User login

For MD-IQ use only

A 62-year-old Black female presented with an epidermal inclusion cyst on her left upper back

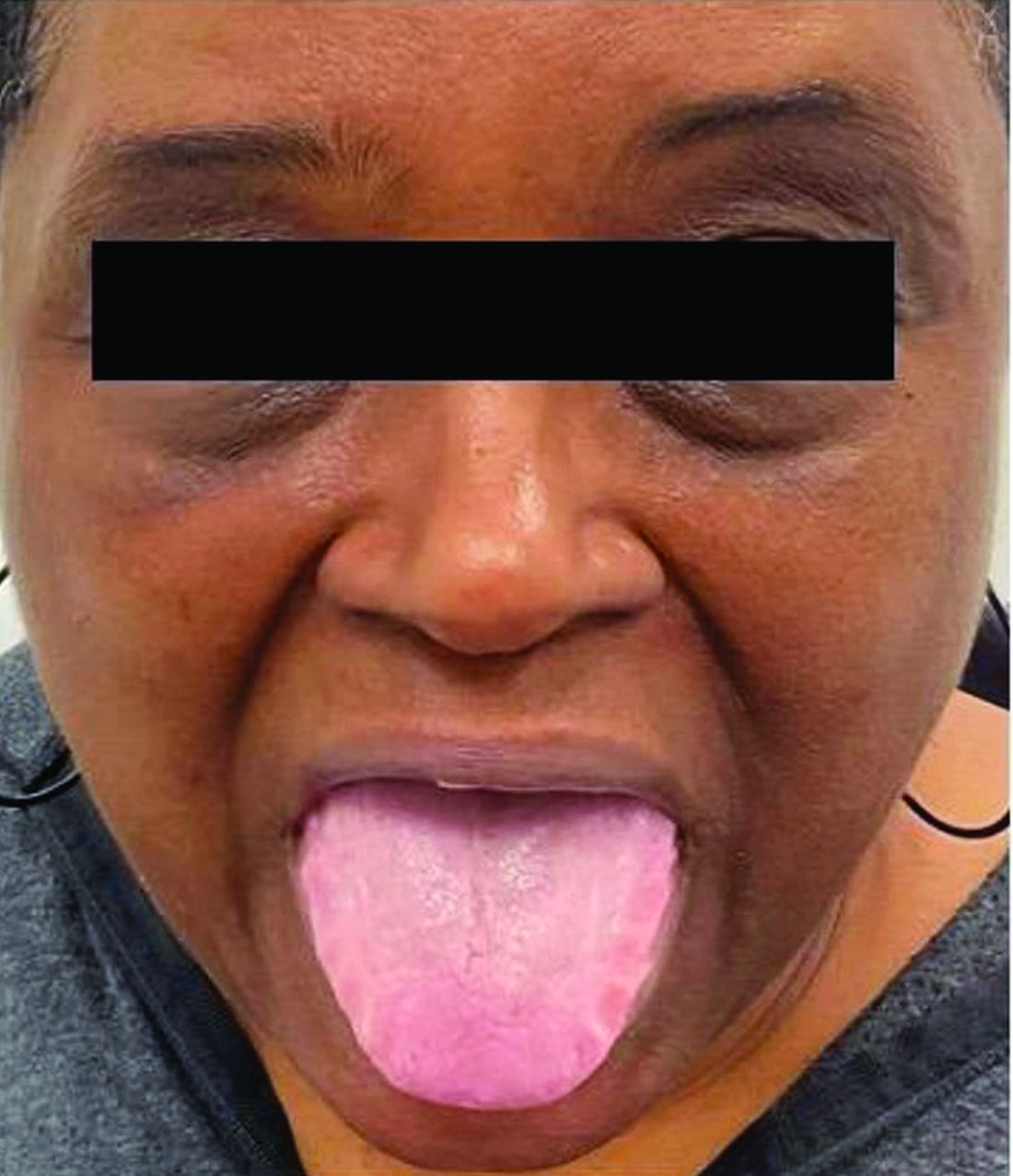

This heterogeneous disorder can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations, including dermatological symptoms that may be the first or predominant feature. Systemic amyloidosis is characterized by macroglossia, periorbital purpura, and waxy skin plaques. Lateral scalloping of the tongue may be seen due to impingement of the teeth. Cutaneous amyloidosis occurs when amyloid is deposited in the skin, without internal organ involvement. Variants of cutaneous amyloidosis include macular, lichen, nodular and biphasic.

This condition requires a thorough diagnostic workup, including serum and urine protein electrophoresis and biopsy of the affected tissue. Biopsy of a cutaneous amyloidosis lesion will show fractured, amorphous, eosinophilic material in the dermis. Pigment and epidermal changes are often found with cutaneous amyloidosis, including hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, parakeratosis, and epidermal atrophy. Stains that may be used include Congo red showing apple-green birefringence, thioflavin T, and crystal violet.

If untreated, the prognosis is generally poor, related to the extent of organ involvement. Cardiac involvement, a common feature of systemic amyloidosis, can lead to restrictive cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias. Management strategies include steroids, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplantation. Medications include dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and melphalan.

This patient went undiagnosed for several years until she began experiencing cardiac issues, including syncope, angina, and restrictive cardiomyopathy with heart failure. A cardiac biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis. This patient is currently awaiting a heart transplant. Early diagnosis of amyloidosis is vital, as it can help prevent severe complications such as heart involvement, significantly impacting the patient’s prognosis and quality of life. When amyloidosis is suspected based on dermatological findings, it is essential to distinguish it from other conditions, such as chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleromyxedema, and lipoid proteinosis. Early identification of characteristic skin lesions and systemic features can lead to timely interventions, more favorable outcomes, and reduction in the risk of advanced organ damage.

The case and photo were submitted by Ms. Cael Aoki and Mr. Shapiro of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Davie, Florida, and Dr. Bartos, of Imperial Dermatology, Hollywood, Florida. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Brunt EM, Tiniakos DG. Clin Liver Dis. 2004 Nov;8(4):915-30, x. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.06.009.

2. Bolognia JL et al. (2017). Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

3. Mehrotra K et al. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Aug;11(8):WC01-WC05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24273.10334.

4. Banypersad SM et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012 Apr;1(2):e000364. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000364.

5. Bustamante JG, Zaidi SRH. Amyloidosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

This heterogeneous disorder can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations, including dermatological symptoms that may be the first or predominant feature. Systemic amyloidosis is characterized by macroglossia, periorbital purpura, and waxy skin plaques. Lateral scalloping of the tongue may be seen due to impingement of the teeth. Cutaneous amyloidosis occurs when amyloid is deposited in the skin, without internal organ involvement. Variants of cutaneous amyloidosis include macular, lichen, nodular and biphasic.

This condition requires a thorough diagnostic workup, including serum and urine protein electrophoresis and biopsy of the affected tissue. Biopsy of a cutaneous amyloidosis lesion will show fractured, amorphous, eosinophilic material in the dermis. Pigment and epidermal changes are often found with cutaneous amyloidosis, including hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, parakeratosis, and epidermal atrophy. Stains that may be used include Congo red showing apple-green birefringence, thioflavin T, and crystal violet.

If untreated, the prognosis is generally poor, related to the extent of organ involvement. Cardiac involvement, a common feature of systemic amyloidosis, can lead to restrictive cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias. Management strategies include steroids, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplantation. Medications include dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and melphalan.

This patient went undiagnosed for several years until she began experiencing cardiac issues, including syncope, angina, and restrictive cardiomyopathy with heart failure. A cardiac biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis. This patient is currently awaiting a heart transplant. Early diagnosis of amyloidosis is vital, as it can help prevent severe complications such as heart involvement, significantly impacting the patient’s prognosis and quality of life. When amyloidosis is suspected based on dermatological findings, it is essential to distinguish it from other conditions, such as chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleromyxedema, and lipoid proteinosis. Early identification of characteristic skin lesions and systemic features can lead to timely interventions, more favorable outcomes, and reduction in the risk of advanced organ damage.

