User login

COVID-19 symptoms persist months after acute infection

, according to a follow-up study involving 1,733 patients.

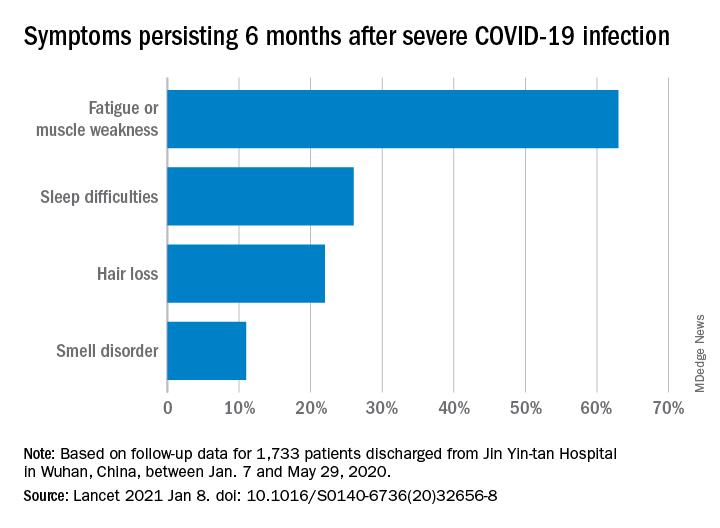

“Patients with COVID-19 had symptoms of fatigue or muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and anxiety or depression,” and those with “more severe illness during their hospital stay had increasingly impaired pulmonary diffusion capacities and abnormal chest imaging manifestations,” Chaolin Huang, MD, of Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, China, and associates wrote in the Lancet.

Fatigue or muscle weakness, reported by 63% of patients, was the most common symptom, followed by sleep difficulties, hair loss, and smell disorder. Altogether, 76% of those examined 6 months after discharge from Jin Yin-tan hospital – the first designated for patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan – reported at least one symptom, they said.

Symptoms were more common in women than men: 81% vs. 73% had at least one symptom, and 66% vs. 59% had fatigue or muscle weakness. Women were also more likely than men to report anxiety or depression at follow-up: 28% vs. 18% (23% overall), the investigators said.

Patients with the most severe COVID-19 were 2.4 times as likely to report any symptom later, compared with those who had the least severe levels of infection. Among the 349 participants who completed a lung function test at follow-up, lung diffusion impairment was seen in 56% of those with the most severe illness and 22% of those with the lowest level, Dr. Huang and associates reported.

In a different subset of 94 patients from whom plasma samples were collected, the “seropositivity and median titres of the neutralising antibodies were significantly lower than at the acute phase,” raising concern for reinfection, they said.

The results of the study, the investigators noted, “support that those with severe disease need post-discharge care. Longer follow-up studies in a larger population are necessary to understand the full spectrum of health consequences from COVID-19.”

, according to a follow-up study involving 1,733 patients.

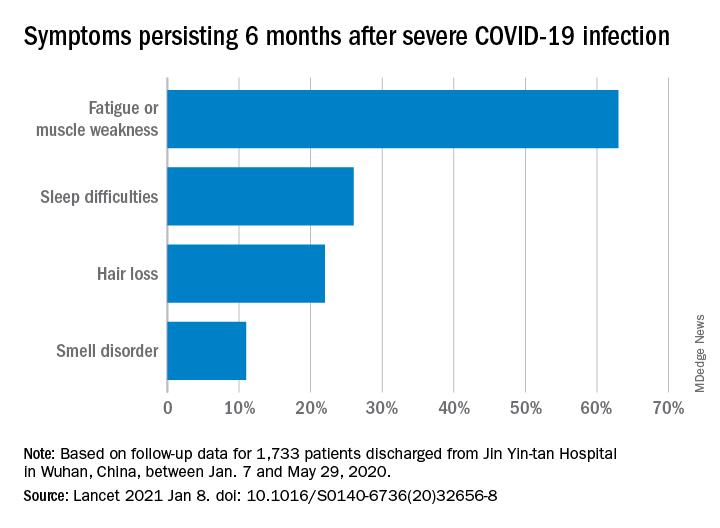

“Patients with COVID-19 had symptoms of fatigue or muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and anxiety or depression,” and those with “more severe illness during their hospital stay had increasingly impaired pulmonary diffusion capacities and abnormal chest imaging manifestations,” Chaolin Huang, MD, of Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, China, and associates wrote in the Lancet.

Fatigue or muscle weakness, reported by 63% of patients, was the most common symptom, followed by sleep difficulties, hair loss, and smell disorder. Altogether, 76% of those examined 6 months after discharge from Jin Yin-tan hospital – the first designated for patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan – reported at least one symptom, they said.

Symptoms were more common in women than men: 81% vs. 73% had at least one symptom, and 66% vs. 59% had fatigue or muscle weakness. Women were also more likely than men to report anxiety or depression at follow-up: 28% vs. 18% (23% overall), the investigators said.

Patients with the most severe COVID-19 were 2.4 times as likely to report any symptom later, compared with those who had the least severe levels of infection. Among the 349 participants who completed a lung function test at follow-up, lung diffusion impairment was seen in 56% of those with the most severe illness and 22% of those with the lowest level, Dr. Huang and associates reported.

In a different subset of 94 patients from whom plasma samples were collected, the “seropositivity and median titres of the neutralising antibodies were significantly lower than at the acute phase,” raising concern for reinfection, they said.

The results of the study, the investigators noted, “support that those with severe disease need post-discharge care. Longer follow-up studies in a larger population are necessary to understand the full spectrum of health consequences from COVID-19.”

, according to a follow-up study involving 1,733 patients.

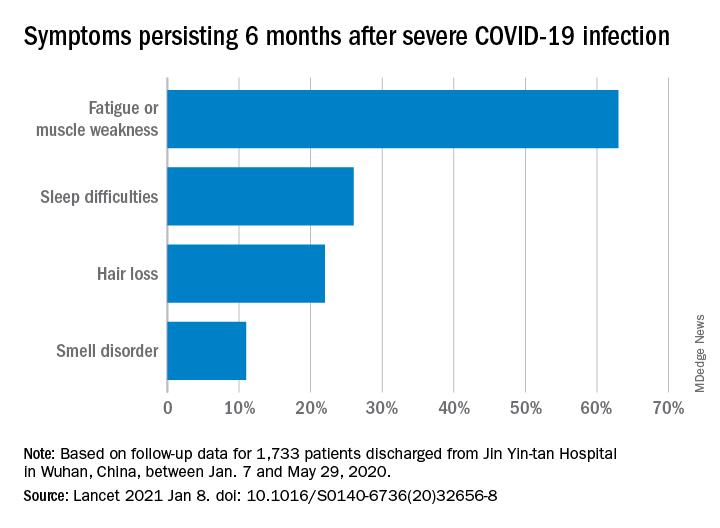

“Patients with COVID-19 had symptoms of fatigue or muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and anxiety or depression,” and those with “more severe illness during their hospital stay had increasingly impaired pulmonary diffusion capacities and abnormal chest imaging manifestations,” Chaolin Huang, MD, of Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, China, and associates wrote in the Lancet.

Fatigue or muscle weakness, reported by 63% of patients, was the most common symptom, followed by sleep difficulties, hair loss, and smell disorder. Altogether, 76% of those examined 6 months after discharge from Jin Yin-tan hospital – the first designated for patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan – reported at least one symptom, they said.

Symptoms were more common in women than men: 81% vs. 73% had at least one symptom, and 66% vs. 59% had fatigue or muscle weakness. Women were also more likely than men to report anxiety or depression at follow-up: 28% vs. 18% (23% overall), the investigators said.

Patients with the most severe COVID-19 were 2.4 times as likely to report any symptom later, compared with those who had the least severe levels of infection. Among the 349 participants who completed a lung function test at follow-up, lung diffusion impairment was seen in 56% of those with the most severe illness and 22% of those with the lowest level, Dr. Huang and associates reported.

