User login

Analysis of Education on Nail Conditions at the American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meetings

To the Editor:

The diagnosis and treatment of nail conditions are necessary competencies for board-certified dermatologists, but appropriate education often is lacking.1 The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) annual meeting is one of the largest and most highly attended dermatology educational conferences worldwide. We sought to determine the number of hours dedicated to nail-related topics at the AAD annual meetings from 2013 to 2019.

We accessed programs from the AAD annual meetings archive online (https://www.aad.org/meetings/previous-meetings-archive), and we used hair and psoriasis content for comparison. Event titles and descriptions were searched for nail-related content (using search terms nail, onychia, and onycho), hair-related content (hair, alopecia, trichosis, hirsutism), and psoriasis content (psoriasis). Data acquired for each event included the date, hours, title, and event type (eg, forum, course, focus session, symposium, discussion group, workshop, plenary session).

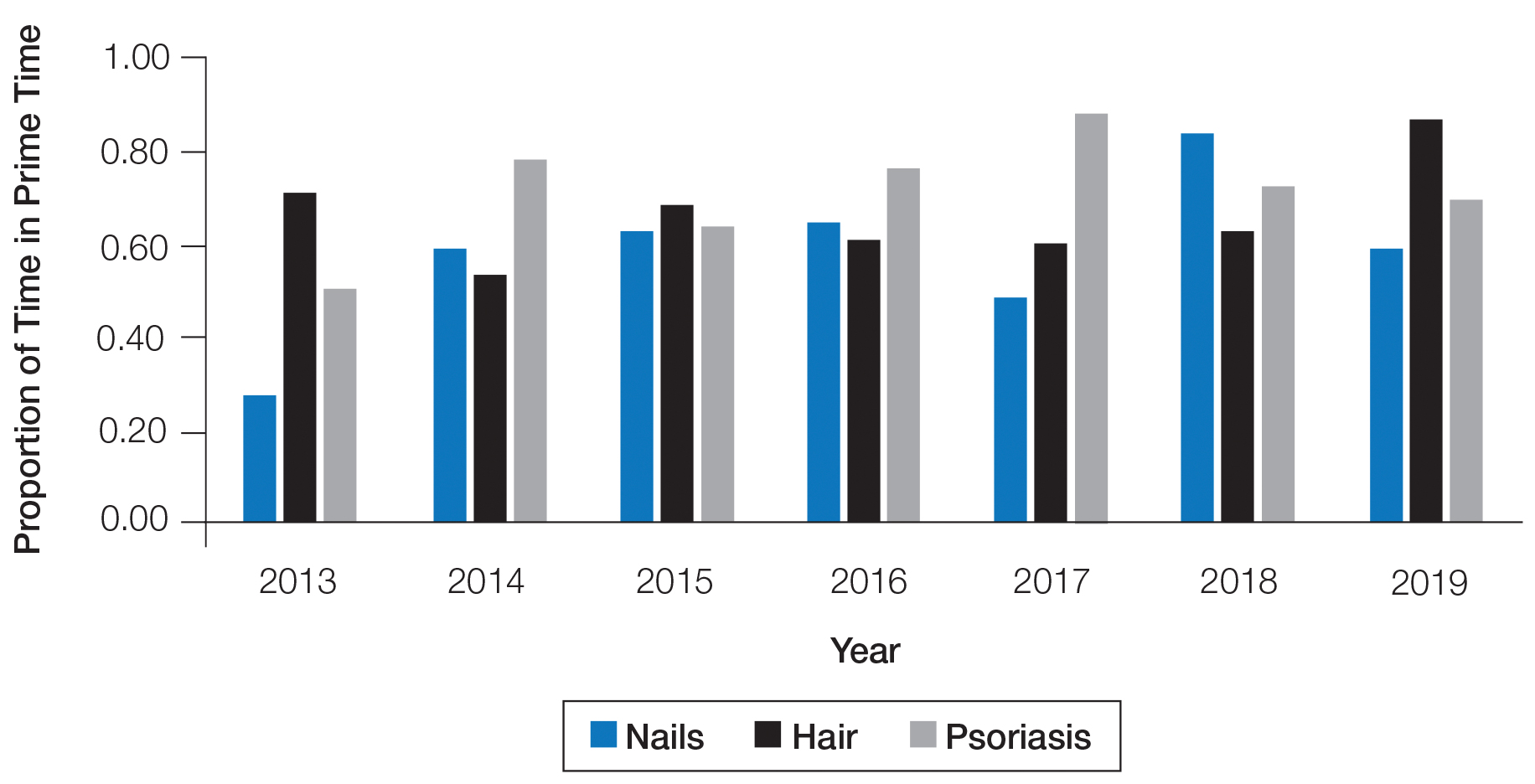

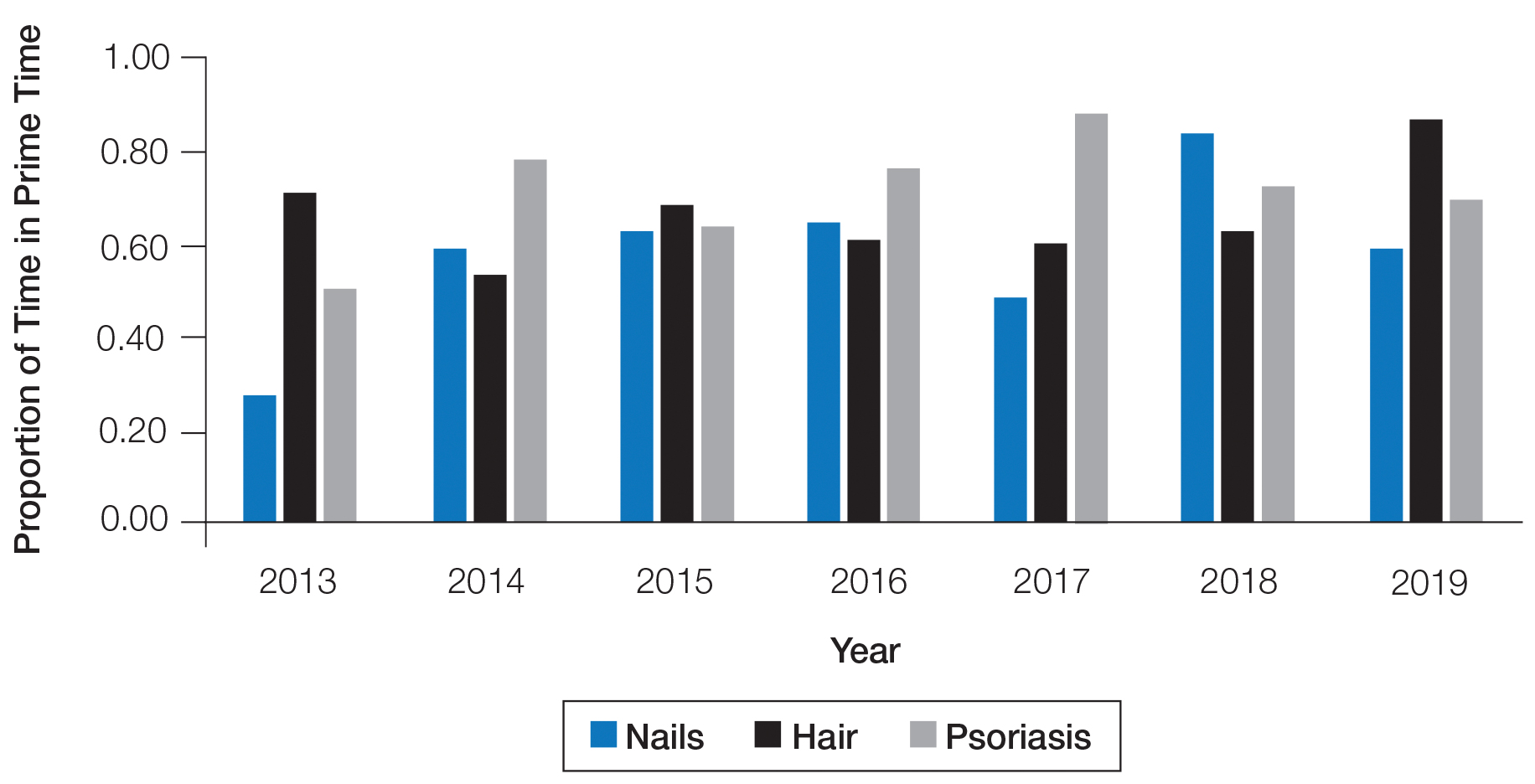

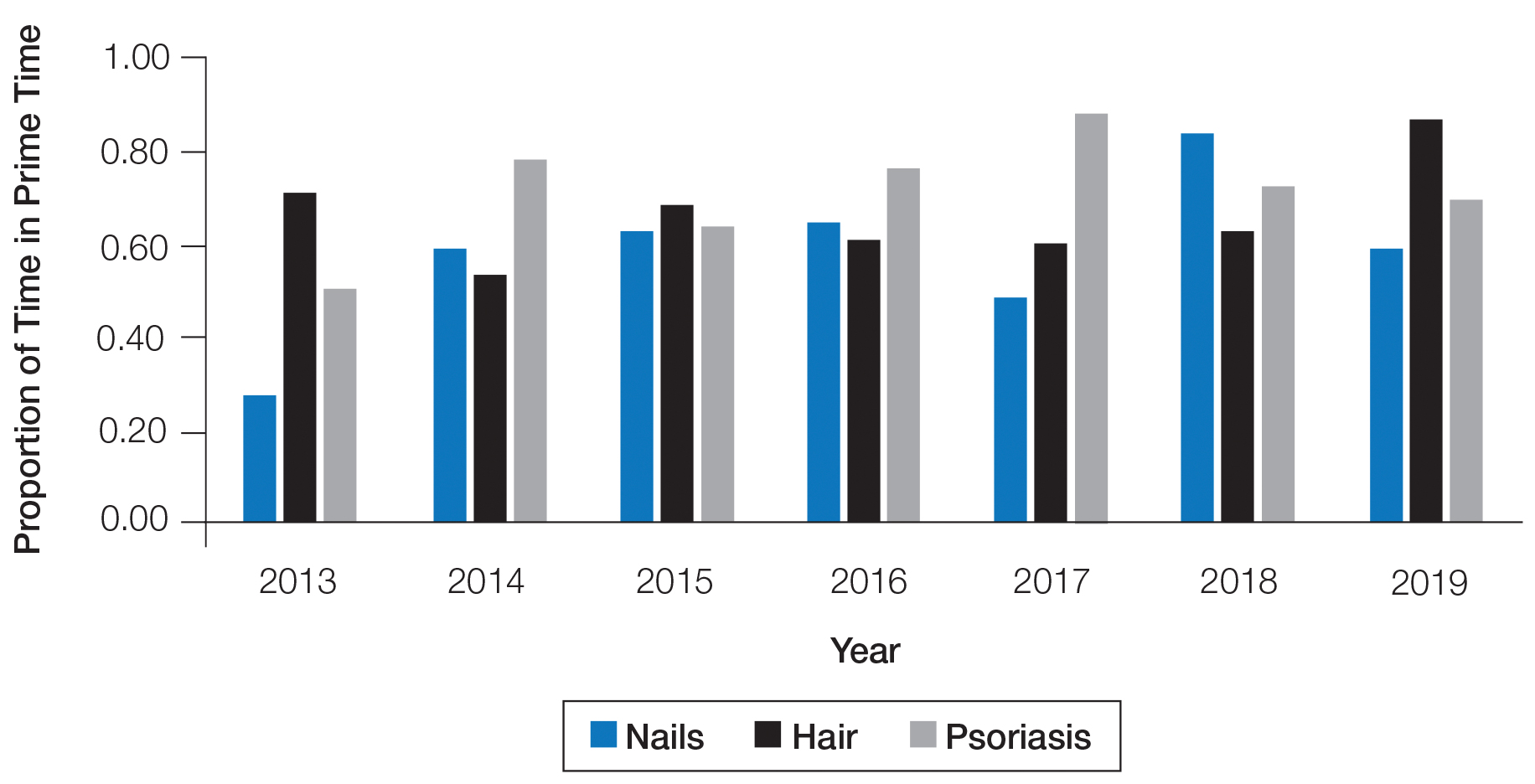

The number of hours dedicated to nail education consistently lagged behind those related to hair and psoriasis content during the study period (Figure 1). According to the AAD, the conference runs Friday to Tuesday with higher attendance Friday to Sunday (Tim Moses, personal communication, July 9, 2019). Lectures during the weekend are likely to have a broader reach than lectures on Monday and Tuesday. The proportion of nail content during weekend prime time slots was similar to that of hair and psoriasis (Figure 2). Plenary sessions often are presented by renowned experts on hot topics in dermatology. Notably, hair (2014-2015) and psoriasis (2015-2017) content were represented in the plenary sessions during the study period, while nail content was not featured.

Our study shows that nail-related education was underrepresented at the AAD annual meetings from 2013 to 2019 compared to hair- and psoriasis-related content. Educational gaps in the diagnosis of fignail conditions previously have been delineated, and prioritization of instruction on nail disease pathology and diagnostic procedures has been recommended to improve patient care.1 The majority of nail unit melanomas are diagnosed at late stages, which has been attributed to deficiencies in clinical knowledge and failure to perform or inadequate biopsy techniques.2 Notably, a survey of third-year dermatology residents (N=240) assessing experience in procedural dermatology showed that 58% performed 10 or fewer nail procedures and 30% did not feel competent in performing nail surgery.3 Furthermore, a survey examining the management of longitudinal melanonychia among attending and resident dermatologists (N=402) found that 62% of residents and 28% of total respondents were not confident in managing melanonychia.4

A limitation of this study was the lack of online data available for AAD annual meetings before 2013, so we were unable to characterize any long-term trends. Furthermore, we were unable to assess the educational reach of these sessions, as data on attendance are lacking.

