User login

VTE, sepsis risk increased among COVID-19 patients with cancer

, according to data from a registry study.

Researchers analyzed data on 5,556 patients with COVID-19 who had an inpatient or emergency encounter at Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) in New York between March 1 and May 27, 2020. Patients were included in an anonymous MSHS COVID-19 registry.

There were 421 patients who had cancer: 96 with a hematologic malignancy and 325 with solid tumors.

After adjustment for age, gender, and number of comorbidities, the odds ratios for acute VTE and sepsis for patients with cancer (versus those without cancer) were 1.77 and 1.34, respectively. The adjusted odds ratio for mortality in cancer patients was 1.02.

The results remained “relatively consistent” after stratification by solid and nonsolid cancer types, with no significant difference in outcomes between those two groups, and results remained consistent in a propensity-matched model, according to Naomi Alpert, a biostatistician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Ms. Alpert reported these findings at the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer.

She noted that the cancer patients were older than the noncancer patients (mean age, 69.2 years vs. 63.8 years), and cancer patients were more likely to have two or more comorbid conditions (48.2% vs. 30.4%). Cancer patients also had significantly lower hemoglobin levels and red blood cell, platelet, and white blood cell counts (P < .01 for all).

“Low white blood cell count may be one of the reasons for higher risk of sepsis in cancer patients, as it may lead to a higher risk of infection,” Ms. Alpert said. “However, it’s not clear what role cancer therapies play in the risks of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, so there is still quite a bit to learn.”

In fact, the findings are limited by a lack of information about cancer treatment, as the registry was not designed for that purpose, she noted.

Another study limitation is the short follow-up of a month or less in most patients, due, in part, to the novelty of COVID-19, but also to the lack of information on patients after they left the hospital.

“However, we had a very large sample size, with more than 400 cancer patients included, and, to our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of its kind to be done so far,” Ms. Alpert said. “In the future, it’s going to be very important to assess the effect of cancer therapies on COVID-19 complications and to see if prior therapies had any effect on outcomes.”

Longer follow-up would also be helpful for assessing the chronic effects of COVID-19 on cancer patients over time, she said. “It would be important to see whether some of these elevated risks of venous thromboembolism and sepsis are associated with longer-term mortality risks than what we were able to measure here,” she added.

Asked about the discrepancy between mortality in this study and those of larger registries, such as the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) and TERAVOLT, Ms. Alpert noted that the current study included only patients who required hospitalization or emergency care.

“Our mortality rate was actually a bit higher than what was reported in some of the other studies,” she said. “We had about a 30% mortality rate in the cancer patients and about 25% for the noncancer patients, so ... we’re sort of looking at a subset of patients who we know are the sickest of the sick, which may explain some of the higher mortality that we’re seeing.”

Ms. Alpert reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Alpert N et al. AACR COVID-19 and Cancer, Abstract S12-02.

, according to data from a registry study.

Researchers analyzed data on 5,556 patients with COVID-19 who had an inpatient or emergency encounter at Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) in New York between March 1 and May 27, 2020. Patients were included in an anonymous MSHS COVID-19 registry.

There were 421 patients who had cancer: 96 with a hematologic malignancy and 325 with solid tumors.

After adjustment for age, gender, and number of comorbidities, the odds ratios for acute VTE and sepsis for patients with cancer (versus those without cancer) were 1.77 and 1.34, respectively. The adjusted odds ratio for mortality in cancer patients was 1.02.

The results remained “relatively consistent” after stratification by solid and nonsolid cancer types, with no significant difference in outcomes between those two groups, and results remained consistent in a propensity-matched model, according to Naomi Alpert, a biostatistician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Ms. Alpert reported these findings at the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer.

She noted that the cancer patients were older than the noncancer patients (mean age, 69.2 years vs. 63.8 years), and cancer patients were more likely to have two or more comorbid conditions (48.2% vs. 30.4%). Cancer patients also had significantly lower hemoglobin levels and red blood cell, platelet, and white blood cell counts (P < .01 for all).

“Low white blood cell count may be one of the reasons for higher risk of sepsis in cancer patients, as it may lead to a higher risk of infection,” Ms. Alpert said. “However, it’s not clear what role cancer therapies play in the risks of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, so there is still quite a bit to learn.”

In fact, the findings are limited by a lack of information about cancer treatment, as the registry was not designed for that purpose, she noted.

Another study limitation is the short follow-up of a month or less in most patients, due, in part, to the novelty of COVID-19, but also to the lack of information on patients after they left the hospital.

“However, we had a very large sample size, with more than 400 cancer patients included, and, to our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of its kind to be done so far,” Ms. Alpert said. “In the future, it’s going to be very important to assess the effect of cancer therapies on COVID-19 complications and to see if prior therapies had any effect on outcomes.”

Longer follow-up would also be helpful for assessing the chronic effects of COVID-19 on cancer patients over time, she said. “It would be important to see whether some of these elevated risks of venous thromboembolism and sepsis are associated with longer-term mortality risks than what we were able to measure here,” she added.

Asked about the discrepancy between mortality in this study and those of larger registries, such as the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) and TERAVOLT, Ms. Alpert noted that the current study included only patients who required hospitalization or emergency care.

“Our mortality rate was actually a bit higher than what was reported in some of the other studies,” she said. “We had about a 30% mortality rate in the cancer patients and about 25% for the noncancer patients, so ... we’re sort of looking at a subset of patients who we know are the sickest of the sick, which may explain some of the higher mortality that we’re seeing.”

Ms. Alpert reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Alpert N et al. AACR COVID-19 and Cancer, Abstract S12-02.

, according to data from a registry study.

Researchers analyzed data on 5,556 patients with COVID-19 who had an inpatient or emergency encounter at Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) in New York between March 1 and May 27, 2020. Patients were included in an anonymous MSHS COVID-19 registry.

There were 421 patients who had cancer: 96 with a hematologic malignancy and 325 with solid tumors.

After adjustment for age, gender, and number of comorbidities, the odds ratios for acute VTE and sepsis for patients with cancer (versus those without cancer) were 1.77 and 1.34, respectively. The adjusted odds ratio for mortality in cancer patients was 1.02.

The results remained “relatively consistent” after stratification by solid and nonsolid cancer types, with no significant difference in outcomes between those two groups, and results remained consistent in a propensity-matched model, according to Naomi Alpert, a biostatistician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Ms. Alpert reported these findings at the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer.

