User login

FDA approves first live vaccine for smallpox, monkeypox prevention

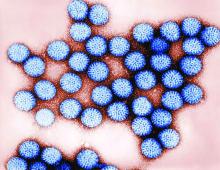

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Jynneos, a live, nonreplicating vaccine based on the vaccinia virus, for smallpox and monkeypox, becoming the first FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of monkeypox disease.

FDA approval for Jynneos for smallpox is based on results from a clinical trial that compared Jynneos with ACAM2000, a previously FDA-approved smallpox vaccine, in about 400 healthy adults aged 18-42 years. Adults who received Jynneos had a noninferior immune response to those who received ACAM2000. In addition, safety was assessed in 7,800 people who received at least one vaccine dose, with the most commonly reported side effects including pain, redness, swelling, itching, firmness at the injection site, muscle pain, headache, and fatigue.

The effectiveness of Jynneos to prevent monkeypox – a disease similar to but somewhat milder than smallpox caused by the non–U.S.-native monkeypox virus – was inferred from antibody responses of participants in the smallpox clinical trial and from studies on nonhuman primates that showed protection from the monkeypox virus after being vaccinated with Jynneos.

“Routine [smallpox] vaccination of the American public was stopped in 1972 after the disease was eradicated in the U.S. and, as a result, a large proportion of the U.S., as well as the global population has no immunity,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. “Although naturally occurring smallpox disease is no longer a global threat, the intentional release of this highly contagious virus could have a devastating effect.”

This vaccine is also part of the Strategic National Stockpile, the nation’s largest supply of potentially lifesaving pharmaceuticals and medical supplies for use in a public health emergency, according to the announcement.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Jynneos, a live, nonreplicating vaccine based on the vaccinia virus, for smallpox and monkeypox, becoming the first FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of monkeypox disease.

FDA approval for Jynneos for smallpox is based on results from a clinical trial that compared Jynneos with ACAM2000, a previously FDA-approved smallpox vaccine, in about 400 healthy adults aged 18-42 years. Adults who received Jynneos had a noninferior immune response to those who received ACAM2000. In addition, safety was assessed in 7,800 people who received at least one vaccine dose, with the most commonly reported side effects including pain, redness, swelling, itching, firmness at the injection site, muscle pain, headache, and fatigue.

The effectiveness of Jynneos to prevent monkeypox – a disease similar to but somewhat milder than smallpox caused by the non–U.S.-native monkeypox virus – was inferred from antibody responses of participants in the smallpox clinical trial and from studies on nonhuman primates that showed protection from the monkeypox virus after being vaccinated with Jynneos.

“Routine [smallpox] vaccination of the American public was stopped in 1972 after the disease was eradicated in the U.S. and, as a result, a large proportion of the U.S., as well as the global population has no immunity,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. “Although naturally occurring smallpox disease is no longer a global threat, the intentional release of this highly contagious virus could have a devastating effect.”

This vaccine is also part of the Strategic National Stockpile, the nation’s largest supply of potentially lifesaving pharmaceuticals and medical supplies for use in a public health emergency, according to the announcement.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Jynneos, a live, nonreplicating vaccine based on the vaccinia virus, for smallpox and monkeypox, becoming the first FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of monkeypox disease.

FDA approval for Jynneos for smallpox is based on results from a clinical trial that compared Jynneos with ACAM2000, a previously FDA-approved smallpox vaccine, in about 400 healthy adults aged 18-42 years. Adults who received Jynneos had a noninferior immune response to those who received ACAM2000. In addition, safety was assessed in 7,800 people who received at least one vaccine dose, with the most commonly reported side effects including pain, redness, swelling, itching, firmness at the injection site, muscle pain, headache, and fatigue.

The effectiveness of Jynneos to prevent monkeypox – a disease similar to but somewhat milder than smallpox caused by the non–U.S.-native monkeypox virus – was inferred from antibody responses of participants in the smallpox clinical trial and from studies on nonhuman primates that showed protection from the monkeypox virus after being vaccinated with Jynneos.

“Routine [smallpox] vaccination of the American public was stopped in 1972 after the disease was eradicated in the U.S. and, as a result, a large proportion of the U.S., as well as the global population has no immunity,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. “Although naturally occurring smallpox disease is no longer a global threat, the intentional release of this highly contagious virus could have a devastating effect.”

This vaccine is also part of the Strategic National Stockpile, the nation’s largest supply of potentially lifesaving pharmaceuticals and medical supplies for use in a public health emergency, according to the announcement.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

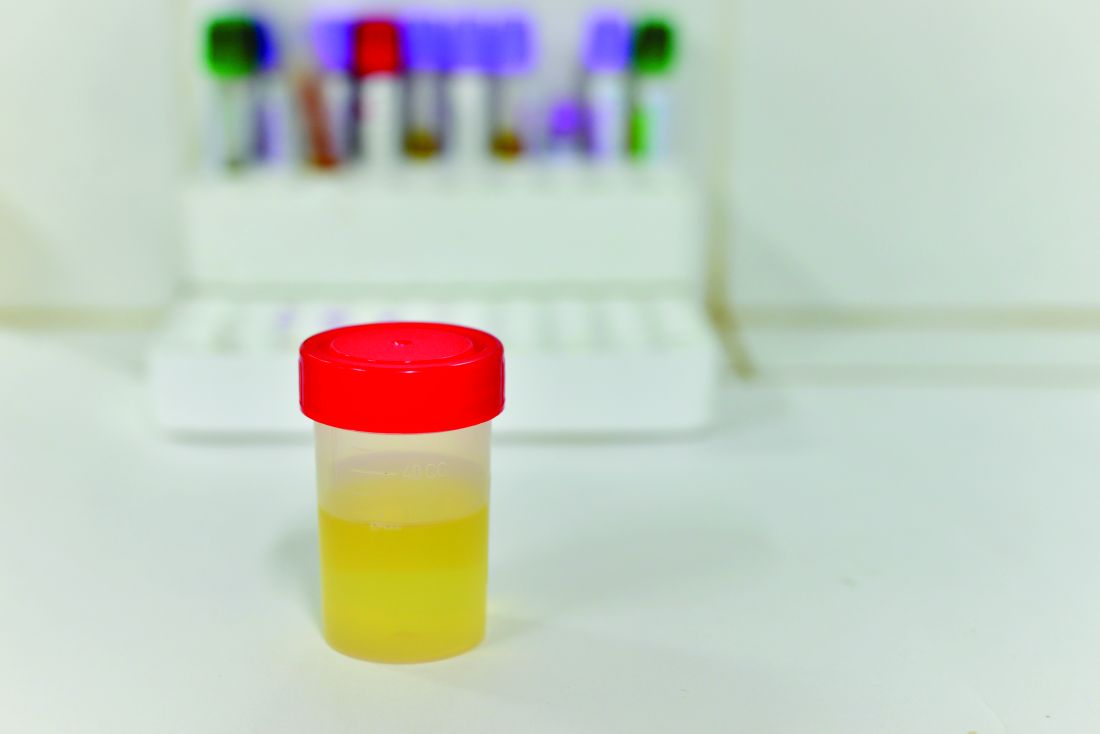

USPSTF: Screening pregnant women for asymptomatic bacteriuria cuts pyelonephritis risk

according to new recommendations set forth by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

