User login

All Hands on Deck: The Federal Health Care Response to the COVID-19 National Emergency

A torrent of blame has deluged the administration’s management of the pandemic. There is though one part of the government that deserves the praise of the nation for its response to this public health crisis—the federal health care system. In this column, we discuss the ways in which the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Department of Defense (DoD), and the US Public Health Service (PHS) Commissioned Corps especially have bravely and generously responded to the medical emergency of COVID-19 in the US.

Four missions drive the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Though the fourth of these missions usually is in the background, it has risen to the forefront during the pandemic. To put the fourth mission in its proper perspective, we first should review the other 3 charges given to the largest integrated health care system in the country.

The first mission is to provide the highest quality care possible for the more than 9 million veterans enrolled in that system at each of the 1,255 VHA locations. The second mission is to ensure that the Veterans Benefits Administration delivers the full range of benefits that veterans earned through their service. These including funding for education, loans for homes, and many other types of support that assist service men and women to be successful in their transition from military to civilian life. The third mission is to honor the commitment of those who fought for their country unto death. The National Cemeteries Administration oversees 142 national cemeteries where veterans are buried with dignity and remembered with gratitude for their uniformed service. The purpose of these 3 internally focused missions is to provide a safety net for eligible veterans from the day they separate from the military until the hour they pass from this earth.

The fourth mission is different. This mission looks outside the military family to the civilian world. Its goal is to bolster the ability of the nation as a whole to handle wars, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters. It does this through emergency response plans that preserve the integrity of the 3 other missions to veterans while enhancing the capacity of local and state governments to manage the threat of these public health, safety, or security crises.1

At the same time the VA was aggressively mounting a defense against the threat COVID-19 posed to the other missions, it also launched the fourth mission. In announcing these actions in April 2020, VA Secretary Robert Wilke succinctly summarized the need to balance the fourth mission with the other 3. “VA is committed to helping the nation in this effort to combat COVID-19. Helping veterans is our first mission, but in many locations across the country we’re helping states and local communities. VA is in this fight not only for the millions of veterans we serve each day; we’re in the fight for the people of the United States.”2

During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic I saw firsthand how VA disaster preparedness and emergency training were far superior to many academic and community health care systems. Given VA’s detailed and drilled crisis response plans, its specialized expertise in public health disasters, and its immense resources, it is no wonder that as the virus stretched civilian health care systems, some states turned to the VA for help. At my Albuquerque, New Mexico, VA medical center, 5 medical surgical beds and 3 intensive care beds were opened to the Indian Health Service overwhelmed with cases of COVID-19 in the hard-hit Navajo Nation. In New Jersey where Federal Practitioner is published, the fourth mission reached out to the state-run veterans homes as 90 VA nurses and gerontologists were deployed to 2 of its veterans facilities where close to 150 veterans have died.3 State veterans homes in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Alabama, and many other states have received supplies, including direly needed testing and personal protective equipment, staff, technology, and training.4

In July, VA published an impressive summary of fourth mission activities, which I encourage you to read. When you are look at this site, remember with a moment of silent appreciation all the altruistic and courageous VA clinical and administrative staff who volunteered for these assignments many of which put them directly in harm’s way.5

The VA is not alone in answering the call of COVID-19. In March, despite the grave risk to their health, their life, and their families, the USNS Comfort was deployed to New York City to help with its COVID-19 response while the USNS Mercy assisted in the efforts in Los Angeles. More recently, the military deployed > 700 Military Health System medical and support professionals to support COVID-19 operations in both Texas and California. Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio has taken on a handful of civilian patients with COVID-19 and increase its level I trauma cases as local hospitals have strained under the caseload.6

For the PHS Commissioned Corps its first mission is to serve as “America’s health responders.”7 This pandemic has intensified the extant health inequities in our country and compounded them with racial injustice and economic disparity. Thus, it is important to recognize that the very purpose of the PHS is to “fight disease, conduct research, and care for patients in underserved communities across the nation.”8 More than 3,900 PHS officers have been deployed nationally and internationally in COVID-19 clinical strike teams. Early in the pandemic the clinical response teams were deployed to a long-term care facility in Kirkland, Washington; convention center-based hospitals in New York City, Detroit, Michigan, and Washington DC, and Navajo Nation facilities. PHS officers also are providing clinical guidance at Bureau of Prison facilities for infection control and personal protective equipment training.

We know that there are many more examples of heroic service by federal health care professionals and staff than we could locate or celebrate in this brief column. Readers of this journal are well aware of the near constant criticism of the VA and calls for privatization,9 the inadequate funding of the PHS,10 and the recent downsizing of DoD health care11 that threatens to undermine its core functions. The pandemic has powerfully demonstrated that degrading the ability of federal health care to agilely and masterfully mobilize in the event of a public health disaster endangers not just veterans and the military but the health and well-being of a nation, particularly its most vulnerable citizens.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA: VA mission statement. https://www.va.gov/about_va. Updated April 8, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA announces ‘Fourth Mission’ actions to help America respond to COVID-19. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5420. Published April 14, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

3. Dyer J. COVID-19 strikes hard at state-run veterans nursing homes. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/article/221098/coronavirus-updates/covid-19-strikes-hard-state-run-veterans-nursing-homes. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

4. Leigh D. Coronavirus news: VA secretary addresses COVID-19 deaths among veterans in the tri-state. https://abc7ny.com/va-secretary-veteran-covid-19-deaths-nursing-homes-veterans-memorial-home/6227770. Published June 3, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VA Fourth Mission Summary. https://www.va.gov/health/coronavirus/statesupport.asp. Updated August 3, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

6. Sanchez E. BAMC adapts to support greater San Antonio community during COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2020/07/15/BAMC-adapts-to-support-greater-San-Antonio-community-during-COVID-19-pandemic. Published July 17, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

7. US Public Health Service. Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service: America’s health responders. https://www.usphs.gov/default.aspx. Accessed August 3, 2020.

8. Kim EJ, Marrast L, Conigliaro J. COVID-19: magnifying the effect of health disparities. J Gen Intern Med . 2020;35(8):2441-2442. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05881-4

9. Gordon S, Craven J. The best health system to react to COVID-19. The American Prospect. March 20, 2020. https://prospect.org/coronavirus/the-best-health-system-to-react-to-covid-19. Accessed August 1, 2020.

10. Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic: it’s time to invest in public health. Fed Pract . 2020;37(suppl 3):S8-S11.

11. Wright O, Zuegel K. COVID-19 shows why military health care shouldn’t be downsized. https://www.militarytimes.com/opinion/commentary/2020/03/31/covid-19-shows-why-military-health-care-shouldnt-be-downsized. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed August 1,2020.

A torrent of blame has deluged the administration’s management of the pandemic. There is though one part of the government that deserves the praise of the nation for its response to this public health crisis—the federal health care system. In this column, we discuss the ways in which the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Department of Defense (DoD), and the US Public Health Service (PHS) Commissioned Corps especially have bravely and generously responded to the medical emergency of COVID-19 in the US.

Four missions drive the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Though the fourth of these missions usually is in the background, it has risen to the forefront during the pandemic. To put the fourth mission in its proper perspective, we first should review the other 3 charges given to the largest integrated health care system in the country.

