User login

Alopecia areata: Positive results reported for two investigational JAK inhibitors

in separate studies reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

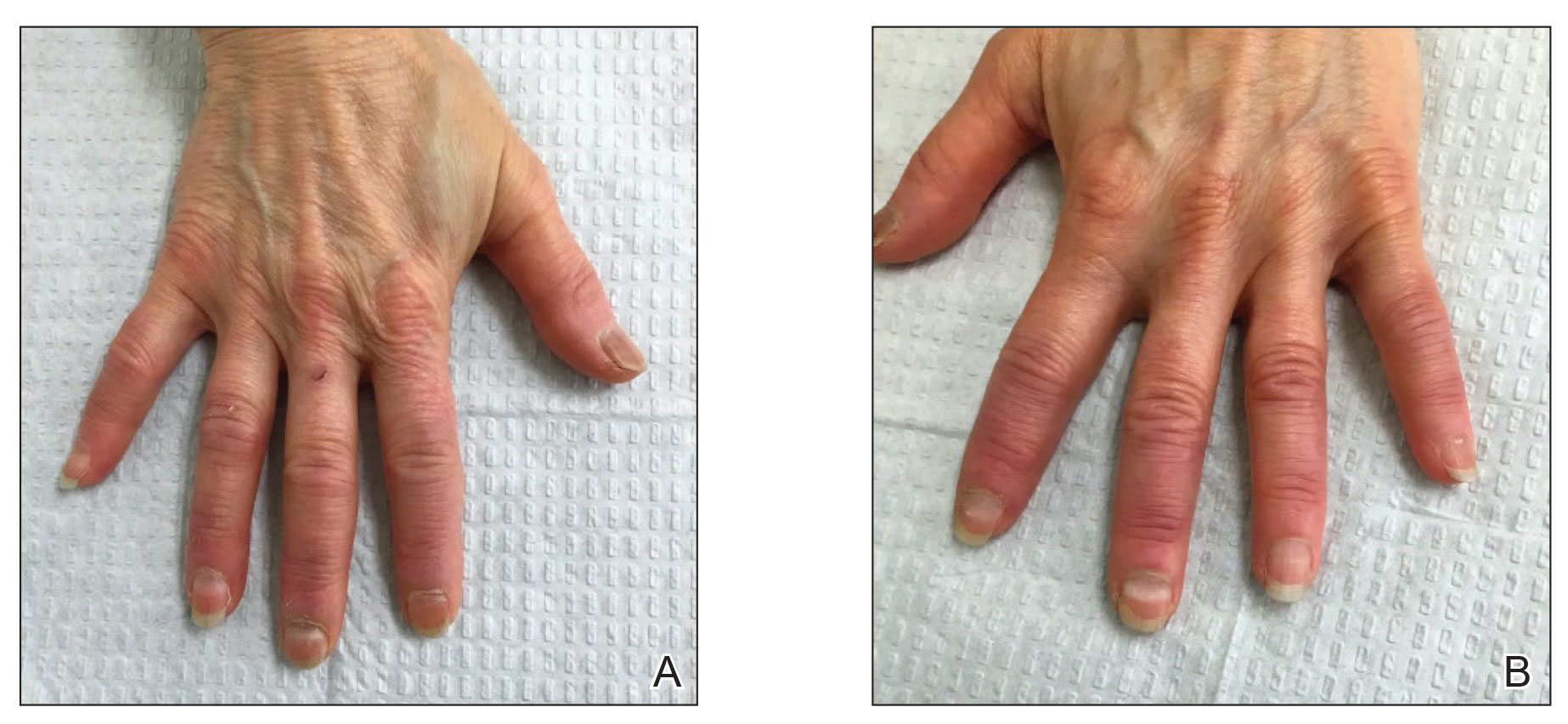

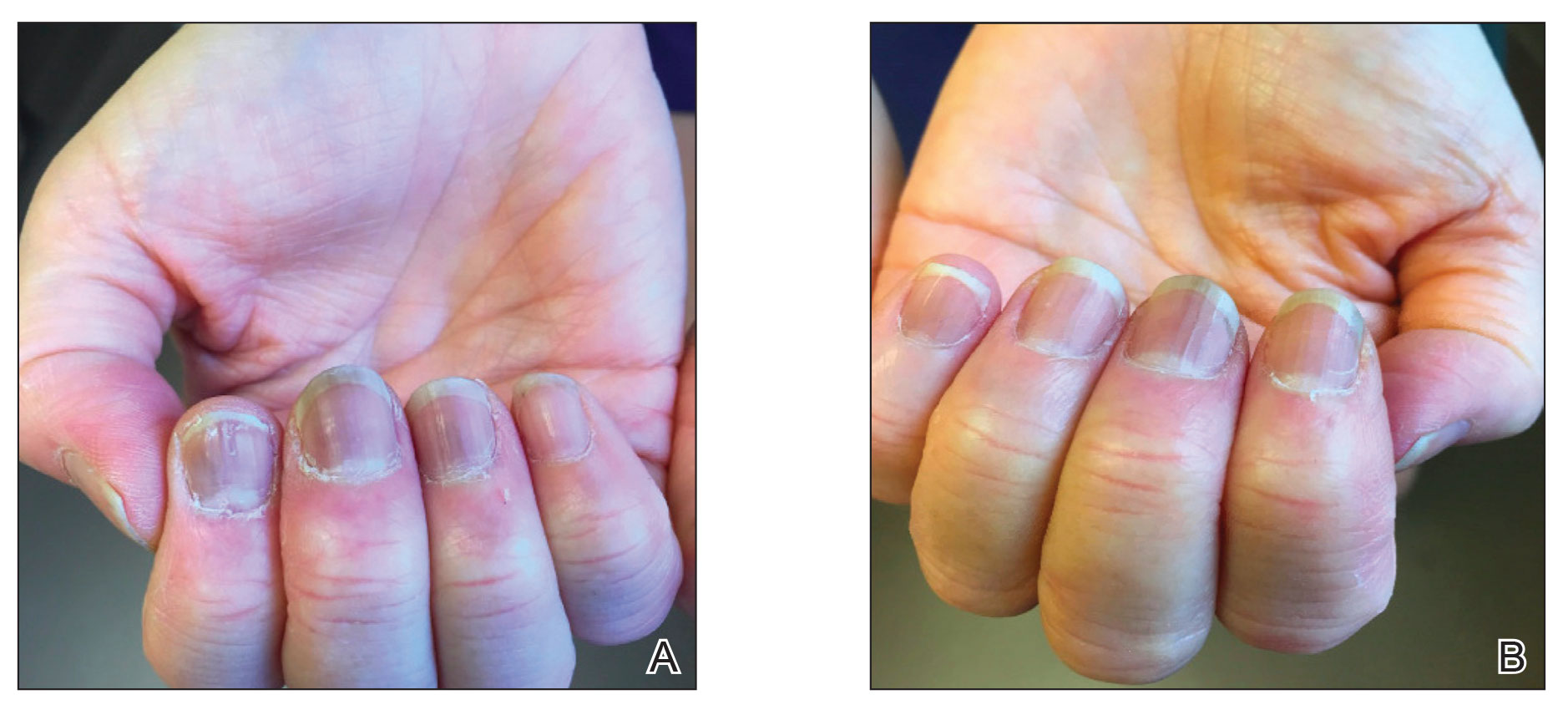

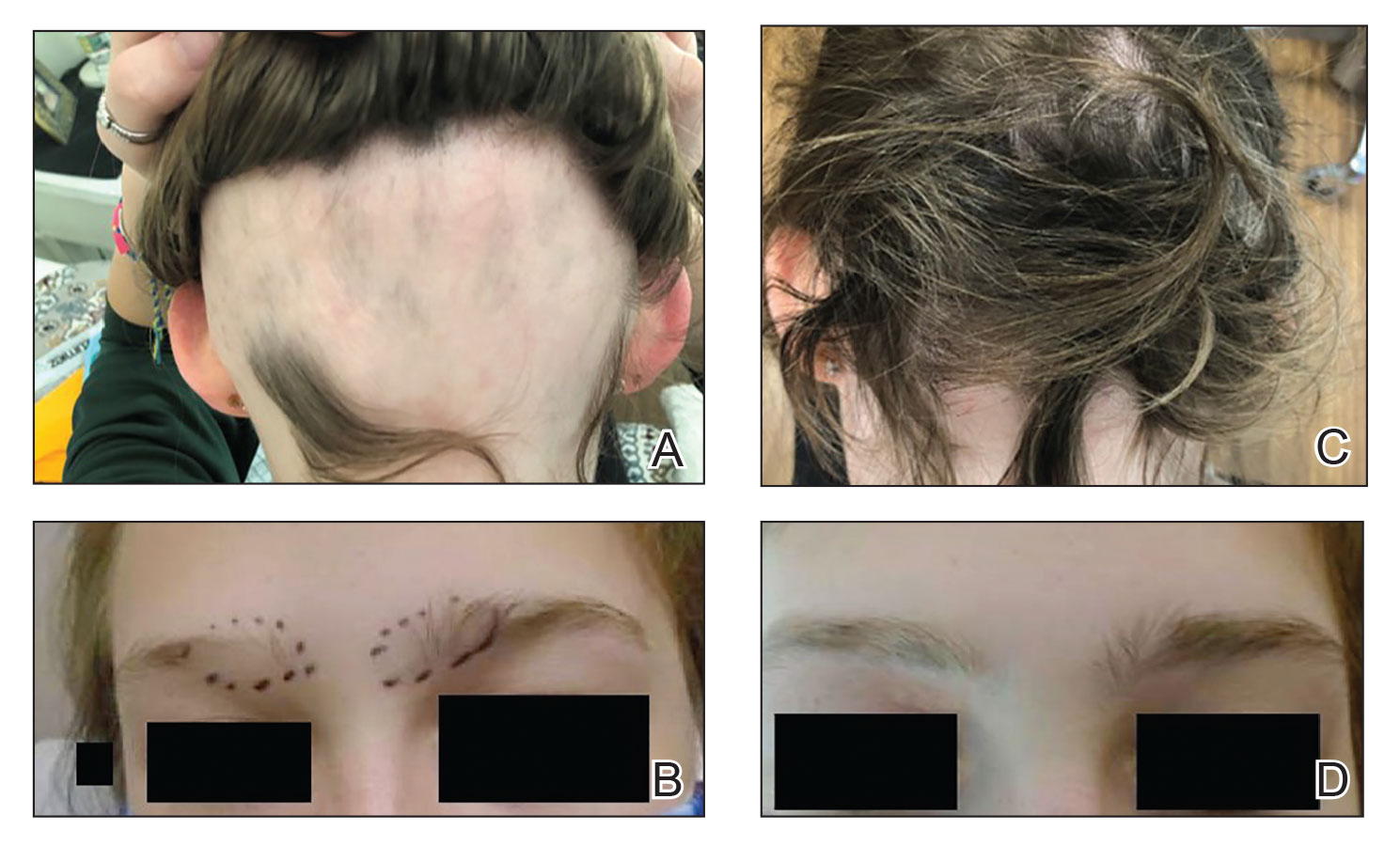

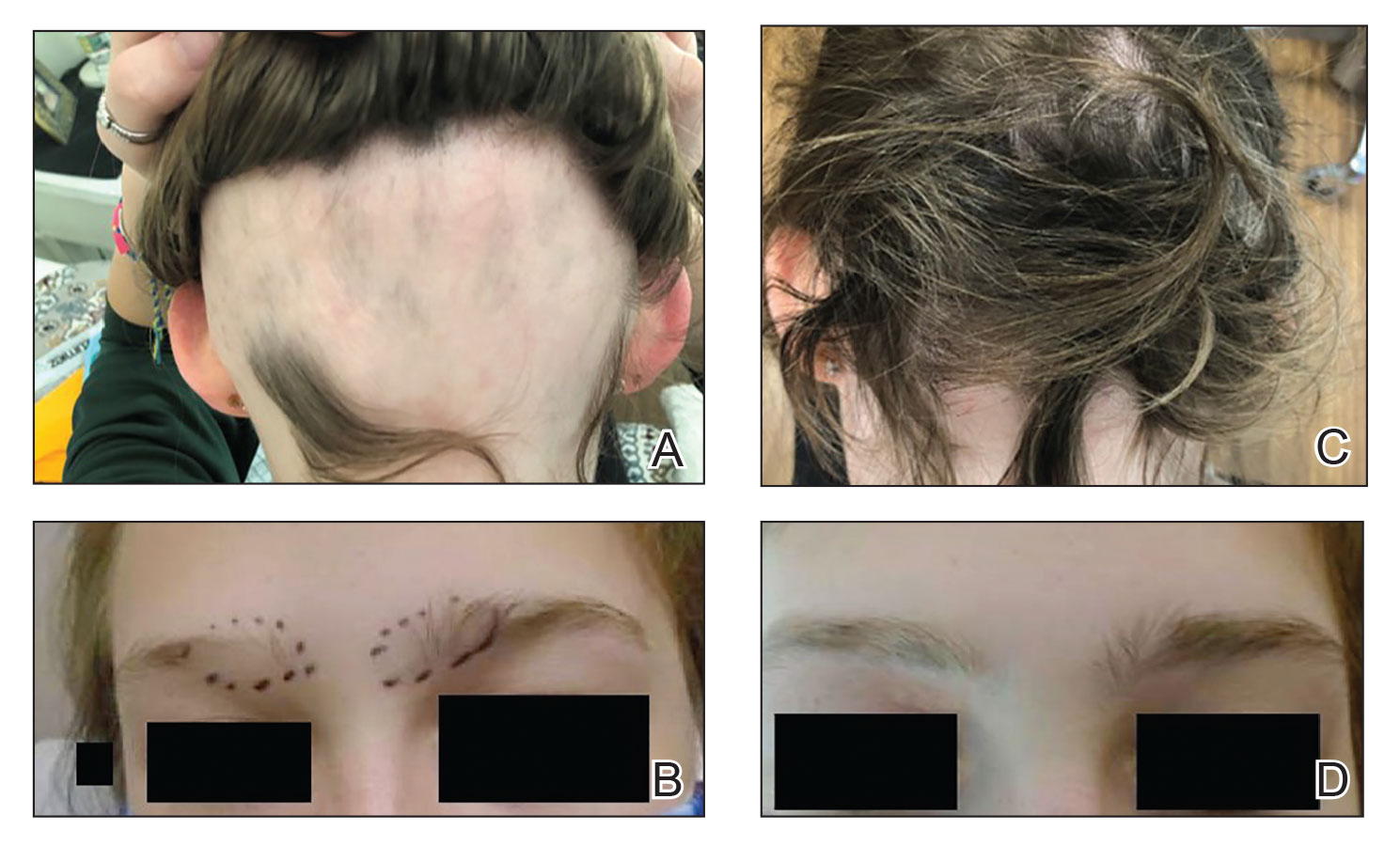

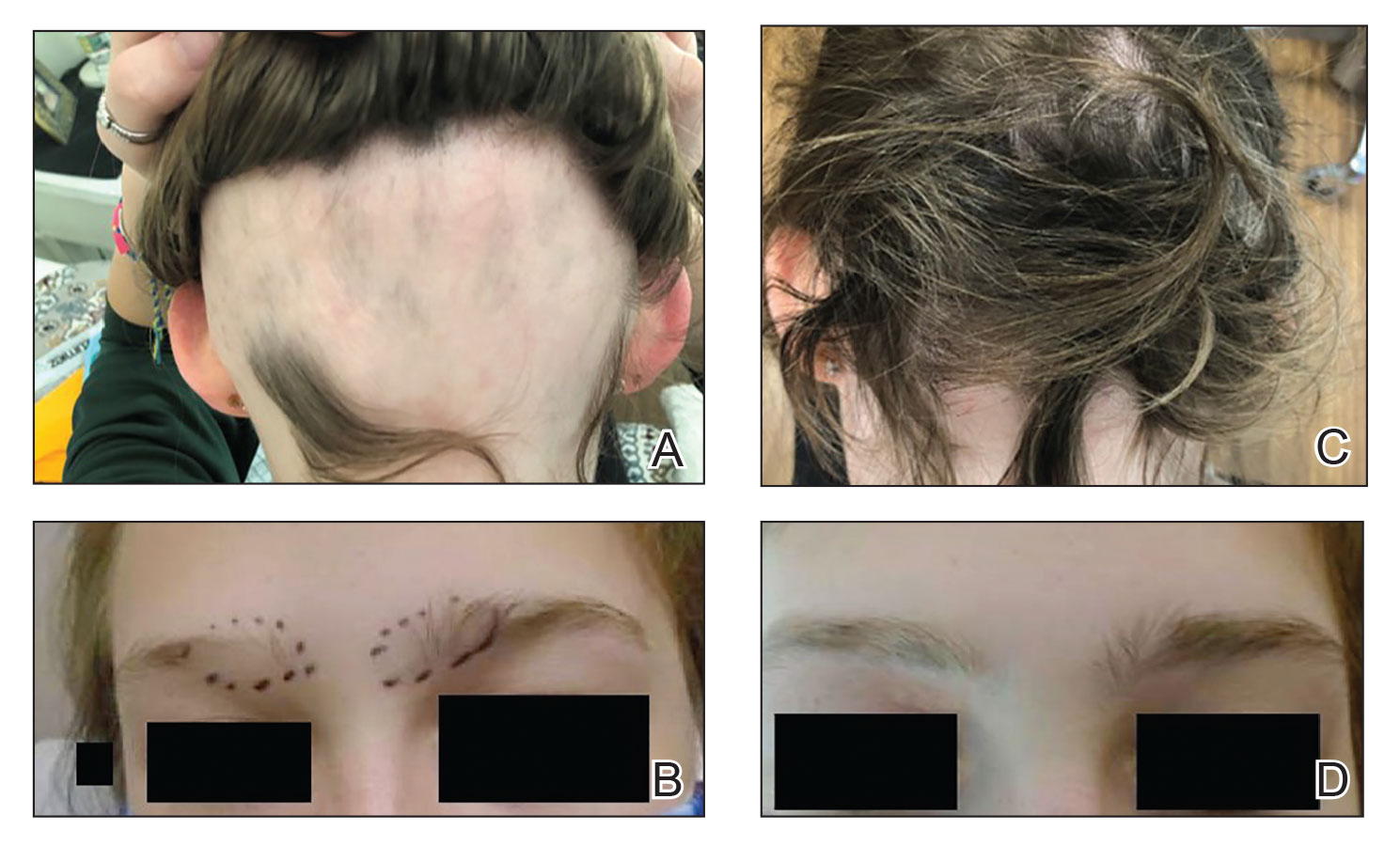

In the THRIVE-AA1 study, the primary endpoint of a Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of 20 or lower –which indicates that hair regrowth has occurred on at least 80% of the scalp – was achieved among patients taking deuruxolitinib, which was a significantly higher proportion than with placebo (P < .0001). Importantly, the JAK inhibitor’s effects were seen in as early as 4 weeks, and there was significant improvement in both eyelash and eyebrow hair regrowth.

In the unrelated ALLEGRO-LT study, effects from treatment with the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib appeared to be sustained for 2 years; 69.6% of patients treated with ritlecitinib had a SALT score of 20 or lower by 24 months.

These data are “very exciting for alopecia areata because the patients selected are very severe,” observed Mahtab Samimi, MD, PhD, who cochaired the late-breaking session in which the study findings were discussed.

THRIVE-AA1 included only patients with hair loss of 50% or more. The ALLEGRO-LT study included patients with total scalp or total body hair loss (areata totalis/areata universalis) of 25%-50% at enrollment.

Moreover, “very stringent criteria” were used. SALT scores of 10 or less were evaluated in both studies, observed Dr. Samimi, professor of dermatology at the University of Tours (France).

“We can be ambitious now for our patients with alopecia areata; that’s really good news,” Dr. Samimi added.

Deuruxolitinib and the THRIVE trials

Deuruxolitinib is an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor that has been tested in two similarly designed, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials in patients with AA, THRIVE-AA1 and THRIVE-AA2.

