User login

Sotagliflozin use in T2D patients linked with posthospitalization benefits in analysis

The outcome measure –days alive and out of the hospital – may be a meaningful, patient-centered way of capturing disease burden, the researchers wrote in their paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The question was: Can we keep patients alive and out of the hospital for any reason, accounting for the duration of each hospitalization?” author Michael Szarek, PhD, a visiting professor in the division of cardiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

“For every 100 days of follow-up, patients in the sotagliflozin group were alive and out of the hospital 3% more days in relative terms or 2.9 days in absolute terms than those in the placebo group (91.8 vs. 88.9 days),” the researchers reported in their analysis of data from the SOLOIST-WHF trial.

“If you translate that to over the course of a year, that’s more than 10 days,” said Dr. Szarek, who is also a faculty member of CPC Clinical Research, an academic research organization affiliated with the University of Colorado.

Most patients in both groups survived to the end of the study without hospitalization, according to the paper.

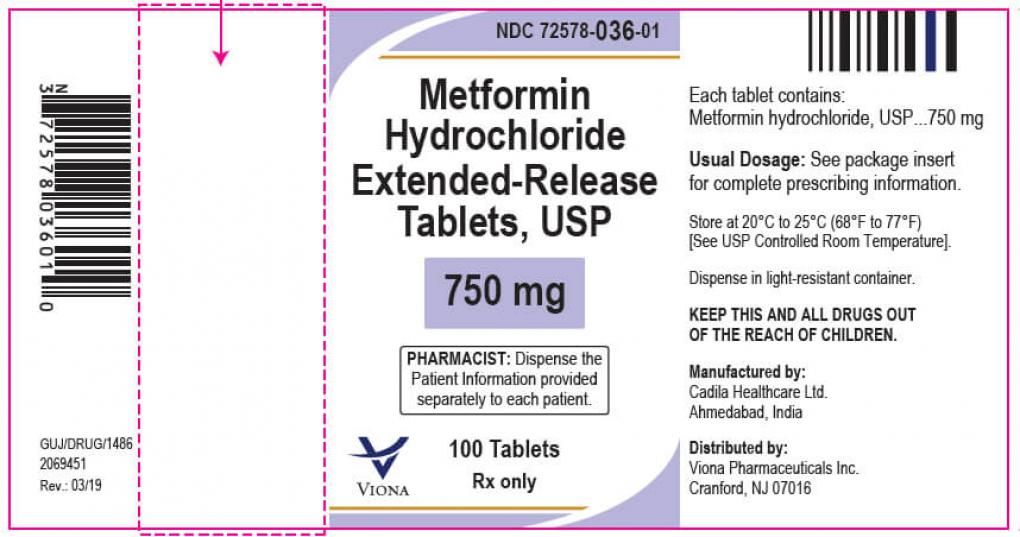

Sotagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 and SGLT2 inhibitor, is not approved in the United States. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration rejected sotagliflozin as an adjunct to insulin for the treatment of type 1 diabetes after members of an advisory committee expressed concerns about an increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis with the drug.

Methods and results

To examine whether sotagliflozin increased days alive and out of the hospital in the SOLOIST-WHF trial, Dr. Szarek and colleagues analyzed data from this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The trial’s primary results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2021. Researchers conducted SOLOIST-WHF at more than 300 sites in 32 countries. The trial included 1,222 patients with type 2 diabetes and reduced or preserved ejection fraction who were recently hospitalized for worsening heart failure.

In the new analysis the researchers looked at hospitalizations for any reason and the duration of hospital admissions after randomization. They analyzed days alive and out of the hospital using prespecified models.

Similar proportions of patients who received sotagliflozin and placebo were hospitalized at least once (38.5% vs. 41.4%) during a median follow-up of 9 months. Fewer patients who received sotagliflozin were hospitalized more than once (16.3% vs. 22.1%). In all, 64 patients in the sotagliflozin group and 76 patients in the placebo group died.

The reason for each hospitalization was unspecified, except for cases of heart failure, the authors noted. About 62% of hospitalizations during the trial were for reasons other than heart failure.

Outside expert cites similarities to initial trial

The results for days alive and out of the hospital are “not particularly surprising given the previous publication” of the trial’s primary results, but the new analysis provides a “different view of outcomes that might be clinically meaningful for patients,” commented Frank Brosius, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The SOLOIST-WHF trial indicated that doctors may be able to effectively treat patients with relatively new heart failure with sotagliflozin as long as patients are relatively stable, said Dr. Brosius, who coauthored an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine that accompanied the initial results from the SOLOIST-WHF trial. It appears that previously reported benefits with regard to heart failure outcomes “showed up in these other indicators” in the secondary analysis.

Still, the effect sizes in the new analysis were relatively small and “probably more studies will be necessary” to examine these end points, he added.

SOLOIST-WHF was funded by Sanofi at initiation and by Lexicon Pharmaceuticals at completion. Dr. Szarek disclosed grants from Lexicon and grants and personal fees from Sanofi, as well as personal fees from other companies. His coauthors included employees of Lexicon and other researchers with financial ties to Lexicon and other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Brosius disclosed personal fees from the American Diabetes Association and is a member of the Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative task force for the American Society of Nephrology that is broadly advocating the use of SGLT2 inhibitors by patients with diabetic kidney diseases. He also has participated in an advisory group for treatment of diabetic kidney disease for Gilead.

The outcome measure –days alive and out of the hospital – may be a meaningful, patient-centered way of capturing disease burden, the researchers wrote in their paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The question was: Can we keep patients alive and out of the hospital for any reason, accounting for the duration of each hospitalization?” author Michael Szarek, PhD, a visiting professor in the division of cardiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

“For every 100 days of follow-up, patients in the sotagliflozin group were alive and out of the hospital 3% more days in relative terms or 2.9 days in absolute terms than those in the placebo group (91.8 vs. 88.9 days),” the researchers reported in their analysis of data from the SOLOIST-WHF trial.

“If you translate that to over the course of a year, that’s more than 10 days,” said Dr. Szarek, who is also a faculty member of CPC Clinical Research, an academic research organization affiliated with the University of Colorado.

Most patients in both groups survived to the end of the study without hospitalization, according to the paper.

Sotagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 and SGLT2 inhibitor, is not approved in the United States. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration rejected sotagliflozin as an adjunct to insulin for the treatment of type 1 diabetes after members of an advisory committee expressed concerns about an increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis with the drug.

Methods and results

To examine whether sotagliflozin increased days alive and out of the hospital in the SOLOIST-WHF trial, Dr. Szarek and colleagues analyzed data from this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The trial’s primary results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2021. Researchers conducted SOLOIST-WHF at more than 300 sites in 32 countries. The trial included 1,222 patients with type 2 diabetes and reduced or preserved ejection fraction who were recently hospitalized for worsening heart failure.

In the new analysis the researchers looked at hospitalizations for any reason and the duration of hospital admissions after randomization. They analyzed days alive and out of the hospital using prespecified models.

Similar proportions of patients who received sotagliflozin and placebo were hospitalized at least once (38.5% vs. 41.4%) during a median follow-up of 9 months. Fewer patients who received sotagliflozin were hospitalized more than once (16.3% vs. 22.1%). In all, 64 patients in the sotagliflozin group and 76 patients in the placebo group died.

The reason for each hospitalization was unspecified, except for cases of heart failure, the authors noted. About 62% of hospitalizations during the trial were for reasons other than heart failure.

Outside expert cites similarities to initial trial

The results for days alive and out of the hospital are “not particularly surprising given the previous publication” of the trial’s primary results, but the new analysis provides a “different view of outcomes that might be clinically meaningful for patients,” commented Frank Brosius, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The SOLOIST-WHF trial indicated that doctors may be able to effectively treat patients with relatively new heart failure with sotagliflozin as long as patients are relatively stable, said Dr. Brosius, who coauthored an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine that accompanied the initial results from the SOLOIST-WHF trial. It appears that previously reported benefits with regard to heart failure outcomes “showed up in these other indicators” in the secondary analysis.

Still, the effect sizes in the new analysis were relatively small and “probably more studies will be necessary” to examine these end points, he added.

SOLOIST-WHF was funded by Sanofi at initiation and by Lexicon Pharmaceuticals at completion. Dr. Szarek disclosed grants from Lexicon and grants and personal fees from Sanofi, as well as personal fees from other companies. His coauthors included employees of Lexicon and other researchers with financial ties to Lexicon and other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Brosius disclosed personal fees from the American Diabetes Association and is a member of the Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative task force for the American Society of Nephrology that is broadly advocating the use of SGLT2 inhibitors by patients with diabetic kidney diseases. He also has participated in an advisory group for treatment of diabetic kidney disease for Gilead.

The outcome measure –days alive and out of the hospital – may be a meaningful, patient-centered way of capturing disease burden, the researchers wrote in their paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The question was: Can we keep patients alive and out of the hospital for any reason, accounting for the duration of each hospitalization?” author Michael Szarek, PhD, a visiting professor in the division of cardiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

“For every 100 days of follow-up, patients in the sotagliflozin group were alive and out of the hospital 3% more days in relative terms or 2.9 days in absolute terms than those in the placebo group (91.8 vs. 88.9 days),” the researchers reported in their analysis of data from the SOLOIST-WHF trial.

“If you translate that to over the course of a year, that’s more than 10 days,” said Dr. Szarek, who is also a faculty member of CPC Clinical Research, an academic research organization affiliated with the University of Colorado.

Most patients in both groups survived to the end of the study without hospitalization, according to the paper.

Sotagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 and SGLT2 inhibitor, is not approved in the United States. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration rejected sotagliflozin as an adjunct to insulin for the treatment of type 1 diabetes after members of an advisory committee expressed concerns about an increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis with the drug.

Methods and results

To examine whether sotagliflozin increased days alive and out of the hospital in the SOLOIST-WHF trial, Dr. Szarek and colleagues analyzed data from this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The trial’s primary results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2021. Researchers conducted SOLOIST-WHF at more than 300 sites in 32 countries. The trial included 1,222 patients with type 2 diabetes and reduced or preserved ejection fraction who were recently hospitalized for worsening heart failure.

In the new analysis the researchers looked at hospitalizations for any reason and the duration of hospital admissions after randomization. They analyzed days alive and out of the hospital using prespecified models.

Similar proportions of patients who received sotagliflozin and placebo were hospitalized at least once (38.5% vs. 41.4%) during a median follow-up of 9 months. Fewer patients who received sotagliflozin were hospitalized more than once (16.3% vs. 22.1%). In all, 64 patients in the sotagliflozin group and 76 patients in the placebo group died.

The reason for each hospitalization was unspecified, except for cases of heart failure, the authors noted. About 62% of hospitalizations during the trial were for reasons other than heart failure.

Outside expert cites similarities to initial trial

The results for days alive and out of the hospital are “not particularly surprising given the previous publication” of the trial’s primary results, but the new analysis provides a “different view of outcomes that might be clinically meaningful for patients,” commented Frank Brosius, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The SOLOIST-WHF trial indicated that doctors may be able to effectively treat patients with relatively new heart failure with sotagliflozin as long as patients are relatively stable, said Dr. Brosius, who coauthored an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine that accompanied the initial results from the SOLOIST-WHF trial. It appears that previously reported benefits with regard to heart failure outcomes “showed up in these other indicators” in the secondary analysis.

Still, the effect sizes in the new analysis were relatively small and “probably more studies will be necessary” to examine these end points, he added.

SOLOIST-WHF was funded by Sanofi at initiation and by Lexicon Pharmaceuticals at completion. Dr. Szarek disclosed grants from Lexicon and grants and personal fees from Sanofi, as well as personal fees from other companies. His coauthors included employees of Lexicon and other researchers with financial ties to Lexicon and other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Brosius disclosed personal fees from the American Diabetes Association and is a member of the Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative task force for the American Society of Nephrology that is broadly advocating the use of SGLT2 inhibitors by patients with diabetic kidney diseases. He also has participated in an advisory group for treatment of diabetic kidney disease for Gilead.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Medicare rule changes allow for broader CGM use

Beginning July 18, 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will no longer require that beneficiaries test their blood sugar four times a day in order to qualify for CGM. In addition, the term “multiple daily injections” of insulin has been changed to multiple daily “administrations” in order to allow coverage for people who use inhaled insulin.

The changes are among those lobbied for by several organizations, including the American Diabetes Association and the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists, which represents the professionals formerly known as “diabetes educators.”

The ADA tweeted on July 11 that “the removal of this criterion has been an effort long-led by the ADA, on which we have been actively engaged with CMS. People with diabetes on Medicare will now be able to more easily access this critical piece of technology, leading to better diabetes management and better health outcomes. A big win for the diabetes community!”

“After years of advocacy from the diabetes community and ADCES, Medicare has taken an important step to make [CGM] more accessible for Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes,” Kate Thomas, ADCES chief advocacy and external affairs officer, wrote in a blog post. “This updated [Local Coverage Determination] was a direct result of coordinated advocacy efforts among patient and provider groups, as well as industry partners, coalitions and other entities.”

It’s tough to test four times a day with only three strips

In a Jan. 29, 2021, letter to the Medicare Administrative Contractors, who oversee the policies for durable medical equipment, ADCES explained why the organization strongly supported removal of the four-daily fingerstick requirement, noting that “There is no evidence to suggest that requiring four or more fingerstick tests per day significantly impacts the outcomes of CGM therapy.”

Moreover, they pointed out that the requirement was particularly burdensome, considering the fact that Medicare only covers three test strips per day for insulin-using beneficiaries. “Removing this coverage requirement would allow for increased access to CGM systems and improved health outcomes for beneficiaries with diabetes by improving glycemic control. This also represents a step toward addressing the disparities that exist around diabetes technology under the Medicare program.”

