User login

Intralymphatic Histiocytosis Associated With an Orthopedic Metal Implant

To the Editor:

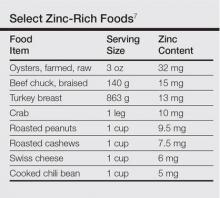

|

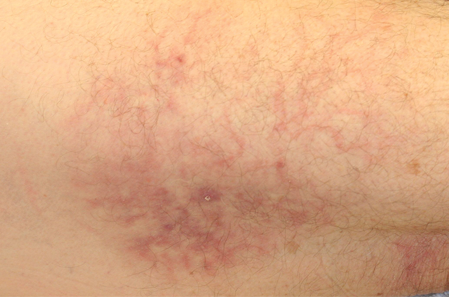

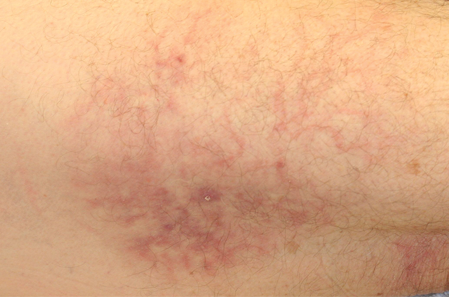

| Figure 1. A 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh. |

|

|

|

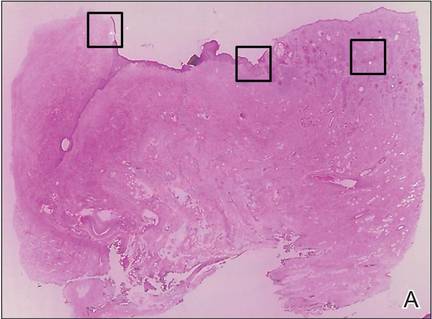

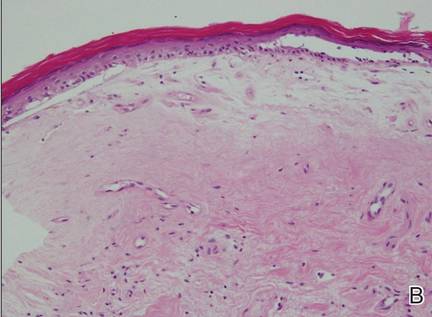

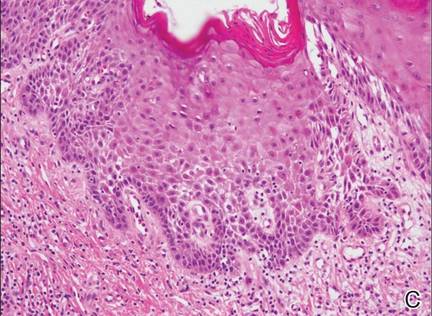

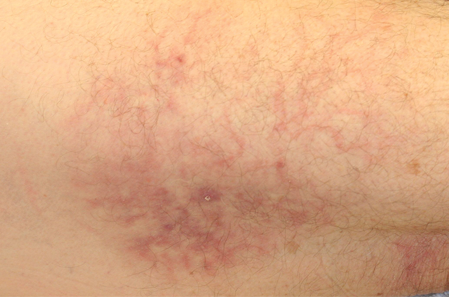

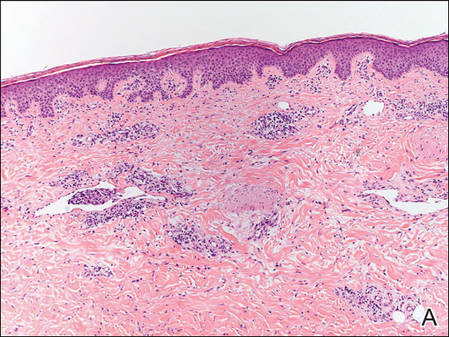

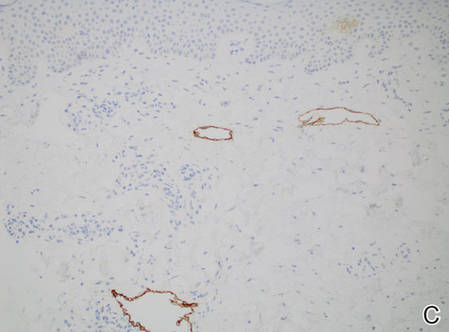

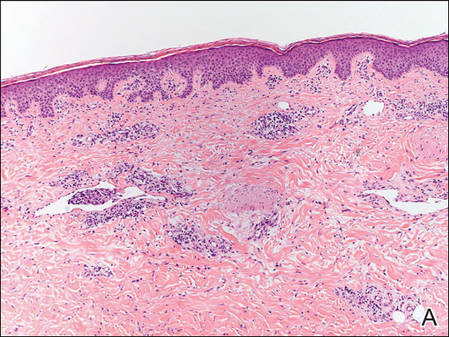

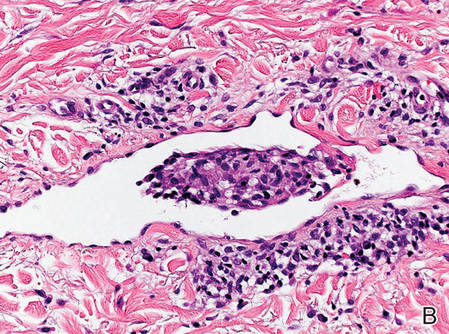

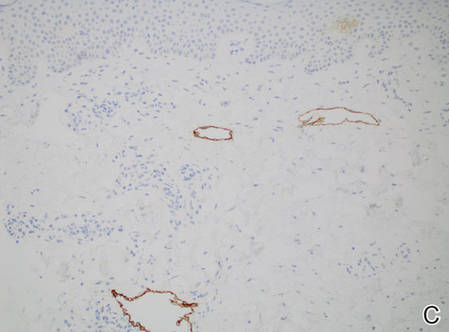

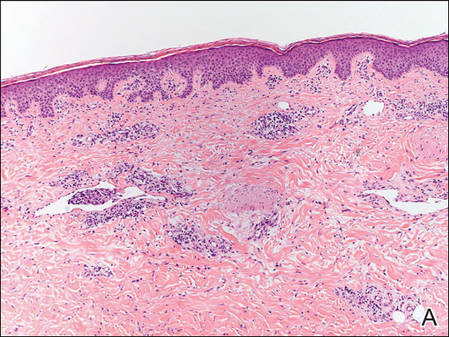

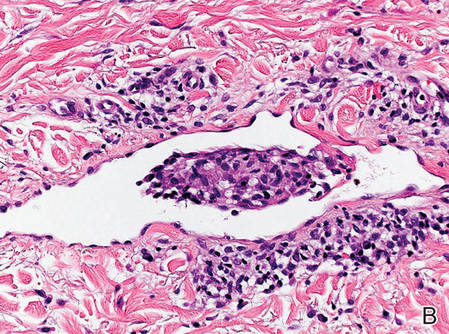

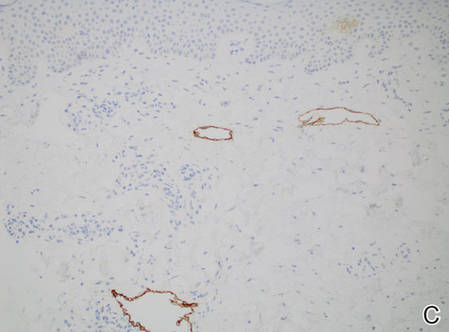

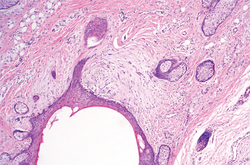

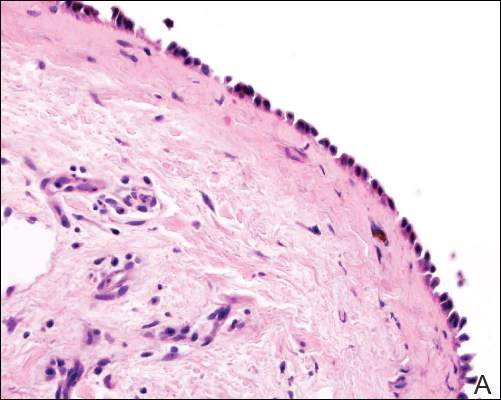

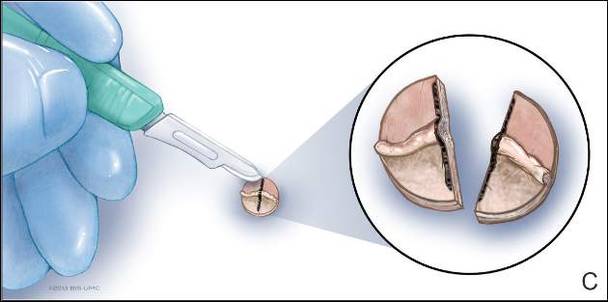

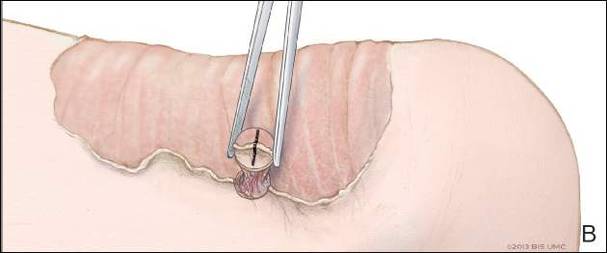

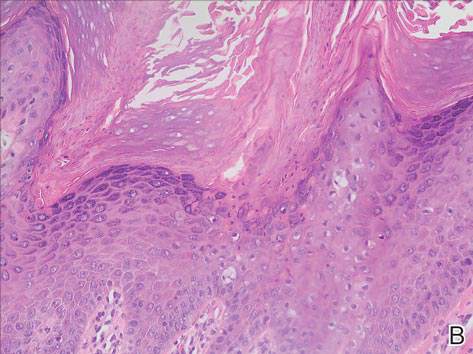

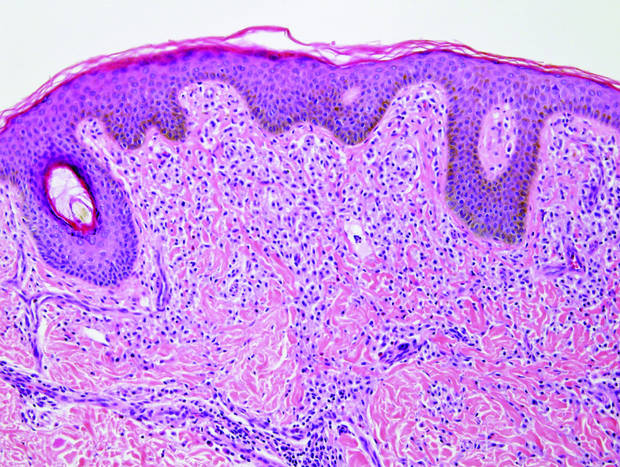

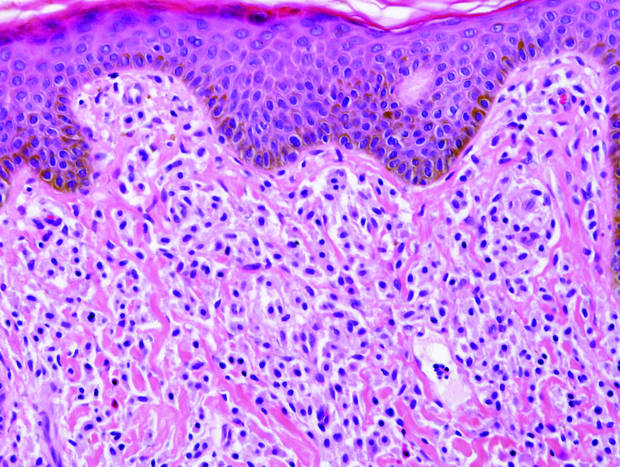

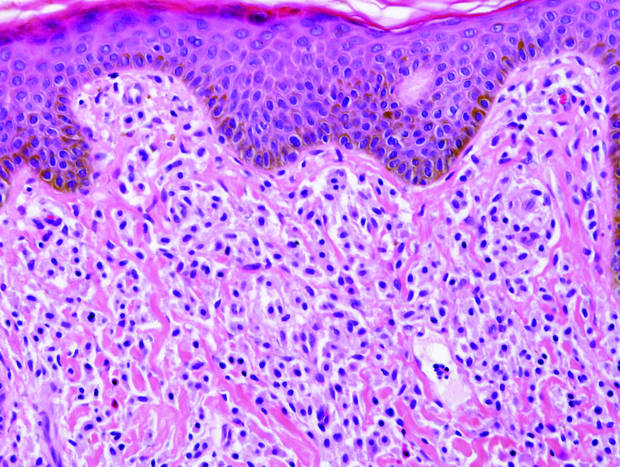

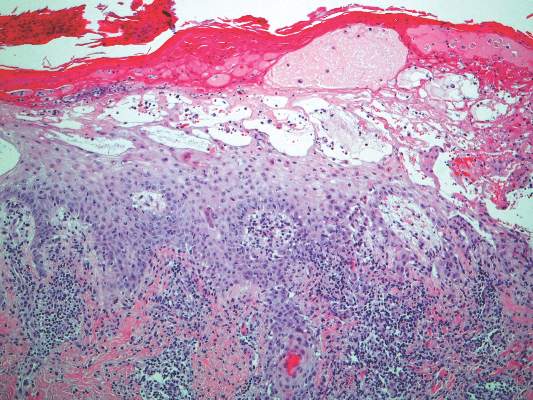

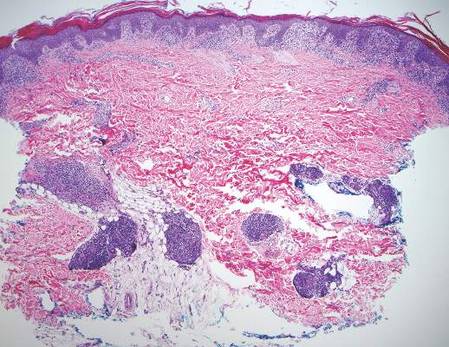

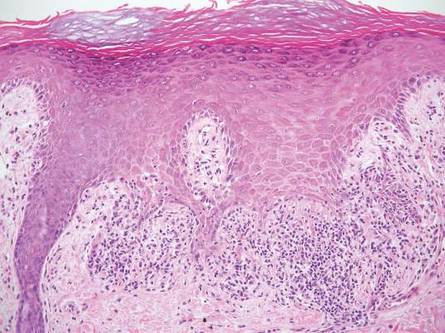

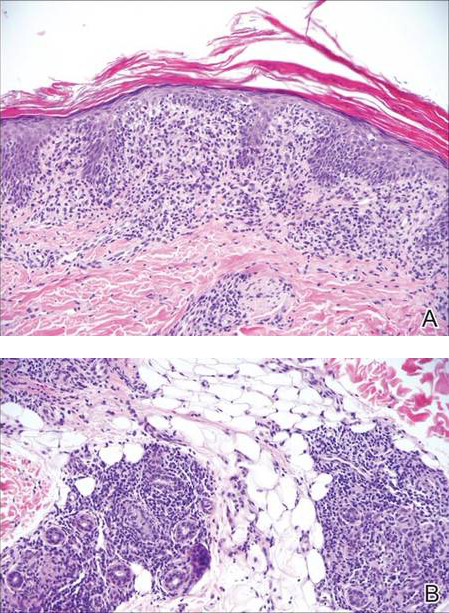

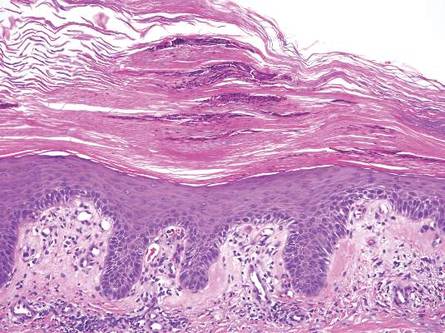

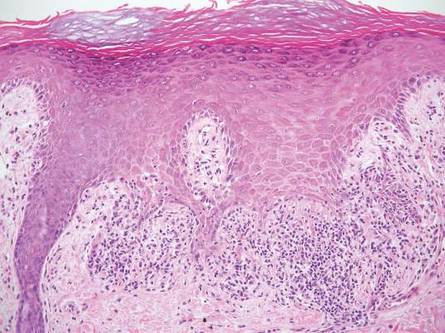

Figure 2. Histopathology revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis with adjacent features of chronic lymphedema (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) as well as a collection of histiocytes in a dilated lymphatic channel (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). D2-40 staining demonstrated ectatic lymphatic vessels in the upper dermins (C)(original magnification ×20).

|

A 70-year-old white man presented with an asymptomatic patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh of 15 months’ duration. The patient believed the patch correlated with a hip replacement 3 years prior; however, it was 6 inches inferior to the incision site. Physical examination revealed a 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch (Figure 1). The patch was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids as well as a short course of oral prednisone. The patient’s medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Histopathologic examination revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis. In addition, adjacent features of chronic lymphedema were present, namely interstitial fibroplasia with dilated lymphatic vessels and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intralymphatic histiocytosis, a rare disease most commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Our patient did not have a history or clinical symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous condition reported by O’Grady et al1 in 1994. This condition has been most frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis2; however, there has been an emerging association in patients with orthopedic metal implants, with and without a concomitant diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Cases associated with metal implants are rare.2-7

The condition presents as asymptomatic red, brown, or violaceous patches, plaques, papules, or nodules that are ill defined and tend to demonstrate a livedo reticularis–like pattern. The lesions typically are overlying or in close proximity to a joint. Histopathologic findings include dilated vascular structures in the reticular dermis, some with empty lumina and others containing collections of mononuclear histiocytes. There also may be an inflammatory infiltrate in the adjacent dermis composed of a mix of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and/or histiocytes. Endothelial cells lining the dilated lumina express immunoreactivity for CD31, CD34, D2-40, Lyve-1, and Prox-1. Intravascular histiocytes are positive for CD68 and CD31.6

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains undefined. Some hypothesize that intralymphatic histiocytosis could be the early stage of reactive angioendotheliomatosis, as these conditions share clinical and histological features.8 Reactive angioendotheliomatosis also is a rare condition that may present as erythematous to violaceous patches or plaques. The lesions are commonly found on the limbs and may be associated with constitutional symptoms. Histologic findings of reactive angioendotheliomatosis include a proliferation of epithelioid, round, or spindle-shaped cells within the lumina of dermal blood vessels, which show positivity for CD31 and CD34.9 Others suggest the lesions of intralymphatic histiocytosis arise from lymphangiectasia; obstruction of lymphatic drainage due to congenital abnormalities; or acquired damage from infection, trauma, surgery, or radiation.2 Due to the common association with rheumatoid arthritis and orthopedic implants, it is likely that lymphatic stasis secondary to chronic inflammation plays a notable role.

