User login

RNA sequencing characterized high-risk squamous cell carcinomas

SAN DIEGO – Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas from organ transplant recipients had a more aggressive molecular profile than did tumor samples from immunocompetent patients, according to an RNA sequencing study presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

Specimens from organ transplant recipients showed greater induction of biologic pathways related to cancer signaling, fibrosis, and extracellular matrix remodeling, said Dr. Cameron Chesnut, a dermatologist in private practice in Spokane, Wash., who carried out the research while he was a dermatologic surgery resident at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Furthermore, the TP53 tumor suppressor gene was inhibited at least five times more in samples from organ transplant recipients, compared with those from immunocompetent patients, Dr. Chesnut said in an interview.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common cancer to occur after organ transplantation, Dr. Chesnut and his associates noted. The malignancy is 65-250 times more common, is more than 4 times more likely to metastasize, and has a mortality rate of 5% compared with a rate of less than 1% in immunocompetent patients, based on data published online in the journal F1000 Prime Reports, they said.

To characterize these high-risk SCCs and compare them with lower-risk SCCs, the researchers performed RNA sequencing of three normal skin samples and SCC specimens from 15 patients – 7 organ transplant recipients and 8 otherwise healthy individuals. The researchers used an Illumina GAIIx RNA Seq instrument to generate RNA sequencing libraries of the specimens. They also used the web-based Ingenuity Pathway Analysis technique to identify the major biological pathways regulated within the tumors.

In all, 690 highly expressed genes were induced at least fivefold in SCCs from organ transplant recipients compared with those from otherwise healthy patients. These genes encoded pathways related to fibrosis, extracellular remodeling, the cell cycle, and tumor signaling, the investigators said. The COX-2 pathway for prostaglandin synthesis also was induced fivefold or more in the high-risk SCCs compared with those from immunocompetent patients, Dr. Chesnut added.

The researchers also identified 1,290 highly expressed genes that were inhibited at least fivefold in SCCs from organ transplant recipients compared with specimens from immunocompetent patients. The most strongly inhibited pathways were related to sterol biosynthesis and epithelial differentiation, followed by nucleotide excision repair, interleukin-6 and IL-17, and apoptosis, they said.

Based on these findings, novel therapeutics might someday be able to target specific biologic pathways that are highly induced in SCCs from organ transplant recipients, Dr. Chesnut said. “It’s hard to say what the most likely candidates are,” but based on the study findings, “regulating inflammation may be a target,” he added. Dr. Chesnut and his associates reported no external funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas from organ transplant recipients had a more aggressive molecular profile than did tumor samples from immunocompetent patients, according to an RNA sequencing study presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

Specimens from organ transplant recipients showed greater induction of biologic pathways related to cancer signaling, fibrosis, and extracellular matrix remodeling, said Dr. Cameron Chesnut, a dermatologist in private practice in Spokane, Wash., who carried out the research while he was a dermatologic surgery resident at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Furthermore, the TP53 tumor suppressor gene was inhibited at least five times more in samples from organ transplant recipients, compared with those from immunocompetent patients, Dr. Chesnut said in an interview.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common cancer to occur after organ transplantation, Dr. Chesnut and his associates noted. The malignancy is 65-250 times more common, is more than 4 times more likely to metastasize, and has a mortality rate of 5% compared with a rate of less than 1% in immunocompetent patients, based on data published online in the journal F1000 Prime Reports, they said.

To characterize these high-risk SCCs and compare them with lower-risk SCCs, the researchers performed RNA sequencing of three normal skin samples and SCC specimens from 15 patients – 7 organ transplant recipients and 8 otherwise healthy individuals. The researchers used an Illumina GAIIx RNA Seq instrument to generate RNA sequencing libraries of the specimens. They also used the web-based Ingenuity Pathway Analysis technique to identify the major biological pathways regulated within the tumors.

In all, 690 highly expressed genes were induced at least fivefold in SCCs from organ transplant recipients compared with those from otherwise healthy patients. These genes encoded pathways related to fibrosis, extracellular remodeling, the cell cycle, and tumor signaling, the investigators said. The COX-2 pathway for prostaglandin synthesis also was induced fivefold or more in the high-risk SCCs compared with those from immunocompetent patients, Dr. Chesnut added.

The researchers also identified 1,290 highly expressed genes that were inhibited at least fivefold in SCCs from organ transplant recipients compared with specimens from immunocompetent patients. The most strongly inhibited pathways were related to sterol biosynthesis and epithelial differentiation, followed by nucleotide excision repair, interleukin-6 and IL-17, and apoptosis, they said.

Based on these findings, novel therapeutics might someday be able to target specific biologic pathways that are highly induced in SCCs from organ transplant recipients, Dr. Chesnut said. “It’s hard to say what the most likely candidates are,” but based on the study findings, “regulating inflammation may be a target,” he added. Dr. Chesnut and his associates reported no external funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas from organ transplant recipients had a more aggressive molecular profile than did tumor samples from immunocompetent patients, according to an RNA sequencing study presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

Specimens from organ transplant recipients showed greater induction of biologic pathways related to cancer signaling, fibrosis, and extracellular matrix remodeling, said Dr. Cameron Chesnut, a dermatologist in private practice in Spokane, Wash., who carried out the research while he was a dermatologic surgery resident at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Furthermore, the TP53 tumor suppressor gene was inhibited at least five times more in samples from organ transplant recipients, compared with those from immunocompetent patients, Dr. Chesnut said in an interview.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common cancer to occur after organ transplantation, Dr. Chesnut and his associates noted. The malignancy is 65-250 times more common, is more than 4 times more likely to metastasize, and has a mortality rate of 5% compared with a rate of less than 1% in immunocompetent patients, based on data published online in the journal F1000 Prime Reports, they said.

To characterize these high-risk SCCs and compare them with lower-risk SCCs, the researchers performed RNA sequencing of three normal skin samples and SCC specimens from 15 patients – 7 organ transplant recipients and 8 otherwise healthy individuals. The researchers used an Illumina GAIIx RNA Seq instrument to generate RNA sequencing libraries of the specimens. They also used the web-based Ingenuity Pathway Analysis technique to identify the major biological pathways regulated within the tumors.

In all, 690 highly expressed genes were induced at least fivefold in SCCs from organ transplant recipients compared with those from otherwise healthy patients. These genes encoded pathways related to fibrosis, extracellular remodeling, the cell cycle, and tumor signaling, the investigators said. The COX-2 pathway for prostaglandin synthesis also was induced fivefold or more in the high-risk SCCs compared with those from immunocompetent patients, Dr. Chesnut added.

The researchers also identified 1,290 highly expressed genes that were inhibited at least fivefold in SCCs from organ transplant recipients compared with specimens from immunocompetent patients. The most strongly inhibited pathways were related to sterol biosynthesis and epithelial differentiation, followed by nucleotide excision repair, interleukin-6 and IL-17, and apoptosis, they said.

Based on these findings, novel therapeutics might someday be able to target specific biologic pathways that are highly induced in SCCs from organ transplant recipients, Dr. Chesnut said. “It’s hard to say what the most likely candidates are,” but based on the study findings, “regulating inflammation may be a target,” he added. Dr. Chesnut and his associates reported no external funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Squamous cell carcinomas from organ transplant recipients showed a more aggressive molecular profile than did those from immunocompetent individuals.

Major finding: The high-risk tumors showed greater induction of biologic pathways related to cancer signaling, fibrosis, and extracellular matrix remodeling, and inhibition of the tp53 tumor suppressor gene.

