User login

Watchful waiting in BCC: Which patients can benefit?

Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), the most common form of skin cancer, are generally slow-growing tumors that occur in older patients.

Given the low rates of metastasis and mortality associated with BCC, some patients do not require treatment. However, there have been no evidence-based recommendations on who may benefit from a watch-and-wait approach.

.

The investigators found that, for older people with low-grade BCCs and limited life expectancy, the risks associated with surgery – bleeding, infection, and wound dehiscence – appeared to outweigh the advantages. According to the authors, these patients “might not live long enough to benefit from treatment.”

This finding mirrors oncologists’ observations regarding low-risk prostate cancer, for which watchful waiting is now the standard of care.

“At present, however, procedure rates [for patients with BCC] increase with age, and many basal cell carcinomas are treated surgically regardless of a patient’s life expectancy,” Eleni Linos, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, and Mary-Margaret Chren, MD, chair of dermatology at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., write in a viewpoint article published in August in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Considering the current treatment patterns for BCC, patients would “benefit from the existence of an evidence-based standard of care that includes active surveillance,” Mackenzie Wehner, MD, assistant professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Tex., writes in an editorial that accompanies the article in JAMA Dermatology.

Insights from the Dutch study

The article in JAMA Dermatology presents a cohort study conducted at Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The study included 89 patients who were managed with watchful waiting. The patients received no treatment for at least 3 months following their diagnoses.

The median age of the patients was 83 years. The patients had a total of 280 BCCs. The median initial diameter of the BCCs was 9.5 mm. Just over half of the patients were men, and about half of the BCCs were in the head and neck region.

The median follow-up was 9 months; the maximum follow-up was 6.5 years. Remarkably, the investigators say, more than half the tumors (53.2%) did not grow, and some even shrank. The majority of patients were asymptomatic at presentation, and fewer than 10% developed new symptoms, such as bleeding and itching, during follow-up.

Among the tumors that did grow, 70% were low-risk superficial/nodular tumors, which only increased in size by an estimated 1.06 mm over a year. Thirty percent were higher-risk micronodular/infiltrative tumors, which grew an estimated 4.46 mm over a 12-month period.

About two-thirds of patients eventually chose to have at least one of their BCCs removed after a median of about 7 months. Only three BCCs (2.8%) needed more extensive surgery – reconstructive surgery, rather than primary closure, for instance – than would have been necessary with an earlier excision.

No deaths from BCC were reported in the study.

The investigators tracked the reasons patients opted for watchful waiting. Many understood that their tumors likely would not cause problems in their remaining years. Others prioritized dealing with more pressing health or family problems. Logistics came into play for some, such as not having reliable transportation for hospital visits.

“In patients with [limited life expectancy] and asymptomatic low-risk tumors, [watchful waiting] should be discussed as a potentially appropriate approach,” the investigators, led by Marieke E. C. van Winden, MD, a dermatology resident at Radboud University, conclude.

For patients who wish to pursue a watchful waiting approach, the Dutch team recommends conducting follow-up visits every 3-6 months to see whether patients wish to continue with watchful waiting and to determine whether the risk-to-benefit ratio has shifted.

These recommendations are in line with criteria Dr. Linos and Dr. Chren propose in their viewpoint article in JAMA Internal Medicine. They characterize low-risk BCCs as asymptomatic, smaller than 1 cm in diameter, and located on the trunk or extremities in immunocompetent patients. They note that details regarding active surveillance for BCCs need to be worked out.

“Active surveillance should be studied as a management option because it is supported by the available evidence, congruent with the care of other low-risk cancers, and in accord with principles of shared decision-making,” Dr. Linos and Dr. Chren write.

No funding source was reported. Dr. Wehner, Dr. van Winden, Dr. Linos, and Dr. Chren have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Two of Dr. van Winden’s coauthors report ties to several companies, including Sanofi Genzyme, AbbVie, Novartis, and Janssen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), the most common form of skin cancer, are generally slow-growing tumors that occur in older patients.

Given the low rates of metastasis and mortality associated with BCC, some patients do not require treatment. However, there have been no evidence-based recommendations on who may benefit from a watch-and-wait approach.

.

The investigators found that, for older people with low-grade BCCs and limited life expectancy, the risks associated with surgery – bleeding, infection, and wound dehiscence – appeared to outweigh the advantages. According to the authors, these patients “might not live long enough to benefit from treatment.”

This finding mirrors oncologists’ observations regarding low-risk prostate cancer, for which watchful waiting is now the standard of care.

“At present, however, procedure rates [for patients with BCC] increase with age, and many basal cell carcinomas are treated surgically regardless of a patient’s life expectancy,” Eleni Linos, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, and Mary-Margaret Chren, MD, chair of dermatology at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., write in a viewpoint article published in August in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Considering the current treatment patterns for BCC, patients would “benefit from the existence of an evidence-based standard of care that includes active surveillance,” Mackenzie Wehner, MD, assistant professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Tex., writes in an editorial that accompanies the article in JAMA Dermatology.

Insights from the Dutch study

The article in JAMA Dermatology presents a cohort study conducted at Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The study included 89 patients who were managed with watchful waiting. The patients received no treatment for at least 3 months following their diagnoses.

The median age of the patients was 83 years. The patients had a total of 280 BCCs. The median initial diameter of the BCCs was 9.5 mm. Just over half of the patients were men, and about half of the BCCs were in the head and neck region.

The median follow-up was 9 months; the maximum follow-up was 6.5 years. Remarkably, the investigators say, more than half the tumors (53.2%) did not grow, and some even shrank. The majority of patients were asymptomatic at presentation, and fewer than 10% developed new symptoms, such as bleeding and itching, during follow-up.

Among the tumors that did grow, 70% were low-risk superficial/nodular tumors, which only increased in size by an estimated 1.06 mm over a year. Thirty percent were higher-risk micronodular/infiltrative tumors, which grew an estimated 4.46 mm over a 12-month period.

About two-thirds of patients eventually chose to have at least one of their BCCs removed after a median of about 7 months. Only three BCCs (2.8%) needed more extensive surgery – reconstructive surgery, rather than primary closure, for instance – than would have been necessary with an earlier excision.

No deaths from BCC were reported in the study.

The investigators tracked the reasons patients opted for watchful waiting. Many understood that their tumors likely would not cause problems in their remaining years. Others prioritized dealing with more pressing health or family problems. Logistics came into play for some, such as not having reliable transportation for hospital visits.

“In patients with [limited life expectancy] and asymptomatic low-risk tumors, [watchful waiting] should be discussed as a potentially appropriate approach,” the investigators, led by Marieke E. C. van Winden, MD, a dermatology resident at Radboud University, conclude.

For patients who wish to pursue a watchful waiting approach, the Dutch team recommends conducting follow-up visits every 3-6 months to see whether patients wish to continue with watchful waiting and to determine whether the risk-to-benefit ratio has shifted.

These recommendations are in line with criteria Dr. Linos and Dr. Chren propose in their viewpoint article in JAMA Internal Medicine. They characterize low-risk BCCs as asymptomatic, smaller than 1 cm in diameter, and located on the trunk or extremities in immunocompetent patients. They note that details regarding active surveillance for BCCs need to be worked out.

“Active surveillance should be studied as a management option because it is supported by the available evidence, congruent with the care of other low-risk cancers, and in accord with principles of shared decision-making,” Dr. Linos and Dr. Chren write.

No funding source was reported. Dr. Wehner, Dr. van Winden, Dr. Linos, and Dr. Chren have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Two of Dr. van Winden’s coauthors report ties to several companies, including Sanofi Genzyme, AbbVie, Novartis, and Janssen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), the most common form of skin cancer, are generally slow-growing tumors that occur in older patients.

Given the low rates of metastasis and mortality associated with BCC, some patients do not require treatment. However, there have been no evidence-based recommendations on who may benefit from a watch-and-wait approach.

.

