User login

For MD-IQ use only

Neurofibromatosis: What Affects Quality of Life Most?

TOPLINE:

Mobile images may be reliable for assessing cutaneous neurofibroma (cNF) features in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), according to a crowd-sourced .

METHODOLOGY:

- To learn more about the association of cNFs with QoL, pain, and itch in patients with this rare disease, researchers enrolled 1016 individuals aged 40 years and older with NF1 who had at least one cNF, from May 2021 to December 2023, after reaching out to patient-led or NF1 advocacy organizations in 13 countries, including the United States.

- Participants provided demographic data, detailed photographs, and saliva samples for genetic sequencing, with 583 participants (mean age, 51.7 years; 65.9% women) submitting high-quality photographs from seven body regions at the time of the study analysis.

- A subset of 50 participants also underwent whole-body imaging.

- Four researchers independently rated the photographs for various cNF features, including general severity, number, size, facial severity, and subtypes.

TAKEAWAY:

- Based on evaluations by NF1 specialists, the agreement between mobile and whole-body images was “substantial” (74%-88% agreement) for the number of cNFs, general severity, and facial severity. Agreement between self-reported numbers of cNFs and investigator-rated numbers based on photographs was “minimal to fair.”

- Female sex, the number of cNFs, severity of cNFs on the face, and globular cNFs were associated with worse QoL (based on Skindex scores); severity of cNFs on the face had the strongest impact on overall QoL (P < .001).

- An increasing number of cNFs and worsening facial severity were strongly correlated with higher emotion subdomain scores.

- A higher number of cNFs, more severe cNFs on the face, and larger cNFs were all slightly associated with increased itch and pain (P < .01).

IN PRACTICE:

“To develop effective therapeutics, meaningful clinical outcomes that are tied with improvement in QoL for persons with NF1 must be clearly defined,” the authors wrote. The results of this study, they added, “suggested the benefit of this crowd-sourced resource by identifying the features of cNFs with the greatest association with QoL and symptoms of pain and itch in persons with NF1, highlighting new intervention strategies and features to target to most improve QoL in NF1.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Michelle Jade Lin, BS, Stanford University School of Medicine, Redwood City, California, and was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included only a small number of individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups and did not capture ethnicity information, which could have provided further insights into disease impact across different demographics.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and the Bloomberg Family Foundation. Ms. Lin reported support from the Stanford Medical Scholars Research Program. Three authors reported personal fees or grants outside this work. Other authors reported no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mobile images may be reliable for assessing cutaneous neurofibroma (cNF) features in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), according to a crowd-sourced .

METHODOLOGY:

- To learn more about the association of cNFs with QoL, pain, and itch in patients with this rare disease, researchers enrolled 1016 individuals aged 40 years and older with NF1 who had at least one cNF, from May 2021 to December 2023, after reaching out to patient-led or NF1 advocacy organizations in 13 countries, including the United States.

- Participants provided demographic data, detailed photographs, and saliva samples for genetic sequencing, with 583 participants (mean age, 51.7 years; 65.9% women) submitting high-quality photographs from seven body regions at the time of the study analysis.

- A subset of 50 participants also underwent whole-body imaging.

- Four researchers independently rated the photographs for various cNF features, including general severity, number, size, facial severity, and subtypes.

TAKEAWAY:

- Based on evaluations by NF1 specialists, the agreement between mobile and whole-body images was “substantial” (74%-88% agreement) for the number of cNFs, general severity, and facial severity. Agreement between self-reported numbers of cNFs and investigator-rated numbers based on photographs was “minimal to fair.”

- Female sex, the number of cNFs, severity of cNFs on the face, and globular cNFs were associated with worse QoL (based on Skindex scores); severity of cNFs on the face had the strongest impact on overall QoL (P < .001).

- An increasing number of cNFs and worsening facial severity were strongly correlated with higher emotion subdomain scores.

- A higher number of cNFs, more severe cNFs on the face, and larger cNFs were all slightly associated with increased itch and pain (P < .01).

IN PRACTICE:

“To develop effective therapeutics, meaningful clinical outcomes that are tied with improvement in QoL for persons with NF1 must be clearly defined,” the authors wrote. The results of this study, they added, “suggested the benefit of this crowd-sourced resource by identifying the features of cNFs with the greatest association with QoL and symptoms of pain and itch in persons with NF1, highlighting new intervention strategies and features to target to most improve QoL in NF1.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Michelle Jade Lin, BS, Stanford University School of Medicine, Redwood City, California, and was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included only a small number of individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups and did not capture ethnicity information, which could have provided further insights into disease impact across different demographics.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and the Bloomberg Family Foundation. Ms. Lin reported support from the Stanford Medical Scholars Research Program. Three authors reported personal fees or grants outside this work. Other authors reported no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mobile images may be reliable for assessing cutaneous neurofibroma (cNF) features in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), according to a crowd-sourced .

METHODOLOGY:

- To learn more about the association of cNFs with QoL, pain, and itch in patients with this rare disease, researchers enrolled 1016 individuals aged 40 years and older with NF1 who had at least one cNF, from May 2021 to December 2023, after reaching out to patient-led or NF1 advocacy organizations in 13 countries, including the United States.

- Participants provided demographic data, detailed photographs, and saliva samples for genetic sequencing, with 583 participants (mean age, 51.7 years; 65.9% women) submitting high-quality photographs from seven body regions at the time of the study analysis.

- A subset of 50 participants also underwent whole-body imaging.

- Four researchers independently rated the photographs for various cNF features, including general severity, number, size, facial severity, and subtypes.

TAKEAWAY:

- Based on evaluations by NF1 specialists, the agreement between mobile and whole-body images was “substantial” (74%-88% agreement) for the number of cNFs, general severity, and facial severity. Agreement between self-reported numbers of cNFs and investigator-rated numbers based on photographs was “minimal to fair.”

- Female sex, the number of cNFs, severity of cNFs on the face, and globular cNFs were associated with worse QoL (based on Skindex scores); severity of cNFs on the face had the strongest impact on overall QoL (P < .001).

- An increasing number of cNFs and worsening facial severity were strongly correlated with higher emotion subdomain scores.

- A higher number of cNFs, more severe cNFs on the face, and larger cNFs were all slightly associated with increased itch and pain (P < .01).

IN PRACTICE:

“To develop effective therapeutics, meaningful clinical outcomes that are tied with improvement in QoL for persons with NF1 must be clearly defined,” the authors wrote. The results of this study, they added, “suggested the benefit of this crowd-sourced resource by identifying the features of cNFs with the greatest association with QoL and symptoms of pain and itch in persons with NF1, highlighting new intervention strategies and features to target to most improve QoL in NF1.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Michelle Jade Lin, BS, Stanford University School of Medicine, Redwood City, California, and was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included only a small number of individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups and did not capture ethnicity information, which could have provided further insights into disease impact across different demographics.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and the Bloomberg Family Foundation. Ms. Lin reported support from the Stanford Medical Scholars Research Program. Three authors reported personal fees or grants outside this work. Other authors reported no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A New Era of Obesity Medicine

Obesity has now reached epidemic proportions, with global prevalence of the condition increasing more than threefold between 1975 and 2022. In the United States alone, roughly two in five adults have obesity. As healthcare providers are intimately aware, obesity is linked to many serious health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease, as well as some forms of cancer. As such, it presents a major challenge to chronic disease prevention and overall health.

For many years, management of obesity was considered within the purview of primary care as part of chronic disease management. However, as obesity has become more common, our understanding of the underlying causes of obesity has improved, and optimal strategies to manage and treat obesity have evolved. From glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists to an expanding armamentarium of bariatric procedures, emerging therapeutics have revolutionized treatment of patients with obesity and related health conditions.

In this month’s Member Spotlight, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Dr. Janese Laster, who has built a successful career with a primary focus on obesity medicine. She shares her passionate perspective on why gastroenterologists should play a more prominent role in management of this complex, chronic disease. We also include a summary of obesity-related content presented as part of this spring’s AGA Post-Graduate Course, with helpful clinical pearls from experts Dr. Andres Acosta, Dr. Violeta Popov, Dr. Sonali Paul, and Dr. Pooja Singhal.

Also in our September issue, we highlight a recent, practice-changing randomized controlled trial from Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology supporting use of snare tip soft coagulation as the preferred thermal margin treatment to reduce recurrence rates following colorectal endoscopic mucosal resection. In our quarterly Perspectives column, Dr. Maggie Ham and Dr. Petr Protiva offer their insights into a pressing question on many of our minds — whether to take the 10-year “high-stakes” exam or opt for the Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment to maintain American Board of Internal Medicine certification. As always, thanks for reading and please don’t hesitate to reach out with suggestions for future coverage.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Obesity has now reached epidemic proportions, with global prevalence of the condition increasing more than threefold between 1975 and 2022. In the United States alone, roughly two in five adults have obesity. As healthcare providers are intimately aware, obesity is linked to many serious health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease, as well as some forms of cancer. As such, it presents a major challenge to chronic disease prevention and overall health.

For many years, management of obesity was considered within the purview of primary care as part of chronic disease management. However, as obesity has become more common, our understanding of the underlying causes of obesity has improved, and optimal strategies to manage and treat obesity have evolved. From glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists to an expanding armamentarium of bariatric procedures, emerging therapeutics have revolutionized treatment of patients with obesity and related health conditions.

In this month’s Member Spotlight, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Dr. Janese Laster, who has built a successful career with a primary focus on obesity medicine. She shares her passionate perspective on why gastroenterologists should play a more prominent role in management of this complex, chronic disease. We also include a summary of obesity-related content presented as part of this spring’s AGA Post-Graduate Course, with helpful clinical pearls from experts Dr. Andres Acosta, Dr. Violeta Popov, Dr. Sonali Paul, and Dr. Pooja Singhal.

Also in our September issue, we highlight a recent, practice-changing randomized controlled trial from Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology supporting use of snare tip soft coagulation as the preferred thermal margin treatment to reduce recurrence rates following colorectal endoscopic mucosal resection. In our quarterly Perspectives column, Dr. Maggie Ham and Dr. Petr Protiva offer their insights into a pressing question on many of our minds — whether to take the 10-year “high-stakes” exam or opt for the Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment to maintain American Board of Internal Medicine certification. As always, thanks for reading and please don’t hesitate to reach out with suggestions for future coverage.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Obesity has now reached epidemic proportions, with global prevalence of the condition increasing more than threefold between 1975 and 2022. In the United States alone, roughly two in five adults have obesity. As healthcare providers are intimately aware, obesity is linked to many serious health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease, as well as some forms of cancer. As such, it presents a major challenge to chronic disease prevention and overall health.

For many years, management of obesity was considered within the purview of primary care as part of chronic disease management. However, as obesity has become more common, our understanding of the underlying causes of obesity has improved, and optimal strategies to manage and treat obesity have evolved. From glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists to an expanding armamentarium of bariatric procedures, emerging therapeutics have revolutionized treatment of patients with obesity and related health conditions.

In this month’s Member Spotlight, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Dr. Janese Laster, who has built a successful career with a primary focus on obesity medicine. She shares her passionate perspective on why gastroenterologists should play a more prominent role in management of this complex, chronic disease. We also include a summary of obesity-related content presented as part of this spring’s AGA Post-Graduate Course, with helpful clinical pearls from experts Dr. Andres Acosta, Dr. Violeta Popov, Dr. Sonali Paul, and Dr. Pooja Singhal.

Also in our September issue, we highlight a recent, practice-changing randomized controlled trial from Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology supporting use of snare tip soft coagulation as the preferred thermal margin treatment to reduce recurrence rates following colorectal endoscopic mucosal resection. In our quarterly Perspectives column, Dr. Maggie Ham and Dr. Petr Protiva offer their insights into a pressing question on many of our minds — whether to take the 10-year “high-stakes” exam or opt for the Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment to maintain American Board of Internal Medicine certification. As always, thanks for reading and please don’t hesitate to reach out with suggestions for future coverage.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

SBRT vs Surgery in CRC Lung Metastases: Which Is Better?

TOPLINE:

However, those who received surgery had significantly better progression-free and disease-free survival rates, as well as a longer time to intrathoracic progression.

METHODOLOGY:

- SBRT has been shown to provide effective local control and improve short-term survival for patients with pulmonary oligometastases from CRC and has become an alternative for these patients who are ineligible or reluctant to undergo surgery. It’s unclear, however, whether SBRT should be prioritized over surgery in patients with CRC pulmonary metastases, largely because of a lack of prospective data.

- In the current analysis, researchers compared outcomes among 335 patients (median age, 61 years) with lung metastases from CRC who underwent surgery or SBRT, using data from the Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute between March 2011 and September 2022.

- A total of 251 patients were included in the final analysis after propensity score matching, 173 (68.9%) underwent surgery and 78 (31.1%) received SBRT. The median follow-up was 61.6 months in the surgery group and 54.4 months in the SBRT group.

