User login

Beneath the Surface: Massive Retroperitoneal Liposarcoma Masquerading as Meralgia Paresthetica

In patients presenting with focal neurologic findings involving the lower extremities, a thorough abdominal examination should be considered an integral part of the full neurologic work up.

Meralgia paresthetica (MP) is a sensory mononeuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN), clinically characterized by numbness, pain, and paresthesias involving the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. Estimates of MP incidence are derived largely from observational studies and reported to be about 3.2 to 4.3 cases per 10,000 patient-years.1,2 Although typically arising during midlife and especially in the context of comorbid obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), and excessive alcohol consumption, MP may occur at any age, and bears a slight predilection for males.2-4

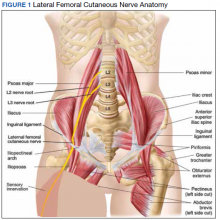

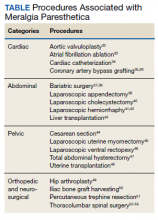

MP may be divided etiologically into iatrogenic and spontaneous subtypes.5 Iatrogenic cases generally are attributable to nerve injury in the setting of direct or indirect trauma (such as with patient malpositioning) arising in the context of multiple forms of procedural or surgical intervention (Table). Spontaneous MP is primarily thought to occur as a result of LFCN compression at the level of the inguinal ligament, wherein internal or external pressures may promote LFCN entrapment and resultant functional disruption (Figure 1).6,7

External forces, such as tight garments, wallets, or even elements of modern body armor, have been reported to provoke MP.8-11 Alternatively, states of increased intraabdominal pressure, such as obesity, ascites, and pregnancy may predispose to LFCN compression.2,12,13 Less commonly, lumbar radiculopathy, pelvic masses, and several forms of retroperitoneal pathology may present with clinical symptomatology indistinguishable from MP.14-17 Importantly, many of these represent must-not-miss diagnoses, and may be suggested via a focused history and physical examination.

Here, we present a case of MP secondary to a massive retroperitoneal sarcoma, ultimately drawing renewed attention to the known association of MP and retroperitoneal pathology, and therein highlighting the utility of a dedicated review of systems to identify red-flag features in patients who present with MP and a thorough abdominal examination in all patients presenting with focal neurologic deficits involving the lower extremities.

Case Presentation

A male Vietnam War veteran aged 69 years presented to a primary care clinic at West Roxbury Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WRVAMC) in Massachusetts with progressive right lower extremity numbness. Three months prior to this visit, he was evaluated in an urgent care clinic at WRVAMC for 6 months of numbness and increasingly painful nocturnal paresthesias involving the same extremity. A targeted physical examination at that visit revealed an obese male wearing tight suspenders, as well as focally diminished sensation to light touch involving the anterolateral aspect of the thigh, extending from just below the right hip to above the knee. Sensation in the medial thigh was spared. Strength and reflexes were normal in the bilateral lower extremities. An abdominal examination was not performed. He received a diagnosis of MP and counseled regarding weight loss, glycemic control, garment optimization, and conservative analgesia with as-needed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. He was instructed to follow-up closely with his primary care physician for further monitoring.

During the current visit, the patient reported 2 atraumatic falls the prior 2 months, attributed to escalating right leg weakness. The patient reported that ascending stairs had become difficult, and he was unable to cross his right leg over his left while in a seated position. The territory of numbness expanded to his front and inner thigh. Although previously he was able to hike 4 miles, he now was unable to walk more than half of a mile without developing shortness of breath. He reported frequent urination without hematuria and a recent weight gain of 8 pounds despite early satiety.

His medical history included hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, truncal obesity, noninsulin dependent DM, coronary artery disease, atrial flutter, transient ischemic attack, and benign positional paroxysmal vertigo. He was exposed to Agent Orange during his service in Vietnam. Family history was notable for breast cancer (mother), lung cancer (father), and an unspecified form of lymphoma (brother). He had smoked approximately 2 packs of cigarettes daily for 15 years but quit 38 years prior. He reported consuming on average 3 alcohol-containing drinks per week and no illicit drug use. He was adherent with all medications, including furosemide 40 mg daily, losartan 25 mg daily, metoprolol succinate 50 mg daily, atorvastatin 80 mg daily, metformin 500 mg twice daily, and rivaroxaban 20 mg daily with dinner.

His vital signs included a blood pressure of 123/58 mmHg, a pulse of 74 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 94% on ambient air. His temperature was recorded at 96.7°F, and his weight was 234 pounds with a body mass index (BMI) of 34. He was well groomed and in no acute distress. His cardiopulmonary examination was normal. Carotid, radial, and bilateral dorsalis pedis pulsations were 2+ bilaterally, and no jugular venous distension was observed at 30°. The abdomen was protuberant. Nonshifting dullness to percussion and firmness to palpation was observed throughout right upper and lower quadrants, with hyperactive bowel sounds primarily localized to the left upper and lower quadrants.

Neurologic examination revealed symmetric facies with normal phonation and diction. He was spontaneously moving all extremities, and his gait was normal. Sensation to light touch was severely diminished throughout the anterolateral and medial thigh, extending to the level of the knee, and otherwise reduced in a stocking-type pattern over the bilateral feet and toes. His right hip flexion, adduction, as well as internal and external rotation were focally diminished to 4- out of 5. Right knee extension was 4+ out of 5. Strength was otherwise 5 out of 5. The patient exhibited asymmetric Patellar reflexes—absent on the right and 2+ on the left. Achilles reflexes were absent bilaterally. Straight-leg raise test was negative bilaterally and did not clearly exacerbate his right leg numbness or paresthesias. There were no notable fasciculations. There was 2+ bilateral lower extremity pitting edema appreciated to the level of the midshin (right greater than left), without palpable cords or new skin lesions.

Upon referral to the neurology service, the patient underwent electromyography, which revealed complex repetitive discharges in the right tibialis anterior and pattern of reduced recruitment upon activation of the right vastus medialis, collectively suggestive of an L3-4 plexopathy. The patient was admitted for expedited workup.

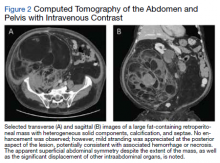

A complete blood count and metabolic panel that were taken in the emergency department were normal, save for a serum bicarbonate of 30 mEq/L. His hemoglobin A1c was 6.6%. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast was obtained, and notable for a 30 cm fat-containing right-sided retroperitoneal mass with associated solid nodular components and calcification (Figure 2). No enhancement of the lesion was observed. There was significant associated mass effect, with superior displacement of the liver and right hemidiaphragm, as well as superomedial deflection of the right kidney, inferior vena cava, and other intraabdominal organs. Subsequent imaging with a CT of the chest, as well as magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, were without evidence of metastatic disease.

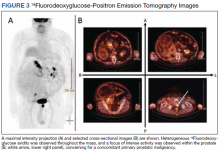

18Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) was performed and demonstrated heterogeneous FDG avidity throughout the mass (SUVmax 5.9), as well as poor delineation of the boundary of the right psoas major, consistent with muscular invasion (Figure 3). The FDG-PET also revealed intense tracer uptake within the left prostate (SUVmax 26), concerning for a concomitant prostate malignancy.

To facilitate tissue diagnosis, the patient underwent a CT-guided biopsy of the retroperitoneal mass. Subsequent histopathologic analysis revealed a primarily well-differentiated spindle cell lesion with occasional adipocytic atypia, and a superimposed hypercellular element characterized by the presence of pleomorphic high-grade spindled cells. The neoplastic spindle cells were MDM2-positive by both immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and negative for pancytokeratin, smooth muscle myosin, and S100. The findings were collectively consistent with a dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLPS).

Given the focus of FDG avidity observed on the PET, the patient underwent a transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate, which yielded diagnosis of a concomitant high-risk (Gleason 4+4) prostate adenocarcinoma. A bone scan did not reveal evidence of osseous metastatic disease.

Outcome

The patient was treated with external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) delivered simultaneously to both the prostate and high-risk retroperitoneal margins of the DDLPS, as well as concurrent androgen deprivation therapy. Five months after completed radiotherapy, resection of the DDLPS was attempted. However, palliative tumor debulking was instead performed due to extensive locoregional invasion with involvement of the posterior peritoneum and ipsilateral quadratus, iliopsoas, and psoas muscles, as well as the adjacent lumbar nerve roots.

At present, the patient is undergoing surveillance imaging every 3 months to reevaluate his underlying disease burden, which has thus far been radiographically stable. Current management at the primary care level is focused on preserving quality of life, particularly maintaining mobility and functional independence.