Data source: RNA sequencing of 15 squamous cell carcinomas, including seven from organ transplant recipients.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no external funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Indoor tanning rates down for high school students in 2013

Indoor tanning by high school girls decreased from 2009 to 2013, according to a recent study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The overall indoor tanning rate for all high school girls dropped to about 20% in 2013, down from just over 25% in 2009. There was a significant drop in indoor tanning for non-Hispanic white girls and a slight decrease for Hispanic girls. The rate of indoor tanning for non-Hispanic black girls remained steady.

Decreases in indoor tanning “may be partly attributable to increased awareness of its harms,” with new or strengthened laws in 40 states having an impact as well, according to Gery P. Guy Jr., Ph.D., of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the CDC in Atlanta.

Non-Hispanic white girls were by far the most likely to indoor tan in 2013, with nearly 31% tanning at least once in the previous year and almost 17% tanning at least 10 times in the same period. No other measured ethnic group had such high rate of usage, with only 2.5% of non-Hispanic blacks, about 8% of Hispanics, and just under 10% of non-Hispanic others engaging in indoor tanning at least once, the investigators reported (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Dec. 23 [doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.4677]).

Indoor tanning by high school boys was much lower than for girls, with about 5% of all boys tanning at least once in 2013. White boys had the highest rate of measured ethnicities, but this was only at about 6%, the researchers said.

The study is based on data collected for the 2009, 2011, and 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys.

Indoor tanning by high school girls decreased from 2009 to 2013, according to a recent study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The overall indoor tanning rate for all high school girls dropped to about 20% in 2013, down from just over 25% in 2009. There was a significant drop in indoor tanning for non-Hispanic white girls and a slight decrease for Hispanic girls. The rate of indoor tanning for non-Hispanic black girls remained steady.

Decreases in indoor tanning “may be partly attributable to increased awareness of its harms,” with new or strengthened laws in 40 states having an impact as well, according to Gery P. Guy Jr., Ph.D., of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the CDC in Atlanta.

Non-Hispanic white girls were by far the most likely to indoor tan in 2013, with nearly 31% tanning at least once in the previous year and almost 17% tanning at least 10 times in the same period. No other measured ethnic group had such high rate of usage, with only 2.5% of non-Hispanic blacks, about 8% of Hispanics, and just under 10% of non-Hispanic others engaging in indoor tanning at least once, the investigators reported (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Dec. 23 [doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.4677]).

Indoor tanning by high school boys was much lower than for girls, with about 5% of all boys tanning at least once in 2013. White boys had the highest rate of measured ethnicities, but this was only at about 6%, the researchers said.

The study is based on data collected for the 2009, 2011, and 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys.

Indoor tanning by high school girls decreased from 2009 to 2013, according to a recent study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The overall indoor tanning rate for all high school girls dropped to about 20% in 2013, down from just over 25% in 2009. There was a significant drop in indoor tanning for non-Hispanic white girls and a slight decrease for Hispanic girls. The rate of indoor tanning for non-Hispanic black girls remained steady.

Decreases in indoor tanning “may be partly attributable to increased awareness of its harms,” with new or strengthened laws in 40 states having an impact as well, according to Gery P. Guy Jr., Ph.D., of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the CDC in Atlanta.

Non-Hispanic white girls were by far the most likely to indoor tan in 2013, with nearly 31% tanning at least once in the previous year and almost 17% tanning at least 10 times in the same period. No other measured ethnic group had such high rate of usage, with only 2.5% of non-Hispanic blacks, about 8% of Hispanics, and just under 10% of non-Hispanic others engaging in indoor tanning at least once, the investigators reported (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Dec. 23 [doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.4677]).

Indoor tanning by high school boys was much lower than for girls, with about 5% of all boys tanning at least once in 2013. White boys had the highest rate of measured ethnicities, but this was only at about 6%, the researchers said.

The study is based on data collected for the 2009, 2011, and 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

FDA approves nivolumab for patients with advanced melanoma

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma who no longer respond to other drugs.

Nivolumab, marketed as Opdivo, is intended for patients who have been previously treated with ipilimumab and, for patients whose tumors express a BRAF V600 mutation, for use after treatment with ipilimumab and a BRAF inhibitor, according to the FDA statement.

“Opdivo is the seventh new melanoma drug approved by the FDA since 2011,” Dr. Richard Pazdur, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the statement. “The continued development and approval of novel therapies based on our increasing understanding of tumor immunology and molecular pathways are changing the treatment paradigm for serious and life-threatening diseases.”

The FDA granted nivolumab breakthrough therapy designation and it was approved under the agency’s accelerated approval program.

Approval was based on CheckMate-037, a trial that demonstrated a 32% objective response rate with nivolumab vs. 11% with investigator’s choice chemotherapy among 120 patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma that progressed despite prior ipilimumab or a BRAF inhibitor, if BRAF mutation-positive.

The most common side effects of the drug were rash, itching, cough, upper respiratory tract infections, and edema. The most serious side effects are severe immune-mediated side effects involving healthy organs, including the lung, colon, liver, kidneys and hormone-producing glands, according to the FDA statement

Opdivo is marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The most common side effects of the drug were rash, itching, cough, upper respiratory tract infections, and edema. The most serious side effects are severe immune-mediated side effects involving healthy organs, including the lung, colon, liver, kidneys and hormone-producing glands, according to the FDA statement

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma who no longer respond to other drugs.

Nivolumab, marketed as Opdivo, is intended for patients who have been previously treated with ipilimumab and, for patients whose tumors express a BRAF V600 mutation, for use after treatment with ipilimumab and a BRAF inhibitor, according to the FDA statement.

“Opdivo is the seventh new melanoma drug approved by the FDA since 2011,” Dr. Richard Pazdur, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the statement. “The continued development and approval of novel therapies based on our increasing understanding of tumor immunology and molecular pathways are changing the treatment paradigm for serious and life-threatening diseases.”

The FDA granted nivolumab breakthrough therapy designation and it was approved under the agency’s accelerated approval program.

Approval was based on CheckMate-037, a trial that demonstrated a 32% objective response rate with nivolumab vs. 11% with investigator’s choice chemotherapy among 120 patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma that progressed despite prior ipilimumab or a BRAF inhibitor, if BRAF mutation-positive.

The most common side effects of the drug were rash, itching, cough, upper respiratory tract infections, and edema. The most serious side effects are severe immune-mediated side effects involving healthy organs, including the lung, colon, liver, kidneys and hormone-producing glands, according to the FDA statement

Opdivo is marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The most common side effects of the drug were rash, itching, cough, upper respiratory tract infections, and edema. The most serious side effects are severe immune-mediated side effects involving healthy organs, including the lung, colon, liver, kidneys and hormone-producing glands, according to the FDA statement

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma who no longer respond to other drugs.

Nivolumab, marketed as Opdivo, is intended for patients who have been previously treated with ipilimumab and, for patients whose tumors express a BRAF V600 mutation, for use after treatment with ipilimumab and a BRAF inhibitor, according to the FDA statement.

“Opdivo is the seventh new melanoma drug approved by the FDA since 2011,” Dr. Richard Pazdur, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the statement. “The continued development and approval of novel therapies based on our increasing understanding of tumor immunology and molecular pathways are changing the treatment paradigm for serious and life-threatening diseases.”

The FDA granted nivolumab breakthrough therapy designation and it was approved under the agency’s accelerated approval program.

