User login

Expanding Verrucous Plaque on the Face

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

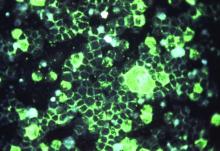

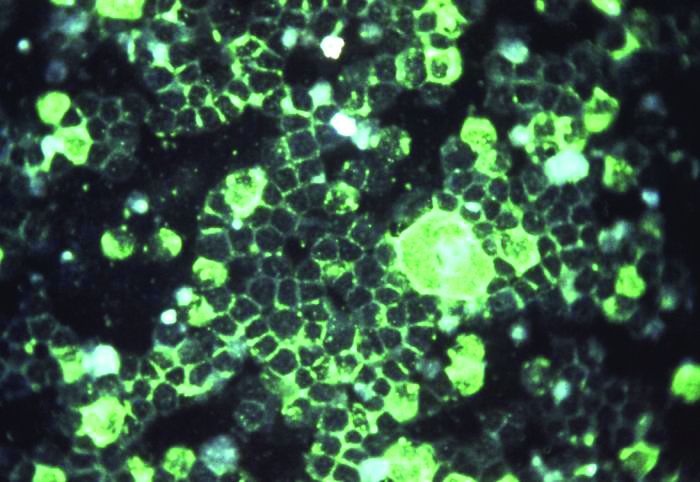

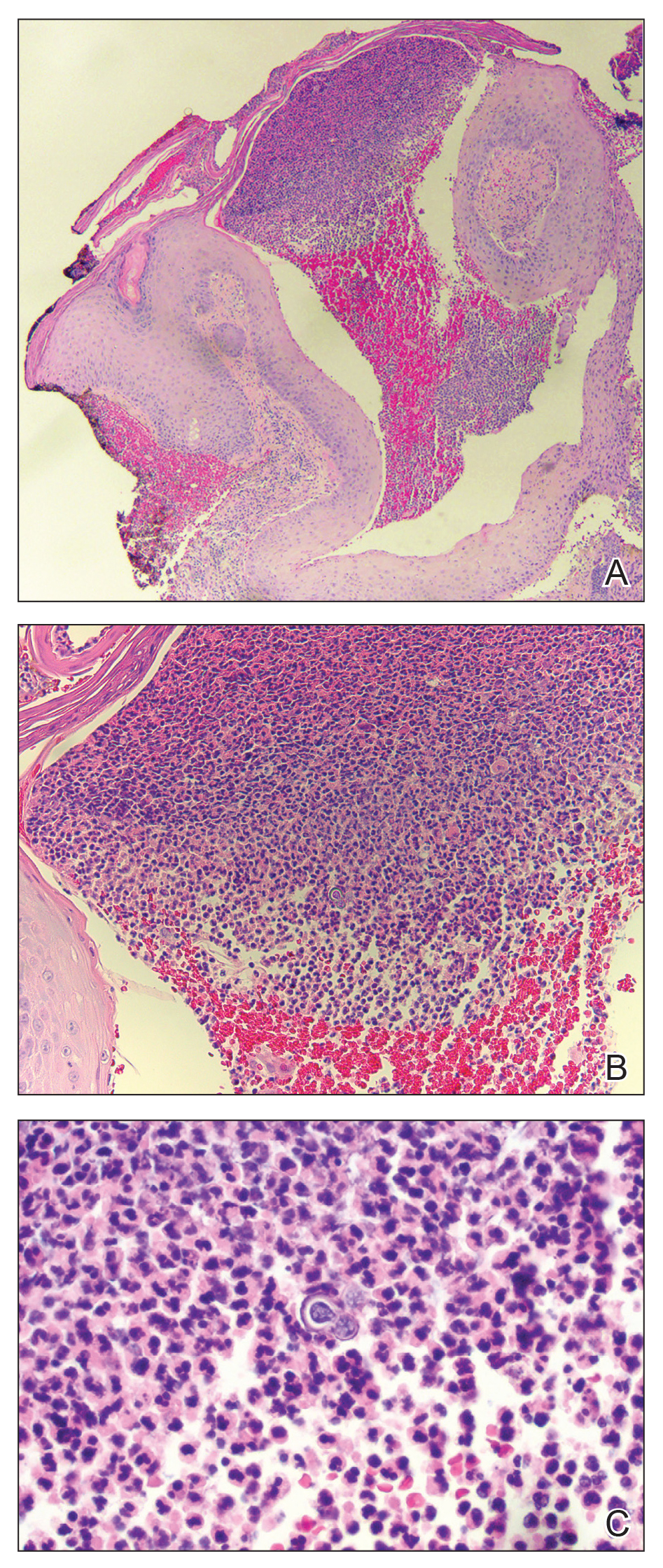

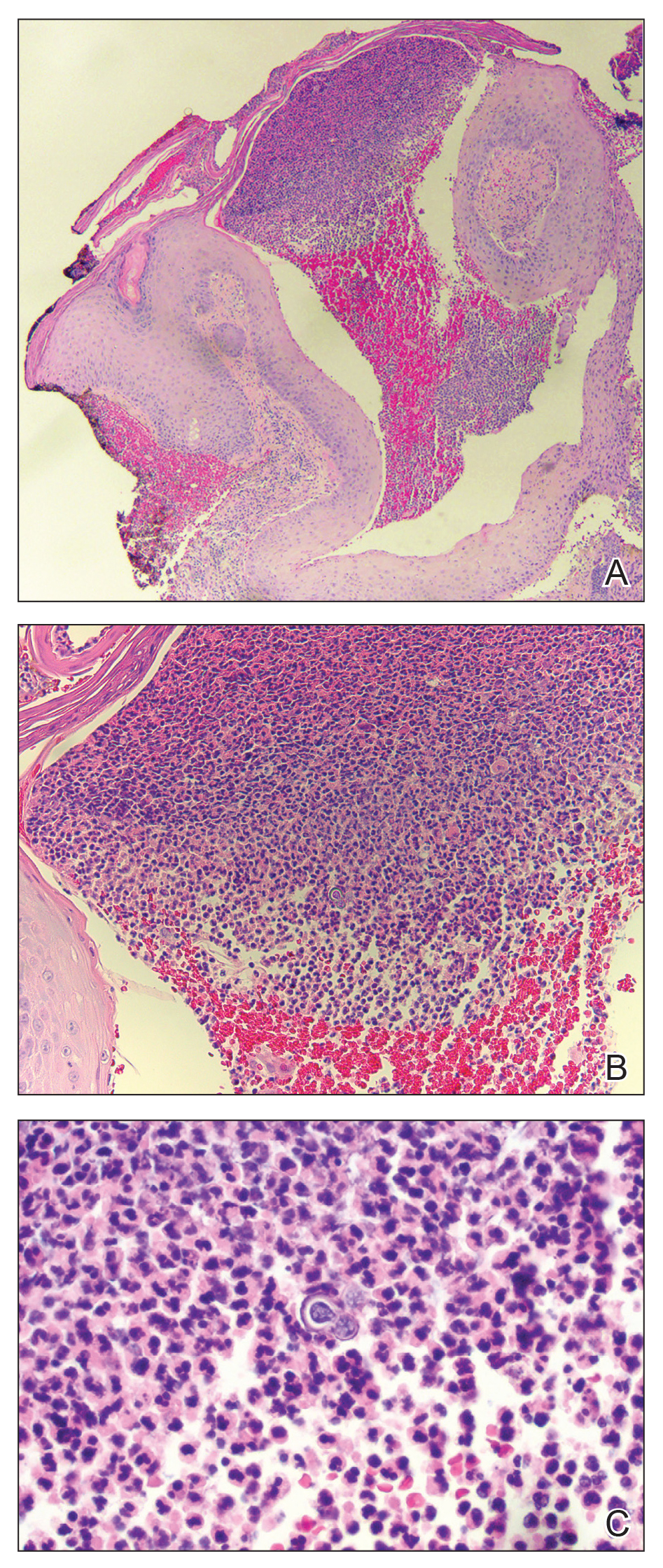

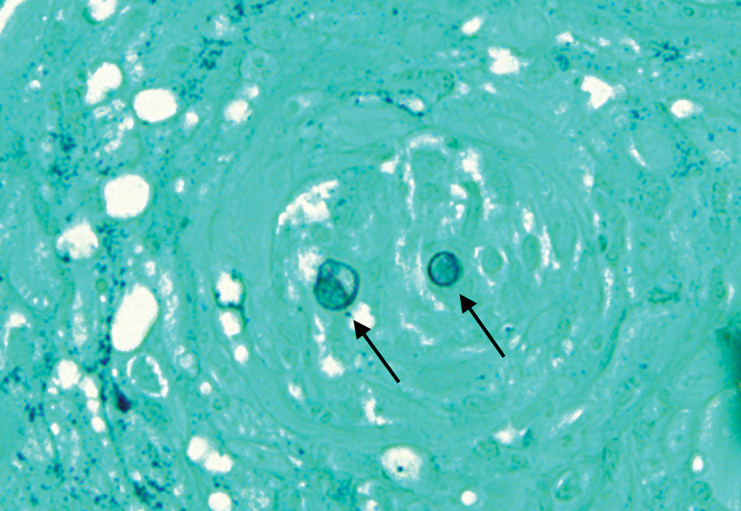

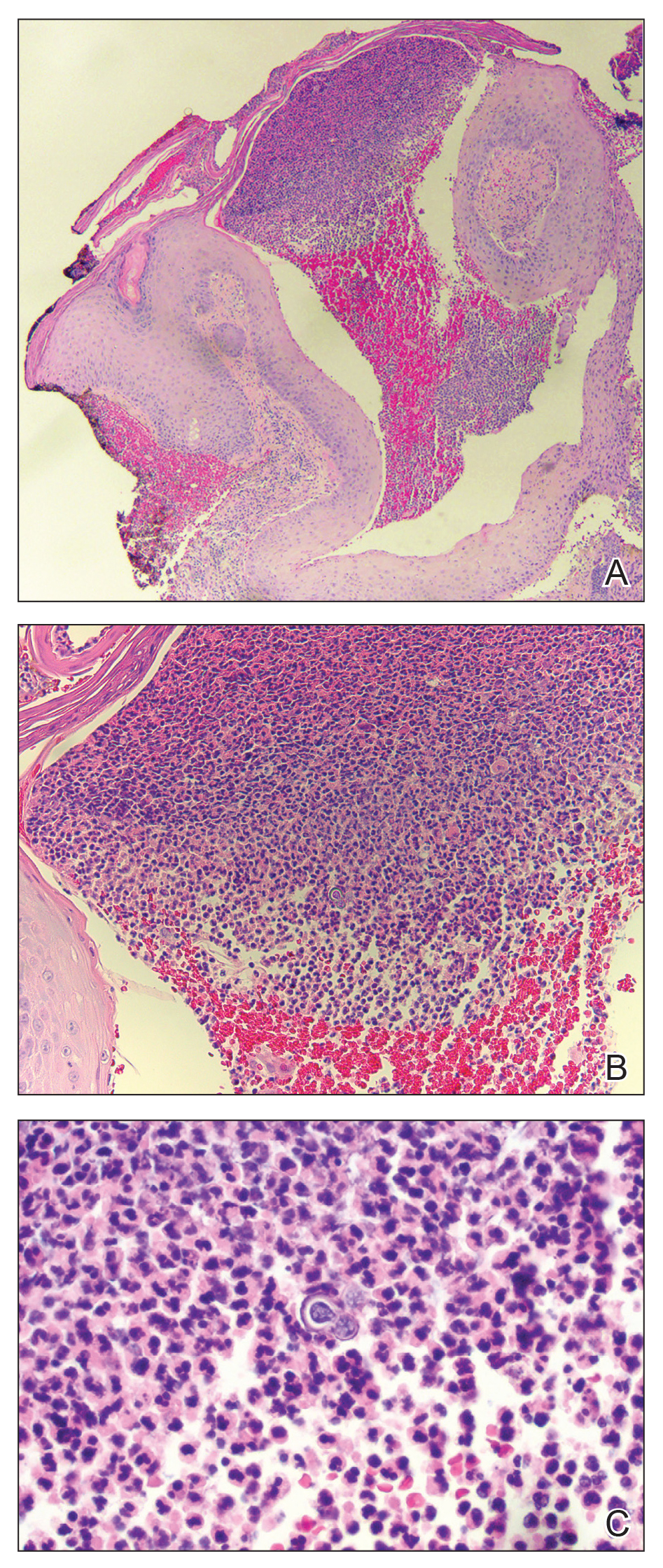

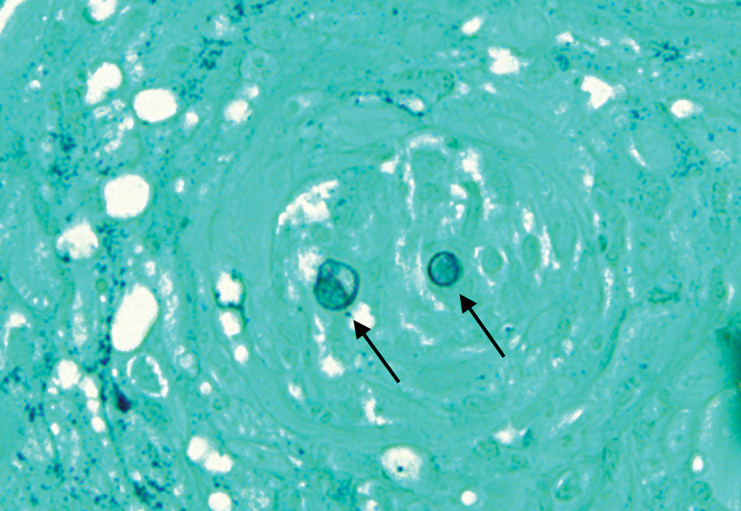

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

A 69-year-old man presented with a slowly expanding, verrucous plaque on the left side of the upper cutaneous lip of 4 months’ duration. The lesion reportedly began as an abscess and had undergone incision and drainage followed by multiple courses of oral antibiotics that were unsuccessful prior to presentation to our clinic. The patient’s hobbies included gardening near his summer home in the mountains of western North Carolina, where he resided when the lesion appeared. Physical examination revealed an approximately 6×4-cm verrucous plaque with central ulceration on the left side of the upper cutaneous and vermilion lip extending to the nasolabial fold. A review of systems was negative for any systemic symptoms. Routine laboratory tests and computed tomography of the head and neck were normal.

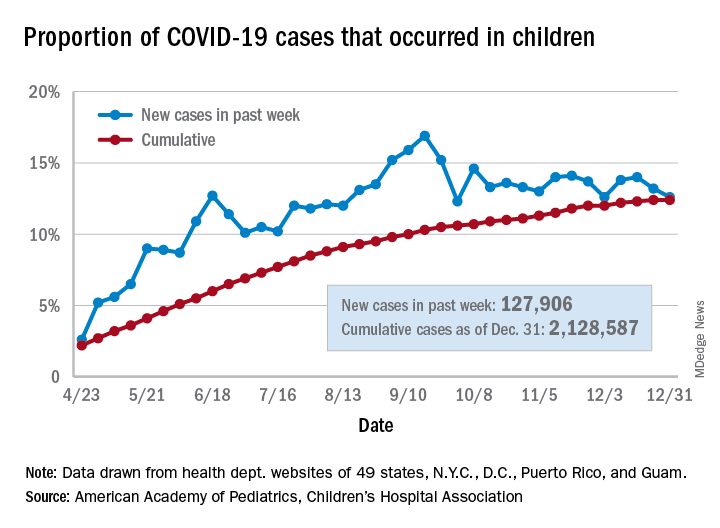

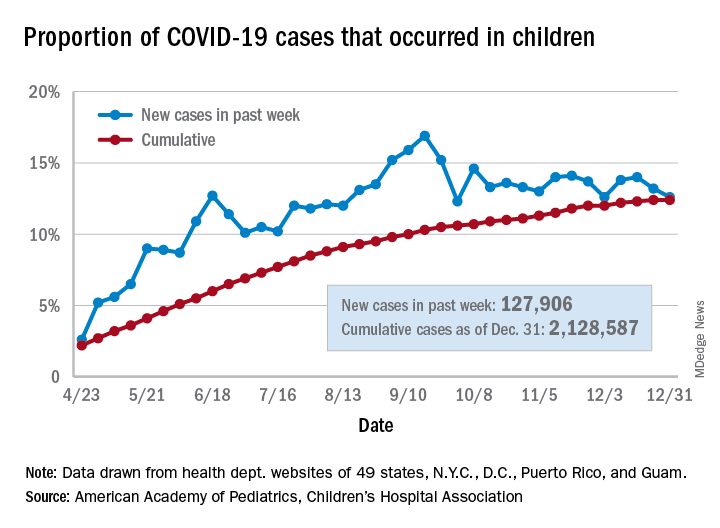

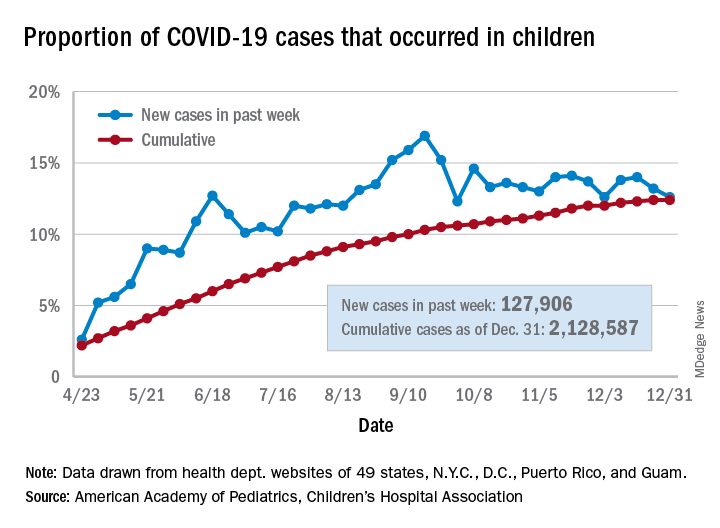

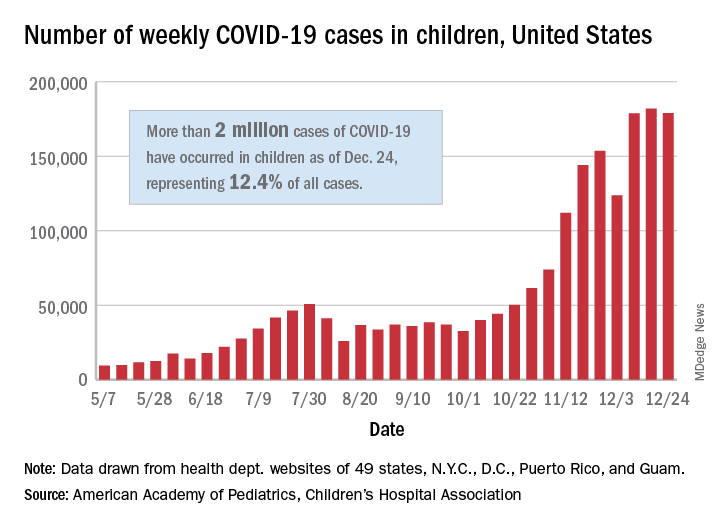

No increase seen in children’s cumulative COVID-19 burden

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

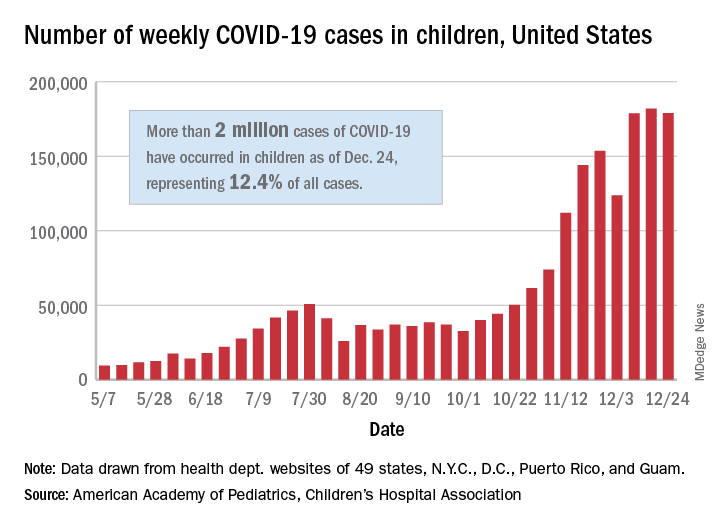

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

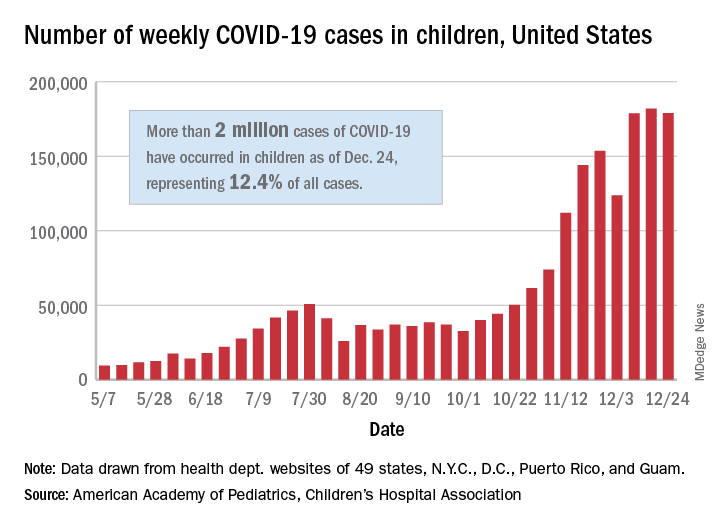

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

COVID-19 vaccines: The rollout, the risks, and the reason to still wear a mask

REFERENCES

- Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M; et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1922-1924. Accessed January 13, 2021. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6950e2.htm

- 2. Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M; et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1653-1656. Accessed January 13, 2021. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm695152e1.htm

- CDC. COVID-19 vaccines: update on allergic reactions, contraindications, and precautions [webinar]. December 30, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2020/callinfo_123020.asp

- CDC. What clinicians need to know about the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines [webinar]. December 18, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2020/callinfo_121820.asp

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team; Food and Drug Administration. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 14-23, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: January 6, 2021. Accessed January 13, 2021. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7002e1.htm

REFERENCES

- Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M; et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1922-1924. Accessed January 13, 2021. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6950e2.htm

