User login

Osteoporosis management: Use a goal-oriented, individualized approach

Recommendations for care are evolving, with increasingly sophisticated screening and diagnostic tools and a broadening array of treatment options.

As the population of older adults rises, primary osteoporosis has become a problem of public health significance, resulting in more than 2 million fractures and $19 billion in related costs annually in the United States.1 Despite the availability of effective primary and secondary preventive measures, many older adults do not receive adequate information on bone health from their primary care provider.2 Initiation of osteoporosis treatment is low even among patients who have had an osteoporotic fracture: Fewer than one-quarter of older adults with hip fracture have begun taking osteoporosis medication within 12 months of hospital discharge.3

In this overview of osteoporosis care, we provide information on how to evaluate and manage older adults in primary care settings who are at risk of, or have been given a diagnosis of, primary osteoporosis. The guidance that we offer reflects the most recent updates and recommendations by relevant professional societies.1,4-7

The nature and scope of an urgent problem

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of bone structure that causes bone fragility and increases the risk of fracture.8 Operationally, it is defined by the World Health Organization as a bone mineral density (BMD) score below 2.5 SD from the mean value for a young White woman (ie, T-score ≤ –2.5).9 Primary osteoporosis is age related and occurs mostly in postmenopausal women and older men, affecting 25% of women and 5% of men ≥ 65 years.10

An osteoporotic fracture is particularly devastating in an older adult because it can cause pain, reduced mobility, depression, and social isolation and can increase the risk of related mortality.1 The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates that 20% of older adults who sustain a hip fracture die within 1 year due to complications of the fracture itself or surgical repair.1 Therefore, it is of paramount importance to identify patients who are at increased risk of fracture and intervene early.

Clinical manifestations

Osteoporosis does not have a primary presentation; rather, disease manifests clinically when a patient develops complications. Often, a fragility fracture is the first sign in an older person.11

A fracture is the most important complication of osteoporosis and can result from low-trauma injury or a fall from standing height—thus, the term “fragility fracture.” Osteoporotic fractures commonly involve the vertebra, hip, and wrist. Hip and extremity fractures can result in limited or lost mobility and depression. Vertebral fractures can be asymptomatic or result in kyphosis and loss of height. Fractures can give rise to pain.

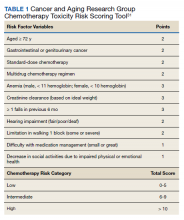

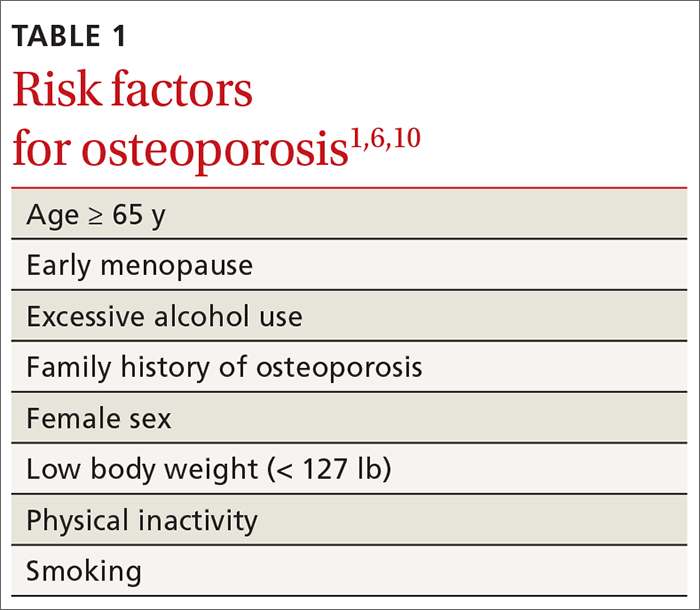

Age and female sexare risk factors

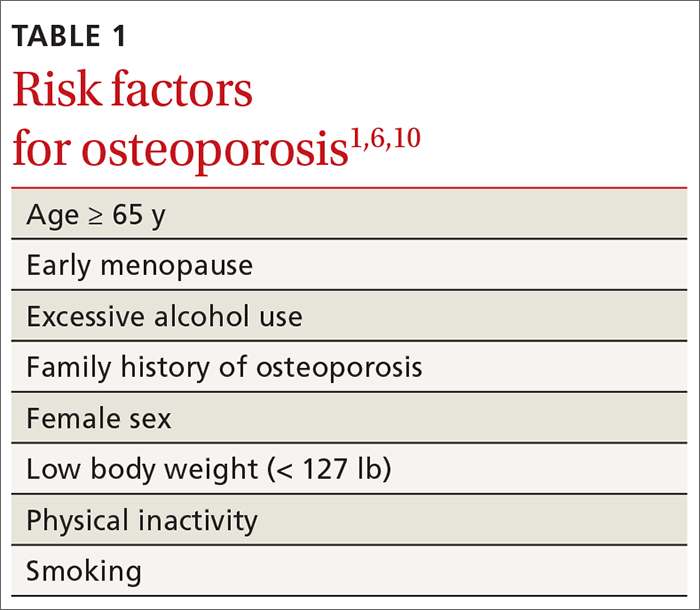

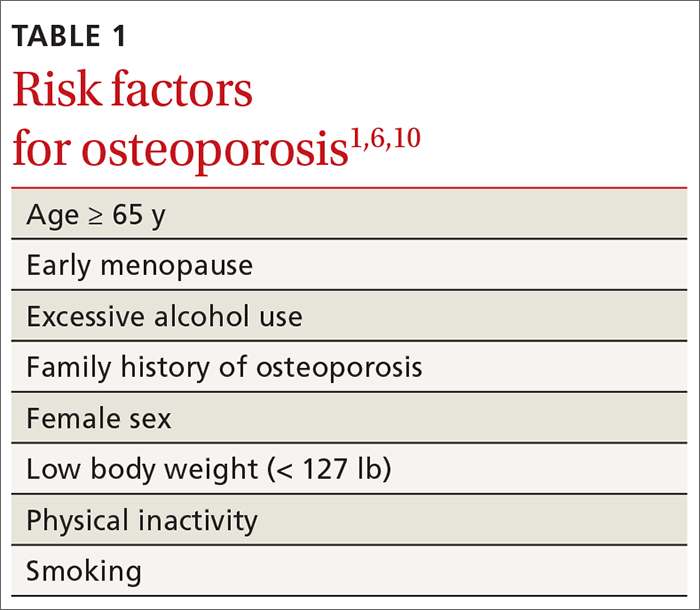

TABLE 11,6,10 lists risk factors associated with osteoporosis. Age is the most important; prevalence of osteoporosis increases with age. Other nonmodifiable risk factors include female sex (the disease appears earlier in women who enter menopause prematurely), family history of osteoporosis, and race and ethnicity. Twenty percent of Asian and non-Hispanic White women > 50 years have osteoporosis.1 A study showed that Mexican Americans are at higher risk of osteoporosis than non-Hispanic Whites; non-Hispanic Blacks are least affected.10

Other risk factors include low body weight (< 127 lb) and a history of fractures after age 50. Behavioral risk factors include smoking, excessive alcohol intake (> 3 drinks/d), poor nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle.1,6

Continue to: Who should be screened?...

Who should be screened?

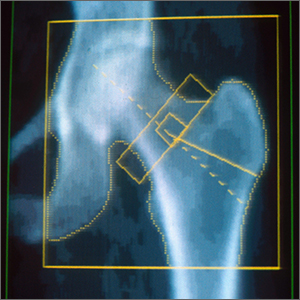

Screening is generally performed with a clinical evaluation and a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan of BMD. Measurement of BMD is generally recommended for screening all women ≥ 65 years and those < 65 years whose 10-year risk of fracture is equivalent to that of a 65-year-old White woman (see “Assessment of fracture risk” later in the article). For men, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening those with a prior fracture or a secondary risk factor for disease.5 However, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends screening all men ≥ 70 years and those 50 to 69 years whose risk profile shows heightened risk.1,4

DXA of the spine and hip is preferred; the distal one-third of the radius (termed “33% radius”) of the nondominant arm can be used when spine and hip BMD cannot be interpreted because of bone changes from the disease process or artifacts, or in certain diseases in which the wrist region shows the earliest change (eg, primary hyperparathyroidism).6,7

Clinical evaluation includes a detailed history, physical examination, laboratory screening, and assessment for risk of fracture.

❚ History. Explore the presence of risk factors, including fractures in adulthood, falls, medication use, alcohol and tobacco use, family history of osteoporosis, and chronic disease.6,7

❚ Physical exam. Assess height, including any loss (> 1.5 in) since the patient’s second or third decade of life; kyphosis; frailty; and balance and mobility problems.4,6,7

❚ Laboratory and imaging studies. Perform basic laboratory testing when DXA is abnormal, including thyroid function, serum calcium, and renal function.6,12 Radiography of the lateral spine might be necessary, especially when there is kyphosis or loss of height. Assess for vertebral fracture, using lateral spine radiography, when vertebral involvement is suspected.6,7

❚ Assessment of fracture risk. Fracture risk can be assessed with any of a number of tools, including:

- Simplified Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE): www.medicalalgorithms.com/simplified-calculated-osteoporosis-risk-estimation-tool

- Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI): www.physio-pedia.com/The_Osteoporosis_Risk_Assessment_Instrument_(ORAI)

- Osteoporosis Index of Risk (OSIRIS): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/gye.16.3.245.250?journalCode=igye20

- Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST): www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45516/figure/ch10.f2/

- FRAX tool5: www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX.

The FRAX tool is widely used. It assesses a patient’s 10-year risk of fracture.

Diagnosis is based on these criteria

Diagnosis of osteoporosis is based on any 1 or more of the following criteria6:

- a history of fragility fracture not explained by metabolic bone disease

- T-score ≤ –2.5 (lumbar, hip, femoral neck, or 33% radius)

- a nation-specific FRAX score (in the absence of access to DXA).

❚ Secondary disease. Patients in whom secondary osteoporosis is suspected should undergo laboratory investigation to ascertain the cause; treatment of the underlying pathology might then be required. Evaluation for a secondary cause might include a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, protein electrophoresis and urinary protein electrophoresis (to rule out myeloproliferative and hematologic diseases), and tests of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, serum calcium, alkaline phosphatase, 24-hour urinary calcium, sodium, and creatinine.6,7 Specialized testing for biochemical markers of bone turnover—so-called bone-turnover markers—can be considered as part of the initial evaluation and follow-up, although the tests are not recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (see “Monitoring the efficacy of treatment,” later in the article, for more information about these markers).6

Although BMD by DXA remains the gold standard in screening for and diagnosing osteoporosis, a high rate of fracture is seen in patients with certain diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and ankylosing spondylitis, who have a nonosteoporotic low T-score. This raises concerns about the usefulness of BMD for diagnosing osteoporosis in patients who have one of these diseases.13-16

❚

❚ Trabecular bone score (TBS), a surrogate bone-quality measure that is calculated based on the spine DXA image, has recently been introduced in clinical practice, and can be used to predict fracture risk in conjunction with BMD assessment by DXA and the FRAX score.17 TBS provides an indirect index of the trabecular microarchitecture using pixel gray-level variation in lumbar spine DXA images.18 Three categories of TBS (≤ 1.200, degraded microarchitecture; 1.200-1.350, partially degraded microarchitecture; and > 1.350, normal microarchitecture) have been reported to correspond with a T-score of, respectively, ≤ −2.5; −2.5 to −1.0; and > −1.0.18 TBS can be used only in patients with a body mass index of 15 to 37.5.19,20

There is no recommendation for monitoring bone quality using TBS after osteoporosis treatment. Such monitoring is at the clinician’s discretion for appropriate patients who might not show a risk of fracture, based on BMD measurement.

Continue to: Putting preventive measures into practice...

