User login

New HIV PrEP guidelines call for clinicians to talk to patients about HIV prevention meds

Starting Dec. 8, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends all clinicians talk to their sexually active adolescent and adult patients about HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) at least once and prescribe the prevention pills to anyone who asks for them, whether or not you understand their need for it.

“PrEP is a part of good primary care,” Demetre Daskalakis, MD, CDC’s director of the division of HIV/AIDS prevention, said in an interview. “Listening to people and what they need, as opposed to assessing what you think they need, is a seismic shift in how PrEP should be offered.”

The expanded recommendation comes as part of the 2021 update to the U.S. Public Health Service’s PrEP prescribing guidelines. It’s the third iteration since the Food and Drug Administration approved the first HIV prevention pill in 2012, and the first to include guidance on how to prescribe and monitor an injectable version of PrEP, which the FDA may approve as early as December 2021.

There are currently two pills, Truvada (emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, Gilead Sciences and generic) and Descovy (emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, Gilead Sciences). The pills have been found to be up to 99% effective in preventing HIV acquisition. The new injectable cabotegravir appears to be even more effective.

The broadened guidance is part of an effort from the country’s top health officials to expand PrEP prescribing from infectious disease specialists and sexual health clinics to health care professionals, including gynecologists, internal medicine physicians, and family practice clinicians. It appears to be necessary. In 2020, just 25% of the 1.2 million Americans who could benefit from PrEP were taking it, according to CDC data.

But those rates belie stark disparities in PrEP use by race and gender. The vast majority of those using PrEP are White Americans and men. About 66% of White Americans who could benefit from PrEP used it in 2020, and more than a quarter of the men who could benefit used it. By contrast, just 16% of Latinx people who could benefit had a prescription. And fewer than 1 in 10 Black Americans, who make up nearly half of those with indications for PrEP, had a prescription. The same was true for the women who could benefit.

Researchers and data from early PrEP demonstration projects have documented that clinicians are less likely to refer or prescribe the HIV prevention pills to Black people, especially the Black cisgender and transgender women and same-gender-loving men who bear the disproportionate burden of new cases in the United States, as well as fail to prescribe the medication to people who inject drugs.

Normalizing PrEP in primary care

When Courtney Sherman, DNP, APRN, first heard about PrEP in the early 2010s, she joked that her reaction was: “You’re ridiculous. You’re making that up. That’s not real.”

Ms. Sherman is now launching a tele-PrEP program from CAN Community Health, a nonprofit network of community health centers in southern Florida. The tele-PrEP program is meant to serve people in Florida and beyond, to increase access to the pill in areas with few health care professionals, or clinicians unwilling to prescribe it.

“When I go other places, I can’t do what I do for a living without getting some sort of bizarre comment or look,” she said. But the looks don’t just come from family, friends, or her children’s teachers. They come from colleagues, too. “What I’ve learned is that anybody – anybody – can be impacted [by HIV] and the illusion that ‘those people who live over there do things that me and my kind don’t do’ is just garbage.”

That’s the PrEP stigma that the universal PrEP counseling in the guidelines is meant to override, said Dr. Daskalakis. Going forward, he said that informing people about PrEP should be treated as normally as counseling people about smoking.

“You can change the blank: You talk to all adolescents and adults about not smoking,” he said. “This is: ‘Tell adolescents and adults about ways you can prevent HIV, and PrEP is one of them.’ ”

The guidelines also simplify for monitoring lab levels for the current daily pills, checking creatinine clearance levels twice a year in people older than age 50 and once a year in those younger than 50 taking the oral pills. Dr. Daskalakis said that should ease the burden of monitoring PrEP patients for health care professionals with busy caseloads.

It’s a move that drew praise from Shawnika Hull, PhD, assistant professor of health communications at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J.. Dr. Hull’s recent data showed that clinicians who espoused more biased racial views were also less likely to prescribe PrEP to Black women who asked for it.

“Public health practitioners and scientists have been advocating for this as a strategy, as one way to address several ongoing barriers to PrEP specifically but also equity in PrEP,” said Dr. Hull. “This sort of universal provision of information is really an important strategy to try to undo some of the deeply intertwined barriers to uptake.”

‘Don’t grill them’

The updated guidelines keep the number and proportion of Americans who could benefit from PrEP the same: 1.2 million Americans, with nearly half of those Black. And the reasons people would qualify for PrEP remain the same: inconsistent condom use, sharing injection drug equipment, and a STI diagnosis in the last 6 months. There are also 57 jurisdictions, including seven rural states, where dating and having sex carries an increased risk of acquiring HIV because of high rates of untreated HIV in the community.

That’s why the other big change in the update is guidance to prescribe PrEP to whoever asks for it, whether the patient divulges their risk or not. Or as Dr. Daskalakis puts it: “If someone asks for PrEP, don’t grill them.”

There are lots of reasons that someone might ask for PrEP without divulging their risk behaviors, said Dr. Daskalakis, who was an infectious disease doctor in New York back in 2012 (and a member of the FDA committee) when the first pill for PrEP was approved. He said he’s seen this particularly with women who ask about it. Asking for PrEP ends up being an “ice breaker” to discussing the woman’s sexual and injection drug use history, which can then improve the kinds of tests and vaccinations clinicians suggest for her.

“So many women will open the door and say, ‘I want to do this,’ and not necessarily want to go into the details,” he said. “Now, will they go into the details later? Absolutely. That’s how you create trust and connection.”

A mandate and a guideline

Leisha McKinley-Beach, MPH, a member of the U.S. Women and PrEP Working Group, has been urging greater funding and mandates to expand PrEP to women since the first pill was approved. And still, Ms. McKinley-Beach said she recently met a woman who worked for a community group scheduling PrEP appointments for gay men. But the woman didn’t know that she, too, could take it.

The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends health care professionals offer PrEP to those who can benefit. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have a 2014 committee opinion stating that PrEP “may be a useful tool for women at highest risk of HIV acquisition.”

But the ACOG opinion is not a recommendation, stating that it “should not be construed as dictating an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed.” Ms. McKinley-Beach said she hopes that the new CDC guidelines will prompt ACOG and other professional organizations to issue statements to include PrEP education in all health assessments. A spokesperson for ACOG said that the organization had not seen the new CDC guidelines and had no statement on them, but pointed out that the 2014 committee opinion is one of the “highest level of documents we produce.

“We have failed for nearly a decade to raise awareness that PrEP is also a prevention strategy for women,” Ms. McKinley-Beach said in an interview. “In many ways, we’re still back in 2012 as it relates to women.”

Dr. Hull reported having done previous research funded by Gilead Sciences and having received consulting fees from Gilead Sciences in 2018. Ms. McKinley-Beach reported receiving honoraria from ViiV Healthcare. Ms. Sherman and Dr. Daskalakis disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Starting Dec. 8, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends all clinicians talk to their sexually active adolescent and adult patients about HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) at least once and prescribe the prevention pills to anyone who asks for them, whether or not you understand their need for it.

“PrEP is a part of good primary care,” Demetre Daskalakis, MD, CDC’s director of the division of HIV/AIDS prevention, said in an interview. “Listening to people and what they need, as opposed to assessing what you think they need, is a seismic shift in how PrEP should be offered.”

The expanded recommendation comes as part of the 2021 update to the U.S. Public Health Service’s PrEP prescribing guidelines. It’s the third iteration since the Food and Drug Administration approved the first HIV prevention pill in 2012, and the first to include guidance on how to prescribe and monitor an injectable version of PrEP, which the FDA may approve as early as December 2021.

There are currently two pills, Truvada (emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, Gilead Sciences and generic) and Descovy (emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, Gilead Sciences). The pills have been found to be up to 99% effective in preventing HIV acquisition. The new injectable cabotegravir appears to be even more effective.

The broadened guidance is part of an effort from the country’s top health officials to expand PrEP prescribing from infectious disease specialists and sexual health clinics to health care professionals, including gynecologists, internal medicine physicians, and family practice clinicians. It appears to be necessary. In 2020, just 25% of the 1.2 million Americans who could benefit from PrEP were taking it, according to CDC data.

But those rates belie stark disparities in PrEP use by race and gender. The vast majority of those using PrEP are White Americans and men. About 66% of White Americans who could benefit from PrEP used it in 2020, and more than a quarter of the men who could benefit used it. By contrast, just 16% of Latinx people who could benefit had a prescription. And fewer than 1 in 10 Black Americans, who make up nearly half of those with indications for PrEP, had a prescription. The same was true for the women who could benefit.

Researchers and data from early PrEP demonstration projects have documented that clinicians are less likely to refer or prescribe the HIV prevention pills to Black people, especially the Black cisgender and transgender women and same-gender-loving men who bear the disproportionate burden of new cases in the United States, as well as fail to prescribe the medication to people who inject drugs.

Normalizing PrEP in primary care

When Courtney Sherman, DNP, APRN, first heard about PrEP in the early 2010s, she joked that her reaction was: “You’re ridiculous. You’re making that up. That’s not real.”

Ms. Sherman is now launching a tele-PrEP program from CAN Community Health, a nonprofit network of community health centers in southern Florida. The tele-PrEP program is meant to serve people in Florida and beyond, to increase access to the pill in areas with few health care professionals, or clinicians unwilling to prescribe it.

“When I go other places, I can’t do what I do for a living without getting some sort of bizarre comment or look,” she said. But the looks don’t just come from family, friends, or her children’s teachers. They come from colleagues, too. “What I’ve learned is that anybody – anybody – can be impacted [by HIV] and the illusion that ‘those people who live over there do things that me and my kind don’t do’ is just garbage.”

That’s the PrEP stigma that the universal PrEP counseling in the guidelines is meant to override, said Dr. Daskalakis. Going forward, he said that informing people about PrEP should be treated as normally as counseling people about smoking.

“You can change the blank: You talk to all adolescents and adults about not smoking,” he said. “This is: ‘Tell adolescents and adults about ways you can prevent HIV, and PrEP is one of them.’ ”

The guidelines also simplify for monitoring lab levels for the current daily pills, checking creatinine clearance levels twice a year in people older than age 50 and once a year in those younger than 50 taking the oral pills. Dr. Daskalakis said that should ease the burden of monitoring PrEP patients for health care professionals with busy caseloads.

It’s a move that drew praise from Shawnika Hull, PhD, assistant professor of health communications at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J.. Dr. Hull’s recent data showed that clinicians who espoused more biased racial views were also less likely to prescribe PrEP to Black women who asked for it.

“Public health practitioners and scientists have been advocating for this as a strategy, as one way to address several ongoing barriers to PrEP specifically but also equity in PrEP,” said Dr. Hull. “This sort of universal provision of information is really an important strategy to try to undo some of the deeply intertwined barriers to uptake.”

‘Don’t grill them’

The updated guidelines keep the number and proportion of Americans who could benefit from PrEP the same: 1.2 million Americans, with nearly half of those Black. And the reasons people would qualify for PrEP remain the same: inconsistent condom use, sharing injection drug equipment, and a STI diagnosis in the last 6 months. There are also 57 jurisdictions, including seven rural states, where dating and having sex carries an increased risk of acquiring HIV because of high rates of untreated HIV in the community.

