User login

Evolocumab safe and effective in pediatric FH

The PCSK9 monoclonal antibody evolocumab (Repatha) was well tolerated and effectively lowered LDL cholesterol by 38% compared with placebo in a randomized controlled trial in pediatric patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) already taking statins with or without ezetimibe.

“HAUSER-RCT is the largest study and the first placebo-controlled randomized trial of a PCSK9 inhibitor in pediatric FH,” senior author Daniel Gaudet, MD, PhD, Universite de Montreal, said in an interview.

“The study showed good safety and efficacy of the drug in this population, with an excellent 44% reduction in LDL cholesterol compared with 6% in the placebo group.”

The trial also found evolocumab to be well tolerated in this group, with adverse effects similar in the active and placebo groups.

“Some people have wondered about using a drug with a monthly injection in a pediatric population, but this was not an issue in our study,” Dr. Gaudet said. “The idea of a monthly injection was well received, and no patient withdrew because of this.”

The HAUSER-RCT trial was presented on Aug. 29 at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC Congress 2020) and simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“With patients recruited from 23 countries in five continents, the study provides an accurate picture of the safety and efficacy of evolocumab in pediatric FH patients worldwide,” Dr. Gaudet said.

The 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involved 157 patients aged 10-17 years with heterozygous FH already taking statins with or without ezetimibe and who had an LDL cholesterol level of 130 mg/dL or more and a triglyceride level of 400 mg/dL or less.

They were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive monthly subcutaneous injections of evolocumab (420 mg) or placebo.

Results showed that at week 24, the mean percentage change from baseline in LDL cholesterol level was −44.5% in the evolocumab group and −6.2% in the placebo group, giving a difference of −38.3 percentage points (P < .001).

The absolute change in the LDL cholesterol level was −77.5 mg/dL in the evolocumab group and −9.0 mg/dL in the placebo group, giving a difference of −68.6 mg/dL (P < .001).

Results for all secondary lipid variables were significantly better with evolocumab than with placebo. The incidence of adverse events that occurred during the treatment period was similar in the evolocumab and placebo groups. Laboratory abnormalities did not differ between groups.

Dr. Gaudet noted that FH is the most common genetic disease worldwide, affecting 1 in 250 people. “It is very treatable, so it is important to identify these patients, but it is massively underdiagnosed, with only around 15%-20% of patients with the condition having been identified,” he said.

“The vast majority of pediatric FH patients can reach target LDL levels with statins and ezetimibe, but there are 5%-10% of patients who may need additional therapy. We have now shown that evolocumab is safe and effective for these patients and can be used to fill this gap,” Dr. Gaudet said. “We can now say that we can cover all situations in treating FH whatever the severity of the disease.”

However, the challenge remains to improve the diagnosis of FH. “If there is one person with FH in a family, then it is essential that the whole extended family is tested. Our toolbox for treating this condition is now sufficiently effective, so there is no reason not to diagnose this disease,” Dr. Gaudet stressed.

The HAUSER-RCT study was supported by Amgen. Gaudet reports grants and personal fees from Amgen during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The PCSK9 monoclonal antibody evolocumab (Repatha) was well tolerated and effectively lowered LDL cholesterol by 38% compared with placebo in a randomized controlled trial in pediatric patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) already taking statins with or without ezetimibe.

“HAUSER-RCT is the largest study and the first placebo-controlled randomized trial of a PCSK9 inhibitor in pediatric FH,” senior author Daniel Gaudet, MD, PhD, Universite de Montreal, said in an interview.

“The study showed good safety and efficacy of the drug in this population, with an excellent 44% reduction in LDL cholesterol compared with 6% in the placebo group.”

The trial also found evolocumab to be well tolerated in this group, with adverse effects similar in the active and placebo groups.

“Some people have wondered about using a drug with a monthly injection in a pediatric population, but this was not an issue in our study,” Dr. Gaudet said. “The idea of a monthly injection was well received, and no patient withdrew because of this.”

The HAUSER-RCT trial was presented on Aug. 29 at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC Congress 2020) and simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“With patients recruited from 23 countries in five continents, the study provides an accurate picture of the safety and efficacy of evolocumab in pediatric FH patients worldwide,” Dr. Gaudet said.

The 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involved 157 patients aged 10-17 years with heterozygous FH already taking statins with or without ezetimibe and who had an LDL cholesterol level of 130 mg/dL or more and a triglyceride level of 400 mg/dL or less.

They were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive monthly subcutaneous injections of evolocumab (420 mg) or placebo.

Results showed that at week 24, the mean percentage change from baseline in LDL cholesterol level was −44.5% in the evolocumab group and −6.2% in the placebo group, giving a difference of −38.3 percentage points (P < .001).

The absolute change in the LDL cholesterol level was −77.5 mg/dL in the evolocumab group and −9.0 mg/dL in the placebo group, giving a difference of −68.6 mg/dL (P < .001).

Results for all secondary lipid variables were significantly better with evolocumab than with placebo. The incidence of adverse events that occurred during the treatment period was similar in the evolocumab and placebo groups. Laboratory abnormalities did not differ between groups.

Dr. Gaudet noted that FH is the most common genetic disease worldwide, affecting 1 in 250 people. “It is very treatable, so it is important to identify these patients, but it is massively underdiagnosed, with only around 15%-20% of patients with the condition having been identified,” he said.

“The vast majority of pediatric FH patients can reach target LDL levels with statins and ezetimibe, but there are 5%-10% of patients who may need additional therapy. We have now shown that evolocumab is safe and effective for these patients and can be used to fill this gap,” Dr. Gaudet said. “We can now say that we can cover all situations in treating FH whatever the severity of the disease.”

However, the challenge remains to improve the diagnosis of FH. “If there is one person with FH in a family, then it is essential that the whole extended family is tested. Our toolbox for treating this condition is now sufficiently effective, so there is no reason not to diagnose this disease,” Dr. Gaudet stressed.

The HAUSER-RCT study was supported by Amgen. Gaudet reports grants and personal fees from Amgen during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The PCSK9 monoclonal antibody evolocumab (Repatha) was well tolerated and effectively lowered LDL cholesterol by 38% compared with placebo in a randomized controlled trial in pediatric patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) already taking statins with or without ezetimibe.

“HAUSER-RCT is the largest study and the first placebo-controlled randomized trial of a PCSK9 inhibitor in pediatric FH,” senior author Daniel Gaudet, MD, PhD, Universite de Montreal, said in an interview.

“The study showed good safety and efficacy of the drug in this population, with an excellent 44% reduction in LDL cholesterol compared with 6% in the placebo group.”

The trial also found evolocumab to be well tolerated in this group, with adverse effects similar in the active and placebo groups.

“Some people have wondered about using a drug with a monthly injection in a pediatric population, but this was not an issue in our study,” Dr. Gaudet said. “The idea of a monthly injection was well received, and no patient withdrew because of this.”

The HAUSER-RCT trial was presented on Aug. 29 at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC Congress 2020) and simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“With patients recruited from 23 countries in five continents, the study provides an accurate picture of the safety and efficacy of evolocumab in pediatric FH patients worldwide,” Dr. Gaudet said.

The 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involved 157 patients aged 10-17 years with heterozygous FH already taking statins with or without ezetimibe and who had an LDL cholesterol level of 130 mg/dL or more and a triglyceride level of 400 mg/dL or less.

They were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive monthly subcutaneous injections of evolocumab (420 mg) or placebo.

Results showed that at week 24, the mean percentage change from baseline in LDL cholesterol level was −44.5% in the evolocumab group and −6.2% in the placebo group, giving a difference of −38.3 percentage points (P < .001).

The absolute change in the LDL cholesterol level was −77.5 mg/dL in the evolocumab group and −9.0 mg/dL in the placebo group, giving a difference of −68.6 mg/dL (P < .001).

Results for all secondary lipid variables were significantly better with evolocumab than with placebo. The incidence of adverse events that occurred during the treatment period was similar in the evolocumab and placebo groups. Laboratory abnormalities did not differ between groups.