Therapies such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, local radiotherapy, cyclophosphamide, pentoxifylline, and arthrocentesis have been attempted without evidence of efficacy.2 Although intralymphatic histiocytosis is chronic and resistant to therapy, patients can be reassured that the condition runs a benign course.

1. O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

2. Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

3. Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

4. Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

5. Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

6. Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

7. Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

8. Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

9. Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

To the Editor:

|

| Figure 1. A 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh. |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Histopathology revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis with adjacent features of chronic lymphedema (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) as well as a collection of histiocytes in a dilated lymphatic channel (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). D2-40 staining demonstrated ectatic lymphatic vessels in the upper dermins (C)(original magnification ×20).

|

A 70-year-old white man presented with an asymptomatic patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh of 15 months’ duration. The patient believed the patch correlated with a hip replacement 3 years prior; however, it was 6 inches inferior to the incision site. Physical examination revealed a 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch (Figure 1). The patch was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids as well as a short course of oral prednisone. The patient’s medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Histopathologic examination revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis. In addition, adjacent features of chronic lymphedema were present, namely interstitial fibroplasia with dilated lymphatic vessels and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intralymphatic histiocytosis, a rare disease most commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Our patient did not have a history or clinical symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous condition reported by O’Grady et al1 in 1994. This condition has been most frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis2; however, there has been an emerging association in patients with orthopedic metal implants, with and without a concomitant diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Cases associated with metal implants are rare.2-7

The condition presents as asymptomatic red, brown, or violaceous patches, plaques, papules, or nodules that are ill defined and tend to demonstrate a livedo reticularis–like pattern. The lesions typically are overlying or in close proximity to a joint. Histopathologic findings include dilated vascular structures in the reticular dermis, some with empty lumina and others containing collections of mononuclear histiocytes. There also may be an inflammatory infiltrate in the adjacent dermis composed of a mix of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and/or histiocytes. Endothelial cells lining the dilated lumina express immunoreactivity for CD31, CD34, D2-40, Lyve-1, and Prox-1. Intravascular histiocytes are positive for CD68 and CD31.6

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains undefined. Some hypothesize that intralymphatic histiocytosis could be the early stage of reactive angioendotheliomatosis, as these conditions share clinical and histological features.8 Reactive angioendotheliomatosis also is a rare condition that may present as erythematous to violaceous patches or plaques. The lesions are commonly found on the limbs and may be associated with constitutional symptoms. Histologic findings of reactive angioendotheliomatosis include a proliferation of epithelioid, round, or spindle-shaped cells within the lumina of dermal blood vessels, which show positivity for CD31 and CD34.9 Others suggest the lesions of intralymphatic histiocytosis arise from lymphangiectasia; obstruction of lymphatic drainage due to congenital abnormalities; or acquired damage from infection, trauma, surgery, or radiation.2 Due to the common association with rheumatoid arthritis and orthopedic implants, it is likely that lymphatic stasis secondary to chronic inflammation plays a notable role.

Therapies such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, local radiotherapy, cyclophosphamide, pentoxifylline, and arthrocentesis have been attempted without evidence of efficacy.2 Although intralymphatic histiocytosis is chronic and resistant to therapy, patients can be reassured that the condition runs a benign course.

