User login

Aleukemic leukemia cutis

On examination, the numerous firm, indurated nodules ranged in size from 1 to 4 cm. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Results of a peripheral blood cell count showed the following:

- Hemoglobin 12.5 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Platelet count 154 × 109/L (130–400)

- White blood cell count 5.0 × 109/L (4.0–11.0)

- Neutrophils 1.7 × 109/L (1.5–8.0)

- Lymphocytes 2.2 × 109/L (1.0–4.0)

- Monocytes 1.0 × 109/L (0.2–1.0)

- Eosinophils 0 (0–0.4)

- Basophils 0 (0–0.2)

- Blasts 0.

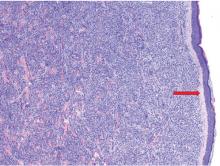

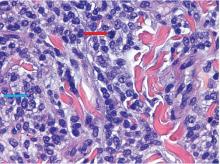

The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation. The infiltrate was unusual because leukemic infiltrates typically demonstrate a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, but in this case the malignant cells had moderate amounts of cytoplasm due to the monocytic differentiation. Also, a grenz zone is more typically seen in B-cell lymphomas, and T cells more typically demonstrate epidermotropism.

Bone marrow aspiration was performed and revealed a hypercellular bone marrow with trilineage maturation with only 2% blasts. The fluorescence in situ hybridization testing for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia was normal. A diagnosis of aleukemic leukemia cutis was made.

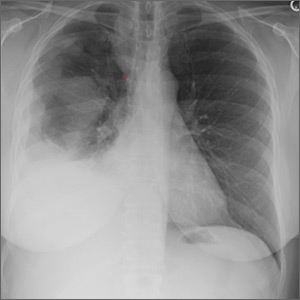

After 2 months of chemotherapy with azacitidine, the nodules were less indurated. Treatment was briefly withdrawn due to the development of acute pneumonia, leading to a rapid progression of cutaneous involvement. Despite restarting chemotherapy, the patient died.

ALEUKEMIC LEUKEMIA CUTIS

The differential diagnosis of leukemia cutis is diverse and extensive. Patients often present with painless, firm, indurated nodules, papules, and plaques.1 The lesions can be small, involving a small amount of body surface area, but can also be very large and diffuse.

In our patient’s case, there were no new drugs or exposures to suggest a drug-related eruption, or pruritus or pain to suggest an inflammatory process. The rapid progression of the lesions suggested either an infectious or malignant process. The top 3 conditions in the differential diagnosis, based on his clinical presentation, were cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and a drug-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Skin biopsy is required to differentiate leukemia cutis from the other conditions. On skin biopsy study, leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by leukemic cells and is seen in 10% to 15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia.2 In 5% of cases, leukemia cutis can present without bone marrow or peripheral signs of leukemia, hence the term aleukemic leukemia cutis.3 Cutaneous signs can occur before, after, or simultaneously with systemic leukemia.4

In the absence of systemic symptoms, the diagnosis is made when progressive cutaneous symptoms are present. The prognosis for aleukemic leukemia cutis is poor. Prompt diagnosis with skin biopsy is paramount to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgment: We would like to recognize Maanasa Devabhaktuni for her assistance in reporting this case.

- Yonal I, Hindilerden F, Coskun R, Dogan OI, Nalcaci M. Aleukemic leukemia cutis manifesting with disseminated nodular eruptions and a plaque preceding acute monocytic leukemia: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2011; 4(3):547–554. doi:10.1159/000334745

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol 2008; 129(1):130–142. doi:10.1309/WYACYWF6NGM3WBRT

- Kang YS, Kim HS, Park HJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 75 patients with leukemia cutis. J Korean Med Sci 2013; 28(4):614–619. doi:10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.614

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21(8)pii:13030/qt6m18g35f. pmid:26437164

On examination, the numerous firm, indurated nodules ranged in size from 1 to 4 cm. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Results of a peripheral blood cell count showed the following:

- Hemoglobin 12.5 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Platelet count 154 × 109/L (130–400)

- White blood cell count 5.0 × 109/L (4.0–11.0)

- Neutrophils 1.7 × 109/L (1.5–8.0)

- Lymphocytes 2.2 × 109/L (1.0–4.0)

- Monocytes 1.0 × 109/L (0.2–1.0)

- Eosinophils 0 (0–0.4)

- Basophils 0 (0–0.2)

- Blasts 0.

The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation. The infiltrate was unusual because leukemic infiltrates typically demonstrate a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, but in this case the malignant cells had moderate amounts of cytoplasm due to the monocytic differentiation. Also, a grenz zone is more typically seen in B-cell lymphomas, and T cells more typically demonstrate epidermotropism.

Bone marrow aspiration was performed and revealed a hypercellular bone marrow with trilineage maturation with only 2% blasts. The fluorescence in situ hybridization testing for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia was normal. A diagnosis of aleukemic leukemia cutis was made.

After 2 months of chemotherapy with azacitidine, the nodules were less indurated. Treatment was briefly withdrawn due to the development of acute pneumonia, leading to a rapid progression of cutaneous involvement. Despite restarting chemotherapy, the patient died.

ALEUKEMIC LEUKEMIA CUTIS

The differential diagnosis of leukemia cutis is diverse and extensive. Patients often present with painless, firm, indurated nodules, papules, and plaques.1 The lesions can be small, involving a small amount of body surface area, but can also be very large and diffuse.

In our patient’s case, there were no new drugs or exposures to suggest a drug-related eruption, or pruritus or pain to suggest an inflammatory process. The rapid progression of the lesions suggested either an infectious or malignant process. The top 3 conditions in the differential diagnosis, based on his clinical presentation, were cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and a drug-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Skin biopsy is required to differentiate leukemia cutis from the other conditions. On skin biopsy study, leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by leukemic cells and is seen in 10% to 15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia.2 In 5% of cases, leukemia cutis can present without bone marrow or peripheral signs of leukemia, hence the term aleukemic leukemia cutis.3 Cutaneous signs can occur before, after, or simultaneously with systemic leukemia.4

In the absence of systemic symptoms, the diagnosis is made when progressive cutaneous symptoms are present. The prognosis for aleukemic leukemia cutis is poor. Prompt diagnosis with skin biopsy is paramount to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgment: We would like to recognize Maanasa Devabhaktuni for her assistance in reporting this case.

On examination, the numerous firm, indurated nodules ranged in size from 1 to 4 cm. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Results of a peripheral blood cell count showed the following:

- Hemoglobin 12.5 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Platelet count 154 × 109/L (130–400)

- White blood cell count 5.0 × 109/L (4.0–11.0)

- Neutrophils 1.7 × 109/L (1.5–8.0)

- Lymphocytes 2.2 × 109/L (1.0–4.0)

- Monocytes 1.0 × 109/L (0.2–1.0)

- Eosinophils 0 (0–0.4)

- Basophils 0 (0–0.2)

- Blasts 0.

The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation. The infiltrate was unusual because leukemic infiltrates typically demonstrate a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, but in this case the malignant cells had moderate amounts of cytoplasm due to the monocytic differentiation. Also, a grenz zone is more typically seen in B-cell lymphomas, and T cells more typically demonstrate epidermotropism.

Bone marrow aspiration was performed and revealed a hypercellular bone marrow with trilineage maturation with only 2% blasts. The fluorescence in situ hybridization testing for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia was normal. A diagnosis of aleukemic leukemia cutis was made.

After 2 months of chemotherapy with azacitidine, the nodules were less indurated. Treatment was briefly withdrawn due to the development of acute pneumonia, leading to a rapid progression of cutaneous involvement. Despite restarting chemotherapy, the patient died.

