User login

What hospitalists need to know about COVID-19

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

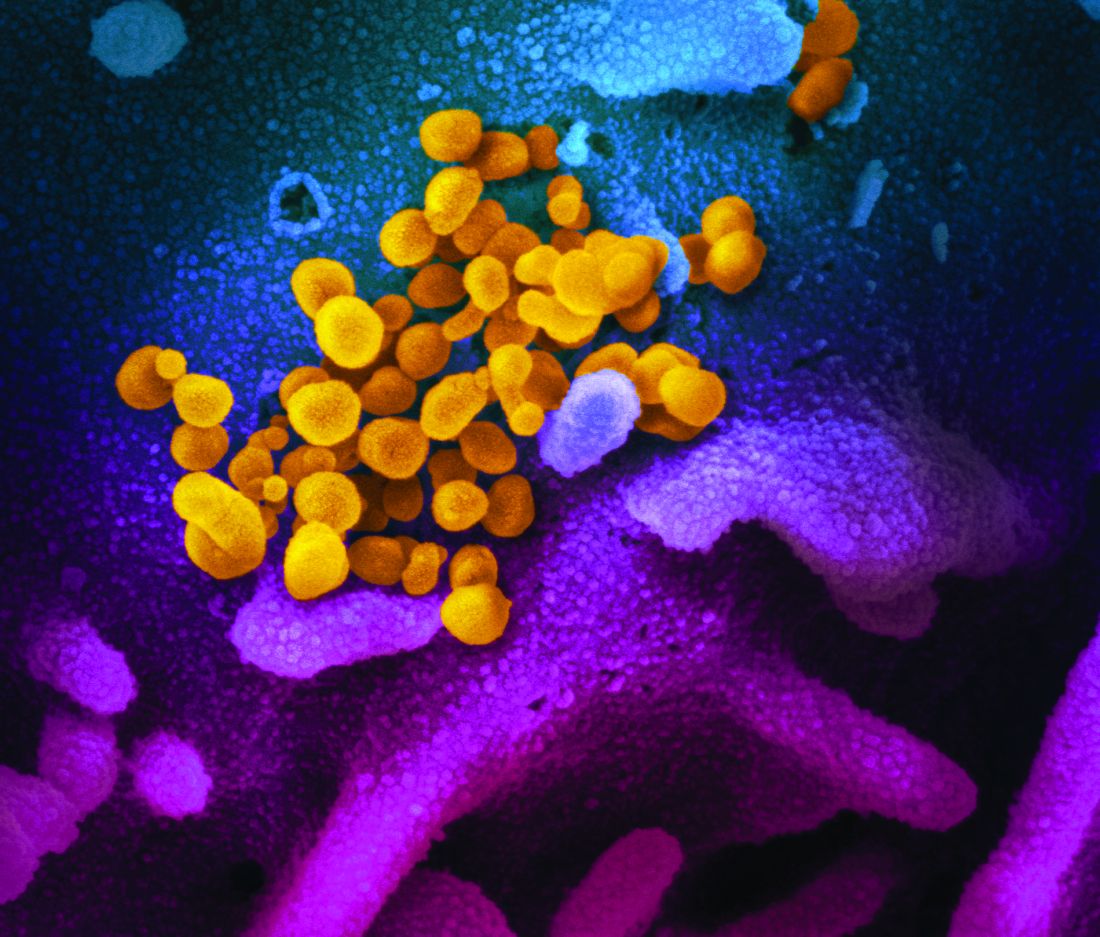

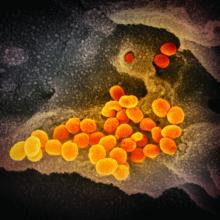

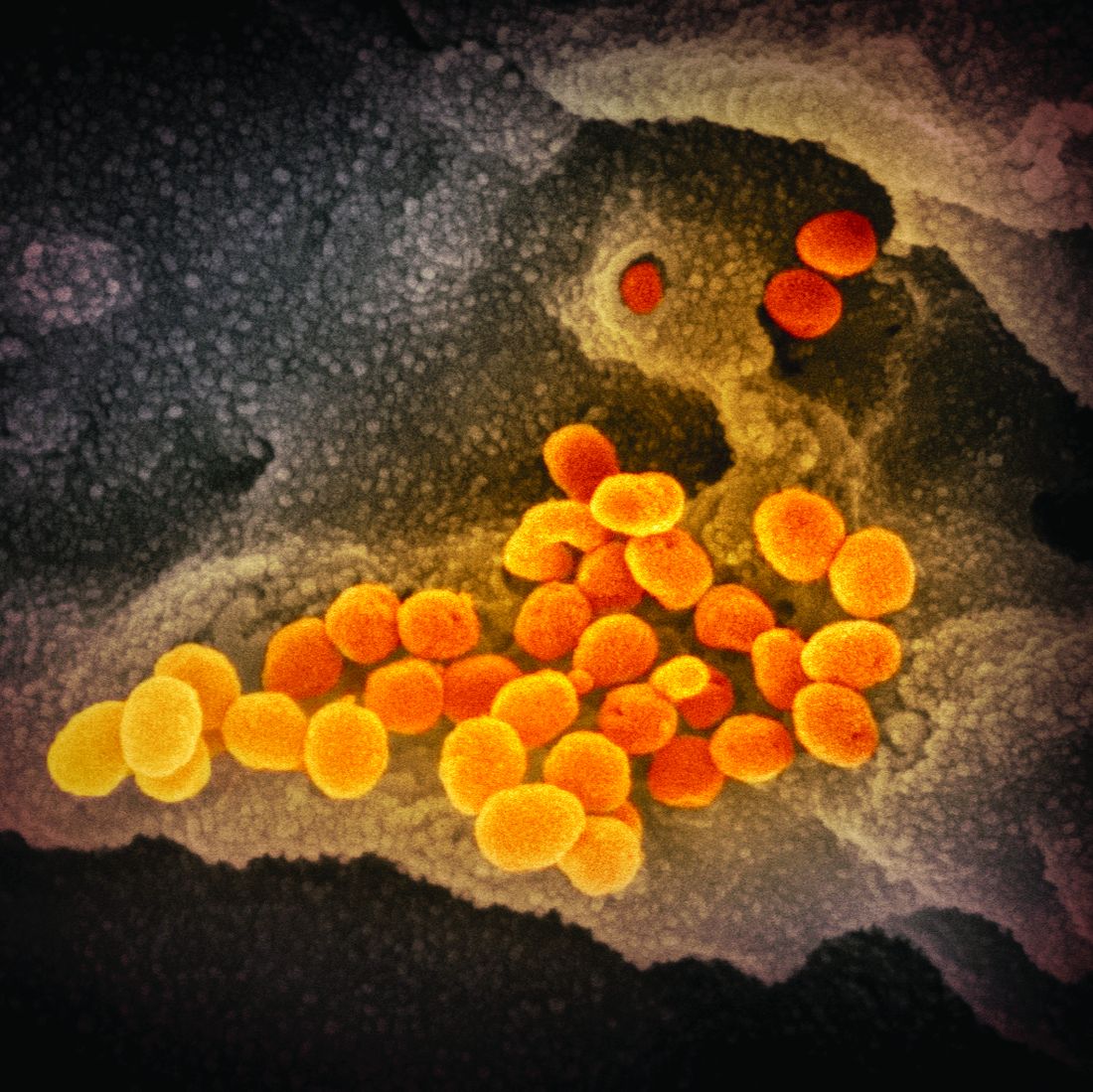

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?

CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a face mask to protect themselves from respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A face mask should be used by people who have COVID-19 and are showing symptoms to protect others from the risk of getting infected.

Should medical waste or general waste from health care facilities treating PUIs and patients with confirmed COVID-19 be handled any differently or need any additional disinfection?

No. CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures.

Can people who recover from COVID-19 be infected again?

Unknown. The immune response to COVID-19 is not yet understood.

What is the mortality rate of COVID-19, and how does it compare to the mortality rate of influenza (flu)?

The average 10-year mortality rate for flu, using CDC data, is found to be around 0.1%. Even though this percentage appears to be small, influenza is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 to 40,000 deaths annually in the U.S.

According to statistics released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 17, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.3%. This calculation was based on cases reported through Feb. 11, and calcuated by dividing the number of coronavirus-related deaths at the time (1,023) by the number of confirmed cases (44,672) of COVID-19 infection. However, this report has its limitations, since Chinese officials have a vague way of defining who has COVID-19 infection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the mortality rate for COVID-19 to be between 2% and 4%.

Dr. Sitammagari is a co-medical director for quality and assistant professor of internal medicine at Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. He is also a physician advisor. He currently serves as treasurer for the NC-Triangle Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine and as an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization. Dr. Skandhan was a cofounder of the Wiregrass chapter of SHM and currently serves on the Advisory board. He is also a member of the editorial board of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Dahlin is a second-year internal medicine resident at Southeast Health, Dothan, Ala. She serves as her class representative and is the cochair/resident liaison for the research committee at SEH. Dr. Dahlin also serves as a resident liaison for the Wiregrass chapter of SHM.

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?

CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a face mask to protect themselves from respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A face mask should be used by people who have COVID-19 and are showing symptoms to protect others from the risk of getting infected.

Should medical waste or general waste from health care facilities treating PUIs and patients with confirmed COVID-19 be handled any differently or need any additional disinfection?

No. CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures.

Can people who recover from COVID-19 be infected again?

Unknown. The immune response to COVID-19 is not yet understood.

What is the mortality rate of COVID-19, and how does it compare to the mortality rate of influenza (flu)?

The average 10-year mortality rate for flu, using CDC data, is found to be around 0.1%. Even though this percentage appears to be small, influenza is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 to 40,000 deaths annually in the U.S.

