User login

CDC: New botulism guidelines focus on mass casualty events

Botulinum toxin is said to be the most lethal substance known. Inhaling just 1-3 nanograms of toxin per kilogram of body mass constitutes a lethal dose.

The CDC has been working on these guidelines since 2015, initially establishing a technical development group and steering committee to prioritize topics for review and make recommendations. Since then, the agency published 15 systematic reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases early in 2018. The reviews addressed the recognition of botulism clinically, treatment with botulinum antitoxin, and complications from that treatment. They also looked at the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks and botulism in the special populations of vulnerable pediatric and pregnant patients.

In 2016, the CDC held two extended forums and convened a workshop with 72 experts. In addition to the more standard topics of diagnosis and treatment, attention was given to crisis standards of care, caring for multiple patients at once, and ethical considerations in management.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, said in an interview that the new guidance “was really specific [and] was meant to address the gap in guidance for mass casualty settings.”

While clinicians are used to focusing on an individual patient, in times of crises, with multiple patients from a food-borne outbreak or a bioterrorism attack, the focus must shift to the population rather than the individual. The workshop explored issues of triaging, adding beds, and caring for patients when a hospital is overwhelmed with an acute influx of severely ill patients.

Such a mass casualty event is similar to the stress encountered this past year with COVID-19 patients swamping the hospitals, which had too little oxygen, too few ventilators, and too few staff members to care for the sudden influx of critically ill patients.

Diagnosis

Leslie Edwards, MHS, BSN, a CDC epidemiologist and botulism expert, said that “botulism is rare and [so] could be difficult to diagnose.” The CDC “wanted to highlight some of those key clinical factors” to speed recognition.

Hospitals and health officials are being urged to develop crisis protocols as part of emergency preparedness plans. And clinicians should be able to recognize four major syndromes: botulism from food, wounds, and inhalation, as well as iatrogenic botulism (from exposure via injection of the neurotoxin).

Botulism has a characteristic and unusual pattern of symptoms, which begin with cranial nerve palsies. Then there is typically a descending, symmetric flaccid paralysis. Symptoms might progress to respiratory failure and death. Other critical clues that implicate botulism include a lack of sensory deficits and the absence of pain.

Symptoms are most likely to be mistaken for myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the latter has an ascending paralysis. Cranial nerve involvement can present as blurred vision, ptosis (drooping lid), diplopia (double vision), ophthalmoplegia (weak eye muscles), or difficulty with speech and swallowing. Shortness of breath and abdominal discomfort can also occur. Respiratory failure may occur from weakness or paralysis of cranial nerves. Cranial nerve signs and symptoms in the absence of fever, along with a descending paralysis, should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

With food-borne botulism, vomiting occurs in half the patients. Improperly sterilized home-canned food is the major risk factor. While the toxin is rapidly destroyed by heat, the bacterial spores are not. Wound botulism is most commonly associated with the injection of drugs, particularly black tar heroin.

Dr. Edwards stressed that “time is of the essence when it comes to botulism diagnostics and treating. Timely administration of the botulism antitoxin early in the course of illness can arrest the progression of paralysis and possibly avert the need for intubation or ventilation.”

It’s essential to note that botulism is an urgent diagnosis that has to be made on clinical grounds. Lab assays for botulinum neurotoxins take too long and are only conducted in public health laboratories. The decision to use antitoxin must not be delayed to wait for confirmation.

Clinicians should immediately contact the local or state health department’s emergency on-call team if botulism is suspected. They will arrange for expert consultation.

Treatment

Botulinum antitoxin is the only specific therapy for this infection. If given early – preferably within 24-48 hours of symptom onset – it can stop the progression of paralysis. But antitoxin will not reverse existing paralysis. If paralysis is still progressing outside of that 24- to 48-hour window, the antitoxin should still provide benefit. The antitoxin is available only through state health departments and a request to the CDC.

Botulism antitoxin is made from horse serum and therefore may cause a variety of allergic reactions. The risk for anaphylaxis is less than 2%, far lower than the mortality from untreated botulism.

While these guidelines have an important focus on triaging and treating mass casualties from botulism, it’s important to note that food-borne outbreaks and prevention issues are covered elsewhere on the CDC site.

Dr. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adalja is a consultant for Emergent BioSolutions, which makes the heptavalent botulism antitoxin.

Dr. Stone is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research,” the essential guide to the topic. You can find her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Botulinum toxin is said to be the most lethal substance known. Inhaling just 1-3 nanograms of toxin per kilogram of body mass constitutes a lethal dose.

The CDC has been working on these guidelines since 2015, initially establishing a technical development group and steering committee to prioritize topics for review and make recommendations. Since then, the agency published 15 systematic reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases early in 2018. The reviews addressed the recognition of botulism clinically, treatment with botulinum antitoxin, and complications from that treatment. They also looked at the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks and botulism in the special populations of vulnerable pediatric and pregnant patients.

In 2016, the CDC held two extended forums and convened a workshop with 72 experts. In addition to the more standard topics of diagnosis and treatment, attention was given to crisis standards of care, caring for multiple patients at once, and ethical considerations in management.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, said in an interview that the new guidance “was really specific [and] was meant to address the gap in guidance for mass casualty settings.”

While clinicians are used to focusing on an individual patient, in times of crises, with multiple patients from a food-borne outbreak or a bioterrorism attack, the focus must shift to the population rather than the individual. The workshop explored issues of triaging, adding beds, and caring for patients when a hospital is overwhelmed with an acute influx of severely ill patients.

Such a mass casualty event is similar to the stress encountered this past year with COVID-19 patients swamping the hospitals, which had too little oxygen, too few ventilators, and too few staff members to care for the sudden influx of critically ill patients.

Diagnosis

Leslie Edwards, MHS, BSN, a CDC epidemiologist and botulism expert, said that “botulism is rare and [so] could be difficult to diagnose.” The CDC “wanted to highlight some of those key clinical factors” to speed recognition.

Hospitals and health officials are being urged to develop crisis protocols as part of emergency preparedness plans. And clinicians should be able to recognize four major syndromes: botulism from food, wounds, and inhalation, as well as iatrogenic botulism (from exposure via injection of the neurotoxin).

Botulism has a characteristic and unusual pattern of symptoms, which begin with cranial nerve palsies. Then there is typically a descending, symmetric flaccid paralysis. Symptoms might progress to respiratory failure and death. Other critical clues that implicate botulism include a lack of sensory deficits and the absence of pain.

Symptoms are most likely to be mistaken for myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the latter has an ascending paralysis. Cranial nerve involvement can present as blurred vision, ptosis (drooping lid), diplopia (double vision), ophthalmoplegia (weak eye muscles), or difficulty with speech and swallowing. Shortness of breath and abdominal discomfort can also occur. Respiratory failure may occur from weakness or paralysis of cranial nerves. Cranial nerve signs and symptoms in the absence of fever, along with a descending paralysis, should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

With food-borne botulism, vomiting occurs in half the patients. Improperly sterilized home-canned food is the major risk factor. While the toxin is rapidly destroyed by heat, the bacterial spores are not. Wound botulism is most commonly associated with the injection of drugs, particularly black tar heroin.

Dr. Edwards stressed that “time is of the essence when it comes to botulism diagnostics and treating. Timely administration of the botulism antitoxin early in the course of illness can arrest the progression of paralysis and possibly avert the need for intubation or ventilation.”

It’s essential to note that botulism is an urgent diagnosis that has to be made on clinical grounds. Lab assays for botulinum neurotoxins take too long and are only conducted in public health laboratories. The decision to use antitoxin must not be delayed to wait for confirmation.

Clinicians should immediately contact the local or state health department’s emergency on-call team if botulism is suspected. They will arrange for expert consultation.

Treatment

Botulinum antitoxin is the only specific therapy for this infection. If given early – preferably within 24-48 hours of symptom onset – it can stop the progression of paralysis. But antitoxin will not reverse existing paralysis. If paralysis is still progressing outside of that 24- to 48-hour window, the antitoxin should still provide benefit. The antitoxin is available only through state health departments and a request to the CDC.

Botulism antitoxin is made from horse serum and therefore may cause a variety of allergic reactions. The risk for anaphylaxis is less than 2%, far lower than the mortality from untreated botulism.

While these guidelines have an important focus on triaging and treating mass casualties from botulism, it’s important to note that food-borne outbreaks and prevention issues are covered elsewhere on the CDC site.

Dr. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adalja is a consultant for Emergent BioSolutions, which makes the heptavalent botulism antitoxin.

Dr. Stone is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research,” the essential guide to the topic. You can find her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Botulinum toxin is said to be the most lethal substance known. Inhaling just 1-3 nanograms of toxin per kilogram of body mass constitutes a lethal dose.

The CDC has been working on these guidelines since 2015, initially establishing a technical development group and steering committee to prioritize topics for review and make recommendations. Since then, the agency published 15 systematic reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases early in 2018. The reviews addressed the recognition of botulism clinically, treatment with botulinum antitoxin, and complications from that treatment. They also looked at the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks and botulism in the special populations of vulnerable pediatric and pregnant patients.

In 2016, the CDC held two extended forums and convened a workshop with 72 experts. In addition to the more standard topics of diagnosis and treatment, attention was given to crisis standards of care, caring for multiple patients at once, and ethical considerations in management.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, said in an interview that the new guidance “was really specific [and] was meant to address the gap in guidance for mass casualty settings.”

While clinicians are used to focusing on an individual patient, in times of crises, with multiple patients from a food-borne outbreak or a bioterrorism attack, the focus must shift to the population rather than the individual. The workshop explored issues of triaging, adding beds, and caring for patients when a hospital is overwhelmed with an acute influx of severely ill patients.

Such a mass casualty event is similar to the stress encountered this past year with COVID-19 patients swamping the hospitals, which had too little oxygen, too few ventilators, and too few staff members to care for the sudden influx of critically ill patients.

Diagnosis

Leslie Edwards, MHS, BSN, a CDC epidemiologist and botulism expert, said that “botulism is rare and [so] could be difficult to diagnose.” The CDC “wanted to highlight some of those key clinical factors” to speed recognition.

Hospitals and health officials are being urged to develop crisis protocols as part of emergency preparedness plans. And clinicians should be able to recognize four major syndromes: botulism from food, wounds, and inhalation, as well as iatrogenic botulism (from exposure via injection of the neurotoxin).

Botulism has a characteristic and unusual pattern of symptoms, which begin with cranial nerve palsies. Then there is typically a descending, symmetric flaccid paralysis. Symptoms might progress to respiratory failure and death. Other critical clues that implicate botulism include a lack of sensory deficits and the absence of pain.

Symptoms are most likely to be mistaken for myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the latter has an ascending paralysis. Cranial nerve involvement can present as blurred vision, ptosis (drooping lid), diplopia (double vision), ophthalmoplegia (weak eye muscles), or difficulty with speech and swallowing. Shortness of breath and abdominal discomfort can also occur. Respiratory failure may occur from weakness or paralysis of cranial nerves. Cranial nerve signs and symptoms in the absence of fever, along with a descending paralysis, should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

With food-borne botulism, vomiting occurs in half the patients. Improperly sterilized home-canned food is the major risk factor. While the toxin is rapidly destroyed by heat, the bacterial spores are not. Wound botulism is most commonly associated with the injection of drugs, particularly black tar heroin.

Dr. Edwards stressed that “time is of the essence when it comes to botulism diagnostics and treating. Timely administration of the botulism antitoxin early in the course of illness can arrest the progression of paralysis and possibly avert the need for intubation or ventilation.”

It’s essential to note that botulism is an urgent diagnosis that has to be made on clinical grounds. Lab assays for botulinum neurotoxins take too long and are only conducted in public health laboratories. The decision to use antitoxin must not be delayed to wait for confirmation.

Clinicians should immediately contact the local or state health department’s emergency on-call team if botulism is suspected. They will arrange for expert consultation.

Treatment

Botulinum antitoxin is the only specific therapy for this infection. If given early – preferably within 24-48 hours of symptom onset – it can stop the progression of paralysis. But antitoxin will not reverse existing paralysis. If paralysis is still progressing outside of that 24- to 48-hour window, the antitoxin should still provide benefit. The antitoxin is available only through state health departments and a request to the CDC.

Botulism antitoxin is made from horse serum and therefore may cause a variety of allergic reactions. The risk for anaphylaxis is less than 2%, far lower than the mortality from untreated botulism.

While these guidelines have an important focus on triaging and treating mass casualties from botulism, it’s important to note that food-borne outbreaks and prevention issues are covered elsewhere on the CDC site.

Dr. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adalja is a consultant for Emergent BioSolutions, which makes the heptavalent botulism antitoxin.

Dr. Stone is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research,” the essential guide to the topic. You can find her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HbA1c Change in Patients With and Without Gaps in Pharmacist Visits at a Safety-Net Resident Physician Primary Care Clinic

From Titus Family Department of Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA (Drs. Chu and Ma and Mimi Lou), and Department of Family Medicine, Keck Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Suh).

Objective: The objective of this study is to describe HbA1c changes in patients who maintained continuous pharmacist care vs patients who had a gap in pharmacist care of 3 months or longer.

Methods: This retrospective study was conducted from October 1, 2018, to September 30, 2019. Electronic health record data from an academic-affiliated, safety-net resident physician primary care clinic were collected to observe HbA1c changes between patients with continuous pharmacist care and patients who had a gap of 3 months or longer in pharmacist care. A total of 189 patients met the inclusion criteria and were divided into 2 groups: those with continuous care and those with gaps in care. Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and the χ2 (or Fisher exact) test for categorical variables. The differences-in-differences model was used to compare the changes in HbA1c between the 2 groups.

Results: There was no significant difference in changes in HbA1c between the continuous care group and the gaps in care group, although the mean magnitude of HbA1c changes was numerically greater in the continuous care group (-1.48% vs -0.97%). Overall, both groups showed improvement in their HbA1c levels and had similar numbers of primary care physician visits and acute care utilizations, while the gaps in care group had longer duration with pharmacists and between the adjacent pharmacist visits.

Conclusion: Maintaining continuous, regular visits with a pharmacist at a safety-net resident physician primary care clinic did not show a significant difference in HbA1c changes compared to having gaps in pharmacist care. Future studies on socioeconomic and behavioral burden on HbA1c improvement and on pharmacist visits in these populations should be explored.

Keywords: clinical pharmacist; diabetes management; continuous visit; primary care clinic.

Pharmacists have unique skills in identifying and resolving problems related to the safety and efficacy of drug therapy while addressing medication adherence and access for patients. Their expertise is especially important to meet the care needs of a growing population with chronic conditions amidst a primary care physician shortage.1 As health care systems move toward value-based care, emphasis on improvement in quality and health measures have become central in care delivery. Pharmacists have been integrated into team-based care in primary care settings, but the value-based shift has opened more opportunities for pharmacists to address unmet quality standards.2-5

Many studies have reported that the integration of pharmacists into team-based care improves health outcomes and reduces overall health care costs.6-9 Specifically, when pharmacists were added to primary care teams to provide diabetes management, hemoglobin HbA1c levels were reduced compared to teams without pharmacists.10-13 Offering pharmacist visits as often as every 2 weeks to 3 months, with each patient having an average of 4.7 visits, resulted in improved therapeutic outcomes.3,7 During visits, pharmacists address the need for additional drug therapy, deprescribe unnecessary therapy, correct insufficient doses or durations, and switch patients to more cost-efficient drug therapy.9 Likewise, patients who visit pharmacists in addition to seeing their primary care physician can have medication-related concerns resolved and improve their therapeutic outcomes.10,11

Not much is known about the magnitude of HbA1c change based on the regularity of pharmacist visits. Although pharmacists offer follow-up appointments in reasonable time intervals, patients do not keep every appointment for a variety of reasons, including forgetfulness, personal issues, and a lack of transportation.14 Such missed appointments can negatively impact health outcomes.14-16 The purpose of this study is to describe HbA1c changes in patients who maintained continuous, regular pharmacist visits without a 3-month gap and in patients who had history of inconsistent pharmacist visits with a gap of 3 months or longer. Furthermore, this study describes the frequency of health care utilization for these 2 groups.

