User login

ASCO goes ahead online, as conference center is used as hospital

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Facial Malignancies in Patients Referred for Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Retrospective Review of the Impact of Hair Growth on Tumor and Defect Size

Male facial hair trends are continuously changing and are influenced by culture, geography, religion, and ethnicity.1 Although the natural pattern of these hairs is largely androgen dependent, the phenotypic presentation often is a result of contemporary grooming practices that reflect prevailing trends.2 Beards are common throughout adulthood, and thus, preserving this facial hair pattern is considered with reconstructive techniques.3,4 Male facial skin physiology and beard hair biology are a dynamic interplay between both internal (eg, hormonal) and external (eg, shaving) variables. The density of beard hair follicles varies within different subunits, ranging between 20 and 80 follicles/cm2. Macroscopically, hairs vary in length, diameter, color, and growth rate across individuals and ethnicities.1,5

There is a paucity of literature assessing if male facial hair offers a protective role for external insults. One study utilized dosimetry to examine the effectiveness of facial hair on mannequins with varying lengths of hair in protecting against erythemal UV radiation (UVR). The authors concluded that, although facial hair provides protection from UVR, it is not significant.6 In a study of 200 male patients with

We sought to determine if facial hair growth is implicated in the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous malignancies. Specifically, we hypothesized that the presence of facial hair leads to a delay in diagnosis with increased subclinical growth given that tumors may be camouflaged and go undetected. Although there is a lack of literature, our anecdotal evidence suggests that male patients with facial hair have larger tumors compared to patients who do not regularly maintain any facial hair.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review following approval from the institutional review board at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We identified all male patients with a cutaneous malignancy located on the face who were treated from January 2015 to December 2018. Photographs were reviewed and patients with tumors located within the following facial hair-bearing anatomic subunits were included: lip, melolabial fold, chin, mandible, preauricular cheek, buccal cheek, and parotid-masseteric cheek. Tumors located within the medial cheek were excluded.

Facial hair growth was determined via image review. Because biopsy photographs were not uploaded into the health record for patients who were referred externally, we reviewed all historical photographs for patients who had undergone prior Mohs micrographic surgery at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, preoperative photographs, and follow-up photographs as a proxy to determine facial hair status. Postoperative photographs taken within 2 weeks following surgery were not reviewed, as any facial hair growth was likely due to disinclination on behalf of the patient to shave near or over the incision. Age, number of days from biopsy to surgery, pathology, preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs layers, and defect size also were extrapolated from our chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were applied to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. An unpaired 2-tailed t test was utilized to test the null hypothesis that the mean difference was zero. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Results achieving P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We reviewed medical records for 171 patients with facial hair and 336 patients without facial hair. The primary outcomes for this study assessed tumor and defect size in patients with facial hair compared to patients with no facial hair (Table 1). On average, patients who had facial hair were younger (67.5 years vs 74.0 years, P<.001). The median number of days from biopsy to surgery (43.0 vs 44.0 days) was comparable across both groups. The majority of patients (47%) exhibited a beard, while 30% had a mustache and 23% had a goatee. The most common tumor location was the preauricular cheek for both groups (29% and 28%, respectively). The mean preoperative tumor size in the facial hair cohort was 1.40 cm compared to 1.22 cm in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The mean number of Mohs layers in the facial hair cohort was 1.53 compared to 1.33 in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The facial hair cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (2.18 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.98 cm); however, this finding was not significant (P=.05).

We then stratified our data to analyze only lip tumors in patients with and without a mustache (Table 2). The mean preoperative tumor size in the mustache cohort was 1.10 cm compared to 0.82 cm in the group with no mustaches (P=.046). The mean number of Mohs layers in the mustache cohort was 1.57 compared to 1.42 in the group with no mustaches (P=.43). The mustache cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (1.63 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.33 cm), though this finding also did not reach significance (P=.13).

Comment

Our findings support anecdotal observations that tumors in men with facial hair are larger, require more Mohs layers, and result in larger defects compared with patients who are clean shaven. Similarly, in lip tumors, men with a mustache had a larger preoperative tumor size. Although these patients also required more Mohs layers to clear and a larger defect size, these parameters did not reach significance. These outcomes may, in part, be explained by a delay in diagnosis, as patients with facial hair may not notice any new suspicious lesions within the underlying skin as easily as patients with glabrous skin.

Although facial hair may shield skin from UVR, we agree with Parisi et al6 that this protection is marginal at best and that early persistent exposure to UVR plays a much more notable role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. As more men continue to grow facial hairstyles that emulate historical or contemporary trends, dermatologists should emphasize the risk for cutaneous malignancies within these sun-exposed areas of the face. Although some facial hair practices may reflect cultural or ethnic settings, the majority reflect a desired appearance that is achieved with grooming or otherwise.

Skin cancer screening in men with facial hair, particularly those with a strong history of UVR exposure and/or family history, should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose cutaneous tumors earlier. We encourage men with facial hair to be cognizant that cutaneous malignancies can arise within hair-bearing skin and to incorporate self–skin checks into grooming routines, which is particularly important in men with dense facial hair who forego regular self-care grooming or trim intermittently. Furthermore, we urge dermatologists to continue to thoroughly examine the underlying skin, especially in patients with full beards, during skin examinations. Diagnosing and treating cutaneous malignancies early is imperative to maximize ideal functional and cosmetic outcomes, particularly within perioral and lip subunits, where marginal millimeters can impact reconstructive complexity.

Conclusion

Men with facial hair who had cutaneous tumors in our study exhibited larger tumors, required more Mohs layers, and had a larger defect size compared to men without any facial hair growth. Similar findings also were noted when we stratified and compared lip tumors in patients with and without mustaches. Given these observations, patients and dermatologists should continue to have a high index of suspicion for any concerning lesion located within skin underlying facial hair. Regular screening in men with facial hair should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose and treat potential cutaneous tumors earlier.

- Wu Y, Konduru R, Deng D. Skin characteristics of Chinese men and their beard removal habits. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:17-21.

- Janif ZJ, Brooks RC, Dixson BJ. Negative frequency-dependent preferences and variation in male facial hair. Biol Lett. 2014;10:20130958.

- Benjegerdes KE, Jamerson J, Housewright CD. Repair of a large submental defect. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:141-143.

- Ninkovic M, Heidekruegger PI, Ehri D, et al. Beard reconstruction: a surgical algorithm. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:E111-E118.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin–challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(suppl 1):3-9.

- Parisi AV, Turnbull DJ, Downs N, et al. Dosimetric investigation of the solar erythemal UV radiation protection provided by beards and moustaches. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2012;150:278-282.

