User login

Gene-replacement therapy shows promise in X-linked myotubular myopathy

, according to research presented at the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, which was held virtually this year. The treatment also appears to improve patients’ motor function significantly and help them to achieve motor milestones.

The results come from a phase 1/2 study of two doses of AT132. Three of 17 patients who received the higher dose had fatal liver dysfunction. The researchers are investigating these cases and will communicate their findings.

X-linked myotubular myopathy is a rare and often fatal neuromuscular disease. Mutations in MTM1, which encodes the myotubularin enzyme that is required for the development and function of skeletal muscle, cause the disease, which affects about one in 50,000 to one in 40,000 newborn boys. The disease is associated with profound muscle weakness and impairment of neuromuscular and respiratory function. Patients with X-linked myotubular myopathy achieve motor milestones much later or not at all, and most require a ventilator or a feeding tube. The mortality by age 18 months is approximately 50%.

The ASPIRO trial

Investigators theorized that muscle tissue would be an appropriate therapeutic target because it does not display dystrophic or inflammatory changes in most patients. They identified adeno-associated virus AAV8 as a potential carrier for gene therapy, since it targets skeletal muscle effectively.

Nancy L. Kuntz, MD, an attending physician at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and colleagues conducted the ASPIRO trial to examine AT132 as a potential treatment for X-linked myotubular myopathy. Eligible patients were younger than 5 years or had previously enrolled in a natural history study of the disease, required ventilator support at baseline, and had no clinically significant underlying liver disease. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 × 1014 vg/kg of AAT132, 3 × 1014 vg/kg of AT132, or delayed treatment. Participants assigned to delayed treatment served as the study’s control group.

The study’s primary end points were safety and change in hours of daily ventilator support from baseline to week 24 after dosing. The investigators also examined a respiratory endpoint (i.e., maximal inspiratory pressure [MIP]) and neuromuscular endpoints (i.e., motor milestones, CHOP INTEND score, and muscle biopsy).

Treatment improved respiratory function

As of July 28, Dr. Kuntz and colleagues had enrolled 23 patients in the trial. Six participants received the lower dose of therapy, and 17 received the higher dose. Median age was 1.7 years for the low-dose group and 2.6 years for the high-dose group.

Patients assigned to receive the higher dose of therapy received treatment more recently than the low-dose group, and not all of the former have reached 48 weeks since treatment, said Dr. Kuntz. Fewer efficacy data are thus available for the high-dose group.

Each dose of AT132 was associated with a significantly greater decrease from baseline in least squares mean daily hours of ventilator dependence, compared with the control condition. At week 48, the mean reduction was approximately 19 hours/day for patients receiving 1 × 1014 vg/kg of AAT132 and approximately 13 hours per day for patients receiving 3 × 1014 vg/kg of AT132. The investigators did not perform a statistical comparison of the two doses because of differing protocols for ventilator weaning between groups. All six patients who received the lower dose achieved ventilator independence, as did one patient who received the higher dose.

In addition, all treated patients had significantly greater increases from baseline in least squares mean MIP, compared with controls. The mean increase was 45.7 cmH2O for the low-dose group, 46.1 cmH2O for the high-dose group, and −8.0 cmH2O for controls.

Before treatment, most patients had not achieved any of the motor milestones that investigators assessed. After treatment, five of six patients receiving the low dose achieved independent walking, as did one in 10 patients receiving the high dose. No controls achieved this milestone. Treated patients also had significantly greater increases from baseline in least squares mean CHOP INTEND scores, compared with controls. At least at one time point, five of six patients receiving the low dose, six of 10 patients receiving the high dose, and one control patient achieved the mean score observed in healthy infants.

Patients in both treatment arms had improvements in muscle pathology at weeks 24 and 48, including improvements in organelle localization and fiber size. In addition, patients in both treatment arms had continued detectable vector copies and myotubularin protein expression at both time points.

Deaths under investigation

In the low-dose group, one patient had four serious treatment-emergent adverse events, and in the high-dose group, eight patients had 27 serious treatment-emergent adverse events. The three patients in the high-dose group who developed fatal liver dysfunction were among the older, heavier patients in the study and, consequently, received among the highest total doses of treatment. These patients had evidence of likely preexisting intrahepatic cholestasis.

“This clinical trial is on hold pending discussions between regulatory agencies and the study sponsor regarding additional recruitment and the duration of follow-up,” said Dr. Kuntz.

Audentes Therapeutics, which is developing AT132, funded the trial. Dr. Kuntz had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bönnemann CG et al. CNS-ICNA 2020, Abstract P.62.

, according to research presented at the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, which was held virtually this year. The treatment also appears to improve patients’ motor function significantly and help them to achieve motor milestones.

The results come from a phase 1/2 study of two doses of AT132. Three of 17 patients who received the higher dose had fatal liver dysfunction. The researchers are investigating these cases and will communicate their findings.

X-linked myotubular myopathy is a rare and often fatal neuromuscular disease. Mutations in MTM1, which encodes the myotubularin enzyme that is required for the development and function of skeletal muscle, cause the disease, which affects about one in 50,000 to one in 40,000 newborn boys. The disease is associated with profound muscle weakness and impairment of neuromuscular and respiratory function. Patients with X-linked myotubular myopathy achieve motor milestones much later or not at all, and most require a ventilator or a feeding tube. The mortality by age 18 months is approximately 50%.

The ASPIRO trial

Investigators theorized that muscle tissue would be an appropriate therapeutic target because it does not display dystrophic or inflammatory changes in most patients. They identified adeno-associated virus AAV8 as a potential carrier for gene therapy, since it targets skeletal muscle effectively.

Nancy L. Kuntz, MD, an attending physician at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and colleagues conducted the ASPIRO trial to examine AT132 as a potential treatment for X-linked myotubular myopathy. Eligible patients were younger than 5 years or had previously enrolled in a natural history study of the disease, required ventilator support at baseline, and had no clinically significant underlying liver disease. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 × 1014 vg/kg of AAT132, 3 × 1014 vg/kg of AT132, or delayed treatment. Participants assigned to delayed treatment served as the study’s control group.

The study’s primary end points were safety and change in hours of daily ventilator support from baseline to week 24 after dosing. The investigators also examined a respiratory endpoint (i.e., maximal inspiratory pressure [MIP]) and neuromuscular endpoints (i.e., motor milestones, CHOP INTEND score, and muscle biopsy).

Treatment improved respiratory function

As of July 28, Dr. Kuntz and colleagues had enrolled 23 patients in the trial. Six participants received the lower dose of therapy, and 17 received the higher dose. Median age was 1.7 years for the low-dose group and 2.6 years for the high-dose group.

Patients assigned to receive the higher dose of therapy received treatment more recently than the low-dose group, and not all of the former have reached 48 weeks since treatment, said Dr. Kuntz. Fewer efficacy data are thus available for the high-dose group.

Each dose of AT132 was associated with a significantly greater decrease from baseline in least squares mean daily hours of ventilator dependence, compared with the control condition. At week 48, the mean reduction was approximately 19 hours/day for patients receiving 1 × 1014 vg/kg of AAT132 and approximately 13 hours per day for patients receiving 3 × 1014 vg/kg of AT132. The investigators did not perform a statistical comparison of the two doses because of differing protocols for ventilator weaning between groups. All six patients who received the lower dose achieved ventilator independence, as did one patient who received the higher dose.

In addition, all treated patients had significantly greater increases from baseline in least squares mean MIP, compared with controls. The mean increase was 45.7 cmH2O for the low-dose group, 46.1 cmH2O for the high-dose group, and −8.0 cmH2O for controls.