According to statistics released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 17, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.3%. This calculation was based on cases reported through Feb. 11, and calcuated by dividing the number of coronavirus-related deaths at the time (1,023) by the number of confirmed cases (44,672) of COVID-19 infection. However, this report has its limitations, since Chinese officials have a vague way of defining who has COVID-19 infection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the mortality rate for COVID-19 to be between 2% and 4%.

Dr. Sitammagari is a co-medical director for quality and assistant professor of internal medicine at Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. He is also a physician advisor. He currently serves as treasurer for the NC-Triangle Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine and as an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization. Dr. Skandhan was a cofounder of the Wiregrass chapter of SHM and currently serves on the Advisory board. He is also a member of the editorial board of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Dahlin is a second-year internal medicine resident at Southeast Health, Dothan, Ala. She serves as her class representative and is the cochair/resident liaison for the research committee at SEH. Dr. Dahlin also serves as a resident liaison for the Wiregrass chapter of SHM.

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?

CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a face mask to protect themselves from respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A face mask should be used by people who have COVID-19 and are showing symptoms to protect others from the risk of getting infected.

Should medical waste or general waste from health care facilities treating PUIs and patients with confirmed COVID-19 be handled any differently or need any additional disinfection?

No. CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures.

Can people who recover from COVID-19 be infected again?

Unknown. The immune response to COVID-19 is not yet understood.

What is the mortality rate of COVID-19, and how does it compare to the mortality rate of influenza (flu)?

The average 10-year mortality rate for flu, using CDC data, is found to be around 0.1%. Even though this percentage appears to be small, influenza is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 to 40,000 deaths annually in the U.S.

According to statistics released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 17, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.3%. This calculation was based on cases reported through Feb. 11, and calcuated by dividing the number of coronavirus-related deaths at the time (1,023) by the number of confirmed cases (44,672) of COVID-19 infection. However, this report has its limitations, since Chinese officials have a vague way of defining who has COVID-19 infection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the mortality rate for COVID-19 to be between 2% and 4%.

Dr. Sitammagari is a co-medical director for quality and assistant professor of internal medicine at Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. He is also a physician advisor. He currently serves as treasurer for the NC-Triangle Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine and as an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization. Dr. Skandhan was a cofounder of the Wiregrass chapter of SHM and currently serves on the Advisory board. He is also a member of the editorial board of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Dahlin is a second-year internal medicine resident at Southeast Health, Dothan, Ala. She serves as her class representative and is the cochair/resident liaison for the research committee at SEH. Dr. Dahlin also serves as a resident liaison for the Wiregrass chapter of SHM.

Increased risk of infection seen in patients with MS

womensWEST PALM BEACH, FLA. – Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are at increased risk for most types of infection, with the highest risk associated with renal tract infections, according to an analysis of Department of Defense data.

Susan Jick, DSc, director of the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program and professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Boston University, and colleagues sought to understand the rates at which infections occur because they are known to be a common cause of comorbidity and death in patients with MS.

At the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, Dr. Jick and associates presented rates of infection in patients with MS after MS diagnosis, compared with a matched population of patients without MS. The MS cohort included patients who had MS diagnosed and treated between January 2004 and August 2017. Patients had medical history available for at least 1 year before MS diagnosis and at least one prescription for an MS disease-modifying treatment.

Patients without MS were matched to patients with MS 10:1 based on age, sex, geographic region, and cohort entry date. For each patient, the researchers identified the first diagnosed infection of each type after cohort entry. They followed patients until loss of eligibility, death, or end of data collection.

In all, the study included 8,695 patients with MS and 86,934 matched patients without MS. The median age at cohort entry was 41 years, and 71% were female. Median duration of follow-up after study entry was about 6 years. Patients with MS were more likely to have an infection in the year before cohort entry, compared with non-MS patients (43.9% vs. 36.3%).

After cohort entry, the incidence rate of any infection was higher among patients with MS, compared with non-MS patients (4,805 vs. 2,731 per 10,000 person-years; IR ratio, 1.76). In addition, the IR of hospitalized infection was higher among MS patients (125 vs. 51.3 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 2.43). The IR also was increased for several other types of infections, including renal, skin, fungal, pneumonia or influenza, and other infections (such as rickettsial and spirochetal diseases, helminthiases, and nonsyphilitic and nongonococcal venereal diseases). Eye or ear, respiratory or throat, and viral IRRs “were marginally elevated,” the investigators wrote.

In both cohorts, females had a higher risk of infection than males did. The rate of renal tract infection was more than fourfold higher among females, compared with males, in both cohorts. Relative to non-MS patients, however, men with MS had a higher IRR for renal tract infection than women with MS did (2.47 vs. 1.90).

“The risk for any opportunistic infection was slightly increased among MS patients,” the researchers wrote (520 vs. 338 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.54). This was particularly true for candidiasis (252 vs. 166 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.52) and herpes virus infection (221 vs. 150 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.47). “There were few cases of tuberculosis, hepatitis B infection, or hepatitis C infection,” they noted.

The study was funded by a grant from Celgene, a subsidiary of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Four authors are employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb, and one author works for a company that does business with Celgene.

