User login

Smart Mattress to Reduce SUDEP?

LOS ANGELES — says one of the experts involved in its development.

When used along with a seizure detection device, Jong Woo Lee, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology, Harvard Medical School, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts, estimates the smart mattress could cut SUDEP by more than 50%.

In addition, early results from an observational study are backing this up, he said.

The findings were presented at the American Epilepsy Society (AES) 78th Annual Meeting 2024.

Most SUDEP Cases Found Face Down

SUDEP is the leading cause of death in children with epilepsy and in otherwise healthy adult patients with epilepsy. When his fifth patient died of SUDEP, Lee decided it was time to try to tackle the high mortality rate associated with these unexpected deaths. “I desperately wanted to help, ” he said.

About 70% of SUDEP occurs during sleep, and victims are found face down, or in the prone position, 90% of the time, said Lee.

“Of course, the best way to prevent SUDEP is not to have a seizure, but once you have a seizure and once you’re face down, your risk for death goes up by somewhere between 30 and 100 times,” he explained.

Lee was convinced SUDEP could be prevented by simple interventions that stimulate the patient and turn them over. He noted the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome, “which has similar characteristics” to SUDEP, has been reduced by up to 75% through campaigns that simply advise placing babies on their backs.

“Most of SUDEP happens because your arousal system is knocked out and you just don’t take the breath that you’re supposed to. Just the act of turning people over and vibrating the bed will stimulate them,” he said.

However, it’s crucial that this be done quickly, said Lee. “When you look at patients who died on video and see the EEGs, everybody took their last breath within 3 minutes.”

Because the window of opportunity is so short, “we think that seizure detection devices alone are not going to really be effective because you just can’t get there or react within those 3 minutes.”

There are currently no products that detect the prone position or have the ability to reposition a patient quickly into the recovery sideways position.

Lee and his colleagues developed a smart system that can be embedded in a mattress that detects when someone is having a seizure, determines if that person is face down, and if so, safely stimulates and repositions them.

The mattress is made up of a series of programmable inflatable blocks or “cells” that have pressure, vibration, temperature, and humidity sensors embedded within. “Based on the pressure readings, we can figure out whether the patient is right side up, on their right side, on their left side, or face down,” said Lee.

If the person is face down, he or she can be repositioned within a matter of seconds. “Each of the cells can lift 1000 pounds,” he said. The mattress is “very comfortable,” said Lee, who has tried it out himself.

Eighteen normative control participants have been enrolled for development and training purposes. To date, 10 of these individuals, aged 18-53 years, weighing 100-182 lb, and with a height of 5 ft 2 in to 6 ft 1 in, underwent extensive formal testing on the prototype bed.

Researchers found the mattress responded quickly to different body positions and weights. “We were able to reposition everybody in around 20 seconds,” said Lee.

The overall accuracy of detecting the prone position was 96.8%. There were no cases of a supine or prone position being mistaken for each other.

Researchers are refining the algorithm to improve the accuracy for detecting the prone position and expect to have a completely functional prototype within a few years.

Big Step Forward

Commenting on the research, Daniel M. Goldenholz, MD, PhD, assistant professor, Division of Epilepsy, Harvard Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said the study “is a big step forward in the race to provide an actionable tool to prevent SUDEP.”

The technology “appears to mostly be doing what it’s intended to do, with relatively minor technical errors being made,” he said.

However, it is not clear if this technology can truly save lives, said Goldenholz. “The data we have suggests that lying face down in bed after a seizure is correlated with SUDEP, but that does not mean that if we can simply flip people over, they for sure won’t die.”

Even if the new technology “works perfectly,” it’s still an open question, said Goldenholz. If it does save lives, “this will be a major breakthrough, and one that has been needed for a long time.”

However, even if it does not, he congratulates the team for trying to determine if reducing the prone position can help prevent SUDEP. He would like to see more “high-risk, high-reward” studies in the epilepsy field. “We are in so much need of new innovations.”

He said he was “personally very inspired” by this work. “People are dying from this terrible disease, and this team is building what they hope might save lives.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The mattress is being developed by Soterya. Lee reported no equity in Soterya. Goldenholz reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES — says one of the experts involved in its development.

When used along with a seizure detection device, Jong Woo Lee, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology, Harvard Medical School, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts, estimates the smart mattress could cut SUDEP by more than 50%.

In addition, early results from an observational study are backing this up, he said.

The findings were presented at the American Epilepsy Society (AES) 78th Annual Meeting 2024.

Most SUDEP Cases Found Face Down

SUDEP is the leading cause of death in children with epilepsy and in otherwise healthy adult patients with epilepsy. When his fifth patient died of SUDEP, Lee decided it was time to try to tackle the high mortality rate associated with these unexpected deaths. “I desperately wanted to help, ” he said.

About 70% of SUDEP occurs during sleep, and victims are found face down, or in the prone position, 90% of the time, said Lee.

“Of course, the best way to prevent SUDEP is not to have a seizure, but once you have a seizure and once you’re face down, your risk for death goes up by somewhere between 30 and 100 times,” he explained.

Lee was convinced SUDEP could be prevented by simple interventions that stimulate the patient and turn them over. He noted the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome, “which has similar characteristics” to SUDEP, has been reduced by up to 75% through campaigns that simply advise placing babies on their backs.

“Most of SUDEP happens because your arousal system is knocked out and you just don’t take the breath that you’re supposed to. Just the act of turning people over and vibrating the bed will stimulate them,” he said.

However, it’s crucial that this be done quickly, said Lee. “When you look at patients who died on video and see the EEGs, everybody took their last breath within 3 minutes.”

Because the window of opportunity is so short, “we think that seizure detection devices alone are not going to really be effective because you just can’t get there or react within those 3 minutes.”

There are currently no products that detect the prone position or have the ability to reposition a patient quickly into the recovery sideways position.

Lee and his colleagues developed a smart system that can be embedded in a mattress that detects when someone is having a seizure, determines if that person is face down, and if so, safely stimulates and repositions them.

The mattress is made up of a series of programmable inflatable blocks or “cells” that have pressure, vibration, temperature, and humidity sensors embedded within. “Based on the pressure readings, we can figure out whether the patient is right side up, on their right side, on their left side, or face down,” said Lee.

If the person is face down, he or she can be repositioned within a matter of seconds. “Each of the cells can lift 1000 pounds,” he said. The mattress is “very comfortable,” said Lee, who has tried it out himself.

Eighteen normative control participants have been enrolled for development and training purposes. To date, 10 of these individuals, aged 18-53 years, weighing 100-182 lb, and with a height of 5 ft 2 in to 6 ft 1 in, underwent extensive formal testing on the prototype bed.

Researchers found the mattress responded quickly to different body positions and weights. “We were able to reposition everybody in around 20 seconds,” said Lee.

The overall accuracy of detecting the prone position was 96.8%. There were no cases of a supine or prone position being mistaken for each other.

Researchers are refining the algorithm to improve the accuracy for detecting the prone position and expect to have a completely functional prototype within a few years.

Big Step Forward

Commenting on the research, Daniel M. Goldenholz, MD, PhD, assistant professor, Division of Epilepsy, Harvard Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said the study “is a big step forward in the race to provide an actionable tool to prevent SUDEP.”

The technology “appears to mostly be doing what it’s intended to do, with relatively minor technical errors being made,” he said.

However, it is not clear if this technology can truly save lives, said Goldenholz. “The data we have suggests that lying face down in bed after a seizure is correlated with SUDEP, but that does not mean that if we can simply flip people over, they for sure won’t die.”

Even if the new technology “works perfectly,” it’s still an open question, said Goldenholz. If it does save lives, “this will be a major breakthrough, and one that has been needed for a long time.”

However, even if it does not, he congratulates the team for trying to determine if reducing the prone position can help prevent SUDEP. He would like to see more “high-risk, high-reward” studies in the epilepsy field. “We are in so much need of new innovations.”

He said he was “personally very inspired” by this work. “People are dying from this terrible disease, and this team is building what they hope might save lives.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The mattress is being developed by Soterya. Lee reported no equity in Soterya. Goldenholz reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES — says one of the experts involved in its development.

When used along with a seizure detection device, Jong Woo Lee, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology, Harvard Medical School, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts, estimates the smart mattress could cut SUDEP by more than 50%.

In addition, early results from an observational study are backing this up, he said.

The findings were presented at the American Epilepsy Society (AES) 78th Annual Meeting 2024.

Most SUDEP Cases Found Face Down

SUDEP is the leading cause of death in children with epilepsy and in otherwise healthy adult patients with epilepsy. When his fifth patient died of SUDEP, Lee decided it was time to try to tackle the high mortality rate associated with these unexpected deaths. “I desperately wanted to help, ” he said.

About 70% of SUDEP occurs during sleep, and victims are found face down, or in the prone position, 90% of the time, said Lee.

“Of course, the best way to prevent SUDEP is not to have a seizure, but once you have a seizure and once you’re face down, your risk for death goes up by somewhere between 30 and 100 times,” he explained.

Lee was convinced SUDEP could be prevented by simple interventions that stimulate the patient and turn them over. He noted the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome, “which has similar characteristics” to SUDEP, has been reduced by up to 75% through campaigns that simply advise placing babies on their backs.

“Most of SUDEP happens because your arousal system is knocked out and you just don’t take the breath that you’re supposed to. Just the act of turning people over and vibrating the bed will stimulate them,” he said.

However, it’s crucial that this be done quickly, said Lee. “When you look at patients who died on video and see the EEGs, everybody took their last breath within 3 minutes.”

Because the window of opportunity is so short, “we think that seizure detection devices alone are not going to really be effective because you just can’t get there or react within those 3 minutes.”

There are currently no products that detect the prone position or have the ability to reposition a patient quickly into the recovery sideways position.

Lee and his colleagues developed a smart system that can be embedded in a mattress that detects when someone is having a seizure, determines if that person is face down, and if so, safely stimulates and repositions them.

The mattress is made up of a series of programmable inflatable blocks or “cells” that have pressure, vibration, temperature, and humidity sensors embedded within. “Based on the pressure readings, we can figure out whether the patient is right side up, on their right side, on their left side, or face down,” said Lee.

If the person is face down, he or she can be repositioned within a matter of seconds. “Each of the cells can lift 1000 pounds,” he said. The mattress is “very comfortable,” said Lee, who has tried it out himself.

Eighteen normative control participants have been enrolled for development and training purposes. To date, 10 of these individuals, aged 18-53 years, weighing 100-182 lb, and with a height of 5 ft 2 in to 6 ft 1 in, underwent extensive formal testing on the prototype bed.

Researchers found the mattress responded quickly to different body positions and weights. “We were able to reposition everybody in around 20 seconds,” said Lee.

The overall accuracy of detecting the prone position was 96.8%. There were no cases of a supine or prone position being mistaken for each other.

Researchers are refining the algorithm to improve the accuracy for detecting the prone position and expect to have a completely functional prototype within a few years.

Big Step Forward

Commenting on the research, Daniel M. Goldenholz, MD, PhD, assistant professor, Division of Epilepsy, Harvard Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said the study “is a big step forward in the race to provide an actionable tool to prevent SUDEP.”

The technology “appears to mostly be doing what it’s intended to do, with relatively minor technical errors being made,” he said.

However, it is not clear if this technology can truly save lives, said Goldenholz. “The data we have suggests that lying face down in bed after a seizure is correlated with SUDEP, but that does not mean that if we can simply flip people over, they for sure won’t die.”

Even if the new technology “works perfectly,” it’s still an open question, said Goldenholz. If it does save lives, “this will be a major breakthrough, and one that has been needed for a long time.”

However, even if it does not, he congratulates the team for trying to determine if reducing the prone position can help prevent SUDEP. He would like to see more “high-risk, high-reward” studies in the epilepsy field. “We are in so much need of new innovations.”

He said he was “personally very inspired” by this work. “People are dying from this terrible disease, and this team is building what they hope might save lives.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The mattress is being developed by Soterya. Lee reported no equity in Soterya. Goldenholz reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AES 2024

Sleep Apnea Linked to Heightened Mortality in Epilepsy

LOS ANGELES — according to a new analysis of over 2 million patient-years drawn from the Komodo Health Claims Database.