However, the investigating committee reported, there is evidence against screening nonpregnant women and adult men. In fact, the committee found “adequate” evidence of potential harm associated with treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults of both sexes, including adverse effects of antibiotics and on the microbiome.

The new document downgrades from A to B the group’s prior recommendation that urine culture screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria should be performed among pregnant women at 12-16 weeks’ gestation or at their first prenatal visit. The USPSTF recommendation to not screen nonpregnant adults retained its D rating, Jerome A. Leis, MD and Christine Soong, MD said in an accompanying editorial.

“Not screening or treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in this population has long been an ironclad recommendation endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, as well as numerous professional societies as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign,” wrote Dr. Leis of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, and Dr. Soong of the University of Toronto. “Restating this steadfast and pervasive recommendation may seem unremarkable and almost pedantic, yet it remains stubbornly disregarded by clinicians across multiple settings.”

The new recommendations were based on a review of 19 studies involving almost 8,500 pregnant and nonpregnant women, as well as a small number of adult men. Most were carried out in the 1960s or 1970s. The most recent ones were published in 2002 and 2015. The dearth of more recent data may have limited some conclusions and certainly highlighted the need for more research, said Jillian T. Henderson, PhD, chair of the committee assigned to investigate the evidence.

“Few studies of asymptomatic bacteriuria screening or treatment in pregnant populations have been conducted in the past 40 years,” wrote Dr. Henderson of Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, and associates. “Historical evidence established asymptomatic bacteriuria screening and treatment as standard obstetric practice in the United States.” But these trials typically were less rigorous than modern studies, and the results are out of touch with modern clinical settings and treatment protocols, the team noted.

Additionally, Dr. Henderson and coauthors said, rates of pyelonephritis were about 10 times higher then than they are now. In the more recent studies, pyelonephritis rates in control groups were 2.2% and 2.5%; in most of the older studies, control group rates ranged from 33% to 36%.

In commissioning the investigation, the task force looked at the following four questions:

Does screening improve health outcomes?

Neither of two studies involving 5,289 women, one from Spain and one from Turkey, addressed this question in nonpregnant women; however, studies that looked at pregnant women generally found that screening did reduce the risk of pyelonephritis by about 70%. The investigators cautioned that these studies were out of date and perhaps methodologically flawed.

The only study that looked at newborn outcomes found no difference in birth weights or premature births between the screened and unscreened cohorts.

No study examined this question in nonpregnant women or men.

What are the harms of such screening?

A single study of 372 pregnant women described potential prenatal and perinatal harms associated with screening and treatment. It found a slight increase in congenital abnormalities in the screened cohort (1.6%), compared with those who were not screened (1.1%). However, those who were not screened were presumably not prescribed antibiotics.

Does treatment of screening-detected asymptomatic bacteriuria improve health outcomes?

Twelve trials of pregnant women (2,377) addressed this issue. All but two were conducted in the 1960s and 1970s. Treatment varied widely; sulfonamides were the most common, including the now discarded sulfamethazine and sulfadimethoxine. Dosages and duration of treatment also were considerably higher and longer than current practice.

In all but one study, there were higher rates of pyelonephritis in the control group. A pooled risk analysis indicated that treatment reduced the risk of pyelonephritis by nearly 80% (relative risk, 0.24).

Seven studies found higher rates of low birth weight in infants born to mothers who were treated, but two studies reported a significant reduction in the risk of low birth weight.

Among the six trials that examined perinatal mortality, none found significant associations with treatment.

Five studies examined treatment in nonpregnant women with screening-detected asymptomatic bacteriuria, and one included men as well. Of the four that reported the rate of symptomatic infection or pyelonephritis, none found a significant difference between treatment and control groups. The single study that included men also found no significant difference between treatment and control groups.

Among the three studies that focused on older adults, there also were no significant between-group differences in outcomes.

What harms are associated with treatment of screening-detected asymptomatic bacteriuria?

Seven studies comprised pregnant women. Five reported congenital malformations in the intervention and control groups. Overall, there were very few cases of malformations, with more – although not significantly more – in the control groups.

Evidence related to other infant and maternal harms was “sparsely and inconsistently reported,” Dr. Henderson and coauthors noted, “and there was a lack of evidence on long-term neonatal outcomes after antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy.”

Two studies listed maternal adverse events associated with different treatments including vaginitis and diarrhea with ampicillin and rashes and nausea with nalidixic acid.

In terms of nonpregnant women and men, four studies reported adverse events. None occurred with nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim treatment; however, one study that included daily treatment with ofloxacin noted that 6% withdrew because of adverse events – vertigo and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Treatments didn’t affect hematocrit, bilirubin, serum urea, or nitrogen, although some studies found a slight reduction in serum creatinine.

Although there’s a need for additional research into this question, the new recommendations provide a good reason to further reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure, Lindsey E. Nicolle, MD, wrote in a second commentary.

These updated recommendations “contribute to the evolution of management of asymptomatic bacteriuria in healthy women,” wrote Dr. Nicolle of the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. “However, questions remain about the risks and benefits of universal screening for and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women in the context of current clinical practice. The effects of changes in fetal-maternal care, of low- compared with high-risk pregnancies, and of health care access need to be understood. In the short term, application of current diagnostic recommendations for identification of persistent symptomatic bacteriuria with a second urine culture may provide an immediate opportunity to limit unnecessary antimicrobial use for some pregnant women.”

