User login

Treatment for Iron Deficiency Anemia Associated With Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a serious health problem that affects millions of women globally. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is one of the most common causes of IDA in women in North America.

In this supplement to OBG Management, the authors describe the signs, symptoms, and laboratory evaluation for HMB and IDA, including a comprehensive diagnostic and treatment algorithm for the practicing physician. The authors also discuss the characteristics of iron-repletion therapies currently available in the United States to help you make the best choice for your patient.

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a serious health problem that affects millions of women globally. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is one of the most common causes of IDA in women in North America.

In this supplement to OBG Management, the authors describe the signs, symptoms, and laboratory evaluation for HMB and IDA, including a comprehensive diagnostic and treatment algorithm for the practicing physician. The authors also discuss the characteristics of iron-repletion therapies currently available in the United States to help you make the best choice for your patient.

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a serious health problem that affects millions of women globally. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is one of the most common causes of IDA in women in North America.

In this supplement to OBG Management, the authors describe the signs, symptoms, and laboratory evaluation for HMB and IDA, including a comprehensive diagnostic and treatment algorithm for the practicing physician. The authors also discuss the characteristics of iron-repletion therapies currently available in the United States to help you make the best choice for your patient.

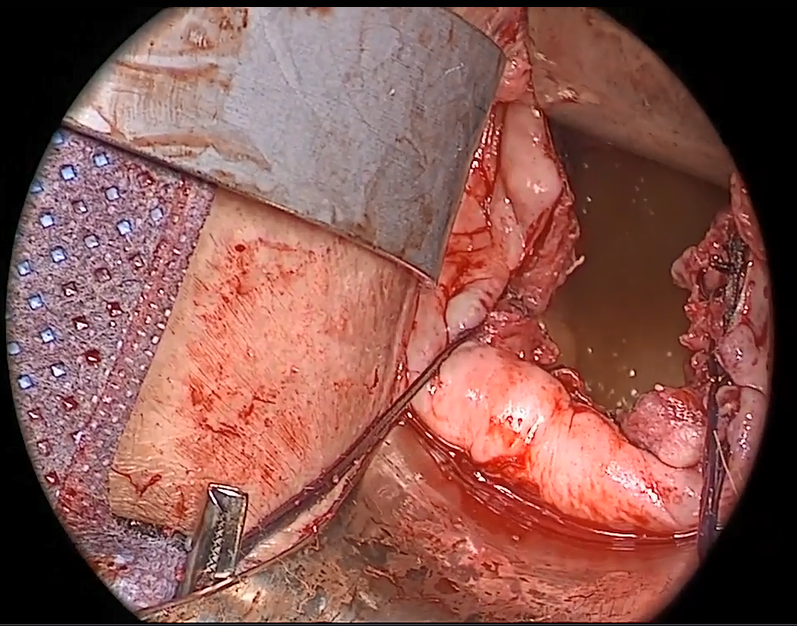

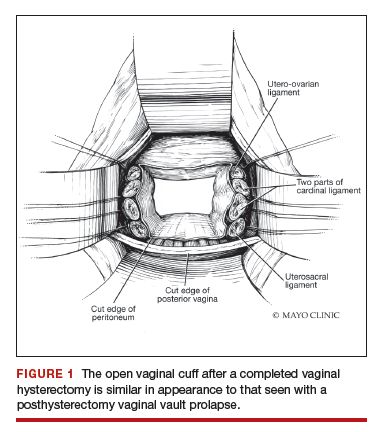

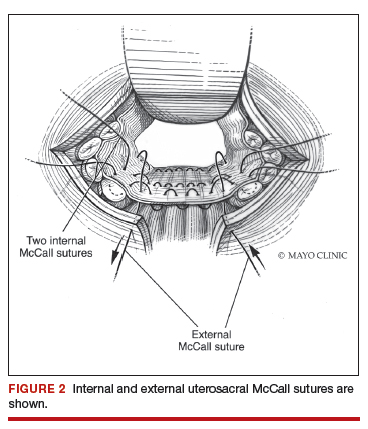

Trial of mesh vs. hysterectomy for prolapse yields inconclusive results

Transvaginal mesh hysteropexy for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse may not significantly reduce treatment failure after 3 years, compared with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension, according to randomized trial results.

Nevertheless, “the point estimate favored hysteropexy,” the study authors wrote in JAMA. The 36-month cumulative treatment failure outcomes – defined as retreatment of prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, or prolapse symptoms – were 33% for patients who underwent hysteropexy, compared with 42% for patients who underwent hysterectomy. In addition, mean operative time was 45 minutes less for patients who underwent hysteropexy.

The publication follows the Food and Drug Administration’s ruling in April 2019 that manufacturers must cease marketing transvaginal mesh kits for repair of anterior or apical compartment prolapse. The investigators plan to continue evaluating patient outcomes to 5 years, and they noted that longer follow-up may lead to different conclusions.

From a class II device to class III

Surgical repair of uterovaginal prolapse is common. Although vaginal hysterectomy is the procedure of choice for many surgeons, “uterine-sparing suspension techniques ... are increasing in usage,” wrote Charles W. Nager, MD, chair and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Diego, and coauthors. However, few high-quality, long-term studies have compared apical transvaginal mesh with native tissue procedures.

The FDA first approved a mesh device for transvaginal repair of prolapse in 2002. In 2008, the agency notified clinicians and patients about an increase in adverse event reports related to vaginal mesh. It later advised that mesh for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse does not conclusively improve clinical outcomes and that serious adverse events are not rare.

In 2016, the FDA reclassified surgical mesh to repair pelvic organ prolapse transvaginally as high risk, citing safety concerns such as severe pelvic pain and organ perforation. And in April 2019, the FDA ordered companies to stop selling transvaginal mesh intended for pelvic organ prolapse repair. “Even though these products can no longer be used in patients moving forward, [manufacturers] are required to continue follow-up” of patients in post–market surveillance studies, the FDA said in a statement.

An FDA panel had concluded that 3-year outcomes for prolapse repair with mesh should be better than the outcomes for repair with native tissue, and that the procedures should have comparable safety profiles.

The SUPeR trial

To compare the efficacy and adverse events of vaginal hysterectomy with suture apical suspension and transvaginal mesh hysteropexy, Dr. Nager and colleagues conducted the Study of Uterine Prolapse Procedures Randomized (SUPeR) trial.

Researchers enrolled 183 postmenopausal women with symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse undergoing surgical intervention at nine sites between April 2013 and February 2015. Investigators randomized 93 women to undergo vaginal mesh hysteropexy and 90 to undergo vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Hysteropexy used the UpholdLITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific). Uterosacral ligament suspension required one permanent and one delayed absorbable suture on each side. The primary analysis included data from 175 patients.

Compared with hysterectomy, hysteropexy resulted in an adjusted hazard ratio of treatment failure of 0.62 after 3 years, which was not statistically significant (P = .06). The 95% confidence interval of 0.38-1.02 “was wide and only slightly crossed the null value,” the researchers said. “The remaining uncertainty is too great” to establish or rule out the benefit of vaginal mesh hysteropexy.

Mean operative time was about 45 minutes shorter in the hysteropexy group versus the hysterectomy group (111.5 minutes vs. 156.7 minutes). Adverse events in the hysteropexy versus hysterectomy groups included mesh exposure (8% vs. 0%), ureteral kinking managed intraoperatively (0% vs. 7%), excessive granulation tissue after 12 weeks (1% vs. 11%), and suture exposure after 12 weeks (3% vs. 21%).

“Both groups reported improvements in sexual function, and dyspareunia and pain and de novo dyspareunia rates were low,” Dr. Nager and colleagues wrote. “All other complications with long-term sequelae were not different between groups.”

“Patients in the current study are being followed up for 60 months and the results and conclusions at 36 months could change with extended follow-up,” they added.

A role for mesh?

“The report ... by Nager and colleagues is particularly timely and important,” Cynthia A. Brincat, MD, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Brincat is affiliated with the division of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at Rush Medical College, Chicago.

Although the mesh exposures, granulation tissue, or suture exposures during the trial did not require reoperation, “management of these adverse events was not described,” the editorialist noted. “Clinically important differences could exist between the management of these reported adverse events.”

