User login

Differences in COVID-19 Outcomes Among Patients With Type 1 Diabetes: First vs Later Surges

From Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr Gallagher), T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Saketh Rompicherla; Drs Ebekozien, Noor, Odugbesan, and Mungmode; Nicole Rioles, Emma Ospelt), University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Drs. Wilkes, O’Malley, and Rapaport), Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (Drs. Antal and Feuer), NYU Long Island School of Medicine, Mineola, NY (Dr. Gabriel), NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr. Golden), Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, CO (Dr. Alonso), Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Dr. Lyons), Stanford University, Stanford, CA (Dr. Prahalad), Children Mercy Kansas City, MO (Dr. Clements), Indiana University School of Medicine, IN (Dr. Neyman), Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, CA (Dr. Demeterco-Berggren).

Background: Patient outcomes of COVID-19 have improved throughout the pandemic. However, because it is not known whether outcomes of COVID-19 in the type 1 diabetes (T1D) population improved over time, we investigated differences in COVID-19 outcomes for patients with T1D in the United States.

Methods: We analyzed data collected via a registry of patients with T1D and COVID-19 from 56 sites between April 2020 and January 2021. We grouped cases into first surge (April 9, 2020, to July 31, 2020, n = 188) and late surge (August 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, n = 410), and then compared outcomes between both groups using descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

Results: Adverse outcomes were more frequent during the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (32% vs 15%, P < .001), severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04), and hospitalization (52% vs 22%, P < .001). Patients in the first surge were older (28 [SD,18.8] years vs 18.0 [SD, 11.1] years, P < .001), had higher median hemoglobin A1c levels (9.3 [interquartile range {IQR}, 4.0] vs 8.4 (IQR, 2.8), P < .001), and were more likely to use public insurance (107 [57%] vs 154 [38%], P < .001). The odds of hospitalization for adults in the first surge were 5 times higher compared to the late surge (odds ratio, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.11-12.63).

Conclusion: Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge had a higher proportion of adverse outcomes than those who presented in a later surge.

Keywords: TD1, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia.

After the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with diabetes as high risk for severe illness.1-7 The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 has significantly improved over the past 2 years. Public health measures, less severe COVID-19 variants, increased access to testing, and new treatments for COVID-19 have contributed to improved outcomes.

The T1D Exchange has previously published findings on COVID-19 outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using data from the T1D COVID-19 Surveillance Registry.8-12 Given improved outcomes in COVID-19 in the general population, we sought to determine if outcomes for cases of COVID-19 reported to this registry changed over time.

Methods

This study was coordinated by the T1D Exchange and approved as nonhuman subject research by the Western Institutional Review Board. All participating centers also obtained local institutional review board approval. No identifiable patient information was collected as part of this noninterventional, cross-sectional study.

The T1D Exchange Multi-center COVID-19 Surveillance Study collected data from endocrinology clinics that completed a retrospective chart review and submitted information to T1D Exchange via an online questionnaire for all patients with T1D at their sites who tested positive for COVID-19.13,14 The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (www.qualtrics.com version XM) and contained 33 pre-coded and free-text response fields to collect patient and clinical attributes.

Each participating center identified 1 team member for reporting to avoid duplicate case submission. Each submitted case was reviewed for potential errors and incomplete information. The coordinating center verified the number of cases per site for data quality assurance.

Quantitative data were represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Categorical data were described as the number (percentage) of patients. Summary statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, were calculated for all patient-related and clinical characteristics. The date August 1, 2021, was selected as the end of the first surge based on a review of national COVID-19 surges.

We used the Fisher’s exact test to assess associations between hospitalization and demographics, HbA1c, diabetes duration, symptoms, and adverse outcomes. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between time of surge and hospitalization separately for both the pediatric and adult populations. Each model was adjusted for potential sociodemographic confounders, specifically age, sex, race, insurance, and HbA1c.

All tests were 2-sided, with type 1 error set at 5%. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed using statistical software R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

