User login

Morcellation use in gynecologic surgery: Current clinical recommendations and cautions

Morcellation of gynecologic surgical specimens became controversial after concerns arose about the potential for inadvertent spread of malignant cells throughout the abdomen and pelvis during tissue morcellation of suspected benign disease. In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warningagainst the use of laparoscopic power morcellation specifically for myomectomy or hysterectomy in the treatment of leiomyomas (fibroids) because of the risk of spreading undiagnosed malignancy throughout the abdomen and pelvis.1 This warning was issued after a high-profile case occurred in Boston in which an occult uterine sarcoma was morcellated during a supracervical robot-assisted hysterectomy for suspected benign fibroids.

Recently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a committee opinion with updated recommendations for practice detailing the risks associated with morcellation and suggestions for patient counseling regarding morcellation.2

In this review, we summarize the techniques and risks of morcellation, the epidemiology of undiagnosed uterine malignancies, practice changes noted at our institution, and clinical recommendations moving forward. A case scenario illustrates keys steps in preoperative evaluation and counseling.

Morcellation uses—and risks

Morcellation is the surgical process of dividing a large tissue specimen into smaller pieces to facilitate their removal through the small incisions made in minimally invasive surgery. Morcellation may be performed with a power instrument or manually.

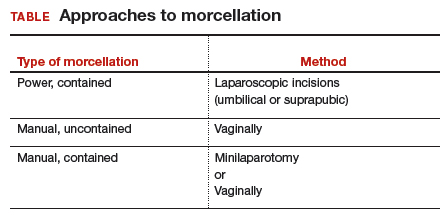

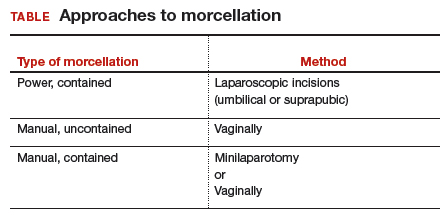

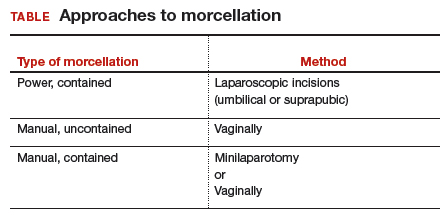

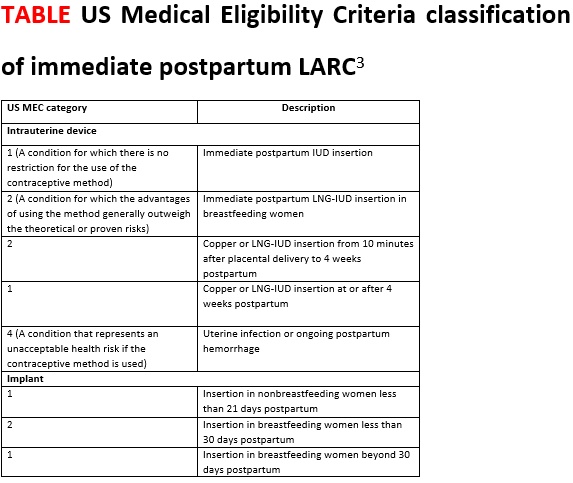

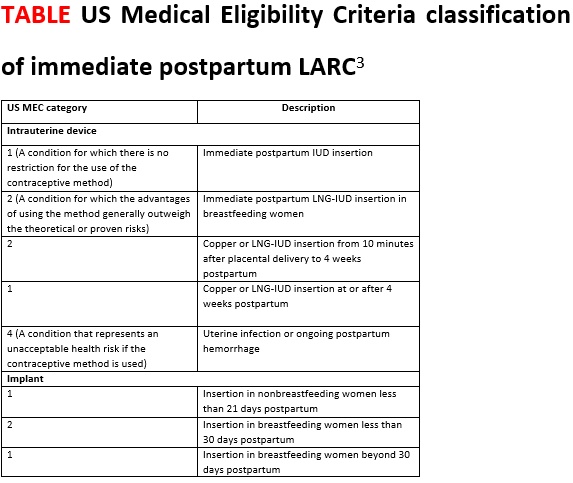

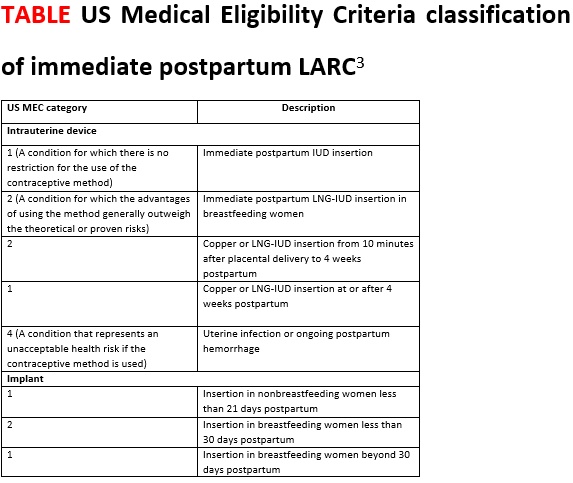

In power morcellation, an electromechanical instrument is used to cut or shave the specimen; in manual morcellation, the surgeon uses a knife to carve the specimen. Power morcellation is performed through a laparoscopic incision, while the manual technique is performed through a minilaparotomy or vaginally after hysterectomy (TABLE). Unlike uncontained morcellation, contained morcellation involves the use of a laparoscopic bag to hold the specimen and therefore prevent tissue dissemination in the abdomen and pelvis.

Morcellation has greatly expanded our ability to perform minimally invasive surgery—for example, in patients with specimens that cannot be extracted en bloc through the vagina after hysterectomy or, in the case of myomectomy or supracervical hysterectomy without a colpotomy, through small laparoscopic ports. Minimally invasive surgery improves patient care, as it is associated with lower rates of infection, blood loss, venous thromboembolism, wound and bowel complications, postoperative pain, and shorter overall recovery time and hospital stay versus traditional open surgery.3,4 Furthermore, laparoscopic hysterectomy has a 3-fold lower risk of mortality compared with open hysterectomy.4 For these reasons, ACOG recommends choosing a minimally invasive approach for all benign hysterectomies whenever feasible.3

With abundant data supporting the use of a minimally invasive approach, laparoscopic morcellation allowed procedures involving larger tissue specimens to be accomplished without the addition of a minilaparotomy for tissue extraction. However, disseminating potentially malignant tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis during the morcellation process remains a risk. While tissue spread can occur with either power or manual morcellation, the case that drew media attention to the controversy used power morcellation, and thus intense scrutiny focused on this technique. Morcellation has additional risks, including direct injury to surrounding organs, disruption of the pathologic specimen, and distribution of benign tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis, such as fibroid, endometriosis, and adenomyosis implants.5-7

Continue to: The challenge of leiomyosarcoma...

The challenge of leiomyosarcoma

The primary controversy surrounding morcellation of fibroid tissue specimens is the potential for undiagnosed malignancy, namely uterine leiomyosarcoma or endometrial stromal sarcoma. While other gynecologic malignancies, including cervical and endometrial cancers, are more common and potentially could be disseminated by morcellation, these cancers are more reliably diagnosed preoperatively with cervical and endometrial biopsies, and they do not tend to mimic benign diseases.

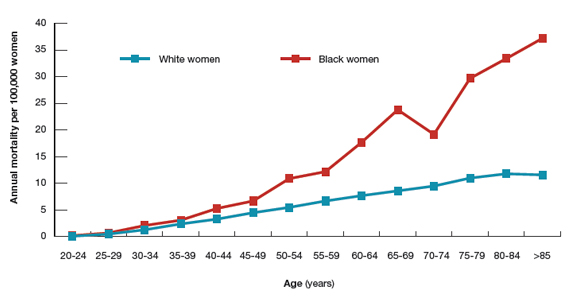

Epidemiology and risk factors. Uterine leiomyosarcoma is rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.36 per 100,000 woman-years.8 However, leiomyosarcoma can mimic the appearance and clinical course of benign fibroids, making preoperative diagnosis difficult. Risk factors for leiomyosarcoma include postmenopausal status, with a median age of 54 years at diagnosis, tamoxifen use longer than 5 years, black race, history of pelvic radiation, and certain hereditary cancer syndromes, such as Lynch syndrome.9-11 Because of these risk factors, preoperative evaluation is crucial to determine the most appropriate surgical method for removal of a large, fibroid uterus (see “Employ shared decision making”).

