User login

Compression therapy prevents recurrence of cellulitis

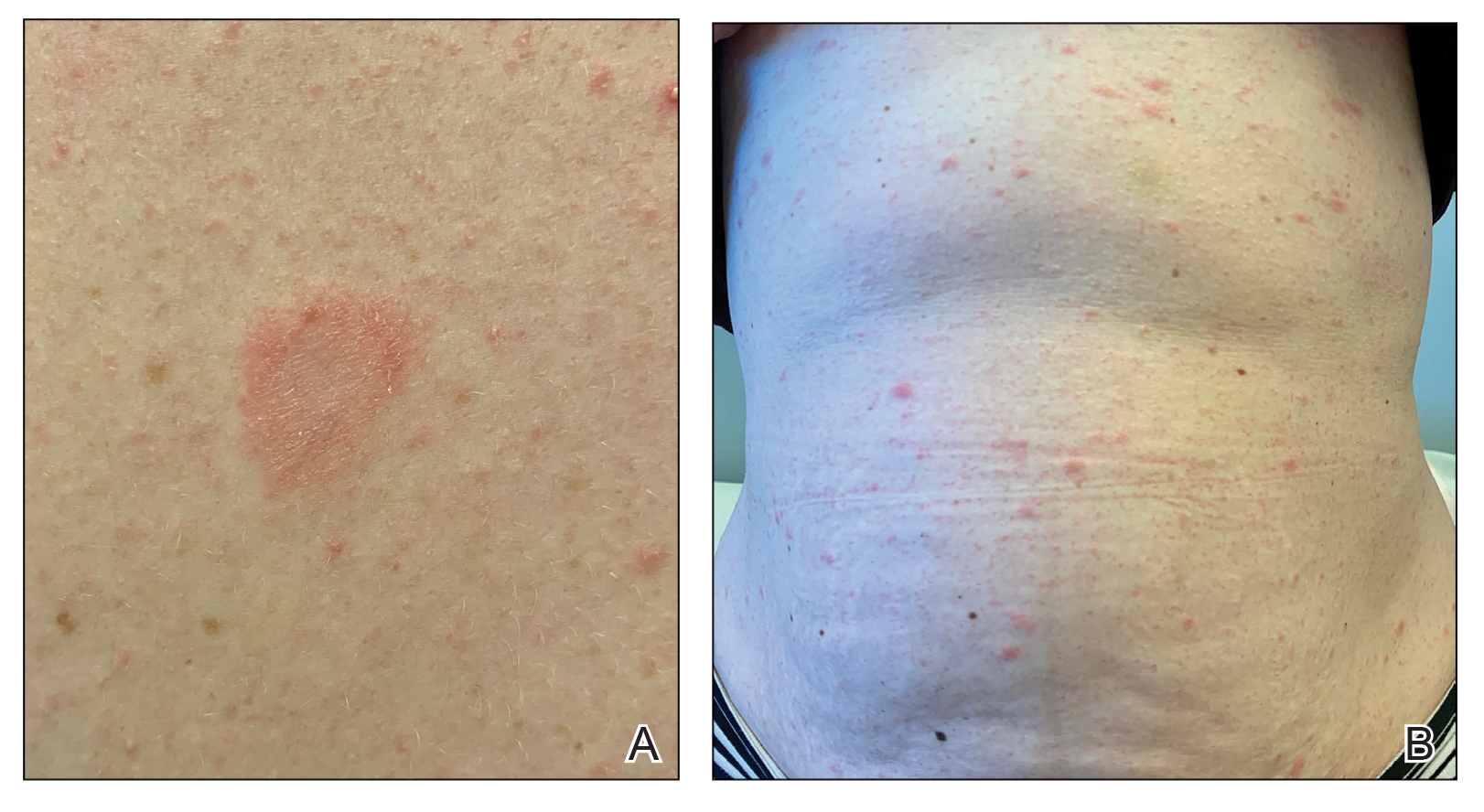

Background: Recurrent cellulitis is a common condition in patients with lower-extremity edema. Although some clinicians recommend compression garments as a preventative treatment, there are no data evaluating their efficacy for this purpose.

Study design: Participants were randomized to receive either education alone or education plus compression therapy. Neither the participants nor the assessors were blinded to the treatment arm.

Setting: Single-center study in Australia.

Synopsis: Participants with cellulitis who also had at least two previous episodes of cellulitis in the previous 2 years and had lower-extremity edema were enrolled. Of participants, 84 were randomized. Both groups received education regarding skin care, body weight, and exercise, while the compression therapy group also received compression garments and instructions for their use. The primary outcome was recurrent cellulitis. Patients in the control group were allowed to cross over after an episode of cellulitis. The trial was stopped early for efficacy. At the time the trial was halted, 17 of 43 (40%) participants in the control group had recurrent cellulitis, compared with only 6 of 41 (15%) in the intervention (hazard ratio, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.09-0.59; P = .002). Limitations include the lack of blinding, which could have introduced bias, although the diagnosis of recurrent cellulitis was made by clinicians external to the trial. This study supports the use of compression garments in preventing recurrent cellulitis in patients with lower-extremity edema.

Bottom line: Compression garments can be used to prevent recurrent cellulitis in patients with edema.

Citation: Webb E et al. Compression therapy to prevent recurrent cellulitis of the leg. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):630-9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917197.

Dr. Herscher is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York.

Background: Recurrent cellulitis is a common condition in patients with lower-extremity edema. Although some clinicians recommend compression garments as a preventative treatment, there are no data evaluating their efficacy for this purpose.

Study design: Participants were randomized to receive either education alone or education plus compression therapy. Neither the participants nor the assessors were blinded to the treatment arm.

Setting: Single-center study in Australia.

Synopsis: Participants with cellulitis who also had at least two previous episodes of cellulitis in the previous 2 years and had lower-extremity edema were enrolled. Of participants, 84 were randomized. Both groups received education regarding skin care, body weight, and exercise, while the compression therapy group also received compression garments and instructions for their use. The primary outcome was recurrent cellulitis. Patients in the control group were allowed to cross over after an episode of cellulitis. The trial was stopped early for efficacy. At the time the trial was halted, 17 of 43 (40%) participants in the control group had recurrent cellulitis, compared with only 6 of 41 (15%) in the intervention (hazard ratio, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.09-0.59; P = .002). Limitations include the lack of blinding, which could have introduced bias, although the diagnosis of recurrent cellulitis was made by clinicians external to the trial. This study supports the use of compression garments in preventing recurrent cellulitis in patients with lower-extremity edema.

Bottom line: Compression garments can be used to prevent recurrent cellulitis in patients with edema.

Citation: Webb E et al. Compression therapy to prevent recurrent cellulitis of the leg. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):630-9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917197.

Dr. Herscher is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York.

Background: Recurrent cellulitis is a common condition in patients with lower-extremity edema. Although some clinicians recommend compression garments as a preventative treatment, there are no data evaluating their efficacy for this purpose.

Study design: Participants were randomized to receive either education alone or education plus compression therapy. Neither the participants nor the assessors were blinded to the treatment arm.

Setting: Single-center study in Australia.

Synopsis: Participants with cellulitis who also had at least two previous episodes of cellulitis in the previous 2 years and had lower-extremity edema were enrolled. Of participants, 84 were randomized. Both groups received education regarding skin care, body weight, and exercise, while the compression therapy group also received compression garments and instructions for their use. The primary outcome was recurrent cellulitis. Patients in the control group were allowed to cross over after an episode of cellulitis. The trial was stopped early for efficacy. At the time the trial was halted, 17 of 43 (40%) participants in the control group had recurrent cellulitis, compared with only 6 of 41 (15%) in the intervention (hazard ratio, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.09-0.59; P = .002). Limitations include the lack of blinding, which could have introduced bias, although the diagnosis of recurrent cellulitis was made by clinicians external to the trial. This study supports the use of compression garments in preventing recurrent cellulitis in patients with lower-extremity edema.

Bottom line: Compression garments can be used to prevent recurrent cellulitis in patients with edema.

Citation: Webb E et al. Compression therapy to prevent recurrent cellulitis of the leg. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):630-9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917197.

Dr. Herscher is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York.

Dr. Fauci: HIV advances ‘breathtaking,’ but steadfast focus on disparities needed

Decades before becoming the go-to authority in the United States on the COVID-19 global pandemic, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, found himself witnessing the earliest perplexing cases of what would become another devastating global pandemic – HIV/AIDS. And while extraordinary advances have transformed treatment and prevention, glaring treatment gaps and challenges remain after 40 years.

“I certainly remember those initial MMWRs [the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports] in the summer of 1981 that introduced us to what would turn out to be the most extraordinary and devastating pandemic of an infectious disease up until that time in the modern era,” said Dr. Fauci when addressing the 2021 United States Conference on HIV/AIDS.

“Now, 40 years into it, we are still in the middle of a global pandemic despite the fact that there have been extraordinary advances,” said Dr. Fauci, who is director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and chief medical advisor to the President of the United States.

Specifically, it was on June 5, 1981, that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued its fateful report on the first five cases of what would soon become known as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.

By 2020, the 5 cases had grown to 79.3 million HIV infections since the start of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, claiming 36.3 million lives, according to the NAIDS Global AIDS update, Dr. Fauci reported.

At the end of 2020, there were 1.5 million new infections, as many as 37.7 million people living with HIV, and 680,000 deaths, according to the report.