Methods

Setting

The Internal Medicine resident physician primary care clinic is 1 of 2 adult primary care clinics at an academic, urban, public medical center. It is in the heart of East Los Angeles, where predominantly Spanish-speaking and minority populations reside. The clinic has approximately 19000 empaneled patients and is the largest resident primary care clinic in the public health system. The clinical pharmacy service addresses unmet quality standards, specifically HbA1c. The clinical pharmacists are co-located and collaborate with resident physicians, attending physicians, care managers, nurses, social workers, and community health workers at the clinic. They operate under collaborative practice agreements with prescriptive authority, except for controlled substances, specialty drugs, and antipsychotic medications.

Pharmacist visit

Patients are primarily referred by resident physicians to clinical pharmacists when their HbA1c level is above 8% for an extended period, when poor adherence and low health literacy are evident regardless of HbA1c level, or when a complex medication regimen requires comprehensive medication review and reconciliation. The referral occurs through warm handoff by resident physicians as well as clinic nurses, and it is embedded in the clinic flow. Patients continue their visits with resident physicians for issues other than their referral to clinical pharmacists. The visits with pharmacists are appointment-based, occur independently from resident physician visits, and continue until the patient’s HbA1c level or adherence is optimized. Clinical pharmacists continue to follow up with patients who may have reached their target HbA1c level but still are deemed unstable due to inconsistency in their self-management and medication adherence.

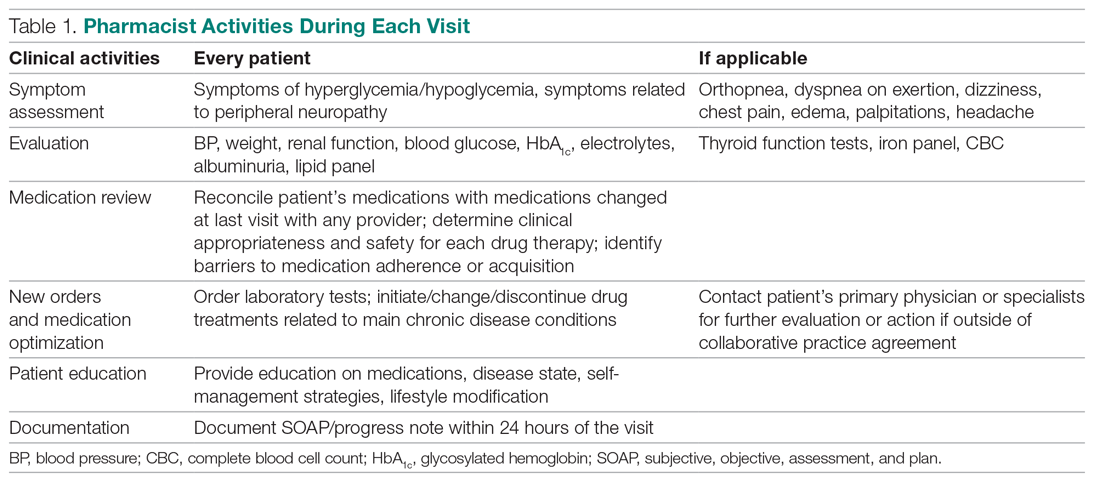

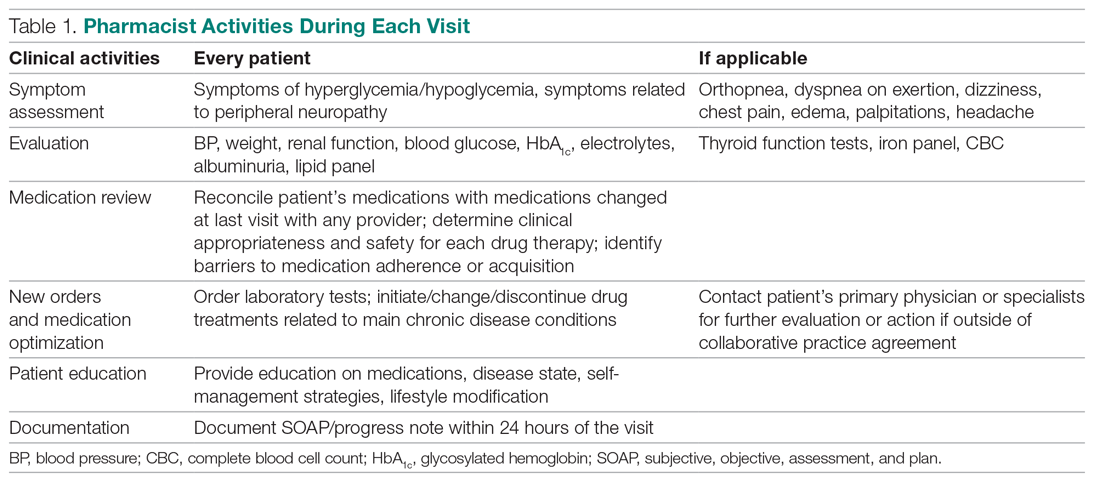

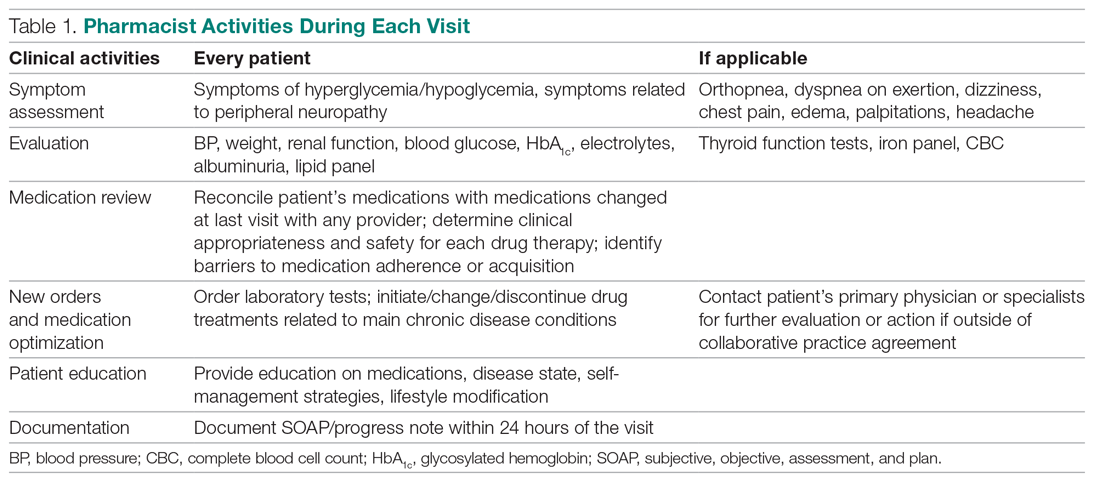

After the desirable HbA1c target is achieved along with full adherence to medications and self-management, clinical pharmacists will hand off patients back to resident physicians. At each visit, pharmacists perform a comprehensive medication assessment and reconciliation that includes adjusting medication therapy, placing orders for necessary laboratory tests and prescriptions, and assessing medication adherence. They also evaluate patients’ signs and symptoms for hyperglycemic complications, hypoglycemia, and other potential treatment-related adverse events. These are all within the pharmacist’s scope of practice in comprehensive medication management. Patient education is provided with the teach-back method and includes lifestyle modifications and medication counseling (Table 1). Pharmacists offer face-to-face visits as frequently as every 1 to 2 weeks to every 4 to 6 weeks, depending on the level of complexity and the severity of a patient’s conditions and medications. For patients whose HbA1c has reached the target range but have not been deemed stable, pharmacists continue to check in with them every 2 months. Phone visits are also utilized as an additional care delivery method for patients having difficulty showing up for face-to-face visits or needing quick assessment of medication adherence and responses to changes in drug treatment in between the face-to-face visits. The maximal interval between pharmacist visits is offered no longer than every 8 weeks. Patients are contacted via phone or mail by the nursing staff to reschedule if they miss their appointments with pharmacists. Every pharmacy visit is documented in the patient’s electronic medical record.

Study design

This is a retrospective study describing the HbA1c changes in a patient group that maintained pharmacist visits, with each interval less than 3 months, and in another group, who had a history of a 3-month or longer gap between pharmacist visits. The data were obtained from patients’ electronic medical records during the study period of October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, and collected using a HIPAA-compliant, electronic data storage website, REDCap. The institutional review board approval was obtained under HS-19-00929. Patients 18 years and older who were referred by primary care resident physicians for diabetes management, and had 2 or more visits with a pharmacist within the study period, were included. Patients were excluded if they had only 1 HbA1c drawn during the study period, were referred to a pharmacist for reasons other than diabetes management, were concurrently managed by an endocrinologist, had only 1 visit with a pharmacist, or had no visits with their primary care resident physician for over a year. The patients were then divided into 2 groups: continuous care cohort (CCC) and gap in care cohort (GCC). Both face-to-face and phone visits were counted as pharmacist visits for each group.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change in HbA1c from baseline between the 2 groups. Baseline HbA1c was considered as the HbA1c value obtained within 3 months prior to, or within 1 month, of the first visit with the pharmacist during the study period. The final HbA1c was considered the value measured within 1 month of, or 3 months after, the patient’s last visit with the pharmacist during the study period.

Several subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between HbA1c and each group. Among patients whose baseline HbA1c was ≥ 8%, we looked at the percentage of patients reaching HbA1c < 8%, the percentage of patients showing any level of improvement in HbA1c, and the change in HbA1c for each group. We also looked at the percentage of patients with baseline HbA1c < 8% maintaining the level throughout the study period and the change in HbA1c for each group. Additionally, we looked at health care utilization, which included pharmacist visits, primary care physician visits, emergency room and urgent care visits, and hospitalizations for each group. The latter 3 types of utilization were grouped as acute care utilization and further analyzed for visit reasons, which were subsequently categorized as diabetes related and non-diabetes related. The diabetes related reasons linking to acute care utilization were defined as any episodes related to hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS), foot ulcers, retinopathy, and osteomyelitis infection. All other reasons leading to acute care utilization were categorized as non-diabetes related.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous data and χ2 (or Fisher exact) test for categorical data. A basic difference-in-differences (D-I-D) method was used to compare the changes of HbA1c between the CCC and GCC over 2 time points: baseline and final measurements. The repeated measures ANOVA was used for analyzing D-I-D. P < .05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline data