This study demonstrates a paucity of nail-related content at the AAD annual meetings. The introduction of the “Hands-on: Nail Surgery” in 2015 is an important step forward to diminish the knowledge gap in the diagnosis of various nail diseases and malignancies. We recommend increasing the number of hours and overall content of didactic nail sessions at the AAD annual meeting to further the knowledge and procedural skills of dermatologists in caring for patients with nail disorders.

- Hare AQ, R ich P. Clinical and educational gaps in diagnosis of nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:269-273.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential pitfalls in diagnosis, and guidelines for histologic reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483.

- Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. A survey-based study of management of longitudinal melanonychia amongst attending and resident dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:994-996.

To the Editor:

The diagnosis and treatment of nail conditions are necessary competencies for board-certified dermatologists, but appropriate education often is lacking.1 The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) annual meeting is one of the largest and most highly attended dermatology educational conferences worldwide. We sought to determine the number of hours dedicated to nail-related topics at the AAD annual meetings from 2013 to 2019.

We accessed programs from the AAD annual meetings archive online (https://www.aad.org/meetings/previous-meetings-archive), and we used hair and psoriasis content for comparison. Event titles and descriptions were searched for nail-related content (using search terms nail, onychia, and onycho), hair-related content (hair, alopecia, trichosis, hirsutism), and psoriasis content (psoriasis). Data acquired for each event included the date, hours, title, and event type (eg, forum, course, focus session, symposium, discussion group, workshop, plenary session).

The number of hours dedicated to nail education consistently lagged behind those related to hair and psoriasis content during the study period (Figure 1). According to the AAD, the conference runs Friday to Tuesday with higher attendance Friday to Sunday (Tim Moses, personal communication, July 9, 2019). Lectures during the weekend are likely to have a broader reach than lectures on Monday and Tuesday. The proportion of nail content during weekend prime time slots was similar to that of hair and psoriasis (Figure 2). Plenary sessions often are presented by renowned experts on hot topics in dermatology. Notably, hair (2014-2015) and psoriasis (2015-2017) content were represented in the plenary sessions during the study period, while nail content was not featured.

Our study shows that nail-related education was underrepresented at the AAD annual meetings from 2013 to 2019 compared to hair- and psoriasis-related content. Educational gaps in the diagnosis of fignail conditions previously have been delineated, and prioritization of instruction on nail disease pathology and diagnostic procedures has been recommended to improve patient care.1 The majority of nail unit melanomas are diagnosed at late stages, which has been attributed to deficiencies in clinical knowledge and failure to perform or inadequate biopsy techniques.2 Notably, a survey of third-year dermatology residents (N=240) assessing experience in procedural dermatology showed that 58% performed 10 or fewer nail procedures and 30% did not feel competent in performing nail surgery.3 Furthermore, a survey examining the management of longitudinal melanonychia among attending and resident dermatologists (N=402) found that 62% of residents and 28% of total respondents were not confident in managing melanonychia.4

A limitation of this study was the lack of online data available for AAD annual meetings before 2013, so we were unable to characterize any long-term trends. Furthermore, we were unable to assess the educational reach of these sessions, as data on attendance are lacking.

This study demonstrates a paucity of nail-related content at the AAD annual meetings. The introduction of the “Hands-on: Nail Surgery” in 2015 is an important step forward to diminish the knowledge gap in the diagnosis of various nail diseases and malignancies. We recommend increasing the number of hours and overall content of didactic nail sessions at the AAD annual meeting to further the knowledge and procedural skills of dermatologists in caring for patients with nail disorders.

To the Editor:

The diagnosis and treatment of nail conditions are necessary competencies for board-certified dermatologists, but appropriate education often is lacking.1 The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) annual meeting is one of the largest and most highly attended dermatology educational conferences worldwide. We sought to determine the number of hours dedicated to nail-related topics at the AAD annual meetings from 2013 to 2019.

We accessed programs from the AAD annual meetings archive online (https://www.aad.org/meetings/previous-meetings-archive), and we used hair and psoriasis content for comparison. Event titles and descriptions were searched for nail-related content (using search terms nail, onychia, and onycho), hair-related content (hair, alopecia, trichosis, hirsutism), and psoriasis content (psoriasis). Data acquired for each event included the date, hours, title, and event type (eg, forum, course, focus session, symposium, discussion group, workshop, plenary session).

The number of hours dedicated to nail education consistently lagged behind those related to hair and psoriasis content during the study period (Figure 1). According to the AAD, the conference runs Friday to Tuesday with higher attendance Friday to Sunday (Tim Moses, personal communication, July 9, 2019). Lectures during the weekend are likely to have a broader reach than lectures on Monday and Tuesday. The proportion of nail content during weekend prime time slots was similar to that of hair and psoriasis (Figure 2). Plenary sessions often are presented by renowned experts on hot topics in dermatology. Notably, hair (2014-2015) and psoriasis (2015-2017) content were represented in the plenary sessions during the study period, while nail content was not featured.

Our study shows that nail-related education was underrepresented at the AAD annual meetings from 2013 to 2019 compared to hair- and psoriasis-related content. Educational gaps in the diagnosis of fignail conditions previously have been delineated, and prioritization of instruction on nail disease pathology and diagnostic procedures has been recommended to improve patient care.1 The majority of nail unit melanomas are diagnosed at late stages, which has been attributed to deficiencies in clinical knowledge and failure to perform or inadequate biopsy techniques.2 Notably, a survey of third-year dermatology residents (N=240) assessing experience in procedural dermatology showed that 58% performed 10 or fewer nail procedures and 30% did not feel competent in performing nail surgery.3 Furthermore, a survey examining the management of longitudinal melanonychia among attending and resident dermatologists (N=402) found that 62% of residents and 28% of total respondents were not confident in managing melanonychia.4

A limitation of this study was the lack of online data available for AAD annual meetings before 2013, so we were unable to characterize any long-term trends. Furthermore, we were unable to assess the educational reach of these sessions, as data on attendance are lacking.

This study demonstrates a paucity of nail-related content at the AAD annual meetings. The introduction of the “Hands-on: Nail Surgery” in 2015 is an important step forward to diminish the knowledge gap in the diagnosis of various nail diseases and malignancies. We recommend increasing the number of hours and overall content of didactic nail sessions at the AAD annual meeting to further the knowledge and procedural skills of dermatologists in caring for patients with nail disorders.

- Hare AQ, R ich P. Clinical and educational gaps in diagnosis of nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:269-273.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential pitfalls in diagnosis, and guidelines for histologic reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483.

- Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. A survey-based study of management of longitudinal melanonychia amongst attending and resident dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:994-996.

- Hare AQ, R ich P. Clinical and educational gaps in diagnosis of nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:269-273.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential pitfalls in diagnosis, and guidelines for histologic reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483.

- Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. A survey-based study of management of longitudinal melanonychia amongst attending and resident dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:994-996.

Practice Points

- Diagnosis and treatment of nail conditions are necessary competencies for board-certified dermatologists, but appropriate education often is lacking.

- We recommend increasing the number of hours and overall content of didactic nail sessions at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting to further the knowledge and procedural skills of dermatologists caring for patients with nail disorders.

Evidence on spironolactone safety, COVID-19 reassuring for acne patients

according to a report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The virus needs androgens to infect cells, and uses androgen-dependent transmembrane protease serine 2 to prime viral protein spikes to anchor onto ACE2 receptors. Without that step, the virus can’t enter cells. Androgens are the only known activator in humans, so androgen blockers like spironolactone probably short-circuit the process, said the report’s lead author Carlos Wambier, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032).

The lack of androgens could be a possible explanation as to why mortality is so rare among children with COVID-19, and why fatalities among men are higher than among women with COVID-19, he said in an interview.

There are a lot of androgen blocker candidates, but he said spironolactone – a mainstay of acne treatment – might well be the best for the pandemic because of its concomitant lung and heart benefits.

The message counters a post on Instagram in March from a New York City dermatologist in private practice, Ellen Marmur, MD, that raised a question about spironolactone. Concerned about the situation in New York, she reviewed the literature and found a 2005 study that reported that macrophages drawn from 10 heart failure patients had increased ACE2 activity and increased messenger RNA expression after the subjects had been on spironolactone 25 mg per day for a month.

In an interview, she said she has been sharing her concerns with patients on spironolactone and offering them an alternative, such as minocycline, until this issue is better elucidated. To date, she has had one young patient who declined to switch to another treatment, and about six patients who were comfortable switching to another treatment for 1-2 months. She said that she is “clearly cautious yet uncertain about the influence of chronic spironolactone for acne on COVID infection in acne patients,” and that eventually she would be interested in seeing retrospective data on outcomes of patients on spironolactone for hypertension versus acne during the pandemic.

Dr. Marmur’s post was spread on social media and was picked up by a few online news outlets.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he’s been addressing concerns about spironolactone in educational webinars because of it.

He tells his audience that “you can’t make any claims” for COVID-19 based on the 2005 study. It was a small clinical study in heart failure patients and only assessed ACE2 expression on macrophages, not respiratory, cardiac, or mesangial cells, which are the relevant locations for viral invasion and damage. In fact, there are studies showing that spironolactone reduced ACE2 in renal mesangial cells. Also of note, spironolactone has been used with no indication of virus risk since the 1950s, he pointed out. The American Academy of Dermatology has not said to stop spironolactone.

At least one study is underway to see if spironolactone is beneficial: 100 mg twice a day for 5 days is being pitted against placebo in Turkey among people hospitalized with acute respiratory distress. The study will evaluate the effect of spironolactone on oxygenation.

“There’s no evidence to show spironolactone can increase mortality levels,” Dr. Wambier said. He is using it more now in patients with acne – a sign of androgen hyperactivity – convinced that it will protect against COVID-19. He even started his sister on it to help with androgenic hair loss, and maybe the virus.

Observations in Spain – increased prevalence of androgenic alopecia among hospitalized patients – support the androgen link; 29 of 41 men (71%) hospitalized with bilateral pneumonia had male pattern baldness, which was severe in 16 (39%), according to a recent report (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13443). The expected prevalence in a similar age-matched population is 31%-53%.

“Based on the scientific rationale combined with this preliminary observation, we believe investigating the potential association between androgens and COVID‐19 disease severity warrants further merit,” concluded the authors, who included Dr. Wambier, and other dermatologists from the United States, as well as Spain, Australia, Croatia, and Switzerland. “If such an association is confirmed, antiandrogens could be evaluated as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 infection,” they wrote.

The numbers are holding up in a larger series from three Spanish hospitals, and also showing a greater prevalence of androgenic hair loss among hospitalized women, Dr. Wambier said in the interview.

Authors of the two studies include an employee of Applied Biology. No conflicts were declared in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology study; no disclosures were listed in the JAAD study. Dr. Friedman had no disclosures.

according to a report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The virus needs androgens to infect cells, and uses androgen-dependent transmembrane protease serine 2 to prime viral protein spikes to anchor onto ACE2 receptors. Without that step, the virus can’t enter cells. Androgens are the only known activator in humans, so androgen blockers like spironolactone probably short-circuit the process, said the report’s lead author Carlos Wambier, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032).

The lack of androgens could be a possible explanation as to why mortality is so rare among children with COVID-19, and why fatalities among men are higher than among women with COVID-19, he said in an interview.

There are a lot of androgen blocker candidates, but he said spironolactone – a mainstay of acne treatment – might well be the best for the pandemic because of its concomitant lung and heart benefits.

The message counters a post on Instagram in March from a New York City dermatologist in private practice, Ellen Marmur, MD, that raised a question about spironolactone. Concerned about the situation in New York, she reviewed the literature and found a 2005 study that reported that macrophages drawn from 10 heart failure patients had increased ACE2 activity and increased messenger RNA expression after the subjects had been on spironolactone 25 mg per day for a month.

In an interview, she said she has been sharing her concerns with patients on spironolactone and offering them an alternative, such as minocycline, until this issue is better elucidated. To date, she has had one young patient who declined to switch to another treatment, and about six patients who were comfortable switching to another treatment for 1-2 months. She said that she is “clearly cautious yet uncertain about the influence of chronic spironolactone for acne on COVID infection in acne patients,” and that eventually she would be interested in seeing retrospective data on outcomes of patients on spironolactone for hypertension versus acne during the pandemic.

Dr. Marmur’s post was spread on social media and was picked up by a few online news outlets.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he’s been addressing concerns about spironolactone in educational webinars because of it.

He tells his audience that “you can’t make any claims” for COVID-19 based on the 2005 study. It was a small clinical study in heart failure patients and only assessed ACE2 expression on macrophages, not respiratory, cardiac, or mesangial cells, which are the relevant locations for viral invasion and damage. In fact, there are studies showing that spironolactone reduced ACE2 in renal mesangial cells. Also of note, spironolactone has been used with no indication of virus risk since the 1950s, he pointed out. The American Academy of Dermatology has not said to stop spironolactone.

At least one study is underway to see if spironolactone is beneficial: 100 mg twice a day for 5 days is being pitted against placebo in Turkey among people hospitalized with acute respiratory distress. The study will evaluate the effect of spironolactone on oxygenation.