That’s why the other big change in the update is guidance to prescribe PrEP to whoever asks for it, whether the patient divulges their risk or not. Or as Dr. Daskalakis puts it: “If someone asks for PrEP, don’t grill them.”

There are lots of reasons that someone might ask for PrEP without divulging their risk behaviors, said Dr. Daskalakis, who was an infectious disease doctor in New York back in 2012 (and a member of the FDA committee) when the first pill for PrEP was approved. He said he’s seen this particularly with women who ask about it. Asking for PrEP ends up being an “ice breaker” to discussing the woman’s sexual and injection drug use history, which can then improve the kinds of tests and vaccinations clinicians suggest for her.

“So many women will open the door and say, ‘I want to do this,’ and not necessarily want to go into the details,” he said. “Now, will they go into the details later? Absolutely. That’s how you create trust and connection.”

A mandate and a guideline

Leisha McKinley-Beach, MPH, a member of the U.S. Women and PrEP Working Group, has been urging greater funding and mandates to expand PrEP to women since the first pill was approved. And still, Ms. McKinley-Beach said she recently met a woman who worked for a community group scheduling PrEP appointments for gay men. But the woman didn’t know that she, too, could take it.

The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends health care professionals offer PrEP to those who can benefit. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have a 2014 committee opinion stating that PrEP “may be a useful tool for women at highest risk of HIV acquisition.”

But the ACOG opinion is not a recommendation, stating that it “should not be construed as dictating an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed.” Ms. McKinley-Beach said she hopes that the new CDC guidelines will prompt ACOG and other professional organizations to issue statements to include PrEP education in all health assessments. A spokesperson for ACOG said that the organization had not seen the new CDC guidelines and had no statement on them, but pointed out that the 2014 committee opinion is one of the “highest level of documents we produce.

“We have failed for nearly a decade to raise awareness that PrEP is also a prevention strategy for women,” Ms. McKinley-Beach said in an interview. “In many ways, we’re still back in 2012 as it relates to women.”

Dr. Hull reported having done previous research funded by Gilead Sciences and having received consulting fees from Gilead Sciences in 2018. Ms. McKinley-Beach reported receiving honoraria from ViiV Healthcare. Ms. Sherman and Dr. Daskalakis disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Starting Dec. 8, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends all clinicians talk to their sexually active adolescent and adult patients about HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) at least once and prescribe the prevention pills to anyone who asks for them, whether or not you understand their need for it.

“PrEP is a part of good primary care,” Demetre Daskalakis, MD, CDC’s director of the division of HIV/AIDS prevention, said in an interview. “Listening to people and what they need, as opposed to assessing what you think they need, is a seismic shift in how PrEP should be offered.”

The expanded recommendation comes as part of the 2021 update to the U.S. Public Health Service’s PrEP prescribing guidelines. It’s the third iteration since the Food and Drug Administration approved the first HIV prevention pill in 2012, and the first to include guidance on how to prescribe and monitor an injectable version of PrEP, which the FDA may approve as early as December 2021.

There are currently two pills, Truvada (emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, Gilead Sciences and generic) and Descovy (emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, Gilead Sciences). The pills have been found to be up to 99% effective in preventing HIV acquisition. The new injectable cabotegravir appears to be even more effective.

The broadened guidance is part of an effort from the country’s top health officials to expand PrEP prescribing from infectious disease specialists and sexual health clinics to health care professionals, including gynecologists, internal medicine physicians, and family practice clinicians. It appears to be necessary. In 2020, just 25% of the 1.2 million Americans who could benefit from PrEP were taking it, according to CDC data.

But those rates belie stark disparities in PrEP use by race and gender. The vast majority of those using PrEP are White Americans and men. About 66% of White Americans who could benefit from PrEP used it in 2020, and more than a quarter of the men who could benefit used it. By contrast, just 16% of Latinx people who could benefit had a prescription. And fewer than 1 in 10 Black Americans, who make up nearly half of those with indications for PrEP, had a prescription. The same was true for the women who could benefit.

Researchers and data from early PrEP demonstration projects have documented that clinicians are less likely to refer or prescribe the HIV prevention pills to Black people, especially the Black cisgender and transgender women and same-gender-loving men who bear the disproportionate burden of new cases in the United States, as well as fail to prescribe the medication to people who inject drugs.

Normalizing PrEP in primary care

When Courtney Sherman, DNP, APRN, first heard about PrEP in the early 2010s, she joked that her reaction was: “You’re ridiculous. You’re making that up. That’s not real.”

Ms. Sherman is now launching a tele-PrEP program from CAN Community Health, a nonprofit network of community health centers in southern Florida. The tele-PrEP program is meant to serve people in Florida and beyond, to increase access to the pill in areas with few health care professionals, or clinicians unwilling to prescribe it.

“When I go other places, I can’t do what I do for a living without getting some sort of bizarre comment or look,” she said. But the looks don’t just come from family, friends, or her children’s teachers. They come from colleagues, too. “What I’ve learned is that anybody – anybody – can be impacted [by HIV] and the illusion that ‘those people who live over there do things that me and my kind don’t do’ is just garbage.”

That’s the PrEP stigma that the universal PrEP counseling in the guidelines is meant to override, said Dr. Daskalakis. Going forward, he said that informing people about PrEP should be treated as normally as counseling people about smoking.

“You can change the blank: You talk to all adolescents and adults about not smoking,” he said. “This is: ‘Tell adolescents and adults about ways you can prevent HIV, and PrEP is one of them.’ ”

The guidelines also simplify for monitoring lab levels for the current daily pills, checking creatinine clearance levels twice a year in people older than age 50 and once a year in those younger than 50 taking the oral pills. Dr. Daskalakis said that should ease the burden of monitoring PrEP patients for health care professionals with busy caseloads.

It’s a move that drew praise from Shawnika Hull, PhD, assistant professor of health communications at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J.. Dr. Hull’s recent data showed that clinicians who espoused more biased racial views were also less likely to prescribe PrEP to Black women who asked for it.

“Public health practitioners and scientists have been advocating for this as a strategy, as one way to address several ongoing barriers to PrEP specifically but also equity in PrEP,” said Dr. Hull. “This sort of universal provision of information is really an important strategy to try to undo some of the deeply intertwined barriers to uptake.”

‘Don’t grill them’

The updated guidelines keep the number and proportion of Americans who could benefit from PrEP the same: 1.2 million Americans, with nearly half of those Black. And the reasons people would qualify for PrEP remain the same: inconsistent condom use, sharing injection drug equipment, and a STI diagnosis in the last 6 months. There are also 57 jurisdictions, including seven rural states, where dating and having sex carries an increased risk of acquiring HIV because of high rates of untreated HIV in the community.

That’s why the other big change in the update is guidance to prescribe PrEP to whoever asks for it, whether the patient divulges their risk or not. Or as Dr. Daskalakis puts it: “If someone asks for PrEP, don’t grill them.”

There are lots of reasons that someone might ask for PrEP without divulging their risk behaviors, said Dr. Daskalakis, who was an infectious disease doctor in New York back in 2012 (and a member of the FDA committee) when the first pill for PrEP was approved. He said he’s seen this particularly with women who ask about it. Asking for PrEP ends up being an “ice breaker” to discussing the woman’s sexual and injection drug use history, which can then improve the kinds of tests and vaccinations clinicians suggest for her.

“So many women will open the door and say, ‘I want to do this,’ and not necessarily want to go into the details,” he said. “Now, will they go into the details later? Absolutely. That’s how you create trust and connection.”

A mandate and a guideline

Leisha McKinley-Beach, MPH, a member of the U.S. Women and PrEP Working Group, has been urging greater funding and mandates to expand PrEP to women since the first pill was approved. And still, Ms. McKinley-Beach said she recently met a woman who worked for a community group scheduling PrEP appointments for gay men. But the woman didn’t know that she, too, could take it.

The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends health care professionals offer PrEP to those who can benefit. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have a 2014 committee opinion stating that PrEP “may be a useful tool for women at highest risk of HIV acquisition.”

But the ACOG opinion is not a recommendation, stating that it “should not be construed as dictating an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed.” Ms. McKinley-Beach said she hopes that the new CDC guidelines will prompt ACOG and other professional organizations to issue statements to include PrEP education in all health assessments. A spokesperson for ACOG said that the organization had not seen the new CDC guidelines and had no statement on them, but pointed out that the 2014 committee opinion is one of the “highest level of documents we produce.

“We have failed for nearly a decade to raise awareness that PrEP is also a prevention strategy for women,” Ms. McKinley-Beach said in an interview. “In many ways, we’re still back in 2012 as it relates to women.”

Dr. Hull reported having done previous research funded by Gilead Sciences and having received consulting fees from Gilead Sciences in 2018. Ms. McKinley-Beach reported receiving honoraria from ViiV Healthcare. Ms. Sherman and Dr. Daskalakis disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration is key to analyzing vitamin D’s effects

The recent Practice Alert by Dr. Campos-Outcalt, “How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292) claimed that the value of vitamin D supplements for prevention is nil or still unknown.1 Most of the references cited in support of this statement were centered on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) based on vitamin D dose rather than achieved 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentration. Since the health effects of vitamin D supplementation are correlated with 25(OH)D concentration, the latter should be used to evaluate the results of vitamin D RCTs—a point I made in my 2018 article on the topic.2

For example, in the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study, in which participants in the treatment arm received 4000 IU/d vitamin D3, there was no reduced rate of progression from prediabetes to diabetes. However, when 25(OH)D concentrations were analyzed for those in the vitamin D arm during the trial, the risk was found to be reduced by 25% (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.82) per 10 ng/mL increase in 25(OH)D.3

Another trial, the Harvard-led VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL), enrolled more than 25,000 participants, with the treatment arm receiving 2000 IU/d vitamin D3.4 There were no significant reductions in incidence of either cancer or cardiovascular disease for the entire group. The mean baseline 25(OH)D concentration for those for whom values were provided was 31 ng/mL (32.2 ng/mL for White participants, 24.9 ng/mL for Black participants). However, there were ~25% reductions in cancer risk among Black participants (who had lower 25(OH)D concentrations than White participants) and those with a body mass index < 25. A posthoc analysis suggested a possible benefit related to the rate of total cancer deaths.

A recent article reported the results of long-term vitamin D supplementation among Veterans Health Administration patients who had an initial 25(OH)D concentration of < 20 ng/mL.5 For those who were treated with vitamin D and achieved a 25(OH)D concentration of > 30 ng/mL (compared to those who were untreated and had an average concentration of < 20 ng/mL), the risk of myocardial infarction was 27% lower (HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.55-0.96) and the risk of all-cause mortality was reduced by 39% (HR = 0.61; 95% CI, 0.56-0.67).

An analysis of SARS-CoV-2 positivity examined data for more than 190,000 patients in the United States who had serum 25(OH)D concentration measurements taken up to 1 year prior to their SARS-CoV-2 test. Positivity rates were 12.5% (95% CI, 12.2%-12.8%) for those with a 25(OH)D concentration < 20 ng/mL vs 5.9% (95% CI, 5.5%-6.4%) for those with a 25(OH)D concentration ≥55 ng/mL.6

Thus, there are significant benefits of vitamin D supplementation to achieve a 25(OH)D concentration of 30 to 60 ng/mL for important health outcomes.

