User login

Family physician Joseph E. Scherger champions lifestyle change

Joseph E. Scherger, MD, MPH, is a family physician of 40 years and an avid runner who has carried over his passion for fitness and nutrition into treating patients.

He achieved this through moving to practicing functional medicine a decade ago.

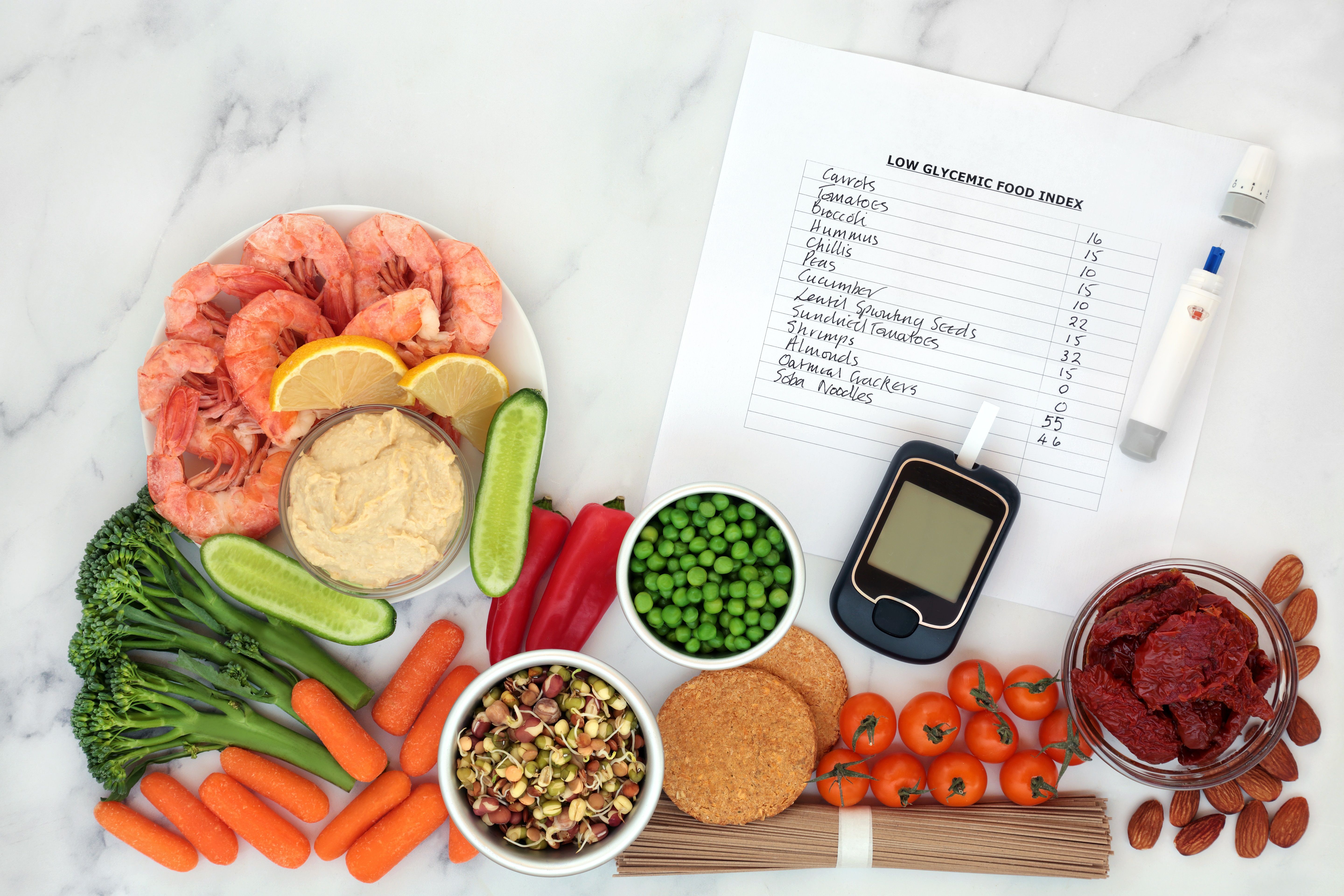

According to Dr. Scherger, functional medicine “shifts the whole approach [to family medicine], recognizing that people’s chronic diseases, like hypertension and diabetes, are completely reversible, and the reason why is because they’re caused by what we eat and how we live.”

Practicing functional medicine continues to make working exciting for Dr. Scherger, he says.

“Now that I’ve shifted into nutrition and lifestyle, I feel like I’m a healer, you know? I’m not just refilling prescriptions anymore,” he said.

The burden of disease brought about by bad nutrition and our profit-hungry food industry is staggering, explained Dr. Scherger, As such, he encourages his patients to adopt lifestyle and nutritional changes that allow the body to become healthy again.

Dr. Scherger’s shift into lifestyle-oriented medicine reflects his own experiences with healthy living, and how it has impacted his life.

“I’m 70 years old, and I’m still running, and I feel the same as when I was 40 or 50.” He has completed 40 marathons, ten 50K and five 50-mile ultramarathon trail runs, and, although retired from long-distance running, he is currently training for an upcoming 5K Thanksgiving turkey trot with his 6-year-old grandson. “He loves it. He’s faster than I am, I have trouble keeping up with him,” he confessed.

Earlier days of career

“I’ve been very blessed to have a career that kept changing every 5-10 years,” he said. “I’ve been able to evolve in a way of shifting my interests from one area to another,” he said.

Dr. Scherger has held many positions in the medical field, from serving in the National Health Service Corps in Dixon, Calif., as a migrant health physician during 1978-1980, to being chair of graduate medical education at Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, Calif., from 2009 to 2015. In between, he taught at the University of California, Davis, and served as founding dean of the Florida State University College of Medicine.

Originally from Ohio, Dr. Scherger was born in 1950 in the small town of Delphos. He graduated from the University of Dayton in 1971 before attending medical school at University of California, Los Angeles, for 4 years. He then completed a family medicine residency and a masters in public health at the University of Washington, Seattle, in 1978.

A resident of the Golden State for 50 years now, Dr. Scherger describes himself as a “true Californian.” Currently, he is in practice at Eisenhower Health in La Quinta, Calif., where he is a core faculty member in the family medicine residency program. He is also a physician under the health center’s Primary Care 365 program, which offers patients regular communication with and increased access to their physicians, emphasizing on telemedicine. He also founded Restore Health – Disease Reversal, a wellness center in Indian Wells, Calif., that focuses on improving patients’ health through changes in nutrition and lifestyle.

Within his medical practice, Dr. Scherger is seen by colleagues as a doctor who not only advocates for his patients, but also goes above and beyond to solve their problems.

“He’s a leader, an advocate, and he inspires others to do what they do,” said Julia L. Martin, MD, a fellow family medicine practitioner who has been working with Dr. Scherger at the Eisenhower Medical Center for the past 5 years. “Being a physician is a very challenging role. You need to be patient and understanding in trying to investigate what the patient wants and work through that to try to find the solution. Dr. Scherger is really good at that.”

Inspiration for writing

Apart from his roles as a physician and faculty member, Dr. Scherger is also an author of two books: “40 Years in Family Medicine” (Scotts Valley, Calif.: CreateSpace, 2014) and “Lean and Fit: A Doctor’s Journey to Healthy Nutrition and Greater Wellness” (Scotts Valley, Calif.: CreateSpace, 2015). He admits to not being a naturally gifted writer, and is more intrinsically skilled at speaking. When he was in medical school, however, a mentor told him that the written word is eternal, and this left a deep impression on him.

“When I think of something that’s worth writing about, that I think will be a contribution to my field, I don’t hesitate to begin to write and develop,” said Dr. Scherger. “ I’ve done some research that I’m proud of, but most of [my writings] are hopefully thoughtful essays to help move my field along, and it’s enormously satisfying to make these contributions.”

Awards and other contributions to family medicine

Dr. Scherger’s contributions to the field of family medicine have been recognized continuously over his career.

