User login

Home visits: A practical approach

CASE

Mr. A is a 30-year-old man with neurofibromatosis and myelopathy with associated quadriplegia, complicated by dysphasia and chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring a tracheostomy. He is cared for at home by his very competent mother but requires regular visits with his medical providers for assistance with his complex care needs. Due to logistical challenges, he had been receiving regular home visits even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

After estimating the risk of exposure to the patient, Mr. A’s family and his physician’s office staff scheduled a home visit. Before the appointment, the doctor conducted a virtual visit with the patient and family members to screen for COVID-19 infection, which proved negative. The doctor arranged a visit to coincide with Mr. A’s regular appointment with the home health nurse. He invited the patient’s social worker to attend, as well.

The providers donned masks, face shields, and gloves before entering the home. Mr. A’s temperature was checked and was normal. The team completed a physical exam, assessed the patient’s current needs, and refilled prescriptions. The doctor, nurse, and social worker met afterward in the family’s driveway to coordinate plans for the patient’s future care.

This encounter allowed a vulnerable patient with special needs to have access to care while reducing his risk of undesirable exposure. Also, his health care team’s provision of care in the home setting reduced Mr. A’s anxiety and that of his family members.

Home visits have long been an integral part of what it means to be a family physician. In 1930, roughly 40% of all patient-physician encounters in the United States occurred in patients’ homes. By 1980, this number had dropped to < 1%.1 Still, a 1994 survey of American doctors in 3 primary care specialties revealed that 63% of family physicians, more than the other 2 specialties, still made house calls.2 A 2016 analysis of Medicare claims data showed that between 2006 and 2011, only 5% of American doctors overall made house calls on Medicare recipients, but interestingly, the total number of home visits was increasing.3

This resurgence of interest in home health care is due in part to the increasing number of homebound patients in America, which exceeds the number of those in nursing homes.4 Further, a growing body of evidence indicates that home visits improve patient outcomes. And finally, many family physicians whose work lives have been centered around a busy office or hospital practice have found satisfaction in once again seeing patients in their own homes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has of course presented unique challenges—and opportunities, too—for home visits, which we discuss at the end of the article.

Why aren’t more of us making home visits?

For most of us, the decision not to make home visits is simply a matter of time and money. Although Medicare reimbursement for a home visit is typically about 150% that of a comparable office visit,5 it’s difficult, if not impossible, to make 2 home visits in the time you could see 3 patients in the office. So, economically it’s a net loss. Furthermore, we tend to feel less comfortable in our patients’ homes than in our offices. We have less control outside our own environment, and what happens away from our office is often less predictable—sometimes to the point that we may be concerned for our safety.

Continue to: So why make home visits at all?

So why make home visits at all?

First and foremost, home visits improve patient outcomes. This is most evident in our more vulnerable patients: newborns and the elderly, those who have been recently hospitalized, and those at risk because of their particular home situation. Multiple studies have shown that, for elders, home visits reduce functional decline, nursing home admissions, and mortality by around 25% to 33%.6-8 For those at risk of abuse, a recent systematic review showed that home visits reduce intimate partner violence and child abuse.9 Another systematic review demonstrated that patients with diabetes who received home visits vs usual care were more likely to show improvements in quality of life.10 These patients were also more likely to have lower HbA1c levels and lower systolic blood pressure readings.10 A few caveats apply to these studies:

- all of them targeted “vulnerable” patients

- most studies enlisted interdisciplinary teams and had regular team meetings

- most findings reached significance only after multiple home visits.

A further reason for choosing to become involved in home care is that it builds relationships, understanding, and empathy with our patients. “There is deep symbolism in the home visit.... It says, ‘I care enough about you to leave my power base … to come and see you on your own ground.’”11 And this benefit is 2-way; we also grow to understand and appreciate our patients better, especially if they are different from us culturally or socioeconomically.

Home visits allow the medical team to see challenges the patient has grown accustomed to, and perhaps ones that the patient has deemed too insignificant to mention. For the patient, home visits foster a strong sense of trust with the individual doctor and our health delivery network, and they decrease the need to seek emergency services. Finally, it has been demonstrated that provider satisfaction improves when home visits are incorporated into the work week.12

What is the role of community health workers in home-based care?

Community health workers (CHWs), defined as “frontline public health workers who are trusted members of and/or have an unusually close understanding of the community they serve,”13 can be an integral part of the home-based care team. Although CHWs have variable amounts of formal training, they have a unique perspective on local health beliefs and practices, which can assist the home-care team in providing culturally competent health care services and reduce health care costs.

In a study of children with asthma in Seattle, Washington, patients were randomized to a group that had 4 home visits by CHWs and a group that received usual care. The group that received home visits demonstrated more asthma symptom–free days, improved quality-of-life scores, and fewer urgent care visits.14 Furthermore, the intervention was estimated to save approximately $1300 per patient, resulting in a return on investment of 190%. Similarly, in a study comparing inappropriate emergency department (ED) visits between children who received CHW visits and those who did not, patients in the intervention group were significantly less likely to visit the ED for ambulatory complaints (18.2% vs 35.1%; P = .004).15

Continue to: What is the role of social workersin home-based care?

What is the role of social workersin home-based care?

Social workers can help meet the complex medical and biopsychosocial needs of the homebound population.16 A study by Cohen et al based in Israel concluded that homebound participants had a significantly higher risk for mortality, higher rates of depression, and difficulty completing instrumental activities of daily living when compared with their non-homebound counterparts.17

The Mount Sinai (New York) Visiting Doctors Program (MSVD) is a home-based care team that uses social workers to meet the needs of their complex patients.18 The social workers in the MSVD program provide direct counseling, make referrals to government and community resources, and monitor caregiver burden. Using a combination of measurement tools to assess caregiver burden, Ornstein et al demonstrated that the MSVD program led to a decrease in unmet needs and in caregiver burden.19,20 Caregiver burnout can be assessed using the Caregiver Burden Inventory, a validated 24-item questionnaire.21

What electronic tools are availableto monitor patients at home?

Although expensive in terms of both dollars and personnel time, telemonitoring allows home care providers to receive real-time, updated information regarding their patients.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). One systematic review showed that although telemonitoring of patients with COPD improved quality of life and decreased COPD exacerbations, it did not reduce the risk of hospitalization and, therefore, did not reduce health care costs.22 Telemonitoring in COPD can include transmission of data about spirometry parameters, weight, temperature, blood pressure, sputum color, and 6-minute walk distance.23,24

Congestive heart failure (CHF). A 2010 Cochrane review found that telemonitoring of patients with CHF reduced all-cause mortality (risk ratio [RR] = 0.66; P < .0001).25 The Telemedical Interventional Management in Heart Failure II (TIM-HF2) trial,conducted from 2013 to 2017, compared usual care for CHF patients with care incorporating daily transmission of body weight, blood pressure, heart rate, electrocardiogram tracings, pulse oximetry, and self-rated health status.26 This study showed that the average number of days lost per year due to hospital admission was less in the telemonitoring group than in the usual care group (17.8 days vs. 24.2 days; P = .046). All-cause mortality was also reduced in the telemonitoring group (hazard ratio = 0.70; P = .028).

Continue to: What role do “home hospitals” play?

What role do “home hospitals” play?

Home hospitals provide acute or subacute treatment in a patient’s home for a condition that would normally require hospitalization.27 In a meta-analysis of 61 studies evaluating the effectiveness of home hospitals, this option was more likely to reduce mortality (odds ratio [OR] = 0.81; P = .008) and to reduce readmission rates (OR = 0.75; P = .02).28 In a study of 455 older adults, Leff et al found that hospital-at-home was associated with a shorter length of stay (3.2 vs. 4.9 days; P = .004) and that the mean cost was lower for hospital-at-home vs traditional hospital care.29

However, a 2016 Cochrane review of 16 randomized controlled trials comparing hospital-at-home with traditional hospital care showed that while care in a hospital-at-home may decrease formal costs, if costs for caregivers are taken into account, any difference in cost may disappear.30

Although the evidence for cost saving is variable, hospital-at-home admission has been shown to reduce the likelihood of living in a residential care facility at 6 months (RR = 0.35; P < .0001).30 Further, the same Cochrane review showed that admission avoidance may increase patient satisfaction with the care provided.30

Finally, a recent randomized trial in a Boston-area hospital system showed that patients cared for in hospital-at-home were significantly less likely to be readmitted within 30 days and that adjusted cost was about two-thirds the cost of traditional hospital care.31

What is the physician’s rolein home health care?

While home health care is a team effort, the physician has several crucial roles. First, he or she must make the determination that home care is appropriate and feasible for a particular patient. Appropriate, meaning there is evidence that this patient is likely to benefit from home care. Feasible, meaning there are resources available in the community and family to safely care for the patient at home. “Often a house call will serve as the first step in developing a home-based-management plan.”32

Continue to: Second, the physician serves...

Second, the physician serves an important role in directing and coordinating the team of professionals involved. This primarily means helping the team to communicate with one another. Before home visits begin, the physician’s office should reach out not only to the patient and family, but also to any other health care personnel involved in the patient’s home care. Otherwise, many of the health care providers involved will never have face-to-face interaction with the physician. Creation of the coordinated health team minimizes duplication and miscommunication; it also builds a valuable bond.

How does one go about making a home visit?

Scheduling. What often works best in a busy practice is to schedule home visits for the end of the workday or to devote an entire afternoon to making home visits to several patients in one locale. Also important is scheduling times, if possible, when important family members or other caregivers are at home or when other members of the home care team can accompany you.