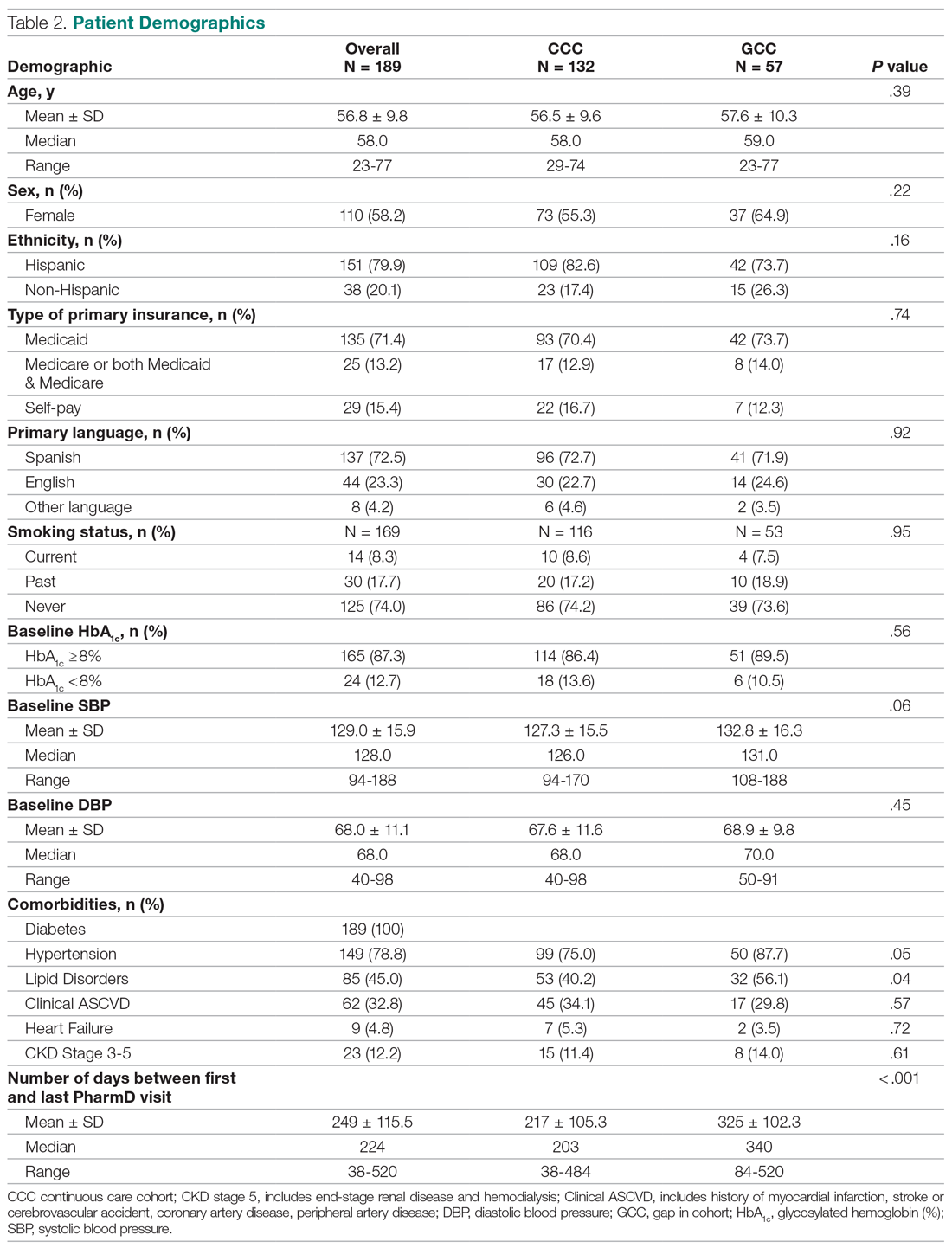

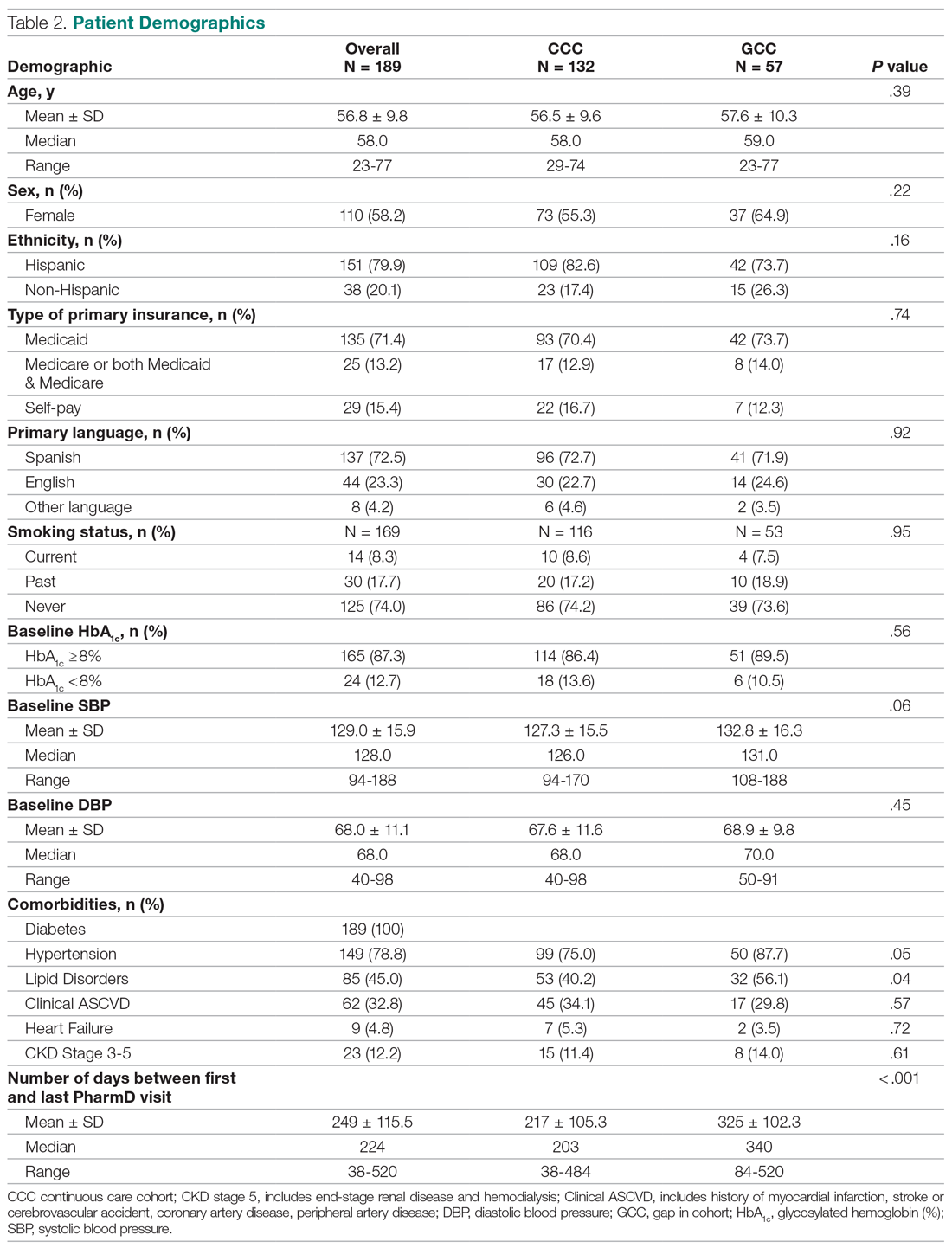

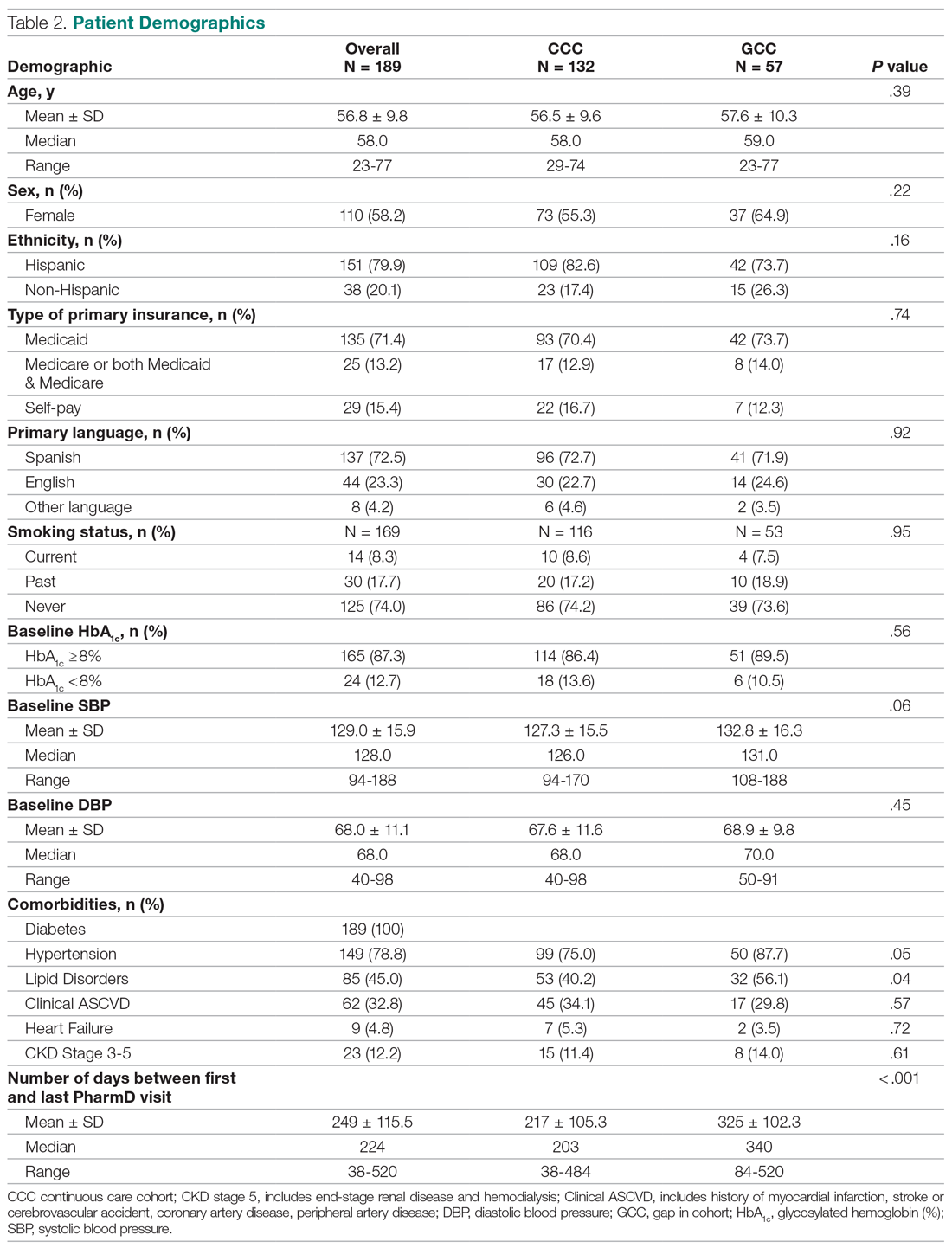

A total of 1272 patients were identified within the study period, and 189 met the study inclusion criteria. The CCC included 132 patients, the GCC 57. The mean age of patients in both groups was similar at 57 years old (P = .39). Most patients had Medicaid as their primary insurance. About one-third of patients in each group experienced clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and about 12% overall had chronic kidney disease stage 3 and higher. The average number of days that patients were under pharmacist care during the study period was longer in the GCC compared to the CCC, and it was statistically significant (P < .001) (Table 2). The mean ± SD baseline HbA1c for the CCC and GCC was 10.0% ± 2.0% and 9.9% ± 1.7%, respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant (P = .93). About 86% of patients in the CCC and 90% in the GCC had a baseline HbA1c of ≥ 8%.