“A 10-year-old with uncontrolled epilepsy and central sleep apnea is about 200 times more likely to die than a general population 10-year-old. That’s comparable to a 10-year-old with {epilepsy and} congestive heart failure. Noncentral sleep apnea is comparable to being paralyzed. It’s a huge risk factor,” said poster presenter Dan Lloyd, advanced analytics lead at UCB, which sponsored the research.

The ordering of sleep apnea tests for patients with epilepsy is widely variable, according to Stefanie Dedeurwaerdere, PhD, who is the innovation and value creation lead at UCB. “Some doctors do that as a general practice, and some don’t. There’s no coherency in the way these studies are requested for epilepsy patients. We want to create some awareness around this topic,” she said, and added that treatment of sleep apnea may improve epileptic seizures.

The findings were presented at the American Epilepsy Society (AES) 78th Annual Meeting 2024.

The study included mortality rates between January 2018 and December 2022, with a total of 2,355,410 patient-years and 968,993 patients, with an age distribution of 19.1% age 1 to less than 18 years, 23.7% age 18-35 years, and 57.2% age 36 years or older. Sleep apnea prevalences were 0.7% for central sleep apnea (CSA), 14.0% for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and 85.3% with no sleep apnea.

Among those aged 1-18 years, the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for those with uncontrolled epilepsy was 27.7. For those with comorbid OSA, the SMR was 74.2, and for comorbid CSA, the SMR was 135.9. The association was less pronounced in older groups, dipping to 7.0, 11.3, and 19.5 in those aged 18-35 years, and 3.3, 3.1, and 2.8 among those aged 36 years or older.

Among the 1-18 age group, SMRs for other comorbidities included 132.3 for heart failure, 74.9 for hemiplegia/paraplegia, 55.3 for cerebrovascular disease, and 44.6 for chronic pulmonary disease.

Asked for comment, Gordon Buchanan, MD, PhD, welcomed the new work. “The results did not surprise me. I study sleep, epilepsy, and [sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP)] in particular ... and every time I speak on these topics, someone asks me about risk of SUDEP in patients with sleep apnea. It’s great to finally have some data,” said Buchanan, a professor of neurology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The authors found that patients undergoing continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)/bi-level positive airway pressure therapy had a higher mortality risk than those not undergoing CPAP therapy but cautioned that uncontrolled confounders may be contributing to the effect.

Buchanan wondered if treatment with CPAP would be associated with a decreased mortality risk. “I think that would be interesting, but I know that, especially in children, it can be difficult to get them to remain compliant with CPAP. I think that would be interesting to know, if pushing harder to get the kids to comply with CPAP would reduce mortality,” he said.

The specific finding of heightened mortality associated with CSA is interesting, according to Buchanan. “We think of seizures propagating through the brain, maybe through direct synaptic connections or through spreading depolarization. So I think it would make sense that it would hit central regions that would then lead to sleep apnea.”

The relationship between OSA and epilepsy is likely complex. Epilepsy medications and special diets may influence body composition, which could in turn affect the risk for OSA, as could medications associated with psychiatric comorbidities, according to Buchanan.

The study is retrospective and based on claims data. It does not prove causation, and claims data do not fully capture mortality, which may lead to conservative SMR estimates. The researchers did not control for socioeconomic status, treatment status, and other comorbidities or conditions.

Lloyd and Dedeurwaerdere are employees of UCB, which sponsored the study. Buchanan had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES — according to a new analysis of over 2 million patient-years drawn from the Komodo Health Claims Database.

“A 10-year-old with uncontrolled epilepsy and central sleep apnea is about 200 times more likely to die than a general population 10-year-old. That’s comparable to a 10-year-old with {epilepsy and} congestive heart failure. Noncentral sleep apnea is comparable to being paralyzed. It’s a huge risk factor,” said poster presenter Dan Lloyd, advanced analytics lead at UCB, which sponsored the research.

The ordering of sleep apnea tests for patients with epilepsy is widely variable, according to Stefanie Dedeurwaerdere, PhD, who is the innovation and value creation lead at UCB. “Some doctors do that as a general practice, and some don’t. There’s no coherency in the way these studies are requested for epilepsy patients. We want to create some awareness around this topic,” she said, and added that treatment of sleep apnea may improve epileptic seizures.

The findings were presented at the American Epilepsy Society (AES) 78th Annual Meeting 2024.

The study included mortality rates between January 2018 and December 2022, with a total of 2,355,410 patient-years and 968,993 patients, with an age distribution of 19.1% age 1 to less than 18 years, 23.7% age 18-35 years, and 57.2% age 36 years or older. Sleep apnea prevalences were 0.7% for central sleep apnea (CSA), 14.0% for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and 85.3% with no sleep apnea.

Among those aged 1-18 years, the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for those with uncontrolled epilepsy was 27.7. For those with comorbid OSA, the SMR was 74.2, and for comorbid CSA, the SMR was 135.9. The association was less pronounced in older groups, dipping to 7.0, 11.3, and 19.5 in those aged 18-35 years, and 3.3, 3.1, and 2.8 among those aged 36 years or older.

Among the 1-18 age group, SMRs for other comorbidities included 132.3 for heart failure, 74.9 for hemiplegia/paraplegia, 55.3 for cerebrovascular disease, and 44.6 for chronic pulmonary disease.

Asked for comment, Gordon Buchanan, MD, PhD, welcomed the new work. “The results did not surprise me. I study sleep, epilepsy, and [sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP)] in particular ... and every time I speak on these topics, someone asks me about risk of SUDEP in patients with sleep apnea. It’s great to finally have some data,” said Buchanan, a professor of neurology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The authors found that patients undergoing continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)/bi-level positive airway pressure therapy had a higher mortality risk than those not undergoing CPAP therapy but cautioned that uncontrolled confounders may be contributing to the effect.

Buchanan wondered if treatment with CPAP would be associated with a decreased mortality risk. “I think that would be interesting, but I know that, especially in children, it can be difficult to get them to remain compliant with CPAP. I think that would be interesting to know, if pushing harder to get the kids to comply with CPAP would reduce mortality,” he said.

The specific finding of heightened mortality associated with CSA is interesting, according to Buchanan. “We think of seizures propagating through the brain, maybe through direct synaptic connections or through spreading depolarization. So I think it would make sense that it would hit central regions that would then lead to sleep apnea.”

The relationship between OSA and epilepsy is likely complex. Epilepsy medications and special diets may influence body composition, which could in turn affect the risk for OSA, as could medications associated with psychiatric comorbidities, according to Buchanan.

The study is retrospective and based on claims data. It does not prove causation, and claims data do not fully capture mortality, which may lead to conservative SMR estimates. The researchers did not control for socioeconomic status, treatment status, and other comorbidities or conditions.

Lloyd and Dedeurwaerdere are employees of UCB, which sponsored the study. Buchanan had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES — according to a new analysis of over 2 million patient-years drawn from the Komodo Health Claims Database.

“A 10-year-old with uncontrolled epilepsy and central sleep apnea is about 200 times more likely to die than a general population 10-year-old. That’s comparable to a 10-year-old with {epilepsy and} congestive heart failure. Noncentral sleep apnea is comparable to being paralyzed. It’s a huge risk factor,” said poster presenter Dan Lloyd, advanced analytics lead at UCB, which sponsored the research.

The ordering of sleep apnea tests for patients with epilepsy is widely variable, according to Stefanie Dedeurwaerdere, PhD, who is the innovation and value creation lead at UCB. “Some doctors do that as a general practice, and some don’t. There’s no coherency in the way these studies are requested for epilepsy patients. We want to create some awareness around this topic,” she said, and added that treatment of sleep apnea may improve epileptic seizures.

The findings were presented at the American Epilepsy Society (AES) 78th Annual Meeting 2024.

The study included mortality rates between January 2018 and December 2022, with a total of 2,355,410 patient-years and 968,993 patients, with an age distribution of 19.1% age 1 to less than 18 years, 23.7% age 18-35 years, and 57.2% age 36 years or older. Sleep apnea prevalences were 0.7% for central sleep apnea (CSA), 14.0% for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and 85.3% with no sleep apnea.

Among those aged 1-18 years, the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for those with uncontrolled epilepsy was 27.7. For those with comorbid OSA, the SMR was 74.2, and for comorbid CSA, the SMR was 135.9. The association was less pronounced in older groups, dipping to 7.0, 11.3, and 19.5 in those aged 18-35 years, and 3.3, 3.1, and 2.8 among those aged 36 years or older.

Among the 1-18 age group, SMRs for other comorbidities included 132.3 for heart failure, 74.9 for hemiplegia/paraplegia, 55.3 for cerebrovascular disease, and 44.6 for chronic pulmonary disease.

Asked for comment, Gordon Buchanan, MD, PhD, welcomed the new work. “The results did not surprise me. I study sleep, epilepsy, and [sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP)] in particular ... and every time I speak on these topics, someone asks me about risk of SUDEP in patients with sleep apnea. It’s great to finally have some data,” said Buchanan, a professor of neurology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The authors found that patients undergoing continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)/bi-level positive airway pressure therapy had a higher mortality risk than those not undergoing CPAP therapy but cautioned that uncontrolled confounders may be contributing to the effect.

Buchanan wondered if treatment with CPAP would be associated with a decreased mortality risk. “I think that would be interesting, but I know that, especially in children, it can be difficult to get them to remain compliant with CPAP. I think that would be interesting to know, if pushing harder to get the kids to comply with CPAP would reduce mortality,” he said.

The specific finding of heightened mortality associated with CSA is interesting, according to Buchanan. “We think of seizures propagating through the brain, maybe through direct synaptic connections or through spreading depolarization. So I think it would make sense that it would hit central regions that would then lead to sleep apnea.”

The relationship between OSA and epilepsy is likely complex. Epilepsy medications and special diets may influence body composition, which could in turn affect the risk for OSA, as could medications associated with psychiatric comorbidities, according to Buchanan.

The study is retrospective and based on claims data. It does not prove causation, and claims data do not fully capture mortality, which may lead to conservative SMR estimates. The researchers did not control for socioeconomic status, treatment status, and other comorbidities or conditions.

Lloyd and Dedeurwaerdere are employees of UCB, which sponsored the study. Buchanan had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AES 2024

Agranulocytosis and Aseptic Meningitis Induced by Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim

Agranulocytosis and Aseptic Meningitis Induced by Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim

Acute agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis are serious adverse effects (AEs) associated with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Acute agranulocytosis is a rare, potentially life-threatening blood dyscrasia characterized by a neutrophil count of < 500 cells per μL, with no relevant decrease in hemoglobin or platelet levels.1 Patients with agranulocytosis may be asymptomatic or experience severe sore throat, pharyngitis, or tonsillitis in combination with high fever, rigors, headaches, or malaise. These AEs are commonly classified as idiosyncratic and, in most cases, attributable to medications. If drug-induced agranulocytosis is suspected, the patient should discontinue the medication immediately.1

Meningitis is an inflammatory disease typically caused by viral or bacterial infections; however, it may also be attributed to medications or malignancy. Inflammation of the meninges with a negative bacterial cerebrospinal fluid culture is classified as aseptic meningitis. Distinguishing between aseptic and bacterial meningitis is crucial due to differences in illness severity, treatment options, and prognosis.2 Symptoms of meningitis may include fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, nausea, or vomiting.3 Several classes of medications can cause drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM), but the most commonly reported antibiotic is sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

DIAM is more prevalent in immunocompromised patients, such as those with a history of HIV/AIDS, organ transplant, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy, who may be prescribed sulfamethoxazoletrimethoprim for prophylaxis or treatment of infection.2 The case described in this article serves as a distinctive example of acute agranulocytosis complicated with aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim in an immunocompetent patient.