She noted that the cancer patients were older than the noncancer patients (mean age, 69.2 years vs. 63.8 years), and cancer patients were more likely to have two or more comorbid conditions (48.2% vs. 30.4%). Cancer patients also had significantly lower hemoglobin levels and red blood cell, platelet, and white blood cell counts (P < .01 for all).

“Low white blood cell count may be one of the reasons for higher risk of sepsis in cancer patients, as it may lead to a higher risk of infection,” Ms. Alpert said. “However, it’s not clear what role cancer therapies play in the risks of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, so there is still quite a bit to learn.”

In fact, the findings are limited by a lack of information about cancer treatment, as the registry was not designed for that purpose, she noted.

Another study limitation is the short follow-up of a month or less in most patients, due, in part, to the novelty of COVID-19, but also to the lack of information on patients after they left the hospital.

“However, we had a very large sample size, with more than 400 cancer patients included, and, to our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of its kind to be done so far,” Ms. Alpert said. “In the future, it’s going to be very important to assess the effect of cancer therapies on COVID-19 complications and to see if prior therapies had any effect on outcomes.”

Longer follow-up would also be helpful for assessing the chronic effects of COVID-19 on cancer patients over time, she said. “It would be important to see whether some of these elevated risks of venous thromboembolism and sepsis are associated with longer-term mortality risks than what we were able to measure here,” she added.

Asked about the discrepancy between mortality in this study and those of larger registries, such as the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) and TERAVOLT, Ms. Alpert noted that the current study included only patients who required hospitalization or emergency care.

“Our mortality rate was actually a bit higher than what was reported in some of the other studies,” she said. “We had about a 30% mortality rate in the cancer patients and about 25% for the noncancer patients, so ... we’re sort of looking at a subset of patients who we know are the sickest of the sick, which may explain some of the higher mortality that we’re seeing.”

Ms. Alpert reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Alpert N et al. AACR COVID-19 and Cancer, Abstract S12-02.

FROM AACR: COVID-19 AND CANCER

Field Cancerization With Multiple Keratoacanthomas Successfully Treated With Topical and Intralesional 5-Fluorouracil

To the Editor:

The concept of field cancerization has been well described since its initial proposal by Slaughter et al1 in 1953. It describes a field of genetically altered cells where multiple clonally related neoplasms can develop.2,3 Treatment of patients with multiple neoplasms within an area of field cancerization can be especially challenging. We report a patient with field cancerization who had multiple squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas (KAs) that arose within the field.

A 78-year-old man initially presented with a papule on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration. He had a medical history of cutaneous SCC, myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout, and diverticulosis. He was not taking any chronic immunosuppressants that may have predisposed him to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer. The papule was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated invasive SCC. A month later it was excised with clear margins.

Approximately 5 weeks after the excision, he returned with an enlarging lesion on the right forearm just medial to the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Two months later the lesion was excised with clear margins. Four weeks later he returned with a new lesion adjacent to the medial aspect of the prior excision. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Four weeks later the lesion was excised with clear margins.

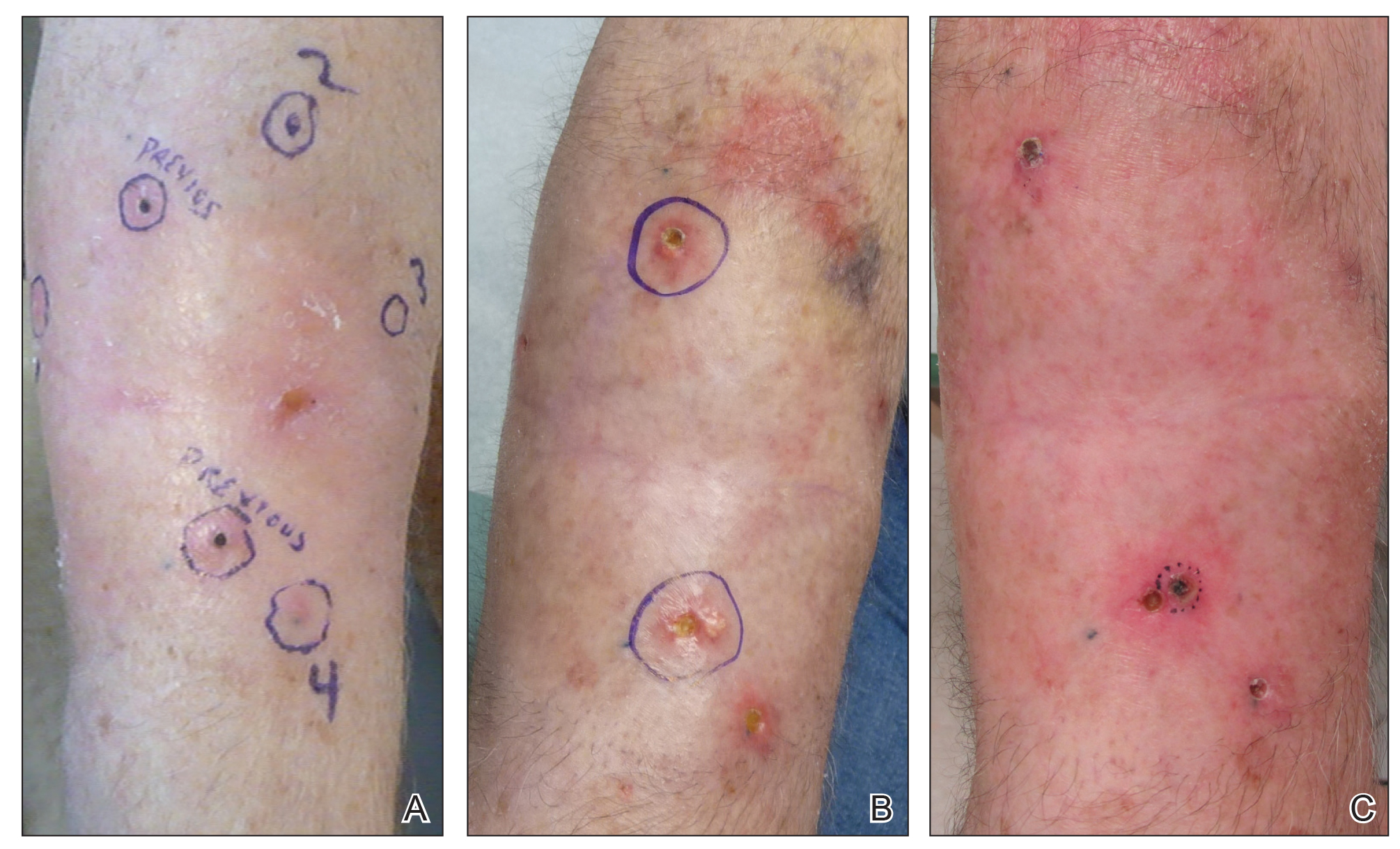

Another 4 weeks later the patient returned with a new lesion on the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. The lesion was treated with radiotherapy, with a 5800-cGy course completed 2 months later. The next month, 2 papules just adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC, KA type. One week later, 2 additional new papules adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as moderately differentiated SCC, KA type. At this time, the patient had 4 biopsy-proven KAs on the right forearm in the area of prior radiation (Figure, A). The radiation oncologist felt that further radiation was no longer indicated. A consultation was sought with surgical oncology, and wide excision of the field with sentinel lymph node biopsy and skin grafting was recommended. Computed tomography with contrast of the chest and right arm ordered by surgical oncology did not reveal metastatic disease.

