User login

Accelerated approval now full for pembro in bladder cancer

But one such accelerated approval has now been converted to a full approval, with a small label change, by the Food and Drug Administration.

The new full approval is for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for first-line use for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC) who are not eligible for any platinum-containing chemotherapy. (The small label change is that mention of PD-L1 status and testing for this have been removed.)

The move is in accordance with recommendations by experts at a recent meeting of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee. They voted 5-3 in favor of this accelerated approval staying. They also voted 10-1 in favor of another immunotherapy, atezolizumab (Tecentriq), for the same indication.

One of the arguments put forward to support these accelerated approvals staying in place is that there is an unmet need in this population of patients who are ineligible for platinum chemotherapy.

But this argument doesn’t hold water – the mere existence of one of these negates the “unmet need” argument for the other, wrote Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., in a commentary on why the FDA’s accelerated approval pathway is broken.

“Even if there is a genuine ‘unmet need’ in a particular setting, these drugs did not meet the standard of improving survival. An unmet need doesn’t imply that the treatment void should be filled with a drug that provides nothing of value to patients,” Dr. Gyawali wrote.

“When we talk about an unmet need, we are speaking of drugs that provide a clinical benefit; any true unmet needs will continue to exist despite maintaining these approvals,” he argued.

After obtaining the accelerated approval for pembrolizumab for patients with bladder cancer who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy, the manufacturer (Merck) carried out a subsequent clinical trial but conducted it in patients who were eligible for platinum-containing chemotherapy (KEYNOTE-361). However, this trial did not meet its prespecified dual primary endpoints of overall survival or progression-free survival in comparison with standard of care chemotherapy, the company noted in a press release.

“We are working with urgency to advance studies to help more patients living with bladder and other types of cancer,” commented Scot Ebbinghaus, MD, vice president of clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories. The company said it has “an extensive clinical development in bladder cancer” and is exploring pembrolizumab use in many settings.

In addition to the new full approval for the first-line indication for patients who are ineligible for platinum chemotherapy, pembrolizumab has two other approved indications in this therapeutic area: the treatment of patients with locally advanced urothelial carcinoma or mUC who experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy; and the treatment of patients with bacillus Calmette-Guérin–unresponsive, high-risk, non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer with carcinoma in situ, with or without papillary tumors, who are ineligible for or have elected not to undergo cystectomy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

But one such accelerated approval has now been converted to a full approval, with a small label change, by the Food and Drug Administration.

The new full approval is for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for first-line use for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC) who are not eligible for any platinum-containing chemotherapy. (The small label change is that mention of PD-L1 status and testing for this have been removed.)

The move is in accordance with recommendations by experts at a recent meeting of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee. They voted 5-3 in favor of this accelerated approval staying. They also voted 10-1 in favor of another immunotherapy, atezolizumab (Tecentriq), for the same indication.

One of the arguments put forward to support these accelerated approvals staying in place is that there is an unmet need in this population of patients who are ineligible for platinum chemotherapy.

But this argument doesn’t hold water – the mere existence of one of these negates the “unmet need” argument for the other, wrote Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., in a commentary on why the FDA’s accelerated approval pathway is broken.

“Even if there is a genuine ‘unmet need’ in a particular setting, these drugs did not meet the standard of improving survival. An unmet need doesn’t imply that the treatment void should be filled with a drug that provides nothing of value to patients,” Dr. Gyawali wrote.

“When we talk about an unmet need, we are speaking of drugs that provide a clinical benefit; any true unmet needs will continue to exist despite maintaining these approvals,” he argued.

After obtaining the accelerated approval for pembrolizumab for patients with bladder cancer who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy, the manufacturer (Merck) carried out a subsequent clinical trial but conducted it in patients who were eligible for platinum-containing chemotherapy (KEYNOTE-361). However, this trial did not meet its prespecified dual primary endpoints of overall survival or progression-free survival in comparison with standard of care chemotherapy, the company noted in a press release.

“We are working with urgency to advance studies to help more patients living with bladder and other types of cancer,” commented Scot Ebbinghaus, MD, vice president of clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories. The company said it has “an extensive clinical development in bladder cancer” and is exploring pembrolizumab use in many settings.

In addition to the new full approval for the first-line indication for patients who are ineligible for platinum chemotherapy, pembrolizumab has two other approved indications in this therapeutic area: the treatment of patients with locally advanced urothelial carcinoma or mUC who experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy; and the treatment of patients with bacillus Calmette-Guérin–unresponsive, high-risk, non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer with carcinoma in situ, with or without papillary tumors, who are ineligible for or have elected not to undergo cystectomy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

But one such accelerated approval has now been converted to a full approval, with a small label change, by the Food and Drug Administration.

The new full approval is for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for first-line use for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC) who are not eligible for any platinum-containing chemotherapy. (The small label change is that mention of PD-L1 status and testing for this have been removed.)

The move is in accordance with recommendations by experts at a recent meeting of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee. They voted 5-3 in favor of this accelerated approval staying. They also voted 10-1 in favor of another immunotherapy, atezolizumab (Tecentriq), for the same indication.

One of the arguments put forward to support these accelerated approvals staying in place is that there is an unmet need in this population of patients who are ineligible for platinum chemotherapy.

But this argument doesn’t hold water – the mere existence of one of these negates the “unmet need” argument for the other, wrote Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., in a commentary on why the FDA’s accelerated approval pathway is broken.

“Even if there is a genuine ‘unmet need’ in a particular setting, these drugs did not meet the standard of improving survival. An unmet need doesn’t imply that the treatment void should be filled with a drug that provides nothing of value to patients,” Dr. Gyawali wrote.

“When we talk about an unmet need, we are speaking of drugs that provide a clinical benefit; any true unmet needs will continue to exist despite maintaining these approvals,” he argued.

After obtaining the accelerated approval for pembrolizumab for patients with bladder cancer who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy, the manufacturer (Merck) carried out a subsequent clinical trial but conducted it in patients who were eligible for platinum-containing chemotherapy (KEYNOTE-361). However, this trial did not meet its prespecified dual primary endpoints of overall survival or progression-free survival in comparison with standard of care chemotherapy, the company noted in a press release.

“We are working with urgency to advance studies to help more patients living with bladder and other types of cancer,” commented Scot Ebbinghaus, MD, vice president of clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories. The company said it has “an extensive clinical development in bladder cancer” and is exploring pembrolizumab use in many settings.

In addition to the new full approval for the first-line indication for patients who are ineligible for platinum chemotherapy, pembrolizumab has two other approved indications in this therapeutic area: the treatment of patients with locally advanced urothelial carcinoma or mUC who experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy; and the treatment of patients with bacillus Calmette-Guérin–unresponsive, high-risk, non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer with carcinoma in situ, with or without papillary tumors, who are ineligible for or have elected not to undergo cystectomy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Old saying about prostate cancer not true when it’s metastatic

.

The findings fill an information gap because, remarkably, “data are lacking” on causes of death among men whose prostate cancer has spread to other sites, say lead author Ahmed Elmehrath, MD, of Cairo University, Egypt, and colleagues.

“It was an important realization by our team that prostate cancer was the cause of death in 78% of patients,” said senior author Omar Alhalabi, MD, of University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, in an email.

“Most patients with metastatic prostate cancer die from it, rather than other possible causes of death,” confirm Samuel Merriel, MSc, Tanimola Martins, PhD, and Sarah Bailey, PhD, University of Exeter, United Kingdom, in an accompanying editorial. The study was published last month in JAMA Network Open.

The findings represent the near opposite of a commonly held – and comforting – belief about early-stage disease: “You die with prostate cancer, not from it.”