“There’s no evidence to show spironolactone can increase mortality levels,” Dr. Wambier said. He is using it more now in patients with acne – a sign of androgen hyperactivity – convinced that it will protect against COVID-19. He even started his sister on it to help with androgenic hair loss, and maybe the virus.

Observations in Spain – increased prevalence of androgenic alopecia among hospitalized patients – support the androgen link; 29 of 41 men (71%) hospitalized with bilateral pneumonia had male pattern baldness, which was severe in 16 (39%), according to a recent report (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13443). The expected prevalence in a similar age-matched population is 31%-53%.

“Based on the scientific rationale combined with this preliminary observation, we believe investigating the potential association between androgens and COVID‐19 disease severity warrants further merit,” concluded the authors, who included Dr. Wambier, and other dermatologists from the United States, as well as Spain, Australia, Croatia, and Switzerland. “If such an association is confirmed, antiandrogens could be evaluated as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 infection,” they wrote.

The numbers are holding up in a larger series from three Spanish hospitals, and also showing a greater prevalence of androgenic hair loss among hospitalized women, Dr. Wambier said in the interview.

Authors of the two studies include an employee of Applied Biology. No conflicts were declared in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology study; no disclosures were listed in the JAAD study. Dr. Friedman had no disclosures.

according to a report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The virus needs androgens to infect cells, and uses androgen-dependent transmembrane protease serine 2 to prime viral protein spikes to anchor onto ACE2 receptors. Without that step, the virus can’t enter cells. Androgens are the only known activator in humans, so androgen blockers like spironolactone probably short-circuit the process, said the report’s lead author Carlos Wambier, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032).

The lack of androgens could be a possible explanation as to why mortality is so rare among children with COVID-19, and why fatalities among men are higher than among women with COVID-19, he said in an interview.

There are a lot of androgen blocker candidates, but he said spironolactone – a mainstay of acne treatment – might well be the best for the pandemic because of its concomitant lung and heart benefits.

The message counters a post on Instagram in March from a New York City dermatologist in private practice, Ellen Marmur, MD, that raised a question about spironolactone. Concerned about the situation in New York, she reviewed the literature and found a 2005 study that reported that macrophages drawn from 10 heart failure patients had increased ACE2 activity and increased messenger RNA expression after the subjects had been on spironolactone 25 mg per day for a month.

In an interview, she said she has been sharing her concerns with patients on spironolactone and offering them an alternative, such as minocycline, until this issue is better elucidated. To date, she has had one young patient who declined to switch to another treatment, and about six patients who were comfortable switching to another treatment for 1-2 months. She said that she is “clearly cautious yet uncertain about the influence of chronic spironolactone for acne on COVID infection in acne patients,” and that eventually she would be interested in seeing retrospective data on outcomes of patients on spironolactone for hypertension versus acne during the pandemic.

Dr. Marmur’s post was spread on social media and was picked up by a few online news outlets.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he’s been addressing concerns about spironolactone in educational webinars because of it.

He tells his audience that “you can’t make any claims” for COVID-19 based on the 2005 study. It was a small clinical study in heart failure patients and only assessed ACE2 expression on macrophages, not respiratory, cardiac, or mesangial cells, which are the relevant locations for viral invasion and damage. In fact, there are studies showing that spironolactone reduced ACE2 in renal mesangial cells. Also of note, spironolactone has been used with no indication of virus risk since the 1950s, he pointed out. The American Academy of Dermatology has not said to stop spironolactone.

At least one study is underway to see if spironolactone is beneficial: 100 mg twice a day for 5 days is being pitted against placebo in Turkey among people hospitalized with acute respiratory distress. The study will evaluate the effect of spironolactone on oxygenation.

“There’s no evidence to show spironolactone can increase mortality levels,” Dr. Wambier said. He is using it more now in patients with acne – a sign of androgen hyperactivity – convinced that it will protect against COVID-19. He even started his sister on it to help with androgenic hair loss, and maybe the virus.

Observations in Spain – increased prevalence of androgenic alopecia among hospitalized patients – support the androgen link; 29 of 41 men (71%) hospitalized with bilateral pneumonia had male pattern baldness, which was severe in 16 (39%), according to a recent report (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13443). The expected prevalence in a similar age-matched population is 31%-53%.

“Based on the scientific rationale combined with this preliminary observation, we believe investigating the potential association between androgens and COVID‐19 disease severity warrants further merit,” concluded the authors, who included Dr. Wambier, and other dermatologists from the United States, as well as Spain, Australia, Croatia, and Switzerland. “If such an association is confirmed, antiandrogens could be evaluated as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 infection,” they wrote.

The numbers are holding up in a larger series from three Spanish hospitals, and also showing a greater prevalence of androgenic hair loss among hospitalized women, Dr. Wambier said in the interview.

Authors of the two studies include an employee of Applied Biology. No conflicts were declared in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology study; no disclosures were listed in the JAAD study. Dr. Friedman had no disclosures.

Lichen Planopilaris in a Patient Treated With Bexarotene for Lymphomatoid Papulosis

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent, self-healing crops of papulonodular eruptions, often resembling cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Oral bexarotene, a retinoid X receptor–selective retinoid, can be used to control the disease.2,3 Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by irreversible hair loss, perifollicular inflammation, and follicular hyperkeratosis, commonly affecting the scalp vertex in adults.4 We report a case of a patient with lymphomatoid papulosis who was treated with bexarotene and subsequently developed LPP. We also discuss a proposed mechanism by which bexarotene may have influenced the onset of LPP.