Case Presentation

A healthy male veteran aged 39 years presented to the Fargo Veterans Affairs Medical Center emergency department (ED) for worsening left testicular pain and increased urinary urgency and frequency for about 48 hours. The patient had no known medication allergies, was current on vaccinations, and his only relevant prescription was valacyclovir for herpes labialis. The evaluation included urinalysis, blood tests, and scrotal ultrasound. The urinalysis, blood tests, and vitals were unremarkable for any signs of systemic infection. The scrotal ultrasound was significant for left focal area of abnormal echogenicity with absent blood flow in the superior left testicle and a significant increase in blood flow around the left epididymis. Mild swelling in the left epididymis was present, with no significant testicular or scrotal swelling or skin changes observed. Urology was consulted and prescribed oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 800-160 mg every 12 hours for 30 days for the treatment of left epididymo-orchitis.

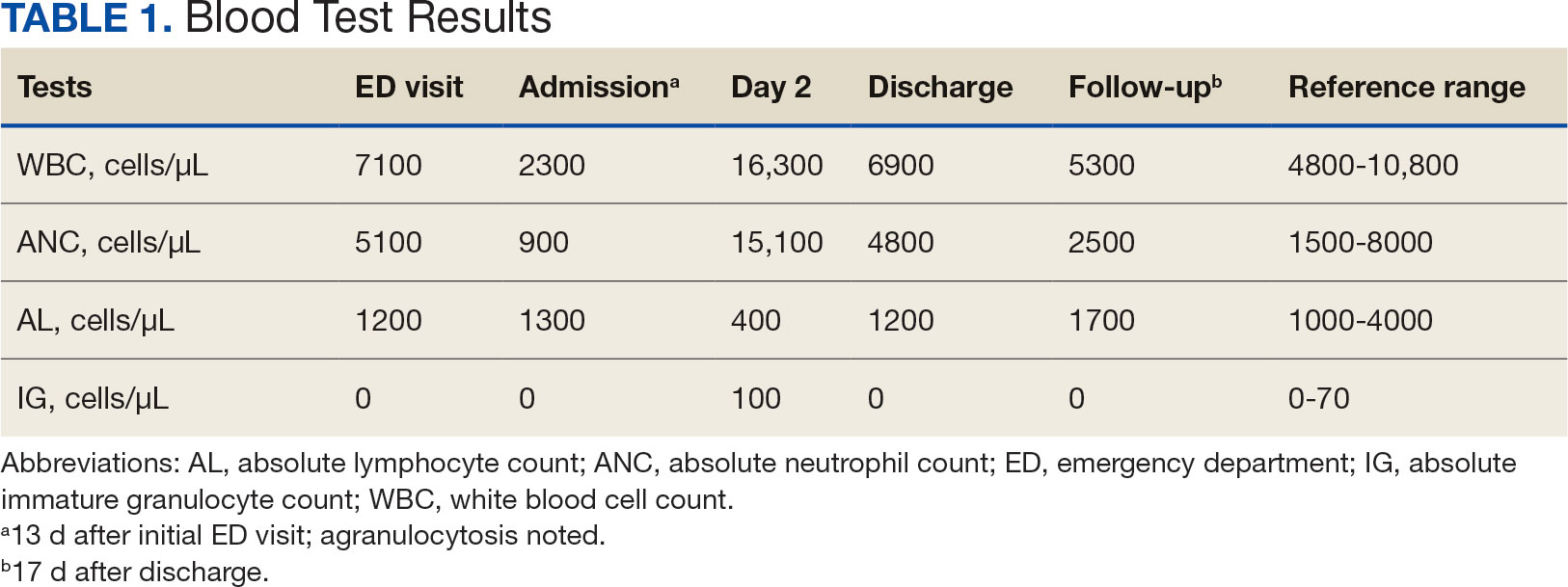

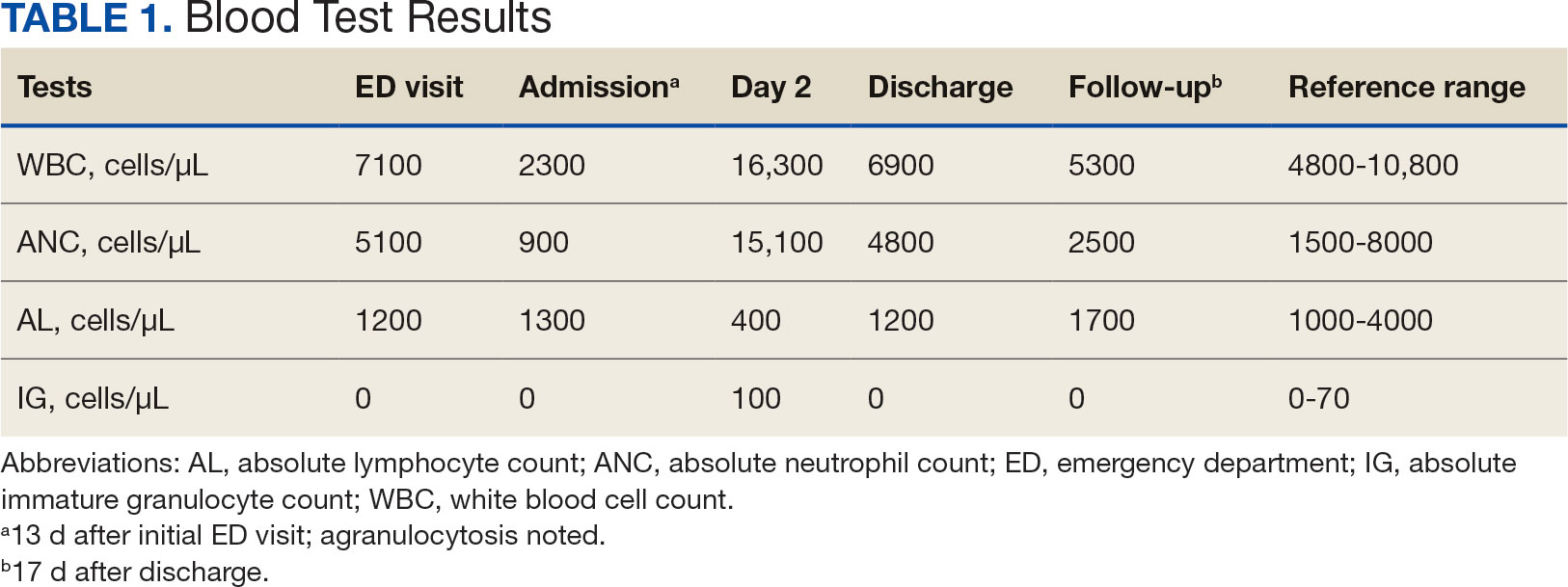

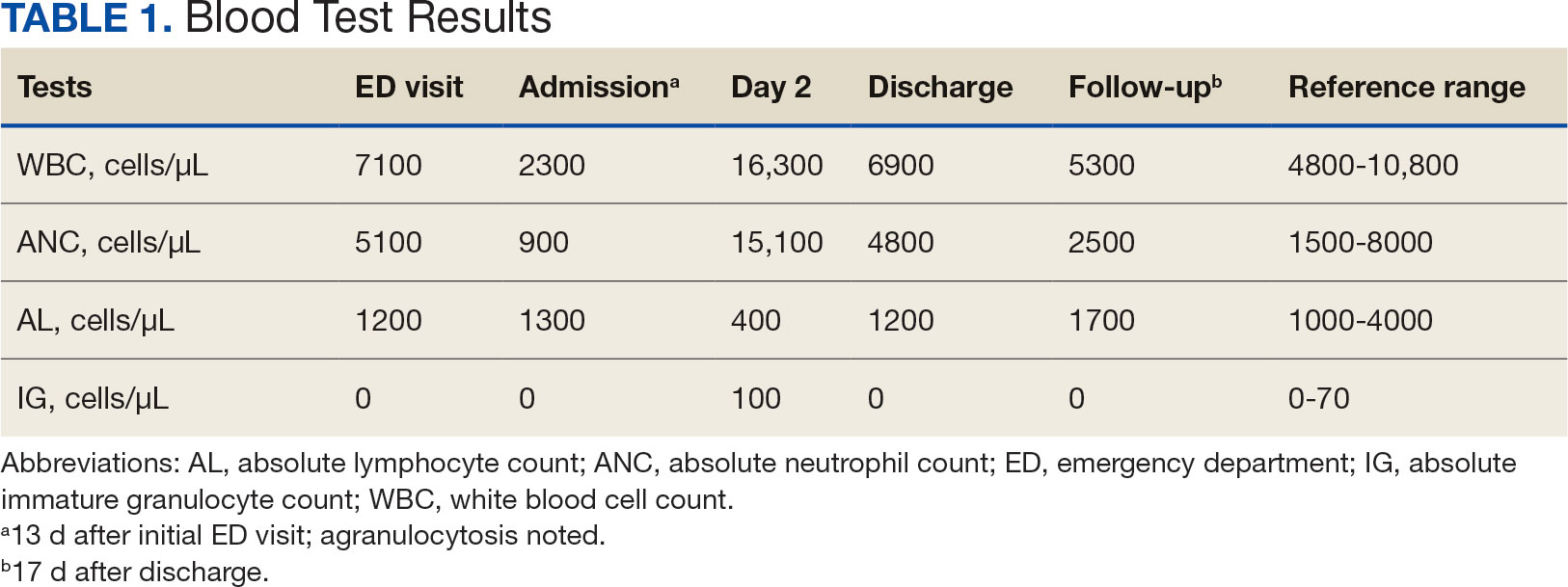

The patient returned to the ED 2 weeks later with fever, chills, headache, generalized body aches, urinary retention, loose stools, and nonspecific chest pressure. A serum blood test revealed significant neutropenia and leukopenia. The patient was admitted for observation, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was discontinued. The patient received sodium chloride intravenous (IV) fluid, oral potassium chloride supplementation, IV ondansetron, and analgesics, including oral acetaminophen, oral ibuprofen, and IV hydromorphone as needed. Repeated laboratory tests were completed with no specific findings; serum laboratory work, urinalysis, chest and abdominal X-rays, and echocardiogram were all unremarkable. The patient’s neutrophil count dropped from 5100 cells/µL at the initial ED presentation to 900 cells/µL (reference range, 1500-8000 cells/µL) (Table 1). Agranulocytosis quickly resolved after antibiotic discontinuation.

Upon further investigation, the patient took the prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for 10 days before stopping due to the resolution of testicular pain and epididymal swelling. The patient reported initial AEs of loose stools and generalized myalgias when first taking the medication. The patient restarted the antibiotic to complete the course of therapy after not taking it for 2 days. Within 20 minutes of restarting the medication, he experienced myalgias with pruritus, prompting him to return to the ED. Agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis developed within 12 days after he was prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, though the exact timeframe is unknown.

