User login

RNase drug shows promise for Sjögren’s fatigue

MADRID – RSLV-132, a novel drug that eliminates circulating nucleic acids, improved the symptoms of mental fatigue in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) in a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled “proof-of-concept” study.

The mental component of fatigue on the Profile of Fatigue (PRO-F) scale improved by 1.53 points among the patients given RSLV-132, while there was a worsening of 0.06 points in the placebo group (P = .046). Scores range from 0 to 7 on the PRO-F.

There were also improvements in some patient-reported outcomes, namely the EULAR pSS Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue (FACIT-F), and improvement of neuropsychological measures of cognitive function, but none were statistically significant. All of these outcomes, including fatigue, were secondary outcomes of the study.

“Fatigue is a major issue for patients with Sjögren’s syndrome,” Wan-Fai Ng, MBChB, PhD, said in an interview at the European Congress of Rheumatology. Indeed, fatigue can be disabling in the majority of individuals, he added.

Currently, the best way to manage fatigue is to first ask about it, said Dr. Ng, who is professor of rheumatology at the Institute of Cellular Medicine at Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. He then checks for any underlying problem that could be better managed – sleep problems or anemia, for example – and optimizes treatment for any underlying disease. “I think many people would at least feel satisfied that people take the symptoms seriously.”

Dr. Ng and his coauthors investigated the effects of RSLV-132, a first-in-class human RNase fused to the human Fc domain of human immunoglobulin (Ig) G1, in the RESOLVE 132-04 study. This novel drug been designed to increase serum RNase activity to digest RNA-associated immune complexes, Dr. Ng and associates observed in their abstract. As a consequence of this, they say, activation of toll-like receptors and the production of interferon (IFN) is affected, as is B-cell proliferation and the production of autoantibodies – all mechanisms that are “key to pSS pathogenesis.”

The IFN pathway has been implicated in fatigue, Dr. Ng observed when he presented the RESOLVE 132-04 study’s findings, which involved 30 patients with pSS who had been treated for 3 months. Inclusion criteria were pSS as defined by the American-European Consensus Group 2002 criteria, anti-Ro antibody positivity, and increased expression of three IFN-regulated genes: HERC5, EPSTI1, and CMPK2. Exclusion criteria were the use of hydroxychloroquine, prednisolone at daily doses above 10 mg, and the use of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Patients were randomized in a 3:1 ratio to receive either 10 mg/kg of RSLV-132 (n = 20) or placebo (n = 8) at weeks 0, 1, 2, and then every fortnight until week 12. Dr. Ng noted that although 30 patients were randomized, two patients had dropped out in the placebo group before they could be “treated.”

The primary endpoint was the change in the blood cell gene expression or serum protein levels indicative of reduced inflammation. The results indicated reductions in noncoding RNA molecules in patients who received RSLV-132 versus placebo, “consistent with the mode of action of the molecule.” In addition, “the majority of inflammatory markers were reduced,” Dr. Ng said.

Another finding showed a nonsignificant trend for improvement of 0.8 units in the physical component in the RSLV-132 group, compared against 0.06 units with placebo (P = .142).

Patients who received RSLV-132 reduced the time needed to complete the Digital Symbol Substitution Test by 16.4 s, compared with an increase of 2.8 s for placebo (P = .024).

Similar trends were observed for ESSPRI and FACIT-F scores.

These are very early data and clearly a bigger study would be needed before any conclusions could be drawn, Dr. Ng said in an interview. What these data suggest is that “maybe there is some way that we could manage fatigue, and we just need to go and explore that.”

RSLV-132 has also been studied in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (Lupus. 2017;26:825-34).

The trial was sponsored by Resolve Therapeutics. Dr. Ng was an investigator in the trial and disclosed other research collaborations with electroCore, GlaxoSmithKline, and AbbVie. He also disclosed acting as a consultant for Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Source: Fisher B et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jun;78(suppl 2):177, Abstract OP0202. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.3098.

MADRID – RSLV-132, a novel drug that eliminates circulating nucleic acids, improved the symptoms of mental fatigue in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) in a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled “proof-of-concept” study.

The mental component of fatigue on the Profile of Fatigue (PRO-F) scale improved by 1.53 points among the patients given RSLV-132, while there was a worsening of 0.06 points in the placebo group (P = .046). Scores range from 0 to 7 on the PRO-F.

There were also improvements in some patient-reported outcomes, namely the EULAR pSS Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue (FACIT-F), and improvement of neuropsychological measures of cognitive function, but none were statistically significant. All of these outcomes, including fatigue, were secondary outcomes of the study.

“Fatigue is a major issue for patients with Sjögren’s syndrome,” Wan-Fai Ng, MBChB, PhD, said in an interview at the European Congress of Rheumatology. Indeed, fatigue can be disabling in the majority of individuals, he added.

Currently, the best way to manage fatigue is to first ask about it, said Dr. Ng, who is professor of rheumatology at the Institute of Cellular Medicine at Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. He then checks for any underlying problem that could be better managed – sleep problems or anemia, for example – and optimizes treatment for any underlying disease. “I think many people would at least feel satisfied that people take the symptoms seriously.”

Dr. Ng and his coauthors investigated the effects of RSLV-132, a first-in-class human RNase fused to the human Fc domain of human immunoglobulin (Ig) G1, in the RESOLVE 132-04 study. This novel drug been designed to increase serum RNase activity to digest RNA-associated immune complexes, Dr. Ng and associates observed in their abstract. As a consequence of this, they say, activation of toll-like receptors and the production of interferon (IFN) is affected, as is B-cell proliferation and the production of autoantibodies – all mechanisms that are “key to pSS pathogenesis.”

The IFN pathway has been implicated in fatigue, Dr. Ng observed when he presented the RESOLVE 132-04 study’s findings, which involved 30 patients with pSS who had been treated for 3 months. Inclusion criteria were pSS as defined by the American-European Consensus Group 2002 criteria, anti-Ro antibody positivity, and increased expression of three IFN-regulated genes: HERC5, EPSTI1, and CMPK2. Exclusion criteria were the use of hydroxychloroquine, prednisolone at daily doses above 10 mg, and the use of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Patients were randomized in a 3:1 ratio to receive either 10 mg/kg of RSLV-132 (n = 20) or placebo (n = 8) at weeks 0, 1, 2, and then every fortnight until week 12. Dr. Ng noted that although 30 patients were randomized, two patients had dropped out in the placebo group before they could be “treated.”

The primary endpoint was the change in the blood cell gene expression or serum protein levels indicative of reduced inflammation. The results indicated reductions in noncoding RNA molecules in patients who received RSLV-132 versus placebo, “consistent with the mode of action of the molecule.” In addition, “the majority of inflammatory markers were reduced,” Dr. Ng said.

Another finding showed a nonsignificant trend for improvement of 0.8 units in the physical component in the RSLV-132 group, compared against 0.06 units with placebo (P = .142).

Patients who received RSLV-132 reduced the time needed to complete the Digital Symbol Substitution Test by 16.4 s, compared with an increase of 2.8 s for placebo (P = .024).

Similar trends were observed for ESSPRI and FACIT-F scores.

These are very early data and clearly a bigger study would be needed before any conclusions could be drawn, Dr. Ng said in an interview. What these data suggest is that “maybe there is some way that we could manage fatigue, and we just need to go and explore that.”

RSLV-132 has also been studied in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (Lupus. 2017;26:825-34).

The trial was sponsored by Resolve Therapeutics. Dr. Ng was an investigator in the trial and disclosed other research collaborations with electroCore, GlaxoSmithKline, and AbbVie. He also disclosed acting as a consultant for Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Source: Fisher B et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jun;78(suppl 2):177, Abstract OP0202. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.3098.

MADRID – RSLV-132, a novel drug that eliminates circulating nucleic acids, improved the symptoms of mental fatigue in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) in a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled “proof-of-concept” study.