The first mission is to provide the highest quality care possible for the more than 9 million veterans enrolled in that system at each of the 1,255 VHA locations. The second mission is to ensure that the Veterans Benefits Administration delivers the full range of benefits that veterans earned through their service. These including funding for education, loans for homes, and many other types of support that assist service men and women to be successful in their transition from military to civilian life. The third mission is to honor the commitment of those who fought for their country unto death. The National Cemeteries Administration oversees 142 national cemeteries where veterans are buried with dignity and remembered with gratitude for their uniformed service. The purpose of these 3 internally focused missions is to provide a safety net for eligible veterans from the day they separate from the military until the hour they pass from this earth.

The fourth mission is different. This mission looks outside the military family to the civilian world. Its goal is to bolster the ability of the nation as a whole to handle wars, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters. It does this through emergency response plans that preserve the integrity of the 3 other missions to veterans while enhancing the capacity of local and state governments to manage the threat of these public health, safety, or security crises.1

At the same time the VA was aggressively mounting a defense against the threat COVID-19 posed to the other missions, it also launched the fourth mission. In announcing these actions in April 2020, VA Secretary Robert Wilke succinctly summarized the need to balance the fourth mission with the other 3. “VA is committed to helping the nation in this effort to combat COVID-19. Helping veterans is our first mission, but in many locations across the country we’re helping states and local communities. VA is in this fight not only for the millions of veterans we serve each day; we’re in the fight for the people of the United States.”2

During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic I saw firsthand how VA disaster preparedness and emergency training were far superior to many academic and community health care systems. Given VA’s detailed and drilled crisis response plans, its specialized expertise in public health disasters, and its immense resources, it is no wonder that as the virus stretched civilian health care systems, some states turned to the VA for help. At my Albuquerque, New Mexico, VA medical center, 5 medical surgical beds and 3 intensive care beds were opened to the Indian Health Service overwhelmed with cases of COVID-19 in the hard-hit Navajo Nation. In New Jersey where Federal Practitioner is published, the fourth mission reached out to the state-run veterans homes as 90 VA nurses and gerontologists were deployed to 2 of its veterans facilities where close to 150 veterans have died.3 State veterans homes in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Alabama, and many other states have received supplies, including direly needed testing and personal protective equipment, staff, technology, and training.4

In July, VA published an impressive summary of fourth mission activities, which I encourage you to read. When you are look at this site, remember with a moment of silent appreciation all the altruistic and courageous VA clinical and administrative staff who volunteered for these assignments many of which put them directly in harm’s way.5

The VA is not alone in answering the call of COVID-19. In March, despite the grave risk to their health, their life, and their families, the USNS Comfort was deployed to New York City to help with its COVID-19 response while the USNS Mercy assisted in the efforts in Los Angeles. More recently, the military deployed > 700 Military Health System medical and support professionals to support COVID-19 operations in both Texas and California. Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio has taken on a handful of civilian patients with COVID-19 and increase its level I trauma cases as local hospitals have strained under the caseload.6

For the PHS Commissioned Corps its first mission is to serve as “America’s health responders.”7 This pandemic has intensified the extant health inequities in our country and compounded them with racial injustice and economic disparity. Thus, it is important to recognize that the very purpose of the PHS is to “fight disease, conduct research, and care for patients in underserved communities across the nation.”8 More than 3,900 PHS officers have been deployed nationally and internationally in COVID-19 clinical strike teams. Early in the pandemic the clinical response teams were deployed to a long-term care facility in Kirkland, Washington; convention center-based hospitals in New York City, Detroit, Michigan, and Washington DC, and Navajo Nation facilities. PHS officers also are providing clinical guidance at Bureau of Prison facilities for infection control and personal protective equipment training.

We know that there are many more examples of heroic service by federal health care professionals and staff than we could locate or celebrate in this brief column. Readers of this journal are well aware of the near constant criticism of the VA and calls for privatization,9 the inadequate funding of the PHS,10 and the recent downsizing of DoD health care11 that threatens to undermine its core functions. The pandemic has powerfully demonstrated that degrading the ability of federal health care to agilely and masterfully mobilize in the event of a public health disaster endangers not just veterans and the military but the health and well-being of a nation, particularly its most vulnerable citizens.

A torrent of blame has deluged the administration’s management of the pandemic. There is though one part of the government that deserves the praise of the nation for its response to this public health crisis—the federal health care system. In this column, we discuss the ways in which the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Department of Defense (DoD), and the US Public Health Service (PHS) Commissioned Corps especially have bravely and generously responded to the medical emergency of COVID-19 in the US.

Four missions drive the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Though the fourth of these missions usually is in the background, it has risen to the forefront during the pandemic. To put the fourth mission in its proper perspective, we first should review the other 3 charges given to the largest integrated health care system in the country.

The first mission is to provide the highest quality care possible for the more than 9 million veterans enrolled in that system at each of the 1,255 VHA locations. The second mission is to ensure that the Veterans Benefits Administration delivers the full range of benefits that veterans earned through their service. These including funding for education, loans for homes, and many other types of support that assist service men and women to be successful in their transition from military to civilian life. The third mission is to honor the commitment of those who fought for their country unto death. The National Cemeteries Administration oversees 142 national cemeteries where veterans are buried with dignity and remembered with gratitude for their uniformed service. The purpose of these 3 internally focused missions is to provide a safety net for eligible veterans from the day they separate from the military until the hour they pass from this earth.

The fourth mission is different. This mission looks outside the military family to the civilian world. Its goal is to bolster the ability of the nation as a whole to handle wars, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters. It does this through emergency response plans that preserve the integrity of the 3 other missions to veterans while enhancing the capacity of local and state governments to manage the threat of these public health, safety, or security crises.1

At the same time the VA was aggressively mounting a defense against the threat COVID-19 posed to the other missions, it also launched the fourth mission. In announcing these actions in April 2020, VA Secretary Robert Wilke succinctly summarized the need to balance the fourth mission with the other 3. “VA is committed to helping the nation in this effort to combat COVID-19. Helping veterans is our first mission, but in many locations across the country we’re helping states and local communities. VA is in this fight not only for the millions of veterans we serve each day; we’re in the fight for the people of the United States.”2

During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic I saw firsthand how VA disaster preparedness and emergency training were far superior to many academic and community health care systems. Given VA’s detailed and drilled crisis response plans, its specialized expertise in public health disasters, and its immense resources, it is no wonder that as the virus stretched civilian health care systems, some states turned to the VA for help. At my Albuquerque, New Mexico, VA medical center, 5 medical surgical beds and 3 intensive care beds were opened to the Indian Health Service overwhelmed with cases of COVID-19 in the hard-hit Navajo Nation. In New Jersey where Federal Practitioner is published, the fourth mission reached out to the state-run veterans homes as 90 VA nurses and gerontologists were deployed to 2 of its veterans facilities where close to 150 veterans have died.3 State veterans homes in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Alabama, and many other states have received supplies, including direly needed testing and personal protective equipment, staff, technology, and training.4

In July, VA published an impressive summary of fourth mission activities, which I encourage you to read. When you are look at this site, remember with a moment of silent appreciation all the altruistic and courageous VA clinical and administrative staff who volunteered for these assignments many of which put them directly in harm’s way.5

The VA is not alone in answering the call of COVID-19. In March, despite the grave risk to their health, their life, and their families, the USNS Comfort was deployed to New York City to help with its COVID-19 response while the USNS Mercy assisted in the efforts in Los Angeles. More recently, the military deployed > 700 Military Health System medical and support professionals to support COVID-19 operations in both Texas and California. Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio has taken on a handful of civilian patients with COVID-19 and increase its level I trauma cases as local hospitals have strained under the caseload.6

For the PHS Commissioned Corps its first mission is to serve as “America’s health responders.”7 This pandemic has intensified the extant health inequities in our country and compounded them with racial injustice and economic disparity. Thus, it is important to recognize that the very purpose of the PHS is to “fight disease, conduct research, and care for patients in underserved communities across the nation.”8 More than 3,900 PHS officers have been deployed nationally and internationally in COVID-19 clinical strike teams. Early in the pandemic the clinical response teams were deployed to a long-term care facility in Kirkland, Washington; convention center-based hospitals in New York City, Detroit, Michigan, and Washington DC, and Navajo Nation facilities. PHS officers also are providing clinical guidance at Bureau of Prison facilities for infection control and personal protective equipment training.