- Liu DY, Gul MI, Wick J, et al. Long-term sheltering mustaches reduce incidence of lower lip actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1757-1758.e1.

Male facial hair trends are continuously changing and are influenced by culture, geography, religion, and ethnicity.1 Although the natural pattern of these hairs is largely androgen dependent, the phenotypic presentation often is a result of contemporary grooming practices that reflect prevailing trends.2 Beards are common throughout adulthood, and thus, preserving this facial hair pattern is considered with reconstructive techniques.3,4 Male facial skin physiology and beard hair biology are a dynamic interplay between both internal (eg, hormonal) and external (eg, shaving) variables. The density of beard hair follicles varies within different subunits, ranging between 20 and 80 follicles/cm2. Macroscopically, hairs vary in length, diameter, color, and growth rate across individuals and ethnicities.1,5

There is a paucity of literature assessing if male facial hair offers a protective role for external insults. One study utilized dosimetry to examine the effectiveness of facial hair on mannequins with varying lengths of hair in protecting against erythemal UV radiation (UVR). The authors concluded that, although facial hair provides protection from UVR, it is not significant.6 In a study of 200 male patients with

We sought to determine if facial hair growth is implicated in the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous malignancies. Specifically, we hypothesized that the presence of facial hair leads to a delay in diagnosis with increased subclinical growth given that tumors may be camouflaged and go undetected. Although there is a lack of literature, our anecdotal evidence suggests that male patients with facial hair have larger tumors compared to patients who do not regularly maintain any facial hair.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review following approval from the institutional review board at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We identified all male patients with a cutaneous malignancy located on the face who were treated from January 2015 to December 2018. Photographs were reviewed and patients with tumors located within the following facial hair-bearing anatomic subunits were included: lip, melolabial fold, chin, mandible, preauricular cheek, buccal cheek, and parotid-masseteric cheek. Tumors located within the medial cheek were excluded.

Facial hair growth was determined via image review. Because biopsy photographs were not uploaded into the health record for patients who were referred externally, we reviewed all historical photographs for patients who had undergone prior Mohs micrographic surgery at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, preoperative photographs, and follow-up photographs as a proxy to determine facial hair status. Postoperative photographs taken within 2 weeks following surgery were not reviewed, as any facial hair growth was likely due to disinclination on behalf of the patient to shave near or over the incision. Age, number of days from biopsy to surgery, pathology, preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs layers, and defect size also were extrapolated from our chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were applied to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. An unpaired 2-tailed t test was utilized to test the null hypothesis that the mean difference was zero. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Results achieving P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We reviewed medical records for 171 patients with facial hair and 336 patients without facial hair. The primary outcomes for this study assessed tumor and defect size in patients with facial hair compared to patients with no facial hair (Table 1). On average, patients who had facial hair were younger (67.5 years vs 74.0 years, P<.001). The median number of days from biopsy to surgery (43.0 vs 44.0 days) was comparable across both groups. The majority of patients (47%) exhibited a beard, while 30% had a mustache and 23% had a goatee. The most common tumor location was the preauricular cheek for both groups (29% and 28%, respectively). The mean preoperative tumor size in the facial hair cohort was 1.40 cm compared to 1.22 cm in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The mean number of Mohs layers in the facial hair cohort was 1.53 compared to 1.33 in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The facial hair cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (2.18 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.98 cm); however, this finding was not significant (P=.05).

We then stratified our data to analyze only lip tumors in patients with and without a mustache (Table 2). The mean preoperative tumor size in the mustache cohort was 1.10 cm compared to 0.82 cm in the group with no mustaches (P=.046). The mean number of Mohs layers in the mustache cohort was 1.57 compared to 1.42 in the group with no mustaches (P=.43). The mustache cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (1.63 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.33 cm), though this finding also did not reach significance (P=.13).

Comment

Our findings support anecdotal observations that tumors in men with facial hair are larger, require more Mohs layers, and result in larger defects compared with patients who are clean shaven. Similarly, in lip tumors, men with a mustache had a larger preoperative tumor size. Although these patients also required more Mohs layers to clear and a larger defect size, these parameters did not reach significance. These outcomes may, in part, be explained by a delay in diagnosis, as patients with facial hair may not notice any new suspicious lesions within the underlying skin as easily as patients with glabrous skin.

Although facial hair may shield skin from UVR, we agree with Parisi et al6 that this protection is marginal at best and that early persistent exposure to UVR plays a much more notable role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. As more men continue to grow facial hairstyles that emulate historical or contemporary trends, dermatologists should emphasize the risk for cutaneous malignancies within these sun-exposed areas of the face. Although some facial hair practices may reflect cultural or ethnic settings, the majority reflect a desired appearance that is achieved with grooming or otherwise.

Skin cancer screening in men with facial hair, particularly those with a strong history of UVR exposure and/or family history, should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose cutaneous tumors earlier. We encourage men with facial hair to be cognizant that cutaneous malignancies can arise within hair-bearing skin and to incorporate self–skin checks into grooming routines, which is particularly important in men with dense facial hair who forego regular self-care grooming or trim intermittently. Furthermore, we urge dermatologists to continue to thoroughly examine the underlying skin, especially in patients with full beards, during skin examinations. Diagnosing and treating cutaneous malignancies early is imperative to maximize ideal functional and cosmetic outcomes, particularly within perioral and lip subunits, where marginal millimeters can impact reconstructive complexity.

Conclusion

Men with facial hair who had cutaneous tumors in our study exhibited larger tumors, required more Mohs layers, and had a larger defect size compared to men without any facial hair growth. Similar findings also were noted when we stratified and compared lip tumors in patients with and without mustaches. Given these observations, patients and dermatologists should continue to have a high index of suspicion for any concerning lesion located within skin underlying facial hair. Regular screening in men with facial hair should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose and treat potential cutaneous tumors earlier.