Discussion

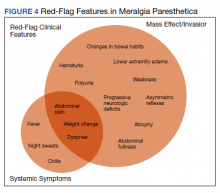

Although generally a benign entrapment neuropathy, MP bears well-established associations with multiple forms of must-not-miss pathology. Here, we present the case of a veteran in whom MP was the index presentation of a massive retroperitoneal liposarcoma, stressing the importance of a thorough history and physical examination in all patients presenting with MP. The case presented herein highlights many of the red-flag signs and symptoms that primary care physicians might encounter in patients with retroperitoneal pathology, including MP and MP-like syndromes (Figure 4).

In this case, the pretest probability of a spontaneous and uncomplicated MP was high given the patient’s sex, age, body habitus, and DM; however, there important atypia that emerged as the case evolved, including: (1) the progressive course; (2) proximal right lower extremity weakness; (3) asymmetric patellar reflexes; and (4) numerous clinical stigmata of intraabdominal mass effect. The patient exhibited abnormalities on abdominal examination that suggested the presence of an underlying intraabdominal mass, providing key diagnostic insight into this case. Given the slowly progressive nature of liposarcomas, we feel the abnormalities appreciated on abdominal examination were likely apparent during the initial presentation.18

There are numerous cognitive biases that may explain why an abdominal examination was not prioritized during the initial presentation. Namely, the patient’s numerous risk factors for spontaneous MP, as detailed above, may have contributed to framing bias that limited consideration of alternative diagnoses. In addition, the patient’s physical examination likely contributed to search satisfaction, whereby alternative diagnoses were not further entertained after discovery of findings consistent with spontaneous MP.19 Finally, it remains conceivable that an abdominal examination was not prioritized as it is often perceived as being distinct from, rather than an integral part of, the neurologic examination.20 Given that numerous neurologic disorders may present with abdominal pathology, we feel a thorough abdominal examination should be considered part of the full neurologic examination, especially in cases presenting with focal neurologic findings involving the lower extremities.21

Collectively, this case alludes to the importance of close clinical follow-up, as well as adequate anticipatory patient guidance in cases of suspected MP. In most patients, the clinical course of spontaneous MP is benign and favorable, with up to 85% of patients experiencing resolution within 4 to 6 months of the initial presentation.22 Common conservative measures include weight loss, garment optimization, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed for analgesia. In refractory cases, procedural interventions such as with neurolysis or resection of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, may be required after the ruling out of alternative diagnoses.23,24

Importantly, in even prolonged and resistant cases of MP, patient discomfort remains localized to the territory of the LFCN. Additional lower motor neuron signs, such as an expanding territory of sensory involvement, muscle weakness, or diminished reflexes, should prompt additional testing for alternative diagnoses. In addition, clinical findings concerning for intraabdominal mass effect, many of which were observed in this case, should lead to further evaluation and expeditious cross-sectional imaging. Although this patient’s early satiety, polyuria, bilateral lower extremity edema, weight gain, and lumbar plexopathy each may be explained by direct compression, invasion, or displacement, his report of progressive exertional dyspnea merits further discussion.

Exertional dyspnea is an uncommon complication of soft tissue sarcoma, reported almost exclusively in cases with cardiac, mediastinal, or other thoracic involvement.25-28 In this case, there was no evidence of thoracic involvement, either through direct extension or metastasis. Instead, the patient’s exertional dyspnea may have been attributable to increased intraabdominal pressure leading to compromised diaphragm excursion and reduced pulmonary reserve. In addition, the radiographic findings also raise the possibility of a potential contribution from preload failure due to IVC compression. Overall, dyspnea is a concerning feature that may suggest advanced disease.

Despite the value of a thorough history and physical examination in patients with MP, major clinical guidelines from neurologic, neurosurgical, and orthopedic organizations do not formally address MP evaluation and management. Further, proposed clinical practice algorithms are inconsistent in their recommendations regarding the identification of red-flag features and ruling out of alternative diagnoses.22,29,30 To supplement the abdominal examination, it would be reasonable to perform a pelvic compression test (PCT) in patients presenting with suspected MP. The PCT is a highly sensitive and specific provocative maneuver shown to enable reliable differentiation between MP and lumbar radiculopathy, and is performed by placing downward force on the anterior superior iliac spine of the affected extremity for 45 seconds with the patient in the lateral recumbent position.31 As this maneuver is intended to force relaxation of the inguinal ligament, thereby relieving pressure on the LFCN, improvement in the patient’s symptoms with the PCT is consistent with MP.

Conclusions

1. van Slobbe AM, Bohnen AM, Bernsen RM, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Incidence rates and determinants in meralgia paresthetica in general practice. J Neurol. 2004;251(3):294-297. doi:10.1007/s00415-004-0310-x

2. Parisi TJ, Mandrekar J, Dyck PJ, Klein CJ. Meralgia paresthetica: relation to obesity, advanced age, and diabetes mellitus. Neurology. 2011;77(16):1538-1542. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318233b356

3. Ecker AD. Diagnosis of meralgia paresthetica. JAMA. 1985;253(7):976.

4. Massey EW, Pellock JM. Meralgia paraesthetica in a child. J Pediatr. 1978;93(2):325-326. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80566-6

5. Harney D, Patijn J. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and management strategies. Pain Med. 2007;8(8):669-677. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00227.x

6. Berini SE, Spinner RJ, Jentoft ME, et al. Chronic meralgia paresthetica and neurectomy: a clinical pathologic study. Neurology. 2014;82(17):1551-1555. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000367

7. Payne RA, Harbaugh K, Specht CS, Rizk E. Correlation of histopathology and clinical symptoms in meralgia paresthetica. Cureus. 2017;9(10):e1789. Published 2017 Oct 20. doi:10.7759/cureus.1789

8. Boyce JR. Meralgia paresthetica and tight trousers. JAMA. 1984;251(12):1553.

9. Orton D. Meralgia paresthetica from a wallet. JAMA. 1984;252(24):3368.

10. Fargo MV, Konitzer LN. Meralgia paresthetica due to body armor wear in U.S. soldiers serving in Iraq: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2007;172(6):663-665. doi:10.7205/milmed.172.6.663

11. Korkmaz N, Ozçakar L. Meralgia paresthetica in a policeman: the belt or the gun. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(4):1012-1013. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000138706.86633.01

12. Gooding MS, Evangelista V, Pereira L. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Meralgia Paresthetica in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2020;75(2):121-126. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000745

13. Pauwels A, Amarenco P, Chazouillères O, Pigot F, Calmus Y, Lévy VG. Une complication rare et méconnue de l’ascite: la méralgie paresthésique [Unusual and unknown complication of ascites: meralgia paresthetica]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14(3):295.

14. Braddom RL. L2 rather than L1 radiculopathy mimics meralgia paresthetica. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42(5):842. doi:10.1002/mus.21826

15. Suber DA, Massey EW. Pelvic mass presenting as meralgia paresthetica. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(2):257-258.

16. Flowers RS. Meralgia paresthetica. A clue to retroperitoneal malignant tumor. Am J Surg. 1968;116(1):89-92. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(68)90423-6

17. Yi TI, Yoon TH, Kim JS, Lee GE, Kim BR. Femoral neuropathy and meralgia paresthetica secondary to an iliacus hematoma. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012;36(2):273-277. doi:10.5535/arm.2012.36.2.273

18. Lee ATJ, Thway K, Huang PH, Jones RL. Clinical and molecular spectrum of liposarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(2):151-159. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.74.9598

19. O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48(3):225-232. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2018.306

20. Bickley, LS. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 12th Edition. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2016.

21. Bhavsar AS, Verma S, Lamba R, Lall CG, Koenigsknecht V, Rajesh A. Abdominal manifestations of neurologic disorders. Radiographics. 2013;33(1):135-153. doi:10.1148/rg.331125097

22. Dureja GP, Gulaya V, Jayalakshmi TS, Mandal P. Management of meralgia paresthetica: a multimodality regimen. Anesth Analg. 1995;80(5):1060-1061. doi:10.1097/00000539-199505000-00043

23. Patijn J, Mekhail N, Hayek S, Lataster A, van Kleef M, Van Zundert J. Meralgia paresthetica. Pain Pract. 2011;11(3):302-308. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00458.x24. Ivins GK. Meralgia paresthetica, the elusive diagnosis: clinical experience with 14 adult patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232(2):281-286. doi:10.1097/00000658-200008000-00019

25. Munin MA, Goerner MS, Raggio I, et al. A rare cause of dyspnea: undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma in the left atrium. Cardiol Res. 2017;8(5):241-245. doi:10.14740/cr590w

26. Nguyen A, Awad WI. Cardiac sarcoma arising from malignant transformation of a preexisting atrial myxoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(4):1571-1573. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.05.129

27. Jiang S, Li J, Zeng Q, Liang J. Pulmonary artery intimal sarcoma misdiagnosed as pulmonary embolism: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(4):2713-2716. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.5775

28. Cojocaru A, Oliveira PJ, Pellecchia C. A pleural presentation of a rare soft tissue sarcoma. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A5201. doi:10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2012.185.1_MeetingAbstracts.A5201

29. Grossman MG, Ducey SA, Nadler SS, Levy AS. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9(5):336-344. doi:10.5435/00124635-200109000-00007

30. Cheatham SW, Kolber MJ, Salamh PA. Meralgia paresthetica: a review of the literature. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8(6):883-893.