The investigators found that, for older people with low-grade BCCs and limited life expectancy, the risks associated with surgery – bleeding, infection, and wound dehiscence – appeared to outweigh the advantages. According to the authors, these patients “might not live long enough to benefit from treatment.”

This finding mirrors oncologists’ observations regarding low-risk prostate cancer, for which watchful waiting is now the standard of care.

“At present, however, procedure rates [for patients with BCC] increase with age, and many basal cell carcinomas are treated surgically regardless of a patient’s life expectancy,” Eleni Linos, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, and Mary-Margaret Chren, MD, chair of dermatology at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., write in a viewpoint article published in August in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Considering the current treatment patterns for BCC, patients would “benefit from the existence of an evidence-based standard of care that includes active surveillance,” Mackenzie Wehner, MD, assistant professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Tex., writes in an editorial that accompanies the article in JAMA Dermatology.

Insights from the Dutch study

The article in JAMA Dermatology presents a cohort study conducted at Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The study included 89 patients who were managed with watchful waiting. The patients received no treatment for at least 3 months following their diagnoses.

The median age of the patients was 83 years. The patients had a total of 280 BCCs. The median initial diameter of the BCCs was 9.5 mm. Just over half of the patients were men, and about half of the BCCs were in the head and neck region.

The median follow-up was 9 months; the maximum follow-up was 6.5 years. Remarkably, the investigators say, more than half the tumors (53.2%) did not grow, and some even shrank. The majority of patients were asymptomatic at presentation, and fewer than 10% developed new symptoms, such as bleeding and itching, during follow-up.

Among the tumors that did grow, 70% were low-risk superficial/nodular tumors, which only increased in size by an estimated 1.06 mm over a year. Thirty percent were higher-risk micronodular/infiltrative tumors, which grew an estimated 4.46 mm over a 12-month period.

About two-thirds of patients eventually chose to have at least one of their BCCs removed after a median of about 7 months. Only three BCCs (2.8%) needed more extensive surgery – reconstructive surgery, rather than primary closure, for instance – than would have been necessary with an earlier excision.

No deaths from BCC were reported in the study.

The investigators tracked the reasons patients opted for watchful waiting. Many understood that their tumors likely would not cause problems in their remaining years. Others prioritized dealing with more pressing health or family problems. Logistics came into play for some, such as not having reliable transportation for hospital visits.

“In patients with [limited life expectancy] and asymptomatic low-risk tumors, [watchful waiting] should be discussed as a potentially appropriate approach,” the investigators, led by Marieke E. C. van Winden, MD, a dermatology resident at Radboud University, conclude.

For patients who wish to pursue a watchful waiting approach, the Dutch team recommends conducting follow-up visits every 3-6 months to see whether patients wish to continue with watchful waiting and to determine whether the risk-to-benefit ratio has shifted.

These recommendations are in line with criteria Dr. Linos and Dr. Chren propose in their viewpoint article in JAMA Internal Medicine. They characterize low-risk BCCs as asymptomatic, smaller than 1 cm in diameter, and located on the trunk or extremities in immunocompetent patients. They note that details regarding active surveillance for BCCs need to be worked out.

“Active surveillance should be studied as a management option because it is supported by the available evidence, congruent with the care of other low-risk cancers, and in accord with principles of shared decision-making,” Dr. Linos and Dr. Chren write.

No funding source was reported. Dr. Wehner, Dr. van Winden, Dr. Linos, and Dr. Chren have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Two of Dr. van Winden’s coauthors report ties to several companies, including Sanofi Genzyme, AbbVie, Novartis, and Janssen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most community-based oncologists skip biomarker testing

A recent survey shows that fewer than half of community oncologists use biomarker testing to guide patient discussions about treatment, which compares with 73% of academic clinicians.

The findings, reported at the 2020 World Conference on Lung Cancer, which was rescheduled for January 2021, highlight the potential for unequal application of the latest advances in cancer genomics and targeted therapies throughout the health care system, which could worsen existing disparities in underserved populations, according to Leigh Boehmer, PharmD, medical director for the Association of Community Cancer Centers, Rockville, Md.

The survey – a mixed-methods approach for assessing practice patterns, attitudes, barriers, and resource needs related to biomarker testing among clinicians – was developed by the ACCC in partnership with the LUNGevity Foundation and administered to clinicians caring for patients with non–small cell lung cancer who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid.

Of 99 respondents, more than 85% were physicians and 68% worked in a community setting. Only 40% indicated they were very familiar or extremely familiar with 2018 Molecular Testing Guidelines for Lung Cancer from the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology.

Clinicians were most confident about selecting appropriate tests to use, interpreting test results, and prognosticating based on test results, with 77%, 74%, and 74%, respectively, saying they are very confident or extremely confident in those areas. They were less confident about determining when to order testing and in coordinating care across the multidisciplinary team, with 59% and 64%, respectively, saying they were very confident or extremely confident in those areas, Dr. Boehmer reported at the conference.

The shortcomings with respect to communication across teams were echoed in two focus groups convened to further validate the survey results, he noted.

As for the reasons why clinicians ordered biomarker testing, 88% and 82% of community and academic clinicians, respectively, said they did so to help make targeted treatment decisions.

“Only 48% of community clinicians indicated that they use biomarker testing to guide patient discussions, compared to 73% of academic clinicians,” he said. “That finding was considered statistically significant.”

With respect to decision-making about biomarker testing, 41% said they prefer to share the responsibility with patients, whereas 52% said they prefer to make the final decision.

“Shedding further light on this situation, focus group participants expressed that patients lacked comprehension and interest about what testing entails and what testing means for their treatment options,” Dr. Boehmer noted.

In order to make more informed decisions about biomarker testing, respondents said they need more information on financial resources for patient assistance (26%) and education around both published guidelines and practical implications of the clinical data (21%).

When asked about patients’ information needs, 23% said their patients need psychosocial support, 22% said they need financial assistance, and 9% said their patients have no additional resource needs.

However, only 27% said they provide patients with resources related to psychosocial support services, and only 44% share financial assistance information, he said.

Further, the fact that 9% said their patients need no additional resources represents “a disconnect” from the findings of the survey and focus groups, he added.

“We believe that this study identifies key areas of ongoing clinician need related to biomarker testing, including things like increased guideline familiarity, practical applications of guideline-concordant testing, and … how to optimally coordinate multidisciplinary care delivery,” Dr. Boehmer said. “Professional organizations … in partnership with patient advocacy organizations or groups should focus on developing those patient education materials … and tools for improving patient-clinician discussions about biomarker testing.”

The ACCC will be working with the LUNGevity Foundation and the Center for Business Models in Healthcare to develop an intervention to ensure that such discussions are “easily integrated into the care process for every patient,” he noted.

Such efforts are important for ensuring that clinicians are informed about the value of biomarker testing and about guidelines for testing so that patients receive the best possible care, said invited discussant Joshua Sabari, MD, of New York University Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center.

“I know that, in clinic, when meeting a new patient with non–small cell lung cancer, it’s critical to understand the driver alteration, not only for prognosis, but also for goals-of-care discussion, as well as potential treatment option,” Dr. Sabari said.

Dr. Boehmer reported consulting for Pfizer. Dr. Sabari reported consulting and advisory board membership for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

A recent survey shows that fewer than half of community oncologists use biomarker testing to guide patient discussions about treatment, which compares with 73% of academic clinicians.

The findings, reported at the 2020 World Conference on Lung Cancer, which was rescheduled for January 2021, highlight the potential for unequal application of the latest advances in cancer genomics and targeted therapies throughout the health care system, which could worsen existing disparities in underserved populations, according to Leigh Boehmer, PharmD, medical director for the Association of Community Cancer Centers, Rockville, Md.

The survey – a mixed-methods approach for assessing practice patterns, attitudes, barriers, and resource needs related to biomarker testing among clinicians – was developed by the ACCC in partnership with the LUNGevity Foundation and administered to clinicians caring for patients with non–small cell lung cancer who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid.

Of 99 respondents, more than 85% were physicians and 68% worked in a community setting. Only 40% indicated they were very familiar or extremely familiar with 2018 Molecular Testing Guidelines for Lung Cancer from the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology.