In a different subset of 94 patients from whom plasma samples were collected, the “seropositivity and median titres of the neutralising antibodies were significantly lower than at the acute phase,” raising concern for reinfection, they said.

The results of the study, the investigators noted, “support that those with severe disease need post-discharge care. Longer follow-up studies in a larger population are necessary to understand the full spectrum of health consequences from COVID-19.”

FROM THE LANCET

Invasive bacterial infections uncommon in afebrile infants with diagnosed AOM

Outpatient management of most afebrile infants with acute otitis media who haven’t been tested for invasive bacterial infection may be reasonable given the low occurrence of adverse events, said Son H. McLaren, MD, MS, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Dr. McLaren and associates conducted an international cross-sectional study at 33 emergency departments participating in the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): 29 in the United States, 2 in Canada and 2 in Spain.

The researchers sought first to assess prevalence of invasive bacterial infections and adverse events tied to acute otitis media (AOM) in infants 90 days and younger. Those who were clinically diagnosed with AOM and presented without fever between January 2007 and December 2017 were included in the study. The presence of fever, they explained, “is a primary driver for more expanded testing and/or empirical treatment of invasive bacterial infection (IBI). Secondarily, they sought to characterize patterns of diagnostic testing and the factors associated with it specifically in this patient population.

Of 5,270 patients screened, 1,637 met study criteria. Included patients were a median age of 68 days. A total of 1,459 (89.1%) met AAP diagnostic criteria for AOM. The remaining 178 patients were examined and found to have more than one of these criteria: 113 had opacification of tympanic membrane, 57 had dull tympanic membrane, 25 had decreased visualization of middle ear structures, 9 had middle ear effusion, 8 had visible tympanic membrane perforation and 5 had decreased tympanic membrane mobility with insufflation. None of the 278 infants with blood cultures had bacteremia, nor were they diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. Two of 645 (0.3%) infants experienced adverse events, as evidenced with 30-day follow-up or history of hospitalization.

Dr. McLaren and colleagues observed that despite a low prevalence of IBI and AOM-associated adverse events, more than one-fifth of patients were prescribed diagnostic testing for IBI and subsequently hospitalized, a practice that appeared more common with younger patients.

Significant testing and hospitalizations persisted despite low prevalence of IBIs

Although diagnostic testing and hospitalizations differed by site, they were, in fact, “substantial in contrast to the low prevalence of IBIs and adverse events,” the researchers noted. “Our data may be used to help guide clinical management of afebrile infants with clinician-diagnosed AOM, who are not included in the current AAP AOM practice guideline,” the authors said. They speculated that this practice may be due, in part, to young-age risk of IBI and the concern for IBI in this population based on febrile infant population data and a general hesitance to begin antibiotics without first evaluating for IBI. They also cited a low prevalence ranging from 0.8% to 2.5% as evidence for low risk of IBI in afebrile infants with AOM.

Also of note, given that roughly three-fourths of infants included in the study were reported to have symptoms of upper respiratory infection that can lead to viral AOM, including these infants who could have a lower likelihood of IBI than those with known bacterial AOM, may have led the researchers to underestimate IBI prevalence. Because existing data do not allow for clear distinction of viral from bacterial AOM without tympanocentesis, and because more than 85% of older patients with clinically diagnosed AOM also have observed bacterial otopathogens, the authors clarify that “it is understandable why clinicians would manage infants with AOM conservatively, regardless of the presence of concurrent viral illnesses.” They also acknowledged that one major challenge in working with infants believed to have AOM is ensuring that it is actually present since it is so hard to diagnose.

Dr. McLaren and colleagues cited several study limitations: 1) completeness and accuracy of data couldn’t be ensured because of the retrospective study design; 2) because not all infants were tested for IBI, its prevalence may have been underestimated; 3) infants whose discharge codes did not include AOM may have been missed, although all infants with positive blood or cerebrospinal fluid cultures were screened for missed AOM diagnosis; and 4) it is important to consider that any issues associated with testing and hospitalization that were identified may have been the result of management decisions driven by factors that cannot be captured retrospectively or by a diagnosis of AOM.

The findings are not generalizable to infants aged younger than 28 days

Finally, the authors cautioned that because the number of infants younger than 28 days was quite small, and it is therefore infinitely more challenging to diagnose AOM for these patients, results of the study should be applied to infants older than 28 days and are not generalizable to febrile infants.

“This report will not resolve the significant challenge faced by clinicians in treating infants aged [younger than] 28 days who have the highest risk of occult bacteremia and systemic spread of a focal bacterial infection,” Joseph Ravera, MD, and M.W. Stevens, MD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, noted in an accompanying editorial. Previous studies have identified this age group “to be at the highest risk for systemic bacterial involvement and the most difficult to risk stratify on the basis of physical examination findings and initial laboratory results,” they noted. That the subjects aged younger than 28 days in this study had nearly a 50% admission rate illustrates the clinical uncertainty pediatric emergency medicine providers are challenged with, they added. Just 100 (6%) of the 1,637 patients in the study sample were in this age category, which makes it difficult, given the lack of sufficient data, to generalize findings to the youngest infants.

“Despite a paucity of young infants and limitations inherent to the design, this study does contribute to the literature with a robust retrospective data set of afebrile infants between 1 and 3 months of age with an ED diagnosis of AOM ... It certainly provides a base of support for carefully designed prospective studies in which researchers aim to determine the best care for AOM in children under 6 months of age,” reflected Dr. Ravera and Dr. Stevens.

In a separate interview, Karalyn Kinsella, MD, private practice, Cheshire, Conn. noted, “What is confusing is the absence of documented symptoms for infants presenting to the emergency department, as the symptoms they presented with would influence our concern for IBI. Diagnosing AOM in infants under 90 days old is extremely uncommon as an outpatient pediatrician. Although the finding of AOM in an afebrile infant is very rare in the outpatient setting, this study assures us the risk of IBI is almost nonexistent. Therefore, further workup is unnecessary unless providers have clinical suspicions to the contrary.”

Dr. McLaren and colleagues as well as Dr. Ravera, Dr. Stevens, and Dr. Kinsella, had no conflicts of interest and no relevant financial disclosures.

Outpatient management of most afebrile infants with acute otitis media who haven’t been tested for invasive bacterial infection may be reasonable given the low occurrence of adverse events, said Son H. McLaren, MD, MS, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Dr. McLaren and associates conducted an international cross-sectional study at 33 emergency departments participating in the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): 29 in the United States, 2 in Canada and 2 in Spain.

The researchers sought first to assess prevalence of invasive bacterial infections and adverse events tied to acute otitis media (AOM) in infants 90 days and younger. Those who were clinically diagnosed with AOM and presented without fever between January 2007 and December 2017 were included in the study. The presence of fever, they explained, “is a primary driver for more expanded testing and/or empirical treatment of invasive bacterial infection (IBI). Secondarily, they sought to characterize patterns of diagnostic testing and the factors associated with it specifically in this patient population.

Of 5,270 patients screened, 1,637 met study criteria. Included patients were a median age of 68 days. A total of 1,459 (89.1%) met AAP diagnostic criteria for AOM. The remaining 178 patients were examined and found to have more than one of these criteria: 113 had opacification of tympanic membrane, 57 had dull tympanic membrane, 25 had decreased visualization of middle ear structures, 9 had middle ear effusion, 8 had visible tympanic membrane perforation and 5 had decreased tympanic membrane mobility with insufflation. None of the 278 infants with blood cultures had bacteremia, nor were they diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. Two of 645 (0.3%) infants experienced adverse events, as evidenced with 30-day follow-up or history of hospitalization.

Dr. McLaren and colleagues observed that despite a low prevalence of IBI and AOM-associated adverse events, more than one-fifth of patients were prescribed diagnostic testing for IBI and subsequently hospitalized, a practice that appeared more common with younger patients.