We know that there are many more examples of heroic service by federal health care professionals and staff than we could locate or celebrate in this brief column. Readers of this journal are well aware of the near constant criticism of the VA and calls for privatization,9 the inadequate funding of the PHS,10 and the recent downsizing of DoD health care11 that threatens to undermine its core functions. The pandemic has powerfully demonstrated that degrading the ability of federal health care to agilely and masterfully mobilize in the event of a public health disaster endangers not just veterans and the military but the health and well-being of a nation, particularly its most vulnerable citizens.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA: VA mission statement. https://www.va.gov/about_va. Updated April 8, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA announces ‘Fourth Mission’ actions to help America respond to COVID-19. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5420. Published April 14, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

3. Dyer J. COVID-19 strikes hard at state-run veterans nursing homes. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/article/221098/coronavirus-updates/covid-19-strikes-hard-state-run-veterans-nursing-homes. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

4. Leigh D. Coronavirus news: VA secretary addresses COVID-19 deaths among veterans in the tri-state. https://abc7ny.com/va-secretary-veteran-covid-19-deaths-nursing-homes-veterans-memorial-home/6227770. Published June 3, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VA Fourth Mission Summary. https://www.va.gov/health/coronavirus/statesupport.asp. Updated August 3, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

6. Sanchez E. BAMC adapts to support greater San Antonio community during COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2020/07/15/BAMC-adapts-to-support-greater-San-Antonio-community-during-COVID-19-pandemic. Published July 17, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

7. US Public Health Service. Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service: America’s health responders. https://www.usphs.gov/default.aspx. Accessed August 3, 2020.

8. Kim EJ, Marrast L, Conigliaro J. COVID-19: magnifying the effect of health disparities. J Gen Intern Med . 2020;35(8):2441-2442. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05881-4

9. Gordon S, Craven J. The best health system to react to COVID-19. The American Prospect. March 20, 2020. https://prospect.org/coronavirus/the-best-health-system-to-react-to-covid-19. Accessed August 1, 2020.

10. Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic: it’s time to invest in public health. Fed Pract . 2020;37(suppl 3):S8-S11.

11. Wright O, Zuegel K. COVID-19 shows why military health care shouldn’t be downsized. https://www.militarytimes.com/opinion/commentary/2020/03/31/covid-19-shows-why-military-health-care-shouldnt-be-downsized. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed August 1,2020.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA: VA mission statement. https://www.va.gov/about_va. Updated April 8, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA announces ‘Fourth Mission’ actions to help America respond to COVID-19. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5420. Published April 14, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

3. Dyer J. COVID-19 strikes hard at state-run veterans nursing homes. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/article/221098/coronavirus-updates/covid-19-strikes-hard-state-run-veterans-nursing-homes. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

4. Leigh D. Coronavirus news: VA secretary addresses COVID-19 deaths among veterans in the tri-state. https://abc7ny.com/va-secretary-veteran-covid-19-deaths-nursing-homes-veterans-memorial-home/6227770. Published June 3, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VA Fourth Mission Summary. https://www.va.gov/health/coronavirus/statesupport.asp. Updated August 3, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

6. Sanchez E. BAMC adapts to support greater San Antonio community during COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2020/07/15/BAMC-adapts-to-support-greater-San-Antonio-community-during-COVID-19-pandemic. Published July 17, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2020.

7. US Public Health Service. Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service: America’s health responders. https://www.usphs.gov/default.aspx. Accessed August 3, 2020.

8. Kim EJ, Marrast L, Conigliaro J. COVID-19: magnifying the effect of health disparities. J Gen Intern Med . 2020;35(8):2441-2442. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05881-4

9. Gordon S, Craven J. The best health system to react to COVID-19. The American Prospect. March 20, 2020. https://prospect.org/coronavirus/the-best-health-system-to-react-to-covid-19. Accessed August 1, 2020.

10. Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic: it’s time to invest in public health. Fed Pract . 2020;37(suppl 3):S8-S11.

11. Wright O, Zuegel K. COVID-19 shows why military health care shouldn’t be downsized. https://www.militarytimes.com/opinion/commentary/2020/03/31/covid-19-shows-why-military-health-care-shouldnt-be-downsized. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed August 1,2020.

APPlying Knowledge: Evidence for and Regulation of Mobile Apps for Dermatologists

Since the first mobile application (app) was developed in the 1990s, apps have become increasingly integrated into medical practice and training. More than 5.5 million apps were downloadable in 2019,1 of which more than 300,000 were health related.2 In the United States, more than 80% of physicians reported using smartphones for professional purposes in 2016.3 As the complexity of apps and their purpose of use has evolved, regulatory bodies have not adapted adequately to monitor apps that have broad-reaching consequences in medicine.