- The study outcomes were freedom from intrathoracic progression, progression-free survival, and overall survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 5 years, rates of freedom from intrathoracic progression were more than twofold higher in the surgery group than in the SBRT group (53% vs 23.4%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.46; P < .001). Progression-free survival rates were also more than twofold higher in the surgery group vs the SBRT group (43.8% vs 18.5%; HR, 0.47; P < .001), respectively. In the SBRT group, a higher percentage of patients had a disease-free interval of less than 12 months compared with the surgery group, with rates of 48.7% and 32.9%, respectively (P = 0.025).

- Overall survival, however, was not significantly different between the two groups at 5 years (72.5% in the surgery group vs 63.7% in the SBRT group; P = .260). The number of pulmonary metastases (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.11-3.14, P = .019 and tumor size (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00-1.05, P = .023) were significant prognostic factors for overall survival.

- Local recurrence was more prevalent after SBRT (33.3%) than surgery (16.9%), while new intrathoracic tumors occurred more frequently after surgery than SBRT (71.8% vs 43.1%). Repeated local treatments were common among patients with intrathoracic progression, which might have contributed to favorable survival outcomes in both groups.

- Both treatments were well-tolerated with no treatment-related mortality or grade ≥ 3 toxicities. In the surgery group, 14 patients experienced complications, including atrial fibrillation (n = 4) and prolonged air leaks (n = 7). In the SBRT group, radiation pneumonitis was the most common adverse event (n = 21).

IN PRACTICE:

SBRT yielded overall survival benefits similar to surgery despite a “higher likelihood of prior extrapulmonary metastases, a shorter disease-free interval, and a greater number of metastatic lesions,” the authors wrote. Still, SBRT should be regarded as an “effective alternative in cases in which surgical intervention is either unviable or declined by the patient,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The study was co-led by Yaqi Wang and Xin Dong, Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute, Beijing, China, and was published online in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics.

LIMITATIONS:

This single-center retrospective study had an inherent selection bias. The lack of balanced sample sizes of the surgery and SBRT groups might have affected the robustness of the statistical analyses. Detailed data on adverse events were not available.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Beijing Natural Science Foundation, and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospital’s Ascent Plan. The authors did not declare any conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

However, those who received surgery had significantly better progression-free and disease-free survival rates, as well as a longer time to intrathoracic progression.

METHODOLOGY:

- SBRT has been shown to provide effective local control and improve short-term survival for patients with pulmonary oligometastases from CRC and has become an alternative for these patients who are ineligible or reluctant to undergo surgery. It’s unclear, however, whether SBRT should be prioritized over surgery in patients with CRC pulmonary metastases, largely because of a lack of prospective data.

- In the current analysis, researchers compared outcomes among 335 patients (median age, 61 years) with lung metastases from CRC who underwent surgery or SBRT, using data from the Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute between March 2011 and September 2022.

- A total of 251 patients were included in the final analysis after propensity score matching, 173 (68.9%) underwent surgery and 78 (31.1%) received SBRT. The median follow-up was 61.6 months in the surgery group and 54.4 months in the SBRT group.

- The study outcomes were freedom from intrathoracic progression, progression-free survival, and overall survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 5 years, rates of freedom from intrathoracic progression were more than twofold higher in the surgery group than in the SBRT group (53% vs 23.4%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.46; P < .001). Progression-free survival rates were also more than twofold higher in the surgery group vs the SBRT group (43.8% vs 18.5%; HR, 0.47; P < .001), respectively. In the SBRT group, a higher percentage of patients had a disease-free interval of less than 12 months compared with the surgery group, with rates of 48.7% and 32.9%, respectively (P = 0.025).

- Overall survival, however, was not significantly different between the two groups at 5 years (72.5% in the surgery group vs 63.7% in the SBRT group; P = .260). The number of pulmonary metastases (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.11-3.14, P = .019 and tumor size (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00-1.05, P = .023) were significant prognostic factors for overall survival.

- Local recurrence was more prevalent after SBRT (33.3%) than surgery (16.9%), while new intrathoracic tumors occurred more frequently after surgery than SBRT (71.8% vs 43.1%). Repeated local treatments were common among patients with intrathoracic progression, which might have contributed to favorable survival outcomes in both groups.

- Both treatments were well-tolerated with no treatment-related mortality or grade ≥ 3 toxicities. In the surgery group, 14 patients experienced complications, including atrial fibrillation (n = 4) and prolonged air leaks (n = 7). In the SBRT group, radiation pneumonitis was the most common adverse event (n = 21).

IN PRACTICE:

SBRT yielded overall survival benefits similar to surgery despite a “higher likelihood of prior extrapulmonary metastases, a shorter disease-free interval, and a greater number of metastatic lesions,” the authors wrote. Still, SBRT should be regarded as an “effective alternative in cases in which surgical intervention is either unviable or declined by the patient,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The study was co-led by Yaqi Wang and Xin Dong, Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute, Beijing, China, and was published online in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics.

LIMITATIONS:

This single-center retrospective study had an inherent selection bias. The lack of balanced sample sizes of the surgery and SBRT groups might have affected the robustness of the statistical analyses. Detailed data on adverse events were not available.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Beijing Natural Science Foundation, and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospital’s Ascent Plan. The authors did not declare any conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

However, those who received surgery had significantly better progression-free and disease-free survival rates, as well as a longer time to intrathoracic progression.

METHODOLOGY:

- SBRT has been shown to provide effective local control and improve short-term survival for patients with pulmonary oligometastases from CRC and has become an alternative for these patients who are ineligible or reluctant to undergo surgery. It’s unclear, however, whether SBRT should be prioritized over surgery in patients with CRC pulmonary metastases, largely because of a lack of prospective data.

- In the current analysis, researchers compared outcomes among 335 patients (median age, 61 years) with lung metastases from CRC who underwent surgery or SBRT, using data from the Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute between March 2011 and September 2022.

- A total of 251 patients were included in the final analysis after propensity score matching, 173 (68.9%) underwent surgery and 78 (31.1%) received SBRT. The median follow-up was 61.6 months in the surgery group and 54.4 months in the SBRT group.

- The study outcomes were freedom from intrathoracic progression, progression-free survival, and overall survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 5 years, rates of freedom from intrathoracic progression were more than twofold higher in the surgery group than in the SBRT group (53% vs 23.4%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.46; P < .001). Progression-free survival rates were also more than twofold higher in the surgery group vs the SBRT group (43.8% vs 18.5%; HR, 0.47; P < .001), respectively. In the SBRT group, a higher percentage of patients had a disease-free interval of less than 12 months compared with the surgery group, with rates of 48.7% and 32.9%, respectively (P = 0.025).

- Overall survival, however, was not significantly different between the two groups at 5 years (72.5% in the surgery group vs 63.7% in the SBRT group; P = .260). The number of pulmonary metastases (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.11-3.14, P = .019 and tumor size (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00-1.05, P = .023) were significant prognostic factors for overall survival.

- Local recurrence was more prevalent after SBRT (33.3%) than surgery (16.9%), while new intrathoracic tumors occurred more frequently after surgery than SBRT (71.8% vs 43.1%). Repeated local treatments were common among patients with intrathoracic progression, which might have contributed to favorable survival outcomes in both groups.

- Both treatments were well-tolerated with no treatment-related mortality or grade ≥ 3 toxicities. In the surgery group, 14 patients experienced complications, including atrial fibrillation (n = 4) and prolonged air leaks (n = 7). In the SBRT group, radiation pneumonitis was the most common adverse event (n = 21).

IN PRACTICE:

SBRT yielded overall survival benefits similar to surgery despite a “higher likelihood of prior extrapulmonary metastases, a shorter disease-free interval, and a greater number of metastatic lesions,” the authors wrote. Still, SBRT should be regarded as an “effective alternative in cases in which surgical intervention is either unviable or declined by the patient,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The study was co-led by Yaqi Wang and Xin Dong, Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute, Beijing, China, and was published online in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics.

LIMITATIONS:

This single-center retrospective study had an inherent selection bias. The lack of balanced sample sizes of the surgery and SBRT groups might have affected the robustness of the statistical analyses. Detailed data on adverse events were not available.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Beijing Natural Science Foundation, and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospital’s Ascent Plan. The authors did not declare any conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer Cases, Deaths in Men Predicted to Surge by 2050

TOPLINE:

— with substantial disparities in cancer cases and deaths by age and region of the world, a recent analysis found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Overall, men have higher cancer incidence and mortality rates, which can be largely attributed to a higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and occupational carcinogens, as well as the underuse of cancer prevention, screening, and treatment services.

- To assess the burden of cancer in men of different ages and from different regions of the world, researchers analyzed data from the 2022 Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), which provides national-level estimates for cancer cases and deaths.

- Study outcomes included the incidence, mortality, and prevalence of cancer among men in 2022, along with projections for 2050. Estimates were stratified by several factors, including age; region; and Human Development Index (HDI), a composite score for health, education, and standard of living.

- Researchers also calculated mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs) for various cancer types, where higher values indicate worse survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers reported an estimated 10.3 million cancer cases and 5.4 million deaths globally in 2022, with almost two thirds of cases and deaths occurring in men aged 65 years or older.

- By 2050, cancer cases and deaths were projected to increase by 84.3% (to 19 million) and 93.2% (to 10.5 million), respectively. The increase from 2022 to 2050 was more than twofold higher for older men and countries with low and medium HDI.

- In 2022, the estimated global cancer MIR among men was nearly 55%, with variations by cancer types, age, and HDI. The MIR was lowest for thyroid cancer (7.6%) and highest for pancreatic cancer (90.9%); among World Health Organization regions, Africa had the highest MIR (72.6%), while the Americas had the lowest MIR (39.1%); countries with the lowest HDI had the highest MIR (73.5% vs 41.1% for very high HDI).

- Lung cancer was the leading cause for cases and deaths in 2022 and was projected to remain the leading cause in 2050.

IN PRACTICE:

“Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality among men were observed across age groups, countries/territories, and HDI in 2022, with these disparities projected to widen further by 2050,” according to the authors, who called for efforts to “reduce disparities in cancer burden and ensure equity in cancer prevention and care for men across the globe.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Habtamu Mellie Bizuayehu, PhD, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, was published online in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings may be influenced by the quality of GLOBOCAN data. Interpretation should be cautious as MIR may not fully reflect cancer outcome inequalities. The study did not include other measures of cancer burden, such as years of life lost or years lived with disability, which were unavailable from the data source.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not disclose any funding information. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

— with substantial disparities in cancer cases and deaths by age and region of the world, a recent analysis found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Overall, men have higher cancer incidence and mortality rates, which can be largely attributed to a higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and occupational carcinogens, as well as the underuse of cancer prevention, screening, and treatment services.

- To assess the burden of cancer in men of different ages and from different regions of the world, researchers analyzed data from the 2022 Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), which provides national-level estimates for cancer cases and deaths.

- Study outcomes included the incidence, mortality, and prevalence of cancer among men in 2022, along with projections for 2050. Estimates were stratified by several factors, including age; region; and Human Development Index (HDI), a composite score for health, education, and standard of living.

- Researchers also calculated mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs) for various cancer types, where higher values indicate worse survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers reported an estimated 10.3 million cancer cases and 5.4 million deaths globally in 2022, with almost two thirds of cases and deaths occurring in men aged 65 years or older.

- By 2050, cancer cases and deaths were projected to increase by 84.3% (to 19 million) and 93.2% (to 10.5 million), respectively. The increase from 2022 to 2050 was more than twofold higher for older men and countries with low and medium HDI.

- In 2022, the estimated global cancer MIR among men was nearly 55%, with variations by cancer types, age, and HDI. The MIR was lowest for thyroid cancer (7.6%) and highest for pancreatic cancer (90.9%); among World Health Organization regions, Africa had the highest MIR (72.6%), while the Americas had the lowest MIR (39.1%); countries with the lowest HDI had the highest MIR (73.5% vs 41.1% for very high HDI).

- Lung cancer was the leading cause for cases and deaths in 2022 and was projected to remain the leading cause in 2050.

IN PRACTICE:

“Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality among men were observed across age groups, countries/territories, and HDI in 2022, with these disparities projected to widen further by 2050,” according to the authors, who called for efforts to “reduce disparities in cancer burden and ensure equity in cancer prevention and care for men across the globe.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Habtamu Mellie Bizuayehu, PhD, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, was published online in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings may be influenced by the quality of GLOBOCAN data. Interpretation should be cautious as MIR may not fully reflect cancer outcome inequalities. The study did not include other measures of cancer burden, such as years of life lost or years lived with disability, which were unavailable from the data source.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not disclose any funding information. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

— with substantial disparities in cancer cases and deaths by age and region of the world, a recent analysis found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Overall, men have higher cancer incidence and mortality rates, which can be largely attributed to a higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and occupational carcinogens, as well as the underuse of cancer prevention, screening, and treatment services.

- To assess the burden of cancer in men of different ages and from different regions of the world, researchers analyzed data from the 2022 Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), which provides national-level estimates for cancer cases and deaths.

- Study outcomes included the incidence, mortality, and prevalence of cancer among men in 2022, along with projections for 2050. Estimates were stratified by several factors, including age; region; and Human Development Index (HDI), a composite score for health, education, and standard of living.