The mental component of fatigue on the Profile of Fatigue (PRO-F) scale improved by 1.53 points among the patients given RSLV-132, while there was a worsening of 0.06 points in the placebo group (P = .046). Scores range from 0 to 7 on the PRO-F.

There were also improvements in some patient-reported outcomes, namely the EULAR pSS Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue (FACIT-F), and improvement of neuropsychological measures of cognitive function, but none were statistically significant. All of these outcomes, including fatigue, were secondary outcomes of the study.

“Fatigue is a major issue for patients with Sjögren’s syndrome,” Wan-Fai Ng, MBChB, PhD, said in an interview at the European Congress of Rheumatology. Indeed, fatigue can be disabling in the majority of individuals, he added.

Currently, the best way to manage fatigue is to first ask about it, said Dr. Ng, who is professor of rheumatology at the Institute of Cellular Medicine at Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. He then checks for any underlying problem that could be better managed – sleep problems or anemia, for example – and optimizes treatment for any underlying disease. “I think many people would at least feel satisfied that people take the symptoms seriously.”

Dr. Ng and his coauthors investigated the effects of RSLV-132, a first-in-class human RNase fused to the human Fc domain of human immunoglobulin (Ig) G1, in the RESOLVE 132-04 study. This novel drug been designed to increase serum RNase activity to digest RNA-associated immune complexes, Dr. Ng and associates observed in their abstract. As a consequence of this, they say, activation of toll-like receptors and the production of interferon (IFN) is affected, as is B-cell proliferation and the production of autoantibodies – all mechanisms that are “key to pSS pathogenesis.”

The IFN pathway has been implicated in fatigue, Dr. Ng observed when he presented the RESOLVE 132-04 study’s findings, which involved 30 patients with pSS who had been treated for 3 months. Inclusion criteria were pSS as defined by the American-European Consensus Group 2002 criteria, anti-Ro antibody positivity, and increased expression of three IFN-regulated genes: HERC5, EPSTI1, and CMPK2. Exclusion criteria were the use of hydroxychloroquine, prednisolone at daily doses above 10 mg, and the use of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Patients were randomized in a 3:1 ratio to receive either 10 mg/kg of RSLV-132 (n = 20) or placebo (n = 8) at weeks 0, 1, 2, and then every fortnight until week 12. Dr. Ng noted that although 30 patients were randomized, two patients had dropped out in the placebo group before they could be “treated.”

The primary endpoint was the change in the blood cell gene expression or serum protein levels indicative of reduced inflammation. The results indicated reductions in noncoding RNA molecules in patients who received RSLV-132 versus placebo, “consistent with the mode of action of the molecule.” In addition, “the majority of inflammatory markers were reduced,” Dr. Ng said.

Another finding showed a nonsignificant trend for improvement of 0.8 units in the physical component in the RSLV-132 group, compared against 0.06 units with placebo (P = .142).

Patients who received RSLV-132 reduced the time needed to complete the Digital Symbol Substitution Test by 16.4 s, compared with an increase of 2.8 s for placebo (P = .024).

Similar trends were observed for ESSPRI and FACIT-F scores.

These are very early data and clearly a bigger study would be needed before any conclusions could be drawn, Dr. Ng said in an interview. What these data suggest is that “maybe there is some way that we could manage fatigue, and we just need to go and explore that.”

RSLV-132 has also been studied in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (Lupus. 2017;26:825-34).

The trial was sponsored by Resolve Therapeutics. Dr. Ng was an investigator in the trial and disclosed other research collaborations with electroCore, GlaxoSmithKline, and AbbVie. He also disclosed acting as a consultant for Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Source: Fisher B et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jun;78(suppl 2):177, Abstract OP0202. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.3098.

REPORTING FROM EULAR 2019 CONGRESS

Genetic variant could dictate rituximab response in lupus

MADRID – Response to rituximab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) might be dictated by the presence of a genetic variant that encodes the Fc gamma receptors (FcGRs), expressed on natural killer (NK) cells, according to findings from a single-center, longitudinal cohort study.

It is well known that not everyone with SLE will respond well to rituximab, but that some will, first author Md Yuzaiful Md Yusof, MBChB, PhD, explained in an interview at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Although data from clinical trials with rituximab in this patient setting have been essentially negative, the methodology of those trials has since been disputed, he observed. Indeed, subsequent data (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1829-36) have suggested that as many as 80% of patients could achieve a response with rituximab, particularly if there is complete B-cell depletion.

Previous researchers (Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:875-7) have shown that a polymorphism (158V) in the Fc gamma receptor IIIA (FCGR3A) gene is associated with the response to rituximab-based therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This gene is important for antibody-dependent cellular-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).

The objective of the current study – an observational, prospective, longitudinal cohort study conducted in Leeds (England) – was therefore to see if the FCGR3A-158V polymorphism might influence response in patients with SLE.

“We were trying to find pretreatment biomarkers that could predict response to rituximab in SLE,” Dr. Md Yusof explained.

For the study, 85 patients who were treated with rituximab were assessed. The cohort was predominantly female (96%), with a mean age of 40 years. All of the patients had antinuclear antibodies, with just over half having anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies, and two-thirds having extractable nuclear antigens. One-third had low complement (C3/C4) levels.

Complete B-cell depletion occurred in 63% of patients with the FCGR3A-158V allele, a significantly higher rate than the 40% observed among those with 158 FF genotype (odds ratio, 2.73; P = .041). A significantly higher percentage of patients with the FCGR3A-158V allele also achieved a major BILAG (British Isles Lupus Assessment Group) response when compared against patients with the 158 FF variant (48% vs. 23%), with an odds ratio of 3.06 (P = .033).

Rituximab’s effect on NK cell-mediated B-cell killing may have played a key role in treatment response. Carrying the FCGR3A-158V allele was associated with greater degranulation activity versus the 158 FF variant.

Lastly, patients were more likely to remain on treatment with rituximab over a 10-year period if they had the FCGR3A-158V allele, compared with the 158 FF variant.

“These data suggest one mechanism by which patients with SLE might become resistant to the effects of rituximab, and could be used to guide therapy in the future,” Dr. Md Yusof suggested.

“Once this finding is validated, the clinical implication is that this genetic testing could be done prior to rituximab to identify those who will respond to therapy,” he postulated. “People with SLE who have this genetic variant with high affinity for rituximab are the ones that are better suited for rituximab therapy,” he added, otherwise a different CD20-directed antibody or alternative B-cell blockade therapies should be used.

The U.K. National Institute for Health Research funded the study. Dr. Md Yusof had no conflicts of interest to disclose; some coauthors disclosed ties to Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca, among other companies.

SOURCE: Md Yusof MY et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):1069-70. Abstract SAT0009, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.6919.

MADRID – Response to rituximab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) might be dictated by the presence of a genetic variant that encodes the Fc gamma receptors (FcGRs), expressed on natural killer (NK) cells, according to findings from a single-center, longitudinal cohort study.

It is well known that not everyone with SLE will respond well to rituximab, but that some will, first author Md Yuzaiful Md Yusof, MBChB, PhD, explained in an interview at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Although data from clinical trials with rituximab in this patient setting have been essentially negative, the methodology of those trials has since been disputed, he observed. Indeed, subsequent data (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1829-36) have suggested that as many as 80% of patients could achieve a response with rituximab, particularly if there is complete B-cell depletion.

Previous researchers (Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:875-7) have shown that a polymorphism (158V) in the Fc gamma receptor IIIA (FCGR3A) gene is associated with the response to rituximab-based therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This gene is important for antibody-dependent cellular-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).

The objective of the current study – an observational, prospective, longitudinal cohort study conducted in Leeds (England) – was therefore to see if the FCGR3A-158V polymorphism might influence response in patients with SLE.

“We were trying to find pretreatment biomarkers that could predict response to rituximab in SLE,” Dr. Md Yusof explained.

For the study, 85 patients who were treated with rituximab were assessed. The cohort was predominantly female (96%), with a mean age of 40 years. All of the patients had antinuclear antibodies, with just over half having anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies, and two-thirds having extractable nuclear antigens. One-third had low complement (C3/C4) levels.

