User login

FDA moves to ban menthol in cigarettes

The Food and Drug Administration said that within a year it will ban menthol in cigarettes and ban all flavors including menthol in cigars.

Menthol makes it easier to start smoking, and also enhances the effects of nicotine, making it more addictive and harder to quit, the FDA said in announcing its actions on Thursday.

Nineteen organizations – including the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Cancer Society, American College of Chest Physicians, American Medical Association, American Heart Association, and the National Medical Association – have pushed the FDA to ban menthol for years. The agency banned all flavors in cigarettes in 2009 but did not take any action against menthol. In 2013, the groups filed a petition demanding that the FDA ban menthol, too. The agency responded months later with a notice that it would start the process.

But it never took any action. Action on Smoking and Health and the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council, later joined by the AMA and the NMA, sued in 2020 to compel the agency to do something. Now it has finally agreed to act.

The African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council welcomed the move but said the fight is not over and encouraged tobacco control activists to fight to ban menthol tobacco products at the local, state and federal level. “We know that this rule-making process could take years and we know that the tobacco industry will continue to do everything in their power to derail any attempt to remove their deadly products from the market,” Phillip Gardiner, MD, council cochair, said in a statement.

The AMA is urging the FDA to quickly implement the ban and remove the products “without further delay,” AMA President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a statement.

“FDA’s long-awaited decision to take action to eliminate menthol flavoring in cigarettes and all flavors in cigars ends a decades-long deference to the tobacco industry, which has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to profit from products that result in death,” Lisa Lacasse, president of the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, said in her own statement.

Ms. Lacasse said banning menthol will help eliminate health disparities. She said 86% of Black people who smoke use menthol cigarettes, compared with 46% of Hispanic people who smoke, 39% of Asian people who smoke, and 29% of White people who smoke. “FDA’s actions today send a clear message that Big Tobacco’s strategy to profit off addicting Black communities will no longer be tolerated,” she said.

Not all groups are on board, however. The American Civil Liberties Union and several other organizations wrote to the country’s top health officials urging them to reconsider.

“Such a ban will trigger criminal penalties which will disproportionately impact people of color, as well as prioritize criminalization over public health and harm reduction,” the letter says. “A ban will also lead to unconstitutional policing and other negative interactions with local law enforcement.”

The letter calls the proposed ban “well intentioned,” but said any effort to reduce death and disease from tobacco “must avoid solutions that will create yet another reason for armed police to engage citizens on the street based on pretext or conduct that does not pose a threat to public safety.”

Instead of a ban, the organizations said, policy makers should consider increased education for adults and minors, stop-smoking programs, and increased funding for health centers in communities of color.

The Biden administration, however, pressed the point that banning menthol will bring many positives. Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD said in a statement that banning menthol “will help significantly reduce youth initiation, increase the chances of smoking cessation among current smokers, and address health disparities experienced by communities of color, low-income populations, and LGBTQ-plus individuals, all of whom are far more likely to use these tobacco products.”

The FDA cited data showing that, in the first year or so after a ban goes into effect, an additional 923,000 smokers would quit, including 230,000 African Americans. Another study suggests that 633,000 deaths would be averted, including 237,000 Black Americans.

Dr. Woodcock added that, “armed with strong scientific evidence, and with full support from the [Biden] administration, we believe these actions will launch us on a trajectory toward ending tobacco-related disease and death in the U.S.”

The FDA estimates that 18.6 million Americans who are current smokers use menthol cigarettes, with a disproportionately high number being Black people. Menthol cigarette use among Black and Hispanic youth increased from 2011 to 2018, but declined for non-Hispanic White youth.

Flavored mass-produced cigars and cigarillos are disproportionately popular among youth, especially non-Hispanic Black high school students, who in 2020 reported past 30-day cigar smoking at levels twice as high as their White counterparts, said the FDA. Three-quarters of 12- to 17-year-olds reported they smoke cigars because they like the flavors. In 2020, more young people tried a cigar every day than tried a cigarette, reports the agency.

“This long-overdue decision will protect future generations of young people from nicotine addiction, especially Black children and communities, which have disproportionately suffered from menthol tobacco use due to targeted efforts from the tobacco industry,” Lee Savio Beers, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said in a statement.

The FDA’s announcement “is only a first step that must be followed with urgent, comprehensive action to remove these flavored products from the market,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Food and Drug Administration said that within a year it will ban menthol in cigarettes and ban all flavors including menthol in cigars.

Menthol makes it easier to start smoking, and also enhances the effects of nicotine, making it more addictive and harder to quit, the FDA said in announcing its actions on Thursday.

Nineteen organizations – including the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Cancer Society, American College of Chest Physicians, American Medical Association, American Heart Association, and the National Medical Association – have pushed the FDA to ban menthol for years. The agency banned all flavors in cigarettes in 2009 but did not take any action against menthol. In 2013, the groups filed a petition demanding that the FDA ban menthol, too. The agency responded months later with a notice that it would start the process.

But it never took any action. Action on Smoking and Health and the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council, later joined by the AMA and the NMA, sued in 2020 to compel the agency to do something. Now it has finally agreed to act.

The African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council welcomed the move but said the fight is not over and encouraged tobacco control activists to fight to ban menthol tobacco products at the local, state and federal level. “We know that this rule-making process could take years and we know that the tobacco industry will continue to do everything in their power to derail any attempt to remove their deadly products from the market,” Phillip Gardiner, MD, council cochair, said in a statement.

The AMA is urging the FDA to quickly implement the ban and remove the products “without further delay,” AMA President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a statement.

“FDA’s long-awaited decision to take action to eliminate menthol flavoring in cigarettes and all flavors in cigars ends a decades-long deference to the tobacco industry, which has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to profit from products that result in death,” Lisa Lacasse, president of the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, said in her own statement.

Ms. Lacasse said banning menthol will help eliminate health disparities. She said 86% of Black people who smoke use menthol cigarettes, compared with 46% of Hispanic people who smoke, 39% of Asian people who smoke, and 29% of White people who smoke. “FDA’s actions today send a clear message that Big Tobacco’s strategy to profit off addicting Black communities will no longer be tolerated,” she said.

Not all groups are on board, however. The American Civil Liberties Union and several other organizations wrote to the country’s top health officials urging them to reconsider.

“Such a ban will trigger criminal penalties which will disproportionately impact people of color, as well as prioritize criminalization over public health and harm reduction,” the letter says. “A ban will also lead to unconstitutional policing and other negative interactions with local law enforcement.”

The letter calls the proposed ban “well intentioned,” but said any effort to reduce death and disease from tobacco “must avoid solutions that will create yet another reason for armed police to engage citizens on the street based on pretext or conduct that does not pose a threat to public safety.”

Instead of a ban, the organizations said, policy makers should consider increased education for adults and minors, stop-smoking programs, and increased funding for health centers in communities of color.

The Biden administration, however, pressed the point that banning menthol will bring many positives. Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD said in a statement that banning menthol “will help significantly reduce youth initiation, increase the chances of smoking cessation among current smokers, and address health disparities experienced by communities of color, low-income populations, and LGBTQ-plus individuals, all of whom are far more likely to use these tobacco products.”

The FDA cited data showing that, in the first year or so after a ban goes into effect, an additional 923,000 smokers would quit, including 230,000 African Americans. Another study suggests that 633,000 deaths would be averted, including 237,000 Black Americans.

Dr. Woodcock added that, “armed with strong scientific evidence, and with full support from the [Biden] administration, we believe these actions will launch us on a trajectory toward ending tobacco-related disease and death in the U.S.”

The FDA estimates that 18.6 million Americans who are current smokers use menthol cigarettes, with a disproportionately high number being Black people. Menthol cigarette use among Black and Hispanic youth increased from 2011 to 2018, but declined for non-Hispanic White youth.

Flavored mass-produced cigars and cigarillos are disproportionately popular among youth, especially non-Hispanic Black high school students, who in 2020 reported past 30-day cigar smoking at levels twice as high as their White counterparts, said the FDA. Three-quarters of 12- to 17-year-olds reported they smoke cigars because they like the flavors. In 2020, more young people tried a cigar every day than tried a cigarette, reports the agency.

“This long-overdue decision will protect future generations of young people from nicotine addiction, especially Black children and communities, which have disproportionately suffered from menthol tobacco use due to targeted efforts from the tobacco industry,” Lee Savio Beers, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said in a statement.

The FDA’s announcement “is only a first step that must be followed with urgent, comprehensive action to remove these flavored products from the market,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Food and Drug Administration said that within a year it will ban menthol in cigarettes and ban all flavors including menthol in cigars.

Menthol makes it easier to start smoking, and also enhances the effects of nicotine, making it more addictive and harder to quit, the FDA said in announcing its actions on Thursday.

Nineteen organizations – including the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Cancer Society, American College of Chest Physicians, American Medical Association, American Heart Association, and the National Medical Association – have pushed the FDA to ban menthol for years. The agency banned all flavors in cigarettes in 2009 but did not take any action against menthol. In 2013, the groups filed a petition demanding that the FDA ban menthol, too. The agency responded months later with a notice that it would start the process.

But it never took any action. Action on Smoking and Health and the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council, later joined by the AMA and the NMA, sued in 2020 to compel the agency to do something. Now it has finally agreed to act.

The African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council welcomed the move but said the fight is not over and encouraged tobacco control activists to fight to ban menthol tobacco products at the local, state and federal level. “We know that this rule-making process could take years and we know that the tobacco industry will continue to do everything in their power to derail any attempt to remove their deadly products from the market,” Phillip Gardiner, MD, council cochair, said in a statement.

The AMA is urging the FDA to quickly implement the ban and remove the products “without further delay,” AMA President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a statement.

“FDA’s long-awaited decision to take action to eliminate menthol flavoring in cigarettes and all flavors in cigars ends a decades-long deference to the tobacco industry, which has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to profit from products that result in death,” Lisa Lacasse, president of the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, said in her own statement.

Ms. Lacasse said banning menthol will help eliminate health disparities. She said 86% of Black people who smoke use menthol cigarettes, compared with 46% of Hispanic people who smoke, 39% of Asian people who smoke, and 29% of White people who smoke. “FDA’s actions today send a clear message that Big Tobacco’s strategy to profit off addicting Black communities will no longer be tolerated,” she said.

Not all groups are on board, however. The American Civil Liberties Union and several other organizations wrote to the country’s top health officials urging them to reconsider.

“Such a ban will trigger criminal penalties which will disproportionately impact people of color, as well as prioritize criminalization over public health and harm reduction,” the letter says. “A ban will also lead to unconstitutional policing and other negative interactions with local law enforcement.”

The letter calls the proposed ban “well intentioned,” but said any effort to reduce death and disease from tobacco “must avoid solutions that will create yet another reason for armed police to engage citizens on the street based on pretext or conduct that does not pose a threat to public safety.”

Instead of a ban, the organizations said, policy makers should consider increased education for adults and minors, stop-smoking programs, and increased funding for health centers in communities of color.

The Biden administration, however, pressed the point that banning menthol will bring many positives. Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD said in a statement that banning menthol “will help significantly reduce youth initiation, increase the chances of smoking cessation among current smokers, and address health disparities experienced by communities of color, low-income populations, and LGBTQ-plus individuals, all of whom are far more likely to use these tobacco products.”

