User login

Compulsivity contributes to poor outcomes in body-focused repetitive behaviors

Although body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs), specifically trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder, are similar in clinical presentation to aspects of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), the role of compulsivity in TTM and SPD has not been well studied, wrote Jon E. Grant, MD, of the University of Chicago and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, the authors recruited 69 women and 22 men who met DSM-5 criteria for TTM and SPD. Participants completed diagnostic interviews, symptom inventories, and measures of disability/functioning. Compulsivity was measured using the 15-item Cambridge-Chicago Compulsivity Trait Scale (CHI-T). The average age of the participants was 30.9 years; 48 had TTM, 37 had SPD, and 2 had both conditions.

Overall, total CHI-T scores were significantly correlated with worse disability and quality of life, based on the Quality of Life Inventory (P = .0278) and the Sheehan Disability Scale (P = .0085) but not with severity of TTM or SPD symptoms. TTM and SPD symptoms were assessed using the Massachusetts General Hospital Hair Pulling Scale and the Skin Picking Symptom Symptom Assessment Scale.

“In the current study, we did not find a link between conventional symptom severity measures for BFRBs and disability or quality of life, whereas trans-diagnostic compulsivity did correlate with these clinically important parameters,” the researchers wrote in their discussion. “These findings might suggest the current symptom measures for BFRBs are not including an important aspect of the disease and that a fuller understanding of these symptoms requires measurement of compulsivity. Including validated measures of compulsivity in clinical trials of therapy or medication would also seem to be important for future work,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of a community sample that may not generalize to a clinical setting, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the cross-sectional design, which prevents conclusions about causality, the lack of a control group, and the relatively small sample size, they said.

However, the study is the first known to use a validated compulsivity measure to assess BFRBs, and the results suggest a clinically relevant impact of compulsivity on both psychosocial dysfunction and poor quality of life in this patient population, with possible implications for treatment, the researchers wrote.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Grant disclosed research grants from Otsuka and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for acting as editor in chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies, and royalties from Oxford University Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, Norton Press, and McGraw Hill.

Although body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs), specifically trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder, are similar in clinical presentation to aspects of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), the role of compulsivity in TTM and SPD has not been well studied, wrote Jon E. Grant, MD, of the University of Chicago and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, the authors recruited 69 women and 22 men who met DSM-5 criteria for TTM and SPD. Participants completed diagnostic interviews, symptom inventories, and measures of disability/functioning. Compulsivity was measured using the 15-item Cambridge-Chicago Compulsivity Trait Scale (CHI-T). The average age of the participants was 30.9 years; 48 had TTM, 37 had SPD, and 2 had both conditions.

Overall, total CHI-T scores were significantly correlated with worse disability and quality of life, based on the Quality of Life Inventory (P = .0278) and the Sheehan Disability Scale (P = .0085) but not with severity of TTM or SPD symptoms. TTM and SPD symptoms were assessed using the Massachusetts General Hospital Hair Pulling Scale and the Skin Picking Symptom Symptom Assessment Scale.

“In the current study, we did not find a link between conventional symptom severity measures for BFRBs and disability or quality of life, whereas trans-diagnostic compulsivity did correlate with these clinically important parameters,” the researchers wrote in their discussion. “These findings might suggest the current symptom measures for BFRBs are not including an important aspect of the disease and that a fuller understanding of these symptoms requires measurement of compulsivity. Including validated measures of compulsivity in clinical trials of therapy or medication would also seem to be important for future work,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of a community sample that may not generalize to a clinical setting, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the cross-sectional design, which prevents conclusions about causality, the lack of a control group, and the relatively small sample size, they said.

However, the study is the first known to use a validated compulsivity measure to assess BFRBs, and the results suggest a clinically relevant impact of compulsivity on both psychosocial dysfunction and poor quality of life in this patient population, with possible implications for treatment, the researchers wrote.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Grant disclosed research grants from Otsuka and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for acting as editor in chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies, and royalties from Oxford University Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, Norton Press, and McGraw Hill.

Although body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs), specifically trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder, are similar in clinical presentation to aspects of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), the role of compulsivity in TTM and SPD has not been well studied, wrote Jon E. Grant, MD, of the University of Chicago and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, the authors recruited 69 women and 22 men who met DSM-5 criteria for TTM and SPD. Participants completed diagnostic interviews, symptom inventories, and measures of disability/functioning. Compulsivity was measured using the 15-item Cambridge-Chicago Compulsivity Trait Scale (CHI-T). The average age of the participants was 30.9 years; 48 had TTM, 37 had SPD, and 2 had both conditions.

Overall, total CHI-T scores were significantly correlated with worse disability and quality of life, based on the Quality of Life Inventory (P = .0278) and the Sheehan Disability Scale (P = .0085) but not with severity of TTM or SPD symptoms. TTM and SPD symptoms were assessed using the Massachusetts General Hospital Hair Pulling Scale and the Skin Picking Symptom Symptom Assessment Scale.

“In the current study, we did not find a link between conventional symptom severity measures for BFRBs and disability or quality of life, whereas trans-diagnostic compulsivity did correlate with these clinically important parameters,” the researchers wrote in their discussion. “These findings might suggest the current symptom measures for BFRBs are not including an important aspect of the disease and that a fuller understanding of these symptoms requires measurement of compulsivity. Including validated measures of compulsivity in clinical trials of therapy or medication would also seem to be important for future work,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of a community sample that may not generalize to a clinical setting, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the cross-sectional design, which prevents conclusions about causality, the lack of a control group, and the relatively small sample size, they said.

However, the study is the first known to use a validated compulsivity measure to assess BFRBs, and the results suggest a clinically relevant impact of compulsivity on both psychosocial dysfunction and poor quality of life in this patient population, with possible implications for treatment, the researchers wrote.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Grant disclosed research grants from Otsuka and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for acting as editor in chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies, and royalties from Oxford University Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, Norton Press, and McGraw Hill.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Baricitinib’s approval for alopecia areata: Considerations for starting patients on treatment

On June 13, the FDA approved baricitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor (Olumiant, Lilly), for severe AA, and two other options may not be far behind. Pfizer and Concert Pharmaceuticals have JAK inhibitors in late-stage development for AA. JAK inhibitors, including baricitinib, are already on the market for treating rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases.

Meanwhile, dermatologists have been fielding calls from hopeful patients and sorting out who should get the treatment, how to advise patients on risks and benefits, and what tests should be used before and after starting treatment.

Uptake for new systemic drugs, such as biologics, can be slow in dermatology, noted Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, as some doctors like to stick with what they know.

He told this news organization that he hopes that uptake for baricitinib is quicker, as it is the only approved oral systemic treatment for patients with severe alopecia areata, which affects about 300,000 people a year in the United States. Other treatments, including steroid injections in the scalp, have lacked efficacy and convenience.

Beyond the physical effects, the mental toll of patchy hair clumps and missing brows and lashes can be devastating for patients with alopecia areata.

Fielding patient inquiries

Word of the FDA approval spread fast, and calls and emails are coming into dermatologists’ offices and clinics from interested patients.

Physicians should be ready for patients with any kind of hair loss, not just severe alopecia areata, to ask about the drug, Dr. Friedman said. Some patients contacting him don’t fit the indication, which “highlights how disabling hair loss” is for people, considering that, in general, “people see this and think it is for them.”

Baricitinib is not a new drug, but a drug with a new indication. It had already been approved for treating moderate to severe RA in patients who have had an inadequate response to one or more tumor necrosis factor blockers, and for treating COVID-19 in certain hospitalized adults.

Boxed warning

Patients may ask about the boxed warning in the baricitinib label about the increased risk for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis.

Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, an investigator in the clinical trials that led to FDA approval of baricitinib and the chief scientific officer at the National Alopecia Areata Foundation, told this news organization that several aspects of the label are important to point out.

One is that the warning is for all the JAK inhibitors used to treat RA and other inflammatory conditions, not just baricitinib. Also, the warning is based mostly on data on patients with RA who, she noted, have substantial comorbidities and have been taking toxic immunosuppressive medications. The RA population is also typically many years older than the alopecia areata population.

“Whether the warnings apply to the alopecia areata patients is as yet unclear,” said Dr. Mesinkovska, who is also an associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine.

Patients are also asking about how well it works.

In one of the two trials that led up to the FDA approval, which enrolled patients with at least 50% scalp hair loss for over 6 months, 22% of the patients who received 2 mg of baricitinib and 35% of those who received 4 mg saw adequate hair coverage (at least 80%) at week 36, compared with 5% on placebo. In the second trial, 17% of those who received 2 mg and 32% who received 4 mg saw adequate hair coverage, compared with 3% on placebo.

Common side effects associated with baricitinib, according to the FDA, are lower respiratory tract infections, headache, acne, high cholesterol, increased creatinine phosphokinase, urinary tract infection, liver enzyme elevations, folliculitis, fatigue, nausea, genital yeast infections, anemia, neutropenia, abdominal pain, herpes zoster (shingles), and weight gain.

The risk-benefit discussions with patients should also include potential benefits beyond hair regrowth on the scalp. Loss of hair in the ears and nose can affect hearing and allergies, Dr. Mesinkovska said.

“About 30%-50% with alopecia areata, depending on age group or part of the world, will have allergies,” she said.

Patients should also know that baricitinib will need to be taken “for a very long time,” Dr. Mesinkovska noted. It’s possible that could be forever and that stopping the medication at any point may result in hair falling out again, she says, but duration will vary from case to case.

