User login

Metabolites implicated in CHD development in African Americans

Selected metabolic biomarkers may influence disease risk and progression in African American and White persons in different ways, a cohort study of the landmark Jackson Heart Study has found.

The investigators identified 22 specific metabolites that seem to influence incident CHD risk in African American patients – 13 metabolites that were also replicated in a multiethnic population and 9 novel metabolites that include N-acylamides and leucine, a branched-chain amino acid.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that an N-acylamide as a class of molecule has been shown to be associated with incident coronary heart disease,” lead study author Daniel E. Cruz, MD, an instructor at Harvard Medical School in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview.

The researchers analyzed targeted plasma metabolomic profiles of 2,346 participants in the Jackson Heart Study, a prospective population-based cohort study in the Mississippi city that included 5,306 African American patients evaluated over 15 years. They then performed a replication analysis of CHD-associated metabolites among 1,588 multiethnic participants in the Women’s Health Initiative, another population-based cohort study that included 161,808 postmenopausal women, also over 15 years. In all, the study, published in JAMA Cardiology, identified 46 metabolites that were associated with incident CHD up to 16 years before the incident event

Dr. Cruz said the “most interesting” findings were the roles of the N-acylamide linoleoyl ethanolamide and leucine. The former is of interest “because it is a lipid-signaling molecule that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages; the influence and effects on macrophages are of particular interest because of macrophages’ central role in atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease,” he said.

Leucine draws interest because, in this study population, it was linked to a reduced risk of incident CHD. The researchers cited four previous studies in predominantly non-Hispanic White populations that found no association between branched-chain amino acids and incident CHD in Circulation, Stroke Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine, and Atherosclerosis. Other branched-amino acids included in the analysis trended toward a decreased risk of CHD, but those didn’t achieve the same statistical significance as that of leucine, Dr. Cruz said.

“In some of the analyses we did, there was a subset of metabolites that the associations with CHD appeared to be different between self-identified African Americans in the Jackson cohort vs. self-identified non-Hispanic Whites, and leucine was one of them,” Dr. Cruz said.

He emphasized that this study “is not a genetic analysis” because the participants self-identified their race. “So our next step is to figure out why this difference appears between these self-identified groups,” Dr. Cruz said. “We suspect environmental factors play a role – psychological stress, diet, income level, to name a few – but we are also interested to see if there are genetic causes.”

The results “are not clinically applicable,” Dr. Cruz said, but they do point to a need for more ethnically and racially diverse study populations. “The big picture is that, before we go implementing novel biomarkers into clinical practice, we need to make sure that they are accurate across different populations of people,” he said. “The only way to do this is to study different groups with the same rigor and vigor and thoughtfulness as any other group.”

These findings fall in line with other studies that found other nonmetabolomic biomarkers have countervailing effects on CHD risk in African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites, said Christie M. Ballantyne, MD, chief of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. For example, African Americans have been found to have lower triglyceride and HDL cholesterol levels than those of Whites.

The study “points out that there may be important biological differences in the metabolic pathways and abnormalities in the development of CHD between races,” Dr. Ballantyne said. “This further emphasizes both the importance and challenge of testing therapies in multiple racial/ethnic groups and with more even representation between men and women.”

Combining metabolomic profiling along with other biomarkers and possibly genetics may be helpful to “personalize” therapies in the future, he added.

Dr. Cruz and Dr. Ballantyne have no relevant relationships to disclose.

Selected metabolic biomarkers may influence disease risk and progression in African American and White persons in different ways, a cohort study of the landmark Jackson Heart Study has found.

The investigators identified 22 specific metabolites that seem to influence incident CHD risk in African American patients – 13 metabolites that were also replicated in a multiethnic population and 9 novel metabolites that include N-acylamides and leucine, a branched-chain amino acid.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that an N-acylamide as a class of molecule has been shown to be associated with incident coronary heart disease,” lead study author Daniel E. Cruz, MD, an instructor at Harvard Medical School in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview.

The researchers analyzed targeted plasma metabolomic profiles of 2,346 participants in the Jackson Heart Study, a prospective population-based cohort study in the Mississippi city that included 5,306 African American patients evaluated over 15 years. They then performed a replication analysis of CHD-associated metabolites among 1,588 multiethnic participants in the Women’s Health Initiative, another population-based cohort study that included 161,808 postmenopausal women, also over 15 years. In all, the study, published in JAMA Cardiology, identified 46 metabolites that were associated with incident CHD up to 16 years before the incident event

Dr. Cruz said the “most interesting” findings were the roles of the N-acylamide linoleoyl ethanolamide and leucine. The former is of interest “because it is a lipid-signaling molecule that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages; the influence and effects on macrophages are of particular interest because of macrophages’ central role in atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease,” he said.

Leucine draws interest because, in this study population, it was linked to a reduced risk of incident CHD. The researchers cited four previous studies in predominantly non-Hispanic White populations that found no association between branched-chain amino acids and incident CHD in Circulation, Stroke Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine, and Atherosclerosis. Other branched-amino acids included in the analysis trended toward a decreased risk of CHD, but those didn’t achieve the same statistical significance as that of leucine, Dr. Cruz said.

“In some of the analyses we did, there was a subset of metabolites that the associations with CHD appeared to be different between self-identified African Americans in the Jackson cohort vs. self-identified non-Hispanic Whites, and leucine was one of them,” Dr. Cruz said.

He emphasized that this study “is not a genetic analysis” because the participants self-identified their race. “So our next step is to figure out why this difference appears between these self-identified groups,” Dr. Cruz said. “We suspect environmental factors play a role – psychological stress, diet, income level, to name a few – but we are also interested to see if there are genetic causes.”

The results “are not clinically applicable,” Dr. Cruz said, but they do point to a need for more ethnically and racially diverse study populations. “The big picture is that, before we go implementing novel biomarkers into clinical practice, we need to make sure that they are accurate across different populations of people,” he said. “The only way to do this is to study different groups with the same rigor and vigor and thoughtfulness as any other group.”

These findings fall in line with other studies that found other nonmetabolomic biomarkers have countervailing effects on CHD risk in African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites, said Christie M. Ballantyne, MD, chief of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. For example, African Americans have been found to have lower triglyceride and HDL cholesterol levels than those of Whites.

The study “points out that there may be important biological differences in the metabolic pathways and abnormalities in the development of CHD between races,” Dr. Ballantyne said. “This further emphasizes both the importance and challenge of testing therapies in multiple racial/ethnic groups and with more even representation between men and women.”

Combining metabolomic profiling along with other biomarkers and possibly genetics may be helpful to “personalize” therapies in the future, he added.

Dr. Cruz and Dr. Ballantyne have no relevant relationships to disclose.

Selected metabolic biomarkers may influence disease risk and progression in African American and White persons in different ways, a cohort study of the landmark Jackson Heart Study has found.

The investigators identified 22 specific metabolites that seem to influence incident CHD risk in African American patients – 13 metabolites that were also replicated in a multiethnic population and 9 novel metabolites that include N-acylamides and leucine, a branched-chain amino acid.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that an N-acylamide as a class of molecule has been shown to be associated with incident coronary heart disease,” lead study author Daniel E. Cruz, MD, an instructor at Harvard Medical School in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview.

The researchers analyzed targeted plasma metabolomic profiles of 2,346 participants in the Jackson Heart Study, a prospective population-based cohort study in the Mississippi city that included 5,306 African American patients evaluated over 15 years. They then performed a replication analysis of CHD-associated metabolites among 1,588 multiethnic participants in the Women’s Health Initiative, another population-based cohort study that included 161,808 postmenopausal women, also over 15 years. In all, the study, published in JAMA Cardiology, identified 46 metabolites that were associated with incident CHD up to 16 years before the incident event

Dr. Cruz said the “most interesting” findings were the roles of the N-acylamide linoleoyl ethanolamide and leucine. The former is of interest “because it is a lipid-signaling molecule that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages; the influence and effects on macrophages are of particular interest because of macrophages’ central role in atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease,” he said.

Leucine draws interest because, in this study population, it was linked to a reduced risk of incident CHD. The researchers cited four previous studies in predominantly non-Hispanic White populations that found no association between branched-chain amino acids and incident CHD in Circulation, Stroke Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine, and Atherosclerosis. Other branched-amino acids included in the analysis trended toward a decreased risk of CHD, but those didn’t achieve the same statistical significance as that of leucine, Dr. Cruz said.

“In some of the analyses we did, there was a subset of metabolites that the associations with CHD appeared to be different between self-identified African Americans in the Jackson cohort vs. self-identified non-Hispanic Whites, and leucine was one of them,” Dr. Cruz said.

He emphasized that this study “is not a genetic analysis” because the participants self-identified their race. “So our next step is to figure out why this difference appears between these self-identified groups,” Dr. Cruz said. “We suspect environmental factors play a role – psychological stress, diet, income level, to name a few – but we are also interested to see if there are genetic causes.”

The results “are not clinically applicable,” Dr. Cruz said, but they do point to a need for more ethnically and racially diverse study populations. “The big picture is that, before we go implementing novel biomarkers into clinical practice, we need to make sure that they are accurate across different populations of people,” he said. “The only way to do this is to study different groups with the same rigor and vigor and thoughtfulness as any other group.”

These findings fall in line with other studies that found other nonmetabolomic biomarkers have countervailing effects on CHD risk in African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites, said Christie M. Ballantyne, MD, chief of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. For example, African Americans have been found to have lower triglyceride and HDL cholesterol levels than those of Whites.

The study “points out that there may be important biological differences in the metabolic pathways and abnormalities in the development of CHD between races,” Dr. Ballantyne said. “This further emphasizes both the importance and challenge of testing therapies in multiple racial/ethnic groups and with more even representation between men and women.”

Combining metabolomic profiling along with other biomarkers and possibly genetics may be helpful to “personalize” therapies in the future, he added.