Complete B-cell depletion occurred in 63% of patients with the FCGR3A-158V allele, a significantly higher rate than the 40% observed among those with 158 FF genotype (odds ratio, 2.73; P = .041). A significantly higher percentage of patients with the FCGR3A-158V allele also achieved a major BILAG (British Isles Lupus Assessment Group) response when compared against patients with the 158 FF variant (48% vs. 23%), with an odds ratio of 3.06 (P = .033).

Rituximab’s effect on NK cell-mediated B-cell killing may have played a key role in treatment response. Carrying the FCGR3A-158V allele was associated with greater degranulation activity versus the 158 FF variant.

Lastly, patients were more likely to remain on treatment with rituximab over a 10-year period if they had the FCGR3A-158V allele, compared with the 158 FF variant.

“These data suggest one mechanism by which patients with SLE might become resistant to the effects of rituximab, and could be used to guide therapy in the future,” Dr. Md Yusof suggested.

“Once this finding is validated, the clinical implication is that this genetic testing could be done prior to rituximab to identify those who will respond to therapy,” he postulated. “People with SLE who have this genetic variant with high affinity for rituximab are the ones that are better suited for rituximab therapy,” he added, otherwise a different CD20-directed antibody or alternative B-cell blockade therapies should be used.

The U.K. National Institute for Health Research funded the study. Dr. Md Yusof had no conflicts of interest to disclose; some coauthors disclosed ties to Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca, among other companies.

SOURCE: Md Yusof MY et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):1069-70. Abstract SAT0009, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.6919.

MADRID – Response to rituximab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) might be dictated by the presence of a genetic variant that encodes the Fc gamma receptors (FcGRs), expressed on natural killer (NK) cells, according to findings from a single-center, longitudinal cohort study.

It is well known that not everyone with SLE will respond well to rituximab, but that some will, first author Md Yuzaiful Md Yusof, MBChB, PhD, explained in an interview at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Although data from clinical trials with rituximab in this patient setting have been essentially negative, the methodology of those trials has since been disputed, he observed. Indeed, subsequent data (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1829-36) have suggested that as many as 80% of patients could achieve a response with rituximab, particularly if there is complete B-cell depletion.

Previous researchers (Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:875-7) have shown that a polymorphism (158V) in the Fc gamma receptor IIIA (FCGR3A) gene is associated with the response to rituximab-based therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This gene is important for antibody-dependent cellular-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).

The objective of the current study – an observational, prospective, longitudinal cohort study conducted in Leeds (England) – was therefore to see if the FCGR3A-158V polymorphism might influence response in patients with SLE.

“We were trying to find pretreatment biomarkers that could predict response to rituximab in SLE,” Dr. Md Yusof explained.

For the study, 85 patients who were treated with rituximab were assessed. The cohort was predominantly female (96%), with a mean age of 40 years. All of the patients had antinuclear antibodies, with just over half having anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies, and two-thirds having extractable nuclear antigens. One-third had low complement (C3/C4) levels.

Complete B-cell depletion occurred in 63% of patients with the FCGR3A-158V allele, a significantly higher rate than the 40% observed among those with 158 FF genotype (odds ratio, 2.73; P = .041). A significantly higher percentage of patients with the FCGR3A-158V allele also achieved a major BILAG (British Isles Lupus Assessment Group) response when compared against patients with the 158 FF variant (48% vs. 23%), with an odds ratio of 3.06 (P = .033).

Rituximab’s effect on NK cell-mediated B-cell killing may have played a key role in treatment response. Carrying the FCGR3A-158V allele was associated with greater degranulation activity versus the 158 FF variant.

Lastly, patients were more likely to remain on treatment with rituximab over a 10-year period if they had the FCGR3A-158V allele, compared with the 158 FF variant.

“These data suggest one mechanism by which patients with SLE might become resistant to the effects of rituximab, and could be used to guide therapy in the future,” Dr. Md Yusof suggested.

“Once this finding is validated, the clinical implication is that this genetic testing could be done prior to rituximab to identify those who will respond to therapy,” he postulated. “People with SLE who have this genetic variant with high affinity for rituximab are the ones that are better suited for rituximab therapy,” he added, otherwise a different CD20-directed antibody or alternative B-cell blockade therapies should be used.

The U.K. National Institute for Health Research funded the study. Dr. Md Yusof had no conflicts of interest to disclose; some coauthors disclosed ties to Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca, among other companies.

SOURCE: Md Yusof MY et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):1069-70. Abstract SAT0009, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.6919.

REPORTING FROM EULAR 2019 CONGRESS

Leflunomide added to glucocorticoids reduces relapse in IgG4-related disease

MADRID – The addition of leflunomide to standard glucocorticoids (GCs) in the treatment of IgG4-related disease increases the median duration of response, reduces the proportion of patients with relapse within 12 months, and permits GCs to be tapered, according to results of a randomized trial presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“The rate of adverse events with the addition of leflunomide was numerically higher, but there were no significant differences in risks of any specific adverse event,” reported Feng Huang, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital in Beijing.

GCs are highly effective in IgG4-related disease, which is an autoimmune process driven by elevated concentrations of the antibody IgG4 in the tissue of affected organs and in the serum. It has been described in a broad array of sites, including the heart, lung, kidneys, and meninges. It has been widely recognized only in the last 10 years, according to Dr. Huang. Although most patients respond to GCs, he said the problem is that about 50% of patients relapse within 12 months and more than 90% within 3 years.

This randomized, controlled study was conducted after positive results were observed with leflunomide in a small, uncontrolled pilot study published several years ago (Intern Med J. 2017 Jun;47[6]:680-9. doi: 10.1111/imj.13430). In this randomized trial, the objectives were to confirm that leflunomide extends the relapse-free period and has acceptable safety relative to GC alone.

Patients with confirmed IgG4-related disease were enrolled. Patients randomized to GC were started on 0.5 to 0.8 mg/kg per day. A predefined taper regimen was employed in those with symptom control. Those randomized to the experimental arm received GC in the same dose and schedule plus 20 mg/day of leflunomide.

The 33 patients in each group were well matched at baseline for age, comorbidities, and disease severity.

At the end of 12 months, 50% of those treated with GC alone versus 21.2% of those treated with GC plus leflunomide had relapse. That translated into a significantly higher hazard ratio (HR) for relapse in the GC monotherapy group (HR, 1.75; P = .034).

The mean duration of remission was 7 months on the combination versus 3 months on GC alone. Dr. Huang also reported a significantly higher proportion of complete responses in the group receiving the combination.

In addition, “more patients on the combination therapy were able to adhere to the steroid-tapering schedule without relapse,” Dr. Huang reported. The rate of 54.5% of patients on combination therapy who were able to reach a daily GC dose of 5 mg/day or less proved significantly higher than the 18.2% rate seen with GC alone (P = .002).

Adverse events were reported by 54% of those on the combination versus 42% of those on monotherapy, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. The biggest differences in adverse events were the proportions of patients with infections (18.2% vs. 12.1%) and elevated liver enzymes (12.1% vs. 3.0%), both of which were more common in the combination therapy group. Neither of these differences was statistically significant.

Of patients with relapses, the most common organs involved were the salivary gland, the pancreas, and the bile ducts, each accounting for relapse in five patients. Other organs in which relapse occurred included the lacrimal gland and the skin. There were three cases of relapse characterized by retroperitoneal fibrosis.

Over the course of follow-up, new-onset diabetes mellitus occurred in 21.2% and 27.3% of the combination and GC-only groups, respectively. This difference also did not reach statistical significance.

Although this study was small with an open-label design, Dr. Huang said the data strongly suggest that a combination of leflunomide and GC is superior to GC alone. Based on these results, he said a starting dose of 20 mg/day of leflunomide is a reasonable standard in this setting.