The fact that so many people are living with HIV – and not dying from it – is largely attributable to “breathtaking” advances in treatment, Dr. Fauci said, underscoring the fact that there are now 13 single-tablet, once-daily, antiretroviral (ART) regimens approved in the United States to replace the multidrug cocktail that has long been necessary with HIV treatment.

“I can remember when the combination therapies were first made available, we were giving patients literally dozens of pills of different types each day, but that is no longer the case,” Dr. Fauci said.

“We can say, without hyperbole, that highly effective antiretroviral therapy for HIV is indeed one of the most important biomedical research advances of our era.”

Furthermore, HIV prevention using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), when used optimally and consistently, has further transformed the HIV landscape with 99% efficacy in preventing sexual HIV acquisition.

Troubling treatment gaps

Despite the advances, disparities and challenges are abundant, Dr. Fauci said.

Notably, the majority of those infected globally – 65% – are concentrated among key populations, including gay men and other men who have sex with men (23%), clients of sex workers (20%), sex workers (11%), people who inject drugs (9%), and transgender people (2%), according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

According to UNAIDS, among the 37.7 million people living with HIV at the end of 2020, 27.5 million were being treated with life-saving ART, leaving a gap of 10.2 million people with HIV who are not receiving the treatment, Dr. Fauci pointed out.

And of those who do receive treatment, retention is suboptimal, with only about 65% of patients in low- and middle-income countries being retained in care at 48 months following ART initiation.

Dr. Fauci underscored encouraging developments that could address some of those problems, notably long-acting ART therapies that, in requiring administration only every 6 months or so, could negate the need for adherence to daily ART therapy.

Likewise, long-acting PrEP provided intermittently over longer periods could prevent transmission.

“We’re looking at [long-acting PrEP] with a great deal of enthusiasm as providing protection with longer durations between doses to get people to essentially have close to 99% protection against HIV acquisition,” Dr. Fauci said.

While several efforts to develop vaccines for HIV in long-term clinical trials have had disappointing results, Dr. Fauci says he stops short of calling them failures.

“We don’t consider the trials to be failures because, in fact, they tell us the way we need to go – which direction,” he said.

“In fact, COVID-19 itself has given us new enthusiasm about the use of vaccine platforms such as mRNA that are now being applied in the vaccine quest for HIV,” Dr. Fauci noted.

Ultimately, “we must steadily and steadfastly move forward to address critical research gaps and unanswered questions [regarding HIV],” Dr. Fauci said. “The scientific advances have been breathtaking and it is up to us to [achieve] greater scientific advances, but also to translate them into something that can be implemented.”

USCHA Executive Director Paul Kawata, MD, commented that he shares Dr. Fauci’s optimism — and his concerns.

“NMAC [formerly the National Minority AIDS Council, which runs USCHA] is very excited about the science,” he said in an interview. “Our ability to make treatment easier should be a pathway to success.”

“Our concern is that we need more implementation science to know if long-acting ART will be used by the communities hardest hit by HIV,” he said.

Dr. Kawata noted that NMAC agrees that vaccine trial “failures” can offer important lessons, “but we are getting impatient,” he said. “Back in the 80s, Secretary Margret Heckler said we would have a vaccine in 5 years.”

Furthermore, ongoing racial disparities, left unaddressed, will hold back meaningful progress in the fight against HIV, he noted. “We are always hopeful, [but] the reality is that race and racism play an outsized role in health outcome in America. Unless we address these inequalities, we will never end HIV.”

NMAC receives funding from Gilead, Viiv, Merck, and Janssen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Decades before becoming the go-to authority in the United States on the COVID-19 global pandemic, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, found himself witnessing the earliest perplexing cases of what would become another devastating global pandemic – HIV/AIDS. And while extraordinary advances have transformed treatment and prevention, glaring treatment gaps and challenges remain after 40 years.

“I certainly remember those initial MMWRs [the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports] in the summer of 1981 that introduced us to what would turn out to be the most extraordinary and devastating pandemic of an infectious disease up until that time in the modern era,” said Dr. Fauci when addressing the 2021 United States Conference on HIV/AIDS.

“Now, 40 years into it, we are still in the middle of a global pandemic despite the fact that there have been extraordinary advances,” said Dr. Fauci, who is director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and chief medical advisor to the President of the United States.

Specifically, it was on June 5, 1981, that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued its fateful report on the first five cases of what would soon become known as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.

By 2020, the 5 cases had grown to 79.3 million HIV infections since the start of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, claiming 36.3 million lives, according to the NAIDS Global AIDS update, Dr. Fauci reported.

At the end of 2020, there were 1.5 million new infections, as many as 37.7 million people living with HIV, and 680,000 deaths, according to the report.

The fact that so many people are living with HIV – and not dying from it – is largely attributable to “breathtaking” advances in treatment, Dr. Fauci said, underscoring the fact that there are now 13 single-tablet, once-daily, antiretroviral (ART) regimens approved in the United States to replace the multidrug cocktail that has long been necessary with HIV treatment.

“I can remember when the combination therapies were first made available, we were giving patients literally dozens of pills of different types each day, but that is no longer the case,” Dr. Fauci said.

“We can say, without hyperbole, that highly effective antiretroviral therapy for HIV is indeed one of the most important biomedical research advances of our era.”

Furthermore, HIV prevention using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), when used optimally and consistently, has further transformed the HIV landscape with 99% efficacy in preventing sexual HIV acquisition.

Troubling treatment gaps

Despite the advances, disparities and challenges are abundant, Dr. Fauci said.

Notably, the majority of those infected globally – 65% – are concentrated among key populations, including gay men and other men who have sex with men (23%), clients of sex workers (20%), sex workers (11%), people who inject drugs (9%), and transgender people (2%), according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

According to UNAIDS, among the 37.7 million people living with HIV at the end of 2020, 27.5 million were being treated with life-saving ART, leaving a gap of 10.2 million people with HIV who are not receiving the treatment, Dr. Fauci pointed out.

And of those who do receive treatment, retention is suboptimal, with only about 65% of patients in low- and middle-income countries being retained in care at 48 months following ART initiation.

Dr. Fauci underscored encouraging developments that could address some of those problems, notably long-acting ART therapies that, in requiring administration only every 6 months or so, could negate the need for adherence to daily ART therapy.

Likewise, long-acting PrEP provided intermittently over longer periods could prevent transmission.

“We’re looking at [long-acting PrEP] with a great deal of enthusiasm as providing protection with longer durations between doses to get people to essentially have close to 99% protection against HIV acquisition,” Dr. Fauci said.

While several efforts to develop vaccines for HIV in long-term clinical trials have had disappointing results, Dr. Fauci says he stops short of calling them failures.

“We don’t consider the trials to be failures because, in fact, they tell us the way we need to go – which direction,” he said.

“In fact, COVID-19 itself has given us new enthusiasm about the use of vaccine platforms such as mRNA that are now being applied in the vaccine quest for HIV,” Dr. Fauci noted.

Ultimately, “we must steadily and steadfastly move forward to address critical research gaps and unanswered questions [regarding HIV],” Dr. Fauci said. “The scientific advances have been breathtaking and it is up to us to [achieve] greater scientific advances, but also to translate them into something that can be implemented.”

USCHA Executive Director Paul Kawata, MD, commented that he shares Dr. Fauci’s optimism — and his concerns.

“NMAC [formerly the National Minority AIDS Council, which runs USCHA] is very excited about the science,” he said in an interview. “Our ability to make treatment easier should be a pathway to success.”

“Our concern is that we need more implementation science to know if long-acting ART will be used by the communities hardest hit by HIV,” he said.

Dr. Kawata noted that NMAC agrees that vaccine trial “failures” can offer important lessons, “but we are getting impatient,” he said. “Back in the 80s, Secretary Margret Heckler said we would have a vaccine in 5 years.”

Furthermore, ongoing racial disparities, left unaddressed, will hold back meaningful progress in the fight against HIV, he noted. “We are always hopeful, [but] the reality is that race and racism play an outsized role in health outcome in America. Unless we address these inequalities, we will never end HIV.”

NMAC receives funding from Gilead, Viiv, Merck, and Janssen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Decades before becoming the go-to authority in the United States on the COVID-19 global pandemic, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, found himself witnessing the earliest perplexing cases of what would become another devastating global pandemic – HIV/AIDS. And while extraordinary advances have transformed treatment and prevention, glaring treatment gaps and challenges remain after 40 years.

“I certainly remember those initial MMWRs [the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports] in the summer of 1981 that introduced us to what would turn out to be the most extraordinary and devastating pandemic of an infectious disease up until that time in the modern era,” said Dr. Fauci when addressing the 2021 United States Conference on HIV/AIDS.

“Now, 40 years into it, we are still in the middle of a global pandemic despite the fact that there have been extraordinary advances,” said Dr. Fauci, who is director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and chief medical advisor to the President of the United States.

Specifically, it was on June 5, 1981, that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued its fateful report on the first five cases of what would soon become known as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.

By 2020, the 5 cases had grown to 79.3 million HIV infections since the start of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, claiming 36.3 million lives, according to the NAIDS Global AIDS update, Dr. Fauci reported.

At the end of 2020, there were 1.5 million new infections, as many as 37.7 million people living with HIV, and 680,000 deaths, according to the report.