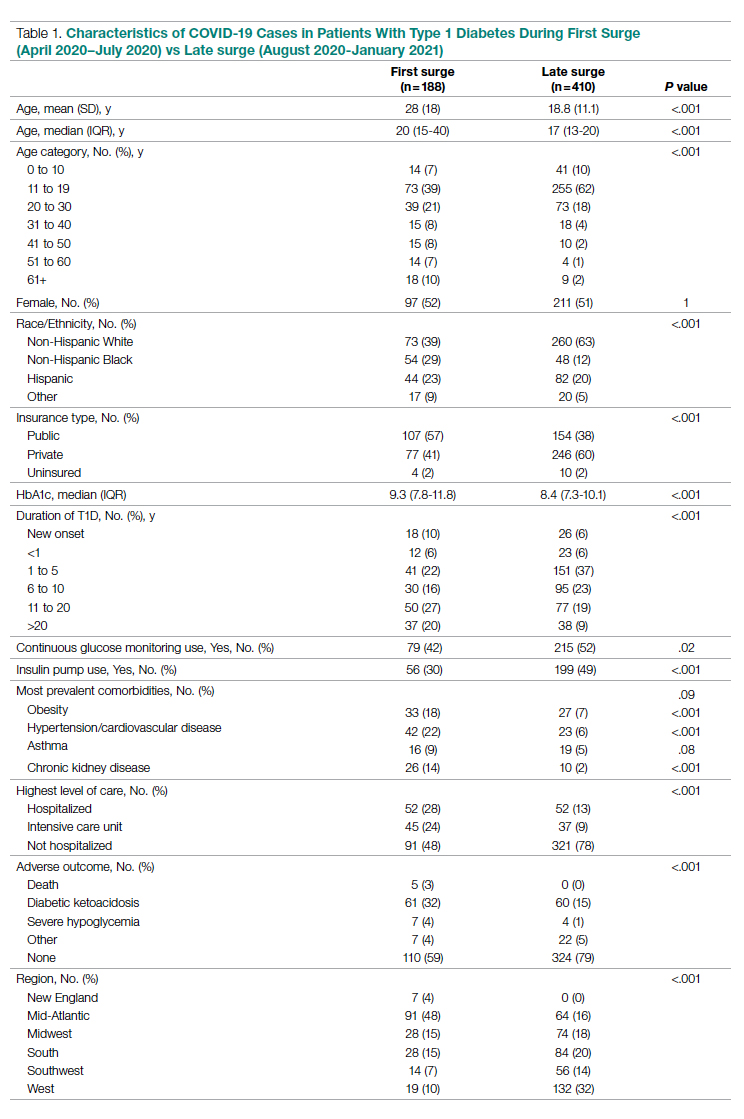

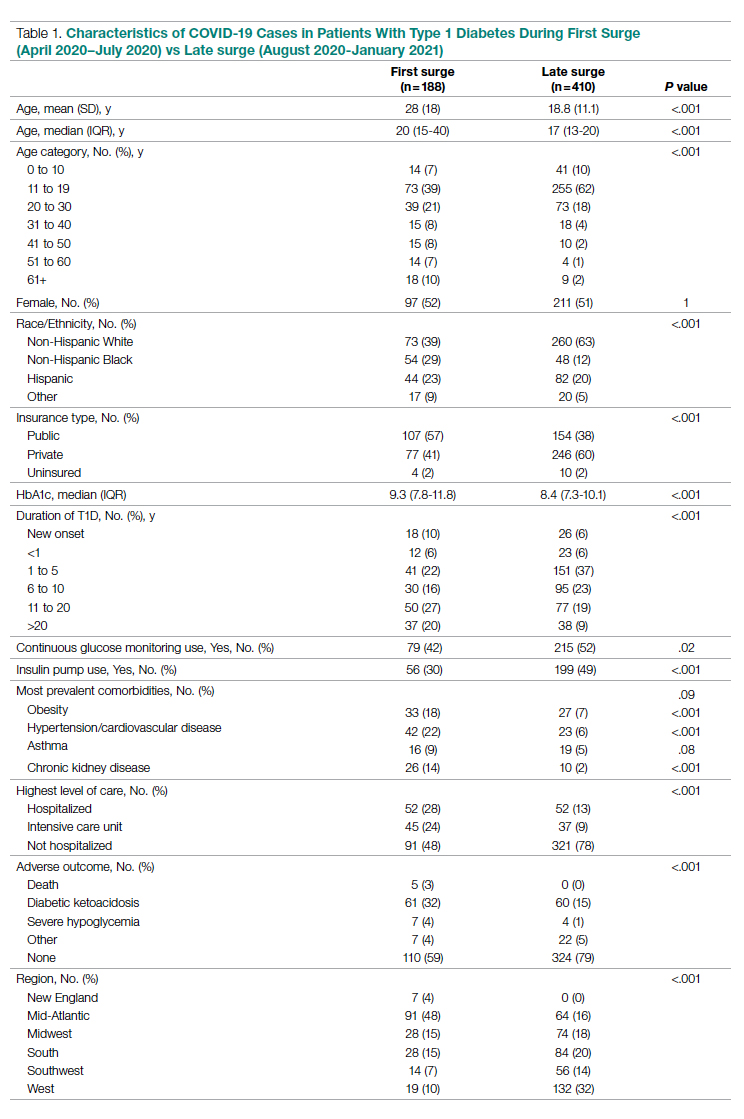

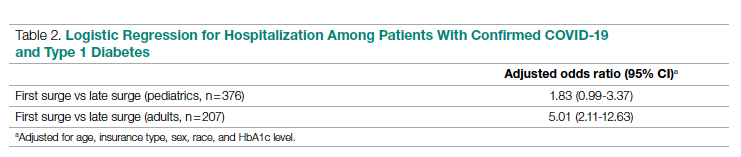

The characteristics of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D that were reported early in the pandemic, before August 1, 2020 (first surge), compared with those of cases reported on and after August 1, 2020 (later surges) are shown in Table 1.

Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge as compared to the later surges were older (mean age 28 [SD, 18.0] years vs 18.8 [SD, 11.1] years; P < .001) and had a longer duration of diabetes (P < .001). The first-surge group also had more patients with >20 years’ diabetes duration (20% vs 9%, P < .001). Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease were also more commonly reported in first-surge cases (all P < .001).

There was a significant difference in race and ethnicity reported in the first surge vs the later surge cases, with fewer patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (39% vs, 63%, P < .001) and more patients identifying as non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 12%, P < .001). The groups also differed significantly in terms of insurance type, with more people on public insurance in the first-surge group (57% vs 38%, P < .001). In addition, median HbA1c was higher (9.3% vs 8.4%, P < .001) and continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump use were less common (P = .02 and <.001, respectively) in the early surge.

All symptoms and adverse outcomes were reported more often in the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA; 32% vs 15%; P < .001) and severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04). Hospitalization (52% vs 13%, P < .001) and ICU admission (24% vs 9%, P < .001) were reported more often in the first-surge group.

Regression Analyses

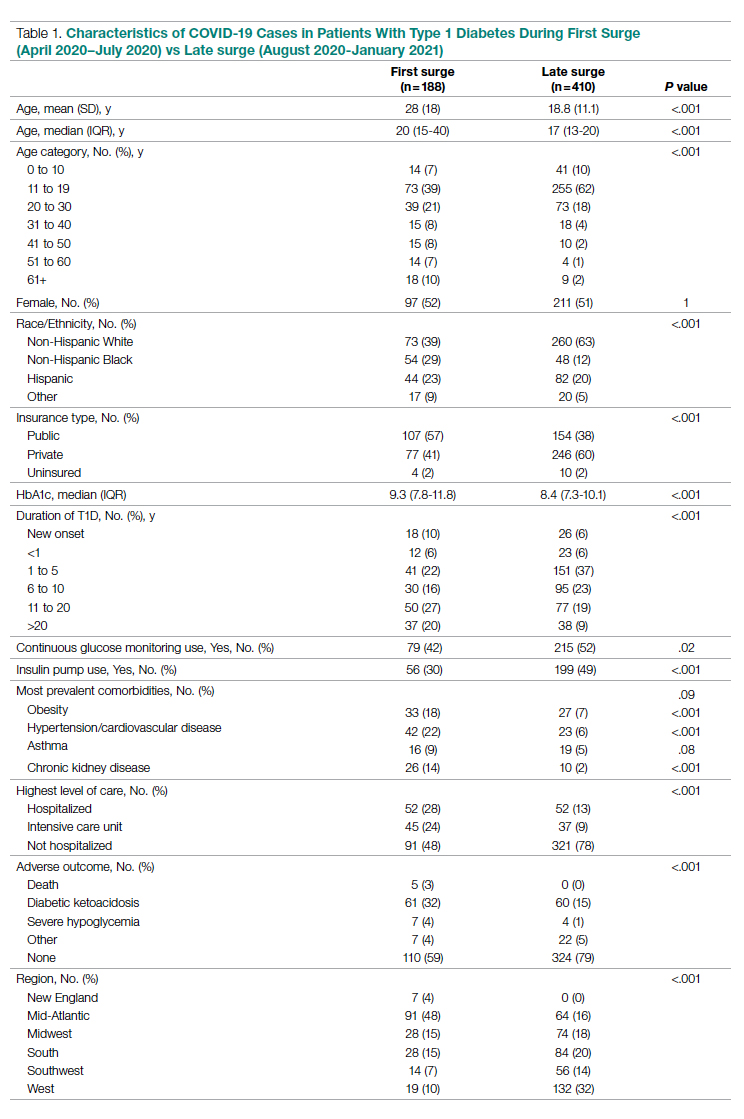

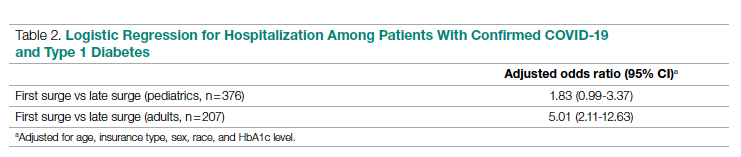

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analyses for hospitalization in the pediatric (≤19 years of age) and adult (>19 years of age) groups, along with the odds of hospitalization during the first vs late surge among COVID-positive people with T1D. Adult patients who tested positive in the first surge were about 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than adults who tested positive for infection in the late surge after adjusting for age, insurance type, sex, race, and HbA1c levels. Pediatric patients also had an increased odds for hospitalization during the first surge, but this increase was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our analysis of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D reported by diabetes providers across the United States found that adverse outcomes were more prevalent early in the pandemic. There may be a number of reasons for this difference in outcomes between patients who presented in the first surge vs a later surge. First, because testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited and reserved for hospitalized patients early in the pandemic, the first-surge patients with confirmed COVID-19 likely represent a skewed population of higher-acuity patients. This may also explain the relative paucity of cases in younger patients reported early in the pandemic. Second, worse outcomes in the early surge may also have been associated with overwhelmed hospitals in New York City at the start of the outbreak. According to Cummings et al, the abrupt surge of critically ill patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome initially outpaced their capacity to provide prone-positioning ventilation, which has been expanded since then.15 While there was very little hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease reported in the pediatric groups, there was a higher prevalence of obesity in the pediatric group from the mid-Atlantic region. Obesity has been associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19 illness in children.16 Finally, there were 5 deaths reported in this study, all of which were reported during the first surge. Older age and increased rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the first surge cases likely contributed to worse outcomes for adults in mid-Atlantic region relative to the other regions. Minority race and the use of public insurance, risk factors for more severe outcomes in all regions, were also more common in cases reported from the mid-Atlantic region.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study that relies upon voluntary provider reports. Second, availability of COVID-19 testing was limited in all regions in spring 2020. Third, different regions of the country experienced subsequent surges at different times within the reported timeframes in this analysis. Fourth, this report time period does not include the impact of the newer COVID-19 variants. Finally, trends in COVID-19 outcomes were affected by the evolution of care that developed throughout 2020.