The FDA cited data showing that, in the first year or so after a ban goes into effect, an additional 923,000 smokers would quit, including 230,000 African Americans. Another study suggests that 633,000 deaths would be averted, including 237,000 Black Americans.

Dr. Woodcock added that, “armed with strong scientific evidence, and with full support from the [Biden] administration, we believe these actions will launch us on a trajectory toward ending tobacco-related disease and death in the U.S.”

The FDA estimates that 18.6 million Americans who are current smokers use menthol cigarettes, with a disproportionately high number being Black people. Menthol cigarette use among Black and Hispanic youth increased from 2011 to 2018, but declined for non-Hispanic White youth.

Flavored mass-produced cigars and cigarillos are disproportionately popular among youth, especially non-Hispanic Black high school students, who in 2020 reported past 30-day cigar smoking at levels twice as high as their White counterparts, said the FDA. Three-quarters of 12- to 17-year-olds reported they smoke cigars because they like the flavors. In 2020, more young people tried a cigar every day than tried a cigarette, reports the agency.

“This long-overdue decision will protect future generations of young people from nicotine addiction, especially Black children and communities, which have disproportionately suffered from menthol tobacco use due to targeted efforts from the tobacco industry,” Lee Savio Beers, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said in a statement.

The FDA’s announcement “is only a first step that must be followed with urgent, comprehensive action to remove these flavored products from the market,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

CDC guidelines coming on long COVID

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is finalizing new guidelines to help clinicians diagnose and manage long COVID, or postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In a day-long congressional hearing on April 28, John Brooks, MD, a medical epidemiologist at the CDC’s division of HIV/AIDS prevention, testified that the guidelines were going through the clearance process at the agency, but would be forthcoming.

“They should be coming out very shortly,” Dr. Brooks said.

The guidelines, which were developed in collaboration with newly established long-COVID clinics and patient advocacy groups, will “illustrate how to diagnose and begin to pull together what we know about management,” of the complex condition, he said.

For many doctors and patients who are struggling to understand symptoms that persist for months after the initial viral infection, the guidelines can’t come soon enough.

National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, who also testified at the hearing, estimated that as many as 3 million people could be left with chronic health problems after even mild COVID infections.

“I can’t overstate how serious this issue is for the health of our nation,” he said.

Dr. Collins said his estimate was based on studies showing that roughly 10% of people who get COVID could be affected by this and whose “long-term course is uncertain,” he said. So far, more than 32 million Americans are known to have been infected with the new coronavirus.

“We need to make sure we put our arms around them and bring answers and care to them,” said Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.), chairwoman of the Subcommittee on Health.

Jennifer Possick, MD, who directs the post-COVID recovery program at Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital, testified that the tidal wave of patients she and her colleagues were seeing was overwhelming.

“We are a well-resourced program at an academic medical center, but we are swamped by the need in our community. This year, we have seen more patients with post COVID-19 conditions in our clinic alone than we have new cases of asthma and COPD combined,” she said. “The magnitude of the challenge is daunting.”

Dr. Possick estimated that there are “over 60” clinics in the United States that have started to treat long-COVID patients, but said they are grassroots efforts and all very different from each other.

“Whoever had the resources, had the time, [and] was able to take the initiative and forge to the relationships because most of them are multidisciplinary, did so,” she said.

Patients testify

Several representatives shared moving personal stories of loved ones or staffers who remained ill months after a COVID diagnosis.

Rep. Ann Kuster, from New Hampshire, talked about her 34-year-old niece, a member of the U.S. Ski Team, who had COVID just over a year ago and “continues to struggle with everything, even the simplest activities of daily living” she said. “She has to choose between taking a shower or making dinner. I’m so proud of her for hanging in there.”

Long-COVID patients invited to testify by the subcommittee described months of disability that left them with soaring medical bills and no ability to work to pay them.

“I am now a poor, Black, disabled woman, living with long COVID,” said Chimere Smith, who said she had been a school teacher in Baltimore. “Saying it aloud makes it no more easy to accept.”

She said COVID had affected her ability to think clearly and caused debilitating fatigue, which prevented her from working. She said she lost her vision for almost 5 months because doctors misdiagnosed a cataract caused by long COVID as dry eye.

“If I did not have a loving family, I [would] be speaking to you today [from] my car, the only property I now own.”

Ms. Smith said that long-COVID clinics, which are mostly housed within academic medical centers, were not going to be accessible for all long-haulers, who are disproportionately women of color. She has started a clinic, based out of her church, to help other patients from her community.

“No one wants to hear that long COVID has decimated my life or the lives of other black women in less than a year,” Ms. Smith said. “We’ve just been waiting and hoping for compassionate doctors and politicians who would acknowledge us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is finalizing new guidelines to help clinicians diagnose and manage long COVID, or postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In a day-long congressional hearing on April 28, John Brooks, MD, a medical epidemiologist at the CDC’s division of HIV/AIDS prevention, testified that the guidelines were going through the clearance process at the agency, but would be forthcoming.

“They should be coming out very shortly,” Dr. Brooks said.

The guidelines, which were developed in collaboration with newly established long-COVID clinics and patient advocacy groups, will “illustrate how to diagnose and begin to pull together what we know about management,” of the complex condition, he said.

For many doctors and patients who are struggling to understand symptoms that persist for months after the initial viral infection, the guidelines can’t come soon enough.

National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, who also testified at the hearing, estimated that as many as 3 million people could be left with chronic health problems after even mild COVID infections.

“I can’t overstate how serious this issue is for the health of our nation,” he said.

Dr. Collins said his estimate was based on studies showing that roughly 10% of people who get COVID could be affected by this and whose “long-term course is uncertain,” he said. So far, more than 32 million Americans are known to have been infected with the new coronavirus.

“We need to make sure we put our arms around them and bring answers and care to them,” said Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.), chairwoman of the Subcommittee on Health.

Jennifer Possick, MD, who directs the post-COVID recovery program at Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital, testified that the tidal wave of patients she and her colleagues were seeing was overwhelming.

“We are a well-resourced program at an academic medical center, but we are swamped by the need in our community. This year, we have seen more patients with post COVID-19 conditions in our clinic alone than we have new cases of asthma and COPD combined,” she said. “The magnitude of the challenge is daunting.”

Dr. Possick estimated that there are “over 60” clinics in the United States that have started to treat long-COVID patients, but said they are grassroots efforts and all very different from each other.

“Whoever had the resources, had the time, [and] was able to take the initiative and forge to the relationships because most of them are multidisciplinary, did so,” she said.

Patients testify

Several representatives shared moving personal stories of loved ones or staffers who remained ill months after a COVID diagnosis.

Rep. Ann Kuster, from New Hampshire, talked about her 34-year-old niece, a member of the U.S. Ski Team, who had COVID just over a year ago and “continues to struggle with everything, even the simplest activities of daily living” she said. “She has to choose between taking a shower or making dinner. I’m so proud of her for hanging in there.”

Long-COVID patients invited to testify by the subcommittee described months of disability that left them with soaring medical bills and no ability to work to pay them.

“I am now a poor, Black, disabled woman, living with long COVID,” said Chimere Smith, who said she had been a school teacher in Baltimore. “Saying it aloud makes it no more easy to accept.”

She said COVID had affected her ability to think clearly and caused debilitating fatigue, which prevented her from working. She said she lost her vision for almost 5 months because doctors misdiagnosed a cataract caused by long COVID as dry eye.

“If I did not have a loving family, I [would] be speaking to you today [from] my car, the only property I now own.”

Ms. Smith said that long-COVID clinics, which are mostly housed within academic medical centers, were not going to be accessible for all long-haulers, who are disproportionately women of color. She has started a clinic, based out of her church, to help other patients from her community.

“No one wants to hear that long COVID has decimated my life or the lives of other black women in less than a year,” Ms. Smith said. “We’ve just been waiting and hoping for compassionate doctors and politicians who would acknowledge us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is finalizing new guidelines to help clinicians diagnose and manage long COVID, or postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In a day-long congressional hearing on April 28, John Brooks, MD, a medical epidemiologist at the CDC’s division of HIV/AIDS prevention, testified that the guidelines were going through the clearance process at the agency, but would be forthcoming.

“They should be coming out very shortly,” Dr. Brooks said.

The guidelines, which were developed in collaboration with newly established long-COVID clinics and patient advocacy groups, will “illustrate how to diagnose and begin to pull together what we know about management,” of the complex condition, he said.

For many doctors and patients who are struggling to understand symptoms that persist for months after the initial viral infection, the guidelines can’t come soon enough.

National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, who also testified at the hearing, estimated that as many as 3 million people could be left with chronic health problems after even mild COVID infections.

“I can’t overstate how serious this issue is for the health of our nation,” he said.

Dr. Collins said his estimate was based on studies showing that roughly 10% of people who get COVID could be affected by this and whose “long-term course is uncertain,” he said. So far, more than 32 million Americans are known to have been infected with the new coronavirus.

“We need to make sure we put our arms around them and bring answers and care to them,” said Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.), chairwoman of the Subcommittee on Health.

Jennifer Possick, MD, who directs the post-COVID recovery program at Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital, testified that the tidal wave of patients she and her colleagues were seeing was overwhelming.

“We are a well-resourced program at an academic medical center, but we are swamped by the need in our community. This year, we have seen more patients with post COVID-19 conditions in our clinic alone than we have new cases of asthma and COPD combined,” she said. “The magnitude of the challenge is daunting.”

Dr. Possick estimated that there are “over 60” clinics in the United States that have started to treat long-COVID patients, but said they are grassroots efforts and all very different from each other.

“Whoever had the resources, had the time, [and] was able to take the initiative and forge to the relationships because most of them are multidisciplinary, did so,” she said.

Patients testify

Several representatives shared moving personal stories of loved ones or staffers who remained ill months after a COVID diagnosis.

Rep. Ann Kuster, from New Hampshire, talked about her 34-year-old niece, a member of the U.S. Ski Team, who had COVID just over a year ago and “continues to struggle with everything, even the simplest activities of daily living” she said. “She has to choose between taking a shower or making dinner. I’m so proud of her for hanging in there.”

Long-COVID patients invited to testify by the subcommittee described months of disability that left them with soaring medical bills and no ability to work to pay them.

“I am now a poor, Black, disabled woman, living with long COVID,” said Chimere Smith, who said she had been a school teacher in Baltimore. “Saying it aloud makes it no more easy to accept.”

She said COVID had affected her ability to think clearly and caused debilitating fatigue, which prevented her from working. She said she lost her vision for almost 5 months because doctors misdiagnosed a cataract caused by long COVID as dry eye.

“If I did not have a loving family, I [would] be speaking to you today [from] my car, the only property I now own.”

Ms. Smith said that long-COVID clinics, which are mostly housed within academic medical centers, were not going to be accessible for all long-haulers, who are disproportionately women of color. She has started a clinic, based out of her church, to help other patients from her community.

“No one wants to hear that long COVID has decimated my life or the lives of other black women in less than a year,” Ms. Smith said. “We’ve just been waiting and hoping for compassionate doctors and politicians who would acknowledge us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Feds lift pause of J&J COVID vaccine, add new warning

Use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine should resume in the United States for all adults, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention said April 23, although health care providers should warn patients of the risk of developing the rare and serious blood clots that caused the agencies to pause the vaccine’s distribution earlier this month.