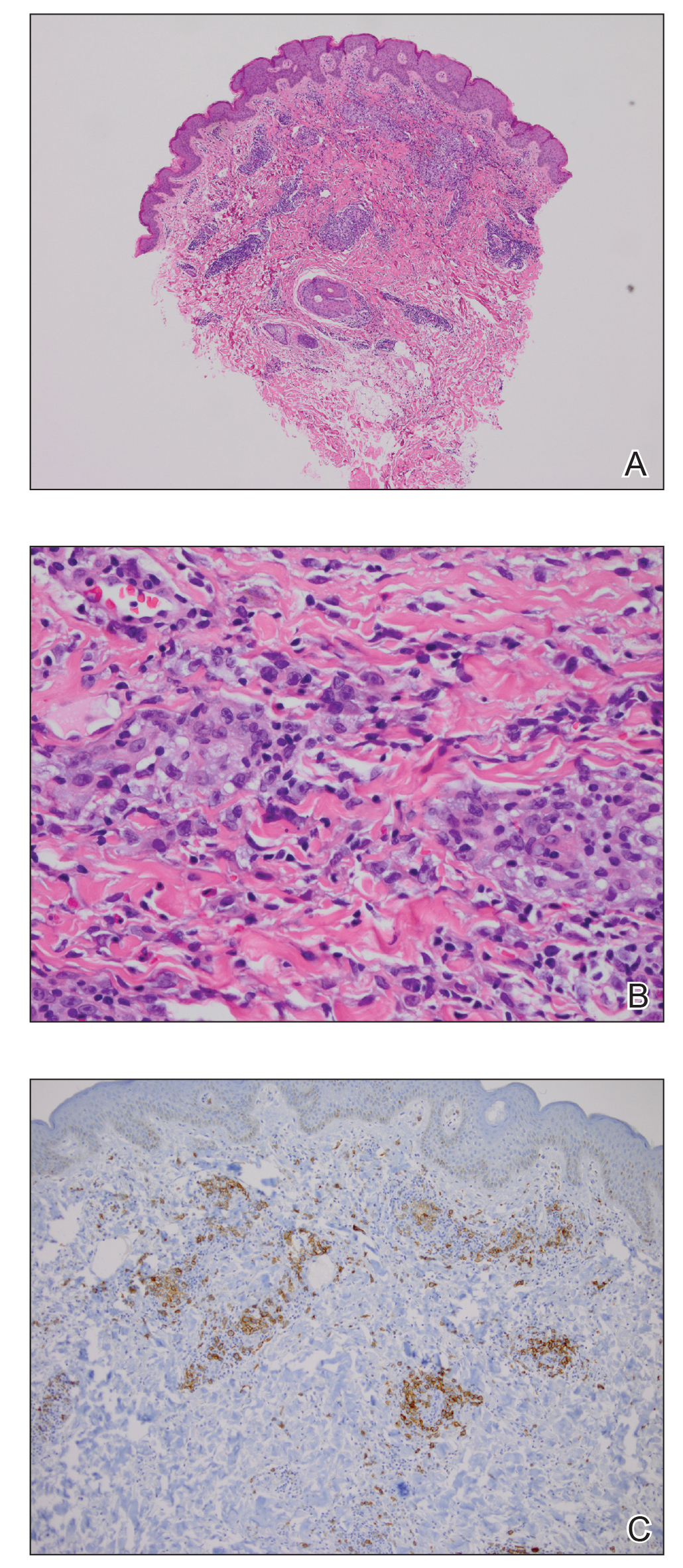

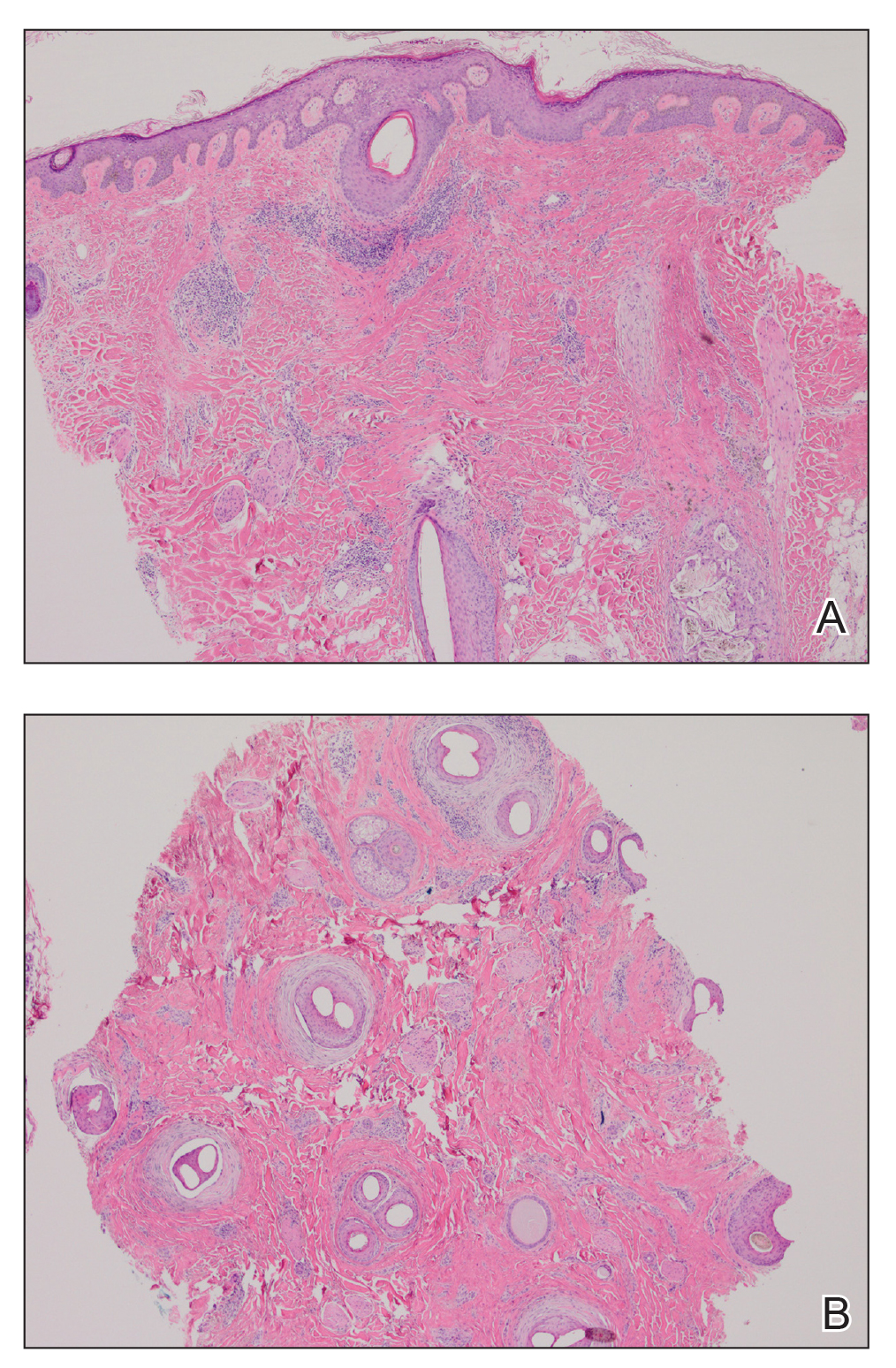

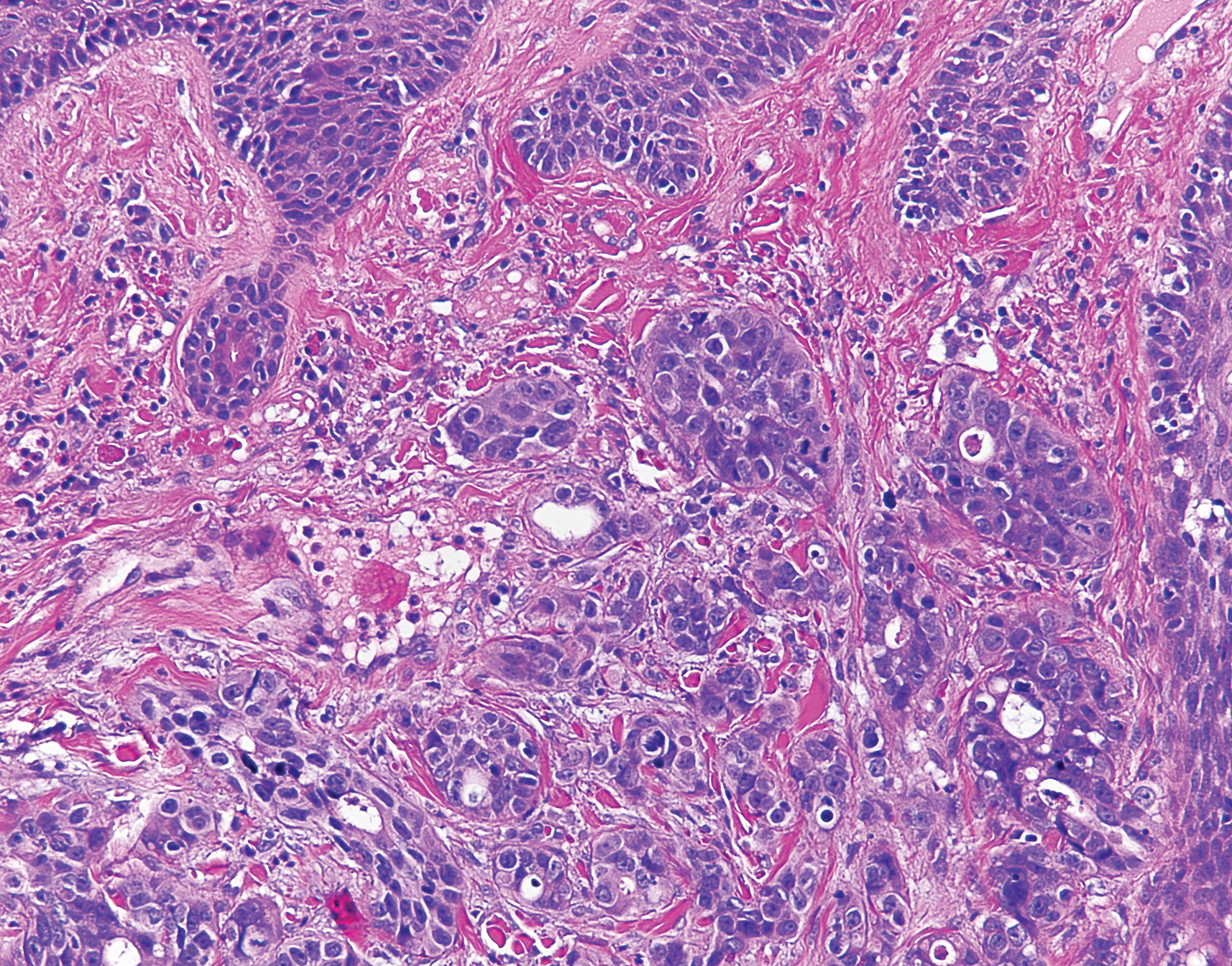

A 35-year-old woman who was previously healthy initially presented with recurrent pruritic papular eruptions on the flank, axillae, and groin of several months’ duration. The lesions appeared as 2-mm, flat-topped, violaceous papules. The patient had no known drug allergies, no medical or family history of skin disease, and was only taking 3000 mg/d of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil). Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen from the inner thigh showed enlarged, atypical, dermal lymphocytes that were CD30+ (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. As she had undergone tubal ligation several years prior, she was prescribed oral bexarotene 300 mg once daily in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, as needed. Symptoms were well controlled on this regimen.

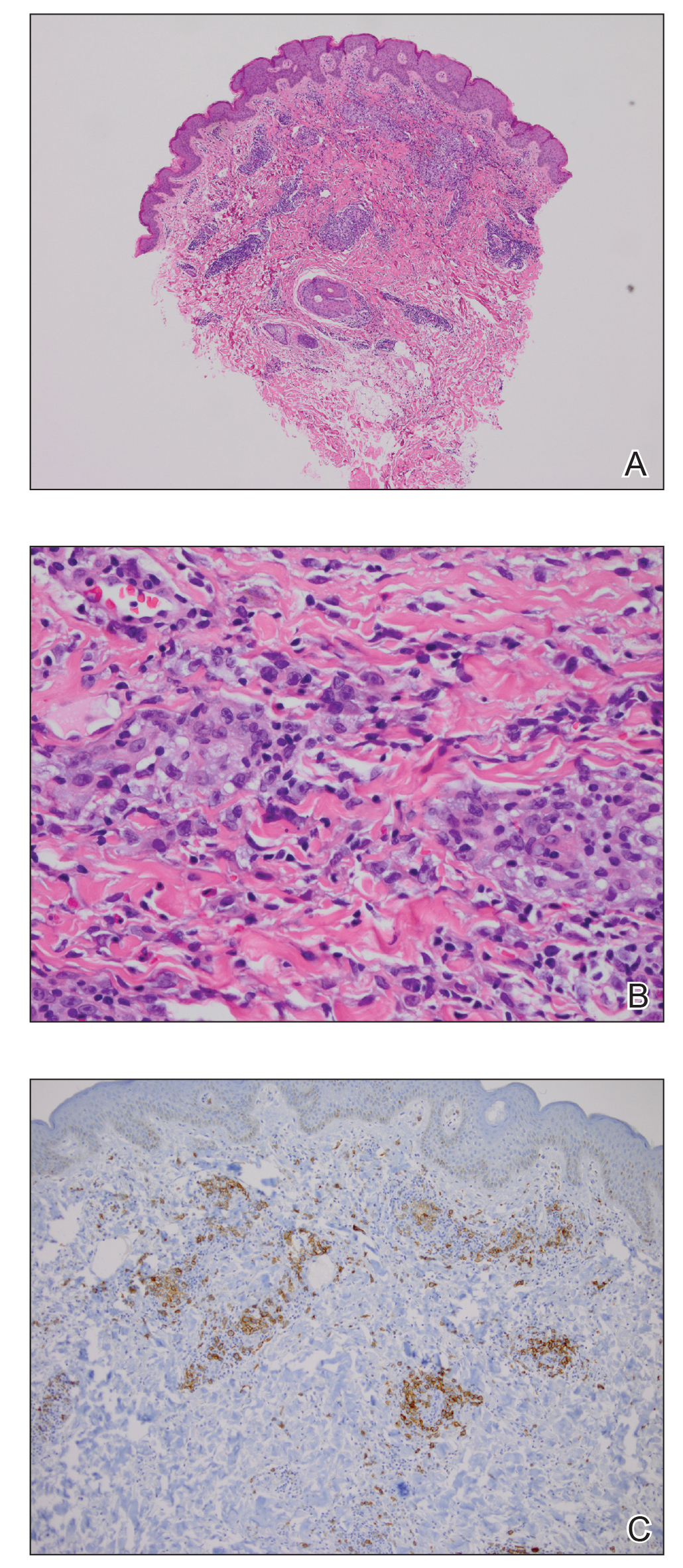

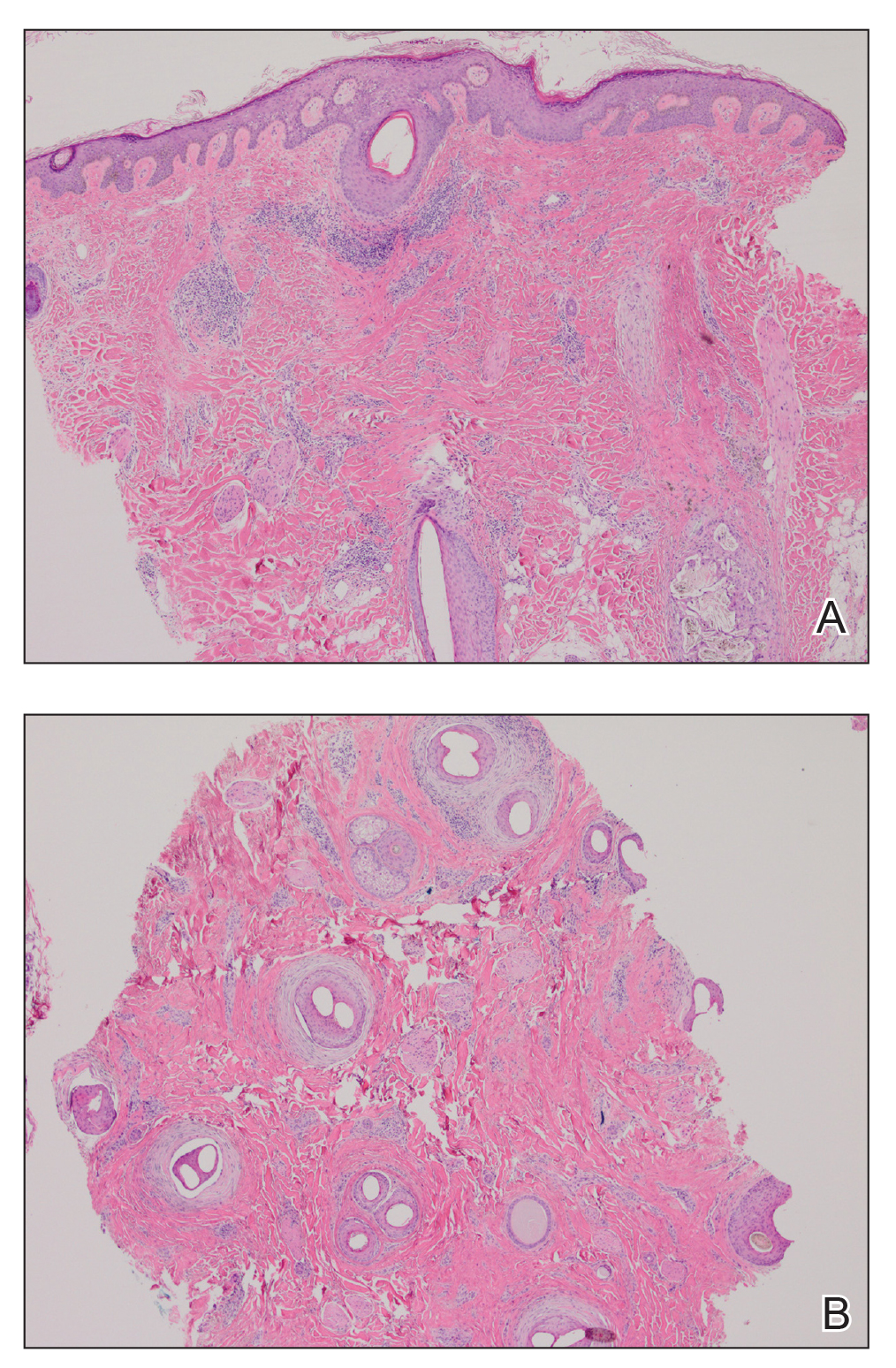

Six months later the patient returned, presenting with a new central patch of scarring alopecia on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 2). Adjacent to the area of hair loss were areas of prominent perifollicular scale that were slightly violaceous in color. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the scalp showed dermal scarring with perifollicular lamellar fibrosis surrounded by a rim of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 3). Sebaceous glands were found to be reduced in number. These findings were consistent with cicatricial alopecia, which was further classified as LPP in conjunction with the clinical findings. No CD30+ lymphocytes were identified in these specimens.

Baseline fasting triglycerides were 123 mg/dL (desirable: <150 mg/dL; borderline: 150–199 mg/dL; high: ≥200 mg/dL) and were stable over the first 4 months on bexarotene. After 5 months of therapy, the triglycerides increased to a high of 255 mg/dL, which corresponded with the onset of LPP. She was treated for the hypertriglyceridemia with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), and subsequent triglyceride levels have normalized and been stable. Her alopecia has not progressed but is persistent. She continues to have central hypothyroidism due to bexarotene and is on levothyroxine. The lymphomatoid papulosis also remains stable with no signs of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Although the exact mechanism of LPP is not fully understood, studies have suggested that cellular lipid metabolism may be responsible for the inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit.4-11 Hyperlipidemia is the most common side effect of oral bexarotene, typically occurring within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.3,12 Considering the insights into the role of lipid regulation on LPP pathogenesis, it is reasonable to suspect that the dyslipidemia caused by bexarotene may have triggered the onset of LPP in our patient. The patient’s lipid values mostly remained within reference range throughout the course of treatment, though she did have elevation of triglycerides around the onset of LPP. Dyslipidemia has been reported in patients with lichen planus but not in patients with LPP. One case-control study showed no dyslipidemia in patients with LPP, but the triglyceride levels were not tracked over time and patients had varying durations since onset of disease at presentation.9-11,13 In our case, we were fortunate to have this information, and it may suggest an interaction between lipid dysregulation and the development of LPP. It would be interesting to explore this further in a larger patient population and to evaluate if control of dyslipidemia reduces progression of disease as it appears to have done for our patient.

- Karp DL, Horn TD. Lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:379-395; quiz 396-398.

- Krathen RA, Ward S, Duvic M. Bexarotene is a new treatment option for lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatology. 2003;206:142-147.

- Targretin (bexarotene) capsule [package insert]. St. Petersburg, FL: Cardinal Health; 2003. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=63656f64-e240-4855-8df9-ca1655863735. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. What’s new in cicatricial alopecia? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:576-90.

- Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, et al. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268-270.

- Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, et al. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067-2075.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-157.

- López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:399-404.

- Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, et al. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1398-1401.

- Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:626-629.

- de Vries-van der Weij J, de Haan W, Hu L, et al. Bexarotene induces dyslipidemia by increased very low-density lipoprotein production and cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2368-2375.

- Conic RRZ, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with dyslipidemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1088-1089.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent, self-healing crops of papulonodular eruptions, often resembling cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Oral bexarotene, a retinoid X receptor–selective retinoid, can be used to control the disease.2,3 Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by irreversible hair loss, perifollicular inflammation, and follicular hyperkeratosis, commonly affecting the scalp vertex in adults.4 We report a case of a patient with lymphomatoid papulosis who was treated with bexarotene and subsequently developed LPP. We also discuss a proposed mechanism by which bexarotene may have influenced the onset of LPP.

A 35-year-old woman who was previously healthy initially presented with recurrent pruritic papular eruptions on the flank, axillae, and groin of several months’ duration. The lesions appeared as 2-mm, flat-topped, violaceous papules. The patient had no known drug allergies, no medical or family history of skin disease, and was only taking 3000 mg/d of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil). Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen from the inner thigh showed enlarged, atypical, dermal lymphocytes that were CD30+ (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. As she had undergone tubal ligation several years prior, she was prescribed oral bexarotene 300 mg once daily in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, as needed. Symptoms were well controlled on this regimen.

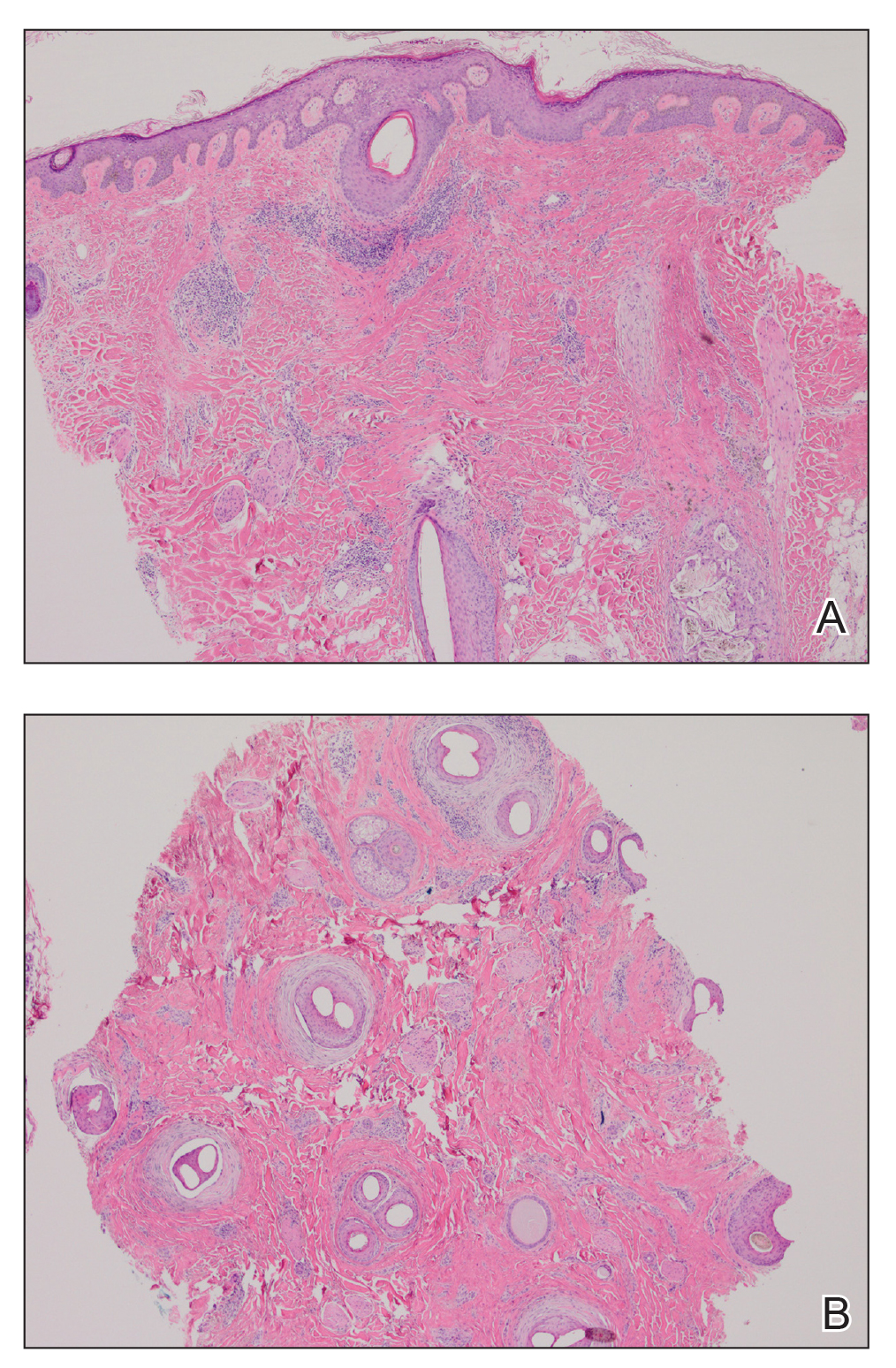

Six months later the patient returned, presenting with a new central patch of scarring alopecia on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 2). Adjacent to the area of hair loss were areas of prominent perifollicular scale that were slightly violaceous in color. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the scalp showed dermal scarring with perifollicular lamellar fibrosis surrounded by a rim of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 3). Sebaceous glands were found to be reduced in number. These findings were consistent with cicatricial alopecia, which was further classified as LPP in conjunction with the clinical findings. No CD30+ lymphocytes were identified in these specimens.

Baseline fasting triglycerides were 123 mg/dL (desirable: <150 mg/dL; borderline: 150–199 mg/dL; high: ≥200 mg/dL) and were stable over the first 4 months on bexarotene. After 5 months of therapy, the triglycerides increased to a high of 255 mg/dL, which corresponded with the onset of LPP. She was treated for the hypertriglyceridemia with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), and subsequent triglyceride levels have normalized and been stable. Her alopecia has not progressed but is persistent. She continues to have central hypothyroidism due to bexarotene and is on levothyroxine. The lymphomatoid papulosis also remains stable with no signs of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Although the exact mechanism of LPP is not fully understood, studies have suggested that cellular lipid metabolism may be responsible for the inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit.4-11 Hyperlipidemia is the most common side effect of oral bexarotene, typically occurring within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.3,12 Considering the insights into the role of lipid regulation on LPP pathogenesis, it is reasonable to suspect that the dyslipidemia caused by bexarotene may have triggered the onset of LPP in our patient. The patient’s lipid values mostly remained within reference range throughout the course of treatment, though she did have elevation of triglycerides around the onset of LPP. Dyslipidemia has been reported in patients with lichen planus but not in patients with LPP. One case-control study showed no dyslipidemia in patients with LPP, but the triglyceride levels were not tracked over time and patients had varying durations since onset of disease at presentation.9-11,13 In our case, we were fortunate to have this information, and it may suggest an interaction between lipid dysregulation and the development of LPP. It would be interesting to explore this further in a larger patient population and to evaluate if control of dyslipidemia reduces progression of disease as it appears to have done for our patient.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent, self-healing crops of papulonodular eruptions, often resembling cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Oral bexarotene, a retinoid X receptor–selective retinoid, can be used to control the disease.2,3 Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by irreversible hair loss, perifollicular inflammation, and follicular hyperkeratosis, commonly affecting the scalp vertex in adults.4 We report a case of a patient with lymphomatoid papulosis who was treated with bexarotene and subsequently developed LPP. We also discuss a proposed mechanism by which bexarotene may have influenced the onset of LPP.

A 35-year-old woman who was previously healthy initially presented with recurrent pruritic papular eruptions on the flank, axillae, and groin of several months’ duration. The lesions appeared as 2-mm, flat-topped, violaceous papules. The patient had no known drug allergies, no medical or family history of skin disease, and was only taking 3000 mg/d of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil). Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen from the inner thigh showed enlarged, atypical, dermal lymphocytes that were CD30+ (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. As she had undergone tubal ligation several years prior, she was prescribed oral bexarotene 300 mg once daily in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, as needed. Symptoms were well controlled on this regimen.

Six months later the patient returned, presenting with a new central patch of scarring alopecia on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 2). Adjacent to the area of hair loss were areas of prominent perifollicular scale that were slightly violaceous in color. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the scalp showed dermal scarring with perifollicular lamellar fibrosis surrounded by a rim of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 3). Sebaceous glands were found to be reduced in number. These findings were consistent with cicatricial alopecia, which was further classified as LPP in conjunction with the clinical findings. No CD30+ lymphocytes were identified in these specimens.

Baseline fasting triglycerides were 123 mg/dL (desirable: <150 mg/dL; borderline: 150–199 mg/dL; high: ≥200 mg/dL) and were stable over the first 4 months on bexarotene. After 5 months of therapy, the triglycerides increased to a high of 255 mg/dL, which corresponded with the onset of LPP. She was treated for the hypertriglyceridemia with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), and subsequent triglyceride levels have normalized and been stable. Her alopecia has not progressed but is persistent. She continues to have central hypothyroidism due to bexarotene and is on levothyroxine. The lymphomatoid papulosis also remains stable with no signs of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Although the exact mechanism of LPP is not fully understood, studies have suggested that cellular lipid metabolism may be responsible for the inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit.4-11 Hyperlipidemia is the most common side effect of oral bexarotene, typically occurring within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.3,12 Considering the insights into the role of lipid regulation on LPP pathogenesis, it is reasonable to suspect that the dyslipidemia caused by bexarotene may have triggered the onset of LPP in our patient. The patient’s lipid values mostly remained within reference range throughout the course of treatment, though she did have elevation of triglycerides around the onset of LPP. Dyslipidemia has been reported in patients with lichen planus but not in patients with LPP. One case-control study showed no dyslipidemia in patients with LPP, but the triglyceride levels were not tracked over time and patients had varying durations since onset of disease at presentation.9-11,13 In our case, we were fortunate to have this information, and it may suggest an interaction between lipid dysregulation and the development of LPP. It would be interesting to explore this further in a larger patient population and to evaluate if control of dyslipidemia reduces progression of disease as it appears to have done for our patient.

- Karp DL, Horn TD. Lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:379-395; quiz 396-398.

- Krathen RA, Ward S, Duvic M. Bexarotene is a new treatment option for lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatology. 2003;206:142-147.

- Targretin (bexarotene) capsule [package insert]. St. Petersburg, FL: Cardinal Health; 2003. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=63656f64-e240-4855-8df9-ca1655863735. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. What’s new in cicatricial alopecia? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:576-90.

- Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, et al. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268-270.

- Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, et al. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067-2075.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-157.

- López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:399-404.

- Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, et al. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1398-1401.

- Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:626-629.

- de Vries-van der Weij J, de Haan W, Hu L, et al. Bexarotene induces dyslipidemia by increased very low-density lipoprotein production and cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2368-2375.

- Conic RRZ, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with dyslipidemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1088-1089.

- Karp DL, Horn TD. Lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:379-395; quiz 396-398.

- Krathen RA, Ward S, Duvic M. Bexarotene is a new treatment option for lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatology. 2003;206:142-147.

- Targretin (bexarotene) capsule [package insert]. St. Petersburg, FL: Cardinal Health; 2003. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=63656f64-e240-4855-8df9-ca1655863735. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. What’s new in cicatricial alopecia? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:576-90.

- Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, et al. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268-270.

- Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, et al. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067-2075.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-157.

- López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:399-404.

- Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, et al. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1398-1401.

- Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:626-629.

- de Vries-van der Weij J, de Haan W, Hu L, et al. Bexarotene induces dyslipidemia by increased very low-density lipoprotein production and cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2368-2375.

- Conic RRZ, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with dyslipidemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1088-1089.

Practice Points

- Oral retinoids may be associated with development of lichen planopilaris (LPP).

- Hypertriglyceridemia may be associated with onset of LPP.

Cutaneous Metastases From Esophageal Adenocarcinoma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right frontal scalp of 4 months’ duration and a lesion on the left frontal scalp of 1 month’s duration. Both lesions were tender, bleeding, nonhealing, and growing in size. The patient reported no improvement with the use of triple antibiotic ointment. He denied any associated symptoms or trauma to the affected areas. He had a history of stage IV esophageal adenocarcinoma that initially had been surgically removed 6 years prior but metastasized to the lungs and bone. The patient subsequently underwent treatment with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), trastuzumab, and radiation therapy.

