis: a case report with literature review. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2016;106:138-140.

6. Bush JS, Watson S. Trench foot. Updated February 3, 2020. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482364/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

7. Musa R, Qurie A. Raynaud disease (Raynaud phenomenon, Raynaud syndrome). Updated February 14, 2019. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499833/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

8. Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546-551; discussion 551-553.

9. Gonzaga T, Jenabzadeh K, Anderson CP, et al. Use of intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy for acute treatment of frostbite in 62 patients with review of thrombolytic therapy in frostbite. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:e323-e334.

10. Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005;59:1350-1354; discussion 1354-1355.

11. Cauchy E, Cheguillaume B, Chetaille E. A controlled trial of a prostacyclin and rt-PA in the treatment of severe frostbite. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:189-190.

12. McIntosh SE, Opacic M, Freer L, et al; Wilderness Medical Society. Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of frostbite: 2014 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2014;25(4 suppl):S43-S54.

1. Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:281-299.

2. Heil K, Thomas R, Robertson G, et al. Freezing and non-freezing cold weather injuries: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2016;117:79-93.

3. Millet JD, Brown RK, Levi B, et al. Frostbite: spectrum of imaging findings and guidelines for management. Radiographics. 2016;36:2154-2169.

4. Long WB 3rd, Edlich RF, Winters KL, et al. Cold injuries. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2005;15:67-78.

5. Baker JS, Miranpuri S. Perniosis: a case report with literature review. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2016;106:138-140.

6. Bush JS, Watson S. Trench foot. Updated February 3, 2020. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482364/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

7. Musa R, Qurie A. Raynaud disease (Raynaud phenomenon, Raynaud syndrome). Updated February 14, 2019. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499833/. Accessed April 22, 2020.

8. Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546-551; discussion 551-553.

9. Gonzaga T, Jenabzadeh K, Anderson CP, et al. Use of intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy for acute treatment of frostbite in 62 patients with review of thrombolytic therapy in frostbite. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:e323-e334.

10. Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005;59:1350-1354; discussion 1354-1355.

11. Cauchy E, Cheguillaume B, Chetaille E. A controlled trial of a prostacyclin and rt-PA in the treatment of severe frostbite. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:189-190.

12. McIntosh SE, Opacic M, Freer L, et al; Wilderness Medical Society. Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of frostbite: 2014 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2014;25(4 suppl):S43-S54.

Sun-damage selfies give kids motivation to protect skin

Photo-manipulated selfies can provide adolescents an influential window into the wrinkled, sun-damaged future that may be theirs if they’re not careful, a new study suggests.

In the study, researchers found that Brazilian teenagers, especially girls, were more likely to protect themselves from the sun if they got glimpses of how sun exposure could damage their faces. “The intervention used in this study was effective in convincing a substantial part of the students to take up regular sunscreen use and to examine their own skin regularly,” they wrote. “Moreover, these effects were maintained for at least half a year.”

The study, led by Titus J. Brinker, MD, of the department of dermatology, in the National Center for Tumor Diseases, German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany, appeared online on May 6 in JAMA Dermatology (2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0511.

Dr. Brinker and colleagues launched the study in 2018 at eight public schools that serve grades 9-12 in Itaúna, a city in southeast Brazil, randomly assigning 1,573 students (52% girls, 48% boys; mean age, 16 years) to the intervention or control group.

Those in the intervention group attended seminars in which medical students showed them selfies of their classmates altered with a mobile phone app called Sunface, developed by Dr. Brinker.

The app, which takes the skin types of the subjects into account, was described by the Vice news site as “terrifying” in a 2018 article. It “could very well scare you into using sunscreen and wearing hats,” the author of that article wrote.

The app appeared to do just that – but not universally, according to the new study.