Male facial hair trends are continuously changing and are influenced by culture, geography, religion, and ethnicity.1 Although the natural pattern of these hairs is largely androgen dependent, the phenotypic presentation often is a result of contemporary grooming practices that reflect prevailing trends.2 Beards are common throughout adulthood, and thus, preserving this facial hair pattern is considered with reconstructive techniques.3,4 Male facial skin physiology and beard hair biology are a dynamic interplay between both internal (eg, hormonal) and external (eg, shaving) variables. The density of beard hair follicles varies within different subunits, ranging between 20 and 80 follicles/cm2. Macroscopically, hairs vary in length, diameter, color, and growth rate across individuals and ethnicities.1,5

There is a paucity of literature assessing if male facial hair offers a protective role for external insults. One study utilized dosimetry to examine the effectiveness of facial hair on mannequins with varying lengths of hair in protecting against erythemal UV radiation (UVR). The authors concluded that, although facial hair provides protection from UVR, it is not significant.6 In a study of 200 male patients with

We sought to determine if facial hair growth is implicated in the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous malignancies. Specifically, we hypothesized that the presence of facial hair leads to a delay in diagnosis with increased subclinical growth given that tumors may be camouflaged and go undetected. Although there is a lack of literature, our anecdotal evidence suggests that male patients with facial hair have larger tumors compared to patients who do not regularly maintain any facial hair.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review following approval from the institutional review board at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We identified all male patients with a cutaneous malignancy located on the face who were treated from January 2015 to December 2018. Photographs were reviewed and patients with tumors located within the following facial hair-bearing anatomic subunits were included: lip, melolabial fold, chin, mandible, preauricular cheek, buccal cheek, and parotid-masseteric cheek. Tumors located within the medial cheek were excluded.

Facial hair growth was determined via image review. Because biopsy photographs were not uploaded into the health record for patients who were referred externally, we reviewed all historical photographs for patients who had undergone prior Mohs micrographic surgery at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, preoperative photographs, and follow-up photographs as a proxy to determine facial hair status. Postoperative photographs taken within 2 weeks following surgery were not reviewed, as any facial hair growth was likely due to disinclination on behalf of the patient to shave near or over the incision. Age, number of days from biopsy to surgery, pathology, preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs layers, and defect size also were extrapolated from our chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were applied to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. An unpaired 2-tailed t test was utilized to test the null hypothesis that the mean difference was zero. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Results achieving P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We reviewed medical records for 171 patients with facial hair and 336 patients without facial hair. The primary outcomes for this study assessed tumor and defect size in patients with facial hair compared to patients with no facial hair (Table 1). On average, patients who had facial hair were younger (67.5 years vs 74.0 years, P<.001). The median number of days from biopsy to surgery (43.0 vs 44.0 days) was comparable across both groups. The majority of patients (47%) exhibited a beard, while 30% had a mustache and 23% had a goatee. The most common tumor location was the preauricular cheek for both groups (29% and 28%, respectively). The mean preoperative tumor size in the facial hair cohort was 1.40 cm compared to 1.22 cm in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The mean number of Mohs layers in the facial hair cohort was 1.53 compared to 1.33 in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The facial hair cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (2.18 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.98 cm); however, this finding was not significant (P=.05).

We then stratified our data to analyze only lip tumors in patients with and without a mustache (Table 2). The mean preoperative tumor size in the mustache cohort was 1.10 cm compared to 0.82 cm in the group with no mustaches (P=.046). The mean number of Mohs layers in the mustache cohort was 1.57 compared to 1.42 in the group with no mustaches (P=.43). The mustache cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (1.63 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.33 cm), though this finding also did not reach significance (P=.13).

Comment

Our findings support anecdotal observations that tumors in men with facial hair are larger, require more Mohs layers, and result in larger defects compared with patients who are clean shaven. Similarly, in lip tumors, men with a mustache had a larger preoperative tumor size. Although these patients also required more Mohs layers to clear and a larger defect size, these parameters did not reach significance. These outcomes may, in part, be explained by a delay in diagnosis, as patients with facial hair may not notice any new suspicious lesions within the underlying skin as easily as patients with glabrous skin.

Although facial hair may shield skin from UVR, we agree with Parisi et al6 that this protection is marginal at best and that early persistent exposure to UVR plays a much more notable role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. As more men continue to grow facial hairstyles that emulate historical or contemporary trends, dermatologists should emphasize the risk for cutaneous malignancies within these sun-exposed areas of the face. Although some facial hair practices may reflect cultural or ethnic settings, the majority reflect a desired appearance that is achieved with grooming or otherwise.

Skin cancer screening in men with facial hair, particularly those with a strong history of UVR exposure and/or family history, should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose cutaneous tumors earlier. We encourage men with facial hair to be cognizant that cutaneous malignancies can arise within hair-bearing skin and to incorporate self–skin checks into grooming routines, which is particularly important in men with dense facial hair who forego regular self-care grooming or trim intermittently. Furthermore, we urge dermatologists to continue to thoroughly examine the underlying skin, especially in patients with full beards, during skin examinations. Diagnosing and treating cutaneous malignancies early is imperative to maximize ideal functional and cosmetic outcomes, particularly within perioral and lip subunits, where marginal millimeters can impact reconstructive complexity.

Conclusion

Men with facial hair who had cutaneous tumors in our study exhibited larger tumors, required more Mohs layers, and had a larger defect size compared to men without any facial hair growth. Similar findings also were noted when we stratified and compared lip tumors in patients with and without mustaches. Given these observations, patients and dermatologists should continue to have a high index of suspicion for any concerning lesion located within skin underlying facial hair. Regular screening in men with facial hair should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose and treat potential cutaneous tumors earlier.

- Wu Y, Konduru R, Deng D. Skin characteristics of Chinese men and their beard removal habits. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:17-21.

- Janif ZJ, Brooks RC, Dixson BJ. Negative frequency-dependent preferences and variation in male facial hair. Biol Lett. 2014;10:20130958.

- Benjegerdes KE, Jamerson J, Housewright CD. Repair of a large submental defect. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:141-143.

- Ninkovic M, Heidekruegger PI, Ehri D, et al. Beard reconstruction: a surgical algorithm. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:E111-E118.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin–challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(suppl 1):3-9.

- Parisi AV, Turnbull DJ, Downs N, et al. Dosimetric investigation of the solar erythemal UV radiation protection provided by beards and moustaches. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2012;150:278-282.

- Liu DY, Gul MI, Wick J, et al. Long-term sheltering mustaches reduce incidence of lower lip actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1757-1758.e1.

- Wu Y, Konduru R, Deng D. Skin characteristics of Chinese men and their beard removal habits. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:17-21.

- Janif ZJ, Brooks RC, Dixson BJ. Negative frequency-dependent preferences and variation in male facial hair. Biol Lett. 2014;10:20130958.

- Benjegerdes KE, Jamerson J, Housewright CD. Repair of a large submental defect. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:141-143.

- Ninkovic M, Heidekruegger PI, Ehri D, et al. Beard reconstruction: a surgical algorithm. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:E111-E118.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin–challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(suppl 1):3-9.

- Parisi AV, Turnbull DJ, Downs N, et al. Dosimetric investigation of the solar erythemal UV radiation protection provided by beards and moustaches. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2012;150:278-282.