- 2. Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M; et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1653-1656. Accessed January 13, 2021. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm695152e1.htm

- CDC. COVID-19 vaccines: update on allergic reactions, contraindications, and precautions [webinar]. December 30, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2020/callinfo_123020.asp

- CDC. What clinicians need to know about the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines [webinar]. December 18, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2020/callinfo_121820.asp

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team; Food and Drug Administration. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 14-23, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: January 6, 2021. Accessed January 13, 2021. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7002e1.htm

REFERENCES

- Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M; et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1922-1924. Accessed January 13, 2021. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6950e2.htm

- 2. Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M; et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1653-1656. Accessed January 13, 2021. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm695152e1.htm

- CDC. COVID-19 vaccines: update on allergic reactions, contraindications, and precautions [webinar]. December 30, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2020/callinfo_123020.asp

- CDC. What clinicians need to know about the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines [webinar]. December 18, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2020/callinfo_121820.asp

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team; Food and Drug Administration. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 14-23, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: January 6, 2021. Accessed January 13, 2021. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7002e1.htm

Skin Cancer Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome novel coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has presented a unique challenge to providing essential care to patients. Increased demand for health care workers and medical supplies, in addition to the risk for COVID-19 infection and asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers and patients, prompted the delay of nonessential services during the surge of cases this summer.1 Key considerations for continuing operation included current and projected COVID-19 cases in the region, ability to implement telehealth, staffing availability, personal protective equipment availability, and office capacity.2 Providing care that is deemed essential often was determined by the urgency of the treatment or service.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services outlined a strategy to stratify patients, based on level of acuity, during the COVID-19 surge3:

- Low-acuity treatments or services: includes routine primary, specialty, or preventive care visits. They should be postponed; telehealth follow-ups should be considered.