Significant testing and hospitalizations persisted despite low prevalence of IBIs

Although diagnostic testing and hospitalizations differed by site, they were, in fact, “substantial in contrast to the low prevalence of IBIs and adverse events,” the researchers noted. “Our data may be used to help guide clinical management of afebrile infants with clinician-diagnosed AOM, who are not included in the current AAP AOM practice guideline,” the authors said. They speculated that this practice may be due, in part, to young-age risk of IBI and the concern for IBI in this population based on febrile infant population data and a general hesitance to begin antibiotics without first evaluating for IBI. They also cited a low prevalence ranging from 0.8% to 2.5% as evidence for low risk of IBI in afebrile infants with AOM.

Also of note, given that roughly three-fourths of infants included in the study were reported to have symptoms of upper respiratory infection that can lead to viral AOM, including these infants who could have a lower likelihood of IBI than those with known bacterial AOM, may have led the researchers to underestimate IBI prevalence. Because existing data do not allow for clear distinction of viral from bacterial AOM without tympanocentesis, and because more than 85% of older patients with clinically diagnosed AOM also have observed bacterial otopathogens, the authors clarify that “it is understandable why clinicians would manage infants with AOM conservatively, regardless of the presence of concurrent viral illnesses.” They also acknowledged that one major challenge in working with infants believed to have AOM is ensuring that it is actually present since it is so hard to diagnose.

Dr. McLaren and colleagues cited several study limitations: 1) completeness and accuracy of data couldn’t be ensured because of the retrospective study design; 2) because not all infants were tested for IBI, its prevalence may have been underestimated; 3) infants whose discharge codes did not include AOM may have been missed, although all infants with positive blood or cerebrospinal fluid cultures were screened for missed AOM diagnosis; and 4) it is important to consider that any issues associated with testing and hospitalization that were identified may have been the result of management decisions driven by factors that cannot be captured retrospectively or by a diagnosis of AOM.

The findings are not generalizable to infants aged younger than 28 days

Finally, the authors cautioned that because the number of infants younger than 28 days was quite small, and it is therefore infinitely more challenging to diagnose AOM for these patients, results of the study should be applied to infants older than 28 days and are not generalizable to febrile infants.

“This report will not resolve the significant challenge faced by clinicians in treating infants aged [younger than] 28 days who have the highest risk of occult bacteremia and systemic spread of a focal bacterial infection,” Joseph Ravera, MD, and M.W. Stevens, MD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, noted in an accompanying editorial. Previous studies have identified this age group “to be at the highest risk for systemic bacterial involvement and the most difficult to risk stratify on the basis of physical examination findings and initial laboratory results,” they noted. That the subjects aged younger than 28 days in this study had nearly a 50% admission rate illustrates the clinical uncertainty pediatric emergency medicine providers are challenged with, they added. Just 100 (6%) of the 1,637 patients in the study sample were in this age category, which makes it difficult, given the lack of sufficient data, to generalize findings to the youngest infants.

“Despite a paucity of young infants and limitations inherent to the design, this study does contribute to the literature with a robust retrospective data set of afebrile infants between 1 and 3 months of age with an ED diagnosis of AOM ... It certainly provides a base of support for carefully designed prospective studies in which researchers aim to determine the best care for AOM in children under 6 months of age,” reflected Dr. Ravera and Dr. Stevens.

In a separate interview, Karalyn Kinsella, MD, private practice, Cheshire, Conn. noted, “What is confusing is the absence of documented symptoms for infants presenting to the emergency department, as the symptoms they presented with would influence our concern for IBI. Diagnosing AOM in infants under 90 days old is extremely uncommon as an outpatient pediatrician. Although the finding of AOM in an afebrile infant is very rare in the outpatient setting, this study assures us the risk of IBI is almost nonexistent. Therefore, further workup is unnecessary unless providers have clinical suspicions to the contrary.”

Dr. McLaren and colleagues as well as Dr. Ravera, Dr. Stevens, and Dr. Kinsella, had no conflicts of interest and no relevant financial disclosures.

Outpatient management of most afebrile infants with acute otitis media who haven’t been tested for invasive bacterial infection may be reasonable given the low occurrence of adverse events, said Son H. McLaren, MD, MS, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Dr. McLaren and associates conducted an international cross-sectional study at 33 emergency departments participating in the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): 29 in the United States, 2 in Canada and 2 in Spain.

The researchers sought first to assess prevalence of invasive bacterial infections and adverse events tied to acute otitis media (AOM) in infants 90 days and younger. Those who were clinically diagnosed with AOM and presented without fever between January 2007 and December 2017 were included in the study. The presence of fever, they explained, “is a primary driver for more expanded testing and/or empirical treatment of invasive bacterial infection (IBI). Secondarily, they sought to characterize patterns of diagnostic testing and the factors associated with it specifically in this patient population.

Of 5,270 patients screened, 1,637 met study criteria. Included patients were a median age of 68 days. A total of 1,459 (89.1%) met AAP diagnostic criteria for AOM. The remaining 178 patients were examined and found to have more than one of these criteria: 113 had opacification of tympanic membrane, 57 had dull tympanic membrane, 25 had decreased visualization of middle ear structures, 9 had middle ear effusion, 8 had visible tympanic membrane perforation and 5 had decreased tympanic membrane mobility with insufflation. None of the 278 infants with blood cultures had bacteremia, nor were they diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. Two of 645 (0.3%) infants experienced adverse events, as evidenced with 30-day follow-up or history of hospitalization.

Dr. McLaren and colleagues observed that despite a low prevalence of IBI and AOM-associated adverse events, more than one-fifth of patients were prescribed diagnostic testing for IBI and subsequently hospitalized, a practice that appeared more common with younger patients.

Significant testing and hospitalizations persisted despite low prevalence of IBIs

Although diagnostic testing and hospitalizations differed by site, they were, in fact, “substantial in contrast to the low prevalence of IBIs and adverse events,” the researchers noted. “Our data may be used to help guide clinical management of afebrile infants with clinician-diagnosed AOM, who are not included in the current AAP AOM practice guideline,” the authors said. They speculated that this practice may be due, in part, to young-age risk of IBI and the concern for IBI in this population based on febrile infant population data and a general hesitance to begin antibiotics without first evaluating for IBI. They also cited a low prevalence ranging from 0.8% to 2.5% as evidence for low risk of IBI in afebrile infants with AOM.

Also of note, given that roughly three-fourths of infants included in the study were reported to have symptoms of upper respiratory infection that can lead to viral AOM, including these infants who could have a lower likelihood of IBI than those with known bacterial AOM, may have led the researchers to underestimate IBI prevalence. Because existing data do not allow for clear distinction of viral from bacterial AOM without tympanocentesis, and because more than 85% of older patients with clinically diagnosed AOM also have observed bacterial otopathogens, the authors clarify that “it is understandable why clinicians would manage infants with AOM conservatively, regardless of the presence of concurrent viral illnesses.” They also acknowledged that one major challenge in working with infants believed to have AOM is ensuring that it is actually present since it is so hard to diagnose.

Dr. McLaren and colleagues cited several study limitations: 1) completeness and accuracy of data couldn’t be ensured because of the retrospective study design; 2) because not all infants were tested for IBI, its prevalence may have been underestimated; 3) infants whose discharge codes did not include AOM may have been missed, although all infants with positive blood or cerebrospinal fluid cultures were screened for missed AOM diagnosis; and 4) it is important to consider that any issues associated with testing and hospitalization that were identified may have been the result of management decisions driven by factors that cannot be captured retrospectively or by a diagnosis of AOM.

The findings are not generalizable to infants aged younger than 28 days

Finally, the authors cautioned that because the number of infants younger than 28 days was quite small, and it is therefore infinitely more challenging to diagnose AOM for these patients, results of the study should be applied to infants older than 28 days and are not generalizable to febrile infants.

