User login

How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D

In April 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published an updated recommendation on screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults. It reaffirmed an “I” statement first made in 2014: evidence is insufficient to balance the benefits and harms of screening.1 This recommendation applies to asymptomatic, community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults without conditions treatable with vitamin D. It’s important to remember that screening refers to testing asymptomatic individuals to detect a condition early before it causes illness. Testing performed to determine whether symptoms are evidence of an underlying condition is not screening but diagnostic testing.

The Task Force statement explains the problems they found with the current level of knowledge about screening for vitamin D deficiency. First, while 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] is considered the best test for vitamin D levels, it is hard to measure accurately and test results vary by the method used and laboratories doing the testing. There also is uncertainty about how best to measure vitamin D status in different racial and ethnic groups, especially those with dark skin pigmentation. In addition, 25(OH)D in the blood is predominantly the bound form, with only 10% to 15% being unbound and bioavailable. Current tests do not determine the amount of bound vs unbound 25(OH)D.1-3

There is no consensus about the optimal blood level of vitamin D or the level that defines deficiency. The Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine—NAM) stated that serum 25(OH)D levels ≥ 20 ng/mL are adequate to meet the metabolic needs of 97.5% of people, and that levels of 12 to 20 ng/mL pose a risk of deficiency, with levels < 12 considered to be very low.4 The Endocrine Society defines deficiency as < 20 ng/mL and insufficiency as 21 to 29 ng/mL.5

The rate of testing for vitamin D deficiency in primary care in unknown, but there is evidence that since 2000, it has increased 80 fold at least among those with Medicare.6 Data from the 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that 5% of the population had 25(OH)D levels < 12 ng/mL and 18% had levels between 12 and 19 ng/mL.7 Some have estimated that as many as half of all adults would be considered vitamin D deficient or insufficient using current less conservative definitions, with higher rates in racial/ethnic minorities.2,8

There are no firm data on the frequency, or benefits, of screening for vitamin D levels in asymptomatic adults (and treating those found to have vitamin D deficiency). The Task Force looked for indirect evidence by examining the effect of treating vitamin D deficiency in a number of conditions and found that for some, there was adequate evidence of no benefit and for others there was inadequate evidence for possible benefits.9 No benefit was found for incidence of fractures, type 2 diabetes, and overall mortality.9 Inadequate evidence was found for incidence of cancer, cardiovascular disease, scores on measures of depression and physical functioning, and urinary tract infections in those with impaired fasting glucose.9

Known risk factors for low vitamin D levels include low vitamin D intake, older age, obesity, low UVB exposure or absorption due to long winter seasons in northern latitudes, sun avoidance, and dark skin pigmentation.1 In addition, certain medical conditions contribute to, or are caused by, low vitamin D levels—eg, osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, malabsorption syndromes, and medication use (ie, glucocorticoids).1-3

The Task Force recommendation on screening for vitamin D deficiency differs from those of some other organizations. However, none recommend universal population-based screening. The Endocrine Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommend screening but only in those at risk for vitamin D deficiency.5,10 The American Academy of Family Physicians endorses the USPSTF recommendation.11

Continue to: Specific USPSTF topics related to vitamin D

Specific USPSTF topics related to vitamin D

The Task Force has specifically addressed 3 topics pertaining to vitamin D.

Prevention of falls in the elderly. In 2018 the Task Force recommended against the use of vitamin D to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults ≥ 65 years.12 This reversed its 2012 recommendation advising vitamin D supplementation to prevent falls. The Task Force re-examined the old evidence and looked at newer studies and concluded that their previous conclusion was wrong and that the evidence showed no benefit from vitamin D in preventing falls in the elderly. The reversal of a prior recommendation is rare for the USPSTF because of the rigor of its evidence reviews and its policy of not making a recommendation unless solid evidence for or against exists.

Prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. The Task Force concludes that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms in the use of single- or paired-nutrient supplements to prevent cardiovascular disease or cancer.13 (The exceptions are beta-carotene and vitamin E, which the Task Force recommends against.) This statement is consistent with the lack of evidence the Task Force found regarding prevention of these conditions by vitamin D supplementation in those who are vitamin D deficient.

Prevention of fractures in men and in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. For men and premenopausal women, the Task Force concludes that evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of vitamin D and calcium supplementation, alone or in combination, to prevent fractures.14 For prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women, there are 2 recommendations. The first one advises against the use of ≤ 400 IU of vitamin D and ≤ 1000 mg of calcium because the evidence indicates ineffectiveness. The second one is another “I” statement for the use of doses > 400 IU of vitamin D and > 1000 mg of calcium. These 3 recommendations apply to adults who live in the community and not in nursing homes or other institutional care facilities; they do not apply to those who have osteoporosis.

What should the family physician do?