- Intermediate-acuity treatments or services: includes pediatric and neonatal care, follow-up visits for existing conditions, and evaluation of new symptoms (including those consistent with COVID-19). These services should initially be evaluated using telehealth, then triaged to the appropriate site and level of care.

- High-acuity treatments or services: address symptoms consistent with COVID-19 or other severe disease, of which the lack of in-person evaluation would result in harm to the patient.

Employees in hospitals and health care clinics were classified as essential, but dermatologists were not given explicit direction regarding clinic operation. Many practices have restricted services, especially those in an area of higher COVID-19 prevalence. However, the challenge of determining day-to-day operation may have been left to the provider in most cases.4 As many states in the United States continue to relax restrictions, total cases and the rate of positivity of COVID-19 have been sharply rising again, after months of decline,5 which suggests increased transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and potential resurgence of the high case burden on our health care system. Furthermore, a lack of a widely distributed vaccine or herd immunity suggests we will need to take many of the same precautions as in the first surge.6

In general, patients with cancer have been found to be at greater risk for adverse outcomes and mortality after COVID-19.7 Therefore, resource rationing is particularly concerning for patients with skin cancer, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, mycosis fungoides, and keratinocyte carcinoma. Triaging patients based on level of acuity, type of skin cancer, disease burden, host immunosuppression, and risk for progression must be carefully considered in this population.2 Treatment and follow-up present additional challenges.