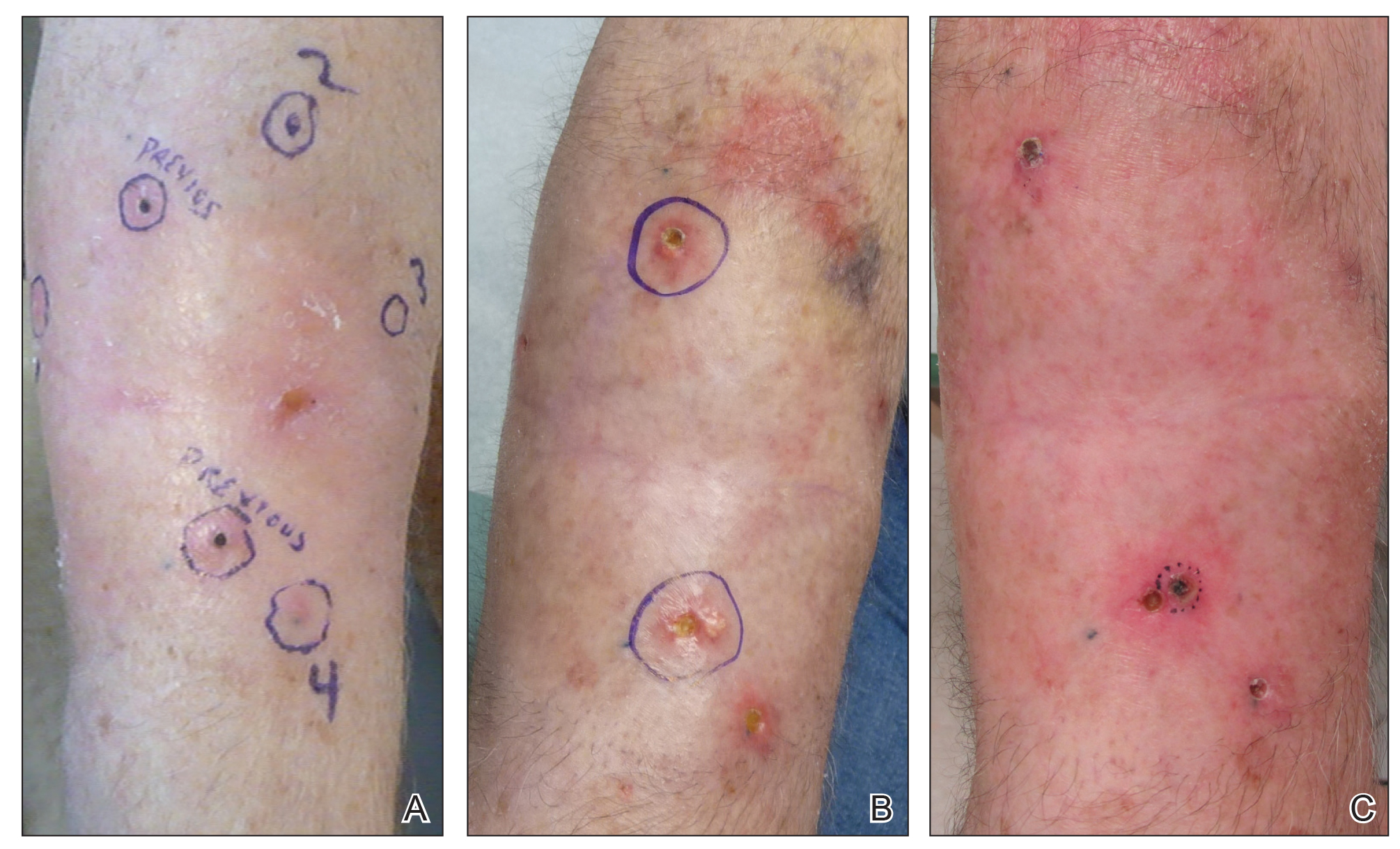

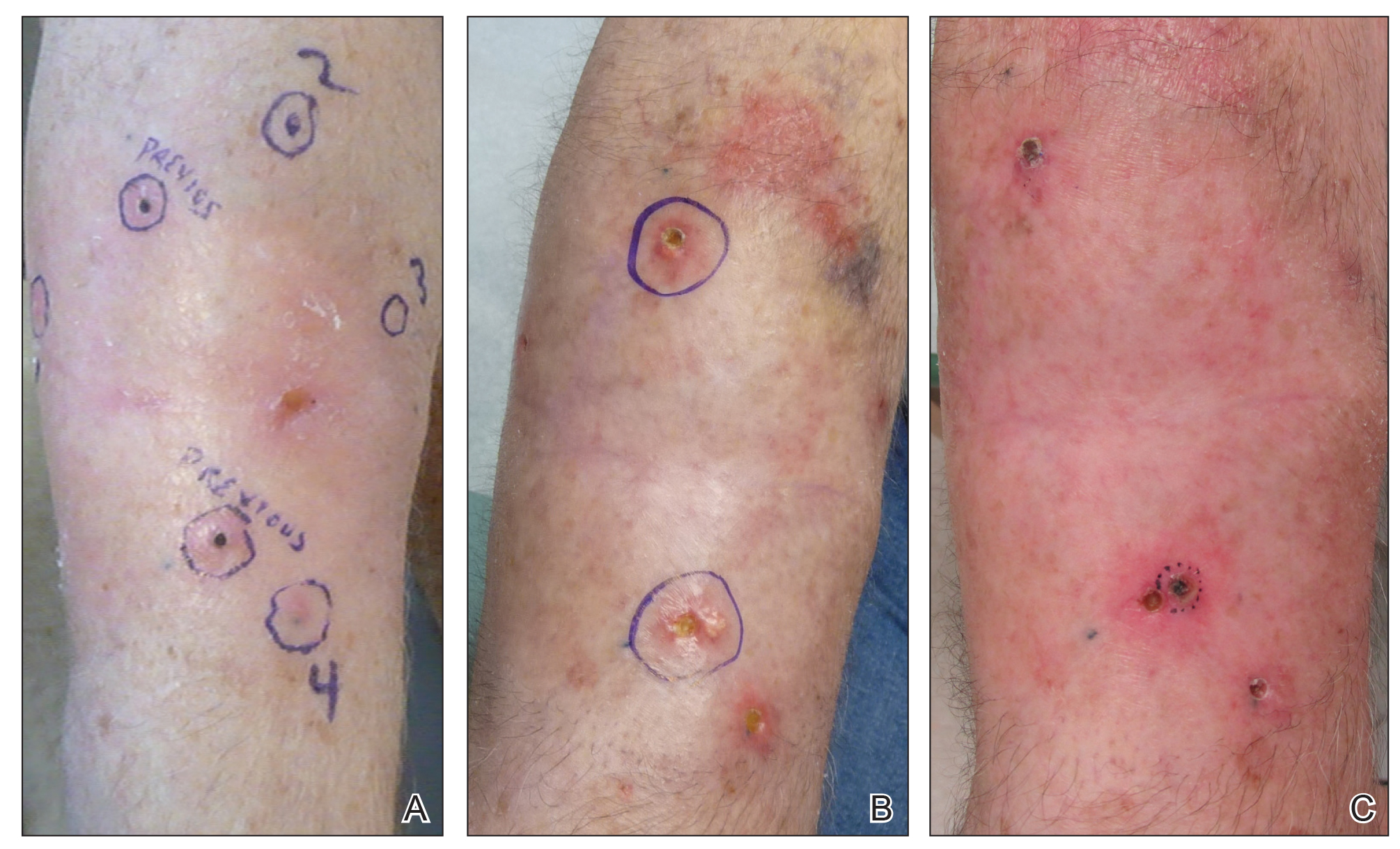

After discussion of the risks, alternatives, and benefits of surgery, the patient elected to try nonsurgical treatment. He was treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream 5% twice daily for 4 weeks. It was applied to the right arm from the elbow to the wrist and occluded under an elastic bandage. The patient stated that the biopsy sites became sore and inflamed during the treatment. After 4 weeks of treatment, all 4 KAs had healed without clinical evidence of tumor. During this time, however, the previously treated 2 sites had developed adjacent firm pink papules (Figure, B); these 2 lesions were then treated with intralesional 5-FU 50 mg/mL once weekly to resolution at 4 and 5 weeks, respectively. The proximal lesion was treated with 7.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, and 4. The larger distal lesion was treated with 12.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. The volume injected was determined by ability to blanch and indurate the lesion and was decreased due to the shrinking size of the tumor. After 3 injections, both tumors had substantially decreased in size (Figure, C). The patient noted pain during injection but found the procedure tolerable and preferable to surgery. There were no other adverse events. At the end of treatment, both tumors had clinically resolved. No recurrence or development of new tumors was reported over 3 years of follow-up after the last injection.

Field cancerization was the outgrowth of the study of oral SCC in an effort to explain the development of multiple primary tumors and locally recurrent cancer.1,2 Histopathologically, the authors observed that oral cancer developed in multifocal areas of precancerous change, histologically abnormal hyperplastic tissue surrounded the tumors, oral cancer consisted of multiple independent areas that sometimes coalesced, and the persistence of abnormal tissue after surgery might explain local recurrences and the development of new lesions in a previously treated area.1,2 Since then, the concept has been applied to several other organ systems including the lungs, vulva, cervix, breasts, bladder, colon, and skin.2

