User login

Nivolumab bests dacarbazine for melanoma survival

Nivolumab achieves significant improvements in overall survival and progression-free survival compared with conventional chemotherapy in untreated patients with advanced melanoma, regardless of PD-L1 status, according to data presented at the International Congress for the Society for Melanoma Research.

Data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial showed patients treated with nivolumab – a PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor – showed there was a 58% lower incidence of death at 1 year among patients treated with nivolumab compared with those treated with dacarbazine (72.9% vs. 42.1% HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.25-0.73, P < .001).

Median progression-free survival was 5.1 months in the nivolumab arm compared with 2.2 months in the dacarbazine group (HR for death or disease progression: 0.43, 95% CI 0.34-0.56, P < .001). The results were published simultaneously online Nov. 16 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers randomly assigned 418 previously untreated patients with BRAF mutation-negative advanced melanoma to nivolumab plus placebo, and dacarbazine plus placebo, finding an objective response rate of 40% in patients receiving nivolumab compared with 13.9% in the dacarbazine group.

While PD-L1-positive patients treated with nivolumab showed a greater median response rate compared with PD-L1-negative or indeterminate patients (52.7% vs. 33.1%), both still achieved greater response than either subgroup treated with dacarbazine (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 Nov. 16 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1412082]).

The overall incidence of treatment-related adverse events was similar in the two study arms, although there was a higher incidence of treatment-related grade 3 and 4 adverse events, such as gastrointestinal and hematologic events, in the dacarbazine group.

“It has generally been accepted that immunotherapy is associated with long-term responses in a subset of patients, whereas targeted therapies, such as BRAF inhibitors, are associated with high response rates and a rapid effect, but the responses are often short-lived,” wrote Dr. Caroline Robert of Institut Gustave Roussy, Paris, and her colleagues.

“The present study shows nivolumab is associated with a high response rate, a rapid median time to response (2.1 months, which is similar to the time to response for dacarbazine), and a durable response (the median duration of response was not reached but the duration of follow-up was short),” the investigators said.

The study was supported by Bristol Myers-Squibb. Some authors declared grants, travel expenses, and personal fees from pharmaceutical companies including Bristol Myers-Squibb, and several were employees of the company.

Nivolumab achieves significant improvements in overall survival and progression-free survival compared with conventional chemotherapy in untreated patients with advanced melanoma, regardless of PD-L1 status, according to data presented at the International Congress for the Society for Melanoma Research.

Data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial showed patients treated with nivolumab – a PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor – showed there was a 58% lower incidence of death at 1 year among patients treated with nivolumab compared with those treated with dacarbazine (72.9% vs. 42.1% HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.25-0.73, P < .001).

Median progression-free survival was 5.1 months in the nivolumab arm compared with 2.2 months in the dacarbazine group (HR for death or disease progression: 0.43, 95% CI 0.34-0.56, P < .001). The results were published simultaneously online Nov. 16 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers randomly assigned 418 previously untreated patients with BRAF mutation-negative advanced melanoma to nivolumab plus placebo, and dacarbazine plus placebo, finding an objective response rate of 40% in patients receiving nivolumab compared with 13.9% in the dacarbazine group.

While PD-L1-positive patients treated with nivolumab showed a greater median response rate compared with PD-L1-negative or indeterminate patients (52.7% vs. 33.1%), both still achieved greater response than either subgroup treated with dacarbazine (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 Nov. 16 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1412082]).

The overall incidence of treatment-related adverse events was similar in the two study arms, although there was a higher incidence of treatment-related grade 3 and 4 adverse events, such as gastrointestinal and hematologic events, in the dacarbazine group.

“It has generally been accepted that immunotherapy is associated with long-term responses in a subset of patients, whereas targeted therapies, such as BRAF inhibitors, are associated with high response rates and a rapid effect, but the responses are often short-lived,” wrote Dr. Caroline Robert of Institut Gustave Roussy, Paris, and her colleagues.

“The present study shows nivolumab is associated with a high response rate, a rapid median time to response (2.1 months, which is similar to the time to response for dacarbazine), and a durable response (the median duration of response was not reached but the duration of follow-up was short),” the investigators said.

The study was supported by Bristol Myers-Squibb. Some authors declared grants, travel expenses, and personal fees from pharmaceutical companies including Bristol Myers-Squibb, and several were employees of the company.

Nivolumab achieves significant improvements in overall survival and progression-free survival compared with conventional chemotherapy in untreated patients with advanced melanoma, regardless of PD-L1 status, according to data presented at the International Congress for the Society for Melanoma Research.

Data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial showed patients treated with nivolumab – a PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor – showed there was a 58% lower incidence of death at 1 year among patients treated with nivolumab compared with those treated with dacarbazine (72.9% vs. 42.1% HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.25-0.73, P < .001).

Median progression-free survival was 5.1 months in the nivolumab arm compared with 2.2 months in the dacarbazine group (HR for death or disease progression: 0.43, 95% CI 0.34-0.56, P < .001). The results were published simultaneously online Nov. 16 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers randomly assigned 418 previously untreated patients with BRAF mutation-negative advanced melanoma to nivolumab plus placebo, and dacarbazine plus placebo, finding an objective response rate of 40% in patients receiving nivolumab compared with 13.9% in the dacarbazine group.

While PD-L1-positive patients treated with nivolumab showed a greater median response rate compared with PD-L1-negative or indeterminate patients (52.7% vs. 33.1%), both still achieved greater response than either subgroup treated with dacarbazine (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 Nov. 16 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1412082]).

The overall incidence of treatment-related adverse events was similar in the two study arms, although there was a higher incidence of treatment-related grade 3 and 4 adverse events, such as gastrointestinal and hematologic events, in the dacarbazine group.

“It has generally been accepted that immunotherapy is associated with long-term responses in a subset of patients, whereas targeted therapies, such as BRAF inhibitors, are associated with high response rates and a rapid effect, but the responses are often short-lived,” wrote Dr. Caroline Robert of Institut Gustave Roussy, Paris, and her colleagues.

“The present study shows nivolumab is associated with a high response rate, a rapid median time to response (2.1 months, which is similar to the time to response for dacarbazine), and a durable response (the median duration of response was not reached but the duration of follow-up was short),” the investigators said.

The study was supported by Bristol Myers-Squibb. Some authors declared grants, travel expenses, and personal fees from pharmaceutical companies including Bristol Myers-Squibb, and several were employees of the company.

FROM THE SMR INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Nivolumab achieves significant improvements in overall survival and progression-free survival compared with dacarbazine in untreated patients with advanced melanoma.

Major finding: Nivolumab was associated with a 58% lower incidence of death at 1 year compared with dacarbazine

Data source: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of 418 previously-untreated patients with advanced melanoma.

Disclosures: Several of the researchers disclosed ties with Bristol-Myers Squibb, which funded the study.