31. Nouraei SA, Anand B, Spink G, O’Neill KS. A novel approach to the diagnosis and management of meralgia paresthetica. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(4):696-700. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000255392.69914.F7

32. Antunes PE, Antunes MJ. Meralgia paresthetica after aortic valve surgery. J Heart Valve Dis. 1997;6(6):589-590.

33. Reddy YM, Singh D, Chikkam V, et al. Postprocedural neuropathy after atrial fibrillation ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2013;36(3):279-285. doi:10.1007/s10840-012-9724-z

34. Butler R, Webster MW. Meralgia paresthetica: an unusual complication of cardiac catheterization via the femoral artery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;56(1):69-71. doi:10.1002/ccd.10149

35. Jellish WS, Oftadeh M. Peripheral nerve injury in cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32(1):495-511. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2017.08.030

36. Parsonnet V, Karasakalides A, Gielchinsky I, Hochberg M, Hussain SM. Meralgia paresthetica after coronary bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(2):219-221.

37. Macgregor AM, Thoburn EK. Meralgia paresthetica following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 1999;9(4):364-368. doi:10.1381/096089299765552945

38. Grace DM. Meralgia paresthetica after gastroplasty for morbid obesity. Can J Surg. 1987;30(1):64-65.

39. Polidori L, Magarelli M, Tramutoli R. Meralgia paresthetica as a complication of laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(5):832. doi:10.1007/s00464-002-4279-1

40. Yamout B, Tayyim A, Farhat W. Meralgia paresthetica as a complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1994;96(2):143-144. doi:10.1016/0303-8467(94)90048-5

41. Broin EO, Horner C, Mealy K, et al. Meralgia paraesthetica following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. an anatomical analysis. Surg Endosc. 1995;9(1):76-78. doi:10.1007/BF00187893

42. Eubanks S, Newman L 3rd, Goehring L, et al. Meralgia paresthetica: a complication of laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3(5):381-385.

43. Atamaz F, Hepgüler S, Karasu Z, Kilic M. Meralgia paresthetica after liver transplantation: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(10):4424-4425. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.11.047

44. Chung KH, Lee JY, Ko TK, et al. Meralgia paresthetica affecting parturient women who underwent cesarean section -a case report-. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;59 Suppl(Suppl):S86-S89. doi:10.4097/kjae.2010.59.S.S86

45. Hutchins FL Jr, Huggins J, Delaney ML. Laparoscopic myomectomy-an unusual cause of meralgia paresthetica. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1998;5(3):309-311. doi:10.1016/s1074-3804(98)80039-x

46. Jones CD, Guiot L, Portelli M, Bullen T, Skaife P. Two interesting cases of meralgia paraesthetica. Pain Physician. 2017;20(6):E987-E989.

47. Peters G, Larner AJ. Meralgia paresthetica following gynecologic and obstetric surgery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(1):42-43. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.05.025

48. Kvarnström N, Järvholm S, Johannesson L, Dahm-Kähler P, Olausson M, Brännström M. Live donors of the initial observational study of uterus transplantation-psychological and medical follow-up until 1 year after surgery in the 9 cases. Transplantation. 2017;101(3):664-670. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000001567

49. Goulding K, Beaulé PE, Kim PR, Fazekas A. Incidence of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve neuropraxia after anterior approach hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2397-2404. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1406-5

50. Yamamoto T, Nagira K, Kurosaka M. Meralgia paresthetica occurring 40 years after iliac bone graft harvesting: case report. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(6):1455-1457. doi:10.1097/00006123-200112000-00028

51. Roqueplan F, Porcher R, Hamzé B, et al. Long-term results of percutaneous resection and interstitial laser ablation of osteoid osteomas. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(1):209-217. doi:10.1007/s00330-009-1537-9

52. Gupta A, Muzumdar D, Ramani PS. Meralgia paraesthetica following lumbar spine surgery: a study in 110 consecutive surgically treated cases. Neurol India. 2004;52(1):64-66.

53. Yang SH, Wu CC, Chen PQ. Postoperative meralgia paresthetica after posterior spine surgery: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(18):E547-E550. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000178821.14102.9d

54. Tejwani SG, Scaduto AA, Bowen RE. Transient meralgia paresthetica after pediatric posterior spine fusion. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(4):530-533. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000217721.95480.9e

55. Peker S, Ay B, Sun I, Ozgen S, Pamir M. Meralgia paraesthetica: complications of prone position during lumbar disc surgery. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2003;8(1):24-29.

In patients presenting with focal neurologic findings involving the lower extremities, a thorough abdominal examination should be considered an integral part of the full neurologic work up.

In patients presenting with focal neurologic findings involving the lower extremities, a thorough abdominal examination should be considered an integral part of the full neurologic work up.

Meralgia paresthetica (MP) is a sensory mononeuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN), clinically characterized by numbness, pain, and paresthesias involving the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. Estimates of MP incidence are derived largely from observational studies and reported to be about 3.2 to 4.3 cases per 10,000 patient-years.1,2 Although typically arising during midlife and especially in the context of comorbid obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), and excessive alcohol consumption, MP may occur at any age, and bears a slight predilection for males.2-4

MP may be divided etiologically into iatrogenic and spontaneous subtypes.5 Iatrogenic cases generally are attributable to nerve injury in the setting of direct or indirect trauma (such as with patient malpositioning) arising in the context of multiple forms of procedural or surgical intervention (Table). Spontaneous MP is primarily thought to occur as a result of LFCN compression at the level of the inguinal ligament, wherein internal or external pressures may promote LFCN entrapment and resultant functional disruption (Figure 1).6,7

External forces, such as tight garments, wallets, or even elements of modern body armor, have been reported to provoke MP.8-11 Alternatively, states of increased intraabdominal pressure, such as obesity, ascites, and pregnancy may predispose to LFCN compression.2,12,13 Less commonly, lumbar radiculopathy, pelvic masses, and several forms of retroperitoneal pathology may present with clinical symptomatology indistinguishable from MP.14-17 Importantly, many of these represent must-not-miss diagnoses, and may be suggested via a focused history and physical examination.

Here, we present a case of MP secondary to a massive retroperitoneal sarcoma, ultimately drawing renewed attention to the known association of MP and retroperitoneal pathology, and therein highlighting the utility of a dedicated review of systems to identify red-flag features in patients who present with MP and a thorough abdominal examination in all patients presenting with focal neurologic deficits involving the lower extremities.

Case Presentation

A male Vietnam War veteran aged 69 years presented to a primary care clinic at West Roxbury Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WRVAMC) in Massachusetts with progressive right lower extremity numbness. Three months prior to this visit, he was evaluated in an urgent care clinic at WRVAMC for 6 months of numbness and increasingly painful nocturnal paresthesias involving the same extremity. A targeted physical examination at that visit revealed an obese male wearing tight suspenders, as well as focally diminished sensation to light touch involving the anterolateral aspect of the thigh, extending from just below the right hip to above the knee. Sensation in the medial thigh was spared. Strength and reflexes were normal in the bilateral lower extremities. An abdominal examination was not performed. He received a diagnosis of MP and counseled regarding weight loss, glycemic control, garment optimization, and conservative analgesia with as-needed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. He was instructed to follow-up closely with his primary care physician for further monitoring.

During the current visit, the patient reported 2 atraumatic falls the prior 2 months, attributed to escalating right leg weakness. The patient reported that ascending stairs had become difficult, and he was unable to cross his right leg over his left while in a seated position. The territory of numbness expanded to his front and inner thigh. Although previously he was able to hike 4 miles, he now was unable to walk more than half of a mile without developing shortness of breath. He reported frequent urination without hematuria and a recent weight gain of 8 pounds despite early satiety.