Dr. Cruz and Dr. Ballantyne have no relevant relationships to disclose.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

Gender Disparities in Income Among Board-Certified Dermatologists

Although the number of female graduates from US medical schools has steadily increased,1 several studies since the 1970s indicate that a disparity exists in salary, academic rank, and promotion among female and male physicians across multiple specialties.2-8 Proposed explanations include women working fewer hours, having lower productivity rates, undernegotiating compensation, and underbilling for the same services. However, when controlling for variables such as time, experience, specialty, rank, and research activities, this gap unequivocally persists. There are limited data on this topic in dermatology, a field in which women comprise more than half of the working population.6,7 Most analyses of gender disparities in dermatology are based on data primarily from academic dermatologists, which may not be representative of the larger population of dermatologists.8,9 The purpose of this study is to determine if an income disparity exists between male and female physicians in dermatology, including those in private practice and those who are specialty trained.

Methods

Population—We performed a cross-sectional self-reported survey to examine compensation of male and female board-certified dermatologists (MDs/DOs). Several populations of dermatologists were surveyed in August and September 2018. Approximately 20% of the members of the American Academy of Dermatology were randomly selected and sent a link to the survey. Additionally, a survey link was emailed to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. A link to the survey also was published on “The Board Certified Dermatologists” Facebook group.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the distribution of variables overall and within gender (male or female). Not all respondents completed every section, and duplicates and incomplete responses were removed. Variables were compared between genders using t tests (continuous), the Pearson χ2 test (nominal), or the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test (ordinal). For categorical variables with small cell counts, an exact χ2 test for small samples was used. For continuous variables, t test P values were calculated using either pooled or Satterthwaithe approximation.

To analyze the effect of different variables on total income using multivariate and univariate linear regression, the income variable was transformed into a continuous variable by using midpoints of the categories. Univariate linear regression was used to assess the effect and significance of each variable on total annual income. Variables that were found to have a P value of less than .05 (α=.05) were deemed as significant predictors of total annual income. These variables were added to a multivariate linear regression model to determine their effect on income when adjusting for other significant (and approaching significance) factors. In addition, variables that were found to have a P value of less than .2 (α=.05) were added to the multivariate linear regression model to assess significance of these specific variables when adjusting for other factors. In this way, we tested and accounted for a multitude of variables as potential sources of confounding.

Results

Demographics—Our survey was emailed to 3079 members of the American Academy of Dermatology, and 277 responses were received. Approximately 144 additional responses were obtained collectively from links sent to the directories of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and from social media. Of these respondents, 53.65% (213/397) were female and 46.35% (184/397) were male. When stratifying by race/ethnicity, 77.33% identified as White; 13.85% identified as Asian; 6.3% identified as Black or African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American; and 2.52% chose not to respond. Although most male and female respondents were White, a significantly higher proportion of female respondents identified as Asian or Black/African American/Hispanic/Latino/Native American (P=.0006). We found that race/ethnicity did not significantly impact income (P=.2736). All US Census regions were represented in this study, and geographic distribution as well as population density of practice location (ie, rural, suburban, urban setting) did not differ significantly between males and females (P=.5982 and P=.1007, respectively) and did not significantly impact income (P=.3225 and P=.10663, respectively).

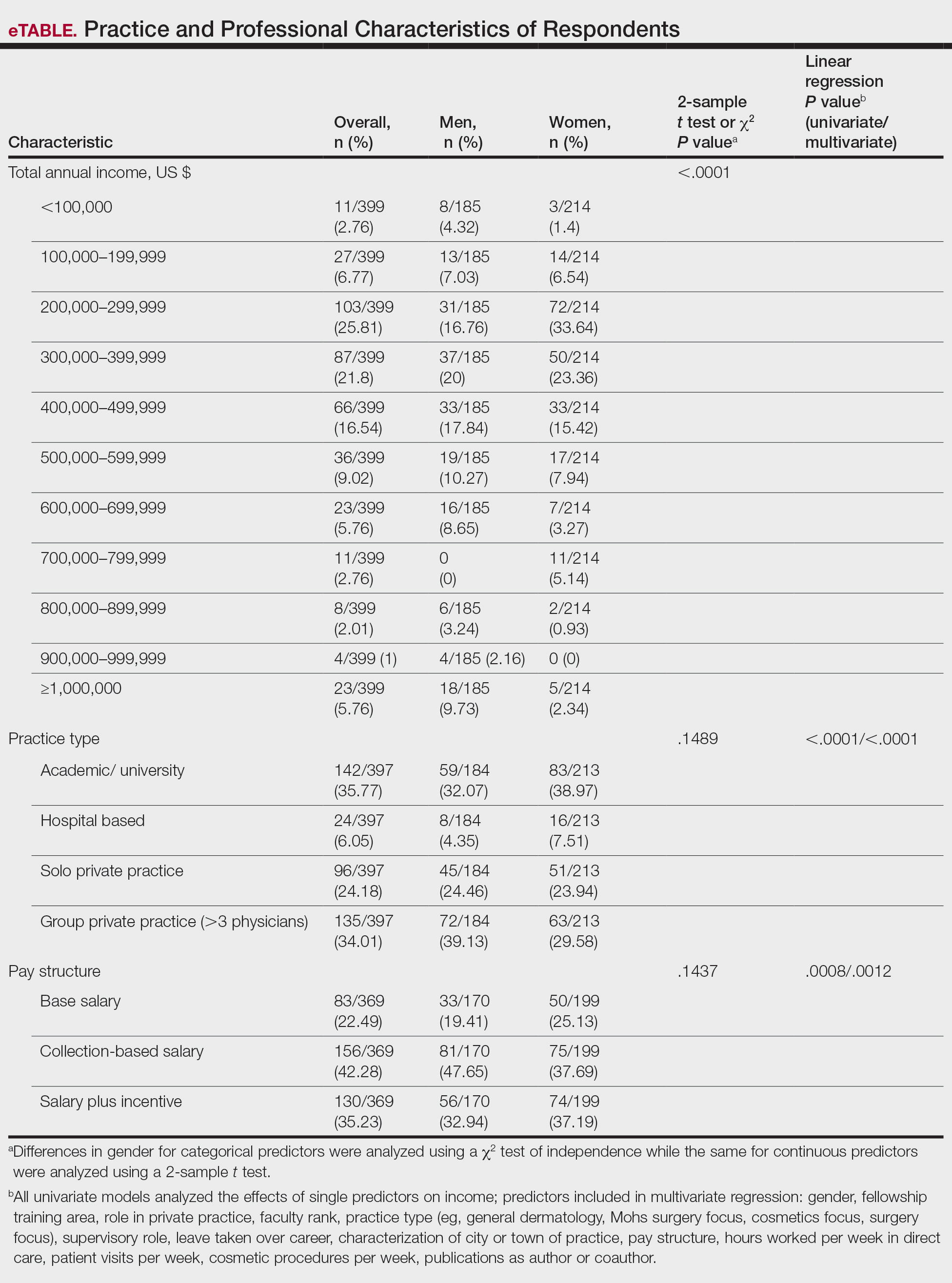

Income—Total annual income was defined as the aggregate sum of all types of financial compensation received in 1 calendar year (eg, salary, bonuses, benefits) and was elicited as an ordinal variable in income brackets of US $100,000. Overall, χ2 analysis showed a statistically significant difference in annual total income between male and female dermatologists (P<.0001), with a higher proportion of males in the highest pay bracket (Figure). Gender remained a statistically significant predictor of income on both univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses (P=.0002 and P<.0001, respectively), indicating that gender has a significant impact on compensation, even after controlling for other variables (eTable). Of note, males in this sample were on average older and in practice longer than females (approximately 6 years, P<.0001). However, when univariate linear regression was performed, both age (P=.8281) and number of years since residency or fellowship completion (P=.8743) were not significant predictors of income.

Practice Type—There were no statistically significant differences between men and women in practice type (P=.1489), including academic/university, hospital based, and solo and group private practice; pay structure (P=.1437), including base salary, collection-based salary, or salary plus incentive; holding a supervisory role (P=.0846); or having ownership of a practice (P=.3565)(eTable). Most respondents were in solo or group private practice (58.2%) and had a component of productivity-based compensation (77.5%). In addition, 62% of private practice dermatologists (133/212) had an ownership interest in their practice. As expected, univariate and multivariate regression analyses showed that practice type, pay structure, supervisory roles, and employee vs ownership roles were significant predictors of income (P<.05)(eTable).