Before treatment, most patients had not achieved any of the motor milestones that investigators assessed. After treatment, five of six patients receiving the low dose achieved independent walking, as did one in 10 patients receiving the high dose. No controls achieved this milestone. Treated patients also had significantly greater increases from baseline in least squares mean CHOP INTEND scores, compared with controls. At least at one time point, five of six patients receiving the low dose, six of 10 patients receiving the high dose, and one control patient achieved the mean score observed in healthy infants.

Patients in both treatment arms had improvements in muscle pathology at weeks 24 and 48, including improvements in organelle localization and fiber size. In addition, patients in both treatment arms had continued detectable vector copies and myotubularin protein expression at both time points.

Deaths under investigation

In the low-dose group, one patient had four serious treatment-emergent adverse events, and in the high-dose group, eight patients had 27 serious treatment-emergent adverse events. The three patients in the high-dose group who developed fatal liver dysfunction were among the older, heavier patients in the study and, consequently, received among the highest total doses of treatment. These patients had evidence of likely preexisting intrahepatic cholestasis.

“This clinical trial is on hold pending discussions between regulatory agencies and the study sponsor regarding additional recruitment and the duration of follow-up,” said Dr. Kuntz.

Audentes Therapeutics, which is developing AT132, funded the trial. Dr. Kuntz had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bönnemann CG et al. CNS-ICNA 2020, Abstract P.62.

, according to research presented at the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, which was held virtually this year. The treatment also appears to improve patients’ motor function significantly and help them to achieve motor milestones.

The results come from a phase 1/2 study of two doses of AT132. Three of 17 patients who received the higher dose had fatal liver dysfunction. The researchers are investigating these cases and will communicate their findings.

X-linked myotubular myopathy is a rare and often fatal neuromuscular disease. Mutations in MTM1, which encodes the myotubularin enzyme that is required for the development and function of skeletal muscle, cause the disease, which affects about one in 50,000 to one in 40,000 newborn boys. The disease is associated with profound muscle weakness and impairment of neuromuscular and respiratory function. Patients with X-linked myotubular myopathy achieve motor milestones much later or not at all, and most require a ventilator or a feeding tube. The mortality by age 18 months is approximately 50%.

The ASPIRO trial

Investigators theorized that muscle tissue would be an appropriate therapeutic target because it does not display dystrophic or inflammatory changes in most patients. They identified adeno-associated virus AAV8 as a potential carrier for gene therapy, since it targets skeletal muscle effectively.

Nancy L. Kuntz, MD, an attending physician at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and colleagues conducted the ASPIRO trial to examine AT132 as a potential treatment for X-linked myotubular myopathy. Eligible patients were younger than 5 years or had previously enrolled in a natural history study of the disease, required ventilator support at baseline, and had no clinically significant underlying liver disease. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 × 1014 vg/kg of AAT132, 3 × 1014 vg/kg of AT132, or delayed treatment. Participants assigned to delayed treatment served as the study’s control group.

The study’s primary end points were safety and change in hours of daily ventilator support from baseline to week 24 after dosing. The investigators also examined a respiratory endpoint (i.e., maximal inspiratory pressure [MIP]) and neuromuscular endpoints (i.e., motor milestones, CHOP INTEND score, and muscle biopsy).

Treatment improved respiratory function

As of July 28, Dr. Kuntz and colleagues had enrolled 23 patients in the trial. Six participants received the lower dose of therapy, and 17 received the higher dose. Median age was 1.7 years for the low-dose group and 2.6 years for the high-dose group.

Patients assigned to receive the higher dose of therapy received treatment more recently than the low-dose group, and not all of the former have reached 48 weeks since treatment, said Dr. Kuntz. Fewer efficacy data are thus available for the high-dose group.

Each dose of AT132 was associated with a significantly greater decrease from baseline in least squares mean daily hours of ventilator dependence, compared with the control condition. At week 48, the mean reduction was approximately 19 hours/day for patients receiving 1 × 1014 vg/kg of AAT132 and approximately 13 hours per day for patients receiving 3 × 1014 vg/kg of AT132. The investigators did not perform a statistical comparison of the two doses because of differing protocols for ventilator weaning between groups. All six patients who received the lower dose achieved ventilator independence, as did one patient who received the higher dose.

In addition, all treated patients had significantly greater increases from baseline in least squares mean MIP, compared with controls. The mean increase was 45.7 cmH2O for the low-dose group, 46.1 cmH2O for the high-dose group, and −8.0 cmH2O for controls.

Before treatment, most patients had not achieved any of the motor milestones that investigators assessed. After treatment, five of six patients receiving the low dose achieved independent walking, as did one in 10 patients receiving the high dose. No controls achieved this milestone. Treated patients also had significantly greater increases from baseline in least squares mean CHOP INTEND scores, compared with controls. At least at one time point, five of six patients receiving the low dose, six of 10 patients receiving the high dose, and one control patient achieved the mean score observed in healthy infants.

Patients in both treatment arms had improvements in muscle pathology at weeks 24 and 48, including improvements in organelle localization and fiber size. In addition, patients in both treatment arms had continued detectable vector copies and myotubularin protein expression at both time points.

Deaths under investigation

In the low-dose group, one patient had four serious treatment-emergent adverse events, and in the high-dose group, eight patients had 27 serious treatment-emergent adverse events. The three patients in the high-dose group who developed fatal liver dysfunction were among the older, heavier patients in the study and, consequently, received among the highest total doses of treatment. These patients had evidence of likely preexisting intrahepatic cholestasis.

“This clinical trial is on hold pending discussions between regulatory agencies and the study sponsor regarding additional recruitment and the duration of follow-up,” said Dr. Kuntz.

Audentes Therapeutics, which is developing AT132, funded the trial. Dr. Kuntz had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bönnemann CG et al. CNS-ICNA 2020, Abstract P.62.

FROM CNS-ICNA 2020

JIA arthritis and uveitis flares ‘often run parallel’

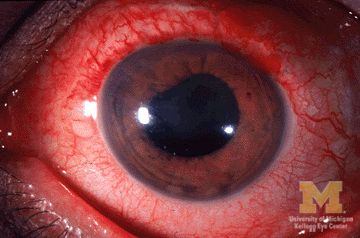

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis–associated uveitis (JIA-U) are significantly more likely to experience a flare in their eye disease if their arthritis is also worsening, a team of U.S.-based researchers has found.

In a longitudinal cohort study, children with active arthritis at the time of a routine rheumatology assessment had an almost 2.5-fold increased risk of also having active uveitis 45 days before or after the assessment than did children whose arthritis was not flaring at the rheumatology assessment.

“We demonstrate that the two diseases often run parallel courses,” corresponding author Emily J. Liebling, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates state in Arthritis Care & Research, noting that the magnitude of the association is striking.

“Although there are known risk factors associated with uveitis development in children with JIA, less data are available about factors associated with uveitis flare or activity,” said Sheila T. Angeles-Han, MD, MSc, of the departments of pediatrics and ophthalmology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center who commented on the study in an interview.

“If proven, this knowledge has the potential to impact practice patterns and current guidelines wherein a pediatric rheumatologist who evaluates a child with JIA-associated uveitis and finds active arthritis would request an expedited ophthalmic examination,” Dr. Angeles-Han suggested.

Dr. Angeles-Han led the development of the first American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of JIA-Associated Uveitis, which recommends regular screening for uveitis in all children with JIA. Children found to have uveitis should then be screened at least every 3 months, and more frequently if they are taking glucocorticoids and treatment is being tapered.

JIA-associated uveitis accounts for around 20%-40% of all cases of noninfectious childhood eye inflammation, and it can run an insidious and chronic course.

“Children with acute anterior uveitis are symptomatic and tend to have a painful red eye, thus prompting an ophthalmic evaluation,” Dr. Angeles-Han explained. “This is different from children with chronic anterior uveitis who tend not to have any symptoms, thus a screening examination is critical to detect ocular inflammation.”