As for the terminology change from “injection” to “administration,” ADCES said that, in addition to allowing CGM coverage for individuals who use rapid-acting inhaled insulin, “we also hope that updating this terminology will help to expedite coverage as future innovations in insulin delivery methods come to market.”

More changes needed, ADCES says

In that January 2021 letter, ADCES recommended several other changes, including covering CGM for anyone diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at any age and without having to meet other requirements except for twice-yearly clinician visits, and for anyone with type 2 diabetes who uses any type of insulin or who has had documented hypoglycemia regardless of therapy.

They also recommended that CGM coverage be considered for patients with chronic kidney disease, and that the required 6-month clinician visits be allowed to take place via telehealth. “ADCES believes that allowing the initiation of CGM therapy through a virtual visit will reduce barriers associated with travel and difficulty accessing a trained provider that are experienced by Medicare beneficiaries.”

In addition, ADCES requested that CMS eliminate the requirement that beneficiaries use insulin three times a day to qualify for CGM, noting that this creates a barrier for patients who can’t afford insulin at all but are at risk for hypoglycemia because they take sulfonylureas or other insulin secretagogues, or for those who use cheaper synthetic human insulins that are only taken twice a day, such as NPH.

“The existing CGM coverage criteria creates an unbalanced and disparate system that excludes from coverage beneficiaries who could greatly benefit from a CGM system, but do not qualify due to issues with insulin affordability,” ADCES wrote in the January letter.

Ms. Thomas wrote in the June 14th blog: “Our work is not done. We know there are more changes that must be made.”

Beginning July 18, 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will no longer require that beneficiaries test their blood sugar four times a day in order to qualify for CGM. In addition, the term “multiple daily injections” of insulin has been changed to multiple daily “administrations” in order to allow coverage for people who use inhaled insulin.

The changes are among those lobbied for by several organizations, including the American Diabetes Association and the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists, which represents the professionals formerly known as “diabetes educators.”

The ADA tweeted on July 11 that “the removal of this criterion has been an effort long-led by the ADA, on which we have been actively engaged with CMS. People with diabetes on Medicare will now be able to more easily access this critical piece of technology, leading to better diabetes management and better health outcomes. A big win for the diabetes community!”

“After years of advocacy from the diabetes community and ADCES, Medicare has taken an important step to make [CGM] more accessible for Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes,” Kate Thomas, ADCES chief advocacy and external affairs officer, wrote in a blog post. “This updated [Local Coverage Determination] was a direct result of coordinated advocacy efforts among patient and provider groups, as well as industry partners, coalitions and other entities.”

It’s tough to test four times a day with only three strips

In a Jan. 29, 2021, letter to the Medicare Administrative Contractors, who oversee the policies for durable medical equipment, ADCES explained why the organization strongly supported removal of the four-daily fingerstick requirement, noting that “There is no evidence to suggest that requiring four or more fingerstick tests per day significantly impacts the outcomes of CGM therapy.”

Moreover, they pointed out that the requirement was particularly burdensome, considering the fact that Medicare only covers three test strips per day for insulin-using beneficiaries. “Removing this coverage requirement would allow for increased access to CGM systems and improved health outcomes for beneficiaries with diabetes by improving glycemic control. This also represents a step toward addressing the disparities that exist around diabetes technology under the Medicare program.”

As for the terminology change from “injection” to “administration,” ADCES said that, in addition to allowing CGM coverage for individuals who use rapid-acting inhaled insulin, “we also hope that updating this terminology will help to expedite coverage as future innovations in insulin delivery methods come to market.”

More changes needed, ADCES says

In that January 2021 letter, ADCES recommended several other changes, including covering CGM for anyone diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at any age and without having to meet other requirements except for twice-yearly clinician visits, and for anyone with type 2 diabetes who uses any type of insulin or who has had documented hypoglycemia regardless of therapy.

They also recommended that CGM coverage be considered for patients with chronic kidney disease, and that the required 6-month clinician visits be allowed to take place via telehealth. “ADCES believes that allowing the initiation of CGM therapy through a virtual visit will reduce barriers associated with travel and difficulty accessing a trained provider that are experienced by Medicare beneficiaries.”

In addition, ADCES requested that CMS eliminate the requirement that beneficiaries use insulin three times a day to qualify for CGM, noting that this creates a barrier for patients who can’t afford insulin at all but are at risk for hypoglycemia because they take sulfonylureas or other insulin secretagogues, or for those who use cheaper synthetic human insulins that are only taken twice a day, such as NPH.

“The existing CGM coverage criteria creates an unbalanced and disparate system that excludes from coverage beneficiaries who could greatly benefit from a CGM system, but do not qualify due to issues with insulin affordability,” ADCES wrote in the January letter.

Ms. Thomas wrote in the June 14th blog: “Our work is not done. We know there are more changes that must be made.”

Beginning July 18, 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will no longer require that beneficiaries test their blood sugar four times a day in order to qualify for CGM. In addition, the term “multiple daily injections” of insulin has been changed to multiple daily “administrations” in order to allow coverage for people who use inhaled insulin.

The changes are among those lobbied for by several organizations, including the American Diabetes Association and the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists, which represents the professionals formerly known as “diabetes educators.”

The ADA tweeted on July 11 that “the removal of this criterion has been an effort long-led by the ADA, on which we have been actively engaged with CMS. People with diabetes on Medicare will now be able to more easily access this critical piece of technology, leading to better diabetes management and better health outcomes. A big win for the diabetes community!”

“After years of advocacy from the diabetes community and ADCES, Medicare has taken an important step to make [CGM] more accessible for Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes,” Kate Thomas, ADCES chief advocacy and external affairs officer, wrote in a blog post. “This updated [Local Coverage Determination] was a direct result of coordinated advocacy efforts among patient and provider groups, as well as industry partners, coalitions and other entities.”

It’s tough to test four times a day with only three strips

In a Jan. 29, 2021, letter to the Medicare Administrative Contractors, who oversee the policies for durable medical equipment, ADCES explained why the organization strongly supported removal of the four-daily fingerstick requirement, noting that “There is no evidence to suggest that requiring four or more fingerstick tests per day significantly impacts the outcomes of CGM therapy.”

Moreover, they pointed out that the requirement was particularly burdensome, considering the fact that Medicare only covers three test strips per day for insulin-using beneficiaries. “Removing this coverage requirement would allow for increased access to CGM systems and improved health outcomes for beneficiaries with diabetes by improving glycemic control. This also represents a step toward addressing the disparities that exist around diabetes technology under the Medicare program.”

As for the terminology change from “injection” to “administration,” ADCES said that, in addition to allowing CGM coverage for individuals who use rapid-acting inhaled insulin, “we also hope that updating this terminology will help to expedite coverage as future innovations in insulin delivery methods come to market.”

More changes needed, ADCES says

In that January 2021 letter, ADCES recommended several other changes, including covering CGM for anyone diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at any age and without having to meet other requirements except for twice-yearly clinician visits, and for anyone with type 2 diabetes who uses any type of insulin or who has had documented hypoglycemia regardless of therapy.

They also recommended that CGM coverage be considered for patients with chronic kidney disease, and that the required 6-month clinician visits be allowed to take place via telehealth. “ADCES believes that allowing the initiation of CGM therapy through a virtual visit will reduce barriers associated with travel and difficulty accessing a trained provider that are experienced by Medicare beneficiaries.”

In addition, ADCES requested that CMS eliminate the requirement that beneficiaries use insulin three times a day to qualify for CGM, noting that this creates a barrier for patients who can’t afford insulin at all but are at risk for hypoglycemia because they take sulfonylureas or other insulin secretagogues, or for those who use cheaper synthetic human insulins that are only taken twice a day, such as NPH.

“The existing CGM coverage criteria creates an unbalanced and disparate system that excludes from coverage beneficiaries who could greatly benefit from a CGM system, but do not qualify due to issues with insulin affordability,” ADCES wrote in the January letter.

Ms. Thomas wrote in the June 14th blog: “Our work is not done. We know there are more changes that must be made.”

Bariatric surgery cuts insulin needs in type 1 diabetes with severe obesity

While bariatric surgery does nothing to directly improve the disease of patients with type 1 diabetes, it can work indirectly by moderating severe obesity and improving insulin sensitivity to cut the total insulin needs of patients with type 1 diabetes and obesity, based on a single-center, retrospective chart review of 38 U.S. patients.

Two years following their bariatric surgery, these 38 patients with confirmed type 1 diabetes and an average body mass index of 43 kg/m2 before surgery saw their average daily insulin requirement nearly halved, dropping from 118 units/day to 60 units/day, a significant decrease, Brian J. Dessify, DO, said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Another measure of this effect showed that the percentage of patients who required more than one drug for treating their hyperglycemia fell from 66% before surgery to 52% 2 years after surgery, a change that was not statistically significant, said Dr. Dessify, a bariatric surgeon at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa.

Appropriate for patients with ‘double diabetes’

These results “provide good evidence for [using] bariatric surgery” in people with both obesity and type 1 diabetes,” he concluded. This includes people with what Dr. Dessify called “double diabetes,” meaning that they do not make endogenous insulin, and are also resistant to the effects of exogenous insulin and hence have features of both type 2 and type 1 diabetes.

“This is a really important study,” commented Ali Aminian, MD, director of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic. “For patients with type 1 diabetes, the primary goal of bariatric surgery is weight loss and improvement of obesity-related comorbidities. Patients with type 2 diabetes can be a candidate for bariatric surgery regardless of their weight,” Dr. Aminian said as designated discussant for the report.

“The goal of bariatric surgery in patients with type 1 diabetes is to promote sensitivity to the exogenous insulin they receive,” agreed Julie Kim, MD, a bariatric surgeon at Mount Auburn Hospital in Waltham, Mass., and a second discussant for the report. Patients with double diabetes “are probably a subclass of patients [with type 1 diabetes] who might benefit even more from bariatric surgery.”

Using gastric sleeves to avoid diabetic ketoacidosis

Dr. Aminian also noted that “at the Cleveland Clinic we consider a sleeve gastrectomy the procedure of choice” for patients with type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes with insulin insufficiency “unless the patient has an absolute contraindication” because of the increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis in these patients “undergoing any surgery, including bariatric surgery.” Patients with insulin insufficiency “require intensive diabetes and insulin management preoperatively to reduce their risk for developing diabetic ketoacidosis,” and using a sleeve rather than bypass generally results in “more reliable absorption of carbohydrates and nutrients” while also reducing the risk for hypoglycemia, Dr. Aminian said.

In the series reported by Dr. Dessify, 33 patients underwent gastric bypass and 5 had sleeve gastrectomy. The decision to use bypass usually stemmed from its “marginal” improvement in weight loss, compared with a sleeve procedure, and an overall preference at Geisinger for bypass procedures. Dr. Dessify added that he had not yet run a comprehensive assessment of diabetic ketoacidosis complications among patients in his reported series.

Those 38 patients underwent their bariatric procedure during 2002-2019, constituting fewer than 1% of the 4,549 total bariatric surgeries done at Geisinger during that period. The 38 patients with type 1 diabetes averaged 41 years of age, 33 (87%) were women, and 37 (97%) were White. Dr. Dessify and associates undertook this review “to help provide supporting evidence for using bariatric surgery in people with obesity and type 1 diabetes,” he noted.

Dr. Dessify, Dr. Aminian, and Dr. Kim had no disclosures.

While bariatric surgery does nothing to directly improve the disease of patients with type 1 diabetes, it can work indirectly by moderating severe obesity and improving insulin sensitivity to cut the total insulin needs of patients with type 1 diabetes and obesity, based on a single-center, retrospective chart review of 38 U.S. patients.

Two years following their bariatric surgery, these 38 patients with confirmed type 1 diabetes and an average body mass index of 43 kg/m2 before surgery saw their average daily insulin requirement nearly halved, dropping from 118 units/day to 60 units/day, a significant decrease, Brian J. Dessify, DO, said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Another measure of this effect showed that the percentage of patients who required more than one drug for treating their hyperglycemia fell from 66% before surgery to 52% 2 years after surgery, a change that was not statistically significant, said Dr. Dessify, a bariatric surgeon at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa.

Appropriate for patients with ‘double diabetes’

These results “provide good evidence for [using] bariatric surgery” in people with both obesity and type 1 diabetes,” he concluded. This includes people with what Dr. Dessify called “double diabetes,” meaning that they do not make endogenous insulin, and are also resistant to the effects of exogenous insulin and hence have features of both type 2 and type 1 diabetes.

“This is a really important study,” commented Ali Aminian, MD, director of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic. “For patients with type 1 diabetes, the primary goal of bariatric surgery is weight loss and improvement of obesity-related comorbidities. Patients with type 2 diabetes can be a candidate for bariatric surgery regardless of their weight,” Dr. Aminian said as designated discussant for the report.

“The goal of bariatric surgery in patients with type 1 diabetes is to promote sensitivity to the exogenous insulin they receive,” agreed Julie Kim, MD, a bariatric surgeon at Mount Auburn Hospital in Waltham, Mass., and a second discussant for the report. Patients with double diabetes “are probably a subclass of patients [with type 1 diabetes] who might benefit even more from bariatric surgery.”

Using gastric sleeves to avoid diabetic ketoacidosis

Dr. Aminian also noted that “at the Cleveland Clinic we consider a sleeve gastrectomy the procedure of choice” for patients with type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes with insulin insufficiency “unless the patient has an absolute contraindication” because of the increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis in these patients “undergoing any surgery, including bariatric surgery.” Patients with insulin insufficiency “require intensive diabetes and insulin management preoperatively to reduce their risk for developing diabetic ketoacidosis,” and using a sleeve rather than bypass generally results in “more reliable absorption of carbohydrates and nutrients” while also reducing the risk for hypoglycemia, Dr. Aminian said.