No conflicts of interest were reported by the USPSTF authors, nor by Dr. Leis, Dr. Soong, or Dr. Nicolle. The USPSTF report was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

SOURCES: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1188-94; Henderson JT et al. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1195-205; Leis JA and Soong C. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4515; Nicolle LE. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1152-4.

according to new recommendations set forth by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

However, the investigating committee reported, there is evidence against screening nonpregnant women and adult men. In fact, the committee found “adequate” evidence of potential harm associated with treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults of both sexes, including adverse effects of antibiotics and on the microbiome.

The new document downgrades from A to B the group’s prior recommendation that urine culture screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria should be performed among pregnant women at 12-16 weeks’ gestation or at their first prenatal visit. The USPSTF recommendation to not screen nonpregnant adults retained its D rating, Jerome A. Leis, MD and Christine Soong, MD said in an accompanying editorial.

“Not screening or treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in this population has long been an ironclad recommendation endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, as well as numerous professional societies as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign,” wrote Dr. Leis of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, and Dr. Soong of the University of Toronto. “Restating this steadfast and pervasive recommendation may seem unremarkable and almost pedantic, yet it remains stubbornly disregarded by clinicians across multiple settings.”

The new recommendations were based on a review of 19 studies involving almost 8,500 pregnant and nonpregnant women, as well as a small number of adult men. Most were carried out in the 1960s or 1970s. The most recent ones were published in 2002 and 2015. The dearth of more recent data may have limited some conclusions and certainly highlighted the need for more research, said Jillian T. Henderson, PhD, chair of the committee assigned to investigate the evidence.

“Few studies of asymptomatic bacteriuria screening or treatment in pregnant populations have been conducted in the past 40 years,” wrote Dr. Henderson of Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, and associates. “Historical evidence established asymptomatic bacteriuria screening and treatment as standard obstetric practice in the United States.” But these trials typically were less rigorous than modern studies, and the results are out of touch with modern clinical settings and treatment protocols, the team noted.

Additionally, Dr. Henderson and coauthors said, rates of pyelonephritis were about 10 times higher then than they are now. In the more recent studies, pyelonephritis rates in control groups were 2.2% and 2.5%; in most of the older studies, control group rates ranged from 33% to 36%.

In commissioning the investigation, the task force looked at the following four questions:

Does screening improve health outcomes?

Neither of two studies involving 5,289 women, one from Spain and one from Turkey, addressed this question in nonpregnant women; however, studies that looked at pregnant women generally found that screening did reduce the risk of pyelonephritis by about 70%. The investigators cautioned that these studies were out of date and perhaps methodologically flawed.

The only study that looked at newborn outcomes found no difference in birth weights or premature births between the screened and unscreened cohorts.

No study examined this question in nonpregnant women or men.

What are the harms of such screening?

A single study of 372 pregnant women described potential prenatal and perinatal harms associated with screening and treatment. It found a slight increase in congenital abnormalities in the screened cohort (1.6%), compared with those who were not screened (1.1%). However, those who were not screened were presumably not prescribed antibiotics.

Does treatment of screening-detected asymptomatic bacteriuria improve health outcomes?

Twelve trials of pregnant women (2,377) addressed this issue. All but two were conducted in the 1960s and 1970s. Treatment varied widely; sulfonamides were the most common, including the now discarded sulfamethazine and sulfadimethoxine. Dosages and duration of treatment also were considerably higher and longer than current practice.

In all but one study, there were higher rates of pyelonephritis in the control group. A pooled risk analysis indicated that treatment reduced the risk of pyelonephritis by nearly 80% (relative risk, 0.24).

Seven studies found higher rates of low birth weight in infants born to mothers who were treated, but two studies reported a significant reduction in the risk of low birth weight.

Among the six trials that examined perinatal mortality, none found significant associations with treatment.

Five studies examined treatment in nonpregnant women with screening-detected asymptomatic bacteriuria, and one included men as well. Of the four that reported the rate of symptomatic infection or pyelonephritis, none found a significant difference between treatment and control groups. The single study that included men also found no significant difference between treatment and control groups.

Among the three studies that focused on older adults, there also were no significant between-group differences in outcomes.

What harms are associated with treatment of screening-detected asymptomatic bacteriuria?

Seven studies comprised pregnant women. Five reported congenital malformations in the intervention and control groups. Overall, there were very few cases of malformations, with more – although not significantly more – in the control groups.

Evidence related to other infant and maternal harms was “sparsely and inconsistently reported,” Dr. Henderson and coauthors noted, “and there was a lack of evidence on long-term neonatal outcomes after antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy.”

Two studies listed maternal adverse events associated with different treatments including vaginitis and diarrhea with ampicillin and rashes and nausea with nalidixic acid.

In terms of nonpregnant women and men, four studies reported adverse events. None occurred with nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim treatment; however, one study that included daily treatment with ofloxacin noted that 6% withdrew because of adverse events – vertigo and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Treatments didn’t affect hematocrit, bilirubin, serum urea, or nitrogen, although some studies found a slight reduction in serum creatinine.

Although there’s a need for additional research into this question, the new recommendations provide a good reason to further reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure, Lindsey E. Nicolle, MD, wrote in a second commentary.

These updated recommendations “contribute to the evolution of management of asymptomatic bacteriuria in healthy women,” wrote Dr. Nicolle of the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. “However, questions remain about the risks and benefits of universal screening for and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women in the context of current clinical practice. The effects of changes in fetal-maternal care, of low- compared with high-risk pregnancies, and of health care access need to be understood. In the short term, application of current diagnostic recommendations for identification of persistent symptomatic bacteriuria with a second urine culture may provide an immediate opportunity to limit unnecessary antimicrobial use for some pregnant women.”

No conflicts of interest were reported by the USPSTF authors, nor by Dr. Leis, Dr. Soong, or Dr. Nicolle. The USPSTF report was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

SOURCES: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1188-94; Henderson JT et al. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1195-205; Leis JA and Soong C. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4515; Nicolle LE. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1152-4.

according to new recommendations set forth by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

However, the investigating committee reported, there is evidence against screening nonpregnant women and adult men. In fact, the committee found “adequate” evidence of potential harm associated with treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults of both sexes, including adverse effects of antibiotics and on the microbiome.

The new document downgrades from A to B the group’s prior recommendation that urine culture screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria should be performed among pregnant women at 12-16 weeks’ gestation or at their first prenatal visit. The USPSTF recommendation to not screen nonpregnant adults retained its D rating, Jerome A. Leis, MD and Christine Soong, MD said in an accompanying editorial.