That old saying is articulated in various ways, such as this from the Prostate Cancer Foundation: “We can confirm that there are those prostate cancers a man may die with and not of, while others are very aggressive.” The American Cancer Society says this: “Prostate cancer can be a serious disease, but most men diagnosed with prostate cancer do not die from it.”

However, these commonplace comments do not cover metastatic disease, which is what the authors of the new study decided to focus on.

The team used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) database to gather a sample of 26,168 U.S. men who received a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer from January 2000 to December 2016. They then analyzed the data in 2020 and found that 16,732 men (64%) had died during the follow-up period.

The majority of these deaths (77.8%) were from prostate cancer, 5.5% were from other cancers, and 16.7% were from noncancer causes, including cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cerebrovascular diseases.

Senior author Dr. Alhalabi acknowledged a limitation in these findings – that the SEER database relies on causes of death extracted from death certificates. “Death certificates have limited granularity in terms of the details they can contain about the cause of death and also have reporting bias,” he said.

Most of the prostate cancer deaths (59%) occurred within 2 years. The 5-year overall survival rate in the study group was 26%.

The deadliness of metastatic disease “reinforces the need for innovations to promote early-stage diagnosis,” comment the editorialists. Striking a hopeful note, they also say that “new tests for prostate cancer detection may reduce the proportion of patients who receive a diagnosis at a late stage.”

Death from other causes

The mean age at metastatic prostate cancer diagnosis in the study was roughly 71 years. Most of the cohort was White (74.5%) and had a diagnosis of stage M1b metastatic prostate cancer (72.7%), which means the cancer had spread to the bones.

Among men in the cohort, the rates of death from septicemia, suicide, accidents, COPD, and cerebrovascular diseases were significantly increased compared with the general U.S. male population, the team observes.

Thus, the study authors were concerned with not only with death from metastatic prostate cancer but death from other causes.

That concern is rooted in the established fact that there is now improved survival among patients with prostate cancer in the U.S., including among men with advanced disease. “Patients tend to live long enough after a prostate cancer diagnosis for non–cancer-related comorbidities to be associated with their overall survival,” they write.

The editorialists agree: Prostate cancer “has a high long-term survival rate compared with almost all other cancer types and signals the need for greater holistic care for patients.”

As noted above, cardiovascular diseases were the most common cause of nonprostate cancer–related deaths in the new study.

As in the management of other cancers, there is concern among clinicians and researchers about the cardiotoxic effects of prostate cancer treatments.

The study authors point to a 2017 analysis that showed that men with prostate cancer and no prior cardiac disease had greater risk of heart failure after taking androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), a common treatment used when the disease recurs after definitive treatment. Another study suggested an association between cardiotoxic effects of ADT and myocardial infarction regardless of medical history in general.

The authors of the current study say that such findings highlight “the importance of multidisciplinary care for such patients and the role of primary care physicians in optimizing cardiovascular risk prevention and providing early referrals to cardiologists.”

Further, the team says that tailoring “ADT to each patient’s needs may be associated with improved survival, especially for patients with factors associated with cardiovascular disease.”

Who should lead the way in multidisciplinary care? “The answer probably is case-by-case,” said Dr. Alhalabi, adding that it might depend on the presence of underlying morbidities such as cardiovascular disease and COPD.

“It is also important for the oncologist (‘the gatekeeper’) to try to mitigate the potential metabolic effects of hormonal deprivation therapy such as weight gain, decreased muscle mass, hyperlipidemia, etc.,” he added.

The study had no specific funding. The study authors and editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

The findings fill an information gap because, remarkably, “data are lacking” on causes of death among men whose prostate cancer has spread to other sites, say lead author Ahmed Elmehrath, MD, of Cairo University, Egypt, and colleagues.

“It was an important realization by our team that prostate cancer was the cause of death in 78% of patients,” said senior author Omar Alhalabi, MD, of University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, in an email.

“Most patients with metastatic prostate cancer die from it, rather than other possible causes of death,” confirm Samuel Merriel, MSc, Tanimola Martins, PhD, and Sarah Bailey, PhD, University of Exeter, United Kingdom, in an accompanying editorial. The study was published last month in JAMA Network Open.

The findings represent the near opposite of a commonly held – and comforting – belief about early-stage disease: “You die with prostate cancer, not from it.”

That old saying is articulated in various ways, such as this from the Prostate Cancer Foundation: “We can confirm that there are those prostate cancers a man may die with and not of, while others are very aggressive.” The American Cancer Society says this: “Prostate cancer can be a serious disease, but most men diagnosed with prostate cancer do not die from it.”

However, these commonplace comments do not cover metastatic disease, which is what the authors of the new study decided to focus on.

The team used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) database to gather a sample of 26,168 U.S. men who received a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer from January 2000 to December 2016. They then analyzed the data in 2020 and found that 16,732 men (64%) had died during the follow-up period.

The majority of these deaths (77.8%) were from prostate cancer, 5.5% were from other cancers, and 16.7% were from noncancer causes, including cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cerebrovascular diseases.

Senior author Dr. Alhalabi acknowledged a limitation in these findings – that the SEER database relies on causes of death extracted from death certificates. “Death certificates have limited granularity in terms of the details they can contain about the cause of death and also have reporting bias,” he said.

Most of the prostate cancer deaths (59%) occurred within 2 years. The 5-year overall survival rate in the study group was 26%.

The deadliness of metastatic disease “reinforces the need for innovations to promote early-stage diagnosis,” comment the editorialists. Striking a hopeful note, they also say that “new tests for prostate cancer detection may reduce the proportion of patients who receive a diagnosis at a late stage.”

Death from other causes

The mean age at metastatic prostate cancer diagnosis in the study was roughly 71 years. Most of the cohort was White (74.5%) and had a diagnosis of stage M1b metastatic prostate cancer (72.7%), which means the cancer had spread to the bones.

Among men in the cohort, the rates of death from septicemia, suicide, accidents, COPD, and cerebrovascular diseases were significantly increased compared with the general U.S. male population, the team observes.

Thus, the study authors were concerned with not only with death from metastatic prostate cancer but death from other causes.

That concern is rooted in the established fact that there is now improved survival among patients with prostate cancer in the U.S., including among men with advanced disease. “Patients tend to live long enough after a prostate cancer diagnosis for non–cancer-related comorbidities to be associated with their overall survival,” they write.

The editorialists agree: Prostate cancer “has a high long-term survival rate compared with almost all other cancer types and signals the need for greater holistic care for patients.”

As noted above, cardiovascular diseases were the most common cause of nonprostate cancer–related deaths in the new study.

As in the management of other cancers, there is concern among clinicians and researchers about the cardiotoxic effects of prostate cancer treatments.

The study authors point to a 2017 analysis that showed that men with prostate cancer and no prior cardiac disease had greater risk of heart failure after taking androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), a common treatment used when the disease recurs after definitive treatment. Another study suggested an association between cardiotoxic effects of ADT and myocardial infarction regardless of medical history in general.

The authors of the current study say that such findings highlight “the importance of multidisciplinary care for such patients and the role of primary care physicians in optimizing cardiovascular risk prevention and providing early referrals to cardiologists.”

Further, the team says that tailoring “ADT to each patient’s needs may be associated with improved survival, especially for patients with factors associated with cardiovascular disease.”

Who should lead the way in multidisciplinary care? “The answer probably is case-by-case,” said Dr. Alhalabi, adding that it might depend on the presence of underlying morbidities such as cardiovascular disease and COPD.