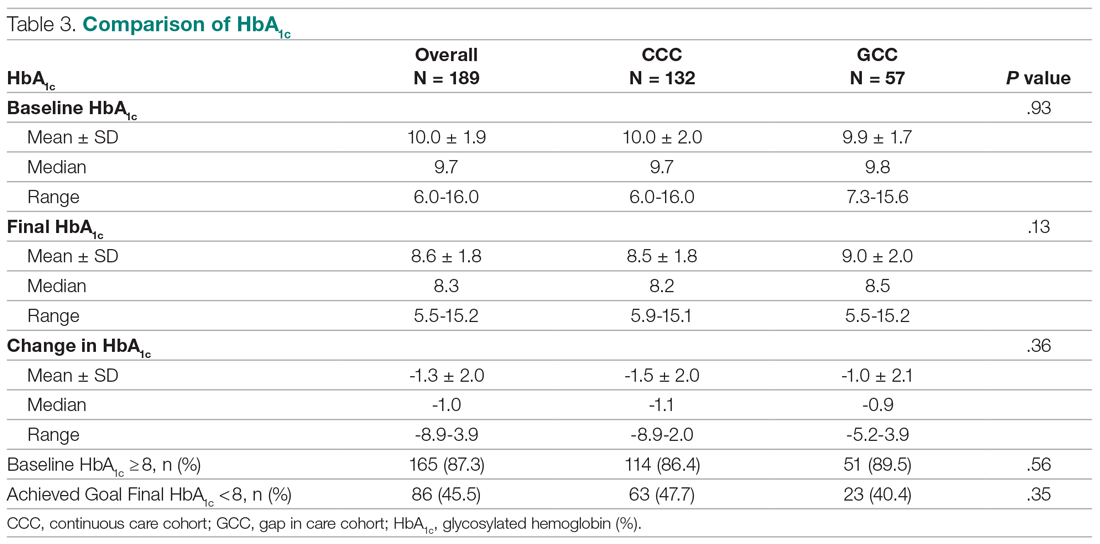

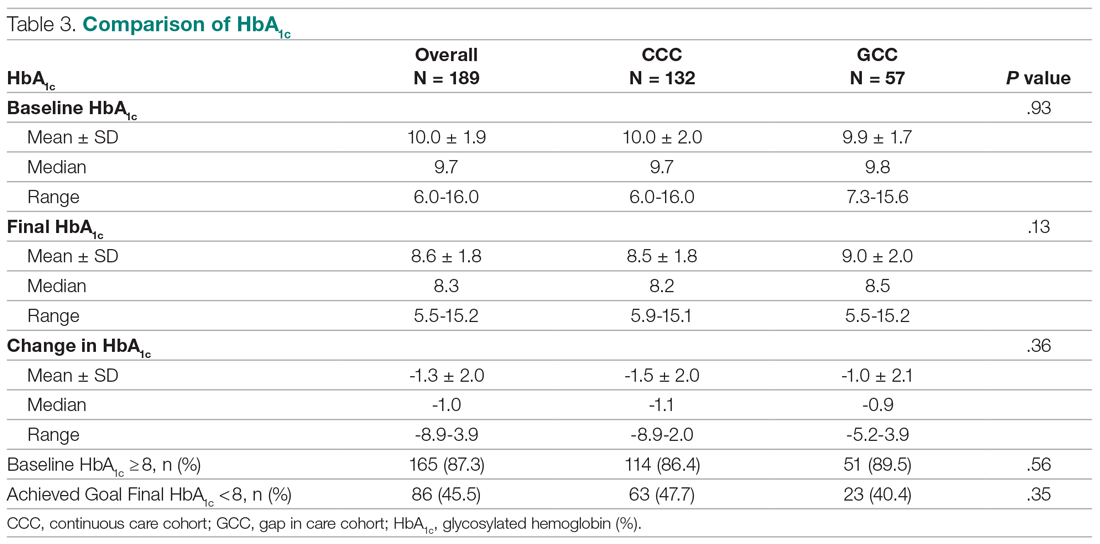

HbA1c

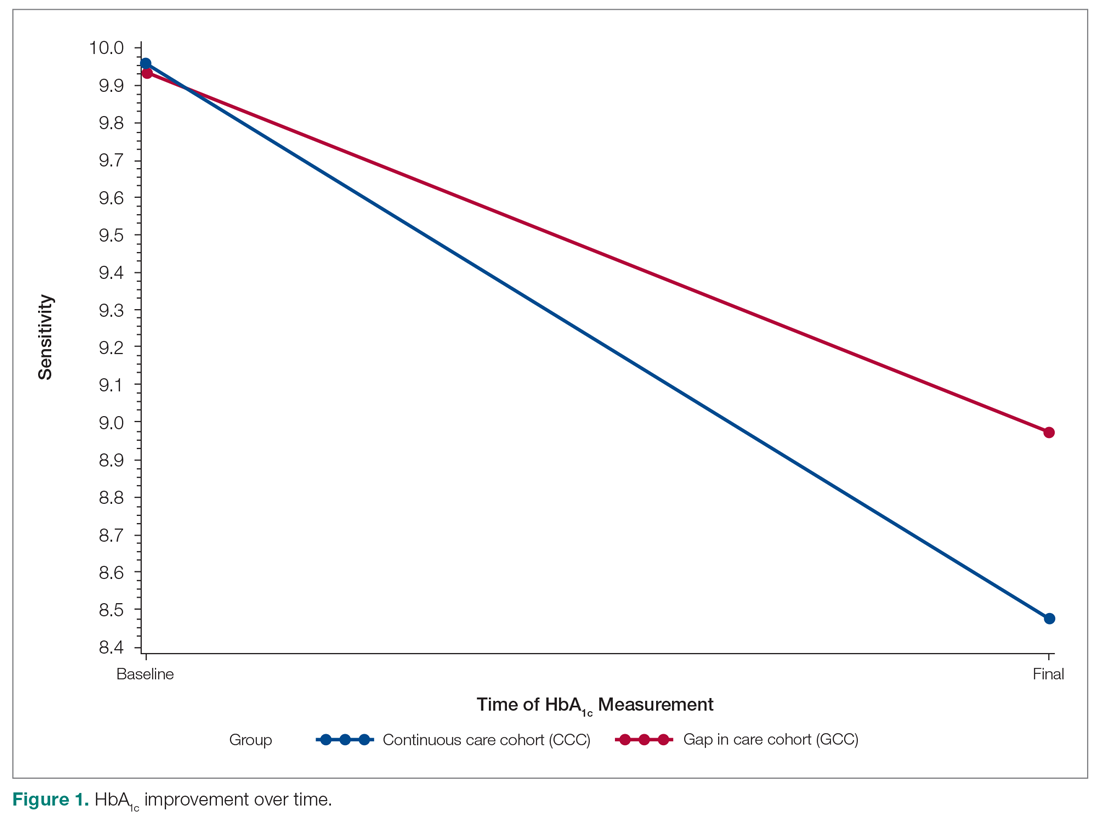

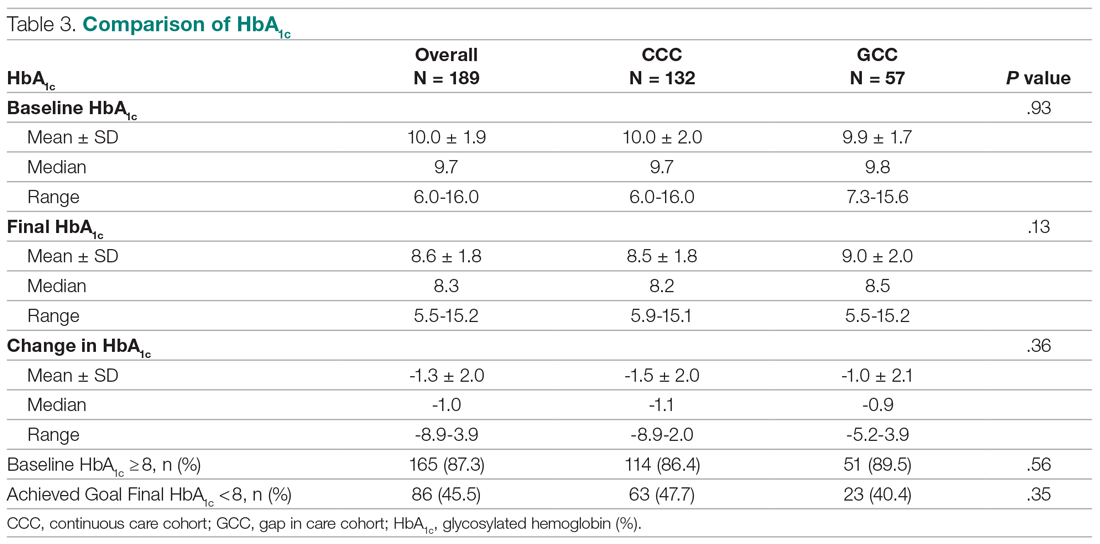

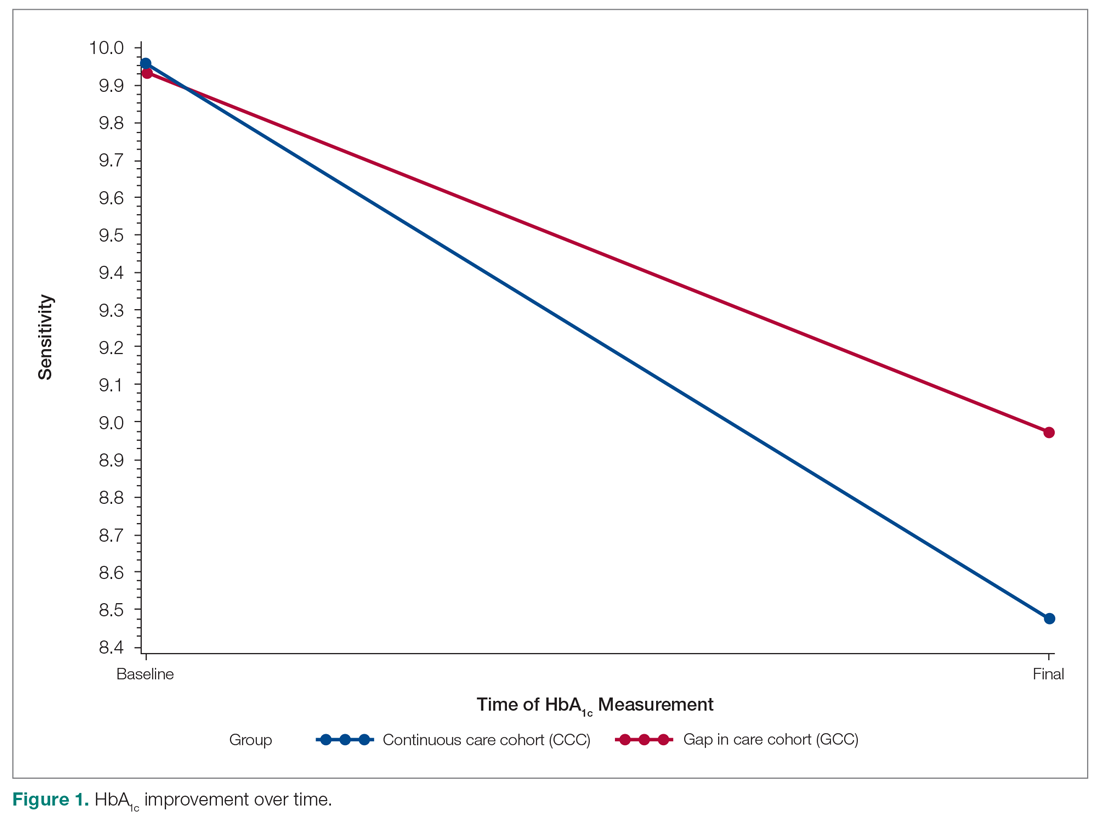

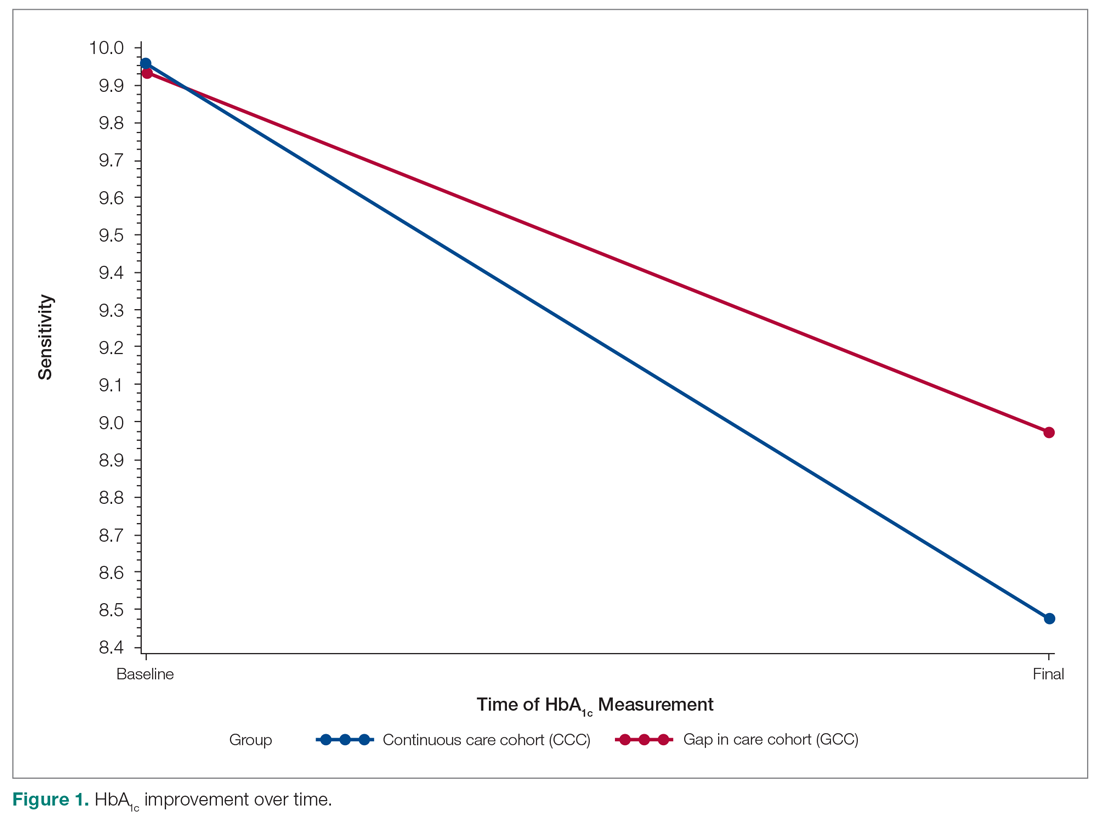

The mean change in HbA1c between the 2 groups was not statistically significant (-1.5% ± 2.0% in the CCC vs -1.0% ± 2.1% in the GCC, P = .36) (Table 3). However, an absolute mean HbA1c reduction of 1.3% was observed in both groups combined at the end of the study. Figure 1 shows a D-I-D model of the 2 groups. Based on the output, the P value of .11 on the interaction term (time*group) indicates that the D-I-D in HbA1c change from baseline to final between the CCC and GCC is not statistically different. However, the magnitude of the difference calculated from the LSMEANS results showed a trend. The HbA1c from baseline to final measurement of patients in the GCC declined by 0.97 percentage points (from 9.94% to 8.97%), while those in the CCC saw their HbA1c decline by 1.48 percentage points (from 9.96% to 8.48%), for a D-I-D of 0.51. In other words, those in the GCC had an HbA1c that decreased by 0.51% less than that of patients in the CCC, suggesting that the CCC shows a steeper line declining from baseline to final HbA1c compared to the GCC, whose line declines less sharply.

