User login

New child COVID-19 cases down in last weekly count

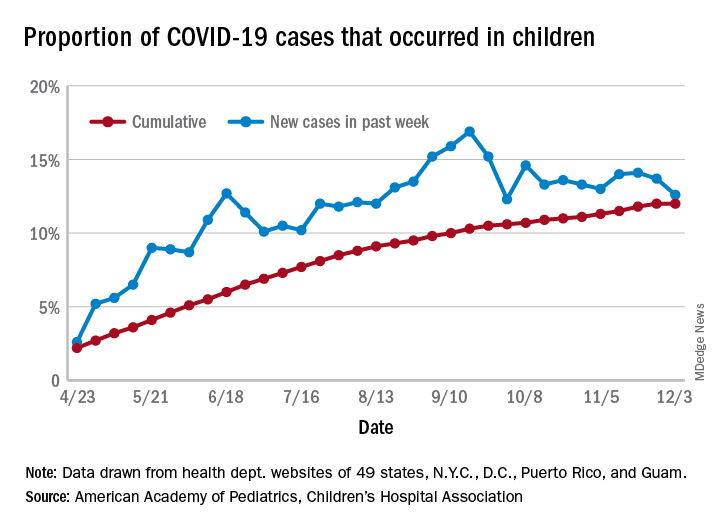

A tiny bit of light may have broken though the COVID-19 storm clouds.

The number of new cases in children in the United States did not set a new weekly high for the first time in months and the cumulative proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children did not go up for the first time since the pandemic started, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

which is the first time since late September that the weekly total has fallen in the United States, the AAP/CHA data show.

Another measure, the cumulative proportion of infected children among all COVID-19 cases, stayed at 12.0% for the second week in a row, and that is the first time there was no increase since the AAP and CHA started tracking health department websites in 49 states (not New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam in April.

For the week ending Dec. 3, those 123,688 children represented 12.6% of all U.S. COVID-19 cases, marking the second consecutive weekly drop in that figure, which has been as high as 16.9% in the previous 3 months, based on data in the AAP/CHA weekly report.

The total number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is now up to 1.46 million, and the overall rate is 1,941 per 100,000 children. Comparable figures for states show that California has the most cumulative cases at over 139,000 and that North Dakota has the highest rate at over 6,800 per 100,000 children. Vermont, the state with the smallest child population, has the fewest cases (687) and the lowest rate (511 per 100,000), the report said.

The total number of COVID-19–related deaths in children has reached 154 in the 44 jurisdictions (43 states and New York City) reporting such data. That number represents 0.06% of all coronavirus deaths, a proportion that has changed little – ranging from 0.04% to 0.07% – over the course of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said.

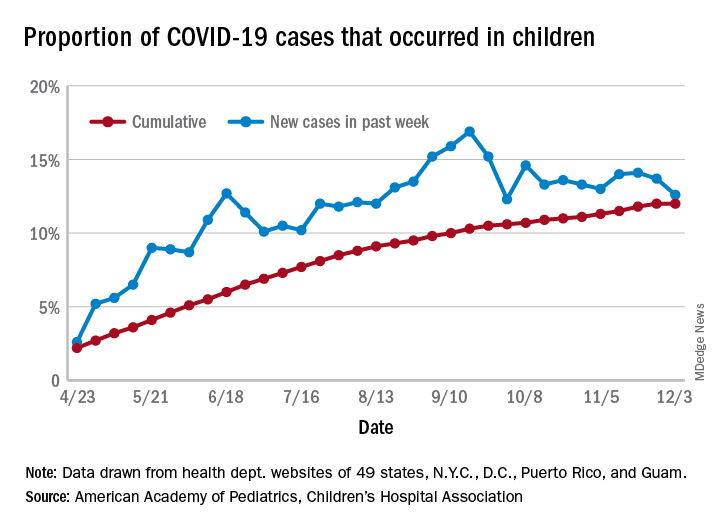

A tiny bit of light may have broken though the COVID-19 storm clouds.

The number of new cases in children in the United States did not set a new weekly high for the first time in months and the cumulative proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children did not go up for the first time since the pandemic started, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

which is the first time since late September that the weekly total has fallen in the United States, the AAP/CHA data show.

Another measure, the cumulative proportion of infected children among all COVID-19 cases, stayed at 12.0% for the second week in a row, and that is the first time there was no increase since the AAP and CHA started tracking health department websites in 49 states (not New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam in April.

For the week ending Dec. 3, those 123,688 children represented 12.6% of all U.S. COVID-19 cases, marking the second consecutive weekly drop in that figure, which has been as high as 16.9% in the previous 3 months, based on data in the AAP/CHA weekly report.

The total number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is now up to 1.46 million, and the overall rate is 1,941 per 100,000 children. Comparable figures for states show that California has the most cumulative cases at over 139,000 and that North Dakota has the highest rate at over 6,800 per 100,000 children. Vermont, the state with the smallest child population, has the fewest cases (687) and the lowest rate (511 per 100,000), the report said.

The total number of COVID-19–related deaths in children has reached 154 in the 44 jurisdictions (43 states and New York City) reporting such data. That number represents 0.06% of all coronavirus deaths, a proportion that has changed little – ranging from 0.04% to 0.07% – over the course of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said.

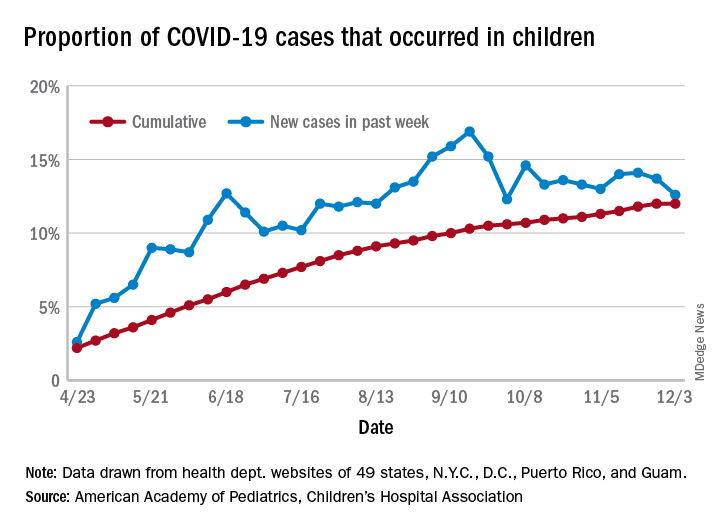

A tiny bit of light may have broken though the COVID-19 storm clouds.

The number of new cases in children in the United States did not set a new weekly high for the first time in months and the cumulative proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children did not go up for the first time since the pandemic started, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

which is the first time since late September that the weekly total has fallen in the United States, the AAP/CHA data show.

Another measure, the cumulative proportion of infected children among all COVID-19 cases, stayed at 12.0% for the second week in a row, and that is the first time there was no increase since the AAP and CHA started tracking health department websites in 49 states (not New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam in April.

For the week ending Dec. 3, those 123,688 children represented 12.6% of all U.S. COVID-19 cases, marking the second consecutive weekly drop in that figure, which has been as high as 16.9% in the previous 3 months, based on data in the AAP/CHA weekly report.

The total number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is now up to 1.46 million, and the overall rate is 1,941 per 100,000 children. Comparable figures for states show that California has the most cumulative cases at over 139,000 and that North Dakota has the highest rate at over 6,800 per 100,000 children. Vermont, the state with the smallest child population, has the fewest cases (687) and the lowest rate (511 per 100,000), the report said.

The total number of COVID-19–related deaths in children has reached 154 in the 44 jurisdictions (43 states and New York City) reporting such data. That number represents 0.06% of all coronavirus deaths, a proportion that has changed little – ranging from 0.04% to 0.07% – over the course of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said.

Joint guidelines favor antibody testing for certain Lyme disease manifestations

New clinical practice guidelines on Lyme disease place a strong emphasis on antibody testing to assess for rheumatologic and neurologic syndromes. “Diagnostically, we recommend testing via antibodies, and an index of antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] versus serum. Importantly, we recommend against using polymerase chain reaction [PCR] in CSF,” Jeffrey A. Rumbaugh, MD, PhD, a coauthor of the guidelines and a member of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America, AAN, and the American College of Rheumatology convened a multidisciplinary panel to develop the 43 recommendations, seeking input from 12 additional medical specialties, and patients. The panel conducted a systematic review of available evidence on preventing, diagnosing, and treating Lyme disease, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation model to evaluate clinical evidence and strength of recommendations. The guidelines were simultaneous published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Neurology, Arthritis & Rheumatology, and Arthritis Care & Research.