Continue to: Author's Response

Author's response

I appreciate the letter from Dr. Grant in response to my previous Practice Alert, as it provides an opportunity to make some important points about assessment of scientific evidence and drawing conclusions based on sound methodology. There is an overabundance of scientific literature published, much of which is of questionable quality, meaning a “study” or 2 can be found to support any preconceived point of view.

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) published a series of recommendations on how trustworthy recommendations and guidelines should be produced.1,2 Key among the steps recommended is a full assessment of the totality of the literature on the subject by an independent, nonconflicted panel. This should be based on a systematic review that includes standard search methods to find all pertinent articles, an assessment of the quality of each study using standardized tools, and an overall assessment of the quality of the evidence. A high-quality systematic review meeting these standards was the basis for my review article on vitamin D.3

To challenge the findings of the unproven benefits of vitamin D, Dr. Grant cited 4 studies to support the purported benefit of achieving a specific serum 25(OH)D level to prevent cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and COVID-19. After reading these studies, I would not consider any of them a “game changer.”

The first study was restricted to those with prediabetes, had limited follow-up (mean of 2.5 years), and found different results for those with the same 25(OH)D concentrations in the placebo and treatment groups.4 The second study was a large, well-conducted clinical trial that found no benefit of vitamin D supplementation in preventing cancer and cardiovascular disease.5 While Dr. Grant claims that benefits were found for some subgroups, I could locate only the statistics on cancer incidence in Black participants, and the confidence intervals showed no statistically significant benefit. It is always questionable to look at multiple outcomes in multiple subgroups without a prior hypothesis because of the likely occurrence of chance findings in so many comparisons. The third was a retrospective observational study with all the potential biases and challenges to validity that such studies present.6 A single study, especially 1 with observational methods, almost never conclusively settles a point.

The role of vitamin D in the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 is an aspect that was not covered in the systematic review by the US Preventive Services Task Force. The study on this issuecited by Dr. Grant was a large retrospective observational study that found an inverse relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates.7 This is 1 observational study with interesting results. However, I believe the conclusion of the National Institutes of Health is currently still the correct one: “There is insufficient evidence to recommend either for or against the use of vitamin D for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.”8

With time and further research, Dr. Grant may eventually prove to be correct on specific points. However, when challenging a high-quality systematic review, one must assess the quality of the studies used while also placing them in context of the totality of the literature.

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA

Phoenix, AZ

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Finding What Works in Health Care. The National Academy Press, 2011.

2. Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. The National Academy Press, 2011.

3. Kahwati LC, LeBlanc E, Weber RP, et al. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults; updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325:1443-1463. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26498

4. Dawson-Hughes B, Staten MA, Knowler WC, et al. Intratrial exposure to vitamin D and new-onset diabetes among adults with prediabetes: a secondary analysis from the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2916-2922. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1765

5. Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee I-M, et al. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:33-44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809944

6. Acharya P, Dalia T, Ranka S, et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab124. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab124

7. Kaufman HW, Niles JK, Kroll MH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

8. National Institutes of Health. Vitamin D. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Updated April 21, 2021. Accessed November 18, 2021. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/supplements/vitamin-d/

1. Campos-Outcalt D. How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0215

2. Grant WB, Boucher BJ, Bhattoa HP, et al. Why vitamin D clinical trials should be based on 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;177:266-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.08.009

3. Dawson-Hughes B, Staten MA, Knowler WC, et al. Intratrial exposure to vitamin D and new-onset diabetes among adults with prediabetes: a secondary analysis from the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2916-2922. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1765

4. Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee I-M, et al. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:33-44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809944

5. Acharya P, Dalia T, Ranka S, et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab124. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab124

6. Kaufman HW, Niles JK, Kroll MH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

The recent Practice Alert by Dr. Campos-Outcalt, “How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292) claimed that the value of vitamin D supplements for prevention is nil or still unknown.1 Most of the references cited in support of this statement were centered on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) based on vitamin D dose rather than achieved 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentration. Since the health effects of vitamin D supplementation are correlated with 25(OH)D concentration, the latter should be used to evaluate the results of vitamin D RCTs—a point I made in my 2018 article on the topic.2

For example, in the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study, in which participants in the treatment arm received 4000 IU/d vitamin D3, there was no reduced rate of progression from prediabetes to diabetes. However, when 25(OH)D concentrations were analyzed for those in the vitamin D arm during the trial, the risk was found to be reduced by 25% (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.82) per 10 ng/mL increase in 25(OH)D.3

Another trial, the Harvard-led VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL), enrolled more than 25,000 participants, with the treatment arm receiving 2000 IU/d vitamin D3.4 There were no significant reductions in incidence of either cancer or cardiovascular disease for the entire group. The mean baseline 25(OH)D concentration for those for whom values were provided was 31 ng/mL (32.2 ng/mL for White participants, 24.9 ng/mL for Black participants). However, there were ~25% reductions in cancer risk among Black participants (who had lower 25(OH)D concentrations than White participants) and those with a body mass index < 25. A posthoc analysis suggested a possible benefit related to the rate of total cancer deaths.

A recent article reported the results of long-term vitamin D supplementation among Veterans Health Administration patients who had an initial 25(OH)D concentration of < 20 ng/mL.5 For those who were treated with vitamin D and achieved a 25(OH)D concentration of > 30 ng/mL (compared to those who were untreated and had an average concentration of < 20 ng/mL), the risk of myocardial infarction was 27% lower (HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.55-0.96) and the risk of all-cause mortality was reduced by 39% (HR = 0.61; 95% CI, 0.56-0.67).

An analysis of SARS-CoV-2 positivity examined data for more than 190,000 patients in the United States who had serum 25(OH)D concentration measurements taken up to 1 year prior to their SARS-CoV-2 test. Positivity rates were 12.5% (95% CI, 12.2%-12.8%) for those with a 25(OH)D concentration < 20 ng/mL vs 5.9% (95% CI, 5.5%-6.4%) for those with a 25(OH)D concentration ≥55 ng/mL.6

Thus, there are significant benefits of vitamin D supplementation to achieve a 25(OH)D concentration of 30 to 60 ng/mL for important health outcomes.

Continue to: Author's Response

Author's response

I appreciate the letter from Dr. Grant in response to my previous Practice Alert, as it provides an opportunity to make some important points about assessment of scientific evidence and drawing conclusions based on sound methodology. There is an overabundance of scientific literature published, much of which is of questionable quality, meaning a “study” or 2 can be found to support any preconceived point of view.

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) published a series of recommendations on how trustworthy recommendations and guidelines should be produced.1,2 Key among the steps recommended is a full assessment of the totality of the literature on the subject by an independent, nonconflicted panel. This should be based on a systematic review that includes standard search methods to find all pertinent articles, an assessment of the quality of each study using standardized tools, and an overall assessment of the quality of the evidence. A high-quality systematic review meeting these standards was the basis for my review article on vitamin D.3

To challenge the findings of the unproven benefits of vitamin D, Dr. Grant cited 4 studies to support the purported benefit of achieving a specific serum 25(OH)D level to prevent cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and COVID-19. After reading these studies, I would not consider any of them a “game changer.”

The first study was restricted to those with prediabetes, had limited follow-up (mean of 2.5 years), and found different results for those with the same 25(OH)D concentrations in the placebo and treatment groups.4 The second study was a large, well-conducted clinical trial that found no benefit of vitamin D supplementation in preventing cancer and cardiovascular disease.5 While Dr. Grant claims that benefits were found for some subgroups, I could locate only the statistics on cancer incidence in Black participants, and the confidence intervals showed no statistically significant benefit. It is always questionable to look at multiple outcomes in multiple subgroups without a prior hypothesis because of the likely occurrence of chance findings in so many comparisons. The third was a retrospective observational study with all the potential biases and challenges to validity that such studies present.6 A single study, especially 1 with observational methods, almost never conclusively settles a point.

The role of vitamin D in the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 is an aspect that was not covered in the systematic review by the US Preventive Services Task Force. The study on this issuecited by Dr. Grant was a large retrospective observational study that found an inverse relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates.7 This is 1 observational study with interesting results. However, I believe the conclusion of the National Institutes of Health is currently still the correct one: “There is insufficient evidence to recommend either for or against the use of vitamin D for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.”8

With time and further research, Dr. Grant may eventually prove to be correct on specific points. However, when challenging a high-quality systematic review, one must assess the quality of the studies used while also placing them in context of the totality of the literature.

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA

Phoenix, AZ

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Finding What Works in Health Care. The National Academy Press, 2011.

2. Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. The National Academy Press, 2011.

3. Kahwati LC, LeBlanc E, Weber RP, et al. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults; updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325:1443-1463. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26498

4. Dawson-Hughes B, Staten MA, Knowler WC, et al. Intratrial exposure to vitamin D and new-onset diabetes among adults with prediabetes: a secondary analysis from the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2916-2922. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1765

5. Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee I-M, et al. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:33-44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809944

6. Acharya P, Dalia T, Ranka S, et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab124. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab124

7. Kaufman HW, Niles JK, Kroll MH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

8. National Institutes of Health. Vitamin D. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Updated April 21, 2021. Accessed November 18, 2021. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/supplements/vitamin-d/

The recent Practice Alert by Dr. Campos-Outcalt, “How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292) claimed that the value of vitamin D supplements for prevention is nil or still unknown.1 Most of the references cited in support of this statement were centered on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) based on vitamin D dose rather than achieved 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentration. Since the health effects of vitamin D supplementation are correlated with 25(OH)D concentration, the latter should be used to evaluate the results of vitamin D RCTs—a point I made in my 2018 article on the topic.2

For example, in the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study, in which participants in the treatment arm received 4000 IU/d vitamin D3, there was no reduced rate of progression from prediabetes to diabetes. However, when 25(OH)D concentrations were analyzed for those in the vitamin D arm during the trial, the risk was found to be reduced by 25% (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.82) per 10 ng/mL increase in 25(OH)D.3

Another trial, the Harvard-led VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL), enrolled more than 25,000 participants, with the treatment arm receiving 2000 IU/d vitamin D3.4 There were no significant reductions in incidence of either cancer or cardiovascular disease for the entire group. The mean baseline 25(OH)D concentration for those for whom values were provided was 31 ng/mL (32.2 ng/mL for White participants, 24.9 ng/mL for Black participants). However, there were ~25% reductions in cancer risk among Black participants (who had lower 25(OH)D concentrations than White participants) and those with a body mass index < 25. A posthoc analysis suggested a possible benefit related to the rate of total cancer deaths.

A recent article reported the results of long-term vitamin D supplementation among Veterans Health Administration patients who had an initial 25(OH)D concentration of < 20 ng/mL.5 For those who were treated with vitamin D and achieved a 25(OH)D concentration of > 30 ng/mL (compared to those who were untreated and had an average concentration of < 20 ng/mL), the risk of myocardial infarction was 27% lower (HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.55-0.96) and the risk of all-cause mortality was reduced by 39% (HR = 0.61; 95% CI, 0.56-0.67).