Skin cancer treatment costs skyrocket over past decade

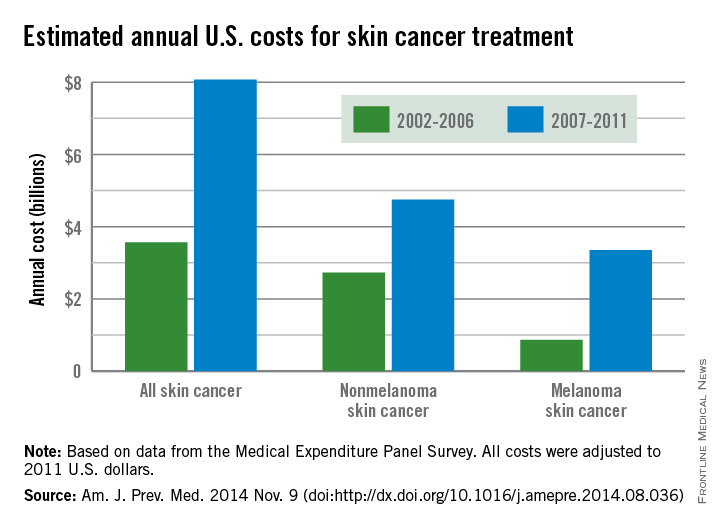

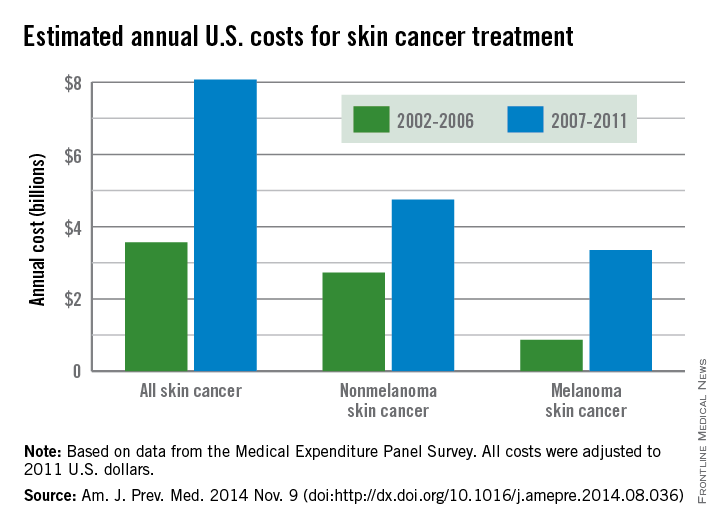

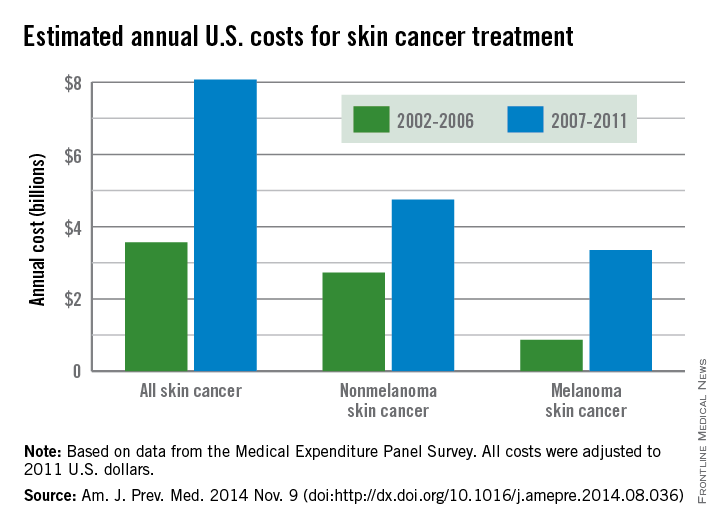

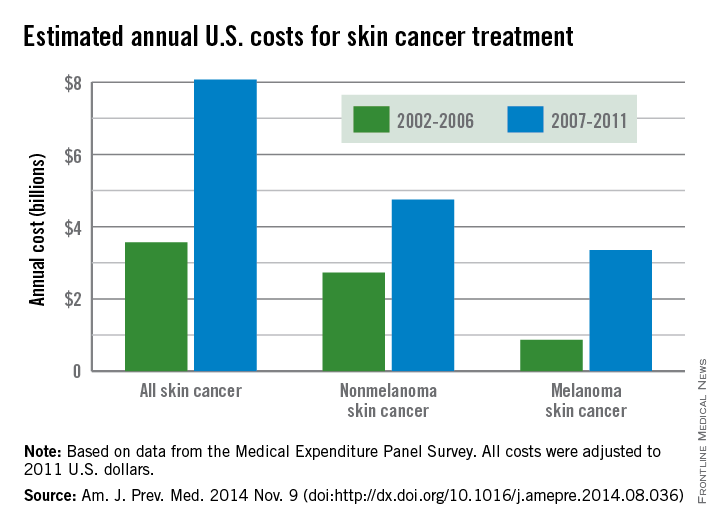

The average annual cost for skin cancer treatment more than doubled from 2002 to 2011, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found.

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual skin cancer treatment cost was $3.6 billion, while for 2007-2011, the average annual cost was $8.1 billion, an increase of about 126%. The cost of nonmelanoma skin cancers increased 74%, from $2.7 billion to $4.8 billion, but the average annual cost for melanoma cancers increased about 280%, from $864 million to $3.3 billion, according to the CDC (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014 Nov. 9 [doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036]).

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual number of adults treated for skin cancer was 3.4 million, which increased to an average annual number of 4.9 million for 2007-2011. The average annual cost per person for all skin cancers increased by 57%, from $1,044 for 2002-2006 to $1,643 for 2007-2011, while the average cost for melanomas more than doubled from $2,320 to $4,780. The increase in annual cost for nonmelanoma skin cancers was more modest; only a 25% increase, from $882 to $1,105, was noted between the two time periods, the CDC reported.

The average annual cost for all cancer treatment rose from $67.3 billion for 2002-2006 to $87.8 billion for 2007-2011, an increase of $20.5 billion. While skin cancer treatment costs represented only 5% of all treatment costs in 2002-2006, the increase in skin cancer costs was 22% of the total increase, so from 2007 to 2011, skin cancer represented 9% of all treatment costs, according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

The average annual cost for skin cancer treatment more than doubled from 2002 to 2011, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found.

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual skin cancer treatment cost was $3.6 billion, while for 2007-2011, the average annual cost was $8.1 billion, an increase of about 126%. The cost of nonmelanoma skin cancers increased 74%, from $2.7 billion to $4.8 billion, but the average annual cost for melanoma cancers increased about 280%, from $864 million to $3.3 billion, according to the CDC (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014 Nov. 9 [doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036]).

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual number of adults treated for skin cancer was 3.4 million, which increased to an average annual number of 4.9 million for 2007-2011. The average annual cost per person for all skin cancers increased by 57%, from $1,044 for 2002-2006 to $1,643 for 2007-2011, while the average cost for melanomas more than doubled from $2,320 to $4,780. The increase in annual cost for nonmelanoma skin cancers was more modest; only a 25% increase, from $882 to $1,105, was noted between the two time periods, the CDC reported.

The average annual cost for all cancer treatment rose from $67.3 billion for 2002-2006 to $87.8 billion for 2007-2011, an increase of $20.5 billion. While skin cancer treatment costs represented only 5% of all treatment costs in 2002-2006, the increase in skin cancer costs was 22% of the total increase, so from 2007 to 2011, skin cancer represented 9% of all treatment costs, according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

The average annual cost for skin cancer treatment more than doubled from 2002 to 2011, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found.

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual skin cancer treatment cost was $3.6 billion, while for 2007-2011, the average annual cost was $8.1 billion, an increase of about 126%. The cost of nonmelanoma skin cancers increased 74%, from $2.7 billion to $4.8 billion, but the average annual cost for melanoma cancers increased about 280%, from $864 million to $3.3 billion, according to the CDC (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014 Nov. 9 [doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036]).

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual number of adults treated for skin cancer was 3.4 million, which increased to an average annual number of 4.9 million for 2007-2011. The average annual cost per person for all skin cancers increased by 57%, from $1,044 for 2002-2006 to $1,643 for 2007-2011, while the average cost for melanomas more than doubled from $2,320 to $4,780. The increase in annual cost for nonmelanoma skin cancers was more modest; only a 25% increase, from $882 to $1,105, was noted between the two time periods, the CDC reported.

The average annual cost for all cancer treatment rose from $67.3 billion for 2002-2006 to $87.8 billion for 2007-2011, an increase of $20.5 billion. While skin cancer treatment costs represented only 5% of all treatment costs in 2002-2006, the increase in skin cancer costs was 22% of the total increase, so from 2007 to 2011, skin cancer represented 9% of all treatment costs, according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Health-Related Quality of Life in Skin Cancer Patients

As the most common form of cancer in the United States,1 dermatologists often focus on treating the physical aspects of skin cancer, but it is equally important to consider the consequences that this disease has on a patient’s quality of life (QOL). Health is a dynamic process, encompassing one’s physical, emotional, and psychosocial well-being. There are a number of ways to measure health outcomes including mortality, morbidity, health status, and QOL. In recent years, health-related QOL (HRQOL) outcomes in dermatology have become increasingly important to clinical practice and may become factors in quality measurement or reimbursement.

Understanding a patient’s HRQOL allows health care providers to better evaluate the burden of disease and disability associated with skin cancer and its treatment. Clinical severity is not always able to capture the extent to which a disease affects one’s life.2 Furthermore, physician estimation of disease severity is not always consistent with patient-reported outcomes.3 As such, clinical questionnaires may be invaluable tools capable of objectively reporting a patient’s perception of improvement in health, which may affect how a dermatologist approaches treatment, discussion, and maintenance.