Conclusion

Adult patients with T1D and COVID-19 who reported during the first surge had about 5 times higher hospitalization odds than those who presented in a later surge.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, MPH, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Ebekozien reports receiving research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom, and receiving honoraria from Medtronic Diabetes.

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813-822. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

2. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Asuni A, Jolly Y, Hessler D. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107748. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107748

3. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823-833. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

4. Wargny M, Gourdy P, Ludwig L, et al. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):e174-e177. doi:10.2337/dc20-1217

5. Gregory JM, Slaughter JC, Duffus SH, et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):526-532. doi:10.2337/dc20-2260

6. Cardona-Hernandez R, Cherubini V, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Luo X, Maahs DM. Children and youth with diabetes are not at increased risk for hospitalization due to COVID-19. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(2):202-206. doi:10.1111/pedi.13158

7. Maahs DM, Alonso GT, Gallagher MP, Ebekozien O. Comment on Gregory et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:526-532. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):e102. doi:10.2337/dc20-3119

8. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the US. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

9. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407

10. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

11. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):e1755-e1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

12. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

13. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

14. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: Data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;dgab668. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

15. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

16. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:246-256. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163

From Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr Gallagher), T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Saketh Rompicherla; Drs Ebekozien, Noor, Odugbesan, and Mungmode; Nicole Rioles, Emma Ospelt), University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Drs. Wilkes, O’Malley, and Rapaport), Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (Drs. Antal and Feuer), NYU Long Island School of Medicine, Mineola, NY (Dr. Gabriel), NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr. Golden), Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, CO (Dr. Alonso), Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Dr. Lyons), Stanford University, Stanford, CA (Dr. Prahalad), Children Mercy Kansas City, MO (Dr. Clements), Indiana University School of Medicine, IN (Dr. Neyman), Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, CA (Dr. Demeterco-Berggren).

Background: Patient outcomes of COVID-19 have improved throughout the pandemic. However, because it is not known whether outcomes of COVID-19 in the type 1 diabetes (T1D) population improved over time, we investigated differences in COVID-19 outcomes for patients with T1D in the United States.

Methods: We analyzed data collected via a registry of patients with T1D and COVID-19 from 56 sites between April 2020 and January 2021. We grouped cases into first surge (April 9, 2020, to July 31, 2020, n = 188) and late surge (August 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, n = 410), and then compared outcomes between both groups using descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

Results: Adverse outcomes were more frequent during the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (32% vs 15%, P < .001), severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04), and hospitalization (52% vs 22%, P < .001). Patients in the first surge were older (28 [SD,18.8] years vs 18.0 [SD, 11.1] years, P < .001), had higher median hemoglobin A1c levels (9.3 [interquartile range {IQR}, 4.0] vs 8.4 (IQR, 2.8), P < .001), and were more likely to use public insurance (107 [57%] vs 154 [38%], P < .001). The odds of hospitalization for adults in the first surge were 5 times higher compared to the late surge (odds ratio, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.11-12.63).

Conclusion: Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge had a higher proportion of adverse outcomes than those who presented in a later surge.

Keywords: TD1, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia.

After the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with diabetes as high risk for severe illness.1-7 The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 has significantly improved over the past 2 years. Public health measures, less severe COVID-19 variants, increased access to testing, and new treatments for COVID-19 have contributed to improved outcomes.

The T1D Exchange has previously published findings on COVID-19 outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using data from the T1D COVID-19 Surveillance Registry.8-12 Given improved outcomes in COVID-19 in the general population, we sought to determine if outcomes for cases of COVID-19 reported to this registry changed over time.

Methods

This study was coordinated by the T1D Exchange and approved as nonhuman subject research by the Western Institutional Review Board. All participating centers also obtained local institutional review board approval. No identifiable patient information was collected as part of this noninterventional, cross-sectional study.

The T1D Exchange Multi-center COVID-19 Surveillance Study collected data from endocrinology clinics that completed a retrospective chart review and submitted information to T1D Exchange via an online questionnaire for all patients with T1D at their sites who tested positive for COVID-19.13,14 The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (www.qualtrics.com version XM) and contained 33 pre-coded and free-text response fields to collect patient and clinical attributes.

Each participating center identified 1 team member for reporting to avoid duplicate case submission. Each submitted case was reviewed for potential errors and incomplete information. The coordinating center verified the number of cases per site for data quality assurance.

Quantitative data were represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Categorical data were described as the number (percentage) of patients. Summary statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, were calculated for all patient-related and clinical characteristics. The date August 1, 2021, was selected as the end of the first surge based on a review of national COVID-19 surges.

We used the Fisher’s exact test to assess associations between hospitalization and demographics, HbA1c, diabetes duration, symptoms, and adverse outcomes. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between time of surge and hospitalization separately for both the pediatric and adult populations. Each model was adjusted for potential sociodemographic confounders, specifically age, sex, race, insurance, and HbA1c.

All tests were 2-sided, with type 1 error set at 5%. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed using statistical software R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

The characteristics of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D that were reported early in the pandemic, before August 1, 2020 (first surge), compared with those of cases reported on and after August 1, 2020 (later surges) are shown in Table 1.

Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge as compared to the later surges were older (mean age 28 [SD, 18.0] years vs 18.8 [SD, 11.1] years; P < .001) and had a longer duration of diabetes (P < .001). The first-surge group also had more patients with >20 years’ diabetes duration (20% vs 9%, P < .001). Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease were also more commonly reported in first-surge cases (all P < .001).

There was a significant difference in race and ethnicity reported in the first surge vs the later surge cases, with fewer patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (39% vs, 63%, P < .001) and more patients identifying as non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 12%, P < .001). The groups also differed significantly in terms of insurance type, with more people on public insurance in the first-surge group (57% vs 38%, P < .001). In addition, median HbA1c was higher (9.3% vs 8.4%, P < .001) and continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump use were less common (P = .02 and <.001, respectively) in the early surge.

All symptoms and adverse outcomes were reported more often in the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA; 32% vs 15%; P < .001) and severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04). Hospitalization (52% vs 13%, P < .001) and ICU admission (24% vs 9%, P < .001) were reported more often in the first-surge group.

Regression Analyses

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analyses for hospitalization in the pediatric (≤19 years of age) and adult (>19 years of age) groups, along with the odds of hospitalization during the first vs late surge among COVID-positive people with T1D. Adult patients who tested positive in the first surge were about 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than adults who tested positive for infection in the late surge after adjusting for age, insurance type, sex, race, and HbA1c levels. Pediatric patients also had an increased odds for hospitalization during the first surge, but this increase was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our analysis of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D reported by diabetes providers across the United States found that adverse outcomes were more prevalent early in the pandemic. There may be a number of reasons for this difference in outcomes between patients who presented in the first surge vs a later surge. First, because testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited and reserved for hospitalized patients early in the pandemic, the first-surge patients with confirmed COVID-19 likely represent a skewed population of higher-acuity patients. This may also explain the relative paucity of cases in younger patients reported early in the pandemic. Second, worse outcomes in the early surge may also have been associated with overwhelmed hospitals in New York City at the start of the outbreak. According to Cummings et al, the abrupt surge of critically ill patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome initially outpaced their capacity to provide prone-positioning ventilation, which has been expanded since then.15 While there was very little hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease reported in the pediatric groups, there was a higher prevalence of obesity in the pediatric group from the mid-Atlantic region. Obesity has been associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19 illness in children.16 Finally, there were 5 deaths reported in this study, all of which were reported during the first surge. Older age and increased rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the first surge cases likely contributed to worse outcomes for adults in mid-Atlantic region relative to the other regions. Minority race and the use of public insurance, risk factors for more severe outcomes in all regions, were also more common in cases reported from the mid-Atlantic region.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study that relies upon voluntary provider reports. Second, availability of COVID-19 testing was limited in all regions in spring 2020. Third, different regions of the country experienced subsequent surges at different times within the reported timeframes in this analysis. Fourth, this report time period does not include the impact of the newer COVID-19 variants. Finally, trends in COVID-19 outcomes were affected by the evolution of care that developed throughout 2020.

