User login

MCC response varies based on immunosuppression type, especially CLL

Patients with Merkel cell carcinoma and chronic immunosuppression may fare better or worse on immunotherapy based on the reason for immunosuppression, according to recent research at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

About 10% of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) are immunosuppressed at diagnosis, and these patients tend to have a more aggressive disease course and worse disease-specific survival compared with immunocompetent patients, Lauren Zawacki, a research assistant in the Nghiem Lab at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in her presentation. Although patients are receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 as treatments, the efficacy and side effects on immunosuppressed patients have not been well studied because many of these patients are not eligible for clinical trials.

Ms. Zawacki and colleagues analyzed data from a prospective Seattle registry of 1,442 patients with MCC, identifying 179 patients with MCC who had chronic immunosuppression due to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), solid organ transplants, autoimmune disorders, other hematological malignancies, and HIV and AIDS. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma comprised 7 of 8 patients in the group with other hematological malignancies, and Crohn’s disease made up 5 of 6 patients in the autoimmune disorder group. Of the 179 patients with MCC and immunosuppression, 31 patients were treated with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy.

There was an objective response rate of 52%, with 14 patients having a complete response, 2 patients having a partial response, and 15 patients experiencing disease progression. Of the patients with disease progression, 11 died of MCC. The response rate in immunocompromised patients is similar to results seen by her group in immunocompetent patients (Nghiem P et al. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:2542-52), said Ms. Zawacki. “While the overall objective response rate is comparable between immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients, the response rates vary greatly between the different types of immunosuppression,” she said.

When grouping response rates by immunosuppression type, they found 2 of 11 patients with CLL (18%) and 2 of 6 patients with autoimmune disease (33%) had an objective response, while 2 of 3 patients with HIV/AIDS (66%) and 7 of 7 patients with other hematologic malignancies (100%) had an objective response.

“While the numbers of the cohort are small, there still seems to be a considerable difference in the response rate between the different types of immune suppression, which is critical when we’re treating patients who typically have a more aggressive disease course,” said Ms. Zawacki.

In particular, the finding of no patients with MCC and CLL achieving a complete response interested Ms. Zawacki and her colleagues, since about one-fourth of patients in the Seattle registry have this combination of disease. “Not only did none of the CLL patients have a complete response, but 7 out of the 11 patients with CLL died from MCC,” she explained. When examining further, the researchers found 45% of patients in this group discontinued because of side effects of immunotherapy and had a median time to recurrence of 1.5 months. “This finding suggests that CLL in particular plays a large role in impairing the function of the immune system, leading to not only a more aggressive disease course, but a poorer response to immunotherapy,” she said.

“There is a significant need for improved interventions for patients with CLL and autoimmune disorders,” she added. “Research for immunosuppressed patients is critical given the associated aggressive disease course and their lack of inclusion in clinical trials.”

Ms. Zawacki acknowledged the small number of patients in the study as a limitation, and patients who received follow-up at outside facilities may have received slightly different care, which could impact adverse event reporting or reasons for study discontinuation.

“A multi-institutional study would be beneficial to expand the number of patients in that cohort and to help confirm the trend observed in this study. In addition, future studies should assess the role of combination systemic therapy, such as neutron radiation and immunotherapy together in order to see if the objective response can be approved among immunosuppressed patients,” she said.

This study was supported by funding from the MCC Patient Gift Fund, the National Cancer Institute, and a grant from NIH. Ms. Zawacki reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zawacki L. SID 2020, Abstract 497.

Patients with Merkel cell carcinoma and chronic immunosuppression may fare better or worse on immunotherapy based on the reason for immunosuppression, according to recent research at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

About 10% of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) are immunosuppressed at diagnosis, and these patients tend to have a more aggressive disease course and worse disease-specific survival compared with immunocompetent patients, Lauren Zawacki, a research assistant in the Nghiem Lab at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in her presentation. Although patients are receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 as treatments, the efficacy and side effects on immunosuppressed patients have not been well studied because many of these patients are not eligible for clinical trials.

Ms. Zawacki and colleagues analyzed data from a prospective Seattle registry of 1,442 patients with MCC, identifying 179 patients with MCC who had chronic immunosuppression due to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), solid organ transplants, autoimmune disorders, other hematological malignancies, and HIV and AIDS. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma comprised 7 of 8 patients in the group with other hematological malignancies, and Crohn’s disease made up 5 of 6 patients in the autoimmune disorder group. Of the 179 patients with MCC and immunosuppression, 31 patients were treated with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy.

There was an objective response rate of 52%, with 14 patients having a complete response, 2 patients having a partial response, and 15 patients experiencing disease progression. Of the patients with disease progression, 11 died of MCC. The response rate in immunocompromised patients is similar to results seen by her group in immunocompetent patients (Nghiem P et al. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:2542-52), said Ms. Zawacki. “While the overall objective response rate is comparable between immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients, the response rates vary greatly between the different types of immunosuppression,” she said.

When grouping response rates by immunosuppression type, they found 2 of 11 patients with CLL (18%) and 2 of 6 patients with autoimmune disease (33%) had an objective response, while 2 of 3 patients with HIV/AIDS (66%) and 7 of 7 patients with other hematologic malignancies (100%) had an objective response.

“While the numbers of the cohort are small, there still seems to be a considerable difference in the response rate between the different types of immune suppression, which is critical when we’re treating patients who typically have a more aggressive disease course,” said Ms. Zawacki.

In particular, the finding of no patients with MCC and CLL achieving a complete response interested Ms. Zawacki and her colleagues, since about one-fourth of patients in the Seattle registry have this combination of disease. “Not only did none of the CLL patients have a complete response, but 7 out of the 11 patients with CLL died from MCC,” she explained. When examining further, the researchers found 45% of patients in this group discontinued because of side effects of immunotherapy and had a median time to recurrence of 1.5 months. “This finding suggests that CLL in particular plays a large role in impairing the function of the immune system, leading to not only a more aggressive disease course, but a poorer response to immunotherapy,” she said.

“There is a significant need for improved interventions for patients with CLL and autoimmune disorders,” she added. “Research for immunosuppressed patients is critical given the associated aggressive disease course and their lack of inclusion in clinical trials.”

Ms. Zawacki acknowledged the small number of patients in the study as a limitation, and patients who received follow-up at outside facilities may have received slightly different care, which could impact adverse event reporting or reasons for study discontinuation.

“A multi-institutional study would be beneficial to expand the number of patients in that cohort and to help confirm the trend observed in this study. In addition, future studies should assess the role of combination systemic therapy, such as neutron radiation and immunotherapy together in order to see if the objective response can be approved among immunosuppressed patients,” she said.

This study was supported by funding from the MCC Patient Gift Fund, the National Cancer Institute, and a grant from NIH. Ms. Zawacki reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zawacki L. SID 2020, Abstract 497.

Patients with Merkel cell carcinoma and chronic immunosuppression may fare better or worse on immunotherapy based on the reason for immunosuppression, according to recent research at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

About 10% of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) are immunosuppressed at diagnosis, and these patients tend to have a more aggressive disease course and worse disease-specific survival compared with immunocompetent patients, Lauren Zawacki, a research assistant in the Nghiem Lab at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in her presentation. Although patients are receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 as treatments, the efficacy and side effects on immunosuppressed patients have not been well studied because many of these patients are not eligible for clinical trials.

Ms. Zawacki and colleagues analyzed data from a prospective Seattle registry of 1,442 patients with MCC, identifying 179 patients with MCC who had chronic immunosuppression due to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), solid organ transplants, autoimmune disorders, other hematological malignancies, and HIV and AIDS. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma comprised 7 of 8 patients in the group with other hematological malignancies, and Crohn’s disease made up 5 of 6 patients in the autoimmune disorder group. Of the 179 patients with MCC and immunosuppression, 31 patients were treated with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy.