An analysis of SARS-CoV-2 positivity examined data for more than 190,000 patients in the United States who had serum 25(OH)D concentration measurements taken up to 1 year prior to their SARS-CoV-2 test. Positivity rates were 12.5% (95% CI, 12.2%-12.8%) for those with a 25(OH)D concentration < 20 ng/mL vs 5.9% (95% CI, 5.5%-6.4%) for those with a 25(OH)D concentration ≥55 ng/mL.6

Thus, there are significant benefits of vitamin D supplementation to achieve a 25(OH)D concentration of 30 to 60 ng/mL for important health outcomes.

Continue to: Author's Response

Author's response

I appreciate the letter from Dr. Grant in response to my previous Practice Alert, as it provides an opportunity to make some important points about assessment of scientific evidence and drawing conclusions based on sound methodology. There is an overabundance of scientific literature published, much of which is of questionable quality, meaning a “study” or 2 can be found to support any preconceived point of view.

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) published a series of recommendations on how trustworthy recommendations and guidelines should be produced.1,2 Key among the steps recommended is a full assessment of the totality of the literature on the subject by an independent, nonconflicted panel. This should be based on a systematic review that includes standard search methods to find all pertinent articles, an assessment of the quality of each study using standardized tools, and an overall assessment of the quality of the evidence. A high-quality systematic review meeting these standards was the basis for my review article on vitamin D.3

To challenge the findings of the unproven benefits of vitamin D, Dr. Grant cited 4 studies to support the purported benefit of achieving a specific serum 25(OH)D level to prevent cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and COVID-19. After reading these studies, I would not consider any of them a “game changer.”

The first study was restricted to those with prediabetes, had limited follow-up (mean of 2.5 years), and found different results for those with the same 25(OH)D concentrations in the placebo and treatment groups.4 The second study was a large, well-conducted clinical trial that found no benefit of vitamin D supplementation in preventing cancer and cardiovascular disease.5 While Dr. Grant claims that benefits were found for some subgroups, I could locate only the statistics on cancer incidence in Black participants, and the confidence intervals showed no statistically significant benefit. It is always questionable to look at multiple outcomes in multiple subgroups without a prior hypothesis because of the likely occurrence of chance findings in so many comparisons. The third was a retrospective observational study with all the potential biases and challenges to validity that such studies present.6 A single study, especially 1 with observational methods, almost never conclusively settles a point.

The role of vitamin D in the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 is an aspect that was not covered in the systematic review by the US Preventive Services Task Force. The study on this issuecited by Dr. Grant was a large retrospective observational study that found an inverse relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates.7 This is 1 observational study with interesting results. However, I believe the conclusion of the National Institutes of Health is currently still the correct one: “There is insufficient evidence to recommend either for or against the use of vitamin D for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.”8

With time and further research, Dr. Grant may eventually prove to be correct on specific points. However, when challenging a high-quality systematic review, one must assess the quality of the studies used while also placing them in context of the totality of the literature.

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA

Phoenix, AZ

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Finding What Works in Health Care. The National Academy Press, 2011.

2. Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. The National Academy Press, 2011.

3. Kahwati LC, LeBlanc E, Weber RP, et al. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults; updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325:1443-1463. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26498

4. Dawson-Hughes B, Staten MA, Knowler WC, et al. Intratrial exposure to vitamin D and new-onset diabetes among adults with prediabetes: a secondary analysis from the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2916-2922. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1765

5. Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee I-M, et al. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:33-44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809944

6. Acharya P, Dalia T, Ranka S, et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab124. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab124

7. Kaufman HW, Niles JK, Kroll MH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

8. National Institutes of Health. Vitamin D. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Updated April 21, 2021. Accessed November 18, 2021. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/supplements/vitamin-d/

1. Campos-Outcalt D. How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0215

2. Grant WB, Boucher BJ, Bhattoa HP, et al. Why vitamin D clinical trials should be based on 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;177:266-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.08.009

3. Dawson-Hughes B, Staten MA, Knowler WC, et al. Intratrial exposure to vitamin D and new-onset diabetes among adults with prediabetes: a secondary analysis from the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2916-2922. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1765

4. Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee I-M, et al. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:33-44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809944

5. Acharya P, Dalia T, Ranka S, et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab124. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab124

6. Kaufman HW, Niles JK, Kroll MH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

1. Campos-Outcalt D. How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0215

2. Grant WB, Boucher BJ, Bhattoa HP, et al. Why vitamin D clinical trials should be based on 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;177:266-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.08.009

3. Dawson-Hughes B, Staten MA, Knowler WC, et al. Intratrial exposure to vitamin D and new-onset diabetes among adults with prediabetes: a secondary analysis from the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2916-2922. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1765

4. Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee I-M, et al. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:33-44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809944

5. Acharya P, Dalia T, Ranka S, et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels on the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab124. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab124

6. Kaufman HW, Niles JK, Kroll MH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

Despite ‘getting it wrong’ we must continue to do what’s right

I have been wrong about the COVID-19 pandemic any number of times. During the early days of the pandemic, a colleague asked me if he should book his airline ticket to Chicago for our annual Essential Evidence conference. I told him to go ahead. The country shut down the next week.

In September of this year, I was ready to book my flight to Phoenix for a presentation at the Arizona Academy of Family Physicians annual meeting. I thought COVID-19 activity was winding down. I was wrong again. The conference was changed to virtual presentations.

And now, as I write this editorial late in November, I find myself wrong a third time. I figured the smoldering COVID-19 activity in Michigan, where I live, would wind down before Thanksgiving. But it is expanding wildly throughout the Midwest.

Wrong again, and again.

I figured most everyone would be vaccinated as soon as vaccines were available, given the dangerous nature of the virus and the benign nature of the vaccines. But here we are, more than 750,000 deaths later and, as a country, we still have not learned our lesson. I won’t get into the disinformation campaign against the existence of the pandemic and the effectiveness and safety of the vaccines; this disinformation campaign seems to be designed to kill as many Americans as possible.

The COVID-19 epidemic is personal for all of us. Not one of us has been immune to its effects. All of us have had a relative or friend die of COVID-19 infection. All of us have had to wear masks and be cautious about contacts with others. All of us have cancelled or restricted travel. My wife and I are debating whether or not we should gather for the holidays with our children and grandchildren in Michigan, despite the fact that all of us have been immunized. One of my sons has a mother-in-law with pulmonary fibrosis; he and his family will all be doing home testing for COVID-19 the day before visiting her.

When will this nightmare end? There is no question that everyone in the United States—and most likely, the entire world—will eventually get vaccinated against COVID-19 or get infected with it. We must continue urging everyone to make the smart, safe choice and get vaccinated.

There are still hundreds of thousands of lives to be saved.

I have been wrong about the COVID-19 pandemic any number of times. During the early days of the pandemic, a colleague asked me if he should book his airline ticket to Chicago for our annual Essential Evidence conference. I told him to go ahead. The country shut down the next week.

In September of this year, I was ready to book my flight to Phoenix for a presentation at the Arizona Academy of Family Physicians annual meeting. I thought COVID-19 activity was winding down. I was wrong again. The conference was changed to virtual presentations.

And now, as I write this editorial late in November, I find myself wrong a third time. I figured the smoldering COVID-19 activity in Michigan, where I live, would wind down before Thanksgiving. But it is expanding wildly throughout the Midwest.

Wrong again, and again.

I figured most everyone would be vaccinated as soon as vaccines were available, given the dangerous nature of the virus and the benign nature of the vaccines. But here we are, more than 750,000 deaths later and, as a country, we still have not learned our lesson. I won’t get into the disinformation campaign against the existence of the pandemic and the effectiveness and safety of the vaccines; this disinformation campaign seems to be designed to kill as many Americans as possible.

The COVID-19 epidemic is personal for all of us. Not one of us has been immune to its effects. All of us have had a relative or friend die of COVID-19 infection. All of us have had to wear masks and be cautious about contacts with others. All of us have cancelled or restricted travel. My wife and I are debating whether or not we should gather for the holidays with our children and grandchildren in Michigan, despite the fact that all of us have been immunized. One of my sons has a mother-in-law with pulmonary fibrosis; he and his family will all be doing home testing for COVID-19 the day before visiting her.

When will this nightmare end? There is no question that everyone in the United States—and most likely, the entire world—will eventually get vaccinated against COVID-19 or get infected with it. We must continue urging everyone to make the smart, safe choice and get vaccinated.

There are still hundreds of thousands of lives to be saved.

I have been wrong about the COVID-19 pandemic any number of times. During the early days of the pandemic, a colleague asked me if he should book his airline ticket to Chicago for our annual Essential Evidence conference. I told him to go ahead. The country shut down the next week.

In September of this year, I was ready to book my flight to Phoenix for a presentation at the Arizona Academy of Family Physicians annual meeting. I thought COVID-19 activity was winding down. I was wrong again. The conference was changed to virtual presentations.

And now, as I write this editorial late in November, I find myself wrong a third time. I figured the smoldering COVID-19 activity in Michigan, where I live, would wind down before Thanksgiving. But it is expanding wildly throughout the Midwest.

Wrong again, and again.

I figured most everyone would be vaccinated as soon as vaccines were available, given the dangerous nature of the virus and the benign nature of the vaccines. But here we are, more than 750,000 deaths later and, as a country, we still have not learned our lesson. I won’t get into the disinformation campaign against the existence of the pandemic and the effectiveness and safety of the vaccines; this disinformation campaign seems to be designed to kill as many Americans as possible.

The COVID-19 epidemic is personal for all of us. Not one of us has been immune to its effects. All of us have had a relative or friend die of COVID-19 infection. All of us have had to wear masks and be cautious about contacts with others. All of us have cancelled or restricted travel. My wife and I are debating whether or not we should gather for the holidays with our children and grandchildren in Michigan, despite the fact that all of us have been immunized. One of my sons has a mother-in-law with pulmonary fibrosis; he and his family will all be doing home testing for COVID-19 the day before visiting her.

When will this nightmare end? There is no question that everyone in the United States—and most likely, the entire world—will eventually get vaccinated against COVID-19 or get infected with it. We must continue urging everyone to make the smart, safe choice and get vaccinated.

There are still hundreds of thousands of lives to be saved.

Cervical cancer update: The latest on screening & management

The World Health Organization estimates that, in 2020, worldwide, there were 604,000 new cases of uterine cervical cancer and approximately 342,000 deaths, 84% of which occurred in developing countries.1 In the United States, as of 2018, the lifetime risk of death from cervical cancer was 2.2 for every 100,000

In this article, we summarize recent updates in the epidemiology, prevention, and treatment of cervical cancer. We emphasize recent information of value to family physicians, including updates in clinical guidelines and other pertinent national recommendations.