Dr. Gaudet noted that FH is the most common genetic disease worldwide, affecting 1 in 250 people. “It is very treatable, so it is important to identify these patients, but it is massively underdiagnosed, with only around 15%-20% of patients with the condition having been identified,” he said.

“The vast majority of pediatric FH patients can reach target LDL levels with statins and ezetimibe, but there are 5%-10% of patients who may need additional therapy. We have now shown that evolocumab is safe and effective for these patients and can be used to fill this gap,” Dr. Gaudet said. “We can now say that we can cover all situations in treating FH whatever the severity of the disease.”

However, the challenge remains to improve the diagnosis of FH. “If there is one person with FH in a family, then it is essential that the whole extended family is tested. Our toolbox for treating this condition is now sufficiently effective, so there is no reason not to diagnose this disease,” Dr. Gaudet stressed.

The HAUSER-RCT study was supported by Amgen. Gaudet reports grants and personal fees from Amgen during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin D pearls

Case: A 56-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity calls clinic to discuss concerns about COVID-19, stating: “I want to do everything I can to reduce my risk of infection.” In addition to physical distancing, mask wearing, hand hygiene, and control of chronic conditions, which of the following supplements would you recommend for this patient?

1. Coenzyme Q10 160 mg twice a day

2. Vitamin D 2,000 IU daily

3. Vitamin E 400 IU daily

4. Vitamin B12 1,000 mcg daily

Of these choices, vitamin D supplementation is likely the best option, based on the limited data that is available.

Risk factors for worse COVID-19 outcome, such as older age, obesity, and more pigmented skin are also risk factors for vitamin D deficiency. This makes the study of vitamin D and COVID-19 both challenging and relevant.

In a recent study of 7,807 people living in Israel, Merzon and colleagues found that low plasma vitamin D level was an independent risk factor for COVID-19 infection. Mean plasma vitamin D level was significantly lower among those who tested positive for COVID-19 (19.00 ng/mL) than negative (20.55 ng/ mL). After controlling for demographic variables and several medical conditions, the adjusted odds ratio of COVID-19 infection in those with lower vitamin D was 1.45 (95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.95; P < .001). However, the odds of hospitalization for COVID-19 was not significantly associated with vitamin D level.1

Prior studies have also looked at vitamin D and respiratory infection. Martineau and colleagues analyzed 25 randomized, controlled trials with a pooled number of 11,321 individuals, including healthy ones and those with comorbidities, and found that oral vitamin D supplementation in daily or weekly doses had a protective effect against acute respiratory infection (adjusted odds ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81-0.96; P < .001). Patients with vitamin D deficiency (less than 25 nmol/L) experienced the most protective benefit. Vitamin D did not influence respiratory infection outcome.2

These studies suggest an adequate vitamin D level may be protective against infection with COVID-19, but who will benefit from vitamin D supplementation, and in what dose? Per U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults. Regarding daily dietary intake, the Institute of Medicine recommends 600 IU for persons aged 1-70, and 800 IU for those aged over 70 years. Salmon (447 IU per 3 oz serving), tuna (154 IU), and fortified milk (116 IU) are among the most vitamin D–rich foods.3 The recommended upper level of intake is 4,000 IU/day.

Too much of a good thing?

Extra vitamin D is stored in adipose tissue. If it builds up over time, storage sites may be overwhelmed, causing a rise in serum D level. While one might expect a subsequent rise in calcium levels, studies have shown this happens inconsistently, and at very high vitamin D levels, over 120 ng/mL.4 Most people would have to take at least 50,000 IU daily for several months to see an effect. The main adverse outcome of vitamin D toxicity is kidney stones, mediated by increased calcium in the blood and urine.

Several animal models have demonstrated hypervitaminosis D–induced aortic and coronary artery calcification. Like with kidney stones, the mechanism appears to be through increased calcium and phosphate levels. Shroff and colleagues studied serum vitamin D levels and vascular disease in children with renal disease on dialysis and found a U-shaped distribution: Children with both low and high vitamin D levels had significantly increased carotid artery intima-media thickness and calcification.5 Given the specialized nature of this population, it’s unclear whether these results can be generalized to most people. More studies are warranted on this topic.

Other benefits

Vitamin D is perhaps most famous for helping to build strong bones. Avenell and colleagues performed a Cochrane meta-analysis of vitamin D supplementation in older adults and found that vitamin D alone did not significantly reduce the risk of hip or other new fracture. Vitamin D plus calcium supplementation did reduce the risk of hip fracture (nine trials, pooled number of individuals was 49,853; relative risk, 0.84; P = .01).6

A lesser-known benefit of vitamin D is muscle protection. A prospective study out of the Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati followed 146 adults who were intolerant to two or more statins because of muscle side effects and found to have a vitamin D level below 32 ng per mL. Subjects were given vitamin D replacement (50,000 units weekly) and followed for 2 years. On statin rechallenge, 88-95% tolerated a statin with vitamin D levels 53-55 ng/mL.7

Pearl

Vitamin D supplementation may protect against COVID-19 infection and has very low chance of harm at daily doses at or below 4,000 IU. Other benefits of taking vitamin D include bone protection and reduction in statin-induced myopathy. The main adverse effect is kidney stones.

Ms. Sharninghausen is a medical student at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Merzon E et al. Low plasma 25(OH) vitamin D level is associated with increased risk of COVID‐19 infection: An Israeli population‐based study. FEBS J. 2020. doi: 10.1111/febs.15495.

2. Martineau AR et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6583

3. “How to Get More Vitamin D From Your Food,” Cleveland Clinic. 2019 Oct 23. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/how-to-get-more-vitamin-d-from-your-food/.

4. Galior K et al. Development of vitamin d toxicity from overcorrection of vitamin D Deficiency: A review of case reports. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):953. doi: 10.3390/nu10080953

5. Shroff R et al. A bimodal association of vitamin D levels and vascular disease in children on dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(6):1239-46. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007090993.

6. Avenell A et al. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post‐menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Apr 14;2014(4):CD000227. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000227.pub4.

7. Khayznikov M et al. Statin intolerance because of myalgia, myositis, myopathy, or myonecrosis can in most cases be safely resolved by vitamin D supplementation. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7(3):86-93. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.153919

Case: A 56-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity calls clinic to discuss concerns about COVID-19, stating: “I want to do everything I can to reduce my risk of infection.” In addition to physical distancing, mask wearing, hand hygiene, and control of chronic conditions, which of the following supplements would you recommend for this patient?

1. Coenzyme Q10 160 mg twice a day

2. Vitamin D 2,000 IU daily

3. Vitamin E 400 IU daily

4. Vitamin B12 1,000 mcg daily

Of these choices, vitamin D supplementation is likely the best option, based on the limited data that is available.

Risk factors for worse COVID-19 outcome, such as older age, obesity, and more pigmented skin are also risk factors for vitamin D deficiency. This makes the study of vitamin D and COVID-19 both challenging and relevant.

In a recent study of 7,807 people living in Israel, Merzon and colleagues found that low plasma vitamin D level was an independent risk factor for COVID-19 infection. Mean plasma vitamin D level was significantly lower among those who tested positive for COVID-19 (19.00 ng/mL) than negative (20.55 ng/ mL). After controlling for demographic variables and several medical conditions, the adjusted odds ratio of COVID-19 infection in those with lower vitamin D was 1.45 (95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.95; P < .001). However, the odds of hospitalization for COVID-19 was not significantly associated with vitamin D level.1

Prior studies have also looked at vitamin D and respiratory infection. Martineau and colleagues analyzed 25 randomized, controlled trials with a pooled number of 11,321 individuals, including healthy ones and those with comorbidities, and found that oral vitamin D supplementation in daily or weekly doses had a protective effect against acute respiratory infection (adjusted odds ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81-0.96; P < .001). Patients with vitamin D deficiency (less than 25 nmol/L) experienced the most protective benefit. Vitamin D did not influence respiratory infection outcome.2

These studies suggest an adequate vitamin D level may be protective against infection with COVID-19, but who will benefit from vitamin D supplementation, and in what dose? Per U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults. Regarding daily dietary intake, the Institute of Medicine recommends 600 IU for persons aged 1-70, and 800 IU for those aged over 70 years. Salmon (447 IU per 3 oz serving), tuna (154 IU), and fortified milk (116 IU) are among the most vitamin D–rich foods.3 The recommended upper level of intake is 4,000 IU/day.