The fact that so many people are living with HIV – and not dying from it – is largely attributable to “breathtaking” advances in treatment, Dr. Fauci said, underscoring the fact that there are now 13 single-tablet, once-daily, antiretroviral (ART) regimens approved in the United States to replace the multidrug cocktail that has long been necessary with HIV treatment.

“I can remember when the combination therapies were first made available, we were giving patients literally dozens of pills of different types each day, but that is no longer the case,” Dr. Fauci said.

“We can say, without hyperbole, that highly effective antiretroviral therapy for HIV is indeed one of the most important biomedical research advances of our era.”

Furthermore, HIV prevention using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), when used optimally and consistently, has further transformed the HIV landscape with 99% efficacy in preventing sexual HIV acquisition.

Troubling treatment gaps

Despite the advances, disparities and challenges are abundant, Dr. Fauci said.

Notably, the majority of those infected globally – 65% – are concentrated among key populations, including gay men and other men who have sex with men (23%), clients of sex workers (20%), sex workers (11%), people who inject drugs (9%), and transgender people (2%), according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

According to UNAIDS, among the 37.7 million people living with HIV at the end of 2020, 27.5 million were being treated with life-saving ART, leaving a gap of 10.2 million people with HIV who are not receiving the treatment, Dr. Fauci pointed out.

And of those who do receive treatment, retention is suboptimal, with only about 65% of patients in low- and middle-income countries being retained in care at 48 months following ART initiation.

Dr. Fauci underscored encouraging developments that could address some of those problems, notably long-acting ART therapies that, in requiring administration only every 6 months or so, could negate the need for adherence to daily ART therapy.

Likewise, long-acting PrEP provided intermittently over longer periods could prevent transmission.

“We’re looking at [long-acting PrEP] with a great deal of enthusiasm as providing protection with longer durations between doses to get people to essentially have close to 99% protection against HIV acquisition,” Dr. Fauci said.

While several efforts to develop vaccines for HIV in long-term clinical trials have had disappointing results, Dr. Fauci says he stops short of calling them failures.

“We don’t consider the trials to be failures because, in fact, they tell us the way we need to go – which direction,” he said.

“In fact, COVID-19 itself has given us new enthusiasm about the use of vaccine platforms such as mRNA that are now being applied in the vaccine quest for HIV,” Dr. Fauci noted.

Ultimately, “we must steadily and steadfastly move forward to address critical research gaps and unanswered questions [regarding HIV],” Dr. Fauci said. “The scientific advances have been breathtaking and it is up to us to [achieve] greater scientific advances, but also to translate them into something that can be implemented.”

USCHA Executive Director Paul Kawata, MD, commented that he shares Dr. Fauci’s optimism — and his concerns.

“NMAC [formerly the National Minority AIDS Council, which runs USCHA] is very excited about the science,” he said in an interview. “Our ability to make treatment easier should be a pathway to success.”

“Our concern is that we need more implementation science to know if long-acting ART will be used by the communities hardest hit by HIV,” he said.

Dr. Kawata noted that NMAC agrees that vaccine trial “failures” can offer important lessons, “but we are getting impatient,” he said. “Back in the 80s, Secretary Margret Heckler said we would have a vaccine in 5 years.”

Furthermore, ongoing racial disparities, left unaddressed, will hold back meaningful progress in the fight against HIV, he noted. “We are always hopeful, [but] the reality is that race and racism play an outsized role in health outcome in America. Unless we address these inequalities, we will never end HIV.”

NMAC receives funding from Gilead, Viiv, Merck, and Janssen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Proper Use and Compliance of Facial Masks During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Observational Study of Hospitals in New York City

Although the universal use of masks by both health care professionals and the general public now appears routine, widely differing recommendations were distributed by different health organizations early in the pandemic. In April 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that there was no evidence that healthy individuals wearing a medical mask in the community prevented COVID-19 infection.1 However, these recommendations must be placed in the context of a national shortage of personal protective equipment early in the pandemic. The WHO guidance released on June 5, 2020, recommended continuous use of masks for health care workers in the clinical setting.2 Additional recommendations included mask replacement when wet, soiled, or damaged, and when the wearer touched the mask. The WHO also recommended mask usage by those with underlying medical comorbidities and those living in high population–density areas and in settings where physical distancing was not possible.2

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) officially recommended the use of face coverings for the general public to prevent COVID-19 transmission on April 3, 2020.3 The CDC highlighted that masks should not be worn by children younger than 2 years; individuals with respiratory compromise; and patients who are unconscious, incapacitated, or unable to remove a mask without assistance.4 Medical masks and respirators were only recommended for health care workers. Importantly, masks with valves/vents were not recommended, as respiratory droplets can be emitted, defeating the purpose of source control.4 New York State mandated mask usage in public places starting on April 15, 2020.

These recommendations were based on the hypothesis that COVID-19 transmission occurs primarily via droplets and contact. In reality, SARS-CoV-2 transmission more likely occurs in a continuum from larger droplets to miniscule aerosols expelled from an infected person when talking, coughing, or sneezing.5,6 It should be noted that there was a formal suggestion of the potential for airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by the CDC in a statement on September 18, 2020, that was subsequently retracted 3 days later.7,8 The CDC, reversing their prior recommendations, updated their guidance on October 5, 2020, endorsing prior reports that SARS-CoV-2 can be spread through aerosol transmission.8

Mask usage helps prevent viral spread by all individuals, especially those who are presymptomatic and asymptomatic. Presymptomatic individuals account for approximately 40% to 60% of transmissions, and asymptomatic individuals account for approximately 4% to 30% of infections by some models, which suggest these individuals are the drivers of the pandemic, more so than symptomatic individuals.9-15 Additionally, masking also may in effect reduce the amount of SARS-CoV-2 to which individuals are being exposed in the community.14 Universal masking is a relatively low-cost, low-risk intervention that may provide moderate benefit to the individual but substantial benefit to communities at large.10-13 Universal masking in other countries also has clearly demonstrated major benefits during the pandemic. Implementation of universal masking in Taiwan resulted in only approximately 440 COVID-19 cases and less than 10 deaths, despite a population of 23 million.16 South Korea, having experience with Middle East respiratory syndrome, also was able to quickly institute a mask policy for its citizens, resulting in approximately 94% compliance.17 Moreover, several mathematical models have shown that even imperfect use of masks on a population level can prevent disease transmission and should be instituted.18

Given the importance and potential benefits of mask usage, we investigated compliance and proper utilization of facial masks in New York City (NYC), once the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. New York City and the rest of New York State experienced more than 1.13 million and 1.46 million cases of COVID-19, respectively, as of early November 2021.19 Nationwide, NYC had the greatest absolute death count of more than 34,634 and the greatest rate of death per 100,000 individuals of 412. In contrast, New York State, excluding NYC, had an absolute death count of more than 21,646 and a death rate per 100,000 individuals of 195 as of early November 2021.19 Now entering 20 months since the first case of COVID-19 in NYC, it continues to be vital for facial mask protocols to be emphasized as part of a comprehensive infection prevention protocol, especially in light of continued vaccine resistance, to help stall continued spread of SARS-CoV-2.20

We seek to show that despite months of policies for universal masking in NYC, there is still considerable mask noncompliance by the general public in health care settings where the use of masks is particularly imperative. We conducted an observational study investigating proper use of face masks of adults entering the main entrance of 4 hospitals located in NYC.