Clinicians were most confident about selecting appropriate tests to use, interpreting test results, and prognosticating based on test results, with 77%, 74%, and 74%, respectively, saying they are very confident or extremely confident in those areas. They were less confident about determining when to order testing and in coordinating care across the multidisciplinary team, with 59% and 64%, respectively, saying they were very confident or extremely confident in those areas, Dr. Boehmer reported at the conference.

The shortcomings with respect to communication across teams were echoed in two focus groups convened to further validate the survey results, he noted.

As for the reasons why clinicians ordered biomarker testing, 88% and 82% of community and academic clinicians, respectively, said they did so to help make targeted treatment decisions.

“Only 48% of community clinicians indicated that they use biomarker testing to guide patient discussions, compared to 73% of academic clinicians,” he said. “That finding was considered statistically significant.”

With respect to decision-making about biomarker testing, 41% said they prefer to share the responsibility with patients, whereas 52% said they prefer to make the final decision.

“Shedding further light on this situation, focus group participants expressed that patients lacked comprehension and interest about what testing entails and what testing means for their treatment options,” Dr. Boehmer noted.

In order to make more informed decisions about biomarker testing, respondents said they need more information on financial resources for patient assistance (26%) and education around both published guidelines and practical implications of the clinical data (21%).

When asked about patients’ information needs, 23% said their patients need psychosocial support, 22% said they need financial assistance, and 9% said their patients have no additional resource needs.

However, only 27% said they provide patients with resources related to psychosocial support services, and only 44% share financial assistance information, he said.

Further, the fact that 9% said their patients need no additional resources represents “a disconnect” from the findings of the survey and focus groups, he added.

“We believe that this study identifies key areas of ongoing clinician need related to biomarker testing, including things like increased guideline familiarity, practical applications of guideline-concordant testing, and … how to optimally coordinate multidisciplinary care delivery,” Dr. Boehmer said. “Professional organizations … in partnership with patient advocacy organizations or groups should focus on developing those patient education materials … and tools for improving patient-clinician discussions about biomarker testing.”

The ACCC will be working with the LUNGevity Foundation and the Center for Business Models in Healthcare to develop an intervention to ensure that such discussions are “easily integrated into the care process for every patient,” he noted.

Such efforts are important for ensuring that clinicians are informed about the value of biomarker testing and about guidelines for testing so that patients receive the best possible care, said invited discussant Joshua Sabari, MD, of New York University Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center.

“I know that, in clinic, when meeting a new patient with non–small cell lung cancer, it’s critical to understand the driver alteration, not only for prognosis, but also for goals-of-care discussion, as well as potential treatment option,” Dr. Sabari said.

Dr. Boehmer reported consulting for Pfizer. Dr. Sabari reported consulting and advisory board membership for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

A recent survey shows that fewer than half of community oncologists use biomarker testing to guide patient discussions about treatment, which compares with 73% of academic clinicians.

The findings, reported at the 2020 World Conference on Lung Cancer, which was rescheduled for January 2021, highlight the potential for unequal application of the latest advances in cancer genomics and targeted therapies throughout the health care system, which could worsen existing disparities in underserved populations, according to Leigh Boehmer, PharmD, medical director for the Association of Community Cancer Centers, Rockville, Md.

The survey – a mixed-methods approach for assessing practice patterns, attitudes, barriers, and resource needs related to biomarker testing among clinicians – was developed by the ACCC in partnership with the LUNGevity Foundation and administered to clinicians caring for patients with non–small cell lung cancer who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid.

Of 99 respondents, more than 85% were physicians and 68% worked in a community setting. Only 40% indicated they were very familiar or extremely familiar with 2018 Molecular Testing Guidelines for Lung Cancer from the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology.

Clinicians were most confident about selecting appropriate tests to use, interpreting test results, and prognosticating based on test results, with 77%, 74%, and 74%, respectively, saying they are very confident or extremely confident in those areas. They were less confident about determining when to order testing and in coordinating care across the multidisciplinary team, with 59% and 64%, respectively, saying they were very confident or extremely confident in those areas, Dr. Boehmer reported at the conference.

The shortcomings with respect to communication across teams were echoed in two focus groups convened to further validate the survey results, he noted.

As for the reasons why clinicians ordered biomarker testing, 88% and 82% of community and academic clinicians, respectively, said they did so to help make targeted treatment decisions.

“Only 48% of community clinicians indicated that they use biomarker testing to guide patient discussions, compared to 73% of academic clinicians,” he said. “That finding was considered statistically significant.”

With respect to decision-making about biomarker testing, 41% said they prefer to share the responsibility with patients, whereas 52% said they prefer to make the final decision.

“Shedding further light on this situation, focus group participants expressed that patients lacked comprehension and interest about what testing entails and what testing means for their treatment options,” Dr. Boehmer noted.

In order to make more informed decisions about biomarker testing, respondents said they need more information on financial resources for patient assistance (26%) and education around both published guidelines and practical implications of the clinical data (21%).

When asked about patients’ information needs, 23% said their patients need psychosocial support, 22% said they need financial assistance, and 9% said their patients have no additional resource needs.

However, only 27% said they provide patients with resources related to psychosocial support services, and only 44% share financial assistance information, he said.

Further, the fact that 9% said their patients need no additional resources represents “a disconnect” from the findings of the survey and focus groups, he added.

“We believe that this study identifies key areas of ongoing clinician need related to biomarker testing, including things like increased guideline familiarity, practical applications of guideline-concordant testing, and … how to optimally coordinate multidisciplinary care delivery,” Dr. Boehmer said. “Professional organizations … in partnership with patient advocacy organizations or groups should focus on developing those patient education materials … and tools for improving patient-clinician discussions about biomarker testing.”

The ACCC will be working with the LUNGevity Foundation and the Center for Business Models in Healthcare to develop an intervention to ensure that such discussions are “easily integrated into the care process for every patient,” he noted.

Such efforts are important for ensuring that clinicians are informed about the value of biomarker testing and about guidelines for testing so that patients receive the best possible care, said invited discussant Joshua Sabari, MD, of New York University Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center.

“I know that, in clinic, when meeting a new patient with non–small cell lung cancer, it’s critical to understand the driver alteration, not only for prognosis, but also for goals-of-care discussion, as well as potential treatment option,” Dr. Sabari said.

Dr. Boehmer reported consulting for Pfizer. Dr. Sabari reported consulting and advisory board membership for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM WCLC 2020

Immunotherapy for cancer patients with poor PS needs a rethink

The findings have prompted an expert to argue against the use of immunotherapy for such patients, who may have little time left and very little chance of benefiting.

“It is quite clear from clinical practice that most patients with limited PS do very poorly and do not benefit from immune check point inhibitors (ICI),” Jason Luke, MD, UPMC Hillman Cancer Center and the University of Pittsburgh, said in an email.

“So, my strong opinion is that patients should not be getting an immunotherapy just because it might not cause as many side effects as chemotherapy,” he added.

“Instead of giving an immunotherapy with little chance of success, patients and families deserve to have a direct conversation about what realistic expectations [might be] and how we as the oncology community can support them to achieve whatever their personal goals are in the time that they have left,” he emphasized.

Dr. Luke was the lead author of an editorial in which he commented on the study. Both the study and the editorial were published online in JCO Oncology Practice.

Variety of cancers

The study was conducted by Mridula Krishnan, MD, Nebraska Medicine Fred and Pamela Buffett Cancer Center, Omaha, Nebraska, and colleagues.

The team reviewed 257 patients who had been treated with either a programmed cell death protein–1 inhibitor or programmed cell death–ligand-1 inhibitor for a variety of advanced cancers. The drugs included pembrolizumab (Keytruda), nivolumab (Opdivo), atezolizumab (Tecentique), durvalumab (Imfinzi), and avelumab (Bavencio).

Most of the patients (71%) had good PS, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS of 0-1 on initiation of immunotherapy; 29% of patients had poor PS, with an ECOG PS of greater than or equal to 2.