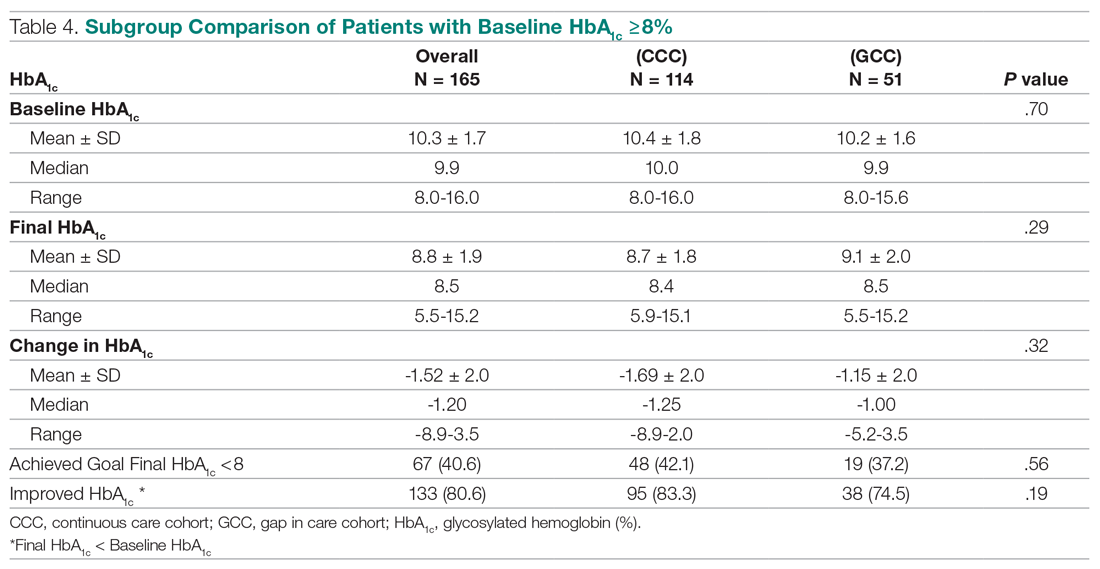

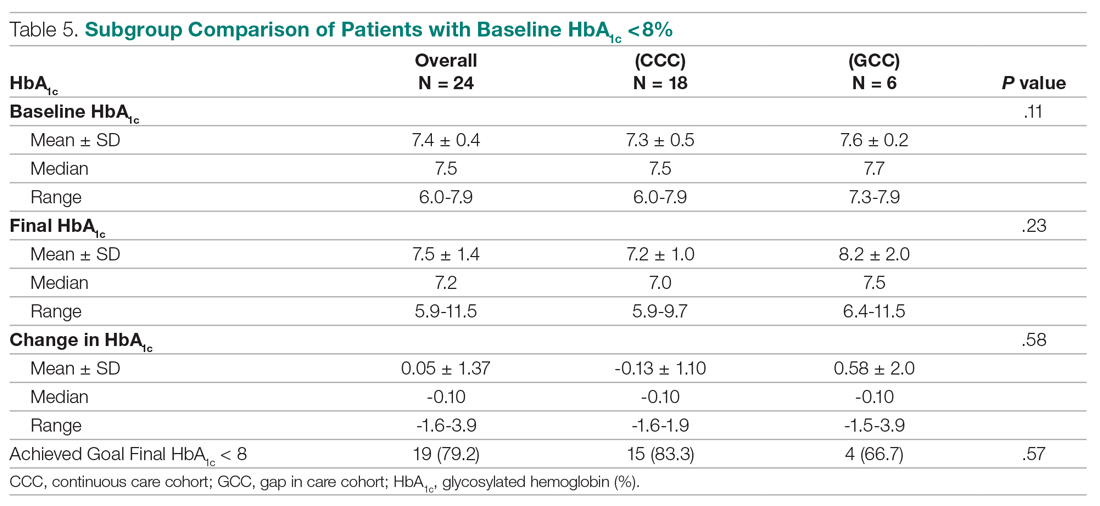

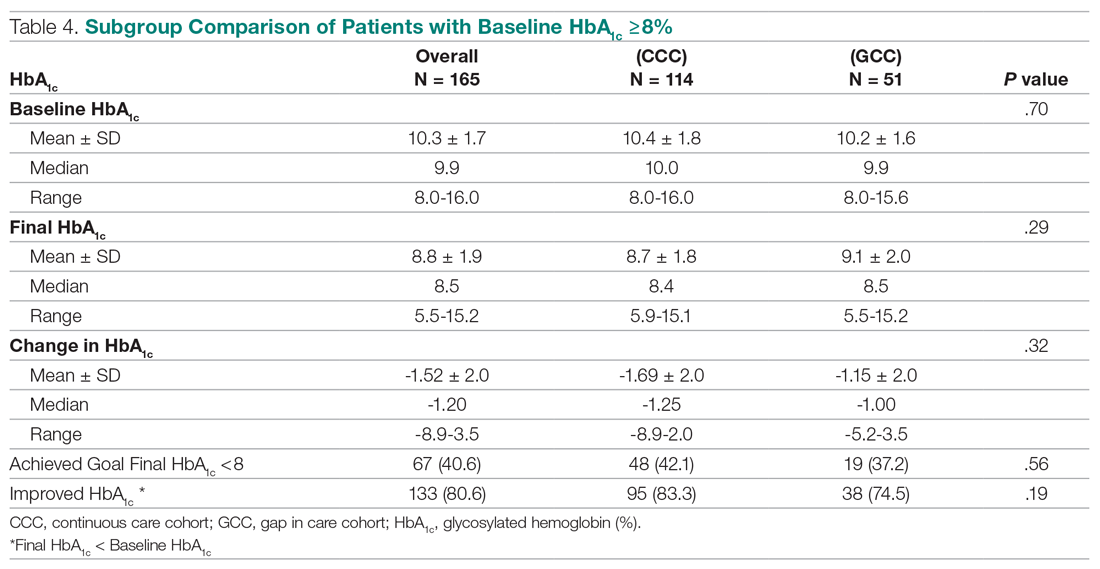

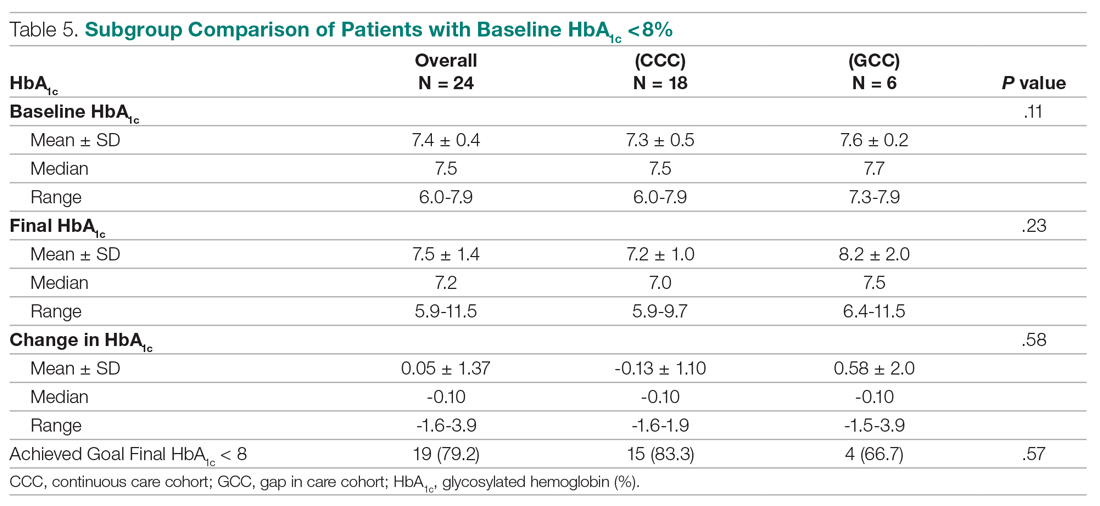

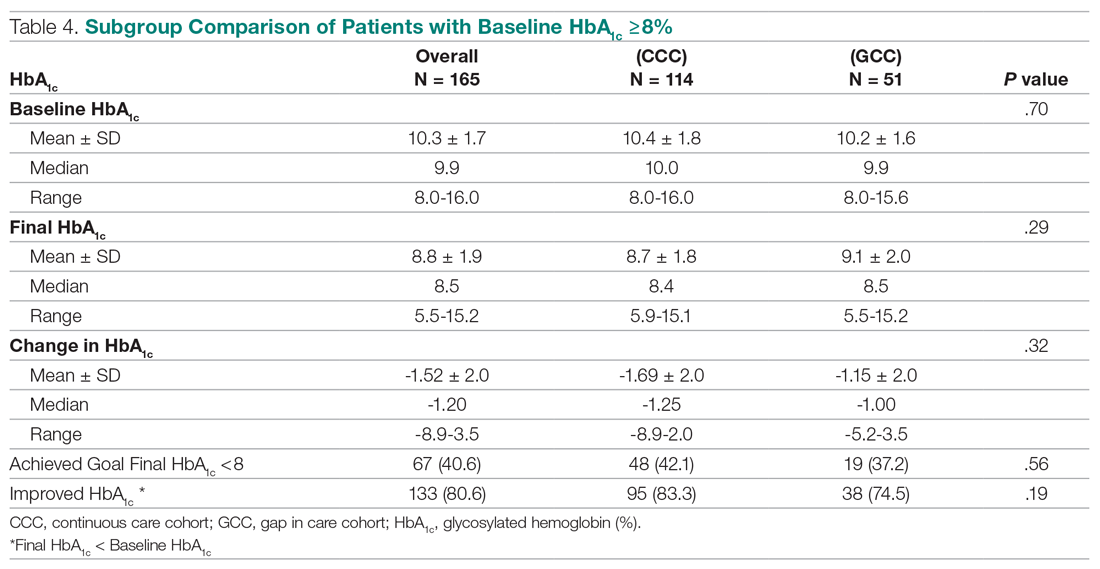

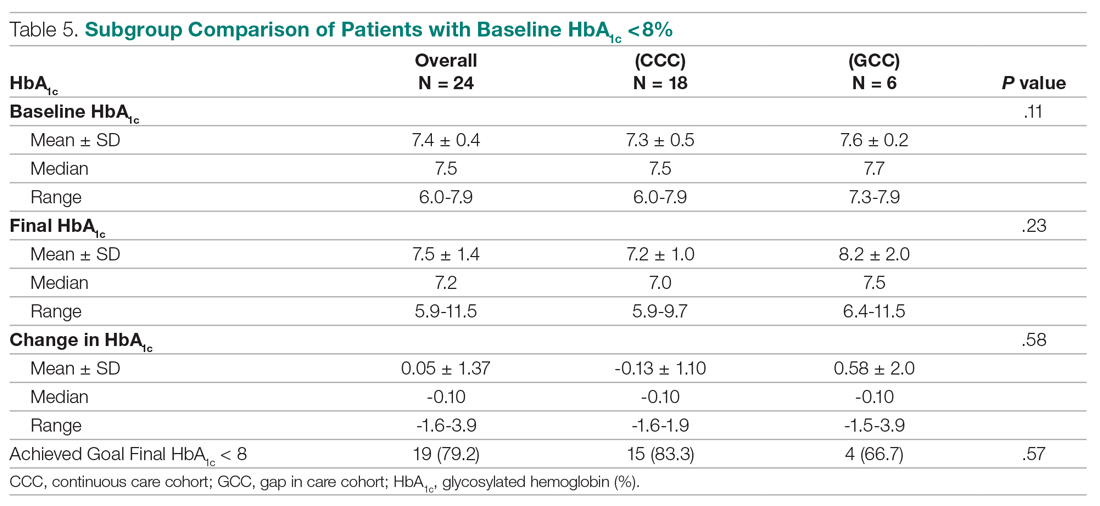

In the subgroup analysis of patients whose baseline HbA1c was ≥ 8%, about 42% in the CCC and 37% in the GCC achieved an HbA1c < 8% (P = .56) (Table 4). Approximately 83% of patients in the CCC had some degree of HbA1c improvement—the final HbA1c was lower than their baseline HbA1c—whereas this was observed in about 75% of patients in the GCC (P = .19). Of patients whose baseline HbA1c was < 8%, there was no significant difference in proportion of patients maintaining an HbA1c < 8% between the groups (P = .57), although some increases in HbA1c and HbA1c changes were observed in the GCC (Table 5).