Conclusion

Adult patients with T1D and COVID-19 who reported during the first surge had about 5 times higher hospitalization odds than those who presented in a later surge.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, MPH, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Ebekozien reports receiving research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom, and receiving honoraria from Medtronic Diabetes.

From Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr Gallagher), T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Saketh Rompicherla; Drs Ebekozien, Noor, Odugbesan, and Mungmode; Nicole Rioles, Emma Ospelt), University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Drs. Wilkes, O’Malley, and Rapaport), Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (Drs. Antal and Feuer), NYU Long Island School of Medicine, Mineola, NY (Dr. Gabriel), NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr. Golden), Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, CO (Dr. Alonso), Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Dr. Lyons), Stanford University, Stanford, CA (Dr. Prahalad), Children Mercy Kansas City, MO (Dr. Clements), Indiana University School of Medicine, IN (Dr. Neyman), Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, CA (Dr. Demeterco-Berggren).

Background: Patient outcomes of COVID-19 have improved throughout the pandemic. However, because it is not known whether outcomes of COVID-19 in the type 1 diabetes (T1D) population improved over time, we investigated differences in COVID-19 outcomes for patients with T1D in the United States.

Methods: We analyzed data collected via a registry of patients with T1D and COVID-19 from 56 sites between April 2020 and January 2021. We grouped cases into first surge (April 9, 2020, to July 31, 2020, n = 188) and late surge (August 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, n = 410), and then compared outcomes between both groups using descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

Results: Adverse outcomes were more frequent during the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (32% vs 15%, P < .001), severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04), and hospitalization (52% vs 22%, P < .001). Patients in the first surge were older (28 [SD,18.8] years vs 18.0 [SD, 11.1] years, P < .001), had higher median hemoglobin A1c levels (9.3 [interquartile range {IQR}, 4.0] vs 8.4 (IQR, 2.8), P < .001), and were more likely to use public insurance (107 [57%] vs 154 [38%], P < .001). The odds of hospitalization for adults in the first surge were 5 times higher compared to the late surge (odds ratio, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.11-12.63).

Conclusion: Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge had a higher proportion of adverse outcomes than those who presented in a later surge.

Keywords: TD1, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia.

After the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with diabetes as high risk for severe illness.1-7 The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 has significantly improved over the past 2 years. Public health measures, less severe COVID-19 variants, increased access to testing, and new treatments for COVID-19 have contributed to improved outcomes.

The T1D Exchange has previously published findings on COVID-19 outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using data from the T1D COVID-19 Surveillance Registry.8-12 Given improved outcomes in COVID-19 in the general population, we sought to determine if outcomes for cases of COVID-19 reported to this registry changed over time.

Methods

This study was coordinated by the T1D Exchange and approved as nonhuman subject research by the Western Institutional Review Board. All participating centers also obtained local institutional review board approval. No identifiable patient information was collected as part of this noninterventional, cross-sectional study.

The T1D Exchange Multi-center COVID-19 Surveillance Study collected data from endocrinology clinics that completed a retrospective chart review and submitted information to T1D Exchange via an online questionnaire for all patients with T1D at their sites who tested positive for COVID-19.13,14 The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (www.qualtrics.com version XM) and contained 33 pre-coded and free-text response fields to collect patient and clinical attributes.

Each participating center identified 1 team member for reporting to avoid duplicate case submission. Each submitted case was reviewed for potential errors and incomplete information. The coordinating center verified the number of cases per site for data quality assurance.

Quantitative data were represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Categorical data were described as the number (percentage) of patients. Summary statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, were calculated for all patient-related and clinical characteristics. The date August 1, 2021, was selected as the end of the first surge based on a review of national COVID-19 surges.

We used the Fisher’s exact test to assess associations between hospitalization and demographics, HbA1c, diabetes duration, symptoms, and adverse outcomes. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between time of surge and hospitalization separately for both the pediatric and adult populations. Each model was adjusted for potential sociodemographic confounders, specifically age, sex, race, insurance, and HbA1c.

All tests were 2-sided, with type 1 error set at 5%. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed using statistical software R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

The characteristics of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D that were reported early in the pandemic, before August 1, 2020 (first surge), compared with those of cases reported on and after August 1, 2020 (later surges) are shown in Table 1.

Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge as compared to the later surges were older (mean age 28 [SD, 18.0] years vs 18.8 [SD, 11.1] years; P < .001) and had a longer duration of diabetes (P < .001). The first-surge group also had more patients with >20 years’ diabetes duration (20% vs 9%, P < .001). Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease were also more commonly reported in first-surge cases (all P < .001).

There was a significant difference in race and ethnicity reported in the first surge vs the later surge cases, with fewer patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (39% vs, 63%, P < .001) and more patients identifying as non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 12%, P < .001). The groups also differed significantly in terms of insurance type, with more people on public insurance in the first-surge group (57% vs 38%, P < .001). In addition, median HbA1c was higher (9.3% vs 8.4%, P < .001) and continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump use were less common (P = .02 and <.001, respectively) in the early surge.

All symptoms and adverse outcomes were reported more often in the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA; 32% vs 15%; P < .001) and severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04). Hospitalization (52% vs 13%, P < .001) and ICU admission (24% vs 9%, P < .001) were reported more often in the first-surge group.

Regression Analyses

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analyses for hospitalization in the pediatric (≤19 years of age) and adult (>19 years of age) groups, along with the odds of hospitalization during the first vs late surge among COVID-positive people with T1D. Adult patients who tested positive in the first surge were about 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than adults who tested positive for infection in the late surge after adjusting for age, insurance type, sex, race, and HbA1c levels. Pediatric patients also had an increased odds for hospitalization during the first surge, but this increase was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our analysis of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D reported by diabetes providers across the United States found that adverse outcomes were more prevalent early in the pandemic. There may be a number of reasons for this difference in outcomes between patients who presented in the first surge vs a later surge. First, because testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited and reserved for hospitalized patients early in the pandemic, the first-surge patients with confirmed COVID-19 likely represent a skewed population of higher-acuity patients. This may also explain the relative paucity of cases in younger patients reported early in the pandemic. Second, worse outcomes in the early surge may also have been associated with overwhelmed hospitals in New York City at the start of the outbreak. According to Cummings et al, the abrupt surge of critically ill patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome initially outpaced their capacity to provide prone-positioning ventilation, which has been expanded since then.15 While there was very little hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease reported in the pediatric groups, there was a higher prevalence of obesity in the pediatric group from the mid-Atlantic region. Obesity has been associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19 illness in children.16 Finally, there were 5 deaths reported in this study, all of which were reported during the first surge. Older age and increased rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the first surge cases likely contributed to worse outcomes for adults in mid-Atlantic region relative to the other regions. Minority race and the use of public insurance, risk factors for more severe outcomes in all regions, were also more common in cases reported from the mid-Atlantic region.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study that relies upon voluntary provider reports. Second, availability of COVID-19 testing was limited in all regions in spring 2020. Third, different regions of the country experienced subsequent surges at different times within the reported timeframes in this analysis. Fourth, this report time period does not include the impact of the newer COVID-19 variants. Finally, trends in COVID-19 outcomes were affected by the evolution of care that developed throughout 2020.

Conclusion

Adult patients with T1D and COVID-19 who reported during the first surge had about 5 times higher hospitalization odds than those who presented in a later surge.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, MPH, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Ebekozien reports receiving research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom, and receiving honoraria from Medtronic Diabetes.