To the Editor:

|

| Figure 1. A 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh. |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Histopathology revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis with adjacent features of chronic lymphedema (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) as well as a collection of histiocytes in a dilated lymphatic channel (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). D2-40 staining demonstrated ectatic lymphatic vessels in the upper dermins (C)(original magnification ×20).

|

A 70-year-old white man presented with an asymptomatic patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh of 15 months’ duration. The patient believed the patch correlated with a hip replacement 3 years prior; however, it was 6 inches inferior to the incision site. Physical examination revealed a 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch (Figure 1). The patch was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids as well as a short course of oral prednisone. The patient’s medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Histopathologic examination revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis. In addition, adjacent features of chronic lymphedema were present, namely interstitial fibroplasia with dilated lymphatic vessels and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intralymphatic histiocytosis, a rare disease most commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Our patient did not have a history or clinical symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous condition reported by O’Grady et al1 in 1994. This condition has been most frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis2; however, there has been an emerging association in patients with orthopedic metal implants, with and without a concomitant diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Cases associated with metal implants are rare.2-7

The condition presents as asymptomatic red, brown, or violaceous patches, plaques, papules, or nodules that are ill defined and tend to demonstrate a livedo reticularis–like pattern. The lesions typically are overlying or in close proximity to a joint. Histopathologic findings include dilated vascular structures in the reticular dermis, some with empty lumina and others containing collections of mononuclear histiocytes. There also may be an inflammatory infiltrate in the adjacent dermis composed of a mix of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and/or histiocytes. Endothelial cells lining the dilated lumina express immunoreactivity for CD31, CD34, D2-40, Lyve-1, and Prox-1. Intravascular histiocytes are positive for CD68 and CD31.6

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains undefined. Some hypothesize that intralymphatic histiocytosis could be the early stage of reactive angioendotheliomatosis, as these conditions share clinical and histological features.8 Reactive angioendotheliomatosis also is a rare condition that may present as erythematous to violaceous patches or plaques. The lesions are commonly found on the limbs and may be associated with constitutional symptoms. Histologic findings of reactive angioendotheliomatosis include a proliferation of epithelioid, round, or spindle-shaped cells within the lumina of dermal blood vessels, which show positivity for CD31 and CD34.9 Others suggest the lesions of intralymphatic histiocytosis arise from lymphangiectasia; obstruction of lymphatic drainage due to congenital abnormalities; or acquired damage from infection, trauma, surgery, or radiation.2 Due to the common association with rheumatoid arthritis and orthopedic implants, it is likely that lymphatic stasis secondary to chronic inflammation plays a notable role.

Therapies such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, local radiotherapy, cyclophosphamide, pentoxifylline, and arthrocentesis have been attempted without evidence of efficacy.2 Although intralymphatic histiocytosis is chronic and resistant to therapy, patients can be reassured that the condition runs a benign course.

1. O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

2. Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

3. Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

4. Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

5. Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

6. Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

7. Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

8. Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

9. Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

1. O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

2. Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

3. Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

4. Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

5. Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

6. Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

7. Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

8. Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

9. Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

Practice Points

- Consider intralymphatic histiocytosis in the differential diagnosis of an asymptomatic skin lesion overlying a joint, particularly in patients with orthopedic metal implants or rheumatoid arthritis.

- Biopsy is essential for the diagnosis of intralymphatic histiocytosis; special stains highlighting dilated lymphatic vessels and intravascular histiocytes may be necessary.

- Intralymphatic histiocytosis is chronic and resistant to therapy; however, patients can be reassured that the condition runs a benign course.

Transition From Lichen Sclerosus to Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a Single Tissue Section

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the anogenital region. Progressive sclerosis results in scarring with distortion of the normal epithelial architecture.1,2 The lifetime risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) as a complication of long-standing LS has been estimated as 4% to 6%.3,4 However, there is no general agreement concerning the exact relationship between anogenital LS and SCC.1 The coexistence of histologic findings of LS, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and SCC in the same tissue is rare. We report a case of VIN and SCC developing in a region of preexisting LS.