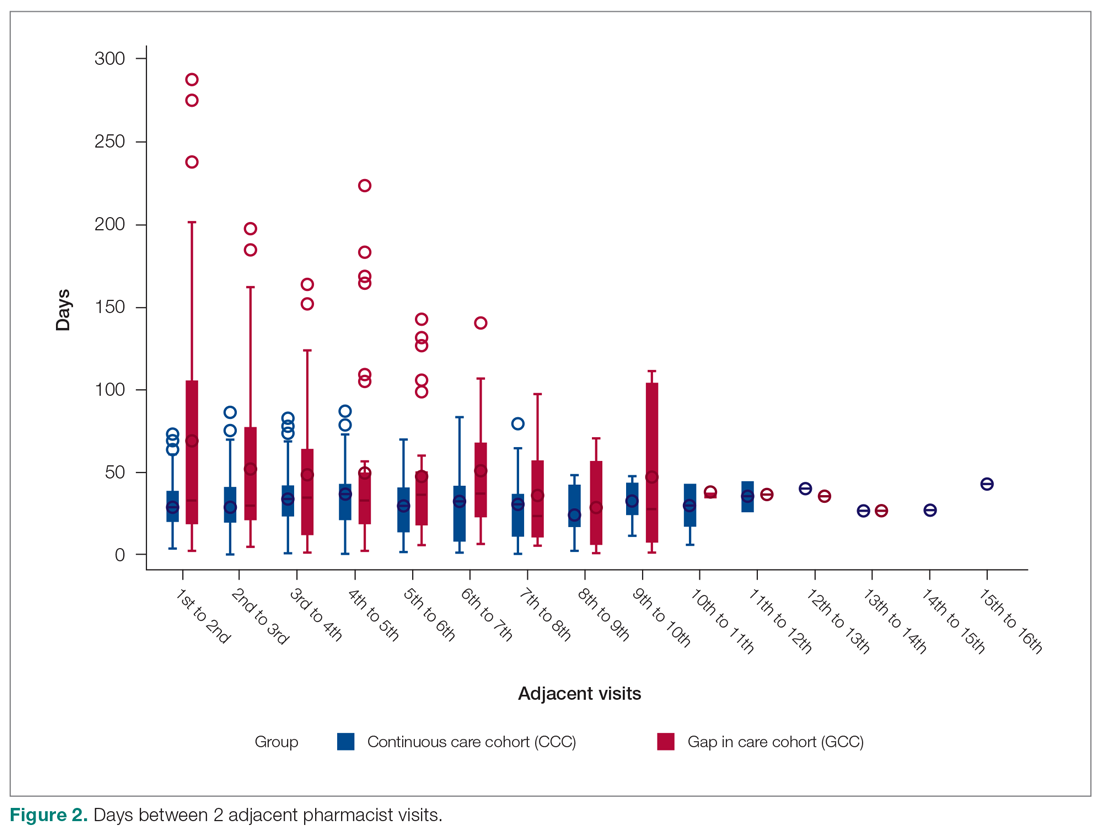

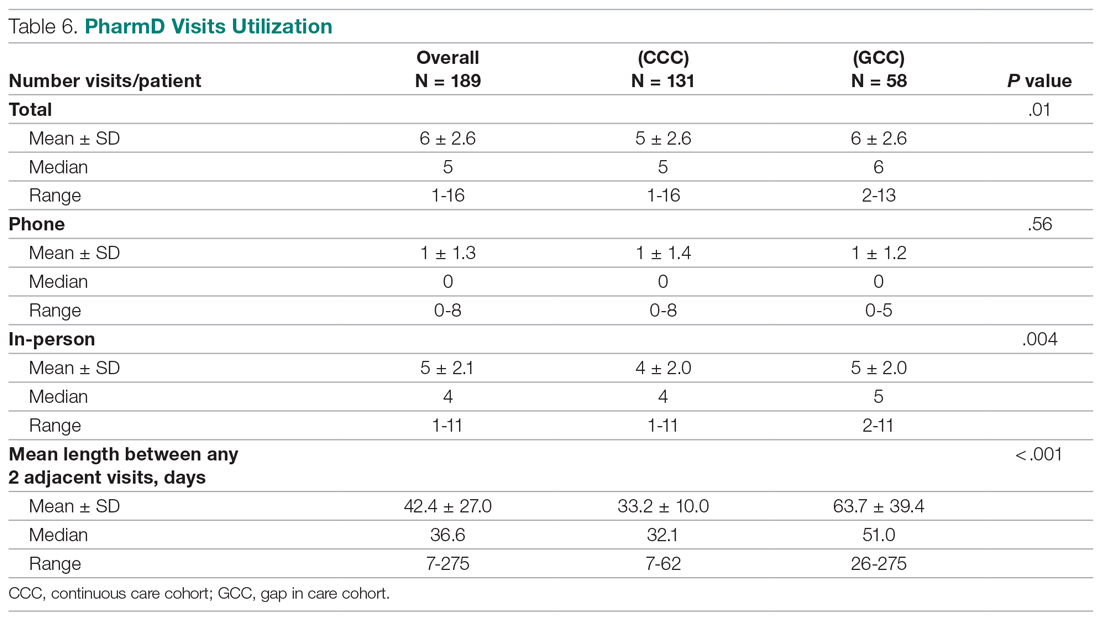

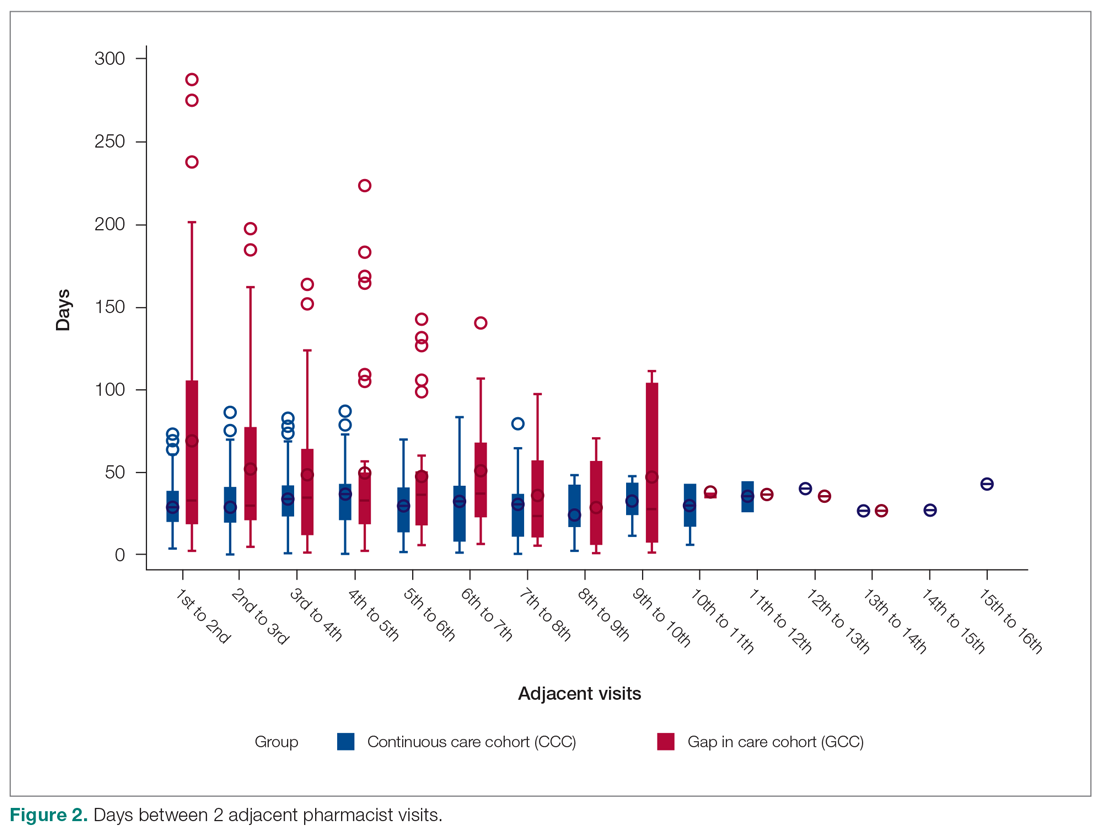

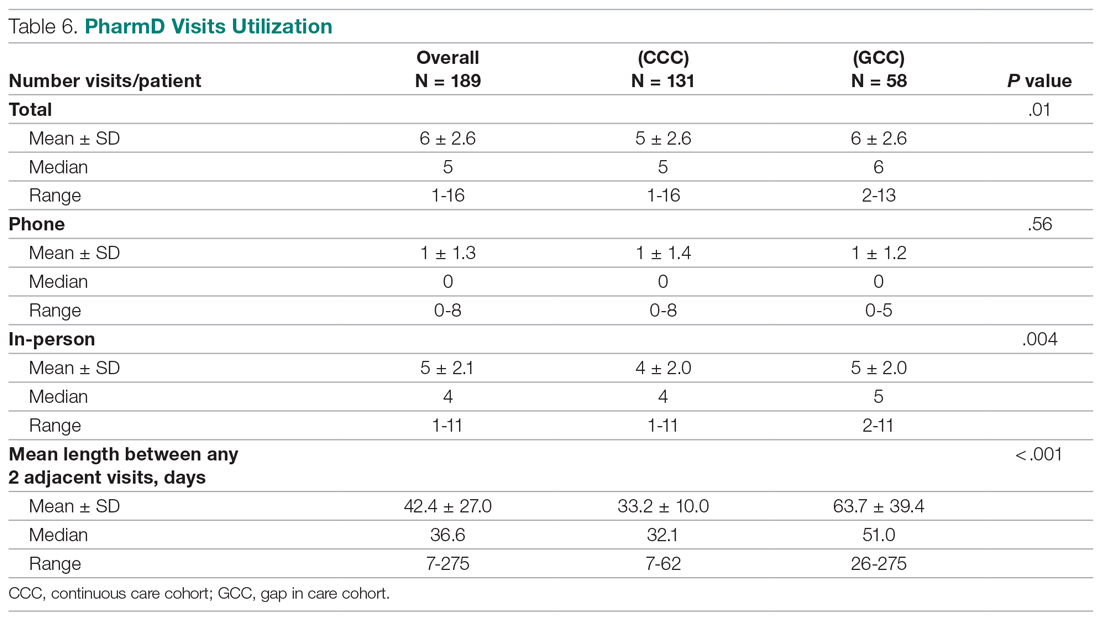

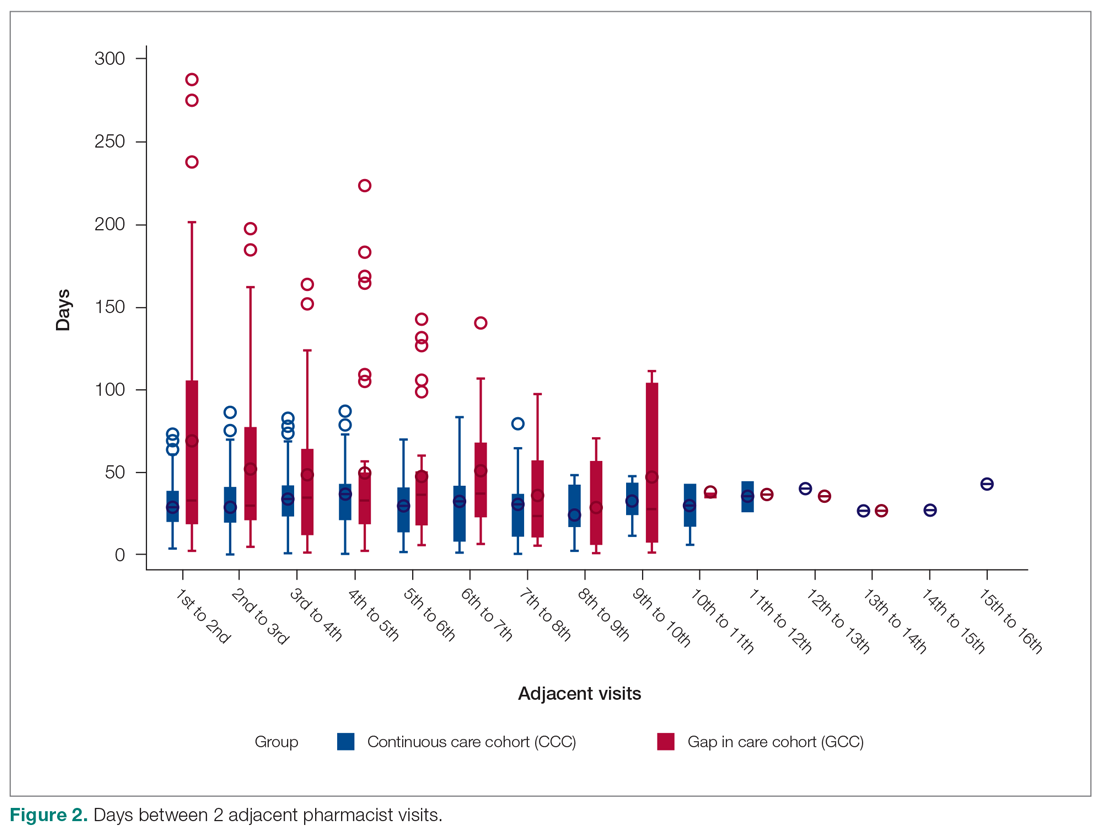

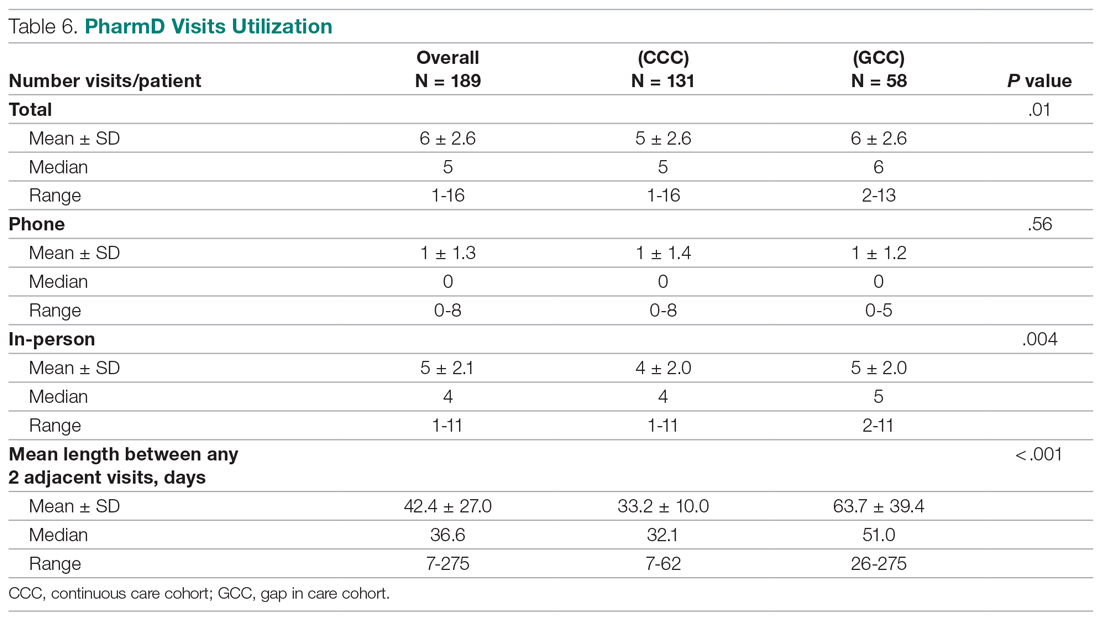

Health care utilization

Patients in the CCC visited pharmacists 5 times on average over 12 months, whereas patients in the GCC had an average of 6 visits (5 ± 2.6 in the CCC vs 6 ± 2.6 in the GCC, P = .01) (Table 6). The mean length between any 2 adjacent visits was significantly different, averaging about 33 days in the CCC compared to 64 days in the GCC (33.2 ± 10 in the CCC vs 63.7 ± 39.4 in the GCC, P < .001). As shown in Figure 2, the GCC shows wider ranges between any adjacent pharmacy visits throughout until the 10th visit. Both groups had a similar number of visits with primary care physicians during the same time period (4.6 ± 1.86 in the CCC vs 4.3 ± 2.51 in the GCC, P = .44). About 30% of patients in the CCC and 47% in the GCC had at least 1 visit to the emergency room or urgent care or had at least 1 hospital admission, for a total of 124 acute care utilizations between the 2 groups combined. Only a small fraction of acute care visits with or without hospitalizations were related to diabetes and its complications (23.1% in the CCC vs 22.0% in the GCC).

Discussion

This is a real-world study that describes HbA1c changes in patients who maintained pharmacy visits regularly and in those who had a history of a 3-month or longer gap in pharmacy visits. Although the study did not show statistically significant differences in HbA1c reduction between the 2 groups, pharmacists’ care, overall, provided mean HbA1c reductions of 1.3%. This result is consistent with those from multiple previous studies.10-13 It is worth noting that the final HbA1c was numerically lower in patients who followed up with pharmacists regularly than in patients with gaps in visits, with a difference of about 0.5 percentage points. This difference is considered clinically significant,17 and potentially could be even greater if the study duration was longer, as depicted by the slope of HbA1c reductions in the D-I-D model (Figure 1).

Previous studies have shown that pharmacist visits are conducted in shorter intervals than primary care physician visits to provide closer follow-up and to resolve any medication-related problems that may hinder therapeutic outcome improvements.3-4,7-9 Increasing access via pharmacists is particularly important in this clinic, where resident physician continuity and access is challenging. The pharmacist-driven program described in this study does not deviate from the norm, and this study confirms that pharmacist care, regardless of gaps in pharmacist visits, may still be beneficial.

Another notable finding from this study was that although the average number of pharmacist visits per patient was significantly different, this difference of 1 visit did not result in a statistically significant improvement in HbA1c. In fact, the average number of pharmacist visits per patient seemed to be within the reported range by Choe et al in a similar setting.7 Conversely, patients with a history of a gap in pharmacist visits spent longer durations under pharmacist care compared to those who had continuous follow-up. This could mean that it may take longer times or 1 additional visit to achieve similar HbA1c results with continuous pharmacist care. Higher number of visits with pharmacists in the group with the history of gaps between pharmacist visits could have been facilitated by resident physicians, as both groups had a similar number of visits with them. Although this is not conclusive, identifying the optimal number of visits with pharmacists in this underserved population could be beneficial in strategizing pharmacist visits. Acute care utilization was not different between the 2 groups, and most cases that led to acute care utilization were not directly related to diabetes or its complications.

The average HbA1c at the end of the study did not measure < 8%, a target that was reached by less than half of patients from each group; however, this study is a snapshot of a series of ongoing clinical pharmacy services. About 25% of our patients started their first visit with a pharmacist less than 6 months from the study end date, and these patients may not have had enough time with pharmacists for their HbA1c to reach below the target goal. In addition, most patients in this clinic were enrolled in public health plans and may carry a significant burden of social and behavioral factors that can affect diabetes management.18,19 These patients may need longer care by pharmacists along with other integrated services, such as behavioral health and social work, to achieve optimal HbA1c levels.20

There are several limitations to this study, including the lack of a propensity matched control group of patients who only had resident physician visits; thus, it is hard to test the true impact of continuous or intermittent pharmacist visits on the therapeutic outcomes. The study also does not address potential social, economic, and physical environment factors that might have contributed to pharmacist visits and to overall diabetes care. These factors can negatively impact diabetes control and addressing them could help with an individualized diabetes management approach.17,18 Additionally, by nature of being a descriptive study, the results may be subject to undetermined confounding factors.

Conclusion

Patients maintaining continuous pharmacist visits do not have statistically significant differences in change in HbA1c compared to patients who had a history of 3-month or longer gaps in pharmacist visits at a resident physician primary care safety-net clinic. However, patients with diabetes will likely derive a benefit in HbA1c reduction regardless of regularity of pharmacist care. This finding still holds true in collaboration with resident physicians who also regularly meet with patients.

The study highlights that it is important to integrate clinical pharmacists into primary care teams for improved therapeutic outcomes. It is our hope that regular visits to pharmacists can be a gateway for behavioral health and social work referrals, thereby addressing pharmacist-identified social barriers. Furthermore, exploration of socioeconomic and behavioral barriers to pharmacist visits is necessary to address and improve the patient experience, health care delivery, and health outcomes.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Roxanna Perez, PharmD, Amy Li, and Julie Dopheide, PharmD, BCPP, FASHP for their contributions to this project.

Corresponding author: Michelle Koun Lee Chu, PharmD, BCACP, APh, Titus Family Department of Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, 1985 Zonal Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90089-9121; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Manolakis PG, Skelton JB. Pharmacists’ contributions to primary care in the United States collaborating to address unmet patient care needs: the emerging role for pharmacists to address the shortage of primary care providers. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):S7.

2. Scott MA, Hitch B, Ray L, Colvin G. Integration of pharmacists into a patient-centered medical home. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2011;51(2):161‐166.

3. Wong SL, Barner JC, Sucic K, et al. Integration of pharmacists into patient-centered medical homes in federally qualified health centers in Texas. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(3):375‐381.

4. Sapp ECH, Francis SM, Hincapie AL. Implementation of pharmacist-driven comprehensive medication management as part of an interdisciplinary team in primary care physicians’ offices. Am J Accountable Care. 2020;8(1):8-11.

5. Cowart K, Olson K. Impact of pharmacist care provision in value-based care settings: How are we measuring value-added services? J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(1):125-128.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pharmacy: Collaborative Practice Agreements to Enable Drug Therapy Management. January 16, 2018. Accessed April 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/guides/best-practices/pharmacist-cdtm.htm

7. Choe HM, Farris KB, Stevenson JG, et al. Patient-centered medical home: developing, expanding, and sustaining a role for pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(12):1063-1071.

8. Coe AB, Choe HM. Pharmacists supporting population health in patient-centered medical homes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(18):1461-1466.

9. Luder HR, Shannon P, Kirby J, Frede SM. Community pharmacist collaboration with a patient-centered medical home: establishment of a patient-centered medical neighborhood and payment model. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018;58(1):44-50.

10. Matzke GR, Moczygemba LR, Williams KJ, et al. Impact of a pharmacist–physician collaborative care model on patient outcomes and health services utilization. 10.05Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(14):1039-1047.

11. Aneese NJ, Halalau A, Muench S, et al. Impact of a pharmacist-managed diabetes clinic on quality measures. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(4 Spec No.):SP116-SP119.

12. Prudencio J, Cutler T, Roberts S, et al. The effect of clinical 10.05pharmacist-led comprehensive medication management on chronic disease state goal attainment in a patient-centered medical home. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(5):423-429.

13. Edwards HD, Webb RD, Scheid DC, et al. A pharmacist visit improves diabetes standards in a patient-centered medical home (PCMH). Am J Med Qual. 2012;27(6) 529-534.

14. Ullah S, Rajan S, Liu T, et al. Why do patients miss their appointments at primary care clinics? J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2018;4:090.

15. Moore CG, Wilson-Witherspoon P, Probst JC. Time and money: effects of no-shows at a family practice residency clinic. Fam Med. 2001;33(7):522-527.

16. Kheirkhah P, Feng Q, Travis LM, et al. Prevalence, predictors and economic consequences of no-shows. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:13.

17. Little RR, Rohlfing C. The long and winding road to optimal HbA10.051c10.05 measurement. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;418:63-71.

18. Hill J, Nielsen M, Fox MH. Understanding the social factors that contribute to diabetes: a means to informing health care and social policies for the chronically ill. Perm J. 2013;17(2):67-72.

19. Gonzalez-Zacarias AA, Mavarez-Martinez A, Arias-Morales CE, et al. Impact of demographic, socioeconomic, and psychological factors on glycemic self-management in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Public Health. 2016;4:195.

20. Pantalone KM, Misra-Hebert AD, Hobbs TD, et al. The probability of A1c goal attainment in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes in a large integrated delivery system: a prediction model. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1910-1919.

From Titus Family Department of Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA (Drs. Chu and Ma and Mimi Lou), and Department of Family Medicine, Keck Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Suh).

Objective: The objective of this study is to describe HbA1c changes in patients who maintained continuous pharmacist care vs patients who had a gap in pharmacist care of 3 months or longer.

Methods: This retrospective study was conducted from October 1, 2018, to September 30, 2019. Electronic health record data from an academic-affiliated, safety-net resident physician primary care clinic were collected to observe HbA1c changes between patients with continuous pharmacist care and patients who had a gap of 3 months or longer in pharmacist care. A total of 189 patients met the inclusion criteria and were divided into 2 groups: those with continuous care and those with gaps in care. Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and the χ2 (or Fisher exact) test for categorical variables. The differences-in-differences model was used to compare the changes in HbA1c between the 2 groups.

Results: There was no significant difference in changes in HbA1c between the continuous care group and the gaps in care group, although the mean magnitude of HbA1c changes was numerically greater in the continuous care group (-1.48% vs -0.97%). Overall, both groups showed improvement in their HbA1c levels and had similar numbers of primary care physician visits and acute care utilizations, while the gaps in care group had longer duration with pharmacists and between the adjacent pharmacist visits.

Conclusion: Maintaining continuous, regular visits with a pharmacist at a safety-net resident physician primary care clinic did not show a significant difference in HbA1c changes compared to having gaps in pharmacist care. Future studies on socioeconomic and behavioral burden on HbA1c improvement and on pharmacist visits in these populations should be explored.

Keywords: clinical pharmacist; diabetes management; continuous visit; primary care clinic.

Pharmacists have unique skills in identifying and resolving problems related to the safety and efficacy of drug therapy while addressing medication adherence and access for patients. Their expertise is especially important to meet the care needs of a growing population with chronic conditions amidst a primary care physician shortage.1 As health care systems move toward value-based care, emphasis on improvement in quality and health measures have become central in care delivery. Pharmacists have been integrated into team-based care in primary care settings, but the value-based shift has opened more opportunities for pharmacists to address unmet quality standards.2-5

Many studies have reported that the integration of pharmacists into team-based care improves health outcomes and reduces overall health care costs.6-9 Specifically, when pharmacists were added to primary care teams to provide diabetes management, hemoglobin HbA1c levels were reduced compared to teams without pharmacists.10-13 Offering pharmacist visits as often as every 2 weeks to 3 months, with each patient having an average of 4.7 visits, resulted in improved therapeutic outcomes.3,7 During visits, pharmacists address the need for additional drug therapy, deprescribe unnecessary therapy, correct insufficient doses or durations, and switch patients to more cost-efficient drug therapy.9 Likewise, patients who visit pharmacists in addition to seeing their primary care physician can have medication-related concerns resolved and improve their therapeutic outcomes.10,11

Not much is known about the magnitude of HbA1c change based on the regularity of pharmacist visits. Although pharmacists offer follow-up appointments in reasonable time intervals, patients do not keep every appointment for a variety of reasons, including forgetfulness, personal issues, and a lack of transportation.14 Such missed appointments can negatively impact health outcomes.14-16 The purpose of this study is to describe HbA1c changes in patients who maintained continuous, regular pharmacist visits without a 3-month gap and in patients who had history of inconsistent pharmacist visits with a gap of 3 months or longer. Furthermore, this study describes the frequency of health care utilization for these 2 groups.

Methods

Setting

The Internal Medicine resident physician primary care clinic is 1 of 2 adult primary care clinics at an academic, urban, public medical center. It is in the heart of East Los Angeles, where predominantly Spanish-speaking and minority populations reside. The clinic has approximately 19000 empaneled patients and is the largest resident primary care clinic in the public health system. The clinical pharmacy service addresses unmet quality standards, specifically HbA1c. The clinical pharmacists are co-located and collaborate with resident physicians, attending physicians, care managers, nurses, social workers, and community health workers at the clinic. They operate under collaborative practice agreements with prescriptive authority, except for controlled substances, specialty drugs, and antipsychotic medications.

Pharmacist visit

Patients are primarily referred by resident physicians to clinical pharmacists when their HbA1c level is above 8% for an extended period, when poor adherence and low health literacy are evident regardless of HbA1c level, or when a complex medication regimen requires comprehensive medication review and reconciliation. The referral occurs through warm handoff by resident physicians as well as clinic nurses, and it is embedded in the clinic flow. Patients continue their visits with resident physicians for issues other than their referral to clinical pharmacists. The visits with pharmacists are appointment-based, occur independently from resident physician visits, and continue until the patient’s HbA1c level or adherence is optimized. Clinical pharmacists continue to follow up with patients who may have reached their target HbA1c level but still are deemed unstable due to inconsistency in their self-management and medication adherence.