While the ACR/AF guideline distinguishes between acute and chronic uveitis, Dr. Liebling and colleagues explain that they did not because their experience shows that “even patients with chronic anterior uveitis, typically thought to have silent disease, may exhibit symptoms of eye pain, redness, vision changes, and photophobia.”

Conversely, they say “the JIA subtypes usually associated with acute anterior uveitis may instead manifest as asymptomatic eye disease.”

For their study, Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators examined the records of children seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia over a 6.5-year period. For inclusion, children had to have a physician diagnosis of JIA of any subtype and a history of uveitis.

A total of 98 children were included in the retrospective evaluation; the median age at diagnosis of JIA was 3.3 years, and the median age at first uveitis diagnosis was 5.1 years. The majority (82%) were female, 69% were antinuclear antibody (ANA) positive, and 60% had oligoarthritis – all of which have been associated with having a higher risk for developing uveitis.

However, independent of these and several other factors, the probability of having active uveitis within 45 days of a rheumatology assessment was 65% in those with active arthritis versus 42% for those with no active joints.

Their data are based on 1,229 rheumatology visits that occurred between 2013 and 2019, with a median of 13 visits per patient. Overall, arthritis was defined as being active in 17% of visits, and active uveitis was observed in 18% of rheumatology visits.

Concordance between arthritis and uveitis activity was observed 73% of the time, the researchers reported. A sensitivity analysis that excluded children with the enthesitis-related arthritis subtype of JIA, who may not undergo frequent eye exams, did not change their findings.

Decreased odds of active uveitis at any time point were seen with the use of combination biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Years from uveitis diagnosis was also associated with lower odds of active uveitis over time.

Other factors associated with lower odds of uveitis were female sex, HLA-B27 positivity, and having any subtype of JIA other than the oligoarticular subtype.

Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators concluded that, contrary to the historical dogma, arthritis and uveitis do not run distinct and unrelated courses: “In patients with JIA-U, there is a significant temporal association between arthritis and uveitis disease activity.”

The study was sponsored by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Rheumatology Research Fund. The investigators for the study had no financial support from commercial sources or any other potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Angeles-Han had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Liebling EJ et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/acr.24483.

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis–associated uveitis (JIA-U) are significantly more likely to experience a flare in their eye disease if their arthritis is also worsening, a team of U.S.-based researchers has found.

In a longitudinal cohort study, children with active arthritis at the time of a routine rheumatology assessment had an almost 2.5-fold increased risk of also having active uveitis 45 days before or after the assessment than did children whose arthritis was not flaring at the rheumatology assessment.

“We demonstrate that the two diseases often run parallel courses,” corresponding author Emily J. Liebling, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates state in Arthritis Care & Research, noting that the magnitude of the association is striking.

“Although there are known risk factors associated with uveitis development in children with JIA, less data are available about factors associated with uveitis flare or activity,” said Sheila T. Angeles-Han, MD, MSc, of the departments of pediatrics and ophthalmology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center who commented on the study in an interview.

“If proven, this knowledge has the potential to impact practice patterns and current guidelines wherein a pediatric rheumatologist who evaluates a child with JIA-associated uveitis and finds active arthritis would request an expedited ophthalmic examination,” Dr. Angeles-Han suggested.

Dr. Angeles-Han led the development of the first American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of JIA-Associated Uveitis, which recommends regular screening for uveitis in all children with JIA. Children found to have uveitis should then be screened at least every 3 months, and more frequently if they are taking glucocorticoids and treatment is being tapered.

JIA-associated uveitis accounts for around 20%-40% of all cases of noninfectious childhood eye inflammation, and it can run an insidious and chronic course.

“Children with acute anterior uveitis are symptomatic and tend to have a painful red eye, thus prompting an ophthalmic evaluation,” Dr. Angeles-Han explained. “This is different from children with chronic anterior uveitis who tend not to have any symptoms, thus a screening examination is critical to detect ocular inflammation.”

While the ACR/AF guideline distinguishes between acute and chronic uveitis, Dr. Liebling and colleagues explain that they did not because their experience shows that “even patients with chronic anterior uveitis, typically thought to have silent disease, may exhibit symptoms of eye pain, redness, vision changes, and photophobia.”

Conversely, they say “the JIA subtypes usually associated with acute anterior uveitis may instead manifest as asymptomatic eye disease.”

For their study, Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators examined the records of children seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia over a 6.5-year period. For inclusion, children had to have a physician diagnosis of JIA of any subtype and a history of uveitis.

A total of 98 children were included in the retrospective evaluation; the median age at diagnosis of JIA was 3.3 years, and the median age at first uveitis diagnosis was 5.1 years. The majority (82%) were female, 69% were antinuclear antibody (ANA) positive, and 60% had oligoarthritis – all of which have been associated with having a higher risk for developing uveitis.

However, independent of these and several other factors, the probability of having active uveitis within 45 days of a rheumatology assessment was 65% in those with active arthritis versus 42% for those with no active joints.

Their data are based on 1,229 rheumatology visits that occurred between 2013 and 2019, with a median of 13 visits per patient. Overall, arthritis was defined as being active in 17% of visits, and active uveitis was observed in 18% of rheumatology visits.

Concordance between arthritis and uveitis activity was observed 73% of the time, the researchers reported. A sensitivity analysis that excluded children with the enthesitis-related arthritis subtype of JIA, who may not undergo frequent eye exams, did not change their findings.

Decreased odds of active uveitis at any time point were seen with the use of combination biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Years from uveitis diagnosis was also associated with lower odds of active uveitis over time.

Other factors associated with lower odds of uveitis were female sex, HLA-B27 positivity, and having any subtype of JIA other than the oligoarticular subtype.

Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators concluded that, contrary to the historical dogma, arthritis and uveitis do not run distinct and unrelated courses: “In patients with JIA-U, there is a significant temporal association between arthritis and uveitis disease activity.”

The study was sponsored by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Rheumatology Research Fund. The investigators for the study had no financial support from commercial sources or any other potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Angeles-Han had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Liebling EJ et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/acr.24483.

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis–associated uveitis (JIA-U) are significantly more likely to experience a flare in their eye disease if their arthritis is also worsening, a team of U.S.-based researchers has found.

In a longitudinal cohort study, children with active arthritis at the time of a routine rheumatology assessment had an almost 2.5-fold increased risk of also having active uveitis 45 days before or after the assessment than did children whose arthritis was not flaring at the rheumatology assessment.

“We demonstrate that the two diseases often run parallel courses,” corresponding author Emily J. Liebling, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates state in Arthritis Care & Research, noting that the magnitude of the association is striking.

“Although there are known risk factors associated with uveitis development in children with JIA, less data are available about factors associated with uveitis flare or activity,” said Sheila T. Angeles-Han, MD, MSc, of the departments of pediatrics and ophthalmology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center who commented on the study in an interview.

“If proven, this knowledge has the potential to impact practice patterns and current guidelines wherein a pediatric rheumatologist who evaluates a child with JIA-associated uveitis and finds active arthritis would request an expedited ophthalmic examination,” Dr. Angeles-Han suggested.

Dr. Angeles-Han led the development of the first American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of JIA-Associated Uveitis, which recommends regular screening for uveitis in all children with JIA. Children found to have uveitis should then be screened at least every 3 months, and more frequently if they are taking glucocorticoids and treatment is being tapered.

JIA-associated uveitis accounts for around 20%-40% of all cases of noninfectious childhood eye inflammation, and it can run an insidious and chronic course.

“Children with acute anterior uveitis are symptomatic and tend to have a painful red eye, thus prompting an ophthalmic evaluation,” Dr. Angeles-Han explained. “This is different from children with chronic anterior uveitis who tend not to have any symptoms, thus a screening examination is critical to detect ocular inflammation.”