The case and photo were submitted by Ms. Cael Aoki and Mr. Shapiro of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Davie, Florida, and Dr. Bartos, of Imperial Dermatology, Hollywood, Florida. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Brunt EM, Tiniakos DG. Clin Liver Dis. 2004 Nov;8(4):915-30, x. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.06.009.

2. Bolognia JL et al. (2017). Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

3. Mehrotra K et al. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Aug;11(8):WC01-WC05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24273.10334.

4. Banypersad SM et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012 Apr;1(2):e000364. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000364.

5. Bustamante JG, Zaidi SRH. Amyloidosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

This heterogeneous disorder can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations, including dermatological symptoms that may be the first or predominant feature. Systemic amyloidosis is characterized by macroglossia, periorbital purpura, and waxy skin plaques. Lateral scalloping of the tongue may be seen due to impingement of the teeth. Cutaneous amyloidosis occurs when amyloid is deposited in the skin, without internal organ involvement. Variants of cutaneous amyloidosis include macular, lichen, nodular and biphasic.

This condition requires a thorough diagnostic workup, including serum and urine protein electrophoresis and biopsy of the affected tissue. Biopsy of a cutaneous amyloidosis lesion will show fractured, amorphous, eosinophilic material in the dermis. Pigment and epidermal changes are often found with cutaneous amyloidosis, including hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, parakeratosis, and epidermal atrophy. Stains that may be used include Congo red showing apple-green birefringence, thioflavin T, and crystal violet.

If untreated, the prognosis is generally poor, related to the extent of organ involvement. Cardiac involvement, a common feature of systemic amyloidosis, can lead to restrictive cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias. Management strategies include steroids, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplantation. Medications include dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and melphalan.

This patient went undiagnosed for several years until she began experiencing cardiac issues, including syncope, angina, and restrictive cardiomyopathy with heart failure. A cardiac biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis. This patient is currently awaiting a heart transplant. Early diagnosis of amyloidosis is vital, as it can help prevent severe complications such as heart involvement, significantly impacting the patient’s prognosis and quality of life. When amyloidosis is suspected based on dermatological findings, it is essential to distinguish it from other conditions, such as chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleromyxedema, and lipoid proteinosis. Early identification of characteristic skin lesions and systemic features can lead to timely interventions, more favorable outcomes, and reduction in the risk of advanced organ damage.

The case and photo were submitted by Ms. Cael Aoki and Mr. Shapiro of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Davie, Florida, and Dr. Bartos, of Imperial Dermatology, Hollywood, Florida. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Brunt EM, Tiniakos DG. Clin Liver Dis. 2004 Nov;8(4):915-30, x. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.06.009.

2. Bolognia JL et al. (2017). Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

3. Mehrotra K et al. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Aug;11(8):WC01-WC05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24273.10334.

4. Banypersad SM et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012 Apr;1(2):e000364. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000364.

5. Bustamante JG, Zaidi SRH. Amyloidosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

Diagnosing, Treating Rashes In Patients on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

WASHINGTON, DC — and with judicious usage and dosing of prednisone when deemed necessary, Blair Allais, MD, said during a session on supportive oncodermatology at the ElderDerm conference on dermatology in the older patient hosted by the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

“It’s important when you see these patients to be as specific as possible” based on morphology and histopathology, and to treat the rashes in a similar way as in the non-ICI setting,” said Dr. Allais, a dermato-oncologist at the Inova Schar Cancer Institute, Fairfax, Virginia.

cirAEs are the most frequently reported and most visible adverse effects of checkpoint inhibition — a treatment that has emerged as a standard therapy for many malignancies since the first ICI was approved in 2011 for metastatic melanoma.

And contrary to what the phenomenon of immunosenescence might suggest, older patients are no less prone to cirAEs than younger patients. “You’d think you’d have fewer rashes and side effects as you age, but that’s not true,” said Dr. Allais, who completed a fellowship in cutaneous oncology after her dermatology residency.

A 2021 multicenter international cohort study of over 900 patients aged ≥ 80 years treated with single-agent ICIs for cancer did not find any significant differences in the development of immune-related adverse events among those younger than 85, those aged 85-89 years, and those 90 and older. Neither did the ELDERS study in the United Kingdom; this prospective observational study found similar rates of high-grade and low-grade immune toxicity in its two cohorts of patients ≥ 70 and < 70 years of age.

At the meeting, Dr. Allais, who coauthored a 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs, reviewed recent developments and provided the following advice:

New diagnostic criteria: “Really exciting” news for more precise diagnosis and optimal therapy of cirAEs, Dr. Allais said, is a position paper published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer that offers consensus-based diagnostic criteria for the 10 most common types of dermatologic immune-related adverse events and an overall diagnostic framework. “Luckily, through the work of a Delphi consensus group, we can now have [more diagnostic specificity],” which is important for both clinical care and research, she said.

Most cirAEs have typically been reported nonspecifically as “rash,” but diagnosing a rash subtype is “critical in tailoring appropriate therapy that it is both effective and the least detrimental to the oncology treatment plan for patients with cancer,” the group’s coauthors wrote.

The 10 core diagnoses include psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, vitiligo, Grover disease, eruptive atypical squamous proliferation, and bullous pemphigoid. Outside of the core diagnoses are other nonspecific presentations that require evaluation to arrive at a diagnosis, if possible, or to reveal data that can allow for targeted therapy and severity grading, the group explains in its paper.

“To prednisone or not to prednisone”: The development of cirAEs is associated with reduced mortality and improved cancer outcomes, making the use of immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids a therapeutic dilemma. “Patients who get these rashes usually do better with respect to their cancer, so the concern has been, if we affect how they respond to their immunotherapy, we may minimize that improvement in mortality,” said Dr. Allais, also assistant professor at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and clinical assistant professor of dermatology at George Washington University.

A widely discussed study published in 2015 reported on 254 patients with melanoma who developed an immune-related adverse event during treatment with ipilimumab — approximately one third of whom required systemic corticosteroids — and concluded that systemic corticosteroids did not affect overall survival or time to (cancer) treatment failure. This study from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York City, “was the first large study looking at this question,” she said, and the subsequent message for several years in conferences and the literature was that steroids do not affect the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors.

“But the study was not without limitations,” Dr. Allais said, “because the patients who got prednisone were mainly those with higher-grade toxicities,” while those not treated with corticosteroids had either no toxicities or low-grade toxicities. “If higher-grade toxicities were associated with better (antitumor) response, the steroids may have just [blunted] that benefit.”

The current totality of data available in the literature suggests that corticosteroids may indeed have an impact on the efficacy of ICI therapy. “Subsequent studies have come out in the community that have shown that we should probably think twice about giving prednisone to some patients, particularly within the first 50 days of ICI treatment, and that we should be mindful of the dose,” Dr. Allais said.

The takeaways from these studies — all published in the past few years — are to use prednisone early and liberally for life-threatening toxicity, to use it at the lowest dose and for the shortest course when there is not an appropriate alternative, to avoid it for diagnoses that are not treated with prednisone outside the ICI setting, and to “have a plan” for a steroid-sparing agent to use after prednisone, she said.

Dr. Allais recommends heightened consideration during the first 50 days of ICI treatment based on a multicenter retrospective study that found a significant association between use of high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 60 mg prednisone equivalent once a day) within 8 weeks of anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monotherapy initiation and poorer progression-free and overall survival. The study covered a cohort of 947 patients with advanced melanoma treated with anti–PD-1 monotherapy between 2009 and 2019, 54% of whom developed immune-related adverse events.

This study and other recent studies addressing the association between steroids and survival outcomes in patients with immune-related adverse events during ICI therapy are described in Dr. Allais’ 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs.