He has served on the board of directors of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Board of Family Medicine. He is also the recipient of numerous awards, such as being chosen as Family Physician of the Year by the American Academy of Family Physicians and the California Academy of Family Physicians in 1989. From 1988 to 1991, he was a fellow in the Kellogg National Fellowship Program.

While he has managed to reinvent his own practice and medical focus, Dr. Scherger is also concerned with the need to remodel the current state of primary care and family medicine. Regarding challenges facing the field, he mentions the burnout faced by many doctors.

Nowadays, the work of family medicine includes much more than those common acute illnesses – it includes preventive medicine, chronic illness management and mental health counseling. “Yet, somehow, the whole economic and schedule model is based on brief visits,” said Dr. Scherger. “I think the most common reason that a lot of family doctors are burned out is that they’re expected to see so many people a day, and they know they don’t have enough time to do a really good job.”

He elaborated: “The real challenge now for family practice is to be re-engineered to be for the modern age, and not be still stuck in a ‘make an appointment, come and get it’ model of care, which is outdated. So I’ve been working a long time in trying to reinvent primary care. And, you know, it’s hard to make those changes, and it’s still a work in progress.”

One of the ways Dr. Scherger has been working on the primary care model is to help redesign it for the computer age. He started doing telemedicine and online care in 1997, even though other doctors gave him pushback for doing so at the time. Today, in his practice, half of his patients are remote, and under Eisenhower’s Primary Care 365 service, he uses telemedicine to its fullest potential.

Dr. Martin calls Dr. Scherger an “innovator,” adding: “He really tries to find what works for a solution, in different ways – not just one cookie cutter way.”

Despite nearly 50 years of being a doctor, the profession has not gotten any less rewarding for Dr. Scherger, who says he does not intend to retire as long as he is any good at it.

“My mother always said, ‘Joe, your life should be dedicated to making the world a better place.’ I really took that to heart and realized that my greatest joy is to help other people.”

Joseph E. Scherger, MD, MPH, is a family physician of 40 years and an avid runner who has carried over his passion for fitness and nutrition into treating patients.

He achieved this through moving to practicing functional medicine a decade ago.

According to Dr. Scherger, functional medicine “shifts the whole approach [to family medicine], recognizing that people’s chronic diseases, like hypertension and diabetes, are completely reversible, and the reason why is because they’re caused by what we eat and how we live.”

Practicing functional medicine continues to make working exciting for Dr. Scherger, he says.

“Now that I’ve shifted into nutrition and lifestyle, I feel like I’m a healer, you know? I’m not just refilling prescriptions anymore,” he said.

The burden of disease brought about by bad nutrition and our profit-hungry food industry is staggering, explained Dr. Scherger, As such, he encourages his patients to adopt lifestyle and nutritional changes that allow the body to become healthy again.

Dr. Scherger’s shift into lifestyle-oriented medicine reflects his own experiences with healthy living, and how it has impacted his life.

“I’m 70 years old, and I’m still running, and I feel the same as when I was 40 or 50.” He has completed 40 marathons, ten 50K and five 50-mile ultramarathon trail runs, and, although retired from long-distance running, he is currently training for an upcoming 5K Thanksgiving turkey trot with his 6-year-old grandson. “He loves it. He’s faster than I am, I have trouble keeping up with him,” he confessed.

Earlier days of career

“I’ve been very blessed to have a career that kept changing every 5-10 years,” he said. “I’ve been able to evolve in a way of shifting my interests from one area to another,” he said.

Dr. Scherger has held many positions in the medical field, from serving in the National Health Service Corps in Dixon, Calif., as a migrant health physician during 1978-1980, to being chair of graduate medical education at Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, Calif., from 2009 to 2015. In between, he taught at the University of California, Davis, and served as founding dean of the Florida State University College of Medicine.

Originally from Ohio, Dr. Scherger was born in 1950 in the small town of Delphos. He graduated from the University of Dayton in 1971 before attending medical school at University of California, Los Angeles, for 4 years. He then completed a family medicine residency and a masters in public health at the University of Washington, Seattle, in 1978.

A resident of the Golden State for 50 years now, Dr. Scherger describes himself as a “true Californian.” Currently, he is in practice at Eisenhower Health in La Quinta, Calif., where he is a core faculty member in the family medicine residency program. He is also a physician under the health center’s Primary Care 365 program, which offers patients regular communication with and increased access to their physicians, emphasizing on telemedicine. He also founded Restore Health – Disease Reversal, a wellness center in Indian Wells, Calif., that focuses on improving patients’ health through changes in nutrition and lifestyle.

Within his medical practice, Dr. Scherger is seen by colleagues as a doctor who not only advocates for his patients, but also goes above and beyond to solve their problems.

“He’s a leader, an advocate, and he inspires others to do what they do,” said Julia L. Martin, MD, a fellow family medicine practitioner who has been working with Dr. Scherger at the Eisenhower Medical Center for the past 5 years. “Being a physician is a very challenging role. You need to be patient and understanding in trying to investigate what the patient wants and work through that to try to find the solution. Dr. Scherger is really good at that.”

Inspiration for writing

Apart from his roles as a physician and faculty member, Dr. Scherger is also an author of two books: “40 Years in Family Medicine” (Scotts Valley, Calif.: CreateSpace, 2014) and “Lean and Fit: A Doctor’s Journey to Healthy Nutrition and Greater Wellness” (Scotts Valley, Calif.: CreateSpace, 2015). He admits to not being a naturally gifted writer, and is more intrinsically skilled at speaking. When he was in medical school, however, a mentor told him that the written word is eternal, and this left a deep impression on him.

“When I think of something that’s worth writing about, that I think will be a contribution to my field, I don’t hesitate to begin to write and develop,” said Dr. Scherger. “ I’ve done some research that I’m proud of, but most of [my writings] are hopefully thoughtful essays to help move my field along, and it’s enormously satisfying to make these contributions.”

Awards and other contributions to family medicine

Dr. Scherger’s contributions to the field of family medicine have been recognized continuously over his career.

He has served on the board of directors of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Board of Family Medicine. He is also the recipient of numerous awards, such as being chosen as Family Physician of the Year by the American Academy of Family Physicians and the California Academy of Family Physicians in 1989. From 1988 to 1991, he was a fellow in the Kellogg National Fellowship Program.

While he has managed to reinvent his own practice and medical focus, Dr. Scherger is also concerned with the need to remodel the current state of primary care and family medicine. Regarding challenges facing the field, he mentions the burnout faced by many doctors.

Nowadays, the work of family medicine includes much more than those common acute illnesses – it includes preventive medicine, chronic illness management and mental health counseling. “Yet, somehow, the whole economic and schedule model is based on brief visits,” said Dr. Scherger. “I think the most common reason that a lot of family doctors are burned out is that they’re expected to see so many people a day, and they know they don’t have enough time to do a really good job.”

He elaborated: “The real challenge now for family practice is to be re-engineered to be for the modern age, and not be still stuck in a ‘make an appointment, come and get it’ model of care, which is outdated. So I’ve been working a long time in trying to reinvent primary care. And, you know, it’s hard to make those changes, and it’s still a work in progress.”

One of the ways Dr. Scherger has been working on the primary care model is to help redesign it for the computer age. He started doing telemedicine and online care in 1997, even though other doctors gave him pushback for doing so at the time. Today, in his practice, half of his patients are remote, and under Eisenhower’s Primary Care 365 service, he uses telemedicine to its fullest potential.

Dr. Martin calls Dr. Scherger an “innovator,” adding: “He really tries to find what works for a solution, in different ways – not just one cookie cutter way.”

Despite nearly 50 years of being a doctor, the profession has not gotten any less rewarding for Dr. Scherger, who says he does not intend to retire as long as he is any good at it.

“My mother always said, ‘Joe, your life should be dedicated to making the world a better place.’ I really took that to heart and realized that my greatest joy is to help other people.”

Joseph E. Scherger, MD, MPH, is a family physician of 40 years and an avid runner who has carried over his passion for fitness and nutrition into treating patients.

He achieved this through moving to practicing functional medicine a decade ago.

According to Dr. Scherger, functional medicine “shifts the whole approach [to family medicine], recognizing that people’s chronic diseases, like hypertension and diabetes, are completely reversible, and the reason why is because they’re caused by what we eat and how we live.”