“What we are seeing is the overall rate of events was 1.9 cases per million people. In women 18 to 29 years there was an approximate 7 cases per million. The risk is even lower in women over the age of 50 at .9 cases per million,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a news briefing the same day.

In the end, the potential benefits of the vaccine far outweighed its risks.

“In terms of benefits, we found that for every 1 million doses of this vaccine, the J&J vaccine could prevent over 650 hospitalizations and 12 deaths among women ages 18-49,” Dr. Walensky said. The potential benefits to women over 50 were even greater: It could prevent 4,700 hospitalizations and 650 deaths.

“In the end, this vaccine was shown to be safe and effective for the vast majority of people,” Dr. Walensky said.

The recommendation to continue the vaccine’s rollout came barely 2 hours after a CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to recommend the pause be lifted. The vote was 10-4 with one abstention.

The decision also includes instructions for the warning directed at women under 50 who have an increased risk of a rare but serious blood clot disorder called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS).

As of April 21, 15 cases of TTS, all in women and 13 of them in women under 50, have been confirmed among 7.98 million doses of the J&J vaccine administered in the United States. Three women have died.

The FDA and CDC recommended the pause on April 13 after reports that 6 women developed a blood clotting disorder 6 to 13 days after they received the J&J vaccine.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and a non-voting ACIP member, said in an interview the panel made the right recommendation.

He applauded both the decision to restart the vaccine and the updated warning information that “will explain [TTS] more fully to people, particularly women, who are coming to be vaccinated.”

As to women in the risk group needing to have a choice of vaccines, Dr. Schaffner said that will be addressed differently across the country.

“Every provider will not have alternative vaccines in their location so there will be many different ways to do this. You may have to get this information and select which site you’re going to depending on which vaccine is available if this matter is important to you,” he noted.

ACIP made the decision after a 6-hour emergency meeting to hear evidence on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine's protective benefits against COVID-19 vs. risk of TTS.

In the CDC-FDA press briefing, Dr. Walensky pointed out that over the past few days, as regulators have reviewed the rare events, newly identified patients had been treated appropriately, without the use of heparin, which is not advised for treating TTS.

As a result, regulators felt as if their messages had gotten out to doctors who now knew how to take special precautions when treating patients with the disorder.

She said the Johnson & Johnson shot remained an important option because it was convenient to give and easier to store than the other vaccines currently authorized in the United States.

Peter Marks, MD, the director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said the agency had already added information describing the risk of the rare clotting disorder to its fact sheets for patients and doctors.

Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the FDA, said vaccination centers could resume giving the “one and done” shots as early as April 24.

This article was updated April 24, 2021, and first appeared on WebMD.com.

Use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine should resume in the United States for all adults, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention said April 23, although health care providers should warn patients of the risk of developing the rare and serious blood clots that caused the agencies to pause the vaccine’s distribution earlier this month.

“What we are seeing is the overall rate of events was 1.9 cases per million people. In women 18 to 29 years there was an approximate 7 cases per million. The risk is even lower in women over the age of 50 at .9 cases per million,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a news briefing the same day.

In the end, the potential benefits of the vaccine far outweighed its risks.

“In terms of benefits, we found that for every 1 million doses of this vaccine, the J&J vaccine could prevent over 650 hospitalizations and 12 deaths among women ages 18-49,” Dr. Walensky said. The potential benefits to women over 50 were even greater: It could prevent 4,700 hospitalizations and 650 deaths.

“In the end, this vaccine was shown to be safe and effective for the vast majority of people,” Dr. Walensky said.

The recommendation to continue the vaccine’s rollout came barely 2 hours after a CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to recommend the pause be lifted. The vote was 10-4 with one abstention.

The decision also includes instructions for the warning directed at women under 50 who have an increased risk of a rare but serious blood clot disorder called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS).

As of April 21, 15 cases of TTS, all in women and 13 of them in women under 50, have been confirmed among 7.98 million doses of the J&J vaccine administered in the United States. Three women have died.

The FDA and CDC recommended the pause on April 13 after reports that 6 women developed a blood clotting disorder 6 to 13 days after they received the J&J vaccine.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and a non-voting ACIP member, said in an interview the panel made the right recommendation.

He applauded both the decision to restart the vaccine and the updated warning information that “will explain [TTS] more fully to people, particularly women, who are coming to be vaccinated.”

As to women in the risk group needing to have a choice of vaccines, Dr. Schaffner said that will be addressed differently across the country.

“Every provider will not have alternative vaccines in their location so there will be many different ways to do this. You may have to get this information and select which site you’re going to depending on which vaccine is available if this matter is important to you,” he noted.

ACIP made the decision after a 6-hour emergency meeting to hear evidence on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine's protective benefits against COVID-19 vs. risk of TTS.

In the CDC-FDA press briefing, Dr. Walensky pointed out that over the past few days, as regulators have reviewed the rare events, newly identified patients had been treated appropriately, without the use of heparin, which is not advised for treating TTS.

As a result, regulators felt as if their messages had gotten out to doctors who now knew how to take special precautions when treating patients with the disorder.

She said the Johnson & Johnson shot remained an important option because it was convenient to give and easier to store than the other vaccines currently authorized in the United States.

Peter Marks, MD, the director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said the agency had already added information describing the risk of the rare clotting disorder to its fact sheets for patients and doctors.

Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the FDA, said vaccination centers could resume giving the “one and done” shots as early as April 24.

This article was updated April 24, 2021, and first appeared on WebMD.com.

Use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine should resume in the United States for all adults, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention said April 23, although health care providers should warn patients of the risk of developing the rare and serious blood clots that caused the agencies to pause the vaccine’s distribution earlier this month.

“What we are seeing is the overall rate of events was 1.9 cases per million people. In women 18 to 29 years there was an approximate 7 cases per million. The risk is even lower in women over the age of 50 at .9 cases per million,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a news briefing the same day.

In the end, the potential benefits of the vaccine far outweighed its risks.

“In terms of benefits, we found that for every 1 million doses of this vaccine, the J&J vaccine could prevent over 650 hospitalizations and 12 deaths among women ages 18-49,” Dr. Walensky said. The potential benefits to women over 50 were even greater: It could prevent 4,700 hospitalizations and 650 deaths.

“In the end, this vaccine was shown to be safe and effective for the vast majority of people,” Dr. Walensky said.

The recommendation to continue the vaccine’s rollout came barely 2 hours after a CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to recommend the pause be lifted. The vote was 10-4 with one abstention.

The decision also includes instructions for the warning directed at women under 50 who have an increased risk of a rare but serious blood clot disorder called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS).

As of April 21, 15 cases of TTS, all in women and 13 of them in women under 50, have been confirmed among 7.98 million doses of the J&J vaccine administered in the United States. Three women have died.

The FDA and CDC recommended the pause on April 13 after reports that 6 women developed a blood clotting disorder 6 to 13 days after they received the J&J vaccine.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and a non-voting ACIP member, said in an interview the panel made the right recommendation.

He applauded both the decision to restart the vaccine and the updated warning information that “will explain [TTS] more fully to people, particularly women, who are coming to be vaccinated.”

As to women in the risk group needing to have a choice of vaccines, Dr. Schaffner said that will be addressed differently across the country.

“Every provider will not have alternative vaccines in their location so there will be many different ways to do this. You may have to get this information and select which site you’re going to depending on which vaccine is available if this matter is important to you,” he noted.

ACIP made the decision after a 6-hour emergency meeting to hear evidence on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine's protective benefits against COVID-19 vs. risk of TTS.

In the CDC-FDA press briefing, Dr. Walensky pointed out that over the past few days, as regulators have reviewed the rare events, newly identified patients had been treated appropriately, without the use of heparin, which is not advised for treating TTS.

As a result, regulators felt as if their messages had gotten out to doctors who now knew how to take special precautions when treating patients with the disorder.

She said the Johnson & Johnson shot remained an important option because it was convenient to give and easier to store than the other vaccines currently authorized in the United States.

Peter Marks, MD, the director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said the agency had already added information describing the risk of the rare clotting disorder to its fact sheets for patients and doctors.

Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the FDA, said vaccination centers could resume giving the “one and done” shots as early as April 24.

This article was updated April 24, 2021, and first appeared on WebMD.com.

HHS proposes overturning Title X ‘gag’ rule

The Department of Health & Human Services has proposed overturning rules issued during the Trump administration that effectively prohibit clinicians at Title X–funded health clinics from discussing abortion or referring patients for abortions.

HHS proposed the overhaul of the Title X regulations on April 14. The previous administration’s 2019 rules “have undermined the public health of the population the program is meant to serve,” HHS said in the introduction to its proposal.

Medical organizations and reproductive health specialists lauded the move.

“Clinicians providing care to patients must be empowered to share the full spectrum of accurate medical information necessary to ensure that their patients are able to make timely, fully informed medical decisions,” Maureen G. Phipps, MD, MPH, CEO of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said in a statement. “This means transparent, respectful, evidence-based conversations about contraception and abortion care. The proposed rule will ensure that those conversations can once again happen without restrictions, interference, or threat of financial loss.”

“Providers of comprehensive reproductive health care, including abortion care, base their relationships with their patients on trust,” Physicians for Reproductive Health President and CEO Jamila Perritt, MD, said in a statement. “The Title X gag rule went against everything we knew as providers of ethical, evidence-based health care by forcing providers at Title X funded clinics to withhold information that their patients needed and requested.”

HHS said that, since 2019, more than 1,000 Title X–funded service sites (25% of the total) have withdrawn from the program. Currently, Title X services – which include family planning, STI testing, cancer screening, and HIV testing and treatment – are not available in six states and are only available on a limited basis in six additional states. Planned Parenthood fully withdrew from Title X.

HHS said that tens of thousands fewer birth control implant procedures have been performed and that hundreds of thousands fewer Pap tests and a half-million or more fewer tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea have been conducted. In addition, the reduction in services may have led to up to 181,477 unintended pregnancies, HHS said.

The closure of sites and decreased availability of services have also exacerbated health inequities, according to the department.

The loss of services “has been especially felt by those already facing disproportionate barriers to accessing care, including the Black, Latinx and Indigenous communities that have also suffered the most harm during the COVID-19 pandemic,” agreed Dr. Phipps.

The new regulation proposes to “ensure access to equitable, affordable, client-centered, quality family-planning services for all clients, especially for low-income clients,” HHS said.

The proposed change in the rules “brings us one step closer to restoring access to necessary care for millions of low-income and uninsured patients who depend on Title X for family planning services,” American Medical Association President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a statement. “We are pleased that the Biden administration shares our commitment to undoing this dangerous and discriminatory ‘gag rule,’ and look forward to its elimination through any means necessary to achieve the best outcome for patients and physicians – improving the health of our nation.”

Planned Parenthood also applauded the move, and the HIV Medicine Association thanked the Biden administration for its proposal, which it called “a major step to improve #HealthEquity for all people in this country,” in a tweet.

March for Life, an antiabortion group, however, said it strongly opposed the HHS proposal. The rules “appear specifically designed to bring America’s largest abortion provider, Planned Parenthood, back into the taxpayer-funded program and keep prolife organizations out,” said the group in a tweet.