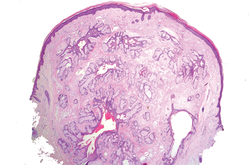

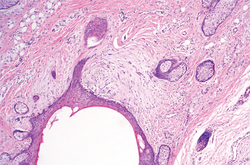

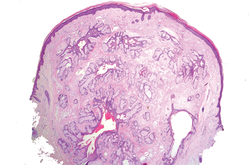

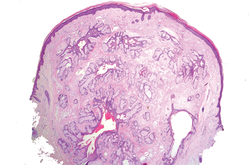

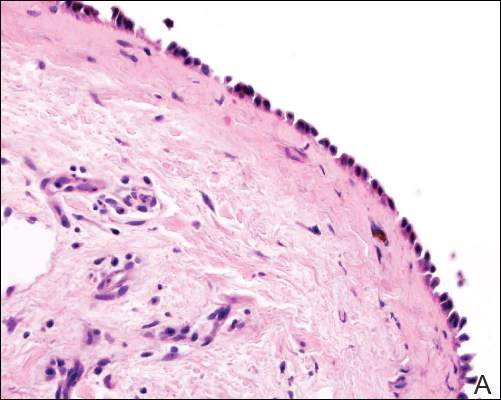

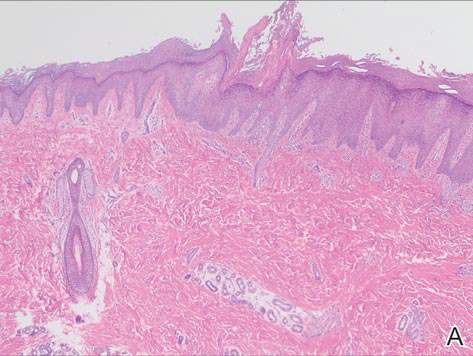

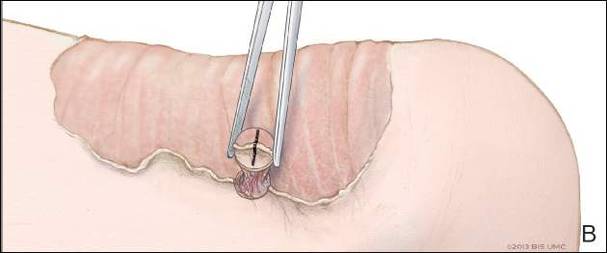

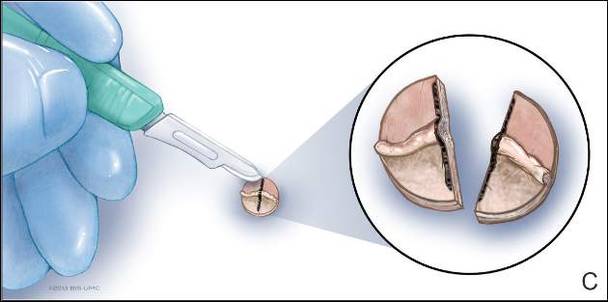

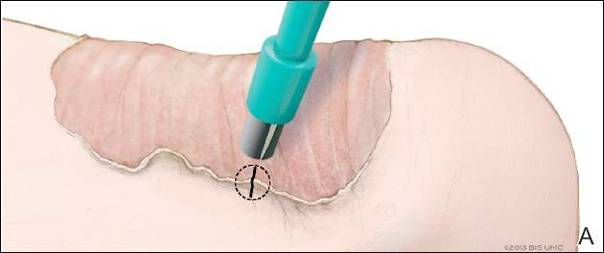

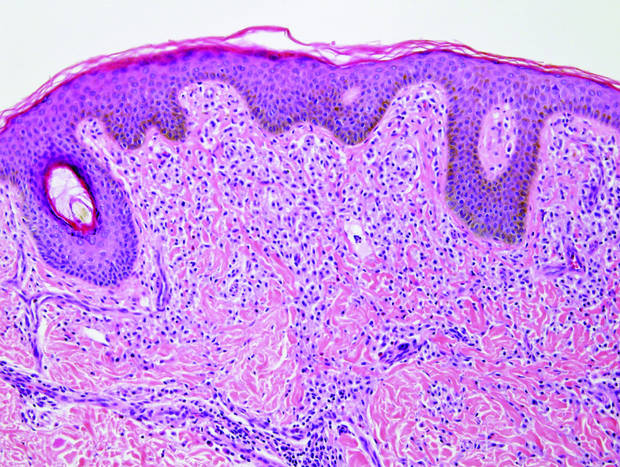

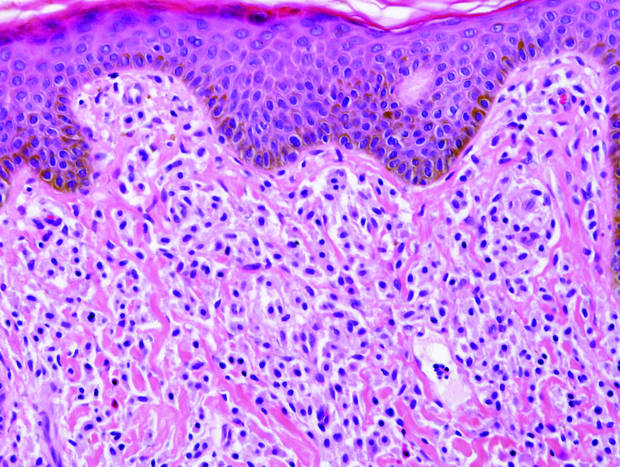

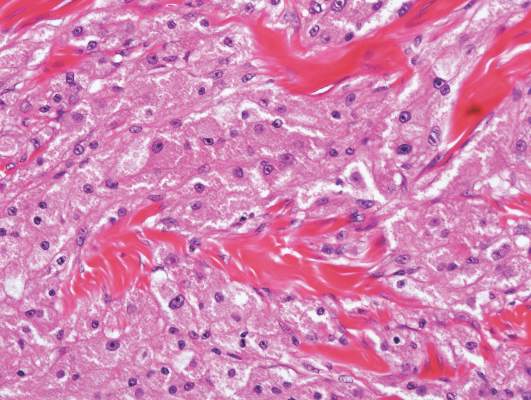

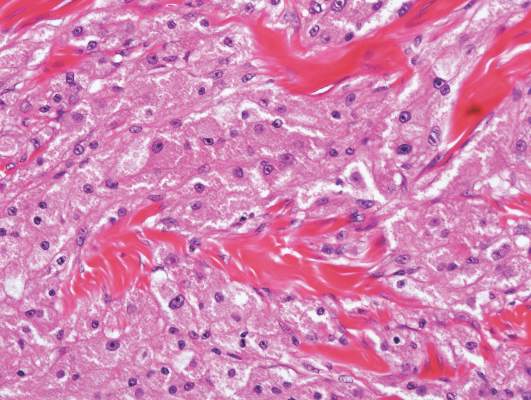

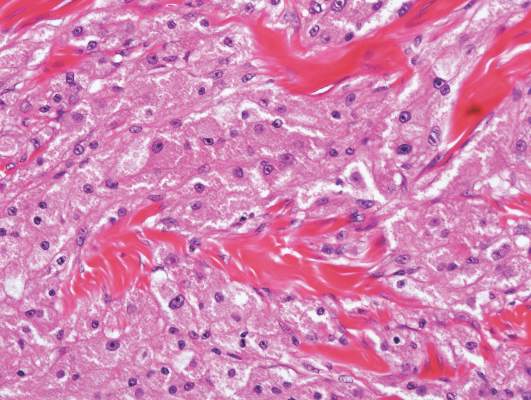

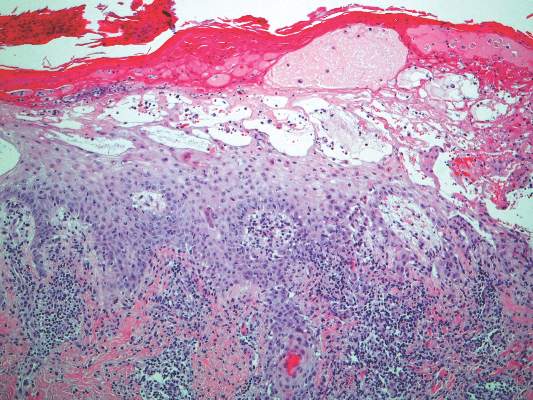

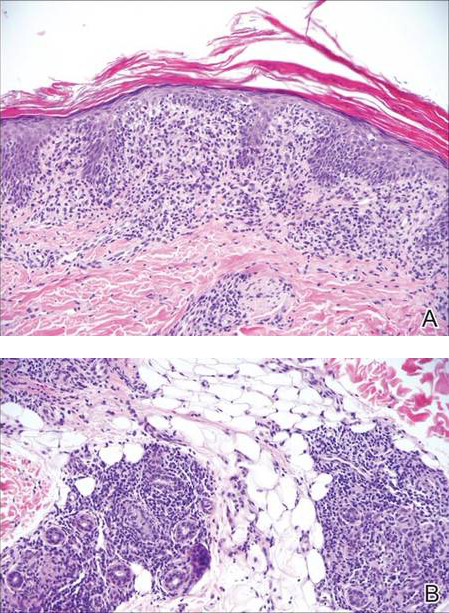

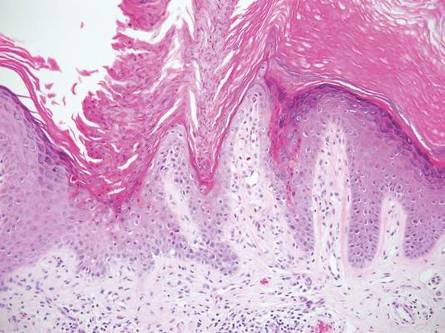

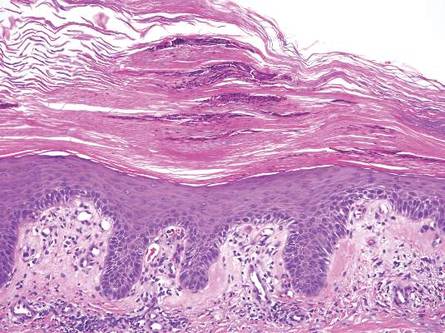

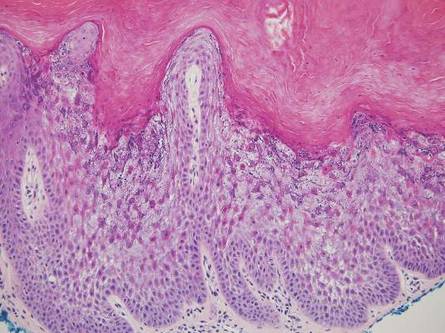

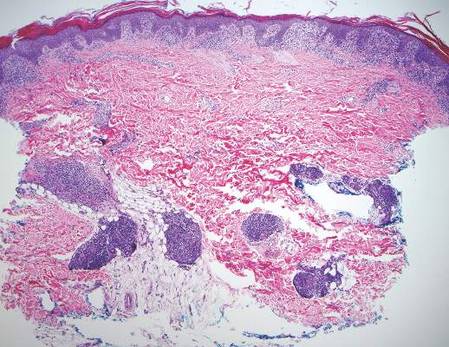

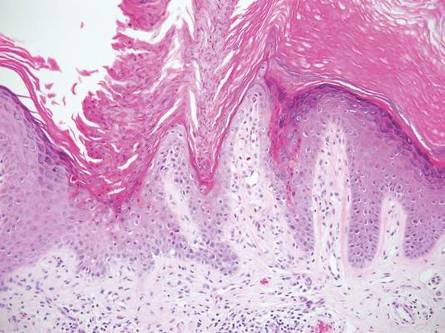

A 76-year-old woman presented with a 7-mm nodule on the clitoris that was surrounded by a pearly white, smooth, glistening area (Figure 1). The patient reported pain and tenderness associated with the nodule. No regional lymphadenopathy was evident. We performed an excisional biopsy of the entire nodule and a small part of the whitish patch (Figure 2A). On histologic examination, the presence of hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was consistent with LS (Figure 2B). The presence of dysplastic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture as well as acanthosis and dyskeratosis in the same tissue confirmed VIN (Figure 2C). Dermal invasion and transition to SCC were seen in the part of the tissue verified as VIN. The presence of dermal tumor nests and an irregular border between the epidermis and dermis pointed to the existence of fully developed SCC (Figure 2D). To prevent the recurrence of SCC, the patient returned for follow-up periodically. There was no recurrence within 6 months after excision.

|

|

|

|

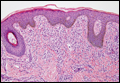

| Figure 2. An excisional biopsy showed epidermal thinning on the left side and invasion of the dermis by a tumor nest on the right side (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Left, center, and right boxes indicate areas shown in Figures 2B, 2C and 2D, respectively. Hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Dysplactic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture accompanied by acanthosis and nuclear atypia were seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Irregular masses of atypical squamous cells spread downward into the dermis representing squamous cell carcinoma of a well-differentiated type (D)(H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

Although LS is considered a premalignant condition, only a small portion of patients with LS ultimately develop vulvar SCC.5 There are a number of reasons for linking LS with the development of vulvar SCC. First, in the majority of cases of vulvar SCC, LS, squamous cell hyperplasia, or VIN is present in the adjacent epithelium. Lichen sclerosus is found in adjacent regions in up to 62% of vulvar SCC cases.6 Second, patients with LS may develop vulvar SCC, as frequently reported. Third, in a series of LS patients who underwent long-term follow-up, 4% to 6% were reported to have developed vulvar SCC.3,4,7

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by clinicopathologic persistence and hypocellular fibrosis.2 Changes in the local environment of the keratinocyte, including chronic inflammation and sclerosis, may be responsible for the promotion of carcinogenesis.8 However, no molecular markers have been proven to identify the LS lesions that are at risk for developing into vulvar SCC.9,10 It has been suggested that VIN is the direct precursor of vulvar SCC.11,12

Histologic diagnosis of VIN is difficult. Its identification is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with the absence of widespread architectural disorder, nuclear pleomorphism, and diffuse nuclear atypia.13 The atypia in VIN lesions is strictly confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium.11 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has seldom been diagnosed as a solitary lesion because it appears to have a short intraepithelial lifetime.

Vulvar SCC can be divided into 2 patterns. The first is found in older women, which is unrelated to human papillomavirus (HPV). This type occurs in a background of LS and/or differentiated VIN. The second is predominantly found in younger women, which is related to high-risk HPV. This type of vulvar SCC frequently is associated with the histologic subtypes of warty and basaloid differentiations and is referred to as undifferentiated VIN. There is no association with LS in these cases.2,14,15

It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis.16 Infection with HPV is an early event in the multistep process of vulvar carcinogenesis, and HPV integration into host cell genome seems to be related to the progression of vulvar dysplasia.17 Viral integration generally disrupts the E2 region, resulting in enhanced expression of E6 and E7. E6 and E7 have the ability to bind and inactivate the protein p53 and retinoblastoma protein, which promotes rapid progression through the cell cycle without p53-mediated control of DNA integrity.18 However, the exact influence of HPV in vulvar SCC is uncertain, as divergent prevalence rates have been published.

In our case, histologic examination revealed the characteristic findings of LS, VIN, and SCC in succession. This sequence is evidence of progressive transition from LS to VIN and then to SCC. Consequently, this case suggests that vulvar LS may act as both an initiator and a promoter of carcinogenesis and that VIN may be the direct precursor of vulvar SCC. In conclusion, LS has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients. Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

1. Bhattacharjee P, Fatteh SM, Lloyd KL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:319-320.

2. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

3. Ulrich RH. Lichen sclerosus. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2007:546-550.

4. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

5. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

6. Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Hermans J, et al. The relevance of various vulvar epithelial changes in the early detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:50-57.

7. Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Anogenital lichen sclerosus in women. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:694-698.

8. Walkden V, Chia Y, Wojnarowska F. The association of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and lichen sclerosus: implications for follow-up. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:551-553.

9. Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:128-133.

10. Wang SH, Chi CC, Wong YW, et al. Genital verrucous carcinoma is associated with lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:815-819.

11. Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:16-30.

12. van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:851-856.

13. Taube JM, Badger J, Kong CS, et al. Differentiated (simplex) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:27-30.

14. Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1217-1223.

15. Crum C, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, et al. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol Pathol. 1997;9:63-69.

16. Ansink AC, Krul MRL, De Weger RA, et al. Human papillomavirus, lichen sclerosus, and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: detection and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:180-184.

17. Hillemanns P, Wang X. Integration of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:276-282.

18. Stoler MH. Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:16-28.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the anogenital region. Progressive sclerosis results in scarring with distortion of the normal epithelial architecture.1,2 The lifetime risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) as a complication of long-standing LS has been estimated as 4% to 6%.3,4 However, there is no general agreement concerning the exact relationship between anogenital LS and SCC.1 The coexistence of histologic findings of LS, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and SCC in the same tissue is rare. We report a case of VIN and SCC developing in a region of preexisting LS.

A 76-year-old woman presented with a 7-mm nodule on the clitoris that was surrounded by a pearly white, smooth, glistening area (Figure 1). The patient reported pain and tenderness associated with the nodule. No regional lymphadenopathy was evident. We performed an excisional biopsy of the entire nodule and a small part of the whitish patch (Figure 2A). On histologic examination, the presence of hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was consistent with LS (Figure 2B). The presence of dysplastic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture as well as acanthosis and dyskeratosis in the same tissue confirmed VIN (Figure 2C). Dermal invasion and transition to SCC were seen in the part of the tissue verified as VIN. The presence of dermal tumor nests and an irregular border between the epidermis and dermis pointed to the existence of fully developed SCC (Figure 2D). To prevent the recurrence of SCC, the patient returned for follow-up periodically. There was no recurrence within 6 months after excision.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. An excisional biopsy showed epidermal thinning on the left side and invasion of the dermis by a tumor nest on the right side (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Left, center, and right boxes indicate areas shown in Figures 2B, 2C and 2D, respectively. Hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Dysplactic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture accompanied by acanthosis and nuclear atypia were seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Irregular masses of atypical squamous cells spread downward into the dermis representing squamous cell carcinoma of a well-differentiated type (D)(H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

Although LS is considered a premalignant condition, only a small portion of patients with LS ultimately develop vulvar SCC.5 There are a number of reasons for linking LS with the development of vulvar SCC. First, in the majority of cases of vulvar SCC, LS, squamous cell hyperplasia, or VIN is present in the adjacent epithelium. Lichen sclerosus is found in adjacent regions in up to 62% of vulvar SCC cases.6 Second, patients with LS may develop vulvar SCC, as frequently reported. Third, in a series of LS patients who underwent long-term follow-up, 4% to 6% were reported to have developed vulvar SCC.3,4,7

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by clinicopathologic persistence and hypocellular fibrosis.2 Changes in the local environment of the keratinocyte, including chronic inflammation and sclerosis, may be responsible for the promotion of carcinogenesis.8 However, no molecular markers have been proven to identify the LS lesions that are at risk for developing into vulvar SCC.9,10 It has been suggested that VIN is the direct precursor of vulvar SCC.11,12

Histologic diagnosis of VIN is difficult. Its identification is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with the absence of widespread architectural disorder, nuclear pleomorphism, and diffuse nuclear atypia.13 The atypia in VIN lesions is strictly confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium.11 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has seldom been diagnosed as a solitary lesion because it appears to have a short intraepithelial lifetime.