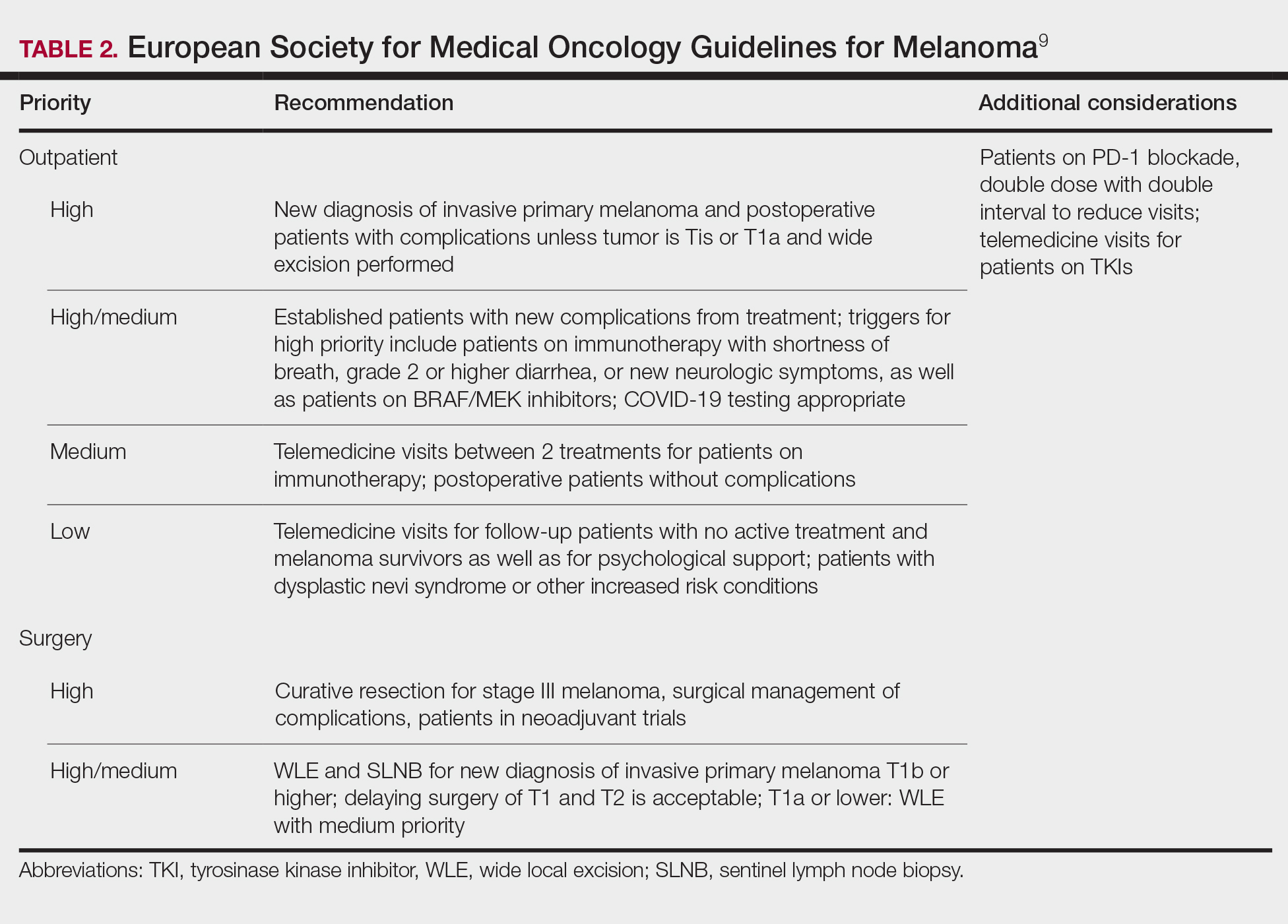

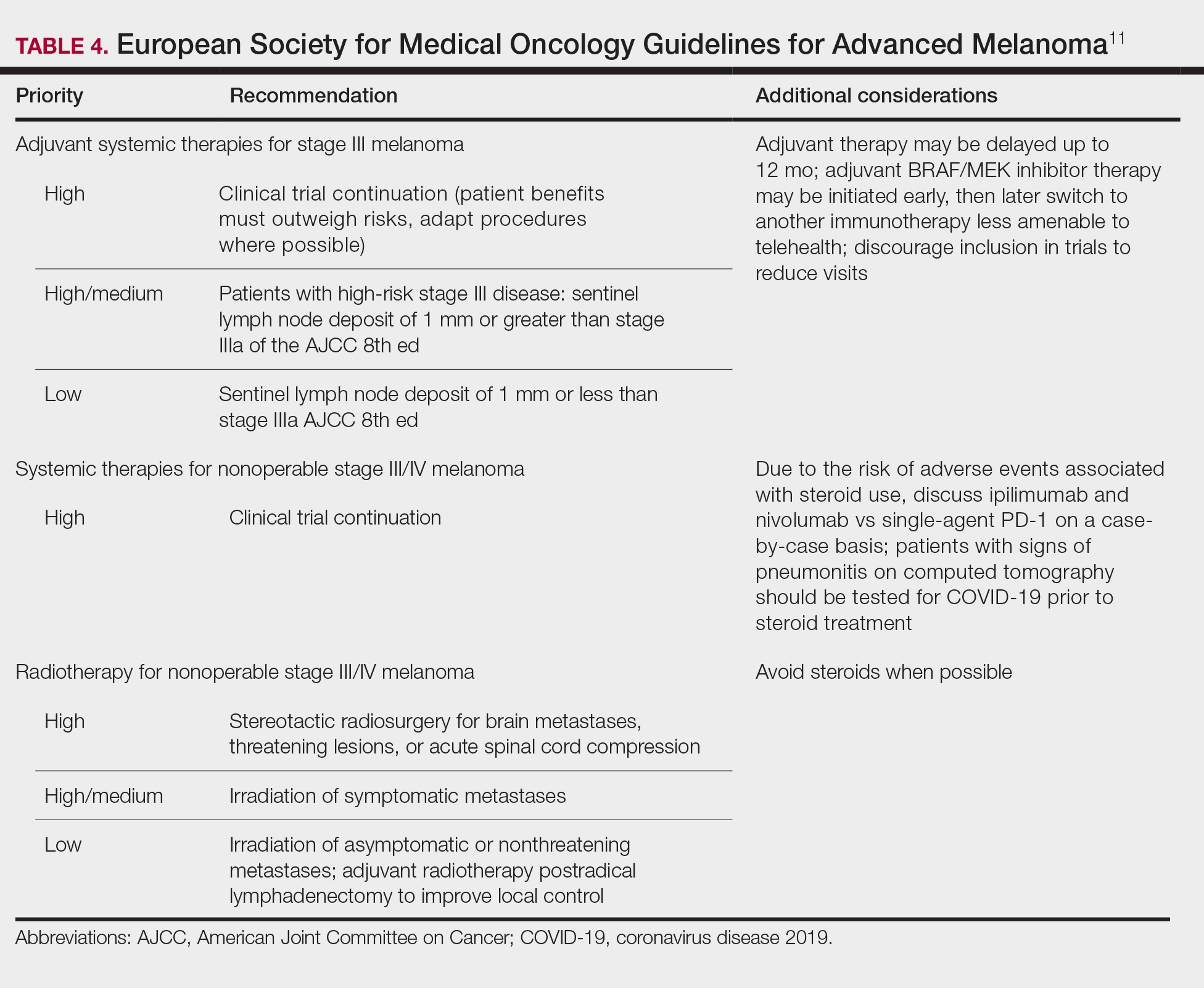

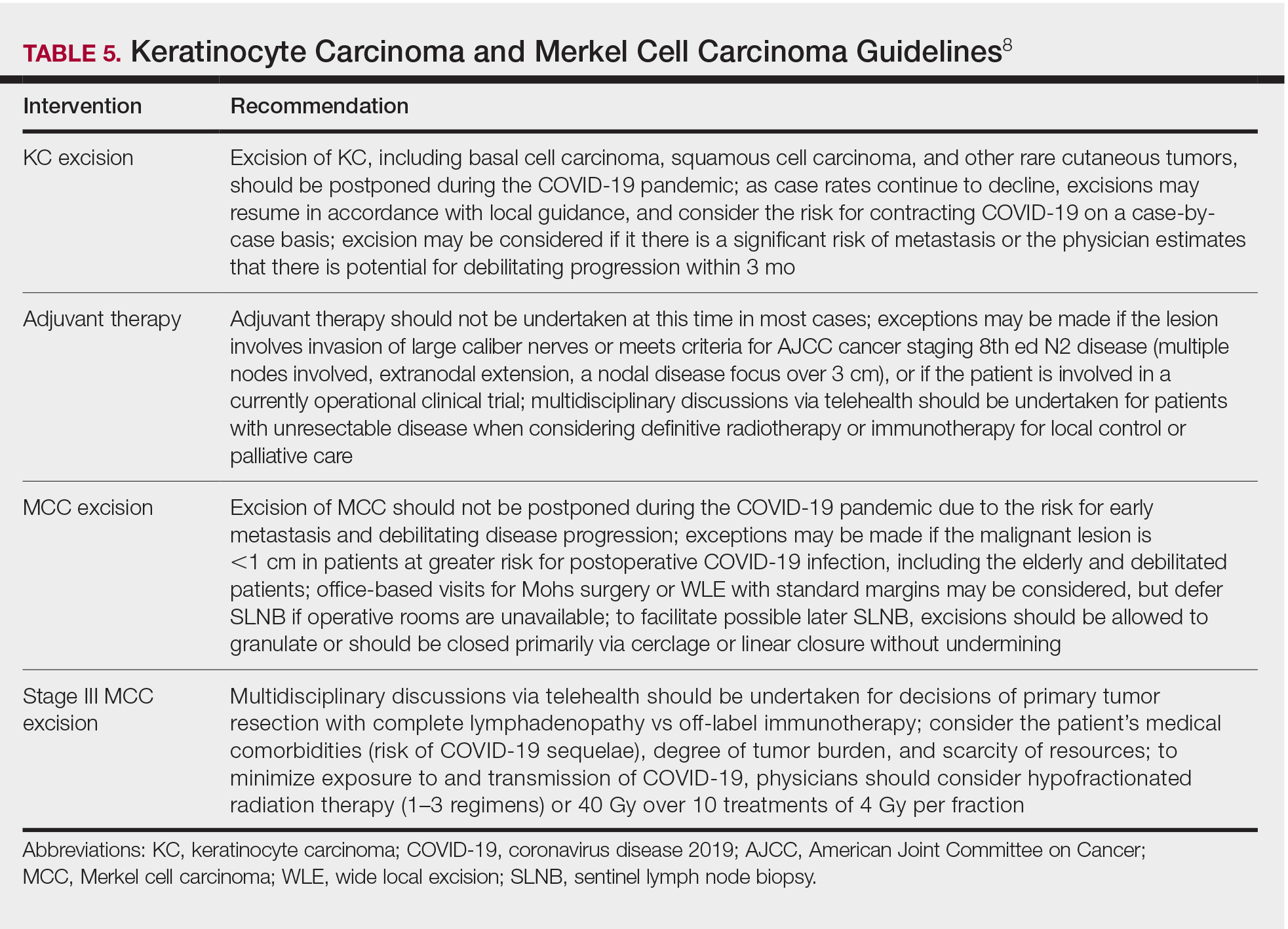

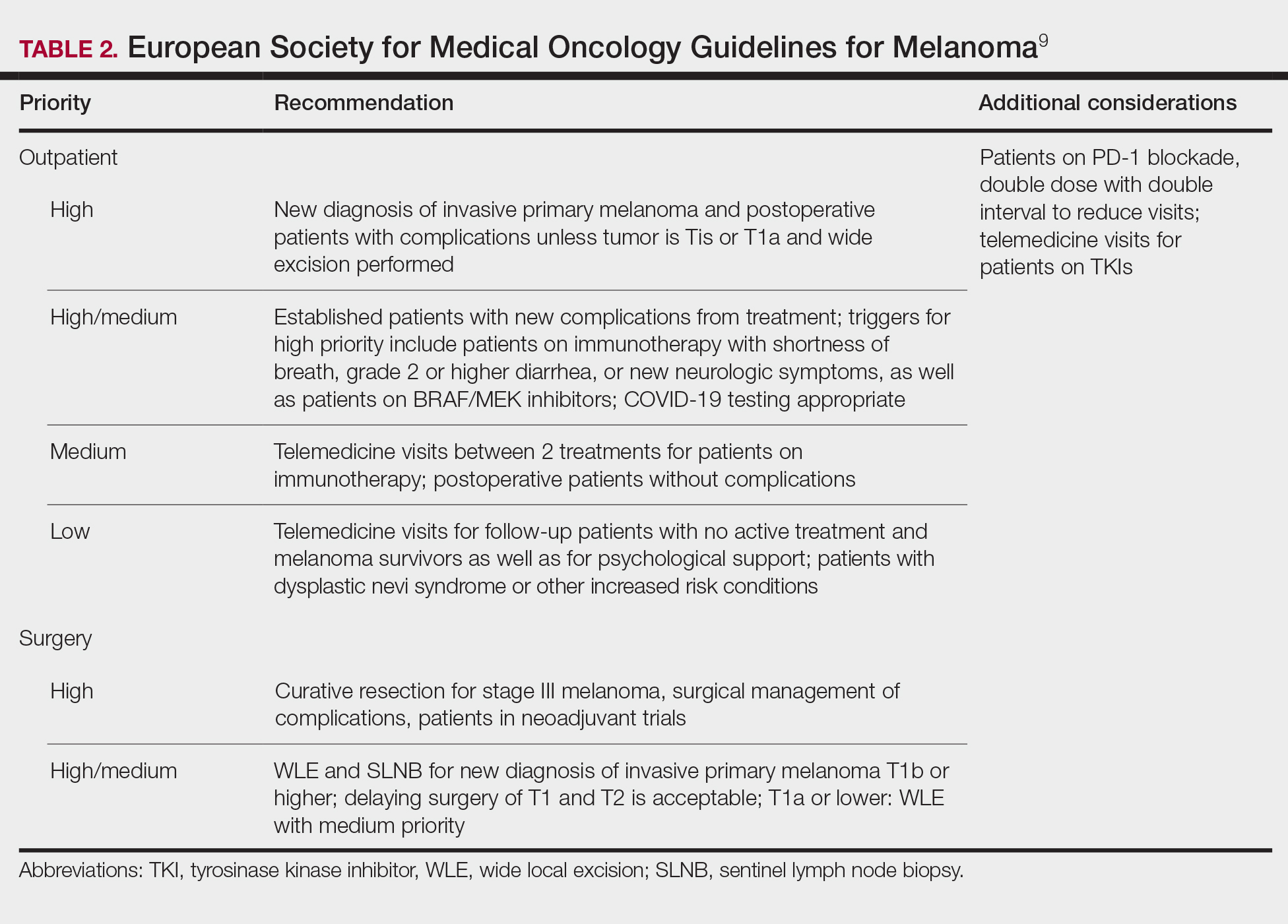

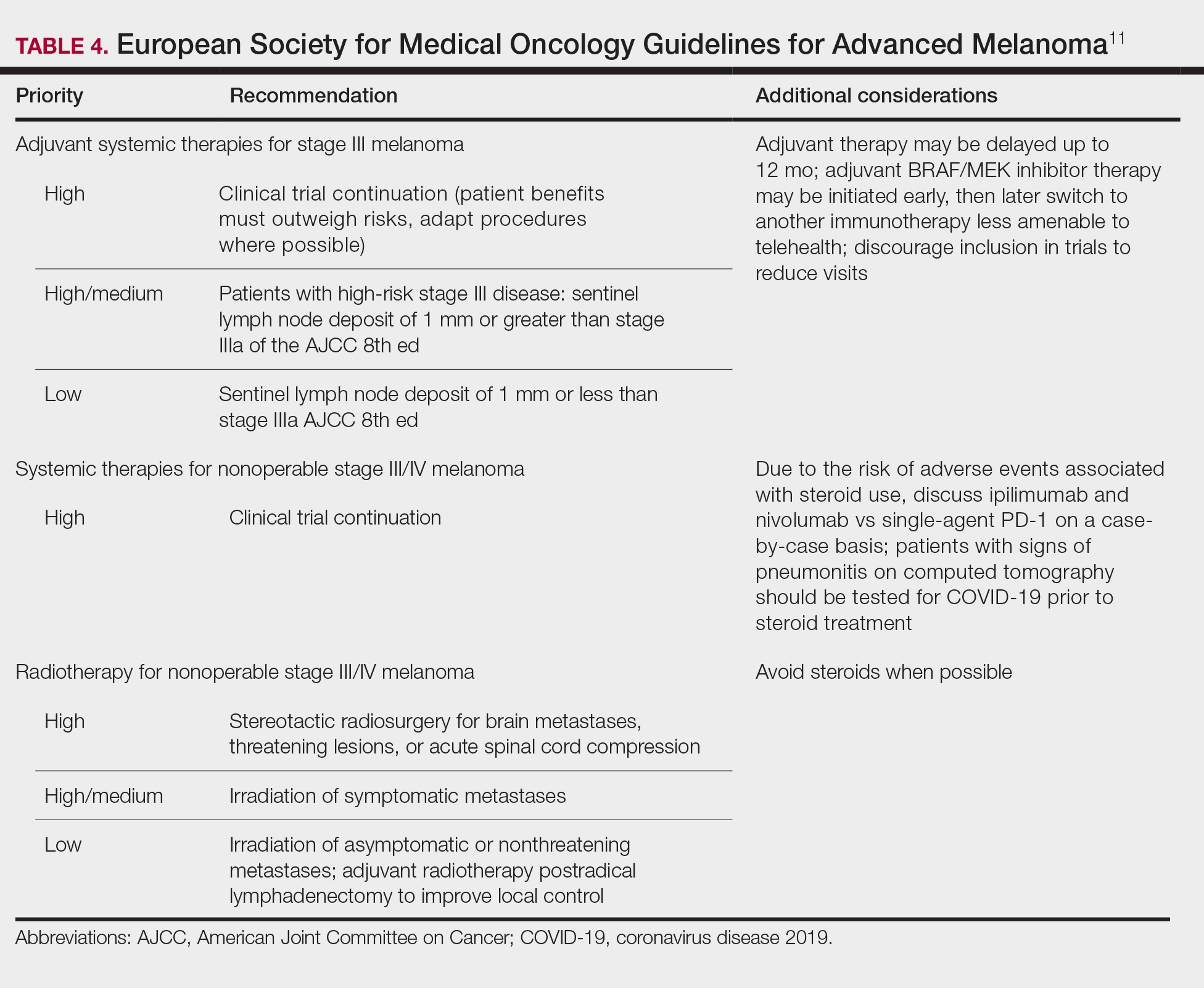

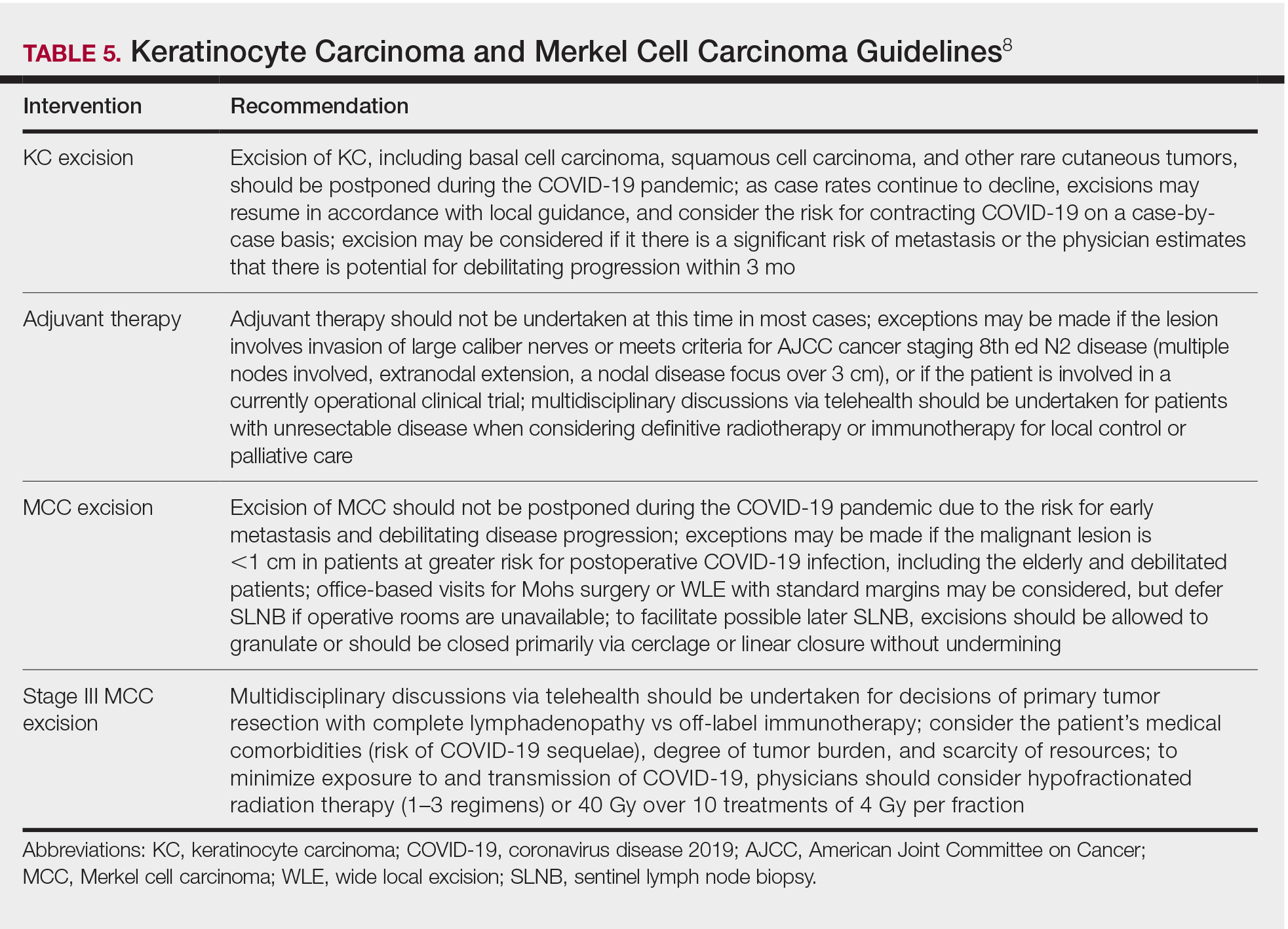

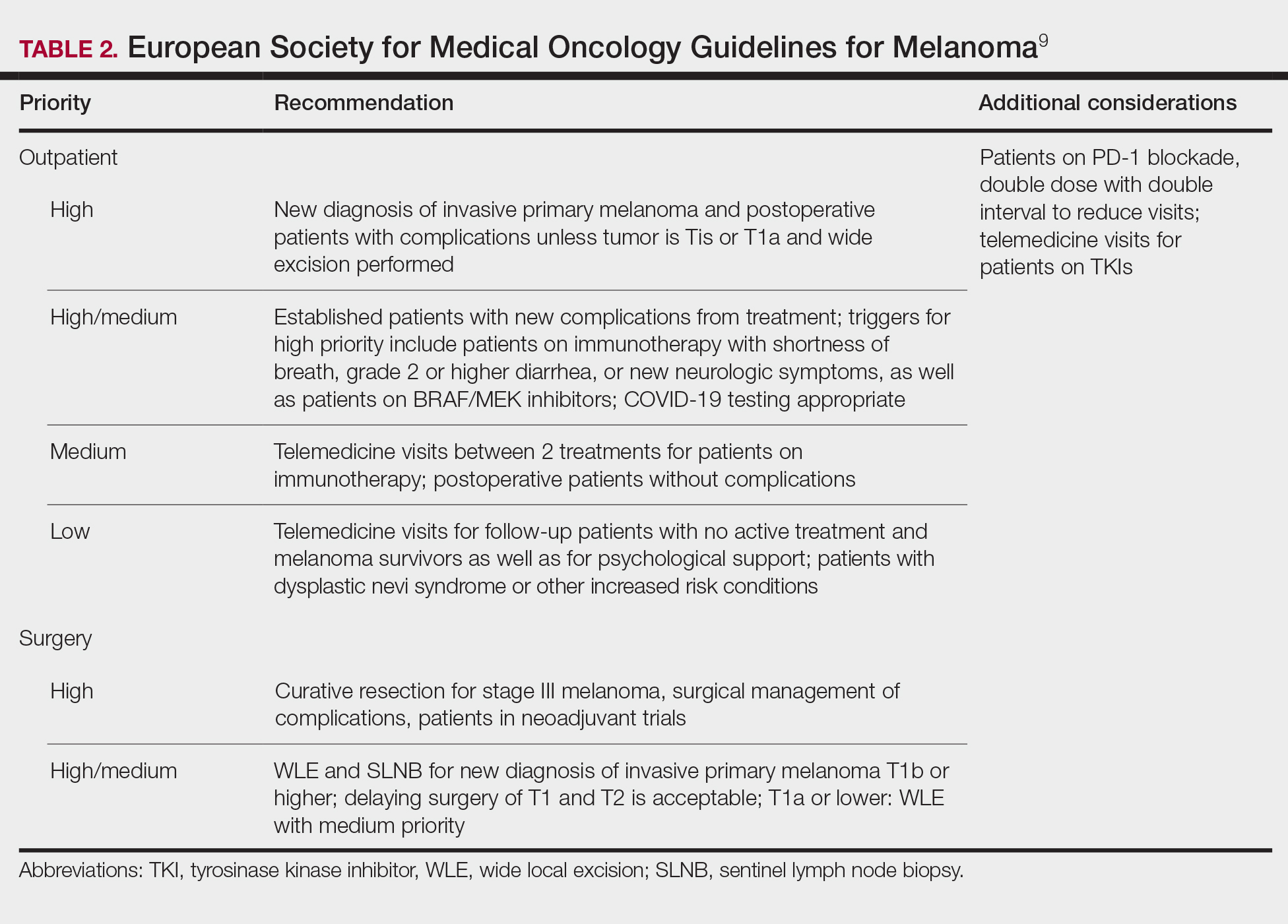

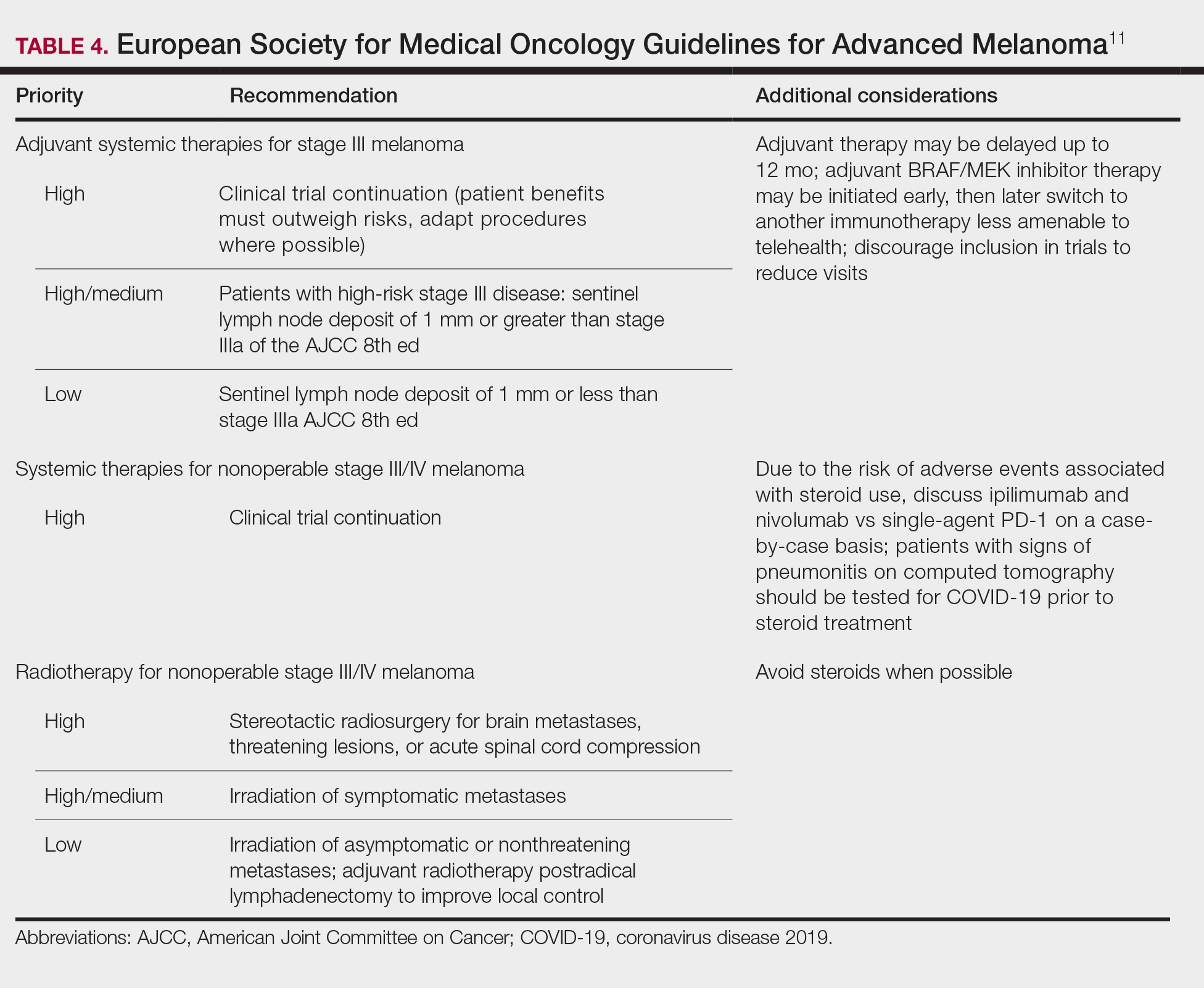

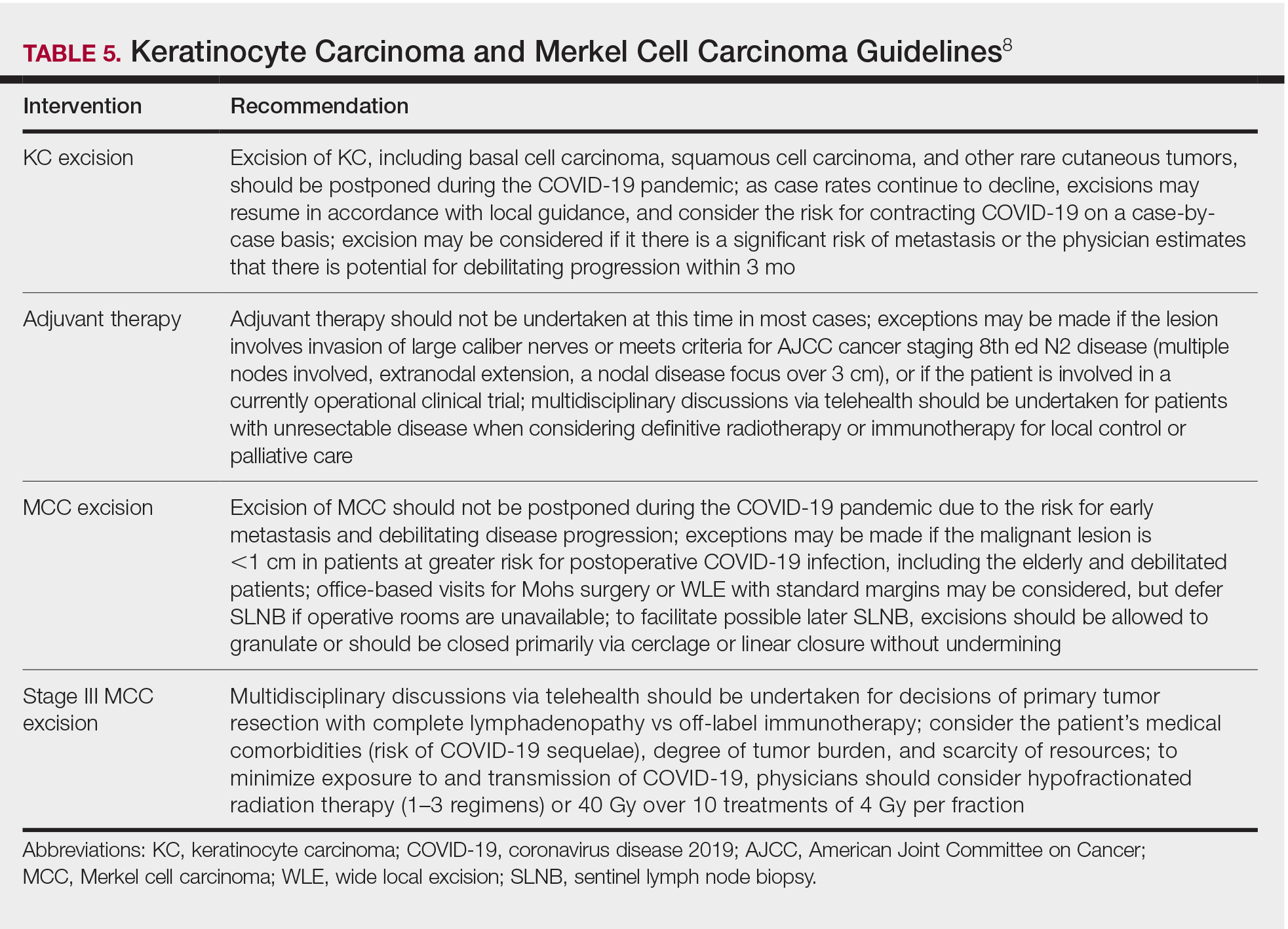

Guidelines provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) elaborated on key considerations for the treatment of melanoma, keratinocyte carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma during the COVID-19 pandemic.8-10 Guidelines from the NCCN concentrated on clear divisions between disease stages to determine provider response. Guidelines for melanoma patients proposed by the ESMO assign tiers by value-based priority in various treatment settings, which offered flexibility to providers as the COVID-19 landscape continued to change. Recommendations from the NCCN and ESMO are summarized in Tables 1 to 5.

Although these guidelines initially may have been proposed to delay treatment of lower-acuity tumors, such delay might not be feasible given the unknown duration of this pandemic and future disease waves. One review of several studies, which addressed the outcomes on melanoma survival following the surgical delay recommended by the NCCN, revealed contradictory evidence.12 Further, sufficiently powered studies will be needed to better understand the impact of delaying treatment during the summer COVID-19 surge on patients with skin cancer. Therefore, physicians must triage patients accordingly to manage and treat while also preventing disease spread.

Tips for Performing Dermatologic Surgery

Careful consideration should be made to protect both the patient and staff during office-based excisional surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. To minimize the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, patients and staff should (1) be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 at least 48 hours prior to entering the office via telephone screening questions, and (2) follow proper hygiene and contact procedures once entering the office. Consider obtaining a nasal polymerase chain reaction swab or saliva test 48 hours prior to the procedure if the patient is undergoing a head and neck procedure or there is risk for transmission.

Guidelines from the ESMO recommended that all patients undergoing surgery or therapy should be swabbed for SARS-CoV-2 before each treatment.11 Patients should wear a mask, remain 6-feet apart in the waiting room, and avoid touching objects until they enter the procedure room. Objects that the patient must touch, such as pens, should be cleaned immediately after such contact with either alcohol or soap and water for 20 seconds.

Office capacity should be reduced by allowing no more than 1 person to accompany the patient and ensuring the presence of only the minimum staff needed for the procedure. Staff who are deemed necessary should wear a mask continuously and gloves during patient contact.

Once in the procedure room, providers might be at elevated risk of contracting COVID-19 or transmitting SARS-CoV-2. A properly fitted N95 respirator and a face shield are recommended, especially for facial cases. N95 respirators can be reused by following the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for reuse and decontamination techniques,13 which may include protecting the N95 respirator with a surgical mask and storing it in a paper bag when not in use. Consider testing asymptomatic patients in facial cases when they cannot wear a mask.

Steps should be taken to reduce in-person visits. Dissolving sutures can help avoid return visits. Follow-up visits and postprocedural questions should be managed by telehealth. However, patients with a high-risk underlying conditions (eg, posttransplantation, immunosuppressed) should continue to obtain regular skin checks because they are at higher risk for more aggressive malignancies, such as Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The future trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic is uncertain. Dermatologists should continue providing care for patients with skin cancer while mitigating the risk for COVID-19 infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Guidelines provided by the NCCN and ESMO should help providers triage patients. Decisions should be made case by case, keeping in mind the availability of resources and practicing in compliance with local guidance.

- Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, et al. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2020;79:180-188.

- Ueda M, Martins R, Hendrie PC, et al. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward common goal. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020:1-4.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Non-emergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. Published April 7, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf

- Muddasani S, Housholder A, Fleischer AB. An assessment of United States dermatology practices during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:436-438.

- Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Rate of positive tests in the US and states over time. Updated December 11, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/individual-states

- Middleton J, Lopes H, Michelson K, et al. Planning for a second wave pandemic of COVID-19 and planning for winter: a statement from the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:1525-1527.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-337.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Advisory statement for non-melanoma skin cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic (version 4). Published May 22, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/NCCN-NMSC.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Short-term recommendations for cutaneous melanoma management during COVID-19 pandemic (version 3). Published May 6, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/Melanoma.pdf - Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Di Meo N, et al. Management of advanced melanoma in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13444.

- ESMO [European Society for Medical Oncology]. Cancer patient management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed Decemeber 11, 2020. https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/cancer-patient-management-during-the-covid-19-pandemic?hit=ehp

- Guhan S, Boland G, Tanabe K, et al. Surgical delay and mortality for primary cutaneous melanoma [published online July 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.078

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementing filtering facepiece respirator (FFR) reuse, including reuse after decontamination, when there are known shortages of N95 respirators. Updated October 19, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respirators.html

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome novel coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has presented a unique challenge to providing essential care to patients. Increased demand for health care workers and medical supplies, in addition to the risk for COVID-19 infection and asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers and patients, prompted the delay of nonessential services during the surge of cases this summer.1 Key considerations for continuing operation included current and projected COVID-19 cases in the region, ability to implement telehealth, staffing availability, personal protective equipment availability, and office capacity.2 Providing care that is deemed essential often was determined by the urgency of the treatment or service.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services outlined a strategy to stratify patients, based on level of acuity, during the COVID-19 surge3:

- Low-acuity treatments or services: includes routine primary, specialty, or preventive care visits. They should be postponed; telehealth follow-ups should be considered.

- Intermediate-acuity treatments or services: includes pediatric and neonatal care, follow-up visits for existing conditions, and evaluation of new symptoms (including those consistent with COVID-19). These services should initially be evaluated using telehealth, then triaged to the appropriate site and level of care.

- High-acuity treatments or services: address symptoms consistent with COVID-19 or other severe disease, of which the lack of in-person evaluation would result in harm to the patient.

Employees in hospitals and health care clinics were classified as essential, but dermatologists were not given explicit direction regarding clinic operation. Many practices have restricted services, especially those in an area of higher COVID-19 prevalence. However, the challenge of determining day-to-day operation may have been left to the provider in most cases.4 As many states in the United States continue to relax restrictions, total cases and the rate of positivity of COVID-19 have been sharply rising again, after months of decline,5 which suggests increased transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and potential resurgence of the high case burden on our health care system. Furthermore, a lack of a widely distributed vaccine or herd immunity suggests we will need to take many of the same precautions as in the first surge.6

In general, patients with cancer have been found to be at greater risk for adverse outcomes and mortality after COVID-19.7 Therefore, resource rationing is particularly concerning for patients with skin cancer, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, mycosis fungoides, and keratinocyte carcinoma. Triaging patients based on level of acuity, type of skin cancer, disease burden, host immunosuppression, and risk for progression must be carefully considered in this population.2 Treatment and follow-up present additional challenges.