This is the first time these organizations have collaborated on joint Lyme disease guidelines, which focus mainly on neurologic, cardiac, and rheumatologic manifestations.

“We are very excited to provide these updated guidelines to assist clinicians working in numerous medical specialties around the country, and even the world, as they care for patients suffering from Lyme disease,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

When to use and not to use PCR

Guideline authors called for specific testing regimens depending on presentation of symptoms. Generally, they advised that individuals with a skin rash suggestive of early disease seek a clinical diagnosis instead of laboratory testing.

Recommendations on Lyme arthritis support previous IDSA guidelines published in 2006, Linda K. Bockenstedt, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a coauthor of the guidelines, said in an interview.

To evaluate for potential Lyme arthritis, clinicians should choose serum antibody testing over PCR or culture of blood or synovial fluid/tissue. However, if a doctor is assessing a seropositive patient for Lyme arthritis diagnosis but needs more information for treatment decisions, the authors recommended PCR applied to synovial fluid or tissue over Borrelia culture.

“Synovial fluid can be analyzed by PCR, but sensitivity is generally lower than serology,” Dr. Bockenstedt explained. Additionally, culture of joint fluid or synovial tissue for Lyme spirochetes has 0% sensitivity in multiple studies. “For these reasons, we recommend serum antibody testing over PCR of joint fluid or other methods for an initial diagnosis.”

Serum antibody testing over PCR or culture is also recommended for identifying Lyme neuroborreliosis in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) or CNS.

Despite the recent popularity of Lyme PCR testing in hospitals and labs, “with Lyme at least, antibodies are better in the CSF,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. Studies have shown that “most patients with even early neurologic Lyme disease are seropositive by conventional antibody testing at time of initial clinical presentation, and that intrathecal antibody production, as demonstrated by an elevated CSF:serum index, is highly specific for CNS involvement.”

If done correctly, antibody testing is both sensitive and specific for neurologic Lyme disease. “On the other hand, sensitivity of Lyme PCR performed on CSF has been only in the 5%-17% range in studies. Incidentally, Lyme PCR on blood is also not sensitive and therefore not recommended,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

Guideline authors recommended testing in patients with the following conditions: acute neurologic disorders such as meningitis, painful radiculoneuritis, mononeuropathy multiplex; evidence of spinal cord or brain inflammation; and acute myocarditis/pericarditis of unknown cause in an appropriate epidemiologic setting.

They did not recommend testing in patients with typical amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; Parkinson’s disease, dementia, or cognitive decline; new-onset seizures; other neurologic syndromes or those lacking clinical or epidemiologic history that would support a diagnosis of Lyme disease; and patients with chronic cardiomyopathy of unknown cause.

The authors also called for judicious use of electrocardiogram to screen for Lyme carditis, recommending it only in patients signs or symptoms of this condition. However, patients at risk for or showing signs of severe cardiac complications of Lyme disease should be hospitalized and monitored via ECG.

Timelines for antibiotics

Most patients with Lyme disease should receive oral antibiotics, although duration times vary depending on the disease state. “We recommend that prophylactic antibiotic therapy be given to adults and children only within 72 hours of removal of an identified high-risk tick bite, but not for bites that are equivocal risk or low risk,” according to the guideline authors.

Specific antibiotic treatment regimens by condition are as follows: 10-14 days for early-stage disease, 14 days for Lyme carditis, 14-21 days for neurologic Lyme disease, and 28 days for late Lyme arthritis.

“Despite arthritis occurring late in the course of infection, treatment with a 28-day course of oral antibiotic is effective, although the rates of complete resolution of joint swelling can vary,” Dr. Bockenstedt said. Clinicians may consider a second 28-day course of oral antibiotics or a 2- to 4-week course of ceftriaxone in patients with persistent swelling, after an initial course of oral antibiotics.

Citing knowledge gaps, the authors made no recommendation on secondary antibiotic treatment for unresolved Lyme arthritis. Rheumatologists can play an important role in the care of this small subset of patients, Dr. Bockenstedt noted. “Studies of patients with ‘postantibiotic Lyme arthritis’ show that they can be treated successfully with intra-articular steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, biologic response modifiers, and even synovectomy with successful outcomes.” Some of these therapies also work in cases where first courses of oral and intravenous antibiotics are unsuccessful.

“Antibiotic therapy for longer than 8 weeks is not expected to provide additional benefit to patients with persistent arthritis if that treatment has included one course of IV therapy,” the authors clarified.

For patients with Lyme disease–associated meningitis, cranial neuropathy, radiculoneuropathy, or other PNS manifestations, the authors recommended intravenous ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, penicillin G, or oral doxycycline over other antimicrobials.

“For most neurologic presentations, oral doxycycline is just as effective as appropriate IV antibiotics,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. “The exception is the relatively rare situation where the patient is felt to have parenchymal involvement of brain or spinal cord, in which case the guidelines recommend IV antibiotics over oral antibiotics.” In the studies, there was no statistically significant difference between oral or intravenous regimens in response rate or risk of adverse effects.

Patients with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, pain, or cognitive impairment following treatment should not receive additional antibiotic therapy if there’s no evidence of treatment failure or infection. These two markers “would include objective signs of disease activity, such as arthritis, meningitis, or neuropathy,” the guideline authors wrote in comments accompanying the recommendation.

Clinicians caring for patients with symptomatic bradycardia caused by Lyme carditis should consider temporary pacing measures instead of a permanent pacemaker. For patients hospitalized with Lyme carditis, “we suggest initially using IV ceftriaxone over oral antibiotics until there is evidence of clinical improvement, then switching to oral antibiotics to complete treatment,” they advised. Outpatients with this condition should receive oral antibiotics instead of intravenous antibiotics.

Advice on antibodies testing ‘particularly cogent’

For individuals without expertise in these areas, the recommendations are clear and useful, Daniel E. Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and research professor at the University of Florence (Italy), said in an interview.

“As a rheumatologist, I would have appreciated literature references for some of the recommendations but, nevertheless, find these useful. I applaud the care with which the evidence was gathered and the general formatting, which tried to review multiple possible scenarios surrounding Lyme arthritis,” said Dr. Furst, offering a third-party perspective.

The advice on using antibodies tests to make a diagnosis of Lyme arthritis “is particularly cogent and more useful than trying to culture these fastidious organisms,” he added.

The IDSA, AAN, and ACR provided support for the guideline. Dr. Bockenstedt reported receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Gordon and the Llura Gund Foundation and remuneration from L2 Diagnostics for investigator-initiated NIH-sponsored research. Dr. Rumbaugh had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Furst reported no conflicts of interest in commenting on these guidelines.

SOURCE: Rumbaugh JA et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Nov 30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1215.

New clinical practice guidelines on Lyme disease place a strong emphasis on antibody testing to assess for rheumatologic and neurologic syndromes. “Diagnostically, we recommend testing via antibodies, and an index of antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] versus serum. Importantly, we recommend against using polymerase chain reaction [PCR] in CSF,” Jeffrey A. Rumbaugh, MD, PhD, a coauthor of the guidelines and a member of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America, AAN, and the American College of Rheumatology convened a multidisciplinary panel to develop the 43 recommendations, seeking input from 12 additional medical specialties, and patients. The panel conducted a systematic review of available evidence on preventing, diagnosing, and treating Lyme disease, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation model to evaluate clinical evidence and strength of recommendations. The guidelines were simultaneous published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Neurology, Arthritis & Rheumatology, and Arthritis Care & Research.

This is the first time these organizations have collaborated on joint Lyme disease guidelines, which focus mainly on neurologic, cardiac, and rheumatologic manifestations.

“We are very excited to provide these updated guidelines to assist clinicians working in numerous medical specialties around the country, and even the world, as they care for patients suffering from Lyme disease,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

When to use and not to use PCR

Guideline authors called for specific testing regimens depending on presentation of symptoms. Generally, they advised that individuals with a skin rash suggestive of early disease seek a clinical diagnosis instead of laboratory testing.

Recommendations on Lyme arthritis support previous IDSA guidelines published in 2006, Linda K. Bockenstedt, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a coauthor of the guidelines, said in an interview.