Approval was based on CheckMate-037, a trial that demonstrated a 32% objective response rate with nivolumab vs. 11% with investigator’s choice chemotherapy among 120 patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma that progressed despite prior ipilimumab or a BRAF inhibitor, if BRAF mutation-positive.

The most common side effects of the drug were rash, itching, cough, upper respiratory tract infections, and edema. The most serious side effects are severe immune-mediated side effects involving healthy organs, including the lung, colon, liver, kidneys and hormone-producing glands, according to the FDA statement

Opdivo is marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The most common side effects of the drug were rash, itching, cough, upper respiratory tract infections, and edema. The most serious side effects are severe immune-mediated side effects involving healthy organs, including the lung, colon, liver, kidneys and hormone-producing glands, according to the FDA statement

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

Small victories add up to paradigm shifts for hard-to-treat tumors

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Ionizing radiation linked to BCC

SAN DIEGO – Patients treated with ionizing radiation were 2.65 to 3.78 times more likely to develop basal cell carcinoma than were controls, and exposure at younger ages or relatively high doses further increased that risk, according to a pooled analysis presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

“Concomitant exposure to ultraviolet radiation may potentiate this effect,” said Dr. Min Deng, a dermatology resident at the University of Chicago. “With newer treatment protocols and improved shielding, it would be interesting to see if the effect of ionizing radiation has changed, or whether we as dermatologists should more actively screen this at-risk population.”

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer worldwide, but relatively few dermatology papers have assessed the effects of ionizing radiation on the incidence of BCC, said Dr. Deng and coauthor Dr. Diana Bolotin, also of the University of Chicago.

To better understand the link, the researchers searched PubMed for controlled studies on the topic by using the terms “radiation,” “risk,” and “basal cell carcinoma.” They excluded case reports, animal studies, studies published in languages other than English, and trials of radiation as a treatment of BCC, they said. They also excluded studies of atomic bomb survivors, because exposure was uncontrolled and methods to estimate exposure in this group have changed over time, they noted.

In all, six studies published between 1991 and 2012 met the inclusion criteria, and all six showed a statistically significant relative risk or odds of BCC with ionizing radiation exposure, the investigators reported. Three analyses calculated the relative risk of BCC in patients who received radiation for tinea capitis or who underwent total-body irradiation before hematopoietic cell transplantation, they said. Two studies evaluated the odds of BCC in patients with a past history of radiation exposure, and one study assessed time to subsequent BCCs in patients with a history of BCC.

For the three studies that calculated relative risk, the researchers calculated a pooled RR of BCC after ionizing radiation treatment of 2.65 (95% confidence interval, 1.22-5.72) compared with controls. The study of total-body irradiation (TBI) did not report or control for the primary disease for which patients were treated, “which may have confounded the results,” they said. When they excluded that study from their calculation, the overall RR rose to 3.78 (95% CI, 2.62 to 5.44).

Notably, in the two studies of patients with tinea capitis, the relative risk of BCC fell by 12% to 16% for every additional year of age at which patients received radiation treatment, the researchers said. Similarly, risk of BCC dropped by 10.9% for every 1-year increase in age at total-body irradiation prior to cell transplantation.

The combined odds ratio for the next two studies was 4.28 (1.45-12.63). “Likewise, both studies found an elevated odds ratio with younger age at radiation exposure,” the researchers added. One study that stratified patients by type of medical condition detected a “markedly elevated” 8.7 odds of BCC after radiation treatment for acne (2.0 to 38.0), they noted.

The sixth study was a nested case-control analysis that found a statistically significant increase in the odds of BCC starting at a 1-Gy dose of ionizing radiation, and rising linearly up to doses of 35-63.3 Gy. “The risk for developing multiple BCCs also appears to be elevated in patients with a history of radiation therapy,” the researchers said. Patients who had been exposed to ionizing ratio were 2.3 times more likely to develop new BCCs compared with unexposed patients (1.7 to 3.1), they said.

The investigators reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Patients treated with ionizing radiation were 2.65 to 3.78 times more likely to develop basal cell carcinoma than were controls, and exposure at younger ages or relatively high doses further increased that risk, according to a pooled analysis presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

“Concomitant exposure to ultraviolet radiation may potentiate this effect,” said Dr. Min Deng, a dermatology resident at the University of Chicago. “With newer treatment protocols and improved shielding, it would be interesting to see if the effect of ionizing radiation has changed, or whether we as dermatologists should more actively screen this at-risk population.”

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer worldwide, but relatively few dermatology papers have assessed the effects of ionizing radiation on the incidence of BCC, said Dr. Deng and coauthor Dr. Diana Bolotin, also of the University of Chicago.

To better understand the link, the researchers searched PubMed for controlled studies on the topic by using the terms “radiation,” “risk,” and “basal cell carcinoma.” They excluded case reports, animal studies, studies published in languages other than English, and trials of radiation as a treatment of BCC, they said. They also excluded studies of atomic bomb survivors, because exposure was uncontrolled and methods to estimate exposure in this group have changed over time, they noted.

In all, six studies published between 1991 and 2012 met the inclusion criteria, and all six showed a statistically significant relative risk or odds of BCC with ionizing radiation exposure, the investigators reported. Three analyses calculated the relative risk of BCC in patients who received radiation for tinea capitis or who underwent total-body irradiation before hematopoietic cell transplantation, they said. Two studies evaluated the odds of BCC in patients with a past history of radiation exposure, and one study assessed time to subsequent BCCs in patients with a history of BCC.

For the three studies that calculated relative risk, the researchers calculated a pooled RR of BCC after ionizing radiation treatment of 2.65 (95% confidence interval, 1.22-5.72) compared with controls. The study of total-body irradiation (TBI) did not report or control for the primary disease for which patients were treated, “which may have confounded the results,” they said. When they excluded that study from their calculation, the overall RR rose to 3.78 (95% CI, 2.62 to 5.44).

Notably, in the two studies of patients with tinea capitis, the relative risk of BCC fell by 12% to 16% for every additional year of age at which patients received radiation treatment, the researchers said. Similarly, risk of BCC dropped by 10.9% for every 1-year increase in age at total-body irradiation prior to cell transplantation.

The combined odds ratio for the next two studies was 4.28 (1.45-12.63). “Likewise, both studies found an elevated odds ratio with younger age at radiation exposure,” the researchers added. One study that stratified patients by type of medical condition detected a “markedly elevated” 8.7 odds of BCC after radiation treatment for acne (2.0 to 38.0), they noted.

The sixth study was a nested case-control analysis that found a statistically significant increase in the odds of BCC starting at a 1-Gy dose of ionizing radiation, and rising linearly up to doses of 35-63.3 Gy. “The risk for developing multiple BCCs also appears to be elevated in patients with a history of radiation therapy,” the researchers said. Patients who had been exposed to ionizing ratio were 2.3 times more likely to develop new BCCs compared with unexposed patients (1.7 to 3.1), they said.

The investigators reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Patients treated with ionizing radiation were 2.65 to 3.78 times more likely to develop basal cell carcinoma than were controls, and exposure at younger ages or relatively high doses further increased that risk, according to a pooled analysis presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

“Concomitant exposure to ultraviolet radiation may potentiate this effect,” said Dr. Min Deng, a dermatology resident at the University of Chicago. “With newer treatment protocols and improved shielding, it would be interesting to see if the effect of ionizing radiation has changed, or whether we as dermatologists should more actively screen this at-risk population.”

