User login

Deprescribing: Nicolas Badre

In this episode of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris speaks with Dr. Nicolas Badre about ways to approach reducing dosages or discontinuing medications that are not beneficial. Dr. Badre, who has written about “deprescribing,” is a forensic psychiatrist who holds teaching positions at the University of California San Diego, and the University of San Diego.

Subscribe here:

Amazon

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

In this episode of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris speaks with Dr. Nicolas Badre about ways to approach reducing dosages or discontinuing medications that are not beneficial. Dr. Badre, who has written about “deprescribing,” is a forensic psychiatrist who holds teaching positions at the University of California San Diego, and the University of San Diego.

Subscribe here:

Amazon

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

In this episode of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris speaks with Dr. Nicolas Badre about ways to approach reducing dosages or discontinuing medications that are not beneficial. Dr. Badre, who has written about “deprescribing,” is a forensic psychiatrist who holds teaching positions at the University of California San Diego, and the University of San Diego.

Subscribe here:

Amazon

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Large survey reveals that few MS patients have long-term care insurance

DALLAS – A number of sociodemographic factors may influence health and disability insurance access by individuals with multiple sclerosis, including employment, age, gender, disease duration, marital status, and ethnicity, results from a large survey suggest.

“The last similar work was conducted over 10 years ago and so much has happened in the meantime, including the Great Recession and the introduction of the Affordable Care Act, that offers protection for health care but not for other important types of insurance (short- and long-term disability, long-term care, and life),” lead study author Sarah Planchon, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. “MS is one of the most costly chronic diseases today. That is not only because of the cost of disease-modifying therapies but also because of lost employment and income. We wanted to better understand the insurance landscape so that we could in turn educate patients and professionals about the protection these insurances offer and advise them on how to obtain these policies.”

In an effort to evaluate factors that affect insurance access in MS, Dr. Planchon, a project scientist at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and her colleagues used the North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS), iConquerMS, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society to survey 2,507 individuals with the disease regarding insurance, demographic, health, disability, and employment status. They used covariate-adjusted nominal logistic regression to estimate odds ratios for the likelihood of having or not having a type of insurance. The majority of respondents (83%) were female, their mean age was 54 years, 91% were white, 65% were currently married, and their mean disease duration at the time of the survey was 16 years. In addition, 43% were employed full/part-time, and 29% were not employed or retired because of disability. Nearly all respondents (96%) reported having health insurance, while 59% had life insurance, 29% had private long-term disability insurance, 18% had short-term disability insurance, and 10% had long-term care insurance.

The researchers found that employment status had the greatest impact on insurance coverage. Of those with health insurance, 33% were employed full-time, compared with 89% of those with short-term disability insurance, 42% of those with private long-term disability insurance, 44% of those with long-term care insurance, and 41% of those with life insurance. Logistic regression analyses indicated that respondents employed part time were significantly more likely to have short-term disability insurance if they were currently married (odds ratio, 4.4). Short-term disability insurance was significantly more likely among fully employed patients with disease duration of 5-10 years vs. more than 20 years (OR, 2.0). Private long-term disability insurance was significantly associated with female gender (OR, 1.6), age 50-59 years vs. younger than 40 (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.3), and shorter disease duration (ORs, 1.4-1.6 for 6-10, 11-15, and 16-20 years’ duration). Long-term care insurance was associated with older age (ORs, 2.5 and 4.3 for those aged 50-59 and 60-65 vs. younger than 40), and having excellent or good general health status vs. fair or poor (OR, 1.8). Life insurance was associated with non-Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.4), older age (ORs, 1.6-1.7 for ages 40-49 and 50-59 vs. younger than 40), and marital status (currently/previously married, ORs, 1.6-2.6). Considering the high rate of survey respondents with health insurance, covariate-adjusted modeling was not applicable.

“The number of people with MS who do not have long-term care insurance was surprisingly high,” Dr. Planchon said. “Although the improved treatment climate recently may decrease the long-term disability levels, we do not yet know this with certainty. A large number of people with MS are likely to need long-term care in the future, which often is a significant financial burden to families.” The findings suggest that clinical care teams “need to initiate early discussions of possible long-term needs with their patients,” she continued. “Incorporation of social work teams, who are familiar with the needs of people with MS and insurance options available to them, within MS specialty practices will bolster the comprehensive care of patients and their families.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the low proportion of respondents who were Hispanic/Latino and African American (about 4% each). “The insurance landscape may differ in these groups compared to the majority Caucasian population who responded to this survey,” Dr. Planchon said.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society funded the study. Dr. Planchon reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Planchon S et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Abstract P295.

DALLAS – A number of sociodemographic factors may influence health and disability insurance access by individuals with multiple sclerosis, including employment, age, gender, disease duration, marital status, and ethnicity, results from a large survey suggest.

“The last similar work was conducted over 10 years ago and so much has happened in the meantime, including the Great Recession and the introduction of the Affordable Care Act, that offers protection for health care but not for other important types of insurance (short- and long-term disability, long-term care, and life),” lead study author Sarah Planchon, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. “MS is one of the most costly chronic diseases today. That is not only because of the cost of disease-modifying therapies but also because of lost employment and income. We wanted to better understand the insurance landscape so that we could in turn educate patients and professionals about the protection these insurances offer and advise them on how to obtain these policies.”

In an effort to evaluate factors that affect insurance access in MS, Dr. Planchon, a project scientist at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and her colleagues used the North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS), iConquerMS, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society to survey 2,507 individuals with the disease regarding insurance, demographic, health, disability, and employment status. They used covariate-adjusted nominal logistic regression to estimate odds ratios for the likelihood of having or not having a type of insurance. The majority of respondents (83%) were female, their mean age was 54 years, 91% were white, 65% were currently married, and their mean disease duration at the time of the survey was 16 years. In addition, 43% were employed full/part-time, and 29% were not employed or retired because of disability. Nearly all respondents (96%) reported having health insurance, while 59% had life insurance, 29% had private long-term disability insurance, 18% had short-term disability insurance, and 10% had long-term care insurance.

The researchers found that employment status had the greatest impact on insurance coverage. Of those with health insurance, 33% were employed full-time, compared with 89% of those with short-term disability insurance, 42% of those with private long-term disability insurance, 44% of those with long-term care insurance, and 41% of those with life insurance. Logistic regression analyses indicated that respondents employed part time were significantly more likely to have short-term disability insurance if they were currently married (odds ratio, 4.4). Short-term disability insurance was significantly more likely among fully employed patients with disease duration of 5-10 years vs. more than 20 years (OR, 2.0). Private long-term disability insurance was significantly associated with female gender (OR, 1.6), age 50-59 years vs. younger than 40 (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.3), and shorter disease duration (ORs, 1.4-1.6 for 6-10, 11-15, and 16-20 years’ duration). Long-term care insurance was associated with older age (ORs, 2.5 and 4.3 for those aged 50-59 and 60-65 vs. younger than 40), and having excellent or good general health status vs. fair or poor (OR, 1.8). Life insurance was associated with non-Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.4), older age (ORs, 1.6-1.7 for ages 40-49 and 50-59 vs. younger than 40), and marital status (currently/previously married, ORs, 1.6-2.6). Considering the high rate of survey respondents with health insurance, covariate-adjusted modeling was not applicable.