Putting preventive measures into practice

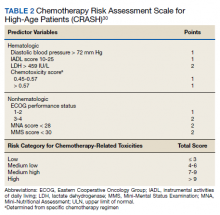

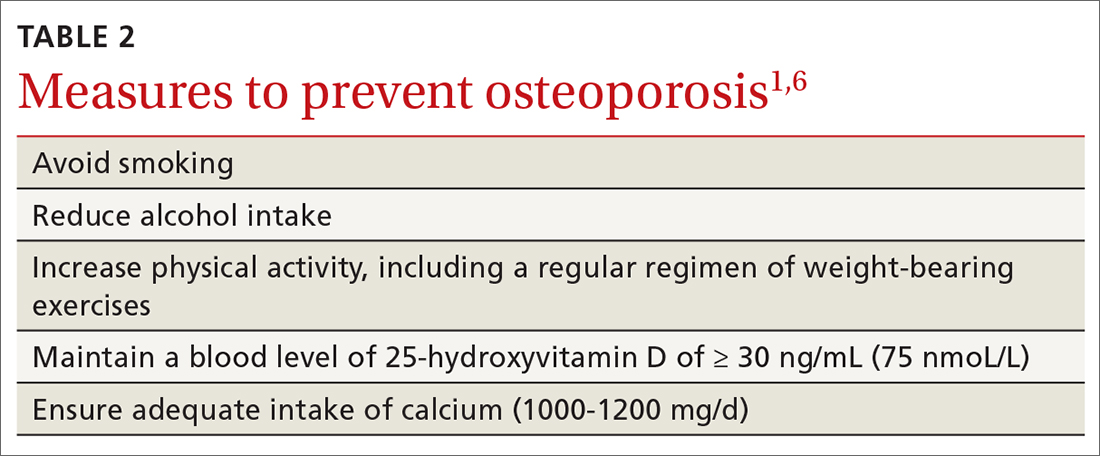

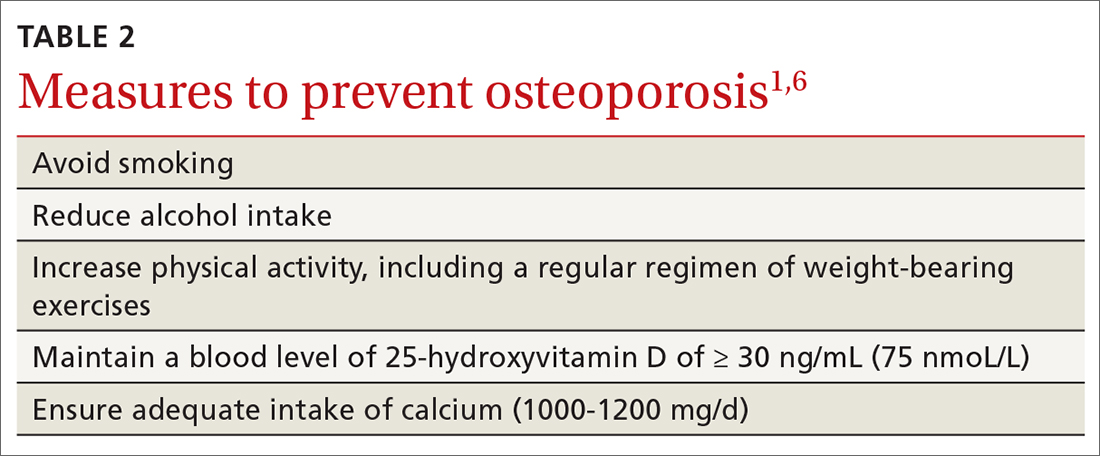

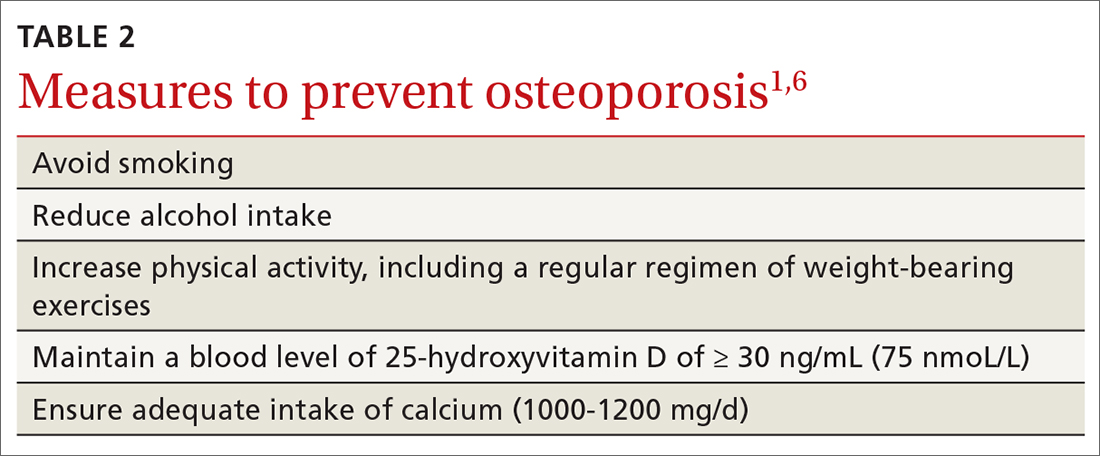

Measures to prevent osteoporosis and preserve bone health (TABLE 21,6) are best started in childhood but can be initiated at any age and maintained through the lifespan. Encourage older adults to adopt dietary and behavioral strategies to improve their bone health and prevent fracture. We recommend the following strategies; take each patient’s individual situation into consideration when electing to adopt any of these measures.

❚ Vitamin D. Consider checking the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and providing supplementation (800-1000 IU daily, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends1) as necessary to maintain the level at 30-50 ng/mL.6

❚ Calcium. Encourage a daily dietary calcium intake of 1000-1200 mg. Supplement calcium if you determine that diet does not provide an adequate amount.

❚ Alcohol. Advise patients to limit consumption to < 3 drinks a day.

❚ Tobacco. Advise smoking cessation.

❚ Activity. Encourage an active lifestyle, including regular weight-bearing and balance exercises and resistance exercises such as Pilates, weightlifting, and tai chi. The regimen should be tailored to the patient’s individual situation.

❚ Medical therapy for concomitant illness. When possible, prescribe medications for chronic comorbidities that can also benefit bone health. For example, long-term use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and thiazide diuretics for hypertension are associated with a slower decline in BMD in some populations.21-23

Tailor treatment to patient’s circumstances

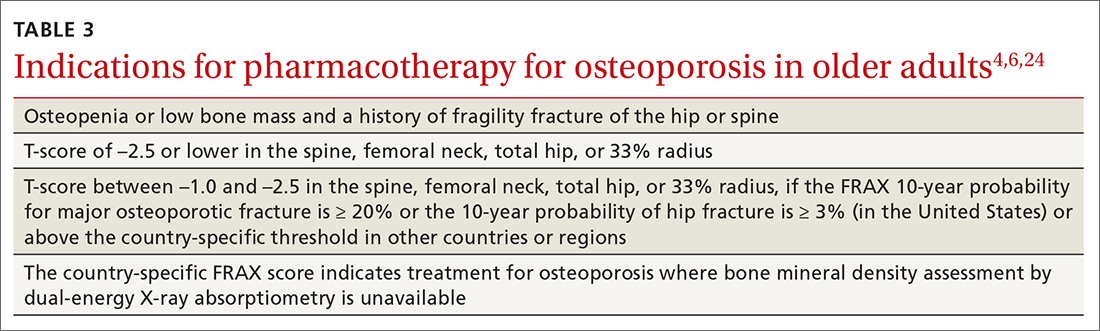

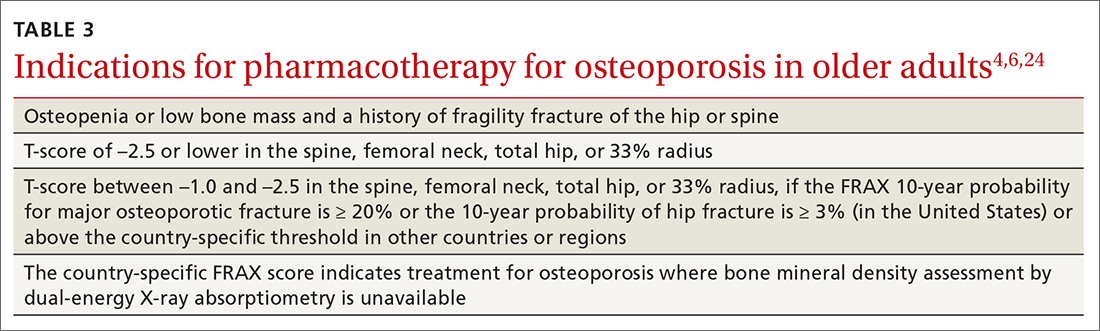

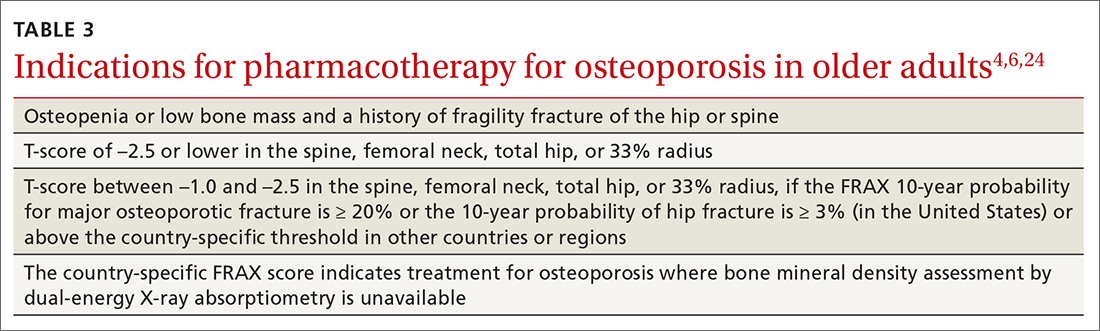

TABLE 34,6,24 describes indications for pharmacotherapy in osteoporosis. Pharmacotherapy is recommended in all cases of osteoporosis and osteopenia when fracture risk is high.24

Generally, you should undertake a discussion with the patient of the relative risks and benefits of treatment, taking into account their values and preferences, to come to a shared decision. Tailoring treatment, based on the patient’s distinctive circumstances, through shared decision-making is key to compliance.25

Pharmacotherapy is not indicated in patients whose risk of fracture is low; however, you should reassess such patients every 2 to 4 years.26 Women with a very high BMD might not need to be retested with DXA any sooner than every 10 to 15 years.