Dr. Huang and colleagues reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wang Y et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):157. Abstract OPO164, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.5717

MADRID – The addition of leflunomide to standard glucocorticoids (GCs) in the treatment of IgG4-related disease increases the median duration of response, reduces the proportion of patients with relapse within 12 months, and permits GCs to be tapered, according to results of a randomized trial presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“The rate of adverse events with the addition of leflunomide was numerically higher, but there were no significant differences in risks of any specific adverse event,” reported Feng Huang, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital in Beijing.

GCs are highly effective in IgG4-related disease, which is an autoimmune process driven by elevated concentrations of the antibody IgG4 in the tissue of affected organs and in the serum. It has been described in a broad array of sites, including the heart, lung, kidneys, and meninges. It has been widely recognized only in the last 10 years, according to Dr. Huang. Although most patients respond to GCs, he said the problem is that about 50% of patients relapse within 12 months and more than 90% within 3 years.

This randomized, controlled study was conducted after positive results were observed with leflunomide in a small, uncontrolled pilot study published several years ago (Intern Med J. 2017 Jun;47[6]:680-9. doi: 10.1111/imj.13430). In this randomized trial, the objectives were to confirm that leflunomide extends the relapse-free period and has acceptable safety relative to GC alone.

Patients with confirmed IgG4-related disease were enrolled. Patients randomized to GC were started on 0.5 to 0.8 mg/kg per day. A predefined taper regimen was employed in those with symptom control. Those randomized to the experimental arm received GC in the same dose and schedule plus 20 mg/day of leflunomide.

The 33 patients in each group were well matched at baseline for age, comorbidities, and disease severity.

At the end of 12 months, 50% of those treated with GC alone versus 21.2% of those treated with GC plus leflunomide had relapse. That translated into a significantly higher hazard ratio (HR) for relapse in the GC monotherapy group (HR, 1.75; P = .034).

The mean duration of remission was 7 months on the combination versus 3 months on GC alone. Dr. Huang also reported a significantly higher proportion of complete responses in the group receiving the combination.

In addition, “more patients on the combination therapy were able to adhere to the steroid-tapering schedule without relapse,” Dr. Huang reported. The rate of 54.5% of patients on combination therapy who were able to reach a daily GC dose of 5 mg/day or less proved significantly higher than the 18.2% rate seen with GC alone (P = .002).

Adverse events were reported by 54% of those on the combination versus 42% of those on monotherapy, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. The biggest differences in adverse events were the proportions of patients with infections (18.2% vs. 12.1%) and elevated liver enzymes (12.1% vs. 3.0%), both of which were more common in the combination therapy group. Neither of these differences was statistically significant.

Of patients with relapses, the most common organs involved were the salivary gland, the pancreas, and the bile ducts, each accounting for relapse in five patients. Other organs in which relapse occurred included the lacrimal gland and the skin. There were three cases of relapse characterized by retroperitoneal fibrosis.

Over the course of follow-up, new-onset diabetes mellitus occurred in 21.2% and 27.3% of the combination and GC-only groups, respectively. This difference also did not reach statistical significance.

Although this study was small with an open-label design, Dr. Huang said the data strongly suggest that a combination of leflunomide and GC is superior to GC alone. Based on these results, he said a starting dose of 20 mg/day of leflunomide is a reasonable standard in this setting.

Dr. Huang and colleagues reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wang Y et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):157. Abstract OPO164, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.5717

MADRID – The addition of leflunomide to standard glucocorticoids (GCs) in the treatment of IgG4-related disease increases the median duration of response, reduces the proportion of patients with relapse within 12 months, and permits GCs to be tapered, according to results of a randomized trial presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“The rate of adverse events with the addition of leflunomide was numerically higher, but there were no significant differences in risks of any specific adverse event,” reported Feng Huang, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital in Beijing.

GCs are highly effective in IgG4-related disease, which is an autoimmune process driven by elevated concentrations of the antibody IgG4 in the tissue of affected organs and in the serum. It has been described in a broad array of sites, including the heart, lung, kidneys, and meninges. It has been widely recognized only in the last 10 years, according to Dr. Huang. Although most patients respond to GCs, he said the problem is that about 50% of patients relapse within 12 months and more than 90% within 3 years.

This randomized, controlled study was conducted after positive results were observed with leflunomide in a small, uncontrolled pilot study published several years ago (Intern Med J. 2017 Jun;47[6]:680-9. doi: 10.1111/imj.13430). In this randomized trial, the objectives were to confirm that leflunomide extends the relapse-free period and has acceptable safety relative to GC alone.

Patients with confirmed IgG4-related disease were enrolled. Patients randomized to GC were started on 0.5 to 0.8 mg/kg per day. A predefined taper regimen was employed in those with symptom control. Those randomized to the experimental arm received GC in the same dose and schedule plus 20 mg/day of leflunomide.

The 33 patients in each group were well matched at baseline for age, comorbidities, and disease severity.

At the end of 12 months, 50% of those treated with GC alone versus 21.2% of those treated with GC plus leflunomide had relapse. That translated into a significantly higher hazard ratio (HR) for relapse in the GC monotherapy group (HR, 1.75; P = .034).

The mean duration of remission was 7 months on the combination versus 3 months on GC alone. Dr. Huang also reported a significantly higher proportion of complete responses in the group receiving the combination.

In addition, “more patients on the combination therapy were able to adhere to the steroid-tapering schedule without relapse,” Dr. Huang reported. The rate of 54.5% of patients on combination therapy who were able to reach a daily GC dose of 5 mg/day or less proved significantly higher than the 18.2% rate seen with GC alone (P = .002).

Adverse events were reported by 54% of those on the combination versus 42% of those on monotherapy, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. The biggest differences in adverse events were the proportions of patients with infections (18.2% vs. 12.1%) and elevated liver enzymes (12.1% vs. 3.0%), both of which were more common in the combination therapy group. Neither of these differences was statistically significant.

Of patients with relapses, the most common organs involved were the salivary gland, the pancreas, and the bile ducts, each accounting for relapse in five patients. Other organs in which relapse occurred included the lacrimal gland and the skin. There were three cases of relapse characterized by retroperitoneal fibrosis.

Over the course of follow-up, new-onset diabetes mellitus occurred in 21.2% and 27.3% of the combination and GC-only groups, respectively. This difference also did not reach statistical significance.

Although this study was small with an open-label design, Dr. Huang said the data strongly suggest that a combination of leflunomide and GC is superior to GC alone. Based on these results, he said a starting dose of 20 mg/day of leflunomide is a reasonable standard in this setting.

Dr. Huang and colleagues reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wang Y et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):157. Abstract OPO164, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.5717

REPORTING FROM EULAR 2019 CONGRESS

Tocilizumab preserves lung function in systemic sclerosis

MADRID – , according to a secondary endpoint analysis of the phase 3, double-blind, randomized, controlled focuSSced trial.

After 48 weeks, a significantly lower proportion of patients treated with tocilizumab than placebo experienced any decline in lung function from baseline (50.5% versus 70.3% (P = .015), as defined by the percentage increase in predicted forced vital capacity (%pFVC). When only patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) were considered, the respective percentages were 51.7% and 75.5% (P = .003).

In SSc-ILD patients, a clinically meaningful decline of 10% or more of the %pFVC in lung function was seen in 24.5% given placebo but in just 8.6% of those treated with tocilizumab.

“ILD is a major complication of scleroderma; it has high morbidity and mortality ... and it’s largely irreversible,” Dinesh Khanna, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“In this day and age, when we treat ILD, we wait for a patient to develop clinical ILD,” added Dr. Khanna, director of the scleroderma program at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Clinical ILD can be defined by symptoms, abnormal pulmonary function tests, and marked abnormalities on high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans. He indicated that if improving ILD was not possible, then the next best thing would be to stabilize the disease and ensure there was no worsening in lung function.

As yet, there are no disease-modifying treatments available to treat SSc but there are “ample data that interleukin-6 plays a very important role in the pathogenesis of scleroderma,” Dr. Khanna observed. Tocilizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor.