His medical history included hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, truncal obesity, noninsulin dependent DM, coronary artery disease, atrial flutter, transient ischemic attack, and benign positional paroxysmal vertigo. He was exposed to Agent Orange during his service in Vietnam. Family history was notable for breast cancer (mother), lung cancer (father), and an unspecified form of lymphoma (brother). He had smoked approximately 2 packs of cigarettes daily for 15 years but quit 38 years prior. He reported consuming on average 3 alcohol-containing drinks per week and no illicit drug use. He was adherent with all medications, including furosemide 40 mg daily, losartan 25 mg daily, metoprolol succinate 50 mg daily, atorvastatin 80 mg daily, metformin 500 mg twice daily, and rivaroxaban 20 mg daily with dinner.

His vital signs included a blood pressure of 123/58 mmHg, a pulse of 74 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 94% on ambient air. His temperature was recorded at 96.7°F, and his weight was 234 pounds with a body mass index (BMI) of 34. He was well groomed and in no acute distress. His cardiopulmonary examination was normal. Carotid, radial, and bilateral dorsalis pedis pulsations were 2+ bilaterally, and no jugular venous distension was observed at 30°. The abdomen was protuberant. Nonshifting dullness to percussion and firmness to palpation was observed throughout right upper and lower quadrants, with hyperactive bowel sounds primarily localized to the left upper and lower quadrants.

Neurologic examination revealed symmetric facies with normal phonation and diction. He was spontaneously moving all extremities, and his gait was normal. Sensation to light touch was severely diminished throughout the anterolateral and medial thigh, extending to the level of the knee, and otherwise reduced in a stocking-type pattern over the bilateral feet and toes. His right hip flexion, adduction, as well as internal and external rotation were focally diminished to 4- out of 5. Right knee extension was 4+ out of 5. Strength was otherwise 5 out of 5. The patient exhibited asymmetric Patellar reflexes—absent on the right and 2+ on the left. Achilles reflexes were absent bilaterally. Straight-leg raise test was negative bilaterally and did not clearly exacerbate his right leg numbness or paresthesias. There were no notable fasciculations. There was 2+ bilateral lower extremity pitting edema appreciated to the level of the midshin (right greater than left), without palpable cords or new skin lesions.

Upon referral to the neurology service, the patient underwent electromyography, which revealed complex repetitive discharges in the right tibialis anterior and pattern of reduced recruitment upon activation of the right vastus medialis, collectively suggestive of an L3-4 plexopathy. The patient was admitted for expedited workup.

A complete blood count and metabolic panel that were taken in the emergency department were normal, save for a serum bicarbonate of 30 mEq/L. His hemoglobin A1c was 6.6%. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast was obtained, and notable for a 30 cm fat-containing right-sided retroperitoneal mass with associated solid nodular components and calcification (Figure 2). No enhancement of the lesion was observed. There was significant associated mass effect, with superior displacement of the liver and right hemidiaphragm, as well as superomedial deflection of the right kidney, inferior vena cava, and other intraabdominal organs. Subsequent imaging with a CT of the chest, as well as magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, were without evidence of metastatic disease.

18Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) was performed and demonstrated heterogeneous FDG avidity throughout the mass (SUVmax 5.9), as well as poor delineation of the boundary of the right psoas major, consistent with muscular invasion (Figure 3). The FDG-PET also revealed intense tracer uptake within the left prostate (SUVmax 26), concerning for a concomitant prostate malignancy.

To facilitate tissue diagnosis, the patient underwent a CT-guided biopsy of the retroperitoneal mass. Subsequent histopathologic analysis revealed a primarily well-differentiated spindle cell lesion with occasional adipocytic atypia, and a superimposed hypercellular element characterized by the presence of pleomorphic high-grade spindled cells. The neoplastic spindle cells were MDM2-positive by both immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and negative for pancytokeratin, smooth muscle myosin, and S100. The findings were collectively consistent with a dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLPS).

Given the focus of FDG avidity observed on the PET, the patient underwent a transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate, which yielded diagnosis of a concomitant high-risk (Gleason 4+4) prostate adenocarcinoma. A bone scan did not reveal evidence of osseous metastatic disease.

Outcome

The patient was treated with external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) delivered simultaneously to both the prostate and high-risk retroperitoneal margins of the DDLPS, as well as concurrent androgen deprivation therapy. Five months after completed radiotherapy, resection of the DDLPS was attempted. However, palliative tumor debulking was instead performed due to extensive locoregional invasion with involvement of the posterior peritoneum and ipsilateral quadratus, iliopsoas, and psoas muscles, as well as the adjacent lumbar nerve roots.

At present, the patient is undergoing surveillance imaging every 3 months to reevaluate his underlying disease burden, which has thus far been radiographically stable. Current management at the primary care level is focused on preserving quality of life, particularly maintaining mobility and functional independence.

Discussion

Although generally a benign entrapment neuropathy, MP bears well-established associations with multiple forms of must-not-miss pathology. Here, we present the case of a veteran in whom MP was the index presentation of a massive retroperitoneal liposarcoma, stressing the importance of a thorough history and physical examination in all patients presenting with MP. The case presented herein highlights many of the red-flag signs and symptoms that primary care physicians might encounter in patients with retroperitoneal pathology, including MP and MP-like syndromes (Figure 4).

In this case, the pretest probability of a spontaneous and uncomplicated MP was high given the patient’s sex, age, body habitus, and DM; however, there important atypia that emerged as the case evolved, including: (1) the progressive course; (2) proximal right lower extremity weakness; (3) asymmetric patellar reflexes; and (4) numerous clinical stigmata of intraabdominal mass effect. The patient exhibited abnormalities on abdominal examination that suggested the presence of an underlying intraabdominal mass, providing key diagnostic insight into this case. Given the slowly progressive nature of liposarcomas, we feel the abnormalities appreciated on abdominal examination were likely apparent during the initial presentation.18

There are numerous cognitive biases that may explain why an abdominal examination was not prioritized during the initial presentation. Namely, the patient’s numerous risk factors for spontaneous MP, as detailed above, may have contributed to framing bias that limited consideration of alternative diagnoses. In addition, the patient’s physical examination likely contributed to search satisfaction, whereby alternative diagnoses were not further entertained after discovery of findings consistent with spontaneous MP.19 Finally, it remains conceivable that an abdominal examination was not prioritized as it is often perceived as being distinct from, rather than an integral part of, the neurologic examination.20 Given that numerous neurologic disorders may present with abdominal pathology, we feel a thorough abdominal examination should be considered part of the full neurologic examination, especially in cases presenting with focal neurologic findings involving the lower extremities.21

Collectively, this case alludes to the importance of close clinical follow-up, as well as adequate anticipatory patient guidance in cases of suspected MP. In most patients, the clinical course of spontaneous MP is benign and favorable, with up to 85% of patients experiencing resolution within 4 to 6 months of the initial presentation.22 Common conservative measures include weight loss, garment optimization, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed for analgesia. In refractory cases, procedural interventions such as with neurolysis or resection of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, may be required after the ruling out of alternative diagnoses.23,24

Importantly, in even prolonged and resistant cases of MP, patient discomfort remains localized to the territory of the LFCN. Additional lower motor neuron signs, such as an expanding territory of sensory involvement, muscle weakness, or diminished reflexes, should prompt additional testing for alternative diagnoses. In addition, clinical findings concerning for intraabdominal mass effect, many of which were observed in this case, should lead to further evaluation and expeditious cross-sectional imaging. Although this patient’s early satiety, polyuria, bilateral lower extremity edema, weight gain, and lumbar plexopathy each may be explained by direct compression, invasion, or displacement, his report of progressive exertional dyspnea merits further discussion.

Exertional dyspnea is an uncommon complication of soft tissue sarcoma, reported almost exclusively in cases with cardiac, mediastinal, or other thoracic involvement.25-28 In this case, there was no evidence of thoracic involvement, either through direct extension or metastasis. Instead, the patient’s exertional dyspnea may have been attributable to increased intraabdominal pressure leading to compromised diaphragm excursion and reduced pulmonary reserve. In addition, the radiographic findings also raise the possibility of a potential contribution from preload failure due to IVC compression. Overall, dyspnea is a concerning feature that may suggest advanced disease.