Two doses of deuruxolitinib, 8 mg and 12 mg given twice daily, were evaluated in the trials, which altogether included just over 1,200 patients.

Results of THRIVE-AA1 have been reported by the manufacturer. Brett King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., presented a more comprehensive review at the EADV meeting.

He reported that at 24 weeks, SALT scores of 20 or lower were achieved by 30% of adults with AA who were treated with deuruxolitinib 8 mg and by 42% of those treated with deuruxolitinib 12 mg. This primary endpoint was seen in only 1% of the placebo-treated patients.

The more stringent endpoint of having a SALT score of 10 or less, which indicates that hair regrowth has occurred over 90% of the scalp, was met by 21% of patients who received deuruxolitinib 8 mg twice a day and by 35% of those who received the 12-mg dose twice a day at 24 weeks. This endpoint was not reached by any of the placebo-treated patients.

“This is truly transformative therapy,” Dr. King said when presenting the findings. “We know that the chances of spontaneous remission when you have severe disease is next to zero,” he added.

There were reasonably high rates of patient satisfaction with the treatment, according to Dr. King. He said that 42% of those who took 8 mg twice a day and 53% of those who took 12 mg twice a day said they were “very satisfied” or “satisfied” with the degree of scalp hair regrowth achieved, compared with 5% for placebo.

Safety was as expected, and there were no signs of any blood clots, said Dr. King. Common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) that affected 5% or more of patients included acne and headache. Serious TEAEs were reported by 1.1% and 0.5% of those taking the 8-mg and 12-mg twice-daily doses, respectively, compared with 2.9% of those who received placebo.

Overall, the results look promising for deuruxolitinib, he added. He noted that almost all patients included in the trial have opted to continue in the open-label long-term safety study.

