User login

Pandemic survey: Forty-six percent of pediatric headache patients got worse

, a newly released survey finds. But some actually found the pandemic era to be less stressful since they were tightly wound and could more easily control their home environments, a researcher said.

“We need to be very mindful of the connections between school and home environments – and social situations – and how they impact headache frequency,” said Marc DiSabella, DO, a pediatric neurologist at Children’s National Hospital/George Washington University, Washington. He is coauthor of a poster presented at the 50th annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

Dr. DiSabella and colleagues launched the survey to understand what headache patients were experiencing during the pandemic. They expected that “things were going to go really terrible in terms of headaches – or things would go great, and then things would crash when we had to reintegrate into society,” he said in an interview.

The team surveyed 113 pediatric patients who were evaluated at the hospital’s headache clinic between summer 2020 and winter 2021. Most of the patients were female (60%) and were aged 12-17 years (63%). Twenty-one percent were younger than 12 and 16% were older than 17. Chronic migraine (37%) was the most common diagnosis, followed by migraine with aura (22%), migraine without aura (19%), and new daily persistent headache (15%).

Nearly half (46%) of patients said their headaches had worsened during the pandemic. Many also reported more anxiety (55%), worsened mood (48%) and more stress (55%).

Dr. DiSabella said it’s especially notable that nearly two-thirds of those surveyed reported they were exercising less during the pandemic. Research has suggested that exercise and proper diet/sleep are crucial to improving headaches in kids, he said, and the survey findings suggest that exercise may be especially important. “Engaging in physical activity changes their pain threshold,” he said.

The researchers also reported that 60% of those surveyed said they looked at screens more than 6 hours per day. According to Dr. DiSabella, high screen use may not be worrisome from a headache perspective. “We have another study in publication that shows there’s not a clear association between frequency of screen use and headache intensity,” he said.

The survey doesn’t examine what has happened in recent weeks as schools have reopened. Anecdotally, Dr. DiSabella said some patients with migraine are feeling the stress of returning to normal routines. “They tend to be type A perfectionists and do well when they’re in control of their environment,” he said. “Now they’ve lost the control they had at home and are being put back into a stressful environment.”

Pandemic effects mixed

Commenting on the study, child neurologist Andrew D. Hershey, MD, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, questioned the finding that many children suffered from more headaches during the pandemic. In his experience, “headaches were overall better when [children] were doing virtual learning,” he said in an interview. “We had fewer admissions, ED visits declined, and patients were maintaining better healthy habits. Some did express anxiety about not seeing friends, but were accommodating by doing this remotely.”

He added: “Since their return, kids are back to the same sleep deprivation issue since schools start too early, and they have more difficulty treating headaches acutely since they have to go to the nurse’s office [to do so]. They self-report a higher degree of stress and anxiety.”

On the other hand, Jack Gladstein, MD, a child neurologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, said in an interview that most of his patients suffered more headaches during the pandemic, although a small number with social anxiety thrived because they got to stay at home.

He agreed with Dr. DiSabella about the value of exercise. “At every visit we remind our youngsters with migraine to eat breakfast, exercise, get regular sleep, and drink fluids,” he said.

No study funding was reported. The study authors, Dr. Hershey, and Dr. Gladstein reported no disclosures.

, a newly released survey finds. But some actually found the pandemic era to be less stressful since they were tightly wound and could more easily control their home environments, a researcher said.

“We need to be very mindful of the connections between school and home environments – and social situations – and how they impact headache frequency,” said Marc DiSabella, DO, a pediatric neurologist at Children’s National Hospital/George Washington University, Washington. He is coauthor of a poster presented at the 50th annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

Dr. DiSabella and colleagues launched the survey to understand what headache patients were experiencing during the pandemic. They expected that “things were going to go really terrible in terms of headaches – or things would go great, and then things would crash when we had to reintegrate into society,” he said in an interview.

The team surveyed 113 pediatric patients who were evaluated at the hospital’s headache clinic between summer 2020 and winter 2021. Most of the patients were female (60%) and were aged 12-17 years (63%). Twenty-one percent were younger than 12 and 16% were older than 17. Chronic migraine (37%) was the most common diagnosis, followed by migraine with aura (22%), migraine without aura (19%), and new daily persistent headache (15%).

Nearly half (46%) of patients said their headaches had worsened during the pandemic. Many also reported more anxiety (55%), worsened mood (48%) and more stress (55%).

Dr. DiSabella said it’s especially notable that nearly two-thirds of those surveyed reported they were exercising less during the pandemic. Research has suggested that exercise and proper diet/sleep are crucial to improving headaches in kids, he said, and the survey findings suggest that exercise may be especially important. “Engaging in physical activity changes their pain threshold,” he said.

The researchers also reported that 60% of those surveyed said they looked at screens more than 6 hours per day. According to Dr. DiSabella, high screen use may not be worrisome from a headache perspective. “We have another study in publication that shows there’s not a clear association between frequency of screen use and headache intensity,” he said.

The survey doesn’t examine what has happened in recent weeks as schools have reopened. Anecdotally, Dr. DiSabella said some patients with migraine are feeling the stress of returning to normal routines. “They tend to be type A perfectionists and do well when they’re in control of their environment,” he said. “Now they’ve lost the control they had at home and are being put back into a stressful environment.”

Pandemic effects mixed

Commenting on the study, child neurologist Andrew D. Hershey, MD, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, questioned the finding that many children suffered from more headaches during the pandemic. In his experience, “headaches were overall better when [children] were doing virtual learning,” he said in an interview. “We had fewer admissions, ED visits declined, and patients were maintaining better healthy habits. Some did express anxiety about not seeing friends, but were accommodating by doing this remotely.”

He added: “Since their return, kids are back to the same sleep deprivation issue since schools start too early, and they have more difficulty treating headaches acutely since they have to go to the nurse’s office [to do so]. They self-report a higher degree of stress and anxiety.”

On the other hand, Jack Gladstein, MD, a child neurologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, said in an interview that most of his patients suffered more headaches during the pandemic, although a small number with social anxiety thrived because they got to stay at home.

He agreed with Dr. DiSabella about the value of exercise. “At every visit we remind our youngsters with migraine to eat breakfast, exercise, get regular sleep, and drink fluids,” he said.

No study funding was reported. The study authors, Dr. Hershey, and Dr. Gladstein reported no disclosures.

, a newly released survey finds. But some actually found the pandemic era to be less stressful since they were tightly wound and could more easily control their home environments, a researcher said.

“We need to be very mindful of the connections between school and home environments – and social situations – and how they impact headache frequency,” said Marc DiSabella, DO, a pediatric neurologist at Children’s National Hospital/George Washington University, Washington. He is coauthor of a poster presented at the 50th annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

Dr. DiSabella and colleagues launched the survey to understand what headache patients were experiencing during the pandemic. They expected that “things were going to go really terrible in terms of headaches – or things would go great, and then things would crash when we had to reintegrate into society,” he said in an interview.