“It is also important for the oncologist (‘the gatekeeper’) to try to mitigate the potential metabolic effects of hormonal deprivation therapy such as weight gain, decreased muscle mass, hyperlipidemia, etc.,” he added.

The study had no specific funding. The study authors and editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

The findings fill an information gap because, remarkably, “data are lacking” on causes of death among men whose prostate cancer has spread to other sites, say lead author Ahmed Elmehrath, MD, of Cairo University, Egypt, and colleagues.

“It was an important realization by our team that prostate cancer was the cause of death in 78% of patients,” said senior author Omar Alhalabi, MD, of University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, in an email.

“Most patients with metastatic prostate cancer die from it, rather than other possible causes of death,” confirm Samuel Merriel, MSc, Tanimola Martins, PhD, and Sarah Bailey, PhD, University of Exeter, United Kingdom, in an accompanying editorial. The study was published last month in JAMA Network Open.

The findings represent the near opposite of a commonly held – and comforting – belief about early-stage disease: “You die with prostate cancer, not from it.”

That old saying is articulated in various ways, such as this from the Prostate Cancer Foundation: “We can confirm that there are those prostate cancers a man may die with and not of, while others are very aggressive.” The American Cancer Society says this: “Prostate cancer can be a serious disease, but most men diagnosed with prostate cancer do not die from it.”

However, these commonplace comments do not cover metastatic disease, which is what the authors of the new study decided to focus on.

The team used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) database to gather a sample of 26,168 U.S. men who received a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer from January 2000 to December 2016. They then analyzed the data in 2020 and found that 16,732 men (64%) had died during the follow-up period.

The majority of these deaths (77.8%) were from prostate cancer, 5.5% were from other cancers, and 16.7% were from noncancer causes, including cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cerebrovascular diseases.

Senior author Dr. Alhalabi acknowledged a limitation in these findings – that the SEER database relies on causes of death extracted from death certificates. “Death certificates have limited granularity in terms of the details they can contain about the cause of death and also have reporting bias,” he said.

Most of the prostate cancer deaths (59%) occurred within 2 years. The 5-year overall survival rate in the study group was 26%.

The deadliness of metastatic disease “reinforces the need for innovations to promote early-stage diagnosis,” comment the editorialists. Striking a hopeful note, they also say that “new tests for prostate cancer detection may reduce the proportion of patients who receive a diagnosis at a late stage.”

Death from other causes

The mean age at metastatic prostate cancer diagnosis in the study was roughly 71 years. Most of the cohort was White (74.5%) and had a diagnosis of stage M1b metastatic prostate cancer (72.7%), which means the cancer had spread to the bones.

Among men in the cohort, the rates of death from septicemia, suicide, accidents, COPD, and cerebrovascular diseases were significantly increased compared with the general U.S. male population, the team observes.

Thus, the study authors were concerned with not only with death from metastatic prostate cancer but death from other causes.

That concern is rooted in the established fact that there is now improved survival among patients with prostate cancer in the U.S., including among men with advanced disease. “Patients tend to live long enough after a prostate cancer diagnosis for non–cancer-related comorbidities to be associated with their overall survival,” they write.

The editorialists agree: Prostate cancer “has a high long-term survival rate compared with almost all other cancer types and signals the need for greater holistic care for patients.”

As noted above, cardiovascular diseases were the most common cause of nonprostate cancer–related deaths in the new study.

As in the management of other cancers, there is concern among clinicians and researchers about the cardiotoxic effects of prostate cancer treatments.

The study authors point to a 2017 analysis that showed that men with prostate cancer and no prior cardiac disease had greater risk of heart failure after taking androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), a common treatment used when the disease recurs after definitive treatment. Another study suggested an association between cardiotoxic effects of ADT and myocardial infarction regardless of medical history in general.

The authors of the current study say that such findings highlight “the importance of multidisciplinary care for such patients and the role of primary care physicians in optimizing cardiovascular risk prevention and providing early referrals to cardiologists.”

Further, the team says that tailoring “ADT to each patient’s needs may be associated with improved survival, especially for patients with factors associated with cardiovascular disease.”

Who should lead the way in multidisciplinary care? “The answer probably is case-by-case,” said Dr. Alhalabi, adding that it might depend on the presence of underlying morbidities such as cardiovascular disease and COPD.

“It is also important for the oncologist (‘the gatekeeper’) to try to mitigate the potential metabolic effects of hormonal deprivation therapy such as weight gain, decreased muscle mass, hyperlipidemia, etc.,” he added.

The study had no specific funding. The study authors and editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Dawn of a new era’ in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma

according to expert opinion.

The high hopes have been generated by results from the randomized, phase 3 KEYNOTE-564 trial, showing that monotherapy with pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) was associated with significantly longer disease-free survival (DFS) after nephrectomy than placebo (77.3% vs. 68.1%, respectively). Median follow-up was 24 months.

The results come from the trial’s first interim analysis of data from 994 patients with clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) at high risk of recurrence.

For the pembrolizumab group, the estimated percentage alive at 24 months was 96.6%, compared with 93.5% in the placebo group (hazard ratio for death, 0.54), said Toni Choueiri, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and colleagues.

However, grade 3 or higher adverse events (any cause) occurred at almost twice the rate in the pembrolizumab versus the placebo group (32.4% vs. 17.7%). The new study was published online Aug. 18, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study results were first presented at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting and described as likely to be practice changing in this setting, as reported by this news organization.

Currently, this patient population has “no options for adjuvant therapy to reduce the risk of recurrence that have high levels of supporting evidence,” observed the authors.

That’s about to change, as the trial results “herald the dawn of a new era in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma,” Rana McKay, MD, University of California San Diego Health, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Multiple studies have investigated potential adjuvant therapies in RCC since the 1980s, she observed.

“For the first time, we now have an effective adjuvant immunotherapy option for patients with resected renal cell carcinoma at high risk of recurrence,” Dr. McKay said in an interview.

To date, the lack of clinically beneficial adjuvant therapy options in RCC has been “humbling,” Dr. Choueiri said in an interview. “We hope we can push the envelope further and get more patients with RCC some good options that make them live longer and better.”

Although the standard of care for patients diagnosed with locoregional RCC is partial or total nephrectomy, nearly half of patients eventually experience disease recurrence following surgery, Dr. Choueiri noted.

“No standard, globally approved adjuvant therapy options are currently available for this population,” he said. Clinical guidelines recommend patients at high risk of disease recurrence after surgery be entered into a clinical trial or undergo active surveillance.

Researchers will continue to follow the results for overall survival, a secondary endpoint. “The very early look suggests encouraging results [in overall survival] with an HR of 0.54,” Dr. Choueiri noted.

In the meantime, the prolongation of DFS represents a clear clinical benefit, said Dr. McKay, “given the magnitude of the increase” and “the limited incidence of toxic effects.”

KEYNOTE-564 will alter the adjuvant treatment landscape for RCC as a positive phase 3 trial of adjuvant immunotherapy for the disease, she added.

A number of earlier studies have investigated the use of adjuvant vascular endothelial growth factor–targeting agents in RCC. Only the 2016 Sunitinib Treatment of Renal Adjuvant Cancer (S-TRAC) trial showed improved DFS with sunitinib, compared with placebo (6.8 vs. 5.6 years). Subsequently, sunitinib was approved for adjuvant use in the United States. However, the S-TRAC trial also showed that sunitinib therapy was associated with an increased incidence of toxic effects and lower quality of life scores, and researchers did not observe any benefit in overall survival.

“Despite regulatory approval in the U.S., sunitinib is not approved for adjuvant use by the European Medicines Agency and has limited utilization in clinical practice given the low benefit-risk ratio,” Dr. McKay pointed out.