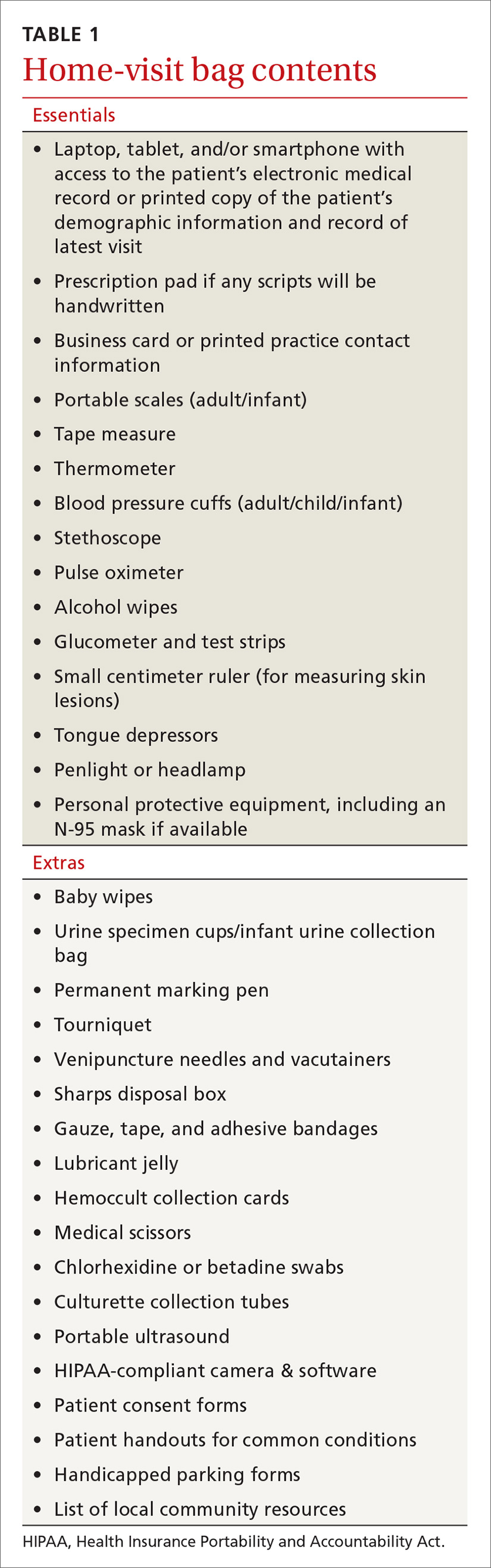

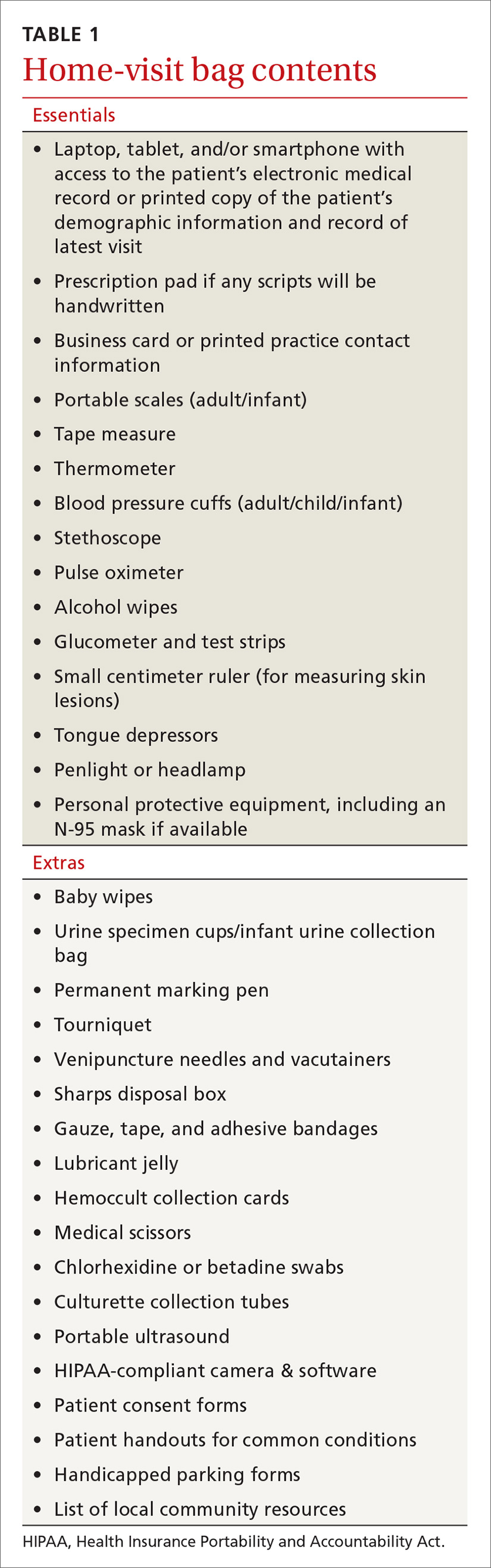

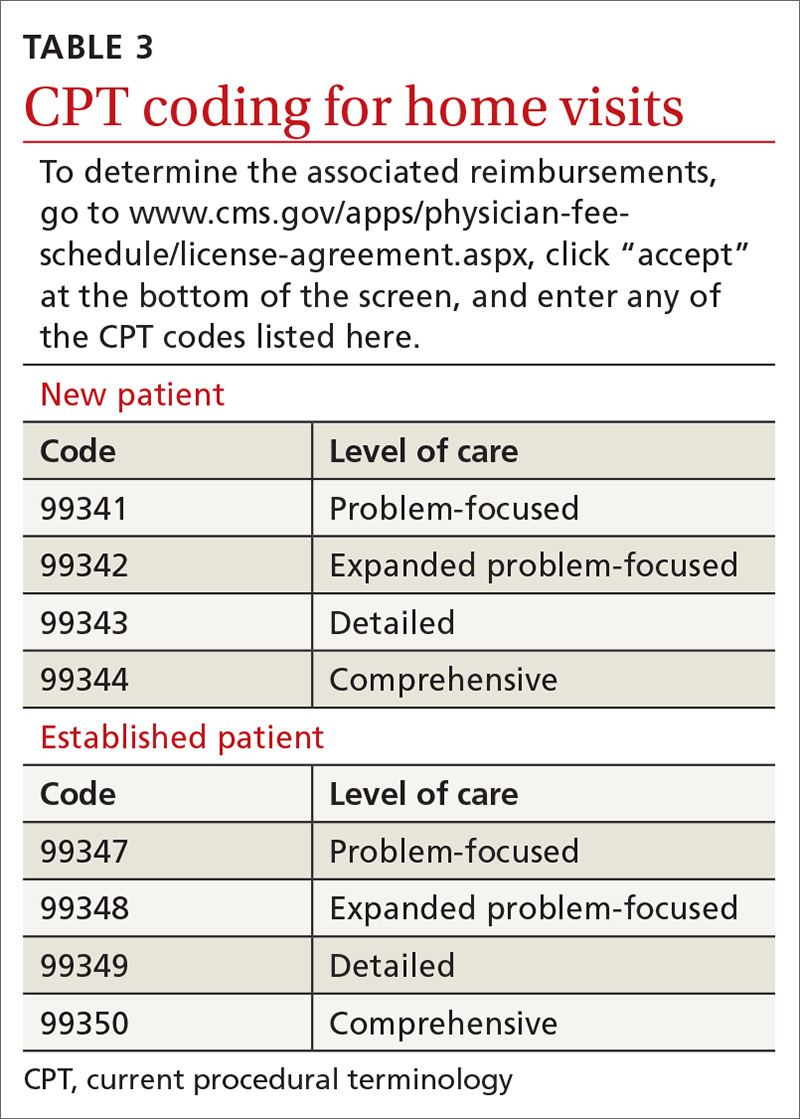

What to bring along. Carry a “home visit bag” that includes equipment you’re likely to need and that is not available away from your office. A minimally equipped visit bag would include different-sized blood pressure cuffs, a glucometer, a pulse oximeter, thermometers, and patient education materials. Other suggested contents are listed in TABLE 1.

Dos and don’ts. Take a few minutes when you first arrive to simply visit with the patient. Sit down and introduce yourself and any members of the home care team that the patient has not met. Take an interim history. While you’re doing this, be observant: Is the home neat or cluttered? Is the indoor temperature comfortable? Are there fall hazards? Is there a smell of cigarette smoke? Are there any indoor combustion sources (eg, wood stove or kerosene heater)? Ask questions such as: Who lives here with you? Can you show me where you keep your medicines? (If the patient keeps insulin or any other medicines in the refrigerator, ask to see it. Note any apparent food scarcity.)

During your exam, pay particular attention to whether vital signs are appreciably different than those measured in the office or hospital. Pay special attention to the patient’s functional abilities. “A subtle, but critical distinction between medical management in the home and medical management in the hospital, clinic, or office is the emphasis on the patient’s functional abilities, family assistance, and environmental factors.”33

Observe the patient’s use of any home technology, if possible; this can be as simple as home oxygenation or as complex as home hemodialysis. Assess for any apparent caregiver stress. Finally, don’t neglect to offer appropriate emotional and spiritual support to the patient and family and to schedule the next follow-up visit before you leave.

Continue to: Documentation and reimbursement.