In the skin, field cancerization involves clusters and contiguous patches of altered cells present in areas of chronic photodamage.2 Genetically altered fields form the foundation in which multiple clonally related neoplastic lesions can develop.2,3 These fields often remain after treatment of the primary tumor and may lead to new cancers that commonly are labeled as a second primary tumor or a local recurrence depending on the exact site and time interval.3 Brennan et al3 found clonal populations of infiltrating tumor cells harboring a p53 gene mutation in more than 50% of histopathologically negative surgical margins of patients with SCC of the head and neck. Furthermore, 40% of the patients with a margin positive for a p53 gene mutation had local recurrence vs none of the patients with negative margins.4 These findings were supported by several other studies where loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite alterations, chromosomal instability, or in situ hybridization was used to demonstrate genetically altered fields.2,4 Histopathologic patterns of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, and pronounced acantholysis as found in Hailey-Hailey disease may be a consequence of clonal expansion of mutated keratinocytes because of long-term exposure to mutagens such as UV light and human papillomavirus.5

The development of an expanding neoplastic field appears to play an important role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. It is necessary to consider the cutaneous field cancerization as a highly photodamaged area that contains clinical and subclinical lesions.2-4 The treatment of cutaneous neoplasms, SCC in particular, should focus not only on the tumor itself but also on the surrounding tissue. Adjunctive field-directed therapies should be considered after treatment of the primary tumor.4

Our patient continued to develop SCCs on the right forearm after multiple excisions with clear margins and subsequently was treated with radiation therapy. He then developed 4 KAs after radiation therapy to the right forearm. Topical 5-FU is a well-described treatment of field cancerization.2 In our patient, 5-FU cream 5% applied twice daily from the wrist to the elbow under occlusion for 4 weeks led to the involution of all 4 KAs. During this time, our patient developed 2 additional firm pink papules near the previously treated sites, which resolved with intralesional 5-FU weekly for 4 and 5 weeks, respectively.