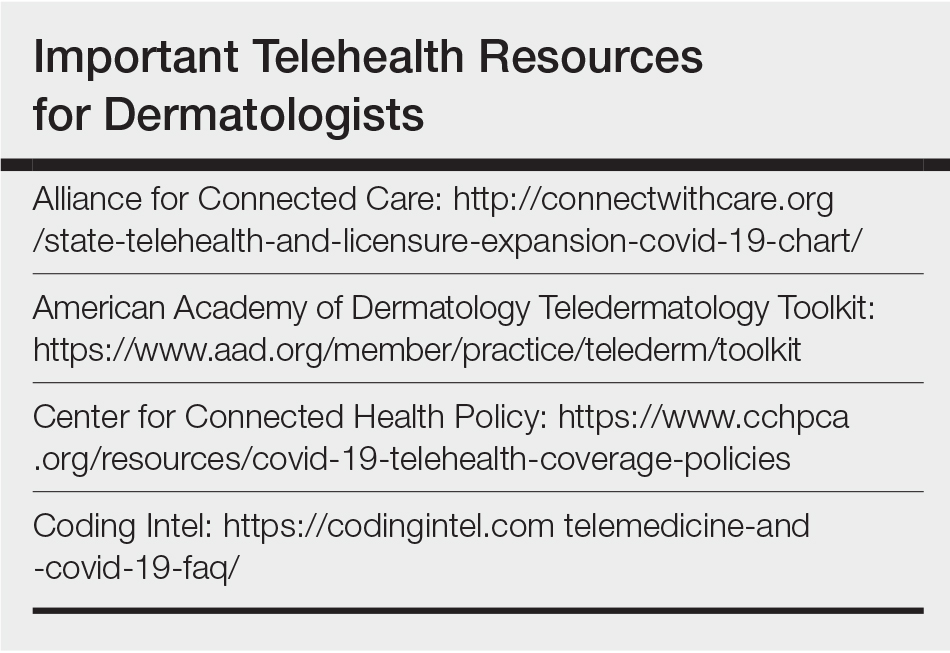

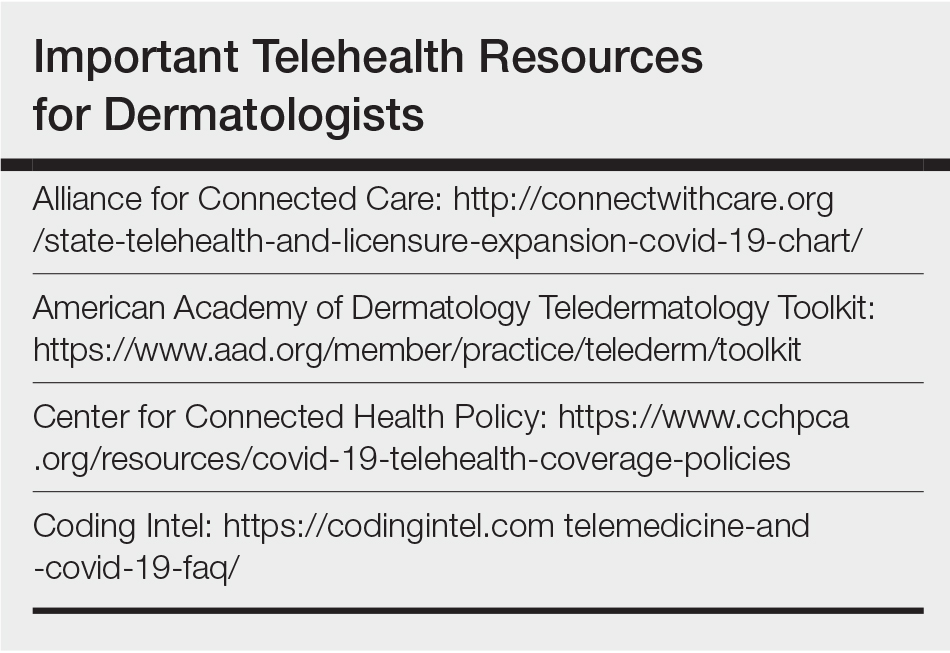

We review the primary literature on PubMed behind health-related apps that impact dermatologists as well as the government regulation of these apps, with a focus on the 3 most prevalent dermatology-related apps used by dermatology residents in the United States: VisualDx, UpToDate, and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria. This prevalence is according to a survey emailed to all dermatology residents in the United States by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in 2019 (unpublished data).

VisualDx

VisualDx, which aims to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient safety, contains peer-reviewed data and more than 32,000 images of dermatologic conditions. The editorial board includes more than 50 physicians. It provides opportunities for continuing medical education credit, is used in more than 2300 medical settings, and costs $399.99 annually for a subscription with partial features. Prior to the launch of the app in 2010, some health science professionals noted that the website version lacked references to primary sources.4 The same issue carried over to the app, which has evolved to offer artificial intelligence (AI) analysis of photographed skin lesions. However, there are no peer-reviewed publications showing positive impact of the app on diagnostic skills among dermatology residents or on patient outcomes.

UpToDate

UpToDate is a web-based database created in the early 1990s. A corresponding app was created around 2010. Both internal and independent research has demonstrated improved outcomes, and the app is advertised as the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes, as shown in more than 80 publications.5 UpToDate covers more than 11,800 medical topics and contains more than 35,000 graphics. It cites primary sources and uses a published system for grading recommendation strength and evidence quality. The data are processed and produced by a team of more than 7100 physicians as authors, editors, and reviewers. The platform grants continuing medical education credit and is used by more than 1.9 million clinicians in more than 190 countries. A 1-year subscription for an individual US-based physician costs $559. An observational study assessed UpToDate articles for potential conflicts of interest between authors and their recommendations. Of the 6 articles that met inclusion criteria of discussing management of medical conditions that have controversial or mostly brand-name treatment options, all had conflicts of interest, such as naming drugs from companies with which the authors and/or editors had financial relationships.6

Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria

The Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria app is a free clinical decision-making tool based on a consensus statement published in 2012 by the AAD, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery.7 It helps guide management of more than 200 dermatologic scenarios. Critique has been made that the criteria are partly based on expert opinion and data largely from the United States and has not been revised to incorporate newer data.8 There are no publications regarding the app itself.

Regulation of Health-Related Apps

Health-related apps that are designed for utilization by health care providers can be a valuable tool. However, given their prevalence, cost, and potential impact on patient lives, these apps should be well regulated and researched. The general paucity of peer-reviewed literature demonstrating the utility, safety, quality, and accuracy of health-related apps commonly used by providers is a reflection of insufficient mobile health regulation in the United States.

There are 3 primary government agencies responsible for regulating mobile medical apps: the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Federal Trade Commission, and Office for Civil Rights.9 The FDA does not regulate all medical devices. Apps intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition are considered to be medical devices.10 The FDA regulates those apps only if they are judged to pose more than minimal risk. Apps that are designed only to provide easy access to information related to health conditions or treatment are considered to be minimal risk but can develop into a different risk level such as by offering AI.11 Although the FDA does update its approach to medical devices, including apps and AI- and machine learning–based software, the rate and direction of update has not kept pace with the rapid evolution of apps.12 In 2019, the FDA began piloting a precertification program that grants long-term approval to organizations that develop apps instead of reviewing each app product individually.13 This decrease in premarket oversight is intended to expedite innovation with the hopeful upside of improving patient outcomes but is inconsistent, with the FDA still reviewing other types of medical devices individually.

For apps that are already in use, the Federal Trade Commission only gets involved in response to deceptive or unfair acts or practices relating to privacy, data security, and false or misleading claims about safety or performance. It may be more beneficial for consumers if those apps had a more stringent initial approval process. The Office for Civil Rights enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act when relevant to apps.

Nongovernment agencies also are involved in app regulation. The FDA believes sharing more regulatory responsibility with private industry would promote efficiency.14 Google does not allow apps that contain false or misleading health claims,15 and Apple may scrutinize medical apps that could provide inaccurate data or be used for diagnosing or treating patients.16 Xcertia, a nonprofit organization founded by the American Medical Association and others, develops standards for the security, privacy, content, and operability of health-related apps, but those standards have not been adopted by other parties. Ultimately, nongovernment agencies are not responsible for public health and do not boast the government’s ability to enforce rules or ensure public safety.

Final Thoughts

The AAD survey of US dermatology residents found that the top consideration when choosing apps was up-to-date and accurate information; however, the 3 most prevalent apps among those same respondents did not need government approval and are not required to contain up-to-date data or to improve clinical outcomes, similar to most other health-related apps. This discrepancy is concerning considering the increasing utilization of apps for physician education and health care delivery and the increasing complexity of those apps. In light of these results, the potential decrease in federal premarket regulation suggested by the FDA’s precertification program seems inappropriate. It is important for the government to take responsibility for regulating health-related apps and to find a balance between too much regulation delaying innovation and too little regulation hurting physician training and patient care. It also is important for providers to be aware of the evidence and oversight behind the technologies they use for professional purposes.

- Clement J. Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 1st quarter 2020. Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/. Published May 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- mHealth App Economics 2017/2018. Current Status and Future Trends in Mobile Health. Berlin, Germany: Research 2 Guidance; 2018.

