User login

Transvaginal mesh, native tissue repair have similar outcomes in 3-year trial

Transvaginal mesh was found to be safe and effective for patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) when compared with native tissue repair (NTR) in a 3-year trial.

Researchers, led by Bruce S. Kahn, MD, with the department of obstetrics & gynecology at Scripps Clinic in San Diego evaluated the two surgical treatment methods and published their findings in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

At completion of the 3-year follow-up in 2016, there were 401 participants in the transvaginal mesh group and 171 in the NTR group.

The prospective, nonrandomized, parallel-cohort, 27-site trial used a primary composite endpoint of anatomical success; subjective success (vaginal bulging); retreatment measures; and serious device-related or serious procedure-related adverse events.

The secondary endpoint was a composite outcome similar to the primary composite outcome but with anatomical success more stringently defined as POP quantification (POP-Q) point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.

The secondary outcome was added to this trial because investigators had criticized the primary endpoint, set by the Food and Drug Administration, because it included anatomic outcome measures that were the same for inclusion criteria (POP-Q point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.)

The secondary-outcome composite also included quality-of-life measures, mesh exposure, and mesh- and procedure-related complications.

Outcomes similar for both groups

The primary outcome demonstrated transvaginal mesh was not superior to native tissue repair (P =.056).

In the secondary outcome, superiority of transvaginal mesh over native tissue repair was shown (P =.009), with a propensity score–adjusted difference of 10.6% (90% confidence interval, 3.3%-17.9%) in favor of transvaginal mesh.

The authors noted that subjective success regarding vaginal bulging, which is important in patient satisfaction, was high and not statistically different between the two groups.

Additionally, transvaginal mesh repair was as safe as NTR regarding serious device-related and/or serious procedure-related side effects.

For the primary safety endpoint, 3.1% in the mesh group and 2.7% in the native tissue repair group experienced serious adverse events, demonstrating that mesh was noninferior to NTR.

Research results have been mixed

Unanswered questions surround surgical options for POP, which, the authors wrote, “affects 3%-6% of women based on symptoms and up to 50% of women based on vaginal examination.”

The FDA in 2011 issued 522 postmarket surveillance study orders for companies that market transvaginal mesh for POP.

Research results have varied and contentious debate has continued in the field. Some studies have shown that mesh has better subjective and objective outcomes than NTR in the anterior compartment. Others have found more complications with transvaginal mesh, such as mesh exposure and painful intercourse.

Complicating comparisons, early versions of the mesh used were larger and denser than today’s versions.

In this postmarket study, patients received either the Uphold LITE brand of transvaginal mesh or native tissue repair for surgical treatment of POP.

Expert: This study unlikely to change minds

In an accompanying editorial, John O.L. DeLancey, MD, professor of gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, pointed out that so far there’s been a lack of randomized trials that could answer whether mesh surgeries result in fewer symptoms or result in sufficient improvements in anatomy to justify their additional risk.

This study may not help with the decision. Dr. DeLancey wrote: “Will this study change the minds of either side of this debate? Probably not. The two sides are deeply entrenched in their positions.”

Two considerations are important in thinking about the issue, he said. Surgical outcomes for POP are “not as good as we would hope.” Also, many women have had serious complications with mesh operations.

He wrote: “Mesh litigation has resulted in more $8 billion in settlements, which is many times the $1 billion annual national cost of providing care for prolapse. Those of us who practice in referral centers have seen women with devastating problems, even though they probably represent a small fraction of cases.”

Dr. DeLancey highlighted some limitations of the study by Dr. Kahn and colleagues, especially regarding differences in the groups studied and the design of the study.

“For example,” he explained, “65% of individuals in the mesh-repair group had a prior hysterectomy as opposed to 30% in the native tissue repair group. In addition, some of the operations in the native tissue group are not typical choices; for example, hysteropexy was used for some patients and had a 47% failure rate.”

He said the all-or-nothing approach to surgical solutions may be clouding the debate – in other words mesh or no mesh for women as a group.

“Rather than asking whether mesh is better than no mesh, knowing which women (if any) stand to benefit from mesh is the critical question. We need to understand, for each woman, what structural failures exist so that we can target our interventions to correct them,” he wrote.

This study was sponsored by Boston Scientific. Dr. Kahn disclosed research support from Solaire, payments from AbbVie and Douchenay as a speaker, payments from Caldera and Cytuity (Boston Scientific) as a medical consultant, and payment from Johnson & Johnson as an expert witness. One coauthor disclosed that money was paid to her institution from Medtronic and Boston Scientific (both unrestricted educational grants for cadaveric lab). Another is chief medical officer at Axonics. One study coauthor receives research funding from Axonics and is a consultant for Group Dynamics, Medpace, and FirstThought. One coauthor received research support, is a consultant for Boston Scientific, and is an expert witness for Johnson & Johnson. Dr. DeLancey declared no relevant financial relationships.

Transvaginal mesh was found to be safe and effective for patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) when compared with native tissue repair (NTR) in a 3-year trial.

Researchers, led by Bruce S. Kahn, MD, with the department of obstetrics & gynecology at Scripps Clinic in San Diego evaluated the two surgical treatment methods and published their findings in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

At completion of the 3-year follow-up in 2016, there were 401 participants in the transvaginal mesh group and 171 in the NTR group.

The prospective, nonrandomized, parallel-cohort, 27-site trial used a primary composite endpoint of anatomical success; subjective success (vaginal bulging); retreatment measures; and serious device-related or serious procedure-related adverse events.

The secondary endpoint was a composite outcome similar to the primary composite outcome but with anatomical success more stringently defined as POP quantification (POP-Q) point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.

The secondary outcome was added to this trial because investigators had criticized the primary endpoint, set by the Food and Drug Administration, because it included anatomic outcome measures that were the same for inclusion criteria (POP-Q point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.)

The secondary-outcome composite also included quality-of-life measures, mesh exposure, and mesh- and procedure-related complications.

Outcomes similar for both groups

The primary outcome demonstrated transvaginal mesh was not superior to native tissue repair (P =.056).

In the secondary outcome, superiority of transvaginal mesh over native tissue repair was shown (P =.009), with a propensity score–adjusted difference of 10.6% (90% confidence interval, 3.3%-17.9%) in favor of transvaginal mesh.

The authors noted that subjective success regarding vaginal bulging, which is important in patient satisfaction, was high and not statistically different between the two groups.

Additionally, transvaginal mesh repair was as safe as NTR regarding serious device-related and/or serious procedure-related side effects.

For the primary safety endpoint, 3.1% in the mesh group and 2.7% in the native tissue repair group experienced serious adverse events, demonstrating that mesh was noninferior to NTR.

Research results have been mixed

Unanswered questions surround surgical options for POP, which, the authors wrote, “affects 3%-6% of women based on symptoms and up to 50% of women based on vaginal examination.”

The FDA in 2011 issued 522 postmarket surveillance study orders for companies that market transvaginal mesh for POP.

Research results have varied and contentious debate has continued in the field. Some studies have shown that mesh has better subjective and objective outcomes than NTR in the anterior compartment. Others have found more complications with transvaginal mesh, such as mesh exposure and painful intercourse.

Complicating comparisons, early versions of the mesh used were larger and denser than today’s versions.

In this postmarket study, patients received either the Uphold LITE brand of transvaginal mesh or native tissue repair for surgical treatment of POP.

Expert: This study unlikely to change minds

In an accompanying editorial, John O.L. DeLancey, MD, professor of gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, pointed out that so far there’s been a lack of randomized trials that could answer whether mesh surgeries result in fewer symptoms or result in sufficient improvements in anatomy to justify their additional risk.

This study may not help with the decision. Dr. DeLancey wrote: “Will this study change the minds of either side of this debate? Probably not. The two sides are deeply entrenched in their positions.”

Two considerations are important in thinking about the issue, he said. Surgical outcomes for POP are “not as good as we would hope.” Also, many women have had serious complications with mesh operations.

He wrote: “Mesh litigation has resulted in more $8 billion in settlements, which is many times the $1 billion annual national cost of providing care for prolapse. Those of us who practice in referral centers have seen women with devastating problems, even though they probably represent a small fraction of cases.”

Dr. DeLancey highlighted some limitations of the study by Dr. Kahn and colleagues, especially regarding differences in the groups studied and the design of the study.

“For example,” he explained, “65% of individuals in the mesh-repair group had a prior hysterectomy as opposed to 30% in the native tissue repair group. In addition, some of the operations in the native tissue group are not typical choices; for example, hysteropexy was used for some patients and had a 47% failure rate.”