Methods

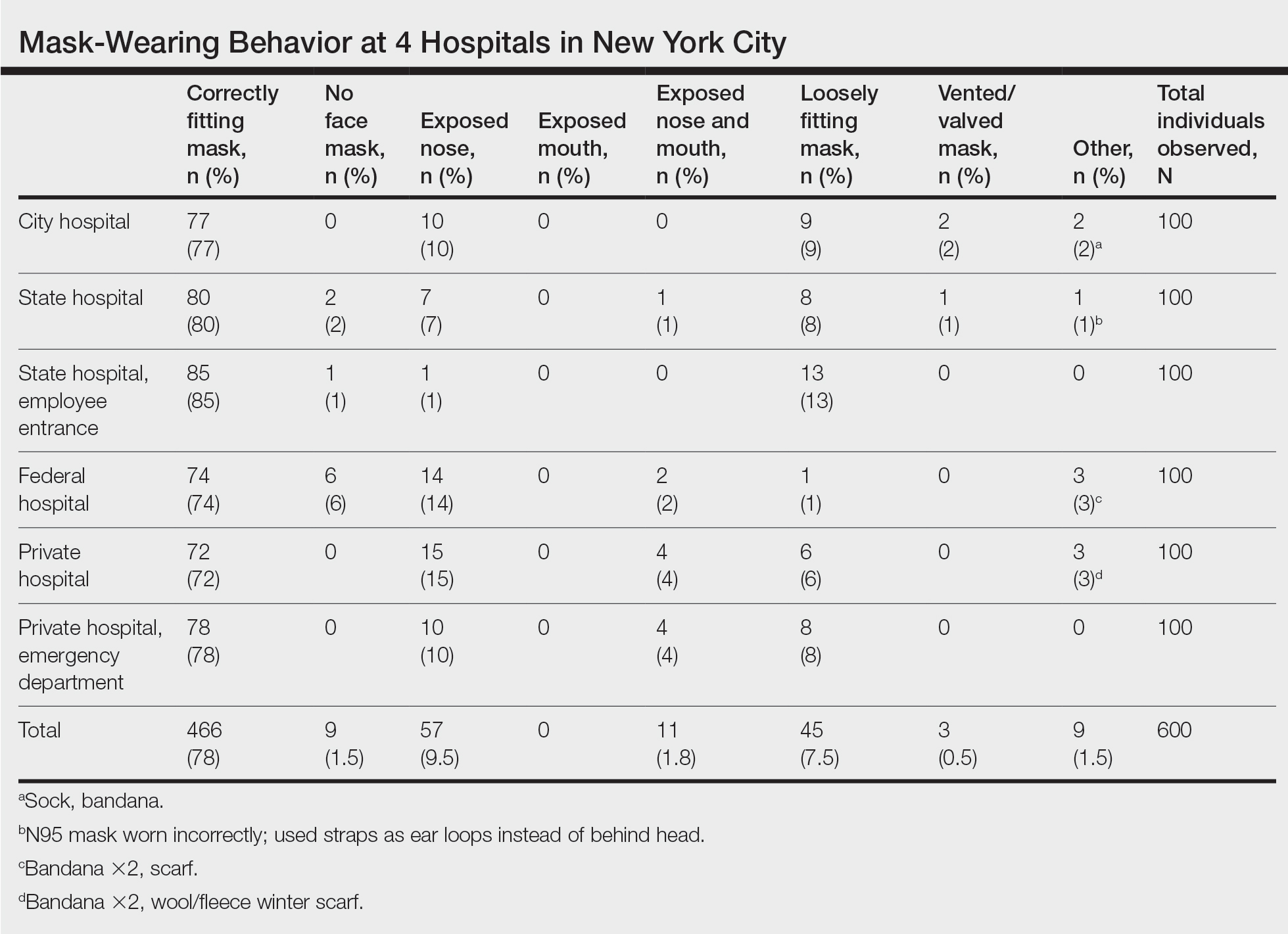

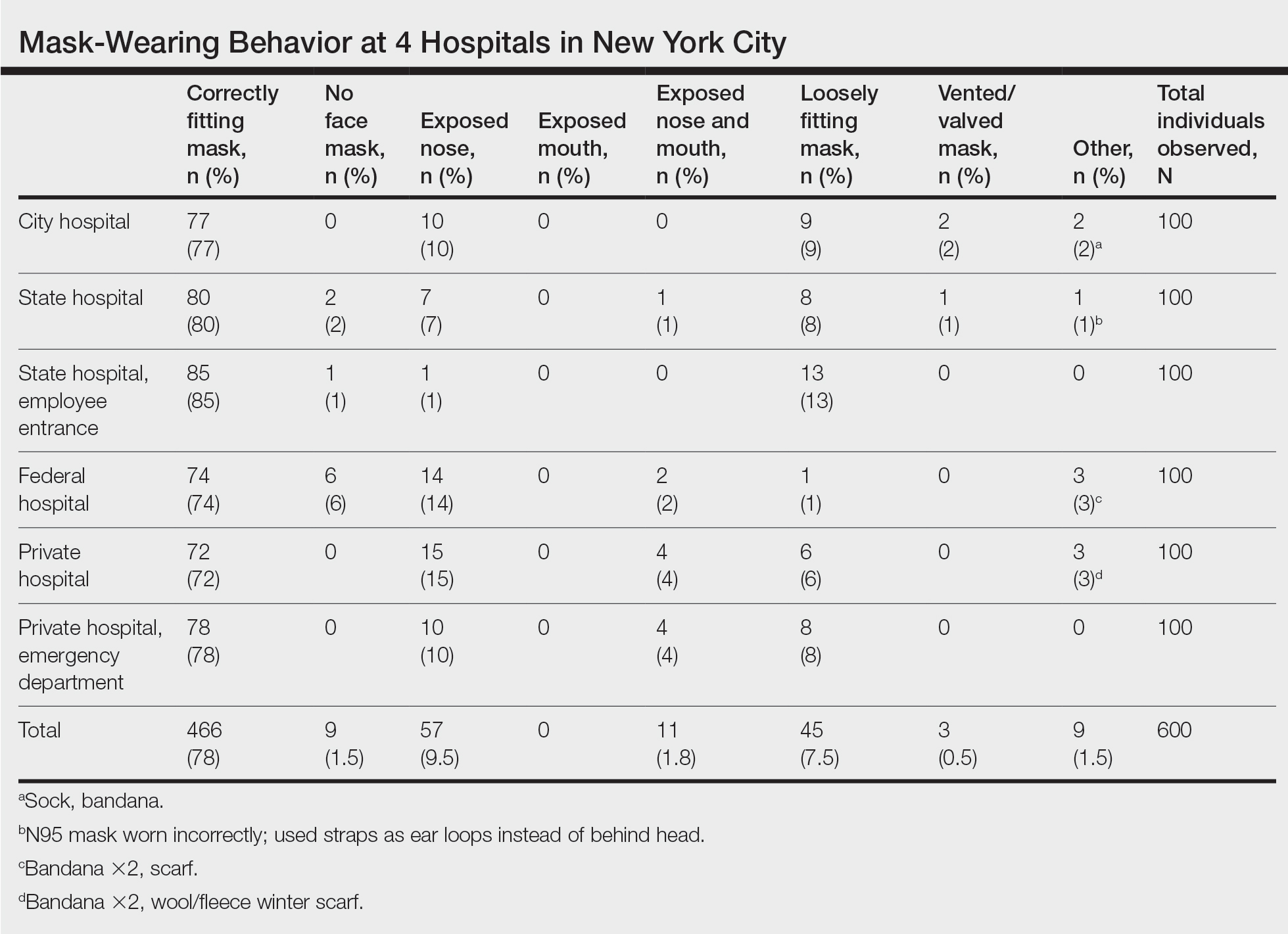

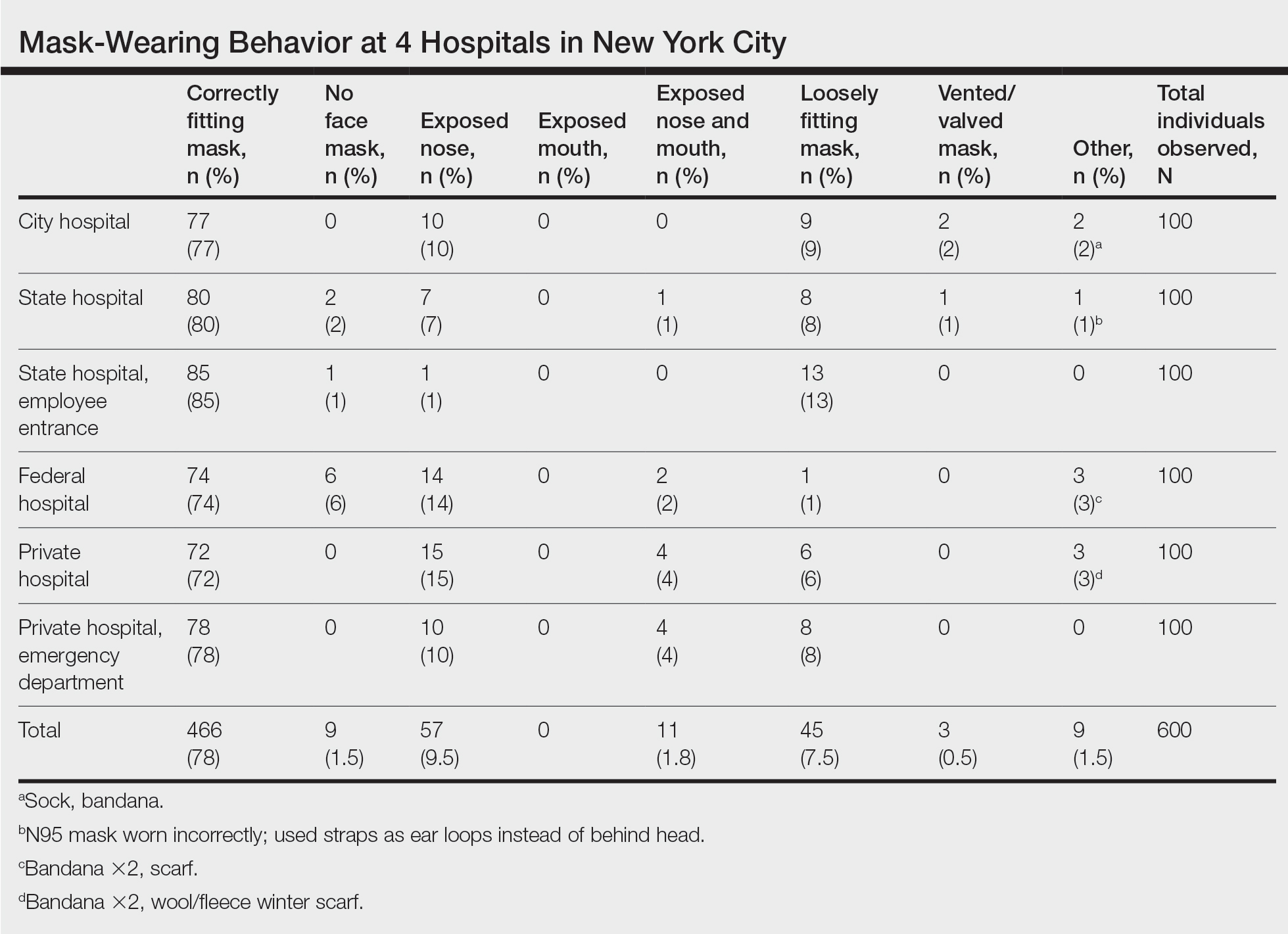

We observed mask usage in adults entering 4 hospitals in September 2020 (postsurge in NYC and prior to the availability of COVID-19 vaccinations). Hospitals were chosen to represent several types of health care delivery systems available in the United States and included a city, state, federal, and private hospital. Data collection was completed during peak traffic hours (8:00

Mask usage was observed and classified into several categories: correctly fitting mask over the nose and mouth, no face mask, mask usage with nose exposed, mask usage with mouth exposed, mask usage with both nose and mouth exposed (ie, mask on the chin/neck area), loosely fitting mask, vented/valved mask, or other form of face covering (eg, bandana, scarf).