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

Most nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) occurs in readily visible areas, namely the head and neck. Surgical treatment minimizes recurrence and complication rates. Nonmelanoma skin cancer has a low mortality and a high cure rate if diagnosed early; therefore, it may be difficult to assess treatment efficacy on cure rates alone. The amalgamation of anxiety associated with the diagnosis, aesthetic and functional concerns regarding treatment, and long-term consequences including fear of future skin cancer may have a lasting effect on an individual’s psychosocial relationships and underscores the need for QOL studies.

Most generic QOL and dermatology-specific QOL instruments fail to accurately detect the concerns of patients with NMSC.4-6 Generic QOL measures used for skin cancer patients report scores of patients that were similar to population norms,4 suggesting that these tools may fail to appropriately assess unique QOL concerns among individuals with skin cancer. Furthermore, dermatology-specific instruments have been reported to be insensitive to specific appearance-related concerns of patients with NMSC, likely because skin cancer patients made up a small percentage of the initial population in their design.4,7 Nevertheless, dermatology-specific instruments may be suitable depending on the objectives of the study.8

Recently, skin cancer–specific QOL instruments have been developed to fill the paucity of appropriate tools for this population. These questionnaires include the Facial Skin Cancer Index, Skin Cancer Index, and the Skin Cancer Quality of Life Impact Tool.7 The Skin Cancer Index is a 15-item questionnaire validated in patients undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery and has been used to assess behavior modification and risk perceptions in NMSC patients. Importantly, it does ask the patient if he/she is worried about scarring. The Facial Skin Cancer Index and the Skin Cancer Quality of Life Impact Tool do not take into account detailed aesthetic concerns regarding facial disfigurement and scarring or expectations of reconstruction.7 It may be prudent to assess these areas with supplemental scales.

Melanoma

Melanoma, the third most common skin cancer, is highly aggressive and can affect young and middle-aged patients. Because the mortality associated with later-stage melanoma is greater, the QOL impact of melanoma differs from NMSC. There are also 3 distinct periods of melanoma HRQOL impact: diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Approximately 30% of patients diagnosed with melanoma report high levels of psychological distress.9 The psychosocial effects of a melanoma diagnosis are longitudinal, as there is a high survival rate in early disease but also an increased future risk for melanoma, affecting future behaviors and overall QOL. The diagnosis of melanoma also affects family members due to the increased risk among first-degree relatives. After removal of deeper melanoma, the patient remains at risk for disease progression, which can have a profound impact on his/her social and professional activities and overall lifestyle. There may be a role for longitudinal QOL assessments to monitor changes over time and direct ongoing therapy.

The proportion of patients with melanoma who report high levels of impairment in QOL is comparable to that seen in other malignancies.10 Generic QOL instruments have found that melanoma patients have medium to high levels of distress and substantial improvement in HRQOL has been achieved with cognitive-behavioral intervention.11 Quality-of-life studies also have shown levels of distress are highest at initial diagnosis and immediately following treatment.12 In a randomized surgical trial, patients with a larger excision margin had poorer mental and physical function scores on assessment.13 Skin-specific QOL instruments have been used in studies of patients with melanoma and found that postmelanoma surveillance did not impact QOL. Also, women experienced greater improvements in QOL over time after reporting lower scores immediately postsurgery.13

The FACT-melanoma (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy) is a melanoma-specific HRQOL assessment that has been used in patients undergoing clinical trials. It has been shown to distinguish between early and advanced-stage (stages III or IV) HRQOL issues.14 Patients with early-stage melanoma are more concerned with cosmetic outcome, and those with later-stage melanoma are more concerned with morbidity and mortality associated with treatment.

Comment

Choosing the best QOL instrument depends on the specific objectives of the study. Although generic QOL questionnaires have performed poorly in studies of specific skin diseases and even dermatology-specific tools have shown limited responsiveness in skin cancer, a combination of tools may be an effective approach. However, dermatologists must be cautious when administering these valuable tools to ensure that they do not become a burdensome task for the patient.15 Although no single skin cancer–specific QOL tool is perfect, it is likely that the current questionnaires still allow for aid with appropriate patient management and comparison of treatments.16

It behooves clinicians to recognize and appreciate the value of QOL instruments as an important adjunct to treatment. These tools have shown QOL to be an independent predictor of survival among many types of cancer patients, including melanoma.10 Currently, the psychological and emotional needs of skin cancer patients often go overlooked and undetected by conventional methods. Within one’s own practice, introducing QOL assessments can improve patient self-awareness and physician awareness of matters that may have a greater impact on patient health. On a larger scale, introducing patient-reported outcome measures can affect resource allocation by identifying patient populations that may be most impacted and can give a comprehensive method for physicians to gauge treatment efficacy, leading to improved outcomes.

1. Robinson JK. Sun exposure, sun protection, and vitamin D. JAMA. 2005;294:1541-1543.

2. Motley RJ, Finlay AY. Practical use of a disability index in the routine management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:1-3.

3. Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, et al. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:707-713.

4. Gibbons EC, Comabella CI, Fitzpatrick R. A structured review of patient-reported outcome measures for patients with skin cancer, 2013. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1176-1186.

5. Burdon-Jones D, Thomas P, Baker R. Quality of life issues in nonmetastatic skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:147-151.

6. Lear W, Akeroyd JD, Mittmann N, et al. Measurement of utility in nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:102-106.

7. Bates AS, Davis CR, Takwale A, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in nonmelanoma skin cancer of the face: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1187-1194.

8. Lee EH, Klassen AF, Nehal KS, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the dermatologic population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e59-e67.

9. Kasparian NA. Psychological stress and melanoma: are we meeting our patients’ psychological needs? Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:41-46.

10. Cormier JN, Cromwell KD, Ross MI. Health-related quality of life in patients with melanoma: overview of instruments and outcomes. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:245-254.

11. Trask PC, Paterson AG, Griffith KA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral intervention for distress in patients with melanoma: comparison with standard medical care and impact on quality of life. Cancer. 2003;98:854-864.

12. Boyle DA. Psychological adjustment to the melanoma experience. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2003;191:70-77.

13. Newton-Bishop JA, Nolan C, Turner F, et al. A quality-of-life study in high-risk (thickness > = or 2 mm) cutaneous melanoma patients in a randomized trial of 1-cm versus 3-cm surgical excision margins. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:152-159.

14. Winstanley JB, Saw R, Boyle F, et al. The FACT-Melanoma quality-of-life instrument: comparison of a five-point and four-point response scale using the Rasch measurement model. Melanoma Res. 2013;23:61-69.

15. Swartz RJ, Baum GP, Askew RL, et al. Reducing patient burden to the FACT-Melanoma quality-of-life questionnaire. Melanoma Res. 2012;22:158-163.

16. Black N. Patient-reported outcome measures in skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1151.

As the most common form of cancer in the United States,1 dermatologists often focus on treating the physical aspects of skin cancer, but it is equally important to consider the consequences that this disease has on a patient’s quality of life (QOL). Health is a dynamic process, encompassing one’s physical, emotional, and psychosocial well-being. There are a number of ways to measure health outcomes including mortality, morbidity, health status, and QOL. In recent years, health-related QOL (HRQOL) outcomes in dermatology have become increasingly important to clinical practice and may become factors in quality measurement or reimbursement.

Understanding a patient’s HRQOL allows health care providers to better evaluate the burden of disease and disability associated with skin cancer and its treatment. Clinical severity is not always able to capture the extent to which a disease affects one’s life.2 Furthermore, physician estimation of disease severity is not always consistent with patient-reported outcomes.3 As such, clinical questionnaires may be invaluable tools capable of objectively reporting a patient’s perception of improvement in health, which may affect how a dermatologist approaches treatment, discussion, and maintenance.

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

Most nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) occurs in readily visible areas, namely the head and neck. Surgical treatment minimizes recurrence and complication rates. Nonmelanoma skin cancer has a low mortality and a high cure rate if diagnosed early; therefore, it may be difficult to assess treatment efficacy on cure rates alone. The amalgamation of anxiety associated with the diagnosis, aesthetic and functional concerns regarding treatment, and long-term consequences including fear of future skin cancer may have a lasting effect on an individual’s psychosocial relationships and underscores the need for QOL studies.