Guidelines provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) elaborated on key considerations for the treatment of melanoma, keratinocyte carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma during the COVID-19 pandemic.8-10 Guidelines from the NCCN concentrated on clear divisions between disease stages to determine provider response. Guidelines for melanoma patients proposed by the ESMO assign tiers by value-based priority in various treatment settings, which offered flexibility to providers as the COVID-19 landscape continued to change. Recommendations from the NCCN and ESMO are summarized in Tables 1 to 5.

Although these guidelines initially may have been proposed to delay treatment of lower-acuity tumors, such delay might not be feasible given the unknown duration of this pandemic and future disease waves. One review of several studies, which addressed the outcomes on melanoma survival following the surgical delay recommended by the NCCN, revealed contradictory evidence.12 Further, sufficiently powered studies will be needed to better understand the impact of delaying treatment during the summer COVID-19 surge on patients with skin cancer. Therefore, physicians must triage patients accordingly to manage and treat while also preventing disease spread.

Tips for Performing Dermatologic Surgery

Careful consideration should be made to protect both the patient and staff during office-based excisional surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. To minimize the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, patients and staff should (1) be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 at least 48 hours prior to entering the office via telephone screening questions, and (2) follow proper hygiene and contact procedures once entering the office. Consider obtaining a nasal polymerase chain reaction swab or saliva test 48 hours prior to the procedure if the patient is undergoing a head and neck procedure or there is risk for transmission.

Guidelines from the ESMO recommended that all patients undergoing surgery or therapy should be swabbed for SARS-CoV-2 before each treatment.11 Patients should wear a mask, remain 6-feet apart in the waiting room, and avoid touching objects until they enter the procedure room. Objects that the patient must touch, such as pens, should be cleaned immediately after such contact with either alcohol or soap and water for 20 seconds.

Office capacity should be reduced by allowing no more than 1 person to accompany the patient and ensuring the presence of only the minimum staff needed for the procedure. Staff who are deemed necessary should wear a mask continuously and gloves during patient contact.

Once in the procedure room, providers might be at elevated risk of contracting COVID-19 or transmitting SARS-CoV-2. A properly fitted N95 respirator and a face shield are recommended, especially for facial cases. N95 respirators can be reused by following the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for reuse and decontamination techniques,13 which may include protecting the N95 respirator with a surgical mask and storing it in a paper bag when not in use. Consider testing asymptomatic patients in facial cases when they cannot wear a mask.

Steps should be taken to reduce in-person visits. Dissolving sutures can help avoid return visits. Follow-up visits and postprocedural questions should be managed by telehealth. However, patients with a high-risk underlying conditions (eg, posttransplantation, immunosuppressed) should continue to obtain regular skin checks because they are at higher risk for more aggressive malignancies, such as Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The future trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic is uncertain. Dermatologists should continue providing care for patients with skin cancer while mitigating the risk for COVID-19 infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Guidelines provided by the NCCN and ESMO should help providers triage patients. Decisions should be made case by case, keeping in mind the availability of resources and practicing in compliance with local guidance.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome novel coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has presented a unique challenge to providing essential care to patients. Increased demand for health care workers and medical supplies, in addition to the risk for COVID-19 infection and asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers and patients, prompted the delay of nonessential services during the surge of cases this summer.1 Key considerations for continuing operation included current and projected COVID-19 cases in the region, ability to implement telehealth, staffing availability, personal protective equipment availability, and office capacity.2 Providing care that is deemed essential often was determined by the urgency of the treatment or service.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services outlined a strategy to stratify patients, based on level of acuity, during the COVID-19 surge3:

- Low-acuity treatments or services: includes routine primary, specialty, or preventive care visits. They should be postponed; telehealth follow-ups should be considered.