SOURCE: Jick S et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2020, Abstract P086.

womensWEST PALM BEACH, FLA. – Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are at increased risk for most types of infection, with the highest risk associated with renal tract infections, according to an analysis of Department of Defense data.

Susan Jick, DSc, director of the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program and professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Boston University, and colleagues sought to understand the rates at which infections occur because they are known to be a common cause of comorbidity and death in patients with MS.

At the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, Dr. Jick and associates presented rates of infection in patients with MS after MS diagnosis, compared with a matched population of patients without MS. The MS cohort included patients who had MS diagnosed and treated between January 2004 and August 2017. Patients had medical history available for at least 1 year before MS diagnosis and at least one prescription for an MS disease-modifying treatment.

Patients without MS were matched to patients with MS 10:1 based on age, sex, geographic region, and cohort entry date. For each patient, the researchers identified the first diagnosed infection of each type after cohort entry. They followed patients until loss of eligibility, death, or end of data collection.

In all, the study included 8,695 patients with MS and 86,934 matched patients without MS. The median age at cohort entry was 41 years, and 71% were female. Median duration of follow-up after study entry was about 6 years. Patients with MS were more likely to have an infection in the year before cohort entry, compared with non-MS patients (43.9% vs. 36.3%).

After cohort entry, the incidence rate of any infection was higher among patients with MS, compared with non-MS patients (4,805 vs. 2,731 per 10,000 person-years; IR ratio, 1.76). In addition, the IR of hospitalized infection was higher among MS patients (125 vs. 51.3 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 2.43). The IR also was increased for several other types of infections, including renal, skin, fungal, pneumonia or influenza, and other infections (such as rickettsial and spirochetal diseases, helminthiases, and nonsyphilitic and nongonococcal venereal diseases). Eye or ear, respiratory or throat, and viral IRRs “were marginally elevated,” the investigators wrote.

In both cohorts, females had a higher risk of infection than males did. The rate of renal tract infection was more than fourfold higher among females, compared with males, in both cohorts. Relative to non-MS patients, however, men with MS had a higher IRR for renal tract infection than women with MS did (2.47 vs. 1.90).

“The risk for any opportunistic infection was slightly increased among MS patients,” the researchers wrote (520 vs. 338 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.54). This was particularly true for candidiasis (252 vs. 166 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.52) and herpes virus infection (221 vs. 150 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.47). “There were few cases of tuberculosis, hepatitis B infection, or hepatitis C infection,” they noted.

The study was funded by a grant from Celgene, a subsidiary of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Four authors are employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb, and one author works for a company that does business with Celgene.

SOURCE: Jick S et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2020, Abstract P086.

womensWEST PALM BEACH, FLA. – Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are at increased risk for most types of infection, with the highest risk associated with renal tract infections, according to an analysis of Department of Defense data.

Susan Jick, DSc, director of the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program and professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Boston University, and colleagues sought to understand the rates at which infections occur because they are known to be a common cause of comorbidity and death in patients with MS.

At the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, Dr. Jick and associates presented rates of infection in patients with MS after MS diagnosis, compared with a matched population of patients without MS. The MS cohort included patients who had MS diagnosed and treated between January 2004 and August 2017. Patients had medical history available for at least 1 year before MS diagnosis and at least one prescription for an MS disease-modifying treatment.

Patients without MS were matched to patients with MS 10:1 based on age, sex, geographic region, and cohort entry date. For each patient, the researchers identified the first diagnosed infection of each type after cohort entry. They followed patients until loss of eligibility, death, or end of data collection.

In all, the study included 8,695 patients with MS and 86,934 matched patients without MS. The median age at cohort entry was 41 years, and 71% were female. Median duration of follow-up after study entry was about 6 years. Patients with MS were more likely to have an infection in the year before cohort entry, compared with non-MS patients (43.9% vs. 36.3%).

After cohort entry, the incidence rate of any infection was higher among patients with MS, compared with non-MS patients (4,805 vs. 2,731 per 10,000 person-years; IR ratio, 1.76). In addition, the IR of hospitalized infection was higher among MS patients (125 vs. 51.3 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 2.43). The IR also was increased for several other types of infections, including renal, skin, fungal, pneumonia or influenza, and other infections (such as rickettsial and spirochetal diseases, helminthiases, and nonsyphilitic and nongonococcal venereal diseases). Eye or ear, respiratory or throat, and viral IRRs “were marginally elevated,” the investigators wrote.

In both cohorts, females had a higher risk of infection than males did. The rate of renal tract infection was more than fourfold higher among females, compared with males, in both cohorts. Relative to non-MS patients, however, men with MS had a higher IRR for renal tract infection than women with MS did (2.47 vs. 1.90).

“The risk for any opportunistic infection was slightly increased among MS patients,” the researchers wrote (520 vs. 338 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.54). This was particularly true for candidiasis (252 vs. 166 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.52) and herpes virus infection (221 vs. 150 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.47). “There were few cases of tuberculosis, hepatitis B infection, or hepatitis C infection,” they noted.