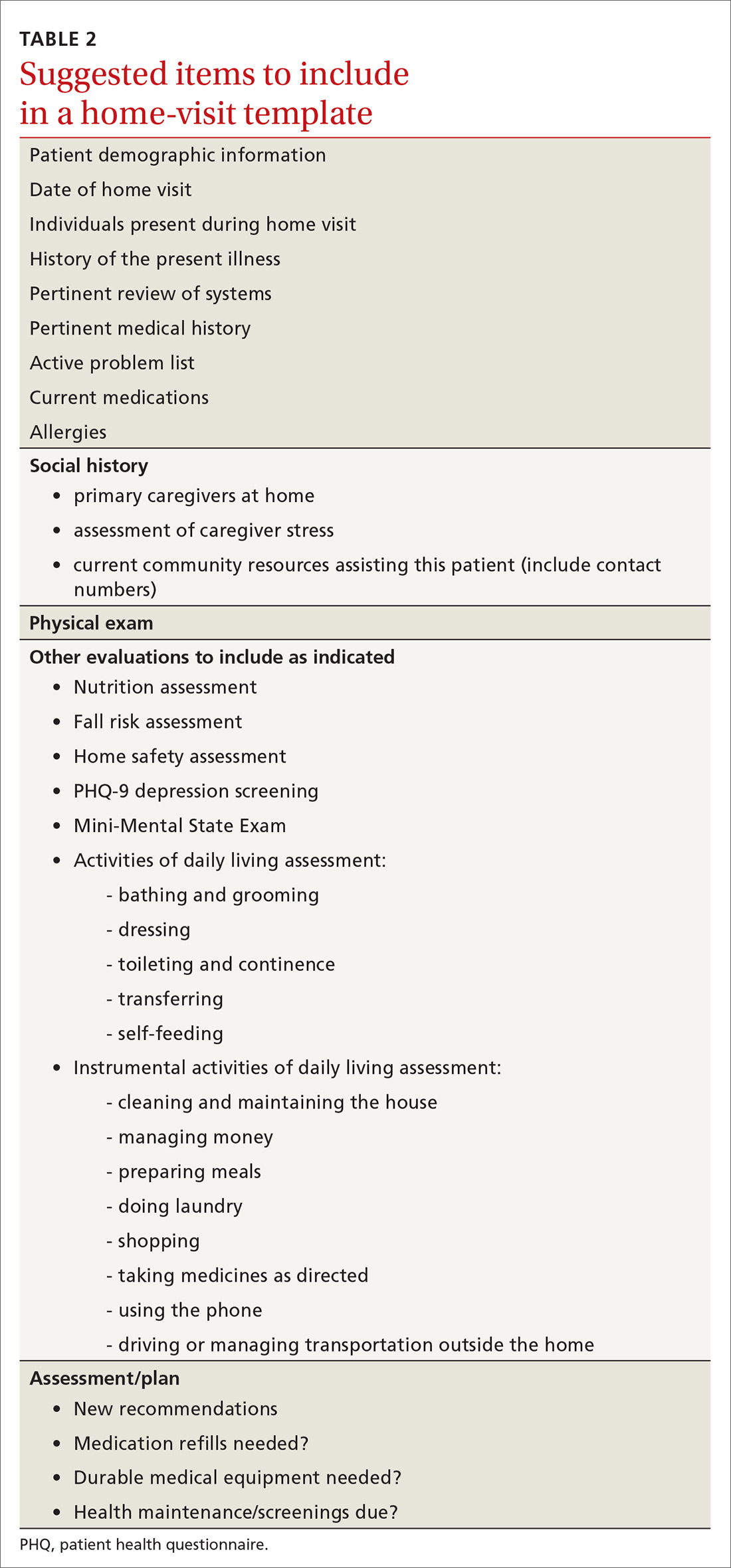

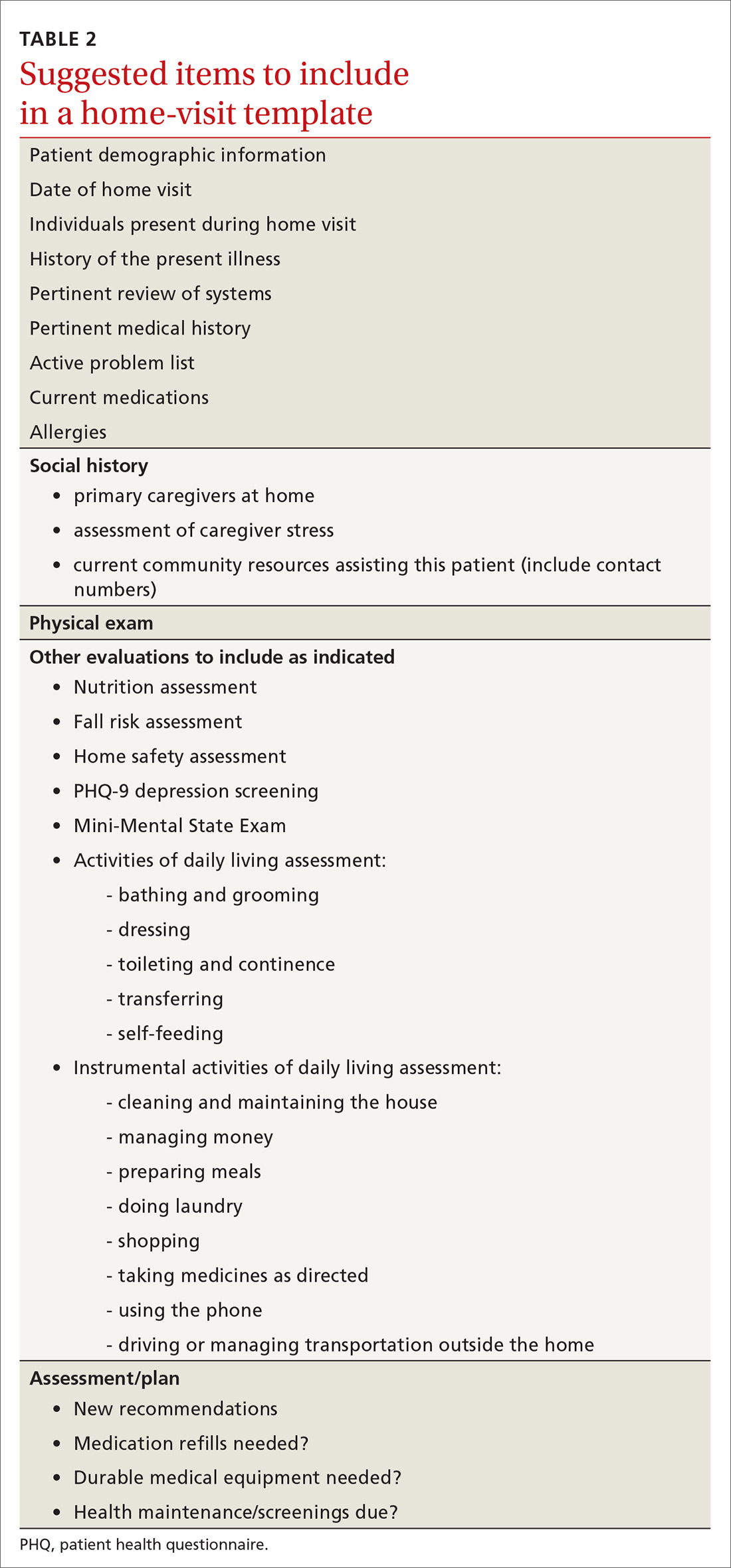

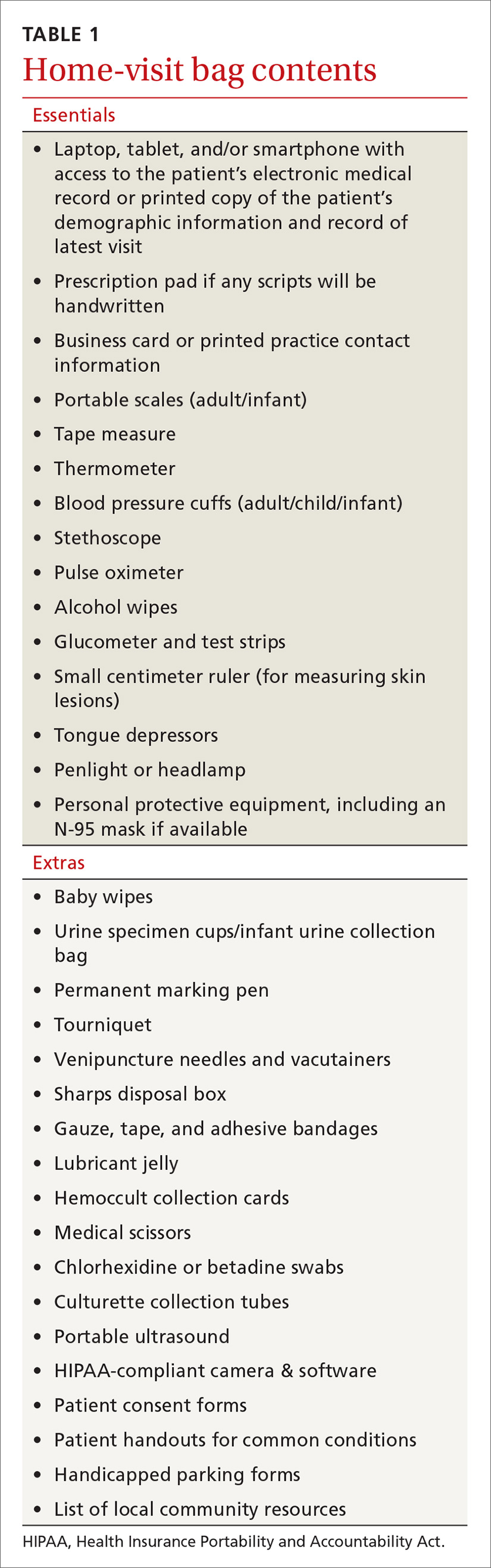

Documentation and reimbursement. While individual electronic medical records may require use of particular forms of documentation, using a home visit template when possible can be extremely helpful (TABLE 2). A template not only assures thoroughness and consistency (pharmacy, home health contacts, billing information) but also serves as a prompt to survey the patient and the caregivers about nonmedical, but essential, social and well-being services. The document should be as simple and user-friendly as possible.