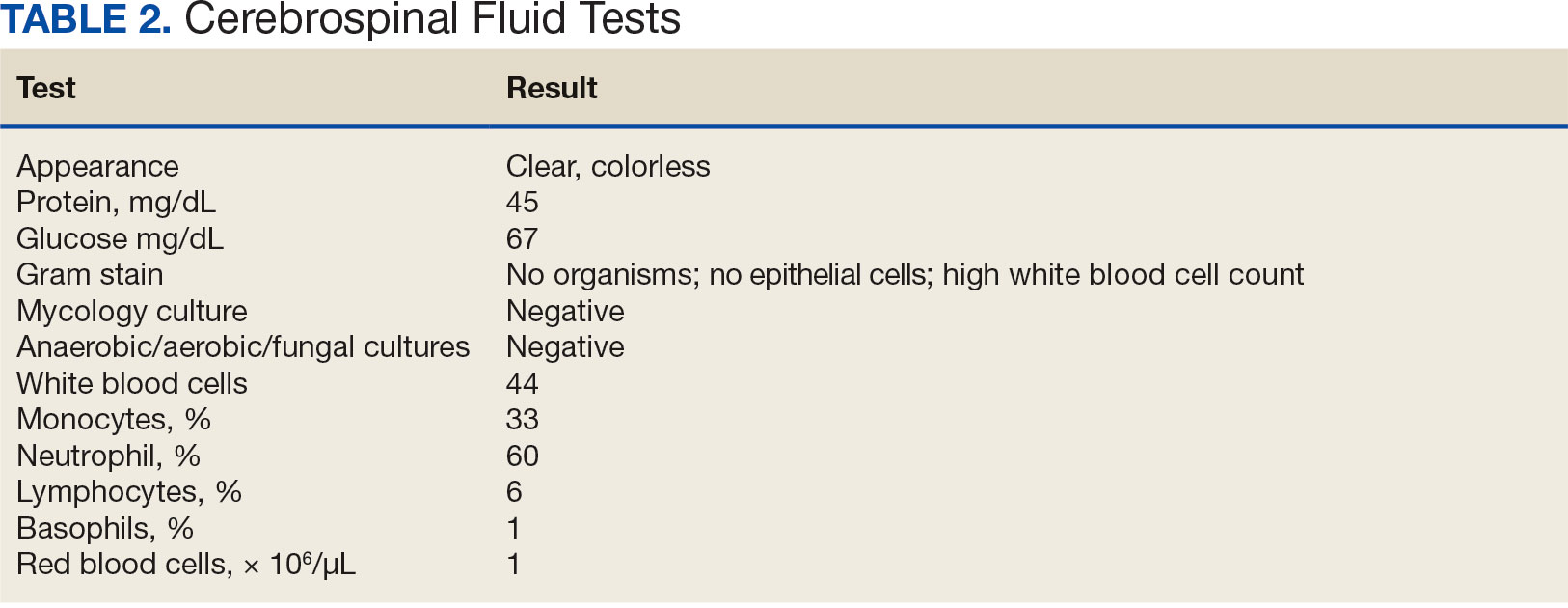

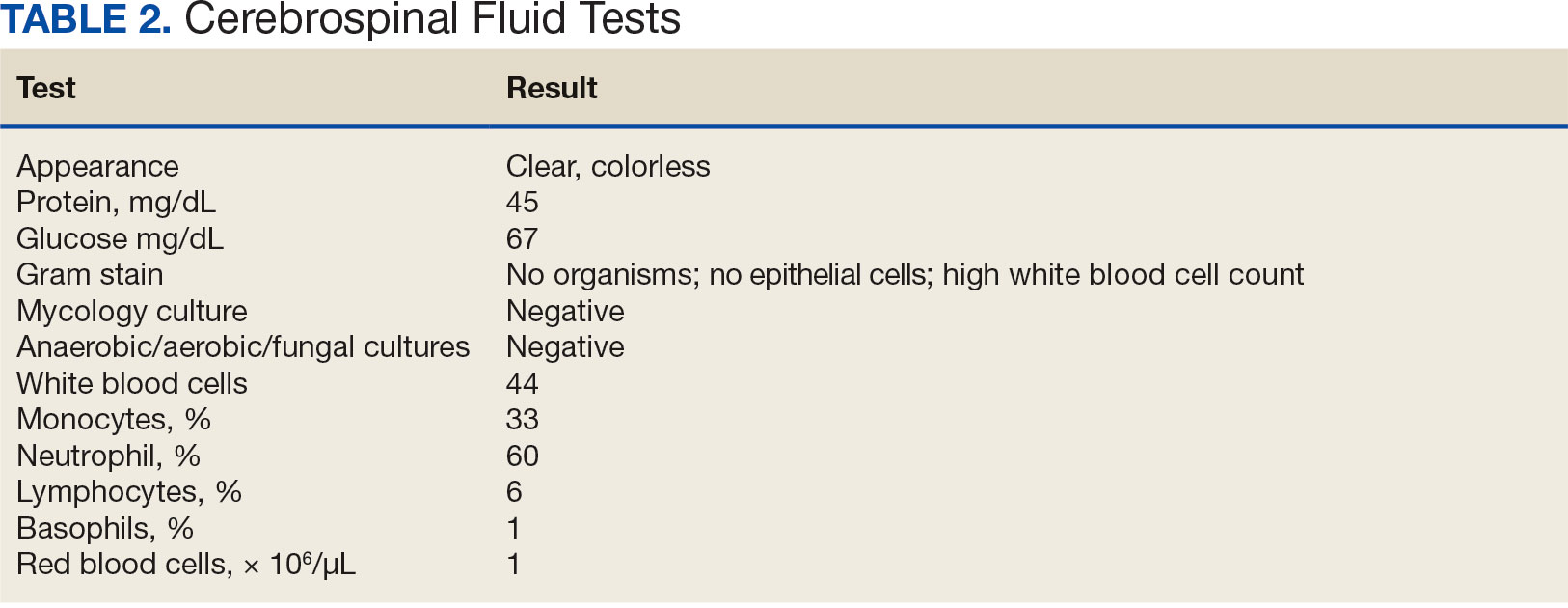

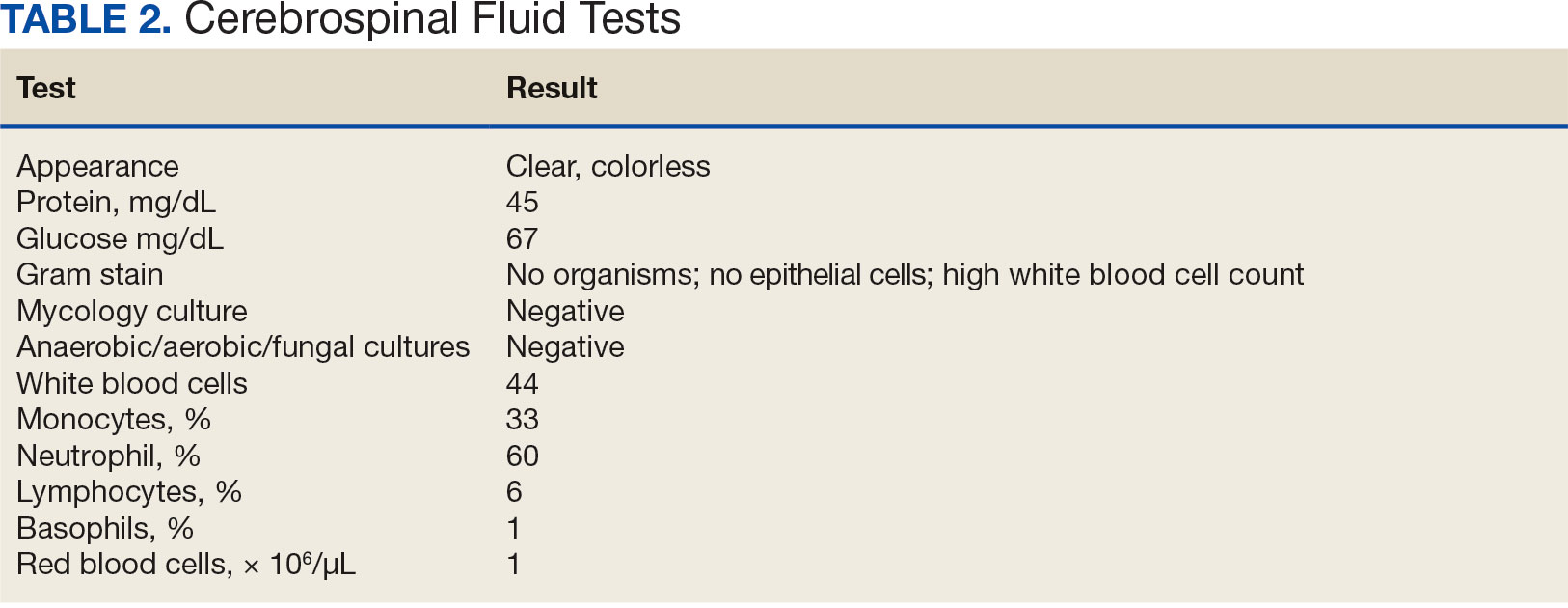

The patient’s symptoms, except for a persistent headache, resolved during hospitalization. Infectious disease was consulted, and a lumbar puncture was performed due to prior fever and ongoing headaches to rule out a treatable cause of meningitis. The lumbar puncture showed clear spinal fluid, an elevated white blood cell count with neutrophil predominance, and normal protein and glucose levels. Cultures showed no aerobic, anaerobic, or fungal organisms. Herpes virus simplex and Lyme disease testing was not completed during hospitalization. Respiratory panel, legionella, and hepatitis A, B, and C tests were negative (Table 2). The negative laboratory test results strengthened the suspicion of aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The neurology consult recommended no additional treatments or tests.

The patient spontaneously recovered 2 days later, with a normalized complete blood count and resolution of headache. Repeat scrotal ultrasounds showed resolution of the left testicle findings. The patient was discharged and seen for a follow-up 14 days later. The final diagnosis requiring hospitalization was aseptic meningitis secondary to a sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

Discussion

Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is a commonly prescribed antibiotic for urinary tract infections, pneumocystis pneumonia, pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Empiric antibiotics for epididymo-orchitis caused by enteric organisms include levofloxacin or ofloxacin; however sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim may be considered as alternative.5,6 Agranulocytosis induced by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim may occur due to the inhibition on folic acid metabolism, which makes the highly proliferating cells of the hematopoietic system more susceptible to neutropenia. Agranulocytosis typically occurs within 7 days of treatment initiation and generally resolves within a month after discontinuation of the offending agent.7 In this case, agranulocytosis resolved overnight, resulting in leukocytosis. One explanation for the rapid increase in white blood cell count may be the concurrent diagnosis of aseptic meningitis. Alternatively, the patient’s health and immunocompetence may have helped generate an adequate immune response. Medication-induced agranulocytosis is often a diagnosis of exclusion because it is typically difficult to diagnose.7 In more severe or complicated cases of agranulocytosis, filgrastim may be indicated.1

Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is a lipophilic small-molecule medication that can cross the blood-brain barrier and penetrate the tissues of the bone, prostate, and central nervous system.8 Specifically, the medication can pass into the cerebrospinal fluid regardless of meningeal inflammation.9 The exact mechanism for aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is unknown; however, it may accumulate in the choroid plexus, causing destructive inflammation of small blood vessels and resulting in aseptic meningitis.10 The onset of aseptic meningitis can vary from 10 minutes to 10 days after initiation of the medication. Pre-exposure to the medication typically results in earlier onset of symptoms, though patients do not need to have previously taken the medication to develop aseptic meningitis. Patients generally become afebrile with resolution of headache and mental status changes within 48 to 72 hours after stopping the medication or after about 5 to 7 half-lives of the medication are eliminated.11 Some patients may continue to experience worsening symptoms after discontinuation because the medication is already absorbed into the serum and tissues.

DIAM is an uncommon drug-induced hypersensitivity AE of the central nervous system. Diagnosing aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim can be challenging, as antibiotics are given to treat suspected infections, and the symptoms of aseptic meningitis can be hard to differentiate from those of infectious meningitis.11 Close monitoring between the initiation of the medication and the onset of clinical symptoms is necessary to assist in distinguishing between aseptic and infectious meningitis.3 If the causative agent is not discontinued, symptoms can quickly worsen, progressing from fever and headache to confusion, coma, and respiratory depression. A DIAM diagnosis can only be made with resolution of aseptic meningitis after stopping the contributory agent. If appropriate, this can be proven by rechallenging the medication in a controlled setting. The usual treatment for aseptic meningitis is supportive care, including hydration, antiemetics, electrolyte supplementation, and adequate analgesia.3

Differential diagnoses in this case included viral infection, meningitis, and allergic reaction to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The patient reported history of experiencing symptoms after restarting his antibiotic, raising strong suspicion for DIAM. Initiation of this antibiotic was the only recent medication change noted. Laboratory testing for infectious agents yielded negative results, including tests for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria as well as viral and fungal infections. A lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid culture was clear, with no organisms shown on gram stain. Bacterial or viral meningitis was presumed less likely due to the duration of symptoms, correlation of symptoms coinciding with restarting the antibiotic, and negative cerebrospinal fluid culture results.