Too much of a good thing?

Extra vitamin D is stored in adipose tissue. If it builds up over time, storage sites may be overwhelmed, causing a rise in serum D level. While one might expect a subsequent rise in calcium levels, studies have shown this happens inconsistently, and at very high vitamin D levels, over 120 ng/mL.4 Most people would have to take at least 50,000 IU daily for several months to see an effect. The main adverse outcome of vitamin D toxicity is kidney stones, mediated by increased calcium in the blood and urine.

Several animal models have demonstrated hypervitaminosis D–induced aortic and coronary artery calcification. Like with kidney stones, the mechanism appears to be through increased calcium and phosphate levels. Shroff and colleagues studied serum vitamin D levels and vascular disease in children with renal disease on dialysis and found a U-shaped distribution: Children with both low and high vitamin D levels had significantly increased carotid artery intima-media thickness and calcification.5 Given the specialized nature of this population, it’s unclear whether these results can be generalized to most people. More studies are warranted on this topic.

Other benefits

Vitamin D is perhaps most famous for helping to build strong bones. Avenell and colleagues performed a Cochrane meta-analysis of vitamin D supplementation in older adults and found that vitamin D alone did not significantly reduce the risk of hip or other new fracture. Vitamin D plus calcium supplementation did reduce the risk of hip fracture (nine trials, pooled number of individuals was 49,853; relative risk, 0.84; P = .01).6

A lesser-known benefit of vitamin D is muscle protection. A prospective study out of the Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati followed 146 adults who were intolerant to two or more statins because of muscle side effects and found to have a vitamin D level below 32 ng per mL. Subjects were given vitamin D replacement (50,000 units weekly) and followed for 2 years. On statin rechallenge, 88-95% tolerated a statin with vitamin D levels 53-55 ng/mL.7

Pearl

Vitamin D supplementation may protect against COVID-19 infection and has very low chance of harm at daily doses at or below 4,000 IU. Other benefits of taking vitamin D include bone protection and reduction in statin-induced myopathy. The main adverse effect is kidney stones.

Ms. Sharninghausen is a medical student at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Merzon E et al. Low plasma 25(OH) vitamin D level is associated with increased risk of COVID‐19 infection: An Israeli population‐based study. FEBS J. 2020. doi: 10.1111/febs.15495.

2. Martineau AR et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6583

3. “How to Get More Vitamin D From Your Food,” Cleveland Clinic. 2019 Oct 23. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/how-to-get-more-vitamin-d-from-your-food/.

4. Galior K et al. Development of vitamin d toxicity from overcorrection of vitamin D Deficiency: A review of case reports. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):953. doi: 10.3390/nu10080953

5. Shroff R et al. A bimodal association of vitamin D levels and vascular disease in children on dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(6):1239-46. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007090993.

6. Avenell A et al. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post‐menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Apr 14;2014(4):CD000227. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000227.pub4.

7. Khayznikov M et al. Statin intolerance because of myalgia, myositis, myopathy, or myonecrosis can in most cases be safely resolved by vitamin D supplementation. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7(3):86-93. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.153919

Case: A 56-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity calls clinic to discuss concerns about COVID-19, stating: “I want to do everything I can to reduce my risk of infection.” In addition to physical distancing, mask wearing, hand hygiene, and control of chronic conditions, which of the following supplements would you recommend for this patient?

1. Coenzyme Q10 160 mg twice a day

2. Vitamin D 2,000 IU daily

3. Vitamin E 400 IU daily

4. Vitamin B12 1,000 mcg daily

Of these choices, vitamin D supplementation is likely the best option, based on the limited data that is available.

Risk factors for worse COVID-19 outcome, such as older age, obesity, and more pigmented skin are also risk factors for vitamin D deficiency. This makes the study of vitamin D and COVID-19 both challenging and relevant.

In a recent study of 7,807 people living in Israel, Merzon and colleagues found that low plasma vitamin D level was an independent risk factor for COVID-19 infection. Mean plasma vitamin D level was significantly lower among those who tested positive for COVID-19 (19.00 ng/mL) than negative (20.55 ng/ mL). After controlling for demographic variables and several medical conditions, the adjusted odds ratio of COVID-19 infection in those with lower vitamin D was 1.45 (95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.95; P < .001). However, the odds of hospitalization for COVID-19 was not significantly associated with vitamin D level.1

Prior studies have also looked at vitamin D and respiratory infection. Martineau and colleagues analyzed 25 randomized, controlled trials with a pooled number of 11,321 individuals, including healthy ones and those with comorbidities, and found that oral vitamin D supplementation in daily or weekly doses had a protective effect against acute respiratory infection (adjusted odds ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81-0.96; P < .001). Patients with vitamin D deficiency (less than 25 nmol/L) experienced the most protective benefit. Vitamin D did not influence respiratory infection outcome.2

These studies suggest an adequate vitamin D level may be protective against infection with COVID-19, but who will benefit from vitamin D supplementation, and in what dose? Per U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening for vitamin D deficiency in asymptomatic adults. Regarding daily dietary intake, the Institute of Medicine recommends 600 IU for persons aged 1-70, and 800 IU for those aged over 70 years. Salmon (447 IU per 3 oz serving), tuna (154 IU), and fortified milk (116 IU) are among the most vitamin D–rich foods.3 The recommended upper level of intake is 4,000 IU/day.

Too much of a good thing?

Extra vitamin D is stored in adipose tissue. If it builds up over time, storage sites may be overwhelmed, causing a rise in serum D level. While one might expect a subsequent rise in calcium levels, studies have shown this happens inconsistently, and at very high vitamin D levels, over 120 ng/mL.4 Most people would have to take at least 50,000 IU daily for several months to see an effect. The main adverse outcome of vitamin D toxicity is kidney stones, mediated by increased calcium in the blood and urine.

Several animal models have demonstrated hypervitaminosis D–induced aortic and coronary artery calcification. Like with kidney stones, the mechanism appears to be through increased calcium and phosphate levels. Shroff and colleagues studied serum vitamin D levels and vascular disease in children with renal disease on dialysis and found a U-shaped distribution: Children with both low and high vitamin D levels had significantly increased carotid artery intima-media thickness and calcification.5 Given the specialized nature of this population, it’s unclear whether these results can be generalized to most people. More studies are warranted on this topic.

Other benefits

Vitamin D is perhaps most famous for helping to build strong bones. Avenell and colleagues performed a Cochrane meta-analysis of vitamin D supplementation in older adults and found that vitamin D alone did not significantly reduce the risk of hip or other new fracture. Vitamin D plus calcium supplementation did reduce the risk of hip fracture (nine trials, pooled number of individuals was 49,853; relative risk, 0.84; P = .01).6

A lesser-known benefit of vitamin D is muscle protection. A prospective study out of the Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati followed 146 adults who were intolerant to two or more statins because of muscle side effects and found to have a vitamin D level below 32 ng per mL. Subjects were given vitamin D replacement (50,000 units weekly) and followed for 2 years. On statin rechallenge, 88-95% tolerated a statin with vitamin D levels 53-55 ng/mL.7

Pearl

Vitamin D supplementation may protect against COVID-19 infection and has very low chance of harm at daily doses at or below 4,000 IU. Other benefits of taking vitamin D include bone protection and reduction in statin-induced myopathy. The main adverse effect is kidney stones.

Ms. Sharninghausen is a medical student at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Merzon E et al. Low plasma 25(OH) vitamin D level is associated with increased risk of COVID‐19 infection: An Israeli population‐based study. FEBS J. 2020. doi: 10.1111/febs.15495.

2. Martineau AR et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6583

3. “How to Get More Vitamin D From Your Food,” Cleveland Clinic. 2019 Oct 23. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/how-to-get-more-vitamin-d-from-your-food/.