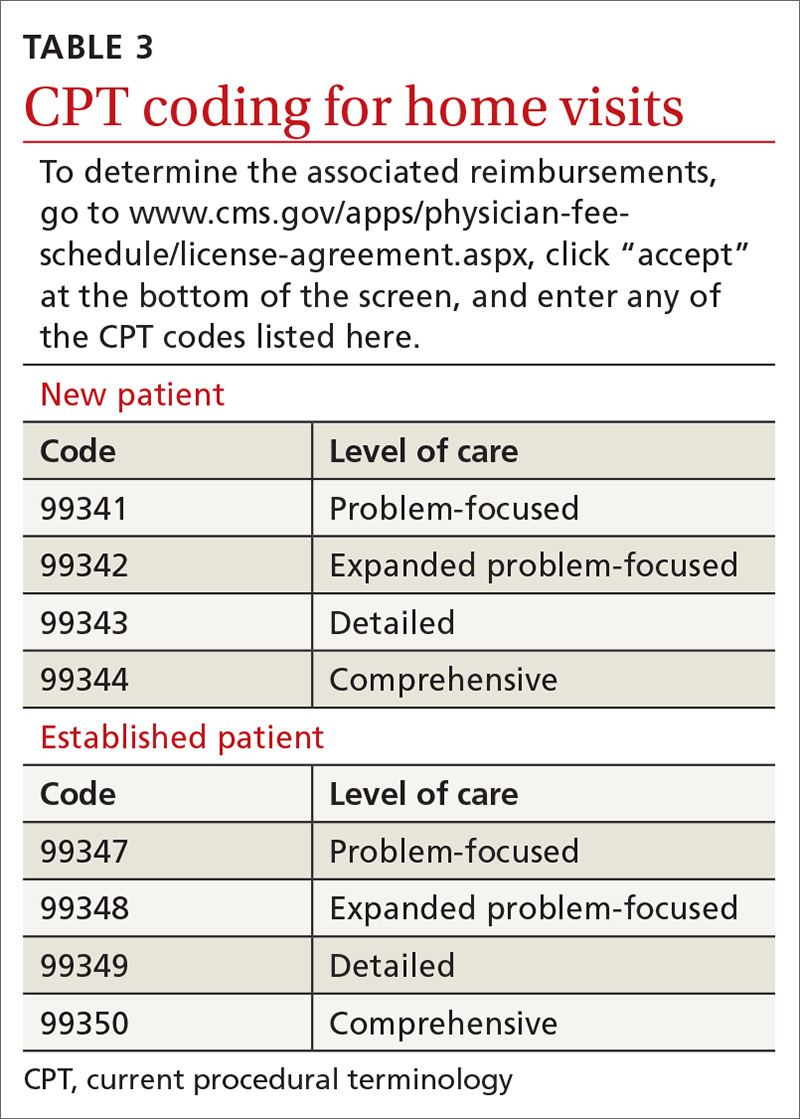

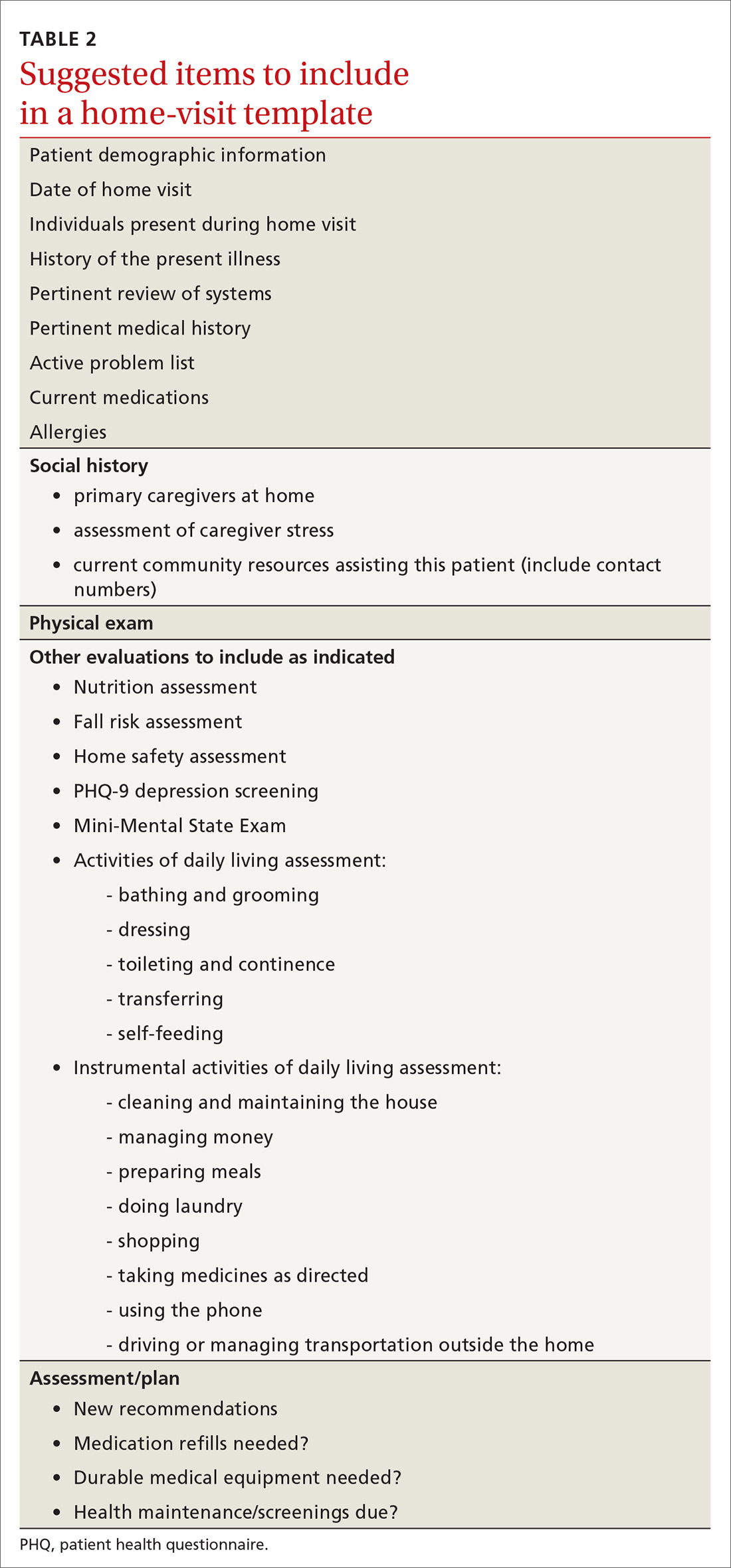

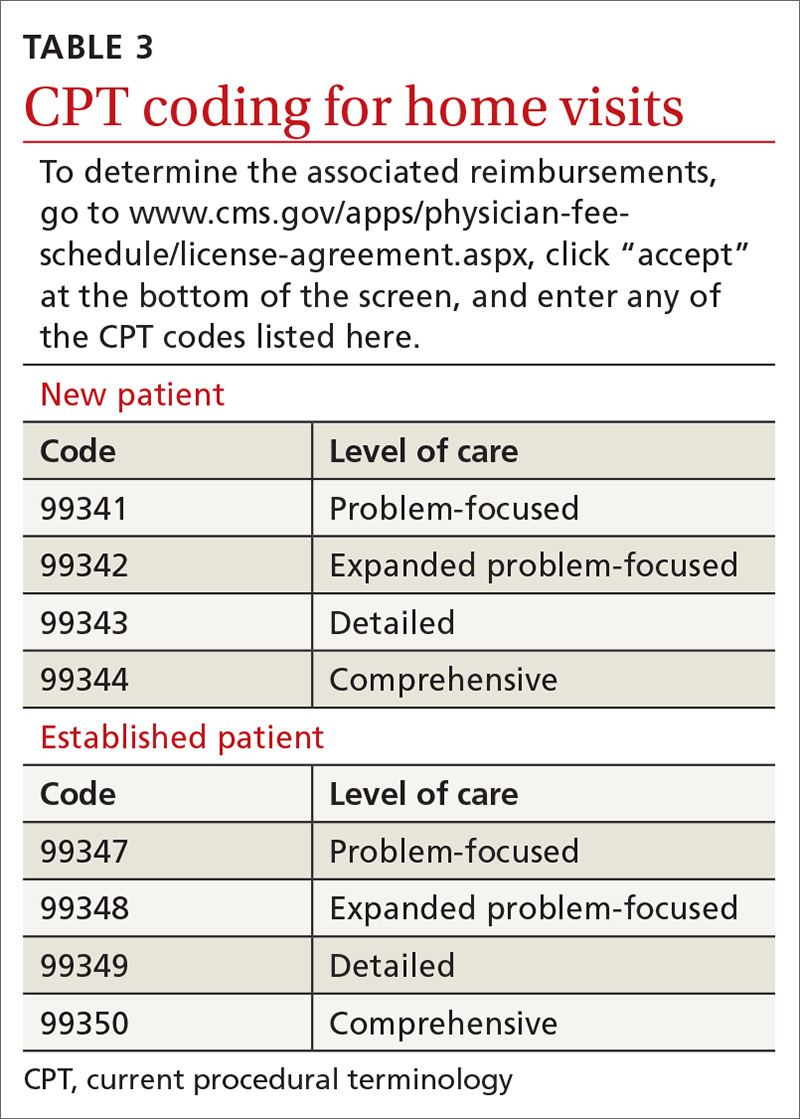

Not all assessments will be able to be done at each visit but seeing them listed in the template can be helpful. Billing follows the same principles as for office visits and has similar requirements for documentation. Codes for the most common types of home visits are listed in TABLE 3.

Where can I get help?

Graduates of family medicine residency programs are required to receive training in home visits by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Current ACGME program requirements stipulate that “residents must demonstrate competence to independently diagnose, manage, and integrate the care of patients of all ages in various outpatient settings, including the FMP [family medicine practice] site and home environment,” and “residents must be primarily responsible for a panel of continuity patients, integrating each patient’s care across all settings, including the home ...” [emphasis added].34

For those already in practice, one of the hardest parts of doing home visits is feeling alone, especially if few other providers in your community engage in home care. As you run into questions and challenges with incorporating home care of patients into your practice, one excellent resource is the American Academy of Home Care Medicine (www.aahcm.org/). Founded in 1988 and headquartered in Chicago, it not only provides numerous helpful resources, but serves as a networking tool for physicians involved in home care.

This unprecedented pandemichas allowed home visits to shine

As depicted in our opening patient case, patients who have high-risk conditions and those who are older than 65 years of age may be cared for more appropriately in a home visit rather than having them come to the office. Home visits may also be a way for providers to “lay eyes” on patients who do not have technology available to participate in virtual visits.

Before performing a home visit, inquire as to whether the patient has symptoms of COVID-19. Adequate PPE should be donned at all times and social distancing should be practiced when appropriate. With adequate PPE, home visits may also allow providers to care for low-risk patients known to have COVID-19 and thereby minimize risks to staff and other patients in the office. JFP

CORRESPONDENCE

Curt Elliott, MD, Prisma Health USC Family Medicine Center, 3209 Colonial Drive, Columbia, SC 29203; [email protected].

1. Unwin BK, Tatum PE. House calls. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:925-938.

3. Sairenji T, Jetty A, Peterson LE. Shifting patterns of physician home visits. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7:71-75.

4. Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky K, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175;1180-1186.

5. CMS. Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition ("CPT®"). www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/license-agreement.aspx. Accessed November 30, 2020.

6. Elkan R, Kendrick D, Dewey M, et al. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:719-725.

7. Stuck AE, Egger M, Hammer A, et al. Home visits to prevent nursing home admission and functional decline in elderly people: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2002;287:1022-1028.

8. Stall N, Nowaczynski M, Sinha SK. Systematic review of outcomes from home-based primary care programs for homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2243-2251.

9. Prosman GJ, Lo Fo Wong SH, van der Wouden JC, et al. Effectiveness of home visiting in reducing partner violence for families experiencing abuse: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2015;32:247-256.

10. Han L, Ma Y, Wei S, et al. Are home visits an effective method for diabetes management? A quantitative systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;8:701-708.

11. McWhinney IR. Fourth annual Nicholas J. Pisacano Lecture. The doctor, the patient, and the home: returning to our roots. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997;10:430-435.

12. Kao H, Conant R, Soriano T, et al. The past, present, and future of house calls. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:19-34.

13. American Public Health Association. Community health workers. www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers. Accessed November 30, 2020.

14. Campbell JD, Brooks M, Hosokawa P, et al. Community health worker home visits for Medicaid-enrolled children with asthma: effects on asthma outcomes and costs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2366-2372.

15. Anugu M, Braksmajer A, Huang J, et al. Enriched medical home intervention using community health worker home visitation and ED use. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20161849.

16. Reckrey JM, Gettenberg G, Ross H, et al. The critical role of social workers in home-based primary care. Soc Work in Health Care. 2014;53:330-343.

17. Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H. The effect of homebound status on older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2358-2362.

18. Mt. Sinai Visiting Doctors Program. www.mountsinai.org/care/primary-care/upper-east-side/visiting-doctors/about. Accessed November 30, 2020.

19. Ornstein K, Hernandez CR, DeCherrie LV, et al. The Mount Sinai (New York) Visiting Doctors Program: meeting the needs of the urban homebound population. Care Manag J. 2011;12:159-163.

20. Ornstein K, Smith K, Boal J. Understanding and improving the burden and unmet needs of informal caregivers of homebound patients enrolled in a home-based primary care program. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28:482-503.

21. Novak M, Guest C. Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist. 1989;29:798-803.

22. Cruz J, Brooks D, Marques A. Home telemonitoring effectiveness in COPD: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:369-378.