“Abortion is neither health care nor family planning, and the Title X program should not be funding it,” said the group.

The Title X program does not pay for abortions, however.

The Trump administration rules prohibit abortion referrals and impose counseling standards for pregnant patients and what the Guttmacher Institute called “unnecessary and stringent requirements for the physical and financial separation of Title X–funded activities from a range of abortion-related activities.”

The new rules would reestablish regulations from 2000, with some new additions. For instance, the program will “formally integrate elements of quality family-planning services guidelines developed by [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and Office of Population Affairs,” tweeted Alina Salganicoff, director of women’s health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “That means that higher standards for providing family planning will be required,” she tweeted. In addition, sites that offer natural family planning and abstinence “will only be able to participate if they offer referrals to other providers that offer clients access to the contraceptive of their choice.”

The proposed rules are open for public comment for 30 days. They could be made final by the fall. The Kaiser Family Foundation reports that many sites could be ready to return to the program by then, especially since the recently passed coronavirus relief package, the American Rescue Plan, included a $50 million supplemental appropriation for Title X.

The 2019 rules remain in effect in the meantime, although the U.S. Supreme Court agreed in February to hear a challenge mounted by 21 states, the city of Baltimore, and organizations that included the AMA and Planned Parenthood. Those plaintiffs have requested that the case be dismissed, but it currently remains on the docket.

Not all medical providers are likely to support the new rules if they go into effect. The American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Christian Medical and Dental Associations, and the Catholic Medical Association filed motions in the Supreme Court case to defend the Trump regulations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Department of Health & Human Services has proposed overturning rules issued during the Trump administration that effectively prohibit clinicians at Title X–funded health clinics from discussing abortion or referring patients for abortions.

HHS proposed the overhaul of the Title X regulations on April 14. The previous administration’s 2019 rules “have undermined the public health of the population the program is meant to serve,” HHS said in the introduction to its proposal.

Medical organizations and reproductive health specialists lauded the move.

“Clinicians providing care to patients must be empowered to share the full spectrum of accurate medical information necessary to ensure that their patients are able to make timely, fully informed medical decisions,” Maureen G. Phipps, MD, MPH, CEO of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said in a statement. “This means transparent, respectful, evidence-based conversations about contraception and abortion care. The proposed rule will ensure that those conversations can once again happen without restrictions, interference, or threat of financial loss.”

“Providers of comprehensive reproductive health care, including abortion care, base their relationships with their patients on trust,” Physicians for Reproductive Health President and CEO Jamila Perritt, MD, said in a statement. “The Title X gag rule went against everything we knew as providers of ethical, evidence-based health care by forcing providers at Title X funded clinics to withhold information that their patients needed and requested.”

HHS said that, since 2019, more than 1,000 Title X–funded service sites (25% of the total) have withdrawn from the program. Currently, Title X services – which include family planning, STI testing, cancer screening, and HIV testing and treatment – are not available in six states and are only available on a limited basis in six additional states. Planned Parenthood fully withdrew from Title X.

HHS said that tens of thousands fewer birth control implant procedures have been performed and that hundreds of thousands fewer Pap tests and a half-million or more fewer tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea have been conducted. In addition, the reduction in services may have led to up to 181,477 unintended pregnancies, HHS said.

The closure of sites and decreased availability of services have also exacerbated health inequities, according to the department.

The loss of services “has been especially felt by those already facing disproportionate barriers to accessing care, including the Black, Latinx and Indigenous communities that have also suffered the most harm during the COVID-19 pandemic,” agreed Dr. Phipps.

The new regulation proposes to “ensure access to equitable, affordable, client-centered, quality family-planning services for all clients, especially for low-income clients,” HHS said.

The proposed change in the rules “brings us one step closer to restoring access to necessary care for millions of low-income and uninsured patients who depend on Title X for family planning services,” American Medical Association President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a statement. “We are pleased that the Biden administration shares our commitment to undoing this dangerous and discriminatory ‘gag rule,’ and look forward to its elimination through any means necessary to achieve the best outcome for patients and physicians – improving the health of our nation.”

Planned Parenthood also applauded the move, and the HIV Medicine Association thanked the Biden administration for its proposal, which it called “a major step to improve #HealthEquity for all people in this country,” in a tweet.

March for Life, an antiabortion group, however, said it strongly opposed the HHS proposal. The rules “appear specifically designed to bring America’s largest abortion provider, Planned Parenthood, back into the taxpayer-funded program and keep prolife organizations out,” said the group in a tweet.

“Abortion is neither health care nor family planning, and the Title X program should not be funding it,” said the group.

The Title X program does not pay for abortions, however.

The Trump administration rules prohibit abortion referrals and impose counseling standards for pregnant patients and what the Guttmacher Institute called “unnecessary and stringent requirements for the physical and financial separation of Title X–funded activities from a range of abortion-related activities.”

The new rules would reestablish regulations from 2000, with some new additions. For instance, the program will “formally integrate elements of quality family-planning services guidelines developed by [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and Office of Population Affairs,” tweeted Alina Salganicoff, director of women’s health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “That means that higher standards for providing family planning will be required,” she tweeted. In addition, sites that offer natural family planning and abstinence “will only be able to participate if they offer referrals to other providers that offer clients access to the contraceptive of their choice.”

The proposed rules are open for public comment for 30 days. They could be made final by the fall. The Kaiser Family Foundation reports that many sites could be ready to return to the program by then, especially since the recently passed coronavirus relief package, the American Rescue Plan, included a $50 million supplemental appropriation for Title X.

The 2019 rules remain in effect in the meantime, although the U.S. Supreme Court agreed in February to hear a challenge mounted by 21 states, the city of Baltimore, and organizations that included the AMA and Planned Parenthood. Those plaintiffs have requested that the case be dismissed, but it currently remains on the docket.

Not all medical providers are likely to support the new rules if they go into effect. The American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Christian Medical and Dental Associations, and the Catholic Medical Association filed motions in the Supreme Court case to defend the Trump regulations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Department of Health & Human Services has proposed overturning rules issued during the Trump administration that effectively prohibit clinicians at Title X–funded health clinics from discussing abortion or referring patients for abortions.

HHS proposed the overhaul of the Title X regulations on April 14. The previous administration’s 2019 rules “have undermined the public health of the population the program is meant to serve,” HHS said in the introduction to its proposal.

Medical organizations and reproductive health specialists lauded the move.

“Clinicians providing care to patients must be empowered to share the full spectrum of accurate medical information necessary to ensure that their patients are able to make timely, fully informed medical decisions,” Maureen G. Phipps, MD, MPH, CEO of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said in a statement. “This means transparent, respectful, evidence-based conversations about contraception and abortion care. The proposed rule will ensure that those conversations can once again happen without restrictions, interference, or threat of financial loss.”

“Providers of comprehensive reproductive health care, including abortion care, base their relationships with their patients on trust,” Physicians for Reproductive Health President and CEO Jamila Perritt, MD, said in a statement. “The Title X gag rule went against everything we knew as providers of ethical, evidence-based health care by forcing providers at Title X funded clinics to withhold information that their patients needed and requested.”

HHS said that, since 2019, more than 1,000 Title X–funded service sites (25% of the total) have withdrawn from the program. Currently, Title X services – which include family planning, STI testing, cancer screening, and HIV testing and treatment – are not available in six states and are only available on a limited basis in six additional states. Planned Parenthood fully withdrew from Title X.

HHS said that tens of thousands fewer birth control implant procedures have been performed and that hundreds of thousands fewer Pap tests and a half-million or more fewer tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea have been conducted. In addition, the reduction in services may have led to up to 181,477 unintended pregnancies, HHS said.

The closure of sites and decreased availability of services have also exacerbated health inequities, according to the department.

The loss of services “has been especially felt by those already facing disproportionate barriers to accessing care, including the Black, Latinx and Indigenous communities that have also suffered the most harm during the COVID-19 pandemic,” agreed Dr. Phipps.

The new regulation proposes to “ensure access to equitable, affordable, client-centered, quality family-planning services for all clients, especially for low-income clients,” HHS said.

The proposed change in the rules “brings us one step closer to restoring access to necessary care for millions of low-income and uninsured patients who depend on Title X for family planning services,” American Medical Association President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a statement. “We are pleased that the Biden administration shares our commitment to undoing this dangerous and discriminatory ‘gag rule,’ and look forward to its elimination through any means necessary to achieve the best outcome for patients and physicians – improving the health of our nation.”

Planned Parenthood also applauded the move, and the HIV Medicine Association thanked the Biden administration for its proposal, which it called “a major step to improve #HealthEquity for all people in this country,” in a tweet.

March for Life, an antiabortion group, however, said it strongly opposed the HHS proposal. The rules “appear specifically designed to bring America’s largest abortion provider, Planned Parenthood, back into the taxpayer-funded program and keep prolife organizations out,” said the group in a tweet.

“Abortion is neither health care nor family planning, and the Title X program should not be funding it,” said the group.

The Title X program does not pay for abortions, however.

The Trump administration rules prohibit abortion referrals and impose counseling standards for pregnant patients and what the Guttmacher Institute called “unnecessary and stringent requirements for the physical and financial separation of Title X–funded activities from a range of abortion-related activities.”

The new rules would reestablish regulations from 2000, with some new additions. For instance, the program will “formally integrate elements of quality family-planning services guidelines developed by [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and Office of Population Affairs,” tweeted Alina Salganicoff, director of women’s health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “That means that higher standards for providing family planning will be required,” she tweeted. In addition, sites that offer natural family planning and abstinence “will only be able to participate if they offer referrals to other providers that offer clients access to the contraceptive of their choice.”

The proposed rules are open for public comment for 30 days. They could be made final by the fall. The Kaiser Family Foundation reports that many sites could be ready to return to the program by then, especially since the recently passed coronavirus relief package, the American Rescue Plan, included a $50 million supplemental appropriation for Title X.

The 2019 rules remain in effect in the meantime, although the U.S. Supreme Court agreed in February to hear a challenge mounted by 21 states, the city of Baltimore, and organizations that included the AMA and Planned Parenthood. Those plaintiffs have requested that the case be dismissed, but it currently remains on the docket.

Not all medical providers are likely to support the new rules if they go into effect. The American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Christian Medical and Dental Associations, and the Catholic Medical Association filed motions in the Supreme Court case to defend the Trump regulations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparison of Dermatologist Ratings on Health Care–Specific and General Consumer Websites

Health care–specific (eg, Healthgrades, Zocdoc, Vitals, WebMD) and general consumer websites (eg, Google, Yelp) are popular platforms for patients to find physicians, schedule appointments, and review physician experiences. Patients find ratings on these websites more trustworthy than standardized surveys distributed by hospitals, but many physicians do not trust the reviews on these sites. For example, in a survey of both physicians (n=828) and patients (n=494), 36% of physicians trusted online reviews compared to 57% of patients.1 The objective of this study was to determine if health care–specific or general consumer websites more accurately reflect overall patient sentiment. This knowledge can help physicians who are seeking to improve the patient experience understand which websites have more accurate and trustworthy reviews.