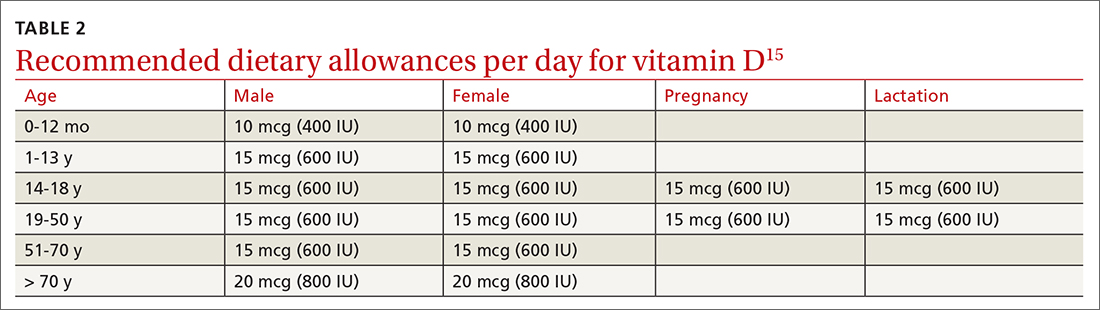

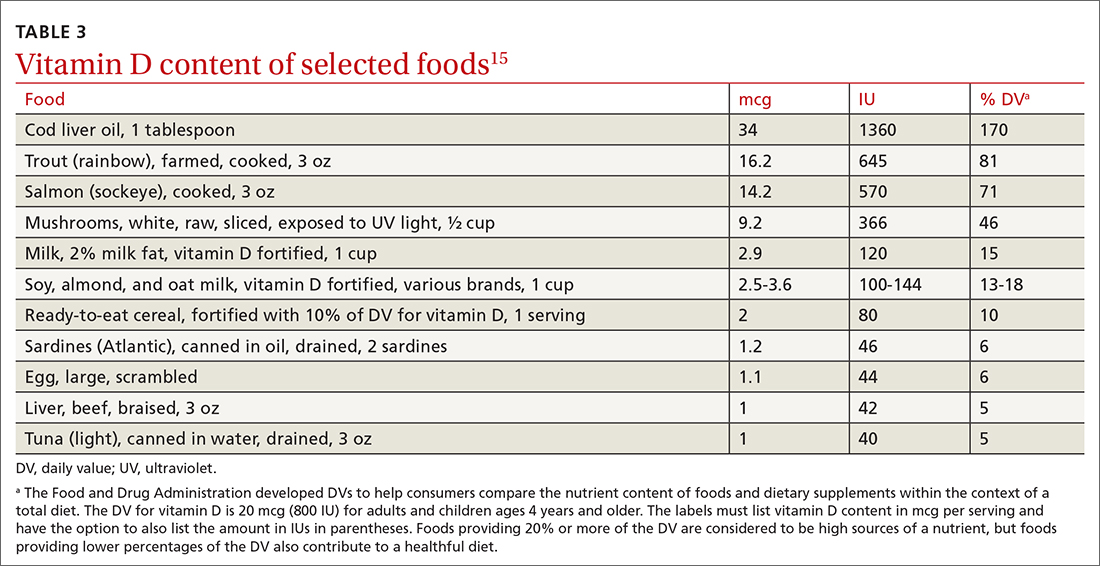

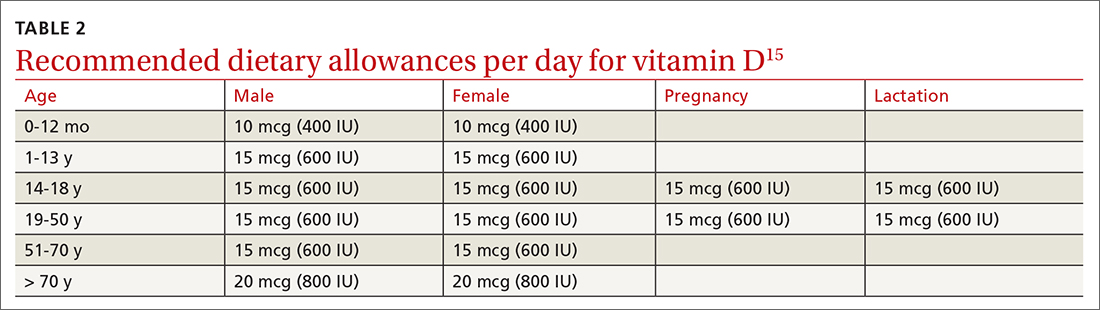

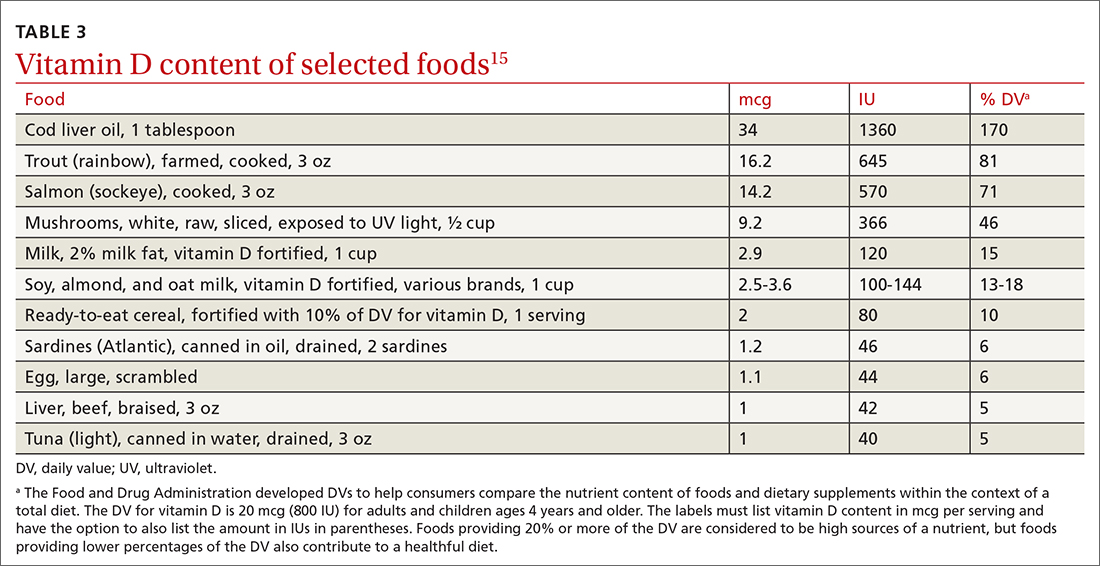

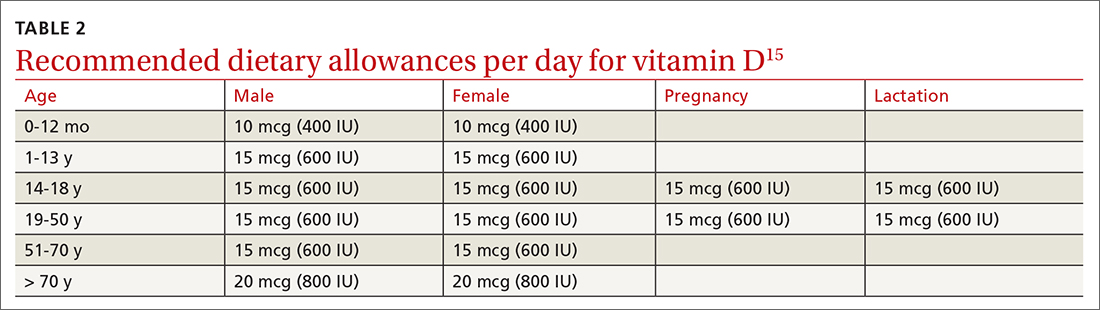

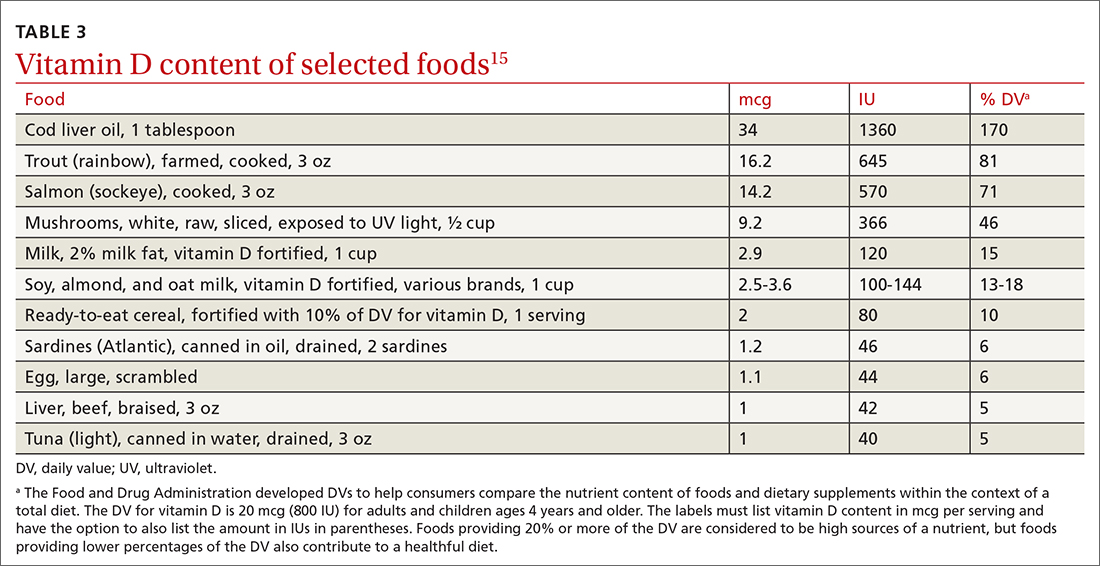

Encourage all patients to take the recommended dietary allowances (RDA) of vitamin D. The RDA is the average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%-98%) healthy individuals. Most professional organizations recommend that adults ≥ 50 years consume 800 to 1000 IU of vitamin D daily. TABLE 2 lists the RDA for vitamin D by age and sex.15 The amount of vitamin D in selected food products is listed in TABLE 3.15 Some increase in levels of vitamin D can occur as a result of sun exposure, but current practices of sun avoidance make it difficult to achieve a significant contribution to vitamin D requirements.15

Continue to: Alternatives to universal screening

Alternatives to universal screening. Screening for vitamin D deficiency might benefit some patients, although there is no evidence to support it. Universal screening will likely lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment based on what is essentially a poorly understood blood test. This was the concern expressed by the NAM.4,16 An editorial accompanying publication of the recent USPSTF recommendation suggested not measuring vitamin D levels but instead advising patients to consume the age-based RDA of vitamin D.3 For those at increased risk for vitamin D deficiency, advise a higher dose of vitamin D (eg, 2000 IU/d, which is still lower than the upper daily limit).3

Other options are to screen for vitamin D deficiency only in those at high risk for low vitamin D levels, and to test for vitamin D deficiency in those with symptoms associated with deficiency such as bone pain and muscle weakness. These options would be consistent with recommendations from the Endocrine Society.5 Some have recommended that if testing is ordered, it should be performed by a laboratory that uses liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry because it is the criterion standard.2

Treatment options. Vitamin D deficiency can be treated with either ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). These treatments can also be recommended for those whose diets may not provide the RDA for vitamin D. Both are readily available over the counter and by prescription. The Task Force found that the harms of treating vitamin D deficiency with vitamin D at recommended doses are small to none.1 There is possibly a small increase in kidney stones with the combined use of 1000 mg/d calcium and 10 mcg (400 IU)/d vitamin D.17 Large doses of vitamin D can cause toxicity including marked hypercalcemia, nausea, vomiting, muscle weakness, neuropsychiatric disturbances, pain, loss of appetite, dehydration, polyuria, excessive thirst, and kidney stones.15A cautious evidence-based approach would be to selectively screen for vitamin D deficiency, conduct diagnostic testing when indicated, and advise vitamin D supplementation as needed.

1. USPSTF. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1436-1442.

2. Michos ED, Kalyani RR, Segal JB. Why USPSTF still finds insufficient evidence to support screening for vitamin D deficiency. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e213627.