He said the all-or-nothing approach to surgical solutions may be clouding the debate – in other words mesh or no mesh for women as a group.

“Rather than asking whether mesh is better than no mesh, knowing which women (if any) stand to benefit from mesh is the critical question. We need to understand, for each woman, what structural failures exist so that we can target our interventions to correct them,” he wrote.

This study was sponsored by Boston Scientific. Dr. Kahn disclosed research support from Solaire, payments from AbbVie and Douchenay as a speaker, payments from Caldera and Cytuity (Boston Scientific) as a medical consultant, and payment from Johnson & Johnson as an expert witness. One coauthor disclosed that money was paid to her institution from Medtronic and Boston Scientific (both unrestricted educational grants for cadaveric lab). Another is chief medical officer at Axonics. One study coauthor receives research funding from Axonics and is a consultant for Group Dynamics, Medpace, and FirstThought. One coauthor received research support, is a consultant for Boston Scientific, and is an expert witness for Johnson & Johnson. Dr. DeLancey declared no relevant financial relationships.

Transvaginal mesh was found to be safe and effective for patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) when compared with native tissue repair (NTR) in a 3-year trial.

Researchers, led by Bruce S. Kahn, MD, with the department of obstetrics & gynecology at Scripps Clinic in San Diego evaluated the two surgical treatment methods and published their findings in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

At completion of the 3-year follow-up in 2016, there were 401 participants in the transvaginal mesh group and 171 in the NTR group.

The prospective, nonrandomized, parallel-cohort, 27-site trial used a primary composite endpoint of anatomical success; subjective success (vaginal bulging); retreatment measures; and serious device-related or serious procedure-related adverse events.

The secondary endpoint was a composite outcome similar to the primary composite outcome but with anatomical success more stringently defined as POP quantification (POP-Q) point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.

The secondary outcome was added to this trial because investigators had criticized the primary endpoint, set by the Food and Drug Administration, because it included anatomic outcome measures that were the same for inclusion criteria (POP-Q point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.)

The secondary-outcome composite also included quality-of-life measures, mesh exposure, and mesh- and procedure-related complications.

Outcomes similar for both groups

The primary outcome demonstrated transvaginal mesh was not superior to native tissue repair (P =.056).

In the secondary outcome, superiority of transvaginal mesh over native tissue repair was shown (P =.009), with a propensity score–adjusted difference of 10.6% (90% confidence interval, 3.3%-17.9%) in favor of transvaginal mesh.

The authors noted that subjective success regarding vaginal bulging, which is important in patient satisfaction, was high and not statistically different between the two groups.

Additionally, transvaginal mesh repair was as safe as NTR regarding serious device-related and/or serious procedure-related side effects.

For the primary safety endpoint, 3.1% in the mesh group and 2.7% in the native tissue repair group experienced serious adverse events, demonstrating that mesh was noninferior to NTR.

Research results have been mixed

Unanswered questions surround surgical options for POP, which, the authors wrote, “affects 3%-6% of women based on symptoms and up to 50% of women based on vaginal examination.”

The FDA in 2011 issued 522 postmarket surveillance study orders for companies that market transvaginal mesh for POP.

Research results have varied and contentious debate has continued in the field. Some studies have shown that mesh has better subjective and objective outcomes than NTR in the anterior compartment. Others have found more complications with transvaginal mesh, such as mesh exposure and painful intercourse.

Complicating comparisons, early versions of the mesh used were larger and denser than today’s versions.

In this postmarket study, patients received either the Uphold LITE brand of transvaginal mesh or native tissue repair for surgical treatment of POP.

Expert: This study unlikely to change minds

In an accompanying editorial, John O.L. DeLancey, MD, professor of gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, pointed out that so far there’s been a lack of randomized trials that could answer whether mesh surgeries result in fewer symptoms or result in sufficient improvements in anatomy to justify their additional risk.

This study may not help with the decision. Dr. DeLancey wrote: “Will this study change the minds of either side of this debate? Probably not. The two sides are deeply entrenched in their positions.”

Two considerations are important in thinking about the issue, he said. Surgical outcomes for POP are “not as good as we would hope.” Also, many women have had serious complications with mesh operations.

He wrote: “Mesh litigation has resulted in more $8 billion in settlements, which is many times the $1 billion annual national cost of providing care for prolapse. Those of us who practice in referral centers have seen women with devastating problems, even though they probably represent a small fraction of cases.”

Dr. DeLancey highlighted some limitations of the study by Dr. Kahn and colleagues, especially regarding differences in the groups studied and the design of the study.

“For example,” he explained, “65% of individuals in the mesh-repair group had a prior hysterectomy as opposed to 30% in the native tissue repair group. In addition, some of the operations in the native tissue group are not typical choices; for example, hysteropexy was used for some patients and had a 47% failure rate.”

He said the all-or-nothing approach to surgical solutions may be clouding the debate – in other words mesh or no mesh for women as a group.

“Rather than asking whether mesh is better than no mesh, knowing which women (if any) stand to benefit from mesh is the critical question. We need to understand, for each woman, what structural failures exist so that we can target our interventions to correct them,” he wrote.

This study was sponsored by Boston Scientific. Dr. Kahn disclosed research support from Solaire, payments from AbbVie and Douchenay as a speaker, payments from Caldera and Cytuity (Boston Scientific) as a medical consultant, and payment from Johnson & Johnson as an expert witness. One coauthor disclosed that money was paid to her institution from Medtronic and Boston Scientific (both unrestricted educational grants for cadaveric lab). Another is chief medical officer at Axonics. One study coauthor receives research funding from Axonics and is a consultant for Group Dynamics, Medpace, and FirstThought. One coauthor received research support, is a consultant for Boston Scientific, and is an expert witness for Johnson & Johnson. Dr. DeLancey declared no relevant financial relationships.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Unraveling primary ovarian insufficiency

In the presentation of secondary amenorrhea, pregnancy is the No. 1 differential diagnosis. Once this has been excluded, an algorithm is initiated to determine the etiology, including an assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. While the early onset of ovarian failure can be physically and psychologically disrupting, the effect on fertility is an especially devastating event. Previously identified by terms including premature ovarian failure and premature menopause, “primary ovarian insufficiency” (POI) is now the preferred designation. This month’s article will address the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of POI.

The definition of POI is the development of primary hypogonadism before the age of 40 years. Spontaneous POI occurs in approximately 1 in 250 women by age 35 years and 1 in 100 by age 40 years. After excluding pregnancy, the clinician should determine signs and symptoms that can lead to expedited and cost-efficient testing.

Consequences

POI is an important risk factor for bone loss and osteoporosis, especially in young women who develop ovarian dysfunction before they achieve peak adult bone mass. At the time of diagnosis of POI, a bone density test (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) should be obtained. Women with POI may also develop depression and anxiety as well as experience an increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, possibly related to endothelial dysfunction.

Young women with spontaneous POI are at increased risk of developing autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (AAI), a potentially fatal disorder. Consequently, to diagnose AAI, serum adrenal cortical and 21-hydroxylase antibodies should be measured in all women who have a karyotype of 46,XX and experience spontaneous POI. Women with AAI have a 50% risk of developing adrenal insufficiency. Despite initial normal adrenal function, women with positive adrenal cortical antibodies should be followed annually.

Causes (see table for a more complete list)

Iatrogenic

Known causes of POI include chemotherapy/radiation often in the setting of cancer treatment. The three most commonly used drugs, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and doxorubicin, cause POI by inducing death and/or accelerated activation of primordial follicles and increased atresia of growing follicles. The most damaging agents are alkylating drugs. A cyclophosphamide equivalent dose calculator has been established for ovarian failure risk stratification from chemotherapy based on the cumulative dose of alkylating agents received.

One study estimated the radiosensitivity of the oocyte to be less than 2 Gy. Based upon this estimate, the authors calculated the dose of radiotherapy that would result in immediate and permanent ovarian failure in 97.5% of patients as follows:

- 20.3 Gy at birth

- 18.4 Gy at age 10 years

- 16.5 Gy at age 20 years

- 14.3 Gy at age 30 years

Genetic

Approximately 10% of cases are familial. A family history of POI raises concern for a fragile X premutation. Fragile X syndrome is an X-linked form of intellectual disability that is one of the most common causes of mental retardation worldwide. There is a strong relationship between age at menopause, including POI, and premutations for fragile X syndrome. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women with POI or an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level before age 40 years without known cause be screened for FMR1 premutations. Approximately 6% of cases of POI are associated with premutations in the FMR1 gene.