23. Antoniades NC, Rochford PD, Pretto JJ, et al. Pilot study of remote telemonitoring in COPD. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18:634-640.

24. Koff PB, Jones RH, Cashman JM, et al. Proactive integrated care improves quality of life in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1031-1038.

25. Inglis SC, Clark RA, McAlister FA, et al. Which components of heart failure programmes are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes of structured telephone support or telemonitoring as the primary component of chronic heart failure management in 8323 patients: abridged Cochrane review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1028-1040.

26. Koehler F, Koehler K, Deckwart O, et al. Efficacy of telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure (TIM-HF2): a randomised, controlled, parallel-group, unmasked trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1047-1057.

27. Ticona L, Schulman KA. Extreme home makeover–the role of intensive home health care. New Eng J Med. 2016;375:1707-1709.

28. Caplan GA. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home.” Med J Aust. 2013;198:195-196.

29. Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:798-808.

30. Shepperd S, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD007491.

31. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:77-85.

32. Cornwell T and Schwartzberg JG, eds. Medical Management of the Home Care Patient: Guidelines for Physicians. 4th ed. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association and American Academy of Home Care Physicians; 2012:p18.

33. Cornwell T and Schwartzberg JG, eds. Medical Management of the Home Care Patient: Guidelines for Physicians. 4th ed. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association and American Academy of Home Care Physicians; 2012:p19.

34. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_FamilyMedicine_2020.pdf. (section IV.C.1.b). Accessed November 30, 2020.

CASE

Mr. A is a 30-year-old man with neurofibromatosis and myelopathy with associated quadriplegia, complicated by dysphasia and chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring a tracheostomy. He is cared for at home by his very competent mother but requires regular visits with his medical providers for assistance with his complex care needs. Due to logistical challenges, he had been receiving regular home visits even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

After estimating the risk of exposure to the patient, Mr. A’s family and his physician’s office staff scheduled a home visit. Before the appointment, the doctor conducted a virtual visit with the patient and family members to screen for COVID-19 infection, which proved negative. The doctor arranged a visit to coincide with Mr. A’s regular appointment with the home health nurse. He invited the patient’s social worker to attend, as well.

The providers donned masks, face shields, and gloves before entering the home. Mr. A’s temperature was checked and was normal. The team completed a physical exam, assessed the patient’s current needs, and refilled prescriptions. The doctor, nurse, and social worker met afterward in the family’s driveway to coordinate plans for the patient’s future care.

This encounter allowed a vulnerable patient with special needs to have access to care while reducing his risk of undesirable exposure. Also, his health care team’s provision of care in the home setting reduced Mr. A’s anxiety and that of his family members.

Home visits have long been an integral part of what it means to be a family physician. In 1930, roughly 40% of all patient-physician encounters in the United States occurred in patients’ homes. By 1980, this number had dropped to < 1%.1 Still, a 1994 survey of American doctors in 3 primary care specialties revealed that 63% of family physicians, more than the other 2 specialties, still made house calls.2 A 2016 analysis of Medicare claims data showed that between 2006 and 2011, only 5% of American doctors overall made house calls on Medicare recipients, but interestingly, the total number of home visits was increasing.3

This resurgence of interest in home health care is due in part to the increasing number of homebound patients in America, which exceeds the number of those in nursing homes.4 Further, a growing body of evidence indicates that home visits improve patient outcomes. And finally, many family physicians whose work lives have been centered around a busy office or hospital practice have found satisfaction in once again seeing patients in their own homes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has of course presented unique challenges—and opportunities, too—for home visits, which we discuss at the end of the article.

Why aren’t more of us making home visits?

For most of us, the decision not to make home visits is simply a matter of time and money. Although Medicare reimbursement for a home visit is typically about 150% that of a comparable office visit,5 it’s difficult, if not impossible, to make 2 home visits in the time you could see 3 patients in the office. So, economically it’s a net loss. Furthermore, we tend to feel less comfortable in our patients’ homes than in our offices. We have less control outside our own environment, and what happens away from our office is often less predictable—sometimes to the point that we may be concerned for our safety.

Continue to: So why make home visits at all?

So why make home visits at all?

First and foremost, home visits improve patient outcomes. This is most evident in our more vulnerable patients: newborns and the elderly, those who have been recently hospitalized, and those at risk because of their particular home situation. Multiple studies have shown that, for elders, home visits reduce functional decline, nursing home admissions, and mortality by around 25% to 33%.6-8 For those at risk of abuse, a recent systematic review showed that home visits reduce intimate partner violence and child abuse.9 Another systematic review demonstrated that patients with diabetes who received home visits vs usual care were more likely to show improvements in quality of life.10 These patients were also more likely to have lower HbA1c levels and lower systolic blood pressure readings.10 A few caveats apply to these studies:

- all of them targeted “vulnerable” patients

- most studies enlisted interdisciplinary teams and had regular team meetings

- most findings reached significance only after multiple home visits.

A further reason for choosing to become involved in home care is that it builds relationships, understanding, and empathy with our patients. “There is deep symbolism in the home visit.... It says, ‘I care enough about you to leave my power base … to come and see you on your own ground.’”11 And this benefit is 2-way; we also grow to understand and appreciate our patients better, especially if they are different from us culturally or socioeconomically.

Home visits allow the medical team to see challenges the patient has grown accustomed to, and perhaps ones that the patient has deemed too insignificant to mention. For the patient, home visits foster a strong sense of trust with the individual doctor and our health delivery network, and they decrease the need to seek emergency services. Finally, it has been demonstrated that provider satisfaction improves when home visits are incorporated into the work week.12

What is the role of community health workers in home-based care?

Community health workers (CHWs), defined as “frontline public health workers who are trusted members of and/or have an unusually close understanding of the community they serve,”13 can be an integral part of the home-based care team. Although CHWs have variable amounts of formal training, they have a unique perspective on local health beliefs and practices, which can assist the home-care team in providing culturally competent health care services and reduce health care costs.

In a study of children with asthma in Seattle, Washington, patients were randomized to a group that had 4 home visits by CHWs and a group that received usual care. The group that received home visits demonstrated more asthma symptom–free days, improved quality-of-life scores, and fewer urgent care visits.14 Furthermore, the intervention was estimated to save approximately $1300 per patient, resulting in a return on investment of 190%. Similarly, in a study comparing inappropriate emergency department (ED) visits between children who received CHW visits and those who did not, patients in the intervention group were significantly less likely to visit the ED for ambulatory complaints (18.2% vs 35.1%; P = .004).15

Continue to: What is the role of social workersin home-based care?

What is the role of social workersin home-based care?

Social workers can help meet the complex medical and biopsychosocial needs of the homebound population.16 A study by Cohen et al based in Israel concluded that homebound participants had a significantly higher risk for mortality, higher rates of depression, and difficulty completing instrumental activities of daily living when compared with their non-homebound counterparts.17

The Mount Sinai (New York) Visiting Doctors Program (MSVD) is a home-based care team that uses social workers to meet the needs of their complex patients.18 The social workers in the MSVD program provide direct counseling, make referrals to government and community resources, and monitor caregiver burden. Using a combination of measurement tools to assess caregiver burden, Ornstein et al demonstrated that the MSVD program led to a decrease in unmet needs and in caregiver burden.19,20 Caregiver burnout can be assessed using the Caregiver Burden Inventory, a validated 24-item questionnaire.21

What electronic tools are availableto monitor patients at home?

Although expensive in terms of both dollars and personnel time, telemonitoring allows home care providers to receive real-time, updated information regarding their patients.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). One systematic review showed that although telemonitoring of patients with COPD improved quality of life and decreased COPD exacerbations, it did not reduce the risk of hospitalization and, therefore, did not reduce health care costs.22 Telemonitoring in COPD can include transmission of data about spirometry parameters, weight, temperature, blood pressure, sputum color, and 6-minute walk distance.23,24

Congestive heart failure (CHF). A 2010 Cochrane review found that telemonitoring of patients with CHF reduced all-cause mortality (risk ratio [RR] = 0.66; P < .0001).25 The Telemedical Interventional Management in Heart Failure II (TIM-HF2) trial,conducted from 2013 to 2017, compared usual care for CHF patients with care incorporating daily transmission of body weight, blood pressure, heart rate, electrocardiogram tracings, pulse oximetry, and self-rated health status.26 This study showed that the average number of days lost per year due to hospital admission was less in the telemonitoring group than in the usual care group (17.8 days vs. 24.2 days; P = .046). All-cause mortality was also reduced in the telemonitoring group (hazard ratio = 0.70; P = .028).

Continue to: What role do “home hospitals” play?

What role do “home hospitals” play?

Home hospitals provide acute or subacute treatment in a patient’s home for a condition that would normally require hospitalization.27 In a meta-analysis of 61 studies evaluating the effectiveness of home hospitals, this option was more likely to reduce mortality (odds ratio [OR] = 0.81; P = .008) and to reduce readmission rates (OR = 0.75; P = .02).28 In a study of 455 older adults, Leff et al found that hospital-at-home was associated with a shorter length of stay (3.2 vs. 4.9 days; P = .004) and that the mean cost was lower for hospital-at-home vs traditional hospital care.29

However, a 2016 Cochrane review of 16 randomized controlled trials comparing hospital-at-home with traditional hospital care showed that while care in a hospital-at-home may decrease formal costs, if costs for caregivers are taken into account, any difference in cost may disappear.30

Although the evidence for cost saving is variable, hospital-at-home admission has been shown to reduce the likelihood of living in a residential care facility at 6 months (RR = 0.35; P < .0001).30 Further, the same Cochrane review showed that admission avoidance may increase patient satisfaction with the care provided.30

Finally, a recent randomized trial in a Boston-area hospital system showed that patients cared for in hospital-at-home were significantly less likely to be readmitted within 30 days and that adjusted cost was about two-thirds the cost of traditional hospital care.31

What is the physician’s rolein home health care?

While home health care is a team effort, the physician has several crucial roles. First, he or she must make the determination that home care is appropriate and feasible for a particular patient. Appropriate, meaning there is evidence that this patient is likely to benefit from home care. Feasible, meaning there are resources available in the community and family to safely care for the patient at home. “Often a house call will serve as the first step in developing a home-based-management plan.”32

Continue to: Second, the physician serves...

Second, the physician serves an important role in directing and coordinating the team of professionals involved. This primarily means helping the team to communicate with one another. Before home visits begin, the physician’s office should reach out not only to the patient and family, but also to any other health care personnel involved in the patient’s home care. Otherwise, many of the health care providers involved will never have face-to-face interaction with the physician. Creation of the coordinated health team minimizes duplication and miscommunication; it also builds a valuable bond.

How does one go about making a home visit?

