User login

Bladder cancer indication withdrawn for durvalumab

The change does not affect this indication outside the United States, nor does it affect other approved durvalumab indications within the United States.

For example, durvalumab remains approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the curative-intent setting of unresectable, stage III non–small cell lung cancer after chemoradiotherapy and for the treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer.

AstraZeneca is continuing with clinical trials of durvalumab in various combinations for the treatment of bladder cancer.

Granted accelerated approval

Durvalumab was granted accelerated approval in May 2017 by the FDA specifically for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or who experience disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with that chemotherapy.

That accelerated approval was based on the surrogate markers of tumor response rate and duration of response from Study 1108, a phase 1/2 trial. In this trial, the overall response rate was 17.8% in a cohort of 191 patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer that had progressed during or after a platinum-based regimen.

However, in the confirmatory phase 3 DANUBE trial in patients with unresectable metastatic bladder cancer, neither durvalumab nor durvalumab plus tremelimumab met the primary endpoint of improving overall survival in comparison with standard-of-care chemotherapy.

“While the withdrawal in previously treated metastatic bladder cancer is disappointing, we respect the principles FDA set out when the accelerated approval pathway was founded,” Dave Fredrickson, executive vice president, Oncology Business Unit, AstraZeneca, said in a company press statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The change does not affect this indication outside the United States, nor does it affect other approved durvalumab indications within the United States.

For example, durvalumab remains approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the curative-intent setting of unresectable, stage III non–small cell lung cancer after chemoradiotherapy and for the treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer.

AstraZeneca is continuing with clinical trials of durvalumab in various combinations for the treatment of bladder cancer.

Granted accelerated approval

Durvalumab was granted accelerated approval in May 2017 by the FDA specifically for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or who experience disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with that chemotherapy.

That accelerated approval was based on the surrogate markers of tumor response rate and duration of response from Study 1108, a phase 1/2 trial. In this trial, the overall response rate was 17.8% in a cohort of 191 patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer that had progressed during or after a platinum-based regimen.

However, in the confirmatory phase 3 DANUBE trial in patients with unresectable metastatic bladder cancer, neither durvalumab nor durvalumab plus tremelimumab met the primary endpoint of improving overall survival in comparison with standard-of-care chemotherapy.

“While the withdrawal in previously treated metastatic bladder cancer is disappointing, we respect the principles FDA set out when the accelerated approval pathway was founded,” Dave Fredrickson, executive vice president, Oncology Business Unit, AstraZeneca, said in a company press statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The change does not affect this indication outside the United States, nor does it affect other approved durvalumab indications within the United States.

For example, durvalumab remains approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the curative-intent setting of unresectable, stage III non–small cell lung cancer after chemoradiotherapy and for the treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer.

AstraZeneca is continuing with clinical trials of durvalumab in various combinations for the treatment of bladder cancer.

Granted accelerated approval

Durvalumab was granted accelerated approval in May 2017 by the FDA specifically for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or who experience disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with that chemotherapy.

That accelerated approval was based on the surrogate markers of tumor response rate and duration of response from Study 1108, a phase 1/2 trial. In this trial, the overall response rate was 17.8% in a cohort of 191 patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer that had progressed during or after a platinum-based regimen.

However, in the confirmatory phase 3 DANUBE trial in patients with unresectable metastatic bladder cancer, neither durvalumab nor durvalumab plus tremelimumab met the primary endpoint of improving overall survival in comparison with standard-of-care chemotherapy.

“While the withdrawal in previously treated metastatic bladder cancer is disappointing, we respect the principles FDA set out when the accelerated approval pathway was founded,” Dave Fredrickson, executive vice president, Oncology Business Unit, AstraZeneca, said in a company press statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prophylactic NPWT may not improve complication rate after gynecologic surgery

Use of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy may not be appropriate in surgical cases where women undergo a laparotomy for presumed gynecologic malignancy, according to recent research in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“The results of our randomized trial do not support the routine use of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy at the time of laparotomy incision closure in women who are undergoing surgery for gynecologic malignancies or in morbidly obese women who are undergoing laparotomy for benign indications,” Mario M. Leitao Jr., MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Leitao and colleagues randomized 663 patients, stratified by body mass index (BMI) after skin closure, to receive negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) or standard gauze after undergoing a laparotomy for gynecological surgery between March 2016 and August 2019. Patients in the study were aged a median 61 years with a median BMI of 26 kg/m2, but 32 patients with a BMI of 40 or higher who underwent a laparotomy for gynecologic surgery regardless of indication were also included in the study. Most women (80%-82%) were undergoing surgery to treat ovary, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer. The most common medical comorbidities in both groups were hypertension (34%-35%) and diabetes (8%-14%). Information on race of patients was not included in the baseline characteristics for the study.

In total, 505 patients were available for evaluation after surgery, which consisted of 254 patients in the NPWT group and 251 patients in the standard gauze group, with 495 patients (98%) having a malignant indication. The researchers examined the incidence of wound complication up to 30 days after surgery.

The results showed a similar rate of wound complications in the NPWT group (44 patients; 17.3%), compared with the group receiving standard gauze (41 patients; 16.3%), with an absolute risk difference between groups of 1% (90% confidence interval, –4.5 to 6.5%; P = .77). Nearly all patients who developed wound complications in both NPWT (92%) and standard gauze (95%) groups had the wound complication diagnosis occur after discharge from the hospital. Dr. Leitao and colleagues noted similarities between groups with regard to wound complications, with most patients having grade 1 complications, and said there were no instances of patients requiring surgery for complications. Among patients in the NPWT group, 33 patients developed skin blistering, compared with 3 patients in the standard gauze group (13% vs. 1.2%; P < .001). After an interim analysis consisting of 444 patients, the study was halted because of “low probability of showing a difference between the two groups at the end of the study.”

The analysis of patients with a BMI of 40 or higher showed 7 of 15 patients (47%) developed wound complications in the NPWT group and 6 of 17 patients (35%) in the standard gauze group (P = .51). In post hoc analyses, the researchers found a median BMI of 26 (range, 17-60) was significantly associated with not developing a wound complication, compared with a BMI of 32 (range, 17-56) (P < .001), and that 41% of patients with a BMI of at least 40 experienced wound complications, compared with 15% of patients with a BMI of less than 40 (P < .001). There was an independent association between developing a wound complication and increasing BMI, according to a multivariate analysis (adjusted odds ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.14).

Applicability of results unclear for patients with higher BMI

Sarah M. Temkin, MD, a gynecologic oncologist who was not involved with the study, said in an interview that the results by Dr. Leitao and colleagues answer the question of whether patients undergoing surgery for gynecologic malignancy require NPWT, but raised questions about patient selection in the study.

“I think it’s hard to take data from this type of high-end surgical practice and apply it to the general population,” she said, who noted the median BMI of 26 for patients included in the study. A study that included only patients with a BMI of 40 or higher “would have made these results more applicable.”

The low rate of wound complications in the study could potentially be explained by patient selection, Dr. Temkin explained. She cited her own retrospective study from 2016 that showed a wound complication rate of 27.3% for patients receiving prophylactic NPWT where the BMI for the group was 41.29, compared with a complication rate of 19.7% for patients receiving standard care who had a BMI of 30.67.

“It’s hard to cross-trial compare, but that’s significantly higher than what they saw in this prospective study, and I would say that’s a difference with the patient population,” she said. “I think the question of how to reduce surgical-site infections and wound complications in the heavy patient with comorbidities is still unanswered.”