“Not screening or treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in this population has long been an ironclad recommendation endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, as well as numerous professional societies as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign,” wrote Dr. Leis of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, and Dr. Soong of the University of Toronto. “Restating this steadfast and pervasive recommendation may seem unremarkable and almost pedantic, yet it remains stubbornly disregarded by clinicians across multiple settings.”

The new recommendations were based on a review of 19 studies involving almost 8,500 pregnant and nonpregnant women, as well as a small number of adult men. Most were carried out in the 1960s or 1970s. The most recent ones were published in 2002 and 2015. The dearth of more recent data may have limited some conclusions and certainly highlighted the need for more research, said Jillian T. Henderson, PhD, chair of the committee assigned to investigate the evidence.

“Few studies of asymptomatic bacteriuria screening or treatment in pregnant populations have been conducted in the past 40 years,” wrote Dr. Henderson of Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, and associates. “Historical evidence established asymptomatic bacteriuria screening and treatment as standard obstetric practice in the United States.” But these trials typically were less rigorous than modern studies, and the results are out of touch with modern clinical settings and treatment protocols, the team noted.

Additionally, Dr. Henderson and coauthors said, rates of pyelonephritis were about 10 times higher then than they are now. In the more recent studies, pyelonephritis rates in control groups were 2.2% and 2.5%; in most of the older studies, control group rates ranged from 33% to 36%.

In commissioning the investigation, the task force looked at the following four questions:

Does screening improve health outcomes?

Neither of two studies involving 5,289 women, one from Spain and one from Turkey, addressed this question in nonpregnant women; however, studies that looked at pregnant women generally found that screening did reduce the risk of pyelonephritis by about 70%. The investigators cautioned that these studies were out of date and perhaps methodologically flawed.

The only study that looked at newborn outcomes found no difference in birth weights or premature births between the screened and unscreened cohorts.

No study examined this question in nonpregnant women or men.

What are the harms of such screening?

A single study of 372 pregnant women described potential prenatal and perinatal harms associated with screening and treatment. It found a slight increase in congenital abnormalities in the screened cohort (1.6%), compared with those who were not screened (1.1%). However, those who were not screened were presumably not prescribed antibiotics.

Does treatment of screening-detected asymptomatic bacteriuria improve health outcomes?

Twelve trials of pregnant women (2,377) addressed this issue. All but two were conducted in the 1960s and 1970s. Treatment varied widely; sulfonamides were the most common, including the now discarded sulfamethazine and sulfadimethoxine. Dosages and duration of treatment also were considerably higher and longer than current practice.

In all but one study, there were higher rates of pyelonephritis in the control group. A pooled risk analysis indicated that treatment reduced the risk of pyelonephritis by nearly 80% (relative risk, 0.24).

Seven studies found higher rates of low birth weight in infants born to mothers who were treated, but two studies reported a significant reduction in the risk of low birth weight.

Among the six trials that examined perinatal mortality, none found significant associations with treatment.

Five studies examined treatment in nonpregnant women with screening-detected asymptomatic bacteriuria, and one included men as well. Of the four that reported the rate of symptomatic infection or pyelonephritis, none found a significant difference between treatment and control groups. The single study that included men also found no significant difference between treatment and control groups.

Among the three studies that focused on older adults, there also were no significant between-group differences in outcomes.

What harms are associated with treatment of screening-detected asymptomatic bacteriuria?

Seven studies comprised pregnant women. Five reported congenital malformations in the intervention and control groups. Overall, there were very few cases of malformations, with more – although not significantly more – in the control groups.

Evidence related to other infant and maternal harms was “sparsely and inconsistently reported,” Dr. Henderson and coauthors noted, “and there was a lack of evidence on long-term neonatal outcomes after antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy.”

Two studies listed maternal adverse events associated with different treatments including vaginitis and diarrhea with ampicillin and rashes and nausea with nalidixic acid.

In terms of nonpregnant women and men, four studies reported adverse events. None occurred with nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim treatment; however, one study that included daily treatment with ofloxacin noted that 6% withdrew because of adverse events – vertigo and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Treatments didn’t affect hematocrit, bilirubin, serum urea, or nitrogen, although some studies found a slight reduction in serum creatinine.

Although there’s a need for additional research into this question, the new recommendations provide a good reason to further reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure, Lindsey E. Nicolle, MD, wrote in a second commentary.

These updated recommendations “contribute to the evolution of management of asymptomatic bacteriuria in healthy women,” wrote Dr. Nicolle of the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. “However, questions remain about the risks and benefits of universal screening for and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women in the context of current clinical practice. The effects of changes in fetal-maternal care, of low- compared with high-risk pregnancies, and of health care access need to be understood. In the short term, application of current diagnostic recommendations for identification of persistent symptomatic bacteriuria with a second urine culture may provide an immediate opportunity to limit unnecessary antimicrobial use for some pregnant women.”

No conflicts of interest were reported by the USPSTF authors, nor by Dr. Leis, Dr. Soong, or Dr. Nicolle. The USPSTF report was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

SOURCES: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1188-94; Henderson JT et al. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1195-205; Leis JA and Soong C. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4515; Nicolle LE. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1152-4.

FROM JAMA

CAR T-cell therapy found safe, effective for HIV-associated lymphoma

HIV positivity does not preclude chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for patients with aggressive lymphoma, a report of two cases suggests. Both of the HIV-positive patients, one of whom had long-term psychiatric comorbidity, achieved durable remission on axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) without undue toxicity.

“To our knowledge, these are the first reported cases of CAR T-cell therapy administered to HIV-infected patients with lymphoma,” Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston and his colleagues wrote in Cancer. “Patients with HIV and AIDS, as well as those with preexisting mental illness, should not be considered disqualified from CAR T-cell therapy and deserve ongoing studies to optimize efficacy and safety in this population.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved two CAR T-cell products that target the B-cell antigen CD19 for the treatment of refractory lymphoma. But their efficacy and safety in HIV-positive patients are unknown because this group has been excluded from pivotal clinical trials.

Dr. Abramson and coauthors detail the two cases of successful anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel in patients with HIV-associated, refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma.

The first patient was an HIV-positive man with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of germinal center B-cell subtype who was intermittently adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His comorbidities included posttraumatic stress disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

Previous treatments for DLBCL included dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (EPOCH-R), and rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (RICE). A recurrence precluded high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support.