“The primary outcome was OS stratified by ECOG PS 0-1 versus ≥2,” note the authors. Across all tumor types, OS was superior for patients in the ECOG 0-1 PS group, the investigators note. The median OS was 12.6 months, compared with only 3.1 months for patients in the ECOG greater than or equal to 2 group (P < .001).

Moreover, overall response rates for patients with a poor PS were low. Only 8%, or 6 of 75 patients with an ECOG PS of greater than or equal to 2, achieved an objective response by RECIST criteria.

This compared to an overall response rate of 23% for patients with an ECOG PS of 0-1, the investigators note (P = .005).

Interestingly, the hospice referral rate for patients with a poor PS (67%) was similar to that of patients with a PS of 1-2 (61.9%), Dr. Krishnan and colleagues observe.

Those with a poor PS were more like to die in-hospital (28.6%) than were patients with a good PS (15.1%; P = .035). The authors point out that it is well known that outcomes with chemotherapy are worse among patients who experience a decline in functional reserve, owing to increased susceptibility to toxicity and complications.

“Regardless of age, patients with ECOG PS >2 usually have poor tolerability to chemotherapy, and this correlates with worse survival outcome,” they emphasize. There is as yet no clear guidance regarding the impact of PS on ICI treatment response, although “there should be,” Dr. Luke believes.

“In a patient with declining performance status, especially ECOG PS 3-4 but potentially 2 as well, there is little likelihood that the functional and immune reserve of the patient will be adequate to mount a robust antitumor response,” he elaborated.

“It’s not impossible, but trying for it should not come at the expense of engaging about end-of-life care and maximizing the palliative opportunities that many only have a short window of time in which to pursue,” he added.

Again, Dr. Luke strongly believes that just giving an ICI without engaging in a frank conversation with the patient and their families – which happens all too often, he feels – is absolutely not the way to go when treating patients with a poor PS and little time left.

“Patients and families might be better served by having a more direct and frank conversation about what the likelihood [is] that ICI therapy will actually do,” Dr. Luke stressed.

In their editorial, Dr. Luke and colleagues write: “Overall, we as an oncology community need to improve our communication with patients regarding goals of care and end-of-life considerations as opposed to reflexive treatment initiation,” he writes.

“Our duty, first and foremost, should focus on the person sitting in front of us – taking a step back may be the best way to move forward with compassionate care,” they add.

The authors and editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The findings have prompted an expert to argue against the use of immunotherapy for such patients, who may have little time left and very little chance of benefiting.

“It is quite clear from clinical practice that most patients with limited PS do very poorly and do not benefit from immune check point inhibitors (ICI),” Jason Luke, MD, UPMC Hillman Cancer Center and the University of Pittsburgh, said in an email.

“So, my strong opinion is that patients should not be getting an immunotherapy just because it might not cause as many side effects as chemotherapy,” he added.

“Instead of giving an immunotherapy with little chance of success, patients and families deserve to have a direct conversation about what realistic expectations [might be] and how we as the oncology community can support them to achieve whatever their personal goals are in the time that they have left,” he emphasized.

Dr. Luke was the lead author of an editorial in which he commented on the study. Both the study and the editorial were published online in JCO Oncology Practice.

Variety of cancers

The study was conducted by Mridula Krishnan, MD, Nebraska Medicine Fred and Pamela Buffett Cancer Center, Omaha, Nebraska, and colleagues.

The team reviewed 257 patients who had been treated with either a programmed cell death protein–1 inhibitor or programmed cell death–ligand-1 inhibitor for a variety of advanced cancers. The drugs included pembrolizumab (Keytruda), nivolumab (Opdivo), atezolizumab (Tecentique), durvalumab (Imfinzi), and avelumab (Bavencio).

Most of the patients (71%) had good PS, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS of 0-1 on initiation of immunotherapy; 29% of patients had poor PS, with an ECOG PS of greater than or equal to 2.

“The primary outcome was OS stratified by ECOG PS 0-1 versus ≥2,” note the authors. Across all tumor types, OS was superior for patients in the ECOG 0-1 PS group, the investigators note. The median OS was 12.6 months, compared with only 3.1 months for patients in the ECOG greater than or equal to 2 group (P < .001).

Moreover, overall response rates for patients with a poor PS were low. Only 8%, or 6 of 75 patients with an ECOG PS of greater than or equal to 2, achieved an objective response by RECIST criteria.

This compared to an overall response rate of 23% for patients with an ECOG PS of 0-1, the investigators note (P = .005).

Interestingly, the hospice referral rate for patients with a poor PS (67%) was similar to that of patients with a PS of 1-2 (61.9%), Dr. Krishnan and colleagues observe.

Those with a poor PS were more like to die in-hospital (28.6%) than were patients with a good PS (15.1%; P = .035). The authors point out that it is well known that outcomes with chemotherapy are worse among patients who experience a decline in functional reserve, owing to increased susceptibility to toxicity and complications.

“Regardless of age, patients with ECOG PS >2 usually have poor tolerability to chemotherapy, and this correlates with worse survival outcome,” they emphasize. There is as yet no clear guidance regarding the impact of PS on ICI treatment response, although “there should be,” Dr. Luke believes.

“In a patient with declining performance status, especially ECOG PS 3-4 but potentially 2 as well, there is little likelihood that the functional and immune reserve of the patient will be adequate to mount a robust antitumor response,” he elaborated.

“It’s not impossible, but trying for it should not come at the expense of engaging about end-of-life care and maximizing the palliative opportunities that many only have a short window of time in which to pursue,” he added.

Again, Dr. Luke strongly believes that just giving an ICI without engaging in a frank conversation with the patient and their families – which happens all too often, he feels – is absolutely not the way to go when treating patients with a poor PS and little time left.

“Patients and families might be better served by having a more direct and frank conversation about what the likelihood [is] that ICI therapy will actually do,” Dr. Luke stressed.

In their editorial, Dr. Luke and colleagues write: “Overall, we as an oncology community need to improve our communication with patients regarding goals of care and end-of-life considerations as opposed to reflexive treatment initiation,” he writes.

“Our duty, first and foremost, should focus on the person sitting in front of us – taking a step back may be the best way to move forward with compassionate care,” they add.

The authors and editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The findings have prompted an expert to argue against the use of immunotherapy for such patients, who may have little time left and very little chance of benefiting.

“It is quite clear from clinical practice that most patients with limited PS do very poorly and do not benefit from immune check point inhibitors (ICI),” Jason Luke, MD, UPMC Hillman Cancer Center and the University of Pittsburgh, said in an email.

“So, my strong opinion is that patients should not be getting an immunotherapy just because it might not cause as many side effects as chemotherapy,” he added.

“Instead of giving an immunotherapy with little chance of success, patients and families deserve to have a direct conversation about what realistic expectations [might be] and how we as the oncology community can support them to achieve whatever their personal goals are in the time that they have left,” he emphasized.

Dr. Luke was the lead author of an editorial in which he commented on the study. Both the study and the editorial were published online in JCO Oncology Practice.

Variety of cancers

The study was conducted by Mridula Krishnan, MD, Nebraska Medicine Fred and Pamela Buffett Cancer Center, Omaha, Nebraska, and colleagues.

The team reviewed 257 patients who had been treated with either a programmed cell death protein–1 inhibitor or programmed cell death–ligand-1 inhibitor for a variety of advanced cancers. The drugs included pembrolizumab (Keytruda), nivolumab (Opdivo), atezolizumab (Tecentique), durvalumab (Imfinzi), and avelumab (Bavencio).

Most of the patients (71%) had good PS, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS of 0-1 on initiation of immunotherapy; 29% of patients had poor PS, with an ECOG PS of greater than or equal to 2.

“The primary outcome was OS stratified by ECOG PS 0-1 versus ≥2,” note the authors. Across all tumor types, OS was superior for patients in the ECOG 0-1 PS group, the investigators note. The median OS was 12.6 months, compared with only 3.1 months for patients in the ECOG greater than or equal to 2 group (P < .001).