The question is important because patients with a higher BMI and medical comorbidities “still need cancer surgery and methods to reduce the morbidity of that surgery,” Dr. Temkin said. “I think this is an unmet need.”

This study was funded in part by a support grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center, and KCI/Acelity provided part of the study protocol. Nine authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, stock ownership, consultancies, and speaker’s bureau positions with AstraZeneca, Biom’Up, Bovie Medical, C Surgeries, CMR, ConMed, Covidien, Ethicon, GlaxoSmithKline, GRAIL, Intuitive Surgical, JNJ, Medtronic, Merck, Mylan, Olympus, Stryker/Novadaq, TransEnterix, UpToDate, and Verthermia. Dr. Temkin reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Use of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy may not be appropriate in surgical cases where women undergo a laparotomy for presumed gynecologic malignancy, according to recent research in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“The results of our randomized trial do not support the routine use of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy at the time of laparotomy incision closure in women who are undergoing surgery for gynecologic malignancies or in morbidly obese women who are undergoing laparotomy for benign indications,” Mario M. Leitao Jr., MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Leitao and colleagues randomized 663 patients, stratified by body mass index (BMI) after skin closure, to receive negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) or standard gauze after undergoing a laparotomy for gynecological surgery between March 2016 and August 2019. Patients in the study were aged a median 61 years with a median BMI of 26 kg/m2, but 32 patients with a BMI of 40 or higher who underwent a laparotomy for gynecologic surgery regardless of indication were also included in the study. Most women (80%-82%) were undergoing surgery to treat ovary, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer. The most common medical comorbidities in both groups were hypertension (34%-35%) and diabetes (8%-14%). Information on race of patients was not included in the baseline characteristics for the study.

In total, 505 patients were available for evaluation after surgery, which consisted of 254 patients in the NPWT group and 251 patients in the standard gauze group, with 495 patients (98%) having a malignant indication. The researchers examined the incidence of wound complication up to 30 days after surgery.

The results showed a similar rate of wound complications in the NPWT group (44 patients; 17.3%), compared with the group receiving standard gauze (41 patients; 16.3%), with an absolute risk difference between groups of 1% (90% confidence interval, –4.5 to 6.5%; P = .77). Nearly all patients who developed wound complications in both NPWT (92%) and standard gauze (95%) groups had the wound complication diagnosis occur after discharge from the hospital. Dr. Leitao and colleagues noted similarities between groups with regard to wound complications, with most patients having grade 1 complications, and said there were no instances of patients requiring surgery for complications. Among patients in the NPWT group, 33 patients developed skin blistering, compared with 3 patients in the standard gauze group (13% vs. 1.2%; P < .001). After an interim analysis consisting of 444 patients, the study was halted because of “low probability of showing a difference between the two groups at the end of the study.”

The analysis of patients with a BMI of 40 or higher showed 7 of 15 patients (47%) developed wound complications in the NPWT group and 6 of 17 patients (35%) in the standard gauze group (P = .51). In post hoc analyses, the researchers found a median BMI of 26 (range, 17-60) was significantly associated with not developing a wound complication, compared with a BMI of 32 (range, 17-56) (P < .001), and that 41% of patients with a BMI of at least 40 experienced wound complications, compared with 15% of patients with a BMI of less than 40 (P < .001). There was an independent association between developing a wound complication and increasing BMI, according to a multivariate analysis (adjusted odds ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.14).

Applicability of results unclear for patients with higher BMI

Sarah M. Temkin, MD, a gynecologic oncologist who was not involved with the study, said in an interview that the results by Dr. Leitao and colleagues answer the question of whether patients undergoing surgery for gynecologic malignancy require NPWT, but raised questions about patient selection in the study.

“I think it’s hard to take data from this type of high-end surgical practice and apply it to the general population,” she said, who noted the median BMI of 26 for patients included in the study. A study that included only patients with a BMI of 40 or higher “would have made these results more applicable.”

The low rate of wound complications in the study could potentially be explained by patient selection, Dr. Temkin explained. She cited her own retrospective study from 2016 that showed a wound complication rate of 27.3% for patients receiving prophylactic NPWT where the BMI for the group was 41.29, compared with a complication rate of 19.7% for patients receiving standard care who had a BMI of 30.67.

“It’s hard to cross-trial compare, but that’s significantly higher than what they saw in this prospective study, and I would say that’s a difference with the patient population,” she said. “I think the question of how to reduce surgical-site infections and wound complications in the heavy patient with comorbidities is still unanswered.”

The question is important because patients with a higher BMI and medical comorbidities “still need cancer surgery and methods to reduce the morbidity of that surgery,” Dr. Temkin said. “I think this is an unmet need.”

This study was funded in part by a support grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center, and KCI/Acelity provided part of the study protocol. Nine authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, stock ownership, consultancies, and speaker’s bureau positions with AstraZeneca, Biom’Up, Bovie Medical, C Surgeries, CMR, ConMed, Covidien, Ethicon, GlaxoSmithKline, GRAIL, Intuitive Surgical, JNJ, Medtronic, Merck, Mylan, Olympus, Stryker/Novadaq, TransEnterix, UpToDate, and Verthermia. Dr. Temkin reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Use of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy may not be appropriate in surgical cases where women undergo a laparotomy for presumed gynecologic malignancy, according to recent research in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“The results of our randomized trial do not support the routine use of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy at the time of laparotomy incision closure in women who are undergoing surgery for gynecologic malignancies or in morbidly obese women who are undergoing laparotomy for benign indications,” Mario M. Leitao Jr., MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Leitao and colleagues randomized 663 patients, stratified by body mass index (BMI) after skin closure, to receive negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) or standard gauze after undergoing a laparotomy for gynecological surgery between March 2016 and August 2019. Patients in the study were aged a median 61 years with a median BMI of 26 kg/m2, but 32 patients with a BMI of 40 or higher who underwent a laparotomy for gynecologic surgery regardless of indication were also included in the study. Most women (80%-82%) were undergoing surgery to treat ovary, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer. The most common medical comorbidities in both groups were hypertension (34%-35%) and diabetes (8%-14%). Information on race of patients was not included in the baseline characteristics for the study.

In total, 505 patients were available for evaluation after surgery, which consisted of 254 patients in the NPWT group and 251 patients in the standard gauze group, with 495 patients (98%) having a malignant indication. The researchers examined the incidence of wound complication up to 30 days after surgery.

The results showed a similar rate of wound complications in the NPWT group (44 patients; 17.3%), compared with the group receiving standard gauze (41 patients; 16.3%), with an absolute risk difference between groups of 1% (90% confidence interval, –4.5 to 6.5%; P = .77). Nearly all patients who developed wound complications in both NPWT (92%) and standard gauze (95%) groups had the wound complication diagnosis occur after discharge from the hospital. Dr. Leitao and colleagues noted similarities between groups with regard to wound complications, with most patients having grade 1 complications, and said there were no instances of patients requiring surgery for complications. Among patients in the NPWT group, 33 patients developed skin blistering, compared with 3 patients in the standard gauze group (13% vs. 1.2%; P < .001). After an interim analysis consisting of 444 patients, the study was halted because of “low probability of showing a difference between the two groups at the end of the study.”

The analysis of patients with a BMI of 40 or higher showed 7 of 15 patients (47%) developed wound complications in the NPWT group and 6 of 17 patients (35%) in the standard gauze group (P = .51). In post hoc analyses, the researchers found a median BMI of 26 (range, 17-60) was significantly associated with not developing a wound complication, compared with a BMI of 32 (range, 17-56) (P < .001), and that 41% of patients with a BMI of at least 40 experienced wound complications, compared with 15% of patients with a BMI of less than 40 (P < .001). There was an independent association between developing a wound complication and increasing BMI, according to a multivariate analysis (adjusted odds ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.14).