Prescribing information of the JAK inhibitors approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration includes a boxed warning about risk of serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and thrombosis. The warning is based on experience with another JAK inhibitor for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Ritlecitinib and the ALLEGRO studies

Interim results of the ongoing, open-label, phase 3 ALLEGRO-LT study with ritlecitinib were presented separately by Athanasios Tsianakas, MD, head of the department of dermatology at Fachklinik Bad Bentheim, Germany.

Ritlecitinib, which targets JAK3 and also the TEC family of tyrosine kinases, had met all of its endpoints in the prior ALLEGRO Phase 2b/3 study, Dr. Tsianakas said. Those included the benchmarks of a SALT score of 20 or less and a SALT score of 10 or less.

“Ritlecitinib showed a very good long-term efficacy and good safety profile in our adolescent and adult patients suffering from alopecia areata,” said Dr. Tsianakas.

A total of 447 patients were included in the trial. They were treated with 50 mg of ritlecitinib every day; some had already participated in the ALLEGRO trial, while others had been newly recruited. The latter group entered the trial after a 4-week run-in period, during which a 200-mg daily loading dose was given for 4 weeks.

Most (86%) patients had been exposed to ritlecitinib for at least 12 months; one-fifth had discontinued treatment at the data cutoff, generally because the patients no longer met the eligibility criteria for the trial.

Safety was paramount, Dr. Tsianakas highlighted. There were few adverse events that led to temporary or permanent discontinuation of the study drug. The most common TEAEs that affected 5% or more of patients included headache and acne. There were two cases of MACE (one nonfatal myocardial infarction and one nonfatal stroke).

The proportion of patients with a SALT score of 20 or less was 2.5% at 1 month, 27.9% at 3 months, 50.1% at 6 months, 59.8% at 9 months, and 65.5% at 12 months. Thereafter, there was little shift in the response. A sustained effect, in which a SALT score of 20 or less was seen out to 24 months, occurred in 69.9% of patients.

A similar pattern was seen for SALT scores of 10 or less, ranging from 16.5% at 3 months to 62.5% at 24 months.

Following in baricitinib’s footsteps?

This not the first time that JAK inhibitors have been shown to have beneficial effects for patients with AA. Baricitinib (Olumiant) recently became the first JAK inhibitor to be granted marketing approval for AA in the United States, largely on the basis of two pivotal phase 3 studies, BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2.

“This is just such an incredibly exciting time,” said Dr. King. “Our discoveries in the lab are being translated into effective therapies for patients with diseases for which we’ve not previously had therapies,” he commented.

“Our concept of interferon gamma– and interleukin-15–mediated disease is probably not true for everybody,” said, Dr. King, who acknowledged that some patients with AA do not respond to JAK-inhibitor therapy or may need additional or alternative treatment.

“It’s probably not that homogeneous a disease,” he added. “It’s fascinating that the very first drugs for this disease are showing efficacy in as many patients as they are.”

The THRIVE-AAI study was funded by CONCERT Pharmaceuticals. Dr. King has served on advisory boards, has provided consulting services to, or has been a trial investigator for multiple pharmaceutical companies, including CoNCERT Pharmaceuticals. The ALLEGRO-LT study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Tsianakas has acted as a clinical trial investigator and speaker for Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in separate studies reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

In the THRIVE-AA1 study, the primary endpoint of a Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of 20 or lower –which indicates that hair regrowth has occurred on at least 80% of the scalp – was achieved among patients taking deuruxolitinib, which was a significantly higher proportion than with placebo (P < .0001). Importantly, the JAK inhibitor’s effects were seen in as early as 4 weeks, and there was significant improvement in both eyelash and eyebrow hair regrowth.

In the unrelated ALLEGRO-LT study, effects from treatment with the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib appeared to be sustained for 2 years; 69.6% of patients treated with ritlecitinib had a SALT score of 20 or lower by 24 months.

These data are “very exciting for alopecia areata because the patients selected are very severe,” observed Mahtab Samimi, MD, PhD, who cochaired the late-breaking session in which the study findings were discussed.

THRIVE-AA1 included only patients with hair loss of 50% or more. The ALLEGRO-LT study included patients with total scalp or total body hair loss (areata totalis/areata universalis) of 25%-50% at enrollment.

Moreover, “very stringent criteria” were used. SALT scores of 10 or less were evaluated in both studies, observed Dr. Samimi, professor of dermatology at the University of Tours (France).

“We can be ambitious now for our patients with alopecia areata; that’s really good news,” Dr. Samimi added.

Deuruxolitinib and the THRIVE trials

Deuruxolitinib is an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor that has been tested in two similarly designed, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials in patients with AA, THRIVE-AA1 and THRIVE-AA2.

Two doses of deuruxolitinib, 8 mg and 12 mg given twice daily, were evaluated in the trials, which altogether included just over 1,200 patients.

Results of THRIVE-AA1 have been reported by the manufacturer. Brett King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., presented a more comprehensive review at the EADV meeting.

He reported that at 24 weeks, SALT scores of 20 or lower were achieved by 30% of adults with AA who were treated with deuruxolitinib 8 mg and by 42% of those treated with deuruxolitinib 12 mg. This primary endpoint was seen in only 1% of the placebo-treated patients.

The more stringent endpoint of having a SALT score of 10 or less, which indicates that hair regrowth has occurred over 90% of the scalp, was met by 21% of patients who received deuruxolitinib 8 mg twice a day and by 35% of those who received the 12-mg dose twice a day at 24 weeks. This endpoint was not reached by any of the placebo-treated patients.

“This is truly transformative therapy,” Dr. King said when presenting the findings. “We know that the chances of spontaneous remission when you have severe disease is next to zero,” he added.

There were reasonably high rates of patient satisfaction with the treatment, according to Dr. King. He said that 42% of those who took 8 mg twice a day and 53% of those who took 12 mg twice a day said they were “very satisfied” or “satisfied” with the degree of scalp hair regrowth achieved, compared with 5% for placebo.

Safety was as expected, and there were no signs of any blood clots, said Dr. King. Common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) that affected 5% or more of patients included acne and headache. Serious TEAEs were reported by 1.1% and 0.5% of those taking the 8-mg and 12-mg twice-daily doses, respectively, compared with 2.9% of those who received placebo.

Overall, the results look promising for deuruxolitinib, he added. He noted that almost all patients included in the trial have opted to continue in the open-label long-term safety study.

Prescribing information of the JAK inhibitors approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration includes a boxed warning about risk of serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and thrombosis. The warning is based on experience with another JAK inhibitor for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Ritlecitinib and the ALLEGRO studies

Interim results of the ongoing, open-label, phase 3 ALLEGRO-LT study with ritlecitinib were presented separately by Athanasios Tsianakas, MD, head of the department of dermatology at Fachklinik Bad Bentheim, Germany.

Ritlecitinib, which targets JAK3 and also the TEC family of tyrosine kinases, had met all of its endpoints in the prior ALLEGRO Phase 2b/3 study, Dr. Tsianakas said. Those included the benchmarks of a SALT score of 20 or less and a SALT score of 10 or less.

“Ritlecitinib showed a very good long-term efficacy and good safety profile in our adolescent and adult patients suffering from alopecia areata,” said Dr. Tsianakas.

A total of 447 patients were included in the trial. They were treated with 50 mg of ritlecitinib every day; some had already participated in the ALLEGRO trial, while others had been newly recruited. The latter group entered the trial after a 4-week run-in period, during which a 200-mg daily loading dose was given for 4 weeks.

Most (86%) patients had been exposed to ritlecitinib for at least 12 months; one-fifth had discontinued treatment at the data cutoff, generally because the patients no longer met the eligibility criteria for the trial.

Safety was paramount, Dr. Tsianakas highlighted. There were few adverse events that led to temporary or permanent discontinuation of the study drug. The most common TEAEs that affected 5% or more of patients included headache and acne. There were two cases of MACE (one nonfatal myocardial infarction and one nonfatal stroke).

The proportion of patients with a SALT score of 20 or less was 2.5% at 1 month, 27.9% at 3 months, 50.1% at 6 months, 59.8% at 9 months, and 65.5% at 12 months. Thereafter, there was little shift in the response. A sustained effect, in which a SALT score of 20 or less was seen out to 24 months, occurred in 69.9% of patients.

A similar pattern was seen for SALT scores of 10 or less, ranging from 16.5% at 3 months to 62.5% at 24 months.

Following in baricitinib’s footsteps?

This not the first time that JAK inhibitors have been shown to have beneficial effects for patients with AA. Baricitinib (Olumiant) recently became the first JAK inhibitor to be granted marketing approval for AA in the United States, largely on the basis of two pivotal phase 3 studies, BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2.

“This is just such an incredibly exciting time,” said Dr. King. “Our discoveries in the lab are being translated into effective therapies for patients with diseases for which we’ve not previously had therapies,” he commented.

“Our concept of interferon gamma– and interleukin-15–mediated disease is probably not true for everybody,” said, Dr. King, who acknowledged that some patients with AA do not respond to JAK-inhibitor therapy or may need additional or alternative treatment.

“It’s probably not that homogeneous a disease,” he added. “It’s fascinating that the very first drugs for this disease are showing efficacy in as many patients as they are.”

The THRIVE-AAI study was funded by CONCERT Pharmaceuticals. Dr. King has served on advisory boards, has provided consulting services to, or has been a trial investigator for multiple pharmaceutical companies, including CoNCERT Pharmaceuticals. The ALLEGRO-LT study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Tsianakas has acted as a clinical trial investigator and speaker for Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in separate studies reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

In the THRIVE-AA1 study, the primary endpoint of a Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of 20 or lower –which indicates that hair regrowth has occurred on at least 80% of the scalp – was achieved among patients taking deuruxolitinib, which was a significantly higher proportion than with placebo (P < .0001). Importantly, the JAK inhibitor’s effects were seen in as early as 4 weeks, and there was significant improvement in both eyelash and eyebrow hair regrowth.

In the unrelated ALLEGRO-LT study, effects from treatment with the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib appeared to be sustained for 2 years; 69.6% of patients treated with ritlecitinib had a SALT score of 20 or lower by 24 months.

These data are “very exciting for alopecia areata because the patients selected are very severe,” observed Mahtab Samimi, MD, PhD, who cochaired the late-breaking session in which the study findings were discussed.

THRIVE-AA1 included only patients with hair loss of 50% or more. The ALLEGRO-LT study included patients with total scalp or total body hair loss (areata totalis/areata universalis) of 25%-50% at enrollment.

Moreover, “very stringent criteria” were used. SALT scores of 10 or less were evaluated in both studies, observed Dr. Samimi, professor of dermatology at the University of Tours (France).

“We can be ambitious now for our patients with alopecia areata; that’s really good news,” Dr. Samimi added.

Deuruxolitinib and the THRIVE trials

Deuruxolitinib is an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor that has been tested in two similarly designed, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials in patients with AA, THRIVE-AA1 and THRIVE-AA2.

Two doses of deuruxolitinib, 8 mg and 12 mg given twice daily, were evaluated in the trials, which altogether included just over 1,200 patients.

Results of THRIVE-AA1 have been reported by the manufacturer. Brett King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., presented a more comprehensive review at the EADV meeting.