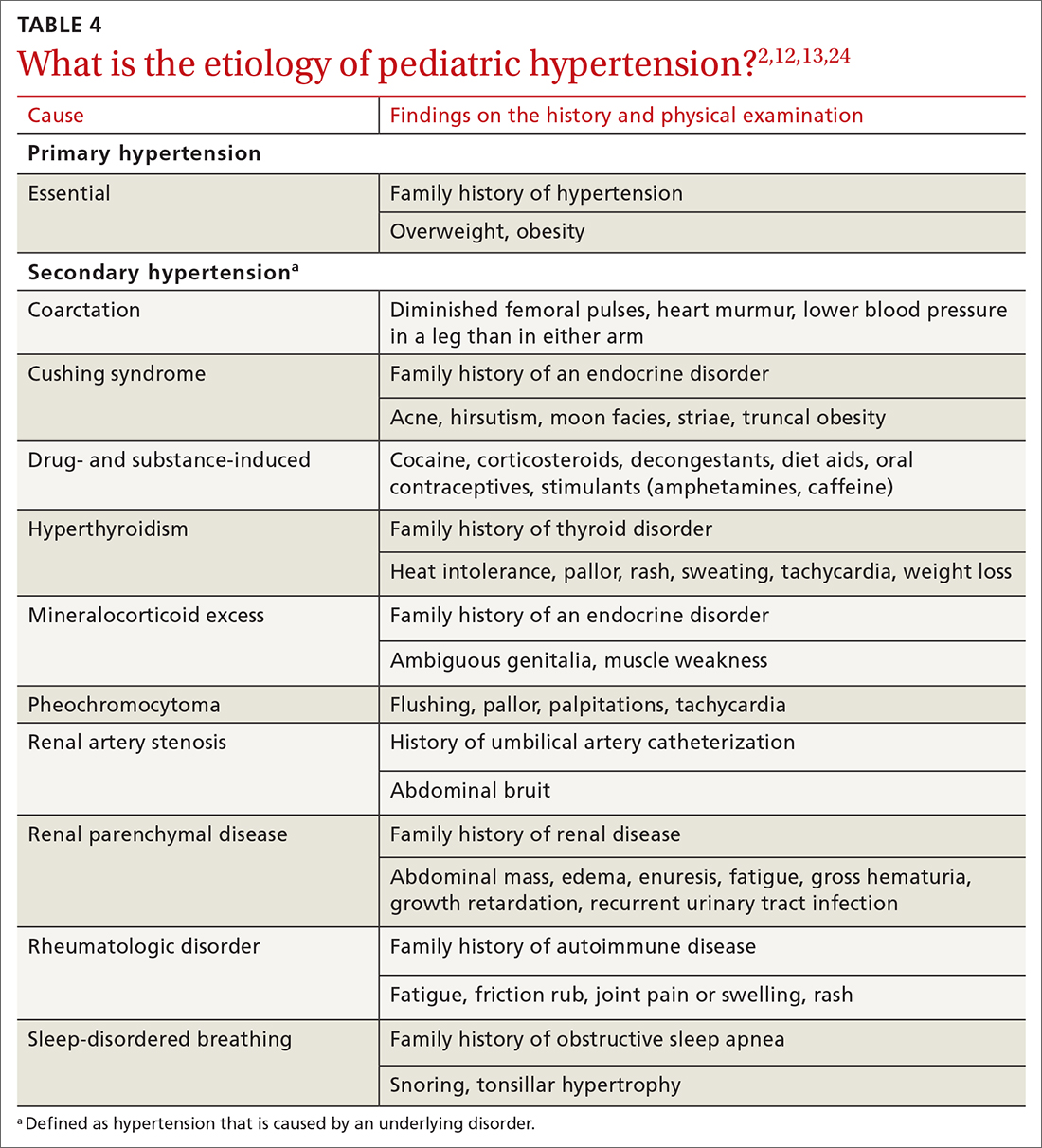

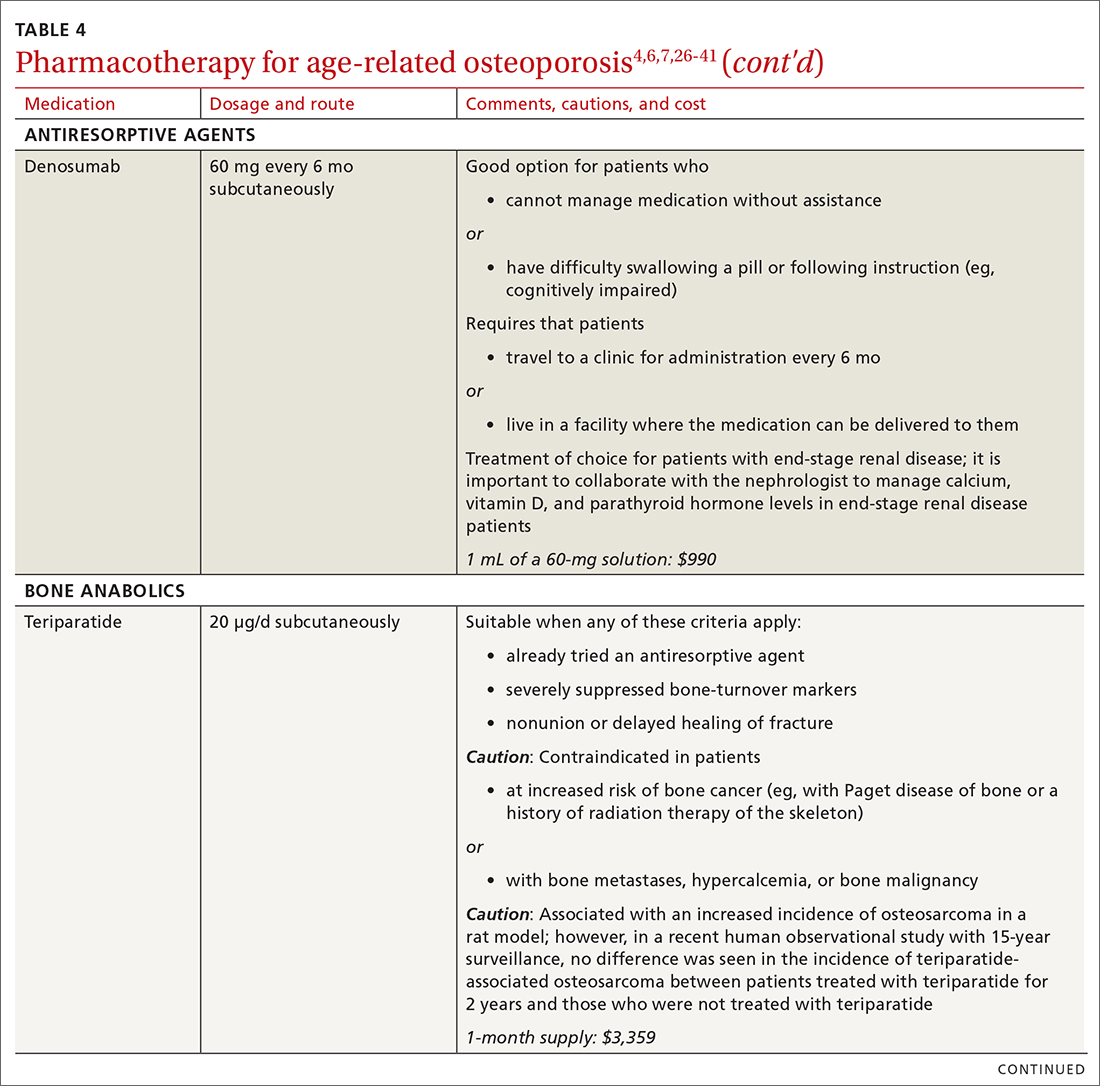

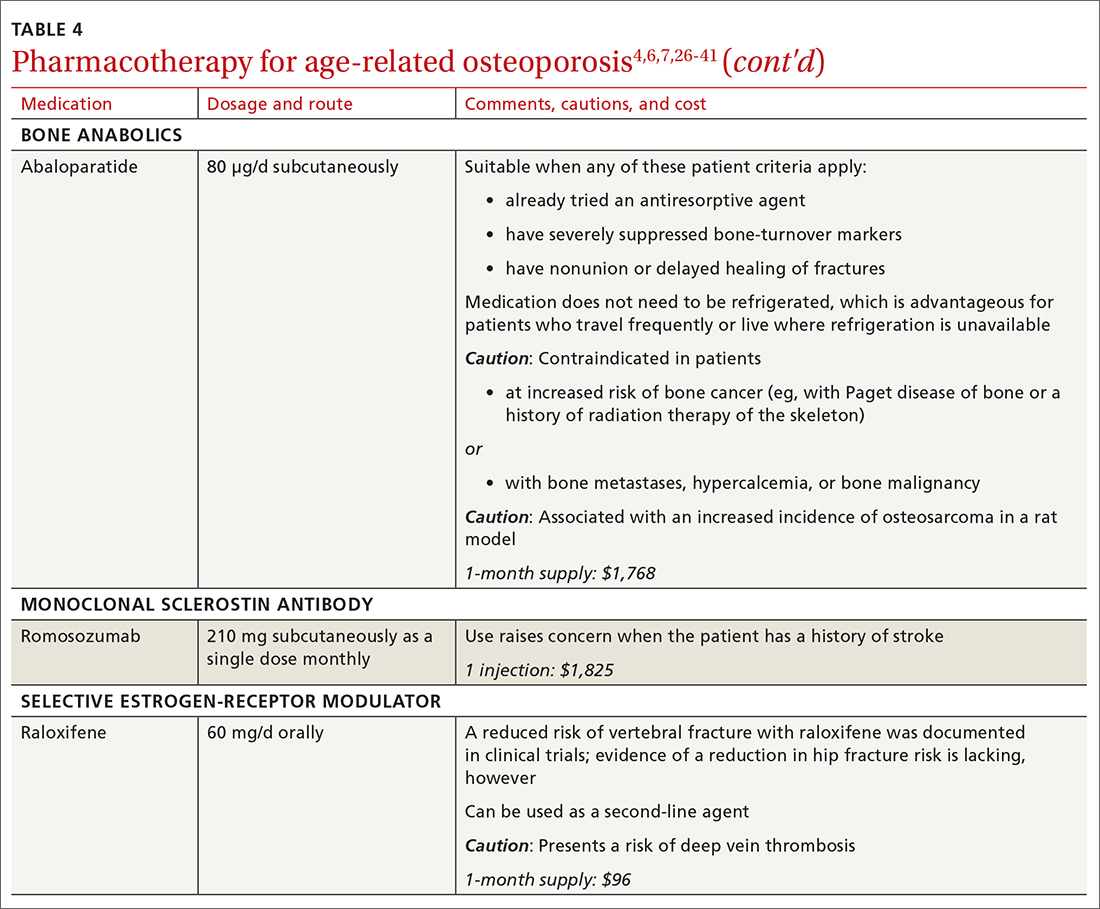

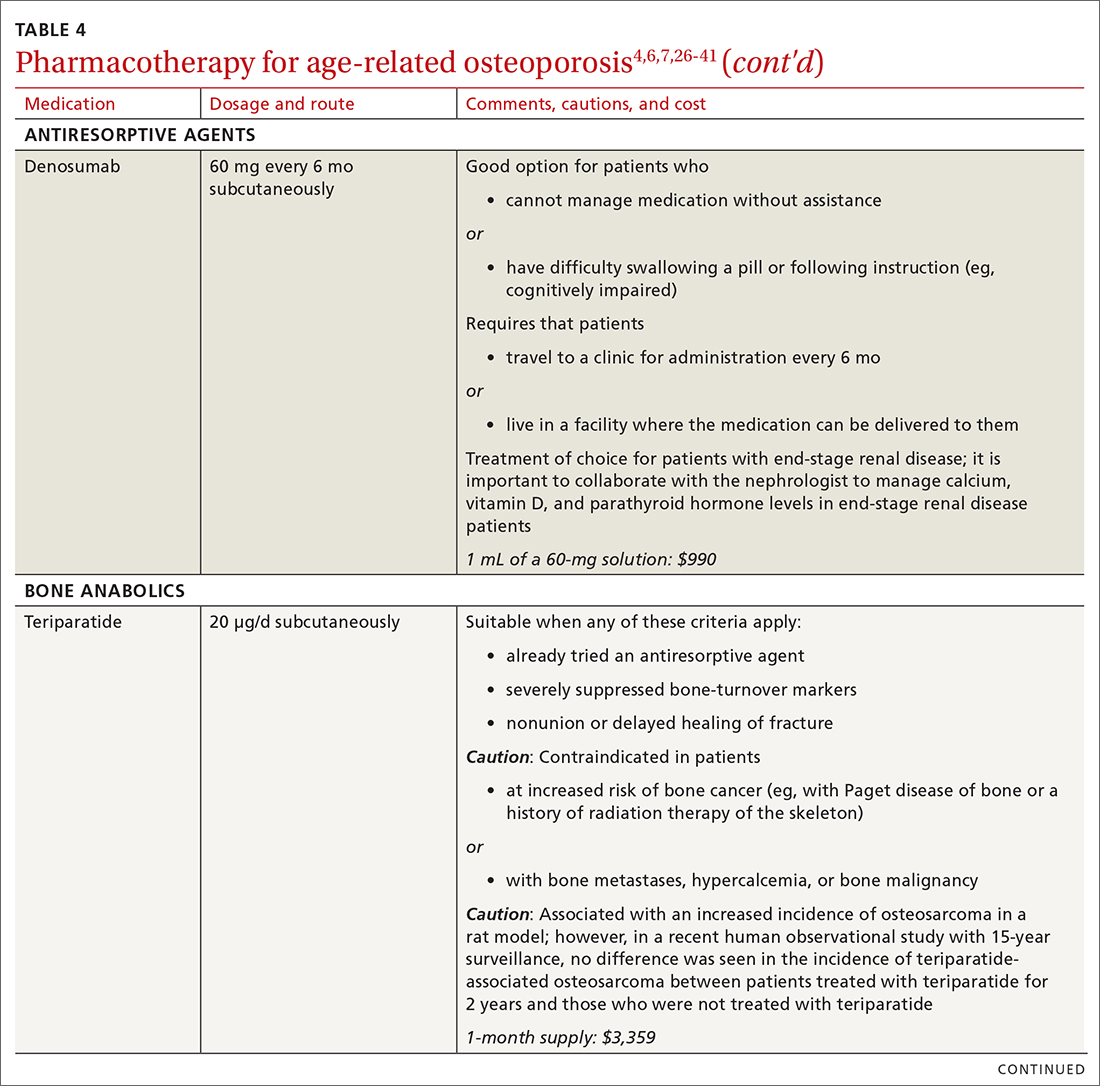

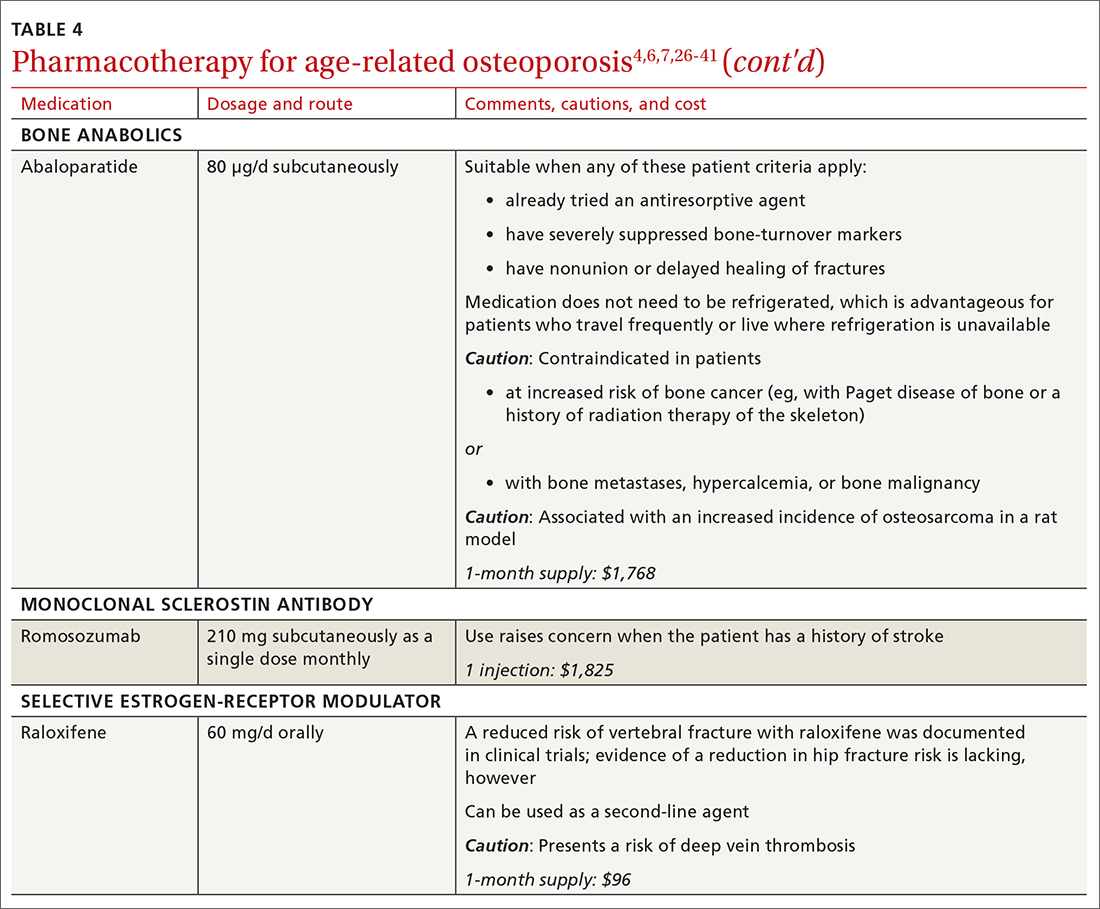

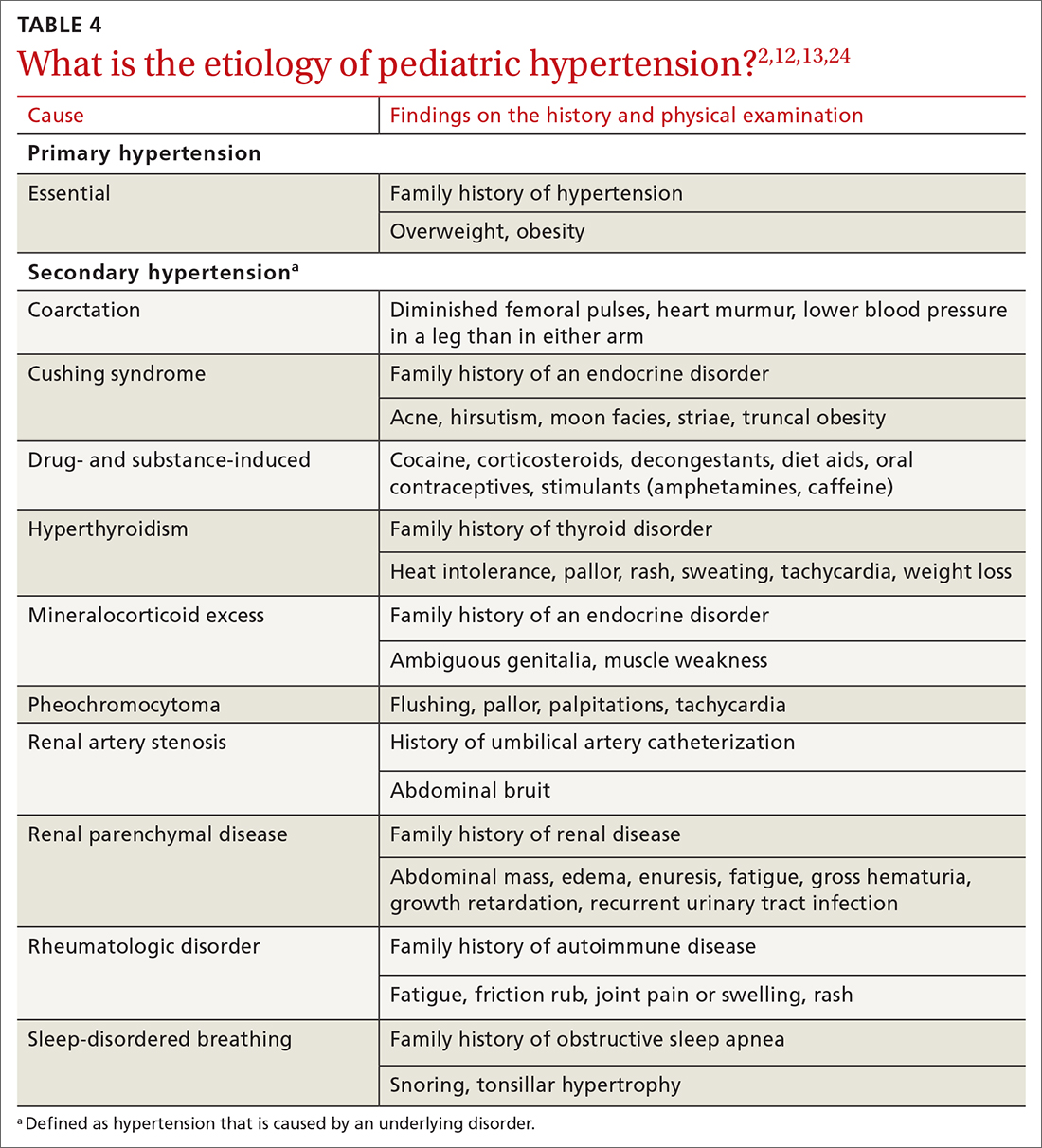

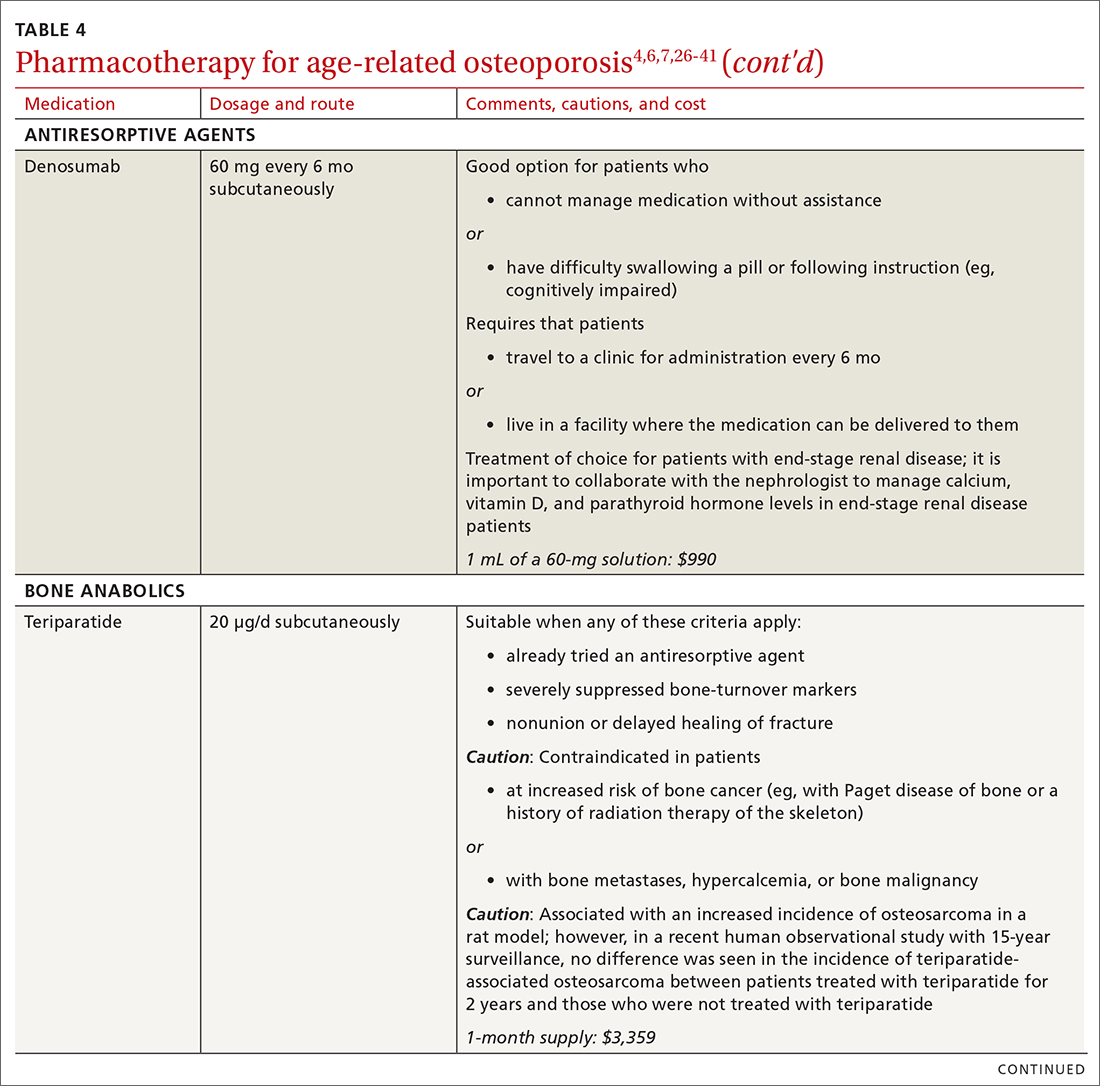

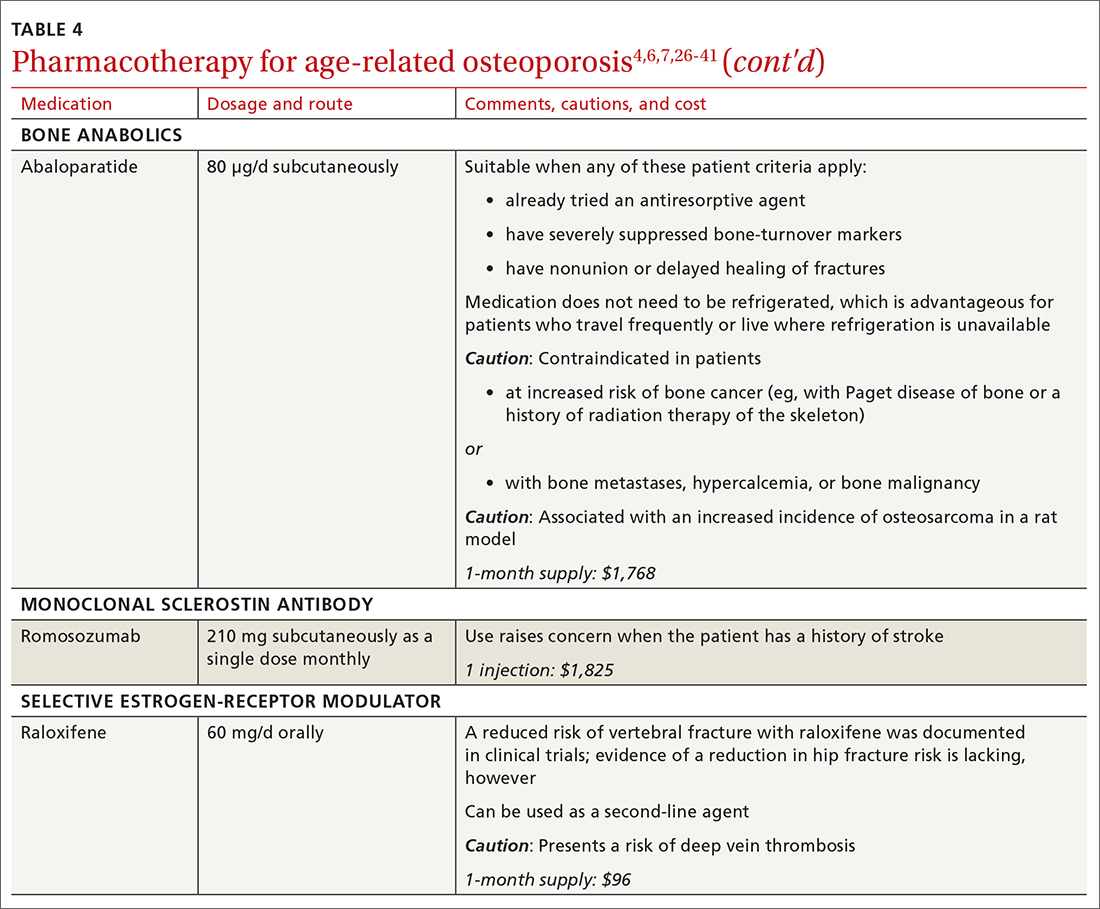

There are 3 main classes of first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for osteoporosis in older adults (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41): antiresorptives (bisphosphonates and denosumab), anabolics (teriparatide and abaloparatide), and a monoclonal sclerostin antibody (romosozumab). (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41 and the discussion in this section also remark on the selective estrogen-receptor modulator raloxifene, which is used in special clinical circumstances but has been removed from the first line of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy.)