Applicability of results unclear for patients with higher BMI

Sarah M. Temkin, MD, a gynecologic oncologist who was not involved with the study, said in an interview that the results by Dr. Leitao and colleagues answer the question of whether patients undergoing surgery for gynecologic malignancy require NPWT, but raised questions about patient selection in the study.

“I think it’s hard to take data from this type of high-end surgical practice and apply it to the general population,” she said, who noted the median BMI of 26 for patients included in the study. A study that included only patients with a BMI of 40 or higher “would have made these results more applicable.”

The low rate of wound complications in the study could potentially be explained by patient selection, Dr. Temkin explained. She cited her own retrospective study from 2016 that showed a wound complication rate of 27.3% for patients receiving prophylactic NPWT where the BMI for the group was 41.29, compared with a complication rate of 19.7% for patients receiving standard care who had a BMI of 30.67.

“It’s hard to cross-trial compare, but that’s significantly higher than what they saw in this prospective study, and I would say that’s a difference with the patient population,” she said. “I think the question of how to reduce surgical-site infections and wound complications in the heavy patient with comorbidities is still unanswered.”

The question is important because patients with a higher BMI and medical comorbidities “still need cancer surgery and methods to reduce the morbidity of that surgery,” Dr. Temkin said. “I think this is an unmet need.”

This study was funded in part by a support grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center, and KCI/Acelity provided part of the study protocol. Nine authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, stock ownership, consultancies, and speaker’s bureau positions with AstraZeneca, Biom’Up, Bovie Medical, C Surgeries, CMR, ConMed, Covidien, Ethicon, GlaxoSmithKline, GRAIL, Intuitive Surgical, JNJ, Medtronic, Merck, Mylan, Olympus, Stryker/Novadaq, TransEnterix, UpToDate, and Verthermia. Dr. Temkin reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer

Endometriosis, which affects 1 in 10 women, is one of the most common conditions that gynecologists treat. It is known to cause pain, pelvic adhesive disease, endometriotic cyst formation, and infertility. However, even more sinister, it also increases a woman’s risk for the development of epithelial ovarian cancer (known as endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer or EAOC). A woman with endometriosis has a two- to threefold increased risk of developing epithelial ovarian cancer, compared with nonaffected women.1 This risk appears to be concentrated in the premenopausal age group, particularly the fifth decade of life. After menopause their risk of developing cancer returns to a baseline level.

EAOC classically presents as clear cell or endometrioid adenocarcinomas, rather than high-grade serous carcinomas. However, low-grade serous carcinomas are also frequently observed in this cohort.2,3 Unlike high-grade serous carcinoma, EAOC is more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage, with the majority at stage I or II, and prognosis is better. After matching for age and stage with cases of high-grade serous carcinoma, there is improved disease-free and overall survival observed among cases of EAOC of clear cell and endometrioid histologic cell types.4 The phenomenon of dual primaries (synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancer) occurs more frequently in EAOC than it does in patients with nonendometriosis-related high-grade serous cancer (25% vs. 4%).

The genomics of these endometriosis-associated cancers are quite distinct. Similar to benign endometriosis implants, EAOC is associated with genomic mutations in ARID1A, PIK3CA, and PTEN, as well as progesterone resistance.1,2 Multiple studies have shown that the adjacent eutopic endometrium carries similar gene mutations as those found in both benign endometriotic implants and EAOC.2 This may explain the higher incidence (twofold) of endometrial cancer in patients with endometriosis as well as the increased incidence of dual ovarian and endometrial cancer primaries.

Just as there are multiple theories regarding the mechanism of benign endometriosis, we have theories rather than conclusions regarding the origins of EAOC. One such theory is that it develops from malignant transformation in an existing endometriotic cyst.5 Endometriotic cysts provide an iron-rich environment which promotes reactive oxygen species that promote carcinogenesis by inducing gene mutations and epigenetic alterations. However, if prolonged exposure to oxidative stress within endometriotic cysts were to be the cause for EAOC, we would expect to see a progressively increasing incidence of ovarian cancer over time in patients with expectantly managed cysts. However, in cases of expectant management, an initial, early, increased risk for cancer within the first 5 years is followed by a subsequent decreasing incidence over time.6 This early incidence spike suggests that some endometriotic cysts may have been misclassified as benign, then rapidly declare themselves as malignant during the observation period rather than a transformation into malignancy from a benign endometrioma over time.

An alternative, and favored, theory for the origins of EAOC are that endometrial cells with carcinogenic genomic alterations reflux through the fallopian tubes during menstruation and settle onto the ovarian epithelium which itself is damaged from recent ovulation thus providing an environment that is highly suitable for oncogenesis.2 Genomic analyses of both the eutopic endometrium and malignant cells in patients with EAOC have shown that both tissues contain the same genomic alterations.1 Given that menstruation, including retrograde menstruation, ends after menopause, this mechanism supports the observation that EAOC is predominantly a malignancy of premenopausal women. Additionally, salpingectomy and hysterectomy confers a protective effect on the development of EAOC, theoretically by preventing the retrograde transfer of these mutant progenitor endometrial cells. Furthermore, the factors that increase the number of menstrual cycles (such as an early age of menarche and delayed or nonchildbearing states) increases the risk for EAOC and factors that inhibit menstruation, such as oral contraceptive pill use, appear to decrease its risk.

EAOC most commonly arises in the ovary, and not in the deep endometriosis implants of adjacent pelvic structures (such as the anterior and posterior cul de sac and pelvic peritoneum). It is suggested that the ovary itself provides a uniquely favorable environment for carcinogenesis. As stated above, it is hypothesized that refluxed endometrial cells, carrying important progenitor mutations, may become trapped in the tissues of traumatized ovarian epithelium, ripe with inflammatory changes, post ovulation.2 This microenvironment may promote the development of malignancy.

Given these theories and their supporting evidence, how can we attempt to reduce the incidence of this cancer for our patients with endometriosis? Despite their increased risk for ovarian and endometrial cancers, current recommendations do not support routine cancer screening in women with endometriosis.7 However, risk-mitigation strategies can still be pursued. Hormonal contraceptives to decrease ovulation and menstrual cycling are protective against ovarian cancer and are also helpful in mitigating the symptoms of endometriosis. While removal of endometriotic cysts may not, in and of itself, be a strategy to prevent EAOC, it is still generally recommended because these cysts are commonly a source of pain and infertility. While they do not appear to undergo malignant transformation, it can be difficult to definitively rule out an early ovarian cancer in these complex ovarian cysts, particularly as they are often associated with tumor marker abnormalities such as elevations in CA 125. Therefore, if surgical excision of an endometriotic cyst is not performed, it should be closely followed for at least 5 years to ensure it is a benign structure. If surgery is pursued and ovarian preservation is desired, removal of the fallopian tubes and uterus can help mitigate the risk for EAOC.8

Endometriosis is a morbid condition for many young women. In addition to causing pain and infertility it increases a woman’s risk for ovarian and endometrial cancer, particularly ovarian clear cell, endometrioid, and low-grade serous cancers and synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancers. Endometriotic cysts should be removed or closely monitored, and clinicians should discuss treatment options that minimize frequency of ovulation and menstruation events as a preventative strategy.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Endocrinology. 2019;160(3):626-38.

2. Cancers. 2020;12(6):1676.

3. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:385-94.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(3):760-6.

5. Redox Rep. 2016;21:119-26.

6. Int. J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:51-8.

7. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:1552-68.

8. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:1097-103.

Endometriosis, which affects 1 in 10 women, is one of the most common conditions that gynecologists treat. It is known to cause pain, pelvic adhesive disease, endometriotic cyst formation, and infertility. However, even more sinister, it also increases a woman’s risk for the development of epithelial ovarian cancer (known as endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer or EAOC). A woman with endometriosis has a two- to threefold increased risk of developing epithelial ovarian cancer, compared with nonaffected women.1 This risk appears to be concentrated in the premenopausal age group, particularly the fifth decade of life. After menopause their risk of developing cancer returns to a baseline level.

EAOC classically presents as clear cell or endometrioid adenocarcinomas, rather than high-grade serous carcinomas. However, low-grade serous carcinomas are also frequently observed in this cohort.2,3 Unlike high-grade serous carcinoma, EAOC is more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage, with the majority at stage I or II, and prognosis is better. After matching for age and stage with cases of high-grade serous carcinoma, there is improved disease-free and overall survival observed among cases of EAOC of clear cell and endometrioid histologic cell types.4 The phenomenon of dual primaries (synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancer) occurs more frequently in EAOC than it does in patients with nonendometriosis-related high-grade serous cancer (25% vs. 4%).

The genomics of these endometriosis-associated cancers are quite distinct. Similar to benign endometriosis implants, EAOC is associated with genomic mutations in ARID1A, PIK3CA, and PTEN, as well as progesterone resistance.1,2 Multiple studies have shown that the adjacent eutopic endometrium carries similar gene mutations as those found in both benign endometriotic implants and EAOC.2 This may explain the higher incidence (twofold) of endometrial cancer in patients with endometriosis as well as the increased incidence of dual ovarian and endometrial cancer primaries.

Just as there are multiple theories regarding the mechanism of benign endometriosis, we have theories rather than conclusions regarding the origins of EAOC. One such theory is that it develops from malignant transformation in an existing endometriotic cyst.5 Endometriotic cysts provide an iron-rich environment which promotes reactive oxygen species that promote carcinogenesis by inducing gene mutations and epigenetic alterations. However, if prolonged exposure to oxidative stress within endometriotic cysts were to be the cause for EAOC, we would expect to see a progressively increasing incidence of ovarian cancer over time in patients with expectantly managed cysts. However, in cases of expectant management, an initial, early, increased risk for cancer within the first 5 years is followed by a subsequent decreasing incidence over time.6 This early incidence spike suggests that some endometriotic cysts may have been misclassified as benign, then rapidly declare themselves as malignant during the observation period rather than a transformation into malignancy from a benign endometrioma over time.

An alternative, and favored, theory for the origins of EAOC are that endometrial cells with carcinogenic genomic alterations reflux through the fallopian tubes during menstruation and settle onto the ovarian epithelium which itself is damaged from recent ovulation thus providing an environment that is highly suitable for oncogenesis.2 Genomic analyses of both the eutopic endometrium and malignant cells in patients with EAOC have shown that both tissues contain the same genomic alterations.1 Given that menstruation, including retrograde menstruation, ends after menopause, this mechanism supports the observation that EAOC is predominantly a malignancy of premenopausal women. Additionally, salpingectomy and hysterectomy confers a protective effect on the development of EAOC, theoretically by preventing the retrograde transfer of these mutant progenitor endometrial cells. Furthermore, the factors that increase the number of menstrual cycles (such as an early age of menarche and delayed or nonchildbearing states) increases the risk for EAOC and factors that inhibit menstruation, such as oral contraceptive pill use, appear to decrease its risk.

EAOC most commonly arises in the ovary, and not in the deep endometriosis implants of adjacent pelvic structures (such as the anterior and posterior cul de sac and pelvic peritoneum). It is suggested that the ovary itself provides a uniquely favorable environment for carcinogenesis. As stated above, it is hypothesized that refluxed endometrial cells, carrying important progenitor mutations, may become trapped in the tissues of traumatized ovarian epithelium, ripe with inflammatory changes, post ovulation.2 This microenvironment may promote the development of malignancy.

Given these theories and their supporting evidence, how can we attempt to reduce the incidence of this cancer for our patients with endometriosis? Despite their increased risk for ovarian and endometrial cancers, current recommendations do not support routine cancer screening in women with endometriosis.7 However, risk-mitigation strategies can still be pursued. Hormonal contraceptives to decrease ovulation and menstrual cycling are protective against ovarian cancer and are also helpful in mitigating the symptoms of endometriosis. While removal of endometriotic cysts may not, in and of itself, be a strategy to prevent EAOC, it is still generally recommended because these cysts are commonly a source of pain and infertility. While they do not appear to undergo malignant transformation, it can be difficult to definitively rule out an early ovarian cancer in these complex ovarian cysts, particularly as they are often associated with tumor marker abnormalities such as elevations in CA 125. Therefore, if surgical excision of an endometriotic cyst is not performed, it should be closely followed for at least 5 years to ensure it is a benign structure. If surgery is pursued and ovarian preservation is desired, removal of the fallopian tubes and uterus can help mitigate the risk for EAOC.8

Endometriosis is a morbid condition for many young women. In addition to causing pain and infertility it increases a woman’s risk for ovarian and endometrial cancer, particularly ovarian clear cell, endometrioid, and low-grade serous cancers and synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancers. Endometriotic cysts should be removed or closely monitored, and clinicians should discuss treatment options that minimize frequency of ovulation and menstruation events as a preventative strategy.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Endocrinology. 2019;160(3):626-38.

2. Cancers. 2020;12(6):1676.

3. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:385-94.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(3):760-6.

5. Redox Rep. 2016;21:119-26.

6. Int. J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:51-8.

7. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:1552-68.

8. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:1097-103.

Endometriosis, which affects 1 in 10 women, is one of the most common conditions that gynecologists treat. It is known to cause pain, pelvic adhesive disease, endometriotic cyst formation, and infertility. However, even more sinister, it also increases a woman’s risk for the development of epithelial ovarian cancer (known as endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer or EAOC). A woman with endometriosis has a two- to threefold increased risk of developing epithelial ovarian cancer, compared with nonaffected women.1 This risk appears to be concentrated in the premenopausal age group, particularly the fifth decade of life. After menopause their risk of developing cancer returns to a baseline level.

EAOC classically presents as clear cell or endometrioid adenocarcinomas, rather than high-grade serous carcinomas. However, low-grade serous carcinomas are also frequently observed in this cohort.2,3 Unlike high-grade serous carcinoma, EAOC is more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage, with the majority at stage I or II, and prognosis is better. After matching for age and stage with cases of high-grade serous carcinoma, there is improved disease-free and overall survival observed among cases of EAOC of clear cell and endometrioid histologic cell types.4 The phenomenon of dual primaries (synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancer) occurs more frequently in EAOC than it does in patients with nonendometriosis-related high-grade serous cancer (25% vs. 4%).

The genomics of these endometriosis-associated cancers are quite distinct. Similar to benign endometriosis implants, EAOC is associated with genomic mutations in ARID1A, PIK3CA, and PTEN, as well as progesterone resistance.1,2 Multiple studies have shown that the adjacent eutopic endometrium carries similar gene mutations as those found in both benign endometriotic implants and EAOC.2 This may explain the higher incidence (twofold) of endometrial cancer in patients with endometriosis as well as the increased incidence of dual ovarian and endometrial cancer primaries.