ALEUKEMIC LEUKEMIA CUTIS

The differential diagnosis of leukemia cutis is diverse and extensive. Patients often present with painless, firm, indurated nodules, papules, and plaques.1 The lesions can be small, involving a small amount of body surface area, but can also be very large and diffuse.

In our patient’s case, there were no new drugs or exposures to suggest a drug-related eruption, or pruritus or pain to suggest an inflammatory process. The rapid progression of the lesions suggested either an infectious or malignant process. The top 3 conditions in the differential diagnosis, based on his clinical presentation, were cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and a drug-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Skin biopsy is required to differentiate leukemia cutis from the other conditions. On skin biopsy study, leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by leukemic cells and is seen in 10% to 15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia.2 In 5% of cases, leukemia cutis can present without bone marrow or peripheral signs of leukemia, hence the term aleukemic leukemia cutis.3 Cutaneous signs can occur before, after, or simultaneously with systemic leukemia.4

In the absence of systemic symptoms, the diagnosis is made when progressive cutaneous symptoms are present. The prognosis for aleukemic leukemia cutis is poor. Prompt diagnosis with skin biopsy is paramount to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgment: We would like to recognize Maanasa Devabhaktuni for her assistance in reporting this case.

- Yonal I, Hindilerden F, Coskun R, Dogan OI, Nalcaci M. Aleukemic leukemia cutis manifesting with disseminated nodular eruptions and a plaque preceding acute monocytic leukemia: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2011; 4(3):547–554. doi:10.1159/000334745

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol 2008; 129(1):130–142. doi:10.1309/WYACYWF6NGM3WBRT

- Kang YS, Kim HS, Park HJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 75 patients with leukemia cutis. J Korean Med Sci 2013; 28(4):614–619. doi:10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.614

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21(8)pii:13030/qt6m18g35f. pmid:26437164

- Yonal I, Hindilerden F, Coskun R, Dogan OI, Nalcaci M. Aleukemic leukemia cutis manifesting with disseminated nodular eruptions and a plaque preceding acute monocytic leukemia: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2011; 4(3):547–554. doi:10.1159/000334745

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol 2008; 129(1):130–142. doi:10.1309/WYACYWF6NGM3WBRT

- Kang YS, Kim HS, Park HJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 75 patients with leukemia cutis. J Korean Med Sci 2013; 28(4):614–619. doi:10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.614

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21(8)pii:13030/qt6m18g35f. pmid:26437164

Mohs Micrographic Surgery in the VHA (FULL)

Skin cancer is one of the most prevalent conditions among VHA patients.1 One of the largest U.S. health care systems, the VHA serves more than 9 million veterans.2 In 2012, 4% of VHA patients had a diagnosis of keratinocyte carcinoma or actinic keratosis; 49,229 cases of basal cell carcinoma and 26,310 cases of squamous cell carcinoma were diagnosed.1 With an aging veteran population and the incidence of skin cancers expected to increase, the development of cost-effective ways to provide easily accessible skin cancer treatments has become a priority for the VHA.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend 3 types of surgical treatment for localized keratinocyte carcinoma: local destruction, wide local excision (WLE), and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). Tumors at low risk for recurrence may be treated with local destruction or WLE, and tumors at high risk may be treated with WLE or MMS.3

Mohs micrographic surgery involves staged narrow-margin excision with intraoperative tumor mapping and complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment (CCPDMA). With the Mohs surgeon acting as both surgeon and dermatopathologist, it is possible to provide intraoperative correlation with the tissue bed and immediate additional margin resection precisely where needed. Relative to WLE, MMS yields improved histopathologic clearance rates and lower 5-year recurrence rates. It also provides improved preservation of normal tissue, optimized aesthetic outcomes, and high patient satisfaction.4-7 All this is achieved in an outpatient setting with the patient under local anesthesia; therefore the cost of ambulatory surgical centers or hospital operating rooms are avoided.5,8,9

The NCCN recommends WLE for high-risk tumors only if CCPDMA can be achieved. However, CCPDMA requires specialized surgical technique, tissue orientation, and pathology and is not equivalent to standard WLE with routine surgical pathology. Even with intraoperative bread-loafed frozen section analysis, WLE does not achieve the 100% margin assessment obtained with MMS.

In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology in collaboration with the American College of Mohs Surgery, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery developed the Mohs Appropriate Use Criteria,which are now widely used as part of the standard of care to determine which cases of skin cancer should be treated with MMS over other modalities.10 These criteria, which are based on both evidence and expert consensus, take into account tumor size, histology, location, and patient factors, such as immunosuppression.

Despite its established benefits, MMS has not been uniformly accessible to veterans seeking VHA care. In 2007, Karen and colleagues surveyed dermatology chiefs and staff dermatologists from 101 VHA hospitals to characterize veterans’ access to MMS and found MMS available at only 11 VHA sites in 9 states.11 Further, access within the VHA was not evenly distributed across the U.S.

The VHA often makes payments, under “non-VA medical care” or “fee-basis care,” to providers in the community for services that the VHA is otherwise unable to provide. In 2014, Congress passed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act and established the Veterans Choice program.2,12 This program allows veterans to obtain medical services from providers outside the VHA, based on veteran wait time and place of residence.12 The goal is to improve access. The present authors distinguish between 2 types of care: there are fee-based referrals managed and tracked by the VHA physician and the Veterans Choice for care without the diagnosing physician involvement or knowledge. In addition to expanding treatment options, the act called for reform within the VHA to improve resources and infrastructure needed to provide the best care for the veteran patient population.2

The authors conducted a study to identify current availability of MMS within the VHA and to provide a 10-year update to the survey findings of Karen and colleagues.11 VHA facilities that offer MMS were surveyed to determine available resources and what is needed to provide MMS within the VHA. Also surveyed were VHA facilities that do not offer MMS to determine how VHA patients with skin cancer receive surgical care from non-VA providers or from other surgical specialties.

Related: Nivolumab Linked to Nephritis in Melanoma

Methods

This study, deemed exempt from review by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board, was a survey of dermatology section and service chiefs across the VHA. Subjects were identified through conference calls with VHA dermatologists, searches of individual VHA websites, and requests on dermatology e-mail listservs and were invited by email to participate in the survey.

The Research Electronic Data Capture platform (REDCap; Vanderbilt University Medical Center) was used for survey creation, implementation, dissemination, and data storage. The survey had 6 sections: site information; MMS availability; Mohs surgeon, Mohs laboratory, and support staff; MMS care; patient referral; and Mohs surgeon recruitment.

Data were collected between June 20 and August 1, 2016. Collected VHA site information included name, location, description, and MMS availability. If MMS was available, data were collected on surgeon training and background, number of MMS cases in 2015, and facility and support staff. In addition, subjects rated statements about various aspects of care provided (eg, patient wait time, patient distance traveled) on a 6-point Likert scale: strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree, or strongly agree. This section included both positive and negative statements.

If MMS was not available at the VHA site, data were collected on patient referrals, including location within or outside the VHA and patient use of the Veterans Choice program. Subjects also rated positive and negative statements about referral experiences on a Likert scale (eg, patient wait time, patient distance traveled).

Categorical data were summarized, means and standard deviations were calculated for nominal data, and data analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA).

Results

The authors identified and surveyed 74 dermatology service and section chiefs across the VHA. Of these chiefs, 52 (70.3%) completed the survey. Completed surveys represented 49 hospital sites and 3 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), including an integrated community-based clinic-hospital.

