User login

Early menopause, early dementia risk, study suggests

Earlier menopause appears to be associated with a higher risk of dementia, and earlier onset of dementia, compared with menopause at normal age or later, according to a large study.

“Being aware of this increased risk can help women practice strategies to prevent dementia and to work with their physicians to closely monitor their cognitive status as they age,” study investigator Wenting Hao, MD, with Shandong University, Jinan, China, says in a news release.

The findings were presented in an e-poster March 1 at the Epidemiology, Prevention, Lifestyle & Cardiometabolic Health (EPI|Lifestyle) 2022 conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

UK Biobank data

Dr. Hao and colleagues examined health data for 153,291 women who were 60 years old on average when they became participants in the UK Biobank.

Age at menopause was categorized as premature (younger than age 40), early (40 to 44 years), reference (45 to 51), 52 to 55 years, and 55+ years.

Compared with women who entered menopause around age 50 years (reference), women who experienced premature menopause were 35% more likely to develop some type of dementia later in life (hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.22 to 1.91).

Women with early menopause were also more likely to develop early-onset dementia, that is, before age 65 (HR, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, 1.07 to 1.72).

Women who entered menopause later (at age 52+) had dementia risk similar to women who entered menopause at the average age of 50 to 51 years.

The results were adjusted for relevant cofactors, including age at last exam, race, educational level, cigarette and alcohol use, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, income, and leisure and physical activities.

Blame it on estrogen?

Reduced estrogen levels may be a factor in the possible connection between early menopause and dementia, Dr. Hao and her colleagues say.

Estradiol plays a key role in a range of neurological functions, so the reduction of endogenous estrogen at menopause may aggravate brain changes related to neurodegenerative disease and speed up progression of dementia, they explain.

“We know that the lack of estrogen over the long term enhances oxidative stress, which may increase brain aging and lead to cognitive impairment,” Dr. Hao adds.

Limitations of the study include reliance on self-reported information about age at menopause onset.

Also, the researchers did not evaluate dementia rates in women who had a naturally occurring early menopause separate from the women with surgery-induced menopause, which may affect the results.

Finally, the data used for this study included mostly White women living in the U.K. and may not generalize to other populations.

Supportive evidence, critical area of research

The U.K. study supports results of a previously reported Kaiser Permanente study, which showed women who entered menopause at age 45 or younger were at 28% greater dementia risk, compared with women who experienced menopause after age 45.

Reached for comment, Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of medical and scientific relations, noted that nearly two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women.

“We know Alzheimer’s and other dementias impact a greater number of women than men, but we don’t know why,” she told this news organization.

“Lifelong differences in women may affect their risk or affect what is contributing to their underlying biology of the disease, and we need more research to better understand what may be these contributing factors,” said Dr. Snyder.

“Reproductive history is one critical area being studied. The physical and hormonal changes that occur during menopause – as well as other hormonal changes throughout life – are considerable, and it’s important to understand what impact, if any, these changes may have on the brain,” Dr. Snyder added.

“The potential link between reproduction history and brain health is intriguing, but much more research in this area is needed to understand these links,” she said.

The study was funded by the Start-up Foundation for Scientific Research at Shandong University. Dr. Hao and Dr. Snyder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Earlier menopause appears to be associated with a higher risk of dementia, and earlier onset of dementia, compared with menopause at normal age or later, according to a large study.

“Being aware of this increased risk can help women practice strategies to prevent dementia and to work with their physicians to closely monitor their cognitive status as they age,” study investigator Wenting Hao, MD, with Shandong University, Jinan, China, says in a news release.

The findings were presented in an e-poster March 1 at the Epidemiology, Prevention, Lifestyle & Cardiometabolic Health (EPI|Lifestyle) 2022 conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

UK Biobank data

Dr. Hao and colleagues examined health data for 153,291 women who were 60 years old on average when they became participants in the UK Biobank.

Age at menopause was categorized as premature (younger than age 40), early (40 to 44 years), reference (45 to 51), 52 to 55 years, and 55+ years.

Compared with women who entered menopause around age 50 years (reference), women who experienced premature menopause were 35% more likely to develop some type of dementia later in life (hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.22 to 1.91).

Women with early menopause were also more likely to develop early-onset dementia, that is, before age 65 (HR, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, 1.07 to 1.72).

Women who entered menopause later (at age 52+) had dementia risk similar to women who entered menopause at the average age of 50 to 51 years.

The results were adjusted for relevant cofactors, including age at last exam, race, educational level, cigarette and alcohol use, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, income, and leisure and physical activities.

Blame it on estrogen?

Reduced estrogen levels may be a factor in the possible connection between early menopause and dementia, Dr. Hao and her colleagues say.

Estradiol plays a key role in a range of neurological functions, so the reduction of endogenous estrogen at menopause may aggravate brain changes related to neurodegenerative disease and speed up progression of dementia, they explain.

“We know that the lack of estrogen over the long term enhances oxidative stress, which may increase brain aging and lead to cognitive impairment,” Dr. Hao adds.

Limitations of the study include reliance on self-reported information about age at menopause onset.

Also, the researchers did not evaluate dementia rates in women who had a naturally occurring early menopause separate from the women with surgery-induced menopause, which may affect the results.

Finally, the data used for this study included mostly White women living in the U.K. and may not generalize to other populations.

Supportive evidence, critical area of research

The U.K. study supports results of a previously reported Kaiser Permanente study, which showed women who entered menopause at age 45 or younger were at 28% greater dementia risk, compared with women who experienced menopause after age 45.

Reached for comment, Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of medical and scientific relations, noted that nearly two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women.

“We know Alzheimer’s and other dementias impact a greater number of women than men, but we don’t know why,” she told this news organization.

“Lifelong differences in women may affect their risk or affect what is contributing to their underlying biology of the disease, and we need more research to better understand what may be these contributing factors,” said Dr. Snyder.

“Reproductive history is one critical area being studied. The physical and hormonal changes that occur during menopause – as well as other hormonal changes throughout life – are considerable, and it’s important to understand what impact, if any, these changes may have on the brain,” Dr. Snyder added.

“The potential link between reproduction history and brain health is intriguing, but much more research in this area is needed to understand these links,” she said.

The study was funded by the Start-up Foundation for Scientific Research at Shandong University. Dr. Hao and Dr. Snyder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Earlier menopause appears to be associated with a higher risk of dementia, and earlier onset of dementia, compared with menopause at normal age or later, according to a large study.

“Being aware of this increased risk can help women practice strategies to prevent dementia and to work with their physicians to closely monitor their cognitive status as they age,” study investigator Wenting Hao, MD, with Shandong University, Jinan, China, says in a news release.

The findings were presented in an e-poster March 1 at the Epidemiology, Prevention, Lifestyle & Cardiometabolic Health (EPI|Lifestyle) 2022 conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

UK Biobank data

Dr. Hao and colleagues examined health data for 153,291 women who were 60 years old on average when they became participants in the UK Biobank.

Age at menopause was categorized as premature (younger than age 40), early (40 to 44 years), reference (45 to 51), 52 to 55 years, and 55+ years.

Compared with women who entered menopause around age 50 years (reference), women who experienced premature menopause were 35% more likely to develop some type of dementia later in life (hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.22 to 1.91).

Women with early menopause were also more likely to develop early-onset dementia, that is, before age 65 (HR, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, 1.07 to 1.72).

Women who entered menopause later (at age 52+) had dementia risk similar to women who entered menopause at the average age of 50 to 51 years.

The results were adjusted for relevant cofactors, including age at last exam, race, educational level, cigarette and alcohol use, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, income, and leisure and physical activities.

Blame it on estrogen?

Reduced estrogen levels may be a factor in the possible connection between early menopause and dementia, Dr. Hao and her colleagues say.

Estradiol plays a key role in a range of neurological functions, so the reduction of endogenous estrogen at menopause may aggravate brain changes related to neurodegenerative disease and speed up progression of dementia, they explain.