Intralesional 5-FU has been described for the treatment of multiple and difficult-to-treat KAs. It is an antimetabolite and structural analog of uracil that disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis. It is contraindicated in liver disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and allergy to the medication.6 Intralesional 5-FU dosing recommendations for KAs include use of a 50-mg/mL solution and injecting 0.1 to 1 mL until the lesion blanches in color, which may be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks.7,8 The maximum recommended daily dose is 800 mg.6 Pretreatment with intralesional 1% lidocaine has been recommended by some authors due to pain with injection.8 Recommendations for laboratory monitoring include a complete blood cell count with differential at baseline and weekly. Side effects include local pain, erythema, crusting, ulceration, and necrosis. Systemic side effects include cytopenia and gastrointestinal tract upset.6 Intralesional 5-FU has been used successfully in a single dose of 10 mg per lesion in combination with systemic acitretin for the treatment of multiple KAs induced by vemurafenib.9 It also has been effective in the treatment of multiple recurrent reactive KAs developing in surgical margins.7 A review article reported that the use of intralesional 5-FU produced a 98% cure rate in 56 treated KAs.6 Alternative intralesional agents that may be considered for KAs include methotrexate, bleomycin, and interferon alfa-2b.6,7

Field cancerization may cause the development of multiple clonally related neoplasms within a field of genetically altered cells that may continue to develop after excision with clear margins or radiation therapy. Given the success of treatment in our patient, we recommend consideration for topical and intralesional 5-FU in patients who develop SCCs and KAs within an area of field cancerization.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. “Field cancerization” in oral stratified squamous epithelium. clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Torezan LA, Festa-Neto C. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban R, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braakhuis, BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Carlson AJ, Scott D, Wharton J, et al. Incidental histopathologic patterns: possible evidence of “field cancerization” surrounding skin tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:494-496.

- Kirby J, Miller C. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702.

- Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

- Que S, Compton L, Schmults C. Eruptive squamous atypia (also known as eruptive keratoacanthoma): definition of the disease entity and successful management via intralesional 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:111-122.

- LaPresto L, Cranmer L, Morrison L, et al. A novel therapeutic combination approach for treating multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas systemic acitretin and intralesional fluorouracil. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:279-281.

To the Editor:

The concept of field cancerization has been well described since its initial proposal by Slaughter et al1 in 1953. It describes a field of genetically altered cells where multiple clonally related neoplasms can develop.2,3 Treatment of patients with multiple neoplasms within an area of field cancerization can be especially challenging. We report a patient with field cancerization who had multiple squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas (KAs) that arose within the field.

A 78-year-old man initially presented with a papule on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration. He had a medical history of cutaneous SCC, myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout, and diverticulosis. He was not taking any chronic immunosuppressants that may have predisposed him to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer. The papule was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated invasive SCC. A month later it was excised with clear margins.

Approximately 5 weeks after the excision, he returned with an enlarging lesion on the right forearm just medial to the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Two months later the lesion was excised with clear margins. Four weeks later he returned with a new lesion adjacent to the medial aspect of the prior excision. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Four weeks later the lesion was excised with clear margins.

Another 4 weeks later the patient returned with a new lesion on the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. The lesion was treated with radiotherapy, with a 5800-cGy course completed 2 months later. The next month, 2 papules just adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC, KA type. One week later, 2 additional new papules adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as moderately differentiated SCC, KA type. At this time, the patient had 4 biopsy-proven KAs on the right forearm in the area of prior radiation (Figure, A). The radiation oncologist felt that further radiation was no longer indicated. A consultation was sought with surgical oncology, and wide excision of the field with sentinel lymph node biopsy and skin grafting was recommended. Computed tomography with contrast of the chest and right arm ordered by surgical oncology did not reveal metastatic disease.

After discussion of the risks, alternatives, and benefits of surgery, the patient elected to try nonsurgical treatment. He was treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream 5% twice daily for 4 weeks. It was applied to the right arm from the elbow to the wrist and occluded under an elastic bandage. The patient stated that the biopsy sites became sore and inflamed during the treatment. After 4 weeks of treatment, all 4 KAs had healed without clinical evidence of tumor. During this time, however, the previously treated 2 sites had developed adjacent firm pink papules (Figure, B); these 2 lesions were then treated with intralesional 5-FU 50 mg/mL once weekly to resolution at 4 and 5 weeks, respectively. The proximal lesion was treated with 7.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, and 4. The larger distal lesion was treated with 12.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. The volume injected was determined by ability to blanch and indurate the lesion and was decreased due to the shrinking size of the tumor. After 3 injections, both tumors had substantially decreased in size (Figure, C). The patient noted pain during injection but found the procedure tolerable and preferable to surgery. There were no other adverse events. At the end of treatment, both tumors had clinically resolved. No recurrence or development of new tumors was reported over 3 years of follow-up after the last injection.

Field cancerization was the outgrowth of the study of oral SCC in an effort to explain the development of multiple primary tumors and locally recurrent cancer.1,2 Histopathologically, the authors observed that oral cancer developed in multifocal areas of precancerous change, histologically abnormal hyperplastic tissue surrounded the tumors, oral cancer consisted of multiple independent areas that sometimes coalesced, and the persistence of abnormal tissue after surgery might explain local recurrences and the development of new lesions in a previously treated area.1,2 Since then, the concept has been applied to several other organ systems including the lungs, vulva, cervix, breasts, bladder, colon, and skin.2

In the skin, field cancerization involves clusters and contiguous patches of altered cells present in areas of chronic photodamage.2 Genetically altered fields form the foundation in which multiple clonally related neoplastic lesions can develop.2,3 These fields often remain after treatment of the primary tumor and may lead to new cancers that commonly are labeled as a second primary tumor or a local recurrence depending on the exact site and time interval.3 Brennan et al3 found clonal populations of infiltrating tumor cells harboring a p53 gene mutation in more than 50% of histopathologically negative surgical margins of patients with SCC of the head and neck. Furthermore, 40% of the patients with a margin positive for a p53 gene mutation had local recurrence vs none of the patients with negative margins.4 These findings were supported by several other studies where loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite alterations, chromosomal instability, or in situ hybridization was used to demonstrate genetically altered fields.2,4 Histopathologic patterns of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, and pronounced acantholysis as found in Hailey-Hailey disease may be a consequence of clonal expansion of mutated keratinocytes because of long-term exposure to mutagens such as UV light and human papillomavirus.5

The development of an expanding neoplastic field appears to play an important role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. It is necessary to consider the cutaneous field cancerization as a highly photodamaged area that contains clinical and subclinical lesions.2-4 The treatment of cutaneous neoplasms, SCC in particular, should focus not only on the tumor itself but also on the surrounding tissue. Adjunctive field-directed therapies should be considered after treatment of the primary tumor.4

Our patient continued to develop SCCs on the right forearm after multiple excisions with clear margins and subsequently was treated with radiation therapy. He then developed 4 KAs after radiation therapy to the right forearm. Topical 5-FU is a well-described treatment of field cancerization.2 In our patient, 5-FU cream 5% applied twice daily from the wrist to the elbow under occlusion for 4 weeks led to the involution of all 4 KAs. During this time, our patient developed 2 additional firm pink papules near the previously treated sites, which resolved with intralesional 5-FU weekly for 4 and 5 weeks, respectively.