- Healthcare Client Services. Professional usage of smartphones by doctors. Kantar website. https://www.kantarmedia.com/us/thinking-and-resources/blog/professional-usage-of-smartphones-by-doctors-2016. Published November 16, 2016. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Skhal KJ, Koffel J. VisualDx. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95:470-471.

- UpToDate is the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/home/research. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Amber KT, Dhiman G, Goodman KW. Conflict of interest in online point-of-care clinical support websites. J Med Ethics. 2014;40:578-580.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs micrographic surgery appropriate use criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:E55.

- Mobile health apps interactive tool. Federal Trade Commission website. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/mobile-health-apps-interactive-tool. Published April 2016. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC §321 (2018).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Examples of software functions for which the FDA will exercise enforcement discretion. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications/examples-software-functions-which-fda-will-exercise-enforcement-discretion. Updated September 26, 2019. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Proposed regulatory framework for modifications to artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML)‐based software as a medical device (SaMD). https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DigitalHealth/SoftwareasaMedicalDevice/UCM635052.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Digital health software precertification (pre-cert) program. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/digital-health-software-precertification-pre-cert-program. Updated July 18, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Gottlieb S. Fostering medical innovation: a plan for digital health devices. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/fostering-medical-innovation-plan-digital-health-devices. Published June 15, 2017. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Restricted content: unapproved substances. Google Play website. https://play.google.com/about/restricted-content/unapproved-substances. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- App store review guidelines. Apple Developer website. https://developer.apple.com/app-store/review/guidelines. Updated March 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

Since the first mobile application (app) was developed in the 1990s, apps have become increasingly integrated into medical practice and training. More than 5.5 million apps were downloadable in 2019,1 of which more than 300,000 were health related.2 In the United States, more than 80% of physicians reported using smartphones for professional purposes in 2016.3 As the complexity of apps and their purpose of use has evolved, regulatory bodies have not adapted adequately to monitor apps that have broad-reaching consequences in medicine.

We review the primary literature on PubMed behind health-related apps that impact dermatologists as well as the government regulation of these apps, with a focus on the 3 most prevalent dermatology-related apps used by dermatology residents in the United States: VisualDx, UpToDate, and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria. This prevalence is according to a survey emailed to all dermatology residents in the United States by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in 2019 (unpublished data).

VisualDx

VisualDx, which aims to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient safety, contains peer-reviewed data and more than 32,000 images of dermatologic conditions. The editorial board includes more than 50 physicians. It provides opportunities for continuing medical education credit, is used in more than 2300 medical settings, and costs $399.99 annually for a subscription with partial features. Prior to the launch of the app in 2010, some health science professionals noted that the website version lacked references to primary sources.4 The same issue carried over to the app, which has evolved to offer artificial intelligence (AI) analysis of photographed skin lesions. However, there are no peer-reviewed publications showing positive impact of the app on diagnostic skills among dermatology residents or on patient outcomes.

UpToDate

UpToDate is a web-based database created in the early 1990s. A corresponding app was created around 2010. Both internal and independent research has demonstrated improved outcomes, and the app is advertised as the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes, as shown in more than 80 publications.5 UpToDate covers more than 11,800 medical topics and contains more than 35,000 graphics. It cites primary sources and uses a published system for grading recommendation strength and evidence quality. The data are processed and produced by a team of more than 7100 physicians as authors, editors, and reviewers. The platform grants continuing medical education credit and is used by more than 1.9 million clinicians in more than 190 countries. A 1-year subscription for an individual US-based physician costs $559. An observational study assessed UpToDate articles for potential conflicts of interest between authors and their recommendations. Of the 6 articles that met inclusion criteria of discussing management of medical conditions that have controversial or mostly brand-name treatment options, all had conflicts of interest, such as naming drugs from companies with which the authors and/or editors had financial relationships.6

Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria

The Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria app is a free clinical decision-making tool based on a consensus statement published in 2012 by the AAD, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery.7 It helps guide management of more than 200 dermatologic scenarios. Critique has been made that the criteria are partly based on expert opinion and data largely from the United States and has not been revised to incorporate newer data.8 There are no publications regarding the app itself.

Regulation of Health-Related Apps

Health-related apps that are designed for utilization by health care providers can be a valuable tool. However, given their prevalence, cost, and potential impact on patient lives, these apps should be well regulated and researched. The general paucity of peer-reviewed literature demonstrating the utility, safety, quality, and accuracy of health-related apps commonly used by providers is a reflection of insufficient mobile health regulation in the United States.

There are 3 primary government agencies responsible for regulating mobile medical apps: the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Federal Trade Commission, and Office for Civil Rights.9 The FDA does not regulate all medical devices. Apps intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition are considered to be medical devices.10 The FDA regulates those apps only if they are judged to pose more than minimal risk. Apps that are designed only to provide easy access to information related to health conditions or treatment are considered to be minimal risk but can develop into a different risk level such as by offering AI.11 Although the FDA does update its approach to medical devices, including apps and AI- and machine learning–based software, the rate and direction of update has not kept pace with the rapid evolution of apps.12 In 2019, the FDA began piloting a precertification program that grants long-term approval to organizations that develop apps instead of reviewing each app product individually.13 This decrease in premarket oversight is intended to expedite innovation with the hopeful upside of improving patient outcomes but is inconsistent, with the FDA still reviewing other types of medical devices individually.

For apps that are already in use, the Federal Trade Commission only gets involved in response to deceptive or unfair acts or practices relating to privacy, data security, and false or misleading claims about safety or performance. It may be more beneficial for consumers if those apps had a more stringent initial approval process. The Office for Civil Rights enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act when relevant to apps.

Nongovernment agencies also are involved in app regulation. The FDA believes sharing more regulatory responsibility with private industry would promote efficiency.14 Google does not allow apps that contain false or misleading health claims,15 and Apple may scrutinize medical apps that could provide inaccurate data or be used for diagnosing or treating patients.16 Xcertia, a nonprofit organization founded by the American Medical Association and others, develops standards for the security, privacy, content, and operability of health-related apps, but those standards have not been adopted by other parties. Ultimately, nongovernment agencies are not responsible for public health and do not boast the government’s ability to enforce rules or ensure public safety.

Final Thoughts

The AAD survey of US dermatology residents found that the top consideration when choosing apps was up-to-date and accurate information; however, the 3 most prevalent apps among those same respondents did not need government approval and are not required to contain up-to-date data or to improve clinical outcomes, similar to most other health-related apps. This discrepancy is concerning considering the increasing utilization of apps for physician education and health care delivery and the increasing complexity of those apps. In light of these results, the potential decrease in federal premarket regulation suggested by the FDA’s precertification program seems inappropriate. It is important for the government to take responsibility for regulating health-related apps and to find a balance between too much regulation delaying innovation and too little regulation hurting physician training and patient care. It also is important for providers to be aware of the evidence and oversight behind the technologies they use for professional purposes.

Since the first mobile application (app) was developed in the 1990s, apps have become increasingly integrated into medical practice and training. More than 5.5 million apps were downloadable in 2019,1 of which more than 300,000 were health related.2 In the United States, more than 80% of physicians reported using smartphones for professional purposes in 2016.3 As the complexity of apps and their purpose of use has evolved, regulatory bodies have not adapted adequately to monitor apps that have broad-reaching consequences in medicine.

We review the primary literature on PubMed behind health-related apps that impact dermatologists as well as the government regulation of these apps, with a focus on the 3 most prevalent dermatology-related apps used by dermatology residents in the United States: VisualDx, UpToDate, and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria. This prevalence is according to a survey emailed to all dermatology residents in the United States by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in 2019 (unpublished data).