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813-822. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

2. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Asuni A, Jolly Y, Hessler D. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107748. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107748

3. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823-833. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

4. Wargny M, Gourdy P, Ludwig L, et al. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):e174-e177. doi:10.2337/dc20-1217

5. Gregory JM, Slaughter JC, Duffus SH, et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):526-532. doi:10.2337/dc20-2260

6. Cardona-Hernandez R, Cherubini V, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Luo X, Maahs DM. Children and youth with diabetes are not at increased risk for hospitalization due to COVID-19. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(2):202-206. doi:10.1111/pedi.13158

7. Maahs DM, Alonso GT, Gallagher MP, Ebekozien O. Comment on Gregory et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:526-532. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):e102. doi:10.2337/dc20-3119

8. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the US. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

9. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407

10. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

11. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):e1755-e1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

12. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

13. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

14. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: Data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;dgab668. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

15. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

16. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:246-256. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813-822. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

2. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Asuni A, Jolly Y, Hessler D. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107748. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107748

3. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823-833. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

4. Wargny M, Gourdy P, Ludwig L, et al. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):e174-e177. doi:10.2337/dc20-1217

5. Gregory JM, Slaughter JC, Duffus SH, et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):526-532. doi:10.2337/dc20-2260

6. Cardona-Hernandez R, Cherubini V, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Luo X, Maahs DM. Children and youth with diabetes are not at increased risk for hospitalization due to COVID-19. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(2):202-206. doi:10.1111/pedi.13158

7. Maahs DM, Alonso GT, Gallagher MP, Ebekozien O. Comment on Gregory et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:526-532. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):e102. doi:10.2337/dc20-3119

8. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the US. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

9. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407

10. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

11. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):e1755-e1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

12. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

13. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

14. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: Data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;dgab668. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

15. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

16. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:246-256. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163

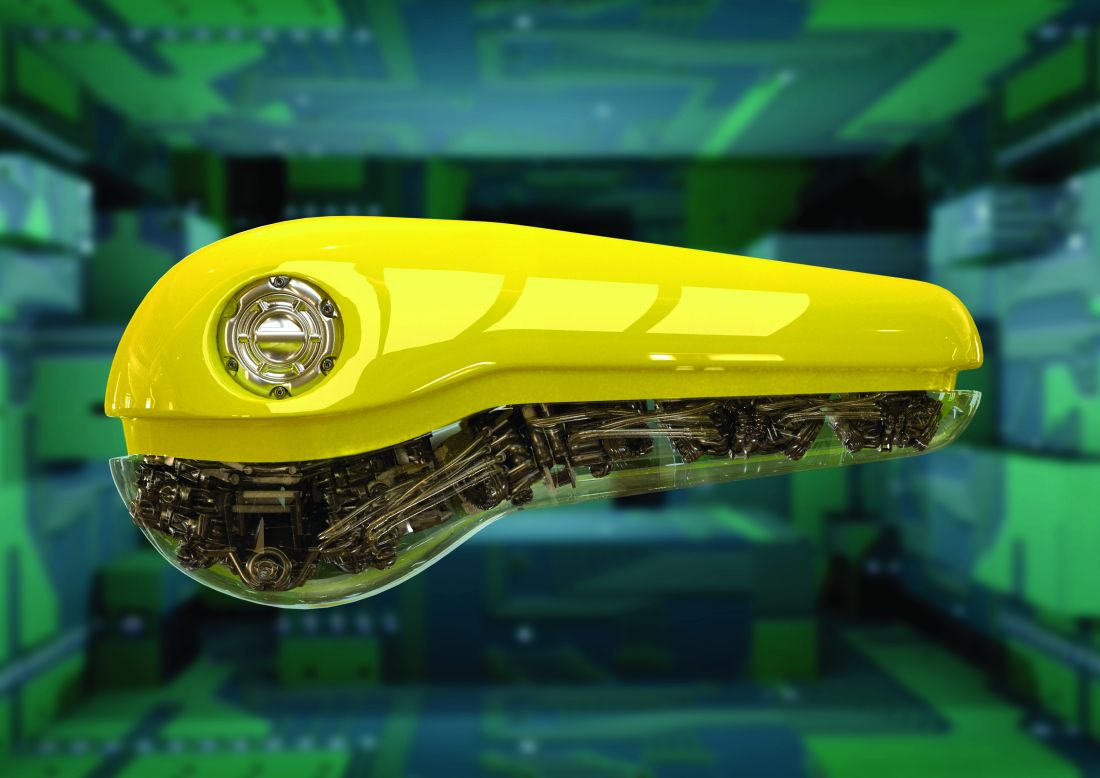

FDA okays first tubing-free ‘artificial pancreas’ Omnipod 5

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared the Omnipod 5 Automated Insulin Delivery System (Insulet), the third semiautomated closed-loop insulin delivery system in the United States and the first that is tubing free.

Omnipod 5 is cleared for people aged 6 years and older with type 1 diabetes. The system integrates the tubeless insulin delivery Pods with Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitors (CGM) and a smartphone app or a separate controller device to automatically adjust insulin to minimize high and low blood glucose levels via SmartAdjust technology.

Within the app is a SmartBolus calculator that receives Dexcom CGM values every 5 minutes and automatically adjusts insulin up or down or pauses it based on predicted values for 60 minutes into the future and the individual’s customized glucose targets.

The Omnipod 5 becomes the third FDA-cleared semiautomated insulin delivery system in the United States, along with systems by Tandem and Medtronic. Others are available outside the United States. All of the currently marketed systems incorporate insulin pumps with tubing, whereas the tubeless Pods are worn directly on the body and changed every 3 days.

In a statement, JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization, said: “Authorization of the Insulet Omnipod 5 is a huge win for the type 1 diabetes community. As the first tubeless hybrid closed-loop system to receive FDA clearance, this is a critical step forward in making day-to-day life better for people living with the disease.”

JDRF, which worked with the FDA to establish regulatory pathways for artificial pancreas technology, supported the development of the Omnipod 5 control algorithm through investigators in the JDRF Artificial Pancreas Consortium.

The Omnipod 5 will be available as a pharmacy product. It will be launched soon in limited market release and broadly thereafter.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared the Omnipod 5 Automated Insulin Delivery System (Insulet), the third semiautomated closed-loop insulin delivery system in the United States and the first that is tubing free.

Omnipod 5 is cleared for people aged 6 years and older with type 1 diabetes. The system integrates the tubeless insulin delivery Pods with Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitors (CGM) and a smartphone app or a separate controller device to automatically adjust insulin to minimize high and low blood glucose levels via SmartAdjust technology.

Within the app is a SmartBolus calculator that receives Dexcom CGM values every 5 minutes and automatically adjusts insulin up or down or pauses it based on predicted values for 60 minutes into the future and the individual’s customized glucose targets.

The Omnipod 5 becomes the third FDA-cleared semiautomated insulin delivery system in the United States, along with systems by Tandem and Medtronic. Others are available outside the United States. All of the currently marketed systems incorporate insulin pumps with tubing, whereas the tubeless Pods are worn directly on the body and changed every 3 days.

In a statement, JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization, said: “Authorization of the Insulet Omnipod 5 is a huge win for the type 1 diabetes community. As the first tubeless hybrid closed-loop system to receive FDA clearance, this is a critical step forward in making day-to-day life better for people living with the disease.”

JDRF, which worked with the FDA to establish regulatory pathways for artificial pancreas technology, supported the development of the Omnipod 5 control algorithm through investigators in the JDRF Artificial Pancreas Consortium.

The Omnipod 5 will be available as a pharmacy product. It will be launched soon in limited market release and broadly thereafter.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared the Omnipod 5 Automated Insulin Delivery System (Insulet), the third semiautomated closed-loop insulin delivery system in the United States and the first that is tubing free.