Based on the findings, gynecologic surgeons “will need to reconsider several important questions regarding the repair of pelvic organ prolapse. For instance, is hysterectomy a necessary component for the repair? What is the role of mesh, and can its use reduce the use of otherwise unnecessary procedures (i.e., hysterectomy) without increasing risk to patients?” she wrote. Other questions center on what constitutes operative failure and how surgeons should augment prolapse repair.

“This study also provides a potential new and well-defined role for the use of mesh in pelvic prolapse surgery, with no significant difference, and perhaps some benefit (i.e., no hysterectomy), compared with a native tissue repair,” Dr. Brincat wrote. “The study also provides useful information for shared decision-making discussions between patients and gynecologic surgeons with respect to selection of procedures and use of mesh for treatment of women with symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse undergoing vaginal surgery.”

The trial was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health. Boston Scientific provided support through an unrestricted grant. One author reported stock ownership in a medical device company, and others reported grants from medical device companies outside the submitted work. Dr. Brincat reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Nager CW et al. JAMA. 2019 Sep 17;322(11):1054-65; Brincat CA. JAMA. 2019 Sep 17;322(11):1047-8.

Transvaginal mesh hysteropexy for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse may not significantly reduce treatment failure after 3 years, compared with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension, according to randomized trial results.

Nevertheless, “the point estimate favored hysteropexy,” the study authors wrote in JAMA. The 36-month cumulative treatment failure outcomes – defined as retreatment of prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, or prolapse symptoms – were 33% for patients who underwent hysteropexy, compared with 42% for patients who underwent hysterectomy. In addition, mean operative time was 45 minutes less for patients who underwent hysteropexy.

The publication follows the Food and Drug Administration’s ruling in April 2019 that manufacturers must cease marketing transvaginal mesh kits for repair of anterior or apical compartment prolapse. The investigators plan to continue evaluating patient outcomes to 5 years, and they noted that longer follow-up may lead to different conclusions.

From a class II device to class III

Surgical repair of uterovaginal prolapse is common. Although vaginal hysterectomy is the procedure of choice for many surgeons, “uterine-sparing suspension techniques ... are increasing in usage,” wrote Charles W. Nager, MD, chair and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Diego, and coauthors. However, few high-quality, long-term studies have compared apical transvaginal mesh with native tissue procedures.

The FDA first approved a mesh device for transvaginal repair of prolapse in 2002. In 2008, the agency notified clinicians and patients about an increase in adverse event reports related to vaginal mesh. It later advised that mesh for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse does not conclusively improve clinical outcomes and that serious adverse events are not rare.

In 2016, the FDA reclassified surgical mesh to repair pelvic organ prolapse transvaginally as high risk, citing safety concerns such as severe pelvic pain and organ perforation. And in April 2019, the FDA ordered companies to stop selling transvaginal mesh intended for pelvic organ prolapse repair. “Even though these products can no longer be used in patients moving forward, [manufacturers] are required to continue follow-up” of patients in post–market surveillance studies, the FDA said in a statement.

An FDA panel had concluded that 3-year outcomes for prolapse repair with mesh should be better than the outcomes for repair with native tissue, and that the procedures should have comparable safety profiles.

The SUPeR trial

To compare the efficacy and adverse events of vaginal hysterectomy with suture apical suspension and transvaginal mesh hysteropexy, Dr. Nager and colleagues conducted the Study of Uterine Prolapse Procedures Randomized (SUPeR) trial.

Researchers enrolled 183 postmenopausal women with symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse undergoing surgical intervention at nine sites between April 2013 and February 2015. Investigators randomized 93 women to undergo vaginal mesh hysteropexy and 90 to undergo vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Hysteropexy used the UpholdLITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific). Uterosacral ligament suspension required one permanent and one delayed absorbable suture on each side. The primary analysis included data from 175 patients.

Compared with hysterectomy, hysteropexy resulted in an adjusted hazard ratio of treatment failure of 0.62 after 3 years, which was not statistically significant (P = .06). The 95% confidence interval of 0.38-1.02 “was wide and only slightly crossed the null value,” the researchers said. “The remaining uncertainty is too great” to establish or rule out the benefit of vaginal mesh hysteropexy.

Mean operative time was about 45 minutes shorter in the hysteropexy group versus the hysterectomy group (111.5 minutes vs. 156.7 minutes). Adverse events in the hysteropexy versus hysterectomy groups included mesh exposure (8% vs. 0%), ureteral kinking managed intraoperatively (0% vs. 7%), excessive granulation tissue after 12 weeks (1% vs. 11%), and suture exposure after 12 weeks (3% vs. 21%).

“Both groups reported improvements in sexual function, and dyspareunia and pain and de novo dyspareunia rates were low,” Dr. Nager and colleagues wrote. “All other complications with long-term sequelae were not different between groups.”

“Patients in the current study are being followed up for 60 months and the results and conclusions at 36 months could change with extended follow-up,” they added.

A role for mesh?

“The report ... by Nager and colleagues is particularly timely and important,” Cynthia A. Brincat, MD, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Brincat is affiliated with the division of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at Rush Medical College, Chicago.

Although the mesh exposures, granulation tissue, or suture exposures during the trial did not require reoperation, “management of these adverse events was not described,” the editorialist noted. “Clinically important differences could exist between the management of these reported adverse events.”

Based on the findings, gynecologic surgeons “will need to reconsider several important questions regarding the repair of pelvic organ prolapse. For instance, is hysterectomy a necessary component for the repair? What is the role of mesh, and can its use reduce the use of otherwise unnecessary procedures (i.e., hysterectomy) without increasing risk to patients?” she wrote. Other questions center on what constitutes operative failure and how surgeons should augment prolapse repair.

“This study also provides a potential new and well-defined role for the use of mesh in pelvic prolapse surgery, with no significant difference, and perhaps some benefit (i.e., no hysterectomy), compared with a native tissue repair,” Dr. Brincat wrote. “The study also provides useful information for shared decision-making discussions between patients and gynecologic surgeons with respect to selection of procedures and use of mesh for treatment of women with symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse undergoing vaginal surgery.”

The trial was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health. Boston Scientific provided support through an unrestricted grant. One author reported stock ownership in a medical device company, and others reported grants from medical device companies outside the submitted work. Dr. Brincat reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Nager CW et al. JAMA. 2019 Sep 17;322(11):1054-65; Brincat CA. JAMA. 2019 Sep 17;322(11):1047-8.

Transvaginal mesh hysteropexy for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse may not significantly reduce treatment failure after 3 years, compared with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension, according to randomized trial results.

Nevertheless, “the point estimate favored hysteropexy,” the study authors wrote in JAMA. The 36-month cumulative treatment failure outcomes – defined as retreatment of prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, or prolapse symptoms – were 33% for patients who underwent hysteropexy, compared with 42% for patients who underwent hysterectomy. In addition, mean operative time was 45 minutes less for patients who underwent hysteropexy.

The publication follows the Food and Drug Administration’s ruling in April 2019 that manufacturers must cease marketing transvaginal mesh kits for repair of anterior or apical compartment prolapse. The investigators plan to continue evaluating patient outcomes to 5 years, and they noted that longer follow-up may lead to different conclusions.

From a class II device to class III

Surgical repair of uterovaginal prolapse is common. Although vaginal hysterectomy is the procedure of choice for many surgeons, “uterine-sparing suspension techniques ... are increasing in usage,” wrote Charles W. Nager, MD, chair and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Diego, and coauthors. However, few high-quality, long-term studies have compared apical transvaginal mesh with native tissue procedures.

The FDA first approved a mesh device for transvaginal repair of prolapse in 2002. In 2008, the agency notified clinicians and patients about an increase in adverse event reports related to vaginal mesh. It later advised that mesh for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse does not conclusively improve clinical outcomes and that serious adverse events are not rare.

In 2016, the FDA reclassified surgical mesh to repair pelvic organ prolapse transvaginally as high risk, citing safety concerns such as severe pelvic pain and organ perforation. And in April 2019, the FDA ordered companies to stop selling transvaginal mesh intended for pelvic organ prolapse repair. “Even though these products can no longer be used in patients moving forward, [manufacturers] are required to continue follow-up” of patients in post–market surveillance studies, the FDA said in a statement.

An FDA panel had concluded that 3-year outcomes for prolapse repair with mesh should be better than the outcomes for repair with native tissue, and that the procedures should have comparable safety profiles.