Most generic QOL and dermatology-specific QOL instruments fail to accurately detect the concerns of patients with NMSC.4-6 Generic QOL measures used for skin cancer patients report scores of patients that were similar to population norms,4 suggesting that these tools may fail to appropriately assess unique QOL concerns among individuals with skin cancer. Furthermore, dermatology-specific instruments have been reported to be insensitive to specific appearance-related concerns of patients with NMSC, likely because skin cancer patients made up a small percentage of the initial population in their design.4,7 Nevertheless, dermatology-specific instruments may be suitable depending on the objectives of the study.8

Recently, skin cancer–specific QOL instruments have been developed to fill the paucity of appropriate tools for this population. These questionnaires include the Facial Skin Cancer Index, Skin Cancer Index, and the Skin Cancer Quality of Life Impact Tool.7 The Skin Cancer Index is a 15-item questionnaire validated in patients undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery and has been used to assess behavior modification and risk perceptions in NMSC patients. Importantly, it does ask the patient if he/she is worried about scarring. The Facial Skin Cancer Index and the Skin Cancer Quality of Life Impact Tool do not take into account detailed aesthetic concerns regarding facial disfigurement and scarring or expectations of reconstruction.7 It may be prudent to assess these areas with supplemental scales.

Melanoma

Melanoma, the third most common skin cancer, is highly aggressive and can affect young and middle-aged patients. Because the mortality associated with later-stage melanoma is greater, the QOL impact of melanoma differs from NMSC. There are also 3 distinct periods of melanoma HRQOL impact: diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Approximately 30% of patients diagnosed with melanoma report high levels of psychological distress.9 The psychosocial effects of a melanoma diagnosis are longitudinal, as there is a high survival rate in early disease but also an increased future risk for melanoma, affecting future behaviors and overall QOL. The diagnosis of melanoma also affects family members due to the increased risk among first-degree relatives. After removal of deeper melanoma, the patient remains at risk for disease progression, which can have a profound impact on his/her social and professional activities and overall lifestyle. There may be a role for longitudinal QOL assessments to monitor changes over time and direct ongoing therapy.

The proportion of patients with melanoma who report high levels of impairment in QOL is comparable to that seen in other malignancies.10 Generic QOL instruments have found that melanoma patients have medium to high levels of distress and substantial improvement in HRQOL has been achieved with cognitive-behavioral intervention.11 Quality-of-life studies also have shown levels of distress are highest at initial diagnosis and immediately following treatment.12 In a randomized surgical trial, patients with a larger excision margin had poorer mental and physical function scores on assessment.13 Skin-specific QOL instruments have been used in studies of patients with melanoma and found that postmelanoma surveillance did not impact QOL. Also, women experienced greater improvements in QOL over time after reporting lower scores immediately postsurgery.13

The FACT-melanoma (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy) is a melanoma-specific HRQOL assessment that has been used in patients undergoing clinical trials. It has been shown to distinguish between early and advanced-stage (stages III or IV) HRQOL issues.14 Patients with early-stage melanoma are more concerned with cosmetic outcome, and those with later-stage melanoma are more concerned with morbidity and mortality associated with treatment.

Comment

Choosing the best QOL instrument depends on the specific objectives of the study. Although generic QOL questionnaires have performed poorly in studies of specific skin diseases and even dermatology-specific tools have shown limited responsiveness in skin cancer, a combination of tools may be an effective approach. However, dermatologists must be cautious when administering these valuable tools to ensure that they do not become a burdensome task for the patient.15 Although no single skin cancer–specific QOL tool is perfect, it is likely that the current questionnaires still allow for aid with appropriate patient management and comparison of treatments.16

It behooves clinicians to recognize and appreciate the value of QOL instruments as an important adjunct to treatment. These tools have shown QOL to be an independent predictor of survival among many types of cancer patients, including melanoma.10 Currently, the psychological and emotional needs of skin cancer patients often go overlooked and undetected by conventional methods. Within one’s own practice, introducing QOL assessments can improve patient self-awareness and physician awareness of matters that may have a greater impact on patient health. On a larger scale, introducing patient-reported outcome measures can affect resource allocation by identifying patient populations that may be most impacted and can give a comprehensive method for physicians to gauge treatment efficacy, leading to improved outcomes.

As the most common form of cancer in the United States,1 dermatologists often focus on treating the physical aspects of skin cancer, but it is equally important to consider the consequences that this disease has on a patient’s quality of life (QOL). Health is a dynamic process, encompassing one’s physical, emotional, and psychosocial well-being. There are a number of ways to measure health outcomes including mortality, morbidity, health status, and QOL. In recent years, health-related QOL (HRQOL) outcomes in dermatology have become increasingly important to clinical practice and may become factors in quality measurement or reimbursement.

Understanding a patient’s HRQOL allows health care providers to better evaluate the burden of disease and disability associated with skin cancer and its treatment. Clinical severity is not always able to capture the extent to which a disease affects one’s life.2 Furthermore, physician estimation of disease severity is not always consistent with patient-reported outcomes.3 As such, clinical questionnaires may be invaluable tools capable of objectively reporting a patient’s perception of improvement in health, which may affect how a dermatologist approaches treatment, discussion, and maintenance.

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

Most nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) occurs in readily visible areas, namely the head and neck. Surgical treatment minimizes recurrence and complication rates. Nonmelanoma skin cancer has a low mortality and a high cure rate if diagnosed early; therefore, it may be difficult to assess treatment efficacy on cure rates alone. The amalgamation of anxiety associated with the diagnosis, aesthetic and functional concerns regarding treatment, and long-term consequences including fear of future skin cancer may have a lasting effect on an individual’s psychosocial relationships and underscores the need for QOL studies.

Most generic QOL and dermatology-specific QOL instruments fail to accurately detect the concerns of patients with NMSC.4-6 Generic QOL measures used for skin cancer patients report scores of patients that were similar to population norms,4 suggesting that these tools may fail to appropriately assess unique QOL concerns among individuals with skin cancer. Furthermore, dermatology-specific instruments have been reported to be insensitive to specific appearance-related concerns of patients with NMSC, likely because skin cancer patients made up a small percentage of the initial population in their design.4,7 Nevertheless, dermatology-specific instruments may be suitable depending on the objectives of the study.8

Recently, skin cancer–specific QOL instruments have been developed to fill the paucity of appropriate tools for this population. These questionnaires include the Facial Skin Cancer Index, Skin Cancer Index, and the Skin Cancer Quality of Life Impact Tool.7 The Skin Cancer Index is a 15-item questionnaire validated in patients undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery and has been used to assess behavior modification and risk perceptions in NMSC patients. Importantly, it does ask the patient if he/she is worried about scarring. The Facial Skin Cancer Index and the Skin Cancer Quality of Life Impact Tool do not take into account detailed aesthetic concerns regarding facial disfigurement and scarring or expectations of reconstruction.7 It may be prudent to assess these areas with supplemental scales.

Melanoma

Melanoma, the third most common skin cancer, is highly aggressive and can affect young and middle-aged patients. Because the mortality associated with later-stage melanoma is greater, the QOL impact of melanoma differs from NMSC. There are also 3 distinct periods of melanoma HRQOL impact: diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Approximately 30% of patients diagnosed with melanoma report high levels of psychological distress.9 The psychosocial effects of a melanoma diagnosis are longitudinal, as there is a high survival rate in early disease but also an increased future risk for melanoma, affecting future behaviors and overall QOL. The diagnosis of melanoma also affects family members due to the increased risk among first-degree relatives. After removal of deeper melanoma, the patient remains at risk for disease progression, which can have a profound impact on his/her social and professional activities and overall lifestyle. There may be a role for longitudinal QOL assessments to monitor changes over time and direct ongoing therapy.

The proportion of patients with melanoma who report high levels of impairment in QOL is comparable to that seen in other malignancies.10 Generic QOL instruments have found that melanoma patients have medium to high levels of distress and substantial improvement in HRQOL has been achieved with cognitive-behavioral intervention.11 Quality-of-life studies also have shown levels of distress are highest at initial diagnosis and immediately following treatment.12 In a randomized surgical trial, patients with a larger excision margin had poorer mental and physical function scores on assessment.13 Skin-specific QOL instruments have been used in studies of patients with melanoma and found that postmelanoma surveillance did not impact QOL. Also, women experienced greater improvements in QOL over time after reporting lower scores immediately postsurgery.13

The FACT-melanoma (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy) is a melanoma-specific HRQOL assessment that has been used in patients undergoing clinical trials. It has been shown to distinguish between early and advanced-stage (stages III or IV) HRQOL issues.14 Patients with early-stage melanoma are more concerned with cosmetic outcome, and those with later-stage melanoma are more concerned with morbidity and mortality associated with treatment.