In the series reported by Dr. Dessify, 33 patients underwent gastric bypass and 5 had sleeve gastrectomy. The decision to use bypass usually stemmed from its “marginal” improvement in weight loss, compared with a sleeve procedure, and an overall preference at Geisinger for bypass procedures. Dr. Dessify added that he had not yet run a comprehensive assessment of diabetic ketoacidosis complications among patients in his reported series.

Those 38 patients underwent their bariatric procedure during 2002-2019, constituting fewer than 1% of the 4,549 total bariatric surgeries done at Geisinger during that period. The 38 patients with type 1 diabetes averaged 41 years of age, 33 (87%) were women, and 37 (97%) were White. Dr. Dessify and associates undertook this review “to help provide supporting evidence for using bariatric surgery in people with obesity and type 1 diabetes,” he noted.

Dr. Dessify, Dr. Aminian, and Dr. Kim had no disclosures.

While bariatric surgery does nothing to directly improve the disease of patients with type 1 diabetes, it can work indirectly by moderating severe obesity and improving insulin sensitivity to cut the total insulin needs of patients with type 1 diabetes and obesity, based on a single-center, retrospective chart review of 38 U.S. patients.

Two years following their bariatric surgery, these 38 patients with confirmed type 1 diabetes and an average body mass index of 43 kg/m2 before surgery saw their average daily insulin requirement nearly halved, dropping from 118 units/day to 60 units/day, a significant decrease, Brian J. Dessify, DO, said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Another measure of this effect showed that the percentage of patients who required more than one drug for treating their hyperglycemia fell from 66% before surgery to 52% 2 years after surgery, a change that was not statistically significant, said Dr. Dessify, a bariatric surgeon at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa.

Appropriate for patients with ‘double diabetes’

These results “provide good evidence for [using] bariatric surgery” in people with both obesity and type 1 diabetes,” he concluded. This includes people with what Dr. Dessify called “double diabetes,” meaning that they do not make endogenous insulin, and are also resistant to the effects of exogenous insulin and hence have features of both type 2 and type 1 diabetes.

“This is a really important study,” commented Ali Aminian, MD, director of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic. “For patients with type 1 diabetes, the primary goal of bariatric surgery is weight loss and improvement of obesity-related comorbidities. Patients with type 2 diabetes can be a candidate for bariatric surgery regardless of their weight,” Dr. Aminian said as designated discussant for the report.

“The goal of bariatric surgery in patients with type 1 diabetes is to promote sensitivity to the exogenous insulin they receive,” agreed Julie Kim, MD, a bariatric surgeon at Mount Auburn Hospital in Waltham, Mass., and a second discussant for the report. Patients with double diabetes “are probably a subclass of patients [with type 1 diabetes] who might benefit even more from bariatric surgery.”

Using gastric sleeves to avoid diabetic ketoacidosis

Dr. Aminian also noted that “at the Cleveland Clinic we consider a sleeve gastrectomy the procedure of choice” for patients with type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes with insulin insufficiency “unless the patient has an absolute contraindication” because of the increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis in these patients “undergoing any surgery, including bariatric surgery.” Patients with insulin insufficiency “require intensive diabetes and insulin management preoperatively to reduce their risk for developing diabetic ketoacidosis,” and using a sleeve rather than bypass generally results in “more reliable absorption of carbohydrates and nutrients” while also reducing the risk for hypoglycemia, Dr. Aminian said.

In the series reported by Dr. Dessify, 33 patients underwent gastric bypass and 5 had sleeve gastrectomy. The decision to use bypass usually stemmed from its “marginal” improvement in weight loss, compared with a sleeve procedure, and an overall preference at Geisinger for bypass procedures. Dr. Dessify added that he had not yet run a comprehensive assessment of diabetic ketoacidosis complications among patients in his reported series.

Those 38 patients underwent their bariatric procedure during 2002-2019, constituting fewer than 1% of the 4,549 total bariatric surgeries done at Geisinger during that period. The 38 patients with type 1 diabetes averaged 41 years of age, 33 (87%) were women, and 37 (97%) were White. Dr. Dessify and associates undertook this review “to help provide supporting evidence for using bariatric surgery in people with obesity and type 1 diabetes,” he noted.

Dr. Dessify, Dr. Aminian, and Dr. Kim had no disclosures.

FROM ASMBS 2021

Getting hypertension under control in the youngest of patients

Hypertension and elevated blood pressure (BP) in children and adolescents correlate to hypertension in adults, insofar as complications and medical therapy increase with age.1,2 Untreated, hypertension in children and adolescents can result in multiple harmful physiologic changes, including left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, diastolic dysfunction, arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction, and neurocognitive deficits.3-5

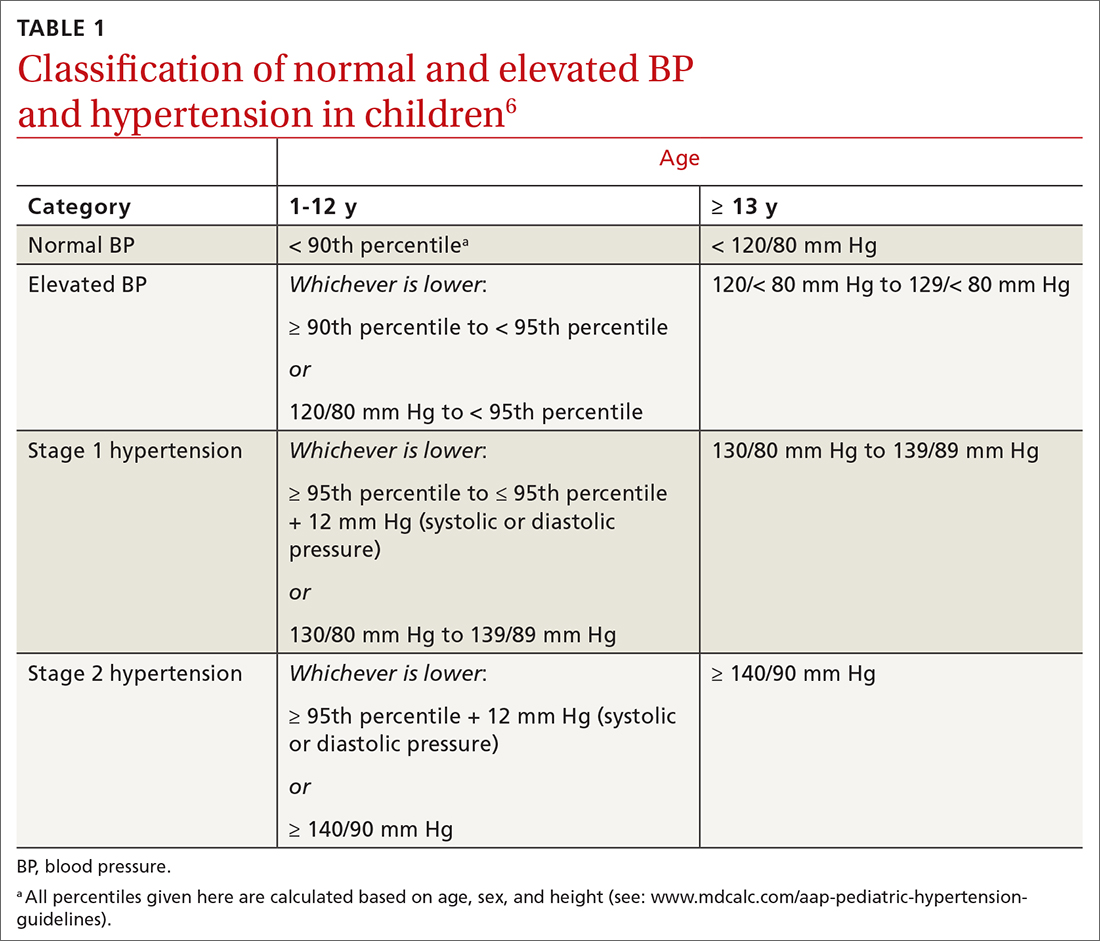

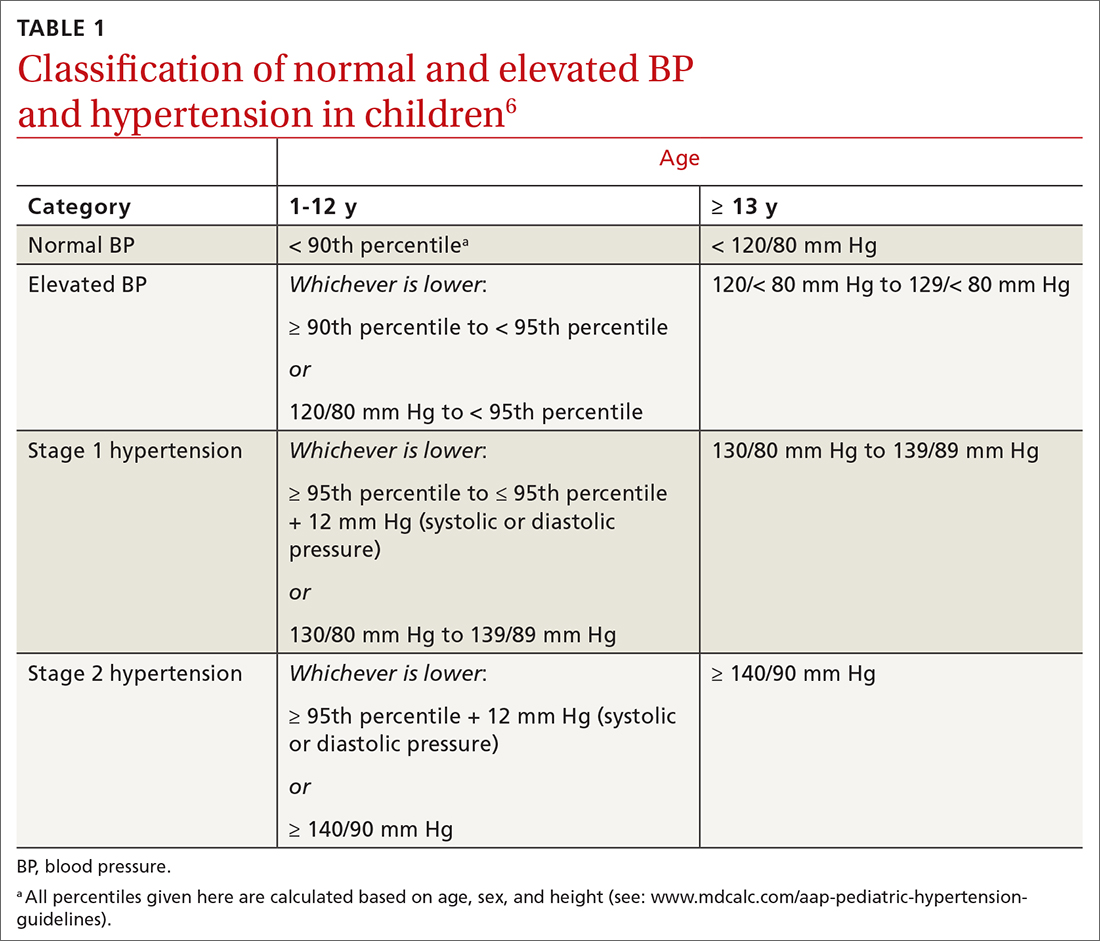

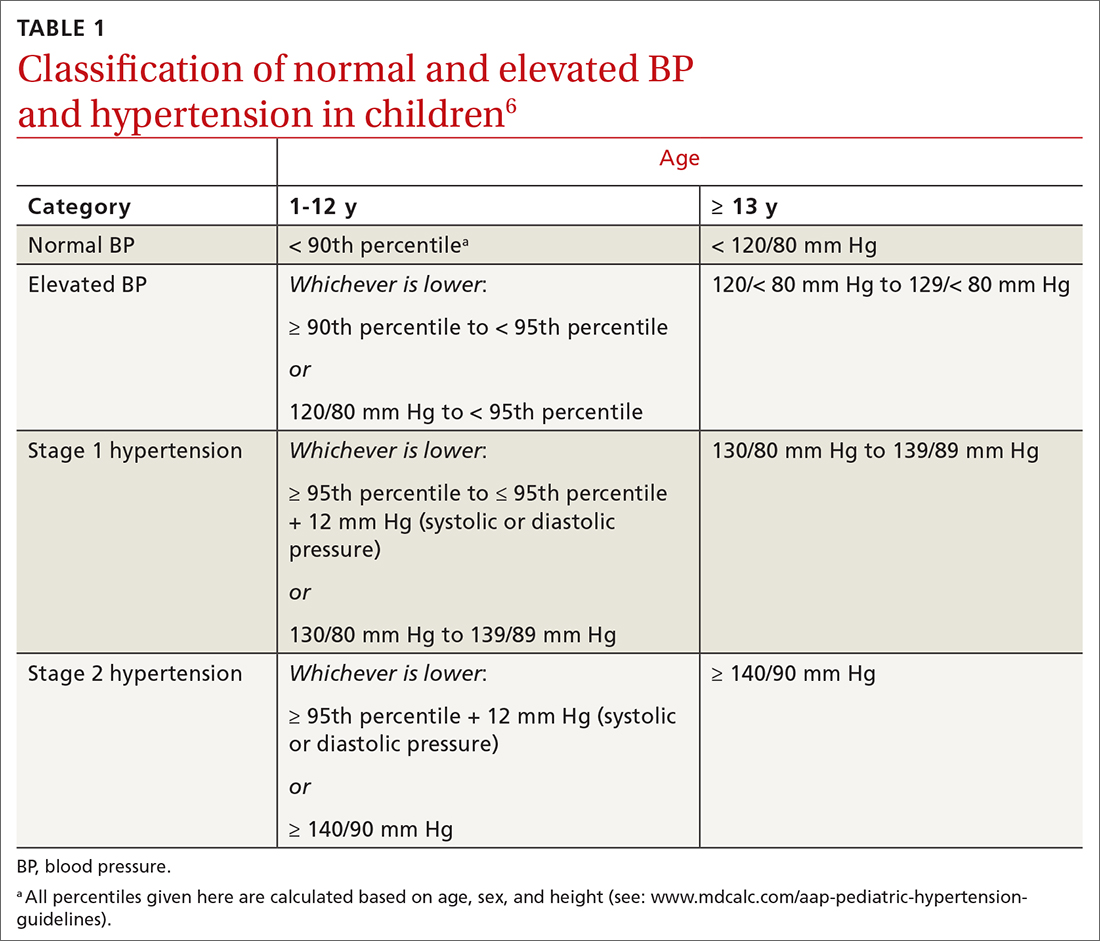

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of elevated BP and hypertension in children and adolescentsa (TABLE 16). Applying the definition of elevated BP set out in these guidelines yielded a 13% prevalence of hypertension in a cohort of subjects 10 to 18 years of age with comorbid obesity and diabetes mellitus (DM). AAP guideline definitions also improved the sensitivity for identifying hypertensive end-organ damage.7

As the prevalence of hypertension increases, screening for and accurate diagnosis of this condition in children are becoming more important. Recognition and management remain a vital part of primary care. In this article, we review the updated guidance on diagnosis and treatment, including lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy.