It was concluded that agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis were likely induced by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim as supported by the improvement upon discontinuing the medication and subsequent worsening upon restarting it. Concurrent agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis is rare, and there is typically no correlation between the 2 reactions. Since agranulocytosis may be asymptomatic, this case highlights the need to monitor blood cell counts in patients using sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The possibility of DIAM should be considered in patients presenting with flu-like symptoms, and a lumbar puncture may be collected to rule out aseptic meningitis if the patient’s AEs are severe following the initiation of an antibiotic, particularly in immunosuppressed patients taking sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. This case is unusual because the patient was healthy and immunocompetent.

This case may not be generalizable and may be difficult to compare to other cases. Every case has patient-specific factors affecting subjective information, including the patient’s baseline, severity of symptoms, and treatment options. This report was based on a single patient case and corresponding results may be found in similar patient cases.

Conclusions

This case emphasizes the rare but serious AEs of acute agranulocytosis complicated with aseptic meningitis after prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. This is a unique case of an immunocompetent patient developing both agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis after restarting the antibiotic to complete therapy. This case highlights the importance of monitoring blood cell counts and monitoring for signs and symptoms of aseptic meningitis, even during short courses of therapy. Further research is needed to recognize characteristics that may increase the risk for these AEs and to develop strategies for their prevention.

- Garbe E. Non-chemotherapy drug-induced agranulocytosis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6(3):323-335. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.3.323

- Jha P, Stromich J, Cohen M, Wainaina JN. A rare complication of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole: drug induced aseptic meningitis. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:3879406. doi:10.1155/2016/3879406

- Hopkins S, Jolles S. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4(2):285-297. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.2.285

- Jarrin I, Sellier P, Lopes A, et al. Etiologies and management of aseptic meningitis in patients admitted to an internal medicine department. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(2):e2372. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002372

- Street EJ, Justice ED, Kopa Z, et al. The 2016 European guideline on the management of epididymo-orchitis. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(8):744-749. doi:10.1177/0956462417699356

- Kbirou A, Alafifi M, Sayah M, Dakir M, Debbagh A, Aboutaieb R. Acute orchiepididymitis: epidemiological and clinical aspects: an analysis of 152 cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;75:103335. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103335

- Rattay B, Benndorf RA. Drug-induced idiosyncratic agranulocytosis - infrequent but dangerous. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:727717. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.727717

- Elmedani S, Albayati A, Udongwo N, Odak M, Khawaja S. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced aseptic meningitis: a new approach. Cureus. 2021;13(6):e15869. doi:10.7759/cureus.15869

- Nau R, Sörgel F, Eiffert H. Penetration of drugs through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid/blood-brain barrier for treatment of central nervous system infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(4):858-883. doi:10.1128/CMR.00007-10

- Moris G, Garcia-Monco JC. The challenge of drug-induced aseptic meningitis. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(11):1185- 1194. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.11.1185

- Bruner KE, Coop CA, White KM. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced aseptic meningitis-not just another sulfa allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(5):520-526. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2014.08.006

Acute agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis are serious adverse effects (AEs) associated with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Acute agranulocytosis is a rare, potentially life-threatening blood dyscrasia characterized by a neutrophil count of < 500 cells per μL, with no relevant decrease in hemoglobin or platelet levels.1 Patients with agranulocytosis may be asymptomatic or experience severe sore throat, pharyngitis, or tonsillitis in combination with high fever, rigors, headaches, or malaise. These AEs are commonly classified as idiosyncratic and, in most cases, attributable to medications. If drug-induced agranulocytosis is suspected, the patient should discontinue the medication immediately.1

Meningitis is an inflammatory disease typically caused by viral or bacterial infections; however, it may also be attributed to medications or malignancy. Inflammation of the meninges with a negative bacterial cerebrospinal fluid culture is classified as aseptic meningitis. Distinguishing between aseptic and bacterial meningitis is crucial due to differences in illness severity, treatment options, and prognosis.2 Symptoms of meningitis may include fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, nausea, or vomiting.3 Several classes of medications can cause drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM), but the most commonly reported antibiotic is sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

DIAM is more prevalent in immunocompromised patients, such as those with a history of HIV/AIDS, organ transplant, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy, who may be prescribed sulfamethoxazoletrimethoprim for prophylaxis or treatment of infection.2 The case described in this article serves as a distinctive example of acute agranulocytosis complicated with aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim in an immunocompetent patient.

Case Presentation

A healthy male veteran aged 39 years presented to the Fargo Veterans Affairs Medical Center emergency department (ED) for worsening left testicular pain and increased urinary urgency and frequency for about 48 hours. The patient had no known medication allergies, was current on vaccinations, and his only relevant prescription was valacyclovir for herpes labialis. The evaluation included urinalysis, blood tests, and scrotal ultrasound. The urinalysis, blood tests, and vitals were unremarkable for any signs of systemic infection. The scrotal ultrasound was significant for left focal area of abnormal echogenicity with absent blood flow in the superior left testicle and a significant increase in blood flow around the left epididymis. Mild swelling in the left epididymis was present, with no significant testicular or scrotal swelling or skin changes observed. Urology was consulted and prescribed oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 800-160 mg every 12 hours for 30 days for the treatment of left epididymo-orchitis.

The patient returned to the ED 2 weeks later with fever, chills, headache, generalized body aches, urinary retention, loose stools, and nonspecific chest pressure. A serum blood test revealed significant neutropenia and leukopenia. The patient was admitted for observation, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was discontinued. The patient received sodium chloride intravenous (IV) fluid, oral potassium chloride supplementation, IV ondansetron, and analgesics, including oral acetaminophen, oral ibuprofen, and IV hydromorphone as needed. Repeated laboratory tests were completed with no specific findings; serum laboratory work, urinalysis, chest and abdominal X-rays, and echocardiogram were all unremarkable. The patient’s neutrophil count dropped from 5100 cells/µL at the initial ED presentation to 900 cells/µL (reference range, 1500-8000 cells/µL) (Table 1). Agranulocytosis quickly resolved after antibiotic discontinuation.

Upon further investigation, the patient took the prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for 10 days before stopping due to the resolution of testicular pain and epididymal swelling. The patient reported initial AEs of loose stools and generalized myalgias when first taking the medication. The patient restarted the antibiotic to complete the course of therapy after not taking it for 2 days. Within 20 minutes of restarting the medication, he experienced myalgias with pruritus, prompting him to return to the ED. Agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis developed within 12 days after he was prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, though the exact timeframe is unknown.

The patient’s symptoms, except for a persistent headache, resolved during hospitalization. Infectious disease was consulted, and a lumbar puncture was performed due to prior fever and ongoing headaches to rule out a treatable cause of meningitis. The lumbar puncture showed clear spinal fluid, an elevated white blood cell count with neutrophil predominance, and normal protein and glucose levels. Cultures showed no aerobic, anaerobic, or fungal organisms. Herpes virus simplex and Lyme disease testing was not completed during hospitalization. Respiratory panel, legionella, and hepatitis A, B, and C tests were negative (Table 2). The negative laboratory test results strengthened the suspicion of aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The neurology consult recommended no additional treatments or tests.

The patient spontaneously recovered 2 days later, with a normalized complete blood count and resolution of headache. Repeat scrotal ultrasounds showed resolution of the left testicle findings. The patient was discharged and seen for a follow-up 14 days later. The final diagnosis requiring hospitalization was aseptic meningitis secondary to a sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

Discussion

Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is a commonly prescribed antibiotic for urinary tract infections, pneumocystis pneumonia, pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Empiric antibiotics for epididymo-orchitis caused by enteric organisms include levofloxacin or ofloxacin; however sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim may be considered as alternative.5,6 Agranulocytosis induced by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim may occur due to the inhibition on folic acid metabolism, which makes the highly proliferating cells of the hematopoietic system more susceptible to neutropenia. Agranulocytosis typically occurs within 7 days of treatment initiation and generally resolves within a month after discontinuation of the offending agent.7 In this case, agranulocytosis resolved overnight, resulting in leukocytosis. One explanation for the rapid increase in white blood cell count may be the concurrent diagnosis of aseptic meningitis. Alternatively, the patient’s health and immunocompetence may have helped generate an adequate immune response. Medication-induced agranulocytosis is often a diagnosis of exclusion because it is typically difficult to diagnose.7 In more severe or complicated cases of agranulocytosis, filgrastim may be indicated.1

Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is a lipophilic small-molecule medication that can cross the blood-brain barrier and penetrate the tissues of the bone, prostate, and central nervous system.8 Specifically, the medication can pass into the cerebrospinal fluid regardless of meningeal inflammation.9 The exact mechanism for aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is unknown; however, it may accumulate in the choroid plexus, causing destructive inflammation of small blood vessels and resulting in aseptic meningitis.10 The onset of aseptic meningitis can vary from 10 minutes to 10 days after initiation of the medication. Pre-exposure to the medication typically results in earlier onset of symptoms, though patients do not need to have previously taken the medication to develop aseptic meningitis. Patients generally become afebrile with resolution of headache and mental status changes within 48 to 72 hours after stopping the medication or after about 5 to 7 half-lives of the medication are eliminated.11 Some patients may continue to experience worsening symptoms after discontinuation because the medication is already absorbed into the serum and tissues.

DIAM is an uncommon drug-induced hypersensitivity AE of the central nervous system. Diagnosing aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim can be challenging, as antibiotics are given to treat suspected infections, and the symptoms of aseptic meningitis can be hard to differentiate from those of infectious meningitis.11 Close monitoring between the initiation of the medication and the onset of clinical symptoms is necessary to assist in distinguishing between aseptic and infectious meningitis.3 If the causative agent is not discontinued, symptoms can quickly worsen, progressing from fever and headache to confusion, coma, and respiratory depression. A DIAM diagnosis can only be made with resolution of aseptic meningitis after stopping the contributory agent. If appropriate, this can be proven by rechallenging the medication in a controlled setting. The usual treatment for aseptic meningitis is supportive care, including hydration, antiemetics, electrolyte supplementation, and adequate analgesia.3

Differential diagnoses in this case included viral infection, meningitis, and allergic reaction to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The patient reported history of experiencing symptoms after restarting his antibiotic, raising strong suspicion for DIAM. Initiation of this antibiotic was the only recent medication change noted. Laboratory testing for infectious agents yielded negative results, including tests for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria as well as viral and fungal infections. A lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid culture was clear, with no organisms shown on gram stain. Bacterial or viral meningitis was presumed less likely due to the duration of symptoms, correlation of symptoms coinciding with restarting the antibiotic, and negative cerebrospinal fluid culture results.

It was concluded that agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis were likely induced by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim as supported by the improvement upon discontinuing the medication and subsequent worsening upon restarting it. Concurrent agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis is rare, and there is typically no correlation between the 2 reactions. Since agranulocytosis may be asymptomatic, this case highlights the need to monitor blood cell counts in patients using sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The possibility of DIAM should be considered in patients presenting with flu-like symptoms, and a lumbar puncture may be collected to rule out aseptic meningitis if the patient’s AEs are severe following the initiation of an antibiotic, particularly in immunosuppressed patients taking sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. This case is unusual because the patient was healthy and immunocompetent.

This case may not be generalizable and may be difficult to compare to other cases. Every case has patient-specific factors affecting subjective information, including the patient’s baseline, severity of symptoms, and treatment options. This report was based on a single patient case and corresponding results may be found in similar patient cases.

Conclusions

This case emphasizes the rare but serious AEs of acute agranulocytosis complicated with aseptic meningitis after prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. This is a unique case of an immunocompetent patient developing both agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis after restarting the antibiotic to complete therapy. This case highlights the importance of monitoring blood cell counts and monitoring for signs and symptoms of aseptic meningitis, even during short courses of therapy. Further research is needed to recognize characteristics that may increase the risk for these AEs and to develop strategies for their prevention.