Practicing functional medicine continues to make working exciting for Dr. Scherger, he says.

“Now that I’ve shifted into nutrition and lifestyle, I feel like I’m a healer, you know? I’m not just refilling prescriptions anymore,” he said.

The burden of disease brought about by bad nutrition and our profit-hungry food industry is staggering, explained Dr. Scherger, As such, he encourages his patients to adopt lifestyle and nutritional changes that allow the body to become healthy again.

Dr. Scherger’s shift into lifestyle-oriented medicine reflects his own experiences with healthy living, and how it has impacted his life.

“I’m 70 years old, and I’m still running, and I feel the same as when I was 40 or 50.” He has completed 40 marathons, ten 50K and five 50-mile ultramarathon trail runs, and, although retired from long-distance running, he is currently training for an upcoming 5K Thanksgiving turkey trot with his 6-year-old grandson. “He loves it. He’s faster than I am, I have trouble keeping up with him,” he confessed.

Earlier days of career

“I’ve been very blessed to have a career that kept changing every 5-10 years,” he said. “I’ve been able to evolve in a way of shifting my interests from one area to another,” he said.

Dr. Scherger has held many positions in the medical field, from serving in the National Health Service Corps in Dixon, Calif., as a migrant health physician during 1978-1980, to being chair of graduate medical education at Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, Calif., from 2009 to 2015. In between, he taught at the University of California, Davis, and served as founding dean of the Florida State University College of Medicine.

Originally from Ohio, Dr. Scherger was born in 1950 in the small town of Delphos. He graduated from the University of Dayton in 1971 before attending medical school at University of California, Los Angeles, for 4 years. He then completed a family medicine residency and a masters in public health at the University of Washington, Seattle, in 1978.

A resident of the Golden State for 50 years now, Dr. Scherger describes himself as a “true Californian.” Currently, he is in practice at Eisenhower Health in La Quinta, Calif., where he is a core faculty member in the family medicine residency program. He is also a physician under the health center’s Primary Care 365 program, which offers patients regular communication with and increased access to their physicians, emphasizing on telemedicine. He also founded Restore Health – Disease Reversal, a wellness center in Indian Wells, Calif., that focuses on improving patients’ health through changes in nutrition and lifestyle.

Within his medical practice, Dr. Scherger is seen by colleagues as a doctor who not only advocates for his patients, but also goes above and beyond to solve their problems.

“He’s a leader, an advocate, and he inspires others to do what they do,” said Julia L. Martin, MD, a fellow family medicine practitioner who has been working with Dr. Scherger at the Eisenhower Medical Center for the past 5 years. “Being a physician is a very challenging role. You need to be patient and understanding in trying to investigate what the patient wants and work through that to try to find the solution. Dr. Scherger is really good at that.”

Inspiration for writing

Apart from his roles as a physician and faculty member, Dr. Scherger is also an author of two books: “40 Years in Family Medicine” (Scotts Valley, Calif.: CreateSpace, 2014) and “Lean and Fit: A Doctor’s Journey to Healthy Nutrition and Greater Wellness” (Scotts Valley, Calif.: CreateSpace, 2015). He admits to not being a naturally gifted writer, and is more intrinsically skilled at speaking. When he was in medical school, however, a mentor told him that the written word is eternal, and this left a deep impression on him.

“When I think of something that’s worth writing about, that I think will be a contribution to my field, I don’t hesitate to begin to write and develop,” said Dr. Scherger. “ I’ve done some research that I’m proud of, but most of [my writings] are hopefully thoughtful essays to help move my field along, and it’s enormously satisfying to make these contributions.”

Awards and other contributions to family medicine

Dr. Scherger’s contributions to the field of family medicine have been recognized continuously over his career.

He has served on the board of directors of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Board of Family Medicine. He is also the recipient of numerous awards, such as being chosen as Family Physician of the Year by the American Academy of Family Physicians and the California Academy of Family Physicians in 1989. From 1988 to 1991, he was a fellow in the Kellogg National Fellowship Program.

While he has managed to reinvent his own practice and medical focus, Dr. Scherger is also concerned with the need to remodel the current state of primary care and family medicine. Regarding challenges facing the field, he mentions the burnout faced by many doctors.

Nowadays, the work of family medicine includes much more than those common acute illnesses – it includes preventive medicine, chronic illness management and mental health counseling. “Yet, somehow, the whole economic and schedule model is based on brief visits,” said Dr. Scherger. “I think the most common reason that a lot of family doctors are burned out is that they’re expected to see so many people a day, and they know they don’t have enough time to do a really good job.”

He elaborated: “The real challenge now for family practice is to be re-engineered to be for the modern age, and not be still stuck in a ‘make an appointment, come and get it’ model of care, which is outdated. So I’ve been working a long time in trying to reinvent primary care. And, you know, it’s hard to make those changes, and it’s still a work in progress.”

One of the ways Dr. Scherger has been working on the primary care model is to help redesign it for the computer age. He started doing telemedicine and online care in 1997, even though other doctors gave him pushback for doing so at the time. Today, in his practice, half of his patients are remote, and under Eisenhower’s Primary Care 365 service, he uses telemedicine to its fullest potential.

Dr. Martin calls Dr. Scherger an “innovator,” adding: “He really tries to find what works for a solution, in different ways – not just one cookie cutter way.”

Despite nearly 50 years of being a doctor, the profession has not gotten any less rewarding for Dr. Scherger, who says he does not intend to retire as long as he is any good at it.

“My mother always said, ‘Joe, your life should be dedicated to making the world a better place.’ I really took that to heart and realized that my greatest joy is to help other people.”

SGLT2 inhibitor use rising in patients with DKD

U.S. prescribing data from 160,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease showed a notable uptick in new prescriptions for sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and less dramatic gains for glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists during 2019 and continuing into early 2020, compared with prior years, with usage levels of both classes during the first quarter of 2020 rivaling those of more traditional agents including metformin and insulin.

During the first 3 months of 2020, initiation of a SGLT2 inhibitor constituted 13% of all new starts of an antidiabetes drug among adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease (DKD). This compared with initiation rates during the same early 2020 period of 17% for GLP-1 receptor agonists, 19% for metformin, 16% for sulfonylureas, 15% for insulins, 14% for thiazolidinediones, and 6% for dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors, the seven drug classes examined in a study published in Diabetes Care.

Early 2020 was the first time that starts of a GLP-1 receptor agonist ranked second (behind only metformin) among these seven drug classes in the studied U.S. population, and early 2020 also marked an unprecedentedly high start rate for SGLT2 inhibitors that nearly tripled the roughly 5% rate in place as recently as 2018.

Rises are ‘what we expected’

The recent rise of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in these patients “was what we expected,” given the evidence for both classes in slowing progression of DKD, said Julie M. Paik, MD, senior author on the study and a nephrologist and pharmacoepidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“We’ve seen other beneficial drugs slow on the uptake, so it’s not surprising to see it here, and I’m optimistic” about further increases going forward, she said in an interview.

Both drug classes “were originally marketed as diabetes drugs,” and it is only since 2019, with the publication of trials showing dramatic renal benefits from canagliflozin (Invokana) in CREDENCE, and from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in DAPA-CKD in 2020 that the evidence became truly compelling for SGLT2 inhibitors. This evidence also led to new renal-protection indications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for canagliflozin and for dapagliflozin, noted Dr. Paik.

Evidence for renal protection also emerged in 2017 for the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide (Victoza) in the LEADER trial, and for dulaglutide (Trulicity) in the AWARD-7 trial, although neither drug has received a renal indication in its labeling.

By 2020, guidelines for managing patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease from the influential Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes organization had identified agents from the SGLT2 inhibitor class as top-tier options, along with metformin, for treating these patients, with agents from the GLP-1 receptor agonist class as the top third class to add in patients who require additional glycemic control.