“This report will not resolve the significant challenge faced by clinicians in treating infants aged [younger than] 28 days who have the highest risk of occult bacteremia and systemic spread of a focal bacterial infection,” Joseph Ravera, MD, and M.W. Stevens, MD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, noted in an accompanying editorial. Previous studies have identified this age group “to be at the highest risk for systemic bacterial involvement and the most difficult to risk stratify on the basis of physical examination findings and initial laboratory results,” they noted. That the subjects aged younger than 28 days in this study had nearly a 50% admission rate illustrates the clinical uncertainty pediatric emergency medicine providers are challenged with, they added. Just 100 (6%) of the 1,637 patients in the study sample were in this age category, which makes it difficult, given the lack of sufficient data, to generalize findings to the youngest infants.

“Despite a paucity of young infants and limitations inherent to the design, this study does contribute to the literature with a robust retrospective data set of afebrile infants between 1 and 3 months of age with an ED diagnosis of AOM ... It certainly provides a base of support for carefully designed prospective studies in which researchers aim to determine the best care for AOM in children under 6 months of age,” reflected Dr. Ravera and Dr. Stevens.

In a separate interview, Karalyn Kinsella, MD, private practice, Cheshire, Conn. noted, “What is confusing is the absence of documented symptoms for infants presenting to the emergency department, as the symptoms they presented with would influence our concern for IBI. Diagnosing AOM in infants under 90 days old is extremely uncommon as an outpatient pediatrician. Although the finding of AOM in an afebrile infant is very rare in the outpatient setting, this study assures us the risk of IBI is almost nonexistent. Therefore, further workup is unnecessary unless providers have clinical suspicions to the contrary.”

Dr. McLaren and colleagues as well as Dr. Ravera, Dr. Stevens, and Dr. Kinsella, had no conflicts of interest and no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Waiting for the COVID 19 vaccine, or not?

A shot of relief. A shot of hope. Those are the words used to describe COVID-19 vaccines on a television commercial running in prime time in Kentucky.

“We all can’t get the vaccine at once,” the announcer says solemnly, “but we’ll all get a turn.”

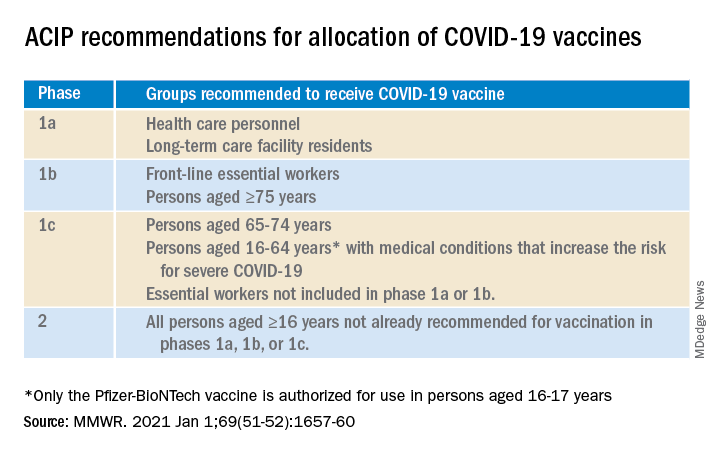

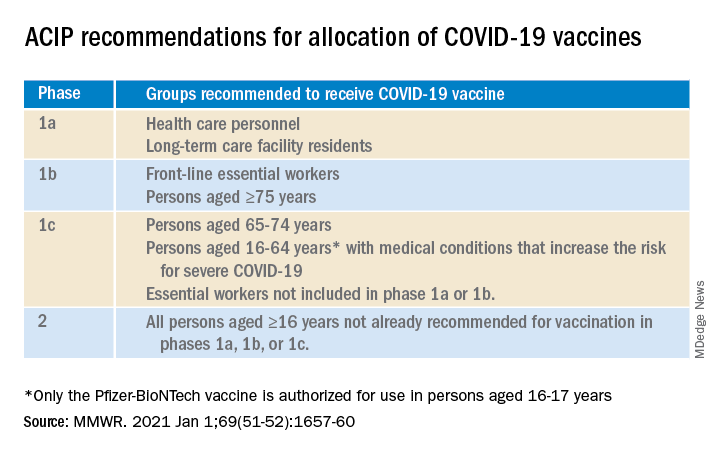

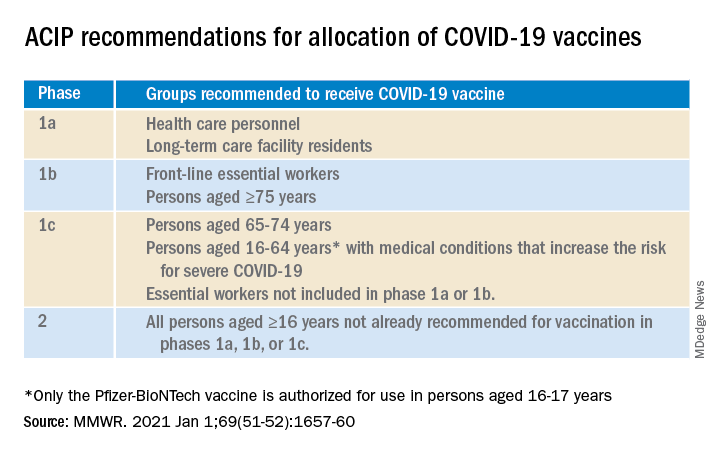

For some of us, that turn came quickly. In December, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that health care personnel (HCP) and long-term care facility residents be the first to be immunized with COVID-19 vaccines (see table).

On Dec. 14, 2020, Sandra Lindsay, a nurse and director of patient care services in the intensive care unit at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, was the first person in the United States to receive a COVID-19 vaccine outside a clinical trial.

In subsequent days, social media sites were quickly flooded with photos of HCP rolling up their sleeves or flashing their immunization cards. There was jubilation ... and perhaps a little bit of jealousy. There were tears of joy and some tears of frustration.

There are more than 21 million HCP in the United States and to date, there have not been enough vaccines nor adequate infrastructure to immunize all of them. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data Tracker, as of Jan. 7, 2021, 21,419,800 doses of vaccine had been distributed to states to immunize everyone identified in phase 1a, but only 5,919,418 people had received a first dose. Limited supply has necessitated prioritization of subgroups of HCP; those in the front of the line have varied by state, and even by hospital or health care systems within states. Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians have noted that primary care providers not employed by a hospital may have more difficulty accessing vaccine.

The mismatch between supply and demand has created an intense focus on improving supply and distribution. Soon though, we’re going to shift our attention to how we increase demand. We don’t have good data on those who being are offered COVID-19 vaccine and declining, but several studies that predate the Emergency Use Authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines suggest significant COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adults in the United States.

One large, longitudinal Internet-based study of U.S. adults found that the proportion who reported they were “somewhat or very likely” to receive COVID-19 vaccine declined from 74% in early April to 56% in early December.

In the Understanding America Study, self-reported likelihood of being vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccine was lower among Black compared to White respondents (38% vs. 59%; aRR, 0.7 [95% confidence interval, 0.6-0.8]), and lower among women compared to men (51% vs. 62%; aRR, 0.9 [95% CI, 0.8-0.9]). Those 65 years of age and older were more likely to report a willingness to be vaccinated than were those 18-49 years of age, as were those with at least a bachelor’s degree compared to those with a high school education or less.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in November – before any COVID-19 vaccines were available – found that only 60% of American adults said they would “definitely or probably get a vaccine for coronavirus” if one were available. That was an increase from 51% in September, but and overall decrease of 72% in May. Of the remaining 40%, just over half said they did not intend to get vaccinated and were “pretty certain” that more information would not change their minds.

Concern about acquiring a serious case of COVID-19 and trust in the vaccine development process were associated with an intent to receive vaccine, as was a personal history of receiving a flu shot annually. Willingness to be vaccinated varied by age, race, and family income, with Black respondents, women, and those with a lower family incomes less likely to accept a vaccine.