Moreover, overall response rates for patients with a poor PS were low. Only 8%, or 6 of 75 patients with an ECOG PS of greater than or equal to 2, achieved an objective response by RECIST criteria.

This compared to an overall response rate of 23% for patients with an ECOG PS of 0-1, the investigators note (P = .005).

Interestingly, the hospice referral rate for patients with a poor PS (67%) was similar to that of patients with a PS of 1-2 (61.9%), Dr. Krishnan and colleagues observe.

Those with a poor PS were more like to die in-hospital (28.6%) than were patients with a good PS (15.1%; P = .035). The authors point out that it is well known that outcomes with chemotherapy are worse among patients who experience a decline in functional reserve, owing to increased susceptibility to toxicity and complications.

“Regardless of age, patients with ECOG PS >2 usually have poor tolerability to chemotherapy, and this correlates with worse survival outcome,” they emphasize. There is as yet no clear guidance regarding the impact of PS on ICI treatment response, although “there should be,” Dr. Luke believes.

“In a patient with declining performance status, especially ECOG PS 3-4 but potentially 2 as well, there is little likelihood that the functional and immune reserve of the patient will be adequate to mount a robust antitumor response,” he elaborated.

“It’s not impossible, but trying for it should not come at the expense of engaging about end-of-life care and maximizing the palliative opportunities that many only have a short window of time in which to pursue,” he added.

Again, Dr. Luke strongly believes that just giving an ICI without engaging in a frank conversation with the patient and their families – which happens all too often, he feels – is absolutely not the way to go when treating patients with a poor PS and little time left.

“Patients and families might be better served by having a more direct and frank conversation about what the likelihood [is] that ICI therapy will actually do,” Dr. Luke stressed.

In their editorial, Dr. Luke and colleagues write: “Overall, we as an oncology community need to improve our communication with patients regarding goals of care and end-of-life considerations as opposed to reflexive treatment initiation,” he writes.

“Our duty, first and foremost, should focus on the person sitting in front of us – taking a step back may be the best way to move forward with compassionate care,” they add.

The authors and editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New guidance on preventing cutaneous SCC in solid organ transplant patients

An expert panel of 48 dermatologists from 13 countries has developed recommendations to guide efforts aimed at preventing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) in solid organ transplant recipients.

The recommendations were published online on Sept. 1 in JAMA Dermatology.

Because of lifelong immunosuppression, solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs) have a risk of CSCC that is 20-200 times higher than in the general population and despite a growing literature on prevention of CSCC in these patients, uncertainty remains regarding best practices for various patient scenarios.

Paul Massey, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues used a Delphi process to identify consensus-based medical management recommendations for prevention of CSCC in SOTRs.

The survey design was guided by a novel actinic damage and skin cancer index (AD-SCI) made up of six ordinal stages corresponding to an increasing burden of actinic damage and CSCC.

The AD-SCI stage-based recommendations were established when consensus was reached (80% or higher concordance) or near consensus was reached (70%-80% concordance) among panel members.

For five of the six AD-SCI stages, the panel was able to make recommendations. Key recommendations include:

- Cryotherapy for scattered AK.

- Field therapy for AK when grouped in one site, unless AKs are thick, in which case field therapy and cryotherapy are recommended.

- Combination lesion-directed and field therapy with fluorouracil for field cancerized skin.

- Initiation of acitretin therapy and discussion of immunosuppression reduction or modification for patients who develop multiple CSCCs at a high rate (10 per year) or develop high-risk CSCC (defined by a tumor with roughly ≥20% risk of nodal metastasis). The panel did not make a recommendation as to the best immunosuppression modification strategy to pursue.

Lingering questions

The panel was unable to reach consensus on a recommendation for SOTRs with a first low-risk CSCC, reflecting “clinical equipoise” in this situation and the need for further study in this clinical scenario, they say.

The panel did not make a recommendation for use of nicotinamide or capecitabine in any of the six stages, which is “notable,” they acknowledge, given results of a double-blind randomized controlled trial in immunocompetent patients demonstrating benefit in preventing AKs and CSCCs, as reported previously.

Nearly three-quarters of the panel felt that a lack of efficacy data specifically for the SOTR population limited their use of nicotinamide. “Given the low cost, high safety, and demonstration of CSCC reduction in non-SOTRs, nicotinamide administration may be an area for further consideration and expanded study,” the panel wrote.

As for capecitabine, the panel notes that case series in SOTRs have found efficacy for chemoprevention, but randomized controlled studies are lacking. More than half of the panel noted that they did not have routine access to capecitabine in their practice.

The panel recommended routine skin surveillance and sunscreen use for all patients.

“These recommendations reflect consensus among expert transplant dermatologists and the incorporation of limited and sometimes contradictory evidence into real-world clinical experience across a range of CSCC disease severity,” the panel said.

“Areas of consensus may aid physicians in establishing best practices regarding prevention of CSCC in SOTRs in the setting of limited high level of evidence data in this population,” they added.

This research had no specific funding. Author disclosures included serving as a consultant to Regeneron, Sanofi, and receiving research funding from Castle Biosciences, Regeneron, Novartis, and Genentech. A complete list of disclosures for panel members is available with the original article.

An expert panel of 48 dermatologists from 13 countries has developed recommendations to guide efforts aimed at preventing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) in solid organ transplant recipients.

The recommendations were published online on Sept. 1 in JAMA Dermatology.

Because of lifelong immunosuppression, solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs) have a risk of CSCC that is 20-200 times higher than in the general population and despite a growing literature on prevention of CSCC in these patients, uncertainty remains regarding best practices for various patient scenarios.

Paul Massey, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues used a Delphi process to identify consensus-based medical management recommendations for prevention of CSCC in SOTRs.

The survey design was guided by a novel actinic damage and skin cancer index (AD-SCI) made up of six ordinal stages corresponding to an increasing burden of actinic damage and CSCC.

The AD-SCI stage-based recommendations were established when consensus was reached (80% or higher concordance) or near consensus was reached (70%-80% concordance) among panel members.

For five of the six AD-SCI stages, the panel was able to make recommendations. Key recommendations include:

- Cryotherapy for scattered AK.

- Field therapy for AK when grouped in one site, unless AKs are thick, in which case field therapy and cryotherapy are recommended.

- Combination lesion-directed and field therapy with fluorouracil for field cancerized skin.

- Initiation of acitretin therapy and discussion of immunosuppression reduction or modification for patients who develop multiple CSCCs at a high rate (10 per year) or develop high-risk CSCC (defined by a tumor with roughly ≥20% risk of nodal metastasis). The panel did not make a recommendation as to the best immunosuppression modification strategy to pursue.

Lingering questions

The panel was unable to reach consensus on a recommendation for SOTRs with a first low-risk CSCC, reflecting “clinical equipoise” in this situation and the need for further study in this clinical scenario, they say.

The panel did not make a recommendation for use of nicotinamide or capecitabine in any of the six stages, which is “notable,” they acknowledge, given results of a double-blind randomized controlled trial in immunocompetent patients demonstrating benefit in preventing AKs and CSCCs, as reported previously.

Nearly three-quarters of the panel felt that a lack of efficacy data specifically for the SOTR population limited their use of nicotinamide. “Given the low cost, high safety, and demonstration of CSCC reduction in non-SOTRs, nicotinamide administration may be an area for further consideration and expanded study,” the panel wrote.

As for capecitabine, the panel notes that case series in SOTRs have found efficacy for chemoprevention, but randomized controlled studies are lacking. More than half of the panel noted that they did not have routine access to capecitabine in their practice.

The panel recommended routine skin surveillance and sunscreen use for all patients.

“These recommendations reflect consensus among expert transplant dermatologists and the incorporation of limited and sometimes contradictory evidence into real-world clinical experience across a range of CSCC disease severity,” the panel said.