The SUPeR trial

To compare the efficacy and adverse events of vaginal hysterectomy with suture apical suspension and transvaginal mesh hysteropexy, Dr. Nager and colleagues conducted the Study of Uterine Prolapse Procedures Randomized (SUPeR) trial.

Researchers enrolled 183 postmenopausal women with symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse undergoing surgical intervention at nine sites between April 2013 and February 2015. Investigators randomized 93 women to undergo vaginal mesh hysteropexy and 90 to undergo vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Hysteropexy used the UpholdLITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific). Uterosacral ligament suspension required one permanent and one delayed absorbable suture on each side. The primary analysis included data from 175 patients.

Compared with hysterectomy, hysteropexy resulted in an adjusted hazard ratio of treatment failure of 0.62 after 3 years, which was not statistically significant (P = .06). The 95% confidence interval of 0.38-1.02 “was wide and only slightly crossed the null value,” the researchers said. “The remaining uncertainty is too great” to establish or rule out the benefit of vaginal mesh hysteropexy.

Mean operative time was about 45 minutes shorter in the hysteropexy group versus the hysterectomy group (111.5 minutes vs. 156.7 minutes). Adverse events in the hysteropexy versus hysterectomy groups included mesh exposure (8% vs. 0%), ureteral kinking managed intraoperatively (0% vs. 7%), excessive granulation tissue after 12 weeks (1% vs. 11%), and suture exposure after 12 weeks (3% vs. 21%).

“Both groups reported improvements in sexual function, and dyspareunia and pain and de novo dyspareunia rates were low,” Dr. Nager and colleagues wrote. “All other complications with long-term sequelae were not different between groups.”

“Patients in the current study are being followed up for 60 months and the results and conclusions at 36 months could change with extended follow-up,” they added.

A role for mesh?

“The report ... by Nager and colleagues is particularly timely and important,” Cynthia A. Brincat, MD, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Brincat is affiliated with the division of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at Rush Medical College, Chicago.

Although the mesh exposures, granulation tissue, or suture exposures during the trial did not require reoperation, “management of these adverse events was not described,” the editorialist noted. “Clinically important differences could exist between the management of these reported adverse events.”

Based on the findings, gynecologic surgeons “will need to reconsider several important questions regarding the repair of pelvic organ prolapse. For instance, is hysterectomy a necessary component for the repair? What is the role of mesh, and can its use reduce the use of otherwise unnecessary procedures (i.e., hysterectomy) without increasing risk to patients?” she wrote. Other questions center on what constitutes operative failure and how surgeons should augment prolapse repair.

“This study also provides a potential new and well-defined role for the use of mesh in pelvic prolapse surgery, with no significant difference, and perhaps some benefit (i.e., no hysterectomy), compared with a native tissue repair,” Dr. Brincat wrote. “The study also provides useful information for shared decision-making discussions between patients and gynecologic surgeons with respect to selection of procedures and use of mesh for treatment of women with symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse undergoing vaginal surgery.”

The trial was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health. Boston Scientific provided support through an unrestricted grant. One author reported stock ownership in a medical device company, and others reported grants from medical device companies outside the submitted work. Dr. Brincat reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Nager CW et al. JAMA. 2019 Sep 17;322(11):1054-65; Brincat CA. JAMA. 2019 Sep 17;322(11):1047-8.

FROM JAMA

Supporting our gender-diverse patients

CASE Patient has adverse effects from halted estrogen pills

JR twists her hands nervously as you step into the room. “They stopped my hormones,” she sighs as you pull up her lab results.

JR recently had been admitted to an inpatient cardiology unit for several days for a heart failure exacerbation. Her ankles are still swollen beneath her floral print skirt, but she is breathing much easier now. She is back at your primary care office, hoping to get clearance to restart her estrogen pills.

JR reports having mood swings and terrible nightmares while not taking her hormones, which she has been taking for more than 3 years. She hesitates before sharing, “One of the doctors kept asking me questions about my sex life that had nothing to do with my heart condition. I don’t want to go back there.”

Providing compassionate and comprehensive care to gender-nonconforming individuals is challenging for a multitude of reasons, from clinician ignorance to systemic discrimination. About 33% of transgender patients reported being harassed, denied care, or even being assaulted when seeking health care, while 23% reported avoiding going to the doctor altogether when sick or injured out of fear of discrimination.1

Unfortunately, now, further increases to barriers to care may be put in place. In late May of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed new regulations that would reverse previous regulations granted through section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—the Health Care Rights Law—which affirmed the rights of gender nonbinary persons to medical care. Among the proposed changes is the elimination of protections against discrimination in health care based on gender identity.2 The proposed regulation changes come on the heels of a federal court case, which seeks to declare that hospital systems may turn away patients based on gender identity.3

Unraveling rights afforded under the ACA

The Health Care Rights Law was passed under the ACA; it prohibits discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, and disability in health programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. Multiple lower courts have supported that the rights of transgender individuals is included within these protections against discrimination on the basis of sex.4 These court rulings not only have ensured the ability of gender-diverse individuals to access care but also have enforced insurance coverage of therapies for gender dysphoria. It was only in 2014 that Medicaid began providing coverage for gender-affirming surgeries and eliminating language that such procedures were “experimental” or “cosmetic.” The 2016 passage of the ACA mandated that private insurance companies follow suit. Unfortunately, the recent proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law may spark a reversal from insurance companies as well. Such a setback would affect gender-diverse individuals’ hormone treatments as well as their ability to access a full spectrum of care within the health care system.

Continue to: ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices...

ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices

The proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law are from the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division of the HHS Office for Civil Rights, which was established in 2018 and has been advocating for the rights of health care providers to refuse to treat patients based on their own religious beliefs.5 We argue, however, that providing care to persons of varying backgrounds is not an assault on our individual liberties but rather a privilege as providers. As obstetrician-gynecologists, it may be easy to only consider cis-gendered women our responsibility. But our field also emphasizes individual empowerment above all else—we fight every day for our patients’ rights to contraception, fertility, pregnancy, parenthood, and sexual freedoms. Let us continue speaking up for the rights of all those who need gynecologic care, regardless of the pronouns they use.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists urges health care providers to foster nondiscriminatory practices and policies to increase identification and to facilitate quality health care for transgender individuals, both in assisting with the transition if desired as well as providing long-term preventive health care.”6

We urge you to take action

- Reach out to your local representatives about protecting transgender health access

- Educate yourself on the unique needs of transgender individuals

- Read personal accounts

- Share your personal story

- Find referring providers near your practice

- 2015 US Transgender Survey. December 2016. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Musumeci M, Kates J, Dawson J, et al. HHS’ proposed changes to non-discrimination regulations under ACA section 1557. July 1, 2019. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/hhss-proposed-changes-to-non-discrimination-regulations-under-aca-section-1557/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Franciscan Alliance v. Burwell. ACLU website. https://www.aclu.org/cases/franciscan-alliance-v-burwell. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Pear R. Trump plan would cut back health care protections for transgender people. April 21, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/21/us/politics/trump-transgender-health-care.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS announces new conscience and religious freedom division. January 18, 2018. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2018/01/18/hhs-ocr-announces-new-conscience-and-religious-freedom-division.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion no. 512: health care for transgender individuals. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1454–1458.

CASE Patient has adverse effects from halted estrogen pills

JR twists her hands nervously as you step into the room. “They stopped my hormones,” she sighs as you pull up her lab results.

JR recently had been admitted to an inpatient cardiology unit for several days for a heart failure exacerbation. Her ankles are still swollen beneath her floral print skirt, but she is breathing much easier now. She is back at your primary care office, hoping to get clearance to restart her estrogen pills.

JR reports having mood swings and terrible nightmares while not taking her hormones, which she has been taking for more than 3 years. She hesitates before sharing, “One of the doctors kept asking me questions about my sex life that had nothing to do with my heart condition. I don’t want to go back there.”