4. Galior K et al. Development of vitamin d toxicity from overcorrection of vitamin D Deficiency: A review of case reports. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):953. doi: 10.3390/nu10080953

5. Shroff R et al. A bimodal association of vitamin D levels and vascular disease in children on dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(6):1239-46. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007090993.

6. Avenell A et al. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post‐menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Apr 14;2014(4):CD000227. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000227.pub4.

7. Khayznikov M et al. Statin intolerance because of myalgia, myositis, myopathy, or myonecrosis can in most cases be safely resolved by vitamin D supplementation. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7(3):86-93. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.153919

Treat obesity like breast cancer, with empathy, say Canadians

A new Canadian clinical practice guideline for treating adults with obesity emphasizes improving health rather than simply losing weight, among other things.

A summary of the guideline, which was developed by Obesity Canada and the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons, was published online August 4 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

This patient-centered update to the 2006 guidelines is “provocative,” starting with its definition of obesity, co–lead author Sean Wharton, MD, adjunct professor at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

The guideline was authored by more than 60 health care professionals and researchers who assessed more than 500,000 peer-reviewed articles and made 80 key recommendations.

These reflect substantial recent advances in the understanding of obesity. Individuals with obesity (from a patient committee of the Obesity Society) helped to shape the key messages.

“People who live with obesity have been shut out of receiving quality health care because of the biased, deeply flawed misconceptions about what drives obesity and how we can improve health,” Lisa Schaffer, chair of Obesity Canada’s Public Engagement Committee, said in a press release.

“Obesity is widely seen as the result of poor personal decisions, but research tells us it is far more complicated than that. Our hope with the [new] clinical practice guideline is that more health care professionals, health policy makers, benefits providers and people living with obesity will have a better understanding of it, so we can help more of those who need it.”

“Obesity management should be about compassion and empathy, and then everything falls into place,” Dr. Wharton said. “Think of obesity like breast cancer.”

Address the root causes of obesity

The guideline defines obesity as “a prevalent, complex, progressive and relapsing chronic disease, characterized by abnormal or excessive body fat (adiposity) that impairs health.”

Aimed at primary care providers, the document stresses that clinicians need to “move beyond simplistic approaches of ‘eat less, move more,’ and address the root drivers of obesity.”

As a first step, doctors should ask a patient for permission to discuss weight (e.g., they can ask: “Would it be all right if we discussed your weight?”) – which demonstrates empathy and can help build patient-provider trust.

Clinicians can still measure body mass index as part of a routine physical examination, but they should also obtain a comprehensive patient history to identify the root causes of any weight gain (which could include genetics or psychological factors such as depression and anxiety), as well as any barriers to managing obesity.

‘Eat less, move more’ is too simple: Employ three pillars

Advice to “eat less and move more is dangerously simplistic,” coauthor Arya M. Sharma, MD, from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and scientific director of Obesity Canada, said in an interview that “the body fights to put back any lost weight.”

Patients with obesity need “medical nutrition therapy.” For patients at risk for heart disease, that may mean following a Mediterranean diet, Dr. Wharton said.

“Physical activity and medical nutrition therapy are absolutely necessary” to manage obesity, he clarified. As a person loses weight, their body “releases a cascade of neurochemicals and hormones that try to push the weight back up” to the original weight or even higher.

Therefore, to maintain weight loss, people need support from one or more of what he calls the “three pillars” of effective long-term weight loss – pharmacotherapy, bariatric surgery, and cognitive-behavioral therapy – which tempers this cascade of neurochemicals.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy could be given by various health care professionals, he noted. A behavioral strategy to stop snacking, for example, is to wait 5 minutes before eating a desired snack to make sure you still want it.

Similarly, Dr. Sharma noted, “the reason obesity is a chronic disease is that once you’ve gained the weight, your body is not going to want to lose it. That is what I tell all my patients: ‘Your body doesn’t care why you put on the weight, but it does care about keeping it there, and it’s going to fight you’ when you try to maintain weight loss.”

“Clinicians should feel very comfortable” treating obesity as a chronic disease, he added, because they are already treating chronic diseases such as heart, lung, and kidney disease.

Don’t play the blame game: ‘Think of obesity like breast cancer’

Clinicians also need to avoid “shaming and blaming patients with obesity,” said Dr. Sharma.

He noted that many patients have internalized weight bias and blame their excess weight on their lack of willpower. They may not want to talk about weight-loss medications or bariatric surgery because they feel that’s “cheating.”

By thinking of obesity in a similar way to cancer, doctors can help themselves respond to patients in a kinder way. “What would we do with somebody who has breast cancer? We would have compassion. We would talk about surgery to get the lump out and medication to keep the cancer from coming back, and we would engage them in psychological treatment or counseling for some of the challenges they have to face,” Dr. Wharton said.

“The right answer is to treat [obesity] like a disease – with surgery, medication, and psychological intervention,” depending on the individual patient, he added.

The complete guideline is available on the Obesity Canada website.

The study was funded by Obesity Canada, the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Wharton has received honoraria and travel expenses and has participated in academic advisory boards for Novo Nordisk, Bausch Health, Eli Lilly, and Janssen. He is the medical director of a medical clinic specializing in weight management and diabetes. Dr. Sharma has received speaker’s bureau and consulting fees from Novo Nordisk, Bausch Pharmaceuticals, and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new Canadian clinical practice guideline for treating adults with obesity emphasizes improving health rather than simply losing weight, among other things.

A summary of the guideline, which was developed by Obesity Canada and the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons, was published online August 4 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

This patient-centered update to the 2006 guidelines is “provocative,” starting with its definition of obesity, co–lead author Sean Wharton, MD, adjunct professor at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

The guideline was authored by more than 60 health care professionals and researchers who assessed more than 500,000 peer-reviewed articles and made 80 key recommendations.

These reflect substantial recent advances in the understanding of obesity. Individuals with obesity (from a patient committee of the Obesity Society) helped to shape the key messages.

“People who live with obesity have been shut out of receiving quality health care because of the biased, deeply flawed misconceptions about what drives obesity and how we can improve health,” Lisa Schaffer, chair of Obesity Canada’s Public Engagement Committee, said in a press release.

“Obesity is widely seen as the result of poor personal decisions, but research tells us it is far more complicated than that. Our hope with the [new] clinical practice guideline is that more health care professionals, health policy makers, benefits providers and people living with obesity will have a better understanding of it, so we can help more of those who need it.”

“Obesity management should be about compassion and empathy, and then everything falls into place,” Dr. Wharton said. “Think of obesity like breast cancer.”

Address the root causes of obesity

The guideline defines obesity as “a prevalent, complex, progressive and relapsing chronic disease, characterized by abnormal or excessive body fat (adiposity) that impairs health.”

Aimed at primary care providers, the document stresses that clinicians need to “move beyond simplistic approaches of ‘eat less, move more,’ and address the root drivers of obesity.”

As a first step, doctors should ask a patient for permission to discuss weight (e.g., they can ask: “Would it be all right if we discussed your weight?”) – which demonstrates empathy and can help build patient-provider trust.

Clinicians can still measure body mass index as part of a routine physical examination, but they should also obtain a comprehensive patient history to identify the root causes of any weight gain (which could include genetics or psychological factors such as depression and anxiety), as well as any barriers to managing obesity.

‘Eat less, move more’ is too simple: Employ three pillars

Advice to “eat less and move more is dangerously simplistic,” coauthor Arya M. Sharma, MD, from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and scientific director of Obesity Canada, said in an interview that “the body fights to put back any lost weight.”

Patients with obesity need “medical nutrition therapy.” For patients at risk for heart disease, that may mean following a Mediterranean diet, Dr. Wharton said.

“Physical activity and medical nutrition therapy are absolutely necessary” to manage obesity, he clarified. As a person loses weight, their body “releases a cascade of neurochemicals and hormones that try to push the weight back up” to the original weight or even higher.