VisualDx

VisualDx, which aims to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient safety, contains peer-reviewed data and more than 32,000 images of dermatologic conditions. The editorial board includes more than 50 physicians. It provides opportunities for continuing medical education credit, is used in more than 2300 medical settings, and costs $399.99 annually for a subscription with partial features. Prior to the launch of the app in 2010, some health science professionals noted that the website version lacked references to primary sources.4 The same issue carried over to the app, which has evolved to offer artificial intelligence (AI) analysis of photographed skin lesions. However, there are no peer-reviewed publications showing positive impact of the app on diagnostic skills among dermatology residents or on patient outcomes.

UpToDate

UpToDate is a web-based database created in the early 1990s. A corresponding app was created around 2010. Both internal and independent research has demonstrated improved outcomes, and the app is advertised as the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes, as shown in more than 80 publications.5 UpToDate covers more than 11,800 medical topics and contains more than 35,000 graphics. It cites primary sources and uses a published system for grading recommendation strength and evidence quality. The data are processed and produced by a team of more than 7100 physicians as authors, editors, and reviewers. The platform grants continuing medical education credit and is used by more than 1.9 million clinicians in more than 190 countries. A 1-year subscription for an individual US-based physician costs $559. An observational study assessed UpToDate articles for potential conflicts of interest between authors and their recommendations. Of the 6 articles that met inclusion criteria of discussing management of medical conditions that have controversial or mostly brand-name treatment options, all had conflicts of interest, such as naming drugs from companies with which the authors and/or editors had financial relationships.6

Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria

The Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria app is a free clinical decision-making tool based on a consensus statement published in 2012 by the AAD, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery.7 It helps guide management of more than 200 dermatologic scenarios. Critique has been made that the criteria are partly based on expert opinion and data largely from the United States and has not been revised to incorporate newer data.8 There are no publications regarding the app itself.

Regulation of Health-Related Apps

Health-related apps that are designed for utilization by health care providers can be a valuable tool. However, given their prevalence, cost, and potential impact on patient lives, these apps should be well regulated and researched. The general paucity of peer-reviewed literature demonstrating the utility, safety, quality, and accuracy of health-related apps commonly used by providers is a reflection of insufficient mobile health regulation in the United States.

There are 3 primary government agencies responsible for regulating mobile medical apps: the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Federal Trade Commission, and Office for Civil Rights.9 The FDA does not regulate all medical devices. Apps intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition are considered to be medical devices.10 The FDA regulates those apps only if they are judged to pose more than minimal risk. Apps that are designed only to provide easy access to information related to health conditions or treatment are considered to be minimal risk but can develop into a different risk level such as by offering AI.11 Although the FDA does update its approach to medical devices, including apps and AI- and machine learning–based software, the rate and direction of update has not kept pace with the rapid evolution of apps.12 In 2019, the FDA began piloting a precertification program that grants long-term approval to organizations that develop apps instead of reviewing each app product individually.13 This decrease in premarket oversight is intended to expedite innovation with the hopeful upside of improving patient outcomes but is inconsistent, with the FDA still reviewing other types of medical devices individually.

For apps that are already in use, the Federal Trade Commission only gets involved in response to deceptive or unfair acts or practices relating to privacy, data security, and false or misleading claims about safety or performance. It may be more beneficial for consumers if those apps had a more stringent initial approval process. The Office for Civil Rights enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act when relevant to apps.

Nongovernment agencies also are involved in app regulation. The FDA believes sharing more regulatory responsibility with private industry would promote efficiency.14 Google does not allow apps that contain false or misleading health claims,15 and Apple may scrutinize medical apps that could provide inaccurate data or be used for diagnosing or treating patients.16 Xcertia, a nonprofit organization founded by the American Medical Association and others, develops standards for the security, privacy, content, and operability of health-related apps, but those standards have not been adopted by other parties. Ultimately, nongovernment agencies are not responsible for public health and do not boast the government’s ability to enforce rules or ensure public safety.

Final Thoughts

The AAD survey of US dermatology residents found that the top consideration when choosing apps was up-to-date and accurate information; however, the 3 most prevalent apps among those same respondents did not need government approval and are not required to contain up-to-date data or to improve clinical outcomes, similar to most other health-related apps. This discrepancy is concerning considering the increasing utilization of apps for physician education and health care delivery and the increasing complexity of those apps. In light of these results, the potential decrease in federal premarket regulation suggested by the FDA’s precertification program seems inappropriate. It is important for the government to take responsibility for regulating health-related apps and to find a balance between too much regulation delaying innovation and too little regulation hurting physician training and patient care. It also is important for providers to be aware of the evidence and oversight behind the technologies they use for professional purposes.

- Clement J. Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 1st quarter 2020. Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/. Published May 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- mHealth App Economics 2017/2018. Current Status and Future Trends in Mobile Health. Berlin, Germany: Research 2 Guidance; 2018.

- Healthcare Client Services. Professional usage of smartphones by doctors. Kantar website. https://www.kantarmedia.com/us/thinking-and-resources/blog/professional-usage-of-smartphones-by-doctors-2016. Published November 16, 2016. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Skhal KJ, Koffel J. VisualDx. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95:470-471.

- UpToDate is the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/home/research. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Amber KT, Dhiman G, Goodman KW. Conflict of interest in online point-of-care clinical support websites. J Med Ethics. 2014;40:578-580.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs micrographic surgery appropriate use criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:E55.

- Mobile health apps interactive tool. Federal Trade Commission website. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/mobile-health-apps-interactive-tool. Published April 2016. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC §321 (2018).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Examples of software functions for which the FDA will exercise enforcement discretion. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications/examples-software-functions-which-fda-will-exercise-enforcement-discretion. Updated September 26, 2019. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Proposed regulatory framework for modifications to artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML)‐based software as a medical device (SaMD). https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DigitalHealth/SoftwareasaMedicalDevice/UCM635052.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Digital health software precertification (pre-cert) program. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/digital-health-software-precertification-pre-cert-program. Updated July 18, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Gottlieb S. Fostering medical innovation: a plan for digital health devices. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/fostering-medical-innovation-plan-digital-health-devices. Published June 15, 2017. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Restricted content: unapproved substances. Google Play website. https://play.google.com/about/restricted-content/unapproved-substances. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- App store review guidelines. Apple Developer website. https://developer.apple.com/app-store/review/guidelines. Updated March 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Clement J. Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 1st quarter 2020. Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/. Published May 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- mHealth App Economics 2017/2018. Current Status and Future Trends in Mobile Health. Berlin, Germany: Research 2 Guidance; 2018.

- Healthcare Client Services. Professional usage of smartphones by doctors. Kantar website. https://www.kantarmedia.com/us/thinking-and-resources/blog/professional-usage-of-smartphones-by-doctors-2016. Published November 16, 2016. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Skhal KJ, Koffel J. VisualDx. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95:470-471.

- UpToDate is the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/home/research. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Amber KT, Dhiman G, Goodman KW. Conflict of interest in online point-of-care clinical support websites. J Med Ethics. 2014;40:578-580.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs micrographic surgery appropriate use criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:E55.