Data from the phase 2 faSScinate trial showed initial promise for the drug in SSc where a numerical, but not statistically significant, improvement in skin thickening was seen, and the results had hinted at a possible benefit on lung function (Lancet. 2016 Jun 25;387:2630-40).

However, in the phase 3 focuSSced trial, there was no statistically significant difference in the change from baseline to week 48 modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) between tocilizumab and placebo, which was the primary endpoint. The least square mean change in mRSS was –6.14 for tocilizumab and –4.41 for placebo (P = .0983).

A total of 205 patients with SSc were studied and randomized, 1:1 in a double-blind fashion, to receive either a once-weekly, subcutaneous dose of 162 mg tocilizumab or a weekly subcutaneous placebo injection for 48 weeks.

For inclusion in the study, patients had to have SSc that met American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria and be diagnosed less than 60 months previously. Patients had to have an mRSS of 10-35 units and active disease with one or more of the following: C-reactive protein of 6 mg/L or higher; erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 28 mm/h or higher; and platelet count of330 x 109 L.

“What was astonishing in the trial was that every patient had HRCT at baseline and at the end of the study,” Dr. Khanna reported. These scans showed that 64% of patients had evidence of ILD at baseline and that those treated with tocilizumab had less evidence of fibrosis at week 48 versus placebo, indicating a stabilization rather than worsening of disease.

A time to treatment failure analysis also favored tocilizumab over placebo, but there were no significant changes in patient-reported outcomes.

Dr. Khanna’s slides stated that “given that the primary endpoint for mRSS was not met, all other P values are presented for information purposes only and cannot be considered statistically significant despite the strength of the evidence.” During the Q&A after his presentation, he noted that it was unlikely that the study’s sponsors (Roche/Genentech) will now pursue a license for tocilizumab in SSc.

Nevertheless, Dr. Khanna concluded, “we have the opportunity, based on these data, to treat these patients early on, where you can preserve the lung function, which is a paradigm shift versus waiting for the lung function to decline, become clinically meaningful, significant, and then treat this patient population.”

Roche/Genentech sponsored the study. Dr. Khanna acts as a consultant to Roche/Genentech and eight other pharmaceutical companies. He owns stock in Eicos Sciences.

SOURCE: Khanna D et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):202-3. Abstract OP0245, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.2120

MADRID – , according to a secondary endpoint analysis of the phase 3, double-blind, randomized, controlled focuSSced trial.

After 48 weeks, a significantly lower proportion of patients treated with tocilizumab than placebo experienced any decline in lung function from baseline (50.5% versus 70.3% (P = .015), as defined by the percentage increase in predicted forced vital capacity (%pFVC). When only patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) were considered, the respective percentages were 51.7% and 75.5% (P = .003).

In SSc-ILD patients, a clinically meaningful decline of 10% or more of the %pFVC in lung function was seen in 24.5% given placebo but in just 8.6% of those treated with tocilizumab.

“ILD is a major complication of scleroderma; it has high morbidity and mortality ... and it’s largely irreversible,” Dinesh Khanna, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“In this day and age, when we treat ILD, we wait for a patient to develop clinical ILD,” added Dr. Khanna, director of the scleroderma program at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Clinical ILD can be defined by symptoms, abnormal pulmonary function tests, and marked abnormalities on high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans. He indicated that if improving ILD was not possible, then the next best thing would be to stabilize the disease and ensure there was no worsening in lung function.

As yet, there are no disease-modifying treatments available to treat SSc but there are “ample data that interleukin-6 plays a very important role in the pathogenesis of scleroderma,” Dr. Khanna observed. Tocilizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor.

Data from the phase 2 faSScinate trial showed initial promise for the drug in SSc where a numerical, but not statistically significant, improvement in skin thickening was seen, and the results had hinted at a possible benefit on lung function (Lancet. 2016 Jun 25;387:2630-40).

However, in the phase 3 focuSSced trial, there was no statistically significant difference in the change from baseline to week 48 modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) between tocilizumab and placebo, which was the primary endpoint. The least square mean change in mRSS was –6.14 for tocilizumab and –4.41 for placebo (P = .0983).

A total of 205 patients with SSc were studied and randomized, 1:1 in a double-blind fashion, to receive either a once-weekly, subcutaneous dose of 162 mg tocilizumab or a weekly subcutaneous placebo injection for 48 weeks.

For inclusion in the study, patients had to have SSc that met American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria and be diagnosed less than 60 months previously. Patients had to have an mRSS of 10-35 units and active disease with one or more of the following: C-reactive protein of 6 mg/L or higher; erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 28 mm/h or higher; and platelet count of330 x 109 L.

“What was astonishing in the trial was that every patient had HRCT at baseline and at the end of the study,” Dr. Khanna reported. These scans showed that 64% of patients had evidence of ILD at baseline and that those treated with tocilizumab had less evidence of fibrosis at week 48 versus placebo, indicating a stabilization rather than worsening of disease.

A time to treatment failure analysis also favored tocilizumab over placebo, but there were no significant changes in patient-reported outcomes.

Dr. Khanna’s slides stated that “given that the primary endpoint for mRSS was not met, all other P values are presented for information purposes only and cannot be considered statistically significant despite the strength of the evidence.” During the Q&A after his presentation, he noted that it was unlikely that the study’s sponsors (Roche/Genentech) will now pursue a license for tocilizumab in SSc.

Nevertheless, Dr. Khanna concluded, “we have the opportunity, based on these data, to treat these patients early on, where you can preserve the lung function, which is a paradigm shift versus waiting for the lung function to decline, become clinically meaningful, significant, and then treat this patient population.”

Roche/Genentech sponsored the study. Dr. Khanna acts as a consultant to Roche/Genentech and eight other pharmaceutical companies. He owns stock in Eicos Sciences.

SOURCE: Khanna D et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):202-3. Abstract OP0245, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.2120

MADRID – , according to a secondary endpoint analysis of the phase 3, double-blind, randomized, controlled focuSSced trial.

After 48 weeks, a significantly lower proportion of patients treated with tocilizumab than placebo experienced any decline in lung function from baseline (50.5% versus 70.3% (P = .015), as defined by the percentage increase in predicted forced vital capacity (%pFVC). When only patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) were considered, the respective percentages were 51.7% and 75.5% (P = .003).

In SSc-ILD patients, a clinically meaningful decline of 10% or more of the %pFVC in lung function was seen in 24.5% given placebo but in just 8.6% of those treated with tocilizumab.

“ILD is a major complication of scleroderma; it has high morbidity and mortality ... and it’s largely irreversible,” Dinesh Khanna, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“In this day and age, when we treat ILD, we wait for a patient to develop clinical ILD,” added Dr. Khanna, director of the scleroderma program at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Clinical ILD can be defined by symptoms, abnormal pulmonary function tests, and marked abnormalities on high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans. He indicated that if improving ILD was not possible, then the next best thing would be to stabilize the disease and ensure there was no worsening in lung function.

As yet, there are no disease-modifying treatments available to treat SSc but there are “ample data that interleukin-6 plays a very important role in the pathogenesis of scleroderma,” Dr. Khanna observed. Tocilizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor.

Data from the phase 2 faSScinate trial showed initial promise for the drug in SSc where a numerical, but not statistically significant, improvement in skin thickening was seen, and the results had hinted at a possible benefit on lung function (Lancet. 2016 Jun 25;387:2630-40).

However, in the phase 3 focuSSced trial, there was no statistically significant difference in the change from baseline to week 48 modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) between tocilizumab and placebo, which was the primary endpoint. The least square mean change in mRSS was –6.14 for tocilizumab and –4.41 for placebo (P = .0983).

A total of 205 patients with SSc were studied and randomized, 1:1 in a double-blind fashion, to receive either a once-weekly, subcutaneous dose of 162 mg tocilizumab or a weekly subcutaneous placebo injection for 48 weeks.