Scheduling. What often works best in a busy practice is to schedule home visits for the end of the workday or to devote an entire afternoon to making home visits to several patients in one locale. Also important is scheduling times, if possible, when important family members or other caregivers are at home or when other members of the home care team can accompany you.

What to bring along. Carry a “home visit bag” that includes equipment you’re likely to need and that is not available away from your office. A minimally equipped visit bag would include different-sized blood pressure cuffs, a glucometer, a pulse oximeter, thermometers, and patient education materials. Other suggested contents are listed in TABLE 1.

Dos and don’ts. Take a few minutes when you first arrive to simply visit with the patient. Sit down and introduce yourself and any members of the home care team that the patient has not met. Take an interim history. While you’re doing this, be observant: Is the home neat or cluttered? Is the indoor temperature comfortable? Are there fall hazards? Is there a smell of cigarette smoke? Are there any indoor combustion sources (eg, wood stove or kerosene heater)? Ask questions such as: Who lives here with you? Can you show me where you keep your medicines? (If the patient keeps insulin or any other medicines in the refrigerator, ask to see it. Note any apparent food scarcity.)

During your exam, pay particular attention to whether vital signs are appreciably different than those measured in the office or hospital. Pay special attention to the patient’s functional abilities. “A subtle, but critical distinction between medical management in the home and medical management in the hospital, clinic, or office is the emphasis on the patient’s functional abilities, family assistance, and environmental factors.”33

Observe the patient’s use of any home technology, if possible; this can be as simple as home oxygenation or as complex as home hemodialysis. Assess for any apparent caregiver stress. Finally, don’t neglect to offer appropriate emotional and spiritual support to the patient and family and to schedule the next follow-up visit before you leave.

Continue to: Documentation and reimbursement.

Documentation and reimbursement. While individual electronic medical records may require use of particular forms of documentation, using a home visit template when possible can be extremely helpful (TABLE 2). A template not only assures thoroughness and consistency (pharmacy, home health contacts, billing information) but also serves as a prompt to survey the patient and the caregivers about nonmedical, but essential, social and well-being services. The document should be as simple and user-friendly as possible.

Not all assessments will be able to be done at each visit but seeing them listed in the template can be helpful. Billing follows the same principles as for office visits and has similar requirements for documentation. Codes for the most common types of home visits are listed in TABLE 3.

Where can I get help?

Graduates of family medicine residency programs are required to receive training in home visits by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Current ACGME program requirements stipulate that “residents must demonstrate competence to independently diagnose, manage, and integrate the care of patients of all ages in various outpatient settings, including the FMP [family medicine practice] site and home environment,” and “residents must be primarily responsible for a panel of continuity patients, integrating each patient’s care across all settings, including the home ...” [emphasis added].34

For those already in practice, one of the hardest parts of doing home visits is feeling alone, especially if few other providers in your community engage in home care. As you run into questions and challenges with incorporating home care of patients into your practice, one excellent resource is the American Academy of Home Care Medicine (www.aahcm.org/). Founded in 1988 and headquartered in Chicago, it not only provides numerous helpful resources, but serves as a networking tool for physicians involved in home care.

This unprecedented pandemichas allowed home visits to shine

As depicted in our opening patient case, patients who have high-risk conditions and those who are older than 65 years of age may be cared for more appropriately in a home visit rather than having them come to the office. Home visits may also be a way for providers to “lay eyes” on patients who do not have technology available to participate in virtual visits.

Before performing a home visit, inquire as to whether the patient has symptoms of COVID-19. Adequate PPE should be donned at all times and social distancing should be practiced when appropriate. With adequate PPE, home visits may also allow providers to care for low-risk patients known to have COVID-19 and thereby minimize risks to staff and other patients in the office. JFP

CORRESPONDENCE

Curt Elliott, MD, Prisma Health USC Family Medicine Center, 3209 Colonial Drive, Columbia, SC 29203; [email protected].

CASE

Mr. A is a 30-year-old man with neurofibromatosis and myelopathy with associated quadriplegia, complicated by dysphasia and chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring a tracheostomy. He is cared for at home by his very competent mother but requires regular visits with his medical providers for assistance with his complex care needs. Due to logistical challenges, he had been receiving regular home visits even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

After estimating the risk of exposure to the patient, Mr. A’s family and his physician’s office staff scheduled a home visit. Before the appointment, the doctor conducted a virtual visit with the patient and family members to screen for COVID-19 infection, which proved negative. The doctor arranged a visit to coincide with Mr. A’s regular appointment with the home health nurse. He invited the patient’s social worker to attend, as well.

The providers donned masks, face shields, and gloves before entering the home. Mr. A’s temperature was checked and was normal. The team completed a physical exam, assessed the patient’s current needs, and refilled prescriptions. The doctor, nurse, and social worker met afterward in the family’s driveway to coordinate plans for the patient’s future care.

This encounter allowed a vulnerable patient with special needs to have access to care while reducing his risk of undesirable exposure. Also, his health care team’s provision of care in the home setting reduced Mr. A’s anxiety and that of his family members.

Home visits have long been an integral part of what it means to be a family physician. In 1930, roughly 40% of all patient-physician encounters in the United States occurred in patients’ homes. By 1980, this number had dropped to < 1%.1 Still, a 1994 survey of American doctors in 3 primary care specialties revealed that 63% of family physicians, more than the other 2 specialties, still made house calls.2 A 2016 analysis of Medicare claims data showed that between 2006 and 2011, only 5% of American doctors overall made house calls on Medicare recipients, but interestingly, the total number of home visits was increasing.3

This resurgence of interest in home health care is due in part to the increasing number of homebound patients in America, which exceeds the number of those in nursing homes.4 Further, a growing body of evidence indicates that home visits improve patient outcomes. And finally, many family physicians whose work lives have been centered around a busy office or hospital practice have found satisfaction in once again seeing patients in their own homes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has of course presented unique challenges—and opportunities, too—for home visits, which we discuss at the end of the article.

Why aren’t more of us making home visits?

For most of us, the decision not to make home visits is simply a matter of time and money. Although Medicare reimbursement for a home visit is typically about 150% that of a comparable office visit,5 it’s difficult, if not impossible, to make 2 home visits in the time you could see 3 patients in the office. So, economically it’s a net loss. Furthermore, we tend to feel less comfortable in our patients’ homes than in our offices. We have less control outside our own environment, and what happens away from our office is often less predictable—sometimes to the point that we may be concerned for our safety.

Continue to: So why make home visits at all?

So why make home visits at all?

First and foremost, home visits improve patient outcomes. This is most evident in our more vulnerable patients: newborns and the elderly, those who have been recently hospitalized, and those at risk because of their particular home situation. Multiple studies have shown that, for elders, home visits reduce functional decline, nursing home admissions, and mortality by around 25% to 33%.6-8 For those at risk of abuse, a recent systematic review showed that home visits reduce intimate partner violence and child abuse.9 Another systematic review demonstrated that patients with diabetes who received home visits vs usual care were more likely to show improvements in quality of life.10 These patients were also more likely to have lower HbA1c levels and lower systolic blood pressure readings.10 A few caveats apply to these studies:

- all of them targeted “vulnerable” patients

- most studies enlisted interdisciplinary teams and had regular team meetings

- most findings reached significance only after multiple home visits.

A further reason for choosing to become involved in home care is that it builds relationships, understanding, and empathy with our patients. “There is deep symbolism in the home visit.... It says, ‘I care enough about you to leave my power base … to come and see you on your own ground.’”11 And this benefit is 2-way; we also grow to understand and appreciate our patients better, especially if they are different from us culturally or socioeconomically.

Home visits allow the medical team to see challenges the patient has grown accustomed to, and perhaps ones that the patient has deemed too insignificant to mention. For the patient, home visits foster a strong sense of trust with the individual doctor and our health delivery network, and they decrease the need to seek emergency services. Finally, it has been demonstrated that provider satisfaction improves when home visits are incorporated into the work week.12

What is the role of community health workers in home-based care?

Community health workers (CHWs), defined as “frontline public health workers who are trusted members of and/or have an unusually close understanding of the community they serve,”13 can be an integral part of the home-based care team. Although CHWs have variable amounts of formal training, they have a unique perspective on local health beliefs and practices, which can assist the home-care team in providing culturally competent health care services and reduce health care costs.

In a study of children with asthma in Seattle, Washington, patients were randomized to a group that had 4 home visits by CHWs and a group that received usual care. The group that received home visits demonstrated more asthma symptom–free days, improved quality-of-life scores, and fewer urgent care visits.14 Furthermore, the intervention was estimated to save approximately $1300 per patient, resulting in a return on investment of 190%. Similarly, in a study comparing inappropriate emergency department (ED) visits between children who received CHW visits and those who did not, patients in the intervention group were significantly less likely to visit the ED for ambulatory complaints (18.2% vs 35.1%; P = .004).15

Continue to: What is the role of social workersin home-based care?

What is the role of social workersin home-based care?

Social workers can help meet the complex medical and biopsychosocial needs of the homebound population.16 A study by Cohen et al based in Israel concluded that homebound participants had a significantly higher risk for mortality, higher rates of depression, and difficulty completing instrumental activities of daily living when compared with their non-homebound counterparts.17

The Mount Sinai (New York) Visiting Doctors Program (MSVD) is a home-based care team that uses social workers to meet the needs of their complex patients.18 The social workers in the MSVD program provide direct counseling, make referrals to government and community resources, and monitor caregiver burden. Using a combination of measurement tools to assess caregiver burden, Ornstein et al demonstrated that the MSVD program led to a decrease in unmet needs and in caregiver burden.19,20 Caregiver burnout can be assessed using the Caregiver Burden Inventory, a validated 24-item questionnaire.21

What electronic tools are availableto monitor patients at home?

Although expensive in terms of both dollars and personnel time, telemonitoring allows home care providers to receive real-time, updated information regarding their patients.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). One systematic review showed that although telemonitoring of patients with COPD improved quality of life and decreased COPD exacerbations, it did not reduce the risk of hospitalization and, therefore, did not reduce health care costs.22 Telemonitoring in COPD can include transmission of data about spirometry parameters, weight, temperature, blood pressure, sputum color, and 6-minute walk distance.23,24

Congestive heart failure (CHF). A 2010 Cochrane review found that telemonitoring of patients with CHF reduced all-cause mortality (risk ratio [RR] = 0.66; P < .0001).25 The Telemedical Interventional Management in Heart Failure II (TIM-HF2) trial,conducted from 2013 to 2017, compared usual care for CHF patients with care incorporating daily transmission of body weight, blood pressure, heart rate, electrocardiogram tracings, pulse oximetry, and self-rated health status.26 This study showed that the average number of days lost per year due to hospital admission was less in the telemonitoring group than in the usual care group (17.8 days vs. 24.2 days; P = .046). All-cause mortality was also reduced in the telemonitoring group (hazard ratio = 0.70; P = .028).