First step: Identifying hypertension

Risk factors

Risk factors for pediatric hypertension are similar to those in adults. These include obesity (body mass index ≥ 95th percentile for age), types 1 and 2 DM, elevated sodium intake, sleep-disordered breathing, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Some risk factors, such as premature birth and coarctation of the aorta, are specific to the pediatric population.8-14 Pediatric obesity strongly correlates with both pediatric and adult hypertension, and accelerated weight gain might increase the risk of elevated BP in adulthood.15,16

Intervening early to mitigate or eliminate some of these modifiable risk factors can prevent or treat hypertension.17 Alternatively, having been breastfed as an infant has been reliably shown to reduce the risk of elevated BP in children.13

Recommendations for screening and measuring BP

The optimal age to start measuring BP is not clearly defined. AAP recommends measurement:

- annually in all children ≥ 3 years of age

- at every encounter in patients who have a specific comorbid condition, including obesity, DM, renal disease, and aortic-arch abnormalities (obstruction and coarctation) and in those who are taking medication known to increase BP.6

Protocol. Measure BP in the right arm for consistency and comparison with reference values. The width of the cuff bladder should be at least 40%, and the length, 80% to 100%, of arm circumference. Position the cuff bladder midway between the olecranon and acromion. Obtain the measurement in a quiet and comfortable environment after the patient has rested for 3 to 5 minutes. The patient should be seated, preferably with feet on the floor; elbows should be supported at the level of the heart.

Continue to: When an initial reading...

When an initial reading is elevated, whether by oscillometric or auscultatory measurement, 2 more auscultatory BP measurements should be taken during the same visit; these measurements are averaged to determine the BP category.18

TABLE 16 defines BP categories based on age, sex, and height. We recommend using the free resource MD Calc (www.mdcalc.com/aap-pediatric-hypertension-guidelines) to assist in calculating the BP category.

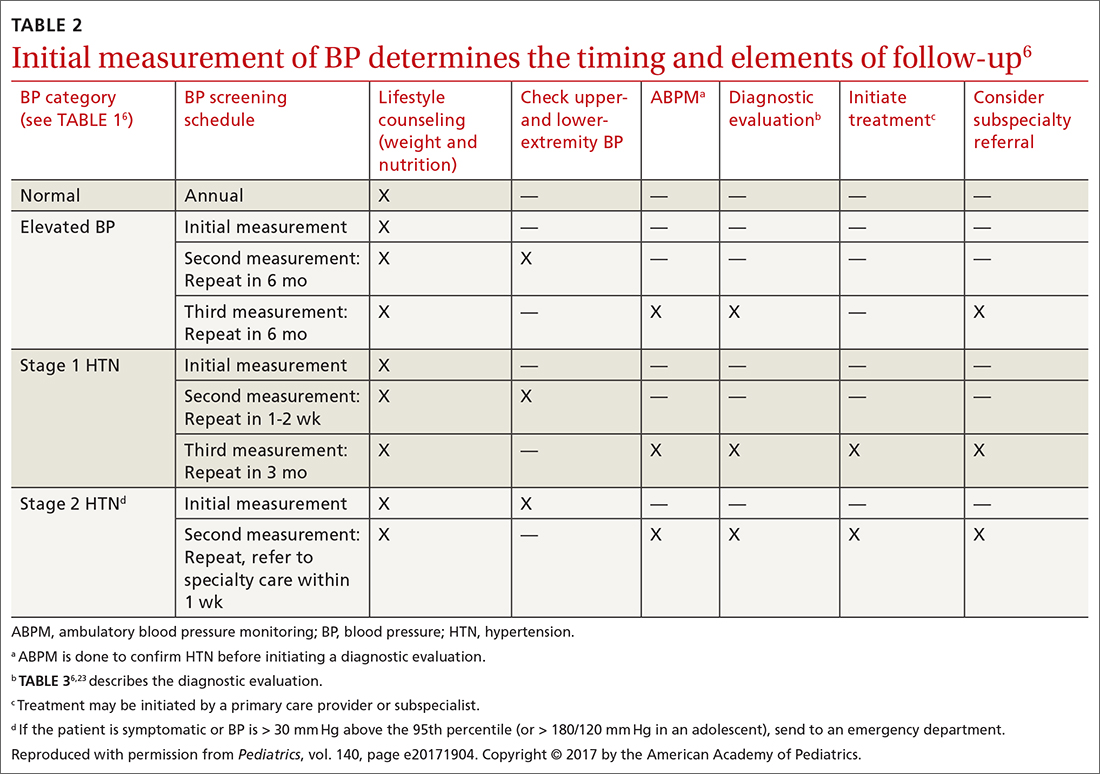

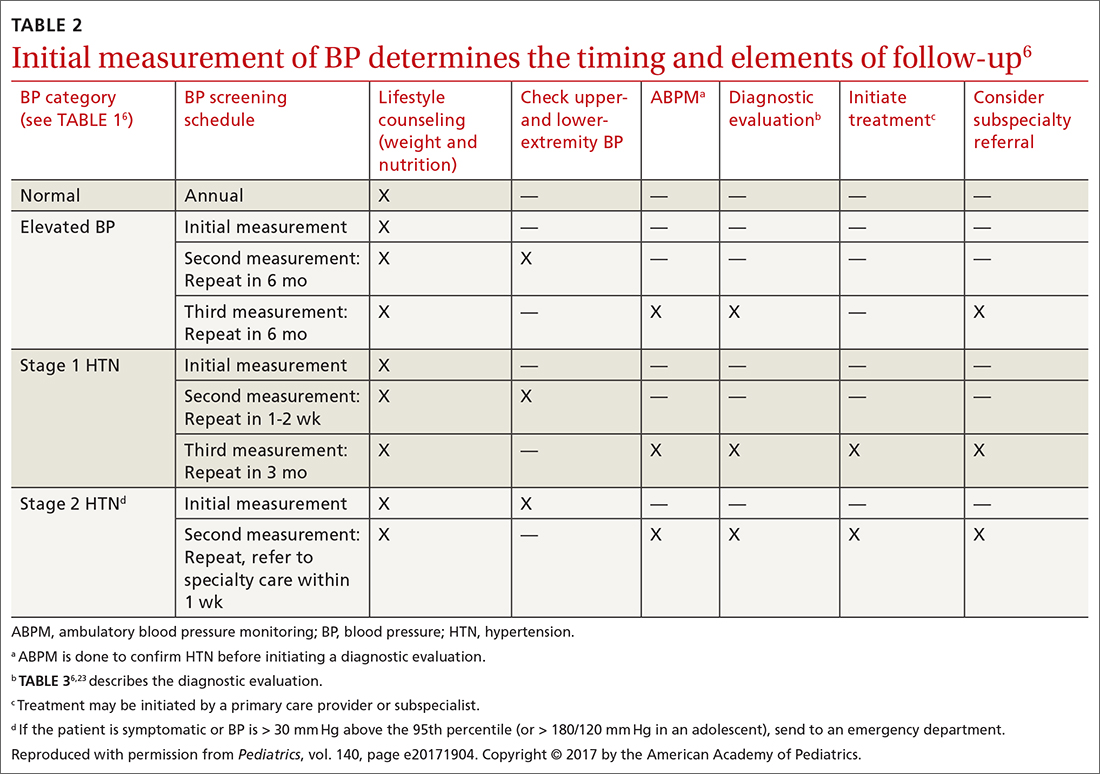

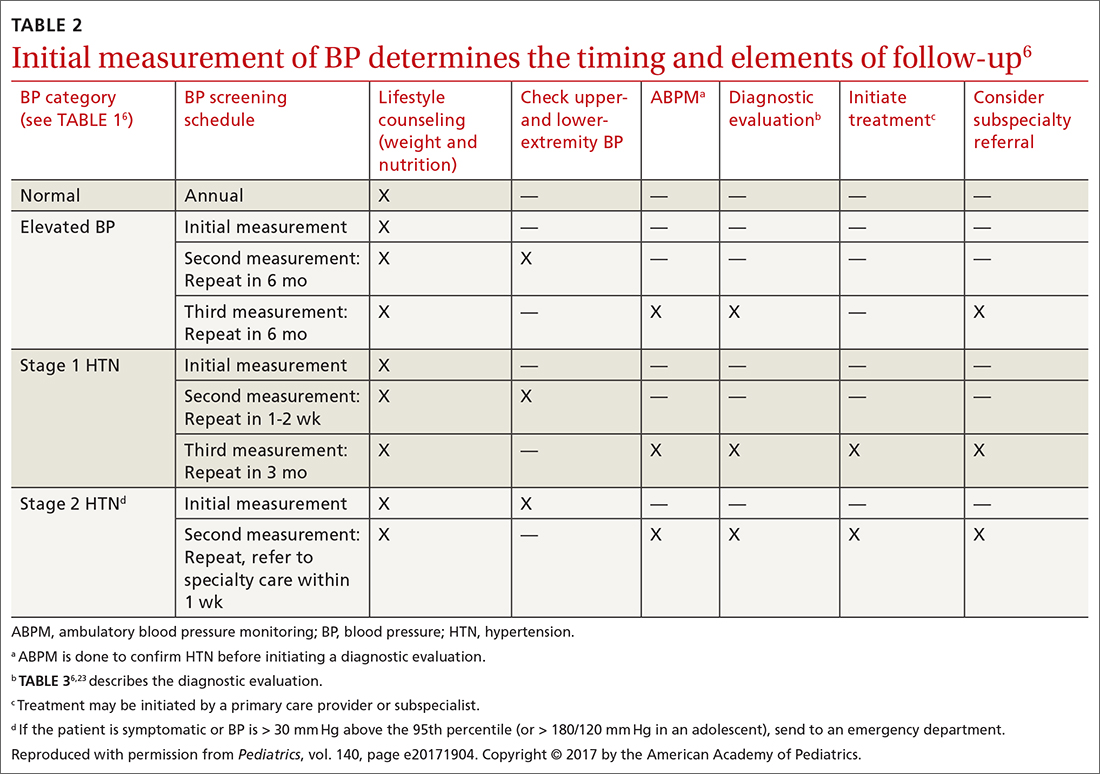

TABLE 26 describes the timing of follow-up based on the initial BP reading and diagnosis.

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is a validated device that measures BP every 20 to 30 minutes throughout the day and night. ABPM should be performed initially in all patients with persistently elevated BP and routinely in children and adolescents with a high-risk comorbidity (TABLE 26). Note: Insurance coverage of ABPM is limited.

ABPM is also used to diagnose so-called white-coat hypertension, defined as BP ≥ 95th percentile for age, sex, and height in the clinic setting but < 95th percentile during ABPM. This phenomenon can be challenging to diagnose.

Continue to: Home monitoring

Home monitoring. Do not use home BP monitoring to establish a diagnosis of hypertension, although one of these devices can be used as an adjunct to office and ambulatory BP monitoring after the diagnosis has been made.6

Evaluating hypertension in children and adolescents

Once a diagnosis of hypertension has been made, undertake a thorough history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing to evaluate for possible causes, comorbidities, and any evidence of end-organ damage.

Comprehensive history. Pertinent aspects include perinatal, nutritional, physical activity, psychosocial, family, medication—and of course, medical—histories.6

Maternal elevated BP or hypertension is related to an offspring’s elevated BP in childhood and adolescence.19 Other pertinent aspects of the perinatal history include complications of pregnancy, gestational age, birth weight, and neonatal complications.6

Nutritional and physical activity histories can highlight contributing factors in the development of hypertension and can be a guide to recommending lifestyle modifications.6 Sodium intake, which influences BP, should be part of the nutritional history.20

Continue to: Important aspects...

Important aspects of the psychosocial history include feelings of depression or anxiety, bullying, and body perception. Children older than 10 years should be asked about smoking, alcohol, and other substance use.

The family history should include notation of first- and second-degree relatives with hypertension.6

Inquire about medications that can raise BP, including oral contraceptives, which are commonly prescribed in this population.21,22

The physical exam should include measured height and weight, with calculation of the body mass index percentile for age; of note, obesity is strongly associated with hypertension, and poor growth might signal underlying chronic disease. Once elevated BP has been confirmed, the exam should include measurement of BP in both arms and in a leg (TABLE 26). BP that is lower in the leg than in the arms (in any given patient, BP readings in the legs are usually higher than in the arms), or weak or absent femoral pulses, suggest coarctation of the aorta.6

Focus the balance of the physical exam on physical findings that suggest secondary causes of hypertension or evidence of end-organ damage.