To date, few data are available about HCP and willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine. A preprint posted at medrxiv.org reports on a cross-sectional study of more than 3,400 HCP surveyed between Oct. 7 and Nov. 9, 2020. In that study, only 36% of respondents voiced a willingness to be immunized as soon as vaccine is available. Vaccine acceptance increased with increasing age, income level, and education. As in other studies, self-reported willingness to accept vaccine was lower in women and Black individuals. While vaccine acceptance was higher in direct medical care providers than others, it was still only 49%.

So here’s the paradox: Even as limited supplies of vaccine are available and many are frustrated about lack of access, we need to promote the value of immunization to those who are hesitant. Pediatricians are trusted sources of vaccine information and we are in a good position to educate our colleagues, our staff, the parents of our patients and the community at-large.

A useful resource for those ready to take that step it is the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccination Communication Toolkit. While this collection is designed to build vaccine confidence and promote immunization among health care providers, many of the strategies will be easily adapted for use with patients.

It’s not clear when we might have a COVID 19 vaccine for most children. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine emergency use authorization includes those as young as 16 years of age, and 16- and 17-year-olds with high risk medical conditions are included in phase 1c of vaccine allocation. Pfizer is currently enrolling children as young as 12 years of age in clinical trials, and Moderna and Janssen are poised to do the same. It is conceivable but far from certain that we could have a vaccine for children late this year. Are parents going to be ready to vaccinate their children?

Limited data about parental acceptance of vaccine for their children mirrors what was seen in the Understanding America Study and the Pew Research Study. In December 2020, the National Parents Union surveyed 1,008 parents of public school students enrolled in kindergarten through 12th grade. Sixty percent of parents said they would allow their children to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, while 25% would not and 15% were unsure. This suggests that now is the time to begin building vaccine confidence with parents. One conversation starter might be, “I am going to be vaccinated as soon as the vaccine is available.” Ideally, many of you will soon be able to say what I do: “I am excited to tell you that I have been immunized with the COVID-19 vaccine. I did this to protect myself, my family, and our community. I’m hopeful that vaccine will soon be available for all of us.”

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

A shot of relief. A shot of hope. Those are the words used to describe COVID-19 vaccines on a television commercial running in prime time in Kentucky.

“We all can’t get the vaccine at once,” the announcer says solemnly, “but we’ll all get a turn.”

For some of us, that turn came quickly. In December, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that health care personnel (HCP) and long-term care facility residents be the first to be immunized with COVID-19 vaccines (see table).

On Dec. 14, 2020, Sandra Lindsay, a nurse and director of patient care services in the intensive care unit at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, was the first person in the United States to receive a COVID-19 vaccine outside a clinical trial.

In subsequent days, social media sites were quickly flooded with photos of HCP rolling up their sleeves or flashing their immunization cards. There was jubilation ... and perhaps a little bit of jealousy. There were tears of joy and some tears of frustration.

There are more than 21 million HCP in the United States and to date, there have not been enough vaccines nor adequate infrastructure to immunize all of them. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data Tracker, as of Jan. 7, 2021, 21,419,800 doses of vaccine had been distributed to states to immunize everyone identified in phase 1a, but only 5,919,418 people had received a first dose. Limited supply has necessitated prioritization of subgroups of HCP; those in the front of the line have varied by state, and even by hospital or health care systems within states. Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians have noted that primary care providers not employed by a hospital may have more difficulty accessing vaccine.

The mismatch between supply and demand has created an intense focus on improving supply and distribution. Soon though, we’re going to shift our attention to how we increase demand. We don’t have good data on those who being are offered COVID-19 vaccine and declining, but several studies that predate the Emergency Use Authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines suggest significant COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adults in the United States.

One large, longitudinal Internet-based study of U.S. adults found that the proportion who reported they were “somewhat or very likely” to receive COVID-19 vaccine declined from 74% in early April to 56% in early December.

In the Understanding America Study, self-reported likelihood of being vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccine was lower among Black compared to White respondents (38% vs. 59%; aRR, 0.7 [95% confidence interval, 0.6-0.8]), and lower among women compared to men (51% vs. 62%; aRR, 0.9 [95% CI, 0.8-0.9]). Those 65 years of age and older were more likely to report a willingness to be vaccinated than were those 18-49 years of age, as were those with at least a bachelor’s degree compared to those with a high school education or less.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in November – before any COVID-19 vaccines were available – found that only 60% of American adults said they would “definitely or probably get a vaccine for coronavirus” if one were available. That was an increase from 51% in September, but and overall decrease of 72% in May. Of the remaining 40%, just over half said they did not intend to get vaccinated and were “pretty certain” that more information would not change their minds.

Concern about acquiring a serious case of COVID-19 and trust in the vaccine development process were associated with an intent to receive vaccine, as was a personal history of receiving a flu shot annually. Willingness to be vaccinated varied by age, race, and family income, with Black respondents, women, and those with a lower family incomes less likely to accept a vaccine.

To date, few data are available about HCP and willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine. A preprint posted at medrxiv.org reports on a cross-sectional study of more than 3,400 HCP surveyed between Oct. 7 and Nov. 9, 2020. In that study, only 36% of respondents voiced a willingness to be immunized as soon as vaccine is available. Vaccine acceptance increased with increasing age, income level, and education. As in other studies, self-reported willingness to accept vaccine was lower in women and Black individuals. While vaccine acceptance was higher in direct medical care providers than others, it was still only 49%.

So here’s the paradox: Even as limited supplies of vaccine are available and many are frustrated about lack of access, we need to promote the value of immunization to those who are hesitant. Pediatricians are trusted sources of vaccine information and we are in a good position to educate our colleagues, our staff, the parents of our patients and the community at-large.

A useful resource for those ready to take that step it is the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccination Communication Toolkit. While this collection is designed to build vaccine confidence and promote immunization among health care providers, many of the strategies will be easily adapted for use with patients.

It’s not clear when we might have a COVID 19 vaccine for most children. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine emergency use authorization includes those as young as 16 years of age, and 16- and 17-year-olds with high risk medical conditions are included in phase 1c of vaccine allocation. Pfizer is currently enrolling children as young as 12 years of age in clinical trials, and Moderna and Janssen are poised to do the same. It is conceivable but far from certain that we could have a vaccine for children late this year. Are parents going to be ready to vaccinate their children?

Limited data about parental acceptance of vaccine for their children mirrors what was seen in the Understanding America Study and the Pew Research Study. In December 2020, the National Parents Union surveyed 1,008 parents of public school students enrolled in kindergarten through 12th grade. Sixty percent of parents said they would allow their children to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, while 25% would not and 15% were unsure. This suggests that now is the time to begin building vaccine confidence with parents. One conversation starter might be, “I am going to be vaccinated as soon as the vaccine is available.” Ideally, many of you will soon be able to say what I do: “I am excited to tell you that I have been immunized with the COVID-19 vaccine. I did this to protect myself, my family, and our community. I’m hopeful that vaccine will soon be available for all of us.”

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

A shot of relief. A shot of hope. Those are the words used to describe COVID-19 vaccines on a television commercial running in prime time in Kentucky.

“We all can’t get the vaccine at once,” the announcer says solemnly, “but we’ll all get a turn.”

For some of us, that turn came quickly. In December, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that health care personnel (HCP) and long-term care facility residents be the first to be immunized with COVID-19 vaccines (see table).

On Dec. 14, 2020, Sandra Lindsay, a nurse and director of patient care services in the intensive care unit at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, was the first person in the United States to receive a COVID-19 vaccine outside a clinical trial.

In subsequent days, social media sites were quickly flooded with photos of HCP rolling up their sleeves or flashing their immunization cards. There was jubilation ... and perhaps a little bit of jealousy. There were tears of joy and some tears of frustration.

There are more than 21 million HCP in the United States and to date, there have not been enough vaccines nor adequate infrastructure to immunize all of them. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data Tracker, as of Jan. 7, 2021, 21,419,800 doses of vaccine had been distributed to states to immunize everyone identified in phase 1a, but only 5,919,418 people had received a first dose. Limited supply has necessitated prioritization of subgroups of HCP; those in the front of the line have varied by state, and even by hospital or health care systems within states. Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians have noted that primary care providers not employed by a hospital may have more difficulty accessing vaccine.