❚ Bisphosphonates. Oral bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate) can be used as initial treatment in patients with a high risk of fracture.35 Bisphosphonates have been shown to reduce fracture risk and improve BMD. When an oral bisphosphonate cannot be tolerated, intravenous zoledronate or ibandronate can be used.41

Patients treated with a bisphosphonate should be assessed for their fracture risk after 3 to 5 years of treatment26; when intravenous zoledronate is given as initial therapy, patients should be assessed after 3 years. After assessment, patients who remain at high risk should continue treatment; those whose fracture risk has decreased to low or moderate should have treatment temporarily suspended (bisphosphonate holiday) for as long as 5 years.26 Patients on bisphosphonate holiday should have their fracture risk assessed at 2- to 4-year intervals.26 Restart treatment if there is an increase in fracture risk (eg, a decrease in BMD) or if a fracture occurs. Bisphosphonates have a prolonged effect on BMD—for many years after treatment is discontinued.27,28

Oral bisphosphonates are associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, difficulty swallowing, and gastritis. Rare adverse effects include osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.29

❚ Denosumab, a recombinant human antibody, is a relatively newer antiresorptive for initial treatment. Denosumab, 60 mg, is given subcutaneously every 6 months. The drug can be used when bisphosphonates are contraindicated, the patient finds the bisphosphonate dosing regimen difficult to follow, or the patient is unresponsive to bisphosphonates.

Patients taking denosumab are reassessed every 5 to 10 years to determine whether to continue therapy or change to a new drug. Abrupt discontinuation of therapy can lead to rebound bone loss and increased risk of fracture.30-32 As with bisphosphonates, long-term use can be associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.33

There is no recommendation for a drug holiday for denosumab. An increase in, or no loss of, bone density and no new fractures while being treated are signs of effective treatment. There is no guideline for stopping denosumab, unless the patient develops adverse effects.

❚ Bone anabolics. Patients with a very high risk of fracture (eg, who have sustained multiple vertebral fractures), can begin treatment with teriparatide (20 μg/d subcutaneously) or abaloparatide (80 μg/d subcutaneously) for as long as 2 years, followed by treatment with an antiresorptive, such as a bisphosphonate.4,6 Teriparatide can be used in patients who have not responded to an antiresorptive as first-line treatment.

Both abaloparatide and teriparatide might be associated with a risk of osteosarcoma and are contraindicated in patients who are at increased risk of osteosarcoma.36,39,40

❚ Romosozumab, a monoclonal sclerostin antibody, can be used in patients with very high risk of fracture or with multiple vertebral fractures. Romosozumab increases bone formation and reduces bone resorption. It is given monthly, 210 mg subcutaneously, for 1 year. The recommendation is that patients who have completed a course of romosozumab continue with antiresorptive treatment.26

Romosozumab is associated with an increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease, including stroke and myocardial infarction.26

❚ Raloxifene, a selective estrogen-receptor modulator, is no longer a first-line agent for osteoporosis in older adults34 because of its association with an increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and lethal stroke. However, raloxifene can be used, at 60 mg/d, when bisphosphonates or denosumab are unsuitable. In addition, raloxifene is particularly useful in women with a high risk of breast cancer and in men who are taking a long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for prostate cancer.37,38

Continue to: Influence of chronic...

Influence of chronic diseaseon bone health

Chronic diseases—hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperthyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and gastroenterologic disorders such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis—are known to affect bone loss that can hasten osteoporosis.16,18,21 Furthermore, medications used to treat chronic diseases are known to affect bone health: Some, such as statins, ACE inhibitors, and hydrochlorothiazide, are bone protective; others, such as steroids, pioglitazone, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, accelerate bone loss.1,14,42,43 It is important to be aware of the effect of a patient’s chronic diseases, and treatments for those diseases, on bone health, to help develop an individualized osteoporosis prevention plan.

Monitoring the efficacy of treatment

Treatment of osteoporosis should not be initiated without baseline measurement of BMD of the spine and hip. Subsequent to establishing that baseline, serial measurement of BMD can be used to (1) determine when treatment needs to be initiated for an untreated patient and (2) assess response in a treated patient. There is no consensus on the interval at which DXA should be repeated for the purpose of monitoring treatment response; frequency depends on the individual’s circumstances and the medication used. Notably, many physicians repeat DXA after 2 years of treatment8; however, the American College of Physicians recommends against repeating DXA within the first 5 years of pharmacotherapy in women.24

Patients with suspected vertebral fracture or those with loss of height > 1.5 inches require lateral radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine to assess the status of fractures.4,6

❚ Bone-turnover markers measured in serum can be used to assess treatment efficacy and patient adherence. The formation marker procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) and the resorption marker beta C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type 1 collagen (bCTX) are preferred for evaluating bone turnover in the clinical setting. Assessing P1NP and bCTX at baseline and after 3 months of treatment might be effective in monitoring adherence, particularly in patients taking a bisphosphonate.44

Be sure to address fall prevention

It is important to address falls, and how to prevent them, in patients with osteoporosis. Falls can precipitate fracture in older adults with reduced BMD, and fractures are the most common and debilitating manifestation of osteoporosis. Your discussion of falls with patients should include45:

- consequences of falls

- cautions about medications that can cloud mental alertness

- use of appropriate footwear

- home safety, such as adequate lighting, removal of floor clutter, and installation of handrails in the bathroom and stairwells and on outside steps.

- having an annual comprehensive eye exam.

Osteoporosis is avoidable and treatable

Earlier research reported various expressions of number needed to treat for medical management of osteoporosis—making it difficult to follow a single number as a reference for gauging the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy.46,47 However, for older adults of different ethnic and racial backgrounds with multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy, it might be more pragmatic in primary care to establish a model of goal-oriented, individualized care. By focusing on prevention of bone loss, and being mindful that the risk of fracture almost doubles with a decrease of 1 SD in BMD, you can translate numbers to goals of care.48

In the United States, approximately one-half of osteoporosis cases in adults ≥ 50 years are managed by primary care providers. As a chronic disease, osteoporosis requires that you, first, provide regular monitoring and assessment, because risk can vary with comorbidities,49 and, second, discuss and initiate screening and treatment as appropriate, which can be done annually during a well-care visit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nahid Rianon, MD, DrPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, UTHealth McGovern Medical School, 6431 Fannin Street #JJL 324C, Houston, TX, 77030; [email protected]

- What is osteoporosis and what causes it? National Osteoporosis Foundation Website. 2020. Accessed April 28, 2021. www.nof.org/patients/what-is-osteoporosis/

- des Bordes J, Prasad S, Pratt G, et al. Knowledge, beliefs, and concerns about bone health from a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227765

- Solomon DH, Johnston SS, Boytsov NN, et al. Osteoporosis medication use after hip fracture in U.S. patients between 2002 and 2011. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1929-1937. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2202

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:2521-2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7498

- Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis - 2016. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(suppl 4):1-42. doi: 10.4158/EP161435.GL

- Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al; Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802-1822. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3045

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2004. Accessed April 28, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45513/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK45513.pdf

- Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;843:1-129.

- Looker AC, Frenk SM. Percentage of adults aged 65 and over with osteoporosis or low bone mass at the femur neck or lumbar spine: United States, 2005--2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. August 2015. Accessed April 28, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/osteoporsis/osteoporosis2005_2010.pdf

- Kerschan-Schindl K. Prevention and rehabilitation of osteoporosis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2016;166:22-27. doi: 10.1007/s10354-015-0417-y

- Tarantino U, Iolascon G, Cianferotti L, et al. Clinical guidelines for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis: summary statements and recommendations from the Italian Society for Orthopaedics and Traumatology. J Orthop Traumatol. 2017;18(suppl 1):3-36. doi: 10.1007/s10195-017-0474-7

- Martineau P, Leslie WD, Johansson H, et al. In which patients does lumbar spine trabecular bone score (TBS) have the largest effect? Bone. 2018;113:161-168. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2018.05.026

- Rianon NJ, Smith SM, Lee M, et al. Glycemic control and bone turnover in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Osteoporos. 2018;2018:7153021. doi: 10.1155/2018/7153021

- Richards C, Hans D, Leslie WD. Trabecular bone score (TBS) predicts fracture in ankylosing spondylitis: The Manitoba BMD Registry. J Clin Densitom. 2020;23:543-548. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2020.01.003

- Xue Y, Baker AL, Nader S, et al. Lumbar spine trabecular bone score (TBS) reflects diminished bone quality in patients with diabetes mellitus and oral glucocorticoid therapy. J Clin Densitom. 2018;21:185-192. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2017.09.003

- Silva BC, Broy SB, Boutroy S, et al. Fracture risk prediction by non-BMD DXA measures: the 2015 ISCD Official Positions Part 2: trabecular bone score. J Clin Densitom. 2015;18:309-330. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2015.06.008

- Silva BC, Leslie WD, Resch H, et al. Trabecular bone score: a noninvasive analytical method based upon the DXA image. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:518-530. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2176

- Leslie WD, Aubry-Rozier B, Lamy O, et al; Manitoba Bone Density Program. TBS (trabecular bone score) and diabetes-related fracture risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:602-609.

- Looker AC, Sarafrazi Isfahani N, Fan B, et al. Trabecular bone scores and lumbar spine bone mineral density of US adults: comparison of relationships with demographic and body size variables. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:2467-2475. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3550-6

- Rianon N, Ambrose CG, Pervin H, et al. Long-term use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors protects against bone loss in African-American elderly men. Arch Osteoporos. 2017;12:94. doi: 10.1007/s11657-017-0387-3

- Morton DJ, Barrett-Connor EL, Edelstein SL. Thiazides and bone mineral density in elderly men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:1107-1115. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116954

- Sigurdsson G, Franzson L. Increased bone mineral density in a population-based group of 70-year-old women on thiazide diuretics, independent of parathyroid hormone levels. J Intern Med. 2001;250:51-56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00850.x

- Qaseem A, Forciea MA, McLean RM, et al; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures in men and women: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:818-839. doi: 10.7326/M15-1361

- des Bordes JKA, Suarez-Almazor ME, Volk RJ, et al. Online educational tool to promote bone health in cancer survivors. J Health Commun. 2017;22:808-817. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2017.1360415

- Shoback D, Rosen CJ, Black DM, et al. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society guideline update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:587-594. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa048

- Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al; FLEX Research Group. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2927-2938. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2927

- Bone HG, Hosking D, Devogelaer J-P, et al. Ten years' experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1189-1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030897

- Khosla S, Burr D, Cauley J, et al; American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1479-1491. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0707onj

- Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, et al. Effects of denosumab treatment and discontinuation on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:972-980. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1502

- Cummings SR, Ferrari S, Eastell R, et al. Vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab: a post hoc analysis of the randomized placebo-controlled FREEDOM Trial and its extension. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33:190-198. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3337

- Symonds C, Kline G. Warning of an increased risk of vertebral fracture after stopping denosumab. CMAJ. 2018;190:E485-E486. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.180115

- Aljohani S, Gaudin R, Weiser J, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients treated with denosumab: a multicenter case series. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46:1515-1525. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.05.046

- Barrett-Connor E, Mosca L, Collins P, et al; Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) Trial Investigators. Effects of raloxifene on cardiovascular events and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:125-137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062462

- Chesnut CH 3rd, Skag A, Christiansen C, et al; Oral Ibandronate Osteoporosis Vertebral Fracture Trial in North America and Europe (BONE). Effects of oral ibandronate administered daily or intermittently on fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1241-1249. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040325

- Gilsenban A, Midkiff K, Kellier-Steele N, et al. Teriparatide did not increase adult osteosarcoma incidence in a 15-year US postmarketing surveillance study. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;36:244-252. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4188

- Cuzick J, Sestak I, Bonanni B, et al; SERM Chemoprevention of Breast Cancer Overview Group. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators in prevention of breast cancer: an updated meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2013;381:1827-1834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60140-3

- Smith MR, Fallon MA, Lee H, et al. Raloxifene to prevent gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist-induced bone loss in men with prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3841-3846. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032058

- TYMLOS. Prescribing information. Radius Health, Inc.; April 2017. Accessed May 20, 2021. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/208743lbl.pdf

- FORTEO. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Co.; April 2020. Accessed May 20, 2021. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/021318s053lbl.pdf

- Wooltorton E. Patients receiving intravenous bisphosphonates should avoid invasive dental procedures. Can Med Assoc J. 2003;172:1684. doi: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050640

- Chiadika SM, Shobayo FO, Naqvi SH, et al. Lower femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) in elderly women not on statins. Women Health. 2019;59:845-853. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2019.1567646

- Saraykar S, John V, Cao B, et al. Association of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and bone mineral density in elderly women. J Clin Densitom. 2018;21:193-199. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2017.05.016

- Lorentzon M, Branco J, Brandi ML, et al. Algorithm for the use of biochemical markers of bone turnover in the diagnosis, assessment and follow-up of treatment for osteoporosis. Adv Ther. 2019;36:2811-2824. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01063-9

- STEADI--older adult fall prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2019. Accessed April 28, 2021. www.cdc.gov/steadi/patient.html

- Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al; FREEDOM Trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756-765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809493

- Zhou Z, Chen C, Zhang J, et al. Safety of denosumab in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis or low bone mineral density: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:2113-2122.