While the ACR/AF guideline distinguishes between acute and chronic uveitis, Dr. Liebling and colleagues explain that they did not because their experience shows that “even patients with chronic anterior uveitis, typically thought to have silent disease, may exhibit symptoms of eye pain, redness, vision changes, and photophobia.”

Conversely, they say “the JIA subtypes usually associated with acute anterior uveitis may instead manifest as asymptomatic eye disease.”

For their study, Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators examined the records of children seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia over a 6.5-year period. For inclusion, children had to have a physician diagnosis of JIA of any subtype and a history of uveitis.

A total of 98 children were included in the retrospective evaluation; the median age at diagnosis of JIA was 3.3 years, and the median age at first uveitis diagnosis was 5.1 years. The majority (82%) were female, 69% were antinuclear antibody (ANA) positive, and 60% had oligoarthritis – all of which have been associated with having a higher risk for developing uveitis.

However, independent of these and several other factors, the probability of having active uveitis within 45 days of a rheumatology assessment was 65% in those with active arthritis versus 42% for those with no active joints.

Their data are based on 1,229 rheumatology visits that occurred between 2013 and 2019, with a median of 13 visits per patient. Overall, arthritis was defined as being active in 17% of visits, and active uveitis was observed in 18% of rheumatology visits.

Concordance between arthritis and uveitis activity was observed 73% of the time, the researchers reported. A sensitivity analysis that excluded children with the enthesitis-related arthritis subtype of JIA, who may not undergo frequent eye exams, did not change their findings.

Decreased odds of active uveitis at any time point were seen with the use of combination biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Years from uveitis diagnosis was also associated with lower odds of active uveitis over time.

Other factors associated with lower odds of uveitis were female sex, HLA-B27 positivity, and having any subtype of JIA other than the oligoarticular subtype.

Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators concluded that, contrary to the historical dogma, arthritis and uveitis do not run distinct and unrelated courses: “In patients with JIA-U, there is a significant temporal association between arthritis and uveitis disease activity.”

The study was sponsored by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Rheumatology Research Fund. The investigators for the study had no financial support from commercial sources or any other potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Angeles-Han had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Liebling EJ et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/acr.24483.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Acute flaccid myelitis: More likely missed than diagnosed

and that can result in loss of valuable time to admit patients and begin treatment to get ahead of the virus that may cause the disease.

At the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, held virtually this year, Leslie H. Hayes, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital presented findings of a retrospective case series from 13 institutions in the United States and Canada that determined 78% of patients eventually found to have AFM were initially misdiagnosed. About 62% were given an alternate diagnosis or multiple diagnoses, and 60% did not get a referral for further care or evaluation. The study included 175 children aged 18 years and younger when symptoms first appeared from 2014 to 2018 and who met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention case definition of AFM.

“As it becomes more evident that AFM outbreaks are driven by enterovirus infections, treatments targeting the viral infection are likely to be most effective very early in the course of disease, necessitating a precise and early diagnosis,” Dr. Hayes said. “Thus awareness is needed to help recognize the signs of symptoms of AFM, particularly among frontline clinicians.”

One reason for misdiagnosis is that AFM has features that overlap with other neuroinflammatory disorders, she said. “In many cases the patients are misdiagnosed as having benign or self-limiting processes that would not prompt the same monitoring and level of care.”

Numbness and prodromal illnesses were associated with misdiagnosis, she said, but otherwise most presenting symptoms were similar between the misdiagnosed and correctly diagnosed patients.

Neurologic disorders with similar features to AFM that the study identified were Guillain-Barré syndrome, spinal cord pathologies such as transverse myelitis, brain pathologies including acute disseminating encephalomyelitis, acute inclusion body encephalitis and stroke, and other neuroinflammatory conditions.

“There were also many patients diagnosed as having processes that in many cases would not prompt inpatient admission, would not involve neurology consultation, and would not be treated in a similar fashion to AFM,” Dr. Hayes said.

Those diagnoses included plexopathy, neuritis, Bell’s palsy, meningoencephalitis, nonspecific infectious illness or parainfectious autoimmune disease, or musculoskeletal problems including toxic or transient synovitis, myositis, fracture or sprain, or torticollis.

“We identified preceding illness and numbness as two features associated with misdiagnosis,” Dr. Hayes said.

“We evaluated illness severity by evaluating the need for invasive and noninvasive ventilation and found that, while not statistically significant, misdiagnosed patients had a trend toward higher need for such respiratory support,” she noted. Specifically, 31.6% of misdiagnosed patients required noninvasive ventilation versus 15.8% of promptly diagnosed patients (P = .06).

Dr. Hayes characterized the rates of ICU admissions between the two groups as not statistically significant: 52.5% and 36.8% for the misdiagnosed and promptly diagnosed groups, respectively (P = .1).

Both groups of patients received intravenous immunoglobulin in similar rates (77.9% and 81.6%, respectively, P = .63), but the misdiagnosed patients were much more likely to receive steroids, 68.2% versus 44.7% (P = .008). That’s likely because steroids are the standard treatment for the neuroinflammatory disorders that they were misdiagnosed with, Dr. Hayes said.

Timely diagnosis and treatment was more of an issue for the misdiagnosed patients; their diagnosis was made on average 5 days after the onset of symptoms versus 3 days (P < .001). “We found that time to treatment, particularly time to IVIg, was significantly longer in the misdiagnosed group,” Dr. Hayes said, at 5 versus 2 days (P < .001).

Dr. Hayes has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

and that can result in loss of valuable time to admit patients and begin treatment to get ahead of the virus that may cause the disease.

At the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, held virtually this year, Leslie H. Hayes, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital presented findings of a retrospective case series from 13 institutions in the United States and Canada that determined 78% of patients eventually found to have AFM were initially misdiagnosed. About 62% were given an alternate diagnosis or multiple diagnoses, and 60% did not get a referral for further care or evaluation. The study included 175 children aged 18 years and younger when symptoms first appeared from 2014 to 2018 and who met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention case definition of AFM.

“As it becomes more evident that AFM outbreaks are driven by enterovirus infections, treatments targeting the viral infection are likely to be most effective very early in the course of disease, necessitating a precise and early diagnosis,” Dr. Hayes said. “Thus awareness is needed to help recognize the signs of symptoms of AFM, particularly among frontline clinicians.”

One reason for misdiagnosis is that AFM has features that overlap with other neuroinflammatory disorders, she said. “In many cases the patients are misdiagnosed as having benign or self-limiting processes that would not prompt the same monitoring and level of care.”

Numbness and prodromal illnesses were associated with misdiagnosis, she said, but otherwise most presenting symptoms were similar between the misdiagnosed and correctly diagnosed patients.

Neurologic disorders with similar features to AFM that the study identified were Guillain-Barré syndrome, spinal cord pathologies such as transverse myelitis, brain pathologies including acute disseminating encephalomyelitis, acute inclusion body encephalitis and stroke, and other neuroinflammatory conditions.

“There were also many patients diagnosed as having processes that in many cases would not prompt inpatient admission, would not involve neurology consultation, and would not be treated in a similar fashion to AFM,” Dr. Hayes said.

Those diagnoses included plexopathy, neuritis, Bell’s palsy, meningoencephalitis, nonspecific infectious illness or parainfectious autoimmune disease, or musculoskeletal problems including toxic or transient synovitis, myositis, fracture or sprain, or torticollis.

“We identified preceding illness and numbness as two features associated with misdiagnosis,” Dr. Hayes said.

“We evaluated illness severity by evaluating the need for invasive and noninvasive ventilation and found that, while not statistically significant, misdiagnosed patients had a trend toward higher need for such respiratory support,” she noted. Specifically, 31.6% of misdiagnosed patients required noninvasive ventilation versus 15.8% of promptly diagnosed patients (P = .06).

Dr. Hayes characterized the rates of ICU admissions between the two groups as not statistically significant: 52.5% and 36.8% for the misdiagnosed and promptly diagnosed groups, respectively (P = .1).