Methods

A list of dermatologists from the top 10 most and least dermatologist–dense areas in the United States was compiled to examine different physician populations.2 Equal numbers of male and female dermatologists were randomly selected from the most dense areas. All physicians were included from the least dense areas because of limited sample size. Ratings were collected from websites most likely to appear on the first page of a Google search for a physician name, as these are most likely to be seen by patients. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study population; mean and median physician rating (using a scale of 1–5); SD; and minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Spearman correlation coefficients were generated to examine the strength of association between ratings from website pairs. P<.05 was considered statistically significant, with analyses performed in R (3.6.2) for Windows (the R Foundation).

Results

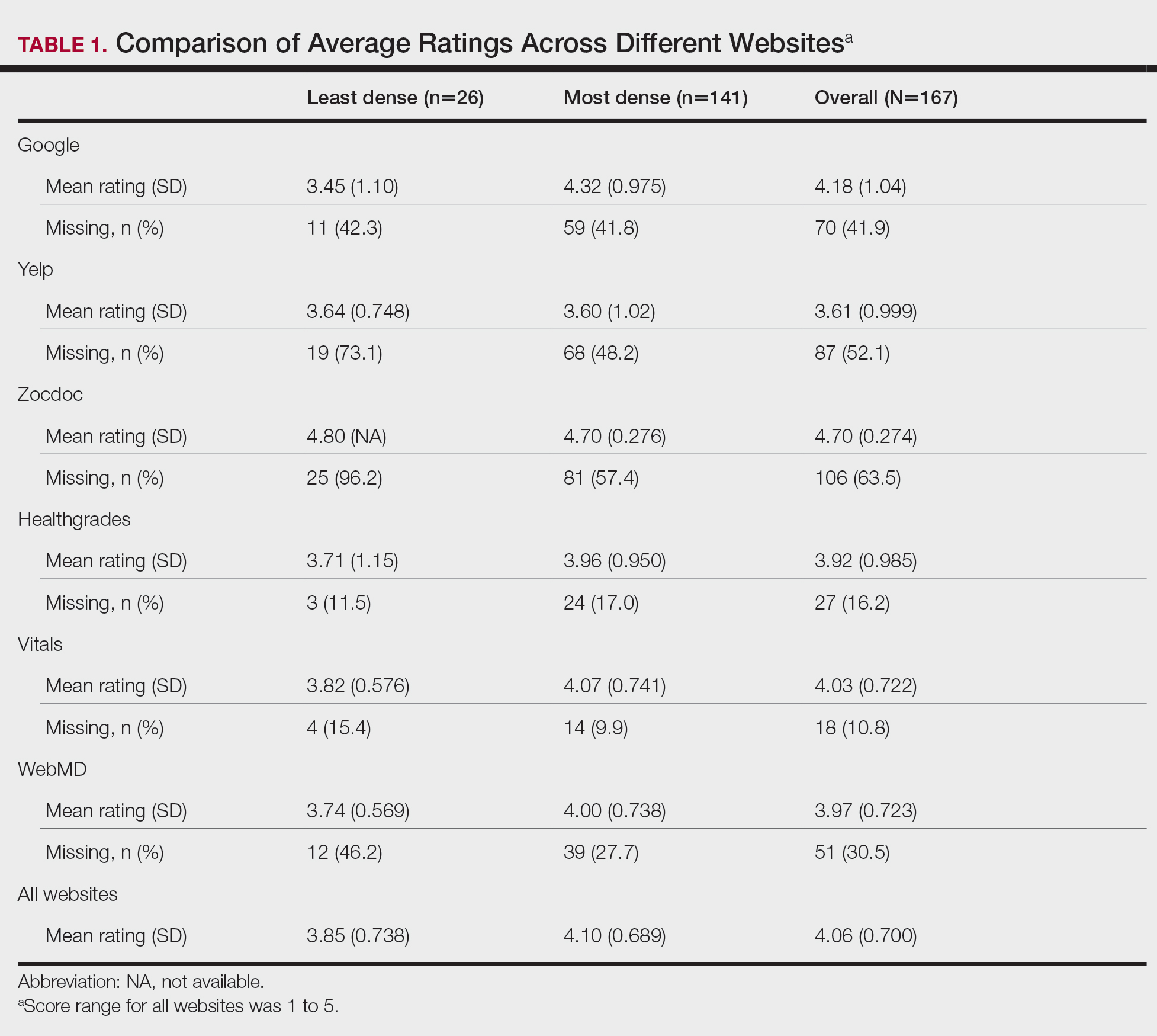

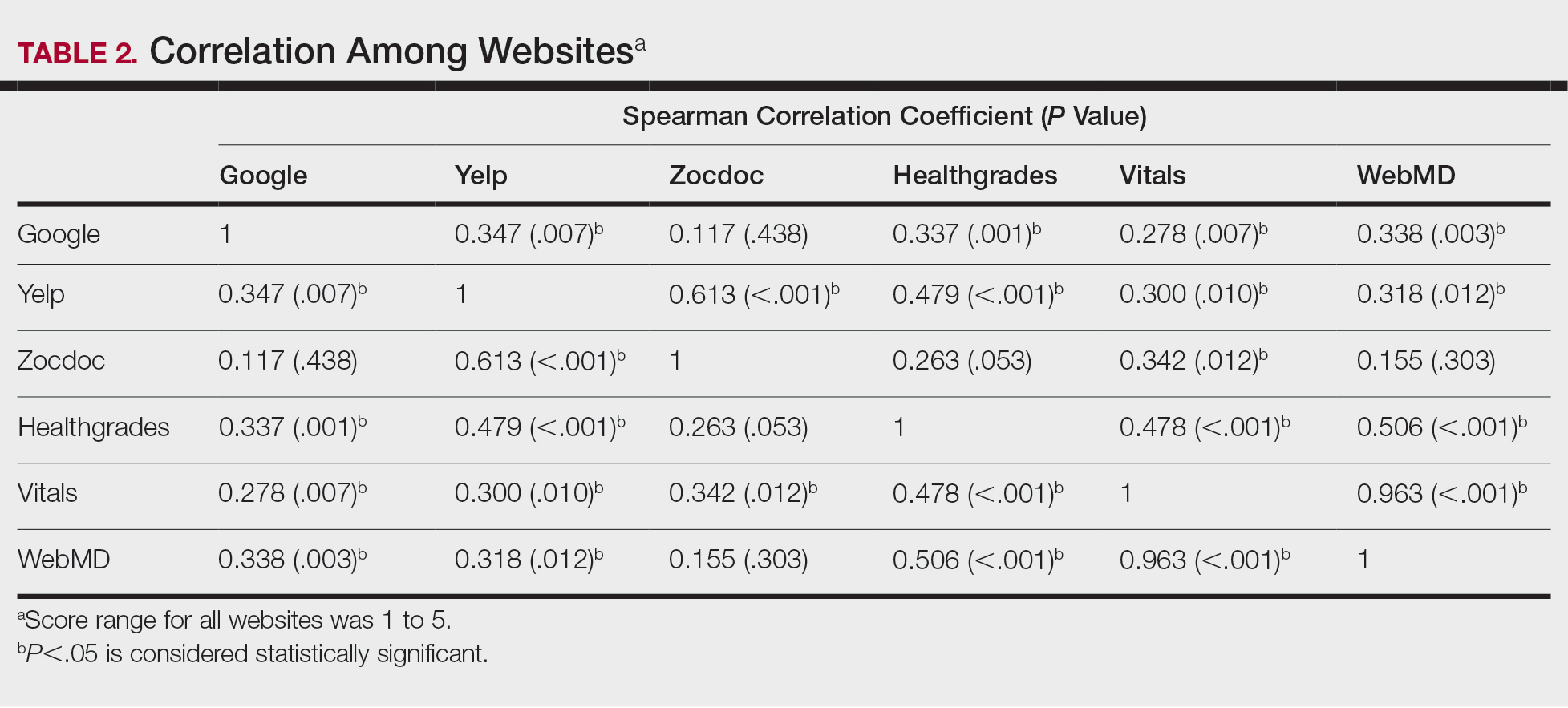

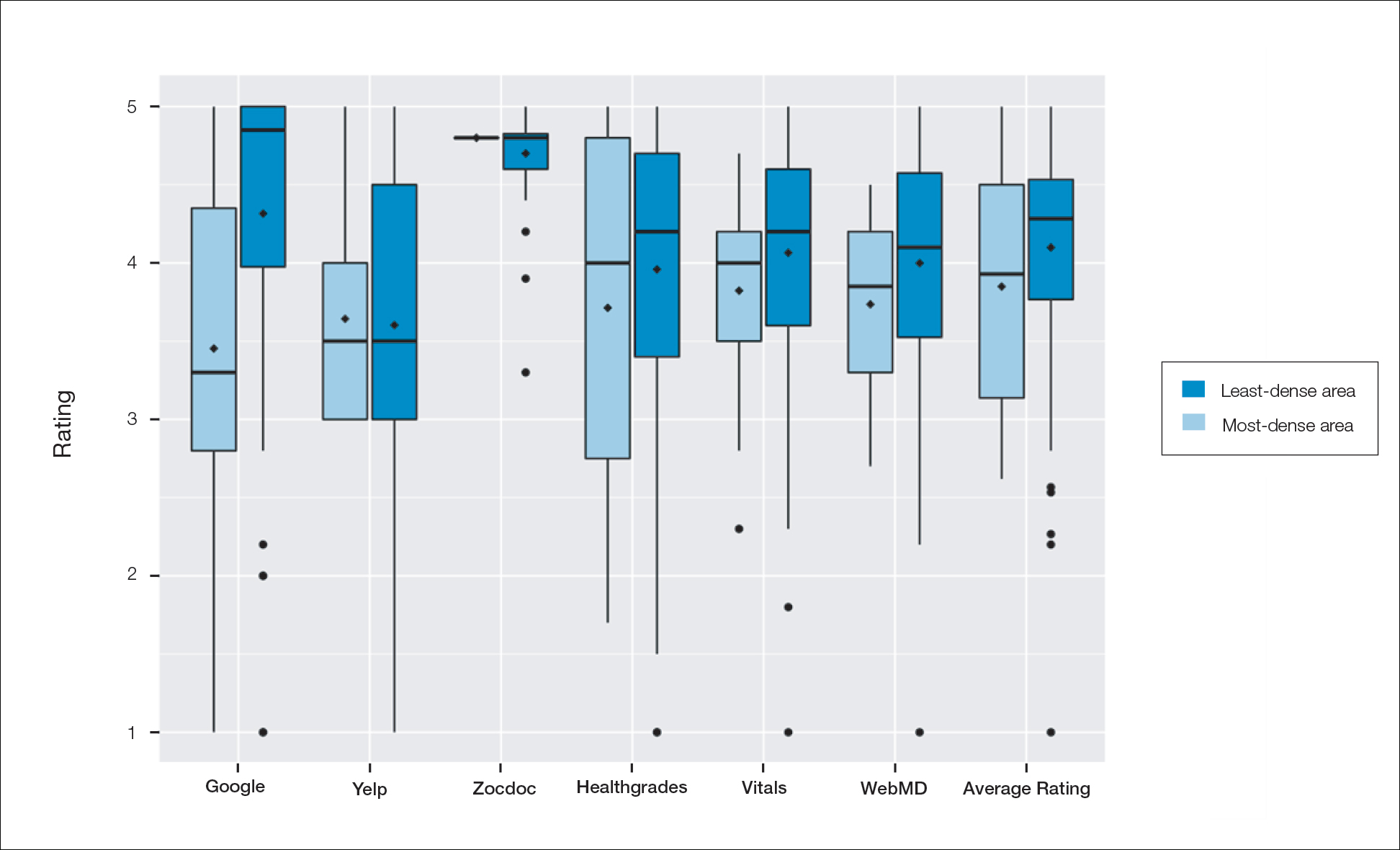

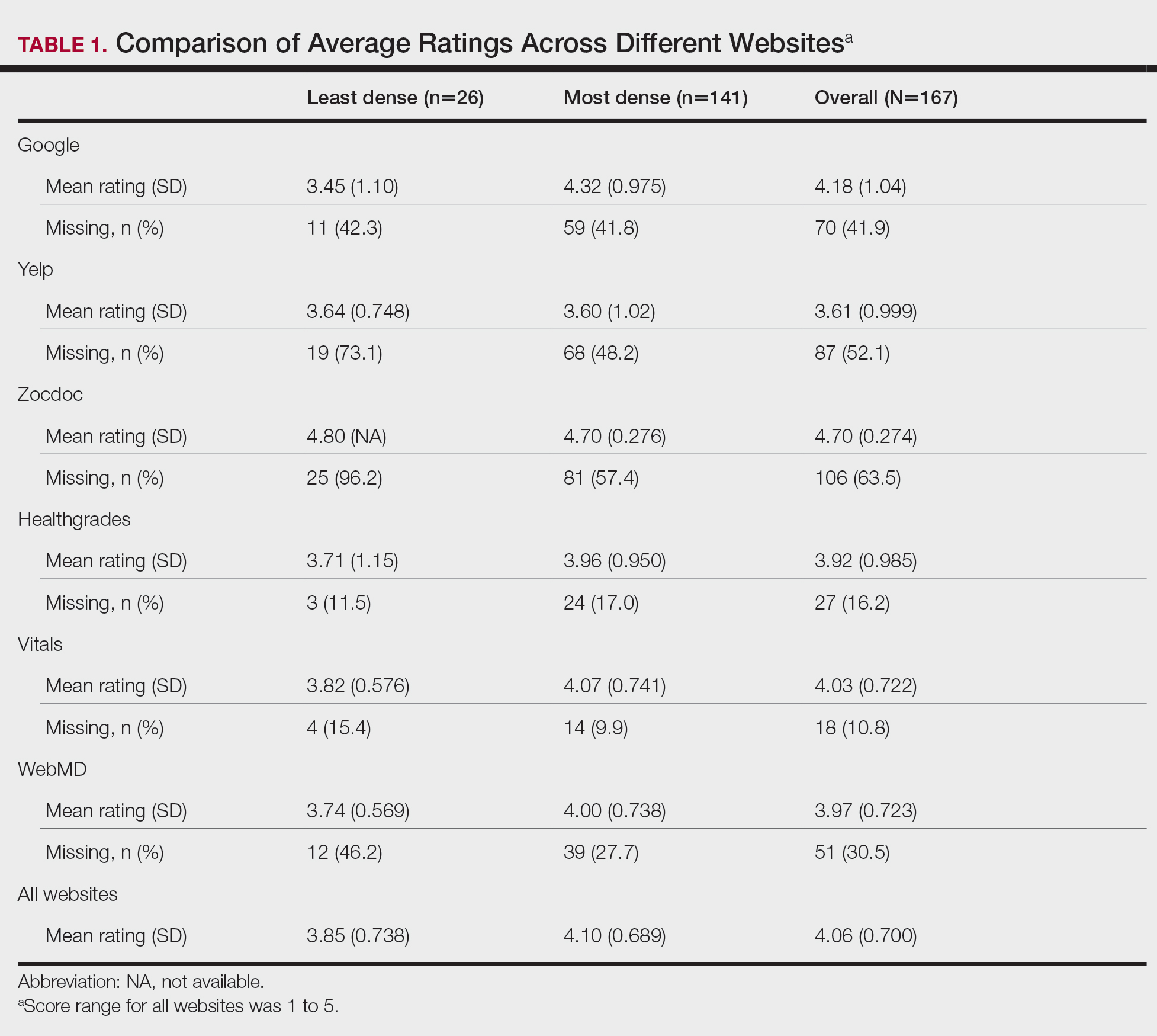

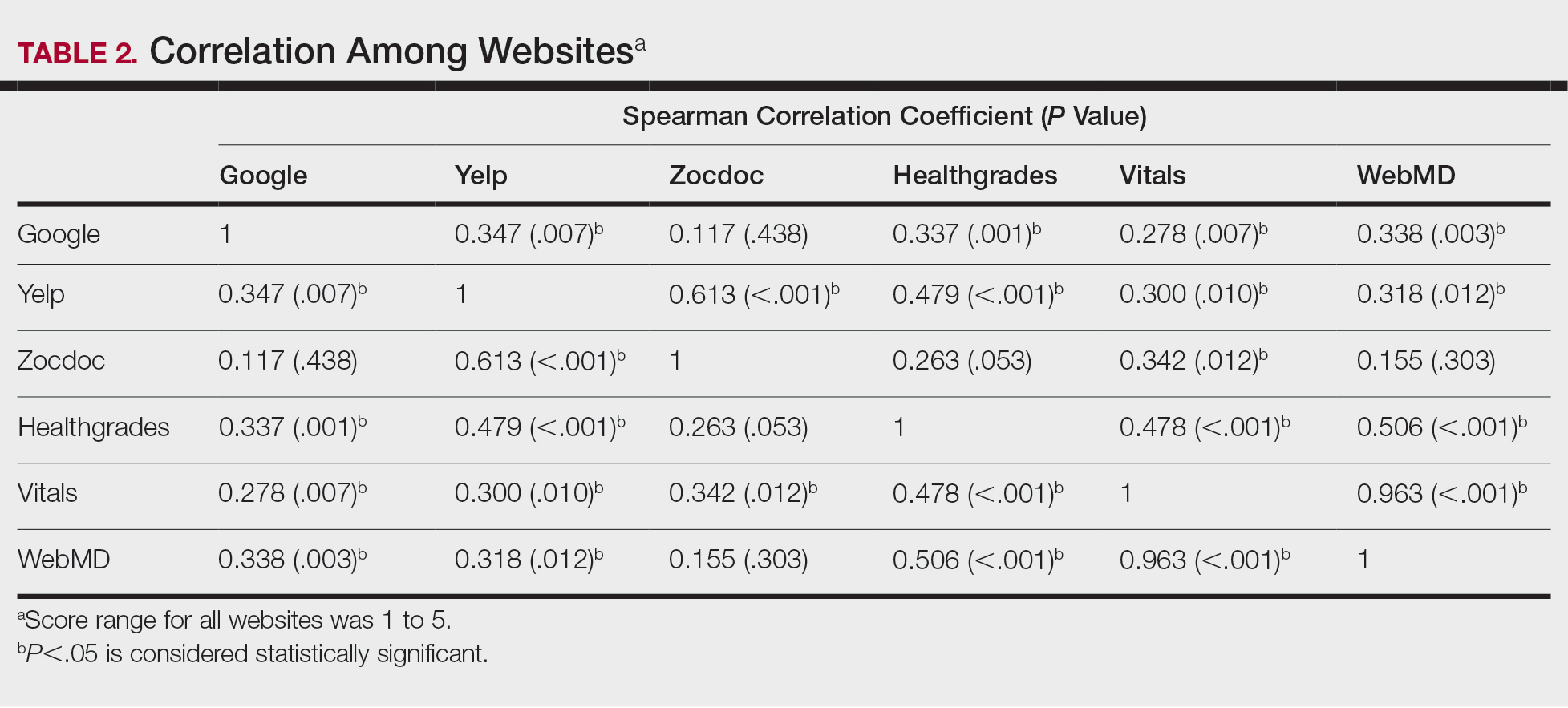

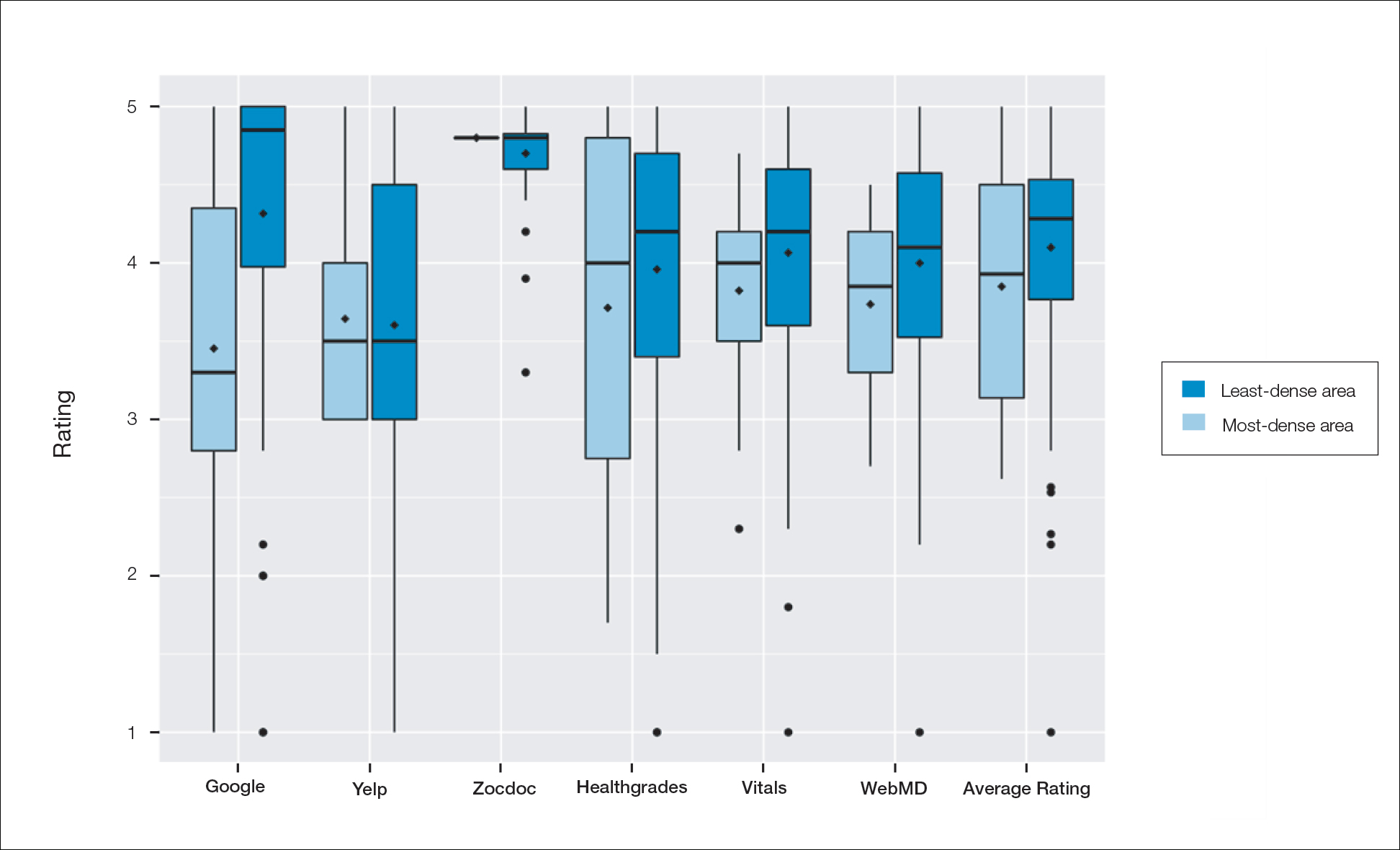

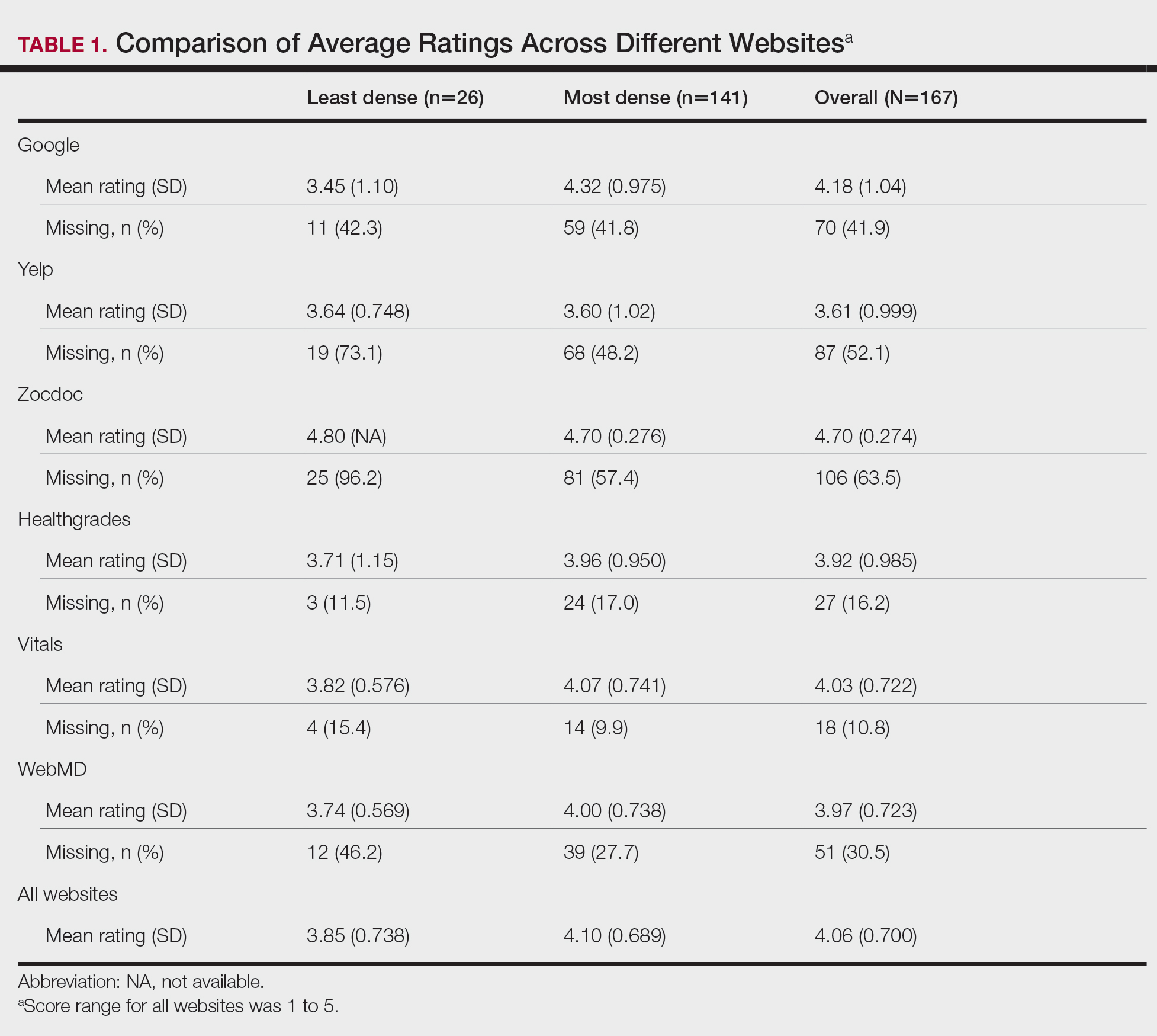

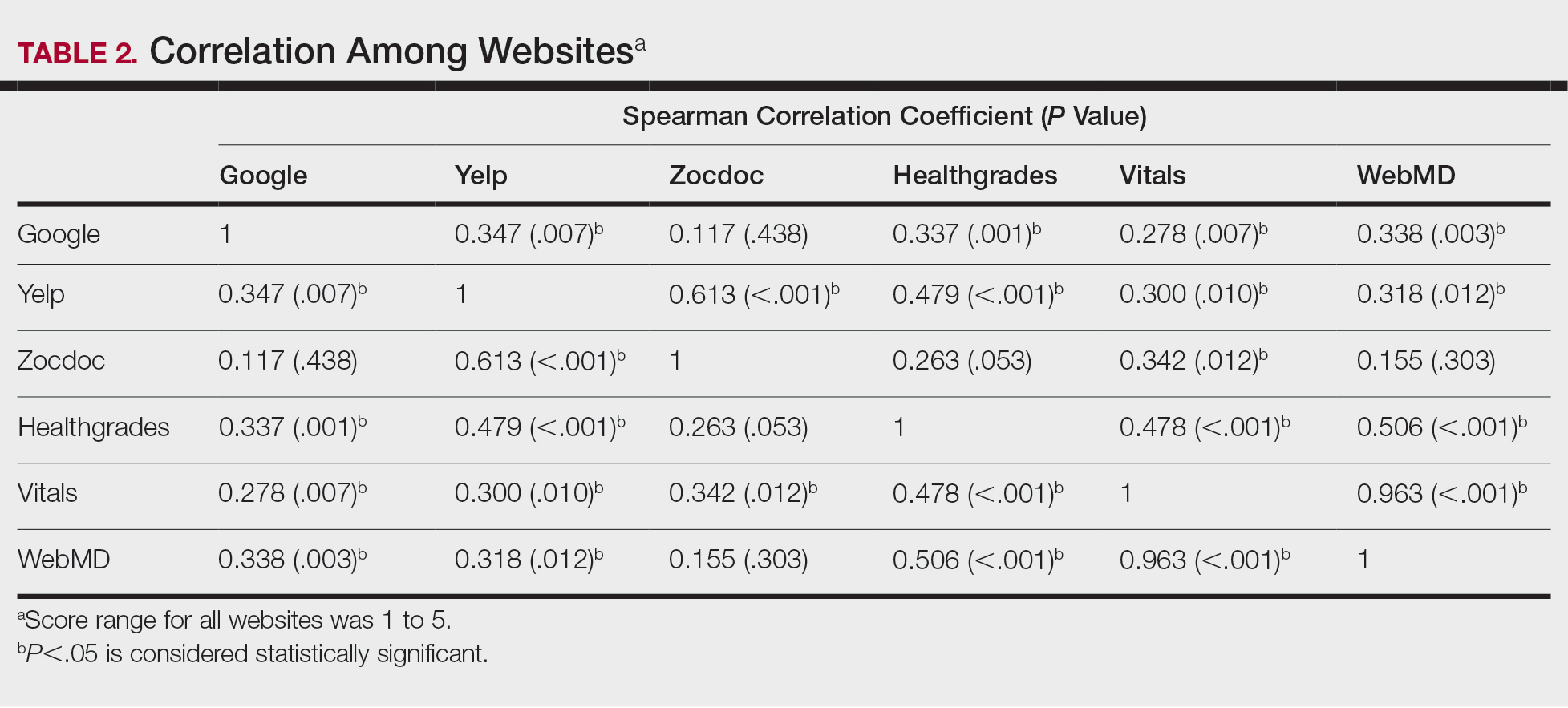