Omnipod 5 is cleared for people aged 6 years and older with type 1 diabetes. The system integrates the tubeless insulin delivery Pods with Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitors (CGM) and a smartphone app or a separate controller device to automatically adjust insulin to minimize high and low blood glucose levels via SmartAdjust technology.

Within the app is a SmartBolus calculator that receives Dexcom CGM values every 5 minutes and automatically adjusts insulin up or down or pauses it based on predicted values for 60 minutes into the future and the individual’s customized glucose targets.

The Omnipod 5 becomes the third FDA-cleared semiautomated insulin delivery system in the United States, along with systems by Tandem and Medtronic. Others are available outside the United States. All of the currently marketed systems incorporate insulin pumps with tubing, whereas the tubeless Pods are worn directly on the body and changed every 3 days.

In a statement, JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization, said: “Authorization of the Insulet Omnipod 5 is a huge win for the type 1 diabetes community. As the first tubeless hybrid closed-loop system to receive FDA clearance, this is a critical step forward in making day-to-day life better for people living with the disease.”

JDRF, which worked with the FDA to establish regulatory pathways for artificial pancreas technology, supported the development of the Omnipod 5 control algorithm through investigators in the JDRF Artificial Pancreas Consortium.

The Omnipod 5 will be available as a pharmacy product. It will be launched soon in limited market release and broadly thereafter.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 1 in 10 people in U.S. have diabetes, CDC says

More than 1 in 10 Americans have diabetes and over a third have prediabetes, according to updated statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The National Diabetes Statistics Report includes data for 2017-2020 from several nationally representative sources on prevalence and incidence of diabetes and prediabetes, risk factors for complications, acute and long-term complications, and costs.

According to the new report, published on Jan. 25, a total of 37.3 million people in the United States have diabetes, or about 11.3% of the population. Of those, 28.7 million are diagnosed (including 28.5 million adults), while 8.5 million, or 23% of those with diabetes, are undiagnosed.

Another 96 million adults have prediabetes, comprising 38.0% of the adult U.S. population, of whom only 19% are aware of their prediabetes status.

In a statement, the American Diabetes Association said the new CDC data “show an alarming increase of diabetes in our nation among adults,” while the high number with prediabetes who don’t know that they have it “is fueling the diabetes epidemic.”

Regarding the total estimated 1.84 million with type 1 diabetes, the advocacy organization JDRF said in a statement: “These data and additional statistical research reinforces the urgency to accelerate life-changing breakthroughs to cure, prevent, and treat [type 1 diabetes] and its complications.”

Overall, the ADA said, “the National Diabetes Statistics Report reaffirms why the ADA is dedicated to innovative research to find a cure for diabetes once and for all.”

Notable increases since 2019

These new data represent notable increases since the CDC’s 2019 Report Card, which gave the U.S. population with diabetes in 2018 as 34.2 million, or 10.5% of the population, including 7.3 million undiagnosed. The prediabetes prevalence that year was 88 million.

Among children and adolescents younger than 20 years, 283,000, or 35 per 10,000 U.S. youths, had diagnosed diabetes in 2019. Of those, 244,000 had type 1 diabetes. Another 1.6 million adults aged 20 and older also reported having type 1 diabetes, comprising 5.7% of U.S. adults with diagnosed diabetes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 1 in 10 Americans have diabetes and over a third have prediabetes, according to updated statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The National Diabetes Statistics Report includes data for 2017-2020 from several nationally representative sources on prevalence and incidence of diabetes and prediabetes, risk factors for complications, acute and long-term complications, and costs.

According to the new report, published on Jan. 25, a total of 37.3 million people in the United States have diabetes, or about 11.3% of the population. Of those, 28.7 million are diagnosed (including 28.5 million adults), while 8.5 million, or 23% of those with diabetes, are undiagnosed.

Another 96 million adults have prediabetes, comprising 38.0% of the adult U.S. population, of whom only 19% are aware of their prediabetes status.

In a statement, the American Diabetes Association said the new CDC data “show an alarming increase of diabetes in our nation among adults,” while the high number with prediabetes who don’t know that they have it “is fueling the diabetes epidemic.”

Regarding the total estimated 1.84 million with type 1 diabetes, the advocacy organization JDRF said in a statement: “These data and additional statistical research reinforces the urgency to accelerate life-changing breakthroughs to cure, prevent, and treat [type 1 diabetes] and its complications.”

Overall, the ADA said, “the National Diabetes Statistics Report reaffirms why the ADA is dedicated to innovative research to find a cure for diabetes once and for all.”

Notable increases since 2019

These new data represent notable increases since the CDC’s 2019 Report Card, which gave the U.S. population with diabetes in 2018 as 34.2 million, or 10.5% of the population, including 7.3 million undiagnosed. The prediabetes prevalence that year was 88 million.

Among children and adolescents younger than 20 years, 283,000, or 35 per 10,000 U.S. youths, had diagnosed diabetes in 2019. Of those, 244,000 had type 1 diabetes. Another 1.6 million adults aged 20 and older also reported having type 1 diabetes, comprising 5.7% of U.S. adults with diagnosed diabetes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 1 in 10 Americans have diabetes and over a third have prediabetes, according to updated statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The National Diabetes Statistics Report includes data for 2017-2020 from several nationally representative sources on prevalence and incidence of diabetes and prediabetes, risk factors for complications, acute and long-term complications, and costs.

According to the new report, published on Jan. 25, a total of 37.3 million people in the United States have diabetes, or about 11.3% of the population. Of those, 28.7 million are diagnosed (including 28.5 million adults), while 8.5 million, or 23% of those with diabetes, are undiagnosed.

Another 96 million adults have prediabetes, comprising 38.0% of the adult U.S. population, of whom only 19% are aware of their prediabetes status.

In a statement, the American Diabetes Association said the new CDC data “show an alarming increase of diabetes in our nation among adults,” while the high number with prediabetes who don’t know that they have it “is fueling the diabetes epidemic.”

Regarding the total estimated 1.84 million with type 1 diabetes, the advocacy organization JDRF said in a statement: “These data and additional statistical research reinforces the urgency to accelerate life-changing breakthroughs to cure, prevent, and treat [type 1 diabetes] and its complications.”

Overall, the ADA said, “the National Diabetes Statistics Report reaffirms why the ADA is dedicated to innovative research to find a cure for diabetes once and for all.”

Notable increases since 2019

These new data represent notable increases since the CDC’s 2019 Report Card, which gave the U.S. population with diabetes in 2018 as 34.2 million, or 10.5% of the population, including 7.3 million undiagnosed. The prediabetes prevalence that year was 88 million.

Among children and adolescents younger than 20 years, 283,000, or 35 per 10,000 U.S. youths, had diagnosed diabetes in 2019. Of those, 244,000 had type 1 diabetes. Another 1.6 million adults aged 20 and older also reported having type 1 diabetes, comprising 5.7% of U.S. adults with diagnosed diabetes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Moderate-vigorous stepping seen to lower diabetes risk in older women

More steps per day, particularly at a higher intensity, may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes in older women, based on a prospective cohort study.

The link between daily stepping and diabetes was not significantly modified by body mass index (BMI) or other common diabetes risk factors, suggesting that the relationship is highly generalizable, lead author Alexis C. Garduno, MPH, a PhD student at the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues reported.

“Physical activity is a key modifiable behavior for diabetes prevention and management,” the investigators wrote in Diabetes Care. “Many prevention studies have demonstrated that regular physical activity, along with improved diet, reduces the risk of diabetes in adults. ... To the best of our knowledge, there are few studies examining the association between objectively measured steps per day and incident diabetes in a community-based setting.”

To this end, the investigators analyzed data from 4,838 older, community-living women in the Objective Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health Study. Upon enrollment, women were without physician-diagnosed diabetes and had a mean age of 78.9 years. For 1 week, participants wore ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometers to measure steps per day, as well as step intensity, graded as light or moderate to vigorous.