To evaluate for potential Lyme arthritis, clinicians should choose serum antibody testing over PCR or culture of blood or synovial fluid/tissue. However, if a doctor is assessing a seropositive patient for Lyme arthritis diagnosis but needs more information for treatment decisions, the authors recommended PCR applied to synovial fluid or tissue over Borrelia culture.

“Synovial fluid can be analyzed by PCR, but sensitivity is generally lower than serology,” Dr. Bockenstedt explained. Additionally, culture of joint fluid or synovial tissue for Lyme spirochetes has 0% sensitivity in multiple studies. “For these reasons, we recommend serum antibody testing over PCR of joint fluid or other methods for an initial diagnosis.”

Serum antibody testing over PCR or culture is also recommended for identifying Lyme neuroborreliosis in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) or CNS.

Despite the recent popularity of Lyme PCR testing in hospitals and labs, “with Lyme at least, antibodies are better in the CSF,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. Studies have shown that “most patients with even early neurologic Lyme disease are seropositive by conventional antibody testing at time of initial clinical presentation, and that intrathecal antibody production, as demonstrated by an elevated CSF:serum index, is highly specific for CNS involvement.”

If done correctly, antibody testing is both sensitive and specific for neurologic Lyme disease. “On the other hand, sensitivity of Lyme PCR performed on CSF has been only in the 5%-17% range in studies. Incidentally, Lyme PCR on blood is also not sensitive and therefore not recommended,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

Guideline authors recommended testing in patients with the following conditions: acute neurologic disorders such as meningitis, painful radiculoneuritis, mononeuropathy multiplex; evidence of spinal cord or brain inflammation; and acute myocarditis/pericarditis of unknown cause in an appropriate epidemiologic setting.

They did not recommend testing in patients with typical amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; Parkinson’s disease, dementia, or cognitive decline; new-onset seizures; other neurologic syndromes or those lacking clinical or epidemiologic history that would support a diagnosis of Lyme disease; and patients with chronic cardiomyopathy of unknown cause.

The authors also called for judicious use of electrocardiogram to screen for Lyme carditis, recommending it only in patients signs or symptoms of this condition. However, patients at risk for or showing signs of severe cardiac complications of Lyme disease should be hospitalized and monitored via ECG.

Timelines for antibiotics

Most patients with Lyme disease should receive oral antibiotics, although duration times vary depending on the disease state. “We recommend that prophylactic antibiotic therapy be given to adults and children only within 72 hours of removal of an identified high-risk tick bite, but not for bites that are equivocal risk or low risk,” according to the guideline authors.

Specific antibiotic treatment regimens by condition are as follows: 10-14 days for early-stage disease, 14 days for Lyme carditis, 14-21 days for neurologic Lyme disease, and 28 days for late Lyme arthritis.

“Despite arthritis occurring late in the course of infection, treatment with a 28-day course of oral antibiotic is effective, although the rates of complete resolution of joint swelling can vary,” Dr. Bockenstedt said. Clinicians may consider a second 28-day course of oral antibiotics or a 2- to 4-week course of ceftriaxone in patients with persistent swelling, after an initial course of oral antibiotics.

Citing knowledge gaps, the authors made no recommendation on secondary antibiotic treatment for unresolved Lyme arthritis. Rheumatologists can play an important role in the care of this small subset of patients, Dr. Bockenstedt noted. “Studies of patients with ‘postantibiotic Lyme arthritis’ show that they can be treated successfully with intra-articular steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, biologic response modifiers, and even synovectomy with successful outcomes.” Some of these therapies also work in cases where first courses of oral and intravenous antibiotics are unsuccessful.

“Antibiotic therapy for longer than 8 weeks is not expected to provide additional benefit to patients with persistent arthritis if that treatment has included one course of IV therapy,” the authors clarified.

For patients with Lyme disease–associated meningitis, cranial neuropathy, radiculoneuropathy, or other PNS manifestations, the authors recommended intravenous ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, penicillin G, or oral doxycycline over other antimicrobials.

“For most neurologic presentations, oral doxycycline is just as effective as appropriate IV antibiotics,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. “The exception is the relatively rare situation where the patient is felt to have parenchymal involvement of brain or spinal cord, in which case the guidelines recommend IV antibiotics over oral antibiotics.” In the studies, there was no statistically significant difference between oral or intravenous regimens in response rate or risk of adverse effects.

Patients with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, pain, or cognitive impairment following treatment should not receive additional antibiotic therapy if there’s no evidence of treatment failure or infection. These two markers “would include objective signs of disease activity, such as arthritis, meningitis, or neuropathy,” the guideline authors wrote in comments accompanying the recommendation.

Clinicians caring for patients with symptomatic bradycardia caused by Lyme carditis should consider temporary pacing measures instead of a permanent pacemaker. For patients hospitalized with Lyme carditis, “we suggest initially using IV ceftriaxone over oral antibiotics until there is evidence of clinical improvement, then switching to oral antibiotics to complete treatment,” they advised. Outpatients with this condition should receive oral antibiotics instead of intravenous antibiotics.

Advice on antibodies testing ‘particularly cogent’

For individuals without expertise in these areas, the recommendations are clear and useful, Daniel E. Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and research professor at the University of Florence (Italy), said in an interview.

“As a rheumatologist, I would have appreciated literature references for some of the recommendations but, nevertheless, find these useful. I applaud the care with which the evidence was gathered and the general formatting, which tried to review multiple possible scenarios surrounding Lyme arthritis,” said Dr. Furst, offering a third-party perspective.

The advice on using antibodies tests to make a diagnosis of Lyme arthritis “is particularly cogent and more useful than trying to culture these fastidious organisms,” he added.

The IDSA, AAN, and ACR provided support for the guideline. Dr. Bockenstedt reported receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Gordon and the Llura Gund Foundation and remuneration from L2 Diagnostics for investigator-initiated NIH-sponsored research. Dr. Rumbaugh had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Furst reported no conflicts of interest in commenting on these guidelines.

SOURCE: Rumbaugh JA et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Nov 30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1215.

New clinical practice guidelines on Lyme disease place a strong emphasis on antibody testing to assess for rheumatologic and neurologic syndromes. “Diagnostically, we recommend testing via antibodies, and an index of antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] versus serum. Importantly, we recommend against using polymerase chain reaction [PCR] in CSF,” Jeffrey A. Rumbaugh, MD, PhD, a coauthor of the guidelines and a member of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America, AAN, and the American College of Rheumatology convened a multidisciplinary panel to develop the 43 recommendations, seeking input from 12 additional medical specialties, and patients. The panel conducted a systematic review of available evidence on preventing, diagnosing, and treating Lyme disease, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation model to evaluate clinical evidence and strength of recommendations. The guidelines were simultaneous published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Neurology, Arthritis & Rheumatology, and Arthritis Care & Research.

This is the first time these organizations have collaborated on joint Lyme disease guidelines, which focus mainly on neurologic, cardiac, and rheumatologic manifestations.

“We are very excited to provide these updated guidelines to assist clinicians working in numerous medical specialties around the country, and even the world, as they care for patients suffering from Lyme disease,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

When to use and not to use PCR

Guideline authors called for specific testing regimens depending on presentation of symptoms. Generally, they advised that individuals with a skin rash suggestive of early disease seek a clinical diagnosis instead of laboratory testing.

Recommendations on Lyme arthritis support previous IDSA guidelines published in 2006, Linda K. Bockenstedt, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a coauthor of the guidelines, said in an interview.

To evaluate for potential Lyme arthritis, clinicians should choose serum antibody testing over PCR or culture of blood or synovial fluid/tissue. However, if a doctor is assessing a seropositive patient for Lyme arthritis diagnosis but needs more information for treatment decisions, the authors recommended PCR applied to synovial fluid or tissue over Borrelia culture.

“Synovial fluid can be analyzed by PCR, but sensitivity is generally lower than serology,” Dr. Bockenstedt explained. Additionally, culture of joint fluid or synovial tissue for Lyme spirochetes has 0% sensitivity in multiple studies. “For these reasons, we recommend serum antibody testing over PCR of joint fluid or other methods for an initial diagnosis.”

Serum antibody testing over PCR or culture is also recommended for identifying Lyme neuroborreliosis in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) or CNS.