Sites That Provided MMS

Of the 52 sites with a completed survey, 19 provided MMS. These 19 sites were in 13 states and the District of Columbia, and the majority were in major cities along the coasts. All 19 sites were hospital medical centers, not community-based outpatient clinics, and all provided MMS through the dermatology department. In 2015, an estimated 6,686 MMS cases were performed, or an average of 371 per site (range, 40-1,000 cases/site) or 4.9 MMS cases per day (range, 3-8). These 19 sites were divided by yearly volume: high (> 500 cases/y), medium (200-500 cases/y), and low (< 200 cases/y).

Physical Space. On average, each site used 2.89 patient rooms (SD, 1.1; range, 1-6) for MMS. The Table lists numbers of patient rooms based on case volume.

The MMS laboratory was adjacent to the surgical suite at 18 of the MMS sites and in the same building as the surgical suite, but not next to it, at 1 site. For their samples, 11 sites used an automated staining method, 7 used hand staining, and 2 used other methods (1 site used both automated and hand staining). Fourteen sites used hematoxlyin-eosin only, 1 used toluidine blue only, 3 used both hematoxlyin-eosin and toluidine blue, and 1 used MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1) with hematoxlyin-eosin.

Related: Systemic Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma

Mohs Micrographic Surgeons. Sites with higher case volumes had more Mohs surgeons and more Mohs surgeons with VA appointments (captured as “eighths” or fraction of 8/8 full-time equivalent [FTE]). Information on fellowships and professional memberships was available for 30 Mohs surgeons: Ten (33.3%) were trained in fellowships accredited by both the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), 8 (26.7%) were trained in ACMS-recognized fellowships only, 7 (23.3%) were trained at ACGME-accredited fellowships only, 2 (6.7%) were trained elsewhere, and 3 (10.0%) had training listed as “uncertain.”

The majority of Mohs surgeons were members of professional societies, and many were members of more than one. Of the 30 Mohs surgeons, 24 (80.0%) were ACMS members, 5 (16.7%) were members of the American Society of Mohs Surgery, and 22 (73.3%) were members of the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery. Twenty-five (89.3%) were affiliated with an academic program.

Of the 30 surgeons, 19 (63.3%) were VHA employees hired by eighths, with an average eighths of 3.9 (SD, 2.7), or 49% of a FTE. Data on these surgeons’ pay tables and tiers were insufficient (only 3 provided the information). Of the other 11 surgeons, 10 (33.3%) were contracted, and 1 (3.3%) volunteered without compensation.

Support Staff. Of the 19 MMS sites, 17 (89.5%) used 1 histotechnician, and 2 (10.5%) used more than 1. Ten sites (52.6%) hired histotechnicians as contractors, 8 (42.1%) as employees, and 1 (5.3%) on a fee basis. In general, sites with higher case volumes had more nursing and support staff. Thirteen sites (68.4%) participated in the training of dermatology residents, and 5 sites (26.3%) trained Mohs fellows.

Wait Time Estimate. The survey also asked for estimates of the average amount of time patients waited for MMS. Of the 19 sites, 8 (42.1%) reported a wait time of less than 1 month, 10 (52.6%) reported 2 to 6 months, and 1 (5.3%) reported 7 months to 1 year. Seventeen (89.5%) of the 19 sites had a grading or triage system for expediting certain cancer types. At 7 sites, cases were prioritized on the basis of physician assessment; at 3 sites, aggressive or invasive squamous cell carcinoma received priority; other sites gave priority to patients with melanoma, patients with carcinoma near the nose or eye, organ transplant recipients, and other immunosuppressed patients.

Sites That Did Not Provide MMS

Of the 52 sites with a completed survey, 33 (63.5%) did not provide on-site MMS. Of these 33 sites, 28 (84.8%) used purchased care to refer patients to fee-basis non-VA dermatologists. In addition, 30 sites (90.9%) had patients activate Veterans Choice. Three sites referred patients to VA sites in another VISN.

Surgeon Recruitment

Five sites (9.6%) had an unfilled Mohs micrographic surgeon position. The average FTE of these unfilled positions was 0.6. One position had been open for less than 6 months, and the other 4 for more than 1 year. All 5 respondents with unfilled positions strongly agreed with the statement, “The position is unfilled because the salary is not competitive with the local market.”

Assessment of Care Provided

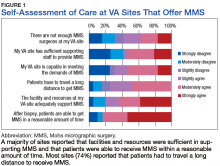

Respondents at sites that provided MMS rated various aspects of care (Figure 1).

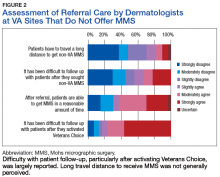

Respondents from sites that purchased MMS care from non-VA medical care rated surgery availability and ease of patient follow-up (Figure 2).

Related: Getting a Better Picture of Skin Cancer

Discussion

Skin cancer is highly prevalent in the veteran patient population, and each year treatment by the VHA requires considerable spending.1 The results of this cross-sectional survey characterize veterans’ access to MMS within the VHA and provide a 10-year update to the survey findings of Karen and colleagues.11 Compared with their study, this survey offers a more granular description of practices and facilities as well as comparisons of VHA care with care purchased from outside sources. In outlining the state of MMS care within the VHA, this study highlights progress made and provides the updated data needed for continued efforts to optimize care and resource allocation for patients who require MMS within the VHA.

Although the number of VHA sites that provide MMS has increased over the past 10 years—from 11 sites in 9 states in 2007 to 19 sites in 13 states now—it is important to note that access to MMS care highly depends on geographic location.11 The VHA sites that provide MMS are clustered in major cities along the coasts. Four states (California, Florida, New York, and Texas) had > 1 MMS site, whereas most other states did not have any. In addition, only 1 MMS site served all of the northwest U.S. To ensure the anonymity of survey respondents, the authors did not further characterize the regional distribution of MMS sites.

Despite the increase in MMS sites, the number of MMS cases performed within the VHA seemed to have decreased. An estimated 8,310 cases were performed within the VHA in 2006,which decreased to 6,686 in 2015.11 Although these are estimates, the number of VHA cases likely decreased because of a rise in purchased care. Reviewing VHA electronic health records, Yoon and colleagues found that 19,681 MMS cases were performed either within the VHA or at non-VA medical care sites in 2012.1 Although the proportions of MMS cases performed within and outside the VHA were not reported, clearly many veterans had MMS performed through the VHA in recent years, and a high percentage of these cases were external referrals. More study is needed to further characterize MMS care within the VHA and MMS care purchased.

The 19 sites that provided MMS were evenly divided by volume: high (> 500 cases/y), medium (200-500 cases/y), and low (< 200 cases/y). Case volume correlated with the numbers of surgeons, nurses, and support staff at each site. Number of patient rooms dedicated to MMS at each site was not correlated with case volume; however, not ascertaining the number of days per week MMS was performed may have contributed to the lack of observed correlation.The majority of Mohs surgeons (25; 89.3%) within the VHA were affiliated with academic programs, which may partly explain the uneven geographic distribution of VHA sites that provide MMS (dermatology residency programs typically are in larger cities). The majority of Mohs surgeons were fellowship-trained through the ACMS or the ACGME. As the ACGME first began accrediting fellowship programs in 2003, younger surgeons were more likely to have completed this fellowship. According to respondents from sites that did not provide MMS, noncompetitive VHA salaries might be a barrier to Mohs surgeon recruitment. If a shift to providing more MMS care within the VHA were desired, an effective strategy could be to raise surgeon salaries. Higher salaries would bring in more Mohs surgeons and thereby yield higher MMS case volumes at VHA sites.