There was an objective response rate of 52%, with 14 patients having a complete response, 2 patients having a partial response, and 15 patients experiencing disease progression. Of the patients with disease progression, 11 died of MCC. The response rate in immunocompromised patients is similar to results seen by her group in immunocompetent patients (Nghiem P et al. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:2542-52), said Ms. Zawacki. “While the overall objective response rate is comparable between immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients, the response rates vary greatly between the different types of immunosuppression,” she said.

When grouping response rates by immunosuppression type, they found 2 of 11 patients with CLL (18%) and 2 of 6 patients with autoimmune disease (33%) had an objective response, while 2 of 3 patients with HIV/AIDS (66%) and 7 of 7 patients with other hematologic malignancies (100%) had an objective response.

“While the numbers of the cohort are small, there still seems to be a considerable difference in the response rate between the different types of immune suppression, which is critical when we’re treating patients who typically have a more aggressive disease course,” said Ms. Zawacki.

In particular, the finding of no patients with MCC and CLL achieving a complete response interested Ms. Zawacki and her colleagues, since about one-fourth of patients in the Seattle registry have this combination of disease. “Not only did none of the CLL patients have a complete response, but 7 out of the 11 patients with CLL died from MCC,” she explained. When examining further, the researchers found 45% of patients in this group discontinued because of side effects of immunotherapy and had a median time to recurrence of 1.5 months. “This finding suggests that CLL in particular plays a large role in impairing the function of the immune system, leading to not only a more aggressive disease course, but a poorer response to immunotherapy,” she said.

“There is a significant need for improved interventions for patients with CLL and autoimmune disorders,” she added. “Research for immunosuppressed patients is critical given the associated aggressive disease course and their lack of inclusion in clinical trials.”

Ms. Zawacki acknowledged the small number of patients in the study as a limitation, and patients who received follow-up at outside facilities may have received slightly different care, which could impact adverse event reporting or reasons for study discontinuation.

“A multi-institutional study would be beneficial to expand the number of patients in that cohort and to help confirm the trend observed in this study. In addition, future studies should assess the role of combination systemic therapy, such as neutron radiation and immunotherapy together in order to see if the objective response can be approved among immunosuppressed patients,” she said.

This study was supported by funding from the MCC Patient Gift Fund, the National Cancer Institute, and a grant from NIH. Ms. Zawacki reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zawacki L. SID 2020, Abstract 497.

FROM SID 2020

California wildfires caused uptick in clinic visits for atopic dermatitis, itch

During the deadliest wildfire in California’s history in 2018, dermatology clinics 175 miles away at the University of California, San Francisco, experienced an increase in the number of pediatric and adult visits for pruritus and atopic dermatitis associated with air pollution created from the wildfire, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

Raj Fadadu, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, said in his presentation.

Not many studies have examined this potential association, but includes those that have found significant positive associations between exposure to air pollution and pruritus, the development of AD, and exacerbation of AD (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Nov;134[5]:993-9). Another study found outpatient visits for patients with eczema and dermatitis in Beijing increased as the level of particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide concentrations increased (Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2019 Jan 23;21[1]:163-73).

Mr. Faduda and colleagues set out to determine whether the number of appointments for and severity of skin disease increased as a result of the 2018 Camp Fire, which started in Paradise, Calif., using measures of air pollution and clinic visits in years where California did not experience a wildfire event as controls. Using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Hazard Mapping System for fire and smoke, the researchers graphed smoke plume density scores and particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations in the area. They then calculated the number of UCSF dermatology clinic visits for AD/eczema, and measured severity of skin disease with appointments for itch symptoms, and the number of prescribed medications during that time using ICD-10 codes.

The Camp Fire rapidly spread over a period of 17 days, between Nov. 8 and 25, 2018, during which time, PM2.5 particulate matter concentrations increased 10-fold, while the NOAA smoke plume density score sharply increased. More pediatric and adult patients also seemed to be visiting clinics during this time, compared with several weeks before and several weeks after the fire, prompting a more expanded analysis of this signal, Mr. Fadadu said.

He and his coinvestigators compared data between October 2015 and February 2016 – a period of time where there were no wildfires in California – with data in 2018, when the Camp Fire occurred. They collected data on 3,448 adults and 699 children across 3 years with a total of 5,539 adult appointments for AD, 924 pediatric appointments for AD, 1,319 adult itch appointments, and 294 pediatric itch appointments. Cumulative and exposure lags were used to measure the effect of the wildfire in a Poisson regression analysis.

They found that, during the wildfire, pediatric AD weekly clinic visits were 1.75 times higher (95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.50) and pediatric itch visits were 2.10 times higher (95% CI, 1.44-3.00), compared with weeks where there was no fire. During the wildfire, pediatric AD clinic visits increased by 8% (rate ratio, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.04-1.12) per 10 mcg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentration.

In adults, clinic visits for AD were 1.28 times higher (95% CI, 1.08-1.51) during the wildfire, compared with nonfire weeks. While there was a positive association between pollution exposure and adult AD, “this effect is less than what we observed” for pediatric AD visits, said Mr. Fadadu. Air pollution was positively associated with the development of itch symptoms in adults and more prescriptions for AD medications, but the results were not statistically significant.

“This may be explained by the fact that 80% of pediatric itch patients carried an AD diagnosis, while in contrast, only half of the adult itch patients also have a diagnosis of AD,” he said.

While there are several possible limitations of the research, including assessment of air pollution exposure, Mr. Fadadu said, “these results can inform how dermatologists counsel patients during future episodes of poor air quality, as well as expand comprehension of the broader health effects of climate change that can significantly impact quality of life.”

This study was funded by the UCSF Summer Explore Fellowship, Marguerite Schoeneman Award, and Joint Medical Program Thesis Grant.

During the deadliest wildfire in California’s history in 2018, dermatology clinics 175 miles away at the University of California, San Francisco, experienced an increase in the number of pediatric and adult visits for pruritus and atopic dermatitis associated with air pollution created from the wildfire, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

Raj Fadadu, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, said in his presentation.

Not many studies have examined this potential association, but includes those that have found significant positive associations between exposure to air pollution and pruritus, the development of AD, and exacerbation of AD (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Nov;134[5]:993-9). Another study found outpatient visits for patients with eczema and dermatitis in Beijing increased as the level of particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide concentrations increased (Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2019 Jan 23;21[1]:163-73).

Mr. Faduda and colleagues set out to determine whether the number of appointments for and severity of skin disease increased as a result of the 2018 Camp Fire, which started in Paradise, Calif., using measures of air pollution and clinic visits in years where California did not experience a wildfire event as controls. Using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Hazard Mapping System for fire and smoke, the researchers graphed smoke plume density scores and particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations in the area. They then calculated the number of UCSF dermatology clinic visits for AD/eczema, and measured severity of skin disease with appointments for itch symptoms, and the number of prescribed medications during that time using ICD-10 codes.

The Camp Fire rapidly spread over a period of 17 days, between Nov. 8 and 25, 2018, during which time, PM2.5 particulate matter concentrations increased 10-fold, while the NOAA smoke plume density score sharply increased. More pediatric and adult patients also seemed to be visiting clinics during this time, compared with several weeks before and several weeks after the fire, prompting a more expanded analysis of this signal, Mr. Fadadu said.

He and his coinvestigators compared data between October 2015 and February 2016 – a period of time where there were no wildfires in California – with data in 2018, when the Camp Fire occurred. They collected data on 3,448 adults and 699 children across 3 years with a total of 5,539 adult appointments for AD, 924 pediatric appointments for AD, 1,319 adult itch appointments, and 294 pediatric itch appointments. Cumulative and exposure lags were used to measure the effect of the wildfire in a Poisson regression analysis.

They found that, during the wildfire, pediatric AD weekly clinic visits were 1.75 times higher (95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.50) and pediatric itch visits were 2.10 times higher (95% CI, 1.44-3.00), compared with weeks where there was no fire. During the wildfire, pediatric AD clinic visits increased by 8% (rate ratio, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.04-1.12) per 10 mcg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentration.