Continue to: What role do “home hospitals” play?

What role do “home hospitals” play?

Home hospitals provide acute or subacute treatment in a patient’s home for a condition that would normally require hospitalization.27 In a meta-analysis of 61 studies evaluating the effectiveness of home hospitals, this option was more likely to reduce mortality (odds ratio [OR] = 0.81; P = .008) and to reduce readmission rates (OR = 0.75; P = .02).28 In a study of 455 older adults, Leff et al found that hospital-at-home was associated with a shorter length of stay (3.2 vs. 4.9 days; P = .004) and that the mean cost was lower for hospital-at-home vs traditional hospital care.29

However, a 2016 Cochrane review of 16 randomized controlled trials comparing hospital-at-home with traditional hospital care showed that while care in a hospital-at-home may decrease formal costs, if costs for caregivers are taken into account, any difference in cost may disappear.30

Although the evidence for cost saving is variable, hospital-at-home admission has been shown to reduce the likelihood of living in a residential care facility at 6 months (RR = 0.35; P < .0001).30 Further, the same Cochrane review showed that admission avoidance may increase patient satisfaction with the care provided.30

Finally, a recent randomized trial in a Boston-area hospital system showed that patients cared for in hospital-at-home were significantly less likely to be readmitted within 30 days and that adjusted cost was about two-thirds the cost of traditional hospital care.31

What is the physician’s rolein home health care?

While home health care is a team effort, the physician has several crucial roles. First, he or she must make the determination that home care is appropriate and feasible for a particular patient. Appropriate, meaning there is evidence that this patient is likely to benefit from home care. Feasible, meaning there are resources available in the community and family to safely care for the patient at home. “Often a house call will serve as the first step in developing a home-based-management plan.”32

Continue to: Second, the physician serves...

Second, the physician serves an important role in directing and coordinating the team of professionals involved. This primarily means helping the team to communicate with one another. Before home visits begin, the physician’s office should reach out not only to the patient and family, but also to any other health care personnel involved in the patient’s home care. Otherwise, many of the health care providers involved will never have face-to-face interaction with the physician. Creation of the coordinated health team minimizes duplication and miscommunication; it also builds a valuable bond.

How does one go about making a home visit?

Scheduling. What often works best in a busy practice is to schedule home visits for the end of the workday or to devote an entire afternoon to making home visits to several patients in one locale. Also important is scheduling times, if possible, when important family members or other caregivers are at home or when other members of the home care team can accompany you.

What to bring along. Carry a “home visit bag” that includes equipment you’re likely to need and that is not available away from your office. A minimally equipped visit bag would include different-sized blood pressure cuffs, a glucometer, a pulse oximeter, thermometers, and patient education materials. Other suggested contents are listed in TABLE 1.

Dos and don’ts. Take a few minutes when you first arrive to simply visit with the patient. Sit down and introduce yourself and any members of the home care team that the patient has not met. Take an interim history. While you’re doing this, be observant: Is the home neat or cluttered? Is the indoor temperature comfortable? Are there fall hazards? Is there a smell of cigarette smoke? Are there any indoor combustion sources (eg, wood stove or kerosene heater)? Ask questions such as: Who lives here with you? Can you show me where you keep your medicines? (If the patient keeps insulin or any other medicines in the refrigerator, ask to see it. Note any apparent food scarcity.)

During your exam, pay particular attention to whether vital signs are appreciably different than those measured in the office or hospital. Pay special attention to the patient’s functional abilities. “A subtle, but critical distinction between medical management in the home and medical management in the hospital, clinic, or office is the emphasis on the patient’s functional abilities, family assistance, and environmental factors.”33

Observe the patient’s use of any home technology, if possible; this can be as simple as home oxygenation or as complex as home hemodialysis. Assess for any apparent caregiver stress. Finally, don’t neglect to offer appropriate emotional and spiritual support to the patient and family and to schedule the next follow-up visit before you leave.

Continue to: Documentation and reimbursement.

Documentation and reimbursement. While individual electronic medical records may require use of particular forms of documentation, using a home visit template when possible can be extremely helpful (TABLE 2). A template not only assures thoroughness and consistency (pharmacy, home health contacts, billing information) but also serves as a prompt to survey the patient and the caregivers about nonmedical, but essential, social and well-being services. The document should be as simple and user-friendly as possible.

Not all assessments will be able to be done at each visit but seeing them listed in the template can be helpful. Billing follows the same principles as for office visits and has similar requirements for documentation. Codes for the most common types of home visits are listed in TABLE 3.

Where can I get help?

Graduates of family medicine residency programs are required to receive training in home visits by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Current ACGME program requirements stipulate that “residents must demonstrate competence to independently diagnose, manage, and integrate the care of patients of all ages in various outpatient settings, including the FMP [family medicine practice] site and home environment,” and “residents must be primarily responsible for a panel of continuity patients, integrating each patient’s care across all settings, including the home ...” [emphasis added].34

For those already in practice, one of the hardest parts of doing home visits is feeling alone, especially if few other providers in your community engage in home care. As you run into questions and challenges with incorporating home care of patients into your practice, one excellent resource is the American Academy of Home Care Medicine (www.aahcm.org/). Founded in 1988 and headquartered in Chicago, it not only provides numerous helpful resources, but serves as a networking tool for physicians involved in home care.

This unprecedented pandemichas allowed home visits to shine

As depicted in our opening patient case, patients who have high-risk conditions and those who are older than 65 years of age may be cared for more appropriately in a home visit rather than having them come to the office. Home visits may also be a way for providers to “lay eyes” on patients who do not have technology available to participate in virtual visits.

Before performing a home visit, inquire as to whether the patient has symptoms of COVID-19. Adequate PPE should be donned at all times and social distancing should be practiced when appropriate. With adequate PPE, home visits may also allow providers to care for low-risk patients known to have COVID-19 and thereby minimize risks to staff and other patients in the office. JFP

CORRESPONDENCE

Curt Elliott, MD, Prisma Health USC Family Medicine Center, 3209 Colonial Drive, Columbia, SC 29203; [email protected].

1. Unwin BK, Tatum PE. House calls. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:925-938.

3. Sairenji T, Jetty A, Peterson LE. Shifting patterns of physician home visits. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7:71-75.

4. Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky K, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175;1180-1186.

5. CMS. Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition ("CPT®"). www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/license-agreement.aspx. Accessed November 30, 2020.

6. Elkan R, Kendrick D, Dewey M, et al. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:719-725.

7. Stuck AE, Egger M, Hammer A, et al. Home visits to prevent nursing home admission and functional decline in elderly people: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2002;287:1022-1028.

8. Stall N, Nowaczynski M, Sinha SK. Systematic review of outcomes from home-based primary care programs for homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2243-2251.

9. Prosman GJ, Lo Fo Wong SH, van der Wouden JC, et al. Effectiveness of home visiting in reducing partner violence for families experiencing abuse: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2015;32:247-256.

10. Han L, Ma Y, Wei S, et al. Are home visits an effective method for diabetes management? A quantitative systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;8:701-708.

11. McWhinney IR. Fourth annual Nicholas J. Pisacano Lecture. The doctor, the patient, and the home: returning to our roots. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997;10:430-435.

12. Kao H, Conant R, Soriano T, et al. The past, present, and future of house calls. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:19-34.

13. American Public Health Association. Community health workers. www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers. Accessed November 30, 2020.

14. Campbell JD, Brooks M, Hosokawa P, et al. Community health worker home visits for Medicaid-enrolled children with asthma: effects on asthma outcomes and costs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2366-2372.

15. Anugu M, Braksmajer A, Huang J, et al. Enriched medical home intervention using community health worker home visitation and ED use. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20161849.

16. Reckrey JM, Gettenberg G, Ross H, et al. The critical role of social workers in home-based primary care. Soc Work in Health Care. 2014;53:330-343.

17. Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H. The effect of homebound status on older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2358-2362.

18. Mt. Sinai Visiting Doctors Program. www.mountsinai.org/care/primary-care/upper-east-side/visiting-doctors/about. Accessed November 30, 2020.

19. Ornstein K, Hernandez CR, DeCherrie LV, et al. The Mount Sinai (New York) Visiting Doctors Program: meeting the needs of the urban homebound population. Care Manag J. 2011;12:159-163.

20. Ornstein K, Smith K, Boal J. Understanding and improving the burden and unmet needs of informal caregivers of homebound patients enrolled in a home-based primary care program. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28:482-503.

21. Novak M, Guest C. Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist. 1989;29:798-803.

22. Cruz J, Brooks D, Marques A. Home telemonitoring effectiveness in COPD: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:369-378.

23. Antoniades NC, Rochford PD, Pretto JJ, et al. Pilot study of remote telemonitoring in COPD. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18:634-640.

24. Koff PB, Jones RH, Cashman JM, et al. Proactive integrated care improves quality of life in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1031-1038.

25. Inglis SC, Clark RA, McAlister FA, et al. Which components of heart failure programmes are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes of structured telephone support or telemonitoring as the primary component of chronic heart failure management in 8323 patients: abridged Cochrane review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1028-1040.

26. Koehler F, Koehler K, Deckwart O, et al. Efficacy of telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure (TIM-HF2): a randomised, controlled, parallel-group, unmasked trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1047-1057.

27. Ticona L, Schulman KA. Extreme home makeover–the role of intensive home health care. New Eng J Med. 2016;375:1707-1709.

28. Caplan GA. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home.” Med J Aust. 2013;198:195-196.

29. Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:798-808.

30. Shepperd S, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD007491.

31. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:77-85.

32. Cornwell T and Schwartzberg JG, eds. Medical Management of the Home Care Patient: Guidelines for Physicians. 4th ed. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association and American Academy of Home Care Physicians; 2012:p18.

33. Cornwell T and Schwartzberg JG, eds. Medical Management of the Home Care Patient: Guidelines for Physicians. 4th ed. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association and American Academy of Home Care Physicians; 2012:p19.

34. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_FamilyMedicine_2020.pdf. (section IV.C.1.b). Accessed November 30, 2020.

1. Unwin BK, Tatum PE. House calls. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:925-938.

3. Sairenji T, Jetty A, Peterson LE. Shifting patterns of physician home visits. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7:71-75.

4. Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky K, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175;1180-1186.

5. CMS. Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition ("CPT®"). www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/license-agreement.aspx. Accessed November 30, 2020.

6. Elkan R, Kendrick D, Dewey M, et al. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:719-725.

7. Stuck AE, Egger M, Hammer A, et al. Home visits to prevent nursing home admission and functional decline in elderly people: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2002;287:1022-1028.

8. Stall N, Nowaczynski M, Sinha SK. Systematic review of outcomes from home-based primary care programs for homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2243-2251.