Providing compassionate and comprehensive care to gender-nonconforming individuals is challenging for a multitude of reasons, from clinician ignorance to systemic discrimination. About 33% of transgender patients reported being harassed, denied care, or even being assaulted when seeking health care, while 23% reported avoiding going to the doctor altogether when sick or injured out of fear of discrimination.1

Unfortunately, now, further increases to barriers to care may be put in place. In late May of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed new regulations that would reverse previous regulations granted through section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—the Health Care Rights Law—which affirmed the rights of gender nonbinary persons to medical care. Among the proposed changes is the elimination of protections against discrimination in health care based on gender identity.2 The proposed regulation changes come on the heels of a federal court case, which seeks to declare that hospital systems may turn away patients based on gender identity.3

Unraveling rights afforded under the ACA

The Health Care Rights Law was passed under the ACA; it prohibits discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, and disability in health programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. Multiple lower courts have supported that the rights of transgender individuals is included within these protections against discrimination on the basis of sex.4 These court rulings not only have ensured the ability of gender-diverse individuals to access care but also have enforced insurance coverage of therapies for gender dysphoria. It was only in 2014 that Medicaid began providing coverage for gender-affirming surgeries and eliminating language that such procedures were “experimental” or “cosmetic.” The 2016 passage of the ACA mandated that private insurance companies follow suit. Unfortunately, the recent proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law may spark a reversal from insurance companies as well. Such a setback would affect gender-diverse individuals’ hormone treatments as well as their ability to access a full spectrum of care within the health care system.

Continue to: ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices...

ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices

The proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law are from the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division of the HHS Office for Civil Rights, which was established in 2018 and has been advocating for the rights of health care providers to refuse to treat patients based on their own religious beliefs.5 We argue, however, that providing care to persons of varying backgrounds is not an assault on our individual liberties but rather a privilege as providers. As obstetrician-gynecologists, it may be easy to only consider cis-gendered women our responsibility. But our field also emphasizes individual empowerment above all else—we fight every day for our patients’ rights to contraception, fertility, pregnancy, parenthood, and sexual freedoms. Let us continue speaking up for the rights of all those who need gynecologic care, regardless of the pronouns they use.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists urges health care providers to foster nondiscriminatory practices and policies to increase identification and to facilitate quality health care for transgender individuals, both in assisting with the transition if desired as well as providing long-term preventive health care.”6

We urge you to take action

- Reach out to your local representatives about protecting transgender health access

- Educate yourself on the unique needs of transgender individuals

- Read personal accounts

- Share your personal story

- Find referring providers near your practice

CASE Patient has adverse effects from halted estrogen pills

JR twists her hands nervously as you step into the room. “They stopped my hormones,” she sighs as you pull up her lab results.

JR recently had been admitted to an inpatient cardiology unit for several days for a heart failure exacerbation. Her ankles are still swollen beneath her floral print skirt, but she is breathing much easier now. She is back at your primary care office, hoping to get clearance to restart her estrogen pills.

JR reports having mood swings and terrible nightmares while not taking her hormones, which she has been taking for more than 3 years. She hesitates before sharing, “One of the doctors kept asking me questions about my sex life that had nothing to do with my heart condition. I don’t want to go back there.”

Providing compassionate and comprehensive care to gender-nonconforming individuals is challenging for a multitude of reasons, from clinician ignorance to systemic discrimination. About 33% of transgender patients reported being harassed, denied care, or even being assaulted when seeking health care, while 23% reported avoiding going to the doctor altogether when sick or injured out of fear of discrimination.1

Unfortunately, now, further increases to barriers to care may be put in place. In late May of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed new regulations that would reverse previous regulations granted through section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—the Health Care Rights Law—which affirmed the rights of gender nonbinary persons to medical care. Among the proposed changes is the elimination of protections against discrimination in health care based on gender identity.2 The proposed regulation changes come on the heels of a federal court case, which seeks to declare that hospital systems may turn away patients based on gender identity.3

Unraveling rights afforded under the ACA

The Health Care Rights Law was passed under the ACA; it prohibits discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, and disability in health programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. Multiple lower courts have supported that the rights of transgender individuals is included within these protections against discrimination on the basis of sex.4 These court rulings not only have ensured the ability of gender-diverse individuals to access care but also have enforced insurance coverage of therapies for gender dysphoria. It was only in 2014 that Medicaid began providing coverage for gender-affirming surgeries and eliminating language that such procedures were “experimental” or “cosmetic.” The 2016 passage of the ACA mandated that private insurance companies follow suit. Unfortunately, the recent proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law may spark a reversal from insurance companies as well. Such a setback would affect gender-diverse individuals’ hormone treatments as well as their ability to access a full spectrum of care within the health care system.

Continue to: ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices...

ACOG urges nondiscriminatory practices

The proposed regulation changes to the Health Care Rights Law are from the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division of the HHS Office for Civil Rights, which was established in 2018 and has been advocating for the rights of health care providers to refuse to treat patients based on their own religious beliefs.5 We argue, however, that providing care to persons of varying backgrounds is not an assault on our individual liberties but rather a privilege as providers. As obstetrician-gynecologists, it may be easy to only consider cis-gendered women our responsibility. But our field also emphasizes individual empowerment above all else—we fight every day for our patients’ rights to contraception, fertility, pregnancy, parenthood, and sexual freedoms. Let us continue speaking up for the rights of all those who need gynecologic care, regardless of the pronouns they use.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists urges health care providers to foster nondiscriminatory practices and policies to increase identification and to facilitate quality health care for transgender individuals, both in assisting with the transition if desired as well as providing long-term preventive health care.”6

We urge you to take action

- Reach out to your local representatives about protecting transgender health access

- Educate yourself on the unique needs of transgender individuals

- Read personal accounts

- Share your personal story

- Find referring providers near your practice

- 2015 US Transgender Survey. December 2016. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Musumeci M, Kates J, Dawson J, et al. HHS’ proposed changes to non-discrimination regulations under ACA section 1557. July 1, 2019. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/hhss-proposed-changes-to-non-discrimination-regulations-under-aca-section-1557/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Franciscan Alliance v. Burwell. ACLU website. https://www.aclu.org/cases/franciscan-alliance-v-burwell. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Pear R. Trump plan would cut back health care protections for transgender people. April 21, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/21/us/politics/trump-transgender-health-care.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS announces new conscience and religious freedom division. January 18, 2018. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2018/01/18/hhs-ocr-announces-new-conscience-and-religious-freedom-division.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion no. 512: health care for transgender individuals. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1454–1458.

- 2015 US Transgender Survey. December 2016. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Musumeci M, Kates J, Dawson J, et al. HHS’ proposed changes to non-discrimination regulations under ACA section 1557. July 1, 2019. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/hhss-proposed-changes-to-non-discrimination-regulations-under-aca-section-1557/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Franciscan Alliance v. Burwell. ACLU website. https://www.aclu.org/cases/franciscan-alliance-v-burwell. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- Pear R. Trump plan would cut back health care protections for transgender people. April 21, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/21/us/politics/trump-transgender-health-care.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS announces new conscience and religious freedom division. January 18, 2018. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2018/01/18/hhs-ocr-announces-new-conscience-and-religious-freedom-division.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion no. 512: health care for transgender individuals. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1454–1458.

Women with epilepsy: 5 clinical pearls for contraception and preconception counseling

In 2015, 1.2% of the US population was estimated to have active epilepsy.1 For neurologists, key goals in the treatment of epilepsy include: controlling seizures, minimizing adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and optimizing quality of life. For obstetrician-gynecologists, women with epilepsy (WWE) have unique contraceptive, preconception, and obstetric needs that require highly specialized approaches to care. Here, I highlight 5 care points that are important to keep in mind when counseling WWE.