Estimated incidence at benign hysterectomy. The incidence of leiomyosarcoma diagnosed at the time of benign hysterectomy or myomectomy has been studied extensively since the FDA’s 2014 warning was released, with varying rates identified.11,12 The FDA’s analysis cited a risk of 1 in 498 for unsuspected leiomyosarcoma and 1 in 352 for uterine sarcoma.1 Notably, this analysis excluded studies of women undergoing surgery for presumed fibroids in which no leiomyosarcoma was found on pathology, likely inflating the quoted prevalence. The FDA and other entities subsequently performed further analyses, but a systematic literature review and meta-analysis by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2017 is probably the most accurate. That review included 160 studies and reported a prevalence of less than 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 770, lower than the FDA-cited rate.13

Prognosis. The overall prognosis for women with leiomyosarcoma is poor. Studies indicate a 5-year survival rate of only 55.4%, even in stage 1 disease that is apparently confined to the uterus.9 Although evidence is limited linking morcellation to increased recurrence of leiomyosarcoma, data from small, single-center, retrospective studies cite a worse prognosis, higher risk of recurrence, and shorter progression-free survival after sarcoma morcellation compared with patients who underwent en bloc resection.12,14 Of note, these studies evaluated patients who underwent uncontained morcellation of specimens with unsuspected leiomyosarcoma.

CASE Woman with enlarged, irregular uterus and heavy bleeding

A 40-year-old woman (G2P2) with a history of 2 uncomplicated vaginal deliveries presents for evaluation of heavy uterine bleeding. She has regular periods, every 28 days, and she bleeds for 7 days, saturating 6 pads per day. She is currently taking only oral iron therapy as recommended by her primary care physician. Over the last 1 to 2 years she has felt that her abdomen has been getting larger and that her pants do not fit as well. She is otherwise in excellent health, exercises regularly, and has a full-time job. She has not been sexually active in several months.

The patient’s vitals are within normal limits and her body mass index (BMI) is 35 kg/m2.Pelvic examination reveals that she has an enlarged, irregular uterus with the fundus at the level of the umbilicus. The exam is otherwise unremarkable. On further questioning, the patient does not desire future fertility.

What next steps would you include in this patient’s workup, including imaging studies or lab tests? What surgical options would you give her? How would your management differ if this patient were 70 years old (postmenopausal)?

Continue to: Perform a thorough preoperative evaluation to optimize outcomes...

Perform a thorough preoperative evaluation to optimize outcomes

Women like this case patient who present with symptoms that may lead to treatment with myomectomy or hysterectomy should undergo appropriate preoperative testing to evaluate for malignancy.

According to ACOG guidance, patients should undergo a preoperative endometrial biopsy if they15:

- are older than 45 years with abnormal uterine bleeding

- are younger than 45 years with unopposed estrogen exposure (including obesity or polycystic ovary syndrome)

- have persistent bleeding, or

- failed medical management.

Our case patient is younger than 45 but is obese (BMI, 35) and therefore is a candidate for endometrial biopsy. Additionally, all patients should have up-to-date cervical cancer screening. ACOG also recommends appropriate use of imaging with ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), although imaging is not recommended solely to evaluate for malignancy, as it cannot rule out the diagnosis of many gynecologic malignancies, including leiomyosarcoma.2

Currently, no tests are available to completely exclude a preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. While studies have evaluated the use of MRI combined with lactate dehydrogenase isoenzyme testing, the evidence is weak, and this method is not recommended. Sarcoma is detected by endometrial sampling only 30% to 60% of the time, but it should be performed if the patient meets criteria for sampling or if she has other risk factors for malignancy.16 There are no data to support biopsy of presumed benign fibroids prior to surgical intervention. Patients should be evaluated with a careful history and physical examination for other uterine sarcoma risk factors.

Employ shared decision making

Clinicians should use shared decision making with patients to facilitate decisions on morcellation use in gynecologic surgeries for suspected benign fibroids. Informed consent must be obtained after thorough discussion and counseling regarding the literature on morcellation.17 For all patients, including the case patient described, this discussion should include alternative treatment options, surgical approach with associated risks, the use of morcellation, the incidence of leiomyosarcoma with presumed benign fibroids, leiomyosarcoma prognosis, and the risk of disseminating benign or undiagnosed cancerous tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis.

Some would argue that the risks of laparotomy outweigh the possible risks associated with morcellation during a minimally invasive myomectomy or hysterectomy. However, this risk analysis is not uniform across all patients, and it is likely that in older women, because they have an a priori increased risk of malignancy in general, including leiomyosarcoma, the risks of power morcellation may outweigh the risks of open surgery.18 Younger women have a much lower risk of leiomyosarcoma, and thus discussion and consideration of the patient’s age should be a part of counseling. If the case patient described was 70 years of age, power morcellation might not be recommended, but these decisions require an in-depth discussion with the patient to make an informed decision and ensure patient autonomy.

The contained morcellation approach

Many surgeons who perform minimally invasive procedures use contained morcellation. In this approach, specimens are placed in a containment bag and morcellated with either power instruments or manually to ensure no dissemination of tissue. Manual contained morcellation can be done through a minilaparotomy or the vagina, depending on the procedure performed, while power contained morcellation is performed through a 15-mm laparoscopic incision.

Continue to: Currently, one containment bag has been...

Currently, one containment bag has been FDA approved for use in laparoscopic contained power morcellation.19 Use of a containment bag increases operative time by approximately 20 minutes, due to the additional steps required to accomplish the procedure.20 Its use, however, suggests a decrease in the risk of possible disease spread and it is feasible with appropriate surgeon training.

One study demonstrated the safety and feasibility of power morcellation within an insufflated containment bag, and subsequent follow-up revealed negative intraperitoneal washings.21,22 In another study evaluating tissue dissemination with contained morcellation of tissue stained with dye, the authors noted actual spillage of tissue fragments in only one case.23 Although more information is needed to confirm prevention of tissue dissemination and the safety of contained tissue morcellation, these studies provide promising data supporting the use of tissue morcellation in appropriate cases in order to perform minimally invasive surgery with larger specimens.

CASE Next steps and treatment outcome

The patient has up-to-date and negative cervical cancer screening. The complete blood count is notable for a hemoglobin level of 11.0 g/dL (normal range, 12.1 to 15.1 g/dL). You perform an endometrial biopsy; results are negative for malignancy. You order pelvic ultrasonography to better characterize the location and size of the fibroids. It shows multiple leiomyomas throughout the myometrium, with the 2 largest fibroids (measuring 5 and 7 cm) located in the left anterior and right posterolateral aspects of the uterus, respectively. Several 3- to 4-cm fibroids appear to be disrupting the endometrial canal, and there is no evidence of an endometrial polyp. There do not appear to be any cervical or lower uterine segment fibroids, which may have further complicated the proposed surgery.

You discuss treatment options for abnormal uterine bleeding with the patient, including initiation of combined oral contraceptive pills, placement of a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device, endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolization, and hysterectomy. You discuss the risks and benefits of each approach, keeping in mind the fibroids that are disrupting the contour of the endometrial canal and causing her bulk symptoms.

The patient ultimately decides to undergo a hysterectomy and would like it to be performed with a minimally invasive procedure, if possible. Because of the size of her uterus, you discuss the use of contained power morcellation, including the risks and benefits. You have a thorough discussion about the risk of occult malignancy, although she is at lower risk because of her age, and she consents.

The patient undergoes an uncomplicated total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy. The specimen is removed using contained power morcellation through the umbilical port site. She has an unremarkable immediate postoperative course and is discharged on postoperative Day 1.

You see the patient in the clinic 2 weeks later. She reports minimal pain or discomfort and has no other complaints. Her abdominal incisions are healing well. You review the final pathology report with her, which showed no evidence of malignancy.

Society guidance on clinical applications

In current clinical practice, many surgeons have converted to exclusively performing contained morcellation in appropriate patients with a low risk of uterine leiomyosarcoma. At our institution, uncontained morcellation has not been performed since the FDA’s 2014 warning.

ACOG and AAGL (formerly the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists) recommend use of containment bags as a solution to continue minimally invasive surgery for large specimens without the risk of possible tissue dissemination, although more in-depth surgeon training is likely required for accurate technique.2,24 The Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) states that power morcellation or any other techniques that divide the uterus in the abdomen are contraindicated in patients with documented or highly suspected malignancy.25

With the presented data of risks associated with uncontained morcellation and agreement of the ACOG, AAGL, and SGO professional societies, we recommend that all morcellation be performed in a contained fashion to prevent the dissemination of benign or undiagnosed malignant tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis. Shared decision making and counseling on the risks, benefits, and alternatives are paramount for patients to make informed decisions about their medical care. Continued exploration of techniques and methods for safe tissue extraction is still needed to improve minimally invasive surgical options for all women.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated: Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication. November 24, 2014; updated April 7, 2016. https://wayback.archiveit.org/7993/20170404182209/https:/www.fda.gov /MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm424443.htm. Accessed July 23, 2019.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 770: Uterine morcellation for presumed leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e238-e248.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 701: Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:1149-1150.

4. Wiser A, Holcroft CA, Tolandi T, et al. Abdominal versus laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign diseases: evaluation of morbidity and mortality among 465,798 cases. Gynecol Surg. 2013;10:117-122.

5. Winner B, Biest S. Uterine morcellation: fact and fiction surrounding the recent controversy. Mo Med. 2017;114:176-180.

6. Tulandi T, Leung A, Jan N. Nonmalignant sequelae of unconfined morcellation at laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:331-337.

7. Milad MP, Milad EA. Laparoscopic morcellator-related complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:486-491.