Comment

Choosing the best QOL instrument depends on the specific objectives of the study. Although generic QOL questionnaires have performed poorly in studies of specific skin diseases and even dermatology-specific tools have shown limited responsiveness in skin cancer, a combination of tools may be an effective approach. However, dermatologists must be cautious when administering these valuable tools to ensure that they do not become a burdensome task for the patient.15 Although no single skin cancer–specific QOL tool is perfect, it is likely that the current questionnaires still allow for aid with appropriate patient management and comparison of treatments.16

It behooves clinicians to recognize and appreciate the value of QOL instruments as an important adjunct to treatment. These tools have shown QOL to be an independent predictor of survival among many types of cancer patients, including melanoma.10 Currently, the psychological and emotional needs of skin cancer patients often go overlooked and undetected by conventional methods. Within one’s own practice, introducing QOL assessments can improve patient self-awareness and physician awareness of matters that may have a greater impact on patient health. On a larger scale, introducing patient-reported outcome measures can affect resource allocation by identifying patient populations that may be most impacted and can give a comprehensive method for physicians to gauge treatment efficacy, leading to improved outcomes.

1. Robinson JK. Sun exposure, sun protection, and vitamin D. JAMA. 2005;294:1541-1543.

2. Motley RJ, Finlay AY. Practical use of a disability index in the routine management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:1-3.

3. Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, et al. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:707-713.

4. Gibbons EC, Comabella CI, Fitzpatrick R. A structured review of patient-reported outcome measures for patients with skin cancer, 2013. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1176-1186.

5. Burdon-Jones D, Thomas P, Baker R. Quality of life issues in nonmetastatic skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:147-151.

6. Lear W, Akeroyd JD, Mittmann N, et al. Measurement of utility in nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:102-106.

7. Bates AS, Davis CR, Takwale A, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in nonmelanoma skin cancer of the face: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1187-1194.

8. Lee EH, Klassen AF, Nehal KS, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the dermatologic population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e59-e67.

9. Kasparian NA. Psychological stress and melanoma: are we meeting our patients’ psychological needs? Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:41-46.

10. Cormier JN, Cromwell KD, Ross MI. Health-related quality of life in patients with melanoma: overview of instruments and outcomes. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:245-254.

11. Trask PC, Paterson AG, Griffith KA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral intervention for distress in patients with melanoma: comparison with standard medical care and impact on quality of life. Cancer. 2003;98:854-864.

12. Boyle DA. Psychological adjustment to the melanoma experience. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2003;191:70-77.

13. Newton-Bishop JA, Nolan C, Turner F, et al. A quality-of-life study in high-risk (thickness > = or 2 mm) cutaneous melanoma patients in a randomized trial of 1-cm versus 3-cm surgical excision margins. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:152-159.

14. Winstanley JB, Saw R, Boyle F, et al. The FACT-Melanoma quality-of-life instrument: comparison of a five-point and four-point response scale using the Rasch measurement model. Melanoma Res. 2013;23:61-69.

15. Swartz RJ, Baum GP, Askew RL, et al. Reducing patient burden to the FACT-Melanoma quality-of-life questionnaire. Melanoma Res. 2012;22:158-163.

16. Black N. Patient-reported outcome measures in skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1151.

1. Robinson JK. Sun exposure, sun protection, and vitamin D. JAMA. 2005;294:1541-1543.

2. Motley RJ, Finlay AY. Practical use of a disability index in the routine management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:1-3.

3. Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, et al. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:707-713.

4. Gibbons EC, Comabella CI, Fitzpatrick R. A structured review of patient-reported outcome measures for patients with skin cancer, 2013. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1176-1186.

5. Burdon-Jones D, Thomas P, Baker R. Quality of life issues in nonmetastatic skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:147-151.

6. Lear W, Akeroyd JD, Mittmann N, et al. Measurement of utility in nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:102-106.

7. Bates AS, Davis CR, Takwale A, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in nonmelanoma skin cancer of the face: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1187-1194.

8. Lee EH, Klassen AF, Nehal KS, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the dermatologic population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e59-e67.

9. Kasparian NA. Psychological stress and melanoma: are we meeting our patients’ psychological needs? Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:41-46.

10. Cormier JN, Cromwell KD, Ross MI. Health-related quality of life in patients with melanoma: overview of instruments and outcomes. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:245-254.

11. Trask PC, Paterson AG, Griffith KA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral intervention for distress in patients with melanoma: comparison with standard medical care and impact on quality of life. Cancer. 2003;98:854-864.

12. Boyle DA. Psychological adjustment to the melanoma experience. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2003;191:70-77.

13. Newton-Bishop JA, Nolan C, Turner F, et al. A quality-of-life study in high-risk (thickness > = or 2 mm) cutaneous melanoma patients in a randomized trial of 1-cm versus 3-cm surgical excision margins. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:152-159.

14. Winstanley JB, Saw R, Boyle F, et al. The FACT-Melanoma quality-of-life instrument: comparison of a five-point and four-point response scale using the Rasch measurement model. Melanoma Res. 2013;23:61-69.

15. Swartz RJ, Baum GP, Askew RL, et al. Reducing patient burden to the FACT-Melanoma quality-of-life questionnaire. Melanoma Res. 2012;22:158-163.

16. Black N. Patient-reported outcome measures in skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1151.

Risk Factors for Malignant Melanoma and Preventive Methods

Cutaneous melanoma is a malignant tumor of the skin that develops from melanin-producing pigment cells known as melanocytes. The development of melanoma is a multifactorial process. External factors, genetic predisposition, or both may cause damage to DNA in melanoma cells. Genetic mutations may occur de novo or can be transferred from generation to generation. The most important environmental risk factor is UV radiation, both natural and artificial. Other risk factors include skin type, ethnicity, number of melanocytic nevi, number and severity of sunburns, frequency and duration of UV exposure, geographic location, and level of awareness about malignant melanoma (MM) and its risk factors.1

Melanoma accounts for only 1% to 2% of all tumors but is known for its rapidly increasing incidence.2 White individuals who reside in sunny areas of North America, northern Europe, Australia, and New Zealand seem to be at the highest risk for developing melanoma.3 The global incidence of MM from 2004 to 2008 was 20.8 individuals per 100,000 people.4 In Central Europe, 10 to 12 individuals per 100,000 people were diagnosed with melanoma, and 50 to 60 individuals per 100,000 people were diagnosed in Australia. In 2011, the lifetime risk of being diagnosed with melanoma was 1% in Central Europe and 4% in Australia.2 The incidence of melanoma is lower in populations with darker skin types (ie, Africans, Asians). In some parts of the world, the overall incidence and/or severity of melanoma has been declining over the last few decades, possibly reflecting improved public awareness.5

Cutaneous MM is an aggressive skin cancer that has fatal consequences if diagnosed late. Chances of survival, however, increase dramatically when melanoma is detected early. Collecting and analyzing data about a certain disease leads to a better understanding of the condition and encourages the development of prevention strategies. Epidemiologic research helps to improve patient care by measuring the occurrence of an event and by investigating the relationship between the occurrence of an event and associated factors; in doing so, epidemiologic research directly enables a better understanding of the disease and promotes effective preventive and therapeutic approaches.6

Although risk factors for melanoma are well established, current epidemiologic research shows that information on UV exposure and its association with this disease in many parts of the world, including Central Europe, is lacking. The aim of this study was to investigate behavioral and sociodemographic factors associated with the development of MM in the Czech Republic and Germany.

Materials and Methods

This hospital-based, case-control study was conducted in the largest dermatology departments in the Czech Republic (Clinic of Dermatology and Venereology, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague) and Germany (Department of Dermatology and Allergology, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich). Data from the Czech Republic and Germany were not evaluated separately. These 2 countries were chosen as a representative sample population from Central Europe.

Study Population

The study population included 207 patients (103 men; 104 women) aged 31 to 94 years who were consecutively diagnosed with MM (cases). Patients with acral lentiginous melanoma were excluded from the study due to the generally accepted theory that the condition is not linked to UV exposure. Melanoma diagnosis was based on histopathologic examination. The study population also included 235 randomly selected controls (110 men; 125 women) from the same 2 study centers who had been hospitalized due to other dermatologic diagnoses with no history of any skin cancer. Among patients asked to take part in the study, the participation rates were 83% among cases and 62% among controls.