Study details

KEYNOTE-564 involved 996 patients with clear-cell RCC at high risk for recurrence after nephrectomy, with or without metastasectomy. They were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive a 200-mg dose of adjuvant pembrolizumab or placebo given intravenously once every 3 weeks for up to 17 cycles for approximately 1 year.

The vast majority of patients enrolled in the study had localized disease with no evidence of metastases (M0) and intermediate to high or high risk of disease recurrence after partial or complete nephrectomy. However, 5.8% of patients in both the pembrolizumab and placebo groups had M1 NED (metastatic stage 1, no evidence of disease) status after nephrectomy and resection of metastatic lesions. These patients were also at intermediate to high or high risk of recurrence.

The benefit of pembrolizumab, compared with placebo, was maintained in this subgroup, said the investigators. “At this point, we continue to look at the data, but we know that there was a benefit for DFS in the population we included,” said Dr. Choueiri. “When we looked at several subgroups such as PD-L1 status, geography, gender, performance status, M0/M1, all HRs were less than 1 suggesting benefit from pembrolizumab over placebo.”

“Subset analyses by stage are going to be important to determine which group of patients will derive the most benefit,” asserted Dr. McKay. “While those with M1 NED appear to derive benefit with HR for DFS of 0.29, those with M1 NED comprise a small percentage of patient enrolled in the trial.”

Studies exploring tissue- and blood-based biomarkers, including circulating tumor DNA, will be key to identify patients at highest risk for recurrence or adjuvant treatment, Dr. McKay emphasized. “The adoption of adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors brings along new questions regarding patient selection, therapeutic use in patients with non–clear-cell renal cell carcinoma, and systemic treatment after recurrence during or after the receipt of adjuvant therapy.”

KEYNOTE-564 was funded by Merck. Multiple study authors including Dr. Choueiri have financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry, including Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to expert opinion.

The high hopes have been generated by results from the randomized, phase 3 KEYNOTE-564 trial, showing that monotherapy with pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) was associated with significantly longer disease-free survival (DFS) after nephrectomy than placebo (77.3% vs. 68.1%, respectively). Median follow-up was 24 months.

The results come from the trial’s first interim analysis of data from 994 patients with clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) at high risk of recurrence.

For the pembrolizumab group, the estimated percentage alive at 24 months was 96.6%, compared with 93.5% in the placebo group (hazard ratio for death, 0.54), said Toni Choueiri, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and colleagues.

However, grade 3 or higher adverse events (any cause) occurred at almost twice the rate in the pembrolizumab versus the placebo group (32.4% vs. 17.7%). The new study was published online Aug. 18, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study results were first presented at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting and described as likely to be practice changing in this setting, as reported by this news organization.

Currently, this patient population has “no options for adjuvant therapy to reduce the risk of recurrence that have high levels of supporting evidence,” observed the authors.

That’s about to change, as the trial results “herald the dawn of a new era in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma,” Rana McKay, MD, University of California San Diego Health, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Multiple studies have investigated potential adjuvant therapies in RCC since the 1980s, she observed.

“For the first time, we now have an effective adjuvant immunotherapy option for patients with resected renal cell carcinoma at high risk of recurrence,” Dr. McKay said in an interview.

To date, the lack of clinically beneficial adjuvant therapy options in RCC has been “humbling,” Dr. Choueiri said in an interview. “We hope we can push the envelope further and get more patients with RCC some good options that make them live longer and better.”

Although the standard of care for patients diagnosed with locoregional RCC is partial or total nephrectomy, nearly half of patients eventually experience disease recurrence following surgery, Dr. Choueiri noted.

“No standard, globally approved adjuvant therapy options are currently available for this population,” he said. Clinical guidelines recommend patients at high risk of disease recurrence after surgery be entered into a clinical trial or undergo active surveillance.

Researchers will continue to follow the results for overall survival, a secondary endpoint. “The very early look suggests encouraging results [in overall survival] with an HR of 0.54,” Dr. Choueiri noted.

In the meantime, the prolongation of DFS represents a clear clinical benefit, said Dr. McKay, “given the magnitude of the increase” and “the limited incidence of toxic effects.”

KEYNOTE-564 will alter the adjuvant treatment landscape for RCC as a positive phase 3 trial of adjuvant immunotherapy for the disease, she added.

A number of earlier studies have investigated the use of adjuvant vascular endothelial growth factor–targeting agents in RCC. Only the 2016 Sunitinib Treatment of Renal Adjuvant Cancer (S-TRAC) trial showed improved DFS with sunitinib, compared with placebo (6.8 vs. 5.6 years). Subsequently, sunitinib was approved for adjuvant use in the United States. However, the S-TRAC trial also showed that sunitinib therapy was associated with an increased incidence of toxic effects and lower quality of life scores, and researchers did not observe any benefit in overall survival.

“Despite regulatory approval in the U.S., sunitinib is not approved for adjuvant use by the European Medicines Agency and has limited utilization in clinical practice given the low benefit-risk ratio,” Dr. McKay pointed out.

Study details

KEYNOTE-564 involved 996 patients with clear-cell RCC at high risk for recurrence after nephrectomy, with or without metastasectomy. They were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive a 200-mg dose of adjuvant pembrolizumab or placebo given intravenously once every 3 weeks for up to 17 cycles for approximately 1 year.

The vast majority of patients enrolled in the study had localized disease with no evidence of metastases (M0) and intermediate to high or high risk of disease recurrence after partial or complete nephrectomy. However, 5.8% of patients in both the pembrolizumab and placebo groups had M1 NED (metastatic stage 1, no evidence of disease) status after nephrectomy and resection of metastatic lesions. These patients were also at intermediate to high or high risk of recurrence.

The benefit of pembrolizumab, compared with placebo, was maintained in this subgroup, said the investigators. “At this point, we continue to look at the data, but we know that there was a benefit for DFS in the population we included,” said Dr. Choueiri. “When we looked at several subgroups such as PD-L1 status, geography, gender, performance status, M0/M1, all HRs were less than 1 suggesting benefit from pembrolizumab over placebo.”

“Subset analyses by stage are going to be important to determine which group of patients will derive the most benefit,” asserted Dr. McKay. “While those with M1 NED appear to derive benefit with HR for DFS of 0.29, those with M1 NED comprise a small percentage of patient enrolled in the trial.”

Studies exploring tissue- and blood-based biomarkers, including circulating tumor DNA, will be key to identify patients at highest risk for recurrence or adjuvant treatment, Dr. McKay emphasized. “The adoption of adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors brings along new questions regarding patient selection, therapeutic use in patients with non–clear-cell renal cell carcinoma, and systemic treatment after recurrence during or after the receipt of adjuvant therapy.”

KEYNOTE-564 was funded by Merck. Multiple study authors including Dr. Choueiri have financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry, including Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to expert opinion.

The high hopes have been generated by results from the randomized, phase 3 KEYNOTE-564 trial, showing that monotherapy with pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) was associated with significantly longer disease-free survival (DFS) after nephrectomy than placebo (77.3% vs. 68.1%, respectively). Median follow-up was 24 months.

The results come from the trial’s first interim analysis of data from 994 patients with clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) at high risk of recurrence.

For the pembrolizumab group, the estimated percentage alive at 24 months was 96.6%, compared with 93.5% in the placebo group (hazard ratio for death, 0.54), said Toni Choueiri, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and colleagues.

However, grade 3 or higher adverse events (any cause) occurred at almost twice the rate in the pembrolizumab versus the placebo group (32.4% vs. 17.7%). The new study was published online Aug. 18, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study results were first presented at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting and described as likely to be practice changing in this setting, as reported by this news organization.