Turner syndrome is one of the most common causes of POI and results from the lack of a second X chromosome. The most common chromosomal defect in humans, TS occurs in up to 1.5% of conceptions, 10% of spontaneous abortions, and 1 of 2,500 live births.

Serum antiadrenal and/or anti–21-hydroxylase antibodies and antithyroid antiperoxidase antibodies, can aid in the diagnosis of adrenal gland, ovary, and thyroid autoimmune causes, which is found in 4% of women with spontaneous POI. Testing for the presence of 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies or adrenal autoantibodies is sufficient to make the diagnosis of autoimmune oophoritis in women with proven spontaneous POI.

The etiology of POI remains unknown in approximately 75%-90% of cases. However, studies using whole exome or whole genome sequencing have identified genetic variants in approximately 30%-35% of these patients.

Risk factors

Factors that are thought to play a role in determining the age of menopause, include genetics (e.g., FMR1 premutation and mosaic Turner syndrome), ethnicity (earlier among Hispanic women and later in Japanese American women when compared with White women), and smoking (reduced by approximately 2 years ).

Regarding ovarian aging, the holy grail of the reproductive life span is to predict menopause. While the definitive age eludes us, anti-Müllerian hormone levels appear to show promise. An ultrasensitive anti-Müllerian hormone assay (< 0.01 ng/mL) predicted a 79% probability of menopause within 12 months for women aged 51 and above; the probability was 51% for women below age 48.

Diagnosis

The three P’s of secondary amenorrhea are physiological, pharmacological, or pathological and can guide the clinician to a targeted evaluation. Physiological causes are pregnancy, the first 6 months of continuous breastfeeding (from elevated prolactin), and natural menopause. Pharmacological etiologies, excluding hormonal treatment that suppresses ovulation (combined oral contraceptives, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist/antagonist, or danazol), include agents that inhibit dopamine thereby increasing serum prolactin, such as metoclopramide; phenothiazine antipsychotics, such as haloperidol; and tardive dystonia dopamine-depleting medications, such as reserpine. Pathological causes include pituitary adenomas, thyroid disease, functional hypothalamic amenorrhea from changes in weight, exercise regimen, and stress.

Management

About 50%-75% of women with 46,XX spontaneous POI experience intermittent ovarian function and 5%-10% of women remain able to conceive. Anecdotally, a 32-year-old woman presented to me with primary infertility, secondary amenorrhea, and suspected POI based on vasomotor symptoms and elevated FSH levels. Pelvic ultrasound showed a hemorrhagic cyst, suspicious for a corpus luteum. Two weeks thereafter she reported a positive home urine human chorionic gonadotropin test and ultimately delivered twins. Her diagnosis of POI with amenorrhea remained postpartum.

Unless there is an absolute contraindication, estrogen therapy should be prescribed to women with POI to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and urogenital atrophy as well as to maintain sexual health and quality of life. For those with an intact uterus, women should receive progesterone because of the risk of endometrial hyperplasia from unopposed estrogen. Rather than oral estrogen, the use of transdermal or vaginal delivery of estrogen is a more physiological approach and provides lower risks of venous thromboembolism and gallbladder disease. Of note, standard postmenopausal hormone therapy, which has a much lower dose of estrogen than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives, does not provide effective contraception. Per ACOG, systemic hormone treatment should be prescribed until age 50-51 years to all women with POI.

For fertility, women with spontaneous POI can be offered oocyte or embryo donation. The uterus does not age reproductively, unlike oocytes, therefore women can achieve reasonable pregnancy success rates through egg donation despite experiencing menopause.

Future potential options

Female germline stem cells have been isolated from neonatal mice and transplanted into sterile adult mice, who then were able to produce offspring. In a second study, oogonial stem cells were isolated from neonatal and adult mouse ovaries; pups were subsequently born from the oocytes. Further experiments are needed before the implications for humans can be determined.

Emotionally traumatic for most women, POI disrupts life plans, hopes, and dreams of raising a family. The approach to the patient with POI involves the above evidence-based testing along with empathy from the health care provider.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

In the presentation of secondary amenorrhea, pregnancy is the No. 1 differential diagnosis. Once this has been excluded, an algorithm is initiated to determine the etiology, including an assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. While the early onset of ovarian failure can be physically and psychologically disrupting, the effect on fertility is an especially devastating event. Previously identified by terms including premature ovarian failure and premature menopause, “primary ovarian insufficiency” (POI) is now the preferred designation. This month’s article will address the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of POI.

The definition of POI is the development of primary hypogonadism before the age of 40 years. Spontaneous POI occurs in approximately 1 in 250 women by age 35 years and 1 in 100 by age 40 years. After excluding pregnancy, the clinician should determine signs and symptoms that can lead to expedited and cost-efficient testing.

Consequences

POI is an important risk factor for bone loss and osteoporosis, especially in young women who develop ovarian dysfunction before they achieve peak adult bone mass. At the time of diagnosis of POI, a bone density test (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) should be obtained. Women with POI may also develop depression and anxiety as well as experience an increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, possibly related to endothelial dysfunction.

Young women with spontaneous POI are at increased risk of developing autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (AAI), a potentially fatal disorder. Consequently, to diagnose AAI, serum adrenal cortical and 21-hydroxylase antibodies should be measured in all women who have a karyotype of 46,XX and experience spontaneous POI. Women with AAI have a 50% risk of developing adrenal insufficiency. Despite initial normal adrenal function, women with positive adrenal cortical antibodies should be followed annually.

Causes (see table for a more complete list)

Iatrogenic

Known causes of POI include chemotherapy/radiation often in the setting of cancer treatment. The three most commonly used drugs, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and doxorubicin, cause POI by inducing death and/or accelerated activation of primordial follicles and increased atresia of growing follicles. The most damaging agents are alkylating drugs. A cyclophosphamide equivalent dose calculator has been established for ovarian failure risk stratification from chemotherapy based on the cumulative dose of alkylating agents received.

One study estimated the radiosensitivity of the oocyte to be less than 2 Gy. Based upon this estimate, the authors calculated the dose of radiotherapy that would result in immediate and permanent ovarian failure in 97.5% of patients as follows:

- 20.3 Gy at birth

- 18.4 Gy at age 10 years

- 16.5 Gy at age 20 years

- 14.3 Gy at age 30 years

Genetic

Approximately 10% of cases are familial. A family history of POI raises concern for a fragile X premutation. Fragile X syndrome is an X-linked form of intellectual disability that is one of the most common causes of mental retardation worldwide. There is a strong relationship between age at menopause, including POI, and premutations for fragile X syndrome. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women with POI or an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level before age 40 years without known cause be screened for FMR1 premutations. Approximately 6% of cases of POI are associated with premutations in the FMR1 gene.

Turner syndrome is one of the most common causes of POI and results from the lack of a second X chromosome. The most common chromosomal defect in humans, TS occurs in up to 1.5% of conceptions, 10% of spontaneous abortions, and 1 of 2,500 live births.

Serum antiadrenal and/or anti–21-hydroxylase antibodies and antithyroid antiperoxidase antibodies, can aid in the diagnosis of adrenal gland, ovary, and thyroid autoimmune causes, which is found in 4% of women with spontaneous POI. Testing for the presence of 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies or adrenal autoantibodies is sufficient to make the diagnosis of autoimmune oophoritis in women with proven spontaneous POI.

The etiology of POI remains unknown in approximately 75%-90% of cases. However, studies using whole exome or whole genome sequencing have identified genetic variants in approximately 30%-35% of these patients.

Risk factors

Factors that are thought to play a role in determining the age of menopause, include genetics (e.g., FMR1 premutation and mosaic Turner syndrome), ethnicity (earlier among Hispanic women and later in Japanese American women when compared with White women), and smoking (reduced by approximately 2 years ).

Regarding ovarian aging, the holy grail of the reproductive life span is to predict menopause. While the definitive age eludes us, anti-Müllerian hormone levels appear to show promise. An ultrasensitive anti-Müllerian hormone assay (< 0.01 ng/mL) predicted a 79% probability of menopause within 12 months for women aged 51 and above; the probability was 51% for women below age 48.