With close multidisciplinary management, including psychiatric consultation, the patient became a candidate for CAR T-cell therapy and received axicabtagene ciloleucel. He experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome and grade 3 neurologic toxicity, both of which resolved with treatment. Imaging showed complete remission at approximately 3 months that was sustained at 1 year. Additionally, he had an undetectable HIV viral load and was psychiatrically stable.

The second patient was a man with AIDS-associated, non–germinal center B-cell, Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL who was adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His lymphoma had recurred rapidly after initially responding to dose-adjusted EPOCH-R and then was refractory to combination rituximab and lenalidomide. He previously had hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, and Mycobacterium avium complex infections.

Because of prolonged cytopenias and infectious complications after the previous lymphoma treatments, the patient was considered a poor candidate for high-dose chemotherapy. He underwent CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel and had a complete remission on day 28. Additionally, his HIV infection remained well controlled.

“Although much remains to be learned regarding CAR T-cell therapy in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies, with or without HIV infection, the cases presented herein demonstrate that patients with chemotherapy-refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma can successfully undergo autologous CAR T-cell manufacturing, and subsequently can safely tolerate CAR T-cell therapy and achieve a durable complete remission,” the researchers wrote. “These cases have further demonstrated the proactive, multidisciplinary care required to navigate a patient with high-risk lymphoma through CAR T-cell therapy with attention to significant medical and psychiatric comorbidities.”

Dr. Abramson reported that he has acted as a paid member of the scientific advisory board and as a paid consultant for Kite Pharma, which markets Yescarta, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Abramson JS et al. Cancer. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32411.

HIV positivity does not preclude chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for patients with aggressive lymphoma, a report of two cases suggests. Both of the HIV-positive patients, one of whom had long-term psychiatric comorbidity, achieved durable remission on axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) without undue toxicity.

“To our knowledge, these are the first reported cases of CAR T-cell therapy administered to HIV-infected patients with lymphoma,” Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston and his colleagues wrote in Cancer. “Patients with HIV and AIDS, as well as those with preexisting mental illness, should not be considered disqualified from CAR T-cell therapy and deserve ongoing studies to optimize efficacy and safety in this population.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved two CAR T-cell products that target the B-cell antigen CD19 for the treatment of refractory lymphoma. But their efficacy and safety in HIV-positive patients are unknown because this group has been excluded from pivotal clinical trials.

Dr. Abramson and coauthors detail the two cases of successful anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel in patients with HIV-associated, refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma.

The first patient was an HIV-positive man with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of germinal center B-cell subtype who was intermittently adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His comorbidities included posttraumatic stress disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

Previous treatments for DLBCL included dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (EPOCH-R), and rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (RICE). A recurrence precluded high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support.

With close multidisciplinary management, including psychiatric consultation, the patient became a candidate for CAR T-cell therapy and received axicabtagene ciloleucel. He experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome and grade 3 neurologic toxicity, both of which resolved with treatment. Imaging showed complete remission at approximately 3 months that was sustained at 1 year. Additionally, he had an undetectable HIV viral load and was psychiatrically stable.

The second patient was a man with AIDS-associated, non–germinal center B-cell, Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL who was adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His lymphoma had recurred rapidly after initially responding to dose-adjusted EPOCH-R and then was refractory to combination rituximab and lenalidomide. He previously had hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, and Mycobacterium avium complex infections.

Because of prolonged cytopenias and infectious complications after the previous lymphoma treatments, the patient was considered a poor candidate for high-dose chemotherapy. He underwent CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel and had a complete remission on day 28. Additionally, his HIV infection remained well controlled.

“Although much remains to be learned regarding CAR T-cell therapy in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies, with or without HIV infection, the cases presented herein demonstrate that patients with chemotherapy-refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma can successfully undergo autologous CAR T-cell manufacturing, and subsequently can safely tolerate CAR T-cell therapy and achieve a durable complete remission,” the researchers wrote. “These cases have further demonstrated the proactive, multidisciplinary care required to navigate a patient with high-risk lymphoma through CAR T-cell therapy with attention to significant medical and psychiatric comorbidities.”

Dr. Abramson reported that he has acted as a paid member of the scientific advisory board and as a paid consultant for Kite Pharma, which markets Yescarta, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Abramson JS et al. Cancer. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32411.

HIV positivity does not preclude chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for patients with aggressive lymphoma, a report of two cases suggests. Both of the HIV-positive patients, one of whom had long-term psychiatric comorbidity, achieved durable remission on axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) without undue toxicity.

“To our knowledge, these are the first reported cases of CAR T-cell therapy administered to HIV-infected patients with lymphoma,” Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston and his colleagues wrote in Cancer. “Patients with HIV and AIDS, as well as those with preexisting mental illness, should not be considered disqualified from CAR T-cell therapy and deserve ongoing studies to optimize efficacy and safety in this population.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved two CAR T-cell products that target the B-cell antigen CD19 for the treatment of refractory lymphoma. But their efficacy and safety in HIV-positive patients are unknown because this group has been excluded from pivotal clinical trials.

Dr. Abramson and coauthors detail the two cases of successful anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel in patients with HIV-associated, refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma.

The first patient was an HIV-positive man with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of germinal center B-cell subtype who was intermittently adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His comorbidities included posttraumatic stress disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

Previous treatments for DLBCL included dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (EPOCH-R), and rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (RICE). A recurrence precluded high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support.

With close multidisciplinary management, including psychiatric consultation, the patient became a candidate for CAR T-cell therapy and received axicabtagene ciloleucel. He experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome and grade 3 neurologic toxicity, both of which resolved with treatment. Imaging showed complete remission at approximately 3 months that was sustained at 1 year. Additionally, he had an undetectable HIV viral load and was psychiatrically stable.

The second patient was a man with AIDS-associated, non–germinal center B-cell, Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL who was adherent to antiretroviral therapy. His lymphoma had recurred rapidly after initially responding to dose-adjusted EPOCH-R and then was refractory to combination rituximab and lenalidomide. He previously had hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, and Mycobacterium avium complex infections.

Because of prolonged cytopenias and infectious complications after the previous lymphoma treatments, the patient was considered a poor candidate for high-dose chemotherapy. He underwent CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel and had a complete remission on day 28. Additionally, his HIV infection remained well controlled.