Additional analyses Dr. Paik and associates ran showed how this played out in terms of which specialists prescribed these drugs during the full period studied beginning in 2013. Throughout this roughly 7-year span, about 70% of the prescriptions written for either SGLT2 inhibitors or for GLP-1 receptor agonists were from internal medicine physicians, followed by about 20% written by endocrinologists. Prescriptions from nephrologists, as well as from cardiologists, have hovered at about 5% each, but seem poised to start rising based on the recently added indications and newer treatment recommendations.

“It’s good to see the recent uptick in use since 2019,” Katherine R. Tuttle, MD, commented in an interview. It’s a positive development for U.S. public health, “but we need to do more to disseminate and implement these life-, kidney-, and heart-saving therapies.”

Future use could approach 80% of DKD patients

Dr. Tuttle estimated that “target” levels of use for SGLT2 inhibitors and for GLP-1 receptor agonists “could reasonably approach 80%” for patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease.

“We will likely move to combination therapy” with simultaneous use of agents from both classes in a targeted way using “precision phenotyping based on clinical characteristics, and eventually perhaps by biomarkers, kidney biopsies, or both.” Combined treatment with both an SGLT2 inhibitor and a GLP-1 receptor agonist may be especially suited to patients with type 2 diabetes, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, low estimated glomerular filtration rate, and need for better glycemic control and weight loss, a profile that is “pretty typical” in real-world practice, said Dr. Tuttle, a nephrologist and endocrinologist and executive director for research at Providence Healthcare in Spokane, Wash.

Study included patients with commercial or Medicare Advantage coverage

The study used information in an Optum database that included patients enrolled in either commercial or in Medicare Advantage health insurance plans from 2013 to the first quarter of 2020. This included 160,489 adults with type 2 diabetes and DKD who started during that period at least one agent from any of the seven included drug classes.

This focus may have biased the findings because, overall, U.S. coverage of the relatively expensive agents from the SGLT2 inhibitor and GLP-1 receptor agonist classes has often been problematic.

“There are issues of cost, coverage, and access” using these medications, as well as limited data on cost-effectiveness, Dr. Paik acknowledged. Additional issues that have helped generate prescribing lags include concerns about possible adverse effects, low familiarity by providers with these drugs early on, and limited trial experience using them in older patients. The process of clinicians growing more comfortable prescribing these new agents has depended on their “working through the evidence,” she explained.

The FDA’s approval in July 2021 of finerenone (Kerendia) for treating patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease threw yet another new variable into the prescribing mix for these patients.

“SGLT2 inhibitors are here to stay as a new standard of care for patients with diabetic kidney disease, but combination with finerenone might be especially useful for patients with diabetic kidney disease and heart failure,” Dr. Tuttle suggested. A new generation of clinical trials will likely soon launch to test these combinations, she predicted.

Dr. Paik had no disclosures. Dr. Tuttle has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Goldfinch Bio, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

U.S. prescribing data from 160,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease showed a notable uptick in new prescriptions for sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and less dramatic gains for glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists during 2019 and continuing into early 2020, compared with prior years, with usage levels of both classes during the first quarter of 2020 rivaling those of more traditional agents including metformin and insulin.

During the first 3 months of 2020, initiation of a SGLT2 inhibitor constituted 13% of all new starts of an antidiabetes drug among adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease (DKD). This compared with initiation rates during the same early 2020 period of 17% for GLP-1 receptor agonists, 19% for metformin, 16% for sulfonylureas, 15% for insulins, 14% for thiazolidinediones, and 6% for dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors, the seven drug classes examined in a study published in Diabetes Care.

Early 2020 was the first time that starts of a GLP-1 receptor agonist ranked second (behind only metformin) among these seven drug classes in the studied U.S. population, and early 2020 also marked an unprecedentedly high start rate for SGLT2 inhibitors that nearly tripled the roughly 5% rate in place as recently as 2018.

Rises are ‘what we expected’

The recent rise of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in these patients “was what we expected,” given the evidence for both classes in slowing progression of DKD, said Julie M. Paik, MD, senior author on the study and a nephrologist and pharmacoepidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“We’ve seen other beneficial drugs slow on the uptake, so it’s not surprising to see it here, and I’m optimistic” about further increases going forward, she said in an interview.

Both drug classes “were originally marketed as diabetes drugs,” and it is only since 2019, with the publication of trials showing dramatic renal benefits from canagliflozin (Invokana) in CREDENCE, and from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in DAPA-CKD in 2020 that the evidence became truly compelling for SGLT2 inhibitors. This evidence also led to new renal-protection indications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for canagliflozin and for dapagliflozin, noted Dr. Paik.

Evidence for renal protection also emerged in 2017 for the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide (Victoza) in the LEADER trial, and for dulaglutide (Trulicity) in the AWARD-7 trial, although neither drug has received a renal indication in its labeling.

By 2020, guidelines for managing patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease from the influential Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes organization had identified agents from the SGLT2 inhibitor class as top-tier options, along with metformin, for treating these patients, with agents from the GLP-1 receptor agonist class as the top third class to add in patients who require additional glycemic control.

Additional analyses Dr. Paik and associates ran showed how this played out in terms of which specialists prescribed these drugs during the full period studied beginning in 2013. Throughout this roughly 7-year span, about 70% of the prescriptions written for either SGLT2 inhibitors or for GLP-1 receptor agonists were from internal medicine physicians, followed by about 20% written by endocrinologists. Prescriptions from nephrologists, as well as from cardiologists, have hovered at about 5% each, but seem poised to start rising based on the recently added indications and newer treatment recommendations.

“It’s good to see the recent uptick in use since 2019,” Katherine R. Tuttle, MD, commented in an interview. It’s a positive development for U.S. public health, “but we need to do more to disseminate and implement these life-, kidney-, and heart-saving therapies.”

Future use could approach 80% of DKD patients

Dr. Tuttle estimated that “target” levels of use for SGLT2 inhibitors and for GLP-1 receptor agonists “could reasonably approach 80%” for patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease.

“We will likely move to combination therapy” with simultaneous use of agents from both classes in a targeted way using “precision phenotyping based on clinical characteristics, and eventually perhaps by biomarkers, kidney biopsies, or both.” Combined treatment with both an SGLT2 inhibitor and a GLP-1 receptor agonist may be especially suited to patients with type 2 diabetes, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, low estimated glomerular filtration rate, and need for better glycemic control and weight loss, a profile that is “pretty typical” in real-world practice, said Dr. Tuttle, a nephrologist and endocrinologist and executive director for research at Providence Healthcare in Spokane, Wash.

Study included patients with commercial or Medicare Advantage coverage

The study used information in an Optum database that included patients enrolled in either commercial or in Medicare Advantage health insurance plans from 2013 to the first quarter of 2020. This included 160,489 adults with type 2 diabetes and DKD who started during that period at least one agent from any of the seven included drug classes.

This focus may have biased the findings because, overall, U.S. coverage of the relatively expensive agents from the SGLT2 inhibitor and GLP-1 receptor agonist classes has often been problematic.

“There are issues of cost, coverage, and access” using these medications, as well as limited data on cost-effectiveness, Dr. Paik acknowledged. Additional issues that have helped generate prescribing lags include concerns about possible adverse effects, low familiarity by providers with these drugs early on, and limited trial experience using them in older patients. The process of clinicians growing more comfortable prescribing these new agents has depended on their “working through the evidence,” she explained.

The FDA’s approval in July 2021 of finerenone (Kerendia) for treating patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease threw yet another new variable into the prescribing mix for these patients.

“SGLT2 inhibitors are here to stay as a new standard of care for patients with diabetic kidney disease, but combination with finerenone might be especially useful for patients with diabetic kidney disease and heart failure,” Dr. Tuttle suggested. A new generation of clinical trials will likely soon launch to test these combinations, she predicted.

Dr. Paik had no disclosures. Dr. Tuttle has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Goldfinch Bio, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

U.S. prescribing data from 160,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease showed a notable uptick in new prescriptions for sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and less dramatic gains for glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists during 2019 and continuing into early 2020, compared with prior years, with usage levels of both classes during the first quarter of 2020 rivaling those of more traditional agents including metformin and insulin.