- Liu DY, Gul MI, Wick J, et al. Long-term sheltering mustaches reduce incidence of lower lip actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1757-1758.e1.

Practice Points

- In our study, men with cutaneous tumors who had facial hair exhibited larger tumors, required more Mohs layers, and had a larger defect size compared to men who do not have any facial hair growth.

- Both patients and dermatologists should have a high index of suspicion for any concerning lesion contained within skin underlying facial hair to ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous tumors.

Patient Questionnaire to Reduce Anxiety Prior to Full-Body Skin Examination

To the Editor:

A thorough full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an integral component of a dermatologic encounter and helps identify potentially malignant and high-risk lesions, particularly in areas that are difficult for the patient to visualize.1 Despite these benefits, many patients experience discomfort and anxiety about this examination because it involves sensitive anatomical areas. The true psychological impact of an FBSE is not clearly understood; however, research into improving patient comfort in these circumstances can have a broad positive impact.2 The purpose of this pilot study was to establish patients’ willingness to complete a pre-encounter questionnaire that defines their FBSE preferences as well as to identify the anatomical areas that are of most concern.

This study was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board as nonhuman subjects research. A pre-encounter questionnaire that included information about the benefits of FBSEs was administered to 34 patients, allowing them to identify anatomic locations that they wanted to exclude from the FBSE.

Following the patient visit (in which the identified anatomical locations were excluded), patients were given a brief exit survey that asked about (1) their preference for a pre-encounter FBSE questionnaire and (2) the impact of the questionnaire on their anxiety level throughout the encounter. Preference for asking was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong preference for the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong preference against the pre-encounter survey). Change in anxiety was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong reduction in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong increase in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey). Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests, with P<.05 considered statistically significant.