- Faulkner KG. Bone matters: are density increases necessary to reduce fracture risk? J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:183-187. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.2.183

- Rianon N, Anand D, Rasu R. Changing trends in osteoporosis care from specialty to primary care physicians. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:881-888. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.809335

Recommendations for care are evolving, with increasingly sophisticated screening and diagnostic tools and a broadening array of treatment options.

Recommendations for care are evolving, with increasingly sophisticated screening and diagnostic tools and a broadening array of treatment options.

As the population of older adults rises, primary osteoporosis has become a problem of public health significance, resulting in more than 2 million fractures and $19 billion in related costs annually in the United States.1 Despite the availability of effective primary and secondary preventive measures, many older adults do not receive adequate information on bone health from their primary care provider.2 Initiation of osteoporosis treatment is low even among patients who have had an osteoporotic fracture: Fewer than one-quarter of older adults with hip fracture have begun taking osteoporosis medication within 12 months of hospital discharge.3

In this overview of osteoporosis care, we provide information on how to evaluate and manage older adults in primary care settings who are at risk of, or have been given a diagnosis of, primary osteoporosis. The guidance that we offer reflects the most recent updates and recommendations by relevant professional societies.1,4-7

The nature and scope of an urgent problem

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of bone structure that causes bone fragility and increases the risk of fracture.8 Operationally, it is defined by the World Health Organization as a bone mineral density (BMD) score below 2.5 SD from the mean value for a young White woman (ie, T-score ≤ –2.5).9 Primary osteoporosis is age related and occurs mostly in postmenopausal women and older men, affecting 25% of women and 5% of men ≥ 65 years.10

An osteoporotic fracture is particularly devastating in an older adult because it can cause pain, reduced mobility, depression, and social isolation and can increase the risk of related mortality.1 The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates that 20% of older adults who sustain a hip fracture die within 1 year due to complications of the fracture itself or surgical repair.1 Therefore, it is of paramount importance to identify patients who are at increased risk of fracture and intervene early.

Clinical manifestations

Osteoporosis does not have a primary presentation; rather, disease manifests clinically when a patient develops complications. Often, a fragility fracture is the first sign in an older person.11

A fracture is the most important complication of osteoporosis and can result from low-trauma injury or a fall from standing height—thus, the term “fragility fracture.” Osteoporotic fractures commonly involve the vertebra, hip, and wrist. Hip and extremity fractures can result in limited or lost mobility and depression. Vertebral fractures can be asymptomatic or result in kyphosis and loss of height. Fractures can give rise to pain.

Age and female sexare risk factors

TABLE 11,6,10 lists risk factors associated with osteoporosis. Age is the most important; prevalence of osteoporosis increases with age. Other nonmodifiable risk factors include female sex (the disease appears earlier in women who enter menopause prematurely), family history of osteoporosis, and race and ethnicity. Twenty percent of Asian and non-Hispanic White women > 50 years have osteoporosis.1 A study showed that Mexican Americans are at higher risk of osteoporosis than non-Hispanic Whites; non-Hispanic Blacks are least affected.10

Other risk factors include low body weight (< 127 lb) and a history of fractures after age 50. Behavioral risk factors include smoking, excessive alcohol intake (> 3 drinks/d), poor nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle.1,6

Continue to: Who should be screened?...

Who should be screened?

Screening is generally performed with a clinical evaluation and a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan of BMD. Measurement of BMD is generally recommended for screening all women ≥ 65 years and those < 65 years whose 10-year risk of fracture is equivalent to that of a 65-year-old White woman (see “Assessment of fracture risk” later in the article). For men, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening those with a prior fracture or a secondary risk factor for disease.5 However, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends screening all men ≥ 70 years and those 50 to 69 years whose risk profile shows heightened risk.1,4

DXA of the spine and hip is preferred; the distal one-third of the radius (termed “33% radius”) of the nondominant arm can be used when spine and hip BMD cannot be interpreted because of bone changes from the disease process or artifacts, or in certain diseases in which the wrist region shows the earliest change (eg, primary hyperparathyroidism).6,7

Clinical evaluation includes a detailed history, physical examination, laboratory screening, and assessment for risk of fracture.

❚ History. Explore the presence of risk factors, including fractures in adulthood, falls, medication use, alcohol and tobacco use, family history of osteoporosis, and chronic disease.6,7

❚ Physical exam. Assess height, including any loss (> 1.5 in) since the patient’s second or third decade of life; kyphosis; frailty; and balance and mobility problems.4,6,7

❚ Laboratory and imaging studies. Perform basic laboratory testing when DXA is abnormal, including thyroid function, serum calcium, and renal function.6,12 Radiography of the lateral spine might be necessary, especially when there is kyphosis or loss of height. Assess for vertebral fracture, using lateral spine radiography, when vertebral involvement is suspected.6,7

❚ Assessment of fracture risk. Fracture risk can be assessed with any of a number of tools, including:

- Simplified Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE): www.medicalalgorithms.com/simplified-calculated-osteoporosis-risk-estimation-tool

- Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI): www.physio-pedia.com/The_Osteoporosis_Risk_Assessment_Instrument_(ORAI)

- Osteoporosis Index of Risk (OSIRIS): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/gye.16.3.245.250?journalCode=igye20

- Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST): www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45516/figure/ch10.f2/

- FRAX tool5: www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX.

The FRAX tool is widely used. It assesses a patient’s 10-year risk of fracture.

Diagnosis is based on these criteria

Diagnosis of osteoporosis is based on any 1 or more of the following criteria6:

- a history of fragility fracture not explained by metabolic bone disease

- T-score ≤ –2.5 (lumbar, hip, femoral neck, or 33% radius)

- a nation-specific FRAX score (in the absence of access to DXA).

❚ Secondary disease. Patients in whom secondary osteoporosis is suspected should undergo laboratory investigation to ascertain the cause; treatment of the underlying pathology might then be required. Evaluation for a secondary cause might include a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, protein electrophoresis and urinary protein electrophoresis (to rule out myeloproliferative and hematologic diseases), and tests of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, serum calcium, alkaline phosphatase, 24-hour urinary calcium, sodium, and creatinine.6,7 Specialized testing for biochemical markers of bone turnover—so-called bone-turnover markers—can be considered as part of the initial evaluation and follow-up, although the tests are not recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (see “Monitoring the efficacy of treatment,” later in the article, for more information about these markers).6

Although BMD by DXA remains the gold standard in screening for and diagnosing osteoporosis, a high rate of fracture is seen in patients with certain diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and ankylosing spondylitis, who have a nonosteoporotic low T-score. This raises concerns about the usefulness of BMD for diagnosing osteoporosis in patients who have one of these diseases.13-16

❚

❚ Trabecular bone score (TBS), a surrogate bone-quality measure that is calculated based on the spine DXA image, has recently been introduced in clinical practice, and can be used to predict fracture risk in conjunction with BMD assessment by DXA and the FRAX score.17 TBS provides an indirect index of the trabecular microarchitecture using pixel gray-level variation in lumbar spine DXA images.18 Three categories of TBS (≤ 1.200, degraded microarchitecture; 1.200-1.350, partially degraded microarchitecture; and > 1.350, normal microarchitecture) have been reported to correspond with a T-score of, respectively, ≤ −2.5; −2.5 to −1.0; and > −1.0.18 TBS can be used only in patients with a body mass index of 15 to 37.5.19,20

There is no recommendation for monitoring bone quality using TBS after osteoporosis treatment. Such monitoring is at the clinician’s discretion for appropriate patients who might not show a risk of fracture, based on BMD measurement.

Continue to: Putting preventive measures into practice...

Putting preventive measures into practice

Measures to prevent osteoporosis and preserve bone health (TABLE 21,6) are best started in childhood but can be initiated at any age and maintained through the lifespan. Encourage older adults to adopt dietary and behavioral strategies to improve their bone health and prevent fracture. We recommend the following strategies; take each patient’s individual situation into consideration when electing to adopt any of these measures.

❚ Vitamin D. Consider checking the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and providing supplementation (800-1000 IU daily, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends1) as necessary to maintain the level at 30-50 ng/mL.6

❚ Calcium. Encourage a daily dietary calcium intake of 1000-1200 mg. Supplement calcium if you determine that diet does not provide an adequate amount.

❚ Alcohol. Advise patients to limit consumption to < 3 drinks a day.

❚ Tobacco. Advise smoking cessation.

❚ Activity. Encourage an active lifestyle, including regular weight-bearing and balance exercises and resistance exercises such as Pilates, weightlifting, and tai chi. The regimen should be tailored to the patient’s individual situation.

❚ Medical therapy for concomitant illness. When possible, prescribe medications for chronic comorbidities that can also benefit bone health. For example, long-term use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and thiazide diuretics for hypertension are associated with a slower decline in BMD in some populations.21-23

Tailor treatment to patient’s circumstances

TABLE 34,6,24 describes indications for pharmacotherapy in osteoporosis. Pharmacotherapy is recommended in all cases of osteoporosis and osteopenia when fracture risk is high.24

Generally, you should undertake a discussion with the patient of the relative risks and benefits of treatment, taking into account their values and preferences, to come to a shared decision. Tailoring treatment, based on the patient’s distinctive circumstances, through shared decision-making is key to compliance.25

Pharmacotherapy is not indicated in patients whose risk of fracture is low; however, you should reassess such patients every 2 to 4 years.26 Women with a very high BMD might not need to be retested with DXA any sooner than every 10 to 15 years.

There are 3 main classes of first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for osteoporosis in older adults (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41): antiresorptives (bisphosphonates and denosumab), anabolics (teriparatide and abaloparatide), and a monoclonal sclerostin antibody (romosozumab). (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41 and the discussion in this section also remark on the selective estrogen-receptor modulator raloxifene, which is used in special clinical circumstances but has been removed from the first line of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy.)

❚ Bisphosphonates. Oral bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate) can be used as initial treatment in patients with a high risk of fracture.35 Bisphosphonates have been shown to reduce fracture risk and improve BMD. When an oral bisphosphonate cannot be tolerated, intravenous zoledronate or ibandronate can be used.41

Patients treated with a bisphosphonate should be assessed for their fracture risk after 3 to 5 years of treatment26; when intravenous zoledronate is given as initial therapy, patients should be assessed after 3 years. After assessment, patients who remain at high risk should continue treatment; those whose fracture risk has decreased to low or moderate should have treatment temporarily suspended (bisphosphonate holiday) for as long as 5 years.26 Patients on bisphosphonate holiday should have their fracture risk assessed at 2- to 4-year intervals.26 Restart treatment if there is an increase in fracture risk (eg, a decrease in BMD) or if a fracture occurs. Bisphosphonates have a prolonged effect on BMD—for many years after treatment is discontinued.27,28

Oral bisphosphonates are associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, difficulty swallowing, and gastritis. Rare adverse effects include osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.29

❚ Denosumab, a recombinant human antibody, is a relatively newer antiresorptive for initial treatment. Denosumab, 60 mg, is given subcutaneously every 6 months. The drug can be used when bisphosphonates are contraindicated, the patient finds the bisphosphonate dosing regimen difficult to follow, or the patient is unresponsive to bisphosphonates.

Patients taking denosumab are reassessed every 5 to 10 years to determine whether to continue therapy or change to a new drug. Abrupt discontinuation of therapy can lead to rebound bone loss and increased risk of fracture.30-32 As with bisphosphonates, long-term use can be associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.33

There is no recommendation for a drug holiday for denosumab. An increase in, or no loss of, bone density and no new fractures while being treated are signs of effective treatment. There is no guideline for stopping denosumab, unless the patient develops adverse effects.