During the first 3 months of 2020, initiation of a SGLT2 inhibitor constituted 13% of all new starts of an antidiabetes drug among adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease (DKD). This compared with initiation rates during the same early 2020 period of 17% for GLP-1 receptor agonists, 19% for metformin, 16% for sulfonylureas, 15% for insulins, 14% for thiazolidinediones, and 6% for dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors, the seven drug classes examined in a study published in Diabetes Care.

Early 2020 was the first time that starts of a GLP-1 receptor agonist ranked second (behind only metformin) among these seven drug classes in the studied U.S. population, and early 2020 also marked an unprecedentedly high start rate for SGLT2 inhibitors that nearly tripled the roughly 5% rate in place as recently as 2018.

Rises are ‘what we expected’

The recent rise of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in these patients “was what we expected,” given the evidence for both classes in slowing progression of DKD, said Julie M. Paik, MD, senior author on the study and a nephrologist and pharmacoepidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“We’ve seen other beneficial drugs slow on the uptake, so it’s not surprising to see it here, and I’m optimistic” about further increases going forward, she said in an interview.

Both drug classes “were originally marketed as diabetes drugs,” and it is only since 2019, with the publication of trials showing dramatic renal benefits from canagliflozin (Invokana) in CREDENCE, and from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in DAPA-CKD in 2020 that the evidence became truly compelling for SGLT2 inhibitors. This evidence also led to new renal-protection indications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for canagliflozin and for dapagliflozin, noted Dr. Paik.

Evidence for renal protection also emerged in 2017 for the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide (Victoza) in the LEADER trial, and for dulaglutide (Trulicity) in the AWARD-7 trial, although neither drug has received a renal indication in its labeling.

By 2020, guidelines for managing patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease from the influential Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes organization had identified agents from the SGLT2 inhibitor class as top-tier options, along with metformin, for treating these patients, with agents from the GLP-1 receptor agonist class as the top third class to add in patients who require additional glycemic control.

Additional analyses Dr. Paik and associates ran showed how this played out in terms of which specialists prescribed these drugs during the full period studied beginning in 2013. Throughout this roughly 7-year span, about 70% of the prescriptions written for either SGLT2 inhibitors or for GLP-1 receptor agonists were from internal medicine physicians, followed by about 20% written by endocrinologists. Prescriptions from nephrologists, as well as from cardiologists, have hovered at about 5% each, but seem poised to start rising based on the recently added indications and newer treatment recommendations.

“It’s good to see the recent uptick in use since 2019,” Katherine R. Tuttle, MD, commented in an interview. It’s a positive development for U.S. public health, “but we need to do more to disseminate and implement these life-, kidney-, and heart-saving therapies.”

Future use could approach 80% of DKD patients

Dr. Tuttle estimated that “target” levels of use for SGLT2 inhibitors and for GLP-1 receptor agonists “could reasonably approach 80%” for patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease.

“We will likely move to combination therapy” with simultaneous use of agents from both classes in a targeted way using “precision phenotyping based on clinical characteristics, and eventually perhaps by biomarkers, kidney biopsies, or both.” Combined treatment with both an SGLT2 inhibitor and a GLP-1 receptor agonist may be especially suited to patients with type 2 diabetes, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, low estimated glomerular filtration rate, and need for better glycemic control and weight loss, a profile that is “pretty typical” in real-world practice, said Dr. Tuttle, a nephrologist and endocrinologist and executive director for research at Providence Healthcare in Spokane, Wash.

Study included patients with commercial or Medicare Advantage coverage

The study used information in an Optum database that included patients enrolled in either commercial or in Medicare Advantage health insurance plans from 2013 to the first quarter of 2020. This included 160,489 adults with type 2 diabetes and DKD who started during that period at least one agent from any of the seven included drug classes.

This focus may have biased the findings because, overall, U.S. coverage of the relatively expensive agents from the SGLT2 inhibitor and GLP-1 receptor agonist classes has often been problematic.

“There are issues of cost, coverage, and access” using these medications, as well as limited data on cost-effectiveness, Dr. Paik acknowledged. Additional issues that have helped generate prescribing lags include concerns about possible adverse effects, low familiarity by providers with these drugs early on, and limited trial experience using them in older patients. The process of clinicians growing more comfortable prescribing these new agents has depended on their “working through the evidence,” she explained.

The FDA’s approval in July 2021 of finerenone (Kerendia) for treating patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease threw yet another new variable into the prescribing mix for these patients.

“SGLT2 inhibitors are here to stay as a new standard of care for patients with diabetic kidney disease, but combination with finerenone might be especially useful for patients with diabetic kidney disease and heart failure,” Dr. Tuttle suggested. A new generation of clinical trials will likely soon launch to test these combinations, she predicted.

Dr. Paik had no disclosures. Dr. Tuttle has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Goldfinch Bio, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Mediterranean diet slows progression of atherosclerosis in CHD

For patients with coronary heart disease (CHD), following a Mediterranean diet is more effective in reducing progression of atherosclerosis than following a low-fat diet, according to new data from the CORDIOPREV randomized, controlled trial.

“The current study is, to our knowledge, the first to establish an effective dietary strategy for secondary cardiovascular prevention, reinforcing the fact that the Mediterranean diet rich in extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) could prevent the progression of atherosclerosis,” the study team said.

The data also show that patients with a higher atherosclerotic burden might benefit the most from the Mediterranean diet.

The study was published online Aug. 10, 2021, in Stroke.

Mediterranean or low fat?

“It is well established that lifestyle and dietary habits powerfully affect cardiovascular risk,” study investigator Elena M. Yubero-Serrano, PhD, with Reina Sofia University Hospital/University of Cordoba (Spain), told this news organization.

“The effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet in reducing cardiovascular risk has been seen in primary prevention. However, currently there is no consensus about a recommended dietary model for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease,” she said.

The Coronary Diet Intervention With Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Prevention (CORDIOPREV) study is an ongoing prospective study comparing the effects of two healthy diets for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 1002 patients.

The comparative effect of the diets in reducing CVD risk, assessed by quantification of intima-media thickness of the common carotid arteries (IMT-CC), is a key secondary endpoint of the study.

During the study, half of the patients follow a Mediterranean diet rich in EVOO, fruit and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and nuts. The other half follow a diet low in fat and rich in complex carbohydrates.

A total of 939 participants (459 in the low-fat diet group and 480 in the Mediterranean diet group) completed IMT-CC evaluation at baseline, and 809 (377 and 432, respectively) completed the IMT-CC evaluation at 5 years; 731 (335 and 396, respectively) did so at 7 years.

The Mediterranean diet significantly decreased IMT-CC both after 5 years (–0.027; P < .001) and after 7 years (–0.031 mm; P < .001), relative to baseline. In contrast, the low-fat diet did not exert any change on IMT-CC after 5 or 7 years, the researchers report.

The higher the IMT-CC at baseline, the greater the reduction in this parameter.

The Mediterranean diet also produced a greater decrease in IMT-CC and carotid plaque maximum height, compared with the low-fat diet throughout follow-up.

There were no between-group differences in carotid plaque numbers during follow-up.

“Our findings, in addition to reinforcing the clinical benefits of the Mediterranean diet, provide a beneficial dietary strategy as a clinical and therapeutic tool that could reduce the high cardiovascular recurrence in the context of secondary prevention,” Dr. Yubero-Serrano said in an interview.

Earlier data from CORDIOPREV showed that, after 1 year of eating a Mediterranean diet, compared with the low-fat diet, endothelial function was improved among patients with CHD, even those with type 2 diabetes, which was associated with a better balance of vascular homeostasis.

The Mediterranean diet may also modulate the lipid profile, particularly by increasing HDL cholesterol levels. The anti-inflammatory capacity of the Mediterranean diet could be another factor that contributes to reducing the progression of atherosclerosis, the researchers say.

Important study

Reached for comment, Alan Rozanski, MD, professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside, New York, said: “We know very well that lifestyle factors, diet, and exercise in particular are extremely important in promoting health, vitality, and decreasing risk for chronic diseases, including heart attack and stroke.