Currently, this patient population has “no options for adjuvant therapy to reduce the risk of recurrence that have high levels of supporting evidence,” observed the authors.

That’s about to change, as the trial results “herald the dawn of a new era in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma,” Rana McKay, MD, University of California San Diego Health, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Multiple studies have investigated potential adjuvant therapies in RCC since the 1980s, she observed.

“For the first time, we now have an effective adjuvant immunotherapy option for patients with resected renal cell carcinoma at high risk of recurrence,” Dr. McKay said in an interview.

To date, the lack of clinically beneficial adjuvant therapy options in RCC has been “humbling,” Dr. Choueiri said in an interview. “We hope we can push the envelope further and get more patients with RCC some good options that make them live longer and better.”

Although the standard of care for patients diagnosed with locoregional RCC is partial or total nephrectomy, nearly half of patients eventually experience disease recurrence following surgery, Dr. Choueiri noted.

“No standard, globally approved adjuvant therapy options are currently available for this population,” he said. Clinical guidelines recommend patients at high risk of disease recurrence after surgery be entered into a clinical trial or undergo active surveillance.

Researchers will continue to follow the results for overall survival, a secondary endpoint. “The very early look suggests encouraging results [in overall survival] with an HR of 0.54,” Dr. Choueiri noted.

In the meantime, the prolongation of DFS represents a clear clinical benefit, said Dr. McKay, “given the magnitude of the increase” and “the limited incidence of toxic effects.”

KEYNOTE-564 will alter the adjuvant treatment landscape for RCC as a positive phase 3 trial of adjuvant immunotherapy for the disease, she added.

A number of earlier studies have investigated the use of adjuvant vascular endothelial growth factor–targeting agents in RCC. Only the 2016 Sunitinib Treatment of Renal Adjuvant Cancer (S-TRAC) trial showed improved DFS with sunitinib, compared with placebo (6.8 vs. 5.6 years). Subsequently, sunitinib was approved for adjuvant use in the United States. However, the S-TRAC trial also showed that sunitinib therapy was associated with an increased incidence of toxic effects and lower quality of life scores, and researchers did not observe any benefit in overall survival.

“Despite regulatory approval in the U.S., sunitinib is not approved for adjuvant use by the European Medicines Agency and has limited utilization in clinical practice given the low benefit-risk ratio,” Dr. McKay pointed out.

Study details

KEYNOTE-564 involved 996 patients with clear-cell RCC at high risk for recurrence after nephrectomy, with or without metastasectomy. They were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive a 200-mg dose of adjuvant pembrolizumab or placebo given intravenously once every 3 weeks for up to 17 cycles for approximately 1 year.

The vast majority of patients enrolled in the study had localized disease with no evidence of metastases (M0) and intermediate to high or high risk of disease recurrence after partial or complete nephrectomy. However, 5.8% of patients in both the pembrolizumab and placebo groups had M1 NED (metastatic stage 1, no evidence of disease) status after nephrectomy and resection of metastatic lesions. These patients were also at intermediate to high or high risk of recurrence.

The benefit of pembrolizumab, compared with placebo, was maintained in this subgroup, said the investigators. “At this point, we continue to look at the data, but we know that there was a benefit for DFS in the population we included,” said Dr. Choueiri. “When we looked at several subgroups such as PD-L1 status, geography, gender, performance status, M0/M1, all HRs were less than 1 suggesting benefit from pembrolizumab over placebo.”

“Subset analyses by stage are going to be important to determine which group of patients will derive the most benefit,” asserted Dr. McKay. “While those with M1 NED appear to derive benefit with HR for DFS of 0.29, those with M1 NED comprise a small percentage of patient enrolled in the trial.”

Studies exploring tissue- and blood-based biomarkers, including circulating tumor DNA, will be key to identify patients at highest risk for recurrence or adjuvant treatment, Dr. McKay emphasized. “The adoption of adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors brings along new questions regarding patient selection, therapeutic use in patients with non–clear-cell renal cell carcinoma, and systemic treatment after recurrence during or after the receipt of adjuvant therapy.”

KEYNOTE-564 was funded by Merck. Multiple study authors including Dr. Choueiri have financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry, including Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although inconclusive, CV safety study of cancer therapy attracts attention

The first global trial to compare the cardiovascular (CV) safety of two therapies for prostate cancer proved inconclusive because of inadequate enrollment and events, but the study is a harbinger of growth in the emerging specialty of cardio-oncology, according to experts.

“Many new cancer agents have extended patient survival, yet some of these agents have significant potential cardiovascular toxicity,” said Renato D. Lopes, MD, in presenting a study at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In the context of improving survival in patients with or at risk for both cancer and cardiovascular disease, he suggested that the prostate cancer study he led could be “a model for interdisciplinary collaboration” needed to address the relative and sometimes competing risks of these disease states.

This point was seconded by several pioneers in cardio-oncology who participated in the discussion of the results of the trial, called PRONOUNCE.

“We know many drugs in oncology increase cardiovascular risk, so these are the types of trials we need,” according Thomas M. Suter, MD, who leads the cardio-oncology service at the University Hospital, Berne, Switzerland. He was the ESC-invited discussant for PRONOUNCE.

More than 100 centers in 12 countries involved

In PRONOUNCE, 545 patients with prostate cancer and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease were randomized to degarelix, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist, or leuprolide, a GnRH agonist. The patients were enrolled at 113 participating centers in 12 countries. All of the patients had an indication for an androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT).

In numerous previous studies, “ADT has been associated with higher CV morbidity and mortality, particularly in men with preexisting CV disease,” explained Dr. Lopes, but the relative cardiovascular safety of GnRH agonists relative to GnRH antagonists has been “controversial.”

The PRONOUNCE study was designed to resolve this issue, but the study was terminated early because of slow enrollment (not related to the COVID-19 pandemic). The planned enrollment was 900 patients.

In addition, the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, or death, was lower over the course of follow-up than anticipated in the study design.

No significant difference on primary endpoint

At the end of 12 months, MACE occurred in 11 (4.1%) of patients randomized to leuprolide and 15 (5.5%) of those randomized to degarelix. The greater hazard ratio for MACE in the degarelix group did not approach statistical significance (hazard ratio, 1.28; P = .53).

As a result, the question of the relative CV safety of these drugs “remains unresolved,” according to Dr. Lopes, professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

This does not diminish the need to answer this question. In the addition to the fact that cancer is a malignancy primarily of advancing age when CV disease is prevalent – the mean age in this study was 73 years and 44% were over age 75 – it is often an indolent disease with long periods of survival, according to Dr. Lopes. About half of prostate cancer patients have concomitant CV disease, and about half will receive ADT at some point in their treatment.

In patients receiving ADT, leuprolide is far more commonly used than GnRH antagonists, which are offered in only about 4% of patients, according to data cited by Dr. Lopes. The underlying hypothesis of this study was that leuprolide is associated with greater CV risk, which might have been relevant to a risk-benefit calculation, if the hypothesis had been confirmed.

Cancer drugs can increase CV risk

Based on experimental data, “there is concern the leuprolide is involved in plaque destabilization,” said Dr. Lopes, but he noted that ADTs in general are associated with adverse metabolic changes, including increases in LDL cholesterol, insulin resistance, and body fat, all of which could be relevant to CV risk.

It is the improving rates of survival for prostate cancer as well for other types of cancer that have increased attention to the potential for cancer drugs to increase CV risk, another major cause of early mortality. For these competing risks, objective data are needed to evaluate a relative risk-to-benefit ratio for treatment choices.