- Intermediate-acuity treatments or services: includes pediatric and neonatal care, follow-up visits for existing conditions, and evaluation of new symptoms (including those consistent with COVID-19). These services should initially be evaluated using telehealth, then triaged to the appropriate site and level of care.

- High-acuity treatments or services: address symptoms consistent with COVID-19 or other severe disease, of which the lack of in-person evaluation would result in harm to the patient.

Employees in hospitals and health care clinics were classified as essential, but dermatologists were not given explicit direction regarding clinic operation. Many practices have restricted services, especially those in an area of higher COVID-19 prevalence. However, the challenge of determining day-to-day operation may have been left to the provider in most cases.4 As many states in the United States continue to relax restrictions, total cases and the rate of positivity of COVID-19 have been sharply rising again, after months of decline,5 which suggests increased transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and potential resurgence of the high case burden on our health care system. Furthermore, a lack of a widely distributed vaccine or herd immunity suggests we will need to take many of the same precautions as in the first surge.6

In general, patients with cancer have been found to be at greater risk for adverse outcomes and mortality after COVID-19.7 Therefore, resource rationing is particularly concerning for patients with skin cancer, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, mycosis fungoides, and keratinocyte carcinoma. Triaging patients based on level of acuity, type of skin cancer, disease burden, host immunosuppression, and risk for progression must be carefully considered in this population.2 Treatment and follow-up present additional challenges.

Guidelines provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) elaborated on key considerations for the treatment of melanoma, keratinocyte carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma during the COVID-19 pandemic.8-10 Guidelines from the NCCN concentrated on clear divisions between disease stages to determine provider response. Guidelines for melanoma patients proposed by the ESMO assign tiers by value-based priority in various treatment settings, which offered flexibility to providers as the COVID-19 landscape continued to change. Recommendations from the NCCN and ESMO are summarized in Tables 1 to 5.

Although these guidelines initially may have been proposed to delay treatment of lower-acuity tumors, such delay might not be feasible given the unknown duration of this pandemic and future disease waves. One review of several studies, which addressed the outcomes on melanoma survival following the surgical delay recommended by the NCCN, revealed contradictory evidence.12 Further, sufficiently powered studies will be needed to better understand the impact of delaying treatment during the summer COVID-19 surge on patients with skin cancer. Therefore, physicians must triage patients accordingly to manage and treat while also preventing disease spread.

Tips for Performing Dermatologic Surgery

Careful consideration should be made to protect both the patient and staff during office-based excisional surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. To minimize the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, patients and staff should (1) be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 at least 48 hours prior to entering the office via telephone screening questions, and (2) follow proper hygiene and contact procedures once entering the office. Consider obtaining a nasal polymerase chain reaction swab or saliva test 48 hours prior to the procedure if the patient is undergoing a head and neck procedure or there is risk for transmission.

Guidelines from the ESMO recommended that all patients undergoing surgery or therapy should be swabbed for SARS-CoV-2 before each treatment.11 Patients should wear a mask, remain 6-feet apart in the waiting room, and avoid touching objects until they enter the procedure room. Objects that the patient must touch, such as pens, should be cleaned immediately after such contact with either alcohol or soap and water for 20 seconds.

Office capacity should be reduced by allowing no more than 1 person to accompany the patient and ensuring the presence of only the minimum staff needed for the procedure. Staff who are deemed necessary should wear a mask continuously and gloves during patient contact.

Once in the procedure room, providers might be at elevated risk of contracting COVID-19 or transmitting SARS-CoV-2. A properly fitted N95 respirator and a face shield are recommended, especially for facial cases. N95 respirators can be reused by following the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for reuse and decontamination techniques,13 which may include protecting the N95 respirator with a surgical mask and storing it in a paper bag when not in use. Consider testing asymptomatic patients in facial cases when they cannot wear a mask.

Steps should be taken to reduce in-person visits. Dissolving sutures can help avoid return visits. Follow-up visits and postprocedural questions should be managed by telehealth. However, patients with a high-risk underlying conditions (eg, posttransplantation, immunosuppressed) should continue to obtain regular skin checks because they are at higher risk for more aggressive malignancies, such as Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The future trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic is uncertain. Dermatologists should continue providing care for patients with skin cancer while mitigating the risk for COVID-19 infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Guidelines provided by the NCCN and ESMO should help providers triage patients. Decisions should be made case by case, keeping in mind the availability of resources and practicing in compliance with local guidance.

- Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, et al. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2020;79:180-188.

- Ueda M, Martins R, Hendrie PC, et al. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward common goal. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020:1-4.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Non-emergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. Published April 7, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf

- Muddasani S, Housholder A, Fleischer AB. An assessment of United States dermatology practices during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:436-438.

- Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Rate of positive tests in the US and states over time. Updated December 11, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/individual-states

- Middleton J, Lopes H, Michelson K, et al. Planning for a second wave pandemic of COVID-19 and planning for winter: a statement from the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:1525-1527.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-337.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Advisory statement for non-melanoma skin cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic (version 4). Published May 22, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/NCCN-NMSC.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Short-term recommendations for cutaneous melanoma management during COVID-19 pandemic (version 3). Published May 6, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/Melanoma.pdf - Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Di Meo N, et al. Management of advanced melanoma in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13444.

- ESMO [European Society for Medical Oncology]. Cancer patient management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed Decemeber 11, 2020. https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/cancer-patient-management-during-the-covid-19-pandemic?hit=ehp

- Guhan S, Boland G, Tanabe K, et al. Surgical delay and mortality for primary cutaneous melanoma [published online July 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.078

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementing filtering facepiece respirator (FFR) reuse, including reuse after decontamination, when there are known shortages of N95 respirators. Updated October 19, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respirators.html

- Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, et al. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2020;79:180-188.

- Ueda M, Martins R, Hendrie PC, et al. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward common goal. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020:1-4.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Non-emergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. Published April 7, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf

- Muddasani S, Housholder A, Fleischer AB. An assessment of United States dermatology practices during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:436-438.

- Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Rate of positive tests in the US and states over time. Updated December 11, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/individual-states

- Middleton J, Lopes H, Michelson K, et al. Planning for a second wave pandemic of COVID-19 and planning for winter: a statement from the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:1525-1527.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-337.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Advisory statement for non-melanoma skin cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic (version 4). Published May 22, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/NCCN-NMSC.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Short-term recommendations for cutaneous melanoma management during COVID-19 pandemic (version 3). Published May 6, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/Melanoma.pdf - Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Di Meo N, et al. Management of advanced melanoma in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13444.

- ESMO [European Society for Medical Oncology]. Cancer patient management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed Decemeber 11, 2020. https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/cancer-patient-management-during-the-covid-19-pandemic?hit=ehp

- Guhan S, Boland G, Tanabe K, et al. Surgical delay and mortality for primary cutaneous melanoma [published online July 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.078

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementing filtering facepiece respirator (FFR) reuse, including reuse after decontamination, when there are known shortages of N95 respirators. Updated October 19, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respirators.html

Practice Points

- Consider the rate of cases and transmission in your area during a pandemic surge when triaging surgical and nonsurgical cases.

- If performing head and neck surgical procedures or cosmetic procedures in which the patient cannot wear a mask, consider testing them 24 to 48 hours before the procedure.

- Follow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines concerning screening asymptomatic patients. Also, follow CDC guidelines on testing patients who have had prior infections.

- Ensure proper personal protective equipment for yourself and staff, including the use of properly fitting N95 respirators and face shields.

Many health plans now must cover full cost of expensive HIV prevention drugs

Ted Howard started taking Truvada a few years ago because he wanted to protect himself against HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. But the daily pill was so pricey he was seriously thinking about giving it up.

Under his insurance plan, the former flight attendant and customer service instructor owed $500 in copayments every month for the drug and an additional $250 every three months for lab work and clinic visits.

Luckily for Howard, his doctor at Las Vegas’ Huntridge Family Clinic, which specializes in LGBTQ care, enrolled him in a clinical trial that covered his medication and other costs in full.

“If I hadn’t been able to get into the trial, I wouldn’t have kept taking PrEP,” said Howard, 68, using the shorthand term for “preexposure prophylaxis.” Taken daily, these drugs — like Truvada — are more than 90% effective at preventing infection with HIV.

(some plans already began doing so last year).

Drugs in this category — Truvada, Descovy and, newly available, a generic version of Truvada — received an “A” recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Under the Affordable Care Act, preventive services that receive an “A” or “B” rating by the task force, a group of medical experts in prevention and primary care, must be covered by most private health plans without making members share the cost, usually through copayments or deductibles. Only plans that are grandfathered under the health law are exempt.

The task force recommended PrEP for people at high risk of HIV infection, including men who have sex with men and injection drug users.

In the United States, more than 1 million people live with HIV, and nearly 40,000 new HIV cases are diagnosed every year. Yet fewer than 10% of people who could benefit from PrEP are taking it. One key reason is that out-of-pocket costs can exceed $1,000 annually, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health last year. Required periodic blood tests and doctor visits can add hundreds of dollars to the cost of the drug, and it’s not clear if insurers are required to pick up all those costs.

“Cost sharing has been a problem,” said Michael Crews, policy director at One Colorado, an advocacy group for the LGBTQ community. “It’s not just getting on PrEP and taking a pill. It’s the lab and clinical services. That’s a huge barrier for folks.”

Whether you’re shopping for a new plan during open enrollment or want to check out what your current plan covers, here are answers to questions you may have about the new preventive coverage requirement.

Q: How can people find out whether their health plan covers PrEP medications without charge?

The plan’s list of covered drugs, called a formulary, should spell out which drugs are covered, along with details about which drug tier they fall into. Drugs placed in higher tiers generally have higher cost sharing. That list should be online with the plan documents that give coverage details.

Sorting out coverage and cost sharing can be tricky. Both Truvada and Descovy can also be used to treat HIV, and if they are taken for that purpose, a plan may require members to pay some of the cost. But if the drugs are taken to prevent HIV infection, patients shouldn’t owe anything out-of-pocket, no matter which tier they are on.

In a recent analysis of online formularies for plans sold on the ACA marketplaces, Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute, found that many plans seemed out of compliance with the requirement to cover PrEP without cost sharing this year.

But representatives for Oscar and Kaiser Permanente, two insurers that were called out in the analysis for lack of compliance, said the drugs are covered without cost sharing in plans nationwide if they are taken to prevent HIV. Schmid later revised his analysis to reflect Oscar’s coverage.

Coverage and cost-sharing information needs to be transparent and easy to find, Schmid said.

“I acted like a shopper of insurance, just like any person would do,” he said. “Even when the information is correct, [it’s so] difficult to find [and there’s] no uniformity.”

It may be necessary to call the insurer directly to confirm coverage details if information on the website is unclear.

Q: Are all three drugs covered without cost sharing?

Health plans have to cover at least one of the drugs in this category — Descovy and the brand and generic versions of Truvada — without cost sharing. People may have to jump through some hoops to get approval for a specific drug, however. For example, Oscar plans sold in 18 states cover the three PrEP options without cost sharing. The generic version of Truvada doesn’t require prior authorization by the insurer. But if someone wants to take the name-brand drug, that person has to go through an approval process. Descovy, a newer drug, is available without cost sharing only if people are unable to use Truvada or its generic version because of clinical intolerance or other issues.

Q: What about the lab work and clinical visits that are necessary while taking PrEP? Are those services also covered without cost sharing?