❚ Bone anabolics. Patients with a very high risk of fracture (eg, who have sustained multiple vertebral fractures), can begin treatment with teriparatide (20 μg/d subcutaneously) or abaloparatide (80 μg/d subcutaneously) for as long as 2 years, followed by treatment with an antiresorptive, such as a bisphosphonate.4,6 Teriparatide can be used in patients who have not responded to an antiresorptive as first-line treatment.

Both abaloparatide and teriparatide might be associated with a risk of osteosarcoma and are contraindicated in patients who are at increased risk of osteosarcoma.36,39,40

❚ Romosozumab, a monoclonal sclerostin antibody, can be used in patients with very high risk of fracture or with multiple vertebral fractures. Romosozumab increases bone formation and reduces bone resorption. It is given monthly, 210 mg subcutaneously, for 1 year. The recommendation is that patients who have completed a course of romosozumab continue with antiresorptive treatment.26

Romosozumab is associated with an increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease, including stroke and myocardial infarction.26

❚ Raloxifene, a selective estrogen-receptor modulator, is no longer a first-line agent for osteoporosis in older adults34 because of its association with an increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and lethal stroke. However, raloxifene can be used, at 60 mg/d, when bisphosphonates or denosumab are unsuitable. In addition, raloxifene is particularly useful in women with a high risk of breast cancer and in men who are taking a long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for prostate cancer.37,38

Continue to: Influence of chronic...

Influence of chronic diseaseon bone health

Chronic diseases—hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperthyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and gastroenterologic disorders such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis—are known to affect bone loss that can hasten osteoporosis.16,18,21 Furthermore, medications used to treat chronic diseases are known to affect bone health: Some, such as statins, ACE inhibitors, and hydrochlorothiazide, are bone protective; others, such as steroids, pioglitazone, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, accelerate bone loss.1,14,42,43 It is important to be aware of the effect of a patient’s chronic diseases, and treatments for those diseases, on bone health, to help develop an individualized osteoporosis prevention plan.

Monitoring the efficacy of treatment

Treatment of osteoporosis should not be initiated without baseline measurement of BMD of the spine and hip. Subsequent to establishing that baseline, serial measurement of BMD can be used to (1) determine when treatment needs to be initiated for an untreated patient and (2) assess response in a treated patient. There is no consensus on the interval at which DXA should be repeated for the purpose of monitoring treatment response; frequency depends on the individual’s circumstances and the medication used. Notably, many physicians repeat DXA after 2 years of treatment8; however, the American College of Physicians recommends against repeating DXA within the first 5 years of pharmacotherapy in women.24

Patients with suspected vertebral fracture or those with loss of height > 1.5 inches require lateral radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine to assess the status of fractures.4,6

❚ Bone-turnover markers measured in serum can be used to assess treatment efficacy and patient adherence. The formation marker procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) and the resorption marker beta C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type 1 collagen (bCTX) are preferred for evaluating bone turnover in the clinical setting. Assessing P1NP and bCTX at baseline and after 3 months of treatment might be effective in monitoring adherence, particularly in patients taking a bisphosphonate.44

Be sure to address fall prevention

It is important to address falls, and how to prevent them, in patients with osteoporosis. Falls can precipitate fracture in older adults with reduced BMD, and fractures are the most common and debilitating manifestation of osteoporosis. Your discussion of falls with patients should include45:

- consequences of falls

- cautions about medications that can cloud mental alertness

- use of appropriate footwear

- home safety, such as adequate lighting, removal of floor clutter, and installation of handrails in the bathroom and stairwells and on outside steps.

- having an annual comprehensive eye exam.

Osteoporosis is avoidable and treatable

Earlier research reported various expressions of number needed to treat for medical management of osteoporosis—making it difficult to follow a single number as a reference for gauging the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy.46,47 However, for older adults of different ethnic and racial backgrounds with multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy, it might be more pragmatic in primary care to establish a model of goal-oriented, individualized care. By focusing on prevention of bone loss, and being mindful that the risk of fracture almost doubles with a decrease of 1 SD in BMD, you can translate numbers to goals of care.48

In the United States, approximately one-half of osteoporosis cases in adults ≥ 50 years are managed by primary care providers. As a chronic disease, osteoporosis requires that you, first, provide regular monitoring and assessment, because risk can vary with comorbidities,49 and, second, discuss and initiate screening and treatment as appropriate, which can be done annually during a well-care visit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nahid Rianon, MD, DrPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, UTHealth McGovern Medical School, 6431 Fannin Street #JJL 324C, Houston, TX, 77030; [email protected]

As the population of older adults rises, primary osteoporosis has become a problem of public health significance, resulting in more than 2 million fractures and $19 billion in related costs annually in the United States.1 Despite the availability of effective primary and secondary preventive measures, many older adults do not receive adequate information on bone health from their primary care provider.2 Initiation of osteoporosis treatment is low even among patients who have had an osteoporotic fracture: Fewer than one-quarter of older adults with hip fracture have begun taking osteoporosis medication within 12 months of hospital discharge.3

In this overview of osteoporosis care, we provide information on how to evaluate and manage older adults in primary care settings who are at risk of, or have been given a diagnosis of, primary osteoporosis. The guidance that we offer reflects the most recent updates and recommendations by relevant professional societies.1,4-7

The nature and scope of an urgent problem

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of bone structure that causes bone fragility and increases the risk of fracture.8 Operationally, it is defined by the World Health Organization as a bone mineral density (BMD) score below 2.5 SD from the mean value for a young White woman (ie, T-score ≤ –2.5).9 Primary osteoporosis is age related and occurs mostly in postmenopausal women and older men, affecting 25% of women and 5% of men ≥ 65 years.10

An osteoporotic fracture is particularly devastating in an older adult because it can cause pain, reduced mobility, depression, and social isolation and can increase the risk of related mortality.1 The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates that 20% of older adults who sustain a hip fracture die within 1 year due to complications of the fracture itself or surgical repair.1 Therefore, it is of paramount importance to identify patients who are at increased risk of fracture and intervene early.

Clinical manifestations

Osteoporosis does not have a primary presentation; rather, disease manifests clinically when a patient develops complications. Often, a fragility fracture is the first sign in an older person.11

A fracture is the most important complication of osteoporosis and can result from low-trauma injury or a fall from standing height—thus, the term “fragility fracture.” Osteoporotic fractures commonly involve the vertebra, hip, and wrist. Hip and extremity fractures can result in limited or lost mobility and depression. Vertebral fractures can be asymptomatic or result in kyphosis and loss of height. Fractures can give rise to pain.

Age and female sexare risk factors

TABLE 11,6,10 lists risk factors associated with osteoporosis. Age is the most important; prevalence of osteoporosis increases with age. Other nonmodifiable risk factors include female sex (the disease appears earlier in women who enter menopause prematurely), family history of osteoporosis, and race and ethnicity. Twenty percent of Asian and non-Hispanic White women > 50 years have osteoporosis.1 A study showed that Mexican Americans are at higher risk of osteoporosis than non-Hispanic Whites; non-Hispanic Blacks are least affected.10

Other risk factors include low body weight (< 127 lb) and a history of fractures after age 50. Behavioral risk factors include smoking, excessive alcohol intake (> 3 drinks/d), poor nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle.1,6

Continue to: Who should be screened?...

Who should be screened?

Screening is generally performed with a clinical evaluation and a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan of BMD. Measurement of BMD is generally recommended for screening all women ≥ 65 years and those < 65 years whose 10-year risk of fracture is equivalent to that of a 65-year-old White woman (see “Assessment of fracture risk” later in the article). For men, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening those with a prior fracture or a secondary risk factor for disease.5 However, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends screening all men ≥ 70 years and those 50 to 69 years whose risk profile shows heightened risk.1,4

DXA of the spine and hip is preferred; the distal one-third of the radius (termed “33% radius”) of the nondominant arm can be used when spine and hip BMD cannot be interpreted because of bone changes from the disease process or artifacts, or in certain diseases in which the wrist region shows the earliest change (eg, primary hyperparathyroidism).6,7

Clinical evaluation includes a detailed history, physical examination, laboratory screening, and assessment for risk of fracture.

❚ History. Explore the presence of risk factors, including fractures in adulthood, falls, medication use, alcohol and tobacco use, family history of osteoporosis, and chronic disease.6,7

❚ Physical exam. Assess height, including any loss (> 1.5 in) since the patient’s second or third decade of life; kyphosis; frailty; and balance and mobility problems.4,6,7

❚ Laboratory and imaging studies. Perform basic laboratory testing when DXA is abnormal, including thyroid function, serum calcium, and renal function.6,12 Radiography of the lateral spine might be necessary, especially when there is kyphosis or loss of height. Assess for vertebral fracture, using lateral spine radiography, when vertebral involvement is suspected.6,7

❚ Assessment of fracture risk. Fracture risk can be assessed with any of a number of tools, including:

- Simplified Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE): www.medicalalgorithms.com/simplified-calculated-osteoporosis-risk-estimation-tool

- Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI): www.physio-pedia.com/The_Osteoporosis_Risk_Assessment_Instrument_(ORAI)

- Osteoporosis Index of Risk (OSIRIS): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/gye.16.3.245.250?journalCode=igye20

- Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST): www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45516/figure/ch10.f2/

- FRAX tool5: www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX.

The FRAX tool is widely used. It assesses a patient’s 10-year risk of fracture.

Diagnosis is based on these criteria

Diagnosis of osteoporosis is based on any 1 or more of the following criteria6:

- a history of fragility fracture not explained by metabolic bone disease

- T-score ≤ –2.5 (lumbar, hip, femoral neck, or 33% radius)

- a nation-specific FRAX score (in the absence of access to DXA).

❚ Secondary disease. Patients in whom secondary osteoporosis is suspected should undergo laboratory investigation to ascertain the cause; treatment of the underlying pathology might then be required. Evaluation for a secondary cause might include a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, protein electrophoresis and urinary protein electrophoresis (to rule out myeloproliferative and hematologic diseases), and tests of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, serum calcium, alkaline phosphatase, 24-hour urinary calcium, sodium, and creatinine.6,7 Specialized testing for biochemical markers of bone turnover—so-called bone-turnover markers—can be considered as part of the initial evaluation and follow-up, although the tests are not recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (see “Monitoring the efficacy of treatment,” later in the article, for more information about these markers).6

Although BMD by DXA remains the gold standard in screening for and diagnosing osteoporosis, a high rate of fracture is seen in patients with certain diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and ankylosing spondylitis, who have a nonosteoporotic low T-score. This raises concerns about the usefulness of BMD for diagnosing osteoporosis in patients who have one of these diseases.13-16

❚

❚ Trabecular bone score (TBS), a surrogate bone-quality measure that is calculated based on the spine DXA image, has recently been introduced in clinical practice, and can be used to predict fracture risk in conjunction with BMD assessment by DXA and the FRAX score.17 TBS provides an indirect index of the trabecular microarchitecture using pixel gray-level variation in lumbar spine DXA images.18 Three categories of TBS (≤ 1.200, degraded microarchitecture; 1.200-1.350, partially degraded microarchitecture; and > 1.350, normal microarchitecture) have been reported to correspond with a T-score of, respectively, ≤ −2.5; −2.5 to −1.0; and > −1.0.18 TBS can be used only in patients with a body mass index of 15 to 37.5.19,20

There is no recommendation for monitoring bone quality using TBS after osteoporosis treatment. Such monitoring is at the clinician’s discretion for appropriate patients who might not show a risk of fracture, based on BMD measurement.

Continue to: Putting preventive measures into practice...

Putting preventive measures into practice

Measures to prevent osteoporosis and preserve bone health (TABLE 21,6) are best started in childhood but can be initiated at any age and maintained through the lifespan. Encourage older adults to adopt dietary and behavioral strategies to improve their bone health and prevent fracture. We recommend the following strategies; take each patient’s individual situation into consideration when electing to adopt any of these measures.

❚ Vitamin D. Consider checking the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and providing supplementation (800-1000 IU daily, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends1) as necessary to maintain the level at 30-50 ng/mL.6

❚ Calcium. Encourage a daily dietary calcium intake of 1000-1200 mg. Supplement calcium if you determine that diet does not provide an adequate amount.

❚ Alcohol. Advise patients to limit consumption to < 3 drinks a day.

❚ Tobacco. Advise smoking cessation.

❚ Activity. Encourage an active lifestyle, including regular weight-bearing and balance exercises and resistance exercises such as Pilates, weightlifting, and tai chi. The regimen should be tailored to the patient’s individual situation.