The team surveyed 113 pediatric patients who were evaluated at the hospital’s headache clinic between summer 2020 and winter 2021. Most of the patients were female (60%) and were aged 12-17 years (63%). Twenty-one percent were younger than 12 and 16% were older than 17. Chronic migraine (37%) was the most common diagnosis, followed by migraine with aura (22%), migraine without aura (19%), and new daily persistent headache (15%).

Nearly half (46%) of patients said their headaches had worsened during the pandemic. Many also reported more anxiety (55%), worsened mood (48%) and more stress (55%).

Dr. DiSabella said it’s especially notable that nearly two-thirds of those surveyed reported they were exercising less during the pandemic. Research has suggested that exercise and proper diet/sleep are crucial to improving headaches in kids, he said, and the survey findings suggest that exercise may be especially important. “Engaging in physical activity changes their pain threshold,” he said.

The researchers also reported that 60% of those surveyed said they looked at screens more than 6 hours per day. According to Dr. DiSabella, high screen use may not be worrisome from a headache perspective. “We have another study in publication that shows there’s not a clear association between frequency of screen use and headache intensity,” he said.

The survey doesn’t examine what has happened in recent weeks as schools have reopened. Anecdotally, Dr. DiSabella said some patients with migraine are feeling the stress of returning to normal routines. “They tend to be type A perfectionists and do well when they’re in control of their environment,” he said. “Now they’ve lost the control they had at home and are being put back into a stressful environment.”

Pandemic effects mixed

Commenting on the study, child neurologist Andrew D. Hershey, MD, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, questioned the finding that many children suffered from more headaches during the pandemic. In his experience, “headaches were overall better when [children] were doing virtual learning,” he said in an interview. “We had fewer admissions, ED visits declined, and patients were maintaining better healthy habits. Some did express anxiety about not seeing friends, but were accommodating by doing this remotely.”

He added: “Since their return, kids are back to the same sleep deprivation issue since schools start too early, and they have more difficulty treating headaches acutely since they have to go to the nurse’s office [to do so]. They self-report a higher degree of stress and anxiety.”

On the other hand, Jack Gladstein, MD, a child neurologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, said in an interview that most of his patients suffered more headaches during the pandemic, although a small number with social anxiety thrived because they got to stay at home.

He agreed with Dr. DiSabella about the value of exercise. “At every visit we remind our youngsters with migraine to eat breakfast, exercise, get regular sleep, and drink fluids,” he said.

No study funding was reported. The study authors, Dr. Hershey, and Dr. Gladstein reported no disclosures.

FROM CNS 2021

‘Fascinating’ link between Alzheimer’s and COVID-19

The findings could lead to new treatment targets to slow progression and severity of both diseases.

Investigators found that a single genetic variant in the oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1) gene increases the risk for AD and that related variants in the same gene increase the likelihood of severe COVID-19 outcomes.

“These findings may allow us to identify new drug targets to slow progression of both diseases and reduce their severity,” Dervis Salih, PhD, senior research associate, UK Dementia Research Institute, University College London, said in an interview.

“Our work also suggests new approaches to treat both diseases with the same drugs,” Dr. Salih added.

The study was published online Oct. 7 in Brain.

Shared genetic network

The OAS1 gene is expressed in microglia, a type of immune cell that makes up around 10% of all cells in the brain.

In earlier work, investigators found evidence suggesting a link between the OAS1 gene and AD, but the function of the gene in microglia was unknown.

To further investigate the gene’s link to AD, they sequenced genetic data from 2,547 people – half with AD, and half without.

The genotyping analysis confirmed that the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs1131454 within OAS1 is significantly associated with AD.

Given that the same OAS1 locus has recently been linked with severe COVID-19 outcomes, the researchers investigated four variants on the OAS1 gene.

Results indicate that SNPs within OAS1 associated with AD also show linkage to SNP variants associated with critical illness in COVID-19.

The rs1131454 (risk allele A) and rs4766676 (risk allele T) are associated with AD, and rs10735079 (risk allele A) and rs6489867 (risk allele T) are associated with critical illness with COVID-19, the investigators reported. All of these risk alleles dampen expression of OAS1.

“This study also provides strong new evidence that interferon signaling by the innate immune system plays a substantial role in the progression of Alzheimer’s,” said Dr. Salih.

“Identifying this shared genetic network in innate immune cells will allow us with future work to identify new biomarkers to track disease progression and also predict disease risk better for both disorders,” he added.

‘Fascinating’ link

In a statement from the UK nonprofit organization, Science Media Center, Kenneth Baillie, MBChB, with the University of Edinburgh, said this study builds on a discovery he and his colleagues made last year that OAS1 variants are associated with severe COVID-19.

“In the ISARIC4C study, we recently found that this is probably due to a change in the way cell membranes detect viruses, but this mechanism doesn’t explain the fascinating association with Alzheimer’s disease reported in this new work,” Dr. Baillie said.

“It is often the case that the same gene can have different roles in different parts of the body. Importantly, it doesn’t mean that having COVID-19 has any effect on your risk of Alzheimer’s,” he added.

Also weighing in on the new study, Jonathan Schott, MD, professor of neurology, University College London, noted that dementia is the “main preexisting health condition associated with COVID-19 mortality, accounting for about one in four deaths from COVID-19 between March and June 2020.

“While some of this excessive mortality may relate to people with dementia being overrepresented in care homes, which were particularly hard hit by the pandemic, or due to general increased vulnerability to infections, there have been questions as to whether there are common factors that might increase susceptibility both to developing dementia and to dying from COVID-19,” Dr. Schott explained.

This “elegant paper” provides evidence for the latter, “suggesting a common genetic mechanism both for Alzheimer’s disease and for severe COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Schott said.

“The identification of a genetic risk factor and elucidation of inflammatory pathways through which it may increase risk has important implications for our understanding of both diseases, with potential implications for novel treatments,” he added.

The study was funded by the UK Dementia Research Institute. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Schott serves as chief medical officer for Alzheimer’s Research UK and is clinical adviser to the UK Dementia Research Institute. Dr. Baillie has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The findings could lead to new treatment targets to slow progression and severity of both diseases.

Investigators found that a single genetic variant in the oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1) gene increases the risk for AD and that related variants in the same gene increase the likelihood of severe COVID-19 outcomes.

“These findings may allow us to identify new drug targets to slow progression of both diseases and reduce their severity,” Dervis Salih, PhD, senior research associate, UK Dementia Research Institute, University College London, said in an interview.

“Our work also suggests new approaches to treat both diseases with the same drugs,” Dr. Salih added.

The study was published online Oct. 7 in Brain.

Shared genetic network

The OAS1 gene is expressed in microglia, a type of immune cell that makes up around 10% of all cells in the brain.

In earlier work, investigators found evidence suggesting a link between the OAS1 gene and AD, but the function of the gene in microglia was unknown.

To further investigate the gene’s link to AD, they sequenced genetic data from 2,547 people – half with AD, and half without.

The genotyping analysis confirmed that the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs1131454 within OAS1 is significantly associated with AD.

Given that the same OAS1 locus has recently been linked with severe COVID-19 outcomes, the researchers investigated four variants on the OAS1 gene.