However, whether MMS is best provided for veterans within the VHA or at outside sites through referrals warrants further study. More than 60% of sites provided access to MMS through purchased care, either by fee-basis/non-VA medical care referrals or by the patient-elected Veterans Choice program. According to 84.2% of respondents at MMS sites and 66.7% of respondents at non-MMS sites, patients received care within a reasonable amount of time. In addition, respondents at MMS sites estimated longer patient travel distance for surgery. Respondents reported being concerned about coordination of care and follow-up for patients who received MMS outside the VHA. Other than referrals to outside sites for MMS, current triage practices include referral to other surgical specialties within the VHA, predominantly ear, nose, and throat and plastic surgery, for WLE. Given that access to on-site MMS varies significantly by geographic location, on-site MMS may be preferable in some locations, and external referrals in others. Based on this study's findings, on-site MMS seems superior to external referrals in all respects except patient travel distance. More research is needed to determine the most cost-effective triage practices. One option would be to have each VISN develop a skin cancer care center of excellence that would assist providers in appropriate triage and management.

Limitations

A decade has passed since Karen and colleagues conducted their study on MMS within the VHA.11 Data from this study suggest some progress has been made in improving veterans’ access to MMS. However, VHA sites that provide MMS are still predominantly located in large cities. In cases in which VHA providers refer patients to outside facilities, care coordination and follow-up are challenging. The present findings provide a basis for continuing VHA efforts to optimize resource allocation and improve longitudinal care for veterans who require MMS for skin cancer. Another area of interest is the comparative cost-effectiveness of MMS care provided within the VHA rather than at outside sites through purchased care. The answer may depend on geographic location, as MMS demand may be higher in some regions than that of others. For patients who receive MMS care outside the VHA, efforts should be made to improve communication and follow-up between VHA and external providers.

This study was limited in that it surveyed only those VHA sites with dermatology services or sections. It is possible, though unlikely, that MMS also was provided through nondermatology services. This study’s 70.3% response rate (52/74 dermatology chiefs) matched that of Karen and colleagues.11 Nevertheless, given that 30% of the surveyed chiefs did not respond and that analysis was performed separately for 2 small subgroups, (19 VHA sites that provided on-site MMS and 33 VHA sites that did not), the present findings may not be representative of the VHA as a whole.

Another limitation was that the survey captured respondent estimates of surgical caseloads and resources. Confirmation of these estimates would require a review of internal medical records and workforce analyses, which was beyond the scope of this study.

Conclusion

Although some progress has been made over the past 10 years, access to MMS within the VHA remains limited. About one-third of VHA sites provide on-site MMS; the other two-thirds refer patients with skin cancer to MMS sites outside the VHA. According to their dermatology chiefs, VHA sites that provide MMS have adequate resources and staffing and acceptable wait times for surgery; the challenge is in patients’ long travel distances. At sites that do not provide MMS, patients have access to MMS as well, and acceptable wait times and travel distances; the challenge is in follow-up, especially with activation of the Veterans Choice program. Studies should focus on standardizing veterans’ care and improving their access to MMS.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Yoon J, Phibbs CS, Chow A, Pomerantz H, Weinstock MA. Costs of keratinocyte carcinoma (nonmelanoma skin cancer) and actinic keratosis treatment in the Veterans Health Administration. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(9):1041-1047.

2. Giroir BP, Wilensky GR. Reforming the Veterans Health Administration—beyond palliation of symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1693-1695.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Basal Cell Skin Cancer 1.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nmsc.pdf. Updated September 18, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2018.

4. Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, Sen S, Landefeld CS. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(6):1351-1357.

5. Cook J, Zitelli JA. Mohs micrographic surgery: a cost analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(5, pt 1):698-703.

6. Kauvar AN, Arpey CJ, Hruza G, Olbricht SM, Bennett R, Mahmoud BH. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment, part ii: squamous cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(11):1214-1240.

7. Kauvar AN, Cronin T Jr, Roenigk R, Hruza G, Bennett R; American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment: basal cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(5):550-571.

8. Chen JT, Kempton SJ, Rao VK. The economics of skin cancer: an analysis of Medicare payment data. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(9):e868.

9. Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Cost effectiveness of Mohs micrographic surgery: review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(10):914-922.

10. Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):531-550.

11. Karen JK, Hale EK, Nehal KS, Levine VJ. Use of Mohs surgery by the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(6):1069-1070.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Expanded access to non-VA care through the Veterans Choice program. Interim final rule. Fed Regist. 2015;80(230):74991-74996.

Skin cancer is one of the most prevalent conditions among VHA patients.1 One of the largest U.S. health care systems, the VHA serves more than 9 million veterans.2 In 2012, 4% of VHA patients had a diagnosis of keratinocyte carcinoma or actinic keratosis; 49,229 cases of basal cell carcinoma and 26,310 cases of squamous cell carcinoma were diagnosed.1 With an aging veteran population and the incidence of skin cancers expected to increase, the development of cost-effective ways to provide easily accessible skin cancer treatments has become a priority for the VHA.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend 3 types of surgical treatment for localized keratinocyte carcinoma: local destruction, wide local excision (WLE), and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). Tumors at low risk for recurrence may be treated with local destruction or WLE, and tumors at high risk may be treated with WLE or MMS.3

Mohs micrographic surgery involves staged narrow-margin excision with intraoperative tumor mapping and complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment (CCPDMA). With the Mohs surgeon acting as both surgeon and dermatopathologist, it is possible to provide intraoperative correlation with the tissue bed and immediate additional margin resection precisely where needed. Relative to WLE, MMS yields improved histopathologic clearance rates and lower 5-year recurrence rates. It also provides improved preservation of normal tissue, optimized aesthetic outcomes, and high patient satisfaction.4-7 All this is achieved in an outpatient setting with the patient under local anesthesia; therefore the cost of ambulatory surgical centers or hospital operating rooms are avoided.5,8,9

The NCCN recommends WLE for high-risk tumors only if CCPDMA can be achieved. However, CCPDMA requires specialized surgical technique, tissue orientation, and pathology and is not equivalent to standard WLE with routine surgical pathology. Even with intraoperative bread-loafed frozen section analysis, WLE does not achieve the 100% margin assessment obtained with MMS.

In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology in collaboration with the American College of Mohs Surgery, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery developed the Mohs Appropriate Use Criteria,which are now widely used as part of the standard of care to determine which cases of skin cancer should be treated with MMS over other modalities.10 These criteria, which are based on both evidence and expert consensus, take into account tumor size, histology, location, and patient factors, such as immunosuppression.

Despite its established benefits, MMS has not been uniformly accessible to veterans seeking VHA care. In 2007, Karen and colleagues surveyed dermatology chiefs and staff dermatologists from 101 VHA hospitals to characterize veterans’ access to MMS and found MMS available at only 11 VHA sites in 9 states.11 Further, access within the VHA was not evenly distributed across the U.S.

The VHA often makes payments, under “non-VA medical care” or “fee-basis care,” to providers in the community for services that the VHA is otherwise unable to provide. In 2014, Congress passed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act and established the Veterans Choice program.2,12 This program allows veterans to obtain medical services from providers outside the VHA, based on veteran wait time and place of residence.12 The goal is to improve access. The present authors distinguish between 2 types of care: there are fee-based referrals managed and tracked by the VHA physician and the Veterans Choice for care without the diagnosing physician involvement or knowledge. In addition to expanding treatment options, the act called for reform within the VHA to improve resources and infrastructure needed to provide the best care for the veteran patient population.2

The authors conducted a study to identify current availability of MMS within the VHA and to provide a 10-year update to the survey findings of Karen and colleagues.11 VHA facilities that offer MMS were surveyed to determine available resources and what is needed to provide MMS within the VHA. Also surveyed were VHA facilities that do not offer MMS to determine how VHA patients with skin cancer receive surgical care from non-VA providers or from other surgical specialties.