“The number of people with MS who do not have long-term care insurance was surprisingly high,” Dr. Planchon said. “Although the improved treatment climate recently may decrease the long-term disability levels, we do not yet know this with certainty. A large number of people with MS are likely to need long-term care in the future, which often is a significant financial burden to families.” The findings suggest that clinical care teams “need to initiate early discussions of possible long-term needs with their patients,” she continued. “Incorporation of social work teams, who are familiar with the needs of people with MS and insurance options available to them, within MS specialty practices will bolster the comprehensive care of patients and their families.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the low proportion of respondents who were Hispanic/Latino and African American (about 4% each). “The insurance landscape may differ in these groups compared to the majority Caucasian population who responded to this survey,” Dr. Planchon said.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society funded the study. Dr. Planchon reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Planchon S et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Abstract P295.

DALLAS – A number of sociodemographic factors may influence health and disability insurance access by individuals with multiple sclerosis, including employment, age, gender, disease duration, marital status, and ethnicity, results from a large survey suggest.

“The last similar work was conducted over 10 years ago and so much has happened in the meantime, including the Great Recession and the introduction of the Affordable Care Act, that offers protection for health care but not for other important types of insurance (short- and long-term disability, long-term care, and life),” lead study author Sarah Planchon, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. “MS is one of the most costly chronic diseases today. That is not only because of the cost of disease-modifying therapies but also because of lost employment and income. We wanted to better understand the insurance landscape so that we could in turn educate patients and professionals about the protection these insurances offer and advise them on how to obtain these policies.”

In an effort to evaluate factors that affect insurance access in MS, Dr. Planchon, a project scientist at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and her colleagues used the North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS), iConquerMS, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society to survey 2,507 individuals with the disease regarding insurance, demographic, health, disability, and employment status. They used covariate-adjusted nominal logistic regression to estimate odds ratios for the likelihood of having or not having a type of insurance. The majority of respondents (83%) were female, their mean age was 54 years, 91% were white, 65% were currently married, and their mean disease duration at the time of the survey was 16 years. In addition, 43% were employed full/part-time, and 29% were not employed or retired because of disability. Nearly all respondents (96%) reported having health insurance, while 59% had life insurance, 29% had private long-term disability insurance, 18% had short-term disability insurance, and 10% had long-term care insurance.

The researchers found that employment status had the greatest impact on insurance coverage. Of those with health insurance, 33% were employed full-time, compared with 89% of those with short-term disability insurance, 42% of those with private long-term disability insurance, 44% of those with long-term care insurance, and 41% of those with life insurance. Logistic regression analyses indicated that respondents employed part time were significantly more likely to have short-term disability insurance if they were currently married (odds ratio, 4.4). Short-term disability insurance was significantly more likely among fully employed patients with disease duration of 5-10 years vs. more than 20 years (OR, 2.0). Private long-term disability insurance was significantly associated with female gender (OR, 1.6), age 50-59 years vs. younger than 40 (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.3), and shorter disease duration (ORs, 1.4-1.6 for 6-10, 11-15, and 16-20 years’ duration). Long-term care insurance was associated with older age (ORs, 2.5 and 4.3 for those aged 50-59 and 60-65 vs. younger than 40), and having excellent or good general health status vs. fair or poor (OR, 1.8). Life insurance was associated with non-Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.4), older age (ORs, 1.6-1.7 for ages 40-49 and 50-59 vs. younger than 40), and marital status (currently/previously married, ORs, 1.6-2.6). Considering the high rate of survey respondents with health insurance, covariate-adjusted modeling was not applicable.

“The number of people with MS who do not have long-term care insurance was surprisingly high,” Dr. Planchon said. “Although the improved treatment climate recently may decrease the long-term disability levels, we do not yet know this with certainty. A large number of people with MS are likely to need long-term care in the future, which often is a significant financial burden to families.” The findings suggest that clinical care teams “need to initiate early discussions of possible long-term needs with their patients,” she continued. “Incorporation of social work teams, who are familiar with the needs of people with MS and insurance options available to them, within MS specialty practices will bolster the comprehensive care of patients and their families.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the low proportion of respondents who were Hispanic/Latino and African American (about 4% each). “The insurance landscape may differ in these groups compared to the majority Caucasian population who responded to this survey,” Dr. Planchon said.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society funded the study. Dr. Planchon reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Planchon S et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Abstract P295.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

Big pharma says it can’t drop drug list prices alone

Top pharmaceutical executives expressed willingness to lower the list prices of their drugs, but only if there were cooperation among all sectors to reform how drugs get from manufacturer to patient.

That theme was common in the testimony of seven pharmaceutical executives before the Senate Finance Committee during a Feb. 26 hearing.

“We are in a system that used to be fit for purpose and really drove enormous savings over the last few years but it is no longer fit for purpose,” Pascal Soriot, executive director and CEO of AstraZeneca, testified before the committee. “It’s one of those situations where nobody in the system can do anything, can fix it by themselves.”

The problem, the executives agreed, is the financial structure of drug delivery that ties list prices and their associated rebates to formulary placement.

“If you went back a few years ago, when we negotiated to get our drugs on formulary, our goal was to have the lowest copay by patients,” Kenneth Frazier, chairman and CEO of Merck, testified before the committee. “Today, the goal is to pay into the supply chain the biggest rebate. That actually puts the patient at a disadvantage since they are the only ones that are paying a portion of the list price. The list price is actually working against the patient.”

When asked why the list prices of prescription drugs are so high, Olivier Brandicourt, MD, CEO of Sanofi, said, “We are trying to get formulary position with those high list price-high rebate. It’s a preferred position. Unfortunately that preferred position doesn’t automatically ensure affordability.”

Mr. Frazier added that if a manufacturer brings a product “with a low list price in this system, you get punished financially and you get no uptake because everyone in the supply chain makes money as a result of a higher list price.”

Executives noted that when accounting for financial incentives such as rebates, discounts, and coupons, net prices for pharmaceuticals have actually come down even as list prices are on the rise to accommodate competition on formulary placement.

But that is obscured at the pharmacy counter, where patients are paying higher and higher out-of-pocket costs because more often than not, payment is tied to the list price of the drug, not the net price after all rebates and other discounts have been taken into consideration.

This is a particular problem in Medicare Part D, said AbbVie Chairman and CEO Richard Gonzalez.

“Due to the structure of the Part D benefit design, patients are charged out-of-pocket costs on a medicine’s list price which does not reflect the market-based rebates that Medicare receives,” he testified.

Despite acknowledging that this is a problem, the executives gathered were hesitant to commit to simply lowering the list prices, or anything for that matter.

The closest the panel came to a commitment to lowering the list prices of their drugs was to do so if all rebates went away in both the public and private sector.

But beyond that, the pharma executives continued to assign responsibility for high out-of-pocket drug costs to other players in the health care system, adding that the only way to change the situation would be to have everyone come to the table simultaneously.

“I understand the dissatisfaction with our industry,” Mr. Frazier said. “I understand why patients are frustrated because they need these medicines and they can’t afford them. I would pledge to do everything that we could, but I would urge you to recognize that the system itself is complex and it is interdependent and no one company can unilaterally lower list prices without running into financial and operating disadvantages that make it impossible to do that. But if we all bring the parties together around the table with the goal of doing what’s best for the patient, I think we can some up with a system that works for all Americans.”

Ultimately, the panel suggested, legislation is going to be required to change the system.

Top pharmaceutical executives expressed willingness to lower the list prices of their drugs, but only if there were cooperation among all sectors to reform how drugs get from manufacturer to patient.

That theme was common in the testimony of seven pharmaceutical executives before the Senate Finance Committee during a Feb. 26 hearing.

“We are in a system that used to be fit for purpose and really drove enormous savings over the last few years but it is no longer fit for purpose,” Pascal Soriot, executive director and CEO of AstraZeneca, testified before the committee. “It’s one of those situations where nobody in the system can do anything, can fix it by themselves.”