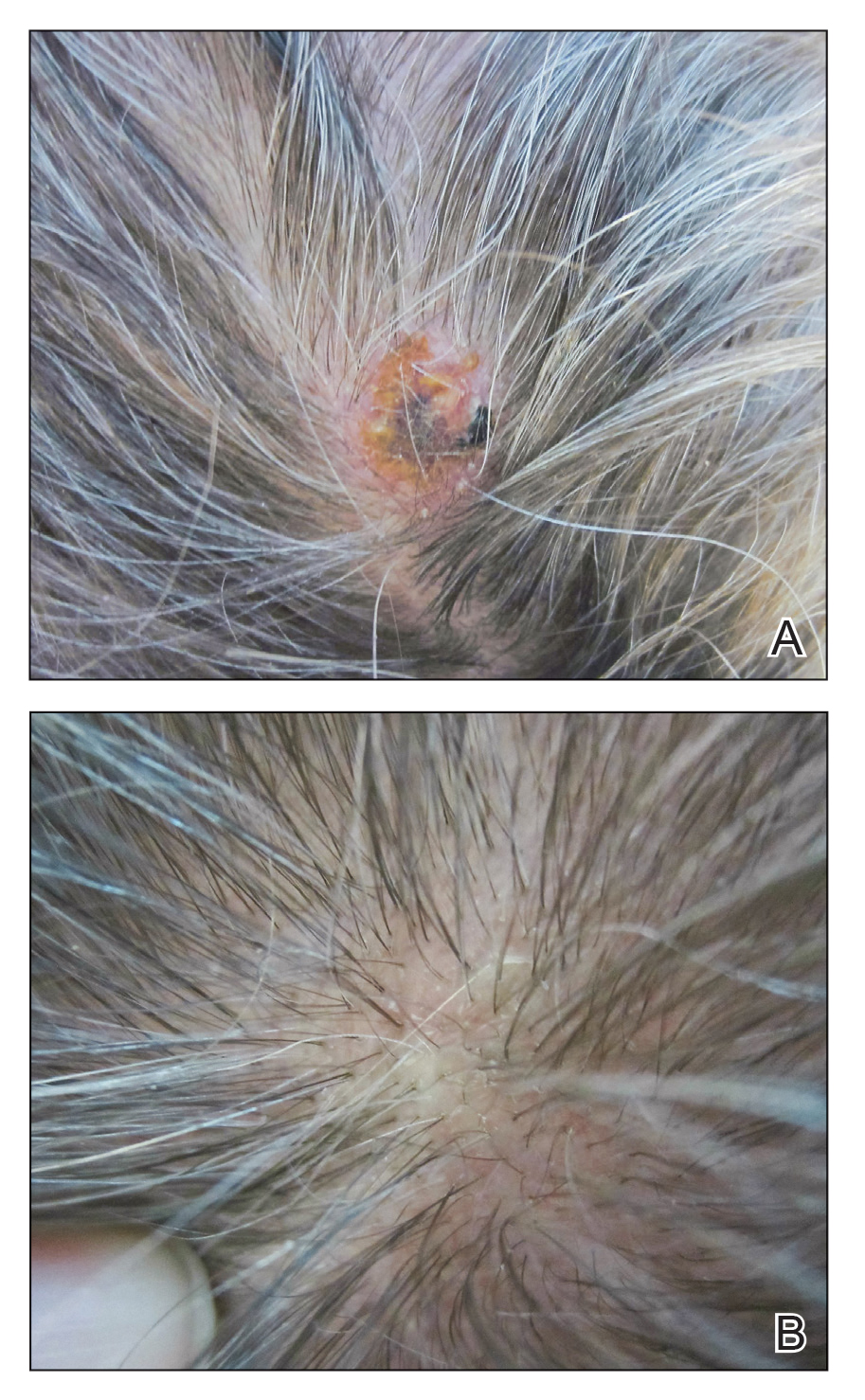

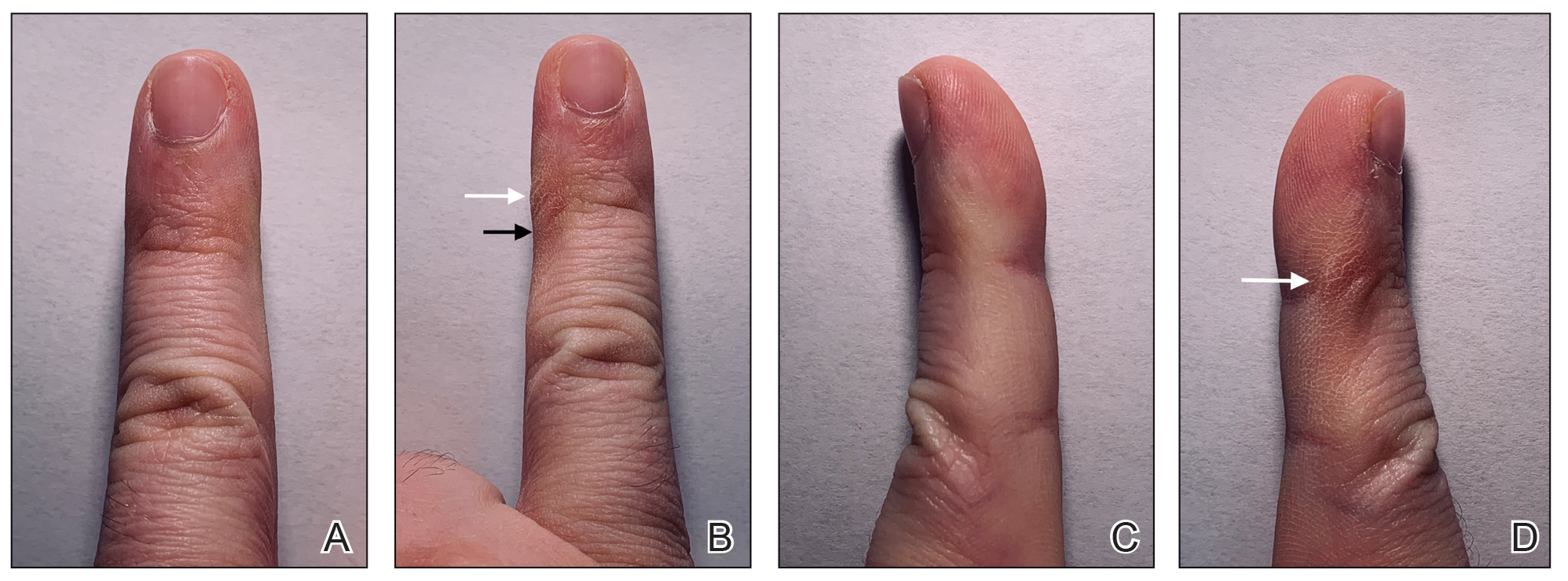

Physical examination revealed a hyperkeratotic pink nodule with a central erosion and crust on the right frontal scalp measuring 1.5×2 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The left frontal scalp lesion was a smooth pearly papule measuring 5×5 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). The differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Shave biopsies were taken of both scalp lesions.

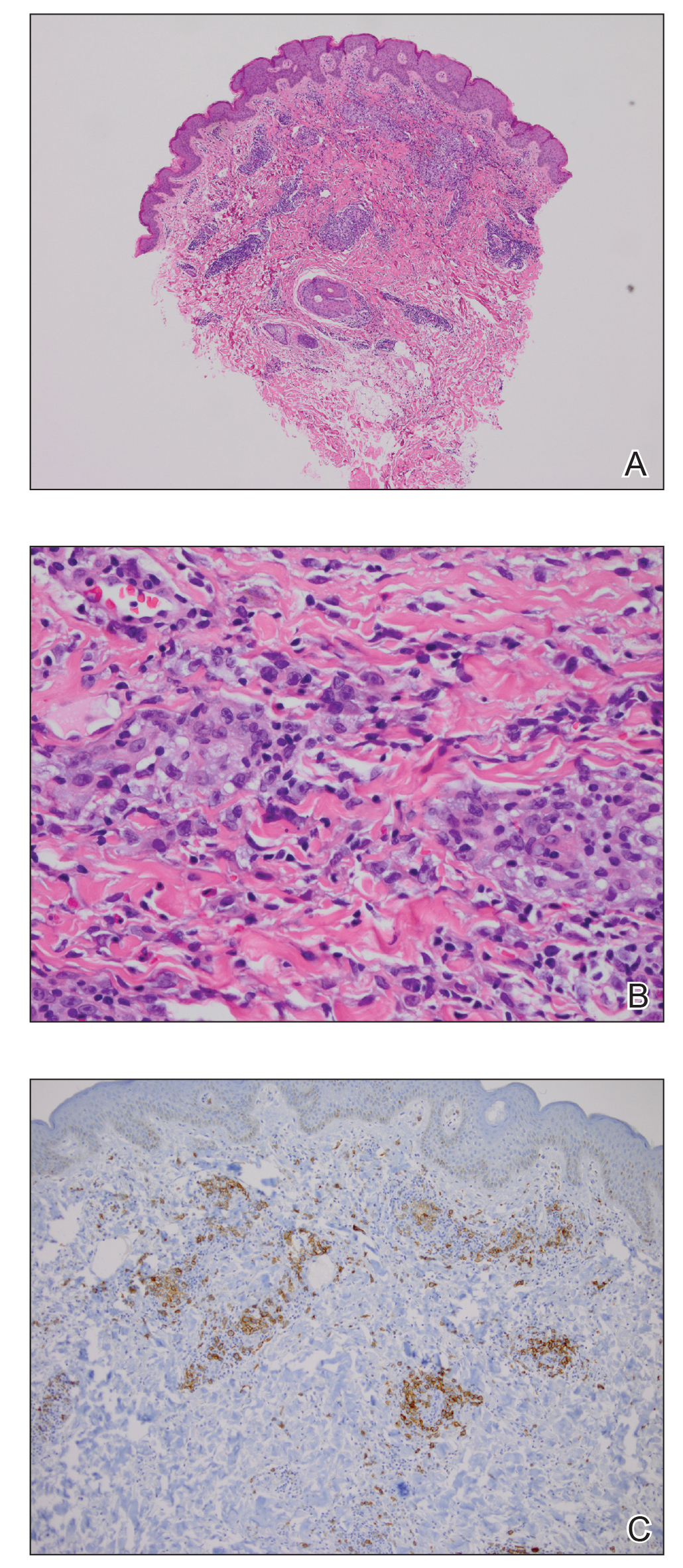

Histologic examination of both scalp lesions demonstrated a dermal gland-forming neoplasm with an infiltrative distribution that was comprised of irregular cribriform glands containing cellular debris (Figure 2). The cells of interest were enlarged and contained pleomorphic crowded nuclei that formed aberrant mitotic division figures. Both biopsies were positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final diagnosis for both scalp lesions was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was most suggestive of cutaneous metastases of the patient’s known esophageal adenocarcinoma. Given further metastasis, the patient was ultimately switched to ramucirumab and paclitaxel per oncology.

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cause of death related to cancer worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic type of esophageal carcinoma, with an incidence as high as 5.69 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 Internal malignancies that lead to cutaneous metastases are not uncommon; however, the literature is limited on cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal cancer. Cutaneous metastases secondary to internal malignancies present in less than 10% of overall cases; tend to derive from the breasts, lungs, and large bowel; and usually present in the sixth to seventh decades of life.2 Further, roughly 1% of all skin metastases originate from the esophagus.3 When there are cutaneous metastases to the scalp, they often arise from breast carcinomas and renal cell carcinomas.4,5 Rarely does esophageal cancer spread to the scalp.2,6-9 When cutaneous metastases originate from the esophagus, multiple cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas can be the etiology of origin.10 Metastases originating from esophageal carcinomas frequently are diagnosed in the abdominal lymph nodes (45%), liver (35%), lungs (20%), cervical/supraclavicular lymph nodes (18%), bones (9%), adrenals (5%), peritoneum (2%), brain (2%), stomach (1%), pancreas (1%), pleura (1%), skin/body wall (1%), pericardium (1%), and spleen (1%).3 Additionally, multiple cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported,7,9 as were seen in our case.

The clinical appearance of cutaneous scalp metastases has been described as inflammatory papules, indurated plaques, or nodules,2 which is consistent with our case, though the spectrum of presentation is admittedly broad. Histopathology of lesions characteristically shows prominent intraluminal necrotic cellular debris, which is common for adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, utilizing immunohistochemical stains to detect specific antigens within tumor cells allows for better specificity of the tumor origin. More specifically, cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 are stained in esophageal metaplasia, such as Barrett esophagus, rather than in intestinal metaplasia inside the stomach.2,11 Therefore, discerning the location of the adenocarcinoma proves fruitful when using cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Although CDX2 is an additional marker that can be used for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas with decent sensitivity and specificity, it can still be expressed in mucinous ovarian carcinomas and urinary bladder adenocarcinomas.12 In our patient, the strong reactivity of cytokeratin 7 in addition to the characteristic morphology in both presenting biopsies was sufficient to make the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma to the scalp.

Our case highlights multiple cutaneous metastases of the scalp from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although cutaneous scalp metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, it is essential to provide a full-body skin examination, including the scalp, in patients with a history of esophageal cancer and to biopsy any suspicious nodules or plaques. The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is less than 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.13 Identifying cutaneous metastasis of an esophageal adenocarcinoma can either change the staging of the cancer (if it was the first distant metastasis noted) or indicate an insufficient response to treatment in a patient with known metastatic disease, prompting a potential change in treatment.7

This case illustrates a rare site of metastasis of a fairly common cancer and highlights the histopathology and accompanying immunohistochemical stains that can be useful in diagnosis as well as the spectrum of its clinical presentation.

- Melhado R, Alderson D, Tucker O. The changing face of esophageal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1379-1404.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Oh SH, et al. A case of esophageal adenocarcinoma metastasized to the scalp [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:164-167.

- Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, et al. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1120.

- Dobson C, Tagor V, Myint A, et al. Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma in face and scalp mimicking cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:635-636.

- Riter H, Ghobrial I. Renal cell carcinoma with acrometastasis and scalp metastasis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:76.

- Roh EK, Nord R, Jukic DM. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2006;77:106.

- Doumit G, Abouhassan W, Piliang M, et al. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma: comparative histopathology dictates surgical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;71:60-62.