Just as there are multiple theories regarding the mechanism of benign endometriosis, we have theories rather than conclusions regarding the origins of EAOC. One such theory is that it develops from malignant transformation in an existing endometriotic cyst.5 Endometriotic cysts provide an iron-rich environment which promotes reactive oxygen species that promote carcinogenesis by inducing gene mutations and epigenetic alterations. However, if prolonged exposure to oxidative stress within endometriotic cysts were to be the cause for EAOC, we would expect to see a progressively increasing incidence of ovarian cancer over time in patients with expectantly managed cysts. However, in cases of expectant management, an initial, early, increased risk for cancer within the first 5 years is followed by a subsequent decreasing incidence over time.6 This early incidence spike suggests that some endometriotic cysts may have been misclassified as benign, then rapidly declare themselves as malignant during the observation period rather than a transformation into malignancy from a benign endometrioma over time.

An alternative, and favored, theory for the origins of EAOC are that endometrial cells with carcinogenic genomic alterations reflux through the fallopian tubes during menstruation and settle onto the ovarian epithelium which itself is damaged from recent ovulation thus providing an environment that is highly suitable for oncogenesis.2 Genomic analyses of both the eutopic endometrium and malignant cells in patients with EAOC have shown that both tissues contain the same genomic alterations.1 Given that menstruation, including retrograde menstruation, ends after menopause, this mechanism supports the observation that EAOC is predominantly a malignancy of premenopausal women. Additionally, salpingectomy and hysterectomy confers a protective effect on the development of EAOC, theoretically by preventing the retrograde transfer of these mutant progenitor endometrial cells. Furthermore, the factors that increase the number of menstrual cycles (such as an early age of menarche and delayed or nonchildbearing states) increases the risk for EAOC and factors that inhibit menstruation, such as oral contraceptive pill use, appear to decrease its risk.

EAOC most commonly arises in the ovary, and not in the deep endometriosis implants of adjacent pelvic structures (such as the anterior and posterior cul de sac and pelvic peritoneum). It is suggested that the ovary itself provides a uniquely favorable environment for carcinogenesis. As stated above, it is hypothesized that refluxed endometrial cells, carrying important progenitor mutations, may become trapped in the tissues of traumatized ovarian epithelium, ripe with inflammatory changes, post ovulation.2 This microenvironment may promote the development of malignancy.

Given these theories and their supporting evidence, how can we attempt to reduce the incidence of this cancer for our patients with endometriosis? Despite their increased risk for ovarian and endometrial cancers, current recommendations do not support routine cancer screening in women with endometriosis.7 However, risk-mitigation strategies can still be pursued. Hormonal contraceptives to decrease ovulation and menstrual cycling are protective against ovarian cancer and are also helpful in mitigating the symptoms of endometriosis. While removal of endometriotic cysts may not, in and of itself, be a strategy to prevent EAOC, it is still generally recommended because these cysts are commonly a source of pain and infertility. While they do not appear to undergo malignant transformation, it can be difficult to definitively rule out an early ovarian cancer in these complex ovarian cysts, particularly as they are often associated with tumor marker abnormalities such as elevations in CA 125. Therefore, if surgical excision of an endometriotic cyst is not performed, it should be closely followed for at least 5 years to ensure it is a benign structure. If surgery is pursued and ovarian preservation is desired, removal of the fallopian tubes and uterus can help mitigate the risk for EAOC.8

Endometriosis is a morbid condition for many young women. In addition to causing pain and infertility it increases a woman’s risk for ovarian and endometrial cancer, particularly ovarian clear cell, endometrioid, and low-grade serous cancers and synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancers. Endometriotic cysts should be removed or closely monitored, and clinicians should discuss treatment options that minimize frequency of ovulation and menstruation events as a preventative strategy.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Endocrinology. 2019;160(3):626-38.

2. Cancers. 2020;12(6):1676.

3. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:385-94.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(3):760-6.

5. Redox Rep. 2016;21:119-26.

6. Int. J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:51-8.

7. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:1552-68.

8. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:1097-103.

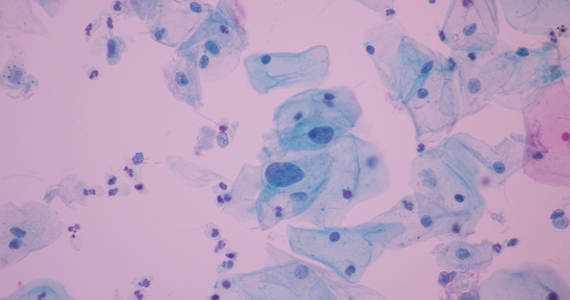

Pap test/cervical swab samples can reveal ovarian cancer biomarkers

Residual fixatives from liquid-based Pap tests and cervical swabs contain tumor-specific biomarkers for ovarian cancer, according to an analysis of proteins found in matched biospecimens from a woman with high grade serous ovarian cancer.

The findings suggest that Pap test fluid or cervical swabs could be used to detect ovarian cancer biomarker proteins to allow for earlier detection of ovarian cancer, reported Kristin L. M. Boylan, PhD, assistant director of the Ovarian Cancer Early Detection Program at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues.

The investigators examined the biospecimens from a 72-year-old woman diagnosed with metastatic high-grade serous adenocarcinoma that did not encompass the cervix. The Pap test, obtained prior to surgery, was negative for malignancy, but nearly 5,000 proteins were detected in the three matched biospecimens, including more than 2,000 that were expressed in each of them.

These proteins included several known ovarian cancer biomarkers, such as CA125, HE4, and mesothelin, the investigators noted.

The findings were published online Feb. 9 in Clinical Proteomics.

“Our data demonstrate that ovarian cancer biomarkers can be detected in Pap test fluid or a cervical swab by MS-based proteomics,” the investigators wrote. “In addition to identifying multiple known biomarkers, over 2,000 proteins were detected in all three biospecimens, suggesting a potential role for novel biomarker discovery.”

Proteins from the cell-free supernatant of the patient’s liquid-based Pap test fixative were concentrated by acetone precipitation or eluted from the cervical swab, and protein was also extracted from the patient’s tumor. Analyses showed similarities in the Pap test fluid and cervical swab proteins, as well as the tumor extract.

The findings are notable, because while early detection of ovarian cancer increases survival, an adequately sensitive and specific screening tool for use in the general population is lacking, the investigators explained.

Pap test screening is widely accepted, suggesting that developing it as a screening tool for both cervical and ovarian cancers could improve testing for this “lethal but elusive disease,” they said, addding that “[W]hile our samples were from a single patient, the results are proof of concept: that Pap test fluid or cervical swabs could be used for detection of ovarian cancer biomarker proteins, and this approach warrants further investigation.”

Senior author Amy Skubitz, PhD, professor and director of the Ovarian Cancer Early Detection Program, stated in a press release that she “sees an opportunity for this method to be translated into a self-administered, at-home test, where swabs could be collected by women at home and sent to a central laboratory for analysis of proteins that would diagnose ovarian cancer.”

However, next steps include using quantitative mass spectrometry to determine if the proteins or peptides identified in this analysis are detected at higher levels in ovarian cancer Pap tests or swabs compared to controls.

“Their presence alone is not sufficient for diagnosis,” she stated.

This study was supported by the Minnesota Ovarian Cancer Alliance, the Cancurables Foundation, Charlene’s Light: A Foundation for Ovarian Cancer, and the Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program Pilot Award. The authors reported having no disclosures.

Residual fixatives from liquid-based Pap tests and cervical swabs contain tumor-specific biomarkers for ovarian cancer, according to an analysis of proteins found in matched biospecimens from a woman with high grade serous ovarian cancer.