After the desirable HbA1c target is achieved along with full adherence to medications and self-management, clinical pharmacists will hand off patients back to resident physicians. At each visit, pharmacists perform a comprehensive medication assessment and reconciliation that includes adjusting medication therapy, placing orders for necessary laboratory tests and prescriptions, and assessing medication adherence. They also evaluate patients’ signs and symptoms for hyperglycemic complications, hypoglycemia, and other potential treatment-related adverse events. These are all within the pharmacist’s scope of practice in comprehensive medication management. Patient education is provided with the teach-back method and includes lifestyle modifications and medication counseling (Table 1). Pharmacists offer face-to-face visits as frequently as every 1 to 2 weeks to every 4 to 6 weeks, depending on the level of complexity and the severity of a patient’s conditions and medications. For patients whose HbA1c has reached the target range but have not been deemed stable, pharmacists continue to check in with them every 2 months. Phone visits are also utilized as an additional care delivery method for patients having difficulty showing up for face-to-face visits or needing quick assessment of medication adherence and responses to changes in drug treatment in between the face-to-face visits. The maximal interval between pharmacist visits is offered no longer than every 8 weeks. Patients are contacted via phone or mail by the nursing staff to reschedule if they miss their appointments with pharmacists. Every pharmacy visit is documented in the patient’s electronic medical record.

Study design

This is a retrospective study describing the HbA1c changes in a patient group that maintained pharmacist visits, with each interval less than 3 months, and in another group, who had a history of a 3-month or longer gap between pharmacist visits. The data were obtained from patients’ electronic medical records during the study period of October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, and collected using a HIPAA-compliant, electronic data storage website, REDCap. The institutional review board approval was obtained under HS-19-00929. Patients 18 years and older who were referred by primary care resident physicians for diabetes management, and had 2 or more visits with a pharmacist within the study period, were included. Patients were excluded if they had only 1 HbA1c drawn during the study period, were referred to a pharmacist for reasons other than diabetes management, were concurrently managed by an endocrinologist, had only 1 visit with a pharmacist, or had no visits with their primary care resident physician for over a year. The patients were then divided into 2 groups: continuous care cohort (CCC) and gap in care cohort (GCC). Both face-to-face and phone visits were counted as pharmacist visits for each group.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change in HbA1c from baseline between the 2 groups. Baseline HbA1c was considered as the HbA1c value obtained within 3 months prior to, or within 1 month, of the first visit with the pharmacist during the study period. The final HbA1c was considered the value measured within 1 month of, or 3 months after, the patient’s last visit with the pharmacist during the study period.

Several subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between HbA1c and each group. Among patients whose baseline HbA1c was ≥ 8%, we looked at the percentage of patients reaching HbA1c < 8%, the percentage of patients showing any level of improvement in HbA1c, and the change in HbA1c for each group. We also looked at the percentage of patients with baseline HbA1c < 8% maintaining the level throughout the study period and the change in HbA1c for each group. Additionally, we looked at health care utilization, which included pharmacist visits, primary care physician visits, emergency room and urgent care visits, and hospitalizations for each group. The latter 3 types of utilization were grouped as acute care utilization and further analyzed for visit reasons, which were subsequently categorized as diabetes related and non-diabetes related. The diabetes related reasons linking to acute care utilization were defined as any episodes related to hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS), foot ulcers, retinopathy, and osteomyelitis infection. All other reasons leading to acute care utilization were categorized as non-diabetes related.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous data and χ2 (or Fisher exact) test for categorical data. A basic difference-in-differences (D-I-D) method was used to compare the changes of HbA1c between the CCC and GCC over 2 time points: baseline and final measurements. The repeated measures ANOVA was used for analyzing D-I-D. P < .05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline data

A total of 1272 patients were identified within the study period, and 189 met the study inclusion criteria. The CCC included 132 patients, the GCC 57. The mean age of patients in both groups was similar at 57 years old (P = .39). Most patients had Medicaid as their primary insurance. About one-third of patients in each group experienced clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and about 12% overall had chronic kidney disease stage 3 and higher. The average number of days that patients were under pharmacist care during the study period was longer in the GCC compared to the CCC, and it was statistically significant (P < .001) (Table 2). The mean ± SD baseline HbA1c for the CCC and GCC was 10.0% ± 2.0% and 9.9% ± 1.7%, respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant (P = .93). About 86% of patients in the CCC and 90% in the GCC had a baseline HbA1c of ≥ 8%.

HbA1c

The mean change in HbA1c between the 2 groups was not statistically significant (-1.5% ± 2.0% in the CCC vs -1.0% ± 2.1% in the GCC, P = .36) (Table 3). However, an absolute mean HbA1c reduction of 1.3% was observed in both groups combined at the end of the study. Figure 1 shows a D-I-D model of the 2 groups. Based on the output, the P value of .11 on the interaction term (time*group) indicates that the D-I-D in HbA1c change from baseline to final between the CCC and GCC is not statistically different. However, the magnitude of the difference calculated from the LSMEANS results showed a trend. The HbA1c from baseline to final measurement of patients in the GCC declined by 0.97 percentage points (from 9.94% to 8.97%), while those in the CCC saw their HbA1c decline by 1.48 percentage points (from 9.96% to 8.48%), for a D-I-D of 0.51. In other words, those in the GCC had an HbA1c that decreased by 0.51% less than that of patients in the CCC, suggesting that the CCC shows a steeper line declining from baseline to final HbA1c compared to the GCC, whose line declines less sharply.

In the subgroup analysis of patients whose baseline HbA1c was ≥ 8%, about 42% in the CCC and 37% in the GCC achieved an HbA1c < 8% (P = .56) (Table 4). Approximately 83% of patients in the CCC had some degree of HbA1c improvement—the final HbA1c was lower than their baseline HbA1c—whereas this was observed in about 75% of patients in the GCC (P = .19). Of patients whose baseline HbA1c was < 8%, there was no significant difference in proportion of patients maintaining an HbA1c < 8% between the groups (P = .57), although some increases in HbA1c and HbA1c changes were observed in the GCC (Table 5).

Health care utilization

Patients in the CCC visited pharmacists 5 times on average over 12 months, whereas patients in the GCC had an average of 6 visits (5 ± 2.6 in the CCC vs 6 ± 2.6 in the GCC, P = .01) (Table 6). The mean length between any 2 adjacent visits was significantly different, averaging about 33 days in the CCC compared to 64 days in the GCC (33.2 ± 10 in the CCC vs 63.7 ± 39.4 in the GCC, P < .001). As shown in Figure 2, the GCC shows wider ranges between any adjacent pharmacy visits throughout until the 10th visit. Both groups had a similar number of visits with primary care physicians during the same time period (4.6 ± 1.86 in the CCC vs 4.3 ± 2.51 in the GCC, P = .44). About 30% of patients in the CCC and 47% in the GCC had at least 1 visit to the emergency room or urgent care or had at least 1 hospital admission, for a total of 124 acute care utilizations between the 2 groups combined. Only a small fraction of acute care visits with or without hospitalizations were related to diabetes and its complications (23.1% in the CCC vs 22.0% in the GCC).

Discussion

This is a real-world study that describes HbA1c changes in patients who maintained pharmacy visits regularly and in those who had a history of a 3-month or longer gap in pharmacy visits. Although the study did not show statistically significant differences in HbA1c reduction between the 2 groups, pharmacists’ care, overall, provided mean HbA1c reductions of 1.3%. This result is consistent with those from multiple previous studies.10-13 It is worth noting that the final HbA1c was numerically lower in patients who followed up with pharmacists regularly than in patients with gaps in visits, with a difference of about 0.5 percentage points. This difference is considered clinically significant,17 and potentially could be even greater if the study duration was longer, as depicted by the slope of HbA1c reductions in the D-I-D model (Figure 1).

Previous studies have shown that pharmacist visits are conducted in shorter intervals than primary care physician visits to provide closer follow-up and to resolve any medication-related problems that may hinder therapeutic outcome improvements.3-4,7-9 Increasing access via pharmacists is particularly important in this clinic, where resident physician continuity and access is challenging. The pharmacist-driven program described in this study does not deviate from the norm, and this study confirms that pharmacist care, regardless of gaps in pharmacist visits, may still be beneficial.

Another notable finding from this study was that although the average number of pharmacist visits per patient was significantly different, this difference of 1 visit did not result in a statistically significant improvement in HbA1c. In fact, the average number of pharmacist visits per patient seemed to be within the reported range by Choe et al in a similar setting.7 Conversely, patients with a history of a gap in pharmacist visits spent longer durations under pharmacist care compared to those who had continuous follow-up. This could mean that it may take longer times or 1 additional visit to achieve similar HbA1c results with continuous pharmacist care. Higher number of visits with pharmacists in the group with the history of gaps between pharmacist visits could have been facilitated by resident physicians, as both groups had a similar number of visits with them. Although this is not conclusive, identifying the optimal number of visits with pharmacists in this underserved population could be beneficial in strategizing pharmacist visits. Acute care utilization was not different between the 2 groups, and most cases that led to acute care utilization were not directly related to diabetes or its complications.

The average HbA1c at the end of the study did not measure < 8%, a target that was reached by less than half of patients from each group; however, this study is a snapshot of a series of ongoing clinical pharmacy services. About 25% of our patients started their first visit with a pharmacist less than 6 months from the study end date, and these patients may not have had enough time with pharmacists for their HbA1c to reach below the target goal. In addition, most patients in this clinic were enrolled in public health plans and may carry a significant burden of social and behavioral factors that can affect diabetes management.18,19 These patients may need longer care by pharmacists along with other integrated services, such as behavioral health and social work, to achieve optimal HbA1c levels.20

There are several limitations to this study, including the lack of a propensity matched control group of patients who only had resident physician visits; thus, it is hard to test the true impact of continuous or intermittent pharmacist visits on the therapeutic outcomes. The study also does not address potential social, economic, and physical environment factors that might have contributed to pharmacist visits and to overall diabetes care. These factors can negatively impact diabetes control and addressing them could help with an individualized diabetes management approach.17,18 Additionally, by nature of being a descriptive study, the results may be subject to undetermined confounding factors.

Conclusion

Patients maintaining continuous pharmacist visits do not have statistically significant differences in change in HbA1c compared to patients who had a history of 3-month or longer gaps in pharmacist visits at a resident physician primary care safety-net clinic. However, patients with diabetes will likely derive a benefit in HbA1c reduction regardless of regularity of pharmacist care. This finding still holds true in collaboration with resident physicians who also regularly meet with patients.

The study highlights that it is important to integrate clinical pharmacists into primary care teams for improved therapeutic outcomes. It is our hope that regular visits to pharmacists can be a gateway for behavioral health and social work referrals, thereby addressing pharmacist-identified social barriers. Furthermore, exploration of socioeconomic and behavioral barriers to pharmacist visits is necessary to address and improve the patient experience, health care delivery, and health outcomes.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Roxanna Perez, PharmD, Amy Li, and Julie Dopheide, PharmD, BCPP, FASHP for their contributions to this project.

Corresponding author: Michelle Koun Lee Chu, PharmD, BCACP, APh, Titus Family Department of Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, 1985 Zonal Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90089-9121; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From Titus Family Department of Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA (Drs. Chu and Ma and Mimi Lou), and Department of Family Medicine, Keck Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Suh).

Objective: The objective of this study is to describe HbA1c changes in patients who maintained continuous pharmacist care vs patients who had a gap in pharmacist care of 3 months or longer.

Methods: This retrospective study was conducted from October 1, 2018, to September 30, 2019. Electronic health record data from an academic-affiliated, safety-net resident physician primary care clinic were collected to observe HbA1c changes between patients with continuous pharmacist care and patients who had a gap of 3 months or longer in pharmacist care. A total of 189 patients met the inclusion criteria and were divided into 2 groups: those with continuous care and those with gaps in care. Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and the χ2 (or Fisher exact) test for categorical variables. The differences-in-differences model was used to compare the changes in HbA1c between the 2 groups.

Results: There was no significant difference in changes in HbA1c between the continuous care group and the gaps in care group, although the mean magnitude of HbA1c changes was numerically greater in the continuous care group (-1.48% vs -0.97%). Overall, both groups showed improvement in their HbA1c levels and had similar numbers of primary care physician visits and acute care utilizations, while the gaps in care group had longer duration with pharmacists and between the adjacent pharmacist visits.

Conclusion: Maintaining continuous, regular visits with a pharmacist at a safety-net resident physician primary care clinic did not show a significant difference in HbA1c changes compared to having gaps in pharmacist care. Future studies on socioeconomic and behavioral burden on HbA1c improvement and on pharmacist visits in these populations should be explored.

Keywords: clinical pharmacist; diabetes management; continuous visit; primary care clinic.

Pharmacists have unique skills in identifying and resolving problems related to the safety and efficacy of drug therapy while addressing medication adherence and access for patients. Their expertise is especially important to meet the care needs of a growing population with chronic conditions amidst a primary care physician shortage.1 As health care systems move toward value-based care, emphasis on improvement in quality and health measures have become central in care delivery. Pharmacists have been integrated into team-based care in primary care settings, but the value-based shift has opened more opportunities for pharmacists to address unmet quality standards.2-5

Many studies have reported that the integration of pharmacists into team-based care improves health outcomes and reduces overall health care costs.6-9 Specifically, when pharmacists were added to primary care teams to provide diabetes management, hemoglobin HbA1c levels were reduced compared to teams without pharmacists.10-13 Offering pharmacist visits as often as every 2 weeks to 3 months, with each patient having an average of 4.7 visits, resulted in improved therapeutic outcomes.3,7 During visits, pharmacists address the need for additional drug therapy, deprescribe unnecessary therapy, correct insufficient doses or durations, and switch patients to more cost-efficient drug therapy.9 Likewise, patients who visit pharmacists in addition to seeing their primary care physician can have medication-related concerns resolved and improve their therapeutic outcomes.10,11

Not much is known about the magnitude of HbA1c change based on the regularity of pharmacist visits. Although pharmacists offer follow-up appointments in reasonable time intervals, patients do not keep every appointment for a variety of reasons, including forgetfulness, personal issues, and a lack of transportation.14 Such missed appointments can negatively impact health outcomes.14-16 The purpose of this study is to describe HbA1c changes in patients who maintained continuous, regular pharmacist visits without a 3-month gap and in patients who had history of inconsistent pharmacist visits with a gap of 3 months or longer. Furthermore, this study describes the frequency of health care utilization for these 2 groups.

Methods

Setting

The Internal Medicine resident physician primary care clinic is 1 of 2 adult primary care clinics at an academic, urban, public medical center. It is in the heart of East Los Angeles, where predominantly Spanish-speaking and minority populations reside. The clinic has approximately 19000 empaneled patients and is the largest resident primary care clinic in the public health system. The clinical pharmacy service addresses unmet quality standards, specifically HbA1c. The clinical pharmacists are co-located and collaborate with resident physicians, attending physicians, care managers, nurses, social workers, and community health workers at the clinic. They operate under collaborative practice agreements with prescriptive authority, except for controlled substances, specialty drugs, and antipsychotic medications.

Pharmacist visit

Patients are primarily referred by resident physicians to clinical pharmacists when their HbA1c level is above 8% for an extended period, when poor adherence and low health literacy are evident regardless of HbA1c level, or when a complex medication regimen requires comprehensive medication review and reconciliation. The referral occurs through warm handoff by resident physicians as well as clinic nurses, and it is embedded in the clinic flow. Patients continue their visits with resident physicians for issues other than their referral to clinical pharmacists. The visits with pharmacists are appointment-based, occur independently from resident physician visits, and continue until the patient’s HbA1c level or adherence is optimized. Clinical pharmacists continue to follow up with patients who may have reached their target HbA1c level but still are deemed unstable due to inconsistency in their self-management and medication adherence.