Therefore, to maintain weight loss, people need support from one or more of what he calls the “three pillars” of effective long-term weight loss – pharmacotherapy, bariatric surgery, and cognitive-behavioral therapy – which tempers this cascade of neurochemicals.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy could be given by various health care professionals, he noted. A behavioral strategy to stop snacking, for example, is to wait 5 minutes before eating a desired snack to make sure you still want it.

Similarly, Dr. Sharma noted, “the reason obesity is a chronic disease is that once you’ve gained the weight, your body is not going to want to lose it. That is what I tell all my patients: ‘Your body doesn’t care why you put on the weight, but it does care about keeping it there, and it’s going to fight you’ when you try to maintain weight loss.”

“Clinicians should feel very comfortable” treating obesity as a chronic disease, he added, because they are already treating chronic diseases such as heart, lung, and kidney disease.

Don’t play the blame game: ‘Think of obesity like breast cancer’

Clinicians also need to avoid “shaming and blaming patients with obesity,” said Dr. Sharma.

He noted that many patients have internalized weight bias and blame their excess weight on their lack of willpower. They may not want to talk about weight-loss medications or bariatric surgery because they feel that’s “cheating.”

By thinking of obesity in a similar way to cancer, doctors can help themselves respond to patients in a kinder way. “What would we do with somebody who has breast cancer? We would have compassion. We would talk about surgery to get the lump out and medication to keep the cancer from coming back, and we would engage them in psychological treatment or counseling for some of the challenges they have to face,” Dr. Wharton said.

“The right answer is to treat [obesity] like a disease – with surgery, medication, and psychological intervention,” depending on the individual patient, he added.

The complete guideline is available on the Obesity Canada website.

The study was funded by Obesity Canada, the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Wharton has received honoraria and travel expenses and has participated in academic advisory boards for Novo Nordisk, Bausch Health, Eli Lilly, and Janssen. He is the medical director of a medical clinic specializing in weight management and diabetes. Dr. Sharma has received speaker’s bureau and consulting fees from Novo Nordisk, Bausch Pharmaceuticals, and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new Canadian clinical practice guideline for treating adults with obesity emphasizes improving health rather than simply losing weight, among other things.

A summary of the guideline, which was developed by Obesity Canada and the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons, was published online August 4 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

This patient-centered update to the 2006 guidelines is “provocative,” starting with its definition of obesity, co–lead author Sean Wharton, MD, adjunct professor at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

The guideline was authored by more than 60 health care professionals and researchers who assessed more than 500,000 peer-reviewed articles and made 80 key recommendations.

These reflect substantial recent advances in the understanding of obesity. Individuals with obesity (from a patient committee of the Obesity Society) helped to shape the key messages.

“People who live with obesity have been shut out of receiving quality health care because of the biased, deeply flawed misconceptions about what drives obesity and how we can improve health,” Lisa Schaffer, chair of Obesity Canada’s Public Engagement Committee, said in a press release.

“Obesity is widely seen as the result of poor personal decisions, but research tells us it is far more complicated than that. Our hope with the [new] clinical practice guideline is that more health care professionals, health policy makers, benefits providers and people living with obesity will have a better understanding of it, so we can help more of those who need it.”

“Obesity management should be about compassion and empathy, and then everything falls into place,” Dr. Wharton said. “Think of obesity like breast cancer.”

Address the root causes of obesity

The guideline defines obesity as “a prevalent, complex, progressive and relapsing chronic disease, characterized by abnormal or excessive body fat (adiposity) that impairs health.”

Aimed at primary care providers, the document stresses that clinicians need to “move beyond simplistic approaches of ‘eat less, move more,’ and address the root drivers of obesity.”

As a first step, doctors should ask a patient for permission to discuss weight (e.g., they can ask: “Would it be all right if we discussed your weight?”) – which demonstrates empathy and can help build patient-provider trust.

Clinicians can still measure body mass index as part of a routine physical examination, but they should also obtain a comprehensive patient history to identify the root causes of any weight gain (which could include genetics or psychological factors such as depression and anxiety), as well as any barriers to managing obesity.

‘Eat less, move more’ is too simple: Employ three pillars

Advice to “eat less and move more is dangerously simplistic,” coauthor Arya M. Sharma, MD, from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and scientific director of Obesity Canada, said in an interview that “the body fights to put back any lost weight.”

Patients with obesity need “medical nutrition therapy.” For patients at risk for heart disease, that may mean following a Mediterranean diet, Dr. Wharton said.

“Physical activity and medical nutrition therapy are absolutely necessary” to manage obesity, he clarified. As a person loses weight, their body “releases a cascade of neurochemicals and hormones that try to push the weight back up” to the original weight or even higher.

Therefore, to maintain weight loss, people need support from one or more of what he calls the “three pillars” of effective long-term weight loss – pharmacotherapy, bariatric surgery, and cognitive-behavioral therapy – which tempers this cascade of neurochemicals.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy could be given by various health care professionals, he noted. A behavioral strategy to stop snacking, for example, is to wait 5 minutes before eating a desired snack to make sure you still want it.

Similarly, Dr. Sharma noted, “the reason obesity is a chronic disease is that once you’ve gained the weight, your body is not going to want to lose it. That is what I tell all my patients: ‘Your body doesn’t care why you put on the weight, but it does care about keeping it there, and it’s going to fight you’ when you try to maintain weight loss.”

“Clinicians should feel very comfortable” treating obesity as a chronic disease, he added, because they are already treating chronic diseases such as heart, lung, and kidney disease.

Don’t play the blame game: ‘Think of obesity like breast cancer’

Clinicians also need to avoid “shaming and blaming patients with obesity,” said Dr. Sharma.

He noted that many patients have internalized weight bias and blame their excess weight on their lack of willpower. They may not want to talk about weight-loss medications or bariatric surgery because they feel that’s “cheating.”

By thinking of obesity in a similar way to cancer, doctors can help themselves respond to patients in a kinder way. “What would we do with somebody who has breast cancer? We would have compassion. We would talk about surgery to get the lump out and medication to keep the cancer from coming back, and we would engage them in psychological treatment or counseling for some of the challenges they have to face,” Dr. Wharton said.

“The right answer is to treat [obesity] like a disease – with surgery, medication, and psychological intervention,” depending on the individual patient, he added.

The complete guideline is available on the Obesity Canada website.

The study was funded by Obesity Canada, the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Wharton has received honoraria and travel expenses and has participated in academic advisory boards for Novo Nordisk, Bausch Health, Eli Lilly, and Janssen. He is the medical director of a medical clinic specializing in weight management and diabetes. Dr. Sharma has received speaker’s bureau and consulting fees from Novo Nordisk, Bausch Pharmaceuticals, and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

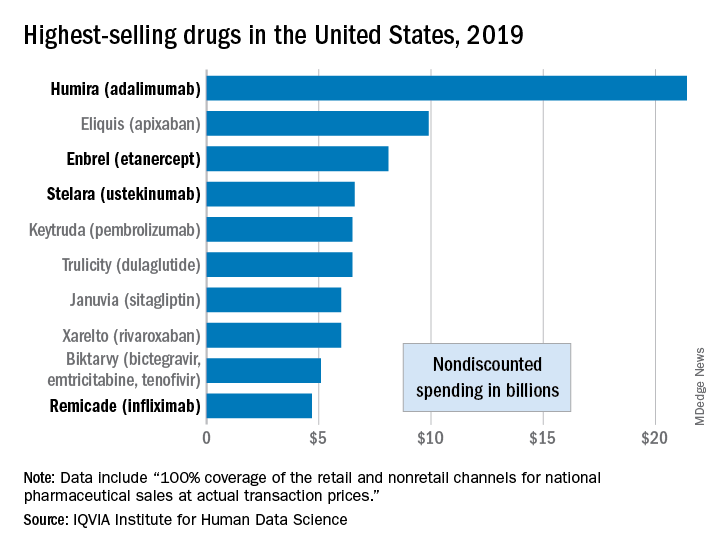

Humira topped drug-revenue list for 2019

Humira outsold all other drugs in 2019 in terms of revenue as cytokine inhibitor medications earned their way to three of the first four spots on the pharmaceutical best-seller list, according to a new analysis from the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science.