Results

We observed a consistent rate of mask compliance between 72% and 85%, with an average of 78% of the 600 individuals observed wearing correctly fitting masks across the 4 hospitals included in this study (Table). The employee entrance included in this study had the highest compliance rate of 85%. An overall low rate of complete mask noncompliance was observed, with only 9 individuals (1.5%) in the entire study not wearing any mask. The federal hospital had the highest rate of mask noncompliance. We also observed a low rate of nose and mouth exposure, with 1.8% of individuals wearing a mask with the nose and mouth exposed (ie, mask tucked under the chin). No individuals were observed with the mouth exposed but with the nose covered by a mask. Additionally, only 3 individuals (0.5%) wore a mask with a vent/valve. The most common way that masks were worn incorrectly was with the nose exposed, accounting for 9.5% of individuals observed. Overall, only 9 individuals (1.5%) wore a nontraditional face covering, with a bandana being the most commonly observed makeshift mask.

Signage regarding the requirement to wear masks and to social distance was universally instituted at all hospital entry points (both inside and outside the hospital) in this study. However, there were no illustrations demonstrating correct and incorrect forms of mask usage. All signage merely displayed a graphic of a facial mask noting the requirement to wear a mask prior to entering the building. Hospital staff also had face masks available for patients who failed to bring a mask or who wore an inappropriate mask (ie, vented/valved masks).

Comment

Mask Effectiveness—Masks reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2 by preventing both droplets and potentially virus-bearing aerosols.6,21,22 It has been demonstrated that well-fitted cotton homemade masks and medical masks provide the most effective method of reducing droplet dispersion. Loosely fitted masks as well as bandana-style facial coverings minimally reduce small aerosolized droplets, and an uncovered mouth and nose can disperse particles at a distance much greater than 6 feet.22

Mask Compliance—We report an overall high compliance rate with mask wearing among individuals visiting a hospital; however, compliance was still imperfect. Overall, 78% of observed individuals wore a correctly fitting mask when entering a hospital, even with hospital staff positioned at entry points to ensure proper mask usage. With all the resources available at health care centers, we anticipated a much higher compliance rate for correctly fitting masks at hospital entrances. We hypothesize that given only 78% of individuals showed proper mask compliance in a setting with enforcement by health care personnel, the mask compliance rate in the larger community is likely much lower. It is imperative to enforce continued mask compliance in medical centers and other public areas given notable vaccine noncompliance in certain parts of the country.

Tools to Prevent Disease Transmission—Mask usage by the general public in NYC helped in its response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yang et al23 demonstrated through mathematical modeling that mask usage in NYC was associated with a 6.6% reduction in transmission overall and a 20% decrease in transmission for individuals 65 years and older during the first month of the universal mask policy going into effect. The authors extrapolated these data during the NYC reopening and found that universal masking reduced transmission by approximately 9% to 11%, accounting for the increase in hours spent outside home quarantine. The authors also hypothesized that if universal masking was as effective in its reduction of transmission for everyone in NYC as it was for older adults, the potential reduction in transmission of SARS-CoV-2 could be as high as 28% to 32%.23

Temperature checks at entrance barricades were standard protocol during the observation period. Although the main purpose of this study was to investigate compliance with and proper use of facial masks in a health care setting, it should be mentioned that, although temperature checks were being done on almost every person entering a hospital, the uniformity and practicality of this intervention has not been backed by substantial evidence. Although many nontouch thermometers are intended to capture a forehead temperature for the most accurate reading, the authors will share that in their observation, medical personnel screening individuals at hospital entrances were observed checking temperatures at any easily accessible body part, such as the forearm, hand, or neck. Furthermore, it has been reported that only approximately 40% of individuals with COVID-19 present with a fever.24 Many hospitals, including the 4 that were included in this investigation, have formal protocols for patients presenting with a fever, especially those presenting to an ambulatory center. Patients are usually instructed to call ahead if they have a fever, and a decision regarding next steps will be discussed with a health care provider. In addition, 1 meta-analysis on the symptoms of COVID-19 suggested that approximately 12% of infected patients are asymptomatic, likely a conservative estimate.25 Although we do not suggest that hospitals stop temperature checks, consistent temperature checks in anatomic locations intended for the specific thermometer used must be employed. Alternatively, a thermographic camera system that could detect heat signatures may be a way to screen faster, only necessitating that those above a threshold be assessed further.

The results of this study suggest that much greater effort is being placed on these temperature checks than on other equally important components of the entrance health assessment. This initial encounter at hospital entrances should serve as an opportunity for education on proper choice and use of masks with clear instructions that masks should not be removed unless directed by a health care provider and in a designated area, such as an examination room. The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is likely the first time an individual is wearing these types of masks. Reiterating when and how often a mask should be changed (eg, when wet or soiled), how a soiled mask is not an effective mask, how a used mask should be discarded, ways to prevent self-contamination (ie, proper donning and doffing), and the importance of other infection-prevention behaviors—hand hygiene; social distancing; avoidance of touching the eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands; and regular disinfecting of surfaces—should be practiced.11,26-29 Extended use and reuse of masks also can result in transmission of infection.30

Throughout the pandemic, our personal experience is that some patients often overtly refuse to wear a mask, citing underlying respiratory issues. The implications of patients not wearing a mask in a medical office and endangering other patients and staff are beyond the scope of this analysis. We will, however, comment briefly on the evidence behind this common concern. Matuschek et al31 found substantial adverse changes in respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and CO2 levels in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who were wearing N95 respirators during a 6-minute walk test. Another study by Chan et al32 showed that nonmedical masks in healthy older adults in the community setting had no impact on oxygen saturation. Ultimately, the most effective mask a patient can wear is a mask that will be worn consistently.32

Populations With Limited Access to Masks—The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted disadvantaged populations, both in socioeconomic status and minority status. A disproportionate number of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths occurred in lower-income and minority populations.10 In fact, Lamb et al33 reported that NYC neighborhoods with a larger proportion of uninsured individuals with limited access to health care and overall lower socioeconomic status had a higher rate of SARS-CoV-2 positivity. A retrospective study in Louisiana showed that Black individuals accounted for 77% of hospitalizations and 71% of deaths due to COVID-19 in a population where only 31% of individuals identified as Black.10 Chu et al6 even asserted that policies should be put into place to address equity issues for populations with limited access to masks. We agree that policies should be put into action to ensure that individuals lacking the means to obtain appropriate masks or unable to obtain an adequate supply of masks be provided this new necessity. It has been calculated that the impact of masks in reducing virus transmission would be greatest if mask availability to disadvantaged populations is ensured.18 We support a plan for masks to be covered by government-sponsored health plans.

Study Limitations—Several limitations exist in our study that should be discussed. Although the data collectors observed a large number of individuals, each hospital entrance was only observed for 1 half-day morning session. There may be variations in the number of people wearing a mask at different times of day and different days of the week with fluctuations in hospital traffic. Although data were collected at a variety of hospitals representing the diverse health care delivery models available in the United States, the NYC hospitals included in this study may have different resources available for infection-prevention strategies than hospitals across the country, given NYC’s unique population density and demographics.

Study Strengths—The generalizability of the study should be recognized. Data were collected by all major health care delivery models available in the United States—private, state, city, and federal hospital systems. This study can be easily replicated in other health care delivery systems to further investigate potential gaps in mask usage and infection prevention. Repeating this study in areas where a large portion of the population does not believe in the virus also will likely show lower levels of mask use.

Conclusion

As the country grapples with vaccine hesitancy and with the new variants of SARS-CoV-2, continued universal masking is still imperative. The effectiveness of universal masking has been demonstrated, and with the combination of vaccinations, we can be assured that the world will continue to emerge from the pandemic.

- World Health Organization. Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19. Interim guidance (6 April 2020). Accessed November 8, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331693/WHO-2019-nCov-IPC_Masks-2020.3-eng.pdf?sequence=1ceisAllowed=y

- World Health Organization. Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19. Interim guidance (5 June 2020). Accessed November 8, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332293/WHO- 2019-nCov-IPC_Masks-2020.4-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Fisher KA, Barile JP, Guerin RJ, et al. Factors associated with cloth face covering use among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, April and May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:933-937.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Considerations for wearing masks (19 April 2021). Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html

- Conly J, Seto WH, Pittet D, et al. Use of medical face masks versus particulate respirators as a component of personal protective equipment for health care workers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9:126.

- Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al; COVID-19 Systematic Urgent Review Group Effort (SURGE) study authors. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395:1973-1987.

- Huang, P. Coronavirus FAQs: Why can’t the CDC make up its mind about airborne transmission? NPR. September 25, 2020. Accessed November 8, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/09/25/916624967/coronavirus-faqs-why-cant-the-cdc-make-up-its-mind-about-airborne-transmission

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). How COVID-19 spreads (14 July 2021). Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html

- Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324:782-793.