The good news is that it has been well tolerated. “We give a lot of medications for acne like doxycycline and other antibiotics and people have more stomach problems and angst with those than with [baricitinib],” she said.

Regrowth takes time

Benjamin Ungar, MD, a dermatologist at the Alopecia Center of Excellence at Mount Sinai, New York, told this news organization that an important message for patients is that hair regrowth takes time. For some other skin conditions, patients start treatment and see almost instant improvement.

“That is not the case for alopecia areata,” he said. “The expectation is that it will take months for regrowth in general.”

He said he hasn’t started prescribing baricitinib yet, but plans to do so soon.

“Obviously, I’ll have conversations with patients about it, but it’s a medication I’m going to be using, definitely. I have no reservations,” Dr. Ungar said.

After initial testing, physicians may find that some patients might not be ideal candidates, he added. People with liver disease, a history of blood clots, abnormal blood counts, or low neutrophils are among those who may not be the best candidates for baricitinib.

For most with severe alopecia areata, though, baricitinib provides hope.

“Treatment options have been not readily available, often inaccessible, ineffective, often dangerous,” he said. “There’s a treatment now that can be accessed, generally is safe and is effective for many people.”

Be up front with patients about the unknown

Additionally, it’s important to tell patients what is not yet known, the experts interviewed say.

“Alopecia areata is a chronic disease. We don’t have long-term data on the patient population yet,” Dr. Friedman said.

Also unknown is how easy it will be for physicians to get insurance to reimburse for baricitinib, which, at the end of June, was priced at about $5,000 a month for the 4-mg dose. FDA approval was important in that regard. Previously, some claims had been rejected for drugs used off label for AA.

“We dermatologists know how much it affects patients,” Dr. Mesinkovska said. “As long as we stick by what we know and convey to insurers how much it affects people’s lives, they should cover it.”

Another unknown is what other drugs can be taken with baricitinib. In clinical trials, it was used alone, she said. Currently, concomitant use of other immune suppressants – such as methotrexate or prednisone – is not recommended. But it remains to be seen what other medications will be safe to use at the same time as more long-term data are available.

Lynne J. Goldberg, MD, professor of dermatology, pathology, and laboratory medicine, Boston University, and director of the Hair Clinic at Boston Medical Center, said that she received a slew of emails from patients asking about baricitinib, but most of them did not have alopecia areata and were not candidates for this treatment.

She said that nurses in her clinic have been instructed on what to tell patients about which patients the drug is meant to treat, side effects, and benefits.

Access won’t be immediate

Dr. Goldberg said the drug’s approval does not mean immediate access. The patient has to come in, discuss the treatment, and get lab tests first. “It’s not a casual drug. This is a potent immunosuppressant drug. You need lab tests and once you start it you need blood tests every 3 months to stay on it.”

Those tests may vary by physician, but people will generally need a standard blood count and a comprehensive metabolic panel and lipid panel. “There’s nothing esoteric,” she said.

She added that physicians will need to check for presence of infections including tuberculosis and hepatitis B and C before prescribing, just as they would before they start prescribing a biologic.

“You don’t want to reactivate something,” she noted.

But, Dr. Goldberg added, the benefits for all who have been either living with only patches of hair or no hair or who put on a wig or hat every day are “life changing.”

Dr. Mesinkovska is on the advisory boards and runs trials for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Concert Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Friedman, Dr. Goldberg, and Dr. Ungar reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On June 13, the FDA approved baricitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor (Olumiant, Lilly), for severe AA, and two other options may not be far behind. Pfizer and Concert Pharmaceuticals have JAK inhibitors in late-stage development for AA. JAK inhibitors, including baricitinib, are already on the market for treating rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases.

Meanwhile, dermatologists have been fielding calls from hopeful patients and sorting out who should get the treatment, how to advise patients on risks and benefits, and what tests should be used before and after starting treatment.

Uptake for new systemic drugs, such as biologics, can be slow in dermatology, noted Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, as some doctors like to stick with what they know.

He told this news organization that he hopes that uptake for baricitinib is quicker, as it is the only approved oral systemic treatment for patients with severe alopecia areata, which affects about 300,000 people a year in the United States. Other treatments, including steroid injections in the scalp, have lacked efficacy and convenience.

Beyond the physical effects, the mental toll of patchy hair clumps and missing brows and lashes can be devastating for patients with alopecia areata.

Fielding patient inquiries

Word of the FDA approval spread fast, and calls and emails are coming into dermatologists’ offices and clinics from interested patients.

Physicians should be ready for patients with any kind of hair loss, not just severe alopecia areata, to ask about the drug, Dr. Friedman said. Some patients contacting him don’t fit the indication, which “highlights how disabling hair loss” is for people, considering that, in general, “people see this and think it is for them.”

Baricitinib is not a new drug, but a drug with a new indication. It had already been approved for treating moderate to severe RA in patients who have had an inadequate response to one or more tumor necrosis factor blockers, and for treating COVID-19 in certain hospitalized adults.

Boxed warning

Patients may ask about the boxed warning in the baricitinib label about the increased risk for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis.

Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, an investigator in the clinical trials that led to FDA approval of baricitinib and the chief scientific officer at the National Alopecia Areata Foundation, told this news organization that several aspects of the label are important to point out.

One is that the warning is for all the JAK inhibitors used to treat RA and other inflammatory conditions, not just baricitinib. Also, the warning is based mostly on data on patients with RA who, she noted, have substantial comorbidities and have been taking toxic immunosuppressive medications. The RA population is also typically many years older than the alopecia areata population.

“Whether the warnings apply to the alopecia areata patients is as yet unclear,” said Dr. Mesinkovska, who is also an associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine.

Patients are also asking about how well it works.

In one of the two trials that led up to the FDA approval, which enrolled patients with at least 50% scalp hair loss for over 6 months, 22% of the patients who received 2 mg of baricitinib and 35% of those who received 4 mg saw adequate hair coverage (at least 80%) at week 36, compared with 5% on placebo. In the second trial, 17% of those who received 2 mg and 32% who received 4 mg saw adequate hair coverage, compared with 3% on placebo.

Common side effects associated with baricitinib, according to the FDA, are lower respiratory tract infections, headache, acne, high cholesterol, increased creatinine phosphokinase, urinary tract infection, liver enzyme elevations, folliculitis, fatigue, nausea, genital yeast infections, anemia, neutropenia, abdominal pain, herpes zoster (shingles), and weight gain.

The risk-benefit discussions with patients should also include potential benefits beyond hair regrowth on the scalp. Loss of hair in the ears and nose can affect hearing and allergies, Dr. Mesinkovska said.

“About 30%-50% with alopecia areata, depending on age group or part of the world, will have allergies,” she said.

Patients should also know that baricitinib will need to be taken “for a very long time,” Dr. Mesinkovska noted. It’s possible that could be forever and that stopping the medication at any point may result in hair falling out again, she says, but duration will vary from case to case.

The good news is that it has been well tolerated. “We give a lot of medications for acne like doxycycline and other antibiotics and people have more stomach problems and angst with those than with [baricitinib],” she said.

Regrowth takes time

Benjamin Ungar, MD, a dermatologist at the Alopecia Center of Excellence at Mount Sinai, New York, told this news organization that an important message for patients is that hair regrowth takes time. For some other skin conditions, patients start treatment and see almost instant improvement.

“That is not the case for alopecia areata,” he said. “The expectation is that it will take months for regrowth in general.”

He said he hasn’t started prescribing baricitinib yet, but plans to do so soon.

“Obviously, I’ll have conversations with patients about it, but it’s a medication I’m going to be using, definitely. I have no reservations,” Dr. Ungar said.

After initial testing, physicians may find that some patients might not be ideal candidates, he added. People with liver disease, a history of blood clots, abnormal blood counts, or low neutrophils are among those who may not be the best candidates for baricitinib.

For most with severe alopecia areata, though, baricitinib provides hope.

“Treatment options have been not readily available, often inaccessible, ineffective, often dangerous,” he said. “There’s a treatment now that can be accessed, generally is safe and is effective for many people.”

Be up front with patients about the unknown

Additionally, it’s important to tell patients what is not yet known, the experts interviewed say.

“Alopecia areata is a chronic disease. We don’t have long-term data on the patient population yet,” Dr. Friedman said.

Also unknown is how easy it will be for physicians to get insurance to reimburse for baricitinib, which, at the end of June, was priced at about $5,000 a month for the 4-mg dose. FDA approval was important in that regard. Previously, some claims had been rejected for drugs used off label for AA.

“We dermatologists know how much it affects patients,” Dr. Mesinkovska said. “As long as we stick by what we know and convey to insurers how much it affects people’s lives, they should cover it.”

Another unknown is what other drugs can be taken with baricitinib. In clinical trials, it was used alone, she said. Currently, concomitant use of other immune suppressants – such as methotrexate or prednisone – is not recommended. But it remains to be seen what other medications will be safe to use at the same time as more long-term data are available.

Lynne J. Goldberg, MD, professor of dermatology, pathology, and laboratory medicine, Boston University, and director of the Hair Clinic at Boston Medical Center, said that she received a slew of emails from patients asking about baricitinib, but most of them did not have alopecia areata and were not candidates for this treatment.

She said that nurses in her clinic have been instructed on what to tell patients about which patients the drug is meant to treat, side effects, and benefits.