Results indicate that SNPs within OAS1 associated with AD also show linkage to SNP variants associated with critical illness in COVID-19.

The rs1131454 (risk allele A) and rs4766676 (risk allele T) are associated with AD, and rs10735079 (risk allele A) and rs6489867 (risk allele T) are associated with critical illness with COVID-19, the investigators reported. All of these risk alleles dampen expression of OAS1.

“This study also provides strong new evidence that interferon signaling by the innate immune system plays a substantial role in the progression of Alzheimer’s,” said Dr. Salih.

“Identifying this shared genetic network in innate immune cells will allow us with future work to identify new biomarkers to track disease progression and also predict disease risk better for both disorders,” he added.

‘Fascinating’ link

In a statement from the UK nonprofit organization, Science Media Center, Kenneth Baillie, MBChB, with the University of Edinburgh, said this study builds on a discovery he and his colleagues made last year that OAS1 variants are associated with severe COVID-19.

“In the ISARIC4C study, we recently found that this is probably due to a change in the way cell membranes detect viruses, but this mechanism doesn’t explain the fascinating association with Alzheimer’s disease reported in this new work,” Dr. Baillie said.

“It is often the case that the same gene can have different roles in different parts of the body. Importantly, it doesn’t mean that having COVID-19 has any effect on your risk of Alzheimer’s,” he added.

Also weighing in on the new study, Jonathan Schott, MD, professor of neurology, University College London, noted that dementia is the “main preexisting health condition associated with COVID-19 mortality, accounting for about one in four deaths from COVID-19 between March and June 2020.

“While some of this excessive mortality may relate to people with dementia being overrepresented in care homes, which were particularly hard hit by the pandemic, or due to general increased vulnerability to infections, there have been questions as to whether there are common factors that might increase susceptibility both to developing dementia and to dying from COVID-19,” Dr. Schott explained.

This “elegant paper” provides evidence for the latter, “suggesting a common genetic mechanism both for Alzheimer’s disease and for severe COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Schott said.

“The identification of a genetic risk factor and elucidation of inflammatory pathways through which it may increase risk has important implications for our understanding of both diseases, with potential implications for novel treatments,” he added.

The study was funded by the UK Dementia Research Institute. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Schott serves as chief medical officer for Alzheimer’s Research UK and is clinical adviser to the UK Dementia Research Institute. Dr. Baillie has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The findings could lead to new treatment targets to slow progression and severity of both diseases.

Investigators found that a single genetic variant in the oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1) gene increases the risk for AD and that related variants in the same gene increase the likelihood of severe COVID-19 outcomes.

“These findings may allow us to identify new drug targets to slow progression of both diseases and reduce their severity,” Dervis Salih, PhD, senior research associate, UK Dementia Research Institute, University College London, said in an interview.

“Our work also suggests new approaches to treat both diseases with the same drugs,” Dr. Salih added.

The study was published online Oct. 7 in Brain.

Shared genetic network

The OAS1 gene is expressed in microglia, a type of immune cell that makes up around 10% of all cells in the brain.

In earlier work, investigators found evidence suggesting a link between the OAS1 gene and AD, but the function of the gene in microglia was unknown.

To further investigate the gene’s link to AD, they sequenced genetic data from 2,547 people – half with AD, and half without.

The genotyping analysis confirmed that the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs1131454 within OAS1 is significantly associated with AD.

Given that the same OAS1 locus has recently been linked with severe COVID-19 outcomes, the researchers investigated four variants on the OAS1 gene.

Results indicate that SNPs within OAS1 associated with AD also show linkage to SNP variants associated with critical illness in COVID-19.

The rs1131454 (risk allele A) and rs4766676 (risk allele T) are associated with AD, and rs10735079 (risk allele A) and rs6489867 (risk allele T) are associated with critical illness with COVID-19, the investigators reported. All of these risk alleles dampen expression of OAS1.

“This study also provides strong new evidence that interferon signaling by the innate immune system plays a substantial role in the progression of Alzheimer’s,” said Dr. Salih.

“Identifying this shared genetic network in innate immune cells will allow us with future work to identify new biomarkers to track disease progression and also predict disease risk better for both disorders,” he added.

‘Fascinating’ link

In a statement from the UK nonprofit organization, Science Media Center, Kenneth Baillie, MBChB, with the University of Edinburgh, said this study builds on a discovery he and his colleagues made last year that OAS1 variants are associated with severe COVID-19.

“In the ISARIC4C study, we recently found that this is probably due to a change in the way cell membranes detect viruses, but this mechanism doesn’t explain the fascinating association with Alzheimer’s disease reported in this new work,” Dr. Baillie said.

“It is often the case that the same gene can have different roles in different parts of the body. Importantly, it doesn’t mean that having COVID-19 has any effect on your risk of Alzheimer’s,” he added.

Also weighing in on the new study, Jonathan Schott, MD, professor of neurology, University College London, noted that dementia is the “main preexisting health condition associated with COVID-19 mortality, accounting for about one in four deaths from COVID-19 between March and June 2020.

“While some of this excessive mortality may relate to people with dementia being overrepresented in care homes, which were particularly hard hit by the pandemic, or due to general increased vulnerability to infections, there have been questions as to whether there are common factors that might increase susceptibility both to developing dementia and to dying from COVID-19,” Dr. Schott explained.

This “elegant paper” provides evidence for the latter, “suggesting a common genetic mechanism both for Alzheimer’s disease and for severe COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Schott said.

“The identification of a genetic risk factor and elucidation of inflammatory pathways through which it may increase risk has important implications for our understanding of both diseases, with potential implications for novel treatments,” he added.

The study was funded by the UK Dementia Research Institute. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Schott serves as chief medical officer for Alzheimer’s Research UK and is clinical adviser to the UK Dementia Research Institute. Dr. Baillie has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Epidiolex plus THC lowers seizures in pediatric epilepsy

the component of cannabis that makes people high in larger quantities, researchers reported.

“THC can contribute to seizure control and mitigation some of the side effects of CBD,” said study coauthor and Austin, Tex., child neurologist Karen Keough, MD, in an interview. Dr. Keough and colleagues presented their findings at the 50th annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

In a landmark move, the Food and Drug Administration approved Epidiolex in 2018 for the treatment of seizures in two rare forms of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. The agency had never before approved a drug with a purified ingredient derived from marijuana.

CBD, the active ingredient in Epidiolex, is nonpsychoactive. The use in medicine of THC, the main driver of marijuana’s ability to make people stoned, is much more controversial.

Dr. Keough said she had treated 60-70 children with CBD, at the same strength as in Epidiolex (100 mg), and 5 mg of THC before the drug was approved. “I was seeing some very impressive results, and some became seizure free who’d always been refractory,” she said.

When the Epidiolex became available, she said, some patients transitioned to it and stopped taking THC. According to her, some patients fared well. But others immediately experienced worse seizures, she said, and some developed side effects to Epidiolex in the absence of THC, such as agitation and appetite suppression.