- Klompas M, Morris CA, Shenoy ES. Universal masking in the covid-19 era. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:E9.

- Middleton JD, Lopes H. Face masks in the covid-19 crisis: caveats, limits, and priorities. BMJ. 2020;369:m2030.

- Cheng KK, Lam TH, Leung CC. Wearing face masks in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic: altruism and solidarity [published online April 16, 2020]. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30918-1

- Javid B, Weekes MP, Matheson NJ. Covid-19: should the public wear face masks? BMJ. 2020;369:m1442.

- Gandhi M, Beyrer C, Goosby E. Masks do more than protect others during COVID-19: reducing the inoculum of SARS-CoV-2 to protect the wearer. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:3063-3066.

- Ngonghala CN, Iboi EA, Gumel AB. Could masks curtail the post-lockdown resurgence of COVID-19 in the US? Math Biosci. 2020;329:108452. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2020.108452

- Yi-Fong Su V, Yen YF, Yang KY, et al. Masks and medical care: two keys to Taiwan’s success in preventing COVID-19 spread. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;38:101780.

- Lim S, Yoon HI, Song KH, et al. Face masks and containment of COVID-19: experience from South Korea. J Hosp Infect. 2020;106:206-207.

- Fisman DN, Greer AL, Tuite AR. Bidirectional impact of imperfect mask use on reproduction number of COVID-19: a next generation matrix approach. Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:405-408.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. United States COVID-19 cases, deaths, and laboratory testing (NAATs) by state, territory, and jurisdiction. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_totalcases

- Francescani C. Timeline: the first 100 days of New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s COVID-19 response. ABC News. June 17, 2020. Accessed November 8, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/US/News/timeline-100-days-york-gov-andrew-cuomos-covid/story?id=71292880

- Zhang R, Li Y, Zhang AL, et al. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:14857-14863.

- Verma S, Dhanak M, Frankenfield J. Visualizing the effectiveness of face masks in obstructing respiratory jets. Phys Fluids (1994). 2020;32:061708.

- Yang W, Shaff J, Shaman J. COVID-19 transmission dynamics and effectiveness of public health interventions in New York City during the 2020 spring pandemic wave. medRxiv. Preprint posted online September 9, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.09.08.20190710

- Zavascki AP, Falci DR. Clinical characteristics of covid-19 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1859.

- Zhu J, Ji P, Pang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 3062 COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1902-1914. doi:10.1002/jmv.25884

- Sommerstein R, Fux CA, Vuichard-Gysin D, et al. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by aerosols, the rational use of masks, and protection of healthcare workers from COVID-19. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9:100.

- Stone TE, Kunaviktikul W, Omura M, et al. Facemasks and the covid 19 pandemic: what advice should health professionals be giving the general public about the wearing of facemasks? Nurs Health Sci. 2020;22:339-342.

- Tam VC, Tam SY, Poon WK, et al. A reality check on the use of face masks during the COVID-19 outbreak in Hong Kong. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;22:100356.

- Chen YJ, Qin G, Chen J, et al. Comparison of face-touching behaviors before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2016924.

- O’Dowd K, Nair KM, Forouzandeh P, et al. Face masks and respirators in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of current materials, advances and future perspectives. Materials (Basel). 2020;13:3363.

- Matuschek C, Moll F, Fangerau H, et al. Face masks: benefits and risks during the COVID-19 crisis. Eur J Med Res. 2020;25:32.

- Chan NC, Li K, Hirsh J. Peripheral oxygen saturation in older persons wearing nonmedical face masks in community settings. JAMA. 2020;324:2323-2324. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.21905

- , , . Differential COVID‐19 case positivity in New York City neighborhoods: socioeconomic factors and mobility. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2021;15:209-217. doi:10.1111/irv.12816

Although the universal use of masks by both health care professionals and the general public now appears routine, widely differing recommendations were distributed by different health organizations early in the pandemic. In April 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that there was no evidence that healthy individuals wearing a medical mask in the community prevented COVID-19 infection.1 However, these recommendations must be placed in the context of a national shortage of personal protective equipment early in the pandemic. The WHO guidance released on June 5, 2020, recommended continuous use of masks for health care workers in the clinical setting.2 Additional recommendations included mask replacement when wet, soiled, or damaged, and when the wearer touched the mask. The WHO also recommended mask usage by those with underlying medical comorbidities and those living in high population–density areas and in settings where physical distancing was not possible.2

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) officially recommended the use of face coverings for the general public to prevent COVID-19 transmission on April 3, 2020.3 The CDC highlighted that masks should not be worn by children younger than 2 years; individuals with respiratory compromise; and patients who are unconscious, incapacitated, or unable to remove a mask without assistance.4 Medical masks and respirators were only recommended for health care workers. Importantly, masks with valves/vents were not recommended, as respiratory droplets can be emitted, defeating the purpose of source control.4 New York State mandated mask usage in public places starting on April 15, 2020.

These recommendations were based on the hypothesis that COVID-19 transmission occurs primarily via droplets and contact. In reality, SARS-CoV-2 transmission more likely occurs in a continuum from larger droplets to miniscule aerosols expelled from an infected person when talking, coughing, or sneezing.5,6 It should be noted that there was a formal suggestion of the potential for airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by the CDC in a statement on September 18, 2020, that was subsequently retracted 3 days later.7,8 The CDC, reversing their prior recommendations, updated their guidance on October 5, 2020, endorsing prior reports that SARS-CoV-2 can be spread through aerosol transmission.8

Mask usage helps prevent viral spread by all individuals, especially those who are presymptomatic and asymptomatic. Presymptomatic individuals account for approximately 40% to 60% of transmissions, and asymptomatic individuals account for approximately 4% to 30% of infections by some models, which suggest these individuals are the drivers of the pandemic, more so than symptomatic individuals.9-15 Additionally, masking also may in effect reduce the amount of SARS-CoV-2 to which individuals are being exposed in the community.14 Universal masking is a relatively low-cost, low-risk intervention that may provide moderate benefit to the individual but substantial benefit to communities at large.10-13 Universal masking in other countries also has clearly demonstrated major benefits during the pandemic. Implementation of universal masking in Taiwan resulted in only approximately 440 COVID-19 cases and less than 10 deaths, despite a population of 23 million.16 South Korea, having experience with Middle East respiratory syndrome, also was able to quickly institute a mask policy for its citizens, resulting in approximately 94% compliance.17 Moreover, several mathematical models have shown that even imperfect use of masks on a population level can prevent disease transmission and should be instituted.18

Given the importance and potential benefits of mask usage, we investigated compliance and proper utilization of facial masks in New York City (NYC), once the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. New York City and the rest of New York State experienced more than 1.13 million and 1.46 million cases of COVID-19, respectively, as of early November 2021.19 Nationwide, NYC had the greatest absolute death count of more than 34,634 and the greatest rate of death per 100,000 individuals of 412. In contrast, New York State, excluding NYC, had an absolute death count of more than 21,646 and a death rate per 100,000 individuals of 195 as of early November 2021.19 Now entering 20 months since the first case of COVID-19 in NYC, it continues to be vital for facial mask protocols to be emphasized as part of a comprehensive infection prevention protocol, especially in light of continued vaccine resistance, to help stall continued spread of SARS-CoV-2.20

We seek to show that despite months of policies for universal masking in NYC, there is still considerable mask noncompliance by the general public in health care settings where the use of masks is particularly imperative. We conducted an observational study investigating proper use of face masks of adults entering the main entrance of 4 hospitals located in NYC.

Methods

We observed mask usage in adults entering 4 hospitals in September 2020 (postsurge in NYC and prior to the availability of COVID-19 vaccinations). Hospitals were chosen to represent several types of health care delivery systems available in the United States and included a city, state, federal, and private hospital. Data collection was completed during peak traffic hours (8:00

Mask usage was observed and classified into several categories: correctly fitting mask over the nose and mouth, no face mask, mask usage with nose exposed, mask usage with mouth exposed, mask usage with both nose and mouth exposed (ie, mask on the chin/neck area), loosely fitting mask, vented/valved mask, or other form of face covering (eg, bandana, scarf).

Results

We observed a consistent rate of mask compliance between 72% and 85%, with an average of 78% of the 600 individuals observed wearing correctly fitting masks across the 4 hospitals included in this study (Table). The employee entrance included in this study had the highest compliance rate of 85%. An overall low rate of complete mask noncompliance was observed, with only 9 individuals (1.5%) in the entire study not wearing any mask. The federal hospital had the highest rate of mask noncompliance. We also observed a low rate of nose and mouth exposure, with 1.8% of individuals wearing a mask with the nose and mouth exposed (ie, mask tucked under the chin). No individuals were observed with the mouth exposed but with the nose covered by a mask. Additionally, only 3 individuals (0.5%) wore a mask with a vent/valve. The most common way that masks were worn incorrectly was with the nose exposed, accounting for 9.5% of individuals observed. Overall, only 9 individuals (1.5%) wore a nontraditional face covering, with a bandana being the most commonly observed makeshift mask.

Signage regarding the requirement to wear masks and to social distance was universally instituted at all hospital entry points (both inside and outside the hospital) in this study. However, there were no illustrations demonstrating correct and incorrect forms of mask usage. All signage merely displayed a graphic of a facial mask noting the requirement to wear a mask prior to entering the building. Hospital staff also had face masks available for patients who failed to bring a mask or who wore an inappropriate mask (ie, vented/valved masks).