Both groups of patients received intravenous immunoglobulin in similar rates (77.9% and 81.6%, respectively, P = .63), but the misdiagnosed patients were much more likely to receive steroids, 68.2% versus 44.7% (P = .008). That’s likely because steroids are the standard treatment for the neuroinflammatory disorders that they were misdiagnosed with, Dr. Hayes said.

Timely diagnosis and treatment was more of an issue for the misdiagnosed patients; their diagnosis was made on average 5 days after the onset of symptoms versus 3 days (P < .001). “We found that time to treatment, particularly time to IVIg, was significantly longer in the misdiagnosed group,” Dr. Hayes said, at 5 versus 2 days (P < .001).

Dr. Hayes has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

and that can result in loss of valuable time to admit patients and begin treatment to get ahead of the virus that may cause the disease.

At the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, held virtually this year, Leslie H. Hayes, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital presented findings of a retrospective case series from 13 institutions in the United States and Canada that determined 78% of patients eventually found to have AFM were initially misdiagnosed. About 62% were given an alternate diagnosis or multiple diagnoses, and 60% did not get a referral for further care or evaluation. The study included 175 children aged 18 years and younger when symptoms first appeared from 2014 to 2018 and who met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention case definition of AFM.

“As it becomes more evident that AFM outbreaks are driven by enterovirus infections, treatments targeting the viral infection are likely to be most effective very early in the course of disease, necessitating a precise and early diagnosis,” Dr. Hayes said. “Thus awareness is needed to help recognize the signs of symptoms of AFM, particularly among frontline clinicians.”

One reason for misdiagnosis is that AFM has features that overlap with other neuroinflammatory disorders, she said. “In many cases the patients are misdiagnosed as having benign or self-limiting processes that would not prompt the same monitoring and level of care.”

Numbness and prodromal illnesses were associated with misdiagnosis, she said, but otherwise most presenting symptoms were similar between the misdiagnosed and correctly diagnosed patients.

Neurologic disorders with similar features to AFM that the study identified were Guillain-Barré syndrome, spinal cord pathologies such as transverse myelitis, brain pathologies including acute disseminating encephalomyelitis, acute inclusion body encephalitis and stroke, and other neuroinflammatory conditions.

“There were also many patients diagnosed as having processes that in many cases would not prompt inpatient admission, would not involve neurology consultation, and would not be treated in a similar fashion to AFM,” Dr. Hayes said.

Those diagnoses included plexopathy, neuritis, Bell’s palsy, meningoencephalitis, nonspecific infectious illness or parainfectious autoimmune disease, or musculoskeletal problems including toxic or transient synovitis, myositis, fracture or sprain, or torticollis.

“We identified preceding illness and numbness as two features associated with misdiagnosis,” Dr. Hayes said.

“We evaluated illness severity by evaluating the need for invasive and noninvasive ventilation and found that, while not statistically significant, misdiagnosed patients had a trend toward higher need for such respiratory support,” she noted. Specifically, 31.6% of misdiagnosed patients required noninvasive ventilation versus 15.8% of promptly diagnosed patients (P = .06).

Dr. Hayes characterized the rates of ICU admissions between the two groups as not statistically significant: 52.5% and 36.8% for the misdiagnosed and promptly diagnosed groups, respectively (P = .1).

Both groups of patients received intravenous immunoglobulin in similar rates (77.9% and 81.6%, respectively, P = .63), but the misdiagnosed patients were much more likely to receive steroids, 68.2% versus 44.7% (P = .008). That’s likely because steroids are the standard treatment for the neuroinflammatory disorders that they were misdiagnosed with, Dr. Hayes said.

Timely diagnosis and treatment was more of an issue for the misdiagnosed patients; their diagnosis was made on average 5 days after the onset of symptoms versus 3 days (P < .001). “We found that time to treatment, particularly time to IVIg, was significantly longer in the misdiagnosed group,” Dr. Hayes said, at 5 versus 2 days (P < .001).

Dr. Hayes has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

FROM CNS-ICNA 2020

Nusinersen provides continued benefits to presymptomatic children with SMA

according to an analysis presented at the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, held virtually this year.

“Children are developing in a manner more consistent with normal development than that expected for children with two and three SMN2 gene copies,” said Russell Chin, MD, a neurologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital. “These data demonstrate the durability of effect over a median of 3.8 years of follow-up, with children aged 2.8-4.8 years at the last visit.”

Many participants in the study achieved motor milestones within normal time limits, and no participant lost any major motor milestones. The investigators did not identify any new safety concerns during a maximum of 4.7 years of follow-up. They will follow participants until they reach approximately 8 years of age.

An ongoing open-label study

Dr. Chin presented interim results of the ongoing NURTURE study, which is examining the efficacy and safety of intrathecal nusinersen when administered to presymptomatic infants with SMA. The open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study is being conducted in various countries. Eligible participants were 6 weeks old or younger at first dose and had two or three copies of SMN2. The primary end point of NURTURE is time to death or respiratory intervention (i.e., invasive or noninvasive ventilation for 6 or more hours per day continuously for 7 or more days or tracheostomy). The natural history of SMA type 1 indicates that the median age at death or requirement for ventilation support is 13.5 months.

The investigators enrolled 25 infants: 15 with two copies of the gene and 10 with three copies. At the February 2020 interim analysis, participants had been in the study for 3.8 years and were aged 2.8-4.8 years at the last visit. No children had discontinued treatment or withdrawn from the study. All participants are alive, and four participants (all of whom have two copies of SMN2) required respiratory intervention. The latter children initiated respiratory support during an acute reversible illness. No subjects have required permanent ventilation, which the investigators define as ventilation for 16 or more hours per day for more than 21 days in the absence of an acute reversible event, or tracheostomy.

Treatment improved motor development

Approximately 84% of children achieved a maximum score on the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND) scale. The population’s mean CHOP INTEND score increased steadily from baseline and stabilized at approximately the maximum score of 64. The population’s mean change in CHOP INTEND score from baseline to last visit was 13.6 points. The mean score at last visit was 62.0 among patients with two copies of SMN2 and 63.4 among patients with three copies. In addition, the time to first achievement of maximum CHOP INTEND score was shorter in participants with three copies of SMN2, compared with those with two. Four participants with two copies of the gene have not yet achieved a maximum CHOP INTEND score.

Many of the children in the study achieved World Health Organization motor milestones within time frames consistent with normal development. About 84% of participants became able to sit without support within the normal time frame in healthy children. Approximately 60% of children achieved walking with assistance within the normal window, and 64% achieved walking alone within the normal window. Of 25 participants, 24 are walking with assistance, and 22 of 25 (88%) can walk alone. Dr. Chin and colleagues observed that lower levels of phosphorylated neurofilament heavy chain in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid on treatment at day 64 were significantly correlated with higher total score on the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination at day 302 and with earlier achievement of the WHO milestone walking alone.

Nusinersen and lumbar puncture were well tolerated. No children discontinued treatment or withdrew from the study because of an adverse event. The investigators did not consider any adverse events or serious adverse events to be related to the study drug. They also did not observe any clinically relevant trends related to nusinersen in hematology, blood chemistry, urinalysis, coagulation, vital signs, or ECGs.

Dr. Chin is an employee of and holds stock in Biogen, which manufactures nusinersen and is sponsoring the study.

SOURCE: Chin R et al. CNS-ICNA 2020, Abstract PL78.

according to an analysis presented at the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, held virtually this year.

“Children are developing in a manner more consistent with normal development than that expected for children with two and three SMN2 gene copies,” said Russell Chin, MD, a neurologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital. “These data demonstrate the durability of effect over a median of 3.8 years of follow-up, with children aged 2.8-4.8 years at the last visit.”