Continue to: Testing

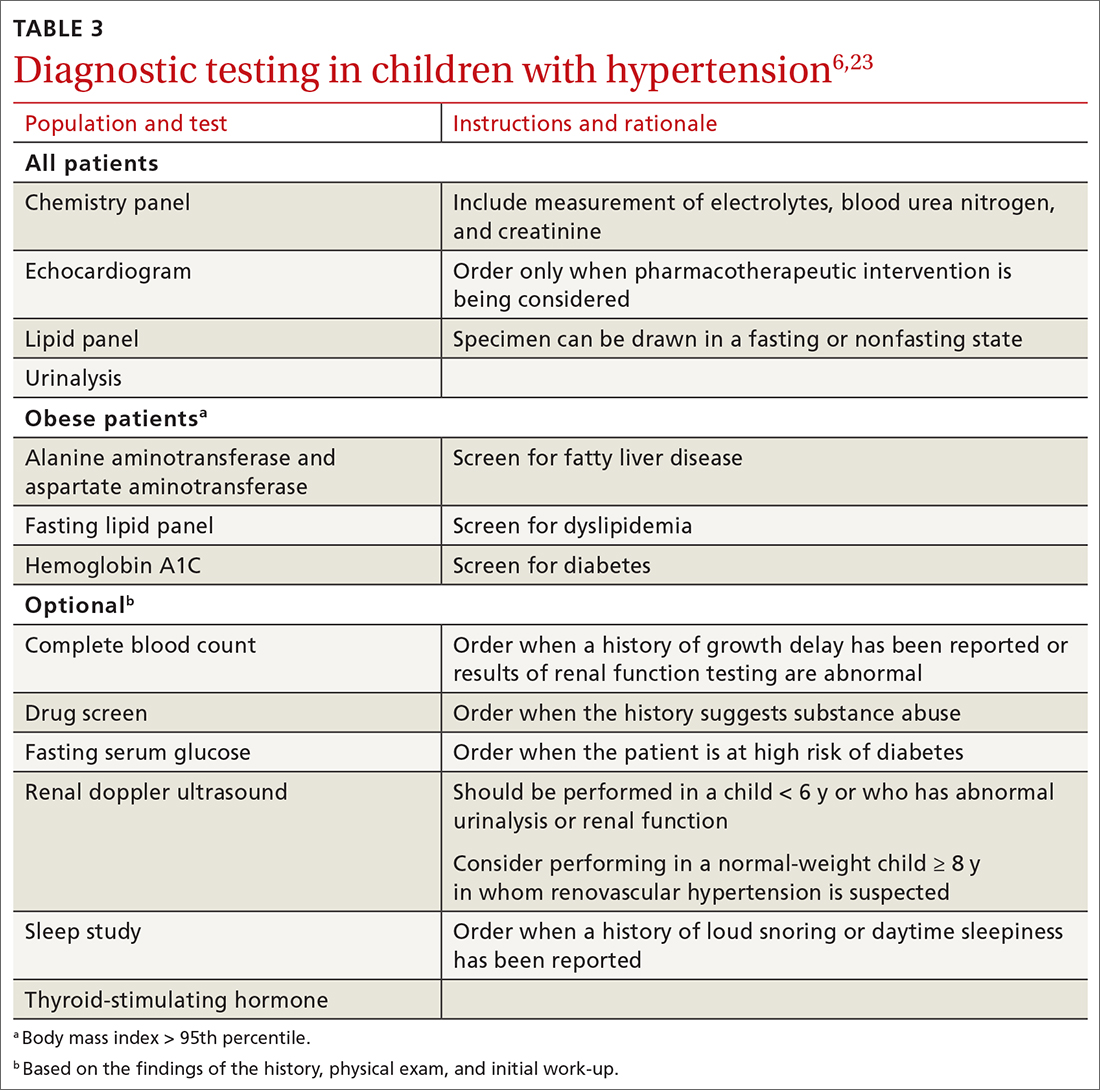

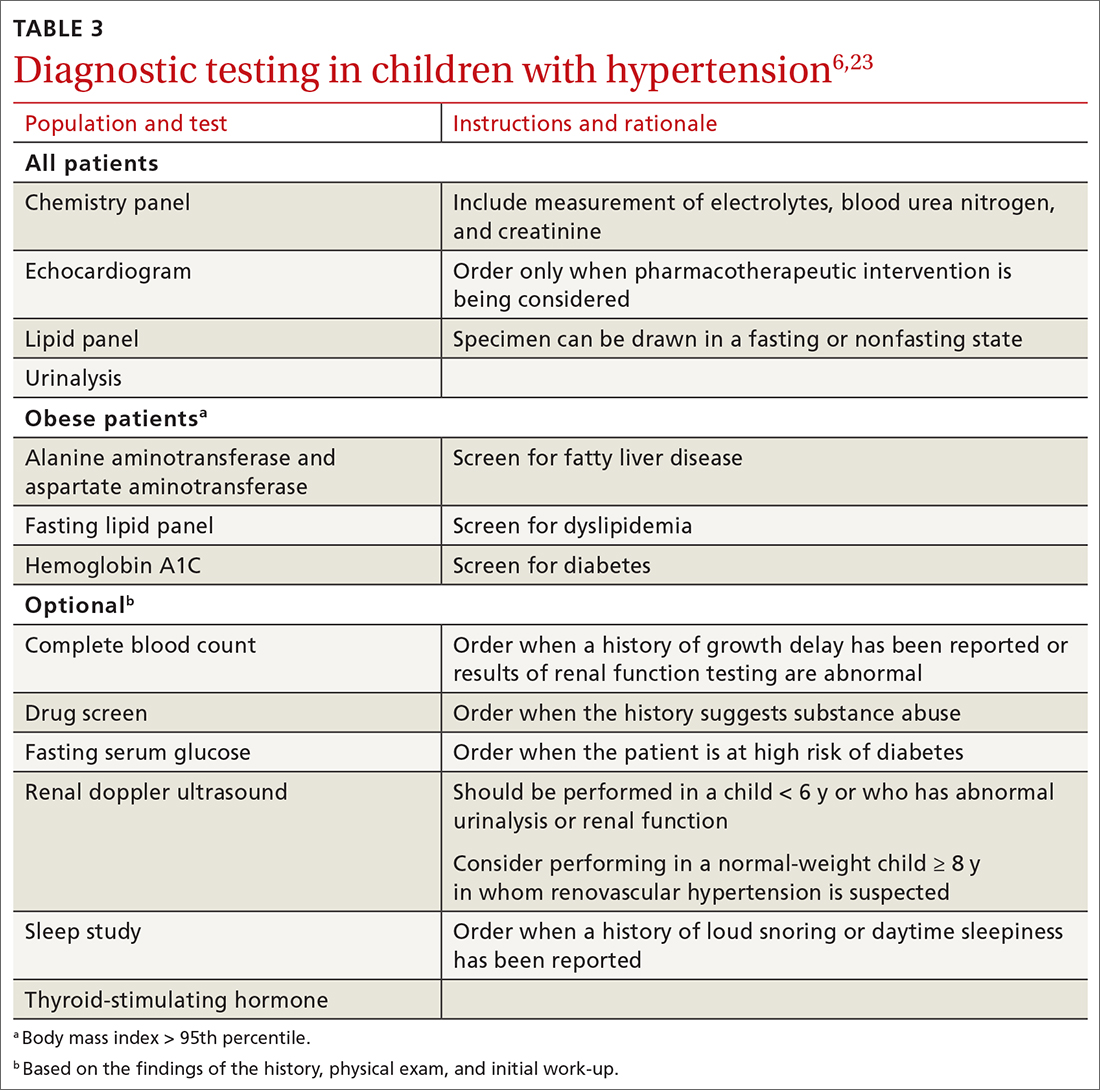

Testing. TABLE 36,23 summarizes the diagnostic testing recommended for all children and for specific populations; TABLE 26 indicates when to obtain diagnostic testing.