Sales of Humira (adalimumab) amounted to $21.4 billion before discounting, Murray Aitken, the institute’s executive director, and associates wrote in their analysis. That’s more than double the total of the anticoagulant Eliquis (apixaban), which brought in $9.9 billion in its last year before generic forms became available.

The next two spots were filled by the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor Enbrel (etanercept) with $8.1 billion in sales and the interleukin 12/23 inhibitor Stelara (ustekinumab) with sales totaling $6.6 billion, followed by the chemotherapy drug Keytruda (pembrolizumab) close behind after racking up $6.5 billion in sales, the researchers reported.

Total nondiscounted spending on all drugs in the U.S. market came to $511 billion in 2019, an increase of 5.7% over the $484 billion spent in 2018, based on data from the July 2020 IQVIA National Sales Perspectives.

These figures are “not adjusted for estimates of off-invoice discounts and rebates,” the authors noted, but they include “prescription and insulin products sold into chain and independent pharmacies, food store pharmacies, mail service pharmacies, long-term care facilities, hospitals, clinics, and other institutional settings.”

Those “discounts and rebates” do exist, however, and they can add up. Drug sales for 2019, “after deducting negotiated rebates, discounts, and other forms of price concessions, such as patient coupons or vouchers that offset out-of-pocket costs,” were $235 billion less than overall nondiscounted spending, the report noted.

Now that we’ve shown you the money, let’s take a quick look at volume. The leading drugs by number of dispensed prescriptions in 2019 were, not surprisingly, quite different. First, with 118 million prescriptions, was atorvastatin, followed by levothyroxine (113 million), lisinopril (96), amlodipine (89), and metoprolol (85), Mr. Aitken and associates reported.

Altogether, over 4.2 billion prescriptions were dispensed last year, with a couple of caveats: 90-day and 30-day fills were both counted as one prescription, and OTC drugs were not included, they pointed out.

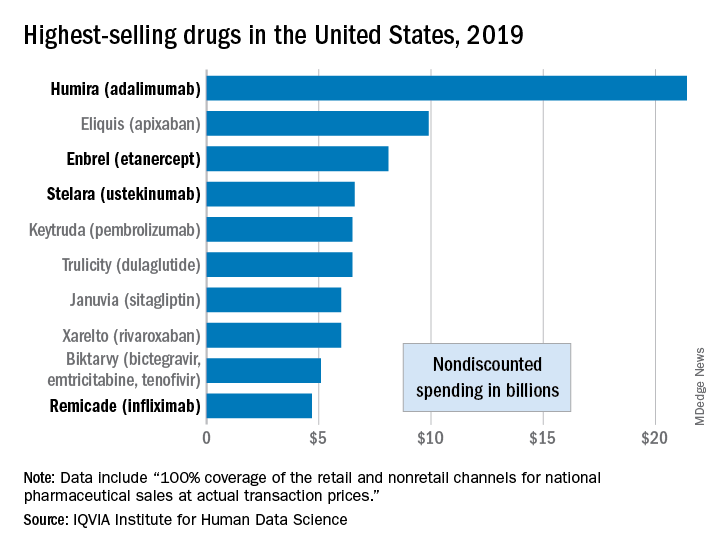

Humira outsold all other drugs in 2019 in terms of revenue as cytokine inhibitor medications earned their way to three of the first four spots on the pharmaceutical best-seller list, according to a new analysis from the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science.

Sales of Humira (adalimumab) amounted to $21.4 billion before discounting, Murray Aitken, the institute’s executive director, and associates wrote in their analysis. That’s more than double the total of the anticoagulant Eliquis (apixaban), which brought in $9.9 billion in its last year before generic forms became available.

The next two spots were filled by the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor Enbrel (etanercept) with $8.1 billion in sales and the interleukin 12/23 inhibitor Stelara (ustekinumab) with sales totaling $6.6 billion, followed by the chemotherapy drug Keytruda (pembrolizumab) close behind after racking up $6.5 billion in sales, the researchers reported.

Total nondiscounted spending on all drugs in the U.S. market came to $511 billion in 2019, an increase of 5.7% over the $484 billion spent in 2018, based on data from the July 2020 IQVIA National Sales Perspectives.

These figures are “not adjusted for estimates of off-invoice discounts and rebates,” the authors noted, but they include “prescription and insulin products sold into chain and independent pharmacies, food store pharmacies, mail service pharmacies, long-term care facilities, hospitals, clinics, and other institutional settings.”

Those “discounts and rebates” do exist, however, and they can add up. Drug sales for 2019, “after deducting negotiated rebates, discounts, and other forms of price concessions, such as patient coupons or vouchers that offset out-of-pocket costs,” were $235 billion less than overall nondiscounted spending, the report noted.

Now that we’ve shown you the money, let’s take a quick look at volume. The leading drugs by number of dispensed prescriptions in 2019 were, not surprisingly, quite different. First, with 118 million prescriptions, was atorvastatin, followed by levothyroxine (113 million), lisinopril (96), amlodipine (89), and metoprolol (85), Mr. Aitken and associates reported.

Altogether, over 4.2 billion prescriptions were dispensed last year, with a couple of caveats: 90-day and 30-day fills were both counted as one prescription, and OTC drugs were not included, they pointed out.

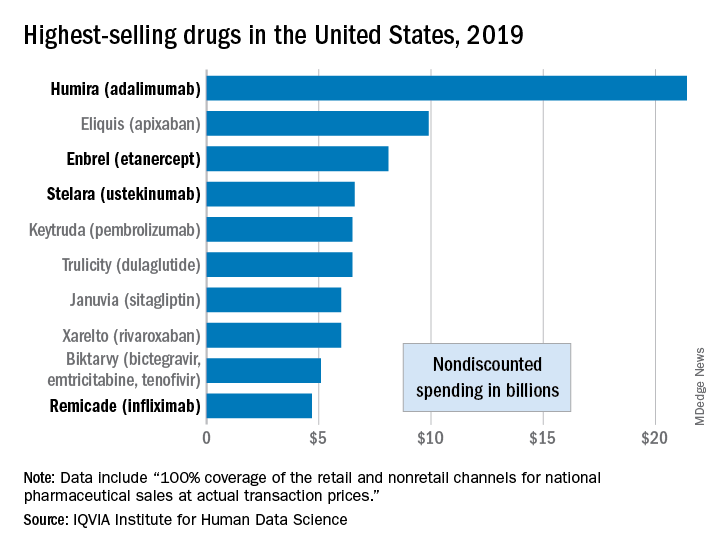

Humira outsold all other drugs in 2019 in terms of revenue as cytokine inhibitor medications earned their way to three of the first four spots on the pharmaceutical best-seller list, according to a new analysis from the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science.

Sales of Humira (adalimumab) amounted to $21.4 billion before discounting, Murray Aitken, the institute’s executive director, and associates wrote in their analysis. That’s more than double the total of the anticoagulant Eliquis (apixaban), which brought in $9.9 billion in its last year before generic forms became available.

The next two spots were filled by the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor Enbrel (etanercept) with $8.1 billion in sales and the interleukin 12/23 inhibitor Stelara (ustekinumab) with sales totaling $6.6 billion, followed by the chemotherapy drug Keytruda (pembrolizumab) close behind after racking up $6.5 billion in sales, the researchers reported.

Total nondiscounted spending on all drugs in the U.S. market came to $511 billion in 2019, an increase of 5.7% over the $484 billion spent in 2018, based on data from the July 2020 IQVIA National Sales Perspectives.

These figures are “not adjusted for estimates of off-invoice discounts and rebates,” the authors noted, but they include “prescription and insulin products sold into chain and independent pharmacies, food store pharmacies, mail service pharmacies, long-term care facilities, hospitals, clinics, and other institutional settings.”

Those “discounts and rebates” do exist, however, and they can add up. Drug sales for 2019, “after deducting negotiated rebates, discounts, and other forms of price concessions, such as patient coupons or vouchers that offset out-of-pocket costs,” were $235 billion less than overall nondiscounted spending, the report noted.