Assessment

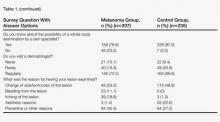

Various sociodemographic factors and factors related to UV exposure were assessed via administration of a structured questionnaire that was completed by all 442 patients.

Four statistical models concerning variables were constructed. The basic model, which was part of all subsequent models, included age, sex, education, and history of skin tumors. Variables included in the biological model were eye color (light vs dark) and Fitzpatrick skin type (I–V). Variables included in the lifestyle model were the use of sunscreen (never and rarely; often; always; always and repetitively), sun exposure during work (yes/no), and seaside vacation (never, rarely, regularly, more than once per year). The variable in the exposure model was the number of sunburns during childhood and adolescence (none, 1–5 times, 6–10 times, ≥11 times).

Sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, education) and prior incidence of skin tumor were included in each model. Although there were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of melanoma associated with sex and age, those variables were kept in the models to control the impact of other variables by sex and age.

Other variables were added into the model one by one, and the likelihood ratio was tested step-by-step. Only the variables that improved the model fit were kept in the final model. Impact of variables on dependent variables also was tested; variables with no significant impact on dependent variables were left out of the model.

Statistical Analysis

The association between risk factors and MM was assessed using multivariate logistic regression. In total, 4 models were included in the results, which were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A significance level of α=.05 was chosen. The statistical program Stata 11 was used for all analyses.

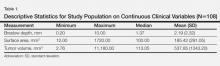

Results

Descriptive data on the 442 patients surveyed are shown in Table 1. The results of the logistic regression in all studied models are shown in Table 2.

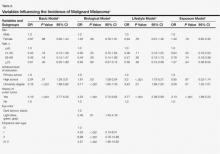

Basic Model

There was no difference in the proportion of men and women in the melanoma and control groups. We observed that more patients in the melanoma group had a university degree than patients in the control group. Patients in the melanoma group with a history of MM showed 4.2 times higher risk for developing another melanoma.

Biological Model

Eye color and Fitzpatrick skin type were the focus of the biological model. The odds of being diagnosed with melanoma were 2.5 times greater in respondents with a light eye color (ie, blue, green, gray) than in respondents with a dark eye color (ie, brown, black). Respondents with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II had a significantly higher association with melanoma (OR, 4.25 and 6.98; 95% CI, 2.13-8.51 and 3.78-12.88) than Fitzpatrick skin type III (OR, 1.0)(P<.001 for both). Respondents with darker skin types (IV and V) also were present in our study population. The numbers were low, and the CI was too wide; nevertheless, the results were statistically significant (P<.001).

Lifestyle Model

The lifestyle model included patients’ use of sunscreen and level of sun exposure at work and on vacation. Respondents who did not use sunscreen were 12 times more likely to develop melanoma than those who always used it (95% CI, 5.56-27.14); however, individuals who used sunscreen always and repetitively (ie, more than once during 1 period of sun exposure) had a higher likelihood of melanoma compared to those who always used it. The incidence of melanoma was lower in respondents who regularly spent their vacations by the sea than those who did not vacation in seaside regions. Respondents who worked in direct sunlight were approximately 2 times more likely to present with melanoma than individuals who did not work outside.

Exposure Model

The number of sunburns sustained during childhood and adolescence was assessed in the exposure model. Respondents with a history of 1 to 5 sunburns during childhood and adolescence did not show a statistically significant increase in the incidence of melanoma diagnosis; however, those with a history of 6 or more sunburns during these periods showed a significant increase in the odds of developing melanoma (OR, 4.95 and 25.52; 95% CI, 2.29-10.71 and 12.16-53.54)(P<.001 for both).

Comment

In this study, we concentrated on UV exposure and various sociodemographic factors that were possibly connected to a higher risk for developing melanoma. We observed that the majority of patients in the melanoma group had achieved a higher level of education than the control group. Most of the melanoma group patients had light-colored eyes and spent more time in direct sunlight at work. Although seaside vacations did not correlate with a higher occurrence of melanoma, it was noted that the melanoma patients used sunscreen much less often than the control group. Major differences among respondents in the melanoma group versus the control group were seen in the reported number of sunburns sustained in childhood and adolescence. More sunburns during these periods seemed to play the most important role in the risk for melanoma. Some of the patient responses to the questionnaire may be biased, as respondents answered the questions by themselves.

Because risk factors for and preventive methods against melanoma are well established, one would assume that general knowledge regarding melanoma is adequate. On the contrary, it has been shown that knowledge about melanoma is insufficient, even among professionals and individuals with higher levels of education. In a study based on a questionnaire administered to plastic surgeons, only 37.5% (27/72) of respondents correctly identified the duration of action of sunscreen to be 3 to 4 hours.7 Approximately half of the respondents (37/72) did not know that geographical conditions such as altitude and latitude as well as shade can alter sunscreen efficacy and also were not aware of the protective action of clothing. These results are alarming and indicate that even medical professionals, who should play a main role in improving the health knowledge of the general population, have an unsatisfactory level of education in prevention of melanoma. Another important part of better education of specialists treating skin disorders is good knowledge of dermatoscopy. In fact, the Annual Skin Cancer Conference 2011 in Australia emphasized the importance of dermatoscopy in primary and secondary prevention of skin cancer.8 Teaching dermatoscopy should be part of melanoma campaigns for professionals.

Our basic model demonstrated that a higher level of education was connected to a higher occurrence of MM, which may seem surprising, considering that most diseases, along with their incidence, prevalence, and mortality, usually are associated with lower levels of education or lower socioeconomic status. A similar trend also was reported in prior studies, with higher socioeconomic groups showing higher incidences of cutaneous melanoma; colon cancer; brain cancer in men; and breast and ovarian cancer in women. Additionally, patients with higher socioeconomic status have been shown to have a survival advantage.9 Individuals with higher socioeconomic status can afford to travel more often for vacation and are more frequently exposed to direct sun. Individuals with higher levels of education also are generally more aware of the importance of disease prevention and therefore go for preventive checkups more often. The detection of melanoma in this socioeconomic group should be higher.

Our biological model demonstrated that respondents with lighter eyes had melanoma almost 3 times more often than individuals with darker eyes. Fitzpatrick skin types I and II also were significantly associated with the development of melanoma (P<.001). These findings are generally confirmed in the literature. In a study of the incidence of melanoma in Spain, statistically significant risk factors included blonde or red hair (P=.002), multiple melanocytic nevi (P=.002), Fitzpatrick skin types I and II (P=.002), and a history of actinic keratosis (P=.021) or nonmelanoma skin cancer (P=.002).10 A group in Italy also has investigated the main risk factors for melanoma. This study suggested dividing patients into high-risk subgroups to help minimize exposure to UV radiation and diagnose melanoma in its early stage.11

The results from our study confirmed the importance of concentrating melanoma prevention campaign efforts on high-risk patients. Dividing these patients into subgroups (eg, individuals who play outdoor sports, individuals with occupations associated with UV exposure, individuals who use indoor tanning beds, individuals with a family history of melanoma) may be helpful. A case-control study on sun-seeking behavior in the Czech Republic showed that the most alarming risk factors were all-day sun exposure during adolescence, frequent holidays spent in the mountains, and inadequate use of sunscreen in adulthood.12 We investigated the effects of sunscreen use on the incidence of melanoma in our lifestyle model and discovered that it decreased the risk for melanoma. Respondents who used it always had a much lower risk for developing melanoma than those who never or rarely applied it. Individuals who used sunscreen always and repetitively (ie, more than once per period of sun exposure) did not show a lower risk than those who used it once per period of sun exposure. This finding could mean that patients who are known to get sunburns or who feel a certain discomfort on direct exposure to the sun tend to use sunscreen always and repetitively.