Combination therapy

For the new study, a retrospective, unblinded cohort analysis, Dr. Keough and colleagues tracked patients who received various doses of CBD, in some cases as Epidiolex, and various doses of THC prescribed by the Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation dispensary, where she serves as chief medical officer.

The initial number of patients was 212; 135 consented to review and 10 were excluded for various reasons leaving a total of 74 subjects in the study. The subjects, whose median age at the start of the study was 12 years (range, 2-25 years), were tracked from 2018 to2021. Just over half (55%) were male, and they remained on the regimen for a median of 805 days (range, 400-1,141).

Of the 74 subjects, 45.9% had a reduction of seizures of more than 75%, and 20.3% had a reduction of 50%-75%. Only 4.1% saw their seizures worsen.

The THC doses varied from none to more than 12 mg/day; CBD doses varied from none to more than 26 mg/kg per day. O the 74 patients, 18 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received no THC; 12 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received 0-2 mg/kg per day of CBD.

Still controversial

Did the patients get high? In some cases they did, Dr. Keough said. However, “a lot of these patients are either too young or too cognitively limited to describe whether they’re feeling intoxicated. That’s one of the many reasons why this is so controversial. You have to go into this with eyes wide open. We’re working in an environment with limited information as to what an intoxicating dose is for a small kid.”

However, she said, it seems clear that “THC can enhance the effect of CBD in children with epilepsy” and reduce CBD side effects. It’s not surprising that the substances work differently since they interact with brain cells in different ways, she said.

For neurologists, she said, “the challenge is to find a reliable source of THC that you can count on and verify so you aren’t overdosing the patients.”

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, child neurologist and cannabinoid researcher Richard Huntsman, MD, who’s familiar with the study findings, said in an interview that they “provide another strong signal that the addition of THC provides benefit, at least in some patients.”

But it’s still unclear “why some children respond best in regards to seizure reduction and side effect profile with combination CBD:THC therapy, and others seemed to do better with CBD alone,” he said. Also unknown: “the ideal THC:CBD ratio that allows optimal seizure control while preventing the potential harmful effects of THC.”

As for the future, he said, “as we are just scratching the surface of our knowledge about the use of cannabis-based therapies in children with neurological disorders, I suspect that the use of these therapies will expand over time.”

No study funding is reported. Dr. Keough disclosed serving as chief medical officer of Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation. Dr. Huntsman disclosed serving as lead investigator of the Cannabidiol in Children with Refractory Epileptic Encephalopathy study and serving on the boards of the Cannabinoid Research Initiative of Saskatchewan (University of Saskatchewan) and Canadian Childhood Cannabinoid Clinical Trials Consortium. He is also cochair of Health Canada’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Cannabinoids for Health Purposes.

the component of cannabis that makes people high in larger quantities, researchers reported.

“THC can contribute to seizure control and mitigation some of the side effects of CBD,” said study coauthor and Austin, Tex., child neurologist Karen Keough, MD, in an interview. Dr. Keough and colleagues presented their findings at the 50th annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

In a landmark move, the Food and Drug Administration approved Epidiolex in 2018 for the treatment of seizures in two rare forms of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. The agency had never before approved a drug with a purified ingredient derived from marijuana.

CBD, the active ingredient in Epidiolex, is nonpsychoactive. The use in medicine of THC, the main driver of marijuana’s ability to make people stoned, is much more controversial.

Dr. Keough said she had treated 60-70 children with CBD, at the same strength as in Epidiolex (100 mg), and 5 mg of THC before the drug was approved. “I was seeing some very impressive results, and some became seizure free who’d always been refractory,” she said.

When the Epidiolex became available, she said, some patients transitioned to it and stopped taking THC. According to her, some patients fared well. But others immediately experienced worse seizures, she said, and some developed side effects to Epidiolex in the absence of THC, such as agitation and appetite suppression.

Combination therapy

For the new study, a retrospective, unblinded cohort analysis, Dr. Keough and colleagues tracked patients who received various doses of CBD, in some cases as Epidiolex, and various doses of THC prescribed by the Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation dispensary, where she serves as chief medical officer.

The initial number of patients was 212; 135 consented to review and 10 were excluded for various reasons leaving a total of 74 subjects in the study. The subjects, whose median age at the start of the study was 12 years (range, 2-25 years), were tracked from 2018 to2021. Just over half (55%) were male, and they remained on the regimen for a median of 805 days (range, 400-1,141).

Of the 74 subjects, 45.9% had a reduction of seizures of more than 75%, and 20.3% had a reduction of 50%-75%. Only 4.1% saw their seizures worsen.

The THC doses varied from none to more than 12 mg/day; CBD doses varied from none to more than 26 mg/kg per day. O the 74 patients, 18 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received no THC; 12 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received 0-2 mg/kg per day of CBD.

Still controversial

Did the patients get high? In some cases they did, Dr. Keough said. However, “a lot of these patients are either too young or too cognitively limited to describe whether they’re feeling intoxicated. That’s one of the many reasons why this is so controversial. You have to go into this with eyes wide open. We’re working in an environment with limited information as to what an intoxicating dose is for a small kid.”

However, she said, it seems clear that “THC can enhance the effect of CBD in children with epilepsy” and reduce CBD side effects. It’s not surprising that the substances work differently since they interact with brain cells in different ways, she said.

For neurologists, she said, “the challenge is to find a reliable source of THC that you can count on and verify so you aren’t overdosing the patients.”

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, child neurologist and cannabinoid researcher Richard Huntsman, MD, who’s familiar with the study findings, said in an interview that they “provide another strong signal that the addition of THC provides benefit, at least in some patients.”

But it’s still unclear “why some children respond best in regards to seizure reduction and side effect profile with combination CBD:THC therapy, and others seemed to do better with CBD alone,” he said. Also unknown: “the ideal THC:CBD ratio that allows optimal seizure control while preventing the potential harmful effects of THC.”

As for the future, he said, “as we are just scratching the surface of our knowledge about the use of cannabis-based therapies in children with neurological disorders, I suspect that the use of these therapies will expand over time.”

No study funding is reported. Dr. Keough disclosed serving as chief medical officer of Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation. Dr. Huntsman disclosed serving as lead investigator of the Cannabidiol in Children with Refractory Epileptic Encephalopathy study and serving on the boards of the Cannabinoid Research Initiative of Saskatchewan (University of Saskatchewan) and Canadian Childhood Cannabinoid Clinical Trials Consortium. He is also cochair of Health Canada’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Cannabinoids for Health Purposes.

the component of cannabis that makes people high in larger quantities, researchers reported.

“THC can contribute to seizure control and mitigation some of the side effects of CBD,” said study coauthor and Austin, Tex., child neurologist Karen Keough, MD, in an interview. Dr. Keough and colleagues presented their findings at the 50th annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

In a landmark move, the Food and Drug Administration approved Epidiolex in 2018 for the treatment of seizures in two rare forms of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. The agency had never before approved a drug with a purified ingredient derived from marijuana.

CBD, the active ingredient in Epidiolex, is nonpsychoactive. The use in medicine of THC, the main driver of marijuana’s ability to make people stoned, is much more controversial.