Spotlight continues to shine on HPV

It has been known for several decades that cervical cancer is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). Of more than 100 known HPV types, 14 or 15 are classified as carcinogenic. HPV 16 is the most common oncogenic type, causing more than 60% of cases of cervical cancer3,4

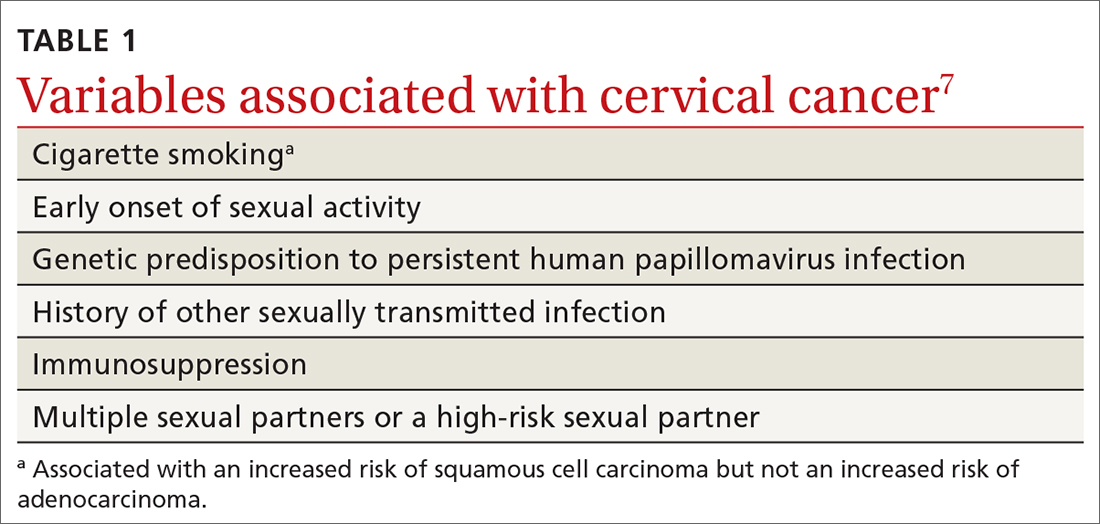

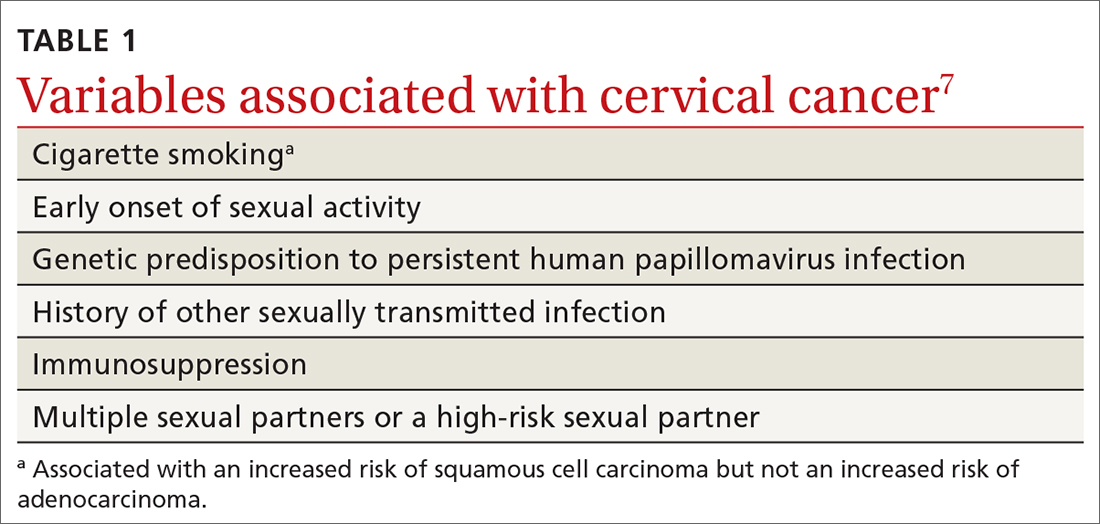

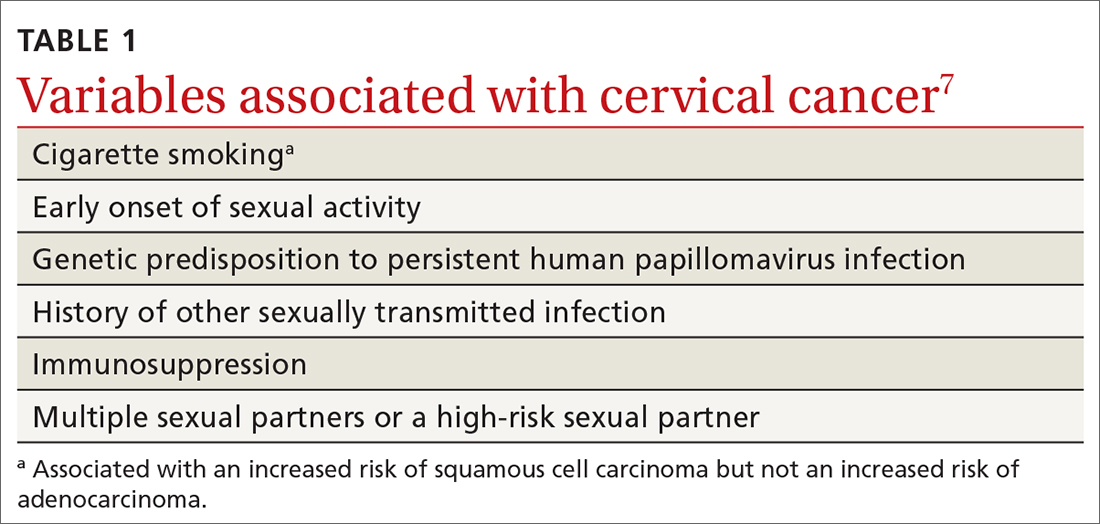

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection, with as many as 80% of sexually active people becoming infected during their lifetime, generally before 50 years of age.5 HPV also causes other anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers; however, worldwide, more than 80% of HPV-associated cancers are cervical.6 Risk factors for cervical cancer are listed in TABLE 1.7 Cervical cancer is less common when partners are circumcised.7

Most cases of HPV infection clear in 1 or 2 years

At least 70% of cervical cancers are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); 20% to 25% are adenocarcinoma (ADC); and < 3% to 5% are adenosquamous carcinoma.10 Almost 100% of cervical SCCs are HPV+, as are 86% of cervical ADCs. The most common reason for HPV-negative status in patients with cervical cancer is false-negative testing because of inadequate methods.

Primary prevention through vaccination

HPV vaccination was introduced in 2006 in the United States for girls,a and for boysa in 2011. The primary reason for vaccinating boys is to reduce the rates of HPV-related anal and oropharyngeal cancer. The only available HPV vaccine in the United States is Gardasil 9 (9-valent vaccine, recombinant; Merck), which provides coverage for 7 high-risk HPV types that account for approximately 90% of cervical cancers and 2 types (6 and 11) that are the principal causes of condylomata acuminata (genital warts). Future generations of prophylactic vaccines are expected to cover additional strains.

Continue to: Vaccine studies...

Vaccine studies have been summarized in a Cochrane review,11 showing that vaccination is highly effective for prevention of cervical dysplasia, especially when given to young girls and womena previously unexposed to the virus. It has not been fully established how long protection lasts, but vaccination appears to be 70% to 90% effective for ≥ 10 years.

Dosing schedule. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a 2-dose schedule 6 to 15 months apart, for both girls and boys between 9 and 14 years of age.12 A third dose is indicated if the first and second doses were given less than 5 months apart, or the person is older than 15 years or is immunocompromised. No recommendation has been made for revaccination after the primary series.

In 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration approved Gardasil 9 for adults 27 to 45 years of age. In June 2019, ACIP recommended vaccination for mena as old as 26 years, and adopted a recommendation that unvaccinated men and women between 27 and 45 years discuss HPV vaccination with their physician.13

The adolescent HPV vaccination rate varies by state; however, all states lag behind the CDC’s Healthy People 2020 goal of 80%.14 Barriers to vaccination include cost, infrastructure limitations, and social stigma.

Secondary prevention: Screening and Tx of precancerous lesions

Cervical cancer screening identifies patients at increased risk of cervical cancer and reassures the great majority of them that their risk of cervical cancer is very low. There are 3 general approaches to cervical cancer screening:

- cytology-based screening, which has been implemented for decades in many countries

- primary testing for DNA or RNA markers of high-risk HPV types

- co-testing with cytology-based screening plus HPV testing.