Despite the value of a thorough history and physical examination in patients with MP, major clinical guidelines from neurologic, neurosurgical, and orthopedic organizations do not formally address MP evaluation and management. Further, proposed clinical practice algorithms are inconsistent in their recommendations regarding the identification of red-flag features and ruling out of alternative diagnoses.22,29,30 To supplement the abdominal examination, it would be reasonable to perform a pelvic compression test (PCT) in patients presenting with suspected MP. The PCT is a highly sensitive and specific provocative maneuver shown to enable reliable differentiation between MP and lumbar radiculopathy, and is performed by placing downward force on the anterior superior iliac spine of the affected extremity for 45 seconds with the patient in the lateral recumbent position.31 As this maneuver is intended to force relaxation of the inguinal ligament, thereby relieving pressure on the LFCN, improvement in the patient’s symptoms with the PCT is consistent with MP.

Conclusions

Meralgia paresthetica (MP) is a sensory mononeuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN), clinically characterized by numbness, pain, and paresthesias involving the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. Estimates of MP incidence are derived largely from observational studies and reported to be about 3.2 to 4.3 cases per 10,000 patient-years.1,2 Although typically arising during midlife and especially in the context of comorbid obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), and excessive alcohol consumption, MP may occur at any age, and bears a slight predilection for males.2-4

MP may be divided etiologically into iatrogenic and spontaneous subtypes.5 Iatrogenic cases generally are attributable to nerve injury in the setting of direct or indirect trauma (such as with patient malpositioning) arising in the context of multiple forms of procedural or surgical intervention (Table). Spontaneous MP is primarily thought to occur as a result of LFCN compression at the level of the inguinal ligament, wherein internal or external pressures may promote LFCN entrapment and resultant functional disruption (Figure 1).6,7

External forces, such as tight garments, wallets, or even elements of modern body armor, have been reported to provoke MP.8-11 Alternatively, states of increased intraabdominal pressure, such as obesity, ascites, and pregnancy may predispose to LFCN compression.2,12,13 Less commonly, lumbar radiculopathy, pelvic masses, and several forms of retroperitoneal pathology may present with clinical symptomatology indistinguishable from MP.14-17 Importantly, many of these represent must-not-miss diagnoses, and may be suggested via a focused history and physical examination.

Here, we present a case of MP secondary to a massive retroperitoneal sarcoma, ultimately drawing renewed attention to the known association of MP and retroperitoneal pathology, and therein highlighting the utility of a dedicated review of systems to identify red-flag features in patients who present with MP and a thorough abdominal examination in all patients presenting with focal neurologic deficits involving the lower extremities.

Case Presentation

A male Vietnam War veteran aged 69 years presented to a primary care clinic at West Roxbury Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WRVAMC) in Massachusetts with progressive right lower extremity numbness. Three months prior to this visit, he was evaluated in an urgent care clinic at WRVAMC for 6 months of numbness and increasingly painful nocturnal paresthesias involving the same extremity. A targeted physical examination at that visit revealed an obese male wearing tight suspenders, as well as focally diminished sensation to light touch involving the anterolateral aspect of the thigh, extending from just below the right hip to above the knee. Sensation in the medial thigh was spared. Strength and reflexes were normal in the bilateral lower extremities. An abdominal examination was not performed. He received a diagnosis of MP and counseled regarding weight loss, glycemic control, garment optimization, and conservative analgesia with as-needed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. He was instructed to follow-up closely with his primary care physician for further monitoring.

During the current visit, the patient reported 2 atraumatic falls the prior 2 months, attributed to escalating right leg weakness. The patient reported that ascending stairs had become difficult, and he was unable to cross his right leg over his left while in a seated position. The territory of numbness expanded to his front and inner thigh. Although previously he was able to hike 4 miles, he now was unable to walk more than half of a mile without developing shortness of breath. He reported frequent urination without hematuria and a recent weight gain of 8 pounds despite early satiety.

His medical history included hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, truncal obesity, noninsulin dependent DM, coronary artery disease, atrial flutter, transient ischemic attack, and benign positional paroxysmal vertigo. He was exposed to Agent Orange during his service in Vietnam. Family history was notable for breast cancer (mother), lung cancer (father), and an unspecified form of lymphoma (brother). He had smoked approximately 2 packs of cigarettes daily for 15 years but quit 38 years prior. He reported consuming on average 3 alcohol-containing drinks per week and no illicit drug use. He was adherent with all medications, including furosemide 40 mg daily, losartan 25 mg daily, metoprolol succinate 50 mg daily, atorvastatin 80 mg daily, metformin 500 mg twice daily, and rivaroxaban 20 mg daily with dinner.

His vital signs included a blood pressure of 123/58 mmHg, a pulse of 74 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 94% on ambient air. His temperature was recorded at 96.7°F, and his weight was 234 pounds with a body mass index (BMI) of 34. He was well groomed and in no acute distress. His cardiopulmonary examination was normal. Carotid, radial, and bilateral dorsalis pedis pulsations were 2+ bilaterally, and no jugular venous distension was observed at 30°. The abdomen was protuberant. Nonshifting dullness to percussion and firmness to palpation was observed throughout right upper and lower quadrants, with hyperactive bowel sounds primarily localized to the left upper and lower quadrants.

Neurologic examination revealed symmetric facies with normal phonation and diction. He was spontaneously moving all extremities, and his gait was normal. Sensation to light touch was severely diminished throughout the anterolateral and medial thigh, extending to the level of the knee, and otherwise reduced in a stocking-type pattern over the bilateral feet and toes. His right hip flexion, adduction, as well as internal and external rotation were focally diminished to 4- out of 5. Right knee extension was 4+ out of 5. Strength was otherwise 5 out of 5. The patient exhibited asymmetric Patellar reflexes—absent on the right and 2+ on the left. Achilles reflexes were absent bilaterally. Straight-leg raise test was negative bilaterally and did not clearly exacerbate his right leg numbness or paresthesias. There were no notable fasciculations. There was 2+ bilateral lower extremity pitting edema appreciated to the level of the midshin (right greater than left), without palpable cords or new skin lesions.

Upon referral to the neurology service, the patient underwent electromyography, which revealed complex repetitive discharges in the right tibialis anterior and pattern of reduced recruitment upon activation of the right vastus medialis, collectively suggestive of an L3-4 plexopathy. The patient was admitted for expedited workup.

A complete blood count and metabolic panel that were taken in the emergency department were normal, save for a serum bicarbonate of 30 mEq/L. His hemoglobin A1c was 6.6%. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast was obtained, and notable for a 30 cm fat-containing right-sided retroperitoneal mass with associated solid nodular components and calcification (Figure 2). No enhancement of the lesion was observed. There was significant associated mass effect, with superior displacement of the liver and right hemidiaphragm, as well as superomedial deflection of the right kidney, inferior vena cava, and other intraabdominal organs. Subsequent imaging with a CT of the chest, as well as magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, were without evidence of metastatic disease.

18Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) was performed and demonstrated heterogeneous FDG avidity throughout the mass (SUVmax 5.9), as well as poor delineation of the boundary of the right psoas major, consistent with muscular invasion (Figure 3). The FDG-PET also revealed intense tracer uptake within the left prostate (SUVmax 26), concerning for a concomitant prostate malignancy.

To facilitate tissue diagnosis, the patient underwent a CT-guided biopsy of the retroperitoneal mass. Subsequent histopathologic analysis revealed a primarily well-differentiated spindle cell lesion with occasional adipocytic atypia, and a superimposed hypercellular element characterized by the presence of pleomorphic high-grade spindled cells. The neoplastic spindle cells were MDM2-positive by both immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and negative for pancytokeratin, smooth muscle myosin, and S100. The findings were collectively consistent with a dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLPS).

Given the focus of FDG avidity observed on the PET, the patient underwent a transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate, which yielded diagnosis of a concomitant high-risk (Gleason 4+4) prostate adenocarcinoma. A bone scan did not reveal evidence of osseous metastatic disease.

Outcome

The patient was treated with external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) delivered simultaneously to both the prostate and high-risk retroperitoneal margins of the DDLPS, as well as concurrent androgen deprivation therapy. Five months after completed radiotherapy, resection of the DDLPS was attempted. However, palliative tumor debulking was instead performed due to extensive locoregional invasion with involvement of the posterior peritoneum and ipsilateral quadratus, iliopsoas, and psoas muscles, as well as the adjacent lumbar nerve roots.

At present, the patient is undergoing surveillance imaging every 3 months to reevaluate his underlying disease burden, which has thus far been radiographically stable. Current management at the primary care level is focused on preserving quality of life, particularly maintaining mobility and functional independence.

Discussion

Although generally a benign entrapment neuropathy, MP bears well-established associations with multiple forms of must-not-miss pathology. Here, we present the case of a veteran in whom MP was the index presentation of a massive retroperitoneal liposarcoma, stressing the importance of a thorough history and physical examination in all patients presenting with MP. The case presented herein highlights many of the red-flag signs and symptoms that primary care physicians might encounter in patients with retroperitoneal pathology, including MP and MP-like syndromes (Figure 4).