The problem, the executives agreed, is the financial structure of drug delivery that ties list prices and their associated rebates to formulary placement.

“If you went back a few years ago, when we negotiated to get our drugs on formulary, our goal was to have the lowest copay by patients,” Kenneth Frazier, chairman and CEO of Merck, testified before the committee. “Today, the goal is to pay into the supply chain the biggest rebate. That actually puts the patient at a disadvantage since they are the only ones that are paying a portion of the list price. The list price is actually working against the patient.”

When asked why the list prices of prescription drugs are so high, Olivier Brandicourt, MD, CEO of Sanofi, said, “We are trying to get formulary position with those high list price-high rebate. It’s a preferred position. Unfortunately that preferred position doesn’t automatically ensure affordability.”

Mr. Frazier added that if a manufacturer brings a product “with a low list price in this system, you get punished financially and you get no uptake because everyone in the supply chain makes money as a result of a higher list price.”

Executives noted that when accounting for financial incentives such as rebates, discounts, and coupons, net prices for pharmaceuticals have actually come down even as list prices are on the rise to accommodate competition on formulary placement.

But that is obscured at the pharmacy counter, where patients are paying higher and higher out-of-pocket costs because more often than not, payment is tied to the list price of the drug, not the net price after all rebates and other discounts have been taken into consideration.

This is a particular problem in Medicare Part D, said AbbVie Chairman and CEO Richard Gonzalez.

“Due to the structure of the Part D benefit design, patients are charged out-of-pocket costs on a medicine’s list price which does not reflect the market-based rebates that Medicare receives,” he testified.

Despite acknowledging that this is a problem, the executives gathered were hesitant to commit to simply lowering the list prices, or anything for that matter.

The closest the panel came to a commitment to lowering the list prices of their drugs was to do so if all rebates went away in both the public and private sector.

But beyond that, the pharma executives continued to assign responsibility for high out-of-pocket drug costs to other players in the health care system, adding that the only way to change the situation would be to have everyone come to the table simultaneously.

“I understand the dissatisfaction with our industry,” Mr. Frazier said. “I understand why patients are frustrated because they need these medicines and they can’t afford them. I would pledge to do everything that we could, but I would urge you to recognize that the system itself is complex and it is interdependent and no one company can unilaterally lower list prices without running into financial and operating disadvantages that make it impossible to do that. But if we all bring the parties together around the table with the goal of doing what’s best for the patient, I think we can some up with a system that works for all Americans.”

Ultimately, the panel suggested, legislation is going to be required to change the system.

Top pharmaceutical executives expressed willingness to lower the list prices of their drugs, but only if there were cooperation among all sectors to reform how drugs get from manufacturer to patient.

That theme was common in the testimony of seven pharmaceutical executives before the Senate Finance Committee during a Feb. 26 hearing.

“We are in a system that used to be fit for purpose and really drove enormous savings over the last few years but it is no longer fit for purpose,” Pascal Soriot, executive director and CEO of AstraZeneca, testified before the committee. “It’s one of those situations where nobody in the system can do anything, can fix it by themselves.”

The problem, the executives agreed, is the financial structure of drug delivery that ties list prices and their associated rebates to formulary placement.

“If you went back a few years ago, when we negotiated to get our drugs on formulary, our goal was to have the lowest copay by patients,” Kenneth Frazier, chairman and CEO of Merck, testified before the committee. “Today, the goal is to pay into the supply chain the biggest rebate. That actually puts the patient at a disadvantage since they are the only ones that are paying a portion of the list price. The list price is actually working against the patient.”

When asked why the list prices of prescription drugs are so high, Olivier Brandicourt, MD, CEO of Sanofi, said, “We are trying to get formulary position with those high list price-high rebate. It’s a preferred position. Unfortunately that preferred position doesn’t automatically ensure affordability.”

Mr. Frazier added that if a manufacturer brings a product “with a low list price in this system, you get punished financially and you get no uptake because everyone in the supply chain makes money as a result of a higher list price.”

Executives noted that when accounting for financial incentives such as rebates, discounts, and coupons, net prices for pharmaceuticals have actually come down even as list prices are on the rise to accommodate competition on formulary placement.

But that is obscured at the pharmacy counter, where patients are paying higher and higher out-of-pocket costs because more often than not, payment is tied to the list price of the drug, not the net price after all rebates and other discounts have been taken into consideration.

This is a particular problem in Medicare Part D, said AbbVie Chairman and CEO Richard Gonzalez.

“Due to the structure of the Part D benefit design, patients are charged out-of-pocket costs on a medicine’s list price which does not reflect the market-based rebates that Medicare receives,” he testified.

Despite acknowledging that this is a problem, the executives gathered were hesitant to commit to simply lowering the list prices, or anything for that matter.

The closest the panel came to a commitment to lowering the list prices of their drugs was to do so if all rebates went away in both the public and private sector.

But beyond that, the pharma executives continued to assign responsibility for high out-of-pocket drug costs to other players in the health care system, adding that the only way to change the situation would be to have everyone come to the table simultaneously.

“I understand the dissatisfaction with our industry,” Mr. Frazier said. “I understand why patients are frustrated because they need these medicines and they can’t afford them. I would pledge to do everything that we could, but I would urge you to recognize that the system itself is complex and it is interdependent and no one company can unilaterally lower list prices without running into financial and operating disadvantages that make it impossible to do that. But if we all bring the parties together around the table with the goal of doing what’s best for the patient, I think we can some up with a system that works for all Americans.”

Ultimately, the panel suggested, legislation is going to be required to change the system.

REPORTING FROM SENATE FINANCE COMMITTEE HEARING

What does 'Medicare for all' mean?