Intralesional 5-FU has been described for the treatment of multiple and difficult-to-treat KAs. It is an antimetabolite and structural analog of uracil that disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis. It is contraindicated in liver disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and allergy to the medication.6 Intralesional 5-FU dosing recommendations for KAs include use of a 50-mg/mL solution and injecting 0.1 to 1 mL until the lesion blanches in color, which may be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks.7,8 The maximum recommended daily dose is 800 mg.6 Pretreatment with intralesional 1% lidocaine has been recommended by some authors due to pain with injection.8 Recommendations for laboratory monitoring include a complete blood cell count with differential at baseline and weekly. Side effects include local pain, erythema, crusting, ulceration, and necrosis. Systemic side effects include cytopenia and gastrointestinal tract upset.6 Intralesional 5-FU has been used successfully in a single dose of 10 mg per lesion in combination with systemic acitretin for the treatment of multiple KAs induced by vemurafenib.9 It also has been effective in the treatment of multiple recurrent reactive KAs developing in surgical margins.7 A review article reported that the use of intralesional 5-FU produced a 98% cure rate in 56 treated KAs.6 Alternative intralesional agents that may be considered for KAs include methotrexate, bleomycin, and interferon alfa-2b.6,7

Field cancerization may cause the development of multiple clonally related neoplasms within a field of genetically altered cells that may continue to develop after excision with clear margins or radiation therapy. Given the success of treatment in our patient, we recommend consideration for topical and intralesional 5-FU in patients who develop SCCs and KAs within an area of field cancerization.

To the Editor:

The concept of field cancerization has been well described since its initial proposal by Slaughter et al1 in 1953. It describes a field of genetically altered cells where multiple clonally related neoplasms can develop.2,3 Treatment of patients with multiple neoplasms within an area of field cancerization can be especially challenging. We report a patient with field cancerization who had multiple squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas (KAs) that arose within the field.

A 78-year-old man initially presented with a papule on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration. He had a medical history of cutaneous SCC, myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout, and diverticulosis. He was not taking any chronic immunosuppressants that may have predisposed him to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer. The papule was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated invasive SCC. A month later it was excised with clear margins.

Approximately 5 weeks after the excision, he returned with an enlarging lesion on the right forearm just medial to the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Two months later the lesion was excised with clear margins. Four weeks later he returned with a new lesion adjacent to the medial aspect of the prior excision. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Four weeks later the lesion was excised with clear margins.

Another 4 weeks later the patient returned with a new lesion on the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. The lesion was treated with radiotherapy, with a 5800-cGy course completed 2 months later. The next month, 2 papules just adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC, KA type. One week later, 2 additional new papules adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as moderately differentiated SCC, KA type. At this time, the patient had 4 biopsy-proven KAs on the right forearm in the area of prior radiation (Figure, A). The radiation oncologist felt that further radiation was no longer indicated. A consultation was sought with surgical oncology, and wide excision of the field with sentinel lymph node biopsy and skin grafting was recommended. Computed tomography with contrast of the chest and right arm ordered by surgical oncology did not reveal metastatic disease.

After discussion of the risks, alternatives, and benefits of surgery, the patient elected to try nonsurgical treatment. He was treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream 5% twice daily for 4 weeks. It was applied to the right arm from the elbow to the wrist and occluded under an elastic bandage. The patient stated that the biopsy sites became sore and inflamed during the treatment. After 4 weeks of treatment, all 4 KAs had healed without clinical evidence of tumor. During this time, however, the previously treated 2 sites had developed adjacent firm pink papules (Figure, B); these 2 lesions were then treated with intralesional 5-FU 50 mg/mL once weekly to resolution at 4 and 5 weeks, respectively. The proximal lesion was treated with 7.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, and 4. The larger distal lesion was treated with 12.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. The volume injected was determined by ability to blanch and indurate the lesion and was decreased due to the shrinking size of the tumor. After 3 injections, both tumors had substantially decreased in size (Figure, C). The patient noted pain during injection but found the procedure tolerable and preferable to surgery. There were no other adverse events. At the end of treatment, both tumors had clinically resolved. No recurrence or development of new tumors was reported over 3 years of follow-up after the last injection.

Field cancerization was the outgrowth of the study of oral SCC in an effort to explain the development of multiple primary tumors and locally recurrent cancer.1,2 Histopathologically, the authors observed that oral cancer developed in multifocal areas of precancerous change, histologically abnormal hyperplastic tissue surrounded the tumors, oral cancer consisted of multiple independent areas that sometimes coalesced, and the persistence of abnormal tissue after surgery might explain local recurrences and the development of new lesions in a previously treated area.1,2 Since then, the concept has been applied to several other organ systems including the lungs, vulva, cervix, breasts, bladder, colon, and skin.2

In the skin, field cancerization involves clusters and contiguous patches of altered cells present in areas of chronic photodamage.2 Genetically altered fields form the foundation in which multiple clonally related neoplastic lesions can develop.2,3 These fields often remain after treatment of the primary tumor and may lead to new cancers that commonly are labeled as a second primary tumor or a local recurrence depending on the exact site and time interval.3 Brennan et al3 found clonal populations of infiltrating tumor cells harboring a p53 gene mutation in more than 50% of histopathologically negative surgical margins of patients with SCC of the head and neck. Furthermore, 40% of the patients with a margin positive for a p53 gene mutation had local recurrence vs none of the patients with negative margins.4 These findings were supported by several other studies where loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite alterations, chromosomal instability, or in situ hybridization was used to demonstrate genetically altered fields.2,4 Histopathologic patterns of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, and pronounced acantholysis as found in Hailey-Hailey disease may be a consequence of clonal expansion of mutated keratinocytes because of long-term exposure to mutagens such as UV light and human papillomavirus.5

The development of an expanding neoplastic field appears to play an important role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. It is necessary to consider the cutaneous field cancerization as a highly photodamaged area that contains clinical and subclinical lesions.2-4 The treatment of cutaneous neoplasms, SCC in particular, should focus not only on the tumor itself but also on the surrounding tissue. Adjunctive field-directed therapies should be considered after treatment of the primary tumor.4

Our patient continued to develop SCCs on the right forearm after multiple excisions with clear margins and subsequently was treated with radiation therapy. He then developed 4 KAs after radiation therapy to the right forearm. Topical 5-FU is a well-described treatment of field cancerization.2 In our patient, 5-FU cream 5% applied twice daily from the wrist to the elbow under occlusion for 4 weeks led to the involution of all 4 KAs. During this time, our patient developed 2 additional firm pink papules near the previously treated sites, which resolved with intralesional 5-FU weekly for 4 and 5 weeks, respectively.