The mismatch between supply and demand has created an intense focus on improving supply and distribution. Soon though, we’re going to shift our attention to how we increase demand. We don’t have good data on those who being are offered COVID-19 vaccine and declining, but several studies that predate the Emergency Use Authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines suggest significant COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adults in the United States.

One large, longitudinal Internet-based study of U.S. adults found that the proportion who reported they were “somewhat or very likely” to receive COVID-19 vaccine declined from 74% in early April to 56% in early December.

In the Understanding America Study, self-reported likelihood of being vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccine was lower among Black compared to White respondents (38% vs. 59%; aRR, 0.7 [95% confidence interval, 0.6-0.8]), and lower among women compared to men (51% vs. 62%; aRR, 0.9 [95% CI, 0.8-0.9]). Those 65 years of age and older were more likely to report a willingness to be vaccinated than were those 18-49 years of age, as were those with at least a bachelor’s degree compared to those with a high school education or less.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in November – before any COVID-19 vaccines were available – found that only 60% of American adults said they would “definitely or probably get a vaccine for coronavirus” if one were available. That was an increase from 51% in September, but and overall decrease of 72% in May. Of the remaining 40%, just over half said they did not intend to get vaccinated and were “pretty certain” that more information would not change their minds.

Concern about acquiring a serious case of COVID-19 and trust in the vaccine development process were associated with an intent to receive vaccine, as was a personal history of receiving a flu shot annually. Willingness to be vaccinated varied by age, race, and family income, with Black respondents, women, and those with a lower family incomes less likely to accept a vaccine.

To date, few data are available about HCP and willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine. A preprint posted at medrxiv.org reports on a cross-sectional study of more than 3,400 HCP surveyed between Oct. 7 and Nov. 9, 2020. In that study, only 36% of respondents voiced a willingness to be immunized as soon as vaccine is available. Vaccine acceptance increased with increasing age, income level, and education. As in other studies, self-reported willingness to accept vaccine was lower in women and Black individuals. While vaccine acceptance was higher in direct medical care providers than others, it was still only 49%.

So here’s the paradox: Even as limited supplies of vaccine are available and many are frustrated about lack of access, we need to promote the value of immunization to those who are hesitant. Pediatricians are trusted sources of vaccine information and we are in a good position to educate our colleagues, our staff, the parents of our patients and the community at-large.

A useful resource for those ready to take that step it is the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccination Communication Toolkit. While this collection is designed to build vaccine confidence and promote immunization among health care providers, many of the strategies will be easily adapted for use with patients.

It’s not clear when we might have a COVID 19 vaccine for most children. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine emergency use authorization includes those as young as 16 years of age, and 16- and 17-year-olds with high risk medical conditions are included in phase 1c of vaccine allocation. Pfizer is currently enrolling children as young as 12 years of age in clinical trials, and Moderna and Janssen are poised to do the same. It is conceivable but far from certain that we could have a vaccine for children late this year. Are parents going to be ready to vaccinate their children?

Limited data about parental acceptance of vaccine for their children mirrors what was seen in the Understanding America Study and the Pew Research Study. In December 2020, the National Parents Union surveyed 1,008 parents of public school students enrolled in kindergarten through 12th grade. Sixty percent of parents said they would allow their children to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, while 25% would not and 15% were unsure. This suggests that now is the time to begin building vaccine confidence with parents. One conversation starter might be, “I am going to be vaccinated as soon as the vaccine is available.” Ideally, many of you will soon be able to say what I do: “I am excited to tell you that I have been immunized with the COVID-19 vaccine. I did this to protect myself, my family, and our community. I’m hopeful that vaccine will soon be available for all of us.”

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Eliminating hepatitis by 2030: HHS releases new strategic plan

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

NEWS FROM HHS

COVID protections suppressed flu season in U.S.

Last fall, health experts said it was possible the United States could experience an easy 2020-21 flu season because health measures to fight COVID-19 would also thwart the spread of influenza.

It looks like that happened – and then some. Numbers are strikingly low for cases of the flu and other common respiratory and gastrointestinal viruses, health experts told the Washington Post.

“It’s crazy,” Lynnette Brammer, MPH, who leads the domestic influenza surveillance team at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told the Washington Post. “This is my 30th flu season. I never would have expected to see flu activity this low.”

Influenza A, influenza B, parainfluenza, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, and the bacteria that cause whooping cough and pneumonia are circulating at near-record-low levels.

As an example, the Washington Post said in the third week of December 2019, the CDC’s network of clinical labs reported 16.2% of almost 30,000 samples tested positive for influenza A. During the same period in 2020, only 0.3% tested positive.

But there’s a possible downside to this suppression of viruses, because flu and other viruses may rebound once the coronavirus is brought under control.

“The best analogy is to a forest fire,” Bryan Grenfell, PhD, an epidemiologist and population biologist at Princeton (N.J.) University, told the Washington Post. “For the fire to spread, it needs to have unburned wood. For epidemics to spread, they require people who haven’t previously been infected. So if people don’t get infected this year by these viruses, they likely will at some point later on.”

American health experts like Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said last fall that they noticed Australia and other nations in the southern hemisphere had easy flu seasons, apparently because of COVID protection measures. The flu season there runs March through August.

COVID-19 now has a very low presence in Australia, but in recent months the flu has been making a comeback. Flu cases among children aged 5 and younger rose sixfold by December, when such cases are usually at their lowest, the Washington Post said.

“That’s an important cautionary tale for us,” said Kevin Messacar, MD, an infectious disease doctor at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. “Just because we get through the winter and don’t see much RSV or influenza doesn’t mean we’ll be out of the woods.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Last fall, health experts said it was possible the United States could experience an easy 2020-21 flu season because health measures to fight COVID-19 would also thwart the spread of influenza.

It looks like that happened – and then some. Numbers are strikingly low for cases of the flu and other common respiratory and gastrointestinal viruses, health experts told the Washington Post.

“It’s crazy,” Lynnette Brammer, MPH, who leads the domestic influenza surveillance team at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told the Washington Post. “This is my 30th flu season. I never would have expected to see flu activity this low.”

Influenza A, influenza B, parainfluenza, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, and the bacteria that cause whooping cough and pneumonia are circulating at near-record-low levels.

As an example, the Washington Post said in the third week of December 2019, the CDC’s network of clinical labs reported 16.2% of almost 30,000 samples tested positive for influenza A. During the same period in 2020, only 0.3% tested positive.

But there’s a possible downside to this suppression of viruses, because flu and other viruses may rebound once the coronavirus is brought under control.

“The best analogy is to a forest fire,” Bryan Grenfell, PhD, an epidemiologist and population biologist at Princeton (N.J.) University, told the Washington Post. “For the fire to spread, it needs to have unburned wood. For epidemics to spread, they require people who haven’t previously been infected. So if people don’t get infected this year by these viruses, they likely will at some point later on.”

American health experts like Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said last fall that they noticed Australia and other nations in the southern hemisphere had easy flu seasons, apparently because of COVID protection measures. The flu season there runs March through August.

COVID-19 now has a very low presence in Australia, but in recent months the flu has been making a comeback. Flu cases among children aged 5 and younger rose sixfold by December, when such cases are usually at their lowest, the Washington Post said.

“That’s an important cautionary tale for us,” said Kevin Messacar, MD, an infectious disease doctor at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. “Just because we get through the winter and don’t see much RSV or influenza doesn’t mean we’ll be out of the woods.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Last fall, health experts said it was possible the United States could experience an easy 2020-21 flu season because health measures to fight COVID-19 would also thwart the spread of influenza.

It looks like that happened – and then some. Numbers are strikingly low for cases of the flu and other common respiratory and gastrointestinal viruses, health experts told the Washington Post.

“It’s crazy,” Lynnette Brammer, MPH, who leads the domestic influenza surveillance team at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told the Washington Post. “This is my 30th flu season. I never would have expected to see flu activity this low.”