- Researchers also calculated mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs) for various cancer types, where higher values indicate worse survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers reported an estimated 10.3 million cancer cases and 5.4 million deaths globally in 2022, with almost two thirds of cases and deaths occurring in men aged 65 years or older.

- By 2050, cancer cases and deaths were projected to increase by 84.3% (to 19 million) and 93.2% (to 10.5 million), respectively. The increase from 2022 to 2050 was more than twofold higher for older men and countries with low and medium HDI.

- In 2022, the estimated global cancer MIR among men was nearly 55%, with variations by cancer types, age, and HDI. The MIR was lowest for thyroid cancer (7.6%) and highest for pancreatic cancer (90.9%); among World Health Organization regions, Africa had the highest MIR (72.6%), while the Americas had the lowest MIR (39.1%); countries with the lowest HDI had the highest MIR (73.5% vs 41.1% for very high HDI).

- Lung cancer was the leading cause for cases and deaths in 2022 and was projected to remain the leading cause in 2050.

IN PRACTICE:

“Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality among men were observed across age groups, countries/territories, and HDI in 2022, with these disparities projected to widen further by 2050,” according to the authors, who called for efforts to “reduce disparities in cancer burden and ensure equity in cancer prevention and care for men across the globe.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Habtamu Mellie Bizuayehu, PhD, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, was published online in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings may be influenced by the quality of GLOBOCAN data. Interpretation should be cautious as MIR may not fully reflect cancer outcome inequalities. The study did not include other measures of cancer burden, such as years of life lost or years lived with disability, which were unavailable from the data source.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not disclose any funding information. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prurigo Nodularis Mechanisms and Current Management Options

Prurigo nodularis (PN)(also called chronic nodular prurigo, prurigo nodularis of Hyde, or picker’s nodules) was first characterized by James Hyde in 1909.1-3 Prurigo nodularis manifests with symmetrical, intensely pruritic, eroded, or hyperkeratotic nodules or papules on the extremities and trunk.1,2,4,5 Studies have shown that individuals with PN experience pruritus, sleep loss, decreased social functioning from the appearance of the nodules, and a higher incidence of anxiety and depression, causing a negative impact on their quality of life.2,6 In addition, the manifestation of PN has been linked to neurologic and psychiatric disorders; however, PN also can be idiopathic and manifest without underlying illnesses.2,6,7

Prurigo nodularis has been associated with other dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis (up to 50%), lichen planus, keratoacanthomas (KAs), and bullous pemphigoid.7-9 It also has been linked to systemic diseases in 38% to 50% of cases, including chronic kidney disease, liver disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, malignancies (hematopoietic, liver, and skin), and HIV infection.6,8,10

The pathophysiology of PN is highly complex and has yet to be fully elucidated. It is thought to be due to dysregulation and interaction of the increase in neural and immunologic responses of proinflammatory and pruritogenic cytokines.2,11 Treatments aim to break the itch-scratch cycle that perpetuates this disorder; however, this proves difficult, as PN is associated with a higher itch intensity than atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.10 Therefore, most patients attempt multiple forms of treatment for PN, ranging from topical therapies, oral immunosuppressants, and phototherapy to the newest and only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of PN—dupilumab.1,7,11 Herein, we provide an updated review of PN with a focus on its epidemiology, histopathology and pathophysiology, comorbidities, clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, and current treatment options.

Epidemiology

There are few studies on the epidemiology of PN; however, middle-aged populations with underlying dermatologic or psychiatric disorders tend to be impacted most frequently.2,12,13 In 2016, it was estimated that almost 88,000 individuals had PN in the United States, with the majority being female; however, this estimate only took into account those aged 18 to 64 years and utilized data from IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database (IBM Watson Health) from October 2015 to December 2016.14 More recently, a retrospective database analysis estimated the prevalence of PN in the United States to be anywhere from 36.7 to 43.9 cases per 100,000 individuals. However, this retrospective review utilized the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code; PN has 2 codes associated with the diagnosis, and the coding accuracy is unknown.15 Sutaria et al16 looked at racial disparities in patients with PN utilizing data from TriNetX and found that patients who received a diagnosis of PN were more likely to be women, non-Hispanic, and Black compared with control patients. However, these estimates are restricted to the health care organizations within this database.

In 2018, Poland reported an annual prevalence of 6.52 cases per 100,000 individuals,17 while England reported a yearly prevalence of 3.27 cases per 100,000 individuals.18 Both countries reported most cases were female. However, these studies are not without limitations. Poland only uses the primary diagnosis code for medical billing to simplify clinical coding, thus underestimating the actual prevalence; furthermore, clinical codes more often than not are assigned by someone other than the diagnosing physician, leaving room for error.17 In addition, England’s PN estimate utilized diagnosis data from primary care and inpatient datasets, leaving out outpatient datasets in which patients with PN may have been referred and obtained the diagnosis, potentially underestimating the prevalence in this population.18

In contrast, Korea estimated the annual prevalence of PN to be 4.82 cases per 1000 dermatology outpatients, with the majority being men, based on results from a cross-sectional study among outpatients from the Catholic Medical Center. Although this is the largest health organization in Korea, the scope of this study is limited and lacks data from other medical centers in Korea.19