In adults, clinic visits for AD were 1.28 times higher (95% CI, 1.08-1.51) during the wildfire, compared with nonfire weeks. While there was a positive association between pollution exposure and adult AD, “this effect is less than what we observed” for pediatric AD visits, said Mr. Fadadu. Air pollution was positively associated with the development of itch symptoms in adults and more prescriptions for AD medications, but the results were not statistically significant.

“This may be explained by the fact that 80% of pediatric itch patients carried an AD diagnosis, while in contrast, only half of the adult itch patients also have a diagnosis of AD,” he said.

While there are several possible limitations of the research, including assessment of air pollution exposure, Mr. Fadadu said, “these results can inform how dermatologists counsel patients during future episodes of poor air quality, as well as expand comprehension of the broader health effects of climate change that can significantly impact quality of life.”

This study was funded by the UCSF Summer Explore Fellowship, Marguerite Schoeneman Award, and Joint Medical Program Thesis Grant.

During the deadliest wildfire in California’s history in 2018, dermatology clinics 175 miles away at the University of California, San Francisco, experienced an increase in the number of pediatric and adult visits for pruritus and atopic dermatitis associated with air pollution created from the wildfire, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

Raj Fadadu, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, said in his presentation.

Not many studies have examined this potential association, but includes those that have found significant positive associations between exposure to air pollution and pruritus, the development of AD, and exacerbation of AD (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Nov;134[5]:993-9). Another study found outpatient visits for patients with eczema and dermatitis in Beijing increased as the level of particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide concentrations increased (Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2019 Jan 23;21[1]:163-73).

Mr. Faduda and colleagues set out to determine whether the number of appointments for and severity of skin disease increased as a result of the 2018 Camp Fire, which started in Paradise, Calif., using measures of air pollution and clinic visits in years where California did not experience a wildfire event as controls. Using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Hazard Mapping System for fire and smoke, the researchers graphed smoke plume density scores and particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations in the area. They then calculated the number of UCSF dermatology clinic visits for AD/eczema, and measured severity of skin disease with appointments for itch symptoms, and the number of prescribed medications during that time using ICD-10 codes.

The Camp Fire rapidly spread over a period of 17 days, between Nov. 8 and 25, 2018, during which time, PM2.5 particulate matter concentrations increased 10-fold, while the NOAA smoke plume density score sharply increased. More pediatric and adult patients also seemed to be visiting clinics during this time, compared with several weeks before and several weeks after the fire, prompting a more expanded analysis of this signal, Mr. Fadadu said.

He and his coinvestigators compared data between October 2015 and February 2016 – a period of time where there were no wildfires in California – with data in 2018, when the Camp Fire occurred. They collected data on 3,448 adults and 699 children across 3 years with a total of 5,539 adult appointments for AD, 924 pediatric appointments for AD, 1,319 adult itch appointments, and 294 pediatric itch appointments. Cumulative and exposure lags were used to measure the effect of the wildfire in a Poisson regression analysis.

They found that, during the wildfire, pediatric AD weekly clinic visits were 1.75 times higher (95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.50) and pediatric itch visits were 2.10 times higher (95% CI, 1.44-3.00), compared with weeks where there was no fire. During the wildfire, pediatric AD clinic visits increased by 8% (rate ratio, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.04-1.12) per 10 mcg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentration.

In adults, clinic visits for AD were 1.28 times higher (95% CI, 1.08-1.51) during the wildfire, compared with nonfire weeks. While there was a positive association between pollution exposure and adult AD, “this effect is less than what we observed” for pediatric AD visits, said Mr. Fadadu. Air pollution was positively associated with the development of itch symptoms in adults and more prescriptions for AD medications, but the results were not statistically significant.

“This may be explained by the fact that 80% of pediatric itch patients carried an AD diagnosis, while in contrast, only half of the adult itch patients also have a diagnosis of AD,” he said.

While there are several possible limitations of the research, including assessment of air pollution exposure, Mr. Fadadu said, “these results can inform how dermatologists counsel patients during future episodes of poor air quality, as well as expand comprehension of the broader health effects of climate change that can significantly impact quality of life.”

This study was funded by the UCSF Summer Explore Fellowship, Marguerite Schoeneman Award, and Joint Medical Program Thesis Grant.

FROM SID 2020

Rapid-onset rash

A diagnosis of guttate psoriasis was made based on the physical exam findings and the preceding group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection.

This condition affects approximately 2% of all patients with psoriasis; it is characterized by the acute onset of multiple erythematous and scaly papules and small plaques that look like droplets (“gutta”). It tends to affect children and young adults and typically occurs following an acute infection (eg, streptococcal pharyngitis). In this case, a rapid strep test was positive for group A Streptococcus, which supported the diagnosis.

The differential includes skin conditions such as pityriasis rosea, tinea corporis, and contact dermatitis.

The first-line treatment for streptococcal infection is amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d [maximum: 1000 mg/d] orally for 10 d) or penicillin G benzathine (for children < 60 lb, 6 × 105 units intramuscularly; children ≥ 60 lb, 1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly). For the psoriasis lesions, treatment options include topical steroids, vitamin D derivatives, or combinations of both. In most cases, guttate psoriasis completely resolves. However, one-third of children with guttate psoriasis go on to develop plaque psoriasis later in life.

This patient was treated with penicillin G benzathine (1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly) and a calcipotriol/betamethasone combination gel. However, a less costly treatment is generic betamethasone (or triamcinolone) and/or generic calcipotriol (a vitamin D derivative). The streptococcal infection and skin lesions completely resolved. No adverse events were reported, and no relapse was observed after 3 months.

This case was adapted from: Matos RS, Torres T. Rapid onset rash in child. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:E1-E2.

A diagnosis of guttate psoriasis was made based on the physical exam findings and the preceding group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection.

This condition affects approximately 2% of all patients with psoriasis; it is characterized by the acute onset of multiple erythematous and scaly papules and small plaques that look like droplets (“gutta”). It tends to affect children and young adults and typically occurs following an acute infection (eg, streptococcal pharyngitis). In this case, a rapid strep test was positive for group A Streptococcus, which supported the diagnosis.

The differential includes skin conditions such as pityriasis rosea, tinea corporis, and contact dermatitis.

The first-line treatment for streptococcal infection is amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d [maximum: 1000 mg/d] orally for 10 d) or penicillin G benzathine (for children < 60 lb, 6 × 105 units intramuscularly; children ≥ 60 lb, 1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly). For the psoriasis lesions, treatment options include topical steroids, vitamin D derivatives, or combinations of both. In most cases, guttate psoriasis completely resolves. However, one-third of children with guttate psoriasis go on to develop plaque psoriasis later in life.

This patient was treated with penicillin G benzathine (1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly) and a calcipotriol/betamethasone combination gel. However, a less costly treatment is generic betamethasone (or triamcinolone) and/or generic calcipotriol (a vitamin D derivative). The streptococcal infection and skin lesions completely resolved. No adverse events were reported, and no relapse was observed after 3 months.

This case was adapted from: Matos RS, Torres T. Rapid onset rash in child. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:E1-E2.

A diagnosis of guttate psoriasis was made based on the physical exam findings and the preceding group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection.

This condition affects approximately 2% of all patients with psoriasis; it is characterized by the acute onset of multiple erythematous and scaly papules and small plaques that look like droplets (“gutta”). It tends to affect children and young adults and typically occurs following an acute infection (eg, streptococcal pharyngitis). In this case, a rapid strep test was positive for group A Streptococcus, which supported the diagnosis.

The differential includes skin conditions such as pityriasis rosea, tinea corporis, and contact dermatitis.

The first-line treatment for streptococcal infection is amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d [maximum: 1000 mg/d] orally for 10 d) or penicillin G benzathine (for children < 60 lb, 6 × 105 units intramuscularly; children ≥ 60 lb, 1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly). For the psoriasis lesions, treatment options include topical steroids, vitamin D derivatives, or combinations of both. In most cases, guttate psoriasis completely resolves. However, one-third of children with guttate psoriasis go on to develop plaque psoriasis later in life.