8. Toro JR, Travis LB, Wu HJ, et al. Incidence patterns of soft tissue sarcomas, regardless of primary site, in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program, 1978-2001: an analysis of 26,758 cases. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2922-2930.

9. Seagle BL, Sobecki-Rausch J, Strohl AE, et al. Prognosis and treatment of uterine leiomyosarcoma: a National Cancer Database study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:61-70.

10. Ricci S, Stone RL, Fader AN. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: epidemiology, contemporary treatment strategies and the impact of uterine morcellation. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:208-216.

11. Leibsohn S, d’Ablaing G, Mishell DR Jr, et al. Leiomyosarcoma in a series of hysterectomies performed for presumed uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:968-974. Discussion 974-976.

12. Rowland M, Lesnock J, Edwards R, et al. Occult uterine cancer in patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation [abstract]. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:S29.

13. Hartmann KE, Fonnesbeck C, Surawicz T, et al. Management of uterine fibroids. Comparative effectiveness review no. 195. AHRQ Publication No. 17(18)-EHC028-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/uterine-fibroids /research-2017. Accessed July 23, 2019.

14. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Brown J, et al. Outcome of occult uterine leiomyosarcoma after surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:26-33.

15. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 128: Diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

16. Bansal N, Herzog TJ, Burke W, et al. The utility of preoperative endometrial sampling for the detection of uterine sarcomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Jul;110(1):43–48.

17. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. ACOG committee opinion no. 439: Informed consent. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:401-408.

18. Wright JD, Cui RR, Wang A, et al. Economic and survival implications of use of electric power morcellation for hysterectomy for presumed benign gynecologic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv251.

19. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA allows marketing of first-of-kind tissue containment system for use with certain laparoscopic power morcellators in select patients [press release]. April 7, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents /Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm494650.htm. Accessed July 23, 2019.

20. Winner B, Porter A, Velloze S, et al. S. Uncontained compared with contained power morcellation in total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Oct;126(4):834–8.

21. Cohen SL, Einarsson JI, Wang KC, et al. Contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:491-497.

22. Cohen SL, Greenberg JA, Wang KC, et al. Risk of leakage and tissue dissemination with various contained tissue extraction (CTE) techniques: an in vitro pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:935-939.

23. Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, et al. Contained tissue extraction using power morcellation: prospective evaluation of leakage parameters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):257. e1-257.e6.

24. AAGL. AAGL practice report: morcellation during uterine tissue extraction. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:517-530.

25. Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Position statement: morcellation. 2013. https://www.sgo.org/newsroom /position-statements-2/morcellation/.Accessed July 23, 2019.

Morcellation of gynecologic surgical specimens became controversial after concerns arose about the potential for inadvertent spread of malignant cells throughout the abdomen and pelvis during tissue morcellation of suspected benign disease. In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warningagainst the use of laparoscopic power morcellation specifically for myomectomy or hysterectomy in the treatment of leiomyomas (fibroids) because of the risk of spreading undiagnosed malignancy throughout the abdomen and pelvis.1 This warning was issued after a high-profile case occurred in Boston in which an occult uterine sarcoma was morcellated during a supracervical robot-assisted hysterectomy for suspected benign fibroids.

Recently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a committee opinion with updated recommendations for practice detailing the risks associated with morcellation and suggestions for patient counseling regarding morcellation.2

In this review, we summarize the techniques and risks of morcellation, the epidemiology of undiagnosed uterine malignancies, practice changes noted at our institution, and clinical recommendations moving forward. A case scenario illustrates keys steps in preoperative evaluation and counseling.

Morcellation uses—and risks

Morcellation is the surgical process of dividing a large tissue specimen into smaller pieces to facilitate their removal through the small incisions made in minimally invasive surgery. Morcellation may be performed with a power instrument or manually.

In power morcellation, an electromechanical instrument is used to cut or shave the specimen; in manual morcellation, the surgeon uses a knife to carve the specimen. Power morcellation is performed through a laparoscopic incision, while the manual technique is performed through a minilaparotomy or vaginally after hysterectomy (TABLE). Unlike uncontained morcellation, contained morcellation involves the use of a laparoscopic bag to hold the specimen and therefore prevent tissue dissemination in the abdomen and pelvis.

Morcellation has greatly expanded our ability to perform minimally invasive surgery—for example, in patients with specimens that cannot be extracted en bloc through the vagina after hysterectomy or, in the case of myomectomy or supracervical hysterectomy without a colpotomy, through small laparoscopic ports. Minimally invasive surgery improves patient care, as it is associated with lower rates of infection, blood loss, venous thromboembolism, wound and bowel complications, postoperative pain, and shorter overall recovery time and hospital stay versus traditional open surgery.3,4 Furthermore, laparoscopic hysterectomy has a 3-fold lower risk of mortality compared with open hysterectomy.4 For these reasons, ACOG recommends choosing a minimally invasive approach for all benign hysterectomies whenever feasible.3

With abundant data supporting the use of a minimally invasive approach, laparoscopic morcellation allowed procedures involving larger tissue specimens to be accomplished without the addition of a minilaparotomy for tissue extraction. However, disseminating potentially malignant tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis during the morcellation process remains a risk. While tissue spread can occur with either power or manual morcellation, the case that drew media attention to the controversy used power morcellation, and thus intense scrutiny focused on this technique. Morcellation has additional risks, including direct injury to surrounding organs, disruption of the pathologic specimen, and distribution of benign tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis, such as fibroid, endometriosis, and adenomyosis implants.5-7

Continue to: The challenge of leiomyosarcoma...

The challenge of leiomyosarcoma

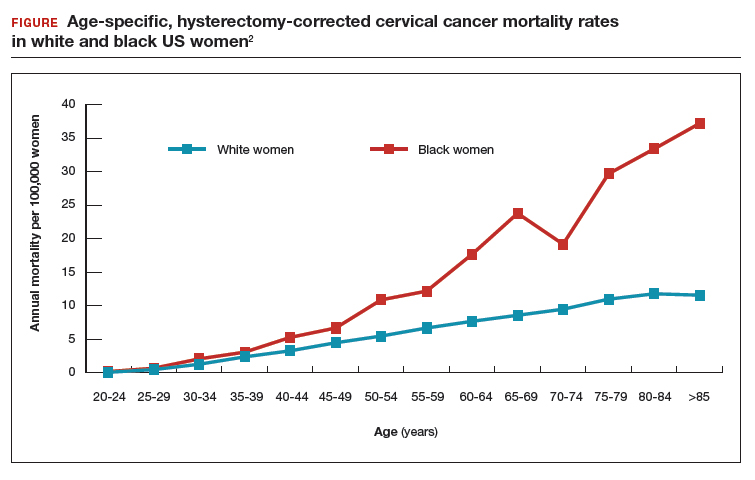

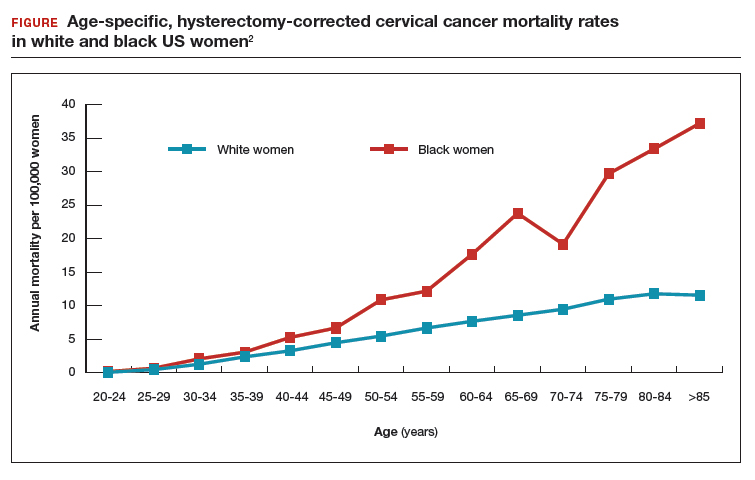

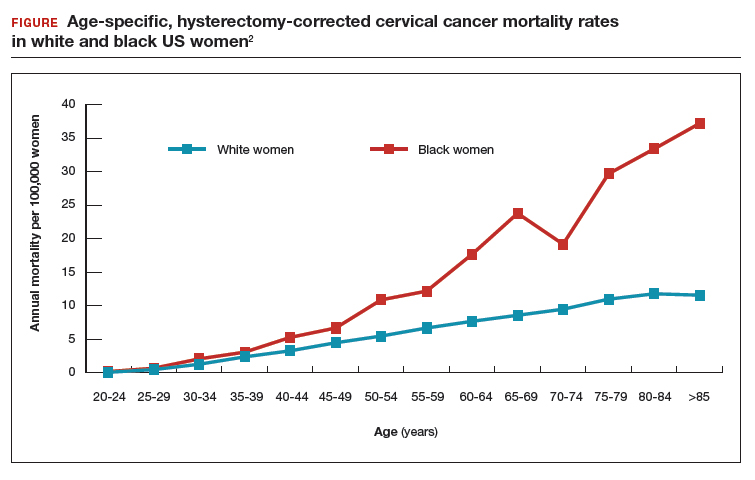

The primary controversy surrounding morcellation of fibroid tissue specimens is the potential for undiagnosed malignancy, namely uterine leiomyosarcoma or endometrial stromal sarcoma. While other gynecologic malignancies, including cervical and endometrial cancers, are more common and potentially could be disseminated by morcellation, these cancers are more reliably diagnosed preoperatively with cervical and endometrial biopsies, and they do not tend to mimic benign diseases.