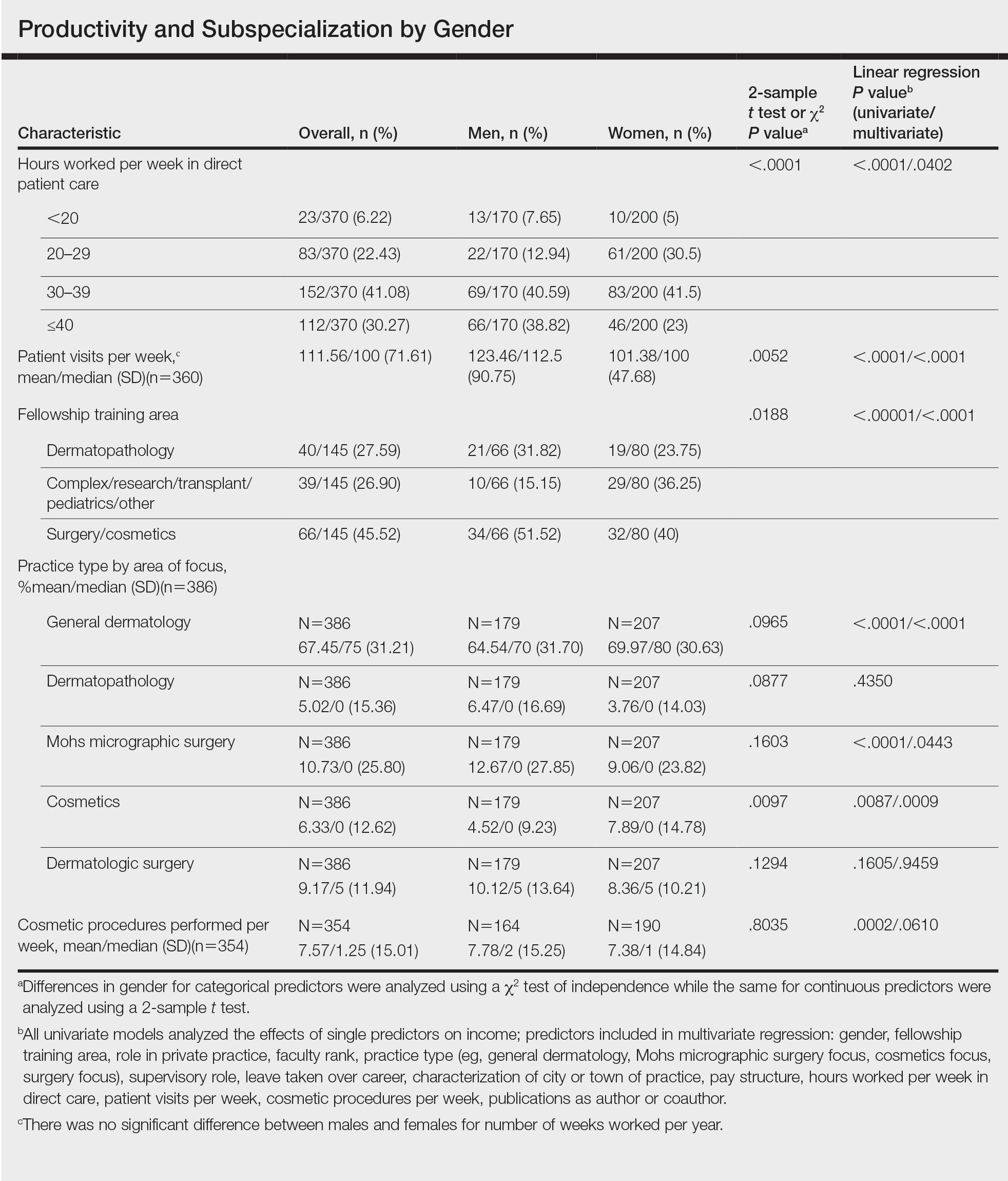

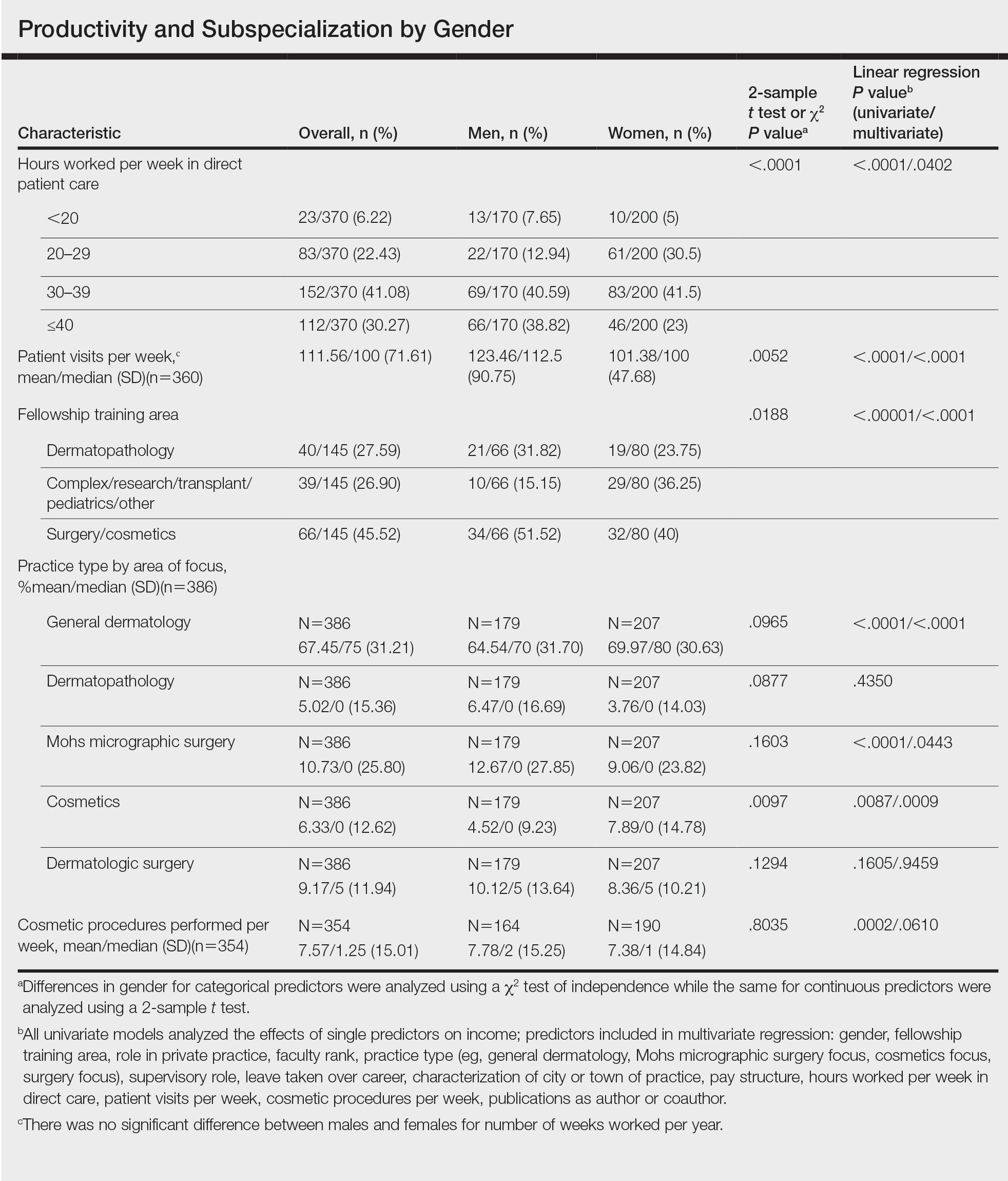

Work Productivity—Statistically significant differences were found between men and women in hours worked per week in direct patient care (P<.0001) and in patient visits per week (P=.0052), with a higher percentage of men working more than 40 hours per week and men seeing an average of approximately 22 more patients per week than women. In the subgroup of all dermatologists working more than 40 hours per week, a statistically significant difference in income persisted between males and females (P=.0001). Hours worked per week and patient visits per week were statistically significant predictors of income on both univariate and multivariate regression analyses (P<.05)(Table).

Education and Fellowship Training—No significant difference existed between males and females in type of undergraduate school attended, namely public or private institutions (P=.1090), but a significant difference existed within type of medical school education, with a higher percentage of females attending private medical schools (53.03%) compared to males (38.24%)(P=.0045). However, type of undergraduate or medical school attended had no impact on income (P=.9103). A higher percentage of males (27.32%) completed additional advanced degrees, such as a master of business administration or a master of public health, compared to females (16.9%)(P=.0122). However, the completion of additional advanced degrees had no significant impact on income (P=.2379). No statistical significance existed between males and females in number of residencies completed (P=.3236), and residencies completed had no significant impact on income (P=.4584).

Of 397 respondents, approximately one-third of respondents completed fellowship training (36.5%). Fellowships included dermatopathology, surgery/cosmetics, and other (encompassing complex medical, research, transplant, and pediatric dermatology). Although similar percentages of men and women completed fellowship training, men and women differed significantly by type of fellowship completed (P=.0188). There were similar rates of dermatopathology and surgical fellowship completion between genders but almost 3 times the number of females who completed other fellowships. Type of fellowship training was a statistically significant predictor of income on both univariate and multivariate regression analyses (P<.00001 and P<.0001, respectively).

Work Activity—Respondents were asked to estimate the amount of time devoted to general dermatology, dermatopathology, Mohs micrographic surgery, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery in their practices (Table). Women devoted a significantly higher average percentage of time to cosmetics (7.89%) compared to men (4.52%)(P=.0097). The number of cosmetic procedures performed per week was not statistically significantly different between men and women (P=.8035) but was a significant factor for income on univariate regression analysis (P=.0002). Time spent performing dermatologic surgery, general dermatology, or Mohs micrographic surgery did not significantly differ between men and women but was found to significantly influence income.

Academic Dermatology—Among the respondents working in academic settings, χ2 analysis identified a significant difference in the faculty rank between males and females, with a tendency for lower academic rank in females (P=.0508). Assistant professorship was comprised of 35% of men vs 51% of women, whereas full professorship consisted of 26% of men but only 13% of women. Academic rank was found to be a significant predictor of income, with higher rank associated with higher income (P<.0001 on univariate regression analysis). However, when adjusting for other factors, academic rank was no longer a significant predictor of income (P=.0840 on multivariate regression analysis). No significant difference existed between men and women in funding received from the National Institutes of Health, conduction of clinical trials, or authorship of scientific publications, and these factors were not found to have a significant impact on income.

Work Leave—Male and female dermatologists showed a statistically significant difference in maternity or Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave taken over their careers, with 56.03% of females reporting leave taken compared to 6.78% of males (P<.0001). Women reported a significantly higher average number of weeks of maternity or FMLA leave taken over their careers (12.92 weeks) compared to men (2.42 weeks) (P<.0001). However, upon univariate regression analysis, whether or not maternity or FMLA leave was taken over their careers (P=.2005), the number of times that maternity or FMLA leave was taken (P=.4350), and weeks of maternity or FMLA leave taken (P=.4057) were all not significant predictors of income.