In this case, the pretest probability of a spontaneous and uncomplicated MP was high given the patient’s sex, age, body habitus, and DM; however, there important atypia that emerged as the case evolved, including: (1) the progressive course; (2) proximal right lower extremity weakness; (3) asymmetric patellar reflexes; and (4) numerous clinical stigmata of intraabdominal mass effect. The patient exhibited abnormalities on abdominal examination that suggested the presence of an underlying intraabdominal mass, providing key diagnostic insight into this case. Given the slowly progressive nature of liposarcomas, we feel the abnormalities appreciated on abdominal examination were likely apparent during the initial presentation.18

There are numerous cognitive biases that may explain why an abdominal examination was not prioritized during the initial presentation. Namely, the patient’s numerous risk factors for spontaneous MP, as detailed above, may have contributed to framing bias that limited consideration of alternative diagnoses. In addition, the patient’s physical examination likely contributed to search satisfaction, whereby alternative diagnoses were not further entertained after discovery of findings consistent with spontaneous MP.19 Finally, it remains conceivable that an abdominal examination was not prioritized as it is often perceived as being distinct from, rather than an integral part of, the neurologic examination.20 Given that numerous neurologic disorders may present with abdominal pathology, we feel a thorough abdominal examination should be considered part of the full neurologic examination, especially in cases presenting with focal neurologic findings involving the lower extremities.21

Collectively, this case alludes to the importance of close clinical follow-up, as well as adequate anticipatory patient guidance in cases of suspected MP. In most patients, the clinical course of spontaneous MP is benign and favorable, with up to 85% of patients experiencing resolution within 4 to 6 months of the initial presentation.22 Common conservative measures include weight loss, garment optimization, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed for analgesia. In refractory cases, procedural interventions such as with neurolysis or resection of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, may be required after the ruling out of alternative diagnoses.23,24

Importantly, in even prolonged and resistant cases of MP, patient discomfort remains localized to the territory of the LFCN. Additional lower motor neuron signs, such as an expanding territory of sensory involvement, muscle weakness, or diminished reflexes, should prompt additional testing for alternative diagnoses. In addition, clinical findings concerning for intraabdominal mass effect, many of which were observed in this case, should lead to further evaluation and expeditious cross-sectional imaging. Although this patient’s early satiety, polyuria, bilateral lower extremity edema, weight gain, and lumbar plexopathy each may be explained by direct compression, invasion, or displacement, his report of progressive exertional dyspnea merits further discussion.

Exertional dyspnea is an uncommon complication of soft tissue sarcoma, reported almost exclusively in cases with cardiac, mediastinal, or other thoracic involvement.25-28 In this case, there was no evidence of thoracic involvement, either through direct extension or metastasis. Instead, the patient’s exertional dyspnea may have been attributable to increased intraabdominal pressure leading to compromised diaphragm excursion and reduced pulmonary reserve. In addition, the radiographic findings also raise the possibility of a potential contribution from preload failure due to IVC compression. Overall, dyspnea is a concerning feature that may suggest advanced disease.

Despite the value of a thorough history and physical examination in patients with MP, major clinical guidelines from neurologic, neurosurgical, and orthopedic organizations do not formally address MP evaluation and management. Further, proposed clinical practice algorithms are inconsistent in their recommendations regarding the identification of red-flag features and ruling out of alternative diagnoses.22,29,30 To supplement the abdominal examination, it would be reasonable to perform a pelvic compression test (PCT) in patients presenting with suspected MP. The PCT is a highly sensitive and specific provocative maneuver shown to enable reliable differentiation between MP and lumbar radiculopathy, and is performed by placing downward force on the anterior superior iliac spine of the affected extremity for 45 seconds with the patient in the lateral recumbent position.31 As this maneuver is intended to force relaxation of the inguinal ligament, thereby relieving pressure on the LFCN, improvement in the patient’s symptoms with the PCT is consistent with MP.

Conclusions

1. van Slobbe AM, Bohnen AM, Bernsen RM, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Incidence rates and determinants in meralgia paresthetica in general practice. J Neurol. 2004;251(3):294-297. doi:10.1007/s00415-004-0310-x

2. Parisi TJ, Mandrekar J, Dyck PJ, Klein CJ. Meralgia paresthetica: relation to obesity, advanced age, and diabetes mellitus. Neurology. 2011;77(16):1538-1542. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318233b356

3. Ecker AD. Diagnosis of meralgia paresthetica. JAMA. 1985;253(7):976.

4. Massey EW, Pellock JM. Meralgia paraesthetica in a child. J Pediatr. 1978;93(2):325-326. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80566-6

5. Harney D, Patijn J. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and management strategies. Pain Med. 2007;8(8):669-677. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00227.x

6. Berini SE, Spinner RJ, Jentoft ME, et al. Chronic meralgia paresthetica and neurectomy: a clinical pathologic study. Neurology. 2014;82(17):1551-1555. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000367

7. Payne RA, Harbaugh K, Specht CS, Rizk E. Correlation of histopathology and clinical symptoms in meralgia paresthetica. Cureus. 2017;9(10):e1789. Published 2017 Oct 20. doi:10.7759/cureus.1789

8. Boyce JR. Meralgia paresthetica and tight trousers. JAMA. 1984;251(12):1553.

9. Orton D. Meralgia paresthetica from a wallet. JAMA. 1984;252(24):3368.

10. Fargo MV, Konitzer LN. Meralgia paresthetica due to body armor wear in U.S. soldiers serving in Iraq: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2007;172(6):663-665. doi:10.7205/milmed.172.6.663

11. Korkmaz N, Ozçakar L. Meralgia paresthetica in a policeman: the belt or the gun. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(4):1012-1013. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000138706.86633.01

12. Gooding MS, Evangelista V, Pereira L. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Meralgia Paresthetica in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2020;75(2):121-126. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000745

13. Pauwels A, Amarenco P, Chazouillères O, Pigot F, Calmus Y, Lévy VG. Une complication rare et méconnue de l’ascite: la méralgie paresthésique [Unusual and unknown complication of ascites: meralgia paresthetica]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14(3):295.

14. Braddom RL. L2 rather than L1 radiculopathy mimics meralgia paresthetica. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42(5):842. doi:10.1002/mus.21826

15. Suber DA, Massey EW. Pelvic mass presenting as meralgia paresthetica. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(2):257-258.

16. Flowers RS. Meralgia paresthetica. A clue to retroperitoneal malignant tumor. Am J Surg. 1968;116(1):89-92. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(68)90423-6

17. Yi TI, Yoon TH, Kim JS, Lee GE, Kim BR. Femoral neuropathy and meralgia paresthetica secondary to an iliacus hematoma. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012;36(2):273-277. doi:10.5535/arm.2012.36.2.273

18. Lee ATJ, Thway K, Huang PH, Jones RL. Clinical and molecular spectrum of liposarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(2):151-159. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.74.9598

19. O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48(3):225-232. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2018.306

20. Bickley, LS. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 12th Edition. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2016.

21. Bhavsar AS, Verma S, Lamba R, Lall CG, Koenigsknecht V, Rajesh A. Abdominal manifestations of neurologic disorders. Radiographics. 2013;33(1):135-153. doi:10.1148/rg.331125097

22. Dureja GP, Gulaya V, Jayalakshmi TS, Mandal P. Management of meralgia paresthetica: a multimodality regimen. Anesth Analg. 1995;80(5):1060-1061. doi:10.1097/00000539-199505000-00043

23. Patijn J, Mekhail N, Hayek S, Lataster A, van Kleef M, Van Zundert J. Meralgia paresthetica. Pain Pract. 2011;11(3):302-308. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00458.x24. Ivins GK. Meralgia paresthetica, the elusive diagnosis: clinical experience with 14 adult patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232(2):281-286. doi:10.1097/00000658-200008000-00019

25. Munin MA, Goerner MS, Raggio I, et al. A rare cause of dyspnea: undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma in the left atrium. Cardiol Res. 2017;8(5):241-245. doi:10.14740/cr590w

26. Nguyen A, Awad WI. Cardiac sarcoma arising from malignant transformation of a preexisting atrial myxoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(4):1571-1573. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.05.129

27. Jiang S, Li J, Zeng Q, Liang J. Pulmonary artery intimal sarcoma misdiagnosed as pulmonary embolism: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(4):2713-2716. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.5775

28. Cojocaru A, Oliveira PJ, Pellecchia C. A pleural presentation of a rare soft tissue sarcoma. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A5201. doi:10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2012.185.1_MeetingAbstracts.A5201

29. Grossman MG, Ducey SA, Nadler SS, Levy AS. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9(5):336-344. doi:10.5435/00124635-200109000-00007

30. Cheatham SW, Kolber MJ, Salamh PA. Meralgia paresthetica: a review of the literature. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8(6):883-893.