This dilemma led the ESC to recently establish its Council on Cardio-Oncology, and many centers around the world are also creating interdisciplinary groups to guide treatment choices for patients with both diseases.

“You will certainly get a lot of referrals,” said Rudolf de Boer, MD, professor of translational cardiology, University Medical Center, Groningen, Netherlands. Basing his remark on his own experience starting a cardio-oncology clinic at his institution, he called this work challenging and agreed that the need for objective data is urgent.

“We need data to provide common ground on which to judge relative risks,” Dr. de Boer said. He also praised the PRONOUNCE investigators for their efforts even if the data failed to answer the question posed.

The PRONOUNCE results were published online in Circulation at the time of Dr. Lopes’s presentation.

The study received funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Lopes reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Dr. Suter reports financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche. Dr. de Boer reports financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Roche.

The first global trial to compare the cardiovascular (CV) safety of two therapies for prostate cancer proved inconclusive because of inadequate enrollment and events, but the study is a harbinger of growth in the emerging specialty of cardio-oncology, according to experts.

“Many new cancer agents have extended patient survival, yet some of these agents have significant potential cardiovascular toxicity,” said Renato D. Lopes, MD, in presenting a study at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In the context of improving survival in patients with or at risk for both cancer and cardiovascular disease, he suggested that the prostate cancer study he led could be “a model for interdisciplinary collaboration” needed to address the relative and sometimes competing risks of these disease states.

This point was seconded by several pioneers in cardio-oncology who participated in the discussion of the results of the trial, called PRONOUNCE.

“We know many drugs in oncology increase cardiovascular risk, so these are the types of trials we need,” according Thomas M. Suter, MD, who leads the cardio-oncology service at the University Hospital, Berne, Switzerland. He was the ESC-invited discussant for PRONOUNCE.

More than 100 centers in 12 countries involved

In PRONOUNCE, 545 patients with prostate cancer and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease were randomized to degarelix, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist, or leuprolide, a GnRH agonist. The patients were enrolled at 113 participating centers in 12 countries. All of the patients had an indication for an androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT).

In numerous previous studies, “ADT has been associated with higher CV morbidity and mortality, particularly in men with preexisting CV disease,” explained Dr. Lopes, but the relative cardiovascular safety of GnRH agonists relative to GnRH antagonists has been “controversial.”

The PRONOUNCE study was designed to resolve this issue, but the study was terminated early because of slow enrollment (not related to the COVID-19 pandemic). The planned enrollment was 900 patients.

In addition, the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, or death, was lower over the course of follow-up than anticipated in the study design.

No significant difference on primary endpoint

At the end of 12 months, MACE occurred in 11 (4.1%) of patients randomized to leuprolide and 15 (5.5%) of those randomized to degarelix. The greater hazard ratio for MACE in the degarelix group did not approach statistical significance (hazard ratio, 1.28; P = .53).

As a result, the question of the relative CV safety of these drugs “remains unresolved,” according to Dr. Lopes, professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

This does not diminish the need to answer this question. In the addition to the fact that cancer is a malignancy primarily of advancing age when CV disease is prevalent – the mean age in this study was 73 years and 44% were over age 75 – it is often an indolent disease with long periods of survival, according to Dr. Lopes. About half of prostate cancer patients have concomitant CV disease, and about half will receive ADT at some point in their treatment.

In patients receiving ADT, leuprolide is far more commonly used than GnRH antagonists, which are offered in only about 4% of patients, according to data cited by Dr. Lopes. The underlying hypothesis of this study was that leuprolide is associated with greater CV risk, which might have been relevant to a risk-benefit calculation, if the hypothesis had been confirmed.

Cancer drugs can increase CV risk

Based on experimental data, “there is concern the leuprolide is involved in plaque destabilization,” said Dr. Lopes, but he noted that ADTs in general are associated with adverse metabolic changes, including increases in LDL cholesterol, insulin resistance, and body fat, all of which could be relevant to CV risk.

It is the improving rates of survival for prostate cancer as well for other types of cancer that have increased attention to the potential for cancer drugs to increase CV risk, another major cause of early mortality. For these competing risks, objective data are needed to evaluate a relative risk-to-benefit ratio for treatment choices.

This dilemma led the ESC to recently establish its Council on Cardio-Oncology, and many centers around the world are also creating interdisciplinary groups to guide treatment choices for patients with both diseases.

“You will certainly get a lot of referrals,” said Rudolf de Boer, MD, professor of translational cardiology, University Medical Center, Groningen, Netherlands. Basing his remark on his own experience starting a cardio-oncology clinic at his institution, he called this work challenging and agreed that the need for objective data is urgent.

“We need data to provide common ground on which to judge relative risks,” Dr. de Boer said. He also praised the PRONOUNCE investigators for their efforts even if the data failed to answer the question posed.

The PRONOUNCE results were published online in Circulation at the time of Dr. Lopes’s presentation.

The study received funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Lopes reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Dr. Suter reports financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche. Dr. de Boer reports financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Roche.

The first global trial to compare the cardiovascular (CV) safety of two therapies for prostate cancer proved inconclusive because of inadequate enrollment and events, but the study is a harbinger of growth in the emerging specialty of cardio-oncology, according to experts.

“Many new cancer agents have extended patient survival, yet some of these agents have significant potential cardiovascular toxicity,” said Renato D. Lopes, MD, in presenting a study at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In the context of improving survival in patients with or at risk for both cancer and cardiovascular disease, he suggested that the prostate cancer study he led could be “a model for interdisciplinary collaboration” needed to address the relative and sometimes competing risks of these disease states.

This point was seconded by several pioneers in cardio-oncology who participated in the discussion of the results of the trial, called PRONOUNCE.

“We know many drugs in oncology increase cardiovascular risk, so these are the types of trials we need,” according Thomas M. Suter, MD, who leads the cardio-oncology service at the University Hospital, Berne, Switzerland. He was the ESC-invited discussant for PRONOUNCE.

More than 100 centers in 12 countries involved

In PRONOUNCE, 545 patients with prostate cancer and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease were randomized to degarelix, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist, or leuprolide, a GnRH agonist. The patients were enrolled at 113 participating centers in 12 countries. All of the patients had an indication for an androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT).

In numerous previous studies, “ADT has been associated with higher CV morbidity and mortality, particularly in men with preexisting CV disease,” explained Dr. Lopes, but the relative cardiovascular safety of GnRH agonists relative to GnRH antagonists has been “controversial.”

The PRONOUNCE study was designed to resolve this issue, but the study was terminated early because of slow enrollment (not related to the COVID-19 pandemic). The planned enrollment was 900 patients.

In addition, the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, or death, was lower over the course of follow-up than anticipated in the study design.

No significant difference on primary endpoint

At the end of 12 months, MACE occurred in 11 (4.1%) of patients randomized to leuprolide and 15 (5.5%) of those randomized to degarelix. The greater hazard ratio for MACE in the degarelix group did not approach statistical significance (hazard ratio, 1.28; P = .53).

As a result, the question of the relative CV safety of these drugs “remains unresolved,” according to Dr. Lopes, professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

This does not diminish the need to answer this question. In the addition to the fact that cancer is a malignancy primarily of advancing age when CV disease is prevalent – the mean age in this study was 73 years and 44% were over age 75 – it is often an indolent disease with long periods of survival, according to Dr. Lopes. About half of prostate cancer patients have concomitant CV disease, and about half will receive ADT at some point in their treatment.

In patients receiving ADT, leuprolide is far more commonly used than GnRH antagonists, which are offered in only about 4% of patients, according to data cited by Dr. Lopes. The underlying hypothesis of this study was that leuprolide is associated with greater CV risk, which might have been relevant to a risk-benefit calculation, if the hypothesis had been confirmed.