Approach to morbilliform eruptions: This rash is “super common” in patients on ICIs, occurring generally within 2-3 weeks of starting treatment. “It tends to be self-limited and can recur with future infusions,” Dr. Allais said.

Systemic steroids should be reserved for severe or refractory eruptions. “Usually, I treat the patients with topical steroids, and I manage their expectations (that the rash may recur with subsequent infusions), but I closely follow them up” within 2-3 weeks, she said. It’s important to rule out a severe cutaneous adverse drug eruption, of course, and to start high-dose systemic steroids immediately if necessary. “Antibiotics are a big culprit” and often can be discontinued.

Soak and smear: “I’m obsessed” with this technique of a 20-minute soak in plain water followed by application of steroid ointment, said Dr. Allais, referring to a small study published in 2005 that reported a complete response after 2 weeks in 60% of patients with psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and other inflammatory skin conditions (none had cancer), who had failed prior systemic therapy. All patients had at least a 75% response.

The method offers a way to “avoid the systemic immunosuppression we’d get with prednisone,” she said. One just needs to make sure the older patient can get in and out of their tub safely.

ICI-induced bullous pemphigoid (BP): BP occurs more frequently in the ICI setting, compared with the general population, with a median time to development of 8.5 months after ICI initiation. It is associated in this setting with improved tumor response, but “many oncologists stop anticancer treatment because of this diagnosis,” she said.

In the supportive oncodermatology space, however, ICI-induced BP exemplifies the value of tailored treatment regimens, she said. A small multi-institutional retrospective cohort study published in 2023 identified 35 cases of ICI-BP among 5636 ICI-treated patients and found that 8 out of 11 patients who received biologic therapy (rituximab, omalizumab, or dupilumab) had a complete response to ICI-BP without flares following subsequent ICI cycles. And while statistical significance was not reached, the study showed that no cancer-related outcomes were worsened.

“If you see someone with ICI-induced BP and they have a lot of involvement, you could start them on steroids and get that steroid-sparing agent initiated for approval. ... And if IgE is elevated, you might reach for omalizumab,” said Dr. Allais, noting that her favored treatment overall is dupilumab.

Risk factors for the development of ICI-induced BP include age > 70, skin cancer, and having an initial response to ICI on first imaging, the latter of which “I find fascinating ... because imaging occurs within the first 12 weeks of treatment, but we don’t see BP popping up until 8.5 months into treatment,” she noted. “So maybe there’s a baseline risk factor that could predispose them.”

Caution with antibiotics: “I try to avoid antibiotics in the ICI setting,” Dr. Allais said, in deference to the “ever-important microbiome.” Studies have demonstrated that the microbiomes of responders to ICI treatment are different from those of nonresponders, she said.

And a “fascinating” study of patients with melanoma undergoing ICI therapy showed not only a higher abundance of Ruminococcaceae bacteria in responders vs nonresponders but a significant impact of dietary fiber. High dietary fiber was associated with significantly improved overall survival in the patients on ICI, with the most pronounced benefit in patients with good fiber intake and no probiotic use. “Even wilder, their T cells changed,” she said. “They had a high expression of genes related to T-cell activation ... so more tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.”

A retrospective study of 568 patients with stages III and IV melanoma treated with ICI showed that those exposed to antibiotics prior to ICI had significantly worse overall survival than those not exposed to antibiotics. “Think before you give them,” Dr. Allais said. “And try to tell your older patients to eat beans and greens.”

Dr. Allais reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON, DC — and with judicious usage and dosing of prednisone when deemed necessary, Blair Allais, MD, said during a session on supportive oncodermatology at the ElderDerm conference on dermatology in the older patient hosted by the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

“It’s important when you see these patients to be as specific as possible” based on morphology and histopathology, and to treat the rashes in a similar way as in the non-ICI setting,” said Dr. Allais, a dermato-oncologist at the Inova Schar Cancer Institute, Fairfax, Virginia.

cirAEs are the most frequently reported and most visible adverse effects of checkpoint inhibition — a treatment that has emerged as a standard therapy for many malignancies since the first ICI was approved in 2011 for metastatic melanoma.

And contrary to what the phenomenon of immunosenescence might suggest, older patients are no less prone to cirAEs than younger patients. “You’d think you’d have fewer rashes and side effects as you age, but that’s not true,” said Dr. Allais, who completed a fellowship in cutaneous oncology after her dermatology residency.

A 2021 multicenter international cohort study of over 900 patients aged ≥ 80 years treated with single-agent ICIs for cancer did not find any significant differences in the development of immune-related adverse events among those younger than 85, those aged 85-89 years, and those 90 and older. Neither did the ELDERS study in the United Kingdom; this prospective observational study found similar rates of high-grade and low-grade immune toxicity in its two cohorts of patients ≥ 70 and < 70 years of age.

At the meeting, Dr. Allais, who coauthored a 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs, reviewed recent developments and provided the following advice:

New diagnostic criteria: “Really exciting” news for more precise diagnosis and optimal therapy of cirAEs, Dr. Allais said, is a position paper published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer that offers consensus-based diagnostic criteria for the 10 most common types of dermatologic immune-related adverse events and an overall diagnostic framework. “Luckily, through the work of a Delphi consensus group, we can now have [more diagnostic specificity],” which is important for both clinical care and research, she said.

Most cirAEs have typically been reported nonspecifically as “rash,” but diagnosing a rash subtype is “critical in tailoring appropriate therapy that it is both effective and the least detrimental to the oncology treatment plan for patients with cancer,” the group’s coauthors wrote.

The 10 core diagnoses include psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, vitiligo, Grover disease, eruptive atypical squamous proliferation, and bullous pemphigoid. Outside of the core diagnoses are other nonspecific presentations that require evaluation to arrive at a diagnosis, if possible, or to reveal data that can allow for targeted therapy and severity grading, the group explains in its paper.

“To prednisone or not to prednisone”: The development of cirAEs is associated with reduced mortality and improved cancer outcomes, making the use of immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids a therapeutic dilemma. “Patients who get these rashes usually do better with respect to their cancer, so the concern has been, if we affect how they respond to their immunotherapy, we may minimize that improvement in mortality,” said Dr. Allais, also assistant professor at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and clinical assistant professor of dermatology at George Washington University.

A widely discussed study published in 2015 reported on 254 patients with melanoma who developed an immune-related adverse event during treatment with ipilimumab — approximately one third of whom required systemic corticosteroids — and concluded that systemic corticosteroids did not affect overall survival or time to (cancer) treatment failure. This study from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York City, “was the first large study looking at this question,” she said, and the subsequent message for several years in conferences and the literature was that steroids do not affect the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors.

“But the study was not without limitations,” Dr. Allais said, “because the patients who got prednisone were mainly those with higher-grade toxicities,” while those not treated with corticosteroids had either no toxicities or low-grade toxicities. “If higher-grade toxicities were associated with better (antitumor) response, the steroids may have just [blunted] that benefit.”

The current totality of data available in the literature suggests that corticosteroids may indeed have an impact on the efficacy of ICI therapy. “Subsequent studies have come out in the community that have shown that we should probably think twice about giving prednisone to some patients, particularly within the first 50 days of ICI treatment, and that we should be mindful of the dose,” Dr. Allais said.

The takeaways from these studies — all published in the past few years — are to use prednisone early and liberally for life-threatening toxicity, to use it at the lowest dose and for the shortest course when there is not an appropriate alternative, to avoid it for diagnoses that are not treated with prednisone outside the ICI setting, and to “have a plan” for a steroid-sparing agent to use after prednisone, she said.

Dr. Allais recommends heightened consideration during the first 50 days of ICI treatment based on a multicenter retrospective study that found a significant association between use of high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 60 mg prednisone equivalent once a day) within 8 weeks of anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monotherapy initiation and poorer progression-free and overall survival. The study covered a cohort of 947 patients with advanced melanoma treated with anti–PD-1 monotherapy between 2009 and 2019, 54% of whom developed immune-related adverse events.