- Roy AD, Sherparpa M, Prasad PR, et al. Scalp metastasis of gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a rare occurrence. 2014;8:159-160.

- Stein R, Spencer J. Painful cutaneous metastases from esophageal carcinoma. Cutis. 2002;70:230.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):161-182.

- Ormsby AH, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, et al. Cytokeratin subsets can reliably distinguish Barrett’s esophagus from intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:288-294.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Skelton H. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus to the skin: new patterns of tumor recurrence and alternate treatments for palliation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:425-431.

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right frontal scalp of 4 months’ duration and a lesion on the left frontal scalp of 1 month’s duration. Both lesions were tender, bleeding, nonhealing, and growing in size. The patient reported no improvement with the use of triple antibiotic ointment. He denied any associated symptoms or trauma to the affected areas. He had a history of stage IV esophageal adenocarcinoma that initially had been surgically removed 6 years prior but metastasized to the lungs and bone. The patient subsequently underwent treatment with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), trastuzumab, and radiation therapy.

Physical examination revealed a hyperkeratotic pink nodule with a central erosion and crust on the right frontal scalp measuring 1.5×2 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The left frontal scalp lesion was a smooth pearly papule measuring 5×5 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). The differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Shave biopsies were taken of both scalp lesions.

Histologic examination of both scalp lesions demonstrated a dermal gland-forming neoplasm with an infiltrative distribution that was comprised of irregular cribriform glands containing cellular debris (Figure 2). The cells of interest were enlarged and contained pleomorphic crowded nuclei that formed aberrant mitotic division figures. Both biopsies were positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final diagnosis for both scalp lesions was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was most suggestive of cutaneous metastases of the patient’s known esophageal adenocarcinoma. Given further metastasis, the patient was ultimately switched to ramucirumab and paclitaxel per oncology.

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cause of death related to cancer worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic type of esophageal carcinoma, with an incidence as high as 5.69 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 Internal malignancies that lead to cutaneous metastases are not uncommon; however, the literature is limited on cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal cancer. Cutaneous metastases secondary to internal malignancies present in less than 10% of overall cases; tend to derive from the breasts, lungs, and large bowel; and usually present in the sixth to seventh decades of life.2 Further, roughly 1% of all skin metastases originate from the esophagus.3 When there are cutaneous metastases to the scalp, they often arise from breast carcinomas and renal cell carcinomas.4,5 Rarely does esophageal cancer spread to the scalp.2,6-9 When cutaneous metastases originate from the esophagus, multiple cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas can be the etiology of origin.10 Metastases originating from esophageal carcinomas frequently are diagnosed in the abdominal lymph nodes (45%), liver (35%), lungs (20%), cervical/supraclavicular lymph nodes (18%), bones (9%), adrenals (5%), peritoneum (2%), brain (2%), stomach (1%), pancreas (1%), pleura (1%), skin/body wall (1%), pericardium (1%), and spleen (1%).3 Additionally, multiple cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported,7,9 as were seen in our case.

The clinical appearance of cutaneous scalp metastases has been described as inflammatory papules, indurated plaques, or nodules,2 which is consistent with our case, though the spectrum of presentation is admittedly broad. Histopathology of lesions characteristically shows prominent intraluminal necrotic cellular debris, which is common for adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, utilizing immunohistochemical stains to detect specific antigens within tumor cells allows for better specificity of the tumor origin. More specifically, cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 are stained in esophageal metaplasia, such as Barrett esophagus, rather than in intestinal metaplasia inside the stomach.2,11 Therefore, discerning the location of the adenocarcinoma proves fruitful when using cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Although CDX2 is an additional marker that can be used for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas with decent sensitivity and specificity, it can still be expressed in mucinous ovarian carcinomas and urinary bladder adenocarcinomas.12 In our patient, the strong reactivity of cytokeratin 7 in addition to the characteristic morphology in both presenting biopsies was sufficient to make the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma to the scalp.

Our case highlights multiple cutaneous metastases of the scalp from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although cutaneous scalp metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, it is essential to provide a full-body skin examination, including the scalp, in patients with a history of esophageal cancer and to biopsy any suspicious nodules or plaques. The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is less than 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.13 Identifying cutaneous metastasis of an esophageal adenocarcinoma can either change the staging of the cancer (if it was the first distant metastasis noted) or indicate an insufficient response to treatment in a patient with known metastatic disease, prompting a potential change in treatment.7

This case illustrates a rare site of metastasis of a fairly common cancer and highlights the histopathology and accompanying immunohistochemical stains that can be useful in diagnosis as well as the spectrum of its clinical presentation.

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right frontal scalp of 4 months’ duration and a lesion on the left frontal scalp of 1 month’s duration. Both lesions were tender, bleeding, nonhealing, and growing in size. The patient reported no improvement with the use of triple antibiotic ointment. He denied any associated symptoms or trauma to the affected areas. He had a history of stage IV esophageal adenocarcinoma that initially had been surgically removed 6 years prior but metastasized to the lungs and bone. The patient subsequently underwent treatment with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), trastuzumab, and radiation therapy.

Physical examination revealed a hyperkeratotic pink nodule with a central erosion and crust on the right frontal scalp measuring 1.5×2 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The left frontal scalp lesion was a smooth pearly papule measuring 5×5 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). The differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Shave biopsies were taken of both scalp lesions.

Histologic examination of both scalp lesions demonstrated a dermal gland-forming neoplasm with an infiltrative distribution that was comprised of irregular cribriform glands containing cellular debris (Figure 2). The cells of interest were enlarged and contained pleomorphic crowded nuclei that formed aberrant mitotic division figures. Both biopsies were positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final diagnosis for both scalp lesions was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was most suggestive of cutaneous metastases of the patient’s known esophageal adenocarcinoma. Given further metastasis, the patient was ultimately switched to ramucirumab and paclitaxel per oncology.

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cause of death related to cancer worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic type of esophageal carcinoma, with an incidence as high as 5.69 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 Internal malignancies that lead to cutaneous metastases are not uncommon; however, the literature is limited on cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal cancer. Cutaneous metastases secondary to internal malignancies present in less than 10% of overall cases; tend to derive from the breasts, lungs, and large bowel; and usually present in the sixth to seventh decades of life.2 Further, roughly 1% of all skin metastases originate from the esophagus.3 When there are cutaneous metastases to the scalp, they often arise from breast carcinomas and renal cell carcinomas.4,5 Rarely does esophageal cancer spread to the scalp.2,6-9 When cutaneous metastases originate from the esophagus, multiple cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas can be the etiology of origin.10 Metastases originating from esophageal carcinomas frequently are diagnosed in the abdominal lymph nodes (45%), liver (35%), lungs (20%), cervical/supraclavicular lymph nodes (18%), bones (9%), adrenals (5%), peritoneum (2%), brain (2%), stomach (1%), pancreas (1%), pleura (1%), skin/body wall (1%), pericardium (1%), and spleen (1%).3 Additionally, multiple cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported,7,9 as were seen in our case.

The clinical appearance of cutaneous scalp metastases has been described as inflammatory papules, indurated plaques, or nodules,2 which is consistent with our case, though the spectrum of presentation is admittedly broad. Histopathology of lesions characteristically shows prominent intraluminal necrotic cellular debris, which is common for adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, utilizing immunohistochemical stains to detect specific antigens within tumor cells allows for better specificity of the tumor origin. More specifically, cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 are stained in esophageal metaplasia, such as Barrett esophagus, rather than in intestinal metaplasia inside the stomach.2,11 Therefore, discerning the location of the adenocarcinoma proves fruitful when using cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Although CDX2 is an additional marker that can be used for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas with decent sensitivity and specificity, it can still be expressed in mucinous ovarian carcinomas and urinary bladder adenocarcinomas.12 In our patient, the strong reactivity of cytokeratin 7 in addition to the characteristic morphology in both presenting biopsies was sufficient to make the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma to the scalp.

Our case highlights multiple cutaneous metastases of the scalp from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although cutaneous scalp metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, it is essential to provide a full-body skin examination, including the scalp, in patients with a history of esophageal cancer and to biopsy any suspicious nodules or plaques. The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is less than 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.13 Identifying cutaneous metastasis of an esophageal adenocarcinoma can either change the staging of the cancer (if it was the first distant metastasis noted) or indicate an insufficient response to treatment in a patient with known metastatic disease, prompting a potential change in treatment.7

This case illustrates a rare site of metastasis of a fairly common cancer and highlights the histopathology and accompanying immunohistochemical stains that can be useful in diagnosis as well as the spectrum of its clinical presentation.

- Melhado R, Alderson D, Tucker O. The changing face of esophageal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1379-1404.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Oh SH, et al. A case of esophageal adenocarcinoma metastasized to the scalp [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:164-167.

- Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, et al. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1120.

- Dobson C, Tagor V, Myint A, et al. Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma in face and scalp mimicking cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:635-636.

- Riter H, Ghobrial I. Renal cell carcinoma with acrometastasis and scalp metastasis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:76.

- Roh EK, Nord R, Jukic DM. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2006;77:106.

- Doumit G, Abouhassan W, Piliang M, et al. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma: comparative histopathology dictates surgical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;71:60-62.

- Roy AD, Sherparpa M, Prasad PR, et al. Scalp metastasis of gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a rare occurrence. 2014;8:159-160.

- Stein R, Spencer J. Painful cutaneous metastases from esophageal carcinoma. Cutis. 2002;70:230.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):161-182.

- Ormsby AH, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, et al. Cytokeratin subsets can reliably distinguish Barrett’s esophagus from intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:288-294.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Skelton H. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus to the skin: new patterns of tumor recurrence and alternate treatments for palliation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:425-431.

- Melhado R, Alderson D, Tucker O. The changing face of esophageal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1379-1404.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Oh SH, et al. A case of esophageal adenocarcinoma metastasized to the scalp [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:164-167.

- Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, et al. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1120.

- Dobson C, Tagor V, Myint A, et al. Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma in face and scalp mimicking cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:635-636.

- Riter H, Ghobrial I. Renal cell carcinoma with acrometastasis and scalp metastasis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:76.

- Roh EK, Nord R, Jukic DM. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2006;77:106.

- Doumit G, Abouhassan W, Piliang M, et al. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma: comparative histopathology dictates surgical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;71:60-62.

- Roy AD, Sherparpa M, Prasad PR, et al. Scalp metastasis of gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a rare occurrence. 2014;8:159-160.

- Stein R, Spencer J. Painful cutaneous metastases from esophageal carcinoma. Cutis. 2002;70:230.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):161-182.

- Ormsby AH, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, et al. Cytokeratin subsets can reliably distinguish Barrett’s esophagus from intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:288-294.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Skelton H. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus to the skin: new patterns of tumor recurrence and alternate treatments for palliation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:425-431.

Practice Points

- In the setting of underlying esophageal adenocarcinoma, metastatic spread to the scalp should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any suspicious scalp lesions.

- Coupling histopathology with immunohistochemical stains may aid in the diagnosis for cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Smartphones: Dermatologic Impact of the Digital Age

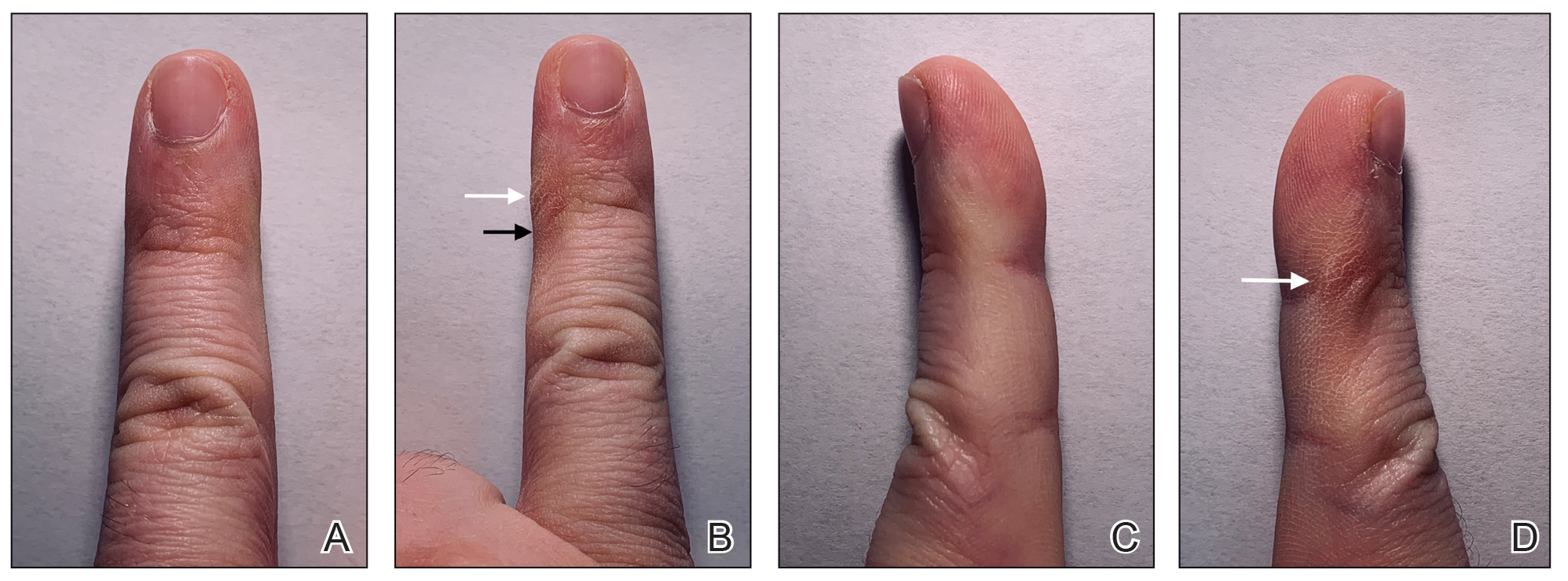

Over the last decade, the use of mobile phones has changed drastically with the advent of more technologically advanced smartphones.1 Mobile phones are no longer used primarily as devices for talking but rather for text messaging, reading the news, drafting emails, browsing websites, and connecting with others on social media. Considering the increased utility and popularity of social media along with the greater reliance on smartphones, individuals in the United States and worldwide are undoubtedly spending more time on their handheld devices.2 With the increase in use and overuse of smartphones, many aspects of society and health are likely affected. Many celebrities who frequently post on social media platforms also have alluded to or directly discussed changes in their dermatologic health secondary to their increased use of smartphones.3 Numerous studies have investigated the positive and negative effects of smartphone use on various musculoskeletal conditions of the upper extremities4,5 and the social effects of smartphone use on behavior and child development.6,7 Lee et al8 studied the effects of smartphone use on upper extremity muscle pain and activity in relation to 1- or 2-handed operation. In this study, Lee et al8 measured the muscle activity and tenderness in 10 women aged 20 to 22 years after a series of timed periods of smartphone use. They concluded that smartphone use resulted in greater muscle activity and tenderness, especially in 1-handed use compared to 2-handed use.8 Inal et al9 investigated smartphone overuse effects on hand strength and function in 102 college students and discovered that smartphone overuse was correlated with decreased pinch strength, increased median nerve cross-sectional area, and pain in the first digits.9