Acute agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis are serious adverse effects (AEs) associated with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Acute agranulocytosis is a rare, potentially life-threatening blood dyscrasia characterized by a neutrophil count of < 500 cells per μL, with no relevant decrease in hemoglobin or platelet levels.1 Patients with agranulocytosis may be asymptomatic or experience severe sore throat, pharyngitis, or tonsillitis in combination with high fever, rigors, headaches, or malaise. These AEs are commonly classified as idiosyncratic and, in most cases, attributable to medications. If drug-induced agranulocytosis is suspected, the patient should discontinue the medication immediately.1

Meningitis is an inflammatory disease typically caused by viral or bacterial infections; however, it may also be attributed to medications or malignancy. Inflammation of the meninges with a negative bacterial cerebrospinal fluid culture is classified as aseptic meningitis. Distinguishing between aseptic and bacterial meningitis is crucial due to differences in illness severity, treatment options, and prognosis.2 Symptoms of meningitis may include fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, nausea, or vomiting.3 Several classes of medications can cause drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM), but the most commonly reported antibiotic is sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

DIAM is more prevalent in immunocompromised patients, such as those with a history of HIV/AIDS, organ transplant, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy, who may be prescribed sulfamethoxazoletrimethoprim for prophylaxis or treatment of infection.2 The case described in this article serves as a distinctive example of acute agranulocytosis complicated with aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim in an immunocompetent patient.

Case Presentation

A healthy male veteran aged 39 years presented to the Fargo Veterans Affairs Medical Center emergency department (ED) for worsening left testicular pain and increased urinary urgency and frequency for about 48 hours. The patient had no known medication allergies, was current on vaccinations, and his only relevant prescription was valacyclovir for herpes labialis. The evaluation included urinalysis, blood tests, and scrotal ultrasound. The urinalysis, blood tests, and vitals were unremarkable for any signs of systemic infection. The scrotal ultrasound was significant for left focal area of abnormal echogenicity with absent blood flow in the superior left testicle and a significant increase in blood flow around the left epididymis. Mild swelling in the left epididymis was present, with no significant testicular or scrotal swelling or skin changes observed. Urology was consulted and prescribed oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 800-160 mg every 12 hours for 30 days for the treatment of left epididymo-orchitis.

The patient returned to the ED 2 weeks later with fever, chills, headache, generalized body aches, urinary retention, loose stools, and nonspecific chest pressure. A serum blood test revealed significant neutropenia and leukopenia. The patient was admitted for observation, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was discontinued. The patient received sodium chloride intravenous (IV) fluid, oral potassium chloride supplementation, IV ondansetron, and analgesics, including oral acetaminophen, oral ibuprofen, and IV hydromorphone as needed. Repeated laboratory tests were completed with no specific findings; serum laboratory work, urinalysis, chest and abdominal X-rays, and echocardiogram were all unremarkable. The patient’s neutrophil count dropped from 5100 cells/µL at the initial ED presentation to 900 cells/µL (reference range, 1500-8000 cells/µL) (Table 1). Agranulocytosis quickly resolved after antibiotic discontinuation.

Upon further investigation, the patient took the prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for 10 days before stopping due to the resolution of testicular pain and epididymal swelling. The patient reported initial AEs of loose stools and generalized myalgias when first taking the medication. The patient restarted the antibiotic to complete the course of therapy after not taking it for 2 days. Within 20 minutes of restarting the medication, he experienced myalgias with pruritus, prompting him to return to the ED. Agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis developed within 12 days after he was prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, though the exact timeframe is unknown.

The patient’s symptoms, except for a persistent headache, resolved during hospitalization. Infectious disease was consulted, and a lumbar puncture was performed due to prior fever and ongoing headaches to rule out a treatable cause of meningitis. The lumbar puncture showed clear spinal fluid, an elevated white blood cell count with neutrophil predominance, and normal protein and glucose levels. Cultures showed no aerobic, anaerobic, or fungal organisms. Herpes virus simplex and Lyme disease testing was not completed during hospitalization. Respiratory panel, legionella, and hepatitis A, B, and C tests were negative (Table 2). The negative laboratory test results strengthened the suspicion of aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The neurology consult recommended no additional treatments or tests.

The patient spontaneously recovered 2 days later, with a normalized complete blood count and resolution of headache. Repeat scrotal ultrasounds showed resolution of the left testicle findings. The patient was discharged and seen for a follow-up 14 days later. The final diagnosis requiring hospitalization was aseptic meningitis secondary to a sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

Discussion

Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is a commonly prescribed antibiotic for urinary tract infections, pneumocystis pneumonia, pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Empiric antibiotics for epididymo-orchitis caused by enteric organisms include levofloxacin or ofloxacin; however sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim may be considered as alternative.5,6 Agranulocytosis induced by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim may occur due to the inhibition on folic acid metabolism, which makes the highly proliferating cells of the hematopoietic system more susceptible to neutropenia. Agranulocytosis typically occurs within 7 days of treatment initiation and generally resolves within a month after discontinuation of the offending agent.7 In this case, agranulocytosis resolved overnight, resulting in leukocytosis. One explanation for the rapid increase in white blood cell count may be the concurrent diagnosis of aseptic meningitis. Alternatively, the patient’s health and immunocompetence may have helped generate an adequate immune response. Medication-induced agranulocytosis is often a diagnosis of exclusion because it is typically difficult to diagnose.7 In more severe or complicated cases of agranulocytosis, filgrastim may be indicated.1

Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is a lipophilic small-molecule medication that can cross the blood-brain barrier and penetrate the tissues of the bone, prostate, and central nervous system.8 Specifically, the medication can pass into the cerebrospinal fluid regardless of meningeal inflammation.9 The exact mechanism for aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is unknown; however, it may accumulate in the choroid plexus, causing destructive inflammation of small blood vessels and resulting in aseptic meningitis.10 The onset of aseptic meningitis can vary from 10 minutes to 10 days after initiation of the medication. Pre-exposure to the medication typically results in earlier onset of symptoms, though patients do not need to have previously taken the medication to develop aseptic meningitis. Patients generally become afebrile with resolution of headache and mental status changes within 48 to 72 hours after stopping the medication or after about 5 to 7 half-lives of the medication are eliminated.11 Some patients may continue to experience worsening symptoms after discontinuation because the medication is already absorbed into the serum and tissues.

DIAM is an uncommon drug-induced hypersensitivity AE of the central nervous system. Diagnosing aseptic meningitis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim can be challenging, as antibiotics are given to treat suspected infections, and the symptoms of aseptic meningitis can be hard to differentiate from those of infectious meningitis.11 Close monitoring between the initiation of the medication and the onset of clinical symptoms is necessary to assist in distinguishing between aseptic and infectious meningitis.3 If the causative agent is not discontinued, symptoms can quickly worsen, progressing from fever and headache to confusion, coma, and respiratory depression. A DIAM diagnosis can only be made with resolution of aseptic meningitis after stopping the contributory agent. If appropriate, this can be proven by rechallenging the medication in a controlled setting. The usual treatment for aseptic meningitis is supportive care, including hydration, antiemetics, electrolyte supplementation, and adequate analgesia.3

Differential diagnoses in this case included viral infection, meningitis, and allergic reaction to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The patient reported history of experiencing symptoms after restarting his antibiotic, raising strong suspicion for DIAM. Initiation of this antibiotic was the only recent medication change noted. Laboratory testing for infectious agents yielded negative results, including tests for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria as well as viral and fungal infections. A lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid culture was clear, with no organisms shown on gram stain. Bacterial or viral meningitis was presumed less likely due to the duration of symptoms, correlation of symptoms coinciding with restarting the antibiotic, and negative cerebrospinal fluid culture results.

It was concluded that agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis were likely induced by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim as supported by the improvement upon discontinuing the medication and subsequent worsening upon restarting it. Concurrent agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis is rare, and there is typically no correlation between the 2 reactions. Since agranulocytosis may be asymptomatic, this case highlights the need to monitor blood cell counts in patients using sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The possibility of DIAM should be considered in patients presenting with flu-like symptoms, and a lumbar puncture may be collected to rule out aseptic meningitis if the patient’s AEs are severe following the initiation of an antibiotic, particularly in immunosuppressed patients taking sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. This case is unusual because the patient was healthy and immunocompetent.

This case may not be generalizable and may be difficult to compare to other cases. Every case has patient-specific factors affecting subjective information, including the patient’s baseline, severity of symptoms, and treatment options. This report was based on a single patient case and corresponding results may be found in similar patient cases.

Conclusions

This case emphasizes the rare but serious AEs of acute agranulocytosis complicated with aseptic meningitis after prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. This is a unique case of an immunocompetent patient developing both agranulocytosis and aseptic meningitis after restarting the antibiotic to complete therapy. This case highlights the importance of monitoring blood cell counts and monitoring for signs and symptoms of aseptic meningitis, even during short courses of therapy. Further research is needed to recognize characteristics that may increase the risk for these AEs and to develop strategies for their prevention.

- Garbe E. Non-chemotherapy drug-induced agranulocytosis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6(3):323-335. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.3.323

- Jha P, Stromich J, Cohen M, Wainaina JN. A rare complication of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole: drug induced aseptic meningitis. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:3879406. doi:10.1155/2016/3879406

- Hopkins S, Jolles S. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4(2):285-297. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.2.285

- Jarrin I, Sellier P, Lopes A, et al. Etiologies and management of aseptic meningitis in patients admitted to an internal medicine department. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(2):e2372. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002372

- Street EJ, Justice ED, Kopa Z, et al. The 2016 European guideline on the management of epididymo-orchitis. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(8):744-749. doi:10.1177/0956462417699356

- Kbirou A, Alafifi M, Sayah M, Dakir M, Debbagh A, Aboutaieb R. Acute orchiepididymitis: epidemiological and clinical aspects: an analysis of 152 cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;75:103335. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103335

- Rattay B, Benndorf RA. Drug-induced idiosyncratic agranulocytosis - infrequent but dangerous. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:727717. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.727717

- Elmedani S, Albayati A, Udongwo N, Odak M, Khawaja S. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced aseptic meningitis: a new approach. Cureus. 2021;13(6):e15869. doi:10.7759/cureus.15869

- Nau R, Sörgel F, Eiffert H. Penetration of drugs through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid/blood-brain barrier for treatment of central nervous system infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(4):858-883. doi:10.1128/CMR.00007-10

- Moris G, Garcia-Monco JC. The challenge of drug-induced aseptic meningitis. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(11):1185- 1194. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.11.1185

- Bruner KE, Coop CA, White KM. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced aseptic meningitis-not just another sulfa allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(5):520-526. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2014.08.006

- Garbe E. Non-chemotherapy drug-induced agranulocytosis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6(3):323-335. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.3.323

- Jha P, Stromich J, Cohen M, Wainaina JN. A rare complication of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole: drug induced aseptic meningitis. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:3879406. doi:10.1155/2016/3879406

- Hopkins S, Jolles S. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4(2):285-297. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.2.285

- Jarrin I, Sellier P, Lopes A, et al. Etiologies and management of aseptic meningitis in patients admitted to an internal medicine department. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(2):e2372. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002372

- Street EJ, Justice ED, Kopa Z, et al. The 2016 European guideline on the management of epididymo-orchitis. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(8):744-749. doi:10.1177/0956462417699356

- Kbirou A, Alafifi M, Sayah M, Dakir M, Debbagh A, Aboutaieb R. Acute orchiepididymitis: epidemiological and clinical aspects: an analysis of 152 cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;75:103335. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103335

- Rattay B, Benndorf RA. Drug-induced idiosyncratic agranulocytosis - infrequent but dangerous. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:727717. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.727717

- Elmedani S, Albayati A, Udongwo N, Odak M, Khawaja S. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced aseptic meningitis: a new approach. Cureus. 2021;13(6):e15869. doi:10.7759/cureus.15869

- Nau R, Sörgel F, Eiffert H. Penetration of drugs through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid/blood-brain barrier for treatment of central nervous system infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(4):858-883. doi:10.1128/CMR.00007-10

- Moris G, Garcia-Monco JC. The challenge of drug-induced aseptic meningitis. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(11):1185- 1194. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.11.1185