Vulvar SCC can be divided into 2 patterns. The first is found in older women, which is unrelated to human papillomavirus (HPV). This type occurs in a background of LS and/or differentiated VIN. The second is predominantly found in younger women, which is related to high-risk HPV. This type of vulvar SCC frequently is associated with the histologic subtypes of warty and basaloid differentiations and is referred to as undifferentiated VIN. There is no association with LS in these cases.2,14,15

It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis.16 Infection with HPV is an early event in the multistep process of vulvar carcinogenesis, and HPV integration into host cell genome seems to be related to the progression of vulvar dysplasia.17 Viral integration generally disrupts the E2 region, resulting in enhanced expression of E6 and E7. E6 and E7 have the ability to bind and inactivate the protein p53 and retinoblastoma protein, which promotes rapid progression through the cell cycle without p53-mediated control of DNA integrity.18 However, the exact influence of HPV in vulvar SCC is uncertain, as divergent prevalence rates have been published.

In our case, histologic examination revealed the characteristic findings of LS, VIN, and SCC in succession. This sequence is evidence of progressive transition from LS to VIN and then to SCC. Consequently, this case suggests that vulvar LS may act as both an initiator and a promoter of carcinogenesis and that VIN may be the direct precursor of vulvar SCC. In conclusion, LS has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients. Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the anogenital region. Progressive sclerosis results in scarring with distortion of the normal epithelial architecture.1,2 The lifetime risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) as a complication of long-standing LS has been estimated as 4% to 6%.3,4 However, there is no general agreement concerning the exact relationship between anogenital LS and SCC.1 The coexistence of histologic findings of LS, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and SCC in the same tissue is rare. We report a case of VIN and SCC developing in a region of preexisting LS.

A 76-year-old woman presented with a 7-mm nodule on the clitoris that was surrounded by a pearly white, smooth, glistening area (Figure 1). The patient reported pain and tenderness associated with the nodule. No regional lymphadenopathy was evident. We performed an excisional biopsy of the entire nodule and a small part of the whitish patch (Figure 2A). On histologic examination, the presence of hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was consistent with LS (Figure 2B). The presence of dysplastic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture as well as acanthosis and dyskeratosis in the same tissue confirmed VIN (Figure 2C). Dermal invasion and transition to SCC were seen in the part of the tissue verified as VIN. The presence of dermal tumor nests and an irregular border between the epidermis and dermis pointed to the existence of fully developed SCC (Figure 2D). To prevent the recurrence of SCC, the patient returned for follow-up periodically. There was no recurrence within 6 months after excision.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. An excisional biopsy showed epidermal thinning on the left side and invasion of the dermis by a tumor nest on the right side (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Left, center, and right boxes indicate areas shown in Figures 2B, 2C and 2D, respectively. Hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, a swollen dermal collagen bundle, and prominent edema was evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Dysplactic changes with mild disturbance of the epithelial architecture accompanied by acanthosis and nuclear atypia were seen (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Irregular masses of atypical squamous cells spread downward into the dermis representing squamous cell carcinoma of a well-differentiated type (D)(H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

Although LS is considered a premalignant condition, only a small portion of patients with LS ultimately develop vulvar SCC.5 There are a number of reasons for linking LS with the development of vulvar SCC. First, in the majority of cases of vulvar SCC, LS, squamous cell hyperplasia, or VIN is present in the adjacent epithelium. Lichen sclerosus is found in adjacent regions in up to 62% of vulvar SCC cases.6 Second, patients with LS may develop vulvar SCC, as frequently reported. Third, in a series of LS patients who underwent long-term follow-up, 4% to 6% were reported to have developed vulvar SCC.3,4,7

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by clinicopathologic persistence and hypocellular fibrosis.2 Changes in the local environment of the keratinocyte, including chronic inflammation and sclerosis, may be responsible for the promotion of carcinogenesis.8 However, no molecular markers have been proven to identify the LS lesions that are at risk for developing into vulvar SCC.9,10 It has been suggested that VIN is the direct precursor of vulvar SCC.11,12

Histologic diagnosis of VIN is difficult. Its identification is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with the absence of widespread architectural disorder, nuclear pleomorphism, and diffuse nuclear atypia.13 The atypia in VIN lesions is strictly confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium.11 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has seldom been diagnosed as a solitary lesion because it appears to have a short intraepithelial lifetime.

Vulvar SCC can be divided into 2 patterns. The first is found in older women, which is unrelated to human papillomavirus (HPV). This type occurs in a background of LS and/or differentiated VIN. The second is predominantly found in younger women, which is related to high-risk HPV. This type of vulvar SCC frequently is associated with the histologic subtypes of warty and basaloid differentiations and is referred to as undifferentiated VIN. There is no association with LS in these cases.2,14,15

It has been suggested that LS and HPV may not be mutually exclusive but may act as cofactors in SCC pathogenesis.16 Infection with HPV is an early event in the multistep process of vulvar carcinogenesis, and HPV integration into host cell genome seems to be related to the progression of vulvar dysplasia.17 Viral integration generally disrupts the E2 region, resulting in enhanced expression of E6 and E7. E6 and E7 have the ability to bind and inactivate the protein p53 and retinoblastoma protein, which promotes rapid progression through the cell cycle without p53-mediated control of DNA integrity.18 However, the exact influence of HPV in vulvar SCC is uncertain, as divergent prevalence rates have been published.

In our case, histologic examination revealed the characteristic findings of LS, VIN, and SCC in succession. This sequence is evidence of progressive transition from LS to VIN and then to SCC. Consequently, this case suggests that vulvar LS may act as both an initiator and a promoter of carcinogenesis and that VIN may be the direct precursor of vulvar SCC. In conclusion, LS has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients. Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

1. Bhattacharjee P, Fatteh SM, Lloyd KL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:319-320.

2. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

3. Ulrich RH. Lichen sclerosus. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2007:546-550.

4. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

5. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

6. Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Hermans J, et al. The relevance of various vulvar epithelial changes in the early detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:50-57.

7. Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Anogenital lichen sclerosus in women. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:694-698.

8. Walkden V, Chia Y, Wojnarowska F. The association of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and lichen sclerosus: implications for follow-up. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:551-553.

9. Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:128-133.

10. Wang SH, Chi CC, Wong YW, et al. Genital verrucous carcinoma is associated with lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:815-819.

11. Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:16-30.

12. van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:851-856.

13. Taube JM, Badger J, Kong CS, et al. Differentiated (simplex) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:27-30.

14. Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1217-1223.

15. Crum C, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, et al. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol Pathol. 1997;9:63-69.

16. Ansink AC, Krul MRL, De Weger RA, et al. Human papillomavirus, lichen sclerosus, and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: detection and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:180-184.

17. Hillemanns P, Wang X. Integration of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:276-282.

18. Stoler MH. Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:16-28.

1. Bhattacharjee P, Fatteh SM, Lloyd KL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:319-320.

2. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

3. Ulrich RH. Lichen sclerosus. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith L, Katz S, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2007:546-550.

4. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

5. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

6. Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Hermans J, et al. The relevance of various vulvar epithelial changes in the early detection of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1997;7:50-57.

7. Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Anogenital lichen sclerosus in women. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:694-698.

8. Walkden V, Chia Y, Wojnarowska F. The association of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and lichen sclerosus: implications for follow-up. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:551-553.

9. Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:128-133.

10. Wang SH, Chi CC, Wong YW, et al. Genital verrucous carcinoma is associated with lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:815-819.

11. Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:16-30.

12. van de Nieuwenhof HP, Massuger LF, van der Avoort IA, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:851-856.

13. Taube JM, Badger J, Kong CS, et al. Differentiated (simplex) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:27-30.

14. Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1217-1223.

15. Crum C, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, et al. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol Pathol. 1997;9:63-69.

16. Ansink AC, Krul MRL, De Weger RA, et al. Human papillomavirus, lichen sclerosus, and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: detection and prognostic significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:180-184.

17. Hillemanns P, Wang X. Integration of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:276-282.

18. Stoler MH. Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:16-28.

Practice Points

- Lichen sclerosus has a considerable risk for malignant transformation and requires continuous follow-up in all patients.

- Early histological detection of invasive lesions is crucial to reduce the risk for vulvar cancer.

Dome-Shaped Papule With a Bloody Crust

The Diagnosis: Congenital Folliculosebaceous Cystic Hamartoma

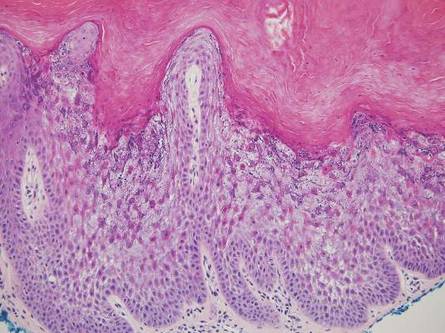

Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma (FSCH) is a rare skin condition that is either congenital or acquired. It presents as a slow-growing and flesh-colored papulonodular lesion1 that mainly occurs on the head and neck. Involvement of the nipples, perineum, back, forearms, genital areas, and subcutaneous tissue also has been reported but usually indicates a larger lesion.1,2

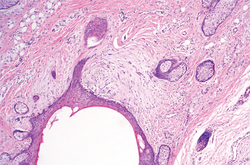

Histologically, FSCH is considered a hamartoma composed of both ectodermal and mesodermal elements.1 Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma is a more complex lesion composed of infundibulocystic structures connected to maloriented folliculosebaceous units surrounded by whorls of highly vascularized fibrous stroma and adipocytes. Clefts between fibroepithelial units and surrounding stroma usually are present.1

Epithelial components contribute to the adnexal and folliculosebaceous cystic proliferations, and mesenchymal elements include vascular tissue, adipose tissue, and fibroblast-rich stroma.1,2 Acquired lesions arising in adults have been described,1-5 but the congenital presentation of FSCH in infancy is rare.

Histopathologically, some variations of FSCH are mainly composed of epithelial components while others are composed of nonepithelial components. Nonepithelial components include neural proliferation, muscle components, vascular proliferation, and mucin deposition.1-4 In some cases, FSCH may coexist with other diseases, such as nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis and neurofibromatosis type I.4,5