He reported that at 24 weeks, SALT scores of 20 or lower were achieved by 30% of adults with AA who were treated with deuruxolitinib 8 mg and by 42% of those treated with deuruxolitinib 12 mg. This primary endpoint was seen in only 1% of the placebo-treated patients.

The more stringent endpoint of having a SALT score of 10 or less, which indicates that hair regrowth has occurred over 90% of the scalp, was met by 21% of patients who received deuruxolitinib 8 mg twice a day and by 35% of those who received the 12-mg dose twice a day at 24 weeks. This endpoint was not reached by any of the placebo-treated patients.

“This is truly transformative therapy,” Dr. King said when presenting the findings. “We know that the chances of spontaneous remission when you have severe disease is next to zero,” he added.

There were reasonably high rates of patient satisfaction with the treatment, according to Dr. King. He said that 42% of those who took 8 mg twice a day and 53% of those who took 12 mg twice a day said they were “very satisfied” or “satisfied” with the degree of scalp hair regrowth achieved, compared with 5% for placebo.

Safety was as expected, and there were no signs of any blood clots, said Dr. King. Common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) that affected 5% or more of patients included acne and headache. Serious TEAEs were reported by 1.1% and 0.5% of those taking the 8-mg and 12-mg twice-daily doses, respectively, compared with 2.9% of those who received placebo.

Overall, the results look promising for deuruxolitinib, he added. He noted that almost all patients included in the trial have opted to continue in the open-label long-term safety study.

Prescribing information of the JAK inhibitors approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration includes a boxed warning about risk of serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and thrombosis. The warning is based on experience with another JAK inhibitor for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Ritlecitinib and the ALLEGRO studies

Interim results of the ongoing, open-label, phase 3 ALLEGRO-LT study with ritlecitinib were presented separately by Athanasios Tsianakas, MD, head of the department of dermatology at Fachklinik Bad Bentheim, Germany.

Ritlecitinib, which targets JAK3 and also the TEC family of tyrosine kinases, had met all of its endpoints in the prior ALLEGRO Phase 2b/3 study, Dr. Tsianakas said. Those included the benchmarks of a SALT score of 20 or less and a SALT score of 10 or less.

“Ritlecitinib showed a very good long-term efficacy and good safety profile in our adolescent and adult patients suffering from alopecia areata,” said Dr. Tsianakas.

A total of 447 patients were included in the trial. They were treated with 50 mg of ritlecitinib every day; some had already participated in the ALLEGRO trial, while others had been newly recruited. The latter group entered the trial after a 4-week run-in period, during which a 200-mg daily loading dose was given for 4 weeks.

Most (86%) patients had been exposed to ritlecitinib for at least 12 months; one-fifth had discontinued treatment at the data cutoff, generally because the patients no longer met the eligibility criteria for the trial.

Safety was paramount, Dr. Tsianakas highlighted. There were few adverse events that led to temporary or permanent discontinuation of the study drug. The most common TEAEs that affected 5% or more of patients included headache and acne. There were two cases of MACE (one nonfatal myocardial infarction and one nonfatal stroke).

The proportion of patients with a SALT score of 20 or less was 2.5% at 1 month, 27.9% at 3 months, 50.1% at 6 months, 59.8% at 9 months, and 65.5% at 12 months. Thereafter, there was little shift in the response. A sustained effect, in which a SALT score of 20 or less was seen out to 24 months, occurred in 69.9% of patients.

A similar pattern was seen for SALT scores of 10 or less, ranging from 16.5% at 3 months to 62.5% at 24 months.

Following in baricitinib’s footsteps?

This not the first time that JAK inhibitors have been shown to have beneficial effects for patients with AA. Baricitinib (Olumiant) recently became the first JAK inhibitor to be granted marketing approval for AA in the United States, largely on the basis of two pivotal phase 3 studies, BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2.

“This is just such an incredibly exciting time,” said Dr. King. “Our discoveries in the lab are being translated into effective therapies for patients with diseases for which we’ve not previously had therapies,” he commented.

“Our concept of interferon gamma– and interleukin-15–mediated disease is probably not true for everybody,” said, Dr. King, who acknowledged that some patients with AA do not respond to JAK-inhibitor therapy or may need additional or alternative treatment.

“It’s probably not that homogeneous a disease,” he added. “It’s fascinating that the very first drugs for this disease are showing efficacy in as many patients as they are.”

The THRIVE-AAI study was funded by CONCERT Pharmaceuticals. Dr. King has served on advisory boards, has provided consulting services to, or has been a trial investigator for multiple pharmaceutical companies, including CoNCERT Pharmaceuticals. The ALLEGRO-LT study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Tsianakas has acted as a clinical trial investigator and speaker for Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Expert calls for thoughtful approach to curbing costs in dermatology

PORTLAND, ORE. – About 10 years ago when Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, became an attending physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, he noticed that some of his dermatology colleagues checked the potassium levels religiously in their female patients taking spironolactone, while others never did.

“It led to this question: Dr. Mostaghimi, director of the dermatology inpatient service at Brigham and Women’s, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

To find out, he and his colleagues reviewed 1,802 serum potassium measurements in a study of healthy young women with no known health conditions who were taking spironolactone, published in 2015. They discovered that 13 of those tests suggested mild hyperkalemia, defined as a level greater than 5.0 mEq/L. Of these, six were rechecked and were normal; no action was taken in the other seven patients.

“This led us to conclude that we spent $78,000 at our institution on testing that did not appear to yield clinically significant information for these patients, and that routine potassium monitoring is unnecessary for most women taking spironolactone for acne,” he said. Their findings have been validated “in many cohorts of data,” he added.

The study serves as an example of efforts dermatologists can take to curb unnecessary costs within the field to be “appropriate stewards of resources,” he continued. “We have to think about the ratio of benefit over cost. It’s not just about the cost, it’s about what you’re getting for the amount of money that you’re spending. The idea of this is not restricting or not giving people medications or access to things that they need. The idea is to do it in a thoughtful way that works across the population.”

Value thresholds

Determining the value thresholds of a particular medicine or procedure is also essential to good dermatology practice. To illustrate, Dr. Mostaghimi cited a prospective cohort study that compared treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in 1,536 consecutive patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) with and without limited life expectancy. More than two-thirds of the NMSCs (69%) were treated surgically. After adjusting for tumor and patient characteristics, the researchers found that 43% of patients with low life expectancy died within 5 years, but not from NMSC.

“Does that mean we shouldn’t do surgery for NMSC patients with low life expectancy?” he asked. “Should we do it less? Should we let the patients decide? It’s complicated. As a society, we have to decide what’s worth doing and what’s not worth doing,” he said. “What about old diseases with new treatments, like alopecia areata? Is alopecia areata a cosmetic condition? Dermatologists and patients wouldn’t classify it that way, but many insurers do. How do you negotiate that?”

In 2013, the American Academy of Dermatology identified 10 evidence-based recommendations that can support conversations between patients and dermatologists about treatments, tests, and procedures that may not be necessary. One of the recommendations was not to prescribe oral antifungal therapy for suspected nail fungus without confirmation of fungal infection.

“If a clinician thinks a patient has onychomycosis, he or she is usually right,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “But what’s the added cost/benefit of performing a KOH followed by PAS testing if negative or performing a PAS test directly versus just treating the patient?”

In 2006, he and his colleagues published the results of a decision analysis to address these questions. They determined that the costs of testing to avoid one case of clinically apparent liver injury with terbinafine treatment was $18.2-$43.7 million for the KOH screening pathway and $37.6 to $90.2 million for the PAS testing pathway.

“Is that worth it?” he asked. “Would we get more value for spending the money elsewhere? In this case, the answer is most likely yes.”

Isotretinoin lab testing

Translating research into recommendations and standards of care is one way to help curb costs in dermatology. As an example, he cited lab monitoring for patients treated with isotretinoin for acne.

“There have been a number of papers over the years that have suggested that the number of labs we do is excessive, that the value that they provide is low, and that abnormal results do not impact our decision-making,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Do some patients on isotretinoin get mildly elevated [liver function tests] and hypertriglyceridemia? Yes, that happens. Does it matter? Nothing has demonstrated that it matters. Does it matter that an 18-year-old has high triglycerides for 6 months? Rarely, if ever.”

To promote a new approach, he and a panel of acne experts from five continents performed a Delphi consensus study. Based on their consensus, they proposed a simple approach: For “generally healthy patients without underlying abnormalities or preexisting conditions warranting further investigation,” check ALT and triglycerides prior to initiating isotretinoin. Then start isotretinoin.

“At the peak dose, recheck ALT and triglycerides – this might be at month 2,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Other people wait a little bit longer. No labs are required once treatment is complete. Of course, adjust this approach based on your assessment of the patient in front of you. None of these recommendations should replace your clinical judgment and intuition.”

He proposed a new paradigm where dermatologists can ask themselves three questions for every patient they see: Why is this intervention or test being done? Why is it being done in this patient? And why do it at that time? “If we think this way, we can identify some inconsistencies in our own thinking and opportunities for improvement,” he said.

Dr. Mostaghimi reported that he is a consultant to Pfizer, Concert, Lilly, and Bioniz. He is also an advisor to Him & Hers Cosmetics and Digital Diagnostics and is an associate editor for JAMA Dermatology.

PORTLAND, ORE. – About 10 years ago when Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, became an attending physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, he noticed that some of his dermatology colleagues checked the potassium levels religiously in their female patients taking spironolactone, while others never did.

“It led to this question: Dr. Mostaghimi, director of the dermatology inpatient service at Brigham and Women’s, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

To find out, he and his colleagues reviewed 1,802 serum potassium measurements in a study of healthy young women with no known health conditions who were taking spironolactone, published in 2015. They discovered that 13 of those tests suggested mild hyperkalemia, defined as a level greater than 5.0 mEq/L. Of these, six were rechecked and were normal; no action was taken in the other seven patients.

“This led us to conclude that we spent $78,000 at our institution on testing that did not appear to yield clinically significant information for these patients, and that routine potassium monitoring is unnecessary for most women taking spironolactone for acne,” he said. Their findings have been validated “in many cohorts of data,” he added.

The study serves as an example of efforts dermatologists can take to curb unnecessary costs within the field to be “appropriate stewards of resources,” he continued. “We have to think about the ratio of benefit over cost. It’s not just about the cost, it’s about what you’re getting for the amount of money that you’re spending. The idea of this is not restricting or not giving people medications or access to things that they need. The idea is to do it in a thoughtful way that works across the population.”

Value thresholds

Determining the value thresholds of a particular medicine or procedure is also essential to good dermatology practice. To illustrate, Dr. Mostaghimi cited a prospective cohort study that compared treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in 1,536 consecutive patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) with and without limited life expectancy. More than two-thirds of the NMSCs (69%) were treated surgically. After adjusting for tumor and patient characteristics, the researchers found that 43% of patients with low life expectancy died within 5 years, but not from NMSC.