Continue to: USPSTF guidance

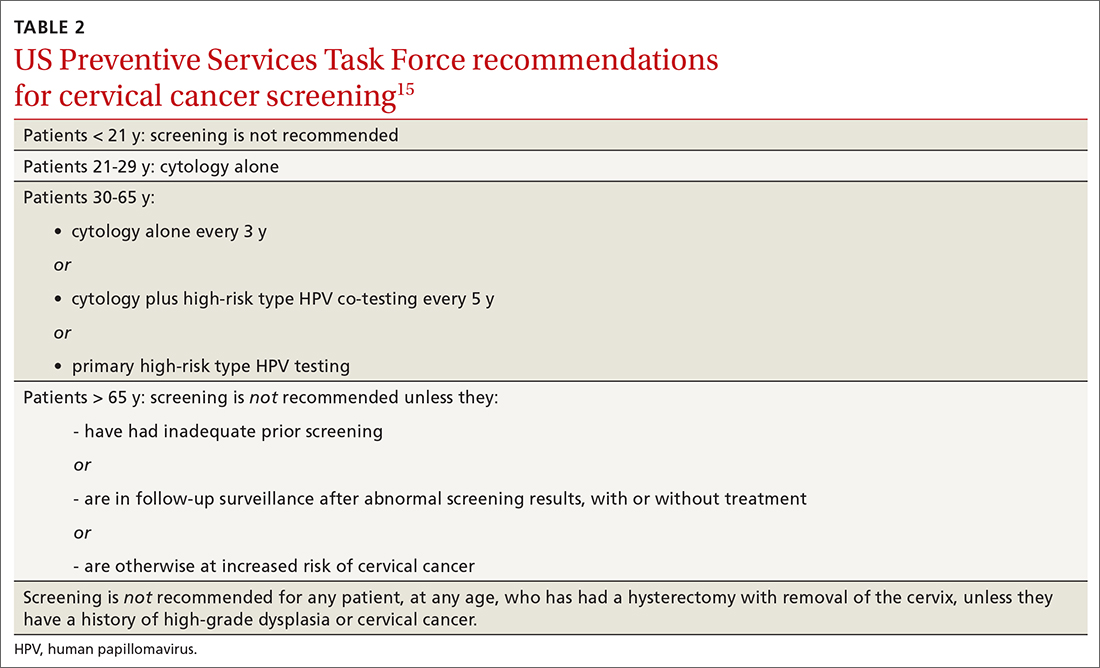

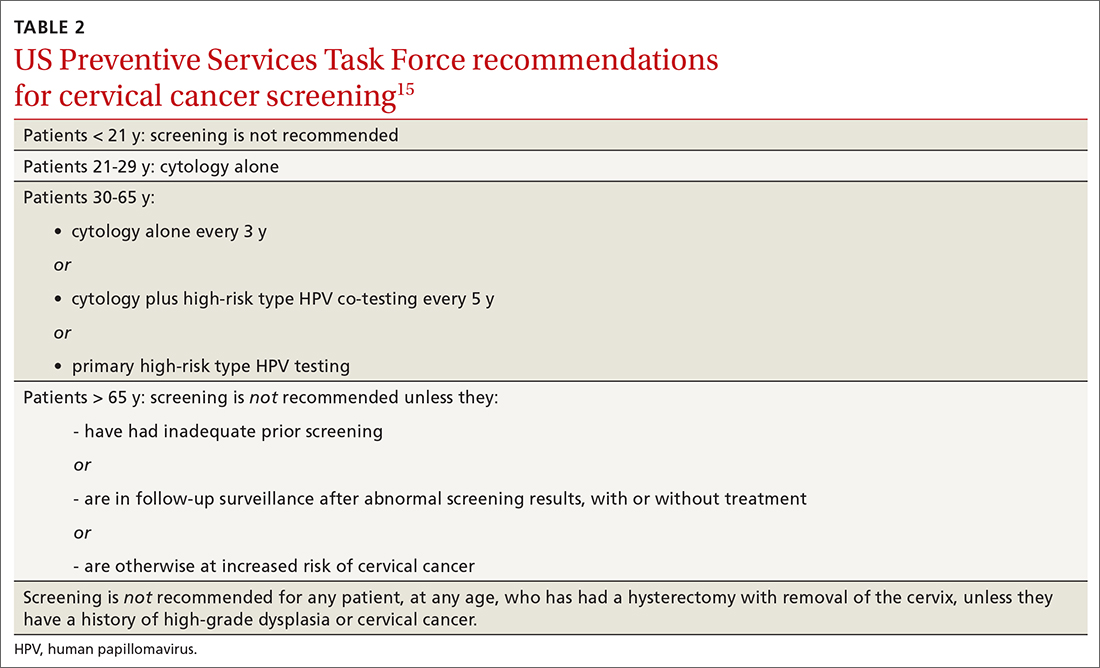

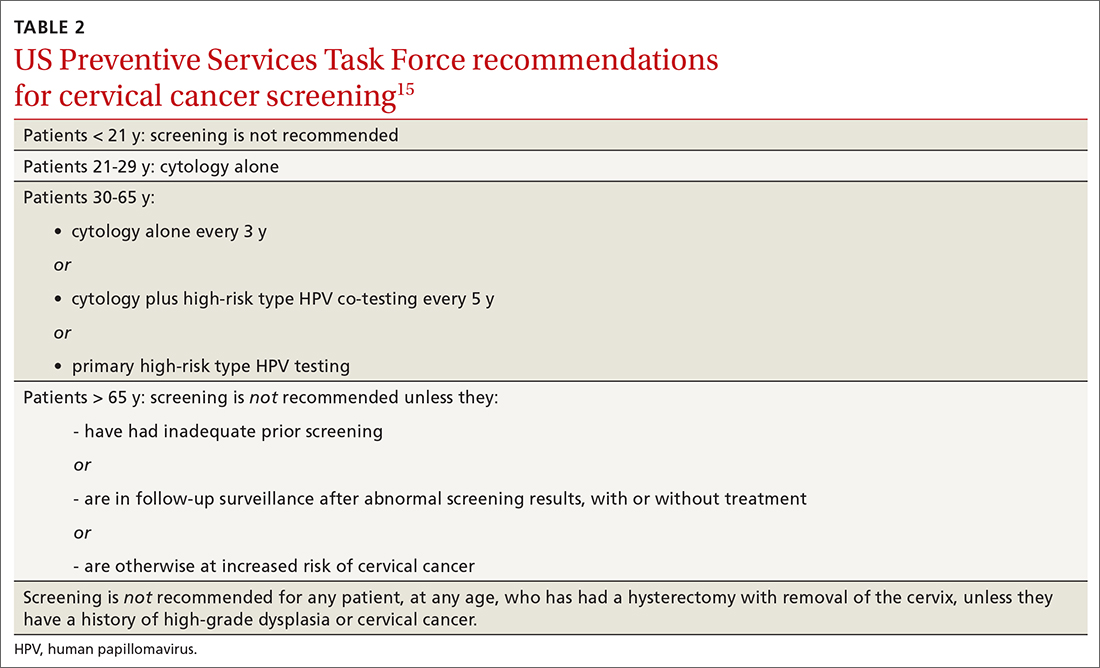

USPSTF guidance. Recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for cervical cancer screening were updated in 2018 (TABLE 215). The recommendations state that high-risk HPV screening alone is a strategy that is amenable to patient self-sampling and self-mailing for processing—a protocol that has the potential to improve access

ASCCP guidance. The American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) makes nearly the same recommendations for cervical cancer screening. An exception is that ASCCP guidelines allow for the possibility of screening using primary high-risk HPV testing for patients starting at 25 years of age.16

Screening programs that can be initiated at a later age and longer intervals should be possible once the adolescent vaccination rate is optimized and vaccination registries are widely implemented.

Cervical cytology protocol

Cervical cytologic abnormalities are reported using the Bethesda system. Specimen adequacy is the most important component of quality assurance,17 and is determined primarily by sufficient cellularity. However, any specimen containing abnormal squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) or atypical glandular cells (AGCs) is considered satisfactory, regardless of the number of cells. Obscuring factors that impair quality include excessive blood; inflammation; air-drying artifact; and an interfering substance, such as lubricant. The presence of reactive changes resulting from inflammation does not require further evaluation unless the patient is immunosuppressed.

Abnormalities are most often of squamous cells, of 2 categories: low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSILs) and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs). HSILs are more likely to be associated with persistent HPV infection and higher risk of progression to cervical cancer.

Continue to: Cytologic findings...

Cytologic findings can be associated with histologic findings that are sometimes more, sometimes less, severe. LSIL cytology specimens that contain a few cells that are suspicious for HSIL, but that do not contain enough cells to be diagnostic, are reported as atypical squamous cells, and do not exclude a high-grade intraepithelial lesion.

Glandular-cell abnormalities usually originate from the glandular epithelium of the endocervix or the endometrium—most often, AGCs. Less frequent are AGCs, favor neoplasia; endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ; and ADC. Rarely, AGCs are associated with adenosquamous carcinoma. Endometrial polyps are a typical benign pathology that can be associated with AGCs.

In about 30% of cases, AGCs are associated with premalignant or malignant disease.18 The risk of malignancy in patients with AGCs increases with age, from < 2% among patients younger than 40 years to approximately 15% among those > 50 years.19 Endometrial malignancy is more common than cervical malignancy among patients > 40 years.

AGC cytology requires endocervical curettage, plus endometrial sampling for patients ≥ 35 years

Cytology-based screening has limitations. Sensitivity is relatively low and dependent on the expertise of the cytologist, although regular repeat testing has been used to overcome this limitation. A substantial subset of results are reported as equivocal—ie, ASCUS.

Continue to: Primary HPV screening

Primary HPV screening

Primary HPV testing was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015 and recommended as an appropriate screening option by professional societies

In contrast to cytology-based screening, HPV testing has high sensitivity (≥ 90%); the population-based negative likelihood ratio is near zero.20 This degree of sensitivity allows for extended screening intervals. However, primary HPV testing lacks specificity for persistent infection and high-grade or invasive lesions, which approximately doubles the number of patients who screen positive. The potential for excess patients to be referred for colposcopy led to the need for secondary triage.

Instituting secondary triage. Cytology is, currently, the primary method of secondary triage, reducing the number of referrals for colposcopy by nearly one-half, compared to referrals for all high-risk HPV results, and with better overall accuracy over cytology with high-risk HPV triage.21 When cytology shows ASCUS, or worse, refer the patient for colposcopy; alternatively, if so-called reflex testing for HPV types 16 and 18 is available and positive, direct referral to colposcopy without cytology is also appropriate.

In the future, secondary triage for cytology is likely to be replaced with improved technologies, such as immunostaining of the specimen for biomarkers associated with cervical precancer or cancer, or for viral genome methylation testing.22