The study was funded by a grant from Celgene, a subsidiary of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Four authors are employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb, and one author works for a company that does business with Celgene.

SOURCE: Jick S et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2020, Abstract P086.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2020

Labor & Delivery: An overlooked entry point for the spread of viral infection

OB hospitalists have a key role to play

A novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China, has killed more than 2,800 people and infected more than 81,000 individuals globally. Public health officials around the world and in the United States are working together to contain the outbreak.

There are 57 confirmed cases in the United States, including 18 people evacuated from the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship docked in Yokohama, Japan.1 But the focus on coronavirus, even in early months of the epidemic, serves as an opportunity to revisit the spread of viral disease in hospital settings.

Multiple points of viral entry

In truth, most hospitals are well prepared for the coronavirus, starting with the same place they prepare for most infectious disease epidemics – the emergency department. Patients who seek treatment for early onset symptoms may start with their primary care physicians, but increasing numbers of patients with respiratory concerns and/or infection-related symptoms will first seek medical attention in an emergency care setting.2

Many experts have acknowledged the ED as a viral point of entry, including the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), which produced an excellent guide for management of influenza that details prevention, diagnoses, and treatment protocols in an ED setting.3

But another important, and often forgotten, point of entry in a hospital setting is the obstetrical (OB) Labor & Delivery (L&D) department. Although triage for most patients begins in the main ED, in almost every hospital in the United States, women who present with pregnancy-related issues are sent directly to and triaged in L&D, where – when the proper protocols are not in place – they may transmit viral infection to others.

Pregnancy imparts higher risk

“High risk” is often associated with older, immune-compromised adults. But pregnant women who may appear “healthy” are actually in a state that a 2015 study calls “immunosuppressed” whereby the “… pregnant woman actually undergoes an immunological transformation, where the immune system is necessary to promote and support the pregnancy and growing fetus.”4 Pregnant women, or women with newborns or babies, are at higher risk when exposed to viral infection, with a higher mortality risk than the general population.5 In the best cases, women who contract viral infections are treated carefully and recover fully. In the worst cases, they end up on ventilators and can even die as a result.

Although we are still learning about the Wuhan coronavirus, we already know it is a respiratory illness with a lot of the same characteristics as the influenza virus, and that it is transmitted through droplets (such as a sneeze) or via bodily secretions. Given the extreme vulnerability and physician exposure of women giving birth – in which not one, but two lives are involved – viruses like coronavirus can pose extreme risk. What’s more, public health researchers are still learning about potential transmission of coronavirus from mothers to babies. In the international cases of infant exposure to coronavirus, the newborn showed symptoms within 36 hours of being born, but it is unclear if exposure happened in utero or was vertical transmission after birth.6

Role of OB hospitalists in identifying risk and treating viral infection

Regardless of the type of virus, OB hospitalists are key to screening for viral exposure and care for women, fetuses, and newborns. Given their 24/7 presence and experience with women in L&D, they must champion protocols and precautions that align with those in an ED.

For coronavirus, if a woman presents in L&D with a cough, difficulty breathing, or signs of pneumonia, clinicians should be accustomed to asking about travel to China within the last 14 days and whether the patient has been around someone who has recently traveled to China. If the answer to either question is yes, the woman needs to be immediately placed in a single patient room at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas, with a minimum of six air changes per hour.

Diagnostic testing should immediately follow. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration just issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the first commercially-available coronavirus diagnostic test, allowing the use of the test at any lab across the country qualified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.7

If exposure is suspected, containment is paramount until definitive results of diagnostic testing are received. The CDC recommends “Standard Precautions,” which assume that every person is potentially infected or colonized with a pathogen that could be transmitted in the health care setting. These precautions include hand hygiene and personal protective equipment (PPE) to ensure health care workers are not exposed.8

In short, protocols in L&D should mirror those of the ED. But in L&D, clinicians and staff haven’t necessarily been trained to look for or ask for these conditions. Hospitalists can educate their peers and colleagues and advocate for changes at the administrative level.

Biggest current threat: The flu

The coronavirus may eventually present a threat in the United States, but as yet, it is a largely unrealized one. From the perspective of an obstetrician, more immediately concerning is the risk of other viral infections. Although viruses like Ebola and Zika capture headlines, influenza remains the most serious threat to pregnant women in the United States.

According to an article by my colleague, Dr. Mark Simon, “pregnant women and their unborn babies are especially vulnerable to influenza and are more likely to develop serious complications from it … pregnant women who develop the flu are more likely to give birth to children with birth defects of the brain and spine.”9

As of Feb. 1, 2020, the CDC estimates there have been at least 22 million flu illnesses, 210,000 hospitalizations, and 12,000 deaths from flu in the 2019-2020 flu season.10 But the CDC data also suggest that only 54% of pregnant women were vaccinated for influenza in 2019 before or during their pregnancy.11 Hospitalists should ensure that patients diagnosed with flu are quickly and safely treated with antivirals at all stages of their pregnancy to keep them and their babies safe, as well as keep others safe from infection.