Access won’t be immediate

Dr. Goldberg said the drug’s approval does not mean immediate access. The patient has to come in, discuss the treatment, and get lab tests first. “It’s not a casual drug. This is a potent immunosuppressant drug. You need lab tests and once you start it you need blood tests every 3 months to stay on it.”

Those tests may vary by physician, but people will generally need a standard blood count and a comprehensive metabolic panel and lipid panel. “There’s nothing esoteric,” she said.

She added that physicians will need to check for presence of infections including tuberculosis and hepatitis B and C before prescribing, just as they would before they start prescribing a biologic.

“You don’t want to reactivate something,” she noted.

But, Dr. Goldberg added, the benefits for all who have been either living with only patches of hair or no hair or who put on a wig or hat every day are “life changing.”

Dr. Mesinkovska is on the advisory boards and runs trials for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Concert Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Friedman, Dr. Goldberg, and Dr. Ungar reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On June 13, the FDA approved baricitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor (Olumiant, Lilly), for severe AA, and two other options may not be far behind. Pfizer and Concert Pharmaceuticals have JAK inhibitors in late-stage development for AA. JAK inhibitors, including baricitinib, are already on the market for treating rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases.

Meanwhile, dermatologists have been fielding calls from hopeful patients and sorting out who should get the treatment, how to advise patients on risks and benefits, and what tests should be used before and after starting treatment.

Uptake for new systemic drugs, such as biologics, can be slow in dermatology, noted Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, as some doctors like to stick with what they know.

He told this news organization that he hopes that uptake for baricitinib is quicker, as it is the only approved oral systemic treatment for patients with severe alopecia areata, which affects about 300,000 people a year in the United States. Other treatments, including steroid injections in the scalp, have lacked efficacy and convenience.

Beyond the physical effects, the mental toll of patchy hair clumps and missing brows and lashes can be devastating for patients with alopecia areata.

Fielding patient inquiries

Word of the FDA approval spread fast, and calls and emails are coming into dermatologists’ offices and clinics from interested patients.

Physicians should be ready for patients with any kind of hair loss, not just severe alopecia areata, to ask about the drug, Dr. Friedman said. Some patients contacting him don’t fit the indication, which “highlights how disabling hair loss” is for people, considering that, in general, “people see this and think it is for them.”

Baricitinib is not a new drug, but a drug with a new indication. It had already been approved for treating moderate to severe RA in patients who have had an inadequate response to one or more tumor necrosis factor blockers, and for treating COVID-19 in certain hospitalized adults.

Boxed warning

Patients may ask about the boxed warning in the baricitinib label about the increased risk for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis.

Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, an investigator in the clinical trials that led to FDA approval of baricitinib and the chief scientific officer at the National Alopecia Areata Foundation, told this news organization that several aspects of the label are important to point out.

One is that the warning is for all the JAK inhibitors used to treat RA and other inflammatory conditions, not just baricitinib. Also, the warning is based mostly on data on patients with RA who, she noted, have substantial comorbidities and have been taking toxic immunosuppressive medications. The RA population is also typically many years older than the alopecia areata population.

“Whether the warnings apply to the alopecia areata patients is as yet unclear,” said Dr. Mesinkovska, who is also an associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine.

Patients are also asking about how well it works.

In one of the two trials that led up to the FDA approval, which enrolled patients with at least 50% scalp hair loss for over 6 months, 22% of the patients who received 2 mg of baricitinib and 35% of those who received 4 mg saw adequate hair coverage (at least 80%) at week 36, compared with 5% on placebo. In the second trial, 17% of those who received 2 mg and 32% who received 4 mg saw adequate hair coverage, compared with 3% on placebo.

Common side effects associated with baricitinib, according to the FDA, are lower respiratory tract infections, headache, acne, high cholesterol, increased creatinine phosphokinase, urinary tract infection, liver enzyme elevations, folliculitis, fatigue, nausea, genital yeast infections, anemia, neutropenia, abdominal pain, herpes zoster (shingles), and weight gain.

The risk-benefit discussions with patients should also include potential benefits beyond hair regrowth on the scalp. Loss of hair in the ears and nose can affect hearing and allergies, Dr. Mesinkovska said.

“About 30%-50% with alopecia areata, depending on age group or part of the world, will have allergies,” she said.

Patients should also know that baricitinib will need to be taken “for a very long time,” Dr. Mesinkovska noted. It’s possible that could be forever and that stopping the medication at any point may result in hair falling out again, she says, but duration will vary from case to case.

The good news is that it has been well tolerated. “We give a lot of medications for acne like doxycycline and other antibiotics and people have more stomach problems and angst with those than with [baricitinib],” she said.

Regrowth takes time

Benjamin Ungar, MD, a dermatologist at the Alopecia Center of Excellence at Mount Sinai, New York, told this news organization that an important message for patients is that hair regrowth takes time. For some other skin conditions, patients start treatment and see almost instant improvement.

“That is not the case for alopecia areata,” he said. “The expectation is that it will take months for regrowth in general.”

He said he hasn’t started prescribing baricitinib yet, but plans to do so soon.

“Obviously, I’ll have conversations with patients about it, but it’s a medication I’m going to be using, definitely. I have no reservations,” Dr. Ungar said.

After initial testing, physicians may find that some patients might not be ideal candidates, he added. People with liver disease, a history of blood clots, abnormal blood counts, or low neutrophils are among those who may not be the best candidates for baricitinib.

For most with severe alopecia areata, though, baricitinib provides hope.

“Treatment options have been not readily available, often inaccessible, ineffective, often dangerous,” he said. “There’s a treatment now that can be accessed, generally is safe and is effective for many people.”

Be up front with patients about the unknown

Additionally, it’s important to tell patients what is not yet known, the experts interviewed say.

“Alopecia areata is a chronic disease. We don’t have long-term data on the patient population yet,” Dr. Friedman said.

Also unknown is how easy it will be for physicians to get insurance to reimburse for baricitinib, which, at the end of June, was priced at about $5,000 a month for the 4-mg dose. FDA approval was important in that regard. Previously, some claims had been rejected for drugs used off label for AA.

“We dermatologists know how much it affects patients,” Dr. Mesinkovska said. “As long as we stick by what we know and convey to insurers how much it affects people’s lives, they should cover it.”

Another unknown is what other drugs can be taken with baricitinib. In clinical trials, it was used alone, she said. Currently, concomitant use of other immune suppressants – such as methotrexate or prednisone – is not recommended. But it remains to be seen what other medications will be safe to use at the same time as more long-term data are available.

Lynne J. Goldberg, MD, professor of dermatology, pathology, and laboratory medicine, Boston University, and director of the Hair Clinic at Boston Medical Center, said that she received a slew of emails from patients asking about baricitinib, but most of them did not have alopecia areata and were not candidates for this treatment.

She said that nurses in her clinic have been instructed on what to tell patients about which patients the drug is meant to treat, side effects, and benefits.

Access won’t be immediate

Dr. Goldberg said the drug’s approval does not mean immediate access. The patient has to come in, discuss the treatment, and get lab tests first. “It’s not a casual drug. This is a potent immunosuppressant drug. You need lab tests and once you start it you need blood tests every 3 months to stay on it.”

Those tests may vary by physician, but people will generally need a standard blood count and a comprehensive metabolic panel and lipid panel. “There’s nothing esoteric,” she said.

She added that physicians will need to check for presence of infections including tuberculosis and hepatitis B and C before prescribing, just as they would before they start prescribing a biologic.

“You don’t want to reactivate something,” she noted.

But, Dr. Goldberg added, the benefits for all who have been either living with only patches of hair or no hair or who put on a wig or hat every day are “life changing.”

Dr. Mesinkovska is on the advisory boards and runs trials for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Concert Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Friedman, Dr. Goldberg, and Dr. Ungar reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hair disorder treatments are evolving

“No matter who the patient is, whether a child, adolescent, or adult, the key to figuring out hair disease is getting a good history,” Maria Hordinsky, MD, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said at the Medscape Live Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

. She also urged physicians and other health care providers to use the electronic medical record and to be thorough in documenting information – noting nutrition, hair care habits, supplement use, and other details.

Lab tests should be selected based on that history, she said. For instance, low iron stores can be associated with hair shedding; and thyroid function studies might be needed.

Other highlights of her presentation included comments on different types of alopecia, and some new treatment approaches:

Androgenetic alopecia. In a meta-analysis and systematic review published in 2017, all treatments tested (2% and 5% minoxidil in men, 1 mg finasteride in men, 2% minoxidil in women, and low-level laser light therapy in men) were superior to placebo. Several photobiomodulation (PBM) devices (also known as low-level laser light) for home use have been cleared for androgenetic alopecia by the Food and Drug Administration; a clinician’s guide, published in 2018, provides information on these devices.

Hair and hormones. Combination therapy for female-pattern hair loss – low-dose minoxidil and spironolactone – is important to know about, she said, adding there are data from an observational pilot study supporting this treatment. Women should not become pregnant while on this treatment, Dr. Hordinsky cautioned.

PRP (platelet rich plasma). This treatment for hair loss can be costly, she cautioned, as it’s viewed as a cosmetic technique, “but it actually can work rather well.”

Hair regrowth measures. Traditionally, measures center on global assessment, the patient’s self-assessment, investigator assessment, and an independent photo review. Enter the dermatoscope. “We can now get pictures as a baseline. Patients can see, and also see the health of their scalp,” and if treatments make it look better or worse, she noted.