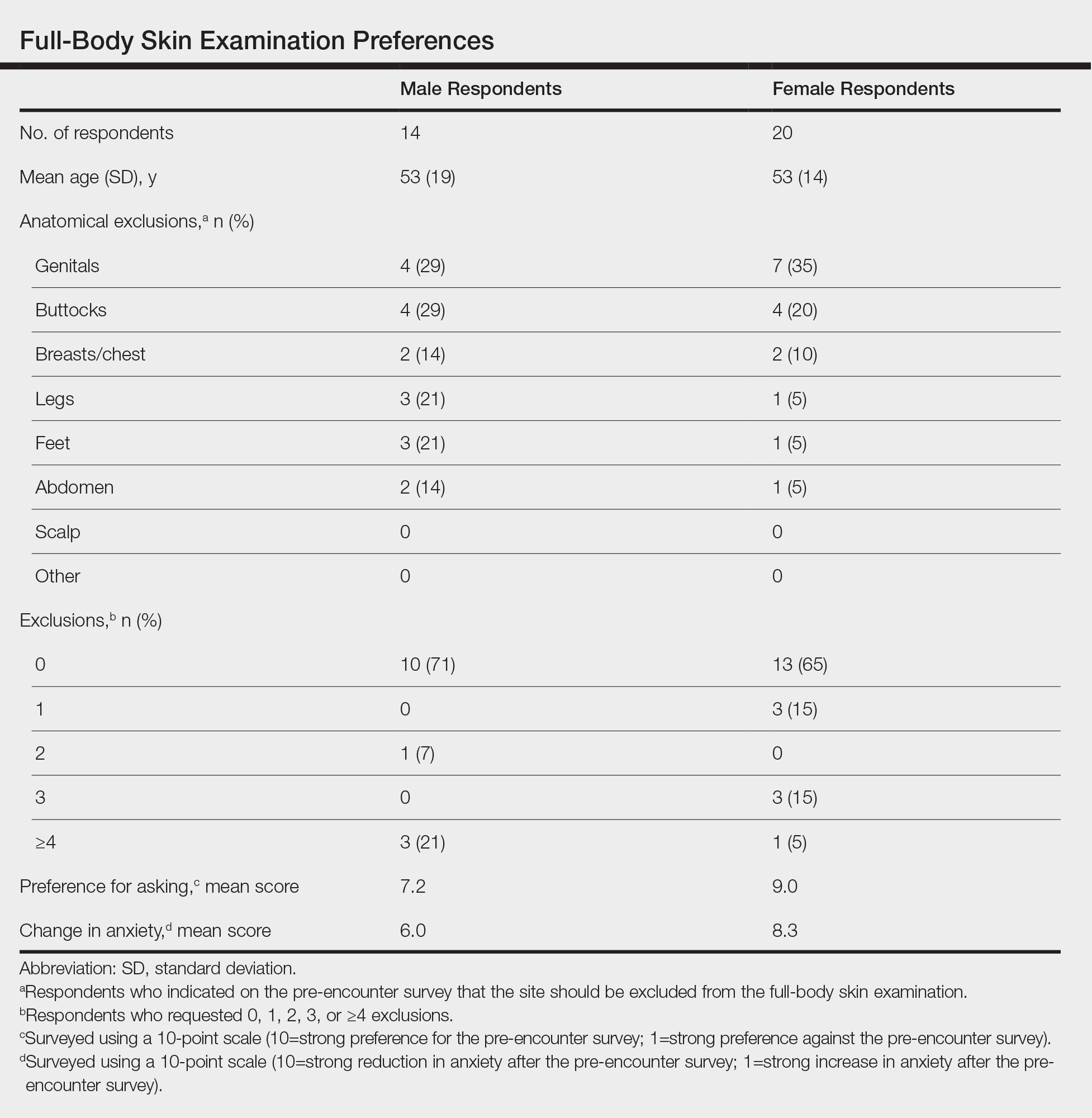

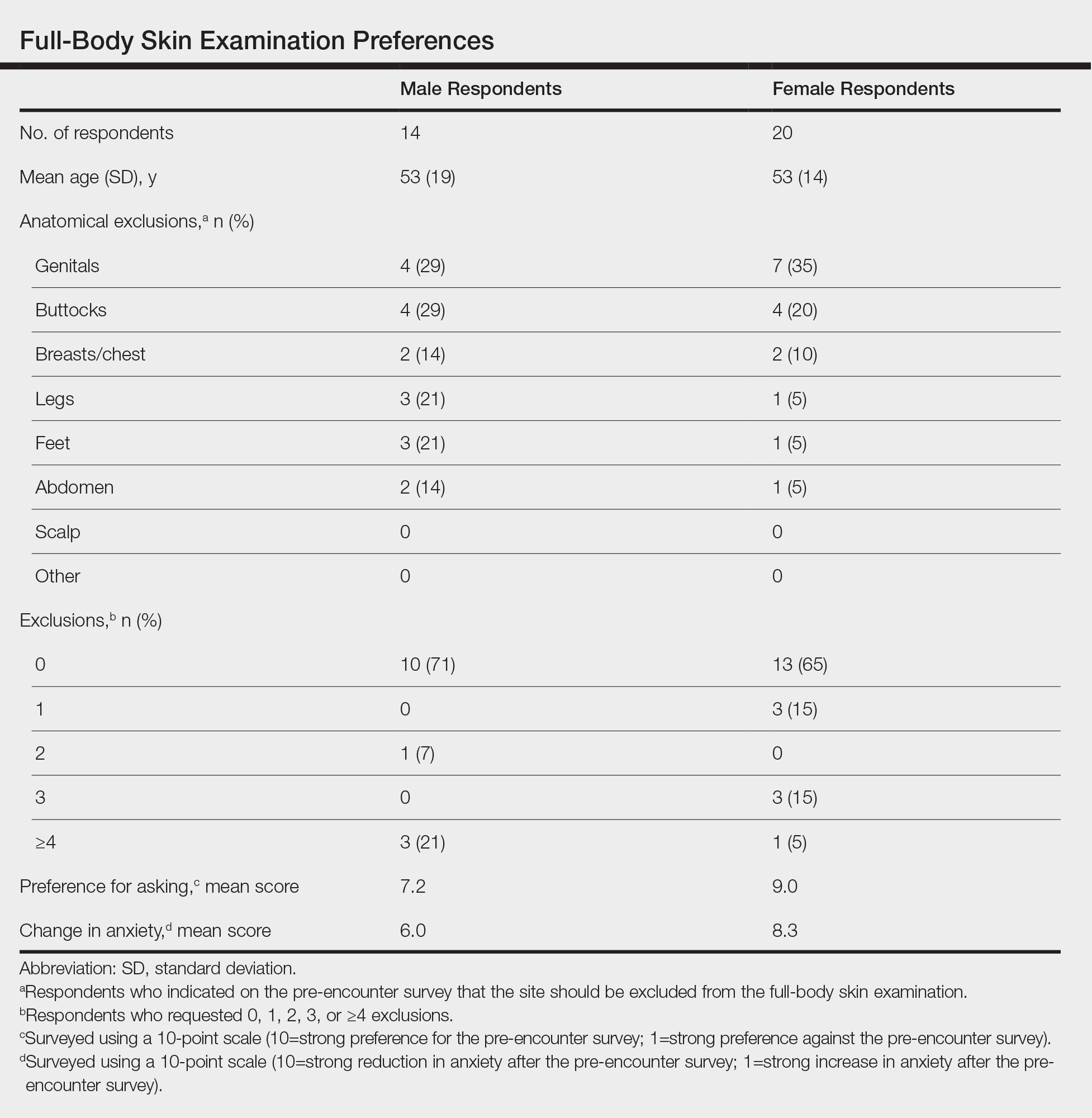

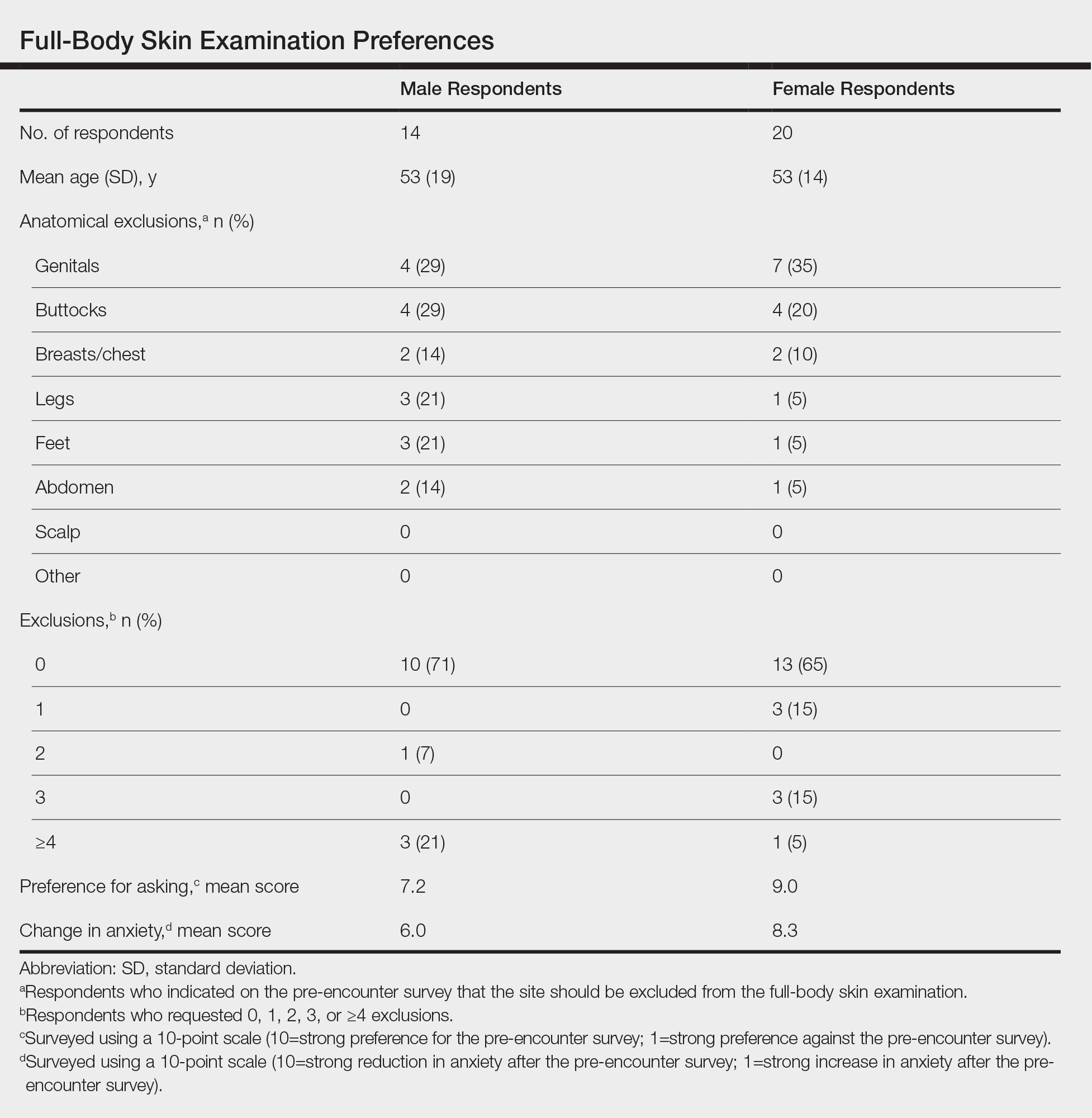

Twenty female and 14 male patients were enrolled (mean age, 53 years)(Table). The most commonly excluded anatomical location on the pre-encounter survey was the genitals, followed by the buttocks, breasts/chest, legs, feet, and abdomen (Table); 10 (71%) male and 13 (65%) female respondents did not exclude any component of the FBSE.