“But a lot of the studies depend on epidemiological work. Until now, we haven’t had important prospective studies evaluating different kinds of dietary approaches and how they affect carotid intimal thickening assessments that we can do by ultrasound. So having this kind of imaging study which shows that diet can halt progression of atherosclerosis is important,” said Dr. Rozanski.

“Changing one’s diet is extremely important and potentially beneficial in many ways, and being able to say to a patient with atherosclerosis that we have data that shows you can halt the progression of the disease can be extraordinarily encouraging to many patients,” he noted.

“When people have disease, they very often gravitate toward drugs, but continuing to emphasize lifestyle changes in these people is extremely important,” he added.

The CORDIOPREV study was supported by the Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero. Dr. Yubero-Serrano and Dr. Rozanski disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with coronary heart disease (CHD), following a Mediterranean diet is more effective in reducing progression of atherosclerosis than following a low-fat diet, according to new data from the CORDIOPREV randomized, controlled trial.

“The current study is, to our knowledge, the first to establish an effective dietary strategy for secondary cardiovascular prevention, reinforcing the fact that the Mediterranean diet rich in extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) could prevent the progression of atherosclerosis,” the study team said.

The data also show that patients with a higher atherosclerotic burden might benefit the most from the Mediterranean diet.

The study was published online Aug. 10, 2021, in Stroke.

Mediterranean or low fat?

“It is well established that lifestyle and dietary habits powerfully affect cardiovascular risk,” study investigator Elena M. Yubero-Serrano, PhD, with Reina Sofia University Hospital/University of Cordoba (Spain), told this news organization.

“The effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet in reducing cardiovascular risk has been seen in primary prevention. However, currently there is no consensus about a recommended dietary model for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease,” she said.

The Coronary Diet Intervention With Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Prevention (CORDIOPREV) study is an ongoing prospective study comparing the effects of two healthy diets for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 1002 patients.

The comparative effect of the diets in reducing CVD risk, assessed by quantification of intima-media thickness of the common carotid arteries (IMT-CC), is a key secondary endpoint of the study.

During the study, half of the patients follow a Mediterranean diet rich in EVOO, fruit and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and nuts. The other half follow a diet low in fat and rich in complex carbohydrates.

A total of 939 participants (459 in the low-fat diet group and 480 in the Mediterranean diet group) completed IMT-CC evaluation at baseline, and 809 (377 and 432, respectively) completed the IMT-CC evaluation at 5 years; 731 (335 and 396, respectively) did so at 7 years.

The Mediterranean diet significantly decreased IMT-CC both after 5 years (–0.027; P < .001) and after 7 years (–0.031 mm; P < .001), relative to baseline. In contrast, the low-fat diet did not exert any change on IMT-CC after 5 or 7 years, the researchers report.

The higher the IMT-CC at baseline, the greater the reduction in this parameter.

The Mediterranean diet also produced a greater decrease in IMT-CC and carotid plaque maximum height, compared with the low-fat diet throughout follow-up.

There were no between-group differences in carotid plaque numbers during follow-up.

“Our findings, in addition to reinforcing the clinical benefits of the Mediterranean diet, provide a beneficial dietary strategy as a clinical and therapeutic tool that could reduce the high cardiovascular recurrence in the context of secondary prevention,” Dr. Yubero-Serrano said in an interview.

Earlier data from CORDIOPREV showed that, after 1 year of eating a Mediterranean diet, compared with the low-fat diet, endothelial function was improved among patients with CHD, even those with type 2 diabetes, which was associated with a better balance of vascular homeostasis.

The Mediterranean diet may also modulate the lipid profile, particularly by increasing HDL cholesterol levels. The anti-inflammatory capacity of the Mediterranean diet could be another factor that contributes to reducing the progression of atherosclerosis, the researchers say.

Important study

Reached for comment, Alan Rozanski, MD, professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside, New York, said: “We know very well that lifestyle factors, diet, and exercise in particular are extremely important in promoting health, vitality, and decreasing risk for chronic diseases, including heart attack and stroke.

“But a lot of the studies depend on epidemiological work. Until now, we haven’t had important prospective studies evaluating different kinds of dietary approaches and how they affect carotid intimal thickening assessments that we can do by ultrasound. So having this kind of imaging study which shows that diet can halt progression of atherosclerosis is important,” said Dr. Rozanski.

“Changing one’s diet is extremely important and potentially beneficial in many ways, and being able to say to a patient with atherosclerosis that we have data that shows you can halt the progression of the disease can be extraordinarily encouraging to many patients,” he noted.

“When people have disease, they very often gravitate toward drugs, but continuing to emphasize lifestyle changes in these people is extremely important,” he added.

The CORDIOPREV study was supported by the Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero. Dr. Yubero-Serrano and Dr. Rozanski disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with coronary heart disease (CHD), following a Mediterranean diet is more effective in reducing progression of atherosclerosis than following a low-fat diet, according to new data from the CORDIOPREV randomized, controlled trial.

“The current study is, to our knowledge, the first to establish an effective dietary strategy for secondary cardiovascular prevention, reinforcing the fact that the Mediterranean diet rich in extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) could prevent the progression of atherosclerosis,” the study team said.

The data also show that patients with a higher atherosclerotic burden might benefit the most from the Mediterranean diet.

The study was published online Aug. 10, 2021, in Stroke.

Mediterranean or low fat?

“It is well established that lifestyle and dietary habits powerfully affect cardiovascular risk,” study investigator Elena M. Yubero-Serrano, PhD, with Reina Sofia University Hospital/University of Cordoba (Spain), told this news organization.

“The effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet in reducing cardiovascular risk has been seen in primary prevention. However, currently there is no consensus about a recommended dietary model for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease,” she said.

The Coronary Diet Intervention With Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Prevention (CORDIOPREV) study is an ongoing prospective study comparing the effects of two healthy diets for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 1002 patients.

The comparative effect of the diets in reducing CVD risk, assessed by quantification of intima-media thickness of the common carotid arteries (IMT-CC), is a key secondary endpoint of the study.

During the study, half of the patients follow a Mediterranean diet rich in EVOO, fruit and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and nuts. The other half follow a diet low in fat and rich in complex carbohydrates.

A total of 939 participants (459 in the low-fat diet group and 480 in the Mediterranean diet group) completed IMT-CC evaluation at baseline, and 809 (377 and 432, respectively) completed the IMT-CC evaluation at 5 years; 731 (335 and 396, respectively) did so at 7 years.

The Mediterranean diet significantly decreased IMT-CC both after 5 years (–0.027; P < .001) and after 7 years (–0.031 mm; P < .001), relative to baseline. In contrast, the low-fat diet did not exert any change on IMT-CC after 5 or 7 years, the researchers report.

The higher the IMT-CC at baseline, the greater the reduction in this parameter.

The Mediterranean diet also produced a greater decrease in IMT-CC and carotid plaque maximum height, compared with the low-fat diet throughout follow-up.

There were no between-group differences in carotid plaque numbers during follow-up.

“Our findings, in addition to reinforcing the clinical benefits of the Mediterranean diet, provide a beneficial dietary strategy as a clinical and therapeutic tool that could reduce the high cardiovascular recurrence in the context of secondary prevention,” Dr. Yubero-Serrano said in an interview.

Earlier data from CORDIOPREV showed that, after 1 year of eating a Mediterranean diet, compared with the low-fat diet, endothelial function was improved among patients with CHD, even those with type 2 diabetes, which was associated with a better balance of vascular homeostasis.

The Mediterranean diet may also modulate the lipid profile, particularly by increasing HDL cholesterol levels. The anti-inflammatory capacity of the Mediterranean diet could be another factor that contributes to reducing the progression of atherosclerosis, the researchers say.

Important study

Reached for comment, Alan Rozanski, MD, professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside, New York, said: “We know very well that lifestyle factors, diet, and exercise in particular are extremely important in promoting health, vitality, and decreasing risk for chronic diseases, including heart attack and stroke.

“But a lot of the studies depend on epidemiological work. Until now, we haven’t had important prospective studies evaluating different kinds of dietary approaches and how they affect carotid intimal thickening assessments that we can do by ultrasound. So having this kind of imaging study which shows that diet can halt progression of atherosclerosis is important,” said Dr. Rozanski.