That is the thousand-dollar question. People who are taking drugs to prevent HIV infection need to meet with a clinician and have blood work every three months to test for HIV, hepatitis B and sexually transmitted infections, and to check their kidney function.

The task force recommendation doesn’t specify whether these services must also be covered without cost sharing, and advocates say federal guidance is necessary to ensure they are free.

“If you’ve got a high-deductible plan and you’ve got to meet it before those services are covered, that’s going to add up,” said Amy Killelea, senior director of health systems and policy at the National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors. “We’re trying to emphasize that it’s integral to the intervention itself.”

A handful of states have programs that help people cover their out-of-pocket costs for lab and clinical visits, generally based on income.

There is precedent for including free ancillary care as part of a recommended preventive service. After consumers and advocates complained, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) clarified that under the ACA removing a polyp during a screening colonoscopy is considered an integral part of the procedure and patients shouldn’t be charged for it.

CMS officials declined to clarify whether PrEP services such as lab work and clinical visits are to be covered without cost sharing as part of the preventive service and noted that states generally enforce such insurance requirements. “CMS intends to contact state regulators, as appropriate, to discuss issuer’s compliance with the federal requirements and whether issuers need further guidance on which services associated with PrEP must be covered without cost sharing,” the agency said in a statement.

Q: What if someone runs into roadblocks getting a plan to cover PrEP or related services without cost sharing?

If an insurer charges for the medication or a follow-up visit, people may have to go through an appeals process to fight it.

“They’d have to appeal to the insurance company and then to the state if they don’t succeed,” said Nadeen Israel, vice president of policy and advocacy at the AIDS Foundation of Chicago. “Most people don’t know to do that.”

Q: Are uninsured people also protected by this new cost-sharing change for PrEP?

Unfortunately, no. The ACA requirement to cover recommended preventive services without charging patients applies only to private insurance plans. People without insurance don’t benefit. Gilead, which makes both Truvada and Descovy, has a patient assistance program for the uninsured.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Ted Howard started taking Truvada a few years ago because he wanted to protect himself against HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. But the daily pill was so pricey he was seriously thinking about giving it up.

Under his insurance plan, the former flight attendant and customer service instructor owed $500 in copayments every month for the drug and an additional $250 every three months for lab work and clinic visits.

Luckily for Howard, his doctor at Las Vegas’ Huntridge Family Clinic, which specializes in LGBTQ care, enrolled him in a clinical trial that covered his medication and other costs in full.

“If I hadn’t been able to get into the trial, I wouldn’t have kept taking PrEP,” said Howard, 68, using the shorthand term for “preexposure prophylaxis.” Taken daily, these drugs — like Truvada — are more than 90% effective at preventing infection with HIV.

(some plans already began doing so last year).

Drugs in this category — Truvada, Descovy and, newly available, a generic version of Truvada — received an “A” recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Under the Affordable Care Act, preventive services that receive an “A” or “B” rating by the task force, a group of medical experts in prevention and primary care, must be covered by most private health plans without making members share the cost, usually through copayments or deductibles. Only plans that are grandfathered under the health law are exempt.

The task force recommended PrEP for people at high risk of HIV infection, including men who have sex with men and injection drug users.

In the United States, more than 1 million people live with HIV, and nearly 40,000 new HIV cases are diagnosed every year. Yet fewer than 10% of people who could benefit from PrEP are taking it. One key reason is that out-of-pocket costs can exceed $1,000 annually, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health last year. Required periodic blood tests and doctor visits can add hundreds of dollars to the cost of the drug, and it’s not clear if insurers are required to pick up all those costs.

“Cost sharing has been a problem,” said Michael Crews, policy director at One Colorado, an advocacy group for the LGBTQ community. “It’s not just getting on PrEP and taking a pill. It’s the lab and clinical services. That’s a huge barrier for folks.”

Whether you’re shopping for a new plan during open enrollment or want to check out what your current plan covers, here are answers to questions you may have about the new preventive coverage requirement.

Q: How can people find out whether their health plan covers PrEP medications without charge?

The plan’s list of covered drugs, called a formulary, should spell out which drugs are covered, along with details about which drug tier they fall into. Drugs placed in higher tiers generally have higher cost sharing. That list should be online with the plan documents that give coverage details.

Sorting out coverage and cost sharing can be tricky. Both Truvada and Descovy can also be used to treat HIV, and if they are taken for that purpose, a plan may require members to pay some of the cost. But if the drugs are taken to prevent HIV infection, patients shouldn’t owe anything out-of-pocket, no matter which tier they are on.

In a recent analysis of online formularies for plans sold on the ACA marketplaces, Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute, found that many plans seemed out of compliance with the requirement to cover PrEP without cost sharing this year.

But representatives for Oscar and Kaiser Permanente, two insurers that were called out in the analysis for lack of compliance, said the drugs are covered without cost sharing in plans nationwide if they are taken to prevent HIV. Schmid later revised his analysis to reflect Oscar’s coverage.

Coverage and cost-sharing information needs to be transparent and easy to find, Schmid said.

“I acted like a shopper of insurance, just like any person would do,” he said. “Even when the information is correct, [it’s so] difficult to find [and there’s] no uniformity.”

It may be necessary to call the insurer directly to confirm coverage details if information on the website is unclear.

Q: Are all three drugs covered without cost sharing?

Health plans have to cover at least one of the drugs in this category — Descovy and the brand and generic versions of Truvada — without cost sharing. People may have to jump through some hoops to get approval for a specific drug, however. For example, Oscar plans sold in 18 states cover the three PrEP options without cost sharing. The generic version of Truvada doesn’t require prior authorization by the insurer. But if someone wants to take the name-brand drug, that person has to go through an approval process. Descovy, a newer drug, is available without cost sharing only if people are unable to use Truvada or its generic version because of clinical intolerance or other issues.

Q: What about the lab work and clinical visits that are necessary while taking PrEP? Are those services also covered without cost sharing?

That is the thousand-dollar question. People who are taking drugs to prevent HIV infection need to meet with a clinician and have blood work every three months to test for HIV, hepatitis B and sexually transmitted infections, and to check their kidney function.

The task force recommendation doesn’t specify whether these services must also be covered without cost sharing, and advocates say federal guidance is necessary to ensure they are free.

“If you’ve got a high-deductible plan and you’ve got to meet it before those services are covered, that’s going to add up,” said Amy Killelea, senior director of health systems and policy at the National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors. “We’re trying to emphasize that it’s integral to the intervention itself.”

A handful of states have programs that help people cover their out-of-pocket costs for lab and clinical visits, generally based on income.

There is precedent for including free ancillary care as part of a recommended preventive service. After consumers and advocates complained, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) clarified that under the ACA removing a polyp during a screening colonoscopy is considered an integral part of the procedure and patients shouldn’t be charged for it.

CMS officials declined to clarify whether PrEP services such as lab work and clinical visits are to be covered without cost sharing as part of the preventive service and noted that states generally enforce such insurance requirements. “CMS intends to contact state regulators, as appropriate, to discuss issuer’s compliance with the federal requirements and whether issuers need further guidance on which services associated with PrEP must be covered without cost sharing,” the agency said in a statement.

Q: What if someone runs into roadblocks getting a plan to cover PrEP or related services without cost sharing?

If an insurer charges for the medication or a follow-up visit, people may have to go through an appeals process to fight it.

“They’d have to appeal to the insurance company and then to the state if they don’t succeed,” said Nadeen Israel, vice president of policy and advocacy at the AIDS Foundation of Chicago. “Most people don’t know to do that.”

Q: Are uninsured people also protected by this new cost-sharing change for PrEP?

Unfortunately, no. The ACA requirement to cover recommended preventive services without charging patients applies only to private insurance plans. People without insurance don’t benefit. Gilead, which makes both Truvada and Descovy, has a patient assistance program for the uninsured.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Ted Howard started taking Truvada a few years ago because he wanted to protect himself against HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. But the daily pill was so pricey he was seriously thinking about giving it up.

Under his insurance plan, the former flight attendant and customer service instructor owed $500 in copayments every month for the drug and an additional $250 every three months for lab work and clinic visits.

Luckily for Howard, his doctor at Las Vegas’ Huntridge Family Clinic, which specializes in LGBTQ care, enrolled him in a clinical trial that covered his medication and other costs in full.

“If I hadn’t been able to get into the trial, I wouldn’t have kept taking PrEP,” said Howard, 68, using the shorthand term for “preexposure prophylaxis.” Taken daily, these drugs — like Truvada — are more than 90% effective at preventing infection with HIV.

(some plans already began doing so last year).

Drugs in this category — Truvada, Descovy and, newly available, a generic version of Truvada — received an “A” recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Under the Affordable Care Act, preventive services that receive an “A” or “B” rating by the task force, a group of medical experts in prevention and primary care, must be covered by most private health plans without making members share the cost, usually through copayments or deductibles. Only plans that are grandfathered under the health law are exempt.

The task force recommended PrEP for people at high risk of HIV infection, including men who have sex with men and injection drug users.

In the United States, more than 1 million people live with HIV, and nearly 40,000 new HIV cases are diagnosed every year. Yet fewer than 10% of people who could benefit from PrEP are taking it. One key reason is that out-of-pocket costs can exceed $1,000 annually, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health last year. Required periodic blood tests and doctor visits can add hundreds of dollars to the cost of the drug, and it’s not clear if insurers are required to pick up all those costs.

“Cost sharing has been a problem,” said Michael Crews, policy director at One Colorado, an advocacy group for the LGBTQ community. “It’s not just getting on PrEP and taking a pill. It’s the lab and clinical services. That’s a huge barrier for folks.”

Whether you’re shopping for a new plan during open enrollment or want to check out what your current plan covers, here are answers to questions you may have about the new preventive coverage requirement.

Q: How can people find out whether their health plan covers PrEP medications without charge?

The plan’s list of covered drugs, called a formulary, should spell out which drugs are covered, along with details about which drug tier they fall into. Drugs placed in higher tiers generally have higher cost sharing. That list should be online with the plan documents that give coverage details.

Sorting out coverage and cost sharing can be tricky. Both Truvada and Descovy can also be used to treat HIV, and if they are taken for that purpose, a plan may require members to pay some of the cost. But if the drugs are taken to prevent HIV infection, patients shouldn’t owe anything out-of-pocket, no matter which tier they are on.

In a recent analysis of online formularies for plans sold on the ACA marketplaces, Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute, found that many plans seemed out of compliance with the requirement to cover PrEP without cost sharing this year.

But representatives for Oscar and Kaiser Permanente, two insurers that were called out in the analysis for lack of compliance, said the drugs are covered without cost sharing in plans nationwide if they are taken to prevent HIV. Schmid later revised his analysis to reflect Oscar’s coverage.

Coverage and cost-sharing information needs to be transparent and easy to find, Schmid said.

“I acted like a shopper of insurance, just like any person would do,” he said. “Even when the information is correct, [it’s so] difficult to find [and there’s] no uniformity.”

It may be necessary to call the insurer directly to confirm coverage details if information on the website is unclear.

Q: Are all three drugs covered without cost sharing?

Health plans have to cover at least one of the drugs in this category — Descovy and the brand and generic versions of Truvada — without cost sharing. People may have to jump through some hoops to get approval for a specific drug, however. For example, Oscar plans sold in 18 states cover the three PrEP options without cost sharing. The generic version of Truvada doesn’t require prior authorization by the insurer. But if someone wants to take the name-brand drug, that person has to go through an approval process. Descovy, a newer drug, is available without cost sharing only if people are unable to use Truvada or its generic version because of clinical intolerance or other issues.