Diagnosis

The three P’s of secondary amenorrhea are physiological, pharmacological, or pathological and can guide the clinician to a targeted evaluation. Physiological causes are pregnancy, the first 6 months of continuous breastfeeding (from elevated prolactin), and natural menopause. Pharmacological etiologies, excluding hormonal treatment that suppresses ovulation (combined oral contraceptives, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist/antagonist, or danazol), include agents that inhibit dopamine thereby increasing serum prolactin, such as metoclopramide; phenothiazine antipsychotics, such as haloperidol; and tardive dystonia dopamine-depleting medications, such as reserpine. Pathological causes include pituitary adenomas, thyroid disease, functional hypothalamic amenorrhea from changes in weight, exercise regimen, and stress.

Management

About 50%-75% of women with 46,XX spontaneous POI experience intermittent ovarian function and 5%-10% of women remain able to conceive. Anecdotally, a 32-year-old woman presented to me with primary infertility, secondary amenorrhea, and suspected POI based on vasomotor symptoms and elevated FSH levels. Pelvic ultrasound showed a hemorrhagic cyst, suspicious for a corpus luteum. Two weeks thereafter she reported a positive home urine human chorionic gonadotropin test and ultimately delivered twins. Her diagnosis of POI with amenorrhea remained postpartum.

Unless there is an absolute contraindication, estrogen therapy should be prescribed to women with POI to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and urogenital atrophy as well as to maintain sexual health and quality of life. For those with an intact uterus, women should receive progesterone because of the risk of endometrial hyperplasia from unopposed estrogen. Rather than oral estrogen, the use of transdermal or vaginal delivery of estrogen is a more physiological approach and provides lower risks of venous thromboembolism and gallbladder disease. Of note, standard postmenopausal hormone therapy, which has a much lower dose of estrogen than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives, does not provide effective contraception. Per ACOG, systemic hormone treatment should be prescribed until age 50-51 years to all women with POI.

For fertility, women with spontaneous POI can be offered oocyte or embryo donation. The uterus does not age reproductively, unlike oocytes, therefore women can achieve reasonable pregnancy success rates through egg donation despite experiencing menopause.

Future potential options

Female germline stem cells have been isolated from neonatal mice and transplanted into sterile adult mice, who then were able to produce offspring. In a second study, oogonial stem cells were isolated from neonatal and adult mouse ovaries; pups were subsequently born from the oocytes. Further experiments are needed before the implications for humans can be determined.

Emotionally traumatic for most women, POI disrupts life plans, hopes, and dreams of raising a family. The approach to the patient with POI involves the above evidence-based testing along with empathy from the health care provider.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

In the presentation of secondary amenorrhea, pregnancy is the No. 1 differential diagnosis. Once this has been excluded, an algorithm is initiated to determine the etiology, including an assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. While the early onset of ovarian failure can be physically and psychologically disrupting, the effect on fertility is an especially devastating event. Previously identified by terms including premature ovarian failure and premature menopause, “primary ovarian insufficiency” (POI) is now the preferred designation. This month’s article will address the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of POI.

The definition of POI is the development of primary hypogonadism before the age of 40 years. Spontaneous POI occurs in approximately 1 in 250 women by age 35 years and 1 in 100 by age 40 years. After excluding pregnancy, the clinician should determine signs and symptoms that can lead to expedited and cost-efficient testing.

Consequences

POI is an important risk factor for bone loss and osteoporosis, especially in young women who develop ovarian dysfunction before they achieve peak adult bone mass. At the time of diagnosis of POI, a bone density test (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) should be obtained. Women with POI may also develop depression and anxiety as well as experience an increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, possibly related to endothelial dysfunction.

Young women with spontaneous POI are at increased risk of developing autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (AAI), a potentially fatal disorder. Consequently, to diagnose AAI, serum adrenal cortical and 21-hydroxylase antibodies should be measured in all women who have a karyotype of 46,XX and experience spontaneous POI. Women with AAI have a 50% risk of developing adrenal insufficiency. Despite initial normal adrenal function, women with positive adrenal cortical antibodies should be followed annually.

Causes (see table for a more complete list)

Iatrogenic

Known causes of POI include chemotherapy/radiation often in the setting of cancer treatment. The three most commonly used drugs, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and doxorubicin, cause POI by inducing death and/or accelerated activation of primordial follicles and increased atresia of growing follicles. The most damaging agents are alkylating drugs. A cyclophosphamide equivalent dose calculator has been established for ovarian failure risk stratification from chemotherapy based on the cumulative dose of alkylating agents received.

One study estimated the radiosensitivity of the oocyte to be less than 2 Gy. Based upon this estimate, the authors calculated the dose of radiotherapy that would result in immediate and permanent ovarian failure in 97.5% of patients as follows:

- 20.3 Gy at birth

- 18.4 Gy at age 10 years

- 16.5 Gy at age 20 years

- 14.3 Gy at age 30 years

Genetic

Approximately 10% of cases are familial. A family history of POI raises concern for a fragile X premutation. Fragile X syndrome is an X-linked form of intellectual disability that is one of the most common causes of mental retardation worldwide. There is a strong relationship between age at menopause, including POI, and premutations for fragile X syndrome. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women with POI or an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level before age 40 years without known cause be screened for FMR1 premutations. Approximately 6% of cases of POI are associated with premutations in the FMR1 gene.

Turner syndrome is one of the most common causes of POI and results from the lack of a second X chromosome. The most common chromosomal defect in humans, TS occurs in up to 1.5% of conceptions, 10% of spontaneous abortions, and 1 of 2,500 live births.

Serum antiadrenal and/or anti–21-hydroxylase antibodies and antithyroid antiperoxidase antibodies, can aid in the diagnosis of adrenal gland, ovary, and thyroid autoimmune causes, which is found in 4% of women with spontaneous POI. Testing for the presence of 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies or adrenal autoantibodies is sufficient to make the diagnosis of autoimmune oophoritis in women with proven spontaneous POI.

The etiology of POI remains unknown in approximately 75%-90% of cases. However, studies using whole exome or whole genome sequencing have identified genetic variants in approximately 30%-35% of these patients.

Risk factors

Factors that are thought to play a role in determining the age of menopause, include genetics (e.g., FMR1 premutation and mosaic Turner syndrome), ethnicity (earlier among Hispanic women and later in Japanese American women when compared with White women), and smoking (reduced by approximately 2 years ).

Regarding ovarian aging, the holy grail of the reproductive life span is to predict menopause. While the definitive age eludes us, anti-Müllerian hormone levels appear to show promise. An ultrasensitive anti-Müllerian hormone assay (< 0.01 ng/mL) predicted a 79% probability of menopause within 12 months for women aged 51 and above; the probability was 51% for women below age 48.

Diagnosis

The three P’s of secondary amenorrhea are physiological, pharmacological, or pathological and can guide the clinician to a targeted evaluation. Physiological causes are pregnancy, the first 6 months of continuous breastfeeding (from elevated prolactin), and natural menopause. Pharmacological etiologies, excluding hormonal treatment that suppresses ovulation (combined oral contraceptives, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist/antagonist, or danazol), include agents that inhibit dopamine thereby increasing serum prolactin, such as metoclopramide; phenothiazine antipsychotics, such as haloperidol; and tardive dystonia dopamine-depleting medications, such as reserpine. Pathological causes include pituitary adenomas, thyroid disease, functional hypothalamic amenorrhea from changes in weight, exercise regimen, and stress.

Management

About 50%-75% of women with 46,XX spontaneous POI experience intermittent ovarian function and 5%-10% of women remain able to conceive. Anecdotally, a 32-year-old woman presented to me with primary infertility, secondary amenorrhea, and suspected POI based on vasomotor symptoms and elevated FSH levels. Pelvic ultrasound showed a hemorrhagic cyst, suspicious for a corpus luteum. Two weeks thereafter she reported a positive home urine human chorionic gonadotropin test and ultimately delivered twins. Her diagnosis of POI with amenorrhea remained postpartum.

Unless there is an absolute contraindication, estrogen therapy should be prescribed to women with POI to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and urogenital atrophy as well as to maintain sexual health and quality of life. For those with an intact uterus, women should receive progesterone because of the risk of endometrial hyperplasia from unopposed estrogen. Rather than oral estrogen, the use of transdermal or vaginal delivery of estrogen is a more physiological approach and provides lower risks of venous thromboembolism and gallbladder disease. Of note, standard postmenopausal hormone therapy, which has a much lower dose of estrogen than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives, does not provide effective contraception. Per ACOG, systemic hormone treatment should be prescribed until age 50-51 years to all women with POI.

For fertility, women with spontaneous POI can be offered oocyte or embryo donation. The uterus does not age reproductively, unlike oocytes, therefore women can achieve reasonable pregnancy success rates through egg donation despite experiencing menopause.