The findings suggest that Pap test fluid or cervical swabs could be used to detect ovarian cancer biomarker proteins to allow for earlier detection of ovarian cancer, reported Kristin L. M. Boylan, PhD, assistant director of the Ovarian Cancer Early Detection Program at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues.

The investigators examined the biospecimens from a 72-year-old woman diagnosed with metastatic high-grade serous adenocarcinoma that did not encompass the cervix. The Pap test, obtained prior to surgery, was negative for malignancy, but nearly 5,000 proteins were detected in the three matched biospecimens, including more than 2,000 that were expressed in each of them.

These proteins included several known ovarian cancer biomarkers, such as CA125, HE4, and mesothelin, the investigators noted.

The findings were published online Feb. 9 in Clinical Proteomics.

“Our data demonstrate that ovarian cancer biomarkers can be detected in Pap test fluid or a cervical swab by MS-based proteomics,” the investigators wrote. “In addition to identifying multiple known biomarkers, over 2,000 proteins were detected in all three biospecimens, suggesting a potential role for novel biomarker discovery.”

Proteins from the cell-free supernatant of the patient’s liquid-based Pap test fixative were concentrated by acetone precipitation or eluted from the cervical swab, and protein was also extracted from the patient’s tumor. Analyses showed similarities in the Pap test fluid and cervical swab proteins, as well as the tumor extract.

The findings are notable, because while early detection of ovarian cancer increases survival, an adequately sensitive and specific screening tool for use in the general population is lacking, the investigators explained.

Pap test screening is widely accepted, suggesting that developing it as a screening tool for both cervical and ovarian cancers could improve testing for this “lethal but elusive disease,” they said, addding that “[W]hile our samples were from a single patient, the results are proof of concept: that Pap test fluid or cervical swabs could be used for detection of ovarian cancer biomarker proteins, and this approach warrants further investigation.”

Senior author Amy Skubitz, PhD, professor and director of the Ovarian Cancer Early Detection Program, stated in a press release that she “sees an opportunity for this method to be translated into a self-administered, at-home test, where swabs could be collected by women at home and sent to a central laboratory for analysis of proteins that would diagnose ovarian cancer.”

However, next steps include using quantitative mass spectrometry to determine if the proteins or peptides identified in this analysis are detected at higher levels in ovarian cancer Pap tests or swabs compared to controls.

“Their presence alone is not sufficient for diagnosis,” she stated.

This study was supported by the Minnesota Ovarian Cancer Alliance, the Cancurables Foundation, Charlene’s Light: A Foundation for Ovarian Cancer, and the Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program Pilot Award. The authors reported having no disclosures.

Residual fixatives from liquid-based Pap tests and cervical swabs contain tumor-specific biomarkers for ovarian cancer, according to an analysis of proteins found in matched biospecimens from a woman with high grade serous ovarian cancer.

The findings suggest that Pap test fluid or cervical swabs could be used to detect ovarian cancer biomarker proteins to allow for earlier detection of ovarian cancer, reported Kristin L. M. Boylan, PhD, assistant director of the Ovarian Cancer Early Detection Program at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues.

The investigators examined the biospecimens from a 72-year-old woman diagnosed with metastatic high-grade serous adenocarcinoma that did not encompass the cervix. The Pap test, obtained prior to surgery, was negative for malignancy, but nearly 5,000 proteins were detected in the three matched biospecimens, including more than 2,000 that were expressed in each of them.

These proteins included several known ovarian cancer biomarkers, such as CA125, HE4, and mesothelin, the investigators noted.

The findings were published online Feb. 9 in Clinical Proteomics.

“Our data demonstrate that ovarian cancer biomarkers can be detected in Pap test fluid or a cervical swab by MS-based proteomics,” the investigators wrote. “In addition to identifying multiple known biomarkers, over 2,000 proteins were detected in all three biospecimens, suggesting a potential role for novel biomarker discovery.”

Proteins from the cell-free supernatant of the patient’s liquid-based Pap test fixative were concentrated by acetone precipitation or eluted from the cervical swab, and protein was also extracted from the patient’s tumor. Analyses showed similarities in the Pap test fluid and cervical swab proteins, as well as the tumor extract.

The findings are notable, because while early detection of ovarian cancer increases survival, an adequately sensitive and specific screening tool for use in the general population is lacking, the investigators explained.

Pap test screening is widely accepted, suggesting that developing it as a screening tool for both cervical and ovarian cancers could improve testing for this “lethal but elusive disease,” they said, addding that “[W]hile our samples were from a single patient, the results are proof of concept: that Pap test fluid or cervical swabs could be used for detection of ovarian cancer biomarker proteins, and this approach warrants further investigation.”

Senior author Amy Skubitz, PhD, professor and director of the Ovarian Cancer Early Detection Program, stated in a press release that she “sees an opportunity for this method to be translated into a self-administered, at-home test, where swabs could be collected by women at home and sent to a central laboratory for analysis of proteins that would diagnose ovarian cancer.”

However, next steps include using quantitative mass spectrometry to determine if the proteins or peptides identified in this analysis are detected at higher levels in ovarian cancer Pap tests or swabs compared to controls.

“Their presence alone is not sufficient for diagnosis,” she stated.

This study was supported by the Minnesota Ovarian Cancer Alliance, the Cancurables Foundation, Charlene’s Light: A Foundation for Ovarian Cancer, and the Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program Pilot Award. The authors reported having no disclosures.

FROM CLINICAL PROTEOMICS

How has the pandemic affected rural and urban cancer patients?

Research has shown that, compared with their urban counterparts, rural cancer patients have higher cancer-related mortality and other negative treatment outcomes.

Among other explanations, the disparity has been attributed to lower education and income levels, medical and behavioral risk factors, differences in health literacy, and lower confidence in the medical system among rural residents (JCO Oncol Pract. 2020 Jul;16(7):422-30).

A new survey has provided some insight into how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted rural and urban cancer patients differently.

The survey showed that urban patients were more likely to report changes to their daily lives, thought themselves more likely to become infected with SARS-CoV-2, and were more likely to take measures to mitigate the risk of infection. However, there were no major differences between urban and rural patients with regard to changes in social interaction.

Bailee Daniels of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, presented these results at the AACR Virtual Meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer (Abstract S04-03).

The COVID-19 and Oncology Patient Experience Consortium

Ms. Daniels explained that the COVID-19 and Oncology Patient Experience (COPES) Consortium was created to investigate various aspects of the patient experience during the pandemic. Three cancer centers – Moffitt Cancer Center, Huntsman Cancer Institute, and the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center – participate in COPES.

At Huntsman, investigators studied social and health behaviors of cancer patients to assess whether there was a difference between those from rural and urban areas. The researchers looked at the impact of the pandemic on psychosocial outcomes, preventive measures patients implemented, and their perceptions of the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The team’s hypothesis was that rural patients might be more vulnerable than urban patients to the effects of social isolation, emotional distress, and health-adverse behaviors, but the investigators noted that there has been no prior research on the topic.

Assessing behaviors, attitudes, and outcomes

Between August and September 2020, the researchers surveyed 1,328 adult cancer patients who had visited Huntsman in the previous 4 years and who were enrolled in Huntsman’s Total Cancer Care or Precision Exercise Prescription studies.

Patients completed questionnaires that encompassed demographic and clinical factors, employment status, health behaviors, and infection preventive measures. Questionnaires were provided in electronic, paper, or phone-based formats. Information regarding age, race, ethnicity, and tumor stage was abstracted from Huntsman’s electronic health record.

Modifications in daily life and social interaction were assessed on a 5-point scale. Changes in exercise habits and alcohol consumption were assessed on a 3-point scale. Infection mitigation measures (the use of face masks and hand sanitizer) and perceptions about the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 infection were measured.