Many participants in the study achieved motor milestones within normal time limits, and no participant lost any major motor milestones. The investigators did not identify any new safety concerns during a maximum of 4.7 years of follow-up. They will follow participants until they reach approximately 8 years of age.

An ongoing open-label study

Dr. Chin presented interim results of the ongoing NURTURE study, which is examining the efficacy and safety of intrathecal nusinersen when administered to presymptomatic infants with SMA. The open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study is being conducted in various countries. Eligible participants were 6 weeks old or younger at first dose and had two or three copies of SMN2. The primary end point of NURTURE is time to death or respiratory intervention (i.e., invasive or noninvasive ventilation for 6 or more hours per day continuously for 7 or more days or tracheostomy). The natural history of SMA type 1 indicates that the median age at death or requirement for ventilation support is 13.5 months.

The investigators enrolled 25 infants: 15 with two copies of the gene and 10 with three copies. At the February 2020 interim analysis, participants had been in the study for 3.8 years and were aged 2.8-4.8 years at the last visit. No children had discontinued treatment or withdrawn from the study. All participants are alive, and four participants (all of whom have two copies of SMN2) required respiratory intervention. The latter children initiated respiratory support during an acute reversible illness. No subjects have required permanent ventilation, which the investigators define as ventilation for 16 or more hours per day for more than 21 days in the absence of an acute reversible event, or tracheostomy.

Treatment improved motor development

Approximately 84% of children achieved a maximum score on the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND) scale. The population’s mean CHOP INTEND score increased steadily from baseline and stabilized at approximately the maximum score of 64. The population’s mean change in CHOP INTEND score from baseline to last visit was 13.6 points. The mean score at last visit was 62.0 among patients with two copies of SMN2 and 63.4 among patients with three copies. In addition, the time to first achievement of maximum CHOP INTEND score was shorter in participants with three copies of SMN2, compared with those with two. Four participants with two copies of the gene have not yet achieved a maximum CHOP INTEND score.

Many of the children in the study achieved World Health Organization motor milestones within time frames consistent with normal development. About 84% of participants became able to sit without support within the normal time frame in healthy children. Approximately 60% of children achieved walking with assistance within the normal window, and 64% achieved walking alone within the normal window. Of 25 participants, 24 are walking with assistance, and 22 of 25 (88%) can walk alone. Dr. Chin and colleagues observed that lower levels of phosphorylated neurofilament heavy chain in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid on treatment at day 64 were significantly correlated with higher total score on the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination at day 302 and with earlier achievement of the WHO milestone walking alone.

Nusinersen and lumbar puncture were well tolerated. No children discontinued treatment or withdrew from the study because of an adverse event. The investigators did not consider any adverse events or serious adverse events to be related to the study drug. They also did not observe any clinically relevant trends related to nusinersen in hematology, blood chemistry, urinalysis, coagulation, vital signs, or ECGs.

Dr. Chin is an employee of and holds stock in Biogen, which manufactures nusinersen and is sponsoring the study.

SOURCE: Chin R et al. CNS-ICNA 2020, Abstract PL78.

according to an analysis presented at the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, held virtually this year.

“Children are developing in a manner more consistent with normal development than that expected for children with two and three SMN2 gene copies,” said Russell Chin, MD, a neurologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital. “These data demonstrate the durability of effect over a median of 3.8 years of follow-up, with children aged 2.8-4.8 years at the last visit.”

Many participants in the study achieved motor milestones within normal time limits, and no participant lost any major motor milestones. The investigators did not identify any new safety concerns during a maximum of 4.7 years of follow-up. They will follow participants until they reach approximately 8 years of age.

An ongoing open-label study

Dr. Chin presented interim results of the ongoing NURTURE study, which is examining the efficacy and safety of intrathecal nusinersen when administered to presymptomatic infants with SMA. The open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study is being conducted in various countries. Eligible participants were 6 weeks old or younger at first dose and had two or three copies of SMN2. The primary end point of NURTURE is time to death or respiratory intervention (i.e., invasive or noninvasive ventilation for 6 or more hours per day continuously for 7 or more days or tracheostomy). The natural history of SMA type 1 indicates that the median age at death or requirement for ventilation support is 13.5 months.

The investigators enrolled 25 infants: 15 with two copies of the gene and 10 with three copies. At the February 2020 interim analysis, participants had been in the study for 3.8 years and were aged 2.8-4.8 years at the last visit. No children had discontinued treatment or withdrawn from the study. All participants are alive, and four participants (all of whom have two copies of SMN2) required respiratory intervention. The latter children initiated respiratory support during an acute reversible illness. No subjects have required permanent ventilation, which the investigators define as ventilation for 16 or more hours per day for more than 21 days in the absence of an acute reversible event, or tracheostomy.

Treatment improved motor development

Approximately 84% of children achieved a maximum score on the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND) scale. The population’s mean CHOP INTEND score increased steadily from baseline and stabilized at approximately the maximum score of 64. The population’s mean change in CHOP INTEND score from baseline to last visit was 13.6 points. The mean score at last visit was 62.0 among patients with two copies of SMN2 and 63.4 among patients with three copies. In addition, the time to first achievement of maximum CHOP INTEND score was shorter in participants with three copies of SMN2, compared with those with two. Four participants with two copies of the gene have not yet achieved a maximum CHOP INTEND score.

Many of the children in the study achieved World Health Organization motor milestones within time frames consistent with normal development. About 84% of participants became able to sit without support within the normal time frame in healthy children. Approximately 60% of children achieved walking with assistance within the normal window, and 64% achieved walking alone within the normal window. Of 25 participants, 24 are walking with assistance, and 22 of 25 (88%) can walk alone. Dr. Chin and colleagues observed that lower levels of phosphorylated neurofilament heavy chain in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid on treatment at day 64 were significantly correlated with higher total score on the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination at day 302 and with earlier achievement of the WHO milestone walking alone.

Nusinersen and lumbar puncture were well tolerated. No children discontinued treatment or withdrew from the study because of an adverse event. The investigators did not consider any adverse events or serious adverse events to be related to the study drug. They also did not observe any clinically relevant trends related to nusinersen in hematology, blood chemistry, urinalysis, coagulation, vital signs, or ECGs.

Dr. Chin is an employee of and holds stock in Biogen, which manufactures nusinersen and is sponsoring the study.

SOURCE: Chin R et al. CNS-ICNA 2020, Abstract PL78.

FROM CNS-ICNA 2020

New lupus classification criteria perform well in children, young adults

, according to results from a single-center, retrospective study.

However, the 2019 criteria, which were developed using cohorts of adult patients with SLE, were statistically no better than the 1997 ACR criteria at identifying those without the disease, first author Najla Aljaberi, MBBS, of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

The 2019 criteria were especially good at correctly classifying SLE in non-White youths, but the two sets of criteria performed equally well among male and female youths with SLE and across age groups.

“Our study confirms superior sensitivity of the new criteria over the 1997-ACR criteria in youths with SLE. The difference in sensitivity estimates between the two criteria sets (2019-EULAR/ACR vs. 1997-ACR) may be explained by a higher weight being assigned to immunologic criteria, less strict hematologic criteria (not requiring >2 occurrences), and the inclusion of subjective features of arthritis. Notably, our estimates of the sensitivity of the 2019-EULAR/ACR criteria were similar to those reported from a Brazilian pediatric study by Fonseca et al. (87.7%) that also used physician diagnosis as reference standard,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Aljaberi and colleagues reviewed electronic medical records of 112 patients with SLE aged 2-21 years and 105 controls aged 1-19 years at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center during 2008-2019. Patients identified in the records at the center were considered to have SLE based on ICD-10 codes assigned by experienced pediatric rheumatologists. The control patients included 69 (66%) with juvenile dermatomyositis and 36 with juvenile scleroderma/systemic sclerosis, based on corresponding ICD-10 codes.