Influenza A, influenza B, parainfluenza, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, and the bacteria that cause whooping cough and pneumonia are circulating at near-record-low levels.

As an example, the Washington Post said in the third week of December 2019, the CDC’s network of clinical labs reported 16.2% of almost 30,000 samples tested positive for influenza A. During the same period in 2020, only 0.3% tested positive.

But there’s a possible downside to this suppression of viruses, because flu and other viruses may rebound once the coronavirus is brought under control.

“The best analogy is to a forest fire,” Bryan Grenfell, PhD, an epidemiologist and population biologist at Princeton (N.J.) University, told the Washington Post. “For the fire to spread, it needs to have unburned wood. For epidemics to spread, they require people who haven’t previously been infected. So if people don’t get infected this year by these viruses, they likely will at some point later on.”

American health experts like Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said last fall that they noticed Australia and other nations in the southern hemisphere had easy flu seasons, apparently because of COVID protection measures. The flu season there runs March through August.

COVID-19 now has a very low presence in Australia, but in recent months the flu has been making a comeback. Flu cases among children aged 5 and younger rose sixfold by December, when such cases are usually at their lowest, the Washington Post said.

“That’s an important cautionary tale for us,” said Kevin Messacar, MD, an infectious disease doctor at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. “Just because we get through the winter and don’t see much RSV or influenza doesn’t mean we’ll be out of the woods.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

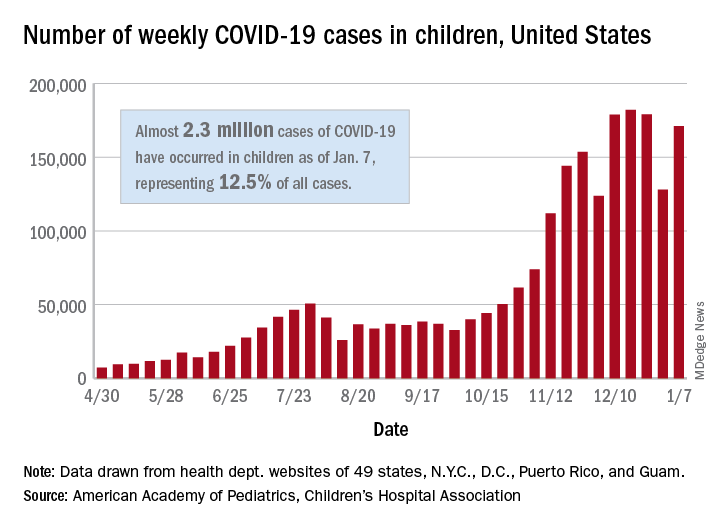

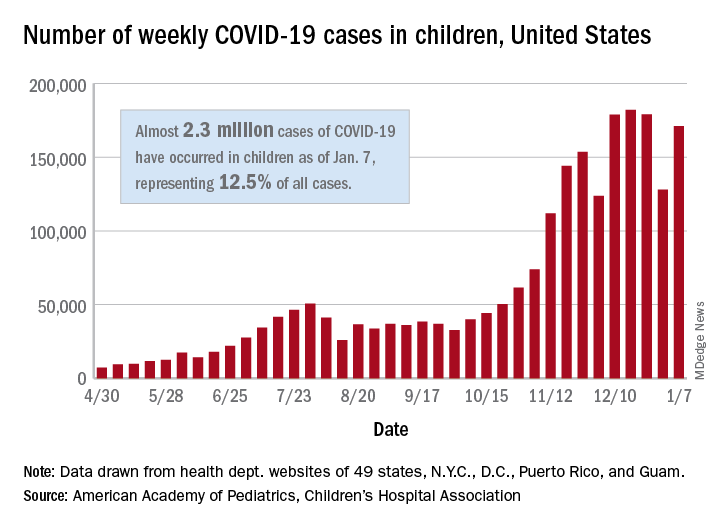

COVID-19 in children: Weekly cases trending downward

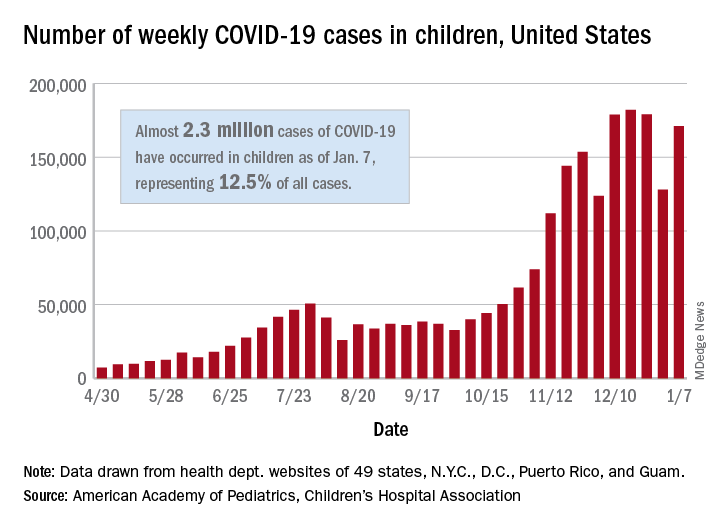

The United States added over 171,000 new COVID-19 cases in children during the week ending Jan. 7, but that figure is lower than 3 of the previous 4 weeks, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Despite an increase compared with the week ending Dec. 31, the most recent weekly total is down from the high of 182,000 cases reported for the week ending Dec. 17, based on data collected from the health department websites of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Those jurisdictions have recorded a total of almost 2.3 million COVID-19 cases in children since the beginning of the pandemic, which amounts to 12.5% of reported cases among all ages. The 171,000 child cases for the most recent week represented 12.9% of the more than 1.3 million cases nationwide, the AAP and CHA said in their latest weekly update.

The United States now has a rate of 3,055 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children in the population, the report shows, with 31 states above that figure and 14 states reporting rates above 4,500 per 100,000 children.

Severe illness, however, continues to be rare among children. So far, children represent 1.8% of all hospitalizations in the jurisdictions reporting such data (24 states and New York City), and just 0.9% of infected children have been hospitalized. There have been 188 deaths among children in 42 states and New York City, which makes up just 0.06% of the total for all ages in those jurisdictions, the AAP and CHA reported.

There are 13 states that have reported no coronavirus-related deaths in children, while Texas (34), New York City (21), Arizona (17), and Illinois (11) are the only jurisdictions with 10 or more. Nevada has the highest proportion of child deaths to all deaths at 0.2%, with Arizona and Nebraska next at 0.18%, according to the AAP/CHA report.

The United States added over 171,000 new COVID-19 cases in children during the week ending Jan. 7, but that figure is lower than 3 of the previous 4 weeks, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Despite an increase compared with the week ending Dec. 31, the most recent weekly total is down from the high of 182,000 cases reported for the week ending Dec. 17, based on data collected from the health department websites of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Those jurisdictions have recorded a total of almost 2.3 million COVID-19 cases in children since the beginning of the pandemic, which amounts to 12.5% of reported cases among all ages. The 171,000 child cases for the most recent week represented 12.9% of the more than 1.3 million cases nationwide, the AAP and CHA said in their latest weekly update.

The United States now has a rate of 3,055 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children in the population, the report shows, with 31 states above that figure and 14 states reporting rates above 4,500 per 100,000 children.

Severe illness, however, continues to be rare among children. So far, children represent 1.8% of all hospitalizations in the jurisdictions reporting such data (24 states and New York City), and just 0.9% of infected children have been hospitalized. There have been 188 deaths among children in 42 states and New York City, which makes up just 0.06% of the total for all ages in those jurisdictions, the AAP and CHA reported.

There are 13 states that have reported no coronavirus-related deaths in children, while Texas (34), New York City (21), Arizona (17), and Illinois (11) are the only jurisdictions with 10 or more. Nevada has the highest proportion of child deaths to all deaths at 0.2%, with Arizona and Nebraska next at 0.18%, according to the AAP/CHA report.