This patient was treated with penicillin G benzathine (1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly) and a calcipotriol/betamethasone combination gel. However, a less costly treatment is generic betamethasone (or triamcinolone) and/or generic calcipotriol (a vitamin D derivative). The streptococcal infection and skin lesions completely resolved. No adverse events were reported, and no relapse was observed after 3 months.

This case was adapted from: Matos RS, Torres T. Rapid onset rash in child. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:E1-E2.

COVID-19 complicates prescribing for children with inflammatory skin disease

designed to offer guidance to specialists and nonspecialists faced with tough choices about risks.

Some 87% reported that they were reducing the frequency of lab monitoring for some medications, while more than half said they had reached out to patients and their families to discuss the implications of continuing or stopping a drug.

Virtually all – 97% – said that the COVID-19 crisis had affected their decision to initiate immunosuppressive medications, with 84% saying the decision depended on a patient’s risk factors for contracting COVID-19 infection, and also the potential consequences of infection while treated, compared with the risks of not optimally treating the skin condition.

To develop a consensus-based guidance for clinicians, published online April 22 in Pediatric Dermatology, Kelly Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, assembled a task force of pediatric dermatologists at academic institutions (the Pediatric Dermatology COVID-19 Response Task Force). Together with Sean Reynolds, MD, a pediatric dermatology fellow at UCSF and colleagues, they issued a survey to the 37 members of the task force with questions on how the pandemic has affected their prescribing decisions and certain therapies specifically. All the recipients responded.

The dermatologists were asked about conventional systemic and biologic medications. Most felt confident in continuing biologics, with 78% saying they would keep patients with no signs of COVID-19 exposure or infection on tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. More than 90% of respondents said they would continue patients on dupilumab, as well as anti–interleukin (IL)–17, anti–IL-12/23, and anti–IL-23 therapies.

Responses varied more on approaches to the nonbiologic treatments. Fewer than half (46%) said they would continue patients without apparent COVID-19 exposure on systemic steroids, with another 46% saying it depended on the clinical context.

For other systemic therapies, respondents were more likely to want to continue their patients with no signs or symptoms of COVID-19 on methotrexate and apremilast (78% and 83%, respectively) than others (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and JAK inhibitors), which saw between 50% and 60% support in the survey.

Patients on any immunosuppressive medications with likely exposure to COVID-19 or who test positive for the virus should be temporarily taken off their medications, the majority concurred. Exceptions were for systemic steroids, which must be tapered. And a significant minority of the dermatologists said that they would continue apremilast or dupilumab (24% and 16%, respectively) in the event of a confirmed COVID-19 infection.

In an interview, Dr. Cordoro commented that, even in normal times, most systemic or biological immunosuppressive treatments are used off-label by pediatric dermatologists. “There’s no way this could have been an evidence-based document, as we didn’t have the data to drive this. Many of the medications have been tested in children but not necessarily for dermatologic indications; some are chemotherapy agents or drugs used in rheumatologic diseases.”

The COVID-19 pandemic complicated an already difficult decision-making process, she said.

The researchers cautioned against attempting to make decisions about medications based on data on other infections from clinical trials. “Infection data from standard infections that were identified and watched for in clinical trials really still has no bearing on COVID-19 because it’s such a different virus,” Dr. Cordoro said.

And while some immunosuppressive medications could potentially attenuate a SARS-CoV-2–induced cytokine storm, “we certainly don’t assume this is necessarily going to help.”

The authors advised that physicians anxious about initiating an immunosuppressive treatment should take into consideration whether early intervention could “prevent permanent physical impairment or disfigurement” in diseases such as erythrodermic pustular psoriasis or rapidly progressive linear morphea.

Other diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, “may be acceptably, though not optimally, managed with topical and other home-based therapeutic options” during the pandemic, they wrote.

Dr. Cordoro commented that, given how fast new findings are emerging from the pandemic, the guidance on medications could change. “We will know so much more 3 months from now,” she said. And while there are no formal plans to reissue the survey, “we’re maintaining communication and will have some kind of follow up” with the academic dermatologists.

“If we recognize any signals that are counter to what we say in this work we will immediately let people know,” she said.

The researchers received no outside funding for their study. Of the study’s 24 coauthors, nine disclosed financial relationships with industry.

SOURCE: Add the first auSOURCE: Reynolds et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/pde.14202.

designed to offer guidance to specialists and nonspecialists faced with tough choices about risks.

Some 87% reported that they were reducing the frequency of lab monitoring for some medications, while more than half said they had reached out to patients and their families to discuss the implications of continuing or stopping a drug.

Virtually all – 97% – said that the COVID-19 crisis had affected their decision to initiate immunosuppressive medications, with 84% saying the decision depended on a patient’s risk factors for contracting COVID-19 infection, and also the potential consequences of infection while treated, compared with the risks of not optimally treating the skin condition.

To develop a consensus-based guidance for clinicians, published online April 22 in Pediatric Dermatology, Kelly Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, assembled a task force of pediatric dermatologists at academic institutions (the Pediatric Dermatology COVID-19 Response Task Force). Together with Sean Reynolds, MD, a pediatric dermatology fellow at UCSF and colleagues, they issued a survey to the 37 members of the task force with questions on how the pandemic has affected their prescribing decisions and certain therapies specifically. All the recipients responded.

The dermatologists were asked about conventional systemic and biologic medications. Most felt confident in continuing biologics, with 78% saying they would keep patients with no signs of COVID-19 exposure or infection on tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. More than 90% of respondents said they would continue patients on dupilumab, as well as anti–interleukin (IL)–17, anti–IL-12/23, and anti–IL-23 therapies.

Responses varied more on approaches to the nonbiologic treatments. Fewer than half (46%) said they would continue patients without apparent COVID-19 exposure on systemic steroids, with another 46% saying it depended on the clinical context.

For other systemic therapies, respondents were more likely to want to continue their patients with no signs or symptoms of COVID-19 on methotrexate and apremilast (78% and 83%, respectively) than others (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and JAK inhibitors), which saw between 50% and 60% support in the survey.

Patients on any immunosuppressive medications with likely exposure to COVID-19 or who test positive for the virus should be temporarily taken off their medications, the majority concurred. Exceptions were for systemic steroids, which must be tapered. And a significant minority of the dermatologists said that they would continue apremilast or dupilumab (24% and 16%, respectively) in the event of a confirmed COVID-19 infection.

In an interview, Dr. Cordoro commented that, even in normal times, most systemic or biological immunosuppressive treatments are used off-label by pediatric dermatologists. “There’s no way this could have been an evidence-based document, as we didn’t have the data to drive this. Many of the medications have been tested in children but not necessarily for dermatologic indications; some are chemotherapy agents or drugs used in rheumatologic diseases.”

The COVID-19 pandemic complicated an already difficult decision-making process, she said.

The researchers cautioned against attempting to make decisions about medications based on data on other infections from clinical trials. “Infection data from standard infections that were identified and watched for in clinical trials really still has no bearing on COVID-19 because it’s such a different virus,” Dr. Cordoro said.

And while some immunosuppressive medications could potentially attenuate a SARS-CoV-2–induced cytokine storm, “we certainly don’t assume this is necessarily going to help.”

The authors advised that physicians anxious about initiating an immunosuppressive treatment should take into consideration whether early intervention could “prevent permanent physical impairment or disfigurement” in diseases such as erythrodermic pustular psoriasis or rapidly progressive linear morphea.

Other diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, “may be acceptably, though not optimally, managed with topical and other home-based therapeutic options” during the pandemic, they wrote.

Dr. Cordoro commented that, given how fast new findings are emerging from the pandemic, the guidance on medications could change. “We will know so much more 3 months from now,” she said. And while there are no formal plans to reissue the survey, “we’re maintaining communication and will have some kind of follow up” with the academic dermatologists.