Epidemiology and risk factors. Uterine leiomyosarcoma is rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.36 per 100,000 woman-years.8 However, leiomyosarcoma can mimic the appearance and clinical course of benign fibroids, making preoperative diagnosis difficult. Risk factors for leiomyosarcoma include postmenopausal status, with a median age of 54 years at diagnosis, tamoxifen use longer than 5 years, black race, history of pelvic radiation, and certain hereditary cancer syndromes, such as Lynch syndrome.9-11 Because of these risk factors, preoperative evaluation is crucial to determine the most appropriate surgical method for removal of a large, fibroid uterus (see “Employ shared decision making”).

Estimated incidence at benign hysterectomy. The incidence of leiomyosarcoma diagnosed at the time of benign hysterectomy or myomectomy has been studied extensively since the FDA’s 2014 warning was released, with varying rates identified.11,12 The FDA’s analysis cited a risk of 1 in 498 for unsuspected leiomyosarcoma and 1 in 352 for uterine sarcoma.1 Notably, this analysis excluded studies of women undergoing surgery for presumed fibroids in which no leiomyosarcoma was found on pathology, likely inflating the quoted prevalence. The FDA and other entities subsequently performed further analyses, but a systematic literature review and meta-analysis by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2017 is probably the most accurate. That review included 160 studies and reported a prevalence of less than 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 770, lower than the FDA-cited rate.13

Prognosis. The overall prognosis for women with leiomyosarcoma is poor. Studies indicate a 5-year survival rate of only 55.4%, even in stage 1 disease that is apparently confined to the uterus.9 Although evidence is limited linking morcellation to increased recurrence of leiomyosarcoma, data from small, single-center, retrospective studies cite a worse prognosis, higher risk of recurrence, and shorter progression-free survival after sarcoma morcellation compared with patients who underwent en bloc resection.12,14 Of note, these studies evaluated patients who underwent uncontained morcellation of specimens with unsuspected leiomyosarcoma.

CASE Woman with enlarged, irregular uterus and heavy bleeding

A 40-year-old woman (G2P2) with a history of 2 uncomplicated vaginal deliveries presents for evaluation of heavy uterine bleeding. She has regular periods, every 28 days, and she bleeds for 7 days, saturating 6 pads per day. She is currently taking only oral iron therapy as recommended by her primary care physician. Over the last 1 to 2 years she has felt that her abdomen has been getting larger and that her pants do not fit as well. She is otherwise in excellent health, exercises regularly, and has a full-time job. She has not been sexually active in several months.

The patient’s vitals are within normal limits and her body mass index (BMI) is 35 kg/m2.Pelvic examination reveals that she has an enlarged, irregular uterus with the fundus at the level of the umbilicus. The exam is otherwise unremarkable. On further questioning, the patient does not desire future fertility.

What next steps would you include in this patient’s workup, including imaging studies or lab tests? What surgical options would you give her? How would your management differ if this patient were 70 years old (postmenopausal)?

Continue to: Perform a thorough preoperative evaluation to optimize outcomes...

Perform a thorough preoperative evaluation to optimize outcomes

Women like this case patient who present with symptoms that may lead to treatment with myomectomy or hysterectomy should undergo appropriate preoperative testing to evaluate for malignancy.

According to ACOG guidance, patients should undergo a preoperative endometrial biopsy if they15:

- are older than 45 years with abnormal uterine bleeding

- are younger than 45 years with unopposed estrogen exposure (including obesity or polycystic ovary syndrome)

- have persistent bleeding, or

- failed medical management.

Our case patient is younger than 45 but is obese (BMI, 35) and therefore is a candidate for endometrial biopsy. Additionally, all patients should have up-to-date cervical cancer screening. ACOG also recommends appropriate use of imaging with ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), although imaging is not recommended solely to evaluate for malignancy, as it cannot rule out the diagnosis of many gynecologic malignancies, including leiomyosarcoma.2

Currently, no tests are available to completely exclude a preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. While studies have evaluated the use of MRI combined with lactate dehydrogenase isoenzyme testing, the evidence is weak, and this method is not recommended. Sarcoma is detected by endometrial sampling only 30% to 60% of the time, but it should be performed if the patient meets criteria for sampling or if she has other risk factors for malignancy.16 There are no data to support biopsy of presumed benign fibroids prior to surgical intervention. Patients should be evaluated with a careful history and physical examination for other uterine sarcoma risk factors.

Employ shared decision making

Clinicians should use shared decision making with patients to facilitate decisions on morcellation use in gynecologic surgeries for suspected benign fibroids. Informed consent must be obtained after thorough discussion and counseling regarding the literature on morcellation.17 For all patients, including the case patient described, this discussion should include alternative treatment options, surgical approach with associated risks, the use of morcellation, the incidence of leiomyosarcoma with presumed benign fibroids, leiomyosarcoma prognosis, and the risk of disseminating benign or undiagnosed cancerous tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis.

Some would argue that the risks of laparotomy outweigh the possible risks associated with morcellation during a minimally invasive myomectomy or hysterectomy. However, this risk analysis is not uniform across all patients, and it is likely that in older women, because they have an a priori increased risk of malignancy in general, including leiomyosarcoma, the risks of power morcellation may outweigh the risks of open surgery.18 Younger women have a much lower risk of leiomyosarcoma, and thus discussion and consideration of the patient’s age should be a part of counseling. If the case patient described was 70 years of age, power morcellation might not be recommended, but these decisions require an in-depth discussion with the patient to make an informed decision and ensure patient autonomy.

The contained morcellation approach

Many surgeons who perform minimally invasive procedures use contained morcellation. In this approach, specimens are placed in a containment bag and morcellated with either power instruments or manually to ensure no dissemination of tissue. Manual contained morcellation can be done through a minilaparotomy or the vagina, depending on the procedure performed, while power contained morcellation is performed through a 15-mm laparoscopic incision.

Continue to: Currently, one containment bag has been...

Currently, one containment bag has been FDA approved for use in laparoscopic contained power morcellation.19 Use of a containment bag increases operative time by approximately 20 minutes, due to the additional steps required to accomplish the procedure.20 Its use, however, suggests a decrease in the risk of possible disease spread and it is feasible with appropriate surgeon training.

One study demonstrated the safety and feasibility of power morcellation within an insufflated containment bag, and subsequent follow-up revealed negative intraperitoneal washings.21,22 In another study evaluating tissue dissemination with contained morcellation of tissue stained with dye, the authors noted actual spillage of tissue fragments in only one case.23 Although more information is needed to confirm prevention of tissue dissemination and the safety of contained tissue morcellation, these studies provide promising data supporting the use of tissue morcellation in appropriate cases in order to perform minimally invasive surgery with larger specimens.

CASE Next steps and treatment outcome

The patient has up-to-date and negative cervical cancer screening. The complete blood count is notable for a hemoglobin level of 11.0 g/dL (normal range, 12.1 to 15.1 g/dL). You perform an endometrial biopsy; results are negative for malignancy. You order pelvic ultrasonography to better characterize the location and size of the fibroids. It shows multiple leiomyomas throughout the myometrium, with the 2 largest fibroids (measuring 5 and 7 cm) located in the left anterior and right posterolateral aspects of the uterus, respectively. Several 3- to 4-cm fibroids appear to be disrupting the endometrial canal, and there is no evidence of an endometrial polyp. There do not appear to be any cervical or lower uterine segment fibroids, which may have further complicated the proposed surgery.

You discuss treatment options for abnormal uterine bleeding with the patient, including initiation of combined oral contraceptive pills, placement of a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device, endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolization, and hysterectomy. You discuss the risks and benefits of each approach, keeping in mind the fibroids that are disrupting the contour of the endometrial canal and causing her bulk symptoms.

The patient ultimately decides to undergo a hysterectomy and would like it to be performed with a minimally invasive procedure, if possible. Because of the size of her uterus, you discuss the use of contained power morcellation, including the risks and benefits. You have a thorough discussion about the risk of occult malignancy, although she is at lower risk because of her age, and she consents.

The patient undergoes an uncomplicated total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy. The specimen is removed using contained power morcellation through the umbilical port site. She has an unremarkable immediate postoperative course and is discharged on postoperative Day 1.

You see the patient in the clinic 2 weeks later. She reports minimal pain or discomfort and has no other complaints. Her abdominal incisions are healing well. You review the final pathology report with her, which showed no evidence of malignancy.