Despite the recent popularity of Lyme PCR testing in hospitals and labs, “with Lyme at least, antibodies are better in the CSF,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. Studies have shown that “most patients with even early neurologic Lyme disease are seropositive by conventional antibody testing at time of initial clinical presentation, and that intrathecal antibody production, as demonstrated by an elevated CSF:serum index, is highly specific for CNS involvement.”

If done correctly, antibody testing is both sensitive and specific for neurologic Lyme disease. “On the other hand, sensitivity of Lyme PCR performed on CSF has been only in the 5%-17% range in studies. Incidentally, Lyme PCR on blood is also not sensitive and therefore not recommended,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

Guideline authors recommended testing in patients with the following conditions: acute neurologic disorders such as meningitis, painful radiculoneuritis, mononeuropathy multiplex; evidence of spinal cord or brain inflammation; and acute myocarditis/pericarditis of unknown cause in an appropriate epidemiologic setting.

They did not recommend testing in patients with typical amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; Parkinson’s disease, dementia, or cognitive decline; new-onset seizures; other neurologic syndromes or those lacking clinical or epidemiologic history that would support a diagnosis of Lyme disease; and patients with chronic cardiomyopathy of unknown cause.

The authors also called for judicious use of electrocardiogram to screen for Lyme carditis, recommending it only in patients signs or symptoms of this condition. However, patients at risk for or showing signs of severe cardiac complications of Lyme disease should be hospitalized and monitored via ECG.

Timelines for antibiotics

Most patients with Lyme disease should receive oral antibiotics, although duration times vary depending on the disease state. “We recommend that prophylactic antibiotic therapy be given to adults and children only within 72 hours of removal of an identified high-risk tick bite, but not for bites that are equivocal risk or low risk,” according to the guideline authors.

Specific antibiotic treatment regimens by condition are as follows: 10-14 days for early-stage disease, 14 days for Lyme carditis, 14-21 days for neurologic Lyme disease, and 28 days for late Lyme arthritis.

“Despite arthritis occurring late in the course of infection, treatment with a 28-day course of oral antibiotic is effective, although the rates of complete resolution of joint swelling can vary,” Dr. Bockenstedt said. Clinicians may consider a second 28-day course of oral antibiotics or a 2- to 4-week course of ceftriaxone in patients with persistent swelling, after an initial course of oral antibiotics.

Citing knowledge gaps, the authors made no recommendation on secondary antibiotic treatment for unresolved Lyme arthritis. Rheumatologists can play an important role in the care of this small subset of patients, Dr. Bockenstedt noted. “Studies of patients with ‘postantibiotic Lyme arthritis’ show that they can be treated successfully with intra-articular steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, biologic response modifiers, and even synovectomy with successful outcomes.” Some of these therapies also work in cases where first courses of oral and intravenous antibiotics are unsuccessful.

“Antibiotic therapy for longer than 8 weeks is not expected to provide additional benefit to patients with persistent arthritis if that treatment has included one course of IV therapy,” the authors clarified.

For patients with Lyme disease–associated meningitis, cranial neuropathy, radiculoneuropathy, or other PNS manifestations, the authors recommended intravenous ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, penicillin G, or oral doxycycline over other antimicrobials.

“For most neurologic presentations, oral doxycycline is just as effective as appropriate IV antibiotics,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. “The exception is the relatively rare situation where the patient is felt to have parenchymal involvement of brain or spinal cord, in which case the guidelines recommend IV antibiotics over oral antibiotics.” In the studies, there was no statistically significant difference between oral or intravenous regimens in response rate or risk of adverse effects.

Patients with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, pain, or cognitive impairment following treatment should not receive additional antibiotic therapy if there’s no evidence of treatment failure or infection. These two markers “would include objective signs of disease activity, such as arthritis, meningitis, or neuropathy,” the guideline authors wrote in comments accompanying the recommendation.

Clinicians caring for patients with symptomatic bradycardia caused by Lyme carditis should consider temporary pacing measures instead of a permanent pacemaker. For patients hospitalized with Lyme carditis, “we suggest initially using IV ceftriaxone over oral antibiotics until there is evidence of clinical improvement, then switching to oral antibiotics to complete treatment,” they advised. Outpatients with this condition should receive oral antibiotics instead of intravenous antibiotics.

Advice on antibodies testing ‘particularly cogent’

For individuals without expertise in these areas, the recommendations are clear and useful, Daniel E. Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and research professor at the University of Florence (Italy), said in an interview.

“As a rheumatologist, I would have appreciated literature references for some of the recommendations but, nevertheless, find these useful. I applaud the care with which the evidence was gathered and the general formatting, which tried to review multiple possible scenarios surrounding Lyme arthritis,” said Dr. Furst, offering a third-party perspective.

The advice on using antibodies tests to make a diagnosis of Lyme arthritis “is particularly cogent and more useful than trying to culture these fastidious organisms,” he added.

The IDSA, AAN, and ACR provided support for the guideline. Dr. Bockenstedt reported receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Gordon and the Llura Gund Foundation and remuneration from L2 Diagnostics for investigator-initiated NIH-sponsored research. Dr. Rumbaugh had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Furst reported no conflicts of interest in commenting on these guidelines.

SOURCE: Rumbaugh JA et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Nov 30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1215.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

COVID-19 and risk of clotting: ‘Be proactive about prevention’

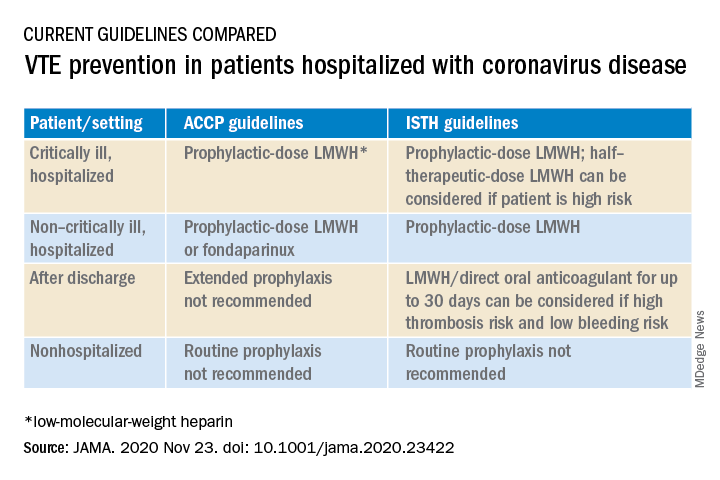

The risk of arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 has been a major issue throughout the pandemic, and how best to manage this risk is the subject of a new review article.

The article, by Gregory Dr. Piazza, MD, and David A. Morrow, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, was published online in JAMA on Nov. 23.

“Basically we’re saying: ‘Be proactive about prevention,’” Dr. Piazza told this news organization.

There is growing recognition among those on the frontline that there is an increased risk of thrombosis in COVID-19 patients, Dr. Piazza said. The risk is highest in patients in the intensive care unit, but the risk is also increased in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, even those not in ICU.

“We don’t really know what the risk is in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients, but we think it’s much lower than in those who are hospitalized,” he said. “We are waiting for data on the optimal way of managing this increased risk of thrombosis in COVID patients, but for the time being, we believe a systematic way of addressing this risk is best, with every patient hospitalized with COVID-19 receiving some type of thromboprophylaxis. This would mainly be with anticoagulation, but in patients in whom anticoagulation is contraindicated, then mechanical methods could be used, such as pneumatic compression boots or compression stockings.”

The authors report thrombotic complication rates of 2.6% in noncritically ill hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and 35.3% in critically ill patients from a recent U.S. registry study.

Autopsy findings of microthrombi in multiple organ systems, including the lungs, heart, and kidneys, suggest that thrombosis may contribute to multisystem organ dysfunction in severe COVID-19, they note. Although the pathophysiology is not fully defined, prothrombotic abnormalities have been identified in patients with COVID-19, including elevated levels of D-dimer, fibrinogen, and factor VIII, they add.

“There are several major questions about which COVID-19 patients to treat with thromboprophylaxis, how to treat them in term of levels of anticoagulation, and there are many ongoing clinical trials to try and answer these questions,” Dr. Piazza commented. “We need results from these randomized trials to provide a better compass for COVID-19 patients at risk of clotting.”

At present, clinicians can follow two different sets of guidelines on the issue, one from the American College of Chest Physicians and the other from the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis, the authors note.