“Does that mean we shouldn’t do surgery for NMSC patients with low life expectancy?” he asked. “Should we do it less? Should we let the patients decide? It’s complicated. As a society, we have to decide what’s worth doing and what’s not worth doing,” he said. “What about old diseases with new treatments, like alopecia areata? Is alopecia areata a cosmetic condition? Dermatologists and patients wouldn’t classify it that way, but many insurers do. How do you negotiate that?”

In 2013, the American Academy of Dermatology identified 10 evidence-based recommendations that can support conversations between patients and dermatologists about treatments, tests, and procedures that may not be necessary. One of the recommendations was not to prescribe oral antifungal therapy for suspected nail fungus without confirmation of fungal infection.

“If a clinician thinks a patient has onychomycosis, he or she is usually right,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “But what’s the added cost/benefit of performing a KOH followed by PAS testing if negative or performing a PAS test directly versus just treating the patient?”

In 2006, he and his colleagues published the results of a decision analysis to address these questions. They determined that the costs of testing to avoid one case of clinically apparent liver injury with terbinafine treatment was $18.2-$43.7 million for the KOH screening pathway and $37.6 to $90.2 million for the PAS testing pathway.

“Is that worth it?” he asked. “Would we get more value for spending the money elsewhere? In this case, the answer is most likely yes.”

Isotretinoin lab testing

Translating research into recommendations and standards of care is one way to help curb costs in dermatology. As an example, he cited lab monitoring for patients treated with isotretinoin for acne.

“There have been a number of papers over the years that have suggested that the number of labs we do is excessive, that the value that they provide is low, and that abnormal results do not impact our decision-making,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Do some patients on isotretinoin get mildly elevated [liver function tests] and hypertriglyceridemia? Yes, that happens. Does it matter? Nothing has demonstrated that it matters. Does it matter that an 18-year-old has high triglycerides for 6 months? Rarely, if ever.”

To promote a new approach, he and a panel of acne experts from five continents performed a Delphi consensus study. Based on their consensus, they proposed a simple approach: For “generally healthy patients without underlying abnormalities or preexisting conditions warranting further investigation,” check ALT and triglycerides prior to initiating isotretinoin. Then start isotretinoin.

“At the peak dose, recheck ALT and triglycerides – this might be at month 2,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Other people wait a little bit longer. No labs are required once treatment is complete. Of course, adjust this approach based on your assessment of the patient in front of you. None of these recommendations should replace your clinical judgment and intuition.”

He proposed a new paradigm where dermatologists can ask themselves three questions for every patient they see: Why is this intervention or test being done? Why is it being done in this patient? And why do it at that time? “If we think this way, we can identify some inconsistencies in our own thinking and opportunities for improvement,” he said.

Dr. Mostaghimi reported that he is a consultant to Pfizer, Concert, Lilly, and Bioniz. He is also an advisor to Him & Hers Cosmetics and Digital Diagnostics and is an associate editor for JAMA Dermatology.

PORTLAND, ORE. – About 10 years ago when Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, became an attending physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, he noticed that some of his dermatology colleagues checked the potassium levels religiously in their female patients taking spironolactone, while others never did.

“It led to this question: Dr. Mostaghimi, director of the dermatology inpatient service at Brigham and Women’s, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

To find out, he and his colleagues reviewed 1,802 serum potassium measurements in a study of healthy young women with no known health conditions who were taking spironolactone, published in 2015. They discovered that 13 of those tests suggested mild hyperkalemia, defined as a level greater than 5.0 mEq/L. Of these, six were rechecked and were normal; no action was taken in the other seven patients.

“This led us to conclude that we spent $78,000 at our institution on testing that did not appear to yield clinically significant information for these patients, and that routine potassium monitoring is unnecessary for most women taking spironolactone for acne,” he said. Their findings have been validated “in many cohorts of data,” he added.

The study serves as an example of efforts dermatologists can take to curb unnecessary costs within the field to be “appropriate stewards of resources,” he continued. “We have to think about the ratio of benefit over cost. It’s not just about the cost, it’s about what you’re getting for the amount of money that you’re spending. The idea of this is not restricting or not giving people medications or access to things that they need. The idea is to do it in a thoughtful way that works across the population.”

Value thresholds

Determining the value thresholds of a particular medicine or procedure is also essential to good dermatology practice. To illustrate, Dr. Mostaghimi cited a prospective cohort study that compared treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in 1,536 consecutive patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) with and without limited life expectancy. More than two-thirds of the NMSCs (69%) were treated surgically. After adjusting for tumor and patient characteristics, the researchers found that 43% of patients with low life expectancy died within 5 years, but not from NMSC.

“Does that mean we shouldn’t do surgery for NMSC patients with low life expectancy?” he asked. “Should we do it less? Should we let the patients decide? It’s complicated. As a society, we have to decide what’s worth doing and what’s not worth doing,” he said. “What about old diseases with new treatments, like alopecia areata? Is alopecia areata a cosmetic condition? Dermatologists and patients wouldn’t classify it that way, but many insurers do. How do you negotiate that?”

In 2013, the American Academy of Dermatology identified 10 evidence-based recommendations that can support conversations between patients and dermatologists about treatments, tests, and procedures that may not be necessary. One of the recommendations was not to prescribe oral antifungal therapy for suspected nail fungus without confirmation of fungal infection.

“If a clinician thinks a patient has onychomycosis, he or she is usually right,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “But what’s the added cost/benefit of performing a KOH followed by PAS testing if negative or performing a PAS test directly versus just treating the patient?”

In 2006, he and his colleagues published the results of a decision analysis to address these questions. They determined that the costs of testing to avoid one case of clinically apparent liver injury with terbinafine treatment was $18.2-$43.7 million for the KOH screening pathway and $37.6 to $90.2 million for the PAS testing pathway.

“Is that worth it?” he asked. “Would we get more value for spending the money elsewhere? In this case, the answer is most likely yes.”

Isotretinoin lab testing

Translating research into recommendations and standards of care is one way to help curb costs in dermatology. As an example, he cited lab monitoring for patients treated with isotretinoin for acne.

“There have been a number of papers over the years that have suggested that the number of labs we do is excessive, that the value that they provide is low, and that abnormal results do not impact our decision-making,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Do some patients on isotretinoin get mildly elevated [liver function tests] and hypertriglyceridemia? Yes, that happens. Does it matter? Nothing has demonstrated that it matters. Does it matter that an 18-year-old has high triglycerides for 6 months? Rarely, if ever.”

To promote a new approach, he and a panel of acne experts from five continents performed a Delphi consensus study. Based on their consensus, they proposed a simple approach: For “generally healthy patients without underlying abnormalities or preexisting conditions warranting further investigation,” check ALT and triglycerides prior to initiating isotretinoin. Then start isotretinoin.

“At the peak dose, recheck ALT and triglycerides – this might be at month 2,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Other people wait a little bit longer. No labs are required once treatment is complete. Of course, adjust this approach based on your assessment of the patient in front of you. None of these recommendations should replace your clinical judgment and intuition.”

He proposed a new paradigm where dermatologists can ask themselves three questions for every patient they see: Why is this intervention or test being done? Why is it being done in this patient? And why do it at that time? “If we think this way, we can identify some inconsistencies in our own thinking and opportunities for improvement,” he said.

Dr. Mostaghimi reported that he is a consultant to Pfizer, Concert, Lilly, and Bioniz. He is also an advisor to Him & Hers Cosmetics and Digital Diagnostics and is an associate editor for JAMA Dermatology.