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer worldwide, but relatively few dermatology papers have assessed the effects of ionizing radiation on the incidence of BCC, said Dr. Deng and coauthor Dr. Diana Bolotin, also of the University of Chicago.

To better understand the link, the researchers searched PubMed for controlled studies on the topic by using the terms “radiation,” “risk,” and “basal cell carcinoma.” They excluded case reports, animal studies, studies published in languages other than English, and trials of radiation as a treatment of BCC, they said. They also excluded studies of atomic bomb survivors, because exposure was uncontrolled and methods to estimate exposure in this group have changed over time, they noted.

In all, six studies published between 1991 and 2012 met the inclusion criteria, and all six showed a statistically significant relative risk or odds of BCC with ionizing radiation exposure, the investigators reported. Three analyses calculated the relative risk of BCC in patients who received radiation for tinea capitis or who underwent total-body irradiation before hematopoietic cell transplantation, they said. Two studies evaluated the odds of BCC in patients with a past history of radiation exposure, and one study assessed time to subsequent BCCs in patients with a history of BCC.

For the three studies that calculated relative risk, the researchers calculated a pooled RR of BCC after ionizing radiation treatment of 2.65 (95% confidence interval, 1.22-5.72) compared with controls. The study of total-body irradiation (TBI) did not report or control for the primary disease for which patients were treated, “which may have confounded the results,” they said. When they excluded that study from their calculation, the overall RR rose to 3.78 (95% CI, 2.62 to 5.44).

Notably, in the two studies of patients with tinea capitis, the relative risk of BCC fell by 12% to 16% for every additional year of age at which patients received radiation treatment, the researchers said. Similarly, risk of BCC dropped by 10.9% for every 1-year increase in age at total-body irradiation prior to cell transplantation.

The combined odds ratio for the next two studies was 4.28 (1.45-12.63). “Likewise, both studies found an elevated odds ratio with younger age at radiation exposure,” the researchers added. One study that stratified patients by type of medical condition detected a “markedly elevated” 8.7 odds of BCC after radiation treatment for acne (2.0 to 38.0), they noted.

The sixth study was a nested case-control analysis that found a statistically significant increase in the odds of BCC starting at a 1-Gy dose of ionizing radiation, and rising linearly up to doses of 35-63.3 Gy. “The risk for developing multiple BCCs also appears to be elevated in patients with a history of radiation therapy,” the researchers said. Patients who had been exposed to ionizing ratio were 2.3 times more likely to develop new BCCs compared with unexposed patients (1.7 to 3.1), they said.

The investigators reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Ionizing radiation therapy significantly increased risk of basal cell carcinoma, especially when patients were younger or were treated at relatively high doses.

Major finding: The pooled relative risk of BCC after ionizing radiation treatment was 2.65 (95% confidence interval, 1.22-5.72) compared with controls.

Data source: Pooled analysis of six studies of ionizing radiation exposure and risk or odds of basal cell carcinoma.

Disclosures: The researchers reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

A Team Approach to Nonmelanotic Skin Cancer Procedures

For many decades, the treatment of choice for nonmetastatic but locally invasive nonmelanotic basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has been complete surgical excision that ensures minimal tissue waste, yet retains adequate tumor-free resection margins. From early on, the primary challenge has been assessing the appropriateness of those margins at the time of the initial surgical procedure, rather than having to recall the patient later for an additional surgery to excise involved margins.

In 1953, Steven Mohs, MD, envisioned the use of a vital dye to distinguish benign from malignant skin tissue at the time of surgery.1-3 At that point intraoperative consultation with a pathologist and the process of examining frozen sections (FS) for diagnosis were not standards of care in oncologic surgery. This process allowed Mohs, with limited success, to excise tumors with negative margins. Mohs repeatedly revised and improved his procedure, including the utilization of intraoperative FS to examine the entire specimen margin, a process that is at the core of the Mohs micrographic surgery.1-3

Currently, the Mohs procedure is one of the most popular approaches to definitive skin cancer surgery, especially in the head and neck region where tissue preservation can be critical. It is usually performed as an outpatient or clinic procedure by a specially trained dermatologist who acts both as a surgeon and a pathologist, excising the lesion and processing it for FS diagnosis.4-6 In a hospital setting, other practitioners (surgeons and pathologists) often use the standard approach of limited sampling of resection margins for FS by serially sectioning a specimen that had already been inked or marked for the appropriate margins and freeze-sectioning representative portions of those margins. Reports published by experienced operators using these different approaches indicate variable cancer recurrence rates of 1% to 6%.7-9

At the VA it is a priority to deliver the same quality health care at a much lower price. In this setting it is prudent to periodically reexamine alternative approaches to patient care delivery that utilize existing resources or excess capacity to achieve comparable, if not superior, outcomes to the usually more costly private sector outsourcing contractual arrangements.

With that goal in mind, a few years ago Robley Rex VAMC (RRVAMC) embarked on a new team approach for resectable nonmelanotic skin cancer cases. The team consisted of a plastic surgeon and a pathologist with the appropriate technical and nursing support (histotechnicians, surgical nurse practitioners, and/or nurse anesthsesists) staff. None of the team members were exclusively dedicated to the procedure but were afforded adequate time and material resources to handle all such cases. In this report, the authors describe their experience and the impact of their approach on the affected patients.

Methods

At RRVAMC, primary care providers were encouraged to refer patients suspected of nonmelanotic skin cancer directly to a hospital-based plastic surgeon, who schedules them for a FS-controlled surgical excision of the suspected lesion. The plastic surgeon also plans to cover the resulting wound, if too large for primary closure, with a micrograft during the same procedure. The procedure is usually performed under local anesthesia. A general surgeon or surgical fellow with basic training in plastic surgery may substitute for the plastic surgeon. When not performing this procedure, the surgeon carries on other routine surgical duties.

A dedicated FS room was set up next to an operating room (OR), which was designated for this specialized skin cancer surgery, among other surgeries. The pathologist could walk into the OR anytime to assess the lesion, its location, and the surgeon’s plan of resection, and both physicians could discuss the best strategy for the initial resection or any subsequent margin reexcision. Both could also discuss whether a permanent section would be more appropriate under the conditions.

A small window separated the FS room from the OR, allowing two-way communication and the delivery of specimens. If the specimen was more complex in terms of margin definition, the pathologist could personally take the specimen after its excision directly from the surgeon who could offer further explanation of the special attributes of the specimen. The specimen was usually placed on a topographic drawing of the body region with one or more permanent marks that denoted specific landmarks for orientation.

Once the specimen was in the FS room, the pathologist proceeded with standard gross description followed by color inking of the margins and sampling, according to the following rules:

- Small specimen (< 0.5 cm): Embed as is; FSs may be cut parallel to epidermal surface and examined until no more tumor is seen.

- Medium specimen (0.5-3.0 cm): Serially cross-section and embed all in ≥ 1 blocks; ≥ 6 FSs (cuts) examined from each block.

- Large specimen (> 3.0 cm): Peripheral margins shaved; few central sections taken through deep margin.

For the very small specimens excised from cosmetically or biologically critical areas, such as the head and neck region, the pathologist could use the classic Mohs sampling technique of freezing the entire specimen as is and sectioning parallel to the skin surface until free margins were reached or the entire specimen was exhausted. The pathologist could use serial cross-sectioning at 2 mm intervals in medium-sized excisions, or limited sampling of peripheral and deep margins in very large specimens. In these latter sampling approaches, at least 6 sections are cut from each slice (block), each 5 µm to 10 µm thick. The sections were mounted on glass slides, stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), and examined thoroughly under a microscope before rendering a diagnosis (assessment of the resection margin).