- Bruner KE, Coop CA, White KM. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced aseptic meningitis-not just another sulfa allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(5):520-526. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2014.08.006

Agranulocytosis and Aseptic Meningitis Induced by Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim

Agranulocytosis and Aseptic Meningitis Induced by Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim

Pharmacist-Driven Deprescribing to Reduce Anticholinergic Burden in Veterans With Dementia

Pharmacist-Driven Deprescribing to Reduce Anticholinergic Burden in Veterans With Dementia

Anticholinergic medications block the activity of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine by binding to either muscarinic or nicotinic receptors in both the peripheral and central nervous system. Anticholinergic medications typically refer to antimuscarinic medications and have been prescribed to treat a variety of conditions common in older adults, including overactive bladder, allergies, muscle spasms, and sleep disorders.1,2 Since muscarinic receptors are present throughout the body, anticholinergic medications are associated with many adverse effects (AEs), including constipation, urinary retention, xerostomia, and delirium. Older adults are more sensitive to these AEs due to physiological changes associated with aging.1

The American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medications Use in Older Adults identifies drugs with strong anticholinergic properties. The Beers Criteria strongly recommends avoiding these medications in patients with dementia or cognitive impairment due to the risk of central nervous system AEs. In the updated 2023 Beers Criteria, the rationale was expanded to recognize the risks of the cumulative anticholinergic burden associated with concurrent anticholinergic use.3,4

Given the prevalent use of anticholinergic medications in older adults, there has been significant research demonstrating their AEs, specifically delirium and cognitive impairment in geriatric patients. A systematic review of 14 articles conducted in 7 different countries of patients with median age of 76.4 to 86.1 years reviewed clinical outcomes of anticholinergic use in patients with dementia. Five studies found anticholinergics were associated with increased all-cause mortality in patients with dementia, and 3 studies found anticholinergics were associated with longer hospital stays. Other studies found that anticholinergics were associated with delirium and reduced health-related quality of life.5

About 35% of veterans with dementia have been prescribed a medication regimen with a high anticholinergic burden.6 In 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benfits Management Center for Medical Safety completed a centrally aggregated medication use evaluation (CAMUE) to assess the appropriateness of anticholinergic medication use in patients with dementia. The retrospective chart review included 1094 veterans from 19 sites. Overall, about 15% of the veterans experienced new falls, delirium, or worsening dementia within 30 days of starting an anticholinergic medication. Furthermore, < 40% had documentation of a nonanticholinergic alternative medication trial, and < 20% had documented nonpharmacologic therapy. The documentation of risk-benefit assessment acknowledging the risks of anticholinergic medication use in veterans with dementia occurred only about 13% of the time. The CAMUE concluded that the risks of initiating an anticholinergic medication in veterans with dementia are likely underdocumented and possibly under considered by prescribers.7

Developed within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not Indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a medication management methodology that aims to reduce polypharmacy and improve patient safety consistent with high-reliability organizations. Since it launched in 2016, VIONE has gradually been implemented at many VHA facilities. The VIONE deprescribing dashboard had not been used at the VA Louisville Healthcare System prior to this quality improvement project.