It is important to note that some investigators disagree with the importance of some generally accepted means of prevention, such as the effect of sunscreen products. Due to insufficient evidence, the role of sunscreen use in reducing the risk for skin cancer, especially cutaneous MM, is controversial.13 Although we could prove there is a considerable difference in the incidence of melanoma in patients who claimed to use sunscreen always versus those who never use it, we agree that more evidence on this topic is needed. Furthermore, it has been reported that risk for melanoma has increased with rising intermittent sun exposure and indoor tanning bed use.14,15

Respondents who regularly traveled to seaside regions showed a surprisingly lower incidence of melanoma than respondents who did not spend their vacations in seaside locations. It is possible that individuals who choose not to spend their vacations at the seaside are more prone to sunburns and therefore do not prefer to spend their free time in direct sunlight. Another possible explanation is that individuals who regularly travel to seaside regions actively try to protect themselves from sunlight and sunburns. A higher incidence of melanoma also was observed in respondents who reported sun exposure during work.

In our exposure model, we demonstrated that a history of sunburns is the strongest risk factor for melanoma. Frequent sunburns during childhood and adolescence were strongly associated with the development of MM. This association has been supported in a systematic review on sun exposure during childhood and associated risks.16

Conclusion

To improve patient knowledge about melanoma prevention, we suggest directing targeted campaigns that address high-risk population groups, such as individuals with red hair and/or light eyes, people with an occupation associated with frequent UV exposure, and individuals with higher levels of education. With regard to younger populations, parents as well as physicians and teachers should be aware that frequent sunburns during childhood and adolescence and use of tanning beds are 2 main risk factors for MM.

1. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. solar and ultraviolet radiation. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1992;55:1-316.

2. Kunte C, Geimer T, Baumert J, et al. Analysis of predictive factors for the outcome of complete lymph node dissection in melanoma patients with metastatic sentinel lymph nodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:655-662.

3. Parkin D, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74-108.

4. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: melanoma of the skin. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2013. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html#incidence-mortality. Accessed October 25, 2014.

5. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-2917.

6. Nijsten T, Stern RS. How epidemiology has contributed to a better understanding of skin disease [published online ahead of print December 8, 2011]. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(3, pt 2):994-1002.

7. Magdum A, Leonforte F, McNaughton E, et al. Sun protection–do we know enough [published online ahead of print February 8, 2012]? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1384-1389.

8. Zalaudek I, Whiteman D, Rosendahl C, et al. Update on melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. Annual Skin Cancer Conference 2011, Hamilton Island, Australia, 2011. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11:1829-1832.

9. Mackenbach JP. Health inequalities: Europe in profile. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/socio_economics/documents/ev_060302_rd06_en.pdf. Published February 2006. Accessed October 25, 2014.

10. Ballester I, Oliver V, Bañuls J, et al. Multicenter case-control study of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma in Valencia, Spain [published online ahead of print May 22, 2012]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:790-797.

11. Jaimes N, Marghoob AA. An update on risk factors, prognosis and management of melanoma patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2012;147:1-19.

12. Vranova J, Arenbergerova M, Arenberger P, et al. Incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma in the Czech Republic: the risks of sun exposure for adolescents. Neoplasma. 2012;59:316-325.

13. Planta MB. Sunscreen and melanoma: is our prevention message correct? J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:735-739.

14. Veierød MB, Adami HO, Lund E, et al. Sun and solarium exposure and melanoma risk: effects of age, pigmentary characteristics, and nevi. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:111-120.

15. Doré JF, Chignol MC. Tanning salons and skin cancer [published online ahead of print August 15, 2011]. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2012;11:30-37.

16. Whiteman DC, Whiteman CA, Green AC. Childhood sun exposure as a risk factor for melanoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:69-82.

Cutaneous melanoma is a malignant tumor of the skin that develops from melanin-producing pigment cells known as melanocytes. The development of melanoma is a multifactorial process. External factors, genetic predisposition, or both may cause damage to DNA in melanoma cells. Genetic mutations may occur de novo or can be transferred from generation to generation. The most important environmental risk factor is UV radiation, both natural and artificial. Other risk factors include skin type, ethnicity, number of melanocytic nevi, number and severity of sunburns, frequency and duration of UV exposure, geographic location, and level of awareness about malignant melanoma (MM) and its risk factors.1

Melanoma accounts for only 1% to 2% of all tumors but is known for its rapidly increasing incidence.2 White individuals who reside in sunny areas of North America, northern Europe, Australia, and New Zealand seem to be at the highest risk for developing melanoma.3 The global incidence of MM from 2004 to 2008 was 20.8 individuals per 100,000 people.4 In Central Europe, 10 to 12 individuals per 100,000 people were diagnosed with melanoma, and 50 to 60 individuals per 100,000 people were diagnosed in Australia. In 2011, the lifetime risk of being diagnosed with melanoma was 1% in Central Europe and 4% in Australia.2 The incidence of melanoma is lower in populations with darker skin types (ie, Africans, Asians). In some parts of the world, the overall incidence and/or severity of melanoma has been declining over the last few decades, possibly reflecting improved public awareness.5

Cutaneous MM is an aggressive skin cancer that has fatal consequences if diagnosed late. Chances of survival, however, increase dramatically when melanoma is detected early. Collecting and analyzing data about a certain disease leads to a better understanding of the condition and encourages the development of prevention strategies. Epidemiologic research helps to improve patient care by measuring the occurrence of an event and by investigating the relationship between the occurrence of an event and associated factors; in doing so, epidemiologic research directly enables a better understanding of the disease and promotes effective preventive and therapeutic approaches.6

Although risk factors for melanoma are well established, current epidemiologic research shows that information on UV exposure and its association with this disease in many parts of the world, including Central Europe, is lacking. The aim of this study was to investigate behavioral and sociodemographic factors associated with the development of MM in the Czech Republic and Germany.

Materials and Methods

This hospital-based, case-control study was conducted in the largest dermatology departments in the Czech Republic (Clinic of Dermatology and Venereology, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague) and Germany (Department of Dermatology and Allergology, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich). Data from the Czech Republic and Germany were not evaluated separately. These 2 countries were chosen as a representative sample population from Central Europe.

Study Population

The study population included 207 patients (103 men; 104 women) aged 31 to 94 years who were consecutively diagnosed with MM (cases). Patients with acral lentiginous melanoma were excluded from the study due to the generally accepted theory that the condition is not linked to UV exposure. Melanoma diagnosis was based on histopathologic examination. The study population also included 235 randomly selected controls (110 men; 125 women) from the same 2 study centers who had been hospitalized due to other dermatologic diagnoses with no history of any skin cancer. Among patients asked to take part in the study, the participation rates were 83% among cases and 62% among controls.

Assessment

Various sociodemographic factors and factors related to UV exposure were assessed via administration of a structured questionnaire that was completed by all 442 patients.

Four statistical models concerning variables were constructed. The basic model, which was part of all subsequent models, included age, sex, education, and history of skin tumors. Variables included in the biological model were eye color (light vs dark) and Fitzpatrick skin type (I–V). Variables included in the lifestyle model were the use of sunscreen (never and rarely; often; always; always and repetitively), sun exposure during work (yes/no), and seaside vacation (never, rarely, regularly, more than once per year). The variable in the exposure model was the number of sunburns during childhood and adolescence (none, 1–5 times, 6–10 times, ≥11 times).

Sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, education) and prior incidence of skin tumor were included in each model. Although there were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of melanoma associated with sex and age, those variables were kept in the models to control the impact of other variables by sex and age.

Other variables were added into the model one by one, and the likelihood ratio was tested step-by-step. Only the variables that improved the model fit were kept in the final model. Impact of variables on dependent variables also was tested; variables with no significant impact on dependent variables were left out of the model.

Statistical Analysis

The association between risk factors and MM was assessed using multivariate logistic regression. In total, 4 models were included in the results, which were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A significance level of α=.05 was chosen. The statistical program Stata 11 was used for all analyses.

Results

Descriptive data on the 442 patients surveyed are shown in Table 1. The results of the logistic regression in all studied models are shown in Table 2.

Basic Model

There was no difference in the proportion of men and women in the melanoma and control groups. We observed that more patients in the melanoma group had a university degree than patients in the control group. Patients in the melanoma group with a history of MM showed 4.2 times higher risk for developing another melanoma.

Biological Model

Eye color and Fitzpatrick skin type were the focus of the biological model. The odds of being diagnosed with melanoma were 2.5 times greater in respondents with a light eye color (ie, blue, green, gray) than in respondents with a dark eye color (ie, brown, black). Respondents with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II had a significantly higher association with melanoma (OR, 4.25 and 6.98; 95% CI, 2.13-8.51 and 3.78-12.88) than Fitzpatrick skin type III (OR, 1.0)(P<.001 for both). Respondents with darker skin types (IV and V) also were present in our study population. The numbers were low, and the CI was too wide; nevertheless, the results were statistically significant (P<.001).