The United States added over 171,000 new COVID-19 cases in children during the week ending Jan. 7, but that figure is lower than 3 of the previous 4 weeks, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Despite an increase compared with the week ending Dec. 31, the most recent weekly total is down from the high of 182,000 cases reported for the week ending Dec. 17, based on data collected from the health department websites of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Those jurisdictions have recorded a total of almost 2.3 million COVID-19 cases in children since the beginning of the pandemic, which amounts to 12.5% of reported cases among all ages. The 171,000 child cases for the most recent week represented 12.9% of the more than 1.3 million cases nationwide, the AAP and CHA said in their latest weekly update.

The United States now has a rate of 3,055 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children in the population, the report shows, with 31 states above that figure and 14 states reporting rates above 4,500 per 100,000 children.

Severe illness, however, continues to be rare among children. So far, children represent 1.8% of all hospitalizations in the jurisdictions reporting such data (24 states and New York City), and just 0.9% of infected children have been hospitalized. There have been 188 deaths among children in 42 states and New York City, which makes up just 0.06% of the total for all ages in those jurisdictions, the AAP and CHA reported.

There are 13 states that have reported no coronavirus-related deaths in children, while Texas (34), New York City (21), Arizona (17), and Illinois (11) are the only jurisdictions with 10 or more. Nevada has the highest proportion of child deaths to all deaths at 0.2%, with Arizona and Nebraska next at 0.18%, according to the AAP/CHA report.

Updated USPSTF HBV screening recommendation may be a ‘lost opportunity’

An update of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation for hepatitis B screening shows little change from the 2014 version, but some wonder if it should have gone farther than a risk-based approach.

The recommendation, which was published in JAMA, reinforces that screening should be conducted among adolescents and adults who are at increased risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. The USPSTF named six categories of individuals at increased risk of infection: Persons born in countries with a 2% or higher prevalence of hepatitis B, such as Asia, Africa, the Pacific Islands, and some areas of South America; unvaccinated individuals born in the United States to parents from regions with a very high prevalence of HBV (≥8%); HIV-positive individuals; those who use injected drugs; men who have sex with men; and people who live with people who have HBV or who have HBV-infected sexual partners. It also recommended that pregnant women be screened for HBV infection during their first prenatal visit.

“I view the updated recommendations as an important document because it validates the importance of HBV screening, and the Grade B recommendation supports mandated insurance coverage for the screening test,” said Joseph Lim, MD, who is a professor of medicine at Yale University and director of the Yale Viral Hepatitis Program, both in New Haven, Conn.

Still, the recommendation could have gone further. Notably absent from the USPSTF document, yet featured in recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, are patients who have diabetes, are on immunosuppressive therapy, or have elevated liver enzymes or liver disease. Furthermore, a single-center study found that, among physicians administering immunosuppressive therapy, a setting in which HBV reactivation is a concern, there were low rates of screening for HBV infection, and the physicians did not reliably identify high-risk patients.

“This may also be viewed as a lost opportunity. Evidence suggests that risk factor–based screening is ineffective for the identification of chronic conditions such as hepatitis B. Risk factor–based screening is difficult to implement across health systems and exacerbates the burden on community-based organizations that are motivated to address viral hepatitis. It may further exacerbate labeling, stigma, and discrimination within already marginalized communities that are deemed to be at high risk,” said Dr. Lim.

A similar view was expressed by Avegail Flores, MD, medical director of liver transplantation at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston. “This is a good launching point, and with further evidence provided, hopefully it will also bring in a broader conversation about other persons who are at risk but not included in these criteria.” Neither Dr. Lim nor Dr. Flores were involved in the study.

She noted that resistance to universal screening may be caused by the relatively low prevalence of hepatitis B infection in the United States. However, the CDC estimates that only about 61% of people infected with HBV are aware of it. “I don’t think we have done a good job screening those who are at risk,” said Dr. Flores.

Universal screening could help, but would have a low yield. Dr. Flores suggested expansion into other at-risk groups, such as Baby Boomers. With respect to other risk groups that could be stigmatized or discriminated against, Dr. Flores recalled her medical school days when some students went directly into underserved communities to provide information and screening services. “We have to think of creative ways of how to reach out to people, not just relying on the usual physician-patient relationship.”

The issue is especially timely because the World Health Organization has declared a target to reduce new hepatitis B infections by 90% by 2030, and that will require addressing gaps in diagnosis. “That’s why these recommendations are so consequential. We are at a critical juncture in terms of global hepatitis elimination efforts. There is a time sensitive need to have multistakeholder engagement in ensuring that all aspects of the care cascade are addressed. Because of the central role of screening and diagnosis, it’s of critical importance that organizations such as USPSTF are in alignment with other organizations that have already issued clear guidance on who should be screened. It is (my) hope that further examination of the evidence-base will further support broadening USPSTF guidance to include a larger group of at-risk individuals, or ideally a universal screening strategy,” said Dr. Lim.

The recommendation’s authors received travel reimbursement for their involvement, and one author reported receiving grants and personal fees from Healthwise. Dr. Flores has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Lim is a member of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease’s Viral Hepatitis Elimination Task Force.

SOURCE: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2020 Dec 15. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22980.

Updated Jan. 20, 2021

An update of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation for hepatitis B screening shows little change from the 2014 version, but some wonder if it should have gone farther than a risk-based approach.

The recommendation, which was published in JAMA, reinforces that screening should be conducted among adolescents and adults who are at increased risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. The USPSTF named six categories of individuals at increased risk of infection: Persons born in countries with a 2% or higher prevalence of hepatitis B, such as Asia, Africa, the Pacific Islands, and some areas of South America; unvaccinated individuals born in the United States to parents from regions with a very high prevalence of HBV (≥8%); HIV-positive individuals; those who use injected drugs; men who have sex with men; and people who live with people who have HBV or who have HBV-infected sexual partners. It also recommended that pregnant women be screened for HBV infection during their first prenatal visit.

“I view the updated recommendations as an important document because it validates the importance of HBV screening, and the Grade B recommendation supports mandated insurance coverage for the screening test,” said Joseph Lim, MD, who is a professor of medicine at Yale University and director of the Yale Viral Hepatitis Program, both in New Haven, Conn.

Still, the recommendation could have gone further. Notably absent from the USPSTF document, yet featured in recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, are patients who have diabetes, are on immunosuppressive therapy, or have elevated liver enzymes or liver disease. Furthermore, a single-center study found that, among physicians administering immunosuppressive therapy, a setting in which HBV reactivation is a concern, there were low rates of screening for HBV infection, and the physicians did not reliably identify high-risk patients.

“This may also be viewed as a lost opportunity. Evidence suggests that risk factor–based screening is ineffective for the identification of chronic conditions such as hepatitis B. Risk factor–based screening is difficult to implement across health systems and exacerbates the burden on community-based organizations that are motivated to address viral hepatitis. It may further exacerbate labeling, stigma, and discrimination within already marginalized communities that are deemed to be at high risk,” said Dr. Lim.

A similar view was expressed by Avegail Flores, MD, medical director of liver transplantation at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston. “This is a good launching point, and with further evidence provided, hopefully it will also bring in a broader conversation about other persons who are at risk but not included in these criteria.” Neither Dr. Lim nor Dr. Flores were involved in the study.

She noted that resistance to universal screening may be caused by the relatively low prevalence of hepatitis B infection in the United States. However, the CDC estimates that only about 61% of people infected with HBV are aware of it. “I don’t think we have done a good job screening those who are at risk,” said Dr. Flores.

Universal screening could help, but would have a low yield. Dr. Flores suggested expansion into other at-risk groups, such as Baby Boomers. With respect to other risk groups that could be stigmatized or discriminated against, Dr. Flores recalled her medical school days when some students went directly into underserved communities to provide information and screening services. “We have to think of creative ways of how to reach out to people, not just relying on the usual physician-patient relationship.”