Future potential options

Female germline stem cells have been isolated from neonatal mice and transplanted into sterile adult mice, who then were able to produce offspring. In a second study, oogonial stem cells were isolated from neonatal and adult mouse ovaries; pups were subsequently born from the oocytes. Further experiments are needed before the implications for humans can be determined.

Emotionally traumatic for most women, POI disrupts life plans, hopes, and dreams of raising a family. The approach to the patient with POI involves the above evidence-based testing along with empathy from the health care provider.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

‘Forever chemicals’ exposures may compound diabetes risk

Women in midlife exposed to combinations of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), dubbed “forever and everywhere chemicals”, are at increased risk of developing diabetes, similar to the magnitude of risk associated with overweight and even greater than the risk associated with smoking, new research shows.

“This is the first study to examine the joint effect of PFAS on incident diabetes,” first author Sung Kyun Park, ScD, MPH, told this news organization.

“We showed that multiple PFAS as mixtures have larger effects than individual PFAS,” said Dr. Park, of the department of epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The results suggest that, “given that 1.5 million Americans are newly diagnosed with diabetes each year in the USA, approximately 370,000 new cases of diabetes annually in the U.S. are attributable to PFAS exposure,” Dr. Park and authors note in the study, published in Diabetologia.

However, Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics, The Open University, U.K., told the UK Science Media Centre: “[Some] doubt about cause still remains. Yes, this study does show that PFAS may increase diabetes risk in middle-aged women, but it certainly can’t rule out other explanations for its findings.”

Is there any way to reduce exposure?

PFASs, known to be ubiquitous in the environment and also often dubbed “endocrine-disrupting” chemicals, have structures similar to fatty acids. They have been detected in the blood of most people and linked to health concerns including pre-eclampsia, altered levels of liver enzymes, inflammation, and altered lipid and glucose metabolism.

Sources of PFAS exposure can run the gamut from nonstick cookware, food wrappers, and waterproof fabrics to cosmetics and even drinking water.

The authors note a recent Consumer Reports investigation of 118 food packaging products, for instance, which reported finding PFAS chemicals in the packaging of every fast-food chain and retailer examined, including Burger King, McDonald’s, and even more health-focused chains, such as Trader Joe’s.

While efforts to pressure industry to limit PFAS in products are ongoing, Dr. Park asserted that “PFAS exposure reduction at the individual-level is very limited, so a more important way is to change policies and to limit PFAS in the air, drinking water, and foods, etc.”

“It is impossible to completely avoid exposure to PFAS, but I think it is important to acknowledge such sources and change our mindset,” he said.

In terms of clinical practice, the authors add that “it is also important for clinicians to be aware of PFAS as unrecognized risk factors for diabetes and to be prepared to counsel patients in terms of sources of exposure and potential health effects.”

Prospective findings from the SWAN-MPS study

The findings come from a prospective study of 1,237 women, with a median age of 49.4 years, who were diabetes-free upon entering the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation – Multi-Pollutant Study (SWAN-MPS) between 1999 and 2000 and followed until 2017.

Blood samples taken throughout the study were analyzed for serum concentrations of seven PFASs.

Over the study period, there were 102 cases of incident diabetes, representing a rate of 6 cases per 1,000 person-years. Type of diabetes was not determined, but given the age of study participants, most were assumed to have type 2 diabetes, Dr. Park and colleagues note.

After adjustment for key confounders including race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, total energy intake, physical activity, menopausal status, and body mass index (BMI), those in the highest tertile of exposure to a combination of all seven of the PFASs were significantly more likely to develop diabetes, compared with those in the lowest tertile for exposure (hazard ratio, 2.62).

This risk was greater than that seen with individual PFASs (HR, 1.36-1.85), suggesting a potential additive or synergistic effect of multiple PFASs on diabetes risk.

The association between the combined exposure to PFASs among the highest versus lowest tertile was similar to the risk of diabetes developing among those with overweight (BMI 25-< 30 kg/m2) versus normal weight (HR, 2.89) and higher than the risk among current versus never smokers (HR, 2.30).

“Our findings suggest that PFAS may be an important risk factor for diabetes that has a substantial public health impact,” the authors say.

“Given the widespread exposure to PFAS in the general population, the expected benefit of reducing exposure to these ubiquitous chemicals might be considerable,” they emphasize.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women in midlife exposed to combinations of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), dubbed “forever and everywhere chemicals”, are at increased risk of developing diabetes, similar to the magnitude of risk associated with overweight and even greater than the risk associated with smoking, new research shows.

“This is the first study to examine the joint effect of PFAS on incident diabetes,” first author Sung Kyun Park, ScD, MPH, told this news organization.

“We showed that multiple PFAS as mixtures have larger effects than individual PFAS,” said Dr. Park, of the department of epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The results suggest that, “given that 1.5 million Americans are newly diagnosed with diabetes each year in the USA, approximately 370,000 new cases of diabetes annually in the U.S. are attributable to PFAS exposure,” Dr. Park and authors note in the study, published in Diabetologia.

However, Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics, The Open University, U.K., told the UK Science Media Centre: “[Some] doubt about cause still remains. Yes, this study does show that PFAS may increase diabetes risk in middle-aged women, but it certainly can’t rule out other explanations for its findings.”

Is there any way to reduce exposure?

PFASs, known to be ubiquitous in the environment and also often dubbed “endocrine-disrupting” chemicals, have structures similar to fatty acids. They have been detected in the blood of most people and linked to health concerns including pre-eclampsia, altered levels of liver enzymes, inflammation, and altered lipid and glucose metabolism.

Sources of PFAS exposure can run the gamut from nonstick cookware, food wrappers, and waterproof fabrics to cosmetics and even drinking water.

The authors note a recent Consumer Reports investigation of 118 food packaging products, for instance, which reported finding PFAS chemicals in the packaging of every fast-food chain and retailer examined, including Burger King, McDonald’s, and even more health-focused chains, such as Trader Joe’s.

While efforts to pressure industry to limit PFAS in products are ongoing, Dr. Park asserted that “PFAS exposure reduction at the individual-level is very limited, so a more important way is to change policies and to limit PFAS in the air, drinking water, and foods, etc.”

“It is impossible to completely avoid exposure to PFAS, but I think it is important to acknowledge such sources and change our mindset,” he said.

In terms of clinical practice, the authors add that “it is also important for clinicians to be aware of PFAS as unrecognized risk factors for diabetes and to be prepared to counsel patients in terms of sources of exposure and potential health effects.”

Prospective findings from the SWAN-MPS study

The findings come from a prospective study of 1,237 women, with a median age of 49.4 years, who were diabetes-free upon entering the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation – Multi-Pollutant Study (SWAN-MPS) between 1999 and 2000 and followed until 2017.

Blood samples taken throughout the study were analyzed for serum concentrations of seven PFASs.

Over the study period, there were 102 cases of incident diabetes, representing a rate of 6 cases per 1,000 person-years. Type of diabetes was not determined, but given the age of study participants, most were assumed to have type 2 diabetes, Dr. Park and colleagues note.

After adjustment for key confounders including race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, total energy intake, physical activity, menopausal status, and body mass index (BMI), those in the highest tertile of exposure to a combination of all seven of the PFASs were significantly more likely to develop diabetes, compared with those in the lowest tertile for exposure (hazard ratio, 2.62).

This risk was greater than that seen with individual PFASs (HR, 1.36-1.85), suggesting a potential additive or synergistic effect of multiple PFASs on diabetes risk.

The association between the combined exposure to PFASs among the highest versus lowest tertile was similar to the risk of diabetes developing among those with overweight (BMI 25-< 30 kg/m2) versus normal weight (HR, 2.89) and higher than the risk among current versus never smokers (HR, 2.30).

“Our findings suggest that PFAS may be an important risk factor for diabetes that has a substantial public health impact,” the authors say.

“Given the widespread exposure to PFAS in the general population, the expected benefit of reducing exposure to these ubiquitous chemicals might be considerable,” they emphasize.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women in midlife exposed to combinations of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), dubbed “forever and everywhere chemicals”, are at increased risk of developing diabetes, similar to the magnitude of risk associated with overweight and even greater than the risk associated with smoking, new research shows.

“This is the first study to examine the joint effect of PFAS on incident diabetes,” first author Sung Kyun Park, ScD, MPH, told this news organization.