Dr. Keough said she had treated 60-70 children with CBD, at the same strength as in Epidiolex (100 mg), and 5 mg of THC before the drug was approved. “I was seeing some very impressive results, and some became seizure free who’d always been refractory,” she said.

When the Epidiolex became available, she said, some patients transitioned to it and stopped taking THC. According to her, some patients fared well. But others immediately experienced worse seizures, she said, and some developed side effects to Epidiolex in the absence of THC, such as agitation and appetite suppression.

Combination therapy

For the new study, a retrospective, unblinded cohort analysis, Dr. Keough and colleagues tracked patients who received various doses of CBD, in some cases as Epidiolex, and various doses of THC prescribed by the Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation dispensary, where she serves as chief medical officer.

The initial number of patients was 212; 135 consented to review and 10 were excluded for various reasons leaving a total of 74 subjects in the study. The subjects, whose median age at the start of the study was 12 years (range, 2-25 years), were tracked from 2018 to2021. Just over half (55%) were male, and they remained on the regimen for a median of 805 days (range, 400-1,141).

Of the 74 subjects, 45.9% had a reduction of seizures of more than 75%, and 20.3% had a reduction of 50%-75%. Only 4.1% saw their seizures worsen.

The THC doses varied from none to more than 12 mg/day; CBD doses varied from none to more than 26 mg/kg per day. O the 74 patients, 18 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received no THC; 12 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received 0-2 mg/kg per day of CBD.

Still controversial

Did the patients get high? In some cases they did, Dr. Keough said. However, “a lot of these patients are either too young or too cognitively limited to describe whether they’re feeling intoxicated. That’s one of the many reasons why this is so controversial. You have to go into this with eyes wide open. We’re working in an environment with limited information as to what an intoxicating dose is for a small kid.”

However, she said, it seems clear that “THC can enhance the effect of CBD in children with epilepsy” and reduce CBD side effects. It’s not surprising that the substances work differently since they interact with brain cells in different ways, she said.

For neurologists, she said, “the challenge is to find a reliable source of THC that you can count on and verify so you aren’t overdosing the patients.”

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, child neurologist and cannabinoid researcher Richard Huntsman, MD, who’s familiar with the study findings, said in an interview that they “provide another strong signal that the addition of THC provides benefit, at least in some patients.”

But it’s still unclear “why some children respond best in regards to seizure reduction and side effect profile with combination CBD:THC therapy, and others seemed to do better with CBD alone,” he said. Also unknown: “the ideal THC:CBD ratio that allows optimal seizure control while preventing the potential harmful effects of THC.”

As for the future, he said, “as we are just scratching the surface of our knowledge about the use of cannabis-based therapies in children with neurological disorders, I suspect that the use of these therapies will expand over time.”

No study funding is reported. Dr. Keough disclosed serving as chief medical officer of Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation. Dr. Huntsman disclosed serving as lead investigator of the Cannabidiol in Children with Refractory Epileptic Encephalopathy study and serving on the boards of the Cannabinoid Research Initiative of Saskatchewan (University of Saskatchewan) and Canadian Childhood Cannabinoid Clinical Trials Consortium. He is also cochair of Health Canada’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Cannabinoids for Health Purposes.

FROM CNS 2021

Is genetic testing valuable in the clinical management of epilepsy?

, new research shows.