Comment

This study sought to investigate the relationship between income and gender in dermatology, and our results demonstrated that statistically significant differences in total annual income exist between male and female dermatologists, with male dermatologists earning a significantly higher income, approximately an additional $80,000. Our results are consistent with other studies of US physician income, which have found a gender gap ranging from $13,399 to $82,000 that persists even when controlling for factors such as specialty choice, practice setting, rank and role in practice, work hours, vacation/leave taken, and others.2-7,10-15

There was a significant difference in rank of male and female academic dermatologists, with fewer females at higher academic ranks. These results are consistent with numerous studies in academic dermatology that show underrepresentation of women at higher academic ranks and leadership positions.8,9,16-18 Poor negotiation may contribute to differences in both rank and income.19,20 There are conflicting data on research productivity of academic dermatologists and length of career, first and senior authorship, and quality and academic impact, all of which add complexity to this topic.8,9,12,16-18,20-23Male and female dermatologists reported significant differences in productivity, with male dermatologists working more hours and seeing more patients per week than female dermatologists. These results are consistent with other studies of dermatologists4,24 and other physicians.12 Regardless, gender was still found to have a significant impact on income even when controlling for differences in productivity and FMLA leave taken. These results are consistent with numerous studies of US physicians that found a gender gap in income even when controlling for hours worked.12,23 Although fellowship training as a whole was found to significantly impact income, our results do not characterize whether the impact on income was positive or negative for each type of fellowship. Fellowship training in specialties such as internal medicine or general surgery likewise has variable effects on income.24,25

A comprehensive survey design and significant data elicited from dermatologists working in private practice for the first time served as the main strengths of this study. Limitations included self-reported design, categorical ranges, and limited sample size in subgroups. Future directions include deeper analysis of subgroups, including fellowship-trained dermatologists, dermatologists working more than 40 hours per week, and female dermatologists by race/ethnicity.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that self-reported discrepancies in salary between male and female dermatologists exist, with male dermatologists earning a significantly higher annual salary than their female counterparts. This study identified and stratified several career factors that comprise the broad field and practice of dermatology. Even when controlling for these variations, we have demonstrated that gender alone remains a significant predictor of income, indicating that an unexplained income gap between the 2 genders exists in dermatology.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B-2.2: Total Graduates by U.S. Medical School and Sex, 2015-2016 through 2019-2020. December 3, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/download/321532/data/factstableb2-2.pdf

- Willett LL, Halvorsen AJ, McDonald FS, et al. Gender differences in salary of internal medicine residency directors: a national survey. Am J Med. 2015;128:659-665.

- Weeks WB, Wallace AE, Mackenzie TA. Gender differences in anesthesiologists’ annual incomes. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:806-811.

- Weeks WB, Wallace AE. Gender differences in ophthalmologists’ annual incomes. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1696-1701.

- Singh A, Burke CA, Larive B, et al. Do gender disparities persist in gastroenterology after 10 years of practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1589-1595.

- Desai T, Ali S, Fang X, et al. Equal work for unequal pay: the gender reimbursement gap for healthcare providers in the United States. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92:571-575.

- Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1294-1304.

- John AM, Gupta AB, John ES, et al. A gender-based comparison of promotion and research productivity in academic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt1hx610pf.

- Sadeghpour M, Bernstein I, Ko C, et al. Role of sex in academic dermatology: results from a national survey. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:809-814.

- Gilbert SB, Allshouse A, Skaznik-Wikiel ME. Gender inequality in salaries among reproductive endocrinology and infertility subspecialists in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:1194-1200.

- Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, et al. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307:2410-2417. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.6183

- Apaydin EA, Chen PGC, Friedberg MW, et al. Differences in physician income by gender in a multiregion survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1574-1581.

- Read S, Butkus R, Weissman A, et al. Compensation disparities by gender in internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:658-661.

- Guss ZD, Chen Q, Hu C, et al. Differences in physician compensation between men and women at United States public academic radiation oncology departments. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103:314-319.

- Lo Sasso AT, Richards MR, Chou CF, et al. The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: the unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:193-201.

- Shah A, Jalal S, Khosa F. Influences for gender disparity in dermatology in North America. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:171-176.

- Shi CR, Olbricht S, Vleugels RA, et al. Sex and leadership in academic dermatology: a nationwide survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:782-784.

- Shih AF, Sun W, Yick C, et al. Trends in scholarly productivity of dermatology faculty by academic status and gender. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1774-1776.

- Sarfaty S, Kolb D, Barnett R, et al. Negotiation in academic medicine: a necessary career skill. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16:235-244.

- Jacobson CC, Nguyen JC, Kimball AB. Gender and parenting significantly affect work hours of recent dermatology program graduates. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:191-196.

- Feramisco JD, Leitenberger JJ, Redfern SI, et al. A gender gap in the dermatology literature? Cross-sectional analysis of manuscript authorship trends in dermatology journals during 3 decades. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:63-69.

- Bendels MHK, Dietz MC, Brüggmann D, et al. Gender disparities in high-quality dermatology research: a descriptive bibliometric study on scientific authorships. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020089.

- Seabury SA, Chandra A, Jena AB. Trends in the earnings of male and female health care professionals in the United States, 1987 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1748-1750.

- Baimas-George M, Fleischer B, Slakey D, et al. Is it all about the money? Not all surgical subspecialization leads to higher lifetime revenue when compared to general surgery. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:E62-E66.

- Leigh JP, Tancredi D, Jerant A, et al. Lifetime earnings for physicians across specialties. Med Care. 2012;50:1093-1101.

Although the number of female graduates from US medical schools has steadily increased,1 several studies since the 1970s indicate that a disparity exists in salary, academic rank, and promotion among female and male physicians across multiple specialties.2-8 Proposed explanations include women working fewer hours, having lower productivity rates, undernegotiating compensation, and underbilling for the same services. However, when controlling for variables such as time, experience, specialty, rank, and research activities, this gap unequivocally persists. There are limited data on this topic in dermatology, a field in which women comprise more than half of the working population.6,7 Most analyses of gender disparities in dermatology are based on data primarily from academic dermatologists, which may not be representative of the larger population of dermatologists.8,9 The purpose of this study is to determine if an income disparity exists between male and female physicians in dermatology, including those in private practice and those who are specialty trained.

Methods

Population—We performed a cross-sectional self-reported survey to examine compensation of male and female board-certified dermatologists (MDs/DOs). Several populations of dermatologists were surveyed in August and September 2018. Approximately 20% of the members of the American Academy of Dermatology were randomly selected and sent a link to the survey. Additionally, a survey link was emailed to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. A link to the survey also was published on “The Board Certified Dermatologists” Facebook group.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the distribution of variables overall and within gender (male or female). Not all respondents completed every section, and duplicates and incomplete responses were removed. Variables were compared between genders using t tests (continuous), the Pearson χ2 test (nominal), or the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test (ordinal). For categorical variables with small cell counts, an exact χ2 test for small samples was used. For continuous variables, t test P values were calculated using either pooled or Satterthwaithe approximation.

To analyze the effect of different variables on total income using multivariate and univariate linear regression, the income variable was transformed into a continuous variable by using midpoints of the categories. Univariate linear regression was used to assess the effect and significance of each variable on total annual income. Variables that were found to have a P value of less than .05 (α=.05) were deemed as significant predictors of total annual income. These variables were added to a multivariate linear regression model to determine their effect on income when adjusting for other significant (and approaching significance) factors. In addition, variables that were found to have a P value of less than .2 (α=.05) were added to the multivariate linear regression model to assess significance of these specific variables when adjusting for other factors. In this way, we tested and accounted for a multitude of variables as potential sources of confounding.

Results

Demographics—Our survey was emailed to 3079 members of the American Academy of Dermatology, and 277 responses were received. Approximately 144 additional responses were obtained collectively from links sent to the directories of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and from social media. Of these respondents, 53.65% (213/397) were female and 46.35% (184/397) were male. When stratifying by race/ethnicity, 77.33% identified as White; 13.85% identified as Asian; 6.3% identified as Black or African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American; and 2.52% chose not to respond. Although most male and female respondents were White, a significantly higher proportion of female respondents identified as Asian or Black/African American/Hispanic/Latino/Native American (P=.0006). We found that race/ethnicity did not significantly impact income (P=.2736). All US Census regions were represented in this study, and geographic distribution as well as population density of practice location (ie, rural, suburban, urban setting) did not differ significantly between males and females (P=.5982 and P=.1007, respectively) and did not significantly impact income (P=.3225 and P=.10663, respectively).