“Areas of consensus may aid physicians in establishing best practices regarding prevention of CSCC in SOTRs in the setting of limited high level of evidence data in this population,” they added.

This research had no specific funding. Author disclosures included serving as a consultant to Regeneron, Sanofi, and receiving research funding from Castle Biosciences, Regeneron, Novartis, and Genentech. A complete list of disclosures for panel members is available with the original article.

An expert panel of 48 dermatologists from 13 countries has developed recommendations to guide efforts aimed at preventing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) in solid organ transplant recipients.

The recommendations were published online on Sept. 1 in JAMA Dermatology.

Because of lifelong immunosuppression, solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs) have a risk of CSCC that is 20-200 times higher than in the general population and despite a growing literature on prevention of CSCC in these patients, uncertainty remains regarding best practices for various patient scenarios.

Paul Massey, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues used a Delphi process to identify consensus-based medical management recommendations for prevention of CSCC in SOTRs.

The survey design was guided by a novel actinic damage and skin cancer index (AD-SCI) made up of six ordinal stages corresponding to an increasing burden of actinic damage and CSCC.

The AD-SCI stage-based recommendations were established when consensus was reached (80% or higher concordance) or near consensus was reached (70%-80% concordance) among panel members.

For five of the six AD-SCI stages, the panel was able to make recommendations. Key recommendations include:

- Cryotherapy for scattered AK.

- Field therapy for AK when grouped in one site, unless AKs are thick, in which case field therapy and cryotherapy are recommended.

- Combination lesion-directed and field therapy with fluorouracil for field cancerized skin.

- Initiation of acitretin therapy and discussion of immunosuppression reduction or modification for patients who develop multiple CSCCs at a high rate (10 per year) or develop high-risk CSCC (defined by a tumor with roughly ≥20% risk of nodal metastasis). The panel did not make a recommendation as to the best immunosuppression modification strategy to pursue.

Lingering questions

The panel was unable to reach consensus on a recommendation for SOTRs with a first low-risk CSCC, reflecting “clinical equipoise” in this situation and the need for further study in this clinical scenario, they say.

The panel did not make a recommendation for use of nicotinamide or capecitabine in any of the six stages, which is “notable,” they acknowledge, given results of a double-blind randomized controlled trial in immunocompetent patients demonstrating benefit in preventing AKs and CSCCs, as reported previously.

Nearly three-quarters of the panel felt that a lack of efficacy data specifically for the SOTR population limited their use of nicotinamide. “Given the low cost, high safety, and demonstration of CSCC reduction in non-SOTRs, nicotinamide administration may be an area for further consideration and expanded study,” the panel wrote.

As for capecitabine, the panel notes that case series in SOTRs have found efficacy for chemoprevention, but randomized controlled studies are lacking. More than half of the panel noted that they did not have routine access to capecitabine in their practice.

The panel recommended routine skin surveillance and sunscreen use for all patients.

“These recommendations reflect consensus among expert transplant dermatologists and the incorporation of limited and sometimes contradictory evidence into real-world clinical experience across a range of CSCC disease severity,” the panel said.

“Areas of consensus may aid physicians in establishing best practices regarding prevention of CSCC in SOTRs in the setting of limited high level of evidence data in this population,” they added.

This research had no specific funding. Author disclosures included serving as a consultant to Regeneron, Sanofi, and receiving research funding from Castle Biosciences, Regeneron, Novartis, and Genentech. A complete list of disclosures for panel members is available with the original article.