The diagnosis was communicated directly to the surgeon by the pathologist who walked into the OR or while viewing the slides with the surgeon at a double-headed microscope located in the FS room. Remnants of any frozen or unprocessed tissue were submitted for permanent section, and the findings of both the FS and permanent diagnosis were compared the following day. Similar to the main laboratory procedures, 10% of cases were subjected to retroactive peer review for quality assurance.

Freeze section duty was handled by a pathologist and a histotechnician. Once the FS case was completed, the pathologist and histotechnician returned to the main laboratory to attend to other routine duties.

The patient’s state of comfort and satisfaction was assessed informally but routinely by the surgical team before discharge and at the follow-up visit. The patient was asked about the overall experience and invited to submit written comments to the RRVAMC patient representative. A generic mailback card was also available for feedback.

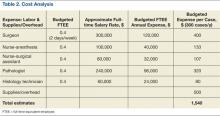

For the cost analysis, budgeting for the recurrent annual cost of labor and supplies was based on a presumed maximum workload of 300 cases/year (3-4 cases/day; 2 days/week or 0.4 full-time equivalent employee [FTEE] for each member of the team) and estimated additional OR and histology laboratory supplies of about $500/case. At the end of the fiscal year, the budgeted estimates were reconciled with the actual expenses or the added financial burden that was associated with the program to calculate the expense per case, which then was compared with the average CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) reimbursement rate for Mohs procedures as usually billed by private practitioners.

Results

From 2006 to 2007, 439 procedures were performed at the RRVAMC program. Patients were followed up for recurrence or other complications through the end of 2012. No serious complications were encountered during any of these procedures. Patients’ comments after each procedure indicated complete satisfaction with the process, and no negative feedback or complaint was received. More than 5 years of follow-up on the initial 439 procedures yielded a rate of cancer recurrence of about 0.5% (2 patients, a 30-year-old woman and a 77-year-old man, both with basal cell carcinoma [BCC] of the nose), which is comparable or slightly better than that reported in relevant literature for the various methods, including the classic Mohs.10,11

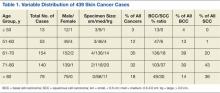

Table 1 shows the distribution of the cases by age, gender, specimen size, and type of cancer. Most patients were white men (98.5%), and almost all (99%) cancers were from the head and neck region. Basal cell carcinoma was the diagnosis in 80% of the cases; the remainder were squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Both types of cancer were prevalent in the older age groups (> 50 years). Basal cell carcinoma was more prevalent in the group aged 51 to 70 years, whereas SCC predominated in patients aged > 70 years. The patients ranged in age from 30 to 89 years. The majority of specimens were medium sized (86%); 11% were large and the remaining 3% were small specimens. These demographics of patient’s age, cancer location, and prevalent diagnosis, were comparable to those of most VAMCs.

All acrediatation standards of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA 88) and College of American Pathologists (CAP) were observed in the RRVAMC FS laboratory, including monitoring frozen vs permanent tissue diagnosis and 10% retroactive peer review. Those indicators were always well below established thresholds or reasonable pathology practice community standards. The RRVAMC laboratory overall error (major discrepancy) rate has been < 0.2%. The FS laboratory has also been in compliance with the technical quality CAP accreditation standards, such as those for equipment, reagents, personnel, and environment controls.

Cost analysis data are presented in Table 2. The data are based on realistic estimates in a hospital setting. The provided numbers for the FTEE salaries are average local estimates (based on VA-wide pay scale for employees according to their grades and within grade steps), though actual salary structure varied widely among institutions. Although budgeted estimates suggest an average expense of about $1,500 per case (including cases with multiple lesions that could be removed at the same session), the actual or realistic expense is far less, because some of the resources were preexisting or shared across the Surgical and Pathology Services, including FTEE time commitments. The RRVAMC planning strategy assumed 200 to 300 cases/year at $1,000 to $2,000/case.

Discussion

The RRVAMC approach of direct patient referral to the in-house plastic surgeon often spared the patient 2 additional clinical visits or procedures, which might otherwise have been required. Often, the primary care provider referred the patient to a dermatologist who would perform a shave or punch biopsy, awaiting a pathologist’s diagnosis before scheduling definitive (eg, Mohs) surgery with a separate provider. After that, the patient might be scheduled for reconstructive surgery, if necessary, by a plastic surgeon. With the RRVAMC approach, not only were the number of visits/procedures reduced, but the total time was shortened by several weeks, sparing the patient discomfort and uncertainty.

The RRVAMC cost analysis data show an average realistic cost at this setting (considering already available resources) of far less than $2,000 ($1,000-$1,500). This is substantially below the $2,000 to $10,000 cost per case (or lesion in patients with multiple lesions) that would have been required for a private sector referral, based on CMS reimbursement rates for Mohs procedures (CPT codes 17311-17315).

An important element in the cost-effectiveness, quality assurance, and time use in this approach is the flexibility of the key operators (surgery and pathology staff) and the sampling technique. For the latter, the pathologist can use the most efficient technique, depending on specimen source and size: The classic Mohs technique for very small (head and neck area) specimens, but serial cross-sectioning or limited sampling of peripheral and deep margins in other situations. All 3 sectioning approaches in the RRVAMC practice proved reliable in assessing the margins, as they were always verified either on permanent sections and/or through retroactive peer review. Furthermore, in a mostly elderly patient population, there is rarely a need for extremely conservative resection of the margins, as the skin often shows wrinkling or redundancy that allows for a more generous healthy rim around the lesion. In such cases, it may be indeed superfluous to apply the protracted and expensive Mohs procedural variant.

The quality assurance aspect of the RRVAMC approach is also important. Examining permanent sections as well as retroactive peer review can uncover diagnostic or processing errors even in the best of laboratories. That error rate in the surgical pathology community may reach more than 1% to 2%.12 In the RRVAMC practice, the major discrepancy rate is usually below 0.2%. There is a reason for concern in any FS laboratory where such monitoring is not done, considering that even BCC can be occasionally confused on FS with other small blue cell malignancies, such as lymphoma or Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The authors offer the RRVAMC pathologist-plastic surgeon team approach to definitive skin cancer surgery as a reliable and less expensive in-house alternative to contractual outsourcing for those VA (or non-VA) medical centers that have a plastic surgeon (or trained equivalent) and a surgical pathologist on staff.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Robley Rex VAMC in Louisville, Kentucky.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Robins P, Albom MJ. Mohs’ surgery—fresh tissue technique. J Dermatol Surg. 1975;1(2):37-41.

2. Mohs FE. Mohs micrographic surgery. A historical perspective. Dermatol Clin. 1989;7(4):609-611.

3. Mohs FE. Origin and progress of Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Mikhail GR, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1991:1-10.

4. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):976-990.

5. Rowe DE. Comparison of treatment modalities for basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13(6):617-620.

6. Smeets NW, Krekels GA, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: Randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1766-1772.

7. Bentkover SH, Grande DM, Soto H, Kozlicak BA, Guillaume D, Girouard S. Excision of head and neck basal cell carcinoma with a rapid, cross-sectional, frozen-section technique. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4(2):114-119.

8. Kimyai-Asadi A, Goldberg LH, Jih MH. Accuracy of serial transverse cross-sections in detecting residual basal cell carcinoma at the surgical margins of an elliptical excision specimen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;53(3):469-474.