The relationship between daily activity and diabetes was analyzed using three multivariate models: The first included race/ethnicity and age; the second also included family history of diabetes, education, physical functioning, self-rated health, smoking status, and alcohol consumption; and the third added BMI, “a potential mediator in the causal pathway between steps per day and diabetes,” the investigators wrote.

Participants took an average of 3,729 steps per day, divided roughly evenly between light and moderate to vigorous intensity.

After a median follow-up of 5.7 years, 8.1% of women developed diabetes. The least-adjusted model showed a 14% reduction in diabetes risk per 2,000 steps (hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.80-0.92; P = .007), whereas the second model, adjusting for more confounding variables, showed a 12% reduction in diabetes risk per 2,000 steps (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-1.00; P = .045).

The final model, which added BMI, showed a 10% reduction in risk, although it didn’t reach statistical significance (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.80-1.02; P = .11). Furthermore, accelerated failure time models suggested that BMI did not significantly impact the link between steps and diabetes (proportion mediated, 17.7%;95% CI, –55.0 to 142.0; P = .09). Further analyses also found no significant interactions between BMI or other possible confounders.

“The steps per day–diabetes association was not modified by age, race/ethnicity, BMI, physical functioning, or family history of diabetes, which supports the generalizability of these findings to community-living older women,” the investigators wrote.

Increased stepping intensity also appeared to lower risk of diabetes. After adjusting for confounding variables, light stepping was not linked to reduced risk (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.73-1.29; P = .83), whereas moderate to vigorous stepping reduced risk by 14% per 2,000 steps (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-1.00; P = .04).

“This study provides evidence supporting an association between steps per day and lower incident diabetes,” the investigators concluded. “While further work is needed to identify whether there is a minimum number of steps per day that results in a clinically significant reduction of diabetes and to evaluate the role that step intensity plays in diabetes etiology for older adults, findings from this study suggest that moderate-vigorous–intensity steps may be more important than lower-intensity steps with respect to incident diabetes. Steps per day–based interventions are needed to advance diabetes prevention science in older adults.”

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program, and others. The investigators had no potential conflicts of interest.

More steps per day, particularly at a higher intensity, may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes in older women, based on a prospective cohort study.

The link between daily stepping and diabetes was not significantly modified by body mass index (BMI) or other common diabetes risk factors, suggesting that the relationship is highly generalizable, lead author Alexis C. Garduno, MPH, a PhD student at the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues reported.

“Physical activity is a key modifiable behavior for diabetes prevention and management,” the investigators wrote in Diabetes Care. “Many prevention studies have demonstrated that regular physical activity, along with improved diet, reduces the risk of diabetes in adults. ... To the best of our knowledge, there are few studies examining the association between objectively measured steps per day and incident diabetes in a community-based setting.”

To this end, the investigators analyzed data from 4,838 older, community-living women in the Objective Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health Study. Upon enrollment, women were without physician-diagnosed diabetes and had a mean age of 78.9 years. For 1 week, participants wore ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometers to measure steps per day, as well as step intensity, graded as light or moderate to vigorous.

The relationship between daily activity and diabetes was analyzed using three multivariate models: The first included race/ethnicity and age; the second also included family history of diabetes, education, physical functioning, self-rated health, smoking status, and alcohol consumption; and the third added BMI, “a potential mediator in the causal pathway between steps per day and diabetes,” the investigators wrote.

Participants took an average of 3,729 steps per day, divided roughly evenly between light and moderate to vigorous intensity.

After a median follow-up of 5.7 years, 8.1% of women developed diabetes. The least-adjusted model showed a 14% reduction in diabetes risk per 2,000 steps (hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.80-0.92; P = .007), whereas the second model, adjusting for more confounding variables, showed a 12% reduction in diabetes risk per 2,000 steps (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-1.00; P = .045).

The final model, which added BMI, showed a 10% reduction in risk, although it didn’t reach statistical significance (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.80-1.02; P = .11). Furthermore, accelerated failure time models suggested that BMI did not significantly impact the link between steps and diabetes (proportion mediated, 17.7%;95% CI, –55.0 to 142.0; P = .09). Further analyses also found no significant interactions between BMI or other possible confounders.

“The steps per day–diabetes association was not modified by age, race/ethnicity, BMI, physical functioning, or family history of diabetes, which supports the generalizability of these findings to community-living older women,” the investigators wrote.

Increased stepping intensity also appeared to lower risk of diabetes. After adjusting for confounding variables, light stepping was not linked to reduced risk (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.73-1.29; P = .83), whereas moderate to vigorous stepping reduced risk by 14% per 2,000 steps (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-1.00; P = .04).

“This study provides evidence supporting an association between steps per day and lower incident diabetes,” the investigators concluded. “While further work is needed to identify whether there is a minimum number of steps per day that results in a clinically significant reduction of diabetes and to evaluate the role that step intensity plays in diabetes etiology for older adults, findings from this study suggest that moderate-vigorous–intensity steps may be more important than lower-intensity steps with respect to incident diabetes. Steps per day–based interventions are needed to advance diabetes prevention science in older adults.”

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program, and others. The investigators had no potential conflicts of interest.

More steps per day, particularly at a higher intensity, may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes in older women, based on a prospective cohort study.

The link between daily stepping and diabetes was not significantly modified by body mass index (BMI) or other common diabetes risk factors, suggesting that the relationship is highly generalizable, lead author Alexis C. Garduno, MPH, a PhD student at the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues reported.

“Physical activity is a key modifiable behavior for diabetes prevention and management,” the investigators wrote in Diabetes Care. “Many prevention studies have demonstrated that regular physical activity, along with improved diet, reduces the risk of diabetes in adults. ... To the best of our knowledge, there are few studies examining the association between objectively measured steps per day and incident diabetes in a community-based setting.”

To this end, the investigators analyzed data from 4,838 older, community-living women in the Objective Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health Study. Upon enrollment, women were without physician-diagnosed diabetes and had a mean age of 78.9 years. For 1 week, participants wore ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometers to measure steps per day, as well as step intensity, graded as light or moderate to vigorous.

The relationship between daily activity and diabetes was analyzed using three multivariate models: The first included race/ethnicity and age; the second also included family history of diabetes, education, physical functioning, self-rated health, smoking status, and alcohol consumption; and the third added BMI, “a potential mediator in the causal pathway between steps per day and diabetes,” the investigators wrote.

Participants took an average of 3,729 steps per day, divided roughly evenly between light and moderate to vigorous intensity.

After a median follow-up of 5.7 years, 8.1% of women developed diabetes. The least-adjusted model showed a 14% reduction in diabetes risk per 2,000 steps (hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.80-0.92; P = .007), whereas the second model, adjusting for more confounding variables, showed a 12% reduction in diabetes risk per 2,000 steps (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-1.00; P = .045).

The final model, which added BMI, showed a 10% reduction in risk, although it didn’t reach statistical significance (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.80-1.02; P = .11). Furthermore, accelerated failure time models suggested that BMI did not significantly impact the link between steps and diabetes (proportion mediated, 17.7%;95% CI, –55.0 to 142.0; P = .09). Further analyses also found no significant interactions between BMI or other possible confounders.

“The steps per day–diabetes association was not modified by age, race/ethnicity, BMI, physical functioning, or family history of diabetes, which supports the generalizability of these findings to community-living older women,” the investigators wrote.

Increased stepping intensity also appeared to lower risk of diabetes. After adjusting for confounding variables, light stepping was not linked to reduced risk (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.73-1.29; P = .83), whereas moderate to vigorous stepping reduced risk by 14% per 2,000 steps (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-1.00; P = .04).

“This study provides evidence supporting an association between steps per day and lower incident diabetes,” the investigators concluded. “While further work is needed to identify whether there is a minimum number of steps per day that results in a clinically significant reduction of diabetes and to evaluate the role that step intensity plays in diabetes etiology for older adults, findings from this study suggest that moderate-vigorous–intensity steps may be more important than lower-intensity steps with respect to incident diabetes. Steps per day–based interventions are needed to advance diabetes prevention science in older adults.”