Verrucous Carcinoma in a Wounded Military Amputee

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

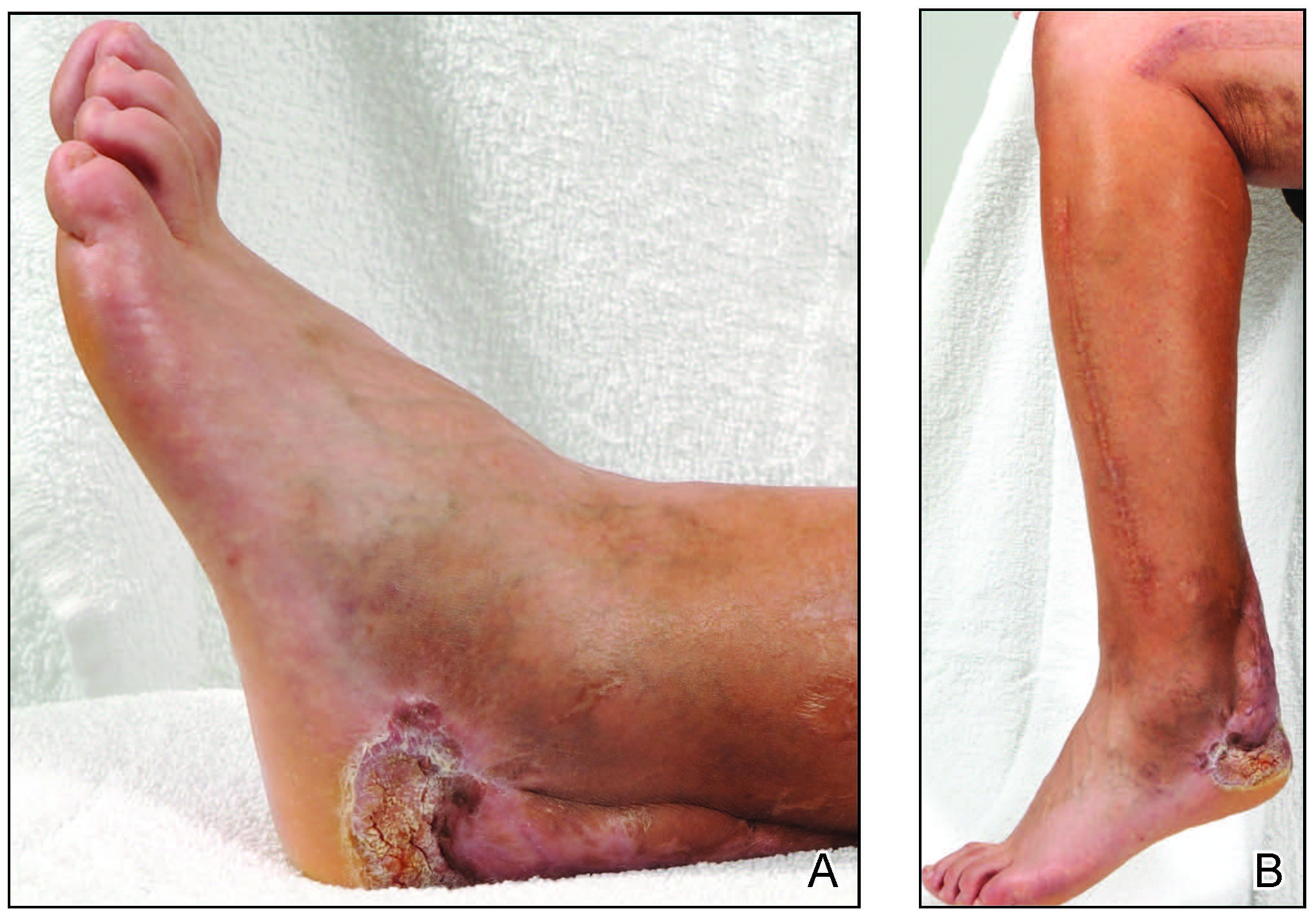

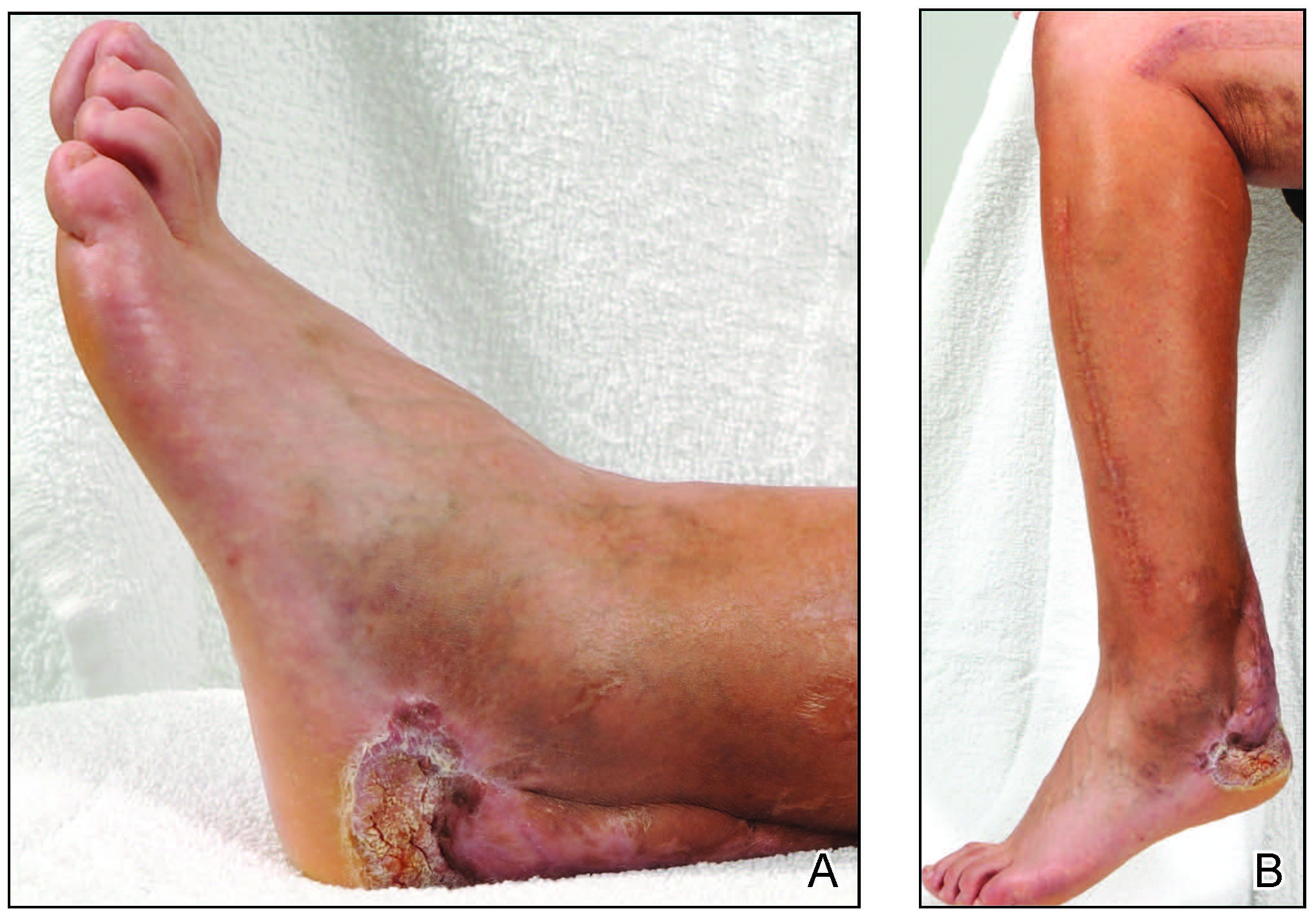

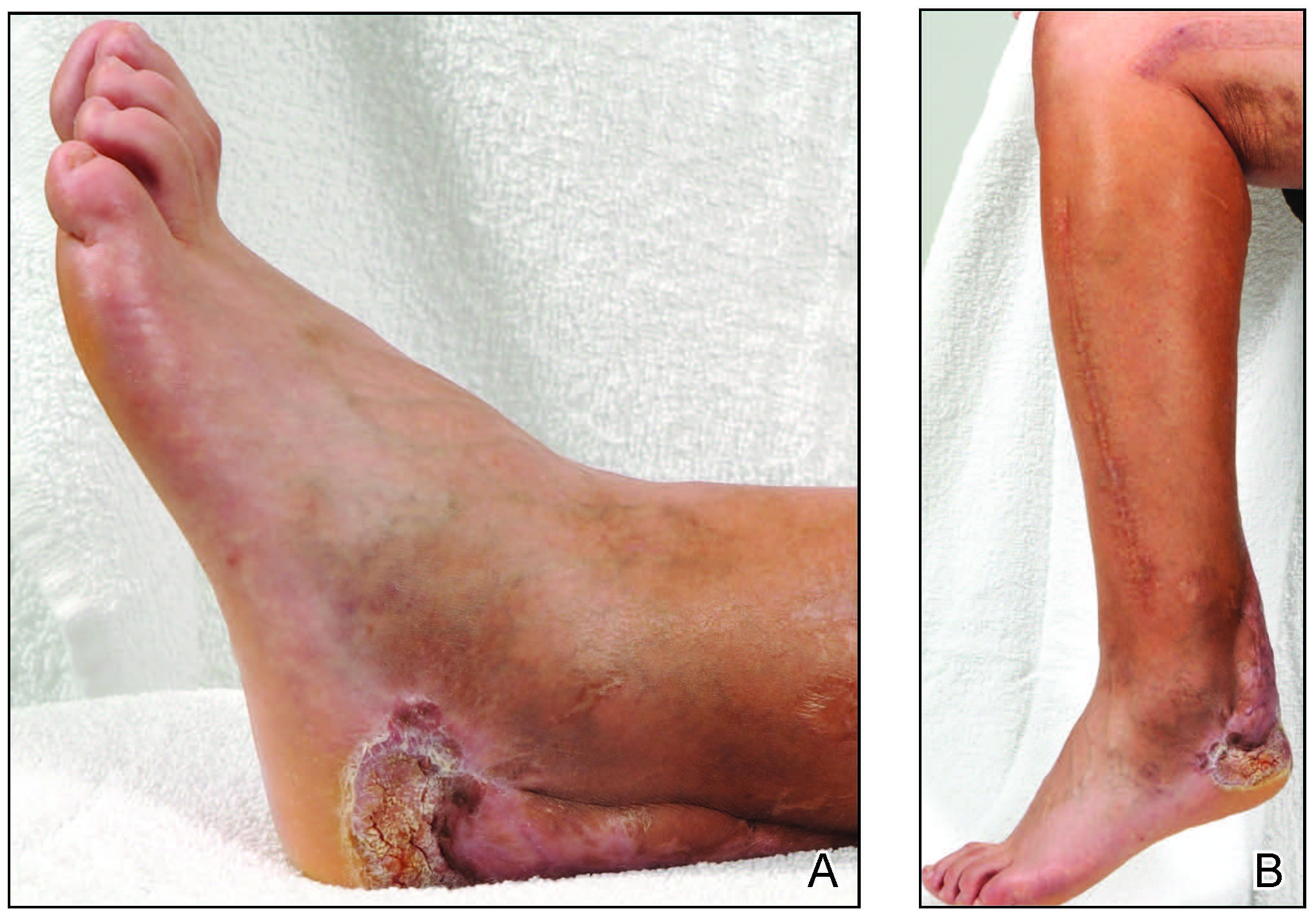

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma first described by Ackerman in 1948.1 There are 4 main clinicopathologic types: oral florid papillomatosis or Ackerman tumor, giant condyloma acuminatum or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, plantar verrucous carcinoma, and cutaneous verrucous carcinoma.2,3 Historically, most patients are older white men. The lesion commonly occurs in sites of inflammation4 or chronic irritation/trauma. Clinically, patients present with a slowly enlarging, exophytic, verrucous plaque violating the skin, fascia, and occasionally bone. Although these lesions have little tendency to metastasize, substantial morbidity can be seen due to local invasion. Despite surgical excision, recurrence is not uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis and higher infiltrative potential.5

A 45-year-old male veteran initially presented to our dermatology clinic with a 4-cm, macerated, verrucous plaque on the left lateral ankle in the area of a skin graft placed during a prior limb salvage surgery (Figure 1). The patient experienced a traumatic blast injury while deployed 7 years prior with a subsequent right-sided below-the-knee amputation and left lower limb salvage. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as verruca vulgaris and treated with daily salicylic acid. Six weeks after the initial presentation, the lesion remained largely unchanged. A biopsy subsequently was obtained to confirm the diagnosis. At that time, the histopathology was consistent with verruca vulgaris without evidence of carcinoma. Due to the persistence of the lesion, lack of improvement with topical treatment, and overall size, the patient opted for surgical excision.