This study and other recent studies addressing the association between steroids and survival outcomes in patients with immune-related adverse events during ICI therapy are described in Dr. Allais’ 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs.

Approach to morbilliform eruptions: This rash is “super common” in patients on ICIs, occurring generally within 2-3 weeks of starting treatment. “It tends to be self-limited and can recur with future infusions,” Dr. Allais said.

Systemic steroids should be reserved for severe or refractory eruptions. “Usually, I treat the patients with topical steroids, and I manage their expectations (that the rash may recur with subsequent infusions), but I closely follow them up” within 2-3 weeks, she said. It’s important to rule out a severe cutaneous adverse drug eruption, of course, and to start high-dose systemic steroids immediately if necessary. “Antibiotics are a big culprit” and often can be discontinued.

Soak and smear: “I’m obsessed” with this technique of a 20-minute soak in plain water followed by application of steroid ointment, said Dr. Allais, referring to a small study published in 2005 that reported a complete response after 2 weeks in 60% of patients with psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and other inflammatory skin conditions (none had cancer), who had failed prior systemic therapy. All patients had at least a 75% response.

The method offers a way to “avoid the systemic immunosuppression we’d get with prednisone,” she said. One just needs to make sure the older patient can get in and out of their tub safely.

ICI-induced bullous pemphigoid (BP): BP occurs more frequently in the ICI setting, compared with the general population, with a median time to development of 8.5 months after ICI initiation. It is associated in this setting with improved tumor response, but “many oncologists stop anticancer treatment because of this diagnosis,” she said.

In the supportive oncodermatology space, however, ICI-induced BP exemplifies the value of tailored treatment regimens, she said. A small multi-institutional retrospective cohort study published in 2023 identified 35 cases of ICI-BP among 5636 ICI-treated patients and found that 8 out of 11 patients who received biologic therapy (rituximab, omalizumab, or dupilumab) had a complete response to ICI-BP without flares following subsequent ICI cycles. And while statistical significance was not reached, the study showed that no cancer-related outcomes were worsened.

“If you see someone with ICI-induced BP and they have a lot of involvement, you could start them on steroids and get that steroid-sparing agent initiated for approval. ... And if IgE is elevated, you might reach for omalizumab,” said Dr. Allais, noting that her favored treatment overall is dupilumab.

Risk factors for the development of ICI-induced BP include age > 70, skin cancer, and having an initial response to ICI on first imaging, the latter of which “I find fascinating ... because imaging occurs within the first 12 weeks of treatment, but we don’t see BP popping up until 8.5 months into treatment,” she noted. “So maybe there’s a baseline risk factor that could predispose them.”

Caution with antibiotics: “I try to avoid antibiotics in the ICI setting,” Dr. Allais said, in deference to the “ever-important microbiome.” Studies have demonstrated that the microbiomes of responders to ICI treatment are different from those of nonresponders, she said.

And a “fascinating” study of patients with melanoma undergoing ICI therapy showed not only a higher abundance of Ruminococcaceae bacteria in responders vs nonresponders but a significant impact of dietary fiber. High dietary fiber was associated with significantly improved overall survival in the patients on ICI, with the most pronounced benefit in patients with good fiber intake and no probiotic use. “Even wilder, their T cells changed,” she said. “They had a high expression of genes related to T-cell activation ... so more tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.”

A retrospective study of 568 patients with stages III and IV melanoma treated with ICI showed that those exposed to antibiotics prior to ICI had significantly worse overall survival than those not exposed to antibiotics. “Think before you give them,” Dr. Allais said. “And try to tell your older patients to eat beans and greens.”

Dr. Allais reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON, DC — and with judicious usage and dosing of prednisone when deemed necessary, Blair Allais, MD, said during a session on supportive oncodermatology at the ElderDerm conference on dermatology in the older patient hosted by the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

“It’s important when you see these patients to be as specific as possible” based on morphology and histopathology, and to treat the rashes in a similar way as in the non-ICI setting,” said Dr. Allais, a dermato-oncologist at the Inova Schar Cancer Institute, Fairfax, Virginia.

cirAEs are the most frequently reported and most visible adverse effects of checkpoint inhibition — a treatment that has emerged as a standard therapy for many malignancies since the first ICI was approved in 2011 for metastatic melanoma.

And contrary to what the phenomenon of immunosenescence might suggest, older patients are no less prone to cirAEs than younger patients. “You’d think you’d have fewer rashes and side effects as you age, but that’s not true,” said Dr. Allais, who completed a fellowship in cutaneous oncology after her dermatology residency.

A 2021 multicenter international cohort study of over 900 patients aged ≥ 80 years treated with single-agent ICIs for cancer did not find any significant differences in the development of immune-related adverse events among those younger than 85, those aged 85-89 years, and those 90 and older. Neither did the ELDERS study in the United Kingdom; this prospective observational study found similar rates of high-grade and low-grade immune toxicity in its two cohorts of patients ≥ 70 and < 70 years of age.

At the meeting, Dr. Allais, who coauthored a 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs, reviewed recent developments and provided the following advice:

New diagnostic criteria: “Really exciting” news for more precise diagnosis and optimal therapy of cirAEs, Dr. Allais said, is a position paper published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer that offers consensus-based diagnostic criteria for the 10 most common types of dermatologic immune-related adverse events and an overall diagnostic framework. “Luckily, through the work of a Delphi consensus group, we can now have [more diagnostic specificity],” which is important for both clinical care and research, she said.

Most cirAEs have typically been reported nonspecifically as “rash,” but diagnosing a rash subtype is “critical in tailoring appropriate therapy that it is both effective and the least detrimental to the oncology treatment plan for patients with cancer,” the group’s coauthors wrote.

The 10 core diagnoses include psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, vitiligo, Grover disease, eruptive atypical squamous proliferation, and bullous pemphigoid. Outside of the core diagnoses are other nonspecific presentations that require evaluation to arrive at a diagnosis, if possible, or to reveal data that can allow for targeted therapy and severity grading, the group explains in its paper.

“To prednisone or not to prednisone”: The development of cirAEs is associated with reduced mortality and improved cancer outcomes, making the use of immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids a therapeutic dilemma. “Patients who get these rashes usually do better with respect to their cancer, so the concern has been, if we affect how they respond to their immunotherapy, we may minimize that improvement in mortality,” said Dr. Allais, also assistant professor at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and clinical assistant professor of dermatology at George Washington University.

A widely discussed study published in 2015 reported on 254 patients with melanoma who developed an immune-related adverse event during treatment with ipilimumab — approximately one third of whom required systemic corticosteroids — and concluded that systemic corticosteroids did not affect overall survival or time to (cancer) treatment failure. This study from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York City, “was the first large study looking at this question,” she said, and the subsequent message for several years in conferences and the literature was that steroids do not affect the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors.

“But the study was not without limitations,” Dr. Allais said, “because the patients who got prednisone were mainly those with higher-grade toxicities,” while those not treated with corticosteroids had either no toxicities or low-grade toxicities. “If higher-grade toxicities were associated with better (antitumor) response, the steroids may have just [blunted] that benefit.”

The current totality of data available in the literature suggests that corticosteroids may indeed have an impact on the efficacy of ICI therapy. “Subsequent studies have come out in the community that have shown that we should probably think twice about giving prednisone to some patients, particularly within the first 50 days of ICI treatment, and that we should be mindful of the dose,” Dr. Allais said.

The takeaways from these studies — all published in the past few years — are to use prednisone early and liberally for life-threatening toxicity, to use it at the lowest dose and for the shortest course when there is not an appropriate alternative, to avoid it for diagnoses that are not treated with prednisone outside the ICI setting, and to “have a plan” for a steroid-sparing agent to use after prednisone, she said.