“The ACCP guidelines are very conservative and basically follow the evidence base for medical patients, while the ISTH guidelines are more aggressive and recommend increased levels of anticoagulation in both ICU and hospitalized non-ICU patients and also extend prophylaxis after discharge,” Dr. Piazza said.

“There is quite a difference between the two sets of guidelines, which can be a point of confusion,” he added.

Dr. Piazza notes that at his center every hospitalized COVID patient who does not have a contraindication to anticoagulation receives a standard prophylactic dose of a once-daily low-molecular-weight heparin (for example, enoxaparin 40 mg). A once-daily product is used to minimize infection risk to staff.

While all COVID patients in the ICU should automatically receive some anticoagulation, the optimal dose is an area of active investigation, he explained. “There were several early reports of ICU patients developing blood clots despite receiving standard thromboprophylaxis so perhaps we need to use higher doses. There are trials underway looking at this, and we would advise enrolling patients into these trials.”

If patients can’t be enrolled into trials, and clinicians feel higher anticoagulation levels are needed, Dr. Piazza advises following the ISTH guidance, which allows an intermediate dose of low-molecular-weight heparin (up to 1 mg/kg enoxaparin).

“Some experts are suggesting even higher doses may be needed in some ICU patients, such as the full therapeutic dose, but I worry about the risk of bleeding with such a strategy,” he said.

Dr. Piazza says they do not routinely give anticoagulation after discharge, but if this is desired then patients could be switched to an oral agent, and some of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants are approved for prophylactic use in medically ill patients.

Dr. Piazza points out that whether thromboprophylaxis should be used for nonhospitalized COVID patients who have risk factors for clotting such as a prior history of thrombosis or obesity is a pressing question, and he encourages clinicians to enroll these patients in clinical trials evaluating this issue, such as the PREVENT-HD trial.

“If they can’t enroll patents in a trial, then they have to make a decision whether the patient is high-enough risk to justify off-label use of anticoagulant. There is a case to be made for this, but there is no evidence for or against such action at present,” he noted.

At this time, neither the ISTH nor ACCP recommend measuring D-dimer to screen for venous thromboembolism or to determine intensity of prophylaxis or treatment, the authors note.

“Ongoing investigation will determine optimal preventive regimens in COVID-19 in the intensive care unit, at hospital discharge, and in nonhospitalized patients at high risk for thrombosis,” they conclude.

Dr. Piazza reported grants from Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boston Scientific, Janssen, and Portola, and personal fees from Agile, Amgen, Pfizer, and the Prairie Education and Research Cooperative outside the submitted work. Dr. Morrow reported grants from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Anthos Therapeutics, Esai, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, and The Medicines Company; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Merck, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics; and personal fees from Bayer Pharma and InCarda outside the submitted work.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

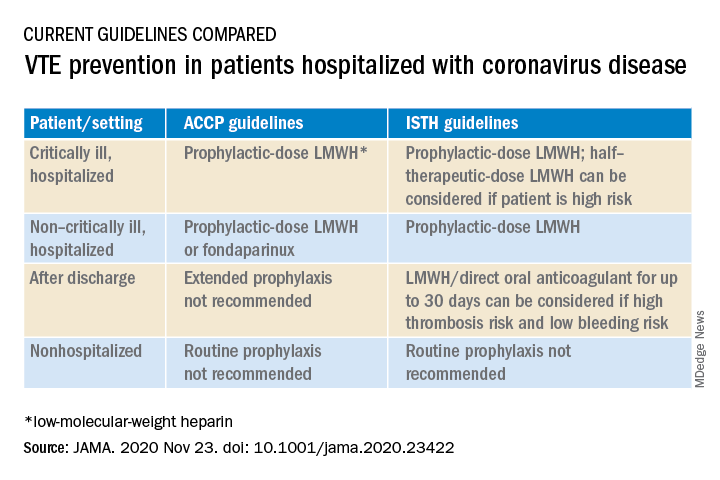

The risk of arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 has been a major issue throughout the pandemic, and how best to manage this risk is the subject of a new review article.

The article, by Gregory Dr. Piazza, MD, and David A. Morrow, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, was published online in JAMA on Nov. 23.

“Basically we’re saying: ‘Be proactive about prevention,’” Dr. Piazza told this news organization.

There is growing recognition among those on the frontline that there is an increased risk of thrombosis in COVID-19 patients, Dr. Piazza said. The risk is highest in patients in the intensive care unit, but the risk is also increased in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, even those not in ICU.

“We don’t really know what the risk is in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients, but we think it’s much lower than in those who are hospitalized,” he said. “We are waiting for data on the optimal way of managing this increased risk of thrombosis in COVID patients, but for the time being, we believe a systematic way of addressing this risk is best, with every patient hospitalized with COVID-19 receiving some type of thromboprophylaxis. This would mainly be with anticoagulation, but in patients in whom anticoagulation is contraindicated, then mechanical methods could be used, such as pneumatic compression boots or compression stockings.”

The authors report thrombotic complication rates of 2.6% in noncritically ill hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and 35.3% in critically ill patients from a recent U.S. registry study.

Autopsy findings of microthrombi in multiple organ systems, including the lungs, heart, and kidneys, suggest that thrombosis may contribute to multisystem organ dysfunction in severe COVID-19, they note. Although the pathophysiology is not fully defined, prothrombotic abnormalities have been identified in patients with COVID-19, including elevated levels of D-dimer, fibrinogen, and factor VIII, they add.

“There are several major questions about which COVID-19 patients to treat with thromboprophylaxis, how to treat them in term of levels of anticoagulation, and there are many ongoing clinical trials to try and answer these questions,” Dr. Piazza commented. “We need results from these randomized trials to provide a better compass for COVID-19 patients at risk of clotting.”

At present, clinicians can follow two different sets of guidelines on the issue, one from the American College of Chest Physicians and the other from the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis, the authors note.

“The ACCP guidelines are very conservative and basically follow the evidence base for medical patients, while the ISTH guidelines are more aggressive and recommend increased levels of anticoagulation in both ICU and hospitalized non-ICU patients and also extend prophylaxis after discharge,” Dr. Piazza said.

“There is quite a difference between the two sets of guidelines, which can be a point of confusion,” he added.

Dr. Piazza notes that at his center every hospitalized COVID patient who does not have a contraindication to anticoagulation receives a standard prophylactic dose of a once-daily low-molecular-weight heparin (for example, enoxaparin 40 mg). A once-daily product is used to minimize infection risk to staff.

While all COVID patients in the ICU should automatically receive some anticoagulation, the optimal dose is an area of active investigation, he explained. “There were several early reports of ICU patients developing blood clots despite receiving standard thromboprophylaxis so perhaps we need to use higher doses. There are trials underway looking at this, and we would advise enrolling patients into these trials.”

If patients can’t be enrolled into trials, and clinicians feel higher anticoagulation levels are needed, Dr. Piazza advises following the ISTH guidance, which allows an intermediate dose of low-molecular-weight heparin (up to 1 mg/kg enoxaparin).

“Some experts are suggesting even higher doses may be needed in some ICU patients, such as the full therapeutic dose, but I worry about the risk of bleeding with such a strategy,” he said.

Dr. Piazza says they do not routinely give anticoagulation after discharge, but if this is desired then patients could be switched to an oral agent, and some of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants are approved for prophylactic use in medically ill patients.

Dr. Piazza points out that whether thromboprophylaxis should be used for nonhospitalized COVID patients who have risk factors for clotting such as a prior history of thrombosis or obesity is a pressing question, and he encourages clinicians to enroll these patients in clinical trials evaluating this issue, such as the PREVENT-HD trial.

“If they can’t enroll patents in a trial, then they have to make a decision whether the patient is high-enough risk to justify off-label use of anticoagulant. There is a case to be made for this, but there is no evidence for or against such action at present,” he noted.

At this time, neither the ISTH nor ACCP recommend measuring D-dimer to screen for venous thromboembolism or to determine intensity of prophylaxis or treatment, the authors note.

“Ongoing investigation will determine optimal preventive regimens in COVID-19 in the intensive care unit, at hospital discharge, and in nonhospitalized patients at high risk for thrombosis,” they conclude.