AT PDA 2022

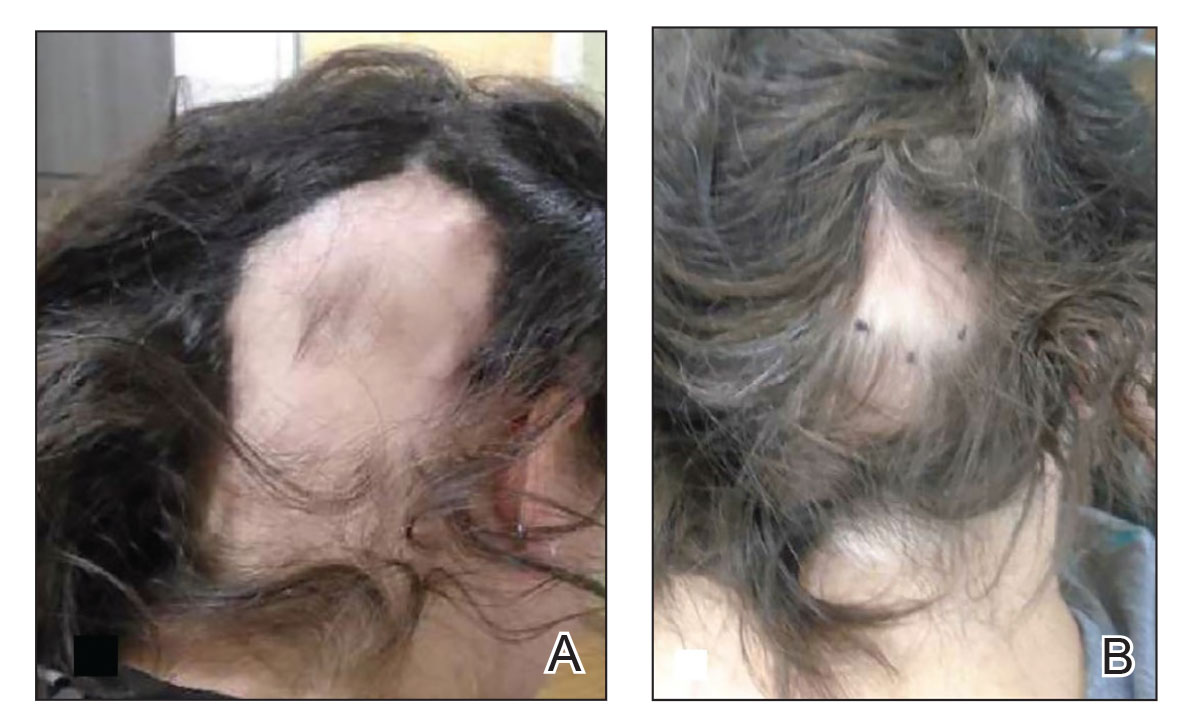

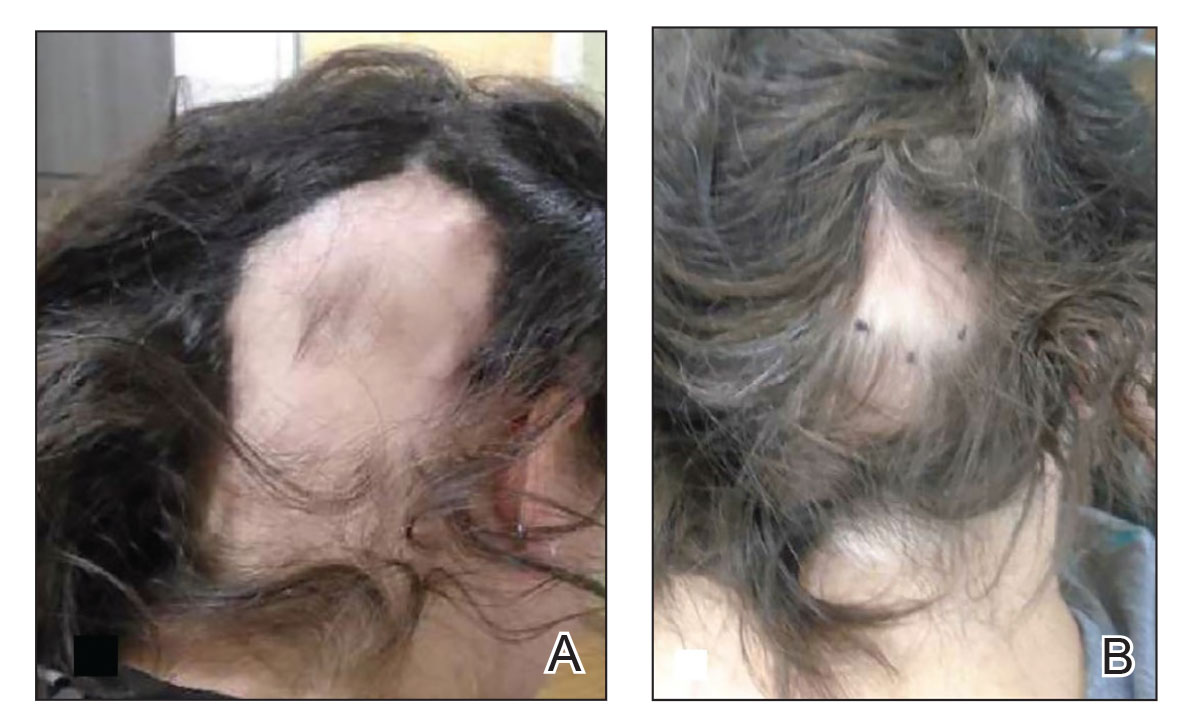

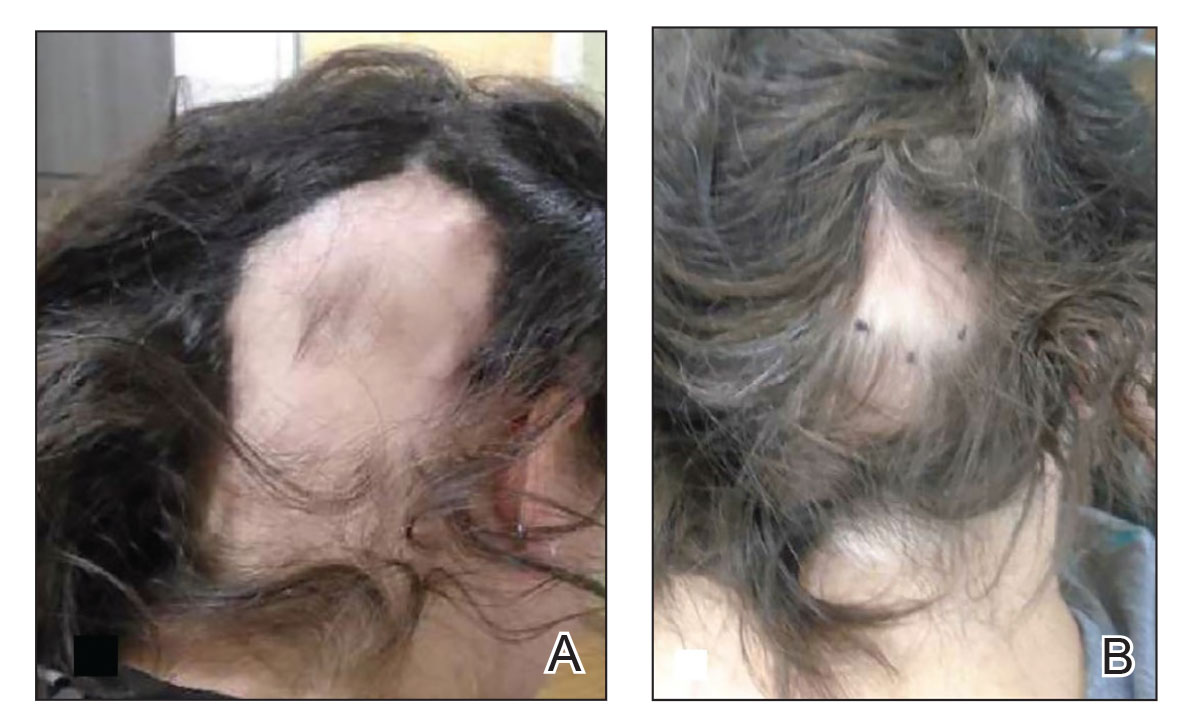

Uncombable hair syndrome: One gene, variants responsible for many cases

that manifests during infancy, investigators have reported.

The findings are from a cohort study published in JAMA Dermatology, which involved 107 unrelated children and adults suspected of having UHS, as well as family members, all of whom were recruited from January 2013 to December 2021. Genetic analyses were conducted in Germany from January 2014 to December 2021 with exome sequencing.

Study builds on prior research

Senior author Regina C. Betz, MD, professor of dermatogenetics at the Institute of Human Genetics, University Hospital Bonn, Germany, said that in 2016, she and her coinvestigators authored a study on the molecular genetics of UHS. That study, which involved 18 people with UHS, identified variants in three genes – PADI3, TCHH, and TGM3 – that encode proteins that play a role in the formation of the hair shaft. The investigators described how a deficiency in the shaping and mechanical strengthening of the hair shaft occurs in the UHS phenotype, which is characterized by dry, frizzy, and wiry hair that cannot be combed flat.

As a result of that previous work, “we base the assignment or confirmation of a clinical diagnosis of UHS on molecular genetic diagnostics,” the authors write in the new study, rather than on the clinical appearance of the hair and the physical examination of the patient, with confirmation on microscopical examination of the hair shaft.

Social media as instrument in finding study participants

Following the 2016 study, Dr. Betz and colleagues were contacted by many clinicians and by the public through Facebook and other social media platforms with details about possible cases of UHS, an autosomal recessive disorder. Through these contacts, blood samples, saliva, or DNA was sent to the investigators’ laboratory from 89 unrelated index patients (69 female patients, 20 male patients) suspected of having UHS. This resulted in the identification of pathogenic variants in 69 cases, the investigators write.

“In the first study, we had 18 patients, and then we tried to collect as many as possible” to determine the main mechanism behind UHS, Dr. Betz said. One question is whether there are additional genes responsible for UHS, she noted. “Even now, we are not sure, because in 25% [of cases in the new study], we didn’t find any mutation in the three known genes.”

The current study resulted in the discovery of eight novel pathogenic variants in PADI3, which are responsible for 71.0% (76) of the 107 cases. Of those, “6 were single observations and 2 were observed in 3 and 2 individuals, respectively,” the investigators write.

Children can grow out of this disorder, but it can also persist into adulthood, Dr. Betz noted. Communication that investigators had with parents of the children with UHS revealed that these children are often the targets of bullying by other children, she added.

She and her and colleagues will continue this research and are currently studying adults who have UHS.

Research leads to possible treatment pathways

Jeff Donovan, MD, FRCPC, FAAD, a dermatologist and medical director of the Donovan Hair Clinic in Whistler, British Columbia, described these findings as fundamental to understanding UHS and creating pathways to possible treatments.

The study “identifies more about the genetic basis of this challenging condition,” said Dr. Donovan, who is also clinical instructor in the department of dermatology at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and president of the Canadian Hair Loss Foundation. “We really need this type of information in order to have any sort of clue in terms of how to treat it,” he told this news organization.

“In the hair loss world, it’s pretty clear that if you can understand the genetic basis of things, or the basic science of a condition, whether it’s the basic genetics or the basic immunology, you give yourself the best chance to develop good treatments,” said Dr. Donovan.

The article provides advanced genetic information of the condition, such that geneticists can test for at least three markers if they are suspecting UHS, Dr. Donovan observed.

Condition can lead to bullying

Dr. Donovan also commented that UHS can have a detrimental impact on children with regard to socializing with their peers. “Having hair that sticks out and is very full like this is challenging because kids do get teased,” he said.

“It is often the parents who are the most affected” when a child aged 2-5 years has a hair condition such as UHS. But at age 5-9, “children are developing self-identity and an understanding of various aspects of self-esteem and what they look like and what others look like. And that’s where the teasing really starts. And that’s where it does become troublesome.”

Dr. Betz and Dr. Donovan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

that manifests during infancy, investigators have reported.

The findings are from a cohort study published in JAMA Dermatology, which involved 107 unrelated children and adults suspected of having UHS, as well as family members, all of whom were recruited from January 2013 to December 2021. Genetic analyses were conducted in Germany from January 2014 to December 2021 with exome sequencing.

Study builds on prior research

Senior author Regina C. Betz, MD, professor of dermatogenetics at the Institute of Human Genetics, University Hospital Bonn, Germany, said that in 2016, she and her coinvestigators authored a study on the molecular genetics of UHS. That study, which involved 18 people with UHS, identified variants in three genes – PADI3, TCHH, and TGM3 – that encode proteins that play a role in the formation of the hair shaft. The investigators described how a deficiency in the shaping and mechanical strengthening of the hair shaft occurs in the UHS phenotype, which is characterized by dry, frizzy, and wiry hair that cannot be combed flat.

As a result of that previous work, “we base the assignment or confirmation of a clinical diagnosis of UHS on molecular genetic diagnostics,” the authors write in the new study, rather than on the clinical appearance of the hair and the physical examination of the patient, with confirmation on microscopical examination of the hair shaft.

Social media as instrument in finding study participants

Following the 2016 study, Dr. Betz and colleagues were contacted by many clinicians and by the public through Facebook and other social media platforms with details about possible cases of UHS, an autosomal recessive disorder. Through these contacts, blood samples, saliva, or DNA was sent to the investigators’ laboratory from 89 unrelated index patients (69 female patients, 20 male patients) suspected of having UHS. This resulted in the identification of pathogenic variants in 69 cases, the investigators write.

“In the first study, we had 18 patients, and then we tried to collect as many as possible” to determine the main mechanism behind UHS, Dr. Betz said. One question is whether there are additional genes responsible for UHS, she noted. “Even now, we are not sure, because in 25% [of cases in the new study], we didn’t find any mutation in the three known genes.”

The current study resulted in the discovery of eight novel pathogenic variants in PADI3, which are responsible for 71.0% (76) of the 107 cases. Of those, “6 were single observations and 2 were observed in 3 and 2 individuals, respectively,” the investigators write.

Children can grow out of this disorder, but it can also persist into adulthood, Dr. Betz noted. Communication that investigators had with parents of the children with UHS revealed that these children are often the targets of bullying by other children, she added.

She and her and colleagues will continue this research and are currently studying adults who have UHS.

Research leads to possible treatment pathways

Jeff Donovan, MD, FRCPC, FAAD, a dermatologist and medical director of the Donovan Hair Clinic in Whistler, British Columbia, described these findings as fundamental to understanding UHS and creating pathways to possible treatments.