Hospitalists can also advocate for across-the-board protocols for the spread of viral illness. The same protocols that protect us from the flu will also protect against coronavirus and viruses that will emerge in the future. Foremost, pregnant women, regardless of trimester, need to receive a flu shot. Women who are pregnant and receive a flu shot can pass on immunity in vitro, and nursing mothers can deliver immunizing agents in their breast milk to their newborn.

Given that hospitalists serve in roles as patient-facing physicians, we should be doing more to protect the public from viral spread, whether coronavirus, influenza, or whatever new viruses the future may hold.

Dr. Dimino is a board-certified ob.gyn. and a Houston-based OB hospitalist with Ob Hospitalist Group. She serves as a faculty member of the TexasAIM Plus Obstetric Hemorrhage Learning Collaborative and currently serves on the Texas Medical Association Council of Science and Public Health.

References

1. The New York Times. Tracking the Coronavirus Map: Tracking the Spread of the Outbreak. Accessed Feb 24, 2020.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

3. Influenza Emergency Department Best Practices. ACEP Public Health & Injury Prevention Committee, Epidemic Expert Panel, https://www.acep.org/globalassets/uploads/uploaded-files/acep/by-medical-focus/influenza-emergency-department-best-practices.pdf.

4. Silasi M, Cardenas I, Kwon JY, Racicot K, Aldo P, Mor G. Viral infections during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73(3):199-213.

5. Kwon JY, Romero R, Mor G. New insights into the relationship between viral infection and pregnancy complications. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:387-390.

6. BBC. Coronavirus: Newborn becomes youngest person diagnosed with virus. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

7. FDA press release. FDA Takes Significant Step in Coronavirus Response Efforts, Issues Emergency Use Authorization for the First 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diagnostic. Feb 4, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or Persons Under Investigation for 2019-nCoV in Healthcare Settings. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

9. STAT First Opinion. Two-thirds of pregnant women aren’t getting the flu vaccine. That needs to change. Jan 18, 2018.

10. CDC. Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report, Key Updates for Week 5, ending February 1, 2020.

11. CDC. Vaccinating Pregnant Women Protects Moms and Babies. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

OB hospitalists have a key role to play

OB hospitalists have a key role to play

A novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China, has killed more than 2,800 people and infected more than 81,000 individuals globally. Public health officials around the world and in the United States are working together to contain the outbreak.

There are 57 confirmed cases in the United States, including 18 people evacuated from the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship docked in Yokohama, Japan.1 But the focus on coronavirus, even in early months of the epidemic, serves as an opportunity to revisit the spread of viral disease in hospital settings.

Multiple points of viral entry

In truth, most hospitals are well prepared for the coronavirus, starting with the same place they prepare for most infectious disease epidemics – the emergency department. Patients who seek treatment for early onset symptoms may start with their primary care physicians, but increasing numbers of patients with respiratory concerns and/or infection-related symptoms will first seek medical attention in an emergency care setting.2

Many experts have acknowledged the ED as a viral point of entry, including the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), which produced an excellent guide for management of influenza that details prevention, diagnoses, and treatment protocols in an ED setting.3

But another important, and often forgotten, point of entry in a hospital setting is the obstetrical (OB) Labor & Delivery (L&D) department. Although triage for most patients begins in the main ED, in almost every hospital in the United States, women who present with pregnancy-related issues are sent directly to and triaged in L&D, where – when the proper protocols are not in place – they may transmit viral infection to others.

Pregnancy imparts higher risk

“High risk” is often associated with older, immune-compromised adults. But pregnant women who may appear “healthy” are actually in a state that a 2015 study calls “immunosuppressed” whereby the “… pregnant woman actually undergoes an immunological transformation, where the immune system is necessary to promote and support the pregnancy and growing fetus.”4 Pregnant women, or women with newborns or babies, are at higher risk when exposed to viral infection, with a higher mortality risk than the general population.5 In the best cases, women who contract viral infections are treated carefully and recover fully. In the worst cases, they end up on ventilators and can even die as a result.

Although we are still learning about the Wuhan coronavirus, we already know it is a respiratory illness with a lot of the same characteristics as the influenza virus, and that it is transmitted through droplets (such as a sneeze) or via bodily secretions. Given the extreme vulnerability and physician exposure of women giving birth – in which not one, but two lives are involved – viruses like coronavirus can pose extreme risk. What’s more, public health researchers are still learning about potential transmission of coronavirus from mothers to babies. In the international cases of infant exposure to coronavirus, the newborn showed symptoms within 36 hours of being born, but it is unclear if exposure happened in utero or was vertical transmission after birth.6

Role of OB hospitalists in identifying risk and treating viral infection

Regardless of the type of virus, OB hospitalists are key to screening for viral exposure and care for women, fetuses, and newborns. Given their 24/7 presence and experience with women in L&D, they must champion protocols and precautions that align with those in an ED.