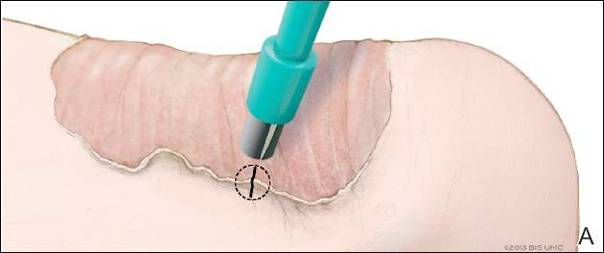

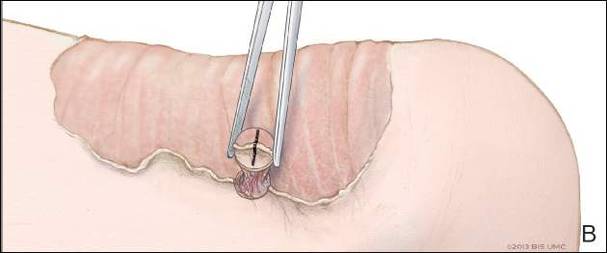

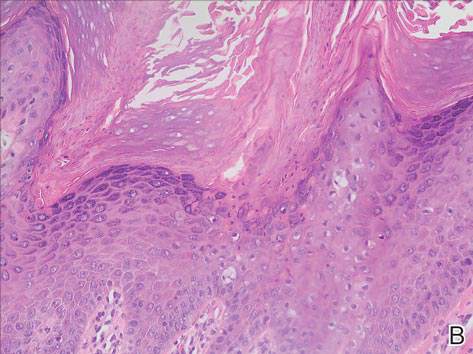

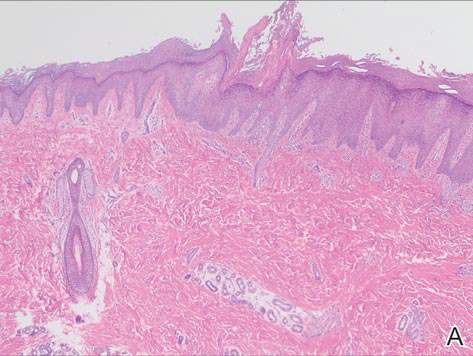

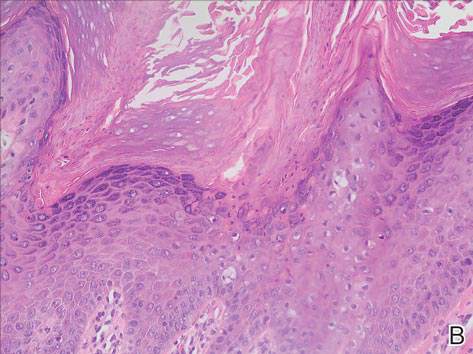

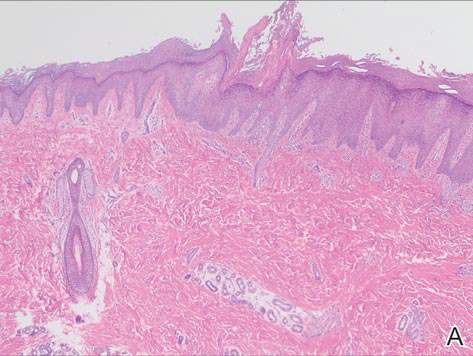

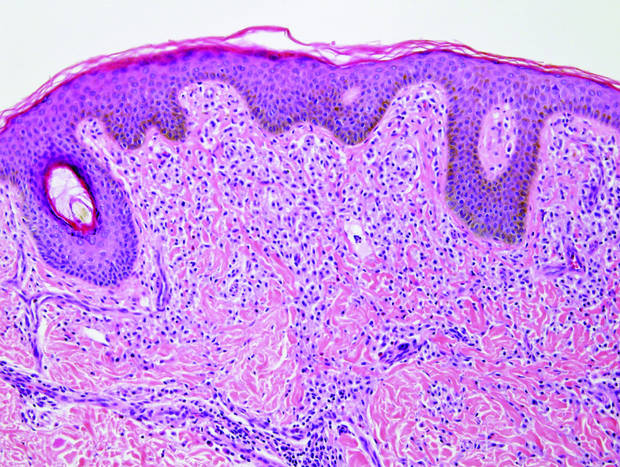

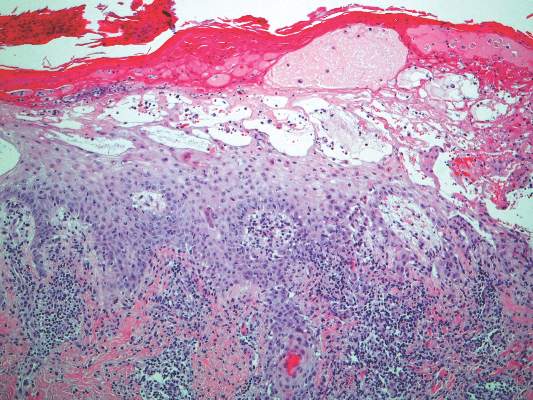

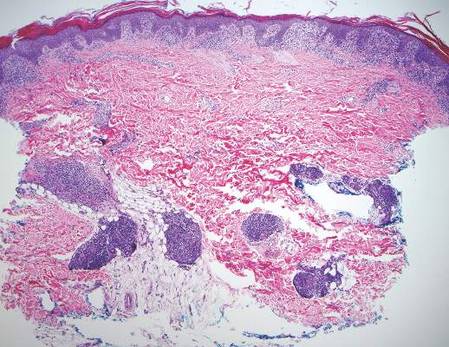

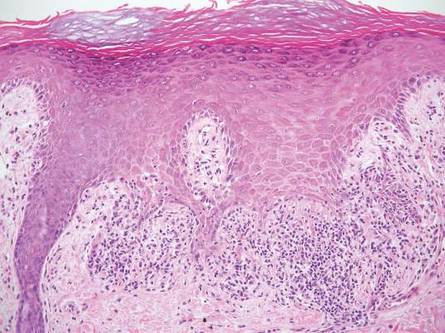

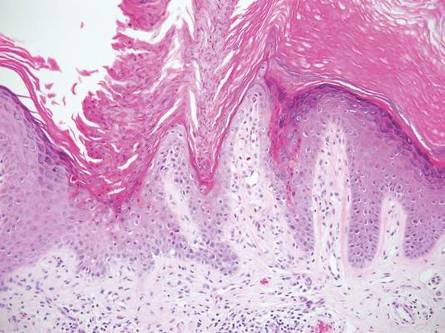

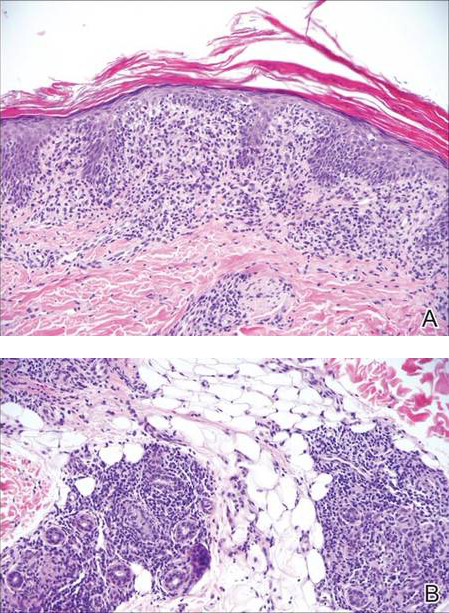

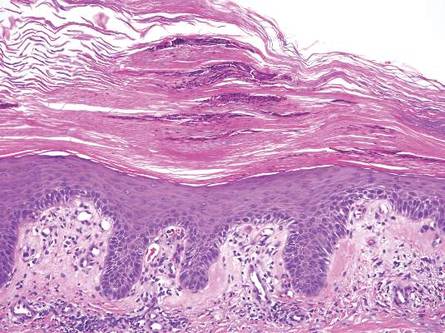

In our case, histopathology showed several dermal infundibulocystic structures that were lined by stratified squamous epithelium and contained horny material (Figure 1). Numerous immature sebaceous lobules and rudimentary hair follicles emanated from some of the cyst walls. Mesenchymal changes around the fibroepithelial units included fibrillary bundles of collagen, clusters of adipocytes, and an increased number of small venules (Figure 2). In addition, the stroma adjacent to the malformed perifollicle contained some amount of mucin. Prominent clefts formed between fibroepithelial units and the surrounding altered stroma.

|

| |

|

The differential diagnosis mainly includes sebaceous trichofolliculoma, molluscum contagiosum, dermoid cysts, pilomatrixoma, Spitz nevus, and nevus lipomatosus superficialis. The differential diagnosis between FSCH and sebaceous trichofolliculoma is challenging. Both lesions show an infundibular cyst and surrounding sebaceous nodules. According to Plewig,6 trichofolliculoma has a wide spectrum ranging from low to high differentiation represented by trichofolliculoma, sebaceous trichofolliculoma, and FSCH, respectively. It is not difficult to distinguish FSCH from other diseases according to its peculiar histopathologic features.

The clinicopathologic features of our case were similar to those of reported FSCH cases, except for the following unique characteristics: congenital lesion, lack of terminal hair, and no sebaceous material extrusion. These features of hair and sebaceous material may be correlated with the patient’s age and hormonal level.1 Androgen may play a key role in sebaceous gland development at puberty, which leads to sebaceous gland hyperplasia and hypertrophy. Therefore, slight pressure from the lesions can make ivory-white sebaceous material discharge. Hence, the dermatologist and pediatrician must be poised and sensitive while making an initial diagnosis of FSCH.

1. Kimura T, Miyazawa H, Aoyagi T, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma: a distinctive malformation of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:213-220.

2. Moriki M, Ito T, Hirakawa S, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma presenting as a subcutaneous nodule on the thigh. J Dermatol. 2013;40:483-484.

3. Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma with perifollicular mucinosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:58-62.

4. Brasanac D, Boricic I. Giant nevus lipomatosus superficialis with multiple folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas and dermoid cysts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:84-86.

5. Noh S, Kwon JE, Lee KG, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S185-S187.

6. Plewig G. In discussion of: Leserbrief zu Zheng LQ, Han XC, Huang Y, Li HW. Several acneiform papules and nodules on the neck. diagnosis: folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:824-825.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Folliculosebaceous Cystic Hamartoma

Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma (FSCH) is a rare skin condition that is either congenital or acquired. It presents as a slow-growing and flesh-colored papulonodular lesion1 that mainly occurs on the head and neck. Involvement of the nipples, perineum, back, forearms, genital areas, and subcutaneous tissue also has been reported but usually indicates a larger lesion.1,2

Histologically, FSCH is considered a hamartoma composed of both ectodermal and mesodermal elements.1 Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma is a more complex lesion composed of infundibulocystic structures connected to maloriented folliculosebaceous units surrounded by whorls of highly vascularized fibrous stroma and adipocytes. Clefts between fibroepithelial units and surrounding stroma usually are present.1

Epithelial components contribute to the adnexal and folliculosebaceous cystic proliferations, and mesenchymal elements include vascular tissue, adipose tissue, and fibroblast-rich stroma.1,2 Acquired lesions arising in adults have been described,1-5 but the congenital presentation of FSCH in infancy is rare.

Histopathologically, some variations of FSCH are mainly composed of epithelial components while others are composed of nonepithelial components. Nonepithelial components include neural proliferation, muscle components, vascular proliferation, and mucin deposition.1-4 In some cases, FSCH may coexist with other diseases, such as nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis and neurofibromatosis type I.4,5

In our case, histopathology showed several dermal infundibulocystic structures that were lined by stratified squamous epithelium and contained horny material (Figure 1). Numerous immature sebaceous lobules and rudimentary hair follicles emanated from some of the cyst walls. Mesenchymal changes around the fibroepithelial units included fibrillary bundles of collagen, clusters of adipocytes, and an increased number of small venules (Figure 2). In addition, the stroma adjacent to the malformed perifollicle contained some amount of mucin. Prominent clefts formed between fibroepithelial units and the surrounding altered stroma.

|

| |

|

The differential diagnosis mainly includes sebaceous trichofolliculoma, molluscum contagiosum, dermoid cysts, pilomatrixoma, Spitz nevus, and nevus lipomatosus superficialis. The differential diagnosis between FSCH and sebaceous trichofolliculoma is challenging. Both lesions show an infundibular cyst and surrounding sebaceous nodules. According to Plewig,6 trichofolliculoma has a wide spectrum ranging from low to high differentiation represented by trichofolliculoma, sebaceous trichofolliculoma, and FSCH, respectively. It is not difficult to distinguish FSCH from other diseases according to its peculiar histopathologic features.