- Mobile health apps interactive tool. Federal Trade Commission website. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/mobile-health-apps-interactive-tool. Published April 2016. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC §321 (2018).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Examples of software functions for which the FDA will exercise enforcement discretion. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications/examples-software-functions-which-fda-will-exercise-enforcement-discretion. Updated September 26, 2019. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Proposed regulatory framework for modifications to artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML)‐based software as a medical device (SaMD). https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DigitalHealth/SoftwareasaMedicalDevice/UCM635052.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Digital health software precertification (pre-cert) program. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/digital-health-software-precertification-pre-cert-program. Updated July 18, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Gottlieb S. Fostering medical innovation: a plan for digital health devices. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/fostering-medical-innovation-plan-digital-health-devices. Published June 15, 2017. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Restricted content: unapproved substances. Google Play website. https://play.google.com/about/restricted-content/unapproved-substances. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- App store review guidelines. Apple Developer website. https://developer.apple.com/app-store/review/guidelines. Updated March 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

Practice Points

- Physicians who are selecting an app for self-education or patient care should take into consideration the strength of the evidence supporting the app as well as the rigor of any approval process the app had to undergo.

- Only a minority of health-related apps are regulated by the government. This regulation has not kept up with the evolution of app software and may become more indirect.

Speaking Up, Questioning Assumptions About Racism

Let me start with these 3 words that really should never have to be said: Black Lives Matter.

It was hard to sit down to write this piece—not just because it’s a sunny Sunday morning, but because I’m still afraid I’ll get it wrong, show my white privilege, offend someone. George Floyd’s murder has been a reckoning for Black Americans, for the police, for the nation (maybe the world), and for me. I live in a multi-racial household, and we have redoubled our efforts to talk about racism and bias and question our assumptions as part of our daily conversations. After Mr. Floyd was killed, I decided that I would try to be less afraid of getting it wrong and be more outspoken about my support for Black Lives Matter and for the work that we need to do in this country, and in ourselves, to become more antiracist.

Here are some things that I know: I know that study after study has shown that health care and health outcomes are worse for Black people than for White people. I know that people of color are sickening and dying with COVID-19 before our eyes, just as other pandemics, such as HIV, differentially affect communities of color. I know, too, that a Black physician executive who lives around the corner from me has been stopped by our local police more than 10 times; I have been stopped by our local police exactly once.

I don’t know how to fix it. But I do know that my silence won’t help. Here are some things I am trying to do at home and at work: I am educating myself about race and racism. I’m not asking my Black peers, patients, or colleagues to teach me, but I am listening to what they tell me, when they want to tell me. I am reading books like Ibram Kendi’s How to Be Antiracist and Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other. I challenge myself to read articles that I might have skipped over—because they were simply too painful. People of color don’t have a choice about facing their pain. I have that choice—it’s a privilege—and I choose to be an ally.

I’m speaking up even when I’m afraid that I might say the wrong thing. This can take several forms—questioning assumptions about race and racism when it comes up, which is often, in medicine. It also means amplifying the voices that don’t always get heard—asking a young person of color her opinion in a meeting, retweeting the thoughts of a Black colleague, thanking someone publicly or personally for a comment, an idea, or the kernel of something important. I ask people to correct me, and I try to be humble in accepting criticism or correction.

Being a better ally also means putting our money where our mouth is, supporting Black-owned businesses and restaurants, and donating to causes that support equality and justice. We can diversify our social media feeds. We have to be willing to be excluded from the conversation—if you’re white or straight or cis-gendered, it’s not about you—and be ready to feel uncomfortable. We can encourag

Black Lives Matter. I’m looking forward to a day when that is so obvious that we don’t have to say it. Until then, I’m going to be hard at work with my head, my ears, and my whole heart.

Let me start with these 3 words that really should never have to be said: Black Lives Matter.

It was hard to sit down to write this piece—not just because it’s a sunny Sunday morning, but because I’m still afraid I’ll get it wrong, show my white privilege, offend someone. George Floyd’s murder has been a reckoning for Black Americans, for the police, for the nation (maybe the world), and for me. I live in a multi-racial household, and we have redoubled our efforts to talk about racism and bias and question our assumptions as part of our daily conversations. After Mr. Floyd was killed, I decided that I would try to be less afraid of getting it wrong and be more outspoken about my support for Black Lives Matter and for the work that we need to do in this country, and in ourselves, to become more antiracist.

Here are some things that I know: I know that study after study has shown that health care and health outcomes are worse for Black people than for White people. I know that people of color are sickening and dying with COVID-19 before our eyes, just as other pandemics, such as HIV, differentially affect communities of color. I know, too, that a Black physician executive who lives around the corner from me has been stopped by our local police more than 10 times; I have been stopped by our local police exactly once.

I don’t know how to fix it. But I do know that my silence won’t help. Here are some things I am trying to do at home and at work: I am educating myself about race and racism. I’m not asking my Black peers, patients, or colleagues to teach me, but I am listening to what they tell me, when they want to tell me. I am reading books like Ibram Kendi’s How to Be Antiracist and Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other. I challenge myself to read articles that I might have skipped over—because they were simply too painful. People of color don’t have a choice about facing their pain. I have that choice—it’s a privilege—and I choose to be an ally.

I’m speaking up even when I’m afraid that I might say the wrong thing. This can take several forms—questioning assumptions about race and racism when it comes up, which is often, in medicine. It also means amplifying the voices that don’t always get heard—asking a young person of color her opinion in a meeting, retweeting the thoughts of a Black colleague, thanking someone publicly or personally for a comment, an idea, or the kernel of something important. I ask people to correct me, and I try to be humble in accepting criticism or correction.

Being a better ally also means putting our money where our mouth is, supporting Black-owned businesses and restaurants, and donating to causes that support equality and justice. We can diversify our social media feeds. We have to be willing to be excluded from the conversation—if you’re white or straight or cis-gendered, it’s not about you—and be ready to feel uncomfortable. We can encourag

Black Lives Matter. I’m looking forward to a day when that is so obvious that we don’t have to say it. Until then, I’m going to be hard at work with my head, my ears, and my whole heart.

Let me start with these 3 words that really should never have to be said: Black Lives Matter.

It was hard to sit down to write this piece—not just because it’s a sunny Sunday morning, but because I’m still afraid I’ll get it wrong, show my white privilege, offend someone. George Floyd’s murder has been a reckoning for Black Americans, for the police, for the nation (maybe the world), and for me. I live in a multi-racial household, and we have redoubled our efforts to talk about racism and bias and question our assumptions as part of our daily conversations. After Mr. Floyd was killed, I decided that I would try to be less afraid of getting it wrong and be more outspoken about my support for Black Lives Matter and for the work that we need to do in this country, and in ourselves, to become more antiracist.

Here are some things that I know: I know that study after study has shown that health care and health outcomes are worse for Black people than for White people. I know that people of color are sickening and dying with COVID-19 before our eyes, just as other pandemics, such as HIV, differentially affect communities of color. I know, too, that a Black physician executive who lives around the corner from me has been stopped by our local police more than 10 times; I have been stopped by our local police exactly once.

I don’t know how to fix it. But I do know that my silence won’t help. Here are some things I am trying to do at home and at work: I am educating myself about race and racism. I’m not asking my Black peers, patients, or colleagues to teach me, but I am listening to what they tell me, when they want to tell me. I am reading books like Ibram Kendi’s How to Be Antiracist and Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other. I challenge myself to read articles that I might have skipped over—because they were simply too painful. People of color don’t have a choice about facing their pain. I have that choice—it’s a privilege—and I choose to be an ally.