Intralesional 5-FU has been described for the treatment of multiple and difficult-to-treat KAs. It is an antimetabolite and structural analog of uracil that disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis. It is contraindicated in liver disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and allergy to the medication.6 Intralesional 5-FU dosing recommendations for KAs include use of a 50-mg/mL solution and injecting 0.1 to 1 mL until the lesion blanches in color, which may be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks.7,8 The maximum recommended daily dose is 800 mg.6 Pretreatment with intralesional 1% lidocaine has been recommended by some authors due to pain with injection.8 Recommendations for laboratory monitoring include a complete blood cell count with differential at baseline and weekly. Side effects include local pain, erythema, crusting, ulceration, and necrosis. Systemic side effects include cytopenia and gastrointestinal tract upset.6 Intralesional 5-FU has been used successfully in a single dose of 10 mg per lesion in combination with systemic acitretin for the treatment of multiple KAs induced by vemurafenib.9 It also has been effective in the treatment of multiple recurrent reactive KAs developing in surgical margins.7 A review article reported that the use of intralesional 5-FU produced a 98% cure rate in 56 treated KAs.6 Alternative intralesional agents that may be considered for KAs include methotrexate, bleomycin, and interferon alfa-2b.6,7

Field cancerization may cause the development of multiple clonally related neoplasms within a field of genetically altered cells that may continue to develop after excision with clear margins or radiation therapy. Given the success of treatment in our patient, we recommend consideration for topical and intralesional 5-FU in patients who develop SCCs and KAs within an area of field cancerization.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. “Field cancerization” in oral stratified squamous epithelium. clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Torezan LA, Festa-Neto C. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban R, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braakhuis, BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Carlson AJ, Scott D, Wharton J, et al. Incidental histopathologic patterns: possible evidence of “field cancerization” surrounding skin tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:494-496.

- Kirby J, Miller C. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702.

- Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

- Que S, Compton L, Schmults C. Eruptive squamous atypia (also known as eruptive keratoacanthoma): definition of the disease entity and successful management via intralesional 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:111-122.

- LaPresto L, Cranmer L, Morrison L, et al. A novel therapeutic combination approach for treating multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas systemic acitretin and intralesional fluorouracil. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:279-281.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. “Field cancerization” in oral stratified squamous epithelium. clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Torezan LA, Festa-Neto C. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban R, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braakhuis, BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Carlson AJ, Scott D, Wharton J, et al. Incidental histopathologic patterns: possible evidence of “field cancerization” surrounding skin tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:494-496.

- Kirby J, Miller C. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702.

- Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

- Que S, Compton L, Schmults C. Eruptive squamous atypia (also known as eruptive keratoacanthoma): definition of the disease entity and successful management via intralesional 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:111-122.

- LaPresto L, Cranmer L, Morrison L, et al. A novel therapeutic combination approach for treating multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas systemic acitretin and intralesional fluorouracil. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:279-281.

Aspirin may accelerate cancer progression in older adults

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

Large study finds no link between TCI use, skin cancer in patients with AD

The results also suggest dose, frequency, and exposure duration to the topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are not associated with an increased risk of keratinocyte carcinomas (KCs), basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), according to Maryam M. Asgari, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration announced the addition of the boxed warning to the labeling of TCIs regarding a possible risk of cancer associated with use of pimecrolimus (Elidel) and with tacrolimus (Protopic), because of an increased risk of KCs associated with oral calcineurin inhibitors and reports of skin cancer in patients on TCIs.

“Controversy has surrounded the association between TCI exposure and KC risk since the black-box warning was issued by the FDA. A hypothesized mechanism of action for TCIs increasing KC risk includes a direct effect of calcineurin inhibition on DNA repair and apoptosis, which could influence keratinocyte carcinogenesis,” the authors of the study wrote in JAMA Dermatology. But, they added, there have been “conflicting results” in research exploring this association.

In the retrospective cohort study, Dr. Asgari and coauthors evaluated 93,746 adult patients with AD at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, diagnosed between January 2002 and December 2013, comparing skin cancer risk among 7,033 patients exposed to TCIs, 73,674 patients taking topical corticosteroids, and 46,141 patients who had not been exposed to TCIs or topical corticosteroids. Results were adjusted in a multivariate Cox regression analysis for age, gender, race/ethnicity, calendar year, number of dermatology visits per year, history of KCs, immunosuppression, prior systemic AD treatment, autoimmune disease, treatment with ultraviolet therapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

The researchers also examined how TCI dose, frequency and exposure duration impacted skin cancer risk. Patients were grouped by high-dose (0.1%) and low-dose (0.03%) formulations of tacrolimus; and the 1% formulation of pimecrolimus. Frequency of use was defined as low (once daily or less) or high (twice daily or more), and exposure duration was based on short- (less than 2 years), moderate- (2-4 years), and long-term (4 years or more) use. Patients were at least 40 years old (mean age, 58.5 years), 58.7% were women, 50.5% were White, 20.6% were Asian, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 7.9% were Black. They were followed for a mean of 7.70 years.

Compared with patients who were exposed to topical corticosteroids, there was no association between risk of KCs and exposure to TCIs in patients with AD (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.13). There were also no significant differences in risk of BCCs and TCI exposure (aHR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.90-1.14) and risk of SCCs and TCI exposure (aHR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.82-1.08), compared with patients exposed to topical corticosteroids.

Results were similar for risk of KCs (aHR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.92-1.14), BCCs (aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.91-1.19), and SCCs (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.78-1.06) when patients exposed to TCIs were compared with those with AD who were unexposed to any medication. In secondary analyses, Dr. Asgari and coauthors found no association with overall risk of KCs, or risk of BCCs or SCCs, and the dose, frequency, or exposure duration to TCIs.

“Our findings appear to support those of smaller postmarketing surveillance studies of TCI and KC risk and may provide some reassurance about the safety profile of this class of topical agents in the treatment of AD,” they concluded.

In an interview, Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, said initial concerns surrounding TCIs were based on high doses potentially increasing the risk of malignancy, and off-label use of TCIs for inflammatory skin diseases other than AD.

“However, the FDA’s concerns may not have been justified,” he said. The manufacturers of pimecrolimus and tacrolimus have published results of 10-year observational registries that assess cancer risk, which “found no evidence of any associations between TCIs and malignancy,” noted Dr. Silverberg, who is also director of clinical research and contact dermatitis at George Washington University.