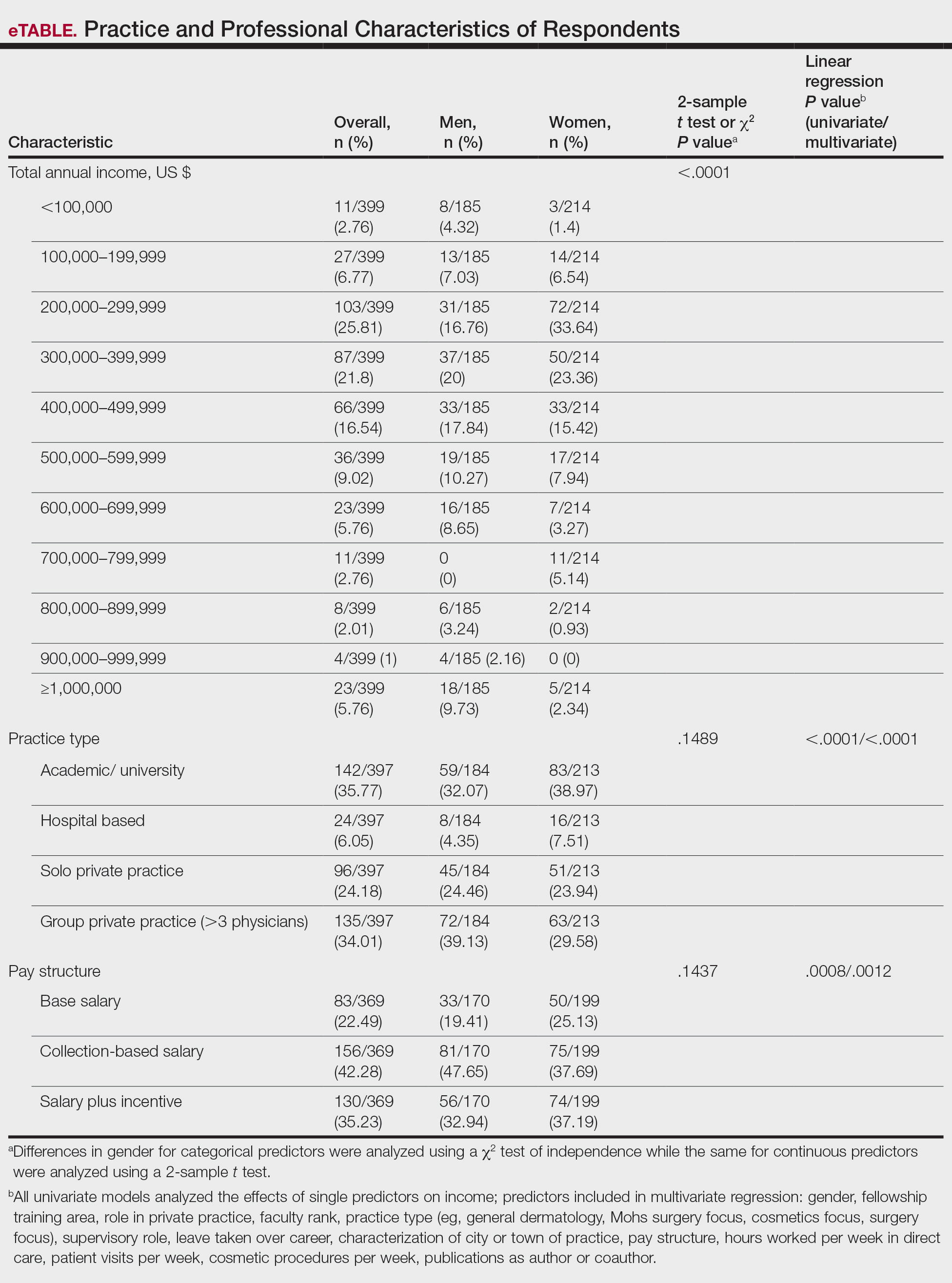

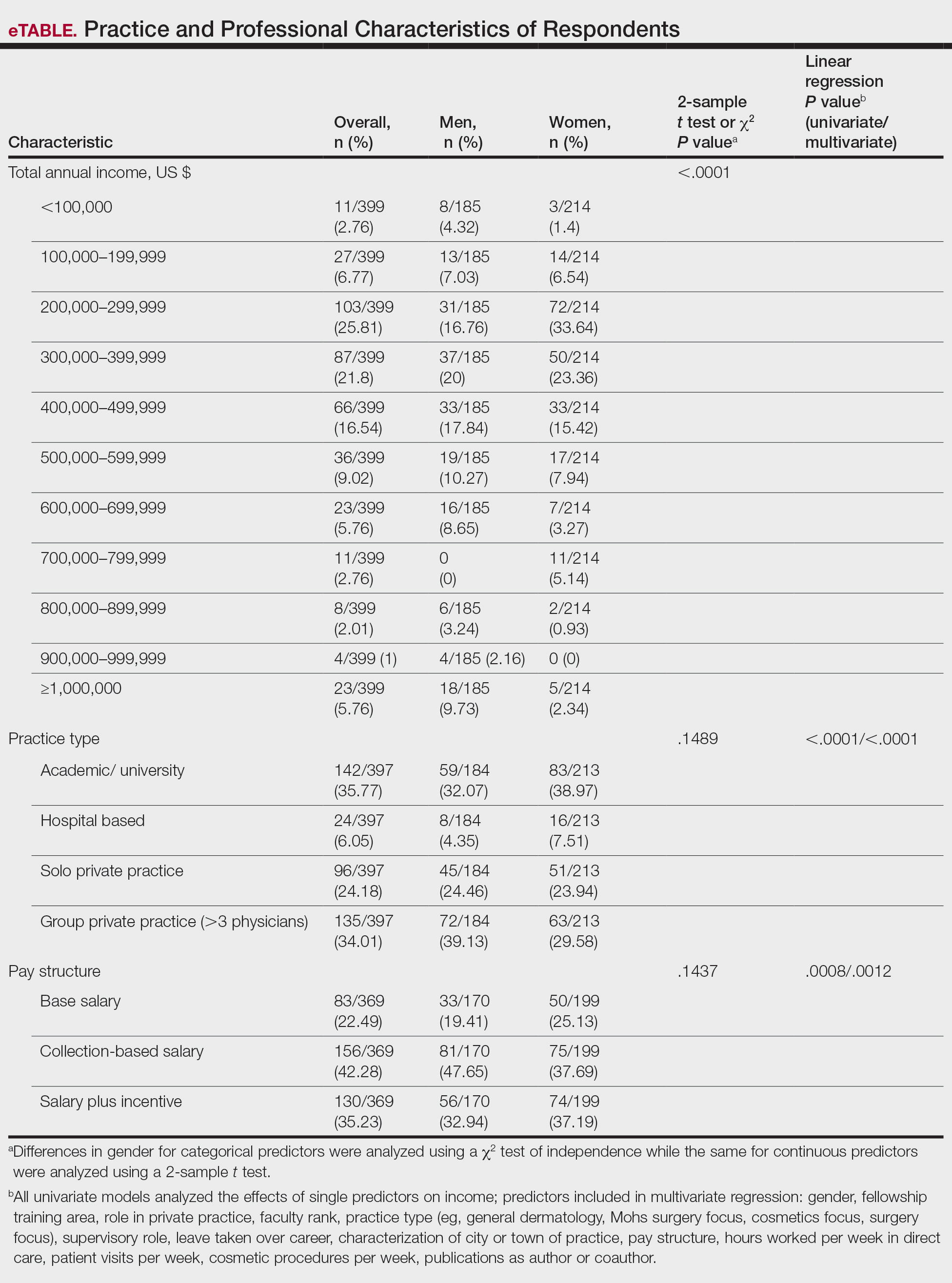

Income—Total annual income was defined as the aggregate sum of all types of financial compensation received in 1 calendar year (eg, salary, bonuses, benefits) and was elicited as an ordinal variable in income brackets of US $100,000. Overall, χ2 analysis showed a statistically significant difference in annual total income between male and female dermatologists (P<.0001), with a higher proportion of males in the highest pay bracket (Figure). Gender remained a statistically significant predictor of income on both univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses (P=.0002 and P<.0001, respectively), indicating that gender has a significant impact on compensation, even after controlling for other variables (eTable). Of note, males in this sample were on average older and in practice longer than females (approximately 6 years, P<.0001). However, when univariate linear regression was performed, both age (P=.8281) and number of years since residency or fellowship completion (P=.8743) were not significant predictors of income.

Practice Type—There were no statistically significant differences between men and women in practice type (P=.1489), including academic/university, hospital based, and solo and group private practice; pay structure (P=.1437), including base salary, collection-based salary, or salary plus incentive; holding a supervisory role (P=.0846); or having ownership of a practice (P=.3565)(eTable). Most respondents were in solo or group private practice (58.2%) and had a component of productivity-based compensation (77.5%). In addition, 62% of private practice dermatologists (133/212) had an ownership interest in their practice. As expected, univariate and multivariate regression analyses showed that practice type, pay structure, supervisory roles, and employee vs ownership roles were significant predictors of income (P<.05)(eTable).

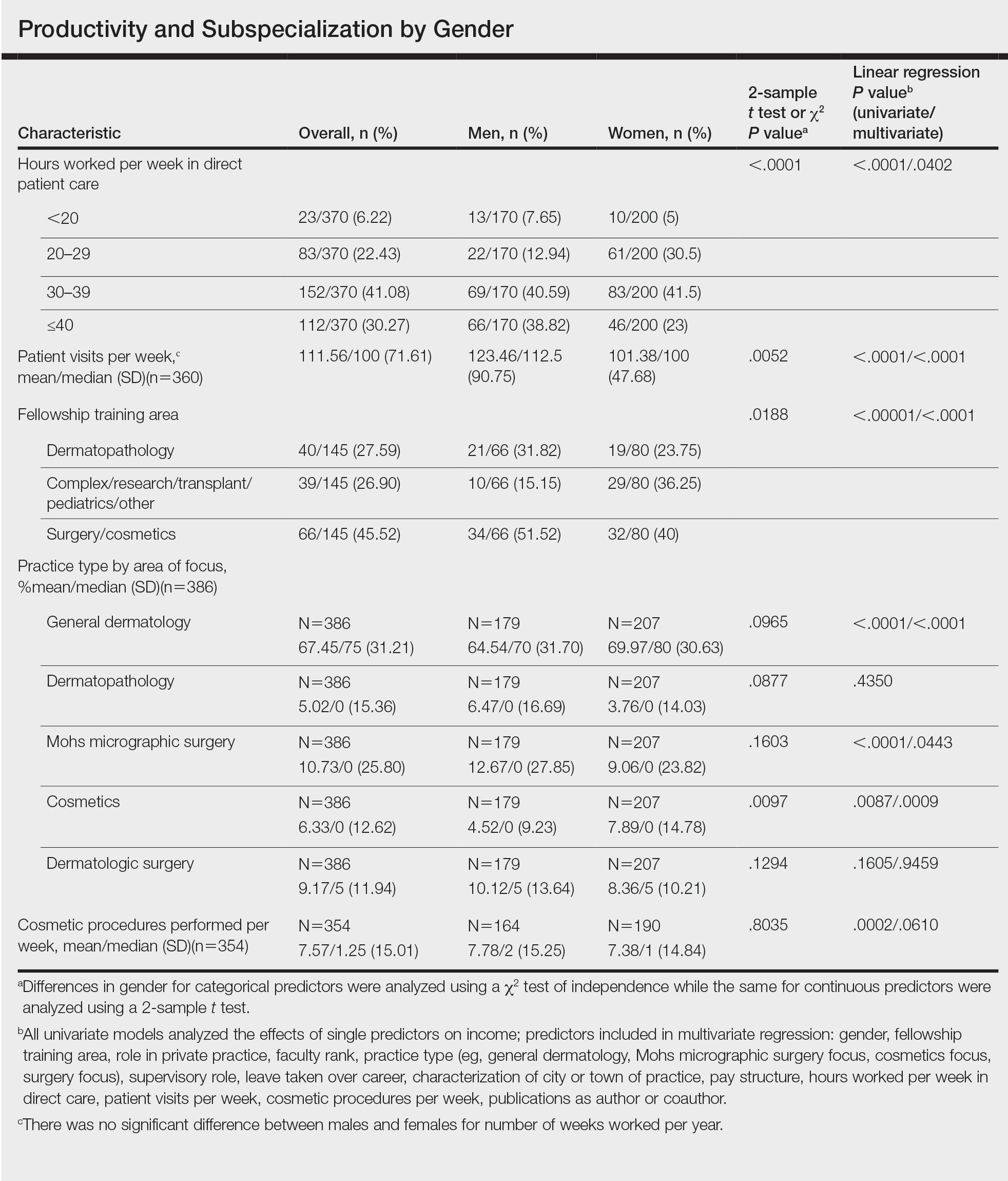

Work Productivity—Statistically significant differences were found between men and women in hours worked per week in direct patient care (P<.0001) and in patient visits per week (P=.0052), with a higher percentage of men working more than 40 hours per week and men seeing an average of approximately 22 more patients per week than women. In the subgroup of all dermatologists working more than 40 hours per week, a statistically significant difference in income persisted between males and females (P=.0001). Hours worked per week and patient visits per week were statistically significant predictors of income on both univariate and multivariate regression analyses (P<.05)(Table).