At 6 months, there was no change in sun protection habits in the control group. But among those remaining in the intervention group, the use of daily sunscreen significantly increased from 15% (110 of 734 students) during the 30 days prior to the survey, to 23% (139 of 607 students) at the 6-month follow-up (P less than .001), as did the percentage of those who performed at least one skin self-examination within the 6 months (25% to 49%; P less than .001). The students were slightly less likely to use tanning beds within the previous month (19% to 15%; P = .04); the researchers speculate that it’s easier to gain a new healthy habit than get rid of an old unhealthy one.

Girls were much more likely to change their habits than boys. The number needed to treat to reach the primary endpoint, daily sunscreen use, was 8 for girls and 31 for boys.

The researchers noted that the dropout rate was higher in the intervention group (17%) vs. the control group (6%). “The intervention may have led to strong adverse reactions in some students, leading to the observed higher dropout rate in the intervention group,” they wrote. Changes to the way the app is used could improve the dropout rate, but potentially hurt the intervention’s impact, they added.

In an accompanying editorial in JAMA Dermatology, two health intervention researchers wrote that “this work represents a needed shift toward scalable interventions that bring messaging to target populations using their preferred technology” (2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0510).

Referring to the finding that sunscreen use did not change much among the boys in the study, the authors, Sherry L. Pagoto, PhD, of the Institute for Collaborations on Health, Interventions, and Policy at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and Alan C. Geller, MPH, RN, of the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, also noted that “teen boys have been largely resistant to traditional and nontraditional forms of sun safety education.”

“Teasing out sex differences is important,” they added, “because sun protection interventions woven into existing programs at pools, beaches, and sporting events might be more appealing and enduring for boys, particularly if the technology they regularly use is leveraged.”

Dr. Brinker disclosed receiving an award from La Fondation la Roche-Posay, which also provided support for the study which partially funded the study, for his research on the Sunface app. The University of Itaúna provided other study funding. Several other study authors had various disclosures. Dr. Pagoto disclosed consulting work and personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, unrelated to the topic of the commentary; Dr. Geller had no disclosures.

SOURCES: Brinker TJ et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0511; Pagoto SL and Geller AC. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0510.

Photo-manipulated selfies can provide adolescents an influential window into the wrinkled, sun-damaged future that may be theirs if they’re not careful, a new study suggests.

In the study, researchers found that Brazilian teenagers, especially girls, were more likely to protect themselves from the sun if they got glimpses of how sun exposure could damage their faces. “The intervention used in this study was effective in convincing a substantial part of the students to take up regular sunscreen use and to examine their own skin regularly,” they wrote. “Moreover, these effects were maintained for at least half a year.”

The study, led by Titus J. Brinker, MD, of the department of dermatology, in the National Center for Tumor Diseases, German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany, appeared online on May 6 in JAMA Dermatology (2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0511.

Dr. Brinker and colleagues launched the study in 2018 at eight public schools that serve grades 9-12 in Itaúna, a city in southeast Brazil, randomly assigning 1,573 students (52% girls, 48% boys; mean age, 16 years) to the intervention or control group.

Those in the intervention group attended seminars in which medical students showed them selfies of their classmates altered with a mobile phone app called Sunface, developed by Dr. Brinker.

The app, which takes the skin types of the subjects into account, was described by the Vice news site as “terrifying” in a 2018 article. It “could very well scare you into using sunscreen and wearing hats,” the author of that article wrote.

The app appeared to do just that – but not universally, according to the new study.

At 6 months, there was no change in sun protection habits in the control group. But among those remaining in the intervention group, the use of daily sunscreen significantly increased from 15% (110 of 734 students) during the 30 days prior to the survey, to 23% (139 of 607 students) at the 6-month follow-up (P less than .001), as did the percentage of those who performed at least one skin self-examination within the 6 months (25% to 49%; P less than .001). The students were slightly less likely to use tanning beds within the previous month (19% to 15%; P = .04); the researchers speculate that it’s easier to gain a new healthy habit than get rid of an old unhealthy one.

Girls were much more likely to change their habits than boys. The number needed to treat to reach the primary endpoint, daily sunscreen use, was 8 for girls and 31 for boys.