Elizabeth Hughes, MD, a dermatologist in private practice in San Antonio, said in an interview that initial enthusiasm was “huge” for use of TCIs like tacrolimus in patients with AD when they first became available, especially in the pediatric population, for whom clinicians are hesitant to use long-term strong topical steroids. However, parents of children taking the medication soon became concerned about potential side effects.

“The TCIs can be absorbed to a small extent through body surface area, so it was not a big leap to become concerned that infants and small children could absorb enough ... into the bloodstream to give a similar side effect profile as oral tacrolimus,” she said.

The addition of the boxed warning in 2006 was frustrating for dermatologists “because a medication we needed very much for a young population now was ‘labeled’ and parents were scared to use it,” Dr. Hughes explained.

Dr. Silverberg noted that, while the results of the new study are unlikely to change clinical practice, they are reassuring, and provide real-world data and “further confirmation of previous studies showing no associations between AD and malignancy.”

“Since AD and skin cancer are both commonly managed by dermatologists, there is potential for increased surveillance and detection of skin cancers in AD patients. So, the greatest chance of seeing a false-positive signal for malignancy would likely occur with skin cancers,” he pointed out. “Yet, even in the case of skin cancers, there were no demonstrable signals.”

Based on the results, “I think it is definitely reasonable to reconsider” the TCI boxed warning, but there isn’t much precedent for boxed warnings to be removed from labeling, Dr. Silverberg commented. “Unfortunately, the black-box warning may persist despite a lot of reassuring data.”

In a related editorial, Aaron M. Drucker, MD, ScM, and Mina Tadrous, PharmD, PhD, of the University of Toronto, said the boxed warning “had the intent of helping patients and clinicians understand possible risks,” but also carried the “potential for harm” if patients discontinued or did not adhere to treatment. “Safety warnings on topical medications could lead to undertreatment of atopic dermatitis, reduced quality of life and, potentially, increased use of more toxic systemic medications.”

Long-term studies of medications and cancer risk are challenging to perform, having to account for dose-response relationships, confounding by indication, and time bias, among other factors, and this study “recognizes and attempts to address many of these challenges,” Dr. Drucker and Dr. Tadrous wrote.

These results are similar to previous studies that have “consistently reported no or minimal association between TCI use and skin cancer,” they noted, adding that, “if an association exists, it is likely very small, meaning that skin cancer attributable to TCI use is rare. Clinicians can use this evidence to counsel and reassure patients for whom the benefits of ongoing treatment with TCIs may outweigh the harms.”

This study was funded by a grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Asgari reported receiving grants from Valeant during the study, and from Pfizer not related to the study. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Drucker reported relationships with the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health, CME Outfitters, Eczema Society of Canada, Sanofi, Regeneron, and RTI Health Solutions in the form of paid fees, consultancies, honoraria, educational grants, and other compensation paid to him and/or his institution. Dr. Tadrous reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Silverberg reported receiving honoraria for advisory board, speaker, and consultant services from numerous pharmaceutical manufacturers, and research grants for investigator services from GlaxoSmithKline and Galderma. Dr. Hughes Tichy reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Silverberg is a member of the Dermatology News editorial advisory board.

SOURCE: Asgari MM et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2240.

The results also suggest dose, frequency, and exposure duration to the topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are not associated with an increased risk of keratinocyte carcinomas (KCs), basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), according to Maryam M. Asgari, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration announced the addition of the boxed warning to the labeling of TCIs regarding a possible risk of cancer associated with use of pimecrolimus (Elidel) and with tacrolimus (Protopic), because of an increased risk of KCs associated with oral calcineurin inhibitors and reports of skin cancer in patients on TCIs.

“Controversy has surrounded the association between TCI exposure and KC risk since the black-box warning was issued by the FDA. A hypothesized mechanism of action for TCIs increasing KC risk includes a direct effect of calcineurin inhibition on DNA repair and apoptosis, which could influence keratinocyte carcinogenesis,” the authors of the study wrote in JAMA Dermatology. But, they added, there have been “conflicting results” in research exploring this association.

In the retrospective cohort study, Dr. Asgari and coauthors evaluated 93,746 adult patients with AD at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, diagnosed between January 2002 and December 2013, comparing skin cancer risk among 7,033 patients exposed to TCIs, 73,674 patients taking topical corticosteroids, and 46,141 patients who had not been exposed to TCIs or topical corticosteroids. Results were adjusted in a multivariate Cox regression analysis for age, gender, race/ethnicity, calendar year, number of dermatology visits per year, history of KCs, immunosuppression, prior systemic AD treatment, autoimmune disease, treatment with ultraviolet therapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

The researchers also examined how TCI dose, frequency and exposure duration impacted skin cancer risk. Patients were grouped by high-dose (0.1%) and low-dose (0.03%) formulations of tacrolimus; and the 1% formulation of pimecrolimus. Frequency of use was defined as low (once daily or less) or high (twice daily or more), and exposure duration was based on short- (less than 2 years), moderate- (2-4 years), and long-term (4 years or more) use. Patients were at least 40 years old (mean age, 58.5 years), 58.7% were women, 50.5% were White, 20.6% were Asian, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 7.9% were Black. They were followed for a mean of 7.70 years.

Compared with patients who were exposed to topical corticosteroids, there was no association between risk of KCs and exposure to TCIs in patients with AD (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.13). There were also no significant differences in risk of BCCs and TCI exposure (aHR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.90-1.14) and risk of SCCs and TCI exposure (aHR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.82-1.08), compared with patients exposed to topical corticosteroids.

Results were similar for risk of KCs (aHR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.92-1.14), BCCs (aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.91-1.19), and SCCs (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.78-1.06) when patients exposed to TCIs were compared with those with AD who were unexposed to any medication. In secondary analyses, Dr. Asgari and coauthors found no association with overall risk of KCs, or risk of BCCs or SCCs, and the dose, frequency, or exposure duration to TCIs.

“Our findings appear to support those of smaller postmarketing surveillance studies of TCI and KC risk and may provide some reassurance about the safety profile of this class of topical agents in the treatment of AD,” they concluded.

In an interview, Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, said initial concerns surrounding TCIs were based on high doses potentially increasing the risk of malignancy, and off-label use of TCIs for inflammatory skin diseases other than AD.

“However, the FDA’s concerns may not have been justified,” he said. The manufacturers of pimecrolimus and tacrolimus have published results of 10-year observational registries that assess cancer risk, which “found no evidence of any associations between TCIs and malignancy,” noted Dr. Silverberg, who is also director of clinical research and contact dermatitis at George Washington University.