Alopecia areata (AA). Patients and families need to be made aware that this is an autoimmune disease that can recur, and if it does recur, the extent of hair loss is not predictable. According to Dr. Hordinsky, the most widely used tool to halt disease activity has been treatment with a corticosteroid (topical, intralesional, oral, or even intravenous corticosteroids).

Clinical trials and publications from 2018 to 2020 have triggered interest in off-label use and further studies of JAK inhibitors for treating AA, which include baricitinib, ruxolitinib, and tofacitinib. At the American Academy of Dermatology meeting in March 2022, results of the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 trial found that the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib (50 mg or 20 mg daily, with or without a 200-mg loading dose), was efficacious in adults and adolescents with AA, compared with placebo, with no safety concerns noted. “This looks to be very, very promising,” she said, “and also very safe.” Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib also presented at the same meeting found it was superior to placebo for hair regrowth in adults with severe AA at 36 weeks. (On June 13, shortly after Dr. Hordinsky spoke at the meeting, the FDA approved baricitinib for treating AA in adults, making this the first systemic treatment to be approved for AA).

Research on topical JAK inhibitors for AA has been disappointing, Dr. Hordinsky said.

Alopecia areata and atopic dermatitis. For patients with both AA and AD, dupilumab may provide relief, she said. She referred to a recently published phase 2a trial in patients with AA (including some with both AA and AD), which found that Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores improved after 48 weeks of treatment, with higher response rates among those with baseline IgE levels of 200 IU/mL or higher. “If your patient has both, and their immunoglobulin-E level is greater than 200, then they may be a good candidate for dupilumab and both diseases may respond,” she said.

Scalp symptoms. It can be challenging when patients complain of itch, pain, or burning on the scalp, but have no obvious skin disease, Dr. Hordinsky said. Her tips: Some of these patients may be experiencing scalp symptoms secondary to a neuropathy; others may have mast cell degranulation, but for others, the basis of the symptoms may be unclear. Special nerve studies may be needed. For relief, a trial of antihistamines or topical or oral gabapentin may be needed, she said.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA). This condition, first described in postmenopausal women, is now reported in men and in younger women. While sunscreen has been suspected, there are no good data that have proven that link, she said. Cosmetics are also considered a possible culprit. For treatment, “the first thing we try to do is treat the inflammation,” Dr. Hordinsky said. Treatment options include topical high-potency corticosteroids, intralesional steroids, and topical nonsteroid anti-inflammatory creams (tier 1); hydroxychloroquine, low-dose antibiotics, and acitretin (tier 2); and cyclosporin and mycophenolate mofetil (tier 3).

In an observational study of mostly women with FFA, she noted, treatment with dutasteride was more effective than commonly used systemic treatments.

“Don’t forget to address the psychosocial needs of the hair loss patient,” Dr. Hordinsky advised. “Hair loss patients are very distressed, and you have to learn how to be fast and nimble and address those needs.” Working with a behavioral health specialist or therapist can help, she said.

She also recommended directing patients to appropriate organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation and the Scarring Alopecia Foundation, as well as conferences, such as the upcoming NAAF conference in Washington. “These organizations do give good information that should complement what you are doing.”

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Hordinsky reported no disclosures.

“No matter who the patient is, whether a child, adolescent, or adult, the key to figuring out hair disease is getting a good history,” Maria Hordinsky, MD, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said at the Medscape Live Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

. She also urged physicians and other health care providers to use the electronic medical record and to be thorough in documenting information – noting nutrition, hair care habits, supplement use, and other details.

Lab tests should be selected based on that history, she said. For instance, low iron stores can be associated with hair shedding; and thyroid function studies might be needed.

Other highlights of her presentation included comments on different types of alopecia, and some new treatment approaches:

Androgenetic alopecia. In a meta-analysis and systematic review published in 2017, all treatments tested (2% and 5% minoxidil in men, 1 mg finasteride in men, 2% minoxidil in women, and low-level laser light therapy in men) were superior to placebo. Several photobiomodulation (PBM) devices (also known as low-level laser light) for home use have been cleared for androgenetic alopecia by the Food and Drug Administration; a clinician’s guide, published in 2018, provides information on these devices.

Hair and hormones. Combination therapy for female-pattern hair loss – low-dose minoxidil and spironolactone – is important to know about, she said, adding there are data from an observational pilot study supporting this treatment. Women should not become pregnant while on this treatment, Dr. Hordinsky cautioned.

PRP (platelet rich plasma). This treatment for hair loss can be costly, she cautioned, as it’s viewed as a cosmetic technique, “but it actually can work rather well.”

Hair regrowth measures. Traditionally, measures center on global assessment, the patient’s self-assessment, investigator assessment, and an independent photo review. Enter the dermatoscope. “We can now get pictures as a baseline. Patients can see, and also see the health of their scalp,” and if treatments make it look better or worse, she noted.

Alopecia areata (AA). Patients and families need to be made aware that this is an autoimmune disease that can recur, and if it does recur, the extent of hair loss is not predictable. According to Dr. Hordinsky, the most widely used tool to halt disease activity has been treatment with a corticosteroid (topical, intralesional, oral, or even intravenous corticosteroids).

Clinical trials and publications from 2018 to 2020 have triggered interest in off-label use and further studies of JAK inhibitors for treating AA, which include baricitinib, ruxolitinib, and tofacitinib. At the American Academy of Dermatology meeting in March 2022, results of the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 trial found that the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib (50 mg or 20 mg daily, with or without a 200-mg loading dose), was efficacious in adults and adolescents with AA, compared with placebo, with no safety concerns noted. “This looks to be very, very promising,” she said, “and also very safe.” Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib also presented at the same meeting found it was superior to placebo for hair regrowth in adults with severe AA at 36 weeks. (On June 13, shortly after Dr. Hordinsky spoke at the meeting, the FDA approved baricitinib for treating AA in adults, making this the first systemic treatment to be approved for AA).

Research on topical JAK inhibitors for AA has been disappointing, Dr. Hordinsky said.

Alopecia areata and atopic dermatitis. For patients with both AA and AD, dupilumab may provide relief, she said. She referred to a recently published phase 2a trial in patients with AA (including some with both AA and AD), which found that Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores improved after 48 weeks of treatment, with higher response rates among those with baseline IgE levels of 200 IU/mL or higher. “If your patient has both, and their immunoglobulin-E level is greater than 200, then they may be a good candidate for dupilumab and both diseases may respond,” she said.

Scalp symptoms. It can be challenging when patients complain of itch, pain, or burning on the scalp, but have no obvious skin disease, Dr. Hordinsky said. Her tips: Some of these patients may be experiencing scalp symptoms secondary to a neuropathy; others may have mast cell degranulation, but for others, the basis of the symptoms may be unclear. Special nerve studies may be needed. For relief, a trial of antihistamines or topical or oral gabapentin may be needed, she said.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA). This condition, first described in postmenopausal women, is now reported in men and in younger women. While sunscreen has been suspected, there are no good data that have proven that link, she said. Cosmetics are also considered a possible culprit. For treatment, “the first thing we try to do is treat the inflammation,” Dr. Hordinsky said. Treatment options include topical high-potency corticosteroids, intralesional steroids, and topical nonsteroid anti-inflammatory creams (tier 1); hydroxychloroquine, low-dose antibiotics, and acitretin (tier 2); and cyclosporin and mycophenolate mofetil (tier 3).

In an observational study of mostly women with FFA, she noted, treatment with dutasteride was more effective than commonly used systemic treatments.

“Don’t forget to address the psychosocial needs of the hair loss patient,” Dr. Hordinsky advised. “Hair loss patients are very distressed, and you have to learn how to be fast and nimble and address those needs.” Working with a behavioral health specialist or therapist can help, she said.

She also recommended directing patients to appropriate organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation and the Scarring Alopecia Foundation, as well as conferences, such as the upcoming NAAF conference in Washington. “These organizations do give good information that should complement what you are doing.”

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Hordinsky reported no disclosures.

“No matter who the patient is, whether a child, adolescent, or adult, the key to figuring out hair disease is getting a good history,” Maria Hordinsky, MD, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said at the Medscape Live Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

. She also urged physicians and other health care providers to use the electronic medical record and to be thorough in documenting information – noting nutrition, hair care habits, supplement use, and other details.

Lab tests should be selected based on that history, she said. For instance, low iron stores can be associated with hair shedding; and thyroid function studies might be needed.

Other highlights of her presentation included comments on different types of alopecia, and some new treatment approaches:

Androgenetic alopecia. In a meta-analysis and systematic review published in 2017, all treatments tested (2% and 5% minoxidil in men, 1 mg finasteride in men, 2% minoxidil in women, and low-level laser light therapy in men) were superior to placebo. Several photobiomodulation (PBM) devices (also known as low-level laser light) for home use have been cleared for androgenetic alopecia by the Food and Drug Administration; a clinician’s guide, published in 2018, provides information on these devices.

Hair and hormones. Combination therapy for female-pattern hair loss – low-dose minoxidil and spironolactone – is important to know about, she said, adding there are data from an observational pilot study supporting this treatment. Women should not become pregnant while on this treatment, Dr. Hordinsky cautioned.

PRP (platelet rich plasma). This treatment for hair loss can be costly, she cautioned, as it’s viewed as a cosmetic technique, “but it actually can work rather well.”

Hair regrowth measures. Traditionally, measures center on global assessment, the patient’s self-assessment, investigator assessment, and an independent photo review. Enter the dermatoscope. “We can now get pictures as a baseline. Patients can see, and also see the health of their scalp,” and if treatments make it look better or worse, she noted.