“We know that the lack of estrogen over the long term enhances oxidative stress, which may increase brain aging and lead to cognitive impairment,” Dr. Hao adds.

Limitations of the study include reliance on self-reported information about age at menopause onset.

Also, the researchers did not evaluate dementia rates in women who had a naturally occurring early menopause separate from the women with surgery-induced menopause, which may affect the results.

Finally, the data used for this study included mostly White women living in the U.K. and may not generalize to other populations.

Supportive evidence, critical area of research

The U.K. study supports results of a previously reported Kaiser Permanente study, which showed women who entered menopause at age 45 or younger were at 28% greater dementia risk, compared with women who experienced menopause after age 45.

Reached for comment, Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of medical and scientific relations, noted that nearly two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s are women.

“We know Alzheimer’s and other dementias impact a greater number of women than men, but we don’t know why,” she told this news organization.

“Lifelong differences in women may affect their risk or affect what is contributing to their underlying biology of the disease, and we need more research to better understand what may be these contributing factors,” said Dr. Snyder.

“Reproductive history is one critical area being studied. The physical and hormonal changes that occur during menopause – as well as other hormonal changes throughout life – are considerable, and it’s important to understand what impact, if any, these changes may have on the brain,” Dr. Snyder added.

“The potential link between reproduction history and brain health is intriguing, but much more research in this area is needed to understand these links,” she said.

The study was funded by the Start-up Foundation for Scientific Research at Shandong University. Dr. Hao and Dr. Snyder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Older age for menopause raises risk for lung cancer

This study was published on Medrxiv.org as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- in analyses of more than 100,000 women that used Mendelian randomization (MR) as a tool to reduce residual confounding.

- The MR analyses showed no significant association between ANM and breast cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease.

- The clear lack of a causal effect of ANM on the outcomes of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke in the MR analyses despite a strong inverse association seen in the observational data of this study (without MR) suggests residual confounding plays a substantial role in driving the observed outcomes.

Why this matters

- The authors said that, to their knowledge, this is the first study that has shown a causal association between older ANM and higher risk of postmenopausal lung cancer.

- This finding was directionally opposite to the significant protective effect of increased ANM documented in an observational analysis of roughly the same data as well as prior reports that did not use MR. This “notable inconsistency” suggests very substantial residual confounding without MR that could be driven by factors such as smoking, diet, and exercise.

- If these results are replicated in additional datasets, it would highlight a need for randomized, controlled trials of antiestrogen therapies in postmenopausal women for the prevention or treatment of lung cancer.

Study design

- The study included data from 106,853 postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and 95,464 women who were 37-73 years old included in the UK Biobank (UKB). Analyses for each outcome also included data from smaller numbers of women obtained from several additional datasets.

- The MR analysis used up to 55 single-nucleotide polymorphisms previously discovered through a genome-wide association study of about 70,000 women of European ancestry and independent of all datasets analyzed in the current study. The authors included all single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a consistent direction of effect on ANM.

- The MR analysis for lung cancer included 113,371 women from the two primary datasets and an additional 3012 women from six additional datasets.

- The MR analysis for bone fracture involved 113,239 women from the WHI and UKB only. The MR analysis for osteoporosis involved 137,080 women from the WHI, UKB, and one additional external dataset.

Key results

- Results from a meta-analysis of the MR results using data from the WHI, UKB, and the additional datasets showed ANM was causally associated with an increased risk of lung cancer by an odds ratio of 1.35 for each 5-year increase in ANM. In contrast, the adjusted observational analysis of data just from the WHI and UKB showed a significant 11% relative risk reduction in the incidence of lung cancer for each 5-year increase in ANM.

- The MR results also showed causally protective effects for fracture, with a 24% relative risk reduction, and for osteoporosis, with a 19% relative risk reduction for each 5-year increase in ANM.

- The MR analyses showed no significant association between AMN and outcome for breast cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Limitations

The main limitation of the MR study was the potential for inadequate power for assessing some outcomes despite the large overall size of the study cohort. Lack of adequate power may be responsible for some of the nonsignificant associations seen in the study, such as for breast and endometrial cancers, where substantial prior evidence has implicated increased risk through the effects of prolonged exposure to endogenous or exogenous estrogens.

The healthy cohort effect in the UKB is a known weakness of this dataset that may have limited the number of cases and generalizability of findings.

Osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s disease were self-reported.

The study only included participants of European ancestry because most subjects in most of the cohorts examined were White women and the applied MR instruments were found by genome-wide association studies run predominantly in White women. The authors said the causal effects of ANM need study in more diverse populations.

Disclosures

- The study received no commercial funding.

- None of the authors had disclosures.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “Genetic evidence for causal relationships between age at natural menopause and the risk of aging-associated adverse health outcomes,” written by authors primarily based at Stanford University School of Medicine i

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This study was published on Medrxiv.org as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- in analyses of more than 100,000 women that used Mendelian randomization (MR) as a tool to reduce residual confounding.

- The MR analyses showed no significant association between ANM and breast cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease.

- The clear lack of a causal effect of ANM on the outcomes of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke in the MR analyses despite a strong inverse association seen in the observational data of this study (without MR) suggests residual confounding plays a substantial role in driving the observed outcomes.

Why this matters

- The authors said that, to their knowledge, this is the first study that has shown a causal association between older ANM and higher risk of postmenopausal lung cancer.

- This finding was directionally opposite to the significant protective effect of increased ANM documented in an observational analysis of roughly the same data as well as prior reports that did not use MR. This “notable inconsistency” suggests very substantial residual confounding without MR that could be driven by factors such as smoking, diet, and exercise.

- If these results are replicated in additional datasets, it would highlight a need for randomized, controlled trials of antiestrogen therapies in postmenopausal women for the prevention or treatment of lung cancer.

Study design

- The study included data from 106,853 postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and 95,464 women who were 37-73 years old included in the UK Biobank (UKB). Analyses for each outcome also included data from smaller numbers of women obtained from several additional datasets.

- The MR analysis used up to 55 single-nucleotide polymorphisms previously discovered through a genome-wide association study of about 70,000 women of European ancestry and independent of all datasets analyzed in the current study. The authors included all single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a consistent direction of effect on ANM.

- The MR analysis for lung cancer included 113,371 women from the two primary datasets and an additional 3012 women from six additional datasets.

- The MR analysis for bone fracture involved 113,239 women from the WHI and UKB only. The MR analysis for osteoporosis involved 137,080 women from the WHI, UKB, and one additional external dataset.

Key results

- Results from a meta-analysis of the MR results using data from the WHI, UKB, and the additional datasets showed ANM was causally associated with an increased risk of lung cancer by an odds ratio of 1.35 for each 5-year increase in ANM. In contrast, the adjusted observational analysis of data just from the WHI and UKB showed a significant 11% relative risk reduction in the incidence of lung cancer for each 5-year increase in ANM.

- The MR results also showed causally protective effects for fracture, with a 24% relative risk reduction, and for osteoporosis, with a 19% relative risk reduction for each 5-year increase in ANM.

- The MR analyses showed no significant association between AMN and outcome for breast cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Limitations

The main limitation of the MR study was the potential for inadequate power for assessing some outcomes despite the large overall size of the study cohort. Lack of adequate power may be responsible for some of the nonsignificant associations seen in the study, such as for breast and endometrial cancers, where substantial prior evidence has implicated increased risk through the effects of prolonged exposure to endogenous or exogenous estrogens.

The healthy cohort effect in the UKB is a known weakness of this dataset that may have limited the number of cases and generalizability of findings.

Osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s disease were self-reported.

The study only included participants of European ancestry because most subjects in most of the cohorts examined were White women and the applied MR instruments were found by genome-wide association studies run predominantly in White women. The authors said the causal effects of ANM need study in more diverse populations.

Disclosures

- The study received no commercial funding.

- None of the authors had disclosures.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “Genetic evidence for causal relationships between age at natural menopause and the risk of aging-associated adverse health outcomes,” written by authors primarily based at Stanford University School of Medicine i

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This study was published on Medrxiv.org as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- in analyses of more than 100,000 women that used Mendelian randomization (MR) as a tool to reduce residual confounding.