31. Nouraei SA, Anand B, Spink G, O’Neill KS. A novel approach to the diagnosis and management of meralgia paresthetica. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(4):696-700. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000255392.69914.F7

32. Antunes PE, Antunes MJ. Meralgia paresthetica after aortic valve surgery. J Heart Valve Dis. 1997;6(6):589-590.

33. Reddy YM, Singh D, Chikkam V, et al. Postprocedural neuropathy after atrial fibrillation ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2013;36(3):279-285. doi:10.1007/s10840-012-9724-z

34. Butler R, Webster MW. Meralgia paresthetica: an unusual complication of cardiac catheterization via the femoral artery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;56(1):69-71. doi:10.1002/ccd.10149

35. Jellish WS, Oftadeh M. Peripheral nerve injury in cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32(1):495-511. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2017.08.030

36. Parsonnet V, Karasakalides A, Gielchinsky I, Hochberg M, Hussain SM. Meralgia paresthetica after coronary bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(2):219-221.

37. Macgregor AM, Thoburn EK. Meralgia paresthetica following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 1999;9(4):364-368. doi:10.1381/096089299765552945

38. Grace DM. Meralgia paresthetica after gastroplasty for morbid obesity. Can J Surg. 1987;30(1):64-65.

39. Polidori L, Magarelli M, Tramutoli R. Meralgia paresthetica as a complication of laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(5):832. doi:10.1007/s00464-002-4279-1

40. Yamout B, Tayyim A, Farhat W. Meralgia paresthetica as a complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1994;96(2):143-144. doi:10.1016/0303-8467(94)90048-5

41. Broin EO, Horner C, Mealy K, et al. Meralgia paraesthetica following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. an anatomical analysis. Surg Endosc. 1995;9(1):76-78. doi:10.1007/BF00187893

42. Eubanks S, Newman L 3rd, Goehring L, et al. Meralgia paresthetica: a complication of laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3(5):381-385.

43. Atamaz F, Hepgüler S, Karasu Z, Kilic M. Meralgia paresthetica after liver transplantation: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(10):4424-4425. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.11.047

44. Chung KH, Lee JY, Ko TK, et al. Meralgia paresthetica affecting parturient women who underwent cesarean section -a case report-. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;59 Suppl(Suppl):S86-S89. doi:10.4097/kjae.2010.59.S.S86

45. Hutchins FL Jr, Huggins J, Delaney ML. Laparoscopic myomectomy-an unusual cause of meralgia paresthetica. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1998;5(3):309-311. doi:10.1016/s1074-3804(98)80039-x

46. Jones CD, Guiot L, Portelli M, Bullen T, Skaife P. Two interesting cases of meralgia paraesthetica. Pain Physician. 2017;20(6):E987-E989.

47. Peters G, Larner AJ. Meralgia paresthetica following gynecologic and obstetric surgery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(1):42-43. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.05.025

48. Kvarnström N, Järvholm S, Johannesson L, Dahm-Kähler P, Olausson M, Brännström M. Live donors of the initial observational study of uterus transplantation-psychological and medical follow-up until 1 year after surgery in the 9 cases. Transplantation. 2017;101(3):664-670. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000001567

49. Goulding K, Beaulé PE, Kim PR, Fazekas A. Incidence of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve neuropraxia after anterior approach hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2397-2404. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1406-5

50. Yamamoto T, Nagira K, Kurosaka M. Meralgia paresthetica occurring 40 years after iliac bone graft harvesting: case report. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(6):1455-1457. doi:10.1097/00006123-200112000-00028

51. Roqueplan F, Porcher R, Hamzé B, et al. Long-term results of percutaneous resection and interstitial laser ablation of osteoid osteomas. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(1):209-217. doi:10.1007/s00330-009-1537-9

52. Gupta A, Muzumdar D, Ramani PS. Meralgia paraesthetica following lumbar spine surgery: a study in 110 consecutive surgically treated cases. Neurol India. 2004;52(1):64-66.

53. Yang SH, Wu CC, Chen PQ. Postoperative meralgia paresthetica after posterior spine surgery: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(18):E547-E550. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000178821.14102.9d

54. Tejwani SG, Scaduto AA, Bowen RE. Transient meralgia paresthetica after pediatric posterior spine fusion. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(4):530-533. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000217721.95480.9e

55. Peker S, Ay B, Sun I, Ozgen S, Pamir M. Meralgia paraesthetica: complications of prone position during lumbar disc surgery. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2003;8(1):24-29.

1. van Slobbe AM, Bohnen AM, Bernsen RM, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Incidence rates and determinants in meralgia paresthetica in general practice. J Neurol. 2004;251(3):294-297. doi:10.1007/s00415-004-0310-x

2. Parisi TJ, Mandrekar J, Dyck PJ, Klein CJ. Meralgia paresthetica: relation to obesity, advanced age, and diabetes mellitus. Neurology. 2011;77(16):1538-1542. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318233b356

3. Ecker AD. Diagnosis of meralgia paresthetica. JAMA. 1985;253(7):976.

4. Massey EW, Pellock JM. Meralgia paraesthetica in a child. J Pediatr. 1978;93(2):325-326. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80566-6

5. Harney D, Patijn J. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and management strategies. Pain Med. 2007;8(8):669-677. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00227.x

6. Berini SE, Spinner RJ, Jentoft ME, et al. Chronic meralgia paresthetica and neurectomy: a clinical pathologic study. Neurology. 2014;82(17):1551-1555. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000367

7. Payne RA, Harbaugh K, Specht CS, Rizk E. Correlation of histopathology and clinical symptoms in meralgia paresthetica. Cureus. 2017;9(10):e1789. Published 2017 Oct 20. doi:10.7759/cureus.1789

8. Boyce JR. Meralgia paresthetica and tight trousers. JAMA. 1984;251(12):1553.

9. Orton D. Meralgia paresthetica from a wallet. JAMA. 1984;252(24):3368.

10. Fargo MV, Konitzer LN. Meralgia paresthetica due to body armor wear in U.S. soldiers serving in Iraq: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2007;172(6):663-665. doi:10.7205/milmed.172.6.663

11. Korkmaz N, Ozçakar L. Meralgia paresthetica in a policeman: the belt or the gun. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(4):1012-1013. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000138706.86633.01

12. Gooding MS, Evangelista V, Pereira L. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Meralgia Paresthetica in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2020;75(2):121-126. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000745

13. Pauwels A, Amarenco P, Chazouillères O, Pigot F, Calmus Y, Lévy VG. Une complication rare et méconnue de l’ascite: la méralgie paresthésique [Unusual and unknown complication of ascites: meralgia paresthetica]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14(3):295.

14. Braddom RL. L2 rather than L1 radiculopathy mimics meralgia paresthetica. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42(5):842. doi:10.1002/mus.21826

15. Suber DA, Massey EW. Pelvic mass presenting as meralgia paresthetica. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(2):257-258.

16. Flowers RS. Meralgia paresthetica. A clue to retroperitoneal malignant tumor. Am J Surg. 1968;116(1):89-92. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(68)90423-6

17. Yi TI, Yoon TH, Kim JS, Lee GE, Kim BR. Femoral neuropathy and meralgia paresthetica secondary to an iliacus hematoma. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012;36(2):273-277. doi:10.5535/arm.2012.36.2.273

18. Lee ATJ, Thway K, Huang PH, Jones RL. Clinical and molecular spectrum of liposarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(2):151-159. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.74.9598

19. O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48(3):225-232. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2018.306

20. Bickley, LS. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 12th Edition. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2016.