Dr. Allais recommends heightened consideration during the first 50 days of ICI treatment based on a multicenter retrospective study that found a significant association between use of high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 60 mg prednisone equivalent once a day) within 8 weeks of anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monotherapy initiation and poorer progression-free and overall survival. The study covered a cohort of 947 patients with advanced melanoma treated with anti–PD-1 monotherapy between 2009 and 2019, 54% of whom developed immune-related adverse events.

This study and other recent studies addressing the association between steroids and survival outcomes in patients with immune-related adverse events during ICI therapy are described in Dr. Allais’ 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs.

Approach to morbilliform eruptions: This rash is “super common” in patients on ICIs, occurring generally within 2-3 weeks of starting treatment. “It tends to be self-limited and can recur with future infusions,” Dr. Allais said.

Systemic steroids should be reserved for severe or refractory eruptions. “Usually, I treat the patients with topical steroids, and I manage their expectations (that the rash may recur with subsequent infusions), but I closely follow them up” within 2-3 weeks, she said. It’s important to rule out a severe cutaneous adverse drug eruption, of course, and to start high-dose systemic steroids immediately if necessary. “Antibiotics are a big culprit” and often can be discontinued.

Soak and smear: “I’m obsessed” with this technique of a 20-minute soak in plain water followed by application of steroid ointment, said Dr. Allais, referring to a small study published in 2005 that reported a complete response after 2 weeks in 60% of patients with psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and other inflammatory skin conditions (none had cancer), who had failed prior systemic therapy. All patients had at least a 75% response.

The method offers a way to “avoid the systemic immunosuppression we’d get with prednisone,” she said. One just needs to make sure the older patient can get in and out of their tub safely.

ICI-induced bullous pemphigoid (BP): BP occurs more frequently in the ICI setting, compared with the general population, with a median time to development of 8.5 months after ICI initiation. It is associated in this setting with improved tumor response, but “many oncologists stop anticancer treatment because of this diagnosis,” she said.

In the supportive oncodermatology space, however, ICI-induced BP exemplifies the value of tailored treatment regimens, she said. A small multi-institutional retrospective cohort study published in 2023 identified 35 cases of ICI-BP among 5636 ICI-treated patients and found that 8 out of 11 patients who received biologic therapy (rituximab, omalizumab, or dupilumab) had a complete response to ICI-BP without flares following subsequent ICI cycles. And while statistical significance was not reached, the study showed that no cancer-related outcomes were worsened.

“If you see someone with ICI-induced BP and they have a lot of involvement, you could start them on steroids and get that steroid-sparing agent initiated for approval. ... And if IgE is elevated, you might reach for omalizumab,” said Dr. Allais, noting that her favored treatment overall is dupilumab.

Risk factors for the development of ICI-induced BP include age > 70, skin cancer, and having an initial response to ICI on first imaging, the latter of which “I find fascinating ... because imaging occurs within the first 12 weeks of treatment, but we don’t see BP popping up until 8.5 months into treatment,” she noted. “So maybe there’s a baseline risk factor that could predispose them.”

Caution with antibiotics: “I try to avoid antibiotics in the ICI setting,” Dr. Allais said, in deference to the “ever-important microbiome.” Studies have demonstrated that the microbiomes of responders to ICI treatment are different from those of nonresponders, she said.

And a “fascinating” study of patients with melanoma undergoing ICI therapy showed not only a higher abundance of Ruminococcaceae bacteria in responders vs nonresponders but a significant impact of dietary fiber. High dietary fiber was associated with significantly improved overall survival in the patients on ICI, with the most pronounced benefit in patients with good fiber intake and no probiotic use. “Even wilder, their T cells changed,” she said. “They had a high expression of genes related to T-cell activation ... so more tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.”

A retrospective study of 568 patients with stages III and IV melanoma treated with ICI showed that those exposed to antibiotics prior to ICI had significantly worse overall survival than those not exposed to antibiotics. “Think before you give them,” Dr. Allais said. “And try to tell your older patients to eat beans and greens.”

Dr. Allais reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ELDERDERM 2024

Jeffrey Weber, MD, PhD, Giant of Cancer Care, Dies

Dr. Weber, a melanoma and cancer immunotherapy specialist, served as deputy director of the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University (NYU) Langone Medical Center in New York City. He also held positions as the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Professor of Oncology in the Department of Medicine at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, director of the Experimental Therapeutics Program, and co-leader of the Clinical Melanoma Program Board at NYU Langone Health.

Dr. Weber was a principal investigator on many studies, including pivotal clinical drug trials in melanoma and trials focused on managing autoimmune side effects from immunotherapy. He published more than 150 articles in top peer-reviewed journals.

For many years, Dr. Weber hosted the popular “Weber on Oncology” series of video contributions for Medscape Oncology, sharing updates and insights on noteworthy research and breakthroughs in melanoma.

“The Melanoma Research Alliance mourns the passing of Dr. Jeffrey S. Weber, a true pioneer in the field of cancer immunotherapy and an extraordinary leader in melanoma research. His contributions have forever changed the landscape of melanoma treatment, bringing groundbreaking advances from the lab into clinical practice and offering hope to countless patients,” the Melanoma Research Alliance posted on LinkedIn.

Many X users also shared condolences and memories of Dr. Weber, praising his numerous contributions and accomplishments.

“[Cancer Research Institute] mourns the loss of Dr. Jeffrey S. Weber ... [a]s an accomplished physician scientist, Dr. Weber drove advances in melanoma research, and played an active role in educating patients about the lifesaving power of immunotherapy,” the Cancer Research Institute posted.

A colleague noted that “[h]e was involved in the early days of cytokine and cell therapy and most recently led studies of personalized vaccines for melanoma patients. ... He was a great friend and colleague to many of us in the melanoma and immunotherapy field and we will remember him as a pioneer, thought leader and compassionate physician.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dr. Weber, a melanoma and cancer immunotherapy specialist, served as deputy director of the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University (NYU) Langone Medical Center in New York City. He also held positions as the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Professor of Oncology in the Department of Medicine at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, director of the Experimental Therapeutics Program, and co-leader of the Clinical Melanoma Program Board at NYU Langone Health.

Dr. Weber was a principal investigator on many studies, including pivotal clinical drug trials in melanoma and trials focused on managing autoimmune side effects from immunotherapy. He published more than 150 articles in top peer-reviewed journals.

For many years, Dr. Weber hosted the popular “Weber on Oncology” series of video contributions for Medscape Oncology, sharing updates and insights on noteworthy research and breakthroughs in melanoma.

“The Melanoma Research Alliance mourns the passing of Dr. Jeffrey S. Weber, a true pioneer in the field of cancer immunotherapy and an extraordinary leader in melanoma research. His contributions have forever changed the landscape of melanoma treatment, bringing groundbreaking advances from the lab into clinical practice and offering hope to countless patients,” the Melanoma Research Alliance posted on LinkedIn.

Many X users also shared condolences and memories of Dr. Weber, praising his numerous contributions and accomplishments.

“[Cancer Research Institute] mourns the loss of Dr. Jeffrey S. Weber ... [a]s an accomplished physician scientist, Dr. Weber drove advances in melanoma research, and played an active role in educating patients about the lifesaving power of immunotherapy,” the Cancer Research Institute posted.

A colleague noted that “[h]e was involved in the early days of cytokine and cell therapy and most recently led studies of personalized vaccines for melanoma patients. ... He was a great friend and colleague to many of us in the melanoma and immunotherapy field and we will remember him as a pioneer, thought leader and compassionate physician.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dr. Weber, a melanoma and cancer immunotherapy specialist, served as deputy director of the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University (NYU) Langone Medical Center in New York City. He also held positions as the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Professor of Oncology in the Department of Medicine at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, director of the Experimental Therapeutics Program, and co-leader of the Clinical Melanoma Program Board at NYU Langone Health.