After the provider visit, females had a higher preference for the pre-encounter survey (mean score, 9.0) compared to males (mean score, 7.2; P=.021). Similarly, females had reduced anxiety about the office visit after survey administration compared to males (mean score, 8.3 vs 6.0; P=.001)(Table).

The results of our pilot study showed that a brief pre-encounter questionnaire may reduce the distress associated with an FBSE. Our survey took less than 1 minute to complete and served as a useful guide to direct the provider during the FBSE. Moreover, recognizing that patients do not want certain anatomic locations examined can serve as an opportunity for the dermatologist to provide helpful home skin check instructions and recommendations.

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. Future studies can assess with greater precision the clear benefits of a pre-encounter survey as well as the benefits or drawbacks of a survey compared to other modalities that are aimed at reducing patient anxiety about the FBSE, such as having the physician directly ask the patient about areas to avoid during the examination.

A pre-encounter survey about the FBSE can serve as an efficient means of determining patient preference and reducing self-reported anxiety about the visit.

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

To the Editor:

A thorough full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an integral component of a dermatologic encounter and helps identify potentially malignant and high-risk lesions, particularly in areas that are difficult for the patient to visualize.1 Despite these benefits, many patients experience discomfort and anxiety about this examination because it involves sensitive anatomical areas. The true psychological impact of an FBSE is not clearly understood; however, research into improving patient comfort in these circumstances can have a broad positive impact.2 The purpose of this pilot study was to establish patients’ willingness to complete a pre-encounter questionnaire that defines their FBSE preferences as well as to identify the anatomical areas that are of most concern.

This study was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board as nonhuman subjects research. A pre-encounter questionnaire that included information about the benefits of FBSEs was administered to 34 patients, allowing them to identify anatomic locations that they wanted to exclude from the FBSE.

Following the patient visit (in which the identified anatomical locations were excluded), patients were given a brief exit survey that asked about (1) their preference for a pre-encounter FBSE questionnaire and (2) the impact of the questionnaire on their anxiety level throughout the encounter. Preference for asking was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong preference for the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong preference against the pre-encounter survey). Change in anxiety was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong reduction in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong increase in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey). Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests, with P<.05 considered statistically significant.

Twenty female and 14 male patients were enrolled (mean age, 53 years)(Table). The most commonly excluded anatomical location on the pre-encounter survey was the genitals, followed by the buttocks, breasts/chest, legs, feet, and abdomen (Table); 10 (71%) male and 13 (65%) female respondents did not exclude any component of the FBSE.

After the provider visit, females had a higher preference for the pre-encounter survey (mean score, 9.0) compared to males (mean score, 7.2; P=.021). Similarly, females had reduced anxiety about the office visit after survey administration compared to males (mean score, 8.3 vs 6.0; P=.001)(Table).

The results of our pilot study showed that a brief pre-encounter questionnaire may reduce the distress associated with an FBSE. Our survey took less than 1 minute to complete and served as a useful guide to direct the provider during the FBSE. Moreover, recognizing that patients do not want certain anatomic locations examined can serve as an opportunity for the dermatologist to provide helpful home skin check instructions and recommendations.

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. Future studies can assess with greater precision the clear benefits of a pre-encounter survey as well as the benefits or drawbacks of a survey compared to other modalities that are aimed at reducing patient anxiety about the FBSE, such as having the physician directly ask the patient about areas to avoid during the examination.

A pre-encounter survey about the FBSE can serve as an efficient means of determining patient preference and reducing self-reported anxiety about the visit.

To the Editor:

A thorough full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an integral component of a dermatologic encounter and helps identify potentially malignant and high-risk lesions, particularly in areas that are difficult for the patient to visualize.1 Despite these benefits, many patients experience discomfort and anxiety about this examination because it involves sensitive anatomical areas. The true psychological impact of an FBSE is not clearly understood; however, research into improving patient comfort in these circumstances can have a broad positive impact.2 The purpose of this pilot study was to establish patients’ willingness to complete a pre-encounter questionnaire that defines their FBSE preferences as well as to identify the anatomical areas that are of most concern.

This study was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board as nonhuman subjects research. A pre-encounter questionnaire that included information about the benefits of FBSEs was administered to 34 patients, allowing them to identify anatomic locations that they wanted to exclude from the FBSE.

Following the patient visit (in which the identified anatomical locations were excluded), patients were given a brief exit survey that asked about (1) their preference for a pre-encounter FBSE questionnaire and (2) the impact of the questionnaire on their anxiety level throughout the encounter. Preference for asking was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong preference for the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong preference against the pre-encounter survey). Change in anxiety was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong reduction in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong increase in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey). Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests, with P<.05 considered statistically significant.

Twenty female and 14 male patients were enrolled (mean age, 53 years)(Table). The most commonly excluded anatomical location on the pre-encounter survey was the genitals, followed by the buttocks, breasts/chest, legs, feet, and abdomen (Table); 10 (71%) male and 13 (65%) female respondents did not exclude any component of the FBSE.

After the provider visit, females had a higher preference for the pre-encounter survey (mean score, 9.0) compared to males (mean score, 7.2; P=.021). Similarly, females had reduced anxiety about the office visit after survey administration compared to males (mean score, 8.3 vs 6.0; P=.001)(Table).

The results of our pilot study showed that a brief pre-encounter questionnaire may reduce the distress associated with an FBSE. Our survey took less than 1 minute to complete and served as a useful guide to direct the provider during the FBSE. Moreover, recognizing that patients do not want certain anatomic locations examined can serve as an opportunity for the dermatologist to provide helpful home skin check instructions and recommendations.

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. Future studies can assess with greater precision the clear benefits of a pre-encounter survey as well as the benefits or drawbacks of a survey compared to other modalities that are aimed at reducing patient anxiety about the FBSE, such as having the physician directly ask the patient about areas to avoid during the examination.