The clinicopathologic features of our case were similar to those of reported FSCH cases, except for the following unique characteristics: congenital lesion, lack of terminal hair, and no sebaceous material extrusion. These features of hair and sebaceous material may be correlated with the patient’s age and hormonal level.1 Androgen may play a key role in sebaceous gland development at puberty, which leads to sebaceous gland hyperplasia and hypertrophy. Therefore, slight pressure from the lesions can make ivory-white sebaceous material discharge. Hence, the dermatologist and pediatrician must be poised and sensitive while making an initial diagnosis of FSCH.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Folliculosebaceous Cystic Hamartoma

Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma (FSCH) is a rare skin condition that is either congenital or acquired. It presents as a slow-growing and flesh-colored papulonodular lesion1 that mainly occurs on the head and neck. Involvement of the nipples, perineum, back, forearms, genital areas, and subcutaneous tissue also has been reported but usually indicates a larger lesion.1,2

Histologically, FSCH is considered a hamartoma composed of both ectodermal and mesodermal elements.1 Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma is a more complex lesion composed of infundibulocystic structures connected to maloriented folliculosebaceous units surrounded by whorls of highly vascularized fibrous stroma and adipocytes. Clefts between fibroepithelial units and surrounding stroma usually are present.1

Epithelial components contribute to the adnexal and folliculosebaceous cystic proliferations, and mesenchymal elements include vascular tissue, adipose tissue, and fibroblast-rich stroma.1,2 Acquired lesions arising in adults have been described,1-5 but the congenital presentation of FSCH in infancy is rare.

Histopathologically, some variations of FSCH are mainly composed of epithelial components while others are composed of nonepithelial components. Nonepithelial components include neural proliferation, muscle components, vascular proliferation, and mucin deposition.1-4 In some cases, FSCH may coexist with other diseases, such as nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis and neurofibromatosis type I.4,5

In our case, histopathology showed several dermal infundibulocystic structures that were lined by stratified squamous epithelium and contained horny material (Figure 1). Numerous immature sebaceous lobules and rudimentary hair follicles emanated from some of the cyst walls. Mesenchymal changes around the fibroepithelial units included fibrillary bundles of collagen, clusters of adipocytes, and an increased number of small venules (Figure 2). In addition, the stroma adjacent to the malformed perifollicle contained some amount of mucin. Prominent clefts formed between fibroepithelial units and the surrounding altered stroma.

|

| |

|

The differential diagnosis mainly includes sebaceous trichofolliculoma, molluscum contagiosum, dermoid cysts, pilomatrixoma, Spitz nevus, and nevus lipomatosus superficialis. The differential diagnosis between FSCH and sebaceous trichofolliculoma is challenging. Both lesions show an infundibular cyst and surrounding sebaceous nodules. According to Plewig,6 trichofolliculoma has a wide spectrum ranging from low to high differentiation represented by trichofolliculoma, sebaceous trichofolliculoma, and FSCH, respectively. It is not difficult to distinguish FSCH from other diseases according to its peculiar histopathologic features.

The clinicopathologic features of our case were similar to those of reported FSCH cases, except for the following unique characteristics: congenital lesion, lack of terminal hair, and no sebaceous material extrusion. These features of hair and sebaceous material may be correlated with the patient’s age and hormonal level.1 Androgen may play a key role in sebaceous gland development at puberty, which leads to sebaceous gland hyperplasia and hypertrophy. Therefore, slight pressure from the lesions can make ivory-white sebaceous material discharge. Hence, the dermatologist and pediatrician must be poised and sensitive while making an initial diagnosis of FSCH.

1. Kimura T, Miyazawa H, Aoyagi T, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma: a distinctive malformation of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:213-220.

2. Moriki M, Ito T, Hirakawa S, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma presenting as a subcutaneous nodule on the thigh. J Dermatol. 2013;40:483-484.

3. Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma with perifollicular mucinosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:58-62.

4. Brasanac D, Boricic I. Giant nevus lipomatosus superficialis with multiple folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas and dermoid cysts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:84-86.

5. Noh S, Kwon JE, Lee KG, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S185-S187.

6. Plewig G. In discussion of: Leserbrief zu Zheng LQ, Han XC, Huang Y, Li HW. Several acneiform papules and nodules on the neck. diagnosis: folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:824-825.

1. Kimura T, Miyazawa H, Aoyagi T, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma: a distinctive malformation of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:213-220.

2. Moriki M, Ito T, Hirakawa S, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma presenting as a subcutaneous nodule on the thigh. J Dermatol. 2013;40:483-484.

3. Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma with perifollicular mucinosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:58-62.

4. Brasanac D, Boricic I. Giant nevus lipomatosus superficialis with multiple folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas and dermoid cysts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:84-86.

5. Noh S, Kwon JE, Lee KG, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S185-S187.

6. Plewig G. In discussion of: Leserbrief zu Zheng LQ, Han XC, Huang Y, Li HW. Several acneiform papules and nodules on the neck. diagnosis: folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:824-825.

A 3-year-old girl was referred to our clinic for a lesion on the face that had been present since birth and had enlarged slowly with slight itching. Physical examination revealed a 1.0×1.0-cm, sessile, flesh-colored, sharply demarcated, and dome-shaped papule with a bloody crust. It was firm and slightly painful to palpation. Dilated hair follicle–like orifices and thick central terminal hair were not found. Sebaceous material was not discharged. There was no notable family history or evidence of systemic disease. The lesion was surgically removed for cosmetic reasons and further histopathologic examination was performed.

Radiation-Induced Pemphigus or Pemphigoid Disease in 3 Patients With Distinct Underlying Malignancies

A number of adverse cutaneous effects may result from radiation therapy, including radiodermatitis, alopecia, and radiation-induced neoplasms. Radiation therapy rarely induces pemphigus or pemphigoid disease, but awareness of this disorder is of clinical importance because these cutaneous lesions may resemble other skin diseases, including recurrent underlying cancer. We report 3 cases of pemphigus or pemphigoid disease that occurred after radiation therapy for in situ ductal carcinoma of the breast, cervical squamous cell carcinoma, and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of unknown origin, respectively.

Case Reports

To identify all the patients with radiation-induced pemphigus, pemphigoid diseases, or both diagnosed and treated at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) from 1988 to 2009, we performed a computerized search of dermatology, laboratory medicine, and pathology medical records using the following keywords: radiation, pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus erythematosus, and blistering disease. Inclusion criteria were a history of radiation therapy and subsequent development of pemphigus or pemphigoid disease within the irradiated fields. Patients with a history of immunobullous disease preceding radiation therapy and patients with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus or paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome were excluded. The diagnoses were confirmed by routine pathology as well as direct and indirect immunofluorescence examinations.

We identified 3 patients with severe extensive radiation-associated pemphigus/pemphigoid disease that had developed within 14 months after they received radiation therapy for their underlying cancer. The identified patients’ medical records were reviewed for underlying malignancy, symptoms at the time of diagnosis, treatment course, and follow-up. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board.

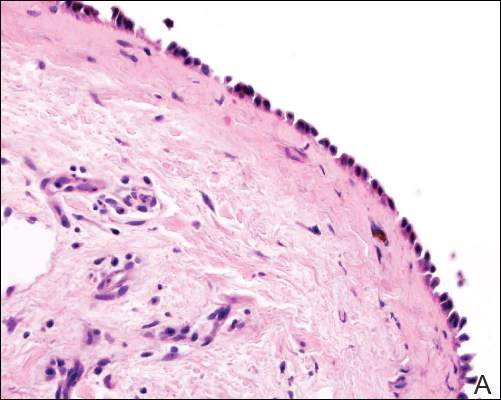

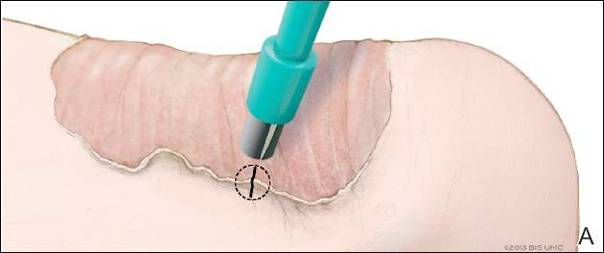

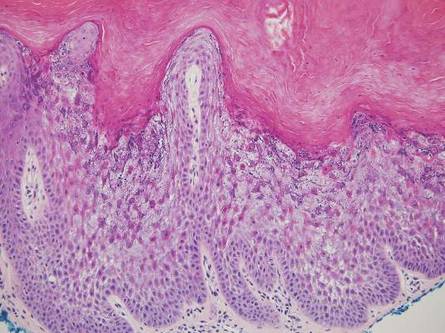

Patient 1—A 58-year-old woman was diagnosed with in situ ductal carcinoma of the right breast and underwent a lumpectomy with subsequent radiation therapy at an outside institution. Fourteen months after the final radiation treatment, she developed localized flaccid blisters and a superficial erosion on the right areola (Figure 1). Routine pathologic and direct immunofluorescence studies performed on shave biopsies in conjunction with serum analysis by indirect immunofluorescence confirmed the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris (Figure 2). Additionally, a deeper 4-mm punch biopsy ruled out metastatic breast carcinoma. The patient initially was treated with prednisone 60 mg and azathioprine 50 mg daily. The prednisone was tapered over 4 to 5 months to a dose of 5 mg every other day for another 4 to 5 months. Azathioprine was discontinued after a few months because of increased liver enzyme levels and a rapid clinical response of the pemphigus to this regimen.

Subsequently, she developed oral and ocular erosions that were compatible with pemphigus and were believed to be precipitated by trauma secondary to dental work and to the use of contact lenses. These flares were treated and stabilized with short courses of prednisone at higher doses that were successfully tapered to a maintenance dose of 5 mg every other day to control the pemphigus. With that prednisone dosage, her disease has remained clinically stable.

Patient 2—A 40-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IIIB cervical squamous carcinoma with para-aortic adenopathy. She was initially treated with primary radiation therapy directed at the pelvis and para-aortic regions using a 4-field approach at our institution, and she received weekly cisplatin chemotherapy at another institution. Nine months later, the patient was admitted to our institution with persistent metastatic cervical carcinoma of the retroperitoneum. She was scheduled for intraoperative radiation therapy as well as aggressive surgical cytoreduction. The day before her surgery she presented to our dermatology clinic with a generalized pruritic rash of 1 month’s duration and occasional blistering without mucosal involvement. Biopsy specimens from the lower back and abdomen were sent for routine histologic studies and direct immunofluorescence. Serum was sent for analysis by indirect immunofluorescence. Pathology results were consistent with a diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid with an infiltrate of eosinophils in the papillary dermis; direct immunofluorescence revealed continuous strong linear deposition of C3, which also was consistent with pemphigoid.

At that time, we recommended application of topical clobetasol 0.05% twice daily to affected areas before initiating prednisone. Postoperatively, her rash improved dramatically with clobetasol monotherapy. However, 4 months after discharge from our hospital, her local dermatologist called us for a telephone consultation regarding clinical and laboratory evidence of pemphigoid relapse. A direct immunofluorescence study showed both linear IgG and C3 deposition. The patient had healed well from the surgery, and the metastatic cervical carcinoma was quiescent. Prednisone in combination with a second immunosuppressive agent was recommended, pending approval by her local oncologist. No further follow-up information is available at this time.

Patient 3—A 72-year-old woman presented with a blistering eruption that had developed on the neck, the upper part of the chest, and other body sites, including the oral mucosa, 6 months after radiation therapy for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of unknown origin on the neck. On admission to the local hospital, she received a diagnosis of pemphigoid, although the outside biopsy specimens and reports were not available.

The patient was initially treated with prednisone, which was rapidly tapered because she was diabetic and her blood glucose levels were labile. Consequently, she was switched to azathioprine 50 mg 3 times daily and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg 3 times daily. The patient was transferred to our institution with mild fatigue, dysphagia, weight loss, and generalized blistering involving the skin and lips. Otolaryngologic consultation and radiographic evaluation revealed no evidence of recurrent carcinoma. A shave biopsy was obtained for routine histologic evaluation and immunofluorescence and confirmed the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. The patient, however, also was found to have pancytopenia, most likely induced by the combination of azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. Her therapeutic regimen was switched to triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to be applied to the eroded areas twice daily and mupirocin ointment to be applied to the hemorrhagic scabs. Subsequently, her complete blood cell count returned to normal.