Related: Nivolumab Linked to Nephritis in Melanoma

Methods

This study, deemed exempt from review by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board, was a survey of dermatology section and service chiefs across the VHA. Subjects were identified through conference calls with VHA dermatologists, searches of individual VHA websites, and requests on dermatology e-mail listservs and were invited by email to participate in the survey.

The Research Electronic Data Capture platform (REDCap; Vanderbilt University Medical Center) was used for survey creation, implementation, dissemination, and data storage. The survey had 6 sections: site information; MMS availability; Mohs surgeon, Mohs laboratory, and support staff; MMS care; patient referral; and Mohs surgeon recruitment.

Data were collected between June 20 and August 1, 2016. Collected VHA site information included name, location, description, and MMS availability. If MMS was available, data were collected on surgeon training and background, number of MMS cases in 2015, and facility and support staff. In addition, subjects rated statements about various aspects of care provided (eg, patient wait time, patient distance traveled) on a 6-point Likert scale: strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree, or strongly agree. This section included both positive and negative statements.

If MMS was not available at the VHA site, data were collected on patient referrals, including location within or outside the VHA and patient use of the Veterans Choice program. Subjects also rated positive and negative statements about referral experiences on a Likert scale (eg, patient wait time, patient distance traveled).

Categorical data were summarized, means and standard deviations were calculated for nominal data, and data analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA).

Results

The authors identified and surveyed 74 dermatology service and section chiefs across the VHA. Of these chiefs, 52 (70.3%) completed the survey. Completed surveys represented 49 hospital sites and 3 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), including an integrated community-based clinic-hospital.

Sites That Provided MMS

Of the 52 sites with a completed survey, 19 provided MMS. These 19 sites were in 13 states and the District of Columbia, and the majority were in major cities along the coasts. All 19 sites were hospital medical centers, not community-based outpatient clinics, and all provided MMS through the dermatology department. In 2015, an estimated 6,686 MMS cases were performed, or an average of 371 per site (range, 40-1,000 cases/site) or 4.9 MMS cases per day (range, 3-8). These 19 sites were divided by yearly volume: high (> 500 cases/y), medium (200-500 cases/y), and low (< 200 cases/y).

Physical Space. On average, each site used 2.89 patient rooms (SD, 1.1; range, 1-6) for MMS. The Table lists numbers of patient rooms based on case volume.

The MMS laboratory was adjacent to the surgical suite at 18 of the MMS sites and in the same building as the surgical suite, but not next to it, at 1 site. For their samples, 11 sites used an automated staining method, 7 used hand staining, and 2 used other methods (1 site used both automated and hand staining). Fourteen sites used hematoxlyin-eosin only, 1 used toluidine blue only, 3 used both hematoxlyin-eosin and toluidine blue, and 1 used MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1) with hematoxlyin-eosin.

Related: Systemic Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma

Mohs Micrographic Surgeons. Sites with higher case volumes had more Mohs surgeons and more Mohs surgeons with VA appointments (captured as “eighths” or fraction of 8/8 full-time equivalent [FTE]). Information on fellowships and professional memberships was available for 30 Mohs surgeons: Ten (33.3%) were trained in fellowships accredited by both the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), 8 (26.7%) were trained in ACMS-recognized fellowships only, 7 (23.3%) were trained at ACGME-accredited fellowships only, 2 (6.7%) were trained elsewhere, and 3 (10.0%) had training listed as “uncertain.”

The majority of Mohs surgeons were members of professional societies, and many were members of more than one. Of the 30 Mohs surgeons, 24 (80.0%) were ACMS members, 5 (16.7%) were members of the American Society of Mohs Surgery, and 22 (73.3%) were members of the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery. Twenty-five (89.3%) were affiliated with an academic program.

Of the 30 surgeons, 19 (63.3%) were VHA employees hired by eighths, with an average eighths of 3.9 (SD, 2.7), or 49% of a FTE. Data on these surgeons’ pay tables and tiers were insufficient (only 3 provided the information). Of the other 11 surgeons, 10 (33.3%) were contracted, and 1 (3.3%) volunteered without compensation.

Support Staff. Of the 19 MMS sites, 17 (89.5%) used 1 histotechnician, and 2 (10.5%) used more than 1. Ten sites (52.6%) hired histotechnicians as contractors, 8 (42.1%) as employees, and 1 (5.3%) on a fee basis. In general, sites with higher case volumes had more nursing and support staff. Thirteen sites (68.4%) participated in the training of dermatology residents, and 5 sites (26.3%) trained Mohs fellows.

Wait Time Estimate. The survey also asked for estimates of the average amount of time patients waited for MMS. Of the 19 sites, 8 (42.1%) reported a wait time of less than 1 month, 10 (52.6%) reported 2 to 6 months, and 1 (5.3%) reported 7 months to 1 year. Seventeen (89.5%) of the 19 sites had a grading or triage system for expediting certain cancer types. At 7 sites, cases were prioritized on the basis of physician assessment; at 3 sites, aggressive or invasive squamous cell carcinoma received priority; other sites gave priority to patients with melanoma, patients with carcinoma near the nose or eye, organ transplant recipients, and other immunosuppressed patients.

Sites That Did Not Provide MMS

Of the 52 sites with a completed survey, 33 (63.5%) did not provide on-site MMS. Of these 33 sites, 28 (84.8%) used purchased care to refer patients to fee-basis non-VA dermatologists. In addition, 30 sites (90.9%) had patients activate Veterans Choice. Three sites referred patients to VA sites in another VISN.

Surgeon Recruitment

Five sites (9.6%) had an unfilled Mohs micrographic surgeon position. The average FTE of these unfilled positions was 0.6. One position had been open for less than 6 months, and the other 4 for more than 1 year. All 5 respondents with unfilled positions strongly agreed with the statement, “The position is unfilled because the salary is not competitive with the local market.”

Assessment of Care Provided

Respondents at sites that provided MMS rated various aspects of care (Figure 1).

Respondents from sites that purchased MMS care from non-VA medical care rated surgery availability and ease of patient follow-up (Figure 2).

Related: Getting a Better Picture of Skin Cancer

Discussion

Skin cancer is highly prevalent in the veteran patient population, and each year treatment by the VHA requires considerable spending.1 The results of this cross-sectional survey characterize veterans’ access to MMS within the VHA and provide a 10-year update to the survey findings of Karen and colleagues.11 Compared with their study, this survey offers a more granular description of practices and facilities as well as comparisons of VHA care with care purchased from outside sources. In outlining the state of MMS care within the VHA, this study highlights progress made and provides the updated data needed for continued efforts to optimize care and resource allocation for patients who require MMS within the VHA.

Although the number of VHA sites that provide MMS has increased over the past 10 years—from 11 sites in 9 states in 2007 to 19 sites in 13 states now—it is important to note that access to MMS care highly depends on geographic location.11 The VHA sites that provide MMS are clustered in major cities along the coasts. Four states (California, Florida, New York, and Texas) had > 1 MMS site, whereas most other states did not have any. In addition, only 1 MMS site served all of the northwest U.S. To ensure the anonymity of survey respondents, the authors did not further characterize the regional distribution of MMS sites.