A pre-encounter survey about the FBSE can serve as an efficient means of determining patient preference and reducing self-reported anxiety about the visit.

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

Practice Points

- Full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an assessment that requires examination of sensitive body areas, any of which can be seen as intrusive by certain patients.

- A pre-encounter survey on the FBSE can offer an efficient means by which to determine patient preference and reduce visit-associated anxiety.

COVID-19 death rate was twice as high in cancer patients in NYC study

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

FROM CANCER DISCOVERY

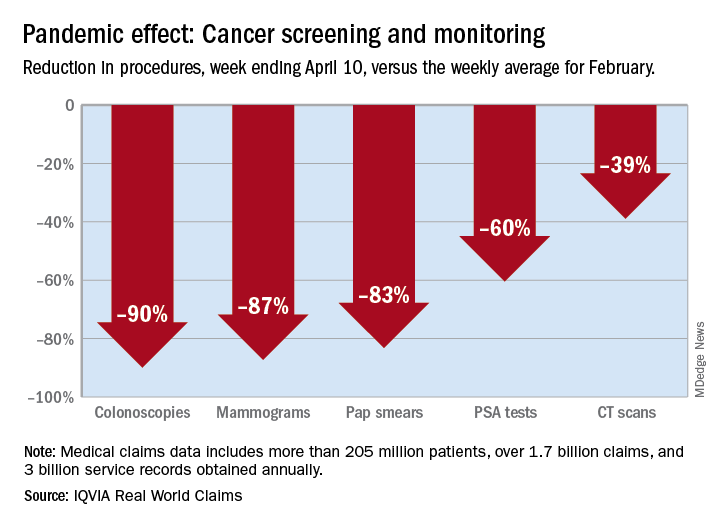

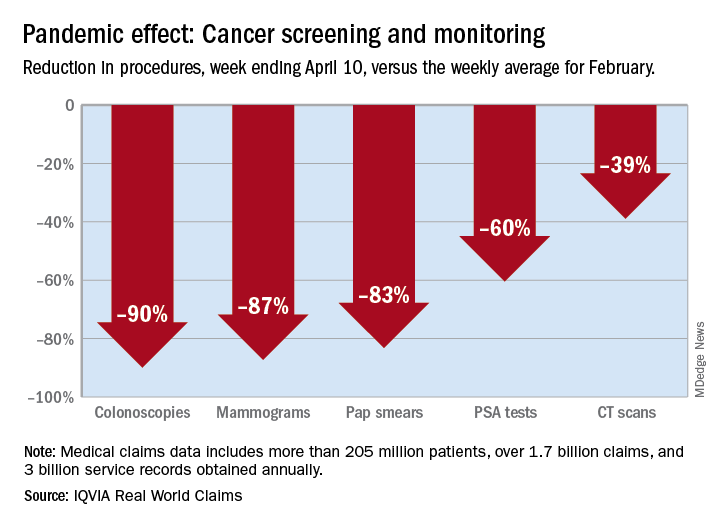

Cancer screening, monitoring down during pandemic

according to a report by the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science.

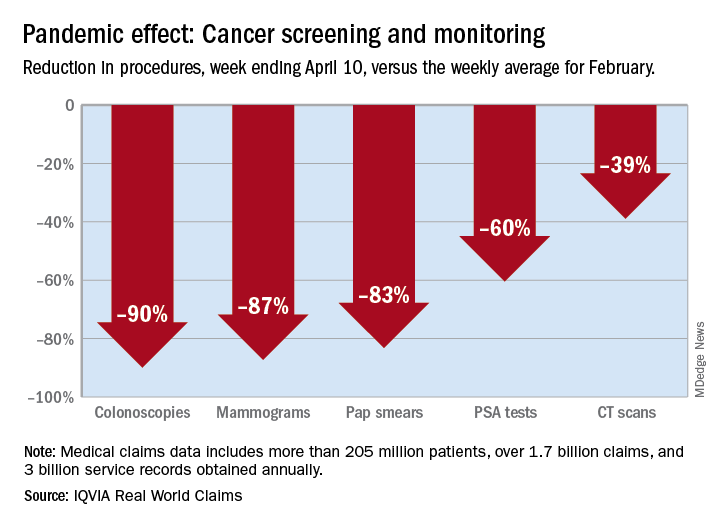

There were 90% fewer colonoscopies ordered during the week ending April 10, compared with the weekly average for Feb. 1-28, based on claims data analyzed by IQVIA.

IQVIA’s medical claims database includes more than 205 million patients, over 1.7 billion claims, and 3 billion service records obtained annually.

The data also showed an 87% reduction in mammograms and an 83% reduction in Pap smears during the week ending April 10. Prostate-specific antigen tests for prostate cancer decreased by 60%, and CT scans for lung cancer decreased by 39%.

The smaller decrease in CT scans for lung cancer “may reflect the generally more serious nature of those tumors or be due to concerns about ruling out COVID-related issues in some patients,” according to report authors Murray Aitken and Michael Kleinrock, both of IQVIA.

The report also showed that overall patient interactions with oncologists were down by 20% through April 3, based on medical and pharmacy claims processed since February, but there was variation by tumor type.

The authors noted “little or no disruption” in oncologist visits in March for patients with aggressive tumors or those diagnosed at advanced stages, compared with February. However, for patients with skin cancer or prostate cancer, visit rates were down by 20%-50% in March.

“This may reflect that oncologists who are providing care across multiple tumor types are prioritizing their time and efforts to those patients with more advanced or aggressive tumors,” the authors wrote.

This report was produced by the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science without industry or government funding.

SOURCE: Murray A and Kleinrock M. Shifts in healthcare demand, delivery and care during the COVID-19 era. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. April 2020.

according to a report by the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science.

There were 90% fewer colonoscopies ordered during the week ending April 10, compared with the weekly average for Feb. 1-28, based on claims data analyzed by IQVIA.

IQVIA’s medical claims database includes more than 205 million patients, over 1.7 billion claims, and 3 billion service records obtained annually.

The data also showed an 87% reduction in mammograms and an 83% reduction in Pap smears during the week ending April 10. Prostate-specific antigen tests for prostate cancer decreased by 60%, and CT scans for lung cancer decreased by 39%.

The smaller decrease in CT scans for lung cancer “may reflect the generally more serious nature of those tumors or be due to concerns about ruling out COVID-related issues in some patients,” according to report authors Murray Aitken and Michael Kleinrock, both of IQVIA.

The report also showed that overall patient interactions with oncologists were down by 20% through April 3, based on medical and pharmacy claims processed since February, but there was variation by tumor type.