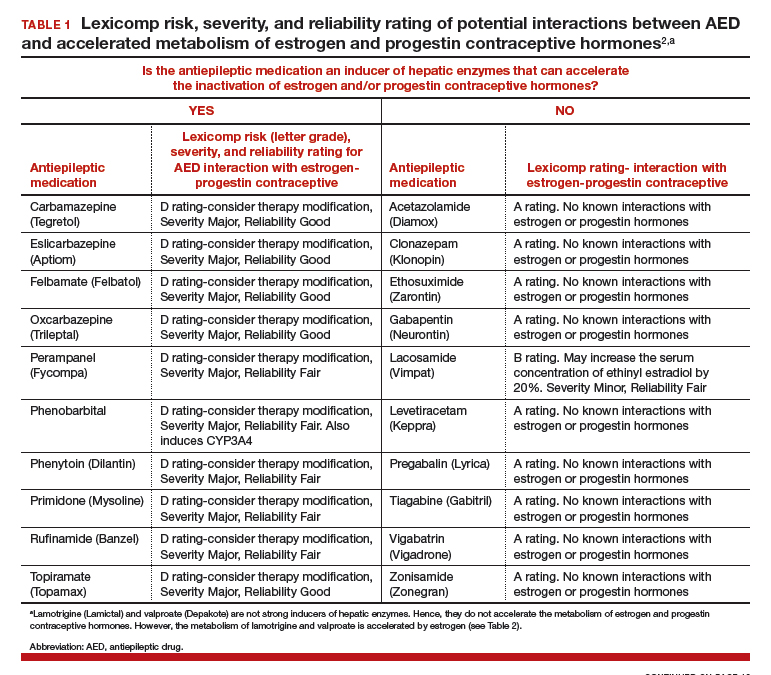

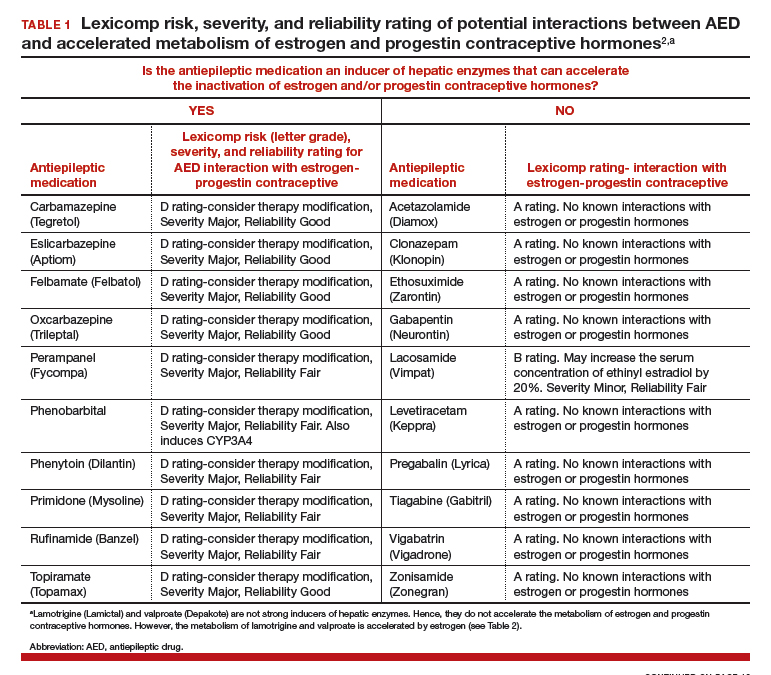

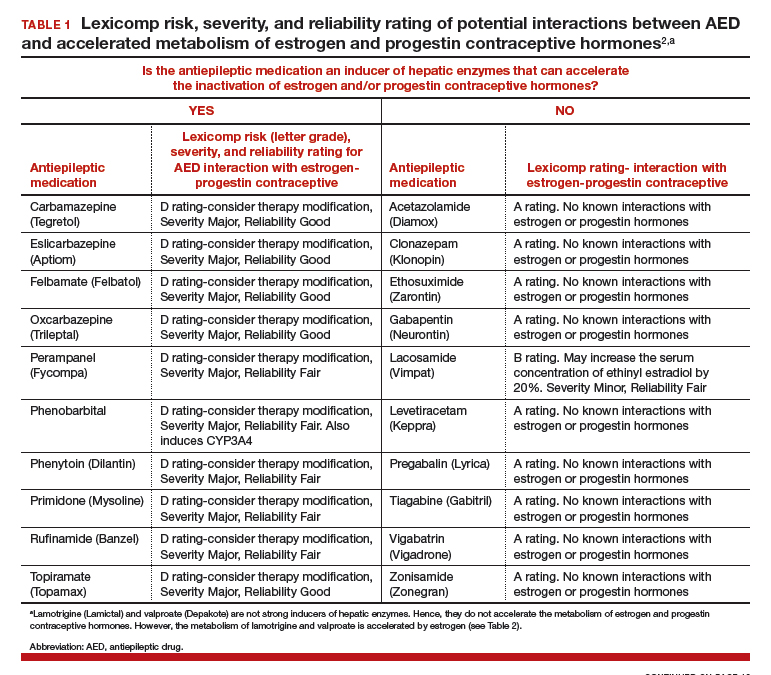

1. Enzyme-inducing AEDs reduce the effectiveness of estrogen-progestin and some progestin contraceptives.

AEDs can induce hepatic enzymes that accelerate steroid hormone metabolism, producing clinically important reductions in bioavailable steroid hormone concentration (TABLE 1). According to Lexicomp, AEDs that are inducers of hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones include: carbamazepine (Tegretol), eslicarbazepine (Aptiom), felbamate (Felbatol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), perampanel (Fycompa), phenobarbital, phenytoin (Dilantin), primidone (Mysoline), rufinamide (Banzel), and topiramate (Topamax) (at dosages >200 mg daily). According to Lexicomp, the following AEDs do not cause clinically significant changes in hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones: acetazolamide (Diamox), clonazepam (Klonopin), ethosuximide (Zarontin), gabapentin (Neurontin), lacosamide (Vimpat), levetiracetam (Keppra), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), vigabatrin (Vigadrone), and zonisamide (Zonegran).2,3 In addition, lamotrigine (Lamictal) and valproate (Depakote) do not significantly influence the metabolism of contraceptive steroids,4,5 but contraceptive steroids significantly influence their metabolism (TABLE 2).

For WWE taking an AED that accelerates steroid hormone metabolism, estrogen-progestin contraceptive failure is common. In a survey of 111 WWE taking both an oral contraceptive and an AED, 27 reported becoming pregnant while taking the oral contraceptive.6 Carbamazepine, a strong inducer of hepatic enzymes, was the most frequently used AED in this sample.

Many studies report that carbamazepine accelerates the metabolisms of estrogen and progestins and reduces contraceptive efficacy. For example, in one study 20 healthy women were administered an ethinyl estradiol (20 µg)-levonorgestrel (100 µg) contraceptive, and randomly assigned to either receive carbamazepine 600 mg daily or a placebo pill.7 In this study, based on serum progesterone measurements, 5 of 10 women in the carbamazepine group ovulated, compared with 1 of 10 women in the placebo group. Women taking carbamazepine had integrated serum ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel concentrations approximately 45% lower than women taking placebo.7 Other studies also report that carbamazepine accelerates steroid hormone metabolism and reduces the circulating concentration of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and levonorgestrel by about 50%.5,8

WWE taking an AED that induces hepatic enzymes should be counseled to use a copper or levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception.9 WWE taking AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes can be offered the full array of contraceptive options, as outlined in Table 1. Occasionally, a WWE taking an AED that is an inducer of hepatic enzymes may strongly prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive and decline the preferred option of using an IUD or DMPA. If an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is to be prescribed, safeguards to reduce the risk of pregnancy include:

- prescribe a contraceptive with ≥35 µg of ethinyl estradiol

- prescribe a contraceptive with the highest dose of progestin with a long half-life (drospirenone, desogestrel, levonorgestrel)

- consider continuous hormonal contraception rather than 4 or 7 days off hormones and

- recommend use of a barrier contraceptive in addition to the hormonal contraceptive.

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel emergency contraception may also be reduced in WWE taking an enzyme-inducing AED. In these cases, some experts recommend a regimen of two doses of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, separated by 12 hours.10 The effectiveness of progestin subdermal contraceptives may be reduced in women taking phenytoin. In one study of 9 WWE using a progestin subdermal implant, phenytoin reduced the circulating levonorgestrel level by approximately 40%.11

Continue to: 2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives...

2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives.

Estrogens, but not progestins, are known to reduce the serum concentration of lamotrigine by about 50%.12,13 This is a clinically significant pharmacologic interaction. Consequently, when a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine, oscillation in lamotrigine serum concentration can occur. When the woman is taking estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels decrease, which increases the risk of seizure. When the woman is not taking the estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels increase, possibly causing such adverse effects as nausea and vomiting. If a woman taking lamotrigine insists on using an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, the medication should be prescribed in a continuous regimen and the neurologist alerted so that they can increase the dose of lamotrigine and intensify their monitoring of lamotrigine levels. Lamotrigine does not change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and has minimal impact on the metabolism of levonorgestrel.4

3. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives require valproate dosage adjustment.