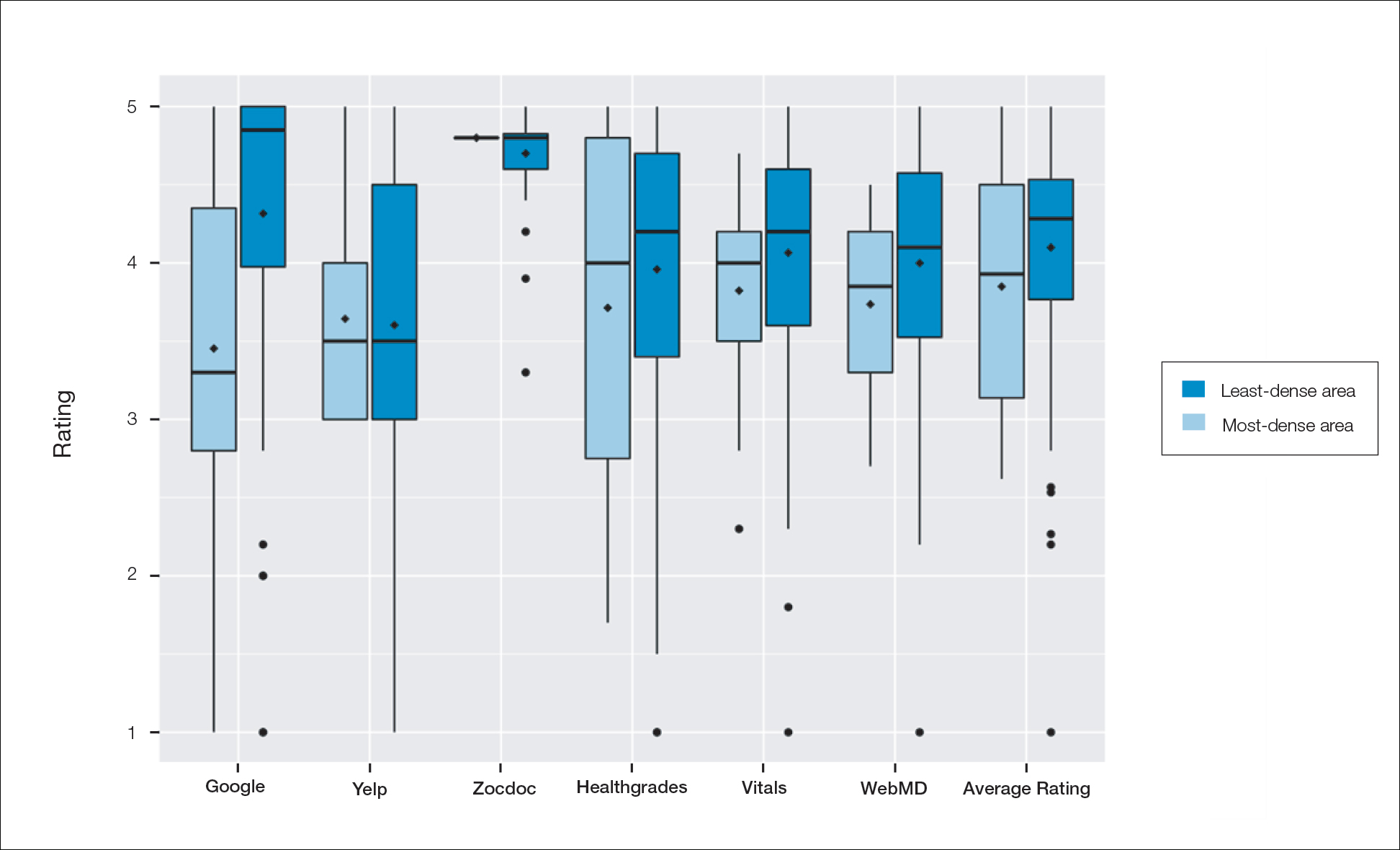

A total of 167 representative physicians were included in this analysis; 141 from the most dense areas, and 26 from the least dense areas. The lowest average ratings for the entire sample and most dermatologist–dense areas were found on Yelp (3.61 and 3.60, respectively), and the lowest ratings in the least dermatologist–dense areas were found on Google (3.45)(Table 1). Correlation coefficient values were lowest for Zocdoc and Healthgrades (0.263) and highest for Vitals and WebMD (0.963)(Table 2). The health care–specific sites were closer to the overall average (4.06) than the general consumer sites (eFigure).