Society guidance on clinical applications

In current clinical practice, many surgeons have converted to exclusively performing contained morcellation in appropriate patients with a low risk of uterine leiomyosarcoma. At our institution, uncontained morcellation has not been performed since the FDA’s 2014 warning.

ACOG and AAGL (formerly the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists) recommend use of containment bags as a solution to continue minimally invasive surgery for large specimens without the risk of possible tissue dissemination, although more in-depth surgeon training is likely required for accurate technique.2,24 The Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) states that power morcellation or any other techniques that divide the uterus in the abdomen are contraindicated in patients with documented or highly suspected malignancy.25

With the presented data of risks associated with uncontained morcellation and agreement of the ACOG, AAGL, and SGO professional societies, we recommend that all morcellation be performed in a contained fashion to prevent the dissemination of benign or undiagnosed malignant tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis. Shared decision making and counseling on the risks, benefits, and alternatives are paramount for patients to make informed decisions about their medical care. Continued exploration of techniques and methods for safe tissue extraction is still needed to improve minimally invasive surgical options for all women.

Morcellation of gynecologic surgical specimens became controversial after concerns arose about the potential for inadvertent spread of malignant cells throughout the abdomen and pelvis during tissue morcellation of suspected benign disease. In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warningagainst the use of laparoscopic power morcellation specifically for myomectomy or hysterectomy in the treatment of leiomyomas (fibroids) because of the risk of spreading undiagnosed malignancy throughout the abdomen and pelvis.1 This warning was issued after a high-profile case occurred in Boston in which an occult uterine sarcoma was morcellated during a supracervical robot-assisted hysterectomy for suspected benign fibroids.

Recently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a committee opinion with updated recommendations for practice detailing the risks associated with morcellation and suggestions for patient counseling regarding morcellation.2

In this review, we summarize the techniques and risks of morcellation, the epidemiology of undiagnosed uterine malignancies, practice changes noted at our institution, and clinical recommendations moving forward. A case scenario illustrates keys steps in preoperative evaluation and counseling.

Morcellation uses—and risks

Morcellation is the surgical process of dividing a large tissue specimen into smaller pieces to facilitate their removal through the small incisions made in minimally invasive surgery. Morcellation may be performed with a power instrument or manually.

In power morcellation, an electromechanical instrument is used to cut or shave the specimen; in manual morcellation, the surgeon uses a knife to carve the specimen. Power morcellation is performed through a laparoscopic incision, while the manual technique is performed through a minilaparotomy or vaginally after hysterectomy (TABLE). Unlike uncontained morcellation, contained morcellation involves the use of a laparoscopic bag to hold the specimen and therefore prevent tissue dissemination in the abdomen and pelvis.

Morcellation has greatly expanded our ability to perform minimally invasive surgery—for example, in patients with specimens that cannot be extracted en bloc through the vagina after hysterectomy or, in the case of myomectomy or supracervical hysterectomy without a colpotomy, through small laparoscopic ports. Minimally invasive surgery improves patient care, as it is associated with lower rates of infection, blood loss, venous thromboembolism, wound and bowel complications, postoperative pain, and shorter overall recovery time and hospital stay versus traditional open surgery.3,4 Furthermore, laparoscopic hysterectomy has a 3-fold lower risk of mortality compared with open hysterectomy.4 For these reasons, ACOG recommends choosing a minimally invasive approach for all benign hysterectomies whenever feasible.3

With abundant data supporting the use of a minimally invasive approach, laparoscopic morcellation allowed procedures involving larger tissue specimens to be accomplished without the addition of a minilaparotomy for tissue extraction. However, disseminating potentially malignant tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis during the morcellation process remains a risk. While tissue spread can occur with either power or manual morcellation, the case that drew media attention to the controversy used power morcellation, and thus intense scrutiny focused on this technique. Morcellation has additional risks, including direct injury to surrounding organs, disruption of the pathologic specimen, and distribution of benign tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis, such as fibroid, endometriosis, and adenomyosis implants.5-7

Continue to: The challenge of leiomyosarcoma...

The challenge of leiomyosarcoma

The primary controversy surrounding morcellation of fibroid tissue specimens is the potential for undiagnosed malignancy, namely uterine leiomyosarcoma or endometrial stromal sarcoma. While other gynecologic malignancies, including cervical and endometrial cancers, are more common and potentially could be disseminated by morcellation, these cancers are more reliably diagnosed preoperatively with cervical and endometrial biopsies, and they do not tend to mimic benign diseases.

Epidemiology and risk factors. Uterine leiomyosarcoma is rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.36 per 100,000 woman-years.8 However, leiomyosarcoma can mimic the appearance and clinical course of benign fibroids, making preoperative diagnosis difficult. Risk factors for leiomyosarcoma include postmenopausal status, with a median age of 54 years at diagnosis, tamoxifen use longer than 5 years, black race, history of pelvic radiation, and certain hereditary cancer syndromes, such as Lynch syndrome.9-11 Because of these risk factors, preoperative evaluation is crucial to determine the most appropriate surgical method for removal of a large, fibroid uterus (see “Employ shared decision making”).

Estimated incidence at benign hysterectomy. The incidence of leiomyosarcoma diagnosed at the time of benign hysterectomy or myomectomy has been studied extensively since the FDA’s 2014 warning was released, with varying rates identified.11,12 The FDA’s analysis cited a risk of 1 in 498 for unsuspected leiomyosarcoma and 1 in 352 for uterine sarcoma.1 Notably, this analysis excluded studies of women undergoing surgery for presumed fibroids in which no leiomyosarcoma was found on pathology, likely inflating the quoted prevalence. The FDA and other entities subsequently performed further analyses, but a systematic literature review and meta-analysis by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2017 is probably the most accurate. That review included 160 studies and reported a prevalence of less than 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 770, lower than the FDA-cited rate.13

Prognosis. The overall prognosis for women with leiomyosarcoma is poor. Studies indicate a 5-year survival rate of only 55.4%, even in stage 1 disease that is apparently confined to the uterus.9 Although evidence is limited linking morcellation to increased recurrence of leiomyosarcoma, data from small, single-center, retrospective studies cite a worse prognosis, higher risk of recurrence, and shorter progression-free survival after sarcoma morcellation compared with patients who underwent en bloc resection.12,14 Of note, these studies evaluated patients who underwent uncontained morcellation of specimens with unsuspected leiomyosarcoma.

CASE Woman with enlarged, irregular uterus and heavy bleeding

A 40-year-old woman (G2P2) with a history of 2 uncomplicated vaginal deliveries presents for evaluation of heavy uterine bleeding. She has regular periods, every 28 days, and she bleeds for 7 days, saturating 6 pads per day. She is currently taking only oral iron therapy as recommended by her primary care physician. Over the last 1 to 2 years she has felt that her abdomen has been getting larger and that her pants do not fit as well. She is otherwise in excellent health, exercises regularly, and has a full-time job. She has not been sexually active in several months.

The patient’s vitals are within normal limits and her body mass index (BMI) is 35 kg/m2.Pelvic examination reveals that she has an enlarged, irregular uterus with the fundus at the level of the umbilicus. The exam is otherwise unremarkable. On further questioning, the patient does not desire future fertility.

What next steps would you include in this patient’s workup, including imaging studies or lab tests? What surgical options would you give her? How would your management differ if this patient were 70 years old (postmenopausal)?

Continue to: Perform a thorough preoperative evaluation to optimize outcomes...

Perform a thorough preoperative evaluation to optimize outcomes

Women like this case patient who present with symptoms that may lead to treatment with myomectomy or hysterectomy should undergo appropriate preoperative testing to evaluate for malignancy.

According to ACOG guidance, patients should undergo a preoperative endometrial biopsy if they15:

- are older than 45 years with abnormal uterine bleeding

- are younger than 45 years with unopposed estrogen exposure (including obesity or polycystic ovary syndrome)

- have persistent bleeding, or

- failed medical management.

Our case patient is younger than 45 but is obese (BMI, 35) and therefore is a candidate for endometrial biopsy. Additionally, all patients should have up-to-date cervical cancer screening. ACOG also recommends appropriate use of imaging with ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), although imaging is not recommended solely to evaluate for malignancy, as it cannot rule out the diagnosis of many gynecologic malignancies, including leiomyosarcoma.2

Currently, no tests are available to completely exclude a preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. While studies have evaluated the use of MRI combined with lactate dehydrogenase isoenzyme testing, the evidence is weak, and this method is not recommended. Sarcoma is detected by endometrial sampling only 30% to 60% of the time, but it should be performed if the patient meets criteria for sampling or if she has other risk factors for malignancy.16 There are no data to support biopsy of presumed benign fibroids prior to surgical intervention. Patients should be evaluated with a careful history and physical examination for other uterine sarcoma risk factors.

Employ shared decision making

Clinicians should use shared decision making with patients to facilitate decisions on morcellation use in gynecologic surgeries for suspected benign fibroids. Informed consent must be obtained after thorough discussion and counseling regarding the literature on morcellation.17 For all patients, including the case patient described, this discussion should include alternative treatment options, surgical approach with associated risks, the use of morcellation, the incidence of leiomyosarcoma with presumed benign fibroids, leiomyosarcoma prognosis, and the risk of disseminating benign or undiagnosed cancerous tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis.