A few studies report that estrogen-progestin contraceptives accelerate the metabolism of valproate and reduce circulating valproate concentration,14,15 as noted in Table 2.In one study, estrogen-progestin contraceptive was associated with 18% and 29% decreases in total and unbound valproate concentrations, respectively.14 Valproate may induce polycystic ovary syndrome in women.16 Therefore, it is common that valproate and an estrogen-progestin contraceptive are co-prescribed. In these situations, the neurologist should be alerted prior to prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to WWE taking valproate so that dosage adjustment may occur, if indicated. Valproate does not appear to change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol or levonorgestrel.5

4. Preconception counseling: Before conception consider using an AED with low teratogenicity.

Valproate is a potent teratogen, and consideration should be given to discontinuing valproate prior to conception. In a study of 1,788 pregnancies exposed to valproate, the risk of a major congenital malformation was 10% for valproate monotherapy, 11.3% for valproate combined with lamotrigine, and 11.7% for valproate combined with another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 At a valproate dose of ≥1,500 mg daily, the risk of major malformation was 24% for valproate monotherapy, 31% for valproate plus lamotrigine, and 19% for valproate plus another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 Valproate is reported to be associated with the following major congenital malformations: spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, pulmonary valve atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, cleft palate, anorectal atresia, and hypospadias.18

In a study of 7,555 pregnancies in women using a single AED, the risk of major congenital anomalies varied greatly among the AEDs, including: valproate (10.3%), phenobarbital (6.5%), phenytoin (6.4%), carbamazepine (5.5%), topiramate (3.9%), oxcarbazepine (3.0%), lamotrigine (2.9%), and levetiracetam (2.8%).19 For WWE considering pregnancy, many experts recommend use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or oxcarbazepine to minimize the risk of fetal anomalies.

Continue to: 5. Folic acid...

5. Folic acid: Although the optimal dose for WWE taking an AED and planning to become pregnant is unknown, a high dose is reasonable.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women planning pregnancy take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least 1 month before pregnancy and continuing through at least the 12th week of gestation.20 ACOG also recommends that women at high risk of a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily. WWE taking a teratogenic AED are known to be at increased risk for fetal malformations, including neural tube defects. Should these women take 4 mg of folic acid daily? ACOG notes that, for women taking valproate, the benefit of high-dose folic acid (4 mg daily) has not been definitively proven,21 and guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend high-dose folic acid for women receiving AEDs.22 Hence, ACOG does not recommend that WWE taking an AED take high-dose folic acid.

By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) recommends that all WWE planning a pregnancy take folic acid 5 mg daily, initiated 3 months before conception and continued through the first trimester of pregnancy.23 The RCOG notes that among WWE taking an AED, intelligence quotient is greater in children whose mothers took folic acid during pregnancy.24 Given the potential benefit of folic acid on long-term outcomes and the known safety of folic acid, it is reasonable to recommend high-dose folic acid for WWE.

Final takeaways

Surveys consistently report that WWE have a low-level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives and the teratogenicity of AEDs. For example, in a survey of 2,000 WWE, 45% who were taking an enzyme-inducing AED and an estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive reported that they had not been warned about the potential interaction between the medications.25 Surprisingly, surveys of neurologists and obstetrician-gynecologists also report that there is a low level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives.26 When providing contraceptive counseling for WWE, prioritize the use of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD. When providing preconception counseling for WWE, educate the patient about the high teratogenicity of valproate and the lower risk of malformations associated with the use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine.

For most women with epilepsy, maintaining a valid driver's license is important for completion of daily life tasks. Most states require that a patient with seizures be seizure-free for 6 to 12 months to operate a motor vehicle. Estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives can reduce the concentration of some AEDs, such as lamotrigine. Hence, it is important that the patient be aware of this interaction and that the primary neurologist be alerted if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine or valproate. Specific state laws related to epilepsy and driving are available at the Epilepsy Foundation website (https://www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws).

- Zack MM, Kobau R. National and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy - United States 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:821-825.

- Lexicomp. https://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/lexicomp-online/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Reimers A, Brodtkorb E, Sabers A. Interactions between hormonal contraception and antiepileptic drugs: clinical and mechanistic considerations. Seizure. 2015;28:66-70.

- Sidhu J, Job S, Singh S, et al. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic consequences of the co-administration of lamotrigine and a combined oral contraceptive in healthy female subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:191-199.

- Crawford P, Chadwick D, Cleland P, et al. The lack of effect of sodium valproate on the pharmacokinetics of oral contraceptive steroids. Contraception. 1986;33:23-29.

- Fairgrieve SD, Jackson M, Jonas P, et al. Population-based, prospective study of the care of women with epilepsy in pregnancy. BMJ. 2000;321:674-675.

- Davis AR, Westhoff CL, Stanczyk FZ. Carbamazepine coadministration with an oral contraceptive: effects on steroid pharmacokinetics, ovulation, and bleeding. Epilepsia. 2011;52:243-247.

- Doose DR, Wang SS, Padmanabhan M, et al. Effect of topiramate or carbamazepine on the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive containing norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol in healthy obese and nonobese female subjects. Epilepsia. 2003;44:540-549.

- Vieira CS, Pack A, Roberts K, et al. A pilot study of levonorgestrel concentrations and bleeding patterns in women with epilepsy using a levonorgestrel IUD and treated with antiepileptic drugs. Contraception. 2019;99:251-255.

- O'Brien MD, Guillebaud J. Contraception for women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1419-1422.

- Haukkamaa M. Contraception by Norplant subdermal capsules is not reliable in epileptic patients on anticonvulsant treatment. Contraception. 1986;33:559-565.

- Sabers A, Buchholt JM, Uldall P, et al. Lamotrigine plasma levels reduced by oral contraceptives. Epilepsy Res. 2001;47:151-154.

- Reimers A, Helde G, Brodtkorb E. Ethinyl estradiol, not progestogens, reduces lamotrigine serum concentrations. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1414-1417.

- Galimberti CA, Mazzucchelli I, Arbasino C, et al. Increased apparent oral clearance of valproic acid during intake of combined contraceptive steroids in women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1569-1572.

- Herzog AG, Farina EL, Blum AS. Serum valproate levels with oral contraceptive use. Epilepsia. 2005;46:970-971.

- Morrell MJ, Hayes FJ, Sluss PM, et al. Hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction, and polycystic ovary syndrome with valproate versus lamotrigine. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:200-211.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Dose-dependent teratogenicity of valproate in mono- and polytherapy: an observational study. Neurology. 2015;85:866-872.

- Blotière PO, Raguideau F, Weill A, et al. Risks of 23 specific malformations associated with prenatal exposure to 10 antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2019;93:e167-e180.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:530-538.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 187: neural tube defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e279-e290.

- Ban L, Fleming KM, Doyle P, et al. Congenital anomalies in children of mothers taking antiepileptic drugs with and without periconceptional high dose folic acid use: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131130.

- Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS, et al; American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy--focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73:142-149.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Epilepsy in pregnancy. Green-top Guideline No. 68; June 2016. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/green-top-guidelines/gtg68_epilepsy.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al; NEAD Study Group. Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:244-252.

- Crawford P, Hudson S. Understanding the information needs of women with epilepsy at different life stages: results of the 'Ideal World' survey. Seizure. 2003;12:502-507.

- Krauss GL, Brandt J, Campbell M, et al. Antiepileptic medication and oral contraceptive interactions: a national survey of neurologists and obstetricians. Neurology. 1996;46:1534-1539.

In 2015, 1.2% of the US population was estimated to have active epilepsy.1 For neurologists, key goals in the treatment of epilepsy include: controlling seizures, minimizing adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and optimizing quality of life. For obstetrician-gynecologists, women with epilepsy (WWE) have unique contraceptive, preconception, and obstetric needs that require highly specialized approaches to care. Here, I highlight 5 care points that are important to keep in mind when counseling WWE.