Among the SLE cases, 57% were White and 81% were female, while Whites represented 83% and females 71% of control patients. Young adults aged 18-21 years represented a minority of SLE cases (18%) and controls (7%).

The 2019 criteria had significantly higher sensitivity than did the 1997 criteria (85% vs. 72%, respectively; P = .023) but similar specificity (83% vs. 87%; P = .456). A total of 17 out of the 112 SLE cases failed to meet the 2019 criteria, 13 (76%) of whom were White. Overall, 31 SLE cases did not meet the 1997 criteria, but 15 of those fulfilled the 2019 criteria. While there was no statistically significant difference in the sensitivity of the 2019 criteria between non-White and White cases (92% vs. 80%, respectively; P = .08), the difference in sensitivity was significant with the 1997 criteria (83% vs. 64%; P < .02).

The 2019 criteria had similar sensitivity in males and females (86% vs. 81%, respectively), as well as specificity (81% vs. 87%). The 1997 criteria also provided similar sensitivity between males and females (71% vs. 76%) as well as specificity (85% vs. 90%).

In only four instances did SLE cases meet 2019 criteria before ICD-10 diagnosis of SLE, whereas in the other 108 cases the ICD-10 diagnosis coincided with reaching the threshold for meeting 2019 criteria.

There was no funding secured for the study, and the authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Aljaberi N et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Aug 25. doi: 10.1002/acr.24430.

, according to results from a single-center, retrospective study.

However, the 2019 criteria, which were developed using cohorts of adult patients with SLE, were statistically no better than the 1997 ACR criteria at identifying those without the disease, first author Najla Aljaberi, MBBS, of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

The 2019 criteria were especially good at correctly classifying SLE in non-White youths, but the two sets of criteria performed equally well among male and female youths with SLE and across age groups.

“Our study confirms superior sensitivity of the new criteria over the 1997-ACR criteria in youths with SLE. The difference in sensitivity estimates between the two criteria sets (2019-EULAR/ACR vs. 1997-ACR) may be explained by a higher weight being assigned to immunologic criteria, less strict hematologic criteria (not requiring >2 occurrences), and the inclusion of subjective features of arthritis. Notably, our estimates of the sensitivity of the 2019-EULAR/ACR criteria were similar to those reported from a Brazilian pediatric study by Fonseca et al. (87.7%) that also used physician diagnosis as reference standard,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Aljaberi and colleagues reviewed electronic medical records of 112 patients with SLE aged 2-21 years and 105 controls aged 1-19 years at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center during 2008-2019. Patients identified in the records at the center were considered to have SLE based on ICD-10 codes assigned by experienced pediatric rheumatologists. The control patients included 69 (66%) with juvenile dermatomyositis and 36 with juvenile scleroderma/systemic sclerosis, based on corresponding ICD-10 codes.

Among the SLE cases, 57% were White and 81% were female, while Whites represented 83% and females 71% of control patients. Young adults aged 18-21 years represented a minority of SLE cases (18%) and controls (7%).

The 2019 criteria had significantly higher sensitivity than did the 1997 criteria (85% vs. 72%, respectively; P = .023) but similar specificity (83% vs. 87%; P = .456). A total of 17 out of the 112 SLE cases failed to meet the 2019 criteria, 13 (76%) of whom were White. Overall, 31 SLE cases did not meet the 1997 criteria, but 15 of those fulfilled the 2019 criteria. While there was no statistically significant difference in the sensitivity of the 2019 criteria between non-White and White cases (92% vs. 80%, respectively; P = .08), the difference in sensitivity was significant with the 1997 criteria (83% vs. 64%; P < .02).

The 2019 criteria had similar sensitivity in males and females (86% vs. 81%, respectively), as well as specificity (81% vs. 87%). The 1997 criteria also provided similar sensitivity between males and females (71% vs. 76%) as well as specificity (85% vs. 90%).

In only four instances did SLE cases meet 2019 criteria before ICD-10 diagnosis of SLE, whereas in the other 108 cases the ICD-10 diagnosis coincided with reaching the threshold for meeting 2019 criteria.

There was no funding secured for the study, and the authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Aljaberi N et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Aug 25. doi: 10.1002/acr.24430.

, according to results from a single-center, retrospective study.

However, the 2019 criteria, which were developed using cohorts of adult patients with SLE, were statistically no better than the 1997 ACR criteria at identifying those without the disease, first author Najla Aljaberi, MBBS, of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

The 2019 criteria were especially good at correctly classifying SLE in non-White youths, but the two sets of criteria performed equally well among male and female youths with SLE and across age groups.

“Our study confirms superior sensitivity of the new criteria over the 1997-ACR criteria in youths with SLE. The difference in sensitivity estimates between the two criteria sets (2019-EULAR/ACR vs. 1997-ACR) may be explained by a higher weight being assigned to immunologic criteria, less strict hematologic criteria (not requiring >2 occurrences), and the inclusion of subjective features of arthritis. Notably, our estimates of the sensitivity of the 2019-EULAR/ACR criteria were similar to those reported from a Brazilian pediatric study by Fonseca et al. (87.7%) that also used physician diagnosis as reference standard,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Aljaberi and colleagues reviewed electronic medical records of 112 patients with SLE aged 2-21 years and 105 controls aged 1-19 years at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center during 2008-2019. Patients identified in the records at the center were considered to have SLE based on ICD-10 codes assigned by experienced pediatric rheumatologists. The control patients included 69 (66%) with juvenile dermatomyositis and 36 with juvenile scleroderma/systemic sclerosis, based on corresponding ICD-10 codes.

Among the SLE cases, 57% were White and 81% were female, while Whites represented 83% and females 71% of control patients. Young adults aged 18-21 years represented a minority of SLE cases (18%) and controls (7%).

The 2019 criteria had significantly higher sensitivity than did the 1997 criteria (85% vs. 72%, respectively; P = .023) but similar specificity (83% vs. 87%; P = .456). A total of 17 out of the 112 SLE cases failed to meet the 2019 criteria, 13 (76%) of whom were White. Overall, 31 SLE cases did not meet the 1997 criteria, but 15 of those fulfilled the 2019 criteria. While there was no statistically significant difference in the sensitivity of the 2019 criteria between non-White and White cases (92% vs. 80%, respectively; P = .08), the difference in sensitivity was significant with the 1997 criteria (83% vs. 64%; P < .02).

The 2019 criteria had similar sensitivity in males and females (86% vs. 81%, respectively), as well as specificity (81% vs. 87%). The 1997 criteria also provided similar sensitivity between males and females (71% vs. 76%) as well as specificity (85% vs. 90%).

In only four instances did SLE cases meet 2019 criteria before ICD-10 diagnosis of SLE, whereas in the other 108 cases the ICD-10 diagnosis coincided with reaching the threshold for meeting 2019 criteria.

There was no funding secured for the study, and the authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Aljaberi N et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Aug 25. doi: 10.1002/acr.24430.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Golimumab approval extended to polyarticular-course JIA and juvenile PsA

after the Food and Drug Administration approved the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor for these indications on Sept. 30, according to an announcement from its manufacturer, Janssen.

Results from the open-label, single-arm, multicenter, phase 3, GO-VIVA clinical trial formed the basis for the agency’s approval of IV golimumab. GO-VIVA was conducted in 127 patients aged 2-17 years with JIA with arthritis in five or more joints (despite receiving treatment with methotrexate for at least 2 months) as part of a postmarketing requirement under the Pediatric Research Equity Act after the intravenous formulation of the biologic was approved for adults with rheumatoid arthritis in 2013. It demonstrated that pediatric patients had a level of pharmacokinetic exposure to golimumab that was similar to what was observed in two pivotal phase 3 trials in adults with moderately to severely active RA and active PsA, as well as efficacy that was generally consistent with responses seen in adult patients with RA, the manufacturer said.