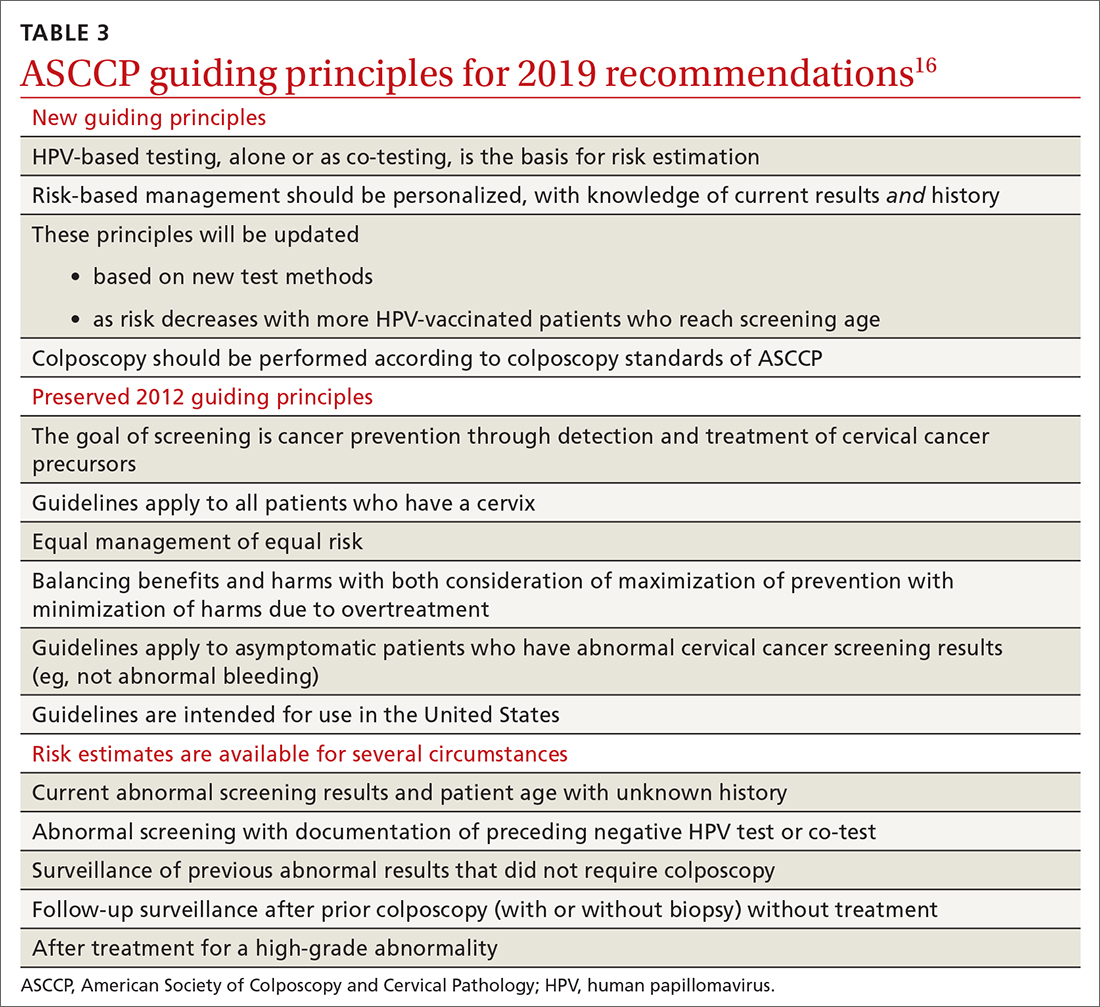

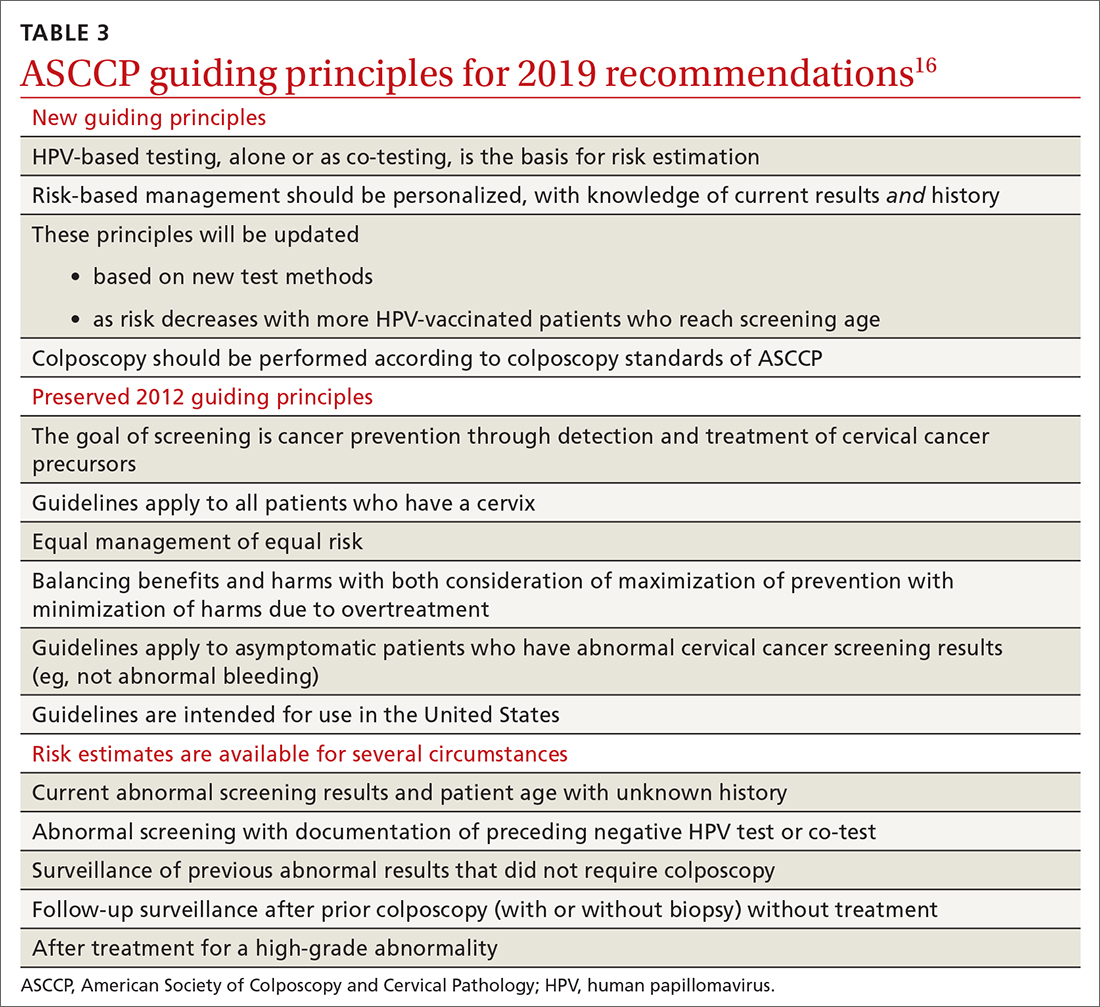

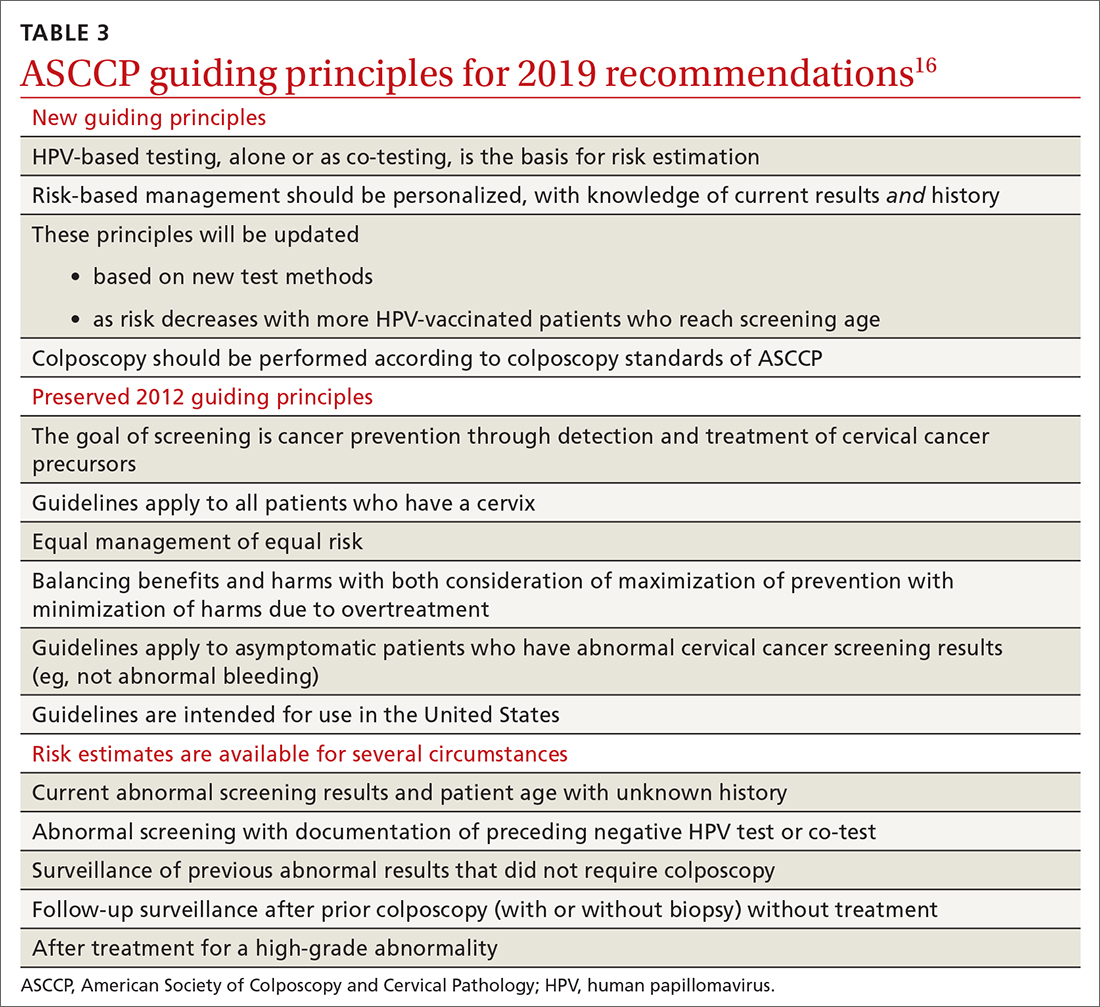

Management of abnormal cervical cancer screening results

Routine screening applies to asymptomatic patients who do not require surveillance because they have not had prior abnormal screening results. In 2020, ASCCP published risk-based management consensus guidelines that were developed for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and for cancer precursors.16 Guiding principles, and screening situations in which the guidelines can be applied, are summarized in TABLE 3

Continue to: ASCCP guidelines...

ASCCP guidelines provide a framework to incorporate new data and technologies without major revision

Some noteworthy scenarios in ASCCP risk-based management are:

- For unsatisfactory cytology with a negative HPV test or no HPV test, repeat age-based screening in 2 to 4 months. (Note: A negative HPV test might reflect an inadequate specimen; do not interpret this result as a true negative.)

- An absent transformation zone (ie, between glandular and squamous cervical cells) with an otherwise adequate specimen should be interpreted as satisfactory for screening in patients 21 to 29 years of age. For those ≥ 30 years and with no HPV testing in this circumstance, HPV testing is preferred; repeating cytology, in 3 years, is also acceptable.

- After a finding of LSIL/CIN1 without evidence of a high-grade abnormality, and after 2 negative annual screenings (including HPV testing), a return to 3-year (not 5-year) screening is recommended.

- A cytology result of an HSIL carries a risk of 26% for CIN3+, in which case colposcopy is recommended, regardless of HPV test results.

- For long-term management after treatment for CIN2+, continue surveillance testing every 3 years after 3 consecutive negative HPV tests or cytology findings, for at least 25 years. If the 25-year threshold is reached before 65 years of age, continuing surveillance every 3 years is optional, as long as the patient is in good health (ie, life expectancy ≥ 10 years).

- After hysterectomy for a high-grade abnormality, annual vaginal HPV testing is recommended until 3 negative tests are returned; after that, surveillance shifts to a 3-year interval until the 25-year threshold.

Treatment of cancer precursors

Treatment for cervical dysplasia is excisional or ablative.