Some would argue that the risks of laparotomy outweigh the possible risks associated with morcellation during a minimally invasive myomectomy or hysterectomy. However, this risk analysis is not uniform across all patients, and it is likely that in older women, because they have an a priori increased risk of malignancy in general, including leiomyosarcoma, the risks of power morcellation may outweigh the risks of open surgery.18 Younger women have a much lower risk of leiomyosarcoma, and thus discussion and consideration of the patient’s age should be a part of counseling. If the case patient described was 70 years of age, power morcellation might not be recommended, but these decisions require an in-depth discussion with the patient to make an informed decision and ensure patient autonomy.

The contained morcellation approach

Many surgeons who perform minimally invasive procedures use contained morcellation. In this approach, specimens are placed in a containment bag and morcellated with either power instruments or manually to ensure no dissemination of tissue. Manual contained morcellation can be done through a minilaparotomy or the vagina, depending on the procedure performed, while power contained morcellation is performed through a 15-mm laparoscopic incision.

Continue to: Currently, one containment bag has been...

Currently, one containment bag has been FDA approved for use in laparoscopic contained power morcellation.19 Use of a containment bag increases operative time by approximately 20 minutes, due to the additional steps required to accomplish the procedure.20 Its use, however, suggests a decrease in the risk of possible disease spread and it is feasible with appropriate surgeon training.

One study demonstrated the safety and feasibility of power morcellation within an insufflated containment bag, and subsequent follow-up revealed negative intraperitoneal washings.21,22 In another study evaluating tissue dissemination with contained morcellation of tissue stained with dye, the authors noted actual spillage of tissue fragments in only one case.23 Although more information is needed to confirm prevention of tissue dissemination and the safety of contained tissue morcellation, these studies provide promising data supporting the use of tissue morcellation in appropriate cases in order to perform minimally invasive surgery with larger specimens.

CASE Next steps and treatment outcome

The patient has up-to-date and negative cervical cancer screening. The complete blood count is notable for a hemoglobin level of 11.0 g/dL (normal range, 12.1 to 15.1 g/dL). You perform an endometrial biopsy; results are negative for malignancy. You order pelvic ultrasonography to better characterize the location and size of the fibroids. It shows multiple leiomyomas throughout the myometrium, with the 2 largest fibroids (measuring 5 and 7 cm) located in the left anterior and right posterolateral aspects of the uterus, respectively. Several 3- to 4-cm fibroids appear to be disrupting the endometrial canal, and there is no evidence of an endometrial polyp. There do not appear to be any cervical or lower uterine segment fibroids, which may have further complicated the proposed surgery.

You discuss treatment options for abnormal uterine bleeding with the patient, including initiation of combined oral contraceptive pills, placement of a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device, endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolization, and hysterectomy. You discuss the risks and benefits of each approach, keeping in mind the fibroids that are disrupting the contour of the endometrial canal and causing her bulk symptoms.

The patient ultimately decides to undergo a hysterectomy and would like it to be performed with a minimally invasive procedure, if possible. Because of the size of her uterus, you discuss the use of contained power morcellation, including the risks and benefits. You have a thorough discussion about the risk of occult malignancy, although she is at lower risk because of her age, and she consents.

The patient undergoes an uncomplicated total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy. The specimen is removed using contained power morcellation through the umbilical port site. She has an unremarkable immediate postoperative course and is discharged on postoperative Day 1.

You see the patient in the clinic 2 weeks later. She reports minimal pain or discomfort and has no other complaints. Her abdominal incisions are healing well. You review the final pathology report with her, which showed no evidence of malignancy.

Society guidance on clinical applications

In current clinical practice, many surgeons have converted to exclusively performing contained morcellation in appropriate patients with a low risk of uterine leiomyosarcoma. At our institution, uncontained morcellation has not been performed since the FDA’s 2014 warning.

ACOG and AAGL (formerly the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists) recommend use of containment bags as a solution to continue minimally invasive surgery for large specimens without the risk of possible tissue dissemination, although more in-depth surgeon training is likely required for accurate technique.2,24 The Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) states that power morcellation or any other techniques that divide the uterus in the abdomen are contraindicated in patients with documented or highly suspected malignancy.25

With the presented data of risks associated with uncontained morcellation and agreement of the ACOG, AAGL, and SGO professional societies, we recommend that all morcellation be performed in a contained fashion to prevent the dissemination of benign or undiagnosed malignant tissue throughout the abdomen and pelvis. Shared decision making and counseling on the risks, benefits, and alternatives are paramount for patients to make informed decisions about their medical care. Continued exploration of techniques and methods for safe tissue extraction is still needed to improve minimally invasive surgical options for all women.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated: Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication. November 24, 2014; updated April 7, 2016. https://wayback.archiveit.org/7993/20170404182209/https:/www.fda.gov /MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm424443.htm. Accessed July 23, 2019.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 770: Uterine morcellation for presumed leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e238-e248.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 701: Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:1149-1150.

4. Wiser A, Holcroft CA, Tolandi T, et al. Abdominal versus laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign diseases: evaluation of morbidity and mortality among 465,798 cases. Gynecol Surg. 2013;10:117-122.

5. Winner B, Biest S. Uterine morcellation: fact and fiction surrounding the recent controversy. Mo Med. 2017;114:176-180.

6. Tulandi T, Leung A, Jan N. Nonmalignant sequelae of unconfined morcellation at laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:331-337.

7. Milad MP, Milad EA. Laparoscopic morcellator-related complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:486-491.

8. Toro JR, Travis LB, Wu HJ, et al. Incidence patterns of soft tissue sarcomas, regardless of primary site, in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program, 1978-2001: an analysis of 26,758 cases. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2922-2930.

9. Seagle BL, Sobecki-Rausch J, Strohl AE, et al. Prognosis and treatment of uterine leiomyosarcoma: a National Cancer Database study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:61-70.

10. Ricci S, Stone RL, Fader AN. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: epidemiology, contemporary treatment strategies and the impact of uterine morcellation. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:208-216.

11. Leibsohn S, d’Ablaing G, Mishell DR Jr, et al. Leiomyosarcoma in a series of hysterectomies performed for presumed uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:968-974. Discussion 974-976.

12. Rowland M, Lesnock J, Edwards R, et al. Occult uterine cancer in patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation [abstract]. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:S29.

13. Hartmann KE, Fonnesbeck C, Surawicz T, et al. Management of uterine fibroids. Comparative effectiveness review no. 195. AHRQ Publication No. 17(18)-EHC028-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/uterine-fibroids /research-2017. Accessed July 23, 2019.

14. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Brown J, et al. Outcome of occult uterine leiomyosarcoma after surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:26-33.

15. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 128: Diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

16. Bansal N, Herzog TJ, Burke W, et al. The utility of preoperative endometrial sampling for the detection of uterine sarcomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Jul;110(1):43–48.

17. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. ACOG committee opinion no. 439: Informed consent. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:401-408.

18. Wright JD, Cui RR, Wang A, et al. Economic and survival implications of use of electric power morcellation for hysterectomy for presumed benign gynecologic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv251.

19. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA allows marketing of first-of-kind tissue containment system for use with certain laparoscopic power morcellators in select patients [press release]. April 7, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents /Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm494650.htm. Accessed July 23, 2019.

20. Winner B, Porter A, Velloze S, et al. S. Uncontained compared with contained power morcellation in total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Oct;126(4):834–8.

21. Cohen SL, Einarsson JI, Wang KC, et al. Contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:491-497.

22. Cohen SL, Greenberg JA, Wang KC, et al. Risk of leakage and tissue dissemination with various contained tissue extraction (CTE) techniques: an in vitro pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:935-939.

23. Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, et al. Contained tissue extraction using power morcellation: prospective evaluation of leakage parameters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):257. e1-257.e6.

24. AAGL. AAGL practice report: morcellation during uterine tissue extraction. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:517-530.

25. Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Position statement: morcellation. 2013. https://www.sgo.org/newsroom /position-statements-2/morcellation/.Accessed July 23, 2019.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated: Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication. November 24, 2014; updated April 7, 2016. https://wayback.archiveit.org/7993/20170404182209/https:/www.fda.gov /MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm424443.htm. Accessed July 23, 2019.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 770: Uterine morcellation for presumed leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e238-e248.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 701: Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:1149-1150.

4. Wiser A, Holcroft CA, Tolandi T, et al. Abdominal versus laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign diseases: evaluation of morbidity and mortality among 465,798 cases. Gynecol Surg. 2013;10:117-122.

5. Winner B, Biest S. Uterine morcellation: fact and fiction surrounding the recent controversy. Mo Med. 2017;114:176-180.

6. Tulandi T, Leung A, Jan N. Nonmalignant sequelae of unconfined morcellation at laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:331-337.

7. Milad MP, Milad EA. Laparoscopic morcellator-related complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:486-491.