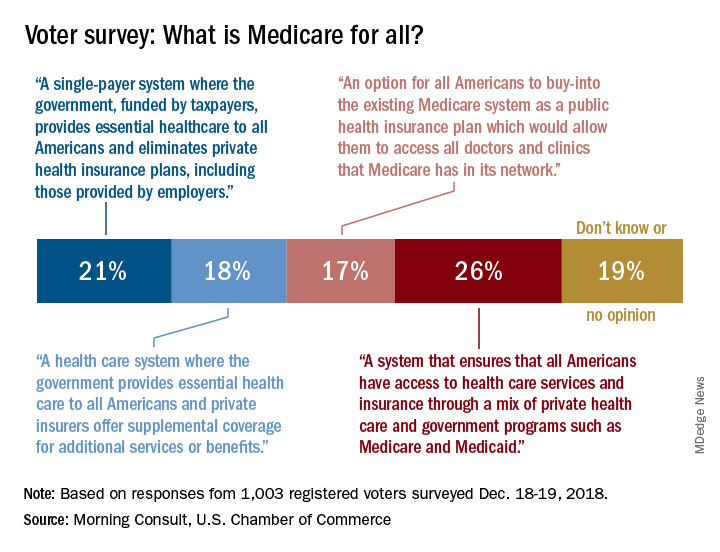

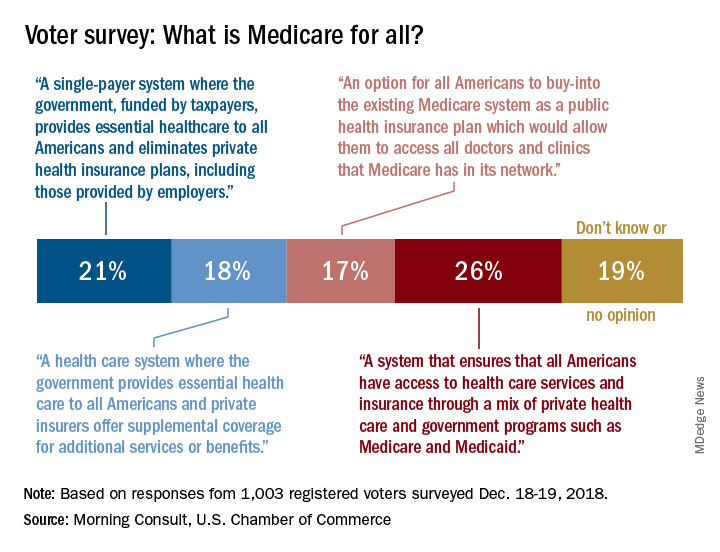

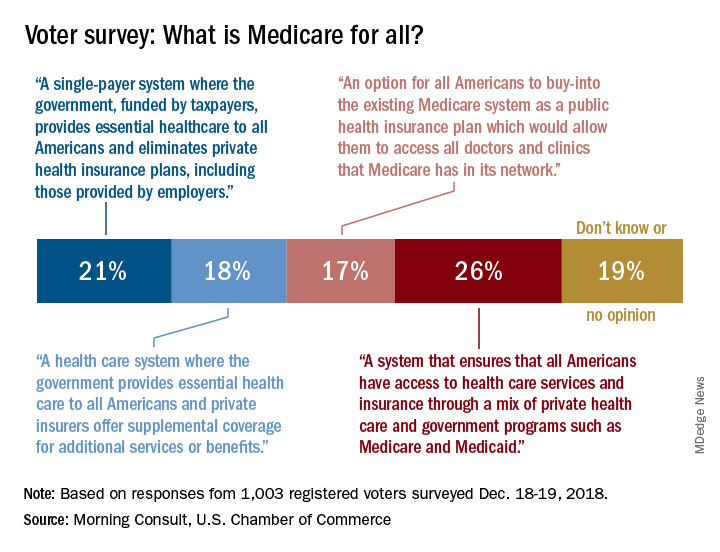

Only about a fifth of Americans correctly identified the description of a Medicare-for-all system in a recent national tracking poll.

Four descriptions of a Medicare-for-all health care system were provided, and only 21% of respondents correctly selected “a single-payer system where the government, funded by taxpayers, provides essential health care to all Americans and eliminates private health insurance plans, including those provided by employers,” according to the tracking poll from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and digital media company Morning Consult.

The most common selection – chosen by 26% of the 1,003 registered voters who answered the question (about half of all the respondents) – involved “a system that ensures that all Americans have access to health care services and insurance through a mix of private health care and government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.”

The other choices covered a federal system with available private supplemental coverage and another with the option of buying in to the existing Medicare system, the report said. Another 19% of respondents to the survey, which was conducted Dec. 18-19, said that they didn’t know or had no opinion.

Questions covering other areas of possible future legislation, which were answered by all of the 2,000 respondents, showed strong support for protection against surprise hospital bills (90%), reforming the Affordable Care Act (73%), and protecting the Affordable Care Act (63%), the U.S. Chamber and Morning Consult reported. The survey’s margin of error was plus or minus two percentage points.

Only about a fifth of Americans correctly identified the description of a Medicare-for-all system in a recent national tracking poll.

Four descriptions of a Medicare-for-all health care system were provided, and only 21% of respondents correctly selected “a single-payer system where the government, funded by taxpayers, provides essential health care to all Americans and eliminates private health insurance plans, including those provided by employers,” according to the tracking poll from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and digital media company Morning Consult.

The most common selection – chosen by 26% of the 1,003 registered voters who answered the question (about half of all the respondents) – involved “a system that ensures that all Americans have access to health care services and insurance through a mix of private health care and government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.”

The other choices covered a federal system with available private supplemental coverage and another with the option of buying in to the existing Medicare system, the report said. Another 19% of respondents to the survey, which was conducted Dec. 18-19, said that they didn’t know or had no opinion.

Questions covering other areas of possible future legislation, which were answered by all of the 2,000 respondents, showed strong support for protection against surprise hospital bills (90%), reforming the Affordable Care Act (73%), and protecting the Affordable Care Act (63%), the U.S. Chamber and Morning Consult reported. The survey’s margin of error was plus or minus two percentage points.

Only about a fifth of Americans correctly identified the description of a Medicare-for-all system in a recent national tracking poll.

Four descriptions of a Medicare-for-all health care system were provided, and only 21% of respondents correctly selected “a single-payer system where the government, funded by taxpayers, provides essential health care to all Americans and eliminates private health insurance plans, including those provided by employers,” according to the tracking poll from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and digital media company Morning Consult.

The most common selection – chosen by 26% of the 1,003 registered voters who answered the question (about half of all the respondents) – involved “a system that ensures that all Americans have access to health care services and insurance through a mix of private health care and government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.”

The other choices covered a federal system with available private supplemental coverage and another with the option of buying in to the existing Medicare system, the report said. Another 19% of respondents to the survey, which was conducted Dec. 18-19, said that they didn’t know or had no opinion.

Questions covering other areas of possible future legislation, which were answered by all of the 2,000 respondents, showed strong support for protection against surprise hospital bills (90%), reforming the Affordable Care Act (73%), and protecting the Affordable Care Act (63%), the U.S. Chamber and Morning Consult reported. The survey’s margin of error was plus or minus two percentage points.

Medicine grapples with COI reporting

Conflict of interest (COI) reporting has moved center stage again in recent months, with some medical journals, professional societies, cancer centers, and academic medical institutions reviewing policies and practices in the wake of a highly publicized disclosure failure last fall at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK).

And in some settings, oncologists and other physician researchers are being encouraged to check what the federal Open Payments database says about their payments from industry.

The spotlight is on the field of cancer research and treatment, where MSK’s chief medical officer, José Baselga, MD, PhD, resigned in September 2018 after the New York Times and ProPublica reported that he’d failed to disclose millions of dollars of industry payments and ownership interests in the majority of journal articles he wrote or cowrote over a 4-year period.

COI disclosure issues have a broad reach, however, and the policy reviews, debates, and hashing out of responsibilities that are now taking place likely will have implications for all of medicine.

Among the questions: Who enforces disclosure rules and how should cases of incomplete or inconsistent disclosure be handled? How can COI declarations be made easier for researchers? Should disclosure be based on self-reported relevancy, or more comprehensive in nature?

Such questions are being debated nationally. On Feb. 12, 2019, leaders from academia, journals, and medical societies came together in Washington, D.C., at the offices of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) for a closed-door meeting focused on COI disclosures. MSK, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies led the charge as cosponsors of the meeting.

“We’ve been dealing with disclosure issues in a siloed way in exchanges [between journal editors and authors, for instance, or between speakers and CME providers]. And academic institutions have their own robust disclosure mechanisms that they use internally,” said Heather Pierce, JD, MPH, senior director of science policy and regulatory counsel for the AAMC. “There’s a growing understanding that these conversations need to be happening across these different sectors.”

Pleas for accuracy

At academic medical institutions, conflicts of interest are identified and then managed; it’s common for researchers’ COI management plans to include requirements for disclosure in all presentations and publications.

Journals and professional medical societies require authors and speakers to submit disclosure forms of varying lengths and with differing questions about relationships with industry, often based on the notion of relevancy to the subject at hand. Disclosure forms are reviewed, but editors and other reviewers rely largely – if not entirely – on the honor system.

Dr. Baselga’s disclosure lapses and his subsequent resignation have rattled leaders in each of these settings. Researchers at MSK were instructed to review their COI disclosures and submit corrections when necessary, and in December 2018 the hospital was reportedly evaluating its process for reviewing conflicts of interest, according to reports in the New York Times and ProPublica. (MSK did not respond to requests for comment about actions taken.)

The Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston similarly has “been reminding faculty and other researchers” of their disclosure responsibilities and is conducting a review of “all our policies in this area,” a spokeswoman said. And at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, a spokesman said they have established an internal task force to review individual and institutional COI policies to ensure that COIs are “appropriately managed while also enabling research collaborations that bring scientific advances to our patients.”

Other centers contacted for this article, such as the Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center and the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, said that they have no new reviews ongoing and no plans to change policies at this time.

The heightened attention to disclosure has, in turn, shone a spotlight on increasingly complex physician-industry relationships and on the Open Payments website run by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Open Payments is a disclosure program and database that tracks payments made to physicians and teaching hospitals by drug and device companies.

Journalists, including those who reported on Dr. Baselga’s disclosures, have searched the public database for industry payment data. So have other researchers who have studied financial disclosure statements; a study reported in JAMA Oncology last year, for instance, concluded through the use of Open Payments data that about one-third of authors of cancer drug trial reports did not completely disclose payments from trial sponsors (JAMA Oncol. 2018;4[10]:1426-8

In a column published in December 2018 in AAMC News, AAMC President and CEO Darrell G. Kirch, MD, wrote that failures to disclose can raise questions about the integrity of research, whether or not there is an actual conflict. He advised institutions to “encourage faculty to review the information posted about them on the Open Payments website” of the CMS to “ensure it is accurate and consistent with disclosures related to all their professional responsibilities.”

ASCO issues similar advice, encouraging authors and CME speakers and participants of other ASCO activities to double-check their disclosures against other sources, including “publicly reported interactions with companies that may have been inadvertently omitted.”

In the world of journals, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) began asking authors at the end of 2018 to “certify that they have reconciled their disclosures” with the Open Payments database, said Jennifer Zeis, a spokeswoman forthe journal.

Time may tell how well such requests work. When the Institute of Medicine (now called the National Academy of Medicine) called on Congress in 2009 to create a national program requiring pharmaceutical, device, and biotechnology companies to publicly report their payments, it envisioned universities, journals, and others using the program to verify disclosures made to them. But the resulting Open Payments database has limitations – for instance, it doesn’t include payments from companies without FDA-approved products, it is not necessarily up to date, and its payment categories do not necessarily match categories of disclosure.

“Some entries in the Open Payments database need further explanation,” said Ms. Zeis of NEJM. “Some authors, for example, have said that the database does not fully and accurately explain that the funds were disbursed not to them personally, but to their academic institutions.” While the database provides transparency, it also “needs context that’s not currently provided,” she said.

Mistakes in the database can also be “very hard to challenge,” said Clifford A. Hudis, MD, CEO of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which produces the Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO).

All in all, he said, “there’s really no timely, comprehensive, and fully reliable source of information with which to verify an individual’s disclosures.”

Policies and practices are also under review at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and the American Society of Hematology (ASH).

The AACR has appointed a panel of experts, including physicians, basic scientists, a patient advocate, and others to conduct “a comprehensive review of [its] disclosure policies and to explore whether any current policies need to be revised,” said Rachel Salis-Silverman, director of public relations. It also will convene a session on COI disclosures at its 2019 annual meeting at the end of March, she said.

ASH, which publishes the journal Blood, is exploring possible changes in its “internal processes with regards to ASH publications,” said Matt Gertzog, deputy executive director of the group. COI disclosure is “more of a journey than a destination,” he said. “We are continuously reflecting on and refining our processes.”

Moving away from ‘relevancy’

Physicians and others who have relationships with industry have long complained about a patchwork of disclosure requirements, and significant efforts have been made in the last decade to standardize forms and practices. However, the current system is still “a little bit of a Tower of Babel,” said Dr. Hudis of ASCO. “Every day, physicians have to complete from scratch similar, but not identical, disclosure forms that ask similar, but not identical, questions.”

A disclosable compensation amount “might be first dollar, or it might be over $10,000. [Time periods] might cover 1 year, or 3 years. ... Stock ownership might be dollar value, or a percentage of shares,” he explained. “If you want a system that would make it hard to be compliant and easy to mess up, that’s what we have.”

To standardize the COI disclosure process for all Society-related publications and activities – including CME, JCO, and practice guidelines – ASCO moved about 5 years ago to a system of general disclosure, asking physicians and others to disclose all financial interests and industry relationships rather than what they deem relevant.

The thinking was that general disclosure “would be easier for disclosers, and nobody would ever be accused of hiding anything,” Dr. Hudis said.

“We’d [also] recognized,” he explained, “that there was a risk to the relevancy approach in that it put the judgment for the potential conflict in the hands of the potentially conflicted, while others might have a different point of view about what is or isn’t relevant.”

Those concerned about general disclosure worry that it may “obscure [for the reader or listener] what’s really important or the most meaningful,” he said.

Some physicians have expressed in interviews for this article, moreover, the concern that too many disclosures – too long a list of financial relationships – will be viewed negatively. This is something ASCO aims to guard against as it strives to achieve full transparency, Dr. Hudis said. “If one were to suggest that engagement itself is automatically a negative, then you’re starting to put negative pressure on compliance with disclosure.”

And full disclosure matters, he said. “We have to err in the direction of believing that disclosure is good,” he said, “even if we can’t prove it has clear and measurable impact. That is why our goal is to make full disclosure easier. What potential conflicts are acceptable, or not, is an important but entirely separate matter.”

Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA and the JAMA Network, frames the pros and cons of general and relevant disclosure similarly, and emphasizes that the relationships of authors with industry – particularly with private equity start-up companies – has changed dramatically over the past decade. Editors have “talked about complete versus [more narrowly] relevant disclosures at length,” he said, and have been moving overall “toward more complete disclosure where the reader can make a decision on their own.”

Other journals also are taking this approach. In 2009, in an effort to reduce variability in reporting processes and formats, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) developed a uniform electronic disclosure form that asks about financial relationships and interactions with any entity that could be considered “broadly relevant” to the submitted work. The group updated the form in December 2018.

As an example, the form reads, an article about testing an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antagonist in lung cancer requires the reporting of “all associations with entities pursuing diagnostic or therapeutic strategies in cancer in general, not just in the area of EGFR or lung cancer.” JAMA, NEJM, and The Lancet are among those journals that embrace the ICMJE’s policies and use its form.

To simplify its own disclosure process, JAMA and the network’s journals ended the practice in January 2019 of requiring both the ICMJE form and JAMA’s own separate disclosure form. The journals now use a single electronic form that includes questions from the ICMJE form. And to promote more consistent and complete reporting, the electronic form contains prompts that ask authors each time they answer “no” to one of four specific questions about potential COI whether they are certain of their answers and whether their answers are consistent with other disclosures they recently made.

While relevancy statements “create struggles for authors,” about two-thirds of the disclosure inaccuracies reported by readers and verified by JAMA’s editors (most often through editor-author discussions) involve a complete lack of disclosure rather than questions of relevancy, Dr. Bauchner noted. (JAMA and the network’s journals receive about 30,000 disclosure forms each year.)

The AAMC, in the meantime, has developed a central web-based repository for disclosures called Convey. Physicians and others can maintain secure records of financial interests in the repository, and these records can then be disclosed directly to any journal or organization that uses the system. The tool – born from discussions that followed the 2009 IOM report on COI – is “intended to facilitate more complete, more accurate, and more consistent” disclosures,” said Ms. Pierce of the AAMC. It is now live and in its early stages of use; NEJM assisted in its development and has been one of its pilot testers.

Enforcement questions

Some experts believe that institutions should maintain public databases of disclosures and/or that disclosure requirements should be better enforced in-house.