9. Dhingra N, Gajdasty A, Neal JW, Mukherjee AN, Lane CM. Confident complete excision of lid-margin BCCs using a marginal strip: An alternative to Mohs’ surgery. Brit J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(6):794-796.

10. Minton TJ. Contemporary Mohs surgery applications. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16(4):376-380.

11. Mosterd K, Krekels GA, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: A prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(12):1149-1156.

12. Weiss MA. Analytic variables; diagnostic accuracy. In: Nakhleh RE, Fitzgibbons PL, eds. Quality Management in Anatomic Pathology. Northfield, IL: College of American Pathologists; 2005:50-76.

For many decades, the treatment of choice for nonmetastatic but locally invasive nonmelanotic basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has been complete surgical excision that ensures minimal tissue waste, yet retains adequate tumor-free resection margins. From early on, the primary challenge has been assessing the appropriateness of those margins at the time of the initial surgical procedure, rather than having to recall the patient later for an additional surgery to excise involved margins.

In 1953, Steven Mohs, MD, envisioned the use of a vital dye to distinguish benign from malignant skin tissue at the time of surgery.1-3 At that point intraoperative consultation with a pathologist and the process of examining frozen sections (FS) for diagnosis were not standards of care in oncologic surgery. This process allowed Mohs, with limited success, to excise tumors with negative margins. Mohs repeatedly revised and improved his procedure, including the utilization of intraoperative FS to examine the entire specimen margin, a process that is at the core of the Mohs micrographic surgery.1-3

Currently, the Mohs procedure is one of the most popular approaches to definitive skin cancer surgery, especially in the head and neck region where tissue preservation can be critical. It is usually performed as an outpatient or clinic procedure by a specially trained dermatologist who acts both as a surgeon and a pathologist, excising the lesion and processing it for FS diagnosis.4-6 In a hospital setting, other practitioners (surgeons and pathologists) often use the standard approach of limited sampling of resection margins for FS by serially sectioning a specimen that had already been inked or marked for the appropriate margins and freeze-sectioning representative portions of those margins. Reports published by experienced operators using these different approaches indicate variable cancer recurrence rates of 1% to 6%.7-9

At the VA it is a priority to deliver the same quality health care at a much lower price. In this setting it is prudent to periodically reexamine alternative approaches to patient care delivery that utilize existing resources or excess capacity to achieve comparable, if not superior, outcomes to the usually more costly private sector outsourcing contractual arrangements.

With that goal in mind, a few years ago Robley Rex VAMC (RRVAMC) embarked on a new team approach for resectable nonmelanotic skin cancer cases. The team consisted of a plastic surgeon and a pathologist with the appropriate technical and nursing support (histotechnicians, surgical nurse practitioners, and/or nurse anesthsesists) staff. None of the team members were exclusively dedicated to the procedure but were afforded adequate time and material resources to handle all such cases. In this report, the authors describe their experience and the impact of their approach on the affected patients.

Methods

At RRVAMC, primary care providers were encouraged to refer patients suspected of nonmelanotic skin cancer directly to a hospital-based plastic surgeon, who schedules them for a FS-controlled surgical excision of the suspected lesion. The plastic surgeon also plans to cover the resulting wound, if too large for primary closure, with a micrograft during the same procedure. The procedure is usually performed under local anesthesia. A general surgeon or surgical fellow with basic training in plastic surgery may substitute for the plastic surgeon. When not performing this procedure, the surgeon carries on other routine surgical duties.

A dedicated FS room was set up next to an operating room (OR), which was designated for this specialized skin cancer surgery, among other surgeries. The pathologist could walk into the OR anytime to assess the lesion, its location, and the surgeon’s plan of resection, and both physicians could discuss the best strategy for the initial resection or any subsequent margin reexcision. Both could also discuss whether a permanent section would be more appropriate under the conditions.

A small window separated the FS room from the OR, allowing two-way communication and the delivery of specimens. If the specimen was more complex in terms of margin definition, the pathologist could personally take the specimen after its excision directly from the surgeon who could offer further explanation of the special attributes of the specimen. The specimen was usually placed on a topographic drawing of the body region with one or more permanent marks that denoted specific landmarks for orientation.

Once the specimen was in the FS room, the pathologist proceeded with standard gross description followed by color inking of the margins and sampling, according to the following rules:

- Small specimen (< 0.5 cm): Embed as is; FSs may be cut parallel to epidermal surface and examined until no more tumor is seen.

- Medium specimen (0.5-3.0 cm): Serially cross-section and embed all in ≥ 1 blocks; ≥ 6 FSs (cuts) examined from each block.

- Large specimen (> 3.0 cm): Peripheral margins shaved; few central sections taken through deep margin.

For the very small specimens excised from cosmetically or biologically critical areas, such as the head and neck region, the pathologist could use the classic Mohs sampling technique of freezing the entire specimen as is and sectioning parallel to the skin surface until free margins were reached or the entire specimen was exhausted. The pathologist could use serial cross-sectioning at 2 mm intervals in medium-sized excisions, or limited sampling of peripheral and deep margins in very large specimens. In these latter sampling approaches, at least 6 sections are cut from each slice (block), each 5 µm to 10 µm thick. The sections were mounted on glass slides, stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), and examined thoroughly under a microscope before rendering a diagnosis (assessment of the resection margin).

The diagnosis was communicated directly to the surgeon by the pathologist who walked into the OR or while viewing the slides with the surgeon at a double-headed microscope located in the FS room. Remnants of any frozen or unprocessed tissue were submitted for permanent section, and the findings of both the FS and permanent diagnosis were compared the following day. Similar to the main laboratory procedures, 10% of cases were subjected to retroactive peer review for quality assurance.

Freeze section duty was handled by a pathologist and a histotechnician. Once the FS case was completed, the pathologist and histotechnician returned to the main laboratory to attend to other routine duties.

The patient’s state of comfort and satisfaction was assessed informally but routinely by the surgical team before discharge and at the follow-up visit. The patient was asked about the overall experience and invited to submit written comments to the RRVAMC patient representative. A generic mailback card was also available for feedback.

For the cost analysis, budgeting for the recurrent annual cost of labor and supplies was based on a presumed maximum workload of 300 cases/year (3-4 cases/day; 2 days/week or 0.4 full-time equivalent employee [FTEE] for each member of the team) and estimated additional OR and histology laboratory supplies of about $500/case. At the end of the fiscal year, the budgeted estimates were reconciled with the actual expenses or the added financial burden that was associated with the program to calculate the expense per case, which then was compared with the average CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) reimbursement rate for Mohs procedures as usually billed by private practitioners.

Results

From 2006 to 2007, 439 procedures were performed at the RRVAMC program. Patients were followed up for recurrence or other complications through the end of 2012. No serious complications were encountered during any of these procedures. Patients’ comments after each procedure indicated complete satisfaction with the process, and no negative feedback or complaint was received. More than 5 years of follow-up on the initial 439 procedures yielded a rate of cancer recurrence of about 0.5% (2 patients, a 30-year-old woman and a 77-year-old man, both with basal cell carcinoma [BCC] of the nose), which is comparable or slightly better than that reported in relevant literature for the various methods, including the classic Mohs.10,11

Table 1 shows the distribution of the cases by age, gender, specimen size, and type of cancer. Most patients were white men (98.5%), and almost all (99%) cancers were from the head and neck region. Basal cell carcinoma was the diagnosis in 80% of the cases; the remainder were squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Both types of cancer were prevalent in the older age groups (> 50 years). Basal cell carcinoma was more prevalent in the group aged 51 to 70 years, whereas SCC predominated in patients aged > 70 years. The patients ranged in age from 30 to 89 years. The majority of specimens were medium sized (86%); 11% were large and the remaining 3% were small specimens. These demographics of patient’s age, cancer location, and prevalent diagnosis, were comparable to those of most VAMCs.