Now that we’ve shown you the money, let’s take a quick look at volume. The leading drugs by number of dispensed prescriptions in 2019 were, not surprisingly, quite different. First, with 118 million prescriptions, was atorvastatin, followed by levothyroxine (113 million), lisinopril (96), amlodipine (89), and metoprolol (85), Mr. Aitken and associates reported.

Altogether, over 4.2 billion prescriptions were dispensed last year, with a couple of caveats: 90-day and 30-day fills were both counted as one prescription, and OTC drugs were not included, they pointed out.

NAFLD may predict arrhythmia recurrence post-AFib ablation

Increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib), new research suggests for the first time that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also confers a higher risk for arrhythmia recurrence after AFib ablation.

Over 29 months of postablation follow-up, 56% of patients with NAFLD suffered bouts of arrhythmia, compared with 31% of patients without NAFLD, matched on the basis of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ejection fraction within 5%, and AFib type (P < .0001).

The presence of NAFLD was an independent predictor of arrhythmia recurrence in multivariable analyses adjusted for several confounders, including hemoglobin A1c, BMI, and AFib type (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-4.68).

The association is concerning given that one in four adults in the United States has NAFLD, and up to 6.1 million Americans are estimated to have Afib. Previous studies, such as ARREST-AF and LEGACY, however, have demonstrated the benefits of aggressive preablation cardiometabolic risk factor modification on long-term AFib ablation success.

Indeed, none of the NAFLD patients in the present study who lost at least 10% of their body weight had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 31% who lost less than 10%, and 91% who gained weight prior to ablation (P < .0001).

All 22 patients whose A1c increased during the 12 months prior to ablation had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 36% of patients whose A1c improved (P < .0001).

“I don’t think the findings of the study were particularly surprising, given what we know. It’s just further reinforcement of the essential role of risk-factor modification,” lead author Eoin Donnellan, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

The results were published Augus 12 in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology.

For the study, the researchers examined data from 267 consecutive patients with a mean BMI of 32.7 kg/m2 who underwent radiofrequency ablation (98%) or cryoablation (2%) at the Cleveland Clinic between January 2013 and December 2017.

All patients were followed for at least 12 months after ablation and had scheduled clinic visits at 3, 6, and 12 months after pulmonary vein isolation, and annually thereafter.

NAFLD was diagnosed in 89 patients prior to ablation on the basis of CT imaging and abdominal ultrasound or MRI. On the basis of NAFLD-Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-FS), 13 patients had a low probability of liver fibrosis (F0-F2), 54 had an indeterminate probability, and 22 a high probability of fibrosis (F3-F4).

Compared with patients with no or early fibrosis (F0-F2), patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) had almost a threefold increase in AFib recurrence (82% vs. 31%; P = .003).

“Cardiologists should make an effort to risk-stratify NAFLD patients either by NAFLD-FS or [an] alternative option, such as transient elastography or MR elastography, given these observations, rather than viewing it as either present or absence [sic] and involve expert multidisciplinary team care early in the clinical course of NAFLD patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues wrote.

Coauthor Thomas G. Cotter, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago, said in an interview that cardiologists could use just the NAFLD-FS as part of an algorithm for an AFib.

“Because if it shows low risk, then it’s very, very likely the patient will be fine,” he said. “To use more advanced noninvasive testing, there are subtleties in the interpretation that would require referral to a liver doctor or a gastroenterologist and the cost of referring might bulk up the costs. But the NAFLD-FS is freely available and is a validated tool.”

Although it hasn’t specifically been validated in patients with AFib, the NAFLD-FS has been shown to correlate with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and was recommended for clinical use in U.S. multisociety guidelines for NAFLD.

The score is calculated using six readily available clinical variables (age, BMI, hyperglycemia or diabetes, AST/ALT, platelets, and albumin). It does not include family history or alcohol consumption, which should be carefully detailed given the large overlap between NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease, Dr. Cotter observed.

Of note, the study excluded patients with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day in men and more than 20 g/day in women, chronic viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis.

Finally, CT imaging revealed that epicardial fat volume (EFV) was greater in patients with NAFLD than in those without NAFLD (248 vs. 223 mL; P = .01).

Although increased amounts of epicardial fat have been associated with CAD, there was no significant difference in EFV between patients who did and did not develop recurrent arrhythmia (238 vs. 229 mL; P = .5). Nor was EFV associated with arrhythmia recurrence on Cox proportional hazards analysis (HR, 1.001; P = .17).

“We hypothesized that the increased risk of arrhythmia recurrence may be mediated in part by an increased epicardial fat volume,” Dr. Donnellan said. “The existing literature exploring the link between epicardial fat volume and A[Fib] burden and recurrence is conflicting. But in both this study and our bariatric surgery study, epicardial fat volume was not a significant predictor of arrhythmia recurrence on multivariable analysis.”

It’s likely that the increased recurrence risk is caused by several mechanisms, including NAFLD’s deleterious impact on cardiac structure and function, the bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and sleep apnea, and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade systemic inflammation, he suggested.

“Patients with NAFLD represent a particularly high-risk population for arrhythmia recurrence. NAFLD is a reversible disease, and a multidisciplinary approach incorporating dietary and lifestyle interventions should by instituted prior to ablation,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues concluded.

They noted that serial abdominal imaging to assess for preablation changes in NAFLD was limited in patients and that only 56% of control subjects underwent dedicated abdominal imaging to rule out hepatic steatosis. Also, the heterogeneity of imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD may have influenced the results and the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits their generalizability.

The authors reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib), new research suggests for the first time that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also confers a higher risk for arrhythmia recurrence after AFib ablation.

Over 29 months of postablation follow-up, 56% of patients with NAFLD suffered bouts of arrhythmia, compared with 31% of patients without NAFLD, matched on the basis of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ejection fraction within 5%, and AFib type (P < .0001).

The presence of NAFLD was an independent predictor of arrhythmia recurrence in multivariable analyses adjusted for several confounders, including hemoglobin A1c, BMI, and AFib type (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-4.68).

The association is concerning given that one in four adults in the United States has NAFLD, and up to 6.1 million Americans are estimated to have Afib. Previous studies, such as ARREST-AF and LEGACY, however, have demonstrated the benefits of aggressive preablation cardiometabolic risk factor modification on long-term AFib ablation success.

Indeed, none of the NAFLD patients in the present study who lost at least 10% of their body weight had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 31% who lost less than 10%, and 91% who gained weight prior to ablation (P < .0001).

All 22 patients whose A1c increased during the 12 months prior to ablation had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 36% of patients whose A1c improved (P < .0001).

“I don’t think the findings of the study were particularly surprising, given what we know. It’s just further reinforcement of the essential role of risk-factor modification,” lead author Eoin Donnellan, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

The results were published Augus 12 in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology.

For the study, the researchers examined data from 267 consecutive patients with a mean BMI of 32.7 kg/m2 who underwent radiofrequency ablation (98%) or cryoablation (2%) at the Cleveland Clinic between January 2013 and December 2017.

All patients were followed for at least 12 months after ablation and had scheduled clinic visits at 3, 6, and 12 months after pulmonary vein isolation, and annually thereafter.

NAFLD was diagnosed in 89 patients prior to ablation on the basis of CT imaging and abdominal ultrasound or MRI. On the basis of NAFLD-Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-FS), 13 patients had a low probability of liver fibrosis (F0-F2), 54 had an indeterminate probability, and 22 a high probability of fibrosis (F3-F4).

Compared with patients with no or early fibrosis (F0-F2), patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) had almost a threefold increase in AFib recurrence (82% vs. 31%; P = .003).

“Cardiologists should make an effort to risk-stratify NAFLD patients either by NAFLD-FS or [an] alternative option, such as transient elastography or MR elastography, given these observations, rather than viewing it as either present or absence [sic] and involve expert multidisciplinary team care early in the clinical course of NAFLD patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues wrote.

Coauthor Thomas G. Cotter, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago, said in an interview that cardiologists could use just the NAFLD-FS as part of an algorithm for an AFib.