“There often are no clear guidelines in institutions about how to respond to people who are negligent in how they’re managing their disclosures,” said Jeffrey R. Botkin, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and associate vice president for research at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who has served on a variety of ethics committees and is an elected member of the Hastings Center. Dr. Botkin proposed in a Viewpoint published last October in JAMA that failure to disclose significant COIs should be considered research misconduct (JAMA 2018;320[22]:2307-8).

At the University of Utah, “we’re getting better at saying, ‘show us that you’ve disclosed,’ ” he said. “In some cases we’ll do spot checks of journal articles to make sure [researchers have] followed through with their disclosures.”

John Abramson, MD, a lecturer in the department of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Boston, contends that incomplete declarations of COI have been shown to correlate with reporting of manufacturer-friendly research results. Journals should have “zero tolerance” standards for incomplete or inaccurate COI declarations and should, among other things, “inform academic institutions of breaches of integrity.”

At JAMA, which in 2017 published a theme issue on COI and COI declarations, editors have been discussing whether they will contact an author’s institution “if there’s a pattern involved [with disclosure problems] or if there’s a lack of declaration of multiple COIs,” Dr. Bauchner said.

Conflict of interest (COI) reporting has moved center stage again in recent months, with some medical journals, professional societies, cancer centers, and academic medical institutions reviewing policies and practices in the wake of a highly publicized disclosure failure last fall at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK).

And in some settings, oncologists and other physician researchers are being encouraged to check what the federal Open Payments database says about their payments from industry.

The spotlight is on the field of cancer research and treatment, where MSK’s chief medical officer, José Baselga, MD, PhD, resigned in September 2018 after the New York Times and ProPublica reported that he’d failed to disclose millions of dollars of industry payments and ownership interests in the majority of journal articles he wrote or cowrote over a 4-year period.

COI disclosure issues have a broad reach, however, and the policy reviews, debates, and hashing out of responsibilities that are now taking place likely will have implications for all of medicine.

Among the questions: Who enforces disclosure rules and how should cases of incomplete or inconsistent disclosure be handled? How can COI declarations be made easier for researchers? Should disclosure be based on self-reported relevancy, or more comprehensive in nature?

Such questions are being debated nationally. On Feb. 12, 2019, leaders from academia, journals, and medical societies came together in Washington, D.C., at the offices of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) for a closed-door meeting focused on COI disclosures. MSK, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies led the charge as cosponsors of the meeting.

“We’ve been dealing with disclosure issues in a siloed way in exchanges [between journal editors and authors, for instance, or between speakers and CME providers]. And academic institutions have their own robust disclosure mechanisms that they use internally,” said Heather Pierce, JD, MPH, senior director of science policy and regulatory counsel for the AAMC. “There’s a growing understanding that these conversations need to be happening across these different sectors.”

Pleas for accuracy

At academic medical institutions, conflicts of interest are identified and then managed; it’s common for researchers’ COI management plans to include requirements for disclosure in all presentations and publications.

Journals and professional medical societies require authors and speakers to submit disclosure forms of varying lengths and with differing questions about relationships with industry, often based on the notion of relevancy to the subject at hand. Disclosure forms are reviewed, but editors and other reviewers rely largely – if not entirely – on the honor system.

Dr. Baselga’s disclosure lapses and his subsequent resignation have rattled leaders in each of these settings. Researchers at MSK were instructed to review their COI disclosures and submit corrections when necessary, and in December 2018 the hospital was reportedly evaluating its process for reviewing conflicts of interest, according to reports in the New York Times and ProPublica. (MSK did not respond to requests for comment about actions taken.)

The Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston similarly has “been reminding faculty and other researchers” of their disclosure responsibilities and is conducting a review of “all our policies in this area,” a spokeswoman said. And at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, a spokesman said they have established an internal task force to review individual and institutional COI policies to ensure that COIs are “appropriately managed while also enabling research collaborations that bring scientific advances to our patients.”

Other centers contacted for this article, such as the Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center and the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, said that they have no new reviews ongoing and no plans to change policies at this time.

The heightened attention to disclosure has, in turn, shone a spotlight on increasingly complex physician-industry relationships and on the Open Payments website run by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Open Payments is a disclosure program and database that tracks payments made to physicians and teaching hospitals by drug and device companies.

Journalists, including those who reported on Dr. Baselga’s disclosures, have searched the public database for industry payment data. So have other researchers who have studied financial disclosure statements; a study reported in JAMA Oncology last year, for instance, concluded through the use of Open Payments data that about one-third of authors of cancer drug trial reports did not completely disclose payments from trial sponsors (JAMA Oncol. 2018;4[10]:1426-8

In a column published in December 2018 in AAMC News, AAMC President and CEO Darrell G. Kirch, MD, wrote that failures to disclose can raise questions about the integrity of research, whether or not there is an actual conflict. He advised institutions to “encourage faculty to review the information posted about them on the Open Payments website” of the CMS to “ensure it is accurate and consistent with disclosures related to all their professional responsibilities.”

ASCO issues similar advice, encouraging authors and CME speakers and participants of other ASCO activities to double-check their disclosures against other sources, including “publicly reported interactions with companies that may have been inadvertently omitted.”

In the world of journals, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) began asking authors at the end of 2018 to “certify that they have reconciled their disclosures” with the Open Payments database, said Jennifer Zeis, a spokeswoman forthe journal.

Time may tell how well such requests work. When the Institute of Medicine (now called the National Academy of Medicine) called on Congress in 2009 to create a national program requiring pharmaceutical, device, and biotechnology companies to publicly report their payments, it envisioned universities, journals, and others using the program to verify disclosures made to them. But the resulting Open Payments database has limitations – for instance, it doesn’t include payments from companies without FDA-approved products, it is not necessarily up to date, and its payment categories do not necessarily match categories of disclosure.

“Some entries in the Open Payments database need further explanation,” said Ms. Zeis of NEJM. “Some authors, for example, have said that the database does not fully and accurately explain that the funds were disbursed not to them personally, but to their academic institutions.” While the database provides transparency, it also “needs context that’s not currently provided,” she said.

Mistakes in the database can also be “very hard to challenge,” said Clifford A. Hudis, MD, CEO of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which produces the Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO).

All in all, he said, “there’s really no timely, comprehensive, and fully reliable source of information with which to verify an individual’s disclosures.”

Policies and practices are also under review at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and the American Society of Hematology (ASH).

The AACR has appointed a panel of experts, including physicians, basic scientists, a patient advocate, and others to conduct “a comprehensive review of [its] disclosure policies and to explore whether any current policies need to be revised,” said Rachel Salis-Silverman, director of public relations. It also will convene a session on COI disclosures at its 2019 annual meeting at the end of March, she said.

ASH, which publishes the journal Blood, is exploring possible changes in its “internal processes with regards to ASH publications,” said Matt Gertzog, deputy executive director of the group. COI disclosure is “more of a journey than a destination,” he said. “We are continuously reflecting on and refining our processes.”

Moving away from ‘relevancy’

Physicians and others who have relationships with industry have long complained about a patchwork of disclosure requirements, and significant efforts have been made in the last decade to standardize forms and practices. However, the current system is still “a little bit of a Tower of Babel,” said Dr. Hudis of ASCO. “Every day, physicians have to complete from scratch similar, but not identical, disclosure forms that ask similar, but not identical, questions.”

A disclosable compensation amount “might be first dollar, or it might be over $10,000. [Time periods] might cover 1 year, or 3 years. ... Stock ownership might be dollar value, or a percentage of shares,” he explained. “If you want a system that would make it hard to be compliant and easy to mess up, that’s what we have.”