“We showed that multiple PFAS as mixtures have larger effects than individual PFAS,” said Dr. Park, of the department of epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The results suggest that, “given that 1.5 million Americans are newly diagnosed with diabetes each year in the USA, approximately 370,000 new cases of diabetes annually in the U.S. are attributable to PFAS exposure,” Dr. Park and authors note in the study, published in Diabetologia.

However, Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics, The Open University, U.K., told the UK Science Media Centre: “[Some] doubt about cause still remains. Yes, this study does show that PFAS may increase diabetes risk in middle-aged women, but it certainly can’t rule out other explanations for its findings.”

Is there any way to reduce exposure?

PFASs, known to be ubiquitous in the environment and also often dubbed “endocrine-disrupting” chemicals, have structures similar to fatty acids. They have been detected in the blood of most people and linked to health concerns including pre-eclampsia, altered levels of liver enzymes, inflammation, and altered lipid and glucose metabolism.

Sources of PFAS exposure can run the gamut from nonstick cookware, food wrappers, and waterproof fabrics to cosmetics and even drinking water.

The authors note a recent Consumer Reports investigation of 118 food packaging products, for instance, which reported finding PFAS chemicals in the packaging of every fast-food chain and retailer examined, including Burger King, McDonald’s, and even more health-focused chains, such as Trader Joe’s.

While efforts to pressure industry to limit PFAS in products are ongoing, Dr. Park asserted that “PFAS exposure reduction at the individual-level is very limited, so a more important way is to change policies and to limit PFAS in the air, drinking water, and foods, etc.”

“It is impossible to completely avoid exposure to PFAS, but I think it is important to acknowledge such sources and change our mindset,” he said.

In terms of clinical practice, the authors add that “it is also important for clinicians to be aware of PFAS as unrecognized risk factors for diabetes and to be prepared to counsel patients in terms of sources of exposure and potential health effects.”

Prospective findings from the SWAN-MPS study

The findings come from a prospective study of 1,237 women, with a median age of 49.4 years, who were diabetes-free upon entering the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation – Multi-Pollutant Study (SWAN-MPS) between 1999 and 2000 and followed until 2017.

Blood samples taken throughout the study were analyzed for serum concentrations of seven PFASs.

Over the study period, there were 102 cases of incident diabetes, representing a rate of 6 cases per 1,000 person-years. Type of diabetes was not determined, but given the age of study participants, most were assumed to have type 2 diabetes, Dr. Park and colleagues note.

After adjustment for key confounders including race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, total energy intake, physical activity, menopausal status, and body mass index (BMI), those in the highest tertile of exposure to a combination of all seven of the PFASs were significantly more likely to develop diabetes, compared with those in the lowest tertile for exposure (hazard ratio, 2.62).

This risk was greater than that seen with individual PFASs (HR, 1.36-1.85), suggesting a potential additive or synergistic effect of multiple PFASs on diabetes risk.

The association between the combined exposure to PFASs among the highest versus lowest tertile was similar to the risk of diabetes developing among those with overweight (BMI 25-< 30 kg/m2) versus normal weight (HR, 2.89) and higher than the risk among current versus never smokers (HR, 2.30).

“Our findings suggest that PFAS may be an important risk factor for diabetes that has a substantial public health impact,” the authors say.

“Given the widespread exposure to PFAS in the general population, the expected benefit of reducing exposure to these ubiquitous chemicals might be considerable,” they emphasize.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DIABETOLOGIA

SERMs revisited: Can they improve menopausal care?

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are unique synthetic compounds that bind to the estrogen receptor and initiate either estrogenic agonistic or antagonistic activity, depending on the confirmational change they produce on binding to the receptor. Many SERMs have come to market, others have not. Unlike estrogens, which regardless of dose or route of administration all carry risks as a boxed warning on the label, referred to as class labeling,1 various SERMs exert various effects in some tissues (uterus, vagina) while they have apparent class properties in others (bone, breast).2

The first SERM, for all practical purposes, was tamoxifen (although clomiphene citrate is often considered a SERM). Tamoxifen was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1978 for the treatment of breast cancer and, subsequently, for breast cancer risk reduction. It became the most widely prescribed anticancer drug worldwide.

Subsequently, when data showed that tamoxifen could produce a small number of endometrial cancers and a larger number of endometrial polyps,3,4 there was renewed interest in raloxifene. In preclinical animal studies, raloxifene behaved differently than tamoxifen in the uterus. After clinical trials with raloxifene showed uterine safety,5 the drug was FDA approved for prevention of osteoporosis in 1997, for treatment of osteoporosis in 1999, and for breast cancer risk reduction in 2009. Most clinicians are familiar with these 2 SERMs, which have been in clinical use for more than 4 and 2 decades, respectively.

Ospemifene: A third-generation SERM and its indications

Hormone deficiency from menopause causes vulvovaginal and urogenital changes as well as a multitude of symptoms and signs, including vulvar and vaginal thinning, loss of rugal folds, diminished elasticity, increased pH, and most notably dyspareunia. The nomenclature that previously described vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) has been expanded to include genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM).6 Unfortunately, many health care providers do not ask patients about GSM symptoms, and few women report their symptoms to their clinician.7 Furthermore, although low-dose local estrogens applied vaginally have been the mainstay of therapy for VVA/GSM, only 7% of symptomatic women use any pharmacologic agent,8 mainly because of fear of estrogens due to the class labeling mentioned above.

Ospemifene, a newer SERM, improved superficial cells and reduced parabasal cells as seen on a maturation index compared with placebo, according to results of multiple phase 3 clinical trials9,10; it also lowered vaginal pH and improved most bothersome symptoms (original studies were for dyspareunia). As a result, the FDA approved ospemifene for treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia from VVA of menopause.

Subsequent studies allowed for a broadened indication to include treatment of moderate to severe dryness due to menopause.11 The ospemifene label contains a boxed warning that states, “In the endometrium, [ospemifene] has estrogen agonistic effects.”12 Although ospemifene is not an estrogen (it’s a SERM), the label goes on to state, “There is an increased risk of endometrial cancer in a woman with a uterus who uses unopposed estrogens.” This statement caused The Medical Letter to initially suggest that patients who receive ospemifene also should receive a progestational agent—a suggestion they later retracted.13,14