She continued to use topical corticosteroid therapy to control pemphigoid symptoms, but 6 months later the patient was found to have a lung mass and died secondary to respiratory failure.

|

|

| Figure 2. Pathologic and immunofluorescence studies confirmed the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris. Intraepidermal acantholysis forming a suprabasal blister with a tombstone appearance was seen along the basal cell layer (A)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Intercellular IgG deposition involving the epidermis was noted with direct immunofluorescence (B)(original magnification ×600). | |

|

|

Comment

A wide range of cutaneous reactions are known to occur in conjunction with radiation therapy. Early or acute adverse effects on the skin, such as erythema, edema, and desquamation, can be observed during radiation therapy and for several weeks thereafter. They are usually followed by hair loss and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pemphigus or pemphigoid disease is a rare complication of radiation therapy and has been reported in case reports and small case series.1-17 These disorders include bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, bullous lupus erythematosus, and acquired epidermolysis bullosa.10

The mechanism by which radiation therapy induces pemphigus remains open to speculation. Ionizing radiation may alter the antigenicity of the keratinocyte surface by disrupting the sulfhydryl groups,13 thus changing the immunoreactivity of the desmogleins or unmasking certain epidermal antigens. Another possible explanation is immune surveillance interference by damaged T-suppressor cells, which are preferentially sensitive to radiation.8 Robbins et al12 presented a patient with radiation-induced mucocutaneous pemphigus. They performed immunomapping of perilesional skin for the irradiated field, which illustrated altered expression of desmoglein (Dsg) 1, a commonly targeted antigen in pemphigus. Their study also suggested that radiation changed either the distribution or the expression of Dsg1 in the epidermis.12

Approximately half the reported cases we identified were associated with breast carcinoma,1-4,8,14 as in the case of patient 1. The majority of patients initially experienced blistering confined to the irradiated area followed by a variable degree of dissemination to other sites, probably due to the epitope-spreading phenomenon.12 During the months after radiation therapy, Aguado et al1 documented that their patient, who was initially positive for only anti-Dsg3 antibody, developed anti-Dsg1 antibodies. Therefore, the unusual development of mucosal ulcers, other skin lesions, or both after radiation therapy should raise suspicion for this diagnosis.

Bullous pemphigoid primarily affects elderly patients with blister formation along the dermoepidermal junction. Various causes, such as drugs, trauma, UV light, and ionizing radiation, have been associated with this autoimmune blistering disorder. In a systemic literature review, Mul et al10 discovered 27 case reports of bullous pemphigoid that were associated with radiation. It has been suggested that the alteration of the antigenicity and damaged dermoepidermal junction by radiation is a disease-producing mechanism.15,16 Another explanation is that the patients had subclinical pemphigoid and underwent radiation therapy, which damaged the basal layer sufficiently to produce subepidermal blister formation (triggered pemphigoid).17

The patients in this analysis had clinical presentations similar to those previously reported, with a blistering rash that usually began in the irradiated field, raising the possibility of acute radiation dermatitis. However, unlike acute radiation dermatitis, the lesions extended beyond the radiation fields in all 3 cases with mucosal involvement in patients 1 and 3. Although an onset of pemphigoid was previously observed after a minimum dose of 20 Gy,10 there was no definitive correlation observed between the extent and the severity of the cutaneous eruption and the radiation dose in prior studies. Unfortunately, we could not obtain exact radiation doses in our cases because all 3 patients were treated by radiation oncologists at other institutions. We did not, however, observe in our patients that the eruptions were more severe within the irradiated areas. Our analysis demonstrated that radiation-induced pemphigus or pemphigoid disease does not differ greatly from the endogenous form of the disease in its response to therapy or clinical course.

In summary, radiation-induced pemphigus or pemphigoid disease, a rare but serious adverse effect of radiation therapy, should be considered in patients with new-onset blistering or erosive skin disease who have recently undergone irradiation. The accurate diagnosis of pemphigus or pemphigoid disease is important because such diseases often require long-term immunosuppressive therapy. A thorough history and skin examination must be obtained from all patients who receive radiation therapy and subsequently have blisters or eruptions on the skin, mucous membranes, or both. Appropriate diagnostic studies, including routine biopsy for histologic evaluation and direct immunofluorescence, serum for indirect immunofluorescence, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, should be performed to exclude pemphigus or pemphigoid disease.

1. Aguado L, Marguina M, Pretel M, et al. Lesions of pemphigus vulgaris on irradiated skin [published online January 13, 2009]. Clin Exper Dermatol. 2009;34:e148-e150.

2. Ambay A, Sratman E. Ionizing radiation-induced pemphigus foliaceus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;54(suppl 5):S251-S252.

3. Cianchini G, Lembo L, Colonna L, et al. Pemphigus foliaceus induced by radiotherapy and response to dapsone. J Dermatol Treat. 2006;17:244-246.

4. Correia MP, Santos D, Jorge M, et al. Radiotherapy-induced pemphigus. Acta Med Port. 1998;11:581-583.

5. Delaporte E, Piette F, Bergoend H. Pemphigus vulgaris induced by radiotherapy. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;118:447-451.

6. Girolomoni G, Mazzone E, Zambrunno G. Pemphigus vulgaris following cobalt therapy for bronchial carcinoma. Dermatologica. 1989;178:37-38.

7. Krauze E, Wygledowska-Kania M, Kaminska-Budzinska G, et al. Radiotherapy induced pemphigus vulgaris [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130:549-550.

8. Low GJ, Keeling JH. Ionizing radiation-induced pemphigus. case presentations and literature review. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1319-1323.

9. Mseddi M, Bouassida S, Khemakhem M, et al. Radiotherapy-induced pemphigus: a case report [published online January 18, 2005]. Cancer Radiother. 2005;9:96-98.

10. Mul VE, van Geest AJ, Pijls-Johannesma MC, et al. Radiation-induced bullous pemphigoid: a systemic review of an unusual radiation side effect [published online December 11, 2006]. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82:5-9.

11. Orion E, Matz H, Wolf R. Pemphigus vulgaris induced by radiotherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:508-509.

12. Robbins AC, Lazarova Z, Janson MM, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris presenting in a radiation portal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(suppl 5):S82-S85.

13. Rucco V, Pisani M. Induced pemphigus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1982;274:123-140.

14. Vigna-Taglianti R, Russi EG, Denaro N, et al. Radiation-induced pemphigus vulgaris of the breast [published online April 20, 2011]. Cancer Radiother. 2011;15:334-337.

15. Cliff S, Harland CC, Fallowfield ME, et al. Localised bullous pemphigoid following radiotherapy Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;76:330-331.

16. Ohata C, Shirabe H, Takagi K, et al. Localized bullous pemphigoid after radiation therapy: two cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:157.

17. Bernhardt M. Bullous pemphigoid after irradiation therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:141-142.

A number of adverse cutaneous effects may result from radiation therapy, including radiodermatitis, alopecia, and radiation-induced neoplasms. Radiation therapy rarely induces pemphigus or pemphigoid disease, but awareness of this disorder is of clinical importance because these cutaneous lesions may resemble other skin diseases, including recurrent underlying cancer. We report 3 cases of pemphigus or pemphigoid disease that occurred after radiation therapy for in situ ductal carcinoma of the breast, cervical squamous cell carcinoma, and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of unknown origin, respectively.

Case Reports

To identify all the patients with radiation-induced pemphigus, pemphigoid diseases, or both diagnosed and treated at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) from 1988 to 2009, we performed a computerized search of dermatology, laboratory medicine, and pathology medical records using the following keywords: radiation, pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus erythematosus, and blistering disease. Inclusion criteria were a history of radiation therapy and subsequent development of pemphigus or pemphigoid disease within the irradiated fields. Patients with a history of immunobullous disease preceding radiation therapy and patients with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus or paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome were excluded. The diagnoses were confirmed by routine pathology as well as direct and indirect immunofluorescence examinations.

We identified 3 patients with severe extensive radiation-associated pemphigus/pemphigoid disease that had developed within 14 months after they received radiation therapy for their underlying cancer. The identified patients’ medical records were reviewed for underlying malignancy, symptoms at the time of diagnosis, treatment course, and follow-up. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board.

Patient 1—A 58-year-old woman was diagnosed with in situ ductal carcinoma of the right breast and underwent a lumpectomy with subsequent radiation therapy at an outside institution. Fourteen months after the final radiation treatment, she developed localized flaccid blisters and a superficial erosion on the right areola (Figure 1). Routine pathologic and direct immunofluorescence studies performed on shave biopsies in conjunction with serum analysis by indirect immunofluorescence confirmed the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris (Figure 2). Additionally, a deeper 4-mm punch biopsy ruled out metastatic breast carcinoma. The patient initially was treated with prednisone 60 mg and azathioprine 50 mg daily. The prednisone was tapered over 4 to 5 months to a dose of 5 mg every other day for another 4 to 5 months. Azathioprine was discontinued after a few months because of increased liver enzyme levels and a rapid clinical response of the pemphigus to this regimen.

Subsequently, she developed oral and ocular erosions that were compatible with pemphigus and were believed to be precipitated by trauma secondary to dental work and to the use of contact lenses. These flares were treated and stabilized with short courses of prednisone at higher doses that were successfully tapered to a maintenance dose of 5 mg every other day to control the pemphigus. With that prednisone dosage, her disease has remained clinically stable.

Patient 2—A 40-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IIIB cervical squamous carcinoma with para-aortic adenopathy. She was initially treated with primary radiation therapy directed at the pelvis and para-aortic regions using a 4-field approach at our institution, and she received weekly cisplatin chemotherapy at another institution. Nine months later, the patient was admitted to our institution with persistent metastatic cervical carcinoma of the retroperitoneum. She was scheduled for intraoperative radiation therapy as well as aggressive surgical cytoreduction. The day before her surgery she presented to our dermatology clinic with a generalized pruritic rash of 1 month’s duration and occasional blistering without mucosal involvement. Biopsy specimens from the lower back and abdomen were sent for routine histologic studies and direct immunofluorescence. Serum was sent for analysis by indirect immunofluorescence. Pathology results were consistent with a diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid with an infiltrate of eosinophils in the papillary dermis; direct immunofluorescence revealed continuous strong linear deposition of C3, which also was consistent with pemphigoid.

At that time, we recommended application of topical clobetasol 0.05% twice daily to affected areas before initiating prednisone. Postoperatively, her rash improved dramatically with clobetasol monotherapy. However, 4 months after discharge from our hospital, her local dermatologist called us for a telephone consultation regarding clinical and laboratory evidence of pemphigoid relapse. A direct immunofluorescence study showed both linear IgG and C3 deposition. The patient had healed well from the surgery, and the metastatic cervical carcinoma was quiescent. Prednisone in combination with a second immunosuppressive agent was recommended, pending approval by her local oncologist. No further follow-up information is available at this time.

Patient 3—A 72-year-old woman presented with a blistering eruption that had developed on the neck, the upper part of the chest, and other body sites, including the oral mucosa, 6 months after radiation therapy for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of unknown origin on the neck. On admission to the local hospital, she received a diagnosis of pemphigoid, although the outside biopsy specimens and reports were not available.