For inclusion in the study, patients had to have SSc that met American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria and be diagnosed less than 60 months previously. Patients had to have an mRSS of 10-35 units and active disease with one or more of the following: C-reactive protein of 6 mg/L or higher; erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 28 mm/h or higher; and platelet count of330 x 109 L.

“What was astonishing in the trial was that every patient had HRCT at baseline and at the end of the study,” Dr. Khanna reported. These scans showed that 64% of patients had evidence of ILD at baseline and that those treated with tocilizumab had less evidence of fibrosis at week 48 versus placebo, indicating a stabilization rather than worsening of disease.

A time to treatment failure analysis also favored tocilizumab over placebo, but there were no significant changes in patient-reported outcomes.

Dr. Khanna’s slides stated that “given that the primary endpoint for mRSS was not met, all other P values are presented for information purposes only and cannot be considered statistically significant despite the strength of the evidence.” During the Q&A after his presentation, he noted that it was unlikely that the study’s sponsors (Roche/Genentech) will now pursue a license for tocilizumab in SSc.

Nevertheless, Dr. Khanna concluded, “we have the opportunity, based on these data, to treat these patients early on, where you can preserve the lung function, which is a paradigm shift versus waiting for the lung function to decline, become clinically meaningful, significant, and then treat this patient population.”

Roche/Genentech sponsored the study. Dr. Khanna acts as a consultant to Roche/Genentech and eight other pharmaceutical companies. He owns stock in Eicos Sciences.

SOURCE: Khanna D et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):202-3. Abstract OP0245, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.2120

REPORTING FROM THE EULAR 2019 CONGRESS

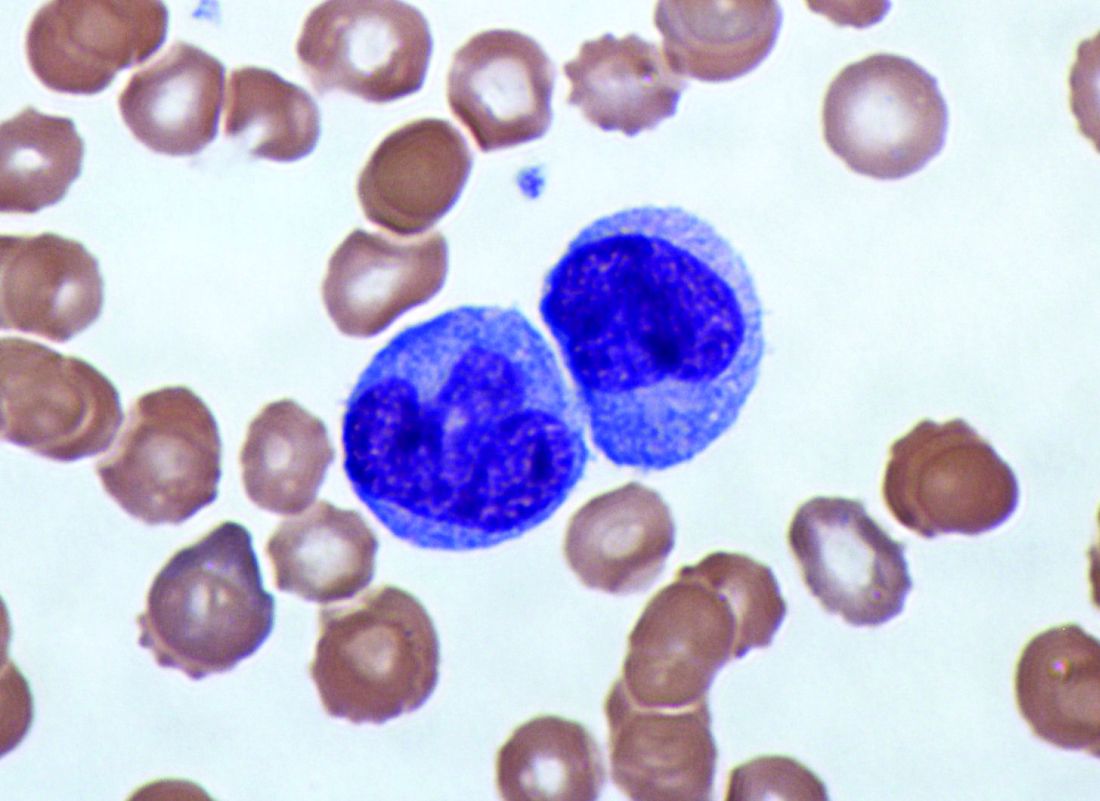

Elevated monocyte count predicts poor outcomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

, including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, systemic sclerosis, and myelofibrosis, according to research published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

The data indicate that “a single threshold value of absolute monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL could be used to identify high-risk patients with a fibrotic disease,” said Madeleine K. D. Scott, a researcher at Stanford (Calif.) University, and coauthors. The results “suggest that monocyte count should be incorporated into the clinical assessment” and may “enable more conscientious allocation of scarce resources, including lung transplantations,” they said.

While other published biomarkers – including gene panels and multicytokine signatures – may be expensive and not readily available, “absolute monocyte count is routinely measured as part of a complete blood count, an inexpensive test used in clinical practice worldwide,” the authors said.

Further study of monocytes’ mechanistic role in fibrosis ultimately could point to new treatment approaches.

A retrospective multicenter cohort study

To assess whether immune cells may identify patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis at greater risk of poor outcomes, Ms. Scott and her collaborators conducted a retrospective multicenter cohort study.

They first analyzed transcriptome data from 120 peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which they obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. They used statistical deconvolution to estimate percentages of 13 immune cell types and examined their associations with transplant-free survival. Their discovery analysis found that estimated CD14+ classical monocyte percentages above the mean correlated with shorter transplant-free survival times (hazard ratio, 1.82), but percentages of T cells and B cells did not.

The researchers then validated these results using samples from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in two independent cohorts. In the COMET validation cohort, which included 45 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis whose monocyte counts were measured using flow cytometry, higher monocyte counts were significantly associated with greater risk of disease progression. In the Yale cohort, which included 15 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the 6 patients who were classified as high risk on the basis of a 52-gene signature had more CD14+ monocytes than the 9 low-risk patients did.

In addition, Ms. Scott and her collaborators looked at complete blood count values in the electronic health records of 45,068 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, systemic sclerosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or myelofibrosis in Stanford, Northwestern, Vanderbilt, and Optum Clinformatics Data Mart cohorts.

Among patients in the COMET, Stanford, and Northwestern datasets, monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL or greater were associated with mortality after adjustment for forced vital capacity (HR, 2.47) and the gender, age, and physiology index (HR, 2.06). Data from 7,459 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis “showed that patients with monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL or greater were at increased risk of mortality with lung transplantation as a censoring event, after adjusting for age at diagnosis and sex” in the Stanford (HR, 2.30), Vanderbilt (HR, 1.52), and Optum (HR, 1.74) cohorts. “Likewise, higher absolute monocyte count was associated with shortened survival in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy across all three cohorts, and in patients with systemic sclerosis or myelofibrosis in two of the three cohorts,” the researchers said.

The study was funded by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and U.S. National Library of Medicine. Ms. Scott had no competing interests. Coauthors disclosed grants, compensation, and support from foundations, agencies, and companies.

SOURCE: Scott MKD et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30508-3.

The study by Scott et al. provides evidence that monocyte count may be a “novel, simple, and inexpensive prognostic biomarker in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” according to an accompanying editorial.

Progress has been made in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, but patient prognosis remains “challenging to predict,” wrote Michael Kreuter, MD, of University of Heidelberg, Germany, and Toby M. Maher, MB, MSc, PhD, of Royal Brompton Hospital in London and Imperial College London. “One lesson that can be learned from other respiratory disorders is that routinely measured cellular biomarkers, such as blood eosinophil counts in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), can predict treatment responses” (Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[19]30050-5).