3. Burnett-Bowie AAM, Cappola AR. The USPSTF 2021 recommendations on screening for asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency in adults: the challenge for clinicians continues. JAMA. 2021;325:1401-1402.

4. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. National Academies Press; 2011. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21796828/

5. Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinolgy Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930.

6. Shahangian S, Alspach TD, Astles JR, et al. Trends in laboratory test volumes for Medicare part B reimbursements, 2000-2010. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:189-203.

7. Herrick KA, Storandt RJ, Afful J, et al. Vitamin D status in the United States, 2011-2014. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110:150-157.

8. Forrest KYZ, Stuhldreher WL. Prevalence and correlates of vitamin D deficiency in US adults. Nutr Res. 2011;31:48-54.

9. Kahwati LC, LeBlanc E, Weber RP, et al. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325:1443-1463.

10. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2016. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(supp 4):1-42.

11. AAFP. Clinical preventive services. Accessed May 22, 2021. www.aafp.org/family-physician/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/aafp-cps.html

12. USPSTF. Falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: interventions. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-interventions

13. USPSTF. Vitamin supplementation to prevent cancer and CVD: preventive medication. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-supplementation-to-prevent-cancer-and-cvd-counseling

14. USPSTF. Vitamin D, calcium, or combined supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling adults: preventive medication. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-d-calcium-or-combined-supplementation-for-the-primary-prevention-of-fractures-in-adults-preventive-medication

15. NIH. Vitamin D. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/

16. Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:53-58.

17. Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:669-683.

In April 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published an updated recommendation on screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults. It reaffirmed an “I” statement first made in 2014: evidence is insufficient to balance the benefits and harms of screening.1 This recommendation applies to asymptomatic, community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults without conditions treatable with vitamin D. It’s important to remember that screening refers to testing asymptomatic individuals to detect a condition early before it causes illness. Testing performed to determine whether symptoms are evidence of an underlying condition is not screening but diagnostic testing.

The Task Force statement explains the problems they found with the current level of knowledge about screening for vitamin D deficiency. First, while 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] is considered the best test for vitamin D levels, it is hard to measure accurately and test results vary by the method used and laboratories doing the testing. There also is uncertainty about how best to measure vitamin D status in different racial and ethnic groups, especially those with dark skin pigmentation. In addition, 25(OH)D in the blood is predominantly the bound form, with only 10% to 15% being unbound and bioavailable. Current tests do not determine the amount of bound vs unbound 25(OH)D.1-3

There is no consensus about the optimal blood level of vitamin D or the level that defines deficiency. The Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine—NAM) stated that serum 25(OH)D levels ≥ 20 ng/mL are adequate to meet the metabolic needs of 97.5% of people, and that levels of 12 to 20 ng/mL pose a risk of deficiency, with levels < 12 considered to be very low.4 The Endocrine Society defines deficiency as < 20 ng/mL and insufficiency as 21 to 29 ng/mL.5

The rate of testing for vitamin D deficiency in primary care in unknown, but there is evidence that since 2000, it has increased 80 fold at least among those with Medicare.6 Data from the 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that 5% of the population had 25(OH)D levels < 12 ng/mL and 18% had levels between 12 and 19 ng/mL.7 Some have estimated that as many as half of all adults would be considered vitamin D deficient or insufficient using current less conservative definitions, with higher rates in racial/ethnic minorities.2,8

There are no firm data on the frequency, or benefits, of screening for vitamin D levels in asymptomatic adults (and treating those found to have vitamin D deficiency). The Task Force looked for indirect evidence by examining the effect of treating vitamin D deficiency in a number of conditions and found that for some, there was adequate evidence of no benefit and for others there was inadequate evidence for possible benefits.9 No benefit was found for incidence of fractures, type 2 diabetes, and overall mortality.9 Inadequate evidence was found for incidence of cancer, cardiovascular disease, scores on measures of depression and physical functioning, and urinary tract infections in those with impaired fasting glucose.9

Known risk factors for low vitamin D levels include low vitamin D intake, older age, obesity, low UVB exposure or absorption due to long winter seasons in northern latitudes, sun avoidance, and dark skin pigmentation.1 In addition, certain medical conditions contribute to, or are caused by, low vitamin D levels—eg, osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, malabsorption syndromes, and medication use (ie, glucocorticoids).1-3

The Task Force recommendation on screening for vitamin D deficiency differs from those of some other organizations. However, none recommend universal population-based screening. The Endocrine Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommend screening but only in those at risk for vitamin D deficiency.5,10 The American Academy of Family Physicians endorses the USPSTF recommendation.11

Continue to: Specific USPSTF topics related to vitamin D

Specific USPSTF topics related to vitamin D

The Task Force has specifically addressed 3 topics pertaining to vitamin D.

Prevention of falls in the elderly. In 2018 the Task Force recommended against the use of vitamin D to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults ≥ 65 years.12 This reversed its 2012 recommendation advising vitamin D supplementation to prevent falls. The Task Force re-examined the old evidence and looked at newer studies and concluded that their previous conclusion was wrong and that the evidence showed no benefit from vitamin D in preventing falls in the elderly. The reversal of a prior recommendation is rare for the USPSTF because of the rigor of its evidence reviews and its policy of not making a recommendation unless solid evidence for or against exists.

Prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. The Task Force concludes that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms in the use of single- or paired-nutrient supplements to prevent cardiovascular disease or cancer.13 (The exceptions are beta-carotene and vitamin E, which the Task Force recommends against.) This statement is consistent with the lack of evidence the Task Force found regarding prevention of these conditions by vitamin D supplementation in those who are vitamin D deficient.

Prevention of fractures in men and in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. For men and premenopausal women, the Task Force concludes that evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of vitamin D and calcium supplementation, alone or in combination, to prevent fractures.14 For prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women, there are 2 recommendations. The first one advises against the use of ≤ 400 IU of vitamin D and ≤ 1000 mg of calcium because the evidence indicates ineffectiveness. The second one is another “I” statement for the use of doses > 400 IU of vitamin D and > 1000 mg of calcium. These 3 recommendations apply to adults who live in the community and not in nursing homes or other institutional care facilities; they do not apply to those who have osteoporosis.

What should the family physician do?

Encourage all patients to take the recommended dietary allowances (RDA) of vitamin D. The RDA is the average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%-98%) healthy individuals. Most professional organizations recommend that adults ≥ 50 years consume 800 to 1000 IU of vitamin D daily. TABLE 2 lists the RDA for vitamin D by age and sex.15 The amount of vitamin D in selected food products is listed in TABLE 3.15 Some increase in levels of vitamin D can occur as a result of sun exposure, but current practices of sun avoidance make it difficult to achieve a significant contribution to vitamin D requirements.15

Continue to: Alternatives to universal screening

Alternatives to universal screening. Screening for vitamin D deficiency might benefit some patients, although there is no evidence to support it. Universal screening will likely lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment based on what is essentially a poorly understood blood test. This was the concern expressed by the NAM.4,16 An editorial accompanying publication of the recent USPSTF recommendation suggested not measuring vitamin D levels but instead advising patients to consume the age-based RDA of vitamin D.3 For those at increased risk for vitamin D deficiency, advise a higher dose of vitamin D (eg, 2000 IU/d, which is still lower than the upper daily limit).3

Other options are to screen for vitamin D deficiency only in those at high risk for low vitamin D levels, and to test for vitamin D deficiency in those with symptoms associated with deficiency such as bone pain and muscle weakness. These options would be consistent with recommendations from the Endocrine Society.5 Some have recommended that if testing is ordered, it should be performed by a laboratory that uses liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry because it is the criterion standard.2

Treatment options. Vitamin D deficiency can be treated with either ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). These treatments can also be recommended for those whose diets may not provide the RDA for vitamin D. Both are readily available over the counter and by prescription. The Task Force found that the harms of treating vitamin D deficiency with vitamin D at recommended doses are small to none.1 There is possibly a small increase in kidney stones with the combined use of 1000 mg/d calcium and 10 mcg (400 IU)/d vitamin D.17 Large doses of vitamin D can cause toxicity including marked hypercalcemia, nausea, vomiting, muscle weakness, neuropsychiatric disturbances, pain, loss of appetite, dehydration, polyuria, excessive thirst, and kidney stones.15A cautious evidence-based approach would be to selectively screen for vitamin D deficiency, conduct diagnostic testing when indicated, and advise vitamin D supplementation as needed.