Alopecia areata (AA). Patients and families need to be made aware that this is an autoimmune disease that can recur, and if it does recur, the extent of hair loss is not predictable. According to Dr. Hordinsky, the most widely used tool to halt disease activity has been treatment with a corticosteroid (topical, intralesional, oral, or even intravenous corticosteroids).

Clinical trials and publications from 2018 to 2020 have triggered interest in off-label use and further studies of JAK inhibitors for treating AA, which include baricitinib, ruxolitinib, and tofacitinib. At the American Academy of Dermatology meeting in March 2022, results of the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 trial found that the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib (50 mg or 20 mg daily, with or without a 200-mg loading dose), was efficacious in adults and adolescents with AA, compared with placebo, with no safety concerns noted. “This looks to be very, very promising,” she said, “and also very safe.” Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib also presented at the same meeting found it was superior to placebo for hair regrowth in adults with severe AA at 36 weeks. (On June 13, shortly after Dr. Hordinsky spoke at the meeting, the FDA approved baricitinib for treating AA in adults, making this the first systemic treatment to be approved for AA).

Research on topical JAK inhibitors for AA has been disappointing, Dr. Hordinsky said.

Alopecia areata and atopic dermatitis. For patients with both AA and AD, dupilumab may provide relief, she said. She referred to a recently published phase 2a trial in patients with AA (including some with both AA and AD), which found that Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores improved after 48 weeks of treatment, with higher response rates among those with baseline IgE levels of 200 IU/mL or higher. “If your patient has both, and their immunoglobulin-E level is greater than 200, then they may be a good candidate for dupilumab and both diseases may respond,” she said.

Scalp symptoms. It can be challenging when patients complain of itch, pain, or burning on the scalp, but have no obvious skin disease, Dr. Hordinsky said. Her tips: Some of these patients may be experiencing scalp symptoms secondary to a neuropathy; others may have mast cell degranulation, but for others, the basis of the symptoms may be unclear. Special nerve studies may be needed. For relief, a trial of antihistamines or topical or oral gabapentin may be needed, she said.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA). This condition, first described in postmenopausal women, is now reported in men and in younger women. While sunscreen has been suspected, there are no good data that have proven that link, she said. Cosmetics are also considered a possible culprit. For treatment, “the first thing we try to do is treat the inflammation,” Dr. Hordinsky said. Treatment options include topical high-potency corticosteroids, intralesional steroids, and topical nonsteroid anti-inflammatory creams (tier 1); hydroxychloroquine, low-dose antibiotics, and acitretin (tier 2); and cyclosporin and mycophenolate mofetil (tier 3).

In an observational study of mostly women with FFA, she noted, treatment with dutasteride was more effective than commonly used systemic treatments.

“Don’t forget to address the psychosocial needs of the hair loss patient,” Dr. Hordinsky advised. “Hair loss patients are very distressed, and you have to learn how to be fast and nimble and address those needs.” Working with a behavioral health specialist or therapist can help, she said.

She also recommended directing patients to appropriate organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation and the Scarring Alopecia Foundation, as well as conferences, such as the upcoming NAAF conference in Washington. “These organizations do give good information that should complement what you are doing.”

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Hordinsky reported no disclosures.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE WOMEN’S & PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

FDA OKs first systemic treatment for alopecia areata

.

The disorder with the hallmark signs of patchy baldness affects more than 300,000 people in the United States each year. In patients with the autoimmune disorder, the body attacks its own hair follicles and hair falls out, often in clumps. In February, the FDA granted priority review for baricitinib in adults with severe AA.

Baricitinib (Olumiant) is a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, which blocks the activity of one or more enzymes, interfering with the pathway that leads to inflammation.

The FDA reports the most common side effects include upper respiratory tract infections, headache, acne, hyperlipidemia, increase of creatinine phosphokinase, urinary tract infection, elevated liver enzymes, inflammation of hair follicles, fatigue, lower respiratory tract infections, nausea, Candida infections, anemia, neutropenia, abdominal pain, herpes zoster (shingles), and weight gain. The labeling for baricitinib includes a boxed warning for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis.

Evidence from two trials led to announcement

The decision came after review of the results from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (BRAVE AA-1 and BRAVE AA-2) with patients who had at least 50% scalp hair loss as measured by the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT score) for more than 6 months.

Patients in these trials got either a placebo, 2 mg of baricitinib, or 4 mg of baricitinib every day. The primary endpoint for both trials was the proportion of patients who achieved at least 80% scalp hair coverage at week 36.

In BRAVE AA-1, 22% of the 184 patients who received 2 mg of baricitinib and 35% of the 281 patients who received 4 mg of baricitinib achieved at least 80% scalp hair coverage, compared with 5% of the 189 patients in the placebo group.

In BRAVE AA-2, 17% of the 156 patients who received 2 mg of baricitinib and 32% of the 234 patients who received 4 mg achieved at least 80% scalp hair coverage, compared with 3% of the 156 patients in the placebo group.

The results were reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology meeting in March.

Baricitinib was originally approved in 2018 as a treatment for adult patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis who have had an inadequate response to one or more tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–blockers. It is also approved for treating COVID-19 in certain hospitalized adults.

Two other companies, Pfizer and Concert Pharmaceuticals, have JAK inhibitors in late-stage development for AA. The drugs are already on the market for treating rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. FDA approval is important for insurance coverage of the drugs, which have a list price of nearly $2,500 a month, according to The New York Times.

Until now, the only treatments for moderate to severe AA approved by the FDA have been intralesional steroid injections, contact sensitization, and systemic immunosuppressants, but they have demonstrated limited efficacy, are inconvenient for patients to take, and have been unsuitable for use long term.

“Today’s approval will help fulfill a significant unmet need for patients with severe alopecia areata,” Kendall Marcus, MD, director of the Division of Dermatology and Dentistry in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

As Medscape reported last month, The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval of baricitinib for adults with severe AA.

AA received widespread international attention earlier this year at the Academy Awards ceremony, when actor Will Smith walked from the audience up onto the stage and slapped comedian Chris Rock in the face after he directed a joke at Mr. Smith’s wife, Jada Pinkett Smith, about her shaved head. Mrs. Pinkett Smith has AA and has been public about her struggles with the disease.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

The disorder with the hallmark signs of patchy baldness affects more than 300,000 people in the United States each year. In patients with the autoimmune disorder, the body attacks its own hair follicles and hair falls out, often in clumps. In February, the FDA granted priority review for baricitinib in adults with severe AA.

Baricitinib (Olumiant) is a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, which blocks the activity of one or more enzymes, interfering with the pathway that leads to inflammation.

The FDA reports the most common side effects include upper respiratory tract infections, headache, acne, hyperlipidemia, increase of creatinine phosphokinase, urinary tract infection, elevated liver enzymes, inflammation of hair follicles, fatigue, lower respiratory tract infections, nausea, Candida infections, anemia, neutropenia, abdominal pain, herpes zoster (shingles), and weight gain. The labeling for baricitinib includes a boxed warning for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis.

Evidence from two trials led to announcement

The decision came after review of the results from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (BRAVE AA-1 and BRAVE AA-2) with patients who had at least 50% scalp hair loss as measured by the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT score) for more than 6 months.

Patients in these trials got either a placebo, 2 mg of baricitinib, or 4 mg of baricitinib every day. The primary endpoint for both trials was the proportion of patients who achieved at least 80% scalp hair coverage at week 36.

In BRAVE AA-1, 22% of the 184 patients who received 2 mg of baricitinib and 35% of the 281 patients who received 4 mg of baricitinib achieved at least 80% scalp hair coverage, compared with 5% of the 189 patients in the placebo group.

In BRAVE AA-2, 17% of the 156 patients who received 2 mg of baricitinib and 32% of the 234 patients who received 4 mg achieved at least 80% scalp hair coverage, compared with 3% of the 156 patients in the placebo group.

The results were reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology meeting in March.

Baricitinib was originally approved in 2018 as a treatment for adult patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis who have had an inadequate response to one or more tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–blockers. It is also approved for treating COVID-19 in certain hospitalized adults.

Two other companies, Pfizer and Concert Pharmaceuticals, have JAK inhibitors in late-stage development for AA. The drugs are already on the market for treating rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. FDA approval is important for insurance coverage of the drugs, which have a list price of nearly $2,500 a month, according to The New York Times.

Until now, the only treatments for moderate to severe AA approved by the FDA have been intralesional steroid injections, contact sensitization, and systemic immunosuppressants, but they have demonstrated limited efficacy, are inconvenient for patients to take, and have been unsuitable for use long term.

“Today’s approval will help fulfill a significant unmet need for patients with severe alopecia areata,” Kendall Marcus, MD, director of the Division of Dermatology and Dentistry in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

As Medscape reported last month, The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval of baricitinib for adults with severe AA.

AA received widespread international attention earlier this year at the Academy Awards ceremony, when actor Will Smith walked from the audience up onto the stage and slapped comedian Chris Rock in the face after he directed a joke at Mr. Smith’s wife, Jada Pinkett Smith, about her shaved head. Mrs. Pinkett Smith has AA and has been public about her struggles with the disease.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

The disorder with the hallmark signs of patchy baldness affects more than 300,000 people in the United States each year. In patients with the autoimmune disorder, the body attacks its own hair follicles and hair falls out, often in clumps. In February, the FDA granted priority review for baricitinib in adults with severe AA.