All acrediatation standards of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA 88) and College of American Pathologists (CAP) were observed in the RRVAMC FS laboratory, including monitoring frozen vs permanent tissue diagnosis and 10% retroactive peer review. Those indicators were always well below established thresholds or reasonable pathology practice community standards. The RRVAMC laboratory overall error (major discrepancy) rate has been < 0.2%. The FS laboratory has also been in compliance with the technical quality CAP accreditation standards, such as those for equipment, reagents, personnel, and environment controls.

Cost analysis data are presented in Table 2. The data are based on realistic estimates in a hospital setting. The provided numbers for the FTEE salaries are average local estimates (based on VA-wide pay scale for employees according to their grades and within grade steps), though actual salary structure varied widely among institutions. Although budgeted estimates suggest an average expense of about $1,500 per case (including cases with multiple lesions that could be removed at the same session), the actual or realistic expense is far less, because some of the resources were preexisting or shared across the Surgical and Pathology Services, including FTEE time commitments. The RRVAMC planning strategy assumed 200 to 300 cases/year at $1,000 to $2,000/case.

Discussion

The RRVAMC approach of direct patient referral to the in-house plastic surgeon often spared the patient 2 additional clinical visits or procedures, which might otherwise have been required. Often, the primary care provider referred the patient to a dermatologist who would perform a shave or punch biopsy, awaiting a pathologist’s diagnosis before scheduling definitive (eg, Mohs) surgery with a separate provider. After that, the patient might be scheduled for reconstructive surgery, if necessary, by a plastic surgeon. With the RRVAMC approach, not only were the number of visits/procedures reduced, but the total time was shortened by several weeks, sparing the patient discomfort and uncertainty.

The RRVAMC cost analysis data show an average realistic cost at this setting (considering already available resources) of far less than $2,000 ($1,000-$1,500). This is substantially below the $2,000 to $10,000 cost per case (or lesion in patients with multiple lesions) that would have been required for a private sector referral, based on CMS reimbursement rates for Mohs procedures (CPT codes 17311-17315).

An important element in the cost-effectiveness, quality assurance, and time use in this approach is the flexibility of the key operators (surgery and pathology staff) and the sampling technique. For the latter, the pathologist can use the most efficient technique, depending on specimen source and size: The classic Mohs technique for very small (head and neck area) specimens, but serial cross-sectioning or limited sampling of peripheral and deep margins in other situations. All 3 sectioning approaches in the RRVAMC practice proved reliable in assessing the margins, as they were always verified either on permanent sections and/or through retroactive peer review. Furthermore, in a mostly elderly patient population, there is rarely a need for extremely conservative resection of the margins, as the skin often shows wrinkling or redundancy that allows for a more generous healthy rim around the lesion. In such cases, it may be indeed superfluous to apply the protracted and expensive Mohs procedural variant.

The quality assurance aspect of the RRVAMC approach is also important. Examining permanent sections as well as retroactive peer review can uncover diagnostic or processing errors even in the best of laboratories. That error rate in the surgical pathology community may reach more than 1% to 2%.12 In the RRVAMC practice, the major discrepancy rate is usually below 0.2%. There is a reason for concern in any FS laboratory where such monitoring is not done, considering that even BCC can be occasionally confused on FS with other small blue cell malignancies, such as lymphoma or Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The authors offer the RRVAMC pathologist-plastic surgeon team approach to definitive skin cancer surgery as a reliable and less expensive in-house alternative to contractual outsourcing for those VA (or non-VA) medical centers that have a plastic surgeon (or trained equivalent) and a surgical pathologist on staff.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Robley Rex VAMC in Louisville, Kentucky.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

For many decades, the treatment of choice for nonmetastatic but locally invasive nonmelanotic basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has been complete surgical excision that ensures minimal tissue waste, yet retains adequate tumor-free resection margins. From early on, the primary challenge has been assessing the appropriateness of those margins at the time of the initial surgical procedure, rather than having to recall the patient later for an additional surgery to excise involved margins.

In 1953, Steven Mohs, MD, envisioned the use of a vital dye to distinguish benign from malignant skin tissue at the time of surgery.1-3 At that point intraoperative consultation with a pathologist and the process of examining frozen sections (FS) for diagnosis were not standards of care in oncologic surgery. This process allowed Mohs, with limited success, to excise tumors with negative margins. Mohs repeatedly revised and improved his procedure, including the utilization of intraoperative FS to examine the entire specimen margin, a process that is at the core of the Mohs micrographic surgery.1-3

Currently, the Mohs procedure is one of the most popular approaches to definitive skin cancer surgery, especially in the head and neck region where tissue preservation can be critical. It is usually performed as an outpatient or clinic procedure by a specially trained dermatologist who acts both as a surgeon and a pathologist, excising the lesion and processing it for FS diagnosis.4-6 In a hospital setting, other practitioners (surgeons and pathologists) often use the standard approach of limited sampling of resection margins for FS by serially sectioning a specimen that had already been inked or marked for the appropriate margins and freeze-sectioning representative portions of those margins. Reports published by experienced operators using these different approaches indicate variable cancer recurrence rates of 1% to 6%.7-9

At the VA it is a priority to deliver the same quality health care at a much lower price. In this setting it is prudent to periodically reexamine alternative approaches to patient care delivery that utilize existing resources or excess capacity to achieve comparable, if not superior, outcomes to the usually more costly private sector outsourcing contractual arrangements.

With that goal in mind, a few years ago Robley Rex VAMC (RRVAMC) embarked on a new team approach for resectable nonmelanotic skin cancer cases. The team consisted of a plastic surgeon and a pathologist with the appropriate technical and nursing support (histotechnicians, surgical nurse practitioners, and/or nurse anesthsesists) staff. None of the team members were exclusively dedicated to the procedure but were afforded adequate time and material resources to handle all such cases. In this report, the authors describe their experience and the impact of their approach on the affected patients.

Methods

At RRVAMC, primary care providers were encouraged to refer patients suspected of nonmelanotic skin cancer directly to a hospital-based plastic surgeon, who schedules them for a FS-controlled surgical excision of the suspected lesion. The plastic surgeon also plans to cover the resulting wound, if too large for primary closure, with a micrograft during the same procedure. The procedure is usually performed under local anesthesia. A general surgeon or surgical fellow with basic training in plastic surgery may substitute for the plastic surgeon. When not performing this procedure, the surgeon carries on other routine surgical duties.

A dedicated FS room was set up next to an operating room (OR), which was designated for this specialized skin cancer surgery, among other surgeries. The pathologist could walk into the OR anytime to assess the lesion, its location, and the surgeon’s plan of resection, and both physicians could discuss the best strategy for the initial resection or any subsequent margin reexcision. Both could also discuss whether a permanent section would be more appropriate under the conditions.

A small window separated the FS room from the OR, allowing two-way communication and the delivery of specimens. If the specimen was more complex in terms of margin definition, the pathologist could personally take the specimen after its excision directly from the surgeon who could offer further explanation of the special attributes of the specimen. The specimen was usually placed on a topographic drawing of the body region with one or more permanent marks that denoted specific landmarks for orientation.