In April 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published an updated recommendation on screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults. It reaffirmed an “I” statement first made in 2014: evidence is insufficient to balance the benefits and harms of screening.1 This recommendation applies to asymptomatic, community-dwelling, nonpregnant adults without conditions treatable with vitamin D. It’s important to remember that screening refers to testing asymptomatic individuals to detect a condition early before it causes illness. Testing performed to determine whether symptoms are evidence of an underlying condition is not screening but diagnostic testing.

The Task Force statement explains the problems they found with the current level of knowledge about screening for vitamin D deficiency. First, while 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] is considered the best test for vitamin D levels, it is hard to measure accurately and test results vary by the method used and laboratories doing the testing. There also is uncertainty about how best to measure vitamin D status in different racial and ethnic groups, especially those with dark skin pigmentation. In addition, 25(OH)D in the blood is predominantly the bound form, with only 10% to 15% being unbound and bioavailable. Current tests do not determine the amount of bound vs unbound 25(OH)D.1-3

There is no consensus about the optimal blood level of vitamin D or the level that defines deficiency. The Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine—NAM) stated that serum 25(OH)D levels ≥ 20 ng/mL are adequate to meet the metabolic needs of 97.5% of people, and that levels of 12 to 20 ng/mL pose a risk of deficiency, with levels < 12 considered to be very low.4 The Endocrine Society defines deficiency as < 20 ng/mL and insufficiency as 21 to 29 ng/mL.5

The rate of testing for vitamin D deficiency in primary care in unknown, but there is evidence that since 2000, it has increased 80 fold at least among those with Medicare.6 Data from the 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that 5% of the population had 25(OH)D levels < 12 ng/mL and 18% had levels between 12 and 19 ng/mL.7 Some have estimated that as many as half of all adults would be considered vitamin D deficient or insufficient using current less conservative definitions, with higher rates in racial/ethnic minorities.2,8

There are no firm data on the frequency, or benefits, of screening for vitamin D levels in asymptomatic adults (and treating those found to have vitamin D deficiency). The Task Force looked for indirect evidence by examining the effect of treating vitamin D deficiency in a number of conditions and found that for some, there was adequate evidence of no benefit and for others there was inadequate evidence for possible benefits.9 No benefit was found for incidence of fractures, type 2 diabetes, and overall mortality.9 Inadequate evidence was found for incidence of cancer, cardiovascular disease, scores on measures of depression and physical functioning, and urinary tract infections in those with impaired fasting glucose.9

Known risk factors for low vitamin D levels include low vitamin D intake, older age, obesity, low UVB exposure or absorption due to long winter seasons in northern latitudes, sun avoidance, and dark skin pigmentation.1 In addition, certain medical conditions contribute to, or are caused by, low vitamin D levels—eg, osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, malabsorption syndromes, and medication use (ie, glucocorticoids).1-3

The Task Force recommendation on screening for vitamin D deficiency differs from those of some other organizations. However, none recommend universal population-based screening. The Endocrine Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommend screening but only in those at risk for vitamin D deficiency.5,10 The American Academy of Family Physicians endorses the USPSTF recommendation.11

Continue to: Specific USPSTF topics related to vitamin D

Specific USPSTF topics related to vitamin D

The Task Force has specifically addressed 3 topics pertaining to vitamin D.

Prevention of falls in the elderly. In 2018 the Task Force recommended against the use of vitamin D to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults ≥ 65 years.12 This reversed its 2012 recommendation advising vitamin D supplementation to prevent falls. The Task Force re-examined the old evidence and looked at newer studies and concluded that their previous conclusion was wrong and that the evidence showed no benefit from vitamin D in preventing falls in the elderly. The reversal of a prior recommendation is rare for the USPSTF because of the rigor of its evidence reviews and its policy of not making a recommendation unless solid evidence for or against exists.

Prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. The Task Force concludes that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms in the use of single- or paired-nutrient supplements to prevent cardiovascular disease or cancer.13 (The exceptions are beta-carotene and vitamin E, which the Task Force recommends against.) This statement is consistent with the lack of evidence the Task Force found regarding prevention of these conditions by vitamin D supplementation in those who are vitamin D deficient.

Prevention of fractures in men and in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. For men and premenopausal women, the Task Force concludes that evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of vitamin D and calcium supplementation, alone or in combination, to prevent fractures.14 For prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women, there are 2 recommendations. The first one advises against the use of ≤ 400 IU of vitamin D and ≤ 1000 mg of calcium because the evidence indicates ineffectiveness. The second one is another “I” statement for the use of doses > 400 IU of vitamin D and > 1000 mg of calcium. These 3 recommendations apply to adults who live in the community and not in nursing homes or other institutional care facilities; they do not apply to those who have osteoporosis.

What should the family physician do?

Encourage all patients to take the recommended dietary allowances (RDA) of vitamin D. The RDA is the average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%-98%) healthy individuals. Most professional organizations recommend that adults ≥ 50 years consume 800 to 1000 IU of vitamin D daily. TABLE 2 lists the RDA for vitamin D by age and sex.15 The amount of vitamin D in selected food products is listed in TABLE 3.15 Some increase in levels of vitamin D can occur as a result of sun exposure, but current practices of sun avoidance make it difficult to achieve a significant contribution to vitamin D requirements.15

Continue to: Alternatives to universal screening

Alternatives to universal screening. Screening for vitamin D deficiency might benefit some patients, although there is no evidence to support it. Universal screening will likely lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment based on what is essentially a poorly understood blood test. This was the concern expressed by the NAM.4,16 An editorial accompanying publication of the recent USPSTF recommendation suggested not measuring vitamin D levels but instead advising patients to consume the age-based RDA of vitamin D.3 For those at increased risk for vitamin D deficiency, advise a higher dose of vitamin D (eg, 2000 IU/d, which is still lower than the upper daily limit).3

Other options are to screen for vitamin D deficiency only in those at high risk for low vitamin D levels, and to test for vitamin D deficiency in those with symptoms associated with deficiency such as bone pain and muscle weakness. These options would be consistent with recommendations from the Endocrine Society.5 Some have recommended that if testing is ordered, it should be performed by a laboratory that uses liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry because it is the criterion standard.2

Treatment options. Vitamin D deficiency can be treated with either ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). These treatments can also be recommended for those whose diets may not provide the RDA for vitamin D. Both are readily available over the counter and by prescription. The Task Force found that the harms of treating vitamin D deficiency with vitamin D at recommended doses are small to none.1 There is possibly a small increase in kidney stones with the combined use of 1000 mg/d calcium and 10 mcg (400 IU)/d vitamin D.17 Large doses of vitamin D can cause toxicity including marked hypercalcemia, nausea, vomiting, muscle weakness, neuropsychiatric disturbances, pain, loss of appetite, dehydration, polyuria, excessive thirst, and kidney stones.15A cautious evidence-based approach would be to selectively screen for vitamin D deficiency, conduct diagnostic testing when indicated, and advise vitamin D supplementation as needed.

1. USPSTF. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1436-1442.

2. Michos ED, Kalyani RR, Segal JB. Why USPSTF still finds insufficient evidence to support screening for vitamin D deficiency. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e213627.

3. Burnett-Bowie AAM, Cappola AR. The USPSTF 2021 recommendations on screening for asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency in adults: the challenge for clinicians continues. JAMA. 2021;325:1401-1402.

4. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. National Academies Press; 2011. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21796828/

5. Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinolgy Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930.

6. Shahangian S, Alspach TD, Astles JR, et al. Trends in laboratory test volumes for Medicare part B reimbursements, 2000-2010. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:189-203.

7. Herrick KA, Storandt RJ, Afful J, et al. Vitamin D status in the United States, 2011-2014. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110:150-157.

8. Forrest KYZ, Stuhldreher WL. Prevalence and correlates of vitamin D deficiency in US adults. Nutr Res. 2011;31:48-54.

9. Kahwati LC, LeBlanc E, Weber RP, et al. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325:1443-1463.

10. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2016. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(supp 4):1-42.

11. AAFP. Clinical preventive services. Accessed May 22, 2021. www.aafp.org/family-physician/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/aafp-cps.html

12. USPSTF. Falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: interventions. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-interventions

13. USPSTF. Vitamin supplementation to prevent cancer and CVD: preventive medication. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-supplementation-to-prevent-cancer-and-cvd-counseling

14. USPSTF. Vitamin D, calcium, or combined supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling adults: preventive medication. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-d-calcium-or-combined-supplementation-for-the-primary-prevention-of-fractures-in-adults-preventive-medication

15. NIH. Vitamin D. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/

16. Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:53-58.

17. Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:669-683.

1. USPSTF. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1436-1442.

2. Michos ED, Kalyani RR, Segal JB. Why USPSTF still finds insufficient evidence to support screening for vitamin D deficiency. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e213627.

3. Burnett-Bowie AAM, Cappola AR. The USPSTF 2021 recommendations on screening for asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency in adults: the challenge for clinicians continues. JAMA. 2021;325:1401-1402.

4. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. National Academies Press; 2011. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21796828/

5. Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinolgy Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930.

6. Shahangian S, Alspach TD, Astles JR, et al. Trends in laboratory test volumes for Medicare part B reimbursements, 2000-2010. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:189-203.

7. Herrick KA, Storandt RJ, Afful J, et al. Vitamin D status in the United States, 2011-2014. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110:150-157.

8. Forrest KYZ, Stuhldreher WL. Prevalence and correlates of vitamin D deficiency in US adults. Nutr Res. 2011;31:48-54.

9. Kahwati LC, LeBlanc E, Weber RP, et al. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325:1443-1463.

10. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2016. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(supp 4):1-42.

11. AAFP. Clinical preventive services. Accessed May 22, 2021. www.aafp.org/family-physician/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/aafp-cps.html

12. USPSTF. Falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: interventions. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-interventions

13. USPSTF. Vitamin supplementation to prevent cancer and CVD: preventive medication. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-supplementation-to-prevent-cancer-and-cvd-counseling

14. USPSTF. Vitamin D, calcium, or combined supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling adults: preventive medication. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-d-calcium-or-combined-supplementation-for-the-primary-prevention-of-fractures-in-adults-preventive-medication

15. NIH. Vitamin D. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/

16. Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:53-58.

17. Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:669-683.

Zero benefit of aducanumab for Alzheimer’s disease, expert panel rules

adding to growing opposition from medical experts to the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of this controversial drug.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review asked one of its expert panels, the California Technology Assessment Forum, to consider the available data about aducanumab and requested that members vote on whether there was sufficient evidence of a net benefit of aducanumab plus supportive care versus supportive care alone. All 15 panelists voted no.

Several panelists, including ICER President Steven D. Pearson, MD, talked about their personal experience with family members who have the disease.

There was universal agreement among the panelists that there is an urgent need for effective medications to treat the disease. However, the panel of clinicians and researchers also agreed that the evidence to date does not show that the drug helps patients with this debilitating disease.

Panelist Sei Lee, MD, a geriatrician at the University of California, San Francisco, said he lost his mother to AD 6 years ago. In addition to his clinical work, Dr. Lee has conducted research focused on improving the targeting of preventive AD interventions for older adults to maximize benefits and minimize harms.

Dr. Lee said he frequently felt completely overwhelmed by the challenges of his mother’s disease.

“I absolutely hear everyone who is saying we need an effective therapy for this,” Dr. Lee said.

Dr. Lee added that, as an experienced researcher who has weighed the aducanumab data, he saw no clear proof of a benefit that would outweigh the drug’s documented side effects in the two phase 3 trials of the drug. Those side effects include temporary brain swelling. Dr. Lee suggested that Biogen do more to address concerns about this side effect, saying it should not be ignored.

“There’s clearly substantial uncertainty” about aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “If I had to guess, I think the data is stronger for net harm than it is for that benefit.”

Questions persist about the data Biogen used in support of aducanumab after announcing that the drug had failed in a dual-track phase 3 program.

In March 2019, it was announced that two phase 3 clinical trials, EMERGE and ENGAGE, were scrapped because of disappointing results. The trials were intended to show that aducanumab could slow progression of cognitive and functional impairment, as measured by changes in scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB).

However, in October 2019, there was an about-face – Biogen announced that, in one of the studies, there were positive findings for a subset of patients who received a higher dose of aducanumab.

No treatment benefit was observed in either the high- or low-dose arms at week 78 in the ENGAGE trial. In the EMERGE trial, however, there was a statistically significant difference in change from baseline in CDR-SB score in the high-dose arm (difference vs. placebo, –0.39; 95% confidence interval, –0.69 to –0.09) but not in the low-dose arm, ICER noted in a draft report.

Still, there are questions about whether this difference would translate into clinical benefit. “Although statistically significant, the change in CDR-SB score in the high-dose group was less than the 1- to 2-point change that has been suggested as a minimal clinically important difference,” ICER staff wrote.

More push back

Other influential organizations also remain skeptical.

On July 14, the Cleveland Clinic announced it would not use aducanumab at this time, following a staff review of the evidence. Physicians from the clinic could prescribe it to appropriate patients, who would receive their infusions at external facilities, a spokeswoman for the clinic told this news organization. The Cleveland Clinic said it will reevaluate this position as additional data become available.

In addition, as reported by the New York Times, the Mount Sinai Health System in New York also decided not to administer the drug.

The drug received accelerated approval from the FDA. That approval was conditional upon Biogen’s conducting further research by 2030 that demonstrates that the drug has clinical benefit.

On July 14, the executive committee of the American Neurological Association issued a statement asking for a speedier timeline.

The FDA should ensure that Biogen completes the required confirmatory study “as soon as possible, preferably within 3 years, to confirm or not whether clinical efficacy is observed,” the ANA executive committee wrote in the letter.

The ANA executive committee also criticized the FDA’s decision to allow Biogen to begin sales of the drug. In light of the clinical evidence available at this time, aducanumab “should not have been approved” in the first place, the ANA executive committee stated.

drawing from the discussion at the meeting and the panel’s votes. The work of the Boston-based group is used by private insurers to inform medication coverage decisions.

Lawmakers have taken an interest in aducanumab. On July 12, two top Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives released a letter that they had sent to Biogen as part of their investigation into how the FDA handled the aducanumab approval and Biogen’s pricing for the drug.

In the letter, House Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Pallone Jr. (D-N.J.) and Oversight and Reform Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) wrote that they had “significant questions about the drug’s clinical benefit, and the steep $56,000 annual price tag.”

At the ICER meeting on July 15, Dr. Lee said patients with AD and their caregivers would benefit more from increased spending on supportive services, such as home health care.

“There’s so many things we could do” with money that Biogen may get for aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “To spend it on a medication that is more likely to do more harm than help seems really ill advised.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

adding to growing opposition from medical experts to the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of this controversial drug.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review asked one of its expert panels, the California Technology Assessment Forum, to consider the available data about aducanumab and requested that members vote on whether there was sufficient evidence of a net benefit of aducanumab plus supportive care versus supportive care alone. All 15 panelists voted no.

Several panelists, including ICER President Steven D. Pearson, MD, talked about their personal experience with family members who have the disease.

There was universal agreement among the panelists that there is an urgent need for effective medications to treat the disease. However, the panel of clinicians and researchers also agreed that the evidence to date does not show that the drug helps patients with this debilitating disease.

Panelist Sei Lee, MD, a geriatrician at the University of California, San Francisco, said he lost his mother to AD 6 years ago. In addition to his clinical work, Dr. Lee has conducted research focused on improving the targeting of preventive AD interventions for older adults to maximize benefits and minimize harms.

Dr. Lee said he frequently felt completely overwhelmed by the challenges of his mother’s disease.

“I absolutely hear everyone who is saying we need an effective therapy for this,” Dr. Lee said.

Dr. Lee added that, as an experienced researcher who has weighed the aducanumab data, he saw no clear proof of a benefit that would outweigh the drug’s documented side effects in the two phase 3 trials of the drug. Those side effects include temporary brain swelling. Dr. Lee suggested that Biogen do more to address concerns about this side effect, saying it should not be ignored.

“There’s clearly substantial uncertainty” about aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “If I had to guess, I think the data is stronger for net harm than it is for that benefit.”

Questions persist about the data Biogen used in support of aducanumab after announcing that the drug had failed in a dual-track phase 3 program.

In March 2019, it was announced that two phase 3 clinical trials, EMERGE and ENGAGE, were scrapped because of disappointing results. The trials were intended to show that aducanumab could slow progression of cognitive and functional impairment, as measured by changes in scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB).

However, in October 2019, there was an about-face – Biogen announced that, in one of the studies, there were positive findings for a subset of patients who received a higher dose of aducanumab.

No treatment benefit was observed in either the high- or low-dose arms at week 78 in the ENGAGE trial. In the EMERGE trial, however, there was a statistically significant difference in change from baseline in CDR-SB score in the high-dose arm (difference vs. placebo, –0.39; 95% confidence interval, –0.69 to –0.09) but not in the low-dose arm, ICER noted in a draft report.