The rural-urban community area codes system, which classifies U.S. census tracts by measures of population density, urbanization, and daily commuting, was utilized to categorize patients into rural and urban residences.

Characteristics of urban and rural cancer patients

There were 997 urban and 331 rural participants. The mean age was 60.1 years in the urban population and 62.6 years in the rural population (P = .01). There were no urban-rural differences in sex, ethnicity, cancer stage, or body mass index.

More urban than rural participants were employed full- or part-time (45% vs. 37%; P = .045). The rural counties had more patients who were not currently employed, primarily due to retirement (77% vs. 69% urban; P < .001).

“No health insurance coverage” was reported by 2% of urban and 4% of rural participants (P = .009), and 85% of all patients reported “good” to “excellent” overall health. Cancer patients in rural counties were significantly more likely to have ever smoked (37% vs. 25% urban; P = .001). In addition, alcohol consumption in the previous year was higher in rural patients. “Every day to less than once monthly” alcohol usage was reported by 44% of urban and 60% of rural patients (P < .001).

Changes in daily life and health-related behavior during the pandemic

Urban patients were more likely to report changes in their daily lives due to the pandemic. Specifically, 35% of urban patients and 26% of rural patients said the pandemic had changed their daily life “a lot” (P = .001).

However, there were no major differences between urban and rural patients when it came to changes in social interaction in the past month or feeling lonely in the past month (P = .45 and P = .88, respectively). Similarly, there were no significant differences for changes in alcohol consumption between the groups (P = .90).

Changes in exercise habits due to the pandemic were more common among patients in urban counties (51% vs. 39% rural; P < .001), though similar percentages of patients reported exercising less (44% urban vs. 45% rural) or more frequently (24% urban vs. 20% rural).

In terms of infection mitigation measures, urban patients were more likely to use face masks “very often” (83% vs. 66% rural; P < .001), while hand sanitizer was used “very often” among 66% of urban and 57% of rural participants (P = .05).

Urban participants were more likely than were their rural counterparts to think themselves “somewhat” or “very” likely to develop COVID-19 (22% vs. 14%; P = .04).

It might be short-sighted for oncology and public health specialists to be dismissive of differences in infection mitigation behaviors and perceptions of vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Those behaviors and perceptions of risk could lead to lower vaccination rates in rural areas. If that occurs, there would be major negative consequences for the long-term health of rural communities and their medically vulnerable residents.

Future directions

Although the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic had disparate effects on cancer patients living in rural and urban counties, the reasons for the disparities are complex and not easily explained by this study.

It is possible that sequential administration of the survey during the pandemic would have uncovered greater variances in attitude and health-related behaviors.

As Ms. Daniels noted, when the survey was performed, Utah had not experienced a high frequency of COVID-19 cases. Furthermore, different levels of restrictions were implemented on a county-by-county basis, potentially influencing patients’ behaviors, psychosocial adjustment, and perceptions of risk.

In addition, there may have been differences in unmeasured endpoints (infection rates, medical care utilization via telemedicine, hospitalization rates, late effects, and mortality) between the urban and rural populations.

As the investigators concluded, further research is needed to better characterize the pandemic’s short- and long-term effects on cancer patients in rural and urban settings and appropriate interventions. Such studies may yield insights into the various facets of the well-documented “rural health gap” in cancer outcomes and interventions that could narrow the gap in spheres beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ms. Daniels reported having no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Research has shown that, compared with their urban counterparts, rural cancer patients have higher cancer-related mortality and other negative treatment outcomes.

Among other explanations, the disparity has been attributed to lower education and income levels, medical and behavioral risk factors, differences in health literacy, and lower confidence in the medical system among rural residents (JCO Oncol Pract. 2020 Jul;16(7):422-30).

A new survey has provided some insight into how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted rural and urban cancer patients differently.

The survey showed that urban patients were more likely to report changes to their daily lives, thought themselves more likely to become infected with SARS-CoV-2, and were more likely to take measures to mitigate the risk of infection. However, there were no major differences between urban and rural patients with regard to changes in social interaction.

Bailee Daniels of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, presented these results at the AACR Virtual Meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer (Abstract S04-03).

The COVID-19 and Oncology Patient Experience Consortium

Ms. Daniels explained that the COVID-19 and Oncology Patient Experience (COPES) Consortium was created to investigate various aspects of the patient experience during the pandemic. Three cancer centers – Moffitt Cancer Center, Huntsman Cancer Institute, and the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center – participate in COPES.

At Huntsman, investigators studied social and health behaviors of cancer patients to assess whether there was a difference between those from rural and urban areas. The researchers looked at the impact of the pandemic on psychosocial outcomes, preventive measures patients implemented, and their perceptions of the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The team’s hypothesis was that rural patients might be more vulnerable than urban patients to the effects of social isolation, emotional distress, and health-adverse behaviors, but the investigators noted that there has been no prior research on the topic.

Assessing behaviors, attitudes, and outcomes

Between August and September 2020, the researchers surveyed 1,328 adult cancer patients who had visited Huntsman in the previous 4 years and who were enrolled in Huntsman’s Total Cancer Care or Precision Exercise Prescription studies.

Patients completed questionnaires that encompassed demographic and clinical factors, employment status, health behaviors, and infection preventive measures. Questionnaires were provided in electronic, paper, or phone-based formats. Information regarding age, race, ethnicity, and tumor stage was abstracted from Huntsman’s electronic health record.

Modifications in daily life and social interaction were assessed on a 5-point scale. Changes in exercise habits and alcohol consumption were assessed on a 3-point scale. Infection mitigation measures (the use of face masks and hand sanitizer) and perceptions about the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 infection were measured.

The rural-urban community area codes system, which classifies U.S. census tracts by measures of population density, urbanization, and daily commuting, was utilized to categorize patients into rural and urban residences.

Characteristics of urban and rural cancer patients

There were 997 urban and 331 rural participants. The mean age was 60.1 years in the urban population and 62.6 years in the rural population (P = .01). There were no urban-rural differences in sex, ethnicity, cancer stage, or body mass index.

More urban than rural participants were employed full- or part-time (45% vs. 37%; P = .045). The rural counties had more patients who were not currently employed, primarily due to retirement (77% vs. 69% urban; P < .001).

“No health insurance coverage” was reported by 2% of urban and 4% of rural participants (P = .009), and 85% of all patients reported “good” to “excellent” overall health. Cancer patients in rural counties were significantly more likely to have ever smoked (37% vs. 25% urban; P = .001). In addition, alcohol consumption in the previous year was higher in rural patients. “Every day to less than once monthly” alcohol usage was reported by 44% of urban and 60% of rural patients (P < .001).

Changes in daily life and health-related behavior during the pandemic

Urban patients were more likely to report changes in their daily lives due to the pandemic. Specifically, 35% of urban patients and 26% of rural patients said the pandemic had changed their daily life “a lot” (P = .001).

However, there were no major differences between urban and rural patients when it came to changes in social interaction in the past month or feeling lonely in the past month (P = .45 and P = .88, respectively). Similarly, there were no significant differences for changes in alcohol consumption between the groups (P = .90).

Changes in exercise habits due to the pandemic were more common among patients in urban counties (51% vs. 39% rural; P < .001), though similar percentages of patients reported exercising less (44% urban vs. 45% rural) or more frequently (24% urban vs. 20% rural).

In terms of infection mitigation measures, urban patients were more likely to use face masks “very often” (83% vs. 66% rural; P < .001), while hand sanitizer was used “very often” among 66% of urban and 57% of rural participants (P = .05).