Dr. Piazza reported grants from Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boston Scientific, Janssen, and Portola, and personal fees from Agile, Amgen, Pfizer, and the Prairie Education and Research Cooperative outside the submitted work. Dr. Morrow reported grants from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Anthos Therapeutics, Esai, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, and The Medicines Company; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Merck, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics; and personal fees from Bayer Pharma and InCarda outside the submitted work.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

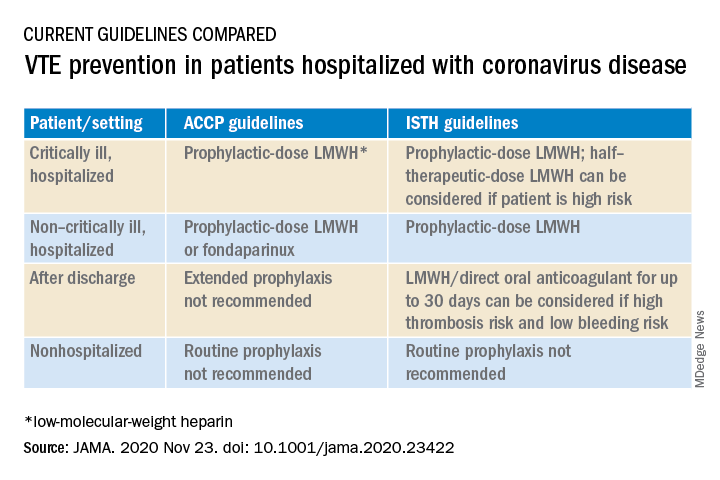

The risk of arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 has been a major issue throughout the pandemic, and how best to manage this risk is the subject of a new review article.

The article, by Gregory Dr. Piazza, MD, and David A. Morrow, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, was published online in JAMA on Nov. 23.

“Basically we’re saying: ‘Be proactive about prevention,’” Dr. Piazza told this news organization.

There is growing recognition among those on the frontline that there is an increased risk of thrombosis in COVID-19 patients, Dr. Piazza said. The risk is highest in patients in the intensive care unit, but the risk is also increased in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, even those not in ICU.

“We don’t really know what the risk is in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients, but we think it’s much lower than in those who are hospitalized,” he said. “We are waiting for data on the optimal way of managing this increased risk of thrombosis in COVID patients, but for the time being, we believe a systematic way of addressing this risk is best, with every patient hospitalized with COVID-19 receiving some type of thromboprophylaxis. This would mainly be with anticoagulation, but in patients in whom anticoagulation is contraindicated, then mechanical methods could be used, such as pneumatic compression boots or compression stockings.”

The authors report thrombotic complication rates of 2.6% in noncritically ill hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and 35.3% in critically ill patients from a recent U.S. registry study.

Autopsy findings of microthrombi in multiple organ systems, including the lungs, heart, and kidneys, suggest that thrombosis may contribute to multisystem organ dysfunction in severe COVID-19, they note. Although the pathophysiology is not fully defined, prothrombotic abnormalities have been identified in patients with COVID-19, including elevated levels of D-dimer, fibrinogen, and factor VIII, they add.

“There are several major questions about which COVID-19 patients to treat with thromboprophylaxis, how to treat them in term of levels of anticoagulation, and there are many ongoing clinical trials to try and answer these questions,” Dr. Piazza commented. “We need results from these randomized trials to provide a better compass for COVID-19 patients at risk of clotting.”

At present, clinicians can follow two different sets of guidelines on the issue, one from the American College of Chest Physicians and the other from the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis, the authors note.

“The ACCP guidelines are very conservative and basically follow the evidence base for medical patients, while the ISTH guidelines are more aggressive and recommend increased levels of anticoagulation in both ICU and hospitalized non-ICU patients and also extend prophylaxis after discharge,” Dr. Piazza said.

“There is quite a difference between the two sets of guidelines, which can be a point of confusion,” he added.

Dr. Piazza notes that at his center every hospitalized COVID patient who does not have a contraindication to anticoagulation receives a standard prophylactic dose of a once-daily low-molecular-weight heparin (for example, enoxaparin 40 mg). A once-daily product is used to minimize infection risk to staff.

While all COVID patients in the ICU should automatically receive some anticoagulation, the optimal dose is an area of active investigation, he explained. “There were several early reports of ICU patients developing blood clots despite receiving standard thromboprophylaxis so perhaps we need to use higher doses. There are trials underway looking at this, and we would advise enrolling patients into these trials.”

If patients can’t be enrolled into trials, and clinicians feel higher anticoagulation levels are needed, Dr. Piazza advises following the ISTH guidance, which allows an intermediate dose of low-molecular-weight heparin (up to 1 mg/kg enoxaparin).

“Some experts are suggesting even higher doses may be needed in some ICU patients, such as the full therapeutic dose, but I worry about the risk of bleeding with such a strategy,” he said.

Dr. Piazza says they do not routinely give anticoagulation after discharge, but if this is desired then patients could be switched to an oral agent, and some of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants are approved for prophylactic use in medically ill patients.

Dr. Piazza points out that whether thromboprophylaxis should be used for nonhospitalized COVID patients who have risk factors for clotting such as a prior history of thrombosis or obesity is a pressing question, and he encourages clinicians to enroll these patients in clinical trials evaluating this issue, such as the PREVENT-HD trial.

“If they can’t enroll patents in a trial, then they have to make a decision whether the patient is high-enough risk to justify off-label use of anticoagulant. There is a case to be made for this, but there is no evidence for or against such action at present,” he noted.

At this time, neither the ISTH nor ACCP recommend measuring D-dimer to screen for venous thromboembolism or to determine intensity of prophylaxis or treatment, the authors note.

“Ongoing investigation will determine optimal preventive regimens in COVID-19 in the intensive care unit, at hospital discharge, and in nonhospitalized patients at high risk for thrombosis,” they conclude.

Dr. Piazza reported grants from Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boston Scientific, Janssen, and Portola, and personal fees from Agile, Amgen, Pfizer, and the Prairie Education and Research Cooperative outside the submitted work. Dr. Morrow reported grants from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Anthos Therapeutics, Esai, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, and The Medicines Company; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Merck, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics; and personal fees from Bayer Pharma and InCarda outside the submitted work.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Excess antibiotics and adverse events in patients with pneumonia

Background: Past surveys of providers revealed a tendency to select longer durations of antibiotics to reduce disease recurrence, but recent studies have shown that shorter courses of antibiotics are safe and equally effective in treatment for pneumonia. In addition, there has been a renewed focus on reducing unnecessary use of antibiotics to decrease adverse effects.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 43 hospitals in the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

Synopsis: A retrospective chart review of 6,481 patients hospitalized with pneumonia revealed that 67.8% of patients received excessive days of antibiotic treatment. On average, patients received 2 days of excessive treatment and 93.2% of the additional days came in the form of antibiotics prescribed at discharge.

Excessive treatment was defined as more than 5 days for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and more than 7 days for health care–associated pneumonia, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or gram-negative organisms. The authors adjusted for time to clinical stability when defining the expected duration of treatment.

After statistical adjustment, excess antibiotic days were not associated with increased rates of C. diff infection, emergency department visits, readmission, or 30-day mortality. Additional treatment was associated with increased patient-reported adverse effects including diarrhea, gastrointestinal distress, and mucosal candidiasis.

The impact of this study is limited by a few factors. The study was observational and relied on provider documentation and patient reporting of adverse events. Also, it was published prior to updates to the Infectious Diseases Society of America CAP guidelines, which may affect how it will be interpreted once those guidelines are released.

Bottom line: Adherence to the shortest effective duration of antibiotic treatment for pneumonia may lead to a reduction in the rates of patient reported adverse effects while not impacting treatment success.

Citation: Vaughn VM et al. Excess antibiotic treatment duration and adverse events in patients hospitalized with pneumonia: A multihospital cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 6;171(3):153-63.

Dr. Purdy is a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at St. Louis University School of Medicine.

Background: Past surveys of providers revealed a tendency to select longer durations of antibiotics to reduce disease recurrence, but recent studies have shown that shorter courses of antibiotics are safe and equally effective in treatment for pneumonia. In addition, there has been a renewed focus on reducing unnecessary use of antibiotics to decrease adverse effects.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 43 hospitals in the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

Synopsis: A retrospective chart review of 6,481 patients hospitalized with pneumonia revealed that 67.8% of patients received excessive days of antibiotic treatment. On average, patients received 2 days of excessive treatment and 93.2% of the additional days came in the form of antibiotics prescribed at discharge.

Excessive treatment was defined as more than 5 days for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and more than 7 days for health care–associated pneumonia, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or gram-negative organisms. The authors adjusted for time to clinical stability when defining the expected duration of treatment.