Baricitinib (Olumiant) is a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, which blocks the activity of one or more enzymes, interfering with the pathway that leads to inflammation.

The FDA reports the most common side effects include upper respiratory tract infections, headache, acne, hyperlipidemia, increase of creatinine phosphokinase, urinary tract infection, elevated liver enzymes, inflammation of hair follicles, fatigue, lower respiratory tract infections, nausea, Candida infections, anemia, neutropenia, abdominal pain, herpes zoster (shingles), and weight gain. The labeling for baricitinib includes a boxed warning for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis.

Evidence from two trials led to announcement

The decision came after review of the results from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (BRAVE AA-1 and BRAVE AA-2) with patients who had at least 50% scalp hair loss as measured by the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT score) for more than 6 months.

Patients in these trials got either a placebo, 2 mg of baricitinib, or 4 mg of baricitinib every day. The primary endpoint for both trials was the proportion of patients who achieved at least 80% scalp hair coverage at week 36.

In BRAVE AA-1, 22% of the 184 patients who received 2 mg of baricitinib and 35% of the 281 patients who received 4 mg of baricitinib achieved at least 80% scalp hair coverage, compared with 5% of the 189 patients in the placebo group.

In BRAVE AA-2, 17% of the 156 patients who received 2 mg of baricitinib and 32% of the 234 patients who received 4 mg achieved at least 80% scalp hair coverage, compared with 3% of the 156 patients in the placebo group.

The results were reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology meeting in March.

Baricitinib was originally approved in 2018 as a treatment for adult patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis who have had an inadequate response to one or more tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–blockers. It is also approved for treating COVID-19 in certain hospitalized adults.

Two other companies, Pfizer and Concert Pharmaceuticals, have JAK inhibitors in late-stage development for AA. The drugs are already on the market for treating rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. FDA approval is important for insurance coverage of the drugs, which have a list price of nearly $2,500 a month, according to The New York Times.

Until now, the only treatments for moderate to severe AA approved by the FDA have been intralesional steroid injections, contact sensitization, and systemic immunosuppressants, but they have demonstrated limited efficacy, are inconvenient for patients to take, and have been unsuitable for use long term.

“Today’s approval will help fulfill a significant unmet need for patients with severe alopecia areata,” Kendall Marcus, MD, director of the Division of Dermatology and Dentistry in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

As Medscape reported last month, The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval of baricitinib for adults with severe AA.

AA received widespread international attention earlier this year at the Academy Awards ceremony, when actor Will Smith walked from the audience up onto the stage and slapped comedian Chris Rock in the face after he directed a joke at Mr. Smith’s wife, Jada Pinkett Smith, about her shaved head. Mrs. Pinkett Smith has AA and has been public about her struggles with the disease.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Acute Alopecia Associated With Albendazole Toxicosis

To the Editor:

Albendazole is a commonly prescribed anthelmintic that typically is well tolerated. Its broadest application is in developing countries that have a high rate of endemic nematode infection.1,2 Albendazole belongs to the benzimidazole class of anthelmintic chemotherapeutic agents that function by inhibiting microtubule dynamics, resulting in cytotoxic antimitotic effects.3 Benzimidazoles (eg, albendazole, mebendazole) have a binding affinity for helminthic β-tubulin that is 25- to 400-times greater than their binding affinity for the mammalian counterpart.4 Consequently, benzimidazoles generally are afforded a very broad therapeutic index for helminthic infection.

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) after an episode of syncope and sudden hair loss. At presentation he had a fever (temperature, 103 °F [39.4 °C]), a heart rate of 120 bpm, and pancytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.4×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.0×103/μL]; hemoglobin, 7.0 g/dL [reference range, 11.2–15.7 g/dL]; platelet count, 100

The patient reported severe gastrointestinal (GI) distress and diarrhea for the last year as well as a 25-lb weight loss. He discussed his belief that his GI symptoms were due to a parasite he had acquired the year prior; however, he reported that an exhaustive outpatient GI workup had been negative. Two weeks before presentation to our ED, the patient presented to another ED with stomach upset and was given a dose of albendazole. Perceiving alleviation of his symptoms, he purchased 2 bottles of veterinary albendazole online and consumed 113,000 mg—approximately 300 times the standard dose of 400 mg.