Histopathology and Pathophysiology

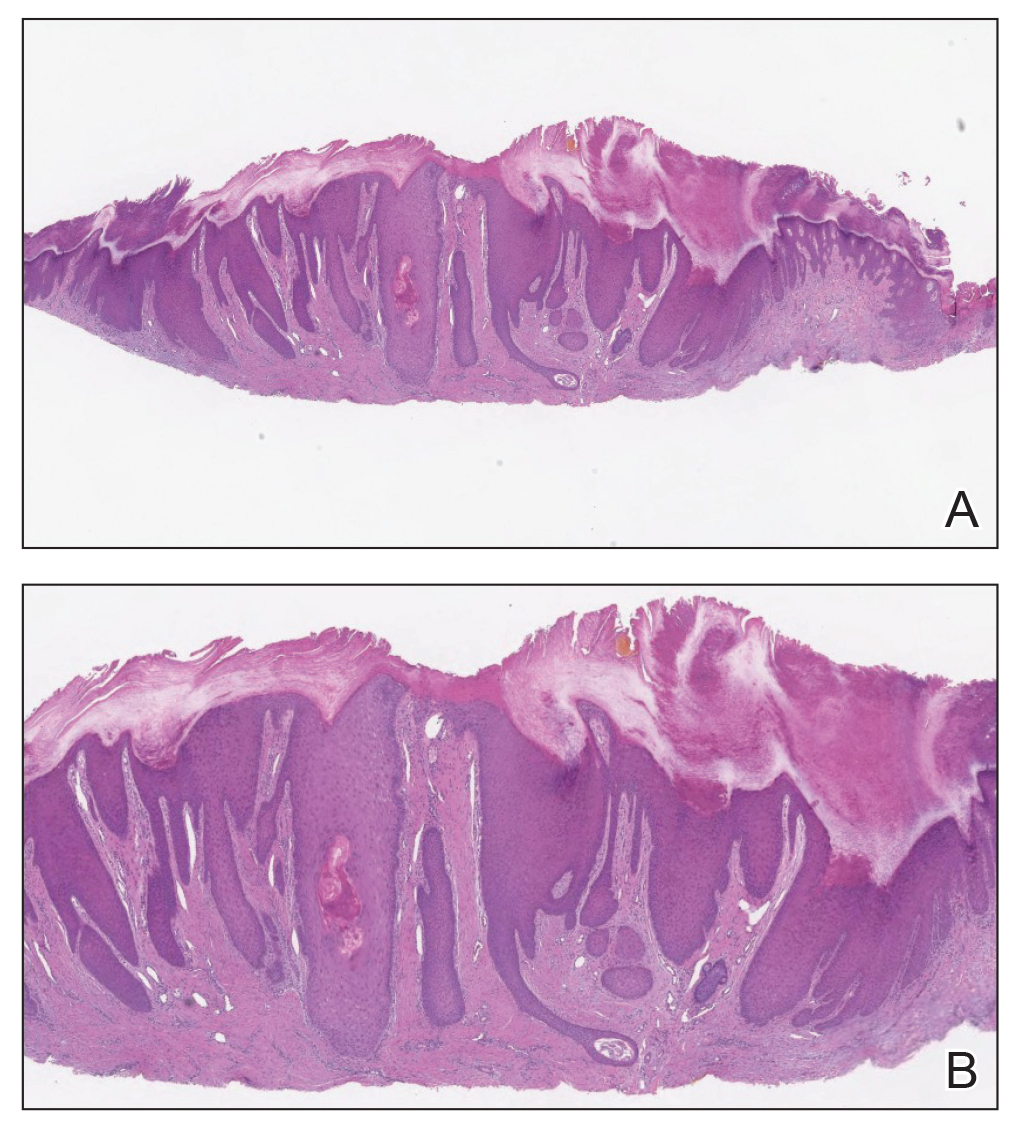

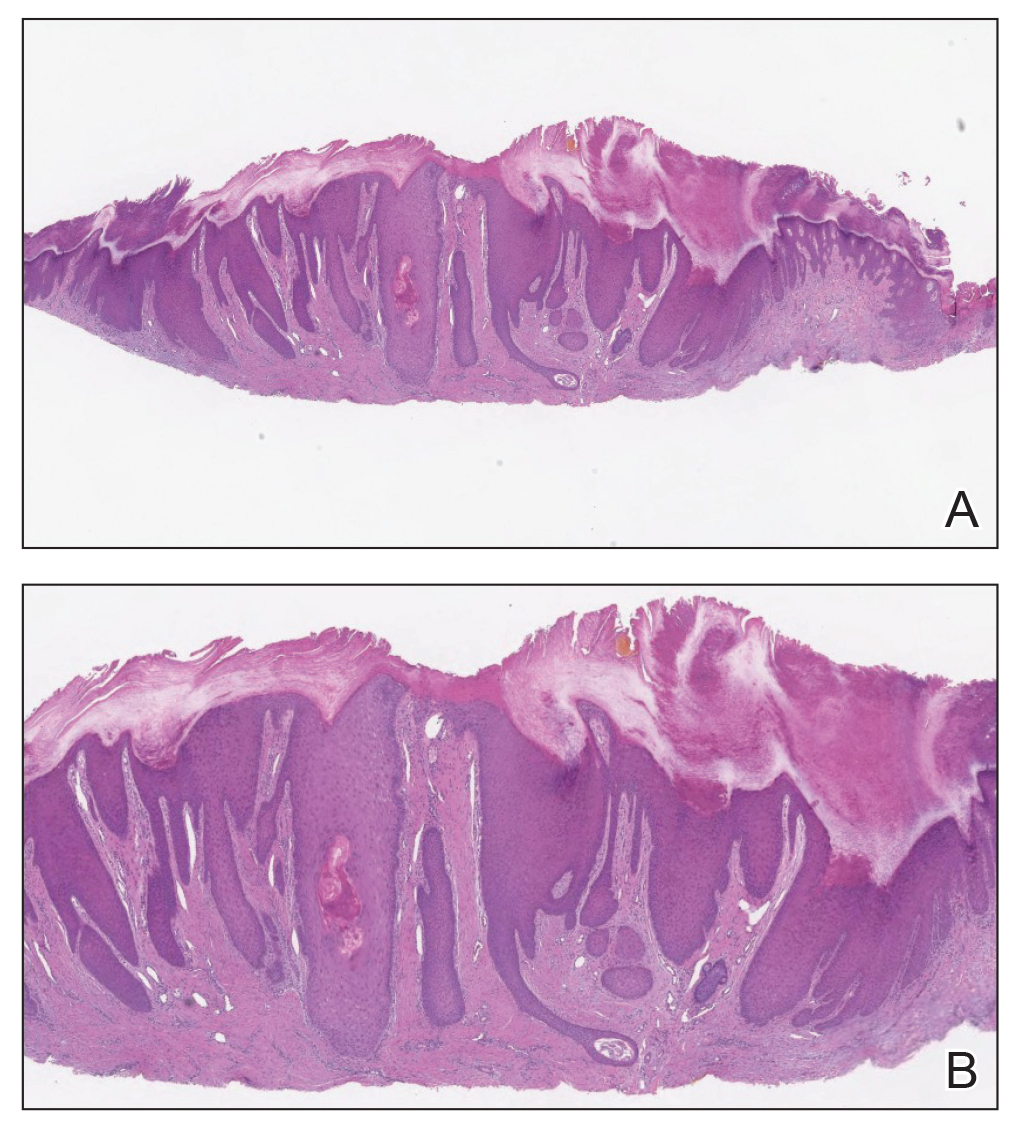

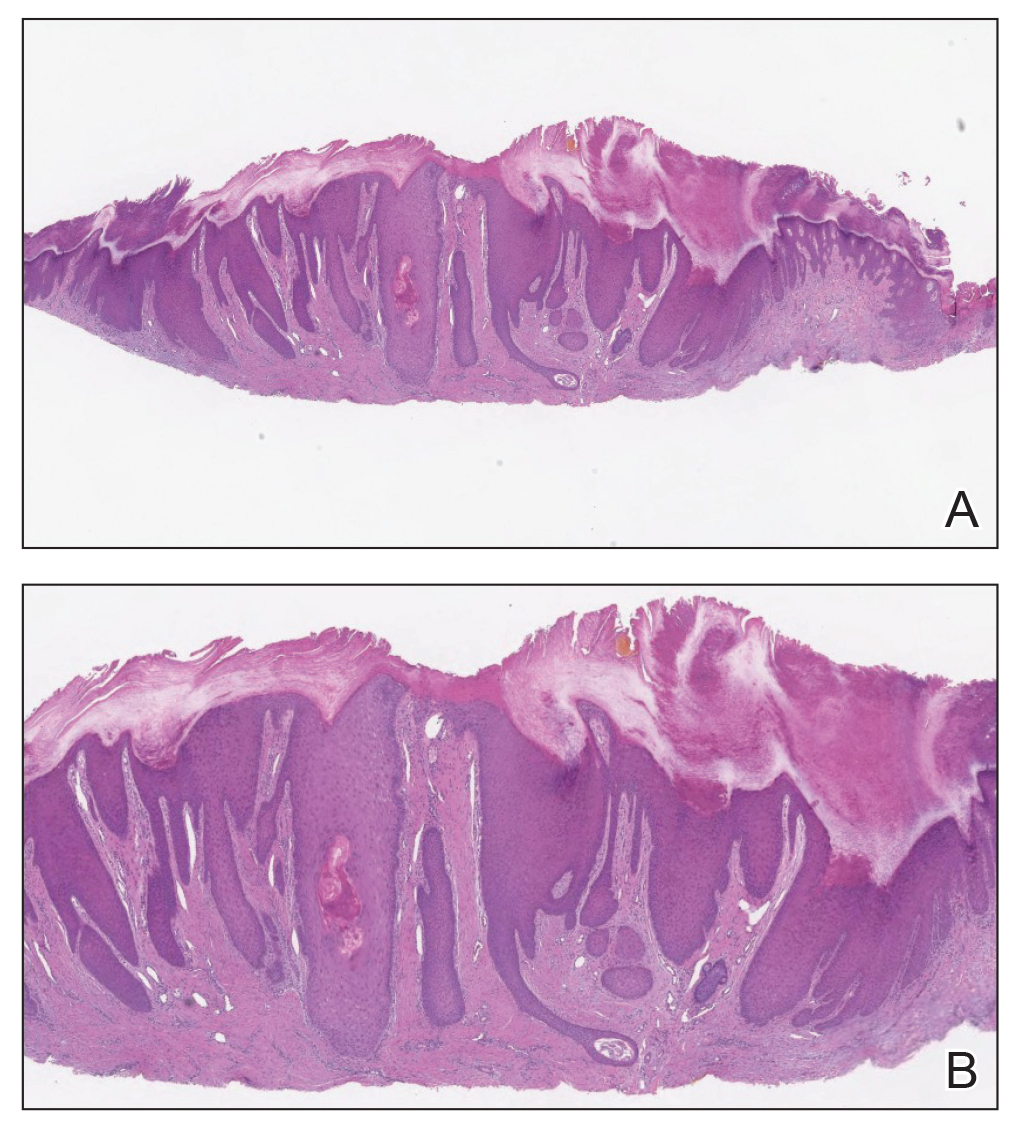

Almost all cells in the skin are involved in PN: keratinocytes, mast cells, dendritic cells, endothelial cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils, collagen fibers, and nerve fibers.11,20 Classically, PN manifests as a dome-shaped lesion with hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with increased thickness of the papillary dermis consisting of coarse collagen with compact interstitial and circumvascular infiltration as well as increased lymphocytes and histocytes in the superficial dermis (Figure 1).20 Hyperkeratosis is thought to be due to either the alteration of keratinocyte structures from scratching or keratinocyte abnormalities triggering PN.21 However, the increase in keratinocytes, which secrete nerve growth factor, allows for neuronal hyperplasia within the dermis.22 Nerve growth factor can stimulate keratinocyte proliferation23 in addition to the upregulation of substance P (SP), a tachykinin that triggers vascular dilation and pruritus in the skin.24 The density of SP nerve fibers in the dermis increases in PN, causing proinflammatory effects, upregulating the immune response to promote endothelial hyperplasia and increased vascularization.25 The increase in these fibers may lead to pruritus associated with PN.2,26

Many inflammatory cytokines and mediators also have been implicated in PN. Increased messenger RNA expression of IL-4, IL-17, IL-22, and IL-31 has been described in PN lesions.3,27 Furthermore, studies also have reported increased helper T cell (TH2) cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13, in the dermis of PN lesions in patients without a history of atopy.3,28 These pruritogenic cytokines in conjunction with the SP fibers may create an intractable itch for those with PN. The interaction and culmination of the neural and immune responses make PN a complex condition to treat with the multifactorial interaction of systems.

Comorbidities

Prurigo nodularis has been associated with a wide array of comorbidities; however, the direction of the relationship between PN and these conditions makes it difficult to discern if PN is a primary or secondary condition.29 Prurigo nodularis commonly has been connected to other inflammatory dermatoses, with a link to atopic dermatitis being the strongest.5,29 However, PN also has been linked to other pruritic inflammatory cutaneous disorders, including psoriasis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, lichen planus, and dermatitis herpetiformis.14,29

Huang et al14 found an increased likelihood of psychiatric illnesses in patients with PN, including eating disorders, nonsuicidal self-injury disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, mood disorders, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders. Treatments directed at the neural aspect of PN have included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which also are utilized to treat these mental health disorders.

Furthermore, systemic diseases also have been found to be associated with PN, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.14 The relationship between PN and systemic conditions may be due to increased systemic inflammation and dysregulation of neural and metabolic functions implicated in these conditions from increased pruritic manifestations.29,30 However, studies also have connected PN to infectious conditions such as HIV. One study found that patients with PN had 2.68 higher odds of infection with HIV compared to age- and sex-matched controls.14 It is unknown if these conditions contributed to the development of PN or PN contributed to the development of these disorders.

Clinical Presentations

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that typically manifests with multiple severely pruritic, dome-shaped, firm, hyperpigmented papulonodules with central scale or crust, often with erosion, due to chronic repetitive scratching and picking secondary to pruritic systemic or dermatologic diseases or psychological disorders (Figure 2).1,2,4,5,8,31 Most often, diagnosis of PN is based on history and physical examination of the lesion; however, biopsies may be performed. These nodules commonly manifest with ulceration distributed symmetrically on extensor extremities in easy-to-reach places, sparing the mid back (called the butterfly sign).8 Lesions—either a few or hundreds—can range from a few millimeters to 2 to 3 cm.8,32 The lesions differ in appearance depending on the pigment in the patient’s skin. In patients with darker skin tones, hyperpigmented or hypopigmented papulonodules are not uncommon, while those with fairer skin tones tend to present with erythema.31

Differential Diagnosis

Because of the variation in manifestation of PN, these lesions may resemble other cutaneous conditions. If the lesions are hyperkeratotic, they can mimic hypertrophic lichen planus, which mainfests with hyperkeratotic plaques or nodules on the lower extremities.8,29 In addition, the histopathology of lichen planus resembles the appearance of PN, with epidermal hyperplasia, hypergranulosis, hyperkeratosis, and increased fibroblasts and capillaries.8,29

Pemphigoid nodularis is a rare subtype of bullous pemphigoid that exhibits characteristics of PN with pruritic plaques and erosions.8,29,33 The patient population for pemphigoid nodularis tends to be aged 50 to 60 years, and females are affected more frequently than males. However, pemphigoid nodularis may manifest with blistering and large plaques, which are not seen commonly with PN.29 On histopathology, pemphigoid nodularis deposits IgG and C3 on the basement membrane and has subepidermal clefting, unlike PN.7,29

Actinic prurigo manifests with pruritic papules or nodules post–UV exposure to unprotected skin.8,29,33 This rare condition usually manifests with cheilitis and conjunctivitis. Unlike PN, which commonly affects elderly populations, actinic prurigo typically is found in young females.8,29 Cytologic examination shows hyperkeratosis, spongiosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis with lymphocytic perivascular infiltration of the dermis.34

Neurotic excoriations also tend to mimic PN with raised excoriated lesions; however, this disorder is due to neurotic picking of the skin without associated pruritus or true hyperkeratosis.8,29,33 Histopathology shows epidermal crusting with inflammation of the upper dermis.35

Infiltrative cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) may imitate PN in appearance. It manifests as tender, ulcerated, scaly plaques or nodules. Histopathology shows cytologic atypia with an infiltrative architectural pattern and presence of collections of compact keratin and parakeratin (called keratin pearls).

Keratoacanthomas can resemble PN lesions. They usually manifest as nodules measuring 1 to 2 cm in diameter and 0.5 cm thick, resembling crateriform tumors.36 On histopathology, KAs can resemble SCCs; however, KAs tend to manifest more frequently with a keratin-filled crater with a ground-glass appearance.36

Inverted follicular keratosis commonly manifests on the face in elderly men as a single, flesh-colored, verrucous papule that may resemble PN. However, cytology of inverted follicular keratosis is characterized by proliferation and squamous eddies.37 Consideration of the histologic findings and clinical appearance are important to differentiate between PN and cutaneous SCC.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia is a benign condition that manifests as a plaque or nodule with crust, scale, or ulceration. Histologically, this condition presents with hyperplastic proliferation of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium.38 The clinical and histologic appearance can mimic PN and other cutaneous eruptions with epidermal hyperplasia.

In clinical cases that are resistant to treatment, biopsy is the best approach to diagnose the lesion. Due to similarities in physical appearance and superficial histologic presentation of PN, KAs from SCC, hypertrophic lichen planus, and other hyperkeratotic lesions, the biopsy should be taken at the base of the lesion to sample deeper layers of skin to differentiate these dermatologic disorders.

Management

Current treatments for PN yield varied results. Many patients with moderate to severe PN attempt multiple therapies before seeing improvement.31 Treatments include topical, oral, and injectable medications and are either directed at the neural or immune components of PN due to the interplay between increased nerve fibers in the lesions (neural axis) as well as increases in cytokines and other immunologic mediators (immune axis) of this condition. However, the FDA recently approved the first treatment for PN—dupilumab—which is an injectable IL-4 receptor antagonist directed at the immunologic interactions affiliated with PN.