Despite the increase in MMS sites, the number of MMS cases performed within the VHA seemed to have decreased. An estimated 8,310 cases were performed within the VHA in 2006,which decreased to 6,686 in 2015.11 Although these are estimates, the number of VHA cases likely decreased because of a rise in purchased care. Reviewing VHA electronic health records, Yoon and colleagues found that 19,681 MMS cases were performed either within the VHA or at non-VA medical care sites in 2012.1 Although the proportions of MMS cases performed within and outside the VHA were not reported, clearly many veterans had MMS performed through the VHA in recent years, and a high percentage of these cases were external referrals. More study is needed to further characterize MMS care within the VHA and MMS care purchased.

The 19 sites that provided MMS were evenly divided by volume: high (> 500 cases/y), medium (200-500 cases/y), and low (< 200 cases/y). Case volume correlated with the numbers of surgeons, nurses, and support staff at each site. Number of patient rooms dedicated to MMS at each site was not correlated with case volume; however, not ascertaining the number of days per week MMS was performed may have contributed to the lack of observed correlation.The majority of Mohs surgeons (25; 89.3%) within the VHA were affiliated with academic programs, which may partly explain the uneven geographic distribution of VHA sites that provide MMS (dermatology residency programs typically are in larger cities). The majority of Mohs surgeons were fellowship-trained through the ACMS or the ACGME. As the ACGME first began accrediting fellowship programs in 2003, younger surgeons were more likely to have completed this fellowship. According to respondents from sites that did not provide MMS, noncompetitive VHA salaries might be a barrier to Mohs surgeon recruitment. If a shift to providing more MMS care within the VHA were desired, an effective strategy could be to raise surgeon salaries. Higher salaries would bring in more Mohs surgeons and thereby yield higher MMS case volumes at VHA sites.

However, whether MMS is best provided for veterans within the VHA or at outside sites through referrals warrants further study. More than 60% of sites provided access to MMS through purchased care, either by fee-basis/non-VA medical care referrals or by the patient-elected Veterans Choice program. According to 84.2% of respondents at MMS sites and 66.7% of respondents at non-MMS sites, patients received care within a reasonable amount of time. In addition, respondents at MMS sites estimated longer patient travel distance for surgery. Respondents reported being concerned about coordination of care and follow-up for patients who received MMS outside the VHA. Other than referrals to outside sites for MMS, current triage practices include referral to other surgical specialties within the VHA, predominantly ear, nose, and throat and plastic surgery, for WLE. Given that access to on-site MMS varies significantly by geographic location, on-site MMS may be preferable in some locations, and external referrals in others. Based on this study's findings, on-site MMS seems superior to external referrals in all respects except patient travel distance. More research is needed to determine the most cost-effective triage practices. One option would be to have each VISN develop a skin cancer care center of excellence that would assist providers in appropriate triage and management.

Limitations

A decade has passed since Karen and colleagues conducted their study on MMS within the VHA.11 Data from this study suggest some progress has been made in improving veterans’ access to MMS. However, VHA sites that provide MMS are still predominantly located in large cities. In cases in which VHA providers refer patients to outside facilities, care coordination and follow-up are challenging. The present findings provide a basis for continuing VHA efforts to optimize resource allocation and improve longitudinal care for veterans who require MMS for skin cancer. Another area of interest is the comparative cost-effectiveness of MMS care provided within the VHA rather than at outside sites through purchased care. The answer may depend on geographic location, as MMS demand may be higher in some regions than that of others. For patients who receive MMS care outside the VHA, efforts should be made to improve communication and follow-up between VHA and external providers.

This study was limited in that it surveyed only those VHA sites with dermatology services or sections. It is possible, though unlikely, that MMS also was provided through nondermatology services. This study’s 70.3% response rate (52/74 dermatology chiefs) matched that of Karen and colleagues.11 Nevertheless, given that 30% of the surveyed chiefs did not respond and that analysis was performed separately for 2 small subgroups, (19 VHA sites that provided on-site MMS and 33 VHA sites that did not), the present findings may not be representative of the VHA as a whole.

Another limitation was that the survey captured respondent estimates of surgical caseloads and resources. Confirmation of these estimates would require a review of internal medical records and workforce analyses, which was beyond the scope of this study.

Conclusion

Although some progress has been made over the past 10 years, access to MMS within the VHA remains limited. About one-third of VHA sites provide on-site MMS; the other two-thirds refer patients with skin cancer to MMS sites outside the VHA. According to their dermatology chiefs, VHA sites that provide MMS have adequate resources and staffing and acceptable wait times for surgery; the challenge is in patients’ long travel distances. At sites that do not provide MMS, patients have access to MMS as well, and acceptable wait times and travel distances; the challenge is in follow-up, especially with activation of the Veterans Choice program. Studies should focus on standardizing veterans’ care and improving their access to MMS.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Skin cancer is one of the most prevalent conditions among VHA patients.1 One of the largest U.S. health care systems, the VHA serves more than 9 million veterans.2 In 2012, 4% of VHA patients had a diagnosis of keratinocyte carcinoma or actinic keratosis; 49,229 cases of basal cell carcinoma and 26,310 cases of squamous cell carcinoma were diagnosed.1 With an aging veteran population and the incidence of skin cancers expected to increase, the development of cost-effective ways to provide easily accessible skin cancer treatments has become a priority for the VHA.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend 3 types of surgical treatment for localized keratinocyte carcinoma: local destruction, wide local excision (WLE), and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). Tumors at low risk for recurrence may be treated with local destruction or WLE, and tumors at high risk may be treated with WLE or MMS.3

Mohs micrographic surgery involves staged narrow-margin excision with intraoperative tumor mapping and complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment (CCPDMA). With the Mohs surgeon acting as both surgeon and dermatopathologist, it is possible to provide intraoperative correlation with the tissue bed and immediate additional margin resection precisely where needed. Relative to WLE, MMS yields improved histopathologic clearance rates and lower 5-year recurrence rates. It also provides improved preservation of normal tissue, optimized aesthetic outcomes, and high patient satisfaction.4-7 All this is achieved in an outpatient setting with the patient under local anesthesia; therefore the cost of ambulatory surgical centers or hospital operating rooms are avoided.5,8,9

The NCCN recommends WLE for high-risk tumors only if CCPDMA can be achieved. However, CCPDMA requires specialized surgical technique, tissue orientation, and pathology and is not equivalent to standard WLE with routine surgical pathology. Even with intraoperative bread-loafed frozen section analysis, WLE does not achieve the 100% margin assessment obtained with MMS.

In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology in collaboration with the American College of Mohs Surgery, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery developed the Mohs Appropriate Use Criteria,which are now widely used as part of the standard of care to determine which cases of skin cancer should be treated with MMS over other modalities.10 These criteria, which are based on both evidence and expert consensus, take into account tumor size, histology, location, and patient factors, such as immunosuppression.

Despite its established benefits, MMS has not been uniformly accessible to veterans seeking VHA care. In 2007, Karen and colleagues surveyed dermatology chiefs and staff dermatologists from 101 VHA hospitals to characterize veterans’ access to MMS and found MMS available at only 11 VHA sites in 9 states.11 Further, access within the VHA was not evenly distributed across the U.S.

The VHA often makes payments, under “non-VA medical care” or “fee-basis care,” to providers in the community for services that the VHA is otherwise unable to provide. In 2014, Congress passed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act and established the Veterans Choice program.2,12 This program allows veterans to obtain medical services from providers outside the VHA, based on veteran wait time and place of residence.12 The goal is to improve access. The present authors distinguish between 2 types of care: there are fee-based referrals managed and tracked by the VHA physician and the Veterans Choice for care without the diagnosing physician involvement or knowledge. In addition to expanding treatment options, the act called for reform within the VHA to improve resources and infrastructure needed to provide the best care for the veteran patient population.2

The authors conducted a study to identify current availability of MMS within the VHA and to provide a 10-year update to the survey findings of Karen and colleagues.11 VHA facilities that offer MMS were surveyed to determine available resources and what is needed to provide MMS within the VHA. Also surveyed were VHA facilities that do not offer MMS to determine how VHA patients with skin cancer receive surgical care from non-VA providers or from other surgical specialties.