A year later, the lesion was excised again by orthopedic surgery, and the tissue was submitted for histopathologic evaluation, which was suggestive of a verrucous neoplasm with some disagreement on whether it was consistent with verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. Following excision, the patient sustained a nonhealing chronic ulcer that required wound care for a total of 6 months. The lesion recurred a year later and was surgically excised a third time. A split-thickness skin graft was utilized to repair the defect. Histopathology again was consistent with verrucous carcinoma. With a fourth and final recurrence of the verrucous plaque 6 months later, the patient elected to undergo a left-sided below-the-knee amputation.

Verrucous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic dilemma, as histologic sections may mimic benign entities. The features of a well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis can be mistaken for verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,6 which are characteristic of verrucous hyperplasia. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult with a superficial biopsy because of the mature appearance of the epithelium,7 prompting the need for multiple and deeper biopsies8 to include sampling of the base of the hyperplastic epithelium in which the characteristic bulbous pushing growth pattern of the rete ridges is visualized. Precise histologic diagnosis can be further confounded by external mechanical factors, such as pressure, which can distort the classic histopathology.7 The histopathologic features leading to the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma in our specimen were minimal squamous atypia present in a predominantly exophytic squamous proliferation with human papillomavirus cytopathic effect and focal endophytic pushing borders by rounded bulbous rete ridges into the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Diagnostic uncertainty can delay surgical excision and lead to progression of verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, even with appropriate surgical intervention, recurrence has been documented; therefore, close clinical follow-up is recommended. The tumor spreads by local invasion and may follow the path of least resistance.4 In our patient, the frequent tissue manipulation may have facilitated aggressive infiltration of the tumor, ultimately resulting in the loss of his remaining leg. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that verrucous carcinoma, especially one that develops on a refractory ulcer or scar tissue, may be a complex malignant neoplasm that requires extensive treatment at onset to prevent the amputation of a limb.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Yoshitasu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Schwartz R. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-14.

- Bernstein SC, Lim KK, Brodland DG, et al. The many faces of squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:243-254.

- Costache M, Tatiana D, Mitrache L, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Shenoy A, Waghmare R, Kavishwar V, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan P. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol.1980;7:88-98.

- Pleat J, Sacks L, Rigby H. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:554-555.

Practice Points

- Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, locally aggressive squamous cell carcinoma that commonly occurs in sites of inflammation or chronic irritation.

- Histologically, verrucous carcinoma can be mistaken for other entities including verruca vulgaris, keratoacanthoma, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, often delaying the appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Medical students lead event addressing disparity in skin cancer morbidity and mortality

WASHINGTON – Those who self-identify as Hispanic or Black have a lower self-perceived risk of melanoma. In fact, people of color receive little to no information concerning skin cancer risks and prevention strategies and experience a longer time from diagnosis to definitive surgery, resulting in far worse outcomes, compared with non-Hispanic Whites.

This disparity is reflected in statistics showing that the average 5-year survival rate for melanoma is 92% in White patients but drops down to 67% in Black patients. Low income is also a contributing factor: Patients with lower incomes experience greater difficulty accessing health care and have greater time to diagnosis and a worse prognosis and survival time with melanoma. Despite economic advancements, Black Americans are still economically deprived when compared with White Americans.

This reality is what led Sarah Millan, a 4th-year medical student at George Washington University, Washington, to focus on the Ward 8 community in Washington – one of the poorest regions in our nation’s capital – well known for limited access to medical care and referred to as a health care desert. “Ward 8 has a population that is 92% Black and does not have a single dermatology clinic in the vicinity – my vision was to bring together the community through an enjoyable attraction conducive to the delivery of quality dermatologic care and education to a community that has none,” said Ms. Millan.

This low-resource population that is socioeconomically and geographically isolated is likely unaware of skin cancer risks, prevention strategies, and signs or symptoms that would warrant a visit to the dermatologist.

, while also exploring the attitudes and behaviors around skin cancer and sunscreen use in the community through data collected from optional surveys.

On Saturday, July 10, 2021, dermatologists from George Washington University, department of dermatology and medical students from George Washington School of Medicine and Health Sciences and Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, transformed Martha’s Outfitters in Ward 8 into a decorated, music-filled venue. Part of the Ward 8 council member’s 40 Days of Peace initiative, the Learn2Derm fair provided free skin cancer screenings by dermatologists, while students staffed various stations, delivering fun and interactive educational lessons organized by Ms. Millan under the mentorship of Adam Friedman, MD, chair of dermatology at George Washington University.

“It is our responsibility to support our communities through care, but even more importantly, combating misinformation and misperceptions that could interfere with healthy living,” said Dr. Friedman.

Activities included arts and crafts sponsored by the American Academy of Dermatology Good Skin Knowledge lessons, games with giveaways sponsored by the Polka Dot Mama Melanoma Foundation and IMPACT Melanoma, Skin Analyzers (to see where sunscreen was applied, and where it was missed) supplied by the Melanoma Research Foundation (MRF) and Children’s Melanoma Prevention Foundation (CMPF), and even Viva Vita virtual reality headsets that are catered towards the senior population – but enjoyable to anyone. Prizes and giveaways ranged from ultraviolet-induced color-changing bracelets and Frisbees, SPF lip balms, sunglasses – and of course – an abundant supply of free sunscreen. Many community members expressed their gratitude for this event and were impressed by the education that was enlivened through interactive games, activities, and giveaways. One participant shared the news of the event with a friend who immediately stopped what she was doing to come by for some education, a skin cancer screening, and free skincare products. While parents went in for a free skin cancer screening, their children were supervised by medical student volunteers as they colored or participated in other stations.

Ms. Millan’s involvement with the National Council on Skin Cancer Prevention’s Skin Smart Campus Initiative facilitated the support and partnership with multiple national organizations central to the event’s success, including the AAD, the National Council on Skin Cancer Prevention, the Skin Cancer Foundation, IMPACT Melanoma, Polka Dot Mama Melanoma Foundation, MRF, and CMPF. The donations of these organizations and businesses in the sun protection industry, along with faculty and medical students who share a passion for delivering dermatologic care and resources brought this exciting plan into fruition. The aim of Learn2Derm is not for this to be a single event, but rather the first of many that will continue to deliver this type of care to a community that is in need of greater dermatologic attention – an ongoing occurrence that can have a lasting impact on the Ward 8 community.

Major sunscreen manufacturers that donated sunscreen for this event included Avène, Black Girl Sunscreen, CeraVe, Cetaphil, EltaMD, and Neutrogena. Coolibar, which specializes in sun-protective clothing, also made a donation of multistyle hats, gaiters, and clothes for attendees.

References

1: Harvey VM et al. Cancer Control. 2014 Oct;21(4):343-9.

2: Tripathi R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep;83(3):854-9.

3. Beyer Don. “The Economic State of Black America in 2020” U.S. Congress: Joint Economic Committee.

4. Culp MaryBeth B and Lunsford Natasha Buchanan. “Melanoma Among Non-Hispanic Black Americans” Prev Chronic Dis;16. 2019 Jun 20. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180640.

5. “Ask the Expert: Is There a Skin Cancer Crisis in People of Color?” The Skin Cancer Foundation. 2020 Jul 5.

6. Salvaggio C et al. Oncology. 2016;90(2):79-87.

WASHINGTON – Those who self-identify as Hispanic or Black have a lower self-perceived risk of melanoma. In fact, people of color receive little to no information concerning skin cancer risks and prevention strategies and experience a longer time from diagnosis to definitive surgery, resulting in far worse outcomes, compared with non-Hispanic Whites.