“Although much remains to be learned regarding CAR T-cell therapy in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies, with or without HIV infection, the cases presented herein demonstrate that patients with chemotherapy-refractory, high-grade B-cell lymphoma can successfully undergo autologous CAR T-cell manufacturing, and subsequently can safely tolerate CAR T-cell therapy and achieve a durable complete remission,” the researchers wrote. “These cases have further demonstrated the proactive, multidisciplinary care required to navigate a patient with high-risk lymphoma through CAR T-cell therapy with attention to significant medical and psychiatric comorbidities.”

Dr. Abramson reported that he has acted as a paid member of the scientific advisory board and as a paid consultant for Kite Pharma, which markets Yescarta, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Abramson JS et al. Cancer. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32411.

FROM CANCER

Does this patient have bacterial conjunctivitis?

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

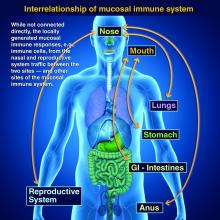

Taking vaccines to the next level via mucosal immunity

Vaccines are marvelous, and there are many well documented success stories, including rotavirus (RV) vaccines, where a live vaccine is administered to the gastrointestinal mucosa via oral drops. Antigens presented at the mucosal/epithelial surface not only induce systemic serum IgG – as do injectable vaccines – but also induce secretory IgA (sIgA), which is most helpful in diseases that directly affect the mucosa.

Mucosal vs. systemic immunity

Antibody being present on mucosal surfaces (point of initial pathogen contact) has a chance to neutralize the pathogen before it gains a foothold. Pathogen-specific mucosal lymphoid elements (e.g. in Peyer’s patches in the gut) also appear critical for optimal protection.1 The presence of both mucosal immune elements means that infection is severely limited or at times entirely prevented. So virus entering the GI tract causes minimal to no gut lining injury. Hence, there is no or mostly reduced vomiting/diarrhea. A downside of mucosally-administered live vaccines is that preexisting antibody to the vaccine antigens can reduce or block vaccine virus replication in the vaccinee, blunting or preventing protection. Note: Preexisting antibody also affects injectable live vaccines, such as the measles vaccine, similarly.

Classic injectable live or nonlive vaccines provide their most potent protection via systemic cellular responses antibody and/or antibodies in serum and extracellular fluid (ECF) where IgG and IgM are in highest concentrations. So even successful injectable vaccines still allow mucosal infection to start but then intercept further spread and prevent most of the downstream damage (think pertussis) or neutralize an infection-generated toxin (pertussis or tetanus). It usually is only after infection-induced damage occurs that systemic IgG and IgM gain better access to respiratory epithelial surfaces, but still only at a fraction of circulating concentrations. Indeed, pertussis vaccine–induced systemic immunity allows the pathogen to attack and replicate in/on host surface cells, causing toxin release and variable amounts of local mucosal injury/inflammation before vaccine-induced systemic immunity gains adequate access to the pathogen and/or to its toxin which may enter systemic circulation.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) induces mucosal immunity

Another “standard” vaccine that induces mucosal immunity – LAIV – was developed to improve on protection afforded by injectable influenza vaccines (IIVs), but LAIV has had hiccups in the United States. One example is several years of negligible protection against H1N1 disease. As long as LAIV’s vaccine strain had reasonably matched the circulating strains, LAIV worked at least as well as injectable influenza vaccine, and even offered some cross-protection against mildly mismatched strains. But after a number of years of LAIV use, vaccine effectiveness in the United States vs. H1N1 strains appeared to fade due to previously undetected but significant changes in the circulating H1N1 strain. The lesson is that mucosal immunity’s advantages are lost if too much change occurs in the pathogen target for sIgA and mucosally-associated lymphoid tissue cells (MALT)).

Other vaccines likely need to induce mucosal immunity

Protection at the mucosal level will likely be needed for success against norovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Neisseria gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Another helpful aspect of mucosal immunity is that immune cells and sIgA not only reside on the mucosa where the antigen was originally presented, but there is also a reasonable chance that these components will traffic to other mucosal surfaces.2

So intranasal vaccine could be expected to protect distant mucosal surfaces (urogenital, GI, and respiratory), leading to vaccine-induced systemic antibody plus mucosal immunity (sIGA and MALT responses) at each site.

Let’s look at a novel “two-site” chlamydia vaccine

Recently a phase 1 chlamydia vaccine that used a novel two-pronged administration site/schedule was successful at inducing both mucosal and systemic immunity in a proof-of-concept study – achieving the best of both worlds.3 This may be a template for vaccines in years to come. British investigators studied 50 healthy women aged 19-45 years in a double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that used a recombinant chlamydia protein subunit antigen (CTH522). The vaccine schedule involved three injectable priming doses followed soon thereafter by two intranasal boosting doses. There were three groups:

1. CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes (CTH522:CAF01).

2. CTH522 adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide (CTH522:AH).

3. Placebo (saline).

The intramuscular (IM) priming schedule was 0, 1, and 4 months. The intranasal vaccine booster doses or placebo were given at 4.5 and 5 months. No related serious adverse reactions occurred. For injectable dosing, the most frequent adverse event was mild local injection-site reactions in all subjects in both vaccine groups vs. in 60% of placebo recipients (P = .053). The adjuvants were the likely cause for local reactions. Intranasal doses had local reactions in 47% of both vaccine groups and 60% of placebo recipients; P = 1.000).

Both vaccines produced systemic IgG seroconversion (including neutralizing antibody) plus small amounts of IgG in the nasal cavity and genital tract in all vaccine recipients; no placebo recipient seroconverted. Interestingly, liposomally-adjuvanted vaccine produced a more rapid systemic IgG response and higher serum titers than the alum-adjuvanted vaccine. Likewise, the IM liposomal vaccine also induced higher but still small mucosal IgG antibody responses (P = .0091). Intranasal IM-induced IgG titers were not boosted by later intranasal vaccine dosing.

Subjects getting liposomal vaccine (but not alum vaccine or placebo) boosters had detectable sIgA titers in both nasal and genital tract secretions. Liposomal vaccine recipients also had fivefold to sixfold higher median titers than alum vaccine recipients after the priming dose, and these higher titers persisted to the end of the study. All liposomal vaccine recipients developed antichlamydial cell-mediated responses vs. 57% alum-adjuvanted vaccine recipients. (P = .01). So both use of two-site dosing and the liposomal adjuvant appeared critical to better responses.