Education and Fellowship Training—No significant difference existed between males and females in type of undergraduate school attended, namely public or private institutions (P=.1090), but a significant difference existed within type of medical school education, with a higher percentage of females attending private medical schools (53.03%) compared to males (38.24%)(P=.0045). However, type of undergraduate or medical school attended had no impact on income (P=.9103). A higher percentage of males (27.32%) completed additional advanced degrees, such as a master of business administration or a master of public health, compared to females (16.9%)(P=.0122). However, the completion of additional advanced degrees had no significant impact on income (P=.2379). No statistical significance existed between males and females in number of residencies completed (P=.3236), and residencies completed had no significant impact on income (P=.4584).

Of 397 respondents, approximately one-third of respondents completed fellowship training (36.5%). Fellowships included dermatopathology, surgery/cosmetics, and other (encompassing complex medical, research, transplant, and pediatric dermatology). Although similar percentages of men and women completed fellowship training, men and women differed significantly by type of fellowship completed (P=.0188). There were similar rates of dermatopathology and surgical fellowship completion between genders but almost 3 times the number of females who completed other fellowships. Type of fellowship training was a statistically significant predictor of income on both univariate and multivariate regression analyses (P<.00001 and P<.0001, respectively).

Work Activity—Respondents were asked to estimate the amount of time devoted to general dermatology, dermatopathology, Mohs micrographic surgery, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery in their practices (Table). Women devoted a significantly higher average percentage of time to cosmetics (7.89%) compared to men (4.52%)(P=.0097). The number of cosmetic procedures performed per week was not statistically significantly different between men and women (P=.8035) but was a significant factor for income on univariate regression analysis (P=.0002). Time spent performing dermatologic surgery, general dermatology, or Mohs micrographic surgery did not significantly differ between men and women but was found to significantly influence income.

Academic Dermatology—Among the respondents working in academic settings, χ2 analysis identified a significant difference in the faculty rank between males and females, with a tendency for lower academic rank in females (P=.0508). Assistant professorship was comprised of 35% of men vs 51% of women, whereas full professorship consisted of 26% of men but only 13% of women. Academic rank was found to be a significant predictor of income, with higher rank associated with higher income (P<.0001 on univariate regression analysis). However, when adjusting for other factors, academic rank was no longer a significant predictor of income (P=.0840 on multivariate regression analysis). No significant difference existed between men and women in funding received from the National Institutes of Health, conduction of clinical trials, or authorship of scientific publications, and these factors were not found to have a significant impact on income.

Work Leave—Male and female dermatologists showed a statistically significant difference in maternity or Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave taken over their careers, with 56.03% of females reporting leave taken compared to 6.78% of males (P<.0001). Women reported a significantly higher average number of weeks of maternity or FMLA leave taken over their careers (12.92 weeks) compared to men (2.42 weeks) (P<.0001). However, upon univariate regression analysis, whether or not maternity or FMLA leave was taken over their careers (P=.2005), the number of times that maternity or FMLA leave was taken (P=.4350), and weeks of maternity or FMLA leave taken (P=.4057) were all not significant predictors of income.

Comment

This study sought to investigate the relationship between income and gender in dermatology, and our results demonstrated that statistically significant differences in total annual income exist between male and female dermatologists, with male dermatologists earning a significantly higher income, approximately an additional $80,000. Our results are consistent with other studies of US physician income, which have found a gender gap ranging from $13,399 to $82,000 that persists even when controlling for factors such as specialty choice, practice setting, rank and role in practice, work hours, vacation/leave taken, and others.2-7,10-15

There was a significant difference in rank of male and female academic dermatologists, with fewer females at higher academic ranks. These results are consistent with numerous studies in academic dermatology that show underrepresentation of women at higher academic ranks and leadership positions.8,9,16-18 Poor negotiation may contribute to differences in both rank and income.19,20 There are conflicting data on research productivity of academic dermatologists and length of career, first and senior authorship, and quality and academic impact, all of which add complexity to this topic.8,9,12,16-18,20-23Male and female dermatologists reported significant differences in productivity, with male dermatologists working more hours and seeing more patients per week than female dermatologists. These results are consistent with other studies of dermatologists4,24 and other physicians.12 Regardless, gender was still found to have a significant impact on income even when controlling for differences in productivity and FMLA leave taken. These results are consistent with numerous studies of US physicians that found a gender gap in income even when controlling for hours worked.12,23 Although fellowship training as a whole was found to significantly impact income, our results do not characterize whether the impact on income was positive or negative for each type of fellowship. Fellowship training in specialties such as internal medicine or general surgery likewise has variable effects on income.24,25

A comprehensive survey design and significant data elicited from dermatologists working in private practice for the first time served as the main strengths of this study. Limitations included self-reported design, categorical ranges, and limited sample size in subgroups. Future directions include deeper analysis of subgroups, including fellowship-trained dermatologists, dermatologists working more than 40 hours per week, and female dermatologists by race/ethnicity.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that self-reported discrepancies in salary between male and female dermatologists exist, with male dermatologists earning a significantly higher annual salary than their female counterparts. This study identified and stratified several career factors that comprise the broad field and practice of dermatology. Even when controlling for these variations, we have demonstrated that gender alone remains a significant predictor of income, indicating that an unexplained income gap between the 2 genders exists in dermatology.

Although the number of female graduates from US medical schools has steadily increased,1 several studies since the 1970s indicate that a disparity exists in salary, academic rank, and promotion among female and male physicians across multiple specialties.2-8 Proposed explanations include women working fewer hours, having lower productivity rates, undernegotiating compensation, and underbilling for the same services. However, when controlling for variables such as time, experience, specialty, rank, and research activities, this gap unequivocally persists. There are limited data on this topic in dermatology, a field in which women comprise more than half of the working population.6,7 Most analyses of gender disparities in dermatology are based on data primarily from academic dermatologists, which may not be representative of the larger population of dermatologists.8,9 The purpose of this study is to determine if an income disparity exists between male and female physicians in dermatology, including those in private practice and those who are specialty trained.

Methods

Population—We performed a cross-sectional self-reported survey to examine compensation of male and female board-certified dermatologists (MDs/DOs). Several populations of dermatologists were surveyed in August and September 2018. Approximately 20% of the members of the American Academy of Dermatology were randomly selected and sent a link to the survey. Additionally, a survey link was emailed to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. A link to the survey also was published on “The Board Certified Dermatologists” Facebook group.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the distribution of variables overall and within gender (male or female). Not all respondents completed every section, and duplicates and incomplete responses were removed. Variables were compared between genders using t tests (continuous), the Pearson χ2 test (nominal), or the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test (ordinal). For categorical variables with small cell counts, an exact χ2 test for small samples was used. For continuous variables, t test P values were calculated using either pooled or Satterthwaithe approximation.

To analyze the effect of different variables on total income using multivariate and univariate linear regression, the income variable was transformed into a continuous variable by using midpoints of the categories. Univariate linear regression was used to assess the effect and significance of each variable on total annual income. Variables that were found to have a P value of less than .05 (α=.05) were deemed as significant predictors of total annual income. These variables were added to a multivariate linear regression model to determine their effect on income when adjusting for other significant (and approaching significance) factors. In addition, variables that were found to have a P value of less than .2 (α=.05) were added to the multivariate linear regression model to assess significance of these specific variables when adjusting for other factors. In this way, we tested and accounted for a multitude of variables as potential sources of confounding.

Results

Demographics—Our survey was emailed to 3079 members of the American Academy of Dermatology, and 277 responses were received. Approximately 144 additional responses were obtained collectively from links sent to the directories of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and from social media. Of these respondents, 53.65% (213/397) were female and 46.35% (184/397) were male. When stratifying by race/ethnicity, 77.33% identified as White; 13.85% identified as Asian; 6.3% identified as Black or African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American; and 2.52% chose not to respond. Although most male and female respondents were White, a significantly higher proportion of female respondents identified as Asian or Black/African American/Hispanic/Latino/Native American (P=.0006). We found that race/ethnicity did not significantly impact income (P=.2736). All US Census regions were represented in this study, and geographic distribution as well as population density of practice location (ie, rural, suburban, urban setting) did not differ significantly between males and females (P=.5982 and P=.1007, respectively) and did not significantly impact income (P=.3225 and P=.10663, respectively).

Income—Total annual income was defined as the aggregate sum of all types of financial compensation received in 1 calendar year (eg, salary, bonuses, benefits) and was elicited as an ordinal variable in income brackets of US $100,000. Overall, χ2 analysis showed a statistically significant difference in annual total income between male and female dermatologists (P<.0001), with a higher proportion of males in the highest pay bracket (Figure). Gender remained a statistically significant predictor of income on both univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses (P=.0002 and P<.0001, respectively), indicating that gender has a significant impact on compensation, even after controlling for other variables (eTable). Of note, males in this sample were on average older and in practice longer than females (approximately 6 years, P<.0001). However, when univariate linear regression was performed, both age (P=.8281) and number of years since residency or fellowship completion (P=.8743) were not significant predictors of income.