“Because if it shows low risk, then it’s very, very likely the patient will be fine,” he said. “To use more advanced noninvasive testing, there are subtleties in the interpretation that would require referral to a liver doctor or a gastroenterologist and the cost of referring might bulk up the costs. But the NAFLD-FS is freely available and is a validated tool.”

Although it hasn’t specifically been validated in patients with AFib, the NAFLD-FS has been shown to correlate with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and was recommended for clinical use in U.S. multisociety guidelines for NAFLD.

The score is calculated using six readily available clinical variables (age, BMI, hyperglycemia or diabetes, AST/ALT, platelets, and albumin). It does not include family history or alcohol consumption, which should be carefully detailed given the large overlap between NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease, Dr. Cotter observed.

Of note, the study excluded patients with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day in men and more than 20 g/day in women, chronic viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis.

Finally, CT imaging revealed that epicardial fat volume (EFV) was greater in patients with NAFLD than in those without NAFLD (248 vs. 223 mL; P = .01).

Although increased amounts of epicardial fat have been associated with CAD, there was no significant difference in EFV between patients who did and did not develop recurrent arrhythmia (238 vs. 229 mL; P = .5). Nor was EFV associated with arrhythmia recurrence on Cox proportional hazards analysis (HR, 1.001; P = .17).

“We hypothesized that the increased risk of arrhythmia recurrence may be mediated in part by an increased epicardial fat volume,” Dr. Donnellan said. “The existing literature exploring the link between epicardial fat volume and A[Fib] burden and recurrence is conflicting. But in both this study and our bariatric surgery study, epicardial fat volume was not a significant predictor of arrhythmia recurrence on multivariable analysis.”

It’s likely that the increased recurrence risk is caused by several mechanisms, including NAFLD’s deleterious impact on cardiac structure and function, the bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and sleep apnea, and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade systemic inflammation, he suggested.

“Patients with NAFLD represent a particularly high-risk population for arrhythmia recurrence. NAFLD is a reversible disease, and a multidisciplinary approach incorporating dietary and lifestyle interventions should by instituted prior to ablation,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues concluded.

They noted that serial abdominal imaging to assess for preablation changes in NAFLD was limited in patients and that only 56% of control subjects underwent dedicated abdominal imaging to rule out hepatic steatosis. Also, the heterogeneity of imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD may have influenced the results and the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits their generalizability.

The authors reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib), new research suggests for the first time that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also confers a higher risk for arrhythmia recurrence after AFib ablation.

Over 29 months of postablation follow-up, 56% of patients with NAFLD suffered bouts of arrhythmia, compared with 31% of patients without NAFLD, matched on the basis of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ejection fraction within 5%, and AFib type (P < .0001).

The presence of NAFLD was an independent predictor of arrhythmia recurrence in multivariable analyses adjusted for several confounders, including hemoglobin A1c, BMI, and AFib type (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-4.68).

The association is concerning given that one in four adults in the United States has NAFLD, and up to 6.1 million Americans are estimated to have Afib. Previous studies, such as ARREST-AF and LEGACY, however, have demonstrated the benefits of aggressive preablation cardiometabolic risk factor modification on long-term AFib ablation success.

Indeed, none of the NAFLD patients in the present study who lost at least 10% of their body weight had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 31% who lost less than 10%, and 91% who gained weight prior to ablation (P < .0001).

All 22 patients whose A1c increased during the 12 months prior to ablation had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 36% of patients whose A1c improved (P < .0001).

“I don’t think the findings of the study were particularly surprising, given what we know. It’s just further reinforcement of the essential role of risk-factor modification,” lead author Eoin Donnellan, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

The results were published Augus 12 in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology.

For the study, the researchers examined data from 267 consecutive patients with a mean BMI of 32.7 kg/m2 who underwent radiofrequency ablation (98%) or cryoablation (2%) at the Cleveland Clinic between January 2013 and December 2017.

All patients were followed for at least 12 months after ablation and had scheduled clinic visits at 3, 6, and 12 months after pulmonary vein isolation, and annually thereafter.

NAFLD was diagnosed in 89 patients prior to ablation on the basis of CT imaging and abdominal ultrasound or MRI. On the basis of NAFLD-Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-FS), 13 patients had a low probability of liver fibrosis (F0-F2), 54 had an indeterminate probability, and 22 a high probability of fibrosis (F3-F4).

Compared with patients with no or early fibrosis (F0-F2), patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) had almost a threefold increase in AFib recurrence (82% vs. 31%; P = .003).

“Cardiologists should make an effort to risk-stratify NAFLD patients either by NAFLD-FS or [an] alternative option, such as transient elastography or MR elastography, given these observations, rather than viewing it as either present or absence [sic] and involve expert multidisciplinary team care early in the clinical course of NAFLD patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues wrote.

Coauthor Thomas G. Cotter, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago, said in an interview that cardiologists could use just the NAFLD-FS as part of an algorithm for an AFib.

“Because if it shows low risk, then it’s very, very likely the patient will be fine,” he said. “To use more advanced noninvasive testing, there are subtleties in the interpretation that would require referral to a liver doctor or a gastroenterologist and the cost of referring might bulk up the costs. But the NAFLD-FS is freely available and is a validated tool.”

Although it hasn’t specifically been validated in patients with AFib, the NAFLD-FS has been shown to correlate with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and was recommended for clinical use in U.S. multisociety guidelines for NAFLD.

The score is calculated using six readily available clinical variables (age, BMI, hyperglycemia or diabetes, AST/ALT, platelets, and albumin). It does not include family history or alcohol consumption, which should be carefully detailed given the large overlap between NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease, Dr. Cotter observed.

Of note, the study excluded patients with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day in men and more than 20 g/day in women, chronic viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis.

Finally, CT imaging revealed that epicardial fat volume (EFV) was greater in patients with NAFLD than in those without NAFLD (248 vs. 223 mL; P = .01).

Although increased amounts of epicardial fat have been associated with CAD, there was no significant difference in EFV between patients who did and did not develop recurrent arrhythmia (238 vs. 229 mL; P = .5). Nor was EFV associated with arrhythmia recurrence on Cox proportional hazards analysis (HR, 1.001; P = .17).

“We hypothesized that the increased risk of arrhythmia recurrence may be mediated in part by an increased epicardial fat volume,” Dr. Donnellan said. “The existing literature exploring the link between epicardial fat volume and A[Fib] burden and recurrence is conflicting. But in both this study and our bariatric surgery study, epicardial fat volume was not a significant predictor of arrhythmia recurrence on multivariable analysis.”

It’s likely that the increased recurrence risk is caused by several mechanisms, including NAFLD’s deleterious impact on cardiac structure and function, the bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and sleep apnea, and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade systemic inflammation, he suggested.

“Patients with NAFLD represent a particularly high-risk population for arrhythmia recurrence. NAFLD is a reversible disease, and a multidisciplinary approach incorporating dietary and lifestyle interventions should by instituted prior to ablation,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues concluded.

They noted that serial abdominal imaging to assess for preablation changes in NAFLD was limited in patients and that only 56% of control subjects underwent dedicated abdominal imaging to rule out hepatic steatosis. Also, the heterogeneity of imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD may have influenced the results and the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits their generalizability.

The authors reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

AHA statement recommends dietary screening at routine checkups

A new scientific statement from the American Heart Association recommends incorporating a rapid diet-screening tool into routine primary care visits to inform dietary counseling and integrating the tool into patients’ electronic health record platforms across all healthcare settings.

The statement authors evaluated 15 existing screening tools and, although they did not recommend a specific tool, they did present advantages and disadvantages of some of the tools and encouraged “critical conversations” among clinicians and other specialists to arrive at a tool that would be most appropriate for use in a particular health care setting.

“The key takeaway is for clinicians to incorporate discussion of dietary patterns into routine preventive care appointments because a suboptimal diet is the No. 1 risk factor for cardiovascular disease,” Maya Vadiveloo, PhD, RD, chair of the statement group, said in an interview.