After the desirable HbA1c target is achieved along with full adherence to medications and self-management, clinical pharmacists will hand off patients back to resident physicians. At each visit, pharmacists perform a comprehensive medication assessment and reconciliation that includes adjusting medication therapy, placing orders for necessary laboratory tests and prescriptions, and assessing medication adherence. They also evaluate patients’ signs and symptoms for hyperglycemic complications, hypoglycemia, and other potential treatment-related adverse events. These are all within the pharmacist’s scope of practice in comprehensive medication management. Patient education is provided with the teach-back method and includes lifestyle modifications and medication counseling (Table 1). Pharmacists offer face-to-face visits as frequently as every 1 to 2 weeks to every 4 to 6 weeks, depending on the level of complexity and the severity of a patient’s conditions and medications. For patients whose HbA1c has reached the target range but have not been deemed stable, pharmacists continue to check in with them every 2 months. Phone visits are also utilized as an additional care delivery method for patients having difficulty showing up for face-to-face visits or needing quick assessment of medication adherence and responses to changes in drug treatment in between the face-to-face visits. The maximal interval between pharmacist visits is offered no longer than every 8 weeks. Patients are contacted via phone or mail by the nursing staff to reschedule if they miss their appointments with pharmacists. Every pharmacy visit is documented in the patient’s electronic medical record.

Study design

This is a retrospective study describing the HbA1c changes in a patient group that maintained pharmacist visits, with each interval less than 3 months, and in another group, who had a history of a 3-month or longer gap between pharmacist visits. The data were obtained from patients’ electronic medical records during the study period of October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, and collected using a HIPAA-compliant, electronic data storage website, REDCap. The institutional review board approval was obtained under HS-19-00929. Patients 18 years and older who were referred by primary care resident physicians for diabetes management, and had 2 or more visits with a pharmacist within the study period, were included. Patients were excluded if they had only 1 HbA1c drawn during the study period, were referred to a pharmacist for reasons other than diabetes management, were concurrently managed by an endocrinologist, had only 1 visit with a pharmacist, or had no visits with their primary care resident physician for over a year. The patients were then divided into 2 groups: continuous care cohort (CCC) and gap in care cohort (GCC). Both face-to-face and phone visits were counted as pharmacist visits for each group.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change in HbA1c from baseline between the 2 groups. Baseline HbA1c was considered as the HbA1c value obtained within 3 months prior to, or within 1 month, of the first visit with the pharmacist during the study period. The final HbA1c was considered the value measured within 1 month of, or 3 months after, the patient’s last visit with the pharmacist during the study period.

Several subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between HbA1c and each group. Among patients whose baseline HbA1c was ≥ 8%, we looked at the percentage of patients reaching HbA1c < 8%, the percentage of patients showing any level of improvement in HbA1c, and the change in HbA1c for each group. We also looked at the percentage of patients with baseline HbA1c < 8% maintaining the level throughout the study period and the change in HbA1c for each group. Additionally, we looked at health care utilization, which included pharmacist visits, primary care physician visits, emergency room and urgent care visits, and hospitalizations for each group. The latter 3 types of utilization were grouped as acute care utilization and further analyzed for visit reasons, which were subsequently categorized as diabetes related and non-diabetes related. The diabetes related reasons linking to acute care utilization were defined as any episodes related to hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS), foot ulcers, retinopathy, and osteomyelitis infection. All other reasons leading to acute care utilization were categorized as non-diabetes related.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous data and χ2 (or Fisher exact) test for categorical data. A basic difference-in-differences (D-I-D) method was used to compare the changes of HbA1c between the CCC and GCC over 2 time points: baseline and final measurements. The repeated measures ANOVA was used for analyzing D-I-D. P < .05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline data

A total of 1272 patients were identified within the study period, and 189 met the study inclusion criteria. The CCC included 132 patients, the GCC 57. The mean age of patients in both groups was similar at 57 years old (P = .39). Most patients had Medicaid as their primary insurance. About one-third of patients in each group experienced clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and about 12% overall had chronic kidney disease stage 3 and higher. The average number of days that patients were under pharmacist care during the study period was longer in the GCC compared to the CCC, and it was statistically significant (P < .001) (Table 2). The mean ± SD baseline HbA1c for the CCC and GCC was 10.0% ± 2.0% and 9.9% ± 1.7%, respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant (P = .93). About 86% of patients in the CCC and 90% in the GCC had a baseline HbA1c of ≥ 8%.

HbA1c

The mean change in HbA1c between the 2 groups was not statistically significant (-1.5% ± 2.0% in the CCC vs -1.0% ± 2.1% in the GCC, P = .36) (Table 3). However, an absolute mean HbA1c reduction of 1.3% was observed in both groups combined at the end of the study. Figure 1 shows a D-I-D model of the 2 groups. Based on the output, the P value of .11 on the interaction term (time*group) indicates that the D-I-D in HbA1c change from baseline to final between the CCC and GCC is not statistically different. However, the magnitude of the difference calculated from the LSMEANS results showed a trend. The HbA1c from baseline to final measurement of patients in the GCC declined by 0.97 percentage points (from 9.94% to 8.97%), while those in the CCC saw their HbA1c decline by 1.48 percentage points (from 9.96% to 8.48%), for a D-I-D of 0.51. In other words, those in the GCC had an HbA1c that decreased by 0.51% less than that of patients in the CCC, suggesting that the CCC shows a steeper line declining from baseline to final HbA1c compared to the GCC, whose line declines less sharply.

In the subgroup analysis of patients whose baseline HbA1c was ≥ 8%, about 42% in the CCC and 37% in the GCC achieved an HbA1c < 8% (P = .56) (Table 4). Approximately 83% of patients in the CCC had some degree of HbA1c improvement—the final HbA1c was lower than their baseline HbA1c—whereas this was observed in about 75% of patients in the GCC (P = .19). Of patients whose baseline HbA1c was < 8%, there was no significant difference in proportion of patients maintaining an HbA1c < 8% between the groups (P = .57), although some increases in HbA1c and HbA1c changes were observed in the GCC (Table 5).

Health care utilization

Patients in the CCC visited pharmacists 5 times on average over 12 months, whereas patients in the GCC had an average of 6 visits (5 ± 2.6 in the CCC vs 6 ± 2.6 in the GCC, P = .01) (Table 6). The mean length between any 2 adjacent visits was significantly different, averaging about 33 days in the CCC compared to 64 days in the GCC (33.2 ± 10 in the CCC vs 63.7 ± 39.4 in the GCC, P < .001). As shown in Figure 2, the GCC shows wider ranges between any adjacent pharmacy visits throughout until the 10th visit. Both groups had a similar number of visits with primary care physicians during the same time period (4.6 ± 1.86 in the CCC vs 4.3 ± 2.51 in the GCC, P = .44). About 30% of patients in the CCC and 47% in the GCC had at least 1 visit to the emergency room or urgent care or had at least 1 hospital admission, for a total of 124 acute care utilizations between the 2 groups combined. Only a small fraction of acute care visits with or without hospitalizations were related to diabetes and its complications (23.1% in the CCC vs 22.0% in the GCC).

Discussion

This is a real-world study that describes HbA1c changes in patients who maintained pharmacy visits regularly and in those who had a history of a 3-month or longer gap in pharmacy visits. Although the study did not show statistically significant differences in HbA1c reduction between the 2 groups, pharmacists’ care, overall, provided mean HbA1c reductions of 1.3%. This result is consistent with those from multiple previous studies.10-13 It is worth noting that the final HbA1c was numerically lower in patients who followed up with pharmacists regularly than in patients with gaps in visits, with a difference of about 0.5 percentage points. This difference is considered clinically significant,17 and potentially could be even greater if the study duration was longer, as depicted by the slope of HbA1c reductions in the D-I-D model (Figure 1).

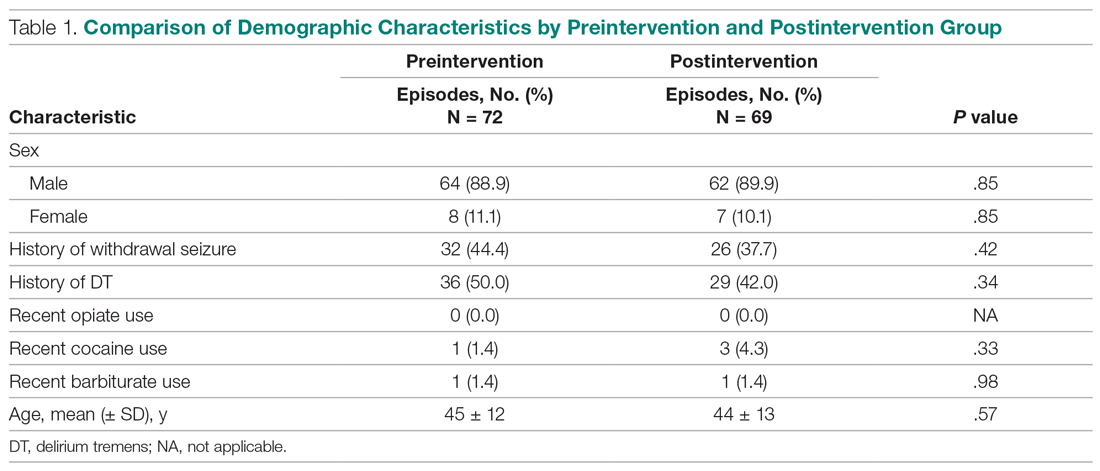

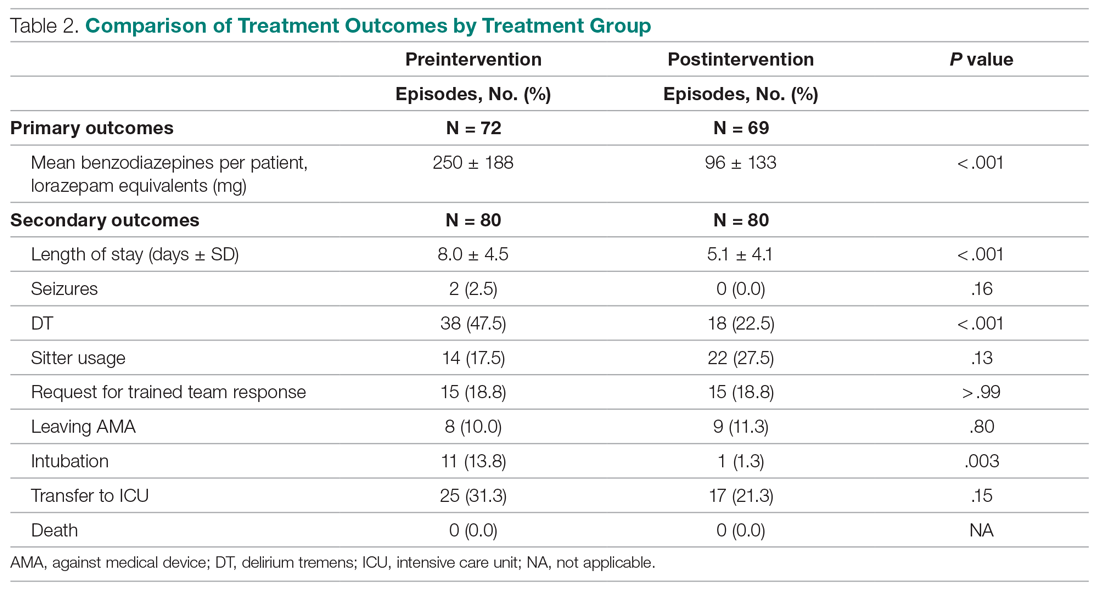

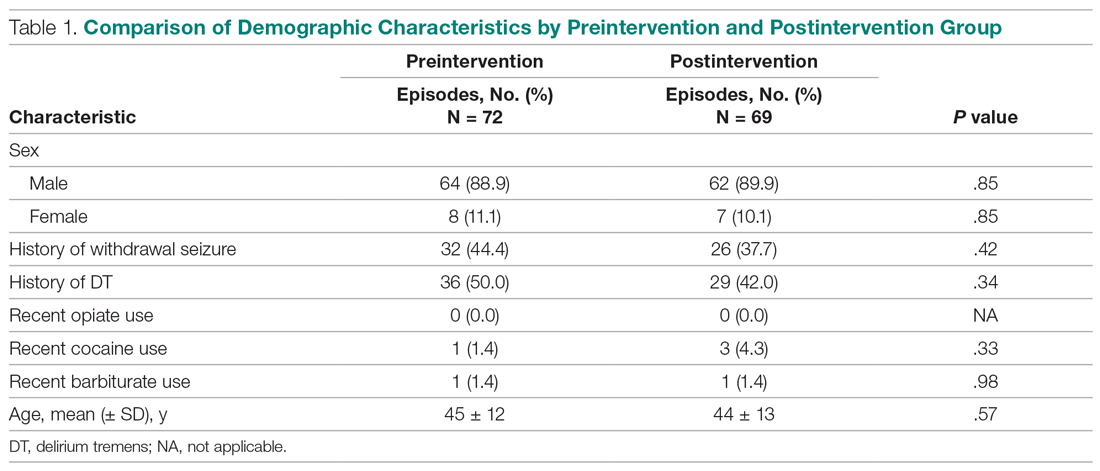

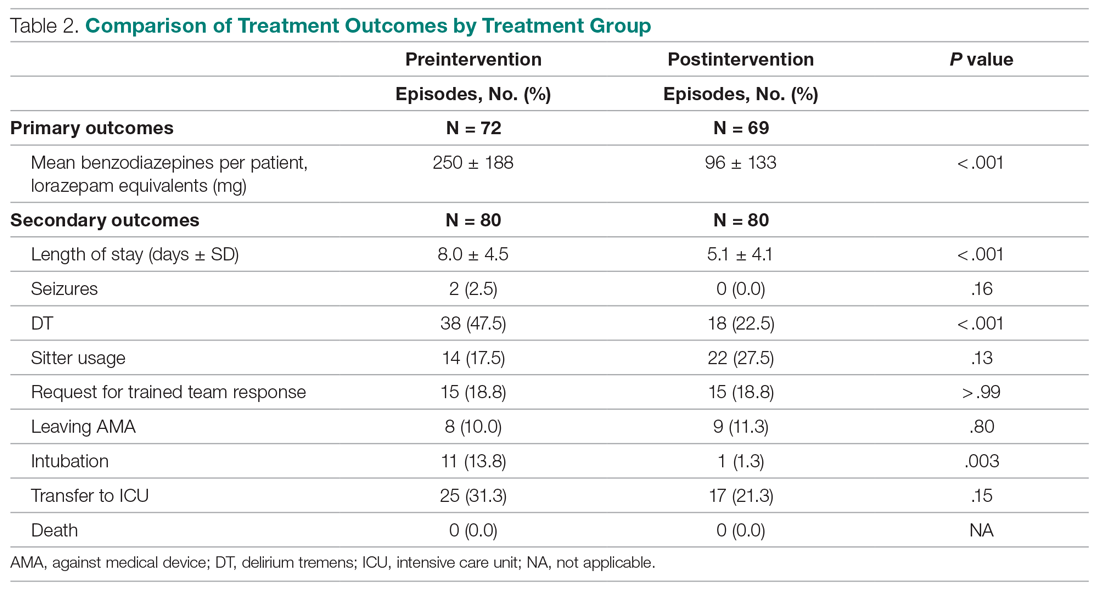

Previous studies have shown that pharmacist visits are conducted in shorter intervals than primary care physician visits to provide closer follow-up and to resolve any medication-related problems that may hinder therapeutic outcome improvements.3-4,7-9 Increasing access via pharmacists is particularly important in this clinic, where resident physician continuity and access is challenging. The pharmacist-driven program described in this study does not deviate from the norm, and this study confirms that pharmacist care, regardless of gaps in pharmacist visits, may still be beneficial.