Cancer drugs can increase CV risk

Based on experimental data, “there is concern the leuprolide is involved in plaque destabilization,” said Dr. Lopes, but he noted that ADTs in general are associated with adverse metabolic changes, including increases in LDL cholesterol, insulin resistance, and body fat, all of which could be relevant to CV risk.

It is the improving rates of survival for prostate cancer as well for other types of cancer that have increased attention to the potential for cancer drugs to increase CV risk, another major cause of early mortality. For these competing risks, objective data are needed to evaluate a relative risk-to-benefit ratio for treatment choices.

This dilemma led the ESC to recently establish its Council on Cardio-Oncology, and many centers around the world are also creating interdisciplinary groups to guide treatment choices for patients with both diseases.

“You will certainly get a lot of referrals,” said Rudolf de Boer, MD, professor of translational cardiology, University Medical Center, Groningen, Netherlands. Basing his remark on his own experience starting a cardio-oncology clinic at his institution, he called this work challenging and agreed that the need for objective data is urgent.

“We need data to provide common ground on which to judge relative risks,” Dr. de Boer said. He also praised the PRONOUNCE investigators for their efforts even if the data failed to answer the question posed.

The PRONOUNCE results were published online in Circulation at the time of Dr. Lopes’s presentation.

The study received funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Lopes reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Dr. Suter reports financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche. Dr. de Boer reports financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Roche.

FROM ESC 2021

Three Primary Cancers in a Veteran With Agent Orange and Agent Blue Exposures

A Vietnam War veteran’s exposures likely contributed to his cancer diagnoses, but these associations are confounded by his substance use, particularly cigarette smoking.

Known as the “6 rainbow herbicides,” based on their identifying color on storage containers, the United States widely deployed the herbicides agents orange, green, pink, purple, white, and blue during the Vietnam War to deny the enemy cover and destroy crops.1 Unfortunately, all these herbicides were found to have contained some form of carcinogen. Agent Blue’s active ingredient consisted of sodium cacodylate trihydrate (C2H6AsNaO2), a compound that is metabolized into the organic form of the carcinogen arsenic before eventually converting into its relatively less toxic inorganic form.2 Agent Orange’s defoliating agent is 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). All rainbow herbicides except Agent Blue were unintentionally contaminated with carcinogenic dioxins. Agent Blue contained the carcinogen cacodylic acid, an organoarsenic acid. Today, herbicides no longer contain polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins such as TCDD or arsenic due to strict manufacturing restrictions.2,3 In the treatment of veteran populations, knowledge of the 6 rainbow herbicides’ carcinogenic potential is important.

Between 1962 and 1971, the United States sprayed more than 45 million liters of Agent Orange on Vietnam and at least 366 kg of TCDD on South Vietnam.1,4 However, because Agent Orange was not a known carcinogen during the Vietnam War, records of exposure are poor. Additionally, individuals in Vietnam during this period were not the only ones exposed to this carcinogen as Agent Orange also was sprayed in Thailand and Korea.5 Even today there are still locations in Vietnam where Agent Orange concentrations exceed internationally acceptable levels. The Da Nang, Bien Hoa, and Phu Cat airports in Vietnam have been found to have dioxin levels exceeding 1000 ppt (parts of dioxin per trillion parts of lipid) toxicity equivalence in the soil. Although the Vietnam government is working toward decontaminating these and many other dioxin hotspots, residents in these locations are exposed to higher than internationally acceptable levels of dioxin.6

Despite receiving less media attention, Vietnam War veterans and Vietnamese soldiers and civilians were exposed to significant amounts of arsenic-based Agent Blue. Arsenic is a compound which has no environmental half-life and is carcinogenic humans if inhaled or ingested.2 Between 1962 and 1971, the United States distributed 7.8 million liters of Agent Blue containing 1,232,400 kg of arsenic across 300,000 hectares of rice paddies, 100,000 hectares of forest, and perimeters of all military bases during the Vietnam War.2,5 According to a review by Saha and colleagues, lower levels of arsenic exposure are associated with acute and chronic diseases, including cancers, of all organ systems.7

The following case presentation involves a Vietnam War veteran aged 70 years who was exposed to Agent Orange and developed 3 primary cancers, including cutaneous large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), high-grade urothelial carcinoma, and anal carcinoma in situ. Epidemiologically, this is an uncommon occurrence as only 8% of cancer survivors in the United States have been diagnosed with > 1 cancer.8

With no family history of cancer, the development of multiple malignancies raises concern for a history of toxin exposure. This report of a Vietnam War veteran with multiple conditions found to be associated with Agent Orange exposure provides an opportunity to discuss the role this exposure may have on the development of a comprehensive list of medical conditions as described by the literature. Additionally, the potential contributions of other confounding toxin exposures such as cigarette smoking, excessive alcohol use, and potential Agent Blue exposure on our patients’ health will be discussed.

Case Presentation

A male aged 70 years with Stage IV primary cutaneous large B-cell NHL, incompletely resected high-grade urothelial cancer, carcinoma in situ of the anal canal, and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) presented to the primary care clinic at the Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center (DCVAMC) with concern for left leg ischemia. He also reported 2 large telangiectasias on his back for 6 months accompanied by lymphadenopathy and intermittent night sweats.

He was last seen at the DCVAMC 15 months prior after his twelfth dose of rituximab treatment for NHL. However, the patient failed to return for completion of his treatment due to frustration with the lengthy chemotherapy and follow-up process. Additionally, the patient's history included 3 failed arterial stents with complete nonadherence to the prescribed clopidogrel, resulting in the failure of 3 more subsequent graft placements. On presentation, the patient continued to report nonadherence with the clopidogrel.

The patient’s medical history included coronary artery disease (CAD) status after 2 stents in the left anterior descending artery and 1 stent in the proximal circumflex artery placed 4 years prior. He also had a history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis, aortic aneurysm, cataracts, obesity, treated hepatitis B and C, and posttraumatic stress disorder. He had no family history of cancer or AL amyloidosis; however, he noted that he was estranged from his family.

His social history was notable for active cigarette smoking up to 3 packs per day for 40 years and consuming large quantities of alcohol—at one point as many as 20 beers per day over a period of 4.5 years. He had a distant history of cocaine use but no current use, which was supported with negative urinary toxicology screens for illicit drugs over the past year.

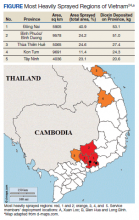

Our patient also reported a history of Agent Orange exposure. As an artilleryman in the US Army III Corps, he was deployed for about 1 year in the most heavily sprayed regions of Vietnam, including Bien Hua, Long Binh, Xuan Loc, and Camp Zion for about 2 to 4 months at each location.

Hospital Course

The patient was treated on an inpatient basis for expedited workup and treatment for his urothelial carcinoma, NHL, and ischemic limb. His urothelial carcinoma was successfully resected, and the telangiectasias on his back were biopsied and found to be consistent with his known cutaneous large B-cell NHL, for which plans to resume outpatient chemotherapy were made. The patient’s 3 arterial grafts in his left leg were confirmed to have failed, and the patient was counseled that he would soon likely require an amputation of his ischemic leg.