9. Prosman GJ, Lo Fo Wong SH, van der Wouden JC, et al. Effectiveness of home visiting in reducing partner violence for families experiencing abuse: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2015;32:247-256.

10. Han L, Ma Y, Wei S, et al. Are home visits an effective method for diabetes management? A quantitative systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;8:701-708.

11. McWhinney IR. Fourth annual Nicholas J. Pisacano Lecture. The doctor, the patient, and the home: returning to our roots. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997;10:430-435.

12. Kao H, Conant R, Soriano T, et al. The past, present, and future of house calls. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:19-34.

13. American Public Health Association. Community health workers. www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers. Accessed November 30, 2020.

14. Campbell JD, Brooks M, Hosokawa P, et al. Community health worker home visits for Medicaid-enrolled children with asthma: effects on asthma outcomes and costs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2366-2372.

15. Anugu M, Braksmajer A, Huang J, et al. Enriched medical home intervention using community health worker home visitation and ED use. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20161849.

16. Reckrey JM, Gettenberg G, Ross H, et al. The critical role of social workers in home-based primary care. Soc Work in Health Care. 2014;53:330-343.

17. Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H. The effect of homebound status on older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2358-2362.

18. Mt. Sinai Visiting Doctors Program. www.mountsinai.org/care/primary-care/upper-east-side/visiting-doctors/about. Accessed November 30, 2020.

19. Ornstein K, Hernandez CR, DeCherrie LV, et al. The Mount Sinai (New York) Visiting Doctors Program: meeting the needs of the urban homebound population. Care Manag J. 2011;12:159-163.

20. Ornstein K, Smith K, Boal J. Understanding and improving the burden and unmet needs of informal caregivers of homebound patients enrolled in a home-based primary care program. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28:482-503.

21. Novak M, Guest C. Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist. 1989;29:798-803.

22. Cruz J, Brooks D, Marques A. Home telemonitoring effectiveness in COPD: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:369-378.

23. Antoniades NC, Rochford PD, Pretto JJ, et al. Pilot study of remote telemonitoring in COPD. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18:634-640.

24. Koff PB, Jones RH, Cashman JM, et al. Proactive integrated care improves quality of life in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1031-1038.

25. Inglis SC, Clark RA, McAlister FA, et al. Which components of heart failure programmes are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes of structured telephone support or telemonitoring as the primary component of chronic heart failure management in 8323 patients: abridged Cochrane review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1028-1040.

26. Koehler F, Koehler K, Deckwart O, et al. Efficacy of telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure (TIM-HF2): a randomised, controlled, parallel-group, unmasked trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1047-1057.

27. Ticona L, Schulman KA. Extreme home makeover–the role of intensive home health care. New Eng J Med. 2016;375:1707-1709.

28. Caplan GA. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home.” Med J Aust. 2013;198:195-196.

29. Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:798-808.

30. Shepperd S, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD007491.

31. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:77-85.

32. Cornwell T and Schwartzberg JG, eds. Medical Management of the Home Care Patient: Guidelines for Physicians. 4th ed. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association and American Academy of Home Care Physicians; 2012:p18.

33. Cornwell T and Schwartzberg JG, eds. Medical Management of the Home Care Patient: Guidelines for Physicians. 4th ed. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association and American Academy of Home Care Physicians; 2012:p19.

34. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_FamilyMedicine_2020.pdf. (section IV.C.1.b). Accessed November 30, 2020.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

❯ Consider incorporating home visits into the primary care of select vulnerable patients because doing so improves clinical outcomes, including mortality rates in neonates and elders. A

❯ Employ team-based home care and include community health workers, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, chaplains, and others. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

COVID-19 vaccines: Preparing for patient questions

With U.S. approval of one coronavirus vaccine likely imminent and approval of a second one expected soon after, physicians will likely be deluged with questions. Public attitudes about the vaccines vary by demographics, with a recent poll showing that men and older adults are more likely to choose vaccination, and women and people of color evincing more wariness.

Although the reasons for reluctance may vary, questions from patient will likely be similar. Some are related to the “warp speed” language about the vaccines. Other concerns arise from the fact that the platform – mRNA – has not been used in human vaccines before. And as with any vaccine, there are rumors and false claims making the rounds on social media.

In anticipation of the most common questions physicians may encounter, two experts, Krutika Kuppalli, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and Angela Rasmussen, PhD, virologist and nonresident affiliate at Georgetown University’s Center for Global Health Science and Security, Washington, talked in an interview about what clinicians can expect and what evidence-based – as well as compassionate – answers might look like.

Q: Will this vaccine give me COVID-19?

“There is not an intact virus in there,” Dr. Rasmussen said. The mRNA-based vaccines cannot cause COVID-19 because they don’t use any part of the coronavirus itself. Instead, the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines contain manufactured mRNA molecules that carry the instructions for building the virus’ spike protein. After vaccine administration, the recipient’s own cells take up this mRNA, use it to build this bit of protein, and display it on their surfaces. The foreign protein flag triggers the immune system response.

The mRNA does not enter the cell nucleus or interact with the recipient’s DNA. And because it’s so fragile, it degrades quite quickly. To keep that from happening before cell entry, the mRNAs are cushioned in protective fats.

Q: Was this vaccine made too quickly?

“People have been working on this platform for 30 years, so it’s not that this is brand new,” Dr. Kuppalli said.

Researchers began working on mRNA vaccines in the 1990s. Technological developments in the last decade have meant that their use has become feasible, and they have been tested in animals against many viral diseases. The mRNA vaccines are attractive because they’re expected to be safe and easily manufactured from common materials. That’s what we’ve seen in the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says on its website. Design of the spike protein mRNA component began as soon as the viral genome became available in January.

Usually, rolling out a vaccine takes years, so less than a year under a program called Operation Warp Speed can seem like moving too fast, Dr. Rasmussen acknowledged. “The name has given people the impression that by going at warp speed, we’re cutting all the corners. [But] the reality is that Operation Warp Speed is mostly for manufacturing and distribution.”

What underlies the speed is a restructuring of the normal vaccine development process, Dr. Kuppalli said. The same phases of development – animal testing, a small initial human phase, a second for safety testing, a third large phase for efficacy – were all conducted as for any vaccine. But in this case, some phases were completed in parallel, rather than sequentially. This approach has proved so successful that there is already talk about making it the model for developing future vaccines.

Two other factors contributed to the speed, said Dr. Kuppalli and Dr. Rasmussen. First, gearing up production can slow a rollout, but with these vaccines, companies ramped up production even before anyone knew if the vaccines would work – the “warp speed” part. The second factor has been the large number of cases, making exposures more likely and thus accelerating the results of the efficacy trials. “There is so much COVID being transmitted everywhere in the United States that it did not take long to hit the threshold of events to read out phase 3,” Dr. Rasmussen said.

Q: This vaccine has never been used in humans. How do we know it’s safe?

The Pfizer phase 3 trial included more than 43,000 people, and Moderna’s had more than 30,000. The first humans received mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines in March. The most common adverse events emerge right after a vaccination, Dr. Kuppalli said.

As with any vaccine that gains approval, monitoring will continue.

UK health officials have reported that two health care workers vaccinated in the initial rollout of the Pfizer vaccine had what seems to have been a severe allergic response. Both recipients had a history of anaphylactic allergic responses and carried EpiPens, and both recovered. During the trial, allergic reaction rates were 0.63% in the vaccine group and 0.51% in the placebo group.

As a result of the two reactions, UK regulators are now recommending that patients with a history of severe allergies not receive the vaccine at the current time.

Q: What are the likely side effects?

So far, the most common side effects are pain at the injection site and an achy, flu-like feeling, Dr. Kuppalli said. More severe reactions have been reported, but were not common in the trials.

Dr. Rasmussen noted that the common side effects are a good sign, and signal that the recipient is generating “a robust immune response.”

“Everybody I’ve talked to who’s had the response has said they would go through it again,” Dr. Kruppalli said. “I definitely plan on lining up and being one of the first people to get the vaccine.”

Q: I already had COVID-19 or had a positive antibody test. Do I still need to get the vaccine?

Dr. Rasmussen said that there are “too many unknowns” to say if a history of COVID-19 would make a difference. “We don’t know how long neutralizing antibodies last” after infection, she said. “What we know is that the vaccine tends to produce antibody titers towards the higher end of the spectrum,” suggesting better immunity with vaccination than after natural infection.

Q: Can patients of color feel safe getting the vaccine?

“People of color might be understandably reluctant to take a vaccine that was developed in a way that appears to be faster [than past development],” said Dr. Rasmussen. She said physicians should acknowledge and understand the history that has led them to feel that way, “everything from Tuskegee to Henrietta Lacks to today.”

Empathy is key, and “providers should meet patients where they are and not condescend to them.”

Dr. Kuppalli agreed. “Clinicians really need to work on trying to strip away their biases.”

Thus far there are no safety signals that differ by race or ethnicity, according to the companies. The Pfizer phase 3 trial enrolled just over 9% Black participants, 0.5% Native American/Alaska Native, 0.2% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 2.3% multiracial participants, and 28% Hispanic/Latinx. For its part, Moderna says that approximately 37% of participants in its phase 3 trial come from communities of color.

Q: What about children and pregnant women?

Although the trials included participants from many different age groups and backgrounds, children and pregnant or lactating women were not among them. Pfizer gained approval in October to include participants as young as age 12 years, and a Moderna spokesperson said in an interview that the company planned pediatric inclusion at the end of 2020, pending approval.

“Unfortunately, we don’t have data on pregnant and lactating women,” Dr. Kuppalli said. She said she hopes that public health organizations such as the CDC will address that in the coming weeks. Dr. Rasmussen called the lack of data in pregnant women and children “a big oversight.”

Dr. Rasmussen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kuppalli is a consultant with GlaxoSmithKline.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

With U.S. approval of one coronavirus vaccine likely imminent and approval of a second one expected soon after, physicians will likely be deluged with questions. Public attitudes about the vaccines vary by demographics, with a recent poll showing that men and older adults are more likely to choose vaccination, and women and people of color evincing more wariness.

Although the reasons for reluctance may vary, questions from patient will likely be similar. Some are related to the “warp speed” language about the vaccines. Other concerns arise from the fact that the platform – mRNA – has not been used in human vaccines before. And as with any vaccine, there are rumors and false claims making the rounds on social media.

In anticipation of the most common questions physicians may encounter, two experts, Krutika Kuppalli, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and Angela Rasmussen, PhD, virologist and nonresident affiliate at Georgetown University’s Center for Global Health Science and Security, Washington, talked in an interview about what clinicians can expect and what evidence-based – as well as compassionate – answers might look like.

Q: Will this vaccine give me COVID-19?