For coronavirus, if a woman presents in L&D with a cough, difficulty breathing, or signs of pneumonia, clinicians should be accustomed to asking about travel to China within the last 14 days and whether the patient has been around someone who has recently traveled to China. If the answer to either question is yes, the woman needs to be immediately placed in a single patient room at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas, with a minimum of six air changes per hour.

Diagnostic testing should immediately follow. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration just issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the first commercially-available coronavirus diagnostic test, allowing the use of the test at any lab across the country qualified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.7

If exposure is suspected, containment is paramount until definitive results of diagnostic testing are received. The CDC recommends “Standard Precautions,” which assume that every person is potentially infected or colonized with a pathogen that could be transmitted in the health care setting. These precautions include hand hygiene and personal protective equipment (PPE) to ensure health care workers are not exposed.8

In short, protocols in L&D should mirror those of the ED. But in L&D, clinicians and staff haven’t necessarily been trained to look for or ask for these conditions. Hospitalists can educate their peers and colleagues and advocate for changes at the administrative level.

Biggest current threat: The flu

The coronavirus may eventually present a threat in the United States, but as yet, it is a largely unrealized one. From the perspective of an obstetrician, more immediately concerning is the risk of other viral infections. Although viruses like Ebola and Zika capture headlines, influenza remains the most serious threat to pregnant women in the United States.

According to an article by my colleague, Dr. Mark Simon, “pregnant women and their unborn babies are especially vulnerable to influenza and are more likely to develop serious complications from it … pregnant women who develop the flu are more likely to give birth to children with birth defects of the brain and spine.”9

As of Feb. 1, 2020, the CDC estimates there have been at least 22 million flu illnesses, 210,000 hospitalizations, and 12,000 deaths from flu in the 2019-2020 flu season.10 But the CDC data also suggest that only 54% of pregnant women were vaccinated for influenza in 2019 before or during their pregnancy.11 Hospitalists should ensure that patients diagnosed with flu are quickly and safely treated with antivirals at all stages of their pregnancy to keep them and their babies safe, as well as keep others safe from infection.

Hospitalists can also advocate for across-the-board protocols for the spread of viral illness. The same protocols that protect us from the flu will also protect against coronavirus and viruses that will emerge in the future. Foremost, pregnant women, regardless of trimester, need to receive a flu shot. Women who are pregnant and receive a flu shot can pass on immunity in vitro, and nursing mothers can deliver immunizing agents in their breast milk to their newborn.

Given that hospitalists serve in roles as patient-facing physicians, we should be doing more to protect the public from viral spread, whether coronavirus, influenza, or whatever new viruses the future may hold.

Dr. Dimino is a board-certified ob.gyn. and a Houston-based OB hospitalist with Ob Hospitalist Group. She serves as a faculty member of the TexasAIM Plus Obstetric Hemorrhage Learning Collaborative and currently serves on the Texas Medical Association Council of Science and Public Health.

References

1. The New York Times. Tracking the Coronavirus Map: Tracking the Spread of the Outbreak. Accessed Feb 24, 2020.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

3. Influenza Emergency Department Best Practices. ACEP Public Health & Injury Prevention Committee, Epidemic Expert Panel, https://www.acep.org/globalassets/uploads/uploaded-files/acep/by-medical-focus/influenza-emergency-department-best-practices.pdf.

4. Silasi M, Cardenas I, Kwon JY, Racicot K, Aldo P, Mor G. Viral infections during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73(3):199-213.

5. Kwon JY, Romero R, Mor G. New insights into the relationship between viral infection and pregnancy complications. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:387-390.

6. BBC. Coronavirus: Newborn becomes youngest person diagnosed with virus. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

7. FDA press release. FDA Takes Significant Step in Coronavirus Response Efforts, Issues Emergency Use Authorization for the First 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diagnostic. Feb 4, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or Persons Under Investigation for 2019-nCoV in Healthcare Settings. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

9. STAT First Opinion. Two-thirds of pregnant women aren’t getting the flu vaccine. That needs to change. Jan 18, 2018.

10. CDC. Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report, Key Updates for Week 5, ending February 1, 2020.

11. CDC. Vaccinating Pregnant Women Protects Moms and Babies. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

A novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China, has killed more than 2,800 people and infected more than 81,000 individuals globally. Public health officials around the world and in the United States are working together to contain the outbreak.

There are 57 confirmed cases in the United States, including 18 people evacuated from the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship docked in Yokohama, Japan.1 But the focus on coronavirus, even in early months of the epidemic, serves as an opportunity to revisit the spread of viral disease in hospital settings.

Multiple points of viral entry

In truth, most hospitals are well prepared for the coronavirus, starting with the same place they prepare for most infectious disease epidemics – the emergency department. Patients who seek treatment for early onset symptoms may start with their primary care physicians, but increasing numbers of patients with respiratory concerns and/or infection-related symptoms will first seek medical attention in an emergency care setting.2

Many experts have acknowledged the ED as a viral point of entry, including the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), which produced an excellent guide for management of influenza that details prevention, diagnoses, and treatment protocols in an ED setting.3

But another important, and often forgotten, point of entry in a hospital setting is the obstetrical (OB) Labor & Delivery (L&D) department. Although triage for most patients begins in the main ED, in almost every hospital in the United States, women who present with pregnancy-related issues are sent directly to and triaged in L&D, where – when the proper protocols are not in place – they may transmit viral infection to others.