However, few articles have been published investigating skin changes to the digits in relation to smartphone use (Figure 1). In a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms smartphone, phone, cell phone, electronic device, handheld device, fifth digit, or skin changes, the authors were unable to find any studies in the literature that involved smartphone use and skin changes to the digits. Based on informal clinical observation and personal experiences, we hypothesized that changes to the fifth digit, likely due to holding a smartphone, would be prevalent and would correlate with amount of time spent on smartphones per day (Figure 2). We also were interested in investigating any other potential correlations with changes to the fifth digit, such as type of smartphone used.

Methods

The study used a cross-sectional design. From September 2018 to December 2018, 374 individuals 18 years or older were recruited to complete a 5-minute anonymous survey online. Using email referrals and social media, participants were presented with a link to a Google survey that only allowed 1 submission per account. On the first page of the survey, participants were presented with a letter explaining that completion of the survey was entirely voluntary, participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time, and participants were providing consent in completing the survey. The protocol was determined to be exempt by the institutional review board at Nova Southeastern University (Fort Lauderdale, Florida) in September 2018.

Survey Design

A 20-item survey was designed to measure the amount of time spent using smartphones per day, classify the type of phone used, and quantify skin changes noticed by each respondent. Demographic information for each respondent also was gathered using the survey. The survey was pilot tested to ensure that respondents were able to understand the items.

One item asked if respondents owned a handheld smartphone. Two items assessed how much time was spent on smartphones per day (ie, <1 hour, 1–2 hours, 2–3 hours, 3–4 hours, 4–5 hours, >5 hours) and the type of smartphone used (ie, Apple iPhone, Samsung Galaxy, Google Pixel, Huawei, LG, other). Six items assessed skin changes to the digits, namely the fifth digit (eg, Do you notice any changes to your fifth digit [pinky finger] that would likely be contributed to how you hold your smartphone, such as divot, callus, bruise, wound, misalignment, bend?). Eleven items were used to collect basic demographic information, including age, sex, legal marital status, ethnicity, race, annual household income, highest-earned educational degree, current employment status, health insurance status, and state of residence.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23. The association between changes to the fifth digit and time spent on the phone, hand dominance, and socioeconomic factors (ie, age,

Results

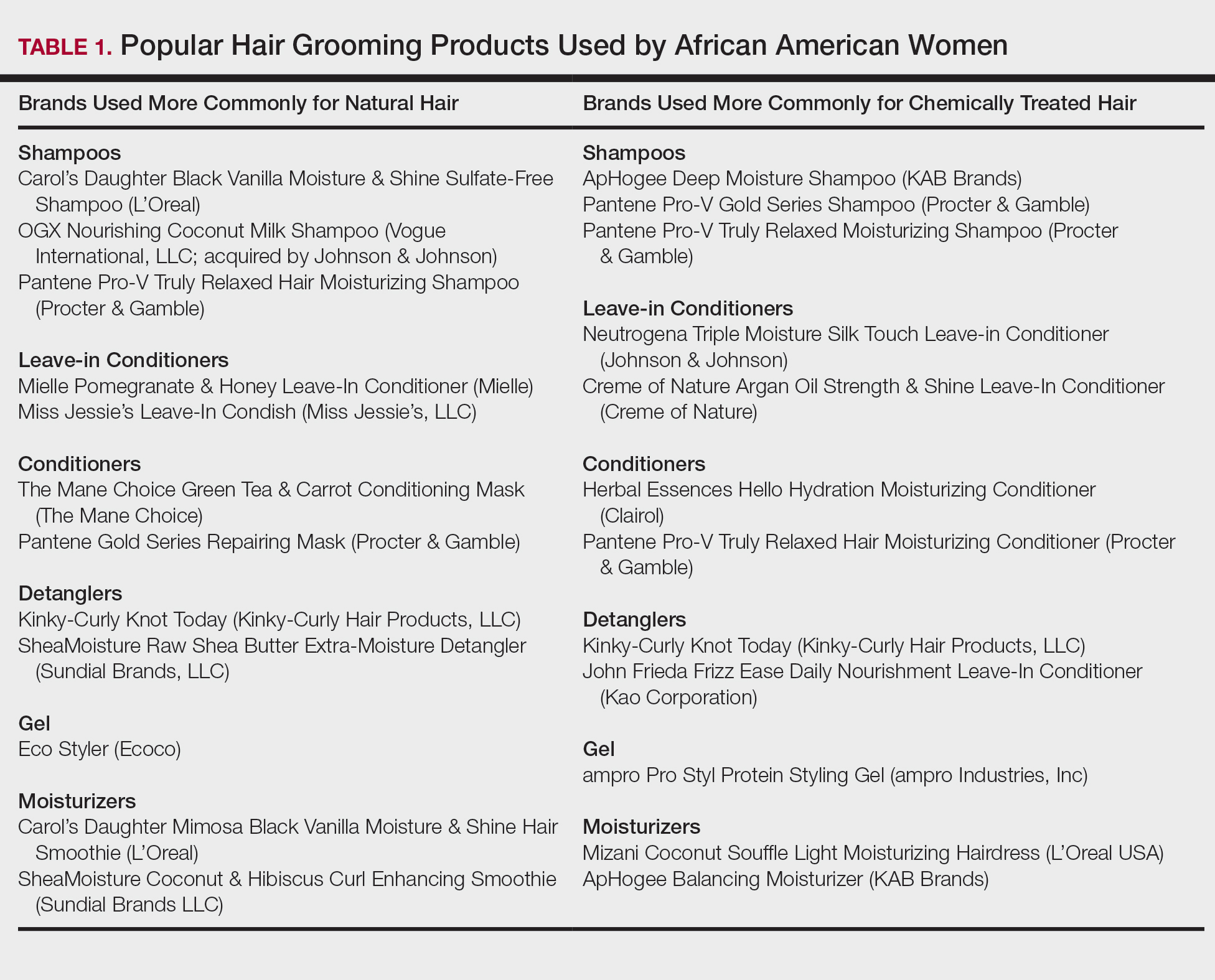

The mean age of the 374 respondents was 33.8 years (range, 18–72 years). One hundred nine respondents were men (29.1%), 262 were women (70.1%), and 3 did not specify (0.8%). Two hundred thirty-four respondents (62.6%) were single, 271 (72.5%) were white, 171 (45.7%) had a bachelor’s degree, and174 (46.5%) were employed full time. Annual household income was normally distributed among the respondents, with 28 (7.5%) earning less than $10,000 per year, 130 (34.8%) earning $10,000 to$49,999 per year, 136 (36.4%) earning $50,000 to $99,999 per year, 52 (13.9%) earning $100,000 to$149,999 per year, and 28 (7.5%) earning more than $150,000 per year. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1.

Eighty-five (22.7%) respondents admitted to changes to the fifth digit that they associated with holding a smartphone, whereas 289 (77.3%) reported no changes. When asked about the average amount of time spent on their smartphone per day, 17 (4.5%) respondents answered less than 1 hour, 70 (18.7%) answered 1 to 2 hours, 69 (18.4%) answered 2 to 3 hours, 77 (20.6%) answered 3 to 4 hours, 57 (15.2%) answered 4 to 5 hours, and 84 (22.5%) answered more than 5 hours. One hundred ninety-nine (53.2%) respondents indicated they used an Apple iPhone, 95 (25.4%) used a Samsung Galaxy phone, 9 (2.4%) used a Google Pixel phone, 3 (0.8%) used a Huawei phone, 23 (6.1%) used an LG phone, and 45 (12.0%) used another type of smartphone. The characteristics of smartphone use as reported by the respondents are presented in Table 2.

Comment

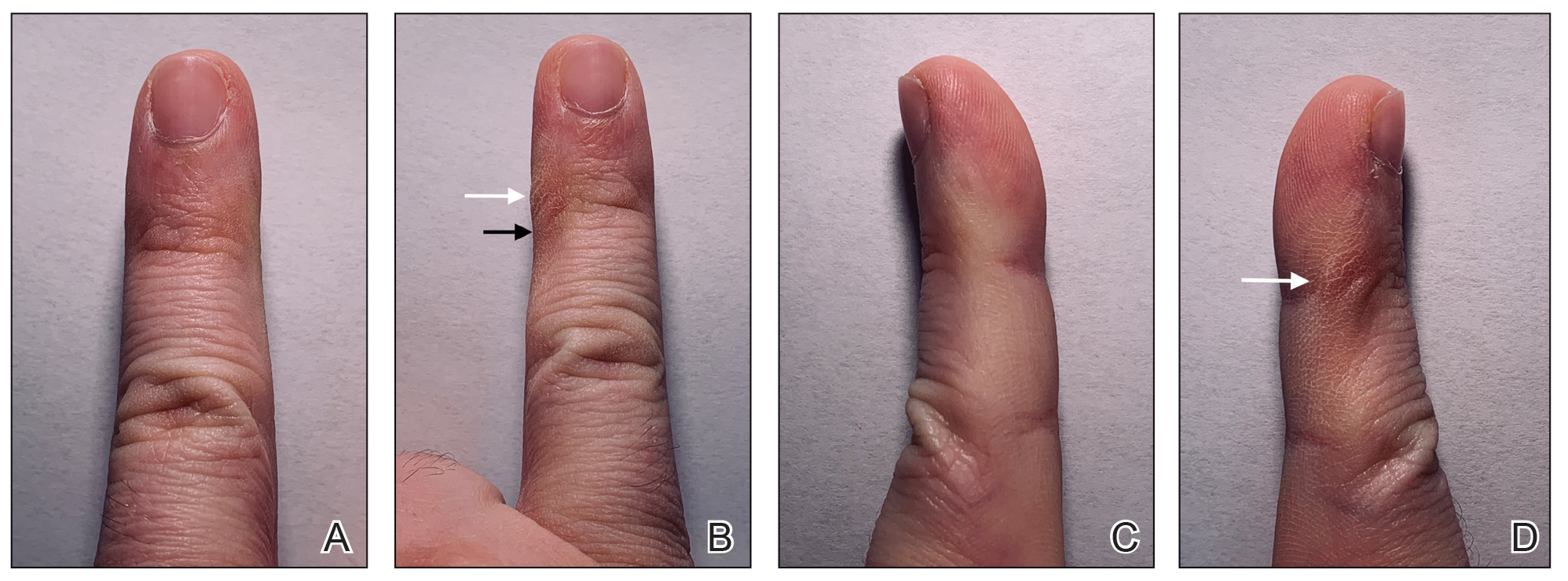

Consistent with our hypothesis, changes to the fifth digit were prevalent in the surveyed population, with 85 (22.7%) respondents admitting to changes to their fifth digit from holding a smartphone. The changes to the fifth digit were described as 1 or more of the following: divot (impression), callus (skin thickening), bruise, wound, misalignment, or bending. Most respondents who noted skin changes on the survey endorsed changes consistent with calluses and/or divots. These changes can be described as scaly, lichenified, well-demarcated papules or plaques with variable overlying hyperpigmentation and surrounding erythema. In cases with resulting chronic indentations of the skin, one also would observe localized sclerosis, atrophy, and/or induration of the area, which we found to be less prevalent than expected considering the popularity and notable reliance on smartphones.2

The most commonly reported chronic skin changes to the fifth digit are similar to those of lichen simplex chronicus and/or exogenous lobular panniculitis, which can be both symptomatically and cosmetically troubling for a patient. Functional impairment in movement of the fifth digit may result from the overlying lichenification and induration, as well as from lipoatrophy of the underlying traumatized subcutaneous fat, especially if the affected area is overlying the proximal interphalangeal joint of the fifth digit. These resulting alterations in the skin of the fifth digit also may be cosmetically displeasing to the patient.