Practice Type—There were no statistically significant differences between men and women in practice type (P=.1489), including academic/university, hospital based, and solo and group private practice; pay structure (P=.1437), including base salary, collection-based salary, or salary plus incentive; holding a supervisory role (P=.0846); or having ownership of a practice (P=.3565)(eTable). Most respondents were in solo or group private practice (58.2%) and had a component of productivity-based compensation (77.5%). In addition, 62% of private practice dermatologists (133/212) had an ownership interest in their practice. As expected, univariate and multivariate regression analyses showed that practice type, pay structure, supervisory roles, and employee vs ownership roles were significant predictors of income (P<.05)(eTable).

Work Productivity—Statistically significant differences were found between men and women in hours worked per week in direct patient care (P<.0001) and in patient visits per week (P=.0052), with a higher percentage of men working more than 40 hours per week and men seeing an average of approximately 22 more patients per week than women. In the subgroup of all dermatologists working more than 40 hours per week, a statistically significant difference in income persisted between males and females (P=.0001). Hours worked per week and patient visits per week were statistically significant predictors of income on both univariate and multivariate regression analyses (P<.05)(Table).

Education and Fellowship Training—No significant difference existed between males and females in type of undergraduate school attended, namely public or private institutions (P=.1090), but a significant difference existed within type of medical school education, with a higher percentage of females attending private medical schools (53.03%) compared to males (38.24%)(P=.0045). However, type of undergraduate or medical school attended had no impact on income (P=.9103). A higher percentage of males (27.32%) completed additional advanced degrees, such as a master of business administration or a master of public health, compared to females (16.9%)(P=.0122). However, the completion of additional advanced degrees had no significant impact on income (P=.2379). No statistical significance existed between males and females in number of residencies completed (P=.3236), and residencies completed had no significant impact on income (P=.4584).

Of 397 respondents, approximately one-third of respondents completed fellowship training (36.5%). Fellowships included dermatopathology, surgery/cosmetics, and other (encompassing complex medical, research, transplant, and pediatric dermatology). Although similar percentages of men and women completed fellowship training, men and women differed significantly by type of fellowship completed (P=.0188). There were similar rates of dermatopathology and surgical fellowship completion between genders but almost 3 times the number of females who completed other fellowships. Type of fellowship training was a statistically significant predictor of income on both univariate and multivariate regression analyses (P<.00001 and P<.0001, respectively).

Work Activity—Respondents were asked to estimate the amount of time devoted to general dermatology, dermatopathology, Mohs micrographic surgery, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery in their practices (Table). Women devoted a significantly higher average percentage of time to cosmetics (7.89%) compared to men (4.52%)(P=.0097). The number of cosmetic procedures performed per week was not statistically significantly different between men and women (P=.8035) but was a significant factor for income on univariate regression analysis (P=.0002). Time spent performing dermatologic surgery, general dermatology, or Mohs micrographic surgery did not significantly differ between men and women but was found to significantly influence income.

Academic Dermatology—Among the respondents working in academic settings, χ2 analysis identified a significant difference in the faculty rank between males and females, with a tendency for lower academic rank in females (P=.0508). Assistant professorship was comprised of 35% of men vs 51% of women, whereas full professorship consisted of 26% of men but only 13% of women. Academic rank was found to be a significant predictor of income, with higher rank associated with higher income (P<.0001 on univariate regression analysis). However, when adjusting for other factors, academic rank was no longer a significant predictor of income (P=.0840 on multivariate regression analysis). No significant difference existed between men and women in funding received from the National Institutes of Health, conduction of clinical trials, or authorship of scientific publications, and these factors were not found to have a significant impact on income.

Work Leave—Male and female dermatologists showed a statistically significant difference in maternity or Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave taken over their careers, with 56.03% of females reporting leave taken compared to 6.78% of males (P<.0001). Women reported a significantly higher average number of weeks of maternity or FMLA leave taken over their careers (12.92 weeks) compared to men (2.42 weeks) (P<.0001). However, upon univariate regression analysis, whether or not maternity or FMLA leave was taken over their careers (P=.2005), the number of times that maternity or FMLA leave was taken (P=.4350), and weeks of maternity or FMLA leave taken (P=.4057) were all not significant predictors of income.

Comment

This study sought to investigate the relationship between income and gender in dermatology, and our results demonstrated that statistically significant differences in total annual income exist between male and female dermatologists, with male dermatologists earning a significantly higher income, approximately an additional $80,000. Our results are consistent with other studies of US physician income, which have found a gender gap ranging from $13,399 to $82,000 that persists even when controlling for factors such as specialty choice, practice setting, rank and role in practice, work hours, vacation/leave taken, and others.2-7,10-15

There was a significant difference in rank of male and female academic dermatologists, with fewer females at higher academic ranks. These results are consistent with numerous studies in academic dermatology that show underrepresentation of women at higher academic ranks and leadership positions.8,9,16-18 Poor negotiation may contribute to differences in both rank and income.19,20 There are conflicting data on research productivity of academic dermatologists and length of career, first and senior authorship, and quality and academic impact, all of which add complexity to this topic.8,9,12,16-18,20-23Male and female dermatologists reported significant differences in productivity, with male dermatologists working more hours and seeing more patients per week than female dermatologists. These results are consistent with other studies of dermatologists4,24 and other physicians.12 Regardless, gender was still found to have a significant impact on income even when controlling for differences in productivity and FMLA leave taken. These results are consistent with numerous studies of US physicians that found a gender gap in income even when controlling for hours worked.12,23 Although fellowship training as a whole was found to significantly impact income, our results do not characterize whether the impact on income was positive or negative for each type of fellowship. Fellowship training in specialties such as internal medicine or general surgery likewise has variable effects on income.24,25

A comprehensive survey design and significant data elicited from dermatologists working in private practice for the first time served as the main strengths of this study. Limitations included self-reported design, categorical ranges, and limited sample size in subgroups. Future directions include deeper analysis of subgroups, including fellowship-trained dermatologists, dermatologists working more than 40 hours per week, and female dermatologists by race/ethnicity.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that self-reported discrepancies in salary between male and female dermatologists exist, with male dermatologists earning a significantly higher annual salary than their female counterparts. This study identified and stratified several career factors that comprise the broad field and practice of dermatology. Even when controlling for these variations, we have demonstrated that gender alone remains a significant predictor of income, indicating that an unexplained income gap between the 2 genders exists in dermatology.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B-2.2: Total Graduates by U.S. Medical School and Sex, 2015-2016 through 2019-2020. December 3, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/download/321532/data/factstableb2-2.pdf

- Willett LL, Halvorsen AJ, McDonald FS, et al. Gender differences in salary of internal medicine residency directors: a national survey. Am J Med. 2015;128:659-665.

- Weeks WB, Wallace AE, Mackenzie TA. Gender differences in anesthesiologists’ annual incomes. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:806-811.

- Weeks WB, Wallace AE. Gender differences in ophthalmologists’ annual incomes. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1696-1701.

- Singh A, Burke CA, Larive B, et al. Do gender disparities persist in gastroenterology after 10 years of practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1589-1595.

- Desai T, Ali S, Fang X, et al. Equal work for unequal pay: the gender reimbursement gap for healthcare providers in the United States. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92:571-575.

- Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1294-1304.

- John AM, Gupta AB, John ES, et al. A gender-based comparison of promotion and research productivity in academic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt1hx610pf.

- Sadeghpour M, Bernstein I, Ko C, et al. Role of sex in academic dermatology: results from a national survey. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:809-814.

- Gilbert SB, Allshouse A, Skaznik-Wikiel ME. Gender inequality in salaries among reproductive endocrinology and infertility subspecialists in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:1194-1200.

- Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, et al. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307:2410-2417. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.6183

- Apaydin EA, Chen PGC, Friedberg MW, et al. Differences in physician income by gender in a multiregion survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1574-1581.

- Read S, Butkus R, Weissman A, et al. Compensation disparities by gender in internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:658-661.

- Guss ZD, Chen Q, Hu C, et al. Differences in physician compensation between men and women at United States public academic radiation oncology departments. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103:314-319.

- Lo Sasso AT, Richards MR, Chou CF, et al. The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: the unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:193-201.

- Shah A, Jalal S, Khosa F. Influences for gender disparity in dermatology in North America. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:171-176.

- Shi CR, Olbricht S, Vleugels RA, et al. Sex and leadership in academic dermatology: a nationwide survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:782-784.

- Shih AF, Sun W, Yick C, et al. Trends in scholarly productivity of dermatology faculty by academic status and gender. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1774-1776.

- Sarfaty S, Kolb D, Barnett R, et al. Negotiation in academic medicine: a necessary career skill. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16:235-244.

- Jacobson CC, Nguyen JC, Kimball AB. Gender and parenting significantly affect work hours of recent dermatology program graduates. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:191-196.

- Feramisco JD, Leitenberger JJ, Redfern SI, et al. A gender gap in the dermatology literature? Cross-sectional analysis of manuscript authorship trends in dermatology journals during 3 decades. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:63-69.

- Bendels MHK, Dietz MC, Brüggmann D, et al. Gender disparities in high-quality dermatology research: a descriptive bibliometric study on scientific authorships. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020089.

- Seabury SA, Chandra A, Jena AB. Trends in the earnings of male and female health care professionals in the United States, 1987 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1748-1750.

- Baimas-George M, Fleischer B, Slakey D, et al. Is it all about the money? Not all surgical subspecialization leads to higher lifetime revenue when compared to general surgery. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:E62-E66.