To standardize the COI disclosure process for all Society-related publications and activities – including CME, JCO, and practice guidelines – ASCO moved about 5 years ago to a system of general disclosure, asking physicians and others to disclose all financial interests and industry relationships rather than what they deem relevant.

The thinking was that general disclosure “would be easier for disclosers, and nobody would ever be accused of hiding anything,” Dr. Hudis said.

“We’d [also] recognized,” he explained, “that there was a risk to the relevancy approach in that it put the judgment for the potential conflict in the hands of the potentially conflicted, while others might have a different point of view about what is or isn’t relevant.”

Those concerned about general disclosure worry that it may “obscure [for the reader or listener] what’s really important or the most meaningful,” he said.

Some physicians have expressed in interviews for this article, moreover, the concern that too many disclosures – too long a list of financial relationships – will be viewed negatively. This is something ASCO aims to guard against as it strives to achieve full transparency, Dr. Hudis said. “If one were to suggest that engagement itself is automatically a negative, then you’re starting to put negative pressure on compliance with disclosure.”

And full disclosure matters, he said. “We have to err in the direction of believing that disclosure is good,” he said, “even if we can’t prove it has clear and measurable impact. That is why our goal is to make full disclosure easier. What potential conflicts are acceptable, or not, is an important but entirely separate matter.”

Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA and the JAMA Network, frames the pros and cons of general and relevant disclosure similarly, and emphasizes that the relationships of authors with industry – particularly with private equity start-up companies – has changed dramatically over the past decade. Editors have “talked about complete versus [more narrowly] relevant disclosures at length,” he said, and have been moving overall “toward more complete disclosure where the reader can make a decision on their own.”

Other journals also are taking this approach. In 2009, in an effort to reduce variability in reporting processes and formats, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) developed a uniform electronic disclosure form that asks about financial relationships and interactions with any entity that could be considered “broadly relevant” to the submitted work. The group updated the form in December 2018.

As an example, the form reads, an article about testing an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antagonist in lung cancer requires the reporting of “all associations with entities pursuing diagnostic or therapeutic strategies in cancer in general, not just in the area of EGFR or lung cancer.” JAMA, NEJM, and The Lancet are among those journals that embrace the ICMJE’s policies and use its form.

To simplify its own disclosure process, JAMA and the network’s journals ended the practice in January 2019 of requiring both the ICMJE form and JAMA’s own separate disclosure form. The journals now use a single electronic form that includes questions from the ICMJE form. And to promote more consistent and complete reporting, the electronic form contains prompts that ask authors each time they answer “no” to one of four specific questions about potential COI whether they are certain of their answers and whether their answers are consistent with other disclosures they recently made.

While relevancy statements “create struggles for authors,” about two-thirds of the disclosure inaccuracies reported by readers and verified by JAMA’s editors (most often through editor-author discussions) involve a complete lack of disclosure rather than questions of relevancy, Dr. Bauchner noted. (JAMA and the network’s journals receive about 30,000 disclosure forms each year.)

The AAMC, in the meantime, has developed a central web-based repository for disclosures called Convey. Physicians and others can maintain secure records of financial interests in the repository, and these records can then be disclosed directly to any journal or organization that uses the system. The tool – born from discussions that followed the 2009 IOM report on COI – is “intended to facilitate more complete, more accurate, and more consistent” disclosures,” said Ms. Pierce of the AAMC. It is now live and in its early stages of use; NEJM assisted in its development and has been one of its pilot testers.

Enforcement questions

Some experts believe that institutions should maintain public databases of disclosures and/or that disclosure requirements should be better enforced in-house.

“There often are no clear guidelines in institutions about how to respond to people who are negligent in how they’re managing their disclosures,” said Jeffrey R. Botkin, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and associate vice president for research at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who has served on a variety of ethics committees and is an elected member of the Hastings Center. Dr. Botkin proposed in a Viewpoint published last October in JAMA that failure to disclose significant COIs should be considered research misconduct (JAMA 2018;320[22]:2307-8).

At the University of Utah, “we’re getting better at saying, ‘show us that you’ve disclosed,’ ” he said. “In some cases we’ll do spot checks of journal articles to make sure [researchers have] followed through with their disclosures.”

John Abramson, MD, a lecturer in the department of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Boston, contends that incomplete declarations of COI have been shown to correlate with reporting of manufacturer-friendly research results. Journals should have “zero tolerance” standards for incomplete or inaccurate COI declarations and should, among other things, “inform academic institutions of breaches of integrity.”

At JAMA, which in 2017 published a theme issue on COI and COI declarations, editors have been discussing whether they will contact an author’s institution “if there’s a pattern involved [with disclosure problems] or if there’s a lack of declaration of multiple COIs,” Dr. Bauchner said.

Conflict of interest (COI) reporting has moved center stage again in recent months, with some medical journals, professional societies, cancer centers, and academic medical institutions reviewing policies and practices in the wake of a highly publicized disclosure failure last fall at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK).

And in some settings, oncologists and other physician researchers are being encouraged to check what the federal Open Payments database says about their payments from industry.

The spotlight is on the field of cancer research and treatment, where MSK’s chief medical officer, José Baselga, MD, PhD, resigned in September 2018 after the New York Times and ProPublica reported that he’d failed to disclose millions of dollars of industry payments and ownership interests in the majority of journal articles he wrote or cowrote over a 4-year period.

COI disclosure issues have a broad reach, however, and the policy reviews, debates, and hashing out of responsibilities that are now taking place likely will have implications for all of medicine.

Among the questions: Who enforces disclosure rules and how should cases of incomplete or inconsistent disclosure be handled? How can COI declarations be made easier for researchers? Should disclosure be based on self-reported relevancy, or more comprehensive in nature?

Such questions are being debated nationally. On Feb. 12, 2019, leaders from academia, journals, and medical societies came together in Washington, D.C., at the offices of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) for a closed-door meeting focused on COI disclosures. MSK, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies led the charge as cosponsors of the meeting.

“We’ve been dealing with disclosure issues in a siloed way in exchanges [between journal editors and authors, for instance, or between speakers and CME providers]. And academic institutions have their own robust disclosure mechanisms that they use internally,” said Heather Pierce, JD, MPH, senior director of science policy and regulatory counsel for the AAMC. “There’s a growing understanding that these conversations need to be happening across these different sectors.”

Pleas for accuracy

At academic medical institutions, conflicts of interest are identified and then managed; it’s common for researchers’ COI management plans to include requirements for disclosure in all presentations and publications.

Journals and professional medical societies require authors and speakers to submit disclosure forms of varying lengths and with differing questions about relationships with industry, often based on the notion of relevancy to the subject at hand. Disclosure forms are reviewed, but editors and other reviewers rely largely – if not entirely – on the honor system.

Dr. Baselga’s disclosure lapses and his subsequent resignation have rattled leaders in each of these settings. Researchers at MSK were instructed to review their COI disclosures and submit corrections when necessary, and in December 2018 the hospital was reportedly evaluating its process for reviewing conflicts of interest, according to reports in the New York Times and ProPublica. (MSK did not respond to requests for comment about actions taken.)

The Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston similarly has “been reminding faculty and other researchers” of their disclosure responsibilities and is conducting a review of “all our policies in this area,” a spokeswoman said. And at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, a spokesman said they have established an internal task force to review individual and institutional COI policies to ensure that COIs are “appropriately managed while also enabling research collaborations that bring scientific advances to our patients.”

Other centers contacted for this article, such as the Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center and the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, said that they have no new reviews ongoing and no plans to change policies at this time.

The heightened attention to disclosure has, in turn, shone a spotlight on increasingly complex physician-industry relationships and on the Open Payments website run by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Open Payments is a disclosure program and database that tracks payments made to physicians and teaching hospitals by drug and device companies.