Still, there are questions about whether this difference would translate into clinical benefit. “Although statistically significant, the change in CDR-SB score in the high-dose group was less than the 1- to 2-point change that has been suggested as a minimal clinically important difference,” ICER staff wrote.

More push back

Other influential organizations also remain skeptical.

On July 14, the Cleveland Clinic announced it would not use aducanumab at this time, following a staff review of the evidence. Physicians from the clinic could prescribe it to appropriate patients, who would receive their infusions at external facilities, a spokeswoman for the clinic told this news organization. The Cleveland Clinic said it will reevaluate this position as additional data become available.

In addition, as reported by the New York Times, the Mount Sinai Health System in New York also decided not to administer the drug.

The drug received accelerated approval from the FDA. That approval was conditional upon Biogen’s conducting further research by 2030 that demonstrates that the drug has clinical benefit.

On July 14, the executive committee of the American Neurological Association issued a statement asking for a speedier timeline.

The FDA should ensure that Biogen completes the required confirmatory study “as soon as possible, preferably within 3 years, to confirm or not whether clinical efficacy is observed,” the ANA executive committee wrote in the letter.

The ANA executive committee also criticized the FDA’s decision to allow Biogen to begin sales of the drug. In light of the clinical evidence available at this time, aducanumab “should not have been approved” in the first place, the ANA executive committee stated.

drawing from the discussion at the meeting and the panel’s votes. The work of the Boston-based group is used by private insurers to inform medication coverage decisions.

Lawmakers have taken an interest in aducanumab. On July 12, two top Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives released a letter that they had sent to Biogen as part of their investigation into how the FDA handled the aducanumab approval and Biogen’s pricing for the drug.

In the letter, House Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Pallone Jr. (D-N.J.) and Oversight and Reform Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) wrote that they had “significant questions about the drug’s clinical benefit, and the steep $56,000 annual price tag.”

At the ICER meeting on July 15, Dr. Lee said patients with AD and their caregivers would benefit more from increased spending on supportive services, such as home health care.

“There’s so many things we could do” with money that Biogen may get for aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “To spend it on a medication that is more likely to do more harm than help seems really ill advised.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

adding to growing opposition from medical experts to the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of this controversial drug.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review asked one of its expert panels, the California Technology Assessment Forum, to consider the available data about aducanumab and requested that members vote on whether there was sufficient evidence of a net benefit of aducanumab plus supportive care versus supportive care alone. All 15 panelists voted no.

Several panelists, including ICER President Steven D. Pearson, MD, talked about their personal experience with family members who have the disease.

There was universal agreement among the panelists that there is an urgent need for effective medications to treat the disease. However, the panel of clinicians and researchers also agreed that the evidence to date does not show that the drug helps patients with this debilitating disease.

Panelist Sei Lee, MD, a geriatrician at the University of California, San Francisco, said he lost his mother to AD 6 years ago. In addition to his clinical work, Dr. Lee has conducted research focused on improving the targeting of preventive AD interventions for older adults to maximize benefits and minimize harms.

Dr. Lee said he frequently felt completely overwhelmed by the challenges of his mother’s disease.

“I absolutely hear everyone who is saying we need an effective therapy for this,” Dr. Lee said.

Dr. Lee added that, as an experienced researcher who has weighed the aducanumab data, he saw no clear proof of a benefit that would outweigh the drug’s documented side effects in the two phase 3 trials of the drug. Those side effects include temporary brain swelling. Dr. Lee suggested that Biogen do more to address concerns about this side effect, saying it should not be ignored.

“There’s clearly substantial uncertainty” about aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “If I had to guess, I think the data is stronger for net harm than it is for that benefit.”

Questions persist about the data Biogen used in support of aducanumab after announcing that the drug had failed in a dual-track phase 3 program.

In March 2019, it was announced that two phase 3 clinical trials, EMERGE and ENGAGE, were scrapped because of disappointing results. The trials were intended to show that aducanumab could slow progression of cognitive and functional impairment, as measured by changes in scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB).

However, in October 2019, there was an about-face – Biogen announced that, in one of the studies, there were positive findings for a subset of patients who received a higher dose of aducanumab.

No treatment benefit was observed in either the high- or low-dose arms at week 78 in the ENGAGE trial. In the EMERGE trial, however, there was a statistically significant difference in change from baseline in CDR-SB score in the high-dose arm (difference vs. placebo, –0.39; 95% confidence interval, –0.69 to –0.09) but not in the low-dose arm, ICER noted in a draft report.

Still, there are questions about whether this difference would translate into clinical benefit. “Although statistically significant, the change in CDR-SB score in the high-dose group was less than the 1- to 2-point change that has been suggested as a minimal clinically important difference,” ICER staff wrote.

More push back

Other influential organizations also remain skeptical.

On July 14, the Cleveland Clinic announced it would not use aducanumab at this time, following a staff review of the evidence. Physicians from the clinic could prescribe it to appropriate patients, who would receive their infusions at external facilities, a spokeswoman for the clinic told this news organization. The Cleveland Clinic said it will reevaluate this position as additional data become available.

In addition, as reported by the New York Times, the Mount Sinai Health System in New York also decided not to administer the drug.

The drug received accelerated approval from the FDA. That approval was conditional upon Biogen’s conducting further research by 2030 that demonstrates that the drug has clinical benefit.

On July 14, the executive committee of the American Neurological Association issued a statement asking for a speedier timeline.

The FDA should ensure that Biogen completes the required confirmatory study “as soon as possible, preferably within 3 years, to confirm or not whether clinical efficacy is observed,” the ANA executive committee wrote in the letter.

The ANA executive committee also criticized the FDA’s decision to allow Biogen to begin sales of the drug. In light of the clinical evidence available at this time, aducanumab “should not have been approved” in the first place, the ANA executive committee stated.

drawing from the discussion at the meeting and the panel’s votes. The work of the Boston-based group is used by private insurers to inform medication coverage decisions.

Lawmakers have taken an interest in aducanumab. On July 12, two top Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives released a letter that they had sent to Biogen as part of their investigation into how the FDA handled the aducanumab approval and Biogen’s pricing for the drug.

In the letter, House Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Pallone Jr. (D-N.J.) and Oversight and Reform Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) wrote that they had “significant questions about the drug’s clinical benefit, and the steep $56,000 annual price tag.”

At the ICER meeting on July 15, Dr. Lee said patients with AD and their caregivers would benefit more from increased spending on supportive services, such as home health care.

“There’s so many things we could do” with money that Biogen may get for aducanumab, Dr. Lee said. “To spend it on a medication that is more likely to do more harm than help seems really ill advised.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Contentious Alzheimer’s drug likely to get national coverage plan, CMS says

On July 12, a process that will take until next year to complete.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said it will accept public comments about how Medicare should cover aducanumab through Aug. 11. The agency intends to post a draft decision memo on its coverage approach by Jan. 12, 2022, and then finalize this policy by April 12. Coverage decisions about aducanumab now are being made at the local level by Medicare’s administrative contractors, CMS said in a press release.

The announcement followed separate public calls for such a review by America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) and the Alzheimer’s Association.

On June 30, AHIP submitted a formal request to the CMS. In it, AHIP requests that CMS take “swift action” on a national coverage determination for aducanumab. In the request, the organization specifically urged CMS to use a policy known as coverage with evidence development (CED) for Aduhelm.

This CED approach would allow access for patients considered most likely to benefit from the drug while Biogen continues research needed to definitively show its clinical benefit, said AHIP chief executive Matt Eyles.

In June, the Food and Drug Administration approved aducanumab based on data suggesting the drug might slow AD progression using the surrogate marker of a reduction in amyloid plaque.

The FDA’s accelerated approval letter set a 2030 deadline for Biogen to produce evidence from a phase 3 clinical trial definitively proving the drug’s efficacy.

Hefty price tag

Even if Biogen meets the FDA’s deadline, patients with AD, their families, clinicians, and insurers likely will wrestle for years with questions about whether to use this costly drug without clear evidence of benefit. The drug is estimated to cost $56,000 per year.

In addition, patients taking the drug will be required to undergo MRI scans to monitor for brain swelling or bleeding, complications that were experienced by those participating in previous studies of the drug, Mr. Eyles noted in his letter to CMS, which AHIP provided to this news organization.

About 80% of those eligible for aducanumab in the United States are enrolled in Medicare, write James D. Chambers, PhD, MPharm, Tufts University, Boston, and coauthors in a June article in the journal Health Affairs. Like AHIP, these authors also recommended CMS consider the CED path for the drug.