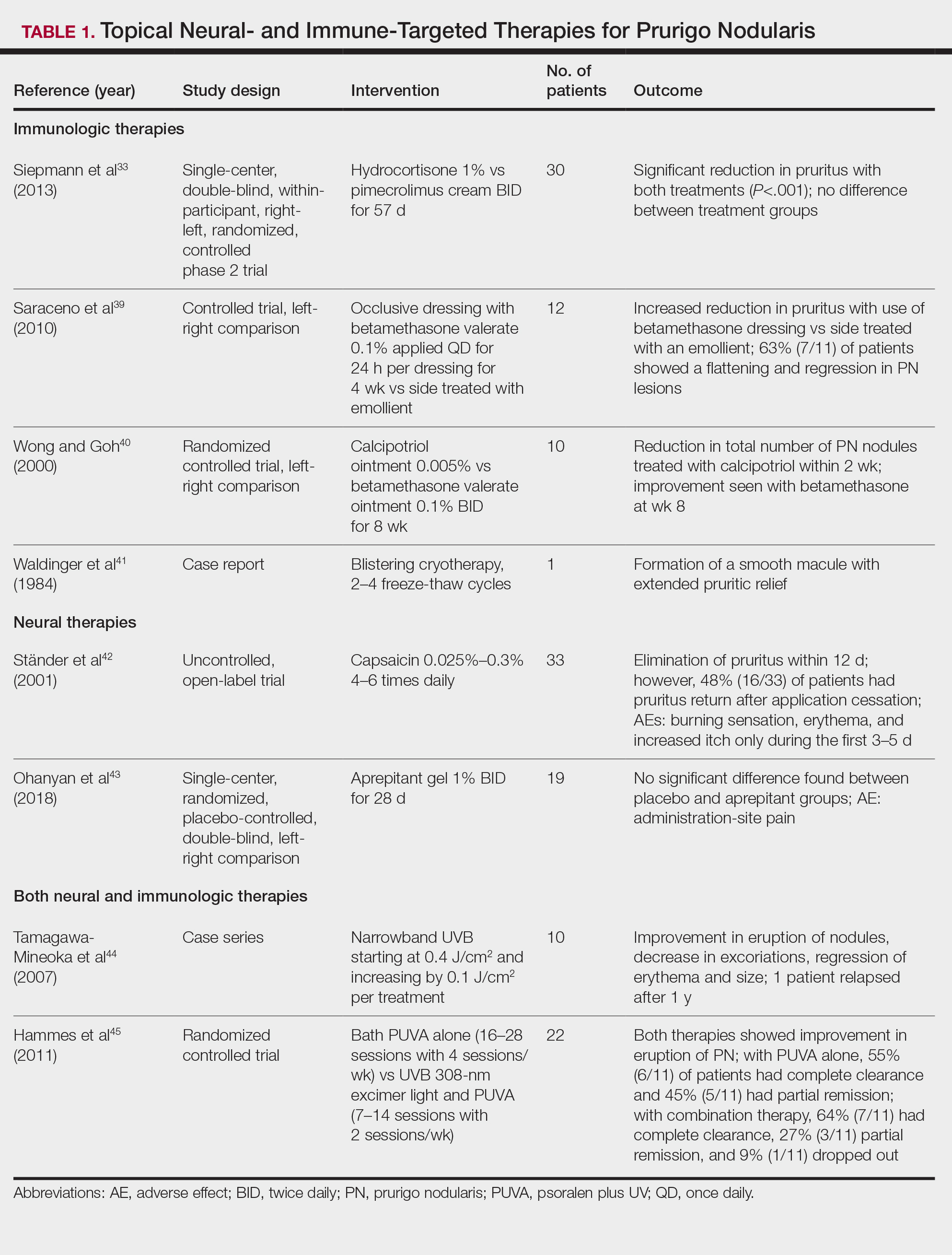

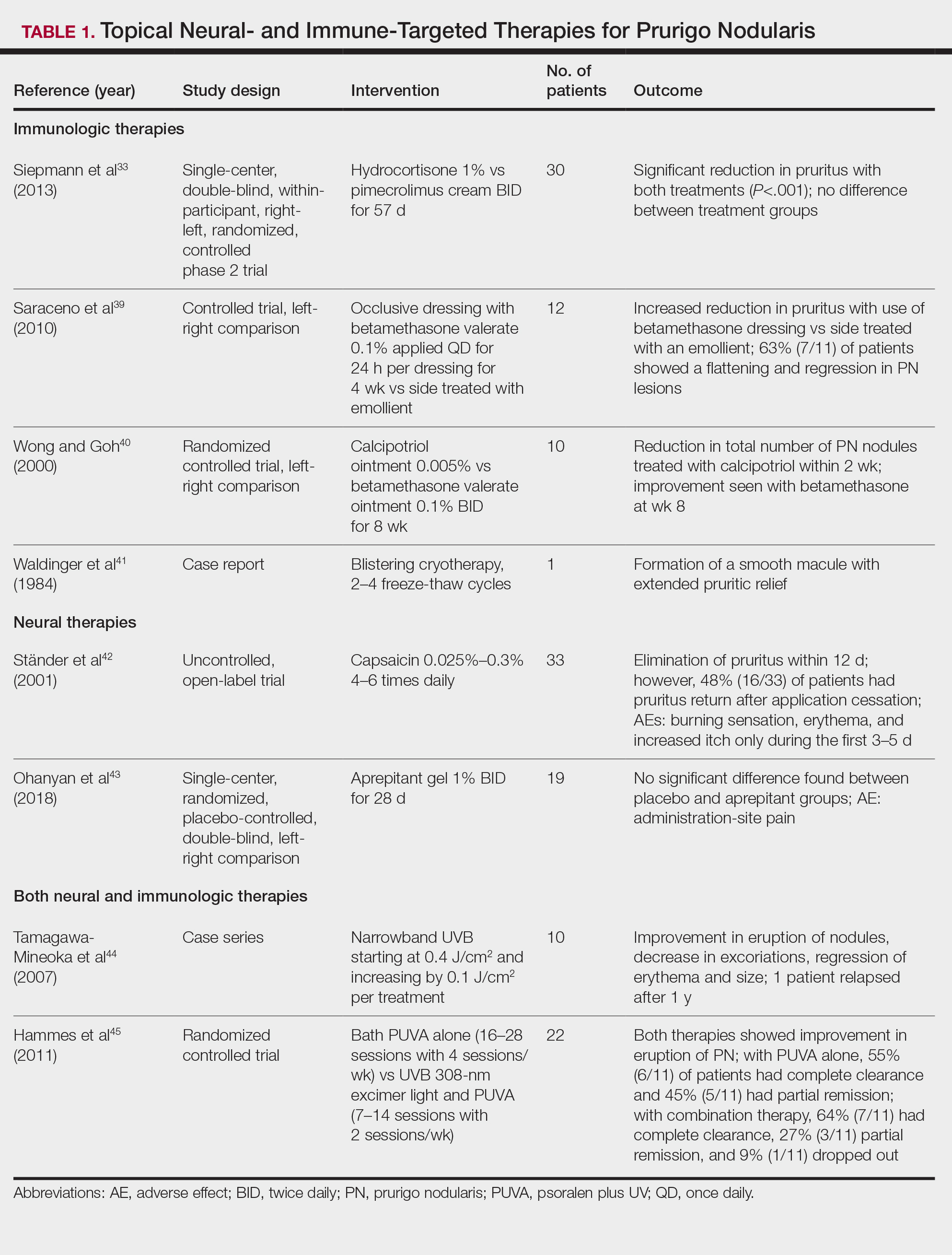

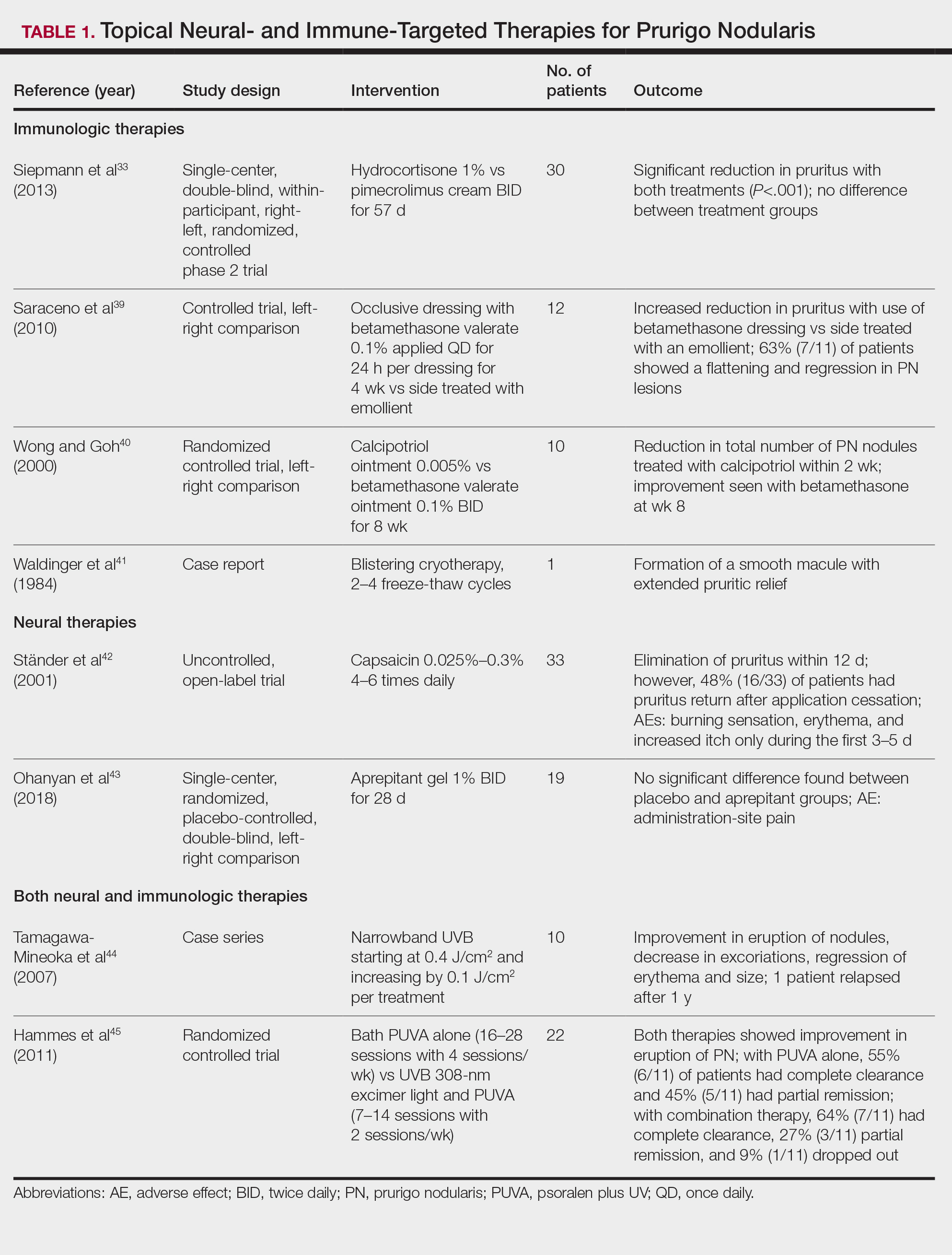

Immune-Mediated Topical Therapies—Immunologic topical therapies include corticosteroids, calcipotriol, and calcineurin inhibitors. Studies that have analyzed these treatments are limited to case reports and small intraindividual and randomized controlled trials (Table 1). Topical therapies usually are first-line agents for most patients. Adverse effects include transient irritation of the skin.40,42,43

Cryotherapy is another topical and immunologic therapy for those with PN; however, this treatment is more appropriate for patients with fewer lesions due to the pain that accompanies lesions treated with liquid nitrogen. In addition, this therapy can cause dyspigmentation of the skin in the treated areas.41

Similar to cryotherapy, intralesional corticosteroid injections are appropriate for patients with few PN lesions. A recent report described intralesional corticosteroid injections of 2.5 mg/mL for a PN nodule with high efficacy.46,47 This treatment has not undergone trials, but success with this modality has been documented, with adverse effects including hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation in the treated area and transient pain.46

Neural-Mediated Topical Therapies—Neural topical therapies include capsaicin and neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists, aprepitant43 and serlopitant. These treatment studies are limited to small open-label and randomized controlled trials. Adverse effects of these treatments include transient cutaneous pain at the site of topical administration. In addition, neural-mediated topical therapies have shown either limited improvements from baseline or return of symptoms after treatment cessation.42,43

Supplements—N-acetyl cysteine is an over-the-counter supplement that has been reported to improve symptoms in patients with skin-picking disorders.48 The mechanism of action includes antioxidant effects such as decreasing reactive oxygen species, decreasing inflammatory markers, regulating neurotransmitters, and inhibiting hyperkeratosis.49 N-acetyl cysteine has been poorly studied for its application in PN. A small study of 3 patients with subacute PN receiving 1200 mg of oral N-acetyl cysteine reported varying levels of improvement in skin appearance and reduction in skin picking.50

Phototherapy—Phototherapy, a typical first- or second-line treatment modality for PN, targets both the neural- and immune-mediated aspects associated with pruritus in PN (Table 1).51 UV light can penetrate through the epidermal layer of the skin and reach the keratinocytes, which play a role in the immune-related response of PN. In addition, the cutaneous sensory nerves are located in the upper dermal layer, from which nerve fibers grow and penetrate into the epidermis, thereby interacting with the keratinocytes where pruritic signals are transmitted from the periphery up to the brain.51

Studies analyzing the effects of phototherapy on PN are limited to case series and a small randomized controlled trial. However, this trial has shown improvements in pruritus in the participants. Adverse effects include transient burning and erythema at the treated sites.44,45