Once the specimen was in the FS room, the pathologist proceeded with standard gross description followed by color inking of the margins and sampling, according to the following rules:

- Small specimen (< 0.5 cm): Embed as is; FSs may be cut parallel to epidermal surface and examined until no more tumor is seen.

- Medium specimen (0.5-3.0 cm): Serially cross-section and embed all in ≥ 1 blocks; ≥ 6 FSs (cuts) examined from each block.

- Large specimen (> 3.0 cm): Peripheral margins shaved; few central sections taken through deep margin.

For the very small specimens excised from cosmetically or biologically critical areas, such as the head and neck region, the pathologist could use the classic Mohs sampling technique of freezing the entire specimen as is and sectioning parallel to the skin surface until free margins were reached or the entire specimen was exhausted. The pathologist could use serial cross-sectioning at 2 mm intervals in medium-sized excisions, or limited sampling of peripheral and deep margins in very large specimens. In these latter sampling approaches, at least 6 sections are cut from each slice (block), each 5 µm to 10 µm thick. The sections were mounted on glass slides, stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), and examined thoroughly under a microscope before rendering a diagnosis (assessment of the resection margin).

The diagnosis was communicated directly to the surgeon by the pathologist who walked into the OR or while viewing the slides with the surgeon at a double-headed microscope located in the FS room. Remnants of any frozen or unprocessed tissue were submitted for permanent section, and the findings of both the FS and permanent diagnosis were compared the following day. Similar to the main laboratory procedures, 10% of cases were subjected to retroactive peer review for quality assurance.

Freeze section duty was handled by a pathologist and a histotechnician. Once the FS case was completed, the pathologist and histotechnician returned to the main laboratory to attend to other routine duties.

The patient’s state of comfort and satisfaction was assessed informally but routinely by the surgical team before discharge and at the follow-up visit. The patient was asked about the overall experience and invited to submit written comments to the RRVAMC patient representative. A generic mailback card was also available for feedback.

For the cost analysis, budgeting for the recurrent annual cost of labor and supplies was based on a presumed maximum workload of 300 cases/year (3-4 cases/day; 2 days/week or 0.4 full-time equivalent employee [FTEE] for each member of the team) and estimated additional OR and histology laboratory supplies of about $500/case. At the end of the fiscal year, the budgeted estimates were reconciled with the actual expenses or the added financial burden that was associated with the program to calculate the expense per case, which then was compared with the average CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) reimbursement rate for Mohs procedures as usually billed by private practitioners.

Results

From 2006 to 2007, 439 procedures were performed at the RRVAMC program. Patients were followed up for recurrence or other complications through the end of 2012. No serious complications were encountered during any of these procedures. Patients’ comments after each procedure indicated complete satisfaction with the process, and no negative feedback or complaint was received. More than 5 years of follow-up on the initial 439 procedures yielded a rate of cancer recurrence of about 0.5% (2 patients, a 30-year-old woman and a 77-year-old man, both with basal cell carcinoma [BCC] of the nose), which is comparable or slightly better than that reported in relevant literature for the various methods, including the classic Mohs.10,11

Table 1 shows the distribution of the cases by age, gender, specimen size, and type of cancer. Most patients were white men (98.5%), and almost all (99%) cancers were from the head and neck region. Basal cell carcinoma was the diagnosis in 80% of the cases; the remainder were squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Both types of cancer were prevalent in the older age groups (> 50 years). Basal cell carcinoma was more prevalent in the group aged 51 to 70 years, whereas SCC predominated in patients aged > 70 years. The patients ranged in age from 30 to 89 years. The majority of specimens were medium sized (86%); 11% were large and the remaining 3% were small specimens. These demographics of patient’s age, cancer location, and prevalent diagnosis, were comparable to those of most VAMCs.

All acrediatation standards of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA 88) and College of American Pathologists (CAP) were observed in the RRVAMC FS laboratory, including monitoring frozen vs permanent tissue diagnosis and 10% retroactive peer review. Those indicators were always well below established thresholds or reasonable pathology practice community standards. The RRVAMC laboratory overall error (major discrepancy) rate has been < 0.2%. The FS laboratory has also been in compliance with the technical quality CAP accreditation standards, such as those for equipment, reagents, personnel, and environment controls.

Cost analysis data are presented in Table 2. The data are based on realistic estimates in a hospital setting. The provided numbers for the FTEE salaries are average local estimates (based on VA-wide pay scale for employees according to their grades and within grade steps), though actual salary structure varied widely among institutions. Although budgeted estimates suggest an average expense of about $1,500 per case (including cases with multiple lesions that could be removed at the same session), the actual or realistic expense is far less, because some of the resources were preexisting or shared across the Surgical and Pathology Services, including FTEE time commitments. The RRVAMC planning strategy assumed 200 to 300 cases/year at $1,000 to $2,000/case.

Discussion

The RRVAMC approach of direct patient referral to the in-house plastic surgeon often spared the patient 2 additional clinical visits or procedures, which might otherwise have been required. Often, the primary care provider referred the patient to a dermatologist who would perform a shave or punch biopsy, awaiting a pathologist’s diagnosis before scheduling definitive (eg, Mohs) surgery with a separate provider. After that, the patient might be scheduled for reconstructive surgery, if necessary, by a plastic surgeon. With the RRVAMC approach, not only were the number of visits/procedures reduced, but the total time was shortened by several weeks, sparing the patient discomfort and uncertainty.

The RRVAMC cost analysis data show an average realistic cost at this setting (considering already available resources) of far less than $2,000 ($1,000-$1,500). This is substantially below the $2,000 to $10,000 cost per case (or lesion in patients with multiple lesions) that would have been required for a private sector referral, based on CMS reimbursement rates for Mohs procedures (CPT codes 17311-17315).

An important element in the cost-effectiveness, quality assurance, and time use in this approach is the flexibility of the key operators (surgery and pathology staff) and the sampling technique. For the latter, the pathologist can use the most efficient technique, depending on specimen source and size: The classic Mohs technique for very small (head and neck area) specimens, but serial cross-sectioning or limited sampling of peripheral and deep margins in other situations. All 3 sectioning approaches in the RRVAMC practice proved reliable in assessing the margins, as they were always verified either on permanent sections and/or through retroactive peer review. Furthermore, in a mostly elderly patient population, there is rarely a need for extremely conservative resection of the margins, as the skin often shows wrinkling or redundancy that allows for a more generous healthy rim around the lesion. In such cases, it may be indeed superfluous to apply the protracted and expensive Mohs procedural variant.

The quality assurance aspect of the RRVAMC approach is also important. Examining permanent sections as well as retroactive peer review can uncover diagnostic or processing errors even in the best of laboratories. That error rate in the surgical pathology community may reach more than 1% to 2%.12 In the RRVAMC practice, the major discrepancy rate is usually below 0.2%. There is a reason for concern in any FS laboratory where such monitoring is not done, considering that even BCC can be occasionally confused on FS with other small blue cell malignancies, such as lymphoma or Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The authors offer the RRVAMC pathologist-plastic surgeon team approach to definitive skin cancer surgery as a reliable and less expensive in-house alternative to contractual outsourcing for those VA (or non-VA) medical centers that have a plastic surgeon (or trained equivalent) and a surgical pathologist on staff.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Robley Rex VAMC in Louisville, Kentucky.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Robins P, Albom MJ. Mohs’ surgery—fresh tissue technique. J Dermatol Surg. 1975;1(2):37-41.

2. Mohs FE. Mohs micrographic surgery. A historical perspective. Dermatol Clin. 1989;7(4):609-611.