“If we recognize any signals that are counter to what we say in this work we will immediately let people know,” she said.

The researchers received no outside funding for their study. Of the study’s 24 coauthors, nine disclosed financial relationships with industry.

SOURCE: Add the first auSOURCE: Reynolds et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/pde.14202.

designed to offer guidance to specialists and nonspecialists faced with tough choices about risks.

Some 87% reported that they were reducing the frequency of lab monitoring for some medications, while more than half said they had reached out to patients and their families to discuss the implications of continuing or stopping a drug.

Virtually all – 97% – said that the COVID-19 crisis had affected their decision to initiate immunosuppressive medications, with 84% saying the decision depended on a patient’s risk factors for contracting COVID-19 infection, and also the potential consequences of infection while treated, compared with the risks of not optimally treating the skin condition.

To develop a consensus-based guidance for clinicians, published online April 22 in Pediatric Dermatology, Kelly Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, assembled a task force of pediatric dermatologists at academic institutions (the Pediatric Dermatology COVID-19 Response Task Force). Together with Sean Reynolds, MD, a pediatric dermatology fellow at UCSF and colleagues, they issued a survey to the 37 members of the task force with questions on how the pandemic has affected their prescribing decisions and certain therapies specifically. All the recipients responded.

The dermatologists were asked about conventional systemic and biologic medications. Most felt confident in continuing biologics, with 78% saying they would keep patients with no signs of COVID-19 exposure or infection on tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. More than 90% of respondents said they would continue patients on dupilumab, as well as anti–interleukin (IL)–17, anti–IL-12/23, and anti–IL-23 therapies.

Responses varied more on approaches to the nonbiologic treatments. Fewer than half (46%) said they would continue patients without apparent COVID-19 exposure on systemic steroids, with another 46% saying it depended on the clinical context.

For other systemic therapies, respondents were more likely to want to continue their patients with no signs or symptoms of COVID-19 on methotrexate and apremilast (78% and 83%, respectively) than others (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and JAK inhibitors), which saw between 50% and 60% support in the survey.

Patients on any immunosuppressive medications with likely exposure to COVID-19 or who test positive for the virus should be temporarily taken off their medications, the majority concurred. Exceptions were for systemic steroids, which must be tapered. And a significant minority of the dermatologists said that they would continue apremilast or dupilumab (24% and 16%, respectively) in the event of a confirmed COVID-19 infection.

In an interview, Dr. Cordoro commented that, even in normal times, most systemic or biological immunosuppressive treatments are used off-label by pediatric dermatologists. “There’s no way this could have been an evidence-based document, as we didn’t have the data to drive this. Many of the medications have been tested in children but not necessarily for dermatologic indications; some are chemotherapy agents or drugs used in rheumatologic diseases.”

The COVID-19 pandemic complicated an already difficult decision-making process, she said.

The researchers cautioned against attempting to make decisions about medications based on data on other infections from clinical trials. “Infection data from standard infections that were identified and watched for in clinical trials really still has no bearing on COVID-19 because it’s such a different virus,” Dr. Cordoro said.

And while some immunosuppressive medications could potentially attenuate a SARS-CoV-2–induced cytokine storm, “we certainly don’t assume this is necessarily going to help.”

The authors advised that physicians anxious about initiating an immunosuppressive treatment should take into consideration whether early intervention could “prevent permanent physical impairment or disfigurement” in diseases such as erythrodermic pustular psoriasis or rapidly progressive linear morphea.

Other diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, “may be acceptably, though not optimally, managed with topical and other home-based therapeutic options” during the pandemic, they wrote.

Dr. Cordoro commented that, given how fast new findings are emerging from the pandemic, the guidance on medications could change. “We will know so much more 3 months from now,” she said. And while there are no formal plans to reissue the survey, “we’re maintaining communication and will have some kind of follow up” with the academic dermatologists.

“If we recognize any signals that are counter to what we say in this work we will immediately let people know,” she said.

The researchers received no outside funding for their study. Of the study’s 24 coauthors, nine disclosed financial relationships with industry.

SOURCE: Add the first auSOURCE: Reynolds et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/pde.14202.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Hyperkalemia most common adverse event in women taking spironolactone

, according to new research.

Spironolactone, which is approved to treat heart failure, hypertension, edema, and primary hyperaldosteronism, has antagonistic effects on progesterone and androgen receptors and has been used as an off-label treatment for acne in women. “Numerous guidelines have recommended its off-label use for acne therapy to avoid antibiotic resistance and potential side effects,” wrote Yu Wang of Stony Brook (N.Y.) University and Shari R. Lipner MD, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Their report is in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

In a retrospective study, the investigators analyzed 7,920 adverse events with spironolactone reported by women of all ages between Jan. 1, 1969, and Dec. 30, 2018, to the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System database, for all indications. The most common adverse event was hyperkalemia, reported in 16.1%, followed by kidney injury (15.2%) and drug interactions (9%). Of the 1,272 cases of hyperkalemia reported, 25 occurred in women aged 45 years or younger; 59.3% occurred in women aged 65-85 years.

While spironolactone prescribing information was not available, the investigators compared yearly reports of adverse events with annual public interest in spironolactone using the Google Trends search term spironolactone and annual scholarly mentions of spironolactone in the Altmetric database. There was a strong correlation between the number of cases reported to the FDA and the Google Trends search (Spearman coefficient, 0.94; P less than .001) and to the Altmetric database (Spearman coefficient, 0.64; P less than .01).

Noting that hyperkalemia is “exceptionally uncommon” in women aged 45 years and younger, the investigators concluded that “in the absence of risk factors for hyperkalemia or reduced renal function, potassium laboratory monitoring is unnecessary in younger females taking spironolactone.” Because the incidence increases with age, “interval laboratory monitoring is recommended for females older than 45 years old,” they noted.

Limitations of the study, they noted, include the retrospective design and no available data before 1969. “In addition, since the [FDA Adverse Event Reporting System] data does not differentiate whether spironolactone was prescribed for heart failure, hypertension, edema, primary hyperaldosteronism, or for acne,” the study could not control for these or other confounding comorbidities or associated therapies.

“For future studies, it is important to analyze drug interactions more carefully to determine which other medications may potentiate the risk for hyperkalemia in patients taking spironolactone. It is also important to quantitate overall U.S. prescription data to better understand the relative frequency of these adverse effects reported to the FDA,” they wrote.

The investigators reported that they had no conflicts of interest; the study had no funding.

SOURCE: Wang Y, Lipner SR. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.05.002.

, according to new research.

Spironolactone, which is approved to treat heart failure, hypertension, edema, and primary hyperaldosteronism, has antagonistic effects on progesterone and androgen receptors and has been used as an off-label treatment for acne in women. “Numerous guidelines have recommended its off-label use for acne therapy to avoid antibiotic resistance and potential side effects,” wrote Yu Wang of Stony Brook (N.Y.) University and Shari R. Lipner MD, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Their report is in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

In a retrospective study, the investigators analyzed 7,920 adverse events with spironolactone reported by women of all ages between Jan. 1, 1969, and Dec. 30, 2018, to the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System database, for all indications. The most common adverse event was hyperkalemia, reported in 16.1%, followed by kidney injury (15.2%) and drug interactions (9%). Of the 1,272 cases of hyperkalemia reported, 25 occurred in women aged 45 years or younger; 59.3% occurred in women aged 65-85 years.

While spironolactone prescribing information was not available, the investigators compared yearly reports of adverse events with annual public interest in spironolactone using the Google Trends search term spironolactone and annual scholarly mentions of spironolactone in the Altmetric database. There was a strong correlation between the number of cases reported to the FDA and the Google Trends search (Spearman coefficient, 0.94; P less than .001) and to the Altmetric database (Spearman coefficient, 0.64; P less than .01).

Noting that hyperkalemia is “exceptionally uncommon” in women aged 45 years and younger, the investigators concluded that “in the absence of risk factors for hyperkalemia or reduced renal function, potassium laboratory monitoring is unnecessary in younger females taking spironolactone.” Because the incidence increases with age, “interval laboratory monitoring is recommended for females older than 45 years old,” they noted.