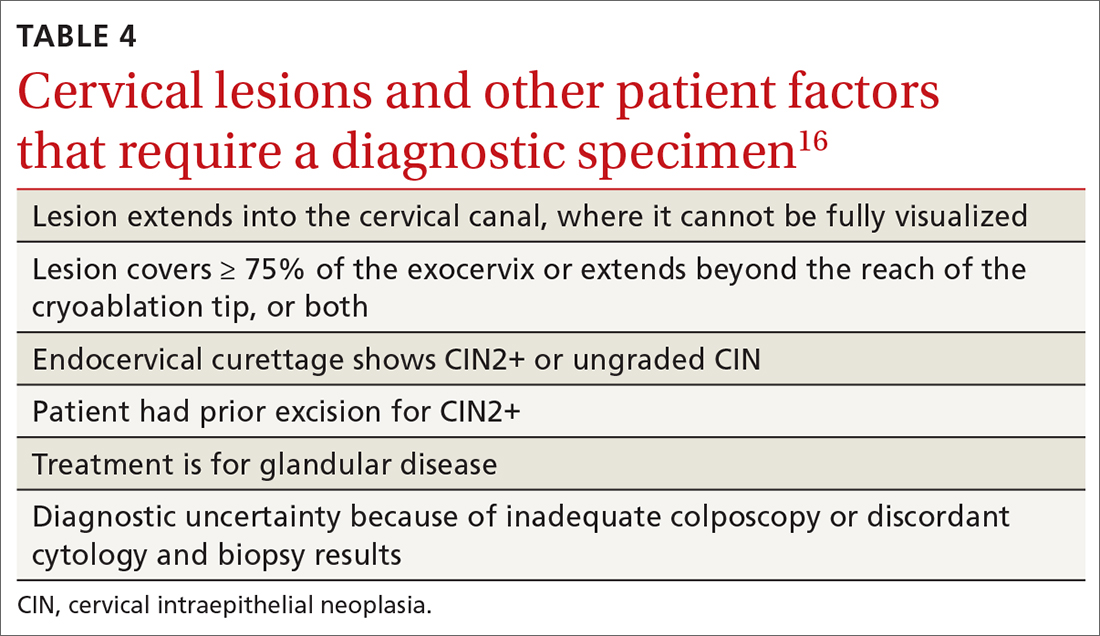

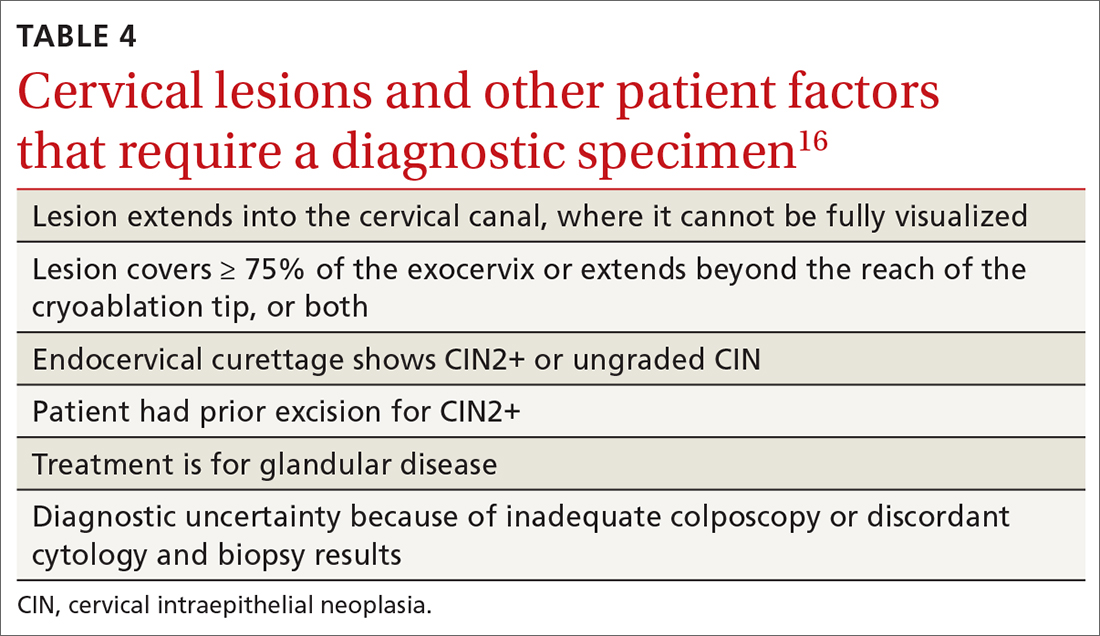

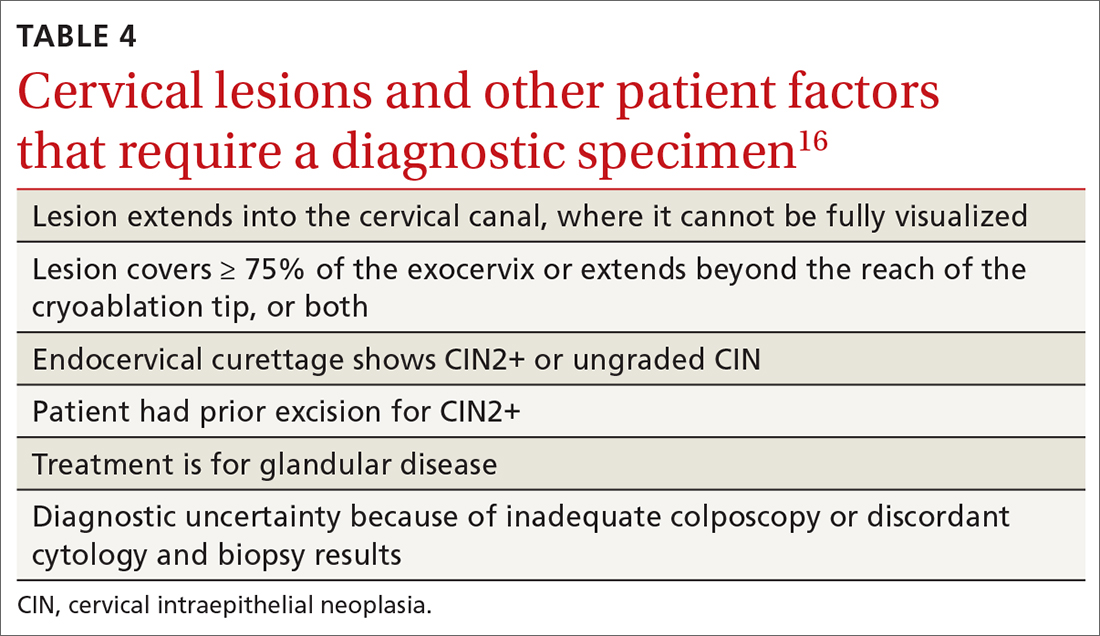

Excisional therapy. In most cases, excisional therapy (either a loop electrosurgical excision procedure [LEEP; also known as large loop excision of the transformation zone, cold knife conization, and laser conization] or cone biopsy) is required, or preferred. Excisional treatment has the advantage of providing a diagnostic specimen.

The World Health Organization recommends LEEP over ablation in settings in which LEEP is available.23 ASCCP states that, in the relatively few cases in which treatment is needed and it is for CIN1, either excision or ablation is acceptable. TABLE 416 lists situations in which excisional treatment is required because a diagnostic specimen is needed.

Continue to: Ablative treatments

Ablative treatments are cryotherapy, CO2 laser ablation, and thermal ablation. Ablative therapy has the advantage of presenting less risk of adverse obstetric outcomes (eg, preterm birth); it can be used if the indication for therapy is:

- CIN1 or CIN2 and HPV type 16 or 18 positivity

- concordant cytology and histology

- satisfactory colposcopy

- negative endocervical curettage.

The most common ablative treatment is liquid nitrogen applied to a metal tip under local anesthesia.

Hysterectomy can be considered for patients with recurrent CIN2+ who have completed childbearing or for whom repeat excision is infeasible (eg, scarring or a short cervix), or both.

Cost, availability, and convenience might play a role in decision-making with regard to the treatment choice for cancer precursors.

Is care after treatment called for? Patients who continue to be at increased risk of (and thus mortality from) cervical and vaginal cancer require enhanced surveillance. The risk of cancer is more than triple for patients who were given their diagnosis, and treated, when they were > 60 years, compared to patients treated in their 30s.1 The excess period of risk covers at least 25 years after treatment, even among patients who have had 3 posttreatment screenings.

Continue to: Persistent HPV positivity...

Persistent HPV positivity is more challenging. Patients infected with HPV type 16 have an increased risk of residual disease.

Cancer management

Invasive cancer. Most cervical cancers (60%) occur among patients who have not been screened during the 5 years before their diagnosis.24 For patients who have a diagnosis of cancer, those detected through screening have a much better prognosis than those identified by symptoms (mean cure rate, 92% and 66%, respectively).25 The median 5-year survival for patients who were not screened during the 5 years before their diagnosis of cervical cancer is 66%.2

In unscreened patients, cervical cancer usually manifests as abnormal vaginal bleeding, especially postcoitally. In approximately 45% of cases, the patient has localized disease at diagnosis; in 36%, regional disease; and in 15%, distant metastases.26

For cancers marked by stromal invasion < 3 mm, appropriate treatment is cone biopsy or simple hysterectomy.27

Most patients with early-stage cervical cancer undergo modified radical hysterectomy. The ovaries are usually conserved, unless the cancer is adenocarcinoma. Sentinel-node dissection has become standard practice. Primary radiation therapy is most often used for patients who are a poor surgical candidate because of medical comorbidity or poor functional status. Antiangiogenic agents (eg, bevacizumab) can be used as adjuvant palliative therapy for advanced and recurrent disease

Continue to: After treatment for...

After treatment for invasive cervical cancer, the goal is early detection of recurrence, although there is no consensus on a protocol. Most recurrences are detected within the first 2 years.

Long-term sequelae after treatment for advanced cancer are considerable. Patients report significantly lower quality of life,

Hormone replacement therapy is generally considered acceptable after treatment of cervical cancer because it does not increase replication of HPV.

Recurrent or metastatic cancer. Recurrence or metastases will develop in 15% to 60% of patients,30 usually within the first 2 years after treatment.

Management depends on location and extent of disease, using mainly radiation therapy or surgical resection. Recurrence or metastasis is usually incurable.

Continue to: Last, there are promising...

Last, there are promising areas of research for more effective treatment for cervical cancer precursors and cancers, including gene editing tools31 and therapeutic

Prospects for better cervical cancer care

Prevention. HPV vaccination is likely to have a large impact on population-based risk of both cancer and cancer precursors in the next generation.

Screening in the foreseeable future will gravitate toward reliance on primary HPV screening, with a self-sampling option.

Surveillance after dysplastic disease. The 2019 ASCCP guidelines for surveillance and intervention decisions after abnormal cancer screening results will evolve to incorporate introduction of new technology into computerized algorithms.

Treatment. New biologic therapies, including monoclonal antibodies and therapeutic vaccines against HPV, will likely be introduced for treating cancer precursors and invasive cancer.

A NOTE FROM THE EDITORS The Editors of The Journal of Family Practice recognize the importance of addressing the reproductive health of gender-diverse individuals. In this article, we use the words “women,” “men,” “girls,” and “boys” in limited circumstances (1) for ease of reading and (2) to reflect the official language of the US Food and Drug Administration and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. The reader should consider the information and guidance offered in this discussion of cervical cancer and other human papillomavirus-related cancers to speak to the care of people with a uterine cervix and people with a penis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Linda Speer, MD, 3000 Arlington Avenue, MS 1179, Toledo, OH 43614; [email protected]

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2. Cancer stat facts: cervical cancer. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results [SEER] Program. Accessed November 14, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html

3. Guan P, Howell-Jones R, Li N, et al. Human papillomavirus types in 115,789 HPV-positive women: a meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer. Int J Cancer 2012;131:2349-2359. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27485

4. Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Early history of incident, type-specific human papillomavirus infections in newly sexually active young women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:699-707. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1108

5. Chesson HW, Dunne EF, Hariri F, et al. The estimated lifetime probability of acquiring human papillomavirus in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:660-664. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000193

6. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. Fact sheet. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; November 11, 2020. Accessed November 14, 2021. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer

7. International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Comparison of risk factors for invasive squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 8,097 women with squamous cell carcinoma and 1,374 women with adenocarcinoma from 12 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:885-891. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22357

8. McCredie MRE, Sharples KJ, Paul C, et al. Natural history of cervical cancer neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008:9:425-434. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70103-7