8. Toro JR, Travis LB, Wu HJ, et al. Incidence patterns of soft tissue sarcomas, regardless of primary site, in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program, 1978-2001: an analysis of 26,758 cases. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2922-2930.

9. Seagle BL, Sobecki-Rausch J, Strohl AE, et al. Prognosis and treatment of uterine leiomyosarcoma: a National Cancer Database study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:61-70.

10. Ricci S, Stone RL, Fader AN. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: epidemiology, contemporary treatment strategies and the impact of uterine morcellation. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:208-216.

11. Leibsohn S, d’Ablaing G, Mishell DR Jr, et al. Leiomyosarcoma in a series of hysterectomies performed for presumed uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:968-974. Discussion 974-976.

12. Rowland M, Lesnock J, Edwards R, et al. Occult uterine cancer in patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation [abstract]. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:S29.

13. Hartmann KE, Fonnesbeck C, Surawicz T, et al. Management of uterine fibroids. Comparative effectiveness review no. 195. AHRQ Publication No. 17(18)-EHC028-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/uterine-fibroids /research-2017. Accessed July 23, 2019.

14. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Brown J, et al. Outcome of occult uterine leiomyosarcoma after surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:26-33.

15. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 128: Diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

16. Bansal N, Herzog TJ, Burke W, et al. The utility of preoperative endometrial sampling for the detection of uterine sarcomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Jul;110(1):43–48.

17. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. ACOG committee opinion no. 439: Informed consent. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:401-408.

18. Wright JD, Cui RR, Wang A, et al. Economic and survival implications of use of electric power morcellation for hysterectomy for presumed benign gynecologic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv251.

19. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA allows marketing of first-of-kind tissue containment system for use with certain laparoscopic power morcellators in select patients [press release]. April 7, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents /Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm494650.htm. Accessed July 23, 2019.

20. Winner B, Porter A, Velloze S, et al. S. Uncontained compared with contained power morcellation in total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Oct;126(4):834–8.

21. Cohen SL, Einarsson JI, Wang KC, et al. Contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:491-497.

22. Cohen SL, Greenberg JA, Wang KC, et al. Risk of leakage and tissue dissemination with various contained tissue extraction (CTE) techniques: an in vitro pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:935-939.

23. Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, et al. Contained tissue extraction using power morcellation: prospective evaluation of leakage parameters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):257. e1-257.e6.

24. AAGL. AAGL practice report: morcellation during uterine tissue extraction. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:517-530.

25. Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Position statement: morcellation. 2013. https://www.sgo.org/newsroom /position-statements-2/morcellation/.Accessed July 23, 2019.

Hormone therapy and cognition: What is best for the midlife brain?

CASE HT for vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal woman with cognitive concerns

Jackie is a 49-year-old woman. Her body mass index is 33 kg/m2, and she has mild hypertension that is effectively controlled with antihypertensive medications. Otherwise, she is in good health.During her annual gynecologic exam, she reports that for the past 9 months her menstrual cycles have not been as regular as they used to be and that 3 months ago she skipped a cycle. She is having bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and is concerned about her memory. She says she is forgetful at work and in social situations. During a recent presentation, she could not remember the name of one of her former clients. At a work happy hour, she forgot the name of her coworker’s husband, although she did remember it later after returning home.

Her mother has Alzheimer disease (AD), and Jackie worries about whether she, too, might be developing dementia and whether her memory will fail her in social situations.

She is concerned about using hormone therapy (HT) for her vasomotor symptoms because she has heard that it can lead to breast cancer and/or AD.

How would you advise her?

HT remains the most effective treatment for bothersome VMS, but concerns about its cognitive safety persist. Such concerns, and indeed a black-box warning about the risk of dementia with HT use, initially arose following the 2003 publication of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of HT for the primary prevention of dementia in women aged 65 years and older at baseline.1 The study found that combination estrogen/progestin therapy was associated with a 2-fold increase in dementia when compared with placebo.

One of the critical questions arising even before WHIMS was whether the cognitive risks associated with HT that were seen in WHIMS apply to younger women. Attempting to answer the question and adding fuel to the fire are the results of a recent case-control study from Finland.2 This study compared HT use in Finnish women with and without AD and found that HT use was higher among Finnish women with AD compared with those without AD, regardless of age. The authors concluded, “Our data must be implemented into information for the present and future users of HT, even though the absolute risk increase is small.”

However, given the limitations inherent to observational and registry studies, and the contrasting findings of 3 high-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs; more details below), providers actually can reassure younger peri- and postmenopausal women about the cognitive safety of HT.3 They also can explain to patients that cognitive symptoms like the ones described in the case example are normal and provide general guidance to midlife women on how to optimize brain health.

Continue to: Closer look at WHI and RCT research pinpoints cognitively neutral HT...

Closer look at WHI and RCT research pinpoints cognitively neutral HT

In WHIMS, the combination of conjugated equine estrogen (CEE; 0.625 mg/d) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; 2.5 mg/d) led to a doubling of the risk of all-cause dementia compared with placebo in a sample of 4,532 women aged 65 years and older at baseline.1 CEE alone (0.625 mg) did not lead to an increased risk of all-cause dementia.4

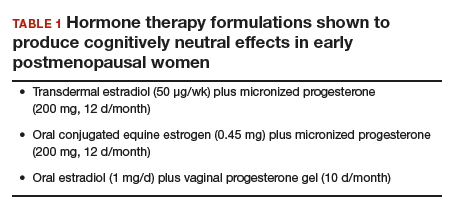

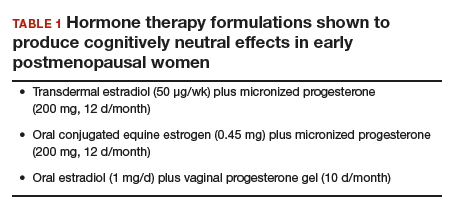

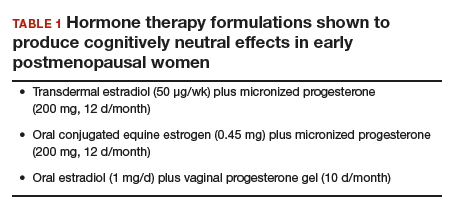

Whether those formulations led to cognitive impairment in younger postmenopausal women was the focus of WHIMS-Younger (WHIMS-Y), which involved WHI participants aged 50 to 55 years at baseline.5 Results revealed neutral cognitive effects (ie, no differences in cognitive performance in women randomly assigned to HT or placebo) in women tested 7.2 years after the end of the WHI trial. WHIMS-Y findings indicated that there were no sustained cognitive risks of CEE or CEE/MPA therapy. Two randomized, placebo-controlled trials involving younger postmenopausal women yielded similar findings.6,7 HT shown to produce cognitively neutral effects during active treatment included transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone,6 CEE plus progesterone,6 and oral estradiol plus vaginal progesterone gel.7 The findings of these randomized trials are critical for guiding decisions regarding the cognitive risks of HT in early postmenopausal women (TABLE 1).

What about women with VMS?

A key gap in knowledge about the cognitive effects of HT is whether HT confers cognitive advantages to women with bothersome VMS. This is a striking absence given that the key indication for HT is the treatment of VMS. While some symptomatic women were included in the trials of HT in younger postmenopausal women described above, no large trial to date has selectively enrolled women with moderate-to-severe VMS to determine if HT is cognitively neutral, beneficial, or detrimental in that group. Some studies involving midlife women have found associations between VMS (as measured with ambulatory skin conductance monitors) and multiple measures of brain health, including memory performance,8 small ischemic lesions on structural brain scans,9 and altered brain function.10 In a small trial of a nonhormonal intervention for VMS, improvement in VMS following the intervention was directly related to improvement in memory performance.11 The reliability of these findings continues to be evaluated but raises the hypothesis that VMS treatments might improve memory in midlife women.

Memory complaints common among midlife women

About 60% of women report an undesirable change in memory performance at midlife as compared with earlier in their lives.12,13 Complaints of forgetfulness are higher in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women compared with premenopausal women, even when those women are similar in age.14 Two large prospective studies found that memory performance decreases during the perimenopause and then rebounds, suggesting a transient decrease in memory.15,16 Although cognitive complaints are common among women in their 40s and 50s, AD is rare in that age group. The risk is largely limited to those women with a parent who developed dementia before age 65, as such cases suggest a familial form of AD.

Continue to: What causes cognitive difficulties during midlife?

What causes cognitive difficulties during midlife?

First, some cognitive decline is expected at midlife based on increasing age. Second, above and beyond the role of chronologic aging (ie, getting one year older each year), ovarian aging plays a role. A role of estrogen was verified in clinical trials showing that memory decreased following oophorectomy in premenopausal women in their 40s but returned to presurgical levels following treatment with estrogen therapy (ET).17 Cohort studies indicate that women who undergo oophorectomy before the typical age of menopause are at increased risk for cognitive impairment or dementia, but those who take ET after oophorectomy until the typical age of menopause do not show that risk.18

Third, cognitive problems are linked not only to VMS but also to sleep disturbance, depressed mood, and increased anxiety—all of which are common in midlife women.15,19 Lastly, health factors play a role. Hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and smoking are associated with adverse brain changes at midlife.20

Giving advice to your patients

First, normalize the cognitive complaints, noting that some cognitive changes are an expected part of aging for all people regardless of whether they are male or female. Advise that while the best studies indicate that these cognitive lapses are especially common in perimenopausal women, they appear to be temporary; women are likely to resume normal cognitive function once the hormonal changes associated with menopause subside.15,16 Note that the one unknown is the role that VMS play in memory problems and that some studies indicate a link between VMS and cognitive problems. Women may experience some cognitive improvement if VMS are effectively treated.