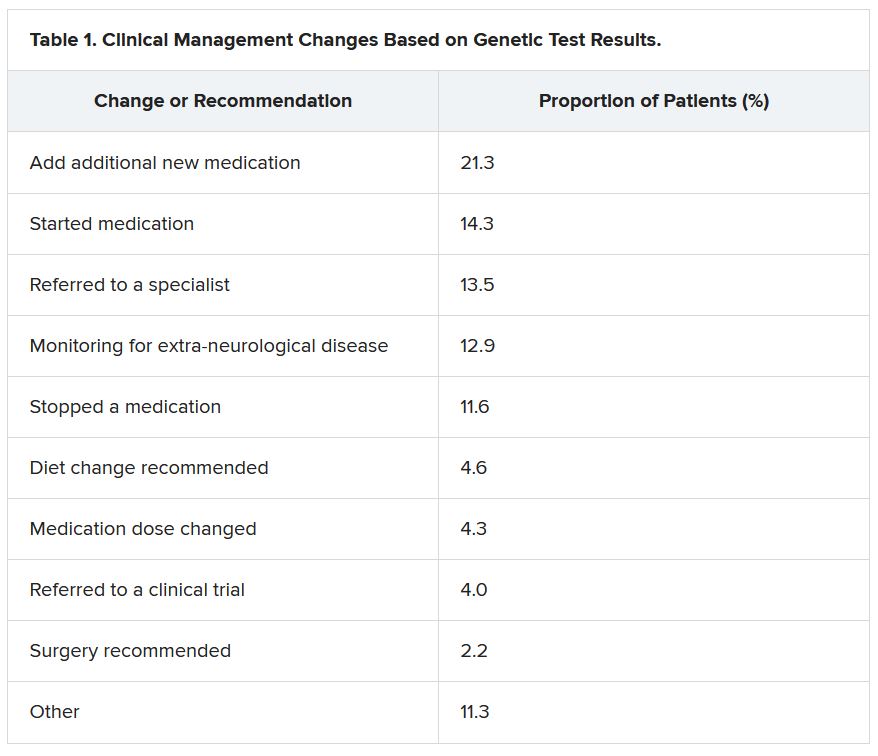

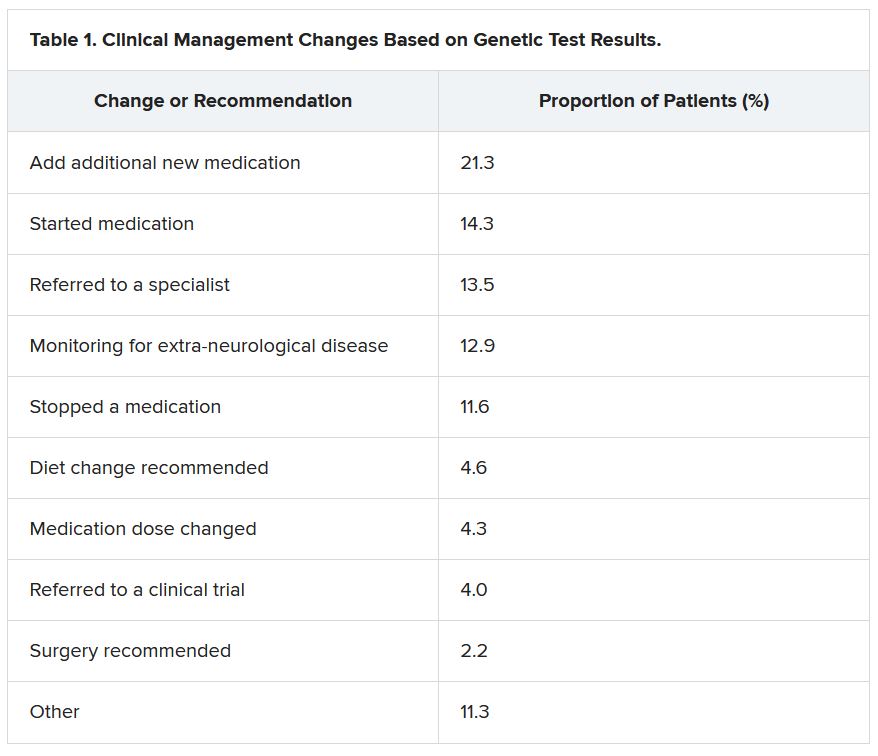

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

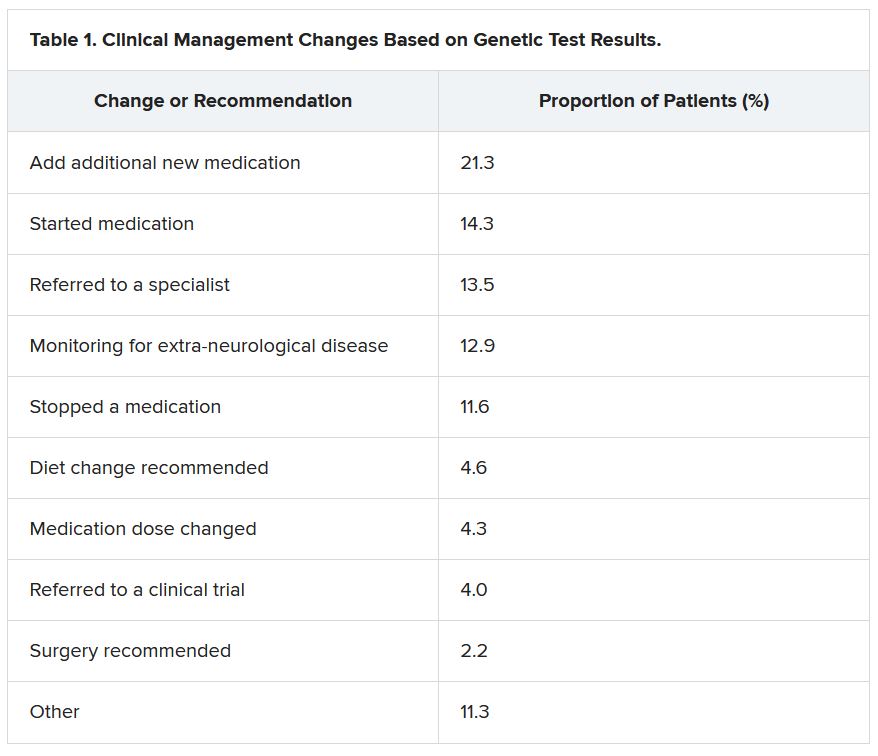

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

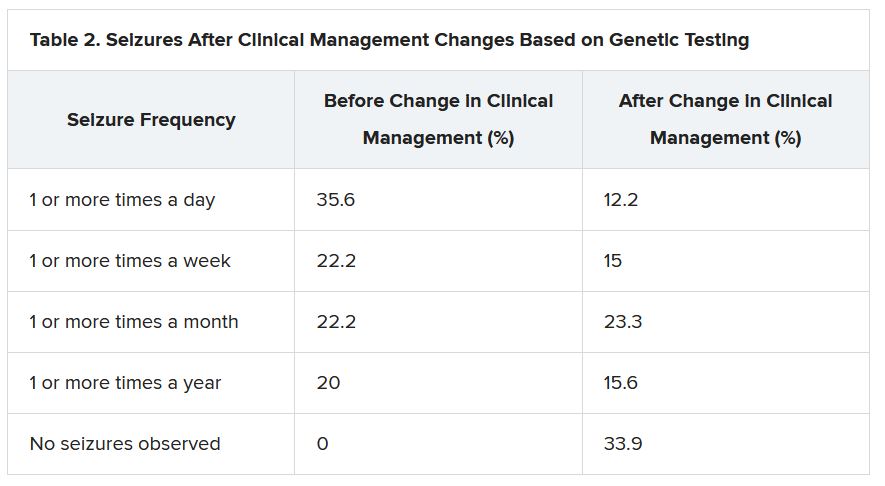

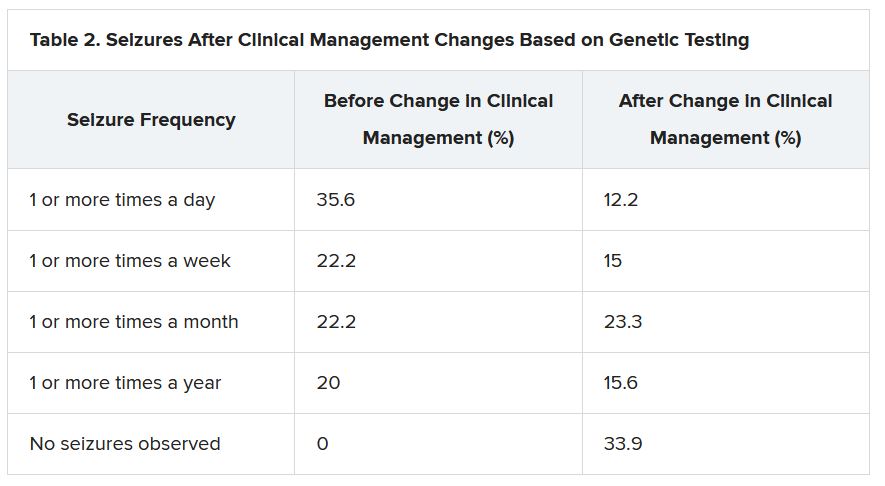

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

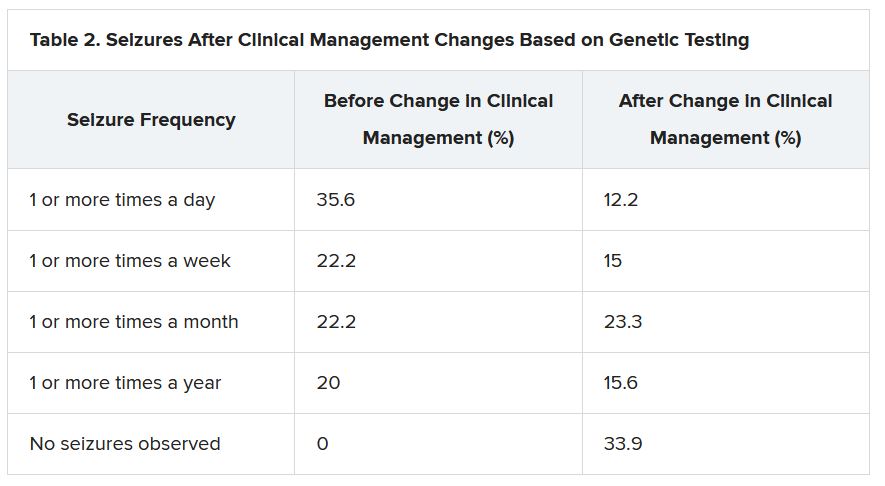

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From WCN 2021

Adolescents who exercised after a concussion recovered faster in RCT

After a concussion, resuming aerobic exercise relatively early on – at an intensity that does not worsen symptoms – may help young athletes recover sooner, compared with stretching, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) shows.