I’m speaking up even when I’m afraid that I might say the wrong thing. This can take several forms—questioning assumptions about race and racism when it comes up, which is often, in medicine. It also means amplifying the voices that don’t always get heard—asking a young person of color her opinion in a meeting, retweeting the thoughts of a Black colleague, thanking someone publicly or personally for a comment, an idea, or the kernel of something important. I ask people to correct me, and I try to be humble in accepting criticism or correction.

Being a better ally also means putting our money where our mouth is, supporting Black-owned businesses and restaurants, and donating to causes that support equality and justice. We can diversify our social media feeds. We have to be willing to be excluded from the conversation—if you’re white or straight or cis-gendered, it’s not about you—and be ready to feel uncomfortable. We can encourag

Black Lives Matter. I’m looking forward to a day when that is so obvious that we don’t have to say it. Until then, I’m going to be hard at work with my head, my ears, and my whole heart.

Confronting the epidemic of racism in ObGyn practice

CASE Black woman in stable labor expresses fear

A 29-year-old Black woman (G1) at 39 0/7 weeks’ gestation presents to your labor and delivery unit reporting leaking fluid and contractions. She is found to have ruptured membranes and reassuring fetal testing. Her cervix is 4 cm dilated, and you recommend admission for expectant management of labor. She is otherwise healthy and has no significant medical history.

As you are finishing admitting this patient, you ask if she has any remaining questions. She asks quietly, “Am I going to die today?”

You provide reassurance of her stable clinical picture, then pause and ask the patient about her fears. She looks at you and says, “They didn’t believe Serena Williams, so why would they believe me?”

Your patient is referencing Serena Williams’ harrowing and public postpartum course, complicated by a pulmonary embolism and several reoperations.1 While many of us in the medical field may read this account as a story of challenges with an ultimate triumph, many expectant Black mothers hold Serena’s experience as a cautionary tale about deep-rooted inequities in our health care system that lead to potentially dangerous outcomes.

Disparities in care

They are right to be concerned. In the United States, Black mothers are 4 times more likely to die during or after pregnancy, mostly from preventable causes,2 and nearly 50% more likely to have a preterm delivery.3 These disparities extend beyond the delivery room to all aspects of ObGyn care. Black women are 2 to 3 times more likely to die from cervical cancer, and they are more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage, thus rendering treatment less effective.4 Black patients also have a higher burden of obesity, diabetes, and cardiac disease, and when they present to the hospital, receive evidence-based treatment at lower rates compared with White patients.5

Mourning the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, amongst the many other Black lives taken unjustly in the United States, has highlighted egregious practices against people of color embedded within the systems meant to protect and serve our communities. We as ObGyn physicians must take professional onus to recognize a devastating but humbling truth—systemic racism has long pervaded our health care practices and systems, and now more than ever, we must do more to stand by and for our patients.

As ObGyns, we help support patients through some of the happiest, most vulnerable, and potentially most dire moments of their lives. We help patients through the birth of their children, reproductive struggles, gynecologic concerns, and cancer diagnoses. Many of us chose this field for the privilege of caring for patients at these critical moments in their lives, but we have often neglected the racism present in our practices, our hospital settings, and the medical system itself. We often fail to acknowledge our own implicit bias and the role that we play in contributing to acts and experiences of racism that our patients and our colleagues face on a daily basis.

Racism in our origins

The history of obstetrics and gynecology shows us a long record of physicians perpetrating injustices that target marginalized communities of color. Dr. James Sims, often given the title of “father of modern gynecology,” performed numerous experiments on unanesthetized Black female slaves to develop procedures for fistulae repair and other surgical techniques.6 Throughout the twentieth century, dating as recent as 1979, state laws written in the name of public safety forcibly sterilized women of color to control an “undesirable population.”7 When a patient of color declines a method of long-acting reversible contraception, birth control pills, or tubal ligation, do you take the time to reflect on the potential context of the patient’s decision?

It is critical to recognize the legacy that these acts have on our patients today, leading to a higher burden of disease and an understandable distrust of the medical system. The uncovering of the unethical practices of the National Institutions of Health‒funded Tuskegee syphilis study, in which hundreds of Black men with latent syphilis were passively monitored despite the knowledge of a proven treatment, has attributed to a measurable decrease in life expectancy among Black males.8 Even as we face the COVID-19 pandemic, the undercurrent of racism continues to do harm. Black patients are 5 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 than their White counterparts. This disparity, in part, is a product of a higher burden of comorbidities and the privilege associated with shelter-in-place policies, which disproportionately strain communities of color.9

We as a medical community need to do better for our patients. No matter how difficult to confront, each of us must acknowledge our own biases and our duty to combat persistent and perpetual racism in our medical system. We need to commit to amplifying the voices of our Black patients and colleagues. It is not enough to celebrate diversity for performance sake—it is time to recognize that diversity saves lives.

We have a responsibility to rectify these traditions of injustice and work toward a safer, more equitable, healthy future for our patients and their families. While this pledge may seem daunting, changes at individual and systems levels can make a difference for all patients that come through our doors. In addition, to honor our oath to “do no harm,” we must act; Black lives matter, and we are charged as medical providers to help our patients thrive, especially those from historically oppressed communities and who continue to suffer inexcusable injustices in health care and beyond.

Take action

Here is a collection of ways to institute an antiracist environment and more equitable care for your patients.

Self-reflect and educate

- Learn about the role racism plays in ObGyn and modern medicine. One place to start: read “Medical Bondage: Race, Gender and the Origins of American Gynecology” by Deidre Cooper Owens. Also check out articles and key readings curated by the Black Mamas Matter Alliance.

- Introduce and sustain antiracism training for all staff in your clinic or hospital system. To start, consider taking these free and quick implicit bias tests at a staff or department meeting.

- Familiarize yourself and your colleagues with facets of reproductive justice—the human right to have children, to not have children, and to nurture children in a safe and healthy environment—and incorporate these values in your practice. Request trainings in reproductive justice from community groups like Sister Song.

- Sign up for updates for state and national bills addressing health inequity and access to reproductive health services. Show your support by calling your congress-people, testifying, or donating to a cause that promotes these bills. You can stay up to date on national issues with government affairs newsletters from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Sign up here.

- Continue the conversation and re-evaluate your personal and institution’s efforts to combat racism and social and reproductive injustices.

Provide access to high-quality reproductive health care

- Ask your patients what barriers they faced to come to your clinic and receive the care they needed. Consider incorporating the following screening tools regarding social determinants of health: PRAPARE screening tool, AAFP screening tool.

- Promote access to insurance and support programs, including nutrition, exercise and wellness, and safe home and school environments. Look up resources available to your patients by their zip codes using AAFP’s Neighborhood Navigator.

- Help patients access their medications at affordable prices in their neighborhoods by using free apps. Use the GoodRx app to identify discounts for prescriptions at various pharmacies, and search the Bedsider app to find out how your patients can get their birth control for free and delivered to their homes.

- Expand access to language services for patients who do not speak English as their first language. If working in a resource-limited setting, use the Google Translate app. Print out these free handouts for birth control fact sheets in different languages.

- Establish standardized protocols for common treatment paradigms to reduce the influence of bias in clinical scenarios. For example, institute a protocol for managing postoperative pain to ensure equal access to treatment.

- Institute the AIM (Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health) patient safety bundle on the Reduction of Peripartum Racial/Ethnic Disparities. Learn more about AIM’s maternal safety and quality improvement initiative to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality here.

Support a diverse workforce