After statistical adjustment, excess antibiotic days were not associated with increased rates of C. diff infection, emergency department visits, readmission, or 30-day mortality. Additional treatment was associated with increased patient-reported adverse effects including diarrhea, gastrointestinal distress, and mucosal candidiasis.

The impact of this study is limited by a few factors. The study was observational and relied on provider documentation and patient reporting of adverse events. Also, it was published prior to updates to the Infectious Diseases Society of America CAP guidelines, which may affect how it will be interpreted once those guidelines are released.

Bottom line: Adherence to the shortest effective duration of antibiotic treatment for pneumonia may lead to a reduction in the rates of patient reported adverse effects while not impacting treatment success.

Citation: Vaughn VM et al. Excess antibiotic treatment duration and adverse events in patients hospitalized with pneumonia: A multihospital cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 6;171(3):153-63.

Dr. Purdy is a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at St. Louis University School of Medicine.

Background: Past surveys of providers revealed a tendency to select longer durations of antibiotics to reduce disease recurrence, but recent studies have shown that shorter courses of antibiotics are safe and equally effective in treatment for pneumonia. In addition, there has been a renewed focus on reducing unnecessary use of antibiotics to decrease adverse effects.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 43 hospitals in the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

Synopsis: A retrospective chart review of 6,481 patients hospitalized with pneumonia revealed that 67.8% of patients received excessive days of antibiotic treatment. On average, patients received 2 days of excessive treatment and 93.2% of the additional days came in the form of antibiotics prescribed at discharge.

Excessive treatment was defined as more than 5 days for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and more than 7 days for health care–associated pneumonia, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or gram-negative organisms. The authors adjusted for time to clinical stability when defining the expected duration of treatment.

After statistical adjustment, excess antibiotic days were not associated with increased rates of C. diff infection, emergency department visits, readmission, or 30-day mortality. Additional treatment was associated with increased patient-reported adverse effects including diarrhea, gastrointestinal distress, and mucosal candidiasis.

The impact of this study is limited by a few factors. The study was observational and relied on provider documentation and patient reporting of adverse events. Also, it was published prior to updates to the Infectious Diseases Society of America CAP guidelines, which may affect how it will be interpreted once those guidelines are released.

Bottom line: Adherence to the shortest effective duration of antibiotic treatment for pneumonia may lead to a reduction in the rates of patient reported adverse effects while not impacting treatment success.

Citation: Vaughn VM et al. Excess antibiotic treatment duration and adverse events in patients hospitalized with pneumonia: A multihospital cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 6;171(3):153-63.

Dr. Purdy is a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at St. Louis University School of Medicine.

Assessing the impact of glucocorticoids on COVID-19 mortality

Clinical question: Is early glucocorticoid therapy associated with reduced mortality or need for mechanical ventilation in hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection?

Background: Glucocorticoids have been used as adjunctive treatment in some infections with inflammatory responses, but their efficacy in COVID-19 infections had not been entirely clear. The RECOVERY trial found a subset of patients with COVID-19 who may benefit from treatment with glucocorticoids. The ideal role of steroids in this infection, and who the subset of patients might be for whom they would benefit, is so far unclear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort analysis.

Setting: Large academic health center in New York.

Synopsis: Researchers analyzed admissions of COVID-19 positive patients hospitalized between March 11, 2020 and April 13, 2020 who did not die or become mechanically ventilated within the first 48 hours of admission. Patients treated with glucocorticoids within 48 hours of admission were compared with patients who were not treated with glucocorticoids during this time frame. In total, 2,998 patients were examined, of whom 1,806 met inclusion criteria, and 140 (7.7%) were treated with glucocorticoids within 48 hours of admission. These treated patients were more likely to have an underlying pulmonary or rheumatologic comorbidity. Early use of glucocorticoids was not associated with in-hospital mortality or mechanical ventilation in either adjusted or unadjusted models. However, if the initial C-reactive protein (CRP) was >20mg/dL, this was associated with a reduced risk of mortality or mechanical ventilation in unadjusted (odds ratio, 0.23; 95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.70) and adjusted analyses for clinical characteristics (adjusted OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06-0.67). Conversely, treatment in patients with CRP <10mg/dL was associated with significantly increased risk of mortality or ventilation during analysis.

Bottom line: Glucocorticoids can benefit patients with significantly elevated CRP but may be harmful to those with lower CRPs.

Citation: Keller MJ et al. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on mortality or mechanical ventilation in patients with COVID-19. J Hosp Med. 2020;8;489-493. Published online first. 2020 Jul 22. doi:10.12788/jhm.3497.

Dr. Halpern is a med-peds hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Clinical question: Is early glucocorticoid therapy associated with reduced mortality or need for mechanical ventilation in hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection?

Background: Glucocorticoids have been used as adjunctive treatment in some infections with inflammatory responses, but their efficacy in COVID-19 infections had not been entirely clear. The RECOVERY trial found a subset of patients with COVID-19 who may benefit from treatment with glucocorticoids. The ideal role of steroids in this infection, and who the subset of patients might be for whom they would benefit, is so far unclear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort analysis.

Setting: Large academic health center in New York.

Synopsis: Researchers analyzed admissions of COVID-19 positive patients hospitalized between March 11, 2020 and April 13, 2020 who did not die or become mechanically ventilated within the first 48 hours of admission. Patients treated with glucocorticoids within 48 hours of admission were compared with patients who were not treated with glucocorticoids during this time frame. In total, 2,998 patients were examined, of whom 1,806 met inclusion criteria, and 140 (7.7%) were treated with glucocorticoids within 48 hours of admission. These treated patients were more likely to have an underlying pulmonary or rheumatologic comorbidity. Early use of glucocorticoids was not associated with in-hospital mortality or mechanical ventilation in either adjusted or unadjusted models. However, if the initial C-reactive protein (CRP) was >20mg/dL, this was associated with a reduced risk of mortality or mechanical ventilation in unadjusted (odds ratio, 0.23; 95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.70) and adjusted analyses for clinical characteristics (adjusted OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06-0.67). Conversely, treatment in patients with CRP <10mg/dL was associated with significantly increased risk of mortality or ventilation during analysis.

Bottom line: Glucocorticoids can benefit patients with significantly elevated CRP but may be harmful to those with lower CRPs.

Citation: Keller MJ et al. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on mortality or mechanical ventilation in patients with COVID-19. J Hosp Med. 2020;8;489-493. Published online first. 2020 Jul 22. doi:10.12788/jhm.3497.

Dr. Halpern is a med-peds hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Clinical question: Is early glucocorticoid therapy associated with reduced mortality or need for mechanical ventilation in hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection?

Background: Glucocorticoids have been used as adjunctive treatment in some infections with inflammatory responses, but their efficacy in COVID-19 infections had not been entirely clear. The RECOVERY trial found a subset of patients with COVID-19 who may benefit from treatment with glucocorticoids. The ideal role of steroids in this infection, and who the subset of patients might be for whom they would benefit, is so far unclear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort analysis.

Setting: Large academic health center in New York.

Synopsis: Researchers analyzed admissions of COVID-19 positive patients hospitalized between March 11, 2020 and April 13, 2020 who did not die or become mechanically ventilated within the first 48 hours of admission. Patients treated with glucocorticoids within 48 hours of admission were compared with patients who were not treated with glucocorticoids during this time frame. In total, 2,998 patients were examined, of whom 1,806 met inclusion criteria, and 140 (7.7%) were treated with glucocorticoids within 48 hours of admission. These treated patients were more likely to have an underlying pulmonary or rheumatologic comorbidity. Early use of glucocorticoids was not associated with in-hospital mortality or mechanical ventilation in either adjusted or unadjusted models. However, if the initial C-reactive protein (CRP) was >20mg/dL, this was associated with a reduced risk of mortality or mechanical ventilation in unadjusted (odds ratio, 0.23; 95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.70) and adjusted analyses for clinical characteristics (adjusted OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06-0.67). Conversely, treatment in patients with CRP <10mg/dL was associated with significantly increased risk of mortality or ventilation during analysis.

Bottom line: Glucocorticoids can benefit patients with significantly elevated CRP but may be harmful to those with lower CRPs.

Citation: Keller MJ et al. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on mortality or mechanical ventilation in patients with COVID-19. J Hosp Med. 2020;8;489-493. Published online first. 2020 Jul 22. doi:10.12788/jhm.3497.