Comment

Although dermatologist ratings on each site had a broad range, we found that patients typically expressed negative interactions on general consumer websites rather than health care–specific websites. When comparing the ratings of the same group of dermatologists across different sites, ratings on health care–specific sites had a higher degree of correlation, with physician ratings more similar between 2 health care–specific sites and less similar between a health care–specific and a general consumer website. This pattern was consistent in both dermatologist-dense and dermatologist-poor areas, despite patients having varying levels of access to dermatologic care and medical resources and potentially different regional preferences of consumer websites. Taken together, these findings imply that health care–specific websites more consistently reflect overall patient sentiment.

Although one 2016 study comparing reviews of dermatology practices on Zocdoc and Yelp also demonstrated lower average ratings on Yelp,3 our study suggests that this trend is not isolated to these 2 sites but can be seen when comparing many health care–specific sites vs general consumer sites.

Our study compared ratings of dermatologists among popular websites to understand those that are most representative of patient attitudes toward physicians. These findings are important because online reviews reflect the entire patient experience, not just the patient-physician interaction, which may explain why physician scores on standardized questionnaires, such as Press Ganey surveys, do not correlate well with their online reviews.4 In a study comparing 98 physicians with negative online ratings to 82 physicians in similar departments with positive ratings, there was no significant difference in scores on patient-physician interaction questions on the Press Ganey survey.5 However, physicians who received negative online reviews scored lower on Press Ganey questions related to nonphysician interactions (eg, office cleanliness, interactions with staff).

The current study was subject to several limitations. Our analysis included all physicians in our random selection without accounting for those physicians with a greater online presence who might be more cognizant of these ratings and try to manipulate them through a reputation-management company or public relations consultant.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that consumer websites are not primarily used by disgruntled patients wishing to express grievances; instead, on average, most physicians received positive reviews. Furthermore, health care–specific websites show a higher degree of concordance than and may more accurately reflect overall patient attitudes toward their physicians than general consumer sites. Reviews from these health care–specific sites may be more helpful than general consumer websites in allowing physicians to understand patient sentiment and improve patient experiences.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52

- Waqas B, Cooley V, Lipner SR. Association of sex, location, and experience with online patient ratings of dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:954-955.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3950

- Chen J, Presson A, Zhang C, et al. Online physician review websites poorly correlate to a validated metric of patient satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2018;227:1-6.

- Widmer RJ, Maurer MJ, Nayar VR, et al. Online physician reviews do not reflect patient satisfaction survey responses. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93:453-457.

Health care–specific (eg, Healthgrades, Zocdoc, Vitals, WebMD) and general consumer websites (eg, Google, Yelp) are popular platforms for patients to find physicians, schedule appointments, and review physician experiences. Patients find ratings on these websites more trustworthy than standardized surveys distributed by hospitals, but many physicians do not trust the reviews on these sites. For example, in a survey of both physicians (n=828) and patients (n=494), 36% of physicians trusted online reviews compared to 57% of patients.1 The objective of this study was to determine if health care–specific or general consumer websites more accurately reflect overall patient sentiment. This knowledge can help physicians who are seeking to improve the patient experience understand which websites have more accurate and trustworthy reviews.

Methods

A list of dermatologists from the top 10 most and least dermatologist–dense areas in the United States was compiled to examine different physician populations.2 Equal numbers of male and female dermatologists were randomly selected from the most dense areas. All physicians were included from the least dense areas because of limited sample size. Ratings were collected from websites most likely to appear on the first page of a Google search for a physician name, as these are most likely to be seen by patients. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study population; mean and median physician rating (using a scale of 1–5); SD; and minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Spearman correlation coefficients were generated to examine the strength of association between ratings from website pairs. P<.05 was considered statistically significant, with analyses performed in R (3.6.2) for Windows (the R Foundation).

Results

A total of 167 representative physicians were included in this analysis; 141 from the most dense areas, and 26 from the least dense areas. The lowest average ratings for the entire sample and most dermatologist–dense areas were found on Yelp (3.61 and 3.60, respectively), and the lowest ratings in the least dermatologist–dense areas were found on Google (3.45)(Table 1). Correlation coefficient values were lowest for Zocdoc and Healthgrades (0.263) and highest for Vitals and WebMD (0.963)(Table 2). The health care–specific sites were closer to the overall average (4.06) than the general consumer sites (eFigure).

Comment

Although dermatologist ratings on each site had a broad range, we found that patients typically expressed negative interactions on general consumer websites rather than health care–specific websites. When comparing the ratings of the same group of dermatologists across different sites, ratings on health care–specific sites had a higher degree of correlation, with physician ratings more similar between 2 health care–specific sites and less similar between a health care–specific and a general consumer website. This pattern was consistent in both dermatologist-dense and dermatologist-poor areas, despite patients having varying levels of access to dermatologic care and medical resources and potentially different regional preferences of consumer websites. Taken together, these findings imply that health care–specific websites more consistently reflect overall patient sentiment.

Although one 2016 study comparing reviews of dermatology practices on Zocdoc and Yelp also demonstrated lower average ratings on Yelp,3 our study suggests that this trend is not isolated to these 2 sites but can be seen when comparing many health care–specific sites vs general consumer sites.

Our study compared ratings of dermatologists among popular websites to understand those that are most representative of patient attitudes toward physicians. These findings are important because online reviews reflect the entire patient experience, not just the patient-physician interaction, which may explain why physician scores on standardized questionnaires, such as Press Ganey surveys, do not correlate well with their online reviews.4 In a study comparing 98 physicians with negative online ratings to 82 physicians in similar departments with positive ratings, there was no significant difference in scores on patient-physician interaction questions on the Press Ganey survey.5 However, physicians who received negative online reviews scored lower on Press Ganey questions related to nonphysician interactions (eg, office cleanliness, interactions with staff).

The current study was subject to several limitations. Our analysis included all physicians in our random selection without accounting for those physicians with a greater online presence who might be more cognizant of these ratings and try to manipulate them through a reputation-management company or public relations consultant.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that consumer websites are not primarily used by disgruntled patients wishing to express grievances; instead, on average, most physicians received positive reviews. Furthermore, health care–specific websites show a higher degree of concordance than and may more accurately reflect overall patient attitudes toward their physicians than general consumer sites. Reviews from these health care–specific sites may be more helpful than general consumer websites in allowing physicians to understand patient sentiment and improve patient experiences.

Health care–specific (eg, Healthgrades, Zocdoc, Vitals, WebMD) and general consumer websites (eg, Google, Yelp) are popular platforms for patients to find physicians, schedule appointments, and review physician experiences. Patients find ratings on these websites more trustworthy than standardized surveys distributed by hospitals, but many physicians do not trust the reviews on these sites. For example, in a survey of both physicians (n=828) and patients (n=494), 36% of physicians trusted online reviews compared to 57% of patients.1 The objective of this study was to determine if health care–specific or general consumer websites more accurately reflect overall patient sentiment. This knowledge can help physicians who are seeking to improve the patient experience understand which websites have more accurate and trustworthy reviews.

Methods

A list of dermatologists from the top 10 most and least dermatologist–dense areas in the United States was compiled to examine different physician populations.2 Equal numbers of male and female dermatologists were randomly selected from the most dense areas. All physicians were included from the least dense areas because of limited sample size. Ratings were collected from websites most likely to appear on the first page of a Google search for a physician name, as these are most likely to be seen by patients. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study population; mean and median physician rating (using a scale of 1–5); SD; and minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Spearman correlation coefficients were generated to examine the strength of association between ratings from website pairs. P<.05 was considered statistically significant, with analyses performed in R (3.6.2) for Windows (the R Foundation).

Results

A total of 167 representative physicians were included in this analysis; 141 from the most dense areas, and 26 from the least dense areas. The lowest average ratings for the entire sample and most dermatologist–dense areas were found on Yelp (3.61 and 3.60, respectively), and the lowest ratings in the least dermatologist–dense areas were found on Google (3.45)(Table 1). Correlation coefficient values were lowest for Zocdoc and Healthgrades (0.263) and highest for Vitals and WebMD (0.963)(Table 2). The health care–specific sites were closer to the overall average (4.06) than the general consumer sites (eFigure).

Comment

Although dermatologist ratings on each site had a broad range, we found that patients typically expressed negative interactions on general consumer websites rather than health care–specific websites. When comparing the ratings of the same group of dermatologists across different sites, ratings on health care–specific sites had a higher degree of correlation, with physician ratings more similar between 2 health care–specific sites and less similar between a health care–specific and a general consumer website. This pattern was consistent in both dermatologist-dense and dermatologist-poor areas, despite patients having varying levels of access to dermatologic care and medical resources and potentially different regional preferences of consumer websites. Taken together, these findings imply that health care–specific websites more consistently reflect overall patient sentiment.

Although one 2016 study comparing reviews of dermatology practices on Zocdoc and Yelp also demonstrated lower average ratings on Yelp,3 our study suggests that this trend is not isolated to these 2 sites but can be seen when comparing many health care–specific sites vs general consumer sites.

Our study compared ratings of dermatologists among popular websites to understand those that are most representative of patient attitudes toward physicians. These findings are important because online reviews reflect the entire patient experience, not just the patient-physician interaction, which may explain why physician scores on standardized questionnaires, such as Press Ganey surveys, do not correlate well with their online reviews.4 In a study comparing 98 physicians with negative online ratings to 82 physicians in similar departments with positive ratings, there was no significant difference in scores on patient-physician interaction questions on the Press Ganey survey.5 However, physicians who received negative online reviews scored lower on Press Ganey questions related to nonphysician interactions (eg, office cleanliness, interactions with staff).

The current study was subject to several limitations. Our analysis included all physicians in our random selection without accounting for those physicians with a greater online presence who might be more cognizant of these ratings and try to manipulate them through a reputation-management company or public relations consultant.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that consumer websites are not primarily used by disgruntled patients wishing to express grievances; instead, on average, most physicians received positive reviews. Furthermore, health care–specific websites show a higher degree of concordance than and may more accurately reflect overall patient attitudes toward their physicians than general consumer sites. Reviews from these health care–specific sites may be more helpful than general consumer websites in allowing physicians to understand patient sentiment and improve patient experiences.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52