CMS has used the CED approach since 2003 to evaluate interventions such as amyloid PET for clinical evaluation of AD to implantable cardioverter defibrillators.

Applying CED to aducanumab “would provide the medical community, patients, caregivers, and payers with additional information long before the FDA’s required postapproval studies are completed,” Dr. Chambers and coauthors wrote. “It would also ensure that data on every patient treated would add to the knowledge base about how aducanumab impacts patient outcomes such as cognition, function, and quality of life.”

In the AHIP request to CMS, Mr. Eyles also noted that an independent review organization, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, said the evidence from studies done to date on aducanumab is “insufficient” to show a net health benefit for patients with mild cognitive impairment because of AD or mild AD.

At the ICER meeting, which will take place July 15, one of ICER’s expert panels, the California Technology Assessment Forum, said it will further consider all of the available scientific data on aducanumab and vote on a series of questions about its efficacy and value.

ICER’s reports have clout because insurers use its recommendations to help determine how to cover drugs and medical treatments. Among the questions ICER has posted online ahead of the meeting is one about the relative effects of aducanumab plus supportive care versus supportive care alone.

‘Dark irony’

Even as the medical community waits for Biogen to present clear evidence of a benefit for aducanumab, clinics specializing in AD may get a financial boost, said Jason Karlawish, MD, professor of medicine, medical ethics, health policy, and neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and codirector of Penn’s Memory Center.

Some clinicians see the arrival of the drug as a “win” for the field despite lingering concerns about its approval, said Dr. Karlawish at a panel discussion held July 12 by the nonprofit Hastings Center, a bioethics research institute. Dr. Karlawish is a fellow at Hastings.

In May, Dr. Karlawish published an article in STAT titled “If the FDA approves Biogen’s Alzheimer’s treatment, I won’t prescribe it.” Dr. Karlawish told this news organization that he was a site investigator for Biogen studies of aducanumab and has worked on studies sponsored by Lilly and Eisai.

During the discussion July 12, Dr. Karlawish said he had altered his view and now might be a “reluctant prescriber.” This shift is because of his commitment “to preserve, protect and defend their autonomy” of patients with AD.

He also noted the drug could draw more money into the field to help care for patients with AD by providing increased access to diagnostics. Additionally, funds provided to clinics for administering aducanumab will aid specialty memory centers, “which have been basically impoverished since their creation,” Dr. Karlawish said.

“There is a dark irony that it takes a questionably beneficial drug to bring in the revenue to finally get memory centers up and functioning,” Dr. Karlawish said, adding that there needs to be “a larger conversation about how a big, vast, and problematic disease is being treated.”

Aducanumab’s approval shows that diseases in the U.S. are not fully considered as diseases until they have “a business model, and much of that business model relies on the pharmaceutical industry,” he noted.

Dr. Woodcock’s ‘personal commitment’

In early July, the FDA took two highly publicized steps to address criticism of its handling of the aducanumab approval. It revised the drug’s label to limit its use to patients with mild cognitive impairment likely related to AD or those in the mild stages of the disease.

In addition, Janet Woodcock, MD, the FDA’s acting commissioner, took to Twitter and posted a letter she sent to the Office of the Inspector General that called for a federal investigation into the drug’s approval that would examine agency staff interactions with Biogen.

AHIP spokesperson Kristine Grow said July 12 that her organization is still seeking a national Medicare coverage decision, but that the label revision was a “step in the right direction.”

“Patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and their families and caregivers, deserve safe, effective treatments. We applaud the FDA for this label adjustment, which brings indicated patients a bit closer to those included in clinical trials,” Ms. Grow said in an interview.

“At the same time, we remain concerned about the limited clinical evidence demonstrating efficacy and the serious safety risks that aducanumab poses for patients. We look forward to additional information from the FDA and other regulators, including CMS’ coverage guidance for patients who are Medicare eligible,” she added.

The controversy surrounding the approval of aducanumab is drawing more attention to the lack of a confirmed FDA commissioner. But in her letter to OIG, Dr. Woodcock wrote as if she intends to remain at the helm of the agency for at least a while longer. She wrote in her letter that OIG has her “personal commitment” that the FDA will fully cooperate if the investigative unit decides to undertake a review.

Dr. Woodcock also urged that a review be conducted as soon as possible, noting “should such a review result in actionable items, you also have my commitment to addressing these issues.”

A former FDA adviser who resigned over the agency’s handling of aducanumab said July 12 there needs to be a broader investigation of the FDA’s actions.

Attending the Hastings Center event was Aaron S. Kesselheim, MD, JD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, one of three former members of an FDA advisory committee who resigned over the agency’s handling of aducanumab. Dr. Kesselheim said in an interview that he has no financial relationships to disclose in connection with this discussion.

“I would suggest that instead all aspects of this approval process should be investigated,” Dr. Kesselheim said, including the relationship between FDA and Biogen.

Dr. Karlawish said he was also concerned that Dr. Woodcock’s request for an investigation was “very narrow,” and noted members of Congress have said they are examining the FDA’s handling of this drug.

In a July 9 joint statement, House Committee on Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Pallone Jr (D-N.J.), and House Committee on Oversight and Reform Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) said they were “pleased” by Dr. Woodcock’s announcement, but they will keep digging into ongoing questions about the drug. In their view, the OIG review of FDA staff interactions with Biogen officials would complement their committees’ “robust investigation of this matter.”

“We continue to have concerns about the approval process for Aduhelm, how Biogen set its price, and the implications for seniors, providers, and taxpayers,” Mr. Pallone and Ms. Maloney added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On July 12, a process that will take until next year to complete.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said it will accept public comments about how Medicare should cover aducanumab through Aug. 11. The agency intends to post a draft decision memo on its coverage approach by Jan. 12, 2022, and then finalize this policy by April 12. Coverage decisions about aducanumab now are being made at the local level by Medicare’s administrative contractors, CMS said in a press release.

The announcement followed separate public calls for such a review by America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) and the Alzheimer’s Association.

On June 30, AHIP submitted a formal request to the CMS. In it, AHIP requests that CMS take “swift action” on a national coverage determination for aducanumab. In the request, the organization specifically urged CMS to use a policy known as coverage with evidence development (CED) for Aduhelm.

This CED approach would allow access for patients considered most likely to benefit from the drug while Biogen continues research needed to definitively show its clinical benefit, said AHIP chief executive Matt Eyles.

In June, the Food and Drug Administration approved aducanumab based on data suggesting the drug might slow AD progression using the surrogate marker of a reduction in amyloid plaque.

The FDA’s accelerated approval letter set a 2030 deadline for Biogen to produce evidence from a phase 3 clinical trial definitively proving the drug’s efficacy.

Hefty price tag

Even if Biogen meets the FDA’s deadline, patients with AD, their families, clinicians, and insurers likely will wrestle for years with questions about whether to use this costly drug without clear evidence of benefit. The drug is estimated to cost $56,000 per year.

In addition, patients taking the drug will be required to undergo MRI scans to monitor for brain swelling or bleeding, complications that were experienced by those participating in previous studies of the drug, Mr. Eyles noted in his letter to CMS, which AHIP provided to this news organization.

About 80% of those eligible for aducanumab in the United States are enrolled in Medicare, write James D. Chambers, PhD, MPharm, Tufts University, Boston, and coauthors in a June article in the journal Health Affairs. Like AHIP, these authors also recommended CMS consider the CED path for the drug.

CMS has used the CED approach since 2003 to evaluate interventions such as amyloid PET for clinical evaluation of AD to implantable cardioverter defibrillators.

Applying CED to aducanumab “would provide the medical community, patients, caregivers, and payers with additional information long before the FDA’s required postapproval studies are completed,” Dr. Chambers and coauthors wrote. “It would also ensure that data on every patient treated would add to the knowledge base about how aducanumab impacts patient outcomes such as cognition, function, and quality of life.”

In the AHIP request to CMS, Mr. Eyles also noted that an independent review organization, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, said the evidence from studies done to date on aducanumab is “insufficient” to show a net health benefit for patients with mild cognitive impairment because of AD or mild AD.

At the ICER meeting, which will take place July 15, one of ICER’s expert panels, the California Technology Assessment Forum, said it will further consider all of the available scientific data on aducanumab and vote on a series of questions about its efficacy and value.