Related: Nivolumab Linked to Nephritis in Melanoma

Methods

This study, deemed exempt from review by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board, was a survey of dermatology section and service chiefs across the VHA. Subjects were identified through conference calls with VHA dermatologists, searches of individual VHA websites, and requests on dermatology e-mail listservs and were invited by email to participate in the survey.

The Research Electronic Data Capture platform (REDCap; Vanderbilt University Medical Center) was used for survey creation, implementation, dissemination, and data storage. The survey had 6 sections: site information; MMS availability; Mohs surgeon, Mohs laboratory, and support staff; MMS care; patient referral; and Mohs surgeon recruitment.

Data were collected between June 20 and August 1, 2016. Collected VHA site information included name, location, description, and MMS availability. If MMS was available, data were collected on surgeon training and background, number of MMS cases in 2015, and facility and support staff. In addition, subjects rated statements about various aspects of care provided (eg, patient wait time, patient distance traveled) on a 6-point Likert scale: strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree, or strongly agree. This section included both positive and negative statements.

If MMS was not available at the VHA site, data were collected on patient referrals, including location within or outside the VHA and patient use of the Veterans Choice program. Subjects also rated positive and negative statements about referral experiences on a Likert scale (eg, patient wait time, patient distance traveled).

Categorical data were summarized, means and standard deviations were calculated for nominal data, and data analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA).

Results

The authors identified and surveyed 74 dermatology service and section chiefs across the VHA. Of these chiefs, 52 (70.3%) completed the survey. Completed surveys represented 49 hospital sites and 3 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), including an integrated community-based clinic-hospital.

Sites That Provided MMS

Of the 52 sites with a completed survey, 19 provided MMS. These 19 sites were in 13 states and the District of Columbia, and the majority were in major cities along the coasts. All 19 sites were hospital medical centers, not community-based outpatient clinics, and all provided MMS through the dermatology department. In 2015, an estimated 6,686 MMS cases were performed, or an average of 371 per site (range, 40-1,000 cases/site) or 4.9 MMS cases per day (range, 3-8). These 19 sites were divided by yearly volume: high (> 500 cases/y), medium (200-500 cases/y), and low (< 200 cases/y).

Physical Space. On average, each site used 2.89 patient rooms (SD, 1.1; range, 1-6) for MMS. The Table lists numbers of patient rooms based on case volume.

The MMS laboratory was adjacent to the surgical suite at 18 of the MMS sites and in the same building as the surgical suite, but not next to it, at 1 site. For their samples, 11 sites used an automated staining method, 7 used hand staining, and 2 used other methods (1 site used both automated and hand staining). Fourteen sites used hematoxlyin-eosin only, 1 used toluidine blue only, 3 used both hematoxlyin-eosin and toluidine blue, and 1 used MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1) with hematoxlyin-eosin.

Related: Systemic Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma

Mohs Micrographic Surgeons. Sites with higher case volumes had more Mohs surgeons and more Mohs surgeons with VA appointments (captured as “eighths” or fraction of 8/8 full-time equivalent [FTE]). Information on fellowships and professional memberships was available for 30 Mohs surgeons: Ten (33.3%) were trained in fellowships accredited by both the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), 8 (26.7%) were trained in ACMS-recognized fellowships only, 7 (23.3%) were trained at ACGME-accredited fellowships only, 2 (6.7%) were trained elsewhere, and 3 (10.0%) had training listed as “uncertain.”

The majority of Mohs surgeons were members of professional societies, and many were members of more than one. Of the 30 Mohs surgeons, 24 (80.0%) were ACMS members, 5 (16.7%) were members of the American Society of Mohs Surgery, and 22 (73.3%) were members of the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery. Twenty-five (89.3%) were affiliated with an academic program.

Of the 30 surgeons, 19 (63.3%) were VHA employees hired by eighths, with an average eighths of 3.9 (SD, 2.7), or 49% of a FTE. Data on these surgeons’ pay tables and tiers were insufficient (only 3 provided the information). Of the other 11 surgeons, 10 (33.3%) were contracted, and 1 (3.3%) volunteered without compensation.

Support Staff. Of the 19 MMS sites, 17 (89.5%) used 1 histotechnician, and 2 (10.5%) used more than 1. Ten sites (52.6%) hired histotechnicians as contractors, 8 (42.1%) as employees, and 1 (5.3%) on a fee basis. In general, sites with higher case volumes had more nursing and support staff. Thirteen sites (68.4%) participated in the training of dermatology residents, and 5 sites (26.3%) trained Mohs fellows.

Wait Time Estimate. The survey also asked for estimates of the average amount of time patients waited for MMS. Of the 19 sites, 8 (42.1%) reported a wait time of less than 1 month, 10 (52.6%) reported 2 to 6 months, and 1 (5.3%) reported 7 months to 1 year. Seventeen (89.5%) of the 19 sites had a grading or triage system for expediting certain cancer types. At 7 sites, cases were prioritized on the basis of physician assessment; at 3 sites, aggressive or invasive squamous cell carcinoma received priority; other sites gave priority to patients with melanoma, patients with carcinoma near the nose or eye, organ transplant recipients, and other immunosuppressed patients.

Sites That Did Not Provide MMS

Of the 52 sites with a completed survey, 33 (63.5%) did not provide on-site MMS. Of these 33 sites, 28 (84.8%) used purchased care to refer patients to fee-basis non-VA dermatologists. In addition, 30 sites (90.9%) had patients activate Veterans Choice. Three sites referred patients to VA sites in another VISN.

Surgeon Recruitment

Five sites (9.6%) had an unfilled Mohs micrographic surgeon position. The average FTE of these unfilled positions was 0.6. One position had been open for less than 6 months, and the other 4 for more than 1 year. All 5 respondents with unfilled positions strongly agreed with the statement, “The position is unfilled because the salary is not competitive with the local market.”

Assessment of Care Provided

Respondents at sites that provided MMS rated various aspects of care (Figure 1).

Respondents from sites that purchased MMS care from non-VA medical care rated surgery availability and ease of patient follow-up (Figure 2).

Related: Getting a Better Picture of Skin Cancer

Discussion

Skin cancer is highly prevalent in the veteran patient population, and each year treatment by the VHA requires considerable spending.1 The results of this cross-sectional survey characterize veterans’ access to MMS within the VHA and provide a 10-year update to the survey findings of Karen and colleagues.11 Compared with their study, this survey offers a more granular description of practices and facilities as well as comparisons of VHA care with care purchased from outside sources. In outlining the state of MMS care within the VHA, this study highlights progress made and provides the updated data needed for continued efforts to optimize care and resource allocation for patients who require MMS within the VHA.

Although the number of VHA sites that provide MMS has increased over the past 10 years—from 11 sites in 9 states in 2007 to 19 sites in 13 states now—it is important to note that access to MMS care highly depends on geographic location.11 The VHA sites that provide MMS are clustered in major cities along the coasts. Four states (California, Florida, New York, and Texas) had > 1 MMS site, whereas most other states did not have any. In addition, only 1 MMS site served all of the northwest U.S. To ensure the anonymity of survey respondents, the authors did not further characterize the regional distribution of MMS sites.