Dr. Weber was a principal investigator on many studies, including pivotal clinical drug trials in melanoma and trials focused on managing autoimmune side effects from immunotherapy. He published more than 150 articles in top peer-reviewed journals.

For many years, Dr. Weber hosted the popular “Weber on Oncology” series of video contributions for Medscape Oncology, sharing updates and insights on noteworthy research and breakthroughs in melanoma.

“The Melanoma Research Alliance mourns the passing of Dr. Jeffrey S. Weber, a true pioneer in the field of cancer immunotherapy and an extraordinary leader in melanoma research. His contributions have forever changed the landscape of melanoma treatment, bringing groundbreaking advances from the lab into clinical practice and offering hope to countless patients,” the Melanoma Research Alliance posted on LinkedIn.

Many X users also shared condolences and memories of Dr. Weber, praising his numerous contributions and accomplishments.

“[Cancer Research Institute] mourns the loss of Dr. Jeffrey S. Weber ... [a]s an accomplished physician scientist, Dr. Weber drove advances in melanoma research, and played an active role in educating patients about the lifesaving power of immunotherapy,” the Cancer Research Institute posted.

A colleague noted that “[h]e was involved in the early days of cytokine and cell therapy and most recently led studies of personalized vaccines for melanoma patients. ... He was a great friend and colleague to many of us in the melanoma and immunotherapy field and we will remember him as a pioneer, thought leader and compassionate physician.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Applications for the CUTIS 2025 Resident Corner Column

The Cutis Editorial Board is now accepting applications for the 2025 Resident Corner column. The Editorial Board will select 2 to 3 residents to serve as the Resident Corner columnists for 1 year. Articles are posted online only at www.mdedge.com/dermatology but will be referenced in Index Medicus. All applicants must be current residents and will be in residency throughout 2025.

For consideration, send your curriculum vitae along with a brief (not to exceed 500 words) statement of why you enjoy Cutis and what you can offer your fellow residents in contributing a monthly column.

A signed letter of recommendation from the Director of the dermatology residency program also should be supplied.

All materials should be submitted via email to Alicia Sonners ([email protected]) by November 1. The residents who are selected to write the column for the upcoming year will be notified by November 15.

We look forward to continuing to educate dermatology residents on topics that are most important to them!

The Cutis Editorial Board is now accepting applications for the 2025 Resident Corner column. The Editorial Board will select 2 to 3 residents to serve as the Resident Corner columnists for 1 year. Articles are posted online only at www.mdedge.com/dermatology but will be referenced in Index Medicus. All applicants must be current residents and will be in residency throughout 2025.

For consideration, send your curriculum vitae along with a brief (not to exceed 500 words) statement of why you enjoy Cutis and what you can offer your fellow residents in contributing a monthly column.

A signed letter of recommendation from the Director of the dermatology residency program also should be supplied.

All materials should be submitted via email to Alicia Sonners ([email protected]) by November 1. The residents who are selected to write the column for the upcoming year will be notified by November 15.

We look forward to continuing to educate dermatology residents on topics that are most important to them!

The Cutis Editorial Board is now accepting applications for the 2025 Resident Corner column. The Editorial Board will select 2 to 3 residents to serve as the Resident Corner columnists for 1 year. Articles are posted online only at www.mdedge.com/dermatology but will be referenced in Index Medicus. All applicants must be current residents and will be in residency throughout 2025.

For consideration, send your curriculum vitae along with a brief (not to exceed 500 words) statement of why you enjoy Cutis and what you can offer your fellow residents in contributing a monthly column.

A signed letter of recommendation from the Director of the dermatology residency program also should be supplied.

All materials should be submitted via email to Alicia Sonners ([email protected]) by November 1. The residents who are selected to write the column for the upcoming year will be notified by November 15.

We look forward to continuing to educate dermatology residents on topics that are most important to them!

Is There a Role for GLP-1s in Neurology and Psychiatry?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I usually report five or six studies in the field of neurology that were published in the last months, but July was a vacation month.

I decided to cover another topic, which is the role of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonists beyond diabetes and obesity, and in particular, for the field of neurology and psychiatry. Until a few years ago, the treatment of diabetes with traditional antidiabetic drugs was frustrating for vascular neurologists.

These drugs would lower glucose and had an impact on small-vessel disease, but they had no impact on large-vessel disease, stroke, and vascular mortality. This changed with the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 antagonists because these drugs were not only effective for diabetes, but they also lowered cardiac mortality, in particular, in patients with cardiac failure.

The next generation of antidiabetic drugs were the GLP-1 receptor agonists and the combined GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. These two polypeptides and their receptors play a very important role in diabetes and in obesity. The receptors are found not only in the pancreas but also in the intestinal system, the liver, and the central nervous system.

We have a number of preclinical models, mostly in transgenic mice, which show that these drugs are not effective only in diabetes and obesity, but also in liver disease, kidney failure, and neurodegenerative diseases. GLP-1 receptor agonists also have powerful anti-inflammatory properties. These drugs reduce body weight, and they have positive effects on blood pressure and lipid metabolism.

In the studies on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in diabetes, a meta-analysis with more than 58,000 patients showed a significant risk reduction for stroke compared with placebo, and this risk reduction was in the range of 80%.

Stroke, Smoking, and Alcohol

A meta-analysis on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in over 30,000 nondiabetic patients with obesity found a significant reduction in blood pressure, mortality, and the risk of myocardial infarction. There was no significant decrease in the risk of stroke, but most probably this is due to the fact that strokes are much less frequent in obesity than in diabetes.

You all know that obesity is also a major risk factor for sleep apnea syndrome. Recently, two large studies with the GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide found a significant improvement in sleep apnea syndrome compared to placebo, regardless of whether patients needed continuous positive airway pressure therapy or not.

In the therapy studies on diabetes and obesity, there were indications that some smokers in the studies stopped their nicotine consumption. A small pilot study with exenatide in 84 overweight patients who were smokers showed that 46% of patients on exenatide stopped smoking compared with 27% in the placebo group. This could be an indication that GLP-1 receptor agonists have activity on the reward system in the brain. Currently, there are a number of larger placebo-controlled trials ongoing.

Another aspect is alcohol consumption. An epidemiologic study in Denmark using data from the National Health Registry showed that the incidence of alcohol-related events decreased significantly in almost 40,000 patients with diabetes when they were treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with other antidiabetic drugs.

A retrospective cohort study from the United States with over 80,000 patients with obesity showed that treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists was associated with a 50%-60% lower risk for occurrence or recurrence of high alcohol consumption. There is only one small study with exenatide, which was not really informative.

There are a number of studies underway for GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with placebo in patients with alcohol dependence or alcohol consumption. Preclinical models also indicate that these drugs might be effective in cocaine abuse, and there is one placebo-controlled study ongoing.

Parkinson’s Disease

Let’s come to neurology. Preclinical models of Parkinson’s disease have shown neuroprotective activities of GLP-1. Until now, we have three randomized placebo-controlled trials with exenatide, NLY01, and lixisenatide. Two of these studies were positive, showing that the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease were stable over time and deteriorated with placebo. One study was neutral. This means we need more large-scale placebo-controlled studies in the early phases of Parkinson’s disease.

Another potential use of GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists is in dementia. These substances, as you know, have positive effects on high blood pressure and vascular risk factors.

A working group in China analyzed 27 studies on the treatment of diabetes. A small number of randomized studies and a large number of cohort studies showed that modern antidiabetic drugs reduce the risk for dementia. The risk reduction for dementia for the GLP-1 receptor agonists was 75%. At the moment, there are only small prospective studies and they are not conclusive. Again, we need large-scale placebo-controlled studies.