Besides RA, intravenous golimumab was previously approved for adults with PsA and ankylosing spondylitis. As opposed to the IV dosing for adults with RA, PsA, and ankylosing spondylitis at 2 mg/kg infused over 30 minutes at weeks 0 and 4, and every 8 weeks thereafter, dosing for pediatric patients with pJIA and PsA is based on body surface area at 80 mg/m2, also given as an IV infusion over 30 minutes at weeks 0 and 4, and every 8 weeks thereafter.

The adverse reactions observed in GO-VIVA were consistent with the established safety profile of intravenous golimumab in adult patients with RA and PsA, according to Janssen.

The full prescribing information for intravenous golimumab can be found on the FDA website.

after the Food and Drug Administration approved the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor for these indications on Sept. 30, according to an announcement from its manufacturer, Janssen.

Results from the open-label, single-arm, multicenter, phase 3, GO-VIVA clinical trial formed the basis for the agency’s approval of IV golimumab. GO-VIVA was conducted in 127 patients aged 2-17 years with JIA with arthritis in five or more joints (despite receiving treatment with methotrexate for at least 2 months) as part of a postmarketing requirement under the Pediatric Research Equity Act after the intravenous formulation of the biologic was approved for adults with rheumatoid arthritis in 2013. It demonstrated that pediatric patients had a level of pharmacokinetic exposure to golimumab that was similar to what was observed in two pivotal phase 3 trials in adults with moderately to severely active RA and active PsA, as well as efficacy that was generally consistent with responses seen in adult patients with RA, the manufacturer said.

Besides RA, intravenous golimumab was previously approved for adults with PsA and ankylosing spondylitis. As opposed to the IV dosing for adults with RA, PsA, and ankylosing spondylitis at 2 mg/kg infused over 30 minutes at weeks 0 and 4, and every 8 weeks thereafter, dosing for pediatric patients with pJIA and PsA is based on body surface area at 80 mg/m2, also given as an IV infusion over 30 minutes at weeks 0 and 4, and every 8 weeks thereafter.

The adverse reactions observed in GO-VIVA were consistent with the established safety profile of intravenous golimumab in adult patients with RA and PsA, according to Janssen.

The full prescribing information for intravenous golimumab can be found on the FDA website.

after the Food and Drug Administration approved the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor for these indications on Sept. 30, according to an announcement from its manufacturer, Janssen.

Results from the open-label, single-arm, multicenter, phase 3, GO-VIVA clinical trial formed the basis for the agency’s approval of IV golimumab. GO-VIVA was conducted in 127 patients aged 2-17 years with JIA with arthritis in five or more joints (despite receiving treatment with methotrexate for at least 2 months) as part of a postmarketing requirement under the Pediatric Research Equity Act after the intravenous formulation of the biologic was approved for adults with rheumatoid arthritis in 2013. It demonstrated that pediatric patients had a level of pharmacokinetic exposure to golimumab that was similar to what was observed in two pivotal phase 3 trials in adults with moderately to severely active RA and active PsA, as well as efficacy that was generally consistent with responses seen in adult patients with RA, the manufacturer said.

Besides RA, intravenous golimumab was previously approved for adults with PsA and ankylosing spondylitis. As opposed to the IV dosing for adults with RA, PsA, and ankylosing spondylitis at 2 mg/kg infused over 30 minutes at weeks 0 and 4, and every 8 weeks thereafter, dosing for pediatric patients with pJIA and PsA is based on body surface area at 80 mg/m2, also given as an IV infusion over 30 minutes at weeks 0 and 4, and every 8 weeks thereafter.

The adverse reactions observed in GO-VIVA were consistent with the established safety profile of intravenous golimumab in adult patients with RA and PsA, according to Janssen.

The full prescribing information for intravenous golimumab can be found on the FDA website.

Orthopedic problems in children can be the first indication of acute lymphoblastic leukemia

The diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) can be delayed because of vague presentation and normal hematological results. Orthopedic manifestations may be the primary presentation of ALL to physicians, and such symptoms in children should be cause for suspicion, even in the absence of hematological abnormalities, according to a report published in the Journal of Orthopaedics.

The study retrospectively assessed 250 consecutive ALL patients at a single institution to identify the frequency of ALL cases presented to the orthopedic department and to determine the number of these patients presenting with normal hematological results, according to Amrath Raj BK, MD, and colleagues at the Manipal (India) Academy of Higher Education.

Suspicion warranted

Twenty-two of the 250 patients (8.8%) presented primarily to the orthopedic department (4 with vertebral compression fractures, 12 with joint pain, and 6 with bone pain), but were subsequently diagnosed with ALL. These results were comparable to previous studies. The mean patient age at the first visit was 5.6 years; 13 patients were boys, and 9 were girls. Six of these 22 patients (27.3%) had a normal peripheral blood smear, according to the researchers.

“Acute leukemia should be considered strongly as a differential diagnosis in children with severe osteoporosis and vertebral fractures. Initial orthopedic manifestations are not uncommon, and the primary physician should maintain a high index of suspicion as a peripheral smear is not diagnostic in all patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that there was no outside funding source and that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Raj BK A et al. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2020;22:326-330.

The diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) can be delayed because of vague presentation and normal hematological results. Orthopedic manifestations may be the primary presentation of ALL to physicians, and such symptoms in children should be cause for suspicion, even in the absence of hematological abnormalities, according to a report published in the Journal of Orthopaedics.

The study retrospectively assessed 250 consecutive ALL patients at a single institution to identify the frequency of ALL cases presented to the orthopedic department and to determine the number of these patients presenting with normal hematological results, according to Amrath Raj BK, MD, and colleagues at the Manipal (India) Academy of Higher Education.

Suspicion warranted

Twenty-two of the 250 patients (8.8%) presented primarily to the orthopedic department (4 with vertebral compression fractures, 12 with joint pain, and 6 with bone pain), but were subsequently diagnosed with ALL. These results were comparable to previous studies. The mean patient age at the first visit was 5.6 years; 13 patients were boys, and 9 were girls. Six of these 22 patients (27.3%) had a normal peripheral blood smear, according to the researchers.

“Acute leukemia should be considered strongly as a differential diagnosis in children with severe osteoporosis and vertebral fractures. Initial orthopedic manifestations are not uncommon, and the primary physician should maintain a high index of suspicion as a peripheral smear is not diagnostic in all patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that there was no outside funding source and that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Raj BK A et al. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2020;22:326-330.

The diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) can be delayed because of vague presentation and normal hematological results. Orthopedic manifestations may be the primary presentation of ALL to physicians, and such symptoms in children should be cause for suspicion, even in the absence of hematological abnormalities, according to a report published in the Journal of Orthopaedics.

The study retrospectively assessed 250 consecutive ALL patients at a single institution to identify the frequency of ALL cases presented to the orthopedic department and to determine the number of these patients presenting with normal hematological results, according to Amrath Raj BK, MD, and colleagues at the Manipal (India) Academy of Higher Education.

Suspicion warranted

Twenty-two of the 250 patients (8.8%) presented primarily to the orthopedic department (4 with vertebral compression fractures, 12 with joint pain, and 6 with bone pain), but were subsequently diagnosed with ALL. These results were comparable to previous studies. The mean patient age at the first visit was 5.6 years; 13 patients were boys, and 9 were girls. Six of these 22 patients (27.3%) had a normal peripheral blood smear, according to the researchers.

“Acute leukemia should be considered strongly as a differential diagnosis in children with severe osteoporosis and vertebral fractures. Initial orthopedic manifestations are not uncommon, and the primary physician should maintain a high index of suspicion as a peripheral smear is not diagnostic in all patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that there was no outside funding source and that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Raj BK A et al. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2020;22:326-330.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDICS

FDA adds polyarticular-course JIA to approved indications for tofacitinib

The Food and Drug Administration has (pJIA).