- Leigh JP, Tancredi D, Jerant A, et al. Lifetime earnings for physicians across specialties. Med Care. 2012;50:1093-1101.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B-2.2: Total Graduates by U.S. Medical School and Sex, 2015-2016 through 2019-2020. December 3, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/download/321532/data/factstableb2-2.pdf

- Willett LL, Halvorsen AJ, McDonald FS, et al. Gender differences in salary of internal medicine residency directors: a national survey. Am J Med. 2015;128:659-665.

- Weeks WB, Wallace AE, Mackenzie TA. Gender differences in anesthesiologists’ annual incomes. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:806-811.

- Weeks WB, Wallace AE. Gender differences in ophthalmologists’ annual incomes. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1696-1701.

- Singh A, Burke CA, Larive B, et al. Do gender disparities persist in gastroenterology after 10 years of practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1589-1595.

- Desai T, Ali S, Fang X, et al. Equal work for unequal pay: the gender reimbursement gap for healthcare providers in the United States. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92:571-575.

- Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1294-1304.

- John AM, Gupta AB, John ES, et al. A gender-based comparison of promotion and research productivity in academic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt1hx610pf.

- Sadeghpour M, Bernstein I, Ko C, et al. Role of sex in academic dermatology: results from a national survey. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:809-814.

- Gilbert SB, Allshouse A, Skaznik-Wikiel ME. Gender inequality in salaries among reproductive endocrinology and infertility subspecialists in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:1194-1200.

- Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, et al. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307:2410-2417. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.6183

- Apaydin EA, Chen PGC, Friedberg MW, et al. Differences in physician income by gender in a multiregion survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1574-1581.

- Read S, Butkus R, Weissman A, et al. Compensation disparities by gender in internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:658-661.

- Guss ZD, Chen Q, Hu C, et al. Differences in physician compensation between men and women at United States public academic radiation oncology departments. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103:314-319.

- Lo Sasso AT, Richards MR, Chou CF, et al. The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: the unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:193-201.

- Shah A, Jalal S, Khosa F. Influences for gender disparity in dermatology in North America. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:171-176.

- Shi CR, Olbricht S, Vleugels RA, et al. Sex and leadership in academic dermatology: a nationwide survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:782-784.

- Shih AF, Sun W, Yick C, et al. Trends in scholarly productivity of dermatology faculty by academic status and gender. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1774-1776.

- Sarfaty S, Kolb D, Barnett R, et al. Negotiation in academic medicine: a necessary career skill. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16:235-244.

- Jacobson CC, Nguyen JC, Kimball AB. Gender and parenting significantly affect work hours of recent dermatology program graduates. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:191-196.

- Feramisco JD, Leitenberger JJ, Redfern SI, et al. A gender gap in the dermatology literature? Cross-sectional analysis of manuscript authorship trends in dermatology journals during 3 decades. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:63-69.

- Bendels MHK, Dietz MC, Brüggmann D, et al. Gender disparities in high-quality dermatology research: a descriptive bibliometric study on scientific authorships. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020089.

- Seabury SA, Chandra A, Jena AB. Trends in the earnings of male and female health care professionals in the United States, 1987 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1748-1750.

- Baimas-George M, Fleischer B, Slakey D, et al. Is it all about the money? Not all surgical subspecialization leads to higher lifetime revenue when compared to general surgery. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:E62-E66.

- Leigh JP, Tancredi D, Jerant A, et al. Lifetime earnings for physicians across specialties. Med Care. 2012;50:1093-1101.

Practice Points

- In this survey-based cross-sectional study, a statistically significant income disparity between male and female dermatologists was found.

- Although several differences were identified between male and female dermatologists that contribute to income, gender remained a statistically significant predictor of income, and this disparity could not be explained by other factors.

Sickle cell raises risk for stillbirth

Both sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease were significantly associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, based on data from more than 50,000 women.

Pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD) are at increased risk of complications, including stillbirth, but many women with the disease in the United States lack access to specialty care, Silvia P. Canelón, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote. Sickle cell trait (SCT), defined as one abnormal allele of the hemoglobin gene, is not considered a disease state because many carriers are asymptomatic, and therefore even less likely to be assessed for potential complications. “However, it is possible for people with SCT to experience sickling of red blood cells under severe hypoxia, dehydration, and hyperthermia. This condition can lead to severe medical complications for sickle cell carriers, including fetal loss, splenic infarction, exercise-related sudden death, and others,” they noted.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 63,334 deliveries in 50,560 women between Jan. 1, 2010, and Aug. 15, 2017, at four quaternary academic medical centers in Pennsylvania. Of these, 1,904 had SCT but not SCD, and 164 had SCD. The mean age of the women was 29.5 years, and approximately 56% were single at the time of delivery. A majority (87%) of the study population was Rhesus-factor positive, 47.0% were Black or African American, 33.7% were White, and 45.2% had ABO blood type O.

Risk factors for stillbirth used in the analysis included SCD, numbers of pain crises and blood transfusions before delivery, delivery episode (to represent parity), history of cesarean delivery, multiple gestation, age, marital status, race and ethnicity, ABO blood type, Rhesus factor, and year of delivery.

Overall, the prevalence of stillbirth in women with SCT was 1.1%, compared with 0.8% in the general study population, and was significantly associated with increased risk of stillbirth after controlling for multiple risk factors. The adjusted odds ratio was 8.94 for stillbirth risk in women with SCT, compared with women without SCT (P = .045), although the risk was greater among women with SCD, compared with those without SCD (aOR, 26.40).

“In addition, the stratified analysis found Black or African American patients with SCD to be at higher risk of stillbirth, compared with Black or African American patients without SCD (aOR, 3.59),” but no significant association was noted between stillbirth and SCT, the researchers wrote. Stillbirth rates were 1.1% in Black or African American women overall, 2.7% in those with SCD, and 1.0% in those with SCT. Overall, multiple gestation was associated with an increased risk of stillbirth (aOR, 4.68), while a history of cesarean delivery and being married at the time of delivery were associated with decreased risk (aOR, 0.44 and 0.72, respectively).

The lack of association between stillbirth and SCT in Black or African American patients supports some previous research, but contradicts other studies, the researchers wrote. “Ultimately, it may be impossible to disentangle the risks due to the disease and those due to disparities associated with the disease that have resulted from longstanding inequity and stigma,” they said. The findings also suggest that biological mechanisms of SCT may contribute to severe clinical complications, and therefore “invite a more critical examination of the assumption that SCT is not a disease state.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of assessment of SCT independent of other comorbidities, such as hypertension, preeclampsia, diabetes, and obesity, and by the use of billing codes that could misclassify patients, the researchers noted.

However, the results support some findings from previous studies of the potential health complications for pregnant SCT patients. The large study population highlights the need to identify women’s SCT status during obstetric care, and to provide both pregnancy guidance for SCT patients and systemic support of comprehensive care for SCD and SCT patients, they concluded.

Disparities may drive stillbirth in sickle cell trait women

“There is a paucity of research evaluating sickle cell trait and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as stillbirth,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Prior studies evaluating the risk of stillbirth have yielded mixed results, and an increased risk of stillbirth in women with sickle cell trait has not been established. This study is unique in that it attempts to address how racial inequities and health disparities may contribute to risk of stillbirth in women with sickle cell trait.”

Although the study findings suggest an increased risk of stillbirth in women with sickle cell trait, an analysis stratified for Black or African American patients showed no association, Dr. Krishna said. “The prevalence of stillbirth was noted to be 1% among Black or African American patients with sickle cell trait compared to the prevalence of stillbirth of 1.1% among Black or African American women with no sickle cell trait or disease. Although, sickle cell trait or sickle cell disease can be found in any racial or ethnic group, it disproportionately affects Black or African Americans, with a sickle cell trait carrier rate of approximately 1 in 10. The mixed findings in this study amongst racial/ethnic groups further suggest that there is more research needed before an association between stillbirth and sickle cell trait can be supported.”

As for clinical implications, “it is well established that for women with sickle cell trait there is an increased risk of urinary tract infections in pregnancy,” said Dr. Krishna. “Women with sickle cell trait should have a urine culture performed at their first prenatal visit and each trimester. At this time, studies evaluating risk of stillbirth in women with sickle cell trait have yielded conflicting results, and current consensus is that women with sickle cell trait are not at increased risk. In comparison, women with sickle cell disease are at increased risk for stillbirth and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Women with sickle cell disease should be followed closely during pregnancy and fetal surveillance implemented at 32 weeks, if not sooner, to reduce risk of stillbirth.

“Prior studies evaluating risk of stillbirth in women with sickle cell trait consist of retrospective cohorts with small study populations,” Dr. Krishna added. Notably, the current study was limited by the inability to adjust for comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, that are not only associated with an increased risk for stillbirth, but also disproportionately common among Black women.

“More studies are needed evaluating the relationship between these comorbidities as well as studies specifically evaluating how race affects care and pregnancy outcomes,” Dr. Krisha emphasized.

The study was funded by the University of Pennsylvania department of biostatistics, epidemiology, and informatics. Lead author Dr. Canelón disclosed grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Clinical and Translational Science Awards, and grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

Both sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease were significantly associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, based on data from more than 50,000 women.

Pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD) are at increased risk of complications, including stillbirth, but many women with the disease in the United States lack access to specialty care, Silvia P. Canelón, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote. Sickle cell trait (SCT), defined as one abnormal allele of the hemoglobin gene, is not considered a disease state because many carriers are asymptomatic, and therefore even less likely to be assessed for potential complications. “However, it is possible for people with SCT to experience sickling of red blood cells under severe hypoxia, dehydration, and hyperthermia. This condition can lead to severe medical complications for sickle cell carriers, including fetal loss, splenic infarction, exercise-related sudden death, and others,” they noted.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 63,334 deliveries in 50,560 women between Jan. 1, 2010, and Aug. 15, 2017, at four quaternary academic medical centers in Pennsylvania. Of these, 1,904 had SCT but not SCD, and 164 had SCD. The mean age of the women was 29.5 years, and approximately 56% were single at the time of delivery. A majority (87%) of the study population was Rhesus-factor positive, 47.0% were Black or African American, 33.7% were White, and 45.2% had ABO blood type O.