The study adds to emerging evidence that clinicians should prescribe exercise, rather than strict rest, to facilitate concussion recovery, researchers said.

Tamara McLeod, PhD, ATC, professor and director of athletic training programs at A.T. Still University in Mesa, Ariz., hopes the findings help clinicians see that “this is an approach that should be taken.”

“Too often with concussion, patients are given a laundry list of things they are NOT allowed to do,” including sports, school, and social activities, said Dr. McLeod, who was not involved in the study.

The research, published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, largely replicates the findings of a prior trial while addressing limitations of the previous study’s design, researchers said.

For the trial, John J. Leddy, MD, with the State University of New York at Buffalo and colleagues recruited 118 male and female adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years who had had a sport-related concussion in the past 10 days. Investigators at three community and hospital-affiliated sports medicine concussion centers in the United States randomly assigned the athletes to individualized subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise (61 participants) or stretching exercise (57 participants) at least 20 minutes per day for up to 4 weeks. Aerobic exercise included walking, jogging, or stationary cycling at home.

“It is important that the general clinician community appreciates that prolonged rest and avoidance of physical activity until spontaneous symptom resolution is no longer an acceptable approach to caring for adolescents with concussion,” Dr. Leddy and coauthors said.

The investigators improved on the “the scientific rigor of their previous RCT by including intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, daily symptom reporting, objective exercise adherence measurements, and greater heterogeneity of concussion severity,” said Carolyn A. Emery, PhD, and Jonathan Smirl, PhD, both with the University of Calgary (Alta.), in a related commentary. The new study is the first to show that early targeted heart rate subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise, relative to stretching, shortened recovery time within 4 weeks after sport-related concussion (hazard ratio, 0.52) when controlling for sex, study site, and average daily exercise time, Dr. Emery and Dr. Smirl said.

A larger proportion of athletes assigned to stretching did not recover by 4 weeks, compared with those assigned to aerobic exercise (32% vs. 21%). The median time to full recovery was longer for the stretching group than for the aerobic exercise group (19 days vs. 14 days).

Among athletes who adhered to their assigned regimens, the differences were more pronounced: The median recovery time was 21 days for the stretching group, compared with 12 days for the aerobic exercise group. The rate of postconcussion symptoms beyond 28 days was 9% in the aerobic exercise group versus 31% in the stretching group, among adherent participants.

More research is needed to establish the efficacy of postconcussion aerobic exercise in adults and for nonsport injury, the researchers noted. Possible mechanisms underlying aerobic exercise’s benefits could include increased parasympathetic autonomic tone, improved cerebral blood flow regulation, or enhanced neuron repair, they suggested.

The right amount and timing of exercise, and doing so at an intensity that does not exacerbate symptoms, may be key. Other research has suggested that too much exercise, too soon may delay recovery, Dr. Emery said in an interview. “But there is now a lot of evidence to support low and moderate levels of physical activity to expedite recovery,” she said.

The study was funded by the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. The study and commentary authors and Dr. McLeod had no disclosures.

After a concussion, resuming aerobic exercise relatively early on – at an intensity that does not worsen symptoms – may help young athletes recover sooner, compared with stretching, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) shows.

The study adds to emerging evidence that clinicians should prescribe exercise, rather than strict rest, to facilitate concussion recovery, researchers said.

Tamara McLeod, PhD, ATC, professor and director of athletic training programs at A.T. Still University in Mesa, Ariz., hopes the findings help clinicians see that “this is an approach that should be taken.”

“Too often with concussion, patients are given a laundry list of things they are NOT allowed to do,” including sports, school, and social activities, said Dr. McLeod, who was not involved in the study.

The research, published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, largely replicates the findings of a prior trial while addressing limitations of the previous study’s design, researchers said.

For the trial, John J. Leddy, MD, with the State University of New York at Buffalo and colleagues recruited 118 male and female adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years who had had a sport-related concussion in the past 10 days. Investigators at three community and hospital-affiliated sports medicine concussion centers in the United States randomly assigned the athletes to individualized subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise (61 participants) or stretching exercise (57 participants) at least 20 minutes per day for up to 4 weeks. Aerobic exercise included walking, jogging, or stationary cycling at home.

“It is important that the general clinician community appreciates that prolonged rest and avoidance of physical activity until spontaneous symptom resolution is no longer an acceptable approach to caring for adolescents with concussion,” Dr. Leddy and coauthors said.

The investigators improved on the “the scientific rigor of their previous RCT by including intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, daily symptom reporting, objective exercise adherence measurements, and greater heterogeneity of concussion severity,” said Carolyn A. Emery, PhD, and Jonathan Smirl, PhD, both with the University of Calgary (Alta.), in a related commentary. The new study is the first to show that early targeted heart rate subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise, relative to stretching, shortened recovery time within 4 weeks after sport-related concussion (hazard ratio, 0.52) when controlling for sex, study site, and average daily exercise time, Dr. Emery and Dr. Smirl said.

A larger proportion of athletes assigned to stretching did not recover by 4 weeks, compared with those assigned to aerobic exercise (32% vs. 21%). The median time to full recovery was longer for the stretching group than for the aerobic exercise group (19 days vs. 14 days).

Among athletes who adhered to their assigned regimens, the differences were more pronounced: The median recovery time was 21 days for the stretching group, compared with 12 days for the aerobic exercise group. The rate of postconcussion symptoms beyond 28 days was 9% in the aerobic exercise group versus 31% in the stretching group, among adherent participants.

More research is needed to establish the efficacy of postconcussion aerobic exercise in adults and for nonsport injury, the researchers noted. Possible mechanisms underlying aerobic exercise’s benefits could include increased parasympathetic autonomic tone, improved cerebral blood flow regulation, or enhanced neuron repair, they suggested.

The right amount and timing of exercise, and doing so at an intensity that does not exacerbate symptoms, may be key. Other research has suggested that too much exercise, too soon may delay recovery, Dr. Emery said in an interview. “But there is now a lot of evidence to support low and moderate levels of physical activity to expedite recovery,” she said.

The study was funded by the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. The study and commentary authors and Dr. McLeod had no disclosures.

After a concussion, resuming aerobic exercise relatively early on – at an intensity that does not worsen symptoms – may help young athletes recover sooner, compared with stretching, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) shows.

The study adds to emerging evidence that clinicians should prescribe exercise, rather than strict rest, to facilitate concussion recovery, researchers said.

Tamara McLeod, PhD, ATC, professor and director of athletic training programs at A.T. Still University in Mesa, Ariz., hopes the findings help clinicians see that “this is an approach that should be taken.”

“Too often with concussion, patients are given a laundry list of things they are NOT allowed to do,” including sports, school, and social activities, said Dr. McLeod, who was not involved in the study.

The research, published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, largely replicates the findings of a prior trial while addressing limitations of the previous study’s design, researchers said.