Comment

Mask Effectiveness—Masks reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2 by preventing both droplets and potentially virus-bearing aerosols.6,21,22 It has been demonstrated that well-fitted cotton homemade masks and medical masks provide the most effective method of reducing droplet dispersion. Loosely fitted masks as well as bandana-style facial coverings minimally reduce small aerosolized droplets, and an uncovered mouth and nose can disperse particles at a distance much greater than 6 feet.22

Mask Compliance—We report an overall high compliance rate with mask wearing among individuals visiting a hospital; however, compliance was still imperfect. Overall, 78% of observed individuals wore a correctly fitting mask when entering a hospital, even with hospital staff positioned at entry points to ensure proper mask usage. With all the resources available at health care centers, we anticipated a much higher compliance rate for correctly fitting masks at hospital entrances. We hypothesize that given only 78% of individuals showed proper mask compliance in a setting with enforcement by health care personnel, the mask compliance rate in the larger community is likely much lower. It is imperative to enforce continued mask compliance in medical centers and other public areas given notable vaccine noncompliance in certain parts of the country.

Tools to Prevent Disease Transmission—Mask usage by the general public in NYC helped in its response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yang et al23 demonstrated through mathematical modeling that mask usage in NYC was associated with a 6.6% reduction in transmission overall and a 20% decrease in transmission for individuals 65 years and older during the first month of the universal mask policy going into effect. The authors extrapolated these data during the NYC reopening and found that universal masking reduced transmission by approximately 9% to 11%, accounting for the increase in hours spent outside home quarantine. The authors also hypothesized that if universal masking was as effective in its reduction of transmission for everyone in NYC as it was for older adults, the potential reduction in transmission of SARS-CoV-2 could be as high as 28% to 32%.23

Temperature checks at entrance barricades were standard protocol during the observation period. Although the main purpose of this study was to investigate compliance with and proper use of facial masks in a health care setting, it should be mentioned that, although temperature checks were being done on almost every person entering a hospital, the uniformity and practicality of this intervention has not been backed by substantial evidence. Although many nontouch thermometers are intended to capture a forehead temperature for the most accurate reading, the authors will share that in their observation, medical personnel screening individuals at hospital entrances were observed checking temperatures at any easily accessible body part, such as the forearm, hand, or neck. Furthermore, it has been reported that only approximately 40% of individuals with COVID-19 present with a fever.24 Many hospitals, including the 4 that were included in this investigation, have formal protocols for patients presenting with a fever, especially those presenting to an ambulatory center. Patients are usually instructed to call ahead if they have a fever, and a decision regarding next steps will be discussed with a health care provider. In addition, 1 meta-analysis on the symptoms of COVID-19 suggested that approximately 12% of infected patients are asymptomatic, likely a conservative estimate.25 Although we do not suggest that hospitals stop temperature checks, consistent temperature checks in anatomic locations intended for the specific thermometer used must be employed. Alternatively, a thermographic camera system that could detect heat signatures may be a way to screen faster, only necessitating that those above a threshold be assessed further.

The results of this study suggest that much greater effort is being placed on these temperature checks than on other equally important components of the entrance health assessment. This initial encounter at hospital entrances should serve as an opportunity for education on proper choice and use of masks with clear instructions that masks should not be removed unless directed by a health care provider and in a designated area, such as an examination room. The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is likely the first time an individual is wearing these types of masks. Reiterating when and how often a mask should be changed (eg, when wet or soiled), how a soiled mask is not an effective mask, how a used mask should be discarded, ways to prevent self-contamination (ie, proper donning and doffing), and the importance of other infection-prevention behaviors—hand hygiene; social distancing; avoidance of touching the eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands; and regular disinfecting of surfaces—should be practiced.11,26-29 Extended use and reuse of masks also can result in transmission of infection.30

Throughout the pandemic, our personal experience is that some patients often overtly refuse to wear a mask, citing underlying respiratory issues. The implications of patients not wearing a mask in a medical office and endangering other patients and staff are beyond the scope of this analysis. We will, however, comment briefly on the evidence behind this common concern. Matuschek et al31 found substantial adverse changes in respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and CO2 levels in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who were wearing N95 respirators during a 6-minute walk test. Another study by Chan et al32 showed that nonmedical masks in healthy older adults in the community setting had no impact on oxygen saturation. Ultimately, the most effective mask a patient can wear is a mask that will be worn consistently.32

Populations With Limited Access to Masks—The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted disadvantaged populations, both in socioeconomic status and minority status. A disproportionate number of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths occurred in lower-income and minority populations.10 In fact, Lamb et al33 reported that NYC neighborhoods with a larger proportion of uninsured individuals with limited access to health care and overall lower socioeconomic status had a higher rate of SARS-CoV-2 positivity. A retrospective study in Louisiana showed that Black individuals accounted for 77% of hospitalizations and 71% of deaths due to COVID-19 in a population where only 31% of individuals identified as Black.10 Chu et al6 even asserted that policies should be put into place to address equity issues for populations with limited access to masks. We agree that policies should be put into action to ensure that individuals lacking the means to obtain appropriate masks or unable to obtain an adequate supply of masks be provided this new necessity. It has been calculated that the impact of masks in reducing virus transmission would be greatest if mask availability to disadvantaged populations is ensured.18 We support a plan for masks to be covered by government-sponsored health plans.

Study Limitations—Several limitations exist in our study that should be discussed. Although the data collectors observed a large number of individuals, each hospital entrance was only observed for 1 half-day morning session. There may be variations in the number of people wearing a mask at different times of day and different days of the week with fluctuations in hospital traffic. Although data were collected at a variety of hospitals representing the diverse health care delivery models available in the United States, the NYC hospitals included in this study may have different resources available for infection-prevention strategies than hospitals across the country, given NYC’s unique population density and demographics.

Study Strengths—The generalizability of the study should be recognized. Data were collected by all major health care delivery models available in the United States—private, state, city, and federal hospital systems. This study can be easily replicated in other health care delivery systems to further investigate potential gaps in mask usage and infection prevention. Repeating this study in areas where a large portion of the population does not believe in the virus also will likely show lower levels of mask use.

Conclusion

As the country grapples with vaccine hesitancy and with the new variants of SARS-CoV-2, continued universal masking is still imperative. The effectiveness of universal masking has been demonstrated, and with the combination of vaccinations, we can be assured that the world will continue to emerge from the pandemic.

Although the universal use of masks by both health care professionals and the general public now appears routine, widely differing recommendations were distributed by different health organizations early in the pandemic. In April 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that there was no evidence that healthy individuals wearing a medical mask in the community prevented COVID-19 infection.1 However, these recommendations must be placed in the context of a national shortage of personal protective equipment early in the pandemic. The WHO guidance released on June 5, 2020, recommended continuous use of masks for health care workers in the clinical setting.2 Additional recommendations included mask replacement when wet, soiled, or damaged, and when the wearer touched the mask. The WHO also recommended mask usage by those with underlying medical comorbidities and those living in high population–density areas and in settings where physical distancing was not possible.2

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) officially recommended the use of face coverings for the general public to prevent COVID-19 transmission on April 3, 2020.3 The CDC highlighted that masks should not be worn by children younger than 2 years; individuals with respiratory compromise; and patients who are unconscious, incapacitated, or unable to remove a mask without assistance.4 Medical masks and respirators were only recommended for health care workers. Importantly, masks with valves/vents were not recommended, as respiratory droplets can be emitted, defeating the purpose of source control.4 New York State mandated mask usage in public places starting on April 15, 2020.

These recommendations were based on the hypothesis that COVID-19 transmission occurs primarily via droplets and contact. In reality, SARS-CoV-2 transmission more likely occurs in a continuum from larger droplets to miniscule aerosols expelled from an infected person when talking, coughing, or sneezing.5,6 It should be noted that there was a formal suggestion of the potential for airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by the CDC in a statement on September 18, 2020, that was subsequently retracted 3 days later.7,8 The CDC, reversing their prior recommendations, updated their guidance on October 5, 2020, endorsing prior reports that SARS-CoV-2 can be spread through aerosol transmission.8

Mask usage helps prevent viral spread by all individuals, especially those who are presymptomatic and asymptomatic. Presymptomatic individuals account for approximately 40% to 60% of transmissions, and asymptomatic individuals account for approximately 4% to 30% of infections by some models, which suggest these individuals are the drivers of the pandemic, more so than symptomatic individuals.9-15 Additionally, masking also may in effect reduce the amount of SARS-CoV-2 to which individuals are being exposed in the community.14 Universal masking is a relatively low-cost, low-risk intervention that may provide moderate benefit to the individual but substantial benefit to communities at large.10-13 Universal masking in other countries also has clearly demonstrated major benefits during the pandemic. Implementation of universal masking in Taiwan resulted in only approximately 440 COVID-19 cases and less than 10 deaths, despite a population of 23 million.16 South Korea, having experience with Middle East respiratory syndrome, also was able to quickly institute a mask policy for its citizens, resulting in approximately 94% compliance.17 Moreover, several mathematical models have shown that even imperfect use of masks on a population level can prevent disease transmission and should be instituted.18

Given the importance and potential benefits of mask usage, we investigated compliance and proper utilization of facial masks in New York City (NYC), once the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. New York City and the rest of New York State experienced more than 1.13 million and 1.46 million cases of COVID-19, respectively, as of early November 2021.19 Nationwide, NYC had the greatest absolute death count of more than 34,634 and the greatest rate of death per 100,000 individuals of 412. In contrast, New York State, excluding NYC, had an absolute death count of more than 21,646 and a death rate per 100,000 individuals of 195 as of early November 2021.19 Now entering 20 months since the first case of COVID-19 in NYC, it continues to be vital for facial mask protocols to be emphasized as part of a comprehensive infection prevention protocol, especially in light of continued vaccine resistance, to help stall continued spread of SARS-CoV-2.20

We seek to show that despite months of policies for universal masking in NYC, there is still considerable mask noncompliance by the general public in health care settings where the use of masks is particularly imperative. We conducted an observational study investigating proper use of face masks of adults entering the main entrance of 4 hospitals located in NYC.