Advise patients that the Endocrine Society, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), and the International Menopause Society all have published guidelines saying that the benefits of HT outweigh the risks for most women aged 50 to 60 years.21 For concerns about the cognitive adverse effects of HT, discuss the best quality evidence—that which comes from randomized trials—which shows no harmful effects of HT in midlife women.5-7 Especially reassuring is that one of these high-quality studies was conducted by the same researchers who found that HT can be risky in older women (ie, the WHI Investigators).5

Going one step further: Protecting brain health

As primary care providers to midlife women, ObGyns can go one step further and advise patients on how to proactively nurture their brain health. Great evidence-based resources for information on maintaining brain health include the Alzheimer’s Association (https://www.alz.org) and the Women’s Brain Health Initiative (https://womensbrainhealth.org). Primary prevention of AD begins decades before the typical age of an AD diagnosis, and many risk factors for AD are modifiable.22 Patients can keep their brains healthy through myriad approaches including treating hypertension, reducing body mass index, engaging in regular aerobic exercise (brisk walking is fine), eating a Mediterranean diet, maintaining an active social life, and engaging in novel challenging activities like learning a new language or a new skill like dancing.20

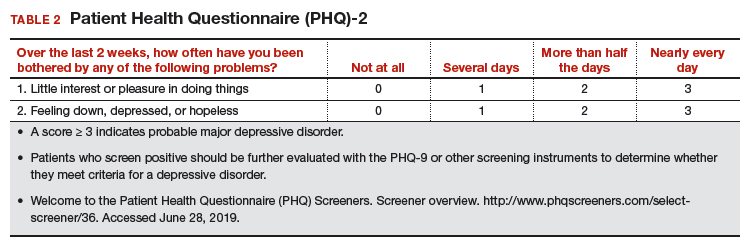

Also important is the overlap between cognitive issues, mood, and alcohol use. In the opening case, Jackie mentions alcohol use and social withdrawal. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), low-risk drinking for women is defined as no more than 3 drinks on any single day and no more than 7 drinks per week.23 Heavy alcohol use not only affects brain function but also mood, and depressed mood can lead women to drink excessively.24

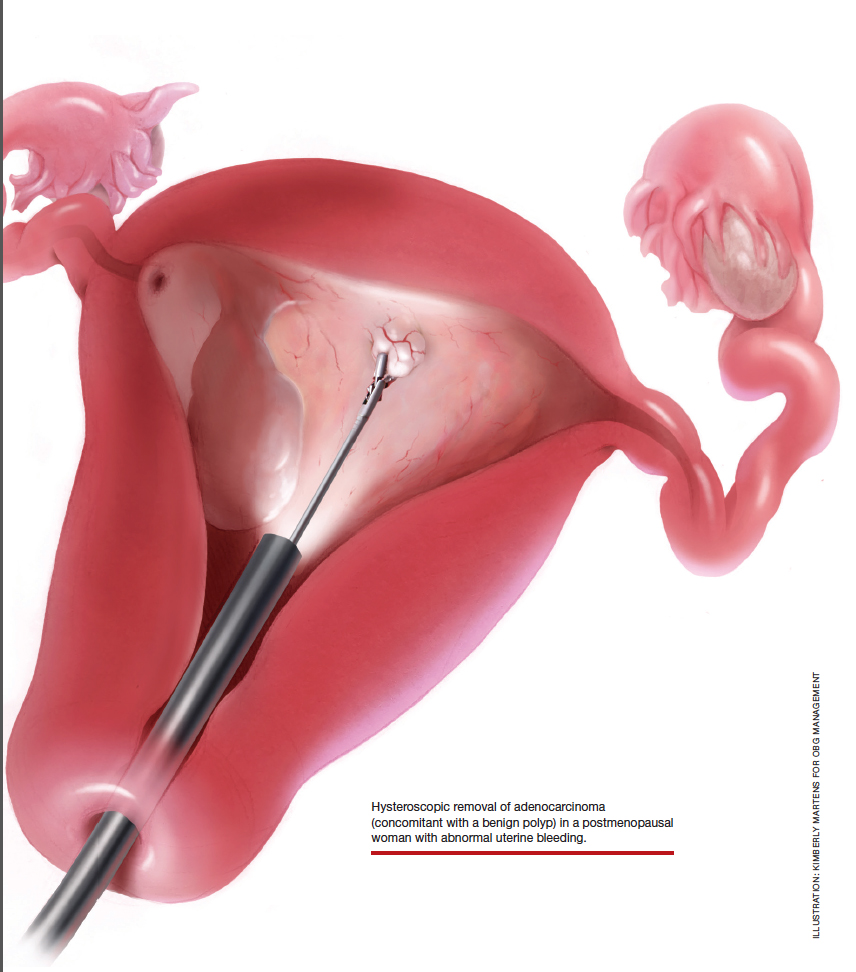

In addition, Jackie’s mother has AD, and that stressor can contribute to depressed feelings, especially if Jackie is involved in caregiving. A quick screen for depression with an instrument like the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2; TABLE 2)25 can rule out a more serious mood disorder—an approach that is particularly important for patients with a history of major depression, as 58% of those patients experience a major depressive episode during the menopausal transition.26 For this reason, it is important to ask patients like Jackie if they have a history of depression; if they do and were treated medically, consider prescribing the antidepressant that worked in the past. For information on menopause and mood-related issues, providers can access new guidelines from NAMS and the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC).27 There is also a handy patient information sheet to accompany those guidelines on the NAMS website (https://www.menopause.org/).

Continue to: CASE Resolved...

CASE Resolved

When approaching Jackie, most importantly, I would normalize her experience and tell her that memory problems are common in the menopausal transition, especially for women with bothersome VMS. Research suggests that the memory problems she is experiencing are related to hormonal changes and not to AD, and that her memory will likely improve once she has transitioned through the menopause. I would tell her that AD is rare at midlife unless there is a family history of early onset of AD (before age 65), and I would verify the age at which her mother was diagnosed to confirm that it was late-onset AD.

For now, I would recommend that she be prescribed HT for her bothersome hot flashes using one of the “safe” formulations in the Table on page 24. I also would tell her that there is much she can do to lower her risk of AD and that it is best to start now as she enters her 50s because that is when AD changes typically start in the brain, and she can start to prevent those changes now.

I would tell her that experts in the field of AD agree that these lifestyle interventions are currently the best way to prevent AD and that the more of them she engages in, the more her brain will benefit. I would advise her to continue to manage her hypertension and to consider ways of lowering her BMI to enhance her brain health. Engaging in regular brisk walking or other aerobic exercise, as well as incorporating more of the Mediterranean diet into her daily food intake would also benefit her brain. As a working woman, she is exercising her brain, and she should consider other cognitively challenging activities to keep her brain in good shape.

I would follow up with her in a few months to see if her memory functioning is better. If it is not, and if her VMS continue to be bothersome, I would increase her dose of HT. Only if her VMS are treated but her memory problems are getting worse would I screen her with a Mini-Mental State Exam and refer her to a neurologist for an evaluation.

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2651-2662.

- Savolainen-Peltonen H, Rahkola-Soisalo P, Hoti F, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Finland: nationwide case-control study. BMJ. 2019;364:1665.

- Maki PM, Girard LM, Manson JE. Menopausal hormone therapy and cognition. BMJ. 2019;364:1877.

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004;291:2947-2958.

- Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Leng I, et al. Long-term effects on cognitive function of postmenopausal hormone therapy prescribed to women aged 50 to 55 years. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1429-1436.

- Gleason CE, Dowling NM, Wharton W, et al. Effects of hormone therapy on cognition and mood in recently postmenopausal women: findings from the randomized, controlled KEEPS-cognitive and affective study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001833.

- Henderson VW, St. John JA, Hodis HN, et al. Cognitive effects of estradiol after menopause: a randomized trial of the timing hypothesis. Neurology. 2016;87:699-708.

- Maki PM, Drogos LL, Rubin LH, et al. Objective hot flashes are negatively related to verbal memory performance in midlife women. Menopause. 2008;15:848-856.

- Thurston RC, Aizenstein HJ, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal hot flashes and white matter hyperintensities. Menopause. 2016;23:27-32.

- Thurston RC, Maki PM, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal hot flashes and the default mode network. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1572-1578.e1.

- Maki PM, Rubin LH, Savarese A, et al. Stellate ganglion blockade and verbal memory in midlife women: evidence from a randomized trial. Maturitas. 2016;92:123-129.