Limitations of the study, they noted, include the retrospective design and no available data before 1969. “In addition, since the [FDA Adverse Event Reporting System] data does not differentiate whether spironolactone was prescribed for heart failure, hypertension, edema, primary hyperaldosteronism, or for acne,” the study could not control for these or other confounding comorbidities or associated therapies.

“For future studies, it is important to analyze drug interactions more carefully to determine which other medications may potentiate the risk for hyperkalemia in patients taking spironolactone. It is also important to quantitate overall U.S. prescription data to better understand the relative frequency of these adverse effects reported to the FDA,” they wrote.

The investigators reported that they had no conflicts of interest; the study had no funding.

SOURCE: Wang Y, Lipner SR. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.05.002.

, according to new research.

Spironolactone, which is approved to treat heart failure, hypertension, edema, and primary hyperaldosteronism, has antagonistic effects on progesterone and androgen receptors and has been used as an off-label treatment for acne in women. “Numerous guidelines have recommended its off-label use for acne therapy to avoid antibiotic resistance and potential side effects,” wrote Yu Wang of Stony Brook (N.Y.) University and Shari R. Lipner MD, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Their report is in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

In a retrospective study, the investigators analyzed 7,920 adverse events with spironolactone reported by women of all ages between Jan. 1, 1969, and Dec. 30, 2018, to the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System database, for all indications. The most common adverse event was hyperkalemia, reported in 16.1%, followed by kidney injury (15.2%) and drug interactions (9%). Of the 1,272 cases of hyperkalemia reported, 25 occurred in women aged 45 years or younger; 59.3% occurred in women aged 65-85 years.

While spironolactone prescribing information was not available, the investigators compared yearly reports of adverse events with annual public interest in spironolactone using the Google Trends search term spironolactone and annual scholarly mentions of spironolactone in the Altmetric database. There was a strong correlation between the number of cases reported to the FDA and the Google Trends search (Spearman coefficient, 0.94; P less than .001) and to the Altmetric database (Spearman coefficient, 0.64; P less than .01).

Noting that hyperkalemia is “exceptionally uncommon” in women aged 45 years and younger, the investigators concluded that “in the absence of risk factors for hyperkalemia or reduced renal function, potassium laboratory monitoring is unnecessary in younger females taking spironolactone.” Because the incidence increases with age, “interval laboratory monitoring is recommended for females older than 45 years old,” they noted.

Limitations of the study, they noted, include the retrospective design and no available data before 1969. “In addition, since the [FDA Adverse Event Reporting System] data does not differentiate whether spironolactone was prescribed for heart failure, hypertension, edema, primary hyperaldosteronism, or for acne,” the study could not control for these or other confounding comorbidities or associated therapies.

“For future studies, it is important to analyze drug interactions more carefully to determine which other medications may potentiate the risk for hyperkalemia in patients taking spironolactone. It is also important to quantitate overall U.S. prescription data to better understand the relative frequency of these adverse effects reported to the FDA,” they wrote.

The investigators reported that they had no conflicts of interest; the study had no funding.

SOURCE: Wang Y, Lipner SR. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.05.002.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S DERMATOLOGY

Biologic approved for atopic dermatitis in children

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dupilumab for children aged 6-11 years with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, the manufacturers announced.

The new indication is for children “whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable,” Regeneron and Sanofi said in a press release, which points out that this is the first biologic approved for AD in this age group.

For children aged 6-11, the two available dupilumab (Dupixent) doses in prefilled syringes are given based on weight – 300 mg every 4 weeks for children between 15 to 29 kg and 200 mg every 2 weeks for children 30 to 59 kg – following an initial loading dose.

In phase 3 trials, children with severe AD who received dupilumab and topical corticosteroids improved significantly in overall disease severity, skin clearance, and itch, compared with those getting steroids alone. Eczema Area and Severity Index-75, for example, was reached by 75% of patients on either dupilumab dose, compared with 28% and 26% , respectively, for those receiving steroids alone every 4 and every 2 weeks, the statement said.

Over the 16-week treatment period, overall rates of adverse events were 65% for those getting dupilumab every 4 weeks and 61% for every 2 weeks – compared with steroids alone (72% and 75%, respectively), the statement said.

The fully human monoclonal antibody inhibits signaling of the interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 proteins and is already approved as an add-on maintenance treatment in children aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma (eosinophilic phenotype or oral-corticosteroid dependent) and in adults with inadequately controlled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, according to the prescribing information.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dupilumab for children aged 6-11 years with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, the manufacturers announced.

The new indication is for children “whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable,” Regeneron and Sanofi said in a press release, which points out that this is the first biologic approved for AD in this age group.

For children aged 6-11, the two available dupilumab (Dupixent) doses in prefilled syringes are given based on weight – 300 mg every 4 weeks for children between 15 to 29 kg and 200 mg every 2 weeks for children 30 to 59 kg – following an initial loading dose.

In phase 3 trials, children with severe AD who received dupilumab and topical corticosteroids improved significantly in overall disease severity, skin clearance, and itch, compared with those getting steroids alone. Eczema Area and Severity Index-75, for example, was reached by 75% of patients on either dupilumab dose, compared with 28% and 26% , respectively, for those receiving steroids alone every 4 and every 2 weeks, the statement said.

Over the 16-week treatment period, overall rates of adverse events were 65% for those getting dupilumab every 4 weeks and 61% for every 2 weeks – compared with steroids alone (72% and 75%, respectively), the statement said.

The fully human monoclonal antibody inhibits signaling of the interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 proteins and is already approved as an add-on maintenance treatment in children aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma (eosinophilic phenotype or oral-corticosteroid dependent) and in adults with inadequately controlled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, according to the prescribing information.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dupilumab for children aged 6-11 years with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, the manufacturers announced.

The new indication is for children “whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable,” Regeneron and Sanofi said in a press release, which points out that this is the first biologic approved for AD in this age group.

For children aged 6-11, the two available dupilumab (Dupixent) doses in prefilled syringes are given based on weight – 300 mg every 4 weeks for children between 15 to 29 kg and 200 mg every 2 weeks for children 30 to 59 kg – following an initial loading dose.

In phase 3 trials, children with severe AD who received dupilumab and topical corticosteroids improved significantly in overall disease severity, skin clearance, and itch, compared with those getting steroids alone. Eczema Area and Severity Index-75, for example, was reached by 75% of patients on either dupilumab dose, compared with 28% and 26% , respectively, for those receiving steroids alone every 4 and every 2 weeks, the statement said.

Over the 16-week treatment period, overall rates of adverse events were 65% for those getting dupilumab every 4 weeks and 61% for every 2 weeks – compared with steroids alone (72% and 75%, respectively), the statement said.

The fully human monoclonal antibody inhibits signaling of the interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 proteins and is already approved as an add-on maintenance treatment in children aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma (eosinophilic phenotype or oral-corticosteroid dependent) and in adults with inadequately controlled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, according to the prescribing information.