❚ Medical therapy for concomitant illness. When possible, prescribe medications for chronic comorbidities that can also benefit bone health. For example, long-term use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and thiazide diuretics for hypertension are associated with a slower decline in BMD in some populations.21-23

Tailor treatment to patient’s circumstances

TABLE 34,6,24 describes indications for pharmacotherapy in osteoporosis. Pharmacotherapy is recommended in all cases of osteoporosis and osteopenia when fracture risk is high.24

Generally, you should undertake a discussion with the patient of the relative risks and benefits of treatment, taking into account their values and preferences, to come to a shared decision. Tailoring treatment, based on the patient’s distinctive circumstances, through shared decision-making is key to compliance.25

Pharmacotherapy is not indicated in patients whose risk of fracture is low; however, you should reassess such patients every 2 to 4 years.26 Women with a very high BMD might not need to be retested with DXA any sooner than every 10 to 15 years.

There are 3 main classes of first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for osteoporosis in older adults (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41): antiresorptives (bisphosphonates and denosumab), anabolics (teriparatide and abaloparatide), and a monoclonal sclerostin antibody (romosozumab). (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41 and the discussion in this section also remark on the selective estrogen-receptor modulator raloxifene, which is used in special clinical circumstances but has been removed from the first line of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy.)

❚ Bisphosphonates. Oral bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate) can be used as initial treatment in patients with a high risk of fracture.35 Bisphosphonates have been shown to reduce fracture risk and improve BMD. When an oral bisphosphonate cannot be tolerated, intravenous zoledronate or ibandronate can be used.41

Patients treated with a bisphosphonate should be assessed for their fracture risk after 3 to 5 years of treatment26; when intravenous zoledronate is given as initial therapy, patients should be assessed after 3 years. After assessment, patients who remain at high risk should continue treatment; those whose fracture risk has decreased to low or moderate should have treatment temporarily suspended (bisphosphonate holiday) for as long as 5 years.26 Patients on bisphosphonate holiday should have their fracture risk assessed at 2- to 4-year intervals.26 Restart treatment if there is an increase in fracture risk (eg, a decrease in BMD) or if a fracture occurs. Bisphosphonates have a prolonged effect on BMD—for many years after treatment is discontinued.27,28

Oral bisphosphonates are associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, difficulty swallowing, and gastritis. Rare adverse effects include osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.29

❚ Denosumab, a recombinant human antibody, is a relatively newer antiresorptive for initial treatment. Denosumab, 60 mg, is given subcutaneously every 6 months. The drug can be used when bisphosphonates are contraindicated, the patient finds the bisphosphonate dosing regimen difficult to follow, or the patient is unresponsive to bisphosphonates.

Patients taking denosumab are reassessed every 5 to 10 years to determine whether to continue therapy or change to a new drug. Abrupt discontinuation of therapy can lead to rebound bone loss and increased risk of fracture.30-32 As with bisphosphonates, long-term use can be associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.33

There is no recommendation for a drug holiday for denosumab. An increase in, or no loss of, bone density and no new fractures while being treated are signs of effective treatment. There is no guideline for stopping denosumab, unless the patient develops adverse effects.

❚ Bone anabolics. Patients with a very high risk of fracture (eg, who have sustained multiple vertebral fractures), can begin treatment with teriparatide (20 μg/d subcutaneously) or abaloparatide (80 μg/d subcutaneously) for as long as 2 years, followed by treatment with an antiresorptive, such as a bisphosphonate.4,6 Teriparatide can be used in patients who have not responded to an antiresorptive as first-line treatment.

Both abaloparatide and teriparatide might be associated with a risk of osteosarcoma and are contraindicated in patients who are at increased risk of osteosarcoma.36,39,40

❚ Romosozumab, a monoclonal sclerostin antibody, can be used in patients with very high risk of fracture or with multiple vertebral fractures. Romosozumab increases bone formation and reduces bone resorption. It is given monthly, 210 mg subcutaneously, for 1 year. The recommendation is that patients who have completed a course of romosozumab continue with antiresorptive treatment.26

Romosozumab is associated with an increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease, including stroke and myocardial infarction.26

❚ Raloxifene, a selective estrogen-receptor modulator, is no longer a first-line agent for osteoporosis in older adults34 because of its association with an increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and lethal stroke. However, raloxifene can be used, at 60 mg/d, when bisphosphonates or denosumab are unsuitable. In addition, raloxifene is particularly useful in women with a high risk of breast cancer and in men who are taking a long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for prostate cancer.37,38

Continue to: Influence of chronic...

Influence of chronic diseaseon bone health

Chronic diseases—hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperthyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and gastroenterologic disorders such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis—are known to affect bone loss that can hasten osteoporosis.16,18,21 Furthermore, medications used to treat chronic diseases are known to affect bone health: Some, such as statins, ACE inhibitors, and hydrochlorothiazide, are bone protective; others, such as steroids, pioglitazone, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, accelerate bone loss.1,14,42,43 It is important to be aware of the effect of a patient’s chronic diseases, and treatments for those diseases, on bone health, to help develop an individualized osteoporosis prevention plan.

Monitoring the efficacy of treatment

Treatment of osteoporosis should not be initiated without baseline measurement of BMD of the spine and hip. Subsequent to establishing that baseline, serial measurement of BMD can be used to (1) determine when treatment needs to be initiated for an untreated patient and (2) assess response in a treated patient. There is no consensus on the interval at which DXA should be repeated for the purpose of monitoring treatment response; frequency depends on the individual’s circumstances and the medication used. Notably, many physicians repeat DXA after 2 years of treatment8; however, the American College of Physicians recommends against repeating DXA within the first 5 years of pharmacotherapy in women.24

Patients with suspected vertebral fracture or those with loss of height > 1.5 inches require lateral radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine to assess the status of fractures.4,6

❚ Bone-turnover markers measured in serum can be used to assess treatment efficacy and patient adherence. The formation marker procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) and the resorption marker beta C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type 1 collagen (bCTX) are preferred for evaluating bone turnover in the clinical setting. Assessing P1NP and bCTX at baseline and after 3 months of treatment might be effective in monitoring adherence, particularly in patients taking a bisphosphonate.44

Be sure to address fall prevention

It is important to address falls, and how to prevent them, in patients with osteoporosis. Falls can precipitate fracture in older adults with reduced BMD, and fractures are the most common and debilitating manifestation of osteoporosis. Your discussion of falls with patients should include45:

- consequences of falls

- cautions about medications that can cloud mental alertness

- use of appropriate footwear

- home safety, such as adequate lighting, removal of floor clutter, and installation of handrails in the bathroom and stairwells and on outside steps.

- having an annual comprehensive eye exam.

Osteoporosis is avoidable and treatable

Earlier research reported various expressions of number needed to treat for medical management of osteoporosis—making it difficult to follow a single number as a reference for gauging the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy.46,47 However, for older adults of different ethnic and racial backgrounds with multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy, it might be more pragmatic in primary care to establish a model of goal-oriented, individualized care. By focusing on prevention of bone loss, and being mindful that the risk of fracture almost doubles with a decrease of 1 SD in BMD, you can translate numbers to goals of care.48

In the United States, approximately one-half of osteoporosis cases in adults ≥ 50 years are managed by primary care providers. As a chronic disease, osteoporosis requires that you, first, provide regular monitoring and assessment, because risk can vary with comorbidities,49 and, second, discuss and initiate screening and treatment as appropriate, which can be done annually during a well-care visit.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nahid Rianon, MD, DrPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, UTHealth McGovern Medical School, 6431 Fannin Street #JJL 324C, Houston, TX, 77030; [email protected]

- What is osteoporosis and what causes it? National Osteoporosis Foundation Website. 2020. Accessed April 28, 2021. www.nof.org/patients/what-is-osteoporosis/

- des Bordes J, Prasad S, Pratt G, et al. Knowledge, beliefs, and concerns about bone health from a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227765

- Solomon DH, Johnston SS, Boytsov NN, et al. Osteoporosis medication use after hip fracture in U.S. patients between 2002 and 2011. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1929-1937. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2202

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:2521-2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7498

- Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis - 2016. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(suppl 4):1-42. doi: 10.4158/EP161435.GL

- Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al; Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802-1822. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3045

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2004. Accessed April 28, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45513/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK45513.pdf

- Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;843:1-129.

- Looker AC, Frenk SM. Percentage of adults aged 65 and over with osteoporosis or low bone mass at the femur neck or lumbar spine: United States, 2005--2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. August 2015. Accessed April 28, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/osteoporsis/osteoporosis2005_2010.pdf

- Kerschan-Schindl K. Prevention and rehabilitation of osteoporosis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2016;166:22-27. doi: 10.1007/s10354-015-0417-y

- Tarantino U, Iolascon G, Cianferotti L, et al. Clinical guidelines for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis: summary statements and recommendations from the Italian Society for Orthopaedics and Traumatology. J Orthop Traumatol. 2017;18(suppl 1):3-36. doi: 10.1007/s10195-017-0474-7

- Martineau P, Leslie WD, Johansson H, et al. In which patients does lumbar spine trabecular bone score (TBS) have the largest effect? Bone. 2018;113:161-168. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2018.05.026

- Rianon NJ, Smith SM, Lee M, et al. Glycemic control and bone turnover in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Osteoporos. 2018;2018:7153021. doi: 10.1155/2018/7153021

- Richards C, Hans D, Leslie WD. Trabecular bone score (TBS) predicts fracture in ankylosing spondylitis: The Manitoba BMD Registry. J Clin Densitom. 2020;23:543-548. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2020.01.003

- Xue Y, Baker AL, Nader S, et al. Lumbar spine trabecular bone score (TBS) reflects diminished bone quality in patients with diabetes mellitus and oral glucocorticoid therapy. J Clin Densitom. 2018;21:185-192. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2017.09.003

- Silva BC, Broy SB, Boutroy S, et al. Fracture risk prediction by non-BMD DXA measures: the 2015 ISCD Official Positions Part 2: trabecular bone score. J Clin Densitom. 2015;18:309-330. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2015.06.008

- Silva BC, Leslie WD, Resch H, et al. Trabecular bone score: a noninvasive analytical method based upon the DXA image. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:518-530. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2176

- Leslie WD, Aubry-Rozier B, Lamy O, et al; Manitoba Bone Density Program. TBS (trabecular bone score) and diabetes-related fracture risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:602-609.

- Looker AC, Sarafrazi Isfahani N, Fan B, et al. Trabecular bone scores and lumbar spine bone mineral density of US adults: comparison of relationships with demographic and body size variables. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:2467-2475. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3550-6

- Rianon N, Ambrose CG, Pervin H, et al. Long-term use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors protects against bone loss in African-American elderly men. Arch Osteoporos. 2017;12:94. doi: 10.1007/s11657-017-0387-3

- Morton DJ, Barrett-Connor EL, Edelstein SL. Thiazides and bone mineral density in elderly men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:1107-1115. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116954

- Sigurdsson G, Franzson L. Increased bone mineral density in a population-based group of 70-year-old women on thiazide diuretics, independent of parathyroid hormone levels. J Intern Med. 2001;250:51-56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00850.x

- Qaseem A, Forciea MA, McLean RM, et al; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures in men and women: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:818-839. doi: 10.7326/M15-1361

- des Bordes JKA, Suarez-Almazor ME, Volk RJ, et al. Online educational tool to promote bone health in cancer survivors. J Health Commun. 2017;22:808-817. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2017.1360415

- Shoback D, Rosen CJ, Black DM, et al. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society guideline update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:587-594. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa048

- Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al; FLEX Research Group. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2927-2938. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2927

- Bone HG, Hosking D, Devogelaer J-P, et al. Ten years' experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1189-1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030897

- Khosla S, Burr D, Cauley J, et al; American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1479-1491. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0707onj

- Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, et al. Effects of denosumab treatment and discontinuation on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:972-980. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1502

- Cummings SR, Ferrari S, Eastell R, et al. Vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab: a post hoc analysis of the randomized placebo-controlled FREEDOM Trial and its extension. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33:190-198. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3337

- Symonds C, Kline G. Warning of an increased risk of vertebral fracture after stopping denosumab. CMAJ. 2018;190:E485-E486. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.180115

- Aljohani S, Gaudin R, Weiser J, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients treated with denosumab: a multicenter case series. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46:1515-1525. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.05.046

- Barrett-Connor E, Mosca L, Collins P, et al; Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) Trial Investigators. Effects of raloxifene on cardiovascular events and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:125-137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062462

- Chesnut CH 3rd, Skag A, Christiansen C, et al; Oral Ibandronate Osteoporosis Vertebral Fracture Trial in North America and Europe (BONE). Effects of oral ibandronate administered daily or intermittently on fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1241-1249. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040325