- The MR analyses showed no significant association between ANM and breast cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease.

- The clear lack of a causal effect of ANM on the outcomes of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke in the MR analyses despite a strong inverse association seen in the observational data of this study (without MR) suggests residual confounding plays a substantial role in driving the observed outcomes.

Why this matters

- The authors said that, to their knowledge, this is the first study that has shown a causal association between older ANM and higher risk of postmenopausal lung cancer.

- This finding was directionally opposite to the significant protective effect of increased ANM documented in an observational analysis of roughly the same data as well as prior reports that did not use MR. This “notable inconsistency” suggests very substantial residual confounding without MR that could be driven by factors such as smoking, diet, and exercise.

- If these results are replicated in additional datasets, it would highlight a need for randomized, controlled trials of antiestrogen therapies in postmenopausal women for the prevention or treatment of lung cancer.

Study design

- The study included data from 106,853 postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and 95,464 women who were 37-73 years old included in the UK Biobank (UKB). Analyses for each outcome also included data from smaller numbers of women obtained from several additional datasets.

- The MR analysis used up to 55 single-nucleotide polymorphisms previously discovered through a genome-wide association study of about 70,000 women of European ancestry and independent of all datasets analyzed in the current study. The authors included all single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a consistent direction of effect on ANM.

- The MR analysis for lung cancer included 113,371 women from the two primary datasets and an additional 3012 women from six additional datasets.

- The MR analysis for bone fracture involved 113,239 women from the WHI and UKB only. The MR analysis for osteoporosis involved 137,080 women from the WHI, UKB, and one additional external dataset.

Key results

- Results from a meta-analysis of the MR results using data from the WHI, UKB, and the additional datasets showed ANM was causally associated with an increased risk of lung cancer by an odds ratio of 1.35 for each 5-year increase in ANM. In contrast, the adjusted observational analysis of data just from the WHI and UKB showed a significant 11% relative risk reduction in the incidence of lung cancer for each 5-year increase in ANM.

- The MR results also showed causally protective effects for fracture, with a 24% relative risk reduction, and for osteoporosis, with a 19% relative risk reduction for each 5-year increase in ANM.

- The MR analyses showed no significant association between AMN and outcome for breast cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Limitations

The main limitation of the MR study was the potential for inadequate power for assessing some outcomes despite the large overall size of the study cohort. Lack of adequate power may be responsible for some of the nonsignificant associations seen in the study, such as for breast and endometrial cancers, where substantial prior evidence has implicated increased risk through the effects of prolonged exposure to endogenous or exogenous estrogens.

The healthy cohort effect in the UKB is a known weakness of this dataset that may have limited the number of cases and generalizability of findings.

Osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s disease were self-reported.

The study only included participants of European ancestry because most subjects in most of the cohorts examined were White women and the applied MR instruments were found by genome-wide association studies run predominantly in White women. The authors said the causal effects of ANM need study in more diverse populations.

Disclosures

- The study received no commercial funding.

- None of the authors had disclosures.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “Genetic evidence for causal relationships between age at natural menopause and the risk of aging-associated adverse health outcomes,” written by authors primarily based at Stanford University School of Medicine i

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HT for women who have had BSO before the age of natural menopause: Discerning the nuances

Women who undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) for various indications prior to menopause experience a rapid decline in ovarian hormone levels and consequent vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms. In addition, the resulting estrogen deprivation is associated with such long-term adverse outcomes as osteoporosis and cardiovascular morbidity.

OBG M

Surgical vs natural menopause

Stephanie Faubion, MD, MBA, NCMP: Since the Women’s Health Initiative study was published in 2002,2 many clinicians have been fearful of using systemic HT in menopausal women, and HT use has declined dramatically such that only about 4% to 6% of menopausal women are now receiving systemic HT. Importantly, however, a group of younger menopausal women also are not receiving HT, and that is women who undergo BSO before they reach the average age of menopause, which in the United States is about age 52; this is sometimes referred to as surgical menopause or early surgical menopause. Early surgical menopause has different connotations for long-term health risks than natural menopause at the average age, and we are here to discuss these health effects and their management.

My name is Stephanie Faubion, and I am a women’s health internist and the Chair of the Department of Medicine at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, and Director of Mayo Clinic Women’s Health. I am here with 2 of my esteemed colleagues, Dr. Andrew Kaunitz and Dr. Ekta Kapoor.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, NCMP: Hello, I am an ObGyn with the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville, with particular interests in contraception, menopause, and gynecologic ultrasonography.

Ekta Kapoor, MBBS, NCMP: And I am an endocrinologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester with a specific interest in menopause and hormone therapy. I am also the Assistant Director for Mayo Clinic Women’s Health.

Higher-than-standard estrogen doses needed in younger menopausal women

Dr. Faubion: Let’s consider a couple of cases so that we can illustrate some important points regarding hormone management in women who have undergone BSO before the age of natural menopause.

Our first case patient is a woman who is 41 years of age and, because of adenomyosis, she will undergo a hysterectomy. She tells her clinician that she is very concerned about ovarian cancer risk because one of her good friends recently was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and together they decide to remove her ovaries at the time of hysterectomy. Notably, her ovaries were healthy.

The patient is now menopausal postsurgery, and she is having significant hot flashes and night sweats. She visits her local internist, who is concerned about initiating HT. She is otherwise a healthy woman and does not have any contraindications to HT. Dr. Kaunitz, what would you tell her internist?

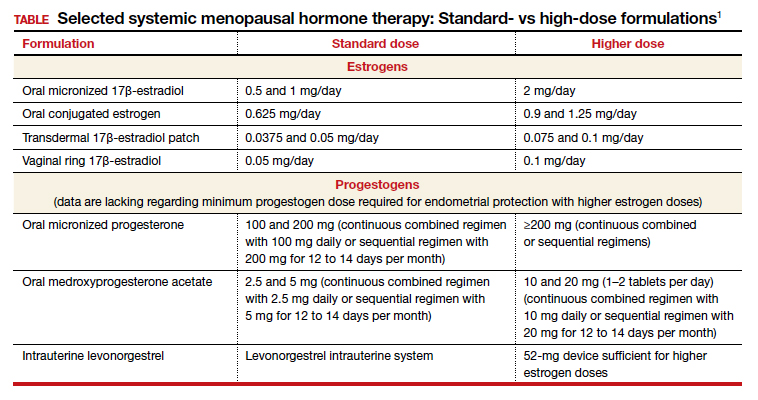

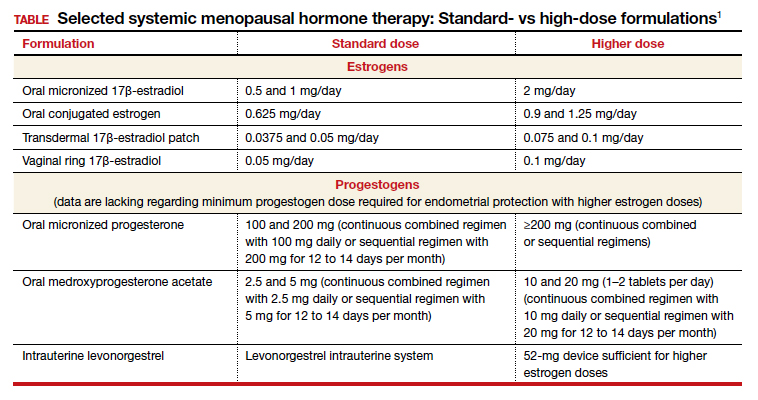

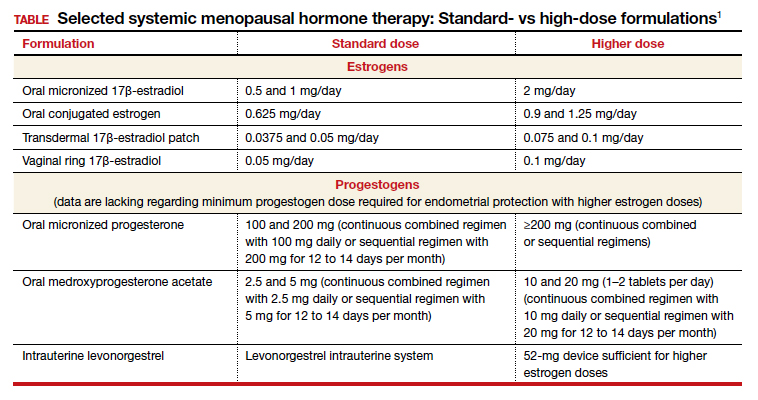

Dr. Kaunitz: We are dealing with 2 different issues in terms of decision making about systemic HT for this 41-year-old who has undergone BSO. First, as you mentioned, Dr. Faubion, she has bothersome hot flashes, or vasomotor symptoms. Unless there are contraindications, systemic HT would be appropriate. Although I might start treatment at standard doses, and the accompanying TABLE depicts standard doses for the 2 most common oral estrogen formulations as well as transdermal estradiol, it’s important to recognize that younger menopausal women often will need to use higher-than-standard doses.