In summary

While this candidate vaccine has hurdles to overcome before coming into routine use, the proof-of-principle that a combination injectable-intranasal vaccine schedule can induce robust systemic and mucosal immunity when given with an appropriate adjuvant is very promising. Adding more vaccines to the schedule then becomes an issue, but that is one of those “good” problems we can deal with later.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines, receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline for studies on pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, and from Pfizer for a study on pneumococcal vaccine on which Dr. Harrison is a sub-investigator. The hospital also receives Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus, and also for rotavirus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. PLOS Biology. 2012 Sep 1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001397.

2. Mucosal Immunity in the Human Female Reproductive Tract in “Mucosal Immunology,” 4th ed., Volume 2 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 2097-124).

3. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30279-8.

Vaccines are marvelous, and there are many well documented success stories, including rotavirus (RV) vaccines, where a live vaccine is administered to the gastrointestinal mucosa via oral drops. Antigens presented at the mucosal/epithelial surface not only induce systemic serum IgG – as do injectable vaccines – but also induce secretory IgA (sIgA), which is most helpful in diseases that directly affect the mucosa.

Mucosal vs. systemic immunity

Antibody being present on mucosal surfaces (point of initial pathogen contact) has a chance to neutralize the pathogen before it gains a foothold. Pathogen-specific mucosal lymphoid elements (e.g. in Peyer’s patches in the gut) also appear critical for optimal protection.1 The presence of both mucosal immune elements means that infection is severely limited or at times entirely prevented. So virus entering the GI tract causes minimal to no gut lining injury. Hence, there is no or mostly reduced vomiting/diarrhea. A downside of mucosally-administered live vaccines is that preexisting antibody to the vaccine antigens can reduce or block vaccine virus replication in the vaccinee, blunting or preventing protection. Note: Preexisting antibody also affects injectable live vaccines, such as the measles vaccine, similarly.

Classic injectable live or nonlive vaccines provide their most potent protection via systemic cellular responses antibody and/or antibodies in serum and extracellular fluid (ECF) where IgG and IgM are in highest concentrations. So even successful injectable vaccines still allow mucosal infection to start but then intercept further spread and prevent most of the downstream damage (think pertussis) or neutralize an infection-generated toxin (pertussis or tetanus). It usually is only after infection-induced damage occurs that systemic IgG and IgM gain better access to respiratory epithelial surfaces, but still only at a fraction of circulating concentrations. Indeed, pertussis vaccine–induced systemic immunity allows the pathogen to attack and replicate in/on host surface cells, causing toxin release and variable amounts of local mucosal injury/inflammation before vaccine-induced systemic immunity gains adequate access to the pathogen and/or to its toxin which may enter systemic circulation.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) induces mucosal immunity

Another “standard” vaccine that induces mucosal immunity – LAIV – was developed to improve on protection afforded by injectable influenza vaccines (IIVs), but LAIV has had hiccups in the United States. One example is several years of negligible protection against H1N1 disease. As long as LAIV’s vaccine strain had reasonably matched the circulating strains, LAIV worked at least as well as injectable influenza vaccine, and even offered some cross-protection against mildly mismatched strains. But after a number of years of LAIV use, vaccine effectiveness in the United States vs. H1N1 strains appeared to fade due to previously undetected but significant changes in the circulating H1N1 strain. The lesson is that mucosal immunity’s advantages are lost if too much change occurs in the pathogen target for sIgA and mucosally-associated lymphoid tissue cells (MALT)).

Other vaccines likely need to induce mucosal immunity

Protection at the mucosal level will likely be needed for success against norovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Neisseria gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Another helpful aspect of mucosal immunity is that immune cells and sIgA not only reside on the mucosa where the antigen was originally presented, but there is also a reasonable chance that these components will traffic to other mucosal surfaces.2

So intranasal vaccine could be expected to protect distant mucosal surfaces (urogenital, GI, and respiratory), leading to vaccine-induced systemic antibody plus mucosal immunity (sIGA and MALT responses) at each site.

Let’s look at a novel “two-site” chlamydia vaccine

Recently a phase 1 chlamydia vaccine that used a novel two-pronged administration site/schedule was successful at inducing both mucosal and systemic immunity in a proof-of-concept study – achieving the best of both worlds.3 This may be a template for vaccines in years to come. British investigators studied 50 healthy women aged 19-45 years in a double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that used a recombinant chlamydia protein subunit antigen (CTH522). The vaccine schedule involved three injectable priming doses followed soon thereafter by two intranasal boosting doses. There were three groups:

1. CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes (CTH522:CAF01).

2. CTH522 adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide (CTH522:AH).

3. Placebo (saline).

The intramuscular (IM) priming schedule was 0, 1, and 4 months. The intranasal vaccine booster doses or placebo were given at 4.5 and 5 months. No related serious adverse reactions occurred. For injectable dosing, the most frequent adverse event was mild local injection-site reactions in all subjects in both vaccine groups vs. in 60% of placebo recipients (P = .053). The adjuvants were the likely cause for local reactions. Intranasal doses had local reactions in 47% of both vaccine groups and 60% of placebo recipients; P = 1.000).

Both vaccines produced systemic IgG seroconversion (including neutralizing antibody) plus small amounts of IgG in the nasal cavity and genital tract in all vaccine recipients; no placebo recipient seroconverted. Interestingly, liposomally-adjuvanted vaccine produced a more rapid systemic IgG response and higher serum titers than the alum-adjuvanted vaccine. Likewise, the IM liposomal vaccine also induced higher but still small mucosal IgG antibody responses (P = .0091). Intranasal IM-induced IgG titers were not boosted by later intranasal vaccine dosing.

Subjects getting liposomal vaccine (but not alum vaccine or placebo) boosters had detectable sIgA titers in both nasal and genital tract secretions. Liposomal vaccine recipients also had fivefold to sixfold higher median titers than alum vaccine recipients after the priming dose, and these higher titers persisted to the end of the study. All liposomal vaccine recipients developed antichlamydial cell-mediated responses vs. 57% alum-adjuvanted vaccine recipients. (P = .01). So both use of two-site dosing and the liposomal adjuvant appeared critical to better responses.

In summary

While this candidate vaccine has hurdles to overcome before coming into routine use, the proof-of-principle that a combination injectable-intranasal vaccine schedule can induce robust systemic and mucosal immunity when given with an appropriate adjuvant is very promising. Adding more vaccines to the schedule then becomes an issue, but that is one of those “good” problems we can deal with later.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines, receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline for studies on pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, and from Pfizer for a study on pneumococcal vaccine on which Dr. Harrison is a sub-investigator. The hospital also receives Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus, and also for rotavirus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. PLOS Biology. 2012 Sep 1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001397.