Urban participants were more likely than were their rural counterparts to think themselves “somewhat” or “very” likely to develop COVID-19 (22% vs. 14%; P = .04).

It might be short-sighted for oncology and public health specialists to be dismissive of differences in infection mitigation behaviors and perceptions of vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Those behaviors and perceptions of risk could lead to lower vaccination rates in rural areas. If that occurs, there would be major negative consequences for the long-term health of rural communities and their medically vulnerable residents.

Future directions

Although the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic had disparate effects on cancer patients living in rural and urban counties, the reasons for the disparities are complex and not easily explained by this study.

It is possible that sequential administration of the survey during the pandemic would have uncovered greater variances in attitude and health-related behaviors.

As Ms. Daniels noted, when the survey was performed, Utah had not experienced a high frequency of COVID-19 cases. Furthermore, different levels of restrictions were implemented on a county-by-county basis, potentially influencing patients’ behaviors, psychosocial adjustment, and perceptions of risk.

In addition, there may have been differences in unmeasured endpoints (infection rates, medical care utilization via telemedicine, hospitalization rates, late effects, and mortality) between the urban and rural populations.

As the investigators concluded, further research is needed to better characterize the pandemic’s short- and long-term effects on cancer patients in rural and urban settings and appropriate interventions. Such studies may yield insights into the various facets of the well-documented “rural health gap” in cancer outcomes and interventions that could narrow the gap in spheres beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ms. Daniels reported having no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Research has shown that, compared with their urban counterparts, rural cancer patients have higher cancer-related mortality and other negative treatment outcomes.

Among other explanations, the disparity has been attributed to lower education and income levels, medical and behavioral risk factors, differences in health literacy, and lower confidence in the medical system among rural residents (JCO Oncol Pract. 2020 Jul;16(7):422-30).

A new survey has provided some insight into how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted rural and urban cancer patients differently.

The survey showed that urban patients were more likely to report changes to their daily lives, thought themselves more likely to become infected with SARS-CoV-2, and were more likely to take measures to mitigate the risk of infection. However, there were no major differences between urban and rural patients with regard to changes in social interaction.

Bailee Daniels of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, presented these results at the AACR Virtual Meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer (Abstract S04-03).

The COVID-19 and Oncology Patient Experience Consortium

Ms. Daniels explained that the COVID-19 and Oncology Patient Experience (COPES) Consortium was created to investigate various aspects of the patient experience during the pandemic. Three cancer centers – Moffitt Cancer Center, Huntsman Cancer Institute, and the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center – participate in COPES.

At Huntsman, investigators studied social and health behaviors of cancer patients to assess whether there was a difference between those from rural and urban areas. The researchers looked at the impact of the pandemic on psychosocial outcomes, preventive measures patients implemented, and their perceptions of the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The team’s hypothesis was that rural patients might be more vulnerable than urban patients to the effects of social isolation, emotional distress, and health-adverse behaviors, but the investigators noted that there has been no prior research on the topic.

Assessing behaviors, attitudes, and outcomes

Between August and September 2020, the researchers surveyed 1,328 adult cancer patients who had visited Huntsman in the previous 4 years and who were enrolled in Huntsman’s Total Cancer Care or Precision Exercise Prescription studies.

Patients completed questionnaires that encompassed demographic and clinical factors, employment status, health behaviors, and infection preventive measures. Questionnaires were provided in electronic, paper, or phone-based formats. Information regarding age, race, ethnicity, and tumor stage was abstracted from Huntsman’s electronic health record.

Modifications in daily life and social interaction were assessed on a 5-point scale. Changes in exercise habits and alcohol consumption were assessed on a 3-point scale. Infection mitigation measures (the use of face masks and hand sanitizer) and perceptions about the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 infection were measured.

The rural-urban community area codes system, which classifies U.S. census tracts by measures of population density, urbanization, and daily commuting, was utilized to categorize patients into rural and urban residences.

Characteristics of urban and rural cancer patients

There were 997 urban and 331 rural participants. The mean age was 60.1 years in the urban population and 62.6 years in the rural population (P = .01). There were no urban-rural differences in sex, ethnicity, cancer stage, or body mass index.

More urban than rural participants were employed full- or part-time (45% vs. 37%; P = .045). The rural counties had more patients who were not currently employed, primarily due to retirement (77% vs. 69% urban; P < .001).

“No health insurance coverage” was reported by 2% of urban and 4% of rural participants (P = .009), and 85% of all patients reported “good” to “excellent” overall health. Cancer patients in rural counties were significantly more likely to have ever smoked (37% vs. 25% urban; P = .001). In addition, alcohol consumption in the previous year was higher in rural patients. “Every day to less than once monthly” alcohol usage was reported by 44% of urban and 60% of rural patients (P < .001).

Changes in daily life and health-related behavior during the pandemic

Urban patients were more likely to report changes in their daily lives due to the pandemic. Specifically, 35% of urban patients and 26% of rural patients said the pandemic had changed their daily life “a lot” (P = .001).

However, there were no major differences between urban and rural patients when it came to changes in social interaction in the past month or feeling lonely in the past month (P = .45 and P = .88, respectively). Similarly, there were no significant differences for changes in alcohol consumption between the groups (P = .90).

Changes in exercise habits due to the pandemic were more common among patients in urban counties (51% vs. 39% rural; P < .001), though similar percentages of patients reported exercising less (44% urban vs. 45% rural) or more frequently (24% urban vs. 20% rural).

In terms of infection mitigation measures, urban patients were more likely to use face masks “very often” (83% vs. 66% rural; P < .001), while hand sanitizer was used “very often” among 66% of urban and 57% of rural participants (P = .05).

Urban participants were more likely than were their rural counterparts to think themselves “somewhat” or “very” likely to develop COVID-19 (22% vs. 14%; P = .04).

It might be short-sighted for oncology and public health specialists to be dismissive of differences in infection mitigation behaviors and perceptions of vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Those behaviors and perceptions of risk could lead to lower vaccination rates in rural areas. If that occurs, there would be major negative consequences for the long-term health of rural communities and their medically vulnerable residents.

Future directions

Although the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic had disparate effects on cancer patients living in rural and urban counties, the reasons for the disparities are complex and not easily explained by this study.

It is possible that sequential administration of the survey during the pandemic would have uncovered greater variances in attitude and health-related behaviors.

As Ms. Daniels noted, when the survey was performed, Utah had not experienced a high frequency of COVID-19 cases. Furthermore, different levels of restrictions were implemented on a county-by-county basis, potentially influencing patients’ behaviors, psychosocial adjustment, and perceptions of risk.

In addition, there may have been differences in unmeasured endpoints (infection rates, medical care utilization via telemedicine, hospitalization rates, late effects, and mortality) between the urban and rural populations.

As the investigators concluded, further research is needed to better characterize the pandemic’s short- and long-term effects on cancer patients in rural and urban settings and appropriate interventions. Such studies may yield insights into the various facets of the well-documented “rural health gap” in cancer outcomes and interventions that could narrow the gap in spheres beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ms. Daniels reported having no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

FROM AACR: COVID-19 AND CANCER 2021

Prophylactic NPWT may not improve complication rate after gynecologic surgery

Use of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy may not be appropriate in surgical cases where women undergo a laparotomy for presumed gynecologic malignancy, according to recent research published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“The results of our randomized trial do not support the routine use of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy at the time of laparotomy incision closure in women who are undergoing surgery for gynecologic malignancies or in morbidly obese women who are undergoing laparotomy for benign indications,” wrote Mario M. Leitao Jr., MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and colleagues.