For example, for a 53-year-old woman who has been menopausal for a year or 2 and now has bothersome symptoms, I might start her on estradiol 1 mg tablets with progestin if a uterus is present. However, in this 41-year-old case patient, while I might start treatment at a standard dose, I would anticipate increasing to higher doses, such as 1.5 or 2 mg of daily estradiol until she feels her menopausal symptoms are adequately addressed.

Dr. Faubion: It is important to note that sometimes women with early BSO tend to have more severe vasomotor symptoms. Do you find that sometimes a higher dose is required just to manage symptoms, Dr. Kaunitz?

Dr. Kaunitz: Absolutely, yes. The decision whether or not to use systemic HT might be considered discretionary or elective in the classic 53-year-old woman recently menopausal with hot flashes, a so-called spontaneously or naturally menopausal woman. But my perspective is that unless there are clear contraindications, the decision to start systemic HT in the 41-year-old BSO case patient is actually not discretionary. Unless contraindications are present, it is important not only to treat symptoms but also to prevent an array of chronic major health concerns that are more likely if we don’t prescribe systemic HT.

Continue to: Health effects of not using HT...

Health effects of not using HT

Dr. Faubion: Dr. Kapoor, can you describe the potential long-term adverse health consequences of not using estrogen therapy? Say the same 41-year-old woman does not have many bothersome symptoms. What would you do?

Dr. Kapoor: Thank you for that important question. Building on what Dr. Kaunitz said, in these patients there are really 2 issues that can seem to be independent but are not: The first relates to the immediate consequences of lack of estrogen, ie, the menopause-related symptoms, but the second and perhaps the bigger issue is the long-term risk associated with estrogen deprivation.

The symptoms in these women are often obvious as they can be quite severe and abrupt; one day these women have normal hormone levels and the next day, after BSO, suddenly their hormones are very low. So if symptoms occur, they are usually hard to miss, simply because they are very drastic and very severe.

Historically, patients and their clinicians have targeted these symptoms. Patients experience menopausal symptoms, they seek treatment, and then the clinicians basically titrate the treatment to manage these symptoms. That misses the bigger issue, however, which is that premature estrogen deprivation leads to a host of chronic health conditions, as Dr. Kaunitz mentioned. These mainly include increased risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, increased risk of mortality, dementia, and osteoporosis.

Fairly strong observational evidence suggests that use of estrogen therapy given in replacement doses—doses higher than those typically used in women after natural menopause, therefore considered replacement doses—helps mitigate the risk of some of these adverse health conditions.

In these women, the bigger goal really is to reinstate the hormonal milieu that exists prior to menopause. To your point, Dr. Faubion, if I have a patient who is younger than 46 years, who has her ovaries taken out, and even if she has zero symptoms (and sometimes that does happen), I would still make a case for this patient to utilize hormone therapy unless there is a contraindication such as breast cancer or other estrogen-sensitive cancers.

Dr. Faubion: Again, would you aim for those higher doses rather than treat with the “lowest dose”?

Dr. Kapoor: Absolutely. My punchline to the patients and clinicians in these discussions is that the rules of the game are different for these women. We cannot extrapolate the risks and benefits of HT use in women after natural menopause to younger women who have surgical menopause. Those rules just do not apply with respect to both benefits and risks.

Dr. Faubion: I think it’s important to say that these same “rules” would apply if the women were to go through premature menopause for any other reason, too, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or premature ovarian insufficiency for any number of reasons, including toxic, metabolic, or genetic causes and so on. Would that be true?

Dr. Kapoor: Yes, absolutely so.

Dr. Faubion: Dr. Kaunitz, do you want to add anything?

Dr. Kaunitz: In terms of practical or clinical issues regarding systemic HT management, for the woman in her early 50s who has experienced normal or natural spontaneous menopause, a starting dose of transdermal estradiol would be, for instance, a 0.05-mg patch, which is a patch that over 24 hours releases 0.05 mg of estradiol daily; or standard oral estrogen, including conjugated equine estrogen, a 0.625-mg tablet daily, or estradiol, a 1-mg tablet daily.

But in younger patients, we want to use higher doses. For a patch, for instance, I would aim for a 0.075- or 0.1-mg estradiol patch, which releases a higher daily dose of estradiol than the standard dose. For oral estrogen, the dose would be 0.9- or even 1.25-mg tablets of conjugated equine estrogen or 1.5 mg, which is a 1-mg plus a 0.5-mg estradiol tablet, or a 2-mg estradiol tablet. Estradiol does come in a 2-mg strength.

For oral estrogen, I prefer estradiol because it’s available as a generic medication and often available at a very low cost, sometimes as low as $4 a month from chain pharmacies.

Continue to: Usefulness of monitoring estradiol levels for dosage adjustment...

Usefulness of monitoring estradiol levels for dosage adjustment

Dr. Faubion: That’s a great point, and again it is important to emphasize that we are aiming to recreate the premenopausal hormonal milieu. If you were to check estradiol levels, that would be aiming for a premenopausal range of approximately 80 to 120 pg per mL. Dr. Kapoor, is there utility in monitoring estrogen levels?

Dr. Kapoor: Great question, Dr. Faubion, and as you know it’s a loaded one. We base this on empiric evidence. We know that if the hormonal milieu in a young patient is changed to a postmenopausal one, her risk for many chronic conditions is increased. So if we were to reinstate a premenopausal hormonal milieu, that risk would probably be reduced. It makes good sense to target an empiric goal of 80 to 120 pg per mL of estradiol, which is the average estradiol level in a premenopausal woman. If you were to ask me, however, are there randomized, controlled trial data to support this practice—that is, if you target that level, can you make sure that the risk of diabetes is lower or that the risk of heart disease is lower—that study has yet to be done, and it may not ever be done on a large scale. However, it intuitively makes good sense to target premenopausal estradiol levels.

Dr. Faubion: When might you check an estradiol level in this population? For example, if you are treating a patient with a 0.1-mg estradiol patch and she still has significant hot flashes, would it be useful to check the level?

Dr. Kapoor: It would. In my practice, I check estradiol levels on these patients on an annual basis, regardless of symptoms, but definitely in the patient who has symptoms. It makes good sense, because sometimes these patients don’t absorb the estrogen well, particularly if administered by the transdermal route.

A general rule of thumb is that in the average population, if a patient is on the 0.1-mg patch, for example, you would expect her level to be around 100. If it is much lower than that, which sometimes happens, that speaks for poor absorption. Options at that point would be to treat her with a higher dose patch, depending on what the level is, or switch to a different formulation, such as oral.

In instances in which I have treated patients with a 0.1-mg patch for example, and their estradiol levels are undetectable, that speaks for very poor absorption. For such patients I make a case for switching them to oral therapy. Most definitely that makes sense in a patient who is symptomatic despite treatment. But even for patients who don’t have symptoms, I like to target that level, acknowledging that there is no evidence as such to support this practice.