The authors noted “little or no disruption” in oncologist visits in March for patients with aggressive tumors or those diagnosed at advanced stages, compared with February. However, for patients with skin cancer or prostate cancer, visit rates were down by 20%-50% in March.

“This may reflect that oncologists who are providing care across multiple tumor types are prioritizing their time and efforts to those patients with more advanced or aggressive tumors,” the authors wrote.

This report was produced by the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science without industry or government funding.

SOURCE: Murray A and Kleinrock M. Shifts in healthcare demand, delivery and care during the COVID-19 era. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. April 2020.

according to a report by the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science.

There were 90% fewer colonoscopies ordered during the week ending April 10, compared with the weekly average for Feb. 1-28, based on claims data analyzed by IQVIA.

IQVIA’s medical claims database includes more than 205 million patients, over 1.7 billion claims, and 3 billion service records obtained annually.

The data also showed an 87% reduction in mammograms and an 83% reduction in Pap smears during the week ending April 10. Prostate-specific antigen tests for prostate cancer decreased by 60%, and CT scans for lung cancer decreased by 39%.

The smaller decrease in CT scans for lung cancer “may reflect the generally more serious nature of those tumors or be due to concerns about ruling out COVID-related issues in some patients,” according to report authors Murray Aitken and Michael Kleinrock, both of IQVIA.

The report also showed that overall patient interactions with oncologists were down by 20% through April 3, based on medical and pharmacy claims processed since February, but there was variation by tumor type.

The authors noted “little or no disruption” in oncologist visits in March for patients with aggressive tumors or those diagnosed at advanced stages, compared with February. However, for patients with skin cancer or prostate cancer, visit rates were down by 20%-50% in March.

“This may reflect that oncologists who are providing care across multiple tumor types are prioritizing their time and efforts to those patients with more advanced or aggressive tumors,” the authors wrote.

This report was produced by the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science without industry or government funding.

SOURCE: Murray A and Kleinrock M. Shifts in healthcare demand, delivery and care during the COVID-19 era. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. April 2020.

Excess cancer deaths predicted as care is disrupted by COVID-19

The majority of patients who have cancer or are suspected of having cancer are not accessing healthcare services in the United Kingdom or the United States because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first report of its kind estimates.

As a result, there will be an excess of deaths among patients who have cancer and multiple comorbidities in both countries during the current coronavirus emergency, the report warns.

The authors calculate that there will be 6,270 excess deaths among cancer patients 1 year from now in England and 33,890 excess deaths among cancer patients in the United States. (In the United States, the estimated excess number of deaths applies only to patients older than 40 years, they note.)

“The recorded underlying cause of these excess deaths may be cancer, COVID-19, or comorbidity (such as myocardial infarction),” Alvina Lai, PhD, University College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues observe.

“Our data have highlighted how cancer patients with multimorbidity are a particularly at-risk group during the current pandemic,” they emphasize.

The study was published on ResearchGate as a preprint and has not undergone peer review.

Commenting on the study on the UK Science Media Center, several experts emphasized the lack of peer review, noting that interpretation of these data needs to be further refined on the basis of that input. One expert suggested that there are “substantial uncertainties that this paper does not adequately communicate.” But others argued that this topic was important enough to warrant early release of the data.

Chris Bunce, PhD, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, said this study represents “a highly valuable contribution.”

“It is universally accepted that early diagnosis and treatment and adherence to treatment regimens saves lives,” he pointed out.

“Therefore, these COVID-19-related impacts will cost lives,” Bunce said.

“And if this information is to influence cancer care and guide policy during the COVID-19 crisis, then it is important that the findings are disseminated and discussed immediately, warranting their release ahead of peer view,” he added.

In a Medscape UK commentary, oncologist Karol Sikora, MD, PhD, argues that “restarting cancer services can’t come soon enough.”

“Resonably Argued Numerical Estimate”

“It’s well known that there have been considerable changes in the provision of health care for many conditions, including cancers, as a result of all the measures to deal with the COVID-19 crisis,” said Kevin McConway, PhD, professor emeritus of applied statistics, the Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom.

“It seems inevitable that there will be increased deaths in cancer patients if they are infected with the virus or because of changes in the health services available to them, and quite possibly also from socio-economic effects of the responses to the crisis,” he continued.

“This study is the first that I have seen that produces a reasonably argued numerical estimate of the number of excess deaths of people with cancer arising from these factors in the UK and the USA,” he added.

Declines in Urgent Referrals and Chemo Attendance

For the study, the team used DATA-CAN, the UK National Health Data Research Hub for Cancer, to assess weekly returns for urgent cancer referrals for early diagnosis and also chemotherapy attendances for hospitals in Leeds, London, and Northern Ireland going back to 2018.

The data revealed that there have been major declines in chemotherapy attendances. There has been, on average, a 60% decrease from prepandemic levels in eight hospitals in the three regions that were assessed.

Urgent cancer referrals have dropped by an average of 76% compared to prepandemic levels in the three regions.

On the conservative assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic will only affect patients with newly diagnosed cancer (incident cases), the researchers estimate that the proportion of the population affected by the emergency (PAE) is 40% and that the relative impact of the emergency (RIE) is 1.5.

PAE is a summary measure of exposure to the adverse health consequences of the emergency; RIE is a summary measure of the combined impact on mortality of infection, health service change, physical distancing, and economic downturn, the authors explain.

Comorbidities Common

“Comorbidities were common in people with cancer,” the study authors note. For example, more than one quarter of the study population had at least one comorbidity; more than 14% had two.

For incident cancers, the number of excess deaths steadily increased in conjunction with an increase in the number of comorbidities, such that more than 80% of deaths occurred in patients with one or more comorbidities.

“When considering both prevalent and incident cancers together with a COVID-19 PAE of 40%, we estimated 17,991 excess deaths at a RIE of 1.5; 78.1% of these deaths occur in patients with ≥1 comorbidities,” the authors report.

“The excess risk of death in people living with cancer during the COVID-19 emergency may be due not only to COVID-19 infection, but also to the unintended health consequences of changes in health service provision, the physical or psychological effects of social distancing, and economic upheaval,” they state.

“This is the first study demonstrating profound recent changes in cancer care delivery in multiple centers,” the authors observe.

Lai has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have various relationships with industry, as listed in their article. The commentators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The majority of patients who have cancer or are suspected of having cancer are not accessing healthcare services in the United Kingdom or the United States because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first report of its kind estimates.

As a result, there will be an excess of deaths among patients who have cancer and multiple comorbidities in both countries during the current coronavirus emergency, the report warns.