Dr. Halpern is a med-peds hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

PPE shortage crisis continues at most hospitals, survey shows

A majority of hospitals and health care facilities surveyed report operating according to “crisis standards of care” as they struggle to provide sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE).

For example, in a national survey, 73% of 1,083 infection prevention experts said respirator shortages related to care for patients with COVID-19 drove their facility to move beyond conventional standards of care. Furthermore, 69% of facilities are using crisis standards of care (CSC) to provide masks, and 76% are apportioning face shields or eye protection.

Almost 76% of respondents who report reusing respirators said their facility allows them to use each respirator either five times or as many times as possible before replacement; 74% allow similar reuse of masks.

Although the majority of institutions remain in this crisis mode, many health care providers have better access to PPE than they did in the spring 2020, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) noted in its latest national survey.

“It is disheartening to see our healthcare system strained and implementing PPE crisis standards of care more than eight months into the pandemic,” APIC President Connie Steed, MSN, RN, said in a December 3 news release.

The association surveyed experts online between Oct. 22 and Nov. 5. The survey was timed to gauge the extent of resource shortages as COVID-19 cases increase and the 2020-2021 flu season begins.

“Many of us on the front lines are waiting for the other shoe to drop. With the upcoming flu season, we implore people to do what they can to keep safe, protect our healthcare personnel, and lessen the strain on our health care system,” Ms. Steed said.

COVID-19 linked to more infections, too

APIC also asked infection prevention specialists about changes in health care–associated infection rates since the onset of the pandemic. The experts reported an almost 28% increase in central line–associated bloodstream infections and 21% more catheter-associated urinary tract infections. They also reported an 18% rise in ventilator-associated pneumonia or ventilator-associated events, compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is the second PPE survey the APIC has conducted during the pandemic. The organization first reported a dire situation in March. For example, the initial survey found that 48% of facilities were almost out or were out of respirators used to care for patients with COVID-19.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A majority of hospitals and health care facilities surveyed report operating according to “crisis standards of care” as they struggle to provide sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE).

For example, in a national survey, 73% of 1,083 infection prevention experts said respirator shortages related to care for patients with COVID-19 drove their facility to move beyond conventional standards of care. Furthermore, 69% of facilities are using crisis standards of care (CSC) to provide masks, and 76% are apportioning face shields or eye protection.

Almost 76% of respondents who report reusing respirators said their facility allows them to use each respirator either five times or as many times as possible before replacement; 74% allow similar reuse of masks.

Although the majority of institutions remain in this crisis mode, many health care providers have better access to PPE than they did in the spring 2020, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) noted in its latest national survey.

“It is disheartening to see our healthcare system strained and implementing PPE crisis standards of care more than eight months into the pandemic,” APIC President Connie Steed, MSN, RN, said in a December 3 news release.

The association surveyed experts online between Oct. 22 and Nov. 5. The survey was timed to gauge the extent of resource shortages as COVID-19 cases increase and the 2020-2021 flu season begins.

“Many of us on the front lines are waiting for the other shoe to drop. With the upcoming flu season, we implore people to do what they can to keep safe, protect our healthcare personnel, and lessen the strain on our health care system,” Ms. Steed said.

COVID-19 linked to more infections, too

APIC also asked infection prevention specialists about changes in health care–associated infection rates since the onset of the pandemic. The experts reported an almost 28% increase in central line–associated bloodstream infections and 21% more catheter-associated urinary tract infections. They also reported an 18% rise in ventilator-associated pneumonia or ventilator-associated events, compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is the second PPE survey the APIC has conducted during the pandemic. The organization first reported a dire situation in March. For example, the initial survey found that 48% of facilities were almost out or were out of respirators used to care for patients with COVID-19.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A majority of hospitals and health care facilities surveyed report operating according to “crisis standards of care” as they struggle to provide sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE).

For example, in a national survey, 73% of 1,083 infection prevention experts said respirator shortages related to care for patients with COVID-19 drove their facility to move beyond conventional standards of care. Furthermore, 69% of facilities are using crisis standards of care (CSC) to provide masks, and 76% are apportioning face shields or eye protection.

Almost 76% of respondents who report reusing respirators said their facility allows them to use each respirator either five times or as many times as possible before replacement; 74% allow similar reuse of masks.

Although the majority of institutions remain in this crisis mode, many health care providers have better access to PPE than they did in the spring 2020, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) noted in its latest national survey.

“It is disheartening to see our healthcare system strained and implementing PPE crisis standards of care more than eight months into the pandemic,” APIC President Connie Steed, MSN, RN, said in a December 3 news release.

The association surveyed experts online between Oct. 22 and Nov. 5. The survey was timed to gauge the extent of resource shortages as COVID-19 cases increase and the 2020-2021 flu season begins.

“Many of us on the front lines are waiting for the other shoe to drop. With the upcoming flu season, we implore people to do what they can to keep safe, protect our healthcare personnel, and lessen the strain on our health care system,” Ms. Steed said.

COVID-19 linked to more infections, too

APIC also asked infection prevention specialists about changes in health care–associated infection rates since the onset of the pandemic. The experts reported an almost 28% increase in central line–associated bloodstream infections and 21% more catheter-associated urinary tract infections. They also reported an 18% rise in ventilator-associated pneumonia or ventilator-associated events, compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is the second PPE survey the APIC has conducted during the pandemic. The organization first reported a dire situation in March. For example, the initial survey found that 48% of facilities were almost out or were out of respirators used to care for patients with COVID-19.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Herpes Zoster May Be a Marker for COVID-19 Infection During Pregnancy

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the most recently identified member of the zoonotic pathogens of coronaviruses. It caused an outbreak of pneumonia in December 2019 in Wuhan, China.1 Among all related acute respiratory syndromes (SARS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus), SARS-CoV-2 remains to be the most infectious, has the highest potential for human transmission, and can eventually result in acute respiratory distress syndrome.2,3

Only 15% of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases progress to pneumonia, and approximately 5% of these cases develop acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, and/or multiple organ failure. The majority of cases only exhibit mild to moderate symptoms.4,5 A wide array of skin manifestations in COVID-19 infection have been reported, including maculopapular eruptions, morbilliform rashes, urticaria, chickenpoxlike lesions, livedo reticularis, COVID toes, erythema multiforme, pityriasis rosea, and several other patterns.6 We report a case of herpes zoster (HZ) complication in a COVID-19–positive woman who was 27 weeks pregnant.

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman who was 27 weeks pregnant was referred by her obstetrician to the dermatology clinic. She presented with a low-grade fever and a vesicular painful rash. Physical examination revealed painful, itchy, dysesthetic papules and vesicles on the left side of the forehead along with mild edema of the left upper eyelid but no watering of the eye or photophobia. She reported episodes of fever (temperature, 38.9°C), fatigue, and myalgia over the last week. She had bouts of dyspnea and tachycardia that she thought were related to being in the late second trimester of pregnancy. The area surrounding the vesicular eruption was tender to touch. No dry cough or any gastrointestinal or urinary tract symptoms were noted. She reported a burning sensation when splashing water on the face or when exposed to air currents. One week following the initial symptoms, she experienced a painful vesicular rash along the upper left forehead (Figure) associated with eyelid edema. Oral and ocular mucosae were free of any presentations. She had no relevant history and had not experienced any complications during pregnancy. A diagnosis of HZ was made, and she was prescribed valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily for 7 days, acetaminophen for the fever, and calamine lotion. We recommended COVID-19 testing based on her symptoms. A chest radiograph and a positive nasopharyngeal smear were consistent with COVID-19 infection. She reported via telephone follow-up 1 week after presentation that her skin condition had improved following the treatment course and that the vesicles eventually dried, leaving a crusting appearance after 5 to 7 days. Regarding her SARS-CoV-2 condition, her oxygen saturation was 95% at presentation; she self-quarantined at home; and she was treated with oseltamivir 75 mg orally every 12 hours for 5 days, azithromycin 500 mg orally daily, acetaminophen, and vitamin C. Electronic fetal heart rate monitoring and ultrasound examinations were performed to assess the condition of the fetus and were reported normal. At the time of writing this article, she was 32 weeks pregnant and tested negative to 2 consecutive nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID-19 and was in good general condition. She continued her pregnancy according to her obstetrician’s recommendations.

Comment