Dr. Faubion: Dr. Kaunitz, do you want to add anything?

Dr. Kaunitz: Yes, a few practical points. Although patches are available in a wider array of doses than oral estrogen formulations, the highest dose available is 0.1 mg. It’s important for clinicians to recognize that while checking serum levels when indicated can be performed in women using transdermal estradiol or patches, in women who are using oral estrogen, checking blood levels is not going to work well because serum estrogen levels have a daily peak and valley in women who use oral versus transdermal estradiol.

I also wanted to talk about progestins. Although many patients who have had a BSO prior to spontaneous menopause also have had a hysterectomy, others have an intact uterus associated with their BSO, so progestins must be used along with estrogen. And if we are using higher-than-standard doses of estrogen, we also need to use higher-than-standard doses of progestin.

In that classic 53-year-old woman I referred to who had spontaneous normal menopause, if she is taking 1 mg of estradiol daily, or a 0.05-mg patch, or 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogen, 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone is fine. In fact, that showed excellent progestational protection of the endometrium in the Women’s Health Initiative and in other studies.

However, if we are going to use double the estrogen dose, we should increase the progestin dose too. In some of my patients on higher estrogen doses who have an intact uterus, I’ll use 5 or even 10 mg of daily medroxyprogesterone acetate to ensure adequate progestational suppression.

Dr. Faubion: Another practical tip is that if one is using conjugated equine estrogens, measuring the serum estradiol levels is not useful either.

Dr. Kaunitz: I agree.

Continue to: Oral contraceptives as replacement HT...

Oral contraceptives as replacement HT

Dr. Faubion: Would you comment on use of a birth control pill in this circumstance? Would it be optimal to use a postmenopausal HT regimen as opposed to a birth control pill or combined hormonal contraception?

Dr. Kapoor: In this younger population, sometimes it seems like a more socially acceptable decision to be on a birth control option than on menopausal HT. But there are some issues with being on a contraceptive regimen. One is that we end up using estrogen doses much higher than what is really needed for replacement purposes. It is also a nonphysiologic way of replacement in another sense—as opposed to estradiol, which is the main hormone made by the ovaries, the hormonal contraceptive regimens contain the synthetic estrogen ethinyl estradiol for the most part.

The other issue that is based on some weak evidence is that it appears that the bone health outcomes are probably inferior with combined hormonal contraception. For these reasons, regimens that are based on replacement doses of estradiol are preferred.

Dr. Faubion: Right, although the data are somewhat weak, I agree that thus far it seems optimal to utilize a postmenopausal regimen for various reasons. Dr. Kaunitz, anything to add?

Dr. Kaunitz: Yes, to underscore Dr. Kapoor’s point, a common oral contraceptive that contains 20 µg of ethinyl estradiol is substantially more estrogenic than 1.0 or 2.0 mg of micronized oral estradiol.

Also consider that a 20-µg ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive may increase the risk of venous thromboembolism more than menopausal doses of oral estradiol, whether it be a micronized estradiol or conjugated equine estrogen.

Dr. Faubion: So the risk may be greater with oral combined hormonal contraception as well?

Dr. Kaunitz: One thing we can do is explain to our patients that their ovaries, prior to surgery or prior to induced menopause, were making substantial quantities of estradiol. Whether we prescribe a patch or oral micronized estradiol, this estrogen is identical to the hormone that their ovaries were making prior to surgery or induced menopause.

Breast cancer concerns

Dr. Faubion: Let’s consider a more complicated case. A 35-year-old woman has an identified BRCA1 mutation; she has not had any cancers but has undergone risk-reducing BSO and her uterus remains. Is this woman a candidate for HT? At what dose, and for how long? Dr. Kaunitz, why don’t you start.

Dr. Kaunitz: That is a challenging case but one that I think our readers will find interesting and maybe even provocative.

We know that women with BRCA1 mutations, the more common of the 2 BRCA mutations, have a very high risk of developing epithelial ovarian cancer at a young age. For this reason, our colleagues in medical oncology who specialize in hereditary ovarian/breast cancer syndromes recommend prophylactic risk-reducing—and I would also say lifesaving—BSO with or without hysterectomy for women with BRCA1 mutations.

However, over the years there has been tremendous reluctance among physicians caring for BRCA patients and the women themselves—I use the term “previvors” to describe BRCA carriers who have not been diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer—to use HT after BSO because of concerns that HT might increase breast cancer risk in women who are already at high risk for breast cancer.

I assume, Dr. Faubion, that in this case the woman had gynecologic surgery but continues to have intact breasts. Is that correct?

Dr. Faubion: That is correct.

Dr. Kaunitz: Although the assumption has been that it is not safe to prescribe HT in this setting, in fact, the reported cohort studies that have looked at this issue have not found an elevated risk of breast cancer when replacement estrogen, with or without progestin, is prescribed to BRCA1 previvors with intact breasts.

Given what Dr. Kapoor said regarding the morbidity that is associated with BSO without replacement of physiologic estrogen, and also given the severe symptoms that so many of these young menopausal women experience, in my practice I do prescribe estrogen or estrogen-progestin therapy and focus on the higher target doses that we discussed for the earlier case patient who had a hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding with adenomyosis.

Dr. Faubion: Dr. Kapoor, do you agree with this approach? How long would you continue therapy?

Dr. Kapoor: First, in this BRCA1 case we need to appreciate that the indication for the BSO is a legitimate one, in contrast to the first case in which the ovaries were removed in a patient whose average risk of ovarian cancer was low. It is important to recognize that surgery performed in this context is the right thing to do because it does significantly reduce the risk of ovarian cancer.

The second thing to appreciate is that while we reduce the risk of ovarian cancer significantly and make sure that these patients survive longer, it’s striking a fine balance in that you want to make sure that their morbidity is not increased as a result of premature estrogen deprivation.

As Dr. Kaunitz told us, the evidence that we have so far, which granted is not very robust but is fairly strong observational evidence, suggests that the risk of breast cancer is not elevated when these patients are treated with replacement doses of HT.

Having said that, I do have very strong discussions with my patients in this category about having the risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy also, because if they were to get breast cancer because of their increased genetic predisposition, the cancer is likely to grow faster if the patient is on HT. So one of my counseling points to patients is that they strongly consider bilateral mastectomy, which reduces their breast cancer risk by more than 90%. At the same time, I also strongly endorse using HT in replacement doses for the reasons that we have already stated.

Dr. Faubion: Continue HT until age 50 or 52?

Dr. Kapoor: Definitely until that age, and possibly longer, depending on their symptoms. The indications for treating beyond the age of natural menopause are much the same as for women who experience natural menopause.

Dr. Faubion: That is assuming they had a bilateral mastectomy?

Dr. Kapoor: Yes.

Continue to: Continuing HT until the age of natural menopause...

Continuing HT until the age of natural menopause

Dr. Kaunitz: Dr. Kapoor brings up the important point of duration of systemic HT. I agree that similar considerations apply both to the healthy 41-year-old who had a hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding and to the 35-year-old who had risk-reducing surgery because of her BRCA1 mutation.

In the 2 cases, both to treat symptoms and to prevent chronic diseases, it makes sense to continue HT at least until the age of natural menopause. That is consistent with 2017 guidance from The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) position statement on the use of systemic HT, that is, continuing systemic HT at least until the age of natural menopause.3 Then at that point, continuing or discontinuing systemic HT becomes discretionary, and that would be true for both cases. If the patient is slender or has a strong family history of osteoporosis, that tends to push the patient more in terms of continuing systemic HT. Those are just some examples, and Dr. Kapoor may want to detail other relevant considerations.

Dr. Kapoor: I completely agree. The decision is driven by symptoms that are not otherwise well managed, for example, with nonhormone strategies. If we have any concerns utilizing HT beyond the age of natural menopause, then nonhormonal options can be considered; but sometimes those are not as effective. And bone health is very important. You want to avoid using bisphosphonates in younger women and reserve them for older patients in their late 60s and 70s. Hormone therapy use is a very reasonable strategy to prevent bone loss.