“Changing one’s diet is extremely important and potentially beneficial in many ways, and being able to say to a patient with atherosclerosis that we have data that shows you can halt the progression of the disease can be extraordinarily encouraging to many patients,” he noted.

“When people have disease, they very often gravitate toward drugs, but continuing to emphasize lifestyle changes in these people is extremely important,” he added.

The CORDIOPREV study was supported by the Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero. Dr. Yubero-Serrano and Dr. Rozanski disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Empagliflozin gets HFrEF approval from FDA

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved empagliflozin (Jardiance) as a treatment for adults with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) regardless of whether patients have diabetes on Aug. 18, making it the second agent from the sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor class to received this indication.

Empagliflozin first received FDA marketing approval in 2014 for improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes, and in 2016 the agency added a second indication of reducing cardiovascular death in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The newly granted indication for patients with HFrEF without regard to glycemic status was for reducing the risk for cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure, according to a statement from Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the two companies that together market empagliflozin.

The statement also said that the approval allowed for empagliflozin treatment in patients with HFrEF and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) as low as 20 mL/min per 1.73 m2, in contrast to its indication for improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes that limits use to patients with an eGFR of at least 30 mL per 1.73 m2.

EMPEROR-Reduced results drive approval

The FDA based its decision on results from the EMPEROR-Reduced study, first reported in August 2020, that showed treatment of patients with HFrEF with empagliflozin on top of standard therapy for a median of 16 months cut the incidence of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for worsening heart failure by 25% relative to placebo, and by an absolute 5.3%, compared with placebo-treated patients.

Patients enrolled in EMPEROR-Reduced had chronic heart failure in New York Heart Association functional class II-IV and with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, the standard ejection fraction criterion for defining HFrEF. Half the enrolled patients had diabetes, and analysis showed no heterogeneity in the primary outcome response based on diabetes status at enrollment.

Empagliflozin joins dapagliflozin for treating HFrEF

Dapagliflozin (Farxiga) was the first agent from the SGLT2 inhibitor class to receive an FDA indication, in 2020, for treating patients with HFrEF regardless of their diabetes status, a decision based on results from the DAPA-HF trial. Results from DAPA-HF showed that treatment with dapagliflozin in patients with HFrEF for a median of 18 months led to a 26% relative reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure and a 4.9% absolute reduction, compared with placebo when added to standard treatment. DAPA-HF enrolled patients using similar criteria to EMPEROR-Reduced, and 42% of enrolled patients had diabetes with no heterogeneity in the primary outcome related to baseline diabetes status.

Subsequent to the report of results from the EMPEROR-Reduced trial nearly a year ago, heart failure experts declared that treatment with an agent from the SGLT2 inhibitor class had become a “new pillar of foundational therapy for HFrEF,” and they urged rapid initiation of an SGLT2 inhibitor (along with other appropriate medications) at the time of initial diagnosis of HFrEF.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved empagliflozin (Jardiance) as a treatment for adults with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) regardless of whether patients have diabetes on Aug. 18, making it the second agent from the sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor class to received this indication.

Empagliflozin first received FDA marketing approval in 2014 for improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes, and in 2016 the agency added a second indication of reducing cardiovascular death in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The newly granted indication for patients with HFrEF without regard to glycemic status was for reducing the risk for cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure, according to a statement from Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the two companies that together market empagliflozin.

The statement also said that the approval allowed for empagliflozin treatment in patients with HFrEF and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) as low as 20 mL/min per 1.73 m2, in contrast to its indication for improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes that limits use to patients with an eGFR of at least 30 mL per 1.73 m2.

EMPEROR-Reduced results drive approval

The FDA based its decision on results from the EMPEROR-Reduced study, first reported in August 2020, that showed treatment of patients with HFrEF with empagliflozin on top of standard therapy for a median of 16 months cut the incidence of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for worsening heart failure by 25% relative to placebo, and by an absolute 5.3%, compared with placebo-treated patients.

Patients enrolled in EMPEROR-Reduced had chronic heart failure in New York Heart Association functional class II-IV and with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, the standard ejection fraction criterion for defining HFrEF. Half the enrolled patients had diabetes, and analysis showed no heterogeneity in the primary outcome response based on diabetes status at enrollment.

Empagliflozin joins dapagliflozin for treating HFrEF

Dapagliflozin (Farxiga) was the first agent from the SGLT2 inhibitor class to receive an FDA indication, in 2020, for treating patients with HFrEF regardless of their diabetes status, a decision based on results from the DAPA-HF trial. Results from DAPA-HF showed that treatment with dapagliflozin in patients with HFrEF for a median of 18 months led to a 26% relative reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure and a 4.9% absolute reduction, compared with placebo when added to standard treatment. DAPA-HF enrolled patients using similar criteria to EMPEROR-Reduced, and 42% of enrolled patients had diabetes with no heterogeneity in the primary outcome related to baseline diabetes status.

Subsequent to the report of results from the EMPEROR-Reduced trial nearly a year ago, heart failure experts declared that treatment with an agent from the SGLT2 inhibitor class had become a “new pillar of foundational therapy for HFrEF,” and they urged rapid initiation of an SGLT2 inhibitor (along with other appropriate medications) at the time of initial diagnosis of HFrEF.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved empagliflozin (Jardiance) as a treatment for adults with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) regardless of whether patients have diabetes on Aug. 18, making it the second agent from the sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor class to received this indication.

Empagliflozin first received FDA marketing approval in 2014 for improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes, and in 2016 the agency added a second indication of reducing cardiovascular death in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The newly granted indication for patients with HFrEF without regard to glycemic status was for reducing the risk for cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure, according to a statement from Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the two companies that together market empagliflozin.

The statement also said that the approval allowed for empagliflozin treatment in patients with HFrEF and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) as low as 20 mL/min per 1.73 m2, in contrast to its indication for improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes that limits use to patients with an eGFR of at least 30 mL per 1.73 m2.

EMPEROR-Reduced results drive approval

The FDA based its decision on results from the EMPEROR-Reduced study, first reported in August 2020, that showed treatment of patients with HFrEF with empagliflozin on top of standard therapy for a median of 16 months cut the incidence of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for worsening heart failure by 25% relative to placebo, and by an absolute 5.3%, compared with placebo-treated patients.

Patients enrolled in EMPEROR-Reduced had chronic heart failure in New York Heart Association functional class II-IV and with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, the standard ejection fraction criterion for defining HFrEF. Half the enrolled patients had diabetes, and analysis showed no heterogeneity in the primary outcome response based on diabetes status at enrollment.

Empagliflozin joins dapagliflozin for treating HFrEF

Dapagliflozin (Farxiga) was the first agent from the SGLT2 inhibitor class to receive an FDA indication, in 2020, for treating patients with HFrEF regardless of their diabetes status, a decision based on results from the DAPA-HF trial. Results from DAPA-HF showed that treatment with dapagliflozin in patients with HFrEF for a median of 18 months led to a 26% relative reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure and a 4.9% absolute reduction, compared with placebo when added to standard treatment. DAPA-HF enrolled patients using similar criteria to EMPEROR-Reduced, and 42% of enrolled patients had diabetes with no heterogeneity in the primary outcome related to baseline diabetes status.

Subsequent to the report of results from the EMPEROR-Reduced trial nearly a year ago, heart failure experts declared that treatment with an agent from the SGLT2 inhibitor class had become a “new pillar of foundational therapy for HFrEF,” and they urged rapid initiation of an SGLT2 inhibitor (along with other appropriate medications) at the time of initial diagnosis of HFrEF.

Pandemic derails small success in lowering diabetes-related amputations

Rates of minor diabetes-related lower extremity amputations (LEAs) in hospitalized patients increased between 2009 and 2017 in all racial and ethnic groups, in both rural and urban areas, and in all geographic regions across the United States, a new retrospective, observational study indicates.

In contrast, major lower extremity amputation rates held steady during the study period with a few exceptions.

There was also a decline in major-to-minor amputation ratios, especially among Native Americans – a sign that diabetes was being better managed and foot ulcers were being caught earlier, preventing the need for a major amputation above the foot or below or above the knee.