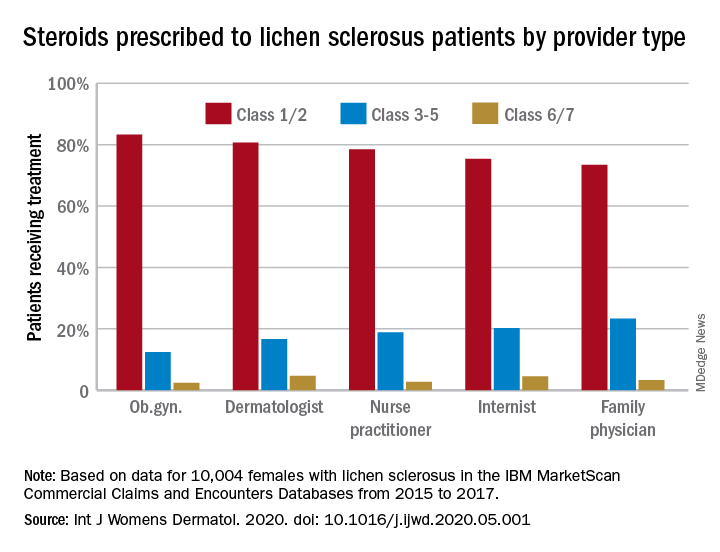

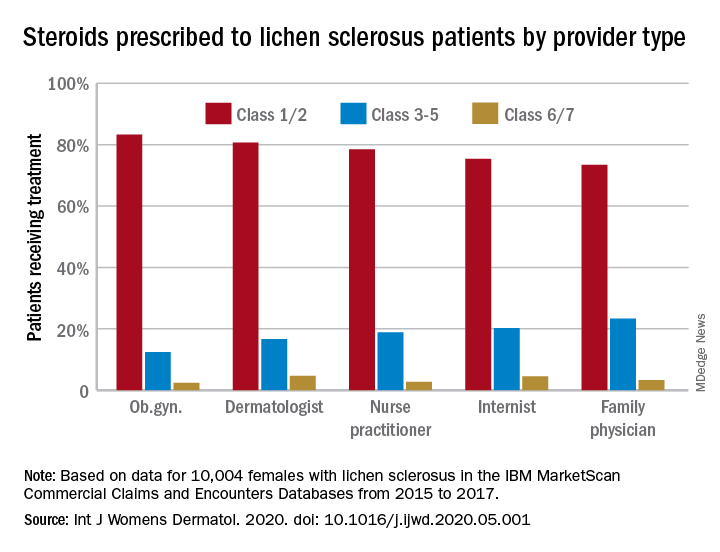

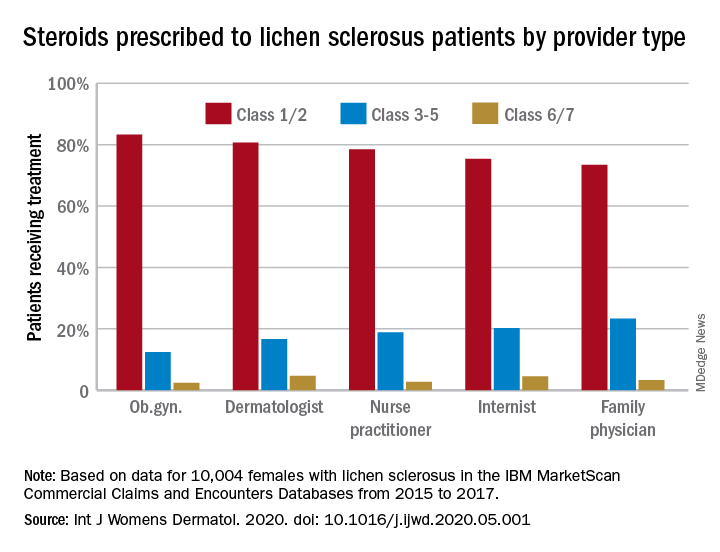

Most patients with lichen sclerosus receive appropriate treatment

The claims-based prevalence of 0.05% found in the study is lower than previously reported, and only 16% of the diagnoses were in women aged 18-44 years, Laura E. Melnick, MD, and associates wrote after identifying 10,004 females aged 0-65 years with lichen sclerosus in the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases from 2015 to 2017. The majority (79%) of those diagnosed were aged 45-65 years (average, 50.8 years).

In pediatric patients (up to age 17 years), the low prevalence (0.01%) “may be attributable to several factors including relative rarity, as well as variability in pediatric clinicians’ familiarity with [lichen sclerosus] and in patients’ clinical symptoms,” said Dr. Melnick and associates in the department of dermatology at New York University.

Just over half of all diagnoses (52.4%) were made by ob.gyns., with dermatologists next at 14.5%, followed by family physicians (6.5%), nurse practitioners (2.5%), and internists (0.4%), they reported in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

Treatment for lichen sclerosus, in the form of high-potency topical corticosteroids, was mostly appropriate. Ob.gyns. prescribed class 1/2 steroids to 83% of their patients, tops among all clinicians. Dermatologists were just over 80%, and the other clinician categories were all over 70%, the investigators said.

“Understanding the current management of [lichen sclerosus] is important given that un- or undertreated disease can significantly impact patients’ quality of life, lead to increased lower urinary tract symptoms and irreversible architectural changes, and predispose women to squamous cell carcinoma,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Melnick LE et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.05.001.

The claims-based prevalence of 0.05% found in the study is lower than previously reported, and only 16% of the diagnoses were in women aged 18-44 years, Laura E. Melnick, MD, and associates wrote after identifying 10,004 females aged 0-65 years with lichen sclerosus in the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases from 2015 to 2017. The majority (79%) of those diagnosed were aged 45-65 years (average, 50.8 years).

In pediatric patients (up to age 17 years), the low prevalence (0.01%) “may be attributable to several factors including relative rarity, as well as variability in pediatric clinicians’ familiarity with [lichen sclerosus] and in patients’ clinical symptoms,” said Dr. Melnick and associates in the department of dermatology at New York University.

Just over half of all diagnoses (52.4%) were made by ob.gyns., with dermatologists next at 14.5%, followed by family physicians (6.5%), nurse practitioners (2.5%), and internists (0.4%), they reported in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

Treatment for lichen sclerosus, in the form of high-potency topical corticosteroids, was mostly appropriate. Ob.gyns. prescribed class 1/2 steroids to 83% of their patients, tops among all clinicians. Dermatologists were just over 80%, and the other clinician categories were all over 70%, the investigators said.

“Understanding the current management of [lichen sclerosus] is important given that un- or undertreated disease can significantly impact patients’ quality of life, lead to increased lower urinary tract symptoms and irreversible architectural changes, and predispose women to squamous cell carcinoma,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Melnick LE et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.05.001.

The claims-based prevalence of 0.05% found in the study is lower than previously reported, and only 16% of the diagnoses were in women aged 18-44 years, Laura E. Melnick, MD, and associates wrote after identifying 10,004 females aged 0-65 years with lichen sclerosus in the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases from 2015 to 2017. The majority (79%) of those diagnosed were aged 45-65 years (average, 50.8 years).

In pediatric patients (up to age 17 years), the low prevalence (0.01%) “may be attributable to several factors including relative rarity, as well as variability in pediatric clinicians’ familiarity with [lichen sclerosus] and in patients’ clinical symptoms,” said Dr. Melnick and associates in the department of dermatology at New York University.

Just over half of all diagnoses (52.4%) were made by ob.gyns., with dermatologists next at 14.5%, followed by family physicians (6.5%), nurse practitioners (2.5%), and internists (0.4%), they reported in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

Treatment for lichen sclerosus, in the form of high-potency topical corticosteroids, was mostly appropriate. Ob.gyns. prescribed class 1/2 steroids to 83% of their patients, tops among all clinicians. Dermatologists were just over 80%, and the other clinician categories were all over 70%, the investigators said.

“Understanding the current management of [lichen sclerosus] is important given that un- or undertreated disease can significantly impact patients’ quality of life, lead to increased lower urinary tract symptoms and irreversible architectural changes, and predispose women to squamous cell carcinoma,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Melnick LE et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.05.001.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S DERMATOLOGY

Chilblain-like lesions reported in children thought to have COVID-19

Two and elsewhere.

These symptoms should be considered a sign of infection with the virus, but the symptoms themselves typically don’t require treatment, according to the authors of the two new reports, from hospitals in Milan and Madrid, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first study, Cristiana Colonna, MD, and colleagues at Hospital Maggiore Polyclinic in Milan described four cases of chilblain-like lesions in children ages 5-11 years with mild COVID-19 symptoms.

In the second, David Andina, MD, and colleagues in the ED and the departments of dermatology and pathology at the Child Jesus University Children’s Hospital in Madrid published a retrospective study of 22 cases in children and adolescents ages 6-17 years who reported to the hospital ED from April 6 to 17, the peak of the pandemic in Madrid.