Dr. Kaunitz: It is also worth mentioning that sometimes the woman involved in shared decision making with her clinician decides to stop systemic HT. In that setting, should the patient start developing new-onset dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, or other genital or sexuality-related concerns, it takes very little for me to advise that she start low-dose local vaginal estrogen therapy.

Dr. Faubion: In either scenario, if a woman were to develop symptoms consistent with genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), would you use vaginal estrogen in addition to the systemic estrogen or alone after the woman elected to discontinue systemic therapy?

Dr. Kapoor: Yes to both, I would say.

Dr. Kaunitz: As my patients using systemic HT age, often I will lower the dose. For instance, the dose I use in a 53-year-old will be higher than when she is 59 or 62. At the same time, as we lower the dose of systemic estrogen therapy, symptoms of vaginal atrophy or GSM often will appear, and these can be effectively treated by adding low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy. A number of my patients, particularly those who are on lower-than-standard doses of systemic HT, are also using low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy.

There is a “hybrid” product available: the 90-day estradiol vaginal ring. Estring is a low-dose, 2-mg, 90-day estradiol ring that is very useful, but it is effective only for treating GSM or vaginal atrophy. A second menopausal vaginal estradiol ring, Femring, is available in 2 doses: 0.05 mg/day and 0.1 mg/day. These are very effective in treating both systemic issues, such as vasomotor symptoms or prevention of osteoporosis, and very effective in treating GSM or vaginal atrophy. One problem is that Femring, depending on insurance coverage, can be very expensive. It’s not available as a generic, so for insurance or financial reasons I don’t often prescribe it. If I could remove those financial barriers, I would prescribe Femring more often because it is very useful.

Dr. Faubion: You raise an important point, and that is, for women who have been on HT for some time, clinicians often feel the need to slowly reduce the dose. Would you do that same thing, Dr. Kapoor, for a 40-year-old woman? Would you reduce the dose as she approaches age 50? Is there pressure that “she shouldn’t be on that much estrogen”?

Dr. Kapoor: No, I would not feel pressured until the patient turns at least 46. I bring up age 46 because the average age range for menopause is 46 to 55. After that, if there is any concern, we can decrease the dose to half and keep the patient on that until she turns 50 or 51. But most of my patients are on replacement doses until the average age of menopause, which is around 51 years, and that’s when you reduce the dose to that of the typical HT regimens used after natural menopause.

Sometimes patients are told something by a friend or they have read something and they worry about the risk of 2 things. One is breast cancer and the other is venous thromboembolism (VTE), and that may be why they want to be on a lower dose. I counsel patients that while the risk of VTE is real with HT, it is the women after natural menopause who are at risk—because age itself is a risk for VTE—and it also has to do with the kind of HT regimen that a patient is on. High doses of oral estrogens and certain progestogens increase the risk. But again, for estradiol used in replacement doses and the more common progestogens that we now use in practice, such as micronized progesterone, the risk is not the same. The same goes for breast cancer. My biggest message to patients and clinicians who take care of these patients is that the rules that apply to women after natural menopause just do not apply to this very different patient population.

Dr. Faubion: Thank you, Dr. Kaunitz and Dr. Kapoor, for sharing your knowledge and experience. ●

Systemic HT past the age of 65

Dr. Kaunitz: Another practical issue relates to long-term or extended use of systemic HT. It’s not infrequent in my practice to receive mail and faxes from insurance carriers of systemic HT users who are age 65 and older in which the company refers to the American Geriatrics Society’s Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults,1 suggesting that systemic HT is inappropriate for all women over age 65. In this age group, I use lower doses if I am continuing systemic HT. But the good news is that both NAMS and the American College Obstetricians and Gynecologists indicate that arbitrarily stopping systemic HT at age 65 or for any other arbitrary reason is inappropriate, and that decisions about continuing or discontinuing therapy should be made on an individualized basis using shared decision making. That’s an important message for our readers.

Counseling regarding elective BSO

Dr. Faubion: One final note about elective BSO in the absence of a genetic mutation that predisposes to increased ovarian or breast cancer risk. Fortunately, we have seen rates of oophorectomy before the age of natural menopause decline, but what would your advice be to women or clinicians of these women who say they are “just afraid of ovarian cancer and would like to have their ovaries removed before the age of natural menopause”?

Dr. Kaunitz: If patients have increased anxiety about ovarian cancer and yet they themselves are not known to be at elevated risk, I emphasize that, fortunately, ovarian cancer is uncommon. It is much less common than other cancers the patient might be familiar with, such as breast or colon or lung cancer. I also emphasize that women who have given birth, particularly multiple times; women who nursed their infants; and women who have used combination hormonal contraceptives, particularly if long term, are at markedly lower risk for ovarian cancer as they get older. We are talking about an uncommon cancer that is even less common if women have given birth, nursed their infants, or used combination contraceptives long term.

Dr. Faubion: Dr. Kapoor, what would you say regarding the increased risk they might incur if they do have their ovaries out?

Dr. Kapoor: As Dr. Kaunitz said, this is an uncommon cancer, and pursuing something to reduce the risk of an uncommon cancer does not benefit the community. That is also my counseling point to patients.

I also talk to them extensively about the risk associated with the ovaries being removed, and I tell them that although we have the option of giving them HT, it is hard to replicate the magic of nature. No matter what concoction or regimen we use, we cannot ensure reinstating health to what it was in the premenopausal state, because estrogen has such myriad effects on the body in so many different organ systems.

Reference

1. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227-2246.

- Kaunitz AM, Kapoor E, Faubion S. Treatment of women after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed prior to natural menopause. JAMA. 2021;326:1429-1430.

- Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321-333.

- North American Menopause Society. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. J North Am Menopause Soc. 2017;24: 728-753.

Women who undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) for various indications prior to menopause experience a rapid decline in ovarian hormone levels and consequent vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms. In addition, the resulting estrogen deprivation is associated with such long-term adverse outcomes as osteoporosis and cardiovascular morbidity.

OBG M

Surgical vs natural menopause

Stephanie Faubion, MD, MBA, NCMP: Since the Women’s Health Initiative study was published in 2002,2 many clinicians have been fearful of using systemic HT in menopausal women, and HT use has declined dramatically such that only about 4% to 6% of menopausal women are now receiving systemic HT. Importantly, however, a group of younger menopausal women also are not receiving HT, and that is women who undergo BSO before they reach the average age of menopause, which in the United States is about age 52; this is sometimes referred to as surgical menopause or early surgical menopause. Early surgical menopause has different connotations for long-term health risks than natural menopause at the average age, and we are here to discuss these health effects and their management.

My name is Stephanie Faubion, and I am a women’s health internist and the Chair of the Department of Medicine at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, and Director of Mayo Clinic Women’s Health. I am here with 2 of my esteemed colleagues, Dr. Andrew Kaunitz and Dr. Ekta Kapoor.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, NCMP: Hello, I am an ObGyn with the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville, with particular interests in contraception, menopause, and gynecologic ultrasonography.

Ekta Kapoor, MBBS, NCMP: And I am an endocrinologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester with a specific interest in menopause and hormone therapy. I am also the Assistant Director for Mayo Clinic Women’s Health.

Higher-than-standard estrogen doses needed in younger menopausal women

Dr. Faubion: Let’s consider a couple of cases so that we can illustrate some important points regarding hormone management in women who have undergone BSO before the age of natural menopause.

Our first case patient is a woman who is 41 years of age and, because of adenomyosis, she will undergo a hysterectomy. She tells her clinician that she is very concerned about ovarian cancer risk because one of her good friends recently was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and together they decide to remove her ovaries at the time of hysterectomy. Notably, her ovaries were healthy.

The patient is now menopausal postsurgery, and she is having significant hot flashes and night sweats. She visits her local internist, who is concerned about initiating HT. She is otherwise a healthy woman and does not have any contraindications to HT. Dr. Kaunitz, what would you tell her internist?