Increased blood monocyte counts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis may reflect disease activity, which “could explain the outcome differences,” said Dr. Kreuter and Dr. Maher. “As highlighted by the investigators themselves, before introducing assessment of monocyte counts as part of routine clinical care for individuals with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the limitations of this research should be taken into account. These include uncertainty around diagnosis and disease severity in a substantial subset of the patients, and the unknown effect of medical therapies (including corticosteroids and immunosuppressant and antifibrotic drugs) on monocyte counts and prognosis.” Researchers should validate the clinical value of blood monocyte counts in existing and future cohorts and evaluate the biomarker in clinical trials.

The editorialists have received compensation and funding from various pharmaceutical companies.

The study by Scott et al. provides evidence that monocyte count may be a “novel, simple, and inexpensive prognostic biomarker in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” according to an accompanying editorial.

Progress has been made in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, but patient prognosis remains “challenging to predict,” wrote Michael Kreuter, MD, of University of Heidelberg, Germany, and Toby M. Maher, MB, MSc, PhD, of Royal Brompton Hospital in London and Imperial College London. “One lesson that can be learned from other respiratory disorders is that routinely measured cellular biomarkers, such as blood eosinophil counts in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), can predict treatment responses” (Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[19]30050-5).

Increased blood monocyte counts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis may reflect disease activity, which “could explain the outcome differences,” said Dr. Kreuter and Dr. Maher. “As highlighted by the investigators themselves, before introducing assessment of monocyte counts as part of routine clinical care for individuals with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the limitations of this research should be taken into account. These include uncertainty around diagnosis and disease severity in a substantial subset of the patients, and the unknown effect of medical therapies (including corticosteroids and immunosuppressant and antifibrotic drugs) on monocyte counts and prognosis.” Researchers should validate the clinical value of blood monocyte counts in existing and future cohorts and evaluate the biomarker in clinical trials.

The editorialists have received compensation and funding from various pharmaceutical companies.

The study by Scott et al. provides evidence that monocyte count may be a “novel, simple, and inexpensive prognostic biomarker in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” according to an accompanying editorial.

Progress has been made in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, but patient prognosis remains “challenging to predict,” wrote Michael Kreuter, MD, of University of Heidelberg, Germany, and Toby M. Maher, MB, MSc, PhD, of Royal Brompton Hospital in London and Imperial College London. “One lesson that can be learned from other respiratory disorders is that routinely measured cellular biomarkers, such as blood eosinophil counts in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), can predict treatment responses” (Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[19]30050-5).

Increased blood monocyte counts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis may reflect disease activity, which “could explain the outcome differences,” said Dr. Kreuter and Dr. Maher. “As highlighted by the investigators themselves, before introducing assessment of monocyte counts as part of routine clinical care for individuals with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the limitations of this research should be taken into account. These include uncertainty around diagnosis and disease severity in a substantial subset of the patients, and the unknown effect of medical therapies (including corticosteroids and immunosuppressant and antifibrotic drugs) on monocyte counts and prognosis.” Researchers should validate the clinical value of blood monocyte counts in existing and future cohorts and evaluate the biomarker in clinical trials.

The editorialists have received compensation and funding from various pharmaceutical companies.

, including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, systemic sclerosis, and myelofibrosis, according to research published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

The data indicate that “a single threshold value of absolute monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL could be used to identify high-risk patients with a fibrotic disease,” said Madeleine K. D. Scott, a researcher at Stanford (Calif.) University, and coauthors. The results “suggest that monocyte count should be incorporated into the clinical assessment” and may “enable more conscientious allocation of scarce resources, including lung transplantations,” they said.

While other published biomarkers – including gene panels and multicytokine signatures – may be expensive and not readily available, “absolute monocyte count is routinely measured as part of a complete blood count, an inexpensive test used in clinical practice worldwide,” the authors said.

Further study of monocytes’ mechanistic role in fibrosis ultimately could point to new treatment approaches.

A retrospective multicenter cohort study

To assess whether immune cells may identify patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis at greater risk of poor outcomes, Ms. Scott and her collaborators conducted a retrospective multicenter cohort study.

They first analyzed transcriptome data from 120 peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which they obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. They used statistical deconvolution to estimate percentages of 13 immune cell types and examined their associations with transplant-free survival. Their discovery analysis found that estimated CD14+ classical monocyte percentages above the mean correlated with shorter transplant-free survival times (hazard ratio, 1.82), but percentages of T cells and B cells did not.

The researchers then validated these results using samples from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in two independent cohorts. In the COMET validation cohort, which included 45 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis whose monocyte counts were measured using flow cytometry, higher monocyte counts were significantly associated with greater risk of disease progression. In the Yale cohort, which included 15 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the 6 patients who were classified as high risk on the basis of a 52-gene signature had more CD14+ monocytes than the 9 low-risk patients did.

In addition, Ms. Scott and her collaborators looked at complete blood count values in the electronic health records of 45,068 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, systemic sclerosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or myelofibrosis in Stanford, Northwestern, Vanderbilt, and Optum Clinformatics Data Mart cohorts.

Among patients in the COMET, Stanford, and Northwestern datasets, monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL or greater were associated with mortality after adjustment for forced vital capacity (HR, 2.47) and the gender, age, and physiology index (HR, 2.06). Data from 7,459 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis “showed that patients with monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL or greater were at increased risk of mortality with lung transplantation as a censoring event, after adjusting for age at diagnosis and sex” in the Stanford (HR, 2.30), Vanderbilt (HR, 1.52), and Optum (HR, 1.74) cohorts. “Likewise, higher absolute monocyte count was associated with shortened survival in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy across all three cohorts, and in patients with systemic sclerosis or myelofibrosis in two of the three cohorts,” the researchers said.

The study was funded by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and U.S. National Library of Medicine. Ms. Scott had no competing interests. Coauthors disclosed grants, compensation, and support from foundations, agencies, and companies.

SOURCE: Scott MKD et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30508-3.

, including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, systemic sclerosis, and myelofibrosis, according to research published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

The data indicate that “a single threshold value of absolute monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL could be used to identify high-risk patients with a fibrotic disease,” said Madeleine K. D. Scott, a researcher at Stanford (Calif.) University, and coauthors. The results “suggest that monocyte count should be incorporated into the clinical assessment” and may “enable more conscientious allocation of scarce resources, including lung transplantations,” they said.

While other published biomarkers – including gene panels and multicytokine signatures – may be expensive and not readily available, “absolute monocyte count is routinely measured as part of a complete blood count, an inexpensive test used in clinical practice worldwide,” the authors said.

Further study of monocytes’ mechanistic role in fibrosis ultimately could point to new treatment approaches.

A retrospective multicenter cohort study

To assess whether immune cells may identify patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis at greater risk of poor outcomes, Ms. Scott and her collaborators conducted a retrospective multicenter cohort study.

They first analyzed transcriptome data from 120 peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which they obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. They used statistical deconvolution to estimate percentages of 13 immune cell types and examined their associations with transplant-free survival. Their discovery analysis found that estimated CD14+ classical monocyte percentages above the mean correlated with shorter transplant-free survival times (hazard ratio, 1.82), but percentages of T cells and B cells did not.

The researchers then validated these results using samples from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in two independent cohorts. In the COMET validation cohort, which included 45 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis whose monocyte counts were measured using flow cytometry, higher monocyte counts were significantly associated with greater risk of disease progression. In the Yale cohort, which included 15 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the 6 patients who were classified as high risk on the basis of a 52-gene signature had more CD14+ monocytes than the 9 low-risk patients did.

In addition, Ms. Scott and her collaborators looked at complete blood count values in the electronic health records of 45,068 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, systemic sclerosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or myelofibrosis in Stanford, Northwestern, Vanderbilt, and Optum Clinformatics Data Mart cohorts.