1. Enzyme-inducing AEDs reduce the effectiveness of estrogen-progestin and some progestin contraceptives.

AEDs can induce hepatic enzymes that accelerate steroid hormone metabolism, producing clinically important reductions in bioavailable steroid hormone concentration (TABLE 1). According to Lexicomp, AEDs that are inducers of hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones include: carbamazepine (Tegretol), eslicarbazepine (Aptiom), felbamate (Felbatol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), perampanel (Fycompa), phenobarbital, phenytoin (Dilantin), primidone (Mysoline), rufinamide (Banzel), and topiramate (Topamax) (at dosages >200 mg daily). According to Lexicomp, the following AEDs do not cause clinically significant changes in hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones: acetazolamide (Diamox), clonazepam (Klonopin), ethosuximide (Zarontin), gabapentin (Neurontin), lacosamide (Vimpat), levetiracetam (Keppra), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), vigabatrin (Vigadrone), and zonisamide (Zonegran).2,3 In addition, lamotrigine (Lamictal) and valproate (Depakote) do not significantly influence the metabolism of contraceptive steroids,4,5 but contraceptive steroids significantly influence their metabolism (TABLE 2).

For WWE taking an AED that accelerates steroid hormone metabolism, estrogen-progestin contraceptive failure is common. In a survey of 111 WWE taking both an oral contraceptive and an AED, 27 reported becoming pregnant while taking the oral contraceptive.6 Carbamazepine, a strong inducer of hepatic enzymes, was the most frequently used AED in this sample.

Many studies report that carbamazepine accelerates the metabolisms of estrogen and progestins and reduces contraceptive efficacy. For example, in one study 20 healthy women were administered an ethinyl estradiol (20 µg)-levonorgestrel (100 µg) contraceptive, and randomly assigned to either receive carbamazepine 600 mg daily or a placebo pill.7 In this study, based on serum progesterone measurements, 5 of 10 women in the carbamazepine group ovulated, compared with 1 of 10 women in the placebo group. Women taking carbamazepine had integrated serum ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel concentrations approximately 45% lower than women taking placebo.7 Other studies also report that carbamazepine accelerates steroid hormone metabolism and reduces the circulating concentration of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and levonorgestrel by about 50%.5,8

WWE taking an AED that induces hepatic enzymes should be counseled to use a copper or levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception.9 WWE taking AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes can be offered the full array of contraceptive options, as outlined in Table 1. Occasionally, a WWE taking an AED that is an inducer of hepatic enzymes may strongly prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive and decline the preferred option of using an IUD or DMPA. If an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is to be prescribed, safeguards to reduce the risk of pregnancy include:

- prescribe a contraceptive with ≥35 µg of ethinyl estradiol

- prescribe a contraceptive with the highest dose of progestin with a long half-life (drospirenone, desogestrel, levonorgestrel)

- consider continuous hormonal contraception rather than 4 or 7 days off hormones and

- recommend use of a barrier contraceptive in addition to the hormonal contraceptive.

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel emergency contraception may also be reduced in WWE taking an enzyme-inducing AED. In these cases, some experts recommend a regimen of two doses of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, separated by 12 hours.10 The effectiveness of progestin subdermal contraceptives may be reduced in women taking phenytoin. In one study of 9 WWE using a progestin subdermal implant, phenytoin reduced the circulating levonorgestrel level by approximately 40%.11

Continue to: 2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives...

2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives.

Estrogens, but not progestins, are known to reduce the serum concentration of lamotrigine by about 50%.12,13 This is a clinically significant pharmacologic interaction. Consequently, when a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine, oscillation in lamotrigine serum concentration can occur. When the woman is taking estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels decrease, which increases the risk of seizure. When the woman is not taking the estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels increase, possibly causing such adverse effects as nausea and vomiting. If a woman taking lamotrigine insists on using an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, the medication should be prescribed in a continuous regimen and the neurologist alerted so that they can increase the dose of lamotrigine and intensify their monitoring of lamotrigine levels. Lamotrigine does not change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and has minimal impact on the metabolism of levonorgestrel.4

3. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives require valproate dosage adjustment.

A few studies report that estrogen-progestin contraceptives accelerate the metabolism of valproate and reduce circulating valproate concentration,14,15 as noted in Table 2.In one study, estrogen-progestin contraceptive was associated with 18% and 29% decreases in total and unbound valproate concentrations, respectively.14 Valproate may induce polycystic ovary syndrome in women.16 Therefore, it is common that valproate and an estrogen-progestin contraceptive are co-prescribed. In these situations, the neurologist should be alerted prior to prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to WWE taking valproate so that dosage adjustment may occur, if indicated. Valproate does not appear to change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol or levonorgestrel.5

4. Preconception counseling: Before conception consider using an AED with low teratogenicity.

Valproate is a potent teratogen, and consideration should be given to discontinuing valproate prior to conception. In a study of 1,788 pregnancies exposed to valproate, the risk of a major congenital malformation was 10% for valproate monotherapy, 11.3% for valproate combined with lamotrigine, and 11.7% for valproate combined with another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 At a valproate dose of ≥1,500 mg daily, the risk of major malformation was 24% for valproate monotherapy, 31% for valproate plus lamotrigine, and 19% for valproate plus another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 Valproate is reported to be associated with the following major congenital malformations: spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, pulmonary valve atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, cleft palate, anorectal atresia, and hypospadias.18

In a study of 7,555 pregnancies in women using a single AED, the risk of major congenital anomalies varied greatly among the AEDs, including: valproate (10.3%), phenobarbital (6.5%), phenytoin (6.4%), carbamazepine (5.5%), topiramate (3.9%), oxcarbazepine (3.0%), lamotrigine (2.9%), and levetiracetam (2.8%).19 For WWE considering pregnancy, many experts recommend use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or oxcarbazepine to minimize the risk of fetal anomalies.

Continue to: 5. Folic acid...

5. Folic acid: Although the optimal dose for WWE taking an AED and planning to become pregnant is unknown, a high dose is reasonable.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women planning pregnancy take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least 1 month before pregnancy and continuing through at least the 12th week of gestation.20 ACOG also recommends that women at high risk of a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily. WWE taking a teratogenic AED are known to be at increased risk for fetal malformations, including neural tube defects. Should these women take 4 mg of folic acid daily? ACOG notes that, for women taking valproate, the benefit of high-dose folic acid (4 mg daily) has not been definitively proven,21 and guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend high-dose folic acid for women receiving AEDs.22 Hence, ACOG does not recommend that WWE taking an AED take high-dose folic acid.

By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) recommends that all WWE planning a pregnancy take folic acid 5 mg daily, initiated 3 months before conception and continued through the first trimester of pregnancy.23 The RCOG notes that among WWE taking an AED, intelligence quotient is greater in children whose mothers took folic acid during pregnancy.24 Given the potential benefit of folic acid on long-term outcomes and the known safety of folic acid, it is reasonable to recommend high-dose folic acid for WWE.

Final takeaways

Surveys consistently report that WWE have a low-level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives and the teratogenicity of AEDs. For example, in a survey of 2,000 WWE, 45% who were taking an enzyme-inducing AED and an estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive reported that they had not been warned about the potential interaction between the medications.25 Surprisingly, surveys of neurologists and obstetrician-gynecologists also report that there is a low level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives.26 When providing contraceptive counseling for WWE, prioritize the use of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD. When providing preconception counseling for WWE, educate the patient about the high teratogenicity of valproate and the lower risk of malformations associated with the use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine.

For most women with epilepsy, maintaining a valid driver's license is important for completion of daily life tasks. Most states require that a patient with seizures be seizure-free for 6 to 12 months to operate a motor vehicle. Estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives can reduce the concentration of some AEDs, such as lamotrigine. Hence, it is important that the patient be aware of this interaction and that the primary neurologist be alerted if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine or valproate. Specific state laws related to epilepsy and driving are available at the Epilepsy Foundation website (https://www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws).

In 2015, 1.2% of the US population was estimated to have active epilepsy.1 For neurologists, key goals in the treatment of epilepsy include: controlling seizures, minimizing adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and optimizing quality of life. For obstetrician-gynecologists, women with epilepsy (WWE) have unique contraceptive, preconception, and obstetric needs that require highly specialized approaches to care. Here, I highlight 5 care points that are important to keep in mind when counseling WWE.