The study “identifies more about the genetic basis of this challenging condition,” said Dr. Donovan, who is also clinical instructor in the department of dermatology at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and president of the Canadian Hair Loss Foundation. “We really need this type of information in order to have any sort of clue in terms of how to treat it,” he told this news organization.

“In the hair loss world, it’s pretty clear that if you can understand the genetic basis of things, or the basic science of a condition, whether it’s the basic genetics or the basic immunology, you give yourself the best chance to develop good treatments,” said Dr. Donovan.

The article provides advanced genetic information of the condition, such that geneticists can test for at least three markers if they are suspecting UHS, Dr. Donovan observed.

Condition can lead to bullying

Dr. Donovan also commented that UHS can have a detrimental impact on children with regard to socializing with their peers. “Having hair that sticks out and is very full like this is challenging because kids do get teased,” he said.

“It is often the parents who are the most affected” when a child aged 2-5 years has a hair condition such as UHS. But at age 5-9, “children are developing self-identity and an understanding of various aspects of self-esteem and what they look like and what others look like. And that’s where the teasing really starts. And that’s where it does become troublesome.”

Dr. Betz and Dr. Donovan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

that manifests during infancy, investigators have reported.

The findings are from a cohort study published in JAMA Dermatology, which involved 107 unrelated children and adults suspected of having UHS, as well as family members, all of whom were recruited from January 2013 to December 2021. Genetic analyses were conducted in Germany from January 2014 to December 2021 with exome sequencing.

Study builds on prior research

Senior author Regina C. Betz, MD, professor of dermatogenetics at the Institute of Human Genetics, University Hospital Bonn, Germany, said that in 2016, she and her coinvestigators authored a study on the molecular genetics of UHS. That study, which involved 18 people with UHS, identified variants in three genes – PADI3, TCHH, and TGM3 – that encode proteins that play a role in the formation of the hair shaft. The investigators described how a deficiency in the shaping and mechanical strengthening of the hair shaft occurs in the UHS phenotype, which is characterized by dry, frizzy, and wiry hair that cannot be combed flat.

As a result of that previous work, “we base the assignment or confirmation of a clinical diagnosis of UHS on molecular genetic diagnostics,” the authors write in the new study, rather than on the clinical appearance of the hair and the physical examination of the patient, with confirmation on microscopical examination of the hair shaft.

Social media as instrument in finding study participants

Following the 2016 study, Dr. Betz and colleagues were contacted by many clinicians and by the public through Facebook and other social media platforms with details about possible cases of UHS, an autosomal recessive disorder. Through these contacts, blood samples, saliva, or DNA was sent to the investigators’ laboratory from 89 unrelated index patients (69 female patients, 20 male patients) suspected of having UHS. This resulted in the identification of pathogenic variants in 69 cases, the investigators write.

“In the first study, we had 18 patients, and then we tried to collect as many as possible” to determine the main mechanism behind UHS, Dr. Betz said. One question is whether there are additional genes responsible for UHS, she noted. “Even now, we are not sure, because in 25% [of cases in the new study], we didn’t find any mutation in the three known genes.”

The current study resulted in the discovery of eight novel pathogenic variants in PADI3, which are responsible for 71.0% (76) of the 107 cases. Of those, “6 were single observations and 2 were observed in 3 and 2 individuals, respectively,” the investigators write.

Children can grow out of this disorder, but it can also persist into adulthood, Dr. Betz noted. Communication that investigators had with parents of the children with UHS revealed that these children are often the targets of bullying by other children, she added.

She and her and colleagues will continue this research and are currently studying adults who have UHS.

Research leads to possible treatment pathways

Jeff Donovan, MD, FRCPC, FAAD, a dermatologist and medical director of the Donovan Hair Clinic in Whistler, British Columbia, described these findings as fundamental to understanding UHS and creating pathways to possible treatments.

The study “identifies more about the genetic basis of this challenging condition,” said Dr. Donovan, who is also clinical instructor in the department of dermatology at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and president of the Canadian Hair Loss Foundation. “We really need this type of information in order to have any sort of clue in terms of how to treat it,” he told this news organization.

“In the hair loss world, it’s pretty clear that if you can understand the genetic basis of things, or the basic science of a condition, whether it’s the basic genetics or the basic immunology, you give yourself the best chance to develop good treatments,” said Dr. Donovan.

The article provides advanced genetic information of the condition, such that geneticists can test for at least three markers if they are suspecting UHS, Dr. Donovan observed.

Condition can lead to bullying

Dr. Donovan also commented that UHS can have a detrimental impact on children with regard to socializing with their peers. “Having hair that sticks out and is very full like this is challenging because kids do get teased,” he said.

“It is often the parents who are the most affected” when a child aged 2-5 years has a hair condition such as UHS. But at age 5-9, “children are developing self-identity and an understanding of various aspects of self-esteem and what they look like and what others look like. And that’s where the teasing really starts. And that’s where it does become troublesome.”

Dr. Betz and Dr. Donovan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Low-dose oral minoxidil for the treatment of alopecia

Other than oral finasteride, vitamins, and topicals, there has been little advancement in the treatment of AGA leaving many (including me) desperate for anything remotely new.

Oral minoxidil is a peripheral vasodilator approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with hypertensive disease taken at doses ranging between 10 mg to 40 mg daily. Animal studies have shown that minoxidil affects the hair growth cycle by shortening the telogen phase and prolonging the anagen phase.

Recent case studies have also shown growing evidence for the off-label use of low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) for treating different types of alopecia. Topical minoxidil is metabolized into its active metabolite minoxidil sulfate, by sulfotransferase enzymes located in the outer root sheath of hair follicles. The expression of sulfotransferase varies greatly in the scalp of different individuals, and this difference is directly correlated to the wide range of responses to minoxidil treatment. LDOM is, however, more widely effective because it requires decreased follicular enzymatic activity to form its active metabolite as compared with its topical form.

In a retrospective series by Beach and colleagues evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of LDOM for treating AGA, there was increased scalp hair growth in 33 of 51 patients (65%) and decreased hair shedding in 14 of the 51 patients (27%) with LDOM. Patients with nonscarring alopecia were most likely to show improvement. Side effects were dose dependent and infrequent. The most frequent adverse effects were hypertrichosis, lightheadedness, edema, and tachycardia. No life-threatening adverse effects were observed. Although there has been a recently reported case report of severe pericardial effusion, edema, and anasarca in a woman with frontal fibrosing alopecia treated with LDOM, life threatening side effects are rare.3

To compare the efficacy of topical versus oral minoxidil, Ramos and colleagues performed a 24-week prospective study of low-dose (1 mg/day) oral minoxidil, compared with topical 5% minoxidil, in the treatment of 52 women with female pattern hair loss. Blinded analysis of trichoscopic images were evaluated to compare the change in total hair density in a target area from baseline to week 24 by three dermatologists.

Results after 24 weeks of treatment showed an increase in total hair density (12%) among the women taking oral minoxidil, compared with 7.2% in women who applied topical minoxidil (P =.09).

In the armamentarium of hair-loss treatments, dermatologists have limited choices. LDOM can be used in patients with both scarring and nonscarring alopecia if monitored regularly. Treatment doses I recommend are 1.25-5 mg daily titrated up slowly in properly selected patients without contraindications and those who are not taking other vasodilators. Self-reported dizziness, edema, and headache are common and treatments for facial hypertrichosis in women are always discussed. Clinical efficacy can be evaluated after 10-12 months of therapy and concomitant spironolactone can be given to mitigate the side effect of hypertrichosis.Patient selection is crucial as patients with severe scarring alopecia and those with active inflammatory diseases of the scalp may not see similar results. Similar to other hair loss treatments, treatment courses of 10-12 months are often needed to see visible signs of hair growth.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Talakoub had no relevant disclosures.

References

Beach RA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):761-3.

Dlova et al. JAAD Case Reports. 2022 Oct;28:94-6.

Jimenez-Cauhe J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jan;84(1):222-3.

Ramos PM et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jan;34(1):e40-1.

Ramos PM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82(1):252-3.

Randolph M and Tosti A. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):737-46.

Vañó-Galván S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jun;84(6):1644-51.

Other than oral finasteride, vitamins, and topicals, there has been little advancement in the treatment of AGA leaving many (including me) desperate for anything remotely new.

Oral minoxidil is a peripheral vasodilator approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with hypertensive disease taken at doses ranging between 10 mg to 40 mg daily. Animal studies have shown that minoxidil affects the hair growth cycle by shortening the telogen phase and prolonging the anagen phase.

Recent case studies have also shown growing evidence for the off-label use of low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) for treating different types of alopecia. Topical minoxidil is metabolized into its active metabolite minoxidil sulfate, by sulfotransferase enzymes located in the outer root sheath of hair follicles. The expression of sulfotransferase varies greatly in the scalp of different individuals, and this difference is directly correlated to the wide range of responses to minoxidil treatment. LDOM is, however, more widely effective because it requires decreased follicular enzymatic activity to form its active metabolite as compared with its topical form.

In a retrospective series by Beach and colleagues evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of LDOM for treating AGA, there was increased scalp hair growth in 33 of 51 patients (65%) and decreased hair shedding in 14 of the 51 patients (27%) with LDOM. Patients with nonscarring alopecia were most likely to show improvement. Side effects were dose dependent and infrequent. The most frequent adverse effects were hypertrichosis, lightheadedness, edema, and tachycardia. No life-threatening adverse effects were observed. Although there has been a recently reported case report of severe pericardial effusion, edema, and anasarca in a woman with frontal fibrosing alopecia treated with LDOM, life threatening side effects are rare.3

To compare the efficacy of topical versus oral minoxidil, Ramos and colleagues performed a 24-week prospective study of low-dose (1 mg/day) oral minoxidil, compared with topical 5% minoxidil, in the treatment of 52 women with female pattern hair loss. Blinded analysis of trichoscopic images were evaluated to compare the change in total hair density in a target area from baseline to week 24 by three dermatologists.

Results after 24 weeks of treatment showed an increase in total hair density (12%) among the women taking oral minoxidil, compared with 7.2% in women who applied topical minoxidil (P =.09).

In the armamentarium of hair-loss treatments, dermatologists have limited choices. LDOM can be used in patients with both scarring and nonscarring alopecia if monitored regularly. Treatment doses I recommend are 1.25-5 mg daily titrated up slowly in properly selected patients without contraindications and those who are not taking other vasodilators. Self-reported dizziness, edema, and headache are common and treatments for facial hypertrichosis in women are always discussed. Clinical efficacy can be evaluated after 10-12 months of therapy and concomitant spironolactone can be given to mitigate the side effect of hypertrichosis.Patient selection is crucial as patients with severe scarring alopecia and those with active inflammatory diseases of the scalp may not see similar results. Similar to other hair loss treatments, treatment courses of 10-12 months are often needed to see visible signs of hair growth.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Talakoub had no relevant disclosures.

References

Beach RA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):761-3.

Dlova et al. JAAD Case Reports. 2022 Oct;28:94-6.

Jimenez-Cauhe J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jan;84(1):222-3.

Ramos PM et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jan;34(1):e40-1.