The most important limitation at the moment beyond the cost is the other adverse drug reactions with the GLP-1 receptor agonists; these include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. There might be a slightly increased risk for pancreatitis. The US Food and Drug Administration recently reported there is no increased risk for suicide. Another potential adverse drug reaction is nonatherosclerotic anterior optic neuropathy.

These drugs, GLP-1 receptor agonists and GIP agonists, are also investigated in a variety of other non-neurologic diseases. The focus here is on metabolic liver disease, such as fatty liver and kidney diseases. Smaller, positive studies have been conducted in this area, and large placebo-controlled trials for both indications are currently underway.

If these diverse therapeutic properties would turn out to be really the case with GLP-1 receptor agonists, this would lead to a significant expansion of the range of indications. If we consider cost, this would be the end of our healthcare systems because we cannot afford this. In addition, the new antidiabetic drugs and the treatment of obesity are available only to a limited extent.

Finally, at least for neurology, it’s unclear whether the impact of these diseases is in the brain or whether it’s indirect, due to the effectiveness on vascular risk factors and concomitant diseases.

Dr. Diener is Professor in the Department of Neurology, Stroke Center-Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany; he has disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I usually report five or six studies in the field of neurology that were published in the last months, but July was a vacation month.

I decided to cover another topic, which is the role of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonists beyond diabetes and obesity, and in particular, for the field of neurology and psychiatry. Until a few years ago, the treatment of diabetes with traditional antidiabetic drugs was frustrating for vascular neurologists.

These drugs would lower glucose and had an impact on small-vessel disease, but they had no impact on large-vessel disease, stroke, and vascular mortality. This changed with the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 antagonists because these drugs were not only effective for diabetes, but they also lowered cardiac mortality, in particular, in patients with cardiac failure.

The next generation of antidiabetic drugs were the GLP-1 receptor agonists and the combined GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. These two polypeptides and their receptors play a very important role in diabetes and in obesity. The receptors are found not only in the pancreas but also in the intestinal system, the liver, and the central nervous system.

We have a number of preclinical models, mostly in transgenic mice, which show that these drugs are not effective only in diabetes and obesity, but also in liver disease, kidney failure, and neurodegenerative diseases. GLP-1 receptor agonists also have powerful anti-inflammatory properties. These drugs reduce body weight, and they have positive effects on blood pressure and lipid metabolism.

In the studies on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in diabetes, a meta-analysis with more than 58,000 patients showed a significant risk reduction for stroke compared with placebo, and this risk reduction was in the range of 80%.

Stroke, Smoking, and Alcohol

A meta-analysis on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in over 30,000 nondiabetic patients with obesity found a significant reduction in blood pressure, mortality, and the risk of myocardial infarction. There was no significant decrease in the risk of stroke, but most probably this is due to the fact that strokes are much less frequent in obesity than in diabetes.

You all know that obesity is also a major risk factor for sleep apnea syndrome. Recently, two large studies with the GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide found a significant improvement in sleep apnea syndrome compared to placebo, regardless of whether patients needed continuous positive airway pressure therapy or not.

In the therapy studies on diabetes and obesity, there were indications that some smokers in the studies stopped their nicotine consumption. A small pilot study with exenatide in 84 overweight patients who were smokers showed that 46% of patients on exenatide stopped smoking compared with 27% in the placebo group. This could be an indication that GLP-1 receptor agonists have activity on the reward system in the brain. Currently, there are a number of larger placebo-controlled trials ongoing.

Another aspect is alcohol consumption. An epidemiologic study in Denmark using data from the National Health Registry showed that the incidence of alcohol-related events decreased significantly in almost 40,000 patients with diabetes when they were treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with other antidiabetic drugs.

A retrospective cohort study from the United States with over 80,000 patients with obesity showed that treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists was associated with a 50%-60% lower risk for occurrence or recurrence of high alcohol consumption. There is only one small study with exenatide, which was not really informative.

There are a number of studies underway for GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with placebo in patients with alcohol dependence or alcohol consumption. Preclinical models also indicate that these drugs might be effective in cocaine abuse, and there is one placebo-controlled study ongoing.

Parkinson’s Disease

Let’s come to neurology. Preclinical models of Parkinson’s disease have shown neuroprotective activities of GLP-1. Until now, we have three randomized placebo-controlled trials with exenatide, NLY01, and lixisenatide. Two of these studies were positive, showing that the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease were stable over time and deteriorated with placebo. One study was neutral. This means we need more large-scale placebo-controlled studies in the early phases of Parkinson’s disease.

Another potential use of GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists is in dementia. These substances, as you know, have positive effects on high blood pressure and vascular risk factors.

A working group in China analyzed 27 studies on the treatment of diabetes. A small number of randomized studies and a large number of cohort studies showed that modern antidiabetic drugs reduce the risk for dementia. The risk reduction for dementia for the GLP-1 receptor agonists was 75%. At the moment, there are only small prospective studies and they are not conclusive. Again, we need large-scale placebo-controlled studies.

The most important limitation at the moment beyond the cost is the other adverse drug reactions with the GLP-1 receptor agonists; these include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. There might be a slightly increased risk for pancreatitis. The US Food and Drug Administration recently reported there is no increased risk for suicide. Another potential adverse drug reaction is nonatherosclerotic anterior optic neuropathy.

These drugs, GLP-1 receptor agonists and GIP agonists, are also investigated in a variety of other non-neurologic diseases. The focus here is on metabolic liver disease, such as fatty liver and kidney diseases. Smaller, positive studies have been conducted in this area, and large placebo-controlled trials for both indications are currently underway.

If these diverse therapeutic properties would turn out to be really the case with GLP-1 receptor agonists, this would lead to a significant expansion of the range of indications. If we consider cost, this would be the end of our healthcare systems because we cannot afford this. In addition, the new antidiabetic drugs and the treatment of obesity are available only to a limited extent.

Finally, at least for neurology, it’s unclear whether the impact of these diseases is in the brain or whether it’s indirect, due to the effectiveness on vascular risk factors and concomitant diseases.

Dr. Diener is Professor in the Department of Neurology, Stroke Center-Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany; he has disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I usually report five or six studies in the field of neurology that were published in the last months, but July was a vacation month.

I decided to cover another topic, which is the role of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonists beyond diabetes and obesity, and in particular, for the field of neurology and psychiatry. Until a few years ago, the treatment of diabetes with traditional antidiabetic drugs was frustrating for vascular neurologists.

These drugs would lower glucose and had an impact on small-vessel disease, but they had no impact on large-vessel disease, stroke, and vascular mortality. This changed with the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 antagonists because these drugs were not only effective for diabetes, but they also lowered cardiac mortality, in particular, in patients with cardiac failure.

The next generation of antidiabetic drugs were the GLP-1 receptor agonists and the combined GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. These two polypeptides and their receptors play a very important role in diabetes and in obesity. The receptors are found not only in the pancreas but also in the intestinal system, the liver, and the central nervous system.

We have a number of preclinical models, mostly in transgenic mice, which show that these drugs are not effective only in diabetes and obesity, but also in liver disease, kidney failure, and neurodegenerative diseases. GLP-1 receptor agonists also have powerful anti-inflammatory properties. These drugs reduce body weight, and they have positive effects on blood pressure and lipid metabolism.

In the studies on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in diabetes, a meta-analysis with more than 58,000 patients showed a significant risk reduction for stroke compared with placebo, and this risk reduction was in the range of 80%.

Stroke, Smoking, and Alcohol

A meta-analysis on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in over 30,000 nondiabetic patients with obesity found a significant reduction in blood pressure, mortality, and the risk of myocardial infarction. There was no significant decrease in the risk of stroke, but most probably this is due to the fact that strokes are much less frequent in obesity than in diabetes.

You all know that obesity is also a major risk factor for sleep apnea syndrome. Recently, two large studies with the GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide found a significant improvement in sleep apnea syndrome compared to placebo, regardless of whether patients needed continuous positive airway pressure therapy or not.