Despite the increase in MMS sites, the number of MMS cases performed within the VHA seemed to have decreased. An estimated 8,310 cases were performed within the VHA in 2006,which decreased to 6,686 in 2015.11 Although these are estimates, the number of VHA cases likely decreased because of a rise in purchased care. Reviewing VHA electronic health records, Yoon and colleagues found that 19,681 MMS cases were performed either within the VHA or at non-VA medical care sites in 2012.1 Although the proportions of MMS cases performed within and outside the VHA were not reported, clearly many veterans had MMS performed through the VHA in recent years, and a high percentage of these cases were external referrals. More study is needed to further characterize MMS care within the VHA and MMS care purchased.

The 19 sites that provided MMS were evenly divided by volume: high (> 500 cases/y), medium (200-500 cases/y), and low (< 200 cases/y). Case volume correlated with the numbers of surgeons, nurses, and support staff at each site. Number of patient rooms dedicated to MMS at each site was not correlated with case volume; however, not ascertaining the number of days per week MMS was performed may have contributed to the lack of observed correlation.The majority of Mohs surgeons (25; 89.3%) within the VHA were affiliated with academic programs, which may partly explain the uneven geographic distribution of VHA sites that provide MMS (dermatology residency programs typically are in larger cities). The majority of Mohs surgeons were fellowship-trained through the ACMS or the ACGME. As the ACGME first began accrediting fellowship programs in 2003, younger surgeons were more likely to have completed this fellowship. According to respondents from sites that did not provide MMS, noncompetitive VHA salaries might be a barrier to Mohs surgeon recruitment. If a shift to providing more MMS care within the VHA were desired, an effective strategy could be to raise surgeon salaries. Higher salaries would bring in more Mohs surgeons and thereby yield higher MMS case volumes at VHA sites.

However, whether MMS is best provided for veterans within the VHA or at outside sites through referrals warrants further study. More than 60% of sites provided access to MMS through purchased care, either by fee-basis/non-VA medical care referrals or by the patient-elected Veterans Choice program. According to 84.2% of respondents at MMS sites and 66.7% of respondents at non-MMS sites, patients received care within a reasonable amount of time. In addition, respondents at MMS sites estimated longer patient travel distance for surgery. Respondents reported being concerned about coordination of care and follow-up for patients who received MMS outside the VHA. Other than referrals to outside sites for MMS, current triage practices include referral to other surgical specialties within the VHA, predominantly ear, nose, and throat and plastic surgery, for WLE. Given that access to on-site MMS varies significantly by geographic location, on-site MMS may be preferable in some locations, and external referrals in others. Based on this study's findings, on-site MMS seems superior to external referrals in all respects except patient travel distance. More research is needed to determine the most cost-effective triage practices. One option would be to have each VISN develop a skin cancer care center of excellence that would assist providers in appropriate triage and management.

Limitations

A decade has passed since Karen and colleagues conducted their study on MMS within the VHA.11 Data from this study suggest some progress has been made in improving veterans’ access to MMS. However, VHA sites that provide MMS are still predominantly located in large cities. In cases in which VHA providers refer patients to outside facilities, care coordination and follow-up are challenging. The present findings provide a basis for continuing VHA efforts to optimize resource allocation and improve longitudinal care for veterans who require MMS for skin cancer. Another area of interest is the comparative cost-effectiveness of MMS care provided within the VHA rather than at outside sites through purchased care. The answer may depend on geographic location, as MMS demand may be higher in some regions than that of others. For patients who receive MMS care outside the VHA, efforts should be made to improve communication and follow-up between VHA and external providers.

This study was limited in that it surveyed only those VHA sites with dermatology services or sections. It is possible, though unlikely, that MMS also was provided through nondermatology services. This study’s 70.3% response rate (52/74 dermatology chiefs) matched that of Karen and colleagues.11 Nevertheless, given that 30% of the surveyed chiefs did not respond and that analysis was performed separately for 2 small subgroups, (19 VHA sites that provided on-site MMS and 33 VHA sites that did not), the present findings may not be representative of the VHA as a whole.

Another limitation was that the survey captured respondent estimates of surgical caseloads and resources. Confirmation of these estimates would require a review of internal medical records and workforce analyses, which was beyond the scope of this study.

Conclusion

Although some progress has been made over the past 10 years, access to MMS within the VHA remains limited. About one-third of VHA sites provide on-site MMS; the other two-thirds refer patients with skin cancer to MMS sites outside the VHA. According to their dermatology chiefs, VHA sites that provide MMS have adequate resources and staffing and acceptable wait times for surgery; the challenge is in patients’ long travel distances. At sites that do not provide MMS, patients have access to MMS as well, and acceptable wait times and travel distances; the challenge is in follow-up, especially with activation of the Veterans Choice program. Studies should focus on standardizing veterans’ care and improving their access to MMS.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Yoon J, Phibbs CS, Chow A, Pomerantz H, Weinstock MA. Costs of keratinocyte carcinoma (nonmelanoma skin cancer) and actinic keratosis treatment in the Veterans Health Administration. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(9):1041-1047.

2. Giroir BP, Wilensky GR. Reforming the Veterans Health Administration—beyond palliation of symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1693-1695.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Basal Cell Skin Cancer 1.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nmsc.pdf. Updated September 18, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2018.

4. Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, Sen S, Landefeld CS. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(6):1351-1357.

5. Cook J, Zitelli JA. Mohs micrographic surgery: a cost analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(5, pt 1):698-703.

6. Kauvar AN, Arpey CJ, Hruza G, Olbricht SM, Bennett R, Mahmoud BH. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment, part ii: squamous cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(11):1214-1240.

7. Kauvar AN, Cronin T Jr, Roenigk R, Hruza G, Bennett R; American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment: basal cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(5):550-571.

8. Chen JT, Kempton SJ, Rao VK. The economics of skin cancer: an analysis of Medicare payment data. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(9):e868.

9. Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Cost effectiveness of Mohs micrographic surgery: review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(10):914-922.

10. Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):531-550.

11. Karen JK, Hale EK, Nehal KS, Levine VJ. Use of Mohs surgery by the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(6):1069-1070.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Expanded access to non-VA care through the Veterans Choice program. Interim final rule. Fed Regist. 2015;80(230):74991-74996.

1. Yoon J, Phibbs CS, Chow A, Pomerantz H, Weinstock MA. Costs of keratinocyte carcinoma (nonmelanoma skin cancer) and actinic keratosis treatment in the Veterans Health Administration. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(9):1041-1047.

2. Giroir BP, Wilensky GR. Reforming the Veterans Health Administration—beyond palliation of symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1693-1695.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Basal Cell Skin Cancer 1.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nmsc.pdf. Updated September 18, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2018.

4. Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, Sen S, Landefeld CS. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(6):1351-1357.

5. Cook J, Zitelli JA. Mohs micrographic surgery: a cost analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(5, pt 1):698-703.

6. Kauvar AN, Arpey CJ, Hruza G, Olbricht SM, Bennett R, Mahmoud BH. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment, part ii: squamous cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(11):1214-1240.

7. Kauvar AN, Cronin T Jr, Roenigk R, Hruza G, Bennett R; American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment: basal cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(5):550-571.

8. Chen JT, Kempton SJ, Rao VK. The economics of skin cancer: an analysis of Medicare payment data. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(9):e868.

9. Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Cost effectiveness of Mohs micrographic surgery: review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(10):914-922.

10. Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):531-550.

11. Karen JK, Hale EK, Nehal KS, Levine VJ. Use of Mohs surgery by the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(6):1069-1070.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Expanded access to non-VA care through the Veterans Choice program. Interim final rule. Fed Regist. 2015;80(230):74991-74996.

Sore on nose

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.