Discussion

We must rely on our patient’s historical recall as there are no widely available laboratory tests or physical examination findings to confirm and/or determine the magnitude of TCDD or arsenic exposure.9-11

Exposures

The patient was stationed in Bien Hoa, the second highest dioxin-contaminated air base in Vietnam (Figure).6 Dioxin also is known to be a particularly persistent environmental pollutant, such that in January 2018, Bien Hoa was found to still have dioxin levels higher than what is considered internationally acceptable. In fact, these levels were deemed significant enough to lead the United States and Vietnamese government to sign a memorandum of intent to begin cleanup of this airport.6 TCDD is known to have a half-life of about 7.6 years, and its long half-life is mainly attributed to its slow elimination process from its stores within the liver and fat, consisting of passive excretion through the gut wall and slow metabolism by the liver.12,13 Thus, as an artilleryman mainly operating 105 howitzers within the foliage of Vietnam, our patient was exposed not only to high levels of this persistent environmental pollutant on a daily basis, but this toxin likely remained within his system for many years after his return from Vietnam.

Our patient also had a convincing history for potential Agent Blue exposure through both inhalation and ingestion of contaminated food and water. Additionally, his description of deforestations occurring within a matter of days increased the level of suspicion for Agent Blue exposure. This is because Agent Blue was the herbicide of choice for missions requiring rapid deforestation, achieving defoliation as quickly as 1 to 2 days.14 Additionally, our patient was stationed within cities in southern Vietnam near Agent Blue hot spots, such as Da Nang and Saigon, and Agent Blue was sprayed along the perimeter of all military bases.2

Levels of Evidence

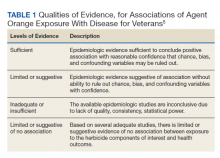

Using the Veterans and Agent Orange Update in 2018 as our guide, we reviewed the quality of evidence suggesting an association between many of our patient’s comorbidities to Agent Orange exposure.5 This publication categorizes the level of evidence for association between health conditions and Agent Orange exposure in 4 main categories (Table 1).

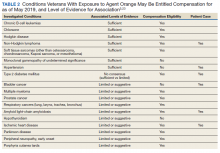

In the Veterans and Agent Orange Update, NHL notably has a sufficient level of evidence of association with Agent Orange exposure.5 Although our patient’s extensive history of polysubstance use confounds the effect Agent Orange may have had on his health, cutaneous large B-cell NHL is an interesting exception as literature does not support even a correlative link between smoking and excessive alcohol use with primary cutaneous large B-cell NHL. Several case-control studies have found little to no association with cigarette smoking and the large B-cell subtype of NHL.15,16 Moreover, several studies have found that moderate- to-heavy alcohol use, especially beer, may have a protective effect against the development of NHL.17 Of note, our patient’s alcoholic beverage of choice was beer. Regarding our patient’s distant history of cocaine use, it has been reported that cocaine use, in the absence of an HIV infection, has not been found to increase the risk of developing NHL.18 Similarly, arsenic exposure has not been associated with NHL in the literature.19,20

The 2018 update also upgraded bladder carcinoma from having inadequate or insufficient to a limited or suggestive level of evidence for association.5 However, our patient’s most significant risk factor for bladder cancer was smoking, with a meta-analysis of 430,000 patients reporting a risk ratio (RR) of 3.14 for current cigarette smokers.21 The patient’s arsenic exposure from Agent Blue also increased his risk of developing bladder cancer. Several studies suggest a strong association between environmental arsenic exposure and bladder cancer.22-26 A 30-year meta-analysis of 40 studies by Saint-Jacques and colleagues reported that the incidence of bladder cancer was found to increase in a dose-dependent manner, with higher concentrations of arsenic contaminated wate, with incidence rising from 2.7 to 5.8 times as the amount of arsenic contamination water increased from 10 to 150 mg/L.

Our patient’s history is concerning for higher than average Agent Blue exposure compared with that of most Vietnam War veterans. Given the dose-dependent effect of arsenic on bladder cancer risk, both our patient’s history of smoking and Agent Blue exposure are risk factors in the development of his bladder cancer.22 These likely played a more significant role in his development of bladder cancer than did his Agent Orange exposure.

Finally, smoking is the most significant risk factor in our patient’s development of anal carcinoma in situ. The 2018 Agent Orange update does report limited/suggested evidence of no association between Agent Orange and anal carcinoma.5 It also is unknown whether Agent Blue exposure is a contributing cause to his development of anal carcinoma in situ.27 However, current smokers are at significant risk of developing anal cancer independent of age.28-30 Given our patient’s extensive smoking history, this is the most likely contributing factor.

Our patient also had several noncancer-related comorbidities with correlative associations with Agent Orange exposure of varying degrees (Table 2). Somewhat surprising, the development of our patient’s hypertension and T2DM may be associated in some way with his history of Agent Orange exposure. Hypertension had been recategorized from having limited or suggestive evidence to sufficient evidence in this committee’s most recent publication, and the committee is undecided on whether T2DM has a sufficient vs limited level of evidence for association with Agent Orange exposure.5 On the other hand, the committee continues to classify both ischemic heart disease and AL amyloidosis as having a limited or suggestive level of evidence that links Agent Orange exposure to these conditions.5

Arsenic may be another risk factor for our patient’s development of CAD and arterial insufficiency. Arsenic exposure is theorized to cause a direct toxic effect on coronary arteries, and arsenic exposure has been linked to PAD, CAD, and hypertension.31-34 Other significant and compelling risk factors for cardiovascular disease in our patient included his extensive history of heavy cigarette smoking, poorly controlled T2DM, obesity, and hypertension.35-37 AL amyloidosis is a rare disorder with an incidence of only 9 to 14 cases per million person-years.38,39 This disorder has not been linked to smoking or arsenic exposure in the literature. As our patient does not have a history of plasma dyscrasias or a family history of AL amyloidosis, the only known risk factors for AL amyloidosis that apply to our patient included NHL and Agent Orange exposure—NHL being a condition that is noted to be strongly correlated with Agent Orange exposure as discussed previously.5,36,40,41

Conclusions

This case describes a Vietnam War veteran with significant exposure to rainbow herbicides and considerable polysubstance who developed 3 primary cancers and several chronic medical conditions. His exposure to Agents Orange and Blue likely contributed to his medical problems, but these associations are confounded by his substance use, particularly cigarette smoking. Of all his comorbidities, our patient’s NHL is the condition most likely to be associated with his history of Agent Orange exposure. His Agent Blue exposure also increased his risk for developing bladder cancer, cardiovascular disease, and PAD.

This case also highlights the importance of evaluating Vietnam War veterans for rainbow herbicide exposure and the complexity associated with attributing diseases to these exposures. All veterans who served in the inland waterways of Vietnam between 1962 and 1975; in the Korean Demilitarized Zone between April 1, 1968 and August 31, 1971; or in Thailand between February 28, 1961 and May 7, 1975 were at risk of rainbow herbicide exposure. These veterans may not only be eligible for disability compensation but also should be screened for associated comorbidities as outlined by current research.42 We hope that this report will serve as an aid in achieving this mission.

1. Stellman JM, Stellman SD, Christian R, Weber T, Tomasallo C. The extent and patterns of usage of Agent Orange and other herbicides in Vietnam. Nature. 2003;422(6933):681-687. doi:10.1038/nature01537

2. Olson K, Cihacek L. The fate of Agent Blue, the arsenic based herbicide, used in South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. Open J Soil Sci. 2020;10:518-577. doi:10.4236/ojss.2020.1011027

3. Lee Chang A, Dym AA, Venegas-Borsellino C, et al. Comparison between simulation-based training and lecture-based education in teaching situation awareness. a randomized controlled study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(4):529-535. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201612-950OC

4. Stellman SD. Agent Orange during the Vietnam War: the lingering issue of its civilian and military health impact. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(6):726-728. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304426

5. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 11 (2018). The National Academies Press; 2018. doi:10.17226/25137