21. Bhavsar AS, Verma S, Lamba R, Lall CG, Koenigsknecht V, Rajesh A. Abdominal manifestations of neurologic disorders. Radiographics. 2013;33(1):135-153. doi:10.1148/rg.331125097

22. Dureja GP, Gulaya V, Jayalakshmi TS, Mandal P. Management of meralgia paresthetica: a multimodality regimen. Anesth Analg. 1995;80(5):1060-1061. doi:10.1097/00000539-199505000-00043

23. Patijn J, Mekhail N, Hayek S, Lataster A, van Kleef M, Van Zundert J. Meralgia paresthetica. Pain Pract. 2011;11(3):302-308. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00458.x24. Ivins GK. Meralgia paresthetica, the elusive diagnosis: clinical experience with 14 adult patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232(2):281-286. doi:10.1097/00000658-200008000-00019

25. Munin MA, Goerner MS, Raggio I, et al. A rare cause of dyspnea: undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma in the left atrium. Cardiol Res. 2017;8(5):241-245. doi:10.14740/cr590w

26. Nguyen A, Awad WI. Cardiac sarcoma arising from malignant transformation of a preexisting atrial myxoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(4):1571-1573. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.05.129

27. Jiang S, Li J, Zeng Q, Liang J. Pulmonary artery intimal sarcoma misdiagnosed as pulmonary embolism: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(4):2713-2716. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.5775

28. Cojocaru A, Oliveira PJ, Pellecchia C. A pleural presentation of a rare soft tissue sarcoma. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A5201. doi:10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2012.185.1_MeetingAbstracts.A5201

29. Grossman MG, Ducey SA, Nadler SS, Levy AS. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9(5):336-344. doi:10.5435/00124635-200109000-00007

30. Cheatham SW, Kolber MJ, Salamh PA. Meralgia paresthetica: a review of the literature. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8(6):883-893.

31. Nouraei SA, Anand B, Spink G, O’Neill KS. A novel approach to the diagnosis and management of meralgia paresthetica. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(4):696-700. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000255392.69914.F7

32. Antunes PE, Antunes MJ. Meralgia paresthetica after aortic valve surgery. J Heart Valve Dis. 1997;6(6):589-590.

33. Reddy YM, Singh D, Chikkam V, et al. Postprocedural neuropathy after atrial fibrillation ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2013;36(3):279-285. doi:10.1007/s10840-012-9724-z

34. Butler R, Webster MW. Meralgia paresthetica: an unusual complication of cardiac catheterization via the femoral artery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;56(1):69-71. doi:10.1002/ccd.10149

35. Jellish WS, Oftadeh M. Peripheral nerve injury in cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32(1):495-511. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2017.08.030

36. Parsonnet V, Karasakalides A, Gielchinsky I, Hochberg M, Hussain SM. Meralgia paresthetica after coronary bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(2):219-221.

37. Macgregor AM, Thoburn EK. Meralgia paresthetica following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 1999;9(4):364-368. doi:10.1381/096089299765552945

38. Grace DM. Meralgia paresthetica after gastroplasty for morbid obesity. Can J Surg. 1987;30(1):64-65.

39. Polidori L, Magarelli M, Tramutoli R. Meralgia paresthetica as a complication of laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(5):832. doi:10.1007/s00464-002-4279-1

40. Yamout B, Tayyim A, Farhat W. Meralgia paresthetica as a complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1994;96(2):143-144. doi:10.1016/0303-8467(94)90048-5

41. Broin EO, Horner C, Mealy K, et al. Meralgia paraesthetica following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. an anatomical analysis. Surg Endosc. 1995;9(1):76-78. doi:10.1007/BF00187893

42. Eubanks S, Newman L 3rd, Goehring L, et al. Meralgia paresthetica: a complication of laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3(5):381-385.

43. Atamaz F, Hepgüler S, Karasu Z, Kilic M. Meralgia paresthetica after liver transplantation: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(10):4424-4425. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.11.047

44. Chung KH, Lee JY, Ko TK, et al. Meralgia paresthetica affecting parturient women who underwent cesarean section -a case report-. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;59 Suppl(Suppl):S86-S89. doi:10.4097/kjae.2010.59.S.S86

45. Hutchins FL Jr, Huggins J, Delaney ML. Laparoscopic myomectomy-an unusual cause of meralgia paresthetica. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1998;5(3):309-311. doi:10.1016/s1074-3804(98)80039-x

46. Jones CD, Guiot L, Portelli M, Bullen T, Skaife P. Two interesting cases of meralgia paraesthetica. Pain Physician. 2017;20(6):E987-E989.

47. Peters G, Larner AJ. Meralgia paresthetica following gynecologic and obstetric surgery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(1):42-43. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.05.025

48. Kvarnström N, Järvholm S, Johannesson L, Dahm-Kähler P, Olausson M, Brännström M. Live donors of the initial observational study of uterus transplantation-psychological and medical follow-up until 1 year after surgery in the 9 cases. Transplantation. 2017;101(3):664-670. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000001567

49. Goulding K, Beaulé PE, Kim PR, Fazekas A. Incidence of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve neuropraxia after anterior approach hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2397-2404. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1406-5

50. Yamamoto T, Nagira K, Kurosaka M. Meralgia paresthetica occurring 40 years after iliac bone graft harvesting: case report. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(6):1455-1457. doi:10.1097/00006123-200112000-00028

51. Roqueplan F, Porcher R, Hamzé B, et al. Long-term results of percutaneous resection and interstitial laser ablation of osteoid osteomas. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(1):209-217. doi:10.1007/s00330-009-1537-9

52. Gupta A, Muzumdar D, Ramani PS. Meralgia paraesthetica following lumbar spine surgery: a study in 110 consecutive surgically treated cases. Neurol India. 2004;52(1):64-66.

53. Yang SH, Wu CC, Chen PQ. Postoperative meralgia paresthetica after posterior spine surgery: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(18):E547-E550. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000178821.14102.9d

54. Tejwani SG, Scaduto AA, Bowen RE. Transient meralgia paresthetica after pediatric posterior spine fusion. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(4):530-533. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000217721.95480.9e

55. Peker S, Ay B, Sun I, Ozgen S, Pamir M. Meralgia paraesthetica: complications of prone position during lumbar disc surgery. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2003;8(1):24-29.

NSAIDs don’t make COVID-19 worse in hospitalized patients

NSAIDs don’t boost the risk of more severe disease or death in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, a new study finds.

“To our knowledge, our prospective study includes the largest number of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 to date, and adds to the literature on the safety of NSAIDs and in-hospital outcomes. NSAIDs do not appear to increase the risk of worse in-hospital outcomes ...” the study authors wrote. “NSAIDs are an important analgesic modality and have a vital opioid-sparing role in pain management. Patients and clinicians should be reassured by these findings that NSAIDs are safe in the context of the pandemic.”

The report was published online May 7 in The Lancet Rheumatology and led by clinical research fellow Thomas M. Drake, MBChB, of the University of Edinburgh’s Usher Institute.

For more than a year, researchers worldwide have debated about whether NSAIDs spell trouble for people at risk of COVID-19. In March 2020, French health officials announced that use of the painkillers such as NSAIDs may increase the severity of the disease, and they recommended that patients take acetaminophen instead. The National Health Service in the United Kingdom made a similar recommendation. But other agencies didn’t believe there was enough evidence to support ditching NSAIDs, and recent research studies published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases and PLoS Medicine suggested they may be right.

For the new study, researchers identified 72,179 patients who were treated for COVID-19 in British hospitals during January-August 2020. About 56% were men, 74% were White, and 6% took NSAIDs on a regular basis before they entered the hospital. The average age was 70.

The researchers examined whether the patients in either group were more or less likely to die in the hospital, be admitted into a critical care unit, need oxygen treatment, need a ventilator, or suffer kidney injury.

In terms of outcomes, there weren’t any major gaps between the groups overall. The differences in most comparisons were statistically insignificant. For example, 31% of those who didn’t take NSAIDs died vs. 30% of those who did (P = .227). In both groups, 14% required critical care admission (P = .476).

The researchers then focused on two matched groups of 4,205 patients: One group used NSAIDs regularly, and the other group didn’t. The difference in risk of death in those who took NSAIDs vs. those who didn’t was statistically insignificant (odds ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.84-1.07; P = .35). Other comparisons were also statistically insignificant.

The findings offer insight into whether the use of NSAIDs might actually be helpful for patients who develop COVID-19. Scientists believe that COVID-19 is linked to inflammation in the body, and NSAIDs, of course, reduce inflammation. But the researchers didn’t turn up any sign of a benefit.

The new study has some weaknesses: It doesn’t say anything about whether NSAIDs have an impact on whether people get COVID-19 in the first place. Researchers don’t know if high use of NSAIDs may affect the severity of the disease. And it doesn’t examine the potential effect of acetaminophen, although other research suggests the drug also may not cause harm in patients with COVID-19.

Still, the researchers say the study is the largest of its kind to look at the use of NSAIDs by patients who are admitted to the hospital with COVID-19. “Considering all the evidence, if there was an extreme effect of NSAIDs on COVID-19 outcomes or severity, this would have been observed in one or more of the studies that have been done, including the present study,” they wrote.