Among patients in the COMET, Stanford, and Northwestern datasets, monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL or greater were associated with mortality after adjustment for forced vital capacity (HR, 2.47) and the gender, age, and physiology index (HR, 2.06). Data from 7,459 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis “showed that patients with monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL or greater were at increased risk of mortality with lung transplantation as a censoring event, after adjusting for age at diagnosis and sex” in the Stanford (HR, 2.30), Vanderbilt (HR, 1.52), and Optum (HR, 1.74) cohorts. “Likewise, higher absolute monocyte count was associated with shortened survival in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy across all three cohorts, and in patients with systemic sclerosis or myelofibrosis in two of the three cohorts,” the researchers said.

The study was funded by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and U.S. National Library of Medicine. Ms. Scott had no competing interests. Coauthors disclosed grants, compensation, and support from foundations, agencies, and companies.

SOURCE: Scott MKD et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30508-3.

FROM THE LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Key clinical point: An increased monocyte count predicts poor outcomes among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and other fibrotic diseases.

Major finding: Among patients in three cohorts, monocyte counts of 0.95 K/mcL or greater were associated with mortality after adjustment for forced vital capacity (hazard ratio, 2.47) and the gender, age, and physiology index (HR, 2.06).

Study details: A retrospective analysis of data from 7,000 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis from five independent cohorts.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and U.S. National Library of Medicine. Ms. Scott had no competing interests. Coauthors disclosed grants, compensation, and support from foundations, agencies, and companies.

Source: Scott MKD et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30508-3.

Experts agree on routine lung disease screening in systemic sclerosis

MADRID – The for early detection, monitoring, and, when warranted, treatment, Anna-Maria Hoffmann-Vold, MD, PhD, reported at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“Everyone with systemic sclerosis needs to be screened because this is the most important risk factor for ILD,” said Dr. Hoffmann-Vold, a clinical scientist in the division of rheumatology at the University of Oslo and head of scleroderma research at Oslo University Hospital.

Although the frequency of screening is not specified based on the opinion that this should be based on risk factors and other clinical characteristics, there was unanimous agreement that lung function tests do not represent an adequate screening tool or method for assessing ILD severity. Rather, the recommendations make clear that lung function studies are adjunctive to high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT).

“HRCT is the primary tool for evaluating ILD, but there was 100% agreement that assessment should include more than one measure, including lung function tests and clinical assessment,” Dr. Hoffmann-Vold reported.

There was a strong opinion that the numerous potential biomarkers described for ILD, although promising, are not yet ready for clinical use.

In developing these new recommendations, 95 potential statements were considered by the panel of 27 rheumatologists, pulmonologists, and others with experience in this field. A Delphi process was used for members of the panel to identify areas of agreement to produce consensus statements.

The result has been more than 50 statements issued in six major domains. These include statements on risk factors, appropriate methodology for diagnosis and severity assessment, when to initiate therapy, and when and how to initiate treatment escalation.

“We want to increase clinician awareness and provide standardized guidance for evaluating patients for the presence and medical management of ILD-SSc,” Dr. Hoffmann-Vold explained.

ILD occurs in about half of all patients with systemic sclerosis. Among these, approximately one out of three will experience lung disease progression. Although these high prevalence rates are well recognized and associated with high morbidity and mortality, Dr. Hoffmann-Vold said that there has been uncertainty about how to screen systemic sclerosis patients for ILD and what steps to take when it was found. It is this uncertainty that prompted the present initiative.

The consensus recommendations are an initial step to guide clinicians, but Dr. Hoffmann-Vold noted that the many statements are based on expert opinion, suggesting more studies are needed to compare strategies for objective severity grading and prediction of which patients are most at risk for ILD progression.

“There are still huge knowledge gaps we need to fill,” she stated. Still, she believes these recommendations represent progress in this field. While they are likely “to increase the standard of care” for those who develop ILD-SSc, they also have identified where to concentrate further research.

Dr. Hoffmann-Vold reported financial relationships with Actelion, Boehringer Ingelheim, and GlaxoSmithKline.

SOURCE: Hoffmann-Vold A-M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):104, Abstract OPO064, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.3225.

MADRID – The for early detection, monitoring, and, when warranted, treatment, Anna-Maria Hoffmann-Vold, MD, PhD, reported at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“Everyone with systemic sclerosis needs to be screened because this is the most important risk factor for ILD,” said Dr. Hoffmann-Vold, a clinical scientist in the division of rheumatology at the University of Oslo and head of scleroderma research at Oslo University Hospital.

Although the frequency of screening is not specified based on the opinion that this should be based on risk factors and other clinical characteristics, there was unanimous agreement that lung function tests do not represent an adequate screening tool or method for assessing ILD severity. Rather, the recommendations make clear that lung function studies are adjunctive to high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT).

“HRCT is the primary tool for evaluating ILD, but there was 100% agreement that assessment should include more than one measure, including lung function tests and clinical assessment,” Dr. Hoffmann-Vold reported.

There was a strong opinion that the numerous potential biomarkers described for ILD, although promising, are not yet ready for clinical use.

In developing these new recommendations, 95 potential statements were considered by the panel of 27 rheumatologists, pulmonologists, and others with experience in this field. A Delphi process was used for members of the panel to identify areas of agreement to produce consensus statements.

The result has been more than 50 statements issued in six major domains. These include statements on risk factors, appropriate methodology for diagnosis and severity assessment, when to initiate therapy, and when and how to initiate treatment escalation.

“We want to increase clinician awareness and provide standardized guidance for evaluating patients for the presence and medical management of ILD-SSc,” Dr. Hoffmann-Vold explained.

ILD occurs in about half of all patients with systemic sclerosis. Among these, approximately one out of three will experience lung disease progression. Although these high prevalence rates are well recognized and associated with high morbidity and mortality, Dr. Hoffmann-Vold said that there has been uncertainty about how to screen systemic sclerosis patients for ILD and what steps to take when it was found. It is this uncertainty that prompted the present initiative.

The consensus recommendations are an initial step to guide clinicians, but Dr. Hoffmann-Vold noted that the many statements are based on expert opinion, suggesting more studies are needed to compare strategies for objective severity grading and prediction of which patients are most at risk for ILD progression.

“There are still huge knowledge gaps we need to fill,” she stated. Still, she believes these recommendations represent progress in this field. While they are likely “to increase the standard of care” for those who develop ILD-SSc, they also have identified where to concentrate further research.

Dr. Hoffmann-Vold reported financial relationships with Actelion, Boehringer Ingelheim, and GlaxoSmithKline.

SOURCE: Hoffmann-Vold A-M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):104, Abstract OPO064, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.3225.

MADRID – The for early detection, monitoring, and, when warranted, treatment, Anna-Maria Hoffmann-Vold, MD, PhD, reported at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“Everyone with systemic sclerosis needs to be screened because this is the most important risk factor for ILD,” said Dr. Hoffmann-Vold, a clinical scientist in the division of rheumatology at the University of Oslo and head of scleroderma research at Oslo University Hospital.

Although the frequency of screening is not specified based on the opinion that this should be based on risk factors and other clinical characteristics, there was unanimous agreement that lung function tests do not represent an adequate screening tool or method for assessing ILD severity. Rather, the recommendations make clear that lung function studies are adjunctive to high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT).

“HRCT is the primary tool for evaluating ILD, but there was 100% agreement that assessment should include more than one measure, including lung function tests and clinical assessment,” Dr. Hoffmann-Vold reported.

There was a strong opinion that the numerous potential biomarkers described for ILD, although promising, are not yet ready for clinical use.

In developing these new recommendations, 95 potential statements were considered by the panel of 27 rheumatologists, pulmonologists, and others with experience in this field. A Delphi process was used for members of the panel to identify areas of agreement to produce consensus statements.

The result has been more than 50 statements issued in six major domains. These include statements on risk factors, appropriate methodology for diagnosis and severity assessment, when to initiate therapy, and when and how to initiate treatment escalation.

“We want to increase clinician awareness and provide standardized guidance for evaluating patients for the presence and medical management of ILD-SSc,” Dr. Hoffmann-Vold explained.