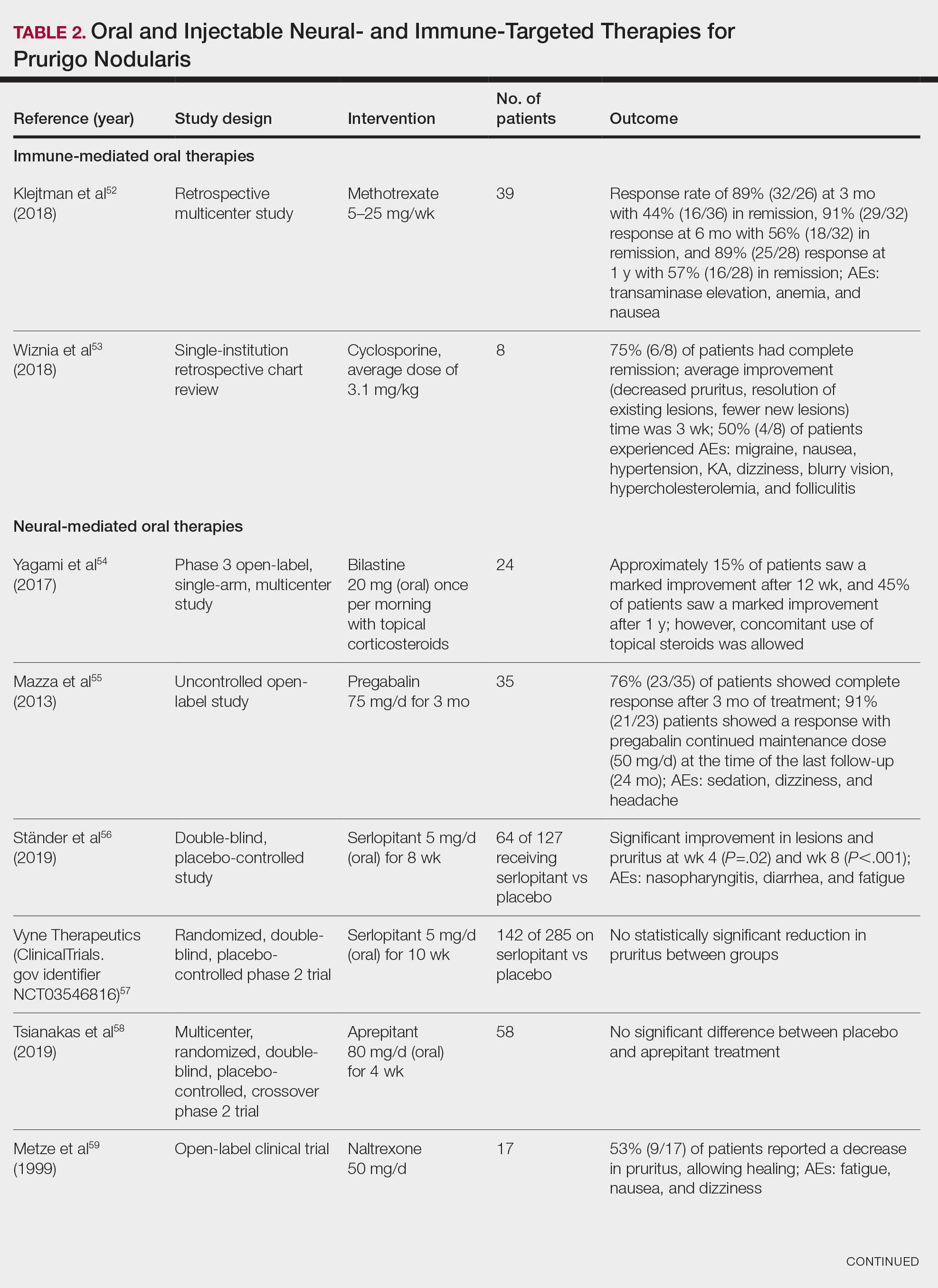

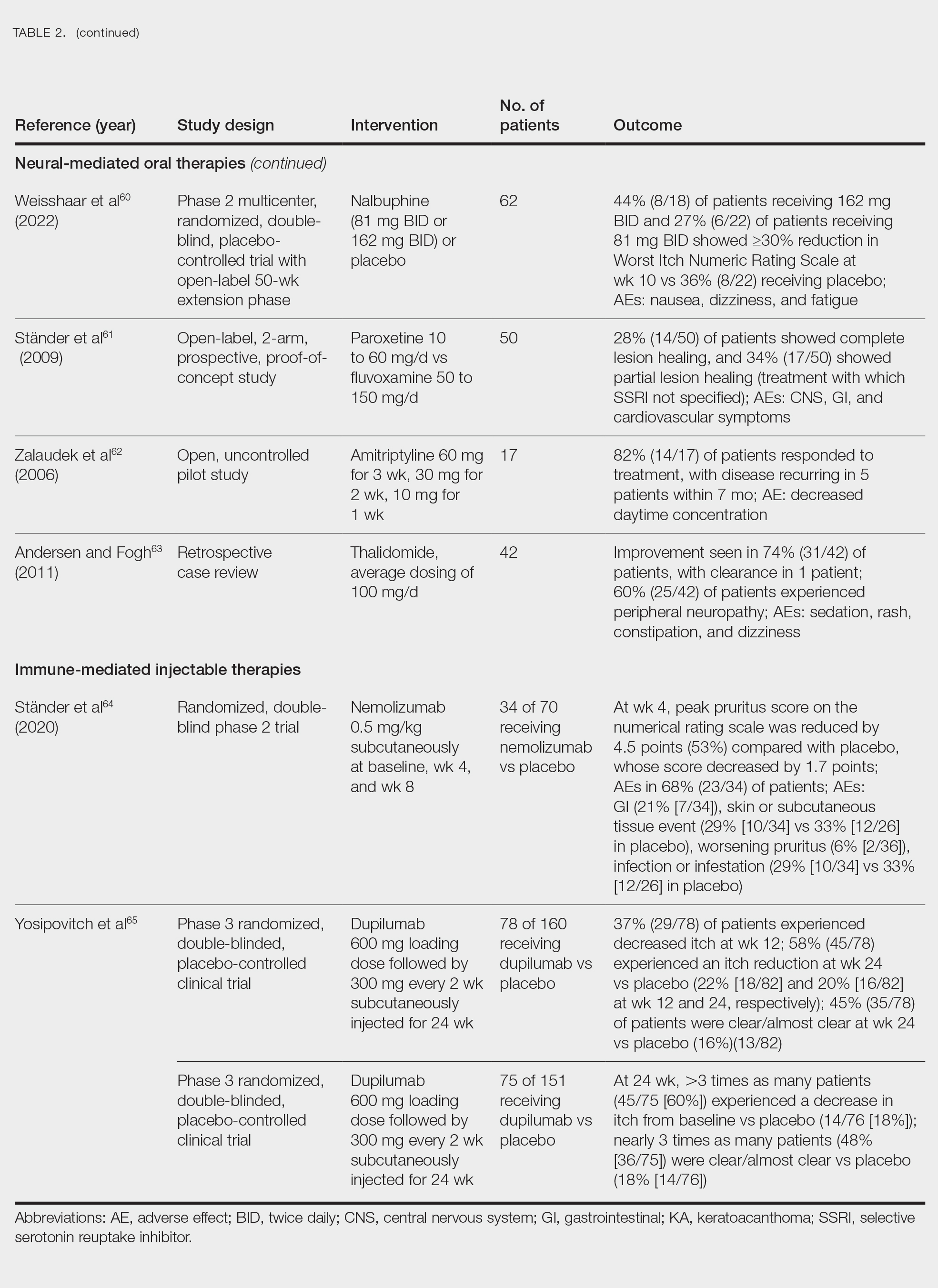

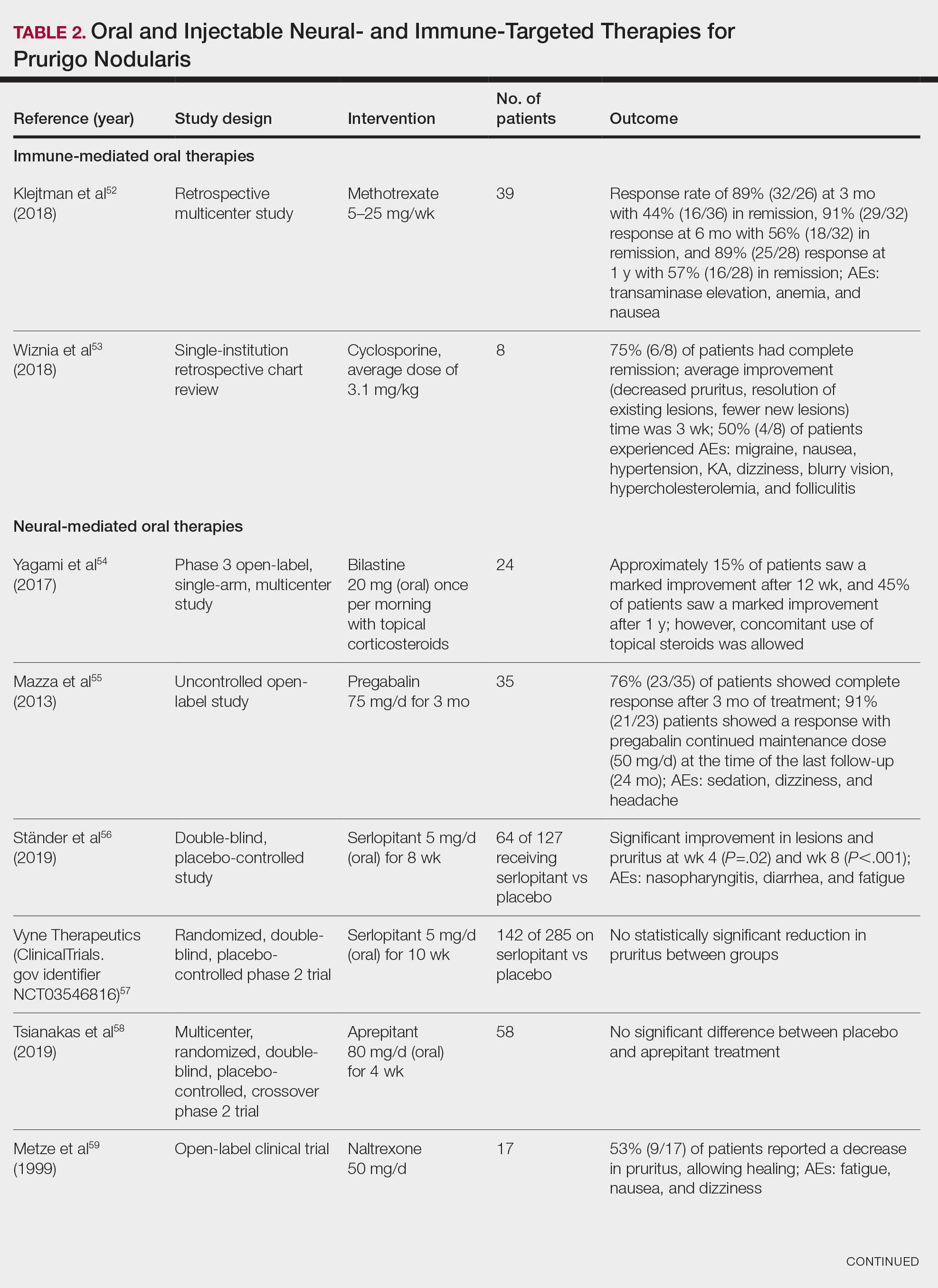

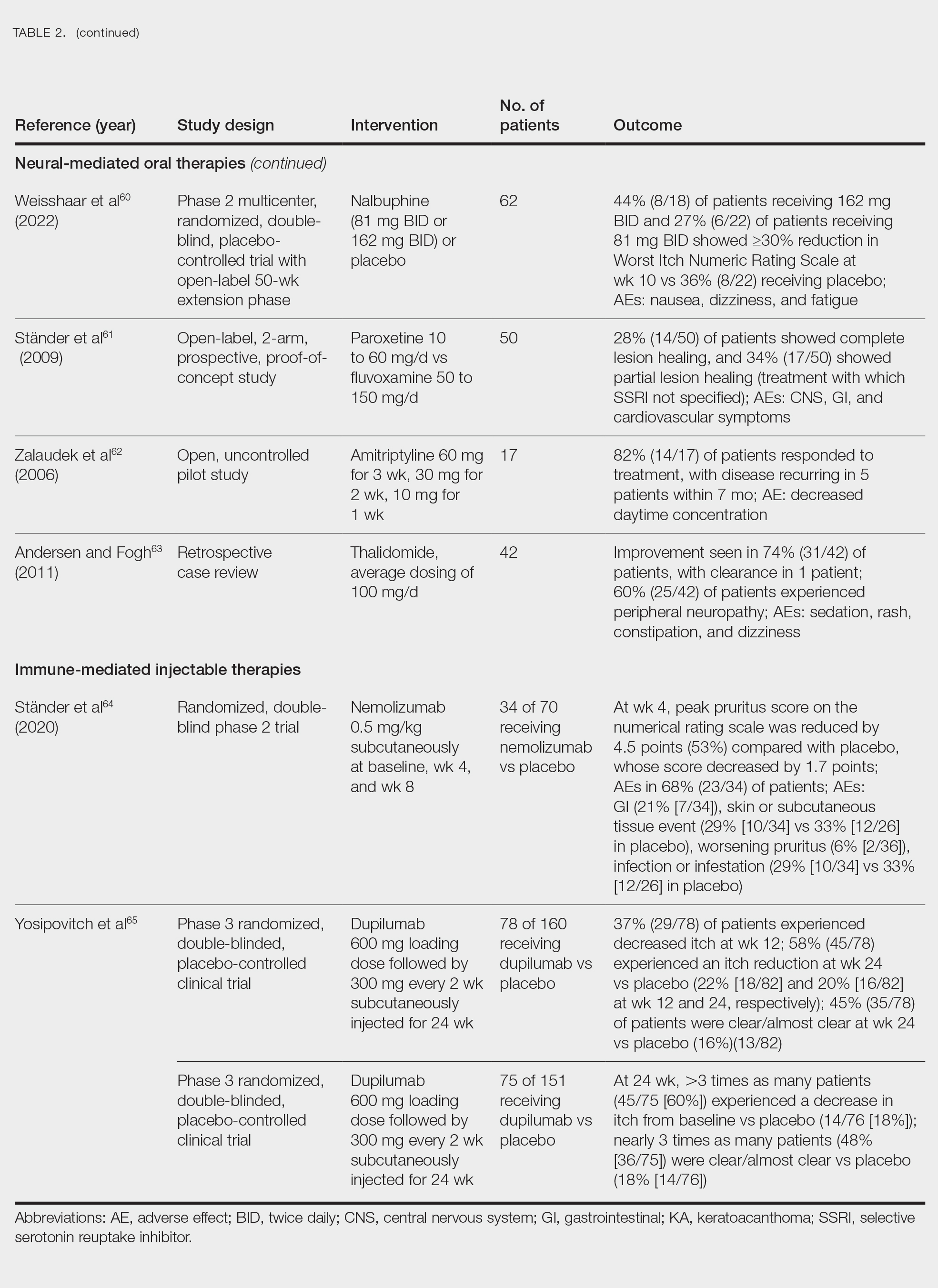

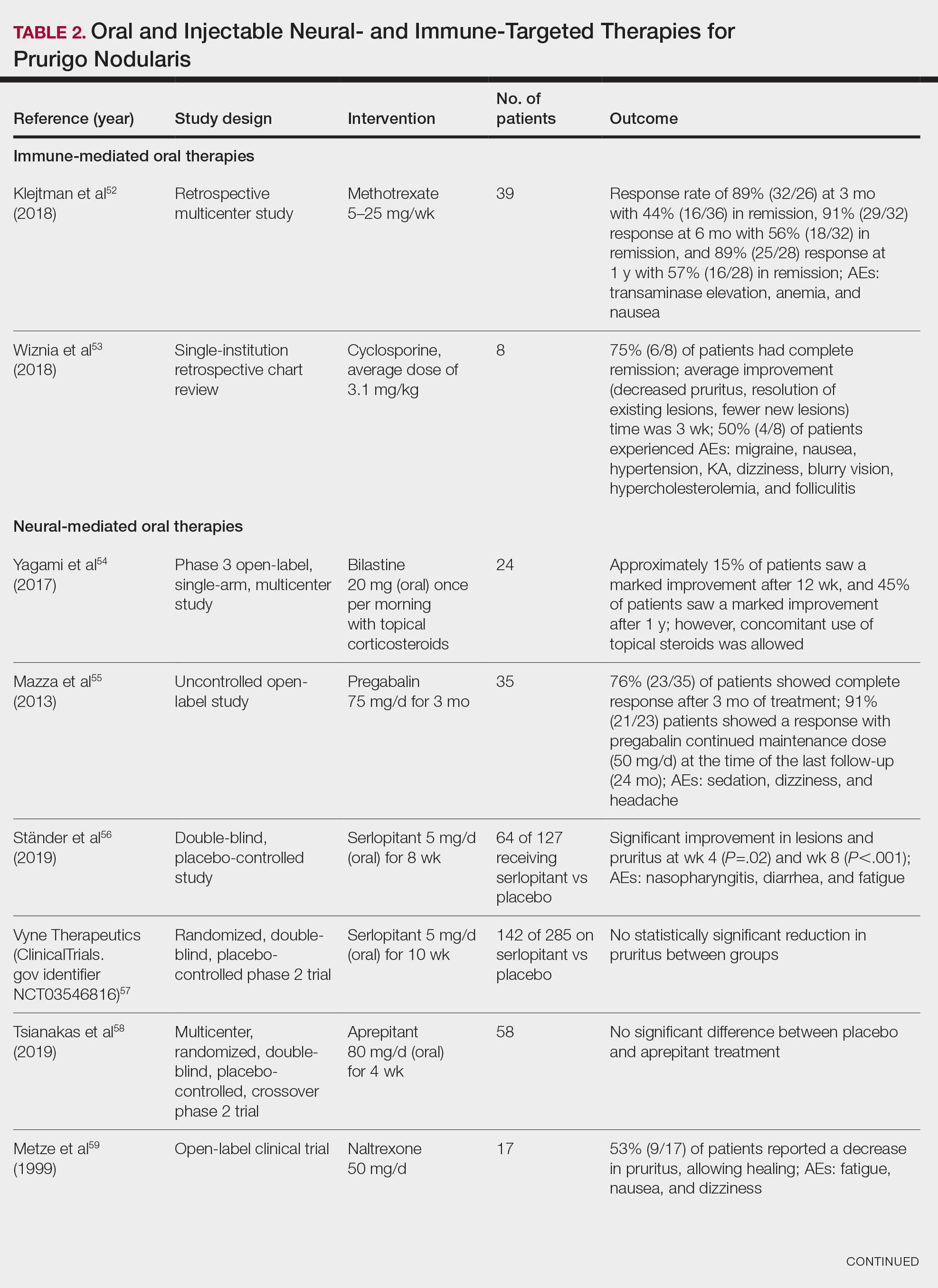

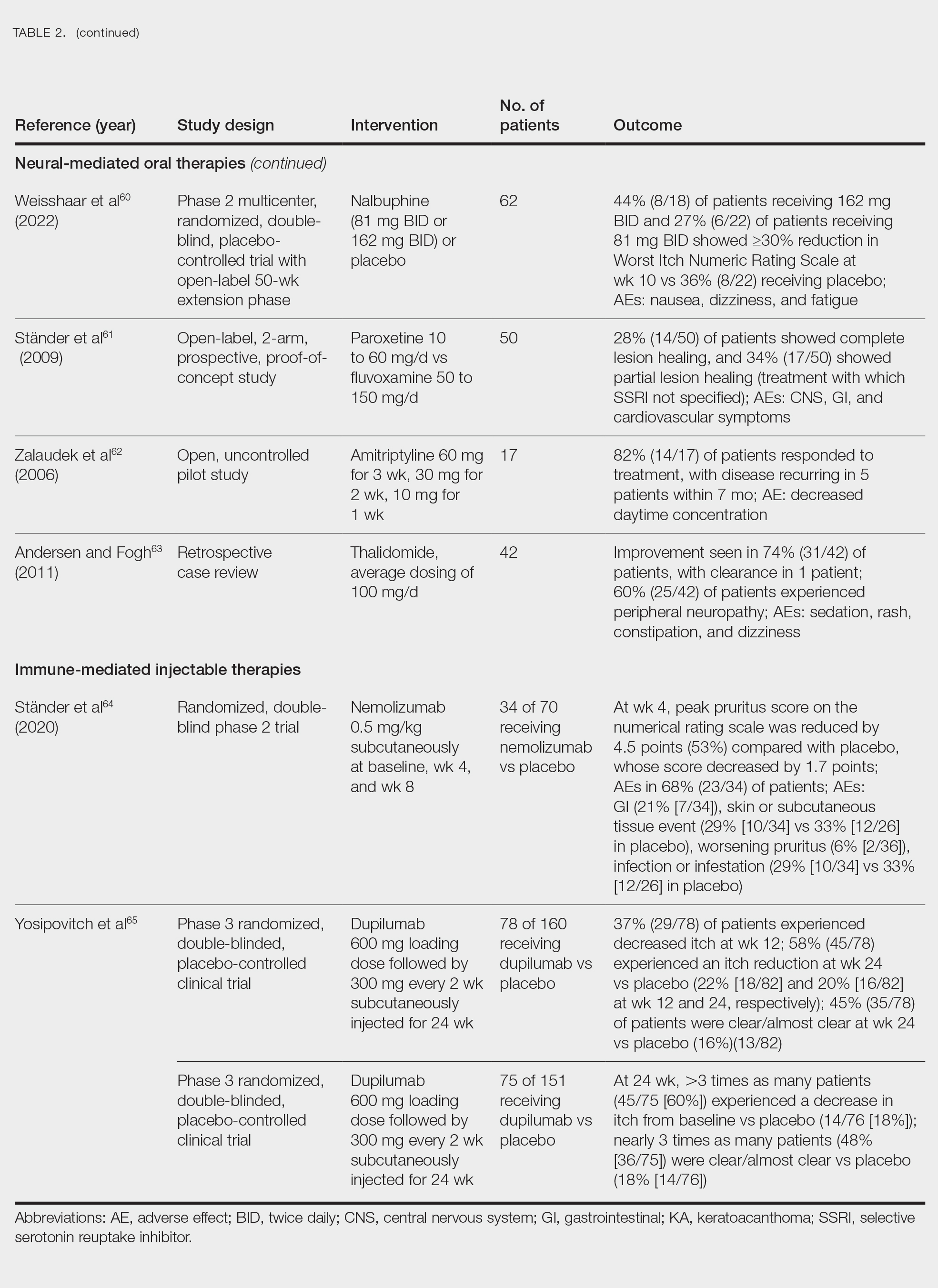

Immune-Mediated Oral Therapies—Immunologic-targeted oral therapies include bilastine, methotrexate, and cyclosporine (Table 2).52,53 Bilastine efficacy was analyzed in a small phase 3, open-label, multicenter study in Japan; however, patients were allowed to use topical steroids in conjunction with the oral antihistamine.54 Methotrexate and cyclosporine are immunosuppressive medications and were analyzed in small retrospective studies. Both treatments yielded notable relief for patients; however, 38.5% (15/39) of patients receiving methotrexate experienced adverse events, and 50.0% (4/8) experienced adverse events with cyclosporine.52,53

Neural-Mediated Oral Therapies—Neural-targeted oral therapies include pregabalin, serlopitant, aprepitant, naltrexone, nalbuphine, SSRIs (paroxetine and fluvoxamine), amitriptyline, and thalidomide. The research on these treatments ranges from case reviews to randomized controlled trials and open-label trials (Table 2).55-63

Thalidomide was studied in a small retrospective case review that showed notable improvement in PN. Dosages of thalidomide varied, but on average the dose was 100 mg/d. However, greater than 50% of patients experienced at least 1 adverse effect with this treatment.63

A study performed in Italy showed promising results for patients treated with pregabalin, with 70.0% (21/30) continuing to take pregabalin for almost 2 years following completion of the initial 3-month trial.55 Naltrexone decreased pruritus in more than half of patients (9/17).59 Amitriptyline yielded improvements in patients with PN; however, disease recurred in 5 patients (29%) after 7 months.62 A study performed in Germany reported promising results for paroxetine and fluvoxamine; however, some patients enrolled in the study had some form of psychiatric disorder.61