Lifestyle Model

The lifestyle model included patients’ use of sunscreen and level of sun exposure at work and on vacation. Respondents who did not use sunscreen were 12 times more likely to develop melanoma than those who always used it (95% CI, 5.56-27.14); however, individuals who used sunscreen always and repetitively (ie, more than once during 1 period of sun exposure) had a higher likelihood of melanoma compared to those who always used it. The incidence of melanoma was lower in respondents who regularly spent their vacations by the sea than those who did not vacation in seaside regions. Respondents who worked in direct sunlight were approximately 2 times more likely to present with melanoma than individuals who did not work outside.

Exposure Model

The number of sunburns sustained during childhood and adolescence was assessed in the exposure model. Respondents with a history of 1 to 5 sunburns during childhood and adolescence did not show a statistically significant increase in the incidence of melanoma diagnosis; however, those with a history of 6 or more sunburns during these periods showed a significant increase in the odds of developing melanoma (OR, 4.95 and 25.52; 95% CI, 2.29-10.71 and 12.16-53.54)(P<.001 for both).

Comment

In this study, we concentrated on UV exposure and various sociodemographic factors that were possibly connected to a higher risk for developing melanoma. We observed that the majority of patients in the melanoma group had achieved a higher level of education than the control group. Most of the melanoma group patients had light-colored eyes and spent more time in direct sunlight at work. Although seaside vacations did not correlate with a higher occurrence of melanoma, it was noted that the melanoma patients used sunscreen much less often than the control group. Major differences among respondents in the melanoma group versus the control group were seen in the reported number of sunburns sustained in childhood and adolescence. More sunburns during these periods seemed to play the most important role in the risk for melanoma. Some of the patient responses to the questionnaire may be biased, as respondents answered the questions by themselves.

Because risk factors for and preventive methods against melanoma are well established, one would assume that general knowledge regarding melanoma is adequate. On the contrary, it has been shown that knowledge about melanoma is insufficient, even among professionals and individuals with higher levels of education. In a study based on a questionnaire administered to plastic surgeons, only 37.5% (27/72) of respondents correctly identified the duration of action of sunscreen to be 3 to 4 hours.7 Approximately half of the respondents (37/72) did not know that geographical conditions such as altitude and latitude as well as shade can alter sunscreen efficacy and also were not aware of the protective action of clothing. These results are alarming and indicate that even medical professionals, who should play a main role in improving the health knowledge of the general population, have an unsatisfactory level of education in prevention of melanoma. Another important part of better education of specialists treating skin disorders is good knowledge of dermatoscopy. In fact, the Annual Skin Cancer Conference 2011 in Australia emphasized the importance of dermatoscopy in primary and secondary prevention of skin cancer.8 Teaching dermatoscopy should be part of melanoma campaigns for professionals.

Our basic model demonstrated that a higher level of education was connected to a higher occurrence of MM, which may seem surprising, considering that most diseases, along with their incidence, prevalence, and mortality, usually are associated with lower levels of education or lower socioeconomic status. A similar trend also was reported in prior studies, with higher socioeconomic groups showing higher incidences of cutaneous melanoma; colon cancer; brain cancer in men; and breast and ovarian cancer in women. Additionally, patients with higher socioeconomic status have been shown to have a survival advantage.9 Individuals with higher socioeconomic status can afford to travel more often for vacation and are more frequently exposed to direct sun. Individuals with higher levels of education also are generally more aware of the importance of disease prevention and therefore go for preventive checkups more often. The detection of melanoma in this socioeconomic group should be higher.

Our biological model demonstrated that respondents with lighter eyes had melanoma almost 3 times more often than individuals with darker eyes. Fitzpatrick skin types I and II also were significantly associated with the development of melanoma (P<.001). These findings are generally confirmed in the literature. In a study of the incidence of melanoma in Spain, statistically significant risk factors included blonde or red hair (P=.002), multiple melanocytic nevi (P=.002), Fitzpatrick skin types I and II (P=.002), and a history of actinic keratosis (P=.021) or nonmelanoma skin cancer (P=.002).10 A group in Italy also has investigated the main risk factors for melanoma. This study suggested dividing patients into high-risk subgroups to help minimize exposure to UV radiation and diagnose melanoma in its early stage.11

The results from our study confirmed the importance of concentrating melanoma prevention campaign efforts on high-risk patients. Dividing these patients into subgroups (eg, individuals who play outdoor sports, individuals with occupations associated with UV exposure, individuals who use indoor tanning beds, individuals with a family history of melanoma) may be helpful. A case-control study on sun-seeking behavior in the Czech Republic showed that the most alarming risk factors were all-day sun exposure during adolescence, frequent holidays spent in the mountains, and inadequate use of sunscreen in adulthood.12 We investigated the effects of sunscreen use on the incidence of melanoma in our lifestyle model and discovered that it decreased the risk for melanoma. Respondents who used it always had a much lower risk for developing melanoma than those who never or rarely applied it. Individuals who used sunscreen always and repetitively (ie, more than once per period of sun exposure) did not show a lower risk than those who used it once per period of sun exposure. This finding could mean that patients who are known to get sunburns or who feel a certain discomfort on direct exposure to the sun tend to use sunscreen always and repetitively.

It is important to note that some investigators disagree with the importance of some generally accepted means of prevention, such as the effect of sunscreen products. Due to insufficient evidence, the role of sunscreen use in reducing the risk for skin cancer, especially cutaneous MM, is controversial.13 Although we could prove there is a considerable difference in the incidence of melanoma in patients who claimed to use sunscreen always versus those who never use it, we agree that more evidence on this topic is needed. Furthermore, it has been reported that risk for melanoma has increased with rising intermittent sun exposure and indoor tanning bed use.14,15

Respondents who regularly traveled to seaside regions showed a surprisingly lower incidence of melanoma than respondents who did not spend their vacations in seaside locations. It is possible that individuals who choose not to spend their vacations at the seaside are more prone to sunburns and therefore do not prefer to spend their free time in direct sunlight. Another possible explanation is that individuals who regularly travel to seaside regions actively try to protect themselves from sunlight and sunburns. A higher incidence of melanoma also was observed in respondents who reported sun exposure during work.

In our exposure model, we demonstrated that a history of sunburns is the strongest risk factor for melanoma. Frequent sunburns during childhood and adolescence were strongly associated with the development of MM. This association has been supported in a systematic review on sun exposure during childhood and associated risks.16

Conclusion

To improve patient knowledge about melanoma prevention, we suggest directing targeted campaigns that address high-risk population groups, such as individuals with red hair and/or light eyes, people with an occupation associated with frequent UV exposure, and individuals with higher levels of education. With regard to younger populations, parents as well as physicians and teachers should be aware that frequent sunburns during childhood and adolescence and use of tanning beds are 2 main risk factors for MM.

Cutaneous melanoma is a malignant tumor of the skin that develops from melanin-producing pigment cells known as melanocytes. The development of melanoma is a multifactorial process. External factors, genetic predisposition, or both may cause damage to DNA in melanoma cells. Genetic mutations may occur de novo or can be transferred from generation to generation. The most important environmental risk factor is UV radiation, both natural and artificial. Other risk factors include skin type, ethnicity, number of melanocytic nevi, number and severity of sunburns, frequency and duration of UV exposure, geographic location, and level of awareness about malignant melanoma (MM) and its risk factors.1

Melanoma accounts for only 1% to 2% of all tumors but is known for its rapidly increasing incidence.2 White individuals who reside in sunny areas of North America, northern Europe, Australia, and New Zealand seem to be at the highest risk for developing melanoma.3 The global incidence of MM from 2004 to 2008 was 20.8 individuals per 100,000 people.4 In Central Europe, 10 to 12 individuals per 100,000 people were diagnosed with melanoma, and 50 to 60 individuals per 100,000 people were diagnosed in Australia. In 2011, the lifetime risk of being diagnosed with melanoma was 1% in Central Europe and 4% in Australia.2 The incidence of melanoma is lower in populations with darker skin types (ie, Africans, Asians). In some parts of the world, the overall incidence and/or severity of melanoma has been declining over the last few decades, possibly reflecting improved public awareness.5