Methods

We observed mask usage in adults entering 4 hospitals in September 2020 (postsurge in NYC and prior to the availability of COVID-19 vaccinations). Hospitals were chosen to represent several types of health care delivery systems available in the United States and included a city, state, federal, and private hospital. Data collection was completed during peak traffic hours (8:00

Mask usage was observed and classified into several categories: correctly fitting mask over the nose and mouth, no face mask, mask usage with nose exposed, mask usage with mouth exposed, mask usage with both nose and mouth exposed (ie, mask on the chin/neck area), loosely fitting mask, vented/valved mask, or other form of face covering (eg, bandana, scarf).

Results

We observed a consistent rate of mask compliance between 72% and 85%, with an average of 78% of the 600 individuals observed wearing correctly fitting masks across the 4 hospitals included in this study (Table). The employee entrance included in this study had the highest compliance rate of 85%. An overall low rate of complete mask noncompliance was observed, with only 9 individuals (1.5%) in the entire study not wearing any mask. The federal hospital had the highest rate of mask noncompliance. We also observed a low rate of nose and mouth exposure, with 1.8% of individuals wearing a mask with the nose and mouth exposed (ie, mask tucked under the chin). No individuals were observed with the mouth exposed but with the nose covered by a mask. Additionally, only 3 individuals (0.5%) wore a mask with a vent/valve. The most common way that masks were worn incorrectly was with the nose exposed, accounting for 9.5% of individuals observed. Overall, only 9 individuals (1.5%) wore a nontraditional face covering, with a bandana being the most commonly observed makeshift mask.

Signage regarding the requirement to wear masks and to social distance was universally instituted at all hospital entry points (both inside and outside the hospital) in this study. However, there were no illustrations demonstrating correct and incorrect forms of mask usage. All signage merely displayed a graphic of a facial mask noting the requirement to wear a mask prior to entering the building. Hospital staff also had face masks available for patients who failed to bring a mask or who wore an inappropriate mask (ie, vented/valved masks).

Comment

Mask Effectiveness—Masks reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2 by preventing both droplets and potentially virus-bearing aerosols.6,21,22 It has been demonstrated that well-fitted cotton homemade masks and medical masks provide the most effective method of reducing droplet dispersion. Loosely fitted masks as well as bandana-style facial coverings minimally reduce small aerosolized droplets, and an uncovered mouth and nose can disperse particles at a distance much greater than 6 feet.22

Mask Compliance—We report an overall high compliance rate with mask wearing among individuals visiting a hospital; however, compliance was still imperfect. Overall, 78% of observed individuals wore a correctly fitting mask when entering a hospital, even with hospital staff positioned at entry points to ensure proper mask usage. With all the resources available at health care centers, we anticipated a much higher compliance rate for correctly fitting masks at hospital entrances. We hypothesize that given only 78% of individuals showed proper mask compliance in a setting with enforcement by health care personnel, the mask compliance rate in the larger community is likely much lower. It is imperative to enforce continued mask compliance in medical centers and other public areas given notable vaccine noncompliance in certain parts of the country.

Tools to Prevent Disease Transmission—Mask usage by the general public in NYC helped in its response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yang et al23 demonstrated through mathematical modeling that mask usage in NYC was associated with a 6.6% reduction in transmission overall and a 20% decrease in transmission for individuals 65 years and older during the first month of the universal mask policy going into effect. The authors extrapolated these data during the NYC reopening and found that universal masking reduced transmission by approximately 9% to 11%, accounting for the increase in hours spent outside home quarantine. The authors also hypothesized that if universal masking was as effective in its reduction of transmission for everyone in NYC as it was for older adults, the potential reduction in transmission of SARS-CoV-2 could be as high as 28% to 32%.23

Temperature checks at entrance barricades were standard protocol during the observation period. Although the main purpose of this study was to investigate compliance with and proper use of facial masks in a health care setting, it should be mentioned that, although temperature checks were being done on almost every person entering a hospital, the uniformity and practicality of this intervention has not been backed by substantial evidence. Although many nontouch thermometers are intended to capture a forehead temperature for the most accurate reading, the authors will share that in their observation, medical personnel screening individuals at hospital entrances were observed checking temperatures at any easily accessible body part, such as the forearm, hand, or neck. Furthermore, it has been reported that only approximately 40% of individuals with COVID-19 present with a fever.24 Many hospitals, including the 4 that were included in this investigation, have formal protocols for patients presenting with a fever, especially those presenting to an ambulatory center. Patients are usually instructed to call ahead if they have a fever, and a decision regarding next steps will be discussed with a health care provider. In addition, 1 meta-analysis on the symptoms of COVID-19 suggested that approximately 12% of infected patients are asymptomatic, likely a conservative estimate.25 Although we do not suggest that hospitals stop temperature checks, consistent temperature checks in anatomic locations intended for the specific thermometer used must be employed. Alternatively, a thermographic camera system that could detect heat signatures may be a way to screen faster, only necessitating that those above a threshold be assessed further.

The results of this study suggest that much greater effort is being placed on these temperature checks than on other equally important components of the entrance health assessment. This initial encounter at hospital entrances should serve as an opportunity for education on proper choice and use of masks with clear instructions that masks should not be removed unless directed by a health care provider and in a designated area, such as an examination room. The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is likely the first time an individual is wearing these types of masks. Reiterating when and how often a mask should be changed (eg, when wet or soiled), how a soiled mask is not an effective mask, how a used mask should be discarded, ways to prevent self-contamination (ie, proper donning and doffing), and the importance of other infection-prevention behaviors—hand hygiene; social distancing; avoidance of touching the eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands; and regular disinfecting of surfaces—should be practiced.11,26-29 Extended use and reuse of masks also can result in transmission of infection.30

Throughout the pandemic, our personal experience is that some patients often overtly refuse to wear a mask, citing underlying respiratory issues. The implications of patients not wearing a mask in a medical office and endangering other patients and staff are beyond the scope of this analysis. We will, however, comment briefly on the evidence behind this common concern. Matuschek et al31 found substantial adverse changes in respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and CO2 levels in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who were wearing N95 respirators during a 6-minute walk test. Another study by Chan et al32 showed that nonmedical masks in healthy older adults in the community setting had no impact on oxygen saturation. Ultimately, the most effective mask a patient can wear is a mask that will be worn consistently.32

Populations With Limited Access to Masks—The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted disadvantaged populations, both in socioeconomic status and minority status. A disproportionate number of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths occurred in lower-income and minority populations.10 In fact, Lamb et al33 reported that NYC neighborhoods with a larger proportion of uninsured individuals with limited access to health care and overall lower socioeconomic status had a higher rate of SARS-CoV-2 positivity. A retrospective study in Louisiana showed that Black individuals accounted for 77% of hospitalizations and 71% of deaths due to COVID-19 in a population where only 31% of individuals identified as Black.10 Chu et al6 even asserted that policies should be put into place to address equity issues for populations with limited access to masks. We agree that policies should be put into action to ensure that individuals lacking the means to obtain appropriate masks or unable to obtain an adequate supply of masks be provided this new necessity. It has been calculated that the impact of masks in reducing virus transmission would be greatest if mask availability to disadvantaged populations is ensured.18 We support a plan for masks to be covered by government-sponsored health plans.

Study Limitations—Several limitations exist in our study that should be discussed. Although the data collectors observed a large number of individuals, each hospital entrance was only observed for 1 half-day morning session. There may be variations in the number of people wearing a mask at different times of day and different days of the week with fluctuations in hospital traffic. Although data were collected at a variety of hospitals representing the diverse health care delivery models available in the United States, the NYC hospitals included in this study may have different resources available for infection-prevention strategies than hospitals across the country, given NYC’s unique population density and demographics.

Study Strengths—The generalizability of the study should be recognized. Data were collected by all major health care delivery models available in the United States—private, state, city, and federal hospital systems. This study can be easily replicated in other health care delivery systems to further investigate potential gaps in mask usage and infection prevention. Repeating this study in areas where a large portion of the population does not believe in the virus also will likely show lower levels of mask use.

Conclusion

As the country grapples with vaccine hesitancy and with the new variants of SARS-CoV-2, continued universal masking is still imperative. The effectiveness of universal masking has been demonstrated, and with the combination of vaccinations, we can be assured that the world will continue to emerge from the pandemic.

- World Health Organization. Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19. Interim guidance (6 April 2020). Accessed November 8, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331693/WHO-2019-nCov-IPC_Masks-2020.3-eng.pdf?sequence=1ceisAllowed=y