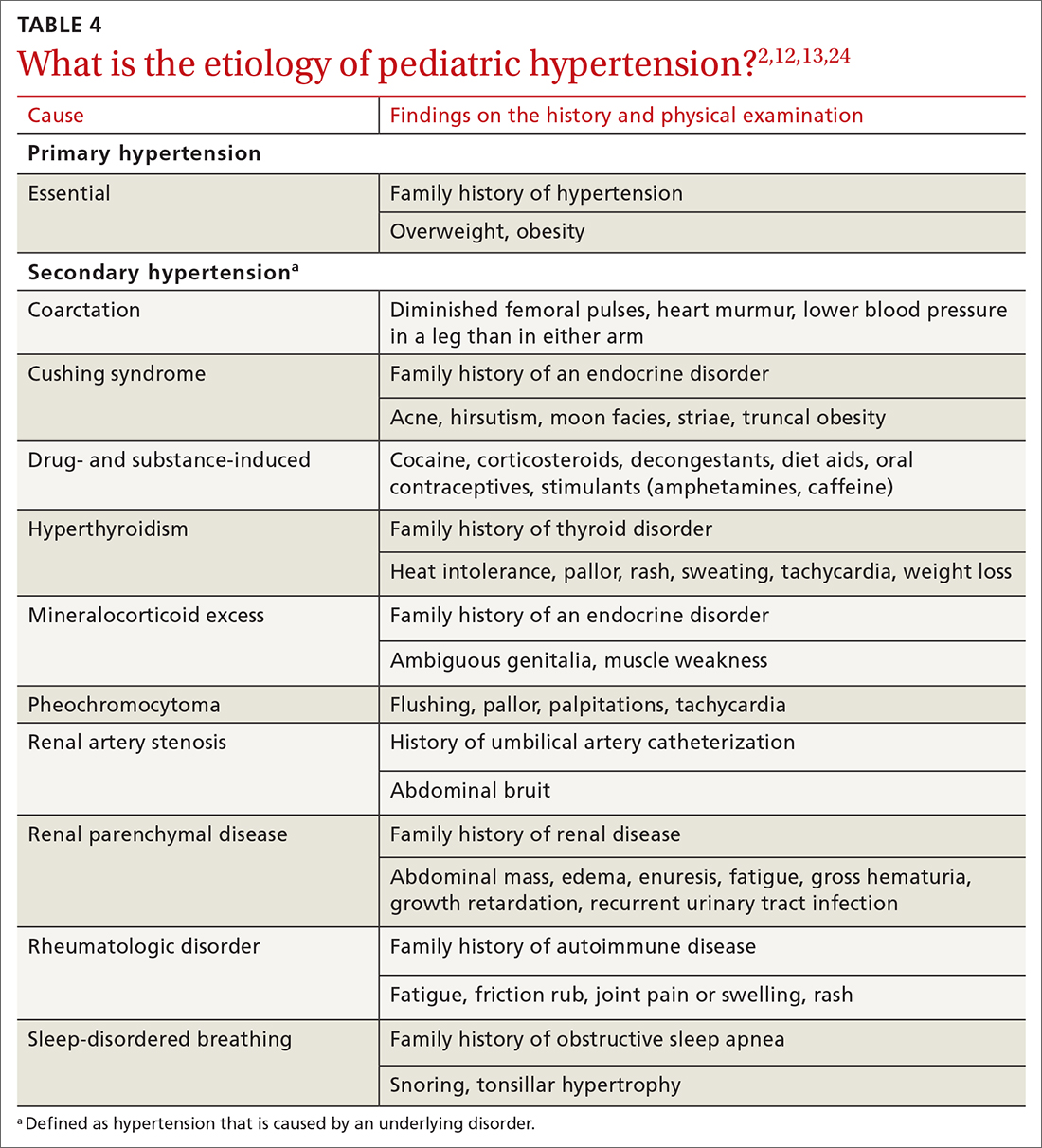

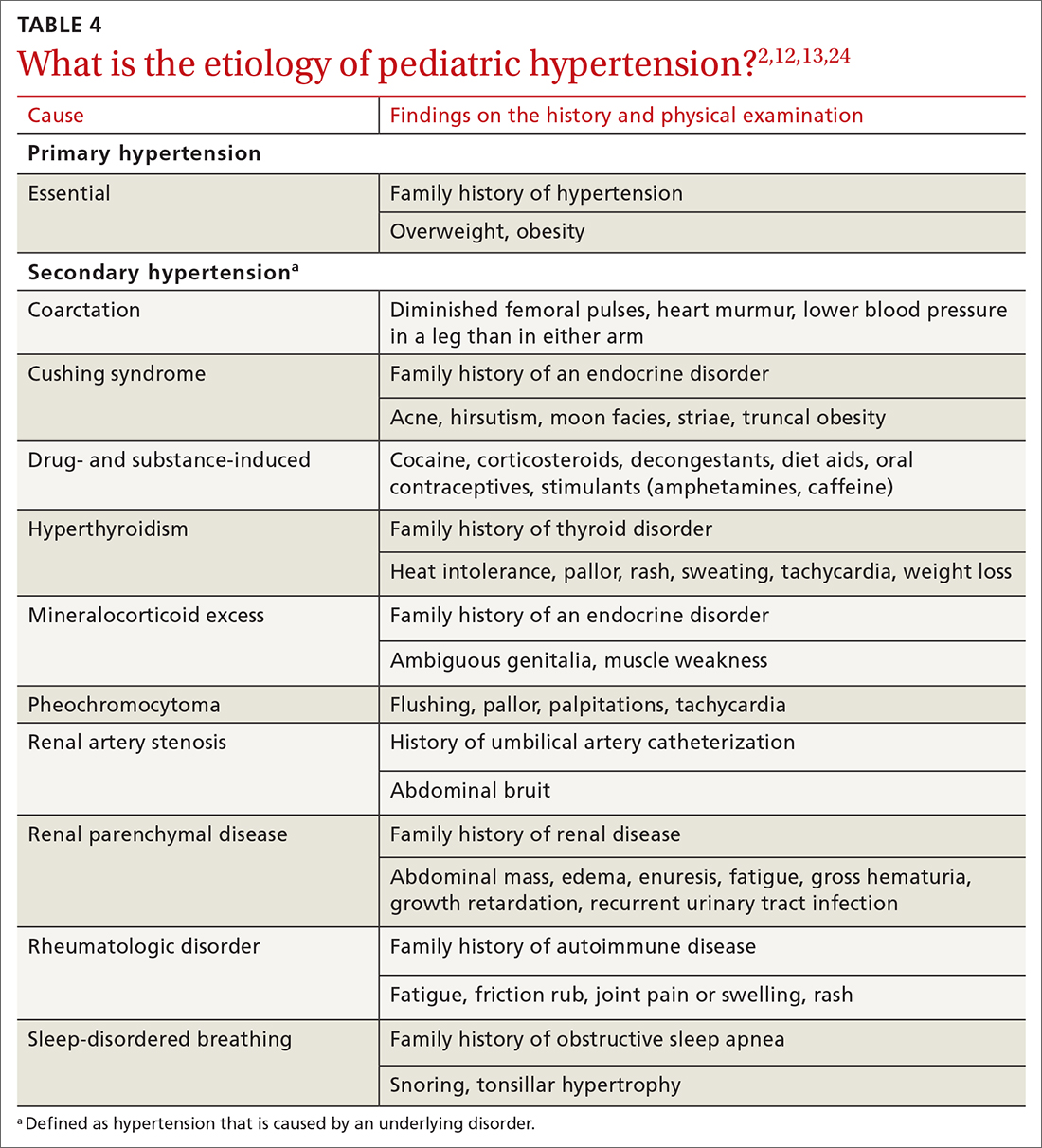

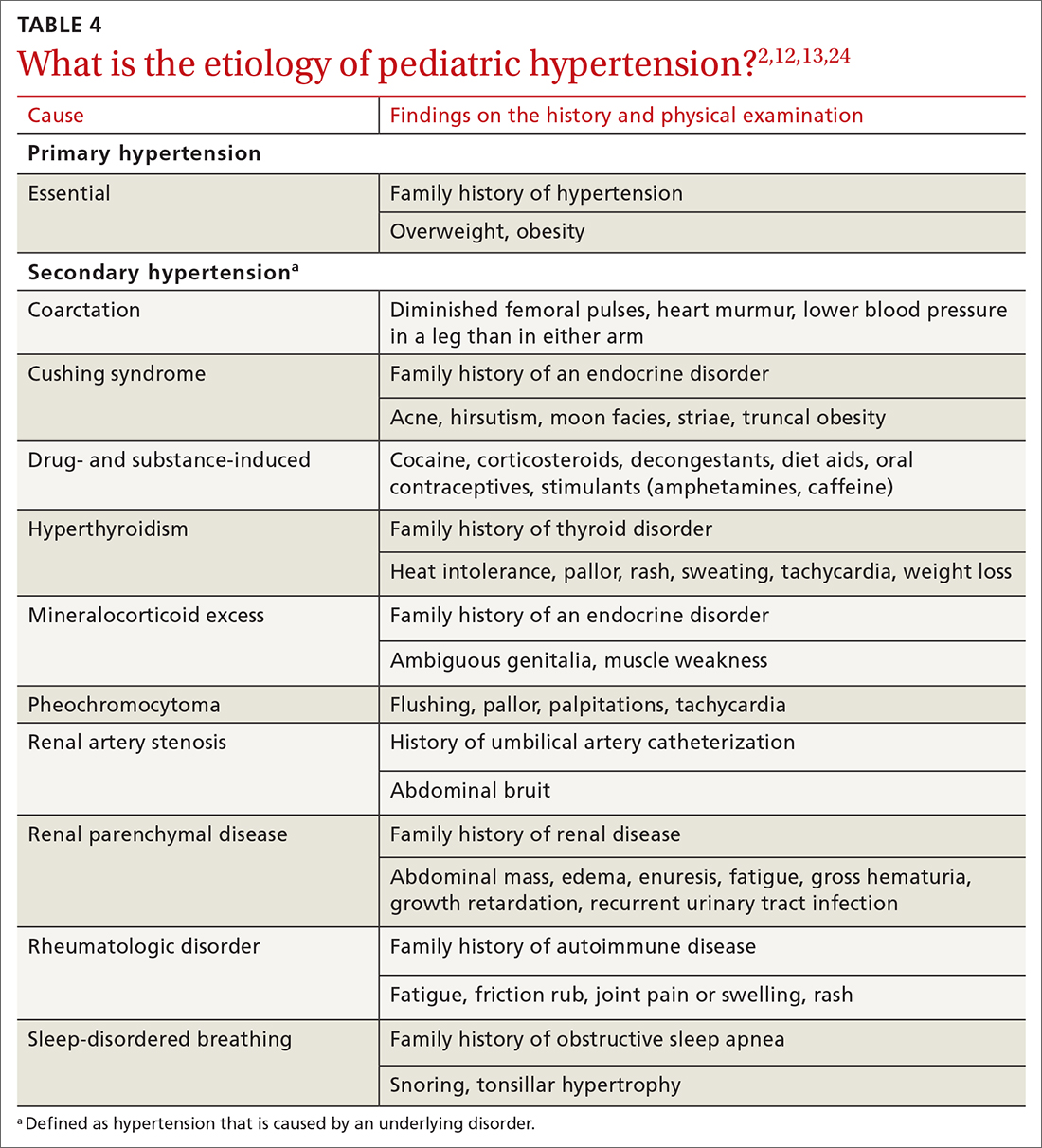

TABLE 42,12,13,24 outlines the basis of primary and of secondary hypertension and common historical and physical findings that suggest a secondary cause.

Mapping out the treatment plan

Pediatric hypertension should be treated in patients with stage 1 or higher hypertension.6 This threshold for therapy is based on evidence that reducing BP below a goal of (1) the 90th percentile (calculated based on age, sex, and height) in children up to 12 years of age or (2) of < 130/80 mm Hg for children ≥ 13 years reduces short- and long-term morbidity and mortality.5,6,25