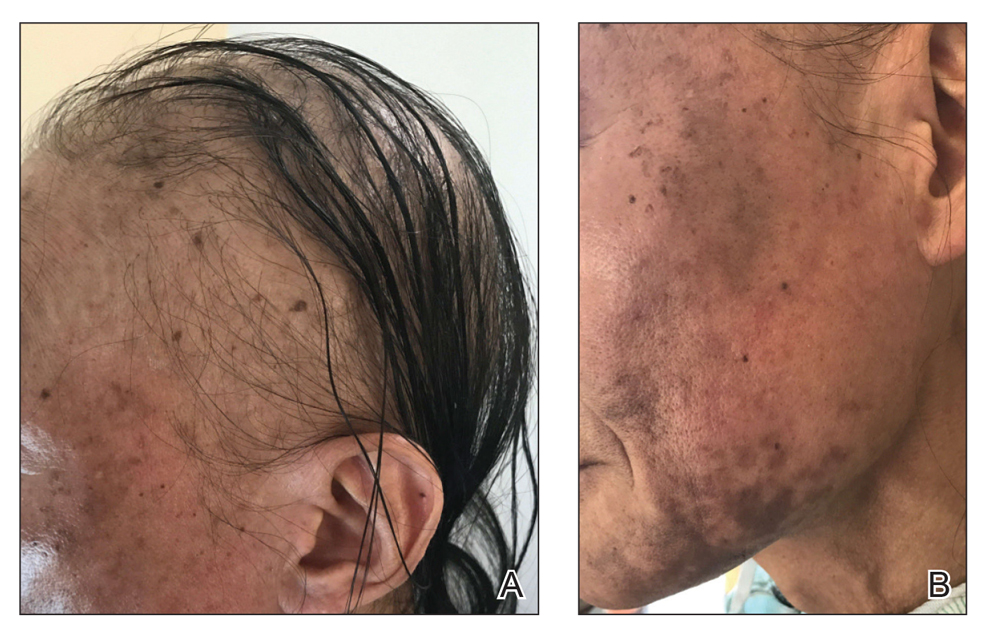

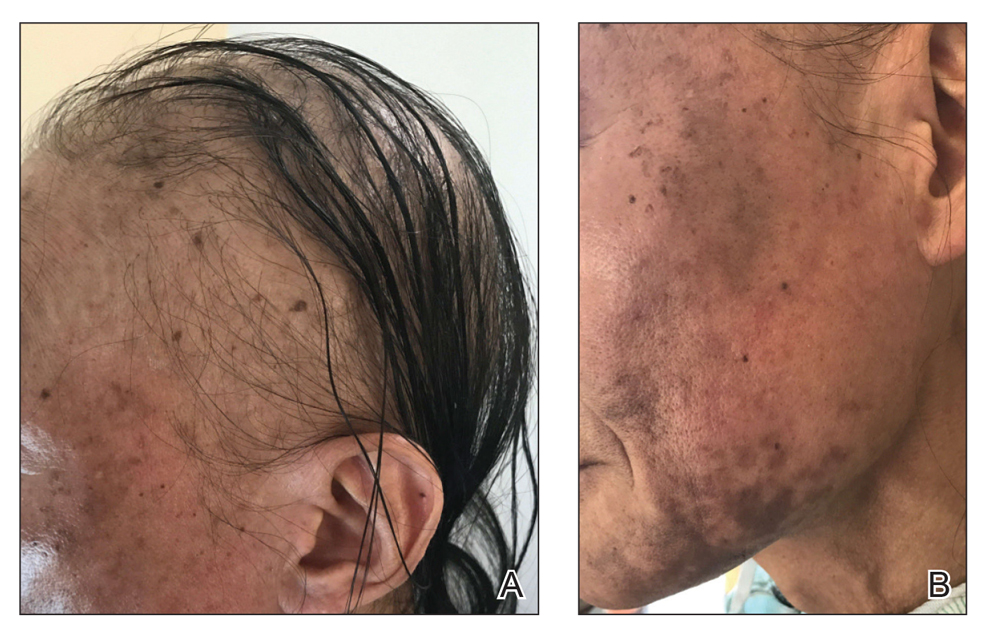

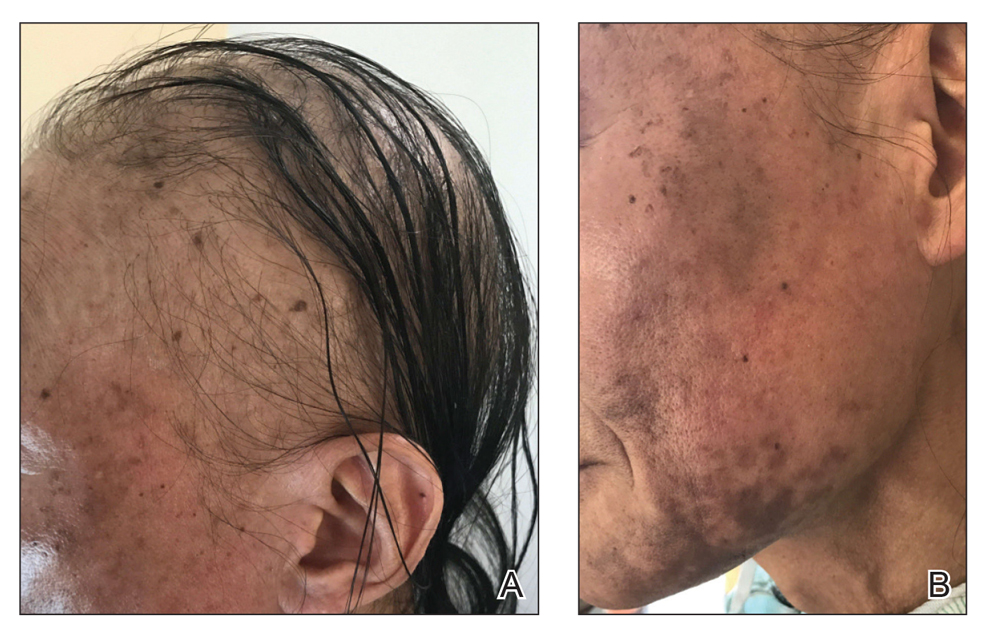

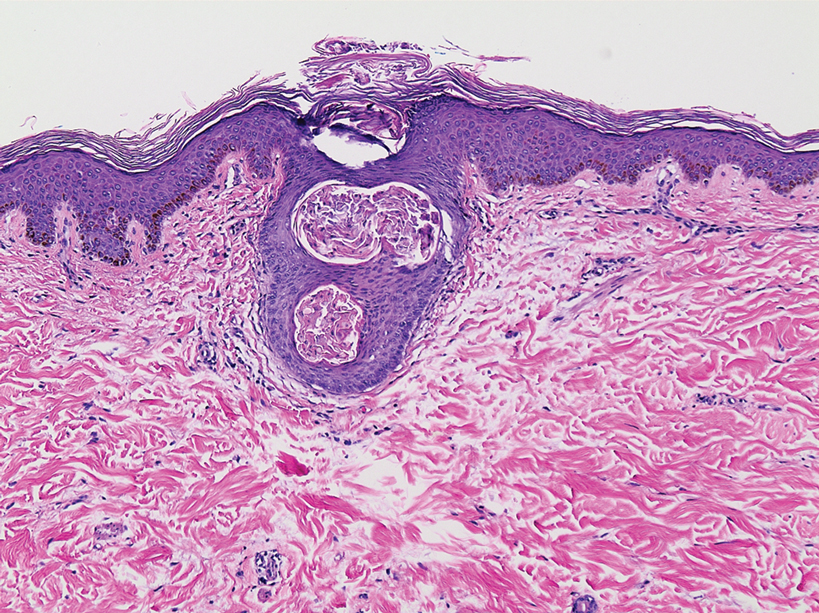

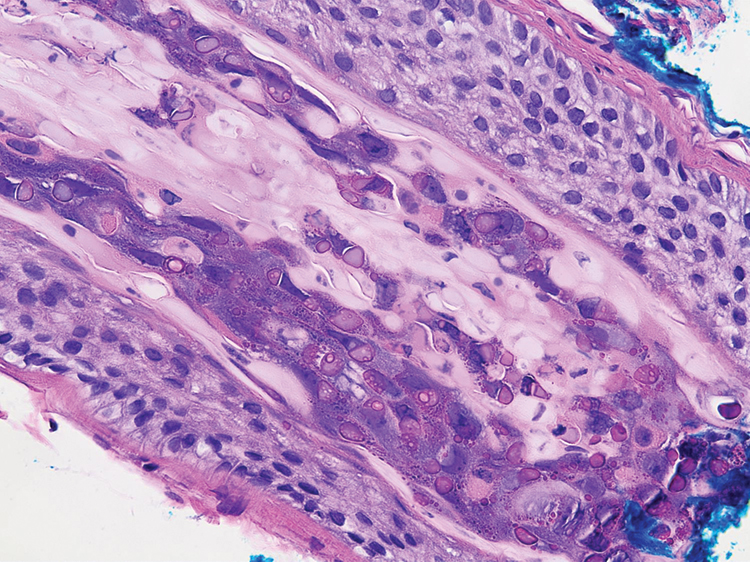

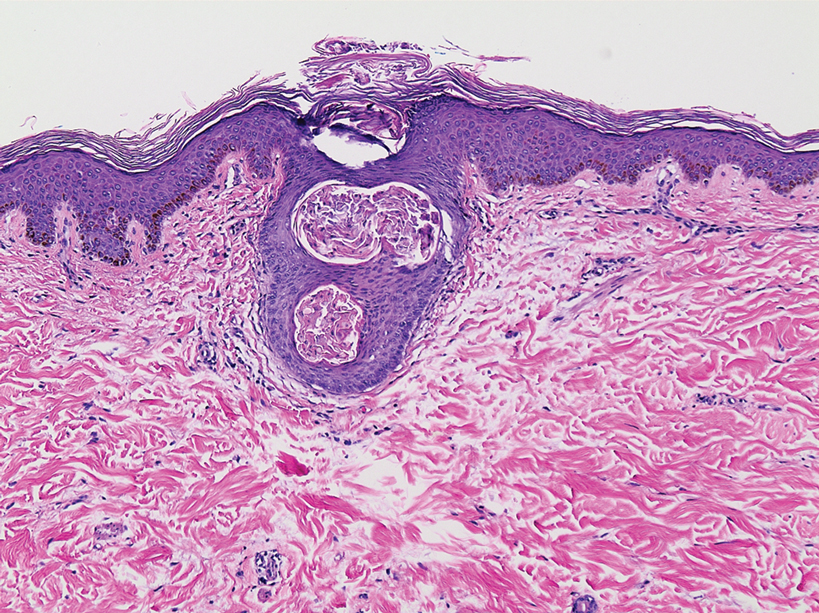

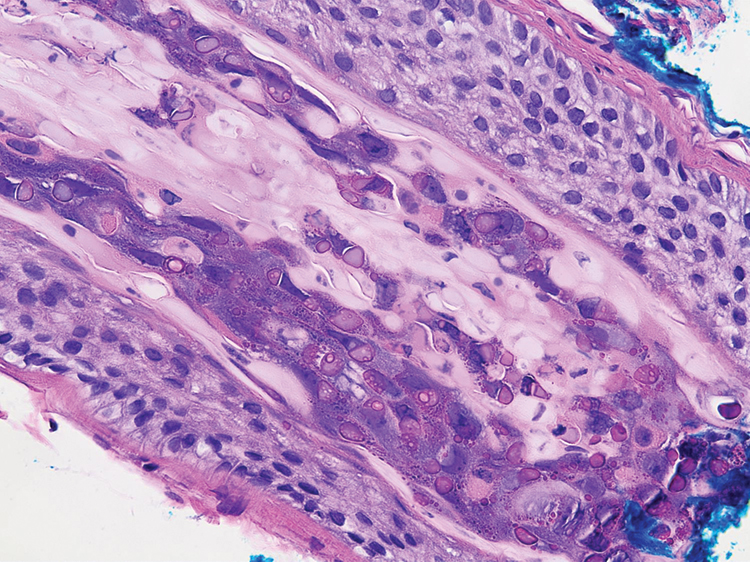

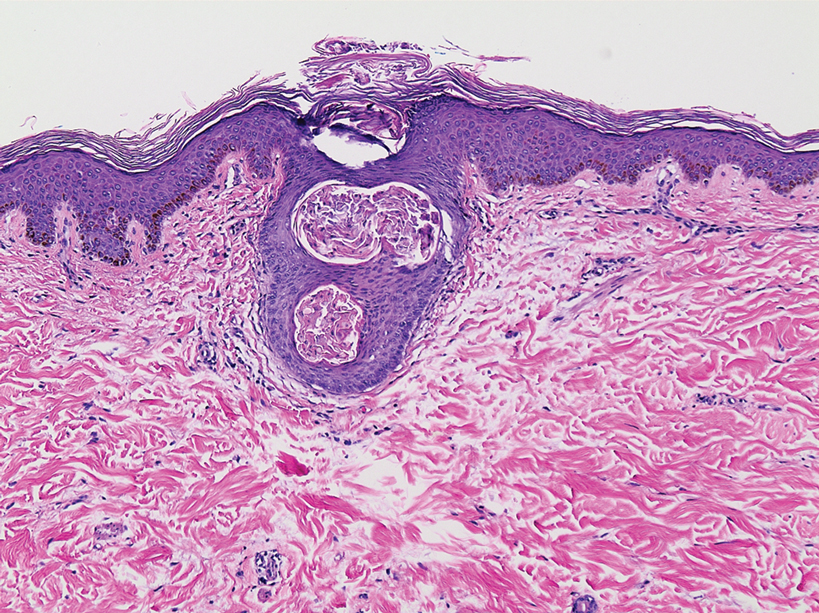

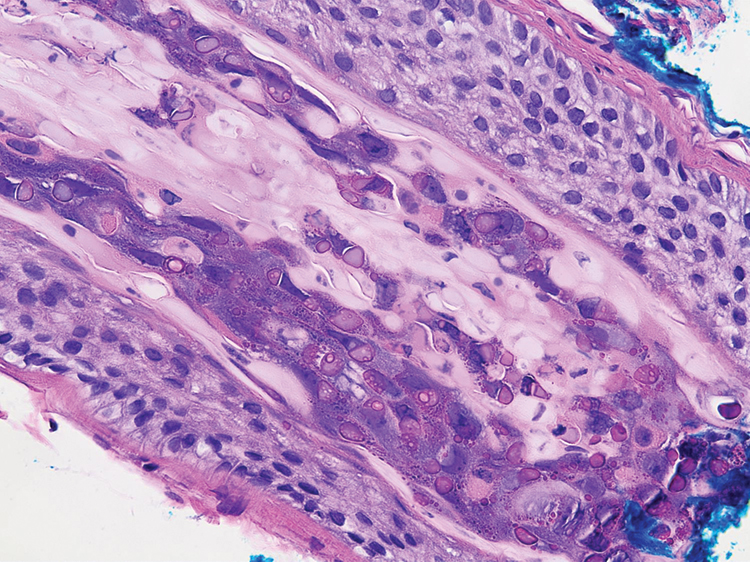

A dermatologic examination in our ED demonstrated reticulated violaceous patches on the face and severe alopecia with preferential sparing of the occipital scalp (Figure 1). Photographs taken by the patient on his phone from a week prior to presentation showed no facial dyschromia or signs of hair loss. A punch biopsy of the chin demonstrated perivascular and perifollicular dermatitis with eosinophils, most consistent with a drug reaction.

The patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care. Blood count parameters normalized, and his hair began to regrow within 2 weeks after albendazole discontinuation (Figure 2).

Our patient exhibited symptoms of tachycardia, pancytopenia, and acute massive hair loss with preferential sparing of the occipital and posterior hair line; this pattern of hair loss is classic in men with chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium.5 Conventional chemotherapeutics include taxanes and Vinca alkaloids, both of which bind mammalian β-tubulin and commonly induce anagen effluvium.

Our patient’s toxicosis syndrome was strikingly similar to common adverse effects in patients treated with conventional chemotherapeutics, including aplastic anemia with severe neutropenia and anagen effluvium.6,7 This adverse effect profile suggests that albendazole exerts an effect on mammalian β-tubulin that is similar to conventional chemotherapy when albendazole is ingested in a massive quantity.

Other reports of albendazole-induced alopecia describe an idiosyncratic, dose-dependent telogen effluvium.8-10 Conventional chemotherapy uncommonly might induce telogen effluvium when given below a threshold necessary to induce anagen effluvium. In those cases, follicular matrix keratinocytes are disrupted without complete follicular fracture and attempt to repair the damaged elongating follicle before entering the telogen phase.7 This observed phenomenon and the inherent susceptibility of matrix keratinocytes to antimicrotubule agents might explain why a therapeutic dose of albendazole has been associated with telogen effluvium in certain individuals.

Our case of albendazole-related toxicosis of this magnitude is unique. Ghias et al11 reported a case of abendazole-induced anagen effluvium. Future reports might clarify whether this toxicosis syndrome is typical or atypical in massive albendazole overdose.

- Keiser J, Utzinger J. Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;299:1937-1948. doi:10.1001/jama.299.16.1937

- Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521-1532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68653-4

- Lanusse CE, Prichard RK. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of benzimidazole anthelmintics in ruminants. Drug Metab Rev. 1993;25:235-279. doi:10.3109/03602539308993977

- Page SW. Antiparasitic drugs. In: Maddison JE, Church DB, Page SW, eds. Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders; 2008:198-260.

- Yun SJ, Kim S-J. Hair loss pattern due to chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium: a cross-sectional observation. Dermatology. 2007;215:36-40. doi:10.1159/000102031

- de Weger VA, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Cellular and clinical pharmacology of the taxanes docetaxel and paclitaxel—a review. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:488-494. doi:10.1097/CAD.0000000000000093

- Paus R, Haslam IS, Sharov AA, et al. Pathobiology of chemotherapy-induced hair loss. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:E50-E59. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70553-3

- Imamkuliev KD, Alekseev VG, Dovgalev AS, et al. A case of alopecia in a patient with hydatid disease treated with Nemozole (albendazole)[in Russian]. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2013:48-50.

- Tas A, Köklü S, Celik H. Loss of body hair as a side effect of albendazole. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:220. doi:10.1007/s00508-011-0112-y

- Pilar García-Muret M, Sitjas D, Tuneu L, et al. Telogen effluvium associated with albendazole therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:669-670. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb02597.x

- Ghias M, Amin B, Kutner A. Albendazole-induced anagen effluvium. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:54-56.

To the Editor:

Albendazole is a commonly prescribed anthelmintic that typically is well tolerated. Its broadest application is in developing countries that have a high rate of endemic nematode infection.1,2 Albendazole belongs to the benzimidazole class of anthelmintic chemotherapeutic agents that function by inhibiting microtubule dynamics, resulting in cytotoxic antimitotic effects.3 Benzimidazoles (eg, albendazole, mebendazole) have a binding affinity for helminthic β-tubulin that is 25- to 400-times greater than their binding affinity for the mammalian counterpart.4 Consequently, benzimidazoles generally are afforded a very broad therapeutic index for helminthic infection.

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) after an episode of syncope and sudden hair loss. At presentation he had a fever (temperature, 103 °F [39.4 °C]), a heart rate of 120 bpm, and pancytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.4×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.0×103/μL]; hemoglobin, 7.0 g/dL [reference range, 11.2–15.7 g/dL]; platelet count, 100

The patient reported severe gastrointestinal (GI) distress and diarrhea for the last year as well as a 25-lb weight loss. He discussed his belief that his GI symptoms were due to a parasite he had acquired the year prior; however, he reported that an exhaustive outpatient GI workup had been negative. Two weeks before presentation to our ED, the patient presented to another ED with stomach upset and was given a dose of albendazole. Perceiving alleviation of his symptoms, he purchased 2 bottles of veterinary albendazole online and consumed 113,000 mg—approximately 300 times the standard dose of 400 mg.

A dermatologic examination in our ED demonstrated reticulated violaceous patches on the face and severe alopecia with preferential sparing of the occipital scalp (Figure 1). Photographs taken by the patient on his phone from a week prior to presentation showed no facial dyschromia or signs of hair loss. A punch biopsy of the chin demonstrated perivascular and perifollicular dermatitis with eosinophils, most consistent with a drug reaction.

The patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care. Blood count parameters normalized, and his hair began to regrow within 2 weeks after albendazole discontinuation (Figure 2).

Our patient exhibited symptoms of tachycardia, pancytopenia, and acute massive hair loss with preferential sparing of the occipital and posterior hair line; this pattern of hair loss is classic in men with chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium.5 Conventional chemotherapeutics include taxanes and Vinca alkaloids, both of which bind mammalian β-tubulin and commonly induce anagen effluvium.

Our patient’s toxicosis syndrome was strikingly similar to common adverse effects in patients treated with conventional chemotherapeutics, including aplastic anemia with severe neutropenia and anagen effluvium.6,7 This adverse effect profile suggests that albendazole exerts an effect on mammalian β-tubulin that is similar to conventional chemotherapy when albendazole is ingested in a massive quantity.

Other reports of albendazole-induced alopecia describe an idiosyncratic, dose-dependent telogen effluvium.8-10 Conventional chemotherapy uncommonly might induce telogen effluvium when given below a threshold necessary to induce anagen effluvium. In those cases, follicular matrix keratinocytes are disrupted without complete follicular fracture and attempt to repair the damaged elongating follicle before entering the telogen phase.7 This observed phenomenon and the inherent susceptibility of matrix keratinocytes to antimicrotubule agents might explain why a therapeutic dose of albendazole has been associated with telogen effluvium in certain individuals.

Our case of albendazole-related toxicosis of this magnitude is unique. Ghias et al11 reported a case of abendazole-induced anagen effluvium. Future reports might clarify whether this toxicosis syndrome is typical or atypical in massive albendazole overdose.

To the Editor:

Albendazole is a commonly prescribed anthelmintic that typically is well tolerated. Its broadest application is in developing countries that have a high rate of endemic nematode infection.1,2 Albendazole belongs to the benzimidazole class of anthelmintic chemotherapeutic agents that function by inhibiting microtubule dynamics, resulting in cytotoxic antimitotic effects.3 Benzimidazoles (eg, albendazole, mebendazole) have a binding affinity for helminthic β-tubulin that is 25- to 400-times greater than their binding affinity for the mammalian counterpart.4 Consequently, benzimidazoles generally are afforded a very broad therapeutic index for helminthic infection.

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) after an episode of syncope and sudden hair loss. At presentation he had a fever (temperature, 103 °F [39.4 °C]), a heart rate of 120 bpm, and pancytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.4×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.0×103/μL]; hemoglobin, 7.0 g/dL [reference range, 11.2–15.7 g/dL]; platelet count, 100

The patient reported severe gastrointestinal (GI) distress and diarrhea for the last year as well as a 25-lb weight loss. He discussed his belief that his GI symptoms were due to a parasite he had acquired the year prior; however, he reported that an exhaustive outpatient GI workup had been negative. Two weeks before presentation to our ED, the patient presented to another ED with stomach upset and was given a dose of albendazole. Perceiving alleviation of his symptoms, he purchased 2 bottles of veterinary albendazole online and consumed 113,000 mg—approximately 300 times the standard dose of 400 mg.

A dermatologic examination in our ED demonstrated reticulated violaceous patches on the face and severe alopecia with preferential sparing of the occipital scalp (Figure 1). Photographs taken by the patient on his phone from a week prior to presentation showed no facial dyschromia or signs of hair loss. A punch biopsy of the chin demonstrated perivascular and perifollicular dermatitis with eosinophils, most consistent with a drug reaction.

The patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care. Blood count parameters normalized, and his hair began to regrow within 2 weeks after albendazole discontinuation (Figure 2).