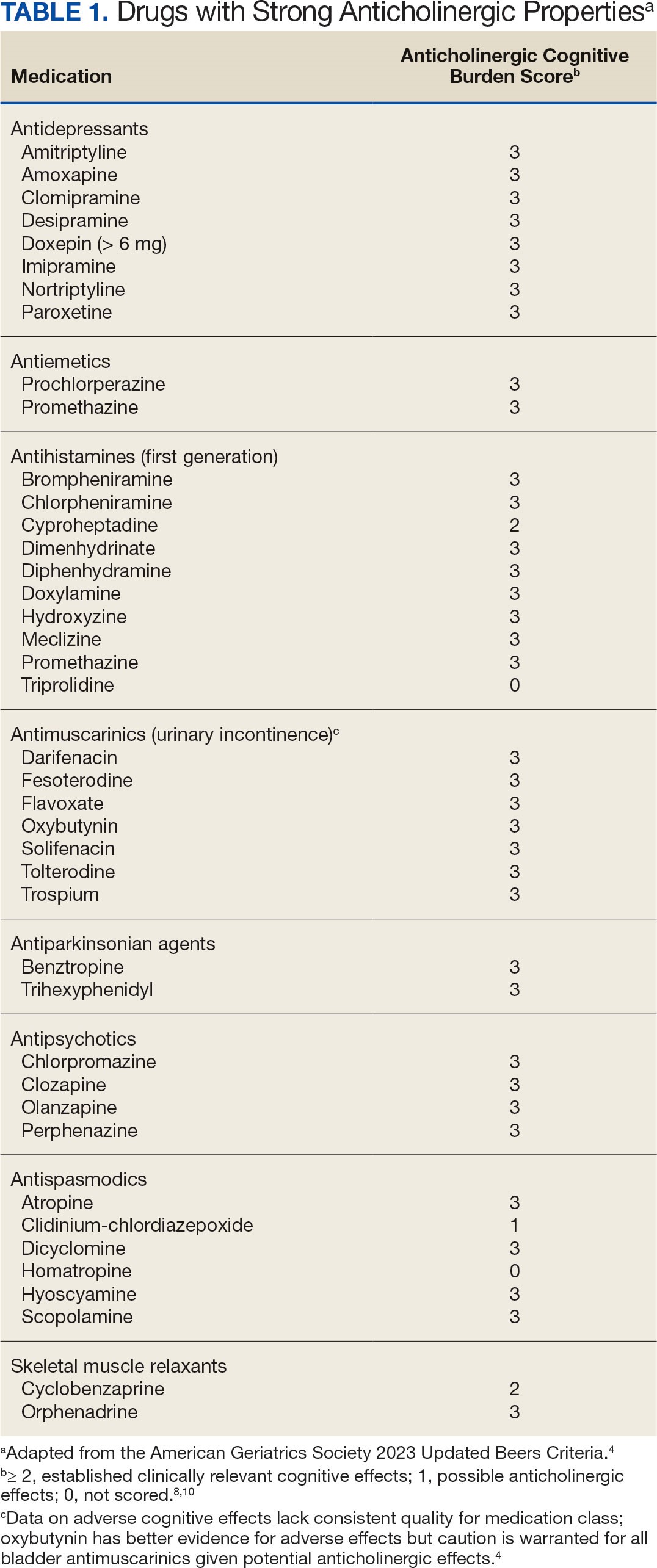

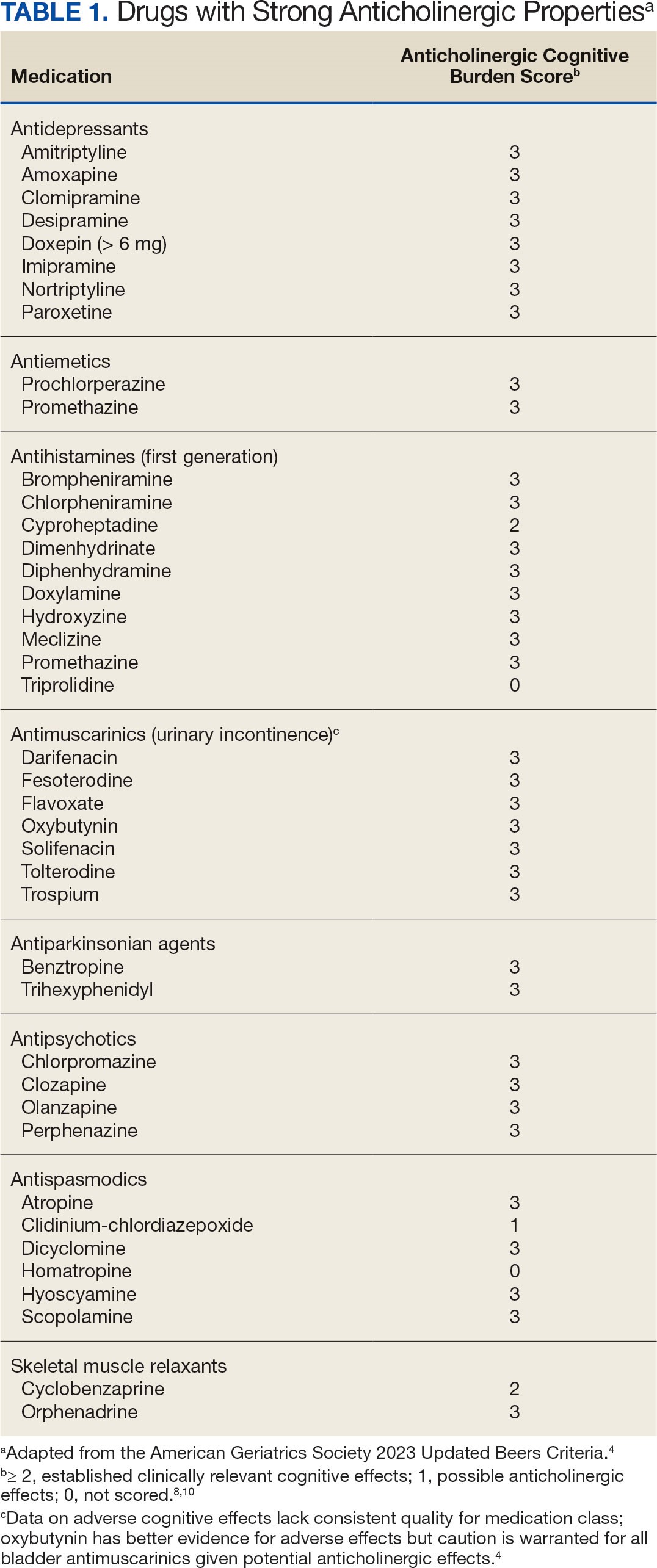

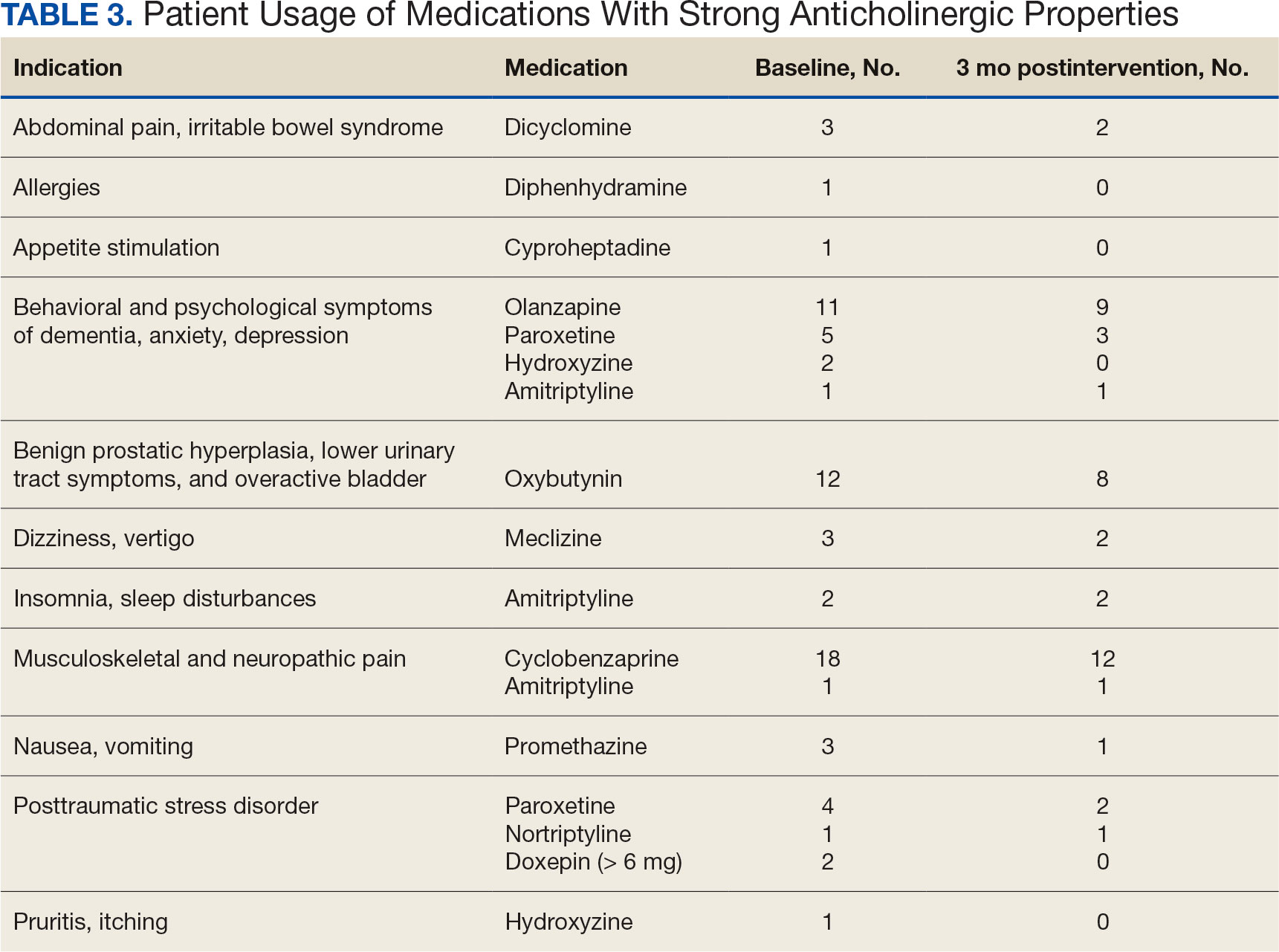

This dashboard uses the Beers Criteria to identify potentially inappropriate anticholinergic medications. It uses the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden (ACB) scale to calculate the cumulative anticholinergic risk for each patient. Medications with an ACB score of 2 or 3 have clinically relevant cognitive effects such as delirium and dementia (Table 1). For each point increase in total ACB score, a decline in mini-mental state examination score of 0.33 points over 2 years has been shown. Each point increase has also been correlated with a 26% increase in risk of death.8-10

Methods

The purpose of this quality improvement project was to determine the impact of pharmacist-driven deprescribing on the anticholinergic burden in veterans with dementia at VA Louisville Healthcare System. Data were obtained through the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and VIONE deprescribing dashboard and entered in a secure Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Pharmacist deprescribing steps were entered as CPRS progress notes. A deprescribing note template was created, and 11 templates with indication-specific recommendations were created for each anticholinergic indication identified (contact authors for deprescribing note template examples). Usage of anticholinergic medications was reexamined 3 months after the deprescribing note was entered.

Eligible patients identified in the VIONE deprescribing dashboard had an outpatient order for a medication with strong anticholinergic properties as identified using the Beers Criteria and were aged ≥ 65 years. Patients also had to be diagnosed with dementia or cognitive impairment. Patients were excluded if they were receiving hospice care or if the anticholinergic medication was from a non-VA prescriber or filled at a non-VA pharmacy. The VIONE deprescribing dashboard also excluded skeletal muscle relaxants if the patient had a spinal cord-related visit in the previous 2 years, first-generation antihistamines if the patient had a vertigo diagnosis, hydroxyzine if the indication was for anxiety, trospium if the indication was for overactive bladder, and antipsychotics if the patient had been diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. The following were included in the deprescribing recommendations if the dashboard identified the patient due to receiving a second strongly anticholinergic medication: first generation antihistamines if the patient was diagnosed with vertigo and hydroxyzine if the indication is for anxiety.

Each eligible patient received a focused medication review by a pharmacist via electronic chart review and a templated CPRS progress note with patient-specific recommendations. The prescriber and the patient’s primary care practitioner were recommended to perform a patient-specific risk-benefit assessment, deprescribe potentially inappropriate anticholinergic medications, and consider nonanticholinergic alternatives (both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic). Data collected included baseline age, sex, prespecified comorbidities (type of dementia, cognitive impairment, delirium, benign prostatic hyperplasia/lower urinary tract symptoms), duration of prescribed anticholinergic medication, indication and deprescribing rate for each anticholinergic agent, and concurrent dementia medications (acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, or both).

The primary outcome was the number of patients that had = 1 medication with strong anticholinergic properties deprescribed. Deprescribing was defined as medication discontinuation or reduction of total daily dose. Secondary outcomes were the mean change in ACB scale, the number of patients with dose tapering, documented patient-specific risk-benefit assessment, and initiated nonanticholinergic alternative per pharmacist recommendation.

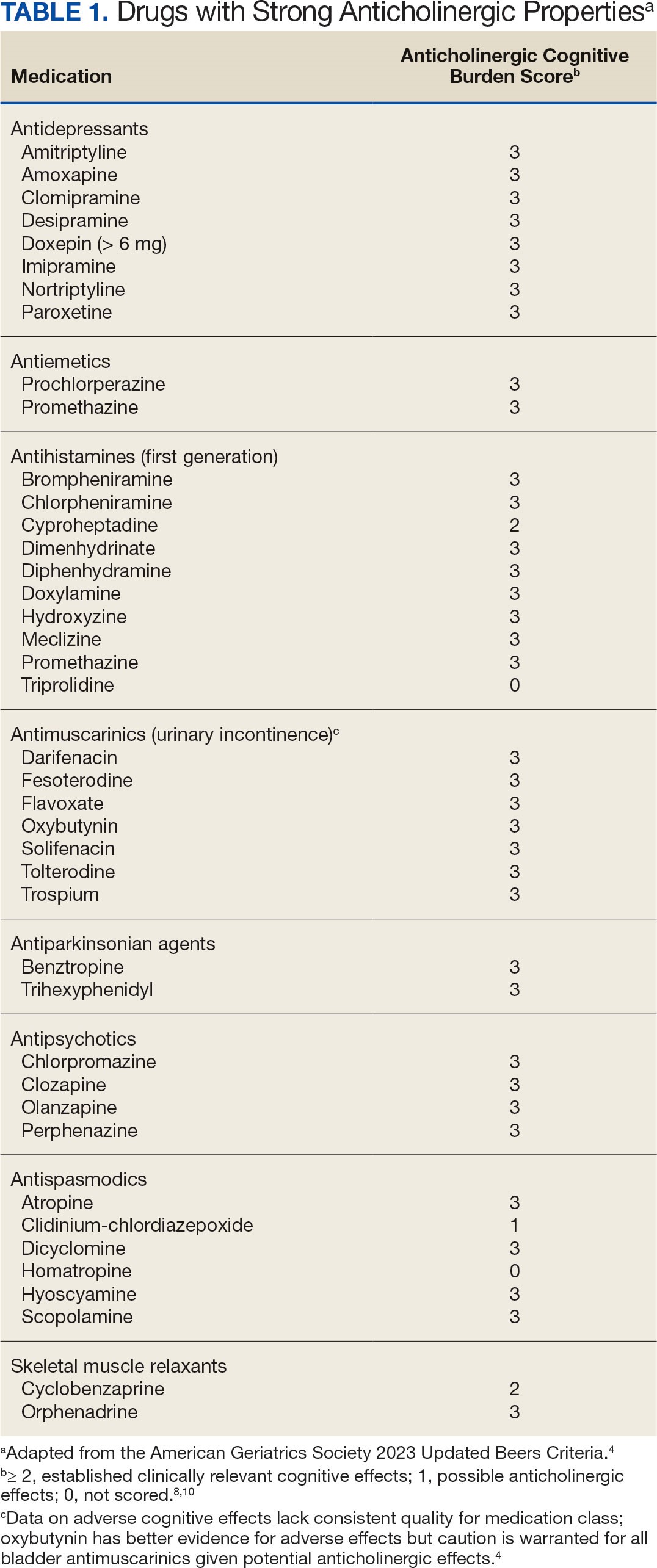

Results

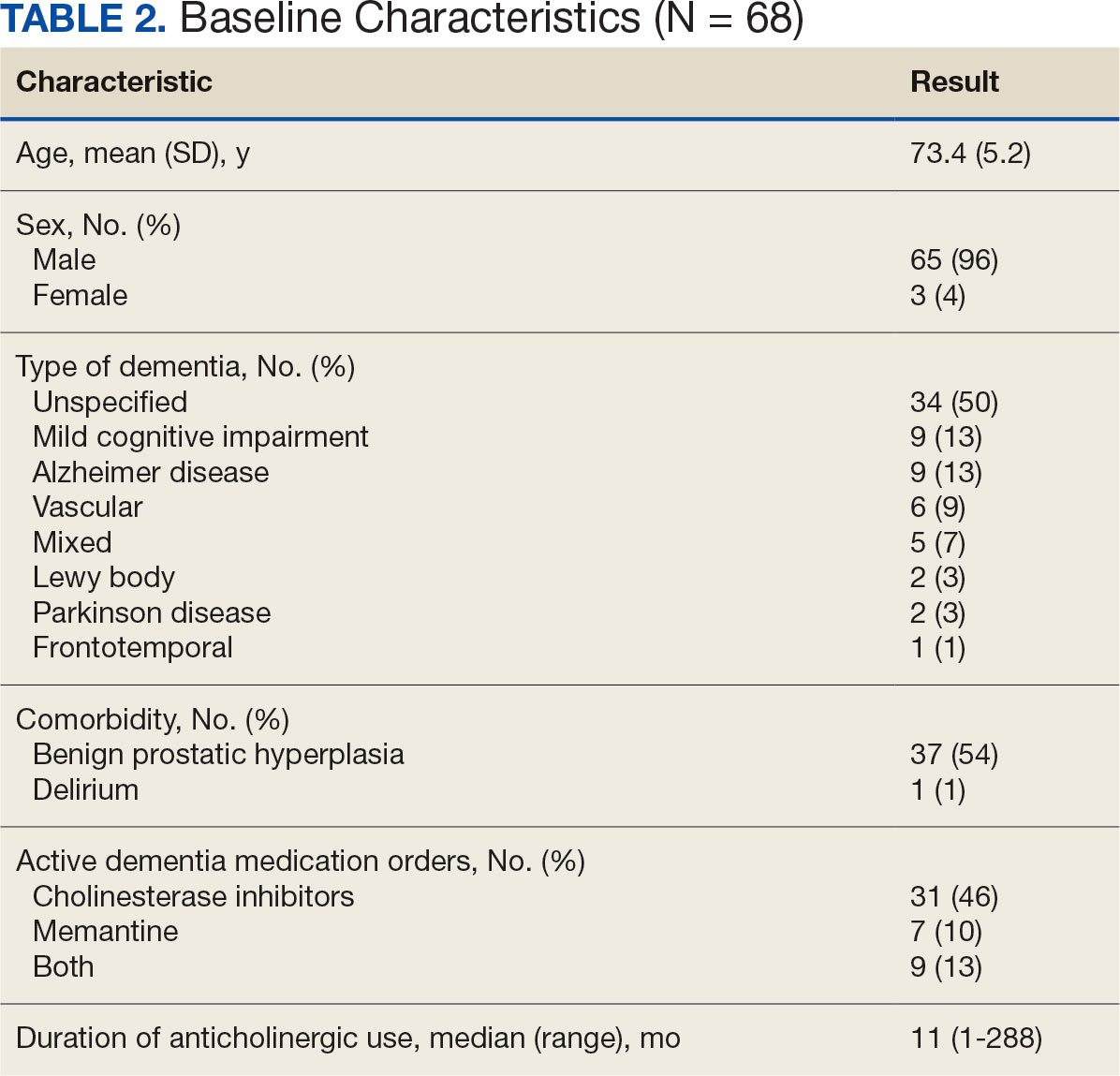

The VIONE deprescribing dashboard identified 121 patients; 45 were excluded for non-VA prescriber or pharmacy, and 8 patients were excluded for other reasons. Sixty-eight patients were included in the deprescribing initiative. The mean age was 73.4 years (range, 67-93), 65 (96%) were male, and 34 (50%) had unspecified dementia (Table 2). Thirty-one patients (46%) had concurrent cholinesterase inhibitor prescriptions for dementia. The median duration of use of a strong anticholinergic medication was 11 months.