Pregnancy imparts higher risk

“High risk” is often associated with older, immune-compromised adults. But pregnant women who may appear “healthy” are actually in a state that a 2015 study calls “immunosuppressed” whereby the “… pregnant woman actually undergoes an immunological transformation, where the immune system is necessary to promote and support the pregnancy and growing fetus.”4 Pregnant women, or women with newborns or babies, are at higher risk when exposed to viral infection, with a higher mortality risk than the general population.5 In the best cases, women who contract viral infections are treated carefully and recover fully. In the worst cases, they end up on ventilators and can even die as a result.

Although we are still learning about the Wuhan coronavirus, we already know it is a respiratory illness with a lot of the same characteristics as the influenza virus, and that it is transmitted through droplets (such as a sneeze) or via bodily secretions. Given the extreme vulnerability and physician exposure of women giving birth – in which not one, but two lives are involved – viruses like coronavirus can pose extreme risk. What’s more, public health researchers are still learning about potential transmission of coronavirus from mothers to babies. In the international cases of infant exposure to coronavirus, the newborn showed symptoms within 36 hours of being born, but it is unclear if exposure happened in utero or was vertical transmission after birth.6

Role of OB hospitalists in identifying risk and treating viral infection

Regardless of the type of virus, OB hospitalists are key to screening for viral exposure and care for women, fetuses, and newborns. Given their 24/7 presence and experience with women in L&D, they must champion protocols and precautions that align with those in an ED.

For coronavirus, if a woman presents in L&D with a cough, difficulty breathing, or signs of pneumonia, clinicians should be accustomed to asking about travel to China within the last 14 days and whether the patient has been around someone who has recently traveled to China. If the answer to either question is yes, the woman needs to be immediately placed in a single patient room at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas, with a minimum of six air changes per hour.

Diagnostic testing should immediately follow. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration just issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the first commercially-available coronavirus diagnostic test, allowing the use of the test at any lab across the country qualified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.7

If exposure is suspected, containment is paramount until definitive results of diagnostic testing are received. The CDC recommends “Standard Precautions,” which assume that every person is potentially infected or colonized with a pathogen that could be transmitted in the health care setting. These precautions include hand hygiene and personal protective equipment (PPE) to ensure health care workers are not exposed.8

In short, protocols in L&D should mirror those of the ED. But in L&D, clinicians and staff haven’t necessarily been trained to look for or ask for these conditions. Hospitalists can educate their peers and colleagues and advocate for changes at the administrative level.

Biggest current threat: The flu

The coronavirus may eventually present a threat in the United States, but as yet, it is a largely unrealized one. From the perspective of an obstetrician, more immediately concerning is the risk of other viral infections. Although viruses like Ebola and Zika capture headlines, influenza remains the most serious threat to pregnant women in the United States.

According to an article by my colleague, Dr. Mark Simon, “pregnant women and their unborn babies are especially vulnerable to influenza and are more likely to develop serious complications from it … pregnant women who develop the flu are more likely to give birth to children with birth defects of the brain and spine.”9

As of Feb. 1, 2020, the CDC estimates there have been at least 22 million flu illnesses, 210,000 hospitalizations, and 12,000 deaths from flu in the 2019-2020 flu season.10 But the CDC data also suggest that only 54% of pregnant women were vaccinated for influenza in 2019 before or during their pregnancy.11 Hospitalists should ensure that patients diagnosed with flu are quickly and safely treated with antivirals at all stages of their pregnancy to keep them and their babies safe, as well as keep others safe from infection.

Hospitalists can also advocate for across-the-board protocols for the spread of viral illness. The same protocols that protect us from the flu will also protect against coronavirus and viruses that will emerge in the future. Foremost, pregnant women, regardless of trimester, need to receive a flu shot. Women who are pregnant and receive a flu shot can pass on immunity in vitro, and nursing mothers can deliver immunizing agents in their breast milk to their newborn.

Given that hospitalists serve in roles as patient-facing physicians, we should be doing more to protect the public from viral spread, whether coronavirus, influenza, or whatever new viruses the future may hold.

Dr. Dimino is a board-certified ob.gyn. and a Houston-based OB hospitalist with Ob Hospitalist Group. She serves as a faculty member of the TexasAIM Plus Obstetric Hemorrhage Learning Collaborative and currently serves on the Texas Medical Association Council of Science and Public Health.

References

1. The New York Times. Tracking the Coronavirus Map: Tracking the Spread of the Outbreak. Accessed Feb 24, 2020.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

3. Influenza Emergency Department Best Practices. ACEP Public Health & Injury Prevention Committee, Epidemic Expert Panel, https://www.acep.org/globalassets/uploads/uploaded-files/acep/by-medical-focus/influenza-emergency-department-best-practices.pdf.