Ramos PM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82(1):252-3.

Randolph M and Tosti A. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):737-46.

Vañó-Galván S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jun;84(6):1644-51.

Other than oral finasteride, vitamins, and topicals, there has been little advancement in the treatment of AGA leaving many (including me) desperate for anything remotely new.

Oral minoxidil is a peripheral vasodilator approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with hypertensive disease taken at doses ranging between 10 mg to 40 mg daily. Animal studies have shown that minoxidil affects the hair growth cycle by shortening the telogen phase and prolonging the anagen phase.

Recent case studies have also shown growing evidence for the off-label use of low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) for treating different types of alopecia. Topical minoxidil is metabolized into its active metabolite minoxidil sulfate, by sulfotransferase enzymes located in the outer root sheath of hair follicles. The expression of sulfotransferase varies greatly in the scalp of different individuals, and this difference is directly correlated to the wide range of responses to minoxidil treatment. LDOM is, however, more widely effective because it requires decreased follicular enzymatic activity to form its active metabolite as compared with its topical form.

In a retrospective series by Beach and colleagues evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of LDOM for treating AGA, there was increased scalp hair growth in 33 of 51 patients (65%) and decreased hair shedding in 14 of the 51 patients (27%) with LDOM. Patients with nonscarring alopecia were most likely to show improvement. Side effects were dose dependent and infrequent. The most frequent adverse effects were hypertrichosis, lightheadedness, edema, and tachycardia. No life-threatening adverse effects were observed. Although there has been a recently reported case report of severe pericardial effusion, edema, and anasarca in a woman with frontal fibrosing alopecia treated with LDOM, life threatening side effects are rare.3

To compare the efficacy of topical versus oral minoxidil, Ramos and colleagues performed a 24-week prospective study of low-dose (1 mg/day) oral minoxidil, compared with topical 5% minoxidil, in the treatment of 52 women with female pattern hair loss. Blinded analysis of trichoscopic images were evaluated to compare the change in total hair density in a target area from baseline to week 24 by three dermatologists.

Results after 24 weeks of treatment showed an increase in total hair density (12%) among the women taking oral minoxidil, compared with 7.2% in women who applied topical minoxidil (P =.09).

In the armamentarium of hair-loss treatments, dermatologists have limited choices. LDOM can be used in patients with both scarring and nonscarring alopecia if monitored regularly. Treatment doses I recommend are 1.25-5 mg daily titrated up slowly in properly selected patients without contraindications and those who are not taking other vasodilators. Self-reported dizziness, edema, and headache are common and treatments for facial hypertrichosis in women are always discussed. Clinical efficacy can be evaluated after 10-12 months of therapy and concomitant spironolactone can be given to mitigate the side effect of hypertrichosis.Patient selection is crucial as patients with severe scarring alopecia and those with active inflammatory diseases of the scalp may not see similar results. Similar to other hair loss treatments, treatment courses of 10-12 months are often needed to see visible signs of hair growth.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Talakoub had no relevant disclosures.

References

Beach RA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):761-3.

Dlova et al. JAAD Case Reports. 2022 Oct;28:94-6.

Jimenez-Cauhe J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jan;84(1):222-3.

Ramos PM et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jan;34(1):e40-1.

Ramos PM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82(1):252-3.

Randolph M and Tosti A. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):737-46.

Vañó-Galván S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jun;84(6):1644-51.

Expert shares tips on hair disorders and photoprotection for patients of color

PORTLAND, ORE. – , but sometimes their doctors fall short.

“Many times, you may not have race concordant visits with patients of color,” Janiene Luke, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. She referred to a survey of 200 Black women aged 21-83 years, which found that 28% had visited a physician to discuss hair or scalp issues. Of those, 68% felt like their dermatologists did not understand African American hair.

“I recommend trying the best you can to familiarize yourself with various common cultural hair styling methods and practices in patients of color. It’s important to understand what your patients are engaging in and the types of styles they’re using,” said Dr. Luke, associate professor of dermatology at Loma Linda (Calif.) University. “Approach all patients with cultural humility. We know from studies that patients value dermatologists who take time to listen to their concerns, involve them in the decision-making process, and educate them about their conditions,” she added.

National efforts to educate clinicians on treating skin of color have emerged in recent years, including textbooks, CME courses at dermatology conferences, and the American Academy of Dermatology’s Skin of Color Curriculum, which consists of 15-minute modules that can be viewed online.

At the meeting, Dr. Luke, shared her approach to assessing hair and scalp disorders in skin of color. She begins by taking a thorough history, “because not all things that are associated with hair styling will be the reason why your patient comes in,” she said. “Patients of color can have telogen effluvium and seborrheic dermatitis just like anyone else. I ask about the hair styling practices they use. I also ask how often they wash their hair, because sometimes our recommendations for treatment are not realistic based on their current routine.”

Next, she examines the scalp with her hands – which sometimes surprises patients. “I’ve had so many patients come in and say, ‘the dermatologist never touched my scalp,’ or ‘they never even looked at my hair,’ ” said Dr. Luke, who directs the university’s dermatology residency program. She asks patients to remove any hair extensions or weaves prior to the office visit and to remove wigs prior to the exam itself. The lab tests she customarily orders include CBC, TSH, iron, total iron binding capacity, ferritin, vitamin D, and zinc. If there are signs of androgen excess, she may check testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S). She routinely incorporates a dermoscopy-directed biopsy into the evaluation.

Dr. Luke examines the patient from above, the sides, and the back to assess the pattern/distribution of hair loss. A visible scalp at the vertex indicates a 50% reduction in normal hair density. “I’m looking at the hairline, their part width, and the length of their hair,” she said. “I also look at the eyebrows and eyelashes, because these can be involved in alopecia areata, frontal fibrosing alopecia, or congenital hair shaft disorders.”

On closeup examination, she looks for scarring versus non-scarring types of hair loss, and for the presence or absence of follicular ostia. “I also look at hair changes,” she said. “Is the texture of their hair different? Are there signs of breakage or fragility? It’s been noted in studies that breakage can be an early sign of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.” (For more tips on examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race discordant patient-physician interactions, she recommended a 2021 article in JAMA Dermatology)..

Trichoscopy allows for magnified observation of the hair shafts, hair follicle openings, perifollicular dermis, and blood vessels. Normal trichoscopy findings in skin of color reveal a perifollicular pigment network (honeycomb pattern) and pinpoint white dots that are regularly distributed between follicular units.

Common abnormalities seen on trichoscopy include central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), with one or two hairs emerging together, surrounded by a gray halo; lichen planopilaris/frontal fibrosing alopecia, characterized by hair with peripilar casts and absence of vellus hairs; discoid lupus erythematosus, characterized by keratotic plugs; and traction, characterized by hair casts.

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, Dr. Luke provides other general advice for optimal skin health, including a balanced (whole food) diet to ensure adequate nutrition. “I tend to find a lot of nutrient deficiencies that contribute to and compound their condition,” she said. Other recommendations include avoiding excess tension on the hair, such as hair styles with tight ponytails, buns, braids, and weaves; avoiding or limiting chemical treatments with hair color, relaxers, and permanents; and avoiding or limiting excessive heat styling with blow dryers, flat irons, and curling irons.

Photoprotection misconceptions

At the meeting, Dr. Luke also discussed three misconceptions of photoprotection in skin of color, drawn from an article on the topic published in 2021.

- Myth No. 1: Endogenous melanin provides complete photoprotection for Fitzpatrick skin types IV-V. Many people with skin of color may believe sunscreen is not needed given the melanin already present in their skin, but research has shown that the epidermis of dark skin has an intrinsic sun protection factor (SPF) of 13.4, compared with an SPF of 3.3 in light skin. “That may not provide them with full protection,” Dr. Luke said. “Many dermatologists are not counseling their skin of color patients about photoprotection.”

- Myth No. 2: Individuals with skin of color have negligible risks associated with skin cancer. Skin cancer prevalence in patients with skin of color is significantly lower compared with those with light skin. However, people with skin of color tend to be diagnosed with cancers at a more advanced stage, and cancers associated with a worse prognosis and poorer survival rate. An analysis of ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma that drew from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program found that Hispanic individuals (odds ratio [OR], 3.6), Black individuals (OR, 4.2), and Asian individuals (OR, 2.4), were more likely than were White individuals to have stage IV melanoma at the time of presentation. “For melanoma in skin of color, UV radiation does not seem to be a major risk factor, as melanoma tends to occur on palmar/plantar and subungual skin as well as mucous membranes,” Dr. Luke said. “For squamous cell carcinoma in skin of color, lesions are more likely to be present in areas that are not sun exposed. The risk factors for this tend to be chronic wounds, nonhealing ulcers, and people with chronic inflammatory conditions.” For basal cell carcinoma, she added, UV radiation seems to play more of a role and tends to occur in sun-exposed areas in patients with lighter Fitzpatrick skin types. Patients are more likely to present with pigmented BCCs.

- Myth No. 3: Broad-spectrum sunscreens provide photoprotection against all wavelengths of light that cause skin damage. To be labeled “broad-spectrum” the Food and Drug Administration requires that sunscreens have a critical wavelength of 370 nm or below, but Dr. Luke noted that broad-spectrum sunscreens do not necessarily protect against visible light (VL) and UV-A1. Research has demonstrated that VL exposure induces both transient and long-term cutaneous pigmentation in a dose-dependent manner.

“This induces free radicals and reactive oxygen species, leading to a cascade of events including the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases, and melanogenesis,” she said. “More intense and persistent VL-induced pigmentation occurs in subjects with darker skin. However, there is increasing evidence that antioxidants may help to mitigate these negative effects, so we are starting to see the addition of antioxidants into sunscreens.”

Dr. Luke recommends a broad-spectrum sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher for skin of color patients. Tinted sunscreens, which contain iron oxide pigments, are recommended for the prevention and treatment of pigmentary disorders in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI skin. “What about adding antioxidants to prevent formation of reactive oxygen species?” she asked. “It’s possible but we don’t have a lot of research yet. You also want a sunscreen that’s aesthetically elegant, meaning it doesn’t leave a white cast.”

Dr. Luke reported having no relevant disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – , but sometimes their doctors fall short.

“Many times, you may not have race concordant visits with patients of color,” Janiene Luke, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. She referred to a survey of 200 Black women aged 21-83 years, which found that 28% had visited a physician to discuss hair or scalp issues. Of those, 68% felt like their dermatologists did not understand African American hair.

“I recommend trying the best you can to familiarize yourself with various common cultural hair styling methods and practices in patients of color. It’s important to understand what your patients are engaging in and the types of styles they’re using,” said Dr. Luke, associate professor of dermatology at Loma Linda (Calif.) University. “Approach all patients with cultural humility. We know from studies that patients value dermatologists who take time to listen to their concerns, involve them in the decision-making process, and educate them about their conditions,” she added.

National efforts to educate clinicians on treating skin of color have emerged in recent years, including textbooks, CME courses at dermatology conferences, and the American Academy of Dermatology’s Skin of Color Curriculum, which consists of 15-minute modules that can be viewed online.