Dr. Kaunitz: We are dealing with 2 different issues in terms of decision making about systemic HT for this 41-year-old who has undergone BSO. First, as you mentioned, Dr. Faubion, she has bothersome hot flashes, or vasomotor symptoms. Unless there are contraindications, systemic HT would be appropriate. Although I might start treatment at standard doses, and the accompanying TABLE depicts standard doses for the 2 most common oral estrogen formulations as well as transdermal estradiol, it’s important to recognize that younger menopausal women often will need to use higher-than-standard doses.

For example, for a 53-year-old woman who has been menopausal for a year or 2 and now has bothersome symptoms, I might start her on estradiol 1 mg tablets with progestin if a uterus is present. However, in this 41-year-old case patient, while I might start treatment at a standard dose, I would anticipate increasing to higher doses, such as 1.5 or 2 mg of daily estradiol until she feels her menopausal symptoms are adequately addressed.

Dr. Faubion: It is important to note that sometimes women with early BSO tend to have more severe vasomotor symptoms. Do you find that sometimes a higher dose is required just to manage symptoms, Dr. Kaunitz?

Dr. Kaunitz: Absolutely, yes. The decision whether or not to use systemic HT might be considered discretionary or elective in the classic 53-year-old woman recently menopausal with hot flashes, a so-called spontaneously or naturally menopausal woman. But my perspective is that unless there are clear contraindications, the decision to start systemic HT in the 41-year-old BSO case patient is actually not discretionary. Unless contraindications are present, it is important not only to treat symptoms but also to prevent an array of chronic major health concerns that are more likely if we don’t prescribe systemic HT.

Continue to: Health effects of not using HT...

Health effects of not using HT

Dr. Faubion: Dr. Kapoor, can you describe the potential long-term adverse health consequences of not using estrogen therapy? Say the same 41-year-old woman does not have many bothersome symptoms. What would you do?

Dr. Kapoor: Thank you for that important question. Building on what Dr. Kaunitz said, in these patients there are really 2 issues that can seem to be independent but are not: The first relates to the immediate consequences of lack of estrogen, ie, the menopause-related symptoms, but the second and perhaps the bigger issue is the long-term risk associated with estrogen deprivation.

The symptoms in these women are often obvious as they can be quite severe and abrupt; one day these women have normal hormone levels and the next day, after BSO, suddenly their hormones are very low. So if symptoms occur, they are usually hard to miss, simply because they are very drastic and very severe.

Historically, patients and their clinicians have targeted these symptoms. Patients experience menopausal symptoms, they seek treatment, and then the clinicians basically titrate the treatment to manage these symptoms. That misses the bigger issue, however, which is that premature estrogen deprivation leads to a host of chronic health conditions, as Dr. Kaunitz mentioned. These mainly include increased risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, increased risk of mortality, dementia, and osteoporosis.

Fairly strong observational evidence suggests that use of estrogen therapy given in replacement doses—doses higher than those typically used in women after natural menopause, therefore considered replacement doses—helps mitigate the risk of some of these adverse health conditions.

In these women, the bigger goal really is to reinstate the hormonal milieu that exists prior to menopause. To your point, Dr. Faubion, if I have a patient who is younger than 46 years, who has her ovaries taken out, and even if she has zero symptoms (and sometimes that does happen), I would still make a case for this patient to utilize hormone therapy unless there is a contraindication such as breast cancer or other estrogen-sensitive cancers.

Dr. Faubion: Again, would you aim for those higher doses rather than treat with the “lowest dose”?

Dr. Kapoor: Absolutely. My punchline to the patients and clinicians in these discussions is that the rules of the game are different for these women. We cannot extrapolate the risks and benefits of HT use in women after natural menopause to younger women who have surgical menopause. Those rules just do not apply with respect to both benefits and risks.

Dr. Faubion: I think it’s important to say that these same “rules” would apply if the women were to go through premature menopause for any other reason, too, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or premature ovarian insufficiency for any number of reasons, including toxic, metabolic, or genetic causes and so on. Would that be true?

Dr. Kapoor: Yes, absolutely so.

Dr. Faubion: Dr. Kaunitz, do you want to add anything?

Dr. Kaunitz: In terms of practical or clinical issues regarding systemic HT management, for the woman in her early 50s who has experienced normal or natural spontaneous menopause, a starting dose of transdermal estradiol would be, for instance, a 0.05-mg patch, which is a patch that over 24 hours releases 0.05 mg of estradiol daily; or standard oral estrogen, including conjugated equine estrogen, a 0.625-mg tablet daily, or estradiol, a 1-mg tablet daily.

But in younger patients, we want to use higher doses. For a patch, for instance, I would aim for a 0.075- or 0.1-mg estradiol patch, which releases a higher daily dose of estradiol than the standard dose. For oral estrogen, the dose would be 0.9- or even 1.25-mg tablets of conjugated equine estrogen or 1.5 mg, which is a 1-mg plus a 0.5-mg estradiol tablet, or a 2-mg estradiol tablet. Estradiol does come in a 2-mg strength.

For oral estrogen, I prefer estradiol because it’s available as a generic medication and often available at a very low cost, sometimes as low as $4 a month from chain pharmacies.

Continue to: Usefulness of monitoring estradiol levels for dosage adjustment...

Usefulness of monitoring estradiol levels for dosage adjustment

Dr. Faubion: That’s a great point, and again it is important to emphasize that we are aiming to recreate the premenopausal hormonal milieu. If you were to check estradiol levels, that would be aiming for a premenopausal range of approximately 80 to 120 pg per mL. Dr. Kapoor, is there utility in monitoring estrogen levels?

Dr. Kapoor: Great question, Dr. Faubion, and as you know it’s a loaded one. We base this on empiric evidence. We know that if the hormonal milieu in a young patient is changed to a postmenopausal one, her risk for many chronic conditions is increased. So if we were to reinstate a premenopausal hormonal milieu, that risk would probably be reduced. It makes good sense to target an empiric goal of 80 to 120 pg per mL of estradiol, which is the average estradiol level in a premenopausal woman. If you were to ask me, however, are there randomized, controlled trial data to support this practice—that is, if you target that level, can you make sure that the risk of diabetes is lower or that the risk of heart disease is lower—that study has yet to be done, and it may not ever be done on a large scale. However, it intuitively makes good sense to target premenopausal estradiol levels.

Dr. Faubion: When might you check an estradiol level in this population? For example, if you are treating a patient with a 0.1-mg estradiol patch and she still has significant hot flashes, would it be useful to check the level?

Dr. Kapoor: It would. In my practice, I check estradiol levels on these patients on an annual basis, regardless of symptoms, but definitely in the patient who has symptoms. It makes good sense, because sometimes these patients don’t absorb the estrogen well, particularly if administered by the transdermal route.

A general rule of thumb is that in the average population, if a patient is on the 0.1-mg patch, for example, you would expect her level to be around 100. If it is much lower than that, which sometimes happens, that speaks for poor absorption. Options at that point would be to treat her with a higher dose patch, depending on what the level is, or switch to a different formulation, such as oral.

In instances in which I have treated patients with a 0.1-mg patch for example, and their estradiol levels are undetectable, that speaks for very poor absorption. For such patients I make a case for switching them to oral therapy. Most definitely that makes sense in a patient who is symptomatic despite treatment. But even for patients who don’t have symptoms, I like to target that level, acknowledging that there is no evidence as such to support this practice.

Dr. Faubion: Dr. Kaunitz, do you want to add anything?

Dr. Kaunitz: Yes, a few practical points. Although patches are available in a wider array of doses than oral estrogen formulations, the highest dose available is 0.1 mg. It’s important for clinicians to recognize that while checking serum levels when indicated can be performed in women using transdermal estradiol or patches, in women who are using oral estrogen, checking blood levels is not going to work well because serum estrogen levels have a daily peak and valley in women who use oral versus transdermal estradiol.