Serlopitant, aprepitant, and nalbuphine were studied in randomized controlled trials. The serlopitant trials were the largest of the neurally mediated oral medication studies; one showed substantial improvement in patients with PN,56 while the most recent trial did not show significant improvement (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03546816).57 On the other hand, aprepitant showed no major difference between the experimental and placebo groups.58 Nalbuphine 162 mg twice daily showed greater improvement in PN than nalbuphine 81 mg twice daily.60

Immune-Mediated Injectable Therapies—Immune-targeted injectables include nemolizumab and dupilumab (Table 2). Nemolizumab is an IL-31 antagonist that has been studied in a small randomized controlled trial that showed great success in decreasing pruritus associated with PN.64 IL-31 has been implicated in PN, and inhibition of the IL-31 receptor has been shown to disrupt the itch-scratch cycle of PN. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody against the IL-4 and IL-13 receptors, and it is the only FDA-approved treatment for PN.65 Blockage of these protein receptors decreases type 2 inflammation and chronic pruritus.66,67 Dupilumab is FDA approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis and recently was approved for adults with PN. Dupilumab acts to block the shared α-subunit of the pruritogenic cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 pathways,29 thereby breaking the itch-scratch cycle associated with PN and allowing for the healing of these lesions. Results from 2 clinical trials showed substantially reduced itch in patients with PN.65 Dupilumab also was approved by the European Medicines Agency for moderate to severe PN.68

Conclusion

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition that affects patient quality of life and can mimic various dermatologic conditions. The epidemiology and pathophysiology of PN have not been fully expounded. More research should be conducted to determine the underpinnings of PN to help identify more consistently effective therapies for this complex condition.