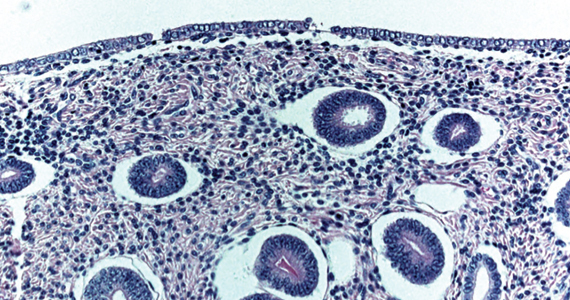

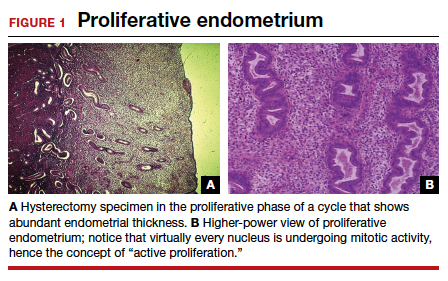

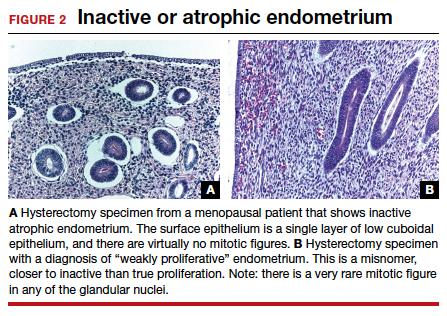

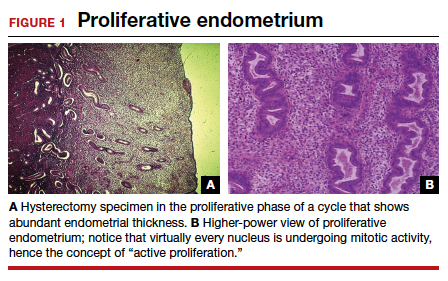

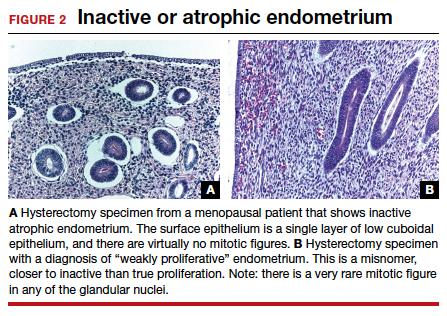

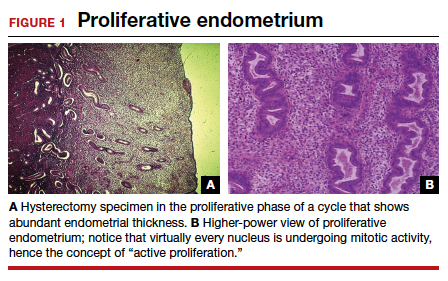

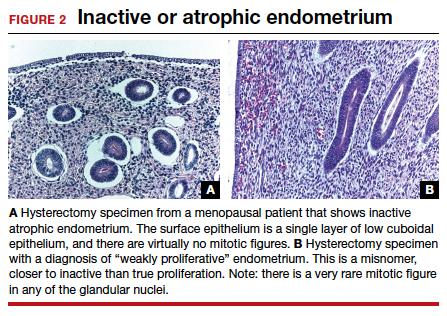

To understand why the ospemifene labeling might be worded in such a way, one must review the data regarding the poorly named entity “weakly proliferative endometrium.” The package labeling combines any proliferative endometrium (“weakly” plus “actively” plus “disordered”) that occurred in the clinical trial. Thus, 86.1 per 1,000 of the ospemifene-treated patients (vs 13.3 per 1,000 of those taking placebo) had any one of the proliferative types. The problem is that “actively proliferative” endometrial glands will have mitotic activity in virtually every nucleus of the gland as well as abundant glandular progression (FIGURE 1), whereas “weakly proliferative” is actually closer to inactive or atrophic endometrium with an occasional mitotic figure in only a few nuclei of each gland (FIGURE 2).

In addition, at 1 year, the incidence of active proliferation with ospemifene was 1%.15 In examining the uterine safety study for raloxifene, both doses of that agent had an active proliferation incidence of 3% at 1 year.5 Furthermore, that study had an estrogen-only arm in which, at end point, the incidence of endometrial proliferation was 39%, and hyperplasia, 23%!5 It therefore is evident that, in the endometrium, ospemifene is much more like the SERM raloxifene than it is like estrogen. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) endorsed ospemifene (level A evidence) as a first-line therapy for dyspareunia, noting absent endometrial stimulation.16

Continue to: Ospemifene effects on breast and bone...

Ospemifene effects on breast and bone

Although ospemifene is approved for treatment of moderate to severe VVA/GSM, it has other SERM effects typical of its class. The label currently states that ospemifene “has not been adequately studied in women with breast cancer; therefore, it should not be used in women with known or suspected breast cancer.”12 We know that tamoxifen reduced breast cancer 49% in high-risk women in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT).17 We also know that in the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial, raloxifene reduced breast cancer 77% in osteoporotic women,18 and in the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial, it performed virtually identically to tamoxifen in breast cancer prevention.19 Previous studies demonstrated that ospemifene inhibits breast cancer cell growth in in vitro cultures as well as in animal studies20 and inhibits proliferation of human breast tissue epithelial cells,21 with breast effects similar to those seen with tamoxifen and raloxifene.

Thus, although one would not choose ospemifene as a primary treatment or risk-reducing agent for a patient with breast cancer, the direction of its activity in breast tissue is indisputable and is likely the reason that in the European Union (unlike in the United States) it is approved to treat dyspareunia from VVA/GSM in women with a prior history of breast cancer.

Virtually all SERMs have estrogen agonistic activity in bone. Bone is a dynamic organ, constantly being laid down and taken away (resorption). Estrogen and SERMs are potent antiresorptives in bone metabolism. Ospemifene effectively reduced bone loss in ovariectomized rats, with activity comparable to that of estradiol and raloxifene.22 Clinical data from 3 phase 1 or 2 clinical trials found that ospemifene 60 mg/day had a positive effect on biochemical markers for bone turnover in healthy postmenopausal women, with significant improvements relative to placebo and effects comparable to those of raloxifene.23 Actual fracture or bone mineral density (BMD) data in postmenopausal women are lacking, but there is a good correlation between biochemical markers for bone turnover and the occurrence of fracture.24 Once again, women who need treatment for osteoporosis should not be treated primarily with ospemifene, but women who use ospemifene for dyspareunia can expect positive activity on bone metabolism.

Clinical application

Ospemifene is an oral SERM approved for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia as well as dryness from VVA due to menopause. In addition, it appears one can safely surmise that the direction of ospemifene’s activity in bone and breast is virtually indisputable. The magnitude of that activity, however, is unstudied. Therefore, in selecting an agent to treat women with dyspareunia or vaginal dryness from VVA of menopause, determining any potential add-on benefit for that particular patient in either bone and/or breast is clinically appropriate.

The SERM bazedoxifene

A meta-analysis of 4 randomized, placebo-controlled trials showed that another SERM, bazedoxifene, can significantly decrease the incidence of vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women at follow-up of 3 and 7 years.25 That meta-analysis also confirmed the long-term favorable safety and tolerability of bazedoxifene, with no increase in adverse events, serious adverse events, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolic events, or breast carcinoma in patients using bazedoxifene. However, bazedoxifene use did result in an increased incidence of hot flushes and leg cramps across 7 years.25 Bazedoxifene is available in a 20-mg dose for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Israel and a number of European Union countries.

Continue to: Enter the concept of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC)...

Enter the concept of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC)

Some postmenopausal women are extremely intolerant of any progestogen added to estrogen therapy to confer endometrial protection in those with a uterus. According to the results of a clinical trial of postmenopausal women, bazedoxifene is the only SERM shown to decrease endometrial thickness compared with placebo.26 This is the basis for thinking that perhaps a SERM like bazedoxifene, instead of a progestogen, could be used to confer endometrial protection.

A further consideration comes out of the evaluation of data derived from the 2 arms of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).27 In the arm that combined conjugated estrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate through 11.3 years, there was a 25% increase in the incidence of invasive breast cancer, which was statistically significant. Contrast that with the arm in hysterectomized women who received only conjugated estrogen (often inaccurately referred to as the “estrogen only” arm of the WHI). In that study arm, the relative risk of invasive breast cancer was reduced 23%, also statistically significant. Thus, the culprit in the breast cancer incidence difference in these 2 arms appears to be the addition of the progestogen medroxyprogesterone acetate.27

Since the progestogen was used only for endometrial protection, could such endometrial protection be provided by a SERM like bazedoxifene? Preclinical trials showed that a combination of bazedoxifene and conjugated estrogen (in various estrogen doses) resulted in uterine wet weight in an ovariectomized rat model that was no different than that with placebo.28

In terms of effects on breast, preclinical models showed that conjugated estrogen use resulted in less mammary duct elongation and end bud proliferation than estradiol by itself, and that the combination of conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene resulted in mammary duct elongation and end bud proliferation that was similar to that in the ovariectomized animals and considerably less than a combination of estradiol with bazedoxifene.29

Five phase 3 studies known as the SMART (Selective estrogens, Menopause, And Response to Therapy) trials were then conducted. Collectively, these studies examined the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms (VMS), BMD, bone turnover markers, lipid profiles, sleep, quality of life, breast density, and endometrial safety with conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene treatment.30 Based on these trials with more than 7,500 women, in 2013 the FDA approved a compound of conjugated estrogen 0.45 mg and bazedoxifene 20 mg (Duavee in the United States and Duavive outside the United States).