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program, and others. The investigators had no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Does COVID-19 induce type 1 diabetes in kids? Jury still out

Two new studies from different parts of the world have identified an increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children since the COVID-19 pandemic began, but the reasons still aren’t clear.

The findings from the two studies, in Germany and the United States, align closely, endocrinologist Jane J. Kim, MD, professor of pediatrics and principal investigator of the U.S. study, told this news organization. “I think that the general conclusion based on their data and our data is that there appears to be an increased rate of new type 1 diabetes diagnoses in children since the onset of the pandemic.”

Dr. Kim noted that because her group’s data pertain to just a single center, she is “heartened to see that the [German team’s] general conclusions are the same as ours.” Moreover, she pointed out that other studies examining this question came from Europe early in the pandemic, whereas “now both they [the German group] and we have had the opportunity to look at what’s happening over a longer period of time.”

But the reason for the association remains unclear. Some answers may be forthcoming from a database designed in mid-2020 specifically to examine the relationship between COVID-19 and new-onset diabetes. Called CoviDiab, the registry aims “to establish the extent and characteristics of new-onset, COVID-19–related diabetes and to investigate its pathogenesis, management, and outcomes,” according to the website.

The first new study, a multicenter German diabetes registry study, was published online Jan. 17 in Diabetes Care by Clemens Kamrath, MD, of Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany, and colleagues.

The other, from Rady Children’s Hospital of San Diego, was published online Jan. 24 in JAMA Pediatrics by Bethany L. Gottesman, MD, and colleagues, all with the University of California, San Diego.

Mechanisms likely to differ for type 1 versus type 2 diabetes

Neither the German nor the U.S. investigators were able to directly correlate current or prior SARS-CoV-2 infection in children with the subsequent development of type 1 diabetes.

Earlier this month, a study from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did examine that issue, but it also included youth with type 2 diabetes and did not separate out the two groups.

Dr. Kim said her institution has also seen an increase in type 2 diabetes among youth since the COVID-19 pandemic began but did not include that in their current article.

“When we started looking at our data, diabetes and COVID-19 in adults had been relatively well established. To see an increase in type 2 [diabetes] was not so surprising to our group. But we had the sense we were seeing more patients with type 1, and when we looked at our hospital that was very much the case. I think that was a surprise to people,” said Dr. Kim.

Although a direct effect of SARS-CoV-2 on pancreatic beta cells has been proposed, in both the German and San Diego datasets the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes was confirmed with autoantibodies that are typically present years prior to the onset of clinical symptoms.

The German group suggests possible other explanations for the link, including the lack of immune system exposure to other common pediatric infections during pandemic-necessitated social distancing – the so-called hygiene hypothesis – as well as the possible role of psychological stress, which several studies have linked to type 1 diabetes.

But as of now, Dr. Kim said, “Nobody really knows.”

Is the effect direct or indirect?

Using data from the multicenter German Diabetes Prospective Follow-up Registry, Dr. Kamrath and colleagues compared the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents from Jan. 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021 with the incidence in 2011-2019.

During the pandemic period, a total of 5,162 youth were newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at 236 German centers. That incidence, 24.4 per 100,000 patient-years, was significantly higher than the 21.2 per 100,000 patient-years expected based on the prior decade, with an incidence rate ratio of 1.15 (P < .001). The increase was similar in both males and females.

There was a difference by age, however, as the phenomenon appeared to be limited to the preadolescent age groups. The incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for ages below 6 years and 6-11 years were 1.23 and 1.18 (both P < .001), respectively, compared to a nonsignificant IRR of 1.06 (P = .13) in those aged 12-17 years.

Compared with the expected monthly incidence, the observed incidence was significantly higher in June 2020 (IRR, 1.43; P = .003), July 2020 (IRR, 1.48; P < 0.001), March 2021 (IRR, 1.29; P = .028), and June 2021 (IRR, 1.39; P = .01).

Among the 3,851 patients for whom data on type 1 diabetes-associated autoantibodies were available, the adjusted rates of autoantibody negativity did not differ from 2018-2019 during the entire pandemic period or during the year 2020 or the first half of 2021.

“Therefore, the increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children appears to be due to immune-mediated type 1 diabetes. However, because autoimmunity and progressive beta-cell destruction typically begin long before the clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, we were surprised to see the incidence of type 1 diabetes followed the peak incidence of COVID-19 and also the pandemic containment measures by only approximately 3 months,” Dr. Kamrath and colleagues write.

Taken together, they say, the data suggest that “the impact on type 1 diabetes incidence is not due to infection with SARS-CoV-2 but rather a consequence of environmental changes resulting from the pandemic itself or pandemic containment measures.”

Similar findings at a U.S. children’s hospital

In the cross-sectional study in San Diego, Dr. Gottesman and colleagues looked at the electronic medical records (EMRs) at Rady Children’s Hospital for patients aged younger than 19 years with at least one positive type 1 diabetes antibody titer.

During March 19, 2020 to March 18, 2021, a total of 187 children were admitted for new-onset type 1 diabetes, compared with just 119 the previous year, a 57% increase.

From July 2020 through February 2021, the number of new type 1 diabetes diagnoses significantly exceeded the number expected based on a quarterly moving average of each of the preceding 5 years.

Only four of the 187 patients (2.1%) diagnosed during the pandemic period had a COVID-19 infection at the time of presentation. Antibody testing to assess prior infection wasn’t feasible, and now that children are receiving the vaccine – and therefore most will have antibodies – “we’ve lost our window of opportunity to look at that question,” Dr. Kim noted.

As has been previously shown, there was an increase in the percentage of patients presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis during the pandemic compared with the prior 5 years (49.7% vs. 40.7% requiring insulin infusion). However, there was no difference in mean age at presentation, body mass index, A1c, or percentage requiring admission to intensive care.

Because these data only go through March 2021, Dr. Kim noted, “We need to see what’s happening with these different variants. We’ll have a chance to look in a month or two to see the effects of Omicron on the rates of diabetes in the hospital.”

Will CoviDiab answer the question?

Data from CoviDiab will include diabetes type in adults and children, registry coprincipal investigator Francesco Rubino, MD, of King’s College London, told this news organization.

“We aimed at having as many as possible cases of new-onset diabetes for which we can have also a minimum set of clinical data including type of diabetes and A1c. By looking at this information we can infer whether a role of COVID-19 in triggering diabetes is clinically plausible – or not – and what type of diabetes is most frequently associated with COVID-19 as this also speaks about mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Rubino said that the CoviDiab team is approaching the data with the assumption that, at least in adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, the explanation might be that the person already had undiagnosed diabetes or that the hyperglycemia may be stress-induced and temporary.

“We’re looking at this question with a skeptical eye ... Is it just an association, or does the virus have a role in inducing diabetes from scratch, or can the virus advance pathophysiology in a way that it ends up in full-blown diabetes in predisposed individuals?”

While no single study will prove that SARS-CoV-2 causes diabetes, “combining observations from various studies and approaches we may get a higher degree of certainty,” Dr. Rubino said, noting that the CoviDiab team plans to publish data from the first 800 cases “soon.”

Dr. Kim has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rubino has reported receiving grants from Ethicon and Medtronic, personal fees from GI Dynamic, Keyron, Novo Nordisk, Ethicon, and Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new studies from different parts of the world have identified an increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children since the COVID-19 pandemic began, but the reasons still aren’t clear.

The findings from the two studies, in Germany and the United States, align closely, endocrinologist Jane J. Kim, MD, professor of pediatrics and principal investigator of the U.S. study, told this news organization. “I think that the general conclusion based on their data and our data is that there appears to be an increased rate of new type 1 diabetes diagnoses in children since the onset of the pandemic.”