Journalists, including those who reported on Dr. Baselga’s disclosures, have searched the public database for industry payment data. So have other researchers who have studied financial disclosure statements; a study reported in JAMA Oncology last year, for instance, concluded through the use of Open Payments data that about one-third of authors of cancer drug trial reports did not completely disclose payments from trial sponsors (JAMA Oncol. 2018;4[10]:1426-8

In a column published in December 2018 in AAMC News, AAMC President and CEO Darrell G. Kirch, MD, wrote that failures to disclose can raise questions about the integrity of research, whether or not there is an actual conflict. He advised institutions to “encourage faculty to review the information posted about them on the Open Payments website” of the CMS to “ensure it is accurate and consistent with disclosures related to all their professional responsibilities.”

ASCO issues similar advice, encouraging authors and CME speakers and participants of other ASCO activities to double-check their disclosures against other sources, including “publicly reported interactions with companies that may have been inadvertently omitted.”

In the world of journals, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) began asking authors at the end of 2018 to “certify that they have reconciled their disclosures” with the Open Payments database, said Jennifer Zeis, a spokeswoman forthe journal.

Time may tell how well such requests work. When the Institute of Medicine (now called the National Academy of Medicine) called on Congress in 2009 to create a national program requiring pharmaceutical, device, and biotechnology companies to publicly report their payments, it envisioned universities, journals, and others using the program to verify disclosures made to them. But the resulting Open Payments database has limitations – for instance, it doesn’t include payments from companies without FDA-approved products, it is not necessarily up to date, and its payment categories do not necessarily match categories of disclosure.

“Some entries in the Open Payments database need further explanation,” said Ms. Zeis of NEJM. “Some authors, for example, have said that the database does not fully and accurately explain that the funds were disbursed not to them personally, but to their academic institutions.” While the database provides transparency, it also “needs context that’s not currently provided,” she said.

Mistakes in the database can also be “very hard to challenge,” said Clifford A. Hudis, MD, CEO of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which produces the Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO).

All in all, he said, “there’s really no timely, comprehensive, and fully reliable source of information with which to verify an individual’s disclosures.”

Policies and practices are also under review at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and the American Society of Hematology (ASH).

The AACR has appointed a panel of experts, including physicians, basic scientists, a patient advocate, and others to conduct “a comprehensive review of [its] disclosure policies and to explore whether any current policies need to be revised,” said Rachel Salis-Silverman, director of public relations. It also will convene a session on COI disclosures at its 2019 annual meeting at the end of March, she said.

ASH, which publishes the journal Blood, is exploring possible changes in its “internal processes with regards to ASH publications,” said Matt Gertzog, deputy executive director of the group. COI disclosure is “more of a journey than a destination,” he said. “We are continuously reflecting on and refining our processes.”

Moving away from ‘relevancy’

Physicians and others who have relationships with industry have long complained about a patchwork of disclosure requirements, and significant efforts have been made in the last decade to standardize forms and practices. However, the current system is still “a little bit of a Tower of Babel,” said Dr. Hudis of ASCO. “Every day, physicians have to complete from scratch similar, but not identical, disclosure forms that ask similar, but not identical, questions.”

A disclosable compensation amount “might be first dollar, or it might be over $10,000. [Time periods] might cover 1 year, or 3 years. ... Stock ownership might be dollar value, or a percentage of shares,” he explained. “If you want a system that would make it hard to be compliant and easy to mess up, that’s what we have.”

To standardize the COI disclosure process for all Society-related publications and activities – including CME, JCO, and practice guidelines – ASCO moved about 5 years ago to a system of general disclosure, asking physicians and others to disclose all financial interests and industry relationships rather than what they deem relevant.

The thinking was that general disclosure “would be easier for disclosers, and nobody would ever be accused of hiding anything,” Dr. Hudis said.

“We’d [also] recognized,” he explained, “that there was a risk to the relevancy approach in that it put the judgment for the potential conflict in the hands of the potentially conflicted, while others might have a different point of view about what is or isn’t relevant.”

Those concerned about general disclosure worry that it may “obscure [for the reader or listener] what’s really important or the most meaningful,” he said.

Some physicians have expressed in interviews for this article, moreover, the concern that too many disclosures – too long a list of financial relationships – will be viewed negatively. This is something ASCO aims to guard against as it strives to achieve full transparency, Dr. Hudis said. “If one were to suggest that engagement itself is automatically a negative, then you’re starting to put negative pressure on compliance with disclosure.”

And full disclosure matters, he said. “We have to err in the direction of believing that disclosure is good,” he said, “even if we can’t prove it has clear and measurable impact. That is why our goal is to make full disclosure easier. What potential conflicts are acceptable, or not, is an important but entirely separate matter.”

Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA and the JAMA Network, frames the pros and cons of general and relevant disclosure similarly, and emphasizes that the relationships of authors with industry – particularly with private equity start-up companies – has changed dramatically over the past decade. Editors have “talked about complete versus [more narrowly] relevant disclosures at length,” he said, and have been moving overall “toward more complete disclosure where the reader can make a decision on their own.”

Other journals also are taking this approach. In 2009, in an effort to reduce variability in reporting processes and formats, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) developed a uniform electronic disclosure form that asks about financial relationships and interactions with any entity that could be considered “broadly relevant” to the submitted work. The group updated the form in December 2018.

As an example, the form reads, an article about testing an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antagonist in lung cancer requires the reporting of “all associations with entities pursuing diagnostic or therapeutic strategies in cancer in general, not just in the area of EGFR or lung cancer.” JAMA, NEJM, and The Lancet are among those journals that embrace the ICMJE’s policies and use its form.

To simplify its own disclosure process, JAMA and the network’s journals ended the practice in January 2019 of requiring both the ICMJE form and JAMA’s own separate disclosure form. The journals now use a single electronic form that includes questions from the ICMJE form. And to promote more consistent and complete reporting, the electronic form contains prompts that ask authors each time they answer “no” to one of four specific questions about potential COI whether they are certain of their answers and whether their answers are consistent with other disclosures they recently made.

While relevancy statements “create struggles for authors,” about two-thirds of the disclosure inaccuracies reported by readers and verified by JAMA’s editors (most often through editor-author discussions) involve a complete lack of disclosure rather than questions of relevancy, Dr. Bauchner noted. (JAMA and the network’s journals receive about 30,000 disclosure forms each year.)

The AAMC, in the meantime, has developed a central web-based repository for disclosures called Convey. Physicians and others can maintain secure records of financial interests in the repository, and these records can then be disclosed directly to any journal or organization that uses the system. The tool – born from discussions that followed the 2009 IOM report on COI – is “intended to facilitate more complete, more accurate, and more consistent” disclosures,” said Ms. Pierce of the AAMC. It is now live and in its early stages of use; NEJM assisted in its development and has been one of its pilot testers.

Enforcement questions

Some experts believe that institutions should maintain public databases of disclosures and/or that disclosure requirements should be better enforced in-house.

“There often are no clear guidelines in institutions about how to respond to people who are negligent in how they’re managing their disclosures,” said Jeffrey R. Botkin, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and associate vice president for research at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who has served on a variety of ethics committees and is an elected member of the Hastings Center. Dr. Botkin proposed in a Viewpoint published last October in JAMA that failure to disclose significant COIs should be considered research misconduct (JAMA 2018;320[22]:2307-8).

At the University of Utah, “we’re getting better at saying, ‘show us that you’ve disclosed,’ ” he said. “In some cases we’ll do spot checks of journal articles to make sure [researchers have] followed through with their disclosures.”