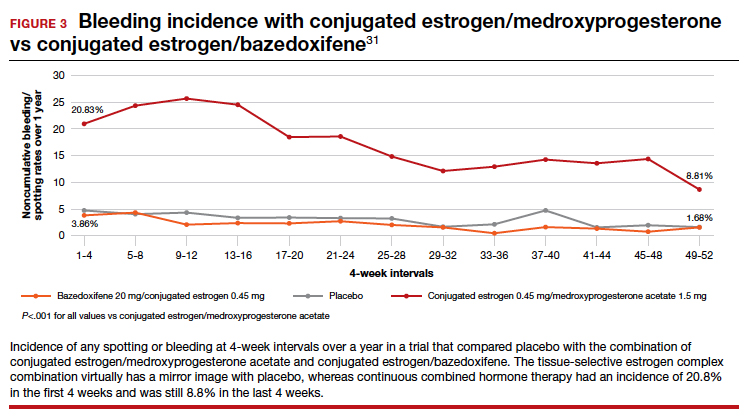

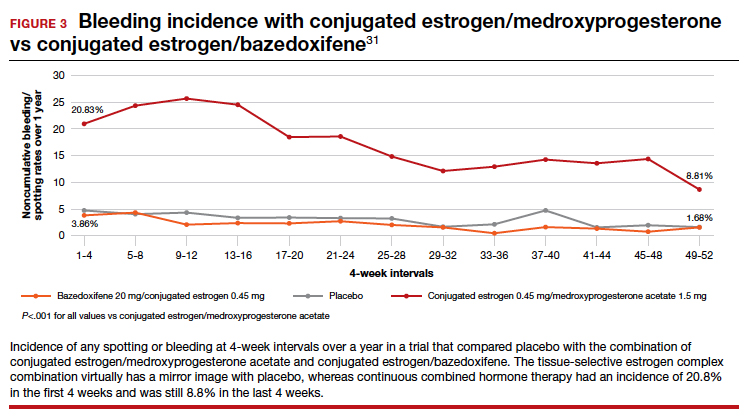

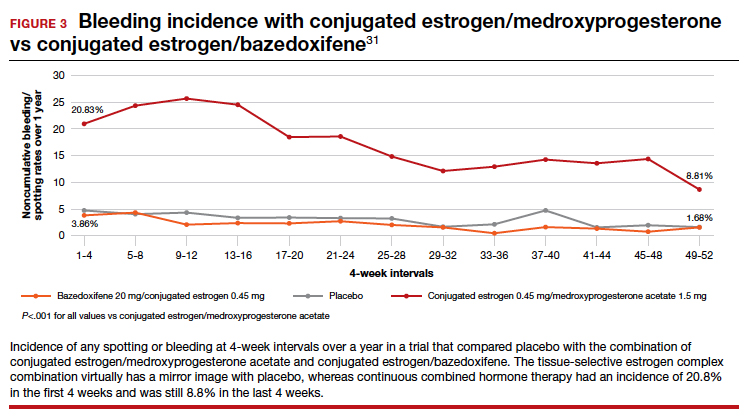

The incidence of endometrial hyperplasia at 12 months was consistently less than 1%, which is the FDA guidance for approval of hormone therapies. The incidence of bleeding or spotting with conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene (FIGURE 3) in each 4-week interval over 12 months mirror-imaged that of placebo and ranged from 3.9% in the first 4-week interval to 1.7% in the last 4 weeks, compared with conjugated estrogen 0.45 mg/medroxyprogesterone acetate 1.5 mg, which had a 20.8% incidence of bleeding or spotting in the first 4-week interval and was still at an 8.8% incidence in the last 4 weeks.31 This is extremely relevant in clinical practice. There was no difference from placebo in breast cancer incidence, breast pain or tenderness, abnormal mammograms, or breast density at month 12.32

In terms of frequency of VMS, there was a 74% reduction from baseline at 12 weeks compared with placebo (P<.001), as well as a 37% reduction in the VMS severity score (P<.001).32 Statistically significant improvements occurred in lumbar spine and hip BMD (P<.01) for women who were 1 to 5 years since menopause as well as for those who were more than 5 years since menopause.33

Packaging issue puts TSEC on back order

In May 2020, Pfizer voluntarily recalled its conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene product after identifying a “flaw in the drug’s foil laminate pouch that introduced oxygen and lowered the dissolution rate of active pharmaceutical ingredient bazedoxifene acetate.”34 The manufacturer then wrote a letter to health care professionals in September 2021 stating, “Duavee continues to be out of stock due to an unexpected and complex packaging issue, resulting in manufacturing delays. This has nothing to do with the safety or quality of the product itself but could affect product stability throughout its shelf life… Given regulatory approval timelines for any new packaging, it is unlikely that Duavee will return to stock in 2022.”35

Other TSECs?

The conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene combination is the first FDA-approved TSEC. Other attempts have been made to achieve similar results with combined raloxifene and 17β-estradiol.36 That study was meant to be a 52-week treatment trial with either raloxifene 60 mg alone or in combination with 17β-estradiol 1 mg per day to assess effects on VMS and endometrial safety. The study was stopped early because signs of endometrial stimulation were observed in the raloxifene plus estradiol group. Thus, one cannot combine any estrogen with any SERM and assume similar results.

Clinical application

The combination of conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene is approved for treatment of VMS of menopause as well as prevention of osteoporosis. Although it is not approved for treatment of moderate to severe VVA, in younger women who initiate treatment it should prevent the development of moderate to severe symptoms of VVA.

Finally, this drug should be protective of the breast. Conjugated estrogen has clearly shown a reduction in breast cancer incidence and mortality, and bazedoxifene is a SERM. All SERMs have, as a class effect, been shown to be antiestrogens in breast tissue, and abundant preclinical data point in that direction.

This combination of conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene, when it is once again clinically available, may well provide a new paradigm of hormone therapy that is progestogen free and has a benefit/risk ratio that tilts toward its benefits.

Potential for wider therapeutic benefits

Newer SERMs like ospemifene, approved for treatment of VVA/GSM, and bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogen combination, approved for treatment of VMS and prevention of bone loss, have other beneficial properties that can and should result in their more widespread use. ●

- Stuenkel CA. More evidence why the product labeling for low-dose vaginal estrogen should be changed? Menopause. 2018;25:4-6.

- Goldstein SR. Not all SERMs are created equal. Menopause. 2006;13:325-327.

- Neven P, De Muylder X, Van Belle Y, et al. Hysteroscopic follow-up during tamoxifen treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1990;35:235-238.

- Schwartz LB, Snyder J, Horan C, et al. The use of transvaginal ultrasound and saline infusion sonohysterography for the evaluation of asymptomatic postmenopausal breast cancer patients on tamoxifen. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;11:48-53.

- Goldstein SR, Scheele WH, Rajagopalan SK, et al. A 12-month comparative study of raloxifene, estrogen, and placebo on the postmenopausal endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:95-103.

- Portman DJ, Gass MLS. Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063-1068.

- Parish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML, et al. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:437-447.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman M, Graham S, et al. The Women’s EMPOWER Survey: identifying women’s perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy and its treatment. J Sex Med. 2017;14:413-424.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17:480-486.

- Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20:623-630.

- Archer DF, Goldstein SR, Simon JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ospemifene in postmenopausal women with moderateto-severe vaginal dryness: a phase 3, randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Menopause. 2019;26:611-621.

- Osphena. Package insert. Shionogi Inc; 2018.

- Ospemifene (Osphena) for dyspareunia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55:55-56.

- Addendum: Ospemifene (Osphena) for dyspareunia (Med Lett Drugs Ther 2013;55:55). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55:84.

- Goldstein SR, Bachmann G, Lin V, et al. Endometrial safety profile of ospemifene 60 mg when used for long-term treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy for up to 1 year. Abstract. Climacteric. 2011;14(suppl 1):S57.

- ACOG practice bulletin no. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371-1388.

- Cummings SR, Eckert S, Krueger KA, et al. The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: results from the MORE randomized trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation. JAMA. 1999;281:2189-2197.

- Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al; National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727-2741.

- Qu Q, Zheng H, Dahllund J, et al. Selective estrogenic effects of a novel triphenylethylene compound, FC1271a, on bone, cholesterol level, and reproductive tissues in intact and ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology. 2000;141:809-820.

- Eigeliene N, Kangas L, Hellmer C, et al. Effects of ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen-receptor modulator, on human breast tissue ex vivo. Menopause. 2016;23:719-730.

- Kangas L, Unkila M. Tissue selectivity of ospemifene: pharmacologic profile and clinical implications. Steroids. 2013;78:1273-1280.

- Constantine GD, Kagan R, Miller PD. Effects of ospemifene on bone parameters including clinical biomarkers in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016;23:638-644.

- Gerdhem P, Ivaska KK, Alatalo SL, et al. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism and prediction of fracture in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:386-393.

- Peng L, Luo Q, Lu H. Efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96(49):e8659.

- Ronkin S, Northington R, Baracat E, et al. Endometrial effects of bazedoxifene acetate, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator, in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1397-1404.

- Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:476-486.

- Kharode Y, Bodine PV, Miller CP, et al. The pairing of a selective estrogen receptor modulator, bazedoxifene, with conjugated estrogens as a new paradigm for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis prevention. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6084-6091.

- Song Y, Santen RJ, Wang JP, et al. Effects of the conjugated equine estrogen/bazedoxifene tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) on mammary gland and breast cancer in mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5706-5715.