- Durmaz K, Ataseven A, Ozer I, et al. Prurigo nodularis responding to intravenous immunoglobulins. Przegl Dermatol. 2022;109:159-162. doi:10.5114/dr.2022.117988

- Kowalski EH, Kneiber D, Valdebran M, et al. Treatment-resistant prurigo nodularis: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:163-172. doi:10.2147/CCID.S188070

- Wong LS, Yen YT. Chronic nodular prurigo: an update on the pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:12390. doi:10.3390/ijms232012390

- Janmohamed SR, Gwillim EC, Yousaf M, et al. The impact of prurigo nodularis on quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;313:669-677. doi:10.1007/s00403-020-02148-0

- Zeidler C, Ständer S. The pathogenesis of prurigo nodularis - ‘super-itch’ in exploration. Eur J Pain. 2016;20:37-40. doi:10.1002/ejp.767

- Kwatra SG. Breaking the itch–scratch cycle in prurigo nodularis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:757-758. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1916733

- Frølunde AS, Wiis MAK, Ben Abdallah H, et al. Non-atopic chronic nodular prurigo (prurigo nodularis hyde): a systematic review of best-evidenced treatment options. Dermatology. 2022;238:950-960. doi:10.1159/000523700

- Kwon CD, Khanna R, Williams KA, et al. Diagnostic workup and evaluation of patients with prurigo nodularis. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:97. doi:10.3390/medicines6040097

- Kowalski EH, Kneiber D, Valdebran M, et al. Distinguishing truly recalcitrant prurigo nodularis from poor treatment adherence: a response to treatment-resistant prurigo nodularis [Response to letter]. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:371-372. doi:10.2147/CCID.S214195

- Whang KA, Le TK, Khanna R, et al. Health-related quality of life and economic burden of prurigo nodularis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:573-580. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.036

- Labib A, Ju T, Vander Does A, et al. Immunotargets and therapy for prurigo nodularis. Immunotargets Ther. 2022;11:11-21. doi:10.2147/ITT.S316602

- Belzberg M, Alphonse MP, Brown I, et al. Prurigo nodularis is characterized by systemic and cutaneous T helper 22 immune polarization. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:2208-2218.e14. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2021.02.749

- Ständer S, Pereira MP, Berger T, et al. IFSI-guideline on chronic prurigo including prurigo nodularis. Itch. 2020;5:e42. doi:10.1097/itx.0000000000000042

- Huang AH, Canner JK, Khanna R, et al. Real-world prevalence of prurigo nodularis and burden of associated diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:480-483.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.07.697

- Ständer S, Augustin M, Berger T, et al. Prevalence of prurigo nodularis in the United States of America: a retrospective database analysis. JAAD Int. 2021;2:28-30. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2020.10.009

- Sutaria N, Adawi W, Brown I, et al. Racial disparities in mortality among patients with prurigo nodularis: a multi-center cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:487-490. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.028

- Ryczek A, Reich A. Prevalence of prurigo nodularis in Poland. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00155. doi:10.2340/00015555-3518

- Morgan CL, Thomas M, Ständer S, et al. Epidemiology of prurigo nodularis in England: a retrospective database analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:188-195. doi:10.1111/bjd.21032

- Woo YR, Wang S, Sohn KA, et al. Epidemiology, comorbidities, and prescription patterns of Korean prurigo nodularis patients: a multi-institution study. J Clin Med Res. 2021;11:95. doi:10.3390/jcm11010095

- Weigelt N, Metze D, Ständer S. Prurigo nodularis: systematic analysis of 58 histological criteria in 136 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:578-586. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01484.x

- Yang LL, Jiang B, Chen SH, et al. Abnormal keratin expression pattern in prurigo nodularis epidermis. Skin Health Dis. 2022;2:e75. doi:10.1002/ski2.75

- Nockher WA, Renz H. Neurotrophins in allergic diseases: from neuronal growth factors to intercellular signaling molecules. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:583-589. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.049

- Di Marco E, Mathor M, Bondanza S, et al. Nerve growth factor binds to normal human keratinocytes through high and low affinity receptors and stimulates their growth by a novel autocrine loop. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22838-22846.

- Hägermark O, Hökfelt T, Pernow B. Flare and itch induced by substance P in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1978;71:233-235. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12515092

- Choi JE, Di Nardo A. Skin neurogenic inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2018;40:249-259. doi:10.1007/s00281-018-0675-z

- Haas S, Capellino S, Phan NQ, et al. Low density of sympathetic nerve fibers relative to substance P-positive nerve fibers in lesional skin of chronic pruritus and prurigo nodularis. J Dermatol Sci. 2010;58:193-197. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.03.020

- Park K, Mori T, Nakamura M, et al. Increased expression of mRNAs for IL-4, IL-17, IL-22 and IL-31 in skin lesions of subacute and chronic forms of prurigo. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:135-136.

- Tokura Y, Yagi H, Hanaoka K, et al. Subacute and chronic prurigo effectively treated with recombination interferon-gamma: implications for participation of Th2 cells in the pathogenesis of prurigo. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:231-234. doi:10.2340/0001555577231234

- Williams KA, Roh YS, Brown I, et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and pharmacological treatment of prurigo nodularis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021;14:67-77. doi:10.1080/17512433.2021.1852080

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Bewley A, Homey B, Pink A. Prurigo nodularis: a review of IL-31RA blockade and other potential treatments. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12:2039-2048. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00782-2

- Zeidler C, Yosipovitch G, Ständer S. Prurigo nodularis and its management. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:189-197. doi:10.1016/j.det.2018.02.003

- Siepmann D, Lotts T, Blome C, et al. Evaluation of the antipruritic effects of topical pimecrolimus in non-atopic prurigo nodularis: results of a randomized, hydrocortisone-controlled, double-blind phase II trial. Dermatology. 2013;227:353-360. doi:10.1159/000355671

- Valbuena MC, Muvdi S, Lim HW. Actinic prurigo. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:335-344, viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.03.010

- Aldhahwani R, Al Hawsawi KA. Neurotic excoriation presenting as solitary papule: case report. J Dermatol Dermatolog Surg. 2022;26:45. doi:10.4103/jdds.jdds_59_21

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Karadag AS, Ozlu E, Uzuncakmak TK, et al. Inverted follicular keratosis successfully treated with imiquimod. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:177-179. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.182354

- Nayak VN, Uma K, Girish HC, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in oral lesions: a review. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:148-152.

- Saraceno R, Chiricozzi A, Nisticò SP, et al. An occlusive dressing containing betamethasone valerate 0.1% for the treatment of prurigo nodularis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:363-366. doi:10.3109/09546630903386606

- Wong SS, Goh CL. Double-blind, right/left comparison of calcipotriol ointment and betamethasone ointment in the treatment of prurigo nodularis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:807-808. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.6.807

- Waldinger TP, Wong RC, Taylor WB, et al. Cryotherapy improves prurigo nodularis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1598-1600.

- Ständer S, Luger T, Metze D. Treatment of prurigo nodularis with topical capsaicin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:471-478. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.110059

- Ohanyan T, Schoepke N, Eirefelt S, et al. Role of substance P and its receptor neurokinin 1 in chronic prurigo: a randomized, proof-of-concept, controlled trial with topical aprepitant. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:26-31. doi:10.2340/00015555-2780

- Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Katoh N, Ueda E, et al. Narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy in patients with recalcitrant nodular prurigo. J Dermatol. 2007;34:691-695. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00360.x

- Hammes S, Hermann J, Roos S, et al. UVB 308-nm excimer light and bath PUVA: combination therapy is very effective in the treatment of prurigo nodularis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:799-803. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03865.x

- Richards RN. Update on intralesional steroid: focus on dermatoses. J Cutan Med Surg. 2010;14:19-23. doi:10.2310/7750.2009.08082

- Elmariah S, Kim B, Berger T, et al. Practical approaches for diagnosis and management of prurigo nodularis: United States expert panel consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:747-760. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.025

- Grant JE Chamberlain SR Redden SA et al. N-Acetylcysteine in the treatment of excoriation disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:490-496. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0060

- Adil M, Amin SS, Mohtashim M. N-acetylcysteine in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:652-659. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_33_18.

- Taylor M, Bhagwandas K. Trichotillosis, skin picking and N-acetylcysteine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.482

- Legat FJ. The antipruritic effect of phototherapy. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:333. doi:10.3389/fmed.2018.00333

- Klejtman T, Beylot-Barry M, Joly P, et al. Treatment of prurigo with methotrexate: a multicentre retrospective study of 39 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:437-440. doi:10.1111/jdv.14646

- Wiznia LE, Callahan SW, Cohen DE, et al. Rapid improvement of prurigo nodularis with cyclosporine treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1209-1211. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.024

- Yagami A, Furue M, Togawa M, et al. One-year safety and efficacy study of bilastine treatment in Japanese patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria or pruritus associated with skin diseases. J Dermatol. 2017;44:375-385. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13644

- Mazza M, Guerriero G, Marano G, et al. Treatment of prurigo nodularis with pregabalin. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2013;38:16-18. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12005

- Ständer S, Kwon P, Hirman J, et al. Serlopitant reduced pruritus in patients with prurigo nodularis in a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1395-1402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.052

- Study of the efficacy, safety and tolerability of serlopitant for the treatment of pruritus (itch) with prurigo nodularis. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03546816. Updated May 20, 2021. Accessed August 8, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03546816

- Tsianakas A, Zeidler C, Riepe C, et al. Aprepitant in anti-histamine-refractory chronic nodular prurigo: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over, phase-II trial (APREPRU). Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:379-385. doi:10.2340/00015555-3120

- Metze D, Reimann S, Beissert S, et al. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone, an oral opiate receptor antagonist, in the treatment of pruritus in internal and dermatological diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:533-539.

- Weisshaar E, Szepietowski JC, Bernhard JD, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral nalbuphine extended release in prurigo nodularis: results of a phase 2 randomized controlled trial with an open‐label extension phase. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:453-461. doi:10.1111/jdv.17816

- Ständer S, Böckenholt B, Schürmeyer-Horst F, et al. Treatment of chronic pruritus with the selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors paroxetine and fluvoxamine: results of an open-labelled, two-arm proof-of-concept study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:45-51. doi:10.2340/00015555-0553

- Zalaudek I, Petrillo G, Baldassarre MA, et al. Amitriptyline as therapeutic and not symptomatic approach in the treatment of prurigo nodularis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2006;141:433-437.

- Andersen TP, Fogh K. Thalidomide in 42 patients with prurigo nodularis Hyde. Dermatology. 2011;223:107-112. doi:10.1159/000331577

- Ständer S, Yosipovitch G, Legat FJ, et al. Trial of nemolizumab in moderate-to-severe prurigo nodularis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:706-716. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908316

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02320-9

- Mastorino L, Rosset F, Gelato F, et al. Chronic pruritus in atopic patients treated with dupilumab: real life response and related parameters in 354 patients. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15:883. doi: 10.3390/ph15070883

- Kishi R, Toyama S, Tominaga M, et al. Effects of dupilumab on itch-related events in atopic dermatitis: implications for assessing treatment efficacy in clinical practice. Cells. 2023;12:239. doi: 10.3390/cells12020239

- Dupixent. European Medicines Agency website. Updated July 15, 2024. Accessed August 27, 2024. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/dupixent

Prurigo nodularis (PN)(also called chronic nodular prurigo, prurigo nodularis of Hyde, or picker’s nodules) was first characterized by James Hyde in 1909.1-3 Prurigo nodularis manifests with symmetrical, intensely pruritic, eroded, or hyperkeratotic nodules or papules on the extremities and trunk.1,2,4,5 Studies have shown that individuals with PN experience pruritus, sleep loss, decreased social functioning from the appearance of the nodules, and a higher incidence of anxiety and depression, causing a negative impact on their quality of life.2,6 In addition, the manifestation of PN has been linked to neurologic and psychiatric disorders; however, PN also can be idiopathic and manifest without underlying illnesses.2,6,7

Prurigo nodularis has been associated with other dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis (up to 50%), lichen planus, keratoacanthomas (KAs), and bullous pemphigoid.7-9 It also has been linked to systemic diseases in 38% to 50% of cases, including chronic kidney disease, liver disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, malignancies (hematopoietic, liver, and skin), and HIV infection.6,8,10

The pathophysiology of PN is highly complex and has yet to be fully elucidated. It is thought to be due to dysregulation and interaction of the increase in neural and immunologic responses of proinflammatory and pruritogenic cytokines.2,11 Treatments aim to break the itch-scratch cycle that perpetuates this disorder; however, this proves difficult, as PN is associated with a higher itch intensity than atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.10 Therefore, most patients attempt multiple forms of treatment for PN, ranging from topical therapies, oral immunosuppressants, and phototherapy to the newest and only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of PN—dupilumab.1,7,11 Herein, we provide an updated review of PN with a focus on its epidemiology, histopathology and pathophysiology, comorbidities, clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, and current treatment options.

Epidemiology

There are few studies on the epidemiology of PN; however, middle-aged populations with underlying dermatologic or psychiatric disorders tend to be impacted most frequently.2,12,13 In 2016, it was estimated that almost 88,000 individuals had PN in the United States, with the majority being female; however, this estimate only took into account those aged 18 to 64 years and utilized data from IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database (IBM Watson Health) from October 2015 to December 2016.14 More recently, a retrospective database analysis estimated the prevalence of PN in the United States to be anywhere from 36.7 to 43.9 cases per 100,000 individuals. However, this retrospective review utilized the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code; PN has 2 codes associated with the diagnosis, and the coding accuracy is unknown.15 Sutaria et al16 looked at racial disparities in patients with PN utilizing data from TriNetX and found that patients who received a diagnosis of PN were more likely to be women, non-Hispanic, and Black compared with control patients. However, these estimates are restricted to the health care organizations within this database.

In 2018, Poland reported an annual prevalence of 6.52 cases per 100,000 individuals,17 while England reported a yearly prevalence of 3.27 cases per 100,000 individuals.18 Both countries reported most cases were female. However, these studies are not without limitations. Poland only uses the primary diagnosis code for medical billing to simplify clinical coding, thus underestimating the actual prevalence; furthermore, clinical codes more often than not are assigned by someone other than the diagnosing physician, leaving room for error.17 In addition, England’s PN estimate utilized diagnosis data from primary care and inpatient datasets, leaving out outpatient datasets in which patients with PN may have been referred and obtained the diagnosis, potentially underestimating the prevalence in this population.18

In contrast, Korea estimated the annual prevalence of PN to be 4.82 cases per 1000 dermatology outpatients, with the majority being men, based on results from a cross-sectional study among outpatients from the Catholic Medical Center. Although this is the largest health organization in Korea, the scope of this study is limited and lacks data from other medical centers in Korea.19

Histopathology and Pathophysiology