Minor LEAs include the loss of a toe, toes, or a foot.

“While I know an amputation is devastating either way, having a minor amputation is better than having a major amputation, and trends [at least to 2017] show that comprehensive foot examinations are paying off,” lead author Marvellous Akinlotan, PhD, MPH, a research associate at the Southwest Rural Health Research Center in Bryan, Texas, said in an interview.

Asked to comment, Marcia Ory, PhD, MPH, director of the Center for Population Health & Aging, Texas A&M School of Public Health, College Station, who was not involved in the study, said: “It points to some successes, but it also points to the need for continued education and preventive care to reduce all types of amputations.”

The study was published online in Diabetes Care.

Amputations increased during COVID-19

However, the study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and amputation rates appear to have significantly worsened during the past 18 months.

In a summary of recent evidence collated by the Amputee Coalition, the authors point out that not only does COVID-19 itself put patients at higher risk for limb loss because severe infection increases the risk of blood clots, but patients with diabetes appear to have been far more likely to undergo any level of amputation during the pandemic than before it began.

In a study of patients with diabetes attending a foot and ankle surgery service in Ohio, the risk of having any level of amputation was 10.8 times higher during compared with before the pandemic. And of patients undergoing any amputation, the odds for receiving a major amputation was 3.1 times higher than before the pandemic.

Telehealth and web-based options for diabetes care and education could help improve health outcomes, particularly during lockdowns.

“Having a diabetes-related amputation is life-changing – it brings disability and functional limitations to the individual – and within the health care system, it reflects the failure of secondary prevention efforts, which ideally should slow the progression of diabetic complications,” noted Dr. Akinlotan.

Race and geography affect risk of amputation

In their study, Dr. Akinlotan and colleagues used data from the National Inpatient Sample to identify trends in LEAs among patients primarily hospitalized for diabetes in the United States between 2009 and 2017.

“The primary outcome variable was documentation of either minor or major LEA during a diabetes-related admission,” they explain.

Minor LEAs increased significantly across all ethnic groups.

Although major amputation rates remained steady, “we did find that some groups remained at risk for having a major amputation,” Dr. Akinlotan noted.

White populations, people in the Midwest, and rural areas saw notable increases in major LEAs, as did “... Blacks, Hispanics, [and] those living in the South,” she said.

Patients need to be encouraged to monitor and control their blood glucose, to offset modifiable risk factors, and to seek regular medical attention to prevent an insidious diabetic complication from developing further, she said.

“It’s important for patients to know that continuing care is necessary,” Dr. Akinlotan stressed. “Diabetes is chronic and complex, but it can be managed, so that’s the good news.”

Dr. Ory agrees: “Effective management will require an all-in approach, with doctors and patients working together.

“Given the limited time in doctor-patient encounters, physicians can benefit patients by referring them to evidence-based, self-management education programs, which are proliferating around in the county,” she added.

The authors and Dr. Ory have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rates of minor diabetes-related lower extremity amputations (LEAs) in hospitalized patients increased between 2009 and 2017 in all racial and ethnic groups, in both rural and urban areas, and in all geographic regions across the United States, a new retrospective, observational study indicates.

In contrast, major lower extremity amputation rates held steady during the study period with a few exceptions.

There was also a decline in major-to-minor amputation ratios, especially among Native Americans – a sign that diabetes was being better managed and foot ulcers were being caught earlier, preventing the need for a major amputation above the foot or below or above the knee.

Minor LEAs include the loss of a toe, toes, or a foot.

“While I know an amputation is devastating either way, having a minor amputation is better than having a major amputation, and trends [at least to 2017] show that comprehensive foot examinations are paying off,” lead author Marvellous Akinlotan, PhD, MPH, a research associate at the Southwest Rural Health Research Center in Bryan, Texas, said in an interview.

Asked to comment, Marcia Ory, PhD, MPH, director of the Center for Population Health & Aging, Texas A&M School of Public Health, College Station, who was not involved in the study, said: “It points to some successes, but it also points to the need for continued education and preventive care to reduce all types of amputations.”

The study was published online in Diabetes Care.

Amputations increased during COVID-19

However, the study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and amputation rates appear to have significantly worsened during the past 18 months.

In a summary of recent evidence collated by the Amputee Coalition, the authors point out that not only does COVID-19 itself put patients at higher risk for limb loss because severe infection increases the risk of blood clots, but patients with diabetes appear to have been far more likely to undergo any level of amputation during the pandemic than before it began.

In a study of patients with diabetes attending a foot and ankle surgery service in Ohio, the risk of having any level of amputation was 10.8 times higher during compared with before the pandemic. And of patients undergoing any amputation, the odds for receiving a major amputation was 3.1 times higher than before the pandemic.

Telehealth and web-based options for diabetes care and education could help improve health outcomes, particularly during lockdowns.

“Having a diabetes-related amputation is life-changing – it brings disability and functional limitations to the individual – and within the health care system, it reflects the failure of secondary prevention efforts, which ideally should slow the progression of diabetic complications,” noted Dr. Akinlotan.

Race and geography affect risk of amputation

In their study, Dr. Akinlotan and colleagues used data from the National Inpatient Sample to identify trends in LEAs among patients primarily hospitalized for diabetes in the United States between 2009 and 2017.

“The primary outcome variable was documentation of either minor or major LEA during a diabetes-related admission,” they explain.

Minor LEAs increased significantly across all ethnic groups.

Although major amputation rates remained steady, “we did find that some groups remained at risk for having a major amputation,” Dr. Akinlotan noted.

White populations, people in the Midwest, and rural areas saw notable increases in major LEAs, as did “... Blacks, Hispanics, [and] those living in the South,” she said.

Patients need to be encouraged to monitor and control their blood glucose, to offset modifiable risk factors, and to seek regular medical attention to prevent an insidious diabetic complication from developing further, she said.

“It’s important for patients to know that continuing care is necessary,” Dr. Akinlotan stressed. “Diabetes is chronic and complex, but it can be managed, so that’s the good news.”

Dr. Ory agrees: “Effective management will require an all-in approach, with doctors and patients working together.

“Given the limited time in doctor-patient encounters, physicians can benefit patients by referring them to evidence-based, self-management education programs, which are proliferating around in the county,” she added.

The authors and Dr. Ory have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rates of minor diabetes-related lower extremity amputations (LEAs) in hospitalized patients increased between 2009 and 2017 in all racial and ethnic groups, in both rural and urban areas, and in all geographic regions across the United States, a new retrospective, observational study indicates.

In contrast, major lower extremity amputation rates held steady during the study period with a few exceptions.

There was also a decline in major-to-minor amputation ratios, especially among Native Americans – a sign that diabetes was being better managed and foot ulcers were being caught earlier, preventing the need for a major amputation above the foot or below or above the knee.

Minor LEAs include the loss of a toe, toes, or a foot.

“While I know an amputation is devastating either way, having a minor amputation is better than having a major amputation, and trends [at least to 2017] show that comprehensive foot examinations are paying off,” lead author Marvellous Akinlotan, PhD, MPH, a research associate at the Southwest Rural Health Research Center in Bryan, Texas, said in an interview.

Asked to comment, Marcia Ory, PhD, MPH, director of the Center for Population Health & Aging, Texas A&M School of Public Health, College Station, who was not involved in the study, said: “It points to some successes, but it also points to the need for continued education and preventive care to reduce all types of amputations.”

The study was published online in Diabetes Care.

Amputations increased during COVID-19

However, the study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and amputation rates appear to have significantly worsened during the past 18 months.

In a summary of recent evidence collated by the Amputee Coalition, the authors point out that not only does COVID-19 itself put patients at higher risk for limb loss because severe infection increases the risk of blood clots, but patients with diabetes appear to have been far more likely to undergo any level of amputation during the pandemic than before it began.

In a study of patients with diabetes attending a foot and ankle surgery service in Ohio, the risk of having any level of amputation was 10.8 times higher during compared with before the pandemic. And of patients undergoing any amputation, the odds for receiving a major amputation was 3.1 times higher than before the pandemic.