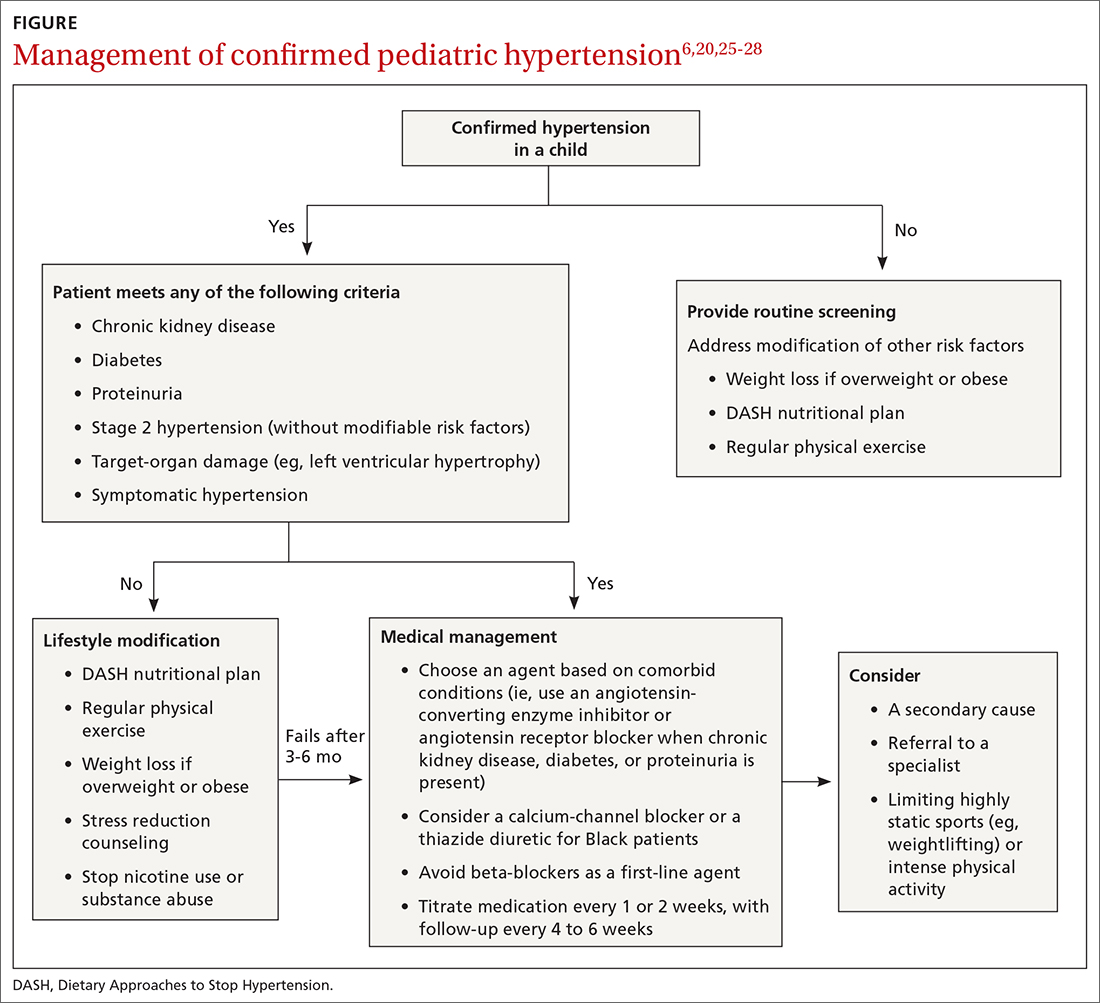

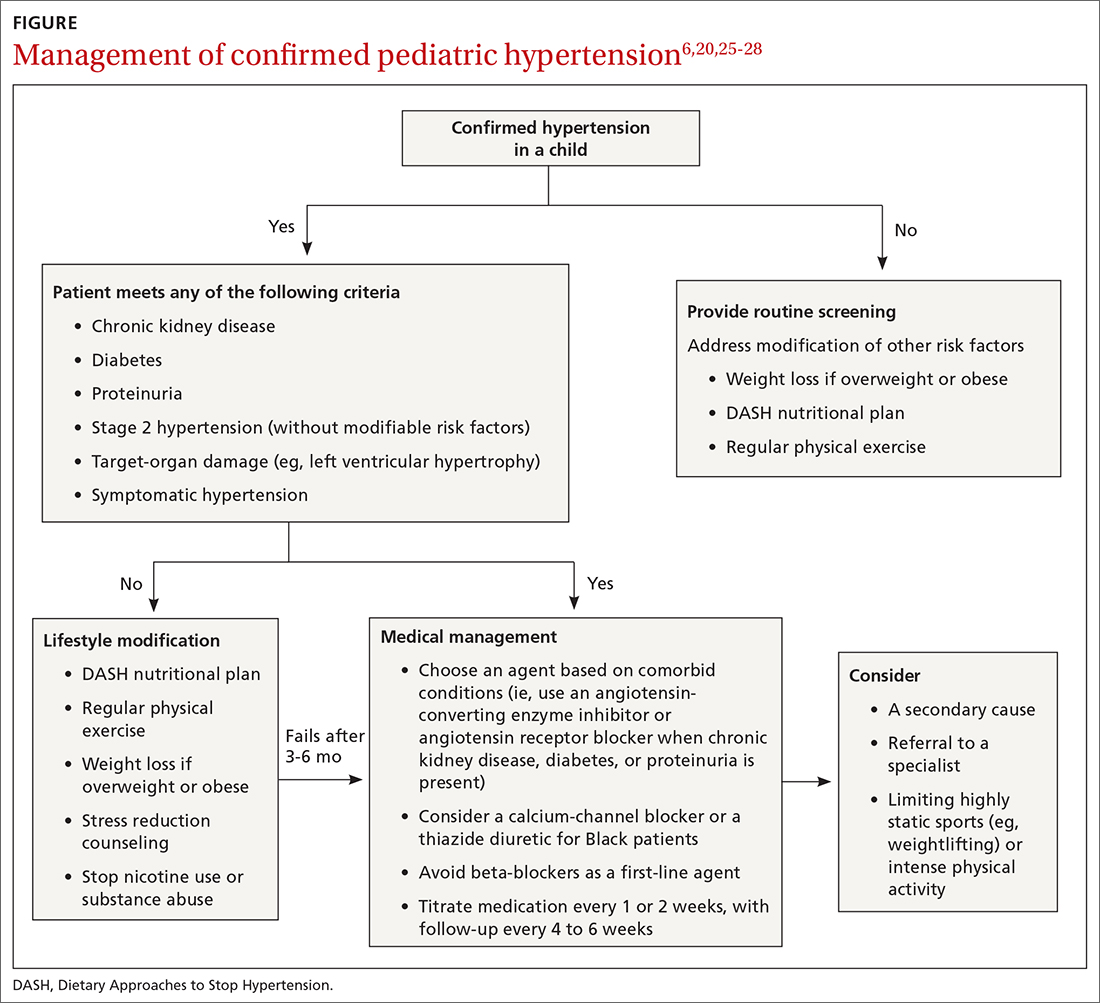

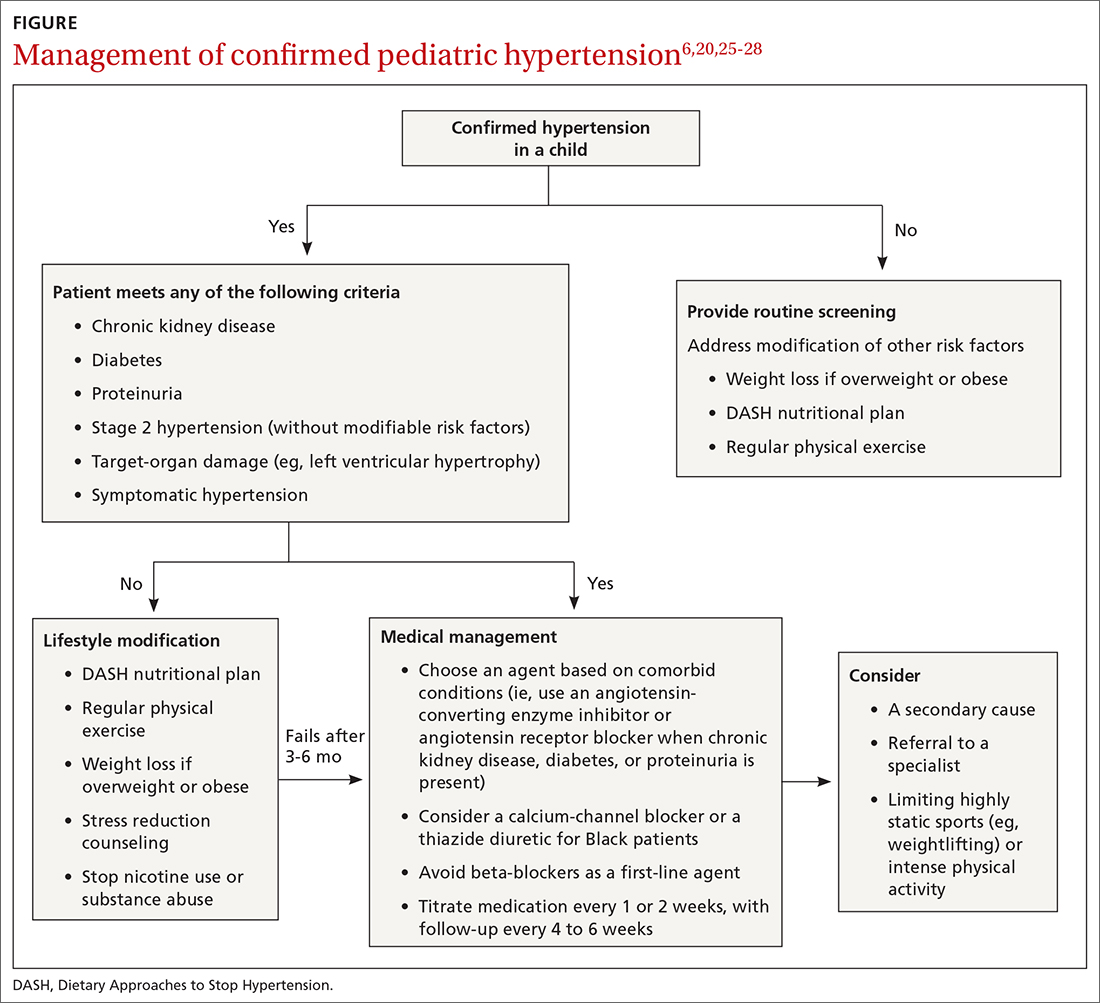

Choice of initial treatment depends on the severity of BP elevation and the presence of comorbidities (FIGURE6,20,25-28). The initial, fundamental treatment recommendation is lifestyle modification,6,29 including regular physical exercise, a change in nutritional habits, weight loss (because obesity is a common comorbid condition), elimination of tobacco and substance use, and stress reduction.25,26 Medications can be used as well, along with other treatments for specific causes of secondary hypertension.

Referral to a specialist can be considered if consultation for assistance with treatment is preferred (TABLE 26) or if the patient has:

- treatment-resistant hypertension

- stage 2 hypertension that is not quickly responsive to initial treatment

- an identified secondary cause of hypertension.

Continue to: Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Exercise. “Regular” physical exercise for children to reduce BP is defined as ≥ 30 to 60 minutes of active play daily.6,29 Studies have shown significant improvement not only in BP but also in other cardiovascular disease risk parameters with regular physical exercise.27 A study found that the reduction in systolic BP is, on average, approximately 6 mm Hg with physical activity alone.30

Nutrition. DASH—Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension—is an evidence-based program to reduce BP. This nutritional guideline focuses on a diet rich in natural foods, including fruits, vegetables, minimally processed carbohydrates and whole grains, and low-fat dairy and meats. It also emphasizes the importance of avoiding foods high in processed sugars and reducing sodium intake.31 Higher-than-recommended sodium intake, based on age and sex (and established as part of dietary recommendations for children on the US Department of Health and Human Services’ website health.gov) directly correlates with the risk of prehypertension and hypertension—especially in overweight and obese children.20,32 DASH has been shown to reliably reduce the incidence of hypertension in children; other studies have supported increased intake of fruits, vegetables, and legumes as strategies to reduce BP.33,34

Other interventions. Techniques to improve adherence to exercise and nutritional modifications for children include motivational interviewing, community programs and education, and family counseling.27,35 A recent study showed that a community-based lifestyle modification program that is focused on weight loss in obese children resulted in a significant reduction in BP values at higher stages of obesity.36 There is evidence that techniques such as controlled breathing and meditation can reduce BP.37 Last, screening and counseling to encourage tobacco and substance use discontinuation are recommended for children and adolescents to improve health outcomes.25

Proceed with pharmacotherapy when these criteria are met

Medical therapy is recommended when certain criteria are met, although this decision should be individualized and made in agreement by the treating physician, patient, and family. These criteria (FIGURE6,20,25-28) are6,29:

- once a diagnosis of stage 1 hypertension has been established, failure to meet a BP goal after 3 to 6 months of attempting lifestyle modifications

- stage 2 hypertension without a modifiable risk factor, such as obesity

- any stage of hypertension with comorbid CKD, DM, or proteinuria

- target-organ damage, such as left ventricular hypertrophy

- symptomatic hypertension.6,29

There are circumstances in which one or another specific antihypertensive agent is recommended for children; however, for most patients with primary hypertension, the following classes are recommended for first-line use6,22:

- angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

- calcium-channel blockers (CCBs)

- thiazide diuretics.

Continue to: For a child with known CKD...

For a child with known CKD, DM, or proteinuria, an ACE inhibitor or ARB is beneficial as first-line therapy.38 Because ACE inhibitors and ARBs have teratogenic effects, however, a thorough review of fertility status is recommended for female patients before any of these agents are started. CCBs and thiazides are typically recommended as first-line agents for Black patients.6,28 Beta-blockers are typically avoided in the first line because of their adverse effect profile.

Most antihypertensive medications can be titrated every 1 or 2 weeks; the patient’s BP can be monitored with a home BP cuff to track the effect of titration. In general, the patient should be seen for follow-up every 4 to 6 weeks for a BP recheck and review of medication tolerance and adverse effects. Once the treatment goal is achieved, it is reasonable to have the patient return every 3 to 6 months to reassess the treatment plan.

If the BP goal is difficult to achieve despite titration of medication and lifestyle changes, consider repeat ABPM assessment, a specialty referral, or both. It is reasonable for children who have been started on medication and have adhered to lifestyle modifications to practice a “step-down” approach to discontinuing medication; this approach can also be considered once any secondary cause has been corrected. Any target-organ abnormalities identified at diagnosis (eg, proteinuria, CKD, left ventricular hypertrophy) need to be reexamined at follow-up.6

Restrict activities—or not?

There is evidence that a child with stage 1 or well-controlled stage 2 hypertension without evidence of end-organ damage should not have restrictions on sports or activity. However, in uncontrolled stage 2 hypertension or when evidence of target end-organ damage is present, you should advise against participation in highly competitive sports and highly static sports (eg, weightlifting, wrestling), based on expert opinion6,25 (FIGURE6,20,25-28).

aAAP guidelines on the management of pediatric hypertension vary from those of the US Preventive Services Task Force. See the Practice Alert, “A review of the latest USPSTF recommendations,” in the May 2021 issue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dustin K. Smith, MD, Family Medicine Department, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL, 32214; [email protected]

1. Theodore RF, Broadbent J, Nagin D, et al. Childhood to early-midlife systolic blood pressure trajectories: early-life predictors, effect modifiers, and adult cardiovascular outcomes. Hypertension. 2015;66:1108-1115. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05831

2. Lurbe E, Agabiti-Rosei E, Cruickshank JK, et al. 2016 European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1887-1920. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001039

3. Weaver DJ, Mitsnefes MM. Effects of systemic hypertension on the cardiovascular system. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;41:59-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppedcard.2015.11.005

4. Ippisch HM, Daniels SR. Hypertension in overweight and obese children. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;25:177-182. doi: org/10.1016/j.ppedcard.2008.05.002

5. Urbina EM, Lande MB, Hooper SR, et al. Target organ abnormalities in pediatric hypertension. J Pediatr. 2018;202:14-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.026

6. Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al; . Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171904. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904

7. Khoury M, Khoury PR, Dolan LM, et al. Clinical implications of the revised AAP pediatric hypertension guidelines. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20180245. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0245

8. Falkner B, Gidding SS, Ramirez-Garnica G, et al. The relationship of body mass index and blood pressure in primary care pediatric patients. J Pediatr. 2006;148:195-200. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.030

9. Rodriguez BL, Dabelea D, Liese AD, et al; SEARCH Study Group. Prevalence and correlates of elevated blood pressure in youth with diabetes mellitus: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J Pediatr. 2010;157:245-251.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.021

10. Shay CM, Ning H, Daniels SR, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adolescents: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2005-2010. Circulation. 2013;127:1369-1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001559

11. Archbold KH, Vasquez MM, Goodwin JL, et al. Effects of sleep patterns and obesity on increases in blood pressure in a 5-year period: report from the Tucson Children’s Assessment of Sleep Apnea Study. J Pediatr. 2012;161:26-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.034

12. Flynn JT, Mitsnefes M, Pierce C, et al; . Blood pressure in children with chronic kidney disease: a report from the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children study. Hypertension. 2008;52:631-637. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110635

13. Martin RM, Ness AR, Gunnell D, et al; ALSPAC Study Team. Does breast-feeding in infancy lower blood pressure in childhood? The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Circulation. 2004;109:1259-1266. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118468.76447.CE

14. Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:256-263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420407

15. Chen X, Wang Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:3171-3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730366

16. Sun SS, Grave GD, Siervogel RM, et al. Systolic blood pressure in childhood predicts hypertension and metabolic syndrome later in life. Pediatrics. 2007;119:237-246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2543

17. Parker ED, Sinaiko AR, Kharbanda EO, et al. Change in weight status and development of hypertension. Pediatrics. 2016; 137:e20151662. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1662

18. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al; . Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142-161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e

19. Staley JR, Bradley J, Silverwood RJ, et al. Associations of blood pressure in pregnancy with offspring blood pressure trajectories during childhood and adolescence: findings from a prospective study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001422. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001422

20. Yang Q, Zhang Z, Zuklina EV, et al. Sodium intake and blood pressure among US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130:611-619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3870

21. Le-Ha C, Beilin LJ, Burrows S, et al. Oral contraceptive use in girls and alcohol consumption in boys are associated with increased blood pressure in late adolescence. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20:947-955. doi: 10.1177/2047487312452966

22. Samuels JA, Franco K, Wan F, Sorof JM. Effect of stimulants on 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in children with ADHD: a double-blind, randomized, cross-over trial. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:92-95. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2051-1

23. Wiesen J, Adkins M, Fortune S, et al. Evaluation of pediatric patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension: yield of diagnostic testing. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e988-993. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0365

24. Kapur G, Ahmed M, Pan C, et al. Secondary hypertension in overweight and stage 1 hypertensive children: a Midwest Pediatric Nephrology Consortium report. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:34-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00195.x

25. Anyaegbu EI, Dharnidharka VR. Hypertension in the teenager. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61:131-151. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.09.011

26. Gandhi B, Cheek S, Campo JV. Anxiety in the pediatric medical setting. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21:643-653. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.013

27. Farpour-Lambert NJ, Aggoun Y, Marchand LM, et al. Physical activity reduces systemic blood pressure and improves early markers of atherosclerosis in pre-pubertal obese children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2396-2406. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.030

28. Li JS, Baker-Smith CM, Smith PB, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure response to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in children: a meta-analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:315-319. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.113

29. Singer PS. Updates on hypertension and new guidelines. Adv Pediatr. 2019;66:177-187. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2019.03.009

30. Torrance B, McGuire KA, Lewanczuk R, et al. Overweight, physical activity and high blood pressure in children: a review of the literature. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:139-149.

31. DASH eating plan. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Accessed April 26, 2021. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/dash-eating-plan

32. Nutritional goals for age-sex groups based on dietary reference intakes and dietary guidelines recommendations (Appendix 7). In: US Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. December 2015;97-98. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf

33. Asghari G, Yuzbashian E, Mirmiran P, et al. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern is associated with reduced incidence of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2016;174:178-184.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.077

34. Damasceno MMC, de Araújo MFM, de Freitas RWJF, et al. The association between blood pressure in adolescents and the consumption of fruits, vegetables and fruit juice–an exploratory study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1553-1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03608.x

35. Anderson KL. A review of the prevention and medical management of childhood obesity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27:63-76. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2017.08.003

36. Kumar S, King EC, Christison, et al; POWER Work Group. Health outcomes of youth in clinical pediatric weight management programs in POWER. J Pediatr. 2019;208:57-65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.049

37. Gregoski MJ, Barnes VA, Tingen MS, et al. Breathing awareness meditation and LifeSkills® Training programs influence upon ambulatory blood pressure and sodium excretion among African American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:59-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.019

38. Escape Trial Group; E, Trivelli A, Picca S, et al. Strict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in children. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1639-1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902066

Hypertension and elevated blood pressure (BP) in children and adolescents correlate to hypertension in adults, insofar as complications and medical therapy increase with age.1,2 Untreated, hypertension in children and adolescents can result in multiple harmful physiologic changes, including left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, diastolic dysfunction, arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction, and neurocognitive deficits.3-5

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of elevated BP and hypertension in children and adolescentsa (TABLE 16). Applying the definition of elevated BP set out in these guidelines yielded a 13% prevalence of hypertension in a cohort of subjects 10 to 18 years of age with comorbid obesity and diabetes mellitus (DM). AAP guideline definitions also improved the sensitivity for identifying hypertensive end-organ damage.7

As the prevalence of hypertension increases, screening for and accurate diagnosis of this condition in children are becoming more important. Recognition and management remain a vital part of primary care. In this article, we review the updated guidance on diagnosis and treatment, including lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy.