In all four of the Milan cases, the skin lesions appeared several days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, although all four patients initially tested negative for COVID-19. However, Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote that, “given the fact that the sensitivity and specificity of both nasopharyngeal swabs and antibody tests for COVID-19 (when available) are not 100% reliable, the question of the origin of these strange chilblain-like lesions is still elusive.” Until further studies are available, they emphasized that clinicians should be “alert to the presentation of chilblain-like findings” in children with mild symptoms “as a possible sign of COVID-19 infection.”

All the patients had lesions on their feet or toes, and a 5-year-old boy also had lesions on the right hand. One patient, an 11-year-old girl, had a biopsy that revealed dense lymphocytic perivascular cuffing and periadnexal infiltration.

“The finding of an elevated d-dimer in one of our patients, along with the clinical features suggestive of a vasoocclusive phenomenon, supports consideration of laboratory evaluation for coagulation defects in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic children with acrovasculitis-like findings,” Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote. None of the four cases in Milan required treatment, with three cases resolving within 5 days.

Like the Milan cases, all 22 patients in the Madrid series had foot or toe lesions and three had lesions on the fingers. This larger series also reported more detailed symptoms about the lesions: pruritus in nine patients (41%) and mild pain in seven (32%). A total of 10 patients had systemic symptoms of COVID-19, predominantly cough and rhinorrhea in 9 patients (41%), but 2 (9%) had abdominal pain and diarrhea. These symptoms, the authors said, appeared a median of 14 days (range, 1-28 days) before they developed chilblains.

A total of 19 patients were tested for COVID-19, but only 1 was positive.

This retrospective study also included contact information, with one patient having household contact with a single confirmed case of COVID-19; 12 patients recalled household contact who were considered probable cases of COVID-19, with respiratory symptoms.

Skin biopsies were obtained from the acral lesions in six patients, all showing similar results, although with varying degrees of intensity. All biopsies showed features of lymphocytic vasculopathy. Some cases showed mild dermal and perieccrine mucinosis, lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis, vascular ectasia, red cell extravasation and focal thrombosis described as “mostly confined to scattered papillary dermal capillaries, but also in vessels of the reticular dermis.”

The only treatments Dr. Andina and colleagues reported were oral analgesics for pain and oral antihistamines for pruritus when needed. One patient was given topical corticosteroids and another a short course of oral steroids, both for erythema multiforme.

Dr. Andina and colleagues wrote that the skin lesions in these patients “were unequivocally categorized as chilblains, both clinically and histopathologically,” and, after 7-10 days, began to fade. None of the patients had complications, and had an “excellent outcome,” they noted.

Dr. Colonna and colleagues had no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Andina and colleagues provided no disclosure statement.

SOURCES: Colonna C et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1111/pde.14210; Andina D et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.14215.

Two and elsewhere.

These symptoms should be considered a sign of infection with the virus, but the symptoms themselves typically don’t require treatment, according to the authors of the two new reports, from hospitals in Milan and Madrid, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first study, Cristiana Colonna, MD, and colleagues at Hospital Maggiore Polyclinic in Milan described four cases of chilblain-like lesions in children ages 5-11 years with mild COVID-19 symptoms.

In the second, David Andina, MD, and colleagues in the ED and the departments of dermatology and pathology at the Child Jesus University Children’s Hospital in Madrid published a retrospective study of 22 cases in children and adolescents ages 6-17 years who reported to the hospital ED from April 6 to 17, the peak of the pandemic in Madrid.

In all four of the Milan cases, the skin lesions appeared several days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, although all four patients initially tested negative for COVID-19. However, Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote that, “given the fact that the sensitivity and specificity of both nasopharyngeal swabs and antibody tests for COVID-19 (when available) are not 100% reliable, the question of the origin of these strange chilblain-like lesions is still elusive.” Until further studies are available, they emphasized that clinicians should be “alert to the presentation of chilblain-like findings” in children with mild symptoms “as a possible sign of COVID-19 infection.”

All the patients had lesions on their feet or toes, and a 5-year-old boy also had lesions on the right hand. One patient, an 11-year-old girl, had a biopsy that revealed dense lymphocytic perivascular cuffing and periadnexal infiltration.

“The finding of an elevated d-dimer in one of our patients, along with the clinical features suggestive of a vasoocclusive phenomenon, supports consideration of laboratory evaluation for coagulation defects in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic children with acrovasculitis-like findings,” Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote. None of the four cases in Milan required treatment, with three cases resolving within 5 days.

Like the Milan cases, all 22 patients in the Madrid series had foot or toe lesions and three had lesions on the fingers. This larger series also reported more detailed symptoms about the lesions: pruritus in nine patients (41%) and mild pain in seven (32%). A total of 10 patients had systemic symptoms of COVID-19, predominantly cough and rhinorrhea in 9 patients (41%), but 2 (9%) had abdominal pain and diarrhea. These symptoms, the authors said, appeared a median of 14 days (range, 1-28 days) before they developed chilblains.

A total of 19 patients were tested for COVID-19, but only 1 was positive.

This retrospective study also included contact information, with one patient having household contact with a single confirmed case of COVID-19; 12 patients recalled household contact who were considered probable cases of COVID-19, with respiratory symptoms.

Skin biopsies were obtained from the acral lesions in six patients, all showing similar results, although with varying degrees of intensity. All biopsies showed features of lymphocytic vasculopathy. Some cases showed mild dermal and perieccrine mucinosis, lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis, vascular ectasia, red cell extravasation and focal thrombosis described as “mostly confined to scattered papillary dermal capillaries, but also in vessels of the reticular dermis.”

The only treatments Dr. Andina and colleagues reported were oral analgesics for pain and oral antihistamines for pruritus when needed. One patient was given topical corticosteroids and another a short course of oral steroids, both for erythema multiforme.

Dr. Andina and colleagues wrote that the skin lesions in these patients “were unequivocally categorized as chilblains, both clinically and histopathologically,” and, after 7-10 days, began to fade. None of the patients had complications, and had an “excellent outcome,” they noted.

Dr. Colonna and colleagues had no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Andina and colleagues provided no disclosure statement.

SOURCES: Colonna C et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1111/pde.14210; Andina D et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.14215.

Two and elsewhere.

These symptoms should be considered a sign of infection with the virus, but the symptoms themselves typically don’t require treatment, according to the authors of the two new reports, from hospitals in Milan and Madrid, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first study, Cristiana Colonna, MD, and colleagues at Hospital Maggiore Polyclinic in Milan described four cases of chilblain-like lesions in children ages 5-11 years with mild COVID-19 symptoms.

In the second, David Andina, MD, and colleagues in the ED and the departments of dermatology and pathology at the Child Jesus University Children’s Hospital in Madrid published a retrospective study of 22 cases in children and adolescents ages 6-17 years who reported to the hospital ED from April 6 to 17, the peak of the pandemic in Madrid.

In all four of the Milan cases, the skin lesions appeared several days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, although all four patients initially tested negative for COVID-19. However, Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote that, “given the fact that the sensitivity and specificity of both nasopharyngeal swabs and antibody tests for COVID-19 (when available) are not 100% reliable, the question of the origin of these strange chilblain-like lesions is still elusive.” Until further studies are available, they emphasized that clinicians should be “alert to the presentation of chilblain-like findings” in children with mild symptoms “as a possible sign of COVID-19 infection.”

All the patients had lesions on their feet or toes, and a 5-year-old boy also had lesions on the right hand. One patient, an 11-year-old girl, had a biopsy that revealed dense lymphocytic perivascular cuffing and periadnexal infiltration.

“The finding of an elevated d-dimer in one of our patients, along with the clinical features suggestive of a vasoocclusive phenomenon, supports consideration of laboratory evaluation for coagulation defects in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic children with acrovasculitis-like findings,” Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote. None of the four cases in Milan required treatment, with three cases resolving within 5 days.