ICER’s reports have clout because insurers use its recommendations to help determine how to cover drugs and medical treatments. Among the questions ICER has posted online ahead of the meeting is one about the relative effects of aducanumab plus supportive care versus supportive care alone.

‘Dark irony’

Even as the medical community waits for Biogen to present clear evidence of a benefit for aducanumab, clinics specializing in AD may get a financial boost, said Jason Karlawish, MD, professor of medicine, medical ethics, health policy, and neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and codirector of Penn’s Memory Center.

Some clinicians see the arrival of the drug as a “win” for the field despite lingering concerns about its approval, said Dr. Karlawish at a panel discussion held July 12 by the nonprofit Hastings Center, a bioethics research institute. Dr. Karlawish is a fellow at Hastings.

In May, Dr. Karlawish published an article in STAT titled “If the FDA approves Biogen’s Alzheimer’s treatment, I won’t prescribe it.” Dr. Karlawish told this news organization that he was a site investigator for Biogen studies of aducanumab and has worked on studies sponsored by Lilly and Eisai.

During the discussion July 12, Dr. Karlawish said he had altered his view and now might be a “reluctant prescriber.” This shift is because of his commitment “to preserve, protect and defend their autonomy” of patients with AD.

He also noted the drug could draw more money into the field to help care for patients with AD by providing increased access to diagnostics. Additionally, funds provided to clinics for administering aducanumab will aid specialty memory centers, “which have been basically impoverished since their creation,” Dr. Karlawish said.

“There is a dark irony that it takes a questionably beneficial drug to bring in the revenue to finally get memory centers up and functioning,” Dr. Karlawish said, adding that there needs to be “a larger conversation about how a big, vast, and problematic disease is being treated.”

Aducanumab’s approval shows that diseases in the U.S. are not fully considered as diseases until they have “a business model, and much of that business model relies on the pharmaceutical industry,” he noted.

Dr. Woodcock’s ‘personal commitment’

In early July, the FDA took two highly publicized steps to address criticism of its handling of the aducanumab approval. It revised the drug’s label to limit its use to patients with mild cognitive impairment likely related to AD or those in the mild stages of the disease.

In addition, Janet Woodcock, MD, the FDA’s acting commissioner, took to Twitter and posted a letter she sent to the Office of the Inspector General that called for a federal investigation into the drug’s approval that would examine agency staff interactions with Biogen.

AHIP spokesperson Kristine Grow said July 12 that her organization is still seeking a national Medicare coverage decision, but that the label revision was a “step in the right direction.”

“Patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and their families and caregivers, deserve safe, effective treatments. We applaud the FDA for this label adjustment, which brings indicated patients a bit closer to those included in clinical trials,” Ms. Grow said in an interview.

“At the same time, we remain concerned about the limited clinical evidence demonstrating efficacy and the serious safety risks that aducanumab poses for patients. We look forward to additional information from the FDA and other regulators, including CMS’ coverage guidance for patients who are Medicare eligible,” she added.

The controversy surrounding the approval of aducanumab is drawing more attention to the lack of a confirmed FDA commissioner. But in her letter to OIG, Dr. Woodcock wrote as if she intends to remain at the helm of the agency for at least a while longer. She wrote in her letter that OIG has her “personal commitment” that the FDA will fully cooperate if the investigative unit decides to undertake a review.

Dr. Woodcock also urged that a review be conducted as soon as possible, noting “should such a review result in actionable items, you also have my commitment to addressing these issues.”

A former FDA adviser who resigned over the agency’s handling of aducanumab said July 12 there needs to be a broader investigation of the FDA’s actions.

Attending the Hastings Center event was Aaron S. Kesselheim, MD, JD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, one of three former members of an FDA advisory committee who resigned over the agency’s handling of aducanumab. Dr. Kesselheim said in an interview that he has no financial relationships to disclose in connection with this discussion.

“I would suggest that instead all aspects of this approval process should be investigated,” Dr. Kesselheim said, including the relationship between FDA and Biogen.

Dr. Karlawish said he was also concerned that Dr. Woodcock’s request for an investigation was “very narrow,” and noted members of Congress have said they are examining the FDA’s handling of this drug.

In a July 9 joint statement, House Committee on Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Pallone Jr (D-N.J.), and House Committee on Oversight and Reform Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) said they were “pleased” by Dr. Woodcock’s announcement, but they will keep digging into ongoing questions about the drug. In their view, the OIG review of FDA staff interactions with Biogen officials would complement their committees’ “robust investigation of this matter.”

“We continue to have concerns about the approval process for Aduhelm, how Biogen set its price, and the implications for seniors, providers, and taxpayers,” Mr. Pallone and Ms. Maloney added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On July 12, a process that will take until next year to complete.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said it will accept public comments about how Medicare should cover aducanumab through Aug. 11. The agency intends to post a draft decision memo on its coverage approach by Jan. 12, 2022, and then finalize this policy by April 12. Coverage decisions about aducanumab now are being made at the local level by Medicare’s administrative contractors, CMS said in a press release.

The announcement followed separate public calls for such a review by America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) and the Alzheimer’s Association.

On June 30, AHIP submitted a formal request to the CMS. In it, AHIP requests that CMS take “swift action” on a national coverage determination for aducanumab. In the request, the organization specifically urged CMS to use a policy known as coverage with evidence development (CED) for Aduhelm.

This CED approach would allow access for patients considered most likely to benefit from the drug while Biogen continues research needed to definitively show its clinical benefit, said AHIP chief executive Matt Eyles.

In June, the Food and Drug Administration approved aducanumab based on data suggesting the drug might slow AD progression using the surrogate marker of a reduction in amyloid plaque.

The FDA’s accelerated approval letter set a 2030 deadline for Biogen to produce evidence from a phase 3 clinical trial definitively proving the drug’s efficacy.

Hefty price tag

Even if Biogen meets the FDA’s deadline, patients with AD, their families, clinicians, and insurers likely will wrestle for years with questions about whether to use this costly drug without clear evidence of benefit. The drug is estimated to cost $56,000 per year.

In addition, patients taking the drug will be required to undergo MRI scans to monitor for brain swelling or bleeding, complications that were experienced by those participating in previous studies of the drug, Mr. Eyles noted in his letter to CMS, which AHIP provided to this news organization.

About 80% of those eligible for aducanumab in the United States are enrolled in Medicare, write James D. Chambers, PhD, MPharm, Tufts University, Boston, and coauthors in a June article in the journal Health Affairs. Like AHIP, these authors also recommended CMS consider the CED path for the drug.

CMS has used the CED approach since 2003 to evaluate interventions such as amyloid PET for clinical evaluation of AD to implantable cardioverter defibrillators.

Applying CED to aducanumab “would provide the medical community, patients, caregivers, and payers with additional information long before the FDA’s required postapproval studies are completed,” Dr. Chambers and coauthors wrote. “It would also ensure that data on every patient treated would add to the knowledge base about how aducanumab impacts patient outcomes such as cognition, function, and quality of life.”

In the AHIP request to CMS, Mr. Eyles also noted that an independent review organization, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, said the evidence from studies done to date on aducanumab is “insufficient” to show a net health benefit for patients with mild cognitive impairment because of AD or mild AD.

At the ICER meeting, which will take place July 15, one of ICER’s expert panels, the California Technology Assessment Forum, said it will further consider all of the available scientific data on aducanumab and vote on a series of questions about its efficacy and value.

ICER’s reports have clout because insurers use its recommendations to help determine how to cover drugs and medical treatments. Among the questions ICER has posted online ahead of the meeting is one about the relative effects of aducanumab plus supportive care versus supportive care alone.

‘Dark irony’

Even as the medical community waits for Biogen to present clear evidence of a benefit for aducanumab, clinics specializing in AD may get a financial boost, said Jason Karlawish, MD, professor of medicine, medical ethics, health policy, and neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and codirector of Penn’s Memory Center.

Some clinicians see the arrival of the drug as a “win” for the field despite lingering concerns about its approval, said Dr. Karlawish at a panel discussion held July 12 by the nonprofit Hastings Center, a bioethics research institute. Dr. Karlawish is a fellow at Hastings.

In May, Dr. Karlawish published an article in STAT titled “If the FDA approves Biogen’s Alzheimer’s treatment, I won’t prescribe it.” Dr. Karlawish told this news organization that he was a site investigator for Biogen studies of aducanumab and has worked on studies sponsored by Lilly and Eisai.

During the discussion July 12, Dr. Karlawish said he had altered his view and now might be a “reluctant prescriber.” This shift is because of his commitment “to preserve, protect and defend their autonomy” of patients with AD.