In the therapy studies on diabetes and obesity, there were indications that some smokers in the studies stopped their nicotine consumption. A small pilot study with exenatide in 84 overweight patients who were smokers showed that 46% of patients on exenatide stopped smoking compared with 27% in the placebo group. This could be an indication that GLP-1 receptor agonists have activity on the reward system in the brain. Currently, there are a number of larger placebo-controlled trials ongoing.

Another aspect is alcohol consumption. An epidemiologic study in Denmark using data from the National Health Registry showed that the incidence of alcohol-related events decreased significantly in almost 40,000 patients with diabetes when they were treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with other antidiabetic drugs.

A retrospective cohort study from the United States with over 80,000 patients with obesity showed that treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists was associated with a 50%-60% lower risk for occurrence or recurrence of high alcohol consumption. There is only one small study with exenatide, which was not really informative.

There are a number of studies underway for GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with placebo in patients with alcohol dependence or alcohol consumption. Preclinical models also indicate that these drugs might be effective in cocaine abuse, and there is one placebo-controlled study ongoing.

Parkinson’s Disease

Let’s come to neurology. Preclinical models of Parkinson’s disease have shown neuroprotective activities of GLP-1. Until now, we have three randomized placebo-controlled trials with exenatide, NLY01, and lixisenatide. Two of these studies were positive, showing that the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease were stable over time and deteriorated with placebo. One study was neutral. This means we need more large-scale placebo-controlled studies in the early phases of Parkinson’s disease.

Another potential use of GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists is in dementia. These substances, as you know, have positive effects on high blood pressure and vascular risk factors.

A working group in China analyzed 27 studies on the treatment of diabetes. A small number of randomized studies and a large number of cohort studies showed that modern antidiabetic drugs reduce the risk for dementia. The risk reduction for dementia for the GLP-1 receptor agonists was 75%. At the moment, there are only small prospective studies and they are not conclusive. Again, we need large-scale placebo-controlled studies.

The most important limitation at the moment beyond the cost is the other adverse drug reactions with the GLP-1 receptor agonists; these include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. There might be a slightly increased risk for pancreatitis. The US Food and Drug Administration recently reported there is no increased risk for suicide. Another potential adverse drug reaction is nonatherosclerotic anterior optic neuropathy.

These drugs, GLP-1 receptor agonists and GIP agonists, are also investigated in a variety of other non-neurologic diseases. The focus here is on metabolic liver disease, such as fatty liver and kidney diseases. Smaller, positive studies have been conducted in this area, and large placebo-controlled trials for both indications are currently underway.

If these diverse therapeutic properties would turn out to be really the case with GLP-1 receptor agonists, this would lead to a significant expansion of the range of indications. If we consider cost, this would be the end of our healthcare systems because we cannot afford this. In addition, the new antidiabetic drugs and the treatment of obesity are available only to a limited extent.

Finally, at least for neurology, it’s unclear whether the impact of these diseases is in the brain or whether it’s indirect, due to the effectiveness on vascular risk factors and concomitant diseases.

Dr. Diener is Professor in the Department of Neurology, Stroke Center-Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany; he has disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Regularly Drinking Alcohol After Age 60 Linked to Early Death

That’s according to the findings of a new, large study that was published in JAMA Network Openand build upon numerous other recent studies concluding that any amount of alcohol consumption is linked to significant health risks. That’s a change from decades of public health messaging suggesting that moderate alcohol intake (one or two drinks per day) wasn’t dangerous. Recently, experts have uncovered flaws in how researchers came to those earlier conclusions.

In this latest study, researchers in Spain analyzed health data for more than 135,000 people, all of whom were at least 60 years old, lived in the United Kingdom, and provided their health information to the UK Biobank database. The average age of people at the start of the analysis period was 64.

The researchers compared 12 years of health outcomes for occasional drinkers with those who averaged drinking at least some alcohol on a daily basis. The greatest health risks were seen between occasional drinkers and those whom the researchers labeled “high risk.” Occasional drinkers had less than about two drinks per week. The high-risk group included men who averaged nearly three drinks per day or more, and women who averaged about a drink and a half per day or more. The analysis showed that, compared with occasional drinking, high-risk drinking was linked to a 33% increased risk of early death, a 39% increased risk of dying from cancer, and a 21% increased risk of dying from problems with the heart and blood vessels.

More moderate drinking habits were also linked to an increased risk of early death and dying from cancer, and even just averaging about one drink or less daily was associated with an 11% higher risk of dying from cancer. Low and moderate drinkers were most at risk if they also had health problems or experienced socioeconomic factors like living in less affluent neighborhoods.

The findings also suggested the potential that mostly drinking wine, or drinking mostly with meals, may be lower risk, but the researchers called for further study on those topics since “it may mostly reflect the effect of healthier lifestyles, slower alcohol absorption, or nonalcoholic components of beverages.”

A recent Gallup poll showed that overall, Americans’ attitudes toward the health impacts of alcohol are changing, with 65% of young adults (ages 18-34) saying that drinking can have negative health effects. But just 39% of adults age 55 or older agreed that drinking is bad for a person’s health. The gap in perspectives between younger and older adults about drinking is the largest on record, Gallup reported.

The study investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

That’s according to the findings of a new, large study that was published in JAMA Network Openand build upon numerous other recent studies concluding that any amount of alcohol consumption is linked to significant health risks. That’s a change from decades of public health messaging suggesting that moderate alcohol intake (one or two drinks per day) wasn’t dangerous. Recently, experts have uncovered flaws in how researchers came to those earlier conclusions.

In this latest study, researchers in Spain analyzed health data for more than 135,000 people, all of whom were at least 60 years old, lived in the United Kingdom, and provided their health information to the UK Biobank database. The average age of people at the start of the analysis period was 64.

The researchers compared 12 years of health outcomes for occasional drinkers with those who averaged drinking at least some alcohol on a daily basis. The greatest health risks were seen between occasional drinkers and those whom the researchers labeled “high risk.” Occasional drinkers had less than about two drinks per week. The high-risk group included men who averaged nearly three drinks per day or more, and women who averaged about a drink and a half per day or more. The analysis showed that, compared with occasional drinking, high-risk drinking was linked to a 33% increased risk of early death, a 39% increased risk of dying from cancer, and a 21% increased risk of dying from problems with the heart and blood vessels.

More moderate drinking habits were also linked to an increased risk of early death and dying from cancer, and even just averaging about one drink or less daily was associated with an 11% higher risk of dying from cancer. Low and moderate drinkers were most at risk if they also had health problems or experienced socioeconomic factors like living in less affluent neighborhoods.

The findings also suggested the potential that mostly drinking wine, or drinking mostly with meals, may be lower risk, but the researchers called for further study on those topics since “it may mostly reflect the effect of healthier lifestyles, slower alcohol absorption, or nonalcoholic components of beverages.”

A recent Gallup poll showed that overall, Americans’ attitudes toward the health impacts of alcohol are changing, with 65% of young adults (ages 18-34) saying that drinking can have negative health effects. But just 39% of adults age 55 or older agreed that drinking is bad for a person’s health. The gap in perspectives between younger and older adults about drinking is the largest on record, Gallup reported.

The study investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

That’s according to the findings of a new, large study that was published in JAMA Network Openand build upon numerous other recent studies concluding that any amount of alcohol consumption is linked to significant health risks. That’s a change from decades of public health messaging suggesting that moderate alcohol intake (one or two drinks per day) wasn’t dangerous. Recently, experts have uncovered flaws in how researchers came to those earlier conclusions.

In this latest study, researchers in Spain analyzed health data for more than 135,000 people, all of whom were at least 60 years old, lived in the United Kingdom, and provided their health information to the UK Biobank database. The average age of people at the start of the analysis period was 64.