1. Enzyme-inducing AEDs reduce the effectiveness of estrogen-progestin and some progestin contraceptives.

AEDs can induce hepatic enzymes that accelerate steroid hormone metabolism, producing clinically important reductions in bioavailable steroid hormone concentration (TABLE 1). According to Lexicomp, AEDs that are inducers of hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones include: carbamazepine (Tegretol), eslicarbazepine (Aptiom), felbamate (Felbatol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), perampanel (Fycompa), phenobarbital, phenytoin (Dilantin), primidone (Mysoline), rufinamide (Banzel), and topiramate (Topamax) (at dosages >200 mg daily). According to Lexicomp, the following AEDs do not cause clinically significant changes in hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones: acetazolamide (Diamox), clonazepam (Klonopin), ethosuximide (Zarontin), gabapentin (Neurontin), lacosamide (Vimpat), levetiracetam (Keppra), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), vigabatrin (Vigadrone), and zonisamide (Zonegran).2,3 In addition, lamotrigine (Lamictal) and valproate (Depakote) do not significantly influence the metabolism of contraceptive steroids,4,5 but contraceptive steroids significantly influence their metabolism (TABLE 2).

For WWE taking an AED that accelerates steroid hormone metabolism, estrogen-progestin contraceptive failure is common. In a survey of 111 WWE taking both an oral contraceptive and an AED, 27 reported becoming pregnant while taking the oral contraceptive.6 Carbamazepine, a strong inducer of hepatic enzymes, was the most frequently used AED in this sample.

Many studies report that carbamazepine accelerates the metabolisms of estrogen and progestins and reduces contraceptive efficacy. For example, in one study 20 healthy women were administered an ethinyl estradiol (20 µg)-levonorgestrel (100 µg) contraceptive, and randomly assigned to either receive carbamazepine 600 mg daily or a placebo pill.7 In this study, based on serum progesterone measurements, 5 of 10 women in the carbamazepine group ovulated, compared with 1 of 10 women in the placebo group. Women taking carbamazepine had integrated serum ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel concentrations approximately 45% lower than women taking placebo.7 Other studies also report that carbamazepine accelerates steroid hormone metabolism and reduces the circulating concentration of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and levonorgestrel by about 50%.5,8

WWE taking an AED that induces hepatic enzymes should be counseled to use a copper or levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception.9 WWE taking AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes can be offered the full array of contraceptive options, as outlined in Table 1. Occasionally, a WWE taking an AED that is an inducer of hepatic enzymes may strongly prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive and decline the preferred option of using an IUD or DMPA. If an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is to be prescribed, safeguards to reduce the risk of pregnancy include:

- prescribe a contraceptive with ≥35 µg of ethinyl estradiol

- prescribe a contraceptive with the highest dose of progestin with a long half-life (drospirenone, desogestrel, levonorgestrel)

- consider continuous hormonal contraception rather than 4 or 7 days off hormones and

- recommend use of a barrier contraceptive in addition to the hormonal contraceptive.

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel emergency contraception may also be reduced in WWE taking an enzyme-inducing AED. In these cases, some experts recommend a regimen of two doses of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, separated by 12 hours.10 The effectiveness of progestin subdermal contraceptives may be reduced in women taking phenytoin. In one study of 9 WWE using a progestin subdermal implant, phenytoin reduced the circulating levonorgestrel level by approximately 40%.11

Continue to: 2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives...

2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives.

Estrogens, but not progestins, are known to reduce the serum concentration of lamotrigine by about 50%.12,13 This is a clinically significant pharmacologic interaction. Consequently, when a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine, oscillation in lamotrigine serum concentration can occur. When the woman is taking estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels decrease, which increases the risk of seizure. When the woman is not taking the estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels increase, possibly causing such adverse effects as nausea and vomiting. If a woman taking lamotrigine insists on using an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, the medication should be prescribed in a continuous regimen and the neurologist alerted so that they can increase the dose of lamotrigine and intensify their monitoring of lamotrigine levels. Lamotrigine does not change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and has minimal impact on the metabolism of levonorgestrel.4

3. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives require valproate dosage adjustment.

A few studies report that estrogen-progestin contraceptives accelerate the metabolism of valproate and reduce circulating valproate concentration,14,15 as noted in Table 2.In one study, estrogen-progestin contraceptive was associated with 18% and 29% decreases in total and unbound valproate concentrations, respectively.14 Valproate may induce polycystic ovary syndrome in women.16 Therefore, it is common that valproate and an estrogen-progestin contraceptive are co-prescribed. In these situations, the neurologist should be alerted prior to prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to WWE taking valproate so that dosage adjustment may occur, if indicated. Valproate does not appear to change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol or levonorgestrel.5

4. Preconception counseling: Before conception consider using an AED with low teratogenicity.

Valproate is a potent teratogen, and consideration should be given to discontinuing valproate prior to conception. In a study of 1,788 pregnancies exposed to valproate, the risk of a major congenital malformation was 10% for valproate monotherapy, 11.3% for valproate combined with lamotrigine, and 11.7% for valproate combined with another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 At a valproate dose of ≥1,500 mg daily, the risk of major malformation was 24% for valproate monotherapy, 31% for valproate plus lamotrigine, and 19% for valproate plus another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 Valproate is reported to be associated with the following major congenital malformations: spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, pulmonary valve atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, cleft palate, anorectal atresia, and hypospadias.18

In a study of 7,555 pregnancies in women using a single AED, the risk of major congenital anomalies varied greatly among the AEDs, including: valproate (10.3%), phenobarbital (6.5%), phenytoin (6.4%), carbamazepine (5.5%), topiramate (3.9%), oxcarbazepine (3.0%), lamotrigine (2.9%), and levetiracetam (2.8%).19 For WWE considering pregnancy, many experts recommend use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or oxcarbazepine to minimize the risk of fetal anomalies.

Continue to: 5. Folic acid...

5. Folic acid: Although the optimal dose for WWE taking an AED and planning to become pregnant is unknown, a high dose is reasonable.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women planning pregnancy take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least 1 month before pregnancy and continuing through at least the 12th week of gestation.20 ACOG also recommends that women at high risk of a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily. WWE taking a teratogenic AED are known to be at increased risk for fetal malformations, including neural tube defects. Should these women take 4 mg of folic acid daily? ACOG notes that, for women taking valproate, the benefit of high-dose folic acid (4 mg daily) has not been definitively proven,21 and guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend high-dose folic acid for women receiving AEDs.22 Hence, ACOG does not recommend that WWE taking an AED take high-dose folic acid.

By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) recommends that all WWE planning a pregnancy take folic acid 5 mg daily, initiated 3 months before conception and continued through the first trimester of pregnancy.23 The RCOG notes that among WWE taking an AED, intelligence quotient is greater in children whose mothers took folic acid during pregnancy.24 Given the potential benefit of folic acid on long-term outcomes and the known safety of folic acid, it is reasonable to recommend high-dose folic acid for WWE.

Final takeaways

Surveys consistently report that WWE have a low-level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives and the teratogenicity of AEDs. For example, in a survey of 2,000 WWE, 45% who were taking an enzyme-inducing AED and an estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive reported that they had not been warned about the potential interaction between the medications.25 Surprisingly, surveys of neurologists and obstetrician-gynecologists also report that there is a low level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives.26 When providing contraceptive counseling for WWE, prioritize the use of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD. When providing preconception counseling for WWE, educate the patient about the high teratogenicity of valproate and the lower risk of malformations associated with the use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine.

For most women with epilepsy, maintaining a valid driver's license is important for completion of daily life tasks. Most states require that a patient with seizures be seizure-free for 6 to 12 months to operate a motor vehicle. Estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives can reduce the concentration of some AEDs, such as lamotrigine. Hence, it is important that the patient be aware of this interaction and that the primary neurologist be alerted if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine or valproate. Specific state laws related to epilepsy and driving are available at the Epilepsy Foundation website (https://www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws).

- Zack MM, Kobau R. National and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy - United States 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:821-825.

- Lexicomp. https://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/lexicomp-online/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Reimers A, Brodtkorb E, Sabers A. Interactions between hormonal contraception and antiepileptic drugs: clinical and mechanistic considerations. Seizure. 2015;28:66-70.

- Sidhu J, Job S, Singh S, et al. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic consequences of the co-administration of lamotrigine and a combined oral contraceptive in healthy female subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:191-199.