For the trial, John J. Leddy, MD, with the State University of New York at Buffalo and colleagues recruited 118 male and female adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years who had had a sport-related concussion in the past 10 days. Investigators at three community and hospital-affiliated sports medicine concussion centers in the United States randomly assigned the athletes to individualized subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise (61 participants) or stretching exercise (57 participants) at least 20 minutes per day for up to 4 weeks. Aerobic exercise included walking, jogging, or stationary cycling at home.

“It is important that the general clinician community appreciates that prolonged rest and avoidance of physical activity until spontaneous symptom resolution is no longer an acceptable approach to caring for adolescents with concussion,” Dr. Leddy and coauthors said.

The investigators improved on the “the scientific rigor of their previous RCT by including intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, daily symptom reporting, objective exercise adherence measurements, and greater heterogeneity of concussion severity,” said Carolyn A. Emery, PhD, and Jonathan Smirl, PhD, both with the University of Calgary (Alta.), in a related commentary. The new study is the first to show that early targeted heart rate subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise, relative to stretching, shortened recovery time within 4 weeks after sport-related concussion (hazard ratio, 0.52) when controlling for sex, study site, and average daily exercise time, Dr. Emery and Dr. Smirl said.

A larger proportion of athletes assigned to stretching did not recover by 4 weeks, compared with those assigned to aerobic exercise (32% vs. 21%). The median time to full recovery was longer for the stretching group than for the aerobic exercise group (19 days vs. 14 days).

Among athletes who adhered to their assigned regimens, the differences were more pronounced: The median recovery time was 21 days for the stretching group, compared with 12 days for the aerobic exercise group. The rate of postconcussion symptoms beyond 28 days was 9% in the aerobic exercise group versus 31% in the stretching group, among adherent participants.

More research is needed to establish the efficacy of postconcussion aerobic exercise in adults and for nonsport injury, the researchers noted. Possible mechanisms underlying aerobic exercise’s benefits could include increased parasympathetic autonomic tone, improved cerebral blood flow regulation, or enhanced neuron repair, they suggested.

The right amount and timing of exercise, and doing so at an intensity that does not exacerbate symptoms, may be key. Other research has suggested that too much exercise, too soon may delay recovery, Dr. Emery said in an interview. “But there is now a lot of evidence to support low and moderate levels of physical activity to expedite recovery,” she said.

The study was funded by the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. The study and commentary authors and Dr. McLeod had no disclosures.

FROM THE LANCET CHILD & ADOLESCENT HEALTH

Cement found in man’s heart after spinal surgery

, according to a new report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The 56-year-old man, who was not identified in the report, went to the emergency room after experiencing 2 days of chest pain and shortness of breath. Imaging scans showed that the chest pain was caused by a foreign object, and he was rushed to surgery.

Surgeons then located and removed a thin, sharp, cylindrical piece of cement and repaired the damage to the patient’s heart. The cement had pierced the upper right chamber of his heart and his right lung, according to the report authors from the Yale University School of Medicine.

A week before, the man had undergone a spinal surgery known as kyphoplasty. The procedure treats spine injuries by injecting a special type of medical cement into damaged vertebrae, according to USA Today. The cement had leaked into the patient’s body, hardened, and traveled to his heart.

The man has now “nearly recovered” since the heart surgery and cement removal, which occurred about a month ago, the journal report stated. He experienced no additional complications.

Cement leakage after kyphoplasty can happen but is an extremely rare complication. Less than 2% of patients who undergo the procedure for osteoporosis or brittle bones have complications, according to patient information from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a new report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The 56-year-old man, who was not identified in the report, went to the emergency room after experiencing 2 days of chest pain and shortness of breath. Imaging scans showed that the chest pain was caused by a foreign object, and he was rushed to surgery.

Surgeons then located and removed a thin, sharp, cylindrical piece of cement and repaired the damage to the patient’s heart. The cement had pierced the upper right chamber of his heart and his right lung, according to the report authors from the Yale University School of Medicine.

A week before, the man had undergone a spinal surgery known as kyphoplasty. The procedure treats spine injuries by injecting a special type of medical cement into damaged vertebrae, according to USA Today. The cement had leaked into the patient’s body, hardened, and traveled to his heart.

The man has now “nearly recovered” since the heart surgery and cement removal, which occurred about a month ago, the journal report stated. He experienced no additional complications.

Cement leakage after kyphoplasty can happen but is an extremely rare complication. Less than 2% of patients who undergo the procedure for osteoporosis or brittle bones have complications, according to patient information from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a new report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The 56-year-old man, who was not identified in the report, went to the emergency room after experiencing 2 days of chest pain and shortness of breath. Imaging scans showed that the chest pain was caused by a foreign object, and he was rushed to surgery.

Surgeons then located and removed a thin, sharp, cylindrical piece of cement and repaired the damage to the patient’s heart. The cement had pierced the upper right chamber of his heart and his right lung, according to the report authors from the Yale University School of Medicine.

A week before, the man had undergone a spinal surgery known as kyphoplasty. The procedure treats spine injuries by injecting a special type of medical cement into damaged vertebrae, according to USA Today. The cement had leaked into the patient’s body, hardened, and traveled to his heart.

The man has now “nearly recovered” since the heart surgery and cement removal, which occurred about a month ago, the journal report stated. He experienced no additional complications.

Cement leakage after kyphoplasty can happen but is an extremely rare complication. Less than 2% of patients who undergo the procedure for osteoporosis or brittle bones have complications, according to patient information from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Constipation med boosts cognitive performance in mental illness

, new research suggests.

In a randomized controlled trial, 44 healthy individuals were assigned to receive the selective serotonin-4 (5-HT4) receptor agonist prucalopride (Motegrity) or placebo for 1 week.

After 6 days, the active-treatment group performed significantly better on memory tests than the participants who received placebo. In addition, the drug increased activity in brain areas related to cognition.

“What we’re hoping is...these agents may be able to help those with cognitive impairment as part of their mental illness,” lead author Angharad N. de Cates, a clinical DPhil student in the department of psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, told meeting attendees.

“Currently, we’re looking to see if we can translate our finding a step further and do a similar study in those with depression,” Ms. de Cates added.

The findings were presented at the 34th European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) Congress and were simultaneously published in Translational Psychiatry.

“Exciting early evidence”

“Even when the low mood associated with depression is well-treated with conventional antidepressants, many patients continue to experience problems with their memory,” co-investigator Susannah Murphy, PhD, a senior research fellow at the University of Oxford, said in a release.

“Our study provides exciting early evidence in humans of a new approach that might be a helpful way to treat these residual cognitive symptoms,” Dr. Murphy added.

Preclinical and animal studies suggest that the 5-HT4 receptor is a promising treatment target for cognitive impairment in individuals with psychiatric disorders, although studies in humans have been limited by the adverse effects of early agents.

“We’ve had our eye on this receptor for a while,” explained de Cates, inasmuch as the animal data “have been so good.”

However, she said in an interview that “a lack of safe human agents made translation tricky.”