2. Mucosal Immunity in the Human Female Reproductive Tract in “Mucosal Immunology,” 4th ed., Volume 2 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 2097-124).

3. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30279-8.

Vaccines are marvelous, and there are many well documented success stories, including rotavirus (RV) vaccines, where a live vaccine is administered to the gastrointestinal mucosa via oral drops. Antigens presented at the mucosal/epithelial surface not only induce systemic serum IgG – as do injectable vaccines – but also induce secretory IgA (sIgA), which is most helpful in diseases that directly affect the mucosa.

Mucosal vs. systemic immunity

Antibody being present on mucosal surfaces (point of initial pathogen contact) has a chance to neutralize the pathogen before it gains a foothold. Pathogen-specific mucosal lymphoid elements (e.g. in Peyer’s patches in the gut) also appear critical for optimal protection.1 The presence of both mucosal immune elements means that infection is severely limited or at times entirely prevented. So virus entering the GI tract causes minimal to no gut lining injury. Hence, there is no or mostly reduced vomiting/diarrhea. A downside of mucosally-administered live vaccines is that preexisting antibody to the vaccine antigens can reduce or block vaccine virus replication in the vaccinee, blunting or preventing protection. Note: Preexisting antibody also affects injectable live vaccines, such as the measles vaccine, similarly.

Classic injectable live or nonlive vaccines provide their most potent protection via systemic cellular responses antibody and/or antibodies in serum and extracellular fluid (ECF) where IgG and IgM are in highest concentrations. So even successful injectable vaccines still allow mucosal infection to start but then intercept further spread and prevent most of the downstream damage (think pertussis) or neutralize an infection-generated toxin (pertussis or tetanus). It usually is only after infection-induced damage occurs that systemic IgG and IgM gain better access to respiratory epithelial surfaces, but still only at a fraction of circulating concentrations. Indeed, pertussis vaccine–induced systemic immunity allows the pathogen to attack and replicate in/on host surface cells, causing toxin release and variable amounts of local mucosal injury/inflammation before vaccine-induced systemic immunity gains adequate access to the pathogen and/or to its toxin which may enter systemic circulation.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) induces mucosal immunity

Another “standard” vaccine that induces mucosal immunity – LAIV – was developed to improve on protection afforded by injectable influenza vaccines (IIVs), but LAIV has had hiccups in the United States. One example is several years of negligible protection against H1N1 disease. As long as LAIV’s vaccine strain had reasonably matched the circulating strains, LAIV worked at least as well as injectable influenza vaccine, and even offered some cross-protection against mildly mismatched strains. But after a number of years of LAIV use, vaccine effectiveness in the United States vs. H1N1 strains appeared to fade due to previously undetected but significant changes in the circulating H1N1 strain. The lesson is that mucosal immunity’s advantages are lost if too much change occurs in the pathogen target for sIgA and mucosally-associated lymphoid tissue cells (MALT)).

Other vaccines likely need to induce mucosal immunity

Protection at the mucosal level will likely be needed for success against norovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Neisseria gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Another helpful aspect of mucosal immunity is that immune cells and sIgA not only reside on the mucosa where the antigen was originally presented, but there is also a reasonable chance that these components will traffic to other mucosal surfaces.2

So intranasal vaccine could be expected to protect distant mucosal surfaces (urogenital, GI, and respiratory), leading to vaccine-induced systemic antibody plus mucosal immunity (sIGA and MALT responses) at each site.

Let’s look at a novel “two-site” chlamydia vaccine

Recently a phase 1 chlamydia vaccine that used a novel two-pronged administration site/schedule was successful at inducing both mucosal and systemic immunity in a proof-of-concept study – achieving the best of both worlds.3 This may be a template for vaccines in years to come. British investigators studied 50 healthy women aged 19-45 years in a double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that used a recombinant chlamydia protein subunit antigen (CTH522). The vaccine schedule involved three injectable priming doses followed soon thereafter by two intranasal boosting doses. There were three groups:

1. CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes (CTH522:CAF01).

2. CTH522 adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide (CTH522:AH).

3. Placebo (saline).

The intramuscular (IM) priming schedule was 0, 1, and 4 months. The intranasal vaccine booster doses or placebo were given at 4.5 and 5 months. No related serious adverse reactions occurred. For injectable dosing, the most frequent adverse event was mild local injection-site reactions in all subjects in both vaccine groups vs. in 60% of placebo recipients (P = .053). The adjuvants were the likely cause for local reactions. Intranasal doses had local reactions in 47% of both vaccine groups and 60% of placebo recipients; P = 1.000).

Both vaccines produced systemic IgG seroconversion (including neutralizing antibody) plus small amounts of IgG in the nasal cavity and genital tract in all vaccine recipients; no placebo recipient seroconverted. Interestingly, liposomally-adjuvanted vaccine produced a more rapid systemic IgG response and higher serum titers than the alum-adjuvanted vaccine. Likewise, the IM liposomal vaccine also induced higher but still small mucosal IgG antibody responses (P = .0091). Intranasal IM-induced IgG titers were not boosted by later intranasal vaccine dosing.

Subjects getting liposomal vaccine (but not alum vaccine or placebo) boosters had detectable sIgA titers in both nasal and genital tract secretions. Liposomal vaccine recipients also had fivefold to sixfold higher median titers than alum vaccine recipients after the priming dose, and these higher titers persisted to the end of the study. All liposomal vaccine recipients developed antichlamydial cell-mediated responses vs. 57% alum-adjuvanted vaccine recipients. (P = .01). So both use of two-site dosing and the liposomal adjuvant appeared critical to better responses.

In summary

While this candidate vaccine has hurdles to overcome before coming into routine use, the proof-of-principle that a combination injectable-intranasal vaccine schedule can induce robust systemic and mucosal immunity when given with an appropriate adjuvant is very promising. Adding more vaccines to the schedule then becomes an issue, but that is one of those “good” problems we can deal with later.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines, receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline for studies on pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, and from Pfizer for a study on pneumococcal vaccine on which Dr. Harrison is a sub-investigator. The hospital also receives Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus, and also for rotavirus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. PLOS Biology. 2012 Sep 1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001397.

2. Mucosal Immunity in the Human Female Reproductive Tract in “Mucosal Immunology,” 4th ed., Volume 2 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 2097-124).

3. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30279-8.

Mycobacterium haemophilum: A Challenging Treatment Dilemma in an Immunocompromised Patient