First step: Identifying hypertension

Risk factors

Risk factors for pediatric hypertension are similar to those in adults. These include obesity (body mass index ≥ 95th percentile for age), types 1 and 2 DM, elevated sodium intake, sleep-disordered breathing, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Some risk factors, such as premature birth and coarctation of the aorta, are specific to the pediatric population.8-14 Pediatric obesity strongly correlates with both pediatric and adult hypertension, and accelerated weight gain might increase the risk of elevated BP in adulthood.15,16

Intervening early to mitigate or eliminate some of these modifiable risk factors can prevent or treat hypertension.17 Alternatively, having been breastfed as an infant has been reliably shown to reduce the risk of elevated BP in children.13

Recommendations for screening and measuring BP

The optimal age to start measuring BP is not clearly defined. AAP recommends measurement:

- annually in all children ≥ 3 years of age

- at every encounter in patients who have a specific comorbid condition, including obesity, DM, renal disease, and aortic-arch abnormalities (obstruction and coarctation) and in those who are taking medication known to increase BP.6

Protocol. Measure BP in the right arm for consistency and comparison with reference values. The width of the cuff bladder should be at least 40%, and the length, 80% to 100%, of arm circumference. Position the cuff bladder midway between the olecranon and acromion. Obtain the measurement in a quiet and comfortable environment after the patient has rested for 3 to 5 minutes. The patient should be seated, preferably with feet on the floor; elbows should be supported at the level of the heart.

Continue to: When an initial reading...

When an initial reading is elevated, whether by oscillometric or auscultatory measurement, 2 more auscultatory BP measurements should be taken during the same visit; these measurements are averaged to determine the BP category.18

TABLE 16 defines BP categories based on age, sex, and height. We recommend using the free resource MD Calc (www.mdcalc.com/aap-pediatric-hypertension-guidelines) to assist in calculating the BP category.

TABLE 26 describes the timing of follow-up based on the initial BP reading and diagnosis.

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is a validated device that measures BP every 20 to 30 minutes throughout the day and night. ABPM should be performed initially in all patients with persistently elevated BP and routinely in children and adolescents with a high-risk comorbidity (TABLE 26). Note: Insurance coverage of ABPM is limited.

ABPM is also used to diagnose so-called white-coat hypertension, defined as BP ≥ 95th percentile for age, sex, and height in the clinic setting but < 95th percentile during ABPM. This phenomenon can be challenging to diagnose.

Continue to: Home monitoring

Home monitoring. Do not use home BP monitoring to establish a diagnosis of hypertension, although one of these devices can be used as an adjunct to office and ambulatory BP monitoring after the diagnosis has been made.6

Evaluating hypertension in children and adolescents

Once a diagnosis of hypertension has been made, undertake a thorough history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing to evaluate for possible causes, comorbidities, and any evidence of end-organ damage.

Comprehensive history. Pertinent aspects include perinatal, nutritional, physical activity, psychosocial, family, medication—and of course, medical—histories.6

Maternal elevated BP or hypertension is related to an offspring’s elevated BP in childhood and adolescence.19 Other pertinent aspects of the perinatal history include complications of pregnancy, gestational age, birth weight, and neonatal complications.6

Nutritional and physical activity histories can highlight contributing factors in the development of hypertension and can be a guide to recommending lifestyle modifications.6 Sodium intake, which influences BP, should be part of the nutritional history.20

Continue to: Important aspects...

Important aspects of the psychosocial history include feelings of depression or anxiety, bullying, and body perception. Children older than 10 years should be asked about smoking, alcohol, and other substance use.

The family history should include notation of first- and second-degree relatives with hypertension.6

Inquire about medications that can raise BP, including oral contraceptives, which are commonly prescribed in this population.21,22

The physical exam should include measured height and weight, with calculation of the body mass index percentile for age; of note, obesity is strongly associated with hypertension, and poor growth might signal underlying chronic disease. Once elevated BP has been confirmed, the exam should include measurement of BP in both arms and in a leg (TABLE 26). BP that is lower in the leg than in the arms (in any given patient, BP readings in the legs are usually higher than in the arms), or weak or absent femoral pulses, suggest coarctation of the aorta.6

Focus the balance of the physical exam on physical findings that suggest secondary causes of hypertension or evidence of end-organ damage.

Continue to: Testing

Testing. TABLE 36,23 summarizes the diagnostic testing recommended for all children and for specific populations; TABLE 26 indicates when to obtain diagnostic testing.

TABLE 42,12,13,24 outlines the basis of primary and of secondary hypertension and common historical and physical findings that suggest a secondary cause.

Mapping out the treatment plan

Pediatric hypertension should be treated in patients with stage 1 or higher hypertension.6 This threshold for therapy is based on evidence that reducing BP below a goal of (1) the 90th percentile (calculated based on age, sex, and height) in children up to 12 years of age or (2) of < 130/80 mm Hg for children ≥ 13 years reduces short- and long-term morbidity and mortality.5,6,25

Choice of initial treatment depends on the severity of BP elevation and the presence of comorbidities (FIGURE6,20,25-28). The initial, fundamental treatment recommendation is lifestyle modification,6,29 including regular physical exercise, a change in nutritional habits, weight loss (because obesity is a common comorbid condition), elimination of tobacco and substance use, and stress reduction.25,26 Medications can be used as well, along with other treatments for specific causes of secondary hypertension.

Referral to a specialist can be considered if consultation for assistance with treatment is preferred (TABLE 26) or if the patient has:

- treatment-resistant hypertension

- stage 2 hypertension that is not quickly responsive to initial treatment

- an identified secondary cause of hypertension.

Continue to: Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Lifestyle modification can make a big difference

Exercise. “Regular” physical exercise for children to reduce BP is defined as ≥ 30 to 60 minutes of active play daily.6,29 Studies have shown significant improvement not only in BP but also in other cardiovascular disease risk parameters with regular physical exercise.27 A study found that the reduction in systolic BP is, on average, approximately 6 mm Hg with physical activity alone.30

Nutrition. DASH—Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension—is an evidence-based program to reduce BP. This nutritional guideline focuses on a diet rich in natural foods, including fruits, vegetables, minimally processed carbohydrates and whole grains, and low-fat dairy and meats. It also emphasizes the importance of avoiding foods high in processed sugars and reducing sodium intake.31 Higher-than-recommended sodium intake, based on age and sex (and established as part of dietary recommendations for children on the US Department of Health and Human Services’ website health.gov) directly correlates with the risk of prehypertension and hypertension—especially in overweight and obese children.20,32 DASH has been shown to reliably reduce the incidence of hypertension in children; other studies have supported increased intake of fruits, vegetables, and legumes as strategies to reduce BP.33,34

Other interventions. Techniques to improve adherence to exercise and nutritional modifications for children include motivational interviewing, community programs and education, and family counseling.27,35 A recent study showed that a community-based lifestyle modification program that is focused on weight loss in obese children resulted in a significant reduction in BP values at higher stages of obesity.36 There is evidence that techniques such as controlled breathing and meditation can reduce BP.37 Last, screening and counseling to encourage tobacco and substance use discontinuation are recommended for children and adolescents to improve health outcomes.25

Proceed with pharmacotherapy when these criteria are met

Medical therapy is recommended when certain criteria are met, although this decision should be individualized and made in agreement by the treating physician, patient, and family. These criteria (FIGURE6,20,25-28) are6,29:

- once a diagnosis of stage 1 hypertension has been established, failure to meet a BP goal after 3 to 6 months of attempting lifestyle modifications

- stage 2 hypertension without a modifiable risk factor, such as obesity

- any stage of hypertension with comorbid CKD, DM, or proteinuria

- target-organ damage, such as left ventricular hypertrophy

- symptomatic hypertension.6,29

There are circumstances in which one or another specific antihypertensive agent is recommended for children; however, for most patients with primary hypertension, the following classes are recommended for first-line use6,22:

- angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

- calcium-channel blockers (CCBs)

- thiazide diuretics.

Continue to: For a child with known CKD...

For a child with known CKD, DM, or proteinuria, an ACE inhibitor or ARB is beneficial as first-line therapy.38 Because ACE inhibitors and ARBs have teratogenic effects, however, a thorough review of fertility status is recommended for female patients before any of these agents are started. CCBs and thiazides are typically recommended as first-line agents for Black patients.6,28 Beta-blockers are typically avoided in the first line because of their adverse effect profile.

Most antihypertensive medications can be titrated every 1 or 2 weeks; the patient’s BP can be monitored with a home BP cuff to track the effect of titration. In general, the patient should be seen for follow-up every 4 to 6 weeks for a BP recheck and review of medication tolerance and adverse effects. Once the treatment goal is achieved, it is reasonable to have the patient return every 3 to 6 months to reassess the treatment plan.

If the BP goal is difficult to achieve despite titration of medication and lifestyle changes, consider repeat ABPM assessment, a specialty referral, or both. It is reasonable for children who have been started on medication and have adhered to lifestyle modifications to practice a “step-down” approach to discontinuing medication; this approach can also be considered once any secondary cause has been corrected. Any target-organ abnormalities identified at diagnosis (eg, proteinuria, CKD, left ventricular hypertrophy) need to be reexamined at follow-up.6

Restrict activities—or not?

There is evidence that a child with stage 1 or well-controlled stage 2 hypertension without evidence of end-organ damage should not have restrictions on sports or activity. However, in uncontrolled stage 2 hypertension or when evidence of target end-organ damage is present, you should advise against participation in highly competitive sports and highly static sports (eg, weightlifting, wrestling), based on expert opinion6,25 (FIGURE6,20,25-28).

aAAP guidelines on the management of pediatric hypertension vary from those of the US Preventive Services Task Force. See the Practice Alert, “A review of the latest USPSTF recommendations,” in the May 2021 issue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dustin K. Smith, MD, Family Medicine Department, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL, 32214; [email protected]

Hypertension and elevated blood pressure (BP) in children and adolescents correlate to hypertension in adults, insofar as complications and medical therapy increase with age.1,2 Untreated, hypertension in children and adolescents can result in multiple harmful physiologic changes, including left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, diastolic dysfunction, arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction, and neurocognitive deficits.3-5

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of elevated BP and hypertension in children and adolescentsa (TABLE 16). Applying the definition of elevated BP set out in these guidelines yielded a 13% prevalence of hypertension in a cohort of subjects 10 to 18 years of age with comorbid obesity and diabetes mellitus (DM). AAP guideline definitions also improved the sensitivity for identifying hypertensive end-organ damage.7

As the prevalence of hypertension increases, screening for and accurate diagnosis of this condition in children are becoming more important. Recognition and management remain a vital part of primary care. In this article, we review the updated guidance on diagnosis and treatment, including lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy.

First step: Identifying hypertension

Risk factors

Risk factors for pediatric hypertension are similar to those in adults. These include obesity (body mass index ≥ 95th percentile for age), types 1 and 2 DM, elevated sodium intake, sleep-disordered breathing, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Some risk factors, such as premature birth and coarctation of the aorta, are specific to the pediatric population.8-14 Pediatric obesity strongly correlates with both pediatric and adult hypertension, and accelerated weight gain might increase the risk of elevated BP in adulthood.15,16

Intervening early to mitigate or eliminate some of these modifiable risk factors can prevent or treat hypertension.17 Alternatively, having been breastfed as an infant has been reliably shown to reduce the risk of elevated BP in children.13

Recommendations for screening and measuring BP

The optimal age to start measuring BP is not clearly defined. AAP recommends measurement:

- annually in all children ≥ 3 years of age

- at every encounter in patients who have a specific comorbid condition, including obesity, DM, renal disease, and aortic-arch abnormalities (obstruction and coarctation) and in those who are taking medication known to increase BP.6

Protocol. Measure BP in the right arm for consistency and comparison with reference values. The width of the cuff bladder should be at least 40%, and the length, 80% to 100%, of arm circumference. Position the cuff bladder midway between the olecranon and acromion. Obtain the measurement in a quiet and comfortable environment after the patient has rested for 3 to 5 minutes. The patient should be seated, preferably with feet on the floor; elbows should be supported at the level of the heart.

Continue to: When an initial reading...

When an initial reading is elevated, whether by oscillometric or auscultatory measurement, 2 more auscultatory BP measurements should be taken during the same visit; these measurements are averaged to determine the BP category.18

TABLE 16 defines BP categories based on age, sex, and height. We recommend using the free resource MD Calc (www.mdcalc.com/aap-pediatric-hypertension-guidelines) to assist in calculating the BP category.

TABLE 26 describes the timing of follow-up based on the initial BP reading and diagnosis.

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is a validated device that measures BP every 20 to 30 minutes throughout the day and night. ABPM should be performed initially in all patients with persistently elevated BP and routinely in children and adolescents with a high-risk comorbidity (TABLE 26). Note: Insurance coverage of ABPM is limited.