I also wanted to talk about progestins. Although many patients who have had a BSO prior to spontaneous menopause also have had a hysterectomy, others have an intact uterus associated with their BSO, so progestins must be used along with estrogen. And if we are using higher-than-standard doses of estrogen, we also need to use higher-than-standard doses of progestin.

In that classic 53-year-old woman I referred to who had spontaneous normal menopause, if she is taking 1 mg of estradiol daily, or a 0.05-mg patch, or 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogen, 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone is fine. In fact, that showed excellent progestational protection of the endometrium in the Women’s Health Initiative and in other studies.

However, if we are going to use double the estrogen dose, we should increase the progestin dose too. In some of my patients on higher estrogen doses who have an intact uterus, I’ll use 5 or even 10 mg of daily medroxyprogesterone acetate to ensure adequate progestational suppression.

Dr. Faubion: Another practical tip is that if one is using conjugated equine estrogens, measuring the serum estradiol levels is not useful either.

Dr. Kaunitz: I agree.

Continue to: Oral contraceptives as replacement HT...

Oral contraceptives as replacement HT

Dr. Faubion: Would you comment on use of a birth control pill in this circumstance? Would it be optimal to use a postmenopausal HT regimen as opposed to a birth control pill or combined hormonal contraception?

Dr. Kapoor: In this younger population, sometimes it seems like a more socially acceptable decision to be on a birth control option than on menopausal HT. But there are some issues with being on a contraceptive regimen. One is that we end up using estrogen doses much higher than what is really needed for replacement purposes. It is also a nonphysiologic way of replacement in another sense—as opposed to estradiol, which is the main hormone made by the ovaries, the hormonal contraceptive regimens contain the synthetic estrogen ethinyl estradiol for the most part.

The other issue that is based on some weak evidence is that it appears that the bone health outcomes are probably inferior with combined hormonal contraception. For these reasons, regimens that are based on replacement doses of estradiol are preferred.

Dr. Faubion: Right, although the data are somewhat weak, I agree that thus far it seems optimal to utilize a postmenopausal regimen for various reasons. Dr. Kaunitz, anything to add?

Dr. Kaunitz: Yes, to underscore Dr. Kapoor’s point, a common oral contraceptive that contains 20 µg of ethinyl estradiol is substantially more estrogenic than 1.0 or 2.0 mg of micronized oral estradiol.

Also consider that a 20-µg ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive may increase the risk of venous thromboembolism more than menopausal doses of oral estradiol, whether it be a micronized estradiol or conjugated equine estrogen.

Dr. Faubion: So the risk may be greater with oral combined hormonal contraception as well?

Dr. Kaunitz: One thing we can do is explain to our patients that their ovaries, prior to surgery or prior to induced menopause, were making substantial quantities of estradiol. Whether we prescribe a patch or oral micronized estradiol, this estrogen is identical to the hormone that their ovaries were making prior to surgery or induced menopause.

Breast cancer concerns

Dr. Faubion: Let’s consider a more complicated case. A 35-year-old woman has an identified BRCA1 mutation; she has not had any cancers but has undergone risk-reducing BSO and her uterus remains. Is this woman a candidate for HT? At what dose, and for how long? Dr. Kaunitz, why don’t you start.

Dr. Kaunitz: That is a challenging case but one that I think our readers will find interesting and maybe even provocative.

We know that women with BRCA1 mutations, the more common of the 2 BRCA mutations, have a very high risk of developing epithelial ovarian cancer at a young age. For this reason, our colleagues in medical oncology who specialize in hereditary ovarian/breast cancer syndromes recommend prophylactic risk-reducing—and I would also say lifesaving—BSO with or without hysterectomy for women with BRCA1 mutations.

However, over the years there has been tremendous reluctance among physicians caring for BRCA patients and the women themselves—I use the term “previvors” to describe BRCA carriers who have not been diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer—to use HT after BSO because of concerns that HT might increase breast cancer risk in women who are already at high risk for breast cancer.

I assume, Dr. Faubion, that in this case the woman had gynecologic surgery but continues to have intact breasts. Is that correct?

Dr. Faubion: That is correct.

Dr. Kaunitz: Although the assumption has been that it is not safe to prescribe HT in this setting, in fact, the reported cohort studies that have looked at this issue have not found an elevated risk of breast cancer when replacement estrogen, with or without progestin, is prescribed to BRCA1 previvors with intact breasts.

Given what Dr. Kapoor said regarding the morbidity that is associated with BSO without replacement of physiologic estrogen, and also given the severe symptoms that so many of these young menopausal women experience, in my practice I do prescribe estrogen or estrogen-progestin therapy and focus on the higher target doses that we discussed for the earlier case patient who had a hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding with adenomyosis.

Dr. Faubion: Dr. Kapoor, do you agree with this approach? How long would you continue therapy?

Dr. Kapoor: First, in this BRCA1 case we need to appreciate that the indication for the BSO is a legitimate one, in contrast to the first case in which the ovaries were removed in a patient whose average risk of ovarian cancer was low. It is important to recognize that surgery performed in this context is the right thing to do because it does significantly reduce the risk of ovarian cancer.

The second thing to appreciate is that while we reduce the risk of ovarian cancer significantly and make sure that these patients survive longer, it’s striking a fine balance in that you want to make sure that their morbidity is not increased as a result of premature estrogen deprivation.

As Dr. Kaunitz told us, the evidence that we have so far, which granted is not very robust but is fairly strong observational evidence, suggests that the risk of breast cancer is not elevated when these patients are treated with replacement doses of HT.

Having said that, I do have very strong discussions with my patients in this category about having the risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy also, because if they were to get breast cancer because of their increased genetic predisposition, the cancer is likely to grow faster if the patient is on HT. So one of my counseling points to patients is that they strongly consider bilateral mastectomy, which reduces their breast cancer risk by more than 90%. At the same time, I also strongly endorse using HT in replacement doses for the reasons that we have already stated.

Dr. Faubion: Continue HT until age 50 or 52?

Dr. Kapoor: Definitely until that age, and possibly longer, depending on their symptoms. The indications for treating beyond the age of natural menopause are much the same as for women who experience natural menopause.

Dr. Faubion: That is assuming they had a bilateral mastectomy?

Dr. Kapoor: Yes.

Continue to: Continuing HT until the age of natural menopause...

Continuing HT until the age of natural menopause

Dr. Kaunitz: Dr. Kapoor brings up the important point of duration of systemic HT. I agree that similar considerations apply both to the healthy 41-year-old who had a hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding and to the 35-year-old who had risk-reducing surgery because of her BRCA1 mutation.

In the 2 cases, both to treat symptoms and to prevent chronic diseases, it makes sense to continue HT at least until the age of natural menopause. That is consistent with 2017 guidance from The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) position statement on the use of systemic HT, that is, continuing systemic HT at least until the age of natural menopause.3 Then at that point, continuing or discontinuing systemic HT becomes discretionary, and that would be true for both cases. If the patient is slender or has a strong family history of osteoporosis, that tends to push the patient more in terms of continuing systemic HT. Those are just some examples, and Dr. Kapoor may want to detail other relevant considerations.

Dr. Kapoor: I completely agree. The decision is driven by symptoms that are not otherwise well managed, for example, with nonhormone strategies. If we have any concerns utilizing HT beyond the age of natural menopause, then nonhormonal options can be considered; but sometimes those are not as effective. And bone health is very important. You want to avoid using bisphosphonates in younger women and reserve them for older patients in their late 60s and 70s. Hormone therapy use is a very reasonable strategy to prevent bone loss.

Dr. Kaunitz: It is also worth mentioning that sometimes the woman involved in shared decision making with her clinician decides to stop systemic HT. In that setting, should the patient start developing new-onset dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, or other genital or sexuality-related concerns, it takes very little for me to advise that she start low-dose local vaginal estrogen therapy.

Dr. Faubion: In either scenario, if a woman were to develop symptoms consistent with genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), would you use vaginal estrogen in addition to the systemic estrogen or alone after the woman elected to discontinue systemic therapy?

Dr. Kapoor: Yes to both, I would say.